Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 11/1016/04. The contractual start date was in July 2012. The final report began editorial review in October 2015 and was accepted for publication in March 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Llewellyn et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Costing at the patient level in health care makes sense. NHS clinicians treat patients, so they should readily connect with individual patient costs. More broadly, understanding cost drivers at the patient level should enable better resource allocation not only along care pathways within hospitals, but also across the whole NHS economy. Patient-level information and costing systems (PLICSs) have the potential to produce a granular analysis of the cost of individual pathways both within trusts [in this report the term ‘trusts’ refers to both foundation trusts (FTs) and NHS trusts, unless otherwise specified], from referral to discharge, and across 1 ‘year of care’ (for chronic conditions that cross organisational boundaries).

In 2009, when PLICSs were first introduced, the Department of Health (DH) gave the following definition:

[PLICS] relates to the primary functions of health providers, which are to diagnose and treat patients . . . [it] is derived from tracing resources used by an individual patient in diagnosis and treatment and calculating the expenditure of those resources using the actual costs incurred by the organisation.

DH1

The use of the term ‘actual costs’ in the above definition heralded a shift in hospital costing methodology from a mainly ‘top-down’ mode of cost allocation to a more direct approach, based on the principles of activity-based costing,2 whereby every effort is made to cost all the interventions and events that could be associated with individual patients. 1 In the NHS, it has been known for some time that a minority of patients drive costs, but PLICS data give specificity to this knowledge; Blunt and Bardsley3 found that 3% of patients account for 45% of costs. PLICSs give the opportunity to discern where, on the care pathway, these costs are incurred.

At the time when the government implemented PLICSs as a new costing methodology, the benefits were expected to be (1) an enhanced ability to understand financial drivers enabling cost benchmarking at patient, specialty and hospital level; (2) ‘dramatically improved clinical ownership’ of costs that would enable a comparison of the cost profiles of different clinicians for similar patients; (3) a detailed knowledge of individual patient costs to inform patient classification, rather than reliance on the average cost; (4) to progress payment by results (PbR) through calculating ‘a long-term sustainable price to an efficient provider’; and (5) informed dialogue between providers and commissioners. 1

In 2012, the Nuffield Trust report supported the use of PLICSs to generate cost savings, but commented that such savings will be achieved only if clinicians actually use PLICSs to investigate how their decisions impact on costs and warned that trusts could use PLICSs to identify unprofitable service areas and, subsequently, pull out of providing them. 3

How trusts can use patient-level information and costing systems

Research indicates the potential for the use of PLICSs in hospitals. The reliability of reference costs (the only widely available hospital cost data before PLICSs were introduced) for benchmarking has been found to be questionable. 4 If trusts are willing to share their PLICS data externally for benchmarking, performances can be enhanced only if there is an internal evaluation of the processes that led to the externally shared results. 5 PLICSs can provide the data for this internal examination of processes. In many clinical areas, especially complex care in which expert judgement is exercised, there is acknowledged variability in resource use between different clinicians (or teams of clinicians). 6 The NHS Institute reported that £3B could be saved if every NHS organisation performed as well as the upper quartile in key areas [e.g. reducing length of stay (LoS), reducing pre-operation bed-days and managing variation in outpatient appointments and emergency admissions]. 7 Current costing practice under Health Resource Groups (HRGs) masks such variability at the consultant level. 8

Care integration along pathways within trusts should enhance the quality of patient care while also making cost savings. 9,10 PLICSs illuminate the care pathway within trusts from admission to discharge, so cost savings associated with care integration along the pathway can be identified.

How patient-level information and costing systems can be used across organisational boundaries

For chronic conditions, such as cancer, heart disease, diabetes mellitus and asthma, tracking patient pathways has been advocated for decades but such pathways have never fully been established. 11 The year-of-care model for long-term conditions that cross organisational boundaries emphasises costed care pathways and anticipates year-of-care prices. 12 PLICSs can potentially cost 1 year of care across organisational boundaries by identifying the direct and indirect costs associated with all the events, procedures and clinical interactions for an individual patient trajectory. If commissioners have access to PLICS data, they can use it to develop tariff currencies to enable commissioning on the basis of care pathways and year of care.

Research aims

Against this background, we aim to analyse the potential of PLICSs in four areas:

-

cost improvement through enhanced technical efficiency

-

better allocative efficiency of resources and congruence with patient preferences within health-care economies (first, within and between trusts; second, between primary and secondary/tertiary care; and, third, along care pathways and year of care)

-

understanding clinical variation in resource use and the relationships between cost and quality

-

greater clinical engagement through more clinical ownership of costs and information systems.

These research aims make reference to both technical and allocative efficiency. Technical efficiency implies the use of resource inputs (e.g. labour, capital or technology) to maximum advantage in terms of either intermediate outputs (e.g. numbers of patients treated) or outcomes (e.g. numbers of patients benefiting from treatment), whereas allocative efficiency implies allocating resources in such a way as to maximise health-care outcomes. 13 In terms of available comparative statistics on outcomes, hospitals use short-term survival rates, health recovery rates after treatment in hospital and changes in waiting times. 14

Technical efficiency implies two criteria: (1) producing as much as possible with a given set of inputs and (2) producing at minimum cost. 15 Therefore, technical efficiency has both transformative (or productive technological) and cost-minimisation elements. Technical efficiency can also be observed under two conditions: (1) an output-transformative approach, which maximises outputs while keeping inputs fixed; and (2) an input approach, which minimises inputs while keeping outputs fixed. 16 In health care, technical efficiency is a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for allocative efficiency because decisions on where to best allocate resources (e.g. acute or community care) are made prior to the achievement of technical efficiency. By contrast, allocative efficiency implies technical efficiency because resources are put to best use only under conditions of technical efficiency. Both technical and allocative efficiency lower hospital costs. 17

Concerns have been raised that technical cost efficiency can be pursued to the detriment of quality of care; however, limited evidence is available and what evidence there is generally employs data envelopment analysis. With this technique, Nayar and Ozcan18 found that improving technical efficiency did not compromise quality of care, Clement et al. 19 reported that lower technical efficiency was linked to worse risk-adjusted quality outcomes and Mark et al. 20 identified patient safety as a mechanism to improve technical efficiency. However, a cross-country data envelopment analysis revealed that enhanced technical efficiency is apparent in some countries with good care outcomes, but also in those with more modest achievements. 21

Another issue regarding technical efficiency is to question the circumstances under which it is achieved. Leibenstein22 argued that technical or ‘X-efficiency’ should not be assumed, as a benign economic climate, especially when allied to a lack of competitive pressures, as it will lead individuals to work less hard to the extent that outputs are not maximised for a certain level of inputs. Although ‘efficiency’ has often been seen as a matter of dry calculation rather than an ethical issue, whenever the resources dedicated to health care result in less health benefit than would have been possible, there are moral implications. 23,24

Research questions

Our research questions are:

-

How are NHS trusts and commissioners using PLICSs?

-

How can PLICSs be used to benefit the total health economy (focusing on cost improvement, resource allocation across services and settings, linking costs with quality and clinical engagement)?

In the first research question, ‘NHS trusts’ refers to FTs and non-FTs. We surveyed all NHS trusts – both FTs and non-FTs. However, all four of our case studies were FTs, so in the case study chapters the ‘trust’ is a FT (see Chapter 3 for more details).

Contribution and significance of the research

Since 2009, the use of PLICSs in the trusts has not been mandatory; however, Monitor (the economic regulator for health) is now planning to use PLICSs to set prices for funding [see Chapter 2 for details on Monitor’s merger with the Trust Development Authority (TDA) in 2015, which occurred during the writing of this report]. Despite the significance of PLICSs, in terms of both policy and impact on NHS service delivery, it is understudied academically. At the time of writing, to our knowledge, there are only two relevant academic reports: one (Chapman and Kern)2 mentions PLICSs only in the context of activity-based costing, and the other (Blunt and Bardsley)3 investigated PLICSs at only one hospital.

In the past, health commentators have pointed out that policy strands frequently cut across each other; indeed, there is often transparent inconsistency between health policy objectives. 25 The NHS is currently characterised by pressures for both competition and collaboration. Although the Health and Social Care Act 201226 requires competition and collaboration, the two are often at variance; when they conflict, some commentators argue that competition will dominate. 27,28 Eighty-two of the 282 clauses in the bill are about competition, so it appears that enabling competition is the governmental intent. 28 In terms of greater competition, however, the professionally dominated NHS has resisted change in the past and may do so again. 29 In 2011, the British Medical Association polled its members on the health and social care bill reforms; > 80% said that they were mostly or very unwelcome and > 50% said that the role of Monitor to promote competition was the most damaging of the reforms. 30

In broad policy terms, PLICSs could be mobilised to support either competition or collaboration. Competition can enable basic cost awareness. As mentioned above, PLICSs are sophisticated costing tools that can support technical efficiency and hence cost improvement in the trusts. A multiplicity of individually competing sellers (providers) and buyers (commissioners) is the essence of market competition and may improve technical or X-efficiency. However, such a situation leads to fragmentation. In a huge and very complex multiagency organisation like the NHS, which is facing ever-increasing demand, collaboration is required to avoid duplication and enable effective resource allocation. As discussed above, PLICSs have the potential to be used in collaborative endeavours to integrate care across organisational boundaries. An important aspect of this research is to track the use of PLICSs against the background of both competition and collaboration in the UK health-care economy.

The structure of this report

We next turn to the policy background for PLICSs (see Chapter 2), before detailing our research methodology (see Chapter 3). The empirical chapters then commence with an analysis of survey findings (see Chapter 4). The four case studies are presented next. First, we discuss ‘Gertrude’ (see Chapter 5) and then ‘Sybil’ (see Chapter 6); both are generalist FTs and early implementers of PLICSs. The third case study chapter discusses ‘Chelsea’ (see Chapter 7), a specialist FT which also has considerable expertise in PLICSs. The last empirical chapter focuses on ‘St Winifred’s’ (see Chapter 8), a FT which implemented a PLICS during our research. Finally, we garner our arguments and evidence to (1) address our research questions and objectives; and (2) discuss the wider implications of our findings. The discussion chapter (see Chapter 9) ends with concluding comments and suggestions for future research.

Chapter 2 Policy background

In this chapter, we set out the policy context for our investigation of current practice and future potential for PLICSs. In Chapter 1, we discussed the policy pressures for both competition and collaboration in the NHS. After outlining our literature search strategy, in the first part of this chapter we explore other aspects of the broad policy background (see The broad policy background) and in the second part we look more closely at the specific policy context for our empirical findings on PLICSs in the four case studies (see The specific policy context for the use of patient-level information and costing systems). Although this distinction is somewhat artificial, we think that there are broad and specific dimensions to the impact of policy on the use of PLICSs.

Academic literature search strategy

The academic literature search strategy used the University of Manchester online library, Manchester e-scholar (University of Manchester, Manchester, UK) and Mendeley databases, version 1.16 (Mendeley, London, UK), through carefully considered keyword combinations. However, at the time of writing, there are few academic articles on PLICSs. To interrogate the policy background for PLICSs, we accessed relevant grey literature and blogs through organisation websites (e.g. the DH, Monitor, NHS Choices, NHS England, The King’s Fund and the Health Foundation). We also created and used a reference database of articles from Healthcare Finance and the Health Service Journal as leading, influential practitioner-oriented publications that have discussed PLICSs. Our time frame for the search was 2000 onwards, because PLICSs are a relatively recent development (from approximately 2006 onwards).

We searched, reviewed and synthesised literature throughout all stages of our research to keep up to date with both new publications, particularly on patient-level costing, and relevant policy developments in the area, for example mandatory policy documents released by Monitor and NHS England. Our approach was narrative in style, being non-linear and iterative, in accordance with the recommendations of Cronin et al. 31 for social science research.

Part 1: the broad policy background

In the past, Monitor and the DH differed somewhat in their approach to PLICSs. Monitor concentrated more on service line reporting (SLR) (see Service line reporting and patient-level information and costing systems), seeing the implementation of PLICSs as a natural progression from SLR once this is in place, whereas the DH promoted costs at the patient level, recognising the value attached to the added granularity of PLICSs. 32 Now, PLICSs are a type of costing system that, under Monitor, look set to become a pricing model. The Healthcare Financial Management Association (HFMA)33 reported that: ‘Monitor regards accurate and comparable patient level cost data as fundamentally important in supporting the development of pricing mechanisms’. Monitor proposes that the first year of mandatory costing based on PLICSs will be 2018–19 for acute trusts. 34

Recent developments in NHS costing/pricing and patient-level information and costing systems

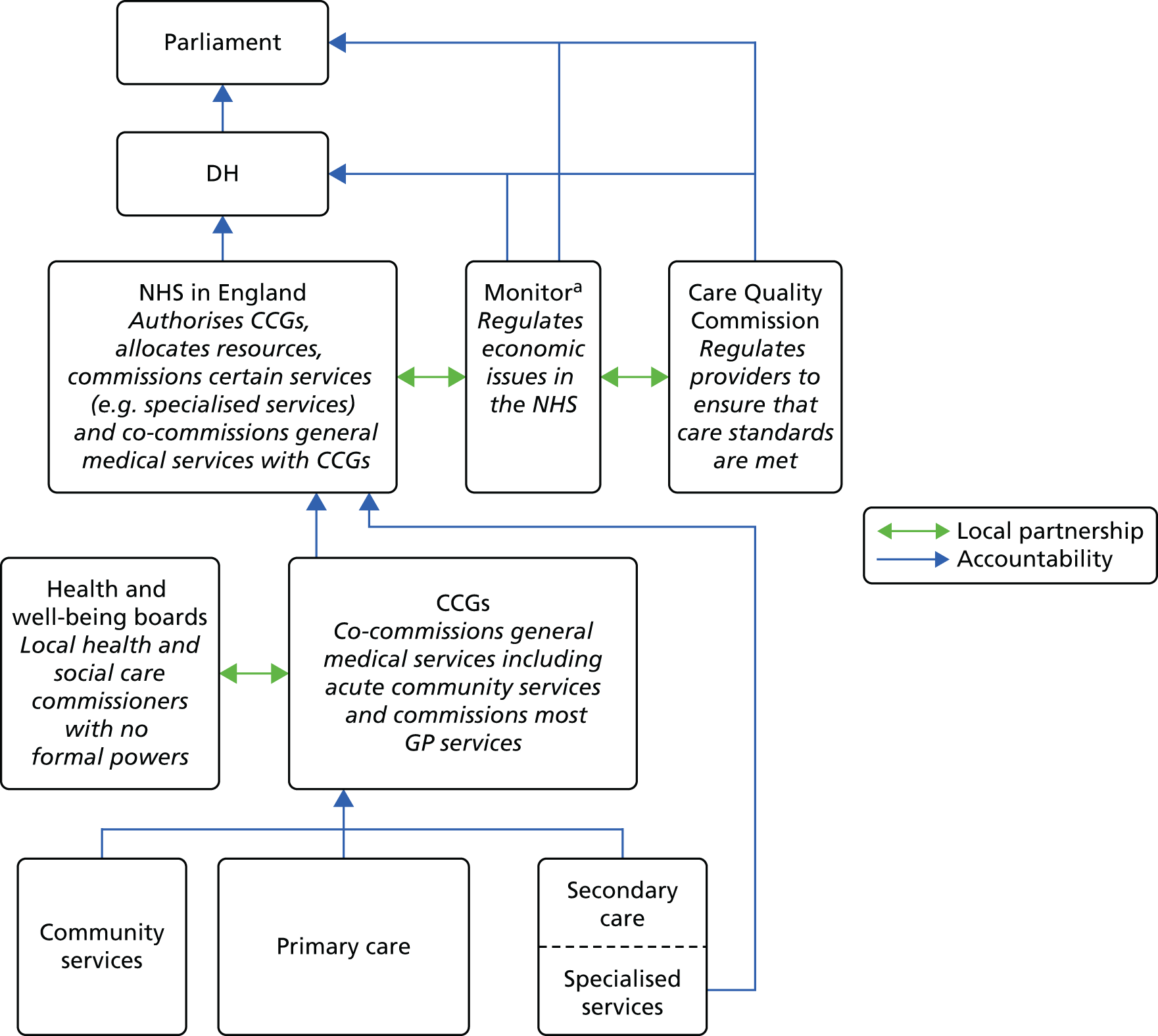

Following the Health and Social Care Act 2012,26 Monitor and NHS England took responsibility for the NHS payment system, a responsibility that previously lay with the DH. The 2012 Act prescribes that NHS England should specify currencies (i.e. units of health care for which there can be a national price), whereas Monitor’s duty is to set those prices. 35 Clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) and health and well-being boards constitute a partnership at the next level. Figure 1 portrays current accountabilities, partnerships and monetary flows in NHS England.

FIGURE 1.

Accountabilities and partnerships in the NHS in England. GP, general practitioner. a, Monitor has now merged with the TDA to become NHS Improvement.

A particularly controversial aspect of the Health and Social Care Act 2012 was to make the standard tariff a maximum, thus allowing providers to compete on price (see Chapter 1, Contribution and significance of the research). There appears to be potential for price competition between trusts; Blunt and Bardsley3 reported that in the majority of cases in which the trust’s tariff funding was under PbR (see Payment by results: the national tariff), they incurred costs which were > 10% higher or lower than the tariff and only 17% of cases were within 10% of the tariff. Another aspect of competition is the enhanced role for the private sector, under the political remit of ‘any qualified provider’. With Monitor as the economic regulator, this may signal a more market-based approach associated with price competition,36 for which PLICSs could supply the most sophisticated data. However, Simon Stevens, the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of NHS England in 2014, remarked recently that ‘It’s unlikely the NHS will ever fully return to Lansley [the former Health Minister]’s price setting system.’37 As yet, it is uncertain what developments there will be on price competition within the national tariff.

There have been tariff consultations. In 2013, Monitor and NHS England published a discussion paper on reforms to the tariff, inviting comment. 38 Following the consultation, Monitor stated: ‘we consider on balance that a rollover [continuing] approach for national prices is the most appropriate approach for the 2014/15 National Tariff Payment System. We propose to apply this approach to determining prices for 2014/15 only; for 2015/16, we are likely to propose a different method for setting national prices, based on updated cost data (which is likely to include reference costs data as well as potentially PLICS data).’39

Another consultation document was issued for the proposed 2015–16 tariff. 40 Tariff proposals for 2015–16 included a 3.8% efficiency savings requirement and marginal rates of 50% for emergency admissions and specialised services. (Trusts have had to find 4% savings annually between 2010 and 2015.) These mandated efficiency targets are referred to as Cost Improvement Programmes (CIPs) at the trusts, including our case study sites. Issues around efficiency savings and marginal tariffs for both emergency admissions and specialised services were raised repeatedly in our interviews at these case study sites. The marginal rate rule restricts tariff payments to only a percentage of the full national average cost when activity (number of patients treated) exceeds a baseline value (commonly the activity level of the previous year).

In any event, providers ‘resoundingly rejected’ the proposed new tariff for 2015–16. Seventy-five per cent of providers (by share of supply) made formal objections; this was well over the 51% threshold for objections that triggers either a referral to the Competition and Markets Authority or another consultation with providers on the basis of revised prices which take account of the formal objections. 41 After providers rejected the new tariff proposals for 2015–16, Dowler42 reported that Monitor and NHS England made a £500M bid to providers to try to agree prices before the start of 2015–16; this bid included a reduced efficiency savings target of 3.5% and uplifts on the cap on payments for specialised services and emergency admissions to 70% (see Exceptions to payment on the national average tarriff). This bid is known as the Enhanced Tariff Option (ETO). The NHS Confederation reported in April 2015 that the majority of NHS trusts and FTs have signed up for the ETO, with the remainder continuing on 2014–15 tariffs – the default tariff rollover. 43 However, it is worth noting that 30 of the 241 trusts that rejected the ETO included all 10 members of the Shelford Group, which comprises major teaching and specialist trusts, such as Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children and Moorfields Eye Hospital. 44 The influential Shelford Group is now expected to engage in further negotiations, both locally and nationally. 45 In addition, those who rejected the ETO are not eligible for Commissioning for Quality and Innovation (CQUIN) payments, worth up to 2.5% of income. Dowler45 reports that providers that accepted the ETO felt ‘blackmailed’ by the threat of losing CQUIN monies (as recommended by Darzi,46 CQUIN money has been top-sliced and paid since 2009).

Providers that signed up to the new ETO will be required to share cost data (including PLICSs) in a new ‘efficiency collaborative’ established by Lord Carter (in 2014, Lord Carter was appointed to be Chair of the NHS Procurement and Efficiency Board). 47 In relation to the Carter efficiency collaborative, Simon Stevens remarked: ‘At the moment 22 trusts are signed up to sharing data on their [PLICSs] costs so we get a granular look at where the efficiency opportunities are sitting . . . I would like to see the vast majority of trusts participating in that.’ In an interim report, the Lord Carter review48 commented: ‘By 2019–20, the review believes £5bn a year could be saved across staffing, medicines, everyday items and estates.’

However, some commentators viewed the clear rejection of the originally proposed 2015–16 tariff as indicating a new era in NHS cost improvement. At The King’s Fund, Murray49 remarked: ‘It signals that the policy of implementing year-on-year reductions in the prices paid to hospitals for their services has reached the end of the line . . . the two main ways used to reduce NHS costs over the last few years – limiting staff salary increases and reducing payments to hospitals – have now been largely exhausted.’

Such views heighten the relevance of care integration across organisational boundaries to both achieve cost savings and improve the care delivered to patients. Allegedly, as a result of the ‘listening exercise’ which followed controversy over the bill,50 the NHS Health and Social Care Act 2012 places responsibilities on NHS England, CCGs and the health and well-being boards (see Figure 1) to better co-ordinate care. 51 Evaluation of the 16 integrated care pilots set up in 2009 demonstrated lower than expected outpatient and elective care but, perhaps surprisingly, no change on emergency admissions. 52 However, clear evidence to substantiate both improved patient satisfaction with integrated care and cost savings is often still lacking. Perhaps unavoidably, proxies for cost savings are often used, such as the avoidance of unnecessary hospital admissions. 53 Clearly, deriving cost savings from counterfactuals is a subjective exercise.

In 2015, there were arguments that integrated care should also be seen in terms of its potential for improved population health. 50 However, such a suggestion does not solve the complexities of clearly demonstrating the benefits of integrated care. Nevertheless, many commentators prescribe integrated care, including a redistribution of resources across health economies to transfer care (when safe to do so) from secondary providers to primary and community services. 9,10,54 We argue that PLICSs could be important tools for promoting care integration – including a transfer of resources from secondary to primary care – but our evidence casts considerable doubt over whether or not this will occur (see The potential for patient-level information and costing systems to cost cross-organisational care pathways).

In summary, costing and pricing models are, potentially, significant drivers for more effective resource distribution across health economies55–57 but, as will be argued in this research report, the specificity of the costing (or pricing) model and its mode of implementation are fundamental to success. Consequently, from an historical perspective, we briefly review costing and pricing models next, before discussing the national tariff and the role of Monitor.

History: the development of costing and pricing models in the NHS

Since the 1970s, NHS financial management policy has been inclined to oscillate between cost benchmarking and market pricing. This oscillation has, at least in part, been driven by the choice of cost object, to which there are three broad alternatives: department or specialty; intervention or diagnosis; or the patient. These alternatives are not, of course, necessarily mutually exclusive. In the 1970s, work was initiated on specialty costing (e.g. Magee et al. 58 and Pugh59). This provided grounds for exploratory work on patient costing. 60 Körner61 recommended the general adoption of specialty costing and associated patient costing through analysing patient groups. Taylor62 confirmed that such patient costing was feasible. This early work clearly formed the basis of a future agenda for SLR and PLICSs (see Service line reporting and patient-level information and costing systems).

Meanwhile, the Griffiths Inquiry63 heralded the introduction of market principles into the NHS. Subsequent to the Griffiths Inquiry, in 1983, four management budgeting pilot sites were initiated;61 these largely proved to be unsuccessful in using costs at a patient level but, in the 1986 Resource Management Initiative,64 they spearheaded improved patient information. Enthoven’s65 notions on the use of competitive markets in health care to enhance cost efficiency proved highly influential on the (then) UK Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher. In 1991, she introduced the NHS and Community Care Act 1990;66 this brought about a NHS internal market to enable competition, which was assumed to drive greater cost-effectiveness and better resource allocation.

The expectation at the time was that contracting between purchasers [health authorities and general practitioner (GP) fund holders] and providers would become more sophisticated, developing from block grants to (1) cost and volume specifications; and (2) cost-per-patient case negotiation. 67 These patient costs were an early forerunner of PLICSs. In the internal market, hospitals had to set prices; in theory, these prices were cost based as, under the internal market, hospitals were not intended to make a profit. 64,68,69 However, these cost-based prices were not robust for three reasons: (1) hospitals’ cost information was inadequate for price-setting;70,71 (2) price differences did not convey information because currencies (the procedures of which were being costed) were not consistently defined; and (3) prices did not adequately reflect provider efficiency because lower or higher prices did not always signal lower or higher cost. 64,68 Moreover, if the present mix of services and their mode of delivery is not optimal, cost-based pricing does not incentivise providers to engage in service reconfiguration. 72

In 1997, the New Labour government announced a policy shift away from the internal market instituted by the Conservatives, back to a cost benchmarking regime. However, this shift was, at least in part, rhetorical because the cost benchmarking was mandatory and would herald funding on the basis of national average costs (rather than providers’ actual costs), although, initially, providers were not cognisant of the intended new funding initiative. 73

Payment by results: the national tariff

There is, currently, a tariff based on national average costs for health-care interventions. This national tariff is derived from reference costs aggregated to HRGs (trusts are mandated to provide reference costs for their services). Since 2003, the funding scheme PbR, based on national tariffs, has been rolled out to fund health-care activity. 74 Examples of the 2014–15 national tariff are £8652 for a major hip operation for trauma with major complications and £339 for a prostate or bladder neck minor endoscopic procedure, done as an outpatient appointment. 75

Under PbR there are strong monetary incentives for increased activity (i.e. to treat more patients). Trusts have incentives to reduce costs and shorten LoS to boost productivity. 76 If income under the tariff exceeds costs, hospitals make a surplus which can be retained. 77 Conversely, if income under the tariff is less than the cost to the provider, the trust will lose money on the activity concerned. Under PbR, revenue to the trusts is usually the full average cost.

Developments on the national tariff

Payments under the national tariff, set under PbR, constitute about one-third of all NHS expenditure. 78 Although it was intended that all hospital services be funded through the national tariff, many are still on block contracts or locally agreed prices.

The scope of the tariff

Calkin79 reported that in the acute sector 66.6% of services were under PbR, with 33.4% being on block contracts or locally agreed prices; for mental health 66% were on block contracts, with 33.4% locally agreed; and for community services, 90% were on block contracts with 10% locally agreed. But even in the acute sector, many trusts were well below the 66.6% average. At one of our case study sites, only 19.6% of services were under PbR, but the vast majority were locally agreed. The trusts commented on the generally advantageous prices secured through local agreement rather than national tariffs. Dowler80 reported that PLICSs may have given trusts an ‘unfair advantage’ in tariff negotiations at both a local and national level, not least because of the current information asymmetry (in the trusts’ favour) of PLICS data.

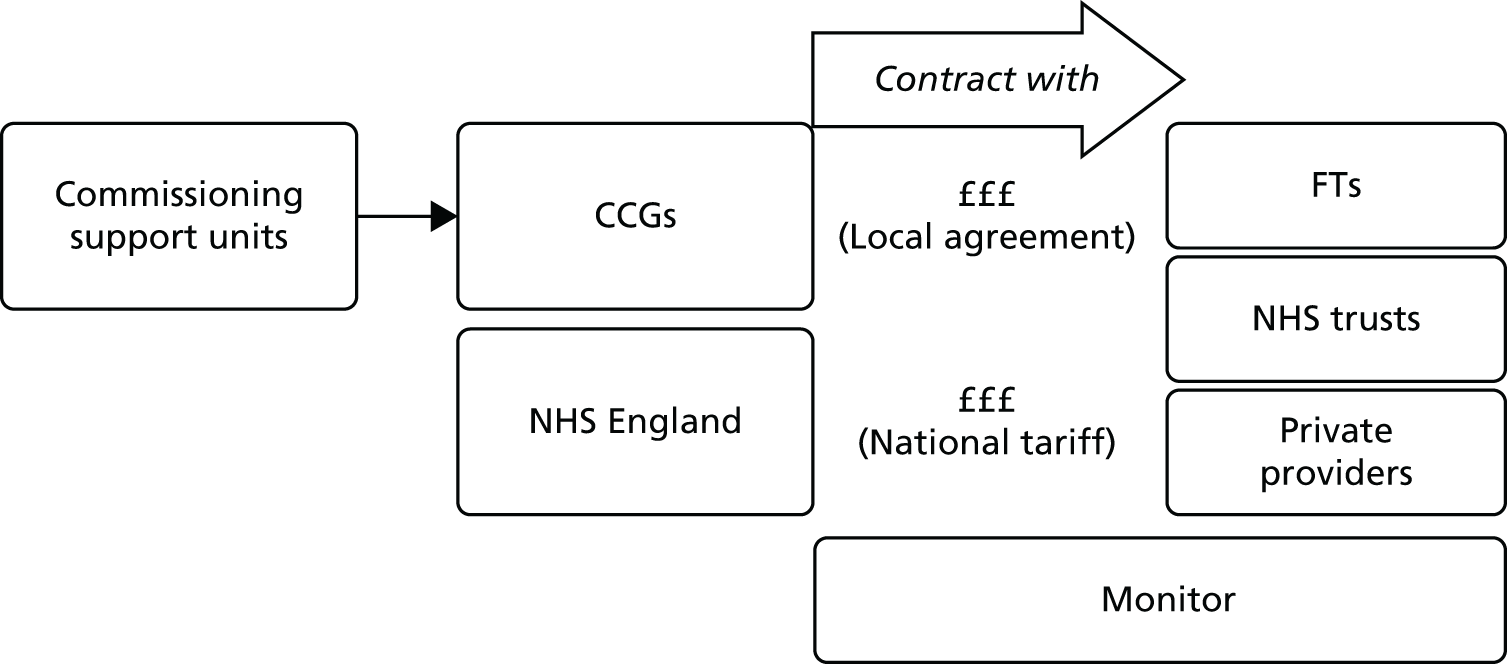

Figure 2 illustrates the contracting regime for secondary-care providers.

Commissioning support units (CSUs) were established in 2012 to support CCGs (see Figure 2). The role of CSUs is described as follows: ‘CCGs are likely to need support in carrying out: transformational commissioning functions, such as service redesign and transactional commissioning functions, such as market management, healthcare procurement, contract negotiation and monitoring, information analysis, and risk stratification.’82 As explained in Chapter 4, our commissioning survey was sent out to CSUs rather than CCGs because they were thought to be more able to give an overview about the actual and potential use of PLICS data for the commissioning function.

Exceptions to payment on the national average tariff

One exception to payment for activity on the basis of the full average cost is for admissions from accident and emergency (A&E) departments. A marginal rate for emergency admissions was introduced in 2009–10 and took full effect in 2010–11. Under this policy, if the value of a trust’s emergency admissions exceeds the previous year’s activity, then the trust receives only 30% of the income for the additional activity. This marginal payment was much commented upon at our case study sites, where there was disquiet about its impact. The marginal rate rule was introduced by the DH ‘in response to concerns about growth in the volume of patients being admitted to hospital as emergencies.’40 This is evidenced by, for example, a calculated 11.8% increase in emergency admissions from 2004–5 to 2008–9, suggesting that the thresholds for admission to hospital have reduced. 83 However, a submission from the Foundation Trust Network84 found there to be only a 6.6% rise in the average number of admissions from 2008–9 to 2012–13 and, on this basis, called for the policy on marginal payments to be abandoned. Despite this submission, Monitor and NHS England decided to retain a marginal rate rule for 2014–15. 40

From the outset of PbR it was recognised that specialised services are frequently more expensive than non-specialised care, so a ‘top-up’ was applied. For example, in 2012–13 there was a 50% top-up for specialised children’s services. 85 NHS England now directly commissions specialised services, which account for around 14% of the total NHS budget. 86 The commissioning budget for non-specialised services is devolved from NHS England to the CCGs. Figure 3 depicts these responsibilities and their associated, vertical monetary flows.

FIGURE 3.

NHS commissioning responsibilities and monetary flows.

One of our case study sites was a specialist centre for cancer so these arrangements were highly relevant to the staff members. Indeed, the introduction of a PLICS at this site was, in part, driven by the need to understand the financial consequences of some of their specialised services moving on to the national tariff; they anticipated that this development would have a negative impact on income for the trust.

In their consultation document for the proposed 2015–16 tariff, Monitor and NHS England87 note the ‘relatively rapid rate of activity and cost growth in acute services without national prices, particularly specialised services.’ NHS England35 described the cost growth in specialised services as ‘unaffordable’. In response to this cost growth in specialised services in the acute sector, it was proposed that only 50% of prices be paid over a prescribed baseline. 43 However, as outlined above, Monitor and NHS England offered what were effectively financial inducements to providers to accept its proposed 2015–16 tariff, including an increase to 70% of the marginal rate for specialised services.

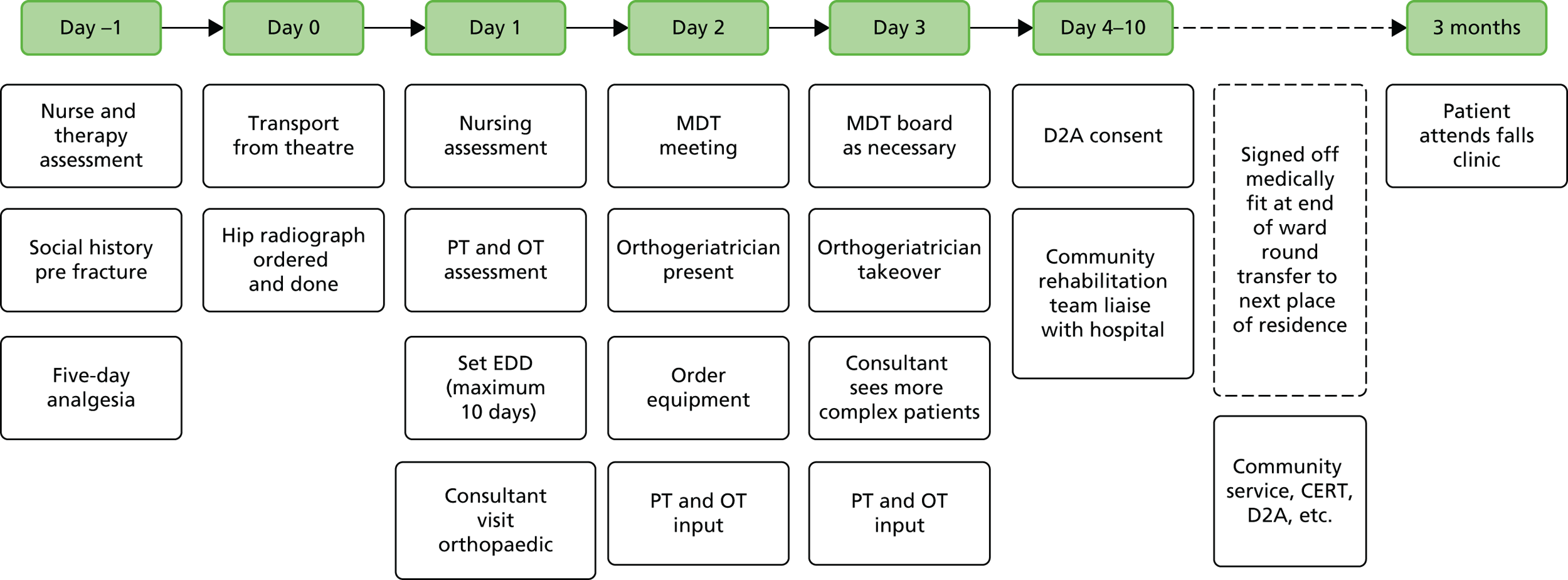

Best practice tariffs (BPTs) are defined as follows: ‘A best practice tariff is a national tariff that has been structured and priced to incentivise and adequately reimburse care that is high quality and cost-effective.’88 These were introduced in 2010, in the first instance covering four procedures with the intent to incentivise day-case surgery for cholecystectomy, pay for best practice for stroke and hip fracture and streamline the care pathway for cataract surgery. For example, there was a 24% increase in price for cholecystectomies undertaken as day cases, which led to a 7% increase in patients treated as day-cases. 89 By 2013–14 there were 18 BPTs. 79 For 2015–16, Monitor and NHS England proposed a new heart failure BPT and some adjustments to existing BPTs.

Advantages and disadvantages of the tariff and payment by results

Under PbR, payments for activity have had advantages, including reduced waiting times and improved access to planned care. 90 An evaluation of PbR undertaken in 2009, using Scotland as a comparator, concluded that PbR led to LoS falling more rapidly and the proportion of day cases increasing more quickly. 91 Appleby et al. 92 stated that PbR is most suited for elective care and is less appropriate when less rather than more activity is required.

The Nuffield Trust reasoned that the cost efficiency of the whole NHS economy will improve only when payment systems cover whole care pathways and create incentives to deliver the ‘right care in the right setting’,93 thus improving allocative efficiency. Currently, payments under PbR are made to geographically separate organisational units; in consequence, although ‘unbundling’ the tariff is possible, the present funding regime does not encourage care integration across services and settings.

Moreover, PbR can have a negative impact on innovation because new technologies change the patient pathway and require staff training. Therefore, although innovation can improve productivity, at least in the short term, innovation can reduce patient throughput and, therefore, income under the tariff. 94

In sum, the adverse effects of PbR are:

-

increased hospital admissions

-

unco-ordinated care across settings

-

undertreatment

-

cost shifting to other budgets

-

cherry-picking lower-risk cases

-

up-coding or misreporting. 79

We found examples of all of these disadvantages in our case studies. Before looking more closely at various aspects of the context for issues raised in the case studies, we review the key role of Monitor in determining NHS payment systems.

The role of Monitor

Monitor is the regulator for health in England. It ensures the maintenance of essential health services in the event of a provider being in serious difficulties. Monitor is responsible for the NHS payment system, which must enable quality and efficiency. More widely, Monitor also ensures patient choice, guards against poor purchasing on behalf of patients and makes judgements on any anticompetitive behaviour by providers. 95,96

It should be noted that, in June 2015, during the writing of this report, Monitor and the TDA were merged97 to form NHS Improvement. In some circles, Monitor was seen as the government’s ‘stick’ with the TDA as the NHS ‘carrot’ because it worked with trusts to achieve foundation status. 98 The performance of the TDA has been less than impressive: set up in 2012 with a goal of making all NHS trusts FTs by 2014, this target was revised in 2014 to at least 2018, and trusts’ deficits may reach £2.1B in 2015. 99 Dixon100 reports that both Monitor and the TDA had run ‘compliance’ regimes, arguing that, given the challenges ahead, a more supportive ‘commitment’ approach may enable more ‘NHS improvement’.

Monitor was dubbed ‘Ofhealth’;101 regulating the financial performance of NHS providers since 2004, its role has been described as ‘totemic . . . a highly charged symbol of the political debate’. 102 In April 2013, Monitor’s remit was extended to all providers of health and adult social services. Debate has focused largely on Monitor’s powers over both competition and collaboration, along with scepticism, in some quarters, over ‘Ofhealth’s’ independence.

The reforms proposed by the coalition government (from 2010 to 2015), as set out by Andrew Lansley, the Secretary of State for Health at the time, in the proposed health and social care bill, referred to Monitor’s duty to promote competition in health care, a role that was vigorously opposed by Nick Clegg, leader of the Liberal Democrat Party, a coalition partner at the time. 103 A focus on promoting competition was controversial in itself, but particularly so in the light of McKinsey (the international management consultancy)’s involvement in drawing up the bill. McKinsey’s clients have included 15 of the 22 largest health-care and pharmaceutical companies. 104 Monitor’s promotion of competition may facilitate its access to the lucrative UK health-care market. At the time of writing, the head of Monitor is a former McKinsey employee, as is its Director of Strategy. During intense lobbying over the bill, the Chair of the Royal College of General Practitioners referred to concerns over ‘conflicts of interest’, commenting that ‘private companies that have advised the Government on how to dismantle the old system stand to derive commercial benefits from the new one’. 105 The government proved unable to quell all the disquiet. In April 2011 there was a ‘pause’ for the ‘listening exercise’ over their health reforms.

At the time of writing, in terms of their background, very few (just 21) of Monitor’s 337 staff had experience of running or being employed in a hospital and only seven had a clinical background. The Chair of the Public Accounts Committee cautioned that this ‘damages Monitor’s credibility and ability to diagnose problems and develop solutions.’106

After amendments, the Health and Social Care Bill was passed in 2012. Subsequently, Monitor’s role remains one of ensuring ‘that choice and competition operate in the best interests of patients [and preventing] . . . anti-competitive behaviour by commissioners or providers where it is against patients’ interests’. 107 However, CCGs will now not have to put all services out to tender and the private sector will be unable to ‘cherry-pick’ profitable, less complex procedures, although it remains unclear how Monitor will guard against the latter. 108 It should also be noted that the number of private patients treated in NHS hospitals has gone up by 58% since 2010. 109 NHS FTs may now take up to 50% of their income from private patients. 108 In 2013, Monitor published a review aimed at securing fairer competition between the NHS trusts and private and voluntary sector providers. 36 NHS England responded by stating, inter alia, that some of Monitor’s proposals would ‘increase tariff variability . . . and potentially put the continuation of certain services at risk’. 110

Monitor is now tasked to ‘enable better integration of care so services are less fragmented and easier to access’. 107 However, integration and collaboration between services, including moving some services out of secondary care, may result in trusts losing income, and Monitor’s focus on the bottom-line results for FTs may, therefore, impede collaboration. 111 Moreover, enabling service integration and ensuring both choice and competition through preventing anticompetitive behaviour will be a difficult balance to strike. For example, a proposed merger between Norfolk and Suffolk Mental Health Trusts should reduce duplication, but was seen as a move that would adversely affect patient choice and competition. 102 Commenting on the likely discrepancy between enabling competition and achieving care integration, Hudson27 stated that the ‘most likely outcome is that as providers proliferate and competitive tendering becomes the norm, integration will become more difficult.’

Evidence on this shows that, between April and December 2013, of 57 contracts (valued at £510M) awarded, 39 (70%) went to private firms, at a total value of £450M. In a different study, a Freedom of Information request to CCGs demonstrated that the private sector won 40% of contracts put out to tender, whereas NHS providers were awarded 41%. 112 An investigation carried out for the British Medical Journal reported that ‘private sector providers have secured a third of the contracts to provide NHS clinical services . . . in England since the Health and Social Care Act came into force in April 2013’;113 however, as the authors point out, it is hard to assess the degree of penetration of the NHS by private firms because many high-value awards to the NHS are for acute care which the private sector is not equipped to provide.

Historically, there has often been transparent discrepancy between health policy objectives. 25 The inconsistency between promoting competition and enabling care integration is a key issue for Monitor’s regulatory role.

Part 2: the specific policy context for the use of patient-level information and costing systems

Here, we discuss three policy initiatives of, arguably, a more local nature, which impact on how PLICSs are being used at our case study sites: SLR; costing care pathways across organisational boundaries; and clinical engagement with costs.

As mentioned earlier, PLICSs have developed within the context of SLR and service line management (SLM). At our case study sites, SLR/SLM tended to be the operational mode for financial management, whereas PLICSs were more of a strategic tool.

Service line reporting and patient-level information and costing systems

Hospital organisation has always been ‘federal’ in nature,114 whereby the clinical specialty (or ‘service line’) is a natural organisational grouping. SLR and SLM form the context within which PLICSs have emerged in the trusts. Service lines are, basically, specialties that SLM casts into profit as well as cost centres. Specialties have had cost reporting responsibilities since ‘clinical directorates’ were introduced as an aspect of the internal market reforms of the early 1990s (see History: the development of costing and pricing models in the NHS). Clinical directors (usually senior clinicians) manage specialties as ‘directorates’ (semi-autonomous, self-managed units); this autonomy is coupled with financial responsibility for the directorate budget. 57,115 So, the organisational building blocks were already in place for SLR/SLM to calculate profit (or loss) for a service line (there can be 10–20 service lines depending on the size of the trust). 6 Monitor developed the concept of SLR/SLM with McKinsey, the management consultancy;116 it identifies SLR as ‘measuring a Trust’s profitability by each of its service lines, rather than just at an aggregated level’. 117 The expectation is that SLR/SLM will have relevance, for both financial and operational aspects of trust management, through driving organisational structure, strategy, performance management and information management. 118

As discussed in detail in Chapters 5–8, PLICSs are more of a strategic tool at the trusts. For example, PLICs are used in business cases to evaluate the financial impact of investment in a particular specialty. Operational financial management occurs through SLR/SLM. Clinicians are naturally aligned to their specialty, which forms a focus for their interests and allegiances. 119 Monitor anticipates that SLM and PLICSs will enable more clinical engagement in resource management: ‘Through SLM, clinicians can play a far more influential role, driving performance and making better use of resources to improve quality and patient care’. 117 Unsurprisingly, the main benefits of SLR – for both clinicians and managers – are increased autonomy and access to any surplus/profit accruing to the service line. 116

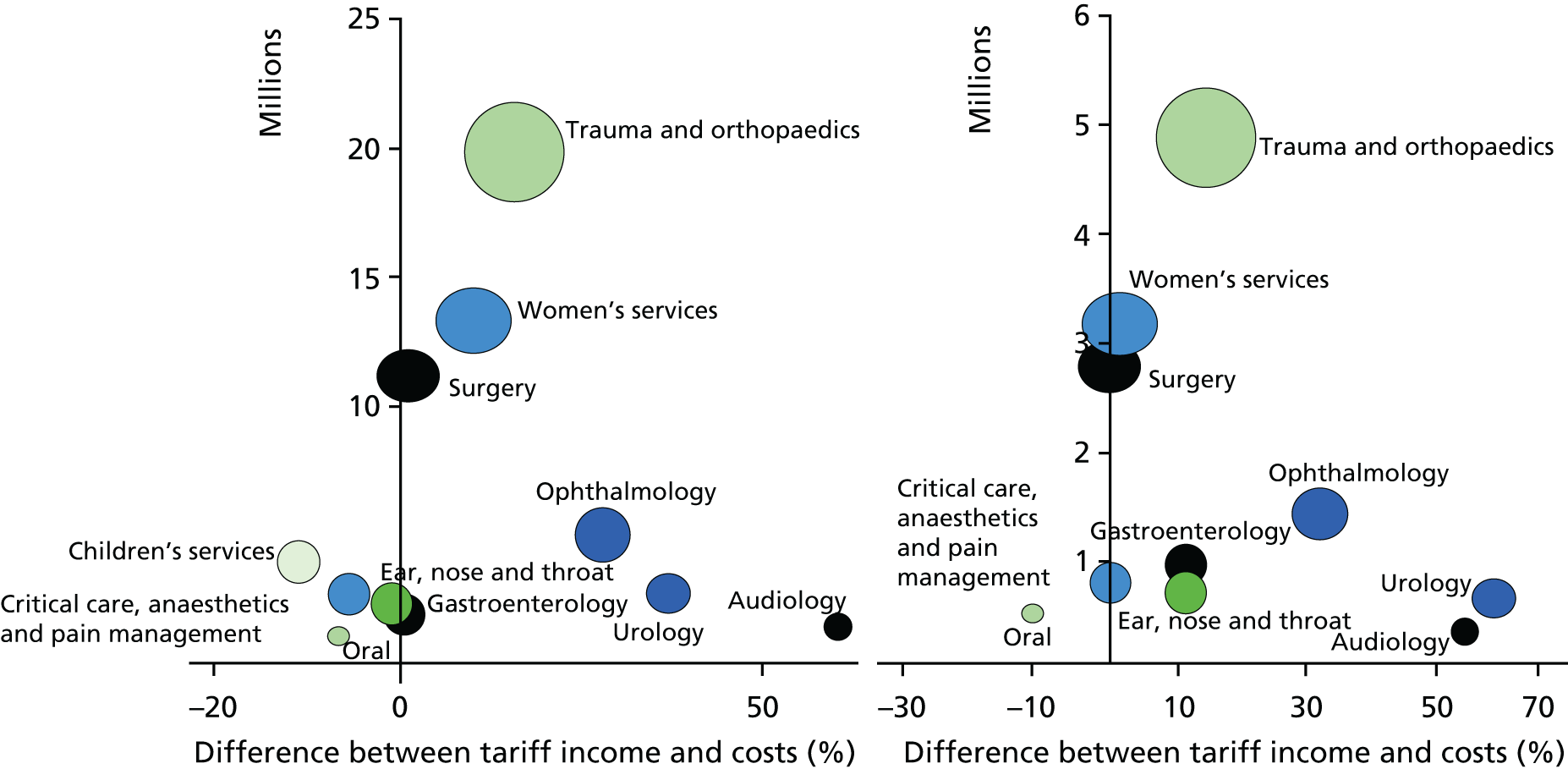

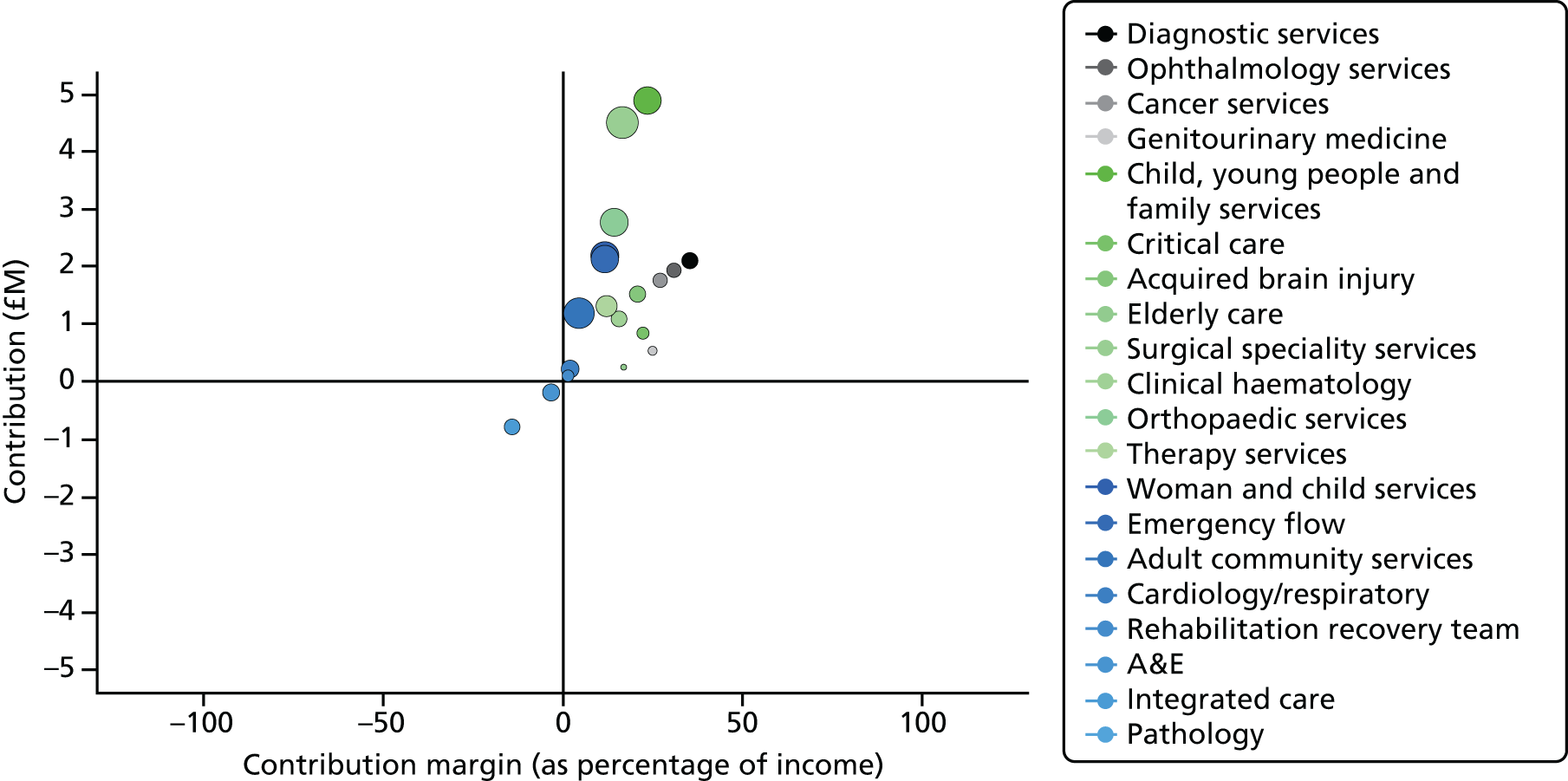

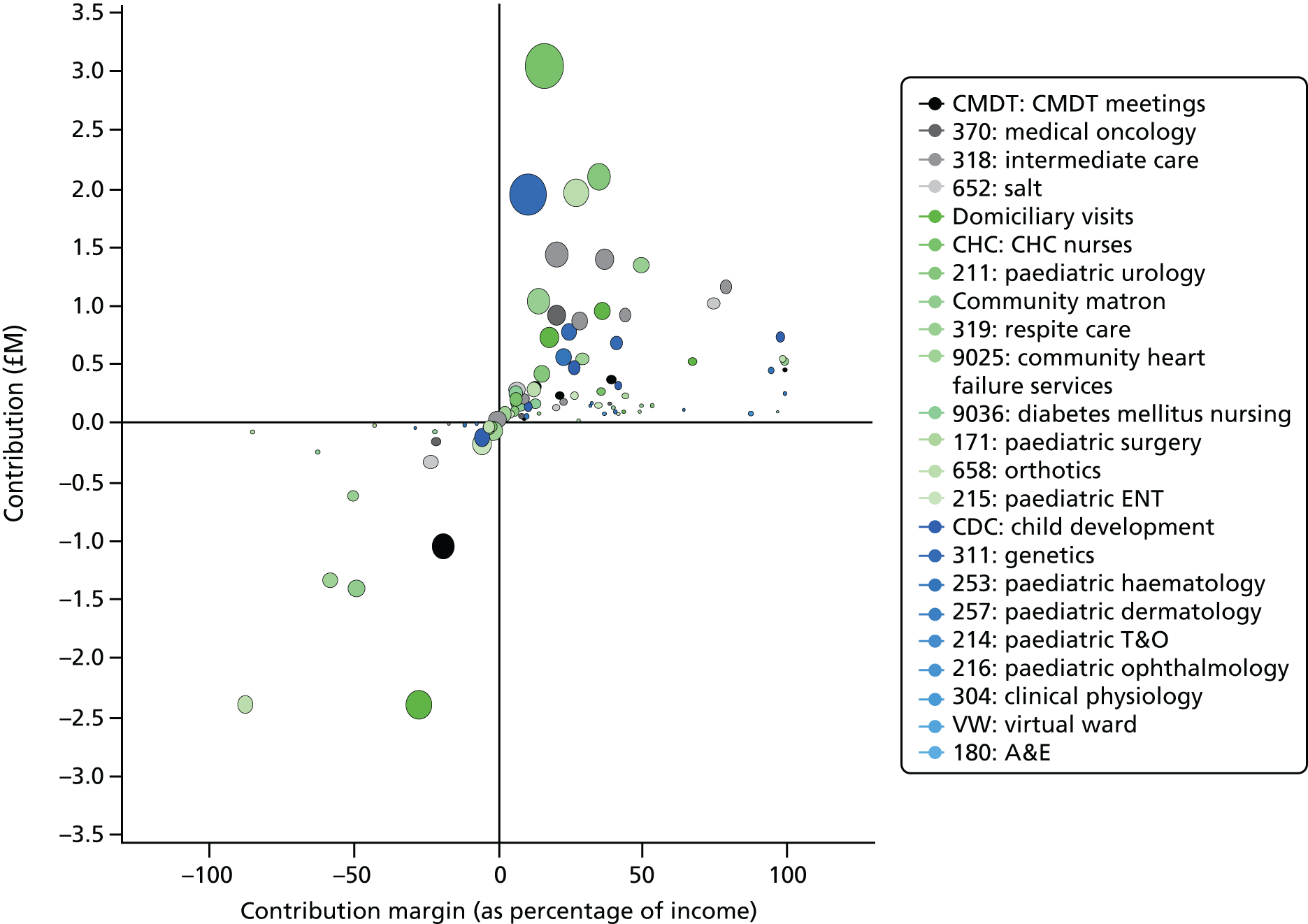

However, taking the whole health economy perspective, a disadvantage of SLR/SLM is likely to be that their success rests on maximising income and minimising costs for a service line, neglecting what this implies for other service lines in a trust and for primary and community services. Service complexity increases cost. 120–122 Not all trusts can disinvest complex services, for example blood and marrow transplantation, to focus investment on less complex and, therefore, potentially more profitable areas. In our case studies we found that trusts dealt with this by cross-subsidising loss-making specialties through ‘contributions’ from surplus-generating specialties. There was, however, some frustration in the profitable specialties insofar as they were frequently not able to retain ‘their own income’ under the tariff.

Furthermore, again from a whole health economy perspective, a service line may be profitable, at least in part, because some primary-care referrals are inappropriate (i.e. ‘false positives’ who are discharged after first appointment). This ‘false-positives’ problem may well be exacerbated by SLM because service lines can retain their own profits, indicating that, alongside SLM, there should be costing that crosses organisational boundaries. However, our evidence shows that, although there is awareness of the potential for PLICSs to cost care pathways, such costing is not currently available outside the trusts. Within the trusts there is work that uses PLICSs to cost internal care pathways (see Chapters 5–8).

The potential for patient-level information and costing systems to cost cross-organisational care pathways

Costing care pathways that cross organisational boundaries necessitates robust systems for identifying and then costing community services. In terms of identifying activities in the community, there are no currencies, no definitions and no adequate data collection systems [Claire Yarwood, NHS England (Greater Manchester) 18 June 2015, personal communication]. Evidently, therefore, PLICSs are not being used to cost community services. In turn, the potential for PLICSs to inform care integration is severely curtailed.

Community services comprise 10% of the NHS budget. 123 The HFMA33 produced a discussion paper on community services, in which it noted that PLICSs are an appropriate methodology for community services and summarised the issues that impede their costing: the lack of a tariff; the absence of detailed descriptions of services; limited use of electronic data systems; issues with data quality and data capture; commissioners giving lower priority to community services; and the wave of mergers and acquisitions in community services, which have distracted from costing as a priority.

For decades, patient pathways for long-term conditions such as cancer, heart disease, renal disease, diabetes mellitus and asthma have been advocated but have never fully emerged. 11 We note the potential for PLICSs to produce ‘year-of-care’ estimates to assist in the management of long-term conditions. We anticipated that all four of our case study sites would use PLICSs to cost care pathways. However, in the event, although three used PLICSs to cost internal care pathways, only one of our four sites had a clear focus on costing care pathways across organisational boundaries and estimating year-of-care costs when these were being developed for frailty. However, it is recognised that new care models, including (1) integrated acute and primary care initiatives and (2) acute care collaboratives, are essential to effective care delivery; NHS England has chosen 50 ‘vanguard’ sites for such models. 124 PLICSs would be appropriate to build a cost-evidence base for these vanguards.

Patient-level information and costing systems and clinical engagement

It has long been apparent that decisions made by senior doctors largely determine hospital costs. 125,126 Specifically, Hillman et al. 127 estimated that doctors’ decision-making accounted for up to 70% of hospital expenditure. In the 1980s, Griffiths63 recommended that in order to ‘involve the clinicians more closely in the management process . . . Clinicians must participate fully in decisions about priorities in the use of resources’. However, research carried out at the time showed clearly that disseminating cost data to clinicians resulted in little change in work patterns or expenditures. 128

However, as mentioned earlier, during the 1990s, the new role of clinical director of a specialty (or support service) was introduced. 57,129 This medical manager model was successful in imbuing key senior clinicians with some cost awareness. 57,130,131 As discussed earlier, SLR/SLM builds on the natural allegiances of clinicians to their specialties. But, if specialties become fully fledged ‘business units’, with an outlook focused on cost improvement and the ‘bottom line’, this could impede other key health policy objectives, such as integrated services and more care in the community.

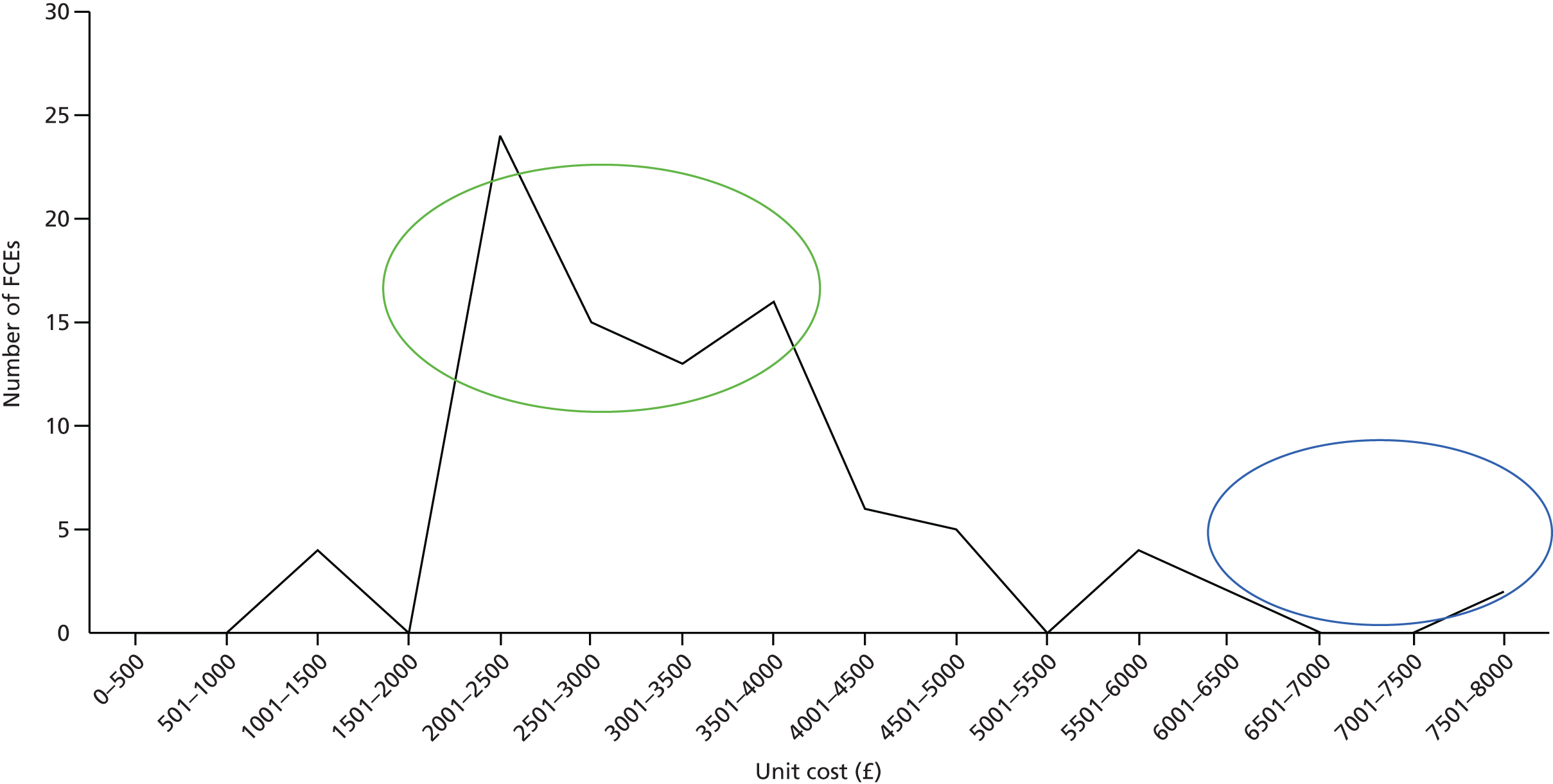

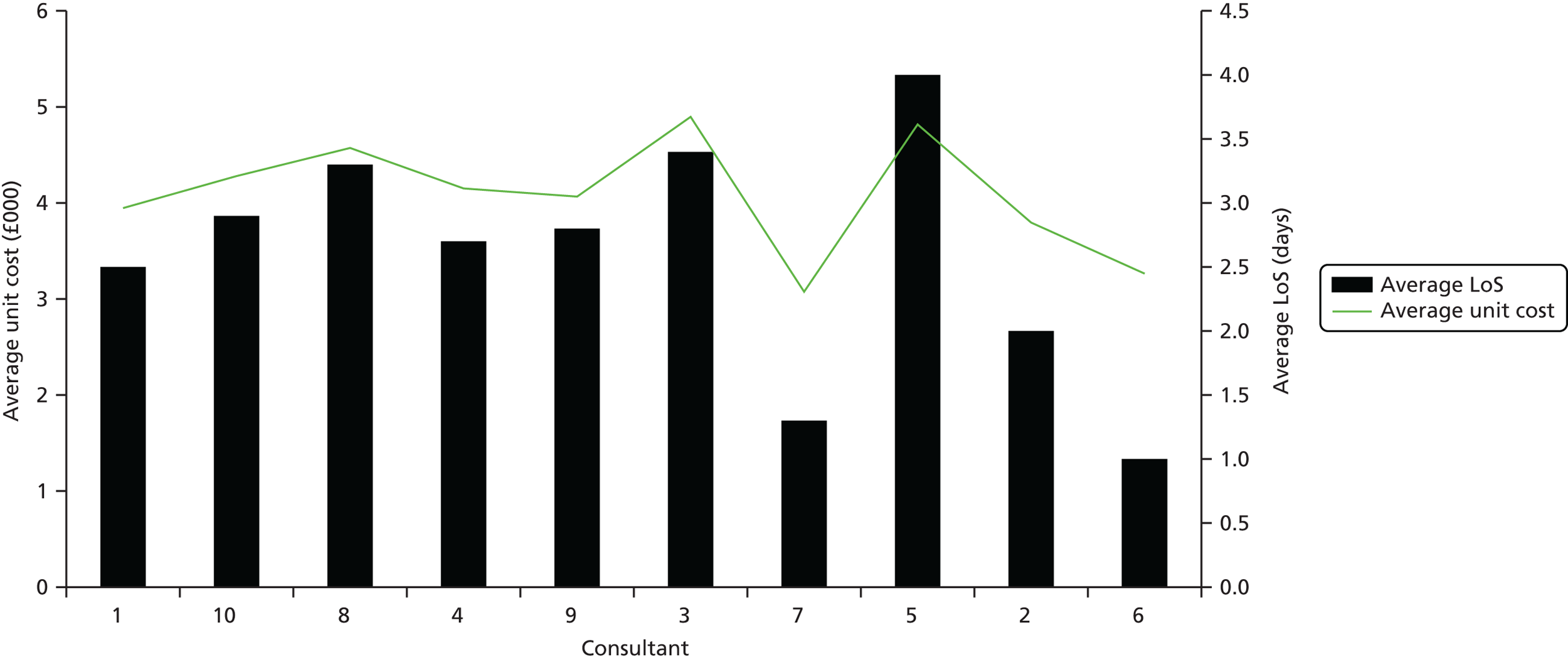

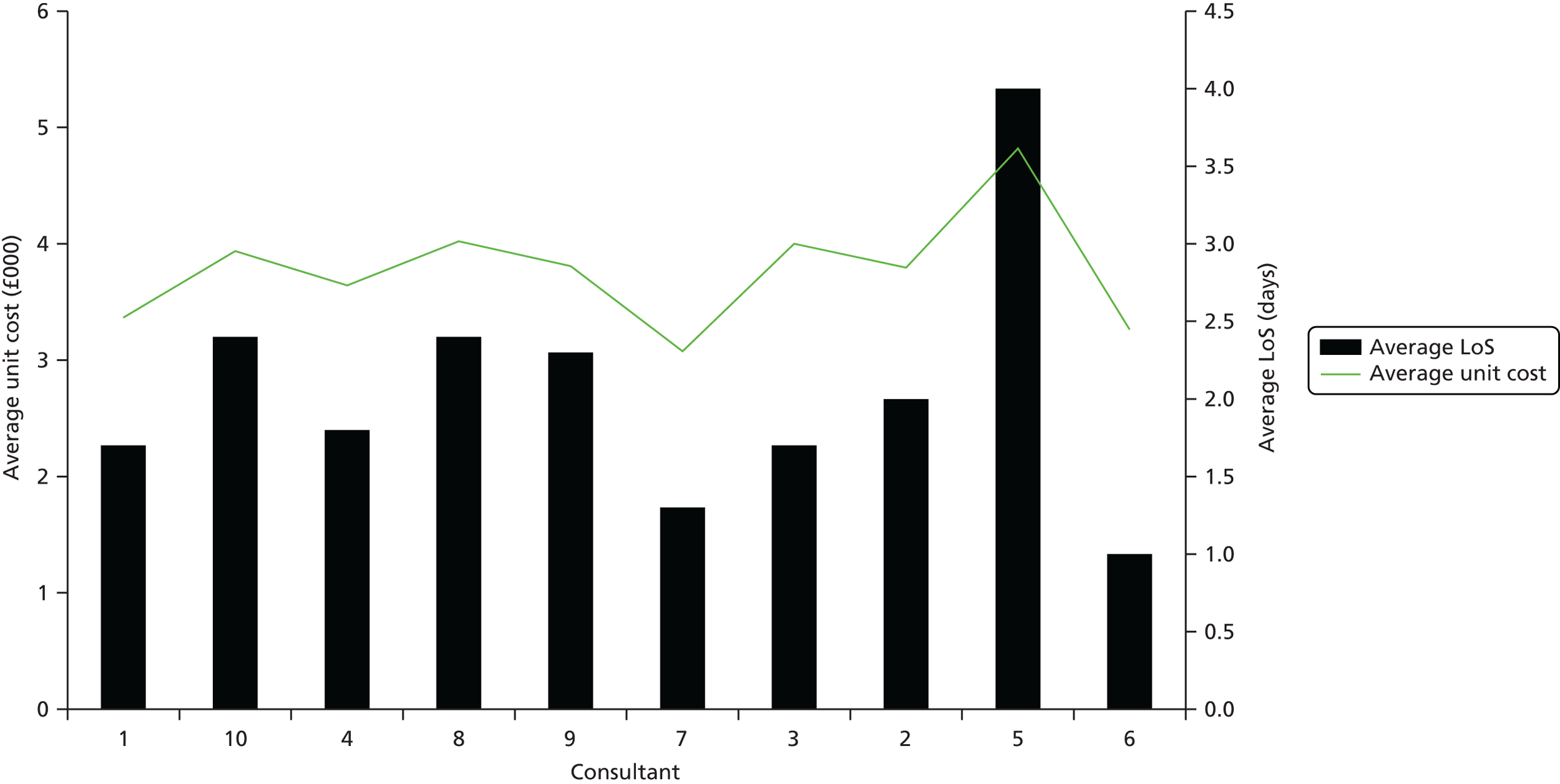

In terms of cost improvement, PLICSs are a form of ‘bottom-up’ costing, which captures the lowest possible level of detail to cost all events (e.g. consultations with clinicians and rehabilitation) and clinical interventions (treatments, theatre time, diagnostic tests, physiotherapy) along a patient pathway. These close links that PLICSs create between costs and patient care foster better clinician engagement than was found with previous costing initiatives and should result in more financially informed clinicians. 7 Through PLICSs, variation in costs per patient is clearly evident. Equally, PLICS costs can be aggregated to investigate variation between consultants, specialties, HRGs and trusts. Illuminating cost variation between consultants proved to be a powerful, if somewhat contentious, practice at the case study sites.

Overall, PLICSs can be an entry point for clinicians into costing discourses. Unlike other costing initiatives, PLICSs take the patient as the cost object (i.e. all costs are related to patients, rather than to diagnoses or medical interventions). These patient-level costs can engender clinical engagement, but may also encounter resistance when mobilised to change clinical practices.

Summary

Exploring the policy background to PLICSs reveals complexity, even conflict, in terms of the policy drivers for PLICS use. On the one hand, financial stringency and a competitive environment incentivise providers to use PLICSs for cost improvement and tariff negotiations, while militating against sharing PLICS data with commissioning bodies. At the specialty level, the use of SLR/SLM incentivises both clinicians and managers to argue for more autonomy and any surplus/profit accruing to service line to be retained within the specialty. Therefore, at both levels, there are tendencies towards fragmentation, with PLICS data being used to serve the financial interests of the trusts, at the provider level, and those of the specialty, at the level below. The increasing presence of the private sector in UK health care can only intensify these competitive pressures.

On the other hand, taking a whole NHS health economy perspective, key health policy goals are integrated services with more primary and community care. In this context, PLICSs have the potential to ensure better allocative efficiency for resources between primary and secondary (or tertiary) care. PLICSs also illuminate the patient pathway and have the potential to enable sophisticated analyses of individual pathways both within trusts and across 1 year of care, for chronic conditions for which the patient pathway crosses organisational boundaries. Such potential will be fulfilled only if there is collaboration between providers and commissioners, with the sharing of PLICS data.

In the chapters that follow Chapter 3, we provide empirical evidence, from a national survey and four case studies, on how these different policy drivers are playing out as we investigate PLICS use.

Chapter 3 Methodology

Introduction

The study was undertaken between July 2012 and October 2015, comprising a large-scale survey of the whole population of English NHS trusts (both FT and non-FT) and four case studies of FTs at different geographical locations in England.

Practitioner team member involvement

A notable aspect of the study was the involvement of practitioner team members: Dr Mahmood Adil (Senior Clinician), Mr Tony Whitfield (Provider Director of Finance) and Mrs Claire Yarwood (Commissioner Director of Finance). As President of the HFMA, Mr Whitfield was instrumental in setting up access to the organisation’s network of finance professionals. Dr Adil brought expertise from previous work on clinical engagement with costing. Mrs Yarwood provided expertise in commissioners’ use of costing data, drawing on experience as the Finance Director (FD) at NHS England (Greater Manchester). All three practitioners were active as core team members and helped to develop the research design in response to the changing NHS financial management landscape during the study period.

Research design

Health care is a complex, open system. Complex systems are defined as those ‘that incorporate a dynamic, emergent, creative, and intuitive view of the world’. 132 When researching complex, open systems it is clear that the experimental approach is not appropriate. 133 However, ‘natural’ experiments do arise in open systems: ‘natural experiments are common in the organisation and management of health care . . . [and] . . . can indicate the scale and nature of [policy] impacts’. 134 As identified in Policy background, policy initiatives have driven the development of PLICSs. The Chartered Institute of Management Accountants32 identifies three natural experiments in the differential approaches to PLICS use: (1) for cost improvement in the context of financial challenge; (2) to underpin a case for investment or reconfiguration of services; or (3) as a better management tool.

These natural experiments in differential PLICS use constitute general themes which could be explored through either quantitative or qualitative methodologies; we chose to examine them through mixed-methods research. 135–137 This approach involves using both quantitative and qualitative methods in tandem to enhance the overall strength of the study. 138 Specifically, we employed ‘sequential exploratory design’ (Figure 4) to conduct quantitative data collection and analysis before qualitative data collection. 136 A sequential exploratory strategy uses the initial quantitative results to inform secondary qualitative data collection, with the two forms of data remaining separate but connected. 139 This approach can be particularly useful when unexpected results arise from the quantitative stage. 140

FIGURE 4.

Methodology: sequential exploratory design.

Quantitative data collection, undertaken through a survey, was the first stage of the research. Using a survey provides a numeric or quantitative description of attitudes, opinions or trends of a population, usually by studying a sample of that population. 141 Informed by analyses of these survey data, the second stage was conducted at four case study sites. Case study research is well developed in the study of organisations (e.g. Yin142). Llewellyn143 argues that case studies seek to develop a holistic understanding of specific phenomena. As a ‘strategy of enquiry’, case studies enable an in-depth exploration of a process, activity or event. 144 Case studies also enable a strong emphasis on context and are recognised as particularly important in evaluating the impact of policy initiatives. 145

Research methods

Research at the case study sites was conducted through a variety of methods, including semistructured interviews, documentary analysis and some limited observational research. Observational research focused on the practice of actors and was ‘essentially exploratory’. 146

The primary data collection method was semistructured interviews. The open design of semistructured interviews can be contrasted with the use of a standardised questionnaire, because an open approach to interview questions is less likely to constrain the variety of possible responses. 147

We wanted to link the data from individual interviews with the emergent PLICSs strategy at the organisational level. To accomplish this, we triangulated the interview data with documentary analyses of the following: samples of PLICS data; business cases for investment; service line reports; presentations on PLICSs; and strategy documents used in discussions at board level.

Patient-level information and costing systems implementation and use are understudied. In the absence of existing studies, documentary analysis provides material for researchers in the form of, for example, written plans. 148 Table 1 shows our documentary sources.

| Number | Document | About | Date | Trust |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Financial report | Surgery | December 2013 | Case study 1 |

| 2 | Business case template | Staffing | April 2014 | Case study 1 |

| 3 | SLR | Women’s services | April 2014 | Case study 1 |

| 4 | PLICSs comparison | Pain injection centre | May 2012 | Case study 2 |

| 5 | PLICSs comparison | Stroke patients | June–December 2012 | Case study 2 |

| 6 | Financial review | Haematology unit | May 2012 | Case study 3 |

| 7 | PbR analysis | Complex activity | November 2012 | Case study 3 |

| 8 | Presentation | Benchmarking | April 2012 | Case study 3 |

| 9 | Presentation | PLICSs introduction and implementation | Undated | Case study 3 |

| 10 | Presentation | Understanding the tariff | February 2012 | Case study 3 |

| 11 | Financial review | Haematology | Undated | Case study 3 |

| 12 | Report on HRG calculations | Haematology | April 2010–March 2011 | Case study 3 |

| 13 | Board meeting papers | SLR-PLC implementation | March–October 2014 | Case study 4 |

| 14 | Presentations | Shortlisted PLICS suppliers | August 2014 | Case study 4 |

| 15 | Briefing paper | The case for PLICSs | June 2013 | Case study 4 |

| 16 | Report | Transformation programme closure | April 2014 | Case study 4 |

| 17 | Financial review | SLR 2013–14 | December 2014 | Case study 4 |

| 18 | Presentations | Annual conference NBG | April 2014 | NBGa |

| 19 | PLICSs comparison | Consultants | Undated | NBG |

| 20 | Presentation | SLR paediatrics | December 2012 | NBG |

| 21 | PLICSs comparison | Urology | July 2013 | NBG |

| 22 | SLR report Microsoft PowerPoint® presentationb | Whole trust | March 2012 | NBG |

| 23 | PLICSs report PowerPoint presentation | Whole trust | 2011–12 | NBG |

| 24 | Business unit review PowerPoint presentation | Surgery | December 2011 | NBG |

| 25 | Guidance document | SLR principles | 2011–12 | NBG |

Methodology and ontology

In the case studies and semistructured interviews we followed a ‘critical realist’ approach149,150 that delineates the extent to which individuals and groups can be studied in the same way as natural systems and through which it is accepted that the nature of the object determines the form of its science. 150 Working from participants’ views, we paid attention to ‘what works’ with PLICSs, specifically in which contexts and with which mechanisms, thus conforming to critical realist research guidelines for social science research. 151–153

Critical realism stems from the work of Roy Bhaskar150,154,155 and has been explicated by others. 149,153,156–158 Critical realists hold that a real world exists. For the natural world, they see a significant distinction between the nature of reality and people’s knowledge of this reality. By contrast, in social science, the research ‘object’ is primarily the meanings that people attribute to their social world; therefore, a clear distinction between the social world and people’s knowledge of it is not possible. 150 Archer149 (pp. 154–90) includes a third reality – the practical. In addition to the natural and the social, the practical is the domain of non-linguistic human practice. Accounting falls into this world of practice but, naturally, people also talk about accounting in the social world and, in doing so, attribute meaning to it. In consequence, this research is informed by critical realism in acknowledging ‘differentiated realities’;159 specifically we locate accounting in both the social and practical domains. Our mixed-methods design (see Work packages) reflects this in that we conducted semistructured interviews to identify meanings and gathered multiple accounting documents which included accounting calculations resulting from practical activity.

Work packages

Work package 1: the survey

Work package 1 has three stages: a preliminary online pilot survey, a main online survey and a follow-up analysis of survey results. Sue and Ritter160 recommend (1) using online surveys for professional groups, (2) piloting test information with intended professionals in the field and (3) pre-notifying respondents of the survey to increase the response rate (see also Ritter and Sue161). We followed these recommendations by:

-

piloting the survey online with finance professionals at one case study site

-

giving our potential respondents advance notice of the main survey (specifically, in the month before distribution we placed a short description of its content and purpose in the HFMA’s professional journal, Healthcare Finance, which is widely read by the health-care finance community in England)

-

selecting the two final case study sites through a third stage follow-up analysis (two case study sites were pre-selected and under way as the pilot survey was being conducted).

Stage 1: pilot study

For PLICS use in the acute sector we identified 11 hypotheses (listed below), drawing from the initial literature review undertaken for the proposal. We piloted our survey to 35 NHS provider trusts in England, with organisations targeted from each of the 10 (former) strategic health authority (SHA) geographical regions. The questionnaire was distributed online by e-mail to either Directors of Finance personally, or to their offices via administrative contacts. The questions in the pilot survey were based on our ‘hypotheses about PLICS use’:

In relation to research question 1 (How are NHS trusts and commissioners using PLICSs?), the pilot survey to providers included 11 hypothesis-based questions on the possible uses for PLICSs:

-

to identify how much a particular patient costs using direct and attributed costs

-

to ascertain whether that cost was more or less than income received under the tariff

-

to engage clinicians with costing issues

-

to identify resource variation and, hence, cost between consultants

-

to inform consultants as to how their decisions impact on cost

-

to reduce LoS when this impacts upon cost

-

to understand the relationship between cost and quality

-

to understand the benefit achieved through BPT

-

to lobby for exemption from the tariff (or flexibilities under the tariff)

-

to prepare a business case for investment in the specialty

-

prepare for the newer environment encompassing ‘any qualified provider’.

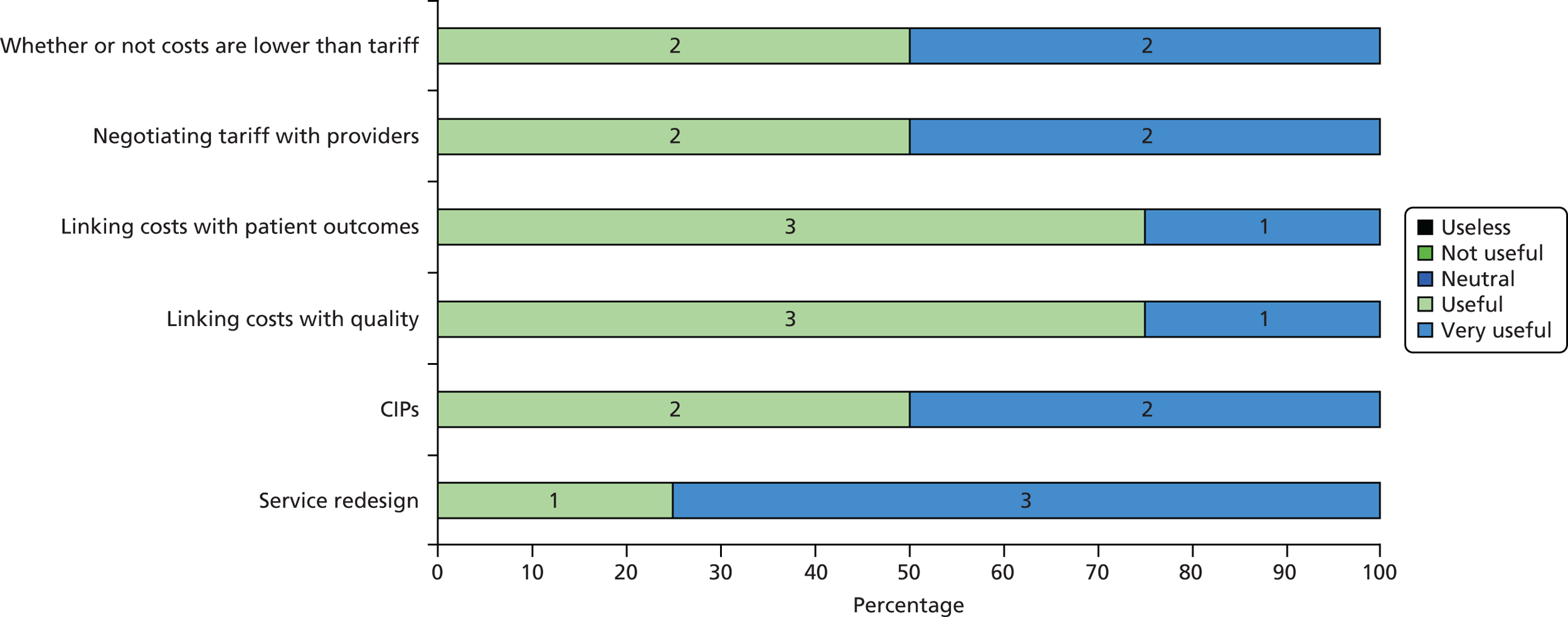

From a NHS economy perspective, PLICSs should inform clinician, management or commissioner decisions on service redesign and referral management. This was the reasoning behind our second research question, ‘How can PLICSs be used to benefit the total health economy (focusing on cost improvement, resource allocation across services and settings, linking cost with quality, and clinical engagement)?’. For the pilot study, we defined a local health economy group as one ‘that includes commissioner and provider representatives and/or multiple other partner relationships, within a specific locality, either as part of a one-off project or longer term initiative’.

We included five hypothesis-based questions about the possible uses of PLICSs in local health economies with a further four hypothesis-based questions about the use of PLICSs in dialogue between acute trusts and commissioners (again our hypotheses were derived from existing literature):

-

Has service redesign for integration, including moving services to primary care when cost-effective and in line with patient preferences, been undertaken?

-

Are services between acute trusts shared to create centres of excellence?

-

Can unnecessary admissions and referrals (false positives) to acute care be reduced?

-

Can unnecessary diagnostics, interventions and treatments be reduced?

-

Can LoS be reduced, when appropriate, while maintaining high-quality care?

We also asked about the extent to which PLICS data are used in dialogue between acute trusts and commissioners:

-

Do you belong to a local health economy group?

-

If yes, do you discuss and analyse PLICS data in this group?

-

-

Have you redesigned services and estimated/calculated savings on the basis of PLICS data?

-

Has service redesign incorporated patient preferences or been prompted by patient preferences?

However, the pilot survey results and initial interviews at the case study sites showed that the extent to which PLICS data are shared across different providers, especially between providers and commissioners, is very limited. Specifically, as reported in Pilot survey results, none of the pilot survey respondents answered the nine questions about the use of PLICSs between providers, or between providers and commissioners – indicating that these questions did not apply to them or did not make sense in the context.

Pilot survey results

There were a total of 11 respondents to the pilot survey, which equates to a response rate of 22.9%. This response rate is close to the average of 24.8% for most online surveys. 162 Most respondents took between 2 and 3 minutes to answer 20 questions in total. We performed analyses of the pilot results and triangulated with data from the initial interviews at the pre-selected case study sites. With regard to the first 11 questions, pilot results chimed with actors’ accounts and provided evidence to develop the main survey prior to full distribution. For example, in line with interview accounts from finance professionals in the pre-selected case studies, almost all of the trusts replying to the pilot survey were using PLICSs. Also, despite more than half of trusts confirming that they were considering using PLICSs to understand the relationship between cost and quality, none was actively doing so.

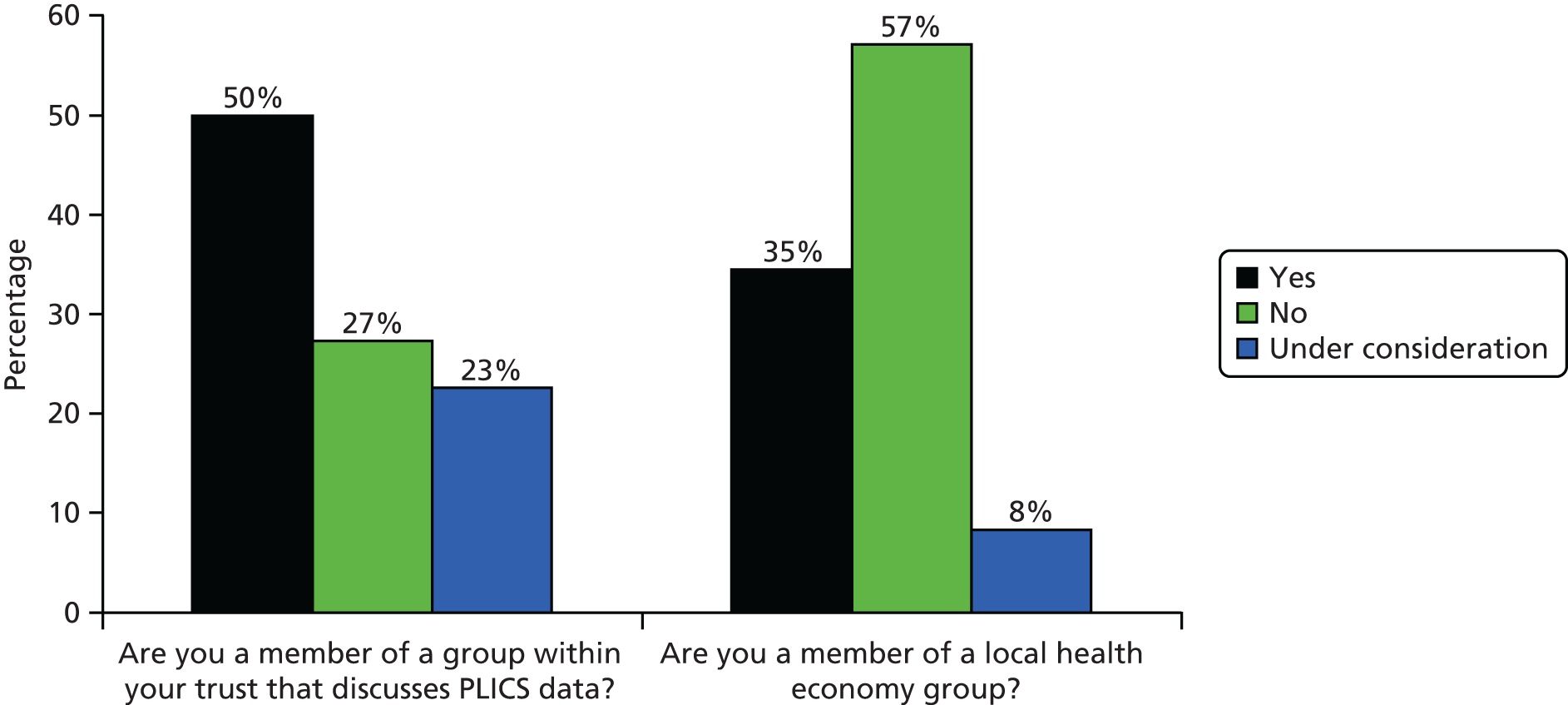

The trusts also reported limited activity in terms of membership of a local health economy group. We asked in the pilot survey if trusts belonged to a local health economy group, if PLICS data were discussed and analysed as part of this group and if savings had been calculated or services redesigned on the basis of PLICS data. Around half of the pilot survey respondents confirmed membership of a local health economy group; however, none of the respondents replied positively in terms of discussing PLICS data as part of this group. There was, consequently, no evidence in the pilot survey responses that PLICS data were being discussed or used in any context across local health economies.

Stage 2: main study

The 11 provider survey questions asked in the pilot survey had proved robust; therefore, we included them in the main survey.

Changes to the main survey on the use of patient-level information and costing systems in acute trusts, consequent on the pilot and team discussion

In preparation for the main survey we sense-checked the pilot survey design and analysis with practitioner team members and also with finance professionals at one of the pre-selected case study sites. We were advised that (1) respondents would be willing to undertake a survey taking 10 minutes (the pilot had taken only 2–3 minutes); (2) respondents may not understand the wording of some of the questions; and (3) further questions should be included. Accordingly, first, we adapted the wording of some of our initial pilot survey questions to accord with current health finance usage. Specifically, we adapted the wording of six questions from the pilot survey (the wording of five stayed the same). Second, we increased the number of questions by adding a further 16, including, for example, questions about how PLICS information is shared and used, both internally and externally; whether or not provider trusts regarded PLICS data as commercially sensitive; and, on a scale of 1–4, trusts’ level of engagement with clinicians in costing, from limited (e.g. board level only: level 1) to advanced (e.g. routine joined-up clinical/finance working across all specialties: level 4) (see Appendix 2 for full main survey questionnaire).

In response to advice from Claire Yarwood, the commissioner team member, the main survey questions on local health economy group activity were redesigned into a four-part matrix. Respondents were asked (1) if they belonged to a group (that discussed finance and costing); (2) if this group was within their own trust; (3) if this group was part of a local health economy of providers and commissioners; and (4) if this group covered a larger geographical footprint [e.g. a National Benchmarking Group (NBG) – see Exploratory observational work]. This reframing of questions relating to local health economy group membership (to include group meetings that were internal to trusts and those that were external) sought to address the disappointing response to local health economy-based questions in the previous pilot survey. Finally, in the main survey, we asked if PLICS data had been used or influenced decision-making in any of the groups selected, with options to indicate the appropriate group.

The full main survey analysis is discussed in Chapter 4.

Stage 3: further case study selection and initial analysis

In our third stage of work package 1, the main survey was analysed, additional interviews were conducted and findings were validated to inform the next phase of the research.

Further case study selection and follow-up interviews

After analysing the results of the main survey we selected the two further case studies on the basis of leading-edge practice with PLICSs, particularly in relation to our four aims, and our four tracer groups (stroke; mastectomy; blood-related cancers; fractured neck of femur – see Table 2). We drew on the expertise of our practitioner team members to guide and confirm our choices of case study selection. To confirm (or question) that our selection was appropriate, we conducted additional interviews with the FD or cost accountant at the two provisionally selected trusts. These interviews confirmed that our choices were appropriate.

Broad survey findings

The main survey data analysis (see Chapter 4) further supported the finding that PLICS data were not being freely used between different providers or between providers and commissioners. However, there were instances of data sharing between networks of providers as part of a NBG (see Exploratory observational work).

Risk assessment and mitigation

As part of the project management strategy, all project tasks, milestones and related activity were tracked using a green–amber–red document. The team used this tool to identify and prioritise tasks according to their status as ‘completed’ (green), ‘incomplete but achievable through current design’ (amber) and ‘incomplete with significant challenges identified’ (red). The document was employed during project meetings and updated iteratively.

Risk in relation to work package 1

The original research proposal risk assessment in relation to work package 1 was as reported below.

Our risk assessment is based on three strategies to reduce a potential poor response rate:

First, Dr Mahmood Adil (a research team member) is currently working at the Department of Health. He contributed to this year’s (2011) ‘DH Reference Cost Survey’, which includes questions on PLICS. This will facilitate access to the e-mail list of the trusts who responded positively to this (and the similar 2010 DH survey) enabling us to use a targeted approach. It is evident from these two surveys that the response rate has increased (from 80% to 85%) among over 400 NHS organisations indicating a high level of interest in PLICS. Hence, we hope to achieve a comparable response level. We are seeking more sophisticated data than was gathered by the DH but we will use the same list to achieve high response as well as depth of information from the relevant individuals/organisations. In line with the affiliations of our practitioner team members, we will seek approval from the Healthcare Financial Management Association to badge our survey with their logo along with those of the Universities of Manchester and Bristol. We anticipate that this badging will increase interest and, hence, response.

Second, we have already selected two of the case study sites (as described below and in the original proposal) so we are not wholly reliant on the survey for case site selection. We will commence work on these two sites at the same time as we undertake the survey, thus employing an element of parallel working in our fundamentally sequential (quantitative followed by qualitative) research design. This will be enabled by the project manager working with the PI on the logistics of the survey whilst the research fellow and other team members work on the already selected case study sites.

Third, we will be guided by the pilot in terms of the impact of the number of questions (i.e. we will reduce the number of questions if this proves to be an impediment). We will also follow up rapidly on any non-responding Trusts, using if necessary the trust finance and accounting contacts of Dr Adil and Mr Whitfield (another team member, FD at Salford and leading PLICS practitioner).

Actual risk contingencies in relation to work package 1

First, we surveyed the whole population of NHS provider trusts rather than targeting only the respondents to the previous 2011 DH reference cost survey. The pilot results indicated that the majority of acute trusts were using PLICSs and, therefore, a whole-population survey was more appropriate.

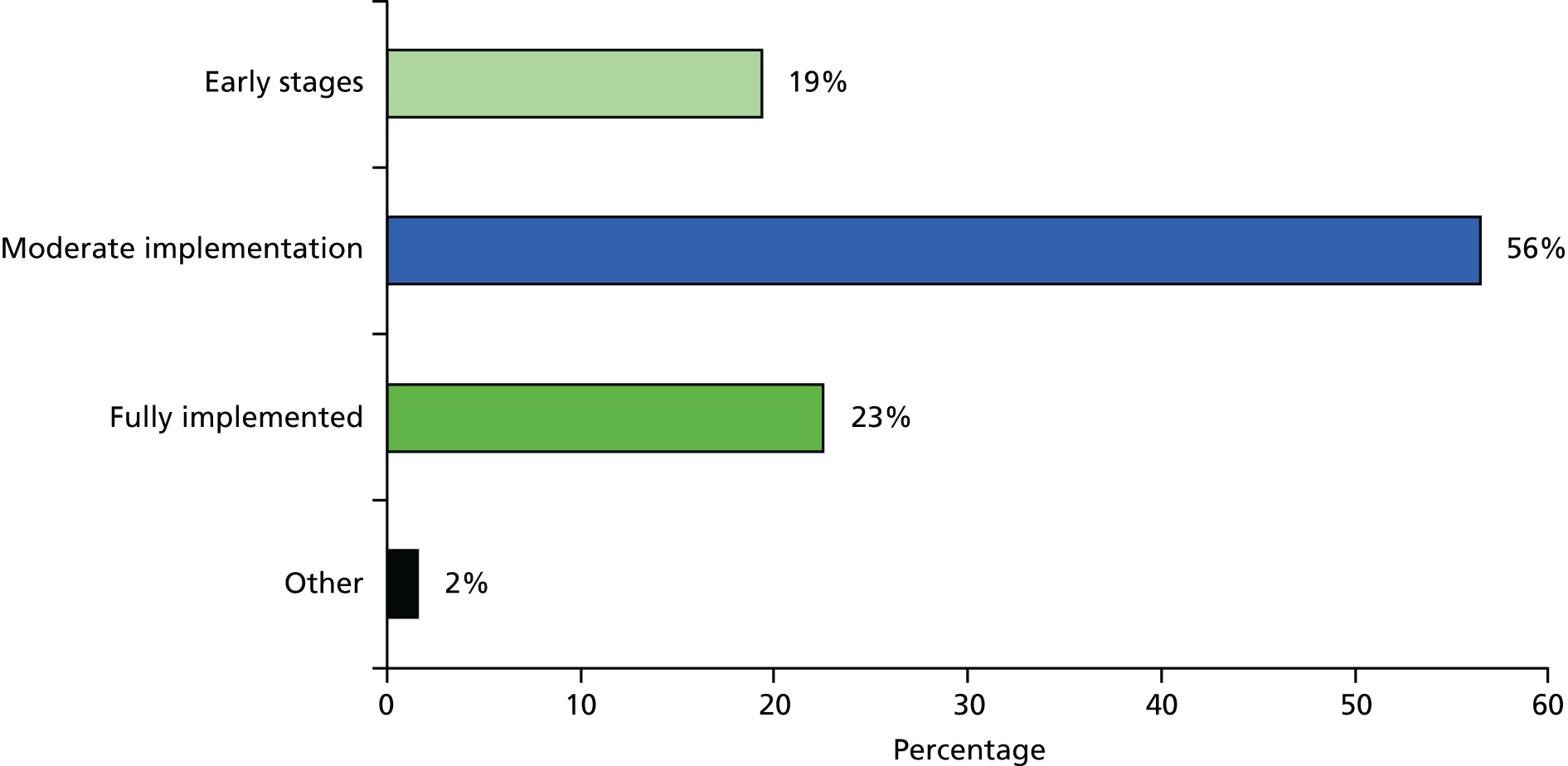

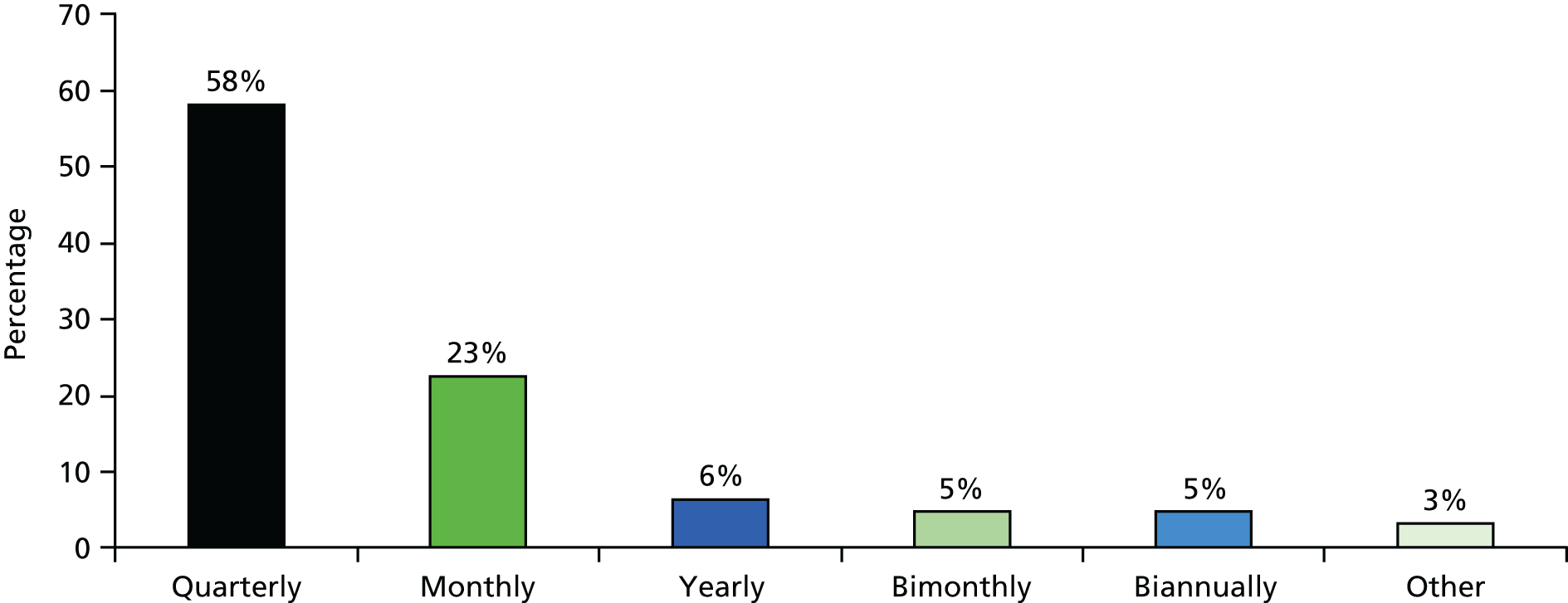

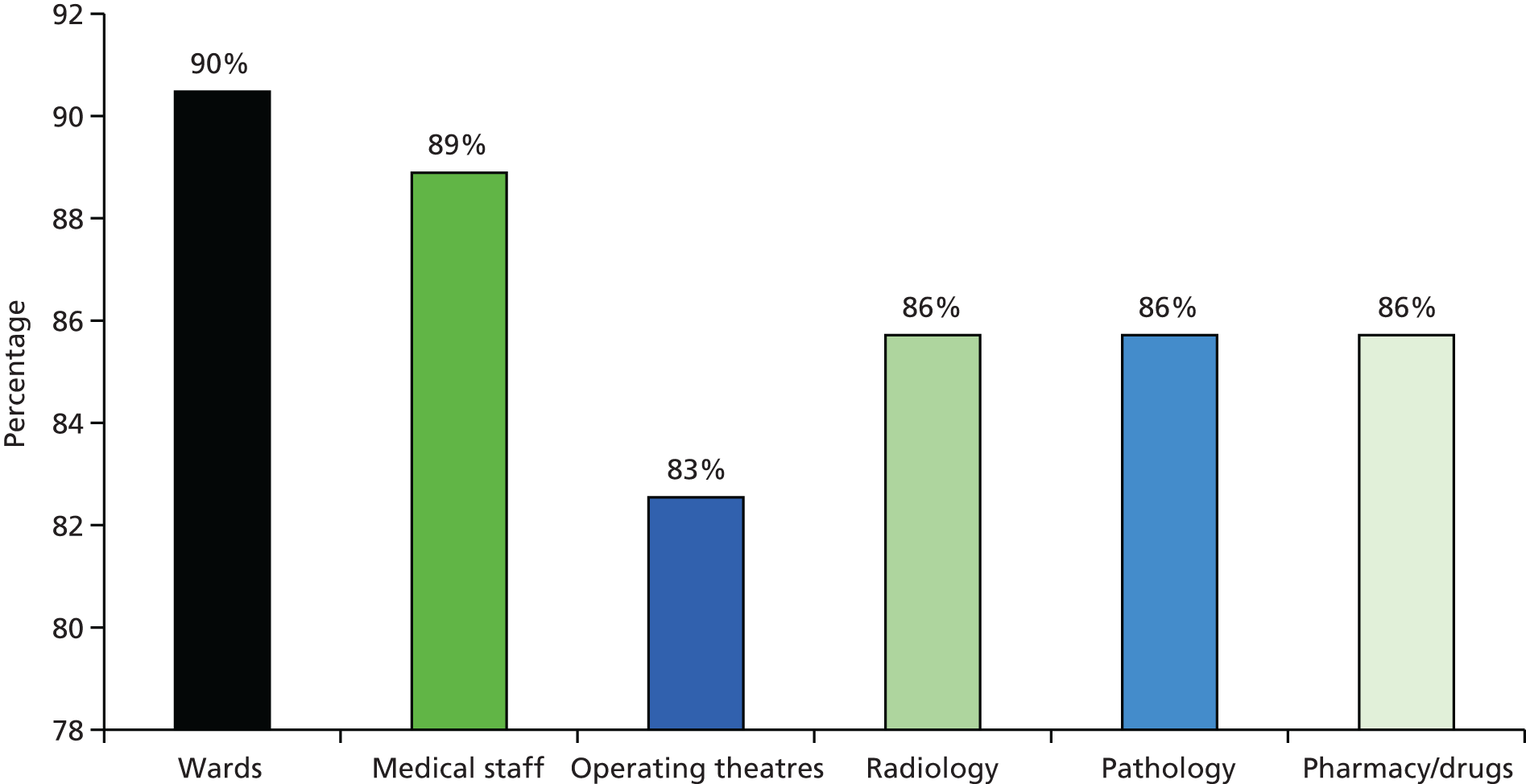

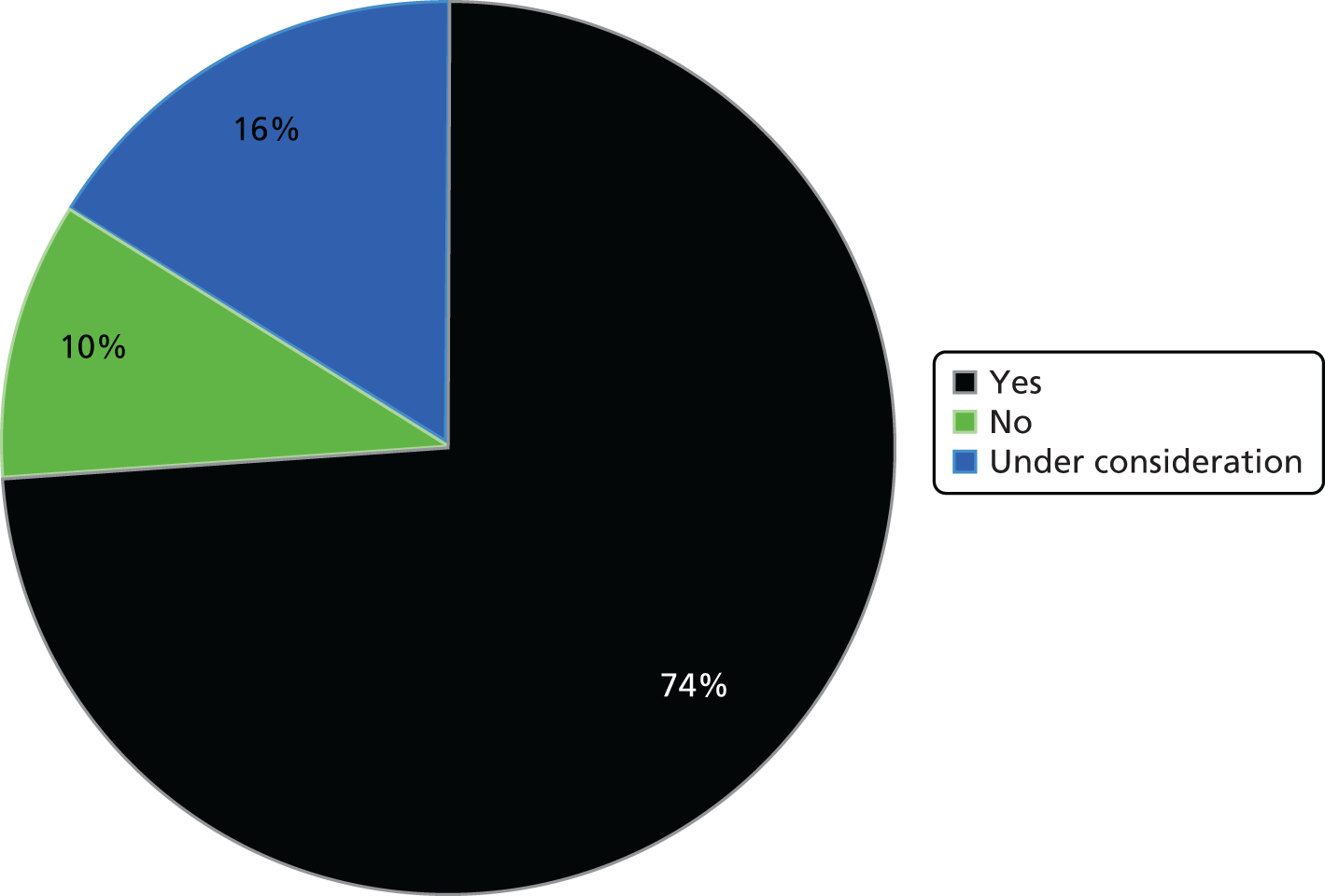

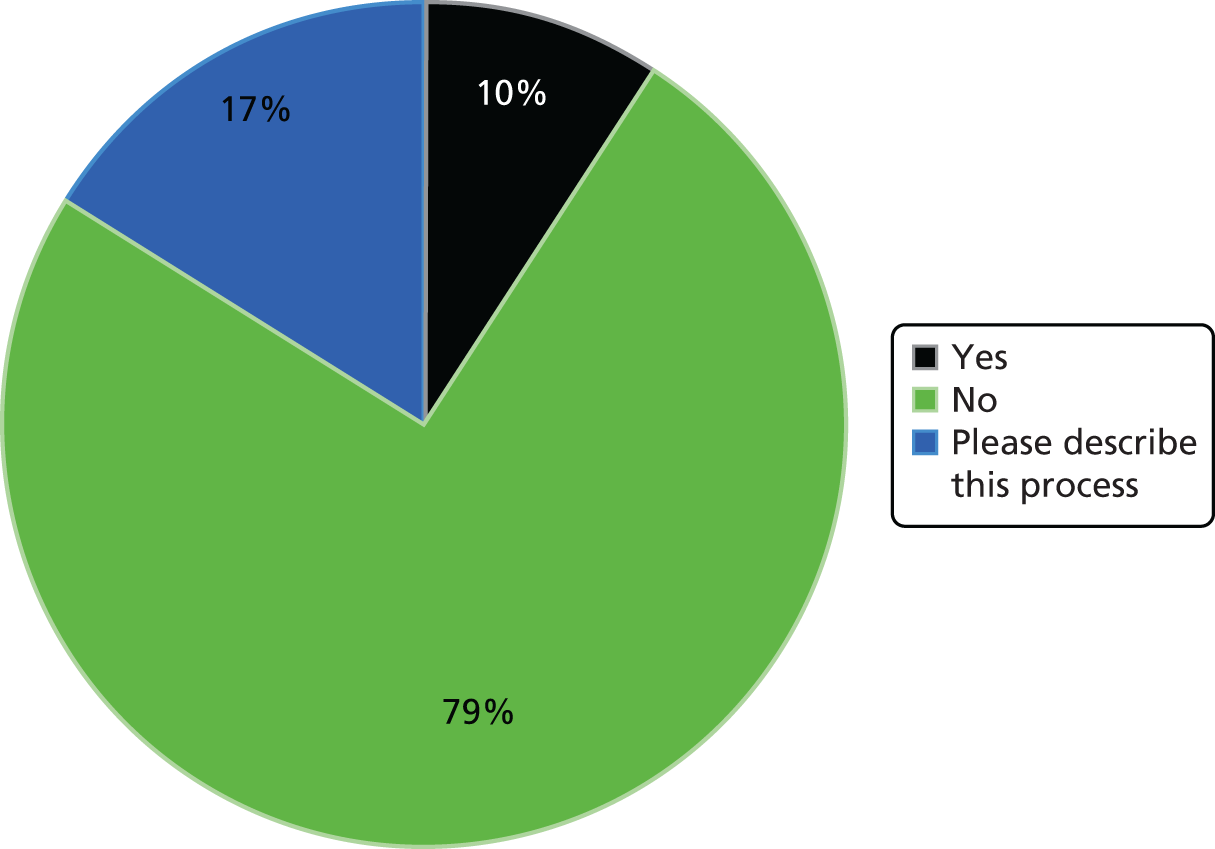

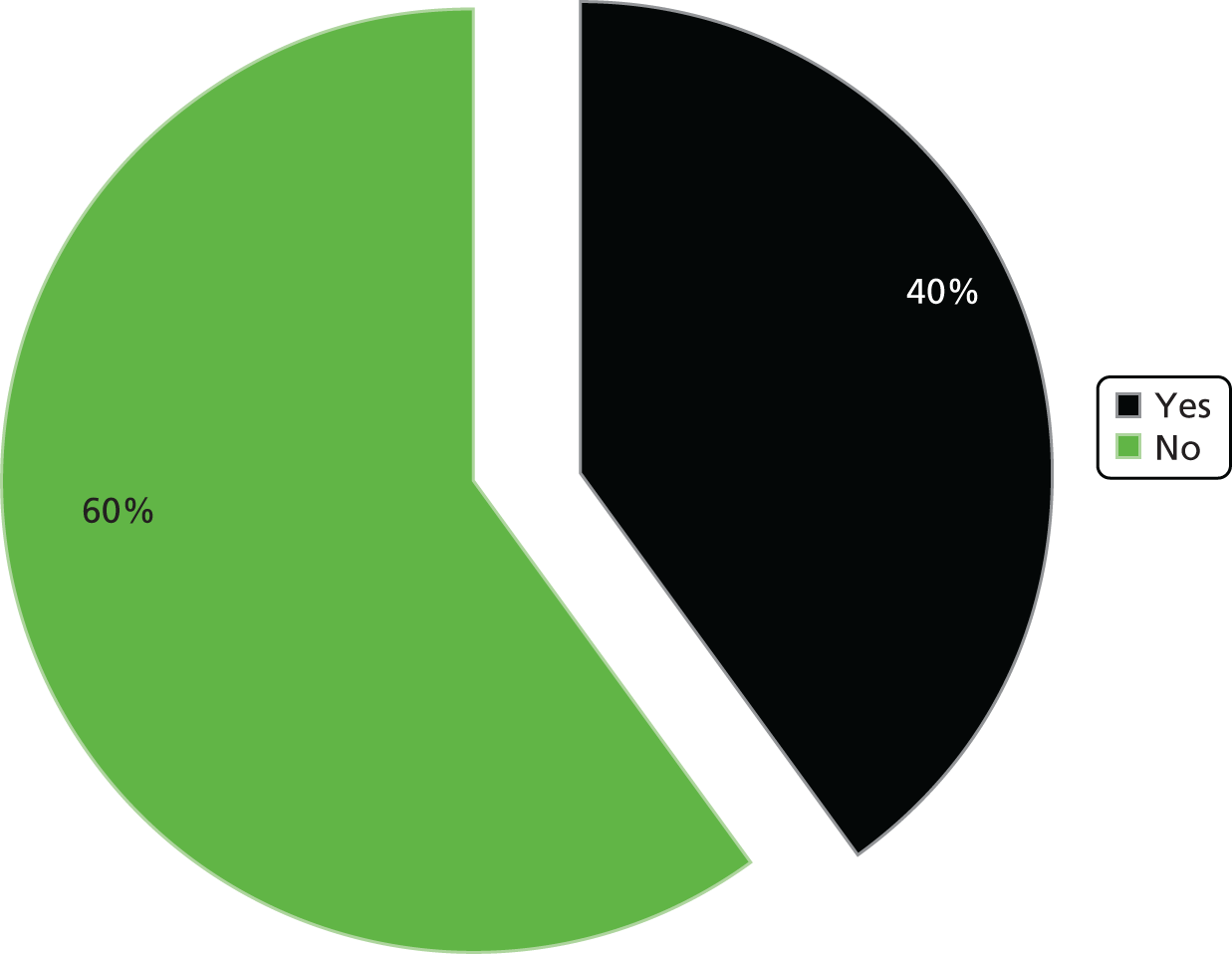

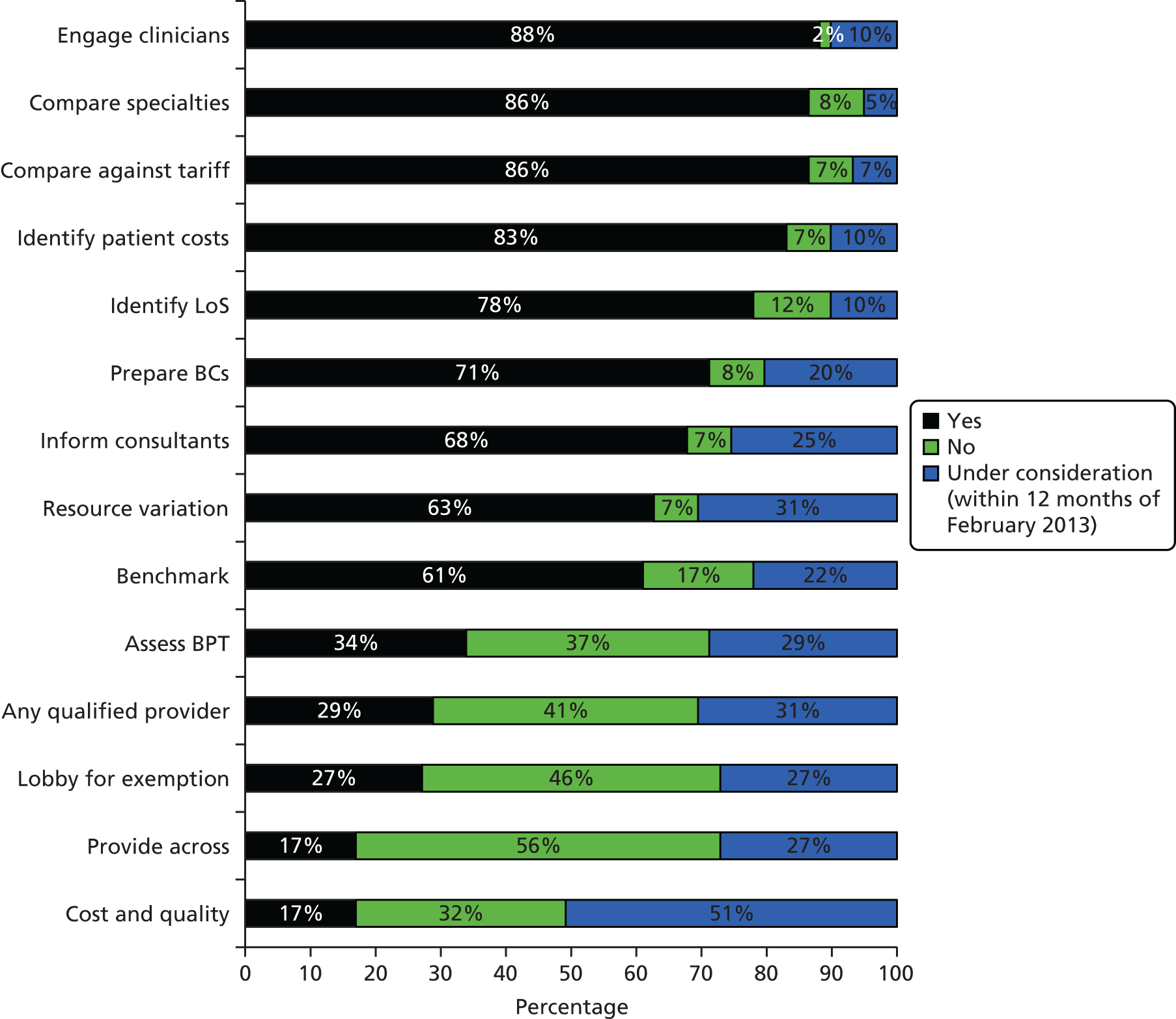

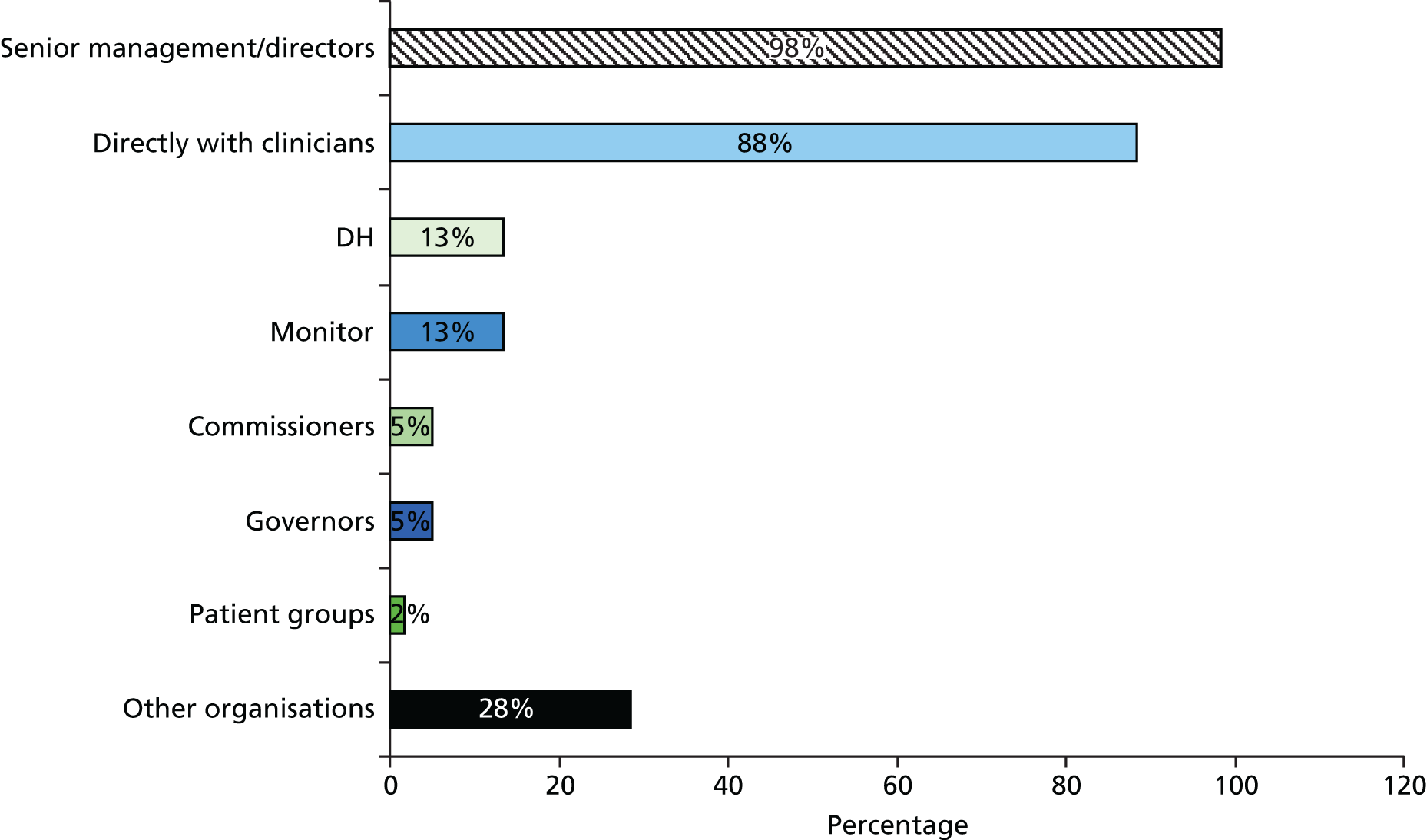

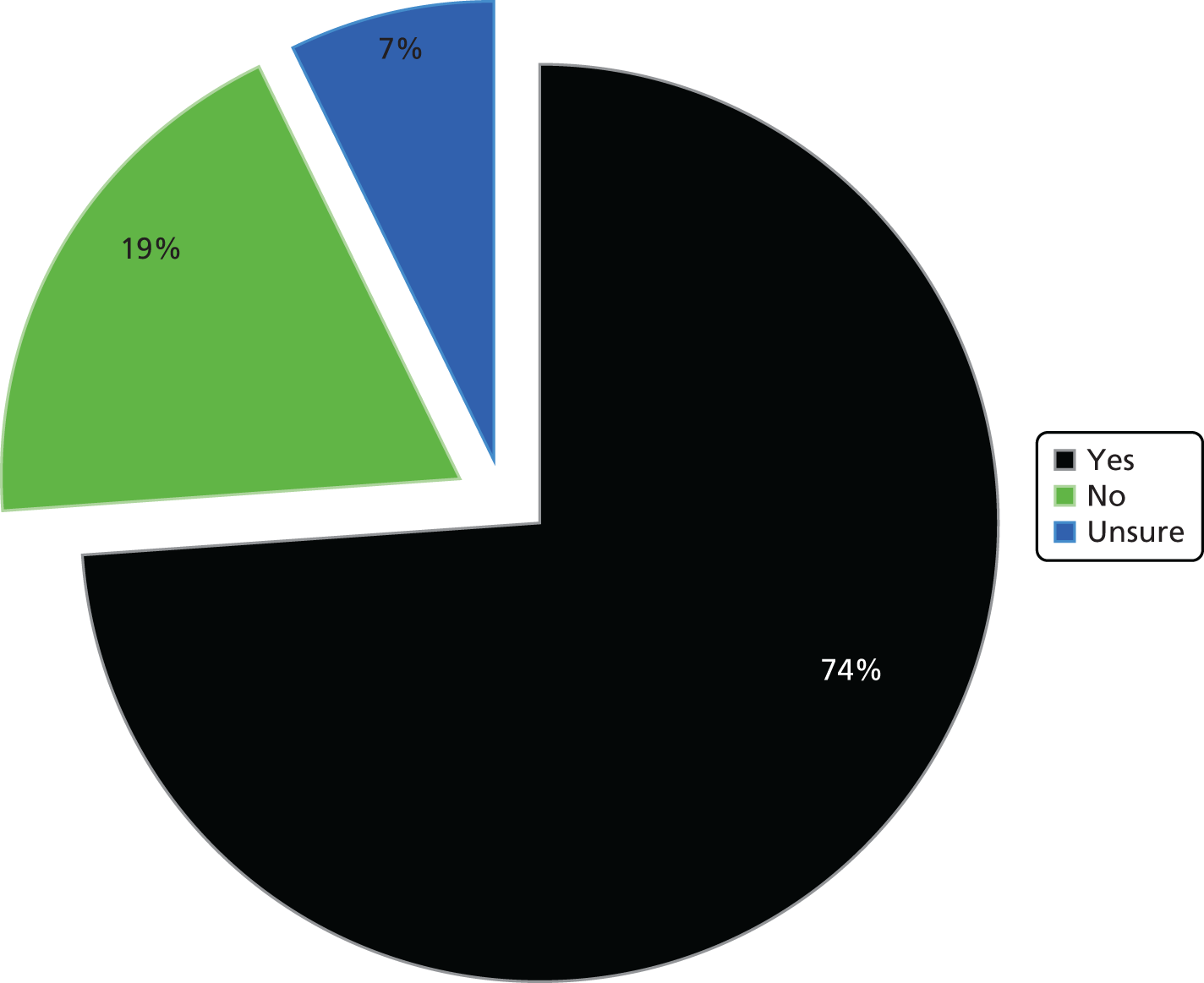

Second, the decision to badge and distribute the main survey through contacts made with the HFMA was revised after the first wave of distribution. Our main contact at HFMA, Steve Brown, agreed to publish our notice to HFMA members about the survey and implemented the first distribution of the survey to this group. Unfortunately, the response rate was disappointing, at < 10%. This was possibly attributable to the high volume of HFMA e-mails to members on a range of different health-care costing issues. Therefore, we subsequently embarked upon our own full-scale distribution of the main survey directly from the University of Manchester to include all provider trusts in England. We conducted three additional follow-up e-mails to all recipients; the final main survey response rate percentage was 45.8%.