Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 11/1015/20. The contractual start date was in April 2012. The final report began editorial review in January 2015 and was accepted for publication in September 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Alex D Tulloch and Graham Thornicroft are employed part-time as consultant psychiatrists for South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust. André Tylee was a director of the Mood Anxiety and Personality Clinical Academic Group and honorary consultant at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust until October 2014. Catherine Polling has worked as a psychiatrist for South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust since 2014. This included salary support for Alex D Tulloch, Anke Görzig, Sophie Pettit, Leonardo Koeser and Andrew Watson and fees paid on a self-employed basis to BS. Additionally, this study represents independent research part funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London, which maintained the infrastructure used and provided salary support for Alex D Tulloch, Catherine Polling and Mizanur Khondoker. Alex D Tulloch, Diana Rose and Graham Thornicroft are currently supported by NIHR Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care South London at King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Tulloch et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

This report concerns an organisational change within the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust (SLaM) associated with its entry into the King’s Health Partners (KHP) Academic Health Sciences Centre (AHSC) in 2009. This change was centred around new structures called Clinical Academic Groups (CAGs), which replaced the directorates through which SLaM had previously managed its operations. Four of these directorates had provided comprehensive adult mental health services to four boroughs in South and Southeast London and the transition to CAGs entailed the loss of these geographically based operational units providing comprehensive adult mental health services to the population within a defined part of SLaM’s geographical catchment. Instead, they were replaced with operational units that divided the work of adult mental services between them by grouping teams and wards with similar functions together and provided services across SLaM’s entire area and, in the case of tertiary services, beyond.

We took a programme evaluation approach to this work. Following Wholey,1 we understand a programme as ‘a set of resources and activities directed towards one or more common goals, typically under the direction of one manager or a management team’ (p. 9). We aimed to define the CAG ‘programme’ straightforwardly enough that another organisation seeking to follow SLaM’s example would know what it would need to do to set itself, at least at the outset, on the same track.

Clarity in relation to the central programme components of the CAG reorganisation was, in reality, achieved only incrementally and over the course of the evaluation. Like many programmes, the CAG reorganisation, especially at first, involved many activities whose relative lack of centrality became evident only over time.

The first programme element was straightforward to identify. This was the CAG restructuring itself, which involved taking a set of geographically based management units and turning them into a new set of service management units in which teams were grouped on the basis of their function or, alternatively, on the basis of the predominant set of problems or diagnoses they treated. As we show in Chapter 3, other NHS trusts in London also undertook this kind of reorganisation around the same time as SLaM; however, unlike SLaM, these other trusts uniformly referred to these new units as service lines, whereas SLaM called them CAGs. This different terminology reflected the special influence in SLaM’s case of the newly formed AHSC.

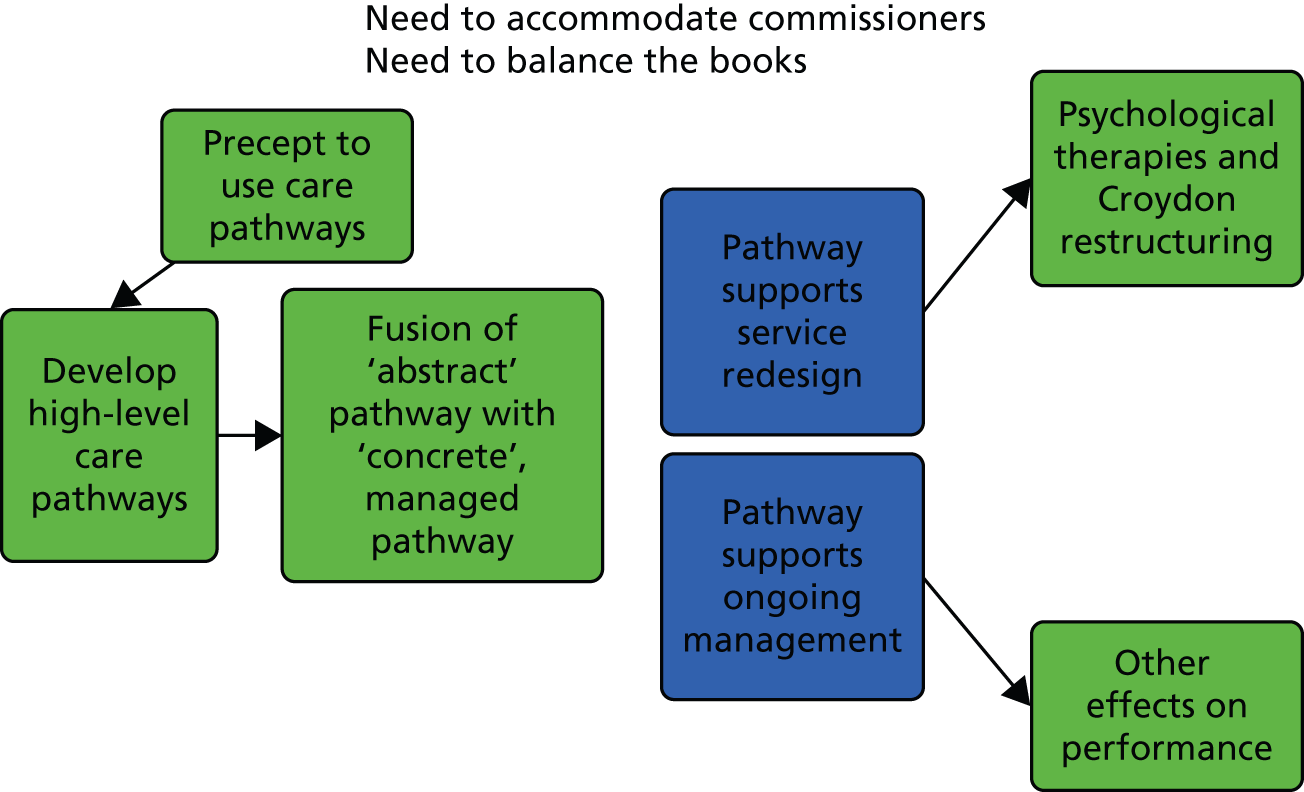

What we came to see as the second programme element was initially a requirement imposed as part of the initial CAG development process managed by SLaM and KHP, but which over time developed into an evolving and open-ended experiment: the newly formed CAGs were guided to use care pathways to describe, redesign, develop and performance manage their services, and this process extended beyond the initial restructuring period and into the stable operating period of the CAG that we studied. We came to see the use of care pathways as a precept, that is, a general principle that care pathways should, when possible, be used as a resource for managing and changing services. However, as we show in Chapter 3, the way that care pathways were introduced and the exigencies of management led SLaM to a distinctive form of ‘high-level care pathway’, which, although demonstrably effective as a tool for management, deviated in some ways from the usual understanding of care pathways described in the literature. This has the important consequence, we believe, that SLaM’s CAG reorganisation cannot be treated as a case study of the use of care pathways as these are usually understood.

Having identified the core programme components, our intention was to draw on the methods of realistic evaluation2 to explore what happened when SLaM introduced CAGs. For each programme component this would require us to consider the key mechanisms through which change was sought, the changing contexts in which this occurred and the outcomes produced by the combined effect of mechanism and context.

Plan of the report

We do not preface the accounts of our methods and results with a separate review of the literature relevant to each programme component. In the case of the CAG restructuring itself, this was because a scoping review of research into service line management indicated that no truly comparable change has been described and studied in the past; the only apparently similar evaluation studied a quite different higher-level separation between acute, mental health and primary care service lines in the Veterans Administration (VA). 3–5 In the case of the use of care pathways, this is because of the particularities of SLaM’s practices compared with those described in other studies. 6,7 However, relevant literature is cited and discussed in other chapters, especially the qualitative results chapter (see Chapter 3).

Chapter 2 outlines our main research questions and describes the methods adopted in this study. In our qualitative and some of our quantitative data collection, we focused on the Mood Anxiety and Personality CAG (MAP CAG) and also on those users of SLaM’s services who have a non-psychotic diagnosis. This limitation to one CAG was necessitated by the resources available to us and we chose the MAP CAG in preference to the Psychosis CAG only because another large research project affecting the latter was anticipated at the time that research funds were being sought. Studying only a single CAG imposed some limitations of scope, but also allowed us to investigate the organisational process in greater depth than had we attempted to evaluate more than one CAG.

Chapter 3 tells the story of the CAG programme, based on documentary evidence and on evidence from interviews with SLaM staff and service users. We look first at the overall circumstances within which this organisational change took place. We then describe the early development of KHP and its CAG programme, provide a brief history of SLaM and the Institute of Psychiatry (IoP) and outline the immediate context within which SLaM decided to reform its operational units as CAGs. We set out what the interviews and documentary sources suggest were the key mechanisms through which change was initially sought at the time of CAG formation. We then use key themes identified from the interviews to set out what actually happened, here contrasting findings in 2012 (our first wave of data collection) with findings in 2014.

Chapter 4 details our quantitative findings, setting out what we were able to discover about activity and costs, effectiveness, safety and patient centredness and how these had changed across SLaM’s four boroughs (Croydon, Lambeth, Lewisham and Southwark) since 2009.

In Chapter 5 we discuss our findings and consider their implications.

Chapter 2 Research questions and methods

This organisational study explored three main research questions: how the SLaM CAG programme (as exemplified through the MAP CAG) was conceptualised and implemented by SLaM staff; the extent to which there were changes in activity levels and in the quality of patient care over the 5 years since the start of the programme in 2009 and the extent to which those changes could reasonably be attributed to the CAG programme; and the main lessons that could be learned and applied more generally. As noted in the previous chapter, to keep the research to a reasonable scale and scope we studied only one CAG (the MAP CAG) and concentrated on its most important services: those provided through community mental health teams (CMHTs) and psychotherapy teams. The MAP CAG was selected in preference to the other large adult CAG (Psychosis) because a large programme of research was envisaged in the latter at the time that we were seeking research funding for this study.

We used a combination of qualitative and quantitative methodologies and data to inform our understanding of the SLaM CAG programme and the definition and implementation of the MAP CAG. The qualitative work included two sets of semistructured interviews at the start and end of the project as well as document analysis and drew on a realistic evaluation framework. 2 The quantitative work identified and analysed data held in a database of anonymised electronic patient records to examine, test and develop the qualitative findings.

Realistic evaluation aims to test and refine programme theories by establishing clear and measurable relationships between an intervention such as the CAG programme and its outcomes that are explained by an underlying theory of change. It is sensitive to contextual effects, identifying a series of context–mechanism–outcome configurations. The underlying assumption is that all programmes do generate regular patterns of results, but only when broken down into their underlying components, and when the context in which those components operate is taken into account. Without this disaggregation and consideration of context, programmes can appear to generate very different results from one implementation to another. Realistic evaluation has previously been used in the analysis of similar programmes in the NHS; although it does not provide a methodological prescription but instead a set of principles and orientations, the use of a comparative case study approach is typical. For example, Rycroft-Malone et al. 8 reported candidate context–mechanism–outcome mechanisms in the Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care programme, using a comparative case study approach based entirely on qualitative data. Rycroft-Malone et al. 9 used similar approaches to study protocol-based care in a variety of settings, whereas Greenhalgh et al. 10 reported a realistic evaluation of a large-scale change programme for stroke, renal services and sexual health services in inner London and also included a review of the existing – limited – literature on the use of realistic evaluation in health-care contexts. Notably, the latter authors10 reported that core tasks of realistic evaluation – definition of programme goals and definition of programme mechanisms – were far from straightforward to perform. Early in the evaluation we attempted to create logic models linking inputs, activities, outcomes and outputs,11 but it was ultimately more straightforward to present the necessary context–mechanism–outcome configurations either in narrative form or using diagrams that directly represented those relationships. 2

In relation to the SLaM CAG programme our objective was to undertake an evaluation that would (1) be meaningful to the managers, clinicians, academics, service users and commissioners who were involved in or who were affected by implementation of the MAP CAG; (2) take advantage of their detailed knowledge of the multiple contexts into which the CAG programme was introduced; (3) support replication of the programme elsewhere; and (4) support research utilisation. 12 We used the professional, tacit and formal knowledge of various actors in the SLaM CAG programme and the MAP CAG to develop a narrative of change that describes how those involved thought their use of resources (money, authority, expertise, time, etc.) had contributed to the changes identified, and we aimed to develop context–mechanism–outcome configurations to illustrate how specific components of the SLaM CAG programme had achieved that change. Our restriction to a single site to some extent limited our ability to apply these methods, as any given mechanism would at most be observed in a single overall CAG context and four potentially different borough context within that CAG. However, if context is understood as a specific, differentiated element, external to the programme, which determines the outcome in combination with a given mechanism – a formulation that we believe is consistent with the principles of realistic evaluation – then we still observed a plurality of contexts, at least in some cases. For example, the programme was applied across four London boroughs, each of which had pre-existing services that had arisen in different ways and would therefore potentially interact differently with the same programme element; differences could also be observed at the individual team level. Moreover, even with a smaller number of different observed contexts per mechanism, realistic evaluation holds out the hope of better generalisability than standard quasi-experimental methods. Because programmes are typically altered when applied elsewhere, and also introduced into contexts that differ from the original site, the effects of any programme when viewed as a whole appear inconsistent across implementations. However, the component context–mechanism–outcome relationships, if correctly specified, operate consistently between different sites, allowing different overall patterns of effects to be explained.

Qualitative data collection

The qualitative work was undertaken in two phases, during the first 4 months and the last 3 months of the study. In phase 1 (months 1–4, May–August 2012), five group meetings were held: three service user-only meetings, one MAP CAG staff meeting and one final joint meeting with self-selected people from both categories who had attended one of the previous meetings. The service user meetings were co-facilitated by the two service user researchers on the team, who also attended the final joint meeting.

The study team prepared a topic guide before the interviews (see Appendix 1).

The service users who attended these meetings came from different boroughs and were drawn from two key groups: ‘involved’ service users (n = 4), that is, those who had a formal but largely voluntary role within the MAP CAG (such as membership of the MAP CAG Service User Advisory Group), and ‘non-involved’ service users (n = 9) and one carer, who had no formal role within the MAP CAG. These latter respondents were contacted through local service user organisations known to the MAP CAG’s Patient and Public Involvement Co-ordinator. The MAP CAG was relatively new at the start of our evaluation and we anticipated that it might be largely unknown to the non-involved service users, whose interactions with the trust are almost exclusively through contact with clinical teams. We therefore separated these early meetings to ensure that each stakeholder group had sufficient opportunity to develop their potentially contrasting views before coming together.

The staff who attended the group meetings were senior individuals who had played a key role in developing the SLaM CAG programme and in defining and developing the MAP CAG and included clinicians, academics and managers from the MAP CAG. Subsequently, we performed a few further interviews with staff members either alone or in pairs; some of these were respondents who we had already interviewed in the group interviews and others were new respondents whose knowledge of the programme had been indicated to us by the initial set of respondents. All staff respondents were approached on the basis of their closeness to the programme, rather than attempting to recruit a predefined number of people; we aimed to select those people who would be able to explain the programme and its history to us and how it worked.

All of the meetings and interviews were recorded and transcribed following prior permission from the participants.

Again taking a lead from our staff respondents, we also gained access to documentary sources relevant to the history of the MAP CAG. These documents were produced by the MAP CAG, by SLaM or by KHP.

All materials are described in Table 1.

| Activity | Number of participants |

|---|---|

| Group meetings | |

| Service users (non-involveda) | 4 (plus 1 carer) |

| Service users (involveda) | 3 |

| Service users (non-involved and involved) | 6 |

| Senior SLaM/MAP CAG staff (managers, clinicians, academics) | 7 |

| Joint meeting (3 service users and 3 staff) | 6 |

| Other interviews | |

| Senior MAP CAG staff (manager) | 1 |

| Senior MAP CAG staff (managers) | 2 |

| Senior MAP CAG staff (financial managers) | 2 |

| Senior MAP CAG staff (borough services) | 1 |

| KHP, SLaM and MAP CAG document review and analysis | – |

In phase 2 (month 27 of the study), follow-up interviews were undertaken with senior MAP CAG staff – a service manager, a clinical manager and a clinical academic, each of whom had contributed as phase 1 respondents – to consider external and internal developments since the first round of meeting and interviews and to present preliminary findings from the quantitative analysis.

Qualitative analysis

The interview and documentary materials were used in two ways.

First, throughout the project we repeatedly read and considered the available materials to develop an understanding of the CAG programme and its effects. We experimented with the use of logic modelling, which represents a programme as an assembly of inputs, activities, outputs and outcomes. We also experimented with representing the CAG programme as a set of context–mechanism–outcome configurations. Alongside both methods we drafted narrative text about the CAG programme and its effects. At the fourth group meeting in phase 1 and during the phase 2 interviews we presented some aspects of our understanding of the programme to cross-check this with respondents’ understandings. Ultimately, these analyses led to the representations of the CAG programme presented in the project report.

Second, we performed a thematic analysis. This was first applied to the phase 1 interview materials. Transcripts were initially reviewed and discussed by two team members. Subsequently, one researcher used qualitative data analysis software (NVivo 10; QSR International, Warrington, UK) to identify content relating to our research questions and to produce an initial set of themes arising from the data, guided at first by the prompts that had been used for the group interviews (see Appendices 1 and 2). The resulting analyses were cross-checked by the second team member. At a project team meeting during phase 2, three project team members considered the initial set of themes produced during phase 1, taking account of both the phase 2 interviews and he understanding that we had gained through the analysis of documents, and then decided on a modified list of themes for use in the final report (see Appendix 3). One team member recoded the phase 1 transcripts using these codes and this coding was rechecked by the other two team members. These themes and associated quotations were used as the basis for writing up the qualitative results.

Subsequent to the phase 2 interviews in July 2014, transcripts were read through and considered by three project team members, with an initial list of themes developed out of that discussion and to a large extent aiming to code issues that had also been raised in phase 1. These additional themes were also used as the basis for writing up the qualitative results, as noted above.

Quantitative work

Quantitative parts of the evaluation were performed using data held in a database of anonymised electronic patient records that is maintained by SLaM – the Clinical Record Interactive Search (CRIS) system. 13

Data management

We worked using the Structured Query Language (SQL) database version of the CRIS system. All data management was performed using Microsoft SQL Server 2008 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and programmed in Transact-SQL.

Based on a comprehensive list of the names of all of the trust’s teams and wards we classified these teams into groups of similar services. We then used a fully cleaned table of activity data to define a set of periods under the care of a CMHT, including all of the various forms of CMHT that SLaM has operated, both before and after the CAG reorganisation, and including teams within the current MAP CAG and also outside it. This allowed us to analyse individuals with non-psychotic disorders before and after the reorganisation. The same was carried out for the psychotherapy teams, which, after the CAG reorganisation, constituted the other major part of the MAP CAG’s services. We included the integrated psychological treatment teams that the MAP CAG formed subsequent to the CAG restructuring but also the predecessor teams that performed a similar function before the reorganisation. Some highly specialised services that do not predominantly serve clients from SLaM’s four home boroughs were not included, such as the outpatient clinic associated with the inpatient Affective Disorders Unit.

The same cleaned activity table was used in combination with the trust’s own internal accounting data to derive unit costs for all forms of community and inpatient care. This required several rounds of error checking, enabling us to define a group of services for which both the financial and the activity data were adequate. Unit costs were calculated per ward or team and per financial year, using a currency of cost per single contact for community locations and cost per day for inpatient locations.

Data sets

Seven data sets were defined.

The main data set was defined as follows: to the periods of CMHT care and psychotherapy team care, we joined data on (1) demographics, (2) diagnosis, (3) referral date, (4) whether or not the episode had included a face-to-face contact, (5) costs of care delivered by CMHTs during the 365 days after the start of treatment, (6) combined costs of CMHT care, home treatment team care and inpatient care during the 365 days after the start of treatment, (7) previous service use, (8) receipt of secondary care psychotherapy during the episode or within 3 months of its end, (9) receipt of Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) individual cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) during the episode or within 3 months of its end, (10) the Health of the Nation Outcome Scales (HoNOS)14 score near the beginning and near the end of the episode and (11) the Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation 10-item version (CORE-10)15 score near the beginning and near the end of the episode.

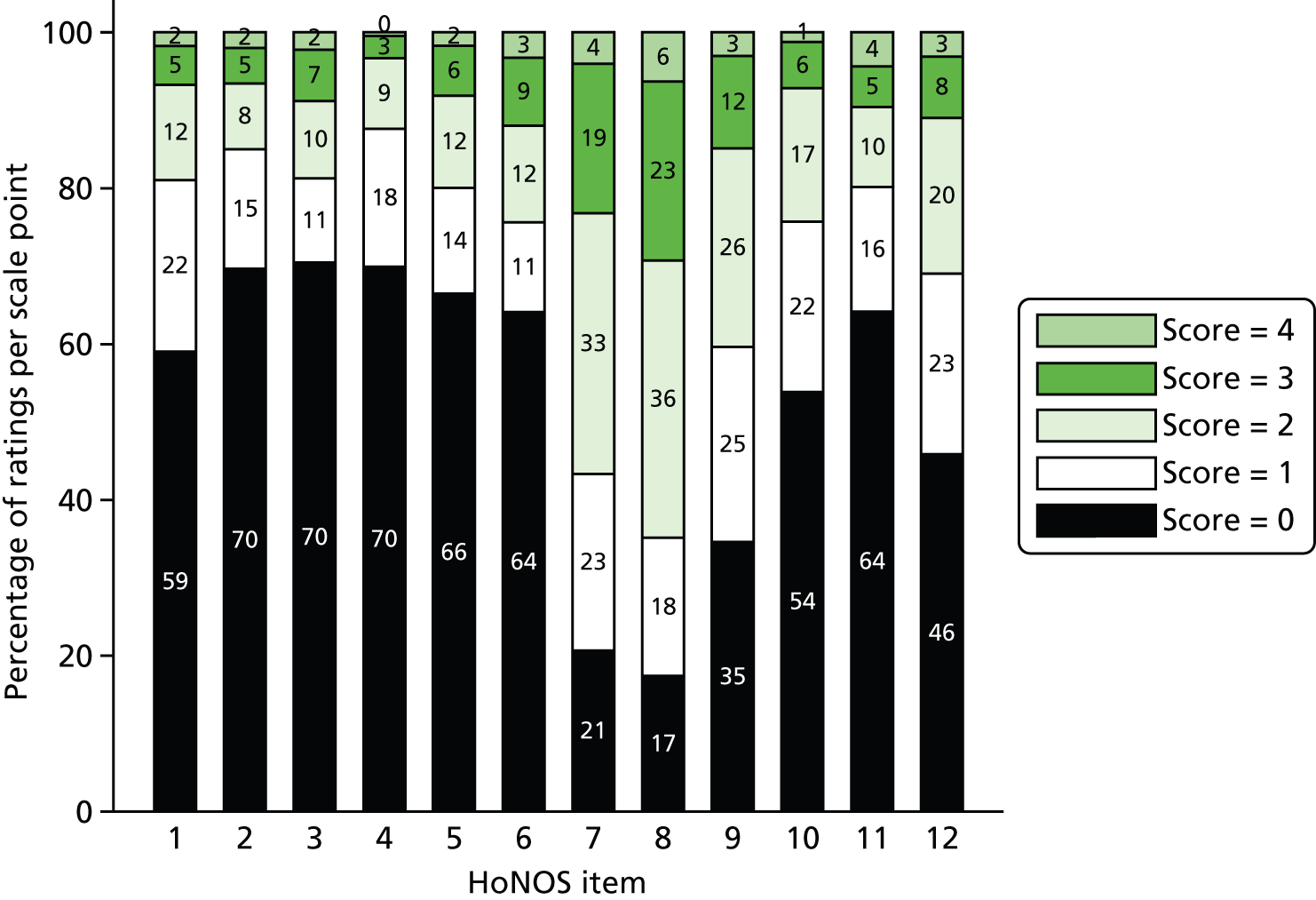

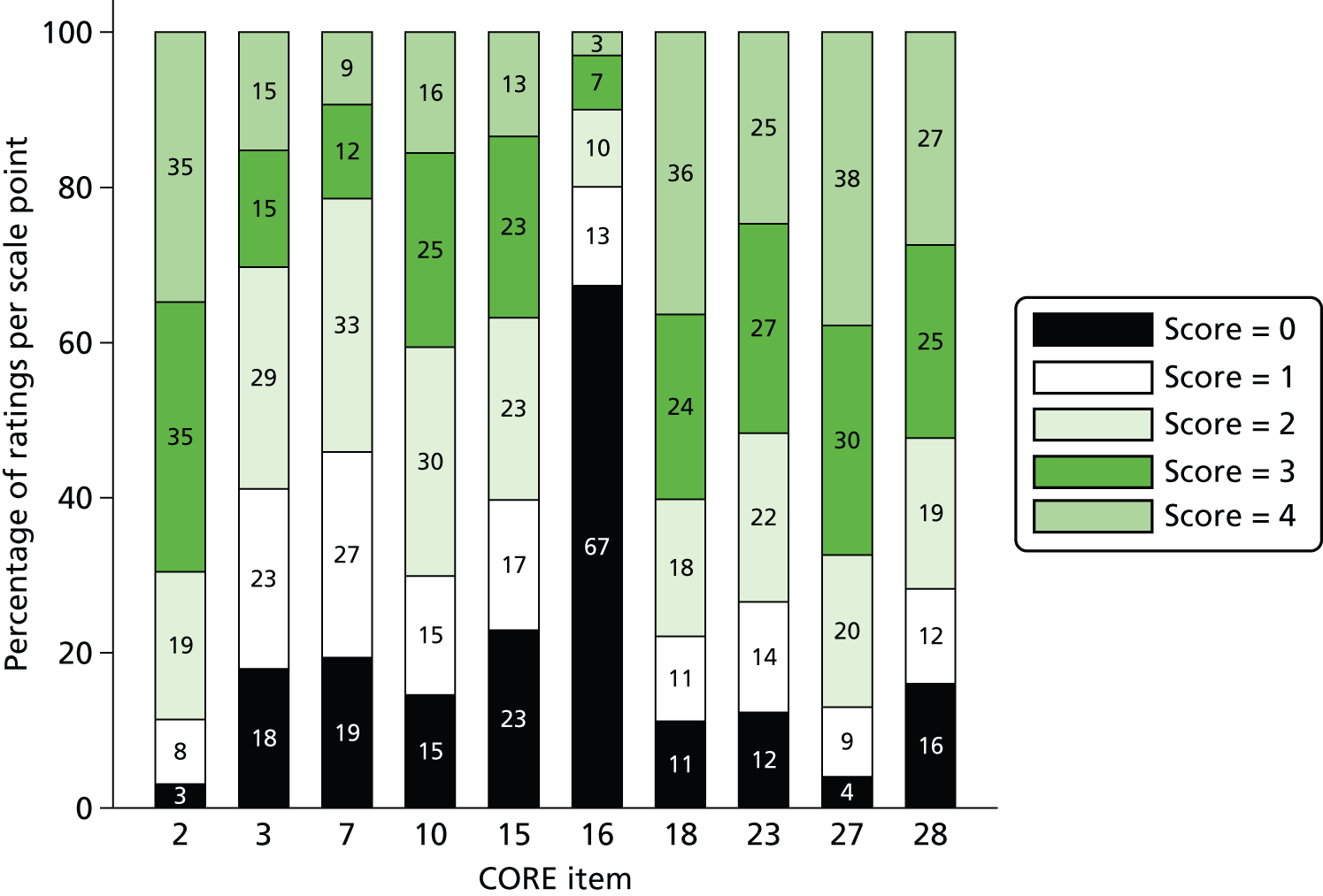

The HoNOS is a 12-item instrument intended for use as a routine outcome measure in community mental health services serving individuals with severe mental illness. It covers symptoms, behaviour and social function. The CORE-10 is a short, 10-item version of a longer instrument, the Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation Outcome Measure (CORE-OM), that may be used as a screening tool and outcome measure in psychology and psychiatric services and specifically addresses symptoms of common mental disorder.

A second data set (the text data set) consisted of 200 randomly selected periods of care under a CMHT, a borough-based psychotherapy team or both with a coded diagnosis of depression [F32–39 in the International Statistical Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10)]. For these episodes, the full anonymised text of the electronic patient record was extracted, allowing manual coding of prescribing and psychotherapy receipt and referral.

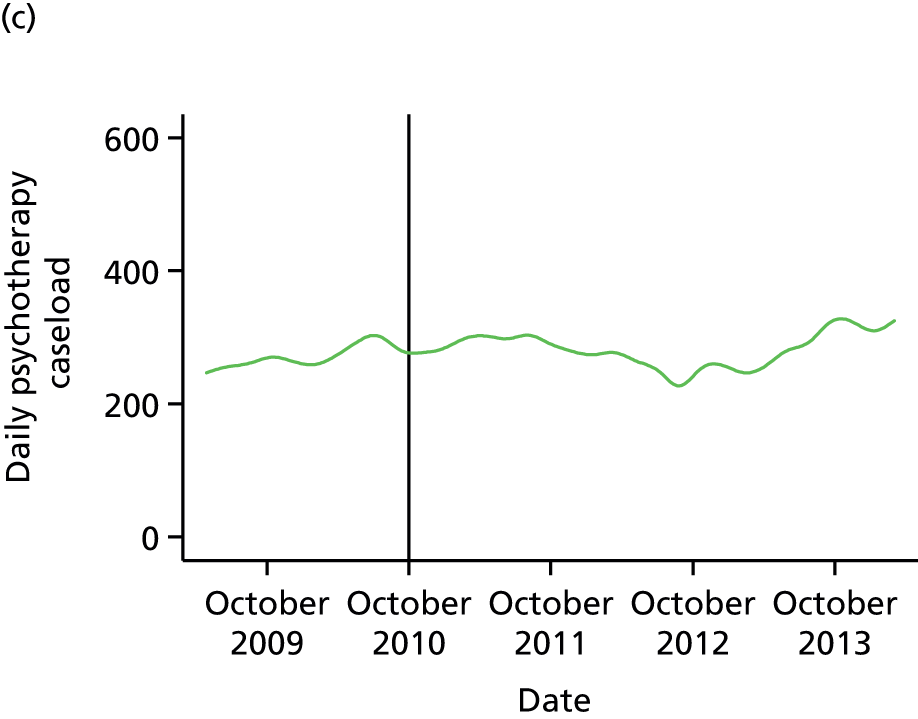

A caseload data set was defined containing data on current caseload per borough on any given calendar day, with different totals being calculated for CMHT care and psychotherapy. The counts in the data set were based on individuals with non-psychotic diagnoses who had been accepted for care by the relevant team and who had not been discharged at the census day.

A current waiting time data set was also defined. On any calendar day, a current waiting time was defined for any individual who had been referred to the CMHT or psychotherapy team but who had neither been seen for a face-to-face contact nor already been discharged. The current waiting time was defined as the number of days between the referral date and the census day. Adopting this method allowed us to investigate waiting time throughout the study period in a way that was not subject to bias as a result of censoring.

Next, we defined a data set of self-harm presentations in accident and emergency – the A&E data set. A data set was created that was identical to the main data set above, except that periods of CMHT care were extended by 3 months to create a data set of current or recent CMHT patients. This data set was then joined to a separate data set of psychiatric liaison consultations in A&E extending from April 2009 to November 2011, selecting only those consultations that had been manually coded as following an episode of self-harm (this A&E data set had been prepared for another study16). The data set was divided into 3-month time bands, for each of which we defined whether or not care co-ordination was in place, whether there was a change of care co-ordinator or care co-ordination was ended, whether or not there was a change in team and whether or not discharge occurred.

We also produced a data set – the acute admission data set – that was identical to the A&E data set except for being based on a data set of acute hospital admissions taken from Hospital Episode Statistics, selecting only those admissions coded as intentional self-injury using the appropriate ICD-10 X chapter headings.

Finally, we extracted a data set – the IAPT data set – including records of IAPT individual CBT treatment within each borough IAPT service.

Quantitative analysis

Initially, we performed descriptive analyses of clinical, demographic and service use variables, both for CMHT episodes and psychotherapy episodes, based on the main data set. These analyses included graphs showing the distribution of scores on each item of the HoNOS (for CMHT episodes) and the CORE-10 (for psychotherapy episodes).

The precise details of the analyses aimed at establishing the effects of the CAG restructuring were not decided in the original study protocol; we hoped that the qualitative interviews would give clear guidance as to the changes in activity and in quality of care that we should expect. Subsequent to the first wave of interviews, which did not in fact provide much clear guidance in this area, we decided to choose a series of indicators that would at least in part cover most domains of quality of care. 17 We grouped these under the following headings: cost and activity, effectiveness (subdivided into process and outcome), safety and patient centredness. Generally, quantitative analyses were guided by preliminary graphical analyses; for example, when the shape of the curve describing a particular indicator could not clearly be fitted by one or two straight lines we did not attempt to fit a trend line but instead simply compared values pre and post the CAG restructuring. Because of differences at baseline in the configuration of services within boroughs and because commissioning intentions also varied by borough we assumed that there were likely to be differences between boroughs. Therefore, all quantitative analyses either analysed boroughs separately or included interaction terms allowing per-borough effects to be examined separately. The choice to analyse by borough was made independently of the attempt to define specific context–mechanism–outcome configurations in the qualitative part of the study.

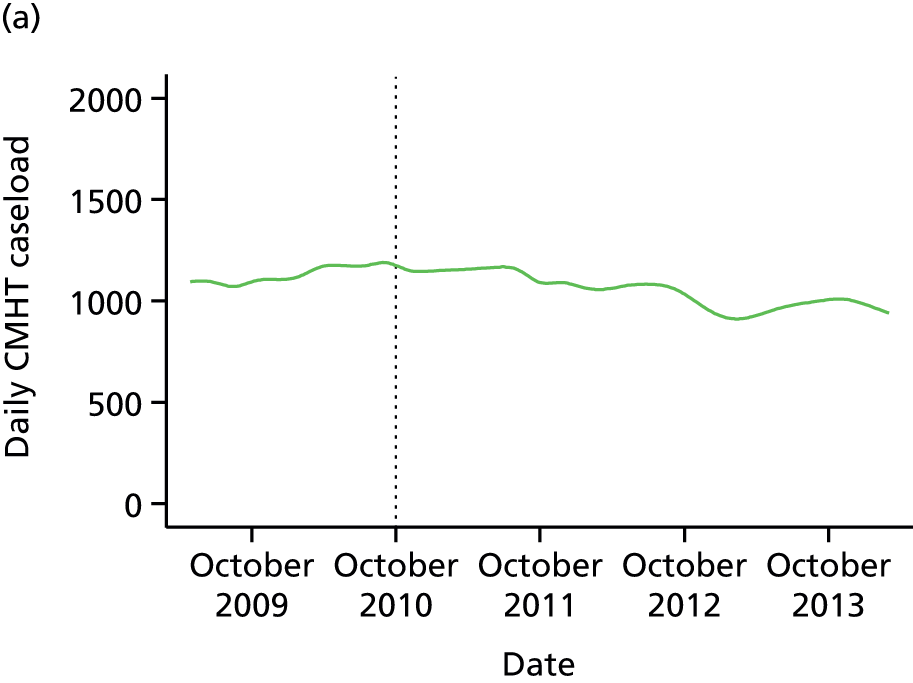

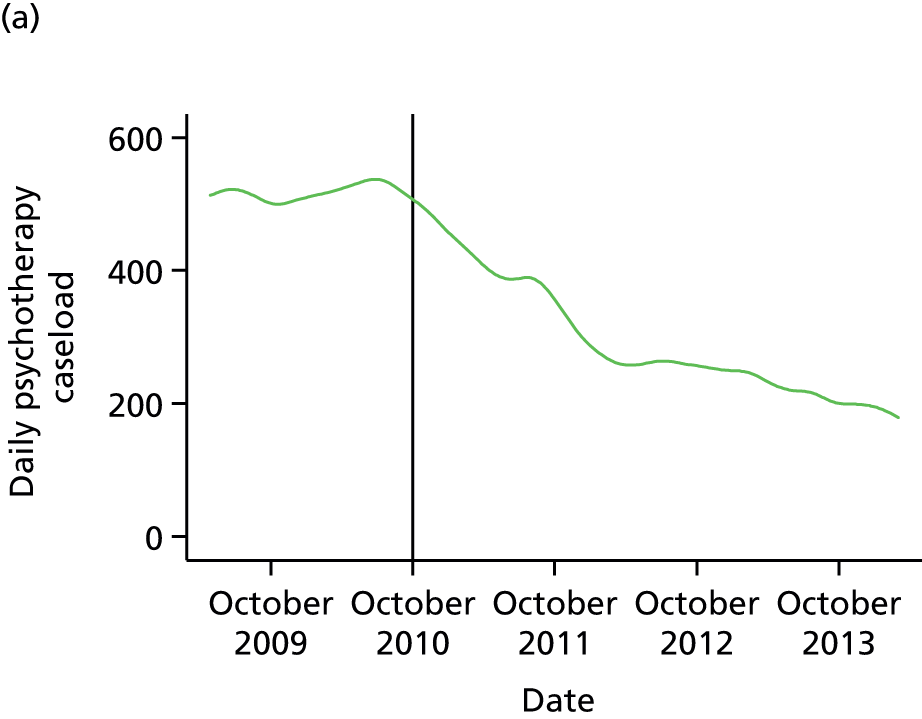

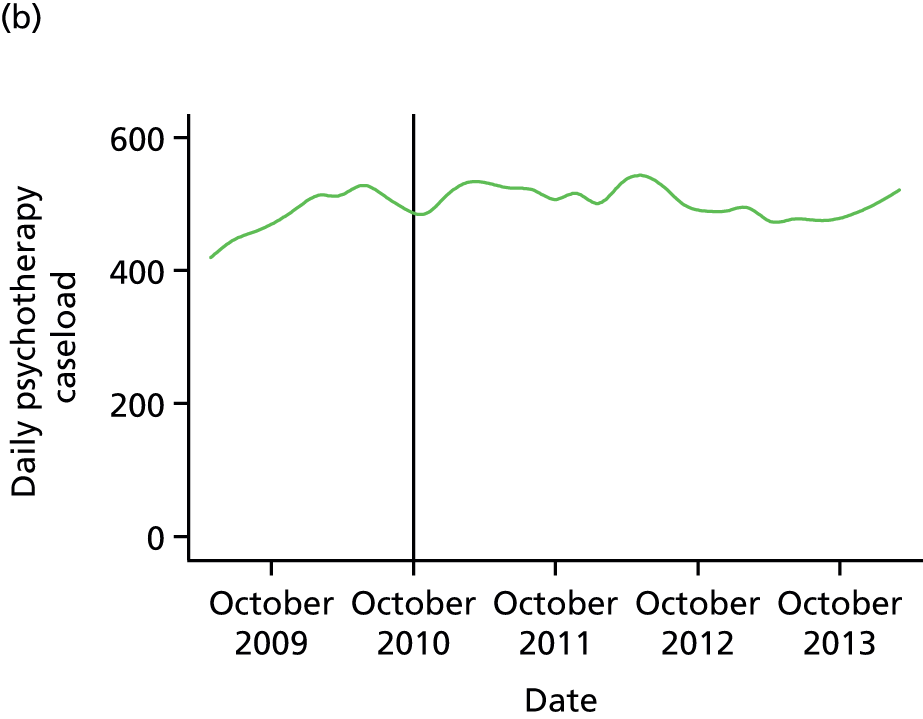

Activity and costs

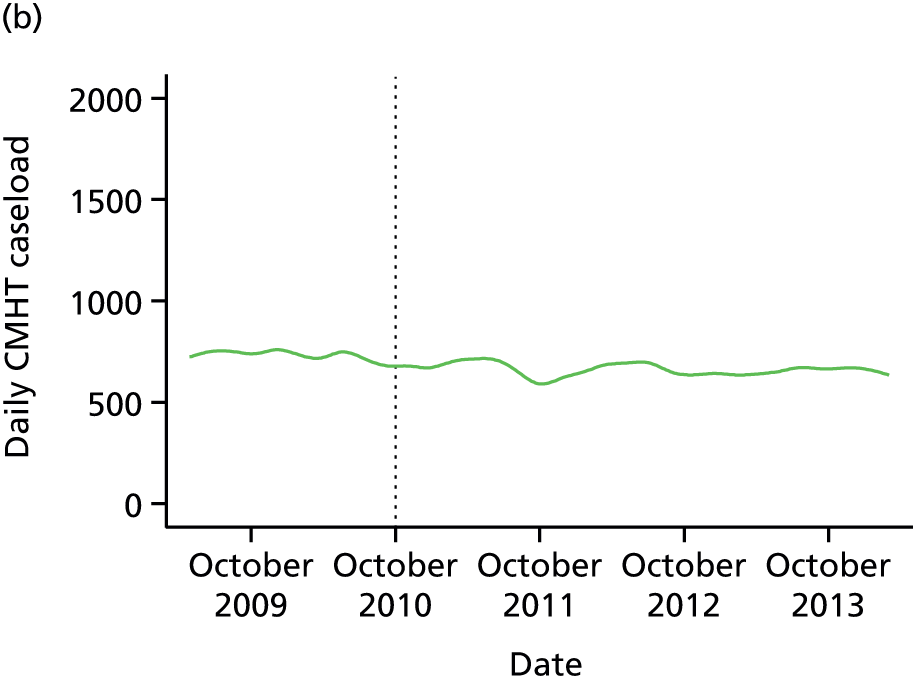

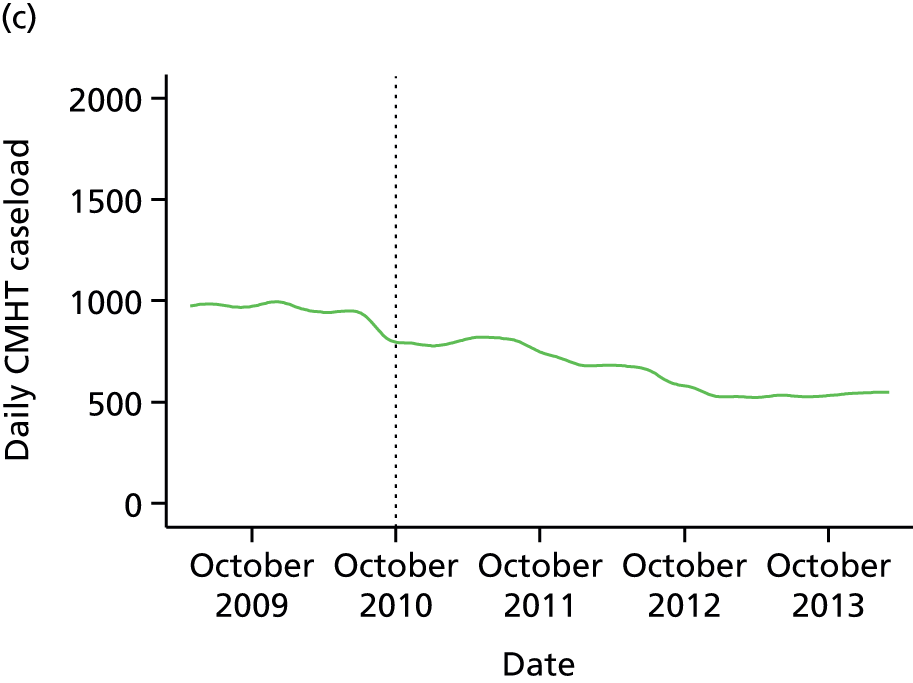

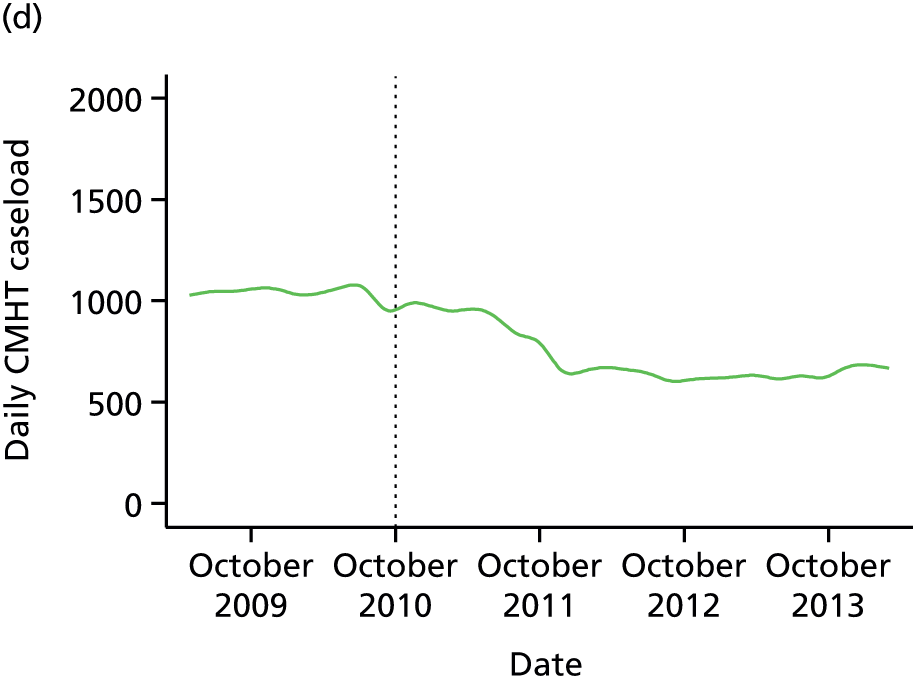

First, we took the caseload data set and plotted daily CMHT caseload for each borough over time. Inspection of these plots suggested that a regression of daily caseload against time, possibly allowing the slope of the fitted line to vary after CAG implementation, would provide a meaningful fit of the data. Each borough was analysed separately. Models in which caseload was regressed only against time (γ = βtimeXtime + β0 + ε) were compared using likelihood ratio (LR) testing with models in which caseload was regressed against time, a pre-/post-CAG indicator variable and an interaction term between the latter and time (γ = βtimeXtime + βCAGXCAG + βCAGxtimeXCAG × time + β0 + ε). We applied Durbin’s alternative test to the initial analyses to test for the presence of autocorrelation and reran them using Newey–West standard errors as necessary.

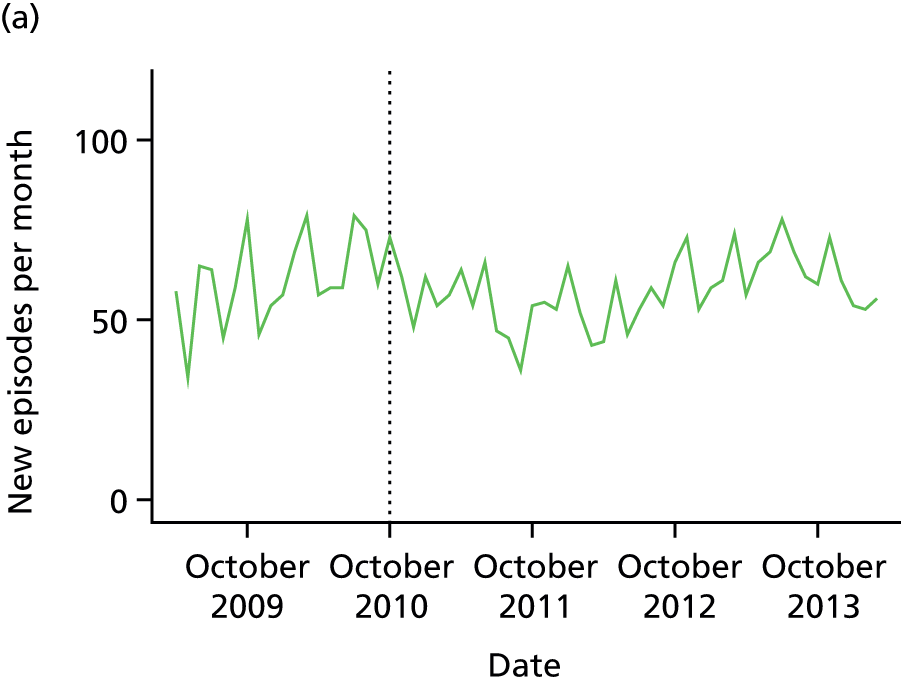

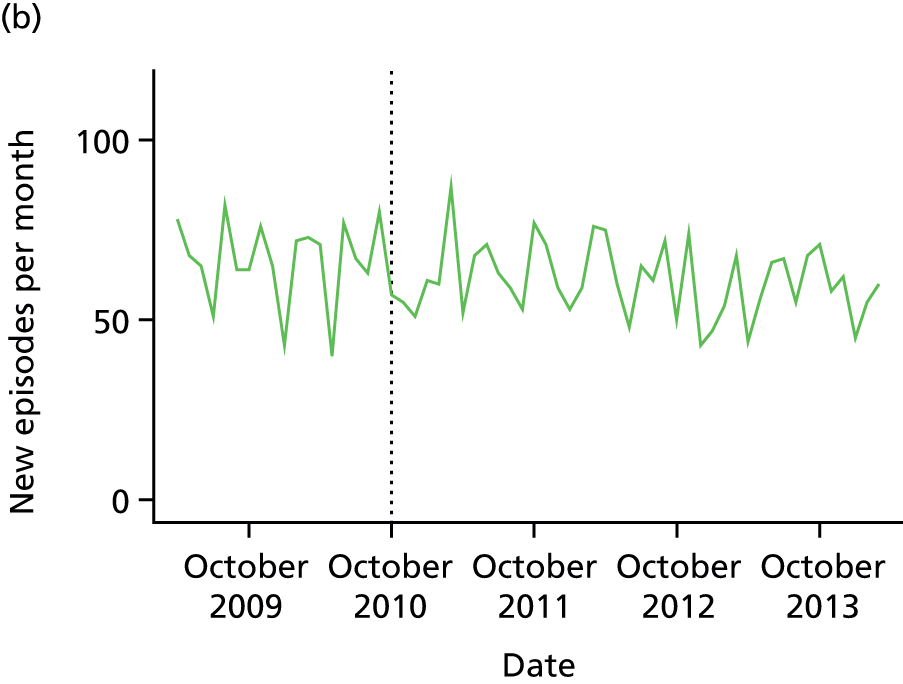

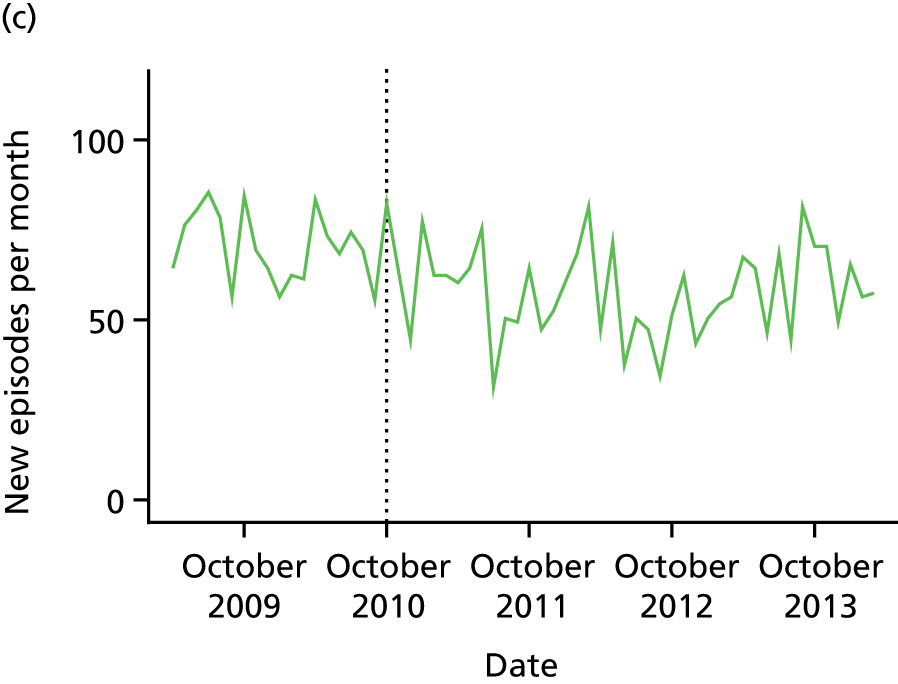

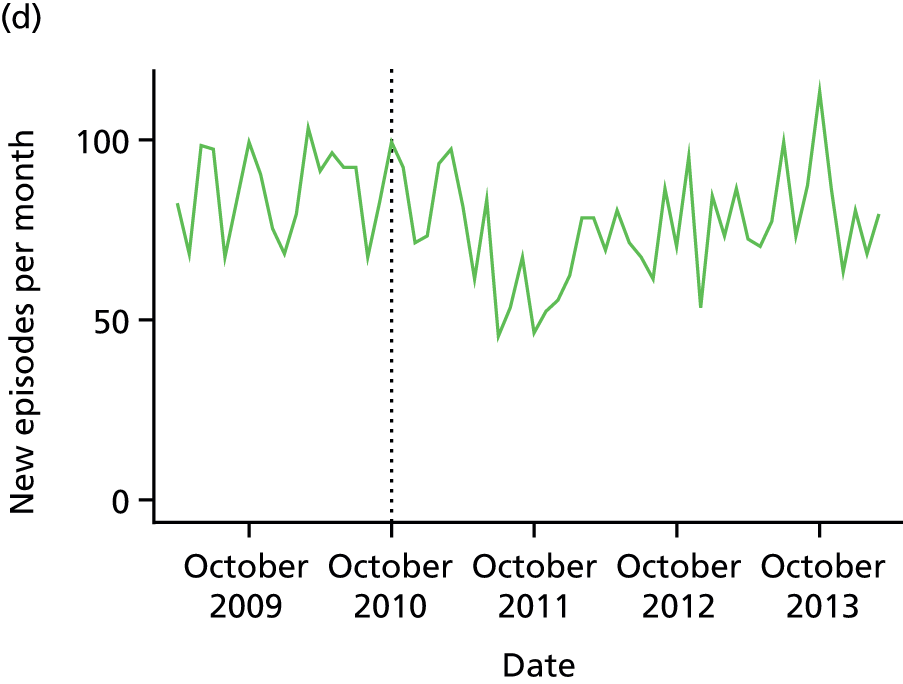

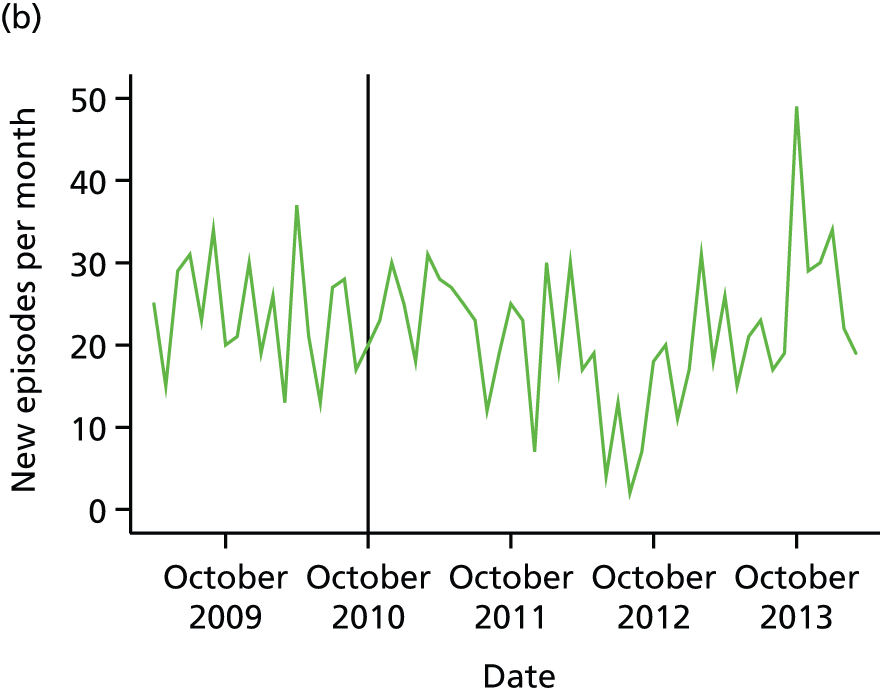

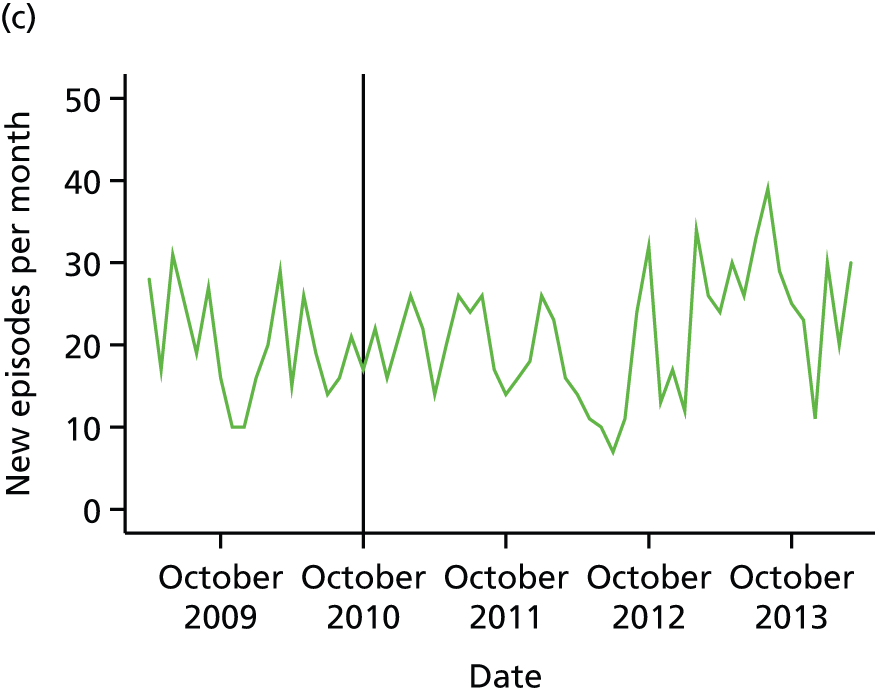

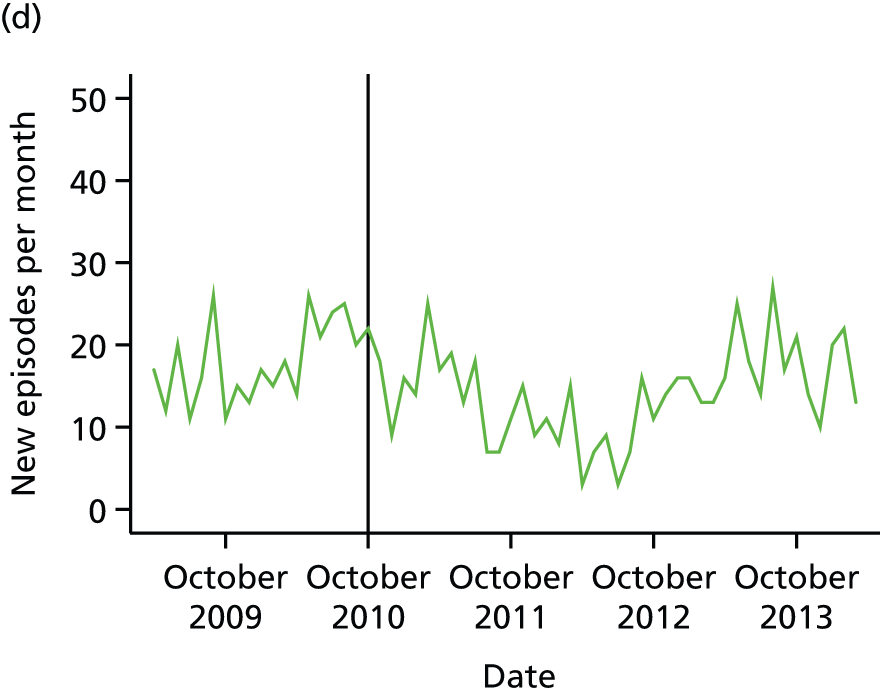

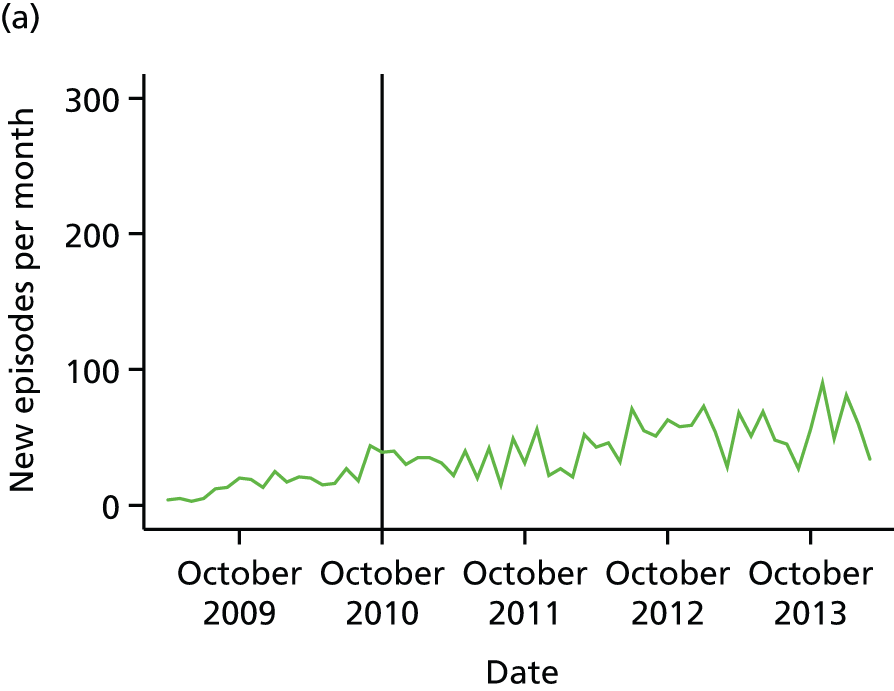

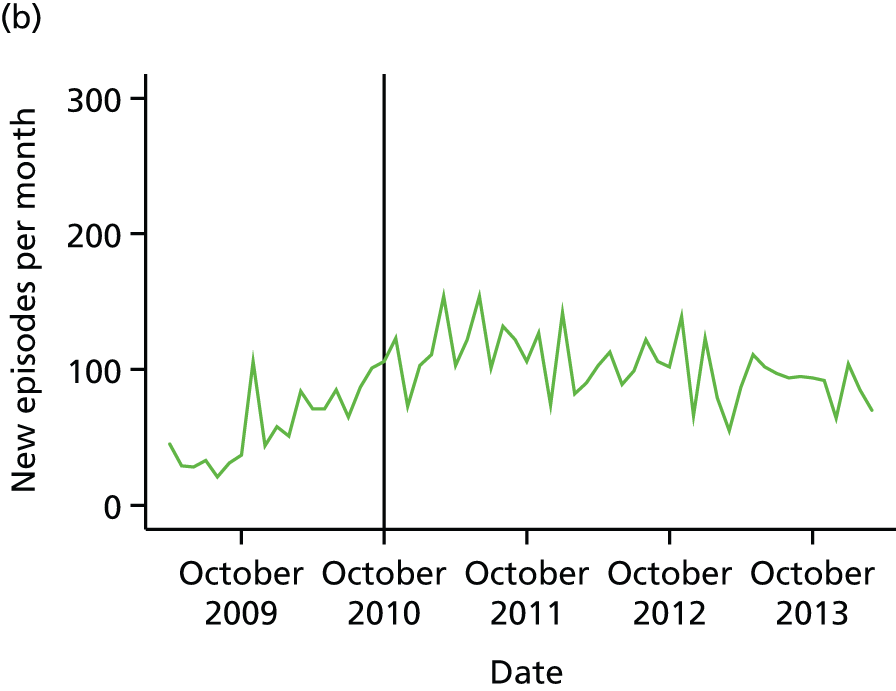

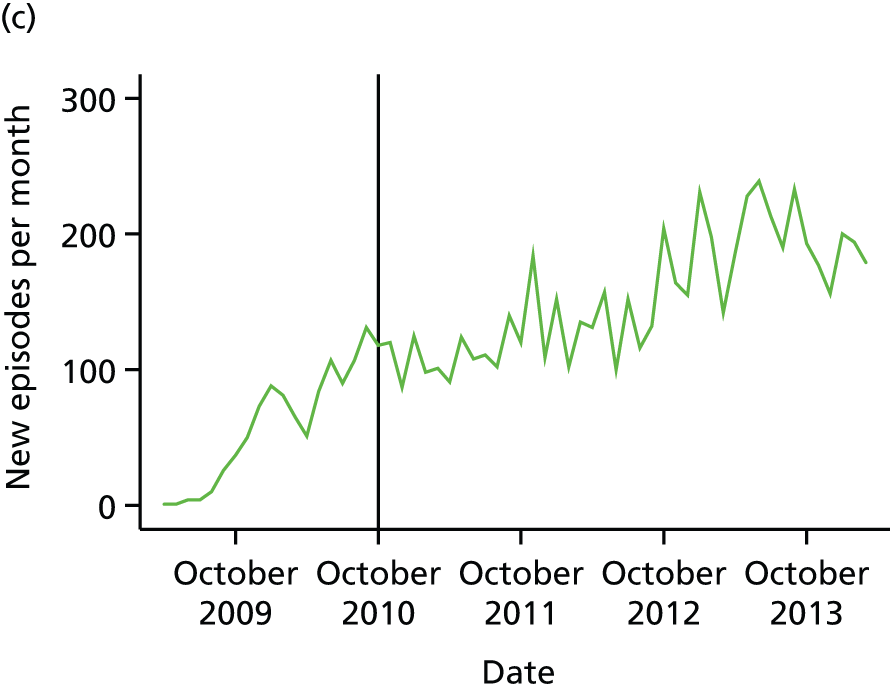

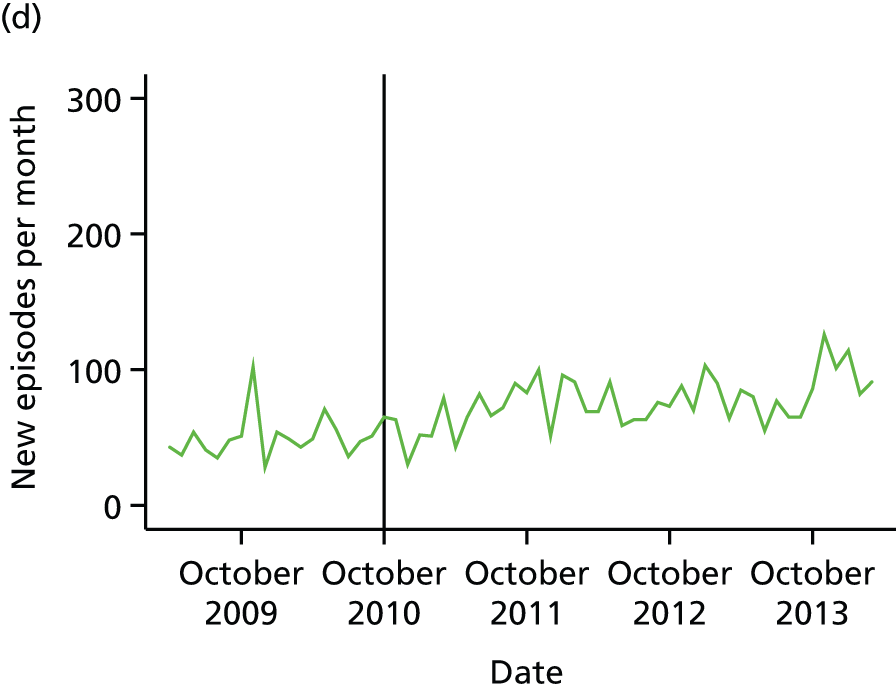

Turning to the main data set, we went on to investigate the number of episodes of CMHT care for those with non-psychotic disorders starting per month. Data were analysed from 1 April 2009 to 31 March 2014. For this analysis, and all other analyses based on this data set, we included only episodes during which there was at least one face-to-face contact. After graphing these monthly counts, we applied a t-test to examine whether or not the mean count of new episodes per month differed before and after CAG implementation.

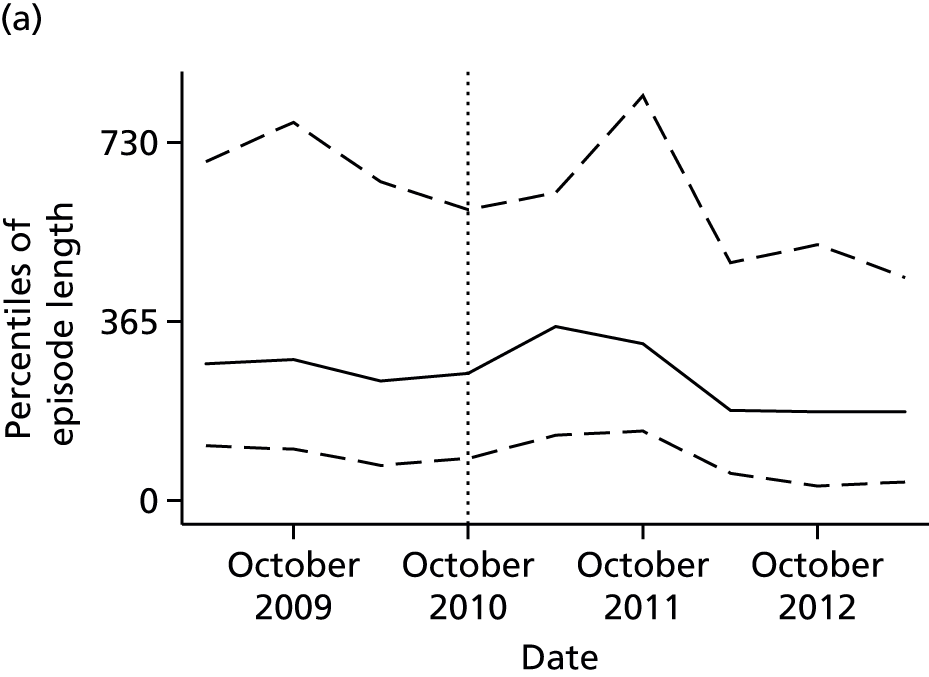

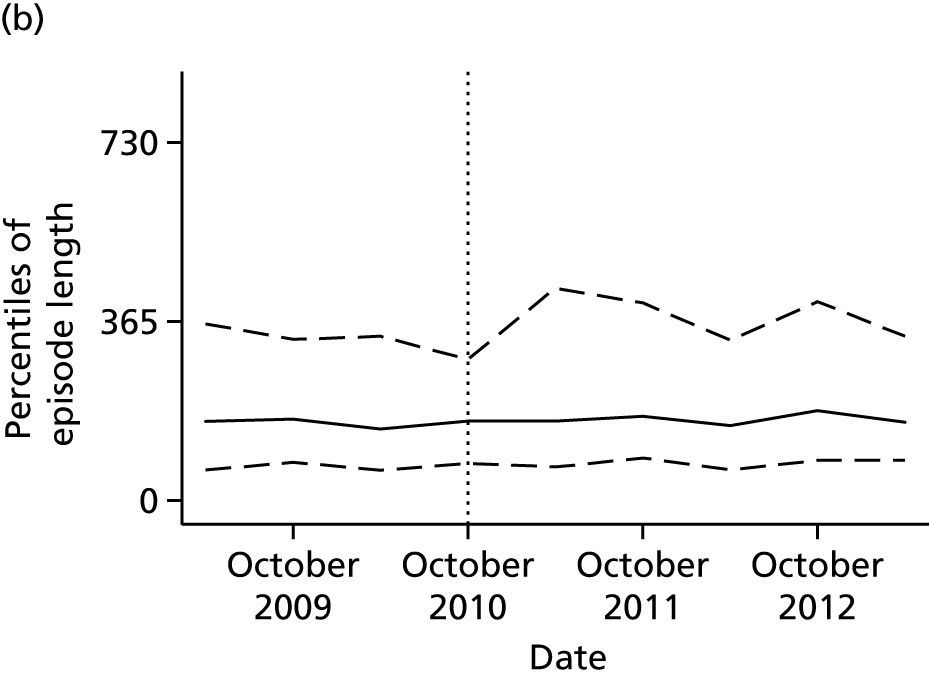

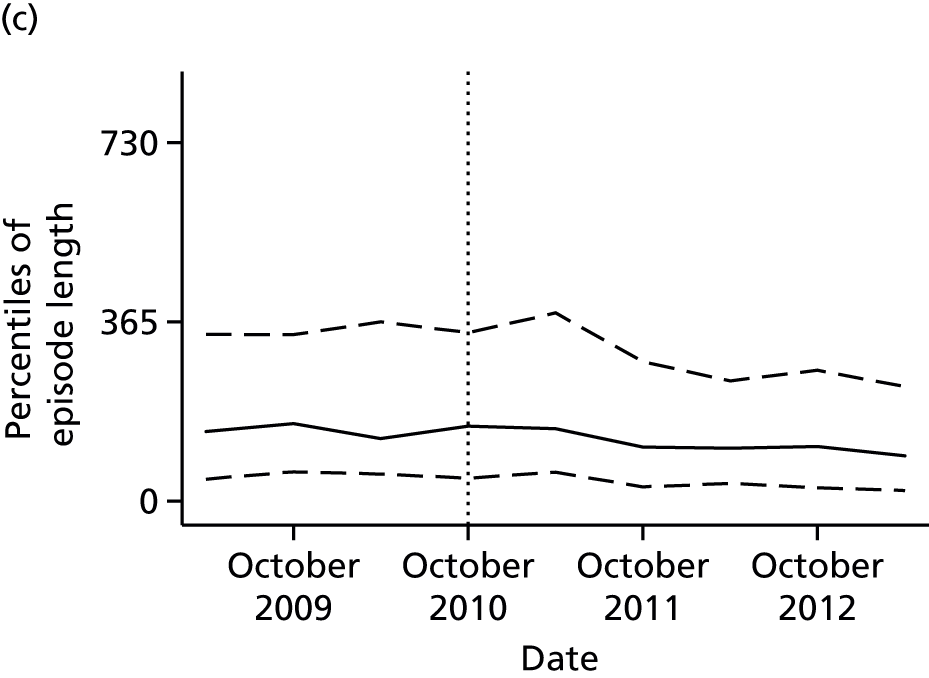

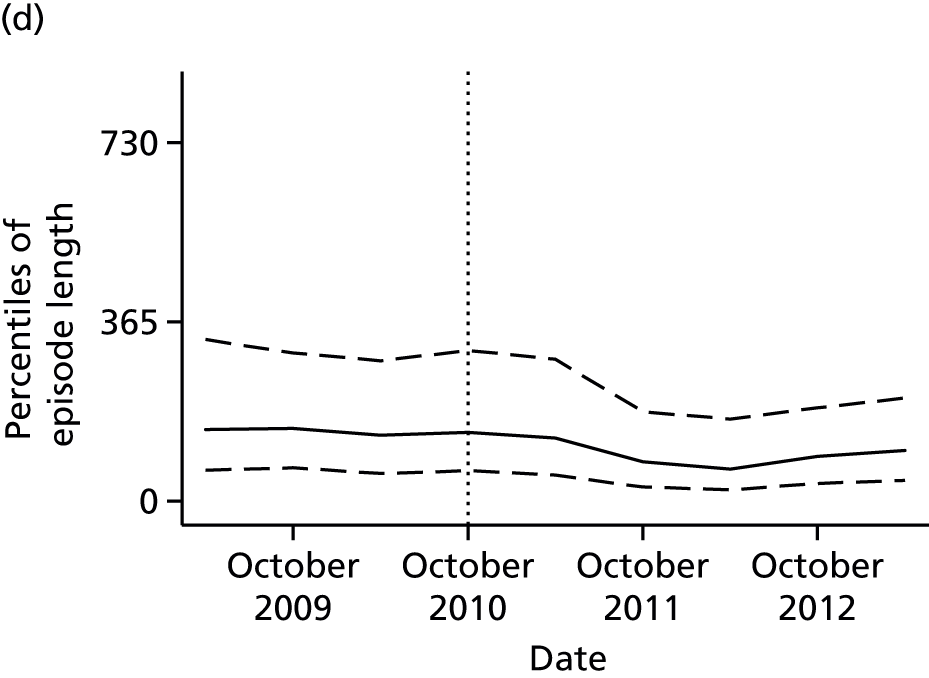

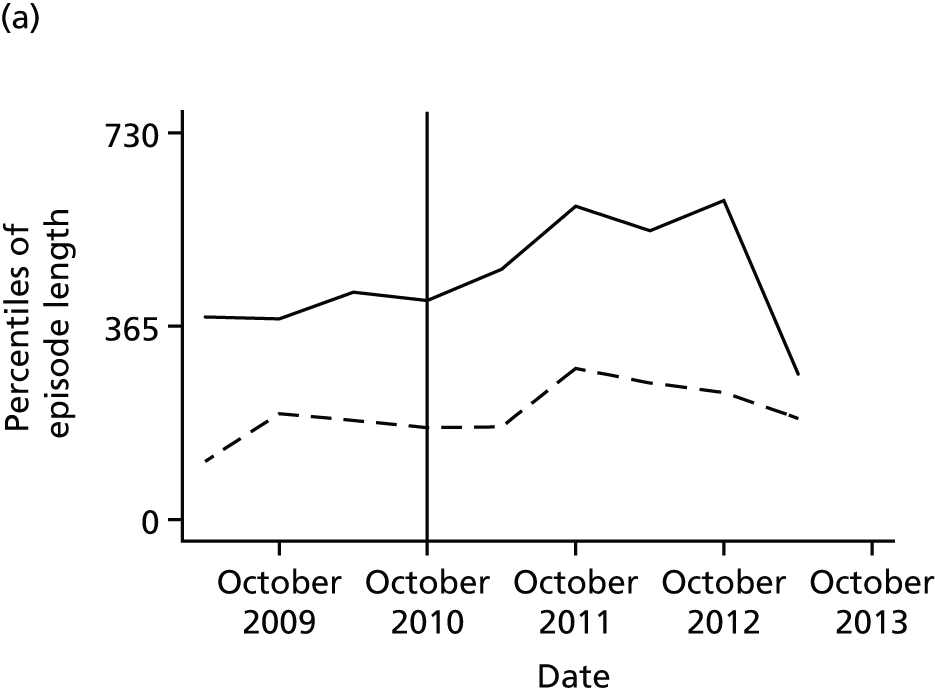

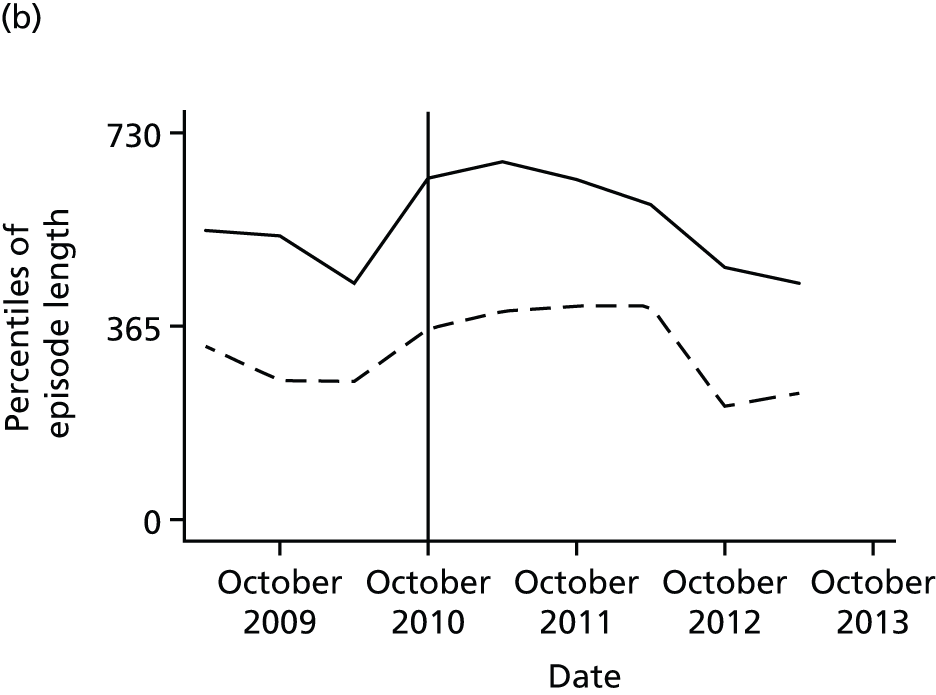

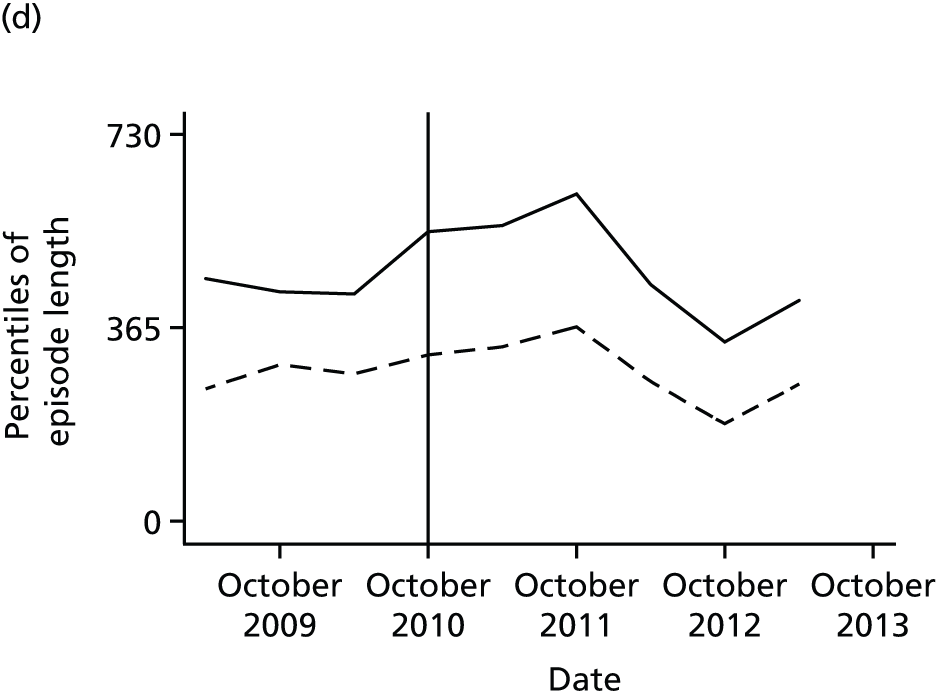

Next, we analysed the length of CMHT episodes, still working with the main data set. We analysed centile values rather than means as this allowed us to include unfinished as well as finished episodes without necessarily introducing bias; by having a follow-up period longer than the centile value of interest, any episode that is unfinished at the point of data extraction will necessarily fall within a higher centile. We analysed episodes starting between 1 April 2009 and 30 September 2013 and extracted data on 5 March 2015; this allowed us to be confident that any centile point below 521 days would be safely unaffected by censoring. After inspection of plots of key centile values over time, we used a non-parametric test for equality of medians to compare median values before and after CAG implementation.

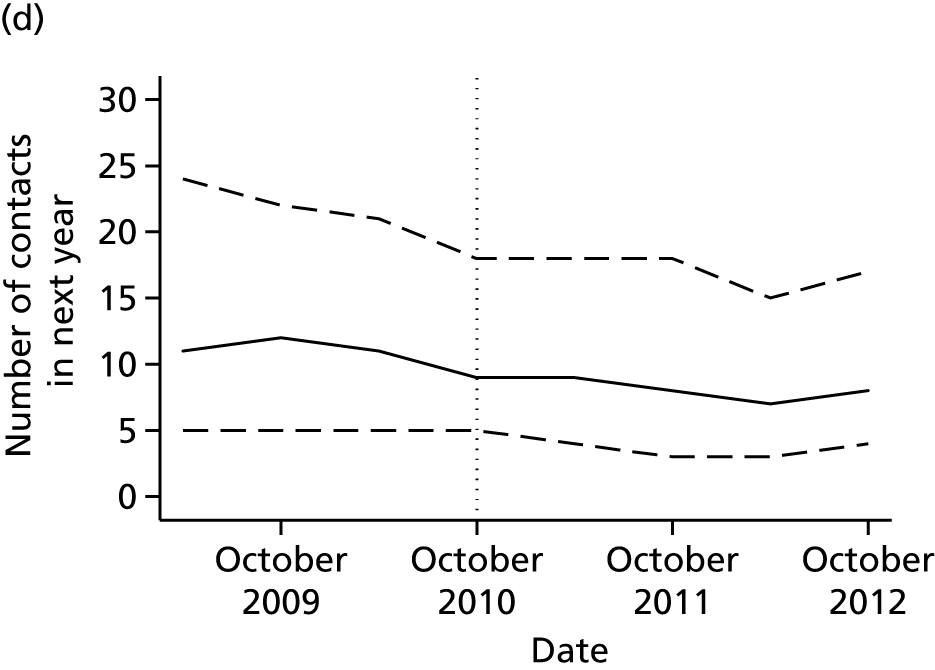

We went on to analyse the number of contacts per CMHT episode during the year subsequent to the start of the episode, again working with the main data set. The mean number of contacts per episode was calculated and plotted per 6-month time band. We also performed a linear regression to test the effect of calendar time on the number of contacts, including a random effect to allow for person-level clustering and testing whether or not any linear trend altered before and after CAG implementation. For this, and the analyses of costs (see below), we studied episodes starting between 1 April 2009 and 31 March 2013.

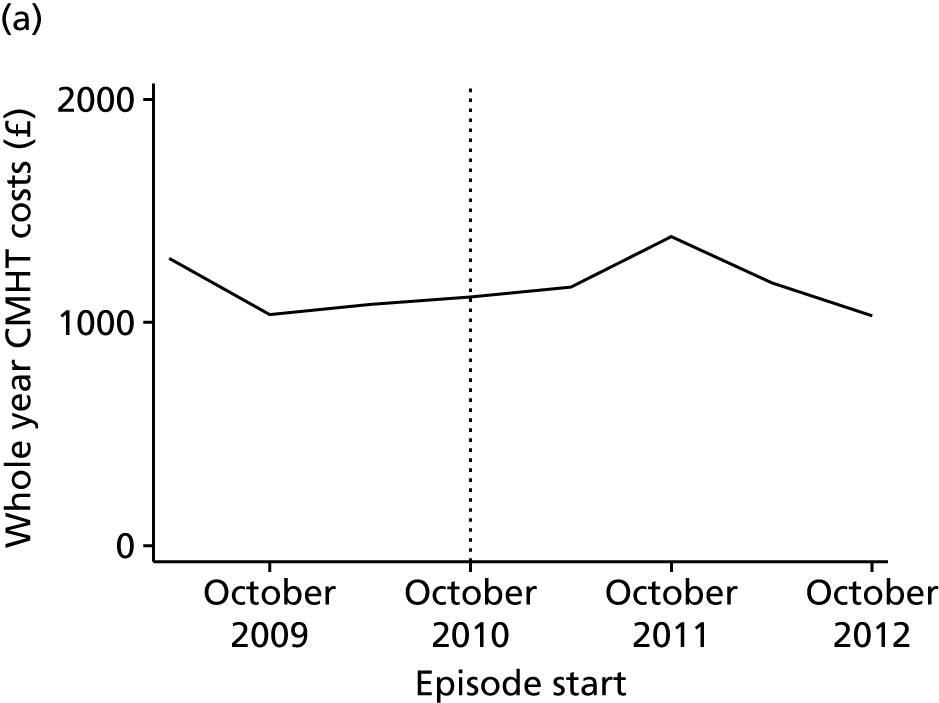

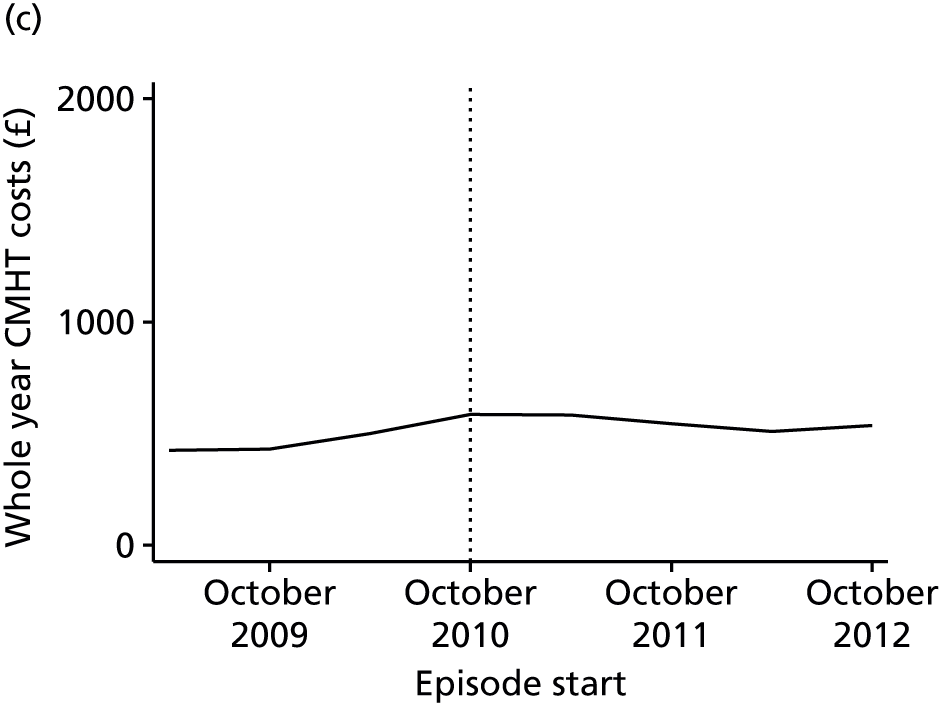

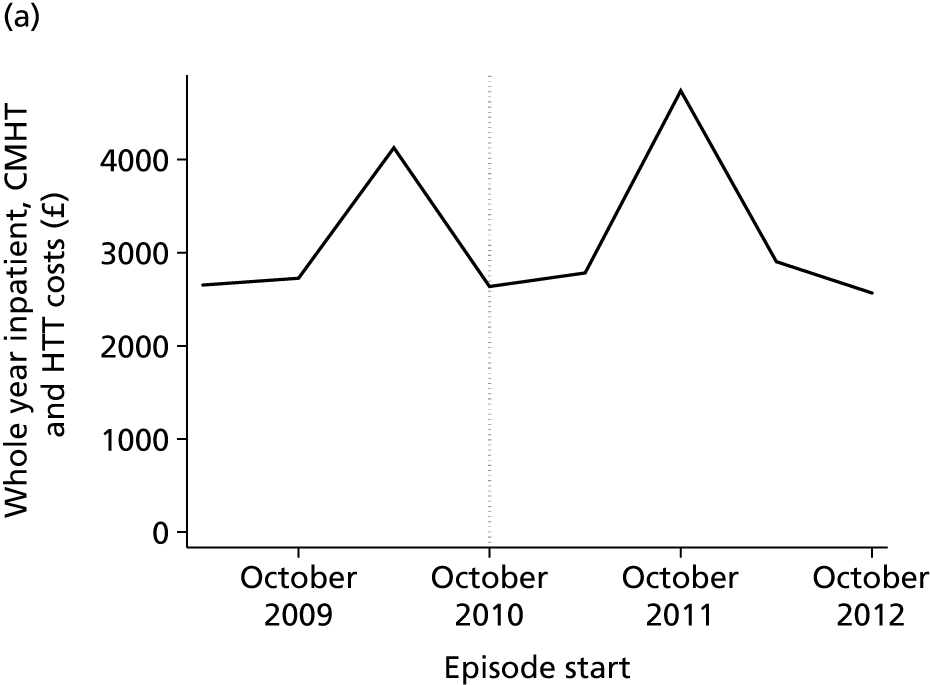

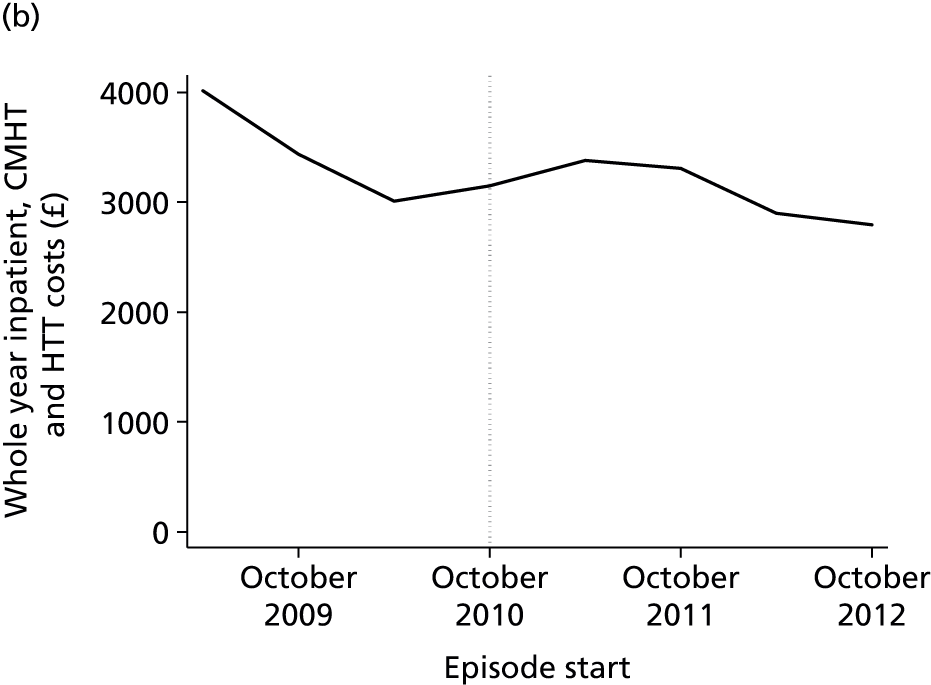

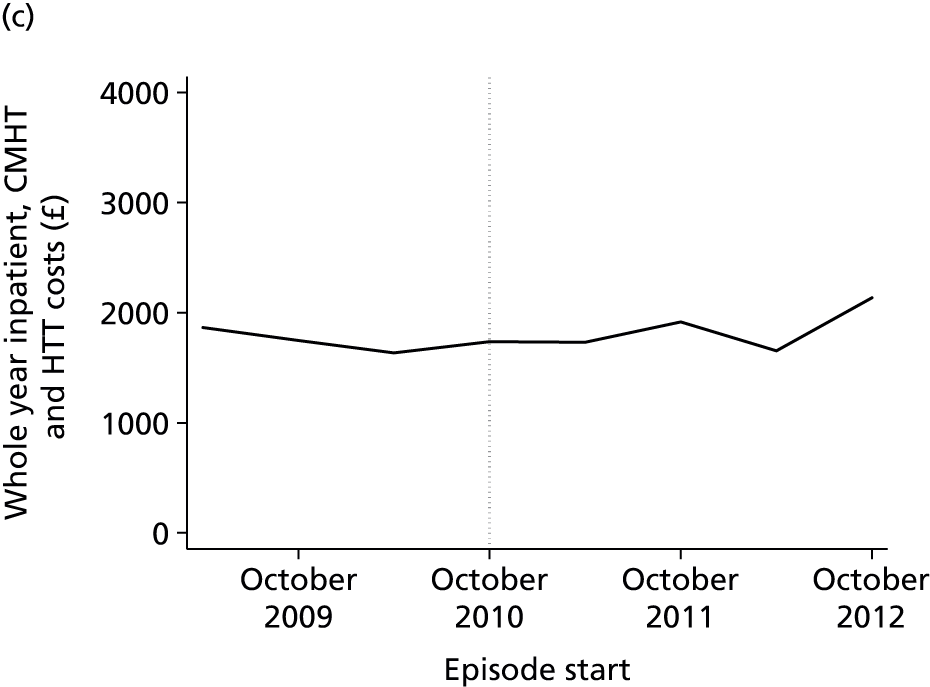

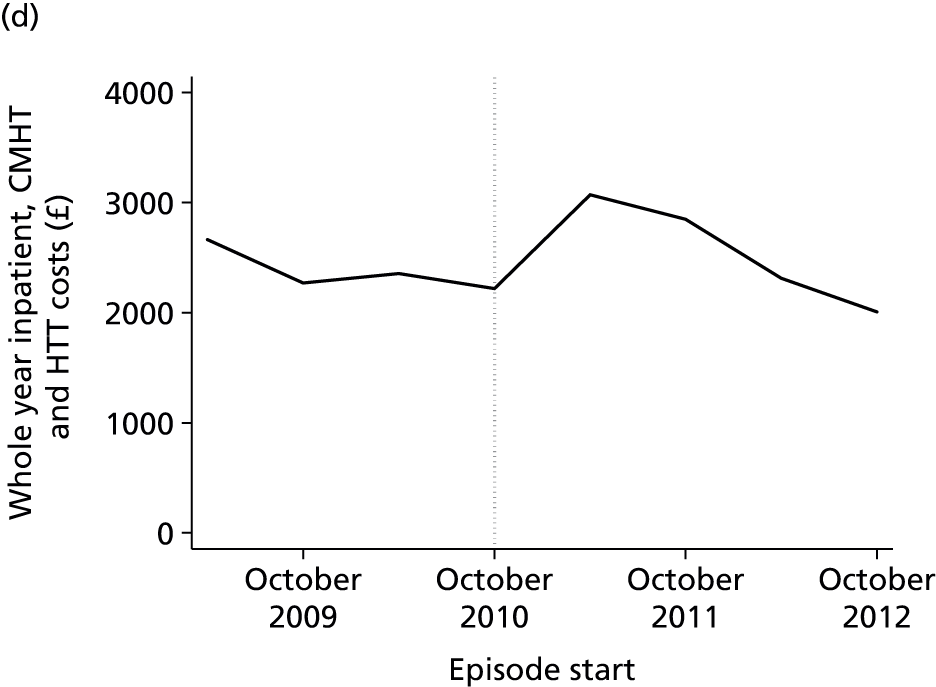

Building on the previous analysis, we analysed CMHT costs on their own and CMHT costs added to inpatient costs and home treatment team costs (a more comprehensive measure of the costs of adult mental health services). We began by graphing mean costs in the first 365 days following the beginning of the episode, aggregating these over 6-month time bands, and graphing each borough separately. Having inspected the curves, we regressed whole-year costs against the pre-/post-CAG indicator variable, including a random effect at person level. The first (unadjusted) analysis did not include other covariates. The second (adjusted) analysis included age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, diagnosis and the number of inpatient days in the preceding year, the regression model being as follows:

Analogous analyses were performed for psychotherapy episodes, although we were unable to investigate numbers of contacts and costs per year of treatment as the recording of activity in psychotherapy teams was very incomplete. This would have affected our results directly (through contacts themselves) and indirectly (through the calculation of unit costs). Analysis of psychotherapy episode length was restricted to the period from 1 April 2009 to 30 September 2012 to ensure that the median episode length was not subject to censoring.

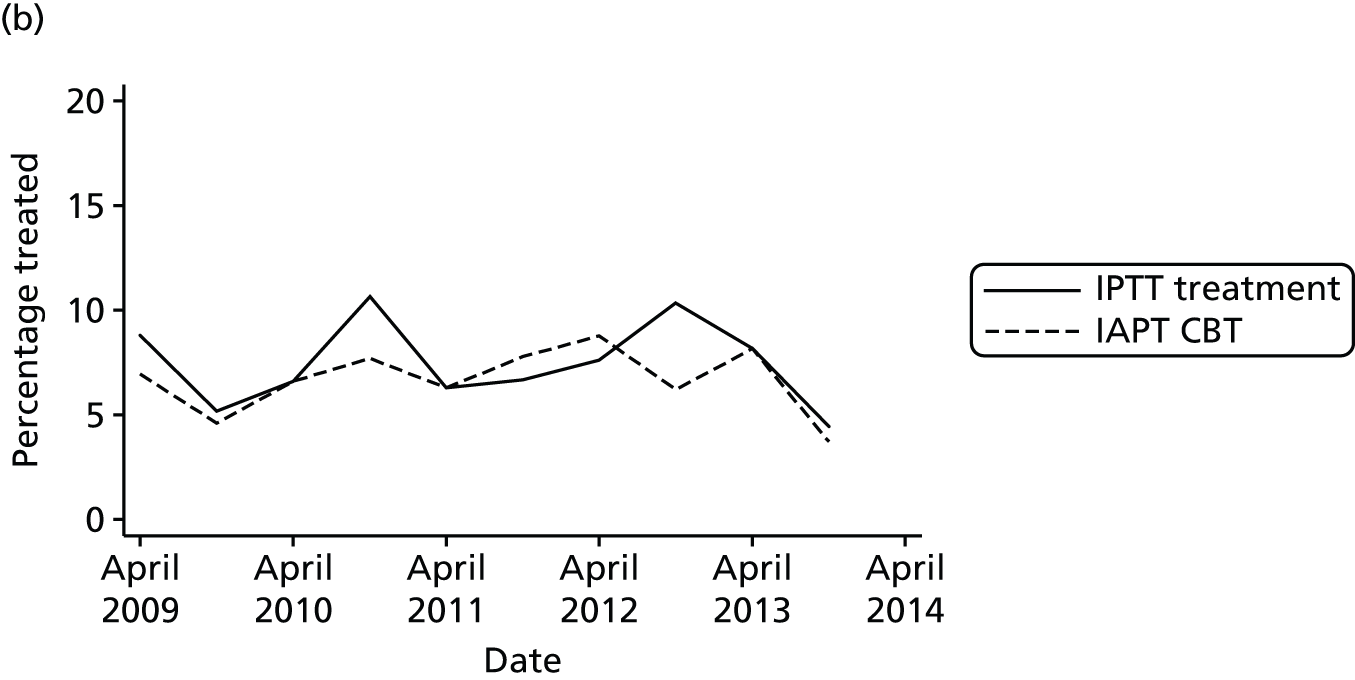

Finally, we used the IAPT data set to graph counts of new episodes of individual CBT within the four boroughs’ IAPT teams against time.

Effectiveness: process measures

Using the text data set we attempted to assess how far treatment for depression followed accepted treatment guidelines such as those produced by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). 18 Initial exploration of the free-text data indicated that it would be impossible to assess the duration of antidepressant treatment and therefore whether switching or augmentation of an antidepressant had happened at a particular point. We therefore adopted the less ambitious aim of documenting patterns of antidepressant use and change in prescribing at the first assessment, alongside documenting whether psychotherapeutic treatment was already in use at the time of the first assessment or if a referral for psychotherapeutic treatment was made at that point.

We calculated the proportions taking antidepressants at the initial consultation, started on antidepressants at that consultation or not taking antidepressants after that consultation and compared these proportions before and after CAG implementation. Among those already taking antidepressants, we compared the proportions given an additional treatment, the proportions with a dose increase and the proportions with a dose decrease. We also calculated the proportions already receiving psychotherapy at the first appointment, the proportions not receiving psychotherapy and not referred for it and the proportions not already receiving psychotherapy and referred for it. Looking at those not already referred, we examined whether or not the proportion referred for psychotherapy had changed since CAG implementation. The significance of any differences was tested using the chi-squared test.

The structured data on prescribing in the CRIS system are unreliable because the source electronic patient record does not support electronic prescribing. Therefore, we restricted our analysis of structured data to the receipt of psychotherapy.

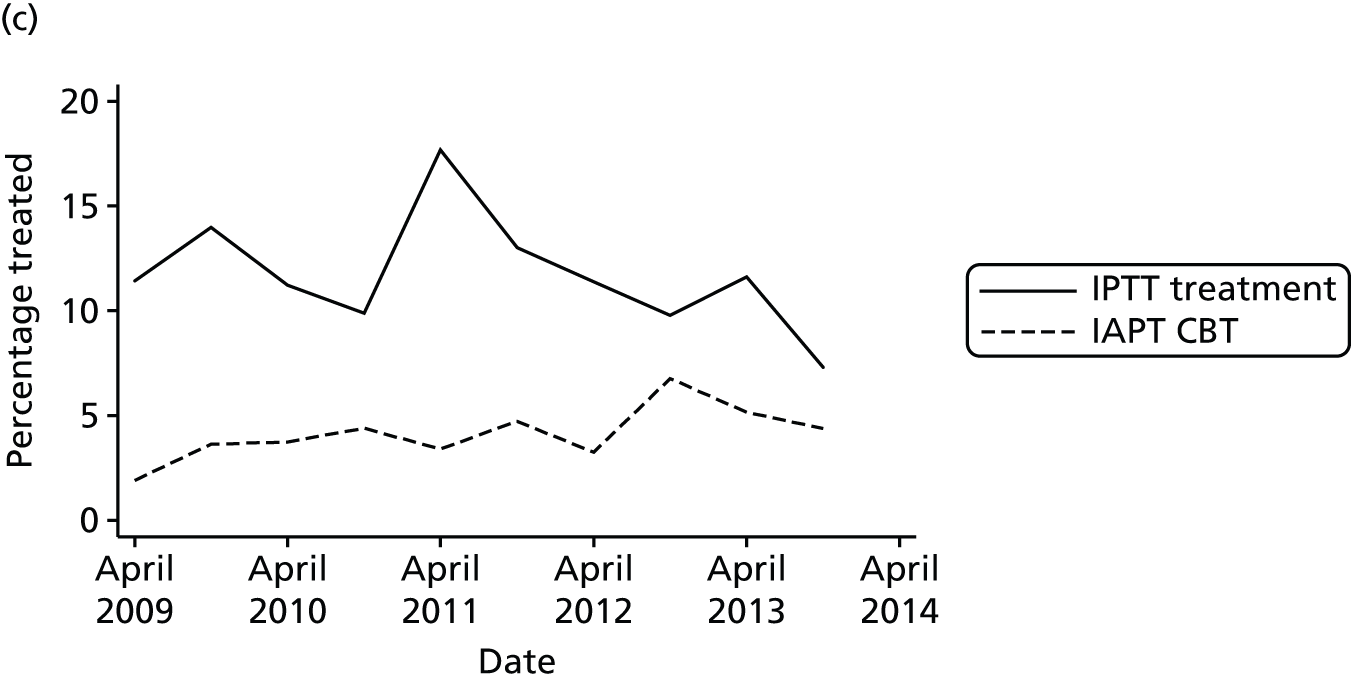

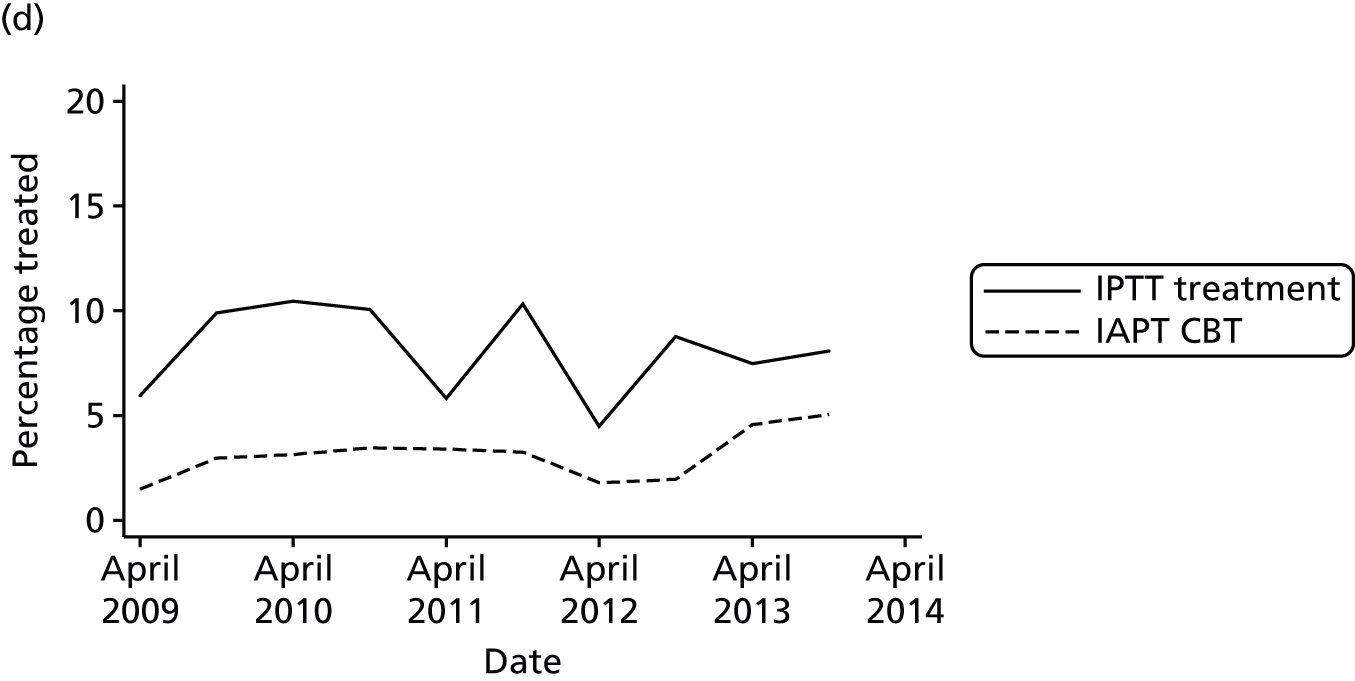

Using the main data set, and selecting individuals under the care of CMHTs and with a diagnosis of a depressive disorder (ICD-10 codes F32–39), we calculated the percentage of episodes for which an episode of psychotherapy in secondary care or individual CBT in IAPT started during that episode or within 3 months of its end. The percentage with such an episode was graphed per borough and per 6-month time band. Logistic regression, with a generalised estimating equation approach to within-subject clustering, but otherwise without any added covariates, was then used to assess the presence of any trend in psychotherapy use (lnγ = βtimeXtime + β0 + ε) and whether or not any such trend altered before and after CAG implementation (lnγ = βtimeXtime + βCAGXCAG + βCAG × timeXCAG × time + β0 + ε).

Effectiveness: outcome measures

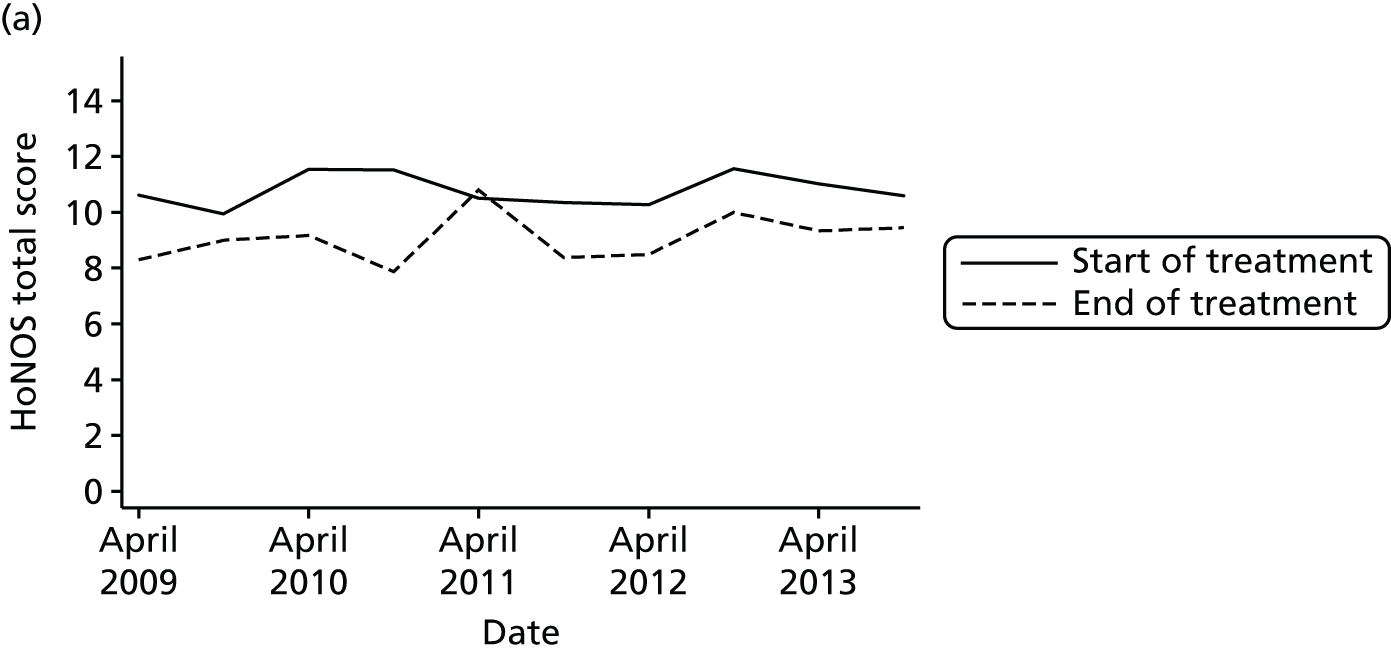

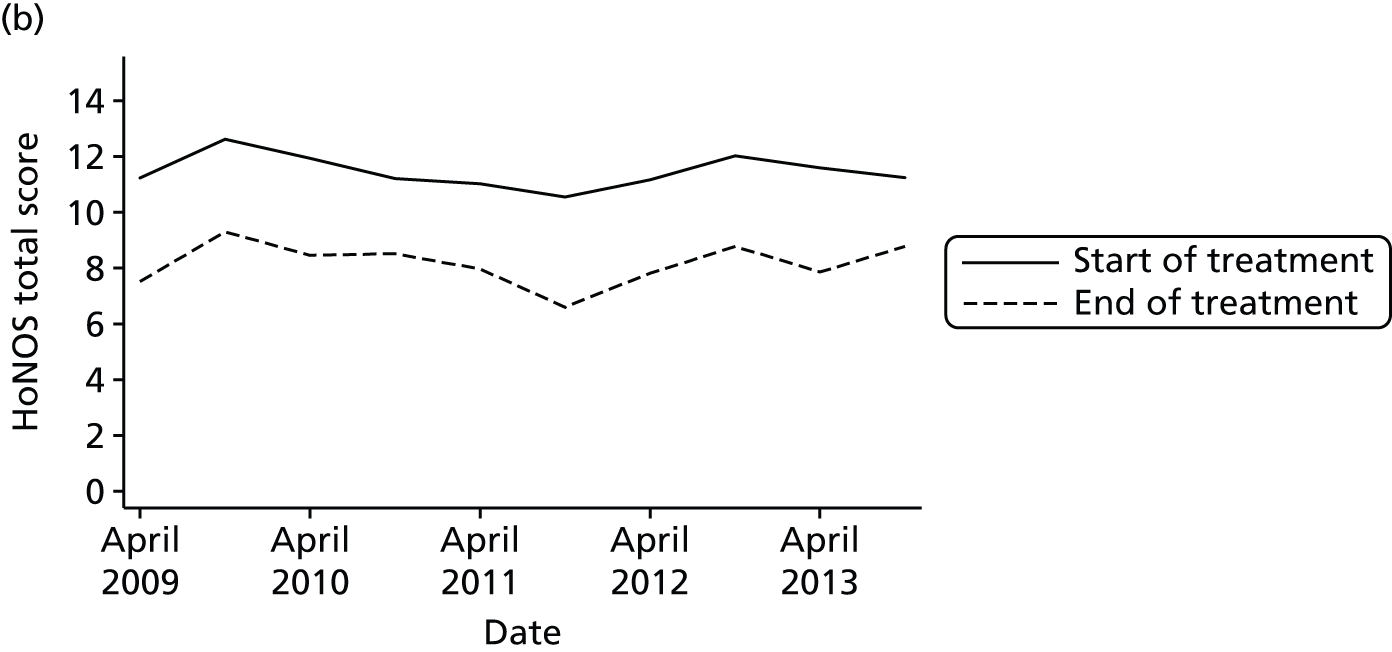

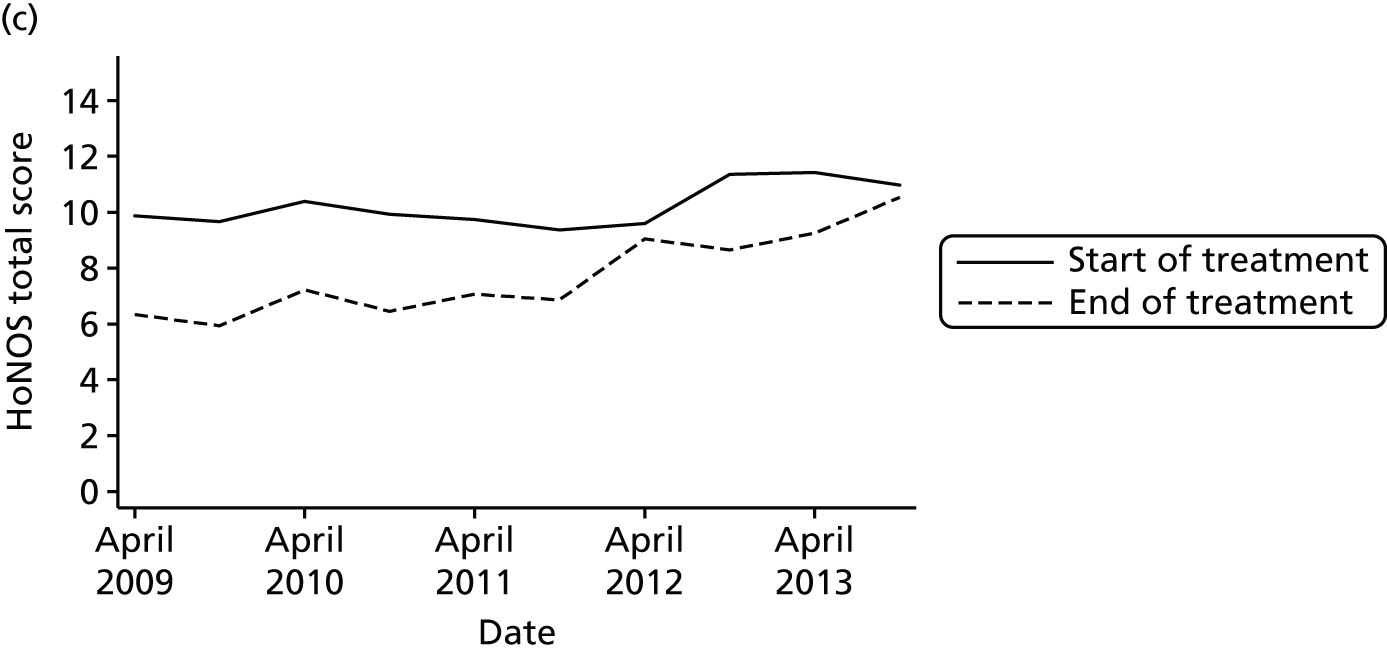

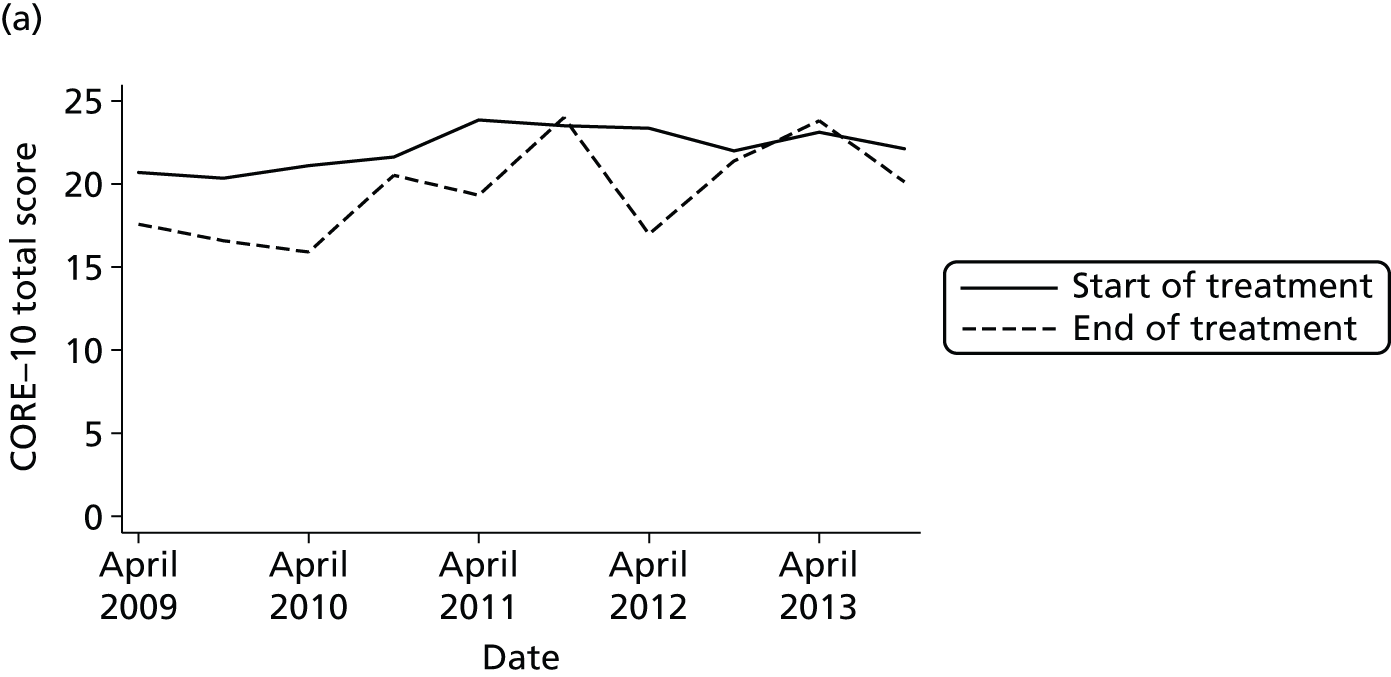

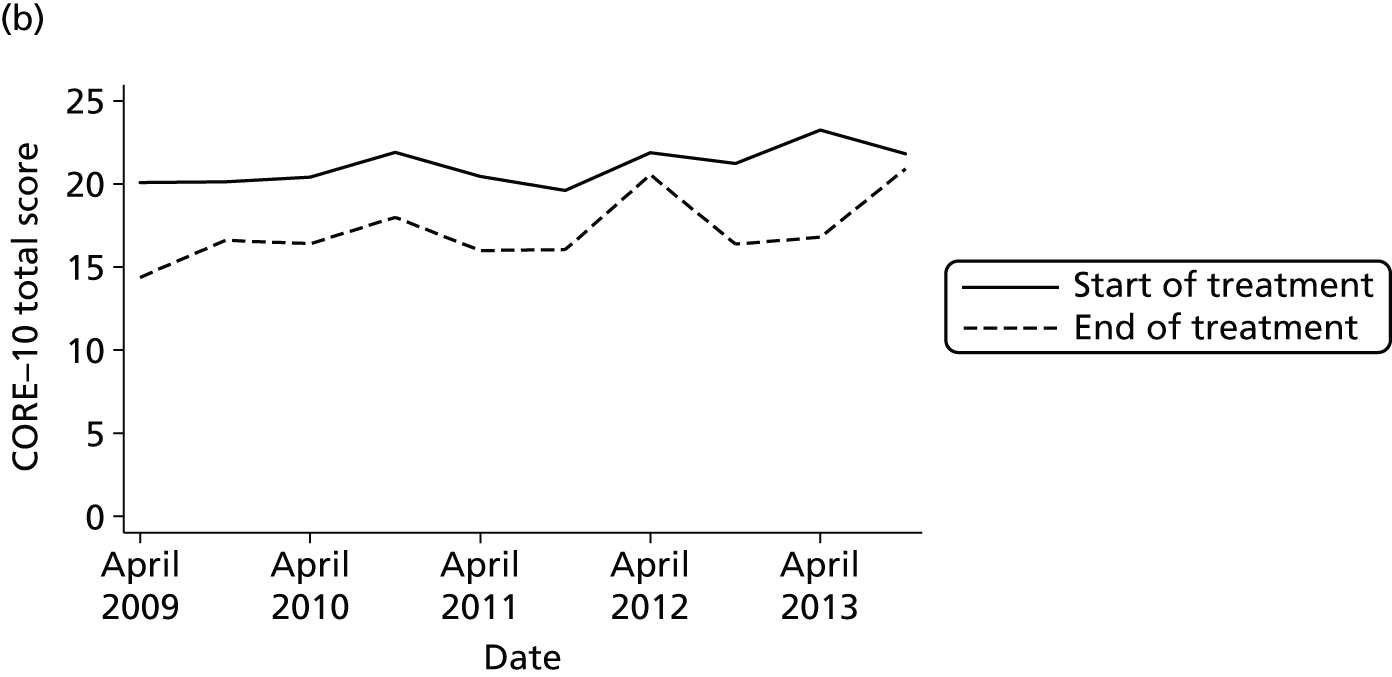

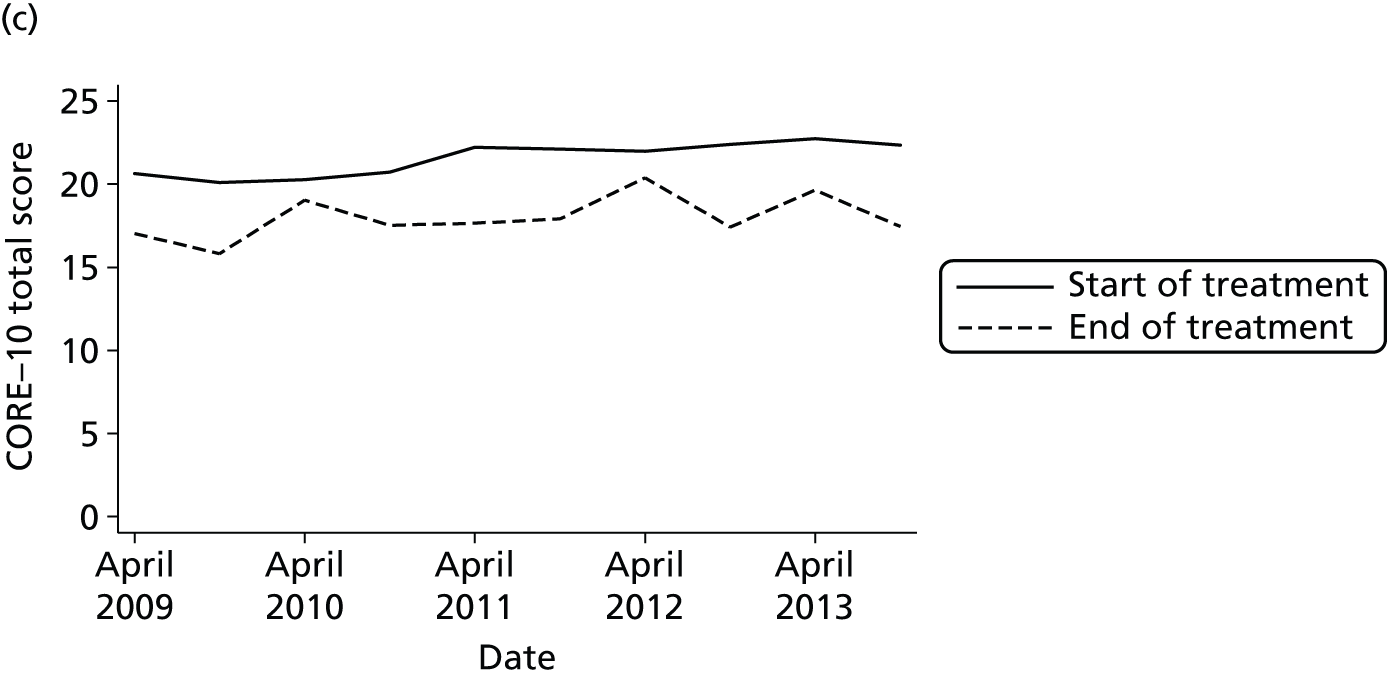

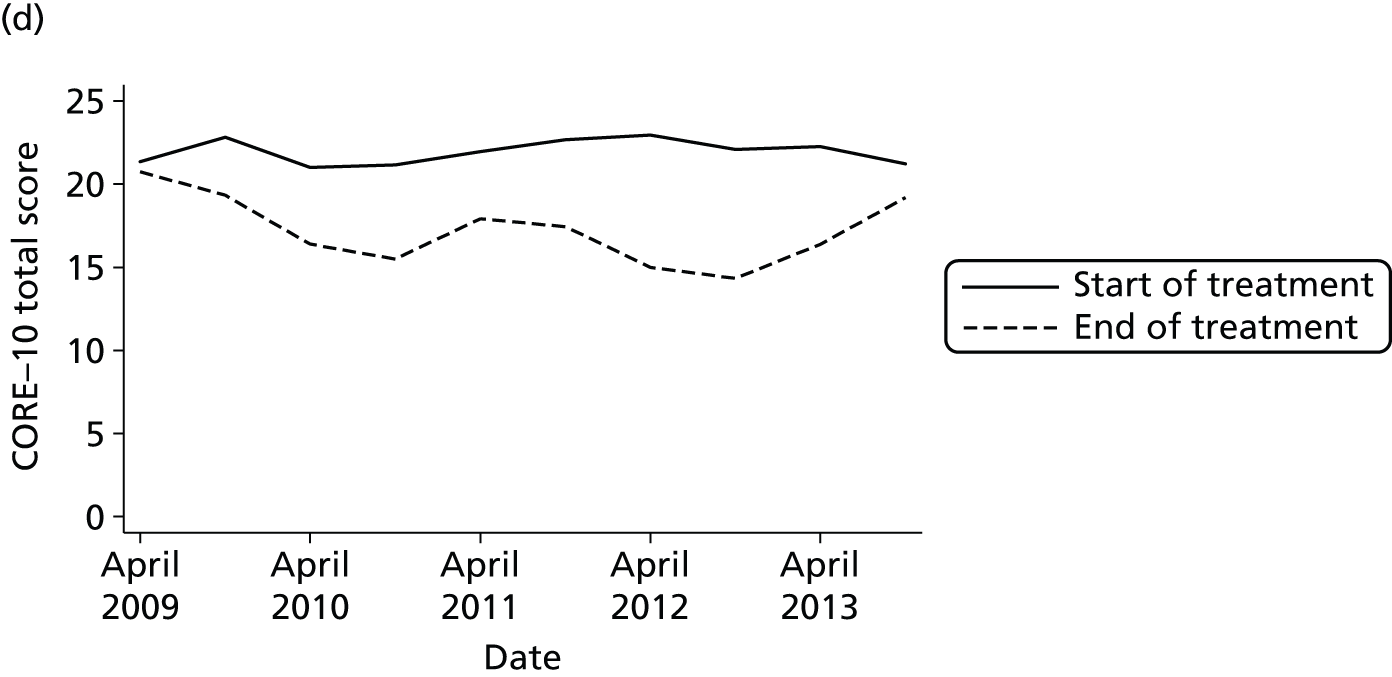

We used outcome measures collected as part of the trust’s routine outcome measurement programme to assess whether or not the change in outcome measures before and after treatment altered over the period straddling the introduction of the MAP CAG.

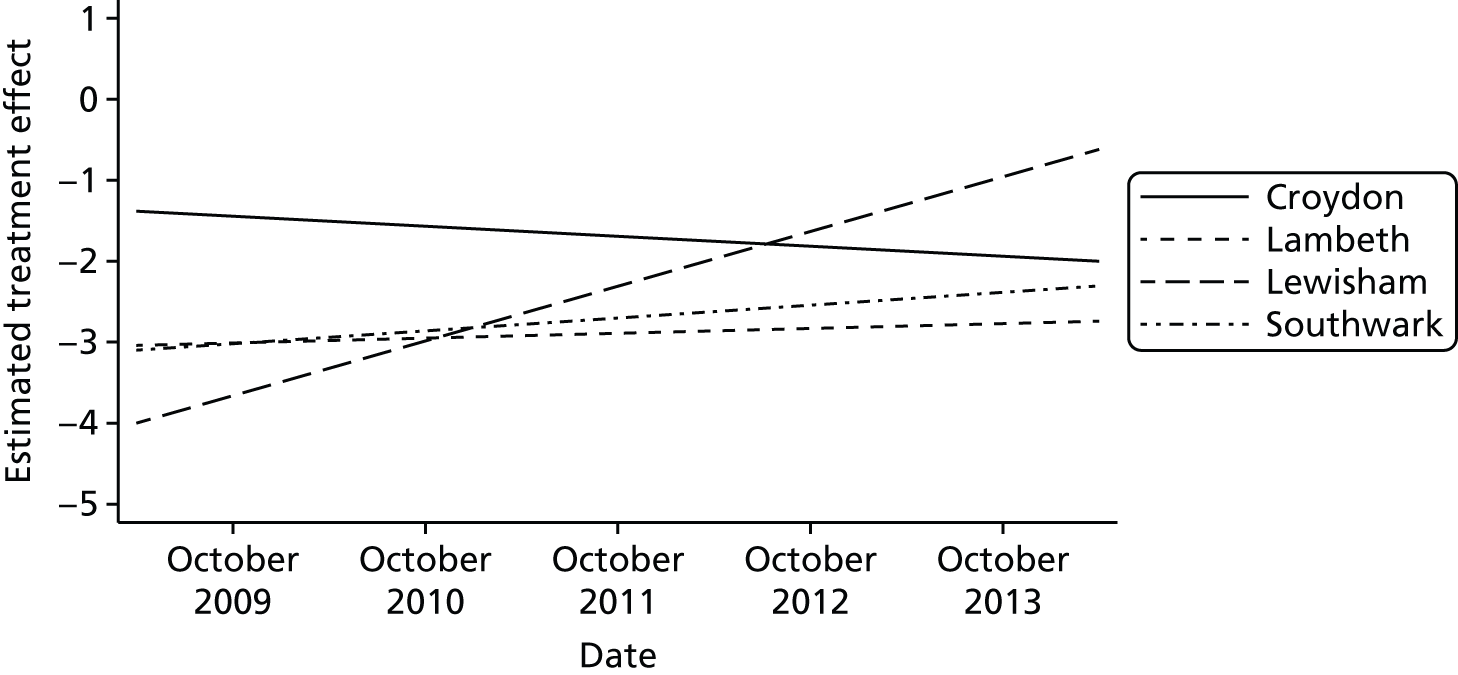

For CMHT episodes, we used the total score on the HoNOS, which was the most frequently used measure. We used the nearest score to the start of the episode and the nearest score to the end of the episode, excluding any score more than 2 months away from the reference point as well as any score later than the middle of the episode (for pre-treatment scores) or earlier than the middle of the episode (for post-treatment scores). Each treatment episode could contribute zero, one or two scores to the analysis. Before embarking on regression analysis, we graphed the mean of the pre-treatment scores and the mean of the post-treatment scores, aggregating data over 6-month time bands and per borough. Next, we constructed a series of mixed-effects analyses, including random effects at person and episode level. The dependent variable for the regression was the total HoNOS score and so the treatment effect was estimated by means of an indicator variable. (This method is superior to the direct regression of the difference between pre- and post-treatment scores as it allows individuals with only one measure to contribute to the analysis.) The steps followed were these:

-

We modelled the size of the treatment effect without entering any covariates in the analysis but including random effects:(Model 1)γ=βtreatment effectXtreatment effect+β0+υpersonZperson+υepisodeZepisode+ε.

-

We added a series of covariates (diagnosis, age, sex, ethnicity, marital status, borough within which service was received, calendar time relative to the date of CAG implementation and a post-CAG indicator variable):(Model 2)γ=βtreatment effectXtreatment effect+βdiagnosis1Xdiagnosis1+βdiagnosis2Xdiagnosis2+ βageXage+βsexXsex+βethnicity1Xethnicity1+βethnicity2Xethnicity2+βmarital1Xmarital1+ βmarital2Xmarital2+βborough1Xborough1+βborough2Xborough2+βborough3Xborough3+ βtimeXtime+βMAPXMAP+β0+υpersonZperson+υepisodeZepisode+ε.

-

We constructed a model in which two-way interaction terms between the treatment effect indicator and important covariates were simultaneously added – this tests for stratum-specific treatment effects by borough and diagnosis and also whether or not the basic treatment effect varies with time:(Model 3a)γ=βtreatment effectXtreatment effect+βdiagnosis1Xdiagnosis1+βdiagnosis2Xdiagnosis2+ βageXage+βsexXsex+βethnicity1Xethnicity1+βethnicity2Xethnicity2+βmarital1Xmarital1+ βmarital2Xmarital2+βborough1Xborough1+βborough2Xborough2+βborough3Xborough3+ βtimeXtime+βMAPXMAP+βtreatment_effect × diagnosis1Xtreatment_effect × diagnosis1+ βtreatment_effect × diagnosis2Xtreatment_effect × diagnosis2+βtreatment_effect × borough1Xtreatment_effect × borough1+ βtreatment_effect × borough2Xtreatment_effect × borough2+βtreatment_effect × borough3Xtreatment_effect × borough3+ βtreatment_effect × timeXtreatment_effect × time+β0+υpersonZperson+υepisodeZepisode+ε.

As appropriate, insignificant interactions were removed, yielding model 3b.

-

Assuming that the related two-way interactions were significant, we tested for three-way interactions between (i) treatment effect, diagnosis and time and (ii) treatment effect, borough and time. The aim of this analysis was to examine whether or not the stratum-specific treatment effects of primary interest varied over time. Insignificant effects were removed from a subsequent model (model 4b):(Model 4a)γ=βtreatment effectXtreatment effect+βdiagnosis1Xdiagnosis1+βdiagnosis2Xdiagnosis2+ βageXage+βsexXsex+βethnicity1Xethnicity1+βethnicity2Xethnicity2+ βmarital1Xmarital1+βmarital2Xmarital2+βborough1Xborough1+ βborough2Xborough2+βborough3Xborough3+βtimeXtime+ βMAPXMAP+βtreatment_effect × diagnosis1Xtreatment_effect × diagnosis1+ βtreatment_effect × diagnosis2Xtreatment_effect × diagnosis2+βtreatment_effect × borough1Xtreatment_effect × borough1+ βtreatment_effect × borough2Xtreatment_effect × borough2+βtreatment_effect × borough3Xtreatment_effect × borough3+ βtreatment_effect × timeXtreatment_effect × time+βtreatment_effect × diagnosis1 × timeXtreatment_effect × diagnosis1 × time+ βtreatment_effect × diagnosis2 × timeXtreatment_effect × diagnosis2 × time+βtreatment_effect × borough1 × timeXtreatment_effect × borough1 × time+ βtreatment_effect × borough2 × timeXtreatment_effect × borough2 × time+βtreatment_effect × borough3 × timeXtreatment_effect × borough3 × time+ β0+υpersonZperson+υepisodeZepisode+ε.

-

We looked for evidence that the overall effect of treatment over time altered after CAG implementation. This required the addition of an interaction between the treatment effect and the post-CAG indicator variable, together with a three-way interaction between the treatment effect, the post-CAG indicator and calendar time:(Model 5)γ=βtreatment effectXtreatment effect+βdiagnosis1Xdiagnosis1+βdiagnosis2Xdiagnosis2+ βageXage+βsexXsex+βethnicity1Xethnicity1+βethnicity2Xethnicity2+ βmarital1Xmarital1+βmarital2Xmarital2+βborough1Xborough1+ βborough2Xborough2+βborough3Xborough3+βtimeXtime+ βMAPXMAP+βtreatment_effect × diagnosis1Xtreatment_effect × diagnosis1+ βtreatment_effect × diagnosis2Xtreatment_effect × diagnosis2+βtreatment_effect × borough1Xtreatment_effect × borough1+ βtreatment_effect × borough2Xtreatment_effect × borough2+βtreatment_effect × borough3Xtreatment_effect × borough3+ βtreatment_effect × timeXtreatment_effect × time+βtreatment_effect × borough1 × timeXtreatment_effect × borough1 × time+ βtreatment_effect × borough2 × timeXtreatment_effect × borough2 × time+βtreatment_effect × borough3 × timeXtreatment_effect × borough3 × time+ βtreatment_effect × MAPXtreatment_effect × MAP+βtreatment_effect × timeXMAPXtreatment_effect × timeXMAP+ β0+υpersonZperson+υepisodeZepisode+ε.

-

Assuming that the added effects in model 5 were significant, we tested whether or not the time trend in the borough- or diagnosis-specific treatment effect varied before and after CAG implementation. This required the fitting and testing of a four-way interaction term between treatment effect, time, borough or diagnosis and the post-CAG indicator:(Model 6)γ=βtreatment effectXtreatment effect+βdiagnosis1Xdiagnosis1+βdiagnosis2Xdiagnosis2+ βageXage+βsexXsex+βethnicity1Xethnicity1+βethnicity2Xethnicity2+ βmarital1Xmarital1+βmarital2Xmarital2+βborough1Xborough1+ βborough2Xborough2+βborough3Xborough3+βtimeXtime+ βMAPXMAP+βtreatment_effect × diagnosis1Xtreatment_effect × diagnosis1+ βtreatment_effect × diagnosis2Xtreatment_effect × diagnosis2+βtreatment_effect × borough1Xtreatment_effect × borough1+ βtreatment_effect × borough2Xtreatment_effect × borough2+βtreatment_effect × borough3Xtreatment_effect × borough3+ βtreatment_effect × timeXtreatment_effect × time+βtreatment_effect × MAPXtreatment_effect × MAP+ βtreatment_effect × borough1 × timeXtreatment_effect × borough1 × time+βtreatment_effect × borough2 × timeXtreatment_effect × borough2 × time+ βtreatment_effect × borough3 × timeXtreatment_effect × borough3 × time+ βtreatment_effect × borough0 × time × MAPXtreatment_effect × borough0 × time × MAP+ βtreatment_effect × borough1 × time × MAPXtreatment_effect × borough1 × time × MAP+ βtreatment_effect × borough2 × time × MAPXtreatment_effect × borough2 × time × MAP+ βtreatment_effect × borough3 × time × MAPXtreatment_effect × borough3 × time × MAP+β0+υpersonZperson+υepisodeZepisode+ε.

For psychotherapy episodes, we followed an identical procedure, except that we used total scores on the CORE-10, which was the more frequently used outcome measure within the psychotherapy services.

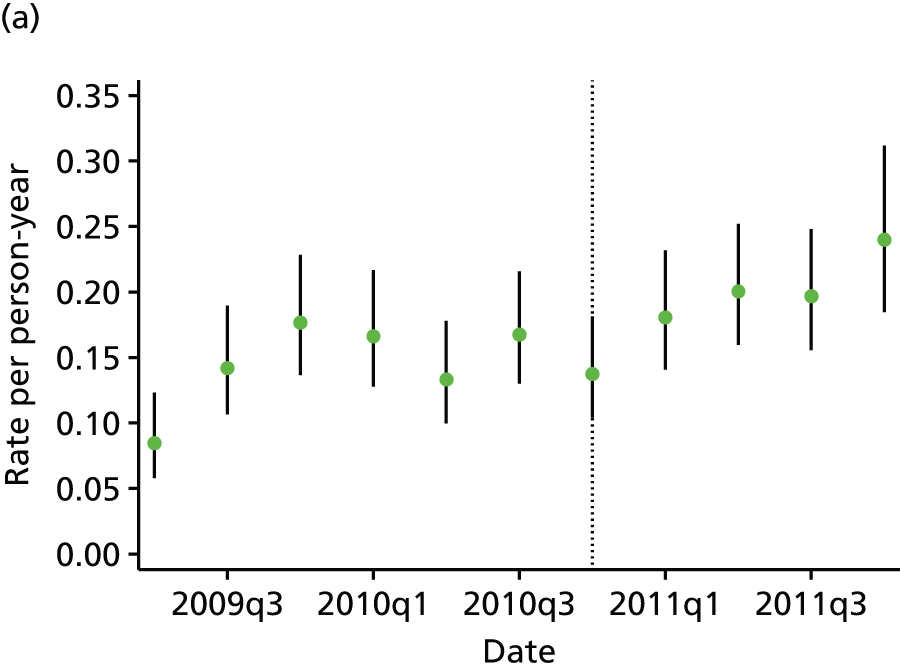

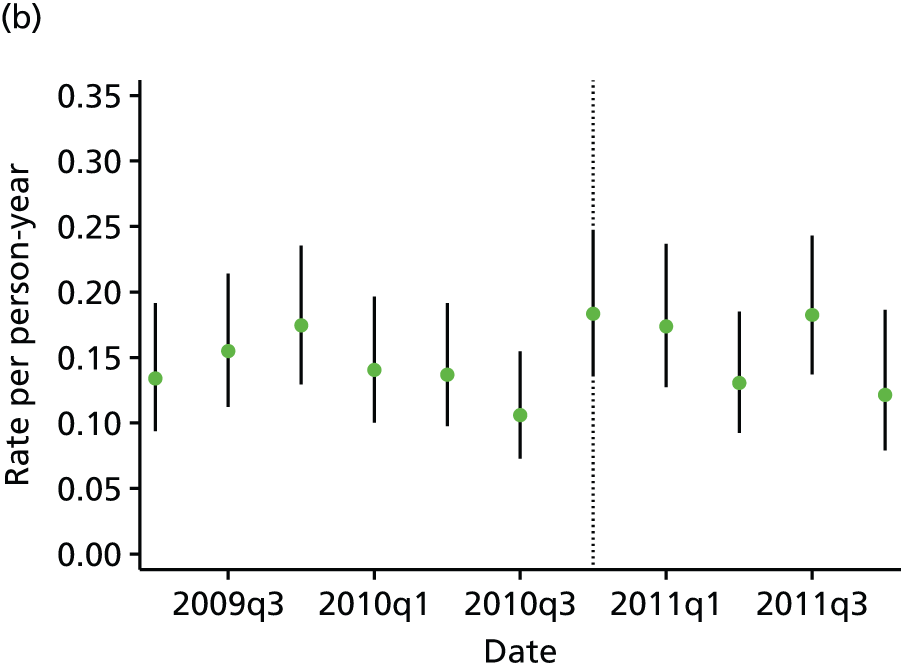

Safety

We investigated safety only for CMHT patients as these made up the largest group.

As described earlier, we worked first with the A&E data set, which consisted of a set of CMHT episodes, divided into quarterly time bands and joined to a set of psychiatric liaison consultations for self-harm. This was treated as a multiple failure time data set, that is, once a person presented to A&E with self-harm, he or she was treated afterwards as having entered the ‘at-risk’ pool.

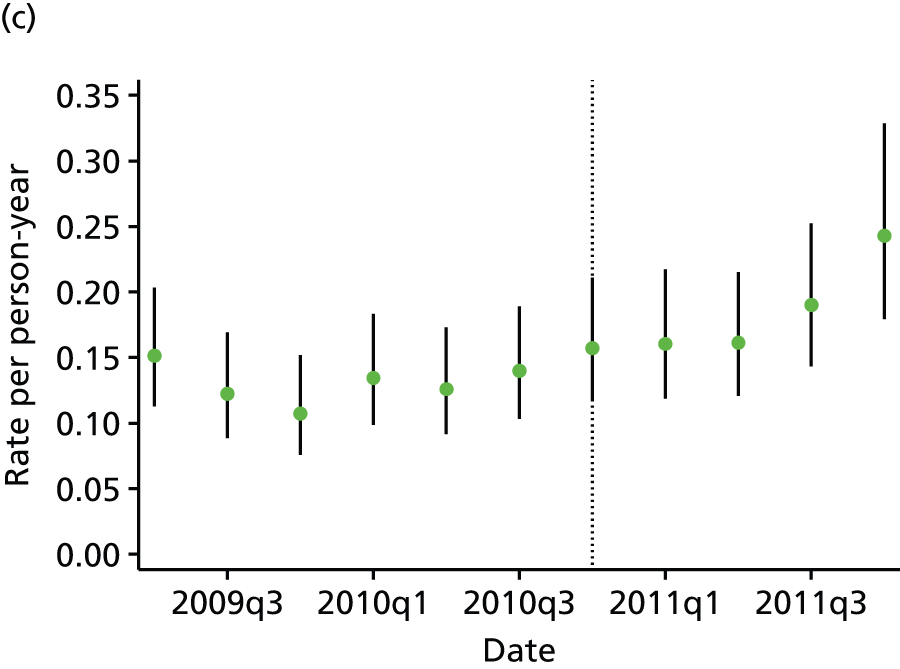

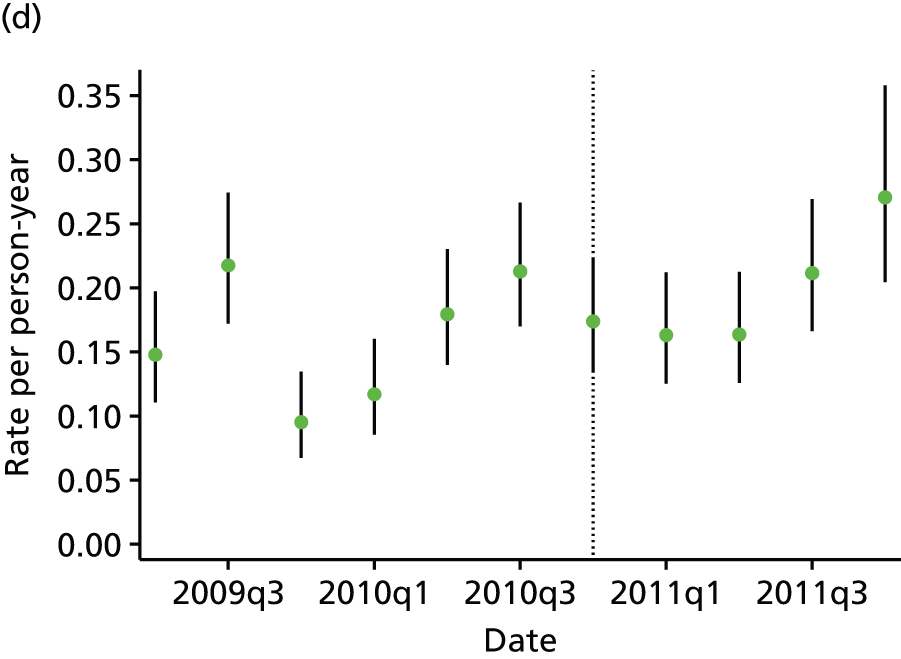

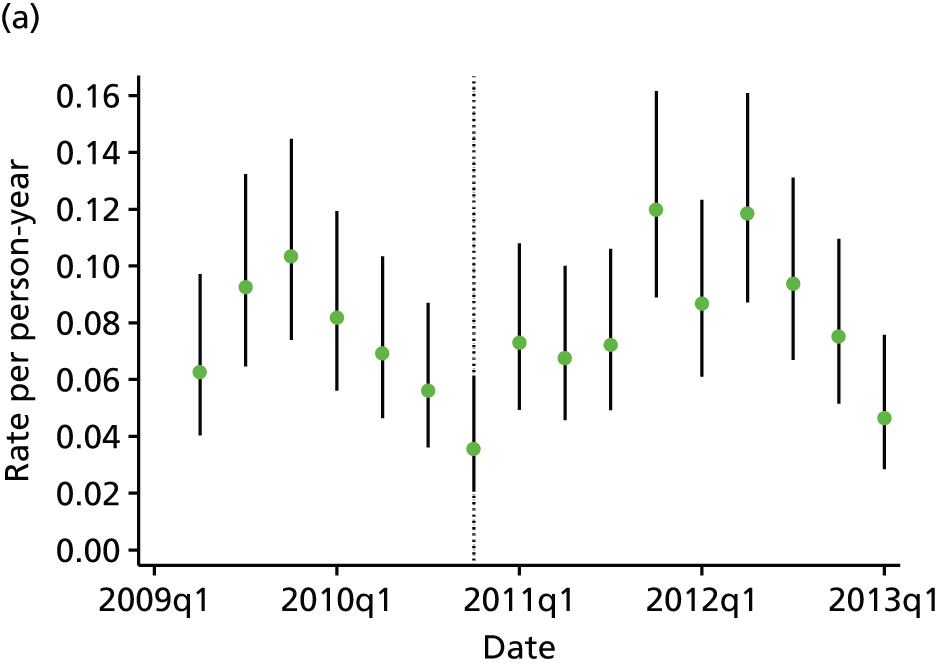

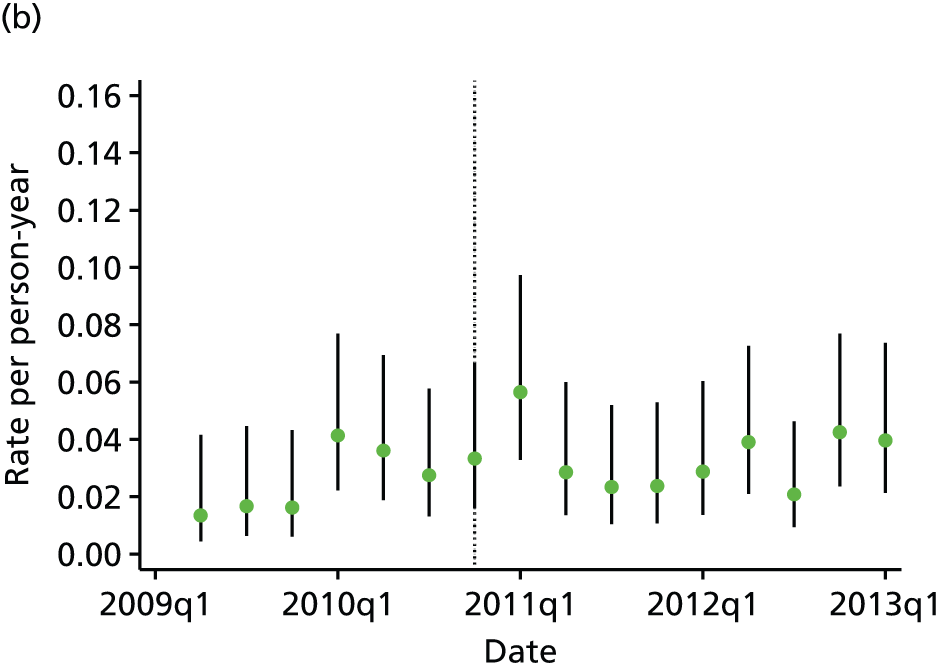

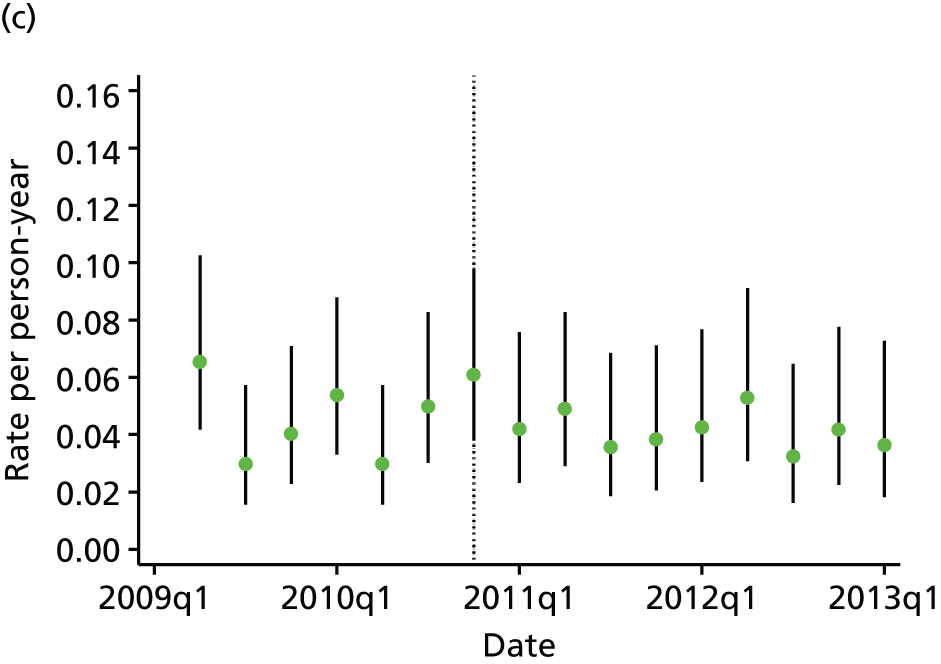

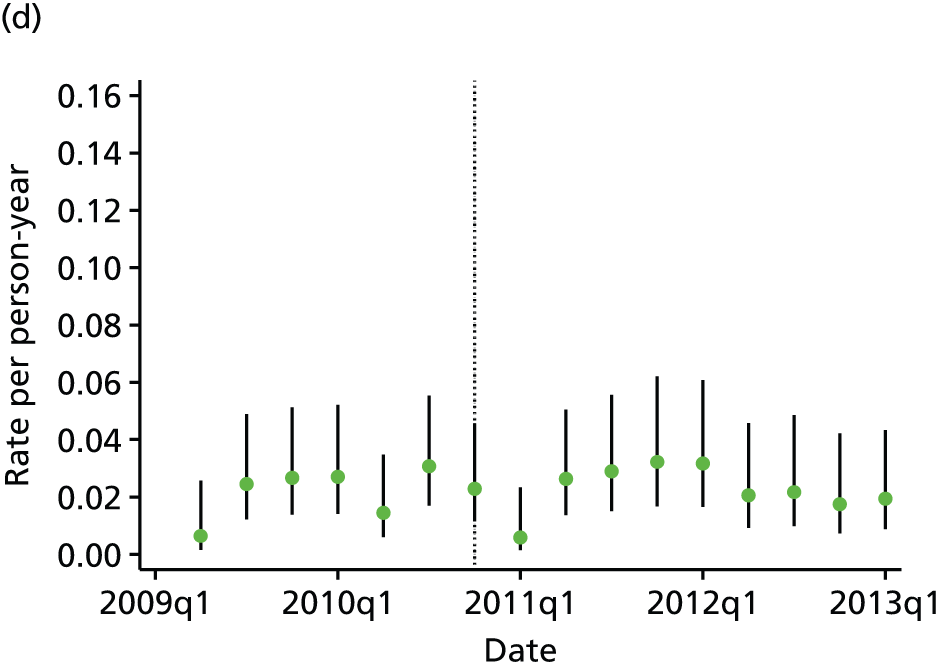

First, we calculated raw rates for each quarter and graphed these for each borough, restricting our analyses to those with a non-psychotic disorder.

Next, we constructed a series of exponential regression models:

-

Looking at each borough separately, we regressed the rate of self-harm presentation against time, whether or not the period of CMHT treatment ended in the quarter, whether or not there was a change of team in the quarter, whether there was a change of care co-ordinator or care co-ordination finished in the quarter, age, sex and ethnicity. Following exploration of the data, an interaction term was also fitted between change of team and change/end of care co-ordinator:ln λ(t)=βtimebandXtimeband+βageXage+βsexXsex+βethnicity1Xethnicity1+βethnicity2Xethnicity2+βCMHT_end(t)XCMHT_end(t)+βteam_change(t)Xteam_change(t)+βCC_end(t)XCC_end+ βteam × CC(t)Xteam × CC(t)+β0+ε.

-

We constructed a set of regression models that were identical except that they allowed the trend in the rate of self-harm presentation to vary before and after CAG implementation. We compared the models using LR testing:ln λ(t)=βtimebandXtimeband+βpostCAGXpostCAG+βtimebandXpostCAGXtimebandXpostCAG+βageXage+βsexXsex+βethnicity1Xethnicity1+βethnicity2Xethnicity2+βCMHT_end(t)XCMHT_end(t)+βteam_change(t)Xteam_change(t)+βCC_end(t)XCC_end+βteam × CC(t)Xteam × CC(t)+β0+ε.

We then went on to perform an analogous set of analyses with the acute admission data set, described earlier.

Patient centredness

As only a very small proportion of trust service users complete Patient Experience Data Information Centre (PEDIC) satisfaction questionnaires and the use of these questionnaires began around the same time as CAG implementation, we did not attempt to analyse patient satisfaction data. Therefore, our analysis of patient centredness consisted of an analysis of waiting time or, more precisely, current wait time among patients accepted for treatment but not yet seen for a face-to-face appointment.

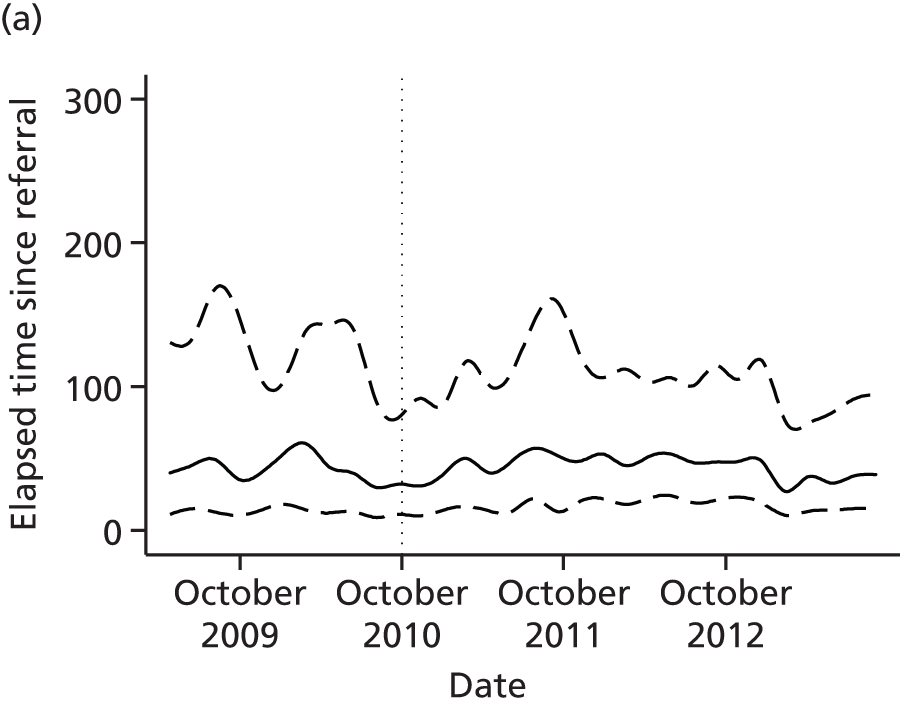

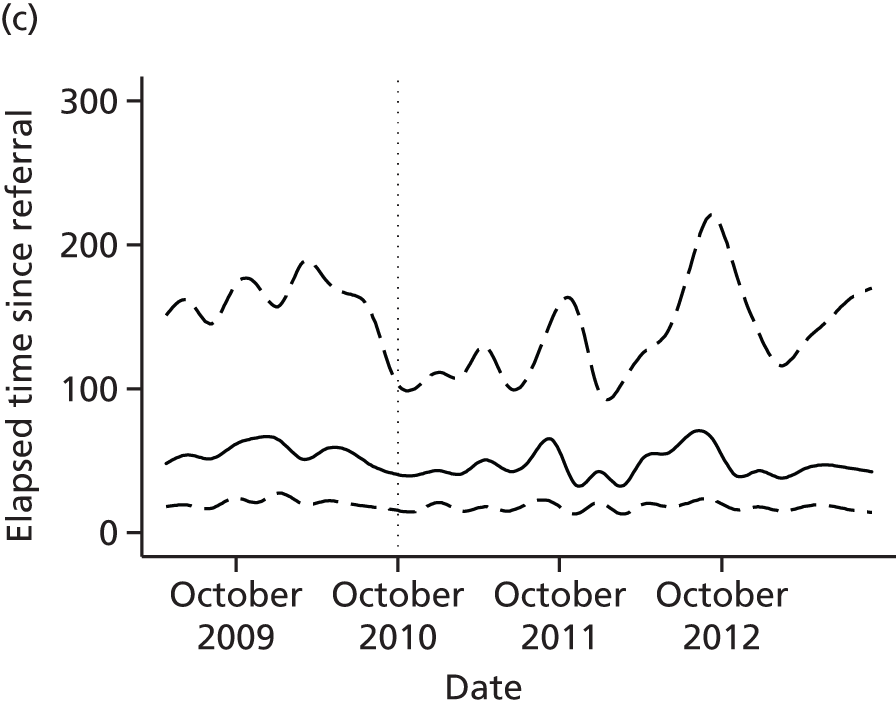

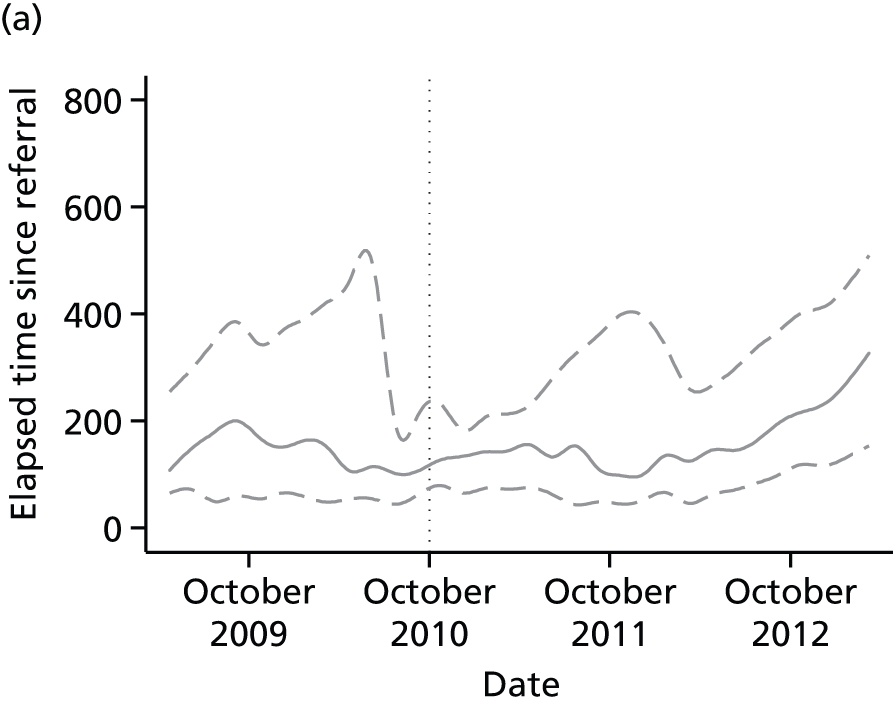

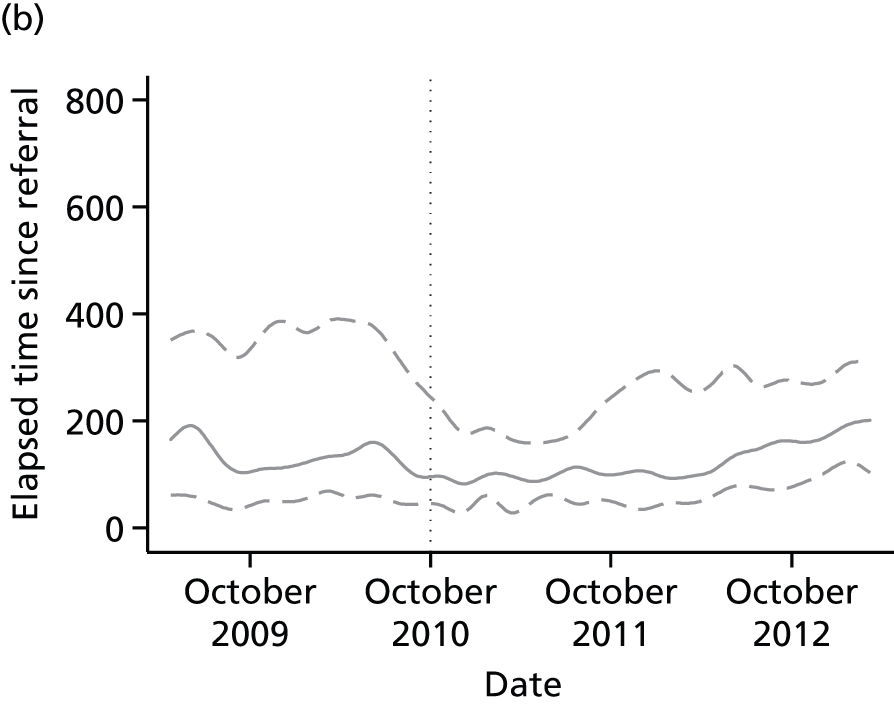

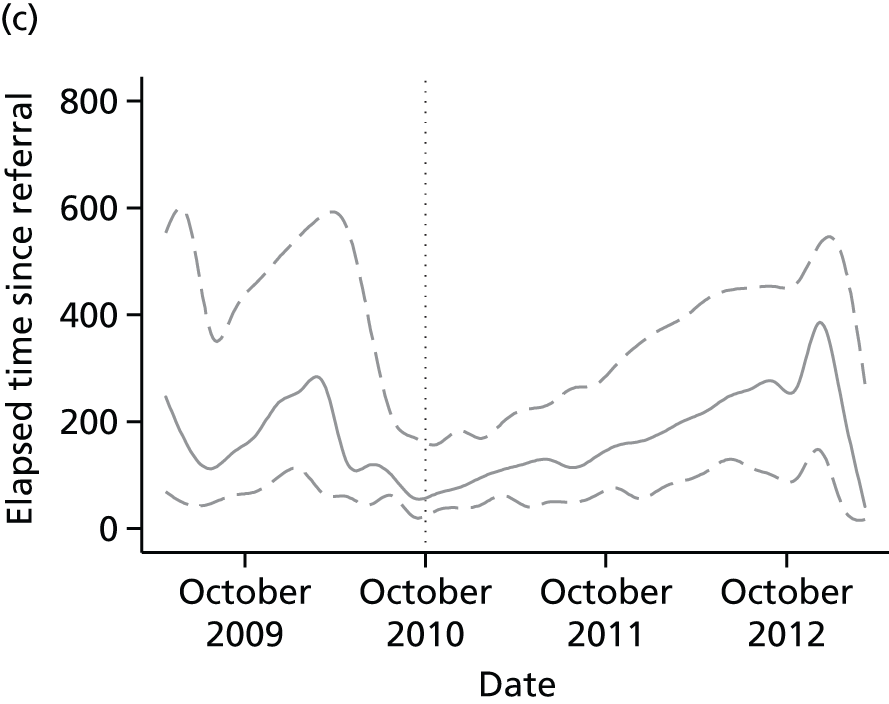

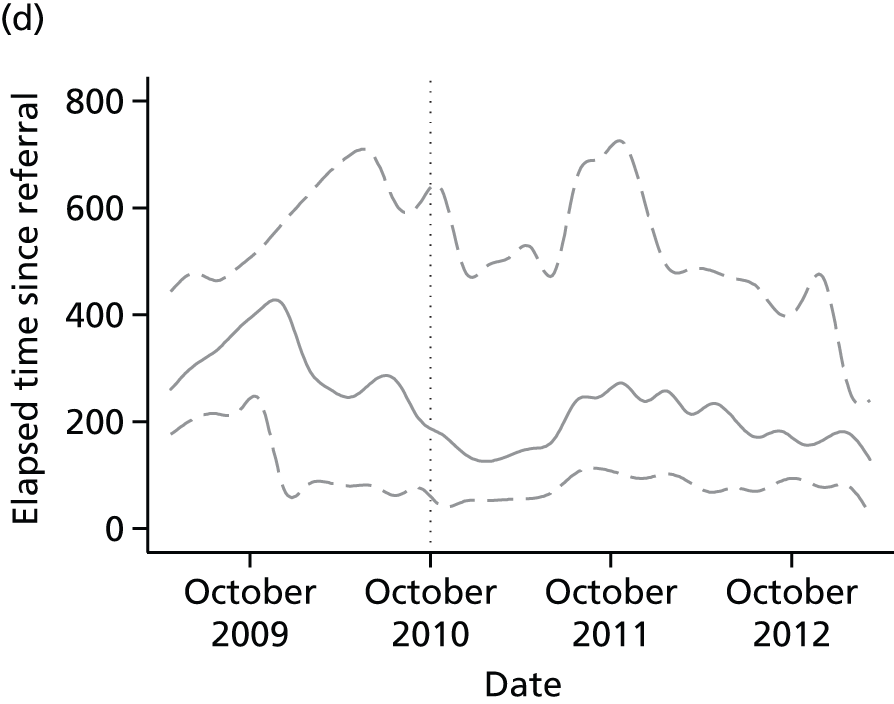

As with previous analyses, we analysed each borough separately and began with a graphical analysis. For each day, 25th, 50th and 75th centile values of current waiting time were calculated and graphed against calendar time for each borough. Following visual inspection of plots, we performed a t-test of mean current waiting time, comparing waiting time before and after CAG implementation. This analysis was performed for CMHT episodes and for psychotherapy episodes.

Overall project timetable

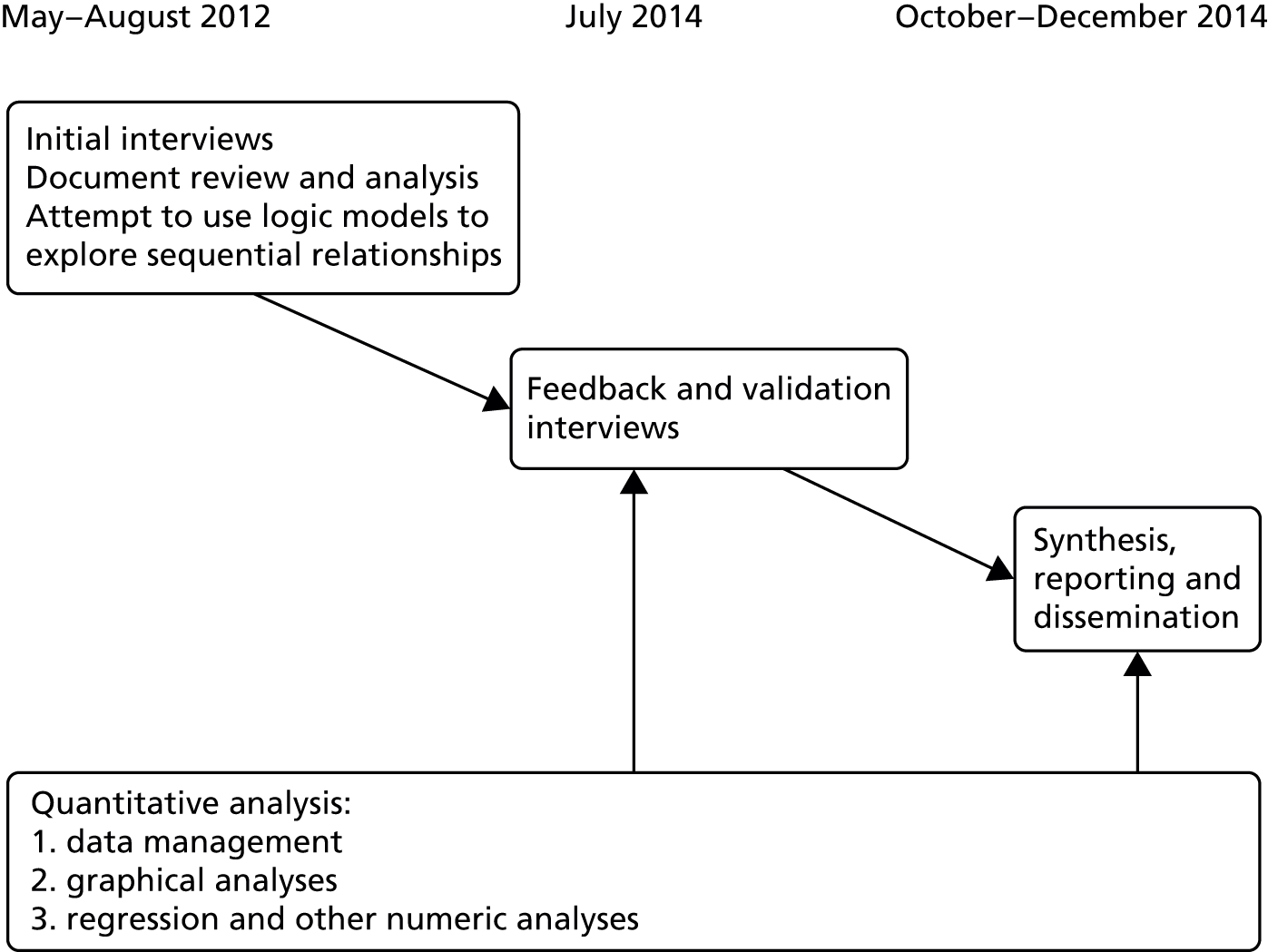

The timing of data collection and analysis for the project as a whole is set out in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

MAPLE study design and timeline.

Ethics and research governance

Neither ethical nor research governance approval was required for the quantitative analysis, which was based on fully anonymised data. The qualitative component of the study was considered and approved by the London (Harrow) Research Ethics Committee (12/LO/0363) and was approved by SLaM’s Research and Development Office. Consent forms and information sheets are provided in Appendix 4.

Chapter 3 Qualitative results

In this chapter we set out the results of our qualitative investigation, which was based on a combination of documentary sources, an initial literature review and interviews with a range of stakeholders.

Background to the changes begins by outlining the history of the organisations involved in or impacted by the CAG restructuring, before moving on to describe how these organisations embarked on the formation of a new AHSC, a process that was the starting point for SLaM’s decision to restructure with CAGs. We then consider what it was intended that the CAG restructuring would achieve, looking at documentary sources, but also setting out what our respondents saw as the need for change, and how their perspectives did or did not align with the public KHP vision. We introduce the topic of the financial climate within the NHS by considering how this may have influenced the decision to restructure and the timing of that restructuring.

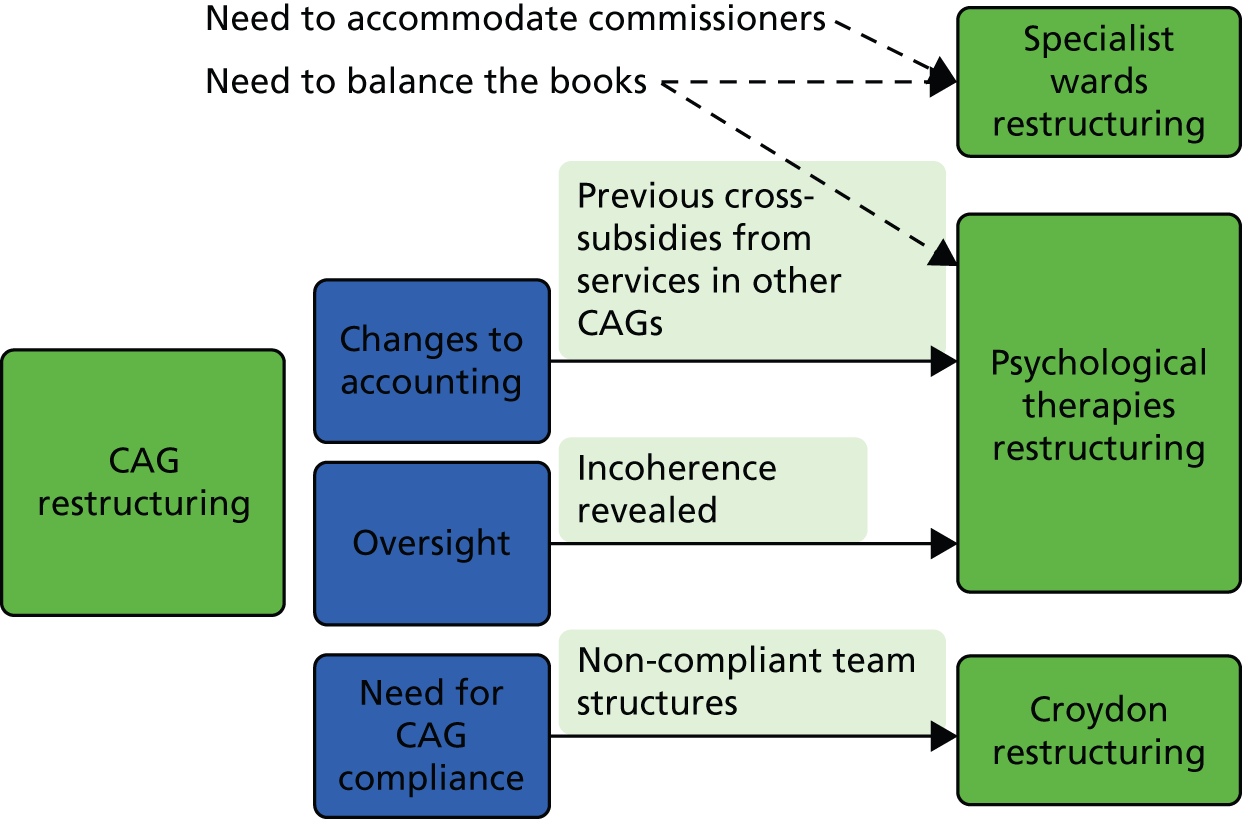

In The Clinical Academic Group restructuring we then move on to the CAG restructuring itself, that is, the process of the transfer of services from the borough directorates to the new CAGs. We set out the details of the structural changes and the rationale provided for them. We make reference to similar service-line reorganisations in other London mental health service providers. Finally, we set out, based on our respondents comments, what appeared to be the key context–mechanism–outcome configurations associated with the CAG restructuring.

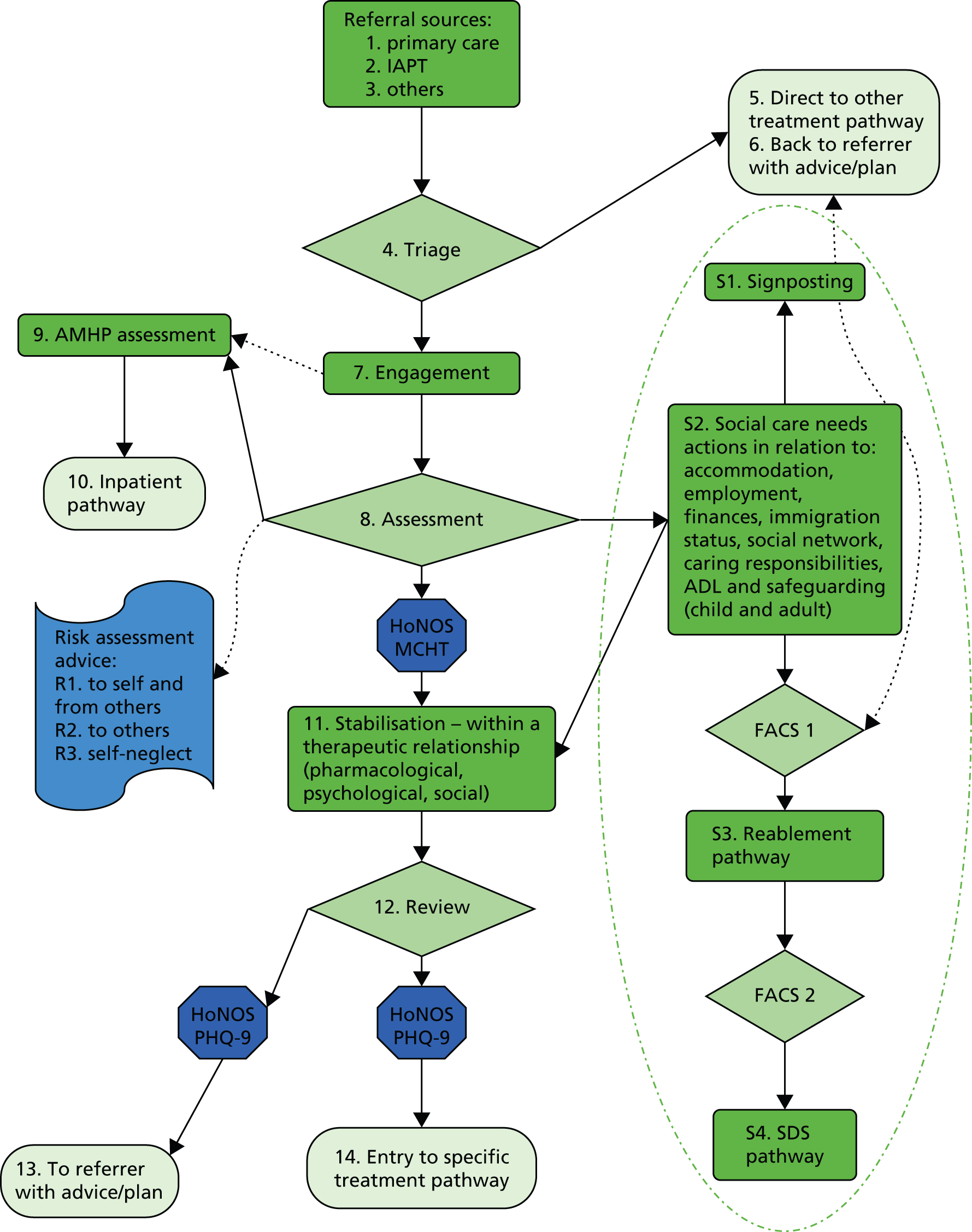

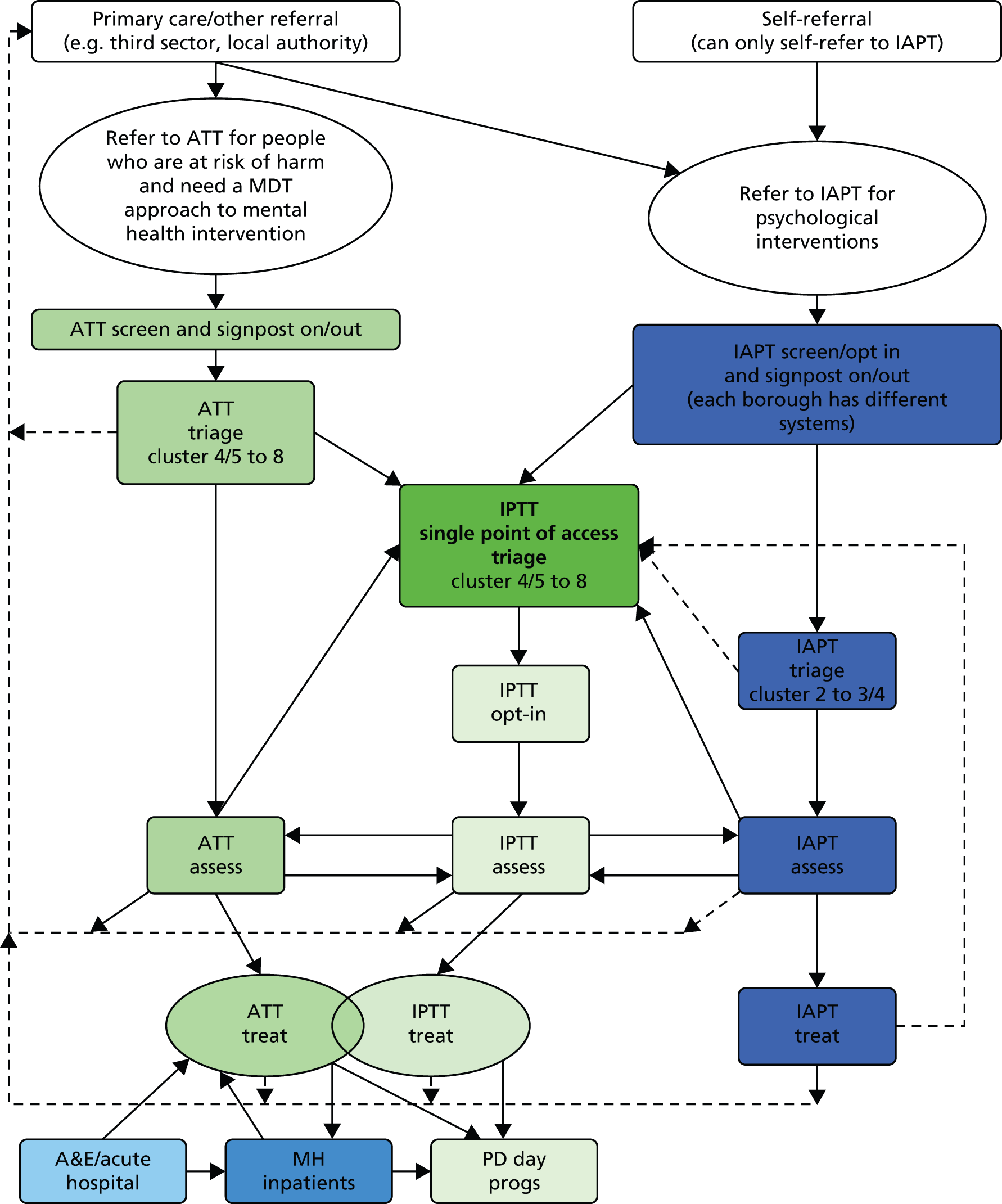

In Care pathways we look at SLaM’s motivations for using care pathways, before an excursus into the literature on care pathways. The remainder of the section describes the MAP CAG’s work to develop and use care pathways, examining which aspects of this work appeared to succeed and why.

In Influences originating outside the Clinical Academic Group programme we consider the other contextual influences that were of critical importance in determining what changes the MAP CAG made and why. In particular, we examine financial issues and the influence of relationships with commissioners. Having set out the mechanisms through which change was sought, and the other contextual factors, we then proceed to look at the major changes that the MAP CAG made and consider the balance of influences over these changes. Finally, we consider briefly what effects being part of the KHP might have had over the MAP CAG.

In Views of service users we look at what service users knew about the CAG programme, what their priorities and preferences were and how the CAG programme related to these.

Finally, in The situation in 2014 we summarise evidence from our second wave of data collection in 2014, looking at ongoing issues and examining what developments there had been since our original investigation.

Background to the changes

The trust and the Institute of Psychiatry: origins and development

The organisational change whose results we attempt to evaluate here most centrally involves an NHS foundation trust – SLaM – whose history is inextricably linked to a predominantly postgraduate research and teaching institute, the IoP at King’s College London (KCL).

The South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust as an organisation dates from 1999, when it was formed by a merger between the Bethlem and Maudsley NHS Trust, the mental health services provided by Lambeth Healthcare NHS Trust and Lewisham and Guy’s Mental Health NHS Trust. Although the last two trusts operated services that mainly served their local populations, the Bethlem and Maudsley NHS Trust had less typical features; indeed, its two constituent hospitals have a unique place in the history of mental illnesses and their treatment: the Bethlem Royal Hospital is the oldest psychiatric hospital in Europe, having operated continuously since 1247, whereas the Maudsley Hospital and its associated medical school (now the IoP) were established expressly to support research into mental disorders and their treatment19 and became pre-eminent in this field in the post-war period. 20 Before the formation of the NHS, the Bethlem Hospital operated as a voluntary hospital, whereas the Maudsley was supported by the London County Council. After the formation of the NHS, the two hospitals were merged under one board, an arrangement that persisted until the formation of SLaM. Although over time the Bethlem and Maudsley acquired greater responsibility for local service provision, especially in the Camberwell area, spanning the London boroughs of Lambeth and Southwark, and later in Croydon, to some extent the hospitals retained their original position as providers of specialised tertiary health care. At the point of the merger between the three trusts, a directorate structure was adopted that in part recognised the unusual nature of many of the services provided by the Bethlem and Maudsley as well as the fact that some services served local populations that extended beyond a single borough. Therefore, as well as borough directorates serving Croydon, Lambeth, Lewisham and Southwark, a National and Specialist Directorate was established that included some services of a tertiary nature as well as some services that served more than one local borough; notably, this included the Maudsley Psychotherapy Department.

The South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust became the 50th NHS foundation trust in 2006. 21 By 2010 (the year in which the CAG structure was adopted) it had come to provide services to a population of around 1,200,000 people resident across the London boroughs of Croydon, Lambeth, Lewisham and Southwark. The structure of those services was in many cases determined by national policy, for example home treatment teams and early-onset teams in line with the National Service Framework. 22 It also continued to provide a range of tertiary services.

The Maudsley Hospital was associated from its inception with a postgraduate medical school, which, since 1948, has been called the IoP. Initially, the IoP was administered on behalf of the University of London by the British Postgraduate Medical Federation. In August 1997 the British Postgraduate Medical Federation was disbanded and the IoP was absorbed as a separate faculty into KCL, but remained apart from KCL’s School of Medicine, which itself subsequently merged with the United Medical and Dental Schools of Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospitals. The links between SLaM and the IoP have always been very close, with many IoP staff also holding contracts with SLaM and much research being carried out within SLaM. (In 2014, the IoP was renamed as the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, but it is referred to here under the name current during the study period.)

Academic Health Science Centres

Academic Health Science Centres are partnerships between one or more universities and health-care providers that aim to break down barriers and increase co-operation, and which combine basic and translational health research, clinical care and education to improve health care. In 2007 a review of health care in London recommended that a number of AHSCs should be created,23 and in 2009 five NHS/university partnerships were designated as AHSCs by the Department of Health in England. One of these was KHP, which brings three NHS foundation trusts – Guy’s and St Thomas’, King’s College Hospital and SLaM – together with KCL, which includes the IoP as well as KCL’s School of Medicine. Guy’s and St Thomas’, King’s College Hospital and SLaM together provide almost all secondary health care across the London boroughs of Lambeth and Southwark and provide a significant portion of secondary and tertiary health care across the rest of south and south-east London.

King’s Health Partners and Clinical Academic Groups

To transcend the traditional distinction between a hospital and its associated medical school, AHSCs typically require new bodies to be created that allow for joint working between the hospital and the university; this may require the modification of existing departmental structures. 24,25 While preparing for its application for accreditation as an AHSC, KHP developed the concept of a CAG as the means by which the AHSC would operate. To demonstrate the practicality of the concept, four pilot CAGs were established in advance of the initial bid for accreditation. It is clear from documentary sources that CAGs have been, and continue to be, central to KHP’s operation. Thus, first among KHP’s stated objectives was to ‘drive the integration of research, education and training, and clinical care for the benefit of patients through our new CAGs’. 26 In more recent documents, CAGs are described as the ‘integration engines’ of the AHSC. 27

An early KHP document describes the structure and rationale of the KHP CAGs as follows:

CAGs will bring together, within a single management structure, academics, clinicians and managers whose work is focused on a single specialty or group of related specialties. Each CAG will be responsible for developing a strategy which addresses the tripartite mission of clinical care, research and education and the CAG leaders will be accountable to KHP for delivery of this tripartite agenda. The CAG model allows the partners to maintain their independent external accountabilities (for clinical delivery by the NHS Foundation Trusts and for academic performance by KCL) which the partners are not permitted to delegate. The CAG leaders will be the principal change agents required to achieve the necessary cultural transformation through supporting changes in structures, policies and incentives. 28

The relationship between CAGs and the broader KHP governance structure was defined from the outset. Broadly, these governance arrangements consisted of a partnership agreement between the partner trusts and KCL, a Partnership Board and an Executive. In relation to the CAGs:

[The Executive] will [. . .] be responsible for the development, co-ordination and performance of CAGs, which will progressively be brought within the formal governance framework through an internal approval process that will ensure they are fit for purpose. This process, which will be managed by the Executive on behalf of the Partnership Board, will require each CAG to demonstrate that it has strong leadership, a coherent strategy and a credible business plan to deliver that strategy. 28

In line with these principles, KHP devoted a small project team to support partner trusts in developing CAGs and preparing submissions for CAG accreditation. This team was complemented within SLaM by the creation of a team dedicated to CAG development, with the two teams working closely together. KHP’s original intention was that each CAG should complete three modules with progress documented in three documents (the accreditation submission) that corresponded to each of the modules. In the end, module 3 was never requested and remained on hold. However, each CAG did make submissions for module 1 and module 2. For module 1, each CAG was required to (a) define an Executive ‘which will be involved in delivering CAG accreditation and the development of the CAG following this’29 and (b) define a communication and engagement plan for internal and external use. For module 2, each CAG was required to (a) set out a clinical strategy addressing quality and productivity and describing CAG innovations, and to (b) set out a research strategy and (c) set out an education and training strategy.

A point that is of critical importance for the present evaluation is that CAGs were innovations that proved to be susceptible to different modes of implementation. As noted in the description of CAGs reproduced above,28 the scope of the KHP CAG programme was explicitly limited so that each hospital partner would retain responsibility for the governance of its clinical services. At Guy’s and St Thomas’ and King’s College Hospital, CAGs were developed as additional structures that supported collaboration between clinicians and academics and between clinicians in different trusts, but which did not take responsibility away from the existing management structure for service delivery. However, SLaM elected to develop CAGs as new organisational units that entirely replaced the existing management structures for clinical services. It is this decision and its consequences that are the focus of our evaluation. Each SLaM CAG was incorporated as a separate internal unit that was charged with responsibility for all aspects of the delivery of defined services within a defined budget and that replaced the operational units that had previously had these responsibilities. This meant that responsibility for both clinical delivery and the development and implementation of a strategy to deliver KHP’s tripartite agenda of research, education and clinical service was devolved to the same managerial units.

This decision was not solely influenced by the need for SLaM to meet its commitments to the AHSC. Rather, it was intended that the restructuring into CAGs would also lead directly to improvements in clinical services. How this might occur was stated most clearly and succinctly in a ‘Frequently Asked Questions’ document distributed to SLaM staff in 2009, in which the question ‘How will mental health Clinical Academic Groups actually work?’ was answered as follows:

Our aim is to provide more specialist services and more focused interventions. We have been discussing for some time the need to improve consistency and have greater clarification about what we are providing and for whom. Care pathway development is an important cornerstone for Clinical Academic Group development.

Other key themes include promoting the integration of physical, psychological and social care, the emphasis on recovery and the interface between acute and mental health services. Our Clinical Academic Groups will be based on a multi-disciplinary approach to care and treatment.

Finally, and crucially, Clinical Academic Groups will empower teams to be innovative. One of the ways we will achieve this is through the development of Service Line Management at SLaM where teams have detailed information about the services they are providing, how effective they are and how much they cost. 30

As noted in Chapter 1, our view is that the key elements of the CAG restructuring were (1) the restructuring itself and (2) the development of a way of working with care pathways. This early document does not entirely reflect this. In our interviews we saw little evidence of the CAG restructuring having led to the changes listed in the second and third paragraph quoted above, including the development of service line management at team rather than CAG level. In contrast, the notion of care pathways being the ‘cornerstone’ of CAG development was fully borne out by interview and other documentary evidence and, moreover, the linkage between care pathway and CAG development postulated here reflects exactly the later course of development, in which care pathways became intertwined with the management of the CAG.

Having sketched out what SLaM’s CAG restructuring was, and how the entry into KHP provided an opportunity for it to happen, we will next consider why SLaM’s leadership might have decided to undertake the restructuring at that particular time. This was a topic that we discussed with our staff respondents. In the next sections we set out why those respondents thought that there was a need for change, the extent to which the KHP vision aligned or could be made to align with what was perceived to be the right strategic direction for SLaM, and what elements of the external environment might have favoured SLaM’s decision to embark on the CAG programme at the time that it did.

The need for change

In mid-2012, around 18 months after the CAG ‘go live’ date of 1 October 2010, we asked our respondents to reflect on the reasons why SLaM had undergone the CAG programme. Broadly, and for a variety of reasons, our respondents (identified as R1, R2, etc.) told us that the old system simply wasn’t working any more:

We had to look at some other way of delivering services that could meet more needs or a wider range of needs. And we weren’t going to do that with the old model.

R6

Fleshing out what this meant in relation to the MAP CAG, interviewees told us that:

-

the local services that the MAP CAG covered had developed in different boroughs in ‘very diverse ways that were not always very rational’ (R5)

-

central psychotherapy services had been managed by a National and Specialist Directorate that took referrals from the boroughs but were not linked to them managerially, with the result that ‘nobody had a coherent vision of psychological therapies in the Trust as a whole’ (R5)

-

many service users were being maintained within the secondary services when they did not need to be:

[Y]ou had an awful lot of people who would have been singularly maintained on depot medication in small doses or something to that effect and might have been seen once every six months or once every twelve months at an outpatient clinic. That was a hangover from previous generations, and, even amidst all the changes, that group had been maintained within the secondary services when they didn’t actually need to be.

R6

These problems were very long-standing and often related to issues that had not been resolved when SLaM was created from its three predecessor trusts. Overall, this situation was described by one interviewee (R5) as a ‘very mixed bag of parallel and incoherent services’.

Managers and senior clinical staff working in SLaM were well aware of these problems. They had sought to implement various changes at various times prior to the CAG programme and, indeed, one reason why SLaM was able to restructure rapidly with CAGs as operational units (as required by the KHP timetable) was that senior people in SLaM and the IoP had been considering approaches such as service line management and care pathways for some time and were therefore ready to embrace this new initiative. As one interviewee said:

a number of us were very involved in the London mental health group . . . so we already had quite a bit of information around the care pathway approaches, pros and cons . . . so we weren’t starting from scratch . . . The timing was perfect.

R2

That level of preparation notwithstanding, the organisational and managerial context into which the CAG programme was introduced was complex and somewhat fluid and the challenges faced were considerable. In the psychotherapy services, which it will be recalled had been divided between the borough directorates and the National and Specialist Directorate prior to the CAG restructuring, previous attempts to make changes had not succeeded:

The whole issue of the psychological therapies has been the elephant in the room for years. It’s the only part of the trust that was never really sorted out at the time [when SLaM was formed].

R1

In the case of Croydon, where the introduction of CAGs would require significant reorganisation of the generic CMHTs existing at that point to create assessment and treatment teams and support and recovery teams:

It was something that was being talked about – an option of what was available and where it could go in context of how we could provide services . . . I suppose, if you look across the other boroughs, most of them had already been working that way in some form or fashion.

R6

Similarly, the difficulty in recasting the relationship between primary care and secondary care was recognised as a long-standing problem in need of a solution, at least in some parts of the trust:

there’s been a bit of a history with the GP practices insofar as there has always been a reluctance to take cases back.

R6

In all, this meant that the reorganisation was seen as a natural next step:

It was a natural progression is the truth of it and it was almost strengthened and restarted but it was the next logical progression and so it didn’t feel odd to anyone.

R2

And the perceived inevitability of this change also meant that, regardless of whether particular individuals were enthusiastic or sceptical about the new structures being implemented, most worked positively towards the progression of this unavoidable reorganisation:

People are determined to make the change work.

R6

And this was partly driven by competition between CAGs to make their own section a success:

[Name] would have been influenced by what was happening in all the directorates because he would not want his directorate to fail, he would want it to get as far down the road as possible.

R6

In summary, there was pre-existing awareness of the need for change within SLaM, but previous attempts to make changes had not worked well. The general view was that the CAG programme provided a chance to overcome these difficulties and had come along at an appropriate time.

The King’s Health Partners vision and its relevance

The decision to form the AHSC and to use CAGs as the ‘integration engines’ of the new partnership was one that had been taken at high level in KCL and the partner NHS trusts in 2008 and 2009. However, the sense in which CAGs were critical to KHP and the sense in which they were critical to SLaM were not necessarily identical. Our respondents reflected in various ways on the relevance of the KHP vision of integrating research, education and clinical service. As we have noted earlier, there was, from the start, a contrast between KHP’s vision of CAGs as the means of advancing its ‘tripartite mission’ and the vision espoused by SLaM wherein CAGs would be the vehicles for other desirable changes to services. None of our respondents opposed the vision of clinical and academic integration espoused by KHP:

It is a sort of vision you can’t quarrel with, anybody would think, yeah that sounds good.

R3

However, it was clear that some leaders and senior managers within SLaM had additional and different reasons for supporting SLaM’s CAG restructuring. Even so, when our respondents discussed the practicalities of clinical work or management or even the work of transforming evidence into practice, they also described the challenges of relating the KHP vision to the everyday reality of their work. For example, one respondent working mostly in a clinical service told us:

[a] lot of people also felt: How does this relate to us on the ground and what we’re struggling with? So there was that, and a lot of real enthusiasm in a group of people but a lot of cynicism in another bit.

R3

A similar view was expressed by another respondent who informed us that:

the overarching rationale of King’s Health Partners . . . I mean that’s not something that feels terribly important to us on a day-to-day basis.

R5

Individual CAGs were required to report regularly to a KHP Performance Council and these sessions, especially, seemed to have been occasions that brought home the difference between the KHP vision and each CAG’s own aim to provide the best possible service within the resources available:

It’s interesting when we go to the KHP Performance Council and talk about what we’ve been doing, and the balance between talking about the KHP vision and talking about our external realities.

R1

Most strikingly, one of our respondents questioned whether or not KHP and CAGs were the best structures to take research and put it into practice:

We’ve already got in the IAPT services an excellent example of how research has been put into practice, it was done quickly and effectively and attracted a huge amount of money and it didn’t require King’s Health Partners to do any of it.

R5

In summary, the KHP agenda was generally seen as important as a driver of the SLaM CAG programme, but it was not the only factor. As one interviewee put it:

There were different voices when the CAGs were set up, there were clearly the KHP voice with their tripartite mission, there was also an internal voice which was very much about, is there a different way we can operationally manage services that might help us get through the next few years?

R1

The financial environment and the decision to restructure

The financial and economic crisis faced by the world economy in 2007–8 and its subsequent impact on NHS finances formed the wider background to the KHP CAG programme and SLaM’s decision to restructure using CAGs. In May 2009, the Chief Executive of the NHS, David Nicholson, made it clear that the recent era of increasing growth and capacity had come to an end and warned about the urgent need to plan for a much tighter financial environment: the NHS would need to release unprecedented levels of efficiency savings between 2011 and 2014 – between £15B and £20B across the service. 31

This was a contextual factor that was of decisive significance for the MAP CAG once established – a point to which we will return – but it was also important in securing support for the initial reorganisation and, most of all, for the decision to implement CAGs during the 2010–11 financial year rather than at a later date. Senior staff within SLaM and the IoP saw the CAG programme as an opportunity to look at services in a new way, and borough directors saw it as helpful because they were running out of ideas about how to maintain quality while continuing, as required, to take 3% per annum out of the budget for clinical services:

[T]hey seem to feel that they run out of ideas of how to do that on a borough basis and maybe having new structures that went across boroughs would help with making efficiencies and reorganising services in a different way.

R3

Overall, the harsh financial climate also increased pressure to make changes rapidly before things got even worse. In a sense, the KHP requirement that the CAG programme be implemented quickly was seen as fortuitous for SLaM; despite the rush, several interviewees believed that CAGs were introduced at the correct time:

We went into CAGs in quite a rushed manner . . . There was a decision taken that we’d either get on and do it now or we’d leave it for a year later. We were anticipating the degree of disruption about to come through with large efficiency savings and if we’d been trying to do it this year on top of the large amounts of money to come out then we would have been in quite a difficult position.

R1

The Clinical Academic Group restructuring

The South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust’s approach to Clinical Academic Group definition

In the preceding section we described why the change to CAGs was seen as desirable, the extent to which the KHP ‘vision’ was relevant to the everyday reality of running services and how SLaM staff may have had a different view of the purpose of CAGs; we also identified the worsening financial climate as relevant to the decision to reorganise into CAGs as soon as possible. Now we move on to the CAG restructuring itself – the taking of a set of services and their recasting into groups of services managed by CAGs – asking why it took the form that it did. At the end of the section, based on our respondents’ comments, we set out how we see the CAG restructuring as the first element of the CAG programme and describe the context–mechanism–outcome configurations associated with it.

The decision about how areas of clinical and academic activity would be defined as CAGs was devolved from KHP to the partner trusts. As noted earlier, the additional challenge for SLaM was how to define CAGs in such a way that they would both meet the requirements set by KHP and be fit for the purpose of managing SLaM’s clinical services.

Some existing directorates, such as Mental Health of Older Adults, Child and Adolescent Mental Health and Addictions, already had responsibility for a defined area of practice throughout the trust and could be reshaped relatively easily as CAGs; indeed, the Mental Health of Older Adults Directorate was rapidly transformed into a pilot CAG. But SLaM’s adult mental health services were organised geographically, with borough directorates (in Croydon, Lambeth, Lewisham and Southwark) dividing work in adult mental health between four separate management units, each of which was responsible for a different geographical area. The solution to transforming these borough directorates into CAGs was sought primarily in the functionally specialised team types that had already developed at borough level. In some cases, these functional teams had arisen because of government policy and especially the NHS Plan,22 which mandated the creation of home treatment teams and first-episode psychosis teams; these teams were present across the four boroughs. Other forms of specialisation had arisen because of local initiatives, leading to differences between the boroughs. Most notably, Croydon had continued to operate generic CMHTs whereas the other boroughs had for several years prior to the CAG restructuring operated assessment and treatment teams, which mostly dealt with short-term treatment and therefore had a user population with a variety of diagnoses, including many with non-psychotic disorders, and support and recovery teams, which predominantly served people with severe mental illness. Croydon was also the only borough that operated a single psychotherapy service, with the other boroughs either using more than one service (Lambeth and Southwark) or being reliant on services provided outside the borough (Lewisham). However, despite the differences between boroughs, and the variable extent to which functional specialisation had occurred, it was reasonably accurate to present the eventual CAG structure as first and foremost ‘[b]uilding on differentiation and specialisation which has already taken place – e.g. Early Intervention in Psychosis and IAPT’. 32 When teams were divided between CAGs, a degree of correspondence was ensured between the nature of the population served and the name of the CAGs, for example the Psychosis CAG acquired responsibility for those inpatient wards and community services whose users mostly have severe mental illness, whereas the Psychological Medicine CAG became responsible for those services physically based in acute hospitals.