Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 10/1010/06. The contractual start date was in July 2012. The final report began editorial review in February 2015 and was accepted for publication in August 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Pinkney et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction, study objectives and literature review

Introduction

The demand for emergency medical care in the UK has escalated annually, leading to unparalleled pressures on emergency departments (EDs) and acute medical admissions units (MAUs). These pressures can adversely affect patient experience through overcrowding, long waiting times, delays in investigation and diagnosis, and potentially suboptimal decision-making. Negative consequences for acute hospitals include a persistent state of near-capacity bed occupancy, cancellation of elective work and pressures on the workforce. There has been a widely held view, supported by some evidence, that a significant proportion of acute admissions might be avoidable. The appropriateness of a hospital admission can be understood by examining the interactions, organisational culture and system contingencies that prevailed at the time that this decision was made. The Avoidable Acute Admissions (3A) project aimed to investigate the interplay of factors influencing decision-making about emergency admissions and to understand how the medical assessment process is experienced by patients, carers and practitioners. The study represented a collaboration involving the universities of Plymouth, Exeter and the West of England, and four acute hospital trusts in South West England, which are anonymised in this report. The research was led by the academic partners in partnership with clinicians and managers at these four hospitals. Patient and public involvement (PPI) throughout the research was supported by the Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care South West Peninsula (PenCLAHRC). The study received research ethics committee approval to commence on 1 July 2012 and was completed on 31 January 2015, following a 6-month no-cost extension agreed with the funder. The study’s final report has been elaborated using a combination of COREQ (consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research) and STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) reporting guidelines. Prior to 3A, there had been little research on acute admissions from a perspective that attempted to understand patients’ and practitioners’ experiences and the processes involved in decision-making. The premise of the 3A study was that acquiring this understanding was a prerequisite for assessing the appropriateness of decision-making in patient journeys in particular. This research aimed to fill an evidence gap and inform policy-makers and NHS managers about the experiences of patients and practitioners in emergency medical departments. By investigating the care models used by different hospitals to organise their emergency service provision, the research aimed to identify service configurations and innovations that were associated with reduced likelihood of hospital admission, enhanced patient experience and best practice. Understanding the patient-centred perspective is likely to be of prime importance in planning improvements to emergency care in the NHS.

Overall aim

To investigate how clinician expertise and models of care in four contrasting hospitals contributed to appropriate decision-making regarding admissions in acute medical care; and to make recommendations about different admission avoidance models and their likely impact on workload management at the hospital front end.

Objectives

-

To investigate influences on decision-making about admissions in acute medical care.

-

To investigate how frontline experience and new models of care contribute to reducing avoidable acute admissions.

Research questions

-

What influences are operating in the acute admissions decision process?

-

This question was considered from the perspective of:

-

patients and relatives or carers

-

medical and other clinical staff responsible for decision-making (the role of early senior input in admission avoidance was specifically considered)

-

organisational factors that may influence decision-making.

-

-

How is the whole admissions process experienced by patients and practitioners?

-

How are the four models of care similar and different?

-

How does patient experience vary in each setting?

-

How are different ideas and policies and incentives adopted in each setting?

-

How often do the potentially critical components of care (e.g. early senior input) occur for potentially avoidable admissions? How does this vary by diagnostic group?

-

How is each model of care associated with demographically adjusted admission rates?

-

How does the cost of providing care during the unplanned admission process relate to different organisational models, and do such models have different impacts on workload management?

-

-

How can frontline expertise and new models safely reduce rates of admission?

Background

Literature relevant to the project was discussed in regular reading groups, where team members reviewed publications in specific areas (see Appendix 1). At the start of the project, researchers met to discuss key texts that had been identified in the initial study proposal. In subsequent meetings, the team developed a method for focusing reading groups on jointly reviewing collections of 6–11 texts relating to particular topics. The topics and texts were selected in response to emerging study findings, such as factors influencing decision-making, patient experience, safety and efficiency, senior input, and teaching and learning. The reading groups identified the themes in the sections that follow as particularly important for the study.

Growth of emergency admissions

The context for the 3A study was the 2010 Nuffield Trust report,1 describing the rapid growth of emergency admissions in the UK between 2004 and 2009, and local concerns in South West England. In this period, numbers of emergency admissions in England rose by 11.8%, resulting in 1.35 million extra admissions. There was a large rise in short-stay admissions, and one possible explanation was that this might reflect a decline in longer-stay admissions. Alternatively, it was possible that increasing numbers of less severe cases were being admitted, perhaps because the clinical threshold for admissions had been reduced. 1 More recently, the National Audit Office observed that there were 5.3 million emergency admissions to hospital in 2012–13, representing a 47% rise over 15 years. The annual cost to the NHS rose to around £12.5B. Overall, 26% of patients attending EDs were admitted. There was a 124% rise in short-stay admissions, and 850,000 acute bed-days were lost because of delayed discharges. Moreover, 50% of emergency medicine training posts were unfilled in 2011–12. 2

There was also significant variation between NHS trusts in England: in some, emergency admissions declined by a third, while in others they almost doubled. There was also variation between primary care trusts. These data suggested that admission rates are influenced by factors unrelated to medical need. Emergency admission rates were found to be twice as high in the most deprived areas as in the least deprived areas. 1 Research by O’Cathain et al. estimated that 22% of admissions were potentially avoidable, and that there was a threefold variation in potentially avoidable admissions. 3 This finding supported the results of an earlier meta-analysis. 4 However, O’Cathain et al. also linked high avoidable admission rates with unemployment. Furthermore, there was demographic variation in sociocultural expectations of emergency care, with evidence of significantly increased avoidable admission rates in urban compared with rural areas, and for younger compared with older patients. 3 Avoidable admission rates were also higher for hospitals with higher ED attendance rates, higher numbers of acute beds per 1000 population, and higher conversion rates from ED attendance to admission. 5

The Nuffield Trust report1 and the research by O’Cathain et al. 3,5 reinforce the idea that many acute hospital admissions are medically non-essential and therefore probably represent suboptimal use of resources, in addition to exposing people to potential iatrogenic harm. However, neither of these studies specifically sought the patient or ‘user’ perspective on ED attendance. The premise for the present study was that a significant proportion of emergency medical admissions are potentially avoidable for a range of different reasons, and that, if ED experience is better understood from the patient perspective, there may be opportunities to handle some acute admissions more appropriately, with resulting benefits for patients and the NHS.

Quality and efficiency

Since its introduction in 2000, the 4-hour standard has had a major influence on the way in which EDs have responded to rising demand. This target was introduced to improve patient experience and outcomes by ending lengthy ED waits, particularly for patients requiring admission. The target was also seen as an instrument to enhance patient safety, but it was not observed to promote safety and quality of care to the same extent as efficiency. NHS quality indicators were introduced in 2011 to address perverse effects of target compliance. 6 Although the target time for discharge or admission was designed to improve patient flow, co-operative working with other services and departments often presented a challenge. 7 Recent studies have found some indications of variation in the coding of admissions, with patients in some clinical areas coded as admissions while patients’ overnight stays in other clinical areas might not be coded as admissions or breaches. 8

The 4-hour target has been considered a blunt tool to drive quality improvement in emergency care systems. 9 The quality of hospital emergency care has come under new scrutiny, and the Royal College of Emergency Medicine has called for wholesale system redesign, better care integration, greater resourcing of clinical decision and ambulatory care units (ACUs), and improved governance, staffing and skill mixing. 10 Much existing literature focuses on systems and patient flow, in contrast to the lack of research on patient experience. 10

Crowding and waiting times

Crowding is a visible manifestation of high demand. While ED waiting times have attracted considerable attention, the phenomenon of crowding has been little addressed in the UK literature. 11 High demand that outstripped capacity was considered to increase risks of certain types of critical incident. 12 High demand appears not to be explained by frequent attenders; rather, this patient group generally has more urgent needs,13 and makes appropriate use of urgent care services. 14 Crowding and long waiting times may lead to poor user experience, and to safety being compromised: times of overcrowding in one ED were associated with an increased 10-day mortality rate. 15

Crowding occurs when demand outstrips capacity and may arise in the face of both appropriate and inappropriate demand. Higginson et al. suggested ways in which demand and capacity planning could address this problem. 16 Strategies to combat overcrowding were the focus of a report by the Royal College of Emergency Medicine,17 which recognised that a range of hospital and community initiatives were required to tackle the problem. Higginson et al. drew attention to the international recognition of crowding as a significant concern, raising the question of how to address this issue in the UK. 11 The 4-hour target alone has been an inadequate instrument to address complex issues responsible for crowding, long waiting times and quality issues. There has been concern that undue focus on flow may detract from patient-centred care. 9

Practitioner experience

High levels of demand for emergency medical assessment associated with ED crowding placed considerable expectations on staff. An ethnographic study from Australia described how the work of ED staff focused on management of patient flow,18 but the experiences of staff working in EDs have received little attention. Workplace pressures may significantly contribute to recruitment and retention problems in this specialty. 19

Several studies have investigated teamwork in EDs. Recent studies using social network analysis found wide variation in the frequency of communication between ED staff working on different shifts,20 which could influence quality of care. A systematic review found evidence that multidisciplinary teams in EDs probably reduce access block, and that physiotherapists could play a role in this. The need for ED teamwork and communication was also related to safety improvement and reduction of waiting times. 21 Communication at team handover was highlighted as an important factor influencing admit/discharge decisions and quality of care. Jeffcott et al. 22,23 introduced the concept of ‘resilience’ and, using clinical handover as the example, suggested that it could be beneficial to understand and adopt elements associated with good outcomes, rather than solely focusing on problems. Another recent study of clinical handover found that only 1.5–5% of handover conversation content related to patients’ social and psychological needs,24 when these were highly likely to influence outcomes.

Demand, capacity and safety

Significant variations in emergency attendances and admissions by day of the week and time of day are well known. 2 Although there are fewer attendances and admissions at weekends, a recent analysis of 4,317,866 episodes of emergency care in the UK observed 10% higher mortality at weekends. 25 Concern about fluctuations in the quality and safety of care across times and days of the week had led to recommendations for 24/7 staffing for acute service provision in hospitals. 10

Measures to reduce avoidable admissions

Decisions about hospital admission reflect the impact of policies generated both by financial and safety concerns. Influences on decision-making include medical need, social considerations, family and carer expectations, experience and seniority of decision-makers, system factors, policy directives and the availability of alternatives to admission. Efforts have been invested in exploring admission prevention and avoidance through the development of community-based chronic disease models. 26 However, there is more limited research to support the wide variety of initiatives currently being developed at the ‘front door’ of NHS hospitals and examined in this project. Early streaming of urgent and less urgent cases was first tested in the 1980s in order to reduce waiting times and reduce duration time in EDs27 and has since become widely adopted in many countries. However, few patient-centred data were found relating to the avoidability of acute admissions.

Early senior input and managing flow

Several studies supported the idea that early triage by more experienced staff might improve decision-making and patient flow. Early research showed that patients assessed by more experienced doctors were substantially less likely to be admitted or subsequently readmitted than those seen by less experienced doctors. 28 More recent research showed that early physician involvement reduced the time spent by patients in ED beds. 29 Physician screening of less urgent cases, and early initiation of care for more complex patients, were associated with reduced treatment and discharge times. 30

Compared with middle-grade and junior doctors, ED consultants admitted significantly fewer patients, referred fewer patients to clinics and had a faster patient turnaround time. 31 A variation of the ‘senior first’ model was a combined doctor–nurse early triage system that expedited medical assessment and discharge from an ED. 32 An observational study found that inpatient admissions were reduced by 12% and admissions to an acute medical assessment unit were reduced by 21% following early review by a senior clinician. 33

In December 2010, the Royal College of Emergency Medicine introduced a clinical standard relating to consultant review of high-risk patients. 34 This concept was adopted by the UK Department of Health as a key quality indicator for emergency care. 6 The Royal College of Emergency Medicine also highlighted the need for consultant expansion if capacity were to match demand for 24/7 access. 35 The Royal College of Emergency Medicine also argued against ‘gate-keeper’ functions and emphasised that early senior input was essential to control crowding. 17 However, most studies on the involvement of senior staff in emergency medicine have adopted a quantitative approach, have been based on relatively small samples and have not explored the experiences of patients and staff.

Reconfiguring hospital emergency care

The debate about how best to configure emergency medical care, and for which patients hospital admission is appropriate, is part of a wider dilemma between ‘senior/specialist first’ and ‘stepped care’ throughout the NHS. Several care configurations have been explored in attempts to reduce ED congestion. The presence in EDs of general practitioners (GPs) focusing on patients with primary care needs was found to reduce costs of emergency care. 36 A review by Carson et al. 37 found fewer referrals for admissions when GPs worked in EDs than with standard care. In another study, a hospital-based acute GP-led service, designed to provide support to community GPs, was found to modestly reduce numbers of GP admissions to the MAU, although the overall number of GP admissions to hospital wards was not necessarily reduced. 38

There was some evidence that specifically targeted measures might reduce inappropriate admissions of certain patient groups. A recent report highlighted the needs of elderly patients, emphasising better community-based services with rapid access, and improved recognition of problems such as confusion, falls, polypharmacy and safeguarding issues. It was suggested that greater use of care of the elderly liaison services in MAUs might increase the proportion of older people who could be managed in a community setting. The commissioning of evidence-based integrated health and social care was seen as essential. 39 A triage and early treatment system for elderly patients in London appeared to reduce avoidable acute hospital admissions. 40

There was much interest in reconfiguring the management of ambulatory care-sensitive conditions to reduce unnecessary admissions. A group of 19 common conditions, accounting for about one in six of all acute admissions, was considered suitable for medical management outside hospital,41 although it was acknowledged that concomitant social factors also had to be addressed. The related issue of avoiding unnecessary admission of people with chronic conditions was also recognised,42 together with evidence to support various interventions that could reduce unnecessary admissions. 43 Many acute hospitals have prioritised the identification and treatment of ambulatory care-sensitive conditions in order to avoid admission, as recently reported from Plymouth. 44

In summary, the literature pointed to potential advantages in reconfiguring various aspects of emergency care. There were possible disadvantages in terms of deployment costs and loss of training opportunities associated with having experienced practitioners at the front line. Given the lack of evidence in this area, there was a need to understand the benefits and disadvantages of different configurations.

Decision-making in acute medical admissions

Although decision-making is pivotal to admission and discharge planning, much remains to be understood about this process. The diversity of system and clinical practices that underpin decision-making during a patient’s journey through emergency care was noted by Lattimer et al. ,45 who studied this subject from the workforce perspective. The patient journey started with help-seeking in the community and initial contact with a professional either in the community or at the hospital ‘front door’. The scenarios and styles of decision-making were variable, ranging from entirely medical ‘paternalistic’ decision-making – particularly in medical emergency situations46 – through to more complex situations where there could be several options in which decision-making was shared between professionals, or between professionals and patients. Skill mixing involving other types of professionals might also enhance the speed and quality of decision-making in EDs, although Lattimer et al. 45 considered that further research was required on this subject. In support of this idea, however, non-medical emergency care practitioners (ECPs) were found to be able to deliver care to a similar standard to that offered by medical practitioners. 47

A priori, it was expected that decision-making would be broadly influenced by patient, practitioner and organisational factors, and that outcomes would be affected by individual beliefs, attitudes and expectations, personal resources and functioning, specific illnesses and comorbidity. 48 Domestic resources and the wishes and interventions of family members and carers could also be relevant. Research examining patients’ views of hospital admissions found that 70% of patients specified possible alternatives. 49 Professional factors included the experience, attitudes and beliefs of doctors. 50 Hensher et al. 51 examined decisions made about alternatives to hospital care, finding that consultants often chose hospital admission and were more likely than GPs to state that there was no alternative to this. A recent study considered why patients with primary care problems – often with long-term conditions – called for ambulances, and concluded that poor knowledge of alternatives, anxieties of carers and attitudes to risk were some of the factors that channelled people unnecessarily towards secondary care. 52

Organisational factors – including commissioning and monitoring arrangements, the model for admissions pathways and the governance and culture of organisations, as well as the wider health and social care system, including the availability of community-based care – could all contribute to the likelihood of hospital admission. Attention to these factors could also help to ensure provision of timely, appropriate and high-quality care. In summary, greater clarity is needed to understand the variations in, and influences on, decision-making in acute admission settings.

Contribution of the study

The aim of this study was to examine the patient journey, from initial help-seeking through to the consequences of the admission decision, in four hospital settings spanning novel and traditional approaches, focusing on research questions (RQs) informed by the above-mentioned evidence. The decision to admit or not to admit was the focal point of the 3A study. The study aimed not to test one approach against another, but rather to explore models developed in South-West England.

This literature review confirmed a paucity of evidence about the patient journey through the acute admission process, and about organisational and professional factors that contribute to individual decisions to admit or to discharge. A review by Nairn et al. 53 identified a range of patients’ concerns in emergency care including waiting times, communication, cultural aspects of care, treatment of pain and the care environment. However, that review did not examine how these concerns affected decision-making.

During the course of the study, new publications emerged in all the areas discussed above. Clinical practice has been influenced by a combination of ‘top-down’ and ‘bottom-up’ initiatives that aim to manage fluctuating demand in a capacity-limited system, maintain patient flow and ensure safety. As highlighted by the 2013 King’s Fund report on patient-centred leadership,54 in the wake of the 2013 Francis report55 there is a need for the NHS to embrace a primary focus on patient care and experience. The Royal College of Physicians’ report Future Hospital: Caring for Medical Patients56 emphasised many related themes including early specialist care when needed, multidisciplinary evaluation that meets the needs of all patients, including the elderly, and the need for improved communication at the community–hospital interface. However, the patient voice has been largely absent from this literature.

As is apparent from the literature review, the patient voice and the experience of patients and practitioners, have been largely absent from previous research on EDs. However, there is growing acknowledgement of the centrality of patient experience for the NHS, and of the need to consider practitioner experience and system design in planning and policy. We therefore undertook a mixed-methods study of patients’ journeys through emergency medicine departments at four acute hospitals with contrasting models of care. In 3A, journeys are captured from the perspectives of patients, carers and practitioners, and set in the context of the resources available in these emergency medical units. The study interprets decision-making in acute admissions by synthesising these streams of evidence and examining them through the lens of realist evaluation.

Chapter 2 Study design and methodology

Overall design

The project used a case study design, drawing on both qualitative and quantitative methods, for an analysis of service design and practitioner deployment on decision-making about admissions in four acute admission sites in South West England. The study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Services and Delivery Research programme as part of a call for new research into the factors affecting emergency medical admissions to hospital (project reference number 10/1010/06) and ethical permission was obtained (Integrated Research Application System reference number 98931, Research Ethics Committee reference number 12/SW/0173).

The primary research comprised two main parts, with qualitative and quantitative phases of research on each site:

-

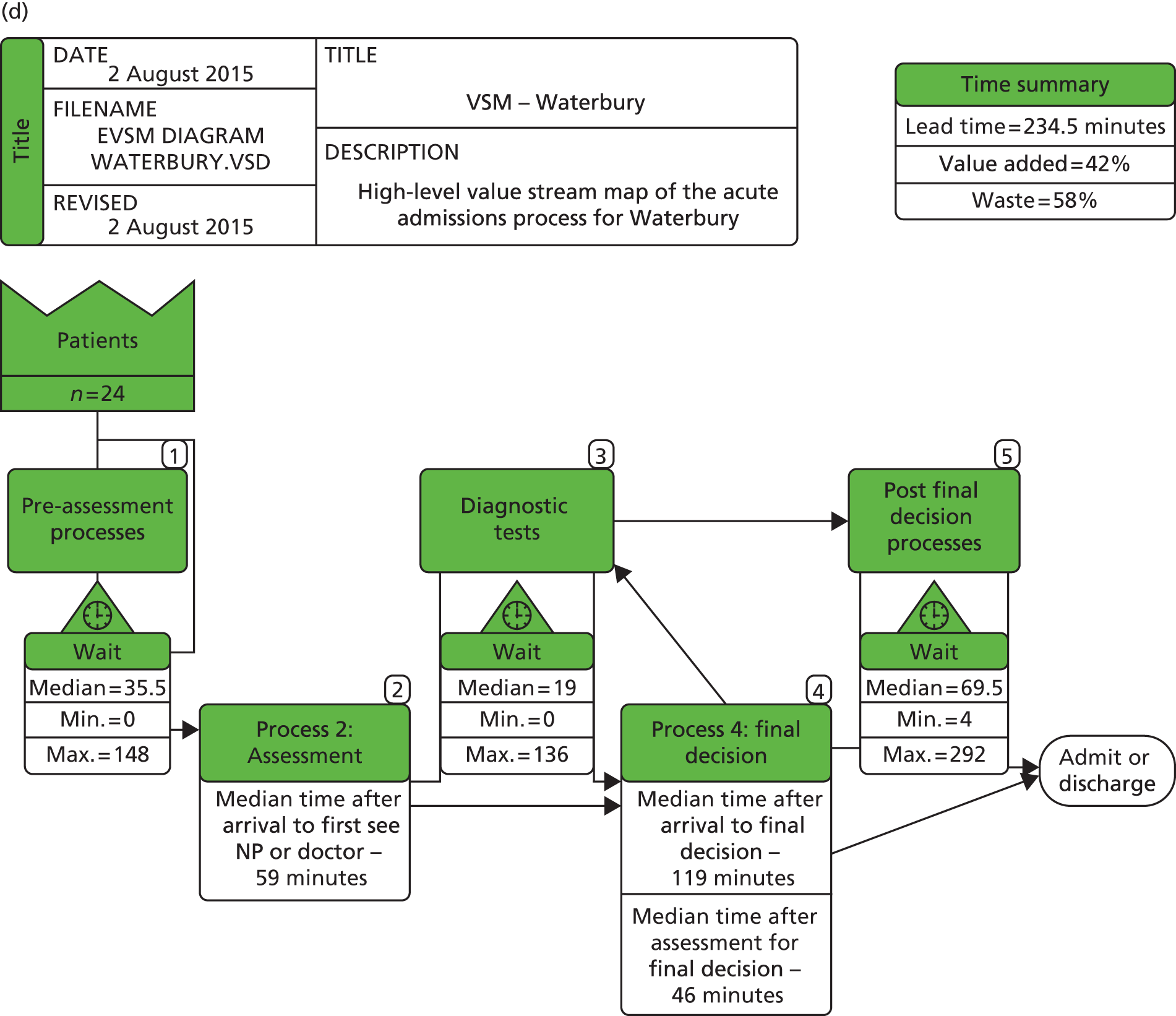

value stream mapping (VSM), to measure time spent on key events in patient pathways, with an embedded study of cost

-

ethnography with participant observation and semistructured interviews, incorporating observation of patient journeys, a selection of which were written up as ethnographic patient case studies.

We also gathered data and received support with interpretation through the involvement of patients and carers, and of managers and practitioners in clinical learning sets, clinical panels (see Appendix 2), and mid-project (see Appendix 3) and end-of-project workshops.

Members of the project’s PPI group, which had a total of 14 lay members, participated in four half-day workshops during the course of the project. In two of the workshops, participants analysed qualitative interview data and a selection of ethnographic patient case studies. Some PPI group members also participated in stakeholder discussions in the mid-term and end-of-project workshops, and in the two clinical panels that examined ethnographic and VSM patient case study material (see Appendix 12). PPI contributions to the project are further detailed in Appendices 4 and 5.

Managers and practitioners from the four research sites joined researchers in learning sets moderated by an experienced action-learning facilitator. The learning sets’ objectives were to channel professionals’ input to the project, enable the exchange of experiences, interpret some study data, validate emerging findings and identify actions that could address some of the problems encountered in the research. A total of 35 learning set members participated in one cross-site meeting, four site-specific meetings, and the mid-term and end-of-project stakeholder workshops. Learning set participants’ common themes, questions to the project and ‘burning issues’ are detailed in Appendix 6.

Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) data and documents from each site were used to describe the contexts in which decisions were made.

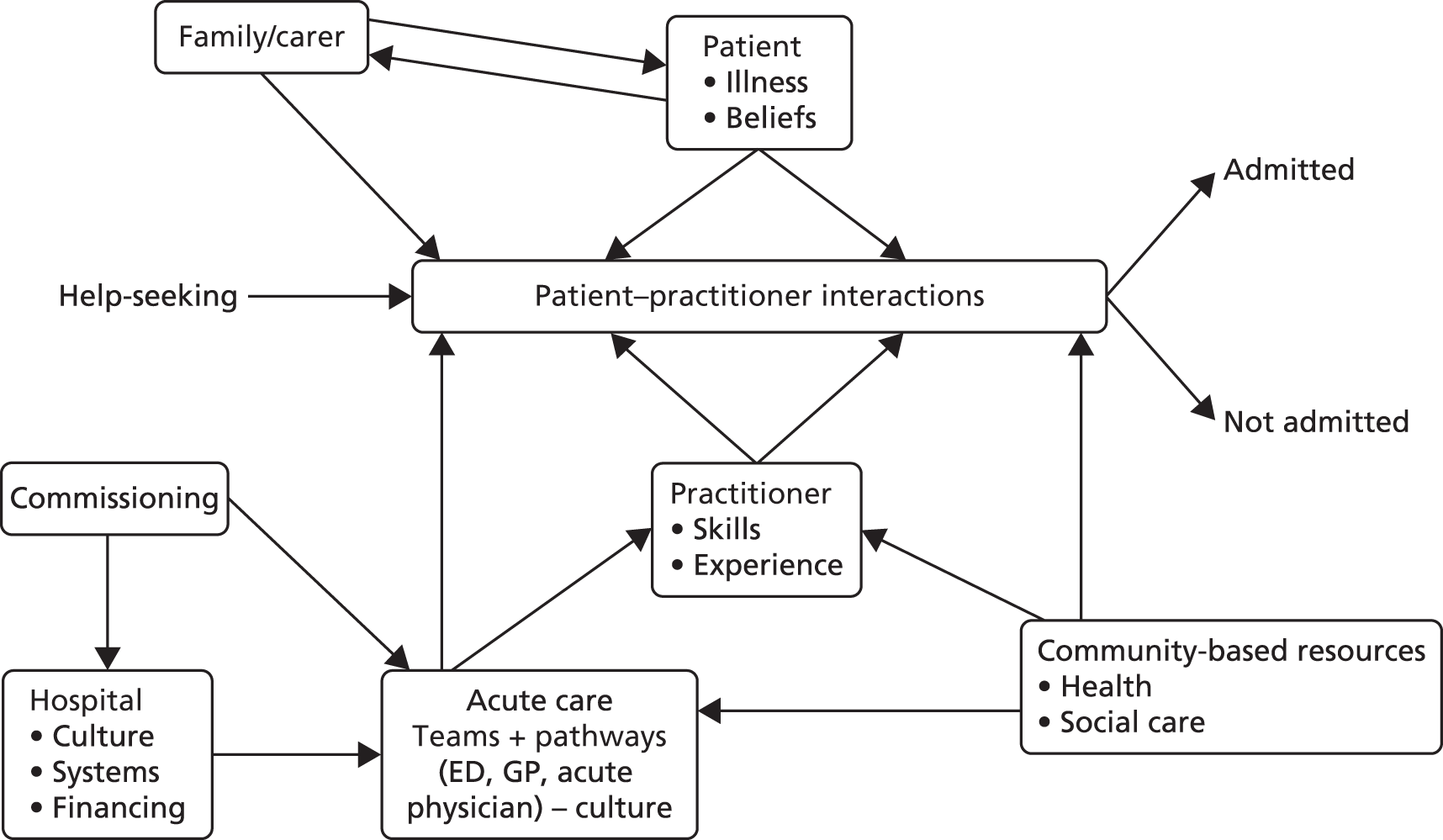

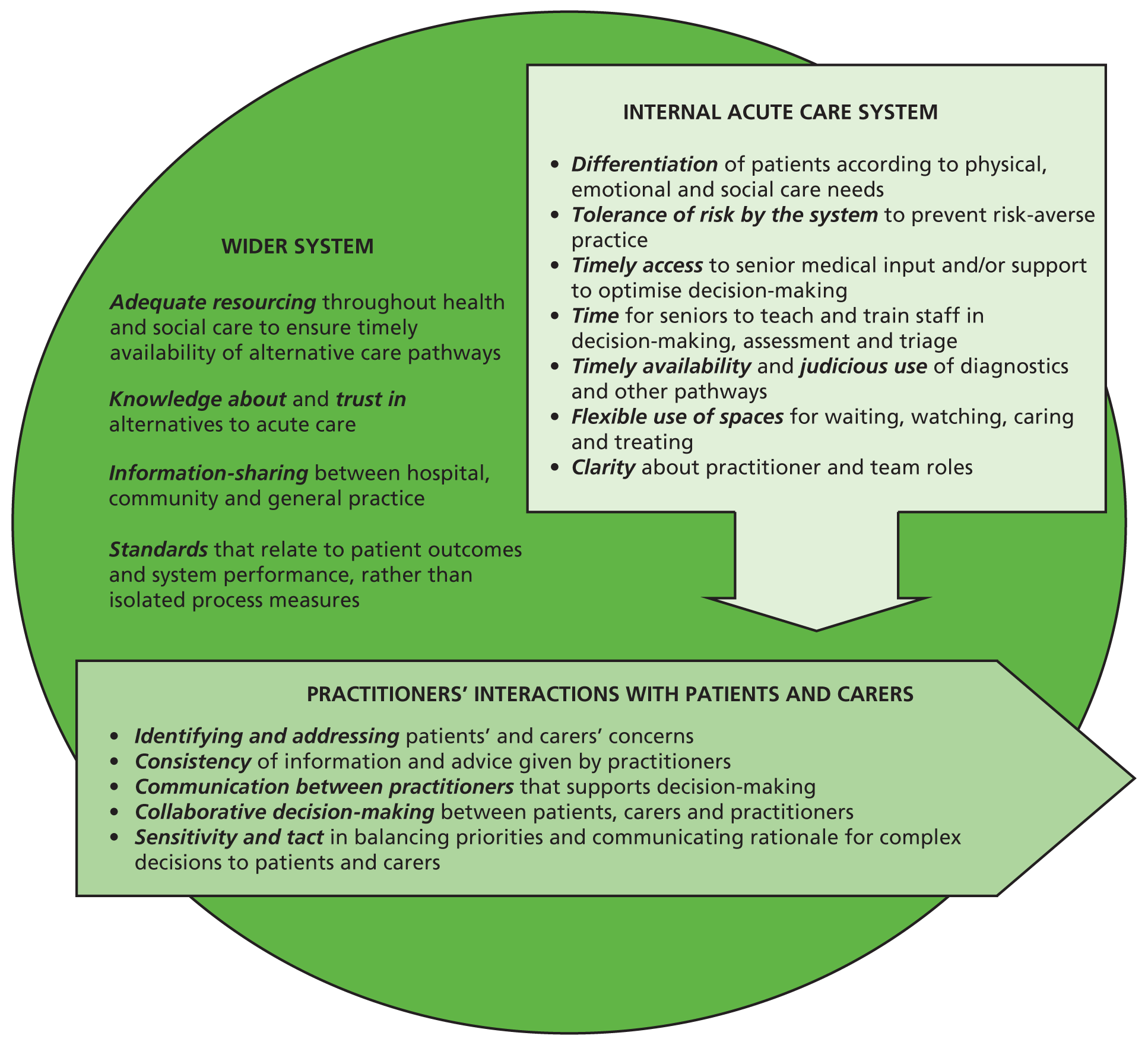

Critical realist evaluation57 was used as an overarching conceptual framework for the study and formed the basis of the method used to synthesise the different data streams and develop best-practice models. Figure 1 depicts the domains of influence on admission decisions that were brought together in the synthesis.

FIGURE 1.

A conceptual map of the influences on acute admission decisions.

Methodology and conceptual/theoretical framework

To achieve the project’s objectives, which were descriptive and exploratory in an area of care that has, to date, received little detailed attention, we selected a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods. We conceptualised each research site as a ‘case’, as set out in Stake’s typology,58 in which the collective case study aims to examine a number of cases in combination, to gain deeper understanding about a more general phenomenon. The idea of this type of study is to select varied cases (our four hospital sites) that are not necessarily representative of a wider pattern, but that show a certain balance and offer opportunities for comparison and learning.

In addition, in the VSM study and synthesis, we compared how components of the four services affected decision-making. Full individual case study analyses were not carried out and we did not aim to identify any one of the cases as having a superior model. The synthesis was concerned with understanding how best to achieve the key outcomes we identified: (1) appropriate admissions, (2) safe discharges and (3) improved patient experience. The synthesis generated a set of principles incorporating statements about how elements of a model of acute care can contribute to these outcomes. It did not aim to determine or quantify actual impact.

We conceived the decision-making process as occurring over some hours, involving practitioners from different teams and potentially a number of settings. While we sought to understand the influences on decision-making, we were aware that it would not be feasible to derive quantitative estimates for the effects of causal factors involving many individuals, teams and locations. We therefore selected methods that could enable in-depth analysis of decision-making alongside a broader investigation of the various influences.

We selected VSM, as a ‘Lean thinking’ method, which has been adapted for use in health services to study the timing and perceived value (or waste) incurred by different procedures and inputs throughout a pathway (see Appendix 7).

Ethnography has been used in many studies of health services. 59,60 It combines researcher observation and interviewing, and provides a flexible means of taking both a wide view on potential influences and a detailed picture of interactions between practitioners, patients and carers. In the qualitative phase of each hospital case study we used an ethnographic approach, incorporating fully participant observation and detailed fieldnotes, based on the epistemological understanding that:

-

the researcher is the primary instrument for generating (rather than ‘collecting’) data

-

the researcher’s identity and presence necessarily affect the process of generating data in interaction with study participants

-

participants’ awareness of the researchers’ presence and the study’s agenda can lead them to enact models of behaviour that exemplify values and practices they deem to be more publicly acceptable, but that nonetheless generate valuable study data.

In accordance with this interpretive approach, researchers pursued rigour from the outset of the study by doing preparatory work, individually and as a team, on our preconceived notions about the study theme and our expectations about fieldwork. We used reflexivity in team discussions throughout the study as a tool to minimise the effects of personal bias on selection of participants and ongoing analysis of data. Other aspects of rigour will be covered in Analysis of ethnographic data.

Ethnography is commonly associated with a constructivist stance but it has also been used in critical realist studies. 61 The critical realist framework allowed us to consider the admissions process as being influenced causally at two levels: that of the opportunities and resources available to practitioners within acute care settings, and that of interactions linking practitioners, patients and family members.

Mixed methods

We conducted the VSM and ethnography components separately, although each influenced the other, and both contributed to answering RQs 1–3 (see Chapter 1, Research questions). The ethnography was carried out during the first half of the project and informed the planning of the VSM study. Integration of VSM fieldwork and ethnographic analysis was promoted through regular meetings of both teams, and through researchers’ day-to-day input to an electronically shared file with notes on field observations. Findings from these and other project components were used to generate hypotheses about causation in acute admission decisions during the project and as part of the final synthesis. Initial analysis of the VSM data led to further analysis of the ethnographic data. To provide continuity following the site descriptions (see Chapter 3), the VSM study (see Chapter 4) precedes the ethnographic chapters (see Chapters 5 and 6), which are exploratory in nature. The synthesis of findings (see Chapter 7) makes some tentative hypotheses about how emergency care could best be provided, answering RQ 4 (see Chapter 1, Research questions).

Patients and carers

A PPI group (see Appendices 4 and 5), whose members had experience of acute admissions, worked with the team on the approach to obtaining informed consent, design of research instruments, interpretation of ethnographic data and patient case studies, and construction of value stream maps.

Managers and practitioners

On each study site, a lead practitioner or manager – who changed over time in two sites – was the main link with the project. A cross-site learning set was developed to enable practitioners, managers and researchers to discuss lessons learned about the acute admission process. Findings from both study phases were discussed for each site in the learning sets (see Appendix 6).

In the mid-project stakeholder workshop (January 2014), a total of 29 patients, carers, clinicians, managers and researchers (study team and external invitees) reflected on the initial analyses in relation to their experiences. In the final stakeholder workshop (November 2014), a similarly conformed group of 27 participants contributed to the synthesis by working together to identify mechanisms influencing acute admissions within and across sites.

Ethical and governance arrangements

Ethical permission was granted by National Research Ethics Service Committee South West – Cornwall & Plymouth, on 22 June 2012. The study steering group of nine members (see Appendix 8) was convened on five occasions. Changes to the protocol as agreed with NIHR are detailed in Appendix 9.

Study sites

Site selection was purposive. Three sites had already adopted innovative ways of providing input from experienced clinicians (including GPs, and emergency medicine and acute physicians) early in the patient pathway. The fourth site followed a more traditional model, but all four sites introduced changes during the course of the study. Quantitative considerations in sampling included numbers of new ED attendances, admissions via EDs and hospital acute beds, and percentages of bed occupancy (see Table 4 and Chapter 3, Hospital Episode Statistics). All the sites approached agreed to participate.

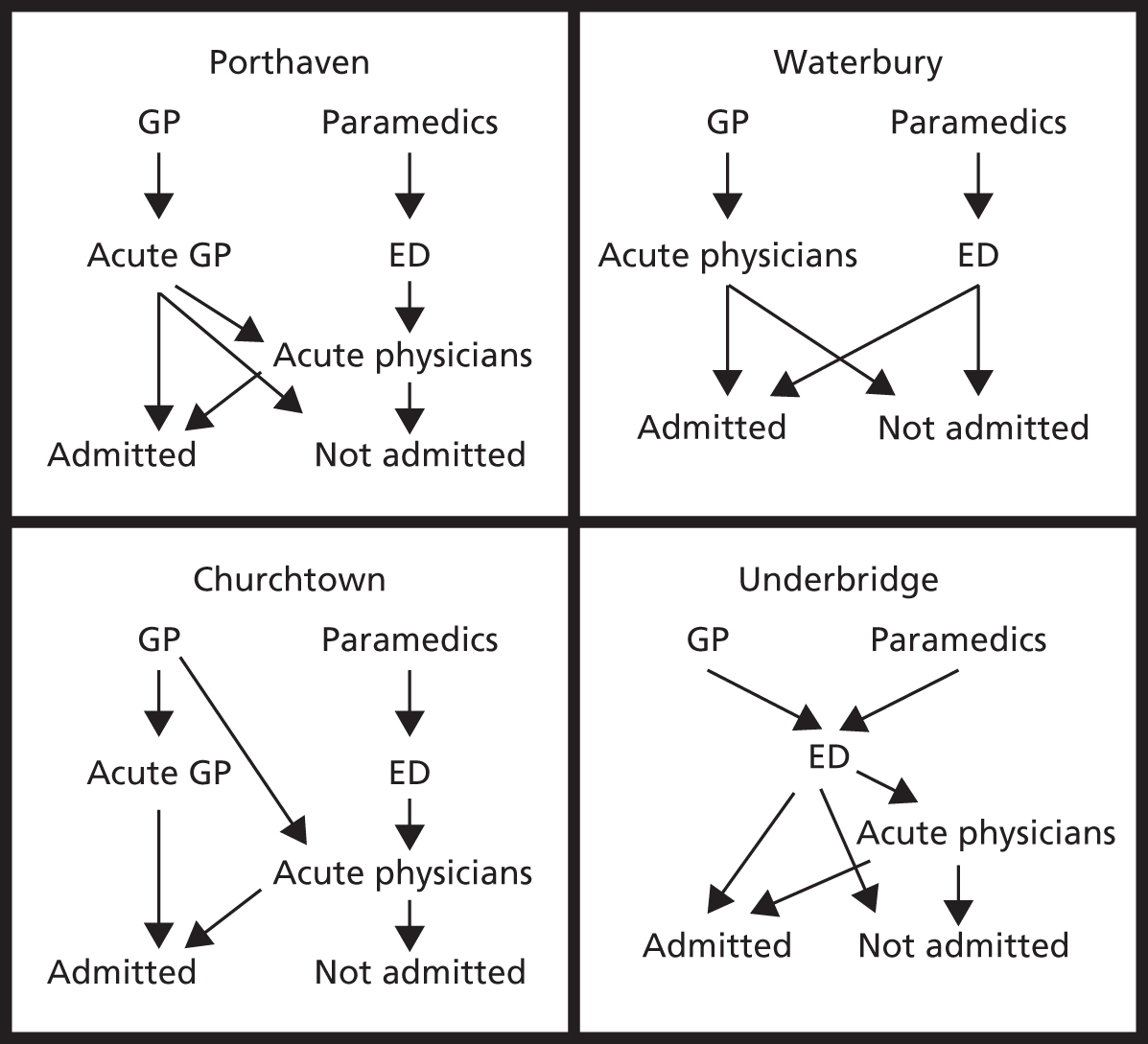

The four sites, for which we use pseudonyms in this report (anonymisation details below), represented different models of acute care. Porthaven and Churchtown offered an alternative acute route into the hospital in addition to their EDs: both had medical assessment units, and in Porthaven an acute GP service (AGPS) operated in peak hours. Underbridge accepted all patients through the ED, where the care model dictated that they should be assessed by ED staff before transfer to a medical team. Waterbury, with a more traditional model, accepted all arrivals through the ED but then used ED staff for medically unexpected patients, and medical team staff for medically expected patients.

Anonymisation and referencing of sites and participants

Study participants recruited at the sites were given unique identifiers for purposes of anonymity and referencing. Each participant included in the study was assigned a unique coded identifier. A simplified version of these identifiers was used to label study participants referred to or quoted in the report; the labels used the site pseudonym and consecutive numbering. Coded identifiers were kept in password-secured files and safe electronic and physical storage.

Clinical panel review used independent numbering systems for patient cases summarised from ethnographic data, in order to guard anonymity of patients and sites. To further protect anonymity, these numbering systems only differentiated between ethnographic patient cases, and did not reference particular sites.

Value stream mapping

Site maps

Site mapping was used to depict the acute access routes into each of the four sites. Preliminary site maps were constructed during the mid-project workshop, with input from participating clinicians.

Study participants

Value stream mapping patient inclusion criteria

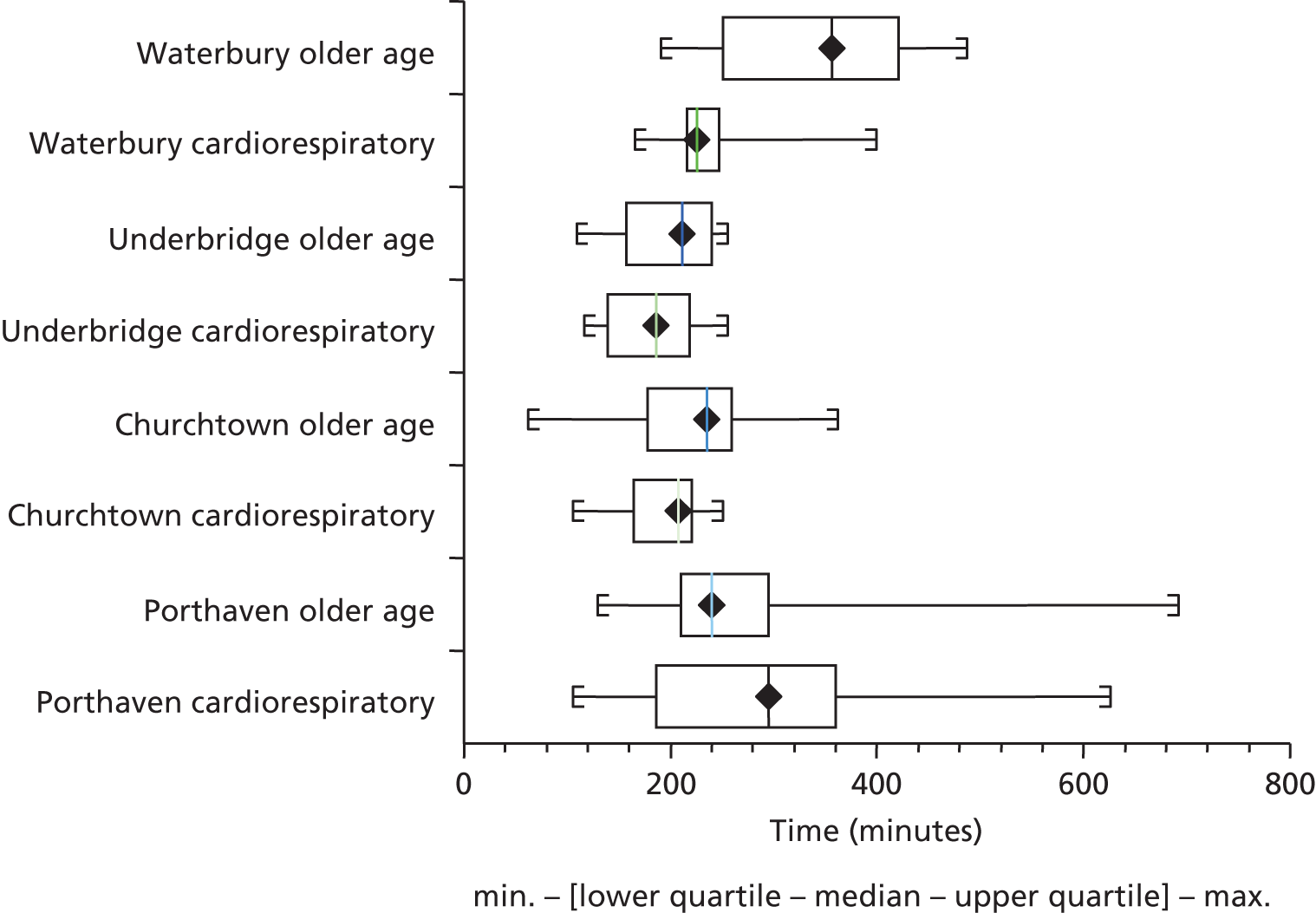

To optimise generalisability, we focused on patients about whom there was known to be uncertainty regarding need for admission on initial assessment. Two groups, for which numbers were predicted to be sufficiently numerous, were defined for the study:

-

cardiorespiratory presentations (excluding those with protocolised admission decisions, such as suspected myocardial infarction)

-

presentations typical of older age, in patients aged 60 years or older (such as acute confusion, falls, incontinence and decreased mobility).

Patients were included from all acute unplanned admissions pathways for adult medical patients. These included EDs, acute medical units (AMUs) and AGPSs. Routes to the hospital (e.g. ambulance, self-presenting, GP referral) were recorded and did not affect the inclusion criteria. To understand the main pathways, we initially aimed for equal numbers of medically expected patients (seen by acute medical teams and acute GPs, as organised by the referring GP) and medically unexpected patients. In Porthaven and Churchtown this meant recruiting in the two separate areas of the hospital housing the EDs and AMUs. Towards the end of data collection there was some targeted sampling of patients to achieve a balanced sample by gender and type of presenting condition (conditions typical of older age vs. cardiorespiratory conditions).

Approach and consent

Study participants were selected opportunistically and consecutively from the time the researchers arrived in the department. Hospital staff were asked to identify patients for whom it was unclear whether they would be admitted or discharged, and who were likely to meet the inclusion criteria.

Staff then consulted the patients about the potential for their involvement in the study. If their cases appeared appropriate and they agreed, staff introduced each patient to the researcher, who explained the study and discussed the possibility of their involvement. In a few cases patients were approached directly by researchers because staff were unavailable for introductions. Patients were included if they were willing and able to give consent.

Participant characteristics

Data collection for phase II of the project, the VSM study, began in April 2014 with a team of four researchers including an academic GP. In total, 108 patient cases were collected, as described in Chapter 4.

Data on the patient journey

The direct observation of the process involved:

-

observation of what was happening (or not happening) to the patient at every step

-

assessment of the process from the perspective of the patients and practitioners involved.

The VSM method was adapted for this project to provide additional data for key liaison activities (e.g. nurses discussing patients with doctors or providing treatment, juniors gaining advice from seniors). These data were gained from direct observation of staff and debriefing with key staff.

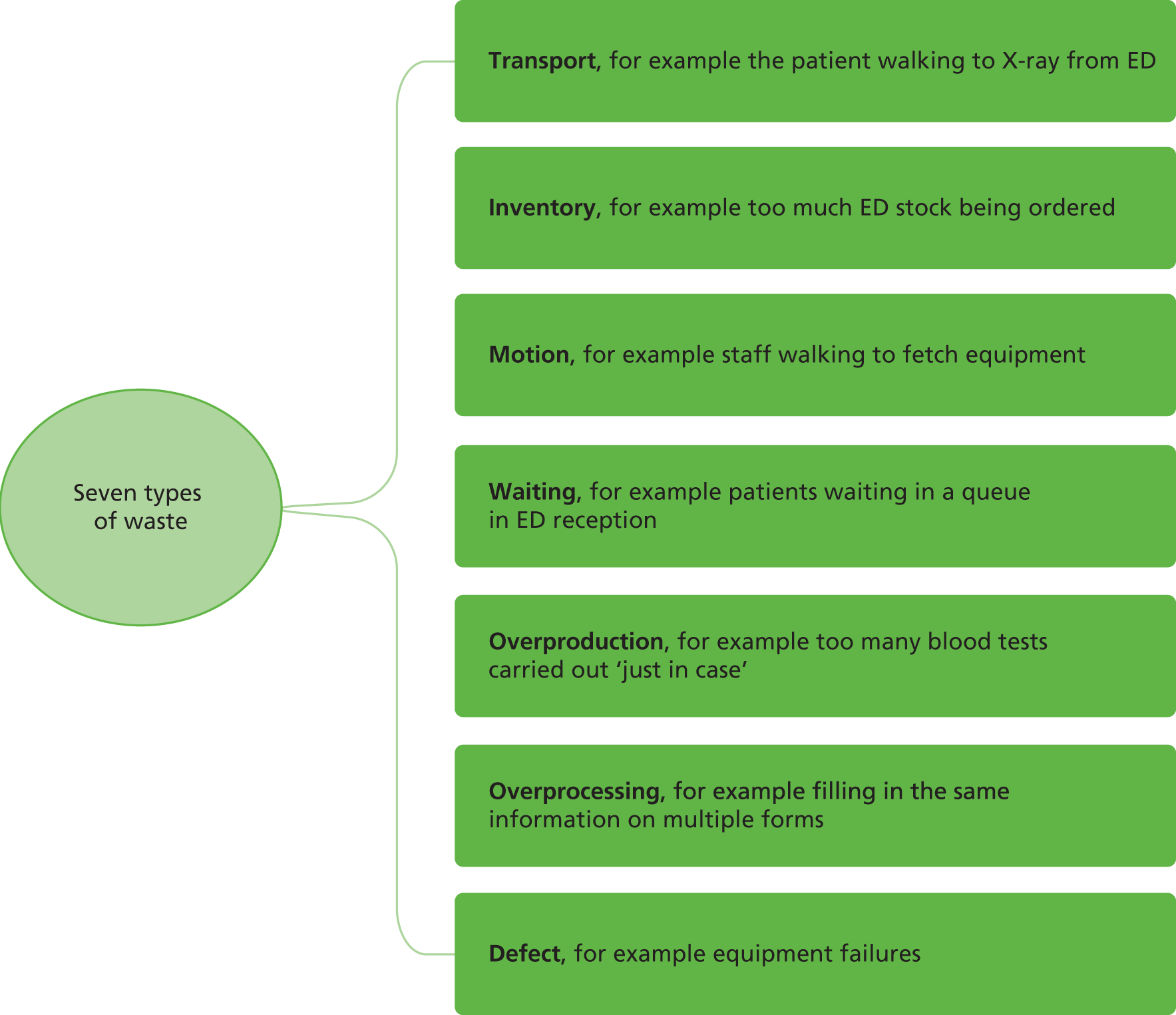

The details of each journey through acute care were recorded minute by minute, using the iPhone ‘HoursTracker’ application (Cribasoft LLC, Round Rock, TX, USA). The mapping process captured the seniority and number of medical staff involved in care, waiting times and diagnostic tests. The waste categories (such as transportation or looking for staff), and Lean values identified by Ohno,62 were applied by the researchers based on their interactions with patients and practitioners, in which they elicited views on the value of the care provided.

The ‘assessment of process’ was elicited from the principal clinical practitioner, who decided whether the patient would be admitted or discharged. These individuals were asked to consider, using a Likert scale, to what degree their decision had been affected by colleagues, the patient or his/her carer, availability of alternative care pathways, and additional factors.

This approach allowed us to apply the Lean principle of ‘thinking deeply’ about the problem to quantify and examine only those aspects of care processes that helped us to contrast the models of care at different sites.

The VSM study’s raw data therefore comprised detailed timings of stages of care throughout each patient’s journey, together with clinicians’ ratings of value, opinions on alternative care pathways and reflections upon their own decision-making.

Value stream mapping analysis

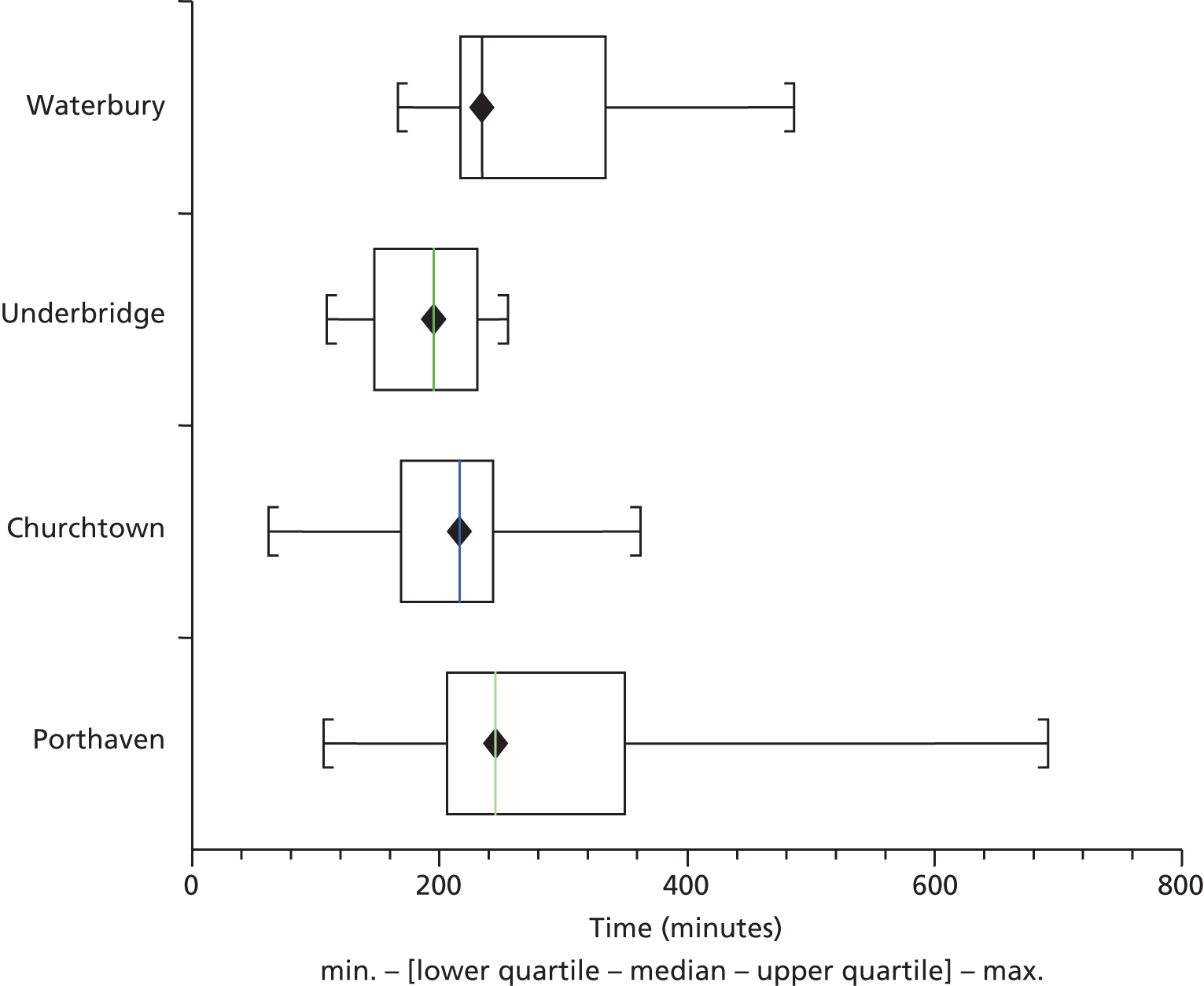

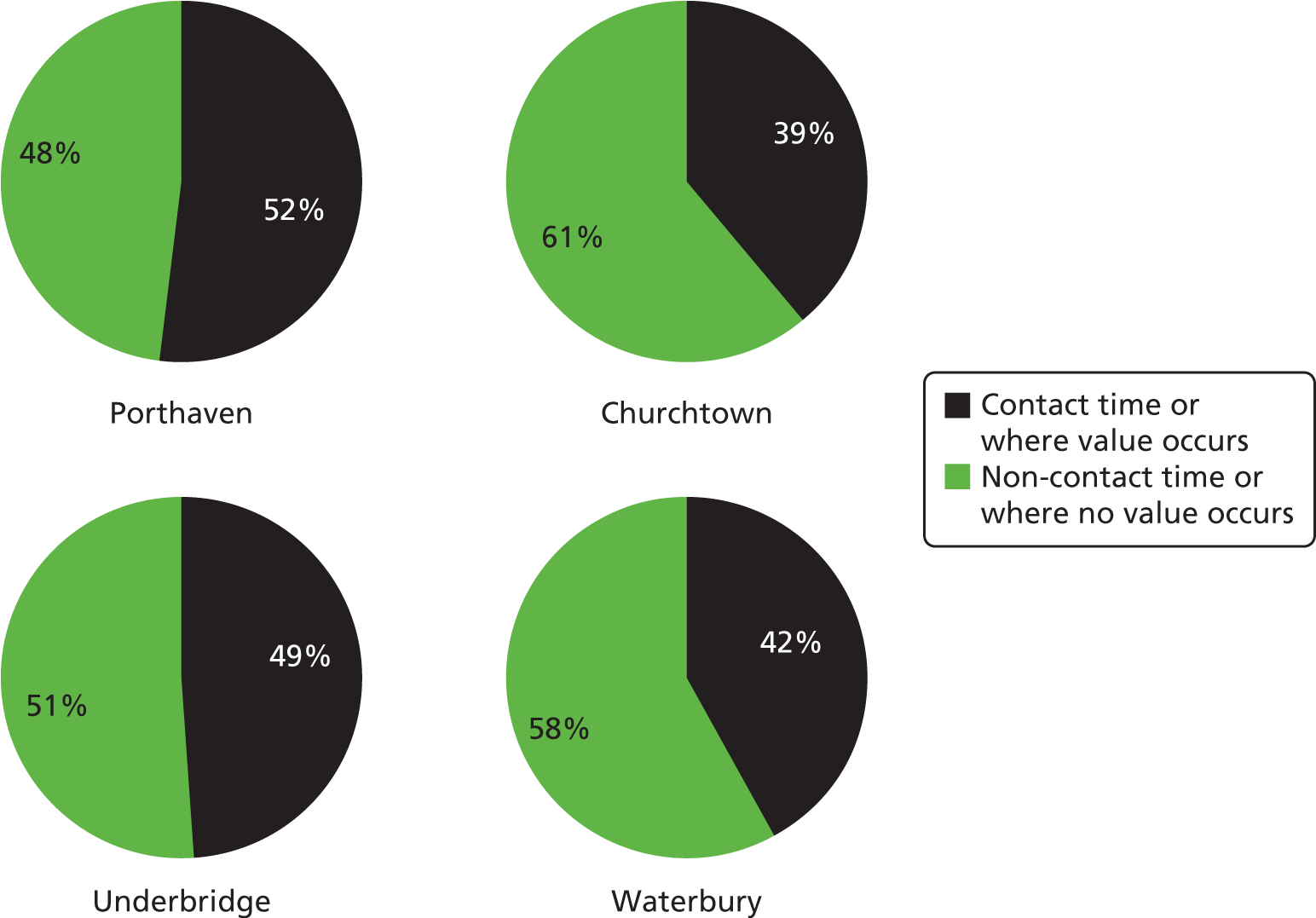

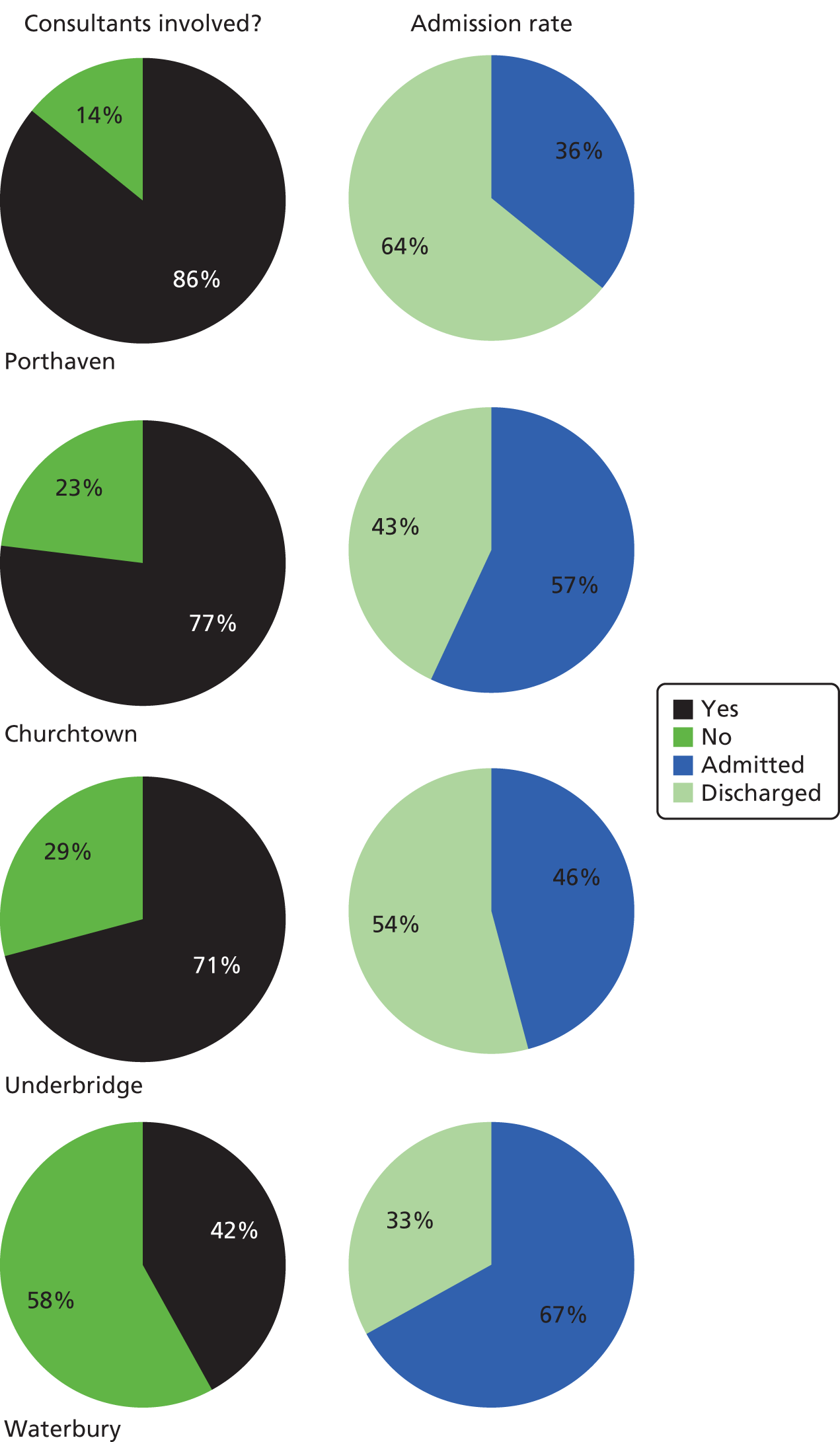

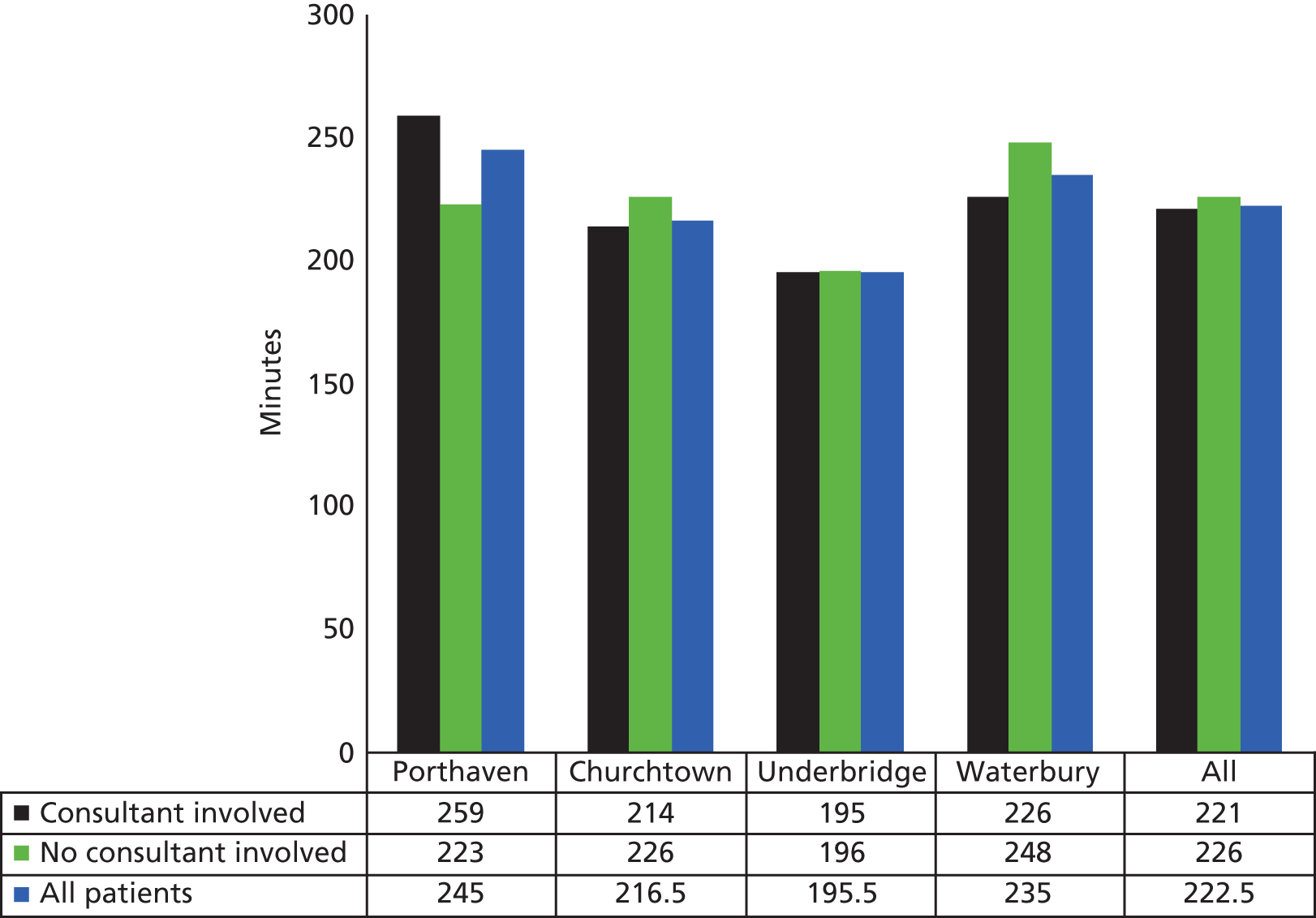

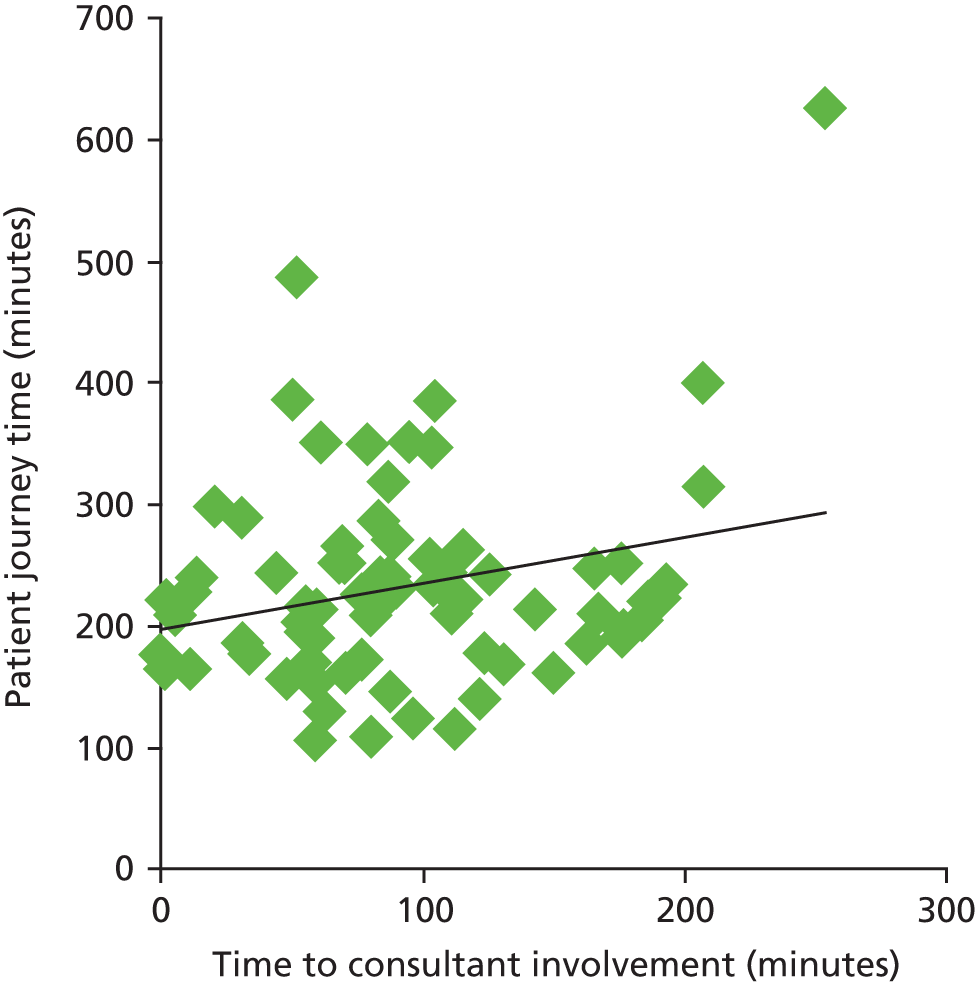

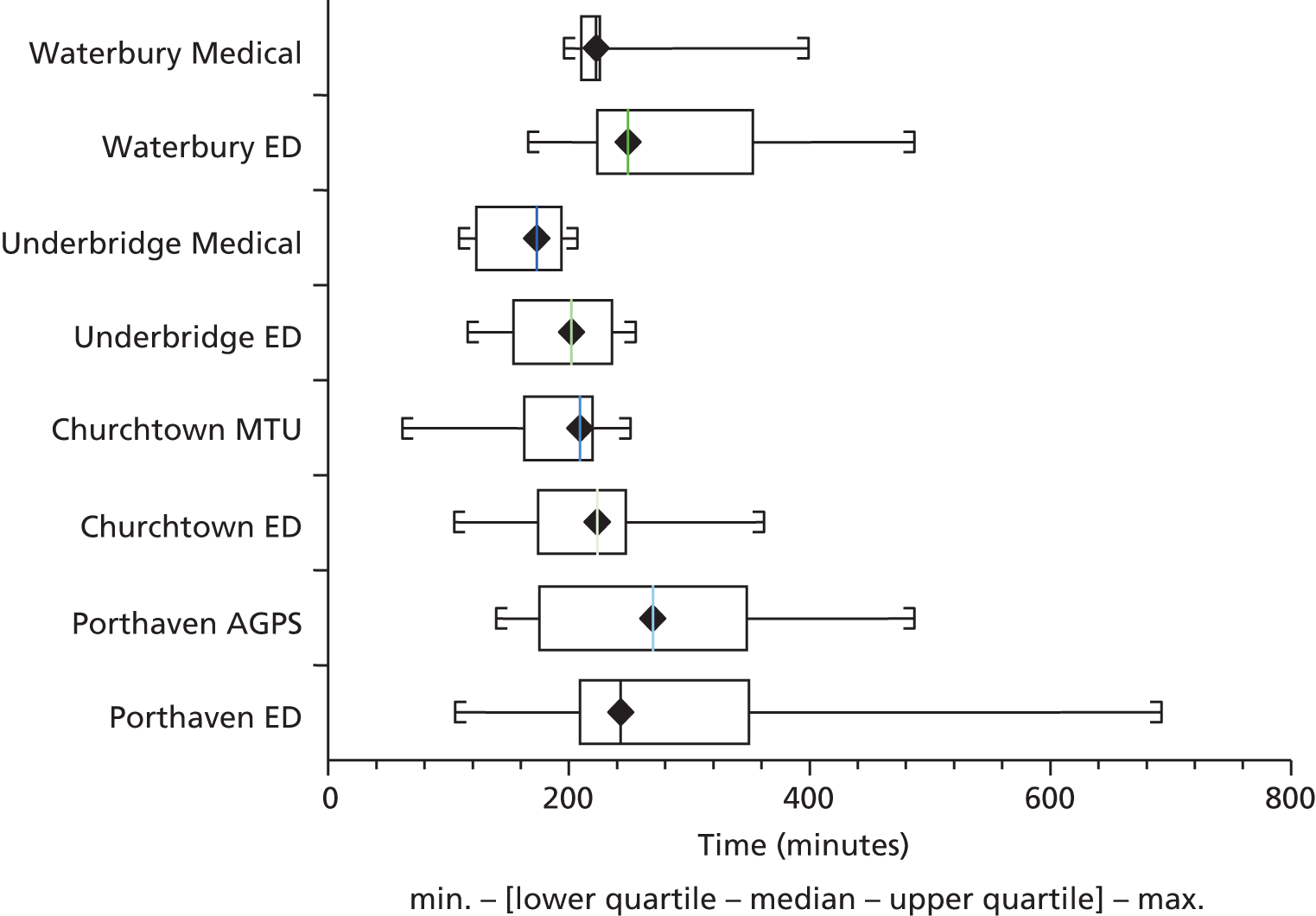

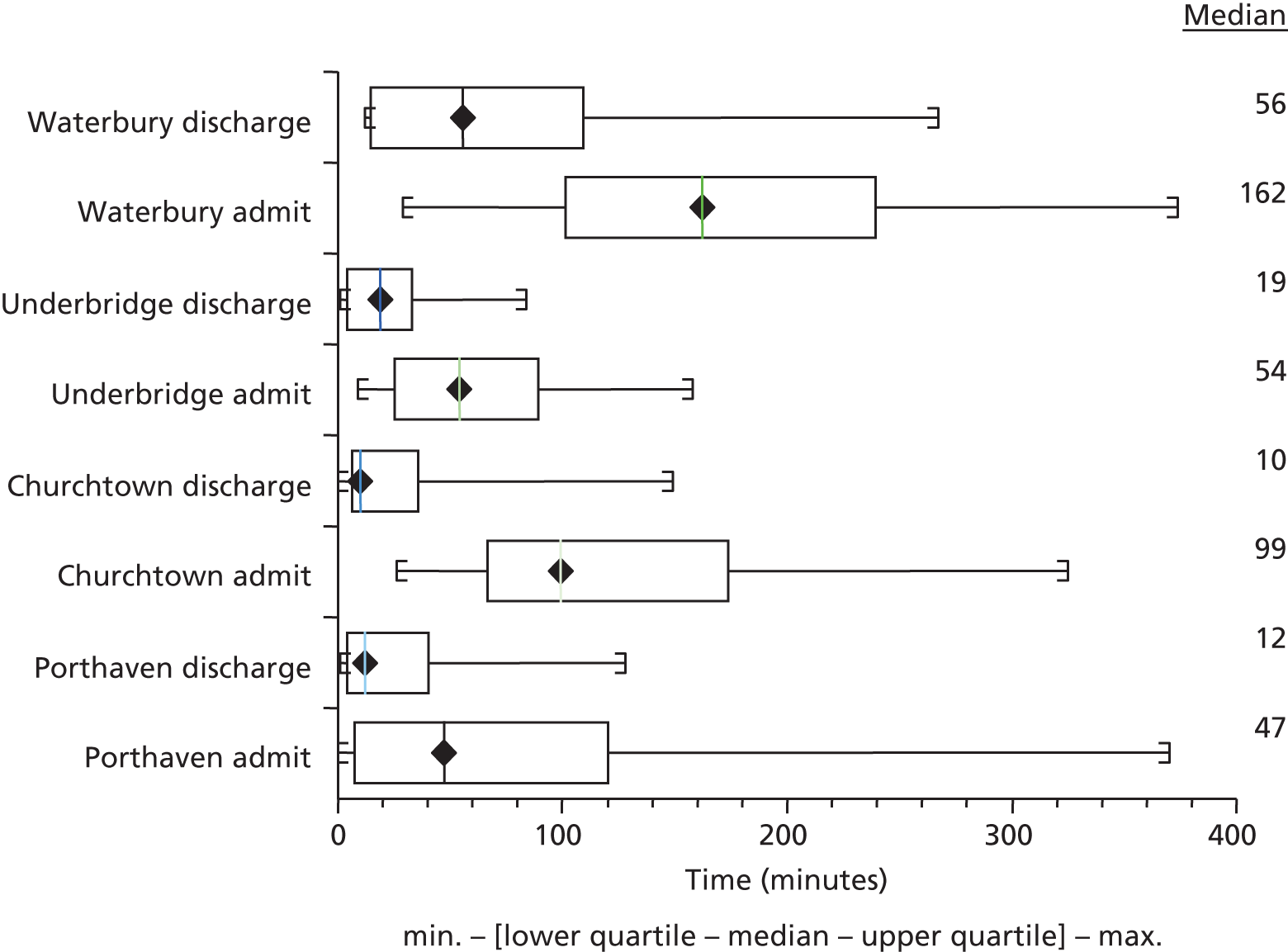

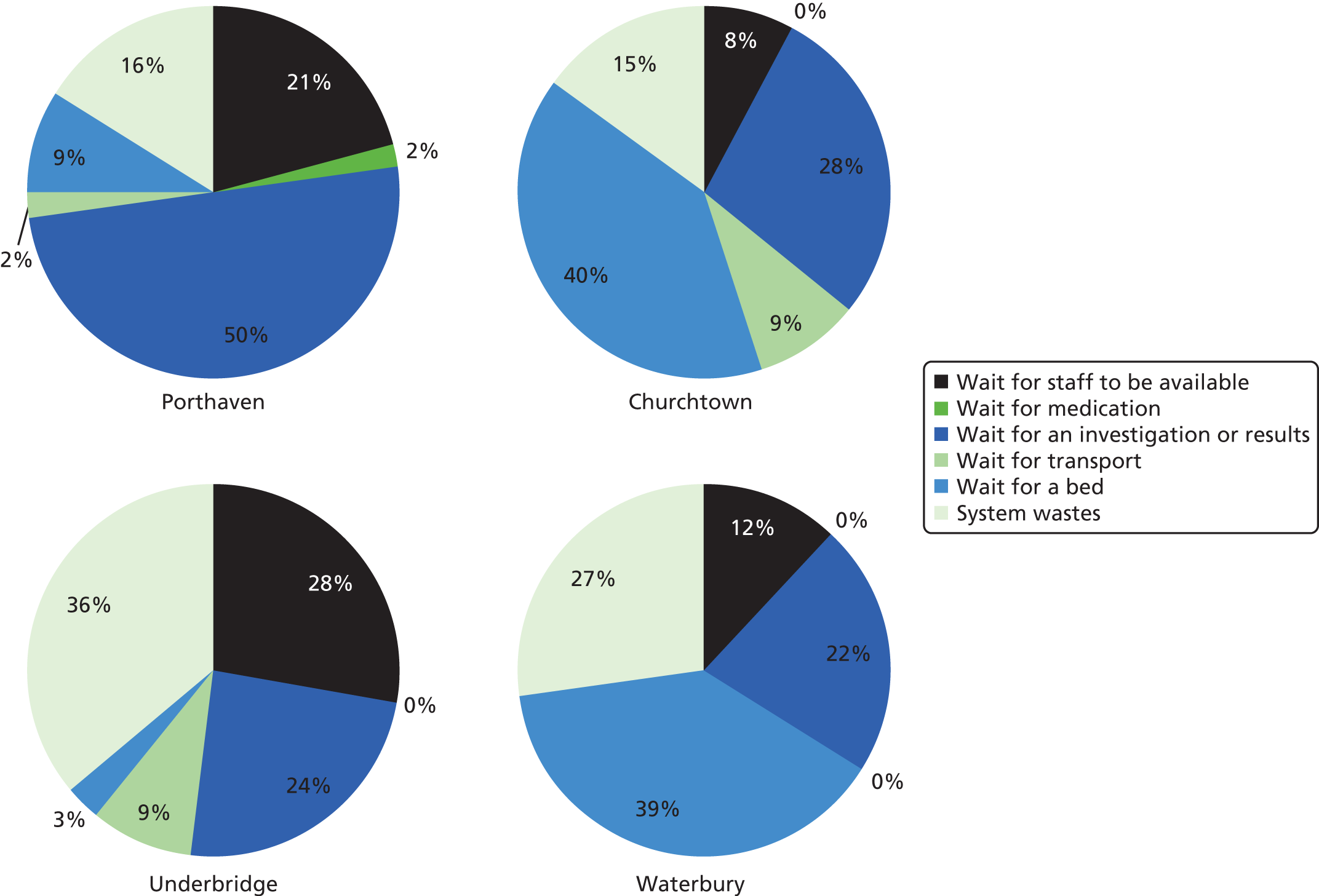

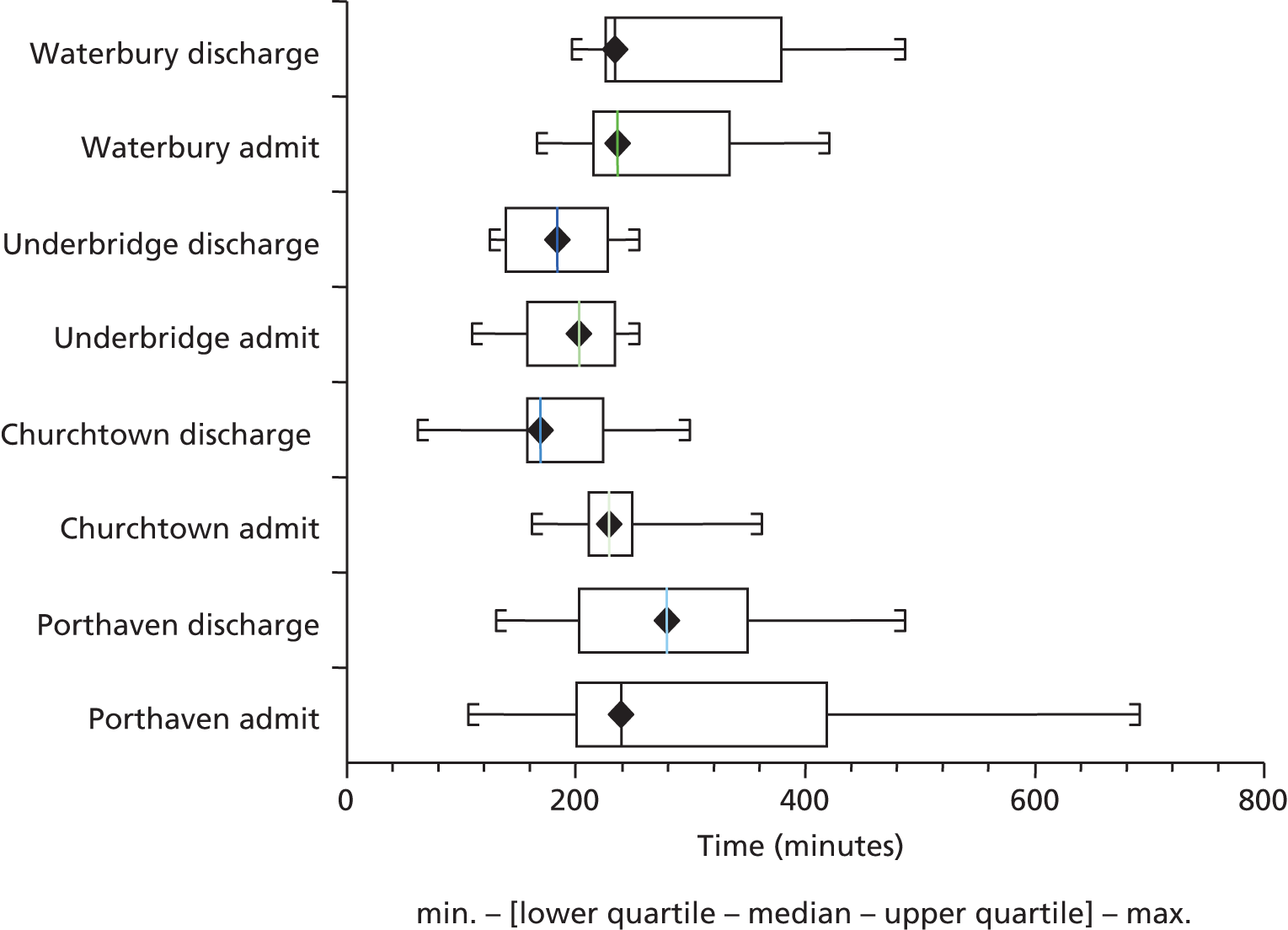

When conducting this analysis, we followed a methodological protocol to quantitatively describe and compare the acute care admissions pathways in the four NHS trusts (RQ 3), including:

-

patient pathway times overall

-

waste-to-value ratio

-

where in the ED process wastes were occurring

-

contrast among the proportions of patients who were admitted, were seen by different practitioners at different times and had investigations, including:

-

proportion of senior involvement

-

proportion of admitted patients

-

time first seen by a doctor

-

differences in patient hospital pathway

-

categorisation of known waits

-

patient pathway time for differing presenting conditions.

-

Economic analysis

We compared resource use and cost implications across the four sites for the core conditions and pathways, mainly through the value stream maps of the sampled patient pathways. Firstly, we compared economic data using data from each site relating to weekly staffing costs (grades and sessions/hours worked), to estimate the overall cost of care. Secondly, we used the data from the value stream maps to estimate how resources from the overall acute care system were reallocated to patients with potentially avoidable admissions. We then assessed the feasibility of estimating the opportunity cost of these resources.

The results of the two levels of cost analysis (hospital-level average costs; per-patient pathway VSM-based opportunity costs) are presented in the form of a ‘cost–consequence analysis’ alongside this provisional evidence of potential productivity differences (i.e. a simple balance sheet approach). Uncertainty and variability in cost estimates have been expressed quantitatively wherever possible (although, given the low number of, and non-randomly sampled, patient pathways for the VSM, these results are inevitably provisional and exploratory).

Ethnographic study

The ethnographic study was designed to generate understanding about influences on admission and discharge decisions, primarily through fully participant observation and semistructured interviews with patients and practitioners. During an initial period of orientation, researchers focused on understanding the ED’s geography, teams, systems and patient pathways; this included some in-depth interviews with managers and practitioners. Subsequently, the researchers collected data by following individual patient journeys.

Practitioners and organisation of services

Approach and consent of practitioners

We designed recruitment of practitioners on each site in conjunction with local collaborators. Flyers with general information about the study were handed out during researcher visits and posted on ward bulletin boards and in meeting rooms. Consent forms were distributed individually and at meetings so that staff had time to read them and decide if they wished to participate. In the case of 41 senior clinicians and managers who were purposively selected to be approached for in-depth interviews, information sheets and consent forms were delivered individually by e-mail or in person, together with a personalised letter. All these seniors gave their consent to be interviewed. The numbers of practitioners who consented to interview at each site is shown in Table 1.

| Site | Practitioners recruited through ethnography (number who gave senior in-depth interviews) | Practitioners recruited through VSM | Total practitioners recruited |

|---|---|---|---|

| A: Porthaven | 58 (11) | 26 | 84 |

| B: Churchtown | 69 (9) | 17 | 86 |

| C: Underbridge | 83 (10) | 39 | 122 |

| D: Waterbury | 72 (11) | 50 | 122 |

| Total | 282 (41) | 132 | 414 |

Semistructured interviews

On each site, 9–11 interviews were conducted with key informants: frontline clinicians (acute care consultants, acute GPs, lead nurses, ED consultants), senior managers and commissioners.

We used purposive sampling to identify individuals who were named by colleagues as experienced in decision-making and influential within the local model of care. Other health workers (including some seniors) were selected on pragmatic grounds to be approached for observation or brief interviews because of their roles in the care of patients who were the focus of ethnographic or VSM patient case studies. The overall strategy, combining purposive and pragmatic sampling, produced a broad sample of professionals that spanned varied staffing levels, types of contract and specialties.

During the set-up period, key informants were identified and topic guides for interviews developed and piloted (see Appendix 10). Interviews with clinicians combined semistructured questions about qualifications and experience of acute care settings, and open questions that explored perceptions about decision-making processes and factors influencing admission avoidance.

Participant observation of organisational processes, team composition and function (research questions 1, 3 and 4)

During set-up, we identified data-rich spaces where acute admission work could be observed. These included EDs, medical assessment and other units, and offices or clinical rooms used by patients and practitioners.

Patient journeys

Case study inclusion and exclusion criteria

Individual cases were selected on the basis of being ‘potentially avoidable’ admissions according to patient presentation. The selection of patients for ethnographic case studies was guided by the following criteria:

-

Cases were to be medical (not clearly surgical, although there was some overlap).

-

Cases were to be ‘uncertain’ enough for a decision to need to be made about whether or not they would be admitted (i.e. not a clear candidate for a predefined care pathway).

-

Patients were excluded if their condition, treatment or cognitive ability was not conducive to being approached by a researcher (e.g. in cases of severe illness, pain, reduced consciousness or states of dementia that did not allow sufficient recall for informed consent).

Sampling

Sampling of patients was both purposive (seeking patients with particular characteristics) and pragmatic (assessing which patients who were present could be suitable and available to participate in the study). We first checked patients who were suggested to us by staff against the inclusion and exclusion criteria listed above. We then enquired about the patient’s condition and treatment needs to avoid causing them any undue or unwanted disturbance. We purposively sought balance in sampling patients with particular types of presenting condition such as chest pain, ‘funny turn’ or collapse, shortness of breath, abdominal pain, and conditions typical of older age. We monitored our evolving sample in an ongoing way to achieve maximum variation in terms of gender, age and ethnicity. Notwithstanding South West England’s predominantly white UK demographic profile, a degree of ethnic diversity was purposively built into the sample on each site to maximise the potential for heterogeneity of patient experience. Pragmatic sampling was used to include relatives and carers who were present when patients were being observed or interviewed.

Approach and consent

Two strategies were used:

-

When researchers arrived for a fieldwork session, they asked co-ordinators and other staff to alert them about patients who might be suitable for case studies.

-

Researchers were guided by their own observations, which led them to identify certain patients as likely participants.

For both strategies, practitioners were asked to act as intermediaries, with the practitioner asking the patient if the researcher could make contact with them. If the patient accepted this initial contact, the researcher provided this patient with an information sheet (also available in large print) and gave further explanation as needed, using language that was comprehensible to that person. If any patients were unable to sign for themselves, relatives or carers could be asked to sign on their behalf.

Participant characteristics

As described in Table 2, 95 patients and carers gave their consent to participate in researcher observations, conversations and interviews. A further seven patients, and one carer, declined consent because they were too distressed or anxious or in too much discomfort to participate, or because they simply did not wish to participate in the study.

| Site | Patients | Gender | Age (years) range (median) | Ethnicity | Relatives and carers | Total participants | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | M | White British | Black and minority ethnic | |||||

| A: Porthaven | 13 | 9 | 4 | 26–92 (69) | 13 | 0 | 8 | 21 |

| B: Churchtown | 10 | 4 | 6 | 31–86 (68.5) | 8 | 2 | 6 | 16 |

| C: Underbridge | 14 | 7 | 7 | 23–89 (65) | 13 | 1 | 5 | 19 |

| D: Waterbury | 28 | 15 | 13 | 23–99 (73) | 24 | 4 | 11 | 39 |

| Total | 65 | 35 | 30 | 23–99 (70) | 58 | 7 | 30 | 95 |

Patient journeys

Ethnographic researchers documented patient journeys by making fieldnotes and holding recorded and non-recorded conversations and informal interviews with patients, carers and staff who had given consent before, during and after assessment and review of the case in question. Researchers made written fieldnotes during participant observation and/or as soon as possible after key events. Fieldnotes included descriptions of people, scenes, dialogues and decision-making processes, as well as personal experiences and reflections. Digital audio-recorders and smartpen recorders with Livescribe software were used to make recordings (Livescribe Echo Smartpen, Oakland, CA).

Transcription

All audio-recorded conversations and interviews were transcribed verbatim and uploaded to an NVivo (Version 10, QSR International Pty Ltd, Warrington, UK) ‘project’, or file used for data coding, which also incorporated researcher fieldnotes.

Analysis of ethnographic data

Coding

A framework approach63 was used to develop researchers’ understanding of key concepts in the study. The initial framework, expressed in the RQs, was based on the study proposal’s literature review. This was progressively adjusted in the light of findings that served to interrogate concepts that had formed part of the proposal, for example: How is an admission defined? Who is a senior? What meanings are given to patient waiting times?

We used two main elements from the framework approach:

-

The construction of a thematic tree that brought together categories from the project’s initial RQs, and categories that were inductively informed by coding of the initial field data. This is evidenced in Appendix 11, showing the final list of NVivo categories we used to code the ethnographic data.

-

Matrices that researchers constructed to tabulate data excerpts from specific NVivo nodes, ordered by research site, under headings referring to contexts, mechanisms and outcomes. We shared these in research team meetings and used them to elaborate context, mechanism and outcome configurations and analytical statements.

The body of data coded using NVivo 9 and included in the framework analysis consisted of ethnographic fieldnotes, interview transcripts and transcripts of audio-recorded conversations. This body of data came directly from fieldwork.

To maintain this coherence, the NVivo project did not include material that had undergone further processing by researchers, such as team meeting notes and the summaries of patient case studies, which were of two kinds: those compiled from ethnographic data, and those compiled from VSM data.

Researchers first coded their own data in separate NVivo projects, gradually adding more categories (‘nodes’) through an inductive process guided by grounded theory. The supervisors reviewed the data set and coded some data produced by each researcher. The four sets of codes were merged and, through a process of team discussion, the number of nodes was reduced to 49 (see Appendix 11); researchers then resumed coding using the agreed set. This instrument made the revised framework operational, and it enabled researchers to rapidly access and share ‘strings’ of data on particular themes. The process of opening up and redefining concepts was also informed by the reading group (see Appendix 1).

Integrated fieldwork, discussion and data analysis

Data analysis continued throughout fieldwork as an integrative part of the ethnographic method. Researchers discussed their insights and interpretations – gleaned from day-to-day field experiences, writing of fieldnotes, coding and revision of literature – in research team meetings (core team meetings, investigator meetings, fieldwork and analysis meetings, and one-to-one meetings with investigators who had specific expertise) and in activities such as the reading group, mid-project workshop, learning sets and PPI workshops. To stimulate input from the wider team, researchers presented emerging findings using visual maps incorporating illustrative quotations. Topics for analysis were chosen using the following criteria:

-

frequency and intensity of their appearance in the data, for example the ‘take-all’ way in which EDs were seen to operate

-

the singular impact of some occurrences, such as ‘stand-offs’ when practitioners expressed overt disagreement

-

conceptual clarification, for example unpicking differences between avoidability and appropriateness or inappropriateness, which aided definition of the clinical panel’s task

-

evidence of the use of divergent definitions, such as practitioners’ various different uses of the term ‘admission’, and the ‘bending’ of definitions and practices associated with breach avoidance

-

need for quantification through the VSM study, through analysis of HES data, or for follow-up in future research, for example number and proportion of acute admissions on each site that decision-makers considered to be ‘social admissions’

-

attention to silenced, taboo, minority-view or contentious issues, for example one stakeholder’s claim that hospitals were ‘hoovering up’ patients, especially the ‘frail elderly’, and seeking to swell their resource base with this justification.

Obvious differences and commonalities between sites were highlighted early on and these led to searches for further confirmatory or disconfirmatory data. We sought evidence of heterogeneity within sites, particularly regarding practitioners’ observed behaviour and reported beliefs and experiences.

In addition to the above procedures, the following methods were used to achieve rigour in the ethnographic data analysis:

-

The semistructured interviews with patients, carers and professionals were responsive to researchers’ ongoing field observations and conversations with participants. Alternation between these activities enabled us to explore, in interviews, some emerging questions and hypotheses.

-

Researchers refined their analytic statements by going from the NVivo node data excerpts ordered in framework analysis tables, back to the source transcripts, which gave greater indication of context.

-

Researchers tested and revised their emerging hypotheses in discussion with groups of research partners who had similar characteristics to the study participants: the PPI group; the learning sets of managers and clinicians on the four sites; the clinical panels; and the wider meetings of stakeholders comprising representation from all the above, and including the principal site collaborators.

-

In research team meetings, colleagues interrogated each other’s analytic statements and requested further examples of confirmatory and disconfirmatory evidence.

Data analysis

Researchers used the analytical method of printing and manually coding a relevant node (e.g. ‘Targets, time of day, time limits and avoiding breaches’), reading and rereading the data, highlighting phrases with particular impact and making notes on themes that became apparent. For example, a typology was developed of practitioners’ varying responses to pressure from busyness of the service and the 4-hour target. These ranged on a continuum from positive engagement to negative reaction, as staff members positioned themselves in different moments as doers and achievers, flexible team players, compliers and victims. These categorisations served to alert researchers about possible patterns to watch out for as they continued their fieldwork. When the ethnographic data set was completed, these provisional patterns were tested by seeking out tendencies within and across sites.

Ethnographic patient case studies

During the ethnographic study, researchers started to observe each patient journey with a view to creating an ethnographic patient case study. From these data, researchers selected the cases where they had been able to observe and conduct interviews during decision-making with involvement of practitioners, patients and sometimes carers. Six or seven of these patient case studies per site were collated and analysed as ethnographic case studies (see Appendix 12). The analysis involved comparing the views of the observer, patient, carer/family member and practitioners about their experience and the process of decision-making. The patient case studies were presented to two clinical panels (see Appendix 2) for discussion and for comments, which were incorporated into completed case studies for analysis within the main ethnography and within the synthesis. Two examples of case studies discussed by the clinical panels are provided in Appendix 2, which includes the clinical panel report.

Additional data sets and analysis

The following additional data were collected and analysed:

-

Documentary analysis (RQs 1, 3 and 4), including financial and business planning, governance, and implementation of process change, was used to identify key contextual features in each site.

-

Hospital Episode Statistics data were used to describe aggregated patient data for each site.

-

Data on costs of staff in each site (RQs 3 and 4), including typical staff mix, grades and sessions/hours worked at different times in each hospital, were used to estimate the cost of staffing EDs. It was not possible to quantify acute physician input owing to the complexity of shifts, rotas and job plans.

-

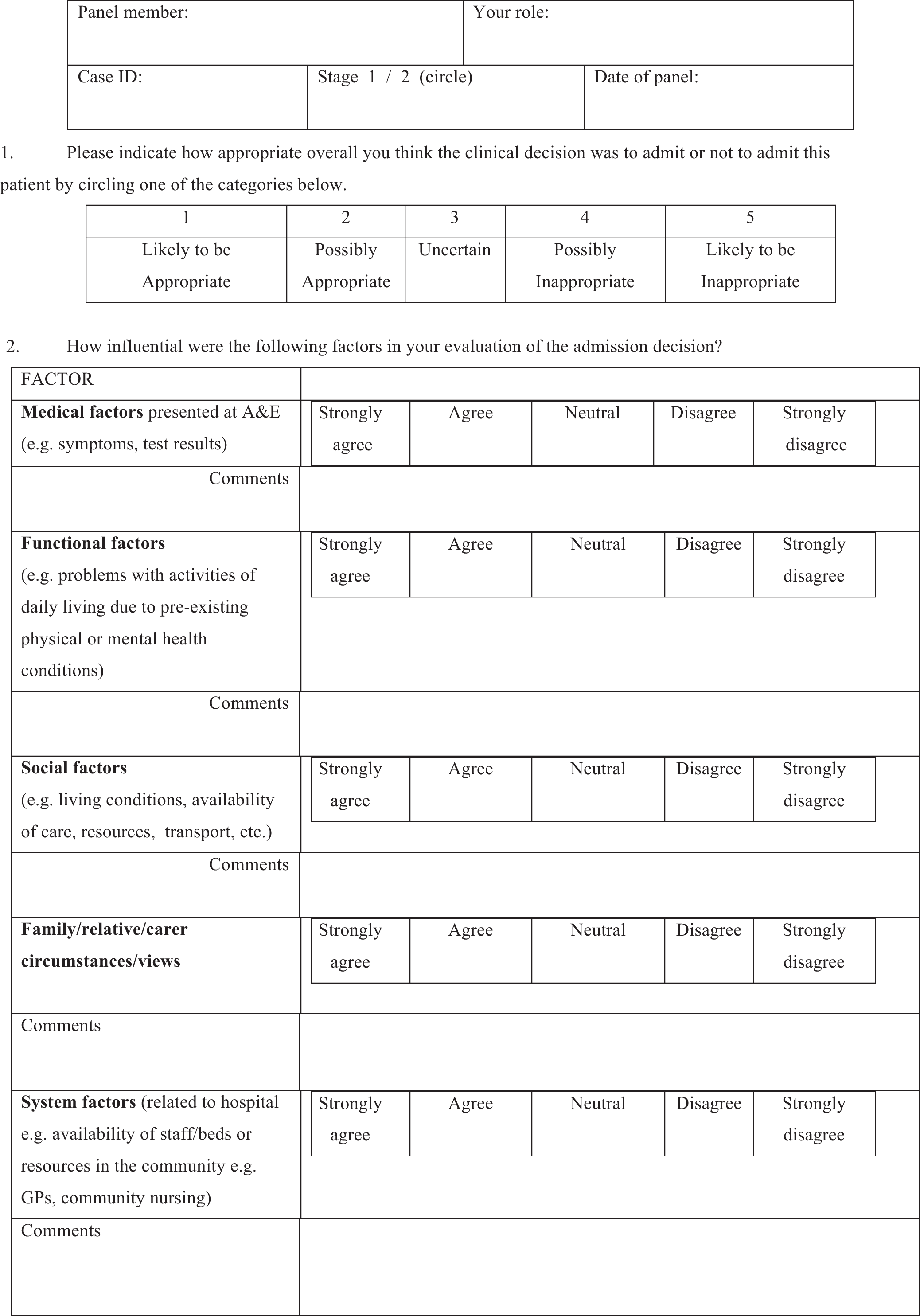

Analysis of the quality of decisions on admissions (RQ 4) by clinical panels of four or five clinicians (senior doctors and nurses in ED and acute medicine) and two local PPI representatives focused on the quality of the decisions made, based on collated ethnographic and VSM case studies. Two panels were assembled and chaired by a chief investigator. The northern panel reviewed cases from the two southern sites (Porthaven and Churchtown), and the southern panel reviewed cases from the two northern sites (Underbridge and Waterbury). First, members individually scored cases for likely appropriateness of decision-making. The research team then identified cases scored as potentially inappropriate or where there was panel disagreement. The panels then met to review these selected ethnographic patient case studies and individual patient VSM ‘charts’ and to agree a consensus score for whether or not the decision to admit or discharge appeared to be appropriate, and to comment in detail if care might have been improved. The panel process is described in detail in Appendix 2.

Synthesis

Approach to the synthesis across component studies

A critical realist approach64,65 provided the framework for integrating knowledge from each of the component studies, the stakeholder workshops, the clinical panels and the learning sets. We aimed to identify mechanisms that could explain how different outcomes arose in complex systems,66 with the goal of producing multifaceted explanations about how frontline expertise and new models can safely reduce admissions. We used the approach of Pawson and Tilley’s57 to identify potential mechanisms that result from the interaction of resource and opportunity with the reasoning of individuals and lead to behavioural change. In order to produce a more fine-grained analysis across the studies, we understood mechanisms as consisting of both reflexive and automatic responses.

Taking a realist perspective

Taking a realist perspective, the admission decision can be seen as a sequence, over time, of beliefs, knowledge and behaviours of the key actors: patients, carers and practitioners. The beliefs and actions of individual patients are affected by their immediate context, which can include both the cultural and structural context of their lives, family and home life, and their current state of physical and cognitive capacity. Patients and carers respond to the opportunities/resources provided (practitioners, acute care environment) with a variety of patterns of reasoning. It is the variety and detail of these patterns that we sought to understand.

Each of the practitioners involved in decision-making also has different beliefs and attitudes, based on previous training and experience that influence behaviours involved in the admission decision, such as further questioning, physical examinations, requesting tests or gathering opinions from other practitioners. Practitioner behaviour is also influenced by the organisational context in which the practitioners work: both structural – the teams, hierarchies, incentives, physical layout – and cultural – the norms and ideals of teamwork and professional conduct. Understanding how the immediate setting and wider hospital and health-care system beyond influence the individual practitioner’s reasoning is an important objective of the 3A study.

Individual practitioners also differ in their patterns of reasoning and capacity and respond differently to the same hospital and team environments, both in the immediate reasoning for the patient before them, and also over time in their acquisition of beliefs and cultural norms. This heterogeneity of practitioner responses may be one of the keys to understanding variations in acute admissions decision-making. In a contrastive way, we were also interested in seeing how practitioners as a group might respond to (1) the common and different resources and opportunities in existence at each of the four sites studied; (2) innovations that have been introduced, such as new types of teams, new diagnostic processes and pathways, or other innovations developed within the acute admissions system.

Integration of findings

We produced a set of analytic statements (see Appendix 13) from each study for presentation and discussion at researcher meetings and at the end-of-project stakeholder workshop. Wherever possible, we expressed these as causal ‘If . . . then’ statements that specified context, mechanism and outcome in relation to patient safety [i.e. appropriate (non-)admission decision]. For example, ‘If there is an acute bed shortage and pressure from management to decrease admissions (context) then clinicians may feel pressurised (mechanism) to discharge inappropriately (outcome)’.

However, in many instances it was necessary for the outcome stated to be a plausible stage on the decision-making route. For example, ‘If there is more than one team involved in the care of a patient (such as a specialist medical team) (context) then there can be confusion between practitioners (mechanism) about who is responsible for the care of the patient (outcome)’. Not all analyses or sources could support these types of causal statement. Where this was the case, we retained statements about context alone, for example, ‘Resource and time constraints may sway doctors towards admission as a safer option’. The statements were shared within and across teams so that an ongoing awareness of findings was cultivated. This also underpinned the development of collaborative working relationships, which in turn facilitated criticism and refinement of the synthesis.

We found that the common language of the ‘If . . . then’ statements helped us to group and look across project component studies. Our integration of findings focused on identifying how practitioners, patients and carers responded to each other, as well as how each responded to the resources and opportunities of the acute care setting.

In summary, the process was:

-

Based on the findings of each project component, ‘If . . . then’ statements (or other analytic statements or scenarios) were developed. A selection of these were further refined at the end-of-project workshop.

-

Refined statements were organised in tables by RQ and grouped by the participants in interactions (e.g. patient–carer–practitioner).

-

Through a process of reflection and discussion based on these refined statements (returning to the original data where necessary to clarify particular issues), we developed explanatory statements that incorporated all of the information in groups of refined statements (documents available on request from the authors). This typically involved the following tasks:

-

reading through to ‘sensitise’ ourselves to the issues

-

‘sense making’ – asking ‘How can we explain what has been observed here?’ and how we could account for context or rival explanations asking ‘What if?’ questions (i.e. looking for alternative explanations)

-

seeking disconfirming cases.

-

The statements were then brought together in narrative form within themes based around practice and service design in a narrative form referencing the analytic statement (see Appendix 13). Finally, we undertook an exercise of transforming negative statements into positive ones and setting these out as principles of practice that were likely to achieve particular objectives.

We focused on identifying mechanisms and the ways in which they could operate differently within varying contexts, as distinct from the pattern of events. 66 We endeavoured to recognise heterogeneity of responses as an inherent phenomenon within the system,67 acknowledging that, although social structures and culture have causal powers, people will interact with and respond differently to the same phenomena. 68

Chapter 3 Site descriptions, Hospital Episode Statistics and economic data

The four acute hospital sites

The 3A study was conducted at four major acute hospitals in South West England. These hospitals provide emergency medical care for much of the population of the south-west peninsula, and they serve varying catchments and populations with contrasting socioeconomic characteristics. The hospitals face similar pressures, demands on their workforces and resource constraints, and they are required to meet the same government targets. In response to these common challenges, however, the four sites also exhibited significant local innovations and therefore differences. In this chapter, the four hospitals are described using data collected by researchers during the study. HES data were used to describe activity and performance at each site, and to compare this data with national data. This chapter provides a detailed context for the ethnographic and VSM data that were subsequently collected, and for their interpretation.

Researchers examined the four hospitals, their structures and approaches to providing emergency medical care, and their innovations to improve performance and/or reduce admissions. Basic descriptive data – including location, catchment population, governance arrangements and some key aspects of infrastructure and staffing arrangements – are summarised in Table 3. While hospital size and overall numbers of emergency attendances and admissions were relatively similar, a range of local initiatives had evolved, some with similarities but others more unique, in order to expedite decision making and reduce admissions. The four hospitals were selected specifically because of these structural contrasts in their emergency medical admissions pathways, which existed at the start of the study (summarised diagrammatically in Appendix 14, Figure 20).

| Site features | A: Porthaven | B: Churchtown | C: Underbridge | D: Waterbury |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital location | 5 miles from city centre | 1.3 miles from city centre | In city centre | 1.5 miles from city centre |

| Population served | ≈450,000 | ≈350,000 | ≈612,000 | ≈500,000 |

| New ED attendances | 94,657 | 90,153 | 75,972 | 69,804 |

| Admissions via ED | 23,069 | 21,356 | 26,196 | 27,254 |

| Admissions to MAU | 3586 | 5332 | 0 | 0 |

| Particularities of trusts and CCGs | Covers a wide geographical area; managed by one CCG | Managed by one CCG; interacts with walk-in centre run by primary care; share site and reception | One trust that operates across two sites, served by one CCG | Covers a wide geographic area covering four counties and is served by four CCGs |

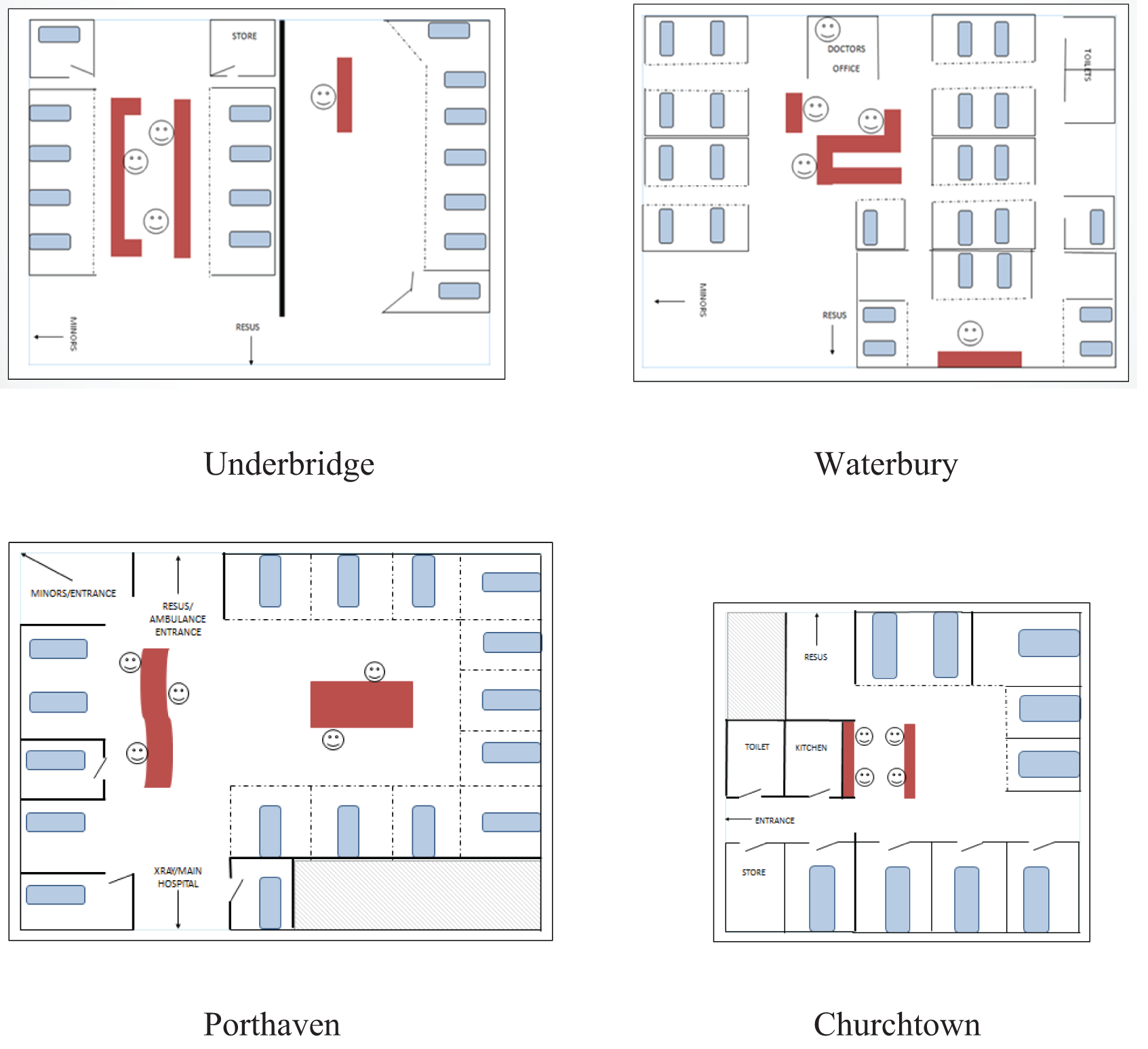

| ED configuration (see Appendix 14, Figure 21) | Minors, six cubicles; majors, 17 cubicles; resuscitation, four bays; CDU, 10 beds and a lounge area | Minors, nine cubicles; majors, nine cubicles; resuscitation, three cubicles; no CDU | Minors, eight cubicles; majors, nine cubicles, + majors 2, seven cubicles; resuscitation, four cubicles; no CDU | Minors, eight cubicles; majors, 18 cubicles; high care, six cubicles; resuscitation, four cubicles; observation ward, eight beds |

| ED senior cover | Consultant cover 09.00 to 20.30 weekdays and 09.00 to 17.00 weekends; 24-hour middle-grade cover | Consultant cover 08.00 to 22.00 weekdays and 09.00 to 22.00 weekends; 24-hour middle-grade cover | Consultant cover 08.00 to 22.00 every day of the week | Consultant cover 08.00 to 22.00 with on-call consultant cover between 22.00 and 08.00; 24-hour middle-grade cover |

| Medical assessment units/triage model | AMU, also called medical assessment unit: 52 beds in two single-sex areas; direct admission from GP referral or referral through ED AGPS 08.00 to 20.00 provides guidance for community GPs, sees ambulatory patients and refers to MAU |

AMU is a short-stay 44-bedded area with two high-care areas and two mixed-sex wards; medical triage unit, one with seven trolleys, one with seven seats, and three ‘see & treat’ rooms; receives patients from specialist clinics and through ED and GPs | Medical assessment unit (acute care unit A), a short-stay 25-bedded unit opposite ED, where admission is determined. Unscheduled treatment of patients in the acute sector: all patients come through ED and are seen by the ED clinicians | MAU with 34 beds located next to ED. All patients arrive through ED first for assessment by the acute medical team and are either discharged from ED or admitted to MAU |

| Ambulatory care model | Ambulatory care run jointly by the AMU and AGPS: eight treatment recliner chairs, four consultation rooms. Runs from 08.00 to 20.00. Consultant physician present 10.00 to 17.00 | Ambulatory area with six discharge seats. AMU consultant present from 08.00 to 22.00 | Ambulatory emergency care, new service being piloted, situated alongside medical day unit, some distance from the ED | Ambulatory care situated by MAU. Operates 08.00 to 22.00: three treatment rooms, two beds, five recliner chairs. Additional waiting area chairs |

Porthaven Hospital

Porthaven is a large university teaching hospital providing secondary and tertiary care services to a population of 450,000. Porthaven opened in 1981 and is situated 5 miles from the city centre. Porthaven serves both a large urban population and a widely dispersed rural population. There is wide socioeconomic variation, with particular pockets of urban deprivation. The hospital trains doctors, nurses and a range of other health-care professionals (HCPs).

Configuration of unscheduled care at Porthaven Hospital

Key initiatives to avoid admission/improve patient flow at Porthaven:

-

ED controller

-

clinical decision unit (CDU)

-

AGPS

-

ACU.

Porthaven receives approximately 95,000 emergency attendances per year. Unscheduled care is provided by two main units:

-

the ED and its associated CDU

-

an AMU/medical assessment unit, which includes an ACU.

The ED has six minors cubicles, 17 majors cubicles and four resuscitation bays. In addition, there is a 10-bed CDU, which incorporates a lounge area to accommodate low-risk patients for whom a quick turnaround may be possible, while they await test results and discharge. This short-stay area averts admission to a hospital ward and patients remain under the care of the ED team. The CDU lounge is an additional ambulatory area, with seats rather than beds, used for a variety of conditions where discharge home is expected.

The ED and the MAU are a 2- to 3-minute walk from each other. The MAU is a short-stay ward with 52 beds, divided into separate areas for female and male patients. The ACU is situated within the MAU and has four consultation rooms and eight treatment chairs. The ACU is run jointly by the acute medical team and an AGPS, and operates from 08.00 to 20.00. Originally, the ACU was set up as a joint venture between the ED and the MAU, but it is now run exclusively by the MAU.

An important innovation at Porthaven is the hospital-based AGPS, established in 2006. The service replaced a previous system wherein AMU nurses received calls from GPs seeking advice on patient treatment. Currently, the AGPS is delivered by GPs who take calls from community GPs from 08.00 to 20.00 on weekdays and provide advice, guidance and signposting for community treatment. Additionally, for ambulatory patients who require investigations or assessment but not admission, the AGPS will accept and see patients in the ACU. Finally, they will refer patients who require admission to the MAU. All referrals from community GPs to the medical team come through the AGPS during these hours. The AGPS also has the ability to directly book patients to a number of outpatient clinics.

Model of care

Patients self-present to the ED, come by ambulance or are referred to unscheduled care by their GP. The GP-referred patients will be seen either by the AGPS or by the acute physicians in the MAU. These patients have direct access to the ACU/MAU without the need to pass through the ED, unless they need emergency medical treatment, in which case they will be sent to the ED. Alternatively, patients who self-present to the ED and require medical admission can also be referred to the MAU. Early senior clinician input is also a key aspect of the staffing model adopted by Porthaven.

Space and working environment