Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 12/129/32. The contractual start date was in November 2013. The final report began editorial review in June 2015 and was accepted for publication in November 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

At the time of receiving funding for this project Jo Rycroft-Malone was a member of the National Institute for Health Research Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) programme’s Commissioning Board and is now its Programme Director. She is editor-in-chief of the HSDR programme.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Rycroft-Malone et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Older people’s care context

The UK’s population is getting older: it is estimated that by 2031 one in five people will be over 65 years old. 1 In the UK older people (aged ≥ 65 years) account for approximately 16% of the population throughout England and Wales, with 14.7% of over-65s residing in Northern Ireland and 20% living in Scotland. 2 Research suggests that older people require care that encompasses both health and social care functions. 3,4 These needs require access to a wide range of generalist and specialist services including from statutory, independent and voluntary services. 5 Older people are the main recipients of care in the NHS, and thus care costs are relatively higher than those for working-age people. 6 The provision of health and social care for older people may be more complex because of existing conditions. For example, it is estimated that 40% of people in hospital care over the age of 65 years have dementia. 7

A series of recent investigations and high-profile cases have questioned current practices in services provided to older people. Both Francis Inquiries were focused on older people’s care. 8 The Care Quality Commission9 identified concerns over the skills, training and availability of the care workforce within hospital settings to deliver dignified and appropriate care and followed on from several other critical reports of the standards of care offered to older patients within the NHS. In particular, the Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman10 called for standards of NHS care for older people to be improved. Health Service Journal/Serco8 reference a range of recent publications in which concerns about older people’s inpatient care have been highlighted, including those from the Joint Committee on Human Rights,11 Age UK/NHS Confederation12 and the Office for National Statistics. 13 Furthermore, the preferences and experiences of older people may not always be reflected in care policies, structures and practices. 14,15

The rapid increase in the older-person population is driving current pressures to develop new service models, processes, roles and expertise for delivering effective and efficient care, especially when people have distinctive and often individualised care needs. Monetary investment in joint funding between the NHS and social care can support preventative care in older people’s services, for example falls prevention and reduced social isolation, and improve discharge pathways. 16 The NHS is increasingly moving to multisectorial services which are integrated around the patient,17 which should promote models of care for the future which prioritise social and medical needs and should be relationship based. 18 However, integration has been in danger of being reduced to political rhetoric19 owing to a lack of joined-up integration across services,20 and fragmented commissioning structures. 21 The personalisation agenda, whereby people fund their own care, direct payments and personal budgets, will lead to changes in the workforce in the future, with more emphasis on personal assistants and social enterprises. 22

As part of these changes, greater use and development of the support workforce in health and social care is likely to remain a long-term priority for NHS managers and other sector organisations. High-quality care provision for older people is a strategic priority. Public policy interest in the support workforce has heightened recently as policy-makers have faced a litany of care delivery failures. 23

Faced with an ageing population, escalating levels of complexity and need in NHS and social care services, and changes in workforce design (which include reduced working hours for doctors, nurse training and advancing roles), the demands on the support workforce will most likely increase in the future. 24

The support workforce

The health and social care support workforce is defined as providers of ‘face to face care or support of a personal or confidential nature to service users in a clinical or therapeutic settings, community facilities or domiciliary settings, but who do not hold qualifications accredited by a professional association and is not formally regulated by a statutory body’25 (quote contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0). The support workforce delivers care alongside the regulated, professional workforce in their day-to-day duties under supervision. 24

Establishing a clear role definition for the support workforce is challenging. Role labels vary across health and social care services, from health-care assistants (HCAs) and support workers26 to health-care support workforce27 to care assistants or therapy assistants. 28

In acute NHS care, terms used to describe the support workforce include HCAs, nursing assistants, nursing auxiliaries, assistant practitioners and personal/clinical or health-care support workers. 23,29 The role is ill-defined in social care, with terms being used interchangeably to generally describe the support workforce, for example support worker, community support worker and social work assistant. 30 There is a lack of a common definition of the support worker role, largely due to the variety of duties that they perform. 31 This diversity and lack of clarity means that often support workers are ‘figuring it out in the moment’. 32

Across health and social care, the support workforce is large; an estimated 1.3 million people are working on the frontline of care,26 which can be categorised into the different types of roles they perform, including direct care, indirect care, administration and facilitation. In the UK, health-care support workers account for 47% of the total NHS workforce;33 thus, they constitute the largest group of staff. 28 Care assistants and health-care support workers account for 60% of estimated contact time with patients. 19,33 In England alone, support workers account for over 300,000 of the people employed in the NHS. 24 UK statistics are similar to those found across the globe. For example, assistant and support workers account for 50% of the health and social care workforce in Australia;34 in Canadian nursing homes, the unregulated support workforce provides 75–80% of direct care35 and health-care aides provide up to 80% of care for older adults in long-term care settings. 36,37 In the UK, most health-care support workers are female. 26,38 The health-care support workforce has been described as tending to comprise ‘mature women with partners and children’39 and to be more embedded within the local community than professional nurses. 40

In general, there is evidence to suggest that support workers are not deployed as effectively as possible and are often undervalued. 29,39 Research concerning this workforce has generally focused on their role and contribution in the acute care sector. 41 In this context, support workers have been described a providing the fundamentals of care by the bedside. 23 Research evidence addresses the development of staff (including support workers) to promote patient-centred care in particular situations, such as dementia services,29,42 and there is evidence about role boundaries for support workers in the context of different professional groups. 39,43 However, we could find only one study that has specifically explored the role of support workers in older people’s services. 44 Moreover, there are evidence gaps in understanding roles across different care settings,24 for example the community, independent sector, home care, third sector and social enterprise. This is despite an escalation in numbers of support worker roles; for example, an unprecedented rise in the numbers of community nursing assistants has occurred over the past 20 years. 45 In the face of policy developments such as personalisation and integrated care, a better understanding of support worker roles within community-based settings will become even more important.

Policy context for support workforce development

The use and role development of the support workforce has been somewhat ad hoc43 and largely dependent on the various activities they perform. 31 In the NHS policy context, the importance of HCA roles has not been underestimated, but the discourse about them has, at times, been ambiguous. 46 The literature reflects a general lack of clarity about the role of support workers,47 with roles developing organically rather than systematically, and, consequently, their preparation and continuing development has tended to be haphazard. 40

Probably the most significant review to emerge in the UK recent years relating to the support workforce is the Cavendish Review. 26 In response to the Francis Inquiry, Cavendish undertook an independent inquiry of the support workforce to ensure that all patients would be treated with care and compassion. 48 Based on the recommendations of the Cavendish report, a new certificate (the Care Certificate) is now under development, which will need to be completed in order to allow new HCAs and support workers to work unsupervised in care settings. 48 The Care Certificate is equally applied to the support workforce across health and social care, replacing the National Minimum Training Standards and Common Induction Standards, and reflecting the ‘6 Cs’ (care, compassion, competence, communication, courage and commitment). 49

In addition, in the UK, a group of recent publications4,26,50–53 have made recommendations for training for nursing assistants and HCAs. These reports have steered the commissioning of the Shape of Caring review. 49 In NHS care, Talent for Care has seen the development of a national strategy for all support roles in the Agenda for Change pay bands 1–4. The Talent for Care consultation in 2014 found universal support across the UK for a national strategic framework to develop the support workforce,27,50 underpinned by the Department of Health,50 which directed Health Education England to improve the training and development for the support workforce. However, although a number of publications point to the need to improve the skills and training approaches currently used to develop support workers,9 education, training and development for the support workforce remain challenging. 33 Further, there are other challenges for the support workforce, including career pathways, role substitution, regulation and retention, described as follows.

Career pathways

One of the recommendations from Cavendish26 was to strengthen the care career trajectory for the support workforce, and there is evidence that a number of health-care support workers aspire to develop their careers. 40 In social care, there is acknowledgement of the benefits of career pathways for support workers, but the picture is mixed. 30 It seems that, currently, the degree of synergy between workforce development and opportunities for job and role development is not always clear. Leadership, supervision and support should be developed in order to get the best out of people. 26,48

Role substitution

Support workers have been traditionally represented as low-cost labour source. 23 In recent times, the division of labour in hospital care has led to delegation of nursing tasks to care assistant roles. 54 Traditional workforce boundaries have altered drastically, with the support workforce taking on tasks previously undertaken by registered staff. 31,38 Although the growth in the support workforce has sometimes been driven by initiatives to reduce costs, involving role substitution for registered staff, there is a degree of evidence to show that support workers can act as an additional resource to enhance older people’s experiences by improving the contact with care practitioners. 35,44 In social care, there is role overlap between support worker and professional roles. 30 When the support worker role is perceived as a substitute for professional nurse tasks,46 this can potentially compromise morale.

Regulation

Regulation for health-care support workers has been debated at length in recent years but as yet remains unresolved. 46 In the UK, a major review of health support workers commissioned in 1999 examined health support workers’ roles and regulation. 55 Core competencies in Scotland were introduced in 2001, which informed further work about regulation for health-care support workers. 56 The current ambiguity about regulation means that there is little control over employment, responsibilities, education, competence, title and pay. 38 In social care, registration of home-care support workers has been recommended,57 with codes of conduct developed for health and social care workers58,59 in addition to governance frameworks. 60

Retention

Consistent employment patterns for clinical health-care support workers have been reported. 40 However, in social care, retention in home care is problematic, with one of the highest staff turnover rates at around 21%, twice the national average. 61 Securing new support staff and retaining those who are already employed in home care should be key priorities. 59 For joint working, staff retention is important, as it has been reported that frequent staff turnover can have consequences for the numbers of staff who champion integration. 16 Recommendations have been made for employers to be supported to test care values at recruitment stage. 26 However, in home care, high turnover demand and low pay can compromise values-based recruitment. 61

Workforce development interventions

For this review, workforce development interventions are defined as the support required to equip those providing care to older people with the right skills, knowledge and behaviours to deliver safe and high-quality services. 22 Evidence about interventions to develop the health and social care support workforce in older people’s care and services is limited, and there have been calls for evidence to inform services about how to improve standards for the future. 40 This is especially timely in the light of the introduction of new service models, for example training for staff in integrated services whereby the workforce is expected to work in different organisations and across traditional boundaries. 16 However, there is scant evidence to show how approaches to training and education can link with impacts for the people who are the users of services. 16 In social care, evaluations have already concluded that National Vocational Qualifications (NVQs) are inadequate and that there is a lack of clarity regarding training. 30

For the design and delivery of workforce development, current provision is inconsistent. 27 Access to good developmental opportunities (e.g. recent reporting of comprehensive and innovative training programmes62) sits alongside variation in mandatory training and induction. 26 NHS trusts and other services have adopted different approaches to workforce design and development models, which confounds attempts to show a universal picture across health and social care. Recommendations included the need to shift to more work-based approaches to learning and development for all staff including the support workforce. 63 In social care, lack of attention to developing skills for support workers to implement person-centred care planning has been noted. 30 In Scotland, recommendations about consultation with stakeholders in the design of workforce training, study skills and support systems were made to improve support workers’ education and training. 40

Previous work on the development of professionals has focused on advancing workers from novices to experts. 64 However, such models of education have focused on individuals who are already highly educated and with additional years of experience to build on, which is often not the case for the support workforce. The general lack of clarity and diversity in models, roles and care settings has resulted in a gap in knowledge about what makes for effective interventions. Moreover, much previous work has focused on how professionals learn, including the different processes for adopting new practices, rather than on considering contextual and structural barriers such as the role of organisational strategy and professional regulation. Further, workforce development interventions are characteristic of complex social programmes with inter-related components, the impacts of which are likely to be contingent on multiple personal, work-related and organisational factors.

Summary

Calls for change across recruitment, training and education for support workforce have been made. 26 The evidence presented in this chapter has shown where gaps exist in knowledge about how to develop staff across health and social care services. The issues highlighted show how it is timely for a review of workforce development for the support workforce, to understand what works and to develop the skills and knowledge of staff.

Review question and aims

This review was designed to identify interventions at individual, team and organisational levels that have the potential to enhance skills and care standards in the support workforce for older people. In addition, the review was designed to uncover how and why workforce development interventions may impact, and on whom, in order to guide future workforce development policy and practice.

Our research question asked ‘how can workforce development interventions improve skills and care standards of support workers within older people’s health and social care services?’.

The main aims of the study were to:

-

identify support worker development interventions from different public services and to synthesise evidence of impact

-

identify the mechanisms through which these interventions deliver support workforce and organisational improvements that are likely to benefit older people

-

investigate the contextual characteristics that will mediate the potential impact of these mechanisms on clinical care standards for older people

-

develop an explanatory framework that synthesises review findings of relevance to services delivering care to older people

-

recommend improvements for the design and implementation of workforce development interventions for support workers.

Chapter 2 Methods

Introduction

Following recognised realist principles and published guidance,65–67 and drawing on the previous experience of the team in undertaking realist review,68,69 we followed a number of stages in completing this project. However, unlike the stages of a traditional systematic review, which tend to follow a linear path, the process of a realist review is more iterative. This is because the review is theory and stakeholder driven, and it is the process of theory development and refinement that guides the search for evidence, the review of evidence (which evolves through the process) and, ultimately, the synthesis process. This process goes back and forth, and although we have presented the methods in stages below we have attempted to reflect an iterative process in the narrative. In this chapter, we provide a detailed description of each of the areas of evidence (stakeholder views, published literature and interview data) which informed programme theory development, refining and testing. In this report we have used the RAMESES (Realist and Meta-review Evidence Synthesis: Evolving Standards) publication standards (i.e. specific publication guidelines for realist syntheses). 67

Stakeholder engagement, including patient and public involvement

Stakeholders are key drivers in realist work. The realist synthesis focus is driven by ‘negotiation between stakeholders and reviewers and therefore the extent of stakeholder involvement throughout the process is high’. 67 Stakeholder contributions for realist synthesis can include clarification, checking meaning and developing theory. 70,71 For this review, stakeholder engagement was designed to help the research team elaborate on the review context, refine the review questions, contribute to programme theory development and interpret the evidence. Stakeholders were involved in a process of (a) prioritising and (b) refining the theory areas and making additions.

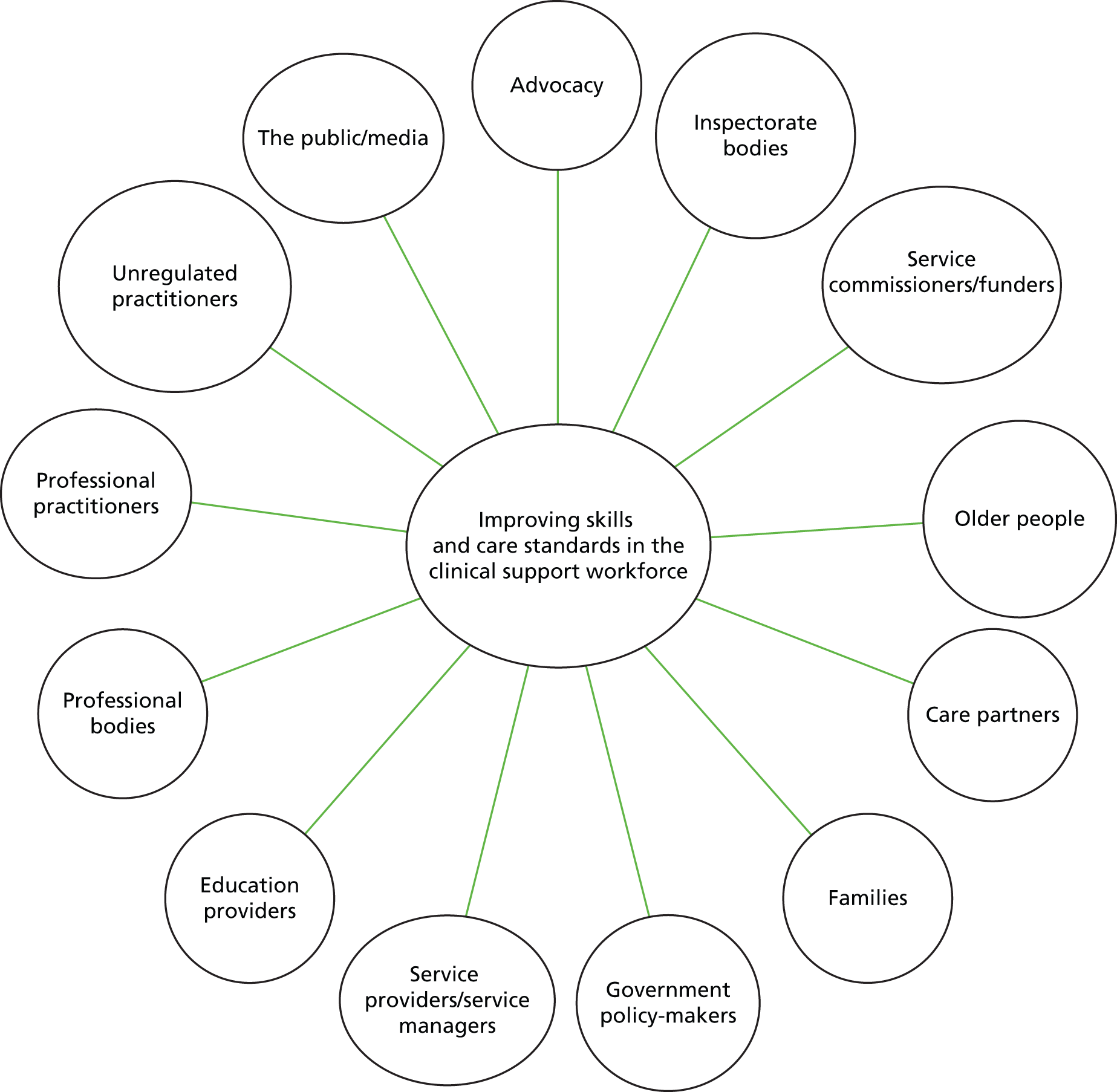

The research team adopted a systematic approach to stakeholder identification based on an impact and influence matrix72 to ensure that the most appropriate people were contributing to the review. Lists of potential stakeholders were drawn up to show who they were and to consider their potential input for the review. Stakeholder categories included users of services (i.e. older people, their care partners and families, and the public/media); providers of services (i.e. unregulated practitioners, professional practitioners and service providers/service managers, and education providers); service commissioners/funders and other relevant bodies (e.g. inspectorate bodies, advocacy, and professional bodies and government/policy-makers). Stakeholder engagement also incorporated the interactions with the Project Advisory Group members.

We identified 13 categories of people/groups who could bring different perspectives to the study (see Appendix 1 for information about stakeholder engagement). To help to identify levels of involvement with the project, the categories were then analysed further to consider the interests of the stakeholders and how, hypothetically, they could affect/be affected by the study’s aims and objectives. Consideration was given to the stakeholders’ interest, their particular influence (that would inform the study), potential impact level, expected concerns and stakeholder management throughout the study’s duration. The results of the stakeholder analysis were mapped onto a matrix to give consideration to the levels of influence and impact, expecting that levels of engagement for different stakeholders would change during the study’s duration. In addition, we searched for people active in representing older people at community level to secure patient and public involvement (PPI) in the project team and steering group. Three individuals were nominated and accepted the team’s invitation to participate. They became project team members and are coauthors of this report (for profiles see http://opswise.bangor.ac.uk/meet-team.php.en).

Stakeholder engagement in the review was as follows:

-

participating in workshops to explore the nature of, and identify key issues in, workforce development for the older persons’ support workforce

-

advising on priority issues within the review theory areas

-

commenting on iterations of the plausible hypotheses and context–mechanism–outcome (CMO) configurations

-

advising on specific stakeholders to participate in interviews

-

advising on knowledge mobilisation – including through a ‘WeNurses’ Twitter chat (Twitter, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA) (see Appendix 2 for a summary).

In addition, PPI representatives attended all monthly meetings of the project team, and were consulted on specific issues in between. Representatives also attended initial exploratory workshops along with other stakeholders and this led the construction of some review artefacts, including a plain English glossary of review terms (see Appendix 3).

Changes to the review process

No changes to the review process were made subsequent to the publication of the review protocol. 73

Rationale for using realist synthesis

Realist synthesis is theory driven. In this way, realist synthesis works under the principle that it is the unseen elements of a programme (the mechanisms) that lead to its success or failure. Contingent relationships are expressed as CMOs, to show how particular contexts or conditions trigger mechanisms to generate outcomes. Mechanisms are ‘the pathway from resource to reasoning and response’,74 and resources can be described as those that are ‘material, cognitive, social or emotional’. 75 The reasoning and response may stem from the perspectives of the receivers, the organisers or those involved in the delivery of programmes/interventions.

As Pawson and Tilley remind us, social programmes (i.e. workforce development interventions/programmes) are ‘theories incarnate’. 76 Programme theory ‘describes the theory built into every programme’77 and is expressed in this way: ‘if we provide these people with these resources it may change their behaviour’. 75 Different sources of evidence are used to construct programme theories but they emerge from a systematic process that includes stakeholder engagement, an overview of relevant extant theory77 and scrutiny of primary research. 78 In this review, theory development work was undertaken in phases 1 and 2, to articulate theories about ‘what works’ in workforce development for the support workforce in health and social care and the conditions that might make them successful.

Workforce development interventions for the support workforce for older people are complex social programmes, involving people, structures and organisations. In this review, workforce development interventions were defined as the support required to equip those providing care to older people with the right skills, knowledge and behaviours to deliver safe and high-quality services. 22 As such, the way in which they might work will be contingent on a variety of factors and, therefore, synthesising evidence to explain this required an approach that could accommodate both complexity and contingency. We consequently undertook a theory-driven approach to evidence synthesis, which was underpinned by the realist philosophy of science and causality. 67,73

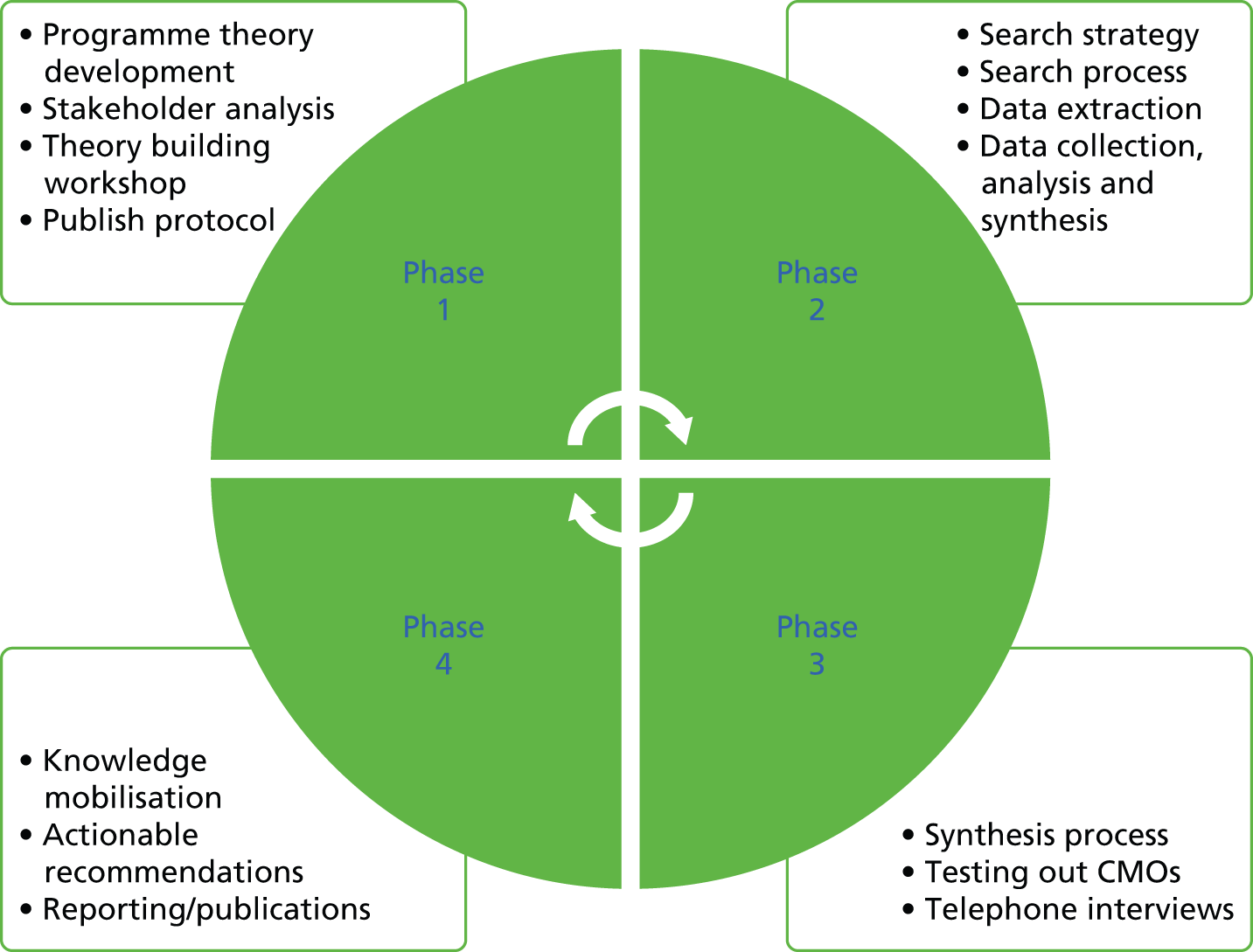

Programme theory development and refinement involved in a number of interconnected processes (Figure 1), including:

-

scoping the literature

-

concept mining

-

conceptualising workforce development – stakeholder workshop, which was guided by soft systems

-

identification of theory areas

-

-

searching processes

-

selection and appraisal of documents

-

data extraction, analysis and synthesis processes.

FIGURE 1.

Phases of the study.

The process and outputs of each of these activities are described in more detail in the following text.

Scoping the literature

Concept mining

Concept mining was undertaken to map evidence about the support workforce, workforce development interventions, older people’s services, how interventions might operate and any reported enablers or barriers to the successful implementation of interventions. Concept mining in realist synthesis describes a process of searching through different bodies of evidence for information that could help build theories. In this review, concept mining involved searching through different bodies of evidence (including the commissioning brief, policy/guidance and grey literature) for information that could build theories about workforce development.

The starting point for the review was the commissioning brief, which was subsequently reflected in the funded proposal. 79 Particular points worth reiterating here relate to the nature of the work of the support worker; how training and support interventions should reflect variety in need across different organisations/settings; the focus of training (task/core competencies vs. values-based approaches); effectiveness and cost-effectiveness; ‘best’ interventions; teaching methods, organisational development and performance management; and impacts of workforce development interventions (for individual support workers, teams and older people).

In a background search of some policy documents,41,60,63 we found literature about the perceptions of support worker roles, gaps identified in skills training, how training and development should be structured for the support worker, approaches to workforce development, professionalism and the working environment. Key concepts identified from this background search included:

-

how support workers who feel valued and empowered are more likely to promote dignified care

-

how management support in the workplace can enhance autonomy and decision-making

-

the challenges of over-reliance on personal experience without specific guidance

-

continuing professionalisation of care work so that support worker roles can be promoted

-

how personal development can build knowledge and skills

-

dimensions of quality, including dignity, communication and understanding of the older person as an individual

-

use of multiple, flexible learning and teaching strategies to promote confidence

-

increase of the attractiveness of care work through the provision of development opportunities.

To guide our development of the programme theories, we conducted an initial exploration of theory which might help to show how workforce development should work and identify what factors can supposedly support or hinder its success, for example learning from theories of professional learning, which included the role played by informal learning80 and role progression, and the development of expertise in developing learning. 81 We drew on the work of authors64 to consider how the mental activity required for skill acquisition varies from novice to expert (i.e. workforce development interventions should meld with the support worker’s developmental stage). Theories of adult and transformational learning were also relevant to be considered in the context of how interventions may be underpinned by holistic education, taking into account cognitive, affective and psychomotor domains. 82 We also examined how workforce development is defined in other disciplines, for example education83,84 and employment. 85 We considered variation in workforce development implementation for the support workforce,26 issues of workforce changes and substitution31 and how to link different development interventions and workforce functions. 33 Theories of behaviour change were also considered, as they focus attention on how to develop individual skills and knowledge. 86 From an implementation perspective (i.e. literature that might help to explain how interventions/programmes get implemented in practice), we considered how knowledge use may be influenced by factors related to the work environment and facilitation,87 and, from education, how the choice of intervention should suit the context. 88 We also mined the practice development literature to be cognisant of how workplace cultures can be improved. 89 We also felt it important to take into account the role of organisational and other contextual influences that might influence workforce development intervention design, delivery and evaluation, including individual, team and organisational foundations for learning organisations90,91 and other factors which enhance or act as barriers to learning. 92

Conceptualising workforce development

At the beginning of the project we held a workshop in which stakeholders contributed to the development of the scope and issues that are relevant to the workforce development of support workers with older people’s health and social care services (see Appendix 4 for workshop participants). The workshop was facilitated by two members of the research team (CB and LW). Stakeholders were purposively sampled to ensure representation from relevant constituencies (i.e. health, social care, education, third sector, patients and the public).

The structure of the workshop was guided by soft systems thinking, a learning approach which offers an interpretive perspective of the complex and adaptive nature of human systems, such as workforce development, within the ‘real world’. 93,94 Soft systems methodology complements the realist approach used in this review, as it takes into account how complex systems within which programmes or interventions are situated may be underpinned by different perspectives. 95 We found that applying the principles of soft systems methodology helped the team to operationalise the workshop in a structured way. In addition, soft systems methodology helped us to guide stakeholders’ thinking, so that they could shed light on some of the complexities behind workforce development for support workers. We chose this approach as we assumed workforce development to be transformative of both individuals and contexts, with the potential for both complementary and conflicting structures, processes, impacts and perspectives. We applied the principles of soft systems in two ways:

-

the use of the CATWOE mnemonic (see below) to structure data collection, discussion and analysis

-

the generation of rich pictures describing how workforce development works.

The CATWOE mnemonic provided a structured way of thinking about the complexity of workforce development programmes by focusing on the beneficiaries of workforce development (customers), the roles and functions of people within workforce development (actors), the changes that workforce development makes (transformations), the beliefs about what is important in workforce development (world views), issues of leadership (ownership) and physical and other constraints on the system (environment). 95

The first phase of the workshop included table discussions around the CATWOE issues (Table 1).

| CATWOE elements | Trigger questions |

|---|---|

| Beneficiaries (customers) and roles and functions (actors) | What are the roles of older people and others in workforce development? |

| Who should be involved in designing workforce development programmes and strategies? In what ways? | |

| Transformations | What changes are required? |

| Where are interventions likely to work/fail? | |

| World views | What are the current problems/challenges facing the staff now? |

| How should these issues be picked up in workforce programmes and strategies? | |

| What are the political/professional and other influences on the support workforce that we need to consider? | |

| Ownership | Who/what can influence success in developing workforce interventions? |

| Constraints (environment) | Can you foresee any constraints/barriers? |

The output from these discussions was used to develop rich pictures to illustrate the complexity of a workforce development ‘system’ by linking the CATWOE elements, for example:

The rich pictures provided the basis on which to develop a stakeholder-driven textual summary of how workforce development for the support workforce for older people should operate:

-

The effectiveness of workforce development interventions/programmes for the older people’s support workforce can span outcomes for the workforce (e.g. knowledge, skills and attitudes, career progression and personal/professional development); for the delivery of services; for older people and their carers (e.g. service effectiveness and experience); and for organisations (e.g. service quality). Interventions/programmes are most effective when positive impacts from workforce development can be identified in all of these areas. For example, changes in the knowledge and skills of the support workforce will often require changes in organisational systems or processes for benefits to be accrued by older people, and vice versa. When these impacts do not meet the expectations of older people or health organisations, then positive, individual changes from workforce development programmes/interventions might be evident but might not be sustained.

-

Workforce development will be effective when it is aligned with organisational and other career development frameworks and opportunities. When these frameworks are used to design and evaluate workforce development, benefits for individual members of the workforce may have greater visibility and meaning.

-

Effective workforce development is designed, implemented and evaluated with the older people’s support workforce and practice. Programmes or interventions that are neither grounded in the reality of daily work completed by the older people’s support workforce, nor delivered within in the workplace, are less likely to be effective.

-

Effectiveness can be mediated by the personal characteristics of members of the older people’s support workforce (e.g. motivation, self-esteem, confidence and learning styles); aspects of human and social geography; characteristics of the organisations in which the support workforce is operating; workforce and service policy; and public experiences and expectations.

Identification of theory areas

This initial conceptualisation was used to generate a longlist of issues in four theory areas for focusing the review (see Appendix 5). These were reviewed and prioritised by stakeholder workshop participants and then by the Project Advisory Group members in a face-to-face meeting. They were broadly grouped into theory areas: career development and strategy, design and delivery, and mediating factors and impacts.

Searching processes

As theory development work was under way, the process of developing the search strategy continued, led by the project’s information scientist (BH) and involving the research team and feedback from the steering group. The process involved searching for evidence relevant to the theory areas.

Reflecting the realist approach, the search strategy was broad and eclectic96 and combined a primary search and purposive searches in order to capture the most relevant evidence to support or refute the ideas within the initial programme theories. For the primary search, a list of search terms was created from the theory development work (concept mining and conceptualising workforce development). Search terms used for the support worker captured data to inform the mediating factors theory area (e.g. personal characteristics, gender, cultural issues). In addition, further searches found other data relevant to mediating factors (e.g. leadership or policy).

Test searches were set up in MEDLINE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) and Social Services Abstracts (SSA) and titles/abstracts were inspected for search terms. Longlists of terms were drawn up for support workers, workforce interventions, and outcomes for support workers, older people/carers/families and organisations. The search term list for the support workforce was adjusted to include terms that emerged from scrutinising the literature, for example care attendants, health-care aides, personal support workers, hybrid workers and care providers (see Appendix 6). Search term lists were rationalised and checked against MeSH (medical subject headings) when available, and checked alongside the developing set of programme theories. Search terms for support workers in education and policing were also retrieved, for example para educator, special education assistant, aide, instructional assistant, paraprofessional, police community support officer, special constable, and operational support grade. The logic for deliberately looking beyond health was to refine the emerging findings from the health and social care literature, and to ascertain whether or not there is any cross-sector learning given that support roles exist in other public services.

Primary search of databases

The major health, social and welfare databases were searched using keywords identified through the search development and database specific ‘keywords’ adapted for each information source (see Appendix 7 for an example of search strategy). The primary search was limited to material from 1986 (the date of the conception of NVQs) to 2013. Methodological filters were not used to avoid excluding any potentially relevant papers. Systematic searches were conducted in 10 electronic databases subscribed to by Bangor University: PsycINFO; SSA; Sociological Abstracts; MEDLINE; NHS Economic Evaluation Database; Web of Science; CINAHL; The Cochrane Library; Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts; and Database of Abstracts and Reviews of Effects.

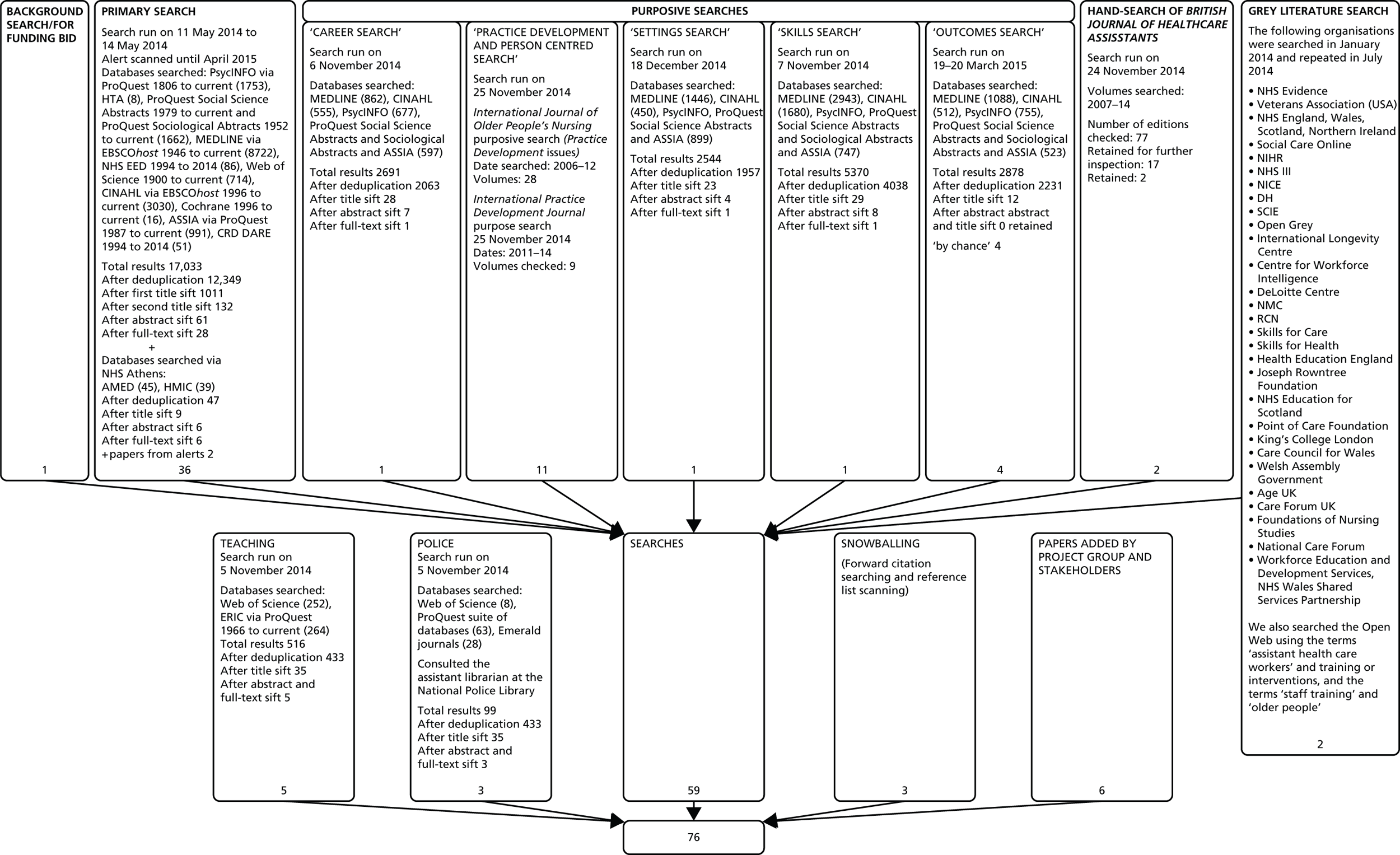

The searches took place in April and May 2014. References were stored in RefWorks database software (ProQuest, Ann Arbor, MI, USA: www.proquest.com/products-services/research-tools/). The systematic databases search yielded 17,033 references; 4684 of these were duplicates, leaving 12,349 hits included for title screening. Hits for each database are shown in Figure 2. Alerts were set up for the database searches and alerts were scanned up to April 2015.

FIGURE 2.

Results of search and retrieval. AMED, Allied and Complementary Medicine Database; ASSIA, Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts; CRD, Centre for Reviews and Dissemination; DARE, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects; DH, Department of Health; ERIC, Education Resources Information Center; HMIC, Health Management Information Consortium; NHS EED, NHS Economic Evaluation Database; NICE, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; NIHR, National Institute for Health Research; NMC, Nursing and Midwifery Council; RCN, Royal College of Nursing; SCIE, Social Care Institute for Excellence.

Purposive searches

In realist synthesis, a Cochrane-type systematic search strategy is unlikely to yield all sources to inform the testing and refinement of the programme theories. 97

In a review related to complex evidence, only 30% of sources were obtained from the database and hand-searches, while 51% were identified by snowballing and 24% were obtained through personal knowledge/contacts. 98

In the current review, purposive searches of the evidence were conducted to provide specific focus on the programme theories. The primary search for references was augmented by other searches for support worker role evaluations or intervention research which made specific reference to embedded implementation or impact (e.g. around careers, location, settings, skills or outcomes). Purposive searches were also conducted in Allied and Complementary Medicine Database, Health Management Information Consortium, education, policing and the practice development literature. In addition, a hand-search was conducted in the British Journal of Healthcare Assistants. Other papers were added through snowballing, from database alerts and from project group and stakeholders (see Figure 2). Internet-based searches for grey literature were conducted for workforce development project reports, national inspection and regulation quality reports, and evaluative information about these initiatives.

Selection and appraisal of documents

Evidence was excluded only if did not relate to the theory areas. The test for inclusion was if the evidence provided was ‘good and relevant enough’ to be included96 (see below for further information about how this criteria was operationalised). Drawing on the previous experiences of the research team,66,69 data were extracted if they were ‘good and relevant enough’. 96

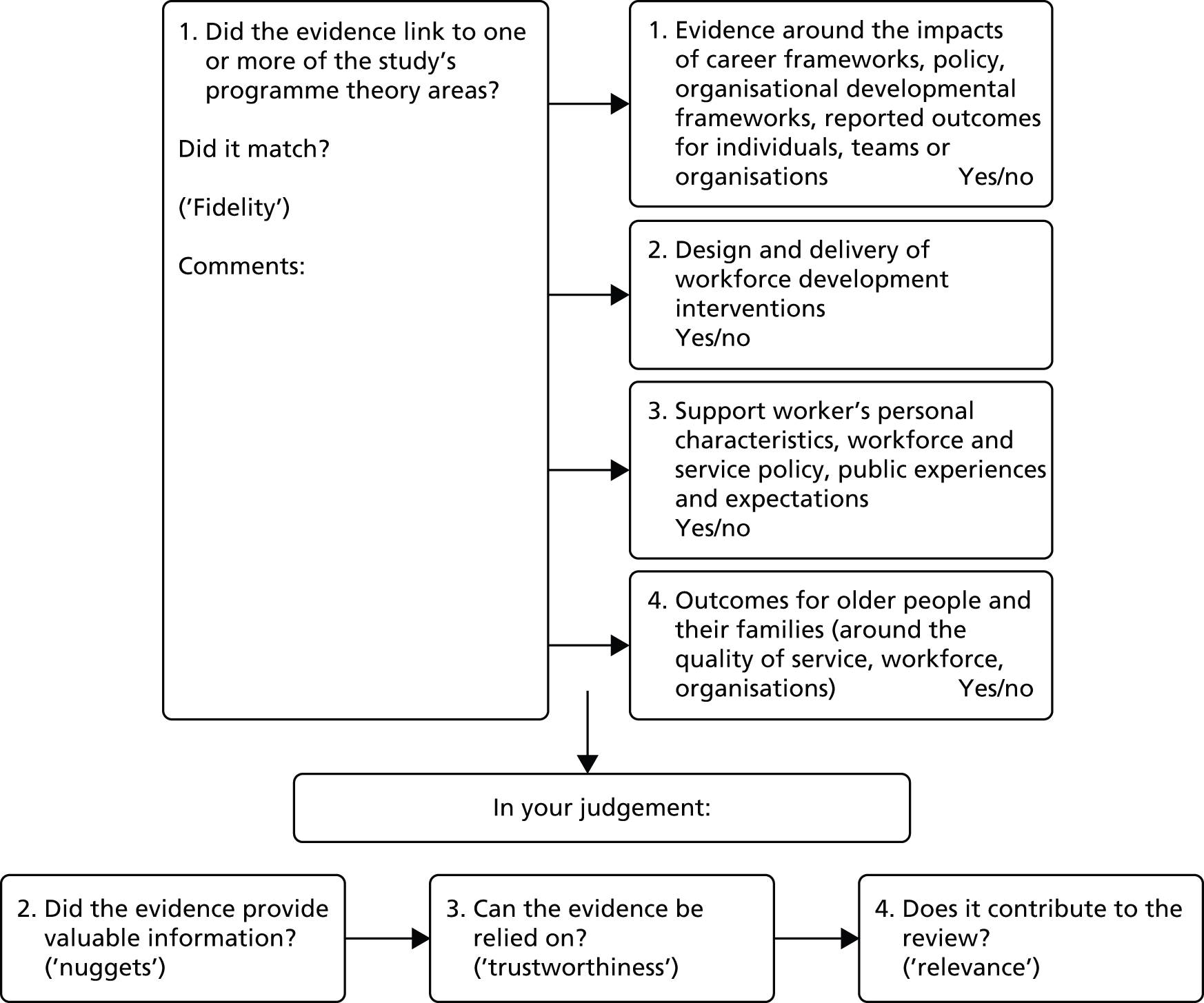

The test of ‘good and relevant’ enough is potentially vague and could lead to a lack of transparency about decision-making. Therefore, through critical discussion within the core team, we developed an additional subset of constructs which were added to the data extraction form in the form of a flow chart (see Appendix 8). The flow chart provided a set of additional questions which affirmed the judgement made of the extracted data, and reported its potential to contribute to the review. ‘Good enough’ was deconstructed as the quality of evidence expressed through fidelity, trustworthiness and value. ‘Relevance’ related to the contribution of the evidence to the theories. Member checking with reviewing took place within the research team. Title-sifting was cross-checked across three team members (JRM, CB and LW). Levels of agreement across reviewers were scored for 6% of the total titles. The title-sifting example was also checked with JRM, CB, LW and BH.

Data extraction, analysis and synthesis processes

In realist synthesis, theory development, refinement and testing is an iterative process of review and refinement and is made visible through bespoke data extraction forms. 66,96 As such, data extraction was undertaken in an iterative way across the review. 99 Initially, a bespoke data extraction form was developed from the four theory areas (see Appendix 9) to provide a template to extract evidence (if it met the test of relevance; see above). Member checking with extraction took place within the core research team. A sample of evidence was cross-checked across three team members (JRM, CB and LW).

Data were organised into evidence tables representing the four theory areas (see Appendix 10 for an example). In addition, data were organised into evidence tables representing a continuum ranging from conceptual (awareness, knowledge and understanding) to instrumental (attitudes and perceptions) to direct impact (practice change). 100 As we were extracting data we also began the process of synthesis.

The realist synthesis is theory-driven and uses abduction to understand CMO configurations. 101 Synthesis is a process of triangulation102 that melds different sources of evidence in a process of theory development, testing and refining. Through the previous experiences of the research team66,69 and building on the suggestions of Pawson96 and the principles of realist enquiry, we undertook an abductive and retroductive analysis of evidence across the tables to look for emerging demiregularities (patterns). Reflecting the interpretive nature of the review, the quality and relevance of the evidence was assessed during the synthesis process103 through weighing up the contribution of each piece of information to the development of the explanatory account and to the review question and aims. 74,104

This contrasts with traditional Cochrane-type reviews, which support the use of more quantitative statements of ‘how much’ evidence (and of what type) to underpin the findings.

This process was facilitated by the development of a set of plausible hypotheses – ‘if . . . then’ statements about what might work, for whom, how, why and in what circumstances – about workforce development interventions for the support care workforce:

-

If workforce development is closely related to practice (cognitive and/or physical), then the intervention is more relevant and more likely to be applied.

-

Taking staff away from practice for workforce development results in them feeling as if there has been an investment made in them and gives them more headspace, and they are more likely to feel valued by employer/organisation.

-

Depending on the nature/issue/purpose of the workforce development intervention, a multiprofessional approach to learning/delivery is more likely to be effective and engender cohesion.

-

When design and delivery of workforce development is seen to be credible, support workers will engage more/it will have more relevance.

-

When workforce development integrates personal perspective and professional perspective so that the support worker knows what is expected of them, it may have more relevance.

-

When/if workforce development fits with the organisational strategy/philosophy, then the support worker will feel more valued.

-

If the focus of workforce development is on where people are coming from/starting from, and design and deliver interventions around this, then the interventions are going to be more effective.

-

If workforce development is operating at more than one level (individual, team, organisation, system), then the impact is likely to be greater.

-

If workforce development is appropriately targeted at individual, team, organisation, system, then it is more likely to be effective.

-

When workforce development reinforces behaviour and learning, it is more likely to be effective.

-

When workforce development is aligned with incentives, it is more likely to be effective.

-

If there is a clearly articulated predefined theory/postulated mechanism of action about workforce development, then it is more likely to be effective.

-

When implementation features are embedded in the design and delivery of workforce development, it is more likely to be effective.

Reflecting the iterative refinement of the theory development process, these plausible hypotheses led to a revision in the data extraction form (see Appendix 11). We did a further ‘dive’ into the evidence with this revised data extraction form.

Following data extraction of the whole pool of evidence, tables were developed that summarised the evidence we extracted relevant to each plausible hypothesis. These evidence tables were then used as the basis for further deliberations about the emerging contingencies we could see within and across the extracted data. The extraction and synthesis process was managed on a day-to-day basis by the local research team (LW, CB and JRM) with regular input (face to face and via e-mail) from the wider project team, including our patient and public representatives.

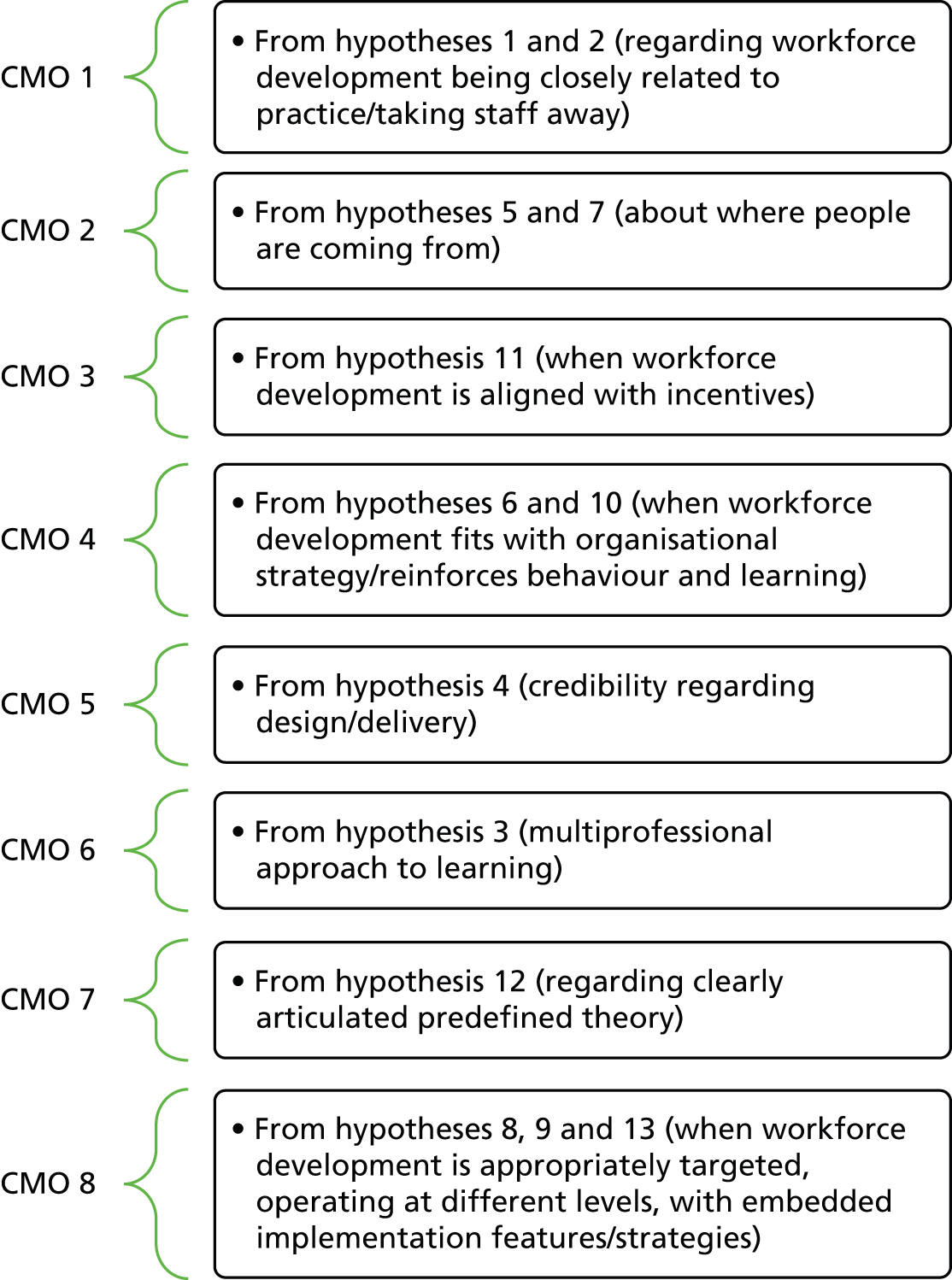

This deliberative and iterative process enabled iteration from plausible hypotheses to the uncovering of CMO configurations (see Appendix 12 for summary of tracking of plausible hypotheses to CMO configurations). The result was eight configurations, which are summarised in Table 2.

| Context | Mechanism | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| ‘Making it real’ [to the work of the (individual) support worker] | ||

| When intervention design and delivery is proximal to the work of the HCA/support worker in that it is close to and pays attention to practice . . . | . . . this prompts resonance, in that the workforce development intervention is relevant because it resonates with individuals participating in it, makes it understandable, is congruent to their experience, has work-related meaning and significance Achieved through activities – vignettes, stories, reflection, reflective conversations . . . building on the oral tradition of the support workforce Situating in the workplace However, taking away from practice can also provide legitimate space, stops disruption, providing opportunities for access to different sorts of expertise . . . |

. . . which results in cognitive and practice changes for individuals including cognitive changes (e.g. seeing things differently, changing mental models, deepening knowledge, self-esteem, confidence, focusing attention on the right things, being able to see what is important, seeing the person as a person) AND practice changes/impacts: appropriate caring behaviours |

| Where the support worker is ‘coming from’ | ||

| If workforce design and delivery pays attention to the support worker’s personal and role starting points and expectations . . . | . . . this prompts increased engagement with the development opportunity, which leads to . . . | . . . personal cognitive impacts (e.g. personal efficacy), instrumental impacts (e.g. skills development) and potentially, organisational impacts (e.g. staff commitment) |

| Tapping into motivations | ||

| If workforce development is incentivised (to turn up to the workforce development intervention and in ongoing engagement), and in some professional and service contexts . . . | . . . then the HCA/support worker will feel rewarded and recognised . . . | . . . and so feel that they have a stake in the workforce development . . . increased participation and engagement |

| Joining things up | ||

| If workforce development interventions are developed in the context of the presence of an organisation’s strategy . . . | . . . this prompts alignment . . . | . . . and leads to more sustained, lasting impact of the workforce development intervention, reducing turnover/supporting retention strategy |

| Co-design | ||

| If the right mix of people (including service users) are engaged in design of workforce development programmes/interventions . . . | . . . this prompts co-design because the workforce development accommodates a collective view about what needs to be done . . . | . . . and leads to workforce development that is more credible, meaningful and impactful for the HCA/support worker |

| ‘Journeying together’ | ||

| If the right mix of people (including service users) are engaged in delivery of workforce development programmes/interventions . . . | . . . this prompts learning together (‘journeying together’) . . . | . . . and leads to engendering cohesion, greater understanding of each other’s roles, impacts on residents’ perceptions of care |

| Taking a planned approach | ||

| If there is use of theory and a planned approach in design, delivery and evaluation of workforce development . . . | . . . this prompts a more systematic process in planning, and delivering workforce development . . . | . . . and leads to greater potential to demonstrate impact, and learn about workforce development effectiveness |

| Spreading impact | ||

| If the workforce development programme/intervention is comprehensive in that it is multilayered (micro, meso, macro) and multifaceted . . . | . . . this prompts paying attention to the way components reinforce each other . . . | . . . which leads to increasing the potential for impacts to embed and spread across organisations |

An evidence-based narrative was developed under each CMO configuration by drawing on evidence in and across the data tables.

Programme theory testing

To enhance the trustworthiness of the resulting CMO configurations and to facilitate the development of a final review narrative, we conducted 10 semistructured, audio-recorded interviews with stakeholders. We used a mixture of purposive and snowballing sampling to obtain the perspectives of people who would reflect those who would have a stake in the findings. The interviews were structured for the purposes of testing out the CMO configurations, with data confirming or disputing each mapped directly onto the CMOs. The interviews facilitated the development of the final CMO narrative. Our sample comprised managers, directors for training/development and support workers. An interview schedule was developed based on the CMO configurations to elicit stakeholders’ views on whether or not they resonated with their experience, and whether or not and how they might operate in practice (see Appendix 13). All the interviews were conducted by telephone and lasted between 45 and 60 minutes. All interviews were audio-recorded and concurrent detailed notes were made.

The audio-recordings were fully transcribed. As the interviews were structured for the purposes of ‘testing’ out the CMO configurations, data confirming or disputing each were mapped directly onto the CMOs. In fact, the interviews provided mainly confirmatory evidence of the CMOs and provided some additional contextual evidence to each. Evidence from the interviews is combined in the narrative for each of the CMO configurations reported in the next chapter.

Ethics

The study fell outside the scope of NHS and social care requirements for ethics review; however, we sought ethics approval from Bangor University’s research ethics committee to conduct the interviews. Approval was granted on 27 August 2014 (number 2014-06-03) (see Appendix 14).

Chapter 3 Findings

Introduction

As Chapter 2 outlined, the theory development, refinement and testing process led to the distillation of eight CMO configurations. These are explanations that, cumulatively, constitute a programme theory about ‘what works’ in workforce development for the older persons’ support workforce. These CMO configurations emerged from the evidence and were verified with stakeholders. They are not mutually exclusive and we hypothesise that, in order for workforce development interventions to have maximum impact, paying attention to elements of each will be important.

In realist review the analytical task is to draw across the evidence base to provide explanations expressed in the form of CMOs; in other words, it is rare that one CMO is reflected in its entirety in a single piece of evidence. Therefore, we describe each CMO configuration in terms of the underpinning evidence, drawing on the included studies (see Appendix 15), interviews and stakeholder perspectives which have been embedded in the conduct of the review. Illustrative excerpts from the literature and quotations from interviews are embedded in these explanations to highlight meaning and salient points. We also include some practical examples of the ways in which the components of each CMO were visible in the interventions included in the review.

The review process, including findings from stakeholder interviews, resulted in eight CMO configurations. These are explanations that, cumulatively, constitute a programme theory about ‘what works’ in workforce development for the older persons’ support workforce. These are:

-

making it real to the work of the support worker

-

where the support worker is coming from

-

tapping into support workers’ motivations

-

joining things up around workforce development

-

co-design

-

‘journeying together’

-

taking a planned approach in workforce development

-

spreading the impacts of workforce development across organisations.

Context–mechanism–outcome 1: making it real to the work of the support worker

If intervention design and delivery is close to the work of the support worker (context), then this prompts resonance with individuals participating in it (mechanism), which can result in cognitive and practice changes in them (outcome) (Box 1).

Tools and techniques: videos, role play, ‘homework’, simulation, debriefing, care planning, visual tools.

Supervision of practice: group, follow-up, one-to-one supervision.

Working together: debriefing, sharing experiences, case conferences.

Focusing on the individual: case studies, biographies, vignettes, goal planning.

Context and mechanism

A strong relationship was evident between the proximity of the workforce development intervention and real-life work of the support worker, and specifically whether their work was immersed or disconnected from the intervention. Proximity was a feature of development initiatives that were closely aligned to the work of the support worker, delivered in practice or closely related to practice. 105–127

Proximity prompted feelings of resonance, when the intervention focused on what the support worker might experience in their work and what was familiar and relevant to them. There were two different forms of proximity in the evidence:

-

cognitive proximity,106–110,112,113,115,117–119,121–125,128 which was evident in intervention specifics or content, and judged by the extent to which the applicability of the intervention to the support worker’s own work practice could be observed, and/or

-

physical proximity,105,107,111,114–116,120,126,127 reflected in intervention delivery, was physically located in the support worker’s workplace.

Cognitive proximity

When the design of interventions was intentionally focused on the role and work of the support worker, this was more likely to prompt resonance. This was exemplified by learning tools and techniques that drew on real-life work, supervision of practice, working together and focusing on the individual, including the use of films. 108,109 To teach person-centred caregiving skills to support workers from an older persons’ service, one intervention included the viewing of Putting Person Before Task, a 7-minute film showing support workers modelling person-centred care, as the basis for participation in further role-playing activities. Visual depictions of the reality of older persons’ services and experiences were also used to make the intervention more engaging:121

Visual tools such as photographs of various situations and story-telling became the bases for discussion. The emphasis was on doing, experiencing, discussing, and team problem-solving-rather than didactic teaching.

p. 3121

Cognitive proximity also featured in interventions that paid attention to the personal backgrounds of older people. Case studies of care home residents were used in one intervention to enable support workers to link the needs of care home residents with their knowledge of the person. 121 Resonance with the work of the support worker was also evident in interventions which focused on individual older people within workers’ services [in this case, certified nursing assistants (CNAs)] through, for example, the creation of care home residents’ biographies:108

. . . an innovative way of making personal information about residents available to CNAs. Creating videotapes of CNA/resident caregiving interactions and using them, in conjunction with behavioral observation instruments, is an innovative way to promote CNAs’ self-awareness of the person centeredness of their caregiving behaviors.

p. 697108

Interventions similarly driven by biography invited support workers to share their feelings about caring with people with dementia128 and helped staff to get to know the person they were caring for:118

. . . collecting biographical material about people’s lives helped them to gain a more dynamic and complete picture of those for whom they were caring, and that knowledge of people’s life stories enabled them to find out more about residents’ needs and behavior.

p. 701118

Role play, with a facilitator playing the role of an older person in a residential care setting, was used to teach communication skills so that the support worker could learn how to individualise their approach. 117 Support workers learned the significance of information in the individual biographies of the older person in shaping communication. In addition, homework sessions were included to promote self-reflection about actual practice, in which participants were asked to design a short- and a long-term care plan to address the specific needs of an individual resident,117 and ‘overcome a care-related problem that they identified within their own clinical settings’. 110 This was reviewed at sessions with their peers and mentors. The use of care planning strategies that drew on real-world challenges, such as how to deal with challenging families, also ensured that the intervention had work-related meaning and significance for the support worker. 110

In training for care staff to recognise depression in residential care settings,127 a bespoke care planning intervention was implemented over an 8-week period, with support workers working together with residents to plan their care, and supported through weekly one-to-one supervision sessions over the 8 weeks. Interview data reinforced the utility of developing, sharing and reviewing care plans to bring learning to life; for example:

I think one of the things that we did that was really . . . beneficial, was writing our own care plans together, and looking at how intricate we were as people, and how bizarre some of the things were that were important to us, as people, and I think for me it was quite a learning curve as a manager.

Telephone interview, participant 1

In a series of seminars provided by a multidisciplinary team, a similar attempt was made to ensure that the intervention was congruent with the support worker’s own experiences of work:

The main aim of goal planning was to encourage care staff to formulate a specific and detailed care plan with a view to positively changing problematic areas of a resident’s behavior.

p. 234125

Other aspects of workforce development interventions that enabled proximity to the work of the support worker included experiential learning approaches,121 which ‘enabled the [support worker] to experience (in some degree), the difficulties that frail residents faced, and to identify the care practices that could be used to ameliorate those difficulties. . .’ (p. 3). 121 In a different report, proximity to the work of the support worker was supported by a clinical component to the education course which consisted of ’24 hours of “hands-on” patient care in a long-term facility under the direction of the course instructor’. 106 Fortnightly group supervision was complemented by individual training sessions for support workers in care home settings,107 whereby trainers observed support workers at their work and provided feedback. When there were opportunities for support workers to share experiences through group debriefing,115 groups were established ‘to use the experience of caring for a resident who has died as a basis for learning about end-of-life care’ (p. 120). 115 In this case, the groups were led by a nurse specialist in palliative care, and open dialogue approaches were used to encourage engagement. In addition, it was reported that debriefing promoted ‘reflection in action’ and made the intervention realistic for participants. 119

Cognitive proximity also featured in other examples, including case conference style approaches in which registered professionals chose the topics and led the case presentation and discussion. 124 This helped to capture support workers’ imagination and challenge their own thinking. The benefits of more interactive approaches that included the discussion of cases were reinforced in interviews; for example:

We’re also using supervision and appraisal very much as a training tool, so I think we’ve missed a trick there with those, it’s been a little bit ‘are you OK’ ‘yes you are that’s fine off you go’, actually using that to really encourage discussion looking at particular case studies, so it’s more like a clinical supervision . . .

Telephone interview, participant 1

In addition to the use of vignettes, practice tools and biography to bring work with older people ‘to life’ for participants, desirable aspects of the support worker’s work were made evident in other parts of workforce development interventions. This included an application process, which used a questionnaire, a written essay and an interview, for participants to access the intervention. In this example, applicants were expected to model professional conduct,106 and contracting was included at the start of the intervention to promote the modelling of professional behaviours106 and to specify prerequisites related to the support worker role. 129,130

There was also evidence to illustrate the advantages of drawing on the experience of older people themselves in the delivery of workforce development in making learning real. For example, in a paper that reported a feasibility study of an education programme, we found that the delivery included people with aphasia as educators,131 which was designed to improve nursing assistant students’ knowledge of aphasia, and supported examining the experiences of participants with aphasia.

Physical proximity

Proximity to the work of the support worker also featured in a physical/geographical sense, when interventions were deliberately based in the workplace. 106,107,114,127 These included interventions that facilitated competency-based assessments,126 focused on behaviour strategies to support the work of the support worker,112 for example learning how to give instruction in small steps or improving the level of stimulation in a service setting.

Alternatively, some workforce development interventions were designed to enable support workers to make, and understand, the close link between the intervention and the context of work. When an intervention was situated in the workplace and designed to fit with the working pattern of the staff, being held during shift changes, this maintained a ‘theoretical and practical link with the daily routine of the institution. Each topic to be taken up in the training program would be closely linked to life in the institution, with the aim of fulfilling the special needs of the residents of the particular institution’ (p. 591). 112

There was consistency with literature about teaching assistants in schools, in which evidence also supported the importance of physical proximity. Where workforce development for teaching assistants was held in the workplace,123 there were increases in the congruence of the intervention with teaching assistants’ experiences, which encouraged co-learning with other colleagues, thereby encouraging teachers and support workers to learn from each other in partnership. 123

Taking support workers out of the workplace for workforce development

We found a different perspective or contradictory evidence around physical proximity, specifically about the positive impacts of removing support workers from their work area, and that learning could be better enabled through the provision of separate space with less disruption. 105,123,131–133

For example, facilitating workforce development on weekend days away from support workers’ jobs was linked with positive impacts about participants’ knowledge and attitudes. 105 An intervention to improve participants’ awareness and knowledge about aphasia, delivered in a college setting, demonstrated improved learning about aphasia. In addition, in this study, participants demonstrated greater incorporation of new learning into their work. Interview data affirmed the feasibility and positive impacts of taking staff out of their work context to participate in workforce development, but noted caution in ensuring no negative consequences for the organisation:

. . . variety and change of scenery does make a difference to people’s learning habits and what they learn and how they learn without a doubt, and I agree with that completely. We also have to do what works well for our organisation, within our care delivery demands as well. So it’s finding that balance.

Telephone interview, participant 3

In two other interviews, reference was also made to the benefits of providing opportunities for support workers to gain understanding of other organisations settings, in which it was ‘interesting to see how different some of the homes operate’ (telephone interview, participant 8) and useful for ‘. . .cross-fertilisation’ (telephone interview, participant 1). Further, from the education literature, we noted reports of interventions which encouraged taking teaching assistants out of the classroom to visit other schools and view different practices. 123

Regardless of the pros and cons of the physical proximity of workforce development, the interviews highlighted the need to think systematically about the delivery location by focusing on its combination of practical or theoretical content:

I think a lot of it depends on the type of training. If you’re going to have an academic session that’s looking at the impact of immobility on tissue for instance, you want to have a session on pressure area care. That can be beneficial in the care home setting, so in [xxxx] there would be some quite logical sense in doing that because you can then say, OK we’re going to go along and see so and so after we’ve done this and we’ll look at our tissue areas and their pressure areas and we’ll look at the colour of them, we’ll look at the state of her skin, we’ll look at the state of her hydration and nutrition, and you can then make the training wheel. That kind of training I consider to be essentially practical. If you’re looking at something that’s perhaps more theoretical, going to talk about say, let’s say it’s going to be the impact of certain drugs on someone who’s got vascular dementia, the effect they’re going to have . . . that works quite well in more of a classroom setting because you can focus, you won’t have the distractions of being in your workplace, you won’t have call bells going off, you and your students will be able to concentrate on the academic side, the technical and the academic rather than the practical.

Telephone interview, participant 9

This interviewee went on to describe the positive personal impacts for support workers that taking them out of the workplace might bring, when ‘taking someone away from their workplace and sending them to somewhere, as a novelty value, creates a break. And that in itself is quite a positive thing’ (telephone interview, participant 9).

Taking participants out of the context of practice may also have implications for continuity of learning, in that learning that has happened away from the setting may have to be reinforced when back in practice to ‘make it real’.

Outcomes

Proximity in workforce development, in either a cognitive or a physical sense, prompted resonance with the individuals participating in it and/or was more likely to lead to cognitive and/or practice changes. Cognitive impacts for support workers included empowerment114,127 and improvements in self-esteem,114 together with increased knowledge and understanding of the behaviours of older people in their care. 108 When interventions were proximal through the use of person-centred training, role play and homework, this led to changes in support workers’ mental models of their role and work. 117,124 For example, coaching in the workplace led to an ‘ah-ha’ moment for one care assistant and a positive difference in a care home resident’s behaviour as a result of the changes in behaviour of the support worker. 117

Practice changes included better cohesion and paying more attention to older people in efforts to meld theory and practice,111 and improved relationships with family members. 113 The use of real-life case studies of older people in residential care settings, as well as visual tools and storytelling, also prompted resonance with the support worker’s practice. Improvements in the appropriateness and adequacy of care, including for those older people with the greatest needs, were affected after intervention. 121

In situating interventions in the workplace, practice changes as a result of making learning more real for the support worker included more attention being paid to older people111 and relationships with family members improving,113 as well as more general aspects of service quality; for example:

Following completion of the educational programme, there was significant increase in the proportion of care that was judged appropriate and adequate provided by healthcare assistants to residents than before.

p. 8121

Summary

In this CMO configuration, we found that a relationship between the cognitive or physical proximity of the support worker and the workforce development prompted resonance with participating individuals which was important in terms of potentially influencing positive cognitive and/or practice changes. The relationship between proximity and resonance was made visible through the use of tools and techniques to draw on real life, supervision of practice, working together, and evidence to prompt understanding and appreciation of older people themselves.

Context–mechanism–outcome 2: where the support worker is coming from

If workforce design and delivery pays attention to the individual support worker’s personal starting points and expectations of the role (context), then this prompts better engagement with the intervention (mechanism). Paying attention to the individual within workforce development can promote positive personal cognitive (e.g. personal efficacy) and instrumental impacts (e.g. skill development) and, potentially, impacts for the organisation (e.g. staff commitment) (outcome) (Box 2).

Personal attributes (e.g. paying attention to personal resources, personal issues/backgrounds, experiences/age, challenges, existing strengths, how one perceives others, values).

Abilities (e.g. assessment of communication skills, technology, literacy, language).

Personal feelings and expectations (e.g. reflection, exploring individual development needs and expectations).

Context and mechanism

There were numerous examples of workforce development interventions paying attention to support workers’ personal and professional perspectives, previous career, age and experiences, values and perceptions of older people’s services, abilities, expectations and life skills. 106,107,109,113,121,122,129,130,134–140 We were able to trace an evidence thread between tailoring to these factors and engagement with the intervention, as the support worker is able to appreciate what is expected of them in the context of ‘where they are at’. This finding was also reflected in interview data. For example: