Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 11/1022/04. The contractual start date was in September 2012. The final report began editorial review in May 2014 and was accepted for publication in November 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Pawson et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 The challenge: reviewing the attempts to solve a ‘wicked problem’

This chapter sets out our agenda. It covers the basic premise, the research strategy, the topic and the structure of this report. Above all, it is an attempt to measure up the considerable challenge we face in reviewing interventions that have sought to contain the burgeoning demand on planned secondary health care.

What follows is a ‘review’, a work of secondary analysis. This approach has become synonymous with the notion of evidence-based policy (evidence-based medicine, evidence-based management and so on). In pursuing it we concur wholeheartedly with the basic premise. Increasingly, the method of choice for tackling organisational problems and bringing about system improvement is the ‘intervention’ or ‘programme’. Most interventions have a long history. They are tried and tried again and researched and researched again. Rather than adding unremittingly to the long list of primary inquiries, it seems sensible to work systematically through all of the existing research, with the idea of synthesising findings in the expectation of providing transferable lessons for future applications of that intervention.

This then is the common cause of all reviewers. Inevitably, given the vast repertoire of primary research methods, there is debate about the best method of drawing together all the extant material (for a wide-ranging appraisal see Suri and Clarke1). Nowadays, secondary analysis is conducted under many different banners and it is possible to locate reviews that have employed systematic review, meta-analysis, meta-study, meta-ethnography, narrative review, meta-narrative synthesis, reviews, configurational reviews, Bayesian reviews, multimethods reviews, best evidence synthesis, critical interpretative reviews, realist synthesis, etc. There is so much activity at this secondary level that there are now tertiary ‘reviews of reviews’. 2

This is no place to argue methodological pros and cons. A potential point of consensus is that the very idea of a producing an ‘aggregation’, a ‘pooling’, a ‘synthesis’, an ‘amalgam’, a ‘composite’ of primary research can have different connotations and that this growing toolbox of synthesis methods allows the reviewer to ask a wide range of subtly different but equally valid questions. In the next section we outline our preferred strategy, pinpointing the specific questions that it is designed to ask.

Research method: realist synthesis

Our method of collecting together and drawing lessons from primary research evidence is known as ‘realist synthesis’. It was developed by one of the current authors. 3 A comprehensive overview on methodological guidance, publication standards, training materials and a bibliography of earlier realist reviews is available as part of a previous Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) report. 4,5 Readers are referred to these sources for a detailed account of the method. In this report, we commence with a brief account of the core principles and of the basic steps of the realist approach, assigning the full details on the conduct of the complex search strategies to Appendix 1.

Realist synthesis avows membership of the ‘theory-driven’ school of evaluative inquiry. It differs from other forms of systematic review in spending a considerable amount of research time in attempting to tease out the ideas, the assumptions, the logic or the ‘programme theories’ that underpin the interventions under inquiry. All policy-making and all interventions begin with theory: accounts of the causes of the problem under scrutiny (diagnosis) and conjectures on what changes must be made to the system in order to alleviate that problem (remedy). This starting point establishes the fundamental question for the review. Did these theories come to fruition? Did the remedy meet the diagnosis? The underlying expectation, and one that holds especially true in the field of demand management, is that social and behavioural interventions tend to meet with partial success. This state of affairs provides realist synthesis with its fundamental task, namely to chart the many contexts and conditions in which interventions work (or fail) and, above all, to explain the reasons for the inevitable mixed picture. Better explanations provide the ammunition to make better policy. They make provision for improved targeting and implementation of interventions.

The conduct of realist synthesis follows an orthodox path, starting with a research question and then finding the means to answer it by searching, identifying, appraising, extracting and combining together materials from the body of existing research. There are significant differences from other review methods, however, most notably in that this sequence is iterative – it is travelled repeatedly. The learning from one tranche of studies provides provisional explanations and new clues that that can be further refined by focusing and refocusing the searching for crucial primary materials. Learning accumulates as the review travels around the research cycle.

We now set out the basic sequence of steps in a realist synthesis. 3 For each, we provide some forward glimpses into our review, illustrating its application in researching the field of demand management.

Identifying the review questions

The process of locating the proposed diagnoses and planned remedies that have gone into the making of an intervention is known as ‘theory elicitation’. A search is undertaken to locate this material, which is normally discovered in the documentation produced in conjunction with the programme under investigation (plans, consultations, thought pieces, administrative accounts, legislation, critiques, etc.). Theory elicitation is an elusive business because the thinking behind interventions is never straightforward. Programme theories may be multiple; they change; they are assembled unevenly; they may be contested. Nevertheless, they prove a strategic point of origin for realist reviews, which then proceed to investigate whether or not, to what extent and why the programme theories have gone on to demonstrate their mettle in practice.

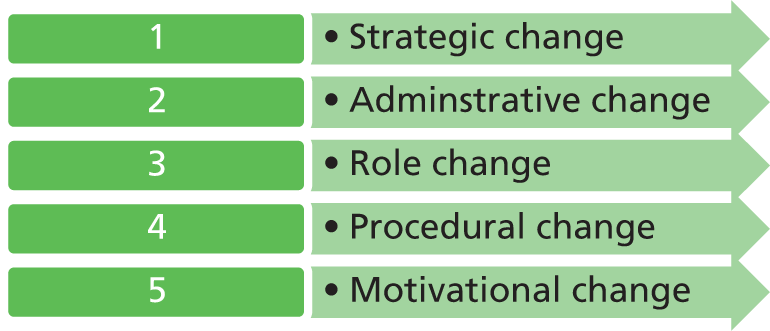

Already we see that an intensive search procedure precedes what is normally the very first stage in a review, namely the setting of the research questions. Advancing a pace or two into the evidence allows the reviewer to pose a better set of questions. In the present case, and prior to the research, we were aware, of course, of the very many schemes mounted in the name of demand management. A preliminary task is thus to sift and sort through this assemblage of schemes, classifying them by the underlying ‘theory of change’. Varied objectives could be discerned, with different interventions seeking improvements at the strategic, administrative, functional, procedural and motivational levels.

We were aware, furthermore, of some of the major impediments to the effectiveness of many schemes. Prior to the review and in our initial research proposal we anticipated that reforms implemented to regulate demand might be snagged because of:

-

the different and sometimes contending motivations that prompt referral

-

the varied and sometimes uneven expertise and mandates of the participants in referral chains

-

the lack of any traditional remit for cost-containment ambitions in NHS staff groups

-

the difficulty in regulating provision while at the same time responding to other initiatives providing patients with an increased choice of provision.

Locating these issues in the ‘grey literature’ allowed us investigate these ideas using the very language of practitioners and in the contexts in which they had experienced them. This pointed us, for example, to very specific concerns about new, special-interest posts located between primary and secondary care. They had the potential to siphon off demand – but could they deal with issues 1 and 2? Could they bridge the disparate motivations and traditional mandates within the two sectors?

In the course of our preliminary search we thus adapted, extended and further specified our provisional hypotheses. Theory elicitation also alerts the reviewer to things they did not know at the outset of the research. A major issue we discovered over and again in the critical debate about demand management was the idea of system complexity. Perhaps the key, emerging programme theory is the idea that multiple, synchronised improvements are necessary to promote sustainable change.

These preliminary investigations provide the eventual structure of our report. We identify four major subsets of demand management programmes and detailed subsets of research questions investigating the potential strains associated with each.

Searching for primary studies

Once there is a clearer, if broader, picture of what the programmes under investigation intend to do, realist synthesis now moves to gather evidence on whether or not they do so. This initiates another search of the literature to locate primary research studies that enable us to test the programme theories. Have the prior expectations proved justified? In this case the search is targeted at what might be considered as the more orthodox empirical literature, that is to say the papers, studies, reports and previous reviews that have undertaken an evaluation of the implementation and effectiveness of particular demand management interventions.

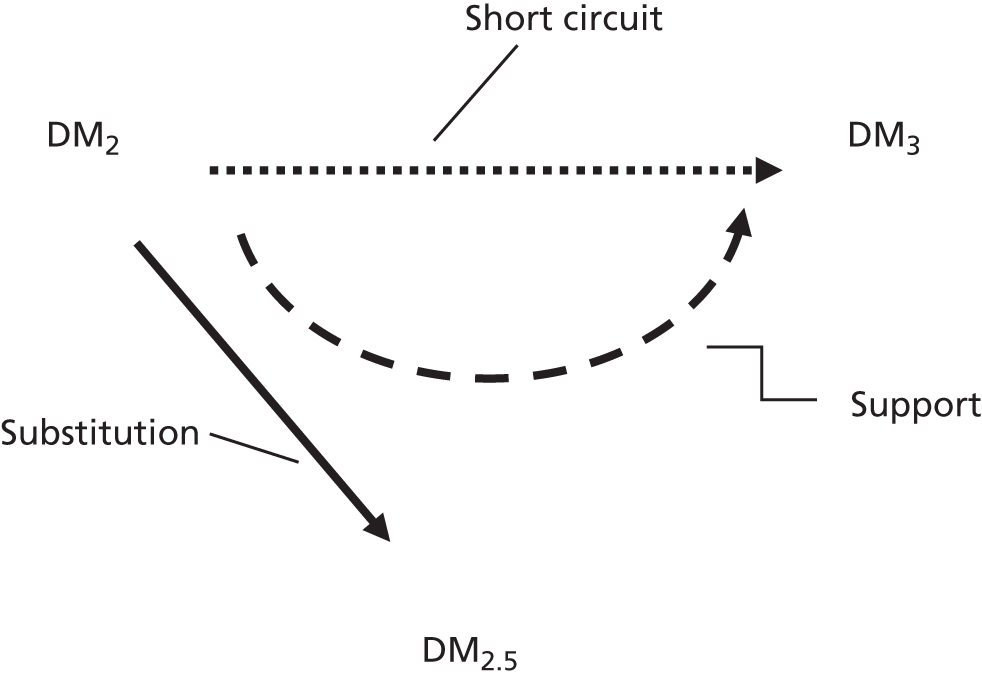

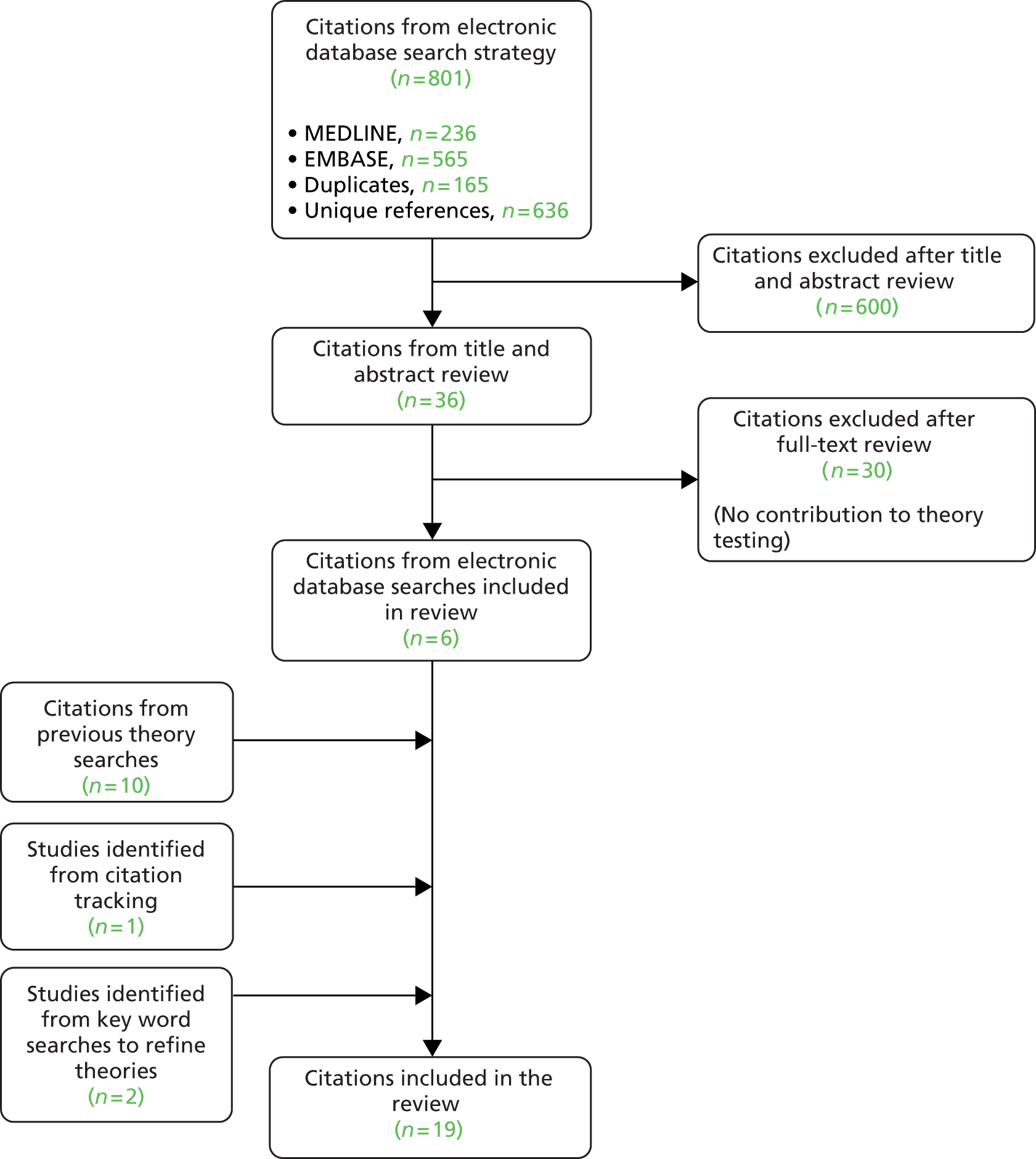

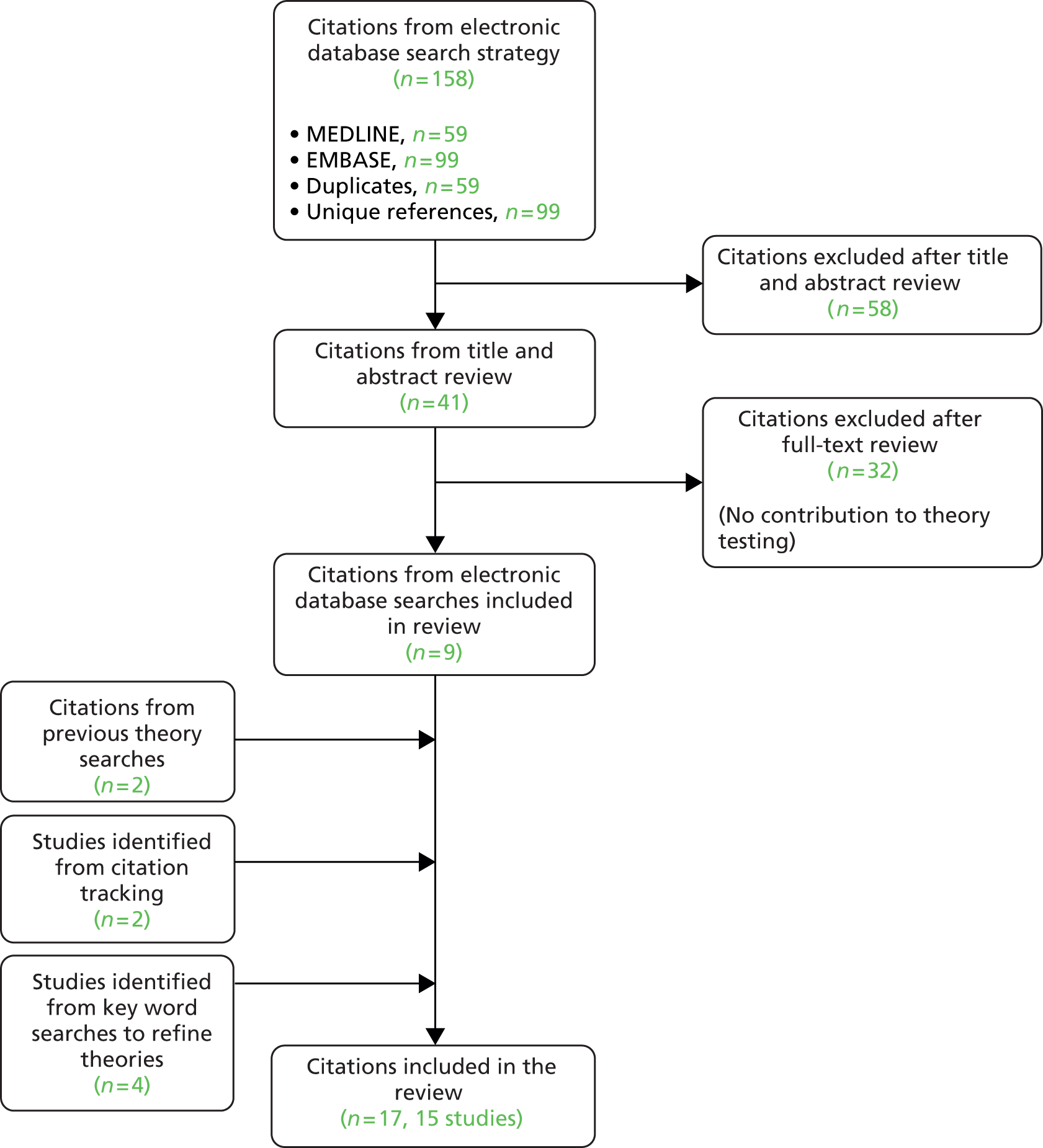

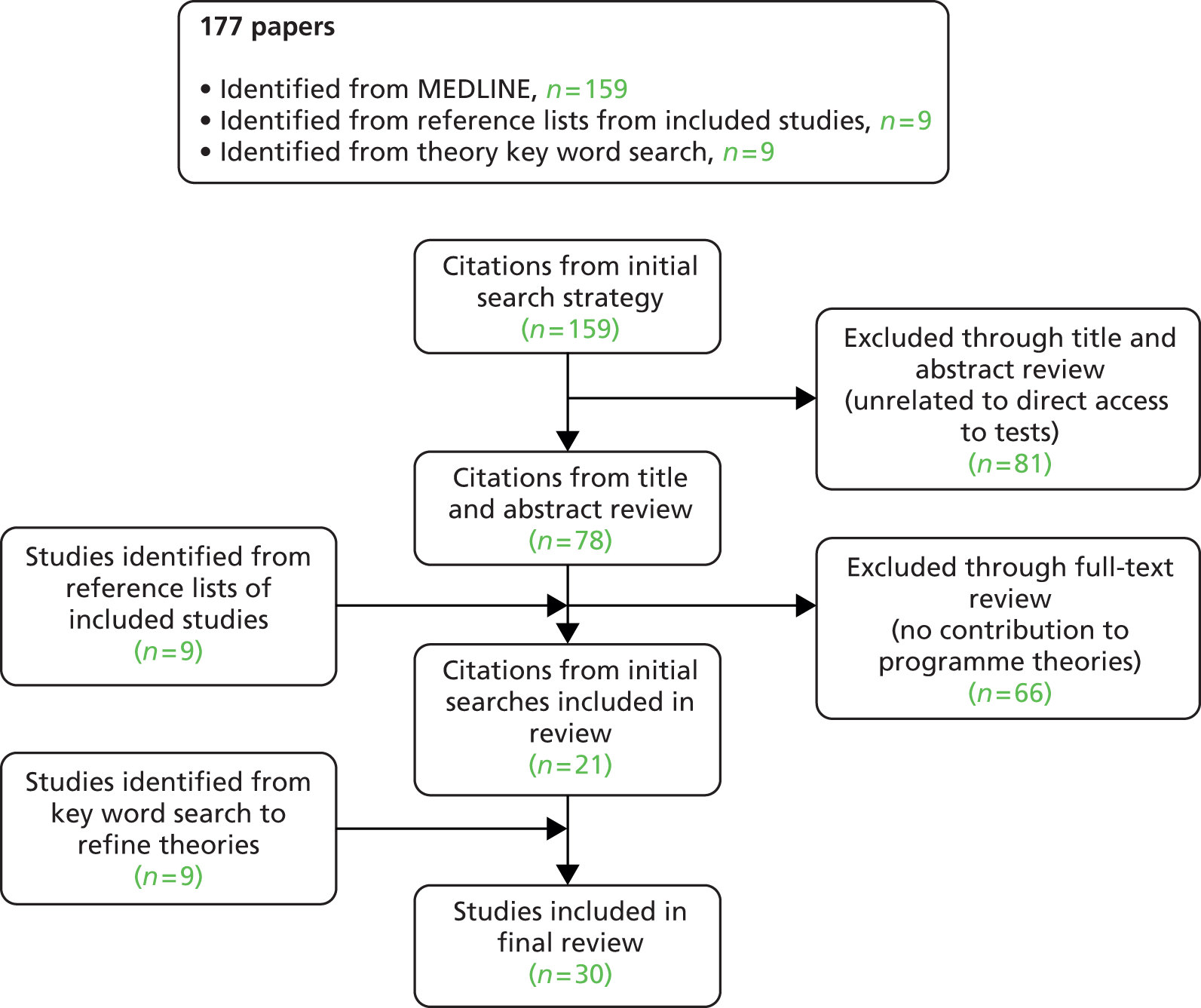

These searches utilise comprehensive databases such as MEDLINE, EMBASE and Google Scholar (https://scholar.google.co.uk; Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA). The search is organised by terms and synonyms describing the relevant interventions and, thus, for instance, might cover referral management ‘centres’ or ‘gateways’ or ‘clinics’ or ‘systems’. Detailed flow charts describing the strategy pursued to underpin the report’s major chapters are included in Appendix 1. More specific search terms were also determined by our prior investigations of programme theory. For instance, the avenue of inquiry on the use of intermediaries such as general practitioners with special interests (GPwSIs) turns on evidence about whether they provide ‘substitution’ or ‘support’ and these terms were used to locate further nuggets of evidence. In pursuing these more specific lines of investigation, realist synthesis turns increasingly to hand-searches and references of references. 6 As noted above, such searches were sometimes renewed in the analytic stages of the review in order to further clarify outcome complexities.

What is achieved by this stage is a foregathering of the evidence matched to the structure of the inquiry devised at stage 1. All of this preliminary activity acts as necessary ground clearing to a review and, as is typical of realist synthesis, it took our exercise through its first third (in time and in the report). It presented us with a large ‘menu’ of potential lines of inquiry, which we then organised in the four ‘empirical’ chapters of the report.

Quality appraisal

Having uncovered a large number of potential primary sources to assist in our explanatory review, we now go on to the next stage, which is to weigh up the quality of the evidence provided by each study. Realist synthesis eschews the idea of a hierarchy of evidence. The interventions under review are complex systems embedded within complex systems. Delving into the assorted implementation process, contextual differences and outcome complexities requires us to call on the entire repertoire of social, behavioural and organisational investigations.

Standards still apply, of course, the first of which is that a primary study has to provide relevant evidence. This requirement commits the reviewers to a large amount of preliminary reading. To continue with a previous example, of the very many reports on GPwSIs, some explored closely the matter of whether the role evolved as support or substitution and how this went on to impact on patient flows. Other research, less relevant, considered the coverage of GPwSIs across clinical specialties and regions and was primarily concerned with the overall level of penetration of a national policy. Study-by-study decisions on relevance were made along these lines.

The second standard relates to rigour. The requirement here is for an investigation to be of sufficient standard within type, be it a qualitative interview, a process evaluation, a demographic analysis, a randomised controlled trial (RCT) and so on. For instance, studies that purported to provide testimony on GPwSIs’ attitudes to their new roles varied from the anecdotal and partisan to those based on transparent and systematic research designs. Study-by-study decisions on rigour were made along these lines, a task requiring substantial methodological expertise on the part of the review team.

Extracting the data

Conventional reviews comb through all included studies, utilising a standard data extraction form mining exactly the same information (typically on treatment modality, population, effect sizes, etc.) from all studies. In realist synthesis the expectation is that each included study will address a different aspect of the programme theory. Broadly speaking: evidence on outcome patterns will be found in trials, survey research and administrative reports; evidence on implementation is found in process evaluations, qualitative interviews and personal testimony; and evidence on context is found in case studies and comparative inquiries. Primary studies vary in the coverage of this terrain. There is no expectation that any inquiry will be all-inclusive and the information extracted is determined by its theory testing potential.

The practical steps of eliciting the evidence begin with a rough annotation of the relevant text, testimony and tables for each included study (this process is aided given the preceding ‘relevance test’). The materials highlighted are quite diverse. One arm of our inquiry tested whether or not providing general practitioners (GPs) with direct access to clinical tests generated demand efficiencies. We developed a hypothesis that gains would follow only according to the specific function of a test, which required the extraction of different bodies of evidence; for example, (1) on that function (from clinical documentation); (2) on the level of GP discretion in interpreting results (from administrative case studies); (3) on the level of reassurance provided by a test (from qualitative studies of physicians and patients); and (4) on subsequent patient referral routes and clinical outcomes (from before-and-after studies and RCTs).

Data elicitation is completed in the reportage of each study within the review. In realist synthesis, significant portions of the primary texts are propelled directly into the review. Looking ahead into this report, the reader will note that each of the included studies is covered in anything from half a side to half a dozen pages. The typical format is to justify the relevance of the study in relation to the theory under test by providing contextual details; to reproduce the pertinent evidence (of whatever type); to report on its quality; to record the inferences drawn by the original authors; and to draw these inferences into the overall explanation developed in our synthesis.

Synthesis

Bringing all this material together brings us to the purpose of a realist review, namely to provide a better understanding of how interventions really work. The aim of the exercise is to discover ‘for whom’, ‘in what circumstances’, ‘in what respects’, ‘over what duration’ and, above all, ‘why’ an intervention might work. And, although it is impossible to cover every single condition and caveat that might influence effectiveness, the parameters that are investigated afford a degree of generalisability to the review.

Realist synthesis refers to the idea of making progress in explanation. For instance, in reviewing interventions that seek to introduce an entirely new referral management centre (RMC) to control the referral process, we begin by discovering a study claiming that its effectiveness depends crucially on developing close collaboration between GPs and local consultants. This inference is hardened as further primary studies are uncovered providing evidence on the same proposition across a number of RMCs. This explanation, however, begs the question of how such collaboration is established and this directs the review to further studies and supplementary explanations about the joint authorship of referral guidelines, the recruitment of local, mutually respected professionals to manage the centres, the negotiation of clear time scales and logistical pathways for each referral, etc.

All of our evidence is presented in this sequential, accumulative manner. The developing explanations do not provide simple blueprints for ‘best practice’ that can be imitated blindly – all supply-and-demand pressure points are, to some extent, unique. The explanations do, however, provide decision aids on system adaptation. They guide the planner and practitioner on the many necessary conditions that lead to programme effectiveness. All of these exigencies require ‘thinking through’ to fit them to local conditions and it is this spirit that we present the conclusions to our synthesis.

Background: what is demand management?

We turn next to our substantive topic, namely to review interventions aimed at curbing demand for planned health care. The problem is immediately familiar to anyone with the slightest association with health service provision. Medicine has been a victim of its own success. All advanced health systems face substantial increases in activity and costs, with a seemingly unstoppable rise in demand for planned care. A particular strain is often felt on the matter of referral management, where the patient is relayed from one part of the system to another, often without due care being given to the balance of resources across the system. These are perennial problems and this is our playing field. As per expectations, putative solutions have been contemplated time and again, exploratory interventions have been implemented over and again and they have been researched again and again.

The task of reviewing demand management interventions, however, does have its particular challenges, which governed our approach and which, in turn, structure this report. The distinctive feature of our chosen ‘intervention’ might be best explained by reaching out to the much contemplated idea of ‘wicked problems’. The basic notion is simple and sensible enough. Not all problems are the same, some are more intractable than others, and essential differences in terms of problem complexity should determine what we should expect by way of a solution and how we search for solutions.

Rittel is usually credited with introducing the distinction between ‘tame’ and ‘wicked’ problems into the planning literature and it is worth rehearsing the essential contrast as a prelude to our review. 7 Tame problems, the argument goes, (1) have a well-defined and stable problem statement; (2) have an easily recognised stopping point when it is clear a solution is reached; (3) have a solution that can be objectively evaluated as right or wrong; and (4) belong to a class of similar problems that can all be solved in similar ways. Wicked problems lie at the opposite poles, where (1) the problem is ill structured, arising from sets of interlocking issues and constraints; (2) there is no overall resolution, only a series of partial and time-limited solutions; (3) there is no stopping point, with each partial solution creating a new system with its own strains; and (4) each manifestation of the problem is different, requiring the production of a revisable and versatile set of solutions. The last point should perhaps be emphasised. Wicked problems are neither unfathomable nor insoluble; rather, they require iterative, adaptive, ongoing responses.

Our thesis in this opening chapter is that the problem of demand management is much better understood as a ‘wicked’ rather than a ‘tame’ issue and that this has significant ramifications for the conduct of an evidential review. We are aware, in using this distinction, that it is in itself an oversimplification. The literature on systems theory and complexity science, originating in contribution by Rittel and Webber,7 has since become byzantine (for an elegant, modern summary see Byrne and Callaghan8). Each of the conceptual anchorages has become contested, with, for instance, wicked problems now being apportioned to somewhat different species as ‘super wicked’, ‘chaotic’ and ‘messes’. Complexity theory itself has spawned many different subschools, each with its own way of describing complexity: general systems theory, morphological analysis, holism, chaos theory, actor–network theory, diffusion models, soft systems theory, agent-based modelling and so on.

Our starting claim avoids all such elaborations. It rests on a straightforward comparison that is difficult to contest – namely, that relative to most topics covered in health-care research the dilemmas of demand management typify all the features of a wicked problem. One characteristic in particular shines through. As we shall see, every reform that is forwarded tends to expose new aspects of the problem, requiring further adjustment to the understanding of the initial problem. Our review thus imitates something that we discovered in the primary testimony, namely that an understanding of the true nature of supply and capacity imbalance develops alongside, rather than prior to, the application of potential remedies.

Coming to its specific features, we shall see as the review unfolds that demand management interventions are ‘relatively complex’ according to the following typology:

-

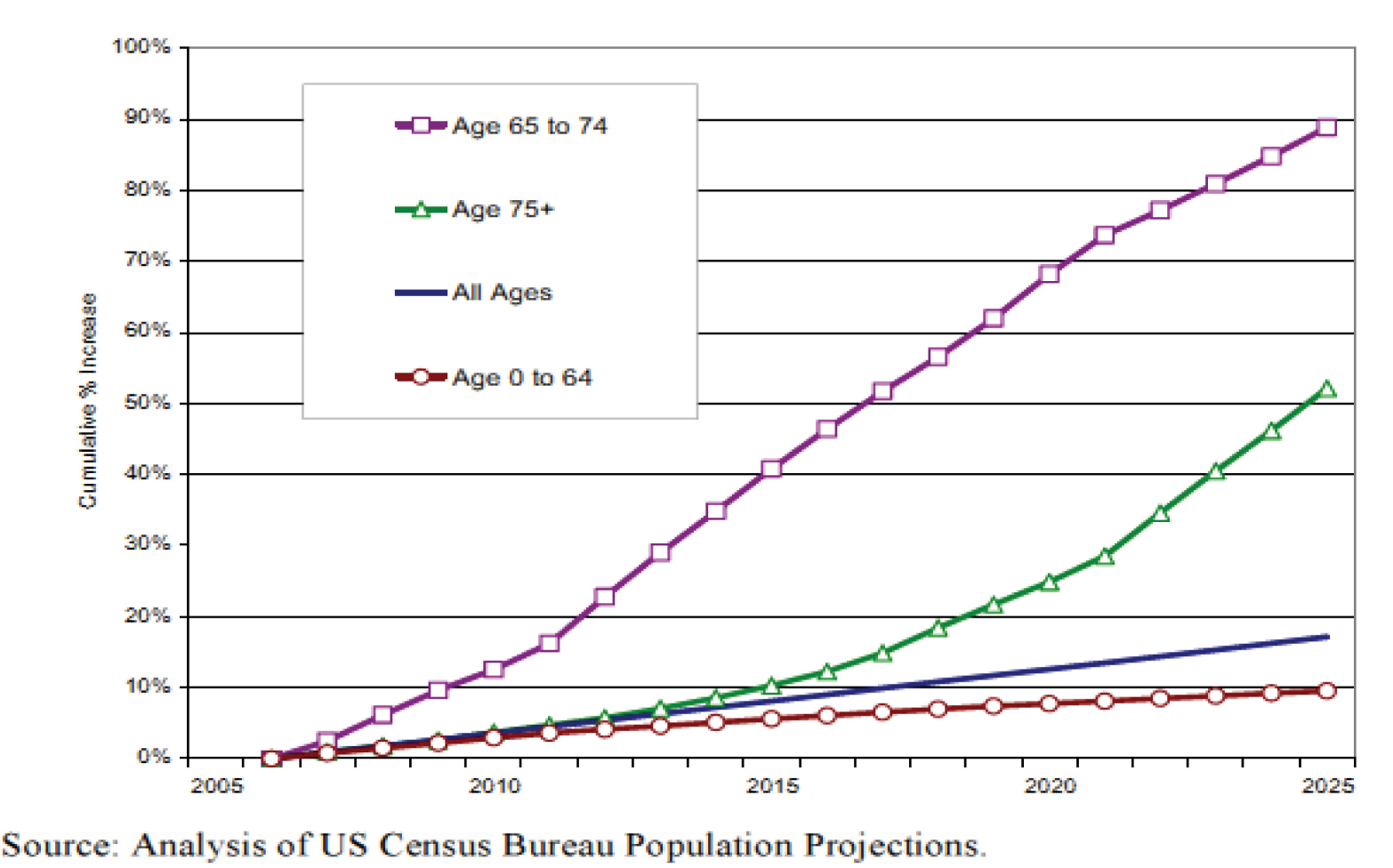

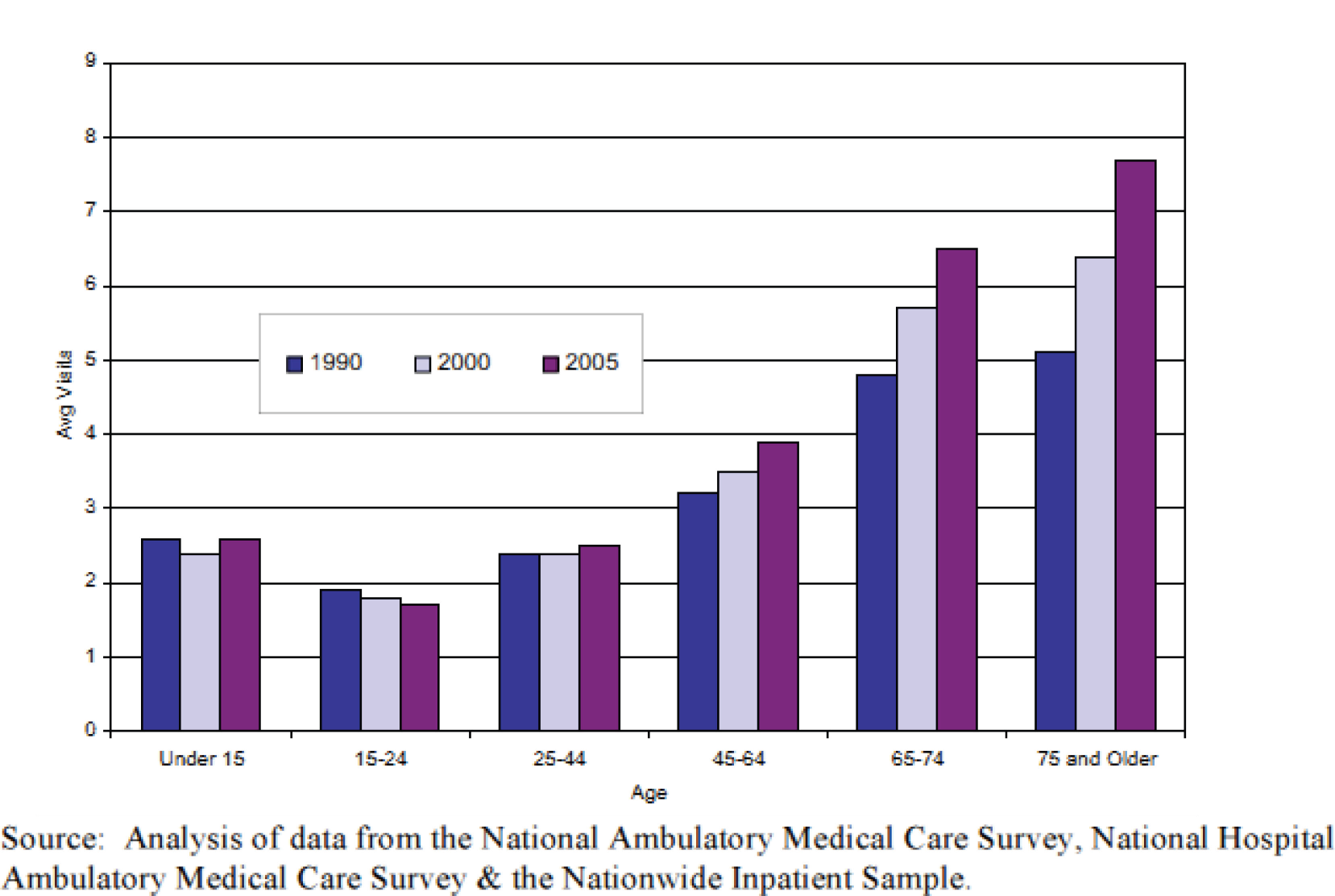

Causal structure. There are many notable interpretations of the causes of rising demand for health care, emanating from quite different sources: the inability to cope with backlogs arising from fluctuations in demand; the blockages in treatment pathways caused by professional closure and turf protection; the diverse motivations for referral that extend beyond formal clinical need; innovations in screening and testing producing self-propelling diagnostic cascades; innovations in treatments and services leading to supply-induced demand; changing patient demographics, particularly in age, driving up need for care and services; and the informed patient and the patient choice agenda increasing demand for all services. These causes, moreover, inter-relate, and their effects can be multiplicative.

-

Contextual diversity. As with its root causes, the locations of the potential demand management reforms are also widely dispersed. Demand has to be managed for every single condition from abdominal aortic aneurysm to zygote intrafallopian transfer. As one moves through the alphabet of disease, and from physical to mental health, and from pre-natal to end-of-life care, it becomes clear that each sphere has quite different supply and demand profiles. The institutional contexts responsible for managing these movements are also diverse. Modern referral services rarely run directly from the GP’s surgery to the outpatient clinic – all manner of appointment, transfer and triaging services are positioned in between (choose-and-book systems, ambulatory monitoring devices, text reminders, community-based specialists, etc.). These managerial systems, moreover, are under the control of the wider apparatus of trusts, commissioning bodies and boards (national, regional and local). Quasi-autonomous non-governmental organisations (QuANGOs) such as the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and the Care Quality Commission as well as targets such as those contained in as the Quality and Outcomes Frameworks (QOFs) all set parameters in which demand and capacity is constricted. All of these features are subject to periodic, top-down reorganisation, continually reconfiguring the scope for adjusting demand.

-

Implementation diversity. Referral chains themselves are long and complex, capable of providing potential pinch points at any point in the existing or newly modelled pathways. Again, in the modern era, the key players in referrals far exceed the traditional axis between the GPs and the specialist. ‘Handovers’ are also the business of practice mangers, assistants, screening personnel, triagers, physiotherapists, radiographers, haematologists, geneticists, practitioners with special interests, appointment clerks and, of course, patients. The communications flowing across these channels are also diverse – referral letters, appointments, reminders, test results, patient records. The communication media are also manifold, with referrals being conducted on paper, by telephone, by text and on the internet. All of these implementation chains need to be reviewed with an eye on the ‘weakest link’ syndrome.

-

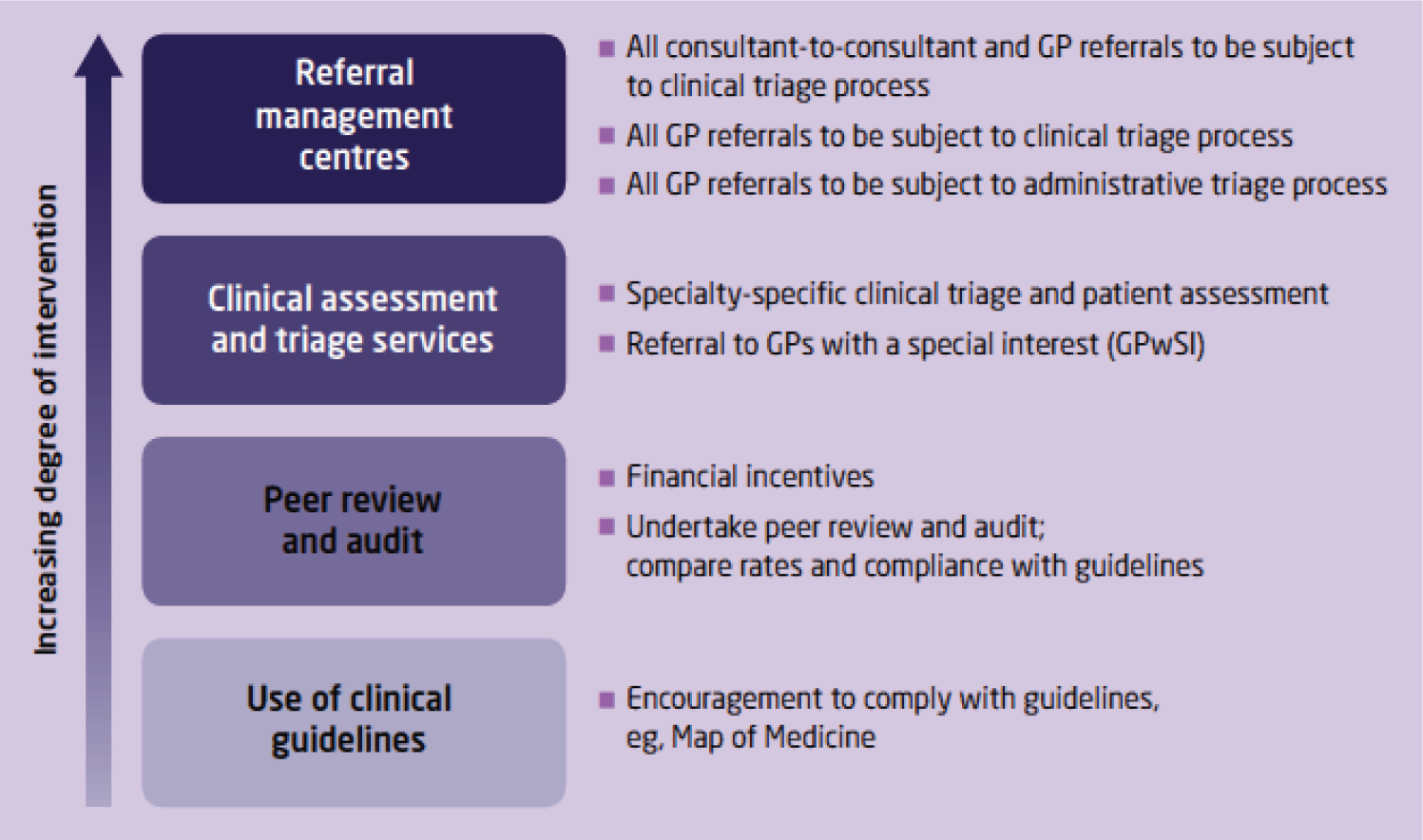

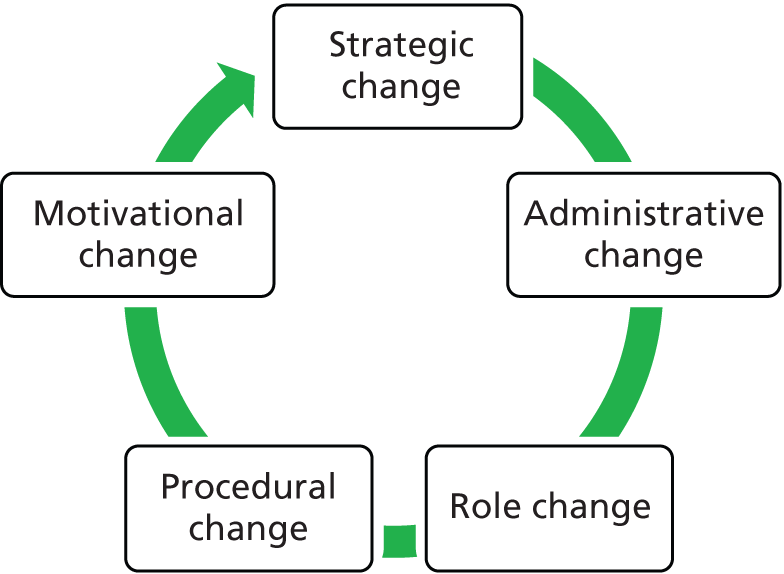

Programme-theory diversity. Perhaps because they echo the diverse range of causes, contexts and channels of demand, it turns out that interventions designed to contain demand not only are huge in number but also vary greatly in their basic ideas and programme theories. The procession of ‘approaches’ includes RMCs, administrative triage, joint working, service relocation, clinical triage, referrals to GPwSIs, financial incentives, audit and feedback, guidelines, queue sculpturing, behaviour change and so on. Another indication of complexity here is that the focus of the intended remedy varies from the macro to the micro, closing in progressively from shifts in overall strategy, to organisational remodelling, to change in individual’s role, to procedural modifications, to motivational change. A further wicked twist here is that many interventions, intentionally or otherwise, end up pursuing change at all of these levels and are thus dependent for their success at achieving change across this entire piste.

-

Outcome conundrums. Although the aim of our class of interventions is seemingly clear, namely to control demand, the intended outcome is sometimes obscure and often contested. The moment when demand is considered ‘unmet’ is difficult to gauge, the politicised wrangling about the measurement of NHS waiting times being a prime example. Issues of quantity and quality also intermingle awkwardly. This is particularly evident in the underlying demand management aspiration concerning the ‘appropriateness’ of referrals. One of the causes of excessive demand is often considered to be the tendency of some practitioners to make improper or premature referrals. But the reasons for referral are themselves complex and judgements on appropriateness/inappropriateness is heavily contested. Indeed, this polarity is a two-way street for, as we shall see, it is quite possible that the goal of manufacturing better considered referrals can lead to an increase in demand.

-

Intervention history. These interventions are not mounted from scratch, that is to say they are never implemented in the absence of existing demand controls. As soon as any service is created (be it for the provision of housing, hamburgers, hunting horns or health care) it has to face the universal issue of managing shortfalls or oversupply in those services. All services wrestle with the permanent challenge of balancing demand with capacity. Accordingly, our inquiry presupposes that informal demand management regimes, in varying shapes and forms and operating at varying levels of success, are generally in place throughout a health service long before its practices become proceduralised and recognised formally as ‘demand management programmes’. This previous history will always limit the effectiveness of ‘new interventions’.

-

Ever-present emergence. The idea of emergence is perhaps the central proposition of complexity theory. It refers to the idea that novel structures are created by the interaction of the existing process within a complex system. It relates closely to the aforementioned wicked issue that some problems have no stopping point, with each partial solution creating a new system with its own strains. The concept of ‘supply-induced demand’ speaks to this very point. A new practitioner role or patient pathway may alleviate demand or referral pressures within some previous service arrangement – in time, however, it may become so popular that it becomes a pressure point of its own.

Hopefully, the above seven dimensions of complexity provide some indication that the problem under scrutiny is indeed wicked. We cease our initial exposition of intricacy at this point, reflecting briefly on the issue of how complexity impacts on the conduct of a systematic review. The implications are considerable and it is instructive to demonstrate this with a brief comparison of how topics are delineated in other modes of systematic review: ‘Systematic reviews should set clear questions, the answers to which will provide meaningful information that can be used to guide decision-making. These should be stated clearly and precisely in the protocol’. 9 Many reviews are traditionally conducted under the assumptions that they are dealing with stable systems – given populations (P), given interventions (I), given comparators (C) and given outcomes (O). When agreed operational definitions of this ‘PICO’ formula are in place, the review proceeds under the assumption that it is dealing with interventions that share these homogenous, reproducible and exact parameters.

To be sure, the more formal traditions of systematic review have also turned their attention to complexity, led in the health domain by the Medical Research Council’s guidance on developing and evaluating complex interventions. 10 This document, however, admits a rather restricted view of complexity into the evaluation palate – in recognising that programmes may have multiple components and multiple outcomes. Programme implementation is still seen as something to be controlled rather being subject to professional judgement, constant negotiation and perpetual improvement regimes. Heterogeneity is seen as a blight rather than an inevitability. 11

To make the point in a less partisan manner, it should be noted that the inclination to limit the remit of inquiry is indisputably not restricted to the statistical tradition. All reviews, whatever their methodological complexion, are assisted if their scope can be reduced. Scope control is clearly evident in existing reviews conducted under the realist banner. The study by Wong and colleagues contains a catalogue of realist health-care reviews conducted up to 2012, with such titles as ‘Efficacy of school feeding programmes’, ‘Water, sanitation & hygiene interventions in reducing childhood diarrhoea’, ‘Role of district nurses in palliative care provision’ and ‘Effectiveness of ban on smoking in cars carrying children’. 4 Although the subject matters here are hardly ‘tame’, and although unforeseen complexity is discovered in each of these inquiries, it a reasonable inference to suppose that the overall scope of each exercise is better circumscribed than in contemplating the full, sevenfold ferocity of entire ‘demand management’ regimes.

Outline and design of the current review

We close this introduction with our plans for squaring this circle and limiting the scope of our investigation. We also set out the chapter-by-chapter structure of the report. All realist reviews involve ‘prioritisation’, a decision on which of the myriad potential programmes theories should be put to investigation. 3 Demand management reaches into every stitch of health service delivery: where should we begin to weave? In this respect it is appropriate to acknowledge some significant circumscription built in to the commissioning of this our review. Our remit from HSDR was to cover demand management for planned care rather than emergency provision. We were also commissioned to review referral management interventions, as they are located between primary and secondary care. At a stroke, this eliminates consideration of the formidable demand dilemmas involved at the very beginning and end of the care cycle. Intricate referral sensitivities permeate preliminary triage initiatives such as NHS Direct and the 111 Service and demographic change places an ever-increasing demand on palliative care. Although we are thankful that these interventions have been removed from our overflowing plate, it is the case that they too could benefit from rigorous secondary analysis.

So, how have we prioritised investigation of the residual, but still formidably complex, sectors of demand management? The most obvious strategy is to limit investigation to a subgroup of the familiar demand management interventions. Previous research has distinguished (at least in name) over a dozen different schemes and strategies. Lacking the resources to tackle them all we have focused on four: RMCs, GPwSIs, GP direct access to tests and referral guidelines. Our reasoning here is that these interventions span quite different theories of change – seeking to modify demand, respectively, by transforming organisations, inserting posts, swapping tasks and improving recommendations. We have attempted to build these subsections of the report in enough detail to supply some decision aids on the contexts and respects in which these different ideas work.

We have also striven to retain a ‘complexity lens’ throughout the report. Partly, this motivation emanates from broader ongoing changes in the focus of health service research. 12,13 The latter group of authors begin a recent paper thus: ‘Incremental approaches to introducing change in Canada’s health systems have not sufficiently improved the quality of services and outcomes. Further progress requires ‘large system transformation’ considered to be the systematic effort to generate coordinated change across organisations sharing a common vision our goal’. Our findings point repeatedly to fact that demand management involves whole-system transformation and our review supplies a modest test of this ambitious thesis.

The main consideration for using a ‘system complexity’ approach, quite literally, is that it has been forced on us in conducting our review. Repeatedly, as we scrutinised the findings of a particular inquiry of a particular demand management initiative in a particular corner of the health service, we have emerged with the interpretation that what transpired was more a matter of the interdependence of the intervention within a wider range of determinants rather than what might be considered as the specific action of each programme. Repeatedly, we came across promising, partial and time-limited solutions that created a new system with its own strains. Over and again, we discover demand management has no stopping point. Rather than just report this as a nervous tic of a conclusion, we have sought to explain why it is the case and structured our report to this end. The remaining coverage is as follows.

Part 1

The runaway train: the multiple, intertwined causes of growth in demand for health care

Chapter 2 aims to ‘size up’ our wicked problem. Basically, the idea is to gain a sound understanding of the essential causes of demand/capacity imbalance – before we go on to study the research on its potential solutions. We undertake it here in pursuit of an idea that that the research team came to think of as the ‘punch-bag hypothesis’. Interventions, via their embedded programme theories, tend to select out and attack specific interpretations of why the underlying problem arose in the first place. In the case of the disproportionate demand for health care we begin with multiple, competing accounts of its genesis. A meta-hypothesis thus lurks, namely that if one manages to land a blow on one of the obstacles to balancing demand and supply, it may simply be absorbed by all the other impediments stuffed in the punch-bag. Whether or not this conjecture turns out to be overly pessimistic will be determined in the remainder of the review.

The preliminary task here is to gauge the contents of the punch-bag, and this is also a task of research synthesis. The coverage here is designed to identify the main ‘schools of thought’ on the seemingly inexorable rise in the demand for health care. These explanations range across the social science disciplines, covering physician motivations, professional closure, demographic change, diagnostic improvements, supply-induced demand and so on. Our task is not to rank or adjudicate between these accounts but simply to provide a typology encompassing the wide range of demand pressures and to provide evidence showing that each one is substantial enough to command a policy response.

The policy response: charting the family of purported solutions

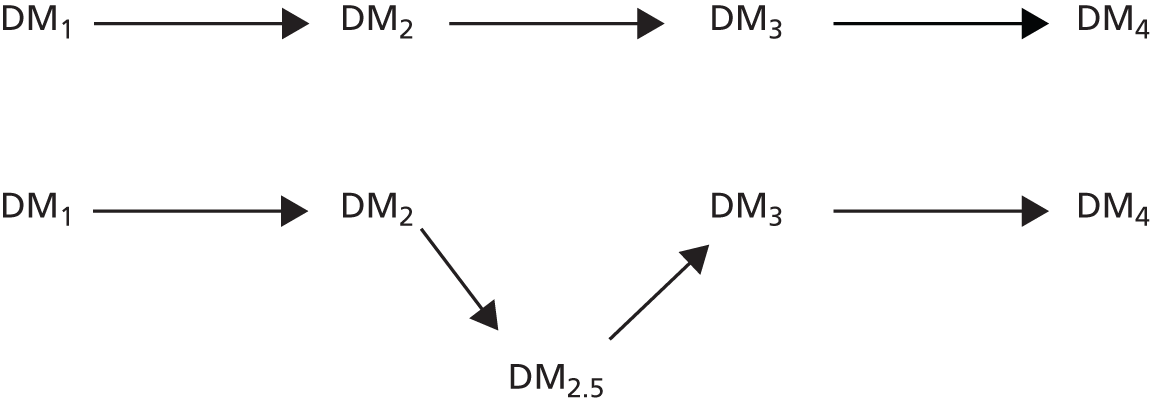

Chapter 3 aims to ‘size up’ the battery of potential solutions aimed at curbing demand for planned health care. As anticipated, they are many in number and include RMCs, clinical assessment and triage services, service relocation, referrals to GPwSIs, financial incentives, audit and feedback, guidelines, queue sculpturing, behaviour change and so on. As per usual in realist synthesis, the aim here is to elicit the programme theories underlying each intervention, as exemplified in their supporting documentation. This task proved unusual and unusually instructive because of the intransigence of the demand problem and the longevity of attempted solutions.

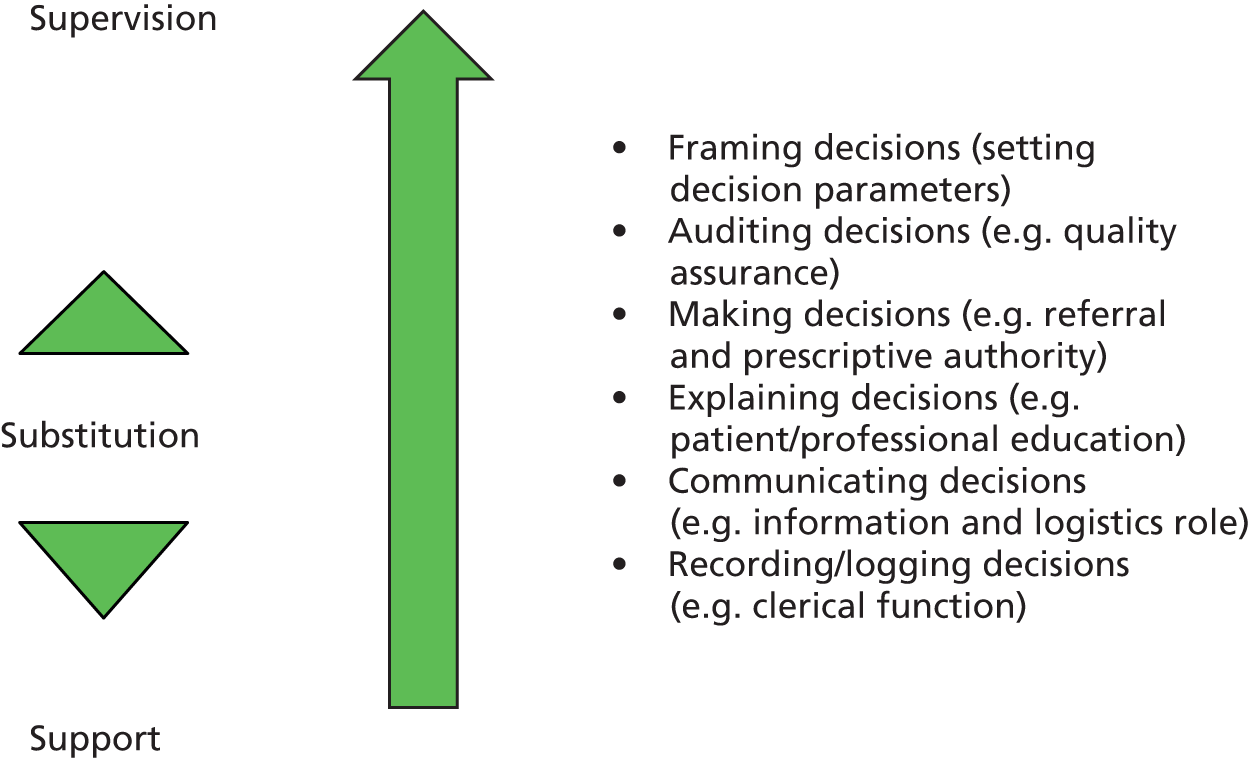

The first notable feature of the programme theories is something we refer to as their ‘ontological depth’. More simply, this refers to the scope of the intended solution, which varied substantially from the micro to the macro as one traversed the thinking behind the different interventions. The main engine of changed is construed, in turn, at strategic, administrative, role, procedural and motivational levels. What also could be clearly observed, with the passage of time, was a process of ‘mission creep’. Programme theories are not static. In the light of experience gained under critical scrutiny and via the trial and error of actual interventions, the core assumptions tended to modify, recommending the need for supplementary action. Invariably, the programme theories became ‘whole-system’ models – suggesting that sustainable change required the interweaving of the various macro, meso and micro mechanisms. Combination punches become the order of the day.

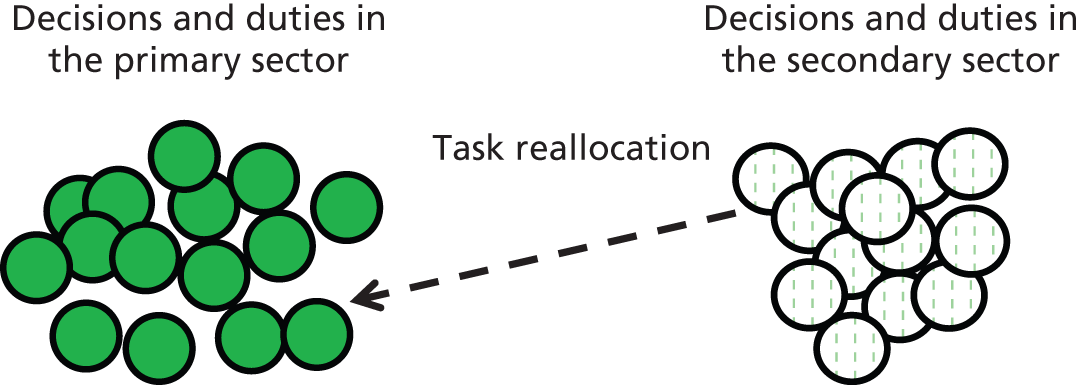

Part 2

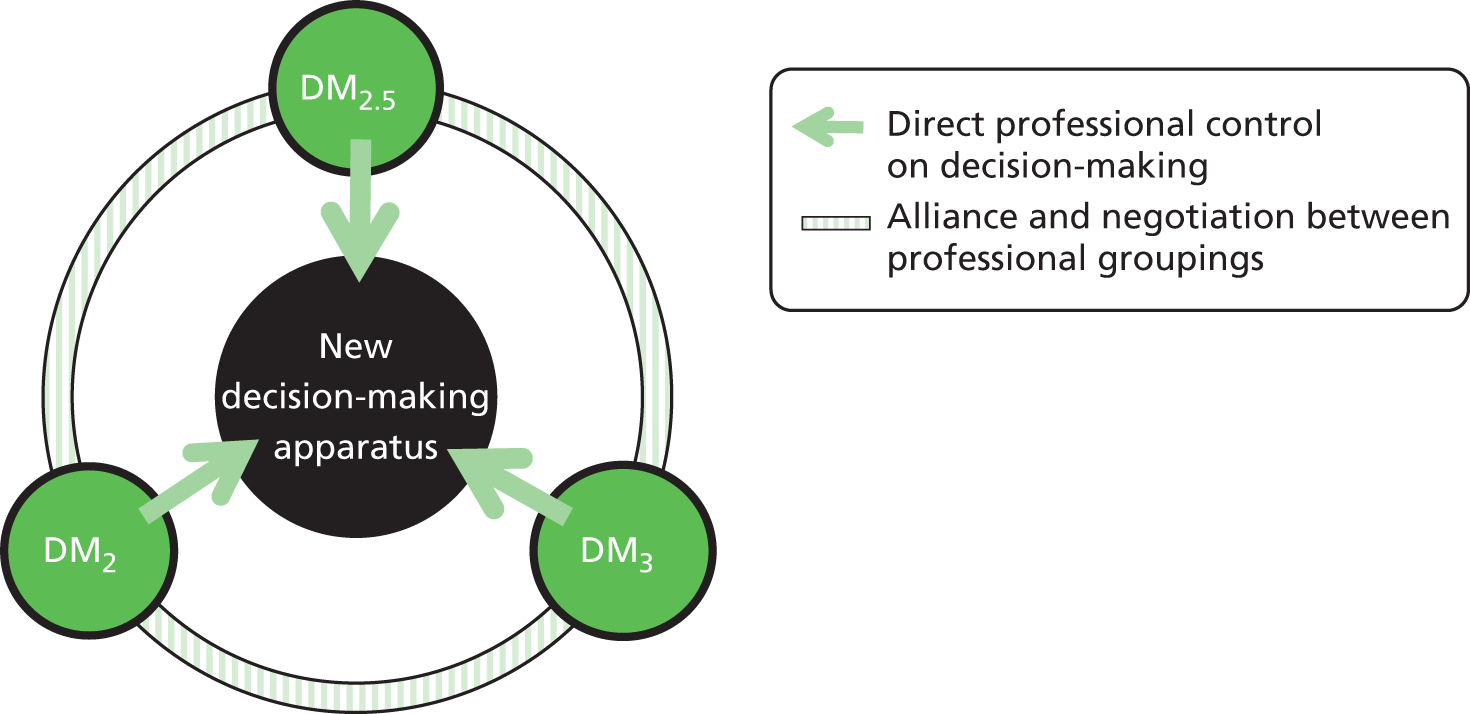

Many different health-care reforms turn on the idea of ‘mandate’ change, with the responsibility for decision-making changing hands among the ranks of health-care professionals, and this notion provides the linkage between Chapters 4, 5 and 6. The patient journey through initial consultation, diagnosis, testing, treatment, care and after-care is long and winding. The institutional and staffing structures originally designed to carry decision-making along this referral pathway have a tendency to become unbalanced under the perpetual rise in demand for health care. These incessant strains have been met by continual adjustments with the idea of introducing an improved division of labour in order to check and smooth the treatment tides. These new regimes differ in their latitude, some involving the implantation of new organisations, some introducing new staff positions and some simply changing responsibilities among existing roles. Each chapter provides a review of the empirical evidence on effectiveness of the new mandates.

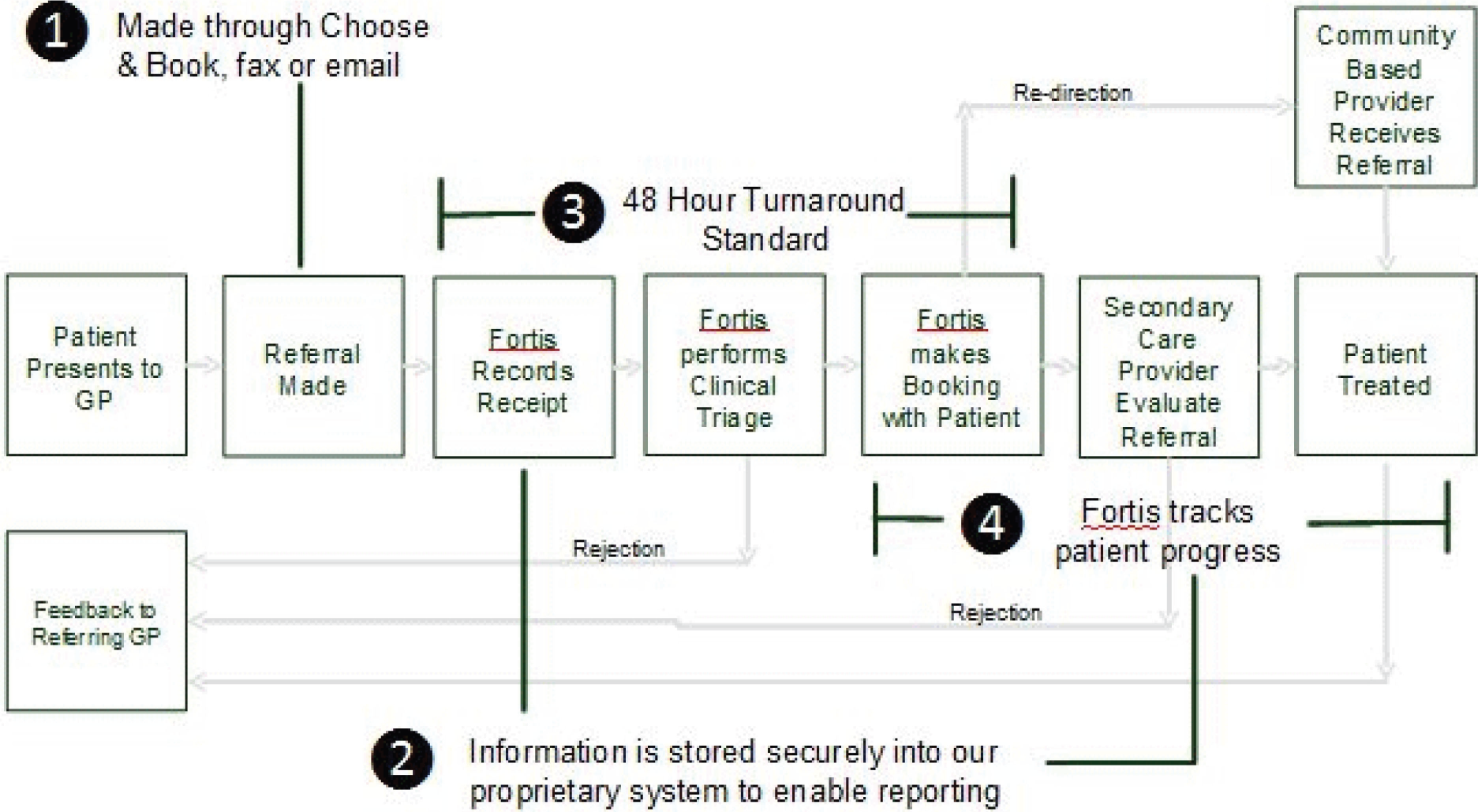

Organisational change: referral management centres – can they control and shape demand?

Referral management centres (and related services including ‘gateways’, ‘triage centres’ and ‘single point of entry services’) are intended to act as intermediaries between primary and secondary care. Their aim is to prevent unwarranted referrals from reaching secondary care, and to redirect them back to GPs or to redirect them to alternative community services. The empirical evidence in respect of these ambitions is mixed. A number of unintended consequences may occur. The co-option of clinicians into such centres may strengthen their power as services are managed according to clinical values. GPs may question the expertise of centre operatives and may bypass the new structures if they no longer retain decision-making powers in respect of patients with whom they are deeply familiar. Conversely, RMCs may also lower GPs threshold for referral and result in the offloading of routine work to lower-status professions. A number of characteristics can be identified in the more successful RMCs: all incumbents need to be engaged in their design; feedback to GPs about why their referrals have been blocked or redirected needs to be issued directly to the referring GP in a timely manner; and the local health economy should contain both the necessary skills and expertise and the capacity to manage the diverted referrals.

Role change: general practitioners with special interests – can they control and shape demand?

The development and formalisation of the innovative role of GPwSIs is usually traced back to the NHS Plan from 2000. 14 These new positions marked a widely supported development away from the role of family practitioner. GPwSI-led services were charged with a number of functions including taking responsibility for an ‘intermediate case-mix’, with consequent reductions in hospital outpatient services and waiting lists as well as improved accessibility for patients. The evidence in respect of these ambitions is mixed. There is little solid evidence that GPwSIs have reduced the outpatient workload or outpatient waiting lists. There is, however, no evidence to suggest that clinical outcomes differ between GPwSIs and outpatient services, although there is a difference in their case mix. There is solid evidence to suggest that GPwSI services attract increasing referrals and offer shorter initial waiting times (which do, however, lengthen with the longevity of their services). There are mixed and indecisive data on cost savings. These irregular outcomes are rooted in the remarkably ragged professional remits of GPwSI posts and the uneven distribution of their posts in different corners of medicine. More successful outcomes ensue if (1) consultants retreat to the specialist role in the treatment of complex patients and become advisor to rather than supervisor of the system to identify them, (2) GPwSIs deal with an agreed and intermediate case mix and work in a (physical and social) space that is independent from the GPs and consultant surgeries and (3) GPs work to agreed referral protocols developed via GPwSI educational and management functions.

Procedural change: direct access to the results of clinical tests – can it control and shape demand?

General practitioner direct access to the results of clinical tests is the oldest intervention we examine in the plethora of demand management solutions; equity of access to pathology and radiography services between primary and secondary care physicians was a topic of much debate as early as the 1960s and 1970s. With the development of ever more sophisticated diagnostic tools and tests, choosing the right test at the right time and interpreting the results in the right way to guide subsequent management are key tasks in the patient diagnostic journey. Allowing direct access to diagnostic testing should enable the GP to distinguish those patients who can be managed in primary care and those who require the expertise of a specialist without the need for an initial referral to secondary care. Once again we find that the evidence is mixed; the nature of tests differs according to their function in patient diagnosis and there are noticeable differences between types of test. GP direct access to tests designed to ‘rule out’ serious pathology or ‘clinical indicator tests’, designed to identify where patients were in a disease trajectory, led to greater efficiencies in demand management than GP direct access to tests designed to provide a differential diagnosis, especially if each of the differential diagnoses required specialist referral. The evidence also showed that specialists in secondary care rarely relinquished control over referral decisions, even with GP direct access to testing. Indeed, maximum utility in terms of demand management was realised when test results include clear guidance from specialists indicating appropriate management in the light of the results.

Learned counsel: can guidelines control and shape demand?

Regardless of health issue, health sector, patient condition or treatment modality, the chances are that provision is supported by ‘a guideline’ making professionally endorsed recommendations on best practice. And so it is with demand management, a major programme theory resting on the idea that demand can be curbed and sculptured with the appropriate formal guidance. This hypothesis has been met with a mountain of primary research and the main and undoubtedly sound conclusion from these inquiries is that guidelines in and of themselves have a limited role in addressing demand problems. The reason why guidelines falter is little to do with their content and format but is mostly due to complex decision structures in which they are embedded (and ignored).

Accordingly, the main body of research has amassed trying to identify the barriers and facilitators surrounding their implementation. Scores and scores of such impediments have been identified covering all manner of cognitive, attitudinal, patient, professional and resource constraints. Such has been the proliferation of these studies that, hitherto, the main task of review work has centred on the production of the definitive set barriers/facilitators producing a practical checklist of challenges that guideline producers and users will have to overcome. We argue that these overarching, itemised frameworks do not resolve into some sort of winning formula because the factors identified are always interdependent. Being alert to a ‘systems’ programme theory, our synthesis explains why some barriers are more intractable than others and why solutions always have emergent effects. Accordingly, we focus the review on some more specific remedies to some key ‘system strains’: (1) the tension in using simple guidelines for complex comorbidity; (2) the tension between (inter)national credibility of and local control over guidelines; (3) the tension between patient choice and top-down guidelines; and (4) the tensions involved when there are competing guidelines and contending targets.

Conclusions: facing the challenge of complexity

The evidence amassed in this report confirms our central hypothesis that demand management constitutes a wicked problem, which has defied clear and easily reproducible solutions. In scouring the evidence base we have unearthed an ever-growing list of contingencies that have to be overcome if such schemes are to succeed. We consider that the task of the impartial reviewer is to be the bearer of reasoned judgements, regardless of whether they constitute good or bad news. Most of the news in this review comes in the form of detailed expositions of the many difficulties and the rare gains in bringing into equilibrium the interlocking systems on which sustainable change depends. At this point it is worth recalling a general principle mentioned earlier, namely that the designation ‘wicked problem’ does not signify a hopeless, unfathomable, insoluble task. It means that solutions are adaptive, iterative, ongoing and, above all, local. We have indeed ‘evidenced’ this hypothesis – finding isolated islands of successful demand control amidst a rather storm-tossed sea.

Our conclusions are thus presented as a small set of principles, gathering together the configurations of ideas that apply in the most effective demand management interventions, pointing to the strains that have to be overcome and the interdependencies that have to be forged. We also reprise vignettes of successful ‘case studies’, showing how they exemplify the key design principles. System improvement is never a matter of blindly imitating ‘best practice’ but always an issue for understating the underlying mechanics of change.

Thinking it through: prompts for practitioners

Chapter 9 provides a small annex to our conclusions. It is aimed squarely at policy-makers, planners, managers and practitioners, providing them with some decisions aids to assist them in resolving demand pressures. It may be read independently from the rest of the report.

Appendices

Search and selection strategies

In Appendix 1, further details and flow charts are provided on the search strategy underpinning the review.

Reviewing the field

Appendix 2 provides a brief examination of previous attempts to review the field of demand management interventions in health-care provision. Given the gravity of the problem addressed, it is a topic that has attracted considerable attention in research review. Rather than engaging in a technical autopsy of each previous review, we have tried to assess them in terms of what is and what is not covered. And what is most often overlooked in the existing analysis is a whole-system perspective.

Stakeholder and patient involvement

Appendix 3 summarises the advice received in our meetings with project stakeholders.

Dissemination activities

In Appendix 4 a table is provided detailing project dissemination activities.

Part 1 Theory elicitation

If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles. If you know yourself but not the enemy, for every victory gained you will also suffer a defeat. If you know neither the enemy nor yourself, you will succumb in every battle.

Sun Tzu, The Art of War, p. 8415

Part 1 provides the conceptual anchor to the study. Realist synthesis operates in the tradition of theory-driven evaluation. Programme theories, the ideas and suppositions underlying an intervention, provide the hypotheses to be investigated. Programme theories can be usefully divided into two types: (1) diagnosis of the problem and (2) the plans underlying the remedy. Chapter 2 seeks to know the enemy: the causes of demand inflation in health care. Chapter 3 pursues an understanding of remedies as they see themselves.

(Part 2 will assess more than 100 battles in order to see who is victorious and who succumbs.)

Chapter 2 The runaway train: the multiple, intertwined causes of growth in demand for health care

It is in vain to speak of cures, or think of remedies, until such time as we have considered of the causes . . . cures must be imperfect, lame and to no purpose, wherein the causes have not first been searched.

Robert Burton, The Anatomy of Melancholy, p. 5216

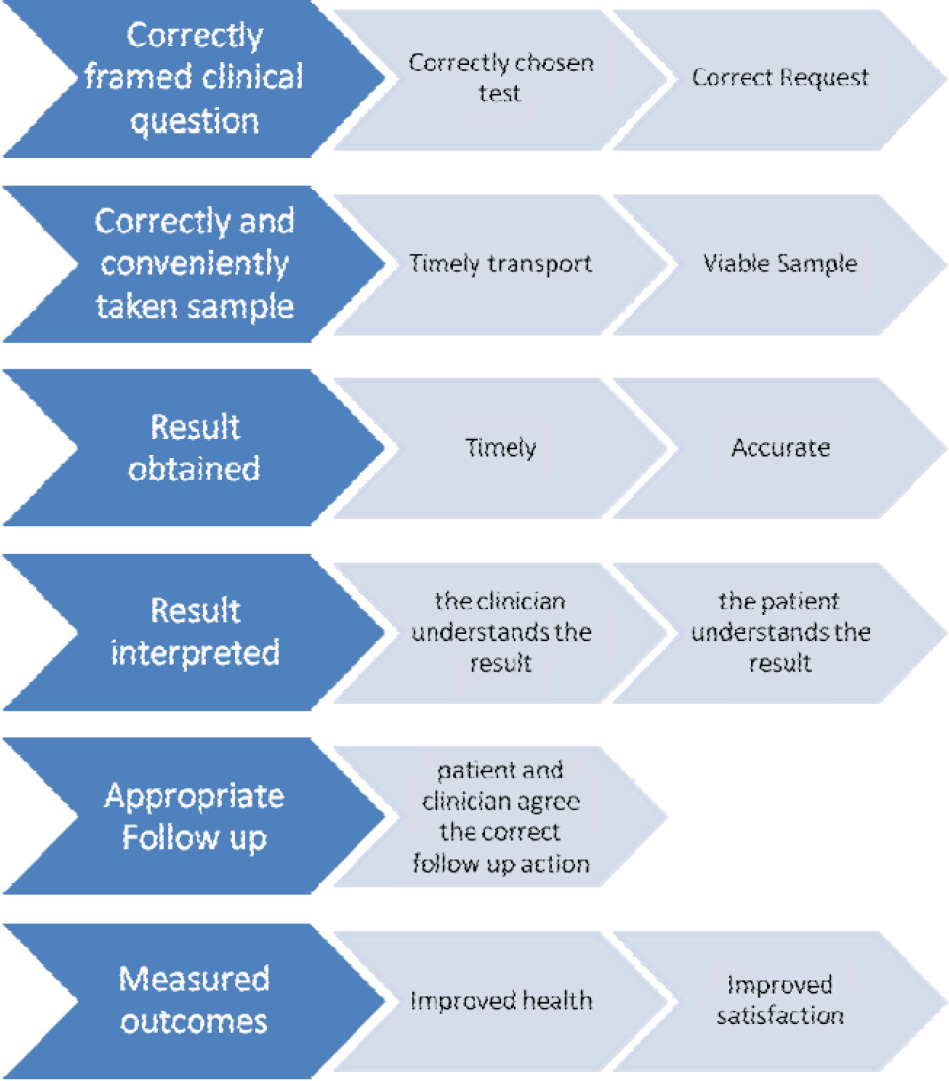

Because the problem of demand management is ubiquitous, it has attracted explanatory attention from a multiplicity of perspectives, both practical and philosophical, as well as from a range of disciplinary perspectives. There are numerous explanations of the notorious imbalance between demand and supply in health care; so extensive that we consider that they command a presence in our inquiry. Figure 1 explains the function of this chapter within the overall report.

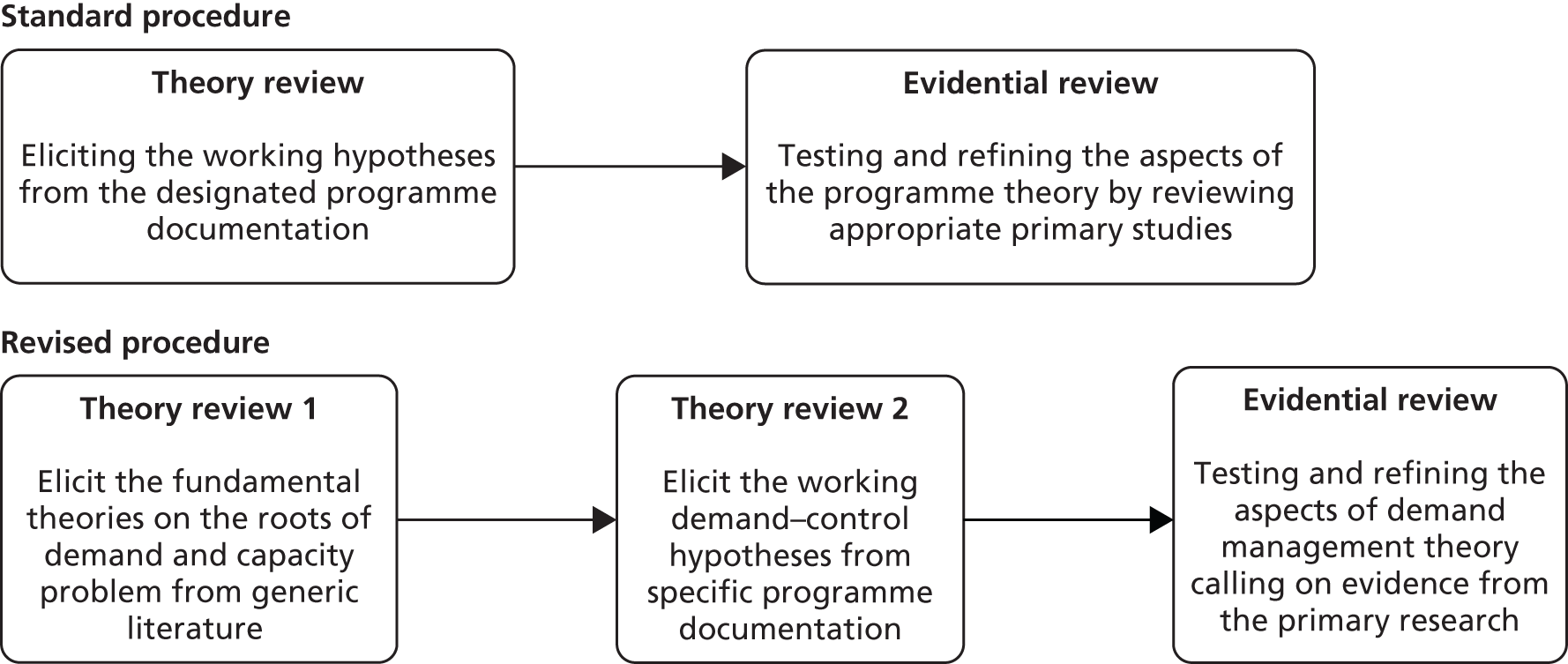

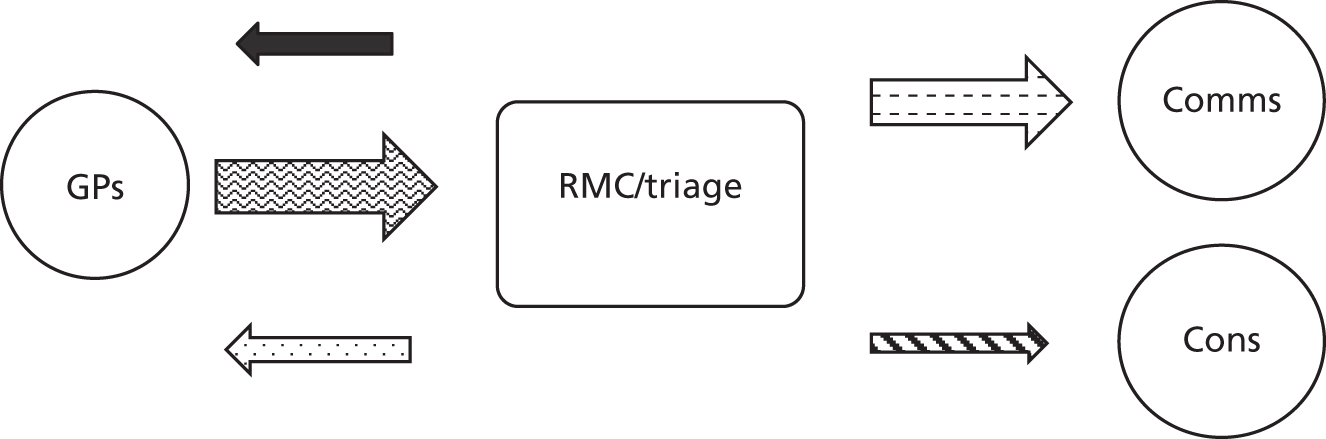

FIGURE 1.

Eliciting theory in reviews of ‘focused’ interventions vs. ‘wicked’ problems.

The top section of the figure depicts the standard routine of realist synthesis as applied in most reviews to date investigating confined interventions aimed at limited problems. Here, the existing literature is reviewed in two stages: (1) uncovering programme theories as expressed in the documentation underpinning the interventions under review and (2) searching for empirical studies that provide opportunities to test and refine the said theories. The lower section of the figure inserts an additional and prior search of the generic literature that is necessary as reviews take the leap from investigating well-delineated interventions to the present case in which we aim to evaluate whole suites of demand management programmes aiming at tackling a particularly longstanding, multifaceted and ‘wicked’ issue.

The entire history of programme evaluation tells us that interventions are never entirely and universally successful. Programme theories prefigure solutions that work only in certain circumstances and in particular respects – and it is the job of realist synthesis to articulate those contingencies. Such a prospectus presents a somewhat chilling challenge when it comes to the complexities of demand management. That is to say, the theories that are uncovered in the specific programmes (at stage 2) may well address only a limited range of theories (uncovered at stage 1) that explain the multifaceted roots of the underlying problem. A morose meta-hypothesis (the punch-bag theory) lurks, namely that we will be reviewing a domain of partial solutions – if one of the impediments to balancing demand and supply is solved, another might well pop up in its wake.

Undoubtedly this is too doleful a starting point, even if it is only hypothetical. Locating our review within this wider problematic does, however, justify beginning it with an overview of the broader literature on capacity problems – and this is the purpose of the remainder of this chapter. The coverage here, itself a review, is designed to achieve two aims. The first is to identify the main ‘schools of thought’, the key explanations for the seemingly inexorable rise in the demand for health care. The second is to assess the veracity and significance of each explanation, which we attempt by incorporating some crucial nuggets of evidence underlying each claim. Basically, the idea is to gain a sound understanding of the basic causes of demand/capacity imbalance – before we go on to study the research on its potential solutions. There is a considerable literature devoted to the issue, which we summarise and analyse into seven schools (Box 1).

-

Queuing theory and the question of time.

-

Professional closure, informal control and turf protection.

-

Micro-dynamics in the decision to refer.

-

Self-propelling diagnostic cascades.

-

Supplier-induced demand.

-

Changing demographics and rising demand.

-

The internet, the informed patient and demand inflation.

Each section ends with a summary of the ‘key issues to be taken forward’, consisting of a preliminary attempt to ‘size up’ the extent of each of the presenting problems. The chapter ends with some overall reflection on the utility and the significance of the typology in Box 1.

Queuing theory and the question of time

Queuing theory is a formal branch of mathematics, which perceives ‘demand’ as a queue for services. And, as anyone who has queued will recognise, ‘time’ is the core concern – the demand management dilemma is understood as the task of bringing into balance these two sides of an equation:

-

‘demand’ = the time required to complete a service/procedure in any period

-

‘capacity’ = the time available to complete the service/procedure per period.

Fluctuating demand is seen as the underlying problem – it is irregularity of demand that creates queues. To use a contemporary example – planes arrive at Heathrow in uneven batches (seasonal and daily) and the immigration officials there to greet passengers sometimes sit twiddling thumbs and sometimes are over-run. How can the problem be managed?

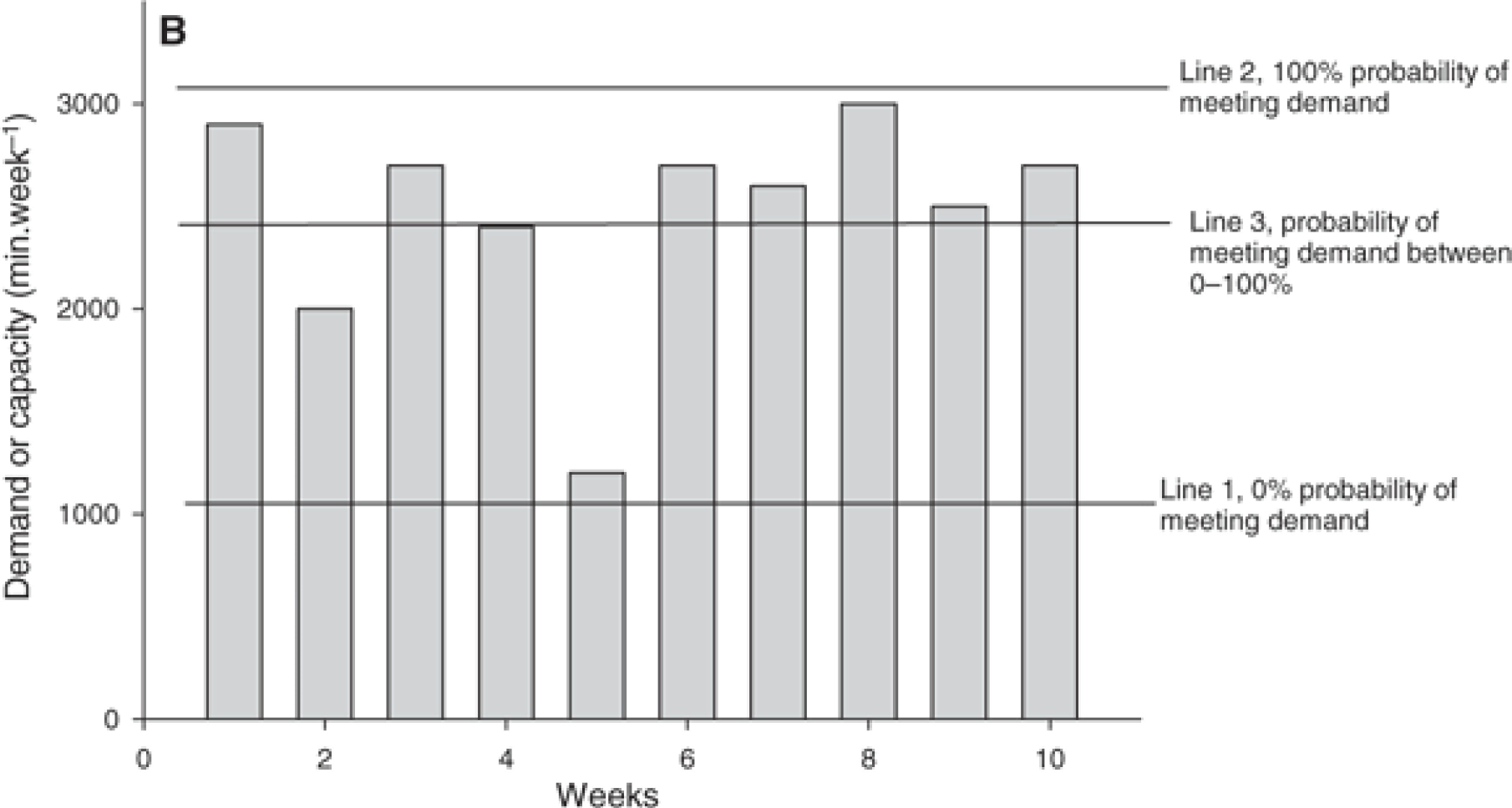

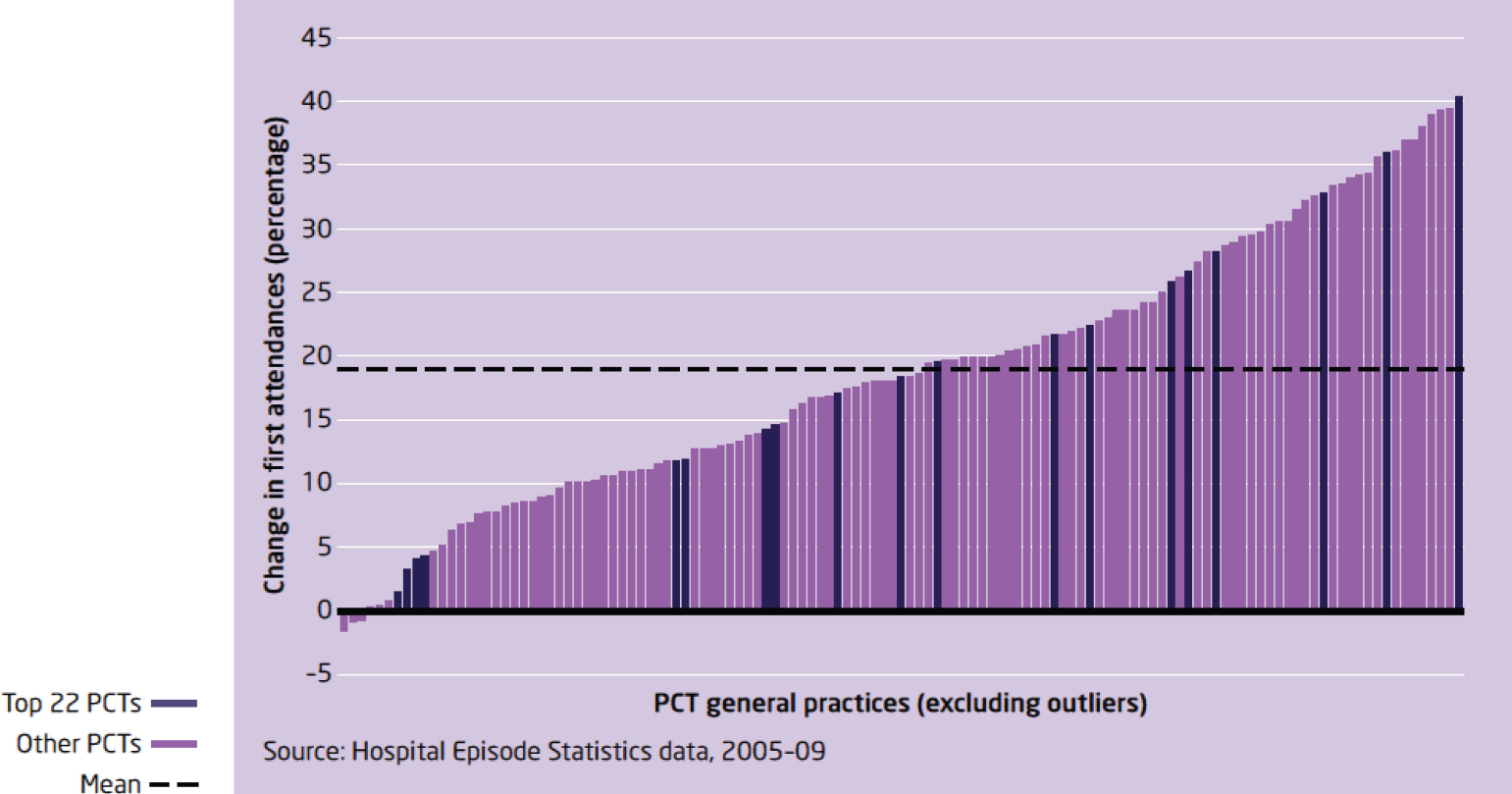

Figure 2 (reproduced from Pandit and colleagues17) demonstrates the problem of setting the appropriate service level in the face of fluctuating demand. The three horizontal lines in Figure 2 represent different ways in which capacity might be set and foretells of a delicate balancing act. Line 1 is set below the minimum weekly demand. Demand is never absorbed and backlog increases unceasingly. Line 2, set above maximum weekly demand, absorbs all demand, eliminates backlog but wastes considerable capacity. Line 3, the practical alternative, sometimes absorbs demand and sometimes increases backlog.

FIGURE 2.

Alternative strategies and probabilities of meeting fluctuating demand. Reproduced with permission of John Wiley & Sons, from Pandit JJ, Pandit M, Reynard JM. Understanding waiting lists as the matching of surgical capacity to demand: are we wasting enough surgical time? Anaesthesia, vol. 65, pp. 625–40, 2010. 17 © 2010 The Authors. Journal compilation © 2010 The Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland.

A basic and perfectly general insight can be drawn directly from the figure.

Spare capacity in one week cannot be carried forward to the next week. Time cannot be stored for future consumption or sale as can manufacture goods such as cars or washing machines. Furthermore it is not always apparent in any week that time is spare, since this is only known after the event. Therefore the occasions when demand outstrips capacity always contribute to backlog, but the occasions where capacity outstrips demand cannot always compensate and capacity is wasted

Reproduced with permission of John Wiley & Sons, from Pandit JS, Pandit M, Reynard JM, Understanding waiting lists as the matching of surgical capacity to demand: are we wasting enough surgical time? Anaesthesia vol. 65, pp. 625–4017

A potential paradox is raised, put mischievously in Pandit and colleagues’ subtitle – ‘are we wasting enough surgical time?’17 Some waste appears to be necessary to ensure that demand is met and this proposition provides us with one of the standard motifs of queuing theory, namely ‘what are acceptable levels of waste?’

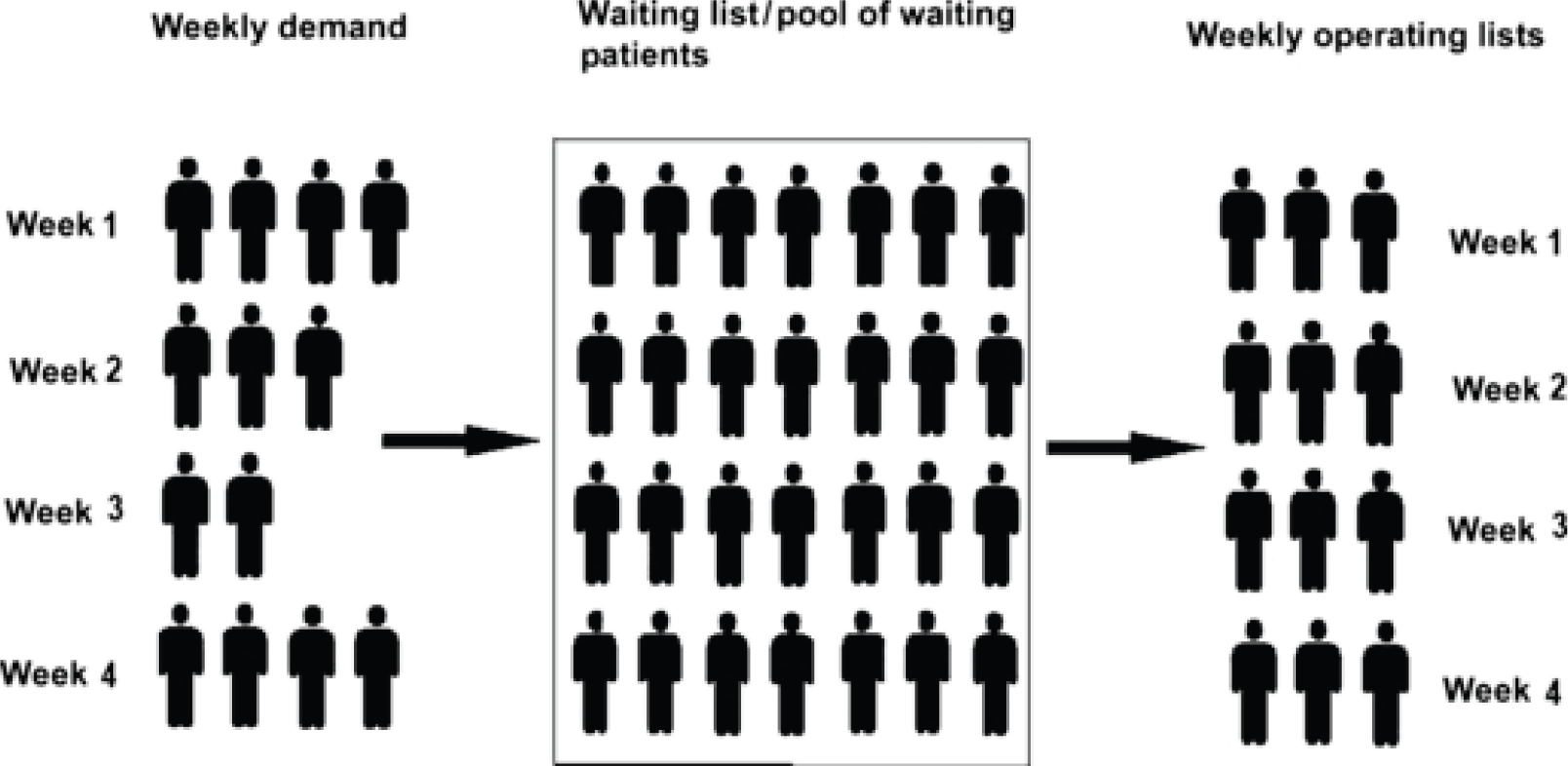

Queuing theory is able to make useful predictions, some counterintuitive, on queue dynamics under more complex conditions – what happens if you increase the number of servers? What happens if service levels also vary? What happens if you create a waiting list ‘buffer’ to even out demand? Figure 3, which is reproduced from Pandit and colleagues’ figure 10, illustrates a standard response to fluctuating demand. The pictogram illustrates varying demand over a 4-week period. Rather than dealing directly with these demand contours, patients are placed on a pooled waiting list, which if operated flexibly and efficiently yields a constant demand in successive weeks. More sophisticated queuing models are able to incorporate and predict the smoothing effect of a range of further demand management strategies.

FIGURE 3.

Pooling strategy to smooth demand. Republished with permission of John Wiley and Sons, from Pandit JJ, Pandit M, Reynard JM. Understanding waiting lists as the matching of surgical capacity to demand: are we wasting enough surgical time? Anaesthesia, vol. 65, pp. 625–40, 2010. 17 © 2010 The Authors. Journal compilation © 2010 The Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland.

Critics have pointed out some limitations of queuing theory, namely that it suffers the characteristic limitations of a mathematical theory. 18 It is defined by those inputs (number of arrivals, service requirements, number of servers, etc.) and outputs (probabilities of delay, queue length, mean occupancy, etc.) that can be modelled. Such models cannot incorporate all of the real world sources of variation and uncertainly, which reach right down into the idiosyncratic dynamics of every single consultation and up into contractual negotiations on service provision. Unwisely, some strict rules on service levels have been adapted on the basis of elementary queuing theory. Bain quotes one oversimplistic edict that was carried directly back into emergency medicine in Australia: ‘Queuing theory developed by Erlang nearly 100 years ago tells us that systems are most efficient when they operate at 85% capacity.[19] This applies to the queues at the local bank waiting for the teller or at a ticket booth at the MCG (Melbourne Cricket Ground)’. 18

Practical resolutions to demand fluctuation involve close tracing of patient flows through every procedure and pause within a particular service. Ironing out demand generally involves close attention to each link in the chain (changing division of labour, changing appointment procedures and priorities, etc.). A glimpse of some specific strategies can be seen in the following ‘case study’ (Box 2) summarised from the NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement. 20

-

Eliminating ‘carve out’. Weekly slots had previously been divided between routine, inpatient and urgent requests without regard for demand.

-

Covering all sessions, rather than having unfilled slots.

-

Training radiographers to perform barium enemas to address the shortage of radiologists.

-

Introducing flexibility.

-

Introducing protocols for checking requests to avoid delay.

-

Giving individual appointment times rather than group booking times.

-

Booking only barium examinations onto lists, rather than booking many different examinations.

-

Introducing measures and targets where there had previously been none.

Our purpose here is not to be drawn into the specifics of this case study, still less to comment on the effectiveness of the suggested improvements. The point is to establish that fluctuation of demand is all-pervasive and operates through all the micro process within a service. It is thus likely to remain pertinent to our review, with the following implications.

Box 3 provides a summary of this section.

-

‘Variation’ in demand rather than just the ‘level’ of demand will itself produce a capacity problem. ‘Time’ is an important aspect of all health service provision and time cannot be stored.

-

A complex system with many stages (i.e. referral systems from GPs to laboratory tests to special consultations to hospital admissions to operating theatre lists to postoperative recovery, etc.) will have ‘internal queues’, each with inherent variability. The characteristically long and back-and-forth chains of modern medicine will have additive or even multiplicative effects on backlog and wastage.

-

Demand management interventions that operate by transforming organisational structures, professional functions or staff motivations are likely to retain a queuing footprint that still may lie at the root of the problem and still may require attention.

Professional closure, informal control and turf protection

From mathematics we move to social science. The sociology of the professions has always had a fascination with the medical establishment’s ability to retain power, restrict entry and control clinical practices. 21,22 The continued social transformation of the medical profession has been explored in terms of the clinicians’ relationship with the state, with management, with patients, with the pharmaceutical industry and with evidence-based policy. 23,24 Here, we want to trace the path of this literature into the daily routine of health care and into the matter of referrals. How might professional power affect the issue of handovers? Here, we report briefly on three of very many case studies that contain the typical features of ‘turf protection’ and show how these go on to create significant demand dilemmas.

Foote and colleagues’ study of the management of ultrasound waiting lists examines a process beginning with the primary patient consultation with the referring GP, moving through radiological investigations and into the secondary care. 25,26 The study begins with the basic predicament, namely that waiting lists are effectively formal institutionalised agreements between hospital departments and referring clinicians ‘to attend to patients at a later date’. 25 Satisfaction with this concordat differs from stakeholder to stakeholder, and a range of strategies evolve to modify, manipulate or circumvent this bureaucratic pact. If they believed it was not in a patient’s interest to wait at the back of the appointed queue, some GPs were quite prepared to load the system at other points. They made attempts to (1) bypass the ultrasound service by making hospital outpatient appointments, (2) send patients directly to the service in the hope of on-the-day cancellations, and (3) queue jump by forwarding urgent requests.

The real turf wars commence with the arrival of another set of stakeholders. Radiologists, sonographers and departmental managers held a different set of priorities: ‘GPs and waiting patients were broadly interested in managing diagnostic uncertainty . . . In contrast, the ultrasounds service’s account of the waiting list centred on difficulties in allocating scarce capacity to patients who were likely to have abnormal pathology in order to minimise the impact of waiting lists on ill patients’. 26 An ‘all clear’ diagnosis thus represented a positive outcome for GPs, while a congregation of ‘all clears’ constitute an unmerited demand for the radiological service.

Much of the immediate contestation between these professional groups occurred on the matter of prioritisation and handling of the ‘urgent’ requests. Radiologists and managers were fearful that the increasing number of urgent requests meant that the regular waiting list grew ever longer and the attendant publicity grew ever darker. As with most other forms of referral, bureaucratic hurdles were constructed to ration urgent requests. GPs were required to forward detailed, urgent requests only by fax/telephone and were heavily discouraged from not simply marking a referral form as urgent. But even under this system the majority of ‘urgent’ notifications fetched up with ‘normal’ scans. The result was a form of stand-off. Given the potential medico-legal consequences of declaring requests as inappropriate, ‘radiologists rarely refused to scan GP requests and only passed judgement on the quality of the referral after the patient had been scanned’. That judgement was often brutal: ‘The ultrasound service referred to such requests as “rubbish” ’ though letting off steam in this manner did little to resolve the numerical log-jam. 26

A further internal fissure, with a considerable impact on demand from radiography, occurred between the professional groups responsible for its implementation: radiographers (clinicians) and sonographers (technicians). Ultrasound imaging occurs in real time, potential abnormalities being best uncovered in an intricate, immediate to-and-fro between the production of scans and their interpretation. Investigation and diagnosis are intertwined with a resultant challenge to the identities and the division of labour between the specialist and the technician. One way that the former group were able to maintain their expert role was through the widespread adoption of ‘second-look stenography’ or ‘double scanning’ – the radiologist rescans the patient to confirm the accuracy of the sonographer’s scan. The demand dilemma is clear: ‘Double scanning restricts session throughput (as patients may be scanned twice), creates session overruns (a single radiologist covers two ultrasound scanners) and makes session throughput vulnerable to the availability of a radiologist (as a radiologist must be present when patients are being scanned)’. 26

Abel and Thompson’s qualitative study27 sheds further light on the ways in which generalists may circumvent attempts by specialists to control their behaviour via guidelines. It also reveals the different perceptions of specialists and generalists regarding what constituted an ‘appropriate’ referral. The authors interviewed 15 GPs and 11 specialists in New Zealand to explore their use of surveillance guidelines for colorectal cancer. These guidelines were written by specialists and contain advice about when a patient should be referred to secondary care. The guidelines classify people into low-, medium- and high-risk categories and seek to control demand by stipulating that only high-risk groups should be referred. In and of themselves, the guidelines can be seen as attempts by specialists to exert control over the behaviour of generalists.

The authors concluded that specialists and generalists have different perceptions of risk by virtue of their clinical remit and relationship with the patient. Specialists, who are one step removed from the patient, managed risk ‘scientifically’, often based only on a referral letter and family history. They perceived that GPs referred people inappropriately, in ways that did not fit the guidelines, which they then assumed were ‘too complex’ for GPs. GPs felt that the formal guidelines often did not ‘fit’ the patient in front of them and made decisions based on their relationship with the patient and their clinical experience. They also took into account the patient’s anxiety about their condition, rather than statistical calculations of risk. Once again, the turf wars resulted in a stand-off. GPs also embellished their referral letters to ‘fit’ with the guidelines in order to get their patient referred at an earlier date; specialists saw these embellishments as ‘lying’.

Currie and colleagues’ qualitative study of the development of genetics services run by GPwSIs provides further insight into the turf wars. 28 The focus in this case is on the rift that occurs between specialists and generalists. Twenty-four interviews were conducted with three key stakeholder groups (GPs, GPwSIs and specialist geneticists). The GPwSI role involves a reconfiguration of the standard health service division of labour. This new group of specialists take referrals from their fellow GPs, offer diagnostic and some treatment services and provide leadership in primary care in the reshaping of services around particular conditions and disease areas.

In the cases examined, GPwSI services that gained ready acceptance were those designed to supplement the work of consultant geneticists. Those that were set up to substitute the work of the geneticists encountered greatest opposition from the consultants. New functions such as ‘raising awareness’ in an ‘educational role’ prompted support; the development of new clinics within primary care did not. Consultants continued to hold sufficient power to constrain the development of GPwSI services through defining what constituted specialist knowledge and controlling access to training, education and support required to set up the new GPwSI services. GPwSI always had to establish consensus with the specialist regarding the purpose of service. Thus, whether or not GPwSI services were successful depended on whether existing inter- and intraprofessional relationships supported or constrained their development. Demand and duplication dilemmas continued and were sometimes exacerbated in new forms of informal control in which ‘geneticists took on the role of appraiser, vetted all referrals to the GPwSI and filled a supervisory role’. 28

Although the case studies noted here refer to specific services dealing with specific conditions, the underlying dynamic undoubtedly will repeat itself in other parts of the health-care system. Note that our analysis in this section does not depend on the original research having tapped the precise extent of professional closure available to each subgroup. Accounts of baronial contestation will always be contested. The point is that, whatever the precise resultant, assertions of territorial expertise, in and of themselves, will shape patterns of supply and demand.

Box 4 provides a summary of this section.

-

Because of their diverse responsibilities, different professionals will hold contrasting constructions of what constitutes the demand management problem and, thus, different opinions on what strategies to follow in the face of continuing blockage in the system.

-

Practical outcomes of this difference of opinion are likely to depend on the extent to which respective professional bodies hold controlling power over the constituent processes. Different coalitions of subprofessions are likely to form in the ‘arms race’ to retain control.

-

Any fresh demand management intervention, be it the introduction of guidelines or the creation of new professional roles, should expect to operate in this contested terrain. The effectiveness of any innovation will, in part, depend on the process of addressing and harmonising contested professional interests and priorities.

Micro-dynamics in the decision to refer

Before corrections are applied to the referral process, it is wise to consider what we know about the inner workings of that process. Numerous studies have explored how generalists – usually GPs – make the decision to refer to specialist care. This work can be traced back to a classic 1981 paper on ‘referral thresholds’. 29 At issue is the identification of the exact point at which the GP decides that specialist help is required and, thus, referral is needed. There is a linkage to the above theories on turf wars, through the explorations of where a generalist’s remit ends and a specialist’s remit begins. Several studies have developed general frameworks describing spectrum of influences on GP’s referral decisions. 30–32

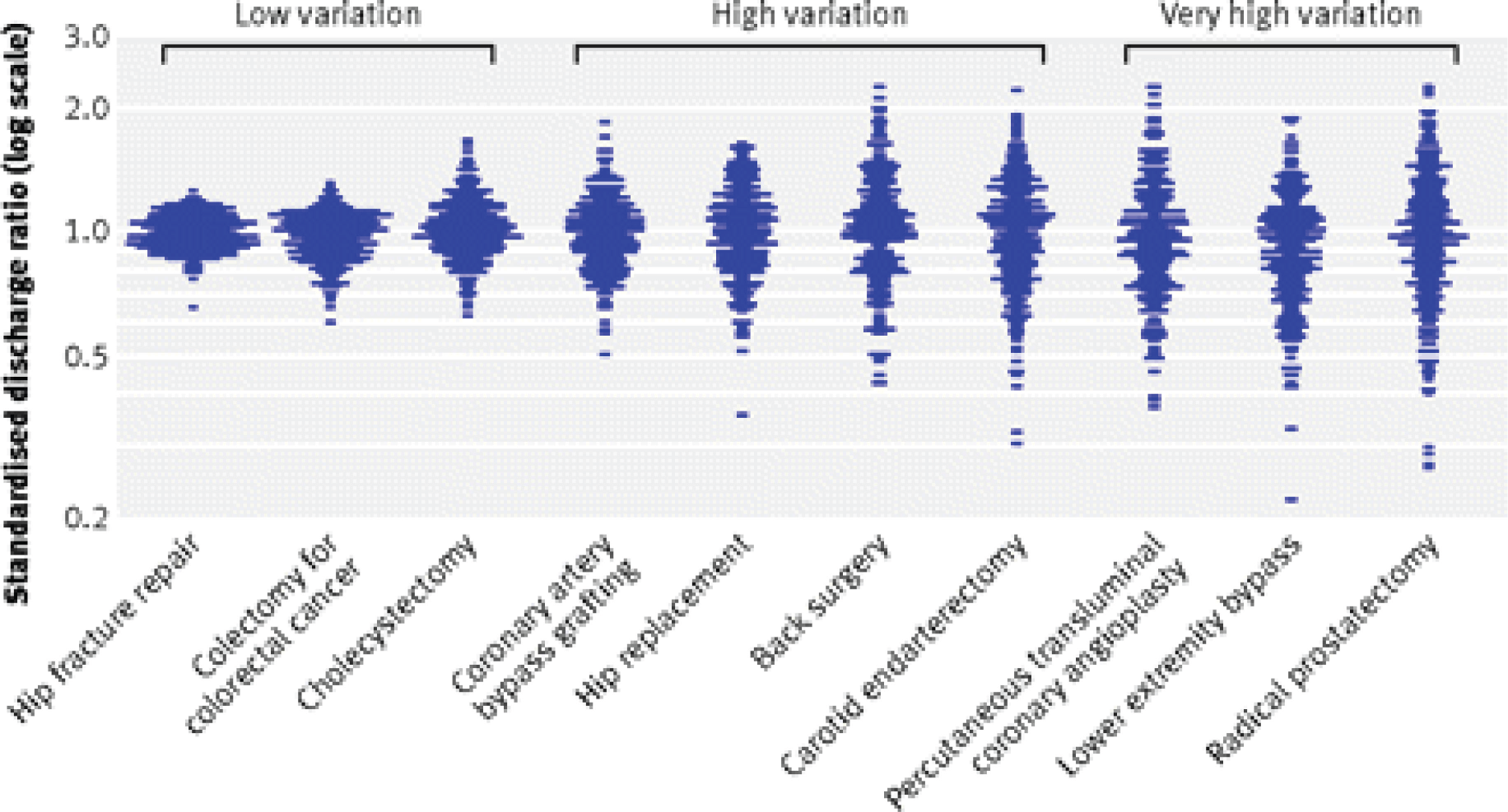

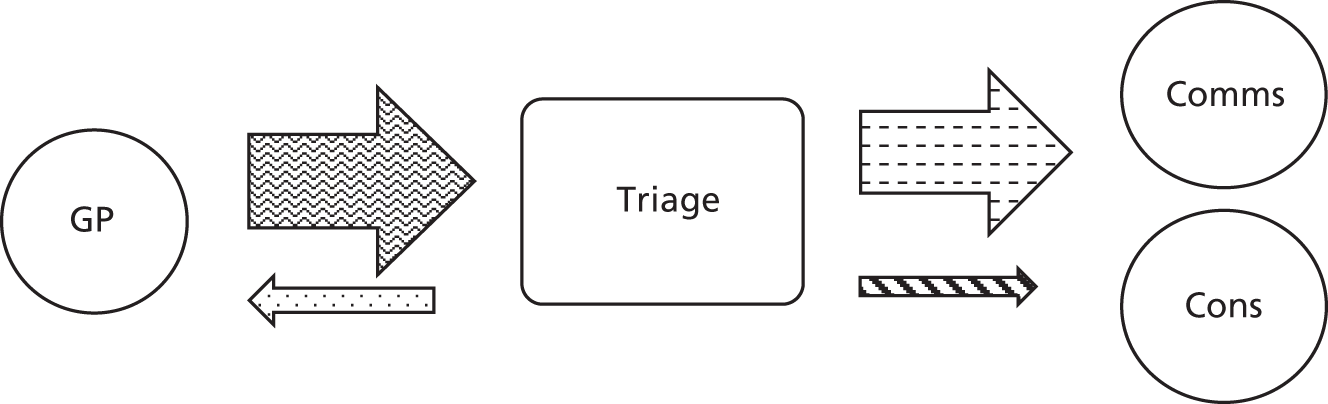

In this section we concentrate on studies in the micro-sociological or social psychological traditions, which attempt to model how GPs explore patients’ problems. 33 Often, this complexity is described using flow diagrams, such as Figure 4, of the interaction and decision-making process. 34 To illustrate these studies, we focus on three inquiries exploring how GPs make decisions to refer patients to psychiatric services. This is a domain with significant variation in referral rates stemming from the considerable uncertainty on whether or not, when and where a patient should be referred to secondary care.

Morgan tracked all new referrals to two outpatient psychiatric clinics over 6 months. 34 Of the 184 patients referred, 62 did not keep their appointment, 14 did not wish to be interviewed and 120 were interviewed to explore the history of their problems and the chronology of events before their referral. A total of 27 out of 31 referring GPs were interviewed to explore their views on the history and nature of the patients’ problems and how the referral came about. In addition, documentary evidence (referral letters, medical records) and clinical data recorded by the psychiatrist for each patient were scrutinised. In most cases, the decision to refer evolved out of a series of encounters between the GP and the patient and their family over a period of months, usually 3–5, but sometimes up to a year. This suggests, significantly, that referrals are best conceptualised as a process rather than as a single decision at a specific point in time.

Morgan identified three ‘patterns’ or types of referrals. The first category were patients experiencing problems that could clearly be labelled ‘psychiatric’ and beyond the remit of primary care – such as patients exhibiting violent, psychotic or suicidal tendencies. These patients were usually referred as soon as the problem was known. The second category, termed ‘elective’, was less clear-cut; in these cases, psychiatric disturbances were masked by physical symptoms, were transient or were accompanied by other events in the patient’s life. The referral was contingent on a series of events shown in Figure 4. 34 The GP first treated the physical symptoms and ruled out a physical cause for the problems, which were then recognised as ‘psychiatric’. The GP then provided reassurance and supporting treatment, which represented an attempt to ‘contain’ the symptoms and gave the GP time to ‘wait and see’. Persistent symptoms and pressure from relatives may undermine previous reassurance from the GP and lead to a referral, often in the context of difficult and unstable doctor–patient relations. In the third category, labelled ‘negotiated referrals’, the GP acted as an intermediary to arrange a psychiatric referral at the request of others – sometimes solicitors or hospital consultants but also patients and relatives with ‘ulterior motives’ (e.g. to gain better housing or sickness benefits, etc.).

FIGURE 4.

A micro model of the referral decision. Republished from Morgan D. Psychiatric cases: an ethnography of the referral process. Psychological Medicine, vol. 19, issue 3, 743–753, 1989, reproduced with permission from Cambridge University Press. 34

The severity of the patient’s symptoms was judged a weak predictor of which category of referral came into operation. The authors conclude that the process of referral is structured by social as well as clinical events. GPs sometimes struggle to focus on symptoms rather than the patients underlying problems, which are not always seen as within their remit. Sometimes GPs do not feel they have the time or skills to address them. Furthermore, GPs find themselves managing not simply the patient’s condition but also their relationship with the patient, and they may choose to refer when this relationship breaks down.