Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 11/1015/09. The contractual start date was in August 2012. The final report began editorial review in May 2015 and was accepted for publication in October 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Ingram et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction, summary of study design and research objectives

Introduction

The improvements in survival of preterm infants over the past 20 years mean that > 90% of all infants born at ≥ 27 weeks’ gestation will survive and go home. For nearly all such infants, a relatively short period in intensive care will be followed by a longer period in ‘high-dependency care’ and then ‘special care’ before discharge to home.

For parents of such infants there is a need to learn how best to look after them following discharge and to prepare themselves and their home environment to care for the baby. There is increasing evidence that ex-preterm infants make a disproportionate demand on emergency and out-of-hours health services, and many parents have expressed concern and uncertainty about how best to respond to minor illness or changes in routine in these very vulnerable infants.

In a preliminary survey of neonatal units in the UK, we found that in most neonatal units the process of preparing families for discharge home with their preterm infant is relatively unstructured and is commonly left until relatively late in the hospital stay. The emphasis is usually on informing the parents about issues that the nursing and medical staff feel are important, rather than addressing the parents’ identified needs and anxieties.

In many other areas of medicine it has been shown that a structured approach to discharge planning, with the use of a pathway of care and predictable timing for discharge, improves the quality of care after discharge, and reduces the need for unexpected readmission after discharge, as well as improving patient satisfaction.

Many parents of preterm infants are routinely informed by medical and nursing staff that their baby will be discharged home at or around the time the baby was due to be born – that is, around 40 weeks’ postmenstrual age (the estimated date of delivery, EDD). This is despite increasing evidence in recent years that improvements in neonatal care were leading to progressively shorter stays in hospital and earlier discharge home. Using EDD as the expected discharge date means that the process of preparing parents to take their baby home is often left until very shortly before the baby is to be discharged, commonly leaving parents feeling unprepared and lacking in confidence in caring for their baby.

In an audit of the length of stay (LOS) of preterm infants in neonatal units in the South West region, we found that almost all infants born at 27–33 weeks’ gestation (see Chapter 4) were discharged home well before their original EDD, and around 50% were discharged home at ≥ 1 month before this date.

We have developed an approach to improving parents’ preparedness to take their baby home – the Train-to-Home package – utilising a number of tools to help increase parents’ involvement in the care of their baby from an early stage, to develop their understanding of their baby’s needs, and to provide, soon after the baby is admitted to hospital, an accurate estimate of when the baby is likely to be discharged from hospital. The pack is parent centred and provides a means of improving communication between staff and parents throughout the baby’s hospital stay.

The aim of this approach was to improve parents’ self-confidence and knowledge about how to care for their baby after discharge, with the potential aim of facilitating earlier discharge to home and reducing the use of emergency or out-of-hours services after discharge.

Study design

The study took place in four local neonatal units (LNUs) in South West England. We used a before-and-after study design, with initial baseline data collection over an 11-month period before the Train-to-Home package was introduced. This was followed by a 1-month ‘washout’ period during which the Train-to-Home package was introduced and intensive staff-teaching in its use was carried out. Then there was a further period of data collection in an 11-month period, during which the Train-to-Home package was routinely used for all infants of 27–33 weeks’ gestation who were admitted to the units. Details of the study methodology are given in Chapter 5 of this report.

Research objectives

The aim of the study was to assess whether the introduction of the parent-centred neonatal discharge package (Train-to-Home) could increase parental confidence in caring for their infant, reduce the LOS of infants in neonatal care and reduce health-care resource use after discharge from hospital.

The primary objective and outcome measure was a comparison of changes in maternal and paternal confidence when caring for a premature baby from just after birth, to around the time of discharge from hospital, and at home 8 weeks after discharge, before and after the introduction of the Train-to-Home package in four LNUs (formerly known as level II units) in South West England.

The secondary objectives were to:

-

measure the LOS of infants born before and after the introduction of the Train-to-Home package, and assess whether this intervention was associated with any reduction in overall LOS in hospital

-

estimate the potential cost savings associated with the introduction of the Train-to-Home intervention in terms of UK NHS and other health-care resources used by parents and infants in the 8-week period after discharge from hospital, before and after introduction of the Train-to-Home package

-

explore parents’ and staff’s views of the intervention and its delivery in greater detail using qualitative interviews.

Chapter 2 Context and background

The organisation of neonatal intensive care

The survival of preterm infants has improved significantly over recent years, with survival rates of 91% for infants born at 28 weeks’ gestation and 98% at 33 weeks’ gestation. 1 This improved survival has resulted in more infants requiring intensive or high-dependency care for longer periods, and increasing the pressure on the scarce resources of neonatal care.

The improved survival rate has brought to the fore the problems associated with infant discharge home after long periods in hospital. It has also raised awareness of the particular needs of such infants and their families in coping successfully with the transition from hospital to home. This transition and community-based follow-up care is an increasing focus of investigation, with attempts to facilitate the processes and reduce the adverse effects of recurrent emergency health-care contacts, which commonly lead to hospital readmission. 2,3 Relatively little attention has been given to the impact and potential importance of this aspect of neonatal care, despite the huge volume of published literature on improving outcomes for preterm infants. 4 Improved education and information provided to families of preterm infants might improve the appropriate use of hospital and community health services after discharge, and reduce the numbers of babies readmitted to hospital,5 although few studies have shown such a relationship.

In the UK, neonatal care is delivered in three types of neonatal unit working together in managed clinical networks. Neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) – formerly referred to as level III neonatal units – provide the full range of intensive care for infants with complex problems, including extreme prematurity drawn from a wide geographical area. They also provide high-dependency and special care services for their local population (similar to LNUs). NICUs commonly function as regional referral centres for infants with complex conditions, and may be linked to other tertiary infant health-care services, including paediatric cardiology, paediatric surgery and other specialist paediatric services. LNUs provide high-dependency care, special care and limited intensive care for their own catchment population. They generally provide the majority of care for infants born at ≥ 27 weeks’ gestation. Special care units provide special care for only their local population. 6

Neonatal care is an expensive and limited health resource, with prematurely born infants occupying the majority of neonatal hospital bed-days. 7 The median LOS for infants born at < 34 weeks’ gestation in South West England LNUs during 2010 was 38 days [audit figures from the ‘Badger’ neonatal data collection system (BadgerNet) – a live patient data management system used by the majority of neonatal units in the UK].

Approximately 70,000 babies born in England each year (10% of all births) require additional medical care after delivery and are admitted to neonatal units. 8 Infants requiring neonatal unit admission are categorised as needing intensive care, high-dependency care or special care. The British Association of Perinatal Medicine (BAPM) have defined the care categories based on the therapeutic and monitoring needs of the baby. 9 Of the 70,000 infants admitted for neonatal care annually, 19,500 are admitted to intensive care. 8 The 2010 BAPM standards recommend that one nurse should provide care to one infant in intensive care, two infants in high-dependency care or four infants in special care. 10 The cost of care is determined mainly by nursing-staff requirements, with intensive care thus costing more than high-dependency or special care. For most infants of < 34 weeks’ gestation, a relatively short period in intensive care is followed by a much longer period in high-dependency care and then special care before discharge home.

The economic cost of neonatal care

Petrou and Khan11 have recently reviewed studies conducting predictive economic modelling of the economic consequences (economic burden) of moderate and late preterm birth. Costs associated with initial hospitalisation were estimated from 10 studies. Mean hospital costs varied between US$1334 for a surviving term infant and US$32,153 for a surviving moderate or late preterm infant (US$ 2008 prices). Studies varied substantially in terms of their methodology, sample size and location. Costs following initial hospital discharge were estimated from 13 studies. 11 Of these studies, 11 focused on a funder perspective, looking at hospital costs after discharge, and excluded costs to other economic sectors, families and carers, and society. Petrou and Khan11 argue that these costs, and the indirect costs associated with days off work and lost productivity, are potentially large in comparison with the perspective for costs taken in most studies. This suggests that most identified studies underestimate the economic cost burden of medium and late preterm babies in the immediate period after discharge. Two studies12,13 within the Petrou and Khan review took a broad perspective on the full range of costs associated with initial hospital discharge and included funder, families and carers, and society. They demonstrated a differential range in cost estimates of 1.3- to almost 10-fold difference between those infants born at between 32 and 36 weeks’ gestation and those born at term. 11

Johnston et al. 14 recently estimated the economic burden of prematurity in Canada by describing and characterising the economic cost burden of premature birth over the first 2 years of life. They accessed high-quality and comprehensive data to populate the parameters of the Markov state–transition decision model and included resource use, direct medical costs, parental out-of-pocket expenses, education costs and mortality. 13 The cost per infant from discharge to age 2 years ranged from CA$9280 to CA$2228 for early preterm births of < 28 weeks’ gestation to late preterm births of 33–36 weeks’ gestation, and total economic cost from discharge to age 2 years was CA$94,081,058 (n = 27,308). They estimated the average number of inpatient hospital days and associated standard error (SE), outpatient costs, and associated indirect costs incurred due to lost productivity by caregivers of preterm infants from discharge to age 2 years. Mean inpatient days [standard deviation (SD)] from discharge to age 2 years were 17.5 (3.32) days, 8.75 (1.27) days and 2.40 (0.17) days for early, moderate and late preterm infants, respectively. Outpatient mean costs for the same groups were CA$2403 (CA$223), CA$1453 (CA$103) and CA$734 (CA$13) respectively. These findings provide a useful basis for this current study for comparison, albeit the period after discharge in our study was only 8 weeks, although it is likely that the consequences of improved parental confidence in caring for their infant will be most easily seen in the first few weeks after discharge, a period during which collection of detailed information from parents is least difficult. The published studies outlined above emphasise the importance of accurate recording of inpatient days post discharge and inclusion of costs associated with emergency department (ED) visits, but, to date, there is very little evidence for the costs related to post-discharge emergency admission of preterm infants.

The average LNU cost in the UK for each very-low-birthweight baby (birthweight of < 1500 g, which is the mean birthweight at 30 weeks’ gestation) is > £13,000. Any increase in parental confidence to care for their infant at this stage could reduce their LOS, and possibly reduce health-care resource use after discharge, making potentially significant health-care savings. 11

The need for discharge planning

Preterm infants of gestational ages 27–33 weeks, inclusive, have a > 90% probability of survival but usually spend a prolonged period in a LNU. Their progress is relatively predictable, which makes a discharge planning process easier because outcomes are anticipated, and parents may be informed ahead of time about expected events and changes over time. Infants born more prematurely will usually be born in a NICU or be transferred to one soon after birth. They will spend a considerable period there before either being transferred to a LNU or discharged directly home.

Infants born at ≥ 33 weeks’ gestation, who develop serious medical problems or have complex anomalies or conditions (e.g. severe intrapartum asphyxia), have extremely variable LOS and a need for tertiary NICU facilities. The range of conditions and the very wide range of possible outcomes, in terms of in-hospital clinical course, make infants outside the 27–33 weeks’ gestation range much less suitable for anticipatory care planning as a group.

The capacity for care of low-birthweight infants is limited by the lack of intensive care cots in NICUs and LNUs. Experience from several UK neonatal networks suggests that moving infants from intensive care to high-dependency or special care cots is a major limitation to the appropriate use of intensive care. This is caused by delays in discharging infants from high-dependency/special care cots. A relatively small reduction in special care or high-dependency care LOS provides a relatively small cost saving, but has a disproportionately greater effect in improving intensive care cot availability and allowing the most effective use of scarce resources.

In the UK, individual health visitors (HVs) are routinely allocated to all infants soon after birth. They carry out a support, advisory and monitoring role for preterm infants after discharge from hospital, which is an important component of routine health care. Changes to NHS workforce planning and commissioning processes have altered HV workload patterns and changed their involvement with mothers and preterm babies. 15 HVs have shifted from providing a generic health promotion/maintenance service for all infants to a focused role concentrating on families at highest risk, namely monitoring, preventing and identifying child neglect and abuse. In many areas this role change has been accompanied by a significant reduction in overall HV numbers, and a loss of expertise in the care and support of preterm infants. This has led many LNUs and NICUs to develop hospital-based outreach teams to provide support, advice and monitoring to families of preterm infants for several weeks after discharge. They also address some of the parents’ psychological and practical needs with individualised support and care programmes. Our unpublished survey of UK neonatal units in 2010 showed the importance that staff attached to having post-discharge care of preterm infants co-ordinated by a team with knowledge and experience of hospital neonatal care.

The importance of involving parents in the discharge planning process

Parents with preterm babies in a neonatal care unit have particular psychological and practical needs, which may be met with individualised developmental and behavioural care programmes. 16–19 Moyer et al. 5 highlight the need to capture and report which types of interventions might support a multidimensional approach to transition from neonatal units to home for this group of infants.

Evidence indicates that early discharge programmes and integrated health-care approaches in neonatal units substantially shorten LOS without increasing health resource use. This approach complements strategies used in adult health-care settings, for which the discharge process is a key part of the patient experience. Hesselink et al. 20 report on a programme to improve adult health-care transitions from hospital to primary care across five European countries. They identified barriers to, and facilitators of, these transitions, which include low prioritisation of discharge consultations by health-care teams owing to busy workloads, insufficient preparation for going home, care at home not meeting individual requirements, and a range of discharge mechanisms from instructing patients and their families to shared decision-making. They conclude that patient and family involvement when preparing for home is determined by the extent to which health teams are patient focused and build discharge around patient wishes, needs and abilities. Further evidence suggests that involving patient carers in patient treatment, and setting provisional discharge dates early in the hospital stay, motivates and prepares them for discharge. 7 When the patient is a child, in this case a preterm baby, involvement and support of the mother, the father and other family members is of vital importance.

The POPPY (Parents of Premature babies Project) systematic review and report of parental experience described the key elements of family-centred care in neonatal units. 21 It found that transition between different levels of care, including hospital to home, was difficult for parents; families valued consistent communication, support in developing readiness for home and improved discharge information when making the transition home. 21 A number of possible cost benefits include reduction in readmission to hospital; reduction in non-scheduled attendance at EDs; increase in attendance at scheduled outpatient appointments after discharge; and reduction in unscheduled use of community health resources, in addition to improving parental confidence and reduced LOS. A risk factor for increased use of health services is parental perception of prematurely born infant vulnerability. 22

The transition from the LNU to home involves a complex process of adaptation by parents and systematic multidisciplinary approaches to families. 23 Discharge home needs to be planned, and families need to be supported by preparation, overnight stays in the unit, HV contact details, and having home visiting/outreach in place. Discharge planning, and the way in which discharge and adjustment to home takes place, are key elements in supporting this transition, especially when vulnerable babies have been very sick. In 2010, we contacted neonatal units across the UK to gain insight into existing discharge practice. This indicated that all participating units had nurse-led documentation, and existing discharge processes were rarely planned and were mainly reactive. These findings mirror Redshaw and Hamilton’s findings24 that family-centred care is inconsistent, despite being emphasised in Department of Health Neonatal Toolkit documents6 and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance. 25 Discharge planning has been shown to work best when it is mutually shared by neonatal unit teams and families. 3

Understanding and improving the discharge planning process for parents and their infants in neonatal units: the importance of parental confidence

McGrath3 noted that parents of infants in neonatal units focus on discharge and the care they need to deliver to facilitate this, even when their infants are in the early and acute phase of care. Parents’ ability to take in and retain complex and frequently changing messages from neonatal health professionals is limited under conditions of stress and anxiety during their baby’s stay on the neonatal unit. Few messages are perceived to be relevant to what parents need to learn and do on discharge from hospital. There is evidence that early practical involvement by parents in providing baby care in neonatal units leads to increased parental confidence and competence in their parenting skills, and greater willingness to take full responsibility for their infant’s care. 3

In the USA, the use of a health-coach programme to prepare families of infants with complex medical problems or born prematurely was explored. 5 The programme sought to help them to act as advocates for their infants. Families receiving health coaching were more likely to view the transition from hospital to home as positive within a few days of discharge, and to report confidence in knowing how to care for their baby.

Raines26 reported on the nature of stress experienced by mothers as they prepare to take their infants home from the NICU, in particular, mothers’ self-perceived ability to assume their maternal role. This challenge to mothers assuming their maternal role is echoed by Finlayson et al. 27 in their report of mothers’ perceptions of family-centred care in three English NICUs, where they describe mothers feeling unable to assume their role. Raines26 suggested that the mothers’ levels of stress impede their learning. She recommended that NICU staff should create low-stress environments where discharge education can be most effective when readying families for home.

Work in the USA and Canada on early educational interventions for parents in neonatal units has shown that parent–infant interactions may be enhanced and LOS reduced. 17 Parents’ concerns evolve as they move from NICU to home, and these may be addressed by providing timely discharge information and early anticipatory guidance to help build parental confidence as they move towards taking their baby home. 22 Supporting and involving parents in the process of preparing to leave neonatal units for home provides them with opportunities for confidence building in their abilities to care for their preterm infant at home. 23 In addition to uncertainty about their ability to care for their baby, a range of parental concerns have been identified when low-birthweight infants make the transition from NICU to home. These include breastfeeding proficiency and losing care from unit staff. 22,28,29

Parenting stress30 undoubtedly affects maternal self-efficacy. Furthermore, parental self-efficacy and parenting competence have been found to be moderated by parent knowledge of development31 and as a possible predictor of child functioning. 32 Teti and Gelfand33 have suggested that maternal efficacy beliefs mediate the effects of depression, social support and infant temperament on parenting behaviours. 33 Studies using infants within the first year of life have found that maternal prior experience34 and social support35 are positively related to maternal self-efficacy. Also, several authors have investigated the longer-term impact of low maternal self-efficacy. For example, Leerkes and Crockenberg36 found that mothers who had low self-efficacy were more likely to display less sensitive behaviour towards their infant (especially when their infant was highly distressed), were more likely to give up when trying to soothe their infant and also exacerbate infant distress.

Self-efficacy tools based on Bandura’s Social Learning Theory may be used to indicate the level of belief and confidence about one’s perceived ability to plan and carry out specific tasks. 37–39 Behaviour-specific scales have been developed to identify people with high or low confidence. Examples of such scales include the Breastfeeding Self-Efficacy Scale,40 Childbirth Self-Efficacy Inventory41 and the Perceived Maternal Parenting Self-Efficacy tool (PMPS-E)42 for mothers of infants receiving neonatal care. The PMPS-E tool is a psychometrically robust, reliable and valid measure of parenting self-efficacy for mothers of relatively healthy preterm neonates. We planned to use this to measure maternal and paternal confidence in caring for their baby at three time points. The developers of the PMPS-E agreed that it would be appropriate to use with fathers in our study, and one of the original authors of this measure (Barnes) was a member of the project steering group for the present study.

Development of parent-orientated approaches to planning for infant discharge from neonatal units

The UK development of focused, hospital-based outreach care rather than generic community-based care is similar to the system that has been developed over many years in Canada. McMaster Neonatal Unit in Canada developed an interactive discharge planning tool to achieve timely transfers between the various levels of care and to give families permission to speak and engage with the process. 43 When using the tool in neonatal units, parents asked more questions than before and the tool opened up dialogue between parents and staff. The Canadian project prepared families for transfer from NICUs to LNUs nearer their home. The Canadian tool emphasised the importance of communicating with parents and focusing on their needs and understanding rather than being driven by clinical staff perception of infant needs. Other features include helping parents to read their baby’s changing cues, and keeping baby and parental readiness as the focus of unit practice. Implementing the approach improved parental involvement in, and understanding of, the discharge planning process; however, a number of barriers to successful implementation were identified, notably a lack of direct engagement by neonatologists. Also some nursing staff thought the newly established discharge planning pathways were redundant because the constituent actions and information were documented elsewhere or formed part of normal nursing care. Despite these limitations, the implementation was successful, as parents and families in the NICU accepted it and engaged with the process.

In 2010, a research team member was seconded to the McMaster University neonatal unit to gain experience in using the intervention tool and investigate the feasibility of developing a UK version for an intervention study. In Chapter 4 of this report we present the outcome of this secondment and our subsequent development of a tool using the same principles but orientated to UK families and neonatal unit staff needs.

Summary and conclusions

Improved survival over the past few years means that large numbers of preterm infants spend long periods of time in neonatal care before being discharged home. There has been increasing awareness of the problems experienced by infants and their parents in the process of preparing for, and dealing with, the consequences of discharge from hospital.

There is growing understanding of infant and family needs for structured discharge preparation, early parental involvement in infant care, and support, before, during and after discharge; however, few neonatal units have structures in place to facilitate these processes and many families feel unprepared to take their baby home. This may contribute to delays in hospital discharge and/or inappropriate use of health-care resources after discharge, with recurrent infant readmissions and overuse of out-of-hours or other urgent care resources by families after infants go home.

Studies show the potential value of parent-orientated practical approaches to involving and educating parents about discharge planning during the infant’s hospital stay. Unfortunately, discharge planning and parental education remains poorly organised and unstructured in most UK neonatal units.

We have developed a UK version of a Canadian approach to preparing families for home using a parent-orientated approach to discharge planning based on underpinning principles of early involvement and empowerment of parents.

This report documents the implementation of this approach in four UK LNUs, and the effects of that implementation on parental self-efficacy scores, patterns and costs of health and social care resources use after discharge from hospital, and infants’ LOS in LNUs.

Literature search

Literature searches were completed by a University of the West of England Faculty Librarian and a Research Fellow in November 2009, and rerun in January 2010, with final searches being rerun in February 2015.

No specific date limitations were applied to the search on either occasion.

Databases: EMBASE; Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC); Maternity and Infant Care (MWIC); Ovid MEDLINE®; PsycINFO; Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) Plus; and Alternative Medicine British Nursing Index 3 (AMED).

Key words used:

neonatal unit* or scbu or special care baby unit* or nicu or neonatal intensive care unit*

prematur*) adj3 baby) or prematur*) adj3 babies) or prematur*) adj3 neonate*) or 32 week*) adj3 baby) or ‘32’) adj3 babies) or 32 week*) adj3 infant*) or 32 week*) adj3 neonate*).

discharg* adj3 plan*) or discharg*) adj3 meet*) or discharg*) adj3 manag*) or going home or leav*).

Chapter 3 Development and implementation of the intervention materials and approaches

The intervention materials used in this study were developed in three closely related, but separate, processes. The materials and innovative approaches to working with the parents of preterm infants were implemented in four LNUs. In this chapter we describe the background, development and implementation of the documentation, together with the approach we used to implement the intervention in LNUs:

-

development of a UK version of the McMaster University ‘train to home’ package

-

development of locally appropriate LOS estimates for infants at each gestational age included in the study

-

development of pathways of care for infants of gestational ages 27–30 weeks’ and 31–33 weeks’ gestation

-

implementation of the interventions in the four LNUs included in the study.

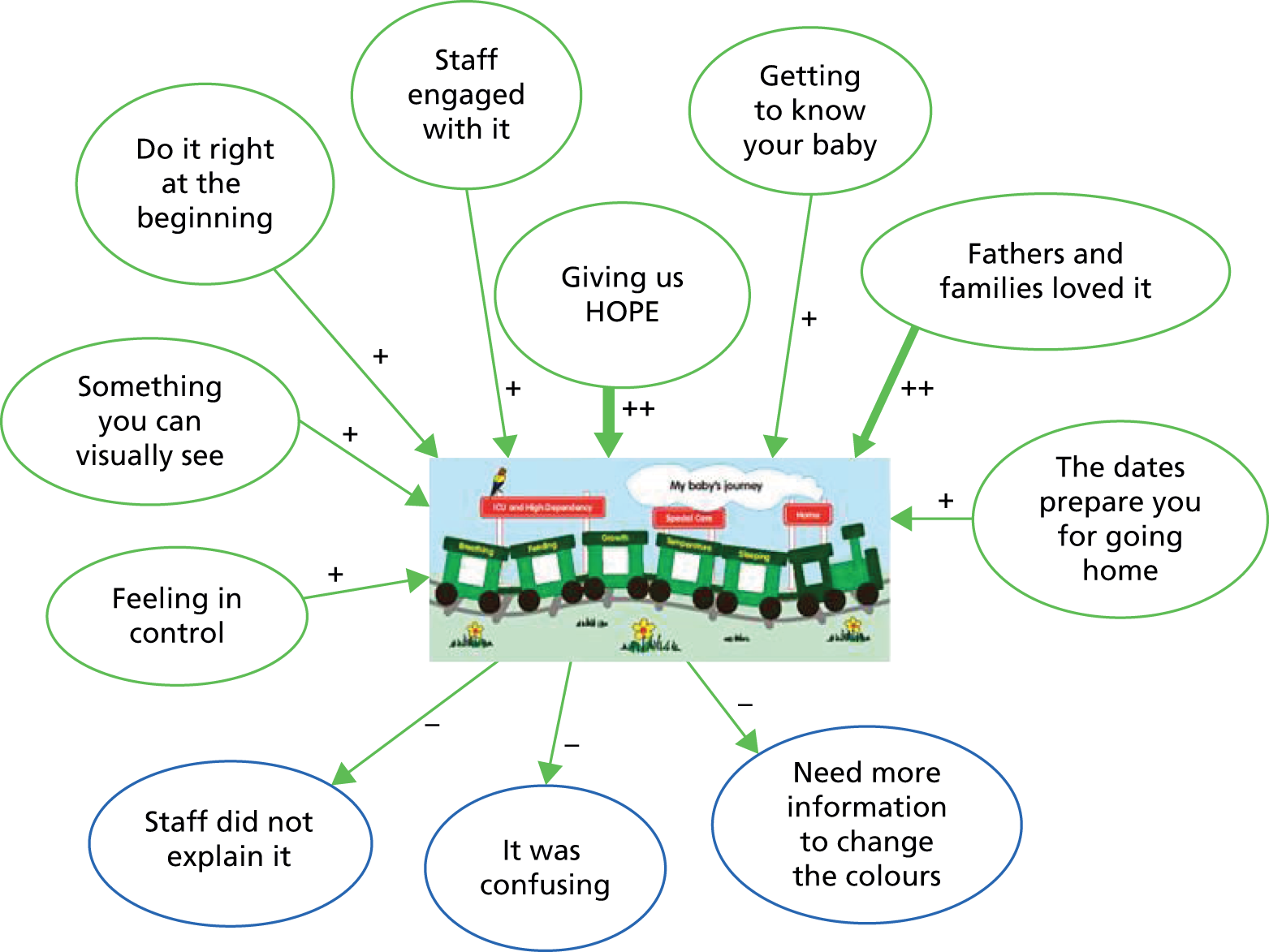

Development of a UK version of the McMaster University ‘Train-to-Home’ package

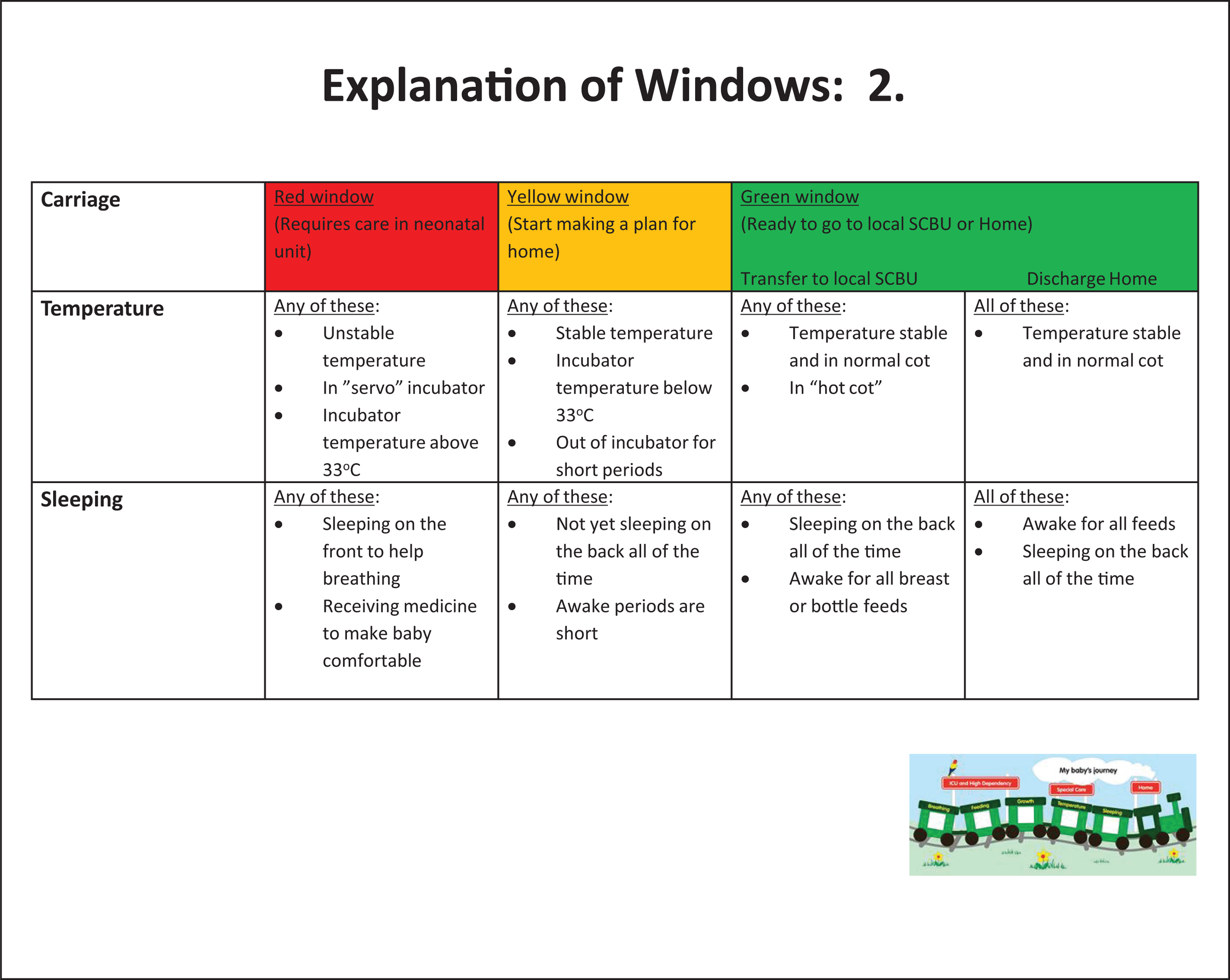

The original Canadian version of the ‘Train-to-Home’ tool used a visual image of a train with five windows, each representing an area of infant condition or care. The five windows represented ‘Tests’, ‘Jaundice’, ‘Growing’, ‘Feeding’ and ‘Breathing’. Each of the windows could be coloured green, yellow or red, depending on the medical condition of the baby. The medical and nursing staff at McMaster University had determined the criteria for colouring the windows in green, yellow or red. 43

Our initial feedback from UK medical and nursing staff who were shown the Canadian documentation was that it had a North American style and approach, and did not reflect the way in which UK medical and nursing staff discussed clinical problems with parents. We established a Parent Advisory Group (PAG) to support the project, whose members all had experience of having a baby in NICU. They also had strong views that certain parts of the Canadian documentation, particularly the emphasis on laboratory tests and neonatal jaundice, were not in line with their perception of how communications between staff and parents worked in UK neonatal units.

Developing a UK form of the ‘Train-to-Home’ package acceptable to the staff in the participating LNUs was the first stage of the study. We needed to ensure that LNU staff would use the documentation and to maximise the chances of that happening, we needed them to have a sense of ownership of this central part of the project.

One way of achieving this was to use a Delphi consensus approach to facilitate development. We considered this to be an appropriate way to maximise project participation by a large group of LNU professionals. Using a Delphi approach has been shown to minimise the risk of a single opinion or senior individual influencing group projects, in our case the content of the final document. It allowed suggestions to be assessed and considered for inclusion regardless of the person from whom they originated: that is, suggestions are viewed in their own right and on the basis of their own merits rather than in the light of who made the suggestion.

Development of the UK Train-to-Home package by a multiple iteration Delphi review process by the Parent Advisory Group and the Clinical Advisory Group

In order to develop a culturally appropriate and acceptable form of the train for use with UK families, nursing and medical staff, we set up two advisory expert panels, a PAG and a Clinical Advisory Group (CAG). The CAG included at least one experienced neonatal nurse and one consultant neonatologist from each of the four participating LNUs. CAG membership also included additional neonatal nurses and consultant neonatologists working in South West England but not in the four study LNUs.

In the first phase we consulted with CAG members individually by e-mail, seeking comments and suggestions on the content and wording of the McMaster ‘Train-to-Home’ documents. In particular, we sought relevant labels for each window, and the criteria to be used to determine window colour: that is, red, yellow or green. The initial responses from each CAG member were not shared with other group members. CAG members were asked open-ended questions on the content and wording of the original McMaster documents, and asked to suggest alternatives to those parts of the documentation that they felt were not appropriate for use in UK neonatal units.

The responses received were collated, categorised and included as a series of unattributed suggestions attached to the original McMaster documentation. These were then forwarded to CAG members individually. Responses from the second round of the Delphi process were collated and a new version of the documentation was constructed using the majority of suggestions received. Where there were significant differences of opinion between CAG members about aspects of the revised documentation (e.g. about how best to categorise types and levels of ventilatory support), these were identified as alternatives and were again forwarded to each CAG member with specific requests for them to consider which approach or wording was the most appropriate. Again, the individual responses from each CAG member were not initially shared with other members of the group. The differences of views were predominantly related to the most appropriate cut-points to use to distinguish between different levels of support that might represent points of change between the different coloured windows, for example the combination of level of inspired oxygen and the use of continuous positive airway pressure to separate ‘red’ from ‘yellow’, and all were easily resolved at this stage.

After the third Delphi round, the documentation was revised in line with the suggestions received, and e-mailed to each member of the PAG for comments and suggestions about content and wording. Delphi methodology was used to involve PAG members individually and seek their comments and suggestions before convening a full PAG meeting to discuss the documentation and suggestions from parents already received. PAG suggestions were incorporated into the third iteration of the documentation. Medical and nursing members of the Project Steering Group reviewed the third iteration, and appropriate comments and suggestions were incorporated into the documentation.

At this stage the proposed documentation was sent, for review, to the senior nurse and a nominated consultant neonatologist in each of the four participating neonatal units, and to ensure that the proposed boundaries defining the red, yellow or green windows on the train were compatible with current management of infants within the defined gestational limits in each of the neonatal units. This process led to a number of relatively minor changes to the definitions of levels of care used in several of the categories, and these changes underwent a further iterative process of refinement to ensure that the wording and definitions used were compatible with current management in all four units.

Finally, a meeting was convened of all members of the CAG, together with the other medical and nursing staff in the participating units who had been involved in the process of developing this documentation who were able to attend – either in person or by telephone conference call. At this meeting the structure, content and presentation of the proposed modified Train-to-Home documentation was discussed and a final version agreed.

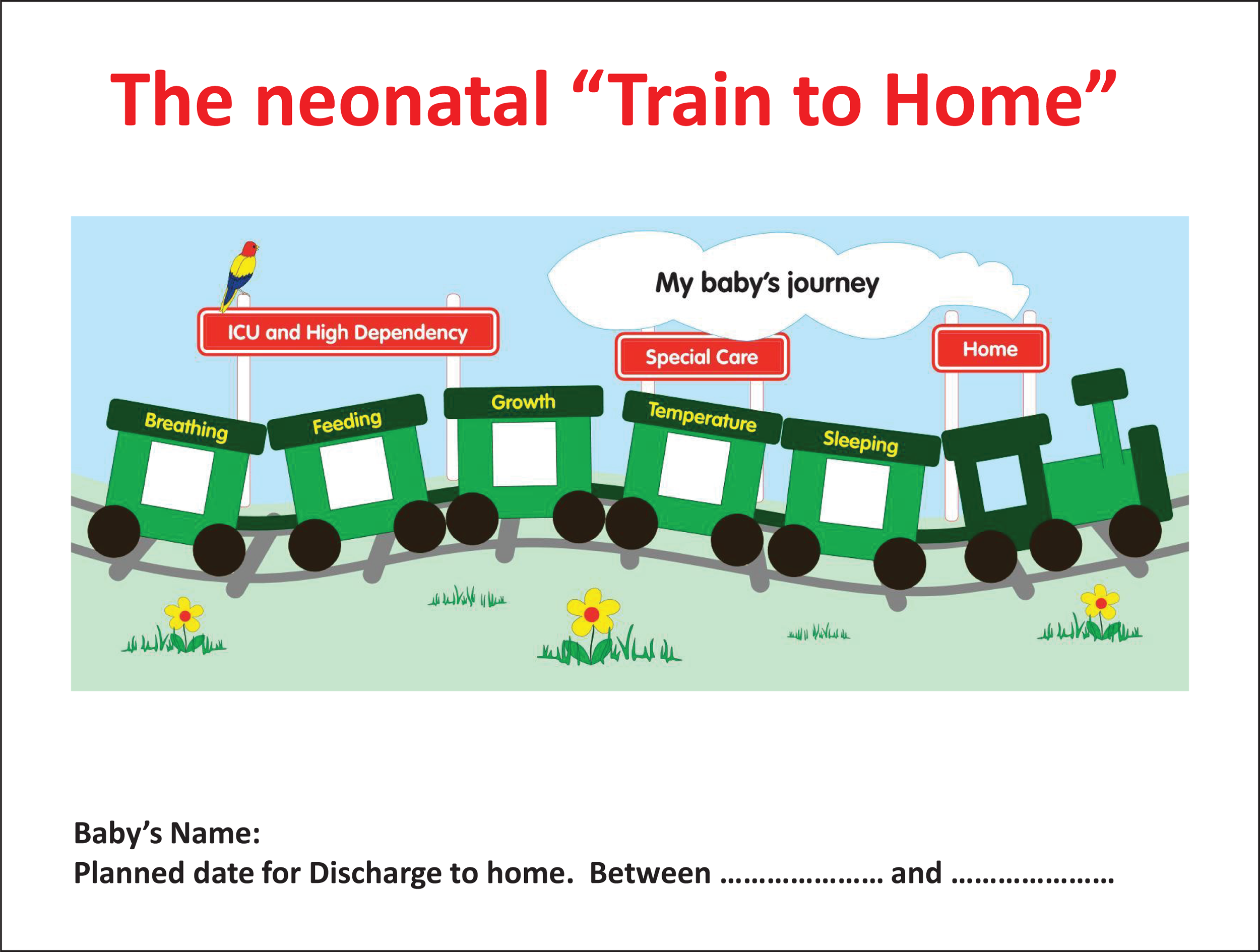

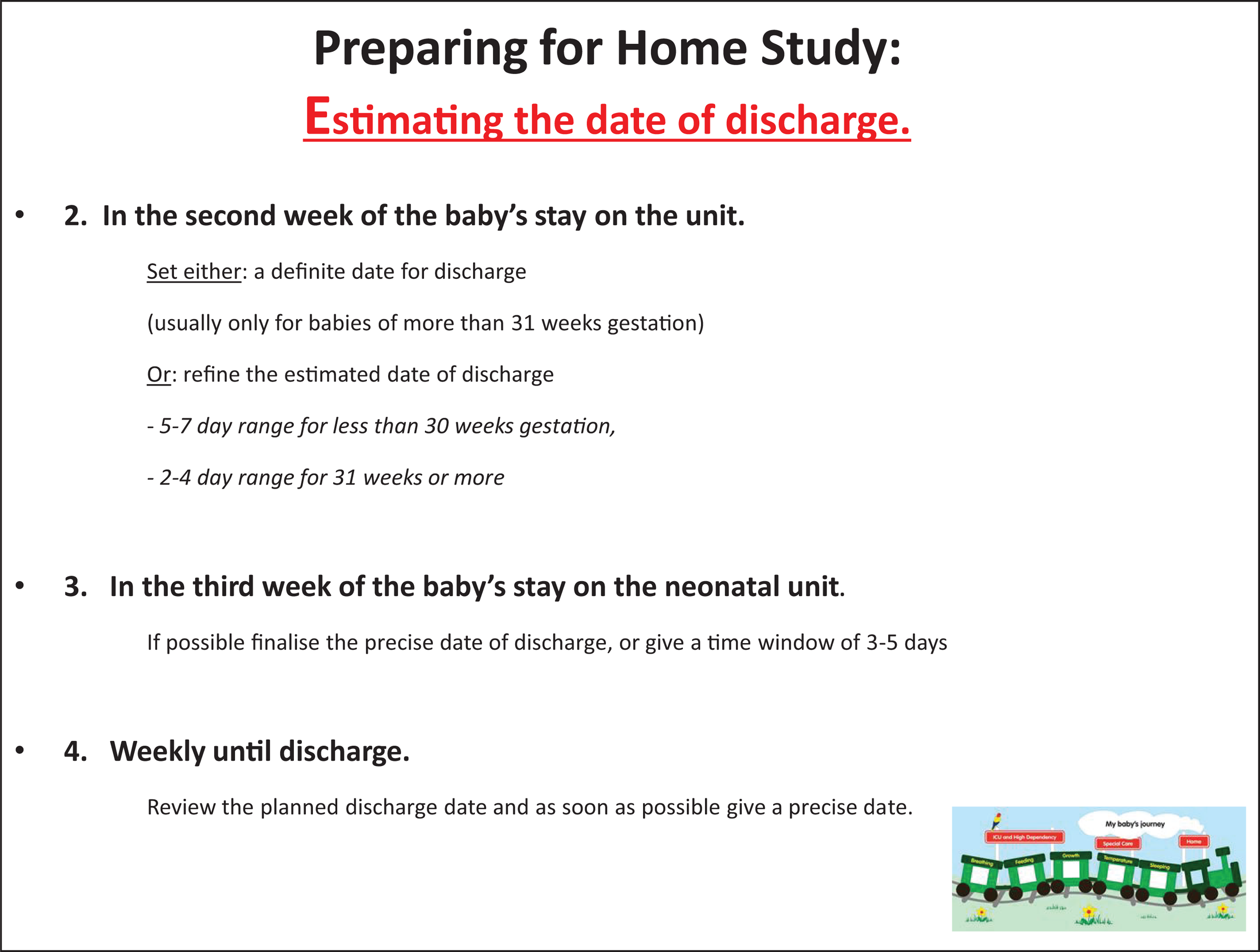

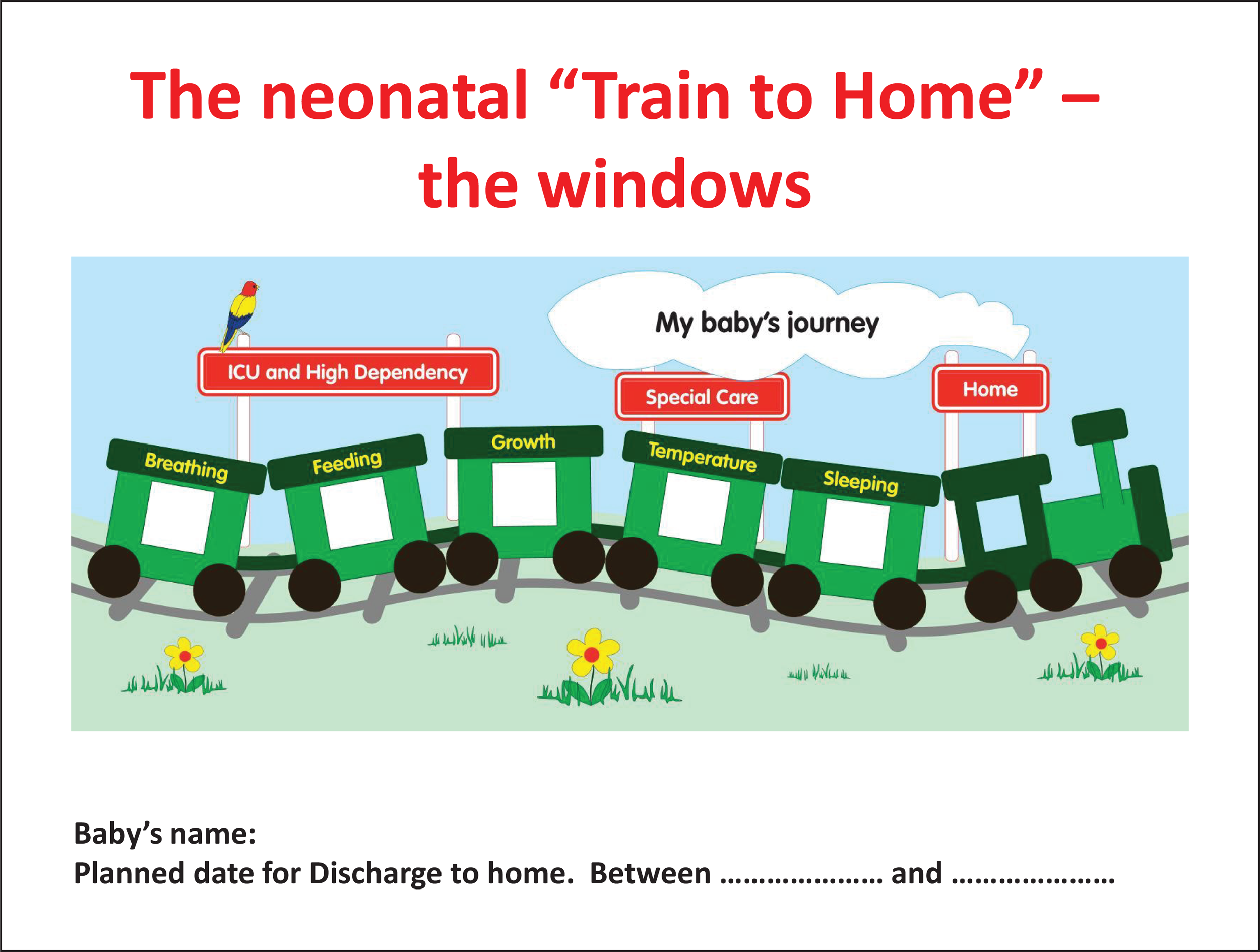

This final version (Figure 1; for further details see Appendix 1) was then sent to the lead consultant neonatologist in each of the four participating neonatal units for formal approval. Once this approval had been received the documentation was adopted by the Project Management Group and the Project Steering Group for use in the study.

FIGURE 1.

The ‘Train-to-Home’ package (© University of Bristol and University of the West of England).

Development of locally appropriate length of stay estimates for infants at each gestational age included in the study

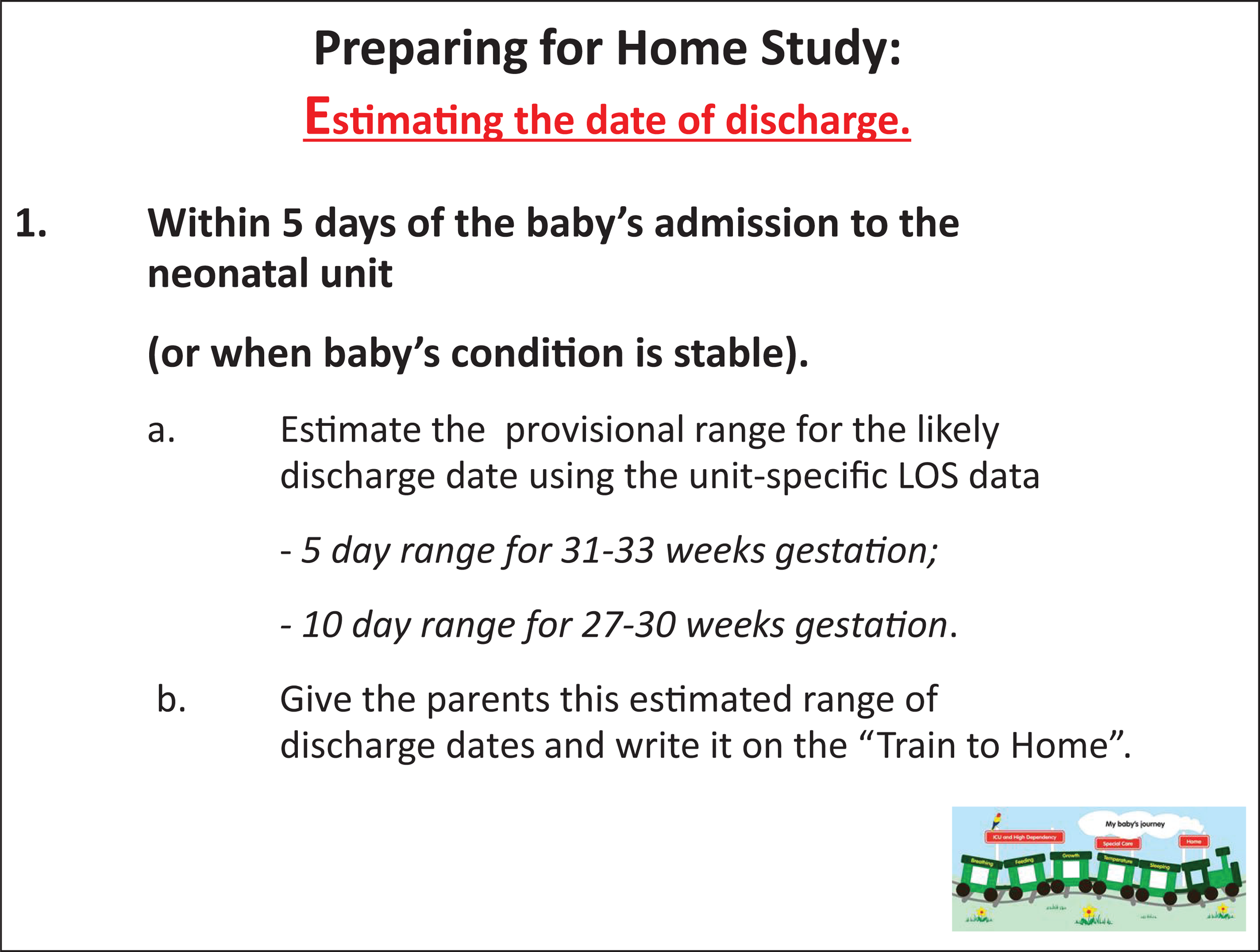

Estimating the likely date of discharge for preterm infants from 27 to 33 weeks’ gestation inclusive

We collected data from the routine neonatal database used in South West England (‘BadgerNet’) to estimate the likely discharge date for infants in the study’s gestational age range. Data were collected on all infants in the gestational age range of 27 weeks 0 days to 33 weeks 6 days, who were born in the four study LNUs from 1 April 2011 to 31 March 2013 (a few months before the planned implementation date for the intervention used in the study). We included only those infants who were born in, and discharged to home from, the same LNU. Those infants who were transferred to a regional NICU but transferred back to the LNU in which they had been born, and subsequently discharged to home from the original LNU, were included. Infants who were transferred from the original LNU to another unit from which they were then discharged home and those who did not survive to discharge home were excluded. The ‘Badger’ database provided information on gestation at birth (in weeks and days) and age in days at the time of discharge to home for all infants in the target gestational age range.

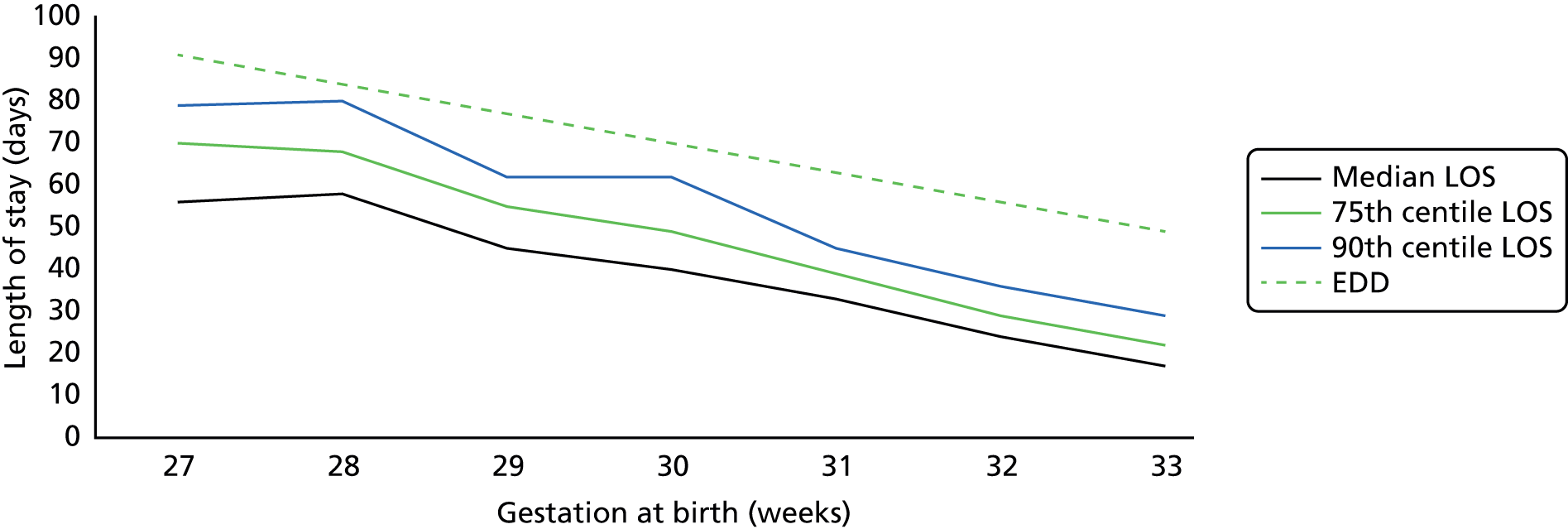

Overall, 531 infants met the criteria and were included in the study. In order to achieve large enough groups of infants to assess LOS, we aggregated the data into weeks of gestational age rather than weeks and days. We then calculated the median (50th centile), 75th and 90th centiles for LOS for each week of gestational age within the study range. The numbers of infants at each week of gestational age are given in Table 1, together with the median, 75th and 90th centiles for LOS for infants in each gestational age group.

| Gestation (weeks) | Number of infants | Median LOS (days) | 75th centile for LOS (days) | 90th centile for LOS (days) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 27 | 26 | 56 | 70 | 79 |

| 28 | 40 | 59 | 68 | 80 |

| 29 | 39 | 45 | 55 | 62 |

| 30 | 55 | 42 | 49 | 62 |

| 31 | 82 | 33 | 39 | 45 |

| 32 | 118 | 24 | 29 | 36 |

| 33 | 171 | 18 | 22 | 29 |

These data are shown graphically in Figure 2. There was considerable random variation in the 90th centile for LOS because of marked variation in the condition and progress of a small number of infants at each gestation, but for infants of all gestations the 90th centile gave a discharge date considerably sooner than the baby’s EDD, equal to 40 weeks’ gestation. The 75th centile showed a more consistent pattern of change with increasing gestational age, although still showed some week-to-week variation. Overall, the 75th centile for the infant’s postmenstrual age (gestation plus postnatal age) at the time of discharge home was between 36 and 37 weeks for all gestations, except for babies born at 28 weeks, for whom it was 37 weeks and 5 days. In other words, the great majority of preterm infants went home 3–4 weeks before the mother’s original EDD, which is the measure that, until now, has been the one most commonly used by neonatal staff to estimate the likely date of discharge for preterm infants.

FIGURE 2.

Median, 75th centile and 90th centile for LOS and estimate date of delivery for preterm infants, 2011–13.

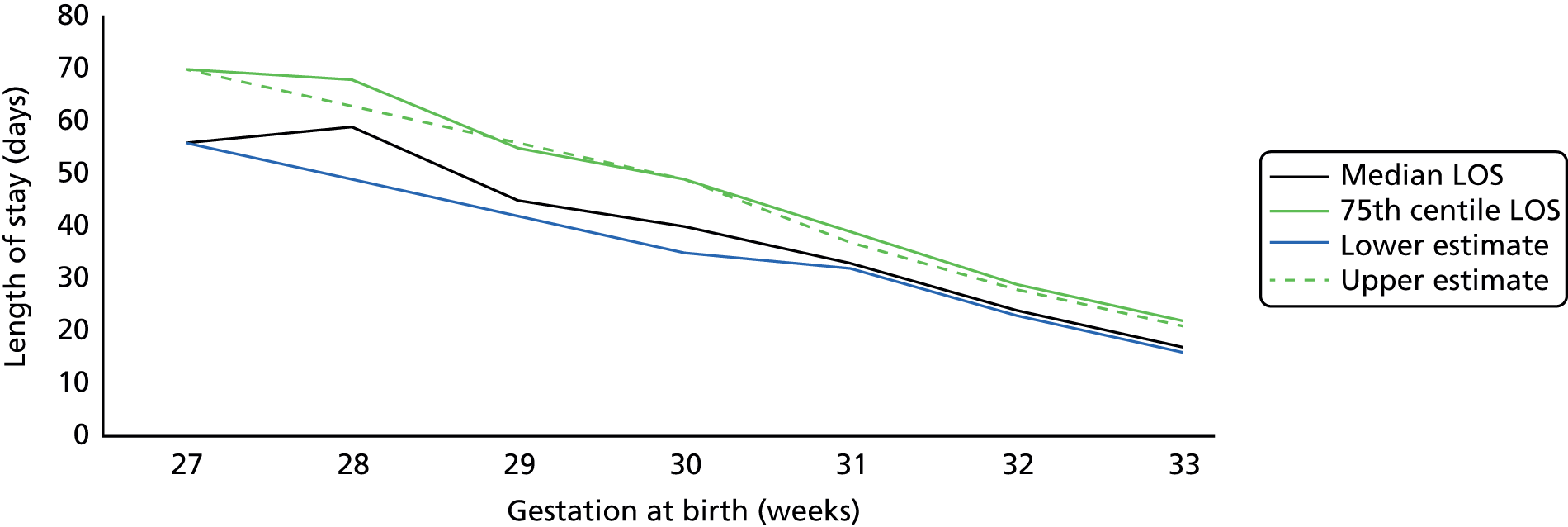

We needed a consistent and usable chart to allow medical and nursing staff to give parents – within 7–10 days after an infant’s birth – an estimated range of dates for discharge from hospital to home. We decided to use the 75th centile, and to smooth the data to avoid the likely random variations in recorded LOS over only a 2-year period. To make the chart usable and avoid staff making time-consuming calculations for each baby, we included estimated LOS in whole weeks for immature infants of < 31 weeks’ gestation. The more mature infants would mostly be discharged home in < 5 weeks, so we gave the estimated LOS in weeks and days. For simplicity and ease of use, we gave a 2-week range of dates for the less mature infants and 5 days for the more mature infants.

Consultation with the CAG and PAG during the development phase indicated that the range of estimated dates should be no wider than 2 weeks for less mature infants, and should be < 1 week for the more mature infants to be helpful in infant discharge planning. The project aim was to refine the initial range of estimated dates for discharge as the infant progressed through the LNU. As more information became available about each infant’s progress, the estimated dates could be adjusted and the window narrowed.

Figure 3 shows the upper estimate of the LOS, based upon the smoothed 75th centile line (representing the initial estimate of the date by which most infants would have been discharged) together with the earlier limit of the estimated date of discharge, superimposed upon the median and 75th centile lines shown on Figure 2. For all gestations the lower estimate of likely discharge date was just below the median LOS.

FIGURE 3.

Median, 75th centile and estimated LOS for preterm infants based on data from 2011 to 2013.

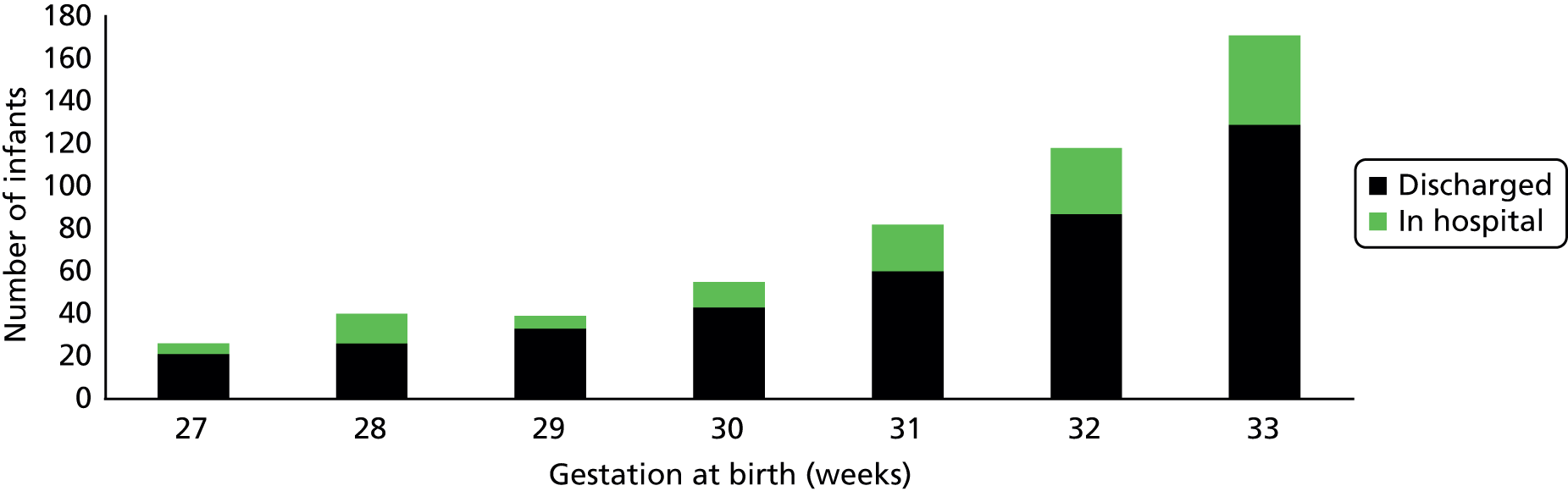

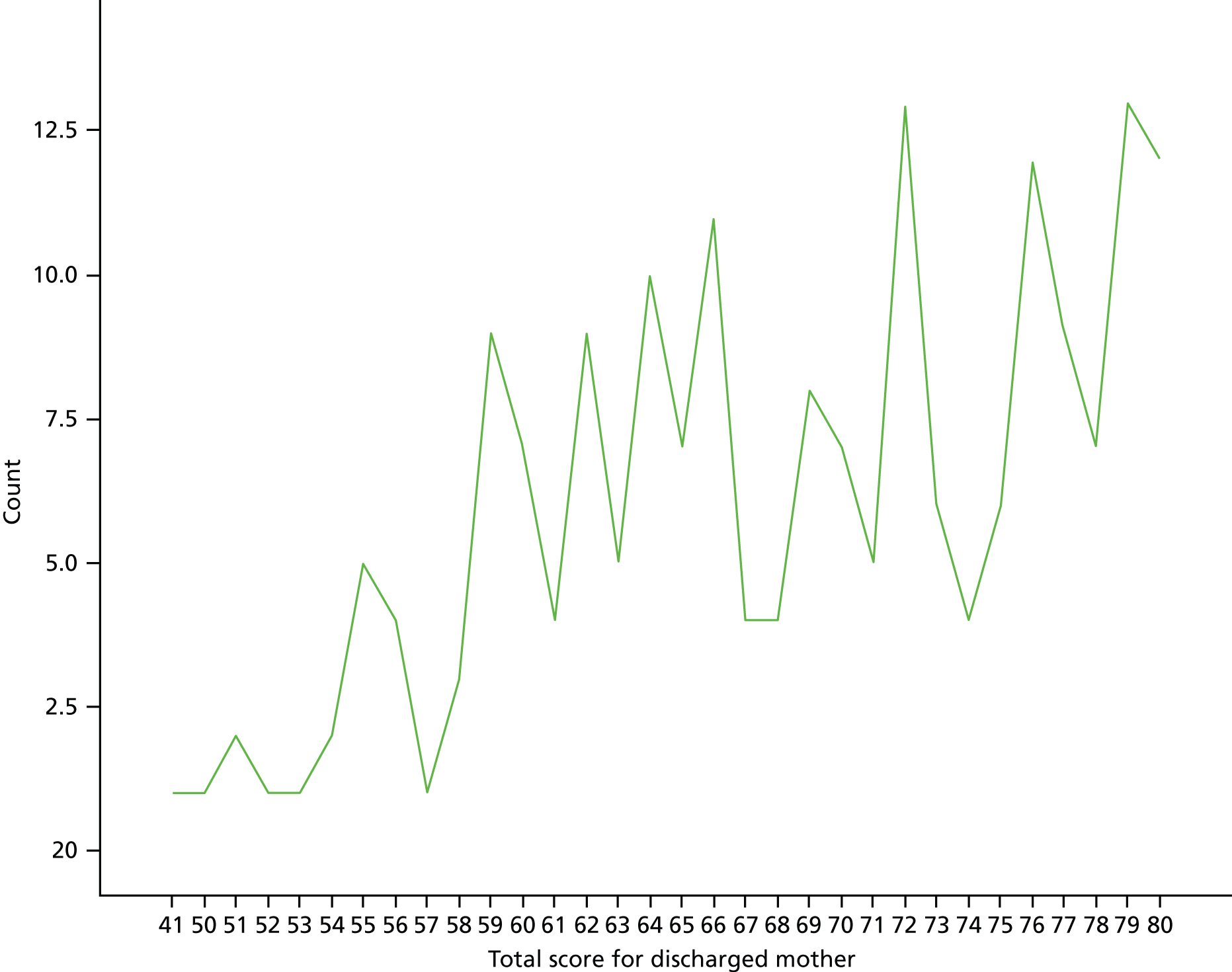

Using 2011–13 data, this range of estimated dates indicates that 77% of infants born at 27–30 weeks’ gestation inclusive would have been discharged home by the later estimated date based on the smoothed 75th centile, and 75% of infants born at 31–33 weeks’ gestation would have been discharged home by this date. The irregularity in the LOS at each gestation meant that there was a larger variation in the proportion of infants discharged home by the later estimated date for some gestational ages (Figure 4). This is inevitable when using a small database derived from a cohort of infants born in a 2-year period. The proportion of infants still in hospital at the later estimated date of discharge was < 25% for all gestations with the exception of 28 weeks (35%) and 31 weeks (27%). For infants born at 27 and 29 weeks the figures were 19% and 15%, respectively.

FIGURE 4.

Numbers of infants at each gestation who had been discharged or were still in hospital by the later estimated discharge date based on data from 2011 to 2013.

The proportion of infants who had been discharged before the first of the two estimated dates of discharge varied between 50% (at 27 weeks’ gestation) and 27% (at 33 weeks’ gestation).

The final version of the tool that was used in the study is shown in Appendix 2.

Summary

We developed a reliable and simple tool to estimate the likely date of discharge home for infants of 27–33 weeks’ gestation born in the four study LNUs. This was based on the LOS of all infants born in the four units over the preceding 2-year period. We used the smoothed 75th centile for LOS as the later estimate of likely discharge date, with a 2-week window of likely discharge date for less-mature infants (< 31 weeks’ gestation) and a 5-day window for more mature infants.

This easy-to-use tool was applied to all infants within the target gestational age range within 7–10 days of birth, and gave estimated dates of likely discharge that were correct for > 75% of infants. The intention was to refine the initial estimated date of discharge on a 1- to 2-weekly basis as the infant progressed through the LNU (see Appendix 2).

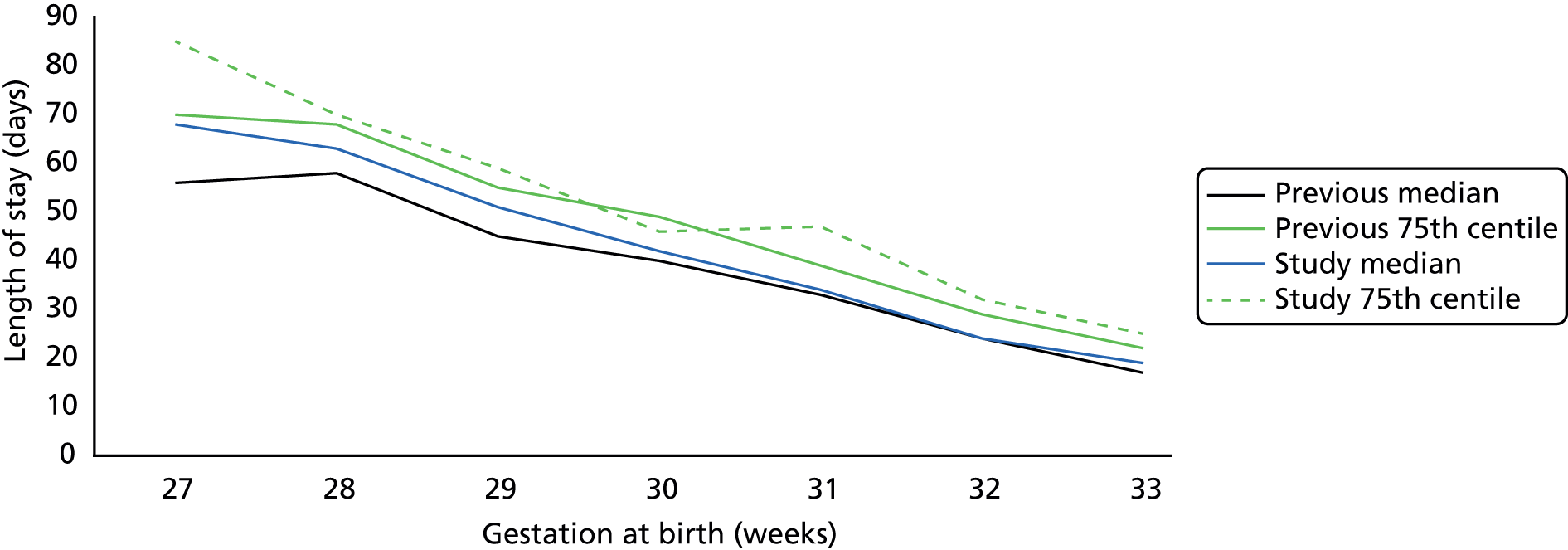

Actual length of stay by gestation for infants included in the study

Figure 5 shows the median (50th centile) and 75th centile of LOS for infants enrolled in the study from the four study LNUs. It shows that the median and 75th centiles for LOS recorded for each gestation for the study period were similar to those in the 2-year period used to develop the tool. However, for infants born at 27 weeks’ gestation, the previously collected data suggested shorter LOS than for infants in the study, although these differences did not reach statistical significance. At all gestations, between 50% and 75% of infants in the study were discharged by the later of the two dates suggested by the tool.

FIGURE 5.

Media and 75th centile for LOS for preterm infants prior to (2011–13), and during, stay period.

Despite considerable variation in infant LOS in the target gestational age range, the tool predicted a likely discharge date for all gestations, by which time close to 75% of the infants had been discharged home. The mean postmenstrual age (i.e. gestation at birth plus postnatal age) at discharge for infants during the study period and during the preceding period from which the above graphs were developed were 36 weeks/4 days and 36 weeks/3 days, respectively – a non-significant difference.

Development of pathways of care for infants of gestational ages 27–30 weeks’ gestation and 31–33 weeks’ gestation

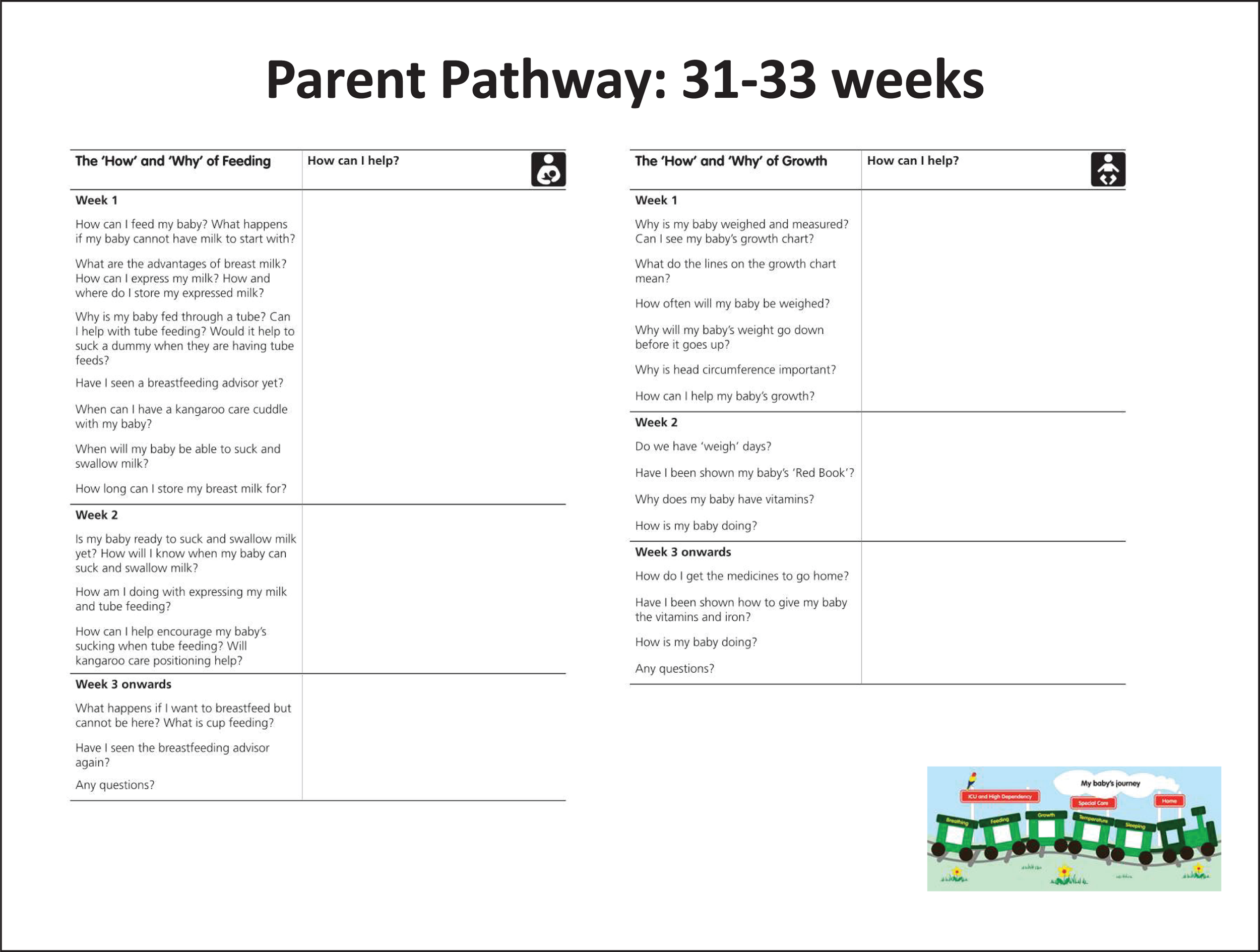

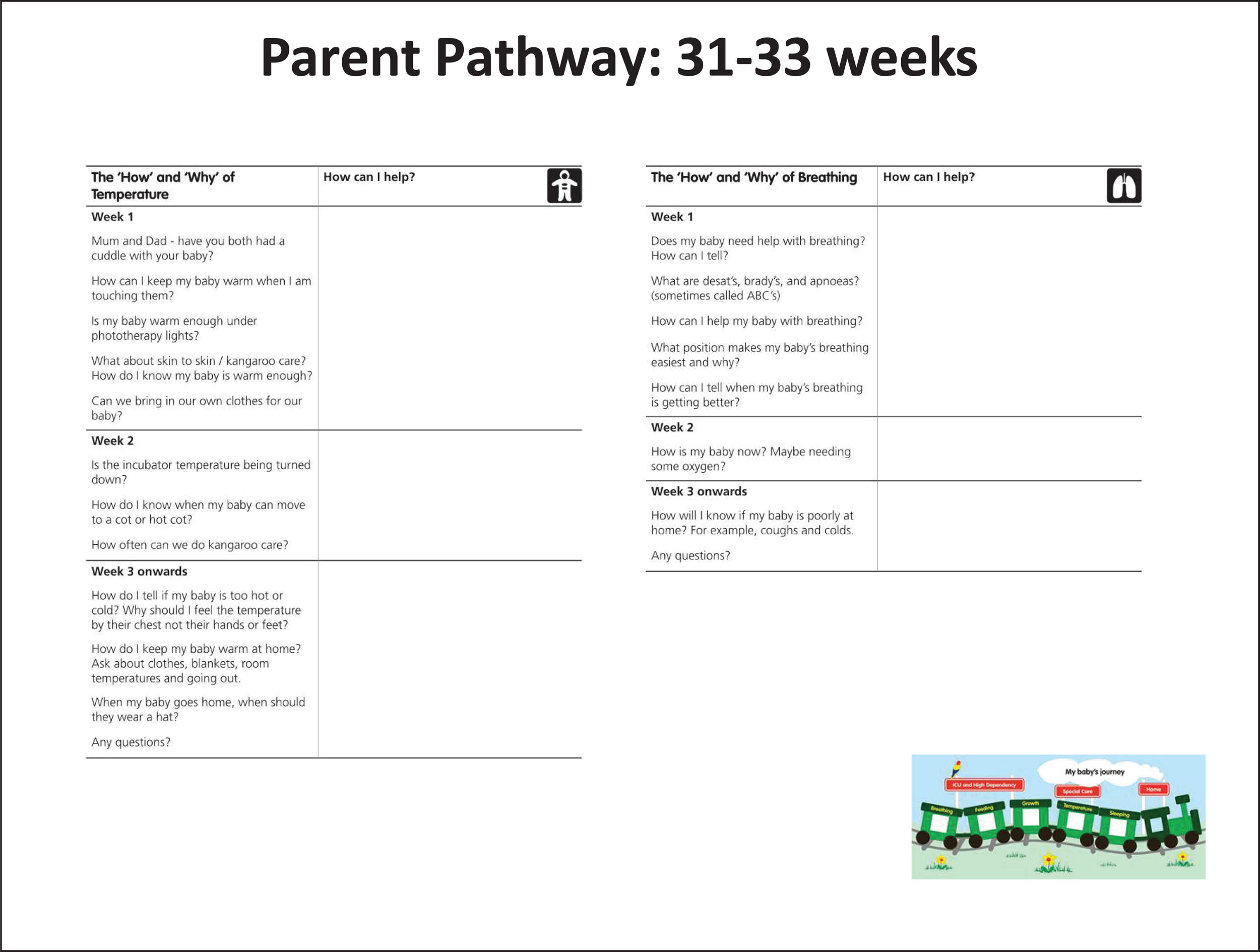

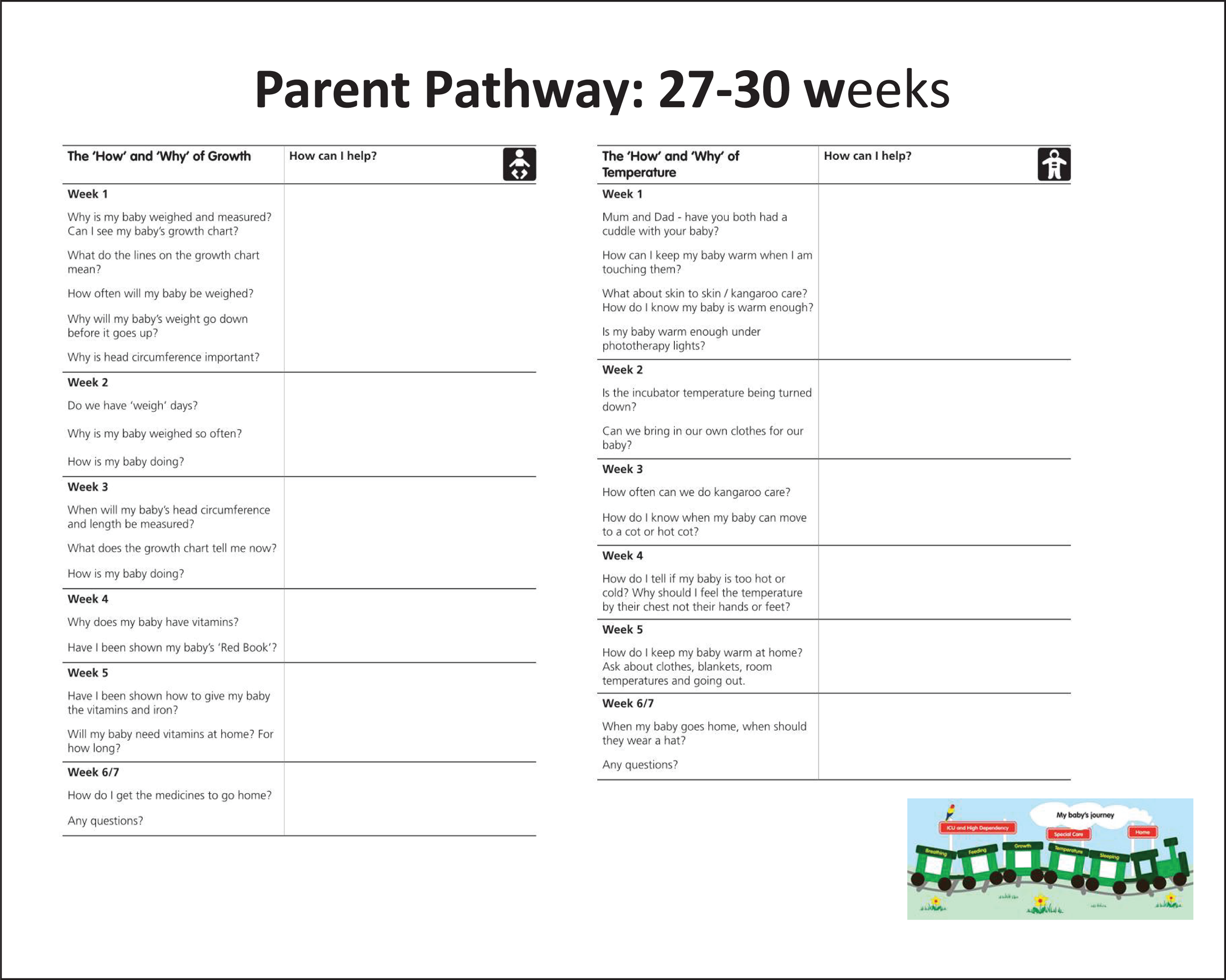

During the development of the UK Train-to-Home package, PAG members said that, in addition to parents having some indication of when their baby would be going home, it would be very helpful for them to have some indication of the pathway the baby might follow during their hospital stay. From our contact with Canadian neonatal units, we were aware that a number of Canadian ‘pathways to home’ had been developed and used to give parents an understanding of likely events and changes that might occur at each stage of a baby’s stay in Canadian NICUs. Unfortunately, the cultural difference in language used in these documents was unsuitable for use in the UK, as the information concentrated on technical aspects of infants’ care. With considerable input from PAG members we developed two pathway documents using the main subject areas described in the UK Train-to-Home package as a template: one for babies of 27–30 weeks’ gestation and one for babies of 31–33 weeks’ gestation.

A number of milestones that were likely to occur during a baby’s stay in a LNU were matched to each of the five areas of care and development symbolised by the train windows (breathing, feeding, growth, temperature and sleeping). In partnership with the PAG members, we linked questions about these milestones to the approximate time during the baby’s stay in LNU when they were likely to be raised or be relevant to parents. Each pathway covered the period from birth to discharge from hospital.

The draft pathway documents were reviewed and modified by CAG members. This iterative process was repeated, with a further review by PAG and CAG members until a form of wording acceptable to both groups was achieved. The final versions of the parent pathway booklets used in the study are shown in Appendix 3.

Implementation of the interventions in the four local neonatal units included in the study

We arranged a number of interactive briefing and training sessions for LNU staff in close consultation with lead clinicians, lead nurses and educational leads from each of the four study LNUs to explain the intervention, the documentation and the approach to be used during the intervention. LNU lead nurses identified two dates for the briefing and training sessions to be run to minimise operational disruption. Two briefing and training sessions per day were delivered.

Throughout the briefing and training events we emphasised that the intervention package was being introduced as a change to routine LNU policy for all infants in the target gestational age range 27–33 weeks inclusive, and was not itself a research intervention. All babies and families were to be involved in the changed approach, rather than only those who gave consent to take part in the study.

Briefing and training sessions: before and during the intervention

Pre-implementation briefing and training sessions took place in September 2013. The intervention started on 1 October 2013. During each session, the background to the project was introduced, as well as the nature and purpose of the intervention. Time was spent going through and explaining the documentation, and how it had been developed. Information was presented using a PowerPoint® (2010) (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) presentation supplemented by paper examples of each of the relevant documents. A project documents pack was given to each LNU attendee. Sessions lasted for between 45 and 60 minutes, with questions taken during the presentations and at the end. LNU attendee feedback was captured by immediate verbal feedback and anonymous written feedback. Feedback was reviewed after each session and used to improve the quality of subsequent presentations.

There was a 15-minute period in between sessions, which allowed for specific detailed discussion with individuals who had particular questions about the project.

The briefing and training sessions were delivered by PJF (a neonatologist) and HB (an experienced neonatal nurse). LNU attendees included a mixture of neonatal nurses, junior medical staff, ancillary staff and consultant neonatologists. Copies of the PowerPoint presentation were made available to each LNU lead clinician to facilitate ‘cascade’ teaching of other LNU medical and nursing staff. A copy of the PowerPoint presentation is given in Appendix 4.

Between 5 and 18 LNU members of staff attended the pre-implementation briefing and training sessions in each unit. At the end of the initial run of sessions we asked LNU lead nurses and lead clinicians to contact us when, and if, further sessions were needed. PJF and HB also visited the LNUs during the first 2 months of implementation to talk informally with LNU staff, answer questions from staff and parents, and arrange further sessions as required. HB delivered a further two to four briefing and training sessions in each LNU during December 2013 and January 2014. PJF delivered two additional sessions each – mostly to LNU junior medical staff in three of the four units. Other planned sessions were cancelled because of heavy LNU workload.

In total, 18 additional sessions were delivered in the four LNUs during the intervention period in addition to the 16 pre-implementation sessions. HB and PJF were available by phone and e-mail to LNU senior staff at each unit to answer queries arising during the intervention process during the period 1 October 2013 to 31 August 2014.

Feedback on the briefing and training session provided for the intervention implementation

A semistructured telephone interview with five of the six LNU lead consultant neonatologists on the briefing and training sessions was carried out at the end of the study. Comments are given below and identities anonymised:

The medical staff found the concepts interesting but the process was ‘not exciting’ to them. Nurses found the initial teaching helpful but it was difficult to cascade the teaching to other nursing staff.

This was really helpful. It was particularly helpful to be able to understand how the estimated discharge dates had been derived.

The teaching was well presented and well explained, but we (i.e. the staff on the unit) were probably too optimistic about how well we would be able to cascade the training to other staff – this was a problem at times.

It was difficult to keep staff up to speed with this because of the rapid turnover of staff – it would probably have been better if we could have made one or possibly two members of the middle grade medical staff responsible for ongoing teaching to ensure all staff understood the project.

The training provided was good and got everyone up and running but cascading training was very difficult – especially for nursing staff. Nurses (or at least some nurses) found it particularly hard to ‘hand over control’ of parts of the process to parents – though this improved as the study progressed.

Chapter 4 Research methods

Design

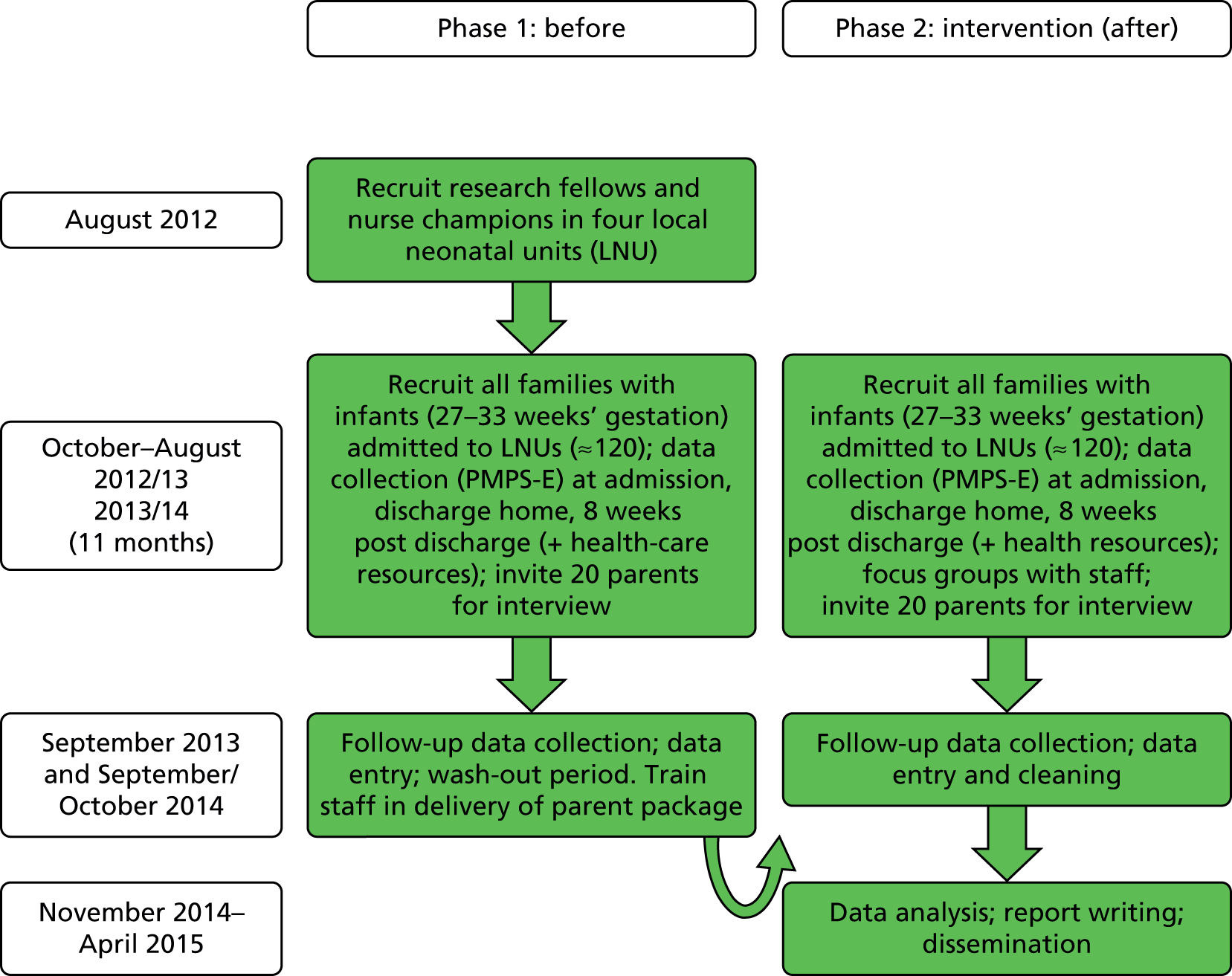

The Preparing for Home study used the PMPS-E (see Appendix 5) to measure parental perception of self-efficacy when caring for their infant soon after birth, at discharge home, and 2 months after discharge home. Parents were recruited to the study before and after the introduction of the parent-centred neonatal discharge Train-to-Home package, as shown in Figure 6. This was designed to facilitate and improve parental confidence in caring for their infant and their experience of discharge home.

FIGURE 6.

Study flow diagram.

Participant inclusion/exclusion criteria

Parents of infants born between 27 weeks 0 days and 33 weeks 6 days were recruited in four LNUs in South West England (Exeter, Taunton, Bath and Swindon). They were recruited during two 11-month periods (October to August in 2012–13 and 2013–14) before and after the introduction in the LNUs of the Train-to-Home package and parent pathways. Infants with major congenital anomalies, those from triplet or higher-order births, or mothers who were aged < 16 years were not eligible for the study.

Description of local neonatal units

The four units involved each had:

-

three or four intensive care cots, four high-dependency cots and 10–14 special care cots

-

between 30 and 53 nursing whole-time equivalents

-

shift patterns, with a combination of 12- and 7.5-hour early/late shifts

-

medical staffing comprising five to seven consultants on a rota, six to eight registrars and two to eleven senior house officers.

All units had experienced organisational change during the study period, some of which had effects on staff workload. All of the units were also working towards World Health Organization (WHO)/United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) Baby Friendly accreditation breastfeeding awards.

The Perceived Maternal Parenting Self-Efficacy and sample size required

The PMPS-E uses 20 statements and a four-point Likert scale (strongly agree to strongly disagree) to generate a minimum score of 20 (indicating a low level of self-efficacy) and a maximum score of 80 (indicating a very high level of self-efficacy). It has been validated using mothers (n = 165) of hospitalised preterm neonates (average age 31.9 weeks’ gestation) with a mean score of just under 60, and a SD of around 10, measured 10 days after birth. 42 A preliminary controlled study conducted by Barnes44 on potential changes in score over a 10-day period (using an intervention such as encouraging the mother to hold and stroke the baby) yielded a 10-point improvement compared with a higher than expected 5-point improvement among the controls (placebo effect). This suggests a potential medium effect size of 0.5 SD. Assuming a more moderate effect size of 0.4 SDs (equivalent to a 4-point improvement more than the controls) and 80% power with a 5% significance level and two-sided test we would need 100 parents in each group (200 in total).

Potential sample size available for the study

In 2010, 181 singletons and 81 twins were born between 27 weeks and < 34 weeks and admitted to the four intervention LNUs within the first week of life over an 11-month period (audit data from the Badger system). This suggested that we would have in excess of 220 mothers to invite into the study for each of the 11-month recruitment periods, of which at least 80% (n = 176) would be eligible for inclusion. If we recruited 70% of mothers with 20% loss to follow-up, we would recruit around 100 mothers per group. Our experience in previous similar work suggested very high uptake and relatively few families lost to attrition. If we achieved higher recruitment rates and lower loss to follow-up rates (i.e. 90% and 5%, respectively), we could recruit 150 mothers per arm, which would increase the power of the study to 93%.

Data collection

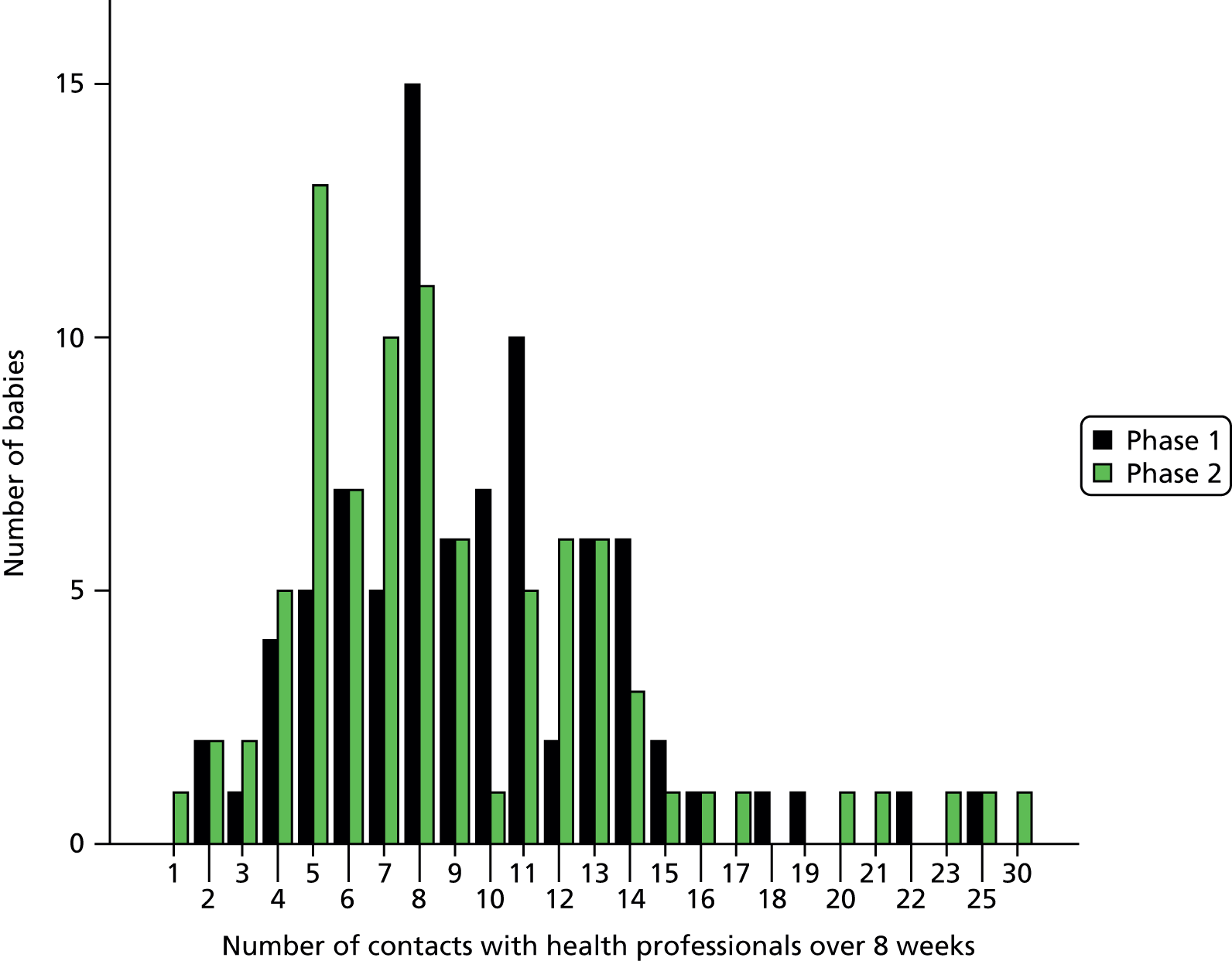

In each LNU, research nurses, or ‘nurse champions’, for the study screened all admitted babies for eligibility and gained parental assent to pass their details to the research team. Parental consent was sought by one of the study researchers and demographic information collected. Both parents were invited to take part in the study and they completed the PMPS-E tool within a few days of their baby’s admission to the LNU. A discharge pack was left in the LNU towards the end of each baby’s stay to be given to parents before they took their baby home. The researcher collected discharge information on LOS and feeding method. Parents were encouraged to complete their discharge PMPS-E questionnaires and leave them in a study box in the LNU. Their discharge pack also contained four 2-week health-care resource-use questionnaires and a further PMPS-E questionnaire to take home. The health-care resource-use sheets recorded all contacts (planned and unplanned) with primary and secondary health-care services fortnightly over the 8-week period from discharge.

Soon after discharge home, the study co-ordinator telephoned each family to check the discharge information, alert them to future calls to be made 4 and 8 weeks later and checked their preferred contact method (phone, text, e-mail or post). At the 4- and 8-week contacts, health-care resource-use data were collected for the previous 4 weeks. At the 8-week contact, the final PMPS-E questionnaire was completed, and families were asked if they would be happy to be contacted one final time for an interview. Data were double-entered on to a Microsoft Access® (Office 14) (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) database and, when data entry was complete, exported into Microsoft Excel® (Office 14) (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) for uploading into statistical packages.

Statistical methods

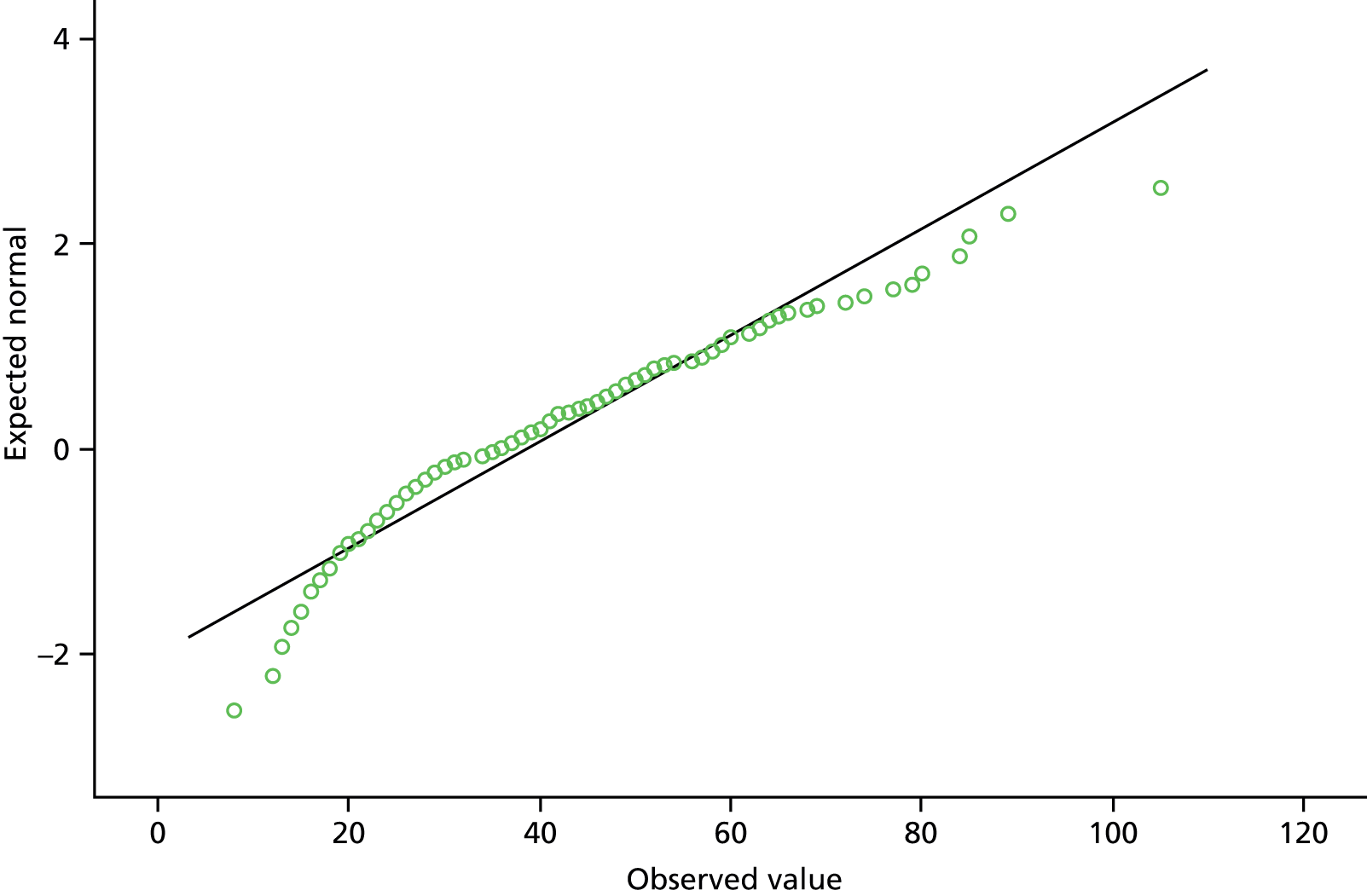

For proportional data, chi-squared tests were used to n – 1 degrees of freedom (df), and a Fisher’s exact test if the expected cell was < 5. Test of normality on continuous data was conducted using the Shapiro–Wilk test and observing the Q–Q plots. The Mann–Whitney U-test was used to compare unpaired data that were not normally distributed and both medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) were reported to describe these distributions.

Multivariable linear regression modelling was used for all variables with valid values to assess the mean differences in PMPS-E scores and 95% confidence interval (CI) between phase 1 and phase 2 at discharge and 8 weeks after discharge; the dependent variable was PMPS-E score at discharge or home and independent variable was the group effect, adjusted for baseline scores. A number of family factors, maternal factors (including pregnancy history) and infant factors were collected for modelling, to be used only if significant differences were identified between the two time periods. As this was not a randomised controlled trial (where differences at baseline could be considered as random), we included any differences in the model if significant at the 5% level. The primary analysis (maternal PMPS-E scores) was conducted on an intention-to-treat basis.

For the primary analysis, multiple imputation techniques were used as a sensitivity analysis to account for missing values. A multivariable imputation model was used to predict missing PMPS-E score values. The standard errors (SEs) of the predicted mean values at each time point were corrected using Rubin’s rule. A per-protocol analysis was conducted as part of the exploratory analysis, which also included an investigation of paternal PMPS-E scores, maternal PMPS-E subscale scores and an investigation of between-centre variation.

Statistical analysis was performed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 21 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) and Stata v13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Qualitative methods

Parent interviews

Semistructured telephone interviews were carried out with a sample of parents. They explored their experiences of time spent on the LNU caring for their infant, perceptions of communication with staff about their infant’s condition, their infant’s discharge to home, and contact with health services after discharge. Two months after discharge, parents were contacted by phone to complete the final PMPS-E and health resource-use questionnaires. At the end of this call, parents were invited to take part in a semistructured telephone interview at a time of their choice. The researcher explained that they would be contacted once more by phone to answer more in-depth questions about their experiences of having an infant in the LNU, preparation for discharge and contact with health services since discharge.

Parents were purposively selected for interview from those who had agreed to further contact and could be contacted by phone. Maximum variation sampling was used to interview parents from different ethnic and socioeconomic groups, with babies of different gestational ages from single and multiple births. Theoretical sampling was used to develop emerging findings by targeting participants with characteristics of interest (such as younger or first-time mothers).

Interviewers used a topic checklist so that similar areas were covered during each study phase, but with flexibility so that parents could raise issues of importance to them (see Appendix 6 for topic guides). Interviews in phase 2 were also used to explore and understand parents’ views and use of the parent package. The topic checklist was developed with the PAG using relevant literature and insights from study management team meetings.

Nursing and medical staff focus groups and interviews

After family recruitment was completed in phase 2, arrangements were made with the LNUs for researchers to run focus groups with nursing staff in each unit. Visit dates were advertised widely throughout the LNUs several weeks in advance to encourage good attendance. Managers arranged the focus group timings to fit in with staff rotas, usually early afternoons. One-to-one interviews were arranged after the focus groups for staff unable to attend the groups. Short telephone interviews were carried out by a senior researcher with consultant neonatologists from each LNU in early 2015. These interviews were not audio-recorded, but detailed and careful notes were taken and transcribed immediately after the interview.

Qualitative analysis

Parent interviews and nursing staff focus groups were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Data items were systematically assigned codes using the qualitative data organisation package NVivo 2010 (QSR International Pt, Warrington, UK). Thematic analysis used constant comparative techniques so that emerging themes could be tested in subsequent interviews. 45 Data analysis was an iterative process that informed further sampling and data collection. Three members of the research team analysed 10% of the data independently to compare coding and enhance its rigour: two researchers independently both analysed most of the interview transcripts and the third researcher selected two early interviews from each phase and from different units to check the coding. Descriptive accounts were produced, and theoretical explanations for behaviours, opinions and decisions were developed.

Health-economic methods

Rationale for approach to design of economic analysis

Our research study evaluated an intervention that the units had all agreed to adopt as a unit policy. Although we provided (unfunded) assistance and training in achieving this, the aim of the study was not to implement the package but to evaluate its efficacy in neonatal units that had implemented it as a part of routine infant and parent care. Thus analysing the costs of developing the intervention and training the staff using a standard costing approach was not appropriate or relevant information for decision-makers. It is important to recognise that commissioners/sponsors of interventions want to see cost savings demonstrated before they will consider rollout of an intervention that is feasible to implement and acceptable to service users. One of the tensions throughout this project was that some staff in the units were unclear about the nature of the study, and some assumed that they needed to use it only with families who agreed to take part in the research. However, delivery of the Train-to-Home intervention was separate from involving families in answering our questionnaires (the PMPS-E and health-care resource-use tool in the 8 weeks after discharge). The changes associated with use of health-care resources before and after implementation of the Train-to-Home intervention using before-and-after samples, 1 year apart, were costed and did not consider the cost of implementation of the intervention.

Development of the health-care resource-use tool

Resource-use data tools are often designed by developing new questionnaires for each study or modifying questionnaires from a previous study. They are not necessarily validated in their current form, unlike patient-reported measures of health outcome. 46 They need to be appropriate, study specific and easily understood so that participant recall and self-report is accurate. We designed a short data collection tool so that parents could complete it during a busy and stressful time as they were caring for preterm infants during an 8-week post-discharge period. It also needed to be long enough to collect data for estimating cost changes from the perspective of the NHS primary and secondary care, society, and families and carers. Our resource-use data collection tool was piloted with the PAG to check ease of completion and understanding before submission for ethical approval (see Appendix 7). The questions were in four blocks: unplanned use of, and contact with, secondary care services; planned outpatient follow-up contacts; family costs from using those services; and use of primary care and other therapists.

Data preparation and cost estimation

Health resource-use data were entered into the Access database, downloaded into Excel spreadsheets and prepared for cost analyses. The data were reviewed manually to identify low coverage or no-response items, and to clean the data for analysis. There were significant numbers of low-/no-response items in question 2 regarding use of trains, buses, overnight accommodation and number of days off work; these variables were removed from the database. Contact with a health professional – face to face and by telephone, and duration of contact time – was separated out and combined, so that each case had one entry indicating the frequency and duration of contact time by each health professional and contact type. This allowed resource-use volumes and the price of those resources to be treated separately in estimating costs when this was applicable.

Costing the care provided in the LNUs is complex because different tariffs or prices are attached to each care level and recent price information to estimate costs at each level of prematurity is not accessible. This mirrors the costing difficulties reported in the Toolkit for High Quality Neonatal Services. 6 Therefore, we have used proxy prices and recorded their sources, and listed assumptions, unit cost estimates and sources of prices used to calculate costs in Appendix 8.

These data were checked against the health resource-use database and added and/or corrected. Resource-use data in volume units were combined with price and unit cost information from published sources47 to estimate costs per item in pounds sterling (2014 prices). All variables were named and defined (see Appendix 8).

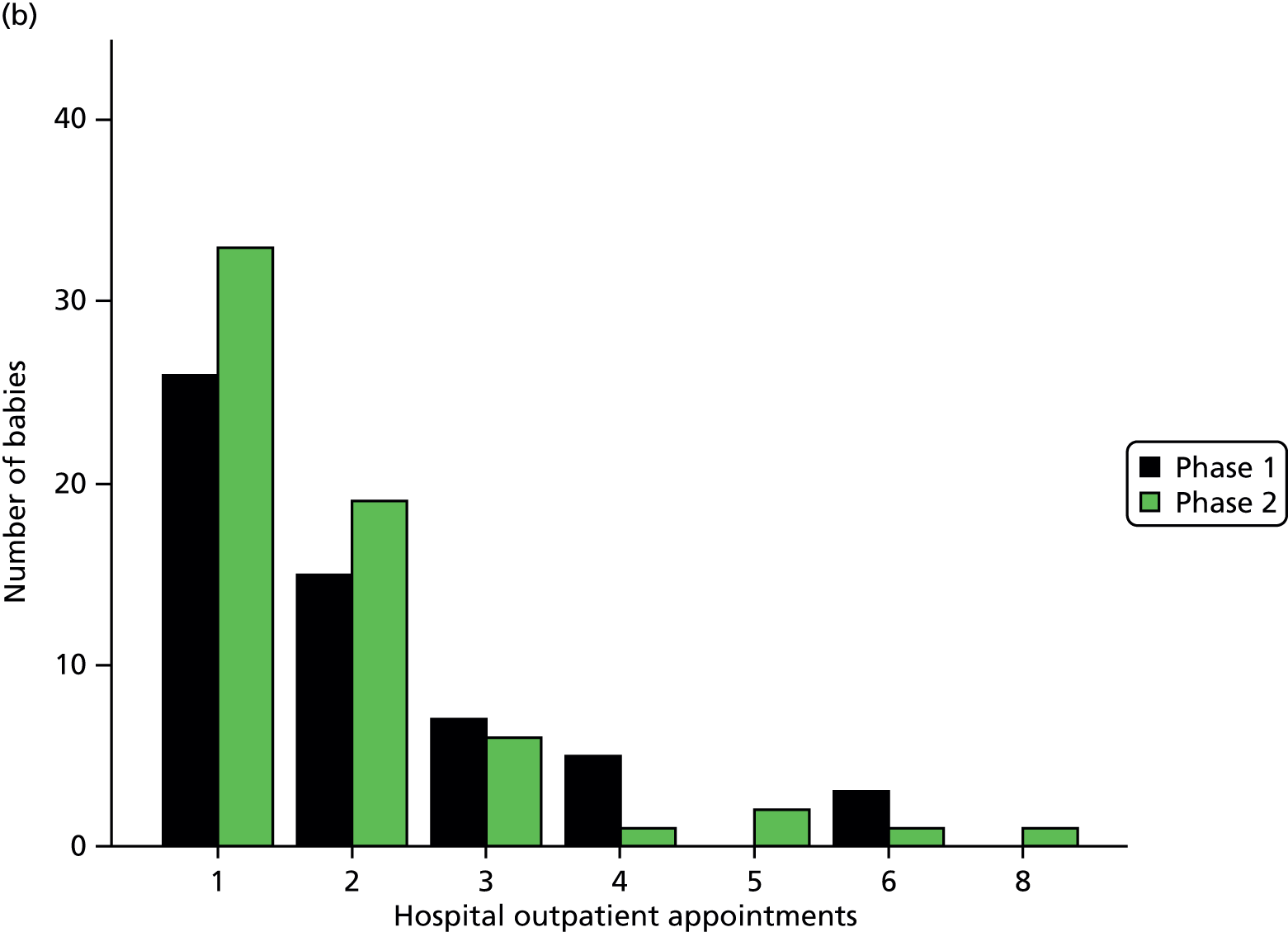

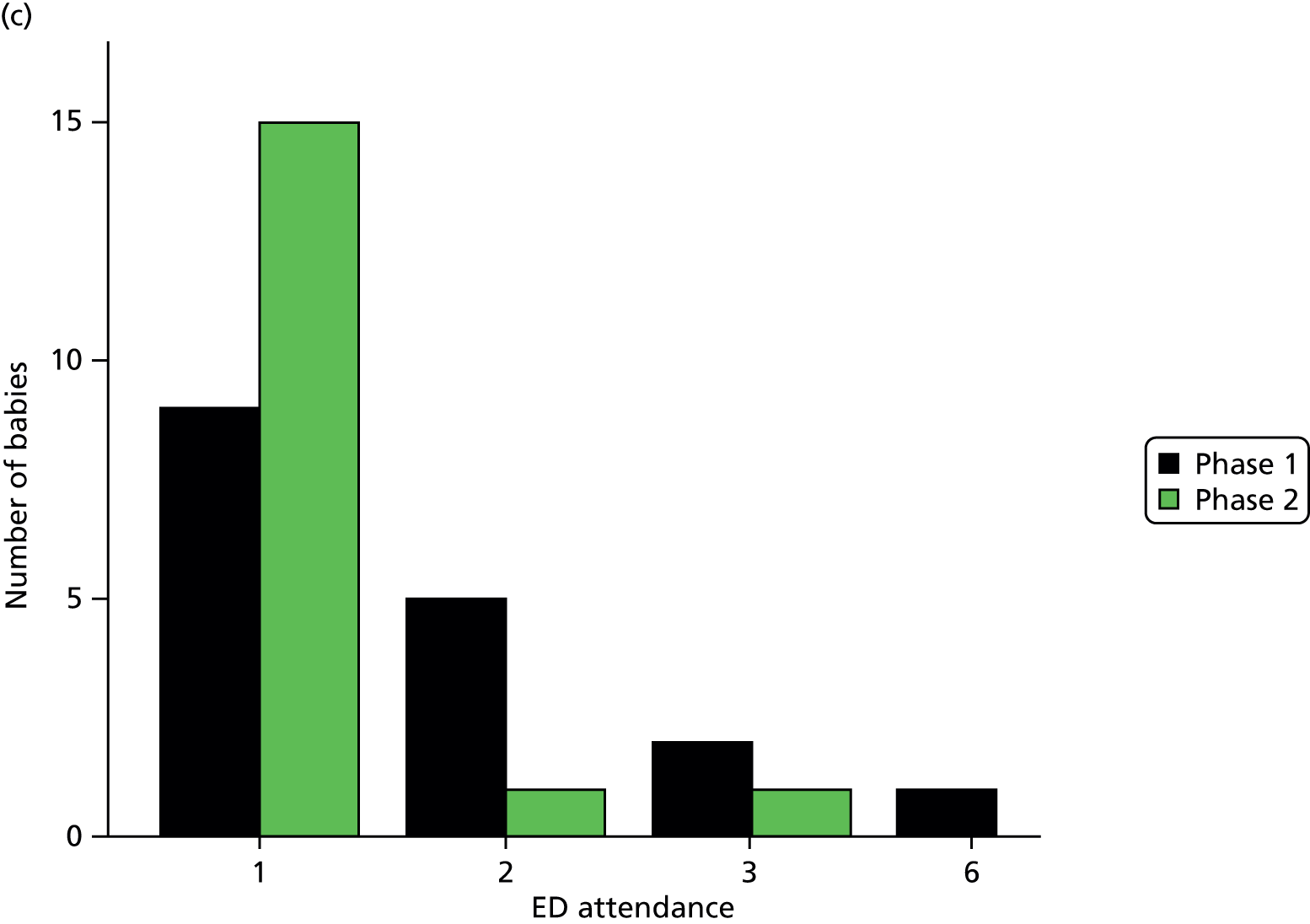

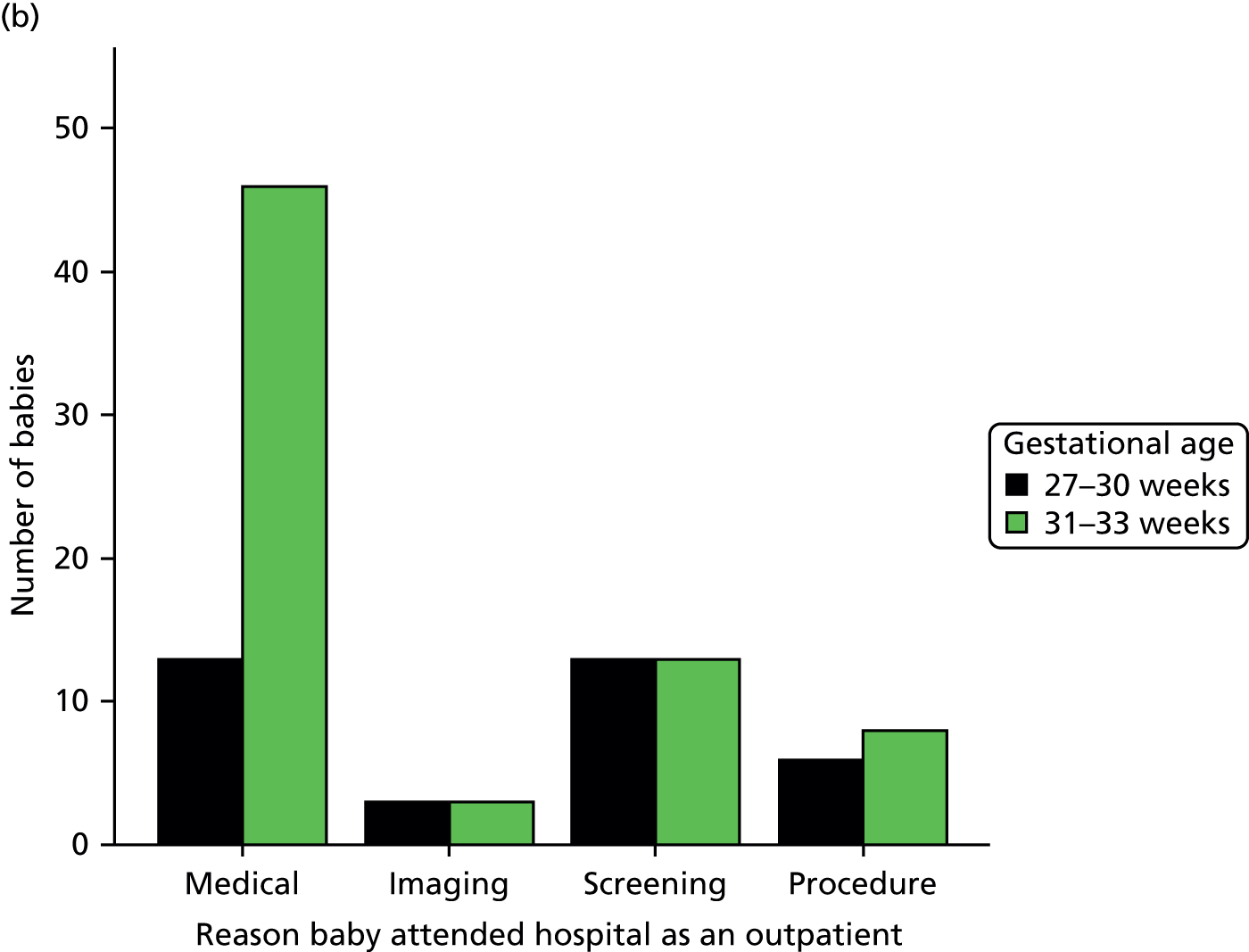

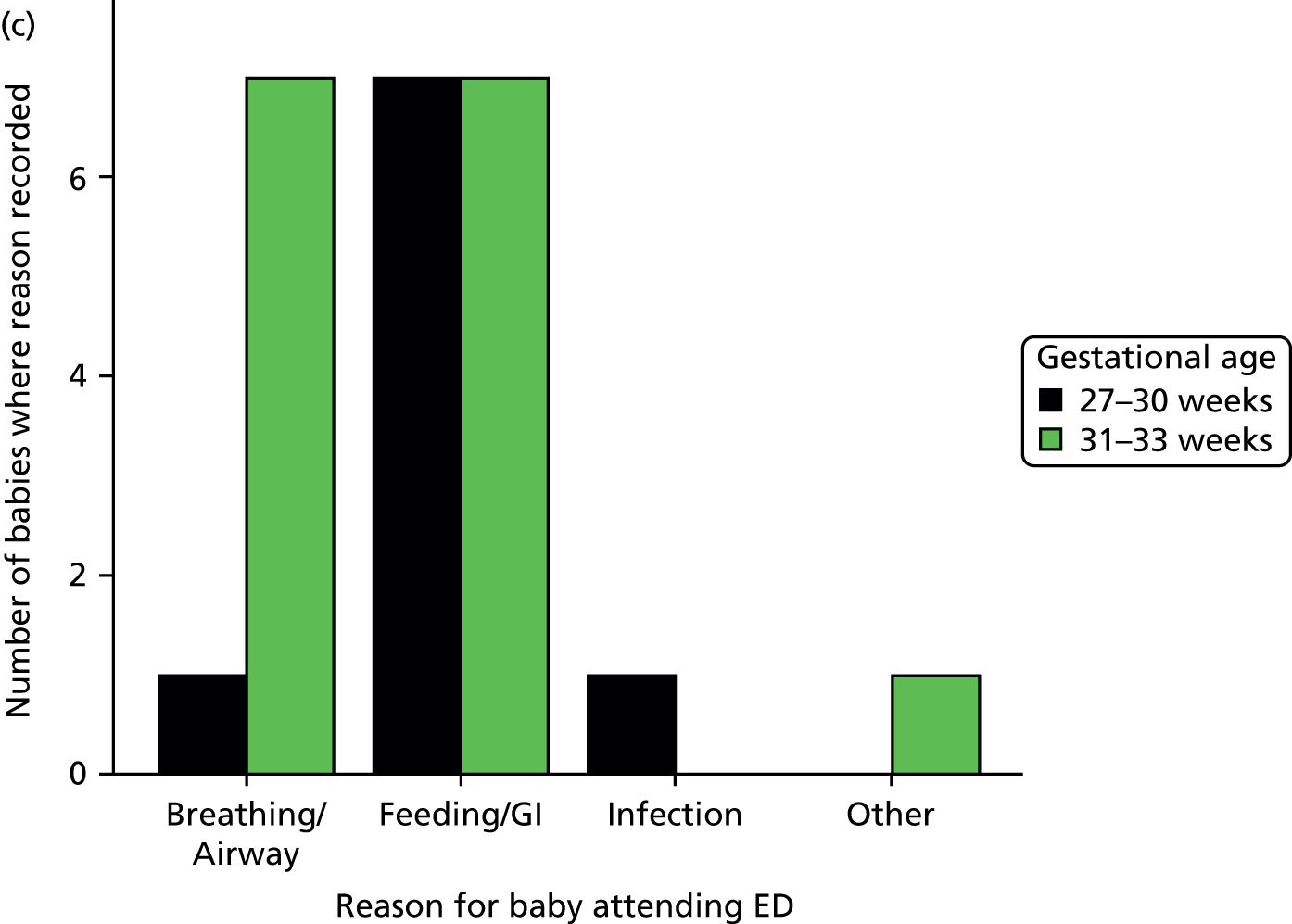

Health-economic data analysis

Cost analysis was performed using SPSS version 21. The reasons for infant inpatient readmission to hospital, outpatient and ED attendance, and hospital centres attended were analysed and compared across the two phases using chi-squared tests. Data were graphed when this was more useful. Continuous data were tested using the Shapiro–Wilk test of normality in distribution (see Appendix 9). These data were not normally distributed, so the Mann–Whitney U-test was applied to test for statistically significant differences in costs during the two phases. We costed the changes associated with use of health-care resources before and after implementation of the Train-to-Home intervention, using before-and-after samples, which were exactly 1 year apart, so we did not adjust for month of discharge or seasonal effects.

Parent Advisory Group input

The PAG was established in 2012 to assist with the study application and comprised six parents who had previous experience of having a baby cared for in a NICU. PAG members met four times (January 2013, June 2013, June 2014 and November 2014) to contribute to study project management. They made extensive comments on the design and content of intervention materials, reviewed training topics and resource-use questionnaire content. PAG members have discussed recruitment issues and how to involve more parents, qualitative interview results, dissemination of findings to parent groups, and future use and format of the intervention including the use of technology (apps and websites). They also contributed extensively by e-mail on the content of the parent pathways, and helped to develop and focus the booklet questions and statements.

The Neonatal Critical Care Service specification document, which sets out what NHS England expects from Trusts providing neonatal services, emphasises the need to provide family-centred care and to help parents understand their baby’s needs. Neonatal staff are required to provide support to enable parents to make informed choices and play an active part in their baby’s care. PAG members felt that the Train-to-Home package was an innovative way to engage parents and assist staff in their efforts to communicate with and encourage parents.

The chairperson of the group, Joanne Ferguson (JF), and another parent, Catherine Miles (CM), are members of the Trial Steering Group and contributed to those discussions from a parent perspective. As a lay member of the Neonatal Clinical Reference Group, JF provided input on national neonatal standards and issues, and, as a champion for the charity Bliss, CM provided input on local experiences and issues. As members of online parent support groups, they also provided details of, and insights from, support networks for parents with babies in neonatal care.

Ethics approval

The study was given National Research Ethics Service (NRES) ethics approval by the NRES Committee London – City & East in June 2012: 12/LO/0944.

Chapter 5 Results: part 1 – study population and quantitative data

Ascertainment

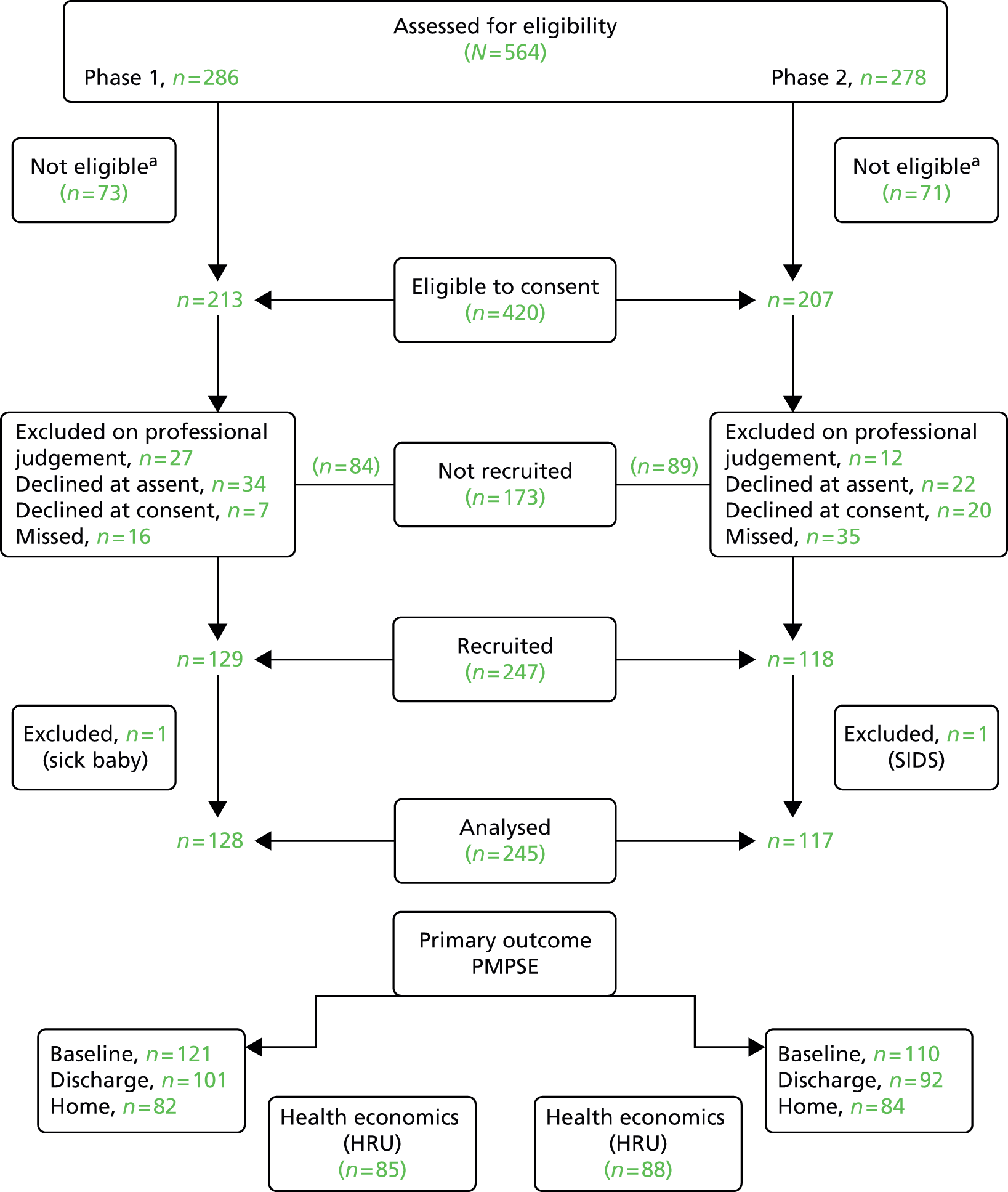

We recruited 247 families in total: 129 received usual care in the first 11-month study period (phase 1, October 2012 to August 2013) and 118 received the intervention in the subsequent 11-month study period (phase 2, October 2013 to August 2014), as shown in Figure 7. We had two withdrawals: one from phase 1 (baby very unwell) and one from phase 2 [baby died of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS)]. The analysis is thus based on 245 infants, 128 receiving usual treatment and 117 receiving the intervention. Table 2 shows the breakdown across units; the contribution from each unit across the two time periods was evenly split (chi-squared on 3 df; p = 0.99).

FIGURE 7.

Recruitment chart. a, Reasons for no-eligibility as per protocol: transfer; language problems; abnormality; triplets, out of area; age. SIDS, sudden infant death syndrome.

| Unit | Phase 1 | Phase 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| 1 | 32 | 25.0 | 29 | 24.8 |

| 2 | 25 | 19.5 | 24 | 20.5 |

| 3 | 34 | 26.6 | 29 | 24.8 |

| 4 | 37 | 28.9 | 35 | 29.9 |

| Total | 128 | 100 | 117 | 100 |

Infant characteristics

Table 3 shows infant characteristics at birth. There was no significant difference between the two groups. In phase 1, there was a higher proportion of twins (only one of the twins was used in the analysis) but this was not quite significant at the 5% level. There were slightly more males in phase 2 and a lower proportion in both groups born during the autumn months because of the September ‘washout period’ of the study. The proportion of infants was similar when split by gestational age pathway and there was no difference in gestational age overall. The mean birthweight was also similar among the two groups. Similarly, there was no significant difference between phases in the month during which infant discharge occurred (p = 0.86).

| Characteristic | Group of interest | Phase 1 | Phase 2 | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n/N | % | n/N | % | |||

| Gender | Male | 64/128 | 50.0 | 62/117 | 53.9 | 0.64 |

| Twin | Yes | 16/128 | 12.5 | 25/117 | 21.4 | 0.06 |

| Month of birth | December to February | 28/128 | 21.9 | 37/117 | 31.6 | |

| March to May | 43/128 | 33.6 | 31/117 | 26.5 | ||

| June to August | 36/128 | 28.1 | 29/117 | 4.8 | ||

| September to November | 21/128 | 16.4 | 20/117 | 17.1 | 0.32 (3 df) | |

| Gestational agea | 27–30 weeks | 37/128 | 28.9 | 35/117 | 29.9 | |

| 31–33 weeks | 91/128 | 71.1 | 82/117 | 70.1 | 0.86 | |

| Units | Mean | N, SD | Mean | N, SD | p-value | |

| Birthweight | kg | 1.70 | 128,0.50 | 1.65 | 114, 0.45 | 0.44 |

| Gestational age | weeks (w)/days (d) | 31w 5d | 128w 13d | 31w 4d | 117w 12d | 0.59 |

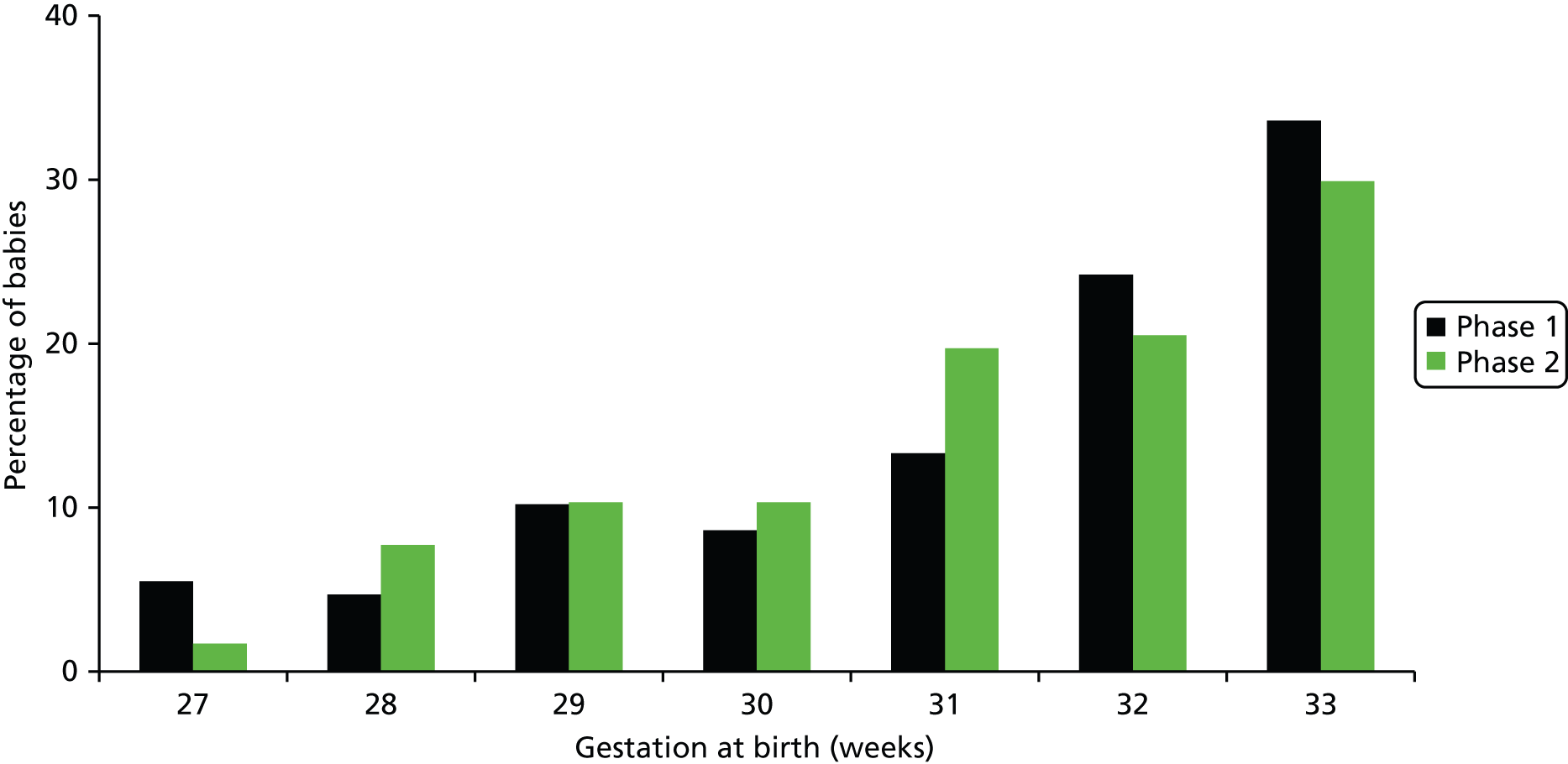

The proportion of children in the study increased with gestational age (Figure 8); fewer than one-third were between 27 and 30 weeks’ gestation but there was no significant difference between gestational ages at birth of infants between phase 1 and phase 2 (Mann–Whitney U-test; p = 0.59).

FIGURE 8.

Gestational age rounded down to whole weeks. Note: n = 128, phase 1; n = 117, phase 2.

Family characteristics

Table 4 shows family characteristics. There was no significant difference between the two groups. There were no significant differences in family size, maternal and paternal education, parental age or deprivation score; more of the mothers had a supporting partner in phase 2 but this was not quite significant at the 5% level. There was no significant difference in maternal or paternal ethnicity, and only one mother and two partners in the study had language difficulties (not shown in table), all of whom were in phase 2.

| Characteristic | Group of interest | Phase 1 | Phase 2 | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n/N | % | n/N | % | |||

| Mother has partner | Yes | 112/124 | 90.3 | 108/112 | 96.4 | 0.06 |

| Other | None | 70/117 | 59.8 | 37/117 | 31.6 | 0.32 (3 df) |

| Dependent | One other child | 28/117 | 19.4 | 31/117 | 26.5 | |

| Childrena | Two other children | 14/117 | 28.1 | 29/117 | 24.8 | |

| Three or more children | 5/117 | 16.4 | 20/117 | 17.1 | ||

| Highest maternal qualification | < GCSEb | 13/107 | 12.1 | 6/103 | 5.8 | 0.19 (3 df) |

| GCSEb | 23/107 | 21.5 | 23/103 | 22.3 | ||

| Advanced level | 25/107 | 23.4 | 35/103 | 34.0 | ||

| Degree | 46/107 | 43.0 | 39/103 | 37.9 | ||

| Highest paternal qualification | < GCSEb | 6/71 | 8.5 | 7/93 | 7.5 | 0.46 (3 df) |

| GCSEb | 22/71 | 31.0 | 24/93 | 25.8 | ||

| Advanced level | 19/71 | 26.8 | 36/93 | 38.7 | ||

| Degree | 24/71 | 33.8 | 26/93 | 28.0 | ||

| Maternal ethnicity | British | 109/119 | 91.6 | 98/106 | 92.5 | 0.18 (2 df) |

| Other whitec | 2/119 | 1.7 | 5/106 | 4.7 | ||

| Otherd | 8/119 | 6.7 | 3/106 | 2.8 | ||

| Paternal ethnicity | British | 73/77 | 94.8 | 86/99 | 86.9 | 0.19 (2 df) |

| Other whitec | 3/77 | 3.9 | 8/99 | 8.1 | ||

| Otherd | 1/77 | 1.3 | 5/99 | 5.1 | ||

| Units | Mean | N, SD | Mean | N, SD | p-value | |

| Maternal age | In years | 30.7 | 120, 5.7 | 30.7 | 111, 5.9 | 0.98 |

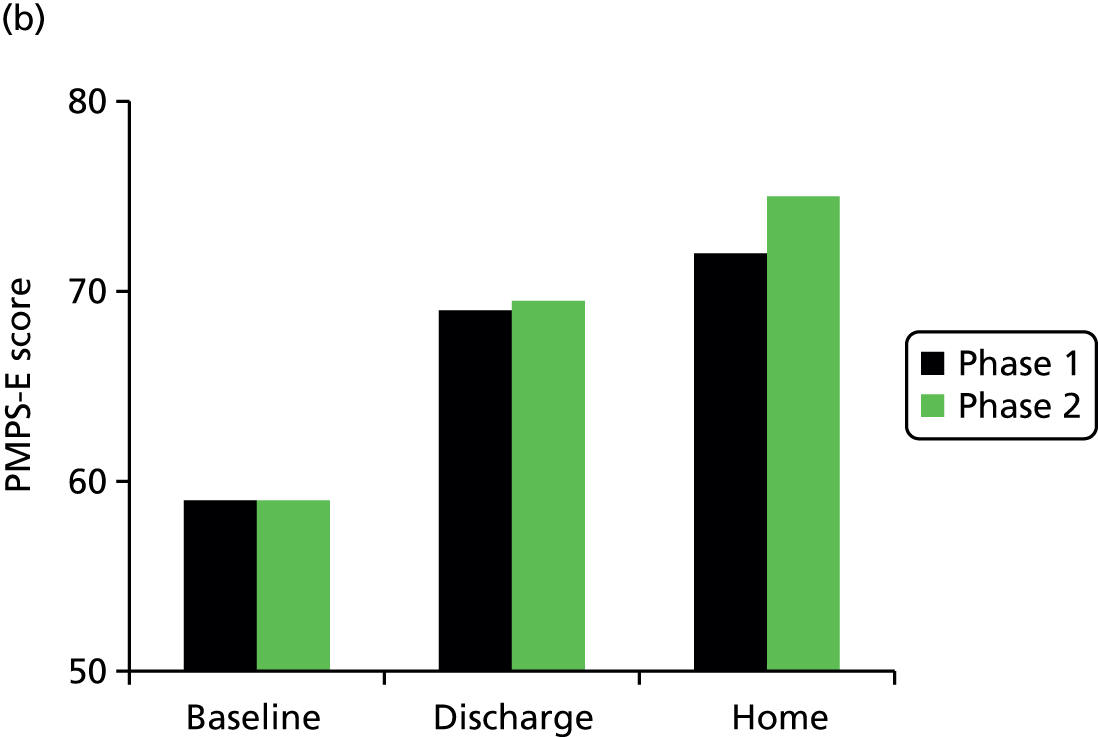

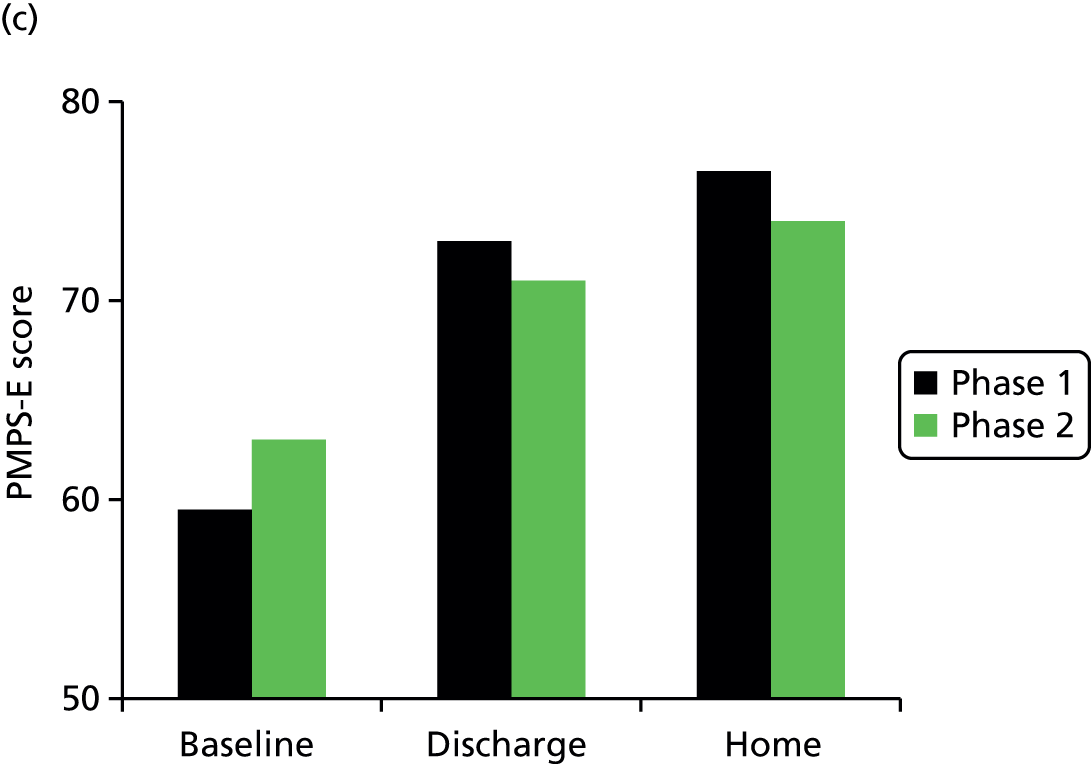

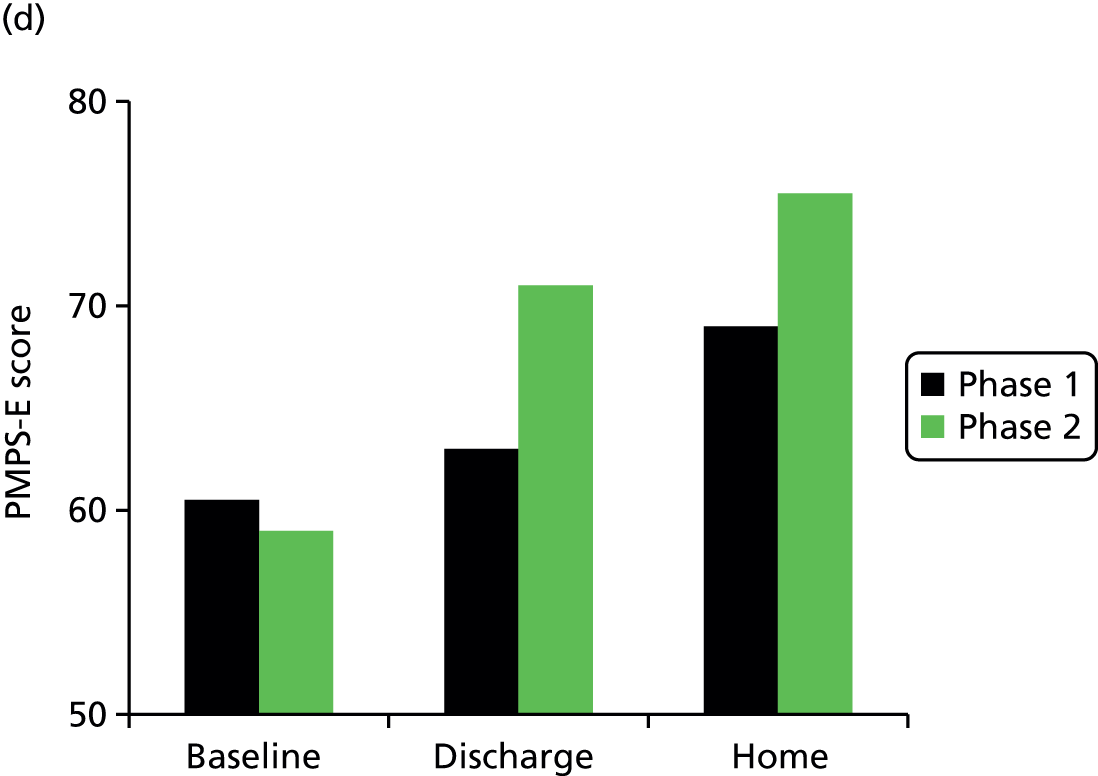

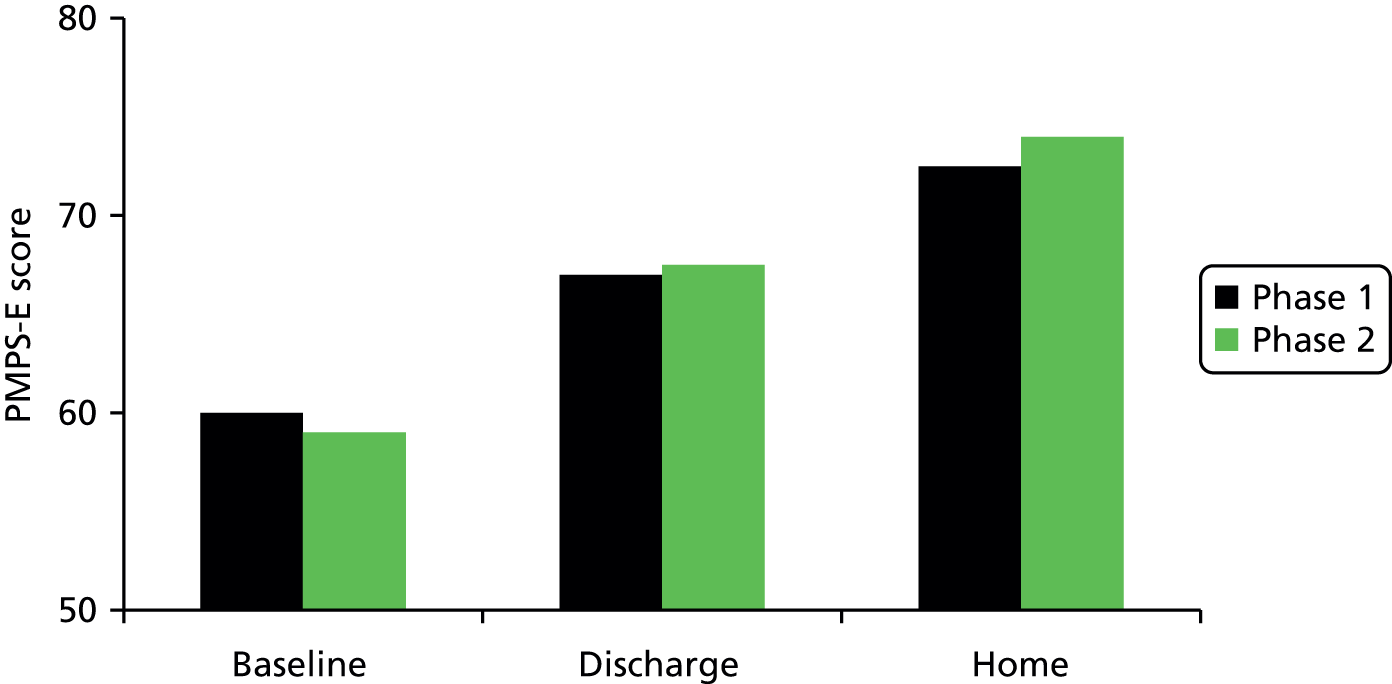

| Paternal age | In years | 33.2 | 77, 6.4 | 32.5 | 101, 6.8 | 0.46 |