Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 11/2004/29. The contractual start date was in May 2013. The final report began editorial review in December 2015 and was accepted for publication in July 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Standing et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Overview of the research

This research study used qualitative methods to investigate patients’, family members’ and professionals’ views about, and experiences of, implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) implantation and deactivation. This chapter presents a synopsis of the study context, rationale, aims and objectives, including an overview of the project team, patient and public involvement (PPI), ethics approval and the subsequent structure of the report.

Context and rationale for the research

In the UK there are 100,000 sudden cardiac deaths per year,1 80% of which are attributable to ventricular tachyarrhythmia. 2 ICDs are recommended for patients at high risk of sudden cardiac death [primary prevention (PP)] and for survivors of cardiac arrest [secondary prevention (SP)]. 2,3 All ICDs combine both a shock function (to treat fast heart rhythms) with a pacing function (to treat slow heart rhythms). In some cases, the pacing function may be very sophisticated and can provide so-called cardiac resynchronisation therapy (CRT) for the treatment of heart failure. CRT itself may be provided by a pacemaker [cardiac resynchronisation therapy with pacemaker (CRT-P)] or in conjunction with an ICD [cardiac resynchronisation therapy with defibrillator (CRT-D)]. The great majority of ICDs are provided for PP for patients with chronic heart failure. They increase life expectancy but may be associated with adverse effects, including unnecessary or inappropriate shocks, device complications, increased hospitalisation and anxiety and depression. 4 Consequently, decision-making about an ICD for individuals should consider the benefit (averting sudden death) against possible future harms, including adverse effects and the potential need for deactivation towards the end of life.

Implantable cardioverter defibrillator implantation rates in the UK vary geographically and are increasing, but the extent to which patients are engaged in decision-making, and what their information and support needs are, is unclear. 5,6 Shared decision-making (SDM), whereby doctors and patients make joint decisions informed by best evidence and aligned with patient values and preferences,7 is associated with improvements in patient involvement, knowledge and accurate risk perception, leading to informed values-based choices and increased treatment adherence. 8,9 There is a dearth of information relating to the role that potential ICD patients can and want to have in the decision-making process and what potential recipients need to know before they decide to have ICD therapy. 5 It is unclear how possible benefits and harms are communicated to patients during the clinical encounter and how patients make sense of this information. A 2014 review10 identified that patients faced with ICD-related decisions often misunderstood the functionality of ICDs, or overestimated their benefit, and the authors recommended a SDM approach to achieve improved patient outcomes.

At the end of life, shocks from ICDs may cause unnecessary pain and suffering to the patient and distress for carers and family members. 11,12 In these circumstances, deactivation may be the most appropriate management. However, there is a paucity of evidence to reflect if, how and when deactivation conversations take place in the UK.

There are clear gaps in the existing body of research with regard to the information needs and preferences of potential ICD recipients with respect to both implantation and deactivation.

The outputs of this study help to address these gaps by providing data on current decision-making while also establishing the information needs, values and preferences of ICD recipients, carers/family members and clinicians, so that decision-making involving patients can be effectively supported. Most patients are not aware of the possibility of ICD deactivation when they have the device implanted and, for those who are, it is unclear when, how and from whom [e.g. general practitioner (GP), cardiologist, heart failure nurse, palliative care clinician] they receive this information. 6,13,14 Little is known about how patients make sense of information about ICDs and what patients’ information needs and preferences are with respect to implantation and deactivation. 5,6,15,16 By documenting current decision-making throughout the care pathway, and by exploring patients’, family members’ and clinicians’ views of decision-making, we have addressed these knowledge gaps to help determine how to better support SDM about ICD implantation and deactivation.

Aims and objectives

Aim

To critically explore lay and professional views on, and experiences of, ICD implantation and deactivation (towards the end of life) and to examine how this information can be used to support SDM.

Objectives

-

To explore patients’, family members’ and clinicians’ views and experiences of decision-making about ICD implantation and deactivation (towards the end of life).

-

To establish how and when ICD risks, benefits and consequences are communicated to patients (including deactivation).

-

To determine patients’, family members’ and clinicians’ information and decision-support needs in the context of SDM.

-

To identify the individual and organisational facilitators and barriers to discussions about implantation and timely decision-making about deactivation.

-

To inform (1) early-stage development of decision support for ICD implantation and (2) improvements in advance care planning for ICD recipients.

Project team

The project was led by Professor Richard Thomson, expert in SDM, and Professor Catherine Exley, medical sociologist and qualitative researcher, in close co-ordination with Dr Kerry Joyce, Senior Research Associate, who was a co-investigator and responsible for the day-to-day project management until September 2014. Dr Joyce’s role was taken over by Holly Standing, Research Assistant, from August 2014, with additional support from Dr Darren Flynn, Senior Research Associate and Practitioner Health Psychologist, from September 2015. The core project team met, on average, once a month to discuss the day-to-day practicalities of running the project, recruitment and data analysis.

The Project Advisory Group consisted of members of the project team and Professor Julian Hughes (Honorary Professor of Philosophy of Ageing and Consultant in Old Age Psychiatry), Dr Stephen Lord and Dr Janet McComb (consultant cardiologists), Dr Paul Paes (Consultant in Palliative Medicine), Mr Tom Bryden, Mr Tom Twedell, Mr Paul Cuskin and Mr Steve Whitely (patient representatives), Mrs Trudie Lobban, Member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (MBE) (founder and trustee of the Arrhythmia Alliance: The Heart Rhythm Charity) and Dr Daniel Matlock (Consultant in Palliative Medicine). The Project Advisory Group provided feedback and advice, and reviewed progress on all aspects of the study.

Patient and public involvement

Active, sustained and non-tokenistic engagement with patients is a crucial component of our research and echoes our commitment to conducting research that supports patients in adopting a more proactive role in decision-making. Public and patient engagement was initiated prior to the development of the outline application and was led by one of the co-investigators, Dr Kerry Joyce. Mrs Trudie Lobban MBE, Founder and Trustee of Arrhythmia Alliance, was contacted at the pre-application stage. Trudie enhanced the focus of the project on patients’ needs by encouraging us to concentrate on both implantation and deactivation decisions, explaining that deactivation is often a key issue that patients and relatives would like to discuss in advance. In this way, deactivation would be addressed in advance rather than leaving it until close to the end of life, when it is often the family/carers who are faced with making the decision rather than the patient themselves, causing additional distress at an extremely emotional time. This benefit of early PPI was used as an example of good practice by INVOLVE, a national advisory group ‘to support active public involvement in NHS, public health and social care research’. 17 Trudie subsequently joined the research team as both a co-applicant and a member of our study advisory group. Trudie provided service user input into all stages, including the development of patient/carer information resources, data analysis, report writing, interpretation and dissemination of study findings. Two patient/carer representatives (with an interest in end-of-life issues) joined the initial project advisory group. The Arrhythmia Alliance and the North of England Cardiovascular Network also reviewed the research proposal and their comments were incorporated, specifically with respect to strengthening the focus on decision-making across the care pathway, including more than one secondary care centre and emphasising patient benefit.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval for this study was obtained on 26 April 2013 from the National Research Ethics Service Committee North East-Sunderland (reference: 13/NE/0105). Two ethics amendments were subsequently given a favourable opinion, on 14 November 2013 (to amend slightly the strategy for recruiting patients to the study and to be able to include patients eligible for a defibrillator in combination with CRT) and 12 May 2014 (a change to the method of approaching bereaved relatives and widening of the eligibility criteria to 12–18 months post bereavement). All potential participants were provided with information about the study and there was an opportunity to address questions to the researchers prior to participation. Individuals were informed that their participation was entirely voluntary and that they were free to withdraw at any time without reason. All personal identifying information was removed to protect confidentiality.

Structure of the report

Chapter 2 presents the background literature on the implantation and deactivation of ICDs, the rationale for the current study and the study aim and objectives. Chapter 3 details the methods used to address the study objectives, which consisted of observation of consultations, in-depth interviews and interactive workshops. An overview of the context and the participants recruited within each of the three phases is presented in Chapter 4. The findings of the interviews and workshops with reference to implantation issues are presented in Chapter 5. Chapter 6 discusses the findings of interviews and workshops with reference to deactivation issues. Chapter 7 presents a summary of the study findings, along with a discussion in relation to the previous literature, the implications of findings for supporting better SDM about ICDs, the strengths and limitations of the current study and future directions for research.

Chapter 2 Background

In the UK there are 100,000 sudden cardiac deaths per year,1 80% of which are attributable to ventricular tachyarrhythmia. 2 ICDs are recommended for patients at high risk of sudden cardiac death [primary prevention (PP)] and for survivors of cardiac arrest [secondary prevention (SP)]. 2,3 All ICDs combine a shock function (to treat fast heart rhythms) with a pacing function (to treat slow heart rhythms). In some cases, the pacing function may be very sophisticated and can provide so-called CRT for the treatment of heart failure. CRT itself may be provided by a pacemaker (CRT-P) or in conjunction with an ICD (CRT-D). The majority of ICDs are used for PP in patients with chronic heart failure. ICDs increase life expectancy but may be associated with adverse effects, including unnecessary or inappropriate shocks, device complications, increased hospitalisation and anxiety and depression. 4 The reported incidence of adverse effects varies greatly from 20% to 60%. 4 Shocks may be painful and distressing and have been compared to being kicked in the chest by a horse or being struck by lightning. 18 Thus, decision-making about an ICD for the individual should include the weighing up of benefits (i.e. averting sudden death) against possible future harms, including adverse effects and the potential need for deactivation towards the end of life.

Implantable cardioverter defibrillator implantation rates in the UK vary geographically and are increasing,19,20 but the extent to which patients are engaged in decision-making and what their information and support needs are, is unclear. 5,6 SDM, whereby doctors and patients make joint decisions informed by best evidence and aligned with patient values and preferences,7 is associated with improvements in patient involvement, knowledge and accurate risk perception, which leads to informed values-based choices and increased treatment adherence. 8,9 There is a dearth of information relating to the role that potential ICD patients can and want to have in the decision-making process, and what potential recipients need to be informed about before they decide to have ICD therapy. 5 It is unclear how possible benefits and harms are communicated to patients during the clinical encounter and how patients make sense of this information. Indeed, data on patients’ expectations of ICDs suggest that survival benefits might be substantially overestimated,21 and improvements to how information on the clinical rationale for ICDs (including the fact that simple ICDs do not confer any symptom or quality-of-life benefits) is communicated to patients and their relatives may be warranted. It has been shown that patients eligible for different therapies might not be fully aware of the benefits and harms of each option,15,16 and the psychosocial impacts of available treatment or management options rarely feature in risk communication. 22 We also do not know how decisions to implant an ICD device align with what is important to the individual patient. However, recent work locally suggests that patients who are more involved in decisions about ICD implantations may be less inclined to have a device fitted. 23

Near the end of life, shocks from ICDs may cause unnecessary pain and suffering for the patient and distress for carers and family members. 11,12 Currently, research suggests that one in four patients experiences shocks during the last month of life. 13 The end-of-life trajectory is difficult to predict for patients with end-stage heart failure, although shocks do act as a marker of deterioration for some and may actually be a useful trigger for the palliative process; in these circumstances, deactivation can be the most appropriate management. Research from the USA suggests that clinicians discuss deactivation of ICDs with only a small subset of patients and, in the majority of cases, these discussions take place only a few hours or days before death. 13 There is a paucity of evidence to reflect if, how and when deactivation conversations take place in the UK. A focus group study with US ICD outpatients (approximately half of whom had experienced at least one shock) found that none recalled discussions about deactivation or knew that deactivation was a possibility. 14 From patients’ perspectives, barriers to deactivation conversations included a reluctance to begin advance care planning discussions and a lack of knowledge about ICD function. 11,14 Reasons for clinicians failing to initiate deactivation conversations were: a lack of knowledge about ICD function; poor quality doctor–patient relationships; the assumption that responsibility for discussing deactivation lies elsewhere; erroneous beliefs that patients are already aware that the device can be deactivated; and the belief that clinicians can accurately predict which patients will experience shock (and distress) towards the end of life. 11,24 This research suggests a level of unease around initiating deactivation discussions. The consequence of this lack of discussion is unnecessary or unwanted shocks towards the end of life. Indeed, one survey demonstrated that nearly half of all hospices in the USA had experience of a patient getting shocked by their ICD because no one thought to have a discussion about turning the ICD off. 25 The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines2 on ICDs published in 2014 present, very briefly, details about the possible need for ICD deactivation, and a regional policy for the deactivation/reactivation of ICDs26 tends to be technical in style and the patient perspective is largely absent. Furthermore, a critical review of six clinical practice guidelines27 for ICD therapy reported that they tended to focus on evidence of device effectiveness, with minimal consideration of impacts on patient quality of life and psychosocial well-being, including the involvement of patients/relatives in decisions.

The implantation and deactivation of ICDs present interesting ethical challenges. The ethical issues around decision-making in connection with ICD implantation are, at first sight, no different from any other treatment decisions. The patient must be able to consent to the treatment, he/she must have the capacity to make the decision – by understanding, retaining, weighing up and communicating their decision – and must make it freely without coercion. 28 Furthermore, the decision can readily be discussed in terms of the four principles of medical ethics. 29 Thus, the person’s autonomy must be respected: they must be able to make the decision themselves having been fully informed about the consequences of having or not having the treatment. Implantation is undertaken in order to do the patient some good (beneficence). Unnecessary shocks (which are painful and distressing), however, would be one way in which the person might be harmed and would go against the principle that the doctor should do no harm (non-maleficence). Finally, the principle of justice also seems pertinent because there are issues around resource allocation.

Another layer of ethical complexity is added to these more ‘mundane’ ethical considerations once deactivation is considered. From a procedural perspective, within the framework of the Mental Capacity Act 2005,30 if the patient has capacity, he or she should make the decision; if the person lacks capacity, a decision must be made in his or her best interests. The purely ethical considerations around deactivation, however, are clearly broader than the more straightforward application of the four principles. For instance, the doctrine of ordinary and extraordinary means is clearly relevant to deactivation because, at the end of life, shocks could be considered both ineffective (defined as no longer leading to the goal that was originally intended) and, thus, futile as well as burdensome. This could, therefore, be considered an extraordinary treatment and, as such, there would be no moral obligation to provide it. 31 The temporality of deactivation discussions is important here. Some of the ethical issues are underpinned by deeper philosophical concerns, for example about the shape of our lives and about the role of health care within our conceptions of life’s purposes. The importance we attach to how our lives end is relevant to a narrative view of ethics. 31 In addition, it may be that deactivation needs to be considered in the context of the relationships of care and trust that exist between a patient and his or her health-care professionals. Finally, the sensitive nature and difficulty of the discussions that might have to be had at implantation about deactivation should alert us to the importance of the inner dispositions, which constitute the requisite professional virtues of fidelity, compassion, prudence, fortitude and integrity. 32 In other words, one of the ethical requirements is that those involved in the sensitive conversations about implantation and deactivation should approach patients in the right way, that is, they should be disposed correctly, which in turn means that they should be on the patient’s side but should act in a manner that is true to all the complexities that have to be weighed up in the course of the SDM conversation with the patient.

Despite these obvious complexities, there is a paucity of research on attitudes to, and practices around, ICD deactivation6 and there have been few systematic attempts to develop decision support for either patients or clinicians to facilitate conversations about ICD implantation and deactivation during end-of-life care. Published research (mostly from the USA) is limited in two key ways. First, it tends to consider decision-making in tertiary care (specialist centres), ignoring what happens earlier in the pathway. Second, the research has generally not sought to change practice; rather, the description of patient experience is viewed as an end in itself. The current study has increasing resonance with the prominence of SDM in NHS reforms33 and the increasing importance attached to advance care planning. 34 By documenting current decision-making throughout the care pathway, and by exploring patients’, family members’ and clinicians’ views of decision-making, we aimed to address these knowledge gaps and to better understand the support needed to enhance SDM about ICD implantation and deactivation.

Rationale

Health need

Implantable cardioverter defibrillator implantation rates are increasing in the UK, with a 10-year mean growth rate of 14.9% for ICDs from 2000 to 2010,35 with more recent figures showing a rate of 72 per 1 million in 2013/14 compared with 66 per 1 million in 2012,36 but with marked geographic variation. 19,20 We do not know if, when or how the risks (including inappropriate shocks and psychopathology), benefits (increases in survival) and consequences (including deactivation) of ICDs are discussed with patients, nor do we know the extent to which patients wish to be engaged in decision-making about ICDs. 5 In terms of implantation decisions, we aimed to provide guidance on how to improve existing decision support and to provide better support for SDM to ensure that implantation decisions are appropriate and fit with the values and preferences of patients. With respect to deactivation decision-making, we sought to better understand how discussions currently take place, and the information needs and preferences of patients at different points in the patient journey, in order to feed into appropriate advance care planning. Together with the ethical imperatives to conduct this piece of research, there are likely to be additional benefits in terms of improving the quality of life for patients with ICDs throughout the pathway and especially when facing end-of-life decisions. In addition, this research should help to reduce any anxiety in clinical staff and carers/family members, given the absence of clear national guidelines/protocols, and to reduce complicated grief among the bereaved associated with poor quality of death. 6

Expressed need

Increasing importance is attached to SDM33 and advance care planning34 in current NHS strategy. Decision-making about ICD implantation is a preference-sensitive decision for which the SDM model is fitting. For example, potential risks (e.g. inappropriate shocks, device complications, psychopathology) and possible consequences of an ICD (e.g. deactivation during end-of-life care) are likely to hold varying levels of importance for different people when they are deliberating between having an ICD fitted or not. Indeed, a recent study found that informed patients who are more involved in SDM may make decisions that contrast to those driven by the strict application of evidence-based guidelines in a more traditional and paternalistic approach to decision-making. 37 This accords with the finding that decision aids used in contexts in which both an invasive and a conservative treatment option are available result in a 25% reduction in patients choosing the invasive option. 8 Thus, there is a cogent, evidence-based argument for the adoption of the SDM model in the context of decisions about ICDs, which is reflected in the American College of Cardiology’s call for implementation of (and research into) models of SDM in cardiology. 38 Furthermore, the existing evidence base shows that the topic of ICD deactivation is seldom discussed in advance. 13 The study sought to examine ways in which to address the timeliness of deactivation conversations while exploring how these might best be supported.

Sustained interest and intent

Rates of ICD implantations are increasing and, with our ageing population, demand is likely to continue to escalate in the future. From both an ethical and practical perspective (in terms of current resource constraints), it is important that patients are supported to make decisions in line with their individual values and preferences, thus ensuring that decisions are appropriate for each individual patient, and that unnecessary or inappropriate implantations are avoided. In line with the increased importance of advance care planning within the NHS, decision-making about future ICD deactivation is an important issue to address, particularly in light of the absence of guidance on deactivation in current NICE guidelines. 2 At a regional level, the North of England Cardiovascular Network guidance26 on deactivation and reactivation of ICDs goes some way to addressing this deficit, but the document is largely technical in nature, with neither the patient perspective nor the importance of SDM featuring strongly. There is therefore potential for these findings to inform both regional and national guidelines about ICDs.

Capacity to generate new knowledge

There are clear gaps in the existing body of research with regard to the information needs and preferences of potential ICD recipients with respect to both implantation and deactivation. This study aimed to address these gaps by providing data on current decision-making while also establishing the information needs, values and preferences of ICD recipients, carers/family members and clinicians, so that decision-making involving patients can be effectively supported. Most patients are not aware of the possibility of ICD deactivation when they have the device implanted and, for those who are, it is unclear when, how and by whom (e.g. GP, cardiologist, heart failure nurse, palliative care clinician) they receive this information. Little is known about how patients make sense of information about ICDs and what patients’ information needs and preferences are with respect to implantation and deactivation. Existing research in this area has been conducted primarily in the USA and is limited to mainly descriptive accounts, which do not attempt to change practice and which focus on decision-making in tertiary care to the detriment of understanding and supporting decision-making earlier in the pathway.

Generalisable findings and prospects for change

By incorporating what is important to the individual patient in decision-making about ICDs, resources can be better targeted to ensure that those people who, after discussion of the benefits and risks of device implantation, make the decision to have an ICD are better equipped to deal with the consequences of an ICD on quality of life and the possible need for deactivation towards the end of life. There is also likely to be transferable learning about how to broach discussions about withdrawal of analogous assistive devices during end-of-life care. 39 This work is directly relevant to those working in clinical practice on individual patient preferences for information giving, levels of involvement in decision-making and how best to support patients and their families with regard to discussions about implantation and deactivation of ICDs. The dual focus on both ICD implantation and deactivation decisions reflects the government’s stated commitment to SDM,33 as well as the importance attached to advance care planning in the NHS. 34 Against this backdrop, our study is timely, particularly with the observation that there is a need for better understanding of how to implement SDM within existing services. 7

Building on existing work

Members of our research team have led and contributed to several studies on variation in the use of ICDs,19 patient involvement in decision-making about cardiac devices,23 patient and clinician perceptions of ICD decision-making,40 and the development of decision support. 41,42 To date, much of the existing (mostly North American) evidence is concerned with what happens in specialist centres, with little consideration of earlier stages of decision-making, particularly in secondary care for initial referral decisions. Equally, there is little available evidence about how decisions on deactivation are made, but a strong suggestion that these are generally made late, and close to death, without planning in advance. 13 This study builds on existing knowledge to (1) support the process of SDM with ICD patients and relatives and (2) disseminate learning to improve advance care planning for ICD patients.

Aim and objectives

Aim

To critically explore lay and professional views about, and experiences of, ICD implantation and deactivation (towards the end of life) and to examine how this information can be used to support SDM.

Objectives

-

To explore patients’, family members’ and clinicians’ views and experiences of decision-making about ICD implantation and deactivation (towards the end of life).

-

To establish how and when ICD risks, benefits and consequences are communicated to patients (including deactivation).

-

To determine patients’, family members’ and clinicians’ information and decision-support needs in the context of SDM.

-

To identify the individual and organisational facilitators and barriers to discussions about implantation and timely decision-making about deactivation.

-

To inform (1) the early-stage development of decision support for ICD implantation and (2) improvements in advance care planning for ICD recipients.

During the inception of the research, a US option grid, booklet and video was published to support SDM about ICD therapy. 43 Consequently, the final objective was amended to focus on the provision of guidance to improve existing decision support and on supporting the process of SDM with ICD patients and relatives.

Chapter 3 Research methodology

Overview of study design

To understand fully the views and experiences of those involved in decision-making about ICD implantation and deactivation, and how such discussions are enacted in practice, requires the use of qualitative methods. In this study, we used a combination of observations of consultations, in-depth individual interviews and interactive group workshops. The study was not longitudinal in nature, that is, we did not follow a particular cohort of patients throughout the care pathway. To reflect the diversity and range of patients’ experiences, we recruited people before and after ICD implantation, as well as people who declined ICD, people considering prospective deactivation and bereaved relatives. We also adhered to the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) guidelines. 44

Patients can be referred for an ICD for either PP of sudden cardiac death or as SP after they have experienced a cardiac arrest. PP patients are likely to have more time to discuss and reflect on their decisions about an ICD than those patients who are referred for SP. With this in mind, and because of the different nature of the decision-making process (after a cardiac event), we focused pre-implantation interviews on patients referred for PP. However, to achieve sufficient numbers and to understand fully the nature of decision-making for the two different groups, we did not exclude patients with SP ICDs. We also included patients eligible for, or living with, CRT: patients eligible for a CRT device can also choose to have CRT alone or CRT-D. The decision is presented to patients as the option of having something to improve symptoms or the option of having something to improve symptoms as well as something to increase the chances of living longer. It is important, therefore, that we captured this group of patients in our sample to understand the full range of options available and the nuances of the decision-making process. Moreover, CRT-D is a common option for ICD patients, and excluding this group of patients would limit how representative the study sample was in terms of the wider population of defibrillator patients.

Data collection and analysis for this study followed the principles of the constant comparative method. 45 This is an iterative process whereby data collection and analysis occurred concurrently, with earlier interviews informing subsequent ones and continuing until no new information emerged. The initial phases used observations and interviews to explore lay and professional views and experiences of decision-making about ICD and CRT-D implantation and deactivation. Observations were conducted at one specialist centre, where ICDs are implanted, and at two district general hospitals (DGHs), with ICDs implanted at one of these. We selected these study sites because they provide different pathways to ICD implantation and, therefore, may provide different insights into decision-making between implanting and non-implanting clinicians, and the importance of different organisational approaches, such as the role of the specialist nurse. Our rationale was to understand patient/clinician interactions, information sharing and decision-making in implanting centres and to explore what happens earlier in the pathway by including two DGHs offering contrasting approaches to patient referral, one of which was cardiologist led and the other of which was nurse led. In-depth interviews were conducted with patients, family members and clinicians at the above sites. We also recruited from two additional sites (one in tertiary care and the other in secondary care) to conduct clinician interviews. For the deactivation conversations, patients and family members were recruited through cardiac physiologists, cardiologists or palliative care physicians directly involved in the patients’ care.

In the final stage of the study, these data were used in the interactive group workshops with patients/family members and clinicians to validate the findings of the initial phases and to provide a vehicle to explore their ideas and views about how the findings could be used to support better SDM about ICD implantation and deactivation, as well as to inform advance care planning for ICD recipients.

Phase 1: observations

In order to understand decision-making across the care pathway, non-participant observation46 was conducted by two researchers (KJ and HS) to familiarise themselves with the clinical environment and patient pathways. Specifically, we were interested in learning more about:

-

the nature of ICD consultations (how ICDs are portrayed within the clinical encounter, the focus and duration of interactions, who interacts with whom, who initiates/ends interactions, how the physical environment might constrain/promote the delivery of good-quality decision-making)

-

the nature of decision-making interactions (how information is shared and by whom, how risk communication is enacted and by whom, how the topic of possible future deactivation is approached and by whom)

-

the patient’s journey through the care pathway (what happens and when, key decision points regarding ICDs and how are these negotiated, the stage of the pathway at which risks, benefits and consequences – e.g. possible future deactivation – are communicated to patients).

Patients received a letter about the study with their outpatient appointment letter explaining that a researcher might be present at his/her clinic appointment to observe the consultation. This letter included clear details of how to opt out of the study (see Appendix 1). The letter of invitation included an opt-out reply slip which patients could return to the receptionist/member of clinical team on arrival to enable the opportunity to opt out without having to approach the issue face to face. The consultant cardiologist further relayed the information at the beginning of the consultation and offered a final chance to opt out. Patients had the opportunity to reflect on their decision and discuss their participation in the study with family members/significant others before deciding whether or not to participate (there was usually a period of several weeks between appointment letter and actual appointment). We chose an opt-out process of consent for the observations for three reasons: (1) we wished to avoid overburdening patients at a time when they are already receiving large volumes of information about ICDs; (2) clinicians would be seeking written consent for device implantation so asking for written consent to observe the consultation may result in confusion over what the patient is actually consenting to; and (3) obtaining written consent would lengthen the consultation and place additional demands on the consultant cardiologist.

Experienced qualitative researchers (KJ and HS) observed consultations with patients being considered for ICD. Initially, it was hoped that we would also be able to observe consultations that focused on deactivation, but this was not possible because of the nature and timing of these discussions. It is unknown how many deactivation conversations took place during the study period. We were made aware of very few deactivation conversations, and in some cases the researchers were not notified in time to permit attendance and observation of these consultations.

Our observations helped to understand how conversations about ICD implantation and subsequent deactivation are enacted. Our approach avoided imposing structure on the observations and brief field notes were written up immediately after the observation period. 47 Prior to beginning data collection, a pilot observation was conducted opportunistically, after which the researcher discussed the consultation with the consultant cardiologist in order to shape an observation grid and coding frame as a guide to their note-taking around the key components of a typical ICD consultation (see Appendix 2). This included, but was not limited to, discussions of diagnosis and checking understanding; communication of the risk of sudden cardiac death; presentation of the ICD, with risks and benefits information; and the impact of the ICD on quality of life and, in some cases, the capacity of the ICD to change the mode of death. It should be noted that this is not a deep ethnographic study and the purpose of the observations was to provide context for subsequent interviews. Consequently, the observations enabled us to understand how decision-making about ICD implantation and deactivation was enacted in different settings and the nature of ICD consultations and decision-making interactions (what is said and what remains unsaid), including the patient’s journey through the care pathway. Notes were taken by hand either during or immediately after the consultation in order to minimise the presence of a researcher within the clinic environment. Observations at each site took place prior to beginning recruitment for phase 2, thus providing local context and helping to inform the purposive sampling strategy and interview guides for in-depth interviews with patients, relatives and clinicians.

Phase 2: in-depth interviews

Interviews were conducted by KJ and HS with patients (aged > 18 years), partners/relatives (aged > 18 years) and clinicians to explore understandings and experiences of, and the factors that influence, decisions about (1) ICD implantation, and (2) deactivation towards the end of life. We excluded patients and family members who lacked capacity to participate in the study and patients and family members who were unable to speak English. Interviews were conducted at a time and place convenient to the interviewee. The majority of interviews were conducted face to face, but a small group of people preferred to be interviewed by telephone. We ensured that patient and family member interviews were conducted during times when support from the clinical team was available in the event that any of the interviewees experienced undue distress. We also made participants aware of sources of support and further information where necessary, including Arrhythmia Alliance, Patient Advice and Liaison Service, and Cruse bereavement support (appropriate information was included in the participant information sheet and was reiterated at the beginning of the interviews).

One-to-one, in-depth interviews are the method of choice where the issue under investigation requires detailed exploration of sensitive issues. In-depth interviews are particularly instructive where the current evidence base is limited,47 as they enable space and flexibility for the interviewee to shape the issues discussed, rather than the direction being predetermined by the researchers’ interests or hypotheses. The interviews investigated how decision-making about ICDs is currently undertaken and if, and at what stage, device deactivation is addressed; patients’ and clinicians’ information and support needs regarding ICDs in general and regarding deactivation in particular; patients’, carers’ and clinicians’ views about how best to support decision-making about the implantation and deactivation of ICDs; and individual and organisational facilitators and barriers to discussions about implantation and timely decision-making about deactivation.

Purposive sampling was used to capture a broad range of views and experiences and, as data collection progressed, we deliberately sought out individuals who had different views or experiences to challenge our analysis. During recruitment we sought to interview people about both implantation and deactivation decisions and purposively sampled so that the views and experiences of the following groups of patients and/or family members were included.

With regard to implantation decisions:

-

before implantation – patients referred for an ICD from secondary care

-

before implantation – patients recruited from implanting centres who elected to have a device implanted

-

after implantation – ICD patients who had a device implanted (we purposively sampled to capture a range of experiences from those recently implanted to others who have lived with the device for up to 12 months)

-

declined ICD – patients who were referred for an ICD but who declined [at either secondary (declined referral) or tertiary (declined device) stages of the pathway].

With regard to deactivation decisions:

-

patients who were prospectively considering device deactivation

-

bereaved family members (4–18 months post bereavement).

Where possible, we sought to interview prospectively patients who were considering deactivation via tertiary care (e.g. advanced cancer patients). However, discussions about deactivation often take place only a few days (or even hours) before death,13 which presented practical and ethical issues with regard to interviewing patients and relatives. Where deactivation was close to the end of life, and we were unable to speak to patients, we sought to interview family members of patients 4–18 months post bereavement.

Our aim was to continue with interviews until no new information emerged (theoretical saturation). The interview schedule focused on understandings of and feelings about ICDs; experiences of decision-making about implantation; if, where, when and how ICD deactivation was discussed; availability and appropriateness of information; preferences for information and decision support; and exploration of patient pathways. In addition, we included some specific prompts to tap into the values and ethical viewpoints that underpinned peoples’ decisions. Interviews were audio-recorded with written consent, transcribed verbatim and anonymised. Permission was sought from participants to retain contact details for the purposes of inviting them to participate in workshops in phase 3.

Clinician interviews

As already noted, clinicians were recruited from the five sites (two tertiary care centres and three DGHs) in total. By including two additional sites, we were able to purposively sample a range of views and experiences that took account of geographic variation in the referral pathway. Increasing the potential sampling population also served to protect the anonymity of clinicians who participated in the interviews. Clinician interviews considered both implantation and deactivation decisions and involved purposively sampling a range of clinical specialties including secondary and tertiary care cardiologists, heart failure nurse specialists, cardiac physiologists and palliative care physicians. Copies of the letter of invitation for participation in an interview, participant information sheet, consent form and interview schedules can be found in Appendix 3.

Recruitment strategy for interviews

A summary of the recruitment process is shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Recruitment process for patient interviews.

We used a slightly different approach to recruit bereaved relatives: a letter of invitation, together with an information sheet, was sent by post to bereaved relatives identified by the physiologists at the tertiary centre, which holds a register of all those people who died with an active ICD in situ and all those people who had their device deactivated before death. We included both groups of patients in our approach (i.e. those who had their device deactivated before death and those whose device was deactivated afterwards). If interested in participating, the individual was asked to return the accompanying consent to contact form. In the first instance, we contacted bereaved relatives 4–6 months post bereavement; however, we were faced with low levels of participation so the eligibility criterion was widened to 12–18 months post bereavement. It was also made clear in the invitation that relatives could choose to be interviewed with a friend or family member if preferred. Equally, if those people contacted did not feel that they were the most appropriate person to complete the interview, they were invited to pass the information on to whoever was most closely involved in the care of their loved one. The letter about the research was accompanied by a cover letter from a cardiologist member of the study team (see Appendix 3). The purpose of the covering letter was to reassure potential participants that the researchers had no access to the clinical data of their loved one and to emphasise that there was no obligation to take part in the research. The consultant’s contact details were also included in the letter to provide a point of contact in the instance that someone encountered distress from our recruitment approach.

Data analysis: interviews

Data collection and analysis was an iterative process. 45 NVivo version 7 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) was used to facilitate data management and retrieval. The research team (KJ, HS, CE initially, then HS and CE) met regularly to discuss emergent themes and to resolve any discrepancies and determine theoretical saturation. Independent coding and cross-checking by members of the research team (KJ, HS, CE) helped to ensure validity of interpretation. A common coding frame was used across all data sets to allow for comparison between the different data sources. Data were examined for deviant cases. 47 The emergent findings were discussed on a regular basis with other members of the active research team as well as with the wider study advisory group.

Phase 3: interactive group workshops with clinicians and patients/relatives

Two interactive group workshops (2 hours in duration), involving Microsoft PowerPoint (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) presentations, small group work and plenary discussions, were conducted with (1) clinicians and (2) patients/relatives. These were aimed at validating the findings of the initial phases and as a vehicle to explore their ideas and views about how the findings could be used to support better SDM about ICD implantation and deactivation, as well as informing advance care planning for ICD recipients.

Workshops were audio-recorded and were facilitated by two researchers (DF and HS). Field notes were taken during workshops, which were audio-recorded.

Recruitment of workshop participants

Patients/relatives and clinicians who had provided written consent to be contacted about later stages of the study were invited to take part in the workshops. The Northern England Cardiovascular Disease Strategic Clinical Network lead also e-mailed a request for participation in an attempt to recruit additional clinicians who had not participated in the earlier phases of the research. Patient representatives of Cardiomyopathy UK (www.cardiomyopathy.org/), Pumping Marvellous (http://pumpingmarvellous.org/) and the British Heart Foundation (www.bhf.org.uk/) were also invited to attend the patient/relative workshop, which took place in a community setting.

Data collection and analysis strategy for workshops

The clinician workshop took place within a tertiary care centre. Following an overview of the aims, objectives and methods, including a brief overview of SDM, attendees were presented with a summary of the key findings from phases 1 and 2 and were invited to comment on whether or not they resonated with their views and experiences in a group plenary. This was followed by group work, in which attendees were allocated to one of two small groups to consider the following issues, with reference to the generic question ‘How can patients and their relatives be better supported to make informed values-based decisions about ICD implantation/deactivation in partnership with clinicians?’:

-

Who should discuss the pros and cons of ICDs with patients/relatives?

-

When should a discussion about the pros and cons of ICDs with patients/relatives take place?

-

What information should be provided to patients/relatives?

-

How could specific barriers to SDM be overcome?

The workshop concluded with key issues identified from each small group being discussed in a plenary session. A copy of the clinician workshop slides can be found in Appendix 4.

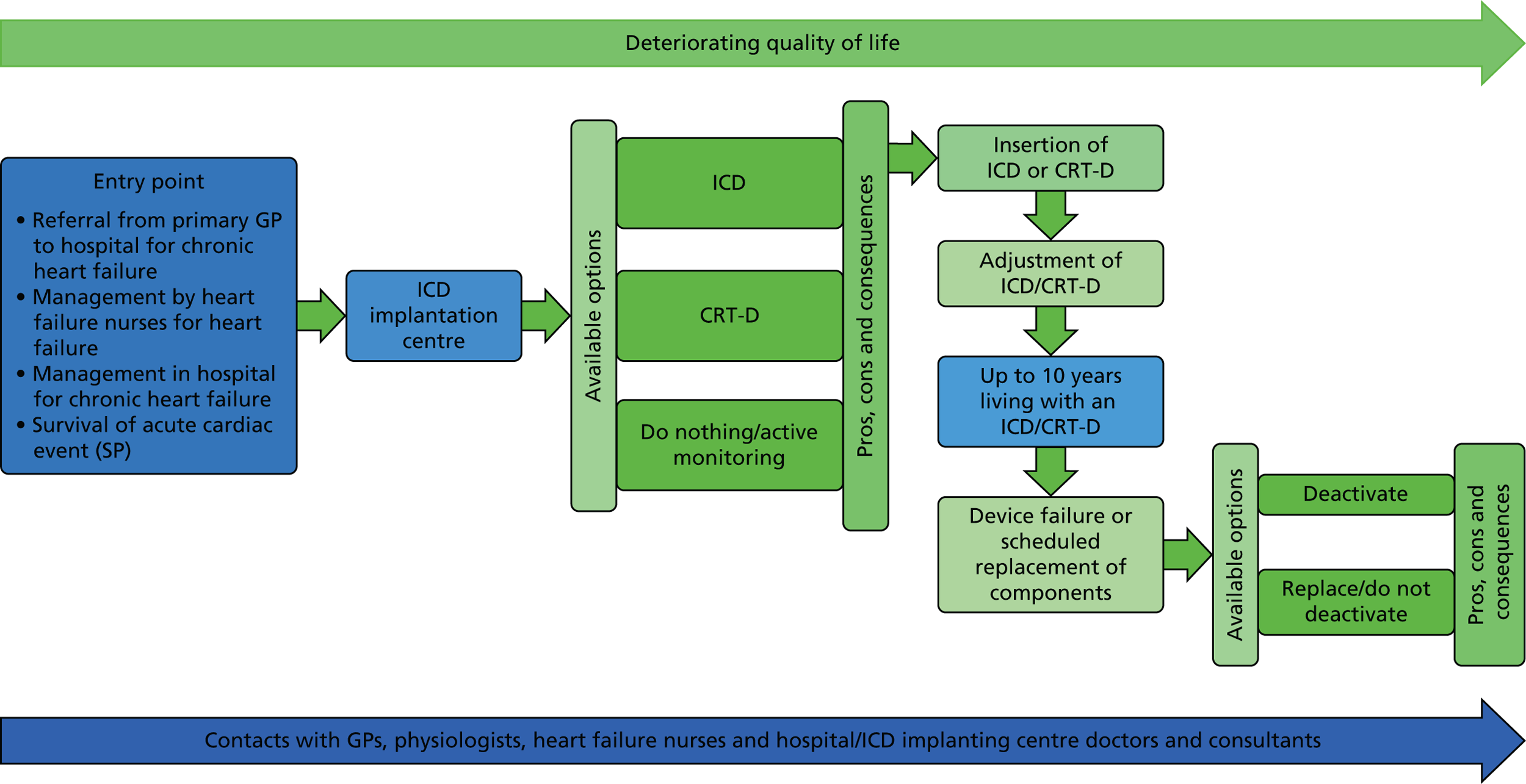

The patient/relative workshop was convened in a community setting. The structure was similar to the clinician workshop, commencing with an overview of the study aims, objectives and methods, including a brief overview of SDM, followed by a summary of the key findings from phases 1 and 2 and a subsequent opportunity to comment on/discuss them within a group plenary session. This was followed by small group work that also focused on eliciting their ideas on how the findings could be used to support better SDM about ICD implantation and deactivation. A structured small group exercise with reference to a summary of preference-sensitive decision points and opportunities for discussions with patients/relatives across the generic heart failure pathway (Figure 2) was used to elicit their ideas on the following questions:

-

What information about options (ICD, CRT-D or doing nothing/active monitoring) should be provided to patients/relatives?

-

Who should discuss the pros and cons of the options (ICD, CRT-D or doing nothing/active monitoring) with patients and their relatives?

-

When should a discussion with patients and their relatives about deactivation of ICDs/CRT-Ds take place?

FIGURE 2.

Decision points and opportunities for discussions with patients/relatives about ICDs.

A copy of the patient/relative workshop slides and structured exercise can be found in Appendix 4.

Field notes and transcriptions of audio-recordings from the workshops were subjected to functional content analysis (use of a priori and emergency coding with the specific function of identifying generic categories of information) for discussion with the wider research team to establish whether or not the descriptions of our findings (presented in Chapters 5 and 6) accorded with the understandings of the participants, and to inform recommendations on how to support better SDM about ICDs.

Chapter 4 Profile of participants in each phase of the study

Phase 1: observations

A total of 38 consultations involving clinicians and patients being considered for both ICD implantation and deactivation were observed across three sites (July 2013 to January 2015). Consultations ranged in length from around 10 to 30 minutes.

-

Site 1: a tertiary care (implanting) centre – 29 observations of two different cardiologists consulting with their patients.

-

Site 2: DGH, nurse-led clinics – three observations of two heart failure nurses consulting with patients.

-

Site 3: DGH – six observations of one cardiologist consulting with patients.

Owing to a lesser frequency of potential ICD candidates seen in secondary care clinics, and the difficulties in managing to observe a consultation (owing to some patients showing improvement in the repeat echo and discussion of the possibility of an ICD or CRT-D no longer being appropriate), lower numbers of observations were conducted in secondary care than initially anticipated.

Phase 2: in-depth interviews

A total of 80 interviews were undertaken with patients/relatives and clinicians (Table 1).

| Patient and family members (and context) | n |

|---|---|

| Patient interviews | |

| Pre implantation (secondary care) | 4 |

| Pre implantation (tertiary care) | 9 |

| Decliners (secondary care) | 5 |

| Decliners (tertiary care) | 3 |

| Post implantation | 18 |

| Post implantation (experience of psychological sequelae) | 3 |

| Prospective deactivation | 2 |

| Total patient interviews | 44 |

| Bereaved relatives interviews | |

| Bereaved spouse | 4 |

| Bereaved spouse and daughter (dyad) | 2 |

| Bereaved son and daughter-in-law (dyad) | 1 |

| Total bereaved relatives interviews | 7 |

| Total patient and family member interviews | 51 |

| Clinician group (and context) | |

| Implanting cardiologists (tertiary care) | 5 |

| Cardiologists (secondary care) | 5 |

| Arrhythmia nurses (tertiary care) | 1 |

| Secondary care and community heart failure nurses | 6 |

| Cardiac physiologists | 4 |

| Health psychologists | 2 |

| Palliative care clinicians | 6 |

| Total clinician interviews | 29 |

| Overall total | 80 |

Fifty-one interviews were conducted with patients and/or relatives in total; of these, seven interviews were conducted with bereaved relatives. Forty-four interviews were undertaken with patients: 33 men and 11 women, aged between 47 and 85 years [mean 68.4 years, standard deviation 10.3 years]. The majority of patients (n = 34) had been offered an ICD for PP and 10 people had received one for SP. Eleven patients had a diagnosis of cardiomyopathy and the remaining patients (n = 33) were diagnosed with ischaemic heart disease. Twenty-seven interviews were conducted with patients alone and 17 were conducted with patients along with a family member (usually a spouse) present. The largest proportion of patients was recruited via tertiary care following implantation of an ICD, or they were recruited in tertiary and secondary care contexts while considering ICD therapy. We were able to interview eight patients who declined an ICD (one of whom accepted CRT but not the ICD), but only two people who had decided in advance to have their ICDs deactivated were interviewed. Of the seven bereaved relative interviews, four were with spouses, in each case the widow of the deceased. A further three group interviews were conducted. These included two interviews with the spouse and daughter of the deceased and one interview with the son and daughter-in-law of the deceased. Our sampling strategy was successful in recruiting the range of medical/clinical specialties involved in the treatment and care of ICD patients across the pathway.

Phase 3: interactive group workshops

A total of 11 clinicians participated in the group workshop from the following specialties: two physiologists; two implanting cardiologists; two consultant cardiologists; one palliative care consultant; one clinical psychologist; two heart failure nurses; and a public health registrar working with the Cardiovascular Clinical Research Network. The patient/relative workshop was attended by 12 participants: five patients, six relatives and a patient representative from a charitable organisation.

Chapter 5 Findings: implantation issues

In this chapter, we present our analysis related to implantation, where we have drawn on and combined data from all three phases of the study in order to critically examine the different perspectives and experiences of those involved in decision-making about ICDs. To protect anonymity, all participants have been given pseudonyms; when presenting patient quotations, to give further context, alongside names we provide information about age and if the ICD had been given for PP or SP.

This chapter begins with a description of themes on how ICDs are presented to potential recipients, outlining the key information that should be given to facilitate SDM as demonstrated using data from interviews and workshops with patients, family members and clinicians. This is followed by a discussion of some of the key factors involved in decision-making. Finally, the potential impact on the outcome of the key actors involved in the decision-making process is discussed.

Information provision to patients/relatives about the rationale for implantable cardioverter defibrillator therapy

As discussed in Chapter 1, the pathway to receiving an ICD is complex as there are a number of potential routes by which patients may come to be offered a device. The patient’s pathway is dependent upon several factors, including if the device is being offered for PP or SP. Furthermore, the pathway for PP patients may also vary depending on if the patient’s heart failure is being managed in the community or in a secondary care setting. Here, we outline some of the key information provided to patients when deciding whether or not to have an ICD implanted.

The purpose of the pre-implantation consultations was to establish the patient’s need for an ICD. The interviews and workshops indicated that there was variability in the timing of the initial ICD discussion. In particular, patients who were being managed for heart failure in a secondary care setting sometimes had an initial discussion about the device before accepting a referral to an implanting centre (and some patients declined the device at this point). However, it was evident from the observations, interviews and workshops that the majority of patients had limited knowledge about the device at the time of the implanting centre consultation. This may be due to one or more possibilities, most probably a combination of patients being unable to recall fully or to understand information provided on ICDs prior to referral to the implanting centre or limited discussion about ICDs before referral.

Conveying information on risk of sudden death and the implantable cardioverter defibrillator role in modifying this

Patients’ levels of awareness regarding their risk of sudden cardiac death appear to be dependent on whether the device is offered for PP or SP. For the majority of patients, including those sampled in this study, the device is more commonly offered for PP purposes. As such, these individuals are less likely to have any prior awareness of their risk of dangerous arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death. This information was often met with shock and disbelief by patients and their families; interviewees described difficulties processing the offer of the device:

She [wife] went through a period of time saying ‘you’re 48 years old there’s nothing been wrong with you, you haven’t fainted, you haven’t been sick, you’re not off work’, you know,’ you’ve never been off work’, blah de blah de blah . . . ‘But why are they fitting anything?’

Dan, 48 years old, PP, post implant, ICD

Patients’ responses indicated that they often had difficulty marrying the idea that they needed an ICD with their own views of their health status. Their experiences and perception of themselves did not fit with their preconceived categories of people who may need life-saving medical intervention.

Furthermore, it was acknowledged by clinicians that the role of ICDs as a protective medical intervention may make it harder for some patients to process:

I wouldn’t say there are common misunderstandings. I think the bit that people have difficulty with is about understanding risk. And so the idea is that they’re a risk modifier. It doesn’t remove risk . . . and we’re not talking about an absolute ‘oh you’re going to die without having this’. It’s all about modifying risk and I think that’s a very difficult concept for many people.

Dr Rosemary, implanting cardiologist

The quotation above indicates that there are potentially two complex issues that need to be conveyed to patients in terms of risk. There is the patient’s risk of experiencing a dangerous arrhythmia and there is also the ICD’s role in managing this risk. Understanding the role of the ICD as a risk modifier is discussed in greater detail in Function of the device and Fostering patients’ and their relatives’ expectations about living with the device.

Data from the observations and clinician interviews show that communicating risk information repeatedly emerged as a challenging aspect of the information-giving process. Clinicians used different ways of presenting such information to patients. Particular reference was given to numerical risk information and the extent to which this was a useful tool in consultations. However, although it was acknowledged that numerical risk data could be useful, clinicians had concerns about the extent to which patients are able to make sense of such information. For example, Dr Oak described how he used elastic language in the first instance to convey risk information to patients, followed by numerical information if considered ‘helpful’:

No, no, no I don’t use numbers. I, I do later on, when I come to the end, but I start off not by using numbers. I use words like, ‘Very unlikely, but, but slightly more likely than somebody to whom one could compare.’ Whether that be me, if they look about the same age, or slightly older than me, or there’s no one else, or if there’s somebody with them like a partner or I might say, ‘Your friend who isn’t known to have heart disease’. But I then say, ‘It could still happen to me or it could still happen to them because we don’t know what my arteries look like.’ Or something like, I might say something like that to emphasise the fact that it’s not, I, I want to try and get a few things over, firstly that it’s not a very, very high risk, because always they go away thinking they’re going to die in the next 10 seconds or the next week, and they may have to wait quite a while for this thing to be put in. And secondly because in absolute terms, actually the risk isn’t that high on a day-to-day basis. And, and so I try, I try and get that over and I try and say, ‘The risk is not very high but it could happen, and it’s something that could happen over years rather than weeks or months, even though, of course, it’s a day-to-day risk.’ . . . But then I do, later on, say that, ‘The, the absolute risk is of the order of 1%–5% depending on where they fit in the . . .’. Or sometimes I might say, if I don’t, you know, if the conversation’s gone in a way which I think might, numbers might not be helpful, I, I say, ‘Very low risk, moderate risk or, or at the higher end of the risk.’

Dr Oak, implanting cardiologist

During observations, clinicians, including Dr Oak, largely gave patients verbal comparisons rather than numbers to position the patient in terms of their risk of sudden cardiac death. Many clinicians indicated that they tried to tailor the manner in which they presented information in response to cues from the patient. On the importance of tailoring information, see Tailored information below.

Function of the device

In addition to conveying risk information, establishing the need for the device involves explaining the functioning by which the device manages a patient’s risk of sudden cardiac death. Through the observations of clinic appointments, interviews and workshops, it was evident that there was no standard way in which clinicians delivered this information; rather, clinicians developed their own methods. One approach in particular that stood out as being particularly useful for patients in understanding the function of the device was personification or anthropomorphism.

Defibrillators are mechanical devices, electrical devices that in and of themselves will not make you feel any different, and, but the device that . . . we would use for you would not make you feel any better, would not make you feel any different, its job essentially is to help you live as long as you can by taking away the risk of an arrhythmic or a heart rhythm abnormality, not that it does away with the heart rhythm abnormality, but it allows it to be treated in a way that it wouldn’t be treated if you didn’t have a paramedic in your chest if you like.

Dr Birch, implanting cardiologist explaining to a patient

Personifications, for example describing the ICD as a paramedic or a sentry, appeared to be a useful means of explaining the role of the ICD, as this enabled the device to be presented in a way that was both easy to understand and easily memorable. The success of such techniques was evidenced by the ease with which many patients were able to effortlessly recall these during the interviews when asked what they remembered and understood about the function of the device:

It’s like a sentry; it’s on guard, waiting.

Iris, 76 years old, PP, post implant, CRT-D

Furthermore, it is possible that such techniques will also have a role in fostering positive views about the device, humanising this piece of machinery that is being fitted to the body.

As noted earlier in Dr Rosemary’s quotation, the ICD is a risk modifier rather than a risk eliminator; as such, it is essential that patients understand that, even with the device in place, it is still possible for them to experience an arrhythmia that could kill them. It was evident in the patient and relative interviews that many did not appreciate or fully understand this distinction:

The only thing that puzzles me now is why it never shocked . . . why didn’t the ICD shock him to put it right? . . . so when he did die 2 days afterwards, I rang up to see if I could keep the appointment just to question, would that ICD have shocked him while he was in there, when he had collapsed? You know.

Mary, bereaved relative of ICD patient

Several of the bereaved relatives expressed misunderstandings regarding the role of the ICD in managing their deceased relatives’ condition and were confused as to why the device had failed to activate and save the patient’s life. This appeared to be particularly acute in cases in which the device had never given a defibrillation and the patient had died.

Implantation procedure

The data from this study demonstrate variation in the extent to which patients felt informed about the implantation procedure itself, suggesting the need for attention to be given to discussing the practicalities of the procedure during pre-implantation consultations. Some patients reported that they were ill prepared for the experience. For example, one patient recounted her shock at the number of clinicians involved in the procedure:

I can’t remember the amount of people [in the operating theatre], I counted at least 10 . . . That was fright, that was, actually that was quite intimidating because you’ve got all these people, again you’re lying flat in a bed, strapped down going, ‘Oh . . .’, ‘I’m just here to . . .’, ‘Oh that’s lovely’.

Molly, 60 years old, PP, post implant, CRT-D

Being unprepared about the implantation procedure had the potential to be distressing for patients, which could leave them feeling vulnerable and exposed. The possibility of discomfort and distress during implantation is enhanced by the use of local anaesthetic as the patient is conscious and cognisant throughout the procedure.

Tailored information

Both patients and clinicians recognised the importance of adequately informing patients about the ICD in order to allow them to make an informed decision. Clinicians must endeavour to strike a balance between giving patients as much information as they need without overloading them with information.

It will range from people who will just say, ‘Well, if you think it’s in my best interest, I’ll happily go along with it’, versus the others who want to know the chapter and verse.

Dr Thyme, non-implanting cardiologist

Yes. I’m, I’m an intelligent man. I have always wanted doctors to tell me. Dr Ash, the cardiologist in [DGH S04], some people find very difficult because one of the nurses described it to me is that he thinks out loud and you get all the information that’s going through his brain. Now I want that, I can handle that. I don’t want it neatly packaged into something that, talking down to the patient, they think I’ll be able to handle . . . I like that, I like to be told what it is they want to do, why, and what it’s going to be like.

Bob, 67 years old, PP, pre implant

Dr Ash was aware of the challenge of communicating information about ICDs and of the difficulty of not being able to provide patients with a definitive answer regarding the ‘best’ option for treatment/management/prevention of sudden cardiac death:

I suspect a lot of patients leave the room maybe more bewildered than when they came I because I’m not able to, sort of, say, ‘look, this is what you should do.’ Some patients say, ‘What should I do?’ and it’s very hard to advise them, but again, if they say them I just try and tell them what I’d want my dad to do, if they were my dad or something like that.

Dr Ash, secondary care cardiologist

The above quotation reflects an issue of recognising the value of expert advice but also that the patient’s values and preferences may differ from the clinician’s. The patient was asking for advice ‘What would you do?’. As a result the clinician can be drawn into saying what their values and preferences would be if he/she was making a decision for themselves, as opposed to using reflective listening to explore and elicit a patient’s preferences and values.

Both clinicians and patients recognised the variation between individuals about the level of information they wanted. Some people wanted very detailed information and others preferred to be told the key points. One suggestion to improve the process of providing information was that a menu of options could be provided to patients allowing them to choose the level of information they desired:

I know there’ll come a point where you [clinicians] don’t want to overload people with information and then it’ll be up to people, somehow, to decide, ‘I don’t want lots of information, give me, I don’t know, the bronze information, not the silver or the gold.’ But I’m a gold one, I want it all ’cause it’s going to be important for me. ’Cause I’ll only be thinking about it anyway. So if you can think of it and you think you should tell your patient, tell your patient. I think . . . there will be a way to say it that is the right way for everybody. And I know not everybody wants all the information. But I need it from the medical people.

Gwen, 53 years old, PP, post implant

However, some patients expressed frustration in eliciting the level of information they desired from the clinicians that they encountered. Clinicians suggested that they sometimes based their assumptions on what patients wanted to know and their desire for involvement in the decision-making process, based on their clinical judgement (as opposed to explicitly using strategies to elicit patients’ information needs and desire to engage in decision-making). Furthermore, patients such as Ted (56 years old, PP, post implant, ICD) also expressed a desire for information to be tailored to issues of key importance to their lives:

‘Well that’s an issue I don’t want to touch on’ that kind of thing, ‘Well actually it’s an issue that I want to talk about’, you know, it might, ‘It’s affecting my life.’ So there needs to be more emphasis on that, the support element.

So listening and empathy?

Listening and empathy, but it’s because what affects one person doesn’t affect somebody else.

Tailoring information to the specific issues of importance to individual patients was a challenge for implanting cardiologists, who had often never met the patient prior to the consultation about implantation. Consequently, owing to the lack of therapeutic alliance, the preferences and values of patients were unknown to clinicians and, if not skilfully elicited, hindered tailoring of information to enable patients to make an informed implantation decision.

Written information

In addition to information that can be given verbally, ICD information booklets are also available; information booklets referenced by participants in this study included those developed by the British Heart Foundation and Arrhythmia Alliance. Our study indicated that these could potentially be a useful tool for patients when deciding whether or not to have an ICD. One of the key benefits of this written information was that it is a resource that patients can refer back to following their consultation. It was suggested that it may be useful for these information booklets to be supplied to patients who may be eligible for an ICD in advance of their implanting centre consultation, which would afford patients the opportunity to formulate potential questions that they may have about the device.

It might be sort of, ‘In the event that you have to have, at some later date – take this.’ Because – and that was the first time – I sat down and read it, or lay down and read it, and you know, I come to understand it all.

Patrick, 78 years old, SP, post implant, ICD

However, it was evident in both the clinician interviews and the clinician workshop that there were concerns that providing patients with information about ICDs prior to their attendance at the implanting centre may raise expectations of receiving a device among individuals who may later be found to be ineligible by the implanting clinicians.

No I would want to make sure they were eligible before I went into any information about how it is and . . . some people have actually said that it’s been mentioned in the past, I might give, I tend to give the British Heart Foundation ICD leaflet. I’ve posted that to a lady this week who’s seen a cardiologist and, in fact, it was the patient’s daughter who asked me, was asking me questions, so I felt as though she was leading round to something, so, I was a little non-committal and she said, she’s been told she might need a special pacemaker.

Nurse Mint, heart failure nurse

Furthermore, some practical issues were also identified regarding written information. The first relates to the availability of the information. Disparities were evident in the extent to which the information booklets were available across the different NHS trusts included in the study. Indeed, clinicians reported experiencing issues maintaining an adequate supply of the booklets, particularly those that needed to be paid for, such as those from the Arrhythmia Alliance.

Second, although patients, and their families, expressed a preference for information that comes from trusted sources such as well-known charities, some clinicians expressed some reservations about the information contained within these. As a result, some clinicians preferred to develop their own information, as this afforded them the opportunity to alter and update the contents as they thought necessary.

Some of the national information is wrong, you know? People writing things, and you look at it, and you go, ‘That’s the wrong thing to say’, you can’t correct it . . . In the BHF [British Heart Foundation] book, it tells defibrillator patients they get two kinds of shocks. Well an electric shock is an electric shock. I wouldn’t describe it as two kind of shocks. So patients say ‘is that the big one or the little one?’ and you go . . . it’s hard to say ‘well actually that nationally revered, you know, venerated organisation, is not well written’, so each department tends to develop their own, rather than going for a generic thing . . . If somebody misinterprets something, I can rewrite it much easier.

Ms Forsythia, physiologist

However, this preference for having local information at different NHS trusts, each of which develops its own resources, further compounds the issue of providing standardised and reliable information to all patients.