Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 12/135/02. The contractual start date was in April 2013. The final report began editorial review in October 2014 and was accepted for publication in February 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Winpenny et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

It is important to make the most cost-effective use of NHS resources; inappropriate overuse of resources wastes money and may expose patients to harm, while inappropriate underuse of resources deprives patients of treatments from which they could benefit. General practitioners (GPs) generate cost in three main ways: by prescribing drugs, by referring patients to outpatients (which may generate elective admissions) and by admitting patients to hospital as emergencies. In this report we address the second of these: outpatient referral. There is known to be wide and unexplained variation in the referral rates of individual GPs. 1 There is inappropriate overuse and inappropriate underuse of specialist resources, and specialist services may be organised in ways which are neither cost-effective nor convenient for patients. As a consequence, there have been many attempts to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of the outpatient referral process, which we summarised in a previous review for the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Service Delivery and Organisation programme. 2

In recent years, the requirement to improve efficiency has been stronger than ever. Through the QIPP (Quality, Innovation, Productivity and Prevention) challenge, the NHS was expected to make £20B worth of efficiency savings by 2015. However, research from the Nuffield Trust suggests that, even were this challenge to be achieved, a potential shortfall of £28–34B would remain by 2021–2. 3

One initiative intended to encourage more efficient use of resources was the transfer of commissioning responsibility to Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs), introduced through the 2012 Health and Social Care Act. 4 As CCGs take over responsibility for commissioning, they need to balance their responsibility to their patients with a responsibility to manage NHS budgets.

This report sets out findings from a scoping review of the literature to update what we know about interventions designed to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of the outpatient referral system. We also provide substudies on a range of more recent innovations taking place in England, which are not yet adequately covered in the published literature. Finally, we include data on international experiences in this area, which may provide lessons for the UK.

Aims and objectives

-

Identify and review what is currently known about strategies involving primary care that are designed to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of outpatient services.

-

Comment on the impact of such schemes on the organisation of primary care, the primary care workforce, access, clinical outcomes for patients and patient experience.

-

Identify and comment on the potential for innovative models of care to be replicated more widely.

-

Identify the needs for future research in this area in terms of both primary research and systematic reviews that might be needed.

-

Summarise the findings in a way that will be readily accessible to policy-makers and managers.

Structure of the report

The main part of the report relates to a scoping review of the literature in which we identify what is currently known about strategies involving primary care that are designed to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of outpatient services.

This is followed by reports of five smaller substudies, in which we investigate referral management centres (RMCs), in-house review of referrals, financial incentives to reduce referrals, consultants with novel types of employment contracts and international experience of improving care at the primary–secondary interface.

Chapter 2 Scoping review (main study)

Introduction

This scoping review aims to update the review undertaken by Roland et al. in 2006. 2,5 That review found that transferring services from secondary to primary care and strategies intended to change the referral behaviour of primary care practitioners were often effective in improving outpatient effectiveness and efficiency. However, relocating specialists to primary care and developing joint working arrangements between primary and secondary clinicians were largely ineffective. Strategies not involving primary care that had the potential to improve outpatient effectiveness and efficiency included the introduction of intermediate care services and the redesign of hospital outpatient services.

As outpatient services have been the focus of considerable attention in the intervening years, the NIHR Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) programme commissioned an update of this review.

Aims

The aims of this current scoping review were to:

-

identify and review what is currently known about strategies involving primary care that are designed to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of outpatient services

-

comment on the impact of such schemes on the organisation of primary care, the primary care workforce, access, clinical outcomes for patients, patient experience and cost.

Methods

Scoping review

The definition of a scoping review is a review which ‘aims to map rapidly the key concepts underpinning a research area and the main sources and types of evidence available’,6 with the basic approach following that of a systematic review: defining the research question, identifying relevant references and screening references for eligibility for inclusion. 7

Defining the scope of the review

Our previous review conceptualised interventions designed to reduce hospital outpatient attendance in four categories:

-

transfer – the substitution of services delivered by hospital clinicians for services delivered by primary care clinicians

-

relocation – shifting the venue of specialist care from outpatient clinics to primary care without changing the people who deliver the service

-

liaison – joint working between specialists and primary care practitioners to provide care to individual patients

-

professional behaviour change – interventions intended to change the referral behaviour of primary care practitioners, including referral guidelines, audit and feedback, professional education and financial incentives.

The previous review included two additional categories that did not directly involve primary care but reflected important changes at the primary–secondary interface. These were:

-

Intermediate care services including community mental health teams (CMHTs) and hospital at home. We did not include intermediate care in the current review, mainly because research on hospital at home is not primarily focused on outpatient attendance. We did, however, include the previous category of community-based mental health teams, but described these in the more appropriate category of ‘Relocation of secondary care to primary care settings – the provider remains a specialist’.

-

Hospital redesign of outpatient services (e.g. the substitution of nurses for doctors in outpatient clinics). We did not include interventions in this review if they solely involved the reorganisation of services within hospital, but we did include studies if they involved some new interface with primary care. These were then included in one of the categories above.

We used these categories in the current scoping review, but also introduced the following three changes from the previous review:

-

Owing to recent advances in the area, we included a new topic of telecare – in particular, remote sensing technology in patients’ homes. We define telecare as ‘offering remote care, often using sensing devices, of old and physically less able people, enabling them to remain living in their own homes’. We did not include admissions as an outcome of telecare interventions in our analysis, keeping to the study’s focus on outpatient attendance. This fits within the broader definition of telemedicine as ‘the use of medical information exchanged from one site to another via electronic communications to improve a patient’s clinical health status’. 8 However, we restricted the definition of telemedicine for the purpose of this review to interventions involving some form of direct contact between specialists (doctors or nurses) and patients. We added telecare and telemedicine under the category of relocation.

-

We included a specific topic for RMCs within the category of professional behaviour change; these are a new approach to demand management for outpatient referrals.

-

We included a new topic of patient education, which involves the use of decision aids and aids to patient choice within a new category of patient behaviour change. This aspect of the review was restricted to decisions about referral to and discharge from outpatients (e.g. not the use of a decision aid used in a specialist clinic to help a patient decide whether or not to have an operation).

The framework for this current scoping review is shown in Table 1.

| Model | Type of working arrangement |

|---|---|

| Transfer: substitution of primary care for secondary care | Surgical clinics (e.g. minor surgery) |

| Medical clinics (e.g. diabetes, asthma) | |

| GPwSIs | |

| Discharge from outpatient to primary care | |

| Direct access to diagnostic tests/investigations | |

| Direct access to services | |

| Relocation: relocation of secondary care to primary care settings – the provider remains a specialist | Shifted outpatient clinic |

| Specialist attachment to primary care teams | |

| CMHTs | |

| Telemedicine (‘the use of telecommunication and information technologies in order to provide clinical health care at a distance’) | |

| Telecare (‘offering remote care, often using sensing devices of old and physically less able people, enabling them to remain living in their own homes’) | |

| Liaison: joint management of patients by primary and secondary care clinicians | Shared care including consultation liaison |

| Professional behaviour change: interventions intended to reduce rates of referral from primary to secondary care | Guidelines, including referral pro formas |

| Audit and feedback | |

| Professional education including academic detailing | |

| In-house review (i.e. second opinion) | |

| Financial incentives | |

| Advice requests – including e-mail advice, sending patient details for ‘paper consultation’, and telephone advice | |

| Patient behaviour change | Decision aids and aids to patient choice designed to influence decisions about referral to and discharge from specialist clinics |

Search strategy

We reran the previous search strategy, adding search terms for the new categories. The literature was searched from February 2005 to April 2014, starting with the end date for each of the previous searches.

The databases searched in the current review were:

-

MEDLINE® (via Ovid) (February 2005 to April 2014)

-

EMBASE (via Ovid) (February 2005 to April 2014)

-

Health Management and Information Consortium Health Management and Policy database (via Ovid) (February 2005 to April 2014)

-

The King’s Fund database of grey literature (http://kingsfund.koha-ptfs.eu/) (February 2005 to April 2014).

The previous review included a search in the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews and a search in the Campbell Collaboration Library of Systematic Reviews. We did not replicate those searches in this update, as we found that references from those databases were picked up in the other searches.

The detailed search strategies can be found in Appendix 1.

We became aware that many primary care trusts (PCTs) have produced guidelines to reducing referrals, often drawing on common sources such as the NHS Institute and The King’s Fund. These were not included in the review as, on investigation, we discovered that they reiterated advice on managing referrals without any evaluative component and did not, therefore, meet our inclusion criteria (see the following section).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Type of study

Any type of observational study was eligible for inclusion in the scoping review. Editorials and modelling studies were also included. Conference abstracts, letters, commentaries, vignette studies, hypothetical cases and articles which were simply referral guidelines were, however, excluded. Only studies conducted in high-income countries were included.

Interventions

To be eligible for inclusion, studies had to evaluate schemes in primary care settings that were designed to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of outpatient services. The categories of interventions that were eligible are described in Table 1. The interventions could also involve direct access of GPs to physiotherapy, osteopathy and alternative medicine (under direct access of primary care providers to specialist services), as long as there was an evaluation of referral to outpatients.

Eligible studies had to report on an intervention that was potentially transferable to the NHS. For example, we excluded studies of interventions led by hospitalists, which are implemented in the USA but have little applicability to the NHS context. 9

Interventions that were excluded included:

-

pharmacist interventions in primary care which did not have outpatient referral as an outcome

-

services where an outpatient clinic (usually in a hospital) is developed as an alternative to hospital admission

-

studies which simply looked at the quality or appropriateness of referrals, that is studies that did not suggest or evaluate a new model

-

hospital-at-home interventions, as these are designed as an alternative to inpatient management rather than to outpatient referral

-

optometry services in primary care

-

support services in the home

-

medical homes (as this is mainly a US concept and does not relate to outpatient referral in the NHS)

-

services which delivered screening or delivered preventative care in GP practices in order to reduce illness later in life, unless they had an evaluative component relating to outpatient services.

Comparators

The studies did not need to include a comparator intervention. If more than one type of intervention was included, these were described.

Outcomes

The interventions had to have some impact on specialist/secondary care, and had to report an evaluation of the outpatient interface rather than provide a simple description of a service. For the purposes of this review, CMHTs were also considered as secondary/specialist care. Outcomes of interest included, but were not limited to, access, including waiting times, referral rates, patient outcomes (clinical and patient experience), service outcomes, physician outcomes and costs.

Outcomes excluded from the scoping review were:

-

self-referral

-

inpatient admission

-

dental and orthodontic referrals

-

studies that evaluated solely accident and emergency or emergency room attendance.

Quality

We did not formally assess the quality of the studies, nor did we exclude studies based on quality criteria. When we had concerns about the quality of a study (e.g. when the study design or the definition of the intervention were not clearly reported), this was noted in the relevant findings section or in the table of included studies (see Appendix 2).

Study selection

Records identified by the searches were assessed for inclusion by scanning titles and abstracts against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Screening was undertaken by three researchers. Initially, the researchers independently screened the same 500 records and compared their results. This was repeated with a further set of 250 records to ensure consistency in deciding both which studies to include and which categories to place them in. All of the remaining titles and abstracts were then screened by one researcher (EW or CM), who deliberately kept in any records for which there was any doubt. This list was then assessed by a second researcher (MR) to determine the final list of papers for inclusion. Full texts were then retrieved of potentially eligible studies and reassessed against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Disagreements or uncertainties between reviewers were resolved by discussion within the research team.

Data extraction

Data from studies identified as eligible were extracted into a Microsoft Excel® spreadsheet template (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). Data were extracted on study design and objective(s), intervention(s) and reported outcomes. The data extraction template was piloted on a small number of studies and refined. Data extraction was undertaken by three researchers, with some duplicate extraction to check for consistency of approach.

Data synthesis

As the purpose of a scoping review is to demonstrate what is presented in the literature and to identify gaps in the literature without a formal synthesis, we did not attempt formally to synthesise the data. Within each category, key messages were extracted initially by MR, and then checked against the references by other members of the research team. We also commented on the implications of the findings for the NHS in each section.

Advisory board and patient and public involvement

We convened an advisory board with representatives from primary care, secondary care and national and local commissioning, and two patient and public representatives. The advisory board commented on the research protocol at the beginning of the study and on a draft report of findings in March 2014. In addition to comments by e-mail, patient and public representatives attended a meeting in March 2014, to help to think through the implications of the study and to provide ideas for dissemination.

Findings

This chapter presents the findings of the scoping review. The data are presented by the type of working arrangement for each of the five models presented above.

Description of studies

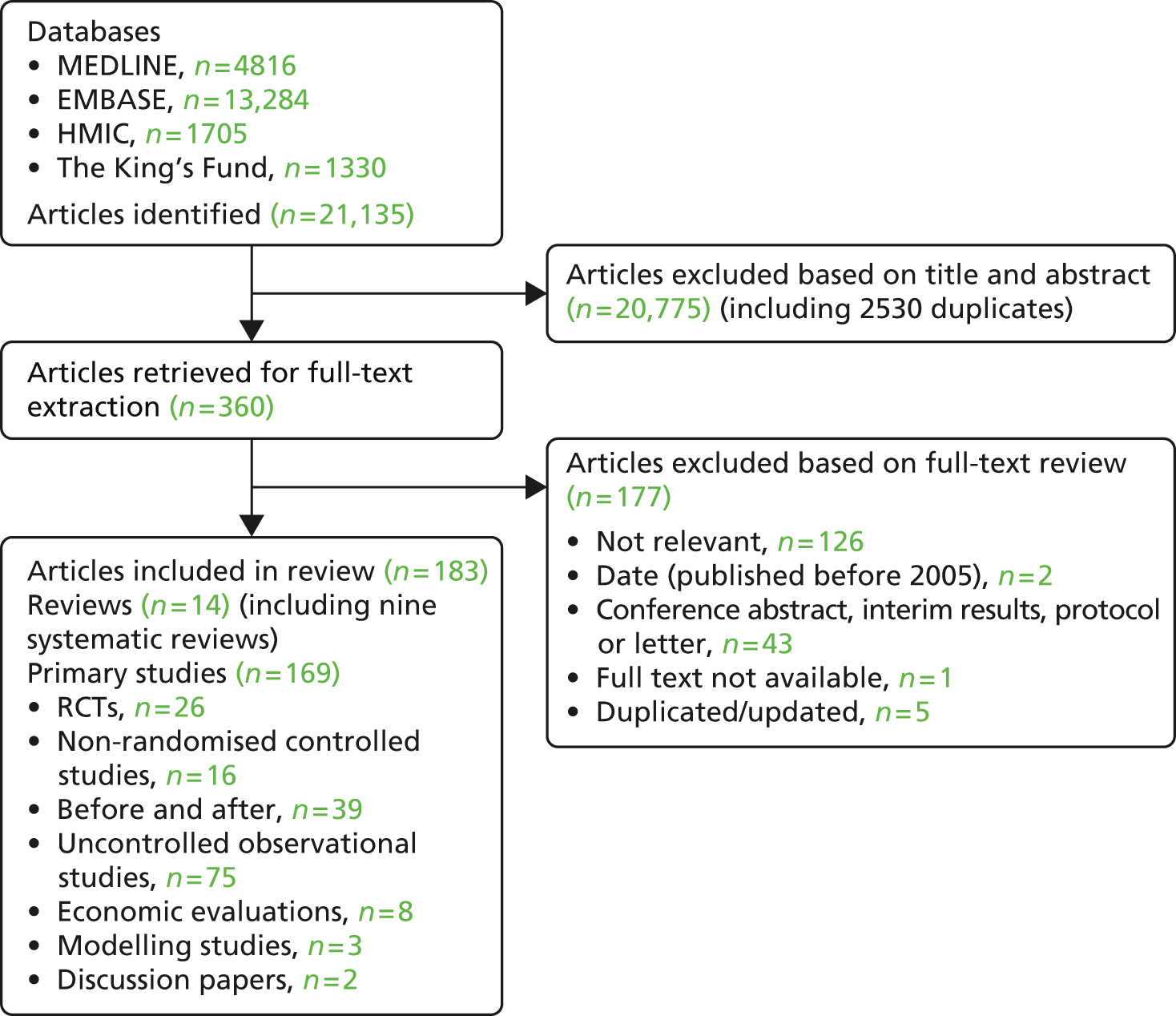

Our search identified a total of 21,135 records across the four databases searched; of these, after removal of duplicates and initial screening of titles and abstracts, we considered 360 references for further evaluation. Of these, 184 studies were identified as eligible for inclusion in the review (Figure 1). Further details of individual studies are presented in Appendix 2. Appendix 3 provides an overview of studies which we excluded from our review based on full-text review.

FIGURE 1.

Peer-reviewed literature included in the study. HMIC, Health Management Information Consortium; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Transfer (substitution of primary for secondary care)

Surgical clinics

Surgical clinics refer to GPs carrying out minor surgery in primary care.

Key summary points:

-

Minor surgery carried out in general practice can be safe and effective, but this depends, critically, on the skill and training of the operator.

-

The cost-effectiveness of minor surgery carried out in general practice is likely to depend on local payment/contractual arrangements.

Minor surgery principally became of interest because the 1990 GP contract included financial incentives for GPs to carry out minor surgery in their own practices.

Nine studies (10 papers) were included in our previous review, from which we concluded that ‘some evidence suggests that the quality of care provided in general practice was initially poor due to inadequacies in GP training, problems in maintaining surgical skills given the low patient volume, and inadequacies in the equipment and/or procedures used to sterilise surgical implements’. We also suggested that ‘many of the additional patients receiving minor surgery under the conditions of the 1990 contract may not have previously been referred to hospital, and that GPs may have used minor surgery in place of cheaper, equally effective treatments’.

Since then, the policy context has changed in that the financial incentives for GPs to carry out minor surgery have reduced. However, some general practitioners with a special interest (GPwSIs) are contracted specifically to carry out minor surgery.

An additional six papers were found in our updated scoping search (Table 2). 10–15

| Article | Country | Study type | Aim/intervention |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dhumale (2004)10 | UK (England) | Prospective observational study | To assess the feasibility of performing hernia surgery in a general practice (n = 4965), involving a GPwSI in surgery, a theatre nurse and a surgical administrator |

| Dhumale et al. (2010)11 | UK (England) | Retrospective case review | To reduce waiting times and relieve pressure on local hospital waiting lists by setting up a surgical centre which offers hernia repair (n = 1164) carried out by two GPwSIs in a practice |

| George et al. (2008)12 | UK (England) | Prospective randomised controlled equivalence trial | To compare competence of GPs and hospital doctors across a range of elective minor surgical procedures, in terms of the safety, quality and cost of care for patients (n = 568) |

| Nelson et al. (2014)13 | USA | Economic modelling | To measure the cost-effectiveness of training rural primary care providers to perform knee injections in community-based outpatient clinics instead of referring patients to specialised care in hospital |

| Olah et al. (2005)14 | UK (England) | Observational study | To test whether or not endometrial thermal ablation is suitable for use in primary care settings (n = 87 women) |

| Van Dijk et al. (2011)15 | The Netherlands | Audit | To examine the association between surgical interventions in general practices (n = 48) and hospital referrals for four skin conditions (n = 14,203 patients) |

One study was a randomised controlled trial (RCT) which concluded that patient satisfaction was high, access to care was improved and costs were lower when procedures were carried out in primary care (the mean cost for hospital-based minor surgery was £1222 and for primary care was £449). However, the quality of minor surgery carried out in general practice was not as high as the quality of that carried out in hospital. 12 This related in particular to the incomplete excision of skin cancers. Using completeness of excision of malignancy as an outcome, hospital minor surgery was more cost-effective than surgery in primary care. However, another study of highly trained GPs (GPwSIs) found no difference in the incomplete excision rate between GPwSIs and hospital doctors. 16

Studies in the past have suggested that, with adequate training, GPs may safely perform procedures such as hernia repairs11 and endometrial thermal ablation14 in primary care.

There is little additional information on the cost-effectiveness of minor surgery in general practice. Van Dijk et al. 15 found that Dutch practices which carried our minor surgery referred fewer patients with those conditions to hospital, but did not carry out a formal cost-effectiveness analysis. In practices in rural USA, Nelson et al. 13 found that it was cost-effective to train primary care doctors to carry out knee injections for patients with osteoarthritis.

Conclusion

Minor surgery carried out in general practice can be safe and effective, but this depends, critically, on the skill and training of the operator, with some studies suggesting that the technical quality of surgery may be lower when operations are carried out by GPs. The cost-effectiveness of minor surgery carried out in general practice is likely to depend on local payment/contractual arrangements. The effect on outpatient utilisation of doing surgery in general practice is also likely to depend on local care pathways. If GPs have incentives to carry out minor surgery, for example through local contracts, there is the potential for ‘supply-induced demand’: that is, minor procedures being carried out that would not necessarily have been referred before. In some cases, these may address previously unmet patient need, but item-of-service fees to GPs to carry out procedures could also lead to unnecessary operations being carried out.

We note that recent National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance is that ‘all GPs and GPs with a Special Interest who diagnose, manage and excise low-risk basal cell carcinomas (skin cancers) in the community are fully accredited to do so, and undergo continuous professional development in the diagnosis and management of skin lesions to maintain their accreditation’. 17 NICE also advises that all patients with suspected malignant melanoma should be referred to a specialist.

Medical clinics

Medical clinics refer to the provision of continued treatment and management of specific conditions within a general practice setting.

Key summary points:

-

With adequate supervision and training, a wide range of conditions can be managed in primary care both safely and effectively.

-

Few studies examine the cost-effectiveness of transferring care into primary care.

In our previous scoping review, we concluded that ‘there was a marked dearth of research comparing general practice care with hospital care’ for major chronic diseases. However, we concluded that ‘If care is well structured – there is a disease register and recall system, with clinical reviews conducted in accordance with evidence-based guidelines – then short-term health outcomes for patients appear to be as good as those achieved in hospital outpatient clinics’. However, there was insufficient evidence to draw conclusions about costs of primary versus secondary care of chronic conditions.

The policy context of the earlier review was the 2004 GP contract which included major financial incentives for GPs to monitor chronic conditions in general practice [the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF)]. These changes have become firmly embedded in the structure and practice of primary care since then.

An additional 16 papers were identified in our updated scoping search (Table 3). 18–33

| Article | Country | Study type | Aim/intervention |

|---|---|---|---|

| Berger et al. (2007)18 | Norway | Economic modelling | To examine the expected outcomes and costs associated with the treatment of patients with painful neuropathies (n = approximately 35,000), and the consequences of shifting care from secondary to primary care |

| van Boeijen et al. (2005)19 | The Netherlands | RCT | To compare the effectiveness and feasibility of three different types of care for patients (n = 154) with diagnosis of panic disorder or generalised anxiety disorders across 46 practices |

| Briggs et al. (2008)20 | UK (England) | Observational study | To measure the impact of a combined nurse-/pharmacist-led clinic in primary care for patients (n = 120) with chronic pain |

| Chew et al. (2010)21 | Australia | Cost-effectiveness analysis (simulation) | To evaluate the cost-effectiveness of a general practice-based programme for managing coronary heart disease patients |

| Coetzee (2011)22 | UK (England) | Observational pilot study | To evaluate a structured clinic supported by a GP in a primary care setting for patients with mild to moderate alcohol dependency (n = 76 treatment episodes) |

| Courtenay et al. (2006)23 | Multiple | Literature review | To identify the impact and effectiveness of nurse-led care in dermatology |

| Dusheiko et al. (2011)24 | UK (England) | Observational study | To examine if the better management of 10 chronic diseases (asthma, CHD, CKD, COPD, dementia, diabetes, hypertension, hypothyroidism, mental health and stroke) is associated with reduced hospital costs in England |

| Johnson et al. (2006)25 | UK (England) | Observational study | To assess a new model of integrated diabetes care in a primary care setting (n = 4 practices) |

| Kuethe et al. (2011)26 | The Netherlands | RCT | To compare outcomes of provision of asthma care by a GP, paediatric pulmonologist or a hospital-based specialist asthma nurse for children (n = 107) with moderate asthma |

| Mahmalji et al. (2010)27 | UK (England) | Observational study | To assess the knowledge, capability and interest of GPs (n = 75) in urology provision |

| Martin et al. (2011)28 | UK (England) | Observational study | To assess the impact on hospital costs and mortality of the QOF to UK general practice in 2004 (population: 50 million) |

| Maruthachalam et al. (2006)29 | UK (England) | Prospective observational study | To assess the impact of a nurse-led flexible sigmoidoscopy clinic established in a GP practice for patients (n = 1000) with colorectal cancer |

| Newman et al. (2005)30 | USA | Retrospective case review | To assess the competency and safety of outpatient colonoscopy by family physicians (n = 2) in an outpatient office setting (n = 731 colonoscopy procedures) |

| Tuomisto et al. (2010)31 | Finland | Retrospective before-and-after study | To report on outcomes after a national asthma programme was launched, establishing a new division of labour between primary and secondary care with asthma co-ordinators (one physician and at least one nurse) nominated at each health-care centre (n = 198 patients) |

| van Dijk et al. (2010)32 | The Netherlands | Observational study | To evaluate referral rates for hospital treatment of patients (n = 6101) with diabetes after the introduction of primary care nurses |

| Zwar et al. (2012)33 | Australia | Cluster RCT | To evaluate a nurse–GP partnership model (including a home visit and an individualised care plan) of care for patients (n = 451) with COPD in 44 general practices |

The additional studies we found confirm that high-quality care can be provided for patients in primary care, including for diabetes,21,25,32 adult asthma,31 childhood asthma,26 colonoscopy,29,30 alcohol dependence22 and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). 33 Providing additional resources in primary care can also reduce secondary care utilisation, for example through the use of a nurse-/pharmacist-led clinic for patients with chronic pain. 20

In some studies, the primary care alternative to specialist referral is a different and less intensive approach to management. For example, van Boeijen et al. 19 found that two management approaches in primary care (guided self-help and structured guidelines) were as effective for patients with anxiety as referral to a psychologist for cognitive–behavioural therapy. This study emphasises that, although a common assumption is made that the same care will be provided whether in a primary or a secondary care setting, this may not in fact be the case, either by design or by default.

The support and training for primary care staff is important. For example, in the case of urological conditions, GPs did not feel that they had the skills to take on the additional roles,27 and primary care nurses in primary care did not feel confident in dealing with some of the skin conditions they were managing. 23 However, the additional studies found in this review support the earlier conclusion that a wide range of conditions can be managed effectively in primary care if adequate training and support is given to staff.

However, there are few studies of the cost-effectiveness of transferring chronic disease management from secondary to primary care. The potential for cost saving by moving services from specialist to primary care was emphasised in a modelling study by Berger et al. ,18 who found that even small increases in the number of patients with neuropathic pain managed in primary rather than secondary care in Norway could result in substantial overall cost savings. Economic analyses depend in part on whether care improves (or gets worse) as a result of transfer to primary care. Two reports of the same study, Dusheiko et al. 24 and Martin et al. ,28 suggested that, for stroke care, improvements in management since the 2004 GP contract had led to a reduction in hospital expenditure (significant for both outpatients and admissions), but they did not find evidence of this for other conditions they studied. 24,28 Several studies report lower rates of secondary care utilisation when care is moved from secondary to primary care but there is a striking absence of studies which estimate the impact of transferring care on the overall health budget (i.e. primary and secondary care combined). For example, in a study of colonoscopy in general practice,29 the cost of the procedure was lower in primary care, but the authors did not report a full economic analysis taking into account the total number of referrals for colonoscopy to hospital and primary care-based clinics combined or referrals from the primary care clinic to secondary care.

Conclusion

The long-term management of major chronic diseases has become routine in UK general practice and the evidence suggests that, with adequate supervision and training, a wide range of conditions can be managed in primary care effectively. However, there is a paucity of studies looking at the cost-effectiveness of transferring care, for example for chronic disease management, from secondary to primary care. Although there is evidence that routine management in primary care reduces the use of specialist care, cost savings will be made only if money is actually transferred from secondary to primary care.

General practitioners with a special interest

A GPwSI is a GP who supplements their core professional role by undertaking advanced procedures not normally done by a GP.

Key summary points:

-

GPwSIs were introduced principally to increase capacity to provide specialist advice.

-

GPwSIs can provide an effective addition to specialist outpatient associated with high levels of patient satisfaction.

-

Whether or not they provide a cost-effective alternative to outpatient clinics remains unclear and may depend on local service configuration and contractual arrangements.

General practitioners with a special interest were developed in the early 2000s principally to increase the capacity of the NHS to provide specialist advice and to reduce outpatient waiting times. In our previous review, we concluded that GPwSIs provided care that was of an equivalent standard to that provided in hospital outpatient clinics, although systems for monitoring quality and outcomes varied, with data on long-term follow-up of patients largely absent. GPwSIs appeared to be costlier than outpatient clinics in part because the rates of pay for GPwSIs are higher than for non-consultant doctors in outpatient clinics. However, we commented that the costs were highly likely to be context specific. It should also be noted that GPwSIs were introduced without there necessarily being an intention to reduce cost, as a main aim was to increase capacity to reduce outpatient waiting times.

We identified 10 additional studies and relevant commentaries in this updated scoping review (Table 4). 10,34–42

| Article | Country | Study type | Aim/intervention |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baker et al. (2005)34 | UK (England) | RCT | To determine whether there are differences in clinical outcomes or patient satisfaction among patients attending GPwSI-run orthopaedic clinics based in hospital outpatient departments and general practices (n = 321 patients) |

| Coast et al. (2005)35 | UK (England) | Cost-effectiveness analysis within RCT | To compare the economic cost of GPwSI service with hospital outpatient care for dermatology patients (n = 556) in 29 primary care practices |

| Dhumale (2004)10 | UK (England) | Prospective observational study | To assess the feasibility of performing hernia surgery in a general practice with local anaesthesia performed by a GPwSI in surgery, a theatre nurse and a surgical administrator (n = 4965 patients) |

| Gilbert et al. (2005)36 | UK (England) | Retrospective case review | To examine the proportion of GP referrals to a hospital respiratory medicine clinic, which might be suitable for a GPwSI respiratory clinic (n = 96 referrals) |

| Jones et al. (2006)37 | UK (England) | Discussion paper | To discuss role of GPwSIs in improving access to specialties with long waiting times |

| Levell et al. (2012)38 | UK (England) | Observational study | To assess the impact of the introduction of dermatology intermediate care services |

| Nocon et al. (2004)39 | UK (England) | Observational study | To evaluate models of diabetes care in 19 clinics with range of organisational models including clinics run by GPs in own practice, clinics run by a community diabetologist and clinics run by specialist nurses |

| Ridsdale et al. (2008)40 | UK (England) | Observational study | To evaluate the outcomes of training GPwSIs (n = 61) for a headache clinic |

| Salisbury et al. (2005)41 | UK (England) | RCT | To evaluate a GPwSI service for dermatology patients (n = 556) |

| Sibbald et al. (2008)42 | UK (England) | Observational study | To evaluate the impact on patients and local health economies of shifting specialist care from hospitals to the community in 30 demonstration sites |

Salisbury et al. 41 randomised dermatology patients to being seen either in a hospital outpatient clinic or by a GPwSI in primary care. They found no difference in clinical outcomes, but waiting times for the GPwSI were shorter and patients preferred being seen in the primary care setting. However, an economic analysis suggested that referrals randomised to the GPwSI were 76% more expensive than the hospital equivalent (£208 vs. £118). 35 In a non-randomised study of a GPwSI for headache compared with a neurology outpatient appointment, there were again no differences in clinical outcomes and patients again preferred the GPwSI setting. However, in this case the costs of the GPwSI appointment were lower than those for the hospital clinic. 40

One study randomised patients to seeing GPwSIs in either a hospital or a practice setting. 34 There were no differences in clinical outcomes, but patients again preferred being seen in primary care settings.

Overall, it is clear that appropriately trained and supported GPwSIs can provide a high-quality service that is valued by patients, and patients generally prefer to be seen in community settings. GPwSIs are now operating in a wide range of specialty areas37 and there is clearly significant potential for patients currently seen in outpatient clinics to be seen by GPwSIs; for example, Gilbert et al. 36 estimated that 23% of patients seen in a chest clinic could be seen by a GPwSI.

When interpreting the impact of GPwSIs on waiting times and costs from studies in the early 1990s, it is important to appreciate that these clinics were generally introduced as additional services designed to reduce waiting times at a time of major investment in the NHS. Now that the NHS faces reduced additional investment, GPwSI services are more likely to be intended as a substitute for hospital care. However, it does not necessarily follow that the introduction of GPwSIs will reduce demand on hospital services, although they have the potential to do so; the provision of additional services could result in ‘supply-induced demand’ if GPs’ referral thresholds change. For example, in an earlier study described in our previous review, Nocon et al. 39 reported that although outpatient attendances reduced following the introduction of GPwSIs, overall attendances rose. Indeed, we found one report in which hospital attendances increased after the introduction of GPwSIs in the community. 38 In an evaluation of practitioners with special interests among a range of ‘closer to home’ demonstration sites set up by the Department of Health in England in the mid-2000s, Sibbald et al. 42 suggested that the difference in cost per patient for commissioners may be lower for GPwSIs than hospital care national tariffs but that this might be explained by GPwSIs seeing less complex cases. They similarly cautioned that GPwSIs may increase demand for outpatient services.

It is, therefore, not clear whether or not GPwSIs provide a cost-effective alternative to outpatient clinics. In addition to the potential for ‘supply-induced demand’ referred to in the previous paragraph, there are two reasons why GPwSI clinics could be more expensive. The first is that hospital clinics are staffed by a mixture of consultants and cheaper subconsultant grades, whereas GPwSIs are paid at the equivalent of consultant grade. There are also economies of scale in hospitals which may allow consultants working in a hospital clinic to give opinions on a larger number of patients when they are supported by junior staff.

Conclusion

General practitioners with a special interest can provide an effective addition to specialist outpatient associated with high levels of patient satisfaction. Whether or not they provide a cost-effective alternative to outpatient clinics remains unclear and may depend on local service configuration and contractual arrangements.

Discharge from outpatients to primary care

Patients may be discharged early from secondary care to be followed up in primary care, instead of receiving continued follow-up in an outpatient clinic.

Key summary points:

-

GPs can follow up patients across a range of diagnostic groups as an alternative to hospital follow-up.

-

It is important to ensure than general practices have the administrative support and resources to ensure that follow-up protocols can be reliably followed, and that there is adequate support from specialists when queries or problems arise.

-

More use could be made of providing patients with information on what to expect from follow-up arrangements.

In our previous review, we found that both patient-initiated outpatient follow-up and transfer of follow-up to primary care are plausible strategies for reducing outpatient attendance rates and overall NHS costs without adverse effects on the quality of care or health outcomes. Patients in general found GP visits more convenient, less time-consuming and less expensive than outpatient attendance. However, the acceptability of alternative discharge arrangements to patients, specialists and GPs was variable and far from universal.

An additional 13 studies43–55 including one systematic review54 were identified in our updated search (Table 5).

| Article | Country | Study type | Aim/intervention |

|---|---|---|---|

| Augestad et al. (2013)43 | Norway | RCT | To reduce the number of hospital visits for respiratory patients (n = 100) through pre-clinic telephone consultation |

| Choudhury et al. (2013)44 | UK (England) | Observational study | To evaluate the impact of LES for patients with diabetes (n = 21,026) through which GPs receive training and monetary incentives |

| Grunfeld et al. (2006)45 | Canada | Multicentre RCT | To assess whether or not follow-up by the patient’s family physician is a safe and acceptable alternative to follow-up in specialist clinics for patients (n = 968) diagnosed with breast cancer in Ontario |

| Hall et al. (2011)46 | UK (Scotland) | Observational study | To explore the views of potential recipients (n = 23) and providers (n = 6) of shared follow-up of cancer and conduct a modelling exercise of shared follow-up |

| Hennessey et al. (2013)55 | UK (Northern Ireland) | Audit | To assess the impact of monitoring stable prostate cancer patients (n = 65) in primary care rather than hospital, using a computerised system to monitor PSA |

| Hewlett (2005)47 | UK (England) | RCT | To determine the impact of a direct access patient initiated review for rheumatoid arthritis vs. rheumatologist initiated review every 3–6 months for patients (n = 209) in a teaching hospital |

| Lau et al. (2010)48 | UK (England) | Retrospective case review | To audit the transfer of patients (n = 134) with successful suppression of recurrent anogenital herpes simplex virus infection to their GPs |

| Lu et al. (2012)49 | The Netherlands | Modelling (simulation) | To assess the impact of three alternatives to current guidelines for breast cancer follow-up |

| Lund et al. (2013)50 | Denmark | Audit | To assess the transfer of prostate cancer patients (n = 2585 patients, including 530 transferred to follow-up with a GP) follow-up consultations from hospital to primary care |

| Meeuwsen et al. (2012)51 | The Netherlands | Multicentre RCT | To measure the cost-effectiveness of a follow-up care delivered by memory clinic or GP for patients (n = 175) with a new diagnosis of mild to moderate dementia living in the community |

| Meran et al. (2011)52 | UK (Wales) | Observational study | To measure the risk associated with a renal patient care pathway for patients (n = 88) discharged from a renal outpatient clinic trust |

| Torregrosa-Maicas et al. (2013)53 | Spain | Observational study | To assess the impact of a quick consultation intervention for CKD patients |

| Thompson-Coon et al. (2013)54 | Multiple | Systematic review (n = 5) | To compare the effectiveness of face-to-face consultations with telephone consultations for surgery follow-up (n = 865 adults across four studies) |

Five of the 13 studies involved cancer patients. 45,46,49,50,55 In one RCT in Canada, there was no difference in outcome at follow-up (for a mean of 3.5 years) when patients (968 women with breast cancer) were seen in an oncology clinic compared with a family practice. 45 Likewise, in a trial in Norway there were no significant differences for a range of outcomes in 110 patients with colon cancer randomised to specialist or GP follow-up, which included a decision support tool for patients and GPs. However, costs were reduced in the GP follow-up arm. 43 The acceptability of follow-up in primary care was assessed by Hall et al. 46 in a qualitative interview study. They found that patients would generally be willing to have GPs share their cancer follow-up, with the caveat that the GPs had received extra training and were appropriately supported by secondary care specialists. GPs in the study stressed the importance of maintaining their own clinical skills and having reliable clinical and administrative support from secondary care. In a modelling study, Lu et al. 49 showed the considerable cost savings that could accrue from transferring follow-up of cancer patients to primary care, with no significant difference in patient outcomes. With the limited evidence on cancer follow-up from our previous review, there is clearly potential for the routine monitoring of patients who have had cancer to be carried out in primary care, provided that clear protocols and training are available to primary care physicians.

Two other studies looked at the follow-up of people, the first following a diagnosis of dementia51 and the second a limited study of patients with renal failure,52 both concluding that patients could be discharged to primary care without adverse consequences. One-third of patients with recurrent anogenital herpes48 could also be successfully be transferred to care from their GPs, although a proportion of patients did not want to be transferred as they did not want their GP to know about their diagnosis.

The systematic review54 related to telephone consultations by the specialist (surgeon or specialist nurse) as an alternative to outpatient clinic attendance following surgery. Because of the poor methodological quality of the studies included, the authors felt unable to draw any firm conclusions about the role of telephone follow-up in this situation.

The additional studies found in this scoping review, although limited in number, support the ability of GPs to follow up patients across a range of diagnostic groups as an alternative to hospital follow-up. Although many of the procedures and investigations required during follow-up may be available to GPs, general practices are not currently as well organised for ongoing follow-up of many conditions as they are, say, for the routine monitoring of diabetes or asthma. Therefore, if patients requiring ongoing follow-up are to be discharged back to primary care, it is important to ensure that general practices have the administrative support and resources to ensure that follow-up protocols can be reliably followed, and that there is adequate support from specialists when queries arise or problems occur. One option is to involve patients more closely in the decision. For example, in the studies by Augestad et al. 43 of colon cancer and Lund et al. 50 of prostate cancer, leaflets were given to the patients explaining what sort of follow-up they should expect from their GP and when to expect particular tests, etc. This information was also provided in leaflets for GPs.

Where the need for follow-up relates to patients’ symptoms, the patient may be able to assess the need for hospital follow up. For example, in a 6-year randomised trial of patients with rheumatoid arthritis47 patients were discharged and allowed to make follow-up appointments when they felt they needed one, rather than being given routine appointments. All outcomes (clinical, patient experience and economic) were in favour of patient-directed follow-up.

The availability of electronic records shared between hospitals and GPs could increase the availability of decision support when patients are no longer seen regularly in the specialist clinic. For example, Hennessey et al. introduced an electronic decision support system into their clinic which decided when prostate cancer patients needed to have their next outpatient appointment and/or prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test. 55 This was based on the computer’s assessment of a PSA test which had been carried out by their GP. Patients were not formally discharged from the clinic, but the authors reported that the number of outpatient attendances was greatly reduced.

One question which this review does not answer is how many patients are being followed up in hospital clinics who could be discharged to primary care. In a study in Birmingham, UK, GPs were given a financial incentive among other things to review the records of patients being followed up in hospital diabetic clinics and discharge those who did not meet specified referral criteria. A substantial reduction in both new and follow-up referrals was reported (odds ratios 0.69 and 0.77, respectively), although there were no data for comparators in this simple before-and-after analysis. 44

Conclusion

The studies found in this scoping review support the ability of GPs to follow up patients across a range of diagnostic groups as an alternative to hospital follow-up. If patients requiring ongoing follow-up are to be discharged back to primary care, it is important to ensure that general practices have the administrative support and resources to ensure that follow-up protocols can be reliably adhered to, and that there is adequate support from specialists when queries or problems arise. More use could be made of providing patients with information on what to expect from follow-up arrangements. It is not known what proportion of patients currently followed up in outpatients could be discharged.

Direct access to diagnostic tests and investigations

GPs may be permitted to directly order or conduct diagnostic tests, rather than having to refer patients to outpatient departments for such procedures.

Key summary points:

-

Patients value being able to have tests ordered directly by their GP, especially where tests are locally available.

-

The costs of providing services in the community compared to in hospital are uncommonly reported.

-

Especially for complex tests such as MRI and CT, increased convenience to patients may need to be balanced against the greater efficiency of tests being carried out in a centralised location.

CT, computerised tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

In our previous study, we described studies evaluating GPs’ access to electrocardiograms (ECGs), echocardiography, ultrasound, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, sigmoidoscopy and various types of radiology, including five studies of direct access to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computerised tomography (CT). We concluded that GPs having direct access to these tests was popular with patients and that a significant proportion of investigations (varying between studies and types of investigation) were thought to save an outpatient referral. Although there were differences in the types of patients referred, the diagnostic yield was similar when comparing tests ordered by GPs and specialists. We found few data to assess whether or not direct access to investigations led to a net reduction in NHS costs (i.e. whether or not the increased costs of testing in primary care were offset by reduced costs of attendance at outpatient clinics).

Since our first review was published, GPs have gained more or less universal direct access to ECGs, echocardiography, ultrasound, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy and, in places, MRI. Sometimes access to these investigations requires a range of criteria to be met, usually contained in a referral pro forma.

In this scoping review, we identified 25 additional papers (Table 6). 56–80 These included direct access to MRI (three studies),63,64,72 CT (three studies),57,70,74 diagnosis and management of deep-vein thrombosis (DVT) (four studies),59,60,73,75 retinal photography for diabetic retinopathy (six studies),56,61,62,67–69 ultrasound (one study)79 and gynaecological ultrasound (two studies),65,78 siascopy for suspicious moles (one study),76 respiratory tests (two studies),66,80 lung cancer diagnostic (one study),58 cardiac arrhythmia monitoring (one study)71 and computer-aided cardiac auscultation (one study). 77

| Article | Country | Study type | Aim/intervention |

|---|---|---|---|

| Andonegui et al. (2012)56 | Spain | Observational study | To assess the appropriateness of diabetic retinopathy diagnosis in general practice (four trained GPs; 2750 referrals) |

| Benamore et al. (2005)57 | UK (England) | Retrospective case review | To assess the effectiveness of primary care access to CT head examinations (n = 1403) for managing common neurological conditions in primary care |

| Bjerager et al. (2006)58 | Denmark | Observational study | To investigate diagnostic delay in primary care for patients with lung cancer (n = 84) |

| Buller et al. (2009)59 | The Netherlands | Prospective management study | To evaluate the safety and efficiency of a new management strategy for patients with suspected DVT (n = 1028), which would reduce unnecessary investigations and treatments |

| Campbell et al. (2008)60 | Canada | Observational study | To help family physicians (n = 80) assess the risk of DVT, and potentially decrease the use of D-dimer tests in hospital |

| Castro et al. (2007)61 | Spain | Retrospective case review | To assess the agreement of digital fundus images between primary care physician and specialist for patients with retinopathy (n = 776 digital fundus images of 194 patients) |

| Cuadros et al. (2009)62 | USA | Observational study | To describe a telemedicine system for diabetic retinopathy screening (EyePACS) |

| DAMASK Trial Team (2008)64 | UK | Pragmatic randomised trial | To evaluate a new referral pathway for patients with continuing knee problems (n = 533 in 11 sites) |

| DAMASK Trial Team (2008)63 | UK | Cost-effectiveness within pragmatic randomised trial | To evaluate a new referral pathway for patients with continuing knee problems (n = 533 in 11 sites) |

| Jawad and Robinson (2009)65 | UK (England) | Retrospective observational study | To assess the feasibility of a gynaecological ultrasound service in the community (n = 327 women) |

| Lucas et al. (2007)66 | The Netherlands | Observational study | To assess a model of care in which GPs refer patients (n = 80) suspected for obstructive pulmonary disease to an asthma/COPD service in which lung function assistants perform spirometry and collect patient data |

| Massin et al. (2008)67 | France | Observational study | To report on a regional telemedical ophthalmology network in which fundus photographs of diabetic patients (n = 13,777) are taken by technicians in 16 screening centres, and then sent to a reference centre where ophthalmologists grade them |

| Newman et al. (2012)68 | USA | Before-and-after study | To assess the impact on screening rates of digital retinal imaging for retinopathy screening in family residency programme (n = 1106 patients) |

| Olayiwola et al. (2011)69 | USA | Observational study | To assess the impact on screening rates of telemedicine diabetic retinopathy screening for at-risk patients (n = 568) |

| Pallan et al. (2005)79 | UK (England) | Observational study | To measure the impact of an independent radiographer-led community diagnostic ultrasound service (n = 373 patients) |

| Simpson et al. (2010)70 | UK (Scotland) | Retrospective case review | To assess the outcomes of direct-access CT for patients with chronic headaches (n = 4404) |

| Skipsey et al. (2012)71 | UK (Scotland) | Prospective audit | To assess the outcomes of direct-access cardiac arrhythmia monitoring for GPs (n = 289 referrals) |

| Starren et al. (2012)80 | UK (England) | Audit | To review the service provided by the Community Respiratory Assessment Unit to primary care health professionals (n = 1156 referrals) |

| Taylor et al. (2012)72 | UK (England) | Retrospective case review | To compare a primary care imaging pathway for neurology outpatients (n = 100) with traditional outpatient referral |

| Ten Cate-Hoek et al. (2009)73 | The Netherlands | Cost-effectiveness analysis | To assess a diagnostic strategy for DVT which employed a clinical decision rule and a point-of-care D-dimer assay, compared with hospital-based strategies (n = 1002 patients) |

| Thomas et al. (2010)74 | UK (Scotland) | Prospective observational study | To evaluate whether or not primary care access to brain CT referral for chronic headache reduced referral to secondary care (n = 232 referrals) |

| van der Velde et al. (2011)75 | The Netherlands | Observational study | To compare the diagnostic performance of two clinical decision rules to rule out DVT in primary care patients (n = 1002) |

| Walter et al. (2012)76 | UK (England) | RCT | To assess the impact of adding a computerised diagnostic tool to current best practice and whether or not it resulted in more appropriate referrals for patients (n = 1297) with pigmented skin lesions |

| Watrous et al. (2008)77 | USA | Observational study | To evaluate the impact of computer-assisted auscultation on physicians’ (n = 7) accuracy of murmur detection as well as their decisions to refer asymptomatic patients with heart murmurs (n = 100 pre-recorded heart sounds) |

| Williams et al. (2007)78 | UK (England) | Audit | To assess the effectiveness of a new referral system for women (n = 277) with post-menopausal bleeding |

Imaging studies

Studies of MRI related to patients with knee pain (two studies)63,64 and headache (one study). 72

The DAMASK (Direct Access to Magnetic Resonance Imaging: Assessment for Suspect Knees) trial team63,64 reported a RCT in which patients with knee problems were randomised to early MRI and a provisional orthopaedic appointment, compared with referral to an orthopaedic specialist without prior MRI. The ‘early MRI’ group showed small but clinically insignificant (as defined by the authors) improvements in quality of life at 24 months and there was no significant difference in the number of patients eventually referred to an orthopaedic surgeon (82% intervention and 86% control). The ‘early MRI’ group were more likely to have had knee surgery during the 2-year follow-up period. Early MRI was associated with increased overall NHS costs, but the authors concluded that the small improvement in quality of life represented a worthwhile investment [£5840 per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY)].

One concern about giving GPs direct access to MRI and CT is that large numbers of patients might get investigations without really needing them, resulting in a very low rate of positive findings. In an observational study, Taylor et al. 72 evaluated MRI scanning in patients with headache, using a locally agreed care pathway for determining eligibility for direct-access MRI scans. Significant abnormalities were found in 7 out of 100 cases but there was no evaluation of the impact of the service on outpatient attendance. Benamore et al. 57 found a significant pick-up rate when GPs had direct access to CT for patients with headache who had defined clinical features. In contrast, GPs in Tayside were given open access to CT for patients with chronic headache and had a very low pick-up rate of abnormalities (1.4%). Nevertheless, these GPs reported that the CT scan had avoided a referral in 86% of cases. 74 Simpson et al. 70 reported similar results for open access to CT for patients with chronic headache: a low pick-up rate of significant abnormalities but a high rate of potentially avoided referrals. It is difficult to draw firm conclusions about the value of negative investigations from these studies, whether in terms of helping the GPs’ management, reassuring patients or avoiding referrals.

Williams et al. developed a protocol in which women with post-menopausal bleeding were referred to a gynaecologist only if their transvaginal ultrasound was abnormal. 78 The study did not consider the absolute impact of the intervention, but rather a change in the radiological criterion for normality (from 3 mm to 4 mm endometrium requiring specialist referral). The introduction of the protocol was associated with a 15.7% increase in referrals for ultrasound, and the change in protocol resulted in 27 fewer women (10%) requiring referral to a gynaecologist without any missed cancers. In a separate study, Jawad and Robinson65 showed that nearly half of women referred for pelvic ultrasound were managed entirely in the community through a community gynaecological ultrasound service, although this ultrasound service also included the removal of intrauterine contraceptive devices with ‘lost strings’ and difficult intrauterine contraceptive device fittings.

Neither of these ultrasound studies shows what proportion of women with these problems would have been referred to specialists in the absence of tests; indeed, they underline the absence of this type of evaluation in the literature. However, the study by Williams et al. shows that when a protocol is developed for the use of a test and onward referral, the details of the protocol may have a significant impact on the effectiveness (and probably cost-effectiveness) of the pathway. 78 It is also important to realise that investigations are not without unintended consequences. Not only are false positives common, especially for investigations such as spinal MRI, but false negatives are common, too; for example, Bjerager et al. 58 found that a normal chest radiograph was a common reason for delay in referring patients with lung cancer.

Other studies of access to tests and investigations

Four papers (two studies)59,60,73,75 examined the use of D-dimer as a blood test to avoid urgent referral to hospital to exclude a diagnosis of DVT, a condition which used to be managed by inpatient admission but now is increasingly managed as outpatient, and hence is included in this review. In the Netherlands, Buller et al. 59 found that 49% of patients with suspected DVT could be managed without hospital referral, with only 1.4% of those not referred developing a DVT over the following 3 months. However, seven DVTs were missed, although none was fatal. A cost-effectiveness analysis showed that the protocol had a 66% chance of being cost-effective at a threshold of €40,000 per QALY (£33,000 per QALY, slightly more than the NICE threshold of £30,000 per QALY). 73 In a parallel analysis of the same study, van der Velde et al. 75 showed that two decision rules on the D-dimer protocol resulted in a similar number of referrals being avoided (45% and 49%) – a result which, although not different in this study, shows the potential for different referral protocols to influence the performance of a test. Indeed, in a study of a similar D-dimer protocol in Canada60 there was a considerable increase in D-dimer tests in primary care without any reduction in the number of patients referred for onward investigation.

Studies of non-mydriatic retinal photography (combined with telemedicine in one study) suggest that it can be used to screen for diabetic eye disease in general practice settings. 56,61,62,67–69 However, these studies are now of relatively limited relevance to the UK, as such screening is now largely contracted to high-street opticians.

Other studies show that GPs can refer appropriately when given direct access to cardiac arrhythmia monitoring71 and respiratory tests,80 with the latter study showing that a substantial number of incorrect provisional diagnoses could be rectified with access to tests. Likewise, computer-assisted auscultation of heart murmurs appeared helpful to GPs in deciding when to refer patients with heart murmurs. 77 However, none of these studies examined what would have happened to these patients without the availability of the tests, or was able to document either improvement in management or the effect on cost (i.e. increased cost of testing vs. potential reduction in cost of referral). Indeed, novel tests are not always beneficial; Walter et al. 76 showed that a siascopic approach to assessing pigmented lesions performed no better than a validated clinical checklist, although the latter was an improvement on what, for many GPs, was routine practice.

A model to assess cost-effectiveness of direct access to tests and investigations

Direct access to tests has the following potential benefits:

-

increased convenience for patients, especially when the investigation is located in the community

-

increased speed of diagnosis/pathway to correct management, avoiding waits for outpatient clinics, especially where the same test is likely to be ordered by the specialist

-

increased diagnostic accuracy in primary care where patients would not otherwise have been referred

-

avoidance of unnecessary outpatient referral (with the potential harms associated with unnecessary investigation).

It also has the following potential disbenefits:

-

overall increase in cost (owing to additional testing)

-

additional referrals (from false-positive testing)

-

false reassurance (from false-negative testing).

The studies reviewed in this and our previous review show that virtually no studies examined all of these potential costs and benefits. They also demonstrated that crude questions (e.g. ‘Is MRI cost-effective?’) are too simplistic, as these tests are often not made available on their own, but are more often combined with a locally agreed protocol with referral criteria for the test.

Where the purpose of a test is simply to expedite one that would be ordered by the specialist, the efficiency of the GP arranging the test in advance is clear, and a proportion (maybe a substantial proportion) of referrals may be avoided. However, the availability of testing in primary care will almost certainly increase the overall number of tests carried out and the net benefit to the NHS in many cases remains unclear.

Conclusion

An overarching issue is the policy context that NHS services should be provided ‘closer to home’ in order to increase convenience for patients. In this case, at least, the results are clear: patients in many studies valued being able to have tests ordered directly by their GP, especially when tests could be conveniently arranged and/or made locally available. However, the costs of providing services in the community compared with in hospital are not commonly reported. Pallan et al. 79 found that an ultrasound service was 39% more expensive per test when provided in the community. Although this difference was not statistically significant, it serves as a reminder that, especially for complex tests such as MRI and CT, the increased convenience to patients may need to be balanced against the greater efficiency of tests being carried out in a centralised location.

Direct access to services

In some areas GPs can refer patients directly to particular services rather than referring to a consultant who would then refer the patient on to the service.

Key summary points:

-

In some cases (e.g. direct access to audiology for hearing aids) the benefits of bypassing an unnecessary specialist referral are clear-cut.

-

Direct access to some services (e.g. physical therapies for musculoskeletal problems) produces a substantial increase in demand. Although popular with patients, their cost-effectiveness as an alternative to referral (or non-referral) is less clear.

-

Rational use of services can be addressed by locally agreed pathways which need to be followed in order for services to be accessed.

In our previous review, we concluded that GPs generally refer appropriately to direct-access services, but that there was inconsistent evidence on the impact on the overall demand for services, with savings in hospital costs sometimes offset by an overall increase in demand.

An additional seven studies81–87 were identified in our updated scoping search (Table 7).

| Article | Country | Study type | Aim/intervention |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bernstein (2011)81 | UK (England) | Audit | To assess the outcomes of a ‘see and treat’ interface for musculoskeletal referrals (audit of > 30,000 referrals each year) |

| Eley and Fitzgerald (2010)82 | UK (England) | Audit | To assess the impact on referrals of a direct referral audiology clinic for patients aged over 60 years old with hearing loss (n = 353) |

| Gurden et al. (2012)83 | UK (England) | Observational study | To describe and evaluate a community-based musculoskeletal service, in terms of patient-reported outcomes and satisfaction for patients (n = 696) consulting for back or neck pain |

| Julian et al. (2007)87 | UK (England) | Prospective observational study | To compare outcomes of integrated care pathway (led by the GP) with a one-stop consultant-led menstrual clinic (n = 99) for women with menstrual disorders, compared with traditional referral (n = 94) |

| Maddison et al. (2004)84 | UK (Wales) | Before-and-after study | To assess new strategies for musculoskeletal problems, including a common pathway for all referrals, a central clinical triage of patients to the appropriate clinical service, a new back-pain pathway led by extended scope physiotherapists and three community-based multidisciplinary clinics run by specially trained GPwSIs and extended scope physiotherapists |

| Ryan et al. (2010)85 | UK (Wales) | Before-and-after study | To evaluate the provision of low-vision service in community through accredited low-vision practitioners (n = over 14,000 appointments) |

| Thomas et al. (2005)86 | UK (England) | RCT | To assess outcomes of referrals to an acupuncture service (n = 159) for patients with persistent non-specific low-back pain (n = 241) in three non-NHS acupuncture clinics, with referrals from 39 GPs working in 16 practices |

For some services, there appears to be a clear-cut benefit in streamlining a manifestly inefficient referral pathway. For example, patients for whom a hearing aid is needed can be referred directly to an audiology clinic without first being seen by an ear, nose and throat (ENT) surgeon. 82 The audiologist is able to pick up those patients requiring assessment by a specialist (in this case, 16%) and it is unlikely that many patients are prescribed hearing aids unnecessarily, making this a highly cost-effective alternative to consultant referral.

Referrals to a service may increase when direct access is provided, and then there is a question of whether or not this addresses an unmet need. For example, the provision of a direct-access low-vision aid service in Wales increased the number of low-vision aid assessments by 51% and identified what the authors described as a ‘considerable unmet burden of need’. 85 There were major reductions in waiting times, significant reductions in visual disability in patients referred and very high patient satisfaction.

Musculoskeletal services are more complex. Many areas have introduced referral pathways to reduce referrals to orthopaedic clinics. These pathways may include direct access to physiotherapy (face to face or by telephone), osteopathy, chiropractic and acupuncture. The difficulty in evaluating these services is that referrals are often for conditions which are themselves self-limiting. For example, RCTs88,89 suggest that the effect of manual therapies for back pain is generally small and shortens the duration of disability rather than curing patients who would otherwise have remained disabled (although one RCT in this review suggested a long-lasting effect of direct access to acupuncture for low-back pain86). In other reports, which indicate high patient satisfaction and improvements in symptoms following direct access to new services (e.g. Bernstein81 and Gurden et al. 83), it is hard to attribute improvements in patients’ symptoms to the new service in the absence of any comparison group.

The issue the NHS faces with musculoskeletal problems is a huge burden of morbidity and a limited specialist resource. Where the patient requires physiotherapy and the only route to this is to see an orthopaedic surgeon (which is no longer commonly the case), is it clearly more efficient to provide direct access to physiotherapy for those patients. However, the provision of direct access also increases demand; for example, a study described in our earlier review showed that when direct access to a musculoskeletal service was introduced in Wales, referrals more than doubled. 84

We found other studies recommending direct access to services but with little comparative evaluation. For example, Julian et al. 87 found that women with menstrual problems could be effectively managed by GPs using a protocol which allowed access to investigations and direct listing for surgery, with no significant differences in patient outcomes compared with a consultant-led menstrual clinic. Studies of direct access to services generally show high patient satisfaction and a decrease in waiting times. However, almost all of these services were introduced at a time of major increases in NHS funding and top-down initiatives to reduce outpatient waiting times between 2000 and 2010. The additional services were often funded in addition to existing outpatient services, with this increase in supply generating its own additional demand. It therefore remains very hard to comment in general on the cost-effectiveness of direct access to services.

Perhaps the most promising change during this period, but one which was addressed only tangentially in the studies we found, was the increasing tendency for locally agreed pathways between GPs and specialists to be used as the basis for access to services (e.g. criteria which need to be met in order for a patient with back pain to be referred directly for MRI). We note also that during this period (though maybe less widespread), specialists have been introducing similar types of criteria for outpatient referrals also. These are often articulated in electronic referral forms which require certain criteria to be met (or tests carried out) before the referral is accepted. We discuss these further in Professional behaviour change, Guidelines, including referral pro formas.

Conclusion

In some cases (e.g. direct access to audiology for hearing aids) the benefits of bypassing an unnecessary specialist referral are clear-cut. However, in other cases – musculoskeletal services being a common example – the benefits are less certain. Direct access to physical therapies for musculoskeletal problems produces a substantial increase in demand for such services and, although they are very popular with patients, their cost-effectiveness as an alternative to referral (or non-referral) is less clear. The rational use of services, including investigations, treatment services such as physiotherapy, and specialist referral, can be addressed by locally agreed pathways which need to be followed for services to be accessed.

Relocation

Shifted outpatient clinics

Shifted outpatient clinics involve hospital specialists providing care in community settings.

Key summary points:

-

Community clinics are popular with patients but may be more expensive than hospital outpatient clinics.

-