Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 11/1023/13. The contractual start date was in June 2013. The final report began editorial review in February 2016 and was accepted for publication in August 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by McCrone et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background, aims and objectives

Background

This study focuses on the health care received by people with serious mental illness (SMI). For practical reasons, SMI is defined in this project in the same way as for inclusion in the SMI register in primary care, namely as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or another psychosis (i.e. non-organic psychosis). 1 The Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF), of which the SMI register is part, is an element of the general medical services contract in the UK, which is designed to encourage and incentivise good clinical practice, especially in the management of long-term conditions such as SMIs.

People with a SMI may require care from a wide range of health and social services. Secondary mental health care services are vital to many and include inpatient and general and specialist community care. Patients receiving secondary care will usually be under the Care Programme Approach. However, most people with a SMI will be in contact with other services including their general practitioner (GP). For many, primary care is the main focus of care. A recent study suggested that about 25% of patients with a SMI are managed entirely in primary care. 2 This study focuses on care provided in Lambeth (in south London), where the rate of primary care management is thought to be higher than in other parts of the UK. Although many benefit from specialist services, it is likely that some of this group are well enough to be managed in primary care if given adequate support (e.g. in relation to their social and economic situation). 3 For some patients, primary care has been shown to be as effective as secondary care across a wide range of areas,4 but it is likely that this is variable. Providing care in primary care settings has the potential to support a holistic approach to meeting mental, physical and social needs. 5 People with SMIs are more likely to have physical comorbidities than the general population, and primary care databases can help to investigate this. 6 There may be a third group of people with SMIs who are not being actively managed in either primary or secondary care. This may be appropriate if recovery has occurred, but it may also be indicative of a problem of engagement with services. 7 However, such people will still usually be a subgroup of those registered as being managed in primary or secondary care (and we shall identify these in the subsequent analyses).

The extent to which patients transfer between secondary and primary care settings is unclear; for instance, the criteria used tend to be implicit rather than explicit and may vary between mental health teams and according to the perceived or actual capabilities of the practice with which a patient is registered. GPs recognise the need for access to specialist knowledge,8 and successful and sustainable transfer to primary care requires effective links with secondary care services that can be accessed promptly when needed. 9 Interventions exist to provide links between primary and secondary care and to prevent inappropriate referrals. 10 In 2011, the then Lambeth primary care trust (PCT) in south-east London initiated an approach to support patient-centred and sustainable transfer from secondary- to primary-led health and social care for people with SMIs. This consisted of three specific interventions: (1) a primary care support service (PASS), led by a GP with a special interest in mental health, to enable practices to manage the long-term treatment, care and recovery of people with SMIs and others with complex life problems with a mental health component not otherwise appropriate for a secondary care referral; (2) a team provided by the voluntary sector to support the transition of people moving from secondary mental health services to the care of their GP, which focuses on action planning with the client to support recovery and social inclusion and access to mainstream services; and (3) peer support offered by a local user and carers organisations. This is an informal arrangement for people with mental health problems who wish to have the support of someone with a mental health history to help them regain confidence and to support their participation in daily life. These initiatives are complemented by social care support using a personalised approach, including the potential for a personal health budget, and an information and resource service to support access to mainstream services (e.g. employment, housing and benefits).

Studies of primary and secondary care for people with SMIs can take time to conduct, particularly if using a trial design. Alternatives include generating evidence through routinely collected data, supplemented with economic modelling. Primary and secondary care data sets are now well established in Lambeth and have been used to investigate a range of health-care issues. 11 Recently developed methods to link these systems provide an excellent opportunity for research at the primary–secondary care interface. Key data sources for this study are the Clinical Record Interactive Search (CRIS) system [an extensive clinical case register of secondary mental health care services provided by the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust (SLaM)], Lambeth DataNet [LDN, a system to extract and aggregate primary care data from Lambeth general practice information technology (IT) systems] and Hospital Episode Statistics (HES). Linking such data would allow us to assess the resource consequences (including costs) of different ways of providing mental health care.

Over and above cost considerations, little is known about how changes in the location of care will affect patients’ mental health care experiences. Despite considerable policy interest in the delivery of mental health services via primary care, it is generally acknowledged that research evidence in this area is very limited. 12 Studies looking at the views of mental health service users themselves have, in the past, drawn mixed conclusions. Although one study concluded that service users view primary care as the ‘cornerstone’ of their physical and mental health care,13 another, earlier, study showed that a majority (59%) of patients with a severe mental illness preferred their GP to have only a low level of involvement in their mental health care. 14 Another, more general, study of users’ views found that, for help during a mental health crisis, service users were least likely to favour a service based on GP support alone. 15 In addition, a Mental Health Foundation study on users’ views of stigma and discrimination reported a high percentage (44%) of people who felt that their GP discriminated against them because they had a mental illness. 16 In recent years there has undoubtedly been much greater emphasis on improving mental health provision in primary care. 17 However, it is not yet clear if this will also translate into improved services for those with more severe mental health conditions.

The current need for comparisons between primary and secondary care

The NHS was asked to make unprecedented savings over 4 years up to the year 2014–15. Although there were a number of arguments about how best these savings could be made, care options that maintain quality but at a lower cost than comparators have been of particular interest. Mental health problems result in high costs. 18 Approximately 12% of the NHS budget goes on mental health care, with the bulk of spending on secondary mental health services. 19 Although there are treatments and therapies with established efficacy for people with SMIs, there is not a consensus as to the best location of care for patients. This is important because prices and costs differ markedly according to where care is provided, owing to differences in contractual arrangements, staff availability, infrastructure costs and overheads. Furthermore, similar to acute providers, care from specialist mental health providers will, in the future, be financed using payment by results and the tariff may be higher than for care provided elsewhere. This suggests that for some patients (e.g. those requiring relatively less specialist care than others) transfer from secondary care to primary care may be justified after their specific needs have been met by appropriate secondary care services. Other patients may initially come into contact with primary care services and it may again be considered appropriate to maintain their care in this location. Providing more care, where appropriate, in primary care settings may also help to address the high level of physical comorbidity in people with mental health problems. 20,21

The referral flows across primary and secondary care boundaries are determined by health service configuration factors such as the relative ease of access to specialist services and GPs. Perceived strengths of specialist services could include their function as a conduit to therapies not available in the practice and as a means by which to access social care services. Some general practices may feel very capable at dealing with SMI patients in distress, whereas others may feel less confident. Practices themselves may differ in their attitudes to SMI work. Some may consider it part of their role and take real pride in looking after ‘difficult’ patients. Others may feel that the complexity is too great. Providing data on the cost and benefits of transfers can inform investigations and assessments of the process of referring between these different agencies.

There are risks in transferring the lead role for co-ordinating and managing mental health care from secondary to primary services. For instance, if there is lack of rapid access to specialist mental health input, unplanned or emergency care may be more frequent. There is thus a need to identify the point at which patients may need care from a particular type of service and what the cost and clinical consequences of this may be. Determining the likelihood of unplanned care in specialist settings for patients managed in or transferred to primary care is crucial for those planning services, as is time to such care contacts. It is furthermore necessary to know what the costs of care would be for patients who are either not transferred or whose transfer is not as rapid as that of others. Information on these issues is currently lacking but may be derived from routinely available data, and may be of benefit to future assessments of patient care.

Specific services that have been set up in Lambeth may facilitate the transfer of ‘management’ to primary care and the maintenance of care in that location. As with any health-care interventions, these should be evaluated in terms of cost-effectiveness. There is a need to conduct evaluations efficiently, and we should make best use of existing data sets as alternatives to more expensive and time-consuming trials. These data will allow simulation models, which assess the costs and benefits of the different interventions, to be populated. There is also a need to assess care that is provided at a ‘whole-system’ level. The use of modelling is needed in such situations to ensure that results are generalisable. Models enable this by allowing specific characteristics/variables to be changed to reflect different circumstances in other areas.

This study therefore addresses a number of policy needs. It also takes account of the experiences and views of people with mental health problems regarding their care. The broad aim of the study is to examine the economic implications of different locations of management of care and the views of service users and staff regarding services set up as alternatives to secondary care. Specific objectives are as follows.

-

To identify people with SMIs whose care is (i) managed in primary care or (ii) managed in secondary care.

-

To identify people with SMIs who could be potentially transferred from secondary to primary care management.

-

To compare the demographic and clinical characteristics of these groups.

-

To measure and compare the use of services and to calculate service costs for these groups for the year prior to identification and the subsequent 34 months, adjusting for clinical and demographic differences in the groups.

-

To generate cost prediction models to enable resource consequences of patients with specific characteristics who are transferred from one form of care to another to be estimated.

-

To produce survival models to identify characteristics associated with time to transition from primary care to secondary care.

-

To investigate the experiences of patients receiving support from interventions designed to facilitate the transition from secondary to primary care.

-

To assess the economic impact of interventions to facilitate the transfer of care management.

The penultimate aim was revised in light of the characteristics of the recipients of the services. It had become apparent that many recipients had not, in fact, been recently discharged from secondary care services and some had conditions that would not be usually defined as SMIs.

In this report objectives 1–6 are explored in Chapter 2, objective 7 is explored in Chapter 3 and objective 8 is explored in Chapter 4. Each of Chapters 2, 3 and 4 contains a discussion. An overall brief discussion and conclusions are provided in Chapter 5.

Changes to protocol

Changes were discussed within the steering group and with NIHR monitors. The key changes were as follows: (1) the time frame for the quantitative analyses was originally January 2009 to October 2013. This was reduced to January 2010 to October 2013 owing to the availability of data; (2) we had hoped to include social care data in the final linked data set but the challenges in linking the health data precluded this and it was discovered that such social care data were historic and covered a small proportion of those in primary care registers; and (3) the intention of the qualitative component was to recruit participants with SMIs who had recently been discharged from secondary care services. However, many participants using the services had not actually been in touch with secondary care services for a long period of time and many did not have disorders usually defined as SMIs. These were still included as we considered it important to reflect the caseloads of the services.

A further change that is addressed in Chapter 5 relates to the input of service users to the research. We had hoped that interviews would be conducted by service users, but this was rarely possible for logistical reasons (timing of interviews, participants not appearing, etc.). However, service users were involved in the design of the topic guide and in the analysis of data. This was also a departure from the protocol, but a positive one.

Chapter 2 Quantitative analyses

This chapter focuses on the objectives of the study for which we used administrative primary and secondary care data. A key aspect of the study was to obtain these data and to link them using a common identifier. This process is described in the next section and this is followed by: group definitions, a description of the comparison groups, an analysis of the service use and costs by group, multiple regression analyses to identify predictors of service costs, Cox regression analysis to identify predictors of time to re-enter secondary care system, and propensity score analysis to identify participants in secondary care who were similar to those in primary care and to assess their costs.

Data

The analyses were conducted on people in Lambeth registered with GPs and who had a record of SMI made by their GP. As such, the starting point was to use primary care records, the source of which was LDN. This consists of anonymised clinical and demographic data collected from all but one GP practice in the London Borough of Lambeth. This area had a 2011 census population of 303,000 and is one of the most deprived areas in the country. LDN was made available to the study after data cleaning in 2014. It included data up to a cut-off date of 31 October 2013. Until recently, LDN was administered by a private company. One limitation of LDN was that it did not include information on primary care consultations. This was crucial for this and other studies, and the Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) agreed for a researcher to visit GP practices and to extract these data and for them to be uploaded in LDN. These consultation data related to GP contacts (face to face, home visits or by telephone) and nurse contacts (face to face or by telephone) for the calendar years 2010–13 and were available for all but three practices.

Data on secondary mental health care provided in the local area were obtained from the CRIS database housed at the Biomedical Research Centre at the SLaM NHS Foundation Trust. CRIS extracts clinical, demographic and service use data from electronic records. It covers the population (about 1.1 million) for which SLaM is the main care provider and consists of data going back nearly 10 years. As with LDN, CRIS is anonymised and is designed for use in research studies. Permission to use CRIS was obtained through submission of a project proposal to the CRIS oversight committee. Although each of these data sets are of use on their own, for the purposes of this and three other as yet unpublished studies it was desired to link them. Permission to do this was obtained after submitting a Section 251 proposal to the Health Research Authority who approved the linkage.

The third source of data was HES. These were required so that we could measure the use of inpatient and outpatient care provided outside SlaM, as well as use of accident and emergency (A&E) departments. Permission had already been granted to link HES data to CRIS, but we did not have HES data on people in LDN who had never had a SLaM contact.

We had originally anticipated making links with social care data that were held by the local PCT. However, these data applied only to a very small proportion of the population, and given the problems encountered in obtaining health data and making appropriate linkages (see Chapter 5), we did not proceed with this.

Group definitions

The overall aim of the quantitative analyses was to make comparisons between primary and secondary care management of patients with SMI registered with Lambeth GPs. To allow for a reasonable time frame over which to record and analyse service use, we included in the sample all those who had been recorded as having a SMI up to 1 January 2011 (the index date). Clearly there are limitations with this approach. We are relying on GP recognition of SMI, and some patients with SMI on the index date will not have been included in LDN on 31 October 2013 because some will have died and others will have moved out of the area and registered elsewhere. Although important, these limitations are outweighed by the practical considerations of obtaining usable data that can be linked to secondary care records.

Once patients had been identified, and primary and secondary care records linked, the next task was to define our groups of interest. A simple indicator of whether patients were managed in primary care or secondary care was not available and so two alternative approaches were used. First, we used CRIS to determine whether or not patients had been discharged from any episode of secondary care prior to the index date and not admitted to another episode of care straightaway. (It was very common for patients to be discharged from one team and admitted to another team, or from inpatient care to community care, immediately.) If patients were between episodes of secondary care on the index date then we assumed that they were managed in primary care. Limitations of this approach are that (1) we are restricted to using data on patients for whom there are both CRIS and LDN records, thereby excluding patients who have never received secondary care services; (2) patients may technically be between episodes of secondary care but they may be fully expected to receive planned care at a future date; and (3) discharge from secondary care does not by default necessarily indicate receipt of primary care. It should be stressed that patients with no contacts with GPs would still be included.

Second, we adopted an approach to defining groups based on the services that had been used in the period prior to the index date. If secondary care mental health services had been used in the preceding 6 months, we assumed that these were patients managed in secondary care. Of the remaining patients, if there had been primary care contacts during the preceding year then we assumed that they were managed in primary care. Finally, we also defined a ‘no care’ group, which consisted of patients not in receipt of secondary care services in the previous 6 months or primary care services in the previous 12 months. Ideally, we would have focused entirely on the previous 6 months but the primary care data were reported for entire calendar years.

Sample characteristics

Data on a total of 3632 patients recorded by GPs as having a SMI prior to the index date were obtained from 47 GP practices in Lambeth. One practice did not provide data to LDN. A list of practices and numbers of patients from each practice is available from the authors. The sample size was reduced to 3463 because GP consultation data, which was a crucial element to the analyses, were not available for all practices. A further reduction occurred when using the first definition of comparison groups (i.e. basing this on discharges from secondary care episodes) because 424 patients had not been referred to secondary care. Using this definition we identified 1410 (46%) patients as being under primary care management on the index date and 1629 (54%) as being under secondary care management. The second definition resulted in 1311 (38%) patients defined as receiving primary care, 1776 (51%) patients defined as receiving secondary care and 376 (11%) patients defined as receiving neither form of care. The analysis of demographic and clinical characteristics below takes the two group definitions in turn.

Group definition 1: groups defined by discharge status

The mean age of patients discharged to primary care was similar to those remaining in secondary care (Table 1), and this was matched by a reasonably similar age distribution in each group as shown by the age bands. There was a slight difference in sex distribution, with relatively more men remaining in secondary care. In each group about one-third of patients were of white ethnicity and one-third were of black ethnicity, with no noticeable differences between the groups.

| Characteristic | Discharged to PC (N = 1410) | Still in SC (N = 1629) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 48.1 (14.4) | 46.2 (14.5) |

| Age, n (%) | ||

| ≤ 19 | 6 (0.4) | 14 (0.9) |

| 20–29 | 139 (9.9) | 208 (12.8) |

| 30–39 | 246 (17.5) | 341 (20.9) |

| 40–49 | 415 (29.4) | 448 (27.5) |

| 50–59 | 310 (22.0) | 331 (20.3) |

| 60–69 | 177 (12.6) | 168 (10.3) |

| 70–79 | 84 (6.0) | 86 (5.3) |

| 80–89 | 31 (2.2) | 33 (2.0) |

| ≥ 90 | 2 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Female | 677 (48.0) | 673 (41.3) |

| Male | 733 (52.0) | 956 (58.7) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| White | 541 (38.4) | 621 (38.1) |

| Mixed race | 82 (5.8) | 102 (6.3) |

| Asian/Asian British | 70 (5.0) | 82 (5.0) |

| Other black | 518 (36.7) | 604 (37.1) |

| Other ethnic group | 27 (1.9) | 43 (2.6) |

| Not recorded | 172 (12.2) | 177 (10.9) |

| History of violence | 172 (12.2) | 744 (45.7) |

| Any use of antipsychotic medication | 1082 (76.7) | 1552 (95.3) |

| Forensic history | 160 (11.4) | 356 (21.9) |

| History of treatment non-compliance | 224 (15.9) | 819 (50.3) |

| Physical health problems | 108 (7.7) | 435 (26.7) |

| Bipolar disorder | 301 (21.4) | 345 (21.2) |

| Organic psychosis | 16 (1.1) | 14 (0.9) |

| Atypical antipsychotics | 64 (4.5) | 66 (4.1) |

| Depot injection | 3 (0.2) | 7 (0.4) |

| Lithium | 24 (1.7) | 22 (1.4) |

| Mood stabiliser | 8 (0.6) | 20 (1.2) |

| Tricyclic antidepressant | 13 (0.9) | 16 (1.0) |

| Monoamine oxidase inhibitors before index | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor before index | 7 (0.5) | 6 (0.4) |

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor before index | 41 (2.9) | 37 (2.3) |

| Mirtazapine (Zispin SolTab, Merck Sharp & Dohme Limited) | 10 (0.7) | 7 (0.4) |

| CRIS diagnosis, n (%) | ||

| Organic disorder | 2 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) |

| Substance-induced psychosis | 0 (0.0) | 1 (73.7) |

| Schizophrenia | 734 (52.1) | 1201 (18.4) |

| Affective disorder | 241 (17.1) | 300 (0.0) |

| Other | 1 (0.1) | 0 (126) |

| No diagnosis recorded | 432 (30.6) | 126 (126) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 7 (0.5) | 8 (0.5) |

| BP | 82 (5.8) | 75 (4.6) |

| Coronary heart disease | 26 (1.8) | 26 (1.6) |

| Heart failure | 13 (0.9) | 8 (0.5) |

| Hypertension | 264 (18.7) | 233 (14.3) |

| Pulmonary embolism | 10 (0.7) | 6 (0.4) |

| Stroke | 25 (1.8) | 19 (1.2) |

| ACE inhibitors | 11 (0.8) | 8 (0.5) |

| Antiplatelet | 41 (2.9) | 34 (2.1) |

| Statin | 8 (0.6) | 4 (0.3) |

| Angiotensin II receptor blockers | 3 (0.2) | 3 (0.2) |

| Hypothyroid | 67 (4.8) | 63 (3.9) |

| Diuretic | 16 (1.1) | 22 (1.4) |

| Beta-blocker | 18 (1.3) | 11 (0.7) |

| Calcium-channel blocker | 12 (0.9) | 10 (0.6) |

| TSH test | 194 (13.8) | 185 (11.4) |

| Orlistat (Xenical, Roche) | 15 (1.1) | 7 (0.4) |

| Nicotine replacement therapy | 48 (3.4) | 58 (3.6) |

| Asthma | 104 (7.4) | 116 (7.1) |

| Cancer | 31 (2.2) | 31 (1.9) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 57 (4.0) | 45 (2.8) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 26 (1.8) | 28 (1.7) |

| Dementia | 16 (1.1) | 13 (0.8) |

| Depression | 118 (8.4) | 106 (6.5) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 84 (6.0) | 109 (6.7) |

| Learning difficulties | 18 (1.3) | 72 (4.4) |

| HoNOS scores, mean (SD) | ||

| Total | 7.77 (5.82) | 9.56 (5.97) |

| Agitated | 0.46 (0.84) | 0.54 (0.90) |

| Self-injury | 0.14 (0.55) | 0.14 (0.50) |

| Problem | 0.38 (0.88) | 0.52 (0.99) |

| Cognitive | 0.47 (0.83) | 0.61 (0.88) |

| Physical | 0.70 (1.08) | 0.77 (1.06) |

| Hallucination | 0.84 (1.12) | 1.09 (1.19) |

| Depressed | 0.81 (0.95) | 0.80 (0.95) |

| Other | 1.04 (1.08) | 1.25 (1.07) |

| Relationships | 0.88 (1.05) | 1.12 (1.04) |

| Daily living | 0.71 (0.98) | 0.96 (1.04) |

| Living conditions | 0.55 (0.94) | 0.64 (0.99) |

| Occupation | 0.85 (1.07) | 1.12 (1.12) |

Nearly three-quarters of patients in secondary care had received a diagnosis of schizophrenia from specialist services, compared with only around half of primary care patients. However, about one-third of primary care patients had received no diagnosis from specialist services compared with < 8% of secondary care patients. There were clear differences between the groups in terms of history of violence, a forensic history, non-compliance with treatment and problems with physical health. In each case these were more common in the secondary care than in the primary care group.

Many of the clinical characteristics as recorded on LDN applied to relatively few patients. (It should be noted, however, that this was confined to characteristics recorded prior to the index date.) Hypertension, asthma, depression and diabetes mellitus were among the more common disorders noted by GPs. Receipt of thyroid-stimulating tests was also fairly frequent. However, the groups did not appreciably differ in relation to these.

Health of the Nation Outcome Scale (HoNOS) scores were available for only 2319 participants. This was an imbalance between the groups, with scores available for 94% of secondary care patients and 56% of those managed in primary care. We chose to use the scores that were recorded closest to the index date. The mean total score was 1.79 higher for the secondary care group, indicating greater severity. Subscores that showed the greatest differences were those relating to cognitive problems, hallucinations, relationships, daily living issues, occupation and other problems. These were all markedly higher for the secondary care group.

Group definition 2: groups defined by service use

The average age differed substantially between the three groups, with those managed in primary being, on average, 3.5 years older than those managed in secondary care and 8.4 years older than those who received neither primary nor secondary care (Table 2). Most patients were male, although roughly similar numbers of men and women were managed in primary care. Fewer than half the patients were of white ethnicity and, for those managed in secondary care, there were slightly more patients of black ethnicity.

| Characteristic | Primary care (N = 1311) | Secondary care (N = 1776) | Neither (N = 376) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 50.1 (15.0) | 46.4 (14.6) | 41.7 (14.1) |

| Age (years), n (%) | |||

| ≤ 19 | 3 (0.2) | 16 (0.9) | 2 (0.5) |

| 20–29 | 103 (7.9) | 224 (12.6) | 84 (22.3) |

| 30–39 | 223 (17.0) | 362 (20.4) | 96 (25.5) |

| 40–49 | 351 (26.8) | 490 (27.6) | 99 (26.3) |

| 50–59 | 288 (22.0) | 366 (20.6) | 47 (12.5) |

| 60–69 | 194 (14.8) | 182 (10.3) | 31 (8.2) |

| 70–79 | 107 (8.2) | 100 (5.6) | 12 (3.2) |

| 80–89 | 36 (2.8) | 35 (2.0) | 5 (1.3) |

| ≥ 90 | 6 (0.5) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Female | 634 (48.4) | 760 (42.8) | 158 (42.0 |

| Male | 677 (51.6) | 1016 (57.2) | 218 (58.0) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White | 553 (42.2) | 669 (37.7) | 179 (47.6) |

| Mixed race | 77 (5.9) | 103 (5.8) | 21 (5.6) |

| Asian/Asian British | 80 (6.1) | 85 (4.8) | 21 (5.6) |

| Other Black | 434 (33.1) | 677 (38.1) | 88 (23.4) |

| Other ethnic group | 21 (1.6) | 45 (2.5) | 10 (2.7) |

| Not recorded | 146 (11.1) | 197 (11.1) | 57 (15.2) |

| Bipolar disorder | 312 (23.8) | 375 (21.1) | 107 (28.5) |

| Organic psychosis | 11 (0.8) | 19 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Atypical antipsychotics | 54 (4.1) | 68 (3.8) | 7 (1.9) |

| Depot injection | 1 (0.1) | 9 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Lithium before | 35 (2.7) | 22 (1.2) | 1 (0.3) |

| Mood stabiliser | 5 (0.4) | 20 (1.1) | 2 (0.5) |

| Tricyclic antidepressant | 14 (1.1) | 15 (0.8) | 1 (0.3) |

| Monoamine oxidase inhibitors | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor | 5 (0.4) | 5 (0.3) | 2 (0.5) |

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor before index | 26 (2.0) | 43 (2.4) | 5 (1.3) |

| Mirtazapine (Zispin SolTab, Merck Sharp & Dohme Limited) | 8 (0.6) | 9 (0.5) | 1 (0.3) |

| CRIS diagnosis, n (%) | |||

| Organic disorder | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Substance-induced psychosis | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Schizophrenia | 508 (50.2) | 1292 (72.8) | 93 (38.9) |

| Affective disorder | 173 (17.1) | 331 (18.6) | 42 (17.6) |

| Other | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| No diagnosis recorded | 330 (32.6) | 151 (8.5) | 104 (43.5) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 13 (1.0) | 8 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| BP | 60 (4.6) | 73 (4.1) | 26 (6.9) |

| Coronary heart disease | 35 (2.7) | 27 (1.5) | 4 (1.1) |

| Heart failure | 12 (0.9) | 11 (0.6) | 1 (0.3) |

| Hypertension | 302 (23.0) | 253 (14.3) | 25 (6.7) |

| Pulmonary embolism | 7 (0.5) | 6 (0.3) | 2 (0.5) |

| Stroke | 26 (2.0) | 21 (1.2) | 1 (0.3) |

| ACE inhibitors | 14 (1.1) | 8 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| Antiplatelet | 52 (4.0) | 35 (2.0) | 2 (0.5) |

| Statin | 8 (0.6) | 5 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| Angiotensin II receptor blockers | 4 (0.3) | 4 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Hypothyroid | 68 (5.2) | 70 (3.9) | 5 (1.3) |

| Diuretic | 21 (1.6) | 24 (1.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| Beta-blocker | 14 (1.1) | 13 (0.7) | 1 (0.3) |

| Calcium-channel blocker | 11 (0.8) | 12 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| TSH test | 182 (13.9) | 197 (11.1) | 23 (6.1) |

| Orlistat | 10 (0.8) | 11 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Nicotine replacement therapy | 35 (2.7) | 63 (3.6) | 1 (0.3) |

| Asthma | 108 (8.2) | 124 (7.0) | 16 (4.3) |

| Cancer | 37 (2.8) | 37 (2.1) | 4 (1.1) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 66 (5.0) | 47 (2.7) | 2 (0.5) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 28 (2.1) | 31 (1.8) | 1 (0.3) |

| Dementia | 14 (1.1) | 17 (1.0) | 1 (0.3) |

| Depression | 104 (7.9) | 115 (6.5) | 32 (8.5) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 84 (6.4) | 122 (6.9) | 7 (1.9) |

| Learning difficulties | 18 (1.4) | 68 (3.8) | 1 (0.3) |

| HoNOS scores, mean (SD) | |||

| Total | 7.34 (5.62) | 9.45 (5.97) | 7.71 (5.91) |

| Agitated | 0.43 (0.79) | 0.55 (0.91) | 0.34 (0.70) |

| Self-injury | 0.12 (0.49) | 0.14 (0.50) | 0.30 (0.87) |

| Problem | 0.37 (0.86) | 0.50 (0.98) | 0.45 (0.95) |

| Cognitive | 0.48 (0.84) | 0.59 (0.88) | 0.41 (0.79) |

| Physical | 0.67 (1.04) | 0.78 (1.08) | 0.65 (1.11) |

| Hallucination | 0.80 (1.11) | 1.07 (1.18) | 0.65 (1.05) |

| Depressed | 0.78 (0.96) | 0.80 (0.94) | 0.91 (1.02) |

| Other | 0.93 (1.05) | 1.25 (1.07) | 0.87 (1.03) |

| Relationships | 0.82 (1.00) | 1.10 (1.05) | 1.01 (1.09) |

| Daily living | 0.67 (0.96) | 0.94 (0.94) | 0.68 (0.97) |

| Living conditions | 0.47 (0.82) | 0.64 (1.00) | 0.58 (0.99) |

| Occupation | 0.83 (1.05) | 1.09 (1.11) | 0.80 (1.13) |

Of those managed in primary care, half were diagnosed with schizophrenia but one-third had no diagnosis recorded. Three-quarters of patients managed in secondary care had a diagnosis of schizophrenia with affective disorders, comprising most remaining patients. Those patients who did not receive secondary care in the previous 6 months or primary care in the previous 12 months were most likely not to have a CRIS diagnosis. One-third had a diagnosis of schizophrenia. Interestingly, the LDN data show that relatively similar proportions in each group had a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. Rates of depression as recorded on the QOF were quite similar between groups, and for each group was less than 10%.

Physical health problems, as diagnosed by GPs, tended to be more prevalent in the primary care group and less prevalent in the neither primary nor secondary care group. The most common disorder in the primary care patients was hypertension (around one-quarter of the sample) and this was the same in the secondary care group (< 15%).

Health of the Nation Outcome Scale scores were available for 494 (38%) primary care patients, 1651 (93%) secondary care patients and 77 (20%) no care patients. Given the fact that a HoNOS score is unlikely to be given to a patient with no secondary care contacts, this distribution is unsurprising. Higher HoNOS scores indicating greater severity scores were noticeably higher for secondary care patients than for patients in the other two groups.

Use and cost of health services

The use of primary care services was reported for the calendar years 2010–13. Numbers and percentages using primary care are reported and mean and standard deviations (SDs) of the number of contacts among those using them (i.e. excluding non-users) are also provided. Costs were calculated by combining the service use data with appropriate unit costs (at 2013/14 prices),22 and means and SDs of cost for all the sample are reported. For secondary care services a similar procedure was followed. However, for SLaM services costs had already been calculated as part of another NIHR-funded project and these costs were used here. 23 For comparability we inflated/deflated these costs to 2013/14 prices using data from a recognised source. 22 Use of inpatient, outpatient, and A&E care was reported as before and with costs obtained from published Department of Health figures. 23

Group definition 1: groups defined by discharge status

During the year prior to the index date, around three-quarters of each group had received face-to-face contacts from their GP (Table 3). This increased somewhat in the subsequent years but there were few differences between the groups. Home visits were received by relatively few patients in either group, whereas the numbers receiving telephone contacts increased over time from around one-quarter prior to the index date to nearly half in the final year. Face-to-face nurse contacts were received by one-third to one-half of patients and again there were no clear differences between groups. Again, nurse contacts by telephone were relatively uncommon.

| Type of contact | 2010, n (%) | 2011, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discharged (N = 1335) | Still in SC (N = 1566) | Discharged (N = 1335) | Still in SC (N = 1566) | |

| GP, face to face | 1044 (78.2) | 1234 (78.8) | 1104 (82.7) | 1279 (81.7) |

| GP, home | 53 (4.0) | 80 (5.1) | 63 (4.7) | 97 (6.2) |

| GP, telephone | 345 (25.8) | 466 (29.8) | 409 (30.6) | 504 (32.2) |

| Nurse, face to face | 489 (36.6) | 562 (35.9) | 559 (41.9) | 657 (42.0) |

| Nurse, telephone | 41 (3.1) | 34 (2.2) | 43 (3.2) | 83 (5.3) |

| Type of contact | 2012, n (%) | 2013, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discharged (n = 1335) | Still in SC (n = 1566) | Discharged (n = 1335) | Still in SC (n = 1566) | |

| GP, face to face | 1163 (87.1) | 1358 (86.7) | 1166 (87.3) | 1356 (86.6) |

| GP, home | 76 (5.7) | 102 (6.5) | 84 (6.3) | 115 (7.3) |

| GP, telephone | 508 (38.1) | 592 (37.8) | 615 (46.1) | 701 (44.8) |

| Nurse, face to face | 627 (47.0) | 709 (45.3) | 638 (47.8) | 773 (49.4) |

| Nurse, telephone | 55 (4.1) | 75 (4.8) | 86 (6.4) | 108 (6.9) |

The number of patients with primary care consultations is shown in Table 4. Face-to-face GP consultations occurred, on average, about every 2 months, whereas face-to-face nurse contacts occurred around every 3 months. Differences between the two groups were limited. The costs of primary care were dominated by face-to-face GP contacts, accounting for between 74% and 84% of the total (Table 5). Contacts with nurses by telephone accounted for < 1% of the total.

| Type of contact | 2010, mean (SD) | 2011, mean (SD) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discharged | Still in SC | Discharged | Still in SC | |

| GP, face to face | 6.3 (6.1) | 7.0 (7.2) | 7.1 (7.2) | 7.3 (7.4) |

| GP, home | 2.1 (2.2) | 1.8 (1.8) | 2.2 (2.2) | 2.0 (2.2) |

| GP, telephone | 2.7 (3.5) | 3.2 (4.5) | 2.8 (3.6) | 3.0 (4.6) |

| Nurse, face to face | 4.1 (6.1) | 3.1 (3.7) | 4.6 (6.2) | 3.8 (4.9) |

| Nurse, telephone | 1.4 (1.0) | 1.2 (0.5) | 2.1 (2.7) | 1.6 (1.4) |

| Type of contact | 2012, mean (SD) | 2013, mean (SD) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discharged | Still in SC | Discharged | Still in SC | |

| GP, face to face | 7.6 (7.3) | 7.4 (7.2) | 6.5 (5.7) | 6.2 (5.5) |

| GP, home | 1.9 (1.8) | 2.0 (2.4) | 2.3 (2.1) | 2.2 (2.2) |

| GP, telephone | 3.3 (4.0) | 3.2 (4.2) | 3.6 (4.6) | 3.5 (4.7) |

| Nurse, face to face | 4.4 (6.3) | 4.5 (6.0) | 4.4 (6.1) | 4.7 (6.8) |

| Nurse, telephone | 1.7 (1.4) | 2.0 (1.8) | 1.8 (1.8) | 2.3 (2.2) |

| Type of contact | 2010, mean (SD) | 2011, mean (SD) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discharged (n = 1335) | Still in SC (n = 1566) | Discharged (n = 1335) | Still in SC (n = 566) | |

| GP, face to face | 208 (251) | 232 (295) | 247 (296) | 251 (305) |

| GP, home | 5 (37) | 6 (35) | 6 (41) | 8 (45) |

| GP, telephone | 17 (54) | 24 (72) | 21 (59) | 25 (74) |

| Nurse, face to face | 20 (55) | 15 (36) | 25 (61) | 21 (49) |

| Nurse, telephone | 0.2 (1.2) | 0.1 (0.8) | 0.1 (1.2) | 0.2 (1.0) |

| Total primary care costs | 251 (284) | 277 (332) | 301 (330) | 304 (345) |

| Type of contact | 2012, mean (SD) | 2013, mean (SD) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discharged (n = 335) | Still in SC (n = 1566) | Discharged (n = 1335) | Still in SC (n = 1566) | |

| GP, face to face | 276 (304) | 269 (300) | 237 (242) | 227 (234) |

| GP, home | 7 (38) | 8 (49) | 9 (47) | 10 (51) |

| GP, telephone | 31 (74) | 30 (75) | 42 (90) | 39 (90) |

| Nurse, face to face | 27 (64) | 27 (61) | 28 (63) | 31 (71) |

| Nurse, telephone | 0.1 (0.9) | 0.2 (1.2) | 0.2 (1.3) | 0.3 (1.7) |

| Total primary care costs | 342 (350) | 335 (350) | 315 (299) | 307 (305) |

Not surprisingly, use of secondary care services from the local NHS trust differed between the groups (Table 6). In the year prior to the index date there was a five-fold difference in the number of patients admitted to inpatient care, and in the subsequent years the difference remained substantial. For those who were admitted, the total length of stay across each year was fairly similar, with the exception of the first year where those who were subsequently discharged after the index date had more days in hospital (but were far less likely to be hospitalised in the first place). Although the number of days may seem high, this reflects multiple admissions and is also affected by extreme outliers. The cost of inpatient care mirrors the above findings, with far higher costs for the secondary care group. The proportion of patients with community contacts was also much higher among the secondary care patients, again with the largest difference during the first year. In each year, the number of community contacts for those who had them was substantially higher in the secondary care group. Finally, the table reveals that use and cost of psychotropic medication (as prescribed by the trust) was also much higher in the secondary care patients. Total mental health care costs in the year prior to the index date were 3.4 times higher among those in the discharged to primary care group. This ratio fell to 2.8 and 2.5 in 2011 and 2012, respectively, before rising again to 3.0 in 2013.

| Type of contact | 2010 | 2011 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discharged (N = 1335) | Still in SC (N = 1566) | Discharged (N = 1335) | Still in SC (N = 1566) | |

| Inpatient, n (%) | 58 (4.3) | 365 (23.3) | 108 (8.1) | 302 (19.3) |

| Number of days, mean (SD) | 150.3 (147.9) | 83.6 (86.5) | 96.5 (125.4) | 94.7 (104.9) |

| Costs (£), mean (SD) | 3448 (25,433) | 8702 (28,660) | 4229 (27,741) | 8209 (27,873) |

| Community contacts, n (%) | 387 (29.0) | 1497 (95.6) | 301 (22.6) | 1440 (92.0) |

| Number of contacts, mean (SD) | 7.3 (11.9) | 28.9 (49.7) | 10.2 (15.5) | 28.1 (51.2) |

| Costs (£), mean (SD) | 288 (1057) | 3887 (7508) | 306 (1201) | 3493 (6841) |

| Psychotropic medication, n (%) | 284 (21.3) | 1282 (81.9) | 227 (17.0) | 1245 (79.5) |

| Cost (£), mean (SD) | 77 (470) | 765 (1665) | 95 (526) | 803 (1721) |

| Total mental health care costs (£), mean (SD) | 3802 (26,191) | 13,039 (28,984) | 4412 (26,930) | 12397 (29,370) |

| Type of contact | 2012 | 2013 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discharged (N = 1335) | Still in SC (N = 1566) | Discharged (N = 335) | Still in SC (N = 1566) | |

| Inpatient, n (%) | 105 (7.9) | 306 (19.5) | 73 (5.5) | 220 (14.1) |

| Number of days, mean (SD) | 84.4 (110.1) | 84.7 (98.2) | 98.6 (115.5) | 92.2 (101.7) |

| Costs (£), mean (SD) | 3804 (23,237) | 7460 (26,155) | 2450 (17,208) | 6500 (25,215) |

| Community contacts, n (%) | 396 (29.7) | 1295 (82.7) | 426 (31.9) | 1226 (78.3) |

| Number of contacts, mean (SD) | 14.2 (17.5) | 25.8 (39.7) | 12.0 (18.2) | 19.9 (27.3) |

| Costs (£), mean (SD) | 547 (1567) | 2796 (5172) | 485 (1557) | 1979 (3452) |

| Psychotropic medication, n (%) | 303 (22.7) | 1096 (70.0) | 321 (24.0) | 1004 (64.1) |

| Cost (£), mean (SD) | 141 (643) | 840 (1977) | 115 (535) | 722 (1625) |

| Total mental health care costs (£), mean (SD) | 4310 (22,332) | 10,912 (27,280) | 3027 (17,339) | 9167 (26,182) |

Between 14% and 20% of the patients had admissions for physical health reasons in each year (Table 7). This excludes the final period, where the figures are substantially lower than for other years, indicating that the data set was not fully updated. Inpatient days in the first years were somewhat higher for the secondary care group. During this year, the cost of inpatient care for physical health reasons was also higher for the secondary care group and thereafter the costs were more similar.

| Type of contact | 2010 | 2011 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discharged (N = 1333) | Still in SC (N = 1557) | Discharged (N = 1333) | Still in SC (N = 1557) | |

| Physical inpatient, n (%) | 191 (14.3) | 272 (17.5) | 197 (14.8) | 308 (19.8) |

| Days in hospital, mean (SD) | 7.8 (19.7) | 10.5 (29.3) | 6.0 (12.1) | 8.1 (18.6) |

| Cost (£), mean (SD) | 650 (4624) | 1072 (7489) | 518 (2982) | 936 (5172) |

| Psychiatric inpatient, n (%) | 18 (1.4) | 27 (1.7) | 25 (1.9) | 24 (1.5) |

| Days in hospital, mean (SD) | 5.4 (13.6) | 2.6 (5.4) | 6.9 (14.5) | 9.6 (20.3) |

| Cost (£), mean (SD) | 25 (580) | 16 (271) | 46 (758) | 52 (962) |

| Outpatient contacts, n (%) | 469 (35.2) | 531 (34.1) | 486 (36.5) | 547 (35.1) |

| Number of contacts, mean (SD) | 3.7 (4.3) | 4.1 (5.0) | 3.7 (4.0) | 4.6 (5.3) |

| Cost (£), mean (SD) | 143 (339) | 153 (381) | 149 (331) | 175 (418) |

| A&E visits, n (%) | 344 (25.8) | 560 (36.0) | 363 (27.2) | 528 (33.9) |

| Number of visits, mean (SD) | 1.9 (2.0) | 2.7 (3.9) | 1.9 (1.8) | 3.0 (6.5) |

| Cost (£), mean (SD) | 58 (157) | 117 (318) | 62 (153) | 118 (474) |

| Type of contact | 2012 | 2013 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discharged (N = 1335) | Still in SC (N = 1566) | Discharged (N = 1335) | Still in SC (N = 1566) | |

| Physical inpatient, n (%) | 196 (14.7) | 270 (17.3) | 84 (6.3) | 101 (6.5) |

| Days in hospital, mean (SD) | 9.0 (20.2) | 7.7 (15.8) | 3.8 (5.8) | 5.2 (8.7) |

| Cost (£), mean (SD) | 775 (4884) | 779 (4202) | 141 (1003) | 195 (1483) |

| Psychiatric inpatient, n (%) | 18 (1.4) | 17 (1.1) | 3 (0.2) | 10 (0.6) |

| Days in hospital, mean (SD) | 5.4 (10.5) | 5.4 (10.1) | 1.8 (1.5) | 1.5 (1.4) |

| Cost (£), mean (SD) | 26 (470) | 21 (409) | 1 (37) | 3 (57) |

| Outpatient contacts, n (%) | 502 (37.7) | 551 (35.4) | 256 (19.2) | 258 (16.6) |

| Number of contacts, mean (SD) | 4.0 (4.3) | 4.3 (5.0) | 1.8 (1.5) | 2.2 (2.2) |

| Cost (£), mean (SD) | 162 (358) | 165 (396) | 38 (105) | 39 (129) |

| A&E visits, n (%) | 407 (30.5) | 519 (33.3) | 140 (10.5) | 197 (12.7) |

| Number of visits, mean (SD) | 2.0 (2.3) | 2.9 (5.1) | 1.4 (1.0) | 2.0 (3.4) |

| Cost (£), mean (SD) | 74 (185) | 114 (380) | 17 (62) | 30 (161) |

There was very little use of psychiatric inpatient care from other trusts, and differences between the groups were small. Around one-third of patients had outpatient contacts in each year (excluding 2013 for the above reasons) with around 4–5 contacts per user. Finally, one-quarter to one-third of patients visited A&E in each year. Use and cost of A&E was higher for the secondary care patients.

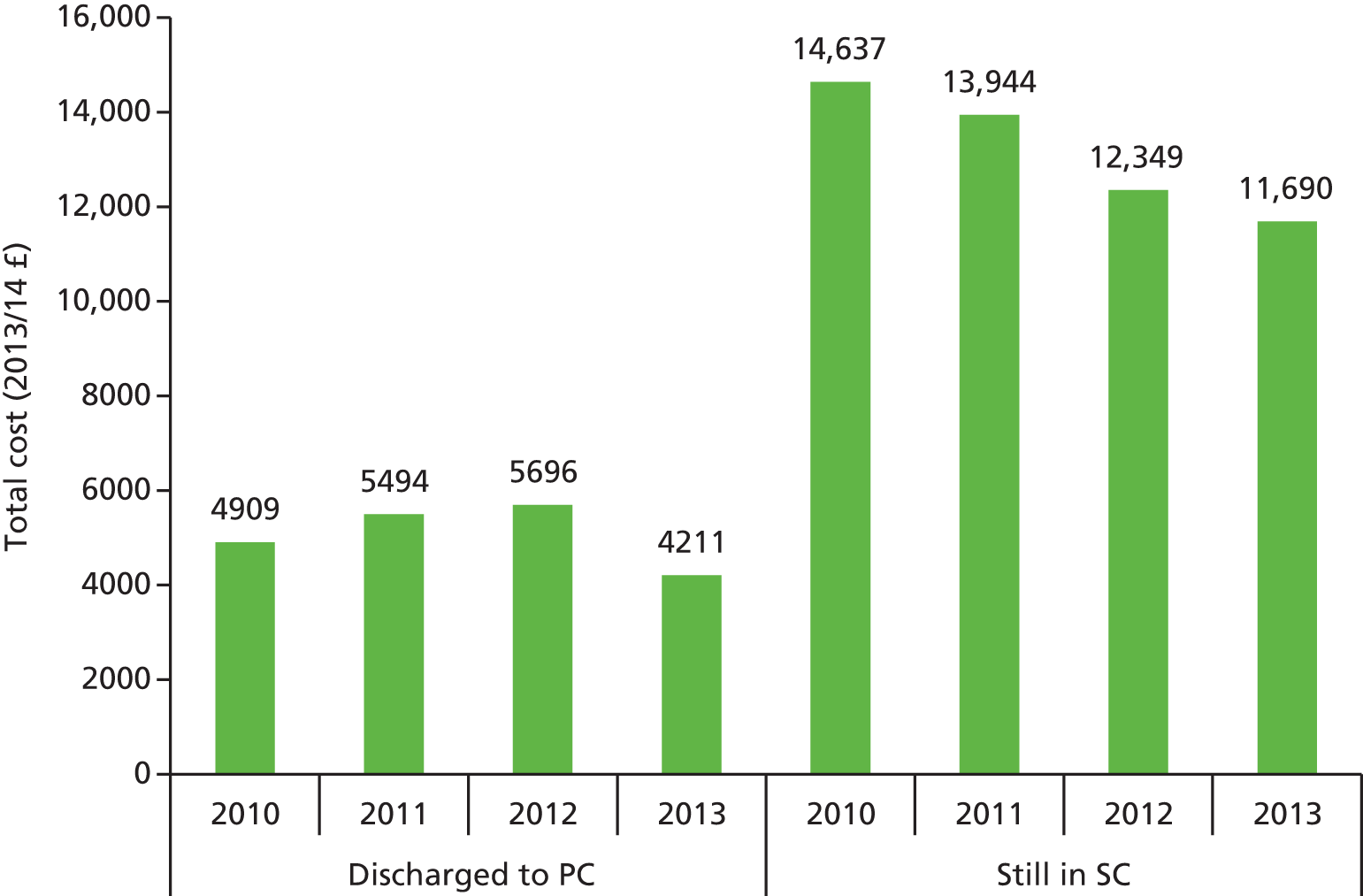

The mean total cost of the above services reveals that those in the discharged to primary care group had consistently lower costs than those in secondary care on the index date (Figure 1). The costs were lower in 2013 partly because this covered only 10 months. The mean (SD) costs for the combined follow-up period (2011–13) were £14,730 (£58,627) for the discharged group and £36,075 (£67,454) for the secondary care group.

FIGURE 1.

Mean costs per year by discharge group (2013/14 £s). PC, primary care; SC, secondary care.

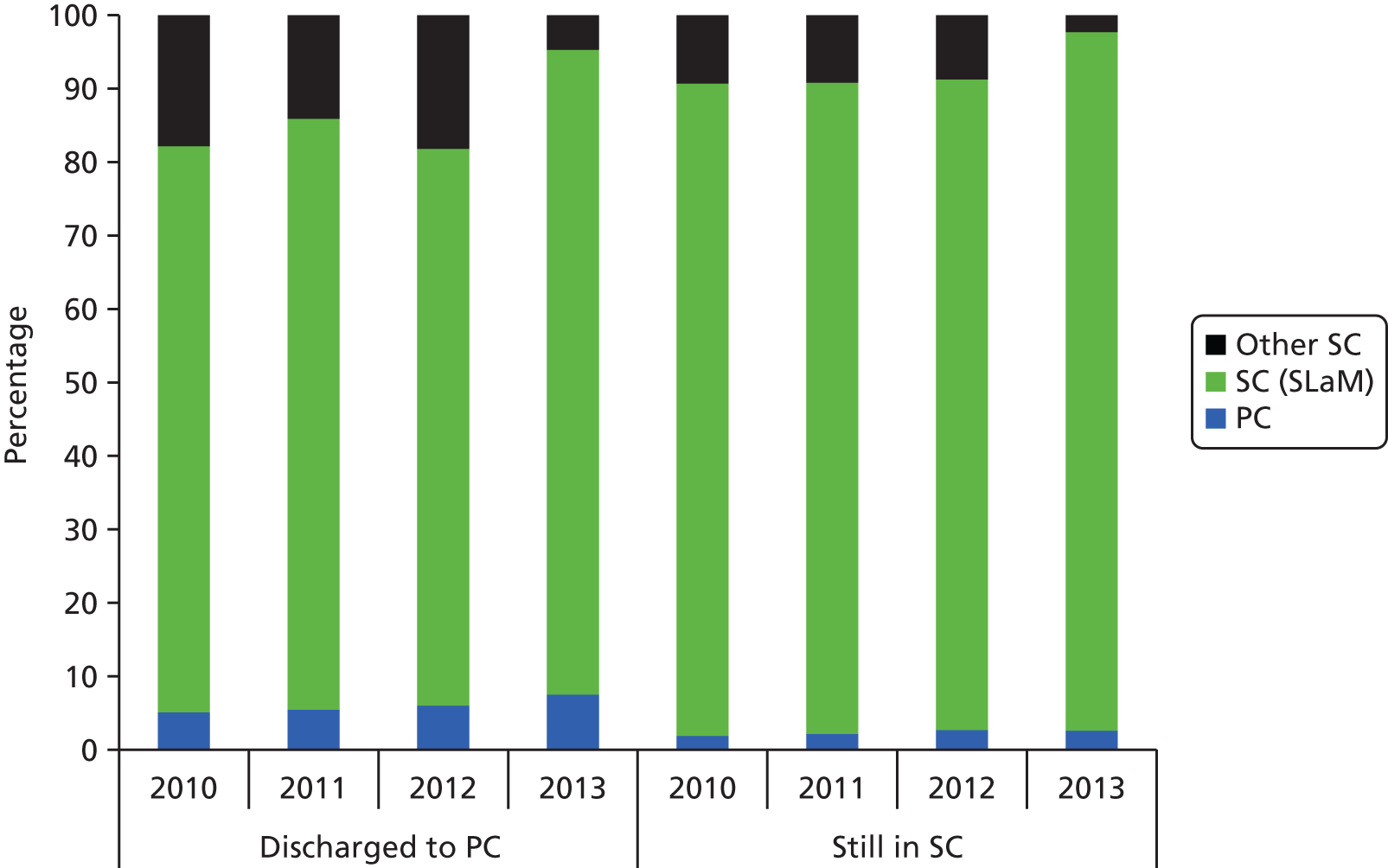

The distribution of costs over time demonstrates that SLaM-provided secondary care accounted for most cost in each year (Figure 2). However, as a proportion it was (not surprisingly) somewhat greater among the secondary care patients.

FIGURE 2.

Distribution of service costs by discharge group. PC, primary care; SC, secondary care.

Group definition 2: groups defined by service use

More than 90% of the primary care group had received face-to-face GP contacts in the year prior to the index date (Table 8). This was substantially higher than for the secondary care group, and, by definition, none of the no care group had such contacts recorded for this period. For each of the 3 years following the index date, the proportion of the secondary care group with face-to-face GP contacts increased slightly, whereas the primary care group maintained similar levels of contact. What is striking, however, is that the patients in the no care group were increasingly likely to have GP contacts over the subsequent years. Telephone contacts with GPs were received by slightly more secondary care than primary care patients in 2010. The proportion of patients having such contacts increased in each group, particularly during the final year. For the no care group, telephone contacts did increase substantially but remained noticeably lower than in the other groups. Home visits by GPs were received by relatively few patients and proportions were always slightly higher for the secondary care group. Face-to-face contacts with primary care nurses were relatively common in the primary care and secondary care groups, with the rate being slightly higher in the former. By 2013 about half of each of these groups had such contacts. The no care group again saw increased use of this service, and by 2013 about one-third had these contacts. Telephone contacts with primary care nurses were far less frequently received by patients.

| Type of contact | 2010, n (%) | 2011, n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC (N = 1311) | SC (N = 1776) | NC (N = 376) | PC (N = 1311) | SC (N = 1776) | NC (N = 376) | |

| GP, face to face | 1203 (91.8) | 1401 (78.9) | 0 (0.0) | 1159 (88.4) | 1452 (81.8) | 142 (37.8) |

| GP, home | 54 (4.1) | 93 (5.2) | 0 (0.0) | 65 (5.0) | 109 (6.1) | 6 (1.6) |

| GP, telephone | 348 (26.5) | 549 (30.9) | 0 (0.0) | 400 (30.5) | 586 (33.0) | 31 (8.2) |

| Nurse, face to face | 593 (45.2) | 627 (35.3) | 0 (0.0) | 643 (49.1) | 726 (40.9) | 62 (16.5) |

| Nurse, telephone | 42 (3.2) | 40 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | 45 (3.4) | 91 (5.1) | 1 (0.3) |

| Type of contact | 2012, n (%) | 2013, n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC (N = 1311) | SC (N = 1776) | NC (N = 376) | PC (N = 1311) | SC (N = 1776) | NC (N = 376) | |

| GP, face to face | 1185 (90.4) | 1530 (86.2) | 254 (67.8) | 1156 (88.2) | 1538 (86.6) | 300 (79.8) |

| GP, home | 79 (6.0) | 115 (6.5) | 10 (2.7) | 77 (5.9) | 131 (7.4) | 17 (4.5) |

| GP, telephone | 473 (36.1) | 684 (38.5) | 108 (28.7) | 607 (46.3) | 796 (44.8) | 131 (34.8) |

| Nurse, face to face | 677 (51.6) | 788 (44.4) | 110 (29.3) | 659 (50.3) | 859 (48.4) | 139 (37.0) |

| Nurse, telephone | 67 (5.1) | 82 (4.6) | 7 (1.9) | 80 (6.1) | 123 (6.9) | 15 (4.0) |

For those with primary care contacts, the numbers of these are reported in Table 9. It can be seen that the intensity of contacts did not differ markedly between the primary care and secondary care groups. Patients in the no care group who did have contacts in 2011–13 tended to have a lower rate of these than patients in the other two groups. Costs of care were again dominated by face-to-face GP consultations (Table 10). The costs of face-to-face GP contacts were very similar between the primary care and secondary care groups, and for each year both groups had higher costs than the no care group.

| Type of contact | 2010, mean (SD) | 2011, mean (SD) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC | SC | NC | PC | SC | NC | ||

| GP, face to face | 6.0 (6.0) | 7.0 (7.1) | – | – | 7.3 (7.5) | 7.2 (7.3) | 4.0 (4.7) |

| GP, home | 2.2 (2.3) | 1.8 (1.7) | – | – | 1.9 (1.9) | 2.0 (2.2) | 2.2 (2.9) |

| GP, telephone | 2.6 (3.1) | 3.2 (4.6) | – | – | 2.8 (3.4) | 3.1 (4.5) | 1.9 (1.7) |

| Nurse, face to face | 3.7 (5.5) | 3.1 (3.9) | – | – | 4.1 (5.6) | 4.0 (5.1) | 2.5 (2.2) |

| Nurse, telephone | 1.5 (1.1) | 1.1 (0.4) | – | – | 2.0 (2.3) | 1.6 (1.6) | 1.0 (0.0) |

| Type of contact | 2012, mean (SD) | 2013, mean (SD) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC | SC | NC | PC | SC | NC | |

| GP, face to face | 7.3 (6.9) | 7.5 (7.2) | 5.8 (6.7) | 6.3 (5.4) | 6.3 (5.6) | 5.0 (4.6) |

| GP, home | 2.1 (2.0) | 2.0 (2.3) | 1.3 (0.7) | 2.5 (2.6) | 2.2 (2.2) | 2.2 (2.5) |

| GP, telephone | 3.4 (4.2) | 3.2 (4.1) | 2.3 (1.9) | 3.6 (4.7) | 3.5 (4.8) | 2.9 (3.6) |

| Nurse, face to face | 4.1 (5.8) | 4.5 (6.1) | 2.9 (3.2) | 4.1 (5.7) | 4.6 (6.7) | 2.8 (3.2) |

| Nurse, telephone | 1.7 (1.5) | 1.9 (1.8) | 1.1 (0.4) | 1.9 (1.9) | 2.1 (2.1) | 1.5 (1.1) |

| Type of contact | 2010, mean (SD) | 2011, mean (SD) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC (n = 1311) | SC (n = 1776) | NC (n = 376) | PC (n = 1311) | SC (n = 1776) | NC (n = 376) | |

| GP, face to face | 232 (252) | 233 (292) | 0 (0) | 272 (311) | 249 (302) | 63 (146) |

| GP, home | 6 (40) | 6 (34) | 0 (0) | 6 (36) | 8 (45) | 2 (27) |

| GP, telephone | 17 (49) | 24 (73) | 0 (0) | 21 (56) | 25 (74) | 4 (18) |

| Nurse, face to face | 22 (55) | 15 (6) | 0 (0) | 27 (59) | 21 (50) | 5 (17) |

| Nurse, telephone | 0.2 (1.5) | 0.1 (0.8) | 0 (0) | 0.1 (1.2) | 0.2 (1.1) | < 0.1 (0.1) |

| Type of contact | 2012, mean (SD) | 2013, mean (SD) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC (n = 1311) | SC (n = 1776) | NC (n = 376) | PC (n = 1311) | SC (n = 1776) | NC (n = 376) | |

| GP, face to face | 277 (289) | 270 (301) | 163 (257) | 232 (231) | 229 (238) | 166 (192) |

| GP, home | 8 (43) | 8 (48) | 2 (15) | 9 (53) | 10 (51) | 6 (42) |

| GP, telephone | 31 (75) | 31 (75) | 17 (37) | 42 (92) | 39 (92) | 26 (64) |

| Nurse, face to face | 28 (61) | 27 (61) | 11 (28) | 28 (60) | 30 (69) | 14 (32) |

| Nurse, telephone | 0.2 (1.0) | 0.2 (1.1) | < 0.1 (0.3) | 0.2 (1.30 | 0.3 (1.6) | 0.1 (0.8) |

Around one-quarter of secondary care patients had psychiatric inpatient admissions to the local trust during the year prior to the index date (Table 11). This occurred for very few of the patients in the primary care or no care group (both of which by definition had zero use in the last 6 months of that year). Inpatient use fell slightly for the secondary care group in subsequent years, whereas the other two groups saw a slight increase. For those who were admitted, the number of days in hospital was always far higher in the secondary care group than in other two groups. Not surprisingly, the costs of inpatient care were by far the highest in the secondary care group.

| Type of contact | 2010 | 2011 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC (N = 1311) | SC (N = 1776) | NC (N = 376) | PC (N = 1311) | SC (N = 1776) | NC (N = 376) | |

| Inpatient, n (%) | 5 (0.4) | 420 (23.7) | 1 (0.3) | 54 (4.1) | 349 (19.7) | 16 (4.3) |

| Number of days, mean (SD) | 21.0 (21.9) | 95.7 (102.2) | 23.0 (0.0) | 40.2 (36.4) | 107.6 (118.4) | 28.6 (35.8) |

| Costs (£), mean (SD) | 47 (662) | 9737 (32,762) | 18 (290) | 342 (2842) | 9874 (34,021) | 222 (2166) |

| Community contacts, n (%) | 167 (12.7) | 1705 (96.0) | 16 (4.3) | 197 (15.0) | 1527 (86.0) | 42 (11.2) |

| Number of contacts, mean (SD) | 3.8 (5.3) | 26.6 (47.2) | 3.7 (4.1) | 8.3 (13.6) | 27.4 (50.1) | 9.5 (11.2) |

| Costs (£), mean (SD) | 68 (360) | 3418 (6799) | 23 (168) | 169 (876) | 3088 (6341) | 146 (664) |

| Psychotropic medication, n (%) | 135 (10.3) | 1421 (80.0) | 13 (3.5) | 137 (10.5) | 1330 (74.9) | 28 (7.5) |

| Cost (£), mean (SD) | 19 (355) | 719 (1588) | 5 (49) | 25 (229) | 763 (1669) | 9 (65) |

| Total mental health care costs (£), mean (SD) | 139 (995) | 14,529 (35,450) | 48 (476) | 550 (3677) | 14,092 (36,034) | 388 (2521) |

| Type of contact | 2012 | 2013 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC (N = 1311) | SC (N = 1776) | NC (N = 376) | PC (N = 1311) | SC (N = 1776) | NC (N = 376) | |

| Inpatient, n (%) | 58 (4.4) | 345 (19.4) | 20 (5.3) | 33 (2.5) | 252 (14.2) | 13 (3.5) |

| Number of days, mean (SD) | 53.4 (67.8) | 93.5 (108.1) | 43.7 (48.9) | 65.6 (99.0) | 100.6 (106.7) | 45.5 (53.6) |

| Costs (£), mean (SD) | 1007 (7013) | 8466 (30,445) | 1027 (5419) | 766 (7893) | 7212 (28,372) | 691 (5206) |

| Community contacts, n (%) | 265 (20.2) | 1395 (78.6) | 89 (23.7) | 283 (21.6) | 1336 (75.2) | 95 (25.3) |

| Number of contacts, mean (SD) | 12.1 (15.9) | 25.2 (38.7) | 14.1 (16.0) | 10.0 (12.9) | 19.7 (27.3) | 9.4 (10.7) |

| Costs (£), mean (SD) | 327 (1181) | 2550 (4893) | 432 (1326) | 278 (972) | 1878 (3407) | 307 (906) |

| Psychotropic medication, n (%) | 196 (15.0) | 1187 (66.80 | 54 (14.4) | 198 (15.1) | 1098 (61.8) | 66 (17.6) |

| Cost (£), mean (SD) | 63 (371) | 795 (1911) | 60 (374) | 52 (291) | 679 (1573) | 48 (298) |

| Total mental health care costs (£), mean (SD) | 1412 (7836) | 11,934 (31,870) | 1536 (6416) | 1096 (8253) | 9768 (29,220) | 1046 (5585) |

Almost all secondary care patients had community contacts during the year prior to the index date. The proportion then fell over time to around one-quarter. The primary care group initially had a higher rate of community contacts than the no care group, but this difference disappeared over time. As with inpatient care, the cost of community contacts was much greater in the secondary care group than in the other two groups. Finally, the table shows that the use and cost of psychotropic medication was greatest in the secondary care group.

Use of inpatient care for physical health reasons was similar for the primary care and secondary care groups (Table 12). The no care group had a lower rate of use, except in the final year. For those who were admitted, the number of days in hospital was not consistently different between the groups. As in the earlier analyses, the use of psychiatric inpatient care in other trusts was uncommon. In each year excluding 2013, around one-third of primary care and secondary care patients had outpatient contacts, and the number and cost of these was similar. The no care group generally made less use of outpatient care. Finally, and similar to the earlier analyses, about one-quarter of primary care and one-third of secondary care patients visited A&E in each year (except 2013).

| Type of contact | 2010 | 2011 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC (N = 1012) | SC (N = 1765) | NC (N = 239) | PC (N = 1012) | SC (N = 1765) | NC (N = 239) | |

| Physical inpatient, n (%) | 150 (14.8) | 309 (17.5) | 21 (8.8) | 161 (15.9) | 342 (19.4) | 23 (9.6) |

| Days in hospital, mean (SD) | 7.5 (16.8) | 10.1 (28.1) | 11.7 (35.5) | 6.1 (13.4) | 8.3 (18.5) | 5.7 (8.3) |

| Cost (£), mean (SD) | 647 (4072) | 1027 (7211) | 600 (6308) | 565 (3371) | 934 (5104) | 322 (1777) |

| Psychiatric inpatient, n (%) | 7 (0.7) | 36 (2.0) | 2 (0.8) | 14 (1.4) | 31 (1.8) | 5 (2.1) |

| Days in hospital, mean (SD) | 1.1 (0.8) | 4.1 (10.5) | 6.0 (7.8) | 7.4 (15.4) | 8.1 (18.1) | 12.6 (19.9) |

| Cost (£), mean (SD) | 3 (38) | 29 (555) | 18 (261) | 36 (682) | 50 (911) | 93 (1104) |

| Outpatient contacts, n (%) | 375 (37.1) | 605 (34.3) | 50 (20.9) | 382 (37.7) | 625 (35.4) | 62 (25.9) |

| Number of contacts, mean (SD) | 4.0 (5.1) | 4.1 (4.8) | 2.8 (2.9) | 4.1 (4.7) | 4.4 (5.3) | 2.9 (2.8) |

| Cost (£), mean (SD) | 163 (402) | 152 (372) | 64 (192) | 169 (381) | 170 (411) | 81 (204) |

| A&E visits, n (%) | 229 (22.6) | 647 (36.7) | 60 (25.1) | 266 (26.3) | 600 (34.0) | 63 (26.4) |

| Number of visits, mean (SD) | 1.9 (2.0) | 2.7 (3.8) | 1.9 (2.6) | 1.8 (1.8) | 2.9 (6.1) | 2.0 (1.7) |

| Cost (£), mean (SD) | 52 (147) | 115 (309) | 56 (183) | 57 (143) | 115 (451) | 62 (146) |

| Type of contact | 2012 | 2013 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC (n = 1012) | SC (n = 1765) | NC (n = 239) | PC (n = 1012) | SC (n = 1775) | NC (n = 239) | |

| Physical inpatient, n (%) | 150 (14.8) | 311 (17.6) | 27 (11.3) | 66 (6.5) | 115 (6.5) | 14 (5.9) |

| Days in hospital, mean (SD) | 9.3 (20.3) | 8.2 (17.1) | 9.5 (17.7) | 4.3 (7.1) | 5.0 (8.4) | 4.2 (5.0) |

| Cost (£), mean (SD) | 800 (4939) | 845 (4568) | 624 (3839) | 163 (1223) | 190 (1441) | 144 (898) |

| Psychiatric inpatient, n (%) | 9 (0.9) | 21 (1.2) | 9 (3.8) | 2 (0.2) | 11 (0.6) | 2 (0.8) |

| Days in hospital, mean (SD) | 4.7 (7.5) | 6.6 (12.0) | 3.3 (4.8) | 1.0 (0.7) | 1.7 (1.5) | 1.0 (0.7) |

| Cost (£), mean (SD) | 15 (282) | 28 (516) | 44 (381) | 1 (17) | 4 (61) | 3 (36) |

| Outpatient contacts, n (%) | 391 (38.6) | 634 (35.9) | 73 (30.5) | 213 (21.0) | 295 (16.7) | 29 (12.1) |

| Number of contacts, mean (SD) | 4.4 (5.3) | 4.1 (4.9) | 3.3 (3.1) | 1.9 (1.6) | 2.1 (2.1) | 2.0 (1.7) |

| Cost (£), mean (SD) | 185 (429) | 162 (385) | 109 (248) | 43 (115) | 38 (125) | 26 (96) |

| A&E visits, n (%) | 288 (28.5) | 596 (33.8) | 81 (33.9) | 92 (9.0) | 232 (13.1) | 23 (9.6) |

| Number of visits, mean (SD) | 1.9 (1.9) | 2.8 (4.8) | 2.7 (3.6) | 1.3 (0.5) | 1.9 (3.2) | 1.5 (0.9) |

| Cost (£), mean (SD) | 65 (155) | 111 (362) | 106 (288) | 14 (48) | 30 (155) | 17 (63) |

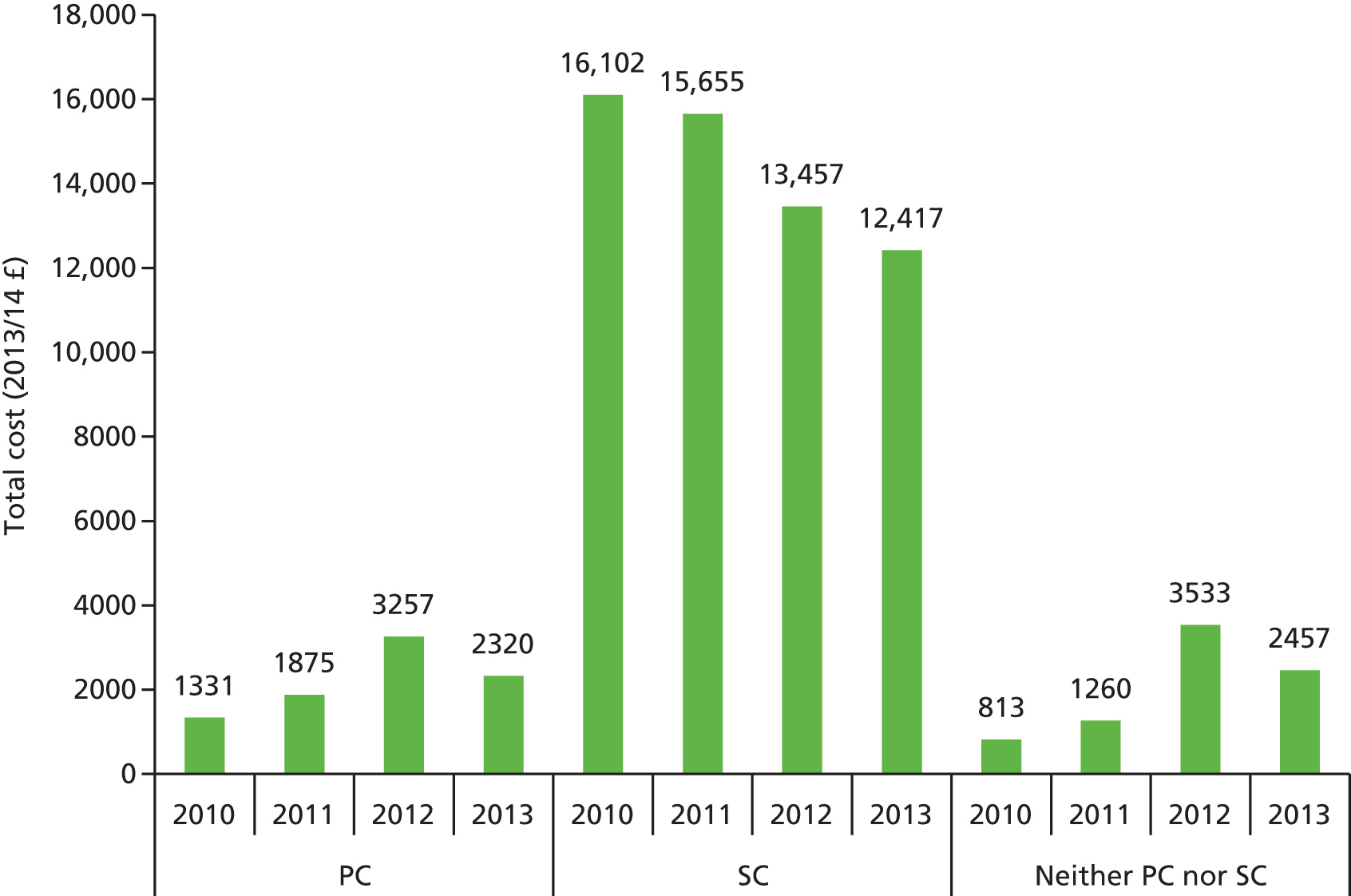

The mean total cost of the above services reveals that those in the primary care and neither primary nor secondary care groups have substantially lower costs than those in the secondary care group (Figure 3). The mean costs for the combined follow-up period (2011–13) were £7100 (SD £18,796) for the primary care group, £39,438 (SD £81,666) for the secondary care group, and £6870 (SD £13,655) for the neither primary nor secondary care group.

FIGURE 3.

Mean costs per year by service use group (2013/14 £s). IAPT, Improving Access to Psychological Therapies; PC, primary care; SC, secondary care.

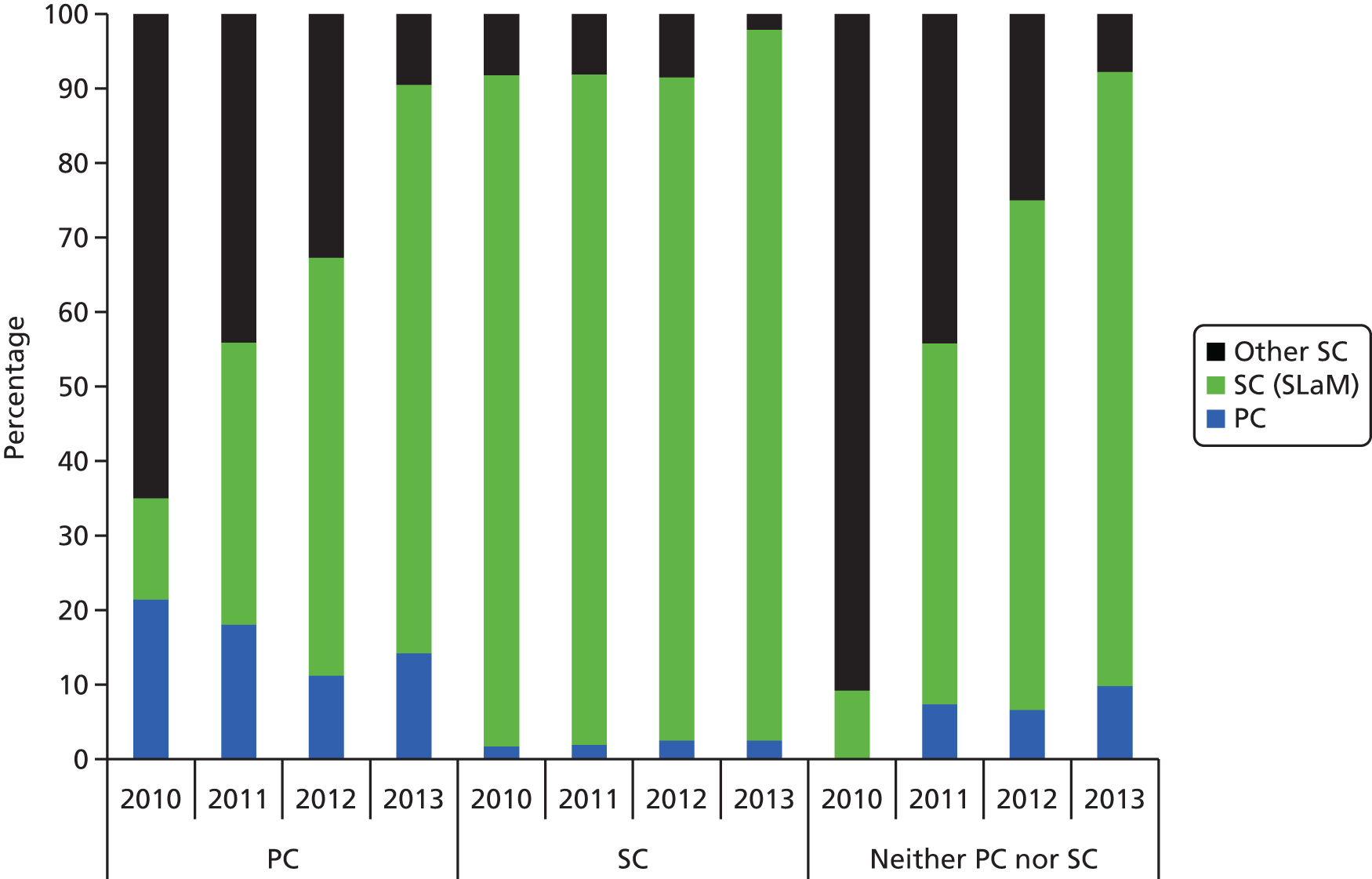

The distribution of costs shows that secondary mental health care accounts for an increasing amount of cost in the groups defined on the index date as being in primary care or neither primary nor secondary care (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Distribution of service costs by service use group. PC, primary care; SC, secondary care.

Regression analyses

The previous section has demonstrated that those discharged to primary care or those receiving predominantly primary care up to the index date have substantially lower mental health care costs than those in secondary care. This is hardly surprising but we have also seen that there are clear differences between the samples in terms of demographic and clinical characteristics. It is quite possible that these characteristics exert an impact on cost regardless of where care is located. In order to determine the specific impact of location of care on subsequent health-care costs with these characteristics held constant, a series of multiple regression models were developed. These took primary care costs, secondary mental health care costs and total costs as dependent variables over the follow-up period of January 2011 to October 2013. These three groups of models were further refined by using the two aforementioned definitions of location as independent variables (i.e. group membership defined by discharge status and by service use). Other independent variables included demographic details (age, age squared, sex, ethnicity), previous history of key events (forensic use, violence, antipsychotic, non-compliance, physical health problems), clinical data from primary care (blood pressure, hypertension, thyroid-stimulating hormone test, asthma, depression, diabetes mellitus) and time since the first primary care record of SMI. Service costs from 2010 (primary care, secondary mental health care from SLaM, outpatient care from other trusts, A&E costs, inpatient costs) not corresponding to the follow-up measure were also included (i.e. for analysis of primary care costs we did not include 2010 primary care costs). In further analyses, reported in Appendix 1, all 2010 costs were included as were HoNOS scores. (HoNOS scores were missing for a large number of participants and it was not felt appropriate to impute these. The use of previous costs may ‘mask’ some of the impacts of other variables.) The analyses were exploratory rather than being hypothesis driven and the main criteria for background variables to be included were that they had to be ‘positive’ for at least 5% of the sample.

General practice was entered as a clustering variable in each model with robust standard errors generated. Cost data are usually skewed and so generalised linear models with gamma distributions and log links were used. The exponentials of the coefficients were extracted to indicate the proportional impact on cost of a one-unit difference in the independent variables. Although presenting marginal effects would be an alternative way of enabling interpretation (by focusing on costs rather than log costs), we feel that that current method, whereby a proportional impact on cost is shown, is also valid and is our preferred approach.

Analysis of primary care costs

Primary care costs were positively related to prior general medical outpatient costs, physical inpatient costs from other providers, A&E costs, age, use of antipsychotic medication, affective disorder presence, hypertension, asthma, depression and diabetes mellitus (Table 13). Lower costs were linked to prior psychiatric inpatient costs from SLaM, being male, being from a black and minority ethnic group, treatment non-compliance, having had blood pressure taken prior to the index date and having had a thyroid-stimulating test.

| Variable | Exp B | Robust SE | z-statistic | p-value | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower limit | Upper limit | |||||

| Discharged to primary care | 1.0303 | 0.0389 | 0.79 | 0.429 | 0.9568 | 1.1095 |

| Community contact cost 2010a | 1.0000 | 0.0002 | –0.13 | 0.894 | 0.9996 | 1.0004 |

| Inpatient cost 2010a | 0.9996 | 0.0001 | –7.19 | < 0.001 | 0.9995 | 0.9997 |

| Drug cost 2010a | 1.0006 | 0.0011 | 0.49 | 0.623 | 0.9983 | 1.0028 |

| Physical inpatient cost 2010a | 1.0004 | 0.0002 | 1.97 | 0.048 | 1.0000 | 1.0009 |

| Psychiatric inpatient cost 2010a | 0.9973 | 0.0016 | –1.72 | 0.085 | 0.9943 | 1.0004 |

| Outpatient cost 2010a | 1.0367 | 0.0066 | 5.66 | < 0.001 | 1.0239 | 1.0497 |

| A&E cost 2010a | 1.0243 | 0.0095 | 2.60 | 0.009 | 1.0059 | 1.0430 |

| Age | 1.0194 | 0.0069 | 2.82 | 0.005 | 1.0058 | 1.0331 |

| Age squared | 0.9999 | 0.0001 | –2.00 | 0.046 | 0.9997 | 1.0000 |

| Male | 0.7652 | 0.0246 | –8.32 | < 0.001 | 0.7184 | 0.8150 |

| Black and minority ethnic | 0.9039 | 0.0306 | –2.99 | 0.003 | 0.8458 | 0.9659 |

| History of violence | 1.0034 | 0.0408 | 0.08 | 0.933 | 0.9266 | 1.0866 |

| Physical health problems | 1.0818 | 0.0476 | 1.79 | 0.074 | 0.9924 | 1.1793 |

| History of non-compliance | 0.9025 | 0.0309 | –3.00 | 0.003 | 0.8440 | 0.9651 |

| Use of antipsychotic medication | 1.2828 | 0.0739 | 4.32 | < 0.001 | 1.1458 | 1.4362 |

| Forensic history | 1.0205 | 0.0594 | 0.35 | 0.728 | 0.9104 | 1.1438 |

| Diagnosis of schizophrenia | 1.0204 | 0.0512 | 0.40 | 0.688 | 0.9248 | 1.1258 |

| Diagnosis of affective disorder | 1.1924 | 0.0616 | 3.40 | 0.001 | 1.0775 | 1.3194 |

| Blood pressure taken | 0.3833 | 0.0417 | –8.82 | < 0.001 | 0.3098 | 0.4743 |

| Hypertension | 1.2022 | 0.0512 | 4.33 | < 0.001 | 1.1060 | 1.3068 |

| TSH test | 0.8582 | 0.0407 | –3.23 | 0.001 | 0.7820 | 0.9418 |

| Asthma | 1.2369 | 0.0630 | 4.18 | < 0.001 | 1.1194 | 1.3667 |

| Depression | 1.2427 | 0.1059 | 2.55 | 0.011 | 1.0516 | 1.4686 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.2336 | 0.0486 | 5.33 | < 0.001 | 1.1420 | 1.3325 |

| Days since first SMI diagnosis | 1.0000 | 0.0000 | 1.41 | 0.158 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| Constant term | 445.6495 | 102.4139 | 26.54 | < 0.001 | 284.0406 | 699.2081 |

When groups were defined by service use, there was a negative impact of receiving neither primary nor secondary care on subsequent primary care costs (Table 14). Costs were positively associated with prior general medical outpatient costs, A&E costs, age, use of antipsychotic medication, physical health problems, presence of hypertension, affective disorders, asthma, depression and diabetes mellitus. Lower costs were associated with prior psychiatric inpatient costs, being male, being from a black and minority ethnic group, history of non-compliance with treatment, having had blood pressure taken and receipt of a thyroid-stimulating test.

| Variable | Exp B | Robust SE | z-statistic | p-value | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower limit | Upper limit | |||||

| PC | 1.0459 | 0.0410 | 1.14 | 0.253 | 0.9684 | 1.1295 |

| Neither PC nor SC | 0.6942 | 0.0470 | –5.39 | < 0.001 | 0.6079 | 0.7927 |

| Community contact cost 2010a | 0.9999 | 0.0002 | –0.55 | 0.584 | 0.9995 | 1.0003 |

| Inpatient cost 2010a | 0.9996 | 0.0001 | –7.74 | < 0.001 | 0.9994 | 0.9997 |

| Drug cost 2010a | 1.0003 | 0.0012 | 0.25 | 0.799 | 0.9980 | 1.0026 |

| Physical inpatient cost 2010a | 1.0004 | 0.0002 | 1.66 | 0.098 | 0.9999 | 1.0008 |

| Psychiatric inpatient cost 2010a | 0.9970 | 0.0015 | –1.98 | 0.048 | 0.9939 | 1.0000 |

| Outpatient cost 2010a | 1.0326 | 0.0058 | 5.69 | < 0.001 | 1.0213 | 1.0441 |

| A&E cost 2010a | 1.0267 | 0.0091 | 2.98 | 0.003 | 1.0091 | 1.0446 |

| Age | 1.0213 | 0.0064 | 3.34 | 0.001 | 1.0088 | 1.0340 |

| Age squared | 0.9999 | 0.0001 | –2.38 | 0.018 | 0.9997 | 1.0000 |

| Male | 0.7664 | 0.0235 | –8.67 | < 0.001 | 0.7217 | 0.8140 |

| Black and minority ethnic | 0.9248 | 0.0278 | –2.60 | 0.009 | 0.8719 | 0.9808 |

| History of violence | 0.9917 | 0.0414 | –0.20 | 0.842 | 0.9139 | 1.0762 |

| Physical health problems | 1.1012 | 0.0513 | 2.07 | 0.038 | 1.0051 | 1.2065 |

| History of non-compliance | 0.9048 | 0.0288 | –3.14 | 0.002 | 0.8501 | 0.9631 |

| Use of antipsychotic medication | 1.2878 | 0.0655 | 4.97 | < 0.001 | 1.1656 | 1.4229 |

| Forensic history | 1.0242 | 0.0590 | 0.42 | 0.677 | 0.9149 | 1.1466 |

| Diagnosis of schizophrenia | 0.9800 | 0.0504 | –0.39 | 0.695 | 0.8861 | 1.0839 |

| Diagnosis of affective disorder | 1.1559 | 0.0589 | 2.84 | 0.004 | 1.0461 | 1.2772 |

| Blood pressure taken | 0.3877 | 0.0430 | –8.54 | < 0.001 | 0.3120 | 0.4820 |

| Hypertension | 1.1820 | 0.0482 | 4.10 | < 0.001 | 1.0913 | 1.2803 |

| TSH test | 0.8507 | 0.0398 | –3.45 | < 0.001 | 0.7761 | 0.9324 |

| Asthma | 1.2183 | 0.0594 | 4.05 | < 0.001 | 1.1072 | 1.3405 |

| Depression | 1.2088 | 0.0973 | 2.36 | 0.018 | 1.0324 | 1.4154 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.2091 | 0.0445 | 5.16 | < 0.001 | 1.1249 | 1.2995 |

| Days since first SMI diagnosis | 1.0000 | 0.0000 | 1.28 | 0.199 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| Constant term | 435.2254 | 89.8651 | 29.43 | < 0.001 | 290.3746 | 652.3337 |

Analysis of mental health care costs

Those discharged to primary care had mental health care costs that were 54% lower than for those remaining in secondary care (Table 15). Costs were positively associated with history of violence, physical health problems, treatment non-compliance, forensic care, antipsychotics, presence of schizophrenia and affective disorder hypertension. Costs were lower for those with higher previous primary care costs.

| Variable | Exp B | Robust SE | z-statistic | p-value | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower limit | Upper limit | |||||

| Discharged to primary care | 0.4627 | 0.0488 | –7.31 | < 0.001 | 0.3764 | 0.5689 |

| Primary care cost 2010a | 0.9798 | 0.0097 | –2.06 | 0.040 | 0.9609 | 0.9990 |

| Physical inpatient cost 2010a | 0.9992 | 0.0009 | –0.82 | 0.411 | 0.9974 | 1.0011 |

| Psychiatric inpatient cost 2010a | 0.9999 | 0.0035 | –0.03 | 0.974 | 0.9931 | 1.0067 |

| Outpatient cost 2010a | 0.9937 | 0.0106 | –0.59 | 0.554 | 0.9732 | 1.0147 |

| A&E cost 2010a | 1.0785 | 0.0275 | 2.96 | 0.003 | 1.0259 | 1.1337 |

| Age | 0.9843 | 0.0177 | –0.88 | 0.378 | 0.9502 | 1.0196 |

| Age squared | 1.0001 | 0.0002 | 0.75 | 0.456 | 0.9998 | 1.0005 |

| Male | 0.9808 | 0.0991 | –0.19 | 0.848 | 0.8045 | 1.1957 |

| Black and minority ethnic | 0.8721 | 0.1095 | –1.09 | 0.276 | 0.6819 | 1.1154 |

| History of violence | 3.2134 | 0.3157 | 11.88 | < 0.001 | 2.6506 | 3.8958 |

| Physical health problems | 1.9090 | 0.1885 | 6.55 | < 0.001 | 1.5731 | 2.3166 |

| History of non-compliance | 2.9694 | 0.3508 | 9.21 | < 0.001 | 2.3556 | 3.7430 |

| Use of antipsychotic medication | 2.0772 | 0.3912 | 3.86 | < 0.001 | 1.4314 | 2.9999 |

| Forensic history | 1.8070 | 0.2284 | 4.68 | < 0.001 | 1.4105 | 2.3151 |

| Diagnosis of schizophrenia | 3.2759 | 0.4816 | 8.07 | < 0.001 | 2.4557 | 4.3699 |

| Diagnosis of affective disorder | 2.4593 | 0.3408 | 6.49 | < 0.001 | 1.8744 | 3.2268 |

| Blood pressure taken | 1.0166 | 0.2112 | 0.08 | 0.937 | 0.6766 | 1.5275 |

| Hypertension | 1.3993 | 0.1692 | 2.78 | 0.005 | 1.1041 | 1.7735 |

| TSH test | 0.8491 | 0.1193 | –1.16 | 0.244 | 0.6448 | 1.1183 |

| Asthma | 0.9283 | 0.1298 | –0.53 | 0.595 | 0.7057 | 1.2210 |

| Depression | 1.3422 | 0.4201 | 0.94 | 0.347 | 0.7268 | 2.4788 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.7516 | 0.1154 | –1.86 | 0.063 | 0.5563 | 1.0155 |

| Days since first SMI diagnosis | 1.0000 | 0.0000 | 1.25 | 0.211 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| Constant term | 36.9255 | 20.5668 | 6.48 | < 0.001 | 12.3943 | 110.0096 |

With the service use definition of groups, it was found that costs for those in secondary care were significantly higher than for the other two groups (Table 16). Costs of mental health care were positively associated with prior A&E costs, history of violence, treatment non-compliance, physical health problems, antipsychotic use, forensic services, schizophrenia, affective disorders and hypertension. Costs were negatively associated with prior psychiatric inpatient costs from other providers and the presence of diabetes mellitus.

| Variable | Exp B | Robust SE | z-statistic | p-value | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower limit | Upper limit | |||||

| PC | 0.2821 | 0.0325 | –10.99 | < 0.001 | 0.2251 | 0.3536 |

| Neither PC nor SC | 0.4165 | 0.0642 | –5.69 | < 0.001 | 0.3079 | 0.5633 |

| Primary care cost 2010a | 0.9777 | 0.0130 | –1.69 | 0.091 | 0.9524 | 1.0036 |

| Physical inpatient cost 2010a | 0.9987 | 0.0007 | –1.73 | 0.083 | 0.9973 | 1.0002 |

| Psychiatric inpatient cost 2010a | 0.9934 | 0.0029 | –2.27 | 0.023 | 0.9878 | 0.9991 |

| Outpatient cost 2010a | 0.9946 | 0.0101 | –0.54 | 0.589 | 0.9751 | 1.0145 |

| A&E cost 2010a | 1.0749 | 0.0253 | 3.07 | 0.002 | 1.0265 | 1.1257 |

| Age | 0.9908 | 0.0177 | –0.52 | 0.604 | 0.9567 | 1.0261 |

| Age squared | 1.0001 | 0.0002 | 0.42 | 0.675 | 0.9997 | 1.0005 |

| Male | 1.0455 | 0.1069 | 0.44 | 0.663 | 0.8557 | 1.2774 |

| Black and minority ethnic | 0.9280 | 0.0912 | –0.76 | 0.447 | 0.7654 | 1.1252 |

| History of violence | 2.8554 | 0.2868 | 10.44 | < 0.001 | 2.3450 | 3.4768 |

| Physical health problems | 2.0691 | 0.2388 | 6.30 | < 0.001 | 1.6503 | 2.5943 |

| History of non-compliance | 2.6492 | 0.3198 | 8.07 | < 0.001 | 2.0911 | 3.3563 |

| Use of antipsychotic medication | 2.2194 | 0.3725 | 4.75 | < 0.001 | 1.5973 | 3.0839 |

| Forensic history | 1.6347 | 0.2160 | 3.72 | < 0.001 | 1.2618 | 2.1179 |

| Diagnosis of schizophrenia | 2.5589 | 0.4311 | 5.58 | < 0.001 | 1.8393 | 3.5600 |

| Diagnosis of affective disorder | 1.8650 | 0.2857 | 4.07 | < 0.001 | 1.3813 | 2.5181 |

| Blood pressure taken | 0.9967 | 0.2051 | –0.02 | 0.987 | 0.6658 | 1.4918 |

| Hypertension | 1.4083 | 0.1656 | 2.91 | 0.004 | 1.1184 | 1.7733 |

| TSH test | 0.8016 | 0.1015 | –1.75 | 0.081 | 0.6254 | 1.0275 |

| Asthma | 0.9265 | 0.1329 | –0.53 | 0.594 | 0.6994 | 1.2273 |

| Depression | 1.4861 | 0.4147 | 1.42 | 0.156 | 0.8600 | 2.5681 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.6585 | 0.1026 | –2.68 | 0.007 | 0.4853 | 0.8936 |

| Days since first SMI diagnosis | 1.0000 | 0.0000 | 1.03 | 0.304 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| Constant term | 41.7450 | 20.2958 | 7.68 | < 0.001 | 16.0976 | 108.2547 |

Analysis of total care costs

Total health costs were significantly lower for those discharged to primary care (Table 17). Costs were positively associated with a history of violence, physical health problems, non-compliance, a forensic history, use of antipsychotics, presence of schizophrenia or affective disorders, and hypertension. Lower costs were associated with having had blood pressure taken.

| Variable | Exp B | Robust SE | z-statistic | p-value | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

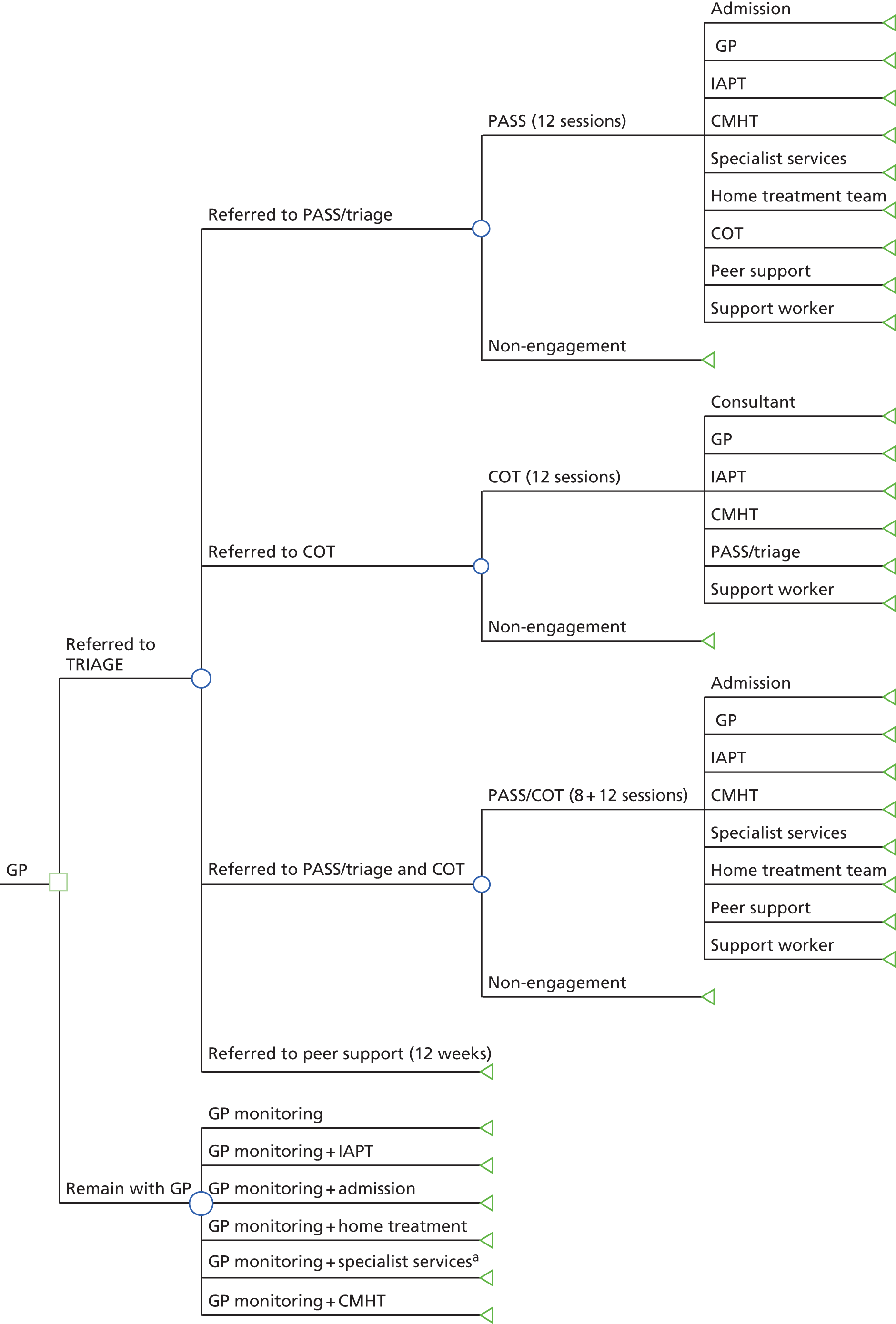

| Lower limit | Upper limit | |||||