Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 11/2004/12. The contractual start date was in October 2012. The final report began editorial review in December 2014 and was accepted for publication in May 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Ms Alison Faulker received consultancy fees for her role in the project. The authors declare no other competing interests.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Simpson et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction, background and aims

The context and delivery of mental health care are diverging between the countries of England and Wales, although they retain points of common interest and hence provide a rich geographical comparison for research. Across England, the key vehicle for the provision of recovery-focused, personalised, collaborative mental health care is the care programme approach (CPA). The CPA is a form of case management introduced in England in 1991, then revised and refocused. 1 In Wales, the CPA was introduced in 20032 but it has now been superseded by The Mental Health [care and treatment planning (CTP)] Regulations (Mental Health Measure), a new statutory framework. 3 Data for England show that 403,615 people were on the CPA in 2011/12. 4 Centrally held CPA numbers supplied by the Corporate Analysis Team at the Welsh Government indicate 22,776 people in receipt of services as of December 2011, just 6 months prior to the introduction of CTP under the Mental Health Measure.

In both countries, the CPA/CTP requires providers to comprehensively assess health/social care needs and risks; to develop a written care plan (which may incorporate risk assessments, crisis and contingency plans, advanced directives, relapse prevention plans, etc.) in collaboration with the service user and carer(s); to allocate a care co-ordinator; and to regularly review care. Both the CPA and CTP processes are now also expected to reflect a philosophy of recovery and to promote personalised care,1,5 although interpretations of personalisation may vary between countries. 6

The concept of recovery in mental health was initially developed by service users and has led to disparate conceptualisations7 but broadly refers to ‘a way of living a satisfying, hopeful, and contributing life even with limitations caused by illness,’ while developing new purpose or meaning. 8(p. 527) The importance of addressing service users’ personal recovery alongside more conventional ideas of clinical recovery9 is now supported in guidance for all key professions. 10–13 To this has been added the more recent idea of personalisation. Underpinned by recovery concepts, this aims to see people and their families taking much more control over their own support and treatment options, alongside new levels of partnership and collaboration between service users and professionals. 14 Recovery and personalisation in combination require practitioners to tailor support and services to fit the specific needs of the individual and enable social integration through greater involvement of local communities.

Cochrane systematic reviews of case management including the CPA15 did not consider recovery-oriented outcomes and few studies are explicitly conducted into the practices of the CPA care planning and co-ordination. Early investigations in England prior to the refocus on recovery drew attention to the bureaucracy associated with care co-ordination which, combined with high caseloads, deflected practitioners from therapeutic interventions linked to positive outcomes. 16,17

National audits in England reported considerable local variation in implementation of the CPA, and despite improvements in performance, significant numbers of service users were not receiving care in line with guidelines. 18 A review conducted in Wales reflected concerns in risk assessment, care planning, unmet need and service planning, training, information requirements and systems, transfer of care arrangements, and leadership. 19 The authors concluded that there was a high risk that services were not effectively meeting users’ and carers’ needs and that significant improvement was required.

Service users appear to remain largely mystified by care planning and review processes. In a national quality survey of over 17,000 community mental health (CMH) service users across 65 English NHS trusts, 42% said that their care was co-ordinated under the CPA. 20 Over 90% of all respondents described their care as well organised and 83% of those on the CPA knew who their care co-ordinators were. Despite this, over half did not understand their care plans; only 16% had written copies; 20% said that their care plans did not set out their goals; and 11% said that their views had not been taken into account during care planning. In Wales, 310 users of NHS/local authority (LA) mental health services responded to a similar survey. 21 Only 58% knew who their care co-ordinator was; just half were given or offered copies of their care plans, with only 51% ‘definitely’ understanding the content of care plans and 43% ‘definitely’ involved in ‘co-producing’ the content.

The need for greater co-production has also been found in the area of risk management. Research for the Joseph Rowntree Foundation22 on service users’ views on risk reported that perceptions of risk and rights were significantly different for mental health service users. Practitioners tended to perceive service users as a source of risk first rather than to consider them potentially at risk in vulnerable situations; they appeared to be overlooked by adult safeguarding practices; and their individual rights were compromised by mental health legislation.

This evidence, which points to the relative lack of genuine service-user involvement in CPA/CTP processes, is significant in the context of what we know about therapeutic relationships and recovery. The therapeutic relationship is a reliable predictor of patient outcomes in mainstream psychiatric care. 23,24 Strong, collaborative, working alliances between case managers and people with long-term mental health difficulties have been shown to reduce symptoms, improve levels of functioning and social skills, promote quality of life, enhance medication compliance and raise levels of satisfaction with care received. 25 Yamashita et al. 26 describe negotiating care within a trusting relationship as key in case management and this relationship may influence users’ perceptions of stigma. 27

In summary, the limited available evidence contrasts with the aspiration that CPA/CTP care planning and related processes should be collaborative, personalised and recovery-oriented. In addition, the current approach to assessing and managing risk under the CPA may not be satisfactory for either service providers or service users.

Aims

In this multisite, cross-national comparative study we aimed to identify and describe the factors that ensure CPA/CTP care planning and co-ordination is personalised, recovery-focused and conducted collaboratively.

As an exploratory study guided by the Medical Research Council Complex Interventions Framework28 we aimed to generate empirical data, new theoretical knowledge and greater understanding of the complex relationships between care planning, recovery and personalisation. It was the intention that this study would produce theory and empirical evidence that will inform commissioners, service managers, practitioners and service users and provide the rationale for a future intervention and evaluation.

In order to develop studies to examine interventions aimed at improving patient experience and outcomes, we aimed to collate and synthesise theoretical and empirical data using a range of methods in order to inform and develop a pragmatic and feasible intervention likely to be acceptable to service users, families/carers, practitioners and service managers. Our study will also provide lessons for similar, equally problematic, care planning and co-ordination processes for people with long-term conditions in a range of other health/social care settings. 29,30

Research question

What components need to be in place in order to ensure that care planning and co-ordination for people with severe mental illness are personalised, collaborative and recovery-focused?

Objectives

-

To review the international peer-reviewed literature on personalised recovery-oriented care co-ordination, and compare and contrast the English and Welsh contexts for recovery-based mental health care.

-

To conduct a series of case studies to examine in detail how the needs of people with severe mental illness using CMH services are assessed, planned and co-ordinated.

-

To investigate service users’, informal carers’, practitioners’ and managers’ views of these processes and how to improve them in line with a personalised, recovery-oriented focus.

-

To measure service users’ and staffs’ perceptions of recovery-oriented practices.

-

To measure service users’ views of the quality of therapeutic relationships and empowerment.

-

To identify methods, measures and processes for successfully evaluating a complex intervention aimed at delivering personalised, recovery-focused care planning and co-ordination and improved patient outcomes.

Structure of report

This report presents the key findings of our empirical research building upon a meta-narrative policy and literature review within the context of continuing developments in the organisation, structure and delivery of community mental health care in England and Wales.

In Chapter 2 we outline the methodology and design of the study, including public and patient involvement and ethical issues. In Chapter 3 we outline the methods and findings of the comparative policy analysis and meta-narrative literature review. In Chapter 4 we present the results from the within-case analysis, with findings from quantitative and qualitative analyses for both meso- and micro-level data presented for each case-study site. Then, in Chapter 5 we draw out comparisons and contrasts across sites set within the cross-national policy contexts and provide summary charts of the factors identified from this cross-case analysis that appear to function as facilitators of and barriers to the provision of recovery-focused, personalised care planning and delivery. Finally, in Chapter 6, we consider the limitations of the study and then explore the findings in relation to our aims and objectives and recent and ongoing research in relevant and overlapping areas. We end by outlining some tentative implications for mental health care commissioning, service organisation and delivery, clinical practice and health-care professional education and training, and recommendations for future research.

Chapter 2 Methods

Design

We conducted a cross-national comparative study of recovery-focused care planning and co-ordination in community mental health care settings, employing a concurrent transformative mixed-methods approach with embedded case studies. 31(p. 15) Concurrent procedures required us to collect quantitative and qualitative data at the same time during the study and then integrate that data in order to provide a comprehensive analysis of the research problem. One form of data is nested within another larger data collection procedure in order to analyse different questions or levels of units in an organisation.

In this study, in-depth micro-level case studies of everyday ‘frontline’ practice and experience with detailed qualitative data from interviews and reviews of individual care plans are nested within larger meso-level survey data sets, senior-level interviews and policy reviews in order to provide potential explanations and understanding.

At the macro-level is the national context. Cross-national comparative research involves ‘comparisons of political and economic systems . . . and social structures’32(p. 93) where ‘one or more units in two or more societies, cultures or countries are compared in respect of the same concepts and concerning the systematic analysis of phenomena, usually with the intention of explaining them and generalising from them’. 33(pp. 1–2) In this study, devolved government and the emergence of similar but distinct health policy, legislation and service development in England and Wales provided a fascinating backdrop for the investigation of community mental health care.

Such an approach fits well with a case-study method34 that allows the exploration of a particular phenomenon within dynamic contexts where multiple influencing variables are difficult to isolate. 35 It allows consideration of historical and social contexts36 and is especially useful in explaining real-life causal links that are potentially too complex for survey or experimental approaches. 37 So, in this study, we have conducted a detailed comparative analysis of ostensibly similar approaches to recovery-focused care planning and co-ordination within different historical, governmental, legislative, policy and provider contexts in England and Wales.

In our study the definitions of the case studies were predetermined,38 focusing on six selected NHS trust/health boards. Data collection at this level included identifying local policy and service developments alongside empirical investigations of care planning and co-ordination, recovery, personalisation, therapeutic relationships and empowerment, employing mixed quantitative and qualitative methods.

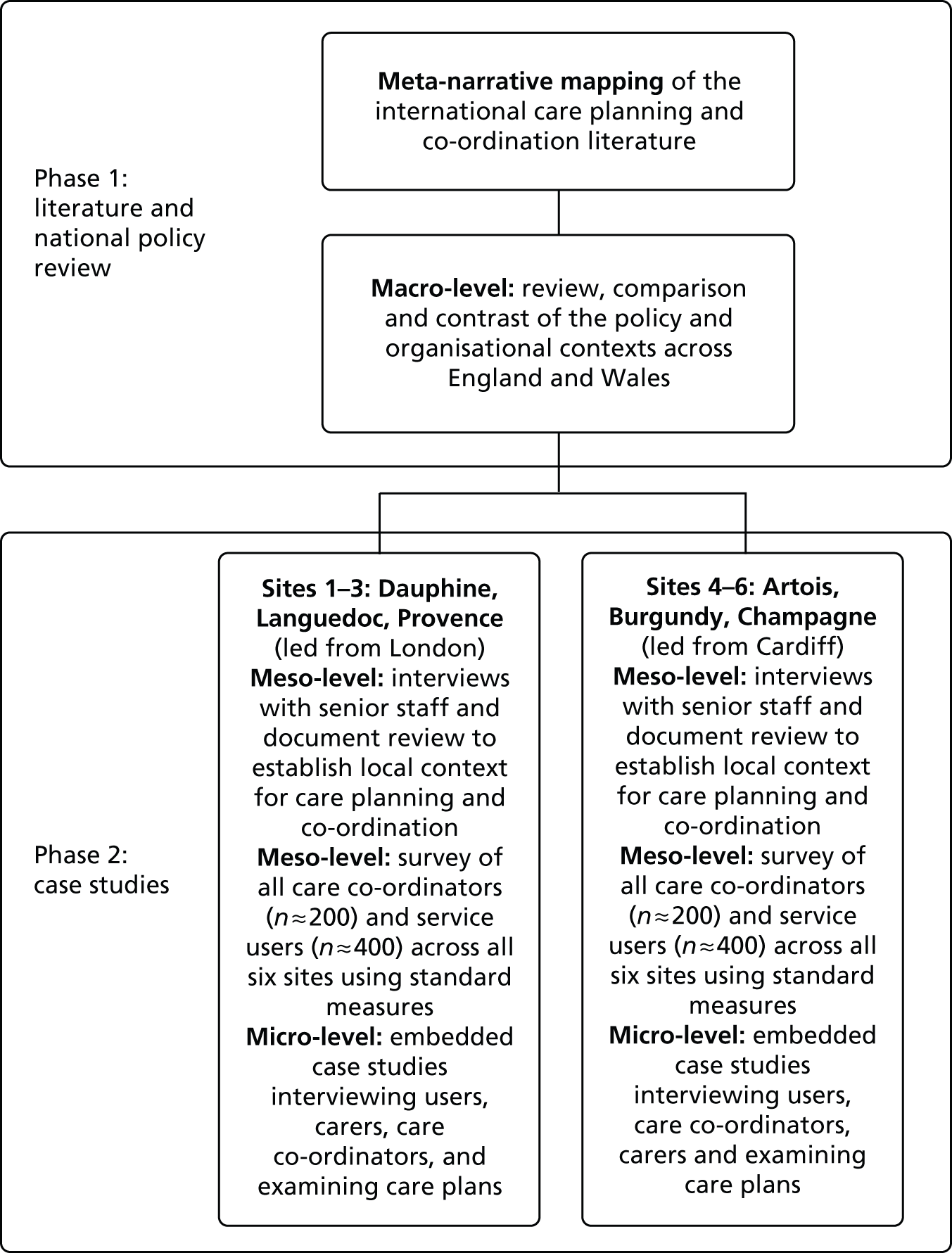

Within each of the six case-study sites we attempted to recruit participants within six embedded case studies made up of a service user, carer/family member and care co-ordinator triad. These explored the views and experiences of care planning and co-ordination from the triangulated perspectives of service users, carers and care co-ordinators. This design is represented in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Diagram of study design with embedded case studies.

Theoretical/conceptual framework

Transformative research seeks to include an explicit ‘intent to advocate for an improvement in human interests and society through addressing issues of power and social relationships’. 39(p. 441) In line with this, transformative procedures require the researcher to employ a transformative theoretical lens as an overarching perspective. 40 This lens provides a framework for topics of interest, methods for collecting data, and outcomes or changes anticipated by the study. In our study, our choice of methods, data collection and approach to analysis is guided by a theoretical framework emphasising the connections between different ‘macro/meso/micro’ levels of organisation41 and concepts of recovery and personalisation that foreground the service-user perspective and, arguably, may challenge more traditional service/professional perspectives. Furthermore, our research team and processes involve mental health service users throughout.

Methodology

Phase 1: literature and policy review and synthesis

Literature review on mental health care planning and co-ordination processes

We employed Greenhalgh et al. ’s42 meta-narrative mapping method (MNM), which focuses on providing a review of evidence that is most useful, rigorous and relevant for service providers and decision-makers and that integrates a wide range of evidence. 43 Our MNM review provides a preliminary map of current mental health care planning and co-ordination by addressing four points: (1) how the topic is conceptualised in different research traditions; (2) what the key theories are; (3) what the preferred study designs and approaches are; and (4) what the main empirical findings are. The methods employed are described in Chapter 3 where we also bring together our broad narrative synthesis.

Comparative analysis of policy and service frameworks

Through searching English and Welsh Government websites we also identified all key, current, national-level policy and guidance documents directly relating to mental health care planning and co-ordination across the two countries, along with those that relate directly to the promotion of recovery and the delivery of personalised care. Drawing on these we produce a narrative synthesis identifying major themes and areas of policy convergence and divergence (see Chapter 3), and use these materials to lay out the large-scale (or ‘macro-level’) national policy contexts to inform our case-study research interviews (see Chapter 4).

Phase 2: case studies

In Phase 2, we conducted six in-depth case-study investigations34 across six contrasting NHS trust/health board case-study sites in England (n = 4) and Wales (n = 2) (meso-level) employing mixed quantitative and qualitative methods. Then, in each site, access was secured to a single Community Mental Health Team (CMHT) from which up to six service users, their care co-ordinators and informal carers were sampled as embedded micro-level case studies. 31 Qualitative data were generated related to care planning and co-ordination processes in each (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Diagram of study plan.

Sampling

We selected six case-study sites: four NHS trusts in England and two local health boards (LHBs) in Wales that are commissioned to deliver CMH services. These sites were identified to reflect variety in geography and population and include a mix of rural, urban and inner city settings in which routine community care is provided to people with complex and enduring mental health problems from across the spectrum of need. The six trusts and health boards initially approached were all within 3 hours’ travelling distance of the two lead universities to facilitate data generation. Selection of the six sites followed advice from the reviewers and was a pragmatic decision, balancing a variety of settings and populations with logistical and data management pressures in the time available.

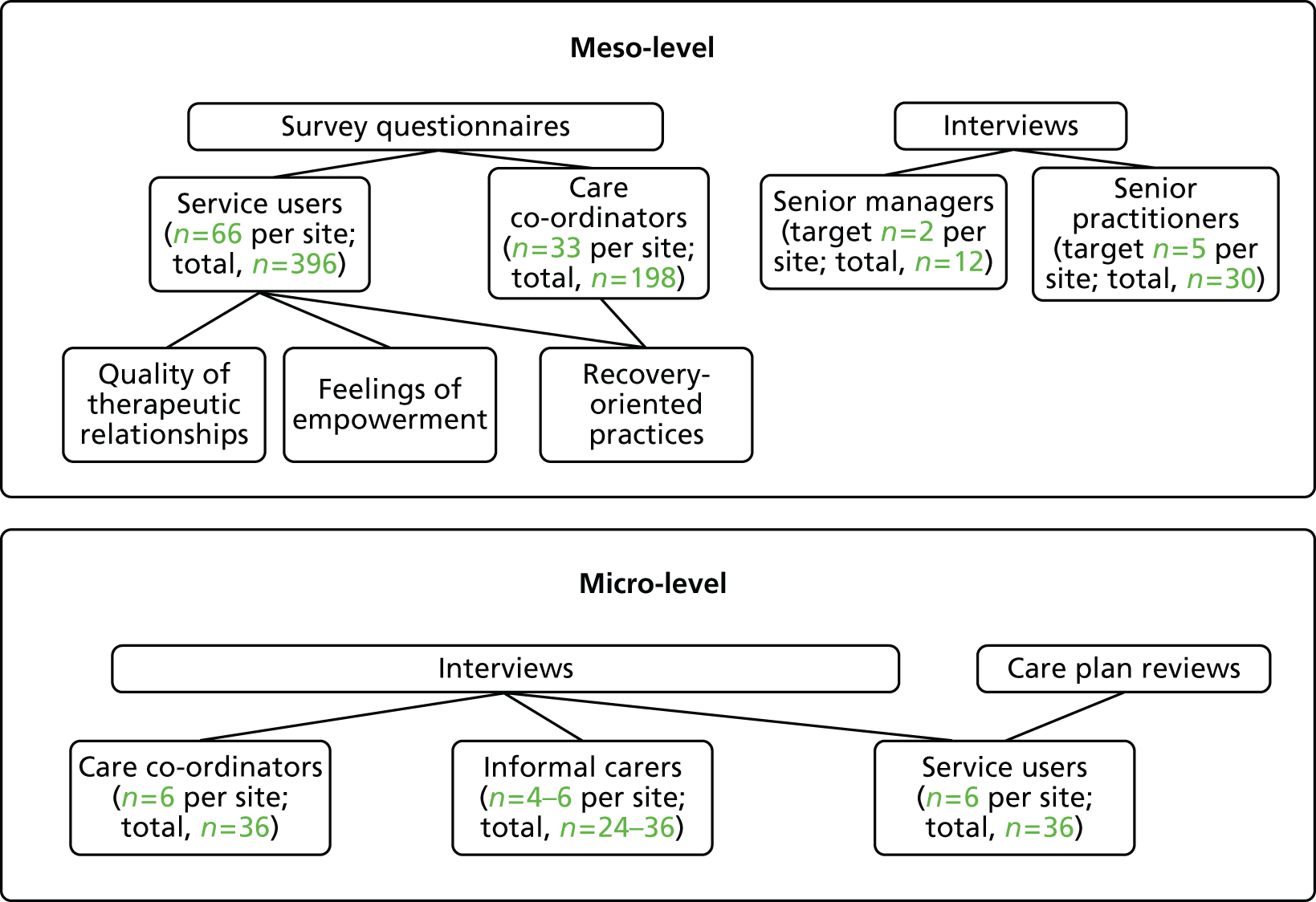

Within each meso-level trust/health board site we aimed to survey a large sample of service users and care co-ordinators (Figure 3). Survey questionnaires focused on recovery-oriented practices (both groups), and quality of therapeutic relationships and feelings of empowerment (service users only). Interview data were also generated relating to local contexts, policies, practices and experiences from senior managers and senior practitioners, purposively selected to include psychiatrists, senior nurses, psychologists, social workers and occupational therapists (OTs).

FIGURE 3.

Sample size and data collection targets.

In each trust/board site we also selected a single team providing routine CMH care that met our inclusion criteria (i.e. providing CMH care to adults; team manager in post; reasonably stable staffing; not due for merger or closure). We then invited a sample of six service users under the care of that CMHT to become the starting point for a series of embedded case studies nested within each larger (meso-level) organisational case study. To generate knowledge of how care is planned, co-ordinated and experienced at the ‘micro-level’, each service user, their informal carer and their care co-ordinator were invited to be interviewed and (with appropriate permissions) their written care plans reviewed (see Figure 3).

Sample size calculations

The key variables of interest for this study were the responses of service users and health-care staff in relation to the extent to which recovery-oriented practices were evident in the services surveyed. An established measure, the Recovery Self-Assessment (RSA) scale44 was used for this purpose, and prior investigations among US mental health services provided mean and standard deviation (SD) values on which to base estimates using the standard formula for scaled and categorical items. 45 Findings from the prior study provided a range of mean values for the RSA summary score from mean (SD) 3.87 (0.62) (providers) to 4.06 (0.69) (people in recovery). Applying a 0.69 SD value and an error margin or precision level of 3% provided a total sample size of 127. Anticipating a potential non-response rate of 40% requires inflation of the sample size to 250 to allow for this. In our study, we planned to seek RSA scale responses from service users (n = 400) and care co-ordinators (n = 200); these calculations indicate that generalisability to the target population and appropriate precision in findings is likely, even in the event of a poor survey response rate.

Sample size calculations for the interviews were based on informed estimations of the number of care co-ordinators per CMHT (six). Assuming half agreed to take part, this then gave us a suggested number of service users to randomly select from care co-ordinator caseloads (approximately 25 per care co-ordinator with a predicted response rate of 10%) for research interviews and care plan reviews, giving us a total of seven service users per CMHT. We aimed to recruit six service users per team and where possible their associated informal carer and care co-ordinator.

Instrumentation

-

Documentation and officially collected data. Local meso-level CPA policy and procedure documents, Care Quality Commission, national and local audits and reviews were collated where possible.

-

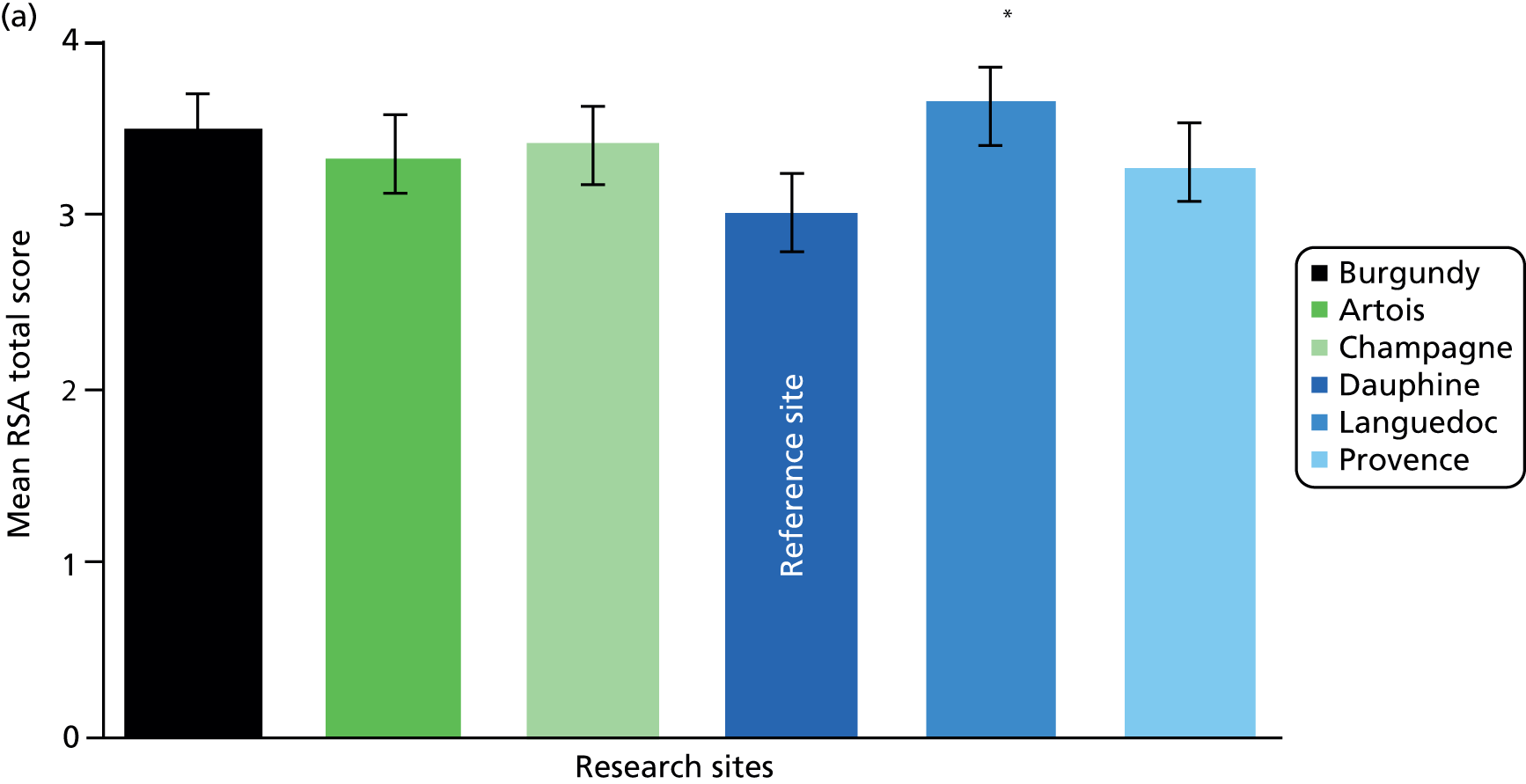

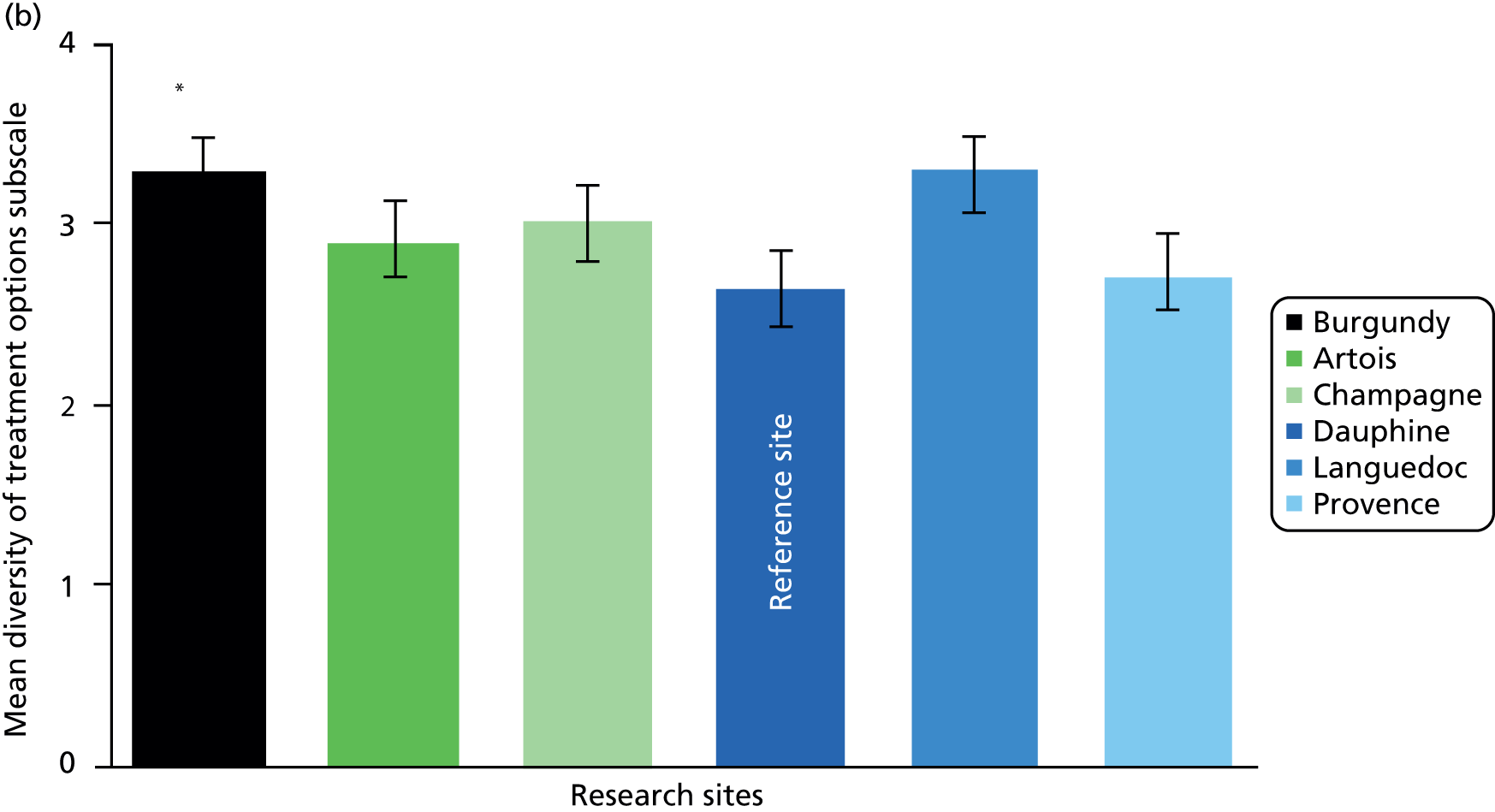

The RSA44 scale is designed to measure the extent to which recovery-oriented practices are evident in services. It is a 36-item self-administered questionnaire completed in this study by service users and care co-ordinators. The scale addresses the domains of life goals, involvement, treatment options, choice and individually tailored services. The RSA scale has been tested for use with people with enduring and complex mental health problems and across a range of ethnic backgrounds.

-

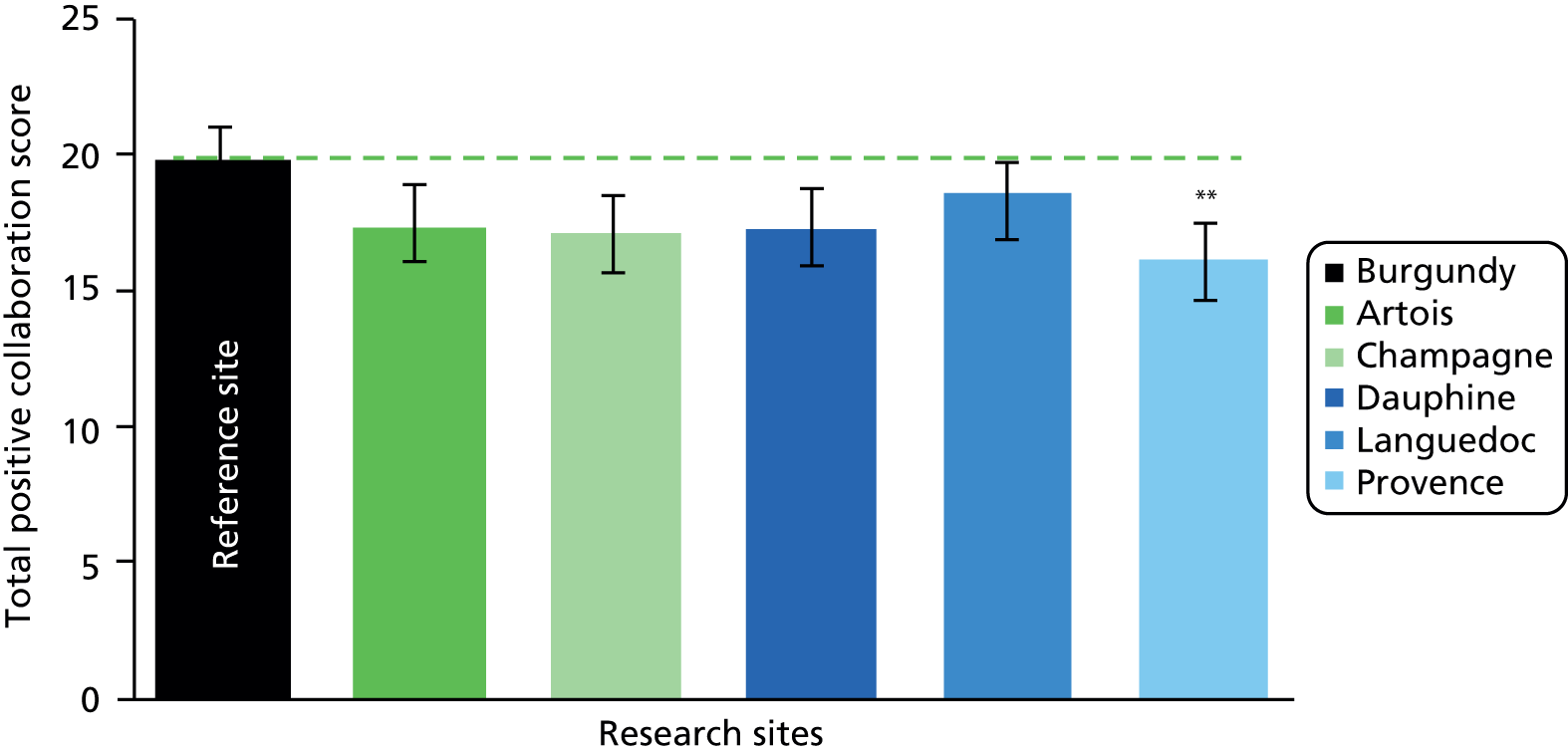

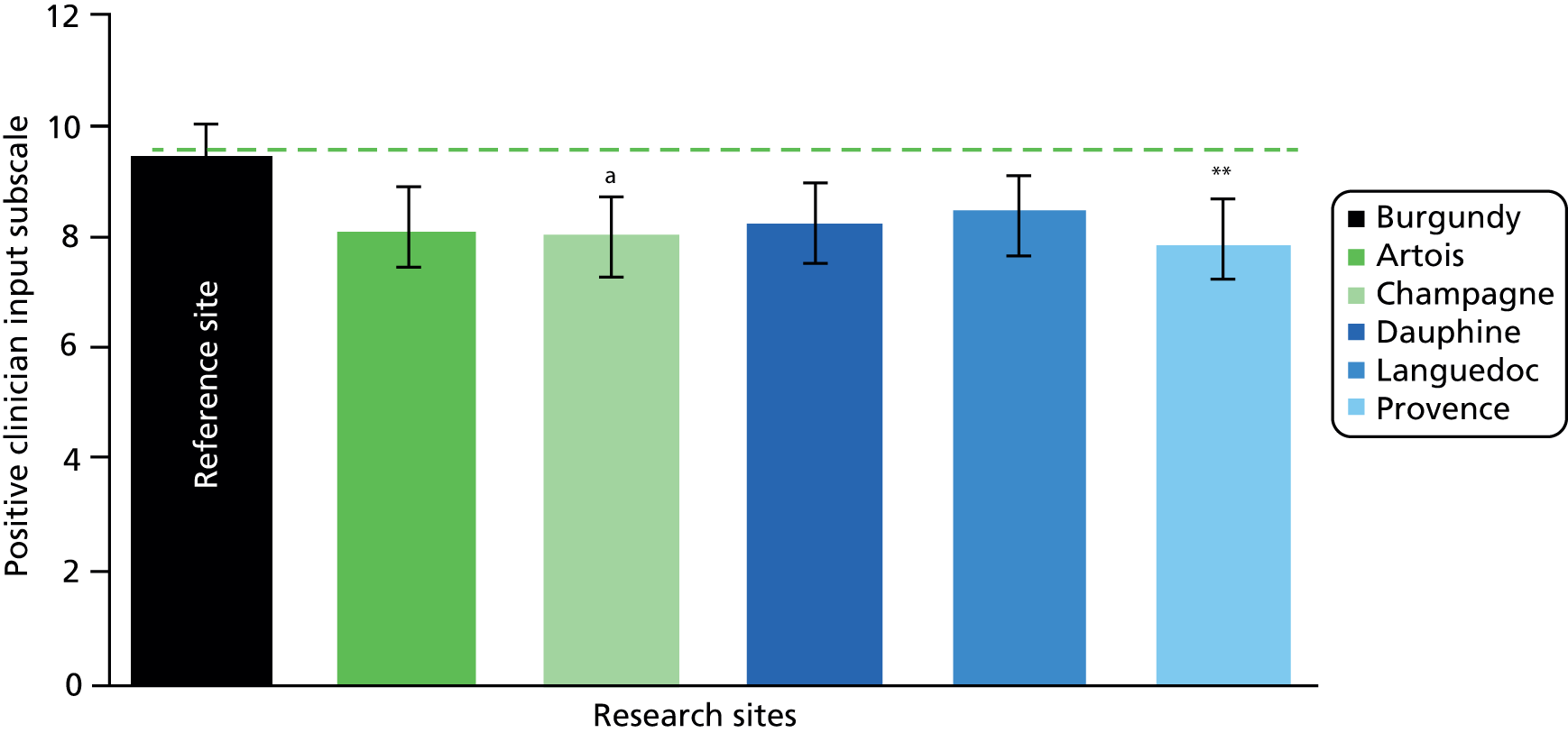

The Scale to Assess the Therapeutic Relationship – Patient version (STAR-P)46 is a specifically developed, brief (12-item) scale that assesses therapeutic relationships in community psychiatry. It has good psychometric properties and is suitable for use in research and routine care. The subscales measure positive collaborations, positive clinician input and non-supportive clinician input in the patient version. It was completed by service users.

-

The Empowerment Scale (ES)47 is a 28-item questionnaire with five distinct subscales: self-esteem, power, community activism, optimism and righteous anger. Empowerment is strongly associated with recovery and this is the most widely used scale, with good psychometric properties. It was completed by service users (see Appendix 1 for all questionnaires).

-

Structured interviews with senior managers, senior practitioners, care co-ordinators, service users and carers. Interview schedules were developed by the study team in consultation with our Project Advisory Group (PAG) and Lived Experience Advisory Group (LEAG) and drawing on relevant literature. All interviews aimed to explore participants’ views and experiences of care planning and co-ordination, safety and risk, recovery and personalisation and the context within which these operated. Interview schedules for each group of respondents included 15 lead questions with numerous prompts suggested for the interviewer (see example question below and full schedule in Appendix 2). Schedules were slightly amended following piloting with our service user researchers.

Example question: Q1. What does the CPA/CTP mean to you?

Prompts: What is the purpose of care planning? What are the most important aspects of the CPA/CTP? What works/does not work? Have your views about the CPA/CTP changed at all over time? In what way/why?

-

CPA care plan review: within each ‘embedded case study’, the six purposively selected service users’ written care plans were systematically reviewed and appraised against a structured template incorporating the identified key concepts of personalisation and recovery (see Appendix 3). Care plans were also used to collate demographic, diagnostic and service use data.

Research ethics

The study received NHS Research Ethics approval from the National Research Ethics Service Committee Yorkshire and The Humber – Sheffield (Ref.: 13/YH/0056 A) on 13 February 2013. A major amendment was approved on 7 May 2013 to allow a reminder letter to be sent to service users for the questionnaire component and for the interview invitation letter to include information about interviewees receiving a £15 payment.

Considerable attention was given to ensuring the welfare of the service user, carer and other participants and of the researchers. This included providing opportunities to pause or withdraw from interviews, assurances of anonymity and confidentiality and responding to concerns for people’s welfare. Careful arrangements were made for the location and conduct of interviews and all researchers received training, supervision and opportunities for debriefing.

Procedure

Provisional agreement to participate in the study was obtained in writing from senior trust/health board managers (e.g. Chief Executive) prior to submission of the research proposal for funding. Following commissioning of the study, a formal invitation to take part in the study was communicated to a senior manager, such as the Chief Executive, in each organisation and all accepted and identified a principle investigator/link person to facilitate research ethics and governance approvals and contacts with other staff.

Suitable local CMHTs meeting inclusion criteria were identified with the assistance of local NHS trust principal investigators. Team leaders were approached by a researcher who explained the study, responded to any queries and invited them to participate. Nobody declined to take part. Key personnel were identified using purposive sampling and were invited to participate in interviews and to forward local policies and information. Researchers with help from clinical studies officers and research nurses distributed information sheets, consent forms and questionnaires to CMHT care co-ordinators and collated completed questionnaires. Where the identified CMHT had insufficient numbers of care co-ordinators, a second (or third) team was approached within the host site with the questionnaire survey.

Questionnaire packs and invitations to participate in the survey were distributed by post to service users following discussions with the PAG and the LEAG, who wanted to prevent undue pressure or paternalistic ‘gate keeping’ by clinicians. Service users from CMHT caseloads were randomly selected for invitation to participate via the service provider team using agreed criteria (e.g. under care of the CPA/CTP, minimum of 6 months of contact with service). With the help of the Mental Health Research Network (MHRN) and the National Institute for Social Care and Health Research Clinical Research Centre (NISCHR CRC) clinical studies officers, and after checks with the clinical team to prevent inappropriate mailings (e.g. to recently deceased patients), service users were posted the survey pack. The pack included a covering letter, an invitation to participate, the patient information sheet, the pack of three questionnaires and a demographic information sheet. The envelope also included a brief description of the study in numerous languages with details of who to contact for more information in other languages (we received no contact in response to this insertion). A freepost return envelope was included. In line with evidence-based recommendations to maximise returns of postal surveys,48 questionnaires were printed single-sided and some envelopes were stamped with ‘Private and Confidential’ and the University logo. Reminder letters were posted out to all recipients 2–3 weeks after the initial mail-out.

For the service user interviews, again with the help of the MHRN/NISCHR CRC clinical study officers and research nurses, lists of service users under the care of the selected CMHT and subject to the CPA/CTP, were checked with the responsible psychiatrist or team leader to prevent inappropriate mailings.

In each setting the final list of service users for sampling were grouped into care co-ordinator categories to enable us to gain different service user/carer/care co-ordinator triads. Any care co-ordinators already interviewed as senior practitioners were excluded. From the remaining lists, up to four service users per care co-ordinator were randomly selected and letters were posted inviting them to contact the research team by phone, post or e-mail if they wished to participate in an interview about their experiences of care planning and co-ordination. Once a service user contacted the team, a researcher would explain the study, answer any questions and arrange a date, time and venue for the interview. If insufficient responses had been received within 4 weeks of the mail-out, a second batch of invitations was posted. This was repeated until the target number was met or time ran out.

When a service user agreed to be interviewed, they were asked for the name of anyone they considered to be an informal carer that we might contact for interview, and their care co-ordinator was identified. It was made clear that there would be no disclosure of shared information between parties and the care co-ordinator would not be told which specific service user had taken part in the interview. Service users were also asked for permission to review their care plans.

Senior manager, senior practitioner and care co-ordinator interviews were conducted by academic researchers (SB, JE, JV, BH, MC) and clinical study officers. Service user and carer interviews were conducted by service user researchers (JT, DH, KB, BE, AM) with one of the academic researchers in attendance, or occasionally by academic researchers (BH, MC). Care plan reviews were undertaken by clinical study officers using the template provided.

Public and patient involvement

The study was developed and designed with full involvement of co-investigator and independent service user researcher Alison Faulkner (AF) and in consultation with the Service User and Carer Group Advising on Research (SUGAR), based at City University London and facilitated by the Chief Investigator (AS). In addition, a LEAG was established, consisting of 10 service users and one carer with direct experience of mental health care planning and co-ordination. This separate advisory group for ‘experts through experience’ ensured that more time could be spent exploring the service user and carer views and ensuring that their perspectives were able to inform the study. Members were recruited via MHRN, Involving People and other patient and public involvement networks and came from London, the north of England, south-east England, and South and North Wales.

The group was facilitated by AF and met with members of the research team five times during the course of the study. The LEAG:

-

drew on personal lived experiences of care planning, care co-ordination and mental health services to inform the interview topic guide and advise the research team

-

suggested changes to the design, ordering and wording of questions on the interview schedules (adopted)

-

suggested changes to the method of inviting service users to participate in the study (adopted)

-

advised on the participant information sheets before these were submitted for NHS ethics review (adopted)

-

suggested relevant literature to inform the literature review (adopted)

-

explored and discussed initial analysis of interview transcripts

-

discussed with the service-user researchers their experiences of interviewing service users and using the interview schedules

-

explored possible reasons for low response rates in some areas (language, literacy, stigma, poor experiences of services so low motivation to help)

-

explored tentative findings from initial framework analysis.

The PAG consisted of representatives with a clinical or research background from each of the participating NHS trusts/health boards, as well as independent academics. One service user and one carer member also represented the LEAG on the PAG, with input from the LEAG timetabled on the agenda of all meetings, which were chaired by John Larsen, then Head of Research and Evaluation at Rethink Mental Illness.

Five service user researcher assistants/service user project assistants were employed to work on the study on a temporary contract basis, three of whom were based in London, and two of whom were based in Cardiff. All received training and ongoing support throughout the study.

Analytical framework

We framed our data analysis by drawing on social scientific ideas and the findings of our Phase-1 evidence and policy review, an approach used by co-investigators in previous studies. 49 Our concern to explore commonplace practices in CMH is congruent with interactionist interests in social processes and human action. 50 This perspective also recognises the importance of social structures, so that in any given setting person-to-person negotiations are shaped by features of organisational context. 51 The immediate context for frontline practitioners/care co-ordinators in this study is the CMHT workplace, each of which we view as a complex open system. Each participating team also sits within a larger meso-level NHS trust/health board site, which in turn is located within a national-level system of mental health services. This idea of ‘nested systems’ is a feature of complexity thinking,41 and informed our plan to generate, analyse and connect data at different (but interlocking) macro/meso/micro ‘levels’ of organisation. Analysis and interpretation of the case-study data were informed by a conceptual framework that emphasised the connections between different (macro/meso/micro) levels of policy and service organisation, and that drew on the findings of the literature and national policy review in relation to care planning, recovery and personalisation.

Quantitative analysis

Preparation of the data

Data from the questionnaires were entered into SPSS package, version 21 (Armonk, NY, USA). The data were checked and cleaned by a second researcher prior to statistical analysis. The distribution of the questionnaire data was assessed for normality by exploring the data graphically. Comprehensive sensitivity analyses were completed in order to determine what parameters to use when dealing with missing data. The service-user version of the RSA scale questionnaire in particular had a moderate number of missing data and therefore the parameters that were used for calculating the subscales were based on 50% completion levels.

Exploring the data

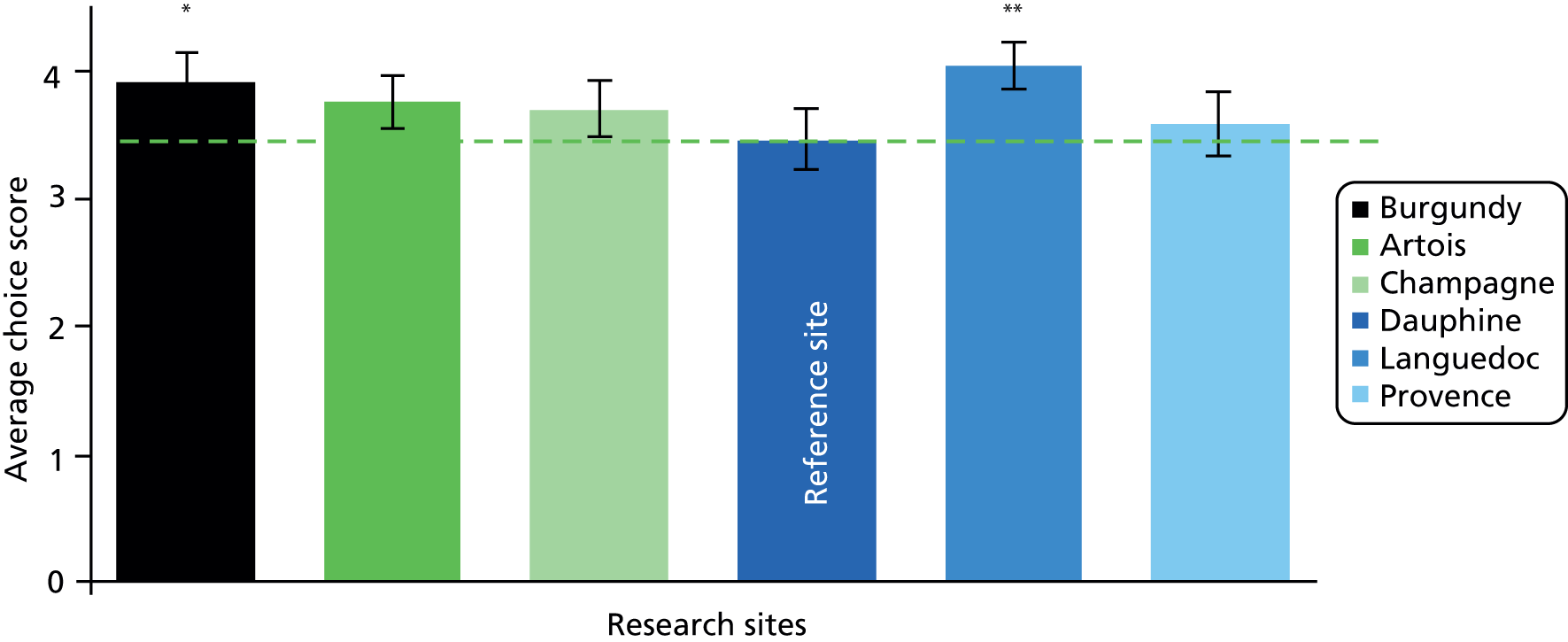

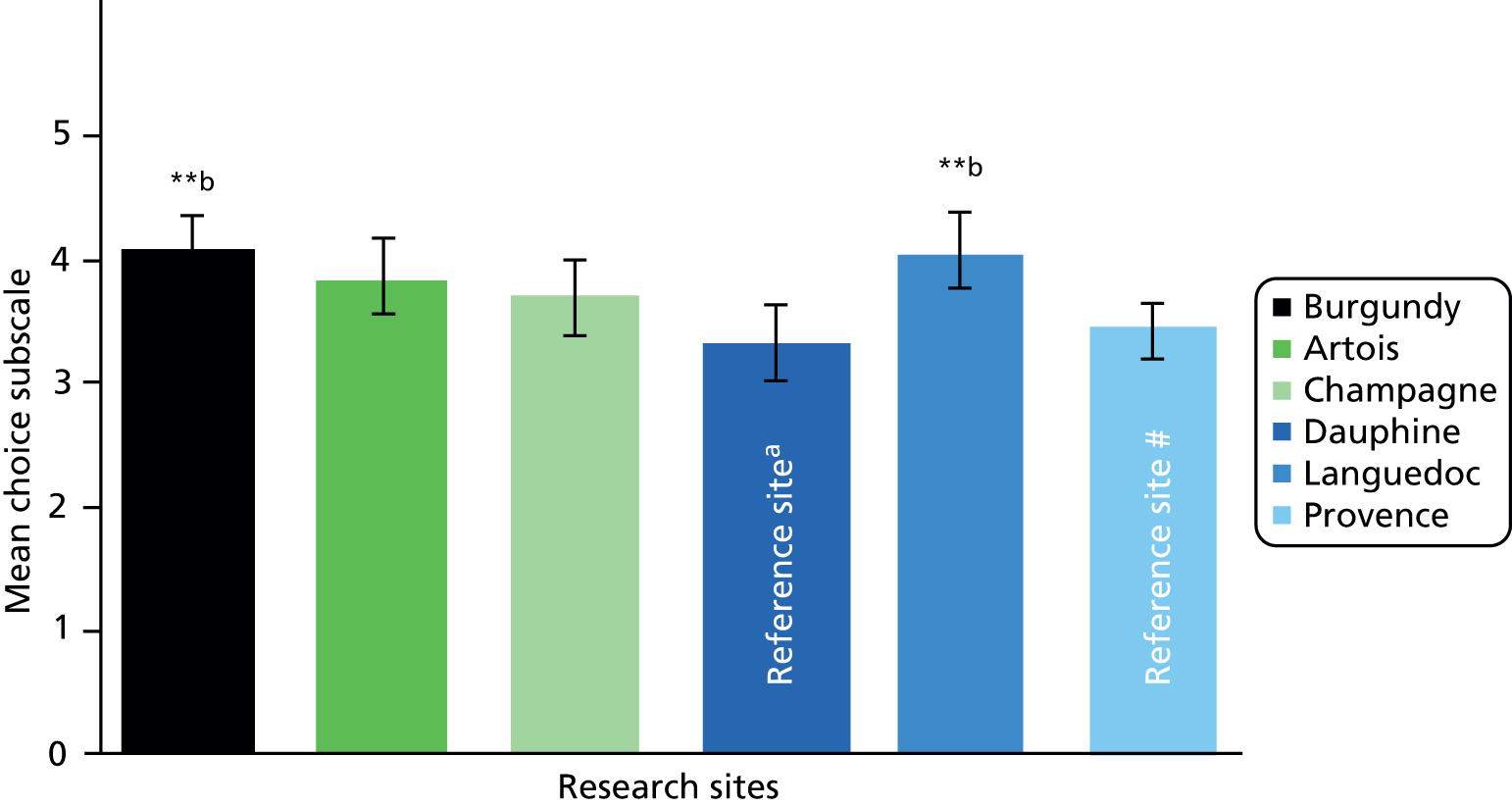

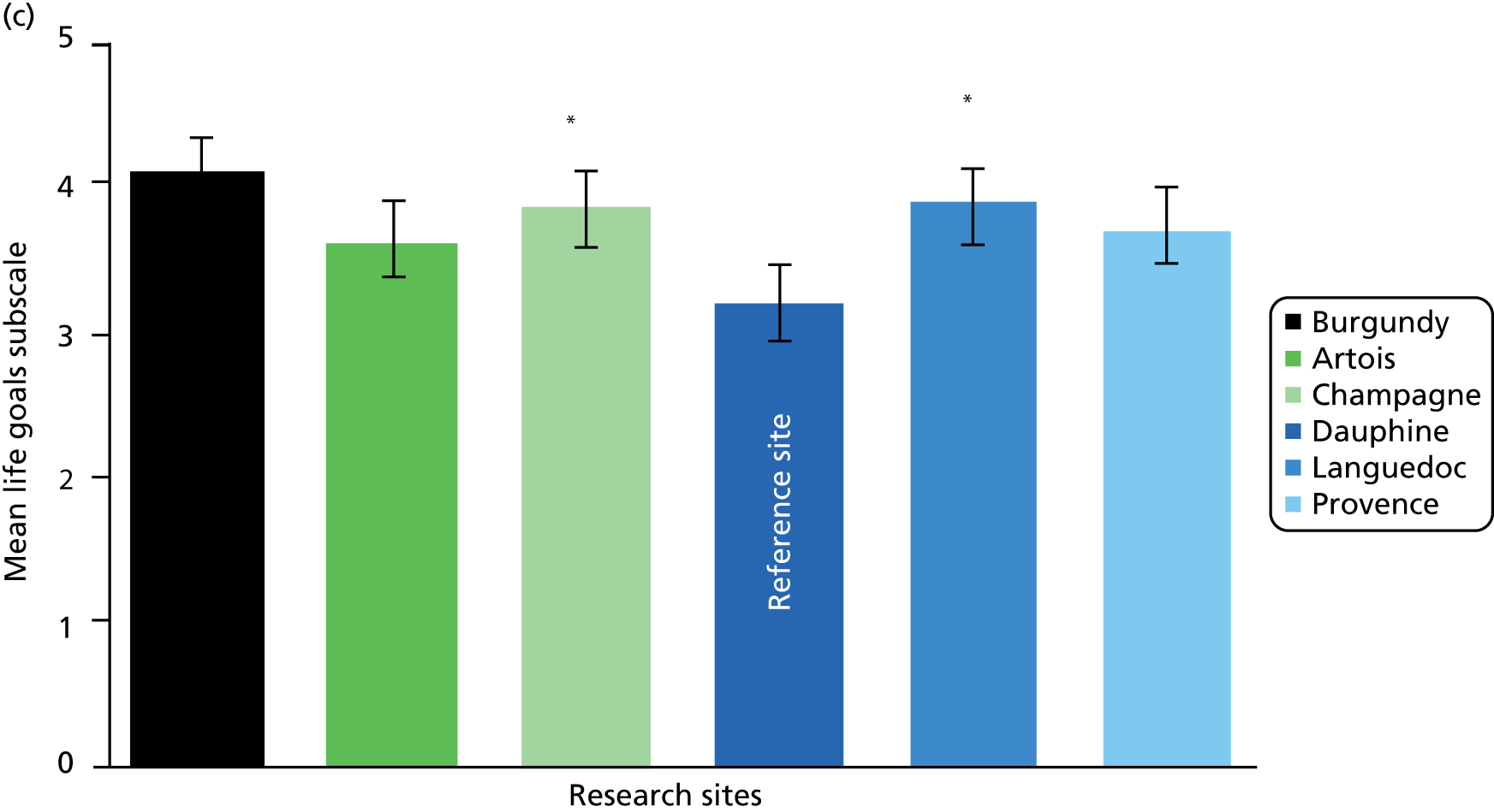

Descriptive statistics were calculated for the three questionnaires (the RSA scale, STAR-P and ES). The total scores, subscale means and SDs were derived to produce a ‘recovery profile’ for each site. Where appropriate, these scores were compared against reference values (STAR-P and ES) or the participant groups (the RSA scale). Some further detailed analysis at a descriptive level was completed on the primary outcome scale (the RSA scale) to aid with the triangulation of the qualitative and quantitative data. This was completed at an individual item level on the scale by ranking the mean responses for each question to determine where the most agreement was for the participant groups. The top five items were selected from the questionnaire and presented as a recovery profile for the site.

Inferential statistics

Several one-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were conducted to compare differences between the six sites on the RSA scale, STAR-P and ES measures. Subsequent Tukey post-hoc tests were conducted to ascertain which measures differed between which locations. A series of one-way analyses of covariance (ANCOVAs) were completed to adjust the analyses for potential confounders. The variables that were chosen for service users were: age; gender; ethnicity; relationship status and time in mental health services. The variables that were chosen for staff were: age, gender, ethnicity, time working in mental health services and time as a care co-ordinator. The criteria for adjusted analysis between the ANOVA and ANCOVA were the p-value from the omnibus test, the adjusted means and the p-value from the post-hoc test. If the p-value from the omnibus test for the ANCOVAs were not substantively different from the ANOVAs then no further post-hoc analyses were completed.

Correlations

Correlations were carried out to identify if there was a relationship between the outcome measures and to determine if there were relationships among the patients on recovery-oriented focus, empowerment and the quality of therapeutic relationship. Three Pearson’s correlations were completed on the mean total scores for the measures RSA scale and STAR-P, RSA scale and ES, and STAR-P and ES for all participants and by individual site. Cohen’s effect sizes were used to describe the data (small r = 0.10, medium r = 0.30, and large r = 0.50).

For all analyses the significance level was set at a level of 0.05.

Qualitative analysis

All digital interview recordings were professionally transcribed and transcripts checked against original recordings for accuracy, and any identifying information redacted, before being imported into QSR International’s NVivo 10 (QSR International, Doncaster, VIC, Australia) qualitative data analysis software for analysis using framework method. 52,53

In this study, numerous transcripts were read by all members of the research team to familiarise themselves with the data. The framework matrix was developed a priori from the interview schedules, with sections focusing on organisational background and developments, care planning, recovery, personalisation and recommendations for improvement. Each matrix section also had an ‘other’ column for the inclusion of data-led emergent categories.

Summarising and charting of 10 transcripts using the matrix was undertaken by two researchers (JV, SB), and was then checked and discussed by AS, BH and MC. Slight amendments to the matrix were made before summarising and charting of all transcripts ensued (by RC, SB, JV, NA, AT, BH and MC), following an agreed format for notation and linking to text. Researchers read and checked 10% of each other’s summarising against transcripts to ensure accuracy and consistency of approach.

Once all charting was completed, second-level summarising was undertaken (by BH, MC, AS, AF and RC) to further precis data and to identify commonalities and differences within trust/health board sites and groups (e.g. senior managers).

In addition, summarised data from the embedded micro-level case studies at each site were subject to further comparison of the views expressed by linked service users, carers and care co-ordinators. These data were then compared against the review of the care plan. This allowed us to tease out agreements and disagreements in the perspectives of the participants within these triads.

Integration and synthesis of data sets

The framework method was also employed to bring together charted summaries of qualitative data alongside summary statistics of the quantitative measures for each case-study site, noting points of comparison and contrast between what we found in our analysis of each type of data.

Armed with our set of six within-case analyses we then conducted a cross-case analysis to draw out key findings from across all sites. We then considered the relationships between stated orientations to recovery and personalisation in national and local policy and senior staff interviews, and what we have found by studying the accounts of users, carers and care co-ordinators and by reviewing written care plans. In this way we were able to investigate the data to identify ‘evidence’ at the intersections between macro-meso-micro levels and CPA/CTP care planning, recovery and personalisation; hence the ‘transformative’ nature of the study design. 31 This is represented in Table 1.

| Level of analysis | Local context/background | CPA/CTP care planning | Recovery | Personalisation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Macro-level (national policy, regional drivers, etc.) | ||||

| Meso-level (trust/board policies; senior manager/practitioner interviews, etc.) | ||||

| Micro-level (service delivery: user/carer/care co-ordinator experiences) |

The results of these within-case and across-case analyses are presented in Chapters 4 and 5. We have then drawn on these findings to produce charts identifying the key facilitators and barriers to the delivery of recovery-focused, personalised care planning and co-ordination (see Chapter 5).

Chapter 3 Meta-narrative review and comparative cross-national policy analysis

Literature review

Introduction

It has long been recognised that patients with a variety of chronic and complex health conditions often require long-term care from different health and social care professionals working across community and hospital settings. However, those living with multiple health and social care needs often experience a highly fragmented service, leading to suboptimal care experiences, outcomes and costs. 54,55 Many countries have developed strategies to enable better co-ordination of care; however, evidence suggests that these have often not achieved their objectives. 56

The aim of this literature review is to give an account of care co-ordination and care planning in CMH settings. The question underpinning the review is: ‘What interventions have proved more or less effective in promoting personalised recovery-oriented care co-ordination for CMH service users?’. The focus of the review is care co-ordination in UK CMH contexts, but some research from non-UK settings will also be discussed.

Background and context setting

High-profile failures in mental health care in the UK during the 1980s led to an unprecedented evaluation of care co-ordination between hospital and community services to ensure better quality care. The most immediate trigger was the recommendations of the Spokes Inquiry57 into the killing of a hospital social worker by a psychiatric patient. At the time of the inquiry, care for people with severe mental illness in the community had been described as haphazard and unco-ordinated,58 a view reinforced within the Spokes report,57 which described how, prior to the killing, the patient had been able to ‘drop out of sight’ of mental health services whenever she was discharged from hospital. This, allied to fears about high levels of mental illness among the homeless and in the criminal justice system,59 led to the introduction of a raft of strategies and policies to improve the organisation and delivery of mental health care in the late 1980s to early 1990s.

However, the deterioration in standards of mental health care evidenced in the 1980s can be seen as a culmination of public policy decisions over previous decades. This included a reduction in inpatient mental health beds in the UK from 150,000 in the early 1950s to approximately 50,000 in the early 1990s,55 and the medicalisation and professionalisation of mental disorder, which were key themes of the Royal Commission on the Law Relating to Mental Illness and Mental Deficiency. The subsequent Percy Commission Report60 concluded that mental disorder should be regarded ‘in much the same way as physical illness and disability’ (paragraph 5) and that mental hospitals should be run as much as possible like hospitals for physical disorders. In addition, the 1959 Mental Health Act61 separated health and social care for people who did not need inpatient treatment by handing over responsibility for social care to LAs and councils.

The shifts described above created ideal incubating conditions for subsequent failures in care co-ordination that became increasingly evident in the 1980s. Such was the disarray that some commentators at the time described CMH care in England as an ‘unwieldy dinosaur with its health and social care brains working independently’. 62(p. 2)

In the context of an accelerating, policy-driven shift away from hospital care, the CPA was introduced in England in 1991 and in Wales in 2004 to provide case management and to give shape and coherence to the delivery of CMH services. Case management is a method of working designed to ensure that service users are provided with services that are co-ordinated, effective and efficient. However, the CPA was not developed with a particular model of case management in mind and therefore lacked a single or coherent underpinning philosophy of care. 58 As a result, the introduction of the CPA was very much shaped by the local context, and differences in local approaches were tolerated provided that the fundamental features of the CPA were implemented.

The fundamental features included systematic assessments of health and social care needs; the provision and regular review of a written care plan; close monitoring and co-ordination by a named key worker; the involvement of users and carers in planning and provision of care; and inter-professional and inter-agency collaboration. A CPA register was also established to record details of those cared for under the CPA.

The role of the care co-ordinator and effective teamwork were identified at the time of the CPA’s inception as key to successful implementation,63 given the previous repeated failures of agencies and professionals to communicate and successfully deliver co-ordinated care.

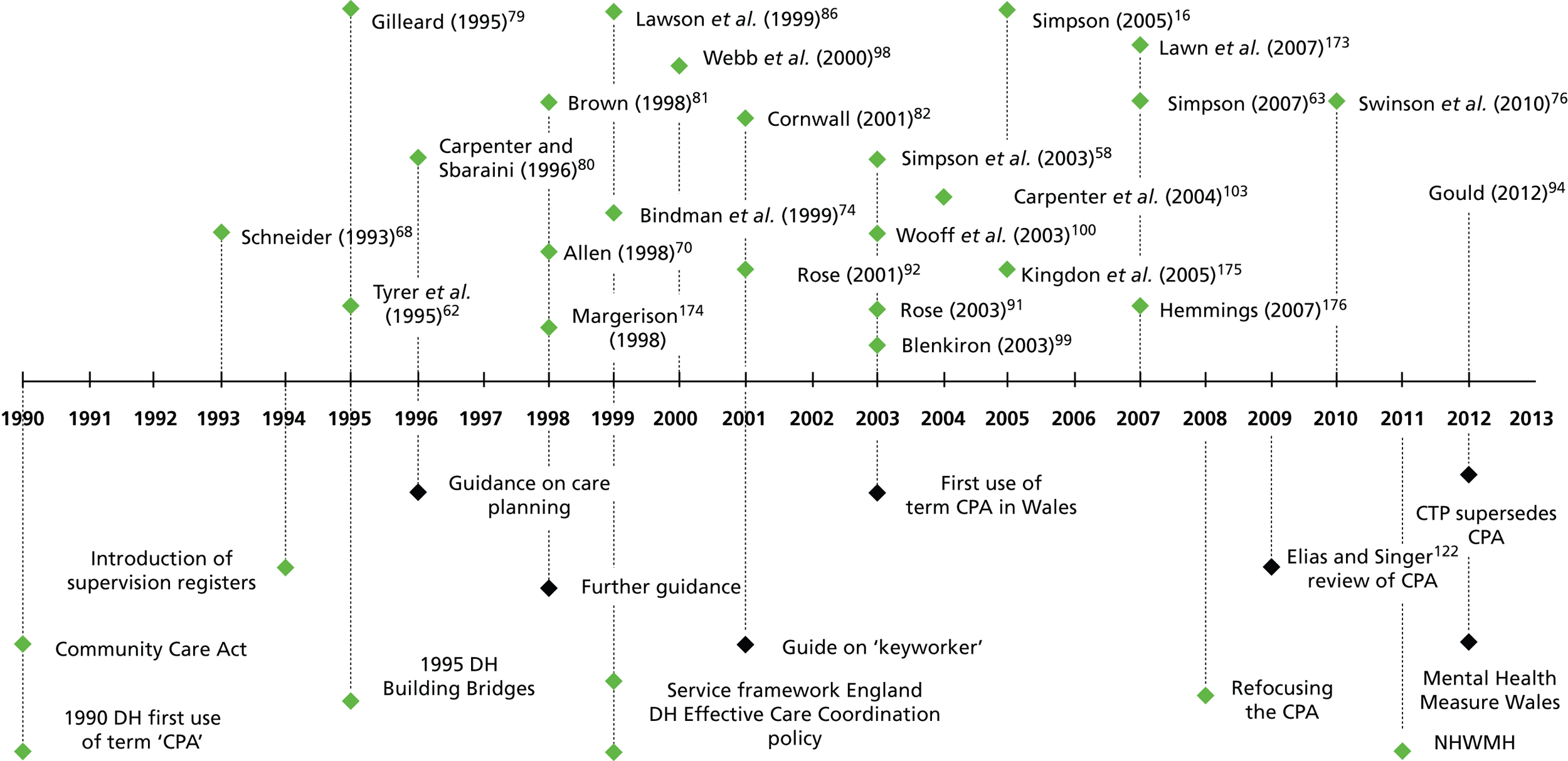

Search strategy

Initial literature searches were undertaken using the following key words and terms: ‘mental health’, ‘care planning’, ‘care co-ordination’ (and ‘co-ordination’), ‘collaborative care’, ‘recovery’, ‘recovery focus(ed)’, personali*. JE ran a preliminary search from which a random sample of articles was assessed by BH and MC, to identify relevant papers and possible additional search terms/phrases. Further discussions were carried out by BH, AJ and JE on the modification of the search strategy.

As a result, additional key words/search terms were included: ‘mental illness’, ‘care collaboration’, ‘patient care planning’ and ‘person-centred care’. We also included proximity indicators (such as ADJ or N- as appropriate of each database), truncation ($) and wildcard (*) symbols as well as Boolean commands (AND and OR) where appropriate. Key search terms were searched by their subject (MeSH headings) and by keyword. The following databases were searched: Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Allied and Complementary Medicine Database, EMBASE, The Cochrane Library, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Education Resources Information Center, British Humanities Index, Scopus, Social Care Online and Web of Science. The search was limited to the period 1990 to date and included articles in the English language only. This search was rerun on the databases ASSIA and CINAHL and the search strategy was verified by a health and social care librarian working for the Information Sciences service at Cardiff University.

During a meeting on the 20 November 2012 with the LEAG and the PAG, it was suggested that the term ‘user experience’ be included in the search strategy. Further discussions among the PAG advised that the addition of terms such as ‘recovery’ or ‘recovery focused’ to the search strategy would narrow the focus too much and that research covering these topics in CMH settings should be captured by using the existing search terms. The issue of rejecting papers where research was considered low quality was weighed against an interest in a broad representation of approaches and views. However, some studies were excluded on the grounds of insufficient detail about the research process undertaken within each study. 64,65

Following removal of duplicate cases, 811 references were retrieved and entered into an EndNote version X7 (Thomson Reuters, New York, NY, USA) library. These references were then screened by BH and MC to identify key papers for the meta-narrative synthesis focusing on papers about care planning and co-ordination in mental health in the community. The papers were labelled as Y (Yes), N (No) and M (Maybe). In the end, there were 45 papers labelled Y, 617 labelled N, and 94 labelled M. There was an agreement among the team on the papers excluded. A further snowball search on the web and using Google Scholar (Google, Mountain View, CA, USA) produced 81 references. From this there were none labelled Y, 69 labelled N and 12 labelled M. A final review of the M papers and back-chaining revealed a further three papers that were added to the original 45, giving a final total of 48.

Meta-narrative review

Meta-narrative review looks historically at how particular research traditions have unfolded over time and shaped the kind of questions being asked and the methods used to answer them. As outlined by Greenhalgh and Wong, a research tradition is a ‘series of linked studies, each building on what has gone before and taking place within a coherent paradigm (that is, within a shared set of assumptions and preferred methodological approach shared by a group of scientists)’. 66(p. 4)

Given the wider social, political and historical context outlined above it is unsurprising that the ‘unfolding plot of the research’67(p. 423) from the UK is dominated by researchers’ efforts to understand whether or not the CPA has led to changes in management, service organisation and delivery (Tradition 1). Although our searches were limited to the period 1990 onwards (when the CPA came in), there is little history of research into care planning and co-ordination within CMH settings prior to this date. There are no pre- and post-evaluation studies of the introduction of the CPA, comparing changes, if any, in care planning and co-ordination in CMH settings.

Instead, researchers initially framed their studies within the findings of public inquiries or governmental reviews into difficulties and failures within CMH settings. It seems reasonable to conclude, therefore, that the CPA resulted in changes both to working practices within clinical CMH settings, and also to research priorities and practices within the UK, creating a hitherto unseen tradition of research within mental health services with a focus on care planning and co-ordination.

Another narrative and tradition of research focuses on service-users’ and carers’ experiences of CMH provision (Tradition 2). Although its emergence may not be surprising given that one of the primary aims of the CPA was to increase the involvement of service users and carers in care planning and provision, this focus was rare in the context of the early to mid-1990s. Another notable feature of this tradition is the emphasis on involving service users and carers in the design and execution of research projects68–71 at a time where both government policy promoting service user involvement and the ‘service user movement’ were in their infancy. 72,73 It is within this tradition that the current study most comfortably sits.

Service-user involvement within this tradition includes involvement in some aspects of conventional research projects (such as question setting or data collection) as well as collaborative research where service users work on most if not all aspects of projects as co-investigators alongside academic researchers. There is less evidence of there being user-controlled research in which service users set the agenda, design and conduct the research. 73

Finally, several studies have sought to determine whether interventions have improved the functioning and performance of the CPA (Tradition 3) in terms of improved care co-ordination and care planning. This tradition of research focuses on processes and outcomes of care, and the prevailing language positions the CPA and CMH work as being driven by requirements to demonstrate organisational efficiency. For example, some studies frame mental health work as requiring standardisation owing to its complex nature and the mental health workforce as having a deficit of knowledge as regards effective care co-ordination and planning.

The three research traditions identified are summarised in Table 2.

| Research traditions | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Tradition 1: CMH care co-ordination and planning, the CPA and the organisation, management and delivery of services | A tradition of research that explores the organisation and delivery of CMH services that has come about since the inception of the CPA |

| Tradition 2: Service-users’ and carers’ experiences of CMH care co-ordination and planning and their involvement in research | A tradition of research that focuses on service users’ and carers’ experiences of CMH services. A tradition that also involves these groups directly as researchers in some or all aspects of the research process |

| Tradition 3: Improvement to the functioning and performance of co-ordination and care planning in CMH services | A tradition of research from the UK and internationally that aims to determine whether or not improvements to planning and co-ordination of CMH services occur following interventions |

Striking in the review was the increase in non-UK research into care planning and co-ordination in community settings with only two studies appearing before 2005, at which point the number increases and surpasses UK research output. These non-UK studies were also aligned with the three research traditions described above but are not included here due to space restrictions.

Tradition 1: community mental health care co-ordination and planning, the care programme approach and the organisation, management and delivery of services

The first tradition of research consists of a series of studies primarily from the 1990s that seek to understand the impact of the CPA on the organisation and delivery of CMH services. This tradition of research draws on a range of methodological approaches (see Appendix 4). The CPA is often discussed as a uniform approach, yet it is noticeable that the earliest study of the CPA68 undertaken in three English health districts demonstrates clear variation in CPA interpretation and implementation. Adherence to the principles of care programming within each district’s community care plans ranged from minimal mention of care programmes to the wholesale adoption of the concept into mental health planning and service evaluation. Later published studies also draw attention to the degree of variation in the implementation of the CPA between different trusts within the same health authority and within the same trust. 16,74–78

Variable implementation of the CPA may well contribute to inconsistency in research findings within and across sites. For example, Schneider’s68 study of three health authorities describes how staff perceived the CPA as offering ways of working that were both creative and flexible as well as rigid and lacking flexibility. Similarly, more rigorous documentation and better care planning are reported in some studies,68,79,80 whereas others report a lack of coverage of psychosocial aspects16,77 or risk assessments not completed fully or jointly. 76 Claims that the CPA led to improved continuity of care,68 better team-working across professions16,68,79 and overall effectiveness of care68,70,81,82 also need to be balanced with findings that most general practitioners (GPs) had not heard of the CPA,83 that the role and function of the CPA had not been explained properly to staff,16,70,83 leading to managers not knowing which patients were on the CPA. 81

Uncertainty also exists in terms of the relationship between the CPA and inpatient bed occupancy rates, with Tyrer et al. ’s62 claims of increased admission to hospital following the introduction of the CPA being contradicted elsewhere. 82 The use of hospitalisation as an outcome measure has been criticised as inadequate for assessing programme success in this population, given that rates of hospital admission and length of inpatient stay can be influenced by other factors, such as local service configuration and bed availability. 84

Such uncertainty and variability raise crucial questions regarding the use and effectiveness of the CPA in practice, especially where researchers attempt to make judgements on programme outcome or cause–effect comparisons across more than one research site. The lack of clarity regarding the exact nature of the CPA in practice reflects a similar vagueness globally about the concept of care co-ordination. For example, a review of research found over 40 heterogeneous definitions and models of care co-ordination to be in existence. 85 The lack of clarity and homogeneity has also been identified as an explanatory factor for the failure of many strategies that seek to improve care co-ordination. 56

Sociopolitical factors partly explain the large variations in the way organisations adapted or assimilated the CPA’s requirements. For example, the CPA was introduced with no or limited additional resources,68,83,86 at a time when health and social care spending was being cut and the vast majority of resources for mental health services were allocated to inpatient care rather than day and community services. 87 As a result, little or no staff training was provided, no particular philosophy of care emerged to underpin CPA implementation and employees were left to manage a change in process as best they could. 58

In an era of increased managerialism in the NHS, the introduction of the CPA was experienced by practitioners as a ‘top-down’ policy imposition that failed to build on the existing knowledge, skills and abilities of the workforce, and resulted in tensions over clinical values and cultures. Staff perceived the CPA as leading to more work16,68,82,83 and a sense of being overworked16,68 especially owing to increasing levels of bureaucracy. 16,68,71 Staff also reported that the additional burden of work that accompanied the implementation and day-to-day operation of the CPA led to increased time being spent away from patients. 16,68,83

The unintended consequence of a lack of detailed, national policy implementation strategy for the CPA was a considerable variation in the delivery of services, as well as variation in staff and patient experiences both within and across health authorities. A review of CPA implementation links the ‘paradoxical effect’ (p. 24) of burgeoning levels of local bureaucracy to the national policy decision not to be overly prescriptive about CPA documentation. 1

Overall, this tradition of research has been firmly focused on developing a better understanding of how the introduction of the CPA influenced the organisation and delivery of nascent and arguably inadequate CMH services. Researchers frame the CPA as a policy intervention that attempted to reverse several decades of deteriorating mental health services characterised by, among other things, inadequate co-ordination and organisation of care within and across different professional groups. There is little research that seeks to delineate or explore developments in multiprofessional and multiagency working in the wake of CPA implementation; studies undertaken in this tradition perpetuate the status quo of multiprofessional working at that time, failing to mention or merely hinting at different ways of working within and across teams. However, Simpson’s16 study describes some of the effects of team working in CMHTs, such as finding that care co-ordination was enhanced within teams when members demonstrated respect for co-workers.

The combination of three decades of profound changes in the policy definition of mental health and illness, together with the broader context of large-scale change towards managerialism within the health and social care sector during the late 1980s and early 1990s, leaves the impression that the CPA was destined to fail before it had been launched.

Tradition 2: service users’ and carers’ experiences of community mental health care co-ordination and planning and their involvement in research

Until the 1990s there were few attempts to involve service users in the planning and delivery of their care and treatment. As Perkins and Repper88 point out, service users were excluded from service planning meetings and were only involved via demonstrating their symptoms and hearing the doctor’s prescription. Implementation of the CPA was fairly novel in responding to service user and carer demands for greater involvement in the care planning process, both of which began to be more explicitly promoted as indicators of good practice. 80

Alongside these developments, a view also emerged that service user involvement in research could make an important contribution to the empowerment of mental health service users. For example, service users have long argued that dominant research approaches to mental illness can perpetuate patients’ inequality and disempowerment. 89 Consequently, the coproduction of new knowledge and the transformation of the terms and concepts used by mental health researchers have been promoted as a potentially influential means to achieve broader social and political change. 90

A tradition of undertaking research that involves service users and carers is rooted in the origins of research into care co-ordination and care planning in CMH work (see Appendix 5). Early studies not only focused on service user and carer experiences of CMH but also involved service users and carers as collaborators in the design and implementation of research studies. For example, Carpenter and Sbaraini80 involved service users and a carer in a PAG and in formulating a questionnaire to explore users’ perceptions of the extent to which the CPA empowered user and/or carer involvement. Rose et al. 71 not only involved service users in designing a data collection instrument (semistructured interview schedule) but also extended service user involvement to data collection, with 12 service users being trained to undertake interviews alongside researchers.

Interestingly, Rose et al. 71 describe how, on many occasions, the project team were warned about the potential negative consequences of service users’ involvement in research. In particular, care co-ordinators worried that users were unable to sustain confidentiality about other users. No such difficulties emerged during the study, leading the authors to conclude that ‘users can be successfully interviewed by other users who have been trained to do this. We argue that, in fact, the user interviewers elicit more open and honest responses than professionals do.’71(p. 29) Subsequent studies in this tradition of service-user involvement in research have since reached similar conclusions. 91–94 The narrative within this research tradition positions service users and carers as having much ‘insider knowledge’ to share and that, as a result, questions are framed and studies conducted in ways that are most relevant to users of CMH services.

A moot question is whether or not this makes any difference in terms of the quality and relevance of data collection and interpretation. For example, Rose et al. 95 conclude that the literature is ambivalent about whether or not service-user researchers obtain different quantitative data to conventional mental health researchers (e.g. Rose91 suggesting differences but Rose et al. 96 finding none). However, there is evidence that service-user researchers both collect and interpret qualitative data differently from conventional researchers and in a way that is more in tune with the priorities of service users themselves. 94,97

It is also important to note that most studies of service users’ and carers’ experiences did not involve them in study design and implementation. 70,80,81,86,98–102 However, a commitment to learning more about service users’ and carers’ experiences resonates throughout these studies. This research tradition has also contributed significantly to the debate about whether or not policy changes that were meant to embed principles aimed at increasing service user and carer involvement in CMH practices actually resulted in the desired changes to carers’ and service users’ experiences.

Overall, this corpus of research demonstrates that the introduction of the CPA has mostly failed to deliver on the promises of increasing service-user understanding70,71,86,91 and involvement71,75,77,86,91,92,94,98,101 in care planning and care co-ordination. Research also suggests that other fundamental aspirations of the CPA have similarly had a limited effect on the actual practices of CMH workers. For example, studies show that service users were not aware of, or not allocated, key workers or care co-ordinators70,71,81,92 and had not seen or were not in possession of a care plan or CPA documentation. 70,71,81,86,92,98,101,103

However, the variation in approaches to CPA implementation noted earlier is also apparent when reviewing research findings in this tradition. For example, a small number of studies running counter to the findings listed above have suggested that service users were well informed about their care and treatment plans92,98,103 leading to service users having more trust in staff68,80 and influence and choice in their care. 68,80,103 However, it is worth noting that a considerable weight of evidence suggests the lack of desired impact made by the CPA on service-users’ experiences.

A similar picture emerges in research on carers’ experiences. Studies demonstrate that carers lacked information about the CPA70,100,103 and that carers felt frustrated and isolated70 by not having their views sought or taken seriously. 70,75,86 These findings are not surprising in light of evidence that suggests health authorities often had no formal policy for carer involvement, instead relying upon ad hoc arrangements. 70,75,100 On a more positive note, the CPA had the effect of generating more contact with carers in some areas,68,80 which resulted in greater levels of carer satisfaction. 68,100

None of the studies reports overt organisational and professional strategies of resistance that served to suppress the involvement of service users and carers. Instead, indicators of professional or medical dominance are more subtle but arguably just as profound in diminishing the opportunities for user or carer involvement. For example, Newbigging et al. 77 describe how Independent Mental Health Advocates (IMHA), who play an important part in representing and advocating for service users’ best interests in CPA meetings, are frequently not invited to CPA meetings through apparent lapses in effective communication and diary planning by care teams.

Similarly, when IMHAs were invited, the CPA meetings were poorly organised and often overrun, with the result that IMHAs had to leave meetings before they had finished owing to other commitments. Foucault neatly captures the fact that subtlety is often an overlooked essential for the effective operation of power, stating that ‘Power is tolerable only on condition that it masks a substantial part of itself. Its success is proportional to its ability to hide its own mechanisms’. 104(p. 86)

The CPA has been described as encouraging a focus on service users’ problems rather than their strengths71,92 and as a way of working that prioritises a preoccupation with illness,16,82,94 which is indicative of an approach to caring that creates patient dependency on practitioners through ‘pathologising’ individuals. It is also an approach that means illness comes to define the totality of the person. The nature of the CPA has arguably reinforced a reluctance in some practitioners to move away from an illness model towards a more person-centred and participative mode of mental health practice.

Very few studies explored whether aspects of workplace culture or organisation were prevalent in resisting, frustrating or promoting policy objectives to increase service-user and carer involvement. How far underlying cultural change has kept pace with the more obvious structural reforms in CMH care remains a matter of debate 20 years after the introduction of the CPA. A number of important questions remain about the conditions responsible for promoting or suppressing service-user and carer involvement, the relationship between hierarchies and power structures within CMH workplaces, and the most conducive ways of navigating these to ensure greater participation.

Although those who introduced the CPA deserve praise for encouraging and promoting the development of service-user and carer involvement, this research tradition demonstrates that taking action to involve users requires a willingness to change attitudes and practice, not merely the introduction of policy or best practice imperatives. The danger otherwise is that, without a genuine commitment, calls for greater involvement merely become ‘an exercise in rhetoric’ that leaves existing power relations between professionals and service users/carers untouched.

Many in this research tradition have pioneered approaches to service-user and carer involvement. As a result, service users and carers have contributed greatly to changing how mental ill health is conceptualised and have aided in the production of new knowledge, which has led to a better understanding of methods for improving the lives and advancing the rights of people with mental health problems. It has challenged a model of mental illness as simply deficit and pathology of a psychiatric diagnosis as a ‘master status’105 that swamps any other aspects of the person.

Tradition 3: interventions to improve the care programme approach

The demonstration of clinical effectiveness of health-care interventions has had an increasing role in the UK and devolved governments’ health strategy since the mid-1990s. 106 At the same time, national policy at the macro-level has focused on the CPA as a means of systematically assessing the health and social care needs of those in greatest need, leading to the development of an individual care plan, co-ordinated by a keyworker. As already discussed, however, very different versions of the CPA were implemented at the level of service delivery within and across regions of England. A tradition of research therefore emerged during the late 1990s that reflected both the perceived need to demonstrate and improve clinical effectiveness, as well as capturing the early difficulties and variation in the implementation of the CPA (see Appendix 6).

As already discussed, the CPA led to diverse, often time-consuming, bureaucratic practices that meant staff spent less time with patients. 16,68,83 CPA documentation is framed by researchers and clinicians as problematic, since poor documentation increases the risk of vital patient and treatment information being missing when planning and co-ordinating care. Consequently, the third research tradition describes how the elimination of variation in documentation processes can lead to improved performance and reliability in care planning and outcome measurement.

Macpherson et al. 106 provide an example of a study that encompasses issues related to variation and effectiveness; stating that standardised documentation for individual care planning should be combined with outcome measurement, to give a meaningful measure of the effectiveness of care. To better understand the relationship between care planning and patient outcomes, a formalised space was introduced to the CPA documentation for establishing and standardising treatment goals. Goals were set within a care planning assessment and review meeting and agreed with patients (n = 139), relatives, professionals and advocates prior to the meeting’s conclusion. One year later a clinical review meeting found that 68% of goals were fully and 11% partially achieved (43% of goals were partially or not achieved). Goals targeting drug treatment of psychiatric syndromes were most likely to be fully successful (84%), whereas approaches to self-care skills, side effects, physical/medical problems and family relationships were moderately successful.

Recent UK mental health policy has emphasised the need for services to adopt a ‘recovery orientation’ to improve service users’ experience of care, social inclusion and recovery. An attempt to standardise outcome measurements for recovery was undertaken by Killaspy et al. 102 who assessed a measure of recovery, the Mental Health Recovery Star (MHRS) for acceptability, reliability and convergent validity. Recovery was defined by the authors as ‘a personal and dynamic process of adjustment and growth following the development of a mental health problem’ (p. 65).

Although the MHRS was relatively quick and easy to use and had good test–retest reliability, inter-rater reliability was inadequate. Furthermore, convergent validity suggests that MHRS assesses social function more than recovery, leading to the conclusion that it cannot be recommended as a routine clinical outcome tool but may facilitate collaborative care planning. Interestingly Gould’s94 study reviewed in Tradition 2 also suggested that the MHRS operated more as a measure of social functioning than recovery. Others saw the MHRS as too complicated, putting too much pressure on service users with long-term problems to find employment and being a rigid tool.

Both Lockwood and Marshall107 and Marshall et al. 108 researched interventions aimed at standardising patients’ needs assessments; the first of these studies was a pilot study, which led to the second study. The intervention in both studies is relatively convoluted and complex, initially involving a research nurse undertaking a baseline assessment of the patient to identify needs. Data from these assessments were then entered into computer software to determine which of the practitioner-identified needs or problems required action. When needs required action, the research nurse and consultant psychiatrist considered a list of pre-defined interventions provided by the software, before deciding whether or not the patient was likely to benefit from any of the interventions. The research nurse then provided the keyworker with a report of the needs identified, which were then used to guide care plan discussions between the keyworker and the patient.

In the pilot study significant reductions were seen in ‘unmet’ needs and the level of anxious/depressive symptoms, suggesting that needs feedback improved the quality of nursing assessment and care planning within the CPA. However, the follow-up study108 found that standardised needs assessment did not substantially enhance care planning. The process of using an independent registered nurse, who was not a keyworker or a member of the clinical team to undertake the needs assessment, allied to having to search a computer database for interventions associated to needs, would have made transferability of these findings into clinical practice difficult, as the trial intervention differed greatly from usual practices.

The CUES-U tool (Carers’ and Users’ Expectations of Service – User version) tested by Blenkiron et al. 99 consisted of a 17-item service user outcome scale in booklet form developed by academics, clinicians and service users. CUES-U was described as an ‘important tool’ (p. 334) because it focuses on issues of quality of life and satisfaction that mental health service users (rather than professionals) identified as priorities. Service users (n = 86) completed the CUES-U booklet before returning and discussing the contents of the booklet with care co-ordinators, who then recorded changes made to care plans as a result of receiving the CUES-U feedback.

The CUES-U mediated discussion led to a change in clinical care for 49% of respondents. Care co-ordinators rated CUES-U as a good use of their time in 64% of cases. A large proportion (84%) of service users were satisfied with the level of control and consultation they received; 87% were satisfied with their relationships with mental health workers and > 70% were satisfied with levels of information and advice and access to services. However, a significant limitation of high levels of satisfaction was that patients knew that their care co-ordinator would see their replies, although many did write negative comments in free text boxes. The authors concluded that CUES-U can be an effective and practicable tool for increasing users’ involvement in their care and for service benchmarking.

A move from paper documentation towards electronic CPA (eCPA) records was proposed by Howells and Thompsell. 109 The eCPA consisted of a computer-based CPA system for care planning and documentation – using a Microsoft Word template – designed to improve the quality of information in CPA care plans in a CMH team in London. Completed eCPA care plans were e-mailed to the acute ward, the hospital’s emergency clinic and any other agencies. The CPA manager received the original signed copy, a copy was filed in the case notes and the GP, the patient and carer were given a copy. The eCPA was welcomed by staff with a take-up rate of almost 100%. Patients welcomed the legibility and detail of the forms and expressed no concerns about the change to the eCPA. Care plans were longer and more detailed, being no longer constrained by fixed-size boxes on paper forms. Care plans were also adjusted more frequently by CMHT staff, who did not have to completely rewrite the forms by hand. As a result, the plans better reflected the changing needs of patients.