Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 11/2000/13. The contractual start date was in October 2012. The final report began editorial review in October 2014 and was accepted for publication in December 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Michael Bowen reports financial support from the College of Optometrists, London, during the conduct of the study and outside the submitted work as full-time employee of the College of Optometrists. Dave Edgar reports financial support from City University London during the conduct of the study and outside the submitted work and other support from the College of Optometrists during the conduct of the study and outside the submitted work. Beverley Hancock reports financial support from the College of Optometrists outside the submitted work. Sayeed Haque reports support from the College of Optometrists during the conduct of the study and outside the submitted work, and support from the University of Birmingham during the conduct of the study and outside the submitted work. Sayeed Haque provides statistical advice to the College of Optometrists Small Grants holders under a paid consultancy agreement. Rakhee Shah reports support from The Outside Clinic during the conduct of the study and outside the submitted work. Sarah Buchanan reports support from the Thomas Pocklington Trust during the conduct of the study and outside the submitted work. Steve Iliffe reports grants from the European Commission during the conduct of the study and grants from the Thomas Pocklington Trust outside the submitted work, and other support from University College London, during the conduct of the study and outside the submitted work. James Pickett reports other support from the Alzheimer’s Society outside the submitted work and during the conduct of the study. John-Paul Taylor reports support from the Institute for Neuroscience, Newcastle University, outside the submitted work and during the conduct of the study; and support from the Northumberland, Tyne and Wear NHS Trust, Newcastle upon Tyne, outside the submitted work and during the conduct of the study. Neil O’Leary reports support from Trinity College Dublin outside the submitted work and during the conduct of the study and grant funding from The Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA) during the conduct of the study.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Bowen et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Dementia and sight loss

Recent estimates of the number of people in the UK with some form of dementia range from 670,0001 to 835,000. 2 Dementia prevalence increases with age, rising dramatically from 1.7% of people aged between 65 and 69 years to affect > 40% of people over the age of 95 years. 2 It is estimated that by 2021 over 1 million people in the UK will have dementia, a figure expected to rise to over 2 million by 2051,2 reflecting increased longevity. The 2011 Census report Population and Household Estimates for England and Wales3 indicated that the percentage of the population aged ≥ 65 years was 16.4%, the highest recorded in any census. There has been a notable increase in the frequency of the oldest-old, with 430,000 residents aged ≥ 90 years in 2011, compared with 340,000 in 2001 and 13,000 in 1911. 3 The costs of dementia care in the UK were estimated to be approximately £23B per year in 2010,4 and in 2014 alone dementia cost the UK economy £26B. 2

The Royal National Institute of Blind People (RNIB) estimates that almost 2 million people in the UK live with sight loss that has a significant impact on their daily lives, and predicts that this figure will rise to almost 4 million by 2050. 5 Over 50% of sight loss is avoidable; this figure includes people with sight loss which, at least in part, is caused by wearing spectacles that are not of the optimum strength. One in four people aged ≥ 75 years is living with sight loss, and in the population aged > 85 years this rises to one in three. 6 Both dementia and sight loss are increasingly prevalent with age, and the UK’s ageing demographic will result in many more people living with both dementia and sight loss.

Two-thirds of people with dementia live in private households and one-third live in some form of institutional care setting. 1 Many older people with sight loss live in care homes and there is evidence that they are subject to a disproportionally high burden of visual loss, with an estimated 30% of those who are visually impaired living in care homes. 7 The proportion of the total UK population living in care homes was estimated to be 0.55% in 2011 (approximately 350,000 people) and this proportion is likely to rise to 0.85% (600,000 people) by 2031. 7

There is increasing evidence of significant disturbances to visual function in Alzheimer’s disease and other types of dementia, which may affect different aspects of visual performance including contrast sensitivity, colour vision, spatial awareness and depth perception,8 and hallucinations. 9,10 Studies investigating sight loss and dementia have revealed shared changes in nervous system physiology and suggest that the prevalence of sight loss in people with dementia is higher than that in the general population of older people without dementia. 10 People with dementia not only suffer the general visual problems associated with ageing but also experience deficits of higher level visual processing including reading, object recognition and spatial localisation as a result of the damage to, or degeneration of, the brain,11 which can make the differential diagnosis of ‘eye problems’ from functional vision loss caused by dementia or, for example, stroke more difficult. The effects of having both serious sight loss and dementia concurrently are much more severe than those resulting from either dementia or sight loss alone. 10 Dementia alone often has a significant impact on quality of life; however, the ability of a person with dementia to cope with visual impairment (VI) is reduced, which can impact significantly on his or her activities of daily living and cognitive performance. 8

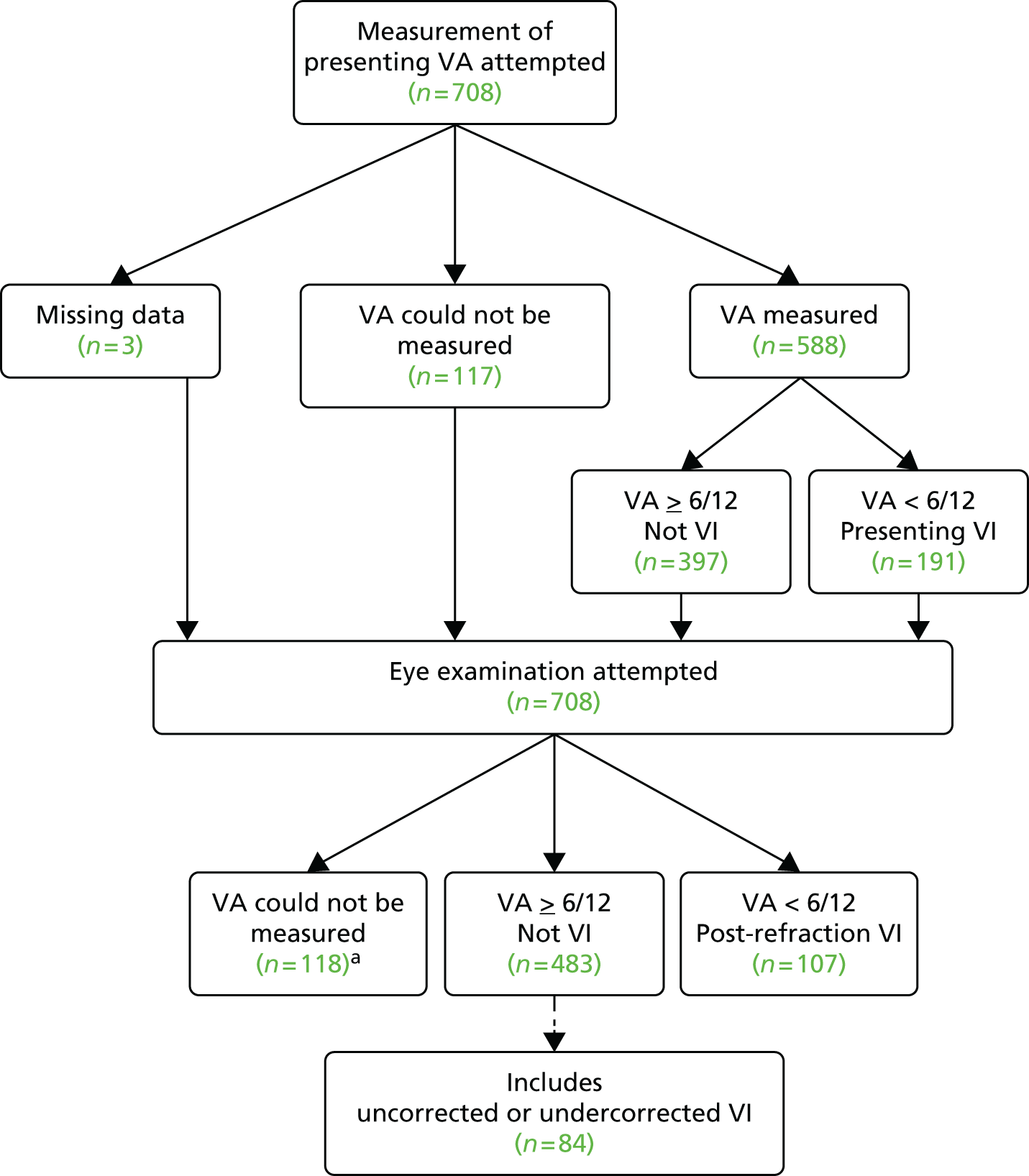

Visual impairment

A variety of definitions of VI have been used in prevalence studies. All of these definitions use criteria for VI based on levels of visual acuity (VA). VA is determined from the size of the smallest line of letters or symbols on a chart which a person can read. The definitions all express VA in terms of Snellen’s fraction (e.g. 6/12, 6/36 or 20/40), where the numerator of the fraction is the standard testing distance (6 metres in most of the world) and the denominator is a measure of the size of the letters on the line of the smallest letters that can be read. There is no standardisation regarding the VA level at which an individual becomes classified as visually impaired. 11 Definitions of the degrees of VI and blindness vary from country to country, with those set by the World Health Organization and those used in the USA and UK influencing the cut-off points for VA adopted in VI prevalence studies. 11

The World Health Organization criterion for VI is poor vision resulting from any cause including uncorrected refractive error. They differentiate between visual impairment and blindness, and their VA cut-off points for VI are:

-

visual impairment – VA < 6/18 but ≥ 3/60 binocularly with presenting correction [International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD-10),12 categories 1 and 2]

-

blindness – VA of < 3/60 in the better eye with presenting correction (ICD-10,12 categories 3–5) or visual field of no greater than 10 degrees in radius around central fixation.

In the USA, VI is defined as the best corrected VA < 6/12 (equivalent to < 20/40) in the better-seeing eye. 13

Since 2003, people with VI in the UK can be classified as either ‘sight impaired’ or ‘severely sight impaired’. Prior to 2003, sight-impaired and severely sight-impaired people were referred to as ‘partially sighted’ and ‘blind’, respectively. There is no legal definition of sight impaired but it is defined in common use as being ‘substantially and permanently handicapped by defective vision caused by congenital defect, illness or injury’. 14 Guidance is given as to defects of binocular VA and visual field that could lead to registration as sight impaired:15

-

3/60 to 6/60 with full field

-

up to 6/24 with a moderate restriction of the field, opacities or aphakia

-

6/18 or better with a gross field defect.

The definition of blindness (severely sight impaired) in the UK is: ‘So blind as to be unable to perform any work for which eyesight is essential’. 14 Guidance is given as to defects of binocular VA and visual field which could lead to registration as severely sight impaired:

-

acuity < 3/60

-

acuity > 3/60 but < 6/60 with significantly contracted field

-

acuity > 6/60 but with substantially contracted fields, especially inferiorly.

It should be noted that neither definition nor the associated guidance makes any reference to near vision, to an individual’s occupation or to any other disabilities they may have.

Common causes of sight loss and visual impairment

An estimated 1.87 million people live with sight loss in the UK. Approximately 360,000 are registered as sight impaired or severely sight impaired. 5,6 Age-related macular degeneration (AMD) is by far the main cause of registrable VI (sight impaired or severely sight impaired) in the adult UK population. 16 Other major causes are diabetic eye disease and glaucoma. However, 1.64 million of the people with sight loss have mild or moderate loss, much of which is correctable. 6 The primary causes of correctable visual loss are cataract and uncorrected refractive error. 7,11

Age-related macular degeneration

Age-related macular degeneration can be defined as ageing changes in the central area of the retina (the macula) occurring in people aged ≥ 55 years in the absence of any other obvious cause. 17 AMD is the leading cause of irreversible severe visual loss in high-income countries in individuals aged > 60 years. 18 It is the most common cause of adult blind registration in many high-income countries, including the UK. 16 However, those registered are an underestimate of the true prevalence of the condition because many with early AMD do not qualify for registration and some elect not to opt for registration.

There are many classifications of AMD; one classification is late AMD, geographic atrophy and neovascular AMD, which have prevalences of 4.8%, 2.6% and 2.5%, respectively, in the UK population aged ≥ 65 years. 19 An alternative classification is into two types: dry (non-exudative) or wet (exudative). Dry AMD is a slow progressive disease which accounts for 90% of cases. The wet type is much less common but can be more devastating. All useful central vision can be lost within days of wet AMD developing. As a result of recent developments in wet AMD treatment, some resultant VI can now be successfully treated. 7 Approximately 1.5 million people are living with the early stage of AMD. 20

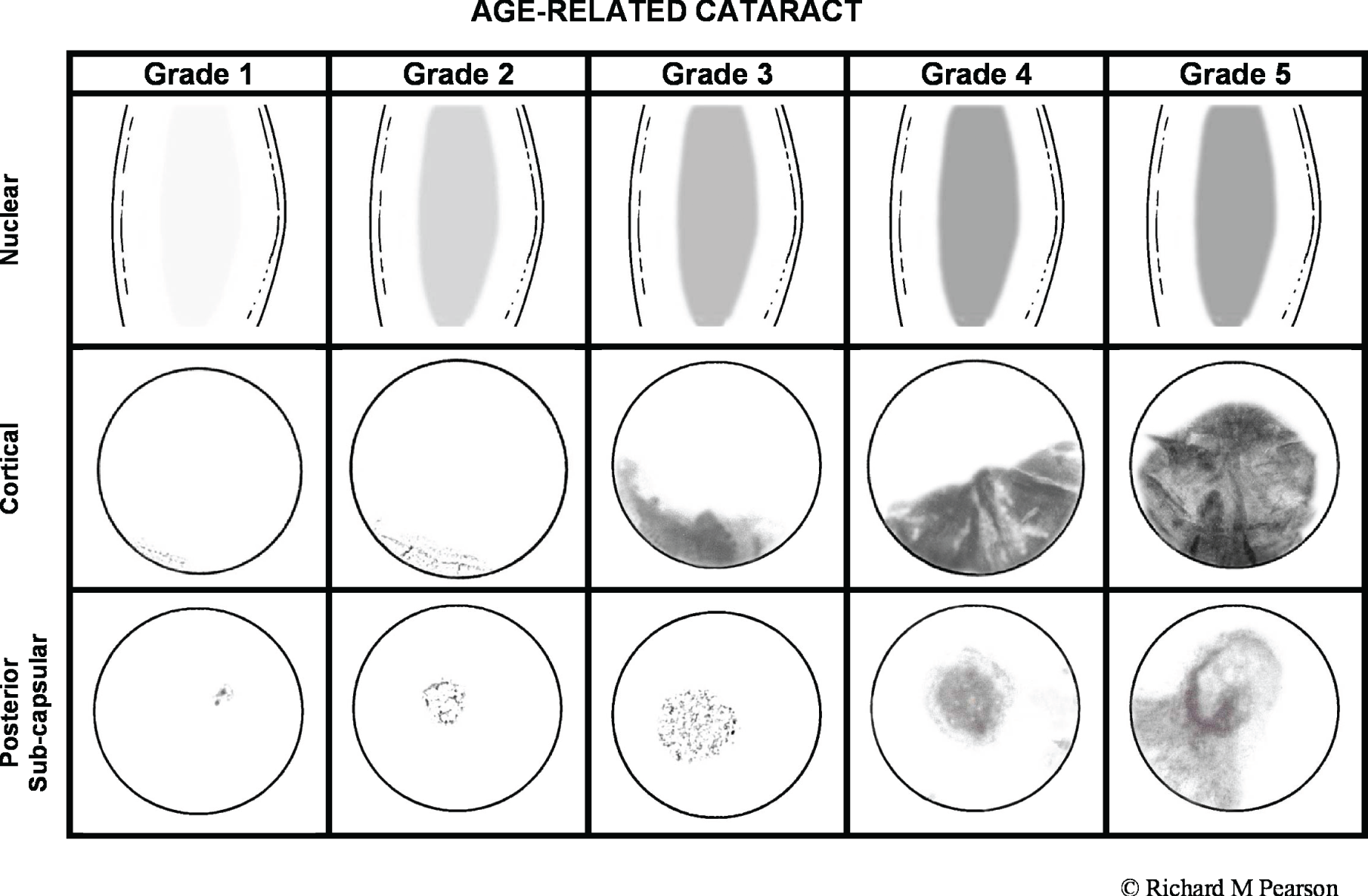

Cataract

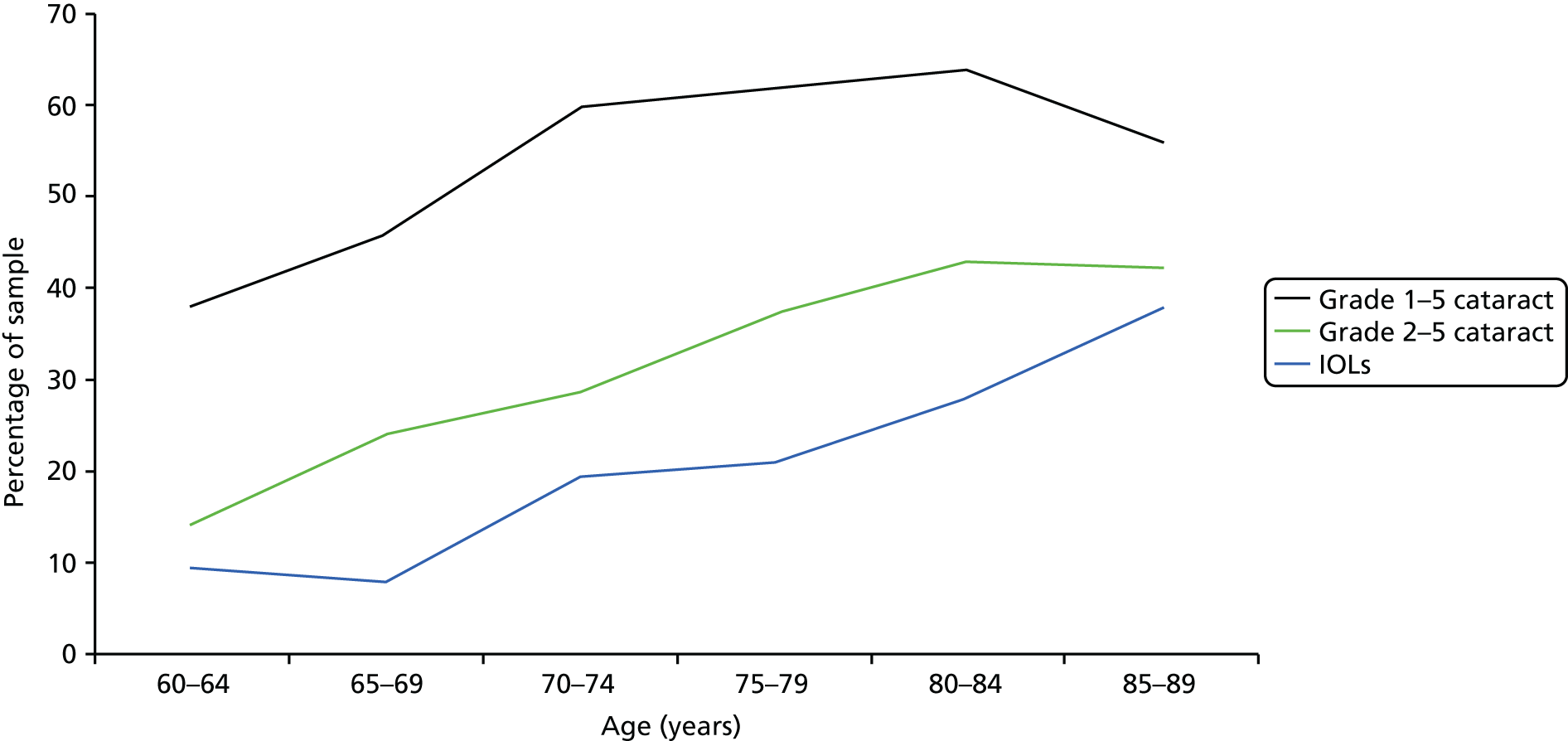

Cataract is loss of transparency of the crystalline lens. Age-related cataract is the most common form. 21 A classic symptom is a slow, gradual, painless progressive reduction in the quality of vision. 22 Not all cataract types are equally deleterious to vision; for example, posterior subcapsular opacities develop near the posterior pole of the lens and can have a dramatic effect on vision owing to their location. 23 Age-related cataract is the most common cause of reversible blindness worldwide. The prevalence of cataract increases with age, with an increased number of advanced cataracts in the older population. 24,25 Acquired cataracts and dementia are both common age-related problems and it is, therefore, likely that they will coexist. 26

Cataract prevalence estimates depend on the definition of when the normal ageing and opacification of the crystalline lens reaches the point at which it becomes sufficient to bring a diagnosis of cataract. Often this point is based on when the cataract causes a significant effect on some aspect(s) of visual performance, normally standard VA measurements. In a study in North London in 1998,27 significant cataract was defined as VA < 6/12, attributable to cataract, in one or both eyes. In this sample of 1547 people aged > 65 years, prevalence of cataract for the whole sample was 30%. Cataract prevalence (including aphakia or pseudophakia) increased with age from 16% (65–69 years) to 24% (70–74 years), 42% (75–79 years) and 59% (80–84 years), to 71% in people aged ≥ 85 years.

Visual impairment resulting from cataract is potentially remediable via surgical removal of the existing lens, replacing it with an intraocular implant. Cataract surgery is now the most commonly performed surgical intervention carried out on the NHS in England,28 with an increase of almost 100,000 cases per annum compared with a decade ago. In England in 2011/12, a total of 337,000 cataract operations were performed as day cases, with the mean age of those undergoing the cataract surgery being 74.4 years. 29 Referral for cataract surgery can be initiated by either the optometrist or the general practitioner (GP). Action on Cataracts30 suggested direct optometrist referral according to locally agreed protocols and there are now many such projects with audited outcomes and high conversion rates from referral to surgery.

Diabetic retinopathy

Diabetic retinopathy, a complication of diabetes, is a chronic, progressive, potentially sight-threatening disease of the retinal microvasculature. 31 Retinopathy which affects the macular region of the eye, responsible for providing optimum VA, is often separately referred to as diabetic maculopathy. There are a number of different classifications of diabetic retinopathy, often with overlap between the different classifications. All refer to the two basic mechanisms which can lead to visual loss: that is, the risk of new vessel growth in retinopathy and the risk of damage to the central part of the macula, known as the fovea. 31 If abnormal new vessels are present, the retinopathy is described as proliferative retinopathy, while in the absence of new vessels it is known as non-proliferative or background retinopathy.

A population screening study in Liverpool reported the prevalence of diabetic retinopathy to be 25.3% in type 1 diabetes and 45.7% in type 2 diabetes. 32 In 2010, an estimated 748,000 people were living with background diabetic retinopathy and 85,000 would be classified as falling into non-proliferative and proliferative diabetic retinopathy combined (the more advanced stages of background diabetic retinopathy). 20 Diabetic maculopathy, which can lead to sight loss more rapidly, was expected to be present in 188,000 people in 2010. 20 When studies are stratified for duration of eye disease and age, there is an increase in diabetic retinopathy in older people and in those with long-standing disease. 33

There is clear evidence that sight-threatening diabetic retinopathy has a recognisable latent or early symptomatic stage. 32 Regular monitoring and vigilant treatment can help to prevent the disease progression which can lead to blindness. All those with diabetes, either type 1 or type 2, are offered an annual appointment for screening for diabetic retinopathy as part of the NHS diabetic eye screening programme. The screening can be carried out in hospital, GP or optometric practice locations and involves taking a fundus photograph which is subsequently graded. 33

Glaucoma

Glaucoma, or, more correctly, the glaucomas, is a group of eye diseases that have in common progressive structural damage to the optic nerve head, resulting in a characteristic glaucomatous optic neuropathy, with functional loss of the corresponding visual field and which can lead to blindness if left untreated. Glaucoma is second to AMD as the most common cause of severe sight impairment (blindness) in adults in the UK and Ireland. 15,16,34,35 Primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) is a chronic, generally bilateral, although asymmetrical, disease, characterised by progressive damage of the optic nerve shown by glaucomatous changes affecting the optic disc, the retinal nerve fibre layer and/or the visual field. 36 POAG accounts for 75–95% of glaucoma among people from white ethnic groups37 and is the most common form of glaucoma in the UK. The prevalence of POAG in the UK population aged > 40 years is estimated to be 2.0%. Prevalence rises steeply with age, from 0.3% at 40 years of age to 3.2% at 70 years. 38 Based on a Bayesian meta-analysis, the pooled prevalence of open-angle glaucoma was estimated to be 6% in white populations, 16% in black populations and 3% in Asian populations. 39

In 2010, there were estimated to be 266,000 people living with detected glaucoma20 and an additional 191,000 people with undetected glaucoma in the UK. 29 A pooled prevalence analysis estimated the number with undetected disease to be as high as 380,000. 40 A further 513,000 people were estimated to have ocular hypertension (OHT), which is elevated intraocular pressure (IOP) in the eye without any other signs of glaucoma but which increases the risk of subsequently developing glaucoma. 20 The prevalence of OHT in those aged > 50 years has been estimated to be between 3.7% and 7.6%. 41

UK community optometrists provide the majority of primary eye care and are responsible for approximately 95% of referrals for suspected glaucoma to secondary care. 42 Late presentation with advanced disease is a risk factor for blindness from glaucoma. 43 Late detection may result from patients not engaging with community eye care, from a failure of health professionals to identify the disease at an early stage or from unusually rapid disease progression. The VI caused by glaucoma is irreversible but the disease is treatable, although successful management is more difficult with late-stage presentation. 36

Uncorrected or undercorrected refractive error

The term refractive error refers to errors in the optical performance of the eye resulting in a distorted or defocused image on the retina. Refractive error is usually not constant throughout life. One reason for recommending that people have regular optometric sight tests is to identify and correct those changes in refractive error that occur over time. People may not be wearing the required lens powers in their spectacles to fully correct their current refractive error. This can occur for various reasons, including people leaving too long an interval between sight tests, people declining to have the recommended prescription for their refractive error made up into spectacles or failing to wear the correct pair of spectacles. People who are not wearing the appropriate strength of lenses to correct their refractive error are referred to as having undercorrected or uncorrected refractive errors. These can be resolved using appropriate spectacles following an eye examination by an eye health professional. The prevalence of undercorrected or uncorrected refractive errors in the UK older population has been reported to be between 9%27 and 40%44 for VI defined as VA < 6/12. However, this 40% figure was obtained from a small, enriched sample of patients admitted to a department of geriatric medicine with acute illness and was unrepresentative of older people in general. The most recent of these studies was published in 1998 and there is a need for updated estimates of undercorrected or uncorrected refractive error to reflect changes in clinical practice, in health and social care policy, and in the life-course of individuals in the population.

Summary of common causes

A review of studies into correctable VI in older people estimated that 20–50% of older people have undetected reduced vision. 11 This wide range of estimates reflects, in part, the different criteria and cut-off points used in studies to define VI. 45 The majority of people with undetected reduced vision in these studies had reduced vision resulting from undercorrected (or uncorrected) refractive error and cataract, and hence their visual loss is potentially correctable following an optometric sight test by the provision and use of a pair of spectacles or contact lenses of the appropriate prescription, or cataract extraction, respectively. 11

Dementia and causes of sight loss develop independently. As people age, they are at an increased risk of developing dementia and having serious sight loss, and hence there will inevitably be people with both conditions. 10

The Prevalence of Visual Impairment in Dementia (PrOVIDe) study limited its scope to the five conditions listed above, as these are the most common eye-related conditions associated with sight loss. Many other eye conditions and non-ocular conditions lead to significant sight loss, notably stroke, head injuries and other neurological conditions. These conditions, particularly those more common in older age, can also make significant contributions to visual dysfunction. However, these conditions fall outside the remit of the current study.

Provision of eye-care services in the UK

The vast majority of UK optometrists work in primary care community optical practices, hospitals or domiciliary settings. Most optometrists work in community optical practices, from where they are the major providers of primary eye-care services. Optometrists are trained to perform sight tests, which include refraction and detection of signs of injury, disease or abnormality in the eye.

Secondary eye care is delivered by the Hospital Eye Service (HES). Secondary eye care is usually provided by a team of eye-care professionals including ophthalmologists, optometrists and orthoptists. There is increasing integration between primary and secondary eye care, with primary care optometrists involved in enhanced schemes to provide a range of services within a community-based setting, often in conjunction with GPs and ophthalmologists, in order to case-find and monitor eye conditions. 46–49

Provision of General Ophthalmic Services and NHS eye examinations in the UK

The vast majority of primary care optometrists have a contract with the NHS via local Clinical Commissioning Groups to provide sight tests to eligible persons. The provision of General Ophthalmic Services (GOS) was largely uniform across the UK until the introduction of devolved powers to Wales and Scotland. This, together with NHS restructuring, created a more diverse provision, with the emergence of a less rigid approach to the provision of primary eye care in some parts of the UK. Examples that illustrate these changes are the Welsh Eye Care Initiative, introduced in 2003, which has evolved into the Eye Health Examination Wales, and the new GOS contract in Scotland, which commenced in 2006. The PrOVIDe study is limited to England, where change to the GOS provision has been more limited.

The GOS regulations require practitioners to be satisfied that a NHS sight test is clinically necessary. 47 In general, people aged between 16 and 70 years at the time of the sight test will not normally have their sight tested under the GOS more frequently than every 2 years. Similarly, people aged ≥ 70 years will not normally have a sight test more frequently than every 12 months. However, under certain circumstances the practitioner can carry out a sight test at a shorter interval than stated above ‘either at the practitioner’s initiative for a clinical reason, or because the patient presents him/herself to the practitioner with symptoms or concerns which might be related to an eye condition’. 50 These recommended minimum sight test intervals are reduced for certain patients; for example, for a diabetic patient of any age the minimum interval between sight tests is reduced to 1 year. 50

In 2012/13, there were 12.3 million NHS-funded sight tests in England,51 with 5.5 million (44.4%) of these carried out for patients aged ≥ 60 years. 51 Private sight tests are an option and an estimated 5.6 million of these were carried out in 2011/12. 52 A section of a survey by the RNIB of people aged > 60 years asked how regularly they had sight tests; 53% reported having annual sight tests, 35% reported having a sight test every 2 years and 11% reported having sight tests less frequently. 53 It has been suggested that the uptake of eye examinations among people with dementia is considerably lower than that in the population without dementia of a similar age. 8,54 A telephone survey by Shah et al. 55 found that 93% of optometrists stated willingness to examine people with dementia, but evidence of the uptake and quality of vision care in this group of the population is lacking.

Provision of domiciliary sight tests

The majority of NHS sight tests are conducted on ophthalmic practitioners’ premises. In 2012/13, 3.2% of NHS tests were domiciliary examinations, conducted in the individual’s place of residence or at a day centre. 51 Anyone eligible for a NHS sight test qualifies for a domiciliary sight test if they are unable to attend a high-street practice unaccompanied because of physical or mental illness or disability. 50 The number of domiciliary sight tests has risen steadily since 2002/3, and the 2012/13 total of 407,000 was an increase of almost 60% compared with a decade earlier. This increase could be attributed to the ageing UK population, with more older people seeking eye examinations in their own home, although there is no evidence to directly support this. 51

Prevalence of visual impairment in people with dementia

Literature searches for the prevalence of VI and eye disease in the elderly, and for the prevalence of VI in people with dementia, revealed a lack of good-quality prevalence data on the topics.

Search strategy

A PubMed search for prevalence of VI and eye disease in the elderly was conducted using the following search strategy: (elderly[tiab] OR “aged”[MeSH Terms] OR geriatric[tiab] OR older) AND (“eye diseases” OR “eye disease” OR “eye diseases” OR “visual acuity” OR “vision disorder” OR “vision disorders” OR “visual impairment” OR “refractive error” OR “refractive errors” OR glaucoma OR presbyopia OR myopia OR astigmatic OR astigmatism OR cataract OR cataracts OR “retinal diseases”[MeSH Terms] OR “retinal diseases”[All Fields] OR retinopathy OR retinopathies OR “diabetic eye disease” OR “macular degeneration” OR “low vision”) AND ((“epidemiology”[Subheading] OR “prevalence”[All Fields] OR “prevalence”[MeSH Terms]) OR epidemiology[tiab]).

The search was initially carried out in 2011, prior to submission of a formal proposal to the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), and identified 9035 papers. It has been updated regularly, most recently in April 2014 when 11,104 papers were identified. These studies vary as to whether the study deals with a single eye disease, or several; whether it only addresses eye disease prevalence or includes it in a study of several pathologies. Only a small number of papers found via this search, and from reference list searches of review articles and reports, specifically address the prevalence of VI in a large sample of elderly people in the UK, although a wider body of international prevalence data exists.

A search of PubMed was conducted for papers dealing with the prevalence of eye disease and/or VI in people with dementia using the following terms: (dementia OR alzheimer’s[tiab]) AND (“eye diseases” OR “eye disease” OR “eye diseases”[MeSH Terms] OR “visual acuity” OR “vision disorder” OR “vision disorders” OR “visual impairment” OR “refractive error” OR “refractive errors” OR glaucoma OR presbyopia OR myopia OR astigmatic OR astigmatism OR cataract OR cataracts OR retinopathy OR “retinal disease” OR “diabetic eye disease” OR “macular degeneration” OR “low vision”) AND (“epidemiology”[Subheading] OR epidemiology[tiab] OR prevalence[tiab] OR prevalence[MeSH Terms]). The search retrieved 295 papers in April 2014. Approximately 10 were prevalence studies and none of these were UK papers.

Review of population-based UK studies into prevalence of visual impairment in older people

Table 1 summarises the key features of the most relevant studies. Although the studies are few in number, comparisons between them are made difficult by the variations in population and methods used. The cut-off point in terms of VA employed to define VI was ‘worse than 6/12’ in some studies and ‘worse than 6/18’ in others, with prevalences for both criteria reported in some studies. There were also variations in the methods used for recording VA; presenting VA was always measured but sometimes binocularly only, sometimes monocularly (with best monocular VA recorded as presenting acuity), and sometimes both monocularly and binocularly. Nor was it always used in the prevalence estimates. 59 Older studies used Snellen VA charts,44,58 while more recent studies have used logarithm of minimum angle of resolution (logMAR) charts of various types. Testing distances varied between the standard 6-m distance and 3 m. Settings varied from broadly national56,57 to local. 27,44,58 Sample sizes ranged from > 14,00056 to around 200. 44,58 The sample ages were generally ≥ 65 years, although the Medical Research Council (MRC) study investigated a sample aged ≥ 75 years. 56

| Survey (year), reference | Location (sample size); age range | Method of recording VA | Sample size for VA testing | VA cut-off point defining VI | Prevalence (%) aged ≥ 65 years (95% CI) | Prevalence (%) aged ≥ 75 years (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study 1: MRC trial (1995–8), Evans et al., 200256 | Great Britain (n = 15,126); aged ≥ 75 years | Presenting binocular VA | 14,600 | < 6/12 | N/A | 19.9 (17.8 to 22.0) |

| < 6/18 | 12.4 (10.8 to 13.9) | |||||

| Pinhole corrected | < 6/18 | 10.2a | ||||

| Study 2: Jack et al., 199544 | Liverpool, UK (n = 200); aged ≥ 65 years | Presenting binocular VA (Snellen) | 200 | < 6/12 | 50.5a | N/A |

| Study 3: North London Study (1995–6), Reidy et al., 199827 | North London, UK (n = 1547); aged ≥ 65 years | Presenting monocular VA. Pinhole-corrected VA (logMAR) | 1547 | < 6/12 | 30.2 (24.8 to 35.5) | N/A |

| Study 4: NDNS (1994–5), van der Pols et al., 200057 | Mainland, UK (n = 2060); aged ≥ 65 years | Best monocular VA, with or without a pinhole | 1362 (not cognitively impaired) | < 6/12 | 28.3a | 39.3a |

| 1362 (not cognitively impaired) | < 6/18 | 14.3a | 21.0a | |||

| 125 (cognitively impaired) | < 6/18 | 64.8a | N/A | |||

| Study 5: Wormald et al., 199258 | London, socially deprived area, UK (n = 207); aged ≥ 65 years | Presenting binocular VA (Snellen) and monocular VA | 207 | < 6/12 | 14.5 (10.3 to 20.0) | 26.4 (18.9 to 35.6) |

| 207 | < 6/18 | 7.7 (4.5 to 12.2) | 14.2 (7.5 to 20.8) | |||

| Study 6: Melton Mowbray, Lavery et al., 198859 | Melton Mowbray, UK (n = 677); aged > 75 years | Best monocular VA (Snellen) | 529 Post-refraction data |

< 6/12 | N/A | 26.2a |

Some people with dementia will have been included in the sample for most studies, as cognitive impairment was not an exclusion criterion. However, only two studies assessed cognitive impairment: Jack et al. 44 specifically excluded those with severe cognitive impairment, while the National Diet and Nutrition Survey (NDNS)’s study analysed those with cognitive impairment separately. 57 Only two studies separately analysed data from a subgroup of participants who lived in care homes. 44,57

Study 1

The MRC study was a large cluster randomised trial taking place in 106 general practices with participants aged ≥ 75 years. VA data were obtained from 14,403 participants and VA was measured using the logMAR Glasgow acuity cards at 3 m. 56 Presenting VA was measured first binocularly and then monocularly. Where presenting VA was worse than 0.5 (equivalent to < 6/18) in either eye, VA was remeasured with a pinhole disc. The pinhole disc is an opaque disc into which a small hole (the pinhole) has been drilled. The effect of the pinhole is to reduce the effective pupil size of the participant. If the participant’s loss of vision is the result of an out-of-focus image on the retina (which should be correctable with the appropriate prescription in the participant’s spectacles), the pinhole can improve the participant’s vision by reducing the size of the blur circles on the retina. All participants with pinhole VA of worse than 0.5 were referred to an ophthalmologist. VA of the better eye was used if binocular VA was not available.

-

Using the criterion of binocular presenting VA < 6/18, 12.4% [95% confidence interval (CI) 10.8% to 13.9%] of the sample had VI.

-

With a pinhole, the prevalence of VI in the better eye was 10.2% using the ‘worse than 6/18’ criterion. The pinhole could only be used successfully on 62% of those with presenting VA < 6/18 in either eye.

-

Using the criterion of binocular presenting VA < 6/12, 19.9% (95% CI 17.8% to 22.0%) of the sample had VI.

-

The prevalence of VI was higher in women and rose steeply with age.

-

The main causes of VI were extracted from GP notes or hospital records. 45

-

When refractive error is excluded from the list, the main causes become AMD (52.9%), cataract (35.9%), glaucoma (11.6%), diabetic eye disease (3.4%) and myopic degeneration (4.2%).

Comment

-

This study had a large sample size covering many areas of Britain and was representative of the UK in terms of mortality and deprivation.

-

No refraction was carried out.

-

Visual acuity was recorded by trained nurses and may not be as accurately recorded as would be the case with optometrists, ophthalmic nurses or ophthalmologists.

Study 2

Jack et al. 44 conducted a prospective study of 200 consecutive mentally competent patients aged ≥ 65 years (mean age 80 years) admitted to hospital with an acute illness. Binocular VA was measured with a Snellen chart at 6 m. Patients with VA of ≤ 6/18 had a full ophthalmic assessment from an ophthalmologist, and a decision was made as to the main cause of VI if more than one potential cause was found.

-

Using the criterion of binocular presenting VA < 6/12, 50.5% of the sample had VI.

-

Of those with VI, 40% were caused by refractive errors and 37% by cataract; a total of 79% were considered as being due to reversible causes.

-

A total of 76% of those admitted to the hospital following a fall had VI.

Comment

-

The last line read correctly on the Snellen chart was taken as the participant’s VA. This was common practice in those studies reported here which used Snellen charts and is a weakness of such studies. A participant able to read most of the letters on a line will not have those successes counted towards their overall VA, which will be determined by a line of larger letters which was read correctly in its entirety. With modern logMAR charts, not available for these early studies, every letter read correctly by the participant counts towards the VA recorded, even if these letters are from a line on the chart that was not read correctly in its entirety. Choosing the last line read correctly on a Snellen chart will tend to underestimate VA and overestimate VI.

-

Patients with severe cognitive impairment were excluded from the study. The sample was an enriched one comprising a selective population of patients admitted to a department of geriatric medicine with an acute illness.

-

The eye examination by the ophthalmologist was carried out only on those with VI. A full refraction was performed on a proportion of those with VI but the number is not stated.

-

An unstated but small number of participants lived in care homes. No effect of location was found when comparing prevalence of VI in participants living in care homes and participants living in their own homes.

Study 3

Reidy et al. 27 conducted a cross-sectional survey using two-stage cluster random sampling in north London. Participants were recruited from general practices and 1547 were examined. Monocular VA was recorded with a logMAR chart at 6 m and was repeated with a pinhole. An autorefractor was used to determine refractive error. VA, autorefraction and visual fields were assessed by trained ophthalmic nurses and a comprehensive eye examination was performed by ophthalmologists.

-

With a criterion of bilateral presenting VA of < 6/12, 30.2% (95% CI 24.8% to 35.5%) of the sample had VI.

-

A total of 72% of those with VI as defined above were classed as potentially remediable.

-

The population prevalence of refractive error causing VI in one or both eyes was 9% (95% CI 7.0% to 11.4%).

-

The age-standardised prevalence of poor vision was significantly higher in residents of the most underprivileged areas.

-

The prevalence of cataract causing VI in one or both eyes was 30% (95% CI 25.1% to 35.3%).

-

The prevalence of open-angle glaucoma and suspected glaucoma was 3% (95% CI 2.3% to 3.6%) and 7% (95% CI 5.4% to 8.4%), respectively.

-

Reasons given for the high level of undetected and untreated morbidity in the population included low levels of attendance at the primary care optometrists or failure to purchase corrective spectacles; suboptimal integration of vision checks into the general primary care of older people; and people’s perceptions of the extent to which their vision has gradually diminished and the point at which help should be sought.

Comment

-

The examination of each participant by an ophthalmologist is a strength of this study.

-

Unusually, the proportion of VI reported was bilateral VI, rather than the more common binocular VI or VI based on the acuity of the better eye.

-

Results on socioeconomic background of the sample were described as ‘tentative’, but the association between the degree of underprivilege and cataract and uncorrected/undercorrected refractive error is informative.

-

A potential strength of the study is the use of an autorefractor to determine refractive error. However, it is unclear how the autorefractor results were used. There is no indication that the current/habitual spectacle correction was measured using a focimeter, so the autorefractor findings could not be used to estimate the change in refraction from the current spectacles. Nor does the VA appear to have been recorded with the participant wearing the autorefractor result. Instead, it seems likely that the pinhole VA recorded monocularly was used to identify VI resulting from uncorrected/undercorrected refractive error.

Study 4

A randomised cross-sectional survey of people living in their own homes or in care homes was carried out as part of the NDNS. 57 Participants were recruited from 80 randomly selected postcode areas of mainland Britain. Acuity measurements were made by a trained nurse in the participant’s place of residence. VA was measured in 1487 participants (1362 not cognitively impaired and 125 cognitively impaired) who received a nurse visit. LogMAR monocular distance VA was measured using the Glasgow acuity card test at 3 m, without any spectacle correction, and repeated with a pinhole. Monocular VAs were then recorded again, both with and without a pinhole, but with the participant now wearing any distance spectacles.

-

With a criterion of best monocular VA of < 6/12, 28.3% of the sample had VI.

-

With a criterion of best monocular VA of < 6/18, 14.3% of the sample had VI.

-

Visual impairment showed a strong positive linear trend with age.

-

Visual impairment was more common in participants living in care homes, with an age-adjusted odds ratio (OR) of 2.59 (95% CI 2.23 to 2.96).

-

Visual impairment was more common in women, with an age-adjusted OR of 1.55 (95% CI 1.21 to 1.89).

-

Of the cognitively impaired participants, 64.8% had VI when the ‘VA worse than 6/18 in the better eye’ criterion was applied.

-

Visual acuity improved by 0.2 logMAR units with a pinhole in 21.2% of participants in the non-cognitively impaired group.

Comment

-

A short memory questionnaire was used to identify participants with cognitive impairment to identify those potential participants for whom proxy consent was needed. There is no indication that any subjects were excluded on the basis of the assessment.

-

This was a national survey which is unusual in including both participants living in their own homes and those living in care homes.

-

Visual acuity measurements were recorded by trained nurses in participants’ homes rather than by optometrists, ophthalmic nurses or ophthalmologists. Standardisation of lighting conditions was not possible and variations would affect the accuracy of results.

-

No refraction was carried out and no causes of VI, apart from those where uncorrected/undercorrected refractive error was suspected, were identified.

-

This is the only study reviewed to have included an analysis of people with cognitive impairment as a subpopulation of the sample.

-

The paper states that ‘The highest Glasgow Acuity Card score from any of the measurements in the better eye is defined here as the best visual acuity’. 57 These measurements include the pinhole VA.

Study 5

A 1992 cross-sectional random sample survey by Wormald et al. 58 recruited 207 participants aged ≥ 65 years from an inner-London general practice. Binocular VA was recorded using a Snellen chart at 6 m, and monocular VA was recorded using a Sonksen Silver chart at 3 m, with a pinhole if 6/9 was not achieved. An improvement of greater than one line in VA monocularly or binocularly was taken as evidence of potential benefit from refraction. The cause of VI was identified by a consultant ophthalmologist, and where participants had more than one possible cause for their visual loss, a clinical decision was made as to the main cause.

-

Using a criterion of presenting VA of < 6/18 in either eye, 7.7% (95% CI 4.5% to 12.2%) of the sample had low vision.

-

A total of 27% of subjects would have benefited from refraction, based on the pinhole results.

-

Cataract was responsible for 63% of VI based on better eye VA of < 6/12 and excluding uncorrected/undercorrected refractive error.

-

A small number (n = 17) of examinations were conducted in participants’ own homes, and 41% of these participants were found to be visually impaired.

-

The prevalence of clinically obvious predisposing changes at the macula associated with visual loss in at least one eye was 25%.

Comment

-

The last line read correctly on the Snellen chart was taken as the VA. No refraction was carried out, with best corrected VA estimated with a pinhole.

-

With a criterion of best presenting acuity of < 6/12, 14.5% (95% CI 10.3% to 20.0%) were calculated to have VI.

-

One strength of the study is the assessment of each participant by an ophthalmologist and the identification of the cause of VI.

-

The high prevalence of cataract will reflect the much lower numbers of cataract surgery procedures carried out in the early 1990s than today.

-

This study is one of the few to record near VA; failure to achieve N6 in a subject with good distance vision served as an indication of the need for a new prescription for reading spectacles.

Study 6

This early 1980s study of residents of Melton Mowbray59 aged > 75 years comprised 529 participants. Monocular VA was recorded with existing spectacles (if any) and unaided vision in each eye was recorded for all subjects using a Snellen chart at 6 m. Best monocular VA was recorded following a full refraction by an optometrist. Subjects also received an ophthalmological examination.

-

Using the criterion of post-refraction best monocular acuity of < 6/12, 26.2% had VI.

-

Of the sample, 11.2% were unable to read N8 post refraction.

-

Of the sample, 10.4% were examined at home or in hospital.

Comment

-

The last line read correctly on the Snellen chart was taken as the VA.

-

A notable strength of the study is that all of the VA measurements and the determination of refractive error were undertaken by an optometrist.

-

Although both the VA with any current spectacles and the unaided vision were recorded on presentation, only unaided vision data are stated in the paper. Neither the proportion of participants presenting with VI nor the undercorrected element of VI were stated.

-

Another strength of the study is the recording of near VA (NVA) with what was presumably the post-refraction correction.

The studies reviewed above are 15–40 years old and reveal inconclusive data on prevalence, largely owing to methodological differences and definitions of VI. However, it is clear that many cases of VI in older people can be either prevented or successfully treated. Evans and Rowlands11 concluded that there is overwhelming evidence that a very large proportion of older people do not receive appropriate eye care and many of these people could be helped by cataract surgery or appropriate refractive correction (spectacles). Improvement in VA is not the only benefit from refractive correction, as behavioural and psychological problems in people with dementia are reduced when VI is prevented or corrected, with a corresponding positive impact on quality of life. 60 Data from older people with dementia have rarely been analysed separately in population studies of VI. The exception is the NDNS, in which 64.8% of the cognitively impaired participants had VI using the ‘VA worse than 6/18 in the better eye’ criterion. 57

A meta-analysis of the prevalence and causes of blindness and low vision in the UK highlighted the urgent need for improved UK epidemiological data, particularly for visual loss among the non-community-dwelling older population. 7 Care home residents were excluded from one VI population study;56 in others, they were possibly included but not separately analysed,27,58,59 or made up a very small proportion of an already small sample. 44 Only the NDNS study included a large care home residency subsample (23.8%), and these residents were more likely to have VI, with an OR of 2.59 when compared with people living in the community. 57

Review of population-based international studies into prevalence of visual impairment in older people

Methodological and sample differences between UK and international population studies, plus health-care variations between countries, make comparisons between studies difficult. A methodological strength of a number of international population studies is the measurement of best corrected VA, obtained after a subjective refraction. 61–64 For presenting VI using the criterion of best VA of < 6/12, prevalences vary from 6.9% in the SEE study of those aged 65–84 years (binocular VA),63 to 7.3%, calculated from the Melbourne study for those aged ≥ 60 years (best monocular VA),61 and to 11.7% in the Baltimore Eye Survey of those aged ≥ 40 years (best monocular VA). 65 For VI defined by best monocular presenting VA of < 6/18, the prevalence calculated from the Melbourne study data was 2.7%. 61 All of these prevalences are lower than those from UK studies, with the younger age of the international cohorts likely to be a major contributory factor.

For best-corrected VI for VA of < 6/12, the prevalences calculated for those aged ≥ 60 years from the two Australian studies (both best monocular VA) were 2.7% for Melbourne61 and 6.5% for Blue Mountains,62 with 5.8% reported in the Rotterdam study of those aged ≥ 55 years. 64 The only UK study using comparable methodology was Melton Mowbray, in which a prevalence of 26.2% was obtained from their sample aged > 75 years. 59 For VA of < 6/18, the best corrected VI prevalences were 1.9% for Melbourne61 and 2.5% for Rotterdam. 64

International studies of people living in care homes have reported high prevalences of VI. In Alabama, USA, the presenting VI based on binocular VA of < 6/12 was 57% in a sample in which those with Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores of < 13 were excluded. 66 In another US study which, like PrOVIDe, included people with all levels of cognitive impairment, presenting VI (best monocular VA of < 6/12) was found in 38% of participants, with best corrected VI of 29%. The sample included 40% who had severe cognitive impairment (MMSE score of 0–9) and 70% who had MMSE score of ≤ 18. The dearth of UK VI data from care homes has been highlighted. 7

Quality of life and visual impairment

Visual impairment, especially in older people, can lead to functional impairment which may adversely affect quality of life. 67 In a ranking of common chronic conditions, which can affect the ability of older people to perform essential tasks,68 VI was ranked third, behind arthritis and heart disease. A number of instruments have been used to measure quality of life. Some assess visual function status (e.g. Visual Function Index and National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire), some are vision-specific quality-of-life questionnaires (e.g. Low Vision Quality of Life Questionnaire) and some use generic health-related quality-of-life instruments (e.g. EuroQol Questionnaire). 69 Measurements of VA and other measures of visual performance, such as contrast sensitivity, are highly correlated with activities of daily living. 9

Performance on various tasks of daily living was assessed in a study of > 2500 participants aged between 65 and 84 years, which excluded those with Standardised Mini-Mental State Examination (sMMSE) scores of < 18 (i.e. those with severe or moderate cognitive impairment). 70 For mobility tasks, at least 50% of participants were disabled [using a cut-off point for disability of one standard deviation (SD) below the population mean performance] if their VA was worse than logMAR 1.0 (6/60). However, for the more demanding visual task of face recognition, disability occurred when VA was < 0.3 (6/12). 70 Interestingly, > 90% of those with a VA of < 0.3 (6/12) were disabled for the visually demanding task of reading at 90 words per minute.

A nested trial within the national MRC Elderly Trial collected data using the 25-item National Eye Institute Visual Function Questionnaire instrument from 1745 participants aged > 75 years. For the analysis, VI was defined in two ways: either presenting VA in the better eye of < 6/12 or VA in the better eye of < 6/18. There was a strong association between VI, using either definition, and reported difficulties with general vision, near activities and social functioning. 45 Although there was a strong association between VA and questionnaire scores, VA accounted for only 20% of a combined score derived from each of the subscales of vision function. The authors note that psychological factors, such as having an optimistic or pessimistic outlook on life or adopting coping strategies to help counteract the impact of VI, may impact on the way people with equivalent levels of sight loss report their general level of visual function. Evidence supporting this view came from the 21% of those with VA of < 6/18 who reported having no problems with their general vision. This percentage was lower for specific activities such as near activities, for which only 11% of those with VA of < 6/18 reported having no problems.

A 2012 RNIB-funded UK study conducted by NatCen Social Research (McManus and Lord71) analysed many aspects of the circumstances of adults with sight loss, using data from two Britain-wide surveys: the Life Opportunities Survey and the Understanding Society Survey. Comparisons were made between participants with self-reported sight loss and the remainder of the population after controlling for differences in age and sex. Notably, 31% of participants with sight loss reported being dissatisfied with life overall, compared with 10% of those without sight loss. A greater proportion of participants with sight loss (94%) experienced some kind of restriction to their ability to take part in society than those without sight loss (83%). Respondents with sight loss were more likely to have experienced difficulty accessing health services (33% of the subsample) than those without sight loss (18%).

Mental well-being

Sight loss is frequently associated with negative feelings including frustration, anger and feeling low. These feelings are part of the normal grieving process, with grief in this context being for loss of sight. Studies in the USA and Canada estimate the prevalence of depression in people attending low-vision clinics with AMD, the leading cause of registrable VI in the older UK population, to be approximately 30%. 60,72,73 A typical study examined 151 adults aged > 60 years (mean age 80 years) with VI living in the community. The definition used for VI was presenting better eye VA of ≤ 6/18, together with VA of ≤ 6/30 in the other eye. The proportion of participants with depression, as determined by standard criteria using a validated instrument for diagnosis of depression (Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition74 Disorders), was 32.5%, which is approximately twice the prevalence of depression in the general population using similar diagnostic methods. 73 The authors noted that the prevalence of depression in their sample of people with VI was similar to prevalences of depression found in patients with life-threatening diseases, such as cancer.

In the UK, the MRC trial of the assessment and management of older people in the community collected data on depression and anxiety, in addition to measuring VA in order to identify participants with VI. 56 The instruments used to assess depression and anxiety were the Geriatric Depression Scale and the anxiety subscale of the General Health Questionnaire, respectively. VI was defined as presenting binocular VA of < 6/18 and depression by a GDS score of ≥ 6. Participants with VI had slightly raised levels of anxiety compared with participants who were not visually impaired when only age and sex were controlled. Control of other confounders removed any association between anxiety and VI. The prevalence of depression in the VI subgroup was 13.5% and was statistically significantly greater than in those without VI (4.6%; p < 0.001). 75 This 13.5% prevalence of depression was lower than that found in other studies, but the MRC trial had a sample drawn from the general population rather than from low-vision and outpatient clinics. The OR, following adjustment for age and sex, for depression with VI was 2.69 (95% CI 2.03 to 3.56), which reduced to 1.26 (95% CI 0.94 to 1.70) when other confounders, notably activities of daily living, were controlled. Although VI is one factor contributing to depression in people with sight loss, depression can be attributed to other factors, notably impairment to functional activities of daily living. It was suggested that VI leads to difficulties with functional activities, which can then result in depression. 75

Another UK study investigated the visual and psychosocial factors, including depression and adjustment to sight loss, which influenced participants with VI who had self-reported difficulties with a range of visual activities. 76 The instruments used to assess the participants’ depression and the level of adjustment to their sight loss were the Geriatric Depression Scale and the 19-item Acceptance and Self-Worth Adjustment Scale. The 100 participants with VI had an average age of 81 years. Visual parameters, including distance VA, NVA and contrast sensitivity, accounted for 28–50% of the variance in self-reported limitations in visual activities. However, depression and levels of adjustment were also statistically significant contributors to limitations in activities, with depression notably accounting for 17% of the variance in self-reported mobility function.

There is evidence that interventions to enhance visual performance can contribute to a reduction in depression symptoms. A sample of 95 adults with a mean age of 77 years (range 65–89 years) with VI were assessed before and after a rehabilitation package, which included provision of low-vision services and optical aids. After controlling for other factors, the rehabilitation package accounted for 10% of the variance in depression, with both the low-vision clinical service and the optical aids remaining statistically significant contributors60 to the reduction in depression symptoms over time.

The 2012 RNIB NatCen study compared many aspects of well-being in those with and those without sight loss, after controlling for age and sex differences. 71 Participants with sight loss (14%) were more likely than those without sight loss (2%) to have been feeling unhappy or depressed a lot more than usual. A loss of self-confidence, that occurred a lot more often than usual, was more prevalent in those with sight loss (11%) than in those without (1%). There was a fourfold difference in the proportion of participants reporting dissatisfaction in their health between those with sight loss (57%) and those without sight loss (14%). Participants with sight loss were approximately twice as likely to have fewer than three people to whom they felt close (15% compared with 8%). An overall well-being index was calculated using the Short Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale, which gave a score of between 7 and 35 for each individual, where the higher the score the better the individual’s well-being. Participants with sight loss had a lower mean score (22.70) than those without sight loss (25.86).

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline on depression in adults with a chronic physical health problem recommends that primary care practitioners, who presumably include optometrists, should screen high-risk groups for depression and initiate a referral to the GP for those who screen positive for depression. 77 The association between VI and depression is complex, with the VI contributing to the depression and the depression contributing to the functional disability associated with the VI. 72 There is widespread agreement that a holistic approach involving collaborative care should be adopted for patients with moderate to severe depression who also have a chronic physical health problem such as VI. 56,72,77

Falls

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence reports that 30% of people aged > 65 years and 50% of people aged > 80 years fall at least once per year. Falls are estimated to cost the NHS more than £2.3B per year. 78 Older people living in care homes or in sheltered housing are more likely to fall than those living in their own homes. 79,80 This increased risk results in part from care home residents often being frailer and more likely to have more of the other fall-related risk factors than those living in their own homes. 81 In a study of > 9000 participants, those with a cognitive impairment had an OR for falls of 2.3 when compared with those with no cognitive impairment. 82

There is considerable evidence that VI, measured in various ways and defined using acuity cut-off points for VI of < 6/12 or < 6/18, is a significant and independent risk factor for falls, with an OR of approximately 2.5. 44,81,83,84 This reflects the significant input provided by vision, both central and peripheral, to balance control. 85,86 Balance when standing was significantly impaired in AMD compared with controls when a mental arithmetic secondary task was introduced. 86 The visual system also provides vital information regarding the location and size of hazards that may lie in the path of people as they ambulate. 80 In a UK cross-sectional study of patients aged ≥ 65 years who had undergone hip fracture surgery, those with presenting VI (binocular VA of < 6/18) were compared with the non-VI group. Significantly more of the participants with VI had fallen in the previous 5 years. Participants with VI were also less likely to have had an optometric eye examination in the 3 years prior to their fall and less likely to have been wearing their glasses at the time of the fall. 87

Although NICE guideline 161 states that vision assessment and referral has been a component of successful multifactorial falls prevention programmes, NICE found no evidence that referral for correction of vision as a single intervention for older people living in the community is effective in reducing the number of people falling. 78 Elliott81 notes that this conclusion was based largely on the results of two randomised controlled trials, and identifies several possible sources of bias, including non-representative participants and potential bias introduced by the trials not being double-blind, both of which could have affected the results of these and other clinical trials.

There are many possible causes of falls, some specific to the person who falls, suggesting that programmes designed to prevent falls should be tailored to the individual. 88 Most falls result from a combination of contributory factors, one of which can be VI. Specialised falls services are provided nationally in the UK, offering advice, providing rehabilitation services and aiming to prevent further falls in those with a history of falling. As part of their assessment, the majority of falls services carry out a vision check, but these vary in terms of frequency and methods used. Reciprocal referral between optometrists and local falls services is recommended to improve continuity of care. 85 It is important to consider the role played in falls by elements of visual performance other than VA, including factors such as reduced contrast sensitivity, visual fields and binocular vision. 88

Reporting standards

Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology statement

The study endeavoured to comply wherever possible with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement, which contains recommendations to improve the quality of reporting of observational studies. 89 The STROBE checklist, with annotations giving details of PrOVIDe’s compliance with each item on the checklist, is available in Appendix 1.

Standards for reporting and measurement of visual impairment

A report, The Prevalence of Visual Impairment in the UK: A Review of the Literature,45 commissioned by the RNIB, concluded with a section on the standards for reporting and measurement in studies investigating the prevalence of VI. The following recommendations were made and have been followed insofar as they were feasible in PrOVIDe:

The Working Group recommended that vision assessment in population-based studies should include a measurement of visual acuity using logMAR charts at distance and near under standardised conditions.

Information collected should record: (i) monocular and binocular distance presenting visual acuity, whether a method of vision correction is used (e.g. spectacles) and, if so, the type and power of vision correction device; (ii) monocular and binocular near presenting visual acuity at 40 cm, whether a method of vision correction is used (e.g. spectacles) and, if so, the type and power of vision correction device; (iii) monocular and binocular best-corrected visual acuity at distance and near, following refraction using an age-appropriate addition for near acuity.

We recommend the use of validated questionnaires or scales for measuring self reported vision problems or vision related quality of life. We emphasize the need to thoroughly test all questions before use in surveys.

Reproduced with permission from RNIB45

Aims and objectives

Previous research suggests that VI, often preventable, is not uncommon in the UK older population. The risks of VI and dementia both increase with age, suggesting that a proportion of people with dementia will also have undiagnosed VI, but evidence to support this is lacking owing to a dearth of research. This, together with evidence of the effects of VI on general well-being, prompted identification of the main research questions and associated objectives.

The main research questions are:

What is the prevalence of a range of vision problems in people with dementia aged 60–89 years and to what extent are these conditions undetected or inappropriately managed?

The four primary objectives of the study were:

-

to measure the prevalence of a range of vision problems in people with dementia

-

to compare the prevalences found in objective 1 with the published data on the general population in a comparable age range

-

to identify and describe reasons for any underdetection or inappropriate management of VI in people with dementia

-

to recommend interventions to improve eye care for people with dementia and further research in this area.

The secondary objectives of the study were:

-

to identify any differences in the level of undetected or inappropriately managed VI between those living in their own homes and those living in care homes

-

to determine estimates for the percentages of those with dementia likely to be able to perform successfully elements of the eye examination

-

to relate vision problems in people with dementia to data from functional and behavioural assessments.

Chapter 2 Methods

Study design

The study had two stages. Stage 1 was a cross-sectional study to establish the prevalence of a range of vision problems among people with dementia. Stage 2 was a qualitative study that used focus groups and interviews to explore and describe issues around detection and management of vision problems among people with dementia from the perspectives of affected individuals, family carers, professional care workers and optometrists.

Stage 1 was an observational cross-sectional study. PrOVIDe endeavoured to follow the STROBE statement for reporting of observational studies wherever possible. The STROBE recommendations have been developed to improve the quality of reporting of observational studies. 89 An annotated version of the STROBE checklist, giving details of PrOVIDe’s compliance with each item, can be found in Appendix 1.

Throughout the report, the term ‘potential participant’ is used to describe individuals who were approached by a member of the research team for involvement in the study. The term ‘participant’ is used to describe individuals who were formally recruited into the study. The term ‘family carer’ is used to describe a family member or friend who cares, unpaid, for their relative or friend. The term ‘care worker’ is used to describe someone who is employed to support individuals with everyday tasks, in their own homes or in residential care settings. The term ‘formal consultee’ has been used to describe a personal consultee who was required to give approval on behalf of individuals who lacked mental capacity to provide informed consent to participate. The term ‘informal consultee’ refers to a family member or personal carer whose opinion was sought regarding an individual’s participation in the study; this was applicable for individuals who had the capacity to provide informed consent to participate. An informal consultee role was sought for all potential participants and participants to provide additional assurance that participation in the study was supported by an independent source concerned with the interests of the participant.

Setting

Participants were recruited from 20 NHS sites in six regions of England. Sites were selected to ensure the recruitment of participants living in rural, urban and city locations and to encourage the participation of people from black and minority ethnic groups. It was originally envisaged that sites in four regions would be included: East Anglia, the North East, North Thames and Thames Valley. Two more regions, Yorkshire and the Humber and the North West, were added later when recruitment rates were lower than predicted in the original regions and concerns were raised that the recruitment target might not be achieved within the time scale. The regions referred to were those defined by the NIHR Dementias and Neurodegenerative Diseases Research Network (DeNDRoN), which subdivided England into nine regions.

Regions and sites were selected in consultation with DeNDRoN. Local network co-ordinators identified local principal investigators willing to support the study and then advised the research team on the numbers of participants that they predicted could be recruited in the time frame, and site-specific recruitment targets were agreed.

Approvals

The study received NHS ethics approval in September 2012 in advance of the scheduled start date. NHS research and development approval was sought from the NHS sites including primary care trusts where participants would be recruited from care homes. The first sites granted approval in November 2012, with the remaining sites gradually joining the study over the next 3 months. Recruitment began in November 2012.

The Association of Directors of Adult Social Services (ADASS) was consulted on whether or not social care research ethics approval was also required for recruitment through care homes. ADASS concluded that NHS ethics approval was sufficient but advised the study team to write to the directors of adult social care in all (n = 47) participating local authorities to inform them of the study and offer additional information if required. One authority declined to support the study.

Sampling

Stage 1

The study sample was people with dementia (any type) aged 60–89 years. To ensure that the spectrum of care was represented, the sample included people living in their own homes and people living in residential care (such as care homes and hospital inpatient wards). An additional inclusion criterion was that, in the case of individuals lacking mental capacity to provide informed consent to participate, a formal consultee was required who could give approval on the individual’s behalf. The opinion of a family member or professional carer in the role of informal consultee was sought in respect of all participants as to whether or not participation would be appropriate. The exclusion criteria were as follows:

-

Individuals who had been in hospital in the preceding 2 weeks following an acute illness, or who had major delirium or a major infection.

-

Individuals unable to understand English, as consent procedures and the eye examination were conducted in English.

-

Individuals unable to comply with the requirements of the eye examination; although it was expected that some participants would not be able to comply with all elements of the examination, individuals were excluded if they were unable to co-operate with the simplest procedures.

-

Individuals participating in a clinical drugs trial, because the eye examination involved the administration of tropicamide eye drops (Mydriacyl, Alcon Laboratories Ltd, Surrey, UK) and all of the potential drug interactions could not be determined. This exclusion criterion was added on completion of the pilot study.

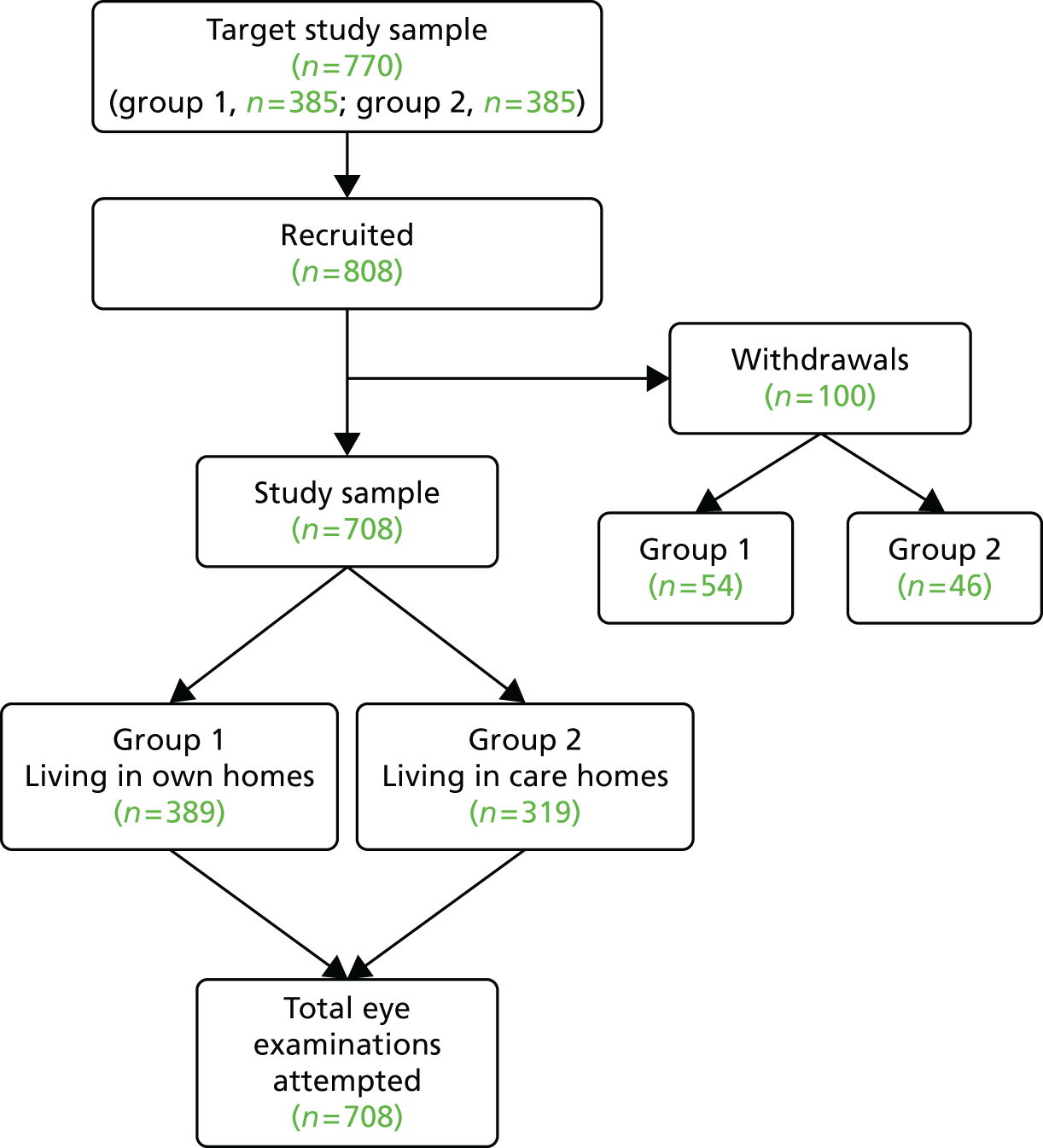

Sample size

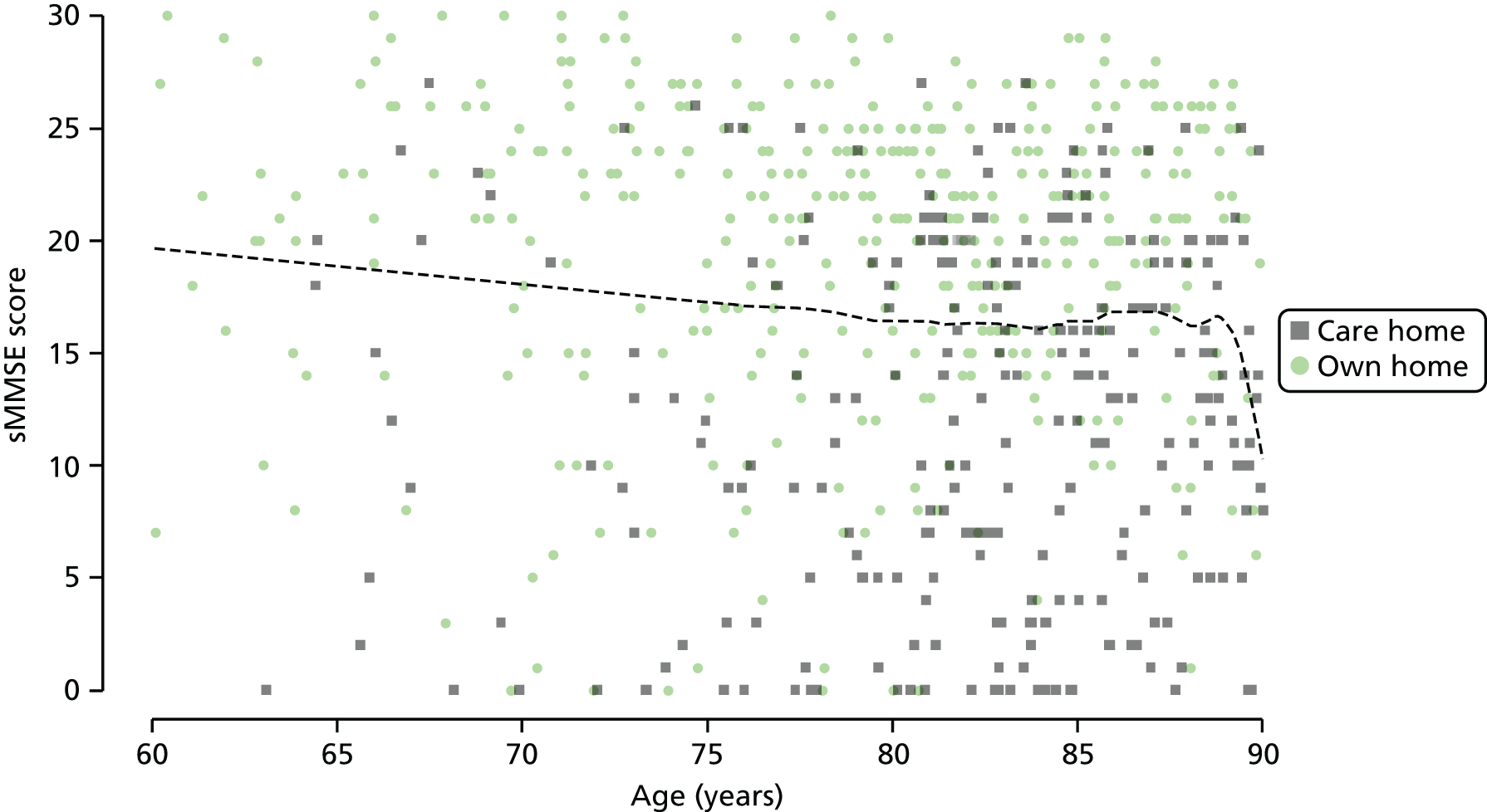

As described in Chapter 1, the prevalence of conditions causing VI has been estimated to be as high as 50%. 44 For the stage 1 cross-sectional study, a sample size of 385 was required to allow detection of an estimated prevalence of 50% with 5% precision and 95% confidence. If the prevalence of a condition was greater than or less than 50%, the study would have required a sample size smaller than 385. It was anticipated that some participants would be unable to perform all of the tests undertaken in a standard optometric examination, but there were no published data on the percentages of those with dementia who would be unable to perform individual elements of the examination. In the absence of published data, a decision was made to assume a worst-case scenario that up to 50% of the subjects might be unable to complete a particular test. This increased the maximum sample for stage 1 to 770 (385 × 2).

This led to a decision to divide the sample into two groups: group 1 was people living in their own homes and group 2 was people living in care. Although the group sizes were not defined to specifically support ‘between-group’ comparisons, the use of equal numbers in the two groups would provide scope for some comparative analysis between groups 1 and 2. With the determined sample size, there would be at least 80% power to detect a difference between proportions of 50% and 42% (or less) in two equal-sized groups. The initial sampling strategy for both groups was to stratify by age and sex to match as closely as possible the best estimates available at the time for the general dementia population. In both group 1 and group 2 the PrOVIDe target sample was one-third male and two-thirds female; 30% of males were aged between 60 and 74 years and 70% of males were aged between 75 and 89 years; and 15% of females were aged between 60 and 74 years and 85% of females were aged between 75 and 89 years.

Stage 2

The population under study in stage 2 was extended beyond people with dementia to include family carers, care workers working in care settings and optometrists. This process of triangulation – posing similar questions to different sources – was employed to increase the validity of findings. Stage 1 participants who had mental capacity to consent themselves into the study and who were able to participate in an interview were considered for inclusion in stage 2. Purposive sampling was applied to identify participants across the age range, of both sexes, and to include individuals who might be particularly informative because of a history of eye disease.

Family carers were also identified through their involvement in stage 1 in that they were the named next of kin or the informal consultee of stage 1 participants. The method of data collection with family carers was focus groups, and the named carers of stage 1 participants living in an area where focus groups were planned were invited to participate. Similarly, the care workers approached for stage 2 worked in care homes that had assisted with recruitment of stage 1 participants.

Optometrists were sampled using the membership of the College of Optometrists (CoO). The College had 10,086 members representing in excess of 70% of the members of the profession registered to practise. The method of data collection used for optometrists was focus groups. All College members living or working in an area where focus groups were planned were invited to participate.

Recruitment of participants

In stage 1, the initial approach to potential participants was made by a member of the direct care team, a member of DeNDRoN, local co-ordinating research staff or a member of the CoO research team. The aim of this initial contact was to inform the potential participant and carers of the study and its remit. This was achieved by direct face-to-face contact (e.g. in a clinic), by telephone or by letter. Potential participants and carers were provided with written information on the study’s purpose, methods and risks, and what was required of participants.

Subsequently, potential participants and personal and professional carers were contacted by either a DeNDRoN staff member or a member of the research team to determine if the potential participant and family member/carer were willing to be involved in the study. They were also given the opportunity to ask any questions or raise any concerns they might have had at that stage. Potential participants were given a minimum of 1 week to consider their possible participation in the study. If the potential participant and carer felt confident and comfortable to participate in the study, consent forms were completed.

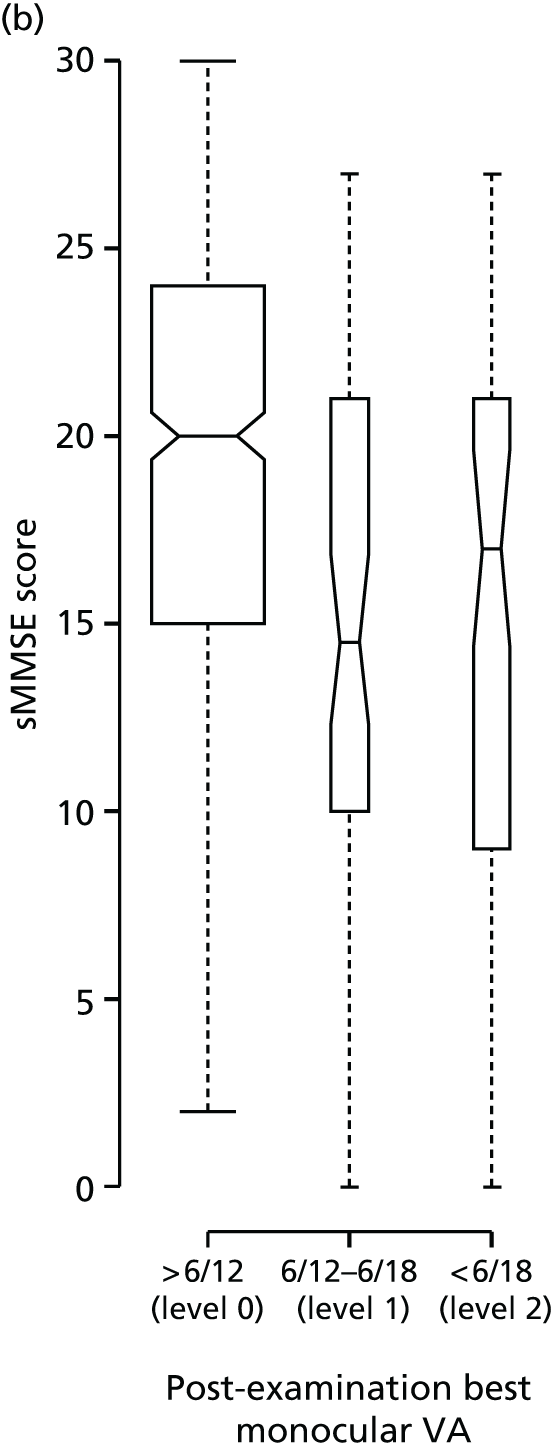

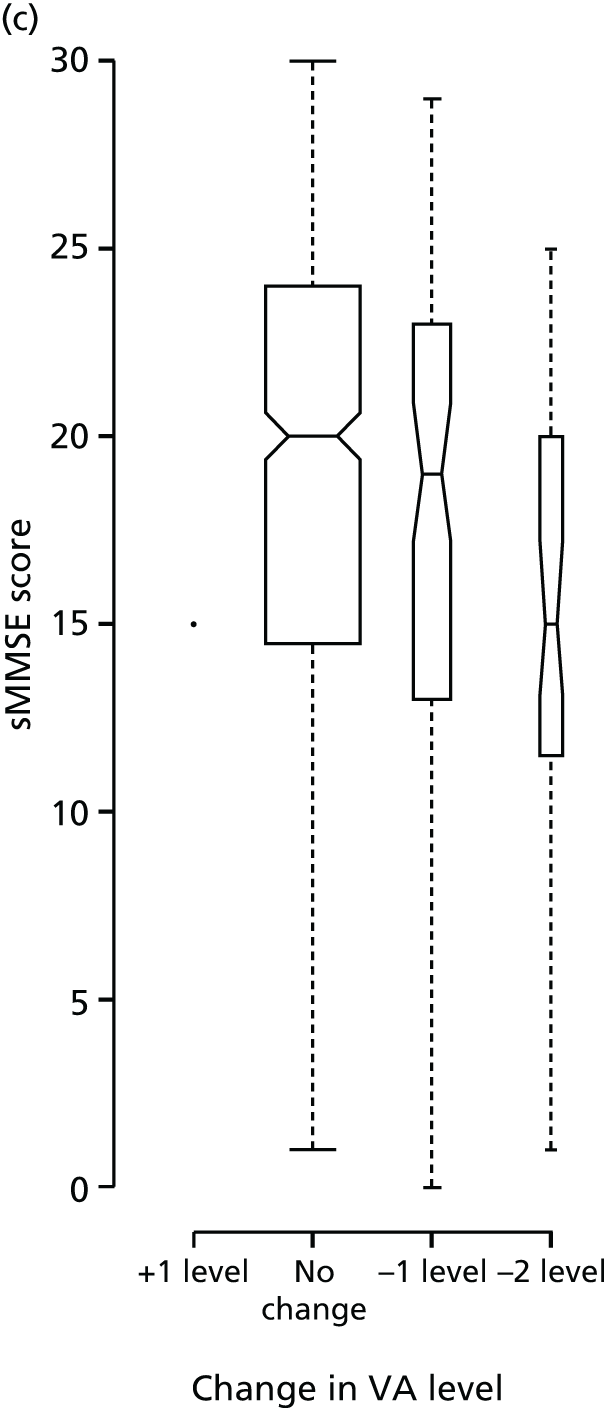

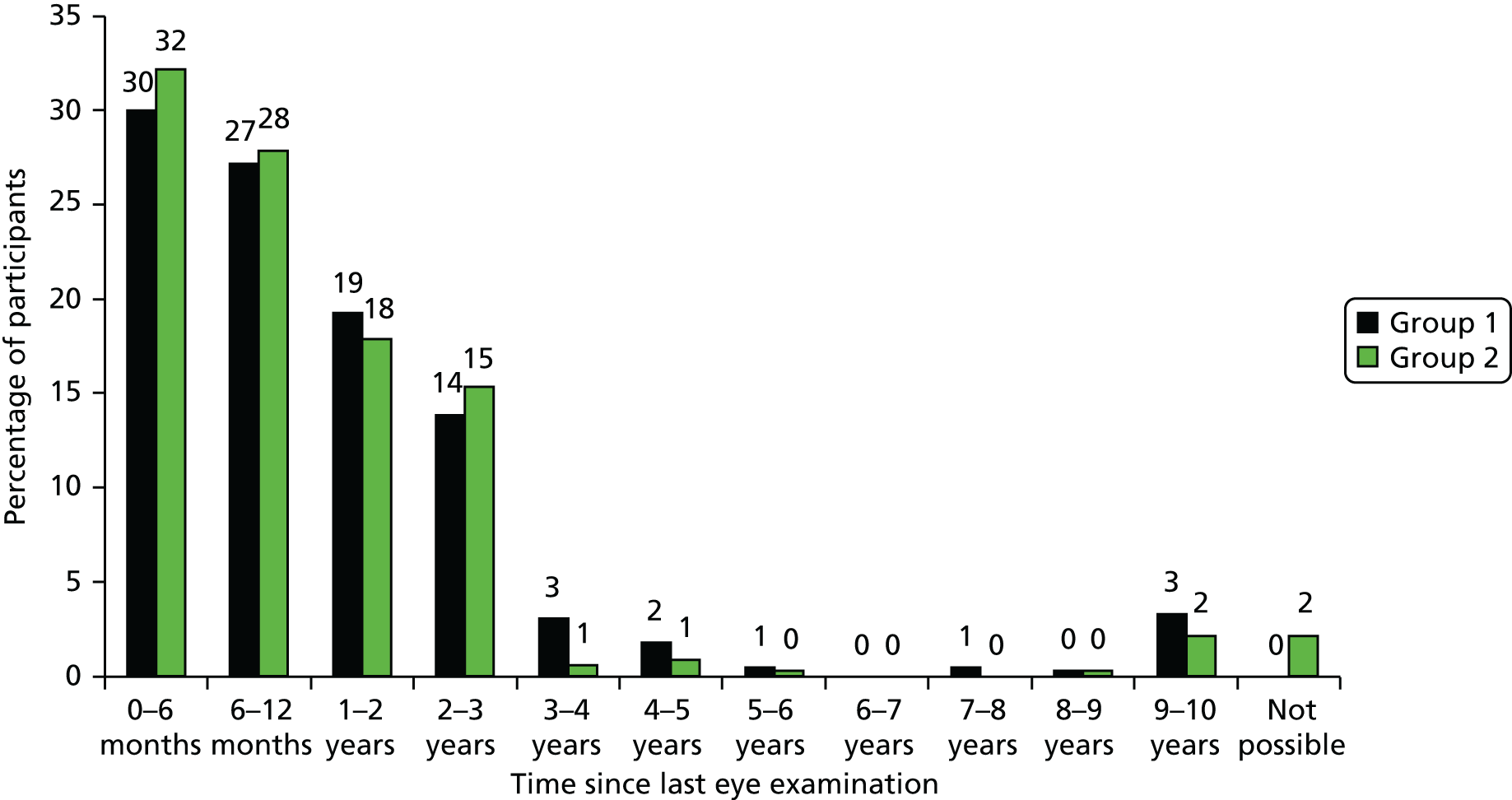

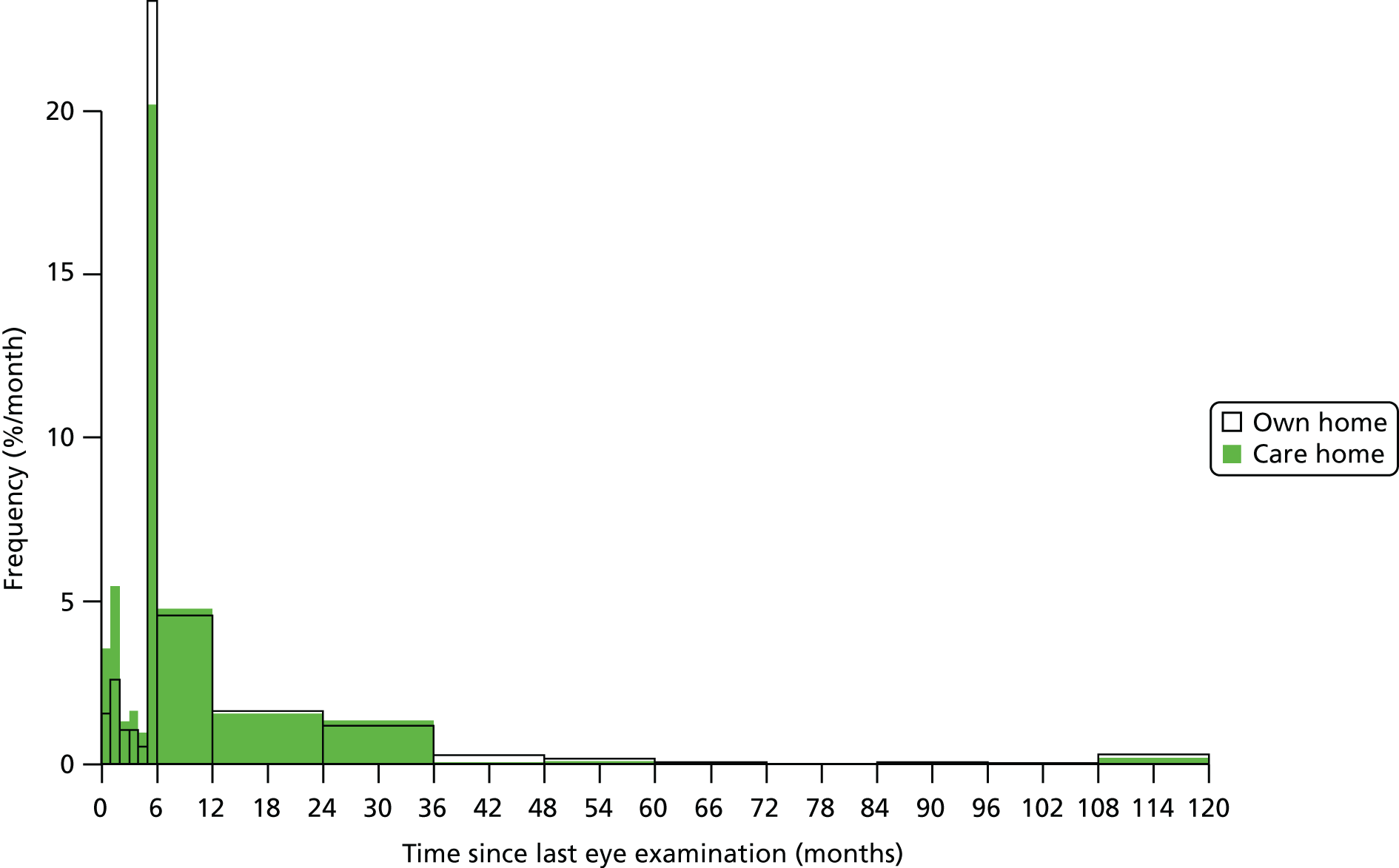

Ethically, and for validity of the findings, it was important and appropriate to include participants who lacked mental capacity to consent within the tenets of the Mental Capacity Act (2005). 90 In recognition of the complexities surrounding informed consent and capacity in people with dementia, all research workers involved in the study received formal NIHR Clinical Research Network training in good clinical practice, informed consent, the ethics of consent and the Mental Capacity Act. 90 In the case of individuals unable to consent for themselves, a formal consultee (family member/dependant/friend) was asked for their opinion. The formal consultee was asked to take into account any advance decisions or previously expressed wishes and feelings, and consider the potential participant’s best interests. In group 1, 67.9% of participants were able to consent themselves into the study and 32.1% required a consultee. In group 2, 27.6% were able to consent themselves into the study and 72.4% required a consultee. The consultee was provided with an information sheet, containing the same information as that for a participant able to consent for themselves, and was asked to sign a consultee declaration form. As an additional measure to safeguard participants’ interests, for participants with the capacity to consent an informal consultee was asked to give their opinion on the potential participant’s suitability to take part in the study.