Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 11/1023/01. The contractual start date was in May 2012. The final report began editorial review in July 2015 and was accepted for publication in November 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Daniel Prieto-Alhambra has received unrestricted research and educational grants from Amgen and Bioibérica S.A. Nigel Arden reports personal fees from Merck Sharp & Dohme (MSD), grants and personal fees from Roche, personal fees from Smith and Nephew, personal fees from Q-Med, personal fees from Nicox, personal fees from Flexion, personal fees from Bioibérica and personal fees from Servier. Cyrus Cooper has received consultancy fees, lecture fees and honoraria from Amgen, GlaxoSmithKline, Alliance for Better Bone Health, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Novartis, MSD, Servier, Medtronic and Roche. M Kassim Javaid has in the last 5 years received honoraria for travel expenses, speaker fees and/or advisory committees from Lilly UK, Amgen, Servier, MSD, Medtronic, Internis, Consilient Health and Jarrow Formulas. He also serves on the Scientific Committee of the National Osteoporosis Society and International Osteoporosis Foundation. Andrew Judge has received consultancy fees, lecture fees and honoraria from Servier, UK Renal Registry, Oxford Craniofacial Unit, IDIAP Jordi Gol and Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer, is a member of the Data Safety and Monitoring Board (which involved receipt of fees) from Anthera Pharmaceuticals, Inc., and received consortium research grants from Roche.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Judge et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

There is a marked disparity in the delivery of secondary fracture prevention for hip fracture across England, despite national guidelines, which is of concern to clinicians, patients and commissioners. Given the substantial societal burden of hip fractures and the subsequent increased risk of fracture, understanding the causes and consequences of this disparity is a matter of urgent priority within the NHS.

Osteoporosis is a common bone disease affecting 3 million patients in the UK. The clinical and public health implications are substantial owing to the mortality, morbidity and cost of medical care associated with osteoporotic fractures. 1 Of all of the types of osteoporotic fracture, hip fractures are the most costly and are a major public health problem because of an ageing population. Hip fractures usually occur as result of a low-impact falls in individuals with underlying bone fragility due to osteoporosis. 2,3 Approximately 87,000 hip fractures occur annually in the UK, with a cost (including medical and social care) amounting to about £2.3B per year. 1,3 Length of stay accounts for the majority of overall hospital costs, and has been estimated to be between £5600 and £12,000 per case. 1 After discharge from hospital, the cost of complex home and institutional care for people who make a poor recovery is very high, with average additional costs for health and social aftercare previously estimated to be £25,000 in the first 2 years. 1

Importantly, patients experiencing hip fracture after low-impact trauma are at considerable risk of subsequent falls, osteoporotic fractures and premature death. 4–6 The risk of second hip fracture ranges from 2.3% to 10.6%, in which the majority of second hip fractures occurred within a few years of the first hip fracture. 7,8 It has been estimated that 55.6% of hip fracture patients had at least one fall within 12 months, 11.8% sustained a fall-related fracture and 5% sustained a fall-related hip fracture. 9 Mortality during the first year after fracture ranges from 8.4% to 36%. 4

Current guidelines in fracture prevention

The onset of osteoporosis is asymptomatic and it is often recognised only after an older person falls and sustains a fracture. There have been widespread calls to improve the identification and treatment of hip fracture patients to reduce the risk of further falls, fractures and mortality. 1,4,10 The risk of further fracture can be reduced by up to half with bone protection therapy. 1,11–13 As most fractures result from a fall, interventions to reduce the risk of falls may be effective in preventing further such events; however, direct evidence is lacking. Over the past decade, guidance from a number of professional bodies has been published for the management of hip fracture patients [British Orthopaedic Association (BOA) Blue Book,1 Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN),14 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)13,15]. NICE technology appraisal (TA) guidelines TA 160/16113 are related to the effectiveness of bone protection therapy and clinical guideline (CG) 21 relates to falls prevention. 15 In the UK, secondary prevention of fracture is underutilised and widely neglected. 1 As a consequence, compliance with NICE publications TA 16113 and CG 2115 is low. Audits by the National Hip Fracture Database (NHFD)16,17 and the Royal College of Physicians18 suggest that the situation is improving but still inadequate, such that prior to discharge only 66% of hip fracture patients were on bone protection medication and 81% received a falls assessment. 17

As almost half of all hip fracture patients have had a prior fracture,4 responding to the first fracture provides a golden opportunity to prevent the second. The BOA Blue Book1 provided guidance on secondary prevention of fragility fractures. A comprehensive service should consist of osteoporosis assessment, including a dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scan to measure bone density, if appropriate, treatment with bone protection therapy in osteoporosis patients, falls risk assessment and systems to improve adherence and persistence with therapy. Organising such services is challenging owing to the multidisciplinary care that patients require. 3 The 2011 NICE hip fracture CGs make specific recommendations regarding the treatment and multidisciplinary management of patients including liaison and integration of services. A fracture liaison service (FLS) is the recommended model proposed by the Department of Health to organise secondary fracture prevention services1 in a ‘one-stop shop’ setting delivered by a nurse specialist supported by a lead clinician (‘champion’) in osteoporosis. 19 However, currently only 30% of hospitals in England have established a FLS. 17 A single model incorporating all components of secondary fracture prevention has not been mandated. Current practice is for various combinations of these components to be used within a hospital (and in some cases no components are used).

Current knowledge

The clinical effectiveness of co-ordinator-based models of care has been demonstrated, in terms of improving the uptake of appropriate osteoporosis management such as measuring bone density and the use of antiresorptive drug therapy. 4,10 There is growing evidence of these models’ cost-effectiveness20,21 and that they can provide cost savings to the NHS. 4,10,22,23 Evidence is emerging on the ability of co-ordinator-based systems to reduce the incidence of hip fractures. A review of the Glasgow Osteoporosis and Falls Strategy reported that hip fracture rates in the city had reduced by 7.3% over the decade, compared with a 17% increase in fracture rates for the entire population of England over the same period. 19,24 These findings are consistent with observational data from the USA by Dell, who reported a 37.2% reduction in hip fracture rates. 25 However, the strongest evidence on effectiveness has recently been provided by an Australian study that was designed as a prospective observational trial with a concurrent control group in which, compared with standard care, targeted identification and management significantly reduced the risk of refracture by > 80%. 26

Across the UK there is variation in the care pathway of the treatment and management of hip fracture patients and in the way secondary fracture prevention services are structured and organised. Even with a co-ordinator-based system in place, the structure of services can vary between hospitals. For example, hospitals use different models of orthogeriatric care, in which some hospitals now have specialised orthogeriatric wards and in others patients are seen on the trauma ward. Some hospitals may co-ordinate the care of hip fracture patients only while such patients are admitted as inpatients, whereas others have ensured that their osteoporosis service is integrated across primary care to monitor patients’ adherence to bone protection therapy.

Aims

The aim of this study was to characterise the delivery of secondary fracture prevention services over the past decade across hospitals in the region. Using qualitative research methods we have identified the reasons why hospitals chose their specific model of service delivery and assessed barriers to change. Using a natural experimental design27 we have established the cost-effectiveness of different models of care and the impact that changes to the delivery of care have had on altering trends in refracture rates, NHS costs and life expectancy.

Objectives

Objective 1: characterise secondary prevention of hip fracture across hospitals in a region of England (work stream 1)

The first phase of this project was to comprehensively describe and explore the variation and disparity in secondary fracture prevention services offered to hip fracture patients across hospitals in a region of England, and to identify the dates of key changes made to service delivery over the past decade.

Objective 2: identify the reasons why hospitals chose their specific model of service delivery and assess barriers to change (work stream 2)

The aims of the qualitative study were to (1) ascertain the reasons why each hospital has adopted their current and most recent models of care; (2) establish factors that facilitate or act as barriers to changes in service delivery; and (3) identify the elements of care of hip fracture patients that health professionals think are most effective.

Objective 3: evaluate the impact that changes to the delivery of secondary fracture prevention has had on health outcomes by altering trends in hip refracture rates, NHS costs and life expectancy (work stream 4)

A natural experimental study design27 evaluates the impact that changes hospitals in the region have made to the way in which they deliver secondary fracture prevention services for hip fracture patients has had on a range of health outcomes (mortality, second hip fracture and other fragility fractures).

Objective 4: establish the cost-effectiveness of different hospital models for delivery of secondary fracture prevention (work stream 3)

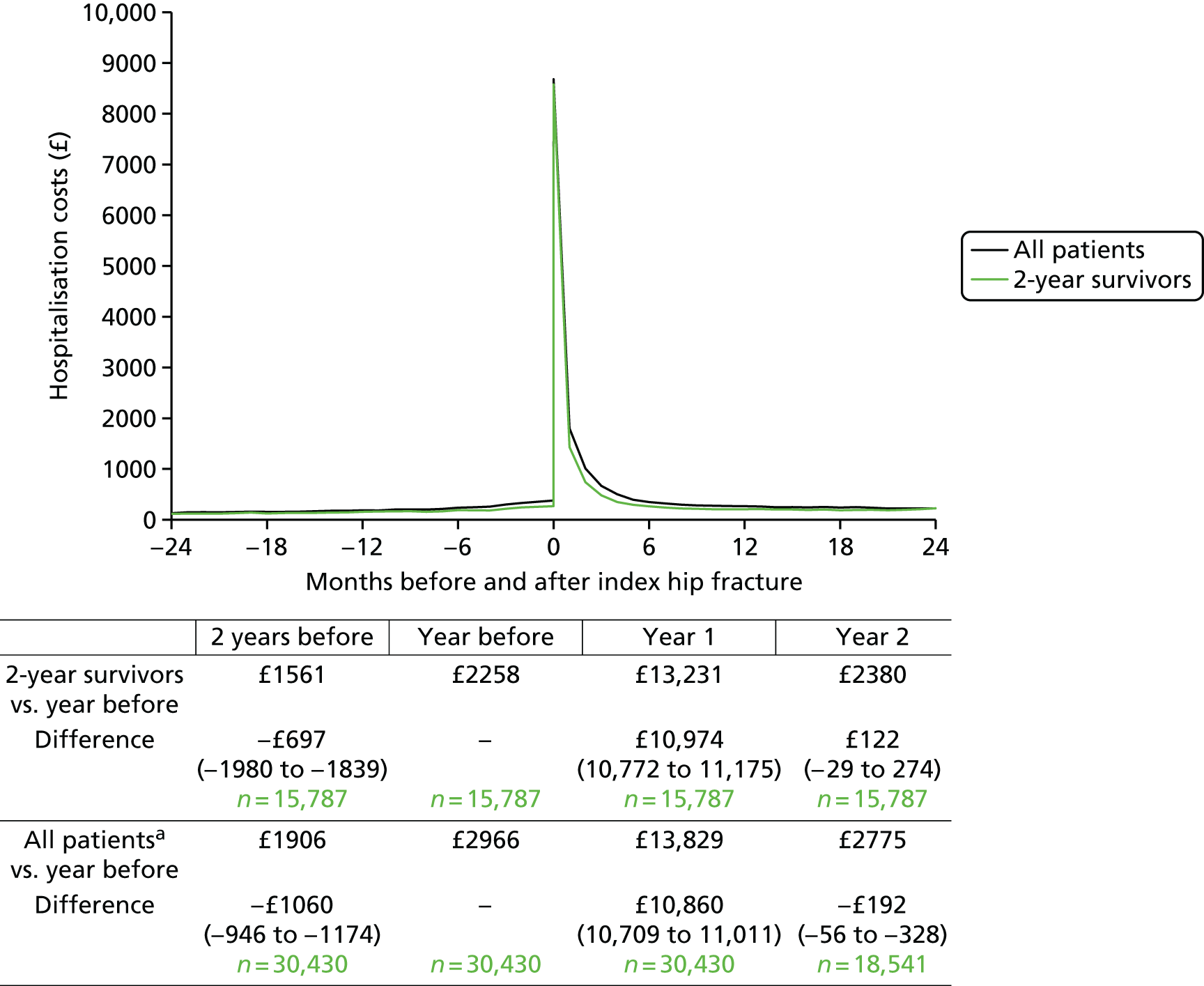

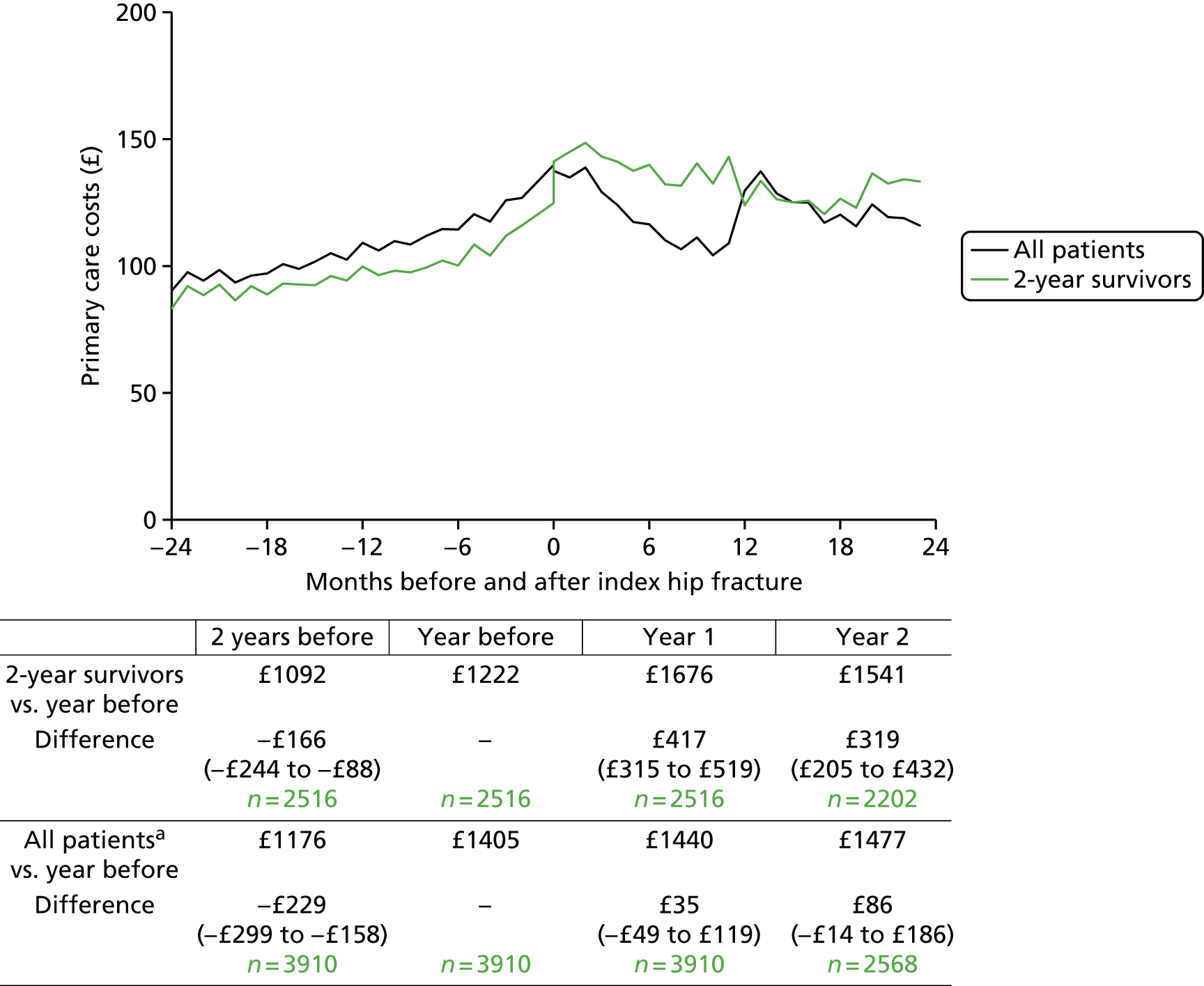

The health economics work calculates the hospital and non-hospital costs associated with hip fracture in the year of fracture and subsequent years and evaluate the costs (quality-adjusted) life expectancy and cost-effectiveness of the different hospital models of care.

Design and methodology

Characterise secondary prevention of hip fracture across hospitals in a region of England (work stream 1)

In order to collect information on models of care for secondary fracture prevention at each hospital, we conducted a service evaluation which comprised:

-

developing a questionnaire to collect information on staffing levels and new appointments over the past decade, procedures for case finding, osteoporosis assessment (including location of DXA scanner), falls assessments, treatment initiation and follow-up, as well as integration across primary, secondary and community care

-

identifying health professionals at each hospital to complete the questionnaire through a regional network of clinicians working in osteoporosis management.

Identify the reasons why hospitals chose their specific model of service delivery and assess barriers to change (work stream 2)

This qualitative research component involved the following stages:

-

identifying a local collaborator at each hospital through a regional network of clinicians and, with their input, identifying other health-care professionals and service mangers working at the hospital in secondary fracture prevention

-

conducting qualitative interviews with 3–5 health-care professionals or service managers at each hospital

-

thematic analysis conducted using codes to identify themes and subthemes.

Evaluate the impact that changes to the delivery of secondary fracture prevention has had on health outcomes by altering trends in hip refracture rates, NHS costs and life expectancy (work stream 3)

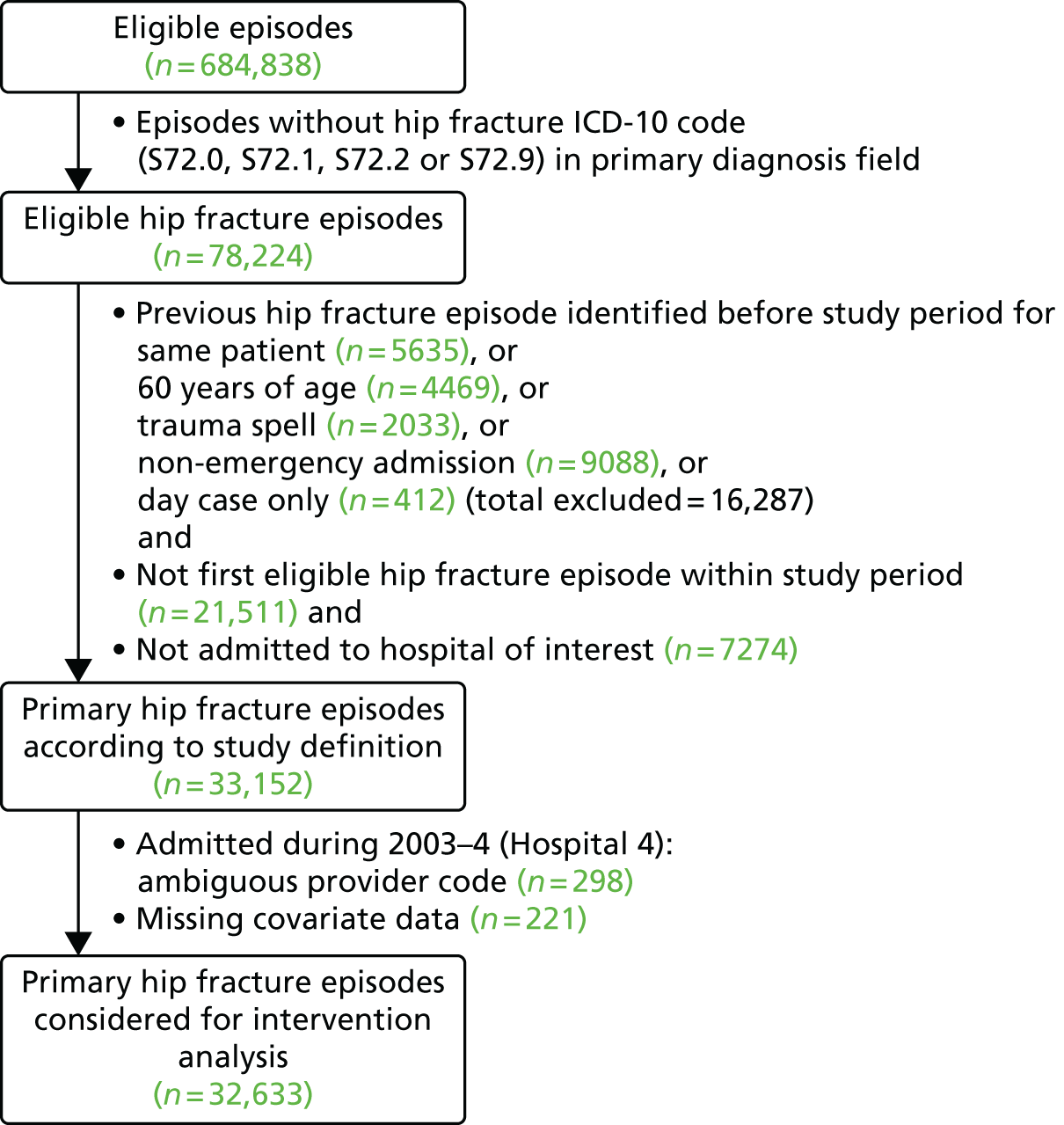

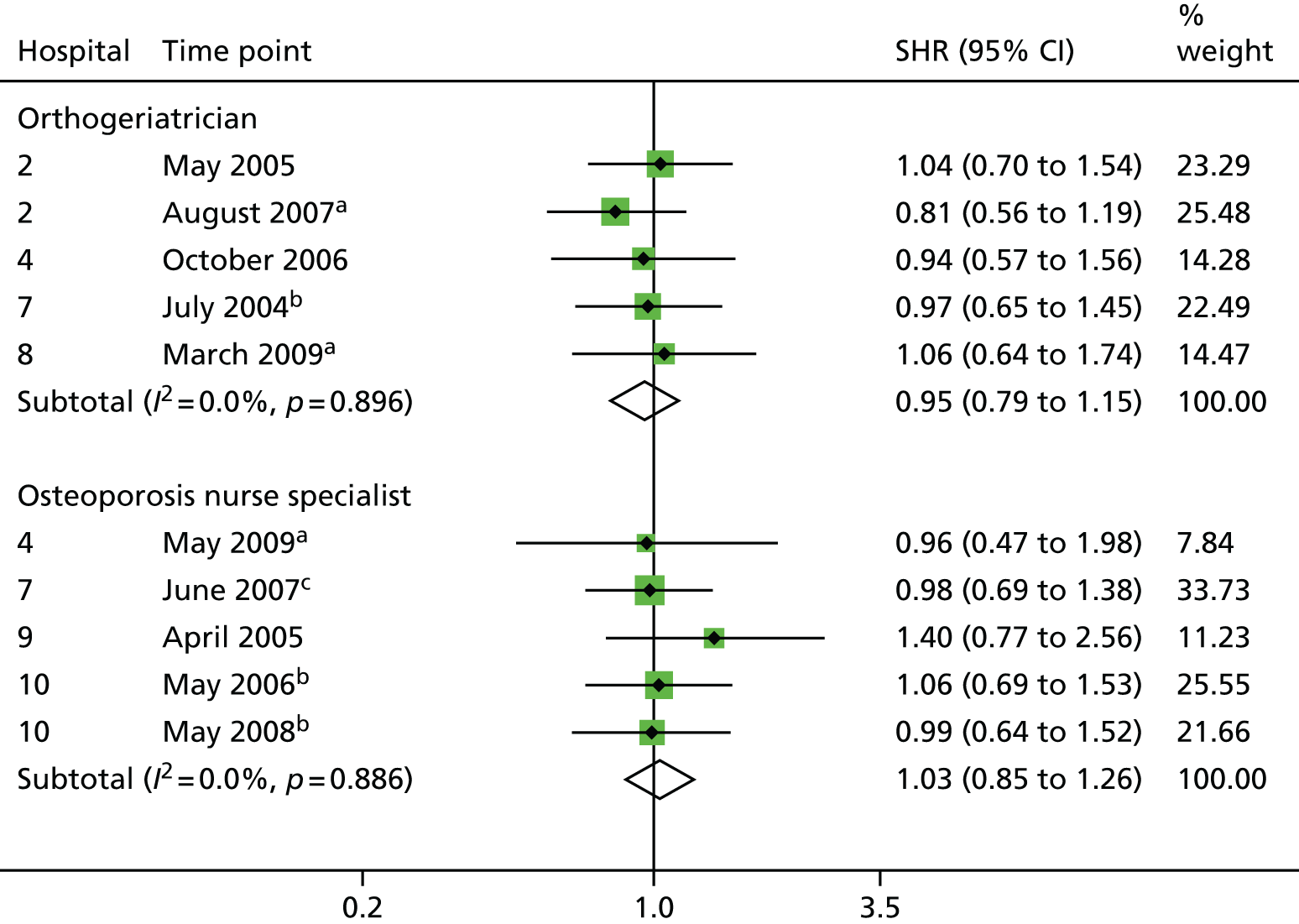

A natural experiment study design was used to assess the clinical effectiveness of changes in service delivery in terms of reducing mortality and secondary fracture rates using the following procedure:

-

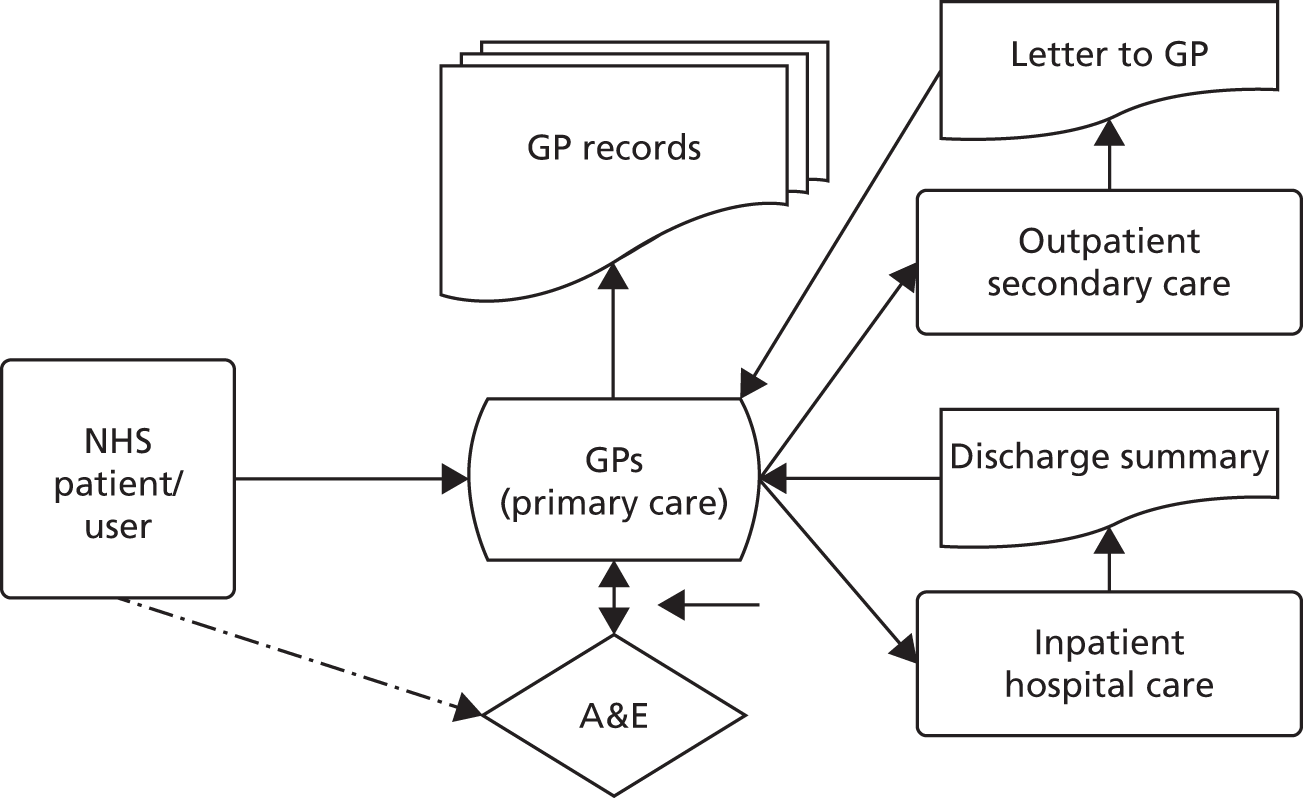

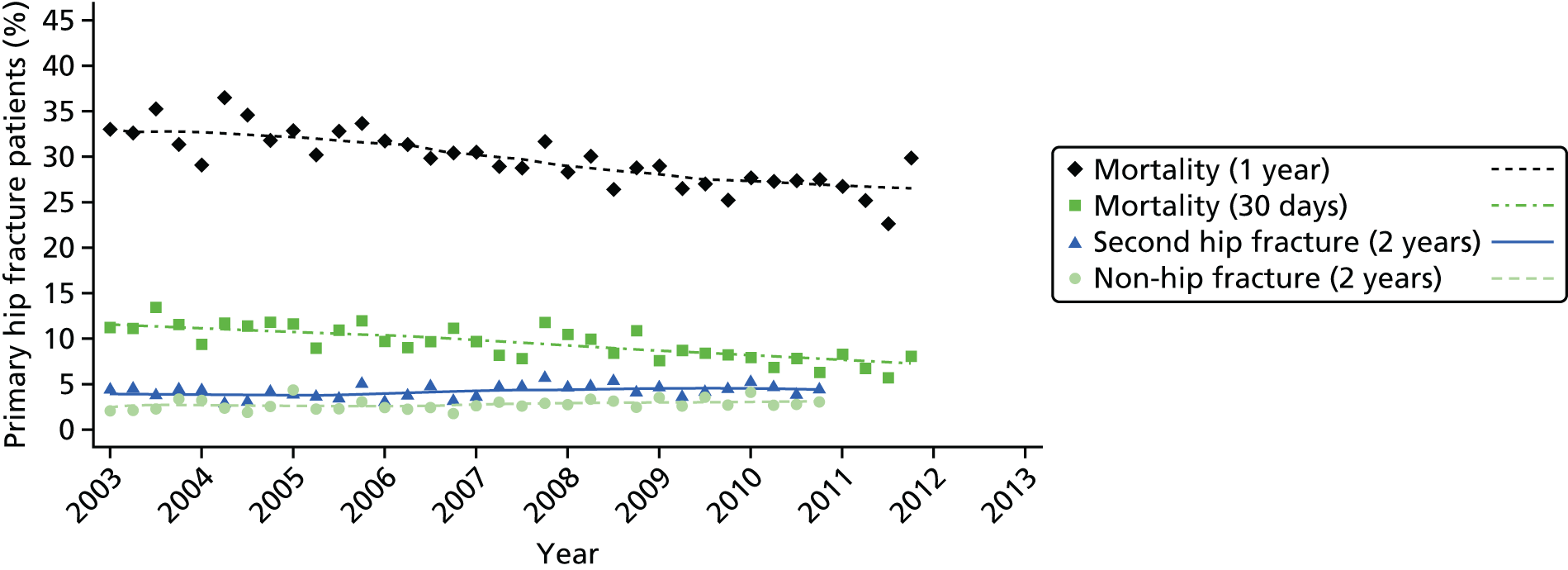

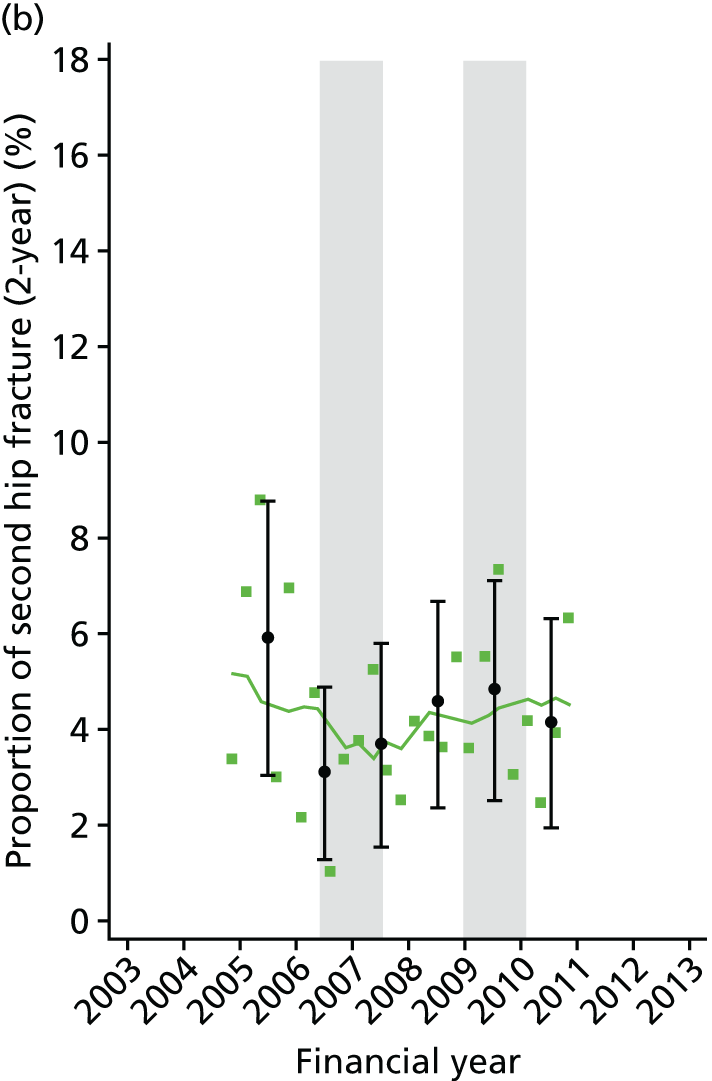

trends in rates of 30-day mortality, 1-year mortality and secondary hip fracture established from Hospital Episodes Statistics (HES) data for hospitals in the region

-

interventions, or changes in service delivery, and their corresponding dates were identified from the service evaluation conducted in work stream 1

-

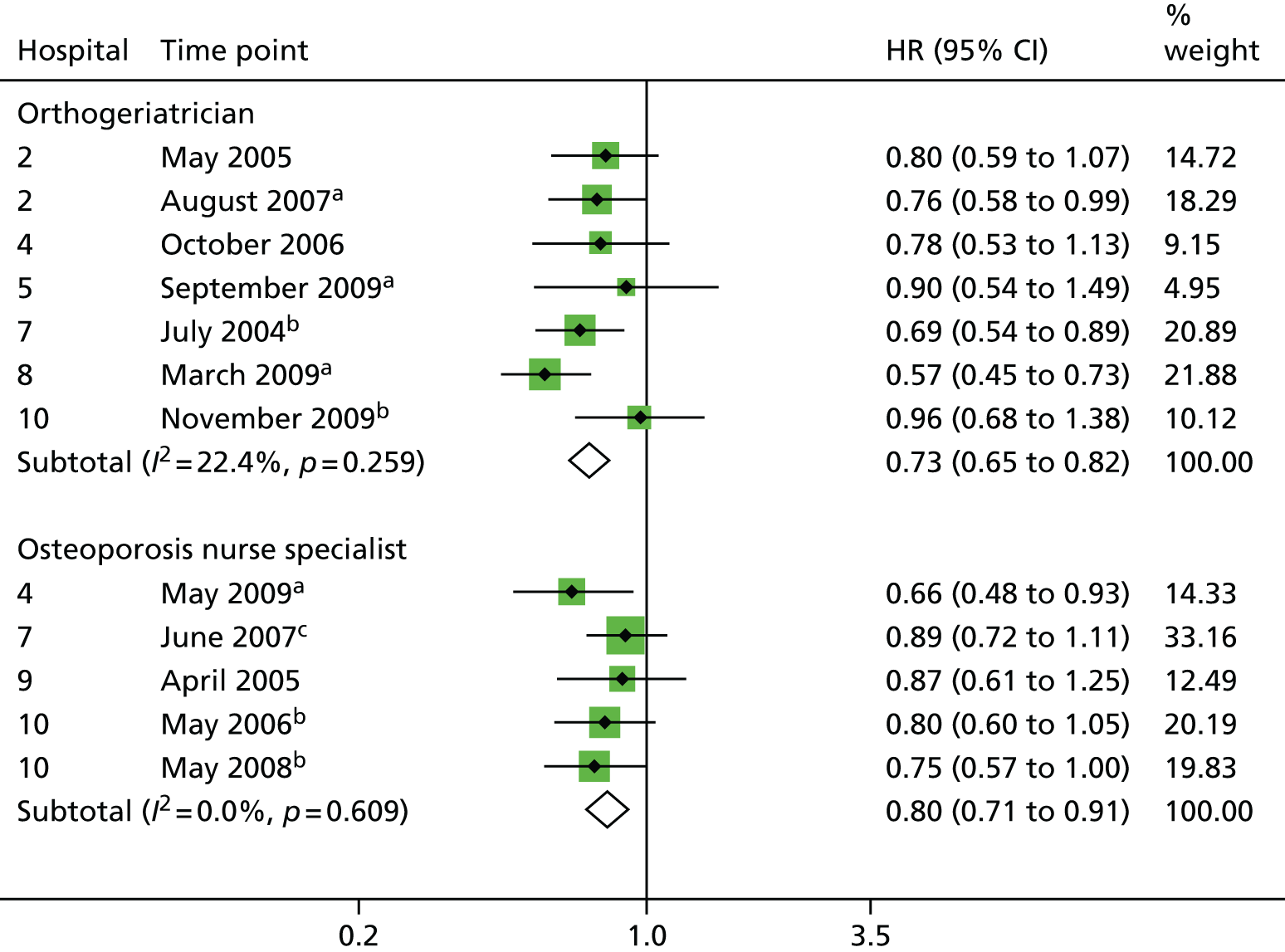

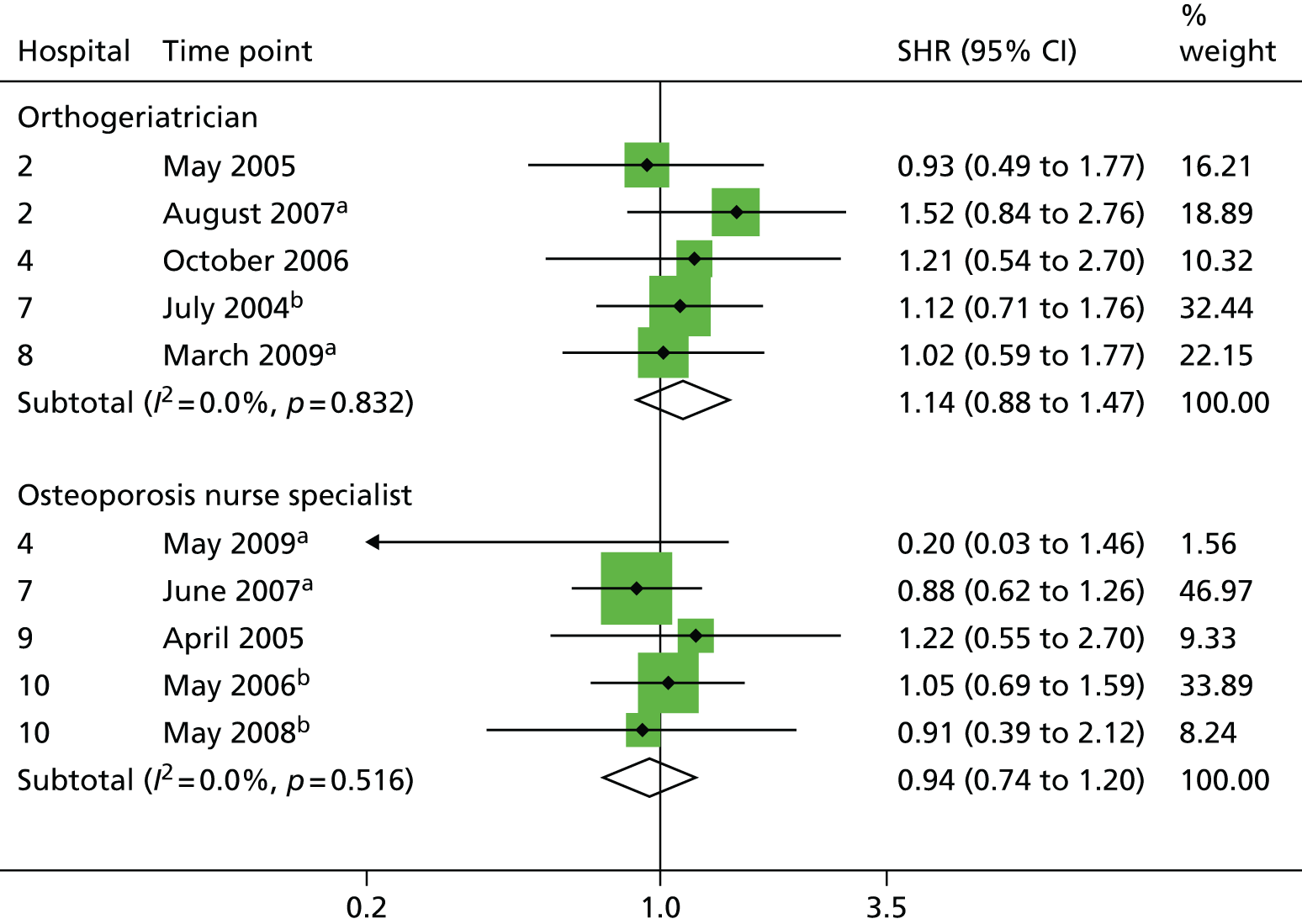

interrupted time series analysis and Cox proportional hazards regression modelling used to analyse impact of each intervention on outcomes of interest.

Establish the cost-effectiveness of different hospital models for delivery of secondary fracture prevention (work stream 4)

An economic analysis of the costs and cost-effectiveness of different services will be undertaken as described below.

-

Data from HES and the Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) will be used to identify the hospital and non-hospital costs of a hip fracture.

-

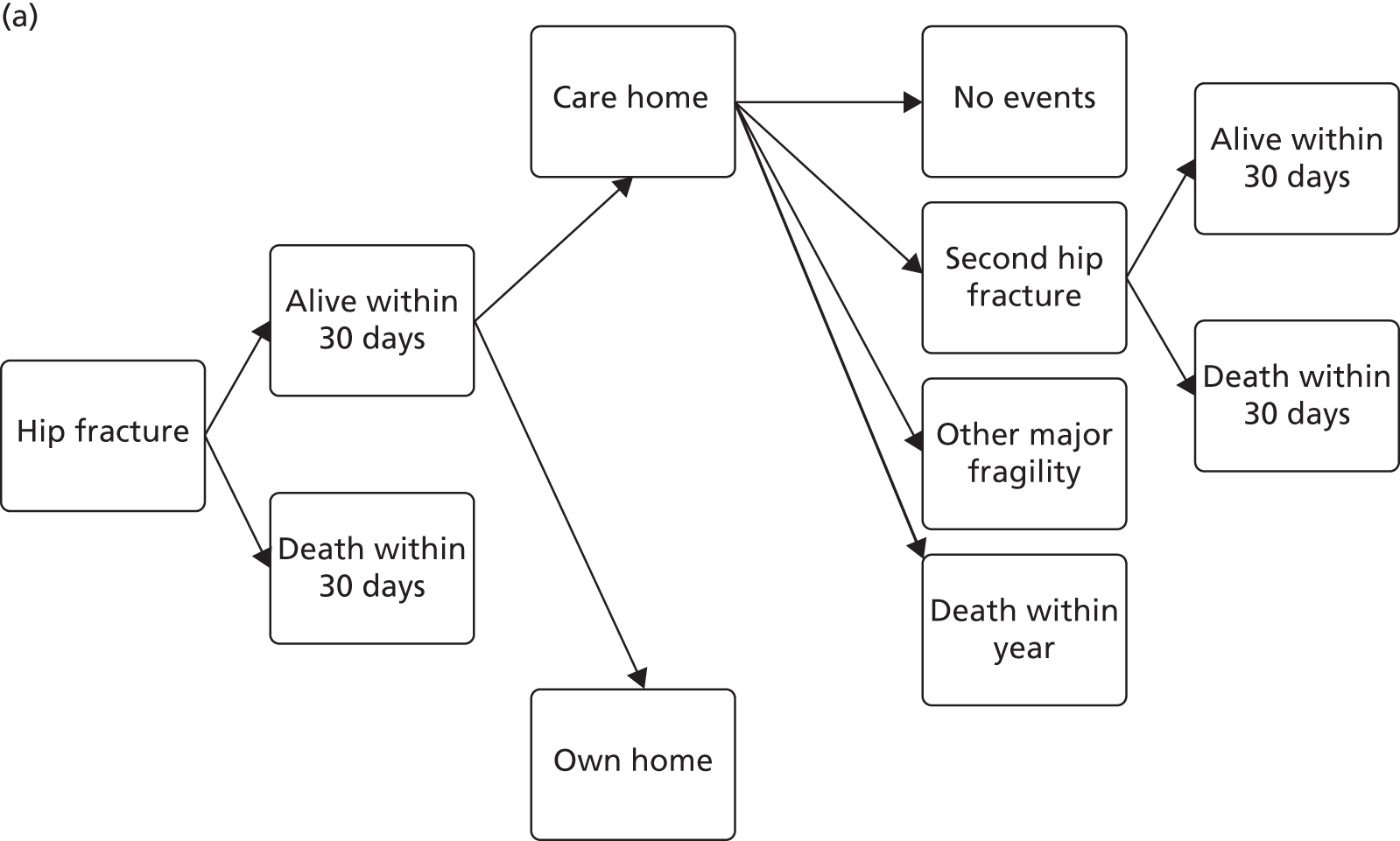

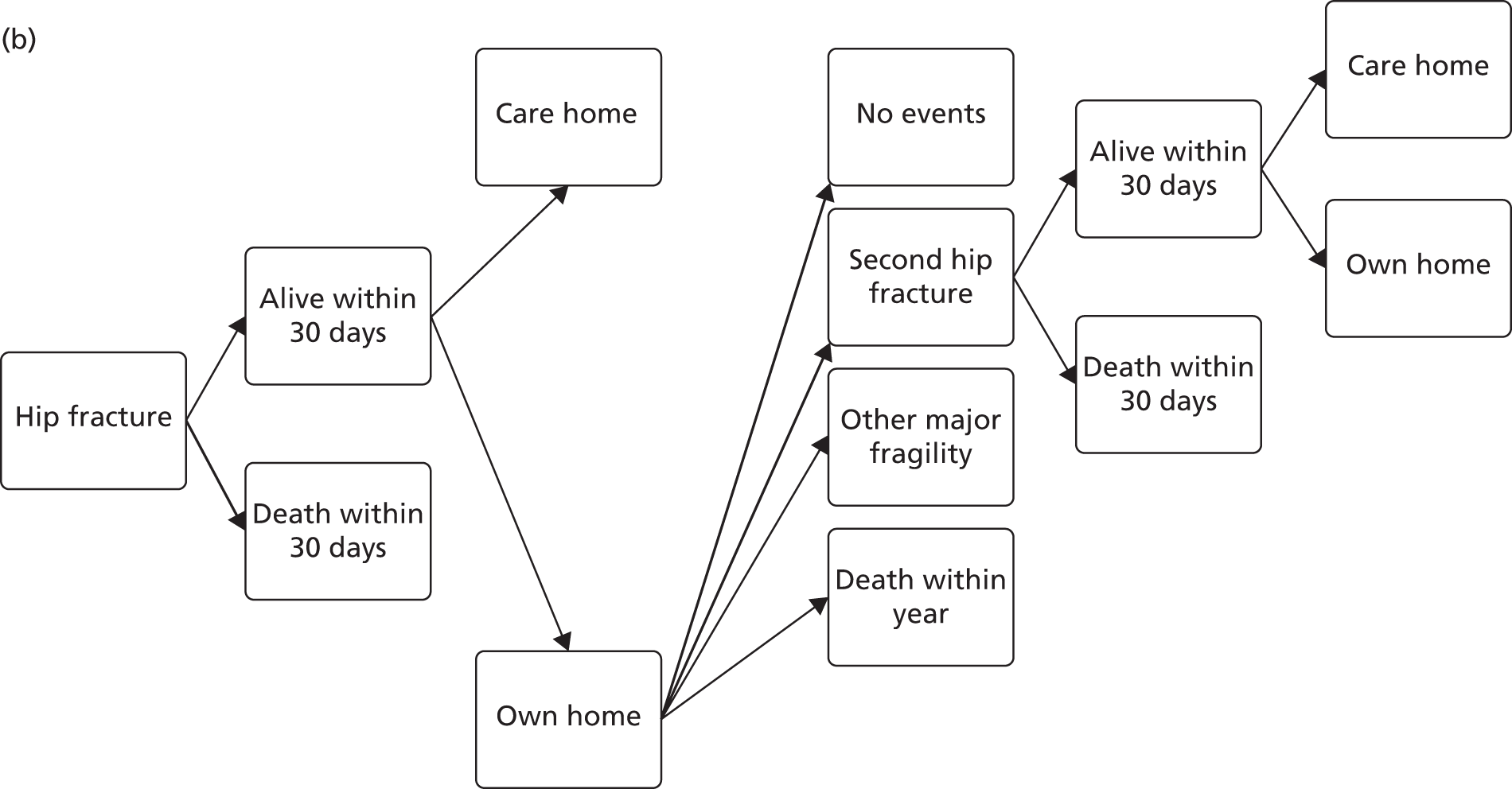

A Markov model will be developed to evaluate costs and cost-effectiveness of each model of care (using a measure of clinical effectiveness from work stream 3).

-

Utility scores (from literature search) will be used to provide the weights required to calculate the quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) of the different models of care under evaluation. 28

Chapter conclusion

This chapter has provided the relevant background information to introduce the health-care need for this area of research. Each of the four work streams are outlined, along with the research methodology involved. These four work streams are described in detail in Chapters 2–8.

Chapter 2 Characterisation of secondary fracture prevention services at hospitals across a region of England, and identification of key changes in service delivery over the past 10 years

Introduction

In this chapter, we present findings of a service evaluation to look at the organisation of orthogeriatric and FLS available to patients being treated for a hip fracture. This was carried out at 11 acute hospitals in one region of England. We also identify the dates of key changes to service delivery, such as the appointment of fracture liaison nurses and orthogeriatricians. This work package was designed to inform the natural experiment study design described in Chapter 5, in which we look at the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the interventions identified here.

We will initially begin by describing the evident variations in the structure of orthogeriatric and FLS across the different hospitals. Exploring the similarities and differences between these services in more detail will help clinicians and commissioners in England to identify gaps in care and provide them with information about which services to develop if necessary, which may help to reduce unwarranted variation.

We will then present the key time points of interest we have identified when interventions occurred, and justify our reasons for these selections.

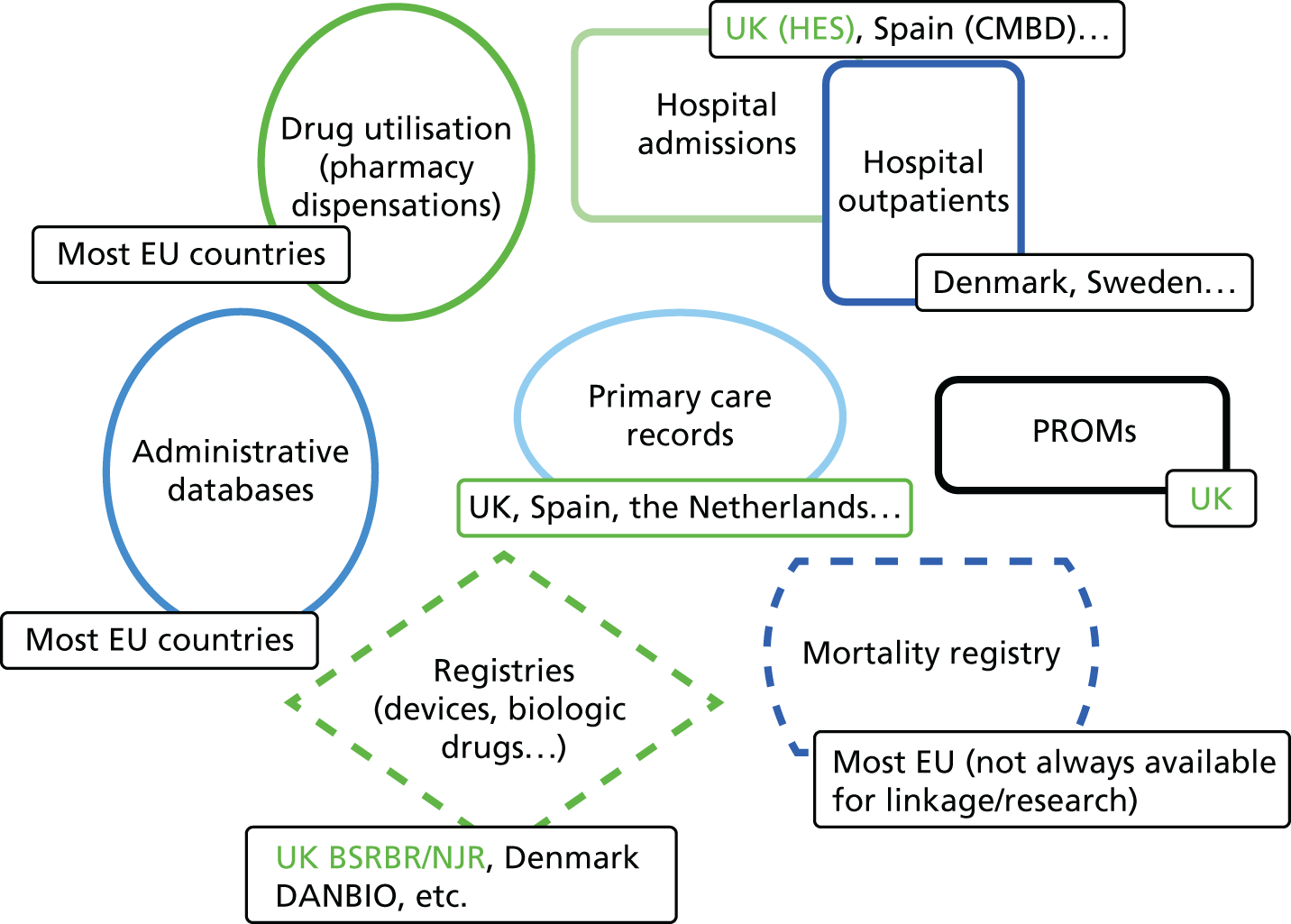

Current knowledge of variations in delivery of fracture prevention services

Studies have shown a major variation in how hospitals organise their services for the treatment of hip fracture patients and management of secondary fracture prevention. The NHFD is a national audit from the Royal College of Physicians that includes information on the number of orthogeriatric sessions and specialist nurses per centre to deliver secondary fracture prevention. 17 Although the number of orthogeriatric hours per week is modestly related to reported hip fracture numbers, there was a wide variation in FLS service delivery. In 2013, 62% of hospitals reported that they had no fracture liaison nurse, 27% reported up to one whole-time equivalent (WTE) post and 11% reported more than one WTE. Furthermore, in those centres with a specialist nurse, there was no relationship between volume of fragility fractures and number of staff (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

The relationship between reported number of WTE specialist nurses for secondary fracture prevention and estimated number of fragility fracture patients seen in that hospital per year. Each data point represents a hospital that returned > 0 WTE of specialist nurse in the NHFD 2014 report. The number of fragility fractures per hospital was estimated using five times the number of proximal femoral fractures. The line shows a lowess plot with a bandwidth of 0.9.

These variations in services using even crude metrics such as staff resource are too great to be explained by local case mix and volume of hip fracture patients across hospitals. Establishing the differences between service models and levels of care in more details will allow clinicians and commissioners to identify existing gaps in care, and could help to reduce unwarranted variation across hospitals.

Current guidelines

A number of professional bodies have provided national guidance for the care of hip fracture patients reflecting two key aspects. The first type of guidance relates to optimising initial recovery after hip fracture and focuses around the provision of patient-centred care29 within three broad categories:

-

optimising surgical procedure – including early timing of surgery, preoperative appropriate correction of comorbidities and type of implant

-

early mobilisation

-

multidisciplinary management from admission to discharge.

The second type of guideline relates to secondary fracture prevention and there are many more guidelines available, including guidance from Canada22,30,31 the USA32 and the UK. 1,14,15,33 The ‘Capture the Fracture’ initiative from the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF) provides additional international guidance. 34 Guidelines describe a comprehensive fracture prevention service consisting of four main components:

-

case finding those at risk of further fractures

-

undertaking an evidence-based osteoporosis assessment, including a DXA scan to measure bone density, if appropriate

-

treatment initiation in accordance with guidelines for both bone health and falls risk reduction

-

monitoring and improving adherence to recommended therapies.

Such services require multidisciplinary care from orthogeriatrics, rheumatology, falls services and primary care. 3 Running such a service can be challenging and, as a result, such services often require a dedicated co-ordinator to provide a link between the different multidisciplinary teams involved in the care pathway. This is known as a co-ordinator-based system of care. 10 This co-ordinated, multidisciplinary approach to patient care is known as a FLS. 19 FLSs have now been introduced internationally. 35,36 In the UK, the Department of Health has proposed a model of best practice which is delivered by a nurse specialist supported by a lead clinician (‘champion’) in osteoporosis. 1 In addition, The Care of Patients with Fragility Fractures, published by the BOA, recommends fully integrating orthogeriatricians into the way the fracture service works in order to best meet the complex needs of hip fracture patients. 1

However, despite the guidance that is in place, there is no overall agreement on the best way to organise these services, and a single model comprising all elements of a FLS has not been mandated.

Changes in hip fracture care over the past decade

Guidance from a number of professional bodies for the management of hip fracture patients (BOA Blue Book,1 SIGN14 and NICE29,33) has led to key changes in hip fracture care across the UK. The NHFD collects data on staffing levels as well as on many other aspects of care, and has shown a significant increase in the number of consultant grade orthogeriatric hours per week since reporting began in 2009, and a particularly sharp upwards trend in the number of fracture liaison nurse hours per week since 2012. 16,17,37,38

Aim

The aim of this work package was to comprehensively describe the models of care for secondary fracture prevention for hip fracture patients across hospitals in one region of England, and describe the similarities and differences that exist across them.

In addition, this work package will identify key changes in these services that have occurred at each hospital over the past 10 years. This will form the basis of the ‘natural experiment’ described in Chapter 5, where the clinical effectiveness of changes to the care pathway established here will be evaluated.

Methods

The service evaluation was conducted in one regional area of England. There are 11 hospitals in this region which receive patients with acute hip fracture. Detail on the variation in size of these hospitals, in terms of catchment population and number of hip fracture patients seen each year, was taken from the NHFD 2013 Report. 17

Data for the service evaluation were collected using a questionnaire designed to identify key changes to service delivery over the past 10 years and characterise the level of service, closely based on the IOF Capture the Fracture Best Practice Framework,34 which defines 13 standards for an effective fracture liaison nurse. A copy of the questionnaire is included in Appendix 1, but, briefly, data were collected on the following aspects of care:

-

dates of employment of orthogeriatricians, fracture liaison nurses, falls nurses and clinical osteoporosis ‘champions’, their role in co-ordinating care and clinical contact, and changes they introduced when appointed

-

type of wards (trauma, geriatric orthopaedic rehabilitation unit, other rehabilitation ward) and date opened

-

presence of any service-level agreement for delivery of secondary fracture prevention

-

co-ordination of multidisciplinary care and across inpatients, outpatients and primary care

-

staff responsible for case finding

-

DXA scanner location and referrals

-

monitoring

-

falls assessments and other assessments.

A regional network of clinicians who work in osteoporosis services helped to identify health-care professionals at each hospital who would be best placed to complete the questionnaire, including fracture liaison nurses, orthogeriatricians, geriatricians, rheumatologists, general practitioners (GPs) with a special interest in osteoporosis, trauma surgeons, anaesthetists, endocrinologists and trauma nurses. Initially, one person at each hospital was approached to complete the questionnaire, and further health-care professionals were identified if additional information was needed. To allow for clarification, the health-care professional completed the questionnaire in the presence of one of the research team. This enabled participants to elaborate on any of the more complex details of each component of care.

Comparison of services across hospitals

To allow direct comparison of service levels between hospitals, staffing levels were calculated as WTEs and as ratios in terms of the number of WTEs per 1000 hip fracture patients, using data on the number of hip fractures reported in the 2013 NHFD report. 17 For simplicity, we grouped all nurses working in fracture prevention (e.g. trauma nurse, osteoporosis nurse specialist) together under the title ‘fracture liaison nurse’. In addition, we identified and described variations in how the four main elements of a fracture prevention service (identification, investigation, initiation and monitoring) are co-ordinated and conducted.

Identification of key changes in service delivery

Information on changes in service delivery, such as the appointment of a new member of staff, the opening of a new ward or changes in procedures for referring patients for DXA scans, was assembled and presented to the study team, which included a number of clinicians. Together, the team identified the dates of the key changes to feed into the analysis in work stream 3. Once a list of changes was assembled for each hospital, the list was sent to a health-care professional at that hospital to ensure that they agreed with the changes that had been identified.

Results

Current disparity in fracture prevention across hospitals

Staffing levels across hospitals in 2013

Table 1 provides the WTEs and proportion of specialist staff per 1000 hip fracture patients at each hospital, including orthogeriatricians, fracture liaison nurses, falls nurses, lead clinicians and ‘osteoporosis champions’. This highlights the differences in staffing levels across hospitals. For example, two hospitals had no consultant-level orthogeriatric support, while one hospital had a full-time consultant orthogeriatrician in place supported by five WTE lower-grade orthogeriatric staff.

| Hospital | Specialist staff (levels expressed as WTE) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consultant OG | Other orthogeriatric support | FLN | Orthopaedic/specialist nurse | Lead clinician | |

| 1 | 0 | 0.5 WTE 2.3 : 1000 patients |

1 WTE 4.5 : 1000 patients |

0 | 1 (rheumatologist) |

| 2 | 1.0 WTE 2 : 1000 patients |

1 WTE 2 : 1000 patients |

0 | 0 | 1 (OG) |

| 3 | 0.1 WTE 0.3 : 1000 patients |

1 WTE 3 : 1000 patients |

0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0.5 WTE 1.3 : 1000 patient |

0.2 WTE 0.5 : 1000 patients |

0.5 WTE 1.3 : 1000 patients |

0 | 1 (rheumatologist) |

| 5 | 0.33 WTE 1.5 : 1000 patients |

0.6 WTE (trust-grade OG) 3.7 : 1000 patients |

0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | 0.5 WTE 2.1 : 1000 people |

0 | 0 | 1 WTE 4 : 1000 patients |

1 (rheumatologist) |

| 7 | 0.7 WTE 1 : 1000 patients |

0.75 WTE 1 : 1000 patients |

0 | 1.8 WTE 2.6 : 1000 patients |

1 (rheumatologist) |

| 8 | 1 WTE (1.6 : 1000 patients) |

5 WTE 8 : 1000 patients |

0 | 0 | 1 (OG) |

| 9 | 0 | 0.25 WTE 1 : 1000 patents |

0 | 2 WTE 8 : 1000 patients |

2 (specialist nurse-outpatient, orthopaedic surgeon-inpatient) |

| 10 | 0.9 WTE 2 : 1000 patients |

1 WTE 2 : 1000 patients |

1.6 WTE 3 : 1000 patients |

2.2 WTE 4.6 : 1000 patients |

1 (rheumatologist) |

| 11 | 0.4 WTE 2.3 : 1000 patients |

1 WTE 5.7 : 1000 patients |

0.2 WTE 1 : 1000 patients |

0 | 1 (OG) |

Several hospitals still had no fracture liaison or specialist nurses in post as of April 2013, while one hospital had 3.8 WTE of specialist nurses. When considering the number of hip fracture patients seen at each hospital, the variation in staffing becomes even more pronounced, with overall orthogeriatric staff ranging from 1 WTE per 1000 patients to 9.6 WTE per 1000 patients, and overall nursing staff ranging from zero input to 7.6 WTE per 1000 patients.

Co-ordinator-based models of care

Information was gathered on the role of orthogeriatricians and fracture liaison nurses in the fracture prevention service. It is clear that some hospitals operated a nurse-led model, in which nurses were responsible for case finding, osteoporosis assessment and making treatment recommendations. In other hospitals, such roles were performed by consultant orthogeriatricians. At some hospitals, specialist nurses such as orthopaedic nurses were essentially performing the role of a fracture liaison nurse despite no one officially being employed in that role. The majority of services were inpatient led only, with only a few services being integrated with outpatient care and, in some cases, also community care. One hospital operated a service which was mainly outpatient led.

The majority of hospitals followed NICE implementation guidelines, holding multidisciplinary team meetings on a regular basis to co-ordinate care between orthopaedics, rheumatology and any other departments involved in care. Some hospitals also used multidisciplinary paperwork, but only two hospitals reported conducting multidisciplinary ward rounds. Only one of the hospitals in the study demonstrated little co-ordination of care and a lack of agreed protocols and meetings with staff from other departments.

Case finding

Fracture liaison nurses or orthogeriatricians were generally responsible for undertaking case finding at most hospitals in an inpatient setting. When questioned about methods for case finding, most hospitals reported ward rounds and multidisciplinary team meetings as the most widely used methods. This interaction was often done informally by liaising with trauma and orthopaedic surgeons and other staff. At one hospital, health-care professionals attended joint trauma meetings which were followed by a joint trauma round that included an orthogeriatrician, an orthopaedic surgeon and a registrar 5 days per week. Computer systems were also important for logging trauma referrals and admissions, allowing staff to search the database for hip fracture patients. Nurses could then look at patient notes to distinguish low-impact, osteoporotic fractures from those caused by high-impact trauma using locally agreed criteria. Table 2 outlines some of the case-finding procedures used at the hospitals with varying methods.

| Hospital | Who? | How? | Patient groups |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | OG, orthopaedic surgeons, registrar | Preoperative joint trauma round, joint trauma meeting | All aged > 60 years with a fragility fracture |

| 9 | Osteoporosis nurse specialist | Referred for outpatient appointment | All inpatient hip fractures |

| 10 | FLN in liaison with OG | Computer system logs admissions and referrals | All aged > 50 years with a fragility fracture |

| 11 | FLN in liaison with OG | Postoperative ward rounds | All aged > 50 years with a fragility fracture |

Osteoporosis assessment

Most hospitals performed an initial inpatient osteoporosis assessment approximately 2 days postoperatively. In several hospitals this assessment was performed preoperatively and in some hospitals the timing of this could vary depending on the needs and condition of the patient, although other hospitals were less flexible. The assessments were performed by a fracture liaison nurse or by one of the orthogeriatric team. Protocols were in place at most hospitals for assessing the patient’s risk of further fractures and identifying other comorbidities which may influence treatment choice. When nurses conducted the assessment, they were often supported and advised by orthogeriatricians and rheumatologists in more complex cases. As shown in Table 3, two hospitals differed by undertaking the osteoporosis assessment in an outpatient setting, whereas the majority of other hospitals conducted theirs on the ward 2 days after surgery.

| Hospital | Who? | Where? | When? | Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rheumatologist | Outpatient appointment | Postoperatively | DXA report reviewed before deciding whether or not patient needs an assessment |

| 2 | OG | On ward and often in a second outpatient appointment | Preoperatively/early postoperatively | Pro forma for integrated care, FRAX® used in patients < 75 years Certain patients seen again by surgeons in outpatients |

| 8 | OG | On ward | 2–3 days postoperatively | Protocol in place, bloods often done in A&E |

| 9 | Osteoporosis nurse specialist | Outpatient appointment | Postoperatively | 15-minute appointment using FRAX® tool |

These outpatient assessments also varied in length and content; in one case a rheumatologist gave all patients a 30-minute assessment, in the second hospital the assessment was performed by an osteoporosis nurse specialist and lasted 15 minutes except in more complex cases when longer appointments could be given.

All hospitals reviewed in this study referred patients < 75 years of age for a DXA scan and initiated treatment without a scan in those > 75 years, in compliance with NICE guidelines. 13 Patients were often referred for a scan by the same clinician who undertook the osteoporosis assessment, although in two cases these referrals had to be approved separately by the rheumatology department. In another case, a clinician made a recommendation for a DXA scan on a patient’s notes and it was left to junior members of the team to follow up on this. At one hospital, a pro forma letter was sent to the patient’s GP, which had to be signed by the GP for DXA referral.

At most hospitals, DXA scanners were located off site, either at a different hospital or at a community hospital, while in several cases DXA scanners were provided by private companies. Scans were performed at varying times post discharge, ranging from 2–3 weeks to 8–12 weeks for an appointment. Only one hospital had a DXA scanner on site and was able to scan patients as inpatients providing that they were well enough.

The DXA reports were usually sent to the clinician responsible for making treatment recommendations, including orthogeriatricians, rheumatologists, fracture liaison nurses and GPs. In most cases, results were communicated to GPs as well as hospital staff.

Falls assessments and prevention

All hospitals provided a falls risk assessment alongside the initial osteoporosis assessment. Hospitals also had various other services available for more comprehensive multifactorial risk assessments looking at cognitive, physical and environmental risk factors such as balance and gait and hazards around the home. If necessary, patients were referred to other specialty clinics if they suspected there was an underlying medical condition putting them at risk of falling. Some hospitals ran a falls clinic in their outpatient department, while one hospital undertook a full assessment of patients while they were inpatients, which began on admission and was conducted by a multidisciplinary falls team. This hospital offered a very comprehensive service, with a specialist falls nurse and a falls champion on each ward. Table 4 shows how the nature, timing and location of the assessment varied across the hospitals studied.

| Hospital | Inpatient assessment | Further assessments |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Community falls prevention service in place but it is unclear if hip fracture patients are accessing this service | |

| 2 | Assessed by OG, occupational therapist and physiotherapist | Patients may be referred for outpatients appointment for physiotherapy or to community occupational therapists |

| 6 | Assessed by senior nurses, physiotherapists and occupational therapists | Geriatricians have a falls clinic in outpatient department for more formal assessment, which is rarely needed as the ward assessment is so comprehensive |

| 10 | 20-minute ward assessment by FLN | If necessary, patients are referred to one of several community hospitals around region for 1.5-hour assessment by a physiotherapist. Patients may even be seen in their own home |

Treatment initiation

At 8 out of the 11 hospitals, osteoporosis treatment was prescribed within inpatients for those aged > 75 years in line with NICE guidelines. 13 Orthogeriatricians were generally able to make treatment recommendations and prescriptions. Fracture liaison nurses were also able to make treatment recommendations in some cases, and these were written up in patient notes and later prescribed by doctors. At one hospital in which the fracture prevention service was mainly run in an outpatient setting, an osteoporosis nurse specialist made treatment recommendations and sent these to the patient’s GP, who was left to initiate treatment.

For those aged < 75 years who had received a DXA scan, treatment was initiated in outpatient clinics or delegated to primary care pending the results of the DXA scan. This also applied to patients who were unable to commence treatment as inpatients for other reasons. Treatment recommendations were usually communicated to GPs via a discharge summary.

Monitoring and treatment adherence

Seven of the 11 hospitals reported undertaking monitoring of patients after discharge in a secondary care setting. Methods for monitoring included telephone calls and questionnaires to check how patients were getting on with their medication. One hospital offered a follow-up appointment 6 weeks post discharge at a fracture clinic run by an orthogeriatrician to those patients who were discharged to their own home. However, most hospitals referred patients to an outpatient clinic only if there were more serious complications, such as fractures while on treatment, or if the patient was severely osteoporotic. At the remaining hospitals, all monitoring was delegated to primary care.

Changes in service delivery at hospitals in the past decade

The changes in service delivery at each hospital are summarised in Table 5. These were identified through the service evaluation questionnaire, with additional information supplemented from the qualitative work. Members of the project working group agreed on the key changes that had occurred based on the data collection, with significant input from clinicians around what factored as a key change.

| Hospital | Date | Change |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | November 2012 | FLN appointed |

| 2 | May 2005 August 2007 |

OG appointed Second OG appointed. Metabolic bone clinic started conducting falls assessments |

| 3 | June 2011 | OG and matron for hip fracture unit appointed |

| 4 | 2006 May 2009 2011 |

OG appointed FLN appointed (began doing falls assessment in June) Community rehabilitation introduced |

| 5 | September 2009 | Trust-grade OG appointed |

| 6 | November 2005 2011 |

OG appointed Trauma specialty nurse appointed |

| 7 | July 2004 June 2007 October 2007 |

Geriatrician appointed, hip fracture ward opened A second trauma specialty nurse appointed Specialty doctor in geriatrics appointed |

| 8 | March 2009 | Clinical lead OG appointed |

| 9 | November 2003 April 2005 2009 |

Orthopaedic nurse specialist appointed Osteoporosis nurse specialist appointed Staff-grade OG |

| 10 | December 2004 May 2006 May 2008 November 2009 November 2011 |

FLN appointed FLNs and consultant lead appointed, comprehensive trauma FLNs appointed Consultant OG appointed New monitoring pathway and two geriatricians appointed |

| 11 | February 2011 November 2011 |

Consultant geriatrician appointed FLN appointed |

Looking specifically at how WTE of specialist staff changed between 2003 and 2013 (Table 6), we see a general increase in the number of consultant orthogeriatricians and specialist nurses across most hospitals in the region, reflecting new guidelines for both optimal recovery after hip fracture and secondary fracture prevention introduced during this period.

| Hospital | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ||||||||||

| OG | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| FLN | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4.5 |

| 2 | ||||||||||

| OG | 0 | 0 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| FLN | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | ||||||||||

| OG | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| FLN | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | ||||||||||

| OG | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| FLN | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| 5 | ||||||||||

| OG | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 4.5a | 4.5 | 4.5 |

| FLN | 8.8 | 8.8 | 8.8 | 8.8 | 8.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | ||||||||||

| OG | 0 | 0 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.1 |

| FLN | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| 7 | ||||||||||

| OG | 0 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 |

| FLN | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.6 |

| 8 | ||||||||||

| OG | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 | 1.6 |

| FLN | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 9 | ||||||||||

| OG | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| FLN | 0 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| 10 | ||||||||||

| OG | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| FLN | 3 | 3 | 1.9 | 3 | 3 | 3b | 3 | 3 | 3 | 7.6 |

| 11 | ||||||||||

| OG | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2.3 |

| FLN | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

Discussion

Description of current services

In conducting a service evaluation designed to look at changes in service delivery at a set of hospitals over the past 10 years, a number of observations were noted. Although there has been an overall increase in service provision in terms of both orthogeriatric and fracture liaison nurse appointments, a considerable variation remains in how fracture prevention services at 11 NHS hospitals in one region of England are organised. The largest disparities were in how the service was run (an inpatient service vs. an outpatient service) and in the levels of staffing provided for the FLS service. Some hospitals had only a consultant-led service in order to improve perioperative care of fracture patients, whereas other hospitals had a nurse-led service to tackle fracture prevention. Few hospitals have both a fracture liaison and orthogeriatric service, as is recommended by CGs. 1,13,15,29

Details on staffing levels across hospitals were already provided by the NHFD; however, this evaluation showed that the role of certain staff members such as orthogeriatricians also varied between hospitals in terms of their role in case finding, osteoporosis assessment, treatment initiation and monitoring. In some cases, these roles were actually performed by more junior members of staff. Although some hospitals reported having an orthogeriatrician in post, their role in fracture prevention may be extremely limited.

Changes in service models

The previous decade has demonstrated marked increases in the provision of both orthogeriatric and/or FLS nurse staff in each of the hospitals. Only in one hospital was a service discontinued. However, the increase in service provision is variable, with little relationship to the number of hip fracture patients. By the end of the period of observation, the number of orthogeriatric staff per 1000 hip fracture patients varied from 0 to 4.3. The equivalent number of FLS nurses to numbers of hip fractures varied from 0 to 9.3. This variability is greater than one would expect for local differences in NHS structure or patient case mix and again demonstrates the need to relate service investment with clinical effectiveness in order to demonstrate the relative value of such services.

Strengths and limitations

A major strength of this evaluation is the heterogeneity of NHS hospitals examined, from smaller district general hospitals to large tertiary major trauma centres, adding to the generalisability of the report’s findings. A limitation is the reliance on clinicians’ recall and understandings of events over the last decade. Although human resources departments can confirm the appointment of new staff, changes may often come about by alterations in the role and responsibilities of existing staff members.

Summary

Although this work stream initially set out to look at changes in fracture prevention services at hospitals in the past 10 years, an important outcome of this work was the detailed description of where similarities and differences in care pathways between different hospitals lay. In addition, this work highlights where gaps have existed in the care provided at one hospital, compared with others in the region.

The work so far provided an overview of the variations in models of care provided by hospitals in one region of England. There is more variability in service provision than can be accounted for by local variations, highlighting the need to link investment in these specialist posts with patient outcomes and effectiveness.

Chapter 3 Identifying the reasons why hospitals chose their specific model of service delivery and assessing barriers to change

Introduction

In this chapter, we present findings from the qualitative component of the study. This had three initial aims: (1) to find out how and why hospitals adopted their models of care; (2) to identify how secondary fracture prevention services can be successfully implemented, with a focus on barriers and enablers to change; and (3) to identify the elements of care that health-care professionals think are most effective. These three aims were addressed using concepts from extended Normalisation Process Theory (NPT) to provide a theoretical basis. In addition, because the process of business case development was a key issue in fracture service planning and delivery, we aimed to describe the experiences of clinicians and service managers of making business cases for FLSs.

This chapter provides a brief background to the qualitative study, describes the methods used and presents our findings. Our findings and discussion will be presented in two parts. Part 1 presents findings relating to the first three aims about how and why secondary fracture prevention services can be successfully implemented in secondary care, and we discuss the place of these findings in relation to current knowledge. Part 2 then describes findings relating to the fourth aim, focusing more specifically on the experiences of clinicians and service managers of making business cases for a FLS, and discusses these in relation to the current literature. After the two findings and discussion sections, we present the study’s strengths and limitations and a concluding section.

Background

Chapter 1 demonstrated that there is considerable variation in how fracture prevention services are organised and delivered in the region. 39 Despite findings from a number of national and international studies that demonstrate the efficacy of FLS,36 only 40% of hospitals in the UK deliver this service. 40 To date, no study has explored how best to implement these services or make effective business cases to obtain funding.

Implementation of complex interventions

The implementation of complex interventions is increasingly being studied using implementation theory. 41 Implementation research comprises a number of approaches and theoretical stances in order to help understand something of the complexity of change within health services. One such theory, extended NPT42 – which builds on two previous theoretical models, the Normalisation Process Model43 and NPT44 – describes how the collective actions of agents drives the implementation of new services. This provides a counterpoint to network perspectives whereby the implementation of innovations is viewed as a process of transmission and stabilisation through networks,45,46 and psychological perspectives that prioritise the role of individuals in instigating change. 47,48 The theory builds on previous iterations of the theory by combining the notion of implementation as a social process with psychological and network approaches to increase our understanding of the phenomena.

Extended Normalisation Process Theory

According to the theory, the successful implementation of an intervention is based on the ability of agents to fulfil four criteria, described using constructs. 42 These are outlined in Table 7.

| Construct | Description |

|---|---|

| ‘Capacity’ | Implementing an intervention depends on participants’ capacity to co-operate and co-ordinate their actions |

| ‘Potential’ | Translating capacity into action depends on participants’ commitment to operationalise the intervention |

| ‘Capability’ | The capability of participants to enact the intervention depends on its workability and integration into everyday practice |

| ‘Contribution’ | The implementation of an intervention over time depends on participants’ contributions to enacting it by investing in meaning, commitment, effort and appraisal |

Making business cases for a fracture liaison service

A potential barrier to the implementation of FLSs is the challenge of making effective cases to obtain funding. 32 Funding for the commissioning of new services is obtained by writing business cases and presenting them to managerial bodies in the trust. These cases may be developed by a range of professionals. Central to this process are the clinicians and service managers working within the department. Finance managers are also involved in costing developments and calculating their potential income generation. Clinicians and service managers from other departments may also have a role, along with patient representatives. If supported, these may be referred to local Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) for final funding approval, especially in the case of larger-scale service developments.

Commissioning (purchasing) processes within the NHS are complex. In April 2013, responsibility for commissioning services changed from the Department of Health and local primary care trusts (PCTs) led by managers, to NHS England, a new organisation overseeing 211 GP-led local CCGs. These currently control 65% of the NHS budget and operate within defined geographical regions. The rationale of this restructure is that GPs are best placed to understand the clinical needs of the local population and are therefore able to utilise resources most effectively. 49 The introduction of CCGs has coincided with a rise in the number of foundation trusts in England. Foundation trusts are independent organisations responsible for providing over half of NHS hospital, mental health and ambulance services operating in local regions. They are contracted to deliver services that have been commissioned by local CCGs and NHS England and are regulated by an independent body called Monitor. A board of directors is responsible for setting budgets for the financial year and establishing targets and health-care priorities. 50

Commissioning has been targeted by the Department of Health as a means of raising standards in the NHS and ensuring that resources are evenly distributed. 1 The NHS Commissioning Board states that funding decisions should be systematic and transparent and that considerations should include cost-effectiveness, improvements in care quality and the strategic plans of NHS trusts. 51 Core public health priorities, prioritising the distribution of resources in key disease areas, have also been identified. 52

There is some support available for clinicians and service managers on how to develop business cases for a FLS. This includes written guidance,32,53 training courses54 and business case templates. 55 According to this support, business cases should describe the health profile of the population, including the numbers of fractures, outline service design with reference to established fracture prevention guidelines, outline costs, particularly how the service will generate savings,55 and utilise a number of different stakeholder groups. 32 More general guidance on the processes of designing services and making business cases also exists and some CCGs have developed business case templates to assist in this process. 56

Several studies have explored the experiences of commissioners of making purchasing decisions in the UK, including those operating under the now abolished PCTs57,58 and the CCGs. 59,60 These have examined relational aspects of commissioning57,61,62 and identified factors that impact on decision-making. 58,63 Recent research has also explored the new roles of GPs in the commissioning process. 64,65 However, only one study has explored the experiences of providers in acute care of making business cases. 66

Aims

This study enabled us to understand how secondary fracture prevention services can be effectively organised and successfully implemented in secondary care to help to inform the implementation and integration of these services into practice. It also provided information about experiences of business case development for FLSs and suggestions for effective strategies for health-care professionals and service managers about how best to develop business cases for FLSs in the future.

Methods

Sample

The sample comprised 43 professionals from all 11 hospitals in one region in England who were involved in the delivery or organisation of secondary fracture prevention after hip fracture. These included orthogeriatricians, fracture prevention nurses, trauma nurses, hospital practitioners in osteoporosis, surgeons and service managers. Participants were purposively sampled to include a range of characteristics such as profession and years in role and to ensure that they were adequately drawn from each of the 11 hospitals. 67

Potential participants were identified by the clinical lead/champion in osteoporosis and an operational service manager in trauma. In three waves of recruitment, the study team approached potential participants by e-mail to provide them with a brief overview of the study, including a participant information booklet for further information. If no response was received within 2 weeks, the e-mail was followed up with a telephone call. Snowball sampling68 was used such that participants recommended other professionals involved in fracture prevention. In total, 82 health-care professionals were contacted to take part in the study, of whom 43 agreed to take part. The remainder either declined or were unavailable. Rather than us aiming to achieve saturation,69 criterion sampling was applied to ensure an adequate range of professionals to enable us to address the issues under study. 70

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was provided by the University of Oxford’s Central University Research Ethics Committee in 2012, reference number MSD-IDREC-C1-2012-147. Each NHS trust involved provided research and development approval. Participants all provided their written consent prior to interview. This consent process emphasised the aims of the research and that participation was voluntary. Participants were also asked to provide their consent to audio-recording and to the inclusion of anonymous quotations in study publications.

Interview procedure

A qualitative researcher (Sarah Drew) undertook interviews in 2013. All interviews except one were conducted face to face at the participants’ workplaces; one interview took place by telephone. Interviews were between 30 and 50 minutes long. A topic guide (see Appendix 2) was used to help to ensure that similar questions were asked of all participants. The topic guide was structured into three areas. The first topic area was based on the four core elements of a fracture prevention service outlined by the IOF as part of the Capture the Fracture initiative. 34 This helped the researcher to explore participants’ views on the best models of care for the secondary fracture across the four main components of a fracture prevention service and co-ordination of care. The second area covered in interviews was structured around the four constructs of extended NPT to enable exploration of participants’ experiences of implementing fracture prevention services. The third area explored in interview was participants’ experiences of making business cases for a FLS, factors that they felt informed the decision of commissioners to approve the new service and what they considered to be the best strategies for making them. The interviewer used standard qualitative interview methods such as ‘probing’ to help achieve depth in the interviews. 71 After the first four interviews we revisited the topic guide and made amendments to it to ensure that it enabled us to successfully explore the issues under study. The topic guide shown in this report is the final topic guide used in the study. All interviews, including the first four pilot interviews, are included in the final data set.

Data analysis

Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed, anonymised and imported into the qualitative data analysis software NVivo (QSR International, Warrington, UK). Analysis took place in two parts. Part 1 used coding and an abductive approach to address how and why secondary fracture prevention services can be successfully implemented in secondary care using extended NPT to provide theoretical basis to the analysis. Part 2 was an inductive thematic analysis, albeit that it was focused on exploring participants’ experiences of making business cases for a FLS, factors that they felt informed the decision of commissioners to approve the new service and what they considered to be the best strategies for making them.

Part 1: how and why secondary fracture prevention services can be successfully implemented in secondary care using extended Normalisation Process Theory

Analysis was undertaken using an abductive approach. 72 This involved initial thematic analysis, which comprised inductive coding of data to identify themes and subthemes in the responses. 73 Coded data were then transposed onto the four constructs of extended NPT. In order to compare and contrast participants’ responses, data were then displayed on charts using the framework approach to data organisation. 74

Part 2: exploring participants’ experiences of making business cases for a fracture liaison service

Data were analysed using a thematic approach to identify themes and subthemes in the responses. 73 A framework approach to data organisation was also applied here to facilitate cross-comparison of responses. 74

In both parts of the analysis, 20% of the interview transcripts were independently coded by another member of the team (RG-H) and codes were compared and discussed to arrive at a single code list which was refined as the analysis progressed. 75 Descriptive accounts of the data were then generated and discussed.

Results

The sample comprised five service managers and 38 health professionals: eight fracture prevention nurses, four orthogeriatricians, four geriatricians, two GP osteoporosis specialists, five consultant trauma orthopaedic surgeons, eight rheumatology consultants, two orthopaedic nurses, one trauma matron, one matron for the hip fracture unit, one falls co-ordinator, one falls nurse, one bone densitometry specialist. Between three and seven participants from each hospital took part in the study. The range of time spent in their current roles ranged from < 1 year to 32 years. Time spent working at the hospital ranged from < 1 year to 27 years. Of the 43 participants, 33 had experience of making business cases for a FLS and only these participants have been included in the second part of the analysis. Participants’ key characteristics are displayed in Table 8, but we present summarised information only in order to avoid the potential for identification of participants.

| Professional group | Number of participants | Years spent working in current roles (range) | Years spent working at the hospital (range) | Number of these participants who had experience of making business cases for a FLS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fracture prevention nurses | 8 | 1–15 | 1–27 | 5 |

| OGs | 4 | 4–13 | 4–16 | 4 |

| Geriatricians | 4 | 3–21 | 2–6 | 4 |

| GP osteoporosis specialists | 2 | 10–43 | 10–20 | 2 |

| Consultant trauma orthopaedic surgeons | 5 | < 1–32 | 2–19 | 3 |

| Rheumatology consultants | 8 | 5–25 | 5–25 | 6 |

| Additional nursing staff (orthopaedic nurses, trauma matrons, matrons for hip fracture units) | 4 | 3–14 | 3–25 | 3 |

| Falls co-ordinators | 1 | 1 | 20 | 0 |

| Falls nurses | 1 | 23 | 23 | 0 |

| Bone densitometry specialists | 1 | 11 | 12 | 1 |

| Service managers | 5 | 2–6 | < 1–5 | 5 |

Findings and subsequent discussions from the two parts of the study are presented in the following sections.

Part 1: using extended Normalisation Process Theory to understand how and why secondary fracture prevention services can be successfully implemented, barriers and enablers to change and elements of care seen as most effective

Findings

A summary of the themes identified and their relation to the four main constructs of extended NPT are outlined in Table 9.

| ‘Capacity’ | ‘Potential’ | ‘Capability’ | ‘Contribution’ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Role of dedicated fracture prevention co-ordinator | High levels of support for introducing service | Fracture prevention co-ordinators ‘freeing up’ professionals previously engaged in care | Multidisciplinary team meetings |

| Multidisciplinary paperwork: protocols and pro forma records | Lack of support for introducing service from some professionals | Lack of time to deliver intervention | Clinical databases |

| Multidisciplinary teamwork: multidisciplinary team meetings, joint ward rounds | Relationships between different professional groups | Lack of capacity to administer DXA scans | Internal monitoring systems |

| Positive working relationships | Multidisciplinary team working | Challenges faced by service users in accessing services | External monitoring systems linked to funding |

| Location of professionals close to the service and each other | Role of fracture prevention co-ordinator | ||

| Challenge of securing co-operation and communication with GPs | Varying commitment from practitioners in primary care | ||

| High workload in primary care impacting on time spent implementing intervention | |||

| Written communication with GPs, especially discharge summaries and DXA reports | |||

| Potential role of fracture prevention co-ordinators in primary care |

Health-care professionals’ views about issues that affect the implementation of services using the four constructs of extended NPT are presented in more detail below.

Capacity

Implementing the service depends on participants’ capacity to co-operate and co-ordinate their actions.

Participants’ capacity to co-operate and co-ordinate their actions was achieved by using dedicated fracture prevention co-ordinators who organised important processes of care and oversaw the delivery of the service. The presence of co-ordinators was seen as a key element in effective interventions because they managed the relationships between different professional groups to ensure that they were aligned with the aims and objectives of the service. Co-ordination was achieved using ‘multidisciplinary paperwork’, such as protocols and pro formas, that meant information was accessible and shared between participants. Multidisciplinary working such as multidisciplinary team meetings also facilitated communication, enabling the team to discuss patients and jointly develop policy. As a result of these factors, co-operation between participants in secondary care was high.

The physical location of professionals in relation to the centre of the service influenced the levels of communication and enthusiasm for the intervention. Participants’ capacity to co-operate and co-ordinate with GPs was, therefore, viewed as challenging. Additional factors that were seen to impact on GPs’ investment in the intervention included the lack of reimbursement for delivering fracture prevention services in relation to other conditions, and high workloads. To facilitate communication, participants suggested improving written communications such as discharge summaries and DXA reports. However, participants also recognised the limitations of these strategies. Introducing fracture liaison nurses into the community was suggested as a means of providing advice and guidance to GPs and overseeing the implementation of services in primary care. Quotations from participants supporting these findings are included below.

[As the fracture prevention co-ordinator] I’m the key link in it all to be honest; it’s very much me who kind of sits in the middle really. I will link out to anybody any service that the patient needs.

Participant identification (ID): 002

[The fracture prevention team] have a separate Monday morning meeting as well to discuss every patient individually. So I think because of that there is a lot of communication both verbally and written as well, so I don’t think we have any issues there at all.

Participant ID: 003

The meetings that we attend [are useful as] you kind of gain a mutual professional respect.

Participant ID: 004

There’s not been a huge amount of engagement with primary care . . . they seem to be very – two separate camps: there’s what actually happens in trauma and then there’s what happens in primary care, and the communication is difficult.

Participant ID: 009

GPs get probably 400 or 500 letters a day, do they read everything? Hopefully they do.

Participant ID: 035

GPs are fantastic, but how can they be experts and know everything . . . and that’s why I think we have a duty to them and to our patients to inform appropriately.

Participant ID: 042

Potential

Translating capacity into action depends on participants’ commitment to operationalise the fracture prevention service.

Professionals were enthusiastic about the introduction of services, and such enthusiasm enabled services to be started and to continue to deliver effective care. Participants described having considered services to be necessary before they were implemented and identified the importance of a ‘strong lead’ in the introduction of a new service. Counter to this, they often characterised less supportive professionals as ‘difficult’ and ‘obstructive’ potential barriers to implementation. It was clear that, in some cases, opposition of colleagues to the introduction of a new service was founded on the complex, hierarchical relationships between different professional groups. However, as these individuals were a minority, their presence was not seen as presenting an insuperable barrier to implementation.

In addition, continued commitment of the multidisciplinary team to enacting the intervention was enabled and facilitated by the fracture prevention co-ordinators who managed different professional cultures within the multidisciplinary team, and ensured that their aims and objectives were aligned. One of the main challenges encountered was the sense that GPs were not as committed to the enactment of the intervention. Quotations from participants supporting these findings are included below [quotations reproduced with permission from Drew S, Judge A, Cooper C, Javaid MK, Farmer A, Gooberman-Hill R. Secondary prevention of fractures after hip fracture: a qualitative study of effective service delivery. Osteopors Int 2016;27:1719–27, under a Creative Commons licence (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/legalcode)].

I mean we were so desperate for it that we bent over backwards to make it work. I mean it was never a problem in the sense that if it’s a service you’ve been asking for a very long time, if someone finally provides it you’re going to make sure it works and give that individual as much support as they need to come into the system.

Participant ID: 001

So there’s some people who historically are the ones that are resistant to change are just dissatisfied, disgruntled, have lost enthusiasm, just mistrust, have become jaded with the system . . . Sometimes it can be very obstructive.

Participant ID: 006

I think those particular individuals probably looked down on geriatricians and so they didn’t like it that a geriatrician was coming and saying . . . this is when you operate and they didn’t like being told what to do.

Participant ID: 005

It’s just about encouraging people to know that they all have a role, we all have a responsibility to deliver the quality care and all of us are important in making that so. You know each of you can’t do it without the other and it’s actually about ownership and responsibility.

Participant ID: 026

It needs a strong lead, it needs a me or equivalent of me really . . . In terms of the orthopaedic team, you know you’re working with orthopaedic nurses so it’s a different culture set . . . So you need to sort of pull in the ethos.

Participant ID: 026

I think the amount of interest from general practice is variable and I think the variability to be honest on the whole is average if you’re lucky. And I think there isn’t an engagement I don’t feel, in the majority of primary care, and ownership of secondary prevention fracture.

Participant ID: 027

Capability

The capability of users to enact the components of a fracture prevention service depends on those components’ potential for workability and integration into everyday practice.

Participants saw the workability and integration of services into everyday practice as high when FLSs provided a new layer of service provision. Their presence freed up the capacity of other professionals previously responsible for undertaking this role and otherwise did not change the content of their work. However, there were also considerable barriers to implementation. Participants viewed some services as under-resourced and understaffed, which limited the time they were able to dedicate to effective patient care. Administrative and communications work was described as particularly time-consuming. Participants also felt that clinicians lacked equipment to deliver certain aspects of patient care, and this sometimes included poor access to DXA scanners. Finally, the organisation and delivery of these services presented patient barriers to access. For instance, participants felt that some patients struggled to reach services because of difficulties with public transport; this was particularly problematic for patients living long distances away. Transport costs were also seen as a barrier for patients with limited financial resources. Quotations from participants supporting these findings are included below [quotations reproduced with permission from Drew S, Judge A, Cooper C, Javaid MK, Farmer A, Gooberman-Hill R. Secondary prevention of fractures after hip fracture: a qualitative study of effective service delivery. Osteopors Int 2016;27:1719–27, under a Creative Commons licence (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/legalcode)].

[The introduction of the service was not that difficult because] the model is that [the fracture prevention co-ordinators] just come in and do everything. So we’re not asking other people to do much else for hip fracture . . . We’re not even asking the trauma team to identify the hip fractures because the fracture liaison service is basically doing everything.

Participant ID: 007

I think there are obviously different demands on people’s time which sometimes means care is delayed.

Participant ID: 018

There is one orthogeriatrician who does all that work but of course she can’t be here 24 hours a day, 7 days a week so there have been some patients who will occasionally come through and slip through the net.

Participant ID: 001

We do at least 3500 scans a year with one scanner and two people . . . We have to meet the government targets, the 6-week diagnostic targets and we are just about making those targets with difficulty.

Participant ID: 025

Our biggest barrier is obviously the fact that we have to drag our patients from [another town] down to [the city] . . . So I guess it’s a demographics and the location in relation of distance travelled, that means sometimes people are reluctant [to attend].

Participant ID: 004

Contribution

Participants’ contributions to enacting a fracture prevention service depend on them investing in meaning, commitment, effort and appraisal.

Fracture prevention co-ordinators did not change the clinical work that was undertaken. Rather, their introduction changed the way the work was organised and delivered. Multidisciplinary meetings were used to sustain the potential and capacity of professionals involved in service delivery.

Clinical databases also enabled providers to deliver services over time as databases helped to define individual roles and ensured that work was not duplicated. Poor data quality presented difficulties, making it challenging for providers to consistently identify patients with hip fracture and to deliver clinical practice. Such data also presented obstacles to monitoring outcomes and this was seen as playing a vital role in ensuring that work was carried out to high standards over time. Monitoring operated in two ways. First, it enabled clinicians within the service to assess levels of adherence to bone protection therapies and evaluate service delivery, allowing them to reconfigure services if necessary. Second, it was a means of linking activity to funding mechanisms such as the Best Practice Tariff76 and Quality and Outcomes Framework77 in primary care, which potentially provided an important impetus for sustaining and developing high-quality services. The respective influence of these funding mechanisms was described as variable. Although participants saw the Best Practice Tariff as useful to provide financial benefit, they saw the Quality and Outcomes Framework as less valuable because it did not. Quotations from participants supporting these findings are included below [quotations reproduced with permission from Drew S, Judge A, Cooper C, Javaid MK, Farmer A, Gooberman-Hill R. Secondary prevention of fractures after hip fracture: a qualitative study of effective service delivery. Osteopors Int 2016;27:1719–27, under a Creative Commons licence (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/legalcode)].

I can modify [the guidelines for assessment] how I want to. You know because it doesn’t work perfectly at the beginning and things change and you know the hospital and the government introduce new requirements so you have to modify your form.

Participant ID: 017

It depends which doctors have been on the night before as to how much has been put onto [the computer system] . . . some of it turns out to be rubbish.

Participant ID: 010

[Auditing] it would be helpful because if you know what your compliance rate is you know whether or not you’re having an impact. So if you’ve got a service whereby you’re suggesting that they have a treatment and then it turns out that no one actually takes these, well then why are you wasting your resources on trying to you know.

Participant ID: 024

We have a score card so we can get all the compartments of the Best Practice Tariff . . . so we keep a track of what things are, which things are going well, which things we are not performing very well and obviously look for the reasons for any shortcomings.

Participant ID: 012

Discussion

The study used extended NPT42 to understand how and why hospitals adopted their models of care for the prevention of secondary fractures after hip fracture and identify how secondary fracture prevention services can be successfully implemented, with a focus on barriers and enablers to change and the elements of care that health-care professionals think are most effective. With regard to successful implementation, professionals’ capacity or levels of communication and co-operation were influenced by their distance in relation to the centre of the service. As a result, communication with GPs was viewed as challenging. Potential or enthusiasm for enacting the intervention was generally high, although participants identified exceptions. Shared commitments were facilitated by multidisciplinary team working. However, GPs were seen to be less committed to delivering fracture prevention.

Introduction of fracture prevention co-ordinators was advocated because their inclusion enhanced professionals’ capability to deliver the service, ‘freeing up’ other members of the team who had been previously responsible for this role. As a result the service could be easily integrated with existing services and the involvement of co-ordinators was seen as central to effective services. In addition, enthusiasm and leadership of professionals enabled services to be implemented and was a key reason for the introduction of new services. However, a lack of time and equipment and the challenges of accessing the services for some patients hindered implementation and had the potential to reduce the effectiveness of services for patients. Participants identified strategies to facilitate the delivery of the service over time, and they saw that good delivery was seen across the key elements of effective care. Strategies included multidisciplinary team meetings, clinical databases recording aspects of patient care, and monitoring to enable professionals to adapt and change the service when necessary.

Relationship to current literature