Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 11/2000/05. The contractual start date was in October 2012. The final report began editorial review in October 2015 and was accepted for publication in March 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Claire Hulme is a member of the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment Commissioning Board.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Closs et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Dementia and pain are common and poorly managed

It has been estimated that 44.4 million people worldwide have dementia,1 including 670,000 people in England, and that one in three people aged > 65 years will develop the condition. 2 Dementias are chronic neurodegenerative syndromes that are most common in older people. They include Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia and frontotemporal dementia,3 and are associated with multiple changes in the brain, causing deterioration in cognitive performance as well as changes in behaviour, personality and communicative functioning. 4,5 Pain is also common among older people, with 45% of people aged > 65 years experiencing chronic pain. 6 A national study in the USA suggested that > 10% of people in the community aged > 65 years have dementia and that, of these, over 60% experience bothersome pain and more than 40% have pain that limits their activities. 7 In the UK the Care Quality Commission (2014)8 investigated people’s experiences of dementia care as they moved between care homes and hospitals, and found that the inability to communicate about pain was one of the most important experiences reported by people and their families. They found that assessments to identify and manage pain were variable, putting people with dementia at risk unnecessarily. 8 The identification and treatment of pain has frequently been poor among people with dementia in both acute9,10 and long-term settings. 11–13

The policy context

The policy imperative for this work is considerable. In England, the 5-year National Dementia Strategy14 (implemented in 2009) prioritised the need to improve the quality of care for people with dementia in general hospitals (objective 8). Then, in 2015, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) published a dementia pathway that emphasised the importance of recognising and treating pain. 15 In addition, two sets of national guidance have been published, one for assessing16 and another for managing17 the pain of older people, each of which considers issues related to cognitive impairment in this group. Although these are useful additions to the information available for clinicians, we do not yet know how to assess and manage the pain of people with cognitive impairment effectively, particularly in acute settings.

The impact of dementia on the experience and expression of pain

Patients with advancing dementia sustain progressive impairments in their cognitive, linguistic and social skills. Nevertheless, they are susceptible to the same potentially painful conditions as those without dementia, and there is little evidence to suggest that they experience less pain than their counterparts without cognitive impairment. 18 While they may experience pain, they may be unable either to understand what they are feeling or to verbalise that they are (or were) in pain. This makes it impossible for health-care professionals (HCPs) to rely on the clinical ‘gold standard’ of self-report for assessing pain in those who are severely cognitively impaired. For those who still have the ability to communicate, their inability to remember, interpret and respond to recent pain may limit their reports to ‘here and now’ experiences. 19

As 88–95% of people with dementia have difficulties with verbal communication,20,21 the recognition and assessment (and therefore management) of pain in this group is a significant challenge for those caring for them. The lack of appropriate pain management may then lead to functional decline, slow rehabilitation, disturbances in sleep routine, depression, agitation, poor appetite, impaired movement, increased risk of falling and a poorer quality of life. 22–24

Pain in hospital patients with dementia

It has been estimated that the cost of health care for people with dementia is around £1.2B, of which hospital inpatient stays account for 44%. 25 Dementia increases the length of hospital admission by an average of 4 days to > 23 days,26,27 resulting in an increase in complications28 and the risk of iatrogenic harm through polypharmacy. 29

An acute hospital ward may be a disorienting and distressing environment for a person with dementia due to heightened/unescapable noise, bright lighting and unfamiliar staff and surroundings. A study undertaken in one UK hospital showed that 95% of patients with advanced dementia were in pain as assessed using three observational pain tools [Abbey Pain Scale, Pain Assessment Checklist for Seniors with Limited Ability to Communicate (PACSLAC) and the Doloplus] as part of a randomised controlled trial in palliative care. 30 Research suggests that hospital patients with dementia are less likely to receive pain control than those without. 31

Poor pain control in the context of the acute environment is associated with neuropsychiatric symptoms, particularly aggression and anxiety,32 as well as behavioural responses such as agitation, vocalisations and withdrawal. 33 Neuropsychiatric symptoms affect over 75% of people with dementia admitted to acute hospitals and can increase the risk of mortality and cognitive decline. 34 Neuropsychiatric symptoms are particularly challenging for clinical staff to manage, and are often associated with suboptimal care or inappropriate prescriptions of antipsychotic medications. 35 Consequently, people with dementia are at higher risk of adverse events during their hospital stay36 and are more likely than their counterparts without cognitive impairment to spend an extended time in hospital. 37–39

There are no behaviours which are exclusively associated with pain, increasing the difficulty of identifying its presence. In people with dementia, many behaviours generally considered to indicate pain may also indicate boredom, hunger, depression, disorientation or other problems. 40 These behaviours lack specificity, some observational pain assessment tools may detect distress as well as pain, and there may be overlap between the two.

As it has been estimated that in general hospitals the prevalence of dementia on acute wards is around 40%,41,42 and more than 45% of those aged > 65 years have chronic pain,6 it is inevitable that hospital staff will regularly provide care for the substantial number of patients who suffer from both of these invisible but highly debilitating conditions. For clinical staff the challenge of interpreting the behaviour of the many patients who have both pain and dementia is considerable, militating against a simple approach to the assessment of pain.

The assessment of pain for people with dementia

In general, because of the subjectivity of pain, self-report is considered to be the gold standard for pain assessment. Although people with mild to moderate dementia are often able to report their pain verbally or use simple visual or numerical pain intensity assessment tools, these options are not feasible for use with people with later-stage dementia in whom communication ability is severely impaired. 43,44 As a result, previous work has shown that pain is frequently underdetected and poorly managed in people with dementia, in both long-term and acute care. 31,45–47

In the absence of accurate self-report it has been necessary to develop observational tools to be used in both research and practice based on the interpretation of behavioural cues as a proxy for the presence of pain. This approach has resulted in a proliferation in the number of pain assessment instruments developed to identify behavioural indicators of pain in people with dementia and other cognitive impairment. The most structured of these are predominantly based on guidance published by the American Geriatrics Society,48 which presents six domains for pain assessment in older adults. These include facial expression, negative vocalisation, body language, changes in activity patterns, changes in interpersonal interactions and mental status changes. However, the interpretation of many of these behaviours is complex when applied to dementia because of the considerable overlap with other common behavioural symptoms or cognitive deficits which may confound an assessment, manifesting from boredom, hunger, anxiety, depression or disorientation. 40 This increases the complexity of identifying the presence of pain accurately in patients with dementia and raises questions about the validity of existing instruments. The psychometric properties, discriminative properties and clinical utility of currently available instruments are as yet unclear. As a result, there is no clear guidance for clinicians and care staff on the effective assessment of pain, or how this should inform treatment and care decision-making. A large number of systematic reviews have been published which analyse the relative value and strength of evidence of existing pain tools. There is a need for guidance on the best evidence available and for an overall comprehensive synthesis.

Most pain tools for use with people with dementia have been developed within long-term care, and more work is required to establish whether or not the use of pain tools is feasible in the acute hospital and if these tools are reliable in detecting pain. There have been no studies in the UK exploring how pain is detected and managed in people with dementia on acute hospital wards. Recognising pain in people with dementia has been described as a ‘guessing game’ by some HCPs,49 and the Counting the Cost: Caring for People with Dementia on Hospital Wards report37 identified that 51% of carers and nurses were dissatisfied with their ability to detect pain and 71% of hospital staff wanted more training in recognising pain.

Dementia, pain and decision-making

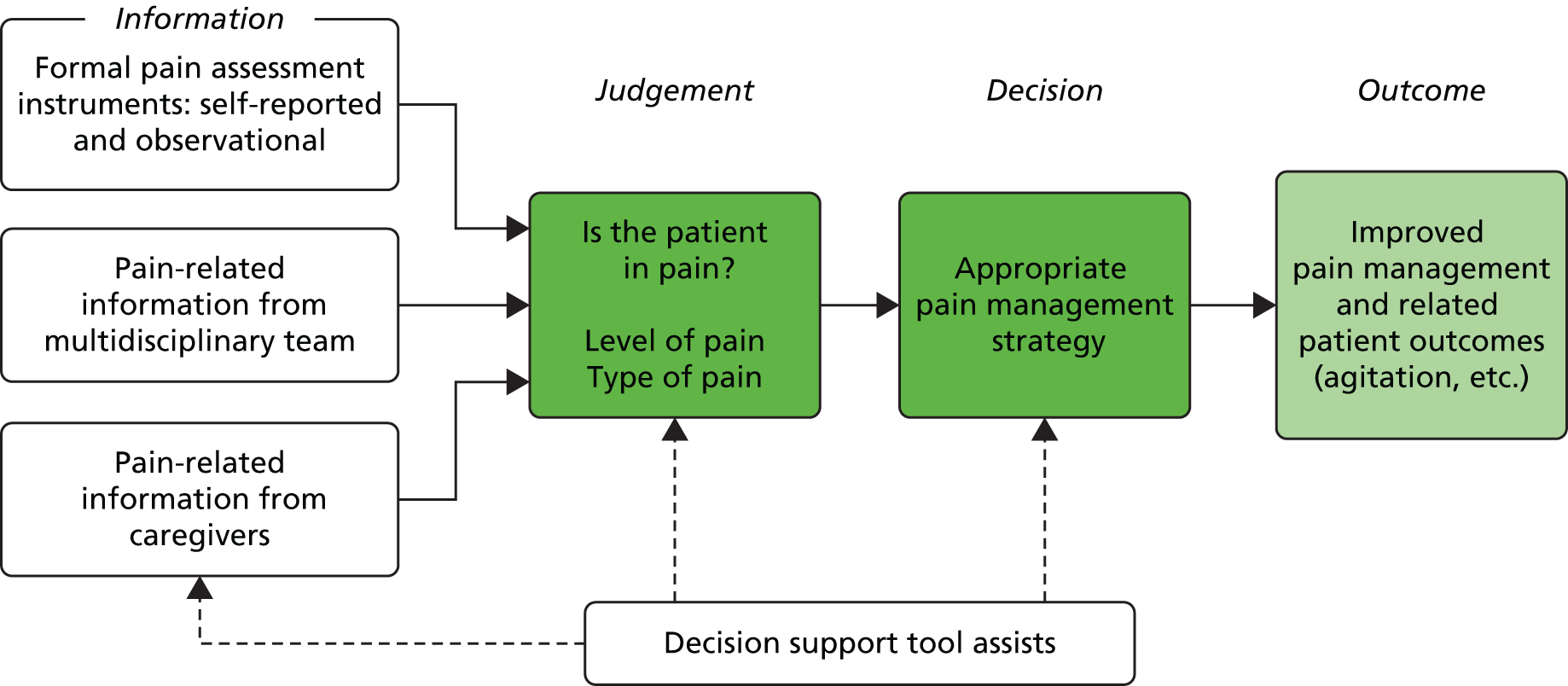

The detection and management of pain are cognitive activities associated with decision-making. Pain detection involves identifying information cues (e.g. from a formal assessment tool, patient self-report, observation of behaviour) that would indicate a patient is experiencing pain. Clinicians then evaluate those cues to reach a judgement regarding the nature of a patient’s pain, before making a decision regarding what to do to manage that pain (the decision process). If individuals fail to assess a patient’s pain effectively, or detect that they have pain but then decide not to do anything to manage it, pain can be poorly controlled. The use of decision support tools can aid clinicians in the decision-making process, improve both the processes and outcomes of care50 and subsequently lead to an improvement in the quality of care for patients. In this study we aimed to develop decision support tools to assist clinicians with both the process of judgement (identification of pain) and decision-making (what actions to take on the basis of the judgement made). Figure 1 provides an overview of the theoretical framework that guided this study. 51,52

FIGURE 1.

Theoretical framework for decision-making.

The framework shows the three main sources of information likely to be used by clinical staff as a basis for making judgements about patients’ pain. This judgement then leads to a decision about how to manage the pain in order to produce the outcome of reduced pain and related outcomes for the patient. This theoretical framework suggests that a decision support tool could assist in the acquisition of appropriate information; the accuracy of judgements; and the making of optimal decisions. Taken together, these should improve outcomes for patients.

There is a paucity of research in this area, with little having been reported in the UK. One recent study undertaken in Australia, which examined the complexities of pain assessment and management for hospitalised older people, identified four key aspects of care: communication among nurses and between older patients and nurses; strategies for pain management; environmental and organisational aspects of care; and complexities in the nature of pain. 53 The intricacies of meeting the analgesic needs of older patients were emphasised, especially for those with communication deficits. There has been no similar research undertaken in the NHS in the UK.

Aims and objectives

The aim of the work reported here, therefore, was to inform the development of a decision support tool to be used by staff in hospital settings, to aid in the recognition, assessment and management of pain among people with dementia. In order to achieve this, two studies were undertaken (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Overview of project and preliminary development of PADDS.

The first study was a systematic review of systematic reviews of observational pain assessment instruments, referred to as the meta-review, which had the following three objectives:

-

to identify all tools which are available to assess pain in adults with dementia

-

to identify the settings and patient populations with which they had been used

-

to assess their reliability, validity and clinical utility.

The second was a multisite observational study of current pain assessment and management practices in a range of wards within four hospital sites across the UK, which had the following four objectives:

-

to identify what information is currently elicited and used by clinicians when detecting and managing pain in patients with dementia in acute hospital settings

-

to explore the existing process of decision-making for detecting and managing pain in patients with dementia in acute hospital settings

-

to identify the role (actual and potential) of carers in this process

-

to explore the organisational context in which HCPs operate with regard to this decision-making process.

Development of intervention and follow-on study: health economics and technical specifications

Data from the observational study were analysed from a health economics perspective, with the aim of developing data collection instruments for the feasibility evaluation of the intervention. The focus of the health economics analysis was twofold: first, to identify cost categories and resource use associated with the intervention developed in this project; and second, design of the instruments, which involved exploration of the use of outcome measures to assess proxy issues and generate hypotheses about the domain of impact. A set of health economic data collection forms was developed as the result of this work.

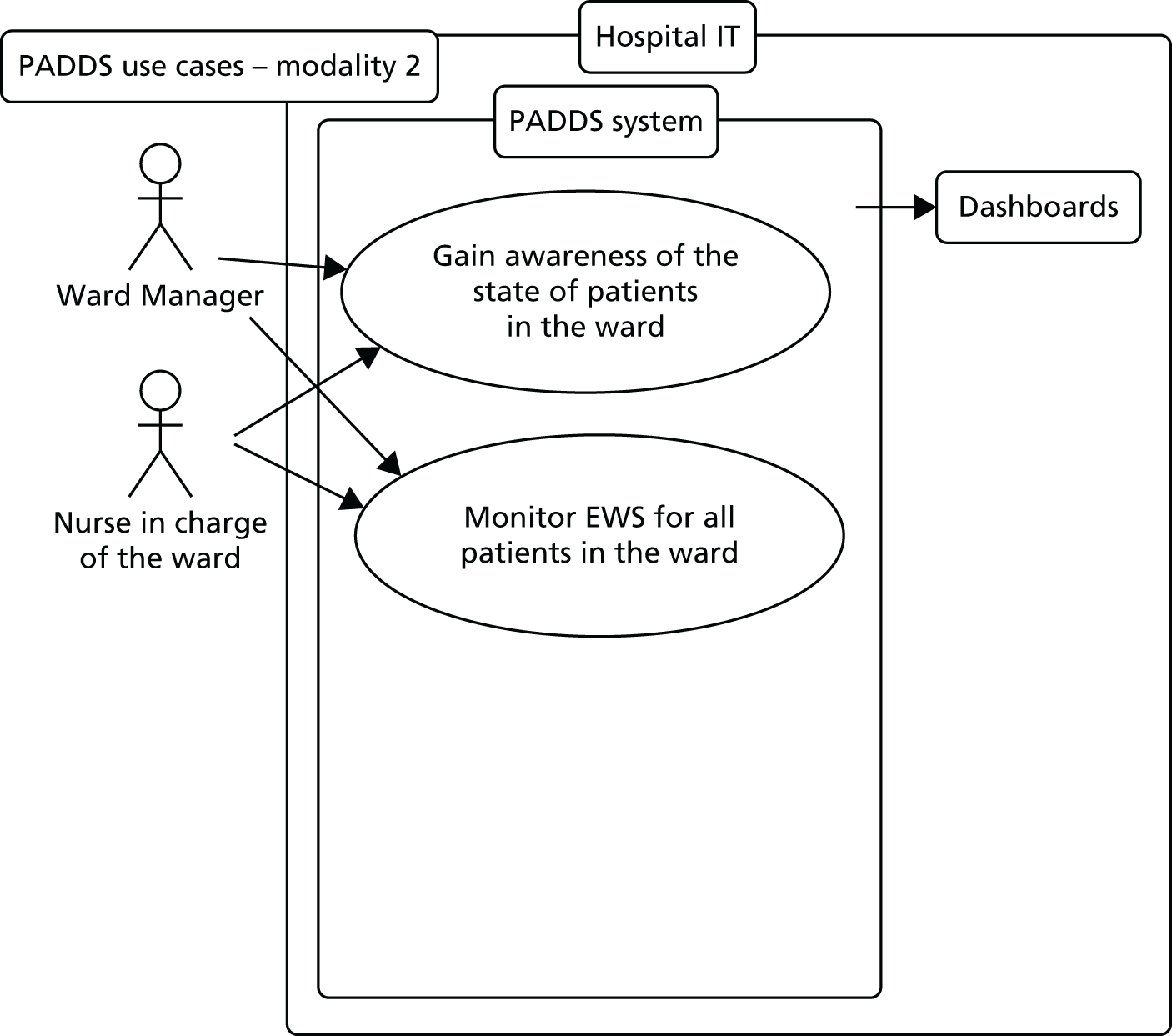

Finally, on the basis of the evidence gathered within this research project, we compiled a technical requirements specification document for the design of a Pain And Dementia Decision Support (PADDS) system.

Study Steering Committee project oversight

A Study Steering Committee (SSC) was established in accordance with Health Service and Delivery Research (HSDR) guidance. The SSC consisted of four experts in the areas of dementia and pain research, together with a representative for carers of patients of dementia.

The SSC and project investigators met three times during the project (June 2014, January 2015 and June 2015) with a final teleconference at the end of the project (1 October 2015). Regular updates on the project were circulated to the chairperson and the SSC by e-mail. Documents shared with the SSC included internal reports, manuscripts for publication, protocol amendments, National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) reports and any significant correspondence with NIHR or sponsor.

Summary

This study was funded by the NIHR HSDR programme (reference number 11/2000/05). The project aimed to generate a theory-based intervention to be used as the basis for providing better-quality care in the assessment and management of pain in people with dementia in hospital settings. The objectives were to identify the best observational pain assessment tool(s) currently available; to understand and support the decision-making processes of HCPs in hospital wards; and to provide insights into how carers’ expertise can be incorporated into the decision-making process. In order to achieve this we undertook two studies, a systematic review of systematic reviews (meta-review) and an observational study, and developed the foundations for the development and implementation of a decision support intervention (see Figure 2).

Structure of the report

The structure and content of each section of this report are outlined below.

Patient and public involvement

The involvement of people with dementia and their carers was an important part of the research process. The composition and participation of our lay advisory group (LAG) are described in Chapter 2, finishing with some reflections on the processes and timing of its involvement.

Meta-review

A systematic review of systematic reviews of observational methods of assessing pain in people with cognitive impairments was undertaken (see Chapters 3 and 4). Given the plethora of instruments that have been developed over the past decade, and the large number of systematic reviews that have produced inconclusive findings, we undertook a systematic review of systematic reviews (meta-review) in order to establish the psychometric properties and clinical utility of existing tools. This review is available as an open-access publication. 54

Observational study

An observational study of current pain assessment and management practices in a range of wards in four hospital sites across the UK was undertaken (see Chapters 5 and 6). This study provided valuable insights into the complexities related to pain communications, documentation and interventions, as well as the influence of the organisation and the ward environment faced by clinical staff when assessing and managing pain in patients with dementia.

Health economics

A health economics analysis was designed to develop methods for assessing costs of implementing a new decision support intervention (see Chapter 8). This analysis was linked to the observational study. It aimed to identify resource use associated with the intervention developed in this project, to develop health economic data collection forms and to explore use of the outcome measures to assess proxy issues and generate hypotheses about the domain of impact.

Discussion and proposal for a new decision support tool

The findings from these two studies are integrated and used to design a new decision support tool (the PADDS system), which requires testing for acceptability and feasibility in acute care settings (see Chapter 8). At the outset of this project it was anticipated that a discrete tool, such as an algorithm, would be developed and subjected to preliminary feasibility testing. However, our findings presented a far more complex picture than anticipated, requiring the development of a broader and more complex support intervention. This involved a conceptual shift, leading to a substantially different approach to decision support. We have discussed the reconceptualisation of pain assessment and management as a distributed, as opposed to a linear, process in more detail elsewhere. 55

As with many projects focusing on sensitive or hard-to-reach populations, ethics, research and development approvals and the recruitment of participants took longer than anticipated for the observational study. Following the development of the preliminary support tool, it became evident that a different approach to testing its feasibility from that originally envisaged was required, namely a realist feasibility evaluation. As the tool and the evaluation required would be substantially different from those in the original protocol, we required further ethics, research and development approvals in order to proceed with the evaluation. Unfortunately, there was insufficient time at the end of the project to complete these processes. We intend to submit a full proposal to the NIHR in order to continue the work by undertaking a realist evaluation of the PADDS’ usability, clinical utility and cost-effectiveness. Such a realist feasibility evaluation is a prerequisite for the refinement of the PADDS system, which may then be rigorously evaluated in a randomised controlled trial.

Chapter 2 Patient and public involvement

Introduction

Patient and public involvement was an important part of the research process. We involved people with dementia and their family members (‘carers’). Patient and public involvement informed the analysis of the findings from our exploratory study on how pain is currently detected, assessed and managed in patients with dementia in hospital settings, and the conclusions we drew from our study. The Alzheimer’s Society (AS) Research Network was instrumental in establishing our connection with the carers of persons with dementia via its research engagement manager.

The lay advisory group

A LAG was established at the beginning of the project. The group was invited to have an oversight and advisory role, informing the running of the project and providing advice on specific aspects of the research if necessary. It was made up of members of the AS Research Network, which is composed of carers and people with dementia who have received training in research methodology.

The LAG was made up of 16 members, one of whom was also a member of our SSC. It was agreed that the group would meet once a year and that they would receive project updates by e-mail, supplemented by further e-mail or telephone contact as and when needed.

More specifically, the involvement of the LAG members took place at three crucial moments in the life of the project:

-

at the beginning

-

on analysis of findings of the meta-review and start of the exploratory study

-

on completion of the exploratory study and initial work towards the development of a decision support intervention.

Each of these three moments of involvement is further detailed below, followed by reflections on how the process informed the development of the project.

The lay advisory group intervention at crucial times of project activities

Beginning of the project

The AS volunteers were consulted about the overall topic and approach of the study at a ‘speed dating’ event held after the themed call was announced by NIHR. Through this, the lay applicants came to be involved in the study and were recruited based on people’s interest after that event. They all provided useful insight and thoughts on the design of the project and where challenges might lie. This consultation resulted in changes and additions to the protocol and funding application. The group helped to review the information sheets and consent forms to make them more readable and user-friendly.

Mid-way through the meta-review and start of the exploratory study

A meeting with the LAG took place in February 2014 at the point when we were in the process of analysing the results of the systematic search for systematic reviews of pain assessment tools, and we had begun data collection for the exploratory study. The meeting was attended by eight lay members and three project team members. Two lay members who had difficulties travelling to the meeting were consulted by e-mail, and their feedback was included in the notes of the meeting which were circulated to all members of the group.

Part of the meeting was dedicated to discussing the findings of the meta-review. Patients’ and carers’ voices seem to be absent in studies of patient assessment scales for persons with dementia. At this meeting we reflected and shared ideas on pain assessment tools we had identified through the review, and we discussed the implications of the design of an alternative decision support tool to assist in pain assessment for patients with dementia.

In the second half of the meeting, the discussion was focused on those carer-facing tools intended to communicate a patient’s preferences and needs to hospital staff, including the patient’s experience of pain. These tools are paper forms known as, for example, ‘patient/carer’s passport’, ‘10 things about me’ or ‘know who I am’,and they are being introduced in hospitals across the NHS, including the sites we studied, as part of an effort to increase awareness and understanding of dementia. Usually carers and relatives are asked to fill in such forms at the time of the patient’s admission to hospital. The group was invited to comment on these kinds of forms and share any experiences they may have had with them.

Mid-way through the analysis of main study findings and start of the development of the intervention

A second meeting with the LAG took place in March 2015, to discuss the initial findings from the exploratory study with the group as we began work on the development of the decision support intervention. The meeting was attended by six lay members and two project team members, with follow-on activities taking place by e-mail that also included those who were unable to attend.

The discussion that took place during this meeting extended beyond pain assessment, touching on several points of interest raised by the participants, including the problem of hospital wards understaffing, the importance of a relationship of trust between patients and clinicians, specifically, the issue of carers experiencing distrust from clinicians (‘I felt a degree of suspicion’), and the importance of considering the patient as an ‘integrated whole’, as opposed to focusing only on the most acute medical condition.

As a follow-on from the meeting, the group was consulted by e-mail about the design of research instruments for the health economics evaluation of the intervention. In preparation for this phase of the research, a questionnaire was developed to collect baseline data from patients, carers and members of staff. The group was invited to comment on this new instrument, still in draft form, specifically, on whether they thought that participants would be able to answer the questions about hospital stays/contact with health services themselves, or if this should be completed by a research nurse, and if they could identify anything missing from the questionnaire (e.g. ‘Who would the patient typically see in hospital in respect of their dementia?’).

Finally, the present report was circulated by e-mail to the group at the end of the study (September 2015) to gather any further comments and feedback, and subsequent amendments were made.

How the lay advisory group intervention influenced the research process

Guidance on pain assessment and management for patients with dementia recommends that carers are be involved in the process, essentially to provide information that may help staff recognise patient-specific pain cues. The use of dementia awareness forms, such as those mentioned above, currently in use in the NHS, are part of this need to gather and share information about the patient as a person.

The contribution of the members of the LAG to our research was of great value for the interpretation of those findings from our exploratory study regarding the sharing of information in a hospital context particularly in relation to the pain recognition, assessment and management processes. Through the discussion with the group it became apparent that this is more complex than it may at first appear for a variety of reasons. For example, two main aspects came to the fore. First, there may be disagreement between family members of a person with dementia over what constitutes ‘the usual’ for the person and their likes or dislikes, and there is no clear answer to how to deal with this disagreement in the hospital context. Second, there is a real concern among the carers about the ‘labelling’ of their loved one associated with the use of the dementia awareness forms. This insight was taken into account during the analysis of the findings and included in the discussion in one of our manuscripts submitted for publication (Lichtner et al. 100).

The group also contributed advice on the design of research instruments. Its input on the design of the health economics questionnaire was particularly valuable.

Examples of the contributions from the group are provided in Table 1, illustrated with quotations from notes of meetings and e-mails from group members.

| Involvement | Contribution to the study |

|---|---|

| Advice on research instruments/documentation for use by patient and public involvement (i.e. information sheets, consent forms and health economics questionnaires) | Gathering lay views on research instruments was especially important to make them more readable and manageable. In particular, in relation to the health economics questionnaire to be filled in by patients with dementia and/or carers, there were concerns over:

|

| Carers’ and patients’ perspectives on the pain assessment and management process with the new tool in development | Members of the group stressed important points confirmed by the exploratory study, such as:

|

| Carers’ and patients’ perspectives on the use of dementia awareness forms currently in use in NHS hospitals and information-sharing with staff | The group agreed that the carers should be asked about the person with dementia’s needs and usual behaviours. Some also recounted how in their experience this had not happened (‘he was restless and nobody spoke to me at all’) |

| The group agreed that the lack of power of attorney is an issue and commented that this is a vital point; that family members can hold up the care of the patient because, for example, nobody has power of attorney; how ‘we should all have it’ (before dementia onset); that it is ‘complicated because of the financial implications’; and how it is difficult for those who do not have relatives and do not know who to ask | |

| Discussion took place over the trade-off between facilitating person identification and protecting confidentiality. This was a major point of discussion – the practice of ‘labelling people’ (e.g. with a butterfly or a flower). Some members of the group had issues with any labelling practice, such as ‘putting stickers at the end of beds’. Patients risk losing their identity (‘you are not Mrs Blog, but a patient with dementia’) and risk not been treated as a whole person (‘I know my mother was not seen holistically because she had dementia’). So, for example, they may not have been given physiotherapy (‘this happened with my mother, they would not give me any equipment after her hip replacement’) |

Evaluation of lay advisory group process

Our project aimed to deliver a decision support intervention to assist HCPs in the care of patients with dementia. A core aspect of this intervention was a decision support tool aimed at staff working in hospital clinical areas. There is a challenge in having meaningful patient and public involvement activities through a research process aimed at developing a working tool for staff – a tool that patients and the public may never use or get access to. They are key stakeholders in the overall process (and the outcomes of patient care delivered with the support of the tool), but not direct end-users of the new tool. Good practices of user-centred design in tool development include involving a varied range of stakeholders, but greater attention is paid often to the direct end-users. We believe that we were successful in overcoming this challenge, and that we were able to involve carers in a meaningful and lucrative way throughout the research.

The members of the LAG provided a complementary perspective over the findings of our study, and important points came out of the discussion that we then took into account at the time of tool development. The timing of the consultation was also important; meeting at ‘transition points’ in the research process enabled feedback from the group to be incorporated into the analysis of findings both for the systematic review and exploratory study, and also into the conclusions of the study, as disseminated in manuscripts for publications.

Face-to-face communication with members of the group happened through yearly meetings. The LAG meetings lasted 3 hours, over lunch, to give enough time for travelling, and they were held at King’s College London, the site of one of the investigators (AC), and a central location. The meetings did not have a formal agenda; rather, they were open and relaxed discussions and provided an opportunity to exchange ideas and inform the group of the progress of the project. Overall, this seemed a good format, allowing space for project presentations to update the group about the progress of the project, as well as substantial time for discussion.

We were aware that family members of persons with dementia are often elderly, possibly with health conditions that make travelling more difficult for them. However, all of the group had access to computers, and we investigated the possibility of using teleconferencing or videoconferencing facilities [such as Skype™ (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA)], as an alternative to meeting in person. We consulted on this with the group, and preference was expressed for meeting face to face. It was therefore agreed that those who could not attend would be consulted by e-mail and their feedback included in the notes of the meeting to be circulated to all members. One of the members who could not attend in person recommended our project to the AS as an exemplar in lay members’ participation, including those who were unable to attend in person. An e-mail was sent to the AS network stating that ‘this project would make an ideal example to take to Society regional meetings to try to explain research projects to the general membership’. Through the process it became apparent that difficulties in attending events in person is a major barrier for patient and public involvement, especially for persons with dementia, and that this is something that needs to be taken into account when planning patient and public involvement activities.

Finally, we never asked the group whether they were happy to be referred to as ‘carers’. Indeed ‘carer’ is not an uncontested label56 and, in retrospect, we should have consulted the group on this. Towards the end of the project one of the group members pointed out that instead of carer she would prefer ‘family supporter (I prefer to call myself that rather than carer)’ and, although this was not raised as an issue, her message was a reminder for future patient and public involvement activities with family members of patients with dementia to consult on this at the start of the research process.

The Alzheimer’s Society Conference

As the research project was coming to its end, in June 2015, we attended the AS research conference. We presented findings from the study to a varied audience including researchers (n = 75), some of whom were clinicians or health professionals, AS staff and trustees (n = 45) and, most importantly for the purpose of patient and public involvement, 72 volunteers, of whom 66 had a personal experience of dementia, including six people with dementia.

Conclusion

Patient and public involvement was very important for the conduct of the research and the conclusions of the study. Through their insight and experiences the members of the LAG helped us to problematise the findings and draw more nuanced conclusions. This chapter, along with the rest of the report, was circulated to the advisory group members, who commented favourably.

Chapter 3 Meta-review: methods

Introduction

This meta-review aimed to identify existing assessment tools with validation data concerning people with dementia. It presents a thorough synthesis of current systematic review literature concerning the psychometric properties and clinical utility of pain assessment tools for the assessment of pain in adults with dementia, and provides a detailed picture of the state of the field in the complex task of assessing pain. 54

For ease of reference, in this report we refer to our systematic review of systematic reviews as a ‘meta-review’. We call the systematic reviews considered for inclusion in the meta-review ‘reviews’, and refer to publications included in the reviews as ‘studies’. We use the term ‘records’ to refer to the bibliographic data of publications of reviews (for the most part retrieved through online database searches). The terms ‘scales’, ‘tools’ and ‘instruments’ (pain assessment) are used interchangeably. The process of the meta-review followed guidance from the Cochrane Collaboration57 and the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI). 58 In undertaking this meta-review, our aims were as follows:

-

to identify all tools available to assess pain in adults with dementia

-

to identify the settings and patient populations with which they had been used

-

to assess their reliability, validity and clinical utility.

Criteria for considering reviews for inclusion

Definitions of criteria for inclusion of reviews in the meta-review followed an adapted setting, population, intervention, comparison, method of evaluation (SPICE) structure. 58 We included systematic reviews of pain assessment tools involving adults with dementia or with cognitive impairment. Dementia and cognitive impairment were defined according to the US National Library of Medicine’s medical subject heading (MeSH) vocabulary. Dementia was defined as ‘an acquired organic mental disorder with loss of intellectual abilities of sufficient severity to interfere with social or occupational functioning’. 59 The dementia MeSH term covered more specific subheadings such as Alzheimer disease or vascular dementia. Cognition disorder was defined as ‘disturbances in the mental process related to thinking, reasoning, and judgment’60 (distinct from, not including, delirium). We did not include learning disorders, defined as ‘Conditions characterized by a significant discrepancy between an individual’s perceived level of intellect and their ability to acquire new language and other cognitive skills’. 61 Examples of learning disorders of this type are dyslexia, dyscalculia and dysgraphia.

We included reviews regardless of setting (e.g. acute or nursing/care homes), type, location or intensity of pain (e.g. acute pain, persistent), and outcomes of the pain assessment (e.g. patients being in pain or not). Reviews were included if they provided psychometric data for the pain assessment tools and were available in English. We excluded publications, such as narrative reviews or case reports, which did not provide psychometric data or were not categorised as systematic reviews62 (Table 2 shows our systematic review definition).

| SPICE category | Criteria | Definitions |

|---|---|---|

| Setting | Reviews pertaining to any setting | Settings are, for example, acute hospitals, nursing homes, community settings |

| Patient population | Reviews of studies limited to adults with dementia or cognitive impairment | Dementia defined as:[. . .] an acquired organic mental disorder with loss of intellectual abilities of sufficient severity to interfere with social or occupational functioning. The dysfunction is multifaceted [. . .]National Library of Medicine59 |

| All stages of dementia in adults were considered (e.g. mild, severe) | Cognitive impairment defined as cognition disorder:Disturbances in the mental process related to thinking, reasoning, and judgmentNational Library of Medicine60Does not include learning disorders. (Source: MeSH vocabulary – www.nlm.nih.gov/mesh/) | |

| Intervention | Reviews of studies of the assessment of pain and of pain assessment tools. Reviews that included management of pain considered if they also covered assessment of pain | Pain assessment as defined by the International Association for the Study of Pain:[. . .] entails a comprehensive evaluation of the patient’s pain, symptoms, functional status, and clinical history [. . .] |

| All forms of pain were considered (e.g. acute pain, persistent), without distinction by location of pain (e.g. abdominal pain) | [. . .] The assessment process is essentially a dialogue between the patient and the health care provider that addresses the nature, location and extent of the pain, and looks at the patient’s daily life, and concludes with the pharmaceutical and nonpharmaceutical treatment options available to manage itPowell et al., pp. 67–7863Evaluation tools may be used in this process:To varying degrees, these tools attempt to locate and quantify the severity and duration of the patient’s subjective pain experience [. . .]Powell et al., pp. 67–7863 | |

| Reviews of studies of pain assessment were included, irrespective of the outcomes of the assessment (e.g. patients being in pain or not) | ||

| Evaluation (method of) | Systematic reviews only were included | Definition of systematic review:

|

| Additional criteria | Reviews were included only if with data and/or assessment of reliability and/or validity and/or clinical utility | Reliability:[. . .] the degree to which the measurement is free from measurement error [. . .]Mokkink et al.65 |

| Validity:[. . .] the degree to which the [instrument] measures the constructs(s) it purports to measure [. . .]Mokkink et al.65 | ||

| Inclusion limited to English language | Clinical utility: ‘the usefulness of the measure for decision-making’ (i.e. to inform further action, such as the administration of analgesics)66 |

Search methods for identification of reviews

The following databases were searched: MEDLINE, All Evidence Based Medicine Reviews [including Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, American College of Physicians (ACP) Journal Club, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, Cochrane controlled trials reports, Cochrane Methodology Register, Health Technology Assessment, and NHS Economic Evaluation Database], EMBASE, PsycINFO, and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; the searches were all carried out on the same date (12 March 2013). Additional searches included The JBI Library (The JBI Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports) and the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination database. Further data were retrieved through reference chaining. No grey literature was sought.

The search strategy used a combination of text words and established indexing terms such as MeSH (see Appendix 1). The search was structured by the relevant SPICE concepts. Search terms were identified by comparing published search strategies adopted by reviews in similar areas,64,67 or on the subject of pain or pain management tools, not specifically for the same patient population,68 using the search strategy for retrieving reviews outlined by Montori et al. 69 Detailed search strategies were optimised for each electronic database searched.

Selection of reviews

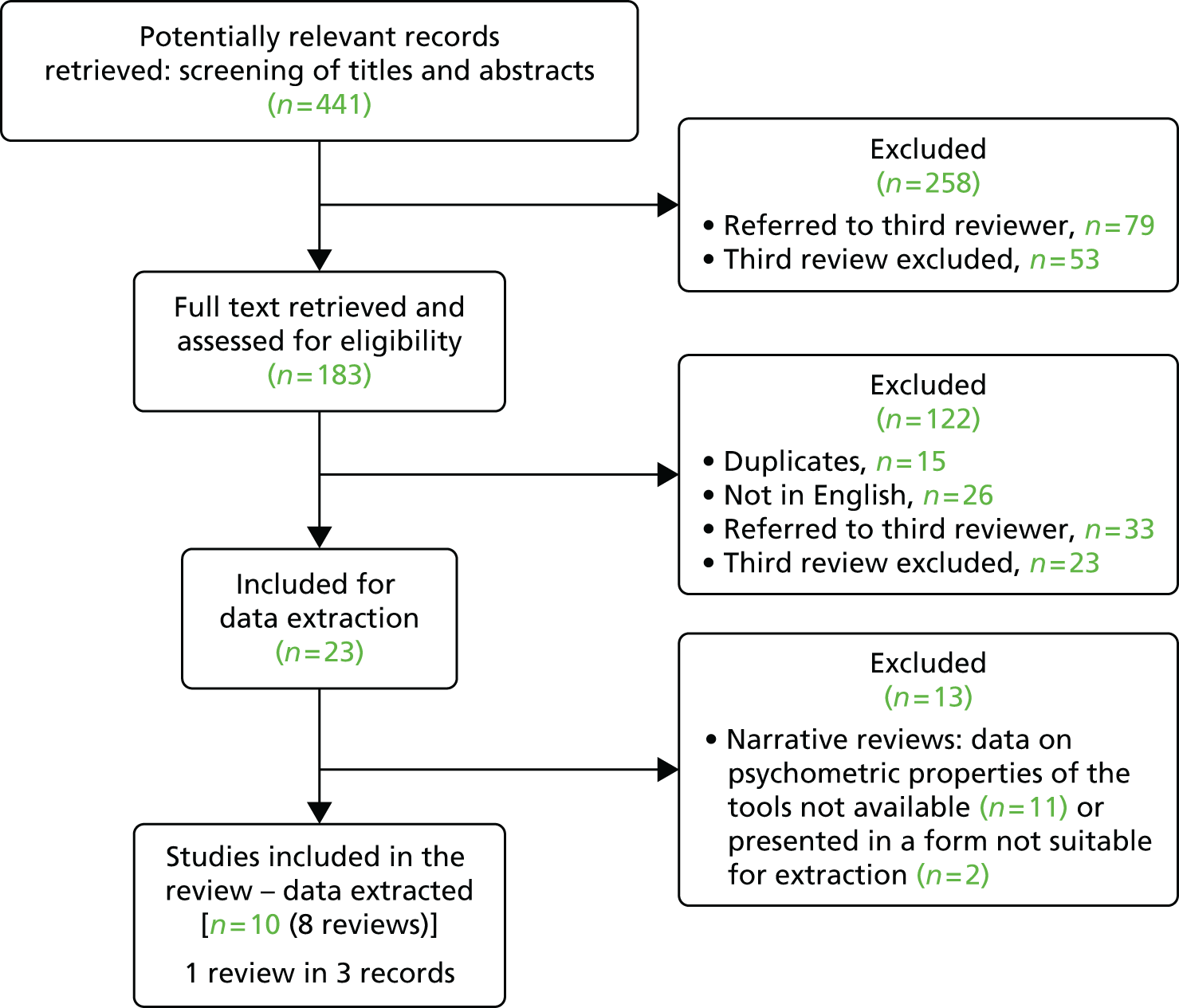

Four reviewers (DD, MB, VL and PE) screened all search results, initially on the basis of title and abstract and then the full text of potentially eligible papers (see Figure 3). The results of the search were divided into two sets among the reviewers, so that each review was first screened by two of the reviewers independently, then assessed, again independently, by the other two reviewers. When consensus could not be reached, the reviews were referred to a third party (SJC).

Assessment of methodological quality of included reviews

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidance on systematic reviews encourages reviewers ‘to think ahead carefully about what risks of bias (methodological and clinical) may have a bearing on the results of their systematic reviews’. 62 In our meta-review, the risk of bias may reside in each review considered for inclusion, as well as in the original studies that make up that review. We did not access the original studies to be able to accurately judge their quality or risk of bias. For each review, we assessed risk of bias in terms of how the review was conducted and the criteria applied for inclusion/exclusion. Critical appraisal was carried out by two independent reviewers, using the A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) systematic review critical appraisal tool. 70 Critical appraisal and evaluation of potential bias were carried out at the time of data extraction, after screening was completed on the basis of the inclusion criteria.

Data extraction and management

Data were extracted by two reviewers independently using a set of data extraction forms which were developed for the meta-review: (1) the AMSTAR checklist;70 (2) two forms for data about the reviews; and (3) one form for data about the tools. The third included a field for data extraction on the user-centredness of the tools, informed by Long and Dixon’s71 work on the development of health status instruments. 71 The data extraction forms were both paper based and built into a Microsoft Access® database (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). At the time of data extraction, the reviews eligible for inclusion were screened further on the basis of availability of psychometric data of tools. At this point, we found that some of the reviews initially identified as being eligible for inclusion in the meta-review did not provide psychometric data of tools and were subsequently excluded (this is discussed in detail in Chapter 4). Data about the characteristics of the tool (e.g. tool design and instructions for use) were extracted from the reviews; we did not search for, or retrieve, the original tools.

The search retrieved 441 potentially eligible unique records. After screening titles and abstracts, and removing duplicates, we obtained the full text of 183 records and assessed these for eligibility. We identified 23 reviews as being potentially eligible for inclusion, of which 13 were excluded as they did not provide data on the psychometric properties of the tools. The remaining set included 10 records reporting data from eight reviews (the Schofield et al. 200572 review was reported in three separate studies;72–74 we have combined the results of this) (Figure 3). The tables of included and excluded reviews are listed in Appendix 2. The reviews were synthesised using a narrative synthesis approach.

FIGURE 3.

Flow chart of retrieved sources and screening process. Reproduced from Lichtner et al. 54 © 2014 Lichtner et al. ; licensee BioMed Central. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Further details about the methods are provided in additional files (see Appendix 3).

Chapter 4 Meta-review: results

Introduction

The findings are structured as follows. First, we briefly summarise the reviews considered at the time of data extraction, but excluded owing to lack of data on psychometric properties of the tools. Second, we describe the reviews included in our analysis, specifically their methods and our quality assessment of them. Third, we describe the findings of these included reviews regarding the characteristics, psychometric properties, feasibility of use and clinical utility of pain assessment tools. We conclude with the reviews’ overall assessment of these tools.

Description of excluded reviews

Thirteen of the 23 reviews were excluded because they did not provide suitable data for extraction (these data were absent or not reported in a format suitable for extraction). Several of these were narrative reviews. They varied in length and details of reporting. Tools were analysed in the broader context of, for example, pain physiology, pain prevalence, and patients’ attitudes and beliefs about pain. For some, the areas of focus were the processes of pain assessment and/or pain management/interventions in the elderly population, including (but not always limited to) persons with dementia (e.g. in Rutledge et al. ,75 Rutledge and Donaldson,76 Andrade et al. 77 and Miller and Talerico78) and/or in specific types of pain (e.g. orofacial pain, Lobbezoo et al. 79). One review80 focused on the barriers to successful pain assessment, identifying non-use of assessment tools as one such barrier.

Two reviews were updated by, or related to, a later review by the same authors (Rutledge et al. 75 is an update of Rutledge and Donaldson76 – both excluded; Herr et al. 81 is related to Herr et al. 82 – the last included in our study – and aimed at reviewing the methods of the previous study).

Two reviews83,84 were reviews of reviews, and they were very specific in their aims, namely to identify pain assessment tools for adults with cognitive impairment recommended for use by paramedics83 and district nurses. 84 They identified two and four reviews, respectively, all of which were among those that we retrieved. Thus, the reasons for exclusion in their case were their nature as reviews of reviews (overviews, as opposed to systematic reviews), that they provided no data for extraction and on the grounds of repetition.

Two other reviews81,85 did report and discuss psychometric data, but not in a form suitable for this meta-review. Their choice of reporting may suggest authors’ methodological concerns for the comparability and presentation of the data in quantitative form, given the heterogeneity of the studies and their methods.

Description of included reviews

Each review included in this meta-review analysed between 8 and 13 tools (Table 3). The most frequently reviewed tools included the Abbey Pain Scale, NOn-communicative Patient’s Pain Assessment Instrument (NOPPAIN), PACSLAC, Pain Assessment for the Dementing Elderly (PADE), Checklist of Nonverbal Pain Indicators (CNPI) and Pain Assessment IN Advanced Dementia (PAINAD). Reviews had searched the literature across a variety of date ranges, from 1980 to 2010. The number of individual studies included in each review varied from 972 to 29,64 although the number of included studies in some reviews was ambiguous. The reasons for this ambiguity were twofold. First, the number of studies included in each review was different for each tool, thus making it difficult to aggregate in one number (‘number of included studies’). Second, the studies included in each review were each found to have reported one or more studies aimed at evaluating a tool. Thus, a number of included studies of ‘1’ may actually have referred to a larger number of studies conducted.

| Tool | Systematic review, authors and year of publication | Number of reviews per tool | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corbett et al., 201267 | Herr et al., 200682 | Park et al., 201087 | Qi et al., 201286 | Schofield et al., 200572 | Smith, 200588 | van Herk et al., 200766 | Zwakhalen et al., 200664 | ||

| Abbey Pain Scale | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 7 | |

| ADD protocol | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 6 | ||

| Behavior Checklist | ✓ | ✓ | 2 | ||||||

| CNPI | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 8 |

| Comfort Checklist | ✓ | 1 | |||||||

| CPAT | ✓ | 1 | |||||||

| Doloplus-2 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 6 | ||

| DS-DAT | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 6 | ||

| ECPA | ✓ | 1 | |||||||

| ECS | ✓ | 1 | |||||||

| EPCA-2 | ✓ | 1 | |||||||

| FACS | ✓ | 1 | |||||||

| FLACC | ✓ | 1 | |||||||

| MPS | ✓ | 1 | |||||||

| MOBID/MOBID-2 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 3 | |||||

| NOPPAIN | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 7 | |

| OPBT | ✓ | ✓ | 2 | ||||||

| PACSLAC | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 7 | |

| PADE | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 6 | ||

| PAINAD | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 8 |

| PAINE | ✓ | 1 | |||||||

| PATCOA | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 3 | |||||

| PATCIA | ✓ | 1 | |||||||

| PBM | ✓ | 1 | |||||||

| PPI | ✓ | 1 | |||||||

| PPQ | ✓ | 1 | |||||||

| RaPID | ✓ | 1 | |||||||

| REPOS | ✓ | 1 | |||||||

The reviews aimed to summarise the available evidence by means of a comprehensive overview. Three reviews82,86,87 also explicitly aimed at an evaluation of the evidence, that is to critically evaluate the existing tools, or to identify key components and analyse the reported psychometric properties of tools. Two reviews64,82 reported a systematic method for evaluation of the tools.

Not all reviews made explicit their assessment of the quality of the studies or risk of bias, or assessment of the scales considered. When this was done, the reviews highlighted the methodological limitations of both studies and scales. For example, in one review64 the overall assessment was ‘generally moderate’, with 11 points being the highest score out of the 20-point evaluation scale applied, and only four of the 12 tools examined reaching this score [these were Doloplus-2, L’Échelle Comportementale pour Personnes Âgées (ECPA), PACSLAC and PAINAD]. The heterogeneity of study designs and/or inconsistencies made aggregation of findings in the reviews difficult and/or methodologically inappropriate. For example, Zwakhalen et al. 64 stressed the ‘Considerable heterogeneity in terms of design (retrospective vs. prospective), method (pain in vivo vs. observational methods), research population (different types of dementia, different levels of impairment, different settings) and conceptualisation of pain’, making their results hard to compare.

We assessed the quality of the systematic reviews through the use of the AMSTAR questionnaire (original questionnaire adapted to a binary scoring: 1 if item is present, 0 if unclear, absent or not applicable) (Tables 4 and 5). The mean score was about 4.9, with a range of 188 to 1086 out of a maximum score of 11.

| Systematic review, authors and year of publication | AMSTAR question | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1: was an ‘a priori’ design provided? | Q2: was there duplicate study selection and data extraction? | Q3: was a comprehensive literature search performed? | Q4: was the status of publication (i.e. grey literature) used as an inclusion criterion? | Q5: was a list of studies included and excluded provided? | Q6: were the characteristics of the included studies provided? | |

| Corbett et al., 201267 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Herr et al., 200682 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Park et al., 201087 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Qi et al., 201286 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Schofield et al., 200572 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Smith, 200588 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| van Herk et al., 200766 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Zwakhalen et al., 200664 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Systematic review, authors and year of publication | AMSTAR question | Total score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q7: Was the scientific quality of the included studies assessed and documented? | Q8: Was the scientific quality of the included studies used appropriately in formulating conclusions? | Q9: Were the methods used to combine the findings of studies appropriate? | Q10: Was the likelihood of publication bias assessed? | Q11: Was the conflict of interest stated? | ||

| Corbett et al., 201267 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 7 |

| Herr et al., 200682 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Park et al., 201087 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 5 |

| Qi et al., 201286 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 10 |

| Schofield et al., 200572 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Smith, 200588 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| van Herk et al., 200766 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Zwakhalen et al., 200664 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| Mean score | 4.875 | |||||

Most (six out of eight) reviews presented an a priori design and a comprehensive literature search (question 1; question 3). However, in general, the reporting lacked detail. For example, as shown in Tables 4 and 5, the list of included/excluded studies was provided in only three reviews,67,86,87 the explicit involvement of two or more independent reviewers (question 2) was reported in only one review,86 only three reviews67,82,86 explained the methods used to combine findings (question 9) and only one review86 seemed to have assessed the likelihood of publication bias. This lack of detail in reporting may be because of restrictions on word limits in publications. We did not contact the authors to obtain missing data.

Reviews’ findings: the pain assessment tools

In total, 28 pain assessment tools were assessed in the eight reviews. Nine tools [Abbey Pain Scale, Assessment of Discomfort in Dementia (ADD) protocol, CNPI, Discomfort Scale – Dementia of the Alzheimer’s Type (DS-DAT), Doloplus-2, NOPPAIN, PACSLAC, PADE and PAINAD] were assessed in five or more reviews. One tool [Mobilization-Observation-Behavior-Intensity-Dementia (MOBID) pain scale] was assessed in three reviews. Three tools [Behavior Checklist, Observational Pain Behaviour Tool (OPBT) and Pain Assessment Tool in Confused Older Adults (PATCOA)] were assessed in two reviews. The remaining 15 tools were each assessed in one review.

It should be noted that there seem to be different versions of PACSLAC, with a preliminary tool comprising 60 items, then a later version modified to 36 items. A Dutch version, PACSLAC-D, was also mentioned. There seems to be ambiguity about which version of the tool the data were reported about. 67 Similar ambiguity was found in relation to the PADE questionnaire; it was unclear which version – or which of its subscales – was studied for psychometric properties. Equally, the MOBID scale has been studied in two different versions. It is also unclear how much the Abbey Pain Scale had been refined across the studies carried out to evaluate it (including a Japanese version).

Description of the tools

The reporting of the tools’ content and intended use was undertaken differently by different reviews, making it difficult to provide a comprehensive comparative descriptive summary of all 28 tools. Six of the eight reviews64,66,67,72,87,88 provided summary tables giving an overview descriptions of the tools’ designs, but these summaries focus on a varied range of aspects, including target population,66 number of items,64,66,67 type of behaviours identified,72,82,88 number of dimensions/behaviours,64 presence of the American Geriatric Society (AGS) categories66,82,87 and scoring range. 64,66

From the eight reviews, it appeared that most tools (24 out of 28) were observational, requiring observations undertaken by HCPs. However, reviewers’ classification of these observational tools varied: the Face, Legs, Activity, Cry, Consolability scale (FLACC) was described as a ‘behavioural scale’ as opposed to observational;82 the Abbey Pain Scale, PADE and Pain Assessment In Noncommunicative Elderly persons (PAINE) were classified by one review67 as ‘caregiver or informant rating scales’; the same review67 classified the ADD tool as ‘interactive’ – that is an ‘interactive method’ including ‘a physical and affective needs assessment, a review of the patient’s history, and the administration of analgesic medication’. 67 In a number of reviews no specific classification is made. Among the remaining four tools of the 28, one, Present Pain Intensity (PPI), relied on patient self-reporting, while another, Proxy Pain Questionnaire (PPQ), was described as relying on caregivers reporting, and compared pain experienced currently with pain experienced the previous week.

Twenty-five of the 28 tools appeared to include an assessment of pain intensity. Three tools (ADD protocol, Behavior Checklist and OPBT) aimed at determining simply the presence or absence of pain, with no scoring or rating of pain intensity. In the case of two tools [Doloplus-2 and Rotterdam Elderly Pain Observation Scale (REPOS)] binary scores were summed up and the total score interpreted as presence/absence of pain.

Methods of scoring and rating of pain varied, from scores made of counting checkmarks – that is yes/no binary responses (item present or absent), to a variety of rating systems; total scores ranges varied from 0–6 to 0–60 {i.e. 0–6 [CNPI], 0–9 [PATCOA], 0–10 [FLACC, MOBID, PAINAD], 0–14 [Edmonton Classification System (ECS)], 0–25 [OPBT], 0–27 [DS-DAT], 0–30 [Doloplus], 0–44 [ECPA], 0–54 [Rating Pain In Dementia (RaPID)], 0–60 [PACSLAC]}. Likert scales, binary scores, multiple choice and visual analogue scale (VAS) systems were mentioned in the reviews; in three cases [PADE, Pain Assessment Tool for use with Cognitively Impaired Adults (PATCIA), PPQ] different rating systems are used in the same tool (Likert scales/VASs; Likert scales/binary scores).

Only 2 out of 28 tools (CNPI and NOPPAIN) appeared to be designed explicitly for pain assessment both at rest and during movement, although data about this aspect of the tool’s design may have been missing for the other tools. For one tool (Doloplus-2) the score was reported to reflect the progression of the pain experienced, rather than the patient’s pain experienced at a specific moment in time.

Two tools (REPOS and the ADD protocol) combined assessment with guidelines for intervention (this is discussed further in Settings in which the tools were studied).

Three reviews66,82,87 explicitly analysed the tools in terms of whether or not their design applied the AGS48 guidelines and categories of potential pain indicators in older persons, namely facial expressions, verbalisations/vocalisations, body movements, changes in interpersonal interactions, changes in activity patterns or routines, and mental status. These reviews covered 15 tools [Abbey Pain Scale, ADD protocol, Behavior Checklist, CNPI, DS-DAT, Doloplus-2, Facial Action Coding System (FACS), FLACC, MOBID, NOPPAIN, PACSLAC, PADE, PAINAD, PATCOA and the Pain Behavior Method (PBM)].

Settings in which the tools were studied

The tools were studied in a variety of settings and with varied patient populations. The terminology used to describe settings varied, and those which appeared to be in non-acute settings included long-term care, nursing homes, dementia care units, psychogeriatric units, rehabilitation facilities, aged care facilities, residential care facilities, long-term care facilities and palliative care, but also included geriatric clinics, care homes, residential and skilled care facilities, long-term-care dementia special care units and a residential dementia care ward.

The terminology used to refer to hospital settings also varied, with reference either to patients and/or type of services. For example, terms used included hospital patients in a long-term stay department, psychiatric hospital setting, hospital medical care unit, dementia special care units in hospital, hospital patients and older hospital patients.

Tools’ psychometric data

Reliability

The reliability of pain assessment scores was measured using inter-rater reliability (agreement between raters), test–retest (extent to which a tool achieved the same result on two or more occasions when the condition was stable) or intrarater reliability (agreement of scores from the same rater at different time points) and internal consistency. There were no reliability data available for four of the tools (ECS, PATCIA, OPBT and Behaviour Checklist). Overall, reliability measures were carried out on small samples of patients and raters, so data for all of the tools were limited.

Inter-rater reliability

This was calculated in different ways for each of the tools. Methods included percentage agreement, kappa coefficients, correlation coefficients, and intraclass correlation coefficients. The variation in calculation of reliability of the different tools made drawing direct comparisons difficult. Percentage agreement is the least robust measurement of reliability, and was used to calculate agreement for the FACS (43–93%), CNPI (93%), DS-DAT (84–94%), PACSLAC (94%), PATCOA (56.5–100%), NOPPAIN (82–100%) and ADD protocol (86–100%). The kappa coefficient measures agreement between two observers and takes into account the agreement expected by chance. It is therefore a more robust measure than percentage agreement. For kappa coefficients, a value of 0.6 or above indicates moderate agreement. Kappa coefficients were provided for the FLACC (0.404), Mahoney Pain Scale (MPS) (0.55–0.77), CNPI (0.625–0.819), MOBID (0.05–0.90), MOBID-2 (0.44–0.90) and NOPPAIN (0.70–0.87). Correlation coefficients were used to assess agreement for the following tools: FACS (0.82–0.92), PAINE (0.711–0.999), RaPID (0.97), DS-DAT (0.61–0.98) and PAINAD (0.72–0.97). Measures of inter-rater reliability using intraclass correlations were as follows: Certified nursing assistant Pain Assessment Tool (CPAT; 0.71), PBM (range 0.10–0.87), DS-DAT (0.74), Doloplus-2 (range 0.77–0.90 total scale and 0.60–0.96 subscales), PACSLAC (range 0.77–0.96), PADE (range 0.54–0.96), ECPA (0.80), Elderly Pain Caring Assessment 2 (EPCA-2; range 0.852–0.897), MOBID (range 0.70–0.96) and Abbey Pain Scale (range 0.44–0.845). There were no inter-rater reliability data provided for the PPQ.

Overall, the majority of the tools assessed had moderate to good inter-rater reliability. However, there were limitations in terms of the sample sizes used to evaluate their reliability.

Test–retest and intrarater reliability

Intrarater reliability was not assessed for the FLACC, MPS, PBM, PPI, PAINAD, PATCOA, ECPA, EPCA-2 and the ADD protocol. Evaluations of intrarater reliability included percentage agreement, correlation, kappa, Nygård test–retest and intraclass correlations. In terms of intrarater reliability, the variation in calculations made direct comparison across the tools difficult and the use of small sample sizes indicated that all of the results should be treated with caution. Percentage agreement for intrarater reliability was provided for the FACS (79–93%); correlations for the FACS (0.88–0.97), PAINE (0.711–0.999) and RaPID (> 0.75), DS-DAT (0.6); kappa coefficients for MOBID-2 [0.41–0.83 (pain behaviour], 0.48–0.93 (visual pain recordings); Nygård test–retest for the CNPI (0.23–0.66); and intraclass correlations for the CPAT (0.67), REPOS (0.90–0.96), PACSLAC (0.72–0.96), PADE (0.70–0.98), MOBID (0.60–0.94) and Abbey Pain Scale (0.657). As with inter-rater reliability, the values indicate moderate to good temporal stability.

Internal consistency

Internal consistency data were available for the MPS (total scale = 0.76; subscales range 0.68–0.75), PAINE (0.75–0.78), RaPID (0.79), REPOS (0.49), CNPI (0.54–0.64), Doloplus-2 (0.668–0.82), PACSLAC (0.74–0.92), PADE (0.24–0.88), PAINAD (0.5–0.74), PATCOA (0.44), ECPA (0.70), EPCA-2 (0.73–0.79), MOBID (0.82–0.91), MOBID-2 (0.82–0.84) and Abbey Pain Scale (0.645–0.81). There was considerable variation in the internal consistency of scales, with the MOBID and MOBID-2 indicating the highest internal consistency and the PADE, PATCOA and PAINAD having some of the lowest ratings.

Validity

The validity of the pain tools was primarily explored using concurrent and/or criterion validity (correlation of the pain scale with other pain scores or a benchmark criterion) and/or discriminant and/or predictive validity (e.g. ability to discriminate, or predict between pain on movement and at rest). Some reviews, for example those by Zwakhalen et al. 64 and Herr et al. ,82 also provided brief insight into the conceptual foundation of the measures and ways content validity was explored. As with measures of reliability, there was considerable variation in how the validity of tools was assessed. Three tools had no validity assessment (the Comfort Checklist, the PATCIA and the OPBT). The NOPPAIN instrument also had little overall formal validity assessment.

Content validity

In general, only limited insight was provided into the conceptual foundation of the tools (as opposed to the tool’s purpose). For the vast majority of tools, their derivation, and thus the implied conceptual basis, lay in literature reviews and/or clinical and/or research experts in pain and older patients with dementia. In the case of other tools, for example the Abbey Pain Scale, the basis was unclear or, as with the Behavior Checklist, no information was provided. Two of the measures, Doloplus-2 and ECPA, were adapted from measures originally developed for a different patient group, namely young children. In contrast, the purpose of all the measures was commonly outlined. It is notable that some were developed for particular users (CPAT, for certified nursing assistant care providers; NOPPAIN, for nursing assistants), another for research purposes (DS-DAT) and two as decision support tools (the ADD protocol and the REPOS).

Concurrent and criterion validity

Concurrent and criterion validity were measured by comparing the scores of one tool to another, by comparing one tool’s scores with nurse/doctor ratings of pain or through comparison with self-report (using VASs). The following is a summary of the comparisons (ranges refer to correlation coefficients):

-

CPAT (r = 0.22; p = 0.076) was compared with DS-DAT (r = 0.25; p = 0.048)

-

PAINAD compared with the DS-DAT (range 0.56–0.76)

-

DS-DAT compared with the Pittsburgh Agitation Scale (r = 0.51) and the Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (r = 0.25)

-

Doloplus-2 compared with the PAINAD (r = 0.34) and PACSLAC (range 0.29–0.38)

-

REPOS compared with PAINAD (range 0.61–0.75)

-

FACS was compared with PBM (range 0.02–0.41)

-

PAINE compared with PADE (r = 0.65)

-

PADE compared with Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Inventory (range 0.30–0.42)

-

PPI compared with the Memorial Pain Assessment subscale (r = 0.67), Verbal Scale (r = 0.54), RAND® Health Survey (RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, CA, USA) and Dartmouth Primary Care Cooperative Information Project chart (r = 0.72)

-

RaPID compared with McGill Pain Scale (range 0.8–0.86).

Comparisons with proxy pain reports (doctor or nurse) were as follows: MPS (r = 0.86), PAINAD (r = 0.84), the PBM (range 0.62–0.73), MOBID (range 0.41–0.64), Abbey Pain Scale (r = 0.586), PACSLAC (range 0.35–0.54) and REPOS (range –0.12 to 0.39).

Comparison with self-report (using a VAS) comprised RaPID (range 0.8–0.86), EPCA-2 (r = 0.846), DS-DAT (range 0.56–0.81), PAINAD (r = 0.75 pain VAS and r = 0.76 discomfort VAS), ECPA (r = 0.67), Doloplus-2 (range 0.31–0.65), PPI (r = 0.55), CNPI (range 0.30–0.50), PATCOA (r = 0.41) and PBM (range 0.11–0.30).

Overall, the tools that had the highest correlations with each other were the RaPID compared with the McGill Pain Scale, the REPOS compared with PAINAD and the PPI compared with the Memorial Pain Assessment subscale. The MPS and the PAINAD had the highest correlation with nurse/doctor ratings of pain, and the RaPID with self-reports of pain/discomfort. There was no one scale that appeared to be superior to the others (or applicable as a gold standard), and no consistency in comparisons across the scales.

Discriminant validity

Discriminant validity was measured by comparing scores before or after a painful event. Several of the reviews reported that tools had discriminant or predictive validity without providing data; this included the reviews of the FACS and PBM. Other scales with a significant difference in scores pre and post interventions/events included the CPAT, CNPI, DS-DAT, PACSLAC, MOBID, Abbey Pain Scale, ADD protocol and the Behavior Checklist.

Construct validity

Construct validity was measured by comparing scores to medication use or prescription of medications. The PPQ scores were correlated to pain medication use (correlation coefficient range 0.37–0.55), and patients assessed with the PADE on psychoactive medications had significantly higher scores on the physical and verbal agitation subscales. With the PAINAD there was a significant fall in score after the administration of pain medication, and the EPCA-2 was correlated with the prescription of opioids (r = 0.782) and non-opioids (r = 0.730).

Feasibility and clinical utility

The feasibility of a tool is ‘its applicability in daily practice’, including aspects such as ease of use and time required to administer it, whereas clinical utility is ‘the usefulness of the measure for decision-making’, that is, to inform further action, such as the administration of analgesics. 66 Data on feasibility and clinical utility of tools were very limited. Often data were not available in the reviews or, when data were available, limitation often pertained to a lack of data in the original studies (e.g. reviewers stating the item was not reported and could therefore not be assessed). More specifically, feasibility data were completely absent for six tools (Comfort Checklist, FLACC, PAINE, PATCOA, PPI and PPQ); clinical utility data were completely or substantially absent for seven tools (ECS, FACS, MPS, PAINE, PBM, PPQ and RaPID). For four tools reviewers explicitly noted that claims of feasibility (e.g. time required to administer the tool) were made from the authors of the study without supporting evidence (Abbey Pain Scale, Doloplus-2, PACSLAC and PADE). There were also two instances (PACSLAC and MOBID) of conflicting data on clinical utility and feasibility from the different reviews, possibly because of an ambiguous reference to different versions of the same tool.

Specific evaluation for feasibility appears to have been carried out only for three tools (CPAT, MPS and PATCIA). In the first two of these cases the evaluation was done by use of questionnaires. It also appeared that users of the Abbey Pain Scale were asked for feedback in the context of the psychometric testing of the tool. In was unclear whether or not the ADD protocol was also assessed for feasibility.

Specific evaluation of clinical utility appeared to have been undertaken for the PATCIA tool, and possibly for the ADD protocol and PAINAD.

It must be stressed that when reviews assessed or mentioned the feasibility and/or clinical utility of the tools, the two aspects were often confounded (reviewers, authors or users typically drawing conclusions from ease of use or brevity of a scale to its usefulness).

Specific dimensions of feasibility assessed were time to complete the assessment (e.g. to complete a checklist), availability of instructions on how to use the tool and/or availability of guidelines on how to score pain, and training needs.

Six tools were reported to be ‘easy to use’ (Abbey Pain Scale, Behavior Checklist, CNPI, CPAT, MPS and NOPPAIN), two were considered manageable/acceptable (ECPA and RaPID) and four were judged to be complex (ADD protocol, DS-DAT, PATCIA and PADE). Conflicting views on the ease of use or complexity of the tools were apparent for five tools (Doloplus-2, MOBID, PACSLAC, PAINAD and PBM).

Instructions for use and/or guidelines on scoring were reported to be available for 13 tools (Abbey Pain Scale, CNPI, CPAT, Doloplus-2, DS-DAT, ECS, FACS, MPS, MOBID, NOPPAIN, PACSLAC, PAINAD and REPOS), with varied assessments in terms of clarity or complexity of the instructions.

Training in the use of the tool was judged as necessary for 10 tools (EPCA-2, MPS, NOPPAIN, PADE, PACSLAC, PAINAD, ADD protocol, CPAT, DS-DAT and MOBID), four of which seemed to require significant training (ADD protocol, CPAT, DS-DAT and MOBID). For six tools it was stated that the authors of studies creators of tools did not report the level and length of training required (Abbey Pain Scale, CNPI, Doloplus-2, PAINAD, PACSLAC and REPOS). For the majority of the tools, however, data about training were not available (Behavior Checklist, Comfort Checklist, ECPA, ECS, FACS, FLACC, OPBT, PATCIA, PAINE, PATCOA, PBM, PPI, PPQ and RaPID).

Specific dimensions of clinical utility were less straightforward. The availability of cut-off scores and interpretation of scores for decision-making appeared to be the two dimensions supporting evidence of clinical utility. The presence of cut-off scores contributes to achieving clinical utility, for example to help discriminate between presence and absence of pain, or to couple the scale with a treatment algorithm. Otherwise, general statements were available related to evidence of use in clinical settings and evidence of clinical utility, the latter being dependent on the former.