Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 12/5002/04. The contractual start date was in June 2013. The final report began editorial review in February 2016 and was accepted for publication in June 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Bullock et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

The focus of this research is NHS and university-based staff in knowledge brokering roles, how they link with knowledge and innovation, and how they transfer this to the health-care practitioner community. The transfer and mobilisation of knowledge from research into health-care delivery is a long-standing international challenge. 1–6 Sebba7 highlights the economic, moral and academic imperatives for investing resources in improving research use. Alongside the need to base decisions on evidence (moral imperative) and the increasing need to demonstrate impact of academic research (academic imperative), the economic imperative to ensure the best use of limited resources and minimise waste is a timely concern. In a time of unprecedented financial restrictions,8 health-care managers face the enormous challenge of purchasing and providing health care to an ageing population with increasing expectations. Management decisions about planning, commissioning and service delivery affect large populations and require large amounts of public money. Failure to inform practice with evidence limits the improvement of the effectiveness of health services, wastes money and potentially adds to the scale of preventable morbidity and mortality.

It is in this context that our study sought to find out how to get the best out of knowledge and innovation transfer (KIT) ‘agents’, that is, NHS practitioners in knowledge brokering or mobilisation roles.

Knowledge mobilisation

Gainforth et al. 9 defined knowledge mobilisation as ‘putting research in the hands of research users’, but the use of evidence is a complex, social and dynamic process. 10 To inform decision-making in practice, research evidence needs to be ‘available to those who may best use it, at the time it is needed . . . in a format that facilitates its uptake’ as well as ‘comprehensible to potential users and . . . relevant and usable in local contexts’. 11 In health care, this process and associated organisational change is widely recognised as complicated, messy, evolving and fraught with challenge. 12–14 For example, practitioners are alleged to lack the time, motivation and capacity to use evidence15,16 or are purported to be overwhelmed by the quantity of diverse evidence. 17–19 Research reports may lack relevance, can be opaque and verbose20 and it can be a long time before they are released. 21 Some argue that research output is dominated by a biomedical focus on drugs, tests and devices. Instead, Walshe and Davies22 suggest that the current ‘predominant concerns’ relate to ‘pathway and process redesign, safety and quality; organizational issues like coordination, integration and networking; workforce issues like training and skill mix; and patient issues like experience, education and empowerment’. Addressing these concerns may require alternative models of knowledge creation in order to close the knowledge–practice gap. 23,24

The policy context

There have been a number of efforts to build bridges between researchers, policy-makers and service providers, and there is growing interest in using collaborations to address the research–practice gap. 25,26 Some of these are institutional partnerships involving colocation of teams, shared resources and so forth, whereas others rely on key individuals to bridge. All aim to link knowledge and innovation producers and users through various means that may or may not include a formal knowledge broker or KIT agent. Our understanding of the work of these KIT agents remains poor, and examples of collaborations can provide insight into potential modes of and mechanisms for engagement.

Linking trusts and health boards to research teams through managers can help organisations to use research findings in their own settings, and enable them to set up service improvement projects to improve health and health-care outcomes. The review led by Sir Ian Carruthers, ‘Innovation, Health and Wealth: Accelerating Adoption and Diffusion in the NHS’,27 placed innovation at the top of the service agenda, setting out ambitious recommendations to encourage quicker transfer of new practice, ranging from infrastructure change to realignment of system incentives and promotion of high-impact initiatives. Central to the Carruthers report27 is the argument for ‘a more systematic delivery mechanism for diffusion and collaboration within the NHS by building strong cross boundary networks’. Although the proposals of the Carruthers report27 are clear – productive regional collaborations between academia, industry and the health sector to identify and spread innovation and so drive service improvement – its recommendations accommodate regional conditions. Capacity to access, understand and use research knowledge is emphasised to ‘bring about a major shift in culture within the NHS, and develop our people by “hard wiring” innovation into training and education for managers and clinicians’. The contents of this report complement these key policy themes.

Academic Health Science Collaborations, Partnerships and Networks

Following the Carruthers report,27 Academic Health Science Networks (AHSNs) have brought most NHS organisations in England into collaboration with universities. In England, 15 AHSNs were licensed in March 2013. AHSNs are tasked with aligning ‘education, clinical research, informatics, training and education and healthcare delivery’ and improving ‘patient and population health outcomes by translating research into practice and developing and implementing integrated health care systems’. 28 Like their predecessors, Academic Health Science Collaborations (AHSCs), the central aim of these collaborations is ‘knowledge mobilisation, rather than research production’. 22 As designated in ‘Innovation Health and Wealth’27 and the ‘Strategy for UK Life Sciences’,29 AHSNs are a systematic delivery mechanism for the adoption and spread of innovation at pace and scale through the NHS. The networks are designed to foster collaborations between academia, industry and health service, and shared aims include diffusing innovation, putting research into practice, and promoting economic growth. 30 They are expected to work closely with industry and funders to bring together researchers, managers, patient groups, planners and policy-makers.

Compared with England, infrastructure targeting knowledge mobilisation and innovation is not well funded in Wales. However, the sole AHSC in Wales has identified knowledge transfer as a priority. The AHSC formed three regional hubs – in the north, south-west and south-east of Wales. In their initial period, these hubs attracted small-scale funding from Health and Care Research Wales [formerly the National Institute for Social Care and Health Research (NISCHR)], but this ceased in 2014. The South East Wales Academic Health Science Partnership (SEWAHSP) became independent and continued to operate. SEWAHSP has two key objectives: (1) to increase the speed and quality of ‘translational’ research; and (2) to promote and support innovation in south-east Wales. 31 A national Task and Finish Group also made recommendations to Health and Care Research Wales on knowledge transfer policy. 32

Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care

Descriptive studies focused on how research does make it into practice point to the importance of close interpersonal relationships between researcher and user. 33–35 This has been built into interventions that seek to develop opportunities for both parties to link and engage. In England, these include programmes such as the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)’s Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRCs), which were designed to address what Cooksey1 termed the ‘second gap in translation’, related to the failure of new ideas and tools to reach practice. CLAHRCs are serviced-led partnerships that aim to contract high-quality applied health research, implement findings and increase NHS capacity to engage in research. 36–39 In 2008, nine CLAHRCs were established and a second wave extended the CLAHRCs reach with tapered funding (from NIHR) for 13 CLAHRCs. This is an indicator of the perceived success of the programme.

The CLAHRCs are the most established and evaluated programmes in the UK. 39–46 The reports to date highlight similarities and differences between structural and content features of the CLAHRCs and point to early successes and challenges. For example, successes include strengthened networks and relationships;39,44,47 new organisational roles that ‘make sense to professionals’; collective action to improve practices;48 and creating a culture of reflection and learning. 47 More specific successes have also been reported. For example, the CLAHRC for Greater Manchester achieved success in improving patient services in chronic kidney disease. 41,49 Although such results demonstrate the impact of CLAHRCs and how the collaborations can change the approach of organisations for the better,39,50 it is very difficult to demonstrate a causal effect given the complexity of what they are and what they are trying to achieve. Walshe and Davies22 are more circumspect and conclude that ‘promising lessons’ can be distilled from the collaborations in England, which, among others, include ‘the development of organizational capacity in knowledge mobilisation’. Currie et al. 43 usefully summarise key areas of uncertainty for CLAHRCs, which include the problem of metrics. They note the following uncertainties:

The balance of activity between research and implementation; whether research should be clinically or implementation focused; appropriate metrics for CLAHRCs; whether CLAHRCs should orientate towards their academic or NHS partners; and whether CLAHRCs should focus upon individual behavioural or organizational/system level change.

They argue that the dominant approach is research focused, fixed on changing individual behaviour rather than ‘wider scale organizational and system level change’, as favoured by those from a social science tradition. 43

Knowledge brokers

Embedded within the concept of knowledge mobilisation are the roles of knowledge broker and boundary spanner. 51–53 Roles vary,42,54 but the essential feature is that they facilitate engagement between research and practice. 55 With the aim of improving the transfer of knowledge and innovation, knowledge brokers seek to close knowledge gaps and foster knowledge-responsive capacity and culture. 5,56–59

To facilitate knowledge mobilisation, many CLAHRCs used knowledge brokers, variously named. 22,60 For example, in the first round of CLAHRCs funding, the Cambridgeshire and Peterborough CLAHRC had a fellowship programme for clinicians, health- and social-care practitioners and managers to work alongside researchers; the Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire and Lincolnshire CLAHRC funded35 ‘diffusion fellows’ attached to their research projects. 61

The NIHR Service Delivery and Organisation (SDO) Management Fellowship programme provided another example, and one aimed exclusively at managers; an evaluation showed benefits from the interactions between the fellows, their NHS colleagues and research teams, but also revealed challenges in maximising those benefits for the workplace. 62 The NIHR SDO scheme was later merged with the NIHR Health Services Research programme to create the NIHR Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) programme.

As knowledge broker roles grew in number and type across the UK, an interest group formed in 2014 looking at fellows in the system. Several organisations, including the Health Foundation, NHS Education for Scotland, NHS Improving Quality, NIHR, and Universities UK, were involved in early data-gathering exercises to understand the characteristics of the wide range of fellows and fellowship programmes that exists across the health and care system. This exercise culminated in a 1-day event, ‘Fellows Connect’, bringing together quality improvement (QI) fellows from across the UK to share experiences. 63 At the same time, Berwick’s report on ‘Improving the safety of patients in England’ recommended a ‘national system of NHS Improvement Fellowships, to recognise the talent of staff and improvement capability and enable this to be available to other organisations’. 64 This resulted in the creation of an initiative called ‘Q for Quality’, led by the Health Foundation and supported and cofunded by NHS England, connecting people skilled in improvement across the UK. The Q initiative aims to grow to be a community of thousands of people: patient-facing front-line staff, managers, researchers, ‘patient leaders’, policy-makers and others in order to accelerate improvements to the quality of care. 65 Together, these recent developments illustrate the interest and also the investment by national organisations in the UK in maximising the potential of knowledge brokers to improve the quality and safety of health care for patients.

The aims and objectives of the study

The focus of this research is KIT ‘agents’ (NHS and university-based staff in knowledge brokering roles), how they link with evidence and innovation and how they transfer this to the health-care practitioner community. The study aimed to examine the work of KIT agents in practice in order to understand how the outcomes of their endeavours might be maximised. Our research questions are:

-

What are commonly shared expectations of the KIT agent role?

-

What, in practice, do KIT agents do?

-

What is their conception of KIT?

-

How do they see their role?

-

With whom do they link?

-

What are their principal activities?

-

-

How does the work of KIT agents impact on health-care practice?

-

How can KIT agents be best supported?

-

What are the barriers to, and enablers of, them meeting their objectives?

-

-

What measures can be used to assess the impact of KIT activity?

Our objectives were to:

-

map the innovation and knowledge transfer intentions of the new AHSNs and SEWAHSP

-

describe, and characterise, the roles of KIT agents and develop a typology of KIT agent roles

-

report the perceived impact of KIT agents on managers’ practice

-

investigate how KIT agents can be best supported

-

generate a set of impact measures for assessing innovation and knowledge transfer activities.

Concluding remarks

This chapter has established the importance of knowledge mobilisation in health care and provided the background policy context to the current position of initiatives designed to address the research–practice gap. We extend this in Chapter 2 by providing a summary of the literature on knowledge mobilisation.

Chapter 3 outlines the theoretical underpinnings, research study design and methods used. Chapter 4 explores the knowledge and innovation mobilisation intentions of the AHSNs in England and an Academic Health Science Partnership (AHSP) in Wales and introduces a suggested typology of the different forms that KIT roles may take.

The main reporting of the results begins in Chapter 5 with an overview of the case study KIT agents. They highlight content-specific knowledge transfer challenges, as well as generic mechanisms that support transfer. We commence the discussion of our findings in Chapter 6. We look across all the case studies to discuss common barriers and enablers reported by the KIT agents, and explore how they can be better supported in carrying out their role.

The focus of Chapter 7 is on assessing outcomes of knowledge brokering activity. It includes a report of the nominal group and also draws on the case study data and wider literature. In Chapter 8 we extend our discussion of outcomes by reviewing our findings through the lens of social marketing theory.

Last, Chapter 9 brings together the main conclusions and implications of the findings, positioning them within the wider literature and suggesting recommendations for future research.

Chapter 2 Learning from the literature

Introduction

A targeted review of literature was undertaken to identify existing KIT practices, attributes of the successful agents (knowledge brokers, boundary spanners) and outcomes. This assisted learning from previous evaluations, supported robust data analysis, informed the questions posed in the nominal group and provided a solid basis from which to consider the generalisability of findings.

Organised into six main sections, the review begins with a brief exploration of terminology from which we offer tentative definitions. We follow this with consideration of the models of knowledge transfer and mobilisation implicit in programmes designed to bridge the gap between research and health-care practice. We follow this with a section on the role of knowledge brokers or KIT agents and we identify factors shown to enable or impede knowledge transfer and mobilisation in the subsequent section. We follow this with a section summarising current knowledge on outcomes and impact of KIT programmes. The literature review concludes with a summary of main messages and an identification of further research needs.

Notes on the literature search

This review updates and builds on work previously carried out by Bullock et al. ;66 therefore, literature searches for the preparation of the current document were limited to publications post 2010. A broad search was carried out on Web of Science, PubMed, Ovid MEDLINE, Scopus, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) via EBSCOhost and Google Scholar™ (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) using appropriate forms of the terms, ‘knowledge AND transfer AND healthcare’, ‘knowledge’ AND (transfer OR translation OR mobili*ation) AND healthcare’, ‘innovation AND healthcare AND implementation’, knowledge AND (transfer OR exchange OR mobili*ation OR intermediatr* OR boundary spanners), ‘knowledge AND broker OR intermediary AND healthcare’, and ‘CLAHRC’. In addition, we sourced earlier papers from the citations of relevant papers and were vigilant for notifications of papers/reports as they were published. We complemented the electronic search by hand-searching two key journals (Implementation Science and Journal of Health Services Research and Policy) and searching the NIHR Journals Library of completed projects (www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk). Grey literature relating to KIT policy in England and Wales was also reviewed (see Appendix 1).

Terminology

In our proposal we adopted the language of the funding call from NIHR (www.nets.nihr.ac.uk/_data/assets/pdf_file/0003/81786/CB-12-5002-04.pdf) and so refer to ‘KIT’. Lack of conceptual clarity around the theme has been noted in the literature67 and is not helped by a confusion of terms, which are ill defined and used interchangeably. 68 In this section, we draw on extant literature to develop tentative operational definitions of KIT. We did not seek to provide a comprehensive review of all terms and issues.

Knowing knowledge

Knowledge is perhaps the most easily grasped of our terms, but the most difficult to define. Some authors have classified knowledge according to the degree of analysis or inherent conceptual complexity. 69,70 Furthermore, literature on knowledge transfer is not narrowly limited to the transfer of facts to answer ‘how’ questions. Rather, although knowledge in this context is seen to include facts and information, importantly, it is also recognised as being about understanding. Knowledge in this sense can be both theoretical and practical, derived from education and experience. However, it is useful to illuminate the interpretation of terms, as they embody implicit assumptions about how knowledge may be transferred, exchanged and mobilised. The different terms used are associated with different concerns and values, and these have practical consequences. Conceptualising knowledge as empirical information, facts or data decontextualises and commodifies it as something that can be ‘moved around’. 4,71 Alavi and Leidner,72 writing about the conceptual foundations of knowledge management, describe the relationship between knowledge and values, experience and context. They explain how knowledge ‘originates and is applied in the minds of knowers’ and how in organisations ‘it often becomes embedded not only in documents or repositories but also in organizational routines, processes, practices and norms’. 72 This quotation raises the distinction between explicit knowledge, written and recorded in documents, and the implicit or tacit knowledge held by individuals, often without awareness of it and revealed in organisational customs.

Related to the tacit–explicit dimension of knowledge is whether it is understood as individual or social. 72 The distance between tacit (residing in the individual, difficult to transfer) and explicit knowledge (socially and organisationally located) underscores the challenge of identifying, articulating and transferring individually held knowledge. 73–76 Szulanski77 also describes how the ‘stickiness’ of knowledge can hamper its movement, and distinguishes different points at which stickiness is important, including initiation stickiness (which may be affected by competing priorities, for example) and implementation stickiness.

These issues are relevant to knowledge transfer and innovation, as they define what counts as knowledge, and influence how and if it can be transferred. A study of knowledge transfer necessarily gives greatest focus to explicit knowledge, and academic research in particular.

Knowledge and evidence

One issue that is particularly important in the health-care context is the relationship between knowledge and evidence. Knowledge and evidence are contested concepts. In health-care literature, knowledge is often synonymous with evidence and aligned with the principles of evidence-based medicine. Innvaer78 notes that a ‘call for evidence-based [decision-making] is also a call for the use of scientific methods in data collection and in the validation of information’. However, in health care, as well as evidence of effectiveness derived from traditional randomised controlled trials, evidence also needs to encompass feasibility, acceptability and appropriateness. 79

The implicit position of the NIHR,80 in relation to this field of inquiry, is complex. In the commissioning brief for this study, they noted the use of various terms and chose to adopt the term ‘innovation and knowledge transfer’. However, this did not appear to be associated with limited positivistic interpretation of research evidence, and, earlier, they recognised that ‘engagement with research is socially and organisationally situated and heavily dependent on local context’. In this interpretation, knowledge is socially situated, generated by a number of participants and methods81 and intertwined with practice. 82 It allows for the idea that knowledge can be coproduced and co-owned, and recognises the importance of tacit knowledge associated with organisational norms and customs. 72 Likewise, in the Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (PARiHS) framework,3 in addition to research, evidence includes ‘professional craft knowledge, patient preferences and experiences, and local information’. Harvey and Kitson83 have recently introduced the i-PARiHS (integrated PARiHS) framework. The ‘i’ stands for integrated and reflects how ‘evidence is incorporated within the broader concept of innovation to reflect the dynamic and iterative way in which knowledge to inform practice is generated and applied’. Neither of these definitions fit well with more formal definitions of evidence.

For clarity, we would prefer to hold the two terms as conceptually distinct, although connected, using the term ‘evidence’ to relate to a sort of knowledge defined by the way it was generated. Yet it is imperative that we use both terms as they are applied by the participants in the study in order to understand the terms and their significance from their perspective. Therefore, knowledge transfer will include forms of knowledge as relevant to participants, not simply the transfer of research findings from the positivist tradition.

The Research Supporting Practice in Education84 group at the Institute for Studies in Education, University of Toronto, has devised a potentially useful set of questions that help to clarify different aspects of knowledge and knowledge use. These questions are:

-

What knowledge (e.g. tacit, research, evidence, best practice)?

-

In whose interests (e.g. organisations, researchers, practitioners, knowledge brokers)?

-

For what purposes (e.g. change, influence, practice, decisions, empowerment)?

-

In what context (e.g. communities, workplaces, universities, boards)?

-

What techniques (e.g. guidelines, training and workshops, facilitation, communities of practice)?

-

With what impact (e.g. instrumental, conceptual, changing practice)?

Innovation

This study is interested in the transfer of innovation and knowledge. Therefore, we also need to give attention to ‘innovation’, a term that has increased in usage since publication of the Carruthers report,27 concerned with the adoption and diffusion of innovation in the NHS. This report places innovation at the top of the service agenda and sets out recommendations to encourage quicker transfer of new practice. 27

Carruthers’ definition of innovation built on Rogers’85 interpretation of innovation as a new idea, practice, or object but requiring that it is applied. According to Carruthers,27 innovation is ‘an idea, service or product, new to the NHS or applied in a way that is new to the NHS, which significantly improves the quality of health and care wherever it is applied’. Given the focus of our study on the benefits of innovation to patient care, this explicit inclusion of application in the definition seems helpful.

Alongside policy runs a literature looking at aspects of innovation in more detail. For example, Terwiesch and Ulrich52 have drawn a distinction between innovation that is ‘conceptual’ (new to a field) and innovation that is ‘contextual’ (new to an organisation). This is a potentially helpful distinction, allowing the term innovation to cover a range of ideas, services and products.

Implicit in the application of new ideas, services and products is a change in organisation and or individual behaviour. Birken et al. 86 explain that innovation implementation is a process in which organisational members become proficient in their use of a new practice. Walshe and Davies22 adopt a broad interpretation of innovation that encompasses both ‘clinical practice and service design’ and they explain that ‘service innovation means people at the front-line finding better ways of caring for patients’. Innovation in this sense may not involve formal and explicit knowledge transfer, unless these better ways are transferred outward to other colleagues and organisations. Walshe and Davies’22 perspective serves as a reminder that the focus of our study is anywhere in the health-care system that is relevant to managers’ ultimate role of improved care for patients within public service constraints, but with particular attention paid to the application of new ideas, services and products that are transferred into an organisation rather than those that emerge in an organic manner from within. It is also worth noting that while innovation can ‘go either way’ in terms of impact on care, most literature and policy appears to start from the assumption that innovation is good.

In terms of the application of innovation, Brockman and Morgan87 argue that knowledge transfer facilitates innovation, and Strach and Everett88 write that the ability to seek and maintain knowledge transfer capability facilitates a higher level of innovation. Radaelli et al. 89 found that individuals who share knowledge are also more likely to be engaged in creating and implementing innovations. This reflects a prevalent assumption that knowledge transfer is (or should be) a means to innovation. Knowledge is something you have; innovation is something you do. Innovation does not transfer, but knowledge about it does.

Transfer

The final element of KIT relates to transfer. This is a well-developed area of literature; in its commissioning brief, NIHR noted the multiplicity of terms. Prefaced by ‘knowledge’, ‘transfer’ is just one option of many. Others include ‘exchange’, ‘mobilisation’ ‘translation’, ‘management’, ‘mediation’, ‘dissemination’, ‘diffusion’, ‘utilisation’. Likewise, those working in roles to support this activity attract a variety of labels, including: ‘knowledge brokers’, ‘translators’, ‘boundary spanners’, ‘diffusion fellows’, ‘research navigators’, ‘research liaison officers’, and so forth. 13 There is both confusion of terms and confusion in the meaning of terms. 90 Knowledge translation, for example, can refer to the job of ‘translating’ lengthy and complex research reports into digests more suitable for busy practitioners; the translation of knowledge into action or practice arising from collaboration between researchers and practitioners;82,91 or the ‘transfer’ of research from one group to another with little interpretation or amendment. 7

Transfer needs to be understood in relation to definitions of knowledge and different models of KIT will prescribe the role for people and organisations responsible for enabling it.

Knowledge transfer models

Dominating policy-thinking and the biomedical research literature on knowledge transfer is a focus on the unidirectional linear flow of knowledge from one domain to the other. This transfer is intended to address an information deficit on the part of the practitioner. 92 However, it is deficient to assume that the production of the ‘right research’ will just get implemented by practitioners. 22 The process is not simply one of transference, that knowledge or innovation is something that can be parcelled up and distributed to ‘grateful recipients’. 81 The linear model, assuming a unidirectional flow of research-based knowledge19,56 and the term ‘knowledge transfer’ has been criticised for oversimplifying ‘the messy engagement of multiple players with diverse sources of knowledge’. 81 Knowledge flows not like water in a pipeline; rather, knowledge morphs and mutates as it is mobilised, being ‘personalised and recast’ by the decision-maker. 11

In an interactive model, both formal and informal links between researchers and research users are emphasised, and interpersonal and exchange relationships are seen as a means of bridging gaps. 33,35,93 Interactive or exchange models are also called ‘partnerships models’,94 ‘knowledge conduit models’,95 ‘linkage and exchange models’93 or ‘alliances, . . . collaborations, and coalitions’,96 as well as ‘mode two’45 and ‘integrative’13 or ‘integrated’ knowledge transfer. 97 Positive deviations is another term used to refer to the adoption of ‘unconventional methods’ to facilitate organisational change. 98

Partnerships in an interactive model come in a number of formats. 94,99,100 Davies et al. 90 suggested six archetypes of knowledge mobiliser: knowledge product pushers; brokers and intermediaries of their own research; brokers and intermediaries of wider research; evidence advocates (champions for evidence-informed practice); network fosterers (developing new ones and enhancing existing ones); and advancers of knowledge mobilisation (enhancing knowledge about KIT work). Within these archetypes, agents carry out three broad overlapping roles: developing and sharing research-based products, brokering and implementation. 90

There is a common expectation that the knowledge changes as a result of the interaction. Such coproduced knowledge demands a broad acceptance of what counts as evidence. 33,101,102 However, as noted earlier, this interpretation fails to fit with the idea of legitimate research evidence in evidence-based medicine. 102 A fuller discussion of linear and interactive models can be found elsewhere. 66

To address the commissioning brief, in this report we have adopted the term ‘KIT’ and we describe those supporting this activity as ‘KIT agents’. However, in our application of the term, we wish to include that sense of interaction and mobilisation, not the limited narrow notion of linear transfer.

The role of knowledge and innovation transfer agents

In this study we use ‘KIT agents’ to identify those people responsible for supporting the transfer and mobilisation of knowledge (broadly conceived) from one group to another. Potentially these groups have little contact with each other and perhaps little trust. 51,70,93,103,104 UK examples of KIT agents, to date, include knowledge transfer associates,105 secondees,106 improvement fellows or diffusion fellows in CLAHRCs, former SDO management fellows, and innovation leads in health boards in Wales. The role-holder seeks to create a link between the two groups, acting as a bridging agent,107 linkage agent108 or mediator. 7,109 Typically, and of interest to our project, the two groups are producers of knowledge (e.g. researchers, although not necessarily based in universities) and users of knowledge (health-care managers/practitioners/decision-makers). 110

The KIT agent roles vary. 42,54 Noting overlapping boundaries, Fisher111 distinguished four roles that grow in responsibility. She labelled the most limited role ‘information intermediary’, which focuses on helping practitioners to access information from multiple sources. The second he labelled ‘knowledge intermediary’, a role concerned with helping practitioners make sense of and apply information. The third was labelled ‘knowledge broker’, which, according to Fisher,111 is about improving knowledge use in decision-making. The most encompassing role is labelled ‘innovation broker’, which is about changing contexts to enable innovation. Fisher111 relates these four roles to the functions of knowledge brokering detailed by Michaels. 112 The six functions are (1) informing (disseminating content); (2) linking (expertise to need for a particular issue); (3) matchmaking (expertise to need across issues, disciplines); (4) focused collaboration (building collaborative relationships around an issue); (5) strategic collaboration (longer-term relationships); and (6) building institutions. These functions can be mapped against a continuum from linear dissemination to coproduction of knowledge and represent an increasing intensity of relationship between knowledge producers and users.

The limitations of the role of bridging agent, disseminating information between two organisations, have been highlighted by Soper et al. 39 and Long et al. ,104 suggesting that collaboration between organisations or groups is more effective. These authors maintain that bridging agents risk becoming gatekeepers or holders of knowledge and that this limits cross-collaboration and imposes pressure on the agent. Collaborative research partnerships were proposed as one mechanism to alleviate barriers to KIT. 15,17,21,22,113 We note that a proportion of the literature, particularly relating to collaboration programmes, refers to relationships between researchers and clinical practitioners114 with little on how managers interact with research,115 which may or may not be different from relationships between researchers and clinicians. Existing research14,66 suggests that in exploring how KIT works in practice, both organisations and individuals need to be taken into account. Enthusiastic individuals can be stonewalled by indifferent organisations, and organisations keen to learn and innovate can be hindered by reticent individuals, for example.

In this study, the essential feature is that KIT agents facilitate engagement between knowledge (broadly conceived) and practice,55 with the aim of improving the transfer and mobilisation of knowledge and innovation. Those in such a role can facilitate dialogue between research and practice,7,93 creating awareness of both sides’ interests and functions,116 and building relationships. 54,57,117 By encouraging greater involvement of decision-makers in knowledge production and knowledge producers in decision-making,117–119 and managing the ‘messy engagement of multiple players’,81 these KIT agents or knowledge brokers help to dismantle the cultural and language barriers between the two worlds. They do this by translating knowledge into appropriate language, highlighting its relevance to practice and emphasising the cross-applicability of each sides’ work. 11,57,116,117,120 More broadly, the role typically includes both ‘hard’ (obtaining and sharing diverse information) and ‘soft’ tasks (facilitating cross-group relationships, mentoring, coaching) to create a bridge across these knowledge gaps and foster a knowledge-responsive capacity and culture. 5,56–59

Managing the ‘messy’ process81 requires the broker to impose some form of structure on the process. There are a wide variety of models of knowledge transfer and mobilisation outlined in various fields of health-care literature. 117,121,122 Typically, methods include workshops or other professional development activities, written communication through print and electronic media and personal face-to-face contact, building linkage and exchange. 57,93,123 Through negotiation and understanding, the knowledge being mobilised across specialisations and organisations is reframed into a mutually agreed upon version. 124 In mobilising knowledge, the broker creates a new version, which Meyer125 labels ‘brokered knowledge’. Brokered knowledge is ‘knowledge made more robust, more accountable, more usable knowledge that ‘serves locally’ at a given time; knowledge that has been de- and reassembled’. 125

One further distinction relates to the location of the knowledge brokers; some are located within the organisation and others outside. Nyström et al. 126 suggested that locally based research and development (R&D) offices have the potential to act as KIT agents. An example of a separate organisation that supports knowledge mobilisation is the IRISS (Institute for Research and Innovation in Social Services), a charitable organisation working with social services in Scotland. For those individuals in knowledge brokering roles within organisations, some may work across departments, whereas the work of others may focus on teams within one department. This reflects an alternative classification of the brokering roles outlined by Gould and Fernandez. 127 They differentiated between brokers who work within their own community (‘co-ordinators’), those who work with a different community (‘itinerant brokers’ or ‘liaisons’), those who work with incoming exchanges (‘gatekeepers’) and those who work with outgoing exchanges (‘representatives’).

In concluding that approaches to knowledge brokering are varied and that a number of writers have grappled with distilling useful models, we note that when planning approaches and objectives, organisations make limited use of the theories and frameworks from the literature. 90 The KIT agent is defined by their work with producers and users of knowledge (in this case, managers/decision-makers) in helping to transfer and mobilise knowledge. The best way to do this is unknown and is a central question of this project.

Enabling knowledge and innovation transfer

There are a number of ways of organising the factors identified in the literature that enable KIT. Walker et al. 128 offer one classification and their four broad factors are:

-

context – factors in the external and internal environment

-

content – the changes being implemented (or knowledge being mobilised)

-

process – actions taken by the change agents

-

individual dispositions – attitudes, behaviours, reactions to change.

We use Walker et al. ’s128 classification as an organising framework. It can be related to other frameworks such as PARiHS. 129,130 In the PARiHS framework, successful implementation is represented as a function of the nature and type of evidence, the qualities of the context in which the evidence is being introduced and the way the process is facilitated. Both frameworks include a context factor; Walker et al. ’s128 ‘content’ can be mapped to ‘evidence’ in the PARiHS framework; and ‘facilitation’ in PARiHS seems to capture Walker et al. ’s128 ‘process’ and ‘individual dispositions’. The extended i-PARiHS framework131 incorporates the role of facilitation of an innovation with the recipients of the innovation in their ‘local, organisational and wider health system context’. We would map this to Walker et al. ’s128 ‘process’ factor.

Context factors

Macro-level context factors relating to the wider social, political and economic environment in which the health-care service, researchers, collaboration and KIT agents sit have been suggested to affect the success of KIT. 6,132 Factors in the external environment known to inhibit KIT include the rapid turnover of policies, ministers and civil servants. Major shifts in health care and other policy, singly and in combination, can have disruptive effects on knowledge transfer and mobilisation. 56

External context factors relating to funders or commissioners of research are a recognised, and under-researched, translational gap. 90 At an organisational level, short-term funding does not support sustainable partnerships. 94,133 Operating within a ‘closed system or fixed budget’,134 commissioners with shorter time horizons risk losing the insight that can arise from longer-term studies, and can be too preoccupied with immediate policy priorities, government targets and financial imperatives, all subject to change at short notice. 94 Thematic funding has also been suggested to engender fragmentation. 135 Restricted time and resources can also limit effective brokering or mobilisation. 15,93,134

Meso- or organisation-level context factors are often overlooked,4,136 but have a major impact. 134 A key factor in the internal context relates to the nature of the organisation – its attitude to research, to knowledge, to change – and the ability of the organisation to receive and process information. 113,137,138 In tune with Currie et al. ,43 Kitson et al. 3 reported that contexts that had ‘transformational leaders . . . learning organisations, and . . . feedback mechanisms’ were better able to implement evidence into practice. A similar conclusion was reached by others: when attempting to implement innovations, organisations face challenges such as professional barriers, inertia,139 misaligned incentives and competing priorities. 139,140 The supporting infrastructure needs ‘effective and inspiring institutional leadership’64,141 to create a ‘consistent and psychologically safe culture’. 134 An evaluation of CLAHRCs revealed a lack of emphasis on leadership (the ‘L’ in CLAHRCs) and concluded with an argument for the selection of leaders with a more systems-level approach who ‘have the capability to work across organisational and professional boundaries’. 43

King et al. 99 explain variation in outcomes and impact by differences in the ‘individual and organisational receptiveness’ or the state of preparedness of the workplace environment. The organisational value of using evidence may be limited. 100 The organisational culture needs to be adaptive142 or absorptive if it is to make use of knowledge, and increasing emphasis is given to organisational readiness. 18,82,138,143 The level of an organisation’s ‘absorptive capacity’144–147 is defined as ‘a firm’s ability to recognise the value of new information, assimilate it, and apply it to commercial ends’. 146 This ‘adaptive and responsive capacity’ is important to knowledge use in practice and is affected by the organisation’s ‘prior related knowledge, a readiness to change, trust between partners, flexible and adaptable work organisations and management support’. 145 Implementing innovations is demanding – cognitively, emotionally, physically, and spiritually. 139 If this capacity to learn, demand and generate new knowledge for the purposes of improvement is absent, then the impact of a KIT agent or knowledge broker is likely to be limited. Traynor et al. 148 concluded that the use of knowledge brokers had increased both individual capacity (improved knowledge searching, appraisal and application skills) and organisational capacity (management support and policies) of the target group.

Oborn149 indicates that ‘absorptive capacity is a strategic level capability which should be developed and nurtured by leadership teams’. Differences in hierarchical structures, leadership, power and professional cultures130 contribute to organisational receptiveness and cross-professional communication. 104,130,150 Cross-organisation and cross-discipline communication and collaboration are seen as vital. 134,150,151 However, Tasselli150 reported that professionals tend to be ‘embedded in distinctive professional cliques’.

Other studies have identified personal challenges for KIT agents around professional boundaries. 137 Career pathways and progression may be uncertain for KIT agents, particularly those in dedicated knowledge brokering roles. 133,137 Support, in the form of collective forums (i.e. communities of practice) and a physical home,137 help individuals to navigate the isolating aspect of the role. The provision of space benefits others; Dopson et al. 115 found that having access to ‘formative spaces’, removed from their organisational context, where managers could engage with knowledge, aided their appraisal of research. 115

Content factors

The work of some KIT agents entails the identification of the relevance of research to practice and the tailoring of findings to service need. Walker et al. 128 use the term ‘content factors’ to refer to the changes being implemented. It is perhaps more helpful to borrow from the PARiHS framework and include in the term issues around the nature of evidence or knowledge. Thus content factors can also relate to the nature and type of knowledge (explicit or tacit) that may be more or less readily transferred and mobilised, and to the type of evidence, varying from research findings to professional experience and local information. It concerns the social nature of knowledge and evidence; what counts, to whom and when.

Before knowledge or innovation can be implemented, the new evidence needs to be interpreted for the local context, integrated with existing knowledge and discussed. Arguably, decision-makers and researchers differ in their view of research;115,140 researchers look at the information for academic rigour, whereas decision-makers assess its local relevance. 140 At both the local and national level, new evidence may be supported or sidelined; it may address or be at odds with local needs;39,141,152 it may require change that is demanding (transformational and rapid) or the change may be incremental and require only fine-tuning. Relevance and benefit to the participants is an important enabler. 153 Decision-makers are more likely to engage if the project suits their needs. For example, an evaluation of the Québec Social Research Council (CQRS)’s partnership programme found that all respondents reported benefits to them as a reason for success. The research had relevance because it was linked to wider policy concerns (saliency). 154

Ross et al. 152 similarly found that decision-makers were more likely to engage with the research team when the research questions aligned with their interests, but also when they perceived their contribution to be essential to the success of the project (e.g. bringing local knowledge). Making a meaningful contribution drives practitioners. Bartunek et al. 75 suggested that short-term relationships, which focus on data collection, might result in the practitioners feeling exploited. Being able to help shape research questions is an important activity for some practitioners. 155

Competing agendas and priorities between partners can be a barrier to success156,157 and need acknowledging and managing. 114,155,156,158,159 Academics and commissioners alike have recognised deficiencies in the communication of research findings across boundaries. Researchers felt they should be involved more closely in the calls for research proposals; commissioners were more concerned that the users of research – policy colleagues and public service managers – should be involved more closely to ensure prioritisation of practical over academic concerns. 56 Commissioners found academics preoccupied with creating new knowledge suitable for publication in high-impact journals rather than policy-driven outputs. 56 Arguably, the ‘impact case studies’ that are a part of the Research Excellence Framework160 have gone some way to address this. However, a review of a sample of impact case studies indicated that impacts were relatively short term, often with limited direct impact on patient outcomes such as morbidity and mortality, and with limited consideration of the processes and interactions that may lead to indirect impact. 161 The time lag between identifying a demand for new knowledge and its synthesis for use in decision-making has also been noted, and decision-making time scales are short compared with research time scales. 162 Information relating to the ‘here and now’ is more likely to be used. 10

Process factors

In Walker et al. ’s128 model, process factors refer to actions undertaken by the change agents. In this sense, agents include all those parties involved in the process of change, not just the KIT agents themselves. Gagnon163 suggests that all parties should ‘plan for collaboration with an explicit description of roles and responsibilities and a commitment to regularly assessing its effectiveness’. The lack of clarity of brokering roles can limit success. 16,35,135,164 Against this, flexibility is also seen as important;66 brokerage roles may differ for different individuals127 or at different times. 165,166 Ross et al. 152 conclude that individual partnerships need to be flexible; one size does not fit all and finding the right person for a particular role is key.

Agreeing roles, goals and expectations is a common recommendation. 16,41,42,152,155,163,167 Roles can take time to be established, and may take on different forms based on specific local organisations. 137,168 One reason given for the success of the CQRS’s partnership programme was that participants were expected to show measurable results. 141 Bullock et al. 62 found examples of interactions between the knowledge brokers and their managers that resulted in frustration because expectations had not been openly articulated. Additionally, individuals in the roles will embrace brokering and linking functions at different paces or not at all. In a study of hybrid physician–manager roles, the authors identified three different groups which they term ‘innovators’, ‘sceptics’ and the ‘late majority’ reflecting the different pace of role adoption. 48 Collaborative policy-setting has been suggested as a mechanism for ensuring needs-led evidence is produced, but it was noted that this method can be more time-consuming. 169

Collaborative partnerships seem to work best where there are effective links between researchers and practitioners. Communication and trust-building, and motivation and commitment by all the organisations involved in the CLAHRC partnerships have been shown to be central to making collaborations work. 36,49,50,58 Effective solutions cannot be ‘developed from the knowledge base in the absence of those who will apply the knowledge’. 170 The key to knowledge mobilisation impacting on organisational performance rests on ‘the transfer of knowledge to locations where it is needed and will be used’. 72 KIT agents typically act as a facilitator of this transfer, using guided interaction to support the uptake and use of knowledge. 171 Their work requires a ‘multi-level, multi-strategy approach’. 172 Current evidence suggests that there is benefit in gaining the bidirectional support of middle managers within organisations:173 ‘they may disseminate information vertically from top managers to front-line employees and from front-line employees to top managers, and horizontally, across top managers and across front-line employees’. 86

Building successful long-term, trusting partnerships between knowledge producers and knowledge users supports the use of research in informing decision-making. 174 However, this takes time and commitment. 137,152,156,159,175 Partnerships need people to attend meetings. 152,155 Bartunek et al. 75 suggest a number of physical links between the two communities – web-based discussion boards, practice-focused meetings and conferences. Baumbusch et al. 91 explain how project meetings were used to feed back emerging findings for practitioners to action, and for practitioners to provide context that would assist interpretation of the findings. Kislov et al. 40 describe such events and artefacts as ‘boundary objects’. Others also write of the importance of colocating the partners, which facilitates not only formal face-to-face meetings but also informal discussion ‘at the water cooler’. 137

Knowledge transfer and innovation carries costs. For example, the time required to develop the necessary skills and relationships with organisations takes people away from other tasks and, therefore, imposes financial costs91,113 for both employers and decision-makers. 152 Financial restrictions impede knowledge mobilisation;159 those in the roles are often unable to use their backfill because of organisational pressures. 106,176

Individual dispositions

Walker et al. ’s128 final area of concern relates to ‘individual dispositions’. This focuses on the KIT agents themselves, but needs to be located more broadly; KIT agents are limited by the context and the character and dispositions of their organisations and colleagues. Evidence suggests that other aspects influence their capacity to transfer knowledge and bring about innovation, not only factors to do with their disposition (e.g. patience and approachability). 148 This includes their role and seniority within the organisation and how they are perceived by others; for example,66 Soper et al. 44 note the importance of ‘understanding each other’s incentives and constraints’.

However, the skills and attitudes of the KIT agent or knowledge broker are a recurrent theme in the literature. Alongside excellent communication skills,176,177 they need to have a good understanding of both the research evidence and policy issues, and be able to transform that knowledge into something that is salient to their practitioner collaborators. 91,159 Platt178 warned of the risk of relying solely on ‘intermediaries’ who might not have the skills needed to interpret the evidence or be motivated by their own interests.

There is an argument that knowledge brokers in hybrid roles (e.g. clinical managers) may be best placed for mobilising both explicit and tacit knowledge because of their membership of multiple communities. 54 However, challenges may arise related to dimensions of their role and interorganisational factors. 179,180 For example, those in hybrid roles have been found to show preference to one aspect of the dual role over the other, to broker knowledge only within their professional sector, or to not be best placed to reach all levels of the organisation. 179,181–183

Mutual trust and respect are frequently reported as enablers. 74,91,114,155,158,175 The issues of trust and reciprocity feature prominently in the management literature on planned collaborations. 184,185 Other reported beneficial dispositions include clinical credibility, being known and having a good reputation60,186 and having good knowledge of the organisation’s culture. 187,188 For those from outside sectors, willingness to learn about the other community is stated rarely,75,188 but would seem to be essential.

For researchers to take part in interactive exchange models of knowledge mobilisation, it is likely that they need to have accepted a broad notion of ‘knowledge’. 75 Researchers’ ‘arrogance’ and power differentials can introduce problems. 175 Engagement with potential users of knowledge may be seen as signifying a lack of independence and objectivity in the work. 57 Concerns about academic rigour and violations to objectivity can be off-putting to academics – ‘if what is required is for researchers to do what policy-makers want them to do, then research may fail to fulfil one of its most important functions, namely to be objective, reliable and unbiased’. 189 Ross et al. 152 note that none of the researchers in their study identified this as an issue.

Measuring outcomes and impact

Knowledge brokering can be conceptualised as a set of complex social activities that are difficult to evaluate. Various studies have found it to be an effective strategy for knowledge mobilisation, but few are explicit about what aspects of the role are most effective. 190 Key questions are what types of brokering outcomes can and should be measured (e.g. increased evidence use, relationships and interactions between researchers and users, linkages and network, increases in capacity to use evidence) and how they can be adequately captured (e.g. via survey, interview, observation documentary analysis). 34

The ultimate test of success is the impact of the KIT agent on knowledge transfer, innovation and patient care. Kothari et al. 191 compared the take-up of research reports on breast cancer prevention between practitioners, some of whom had helped to prepare the report and others who had not. They reported that engaging practitioners in the discussion of findings and the preparation of the report improved their understanding of the limitations of the research and made them more likely to talk about using the research in future services. However, they also found that ‘interaction was not associated with increased utilisation of research findings in programs and policies within the time frame of [the] study’. Despite this, it remains important to discuss whether, and how, process measures can assist monitoring and assess their links to outcomes that are otherwise assumed.

The literature includes little on measurements of impact arising from research partnerships. Davies et al. 90 found learning from informal experience more useful than formal evaluations. One suggested solution to the difficulty of evaluating knowledge brokering is to design research within a clearly articulated theoretical framework, which provides a basis for later evaluation of outcomes. 192,193 PARiHS may be such a framework3 and realist evaluations using clearly defined frameworks are gaining recognition as valuable ways of examining and evaluating complex interventions. 60,194,195

Sustainability was found to be a priority for trainee KIT agents. 196 The NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement’s sustainability model has developed a self-assessment tool, which encourages reflection in three domains: process, staff and organisation. Doyle et al. 197 concluded that the tool was potentially useful, but emphasised the need for capacity building and facilitation for it to be implemented meaningfully.

Demonstrating ways in which KIT agents facilitate desirable service outcomes is critical to many senior managers’ goodwill and willingness to ‘release’ staff to KIT agent roles, not least because there are costs for them. 66 Data gathering for impact assessment is a cost to collaborations, and there is clearly value in aligning (appropriate) approaches and measures sooner rather than later.

Concluding remarks

This chapter has explored the relevant international literature on KIT and mobilisation, highlighting it as a messy, complex, evolving and dynamic process. The use of ‘knowledge brokers’ (KIT agents in our study); people responsible for supporting the transfer and mobilisation of knowledge or innovation between producers (typically researchers) and users (health-care managers/practitioners/decision-makers), is a common approach to addressing the KIT challenge. The literature identifies enablers to developing successful partnerships between researchers and practitioners/decision-makers. These factors relate to context (external and internal, including policy shifts, fiscal restraint, absorptive capacity and leadership), content (e.g. the relevance of research and its match to local priorities), processes (e.g. expectations, flexibility, physical links) and individual dispositions (including extent of mutual trust and respect; KIT agents with the appropriate skills, attitudes and networks; and researcher acceptance of a broad interpretation of ‘knowledge’). The impact of collaborations and the activity of KIT agents/knowledge brokers is hard to measure, although there are some frameworks and tools worthy of further investigation.

Given the growing interest in using collaborations to address the research–practice gap,22 one evident conclusion is the need for further research. However, research about how partnerships between researchers and decision-makers facilitate knowledge exchange ‘is in its infancy’. 51 Oborn149 remarks that although collaborative engagement and reciprocal exchange ‘are increasingly common in health services ‘KT’ literature’, evaluation models ‘continue to focus on more linear and quantitative approaches’. This is insufficient for answering ‘which types of KT network is best?’. Oborn149 concludes that future research needs to contend with the possibility that ‘best practice’ may be socially constructed, rather than scientifically and objectively determined. Waring et al. 54 and Rycroft-Malone et al. 42 point to the need for more research on knowledge brokers. The impact of collaborations and the activity of KIT agents/knowledge brokers is difficult to assess and, despite the existence of some frameworks and tools, there is a need to apply and refine them in further research.

Chapter 3 Design and methods

The focus of this research was KIT agents (NHS and university-based staff in knowledge brokering roles) and the work they do in the knowledge mobilisation process with the health-care practitioner and management community. The study aimed to provide insight into the outcomes and impact of KIT agents’ knowledge brokering with NHS managers and clinicians.

The research used an in-depth qualitative case study approach, focused on a sample of KIT agents drawn from across England and Wales. Data were gathered from interviews, audio-diaries and observations. By examining cases (KIT agents) from a number of discrete initiatives designed to facilitate knowledge mobilisation, the study aimed to reveal how these endeavours worked in practice and how benefits can be maximised. To address one of the research questions, we used a consensus method in a meeting of experts (nominal group technique).

Study design

Theoretical frameworks

Within the case study design, data gathering was shaped by Kirkpatrick’s framework,198 which provides a useful structure for ensuring data collection beyond immediate reactions to an initiative and has been widely used in business and education. 199 The original Kirkpatrick framework comprises four levels. Level 1 is concerned with assessing the participants’ reactions to the activity; for example, did they think it was relevant to their needs? Level 2 relates to learning gains (knowledge acquired by the practitioners). Level 3 focuses on behaviour change as a consequence of participation (application of knowledge to practice). Level 4 is about impact (what difference changed behaviour makes). This framework fits well with social marketing theory and its focus on behaviour.

In earlier work,62 we modified the framework to address known limitations199,200 and to maximise its relevance to innovation and knowledge transfer in the NHS. These adaptations recognise that reactions, learning gains and behaviour change all contribute to outcomes and are themselves ‘impacts’; that these ‘impacts’ are linked to each other and are not arranged hierarchically; and that the processes and dynamics of initiatives (including motivations) and the wider context are important. 62

Our approach to data analysis is described later. In this, we drew on other classifications or frameworks in the literature, notably Walker et al. ’s128 work on factors affecting organisational change and the PARiHS framework. 201

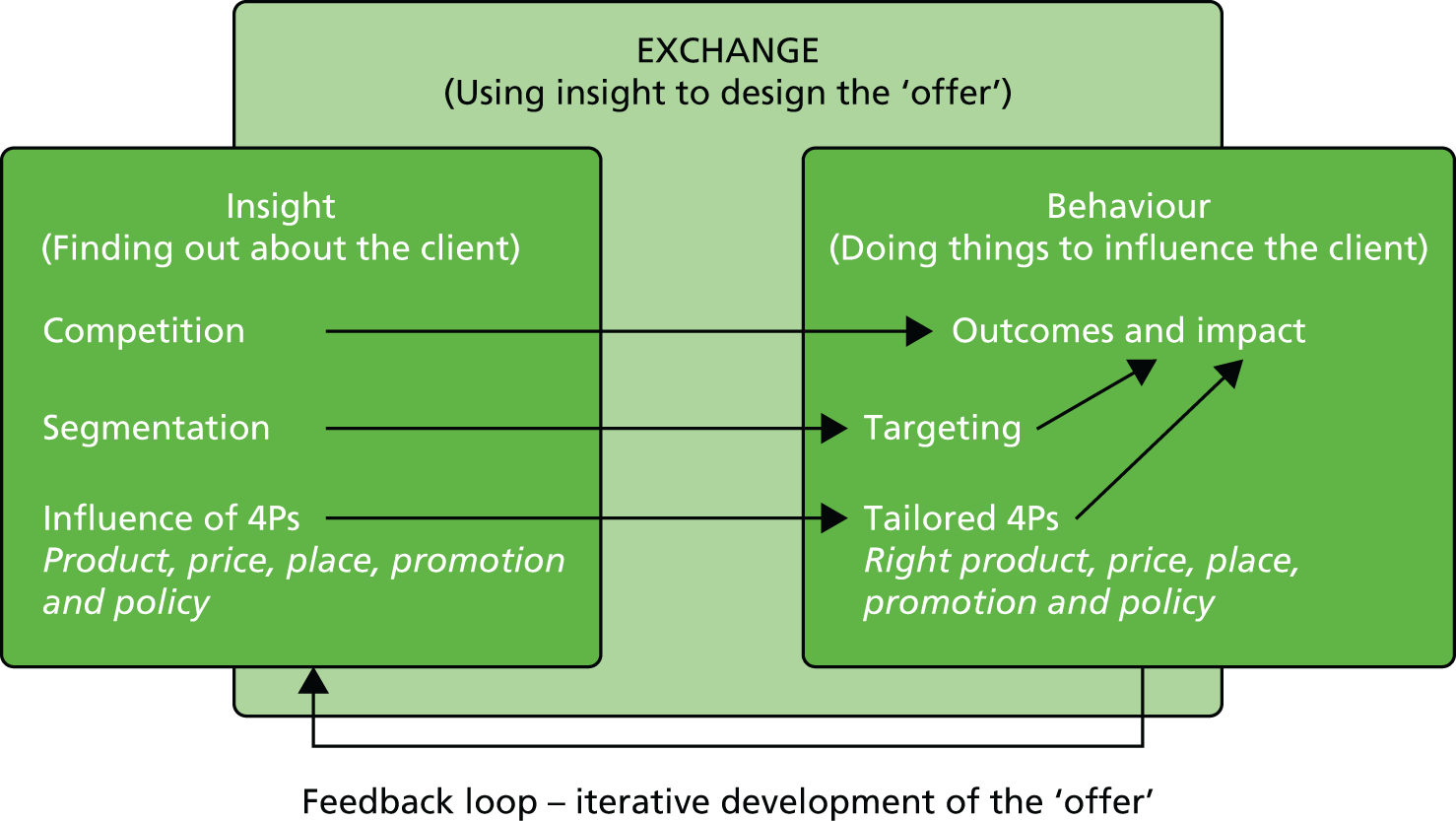

To inform our understanding of the consequences and implications of our findings, we used social marketing theory. Social marketing is defined as ‘the systematic application of commercial marketing concepts and techniques to achieve specific behavioural goals relevant to the social good’. 202 It is focused on understanding (or having ‘insight’ into) why people (e.g. NHS managers) do what they do now (in relation to innovation and knowledge) and what ‘competition’ the new behaviour faces. Social marketing theory recognises that this may vary by subgroups and may require different kinds of support (‘segmentation and targeting’). These insights can be used for ‘creating attractive exchanges’,203 which can encourage the effective uptake of the new behaviour. Part of this is taking account of, and most likely modifying or adding an ‘offer’. 203 The strength of such an approach is that it starts with investigating KIT from the perspective of people who are being asked to do it. It seeks to understand the meaning they attach to it and the barriers to, and enablers of, doing it, without attempting to prejudge issues. The approach allows factors that challenge or enable KIT to be identified and context-specific solutions to be developed. Do different managers, clinicians, innovations, questions and health-care organisations require different activities or transfer pathways? What are the implications for practice? For example, managers with limited access to information technology and statistical support might find it impossible to apply modelling techniques, even if they know about them. The solution lies in improving hardware and support, not in communicating research findings differently. To give another example, to enhance knowledge mobilisation in a setting in which a KIT agent’s line manager expects them to ‘deliver’ without senior support may need a solution that focuses on the line manager and not the agent.

Advisory group

A project advisory group was established that comprised NHS managers, chief executives, representatives of the HSDR programme, academics with expertise in knowledge mobilisation (including from overseas), patient representatives and other partners. These are listed in Appendix 2 along with the main focus of each meeting.

Primary communication with the advisory group was by teleconference, preceded by an e-mailed agenda and supporting papers. Nine meetings were held over the course of the study. The advisory group helped to resolve practical issues and acted as a sounding board for sampling, data collection and analysis decisions. Most notable was its contribution to the discussions of early findings. Throughout the project, we presented drafts and questions to the advisory group members who used their knowledge and experience to inform our way forward. As a group, they provided a strategic voice for service users and service leaders. By facilitating the ongoing validation of research findings, the advisory group enhanced the credibility and relevance of the research project and contributed to early feedback of findings to stakeholder communities.

Patient and public involvement

As this project arose in response to a specific HSDR programme call for ‘research to improve knowledge transfer and innovation in health-care delivery and organisation’, patients and the public were not actively involved in identifying the research topic. 204 Public involvement was defined broadly in the call to include ‘local communities . . . members of the public, users of services, carers and minority ethnic groups as well as healthcare practitioners and managers’. 204 Our proposal was developed with the direct input of the research networks lead (de Pury), the director of an AHSP (Denman) and a health board manager (Howell). They made a significant contribution to prioritising and adding detail and contextual understanding to the objectives. Their views and opinion of their needs regarding innovation and knowledge transfer shaped the detail of the questions we asked.

Users are motivated to take part in research management when they feel they can make a contribution given their own expertise, experience and interest. For this reason, we focused our inclusion on patient representatives in the advisory group and the nominal group, in which discussion could be informed by their first-hand experience of services.

Data collection and sampling

We describe data collection methods in relation to three parts of the study: the initial mapping and typology development; the case studies; and the nominal group.

Mapping and typology development

For the national mapping of the KIT intentions of the networks (AHSNs and SEWAHSP) and the development of a typology of KIT agents we collected data from desk research and telephone interviews.

Desk research (June–August 2013)

The 15 AHSN prospectuses and business plan documents (versions submitted to NHS England for licensing in 2012) together with the SEWAHSP’s Five Year Strategy31 (July 2012) were reviewed to understand their interpretation of knowledge mobilisation and their planned approach and, in particular, their intentions to engage knowledge broker roles. The documents were scrutinised and searched for the terms ‘fellow’; ‘associate’; ‘lead’; ‘broker’; ‘agent’; ‘manager’; ‘boundary’; ‘transfer’; ‘exchange’; ‘span’; ‘connect’; ‘linkage’; ‘mobilise’; and ‘gap’.

Telephone interviews (November 2013–February 2014)

In order to supplement the initial mapping of knowledge mobilisation intentions, as set out in the documentation of the respective networks, the managing directors of the networks were approached by e-mail. The initial contact described the project’s aims and requested a 30-minute conversation, either in person or over the telephone, to understand their approaches to knowledge mobilisation. This was followed up with support staff to schedule the discussion and provide further background on the study’s aim and objectives. Interviews were conducted using a semistructured interview schedule (see Appendix 3).

Fourteen of the 16 network managing directors (including SEWAHSP) agreed to share their regional approach to knowledge mobilisation. Most managing directors stated that they were still in the planning and set-up stages of establishing their organisation and, therefore, could discuss their intentions around the use of KIT agents but not specific individuals. Eleven telephone and three face-to-face meetings were held between November 2013 and February 2014, ranging in length from 20 minutes to 1 hour. Twelve of the 14 discussions were held with the managing director and the other three were held with a named lead in the region. Two managing directors out of the 16 did not respond to multiple attempts to secure a discussion.

Appendix 4 summarises the main findings of the document review stage and the results are described in Chapter 4.

Case studies

Sampling

Using data from the intentions of the AHSNs and SEWAHSP, we purposively sampled five diverse sites, from which we selected case study KIT agents. The five networks were selected on the basis of:

-

stage of network development (e.g. ranging from de novo to well established)

-

diversity in regional research infrastructure (e.g. established links with CLAHRCs/no CLAHRCs; AHSCs/no AHSCs)

-

planned KIT roles in the region (e.g. part of the core team, secondments, fellowships)

-

geographical diversity (largely urban/rural and north/south representation)

-

willingness to engage with the project.

Our target population was KIT agents across England and Wales, that is, individuals who facilitate the mobilisation of knowledge to practice, knowledge brokers who link NHS managers/clinicians and the developers of knowledge and innovation. In the national mapping exercise we delineated definitions and expectations of the KIT agent role. From this, we drafted a typology of KIT agent roles, which we used to inform the identification of our individual case studies. In making our purposive selection of 13 KIT agents we actively sought variation of role, sampling within 4 of 15 AHSNs in place in 2013 and the first AHSP in Wales. We selected a number small enough to enable in-depth study of the work and impact of these KIT agents over time and yet provide good geographical coverage and system contrast. As a qualitative study, the sample size was necessarily small to enable richness and depth of data gathering and analysis. The specific innovations and knowledge that the agents helped to mobilise was diverse. This diversity enabled the detection of content-specific knowledge transfer challenges, as well as generic mechanisms that support transfer and mobilisation.

Data collection

Detailed case studies of KIT agents and their work were the source material for describing the roles of KIT agents, their linkages, relationships and engagement activities, and reporting the outcomes and perceived impact of their work on practice and management. They also provided data that enabled us to investigate how KIT agents can be best supported. We collected data from observation of KIT events/meetings; recurrent semistructured interviews with agents and interviews with their key Links (NHS managers/practitioners); and, when possible, audio-diaries kept by agents over 4 months.

Observations

We aimed to observe two or three activities of each case study agent. These were at the invitation of the KIT agent and included showcase events, reports to workplace colleagues, presentations of research and meetings to discuss progress on initiatives. These diverse, non-participant observations varied in length from relatively short meetings (< 2 hours) to 1-day events. Larger showcase events lasting 1 day were attended by two members of the research team; others were attended by one. Field notes were made, recording who was involved, what happened, reactions and reflections. These events also provided opportunities for informal discussion with people with whom the agent linked. We collected copies of any documentation used during the event.

Interviews

All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed. An initial face-to-face lengthy interview was held with each of the case study agents. The schedule is presented in Appendix 5. In most cases, further interviews were conducted. These provided an opportunity to gain updates on specific activities and further explore outcomes and perceptions of impact. One agent withdrew from the study after the initial interview.

We had contact with agents’ line managers as part of arranging access and most agreed to a one-to-one interview, face to face or by telephone, depending on their preference (see Appendix 6 for the interview schedule).

We also conducted semistructured interviews with some of the key people with whom each agent linked. These Links were identified by the agents. Further details regarding the background of the Links are presented in Table 1, and it should be noted that these individuals do not represent the entire range of an agent’s network of contacts. The content of the interview varied depending on the nature and reason for the connection to the agent.

| Organisation | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greenhills | Riverside | Moorlands | Wetlands | Homefields | |||||||||

| James | Grace | Sophie | Amy | Isabelle | Fran | Jessica | Holly | Daisy | Erin | Janice | Chloe | Molly | |

| Line manager | Chief executive | – | Chief executive | – | – | – | Managing director | – | Senior academic | – | Managing director | ||

| Link | Doctor | Doctor | Lead nurse | Associate medical director | Operational lead | Doctor | Regional lead | Quality director | – | Engineer | Clinical teacher | – | – |

| Link | Nurse | Board chairperson | Lead nurse | Effectiveness manager | – | Lead nurse | Director | Manager of services | – | Director | – | – | – |

| Link | Doctor | Development manager | Chief operating officer | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Link | – | – | Assistant director | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

Audio-diaries