Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 10/1007/02. The contractual start date was in September 2011. The final report began editorial review in October 2014 and was accepted for publication in April 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Mannion et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Policy context

The UK NHS is widely acknowledged as providing some of the best health care in the world, with the vast majority of patients receiving care which is safe and effective. 1 However, as in every other health system, not all care is as safe as it could be and, although estimates vary, there is growing evidence to suggest that about 1 in 10 patients admitted to hospital may be harmed as a result of their care. 2 This harm is not limited to minor events but is often serious, including major iatrogenic disability, health-care-associated infection (HCAI) and avoidable deaths. In addition to human suffering, this results in significant financial costs, with prolonged hospital stays alone costing over £2B per year. 3 In response to evidence of widespread harm there has been a concerted effort to make health care safer, and numerous initiatives and significant resources are being invested in developing national and local strategies to improve patient safety in NHS organisations. However, change has proved difficult to effect and the optimal mix of strategies remains unclear, with the NHS acknowledging that it is not yet able to prevent errors and major service failures recurring. 4,5

Over the past decade it has become increasingly recognised that most harm to patients in hospital settings is not deliberate, negligent or the result of serious incompetence. Instead, harm more usually arises as an emergent outcome of a complex system in which typically competent clinicians, professionals and managers interact in inadequate systems and unsafe organisational environments. Yet we still know very little about the role of organisational and governance processes in developing safer health-care environments. More specifically, we know very little about how hospital trust boards can contribute to safer patient care, although such boards have been the focus of increasing scrutiny for shortcomings in its governance role. Most recently, the report of the public inquiry into Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust concluded that unnecessary suffering and neglect of patients was primarily caused by a serious failure on the part of the hospital trust board, which ‘did not listen sufficiently to its patients and staff or ensure the correction of deficiencies brought to the trust’s attention. Above all, it failed to tackle an insidious negative culture involving a tolerance of poor standards and disengagement from management and leadership responsibilities’. 4 Similar failures in hospital board leadership and governance are a recurring theme of earlier inquiries into hospital scandals in the English NHS, including the tragic events at Bristol Royal Infirmary in the 1990s, and date as far back as the late 1960s, with the inquiry into the mistreatment of long-stay patients at Ely hospital. 6

The changing role of hospital boards in the English NHS

Hospital trust governing boards, as corporate entities with statutory oversight responsibilities, are accountable for the overall quality and safety of the care its organisations provide. These boards therefore have a fundamental governance role in the oversight of quality and safety, which involves defining priorities and objectives, crafting strategy, shaping culture and designing systems of organisational control. Hospital boards in the English NHS have traditionally shared many similarities with the Anglo-Saxon private sector unitary board model, which typically comprises a chairperson, chief executive, executive directors and non-executive directors (NEDs). 7 All board members share corporate responsibility for key strategic decisions, including the effective oversight of health-care quality and patient safety. Members of the board have specific duties, with the chairperson leading the board [for foundation trusts (FTs), the chairperson also chairs the Council of Governors]. Alongside the chairperson, the chief executive leads the executive arm of the organisation and takes lead responsibility for service delivery.

Within the English NHS, FTs now make up the majority of organisations, with an expectation that all other trusts will follow in due course. At the end of 2013, 147 out of 230 NHS providers in England (64%) (including acute and mental health hospitals and ambulance services) operated as NHS FTs, which have greater freedoms than other types of hospitals and are based on co-operative and mutual traditions. 8 Governance arrangements in FTs are locally determined within a national framework and non-executive board members are appointed by the governors of the hospital, rather than by the NHS Appointments Commission.

The FT ‘social ownership’ model of governance incorporates three tiers of accountability: (1) the membership, (2) the board of governors and (3) the management board. Eligibility criteria for membership include residency (‘the membership community’), patients in the preceding 3 years, staff and representatives of partner agencies on the board of governors. Members have voting rights for electing representatives to the board of governors and have the right to be consulted on key strategic issues. The management board is accountable to members for ensuring developments consistent with the needs of its community of stakeholders across ‘the local health economy and wider NHS’ and for ensuring that a trust’s activities comply with the terms of its licence. The board of governors is charged with acting as a vehicle for influencing change and development – essentially a strategic rather than an operational role. Governors are required to represent communities and hold a responsibility for feeding back discussion to these communities, serving a twofold role of community liaison and linking with members (downwards) and oversight and accountability of FT activities (upwards). There has been no previous research exploring the relative role and influence of boards versus boards of governors in FTs with regard to patient safety.

Recent years have witnessed a stream of formal guidance designed to strengthen NHS board governance in the light of lessons learned from private sector corporate scandals and failures, including:

-

The Healthy NHS Board: Principles for Good Governance 9

-

The NHS Integrated Governance Handbook: a handbook for executives and non-executives in health-care organisations10

-

The Intelligent Commissioning Board: understanding the information needs of Strategic Health Authorities and primary care trust (PCT) boards11

-

Governing the NHS: A Guide to NHS Boards. 12

Despite a plethora of guidance available to NHS boards on effective leadership and governance arrangements, both in general terms and with specific reference to safe care, we nonetheless still have a meagre evidence base (i.e. drawn from empirical study) on which to offer guidance of effective board practice of patient safety.

Previous work in this area

Prior to this study, what limited evidence existed on board roles and impacts in terms of patient safety and service quality originated mostly from the USA, where several studies have investigated the relationship between governance practices and quality processes and clinical outcomes (see Chapter 3 for a detailed review of the literature and evidence). However, a degree of caution is required when attempting to extrapolate recommendations for effective governance to the NHS context. First, hospitals in the USA operate within a very different economic and political environment, which will necessarily impact on the relative priorities and objectives of boards. Second, all these studies are based on large-scale questionnaire surveys and, although they provide an overview of broad patterns and trends in board practice, they nevertheless fail to capture fully the messy internal processes and behavioural dynamics through which board governance is actually played out and which are best explored through more interpretive and qualitative research designs. Third, these studies have tended to be purely empirical and lack clear theoretical and conceptual frameworks for guiding the collection, analysis and interpretation of data. Finally, these studies focus on the more generic topic of ‘service quality’ rather than the more narrowly defined topic of patient safety.

Contemporary issues and challenges

Effective hospital board oversight in the English NHS currently faces a number of challenges. Changes in the policy landscape, particularly in response to the first Francis public inquiry13 and the Darzi review in 2008,14 have seen quality and safety move up the political agenda. However, the oversight of patient safety is often compromised by the number of competing priorities faced by boards. Recent reports conclude that board discussions concerning patient safety often take second or third place after efforts to ensure that hospital finances and central performance targets are met. 15 Within this context, a key challenge facing board oversight of patient safety is the use of risk-based ratings and measures, which are set by Monitor and the Care Quality Commission (CQC). This has the potential to ‘dilute the message’ of patient safety for boards, in being effectively reduced to a series of national standards and priorities or specific issues and campaigns related to infection control, such as meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and Clostridium difficile infection rates. 16 Challenges to effective board oversight may also be attributed to boards’ limited knowledge and understanding of patient safety issues and concepts, and many boards currently lack the necessary skills and understanding to make sense of emerging trends in patient safety. Limited knowledge and understanding of patient safety among board members, particularly non-executives, also means they are often inhibited when challenging and posing critical questions about safety issues and concerns. This is particularly the case for NEDs who tend not to have a clinical or operational background in health-care quality. 17

In light of these current challenges facing boards, discussions with key informants in the scoping phase of this study (see Appendix 1 for details) raised a number of suggestions about how board oversight of patient safety could be improved. At the centre of these proposals were concerns about strengthening and building trust through the development of better interpersonal connectedness within its organisation. Rather than a ‘tick-box’ focus on meeting particular targets, it was suggested that oversight needed to become ‘value driven’ in the development of relationships that were more sensitive and responsive to organisational needs and concerns. To accomplish this, particular board activities and practices were highlighted for enhancing trust in organisational relationships. These included providing a greater amount of time and emphasis on board discussions and dialogue about patient safety, developing enhanced leadership skills that allow patient safety to be more visible and seeing board members as ‘stewards’ with a responsibility for developing a culture of partnership within the organisation. Leadership here was seen as critical to ‘set the tone’ for the organisation with regard to prioritising the quality of care.

Moreover, although board oversight was seen as a collective effort, individual board members with specific roles were noted as being key catalysts for action. For example, the chief executive is central in setting the tone, and the chairperson is key to facilitating open discussion. Medical and nurse directors, acting as custodians for clinical governance, also have an important role to play in setting the patient safety culture of the organisation, as do finance directors in supporting patient safety initiatives. Using NEDs to actively challenge executive decisions and to hold the board to account provides important checks and balances. Some boards needed greater input from NEDs in providing the necessary critical reflection in ‘holding up a mirror’ to the organisation by asking critical and probing questions. An additional suggestion for fostering greater interconnectedness with the wider organisation was opening up board business to greater staff, patient and public scrutiny. This is seen as having the potential, not only to further hold the board to account but also to create connections and interactions with the organisation and the community that the hospital served.

Scoping discussions also raised a number of points about the potential over-reliance on formal quantitative performance measures in relation to patient safety, which possibly came at the expense of ignoring insights gleaned through soft intelligence networks. Boards need to have access to different types of information concerning patient safety in order to increase its intelligence about the issues at hand. Greater reliance on dashboards could help to disaggregate information about particular trends within the organisation rather than simply relying on an aggregated picture of the organisation as red, amber or green ratings. For example, the Quality Risk Profiles (QRPs) capturing mortality data, readmission data, and outlier data combined with data on patient outcomes in relation to dignity, nutrition and privacy can provide a useful basis for hospital board discussions. In addition, scorecards and metric-based approaches can be supplemented with narrative or ‘reality checks’ that connect staff concerns and patient experience to quantitative data.

Collectively, these observations demonstrate the potential to support the development of internal board dynamics to facilitate greater dialogue related to patient safety, alongside external board communications to improve the connection with patients and staff. The insights gathered in the scoping discussions thus informed the development and refinement of the research design and the research questions as set out below.

Defining patient safety

As the focus of this study is on patient safety, it is important that we are clear about how we have interpreted the term and used it in our research design and analysis and how it differs from other quality-of-care issues. Charles Vincent defines patient safety as ‘The avoidance, prevention and amelioration of adverse outcomes or injuries stemming from the process of healthcare’. 18 This definition clearly differentiates patient safety from more generic quality-of-care issues by focusing on the ‘dark side of quality’18 and highlighting care that causes harm to patients rather than merely being of a poor or inadequate standard. It also draws attention to attempts to prevent and reduce errors and adverse patient outcomes in recognition that simply trying to avoid error is not in itself enough and one must seek to reduce errors of all kinds. In this study, we have adopted an approach based on Vincent’s definition of patient safety. We also recognise that safety resides in health-care systems (at all levels) as well as people working within such systems. During the fieldwork for this study, and in particular the case studies, it was often difficult to clearly distinguish patient safety from the broader concept of quality. Indeed, the two are synonymous and often conflated in common usage and expression. Although in our analysis we have attempted to separate out issues related to patient safety, in some areas we have found it very difficult to provide a clear-cut distinction between issues specifically related to quality and those specifically related to safety. This should not necessarily be viewed as a deficiency of the study but rather as a reflection of the complexity and ambiguity inherent in the concept and the many ways in which it can be interpreted and applied in health-care contexts.

Aims and objectives of the study

Against this background, our study aimed to generate theoretically grounded empirical evidence on the associations between board practices, patient safety processes and patient-centred outcomes with the aim of improving NHS hospital boards’ understanding, effectiveness and accountability in relation to safeguarding care. The study was undertaken between October 2011 and September 2014.

The specific aims were:

-

to identify the types of governance activities undertaken by hospital trust boards in the English NHS with regard to ensuring safe care in its organisation

-

in FTs, to explore the role of boards and boards of governors with regards to the oversight of patient safety in its organisation

-

to assess the association between particular hospital trust board oversight activities and patient safety processes and clinical outcomes

-

to identify the facilitators and barriers to developing effective hospital trust board governance of safe care

-

to assess the impact of external commissioning arrangements and incentives on hospital trust board oversight of patient safety

-

on the basis of findings relating to points 1–5, to make evidence-informed recommendations for effective hospital trust board oversight and accountability and board member recruitment, induction, training and support.

Research design and project overview

In essence, the study comprised three distinct but interlocking strands:

-

a literature review of the theoretical and empirical literature relating to hospital board oversight of patient safety (undertaken between December 2011 and December 2014)

-

in-depth mixed-methods case studies in four organisations to assess the impact of hospital board governance and external incentives on patient safety processes and outcomes (undertaken between September 2012 and September 2014)

-

two national surveys of hospital board oversight of patient safety which were then linked to routine data on patient safety processes and outcomes (undertaken between March 2012 and April 2013).

Structure of the report

Chapter 2 provides a detailed explanation of the theories and research methods underpinning the study. Chapter 3 presents the findings from the literature review of theoretical and recent empirical work in this area. The next five chapters present the main findings from fresh empirical studies in the NHS: first from case study work in four purposefully selected NHS foundation hospital trusts (see Chapters 4–7) and then from national quantitative surveys of board activity/competence and patient safety performance linkages across English NHS hospital trusts (see Chapter 8). The report concludes (see Chapter 9) with an integration and discussion of the findings and a look forward at the emerging research agenda around these issues.

Chapter 2 Theories of board behaviour and research design

This chapter outlines the theories of board behaviour that underpinned the study and sets out the research design and methods of data gathering and analysis used in the empirical part of the study.

Theories of board behaviour

Several theoretical frameworks of board governance have been developed,19,20 and here we make the distinction between whether boards are conceptualised in either instrumental or symbolic terms. Guidance on the role and conduct of NHS boards is most usually informed by instrumentalist assumptions of the role of boards as forums for deliberation, conciliation and decision-making. On these terms a ‘successful’ board is one that is able to take decisions on corporate strategy in an efficient and effective manner and can monitor its implementation through to organisational success. Four key instrumentalist frameworks can be discerned in the literature:

-

Agency theory is based on the assumption that, unless scrutinised, staff will seek to pursue their own interests rather than wider organisational objectives (opportunism). Here the board is conceptualised as a monitoring device set up to ensure compliance by developing systems of checking, monitoring and control to hold staff accountable for their actions. This approach has previously been used to understand and classify clinical governance strategies in UK hospitals. 21

-

Stewardship theory works on the assumption that staff are motivated by more than their own narrow self-interests and that managers want to do a good job and serve as effective stewards of an organisation’s resources. 22 The theory assumes a high degree of trust, with the focus of the board being on creating a framework for shared values and enabling staff, rather than monitoring and coercing performance.

-

Stakeholder theory assumes a multiplicity of competing and co-operative interests within organisations and focuses on how various stakeholder interests can be addressed, integrated and balanced. 23 The role of board members within this framework is to understand and represent the views of all those with a stake in the organisation, and it is recognised that the board may need to manage complex trade-offs between stakeholders, including staff, patients and the public.

-

Resource dependency theory derives from the strategic management literature and Zahra and Pearce played a significant part in its original development. 24 From this perspective the organisation is seen as an amalgam of tangible and intangible assets and dynamic capabilities. The main function of the board is to successfully manage internal and external relationships to leverage influence and resources. Board members are selected for their background, contacts and skills in mediation and boundary spanning.

In spite of their differences, all four of these instrumentalist theories assume that board members are able to exercise influence over staff and that, via this influence, they lever beneficial change and enhance organisational performance. Garratt25,26 has integrated the insights from both agency and stewardship theories and posits two main areas of board foci, which he terms ‘conformance’ and ‘performance’ (Table 1). Conformance has both external and internal dimensions: external accountability includes compliance with regulatory and legal requirements, as well as accountability to external stakeholders. In contrast, the internal dimension is associated with management control. The conformance dimension, therefore, shares many similarities with the agency theory perspective on governance. The performance dimension, according to Garratt,25 involves governing the organisation to enhance its achievement of goals and objectives. This, again, consists of two main functions: policy formulation and strategic thinking. The performance dimension is thus closely linked to the stewardship theory of corporate governance. This framework (illustrated in Table 1) suggests that boards need to focus on both conformance and performance aspects of corporate governance and that blended perspectives on agency/stewardship may be necessary.

| Focus | Short-term focus on ‘conformance’ | Long-term focus on ‘performance’ |

|---|---|---|

| External | Accountability Ensuring external accountabilities are met, e.g. to stakeholders, funders, regulators Meeting audit, inspection and reporting requirement |

Policy formulation Setting and safeguarding the organisation’s mission and values Deciding long-term goals Ensuring appropriate policies and systems are in place |

| Internal | Supervision Appointing and rewarding senior management Overseeing management performance Monitoring key performance indicators Monitoring key financial and budgetary controls Managing risks |

Strategic thinking Agreeing strategic direction Shaping and agreeing long-term plans Reviewing and deciding major resource decisions and investments |

A number of board assessment tools have been developed and used in empirical research to assess the instrumental activity of boards and to guide and inform board development programmes. 19,27 For example, the 65-item Board Self-Assessment Questionnaire (BSAQ) has recently been used in studies of hospital boards in the USA28 and a small-scale study of FTs in England. 29 The benefit of theoretically informed instruments such as the BSAQ is that they have predictive power and can be used to assess the implications of adopting different board strategies (rather than merely taxonomic uses). The BSAQ instrument was used in the national surveys of NHS boards (see below).

Although popular management literature and government documents tend to idealise board members’ activities through the use of ‘heroic’ narratives,30 there is considerable debate over the extent to which boards undertake the classic instrumentalist functions of establishing objectives and core strategies. Within the empirical and critical theory literature, boards have been characterised as performing largely non-instrumental roles by acting primarily as legitimating institutions that formally declare decisions negotiated elsewhere. 31 These perspectives indicate the potential importance of the symbolic and ceremonial value of boards and the need to explore efficacy of board performances in a more dramaturgical sense. In this regard, Hajer32,33 and Hajer and Versteeg34 have outlined a framework for the analysis of the performative dimension of board governance. The approach opens up the day-to-day interactions of board members for analysis through consideration of the setting in which deliberation takes place; the scripting in terms of the actors involved in the decision-making forum; the staging in terms of deliberate attempts to organise the interaction between participants by drawing on existing symbols; and the performance in terms of the way in which the interaction constructs new knowledge, understandings and power relationships that project forward to shape future interactions and provide opportunities for challenge and change over time.

These diverse theories provide multiple and complementary perspectives on board governance and each has been used at various times in the analysis to make sense of the data gathered.

Research design for the empirical work

The empirical strand of the study was informed by a review of the theoretical and empirical literature relating to board governance of quality and safety, and explores both instrumentalist and performative aspects of boards. Given the diversity of views and approaches to understanding board governance of patient safety, and the intrinsic complexity of any relationships between board governance and patient safety processes and outcomes, we adopted a multimethod approach, integrating qualitative and quantitative elements in order to examine these relationships in both breadth and depth in the empirical strand of the study. In order to capture the breadth of any associations between board activity and patient safety we conducted a national survey of board practice with regard to patient safety. This was linked to routine national performance data sets on patient safety processes and outcomes. The combined data set was used to explore board practice–patient safety associations at the organisational level. In addition, to contribute depth and richness to our understandings, we used comparative case study methods and qualitative approaches to explore board dynamics and the governance of patient safety in four hospital trusts. We next elaborate on each of these strands in turn, beginning with the case studies, followed by the national quantitative survey and analysis.

Case studies: sampling, data gathering and analysis

We utilised a comparative case study design across multiple study sites to generalise theoretically within and between cases. 35 Although each case has its own integrity in terms of theory building and generating policy implications, we developed common themes across case study sites using comparative case study methods. 36

Case selection

As we intended to consider the enactment of internal governance arrangements and the effects of external financial and regulatory mechanisms with reference to patient safety, each case study had as its centre of investigation an acute foundation hospital trust through which links between governance and patient safety were explored. We selected FTs because this organisational form was the policy direction for acute sector organisations at the time of planning the study. The unit of analysis is thus the FT rather than the wider health economy, with a focus on the operation of the board and its effects within the specific ‘tracer condition’ area of infection control.

It is important to acknowledge that FT boards operate within a national and regional context, and for this reason we undertook some scoping of context with key commissioners and stakeholders. However, our focus on the board as the seat of governance ensured a focus on the formal enactment of governance within board structures.

In addition to normal requirements of ethical approval, cases were selected on the basis of their performance trajectory over the last 3 years on a range of safety and quality indicators selected from the Dr Foster (Dr Foster Limited, London, UK) database. Every year Dr Foster publishes a hospital guide that uses publicly available statistics to measure and assess what is happening in hospitals in England to increase the transparency around variations in performance. The data focuses on indicators in three domains of quality obtained from the available statistics, combined with information from self-reporting of safety aspects from an annual questionnaire, and is informed by the National Patient Safety Agency organisational feedback reports and CQC ‘alert’ lists. We used these data to select case study sites that were indicated to be getting worse (in the light of overall improvement of other hospitals) or getting better, as follows:

-

two foundation hospital trusts with a ‘downwards’ performance trajectory, as indicated above

-

two foundation hospital trusts with an ‘upwards’ performance trajectory, as indicated above.

We then made sure that the sample was drawn from across the country and included large teaching hospitals (THs) and a district general hospital. Throughout the analysis and reporting, trust sites have been anonymised by being renamed after Scottish islands. The two upwards-performing trusts are identified as Lewis and Arran, and the two downwards-performing trusts are known as Islay and Skye. Appendix 2 contains the case study invitation letter and Appendix 3 contains the participant information sheet.

Brief description of the four selected case studies

Lewis is one of the bigger NHS trusts in the UK, delivering services across several sites within a single city. It offers many specialist services, with a large consultant body seen as being at the cutting edge of clinical care. Its long-standing reputation for high-quality clinical care is reflected in it consistently being in the upper quartile of hospital ratings.

Arran is a renowned TH providing general and specialist services across multiple sites. Over the last 5 years the board has been characterised by relative stability, with low levels of turnover. The trust aims to continue to build its ‘brand’ as a provider of leading specialist services, and it is undertaking large-scale redevelopment in order to deal with excess demand within accident and emergency (A&E) services. Organisational performance against the Hospital Standardised Mortality Ratio (HSMR) is very good, but the trust has faced some performance issues with regard to expressed staff satisfaction and, more recently, infection control rates.

Islay is an integrated provider of hospital, community and primary care services. It has a well-documented profile for its achievements in relation to quality and safety, with the board in particular receiving a number of awards and plaudits for these efforts. The trust holds high scores for both patient and staff satisfaction.

Skye is a district general hospital trust providing services across two sites. It was one of the earlier NHS trusts to be awarded foundation status. Over the past 5 years, the board has been characterised by continuous change, with the arrival and departure of several chief executive officers (CEOs), medical directors (MDs) and two nursing directors (NDs) during this period. The trust has one of the highest patient demands in the country and has faced a number of challenges related to bed capacity. Organisational performance is currently a cause for concern, with the HSMR above average, high A&E demand and increasing infection rates.

Data collection in the case studies

In the context of board governance, the focus of our data collection in the case studies was to explore the following areas:

-

to examine board of director oversight of patient safety

-

to understand the relationship between the board of directors and governors with respect to overseeing patient safety issues

-

to understand how the board complies with a particular patient safety issue (conformance)

-

to understand how the board responds to a specific patient safety issue during the course of fieldwork (performance)

-

to explore the commissioning relationships related to patient safety.

Data gathering consisted of interviews and observations at management boards and the governing board.

Exploring board oversight of patient safety

Our research carried out semistructured interviews with the board of directors at each site. This included the executive and NEDs as well as other board directors deemed relevant to the research and included directors of quality and risk. These interviews built on what was understood to be the key themes and issues related to the subject area17 (see Chapter 3) in examining how board members understood their role in terms of strategic vision and leadership activities, to understand how members understood particular board mechanisms associated with effective oversight, to understand how board members understood, analysed and interpreted the information they provided, and to understand how board members understood their relationship with the wider health economy in terms of commissioning and regulation associated with patient safety.

In addition to these interviews, overt non-participant observation was undertaken by the research team at four management board meetings at each case study site. This totalled nearly 50 hours of observation (Table 2). Descriptive free-text field notes were taken by both observers at each meeting, supplemented with documentary data including the agenda, supporting papers and (retrospectively on completion) the minutes of each meeting. Data included an overview of comments made and questions raised and by whom, and a log of the time spent on each agenda item. These have been summarised to provide an overview of patient safety issues within the context of all board activity. Data from field notes were compiled across multiple board meetings within each trust to detail board operations and identify the manner in which patient safety-related issues were discussed.

| Case study site | Number of board meetings | Time observed |

|---|---|---|

| Islay | 4 | 12 hours 46 minutes |

| Skye | 4 | 14 hours 52 minutes |

| Arran | 4 | 6 hours 1 minute |

| Lewis | 4 | 14 hours 5 minutes |

| Total | 16 | 47 hours 44 minutes |

We supplemented our instrumentalist analysis of conformance and performance with a dramaturgical analysis of observation field notes following the framework developed by Hajer33,34 and previously used by members of the team in a study of partnership boards. 37 Reported in Chapter 7, this analysis explores the scripting, setting, staging and performance of patient safety governance, revealing the manner in which such work was conducted and the ability (or otherwise) of board members to ensure action.

Exploring board of governors’ oversight of patient safety

Interviews were undertaken with a variety of governors across the case study sites in order to understand their experiences of working with their board and holding the executive to account in relation to patient safety matters. These interviews asked governors to reflect on their abilities to exercise this function and also explore different ways in which the role of governors could be improved.

In addition to these interviews, overt non-participant observation was undertaken at nine board of governor meetings, totalling over 21 hours of observation (Table 3). This total number was less than the board of directors observation owing to practical difficulties, as board of governor meetings tended to take place only once every 3 months or so. Such a length of time between meetings meant it was difficult to capture four meetings at each site within the study time frame.

| Case study site | Number of board of governor meetings | Time observed |

|---|---|---|

| Islay | 1 | 2 hours 21 minutes |

| Skye | 2 | 4 hours 16 minutes |

| Arran | 2 | 3 hours 43 minutes |

| Lewis | 4 | 11 hours 7 minutes |

| Total | 9 | 21 hours 27 minutes |

As with the board observations, descriptive free-text field notes were taken by both observers at each meeting, supplemented with documentary data including the agenda, supporting papers and (retrospectively on completion) the minutes of each meeting.

Following ‘tracer’ issues in the trusts

In each trust we followed two ‘tracer’ issues on patient safety from board to ward. One of these (called a ‘board conformance issue’) was the same in each trust and reflected a patient safety issue requirement for all trusts imposed by external regulators. The second (called a ‘board performance issue’) was different in each trust and reflected the board’s response to a local issue requiring performance improvement.

This approach was informed by the work of Garratt. 26 As discussed in Chapter 6, Garratt suggests that an effective board is able to balance tasks simultaneously, with a ‘learning board’ having two sides: board conformance (sometimes termed compliance) and board performance. Conformance itself involves two aspects: ‘ensuring accountability’ through appropriate regulation and ‘supervision of management’ through conformance to key performance indicators. Similarly, performance also involves two aspects: ‘policy formulation and foresight’ and ‘strategic thinking’ to drive the enterprise forward by allowing it to survive and grow by maintaining, learning and developing its position in its energy niches.

The tracer condition analysis looked to analyse the different ways in which these four board tasks (policy formulation, strategic thinking, supervision of management and ensuring accountability) interacted with each other.

Board ‘conformance issue’ analysis

In order to explore conformance to requirements within the governance of patient safety, each case study focused on a specific ‘tracer’ related to patient safety activity. The selection of this tracer condition was inductively derived from our initial observations of board and governor meetings, as well as our interviews with board members. What became apparent from these observations and interviews was how boards were required to conform to a range of performance indicators devised by the regulator Monitor. One of the central targets related to patient safety was the monthly performance in relation to cases of C. difficile infection. Across all of the sites, C. difficile infection rate was the central patient safety performance indicator that boards were required to conform to.

As a result, our analysis of board ‘conformance’ related to the management of C. difficile infections as a key performance indicator of infection prevention and control. Such a focus allowed us to explore the manner in which the case study site incorporated patient safety requirements from external agencies within its governance structures (i.e. how it undertook compliance).

Data collection for our conformance analysis built on a series of semistructured interviews with a variety of stakeholders involved in the oversight and delivery of C. difficile infection prevention and control. To achieve this, our research team contacted members of the infection prevention and control (IPC) committees within each of the sites. A purposive sample of stakeholders was interviewed from each committee, which included board members, managers, doctors, nurses and microbiologists. The selection of these stakeholders was made on the basis that they had detailed understanding of the C. difficile infection issue and were in charge of working with the board to successfully achieve the required level of performance.

Board ‘performance issue’ analysis

In order to explore the performance aspect of governance, our research analysed how each case study site dealt with a patient safety issue or incident identified during fieldwork, from ‘board to ward’. As with our board conformance data collection, these issues were inductively derived from our observations of board and governor meetings, as well as interviews with board members. From these we were able to ascertain a number of examples of ‘policy formulation and foresight’ and ‘strategic thinking’ by the board, which looked to respond to and improve patient safety. The eventual selection of issues and interventions would be wide ranging and provided our analysis with the additional benefit of exploring in real-time board development and response to patient safety issues. The selected issues were as follows:

-

board development of a ‘staff stores’ initiative

-

board development of the ‘bed plan’

-

board development of the ‘After Francis’ initiative

-

board development of junior doctors’ dissatisfaction.

A purposive sample was used to identify key stakeholders who were involved in the oversight and delivery of these initiatives. This tended to start with the particular board members who were leading these initiatives. Following on, our research then identified key stakeholders involved within each initiative across the organisation. The eventual sample for each of these ‘performance’ tracers included managers, nurses, doctors and allied health professionals.

Commissioning for patient safety

Where possible, interviews with commissioners were carried out to further understand the external environment in relation to the governance of patient safety. These interviews reflected on the experience of commissioners in their interactions with the FT boards regarding patient safety issues and concerns, as well as documenting any important issues regarding the governance processes associated with commissioning for patient safety.

Investigation of all of these issues entailed numerous interviews in each trust, as detailed in Table 4.

| Case study site | Executive board interviews | Conformance tracer issue (C. difficile infection) | Performance tracer issue (local board initiative) | Governors | Commissioners | Totals |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skye | 16 | 4 | 10 | 2 | 3 | 35 |

| Lewis | 15 | 9 | 7 | 4 | 4 | 39 |

| Islay | 13 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 25 |

| Arran | 13 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 17 |

| Case study totals | 57 | 19 | 23 | 8 | 9 | 116 |

| Scoping interviews | 11 | |||||

| Grand total | 127 |

Manchester Patient Safety Framework

We had originally intended to administer the Manchester Patient Safety Framework (MaPSaF) to provide further supporting information on the maturity of board safety culture within each case study site. Designed as a diagnostic and development tool, the MaPSaF identifies dimensions related to working practices, such as risk management training, the investigation of patient safety incidents and staff education. However, during the course of fieldwork it became evident that most of the case study sites were undertaking assessments of patient safety culture commissioned by external third parties, and the decision was taken to avoid the risk of ‘culture assessment overload’ occasioned by further summary assessment.

Approach to qualitative data analysis

Our approach to qualitative data analysis proceeded through the three flows of activity, as outlined by Miles et al. 38 Here, a ‘data condensation’ process was used to select, focus, simplify and abstract data from field notes of observations and interviews transcripts. A thematic approach to qualitative data analysis was taken, whereby the data were coded, labelled and clustered into themes that both emerged from data as well as directly related to our research questions and theoretical frameworks influencing the study. 39

Approach to thematic analysis

For the interviews with board members, our analysis built on our literature review,17 which highlighted a number of issues for boards in relation to the governance of patient safety. These would form the central codes for the analysis (deductive); however, our analysis was also open to a variety of emerging themes that occurred during the course of the fieldwork (inductive). The response to the Francis Inquiry findings was an example of a code which emerged from the interview data.

Data analysis for the observation of board meetings was informed by Hajer33 and Hajer and Versteeg’s34 governance framework; their analytic dimensions of scripting, setting, staging and performance were used as a deductive, a priori template (‘code book’) against which qualitative material within field notes were organised. Thematic analysis revealed patterns (similarities and differences) within the data that were important to the operation of governance,40,41 showing the divergent dramaturgies at play within each specific site.

The tracer condition interviews were analysed using a combination of deductive and indicative approaches. Our analysis was informed by the research questions (deductive); for example, our conformance data analysis was particularly interested in the role of performance targets and measurement for C. difficile infections. Our analysis was also inductive, particularly for the ‘performance’ interviews, as this sample of interviews was one that emerged from the fieldwork as examples of board activity in relation to patient safety.

The interviews with governors and commissioners would also proceed through a thematic approach, whereby codes were generated specifically from the research questions (deductive); for example, from analysing the experience of these groups in holding each hospital board to account. Our analysis would also generate a selection of emergent codes (inductive) from the data. For example, the dynamic and often turbulent environment of recent changes to the commissioning environment was something that emerged as important to our research area. Our approach to these interviews was also iterative in that our fieldwork had already carried out many of the board interviews and observations. These caused a number of points worthy of further investigation to surface, which we then looked to explore.

Our ‘data display’ organised and compressed the transcribed interviews using the NVivo software programme (QSR International, Warrington, UK). An example of each of our interview coding frames can be found in Appendix 4. To provide inter-rater reliability, two members of the research team independently coded data and discussed the application of the coding frames.

The case study analysis presents data drawn from multiple sources (interviews with a range of internal and external stakeholders, observations and secondary documents), with a reporting structure organised in relation to our main research questions. Data analysis proceeded in parallel with collection to iteratively inform subsequent collection and refine the emerging analysis. Data from multiple sources was initially coded against our main research questions drawn from the literature, the coding categories for individual case study analysis being strategic vision; leadership activity; board mechanisms; governor relations; assessment of performance; relationships with commissioners and regulators. These concerns are presented as detailed individual case studies, with the initial research questions used as a point of departure to explore the range of concerns revealed inductively within each case. The individual case studies were then aggregated thematically to provide a summary overview chapter, with a subsequent analysis offered of emergent themes across the case studies – principally concerning getting and using hard and soft intelligence (as opposed to data) and exploring resulting concerns and tensions between conformance and performance.

Our purposive sampling strategy meant that decisions regarding data saturation point were made based on practical purposes.

For the board interviews, our sample was the executive board. Saturation point was reached when all of these interviews were included, with the exception of those members who declined to participate.

For the governor interviews, our sample criteria were built on capturing a subsection of governors who could outline the central issues facing governors. We spoke to a selection of public governors at each site. We did try to contact staff governors; however, we were unsuccessful in getting any to agree to participate.

For the tracer condition interviews, our purposive samples and decisions about saturation point varied. The conformance tracer condition (C. difficile infection) saturation point was reached when we had interviewed all or near to all members of the IPC teams. The performance tracer condition would reach a saturation point when we had spoken to range of stakeholders.

Surveying English NHS boards

Given the paucity of information available on English NHS boards, we used the BSAQ tool (discussed shortly) along with other survey instruments as a means of providing an account of board composition, activities and orientations. Our goals were as follows: first, to provide a basic descriptive account of English NHS boards in acute hospitals, which is currently lacking in the literature; second, we wanted to provide a snapshot of the BSAQ six-dimensional structure applied to English NHS boards; and, finally, we sought to explore whether there were major differences between different types of hospitals, looking at FTs versus non-FTs and THs versus non-THs.

Two national surveys were undertaken about board management in NHS acute and specialist hospital trusts in England. The first of these surveys was issued to 150 trusts in the financial year 2011/12 as part of the annual trust survey carried out by Dr Foster. The questionnaire was completed online via a dedicated web tool. This survey gathered data on each trust’s board and activities related to the oversight of patient safety; 145 replies were received, making for an overall response rate of 97%. We believe that this response rate is unusually high because of the levels of engagement of NHS trusts with Dr Foster (in some cases responses were omitted from individual questions, making the effective response rate slightly lower for some data items). The national survey questions are contained in Appendix 5.

The second survey targeted individual board members from these trusts. We used an adapted version of the BSAQ questionnaire that had been tested previously with a small sample of FTs in the English NHS29 (see Appendix 6 for the BSAQ questions). This survey was also completed through online means and data were gathered between May 2012 and April 2013. By this time period, trust numbers were reduced to 144 because of merger activity in the sector. A total of 334 responses were received from 165 executive and 169 non-executive board members, providing at least one response from 95 of the 144 NHS trusts then in existence (66%). In order to gain trust-based estimates on each of the six BSAQ dimensions, replies from individuals from the same trust were aggregated.

For all of the main indicators calculated across both surveys we explored differences between FTs and non-FTs and between THs and non-THs.

Assessing boards with the Board Self-Assessment Questionnaire

As interest has grown in understanding the effectiveness of boards, both inside and outside health care, a range of board assessment tools have been developed and applied. Most prominent among these, and a tool that has seen some use in health care, is the 65-item BSAQ. The BSAQ is derived from research highlighting the characteristics of effective non-profit governing boards in the USA. 42,43

The initial research on the BSAQ examined the practices of boards identified by a panel of experts on board development as either reputedly very effective or reputedly very ineffective. On the basis of this dichotomy of board development, the researchers isolated observable behaviours that were distinctive to the more effective boards and, using the critical incident technique as part of a qualitative study, identified six dimensions or competencies of effective board performance. 42 Following the qualitative phase, structured interviews with boards of trustees were used to aid the development of a self-administered 65-item questionnaire, in which each item is answered using a 4-point Likert-type scale. The BSAQ has subsequently been subject to extensive testing for validity, reliability and sensitivity, and this process confirmed that the six theoretically derived dimensions also had some empirical distinctiveness. 44,45

These six dimensions are labelled: contextual, educational, interpersonal, analytical, political and strategic (Box 1 provides more details). Four of these dimensions relate directly to Garratt’s instrumental board tasks (located in Table 1) and the remaining two (educational and interpersonal) are more behavioural, reflecting recognition of the need for boards to develop group cohesion, reflection and development.

-

Contextual dimension. The board understands and takes into account the culture, values and norms of the organisation it governs.

-

Educational dimension. The board takes the necessary steps to ensure that all board members are well informed about the organisation and the professions working there, as well as the board’s own roles, responsibilities and performance.

-

Interpersonal dimension. The board nurtures the development of board members as a group, attends to the board’s collective welfare and fosters a sense of cohesiveness.

-

Analytical dimension. The board recognises complexities and subtleties in the issues it faces and draws upon multiple perspectives to dissect complex problems and to synthesise appropriate responses.

-

Political dimension. The board accepts as one of its primary responsibilities the need to develop and maintain healthy relationships among key stakeholders.

-

Strategic dimension. The board helps envisage and shape institutional direction and helps ensure a strategic approach to the organisation’s future.

Evaluating the Board Self-Assessment Questionnaire in the English NHS context

Because the BSAQ has seen only limited use in the UK context, we revalidated the data structure of the instrument using the data from English NHS boards. Factor analysis was performed at the respondent level to explore underlying factors that characterise boards. This analytic strategy is more fully explored in Chapter 8, in which the eigenvalues and item loadings are also presented.

Relating board-level variables to organisation-level quality and safety

After constructing the factor scores representing the six BSAQ dimensions and the total BSAQ score, we explored whether or not these were correlated with patient safety measures (although we did not explore a priori hypotheses). In doing so, we estimated various multivariate models regressing patient safety measures (from Dr Foster) and measures of hospital ability to handle errors, near-misses and incidents, taken from the National NHS Staff Survey (NSS) for 2012 on the total BSAQ score, controlling for a number of hospital-level characteristics. The full range of dependent variables are described and presented in Chapter 8 and more fully in Appendix 7.

Integrating quantitative and qualitative data

The implications of the findings from the literature review, qualitative case studies and the national surveys were discussed at meetings of the whole research team. The original research objectives were used to structure the discussion; for each of the five keys objectives the relevant qualitative data were discussed and a consensus achieved regarding how to interlock the findings relating to each objective. Chapter 5 presents the ‘integrated’ findings relating to each research objective.

Concluding remarks

In this chapter we have set out the basic theoretical framings used to shape data collection and interpret the findings, and we have laid out the various stages of qualitative and quantitative data gathering. Subsequently, Chapters 4–7 present various aspects of the qualitative data and Chapter 8 provides a full account of the quantitative data. The qualitative data have been structured in the following way: Chapter 4 provides an overview of findings across all four case sites; Chapter 5 provides more detailed analysis on a case-by-case basis; Chapter 6 displays the findings from our tracer issues (two for each trust site); and, finally, Chapter 7 takes a dramaturgical view of board performance to explore the more symbolic aspects of board practice(s).

First, however, we turn to the literature that underpins the work: Chapter 3 provides a synthesis of existing empirical work and a systematic narrative review exploring board composition and activities alongside organisational performance.

Chapter 3 Systematic narrative review and synthesis

Introduction

Although standards and guidance on board oversight have been produced, as have summaries of evidence of the effectiveness of board oversight of quality and safety, the research base in relation to board oversight of patient safety has not yet been fully exploited. The purpose of this chapter is to review and synthesise this evidence base. It begins with an overview of the literature review methods employed, before presenting the results, which are connected to four discernible storylines regarding board governance of patient safety.

Review methods

The research carried out a narrative systematic review in order to describe, interpret and synthesise key findings and debates concerning board oversight of patient safety. 46 We also produced a synthesis of these findings with the intention of supporting the development of our empirical work and contributing to wider debates regarding policy and practice within this area.

An initial systematic search of the area (Table 5) enabled us to map the broad parameters of the literature and map their development over time. To ensure rigour, we followed accepted practice in identifying the review focus, specifying the review question, searching for and mapping the available evidence and identifying studies for inclusion. 46 In selecting papers, we focused on those that considered board oversight in the context of quality and safety, and the research team and expert panel suggested seminal works and advised on search terms. The team drew up a list of key terms and searched the published literature from 1991 to 2012 across a number of databases, excluding non-English-language articles.

| Search title and abstract from 1991 to 2012 | |

|---|---|

| Board governance Hospital board Board of trustees Boards of management Management boards Board members Board chairpersons AND patient safety or safety AND quality |

|

| Database searched | Number of results |

| HMIC | 11 |

| EMBASE | 103 |

| MEDLINE | 32 |

| ASSIA | 20 |

| EBSCOhost (CINAHL and Business Premier) | 52 |

| SSCI | 39 |

| Total with duplicates removed | 187 |

The team then reviewed titles and abstracts for relevance, using broad inclusion criteria to identify studies of hospital board directors’ or boards of trustees’ oversight of quality and patient safety. Our initial search uncovered 187 articles and, after reviewing the titles and abstracts, we identified a subset of 66 papers for detailed study, which we added to those identified by earlier reviews,47 removing duplicates. Disagreements about whether or not to select a reference for full review were resolved by discussion within the team. Finally, we used snowballing techniques to augment papers for review – manually, by searching references of included papers, and electronically, by using citation-tracking software to identify papers that cited already included papers. These searches were adapted iteratively to ensure maximum capture of empirical work; at the end of the process 124 publications were deemed relevant.

We followed guidance on narrative synthesis from Popay et al. 48 in our data extraction and appraisal of study quality. Our key concern was to understand the effectiveness of oversight in terms of board composition and interventions with boards, such as the setting of standards and benchmarks. In particular, we were keen to explore any evidence for improved performance and patient outcomes, such as reductions in mortality and morbidity, from board interventions, as well as identifying factors that impact on the effective implementation of those board interventions. The synthesis phase of the review explored key aspects of board oversight of quality and patient safety and identified four common storylines:

-

leading for safer care

-

measuring safe care

-

internal board oversight

-

external regulation and accountability.

After a brief historical account of the growth of the field, we will examine each storyline in turn and present a narrative synthesis.

The literature uncovered

A growing field of enquiry

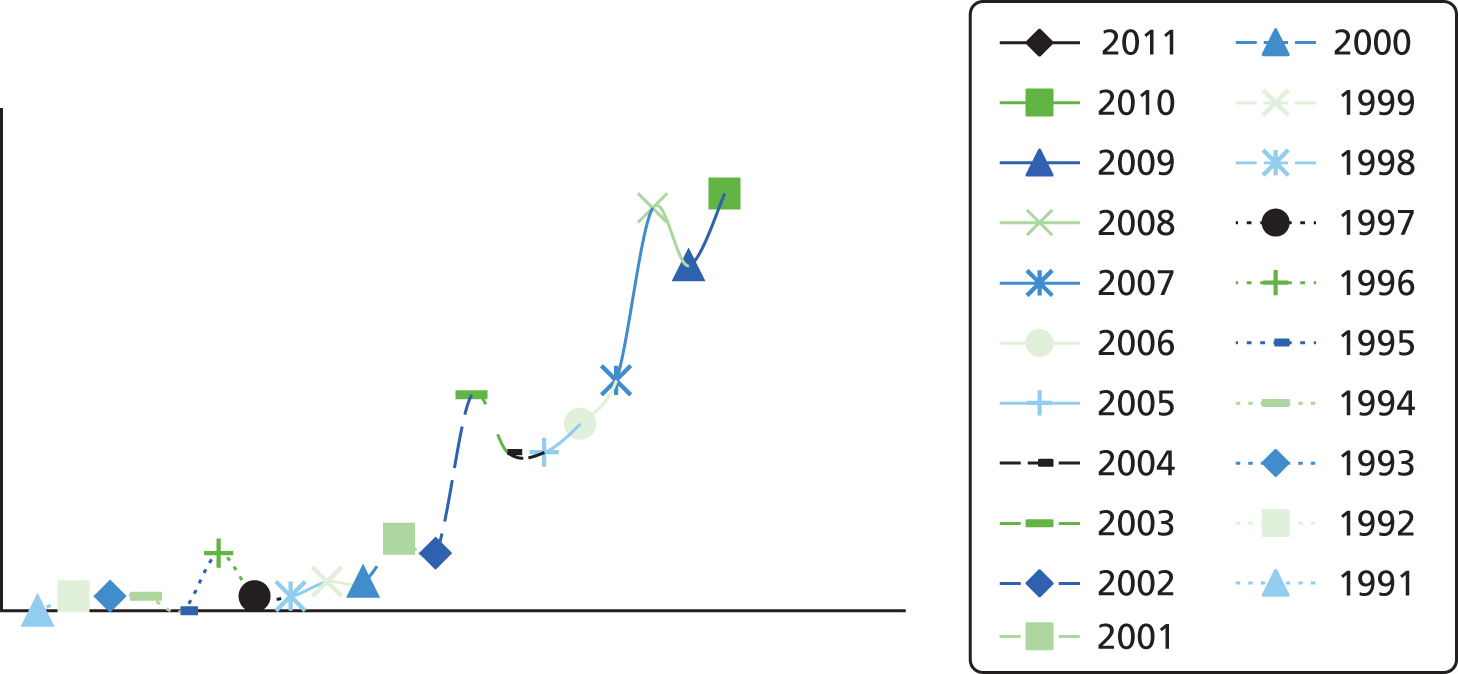

The US Institute of Medicine’s reports, To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System49 and Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century,50 and the UK Chief Medical Officer’s report into learning from adverse events, An Organisation with a Memory,51 were hugely influential in calling for changes to health-care systems and organisations that would improve quality and safety. It is, therefore, unsurprising that our results show large and rapid growth since 2000 in the number of published articles that relate to hospital board oversight of quality and patient safety (Figure 1), a trend that reinforces the increased policy salience of board oversight of safety.

FIGURE 1.

Results of the systematic search of board oversight and patient safety.

The study of board oversight in relation to quality and patient safety can be situated within the broader literature that addresses the role of leadership in improving quality in US hospitals. 52–56 With variable successes achieved by hospitals in implementing quality improvement programmes and initiatives,57,58 the publication of empirical studies of US hospitals emerges from 2004 onwards, revealing variation in the adoption of board practices that are thought to be associated with higher performance and better patient outcomes (Table 6). 53,66 These cross-sectional surveys of predominantly non-profit hospitals indicate the importance of examining the leadership actions that are thought to influence the effectiveness of quality improvement activities in hospital settings. 71

| Author (year) country | Participants | Context (aims) | Board assessment (methods) | Summary of findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baker et al. (2010),59 Canada and the USA | 15 governance experts, average of 10 board members across four case studies, survey of Quebec and Ontario health economies | To identify governance practices and improve governance related to patient safety | Semistructured interviews, documentary analysis and survey | Effective governance is in its early stages. Better information, expertise, plans, skills and relationships still required |

| Grey and Weiss (2004),60 USA | 98 CEOs and trustees from 16 non-profit hospitals in the New York area | To learn about how trustees define their responsibilities, how they relate to hospital activities and their decision-making processes | Structured, open-ended interviews with trustees and CEOs | Governance by boards was a strength and weakness for non-profit hospitals. Fundamental ambiguities in the ethical significance of the trustee role were identified |

| Goeschel et al. (2011),61 USA | 35 boards from cross-section of hospitals across Tennessee and Michigan | To identify effective measures to monitor quality | Survey and voluntary site request for safety scorecards | Measures varied widely with uncertain validity. More valid outcome measures required |

| Jha and Epstein (2010),57 USA | 722 chairpersons from non-profit acute care hospitals | To determine board engagement and activities in relation to quality of care | Survey and composite measures of hospital performance | Quality of care often not a top priority. Differences in quality-related activities between high- and low-performing institutions |

| Jha and Epstein (2012),62 USA | 722 chairpersons from ‘black-serving’ and ‘non-black-serving’ non-profit hospitals | To compare how boards at black-serving and non-black-serving hospitals engage in quality-of-care issues | Survey and composite measures of hospital performance | Board chairpersons of black-serving hospitals report fewer expertise and priorities regarding quality issues than chairpersons of non-black serving hospitals |

| Jha and Epstein (2013),63 UK | 132 chairpersons from a cross-section of English hospitals | To compare governance practices among English and US hospital boards | Survey and composite measures of hospital performance | English board chairpersons report more expertise and emphasis on quality-of-care issues than the USA; however, hospital performance against quality metrics not as substantial as the USA |

| Jiang et al. (2008),52 USA | 562 hospital presidents/CEOs across 50 states selected from the 2006 TGI survey | To examine the prevalence and impact of particular board activities | Survey and composite measures of hospital performance | Governing boards are engaged in quality oversight, particularly through internal data and national benchmarks |

| Jiang et al. (2009),64 USA | Based on a data set from Jiang et al. (2008)52 | To examine differences in hospital quality performance associated with particular practices | Based on Jiang et al. (2008)52 | Better performance associated with having a board quality committee, strategic goals, a quality agenda, safety dashboards/benchmarks and involvement of physician leaders |

| Jiang et al. (2011),65 USA | 445 hospitals selected from the 2007 TGI survey | To explore the practices of governing boards in quality oversight through the lens of agency theory | Survey and composite measures of care and mortality | Regular review of quality performance is the most common practice |

| Joshi and Hines (2006),66 USA | 47 CEOs and board chairpersons from cross-section of 30 hospitals across 14 states | To determine whether or not hospital leaders understand safety and quality issues and activities | Interview survey and composite measures of clinical quality | Overall level of knowledge low. Significant differences between perceptions. Mild association between board engagement and hospital performance |

| Kroch et al. (2006),53 USA | Convenience sample of 139 hospitals across nine states | To analyse hospital board dashboards and its relationship to leadership engagement | Online dashboard implementation survey and performance data analysis using composite measures | Variation and commonalities in the way dashboards are created and used. Improved quality linked to shorter, more focused dashboards |

| Machell et al. (2010),15 UK | Nurse executives and boards in six English NHS hospital trusts | To examine board focus on clinical quality and nurse executives in supporting this | Observations | Clinical quality occupied a fragile position. Nurse executives are well placed to help |

| Mastal et al. (2007),67 USA | 73 hospital chief executives, CNOs and chairpersons from 63 hospitals | To analyse board engagement in quality and safety and the role of nursing within this | Telephone interviews and focus group | Significant differences in perceptions between CNOs, chairpersons and CEOs. Boards had limited comprehension of salient nursing quality issues |

| Prybil et al. (2010),68 USA | CEOs from 123 non-profit community health systems | To examine oversight of patient quality at non-profit community health systems and compare with benchmarks of good governance | Survey and benchmark analysis | Activities associated with effective governance include standing committees and safety targets/reports. Gaps continue between present reality and current benchmarks |

| Prybil et al. (2013),69 USA | Senior trustees and CEOs from 14 private non-profit health systems | To examine board oversight of quality in private non-profit health systems and compare with benchmarks of good governance | Documents, interviews and benchmark analysis | Effective governance identified in majority of boards with presence of standing committees, system wide quality measures and action plans directed at improving quality |

| Ramsay et al. (2010),70 UK | Case study of 21 personnel, including board members from a hospital trust in England | To describe the external and internal governance systems for HCAIs and medication errors in a NHS trust | Documentary analysis and interviews | Nationally, HCAIs a higher priority than medication errors. Governance of medication errors took place at divisional or ward level |

| Vaughn et al. (2006),71 USA | CEOs and senior executives from a cross-section sample of 413 hospitals in eight states | Identify characteristics of hospital leadership engagement in quality improvement | Survey and composite measures of clinical quality | Better quality associated with boards spending more than 25% of time on quality issues; that received formal measurement reports; and communicating a quality strategy to medical staff |

From 2008, larger-scale studies covering wider geographical areas begin to feature. Building on the cross-sectional survey of the prevalence and impact of board activities in US hospitals,52 Jiang et al. 64 developed the scope of their evaluation of board oversight to include impact on clinical outcome measures such as mortality, morbidity and complications, as well as differences in the processes of care. Jha and Epstein57 carried out the first national survey of board chairpersons in the USA to analyse board engagement with clinical quality and identify differences between board activities in high- and low-performing organisations.

From 2010, studies have emerged that seek to differentiate and explore board activities related to patient safety in specific socioeconomic, organisational and geographical contexts. Jha and Epstein62 pursued an explicitly socioeconomic focus to compare boards of directors’ priorities and practices in serving the interests of minority-group patients. Prybil et al. 68 examined specific board structures, practices and cultures that relate to good governance in US non-profit community health systems. Baker et al. 59 carried out the first significant study of board governance and quality and safety in Canadian health-care organisations, and studies from the UK have emerged that analyse the formal governance arrangements for HCAIs and medication errors. 70 More recently, Jha and Epstein63 conducted the first national survey of English hospital board activities, providing an international comparison with their survey of non-profit acute care hospital boards in the USA. In addition, studies have also been published examining health board oversight of quality and safety in the Netherlands,72 Scotland73 and Australia. 74

The theoretical and conceptual dimensions of board oversight have also received more explicit attention. Jiang et al. 65 employ the agency theory perspective as a lens through which to explore the role and practices of hospital governing boards, while Ford-Eickoff et al. 75 explore how concepts such as complexity absorption and requisite variety can support hospital board governance and oversight, hypothesising that boards with greater variety and breadth of expertise among its membership can better respond to complex environments and have greater potential for sense-making and learning.

Emerging storylines

Our review of board oversight of patient safety identifies a variety of empirical evidence and expert advice that suggests that specific board activities are associated with improvement in the quality and safety of hospital care. However, the results also suggest that the adoption of such activities remains variable and that our understanding of boards’ impact on patient safety is currently limited. We present the findings thematically, as four storylines derived from the narrative review: (1) leading for safer care, (2) measuring safe care, (3) internal board oversight and (4) external regulation and accountability.

Leading for safer care

Board oversight of patient safety tends to reflect a key message from the quality improvement literature as a whole; that is, that strong and committed leadership from the CEO and the board is vital to the success of quality improvement and safety programmes. 56,76–79 A review by Clarke et al. 80 suggests that leadership on patient safety should learn from the characteristics and behaviours of high-reliability organisations, such as those found in the nuclear and aviation industries. In health care, leadership is associated with perceiving lapses in patient safety to be a problem of the system rather than individual employees, and with words and actions that promote a culture that encourages the identification of mistakes, emphasises system improvements that reduce variability and makes safety a given.

Empirical evidence from cross-sectional surveys in the USA suggests that boards that demonstrate such leadership have a positive impact on the safety performance of its organisations. Boards that place a high priority on quality and safety are associated with higher performance,64 as are boards that set strategic goals for quality improvement and demand reports on the progress of action in response to adverse events. 52,72,81 A US national survey of 722 chairpersons in 2007 and 2008 by Jha and Epstein found that respondents from high-performing non-profit hospitals were more likely than respondents from low-performing non-profit hospitals to establish and publicly disseminate goals and to perceive themselves as influential throughout the organisation. 57

Although such practices have been found to be associated with effective leadership on patient safety, empirical evidence suggests significant variation in the implementation. Drawing on the 2006 TGI (The Governance Institute, San Diego, CA, USA) survey of 562 chairpersons and CEOs from hospitals across the USA, Jiang et al. 52 found that fewer than half the CEOs regarded their organisations’ governing boards as very effective in overseeing quality. Similarly, Baker et al. 59 found in case studies of Canadian and US health-care organisations that, although most boards had established strategic goals for quality improvement, many did not have specific objectives with clearly defined targets, which suggests that words are not necessarily backed up by actions. Observational research by Machell et al. 15 of how nurse executives and boards work in acute care hospitals and mental health trusts across England found that many chief nursing officers (CNOs) perceived board members to be only moderately engaged in quality improvement initiatives. This was attributed to members’ lack of knowledge about quality and patient safety issues, the limited time available for participating in quality initiatives and to a lack of quality champions at board level. Such a view is echoed in qualitative research of non-profit hospitals in the USA. Interviews with CEOs and trustees by Grey and Weiss60 in 1998 and 1999 found that the two most important issues for local non-profit hospital boards in the New York area were mergers/acquisitions and financial management, with hospital quality and safety receiving far less attention. These findings are consistent with US national survey data from Jha and Epstein,57 which revealed that approximately half of the non-profit hospital boards did not rate quality of care as a top priority for board oversight or for CEO performance evaluation. Most boards were primarily focused on financial issues, assuming that its quality of care was adequate.

Measuring safe care