Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 12/5001/55. The contractual start date was in January 2013. The final report began editorial review in November 2014 and was accepted for publication in September 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Gavin D Perkins, Frances Griffiths, Anne-Marie Slowther, Robert George, Philip Satherley, Barry Williams, Norman Waugh and Matthew W Cooke received a grant to conduct this work from the National Institute for Health Research Health Services and Delivery Research programme (grant number 12/5001/55). Gavin D Perkins reports serving on the Resuscitation Council (UK) Executive Committee and Health Services and Delivery Research programme researcher-led panel. Anne-Marie Slowther received funding from the General Medical Council and serves as a Trustee of the UK Clinical Ethics Network Charity. Zoe Fritz was involved in developing and evaluating the Universal Form of Treatment Options.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Perkins et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Cardiac arrest

Cardiac arrest is the term used to describe the cessation of cardiac mechanical activity and is diagnosed clinically by the absence of signs of circulation. 1 Cardiac arrest may occur suddenly and unexpectedly in someone who was otherwise fit and healthy and in whom prompt initiation of treatment has the potential to be lifesaving. By contrast, cardiac arrest is also the final common pathway of the dying process, which occurs as someone reaches the end of his or her natural life.

Resuscitation

The act of attempting to revive somebody from death is termed resuscitation. The first description of resuscitation is widely attributed to biblical times, when the prophet Elisha restored the life of a boy through a form of mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. 2 The concept of resuscitation then lay largely dormant until the mid-17th century, when the Dutch Humane Society recommended the use of expired air ventilation to resuscitate victims of drowning. 3 The first successful attempts at defibrillation (the application of electric shocks directly to the heart through an open chest) to treat cardiac arrest due to the disordered heart rhythm known as ventricular fibrillation were reported in the 1940s,4 followed by reports of successful external defibrillation (defibrillation electrodes applied to the outside of the chest wall) becoming available in the 1950s. 5

The landmark paper by Kouwenhoven et al. ,6 published in the Journal of the American Medical Association in 1960, is widely regarded as the birth of modern-day cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). In this paper the authors described a case series of 20 patients in whom the combination of external chest compressions and expired air ventilation was used to resuscitate mostly victims of witnessed, in-hospital cardiac arrest with potentially reversible causes of cardiac arrest. The permanent survival rate was reported as 70%. The authors concluded that ‘Anyone, anywhere, can now initiate cardiac resuscitative procedures. All that is needed are two hands’.

A further report describing their experience in 118 patients provided further detail on the indications and contraindications for resuscitation. 7 The authors noted:

Not all dying patients should have CPR attempted. Some evaluation should be made before proceeding. The cardiac arrest should be sudden and unexpected. The patient should not be in the terminal stages of a malignant or other chronic disease and there should be some possibility of a return to a functional existence.

So, CPR developed to deal with very acute situations – people drowning, or having arrhythmias such as ventricular fibrillation after an acute myocardial infarction. In these cases, the underlying organs (lungs or heart) were capable of sustaining life after a short period of resuscitation. The success of these early cases encouraged the widespread dissemination of resuscitation techniques. Hospitals started having ‘crash teams’ which included a resuscitation trolley with electrocardiogram defibrillators and equipment for ventilating people. These teams would be called to wherever in the hospital a cardiac arrest occurred, although in coronary care units, where many arrests occurred, staff would defibrillate at once, alerted by continuous electrocardiogram monitors with alarm devices.

Do-not-attempt-cardiopulmonary-resuscitation orders

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation can be very successful, especially if used after heart attacks, where a mostly healthy heart may arrest as a result of arrhythmias. However, CPR can also cause harm. A systematic review of injuries following CPR attempts identified rib fractures with a frequency of up to 97% and sternal fractures with a frequency of up to 43% in cases of attempted resuscitation. 8 There is also a risk of internal injuries, with the systematic review noting a frequency of 1–5% of cases sustaining cardiac, pulmonary or intra-abdominal organ injuries. 8 Even if the heart is initially restarted, fewer than half of those who survive initially will survive to go home from hospital. 9

A do-not-attempt-resuscitation (DNAR) order, or, as it has more latterly been known, a do-not-attempt-cardiopulmonary-resuscitation (DNACPR) order, provides a mechanism for making a decision to withhold CPR prior to a cardiac arrest occurring. DNACPR decisions have been recorded in medical records since the early 1970s. 10 Despite the fact that processes to record resuscitation decisions have been in place for almost 40 years, their application is variable. The Office for National Statistics reports that over 500,000 people die each year in England and Wales. The majority (approximately 285,000) deaths occur in hospital, with the remaining deaths occurring in public places, community care settings or the patient’s own home. The UK National Cardiac Arrest Audit indicates that hospital-based resuscitation teams attempt resuscitation in about 20,000 patients annually. 9 As current practice is to resuscitate all patients unless they have a DNACPR decision recorded, this implies that the majority (90%) of in-hospital deaths occur with a DNACPR decision in place.

A multicentre cohort study conducted in the UK examined the case records of over 500 patients who sustained an in-hospital cardiac arrest during a 2-week period in November 2011. 11,12 Reviewers found that one-quarter of patients who received CPR had substantial functional limitations and two-thirds had an underlying fatal disease. 11 The independent reviewers suggested that a DNACPR decision could have been made prior to cardiac arrest in 85% of cases. 11 There were also 52 cases in which CPR was commenced despite a DNACPR decision being in place. 11 In addition to this report, other research has demonstrated deficiencies in several aspects surrounding DNACPR decisions, including failure to recognise patients for whom resuscitation is not appropriate and failure to make a timely DNACPR decision. 13,14 Even when decisions are made there is unclear communication of the decision both within the health-care team and to patients/surrogates. 13–15 In addition, documentation is often suboptimal and there are misunderstandings about what a DNACPR decision means. 13,14,16 This highlights a major gap in current approaches to making and applying DNACPR decisions. There is significant regional and international variation in how DNACPR orders are approached, with many institutions initiating changes to improve DNACPR practice. 17,18 DNACPR decisions are broadly based around three categories; these are:

-

perceived futility of CPR (CPR is unlikely to restore spontaneous circulation)

-

refusal of CPR by the patient with capacity or through an advance decision to refuse treatment

-

when the burdens of the resuscitation attempt are thought to outweigh the benefits.

In the UK and many other countries there is no legal obligation for a doctor to provide CPR if they consider that doing so would be futile. However, in some countries it would be illegal to make such decisions without patient consent. Irrespective of international differences in decision-making, DNACPR decisions form part of an essential framework to enable a dignified death which is uninterrupted by a futile resuscitation attempt.

Aims and objectives

Aims

This research aims to identify the frequency with which and reasons why conflict and complaints arise, identify inconsistencies in implementation of national guidelines across NHS acute trusts, understand the experience of health professionals in relation to DNACPR, its process and ethical implications, and summarise the research evidence around DNACPR decisions.

A stakeholder group comprising health-care users, providers, ethicists, legal personnel and policy-makers maintained oversight during the project to ensure that the project remained focused on the issues that are important to patients and their families and relevant to NHS staff, and incorporated relevant ethical and legal frameworks.

Objectives

The objectives are to:

-

review and summarise the published evidence base informing DNACPR policy and practice

-

identify the themes of current complaints/conflict in relation to DNACPR decisions and explore local solutions developed to tackle these problems

-

examine current acute hospital, community and ambulance service policies to identify inconsistencies and examples of best practice across NHS organisations

-

explore health professionals’ experiences of DNACPR policy and practice

-

summarise and disseminate findings from this research.

Overview

Chapter 2 presents the results of the review of published literature concerning two aspects of DNACPR decisions: first, a review of published studies that have used interventions to improve DNACPR decision-making practice, and, second, a review of the published evidence concerning barriers to and facilitators of good DNACPR decision-making practice.

Chapter 3 aims to establish the size of problems associated with DNACPR decision-making in the UK by exploring evidence from complaints made to the NHS and incidents reported by the NHS to the National Learning Reporting System, from Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman and coroners’ reports involving DNACPR decisions and by reviewing the nature of calls from the general public to a national helpline related to DNACPR.

The review of NHS trust policies (see Chapter 4) evaluates similarities and differences between a sample of DNACPR policies from acute, community and ambulance service NHS trusts and identifies examples of good practice.

Chapter 5 considers health professionals’ experiences, reporting on a focus group study exploring service providers’ perspectives of DNACPR decisions.

At several stages throughout the study, stakeholders were invited to contribute to the study. Chapter 6 reports on this engagement, including a final event at which they recommended priorities for future research.

Chapter 7 brings together findings from all of the data sources through a discussion of the key issues identified and concludes with implications for practice and recommendations for research.

Chapter 2 Review of published evidence

Overview

A systematic review of the worldwide literature sought to synthesise existing research evidence for the processes, barriers and facilitators related to DNACPR decision-making and the implementation of DNACPR decisions (PROSPERO CRD42012002669). The review was conducted in two phases. First, a scoping review was undertaken to explore the literature for evidence of interventions that improved the process or recording of DNACPR decisions. 19 Second, a more in-depth review of the international literature was undertaken to explore the literature for evidence of barriers to and facilitators of DNACPR decision-making. 20 Overall, 84 papers were included in the review (37 in the scoping review and 47 in the full review).

Introduction to the scoping review

The purpose of the scoping review was to evaluate evidence about systems for improving the appropriate use of DNACPR decisions.

Method of the scoping review

Identification of studies

We identified recent studies (2001–February 2014) investigating interventions designed to improve how DNCAPR policies are applied in practice. An initial search for the scoping study was conducted in 2011, covering 10 years, and this study updated that search.

Medical subject heading (MeSH) terms and text words covering different terms used for DNACPR and for systems used to implement them were used and combined to develop the search strategy. These included the MeSH term Resuscitation Orders (covering Do-Not-Resuscitate Orders; Resuscitation Decisions; Resuscitation Policies; Withholding Resuscitation) and do not resuscitate, do not attempt resuscitation, not for resuscitation, allow natural death (AND), DNR, DNAR, NFR (not for resuscitation) and DNACPR as text words. Results were limited to English-language articles.

Information sources

Predetermined relevant databases were searched: MEDLINE (Ovid), EMBASE (Ovid) and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (EBSCOhost). MEDLINE was searched first, followed by EMBASE and then CINAHL.

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria for studies were:

-

randomised controlled trials, before-and-after studies and observational studies with a control group

-

studies that involved DNACPR decisions on adults in hospitals, nursing homes or the community

-

studies that tested an intervention designed to improve the application of DNACPR policy into practice.

Study selection

Two reviewers independently screened the search results titles and abstracts for relevance. The full text of eligible and potentially eligible articles were retrieved and independently reviewed during a second phase of study selection by both reviewers. Disagreements between reviewers were resolved by discussion.

Data extraction

Four randomly selected studies were used to test and refine a data extraction form developed specifically for this review. Data were extracted by one reviewer and checked by a second, with disagreements resolved through discussion. Information extracted was on:

-

country/countries of origin

-

study design

-

population studied, including number in each group (unless otherwise stated it was assumed that all participants were adults)

-

the type of intervention used

-

details on the control group

-

outcome measure used

-

the effect of the intervention.

Risk of bias and quality assessment

The studies were assessed for risk of bias using the criteria given by Thomas et al. 21 This tool assesses selection bias, study design, confounders, blinding, data collection methods and withdrawals and dropouts. Each element was rated as strong, moderate or weak to give an overall global rating. Two reviewers independently rated all studies and any discrepancies were settled by consensus.

Evidence synthesis

A meta-analysis of included studies was planned, determined by assessment of heterogeneity of setting, participant, intervention and outcome. Where meta-analysis was not possible, a narrative thematic analysis of the studies’ findings was planned.

Results of the scoping review

Study selection

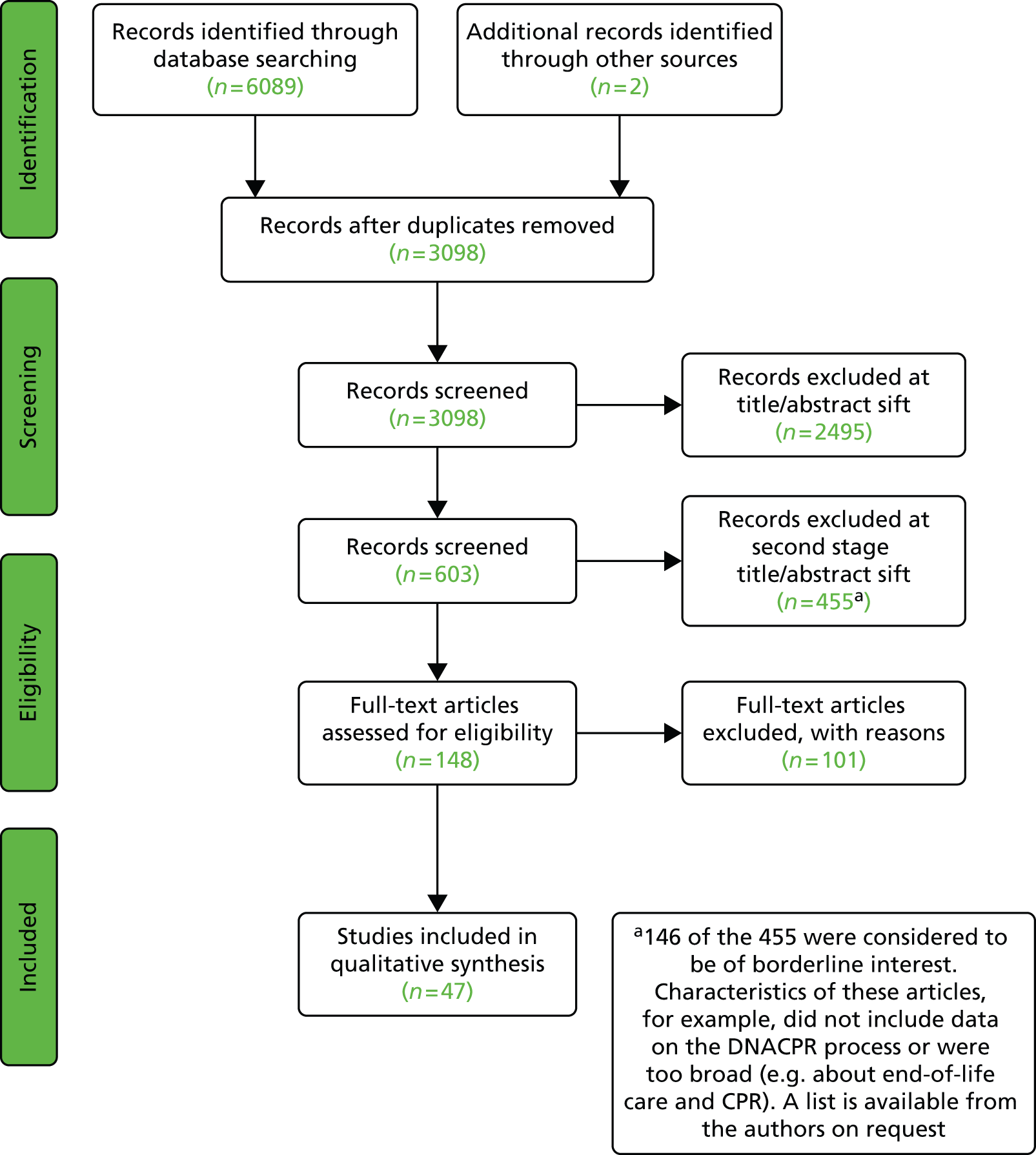

Thirty-seven studies were identified for inclusion in the review (see Appendix 1). 16,22–57 The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram (Figure 1) shows the numbers of studies identified at each stage of the selection process.

FIGURE 1.

The PRISMA flow diagram: scoping review.

Setting

Over half (20/37) of the studies were conducted in the USA,22,25,28–31,39,41,42,45,47–50,52–57 nine were conducted in the UK,26,32–35,37,40,43,44 two were conducted in Australia23,24 and one study was conducted in each of Germany,46 Belgium,38 Switzerland,51 the Netherlands,16 Singapore36 and Saudi Arabia. 27

Quality of evidence

Of the 37 studies, eight were randomised controlled trials,22–24,30,45,54,55,57 27 were before-and-after studies16,25–29,31–44,48–53,56 and two were cluster controlled studies. 46,47 Two studies were assessed as providing strong evidence,24,40 12 were assessed as providing moderate evidence16,22,23,29,30,35–38,54,55,57 and 23 were assessed as providing weak evidence. 25–28,31–34,39,41–53,56

Synthesis of findings

The settings and outcomes were too heterogeneous to allow meta-analysis. Studies were, therefore, grouped into four themes. See Appendix 1 for characteristics and results of the studies for each of the themes: (1) structured communication and specialist teams, (2) DNACPR documentation, (3) nursing home and community interventions and (4) education (physician and patient). One paper, investigating a change in legislation, did not fall into these themes.

Structured communication

In a prospective randomised trial,22 general medical patients were randomised to a scripted intervention (involving talking about what resuscitation involves and asking the patients’ preferences with regard to resuscitation status) or standard clerking. There was significant improvement in documentation in the intervention arm. Patients (98%) in the intervention group reported being happy to take part in a discussion about resuscitation. In a second study,23 patients with advanced cancer were randomised to either a combination of a patient information leaflet and a resuscitation discussion with a psychologist or standard care. DNACPR decisions were placed earlier in the intervention group but the overall frequency of decisions was the same.

Introducing specialist teams

Medical emergency teams (METs) have been introduced to respond to acute deterioration in patients admitted to hospital. Four studies investigated the relationship between MET and DNACPR decisions. 24,58,25,26,27 Chen et al. 24 and Hillman et al. 58 assessed the role of the MET on the issuing of DNACPR orders as part of the MERIT cluster randomised study involving 23 hospitals in Australia. Issuing a DNACPR order at time of appropriate call-out was 10 times higher per 1000 admissions in hospitals with a MET, although this represented only 5% of total DNACPR activity. Two retrospective audits of the impact of the MET on the number of patients dying with DNACPR decisions in place had conflicting results: Smith et al. 25 found there to be a significant increase, while Kenward et al. 26 found no significant differences between the two periods. They did, however, observe that 24% of patients (not in cardiac arrest at time of call) seen by the MET received DNACPR decisions within 24 hours of review. 26 Finally, Al-Qahtani et al. 27 found the introduction of an intensivist-led rapid response team significantly increased the number of ward-based DNACPR decisions initiated by the intensive care team.

Three studies (two cohort and one quasi-randomised) demonstrated that specialist teams such as palliative care, acute care for the elderly and ethics were associated with an increased proportion of patients with documented resuscitation decisions. 28–30 A further cohort study31 evaluated the effect of 24-hour intensivist cover on DNACPR processes: there was an improvement in the time taken to document DNACPR decisions but no significant differences in the number of patients receiving CPR within 24 hours prior to death.

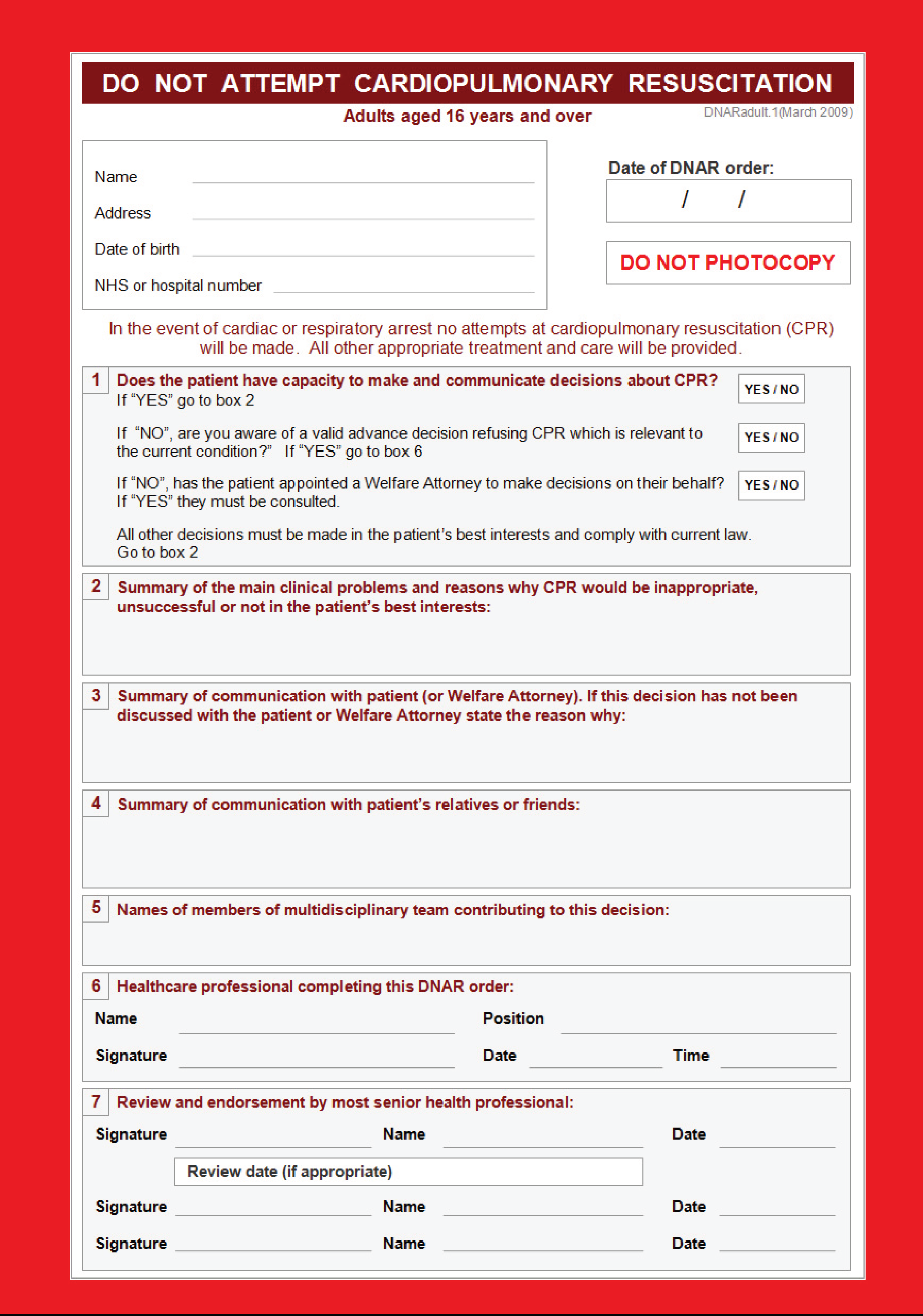

Do-not-attempt-cardiopulmonary-resuscitation documentation

Two prospective chart audits and three retrospective chart audits evaluated the introduction of pre-printed DNACPR forms compared with hand-written notes in the medical records. 32–36 Butler et al. 32 found significant improvement in recording a valid reason, consultant authorisation, consultant review and patient involvement. There were also increases in surrogate involvement and documentation in nursing notes. 32 By contrast, Lewis et al. 33 found no difference in the number of resuscitation attempts, demographics and survival to discharge. In retrospective studies, Castle et al. 34 found improvements in clarity of decision, date, clinician name and signature and reason for decision. No significant improvement in patient or surrogate involvement was observed. 34 Diggory et al. 35 found that the introduction of a clerking pro forma to record patients’ resuscitation status on admission was associated with an increased documentation of decisions. Tan et al. 36 showed the introduction of a physician order form for DNACPR decisions was associated with fewer patients receiving CPR within the 24 hours prior to death and more patients dying with a DNACPR decision in place.

Five studies examined modifications to existing DNACPR forms. Diggory’s team37 continued the audit cycles from their 2003 study and found that removing the statement indicating that all DNACPR decisions should be discussed with the patient increased the recording of resuscitation status and the number of DNACPR decisions issued. Piers et al. 38 updated the DNACPR form to emphasise the reason for the DNACPR decision and involvement of others (surrogates, nurses) in the decision-making process. In addition, they provided a 45-minute briefing on patient rights. 38 There was improved completion of reason for decision, nurse involvement and surrogate involvement. 38 However, there was no improvement in number of deaths occurring with DNACPR decisions. 38

Reducing complexity of the DNACPR form from a seven-page to a one-page document increased junior doctors’ confidence, reduced stress and improved the number of DNACPR decisions per 100 admissions. 39 Changing to a form [the Universal Form of Treatment Options (UFTO)] which contextualises the DNACPR decision within overall treatment plans was associated with a reduction in harms per 100 admissions as well as a reduction in the harms contributing to patient death. 40 Thematic interviews were suggestive of increased clarity of goals of care, better communication between clinicians and earlier decision-making with the UFTO than with the standard DNACPR form. 40

Finally, linkage between the electronic patient record and printing of DNACPR wristbands reduced the number of discrepancies between patients’ documented wishes and resuscitation-status wristband. 41

Nursing home and community interventions

Six studies42–47 identified interventions which increased the proportion of nursing home residents with DNACPR decisions. Interventions included the introduction of a palliative care team, end-of-life care pathways and staff training/education. The introduction of structured advanced care planning in the community moved preferences towards less invasive levels of care at life’s end and increased compliance with participants’ wishes and deaths at home (including DNACPR). 48

Legislation

Baker et al. 49 evaluated the impact of the American 1991 Patient Self-Determination Act59 on the number of early and late DNACPR decisions for six medical conditions 1 year either side of the Patient Self-Determination Act. There were increases in the percentage of early DNACPR decisions for four of the six conditions, while patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) showed a significant increase in late DNACPR decisions; overall, there was little change in the use of DNACPR decisions. 49

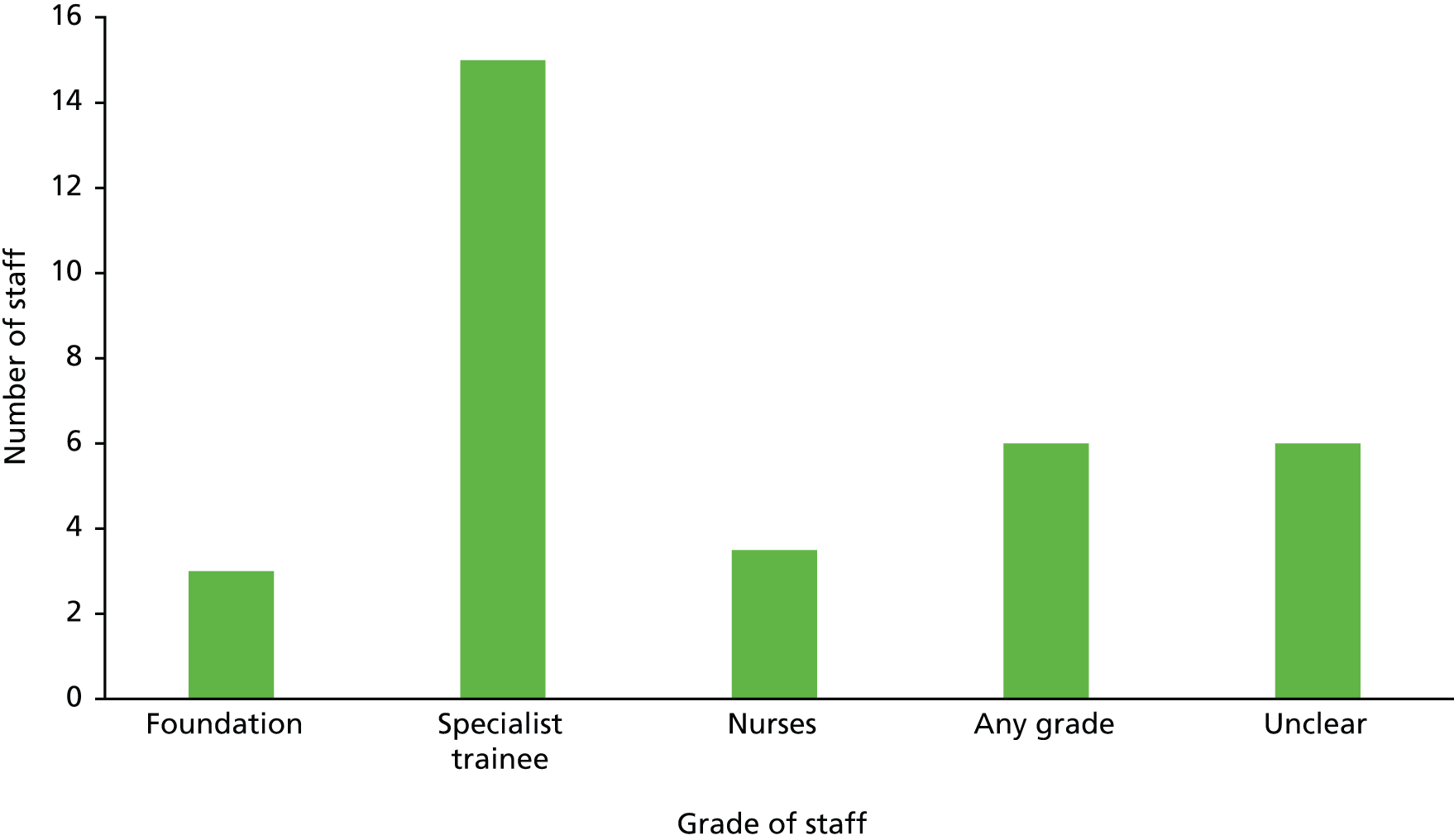

Physician education

Six studies assessed educational interventions. 50–55 Study participants included 44 medical students and 269 junior doctors. 50–54 Studies typically used multifaceted interventions including role play (n = 350,52), provision of information (n = 250,51), reflective practice (n = 351–53) and case-based discussions (n = 252,53).

Two linked studies randomised first-year postgraduate residents to a multimodal educational intervention to improve code status discussions. 54,55 The multimodal package included a 2-hour teaching with deliberate practice of communication skills, online modules and self-reflection in addition to assigned clinical rotations. Control group residents completed clinical rotations alone. Residents’ performances were rated using an 18-point behavioural checklist during a standardised patient encounter with an actor. 54,55 Residents randomised to the educational intervention had significantly higher scores in the simulated discussion with a standardised patient both at 2 months and at 1 year than those who received routine education alone. 54 Residents rated the education programme positively. 54,55

Two studies assessed self-reported changes in comfort and/or confidence in discussing CPR decisions: Seoane et al. 53 found that house officers rated their self-confidence in this area more highly at the end of a rotation which involved a specialised teaching component, while Kahn et al. 52 found that participants reported significantly improved understanding of the legality of DNACPR decisions (but not in comfort of discussing them) after attending a workshop with simulated patients centred on end-of-life discussion skills.

Two studies assessed changes in patients’ outcomes/experiences after training. 50,51 Furman et al. 50 found no change in the number of resuscitation discussions with patients on admission following a half-day training session (including role-playing exercises) for medical residents. Junod Perron et al. 51 trained nine junior doctors on the meaning of and ethics surrounding DNACPR decisions in parallel with introducing a new DNACPR policy and form. The doctors self-reported their performance in DNACPR decision-making. The doctors reported better patient involvement and improved understanding of the scope of the DNACPR decisions post intervention. 51

Patient/surrogate education

Five studies were identified. 16,22,23,56,57 Three studies addressed patient/surrogate education,16,56,57 while two studies evaluated structured communication with patients. 22,23 The overall quality assessment was weak for one study56 and moderate for four. 16,22,23,57

In a large (n = 2517) before-and-after study,16 introduction of a patient information leaflet and provision of written information for doctors in a tertiary hospital in the Netherlands had no effect on the frequency of DNACPR documentation. Showing a short video of CPR to relatives of patients in intensive care improved their knowledge about resuscitation but did not influence their preference about DNACPR decisions. 56 Finally, in a randomised controlled crossover trial,57 cancer patients’ choices about whether they preferred to be asked about their opinion or informed of a DNACPR decision were unchanged after watching two short videos.

Summary of the scoping review

This scoping review suggests that structured discussions at the time of admission to hospital and review by specialist teams at the point of an acute deterioration served as useful triggers to review DNACPR decisions. Linking DNACPR decisions to discussions about overall treatment plans provided greater clarity about goals of care, aided communication between clinicians and reduced harms. Standardised documentation proved helpful for improving the frequency and quality of recording DNACPR decisions. Studies into patient and clinician education were limited in scope and did not provide compelling evidence that education in isolation improved clinical processes or patient outcomes.

Introduction to the full review

The findings of the scoping review were extended in the main review. The objectives of the main review were:

-

to identify factors that influence DNACPR decision-making and who makes the decisions

-

to identify the barriers to and facilitators of the decision-making process

-

to identify factors that influence implementation of DNACPR orders

-

to identify barriers and facilitators to the implementation process.

Method of the full review

Identification of studies

The starting point for this review was 2003; this was influenced by a government publication, Choice, Responsiveness and Equity,60 which supported patient equity in being given, and making choices with health-care professionals about, their health care. This included being consulted and given a choice about where patients would like to die, whether or not their treatment should be withdrawn and whether or not they should be resuscitated. The period of the search was from January 2003 to July 2013.

An iterative procedure was used to develop the search strategy, with input from the stakeholder group, known articles identified in earlier work and the sifting of 200 titles/abstracts randomly selected from results of an initial scoping search undertaken in June 2013. The final search strategy was designed to capture generic terms for DNACPR. The strategy was deliberately sensitive in order to capture all relevant study types including qualitative studies and articles with uninformative titles and no abstracts. The search strategy was developed for MEDLINE® and adapted as appropriate for other databases. All searches were undertaken between 12 and 19 July 2013. The final strategies used are available (see Appendix 2).

Information sources

Studies were identified by searching predetermined relevant electronic databases, scanning reference lists of included studies and contacting key experts in the field. The databases searched were MEDLINE (Ovid), MEDLINE In-Process and Other Non-Indexed Citations (Ovid), EMBASE (Ovid), Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA) (ProQuest), all sections of The Cochrane Library (Wiley) including Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, NHS Economic Evaluation Database, Health Technology Assessment Database, CINAHL, EBSCOhost, PsycINFO (ProQuest), Science Citation Index and Social Science Citation Index (Web of Science), and The King’s Fund library database.

All bibliographic records identified through the electronic searches were collected in a managed reference database.

Inclusion criteria

All types of study were included which reported decision-making and implementation of DNACPR orders, for example qualitative studies, randomised controlled trials, observational designs and systematic reviews. Participants comprised any health-care professional who was involved in decision-making and implementation of DNACPR orders. Any type of intervention for decision-making or implementation and any type of outcome measurement were included, although the review was not limited to outcome measures but included all outcomes if they were reported. International studies were included, although papers were limited to those published in the English language.

Exclusion criteria

Papers were excluded if they were abstract/conference proceedings, editorials, letters, think pieces or commentaries; patient or surrogate experiences; pre-existing patient-led decision-making on DNACPR such as advanced decision-making (this review focuses on decisions made by physicians and other staff members such as paramedics where the patient’s pre-determined wishes regarding CPR are not known. It does, however, touch on patient decision-making from the physicians’ perspective in Communicating the decision to patients and relatives); individual case studies; simulations for training, hypothetical situations and vignettes; pre-2003 data (unless it crossed into 2003 and beyond); studies in which DNACPR was not the primary focus of the study; studies including children (under 18 years of age); and non-English-language publications.

Study selection

References (n = 3098 after deduplication) were screened independently for eligibility by four reviewers (two pairs), who assessed either the MEDLINE abstracts (CM and BC) or the abstracts from other databases (AG and RC). Disagreements were resolved by consensus (between AG and RC or between CM and BC). Titles and abstracts for retrieved studies were screened for eligibility and full texts were obtained when the abstract was unclear. Studies that could not be decided on by one pair of reviewers were deliberated by a reviewer from the other pair.

One reviewer (RC) and one independent reviewer (NW) checked 20% and 100% (respectively) of the second sift of abstracts (n = 603) prior to obtaining full-text papers for inclusion.

Agreement was reached on 146 of the papers to be set aside as of borderline interest. These were records that did not include data on the DNACPR process or were too broad, for example they were about end-of-life care and CPR. Full-text papers (n = 148) were further assessed for eligibility and 101 were excluded with reasons, for example the data were collected prior to 2003.

Data extraction

Using provisional themes, which had emerged from the second sift of abstracts, a broad framework was devised for data extraction and checked with stakeholders by e-mail for any other expert input. This framework was comprehensive and allowed for additional themes to emerge from the data extraction. A data extraction sheet was developed and pilot tested on randomly selected studies (BC) and refined accordingly. One review author (CM) extracted the following data: aims and objectives, research methods, participant characteristics, intervention, data collection and analysis, and results based on the framework. Fifteen papers (32%) had data extracted by other reviewers (RF, RC, BC and ZF) and checked by the main reviewer (CM).

Risk of bias in individual studies and quality assessment

The risk of bias was considered across all studies and results were examined for missing data. Study quality and risk of bias were evaluated in individual studies guided by the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme tool61 for qualitative studies. Owing to the heterogeneity of the research methods and to provide a common comparison of studies, this tool was adjusted slightly to accommodate all other research methods included in papers, by removing the word qualitative and references to only qualitative research methods; for example, ‘is a qualitative methodology appropriate?’ was changed to ‘is the methodology appropriate to the study?’. Other quality assurance checklists were considered but the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme provided the basis for a simple and straightforward check across all study types and enabled studies to be compared for quality throughout the data extraction process.

Half of the studies in the review were perceived to be of low quality: that is, of little value or not generalisable to a wider community. Many of the studies were cross-sectional, and small population samples were included. Studies commonly utilised self-reported non-validated questionnaires which only occasionally were piloted for face and content validity.

The following quality criteria were used:

-

Low: poor quality – not well designed, biased, few if any aims and objectives, data collection tool is not tested or described, small local study.

-

Medium: medium quality – some attempt to test the data collection tool, the study has some robustness, not generalisable, can be a small study.

-

High: good quality – robust methodology, aims and objectives, unbiased, could be generalisable.

Planned methods of analysis

The diversity of the research methods used in the review studies did not lend itself to a meta-analysis. Throughout the title and abstract sifting stage of 3098 hits, a list was compiled of the major recurring categories emerging from the literature. Twelve key categories formed a broad framework for data extraction from the final 47 studies. The stakeholders were invited to comment on or add their expert input to the 12 categories. If other categories emerged during data extraction these would also be incorporated into the framework. Data were extracted which addressed the following 12 categories: (1) staff members and their roles in DNACPR decision-making; (2) information about DNACPR forms; (3) clinical and patient factors considered in decision-making; (4) consultations with patients, surrogates or team members; (5) timing of decision-making, for example early, late or emergency orders; (6) compliance with guidelines or policies, including a brief description of these; (7) following on from consultations with patients and surrogates; (8) skills and characteristics of decision-makers; (9) other outcomes such as resources and costs; (10) description of the implementation of the order, for example who does this and how; (11) description of the documentation used or how decisions are communicated; and (12) interpretation of the DNACPR order, for example levels of care. No further categories were added.

The framework used in data extraction was compiled from 12 key categories; these 12 categories broadly addressed the study’s objectives (objectives 1 and 2 were addressed by categories 1–9 and objectives 3 and 4 were addressed by categories 10–12). Analysis involved familiarisation with and comparison of the studies. Interrogation of the extracted data was conducted for each of the research questions. A narrative synthesis, using similar principles to those described by Thomas and Harden,62 was developed to examine relevant themes, identifying patterns and anomalies across the studies.

Results

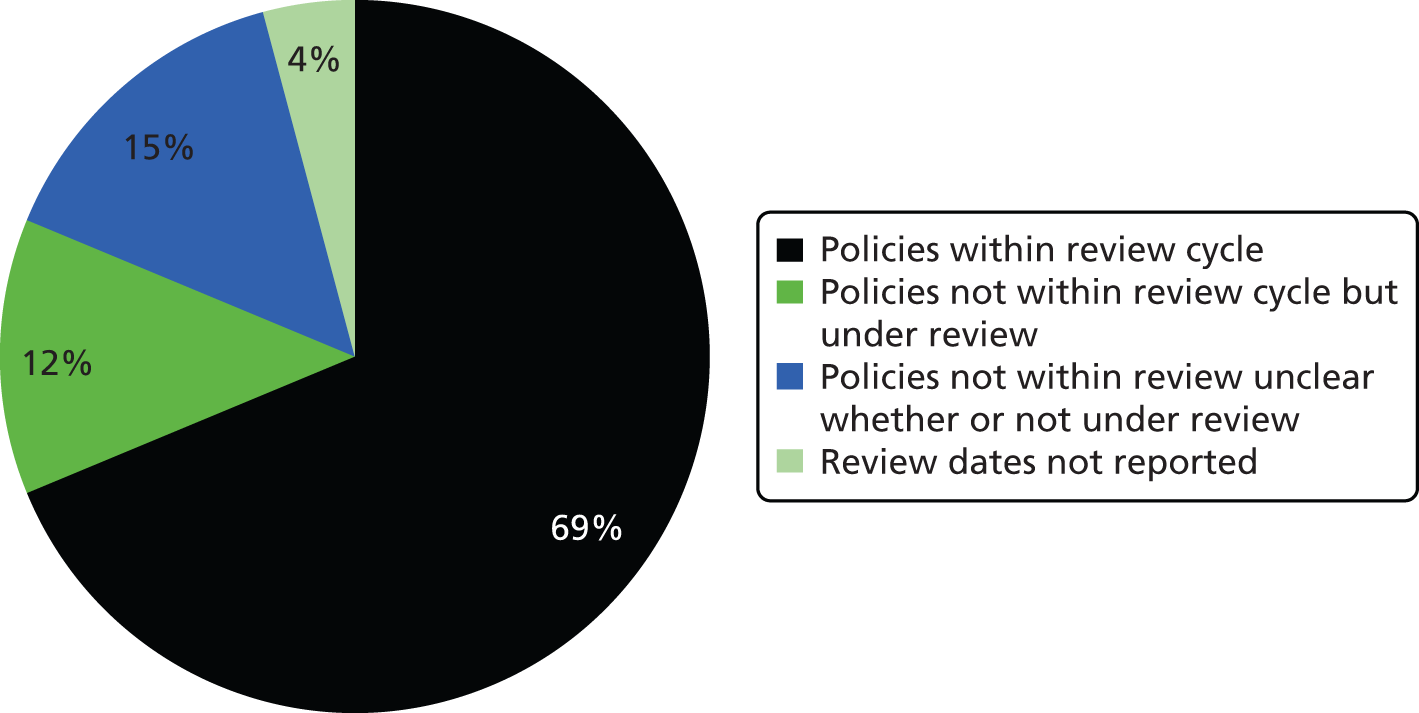

Forty-seven studies were included in the final review (see Appendix 3). The study flow diagram is provided below (Figure 2). From the extracted data there were four emerging overarching themes which were categorised into four key domains: considering the decision, discussing the decision, implementing the decision and the consequences of DNACPR orders. Each domain was synthesised into subcategories.

FIGURE 2.

The PRISMA flow diagram.

Considering the decision

The evidence here is mostly descriptive. It identifies key staff members included in the discussion and decision-making of a DNACPR order. It illustrates the variation in the timing, setting and epidemiology – particularly (a) older people, (b) prognosis, (c) quality of life, (d) other considerations of patients – which affects and influences decision-making regarding DNACPR orders. Thirty-seven articles contributed to this theme and 17 included a questionnaire or survey design. 38,63–78 Of these 17 articles, 12 were deemed low-quality studies,63–68,72–77 two were deemed medium quality38,71 and three were deemed high quality. 69,70,78

Twelve articles included reviews or audits of medical records, registry of deaths or MET calls,16,75,79–88 of which two were of high quality16,86 two were of medium quality85,87 and eight were of low quality. 75,79–84,88

Eight articles included qualitative designs of interviews, focus groups and observations;14,15,40,67,89–92 of these, three were deemed high quality,15,89,92 three were deemed medium quality14,40,91 and two were deemed low quality. 67,90

Key decision-makers

The studies reported that the key decision-maker was usually a senior physician, often the person in charge of the patient63–65,71,79,88 who would either make a lone decision66,79,81,88 or involve other physicians. 63,82 Several studies reported that the nurse may be the first person who broaches the subject of a DNACPR order with the patient, after developing a rapport with them,14 and they are consulted by the physician about DNACPR status38,63,67,69,89 and may follow up the physician’s discussion to check their understanding. 68 Generally, nurses felt that the overall responsibility should lie with the medical consultant or treating physician14,63,70 but specialist registrars in one English study93 had differed in their opinion from that of their consultant at some point (n = 126/235, 54%), with many (n = 198/235, 84%) feeling that the decision should not lie solely with the consultant. Further evidence shows that nurses may have a different approach to CPR and DNACPR from physicians14 and may place more power with the patient and relatives. 71 One study70 reported that nurses felt that decisions were often made by medical staff in the patients’ best interest but another63 found that 80% of nurses felt that the patient’s view should be the decisive factor. Nurses felt that they should be part of the decision-making process. 69,70 Patient and family wishes for resuscitation were sometimes reported as key to decision-making. 83,93 Although patient autonomy played an important role,72,75,89 particularly among nurses,73 one study64 found that it did not significantly change the physician’s decision. However, the presence of family, particularly adult children as surrogate decision-makers,72,84,85 often aided decision-making.

Timing

The studies illustrated a variation in the timing of DNACPR decision-making. The timings were described as days to death or days from admission, so it was difficult to identify commonalities of the timings of decision-making. DNACPR order decision-making ranged from admission or within 24 hours of admission15,74,75,84,88,94 to less than 7 days before death. 79,84,85 Sometimes there were less than 24 hours before death,84,85 with many emergency teams having to decide moments before death whether or not there was a DNACPR order already in place. 66,76,86,90,91 In one Scottish study,87 consultants on general adult wards and those in old-age psychiatry differed in their opinions about whether or not a DNACPR order should be issued at all: some would discuss this with the family in cases where the patient may live for many more years and others would raise it only if the patient was clearly at the end of his or her life. There were indications that the longer the duration of the stay in hospital the more DNACPR orders were documented,16 sometimes after a prolonged stay and aggressive therapeutic measures. 79

Setting

Evidence revealed variations among different specialties over decision-making. 87 There were more DNACPR orders written in acute wards than in planned admissions such as surgical wards. 70 This is illustrated by one study16 which found more DNACPR orders in acute admissions (n = 99/119) than in planned admissions (n = 20/119; p < 0.05); the most frequently written DNACPR orders came from internal medicine and pulmonology, with fewer from cardiology, thoracic surgery and neurosurgery wards. It was found that an inappropriate setting, such as a busy ward with a lack of privacy, could limit DNACPR discussions. 77

Epidemiology

The evidence from these studies showed that a number of factors were considered in DNACPR decision-making. A study of doctors in Germany72 found that decisions were mostly influenced by the patient’s age, underlying disease, chronic malignant disease, previous resuscitations and expected quality of life, and this is reflected in other studies. It was evident from the review that attitudes towards older patients were changing. One study73 found that, between 1989 and 2003, staff attitudes towards DNACPR changed, with fewer staff over this time considering a person’s age as important in DNACPR decision-making; in 2003, an increasing number of staff also felt that the chances of successful CPR were higher, which might have underpinned their change in attitude towards age as a factor. Another study85 appeared to support this, as it found that the significance of age in a bivariate analysis lost significance in a multivariable analysis. Despite this, many other studies indicated that older age was still a key consideration. 16,64,72,79,80,83,85,86,88 The age of the older patient was differently defined but started as young as 67 years. 16 One study66 explained this more broadly, in that the proportion of patients undergoing CPR decreased with increasing age and was significantly lower for patients over 80 years of age; in one example,78,93 it was found that younger patients were more likely to have CPR and longer attempts at CPR, whereas older patients in similar circumstances would have a DNACPR order in place.

Prognosis

A poor prognosis is frequently mentioned as a contributor to a DNACPR decision; this includes cancer (advanced, terminal or untreatable), heart failure, COPD, psychiatric diagnoses75,79,83,92 and other comorbidities. 72,75,79,80,83,93 The frequency of intensive care unit (ICU) stays83 and previous resuscitations64,72 were also important contributors to DNACPR decision-making.

Quality of life

Quality of life was frequently mentioned when making decisions, although the term remained undefined by staff;87 factors staff considered included poor quality of life of the patient prior to cardiopulmonary arrest and expected quality of life after resuscitation. 72,87,93 Similarly mentioned were terms such as futility,77,86 withholding potentially harmful treatment77 and the likelihood of successful CPR. 77,93

Other considerations

Other considerations included race/ethnicity (white compared with African Americans, with African Americans having fewer DNACPR orders, which appeared to be a cultural choice). 80,85 Being unmarried,84 having pastoral care,85 a lack of bystander basic life support at cardiac arrest and ineffectiveness of basic life support66 were also mentioned.

Discussing the decision

The evidence from this review illustrates several challenges in discussions of DNACPR between physicians, patients and relatives. Of the 26 articles in this theme, 16 included cross-sectional questionnaires or surveys,38,39,63–65,68,70,74,75,77,78,83,93,95–97 of which six were deemed high quality,70,78,93,95–97 two were deemed medium quality38,39 and eight were deemed low quality. 63–65,68,74,75,77,83 Eight articles included qualitative methods,13–15,89,91,97–99 of which three were of high quality,15,89,98 four were of medium quality13,14,91,97 and one was of low quality. 99 The remaining three articles are reviews of records or audits,80,81,87 of which two were of medium quality81,87 and one was of low quality. 80 These articles include reported challenges posed by communicating decisions to patients and to relatives, discussion of prognosis and a preference for discussing CPR rather than DNACPR. Limitations were found to include personal hurdles for staff members and a lack of specific skills and training among decision-makers.

Communicating the decision to patients and relatives

Consensual decision-making included patient views, medical expertise and a team approach,89 but often the level of involvement of the patient varied. Key factors for involvement appeared to be that the patient was able to communicate and was competent. 63,95 In those studies which reported on the DNACPR discussion process, it was found that some physicians would normalise the need to discuss resuscitation by explaining that it was something they discussed with all patients. 15,75 Examples were given in which physicians would ease into the conversation by asking about, for example, the patient or surrogate’s understanding of their condition, their understanding of CPR and previous conversations they might have had. 75 One evaluation of a new form, which was more than a DNACPR order, found that doctors thought that following the instructions on this new form made conversations with patients easier. 40 In one study,97 86% of physicians reported that they would normally or always involve the patient or their family before completing a DNACPR order.

These approaches, however, are not consistent. Examples were found which illustrate that findings varied in reporting how often patients were involved in decision-making. One study77 found that hospital-based clinicians reported discussing resuscitation decisions with patients less than 25% of the time but still thought that it was important to do so. In a study in Norway,95 findings reported that of 40 out of 176 patients who were able to take part in a discussion, only 28 out of the 40 (70%) actually did. There were various reports on the different challenges physicians faced with patient discussions which may explain these variations. In countries where patient autonomy was a priority,15,96 sometimes to the point of excluding families,15 physicians could experience difficulties if the patient made a decision that they did not agree with, particularly when they felt that a DNACPR order was appropriate but the patient requested CPR. Other examples included reports that some patients did not want to discuss their resuscitation status65 or be involved in the DNACPR decision-making. 65,75 Clinicians felt that they would not want to enter into discussion if the patient had poor health status65 or if they thought that they would cause the patient anxiety or distress. 70,75,77 Holland et al. 77 reported a participant’s response that it would take away ‘hope’, further pushing the patient into decline, and that it was ‘kinder’ to involve patients only if there was an expected positive outcome to CPR. Patients in one study in Hong Kong68 reported finding it difficult to accept stopping the treatment they were on, with some believing that DNACPR is equivalent to euthanasia.

There is evidence to show that relatives are mostly consulted in DNACPR decision-making,79,93,95 often as a proxy to the patient93 and sometimes without the patient’s involvement. 81 One study found that there were only a small number of cases in which the family was not involved. 79 The number of families consulted increased (n = 34/78, 44%, to n = 46/73, 63%) in one Belgian study after the introduction of a new DNACPR form. 38 Families were frequently involved when the patient lacked capacity (e.g. because of dementia)87 or were unable to communicate. 63 In emergency situations such as those outside hospital, paramedics reported that challenges in interaction with relatives could normally be solved by good communication;91 one Irish study65 reported physicians referring a disagreement with relatives to another medical colleague (n = 73; 42%), a medical defence organisation (n = 41; 24%), the Medical Council (n = 18; 10%) or an ethics board/forum (n = 3). Families, often unaware of the terminal care diagnosis, could demand excessive care, insist on intensive care and act aggressively towards staff. 63 In some cases, it was reported that relatives could become physically or verbally aggressive and threaten legal action, particularly when the patient had requested DNACPR. Attempts to over-rule the patient’s wishes were sometimes successful. 78 Relatives can also change the patient and physicians’ decisions; for example, when a patient’s wife, who disagreed with the patient’s expressed desire for no life support, responded on the patient’s behalf, the physician did not write a DNACPR order. 98

Discussion of prognosis

Information about prognosis and likelihood of survival beyond CPR varied across disciplines. 99 This information is required for patients and families14,99 to gain a realistic understanding of the choices to be made. It was noted that patients often had a poor understanding of the decision they had to make and up to half of physicians in one study15,96 were concerned about this. Patients were reported as focusing on life-sustaining therapies rather than on long-term goals. 99

The evidence illustrated the ways in which physicians communicated to patients and relatives; several studies found that sometimes discussion was delivered in a non-patient-specific15,99 or impartial way,15 contained too much medical jargon and terminology, which the patient might not understand, or might have a different understanding of a term compared with the physician’s meaning of that same term. 15,75,99 In one study,15 discussions were described as scripted, depersonalised and procedure focused, and sometimes came with a disclaimer. The review found a disconnection in communication between physicians, patients and relatives, which was underpinned by differences in the use of patients’ language; for example, ‘vegetable’, ‘invalid’ or ‘quality of life’99 were commonly used phrases but, without further explanation, they could lead to confusion for patients about what CPR or DNACPR is and can do. 15 Patients can have fluctuating preferences or might not fully understand clinical phrases such as ‘life support’; in one example, a patient had not wanted to be on life support until the physician explained the term, after which the patient had a better understanding and changed their mind. 98 Physicians often lacked the time for discussions99 or follow-up for patients to express their views or ask questions. 68 Discussions of DNACPR could be brief, with a median time of between 199 and 10 minutes. 74

Preference for discussing cardiopulmonary resuscitation rather than do not attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation

Some of the evidence indicated a patient’s lack of understanding of CPR and its success rate77 but also that physicians did not always clarify the unpredictability of CPR. 99 CPR was more readily discussed with patients than DNACPR, as illustrated by one Swiss study75 in which it was found that resident physicians initiated more discussions for CPR than DNACPR (83% and 68%, respectively) but patients initiated more discussions for DNACPR than CPR (16% and 8%, respectively). One example found that during discussion a physician changed the minds of 3 out of 4 of patients in this study from DNACPR to CPR. 99 Conversely, the discussion was sometimes framed in such a way that the patient did not request CPR. 15

Limitations

Personal hurdles for staff

Some of the evidence describes a range of negative personal feelings reported by medical staff which may illustrate why patients are not always included in discussions; this includes staff feeling inexperienced and uncomfortable,83,93 being too embarrassed to broach the subject of DNACPR with patients75 and finding it difficult to make decisions by themselves,83 thereby rejecting or avoiding the responsibility of decision-making altogether. 13 This is illuminated further by two studies in which nurses described how they perceived a physician’s reluctance to discuss DNACPR as stemming from physicians’ personal fears, a fear of harming the patient14 and not having enough courage to withdraw treatment as a result of their inability to tolerate medical uncertainty. 63 Nurses, particularly those who often cared for seriously ill patients, appeared to find it easier than physicians to approach a dying patient; the nurses’ particular traits were that they found it rewarding and felt that they were responsible for the physical and emotional support of the patient, and wanted to spend as much time with the patient as they could. 63 The evidence shows that patients felt that it was acceptable to be involved in DNACPR discussions68 and that physicians may underestimate the numbers of patients who want to discuss DNACPR status even though they would find the discussion upsetting. 75 There sometimes appeared to be a discrepancy between a physician’s assessment of the patient’s interest and the patient’s wishes and priorities. 75 One study found that physicians were worried about complaints being made against them. 93

Lack of specific skills and training

The reported lack of adequate skills is illustrated by evidence which found that nearly one-third of physicians in one study96 reported low skills in DNACPR discussions (measured as < 4 on a 5-point scale), with others reporting low satisfaction with the outcome of the discussion and low confidence levels. 39 The latter study describes a significant improvement in house officers’ confidence levels after an intervention (24% to 7%; p = 0.002) but no significant change was seen at the comparison hospital (20% to 15%; p = 0.45). A lack of, or inadequate, training in resuscitation discussions was raised in three studies,77,96,98 with 92% of resident physicians in one study74 reporting a need for formal training to help improve their skills; another study found that medical students’ skill development appeared to stagnate in the latter years of training. 96 Some evidence shows that training can influence physicians’ sensitivity to patients’ autonomy in decision-making. 64

Implementing the decision

Local guidelines, policies and laws variously apply to decision-making but there is no consistent approach to the implementation and review of a DNACPR order. Thirty-four articles are included here,13,14,16,38,39,41,63–65,67–70,73,75,76,78–84,87,89–91,93,95,97,98,100–102 of which 18 are questionnaire or survey studies; six of these are high-quality studies,69,70,78,93,95,102 one is of medium quality38 and 11 are of low quality. 63–65,67,68,73,75,83,90,100,101 Ten articles included chart or medical record audits16,39,41,76,79,80,82–84,87 of which one was of high quality,41 three were of medium quality16,39,87 and six were of low quality. 76,79,80,82–84 Eight included qualitative methods;13,14,39,41,89,91,97,98 of these, three were of high quality41,89,98 and five were of medium quality. 13,14,39,91,97 Staff are alerted not to initiate CPR in a multitude of ways: by written form, electronically or word of mouth. However, these are prone to a breakdown in communication, incomplete documentation, lack of clear reasoning and variation in treatment and care, particularly concerns about suboptimal care, responsibility for changes to care and treatment, and whether the patient should have palliative care or be admitted to an ICU. Staff can be unsure of their actions and have reported having to overcome moral and ethical dilemmas as a result.

Compliance with guidelines, law or local policies

Some countries require compliance with guidelines, law or local policies. In the UK, guidelines include taking into account the wishes of the patient and family, the expected quality of life and prognosis,87 broadly reflecting factors of importance to nurses. 73 A hospital DNACPR policy might be known widely by doctors and nurses101 but less well known by others, for example administrative staff. Guidelines, however, were often not read or known about, and sometimes lacked consensus among medical staff. One example of this was found in a Welsh study of hospital and practice nurses,67 in which it was found that a fraction of hospital nurses (11/49) had read the acute trust policy and national guidelines and most practice nurses had not read them at all. Half of the practice nurses in this study were also unsure if there was a local policy that applied to their place of work. Myint et al. 93 reported that nearly all specialist registrars in their study (n = 227, 97%) were aware of the absence or presence of local trust guidelines and two-thirds of respondents thought that the guidelines were helpful in day-to-day practice; however, there was a discrepancy when they were asked what document or guidance they would recommend. Only one-fifth (n = 48, 21%) would recommend their own trust guideline, with fewer recommending the British Medical Association (BMA) guidelines (n = 45, 19%); 29 (n = 29, 12%) would recommend the BMA/Resuscitation Council (UK) [RC(UK)]/Royal College of Nursing (RCN) guidelines and fewer still (n = 27, 11%) would recommend the General Medical Council (GMC) guidelines.

Other examples from outside the UK indicated little difference. In a study in Ireland,65 only 21% knew that there was a formal resuscitation policy in their hospital, while 54% did not think there was one and 24% did not know. Only 4% reported that the policy was publicly displayed. A study in Norway95 found that more than half of nurses were not aware of any guidelines or policies in their unit; conversely, in another study the participants were adamant about the importance of following legal requirements and nurses’ ethical guidelines related to resuscitation. 14 Swiss guidelines required a senior clinician to be responsible for making DNACPR decisions but, in reality, it was found that interns and resident physicians were involved in the decision-making on a daily basis, and one study found that there was not always consensus among staff, which could lead to non-compliance with an order. 89

In other countries there did not appear to be any common approach to the implementation of DNACPR orders but there was some alignment to European regulations. The default position by the Clinical Ethics Committee in Switzerland75 was one of resuscitation except in cases where there was a refusal by a patient who was competent and informed, or where the patient was in end-of-life care, or where CPR would be considered futile. Patients were included in decisions, unless they were incapable of making decisions, in end-of-life care or if CPR would be futile for them. Hungarian law64 is reputed to reflect European regulations on the limitation of therapy, and patient autonomy is accepted, in certain cases, as more important than the right to life. Outside Europe, legislation varied over DNACPR policy; for example, in Korea, DNACPR was not legal practice and so institutions had individual policies, particularly concerning written or verbal consent by the family which was recorded in notes following a discussion with the family. 81 In Taiwan,84 legislation had been in effect since 2007 and patients were able to forego CPR independent of any physiologic futility, and, once a DNACPR order was signed by a patient or surrogate, the physician was allowed to withhold complete or partial CPR, which included endotracheal intubation, cardiac massage, cardiac defibrillation, resuscitative drugs, pacemakers and mechanical ventilation. Two studies mentioned regular reviewing of DNACPR orders. 75,101 Recommendations required a regular review of CPR or DNACPR orders,75 with one study suggesting that reviews of DNACPR orders in acute hospitals should take place 24-hourly. 101 Ongoing reviews often took place without the patient’s knowledge68 and they took place less urgently for continuing-care patients. 87

Communicating the decision to the wider health team

Highly visible documentation or symbols were commonly used to alert staff to the DNACPR status of a patient and were recorded in the patient’s medical notes. 13,87 However, the colours used to denote this were not consistent (e.g. red and black,13 orange82 or blue). 87 In addition, the content of pre-printed DNACPR order forms varied widely.

High visibility of do-not-attempt-cardiopulmonary-resuscitation orders

In some Scottish wards, blue forms identified which patients had a DNACPR order; however, an audit found that this procedure had broken down for about one-third of patients who should have had blue forms but did not. However, decisions were clearly noted in the notes and staff were clear about which patients were to be resuscitated and which were not. 87 Various visual symbols were used to denote which patients had a DNACPR order, such as a red heart or other symbol,63 armbands,41 a black circle written on a whiteboard or an encircled ‘R’ recorded on an electronic record,13 or ‘resus minus’ (R-minus) was recorded in the patients’ records. 91 In the main, decisions were documented in records and/or nurses’ notes,13,70,79,87 and clarified at staff handover. 70 However, audits had found that this was not always consistent. 16,79,80,102

Pre-printed do-not-attempt-cardiopulmonary-resuscitation order forms

The content of pre-printed DNACPR forms varied widely but those forms described in studies included the date83 and time of the decision,81 discussion with the patient and/or relatives83 or anyone involved in the process,102 nature of the discussion81 and justification of the decision. 83 There might be space for the physician’s formal confirmation of the DNACPR decision81,83,102 and patient and family signatures,81 although this was not always the case where a verbal decision was recorded on the form or just recorded in notes. 81,102

Some studies reported that levels of ceilings of care or objectives of care pre-recorded on the form38,40,82,83,102 listed variously; for example:

-

code one – abstention of CPR (full treatment)

-

code two – no escalation of therapy

-

code three – comfort treatment (sedation, mechanical ventilation, nutrition, intravenous perfusion)

-

code four – no treatment (active therapy removal) in confirmed brain death82

-

0 – full therapy

-

one – no CPR

-

two – withholding of therapy such as dialysis

-

three – withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy

-

four – withdrawal of mechanical ventilation (active dying process had started). 38

One English study40 described the development and evaluation of a form which listed and focused on treatments to be given rather than those to be withdrawn and made a distinction between whether active or supportive care is in the best interest of the patient. Several of the studies described the evaluation of differently designed forms to improve the process of documentation38,40 and some were designed to be completed on admission to hospital. 16,40,83 One US study39 described reducing seven different forms, which covered all aspects of the law in New York (e.g. adults without capacity, adults without surrogates), to a single form including only the relevant detail. Some studies described what had not been included on the forms, including the patient’s condition (e.g. there was nowhere to record fluid and food administration),81,82 documentation of discussion with the patient or relatives and an assessment that CPR would not be beneficial. 82 One study found that there was no consistent approach to patient involvement across several different types of forms. 102

Breakdown in communication

Lack of clear reasoning

The evidence illustrates that reasons for the DNACPR order are not always fully documented, if at all,16 or are inconsistently recorded in different places; for example, 60% of documentation did not record a clear reason why a DNACPR decision had been taken but some information was recorded in clinical notes instead. 87 Very generalised reasons using phrases such as ‘futility’, ‘frailty’ or ‘comorbidities’13 were used with no further explanation. Forty per cent of recorded decisions in one study87 were simply recorded as an advanced state of illness contributing to a poor quality of life, meaning CPR was unlikely to be successful.

Missing, incorrect or incomplete documentation

Several reasons were given for non-documentation of patient discussions, which included the lack of capacity, potential distress, time pressure and the patient not wanting to discuss the topic. 13 Decision-making with patients and/or their relatives was variously documented in the evidence. Most decisions were documented by relatives, particularly when the patient was comatose;84,87 others reported that just a few were documented. 13,16

Although there was little way of knowing if a lack of documentation was an oversight or had been forgotten,13 the impact on the patient could be devastating; for example, one study reported the consequences of not completing documentation in a case where a ‘95-year-old patient’ was resuscitated by a crash team when a doctor forgot to complete an order. 13 Discrepancies in documentation can also have devastating results for the patient. Evidence shows that incorrect documentation arising from discussions with patients can result in resuscitation being withheld or administered when the opposite was requested by the patient. 98

Treatment and care

Interestingly, the review studies clearly illustrate variations in the meaning of a DNACPR order to health-care staff. An English study40 found that doctors believed that a DNACPR order referred to reduced care (e.g. reduced out-of-hours medical escalation, contacting the outreach team, frequency of nursing observations, reduced pain relief and altered fluid intake), despite clear guidelines that DNACPR orders applied only to CPR. Other examples of the misinterpretation of care for patients with DNACPR orders included where some doctors and nurses believed that nursing observations would be reduced63,97 or remain unchanged,100 that contact with outreach teams and other medical staff and out-of-hours medical escalation would be less frequent, although nurses less often felt that this occurred than doctors. 97 It was also suggested that pain relief and amounts of fluids would be altered97 and one Finnish study63 noted that basic care was reduced for patients with a DNACPR order. One Taiwanese study84 reported that patients with a DNACPR order in an ICU were less likely than patients without a DNACPR order to receive life-support therapies at the end of their life, such as vasopressors, resuscitative drugs, cardiac massage, pacemakers, cardiac defibrillation, mechanical ventilation and supplemental oxygen, but were as likely to receive blood transfusions, intravenous fluids, haemodialysis, endotracheal intubations, total parenteral nutrition and nasogastric tube feeding.

Concerns regarding suboptimal care

Concerns were raised regarding the implications of poor care after a DNACPR order was implemented. Examples have been reported where less-experienced staff (< 1 year) reported that they may unknowingly reduce care to patients,68 and many doctors and nurses (n = 16/23, 69.5%) felt a DNACPR order would have negative consequences for the patient and result in suboptimal care. 13 The possibility of the implementation of substandard care led to a refusal by physicians to complete documentation in one study. 78

Responsibility for changes to care and treatment

Responsibility for change in care and treatment was explained differently: junior doctors thought that nursing care would be affected, nurses thought that it would be the responsibility of out-of-hours doctors and consultants gave a mixed response which did not include them. 13 Cohn et al. 13 suggested that although care may be differential, it is not explicit or tangible.

Palliative care or intensive care unit?

Although studies reported on decision-making and implementation of DNACPR orders, there was little evidence comparing the settings in which this took place. The current review raised questions about what type of treatment and care should be stopped in connection with a DNACPR order, and whether or not staff should instigate a palliative care pathway. In a comparison study of the perspectives of doctors and nurses it was found that they differed in their approach to a DNACPR order; most doctors regarded it as not undertaking CPR in the case of cardiopulmonary arrest and nurses regarded it as a ‘new’ phase in which health was deteriorating and a palliative care approach was needed to allow for death with dignity. 89

One study63 found that those working in internal medicine interpreted DNACPR orders as simply not offering resuscitation, whereas those in oncology interpreted it in terms of holistic and palliative care. In a cardiology department,79 therapeutic efforts were limited in the 24 hours preceding death in 34.5% (n = 39/113) of its patients and treatment and care was reduced to morphine chloride and spiritual support but involved little palliative care. The evidence also shows variation in whether or not patients with a DNACPR order should be admitted to an ICU. Patients with a DNACPR order were less likely to survive and be discharged from the ICU (87.2% to 46.4%). 84 One study38 found that half of all patients who died had an ICU admission near the end of their life, while only 17% (n = 66/396) of patients died in a palliative care unit; the authors suggested that the transition from curative to palliative care is suboptimal.

Staff dilemmas

A lack of complete or updated documentation, or poor decision-making, could leave doctors on call and nurses uncertain about what to do in an emergency event. 13,14,79 Performing CPR by default can raise moral and ethical issues for staff and has life-and-death consequences for the patient. 91

Updated documentation is also imperative where a DNACPR status has been reversed, as one example shows: one paramedic91 found that although the records stated ‘resus minus’, this should have been reviewed, as the patient’s health had improved.

Difficulties arise with the implementation of DNACPR orders if the wider health team is unsure of the decision or if they disagree with it. Evidence illustrates how staff may have to perform CPR when they feel that it is inappropriate, particularly in the case of medical teams who work in emergency situations, such as arrest teams78 or paramedics outside the hospital who are obliged to perform CPR if the patient is still alive. 76,90 The last two of these studies described how in 2007 the law was changed in Los Angeles, USA, meaning that paramedics were allowed to forego CPR in certain circumstances (if there was a verbal request, if there was an unwitnessed arrest, if the time to resuscitation was longer than 10 minutes or if the patient met the criteria for irreversible death, i.e. asystole).

Nurses, in particular,69 reported that they would allow the patient’s preferences to influence non-initiation of CPR (n = 97, 83%) or refuse to sign a DNACPR order if they disagreed with it; one example was given of a nurse who would not countersign an order given by an out-of-hours doctor. The order was later stated as incorrect and cancelled by a regular consultant. 13

Consequences of do-not-attempt-cardiopulmonary-resuscitation orders

The practical aspects of not issuing a timely DNACPR order can be prolonged and costly, and just a small amount of evidence from two low-quality studies addresses this:76,79 one study was an audit of the registry of deaths79 and one included a focus group, a survey and patient notes. 76 The evidence reported here is not overly reliant on these two studies but reports on the key findings. The evidence reports on the extra medical and technical costs of keeping a patient alive when perhaps a DNACPR order would be more appropriate. One example in particular illustrated this,79 in which most patients had had a prolonged stay in the department and had undergone aggressive and expensive treatment prior to a DNACPR order; the treatment included orotracheal intubation (n = 49, 43.4%), coronary angiography (n = 27, 23.9%), inotropic drugs (n = 55, 48.7%) and intra-aortic balloon counterpulsation (n = 15, 13.3%). Martinez-Selles et al. 79 argued that physicians find it harder to withdraw treatment than to start it and that they need a tool to help them decide which patients would not benefit from aggressive management.

The evidence also shows that resources can be used unnecessarily when staff are prevented from making a decision not to resuscitate, particularly outside hospital. One example of this is described in an evaluation of a new policy for paramedics in Los Angeles, previous to which unnecessary costs and resources were incurred as paramedics were required to resuscitate a patient and transport them to hospital even when it would have been more appropriate not to resuscitate. However, after the implementation of the new policy allowed them to withhold CPR in certain circumstances, unnecessary costs were still incurred, as paramedics could spend several hours waiting for the police to arrive rather than being free to attend other emergency events. 90

Summary

The objectives of this review were to identify the factors, facilitators of and barriers to DNACPR decision-making and implementation of DNACPR orders. The review found many variations in DNACPR decision-making and implementation processes, in particular who is ultimately responsible for the decision-making, how the decision is made and communicated, in which setting, how the DNACPR order is implemented and who does this.

Overall, the studies did not provide a robust evidence base owing to the low quality of many of the studies, and there was sparse evidence of the cost and resources involved in resuscitating patients who might have been more suitable for a DNACPR order.

The key messages from the analysis indicate that there is good practice in DNACPR decision-making and implementation but there is also a wide variation which is cause for concern. This review of international literature has identified many different practices yet similar problems in DNACPR decision-making and implementation.

The two themes, considering and discussing the decision, illustrate how the facilitators of good practice in DNACPR decision-making included a whole-team approach including the patient, if he or she is able, or their family,89 a professional supporting body,65 early decision-making which is regularly reviewed40,75,83 at a time and in a setting which is amenable to discussion,74,99 and using commonly understood language. 75,98,99 However, examples of good practice were lacking in the literature.