Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 11/1015/12. The contractual start date was in June 2012. The final report began editorial review in August 2015 and was accepted for publication in February 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Spiers et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction and methods overview

Background

Delivering health care ‘closer to home’ for children and young people who are ill was established as a policy directive in the 2004 National Service Framework for Children, Young People and Maternity Services. 1 It followed a long-standing view that ill children were better cared for at home when possible, and concerns about the welfare of children in hospital. 2,3 In the 2004 National Service Framework1 the importance placed on delivering health care close to home was linked with issues of ensuring accessible and timely services that were centred on the needs of families.

Later, the Transforming Community Services programme reiterated the importance of care closer to home in England. 4 As part of an ambition to ‘make everywhere as good as the best’, developing services ‘so that children with support from family members can choose to be cared for at home at all stages of their illness or disability’ was recommended as a ‘high impact’ change. 4

Although the care closer to home policy1,4,5 had its origins in concerns about appropriate settings for the ill child and their family, it later evolved to become part of the wider national agenda of containing demand for urgent care. For example, the Department of Health highlighted the importance of children’s community nursing (CCN) services as a pathway to achieving Quality, Innovation, Productivity and Prevention plans to reduce hospitalisation. 5 Most recently, delivering paediatric care in the community gained traction as a possible solution to a perceived unsustainability of acute inpatient care in the NHS. 6

Realising children’s health care ‘closer to home’ in practice

Designed to care for ill and disabled children in the community, CCN teams have been recognised by national policy as the services to achieve care closer to home. 1,5,7 More recently, the Royal College of Nursing described them as the ‘bedrock to integrated care closer to home’. 8 Despite this, not every health community in England has access to a CCN team. 9,10 CCNs have a long history in the NHS11 and terminology has varied over time; paediatric home care, hospital at home and, to some extent, ambulatory care can all describe types of services known in the contemporary NHS as CCN teams.

Variation in models of care closer to home are evident12,13 and typologies have been conceptualised in a number of ways. For example, dichotomies of generic/specialist, inreach/outreach, community based/hospital based, and long-term/short-term input are all described in the literature. 10,12,14,15 However conceptualised, the key components of such services are that they are led by children’s nurses and deliver nursing interventions and care in community settings, such as home and school.

Evidence shows CCN services provide health care at home for a wide range of needs,9 including acute (e.g. see Callery et al. ,16 Sartain et al. ,17,18 Davies and Dale19,20), long term and complex (e.g. see Carter,21 Carter et al. ,22 Hewitt-Talor23 and Stein and Jessop24) and end of life (Parker et al. 9). They undertake a range of clinical care activities (e.g. home chemotherapy regimens) and, depending on skill mix, may be able to offer advanced nurse practice, such as assessing and prescribing. 25 They can also play a central role in non-clinical aspects of care, such as care co-ordination and empowering parents to support an ill child at home. 16,26

Although CCN services play a key role in facilitating care closer to home, they do not work in isolation. Often, they link with primary and secondary care services, particularly for urgent care pathways. 8 However, the success of these partnerships can be challenged by poor visibility and a lack of understanding more generally about the role of CCN teams in the NHS. 9

What outcomes could children’s community nursing services achieve?

Given the function and nature of CCN services, it is possible that they might influence outcomes such as secondary care use (and the associated costs), and quality of care for families. Secondary care use may change as a result of CCN service provision to families in two ways. First, admission avoidance is a function for some CCN services. 9 This, in turn, may result in a reduced rate of admissions for children. Admission avoidance may be achieved through immediate diversions from the inpatient ward following referral from accident and emergency (A&E) or primary care. It could also be achieved as a long-term consequence of CCN services empowering and educating parents, over time, to manage acute childhood illness at home. For example, in dealing with acute illness in children, parents have anxieties about making ‘wrong’ decisions27 and the risks of longer-term harm to the child. 28 Parents can feel disempowered29 and recent studies have shown a need for reliable information about recognising and managing acute childhood illness. 30,31 Recent evaluations of CCN services show community nurses can counteract these issues by acting as a source of support, advice and reassurance, and increasing parents’ confidence to support an ill child at home. 9,16,17,20,26

Second, CCN services may reduce length of hospital stay. Although children with common conditions that resolve rapidly may not stay long in hospital, their large numbers mean that reductions in length of stay (LOS) of only small amounts, and particularly avoiding a single overnight stay, would add up to changes in the individual average and total LOS. There are also possibilities for shorter hospital stays when a child’s condition is likely to resolve completely after treatment, or for complex care. Children with complex care needs may have longer LOS in hospital when admitted for common acute illnesses, and very long LOS for issues related to their complex care. For example, a study of 15 children in the South West region dependent on long-term ventilation found that they experienced a mean length of hospital stay of 513 days before being discharged home, with one child having stayed for a total of 1460 days. 32

Despite the theoretical possibility of impact of CCN services on secondary care, evidence for this is only just emerging, and is tentative at best. 9,33 Continued increases in emergency admissions lasting < 1 day34 mean efforts by CCN teams to fulfil admission avoidance functions are taking place against greater demand for urgent care. It is therefore important that future service evaluations try to account for this, although doing so is difficult outside the design of randomised controlled trials, an evaluation method inappropriate for this type of intervention.

Evidence for service quality is largely, but not consistently, positive. For example, studies of parental caring for ill children at home, particularly those with complex and ongoing needs, demonstrate a consistent picture of the demands associated with this. 35–40 The support provided by CCN services plays a critical role in supporting families in this situation,26 although other evidence suggests that existing provision is not always sufficient in this respect. 22 However, evaluations of CCN services typically show that parents highly value these teams and are largely satisfied with provision. 16,17,20,26

Despite the evidence trend towards positive evaluations of CCN services, there remains a gap in understanding how views of service quality change over time. For example, the importance parents place on different aspects of service provision may change over time as families become accustomed to being supported by a CCN team at home. Such considerations may be important to managers and commissioners as they plan services. In addition, in Parker et al. ’s evaluation,9 evidence suggested that perceptions of service quality were strongly linked to the quality of relationships with health-care staff,9,26 a finding replicated elsewhere in the context of other services. 41,42 Parent–provider relationships inevitably change and develop over time, and again, this presents questions about the longitudinal experience of CCN service quality for families.

Organisational change in health care

An extensive literature on organisational change indicates a range of factors that influence both the acceptability and sustainability of service change. For example, enabling and sustaining change requires a stable environment with capacity to acquire new knowledge. 43,44 A ‘receptive context’,43 reflected in strong leadership, allowance for risk taking, clear objectives, and dedicated funding is also important. 43,45,46 Consideration should be given to the innovation itself and how it is implemented. For example, there must be compatibility between the change and the organisation in which it is taking place, and changes need to be seen as credible and vital to organisational success, with thought given to timing and order. 43,45 The influence of key stakeholders can support or inhibit efforts to enact change, with the motivations, commitment, skills and values of others all playing a critical role. 43,45,47

The evidence base regarding organisational change in health-care spans both acute and community services, although no work has examined the salience of this evidence specifically for implementing CCN services. Given the national agenda to move care closer to home, which requires a degree of organisational change to introduce and expand new CCN services, understanding the factors that influence efforts to implement change in this particular context may be useful.

The need for research and background to the National Institute for Health Research call

Despite the national policy direction of moving care closer to home, commissioners have stated a need for evidence about the costs and secondary care outcomes of these types of services. 9 The tentative evidence about such outcomes warrants a need for further research in this respect. In addition, questions remain about the longitudinal aspects of perceived service quality for families.

Typically, CCN services have not been formally evaluated using ‘gold standard’ experimental approaches, not least because of the methodological and ethical challenges of doing so. A 2011 National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) call for quasi-experimental evaluations presented the opportunity for robust quasi-experimental evaluation of organisational innovations to develop CCN teams. Such evaluation would make a substantial and timely contribution to evidence, addressing the gaps outlined above. In response to this call, we designed a research project to answer the following questions:

-

Does redesigning children’s health-care services by introducing CCN teams affect acute hospital admission rates for common childhood illnesses and LOS for all conditions?

-

What changes in the quality of care do families caring for children with complex health-care needs experience when CCN teams are introduced?

-

What benefits and challenges do commissioners and providers experience, as the new services are planned, implemented and established?

-

What are the costs and outcomes of the new services compared with those achieved by alternative service configurations?

As the research was taking place during structural changes in commissioning arrangements, a supplementary research aim addressed how these changes affected the planning, implementation and establishment of services (as part of question 3).

Overview of the research

The research took place between 2012 and 2015, using a mixed-methods, multisite case study approach. A mixed-methods approach of this sort is recommended when additional information is needed to interpret quantitative measurements,48 allowing us to understand how service redesign has worked, for whom and in what context (that is, providing a ‘realistic evaluation’49). Case studies are useful for understanding the wider contextual factors that may influence the phenomena being studied, with multiple case studies generally being preferred to single case studies. 50 Health communities aligned to the local primary care trust (PCT) [and later in the research, clinical commissioning group (CCG)] and NHS provider trusts acted as the ‘cases’. Selection of these case sites was based on our previous work, in which we were aware of areas that were planning CCN services that would fit in with the timetable of the proposed research. For those sites that went on to secure these services, each had a slightly different approach to this type of provision. However, the key features across these teams were that they each focused on managing aspects of the child’s condition in the community (mostly, the home), and were nurse led. Two of the case site teams were ‘generic’, that is they provided clinical nursing input to children with a range of needs (acute, chronic, complex and end of life) and conditions. Two of the case site teams were ‘specialist’, that is they supported children with complex (mainly neurological) conditions only. One of these specialist teams was oriented to home respite care, while the second focused on managing acute illness through assessment and prescribing. More detail of the case site CCN services is provided in Chapter 2. Previous work indicates that generic CCN teams, similar to the two studied in this research, are the most typical form of CCN provision. 13

Across the sites, there were four strands of research activity.

Strand 1: a longitudinal qualitative study of service change over time

-

Longitudinal in-depth, semistructured interviews and focus groups with 41 commissioners, managers, practitioners.

-

Documents pertaining to the local service reconfigurations.

-

Field notes.

-

Thematic analysis using the Framework approach. 51

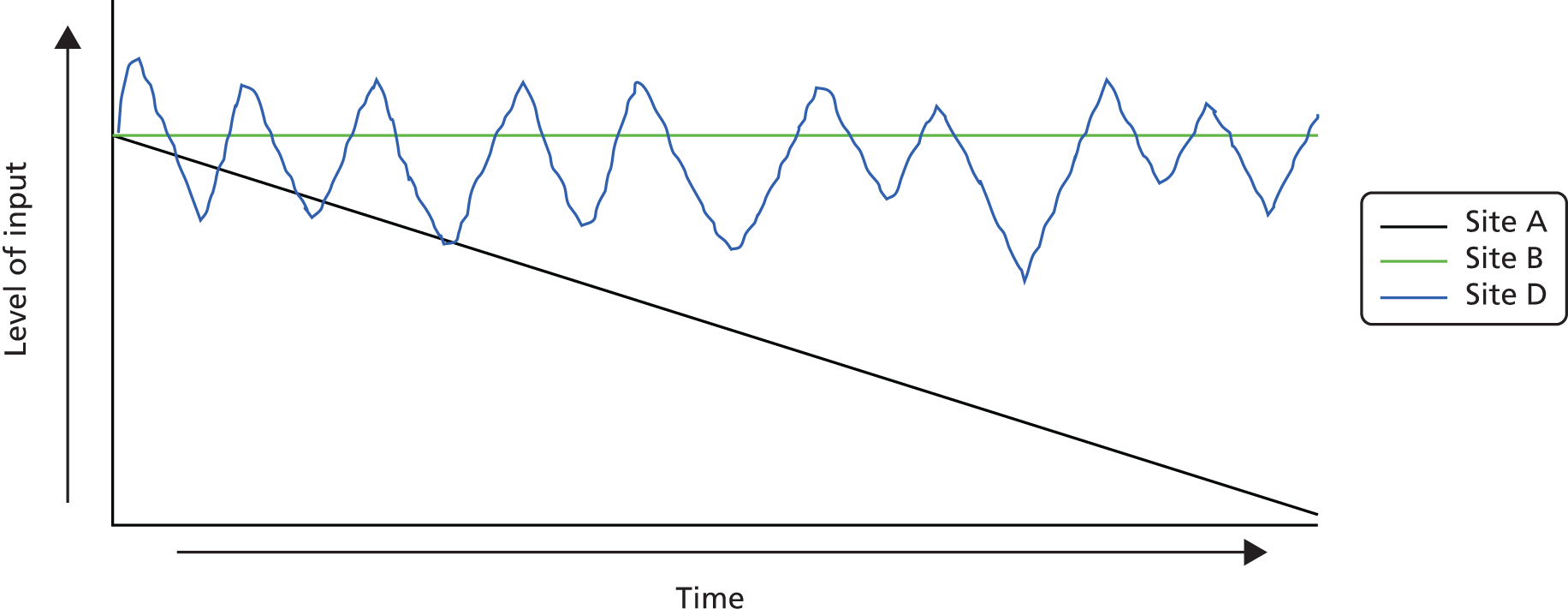

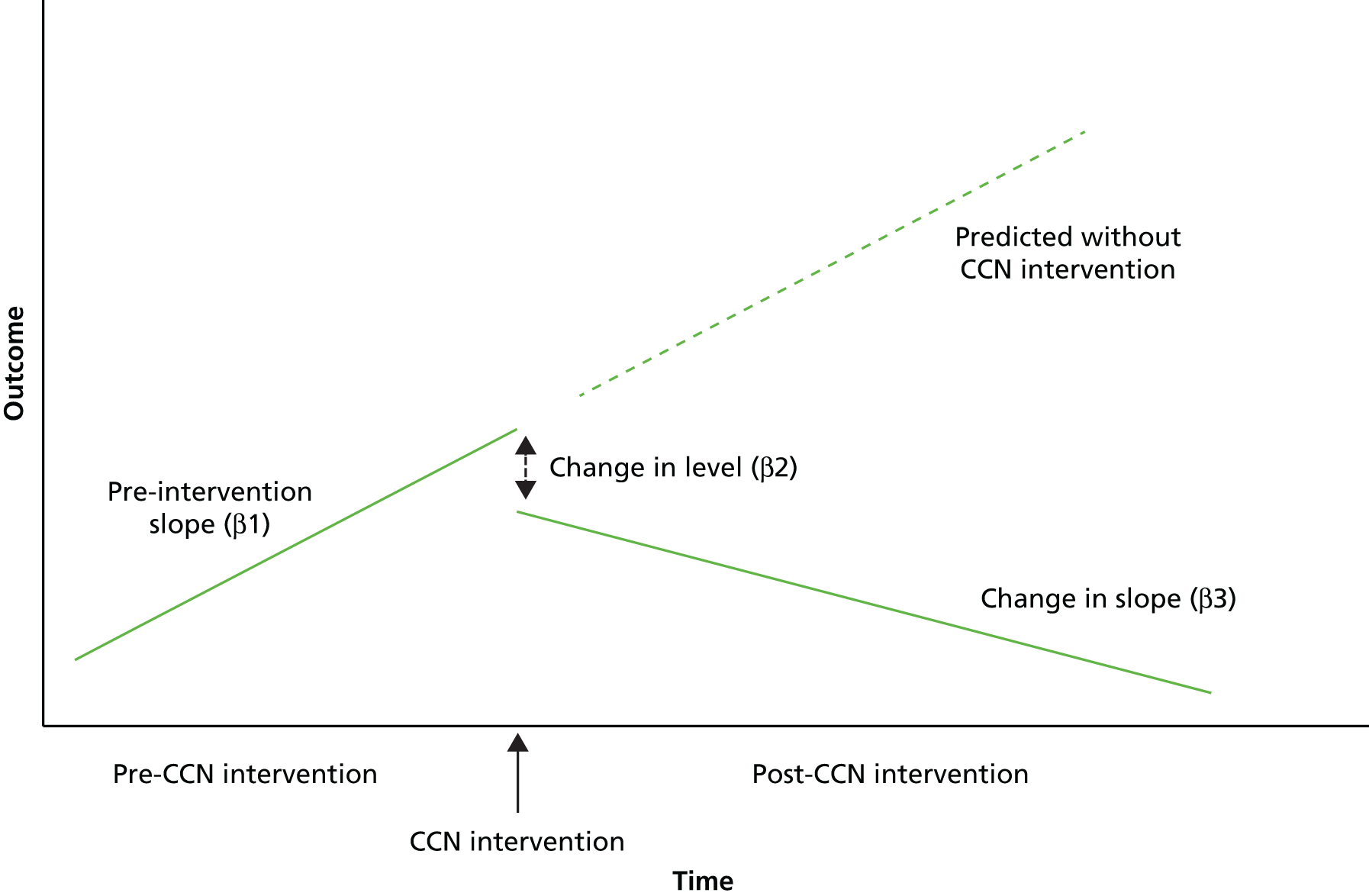

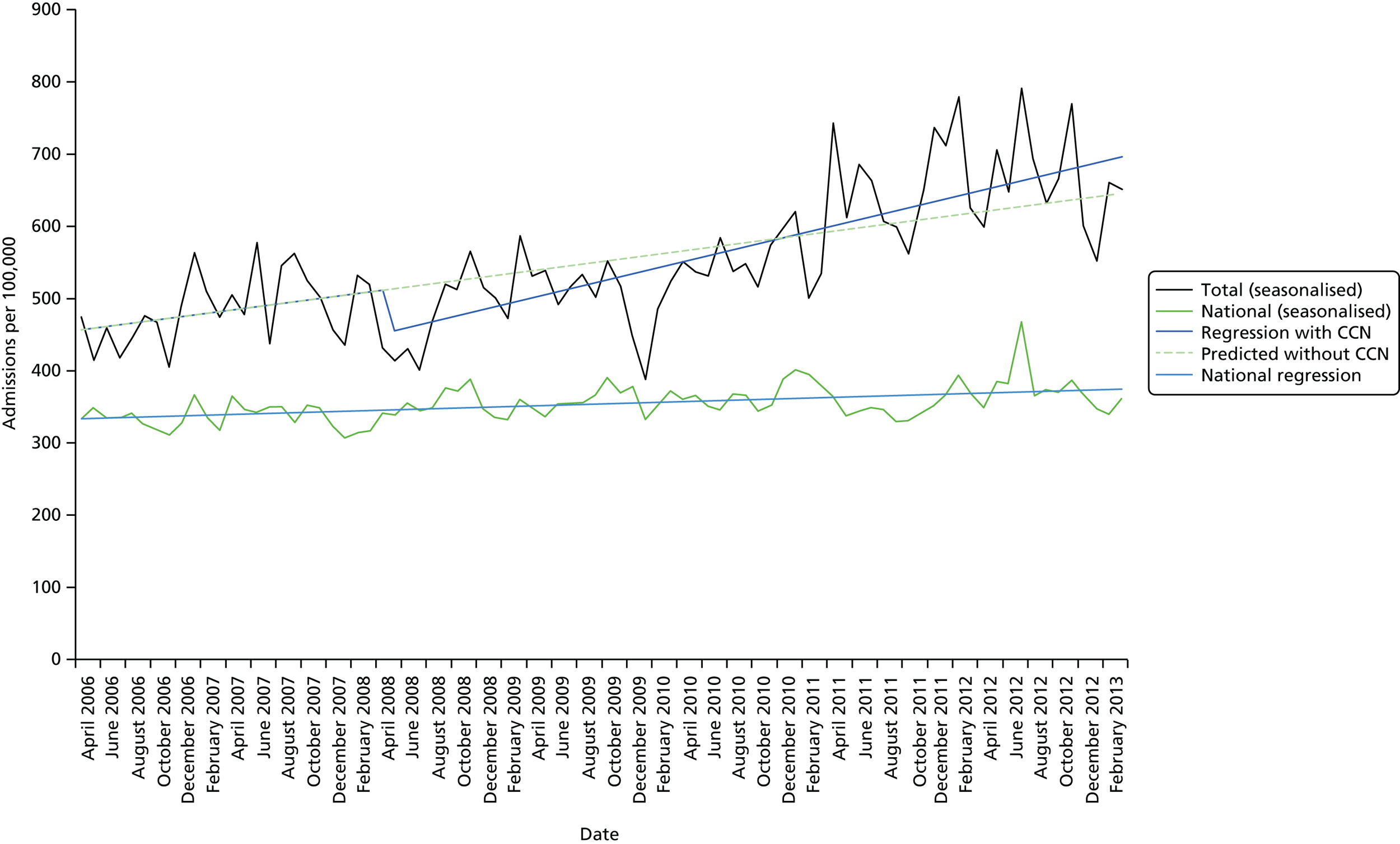

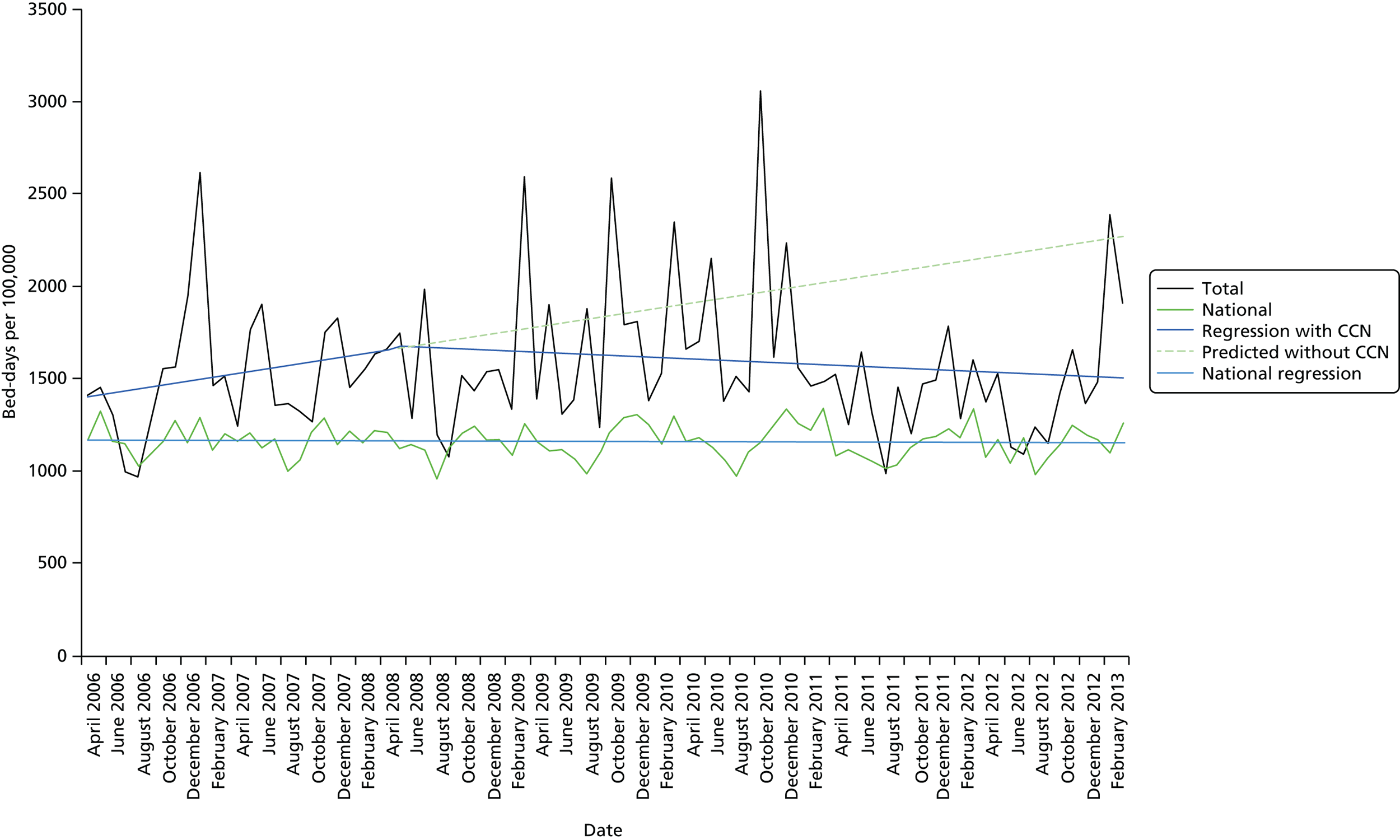

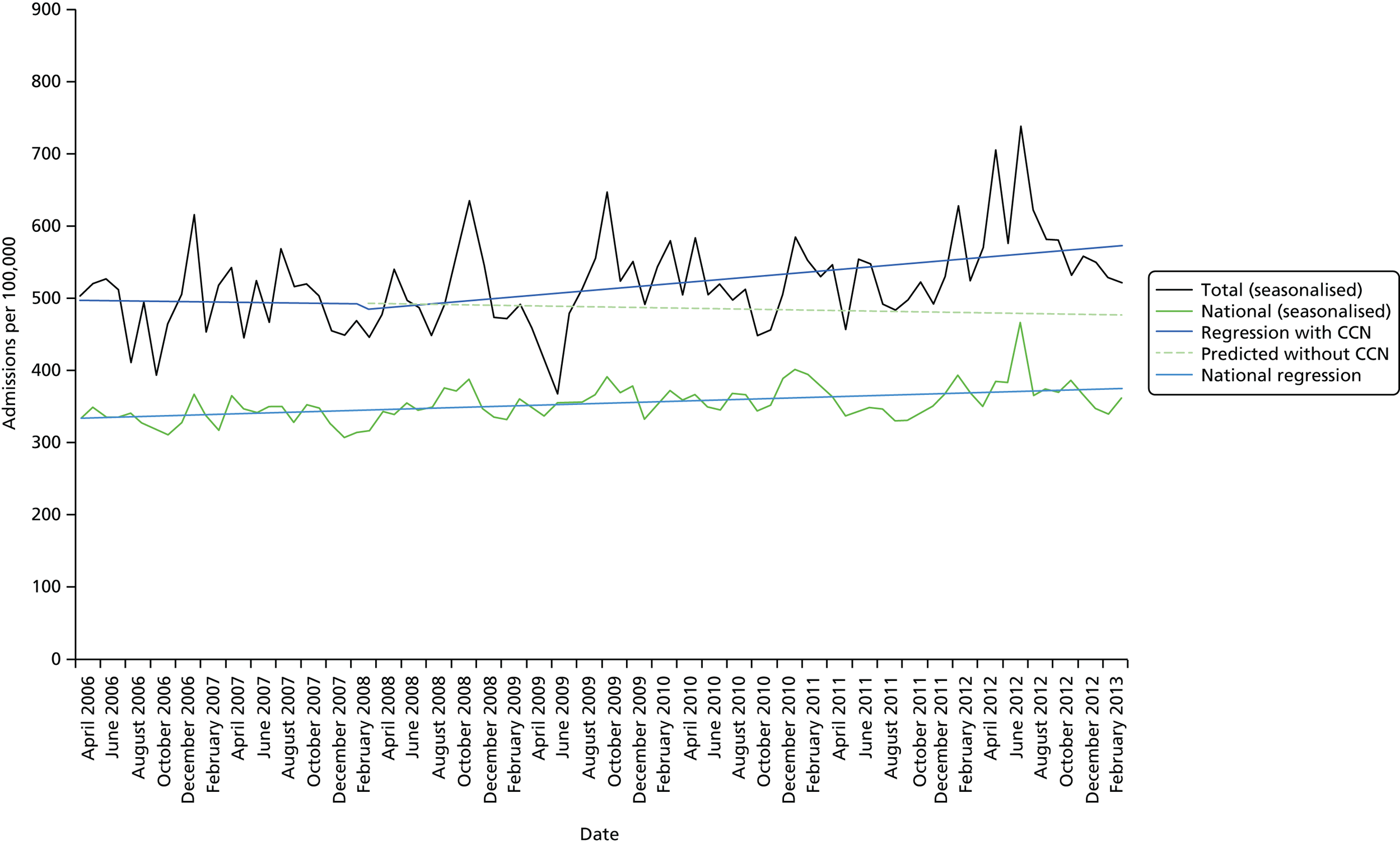

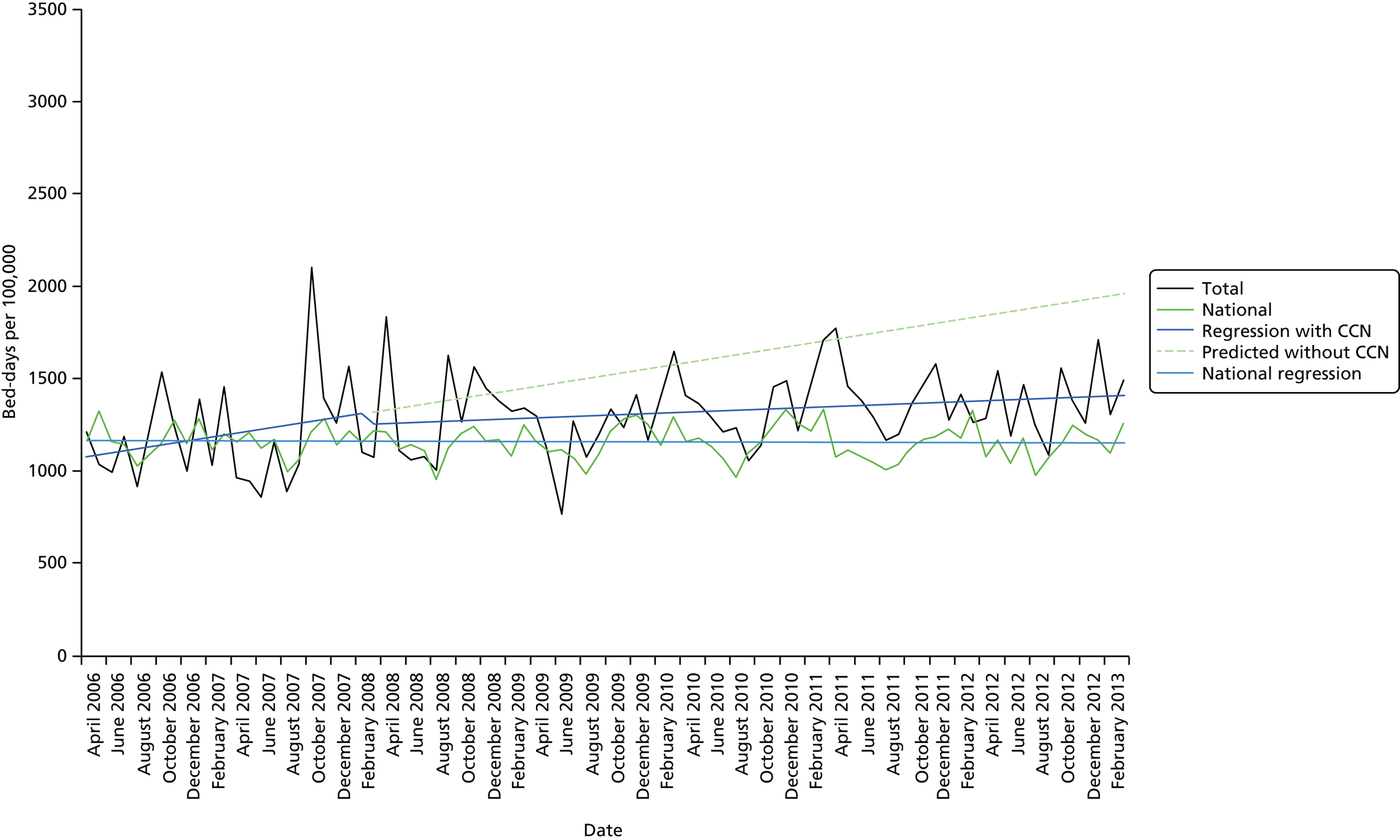

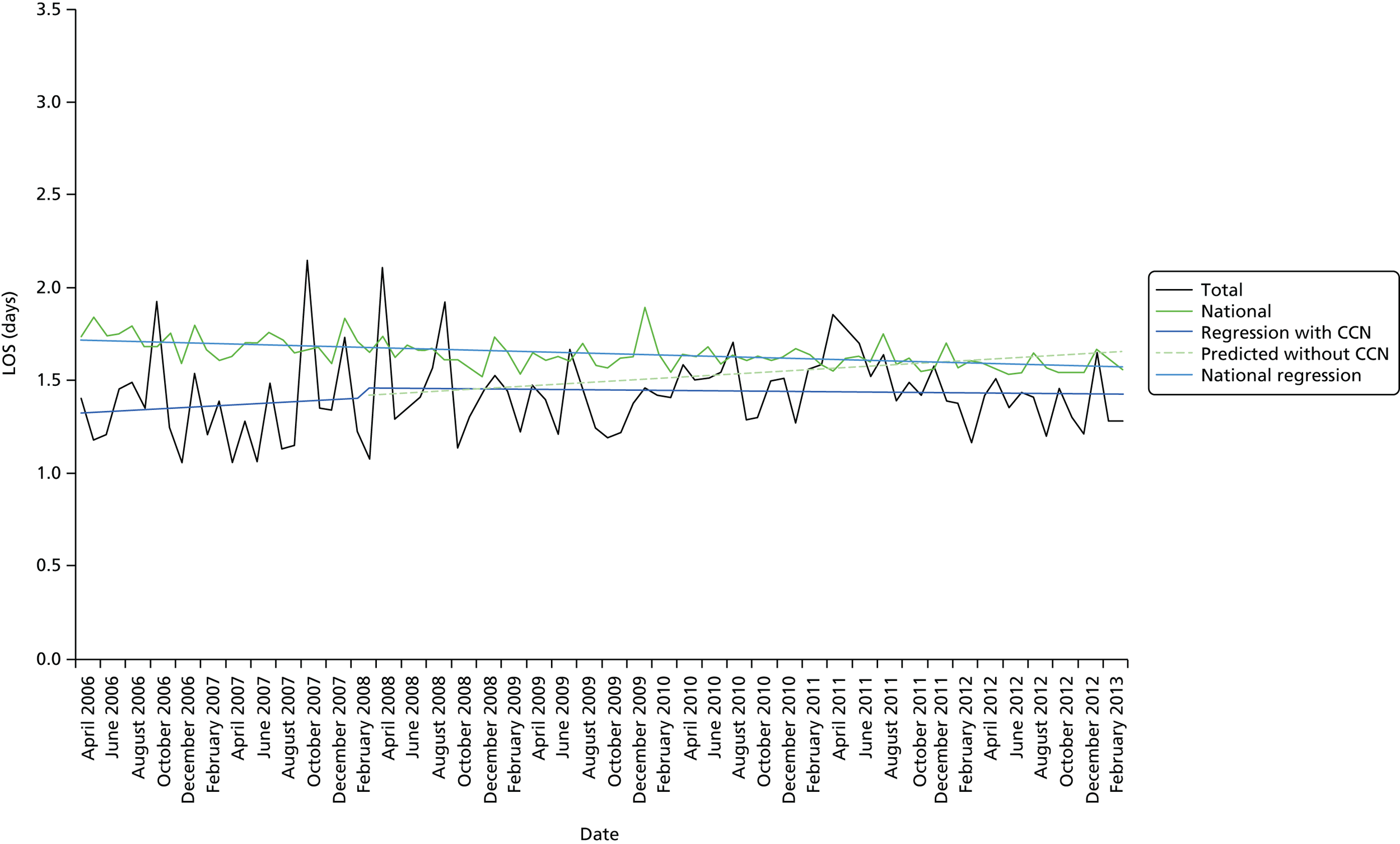

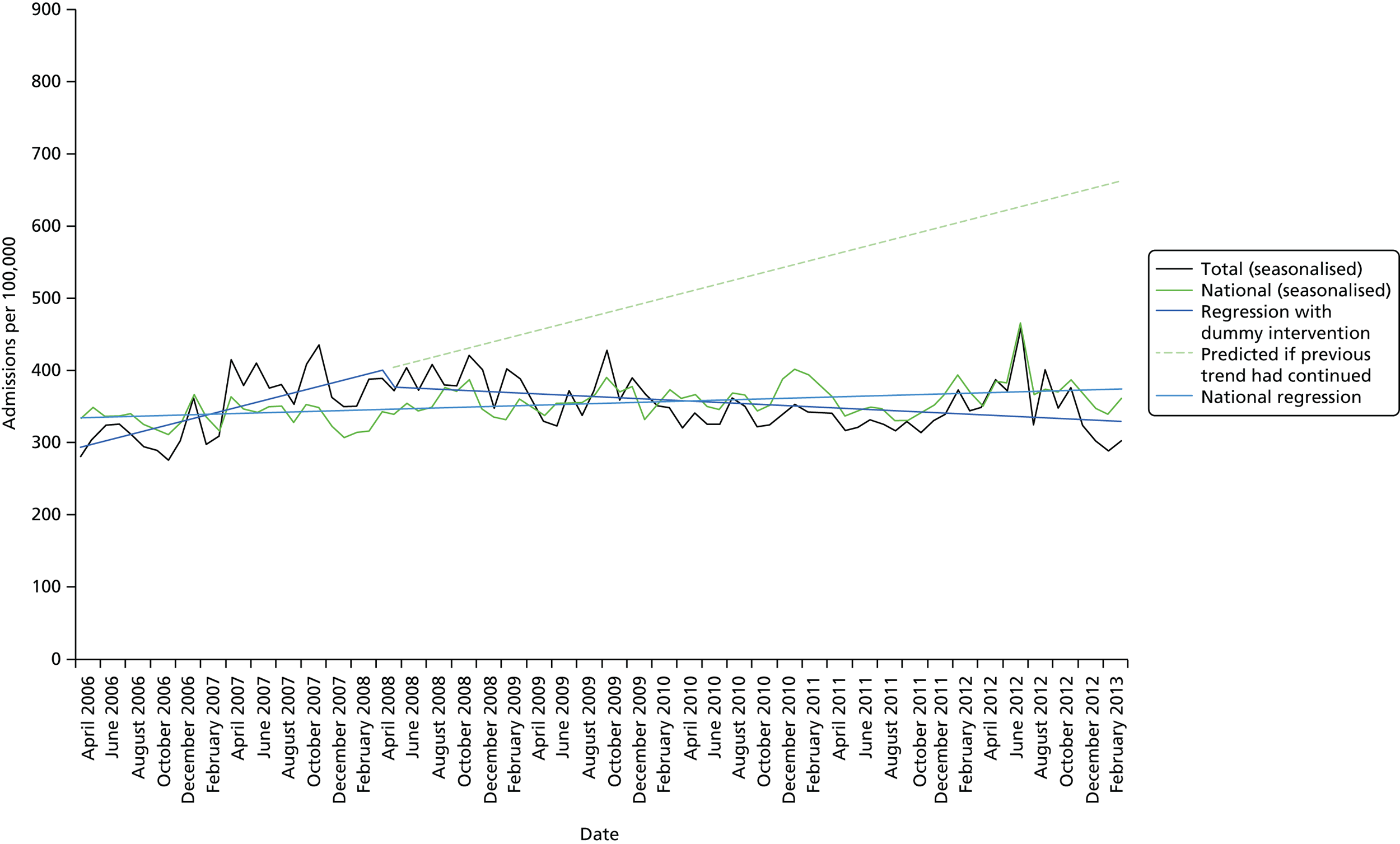

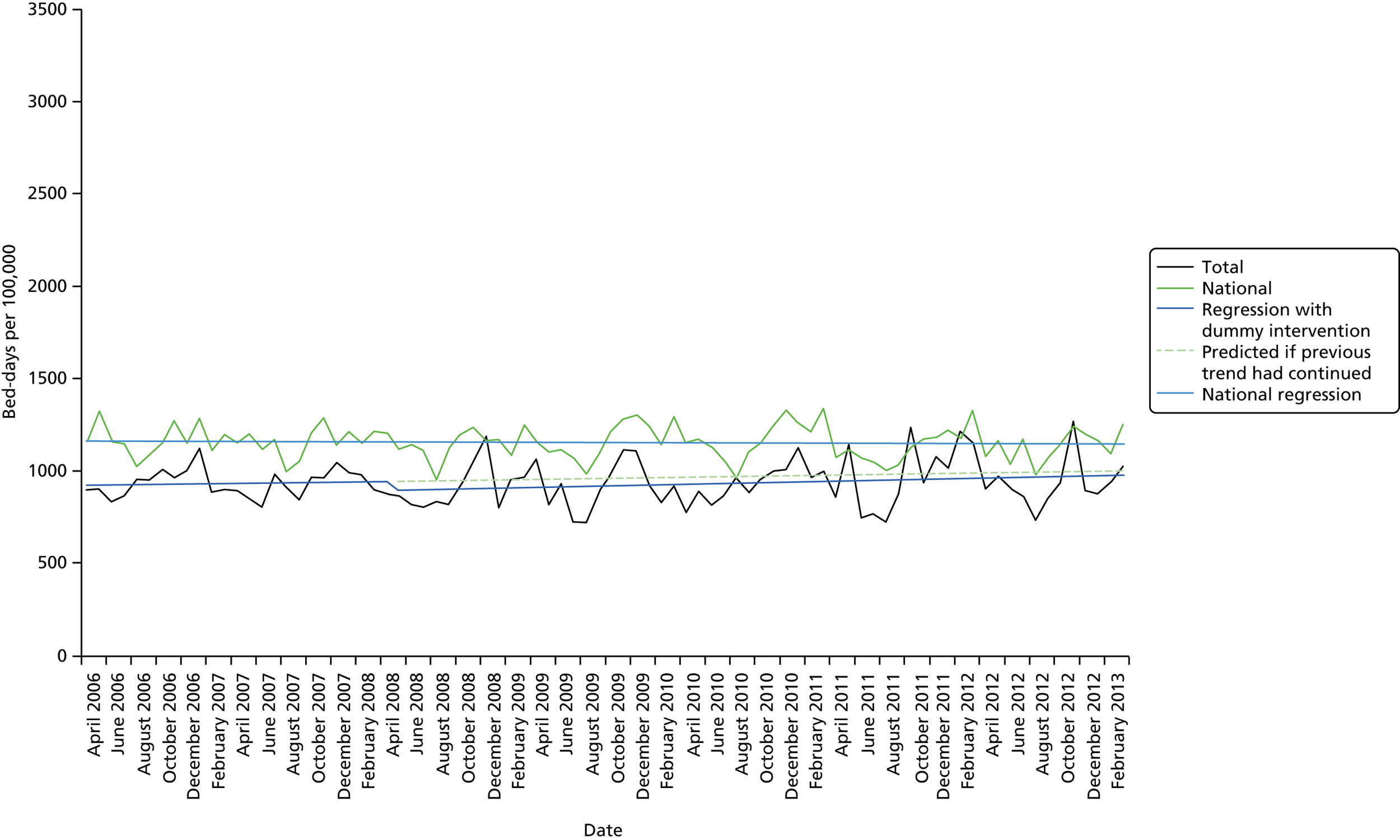

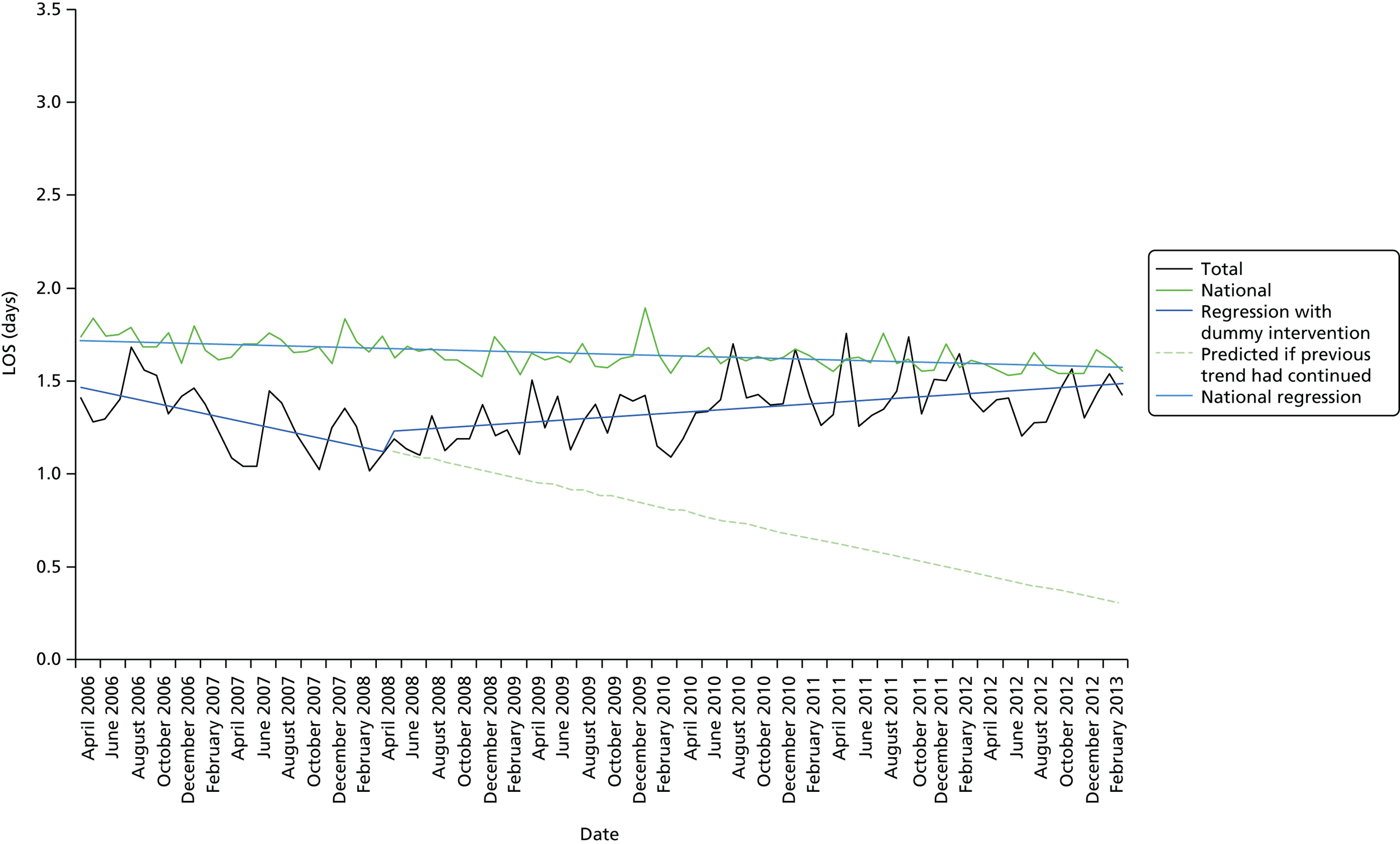

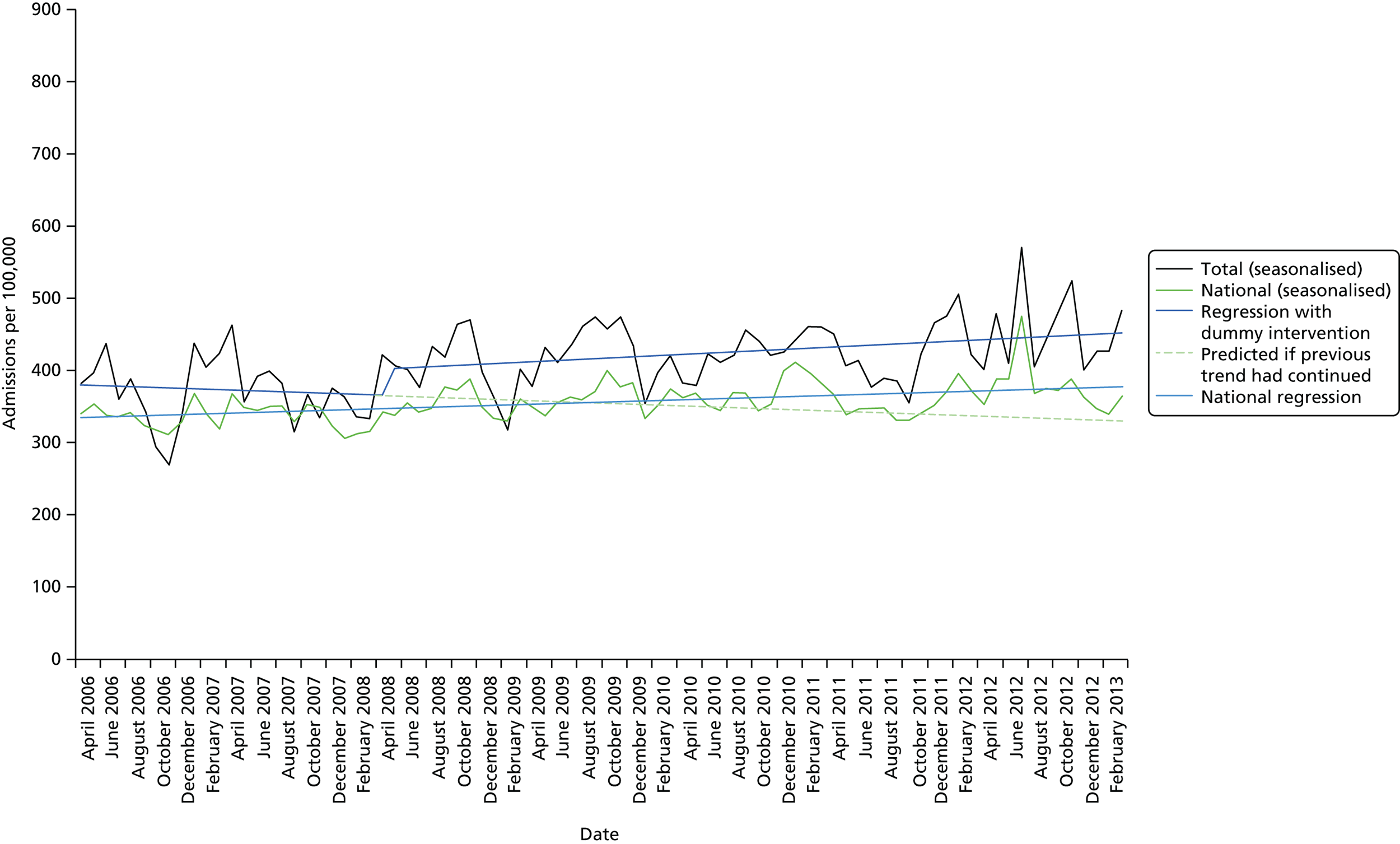

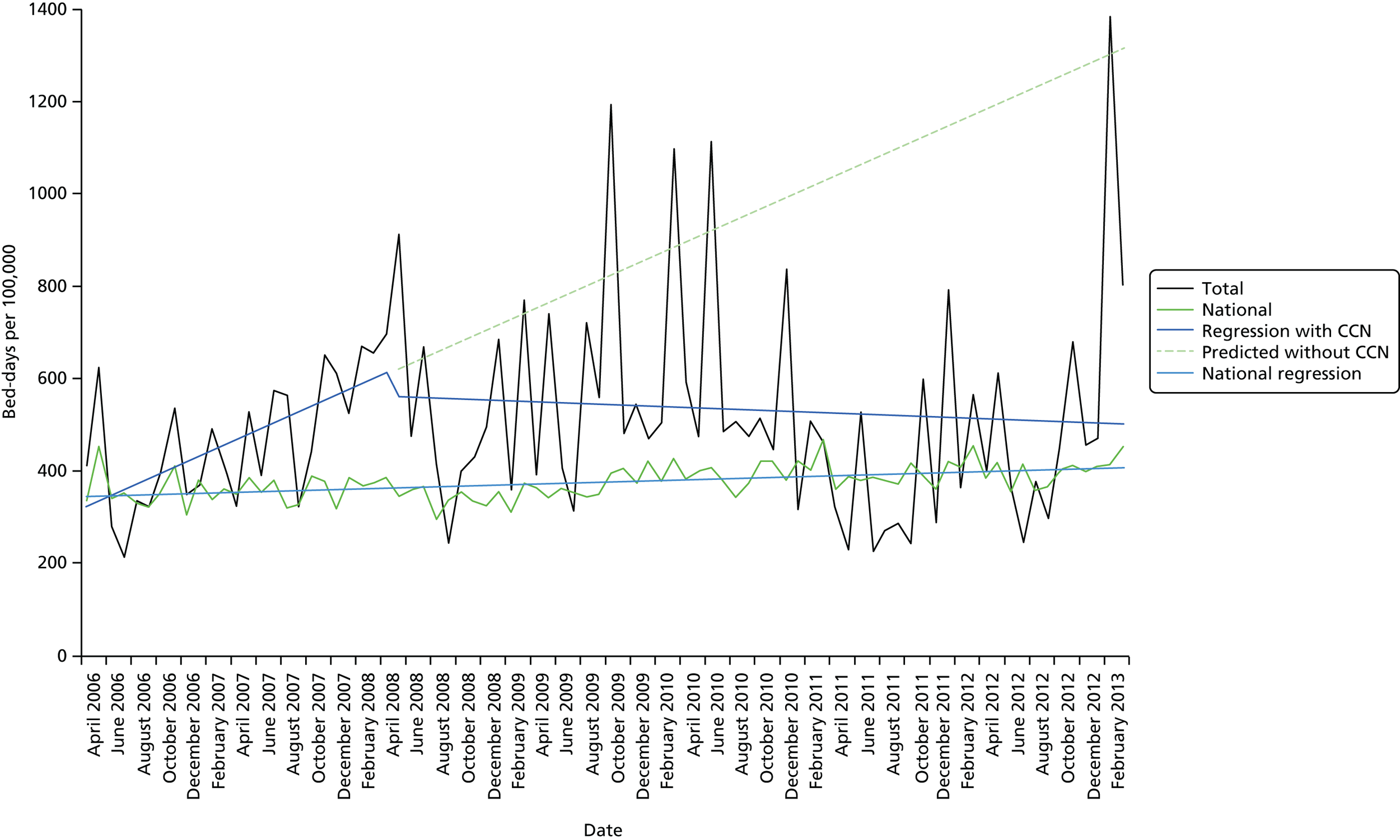

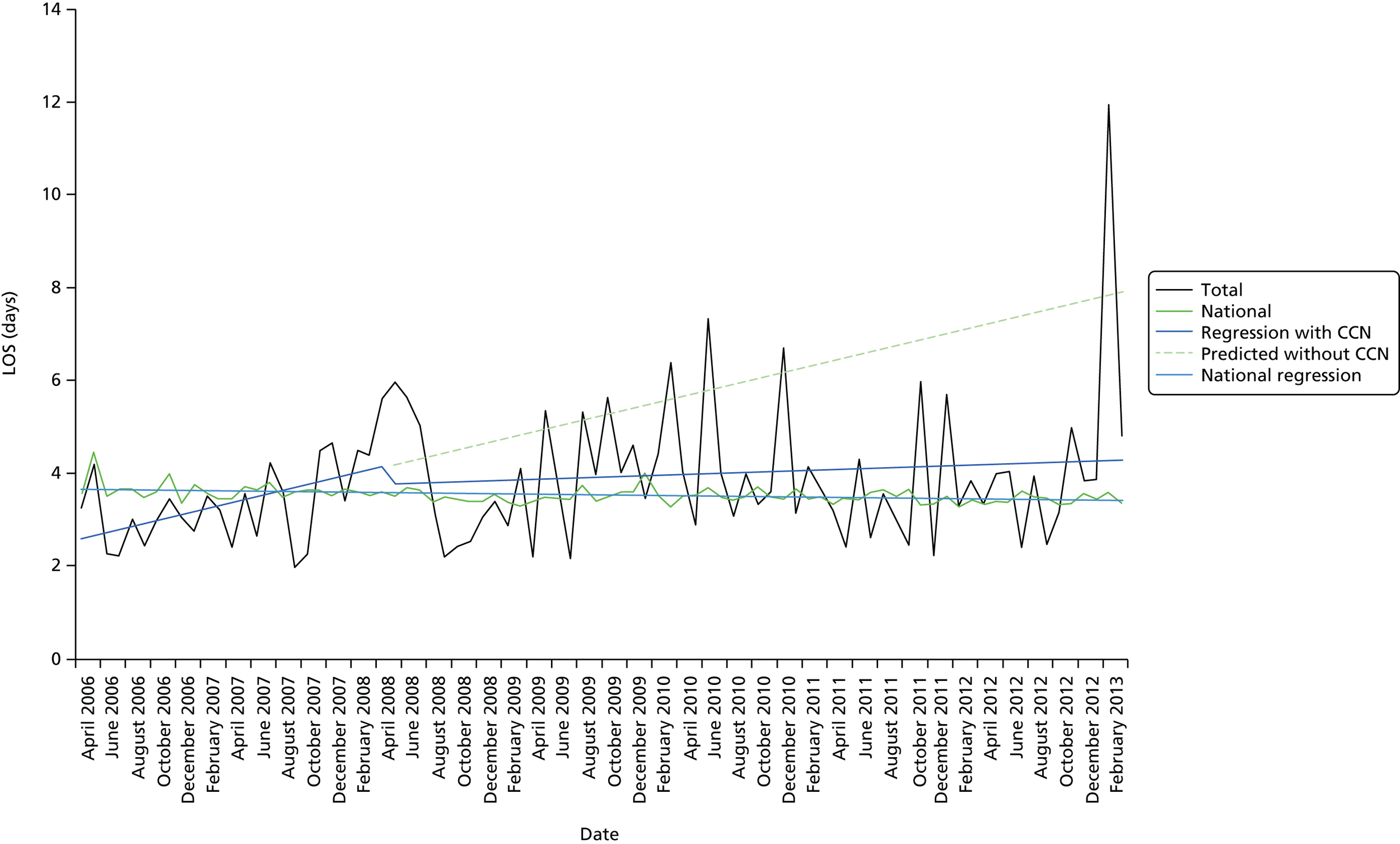

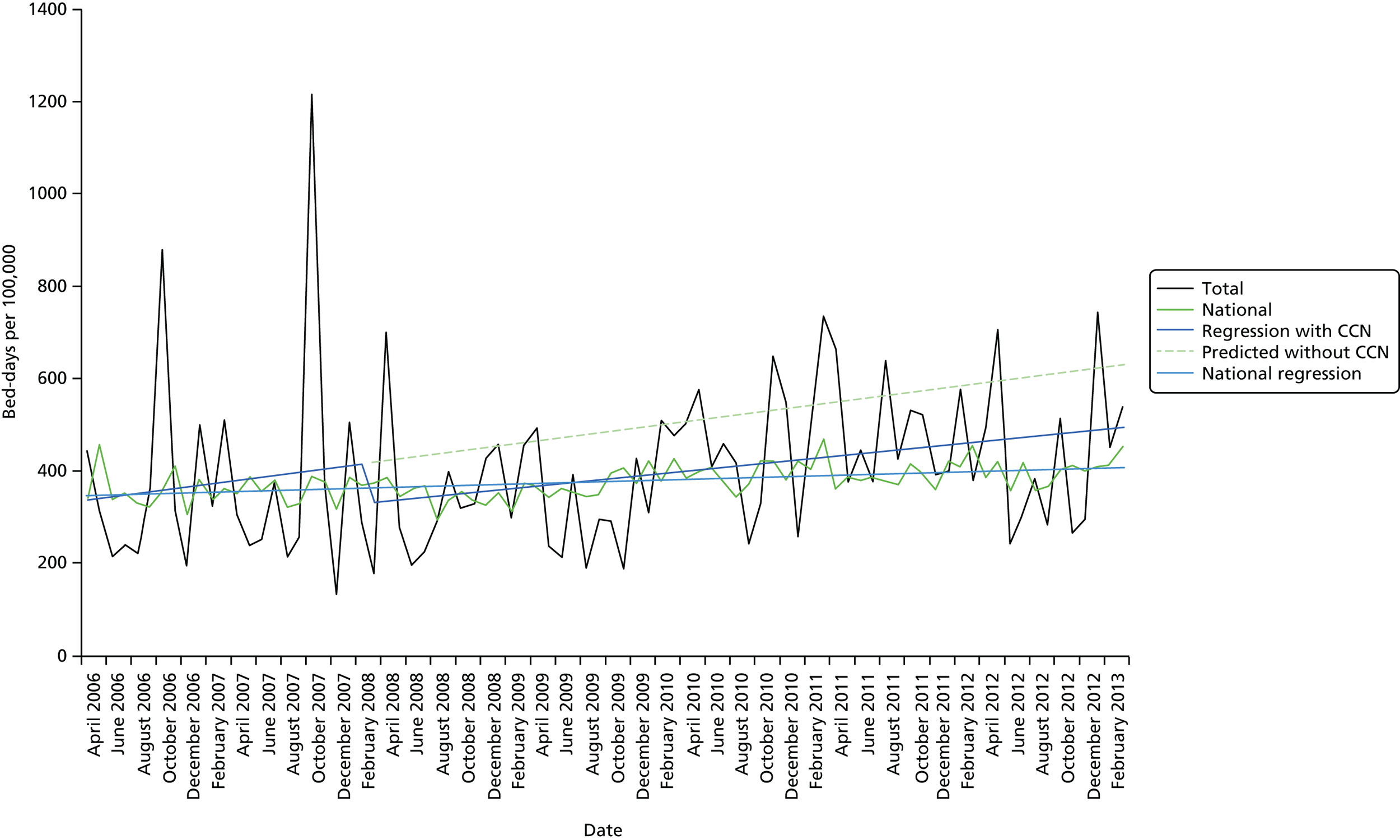

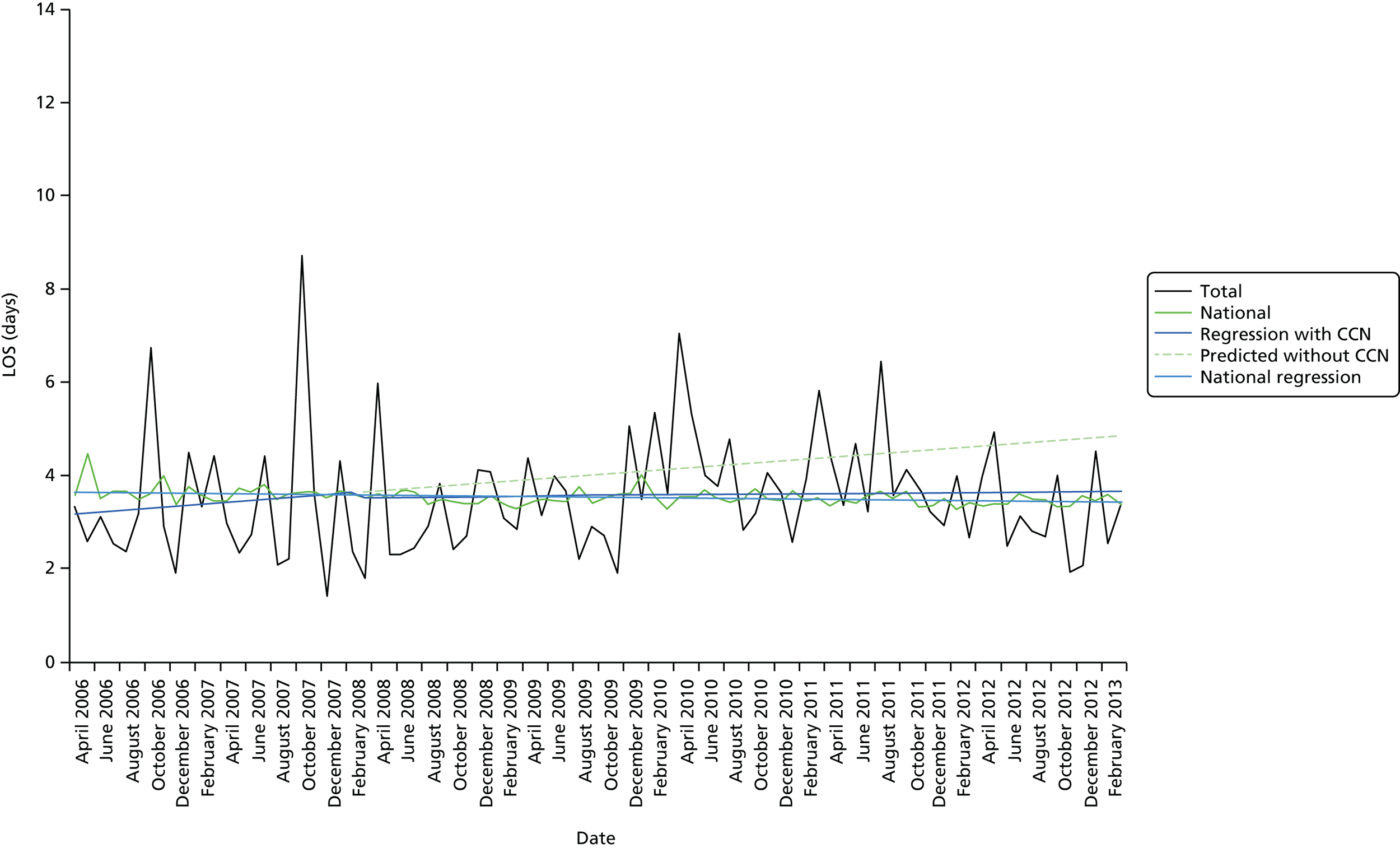

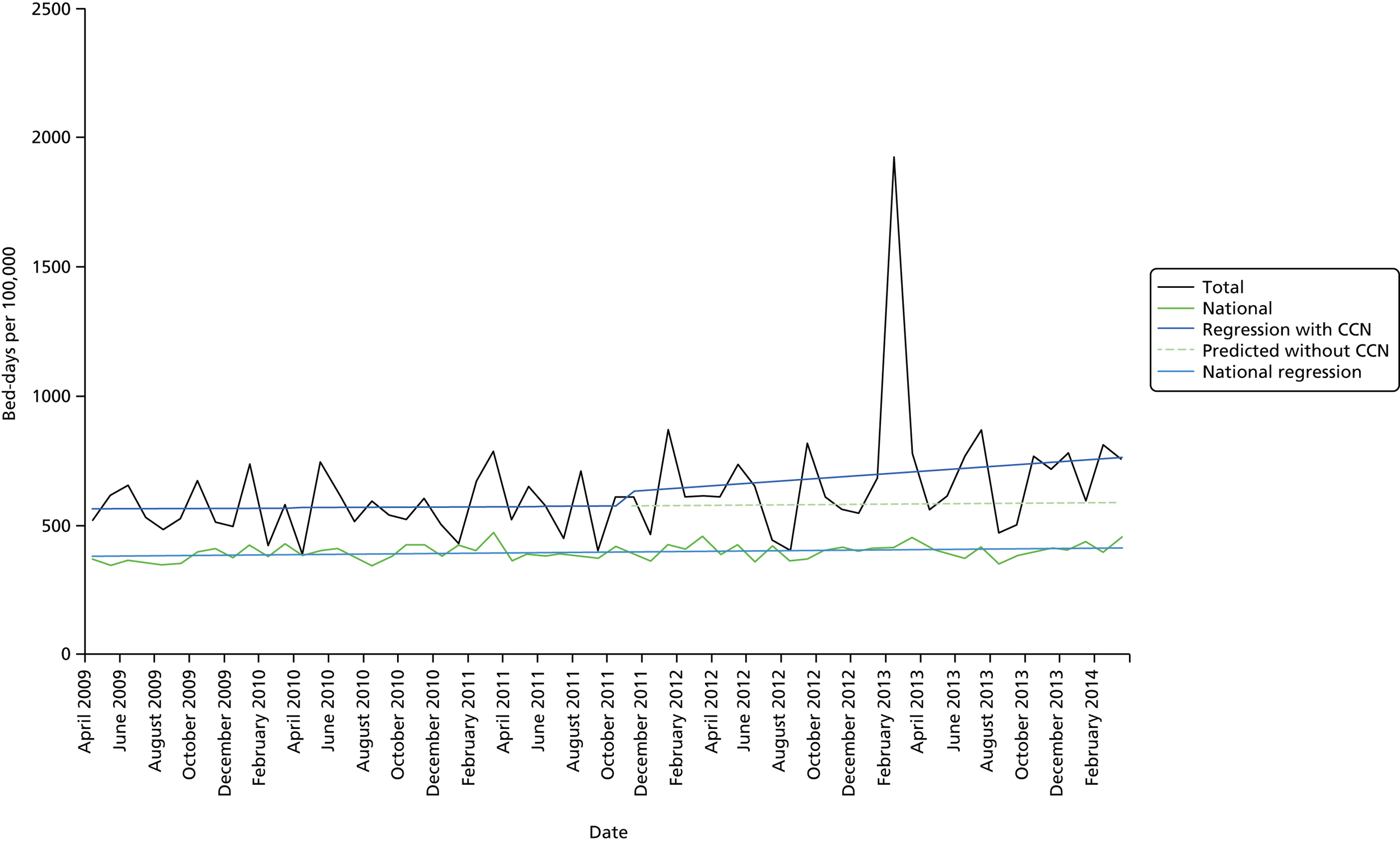

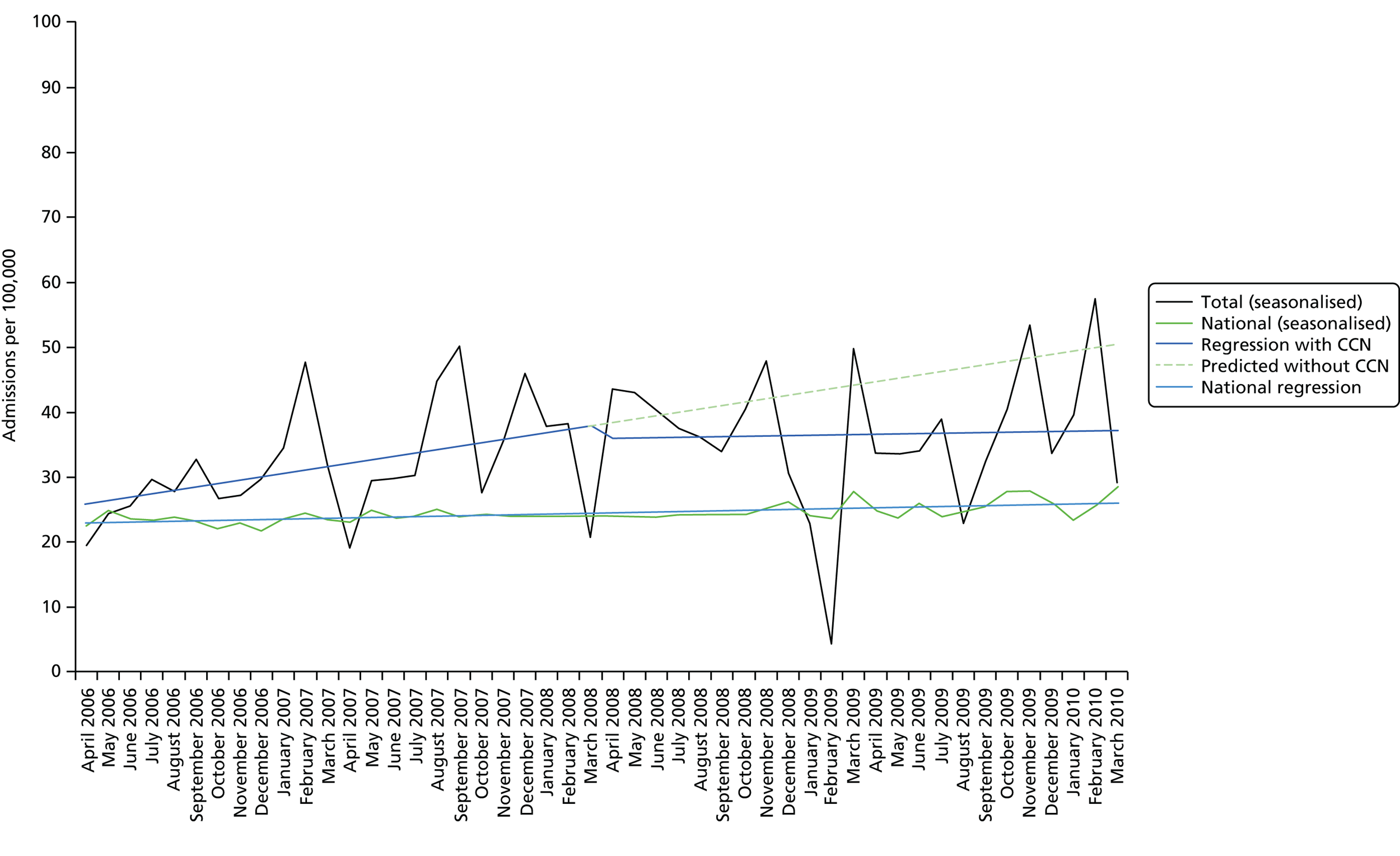

Strand 2: an interrupted time series analysis to explore the impact of introducing children’s community nursing services on acute hospital admission and length of stay

-

Use of Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) data to examine trends in secondary care activity by case site.

-

Time series using between 60 and 84 monthly data points.

-

Looking at impact on acute admissions for common childhood illnesses, bed-days and LOS for all paediatric conditions (including a subset of complex conditions).

Strand 3: a cost–consequence analysis to assess whether or not the introduction of children’s community nursing teams is likely to provide value for money compared with current service provision

-

Data from resource-use questionnaires and the translated Medical Home Family Index (MHFI) (see below) from 32 parents using the case site CCN services.

-

Cost questionnaires for case site CCN teams.

-

Data on acute activity from the interrupted time series (ITS) analysis.

Strand 4: a longitudinal qualitative study of changes in quality of care, with parents of children with complex health care receiving children’s community nursing services

-

Longitudinal in-depth, semistructured interviews with 31 parents of children using the case site CCN services.

-

Thematic analysis using the Framework approach. 51

In addition to the four studies, we translated two service assessment tools, the Medical Home Index (MHI) (paediatric) and the MHFI,52 as part of the research. The purpose and process of translating these tools are described in Appendix 1, Medical Home Index: overview of translation and Medical Home Family Index: overview of translation.

Detailed methods and analysis for each strand are described in the chapters that follow.

Ethical review

The study was approved by a NHS ethics committee in 2012, and all relevant local governance approvals obtained.

Summary of changes to the original protocol

Five key changes were made to the original protocol:

-

One case site (site A) represented a regional approach to service change and there were several CCN services introduced within the same period. Although our site contact (a NHS manager) had identified one team to participate, a second team were also keen to take part in the research. Thus, this case site resulted in two ‘arms’, with two CCN services being studied. One of these teams, however, declined participation in the qualitative study with practitioners and parents (although their managers and commissioners participated). Table 1 summarises the research activity across sites.

-

We had developed the research in partnership with three health communities, and thus, had intended to carry out the research with three case sites. However, because of delays with service reconfiguration in one case site (site C), a fourth (site D) was recruited so that we could undertake the parts of the research we were unable to in the delayed site. Because the service changes in site D were complete with no further expansions or developments, we did not undertake the longitudinal qualitative component with service staff, instead carrying out one set of interviews.

-

We had intended to look at time of admission and discharge as part of the ITS analysis. However, this information was not available within the HES data, and thus we could not examine this as intended.

-

Owing to difficulties recruiting newly referred parents, we amended our approach to recruit ‘established’ parent users of the CCN teams. Details of these changes are described in Chapter 5.

-

We had intended to collect data with commissioners and managers from the translated MHI52 (now the CCN development tool). However, during the process of translating the tool with our NHS partners, quantification of responses was removed, as this was felt to make the translated tool more useful and meaningful in practice. Thus, we were no longer able to collect data using the tool. This did not affect the wider project, as originally data collected with the MHI were to be analysed descriptively, and compared with interview data to examine face validity. Thus, although we could not provide a descriptive analysis of change to compare with interview data, our ability to meet the wider project aims was not affected. The intensive feedback gained from NHS staff about the tool has enhanced its validity as a service development instrument. Full details of the translation and final tool are in Appendix 1.

| Site | Strand 1: qualitative study with NHS staff | Strand 2: ITS analysis | Strand 3: cost–consequence | Strand 4: qualitative study with parents |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| A2 | Yes (limited) | Yes | Yes | No |

| B | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| C | Yes | No | No | No |

| D | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Patient and public involvement

A dedicated project steering group, which consisted of representatives from the Royal College of Nursing and the voluntary sector, a paediatrician and community nursing practitioners, advised on the research process as well as the development of the MHI tool (see Appendix 1, Medical Home Index: overview of translation). The group met five times throughout the 3-year project. Social Policy Research Unit’s parent consultation group (PCG) also advised on the materials developed for the qualitative study with parents.

Learning days

Three learning days were also incorporated into the management of the project, for which representatives from the case sites came together with the research team to discuss the research and developments in services. These learning days also provided an opportunity to develop and translate the MHI tool.

Production of an analytical toolkit

Any area undertaking a review of health services for children is likely to have the aim of preventing unplanned hospital admissions for children or reducing the length of time children spend in hospital following admission.

The Improving Services Toolkit: improving services for children and young people who are ill is aimed at commissioners and service managers who are aiming to redesign acute services for ill children. It provides evidence and data that can be used to help develop strategies and business cases. It examines emergency hospital admissions for children with common childhood conditions, such as respiratory and gastric conditions. It also looks at how long children spend in hospital and presents similar information specifically for children who have complex conditions, such as congenital heart conditions, cerebral palsy or metabolic disorders. The toolkit is available at the following link: www.chimat.org.uk/istoolkits.

Structure of the report

Chapter 2 presents details of the case sites taking part in this research. Given the mixed-methods design of the project, detailed methods and findings for each study are presented in Chapters 3–7. Chapter 8 addresses the strengths and limitations of the project and pulls together the findings of each study to answer the four research questions, and Chapter 9 discusses the implications of the evidence for policy and practice, and outlines future research recommendations.

Chapter 2 Case site overview

This chapter presents an overview of the case sites, including the background to the intended service change, the approaches to service change, and whether or not service change was achieved. References to rural/urban profiles in this chapter are sourced from the Rural Urban Classification Index (www.gov.uk/government/statistics/2001-rural-urban-definition-la-classification-and-other-geographies; accessed 18 December 2014). To describe area-level deprivation, the 152 PCTs ranked by deprivation in the 2001 Indices of Multiple Deprivation53 were split into quintiles, where 1 = very high deprivation, 2 = high deprivation, 3 = average deprivation, 4 = low deprivation and 5 = very low deprivation.

Description of case sites and background to service changes

Site A: generic children’s community nursing teams

Prior to service change in the region, a number of inpatient units and small community or outreach nursing services existed. Across the region, workforce changes meant that inpatient services had to be reduced in order to be sustainable and this, in turn, meant that more care was to be provided in the community. Thus, existing CCN teams were expanded and new CCN teams introduced to support nursing care in the community for children with acute and chronic conditions, reduce multiplicity of care and prevent acute admissions to, and facilitate early discharge from, hospital. Newly expanded or introduced community services were expected to be in place with evidence of competency prior to the closure of inpatient services. In addition to the changes in inpatient and community services, a new children’s hospital was built for the region. We studied two health communities within this region, both of which introduced either new (area 1) or expanded existing (area 2) CCN provision in line with the regional reconfigurations outlined in Chapter 1.

Area A1: generic children’s community nursing team (community based)

This community is a major urban area with a population of around 210,000, of which between 15% and 20% are from black and minority ethnic groups. The area falls with the highest deprivation quintile (1). There were two provider NHS trusts in the PCT area, one an acute hospital trust and one a community health-care trust. Prior to the reconfigurations in this area, there was a small outreach service of two community nurses. As part of the reconfigurations, a large new generic CCN service was introduced. The team was community based, and anyone could make a referral, including parents. Self-referrals tended to be from parents of children with chronic conditions, such as constipation, eczema and asthma. Around 3 years after the CCN team was introduced, the local children’s inpatient ward and A&E department were closed, and a general practitioner (GP)-led urgent care centre introduced.

Area A2: generic children’s community nursing team (hospital based)

This community is a major urban area with a population of around 250,000. The area falls within the ‘high deprivation’ quintile (2), and fewer than 10% of the population are from black and minority ethnic groups. There was one provider NHS trust in the PCT area, which was an acute hospital trust. Prior to the reconfigurations in this area, there was a small generic CCN team of around five nurses. As part of the reconfigurations to move care closer to home, this team expanded its existing provision. The CCN team was hospital based and worked closely with the hospital’s A&E department (in which there was also a consultant in paediatric emergency medicine and advanced paediatric nurse practitioners), the inpatient unit and the paediatric observation and assessment unit (POAU).

Site B: acute and complex care teams

Prior to the service changes, this site, a children’s hospital, had a number of specialist services with outreach nurses and a complex home care team for children with neurological conditions, but no generic CCN team or provision of acute care ‘closer to home’. Continuing health care (CHC) packages for children were an ad hoc commissioned arrangement, drawing on agency resources and, as a result, were seen to delay discharge from hospital. These two issues, an absence of an acute home nursing team and the ad hoc commissioning of CHC packages, led to two proposed service changes. The first was the introduction of an acute home nursing team, intended to reduce hospital admissions, attendances and LOS, and offer families a choice of care at home, school or nursery. The team would support a strategic aim of the commissioner and provider in providing care closer to home.

The second proposed service change was the expansion of the complex home-care team, through an increase in nurses and clinical support workers, to accommodate ‘in-house’ provision of CHC packages. It was intended that this change would allow more nursing care (for CHC packages) to be provided in the community through the existing home-care team rather than through an agency. It was expected that this would enable packages to be in place much more quickly (as staff would be already in place), therefore reducing LOS. Alongside this, a discharge co-ordinator role was created for the high-dependency unit in the hospital, in which children with CHC packages tended to reside prior to discharge. The co-ordinator was intended to work closely with the expanded team to facilitate discharge of the child. Finally, it was proposed that the assessment of CHC would take place through a single point of assessment, in the form of a newly employed nurse assessor and co-ordinator.

The area served by the PCT here is a large urban community with a population of just over half a million. Just over 10% of this population are from black and minority ethnic groups, and the PCT rank falls within the high deprivation quintile (2). In addition to the children’s hospital, there were two NHS providers locally: a hospital trust and a health and social care trust.

Site C: children’s community services in development

This site, which at the start of the research was a large PCT, had historically comprised a number of smaller PCTs, not all of which had CCN provision. When these trusts came together to form one larger PCT, the different models of CCN provision were highlighted. It also resulted in a ‘patch’ that had no access to CCN services except for an acute trust discharge team for children under the care of the trust’s consultant. Thus, children with a consultant in another trust (e.g. a regional centre) would not access this service. This led to plans to standardise existing CCN provision and ensure equity of access for all children and families by introducing a fourth team to cover the patch that had no provision. These proposed changes were embedded within a wider drive to reconfigure a number of other children’s community services in the local area, including continuing health care, school nursing, health visiting and advanced paediatric nurse practitioner-led urgent care pathways.

The area served by the PCT is a mix of both urban and rural geographies, with a population of around 750,000. It has low levels of deprivation, falling within the ‘very low deprivation’ classification (5), and fewer than 10% of the population are from black and minority ethnic groups. Within the PCT boundary there are a number of NHS provider trusts, all acute hospital trusts except one, which is a community provider. The community provider was leading the bid to transform the local CCN services.

Site D: nurse practitioners for complex conditions

In this site, prior to service change, there was an existing CCN team providing clinical nursing care for children. A team of advanced nurse practitioners was proposed to complement this existing CCN team and support children with complex health-care needs who were frequently attending the local hospital for acute care. There was no case management of children with long-term complex conditions, who had tended to rely on the local hospital instead of primary care for this. The new team of advanced nurse practitioners would address this by taking on the case management role, alongside assessing and prescribing. It was also intended that the case management would reduce multiplicity of care for families. The model was to be based on a model of adult community matrons that had previously been introduced, and which was felt to be successful by trust staff.

The area served by the PCT is a major urban community with a population of around 440,000, fewer than 10% of which are from black and minority ethnic groups. The PCT rank falls within the ‘very high deprivation’ quintile (5). Within the PCT boundary there are two NHS provider trusts: one an acute hospital trust and one a community provider. The service change was located in the community provider trust.

Table 2 summarises the intended changes to CCN services across each case site.

| Site | Intended change to CCN services |

|---|---|

| A1 | Introduction of a generic CCN service |

| A2 | Expansion of a generic CCN service |

| B | Introduction of an acute home nursing team and expansion of a complex care team |

| C | Introduction of a generic CCN service, standardisation of existing CCN provision, reconfiguration of continuing health care, school nursing, health visiting and urgent care |

| D | Introduction of a nurse practitioner team for children with complex conditions |

Approaches to service change

The approaches to the service changes taking place across the four case sites differed. These differences encompassed whether or not it was a ‘whole-system’ change (i.e. whether or not all children’s services were reconfigured), whether service change was an expansion of an existing service or introduction of a new service, if there was more than one intended service change and if change took place across more than one provider trust.

In site A, a co-ordinated whole-system service change took place, in which all children’s services (both inpatient and community) were redesigned. Part of this was the introduction and expansion of CCN teams, the closure of inpatient units and the introduction of a new hospital. This whole-systems reconfiguration took place across a number of NHS trusts and was led by a single network.

In site B, there were two intended strands of service change (see Table 2). These intended services changes were not part of a wider ‘whole-systems’ change. The intended and achieved changes took place within one NHS trust.

In site C, a broad set of reconfigurations encompassing a number of community-based children’s services were intended (see Table 2). These intended changes reached across a number of provider trusts in the area, but were led by one trust.

In site D, the service change was the introduction of a new advanced nurse practitioner team. While other new children’s community services had also been introduced earlier, these were isolated changes and not part of a co-ordinated whole-systems approach to change. The service change took place within one trust.

Table 3 summarises these approaches to service change.

| Site | Whole-systems change (i.e. changing all children’s services)? | (Intended) changes to single or multiple services | Did (intended) service change take place across more than one provider trust? | (Intended) expansion to existing service, introduction of new service, or both? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Yes | Multiple | Yes | Both |

| B | No | Multiple | No | Both |

| C | No | Multiple | Yes | Both |

| D | No | Single | No | Introduction of new service |

Achieving service change

Each of the four case sites intended to change their CCN services by either introducing new services and/or changing existing services. In two of the four sites (A and D), service change was achieved, that is both of the areas studied in site A introduced or expanded their generic CCN teams, and in site D, they introduced a nurse practitioner service as planned. In site B, service change was partially achieved, with the expansion of the complex home-care team set in motion. However, plans to introduce an acute home nursing team were abandoned. In site C, plans for service change were ongoing for much of the duration of the research, before most of the intended reconfigurations were terminated towards the end. Thus, not all were able to achieve the service changes they intended.

Table 4 summarises the achieved CCN services across each site.

| Site | Generic/specialist | Summary of intended intervention and functions | Needs covered | Settings of care | Coverage | Referrals to team | Team size, skill mix and bandinga | Years of operation at end of research period |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | Generic | Acute admission avoidance and facilitate early discharge. Case management for children with complex needs | Acute, long-term, complex, palliative and end of life | Home, school, nurse-led clinics | 8.00–20.00, 7 days. On-call for end-of-life care | Anyone can refer, including parents. Self-referrals tend to be those with chronic conditions (e.g. constipation, eczema, asthma) | Around 19 WTE, bands 5–7 children’s nurses with some specialist nurses, some with non-medical prescribing | 7 |

| A2 | Generic | Acute admission avoidance and facilitate early discharge. Admission avoidance is prioritised | Acute, long-term, complex, palliative and end of life | Home, nurse-led clinics | 8.00–20.00, 7 days. On-call for end-of-life care | Consultants, GPs, allied health professionals. No self-referrals from parents. Works closely with A&E, POAU and children’s unit | Around 11 WTE, bands 4–7, health-care assistant and children’s nurses with some specialists nurses | 7 |

| B | Specialist (complex, mostly neurological conditions) | Home respite by trained band 3 support workers, and children’s nurses supporting child at home. Primary function to facilitate early discharge. Intensively support child with acute illness at home (for existing caseload children) | Complex | Home, school | On-call 24/7 nursing, home respite variable | Anyone can refer, including parents if they have a consultant in the trust | Around 12–28 WTE (growing with the accumulation of continuing care packages), bands 3 (support worker), 6 and 7 (children’s nurses), some with non-medical prescribing | Expanded element: 4 years |

| D | Specialist (complex, neurological conditions) | Acute admission avoidance and case management for children with complex needs | Acute needs for children with complex conditions | Home, school | Monday–Friday, 9.00–17.00 | Neonatal unit, intensive care, social care, CCN team | Around 3 WTE, all band 8, advanced nurse practitioners (one paediatric) | 7 |

In the next chapter, we present findings from the staff qualitative study about the factors that influenced their efforts to plan and achieve the intended reconfigurations to CCN services. Chapter 4 discusses the challenges and issues faced by the teams once they were implemented.

Chapter 3 Planning children’s community nursing services: perspectives of NHS staff

Key messages

-

The development and introduction of CCN services is possible but requires dedicated resources, medical support and, when taking place across multiple providers, a mechanism to oversee changes (e.g. a network).

-

Commitment to, and views about, introducing CCN services vary among NHS stakeholders, but some stakeholders appear to be more powerful than others in influencing change.

-

A lack of dedicated financing can lead to competition where multiple providers are involved, which hinders efforts to plan services.

-

Wider instability in the NHS from the recent reforms adds further difficulties, with changes in commissioning arrangements compromising the leadership needed to take forward plans.

-

The ‘magnitude’ of service change does not necessarily correspond to whether or not plans to implement change are successful.

Introduction

In this chapter, we draw on the data collected through the staff qualitative study to present findings about the contextual factors that staff felt mediated their efforts to introduce or expand CCN services in the case sites. As per the realist approach to evaluation, such contextual factors are important for understanding the process and outcomes of service change. 49,54 We begin with a description of the methods used for the staff qualitative study.

Methods

In-depth, semistructured interviews with NHS staff involved in developing children’s community nursing services

In-depth, semistructured interviews are a widely used qualitative data collection tool. 55 Semistructured interviews allow set topics to be covered, but with the participants’ responses determining ‘the kinds of information produced about those topics, and the relative importance of each of them’. 56 They were used here to capture the experiences and views of staff involved in the strategic development of CCN services. These staff included NHS commissioners, senior managers (e.g. heads of nursing, heads of children’s services) and, in one case site (C), a senior nurse. We undertook these interviews longitudinally to understand the drivers, context and planning for service change, the factors enabling and inhibiting service change and perceived outcomes of service change (when applicable) as they occurred. A topic guide was used for interviews (see Appendix 1, Topic guides for interviews and focus groups with staff, parents and children), and all interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed. A record of informed consent was taken prior to all interviews (see Appendix 1, Sample consent form). We treated consent as ‘ongoing’ and, thus, a record of consent was sought prior to each interview when a participant took part in multiple interviews across data collection waves.

Sampling and recruitment

A snowball approach to sampling was used, where an initial interview was undertaken with our key contact in each case site. This person then identified, either independently or as part of the interview, other relevant people to approach. Subsequent participants were also asked to identify any other NHS staff that we could approach for interview. All staff invited to participate in an interview were sent an information sheet about the research and a response form to record their participation decision (see Appendix 1, Sample information sheet). Staff members were contacted by either e-mail or post, depending on the contact details provided. Responses to invitations were given either by response form (returned to the researcher) or via e-mail. If no response was received after 2–3 weeks, a reminder letter/e-mail was sent. No further reminders were sent if a response was not received. In one case, a reminder letter was not sent because of organisational sensitivity in the case site at the time. We felt that sending a reminder letter about the research and possible participation in an interview might aggravate researcher-observed tensions between staff.

In line with the longitudinal approach, all staff members who participated in an interview were contacted for a further interview approximately 6 months later. The information leaflet was resent along with an opt-out form. If an opt-out form was received, or a participant made contact to decline a subsequent interview, we asked if they could recommend anyone else for us to approach for an interview. If no opt-out form was received after approximately 2 weeks, a researcher made contact with the participant to arrange an interview.

We intended to carry out interviews with willing participants at 6-monthly intervals. Based on the timetable, we expected approximately five waves of interviews. However, sometimes the intervals between waves of data collection were longer than 6 months. There were three reasons for this:

-

Sometimes participants asked us to delay the interview until after a particular meeting, when they felt they would be in a better position to tell us about service change plans.

-

The 6-month interval expanded if a participant declined a further interview but recommended another person, or persons, to speak to, as this meant having to approach the new individual and arrange an interview.

-

There were sometimes delays in participants responding to contact about the subsequent interview.

Owing to expanded intervals (as well as longer than expected processes of getting local research governance approvals in some NHS trusts, which delayed the start of data collection with staff), we were able to undertake three waves of interviews with staff involved in developing CCN services.

Owing to the variation in service structures in each case site, we did not set out to recruit a defined number of commissioners and managers involved in service development. Rather, we set out to recruit and interview as many key informants57 as necessary in order to build up a picture of service change in each case site. In the first wave of interviews, we approached 17 individuals to participate in an interview (four of these staff were in site D, for which we did not undertake longitudinal interviews – see Chapter 1). Of these, 13 agreed to participate and 12 took part in an interview. One participant who originally agreed to participate did not respond to later e-mails attempting to arrange the interview. We received no responses from three individuals and a decline from one individual (who recommended another person to approach).

In the second wave of interviews, five of the participants interviewed in the first wave declined participation. In three cases, this was because a change of job following the reconfiguration of NHS commissioning structures. In one case, the participant felt unable to add anything further, but was happy to be contacted later if needed. Three individuals who participated at wave one gave a further interview at wave two, and a further three new individuals were approached and agreed to participate. This gave a total of six interviews (from eleven approached) at the second wave of data collection.

At wave three, nine individuals were approached for an interview. Five of these were those who had been interviewed at wave two, and one individual who participated at wave one but not two (but was happy to be contacted again later). Three were new individuals identified at this wave. Of the nine individuals approached, four agreed and took part in an interview, and five declined or gave no response. We attempted a fourth wave of interviews to further explore the perceived outcomes of service change in sites A and B (partly explored at wave 3). However, we did not receive any response to the invitations to participate in site B, and in site A we were informed there was nothing new to add. Table 25 in Appendix 2 summarises this recruitment and attrition across waves 1 to 3.

Across all waves of data collection, a total of 22 interviews were undertaken with 17 staff involved in strategic service development across sites. Participants included those involved in commissioning children’s health services within the trust, and those with a management role (e.g. heads of CCN services, operational leads and associate directors of children’s services).

Table 5 summarises the recruitment by site across waves, Table 6 gives details of the number of staff approached and interviewed in total by case site and Table 7 gives this information by job designation.

| Site | Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Wave 3 | Wave 4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Approached | Participated | Approached | Participated | Approached | Participated | Approached | Participated | |

| A | 3 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| B | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| C | 6 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| D | 4 | 3 | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Total | 17 | 12 | 11 | 6 | 9 | 4 | 4 | 0 |

| Site | Number of unique individuals approached across waves | Number of unique individuals interviewed across waves | Total number of interviews |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 4 | 4 | 5 |

| B | 6 | 4 | 5 |

| C | 9 | 6 | 9 |

| D | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| Total | 23 | 17 | 22 |

| Job designation | Number of individuals approached | Number of individuals interviewed |

|---|---|---|

| Commissionersa | 11 | 5 |

| Managerial role | 12 | 12 |

Use of documents

Documents are valuable sources of data for case study designs,51 as they ‘play an important role in organizational life’. 58 We used them here to provide contextual insight into the case site area and its service developments. Alongside interviews, we asked participants for copies of any documents that would help us to understand the development and reconfiguration of services and wider contextual developments in children’s health services in their locale. We also asked for copies of documents that participants referenced in interviews. All documents obtained were numbered and read. Any information in the documents that would provide helpful context was used to supplement the analysis. Across the sites, we obtained 34 documents.

Field notes

Field notes are used to provide additional context to data collected from participants in interview studies. 51 They were used here primarily to record observations about service changes between staff interviews and to record notes from any informal discussions or meetings the researchers held with case site staff. These notes were sometimes used to inform later interviews with staff in the case sites.

Non-participant observations

We had intended to use this method as part of the qualitative study, to observe key meetings about the services being developed. Although we identified some meetings that we could potentially observe that might offer some insight into the development of services, these often involved staff members from multiple trusts, including trusts for which we did not have local governance approvals (we had governance approvals from the key trusts involved, but meetings often involved those from other trusts beyond the immediate coverage of the research case site). Thus, in order to carry out these observations, we would have needed to obtain governance approvals from these other trusts, which was not possible given the time this process takes. As an alternative, we followed up the content and outcomes of these meetings with participants in subsequent interviews, when possible. In another case, we identified a meeting that we could observe and we contacted those attending to seek permission. However, despite reminders, not all of those attending responded or gave permission for the observation. Thus, we were unable to carry out the observations as planned.

Analysis

The longitudinal data were managed using the Framework approach51 and analysed thematically. For full details of the analysis, see the analytical plan and summary in Appendix 1, Analytical process and framework for study 2.

Findings

As described in the previous chapter, the intended services were agreed, financed, set up and implemented as planned in sites A and D, partially in site B and not at all in site C. Interviews with commissioners and managers indicated there were four main factors that influenced their efforts to introduce or expand the services they intended. These were financing, medical support for the CCN services, NHS reforms and managing change across multiple providers. Each of these is discussed in turn below.

Financing service change

A theme emerging in the data across all case sites was that of financing service change. In sites A and D, staff reported having money to invest in the service transformations and, therefore, initially they did not face financial challenges:

Obviously we did this growth when we had money, in PCTs, we don’t have money now.

Commissioner, site A

I think, you know, fortunate we’re, we’re, at that time, in a position where we, we did have money to invest.

Manager, site D

Accessing additional investment for further CCN service expansions at a later stage was reported as difficult for some teams in site A, because there was no longer an allocated budget as there had been initially. Instead, they had to go through the process of bidding to local commissioners and not all were successful in securing such additional funds.

In site C, where the initial stages of service change were taking place during the research, it was reported that there was no dedicated money to finance the proposed service change. The lack of available new funds to invest meant existing resources in the local NHS had to be reinvested. This meant a lengthy process of getting different NHS organisations in the local area together to review these existing resources. This was reportedly challenging, as organisations were trying to protect their income in a constrained financial climate. Tensions around withdrawing funds from acute trusts to fund community services were also reported:

So we need to find a system that will enable us to have that open dialogue and find a way forward because the secret to success is releasing funding from the acute sector to support children in their communities.

Manager, site C

In the later stages of planning in site C, the commissioners’ consideration of the proposed service plans for children’s community services was thought to be triggered by the financial viability of some parts of the local health service, although this, in the end, did not facilitate the intended service change.

In site B, there was initial caution about funding expansions to the complex home-care team because of concerns about potential fluctuations of demand for the service. This evidently did not prevent the team expansion, but it was reported that such caution did delay getting the workforce in place. We later learned that the trust had responded to these concerns through an agreement in which, if support workers in the expanded team were released through the termination of a package, they would transfer to the high-dependency unit and intensive care unit until a new package was agreed. Therefore, this staff resource would always be in use, regardless of demand for the complex home-care team. Further funding requests from the team to managers and commissioners for packages were apparently supported by the trust’s clinical director.

Medical support for children’s community nursing services

The support of medical colleagues appeared to mediate the process of service transformation, with such buy-in supporting the planning, development and implementing of CCN services, and a lack of buy-in inhibiting plans for change. For example, in site B, there were plans to pilot and introduce an acute home nursing team to reduce secondary care activity and deliver care closer to home for families. However, this intended service did not materialise because of a lack of ‘medical’ support for it locally. Concerns were raised by the medical directorate about the risks of this care being delivered through a community nursing function. At a later stage of data collection in site B, the theme of medical support arose again, but in relation to the complex home-care team. Here, one nurse reported the value of having a senior consultant that gave legitimacy to the team by supporting them with bids for further funding and working closely with, and having confidence in, the team nurses:

He [consultant] values our opinions and gives us that, you know, confidence to be able to provide the service that we provide … Plus, if there’s any issue with the team, or we want to go forward for further funding or anything like that, then [he] is our clinical lead who will support us in doing that.

Senior nurse, site B

It is not explicitly clear in the available data why there was this contrast in reported level of medical support for the intended acute home nursing service and that for the current complex home-care team. One possible reason may be because the complex home-care team was already in existence (and therefore known and trusted) when it expanded to incorporate continuing care. In contrast, the intended acute home nursing team was a complete innovation, and to our knowledge, this site had never had a service like this before. The lack of support for it may have stemmed from a lack of familiarity with, and trust in, this kind of service.

In site A, the network that oversaw the reconfigurations reportedly won backing from the medical workforce for the proposed changes during the planning stages. In site C, the proposed service changes had some medical support, with a GP lead working closely with commissioners and practitioners to support change. However, this support did not overcome the other barriers this site faced, such as the impact of the NHS reforms and a lack of dedicated finance combined with local competition for business (see NHS reforms). Issues were also highlighted in this site around how some local acute trusts were supportive of CCN services, but others were not, and that this had prevented a cross-provider partnership working to develop a possible service. In site D, it was reported that while GPs were not involved in the development of the new nurse practitioner team, they did support it.

NHS reforms

The changes to CCN services in sites B and C were taking place during the recent NHS reforms, in which new commissioning arrangements, in the form of CCGs, were being set up. The planning stages of transformation in site C, and some aspects of service development in site B, straddled both sides of 1 April 2013, when these new commissioning arrangements officially came into place.

In site C, the NHS reforms were felt to be particularly problematic for the planning of new CCN services in the period before 1 April 2013. Commissioning in this preceding period was characterised as being in a state of flux, with changes to job roles and people. This, it was felt, contributed to the delays in progressing with plans for service change. Others reported the reforms were ‘stifling’, making people less open to change. In subsequent data collection that took place in this site after the 1 April 2013 (between July and September 2013), these challenges continued. With new people coming into post as a result of the reforms, it was felt to be difficult to know who to talk to and when regarding the proposed new services:

I think what seems to have made, made it sort of not quite so clear, in terms of moving forward, is, you know, all the new CCG setting up and people getting into posts and knowing who, who we need to talk to when.

Manager, site C

At the later stage of data collection, it was also apparent how the broader set of plans for changing CCN services (e.g. continuing care, CCNs, urgent care pathway) had been split following the changing commissioning arrangements. The urgent care pathway changes now sat with the CCG and the remainder with the joint commissioning unit (JCU). While the two were reportedly working closely on these changes, this, we were told, could sometimes be challenging. Around November 2013, 7 months after 1 April, there was still uncertainty about who was leading the commissioning arrangements locally, with concerns expressed that this would further delay service change plans. Approximately 1 year later in October 2014, the complexity of local commissioning arrangements between the local CCGs and JCU persisted, with the new arrangements described as a ‘minefield’.

In site B, the NHS reforms were reported to have affected the original plans for supporting children receiving CHC packages (through the complex care team) in schools. Originally, it was intended that the local special school nursing resource would be used to support these children in schools. However, following the NHS reforms, the contracts for special school nursing moved to the local authority and it was no longer possible to go ahead with these plans. At the first round of data collection, it was reported that discussions about this issue between health and education commissioners were ‘uncomfortable’, stalling progress in securing the special school nursing resource. However, at later data collection it was reported that this was now progressing and the two commissioners were working together to develop the school support for children with CHC packages. Later, the team suggested school support was not particularly problematic, with support workers and teaching assistants in school working together for the child’s care.

Managing change across multiple NHS providers

In both sites A and C, the service reconfigurations were taking place across a number of provider trusts, but the nature of this multiple trust involvement differed between the two. In site A, the multiple provider trusts involved were each the recipient of financial investment and their own service change was led by a network. In contrast, the proposed changes in site C were being advanced by one particular provider trust. However, with no new money to invest, existing provision across a range of providers in the local area had to be reviewed, leading to cross-provider talks to address this. These cross-provider talks appeared to be in the form of a clinical group established by a former commissioner who had initiated the original proposal for service change. A lack of clinical consensus was cited as a factor delaying progress with service plans, which may reflect competition for business between the different provider trusts, a factor cited in later data collection in this site. Such competition may have been exacerbated by the lack of new funds to invest and the need to use and review existing NHS resource (see Financing service change).

In site A, a network had centralised the service change and oversaw all contracting, (initial) recruitment and monitoring. The network was felt to be particularly beneficial to the reconfigurations. It was reported to help standardise the process across participating NHS trusts, it created a high profile locally to communicate the changes effectively (‘the network was very key in it getting the priority it needed locally’) and it enabled children’s commissioners to come together, creating opportunities for shared learning.

Such macro-level structures were not reported in sites B and D, and this probably reflects that, in these sites, service changes were isolated to one provider trust and thus no macro structures were required.

Termination of reconfigurations in the planning stage (sites B and C)

As noted earlier, service change was not achieved in site C, and only partially in site B. In site B, a lack of medical support was cited as the reason why the introduction of the acute home nursing team was not achieved. We learned of this early in the research, but it was unclear from interviews and available documentation how much work had been invested in the planning for this service. We know it got as far as a service specification from the commissioner, but as the planning for this appeared to take place before the research we were unable to capture it in detail and in ‘real time’.

By contrast, in site C much of the planning for the intended service change took place during the course of the research, and we were able to capture this ‘as it happened’, including the decision to terminate much of the reconfiguration plan. This provided an opportunity to describe the extent of the work, time and effort invested in the planning of a service change that was not achieved. In previous sections, we have described the factors that participants in site C felt influenced the planning. In this section, we describe these to provide a chronology of events and factors and offer an overarching picture of the difficulties in achieving service change in this case site.

Prior to the research, we had been in touch with this case site in 2010, when the then commissioner was proposing plans to redesign CCN services. The commissioner knew of our previous work in this area9 and wanted to use the learning from the research to inform planning in the site. By the time the current project got under way in 2012, these proposals were ongoing and with the appointment of a new head of nursing, work was under way to plan and research the proposed redesign. For example, we received copies of draft commissioning intentions, and the first round of interviews in late 2012 indicated that there was work being done on business cases, auditing existing services and workforce planning with other local providers. In 2013, further planning work was being done, including a review of services, a public consultation, continued discussions and workforce planning with other provider trusts, and the development and submission of a business case following a service specification from commissioners.

Across these first and second rounds of interviews, there was discussion of tensions and competition with other providers. These discussions indicated that it was not simply a case of one provider negotiating with a commissioner, but multiple providers negotiating with each other as well as commissioners about resources and future service provision. Perhaps most prominent in the discussions were the difficulties of continuing such service planning with the change in commissioning arrangements. This was felt to play a significant role in delaying service change, and was mentioned at each stage of data collection (see NHS reforms for more detail).

It was also apparent that there was much interdependency between stages of planning, with certain aspects or events holding up the progression of others. For example, in 2013 the planning of the new service model became dependent on the outcomes of a public consultation on existing provision. This was because the new service model partly depended on the resources released by the decommissioning of the existing provision. Another example was that the new intended service was dependent on the appointment of a new nursing post in a different trust, to facilitate discussions across providers about workforce planning.

Despite these difficulties, in late 2013, it was reported that the submitted business case had verbal go-ahead, with the provider now planning the phased implementation of the proposed service. These service changes aligned with outcomes of the public consultation regarding existing provision in the area. However, by early 2014, we learnt that this decision had been reversed by the commissioners. It was reported this was because of a lack of financial planning around the redesign. In October 2014, it was reported that despite persisting complexities around the new commissioning arrangements, there was some progress. A number of factors were felt to be responsible. First, the appointment of a new commissioner allowed someone to look at the proposed redesign and the issue of inequity of CCN provision with ‘fresh eyes’. Second, the CCGs were felt to be giving more thought to the redesign. As noted earlier in this chapter, following the new commissioning arrangements, it was the JCU that had largely led the commissioning for the redesign of CCN services in this area. However, by October 2014, it was reported that the CCGs were beginning to grapple with the issues around CCN services, although it was still felt that children’s services more generally was a low priority for them. Third, neighbouring health communities were also redesigning their CCN services as a priority, and this was felt to have influenced the commissioners in this case site in thinking about the possibilities of their own CCN services.

The plans and intentions for the service change in this site had started at least as far back as 2010, and continued into 2014. This represents 4 years of planning for a service change that was eventually abandoned.

Influence of changing commissioning arrangements

As this research was taking place during major NHS reforms, we included a secondary research question about whether or not there would be an impact of changing commissioning arrangements on the intended service reconfigurations. An impact was most evident in site C, and to some extent site B, which we have already described above. As expected, in sites A and D, where the services were established, there was no evidence of impact on service reconfigurations in terms of planning and early implementation (such as that seen in sites C and B, respectively). However, when we asked staff in these sites about the changing commissioning arrangements on existing CCN provision, a common issue raised in site A was how urgent and secondary care was a priority for the CCGs. Findings about this are presented in Chapter 4, in which we discuss the issues teams faced in practice.

Summary

The findings reported here highlight the complexities of achieving service change to move care closer to home. There was clearly a commitment from both providers and commissioners to develop and introduce these services, but other factors were influential in determining the ‘success’ of their plans. Whether or not the plans had the support of medical staff appeared to play a role, to varying extents, in whether or not services were achieved. This suggests that there may be conflicting views about the acceptability of CCN services as a means of delivering care closer to home, but also that the views of some NHS stakeholders hold more ‘weight’ than others. When service reconfiguration takes place across a number of providers (as was the case in sites A and C), a centralised network appears useful for ‘powering’ change. However, smaller, isolated service changes are also possible, as was the case in site D. Thus, the magnitude of the reconfiguration does not necessarily correspond to whether or not service change is successful.

Dedicated finance without the need to disinvest elsewhere in the system was observed in those sites in which service change was achieved. By contrast, a lack of dedicated finances and the need to disinvest in existing services can exacerbate competition between providers, making service planning and development time-consuming. Changing, unstable environments add further difficulties. Nonetheless, some were able to implement the services they intended. In Chapters 6 and 7, we present findings about the impact of the implemented services on secondary care, costs and quality. In the next chapter we present findings from practitioners about the issues they faced once services were implemented, and the perceived outcomes of their provision.

Chapter 4 Implementing children’s community nursing services: perspectives of NHS staff

Key messages

-

Poor visibility of new and expanded CCN services can affect take up by primary and secondary care. Maintaining this visibility can be difficult to do alongside the day-to-day demands of delivering care.

-

Balancing needs of different groups of children on the caseload can be a challenge, particularly when resources are constrained in times of staff absence or when acute need increases during winter months.

-

Demonstrating impact and value is difficult using outcomes relating to secondary care activity. Teams are looking for ways to measure meaningful outcomes relating to quality.

Introduction

In the sites in which service change intentions were realised (sites A, D and partially B), implementing and embedding these new services did not come without challenges. There were some common themes across sites in this respect, but some implementation issues were specific to the individual team and their service context. In this chapter, we draw on data collected from the teams who delivered the services to present findings about the key challenges faced when implementing the new or expanded services. We begin with a description of the methods used.

Methods

Focus groups and in-depth, semistructured interviews with children’s community nursing team practitioners

Focus groups are particularly useful for exploiting group interaction to generate information. 59 To understand issues associated with the implementation of new or expanded services, we undertook focus groups, and some supplementary in-depth interviews, with the practitioners in the CCN teams in sites A1, B and D. As with the data collection with managers and commissioners, we planned to undertake longitudinal focus groups with practitioners to understand expectations and reflections about the changes to practice. For sites B and C, for which the teams were to be introduced during the research period, we expected to undertake the first focus group soon after implementation and the second approximately 6 months later. We were able to do this for site B, in which we explored issues associated with their recent expansion to incorporate CHC provision. However, as the intended new CCN team in site C did not go ahead, it meant we were unable to collect data in this site for this component.

For site A, for which the team was already established, we also undertook two focus groups. The first retrospectively examined the earlier phase of implementation as well as expectations about new developments in the team. The second, approximately 6 months later, examined reflections about these new developments. Topic guides were used for each focus group (see Appendix 1, Topic guides for interviews and focus groups with staff, parents and children). In site D, which was a late addition to the research to compensate for the loss of research activity in site C (because of the delays to service change), we undertook one focus group to explore issues associated implementation retrospectively. A second focus group was not necessary, given that there were no further service changes or developments taking place.

Sampling and recruitment

Owing to variation in local service structures, a set sample size was not feasible. Rather, we intended to recruit as many team members as possible across the three sites. Thus, all available practitioners (n = 35) across sites were approached to participate in focus groups at wave 1. Of these, 21 agreed and took part, and a further individual who had not been approached joined a focus group on the day (site B). Fourteen individuals either declined participation or did not respond. In site A we were advised that it would be difficult to find a date where everyone could attend because of rostering of shift work. Instead, we were advised to set a date for the focus group and those who were present and willing to participate could join in. At wave 2, we approached all those who had participated at wave one in sites A and B (n = 18). Of these, 12 agreed to participate (thus, there was an attrition rate of one-third of the original sample). An additional three individuals, who had not been approached because they had not taken part at wave 1, joined the focus group in site A on the day. At wave 2 in site B, two participants requested an individual interview because of scheduling conflicts with the date set for the focus group.

Participants across the sites were nurses (n = 20) and clinical support workers (n = 4), all of whom worked as part of the teams. Nurses included generic CCNs, specialist nurses and those with advanced practice qualifications. Table 8 details the number of participants approached and the number who took part in a focus group or interview, at each wave of data collection, by site.

| Site | Wave 1 | Wave 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of staff approached | Number of staff participating | Number of staff approached | Number of staff participating | |

| A | 23 | 9 | 9 | 8 |

| B | 9 | 10a | 10 | 7 |

| D | 3 | 3 | Not applicable – one focus group undertaken | |

A record of consent was obtained prior to data collection for participants taking part in both the focus groups and interviews, and for each wave of data collection.

As described in Chapter 1, we also drew on relevant documents for context and contemporaneous field notes.

Analysis

The focus group and interviews were audio-recorded in all cases, transcribed, and data managed and analysed using the Framework approach. 51 In one case, the audio-recording of an interview failed and notes of the interview were made and sent to the participant for confirmation. For full details of the analysis, please see the analytical plan (see Appendix 1, Analytical process and framework for study 2).

Findings

Across the three sites, there were three overarching themes about the challenges faced when implementing the new or expanded services. These were the visibility and legitimacy of CCN services, balancing different caseload demands, and demonstrating impact and value. Alongside these, there were issues specific to individual services and their context. In this next section, we present findings about the implementation challenges faced, starting with the three overarching themes.

Visibility and legitimacy of children’s community nursing services

Once services became operational, there were immediate and ongoing issues about how visible the teams were to others. For example, when the nurse practitioner team in site D was initially introduced, it sat alongside a CCN team in the acute trust. Later, when acquired by a different NHS trust, their base was moved into the community. Although the team preferred being based in the community, visibility to acute trust consultants was felt to be compromised, affecting consultant referrals to the team:

[W]e’re not utmost in people’s, in consultants’ minds for when they’re looking at, you know, care for these children.

Focus group, site D

Problems with visibility were thought to be partly a result of the team being so small at just three advanced nurses, and partly a lack of marketing on their behalf. While the introduction of a similar team in adult services was preceded by a marketing exercise at the senior management level, this did not happen for the nurse practitioner team. When the service was first set up, there was ‘suspicion’ from other services and a lack of clarity about what the team would do. In response, they had to raise their own profile with others through educating them about the service. The team reported that others’ learning about their team continued in everyday practice through joint working, but they still struggled to find time to continually maintain their profile while delivering the service.

Similar accounts were found with the site A generic CCN team, particularly with regard to how they were used and understood by GPs, for whom referral rates had been low. In response, the team implemented a liaison post to increase visibility of the service to, referrals from, and to improve relationships with, primary care. This involved close working with local GP practices, sometimes sitting in on GP consultations to advise on which children could be safely managed by the team. This post was felt to have worked well: referrals from GPs had doubled, and GPs better understood and valued the role of the team. Face-to-face contact between the team nurses and GPs was thought to be a significant part of the liaison post’s success.

Despite this success, visibility of the service to others remained a concern for the team. Earlier implementation was accompanied by a publicity drive, co-ordinated by the network that had overseen the wider reconfigurations (see Chapter 3). Thus, the new service was ‘marketed’, which the team felt was valuable for creating awareness of what they could provide to others in the NHS as well as to the public. However, the network ceased during the period of research, and there was no longer anyone to do this marketing. Having a dedicated person to do this was deemed important to raise and maintain awareness of the service to ensure its continued use:

[W]e need a marketing bod for everything we do really.

Focus group 2, site A