Notes

Article history

The research reported here is the product of a HS&DR Evidence Synthesis Centre, contracted to provide rapid evidence syntheses on issues of relevance to the health service, and to inform future HS&DR calls for new research around identified gaps in evidence. Other reviews by the Evidence Synthesis Centre are also available in the HS&DR journal. The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 13/05/12. The contractual start date was in October 2015. The final report began editorial review in May 2016 and was accepted for publication in September 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Baxter et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease, with latent infection estimated to affect at > 2 billion people worldwide. 1 Although approximately 95% of cases of TB occur in developing countries, the disease also exists in low-incidence countries, including the UK. 2 TB is known to disproportionately affect specific population groups, including socially disadvantaged people, immigrants and those with complex lifestyles (such as users of drugs or excessive alcohol). 3 Although levels of TB may be low in the UK, TB control strategies, including the use of contact-tracing investigations, remain important to control the level of the disease.

The priority of TB disease control programmes is the early identification and successful treatment of people with active infection to avoid further transmission. Strategies for TB control also include the efficient detection and treatment of latent infection to avoid further transmission. Approaches to identifying individuals with either active or latent infection include the screening of high-risk groups, active case finding and contact tracing. 4

The transmission of TB occurs via the inhalation of airborne particles from an infected person. 1 The tracing and screening of people who have had contact with an active case of TB is, therefore, a critical component in the control of transmission and the early detection of infection. 5 Contact tracing/investigation has three main objectives:6 first, to identify additional cases of active TB among contacts (to initiate treatment and avoid further transmission); second, to identify contacts with latent TB infection to offer them preventative treatment (to prevent their progression to active TB infection); and, third, to identify and treat the source of an outbreak. Contacts who show evidence of latent TB infection and who complete a course of prophylactic treatment may reduce their risk of progressing to active TB disease by 60–70%. 7 Investigation to identify contacts of an individual with active TB disease is, therefore, considered a key tool in the control of TB, to enable the early detection of infection and disease and to prevent secondary cases. 8

Research questions

-

What is the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of specific interventions designed to improve TB contact tracing (such as use of community outreach workers/cultural facilitators, specific interviewing techniques, home/hostel/workplace visits, home/hostel/workplace screening and follow up of contacts) in specific population groups (such as migrants/homeless people)?

-

What is the acceptability, feasibility, appropriateness and meaningfulness of specific interventions designed to improve TB contact tracing in these population groups?

-

What are the barriers to, and facilitators of, delivery or uptake of contact tracing in these population groups?

-

What are the elements of the contact investigation pathway from interventions to impact, for TB contact tracing in wider population groups?

-

How might evidence from interventions for wider populations be applied to TB contact tracing in specific population groups, including the similarities and differences, and what elements of the pathway may be important for feasible, applicable and effective interventions?

Chapter 2 Review methods

The review used a two-stage process. We carried out initial mapping work to develop and refine the scope of the work. This was followed by two linked subreviews to identify and synthesise the most directly relevant evidence in this field.

Initial mapping work

An initial phase of mapping was used to broadly describe the published literature on contact tracing for TB in specific population groups, particularly that relevant to the NHS and similar health-care systems. We aimed to examine the potential volume of literature on contact tracing in specific populations to see if a full review of this evidence would be viable and provide potentially useful information. We used the term ‘specific population groups’ to mean any subgroups within whole populations (individuals or groups) who may be at higher risk of TB infection. This includes people described as ‘hard to reach’, those with drug or alcohol problems, homeless people, asylum seekers, immigrants, refugees, people from ethnic minorities and prisoners. The mapping exercise was intended to guide decisions regarding the focus of further review work in this area.

Mapping review search strategy

Targeted searches of key databases were undertaken using search terms in previous reviews, supplemented by the review protocol, and terms harvested from relevant evidence. We applied broad inclusion criteria and did not seek to distinguish between different potential purposes of contact tracing in TB prevention and management during the searching process or during the later stages of the review. The search focused on terms relating to people with TB, with terms relating to the intervention (contact tracing). Although we were primarily interested in finding literature on specific populations who may be at greater risk of TB, we did not use any search terms for particular subgroups. We felt that an a priori decision on terms relating to specific populations might have led to key groups being missed. Therefore, we used general population terms in the mapping review, with the aim of sifting out literature relating to subgroups from the retrieved citations.

The terms relating to contact tracing were harvested from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence evidence review on TB9 and other relevant evidence. The search was limited to studies in the English language and in human populations, as a result of the restricted time scale for this work. Literature published between 2000 and 2015 was retrieved. It was expected that any significant earlier work would be included via review studies. The databases searched in October 2015 were MEDLINE via Ovid SP, EMBASE via Ovid SP, EconLit via Ovid SP, PsycINFO via Ovid SP, Social Policy and Practice via Ovid SP, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature via EBSCOhost, Science and Social Science Citation Indices via Web of Science and The Cochrane Library via Wiley Online Library. We screened reference lists of included studies for relevant grey literature, and requested potentially relevant literature from topic advisors. The search terms used are provided in Appendix 1.

Mapping review sifting and identification of relevant literature

The search results were exported to a reference management database (EndNote version 7, Thomson Reuters, CA, USA) and the software deduplication process was applied. The database of citations was screened at title and abstract (when available) level initially by one reviewer, and blind second screening of the complete database was shared between two further reviewers. Potentially relevant studies on contact tracing were identified.

Full review methods

We incorporated the results of the mapping review into one of two subreviews. The full review encompassed a subreview of contact tracing in specific populations (including and extending the literature found in the mapping work) and a subreview of TB contact tracing in wider populations.

Search strategy

We re-examined the citations retrieved in the mapping review searches, and also extended the date of inclusion to 1995 onwards, in a second search in March 2016, thus examining over 20 years of research. In addition to conducting topic-based searching of electronic databases, we screened the reference lists of included studies.

Sifting and identification of relevant literature

The search results were exported to EndNote version 7 and the software deduplication process was applied. The database of citations was screened at title and abstract (when available) level initially by one reviewer, and blind second screening of the complete database was shared between two further reviewers, with approximately 95% agreement. Potentially relevant studies were coded as either ‘specific populations’ or ‘wider populations’.

Following this screening, all coded records were re-examined to identify literature relating to specific population groups (such as those described as hard to reach, people from ethnic minorities, substance abusers, homeless people, migrants, drug users or prisoners) versus papers that related to wider populations or that included wider populations as well as particular subgroups. We identified and excluded work carried out in countries of less relevance to the UK NHS [countries that are not members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)].

Data extraction

We used a data extraction form developed from the team’s previous experience; this was piloted on several studies before the final version was established. Data in the included studies were systematically extracted to the form, encompassing first author and date, type of document, study design, country of origin, population, research methods, staff involved, measures used, results/data and main conclusions. See Appendices 2 and 3 for the completed data extraction tables.

Quality appraisal

We planned to select appropriate tools for quality appraisal based on the study designs that we found in the included literature. These included checklists such as those developed by Cochrane and the Critical Skills Appraisal Programme. 10,11 The literature that we found, however, was more limited than we had expected. The studies tended to be descriptive reports of contact investigations, either around the time that the investigation was carried out, or at a later point, when records completed at the time were retrospectively examined by the research team. This literature did not use the evaluative experimental or observational designs that are typically included in systematic reviews, and was not suitable for appraisal using established checklists. Criteria that might be used to assess quality, such as sample size, were not indicators of robustness, as a larger number investigated was not representative of a better-quality investigation (indeed, the reverse might be true). Other aspects that may be indicators of quality, such as sampling strategy or robustness of outcome measures, were also not applicable to this literature, which was dominated by descriptions of what happened during investigations with complex outcomes. The studies that we categorised as ‘qualitative’ referred to interviews with cases and contacts; however, qualitative data were not always provided. Although grey literature is typically considered to be of lower quality than peer-reviewed published papers, many of the reports and guidelines we identified were based on reviews of the literature (some of which were robust systematic reviews) and, therefore, was considered to not necessarily be weaker than the published studies. In the following synthesis, however, we have separated the reports and guidelines from the other studies, by describing them last in each section.

Given these assessment challenges, we considered whether or not and how to attempt to grade the identified literature on the basis of quality. We reached the conclusion that a quality criteria checklist approach was not feasible, as there were no clear indicators of quality and study methods were diverse. We therefore adopted an approach to quality appraisal whereby we highlighted those few studies of a stronger design, and any issues of particular concern during the narrative synthesis.

Approach to synthesis

The literature was divided into papers that focused on specific populations versus those that had a wider population focus; these groups of papers formed two subreviews. The content of the literature in each subreview was categorised by characteristics such as country and type of intervention. Narrative synthesis methods were used to provide an overview of the included studies within the two subreviews. The narrative included the exploration of similarities and differences between the subreviews, and highlighted data of importance for TB contact tracing in specific populations. In addition to the narrative, a logic model diagram was used to summarise the findings across the two subreviews. The purpose of the model was to integrate data from both reviews in the form of a pathway for contact-tracing investigations. The logic model diagram outlines key elements of the pathway, from initial decision-making regarding investigations to outcomes and impacts.

Inclusion criteria

-

The initial focus of the review was TB contact tracing in specific population groups; however, following the mapping phase of the work, we broadened the scope to also include TB contact tracing in any population. We considered ‘specific population groups’ as encompassing any subgroups within whole populations, including individuals or groups who may be at a higher risk of TB infection. This includes people described as ‘hard to reach’, those with drug or alcohol problems, homeless people, asylum seekers, immigrants, refugees, people from ethnic minorities and prisoners.

-

We defined contact tracing as any intervention or procedure for identifying and evaluating individuals who have been exposed to someone with active TB. We adopted broad criteria for the types of studies of interest, including those that aimed to evaluate outcomes following contact tracing investigations and also those describing or exploring the delivery of investigations. We aimed to focus on contact-tracing activities rather than screening, active case finding or other interventions to reduce infection and/or transmission. We recognised, however, that these distinctions may not be clear cut, and there may be overlap between these purposes. We therefore included any papers that included reference to contact tracing as part of a TB control strategy.

-

In relation to comparators, we included studies with any comparator and studies with no comparator. As we intended to produce an inclusive review, studies of any design, including experimental, observational, cross-sectional, qualitative and reviews, were eligible, together with grey literature in the form of reports and guidelines.

-

We included studies that reported any outcome related to contact-tracing activity.

Exclusion criteria

-

We excluded research that was published prior to 1995.

-

We excluded studies carried out in countries that are not members of the OECD. We intended to focus the review on low-TB-incidence countries that are most applicable to the UK.

-

We excluded studies that comprised discussion or opinion and those that did not relate to specific investigations.

-

We excluded conference abstracts, theses, letters to the editor and other commentaries.

Chapter 3 Results of the review

Results of the mapping work

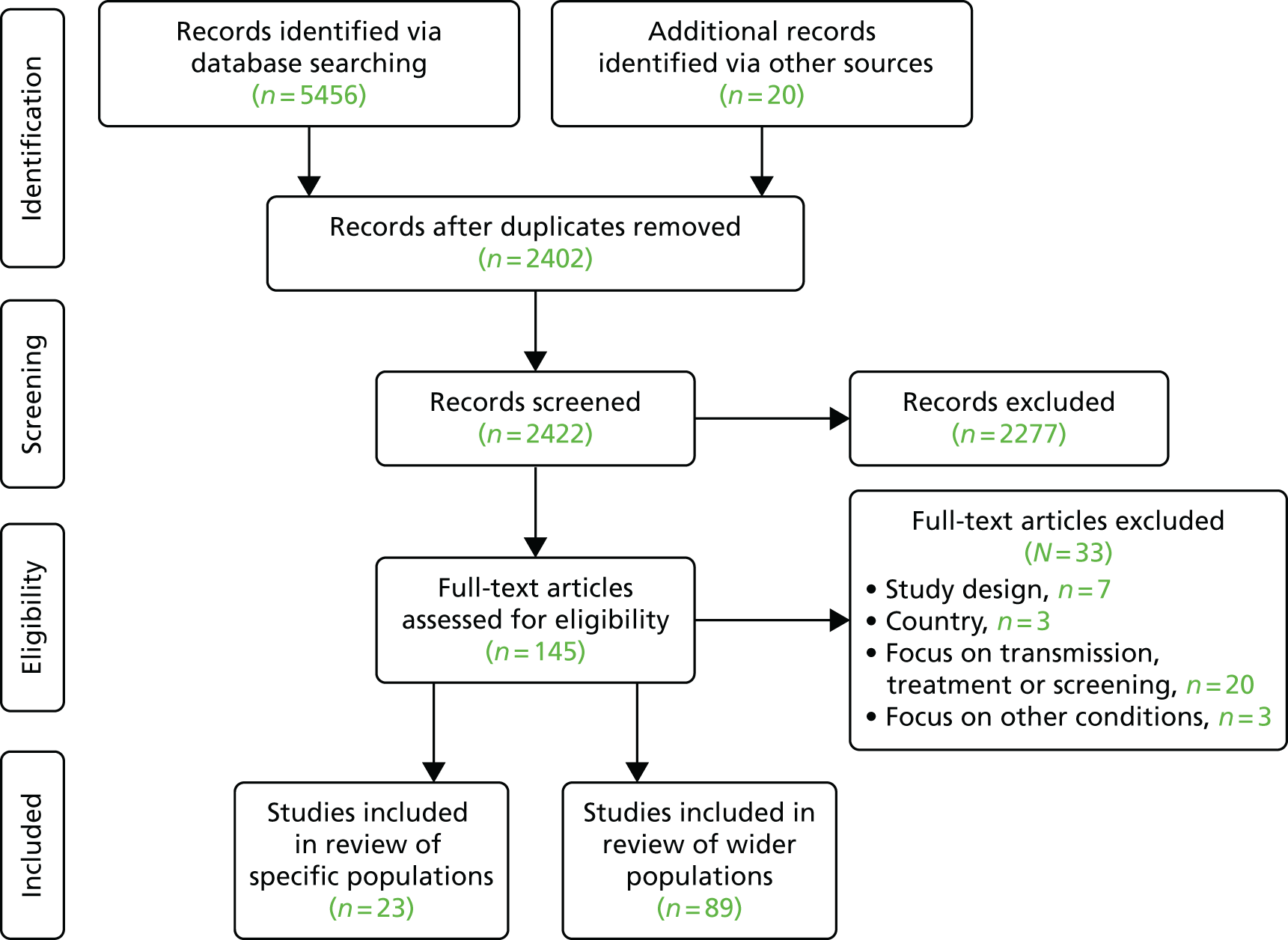

Searching the electronic databases identified 13 articles of relevance to a review of contact tracing in specific populations. Figure 1 provides an overview of the results of the mapping work.

FIGURE 1.

Results of the mapping work.

The mapping exercise indicated that there was unlikely to be a large number of research studies on contact tracing in specific populations and that the data identified were likely to derive from poor-quality studies. It was anticipated that the conclusions that might be drawn from a full review of this literature would be restricted by the limited numbers and quality of the available research studies. Therefore, following the mapping exercise, we proposed three potential options for further review work. These were presented for discussion with local and national policy-makers, topic experts, infectious disease and public health practitioners, specialists in the field and representatives of the review commissioners (the National Institute for Health Research Health Services and Delivery Research programme).

-

Widen the population inclusion criteria to TB contact tracing in any population (not just specific populations) and explore, in particular, implementation processes and feasibility. The mapping work indicated that there would be a substantive number of studies available to synthesise.

-

Examine contact tracing in specific populations for other conditions, drawing on data from existing systematic reviews. The other conditions included would need to be carefully considered to ensure that findings from these research studies would be applicable to TB, with careful documentation regarding the criteria for judging applicability. The review would aim to examine what may be learned from tracing in specific populations in other conditions and applied to contact tracing in TB.

-

The mapping exercise indicated that social network approaches, and use of community workers, may be promising approaches to TB contact tracing in specific populations. Further work could comprise a systematic review of these interventions in relevant conditions.

The three options presented seemed to offer different potential for adding to the knowledge base. The first option would have the advantage of keeping the focus on the condition and using instrumental lessons from the literature. However, coverage would be limited to approaches that have actually been implemented, and, based on the mapping review of interventions in specific populations, there may be a limited number of research studies and of poor quality. The second option would focus on the conceptual/theoretical contribution of the wider literature. It might offer innovative solutions from other populations and settings; however, it might be limited by heterogeneity in the nature of ‘contacts’ and issues of applicability. The third option might shed further light on the mechanisms and processes underpinning these promising interventions, and any issues of implementation reported in other conditions. However, differences in context and delivery may reduce its applicability to TB contact tracing.

Following consultation on the mapping review findings with topic experts in TB and public health, we received feedback that option 2 would have limited value because of the challenges inherent in applying findings from other conditions to contact tracing for TB. Topic experts expressed the opinion that, as a result of the relatively low transmissibility, the long and extremely variable incubation period and the limitations of existing diagnostic tests of infection and disease, among other issues, TB is sufficiently different from other infectious diseases for which contact tracing is conducted. These differences would severely limit the applicability of a review of contact tracing in other conditions to research and practice in the area of TB. Following feedback and discussion with the Health Services and Delivery Research team, the decision was made that further systematic review work would include contact tracing in wider populations, with a particular focus on what could be learned and applied to interventions for specific population groups. We therefore progressed to the implementation of option 1.

Results of the full review

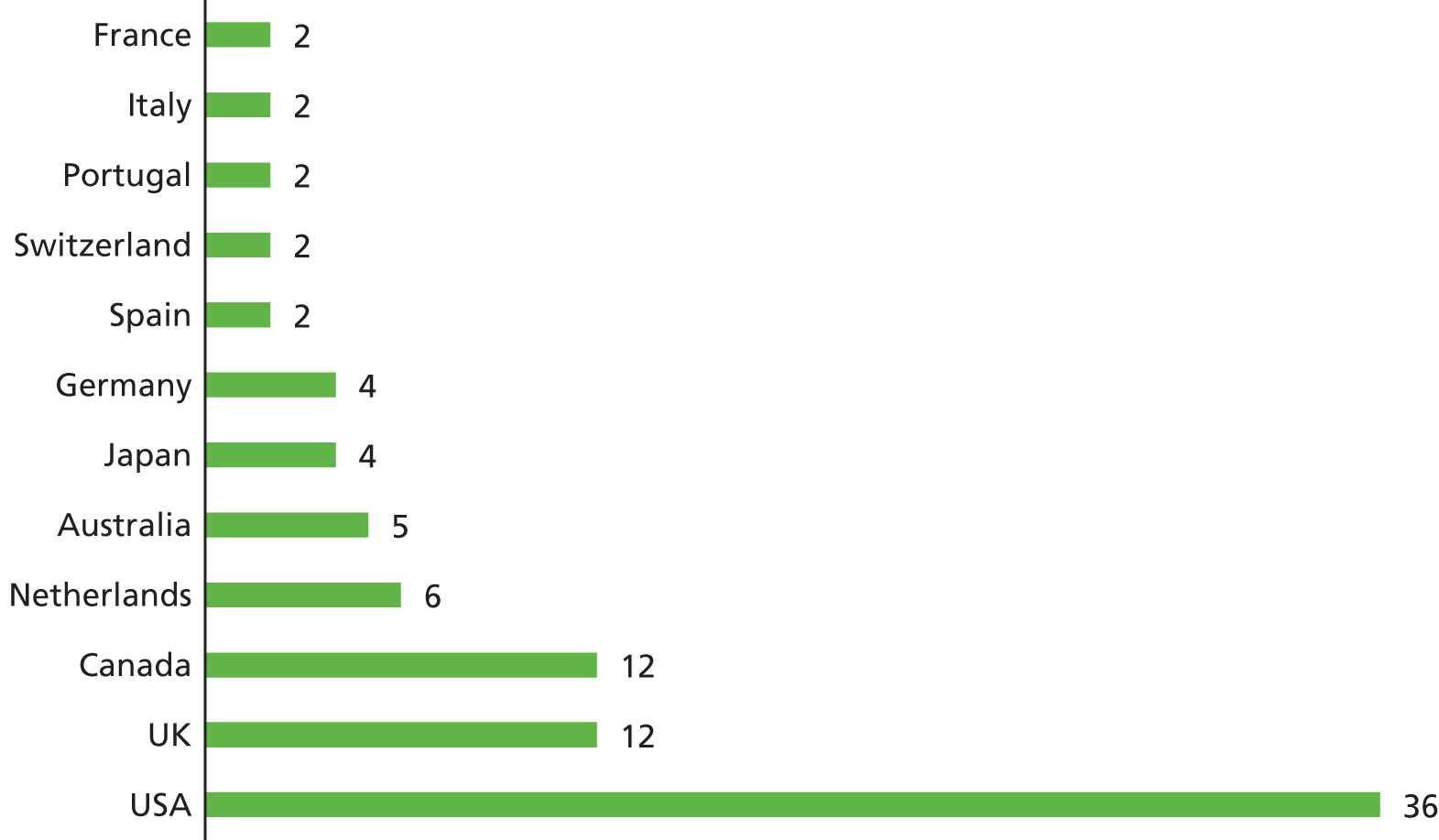

The searching of the electronic databases and the screening of reference lists identified 112 articles of relevance to a review of contact tracing. We identified an additional 10 papers relating to specific populations (further to the 13 papers found in the mapping exercise), giving a total of 23 papers. The remaining 89 papers related to wider populations. Figure 2 provides an overview of the inclusion process. Appendix 3 provides a list of papers excluded at full-text stage and the reasons for their exclusion.

FIGURE 2.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) diagram illustrating the inclusion process.

Results of review of tuberculosis contact tracing in specific populations

Characteristics of the literature

We identified 23 papers with a focus on TB contact tracing in specific populations. 5,7,9,12–31 Sixteen of the papers originated from North America,5,7,12–25 five were from Europe26–30 and one was a systematic review from the UK,9 which formed the basis of national guidance. 31

Contact tracing was examined in five studies in migrants,18,26–29 four studies in drug users (one of which included homeless people),7,15,19,30 five studies in homeless people,12–14,21,24 one study in an ethnic minority group,25 one study in prisoners5 and one study predominantly in individuals with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) who were described as ‘gay, transvestite or transsexual’. 23 One study16 reported a contact investigation involving customers of a bar who mostly ‘used alcohol excessively’, and five further papers9,17,20,22,31 described individuals who were ‘hard to reach’ or from a range of different population subgroups.

Quality of the literature

The quality of the available literature, as indicated by the proxy of study design, was generally low. We found one systematic review29 on rates of contact tracing in migrants versus local populations, one review18 on the cost-effectiveness of control strategies among immigrants and refugees, and an effectiveness and cost-effectiveness review of interventions among hard-to-reach groups that was an unpublished report. 9 One study26 used an evaluative design to examine the period prior to introduction of a community worker intervention, compared with the introduction period itself. Two studies19,20 reported that they included elements of qualitative methods (interviews), although neither provided qualitative data. The literature was dominated by studies that we term ‘descriptive accounts’ of the management of TB outbreaks, in which contact-tracing investigations had been employed. These papers provided narrative about how an investigation was carried out, and often provided data reporting the number of index cases and contacts that were identified. These data do not provide an indication of effectiveness, as each investigation will inevitably differ in terms of the number of contacts who should be approached, and identifying more contacts (rather than appropriately targeting) is not necessarily an optimal outcome. Table 1 provides an overview of the literature by study design.

| Study design | Study and year |

|---|---|

| Systematic review | Mulder et al., 200929 |

| Cost-effectiveness review | Rizzo et al., 20119 |

| Dasgupta and Menzies, 200518 | |

| Uncontrolled comparator design | Ospina et al., 201226 |

| Reported qualitative elements | Ashgar et al., 200919 |

| Wallace et al., 200320 | |

| Descriptive accounts of investigations | Bur et al., 20035 |

| McElroy et al., 20037 | |

| Li et al., 200312 | |

| Lofy et al., 200613 | |

| McElroy et al., 200314 | |

| Oeltmann et al., 200615 | |

| Kline et al., 199516 | |

| Malakmadze et al., 200517 | |

| Yun et al., 200321 | |

| Fitzpatrick et al., 200122 | |

| Sterling et al., 200023 | |

| Curtis et al., 200024 | |

| Cook et al., 201225 | |

| van Loenhout-Rooyacke et al., 200227 | |

| Mulder et al., 201128 | |

| de Vries and van Hest, 200630 | |

| Guidance | National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 201231 |

Decision to instigate contact tracing and prioritisation of contacts

The included papers highlighted factors in the decision-making process that occur prior to, and during, contact-tracing investigations for specific populations. Factors that were described affected the degree and type of response following the identification of a case of active TB infection, including the prioritisation of contacts to trace. These factors were the infection level of the source case and perceived risk, the proportion of close contacts found to have active or latent infection, the estimated period of time for which the case had exhibited active TB, the potential locations of exposure, the potential intensity of exposure and the susceptibility of contacts. One study emphasised that the diversity of elements that need initial and ongoing consideration means that contact-tracing investigation methods need to be tailored to particular circumstances. 20

Types of contact-tracing investigations

The included studies provide a range of descriptive data related to contact-tracing investigations, and only one paper26 could be considered to be evaluating an investigation. Other papers reported strategies used during outbreaks and/or discussed the use of different strategies during the investigation. The strategies described can be broadly categorised into, first, those that targeted all members of a specific population; second, those that targeted individuals within a specific population; third, those that targeted the locations frequented by infected individuals and members of a specific population; and, finally, those that aimed to enhance the quality (efficiency/effectiveness) of contact investigations.

Population-based contact-tracing strategies

Three studies26,29,30 described population-based strategies. In relation to contact-tracing strategies targeting all members of a specific population, the authors described the use of local news/media to publicise an outbreak, and outlined how the media may be used to encourage those who may have been in contact with a case or those who may be exhibiting symptoms to come forward for testing. 29 Community meetings were suggested as useful way of publicising an outbreak or providing health information. 26 One paper30 recommended the use of mobile digital radiography units for the screening of groups such as people addicted to drugs and homeless people, in whom there was expected to be poor compliance with skin testing. The authors of this study provided data on the numbers examined during the outbreak, but did not give data that evaluate the use of the radiography unit versus methods of contact investigation. The study emphasised the overlap between the use of chest radiography during investigations and activities that could be considered population screening. Indeed, following the outbreak, a programme of mobile radiography screening for this population was reported to have been introduced. UK national guidance31 advocates the use of digital mobile radiography screening in settings where at-risk people congregate.

An unpublished report of a systematic review of interventions that aimed to identify people with TB, or raise awareness of TB among hard-to-reach populations,9 concluded that incentives to increase the take-up of the tuberculin skin test (TST) and enhance compliance with further investigation are effective and cost-effective in drug users and homeless populations. The authors recommended that an active approach to case finding, rather than contact tracing, may be more effective in hard-to-reach or at-risk populations. The report formed the basis of national guidelines. 31

Contact-tracing strategies targeting individuals

The literature frequently refers to ‘conventional contact tracing’, a term used to refer to an investigation method based on interviewing an index case and asking them to name individuals with whom they have been in contact. The conventional contact-tracing approach uses principles termed ‘stone in the pond’ or ‘concentric circles’ to refer to widening an investigation from only named close contacts to other contacts (usually described as casual or non-close). Several papers outlined the limitations of the conventional contact-tracing method, in particular a reluctance to name contacts19,23 and the perceived stigma in underpinning this reluctance. 9,29 It was highlighted that index cases may more freely reveal the names of household and workplace contacts than those of social contacts. 22

Three papers12–14 highlighted the limitations of conventional contact-naming approaches when investigating outbreaks centred on homeless shelters. One paper12 found that the number of contacts identified per homeless patient was significantly lower than that per non-homeless patients (median 1 vs. 4, p < 0.001; mean 2.7 vs. 4.8, p < 0.001). Homeless patients were four times more likely to have no contacts identified (p < 0.001). The study suggested that investigation methods other than conventional contact tracing should be used, with strategies focused on identifying the location of exposure rather than eliciting the names of contacts. The authors also suggested that conventional prioritisation systems for widening contacts may need to be revised, with being homeless at the time of diagnosis an indicator that prompt contact evaluation should be prioritised.

Another study13 reported similarly low numbers of contacts being named by homeless persons. In this investigation the median number of named contacts was 3.5 (mean 4.8) per index patient, and 14% of patients named no contacts. Rather than relying on patient contact naming, the authors of this investigation had used attendance records, when available, or staff recollections to prioritise TB screening. The prioritisation of locations for investigation was based on the number of infectious patients who visited each facility and the prevalence of positive TST results compared with other homeless sites. Contacts were prioritised for screening based on their cumulative number of exposed visits. It is important to note that although the methods outlined in this study were described as a contact investigation, they could also be considered to be population screening. The use of screening rather than contact investigation in specific populations was highlighted in the study by Curtis et al. 24 The authors recommended that routine screening should be considered in homeless shelters to overcome the limitations of the conventional contact-tracing approach.

Contact-tracing strategies focused on locations

Six papers7,16,17,19,22,25 emphasised that locations rather than individuals are the key to TB transmission in specific populations. The authors of these papers argued that contact-tracing investigations should, therefore, focus on identifying potential settings of transmission.

The use of a social network analysis approach (referred to as epidemiological investigation by some authors), which explores links between individuals (including the locations frequented), was described as valuable in populations of drug users, aboriginal communities and ‘hard-to-reach’ populations. Network analysis methods create diagrams that illustrate links between key individuals and their contacts, together with the types of activities in which cases and contacts engage. The authors of one paper outlining network methods19 reported that the limitations of conventional contact-naming methods could be overcome by investigation staff visiting and observing locations frequented by an index case. Of 187 contacts in their investigation, 49% were named and 10% were observed at a local ‘crack house’. The contacts that were identified by observation were eight times more likely to have positive skin-test results than those who were named [relative risk 7.8, 95% confidence interval (CI) 3.8 to 16.1].

A study describing a contact investigation that was focused on a neighbourhood bar16 reported that the index patient (a homeless person) named few contacts, but had spent most time in the bar. This index case proved to be highly infectious, with 14 linked cases of active TB and 27 cases of latent infection detected. The bar was the only site where there was any contact with the index patient for most of those who were found to be infected. The use of a network approach to investigation in another study17 echoed the importance of investigating potential locations for transmission. The construction of a social network diagram revealed several previously unrecognised locations of transmission, including a single-room occupancy hotel, homeless shelters, a bar and crack houses. Another study using social networks methods22 found that the majority of people identified with active TB disease were members of a single social network, and reported that the approach had been essential to identify this link.

Cook et al. 25 concluded from their discussion that methods including social network analysis, geographic information systems and genomics could improve the assessment of transmission, together with the prioritising of contacts. These methods were needed to overcome a key limitation of conventional contact-tracing approaches, which was described as not taking sufficient account of the differing social structure of different populations.

UK guidance31 recommends that investigations should be co-ordinated at places where an index case spends significant amounts of time, and where at-risk people congregate.

Elements that enhance the quality (efficiency/effectiveness) of contact-tracing investigations

A study5 outlining a contact investigation in both a prison and the community emphasised the importance of interagency working in carrying out an investigation. Another paper14 reported that at least half of the outbreak patients who were living in homeless shelters had spent time in prison or had visited the local sexually transmitted disease clinic in the prior 2-year period. The authors therefore suggested that TB control strategies would be enhanced by employing a joined-up approach to TB control among the relevant agencies.

Other methods described to improve the efficiency/effectiveness of contact-tracing investigations in specific populations included the use of deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) fingerprinting/molecular epidemiology. These additions to an investigation were described as valuable to permit the further analysis of relationships between cases, and for the establishment of clusters. The use of these technologies was described by authors of several studies as being an essential part of TB control strategies, as contacts could be infected by cases other than the presumed source. 16,29 In addition, DNA fingerprinting was recommended as useful for investigating cases once regular contact-tracing procedures had been completed. 27

The value of investigations having a focus on location rather than individuals was also echoed in a paper outlining the use of molecular epidemiology. 14 It suggested that DNA fingerprinting may offer a useful impetus to further question a patient regarding routine, contacts and places frequented, and thereby to uncover social networks in communities in which contact naming is challenging. 14 A paper describing the further investigation of a cluster of cases in a ‘hard-to-reach’ population17 found that, by using genotyping methods in addition to conventional contact tracing, an additional 98 contacts were identified who had been missed during routine contact investigation. The authors recommended that genotyping should be used alongside other methods of contact tracing, as it can aid the detection of unapparent transmission before an increase in incidence and, thus, help to identify clusters earlier. They highlighted, however, that to be successful, a policy of genotyping isolates from all (not just some) patients with culture-positive TB is required to identify clusters.

Three papers15,23,26 referred to the value of using community workers during contact investigations. One study26 evaluated a staff-based intervention that introduced trained community health workers in areas of high immigration. The workers were described as benefiting the contact-tracing process by acting as translators and cultural mediators, and also as facilitators during treatment. The study found a statistically significant increase in contact tracing coverage among immigrants during the intervention period, compared with the previous period of time (81.6% compared with 65%; p < 0.001). A second paper23 mentioned that community workers were used during contact tracing among ‘highly mobile’ communities. National guidance31 also recommended the use of peer educators when available and appropriate during investigations. One paper15 described the persistence and flexibility required by outreach workers investigating an outbreak among a group of illicit-drug users. Workers had to arrange meetings at times and locations convenient to the group, and spent many hours establishing trust in order to gain co-operation. The authors described how screenings could take place in various locations, including on street corners and in car parks. Often, outreach workers were successful only after spending hours driving around the community, searching for patients and contacts.

UK guidance31 highlights the need for partnership working between organisations in high-quality investigations.

Factors that can influence contact-tracing investigations

Sensitivity and specificity of tests

Three papers10,26,27 discussed the accuracy and feasibility of different testing tools used during investigations. The authors described potential issues of specificity with the TST, particularly from individuals in high-incidence TB countries. 29 A study13 describing an investigation in homeless shelters found that screening contacts with one sputum culture was as sensitive as chest radiography in detecting active TB disease (77% vs. 62%). The authors of one paper30 examining contact investigations in drug-addicted and homeless populations highlighted another factor influencing the success of investigations, namely the poor take-up of testing.

Systems and processes

The authors of two further papers18,19 mentioned other factors that could assist, or provide obstacles to, effective contact investigations. The factors that could assist included local expertise, local capability, communication, co-ordination, prompt action, and effective data management and infrastructure systems. 22 The obstacles described were perceived social stigma, the identification of additional contacts after the investigation had closed and failure to perform the initial evaluation owing to error or a lack of resources. 21

Social factors

One study outlined the need to customise investigations to individuals by taking into account language and cultural differences, and different settings. 20 This paper described challenges in conventional contact tracing in the foreign-born population (owing to the different languages spoken), in prison populations (because of the different systems between prisons and states) and in homeless people (as a result of the movement of individuals between shelters). To address these challenges, the authors recommended different agencies working together efficiently, accurate record-keeping in shelters and the use of photographs rather than relying on names when tracing contacts of homeless people. The work, however, provided few or no data to support these recommendations. A second paper24 highlighted that an index patient’s refusal to visit a hospital for the investigation of their symptoms could result in delay in instigating an investigation, and thereby increase the chance of disease transmission.

Outcomes and impacts following contact-tracing investigations

Study authors5,16,21 highlighted the issue of non-completion of treatment hindering successful outcomes from contact tracing. In one study,21 fewer than one-third of infected prisoner contacts completed treatment, and in another study5 only 44% of homeless people completed treatment. Kline et al. 16 reported that 19 of the 39 people with positive TSTs in their study attended follow-up appointments. Of these, 13 contacts refused prophylaxis or did not complete their treatment, with three individuals progressing to active TB within 2 years. The authors highlighted that chronic alcoholism may be a high-risk factor for progression to active disease, and that major efforts to ensure the completion of 6 months of isoniazid therapy are worthwhile in an alcohol-user population.

The outcomes most frequently reported by studies as indicating the effectiveness of contact-tracing investigations were, first, the number of contacts identified (yield), and, second, the number of positive skin test results. One study18 examined the cost-effectiveness of TB control strategies including screening and contact tracing. The authors concluded that contact tracing (particularly in ethnic minority communities) may be more cost-efficient and less intrusive than screening.

Main findings and implications from review of contact tracing in specific populations

The review found a small number of studies relating to contact investigation in specific populations. This is consistent with other related reviews, such as Rizzo et al. 9 and Fox et al. 32 The findings of the review suggested that methods that focus on locations rather than the individual naming of contacts, and approaches that draw on social network methods, may be of value. The provision of community health workers may also enhance the efficiency/effectiveness of investigations. The use of screening rather than contact investigation may be useful in a homeless population. The evidence base, however, is limited and underpinned by little empirical work. Although we identified a total of 23 papers across specific populations, the data are predominantly descriptive rather than evaluative. The following review of contact tracing, examining literature in wider populations, was carried out with the aim of providing additional insight into what may be learned and applied to contact tracing in specific populations.

Results of review of tuberculosis contact tracing in wider populations

Characteristics of the literature

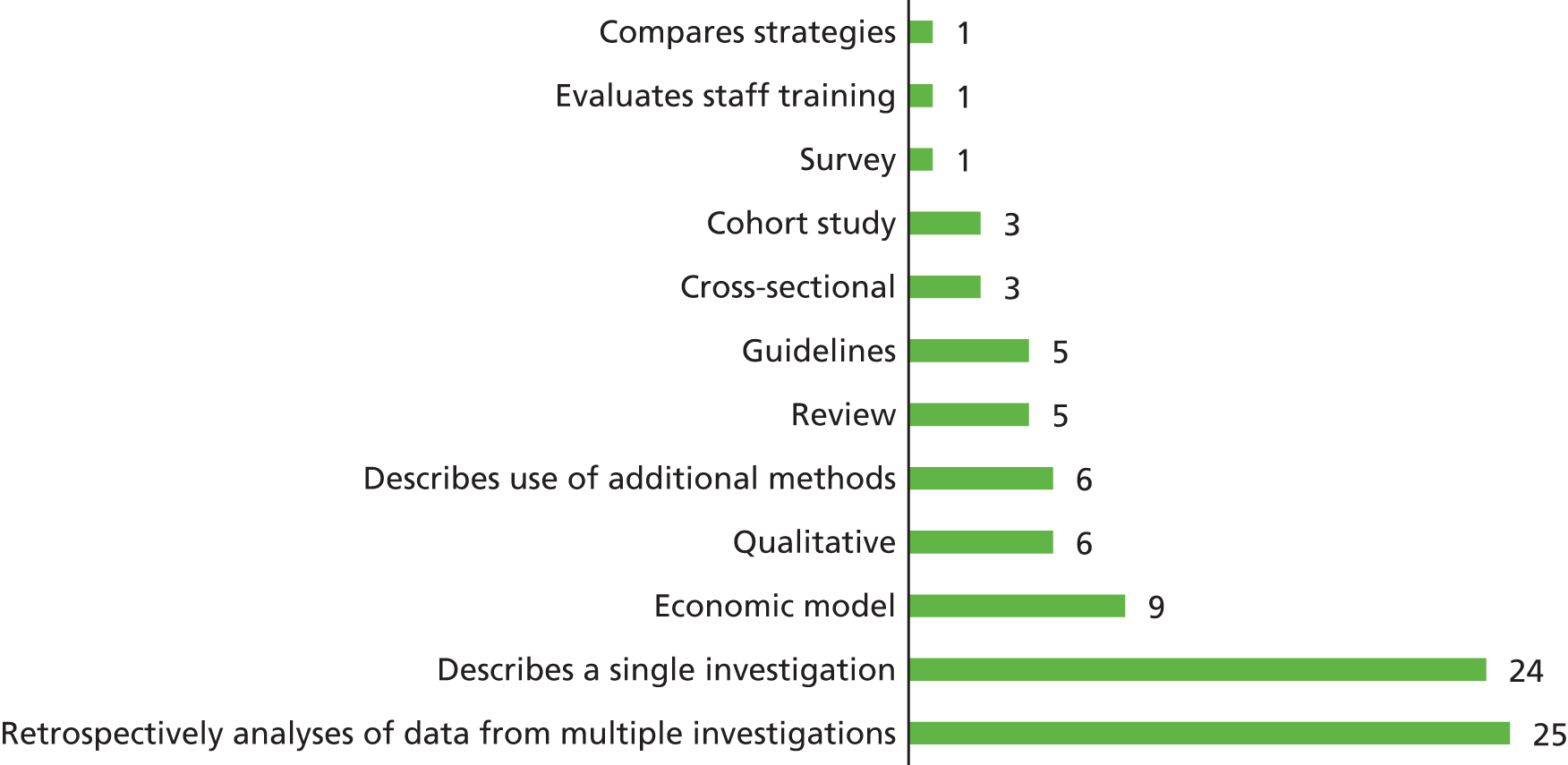

We identified 891–3,6,8,32–115 papers that met our inclusion criteria for the review of wider populations. These studies originated from a variety of countries, with the greatest number from the USA and Canada (Figure 3). We excluded studies from countries that are not members of the OECD; therefore, the included literature is from contexts most applicable to the UK. Although these papers related to investigations in wider populations, some also included data relating to specific groups within their analysis, or mentioned elements of particular relevance to specific groups.

FIGURE 3.

Number of studies by country of origin.

Quality of the literature

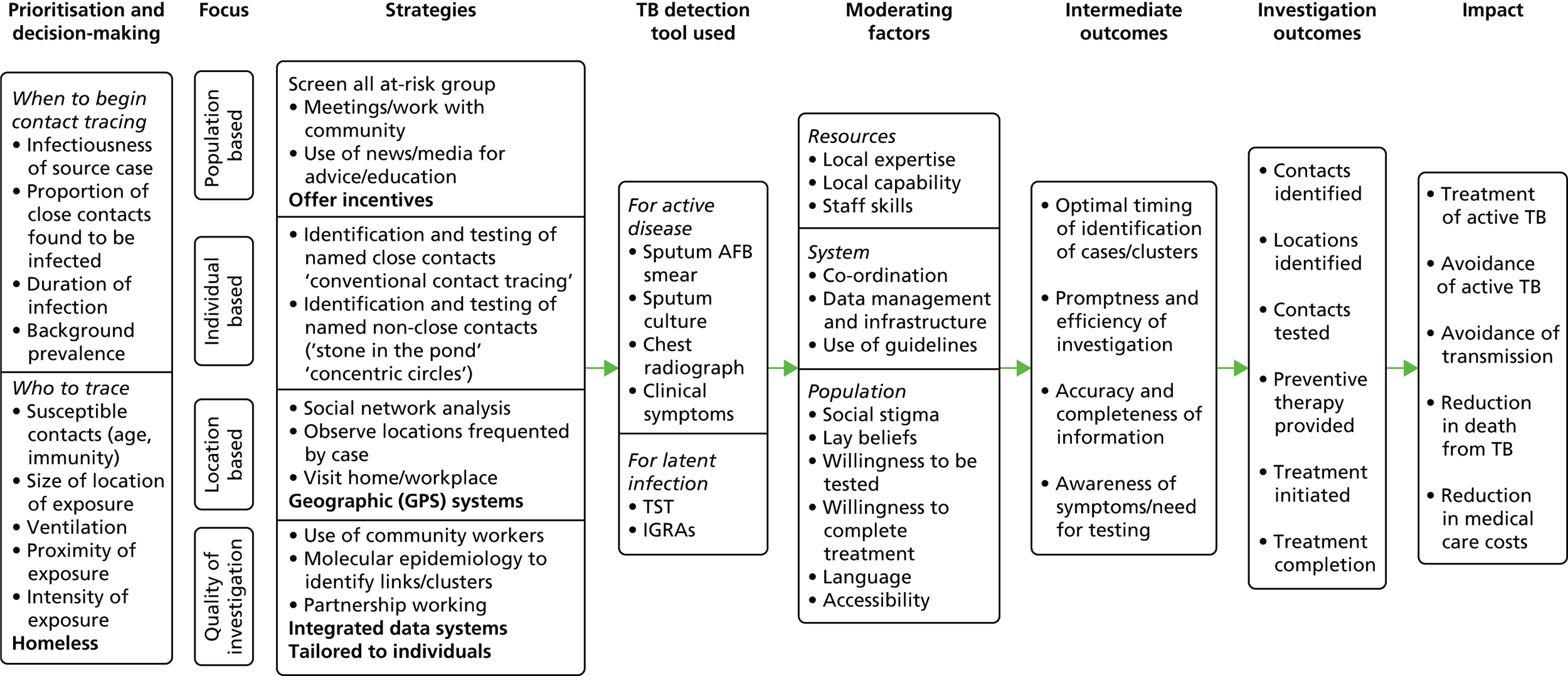

As with the literature on contact tracing in specific populations, the quality of study design was generally low, with little empirical work evaluating contact-tracing methods. The majority of studies retrospectively examined either a group of investigations that had been completed in an area or investigations carried out over a particular time period (Figure 4). These papers scrutinised notes and patient records completed at the time, to describe and further examine the investigations. A second large group of studies ‘told the story’ of a single investigation, describing the process and outcomes, with data relating to the number of cases and contacts, and often outlining when issues and obstacles had been encountered.

FIGURE 4.

Number of studies by study design.

As we outlined in Chapter 2, owing to the diversity of designs, predominantly descriptive data and unclear quality indicators in the included literature, established quality appraisal tools, such as the risk-of-bias tool developed by The Cochrane Collaboration, were not suitable for use in this review. Instead, we used study design as a proxy for quality, and characterised study types during the narrative synthesis, highlighting any particular concerns regarding the quality of individual papers.

Integration and comparison of the specific population and wider population literature

We synthesised the elements of contact tracing described in the two subreviews using a logic model, which sets out the elements of the contact investigation pathway (Figure 5). We used this model to describe and compare data in the review of wider populations with those in the review of specific populations, and highlight data of particular relevance to contact tracing in specific populations.

FIGURE 5.

Logic model outlining elements of the contact-tracing pathway (bold = reported in specific population literature only). AFB, acid-fast bacillus; GPS, Global Positioning System; IGRA, interferon gamma release assay.

The elements of the model are drawn from the included literature. The elements of the model that are in standard typeface were referred to in both reviews; the elements of the model that are in bold typeface were described only with regard to specific populations.

The model pathway progresses from left to right. The first column details elements relating to prioritisation and decision-making required prior to commencing an investigation and during the investigation. The second column provides a categorisation of investigation activities, with the elements of these further itemised in the third column. Columns further to the right indicate the influence of TB detection and diagnosis tools used during investigations, followed by factors that may influence the process of an investigation and outcomes. The final columns detail outcomes that may be achieved during an investigation, and longer-term impacts that may result from contact-tracing investigations.

Prioritisation and decision-making

There was a high level of consensus in the literature regarding elements to consider when making decisions about when to instigate contact-tracing investigations, and then who should be prioritised for tracing and screening. The research studies included in the wider review echoed elements of prioritisation and decision-making that were described in the literature on contact tracing for specific populations. Authors described the need for a risk assessment approach36,60 based on the infection type, level and period of infection,71,87 the characteristics of contacts such as younger age or reduced immunity1,8,45,82,102 the duration of exposure and the proximity of exposure. 33,47,69,115 Elements relating to the specific environment also require consideration, such as the size of an area in which people congregate, together with the levels of ventilation in a location. 57,59,93

Several studies highlighted the importance of considering the background prevalence of TB in population subgroups, such as ethnic minority communities or those born overseas in TB-endemic countries. Having this information was described as a key element of decisions about when to commence or expand contact tracing, with some investigations reportedly expanded inappropriately when background prevalence had not been sufficiently taken into account. 32,44,62,89,94,95 The authors of one study95 highlighted that the ‘stone in the pond’ principle is useful only if accurate data regarding prevalence in specific communities (such as immigrants) are available.

Three papers68,83,92 outlined decision trees or tools for use when considering priorities for investigations. The first of these68 evaluated use of a decision tree for a set of 3162 contacts. The authors reported that the decision tree had a 9% sensitivity, 22% specificity and a false-negative rate of 7–10%. It was estimated that the use of the decision tree could lead to around a 20% reduction in the number of contacts investigated. The priorities for contact tracing detailed in the decision tree are if the index case has cavitary disease or if the total exposure of a contact per month is > 120 hours or if the contact is under the age of 15 years. If none of these criteria applies, then it is recommended that a case should be investigated only if the contact was exposed to a smear-positive case in their home or if the contact was exposed in a place where the ventilation was minimal. A second study83 also described the development of a checklist and decision tree. The tools were intended to be piloted, although it was reported that no suitable investigations were started during the period of the study and, therefore, the testing of the tools had not been carried out.

Mohr et al. 92 consulted experts to develop a decision-making tool for contact-tracing investigations following potential transmission to users of public transport. Nine elements were identified: symptoms of the index case; infectiousness of the index case; drug resistance pattern of index case; evidence of transmission to other contact person; the quality of contact between an index case and contact person (face to face/social interaction); the proximity of contact to case during exposure (more/less than 1 m); the duration of exposure (more/less than 8 hours); the susceptibility of the contact (< 5 years of age/HIV/substance abuse/other disease); and environmental factors (external ventilation present or not/with/without circulation).

Several sets of guidelines were identified during the review, which provide detailed recommendations regarding considerations of priority. 1,6,33–35,96 These guidelines confirm that priorities should be assigned to contacts (high/medium/low priority) based on, first, the likelihood of infection and, second, the potential hazards to the individual contact if he or she is infected (including the characteristics of the index patient, the characteristics of the contact and the intensity, frequency and duration of exposure).

Population-focused strategies

Four included studies40,41,47,65 described the use of media and information provision to reach populations during an investigation. A report of an investigation in a school40 described intense pressure from parents, which was addressed by holding information sessions, sending letters and factsheets to all parents and providing a central point of communication. A second investigation in a school41 found that it was important to counter public fears by providing simple, credible, accurate, consistent and timely information and letting the public know what action they could take. An investigation focused on a hospital47 set up a free telephone helpline, with press releases and media campaigns also used. A telephone helpline and information about TB symptoms/mode of transmission/availability of effective treatment were made freely available to the population of an area in which a public house was suspected to be a site of transmission. 65 The authors of another paper reporting an investigation around a public house97 described how several individuals had come forward as a result of awareness-raising activities among the local population. The authors suggested that targeted health education programmes may improve contact detection.

Papers in the specific populations review30,31 highlighted the potential overlap between contact tracing for population subgroups and population-screening activities. In the wider review we identified one study that compared the effectiveness of contact tracing versus population screening. 111 The paper supports the view that these interventions have areas of overlapping purposes. This UK study111 compared contact tracing among residents in a deprived area of London with the screening of all new entrants to the country. The authors concluded that tracing the contacts of individuals who had been identified with smear-negative pulmonary TB was significantly more effective in identifying individuals requiring intervention than the routine screening of all new entrants (7.7% of contacts of people with smear-negative pulmonary TB required full treatment or chemoprophylaxis vs. 3.1% of new entrants screened). This paper is particularly interesting with regard to specific populations, as it comments that in high-incidence areas contact tracing could be seen as a way of screening communities at particularly high risk, thus emphasising the overlap between these strategies. Another paper included in the wider review70 concluded, from its examination of contact tracing in a workplace setting, that the screening of all new employees from countries of high TB prevalence should be considered.

Individual-focused strategies

As found in the specific populations review, the literature in the wider populations review was dominated by reports of investigations which used ‘conventional contact tracing’ methods to identify individuals with possible active or latent infection. These investigations consisted of an index case being asked to name their close contacts, and ‘stone in the pond/concentric circles’ methods to widen the pool of contacts tested from close/family contacts to less close/casual contacts.

Several papers echoed the review of specific populations in describing the limitations of contact-tracing methods. Bock et al. 43 reported a study in which contacts were reinterviewed following the increase of an outbreak. Reinterviewing identified an additional 282 contacts from the original 61 contacts (19% of these had positive TSTs). It was concluded that contacts were originally missed because the normal daily connections between them were not recognised by investigators. In another study74 it was reported that although 67% of cases identified all of their contacts, 32% did not. The index case was less likely to identify contacts who were employed and those who were not a relative or cohabitant [odds ratio (OR) 4.82, 95% CI 1.71 to 13.54, and OR 0.22, 95% CI 0.10 to 0.47, respectively].

An area of frequent debate within the literature related to the expansion of investigations from close/household contacts to casual contacts. Some investigations prioritised only household contacts. 105 Others concluded that the screening of casual contacts was not cost-effective in low incidence areas,38 should be carried out only for smear-positive respiratory index cases102 or only for highly infectious cases,33 or that there should be only limited screening of casual contacts. 87 The authors of one study113 found that the screening of casual contacts was routinely omitted owing to limited resources. In contrast, the authors of another study97 argued that screening beyond close contacts must always be considered.

Although authors agreed that closeness was an important predictor of infection and should guide prioritisation of investigation,68,108 the definition of ‘close contact’ varied considerably32,113 and different authors used different categories. For example, one study39 defined a close contact as someone having < 4 hours’ exposure indoors or in a confined space, and a casual contact as someone with exposure other than close. Another study42 defined people who spent an estimated total of at least 40–100 hours with the index cases in the 3 months prior to diagnosis or during the infectious period as ‘close contacts’, and those who shared the same front door as the index case as ‘household contacts’. One study89 retrospectively examining a number of investigations reported that, in all of them, ‘household contacts’ were always defined as ‘close’. In other studies, ‘close contact’ was defined as exposure of > 6 hours per week and ‘occasional contact’ was defined as exposure of < 6 hours per week,48 or ‘close contact’ was defined as someone spending > 8 hours per week with the source case. 57 Another study44 reported that testing should be restricted to casual contacts having frequent (at least once per week) contact.

A review69 of published data relating to the likelihood of tuberculin reactions in casual contacts defined casual contacts as ‘persons sharing the same air, but having no direct contact with the index cases’. It concluded that the decision to extend a contact investigation to a group of casual contacts in a workplace or school should be based on the evidence of transmission from the index case to closer contacts, the number of hours of exposure and the likelihood of previous exposure in the population to be screened.

National guidelines tended to provide descriptive information regarding the categorisation of contacts. Guidelines from the USA34 defined close exposure as prolonged exposure in a small, poorly ventilated space or a congregate setting. Guidelines from the UK33 defined close contacts as people from the same household who shared kitchen facilities, and very close associates such as boyfriend or girlfriend or frequent visitors to the home. They noted, however, that contacts at work or in a hospital ward may be as close as a household contact. Guidance from Canada6 divided contacts into high priority (household contacts plus non-household contacts who are immunologically vulnerable), medium priority (close non-household contacts with daily or almost daily exposure, including those at school or at work) and low priority (casual contacts with lower amounts of exposure).

Two included documents6,51 suggested that recommendations for expanding investigations in general population groups may require further consideration in specific populations. The first of these51 carried out a descriptive literature review of contact investigation methods. They concluded that, although conventional strategies have given priority to household contacts, the importance of casual contacts and locations in contact tracing for high-risk or vulnerable groups is not always sufficiently recognised. It was recommended that the closeness of contact should be based on the amount of time an individual is exposed, rather than on environmental or social factors. The second document,6 comprising Canadian guidelines, included the statement that ‘the concentric circles approach does not take into account contacts who are vulnerable but may have had less exposure, and can be difficult to apply in congregate settings’. The guidelines recommended that the level of priority should be the primary consideration, with most effort put into tracing contacts who are most at risk of being infected and/or most at risk of developing active TB disease if infected.

Location-focused strategies

Three studies examined outbreaks among colleagues. 50,67,96 One paper,53 reporting a retrospective review of data from outbreaks across five states in the USA (which used a subset of data from another included study99), concluded that the potential for transmission of TB in the workplace needs further recognition. The study found inconsistent and limited recording of data collected during the investigations, and differences between the locations with regard to who was selected for screening and who was used as the primary source of information. Another study70 also concluded that the workplace can be an important site of transmission.

In a further investigation,96 coworkers had initially been classified as low priority; however, a high rate of infection found in high-priority cases (39%) led to the expansion of the investigation to low-priority contacts, and 15% of these subsequently had positive TSTs. Similarly, Duarte et al. 58 reported that expanding contact investigations to home and workplace visits increased the number of individuals screened and identified further patients with active and latent TB. Interviews identified 950 contacts (an estimate of 0.75 cases of infection per index patient identified); expanding the investigation to home and workplace visits helped to identify 2629 contacts (1.4 cases of infection per index patient). These results support the finding that locations such as the workplace can be important to consider in contact investigations.

A study65 from the UK examined the contact-tracing investigation surrounding an outbreak of TB in the south-west of England. The paper highlighted that few conventional household contacts were identified, but a significant number of secondary cases were detected from tracing contacts at a single public house location. An investigation in a village in Spain48 similarly found that few cases in the outbreak cluster appeared to have a close relationship, but many frequented some of the same bars. The authors of another study55 that highlighted the importance of bar locations concluded that contact investigation should examine the location itself and not focus on personal contacts. Although the bar in this study attracted a mixed clientele, it was located in a red light district and next door to a hostel for homeless people, so the conclusions are particularly relevant to investigations in specific populations.

In contrast to these papers, a retrospective analysis57 of 100 contact investigations carried out over a 5-year period in congregate settings (schools, workplaces, drug treatment centres, single-room hostels and other locations) found that transmission at congregate sites was uncommon (22% of investigations examined in this analysis), concluding that these investigations are resource intensive. The study recommended that decisions to perform testing at a congregate setting (not just among household contacts) should be based on the infectiousness of the source case, the size of the location, the level of crowding, the number of windows at the setting, the characteristics of contacts such as age and immune status, and the presence of case clusters.

Six papers2,39,52,66,76,91 outlined the benefits of a social network analysis approach to contact investigations. Findings from these studies build on the positive findings from the papers in specific populations reported previously. 16,17,19,22,25 Bailey et al. 39 described the development of network diagrams and calculation of reach, degree and ‘betweenness’ scores to examine relationships between an index case and contacts. The highest 20 scores and lowest 5 scores for each metric were used for prioritisation. The network diagram indicated that the index patient was directly linked to 56% and indirectly linked to 18% of secondary cases, and contacts prioritised using network analysis were more likely to have latent infection than non-prioritised contacts (OR 7.8, 95% CI 1.6 to 36.6). A similar study91 that explored an investigation, including contacts from a local community, a prison, a hospital and a school, concurred that the metrics calculated using social network methods enabled contacts with higher scores to be prioritised. Three contacts with high-ranking ‘betweenness’ scores were found to be links to the overall network. The authors concluded that network analysis provided a means to identify linkages among cases, quantify the magnitude of an outbreak and assist the prioritisation of contacts to screen. Gardy et al. 66 reported that social network analysis outperformed contact tracing in identifying a probable source case, as well as indicating several locations and persons who could be subsequently targeted for follow-up.

Another study52 supplemented routine investigation procedures with an interview to collect data on places of social aggregation for use in social network analysis. TB patients not linked via conventional contact tracing were linked by mutual contacts or places of social gathering. An association was found between TST results and being in the denser area of a person–place network (p < 0.01). The authors of a UK study2 reinterviewed patients using a social network enquiry approach. They found that associations detected previously tended to be family–friend relationships, whereas over half of the associations reported during the new interviews related to friends and socialising in public houses. Fourteen of the 43 epidemiological links were newly uncovered, although associations were not discernible for 45% of patients.

One included paper cautioned against the uncritical acceptance of studies advocating the use of social network analysis. 76 It found that betweenness scores (but not centrality scores) were useful for identifying contacts at greater risk of latent TB infection (significant association for contacts with higher betweenness score and latent TB infection, OR 2.12, 95% CI 1.14 to 3.96; p = 0.020). However, the complexity and time-consuming nature of the method reduces the potential for its incorporation into routine contact investigations. The study by Bailey et al. 39 also outlines potential issues of implementation. The authors reported that, although data required to perform network analyses are already routinely collected, they need to be organised into the proper format for analysis. Although the costs to carry out network analysis may be beyond some programmes, the authors recommended that principles such as pursuing repeatedly named contacts should be widely adopted.

Strategies to improve the quality (efficiency/effectiveness) of investigations

We identified only one paper that reported an intervention to improve the delivery of a conventional contact-tracing investigation. 67 Gerald et al. 67 examined existing contact-tracing protocols. They found considerable variance among field workers regarding their understanding of terms used in the protocols. There was also variance in understanding of the methods for eliciting information from index cases, and in the use of ‘concentric circles’ analysis. The authors developed standardised definitions and procedures as part of a new contact exposure and assessment worksheet. They also introduced training sessions to increase TB field worker adherence to the protocols. The quality of the training sessions was evaluated by self-reported questionnaires. Sessions were rated at a mean of 4.61, and the overall value of the training received was rated as 4.71 (on a scale of 1–5, with 5 meaning ‘excellent’). It was mentioned that ‘some further training was required when data entry errors and misunderstandings were identified’. 67

The review of specific populations had indicated the potential value of community health workers during investigations. In the wider review, one paper86 described the nurses’ perception that outreach workers would be of value.

One included study103 reported the linking of data from two different health-care data systems during a contact investigation based around a maternity ward (hospital-based electronic medical records to identify patients exposed to the index case, and an electronic immunisation registry to obtain contact information for exposed infants). There are limited data evaluating the impact of using the integrated system. However, the authors reported that the integrated system aided the identification, notification and evaluation of contacts, thereby reducing the resource burden required for the investigation. 103

A sizable group of papers focused on improving the quality of investigations via the use of epidemiological testing, predominantly with the aim of identifying clusters of cases. This echoes the specific population literature. These approaches were described as complementary strategies to contact tracing,80 and so they have been included in this review. The use of molecular epidemiology [referred to in the papers as DNA fingerprinting, genotyping, whole genome sequencing, spoligotyping, using IS6110-based restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis, mycobacterial interspersed repetitive unit 12 typing or 24 loci mycobacterial interspersed repetitive units variable number of tandem repeats] was described in nine papers42,46,55,61,66,78,80,114 in the review of wider populations.

Lambregts-van Weezenbeek et al. 80 reported that DNA fingerprinting can be useful to confirm suspected epidemiological links, to identify new links when transmission is not suspected and to identify when links between cases of TB are vague or with long periods in between. In their retrospective analysis of clusters over a 5-year period in the Netherlands, the authors found that DNA fingerprinting established an epidemiological link in 31% of clustered cases in which no link had been assumed or documented. Cluster feedback significantly improved the confirmation of documented epidemiological links (p < 0.001). In another study42 it was reported that DNA fingerprinting demonstrated that 30% of contacts with TB developed the disease at nearly the same time as, but not as a result of transmission from, the index case. The authors of a further study that used molecular epidemiology to examine an investigation at a workplace in Italy61 also reported that genotyping was important to establish linkages. Yeo et al. 114 examined public health data over a 4-year period and carried out additional genotyping. Genotyping by the research team identified up to 14 possible additional index cases. The authors described the contact investigations as extensive. The investigations had mostly been able to identify latent TB infection, but had been less successful in identifying the source cases.

The authors of one paper78 analysed data from an initiative to DNA fingerprint all new cases of TB during a 5-year period. Fingerprints were obtained and stored in a database and pattern matching software was used, with a network diagram approach also used and centrality scores calculated. DNA fingerprinting was reported to be valuable in identifying the size of outbreaks and in leading to recognition of the importance of location (bars) in understanding an outbreak. Contact investigation had identified only 12 links among 27 cases. The index case could not be linked to any other case, and half (51%) of cases could not be linked to another case via contact investigation. An analysis using the additional strategy found that around 80% of the patients could be linked by other people or places, and individuals were often linked by multiple places, providing several opportunities for infection.

One study compared DNA fingerprinting with whole sequence molecular epidemiology, with conventional contact tracing and social network analysis methods. 66 The authors reported that DNA fingerprinting had suggested that the outbreak had a single TB lineage, whereas more in-depth whole sequence molecular epidemiology revealed two lineages. Genotyping and contact tracing alone did not capture the true dynamics of the outbreak. Genome sequencing allowed the social network to be divided into subnetworks associated with specific genetic lineages of the disease. Genotyping was also reported to be valuable in excluding social relationships that could not have led to transmission according to the genomic data. This was described as greatly reducing the complexity of the network and aiding identification of index patients.

A study of particular relevance to specific populations46 highlighted that molecular epidemiological methods tended to identify non-household links. These methods also identified more individuals from precarious economic circumstances and social difficulties (p = 0.002) than conventional contact tracing. A second study of note for specific populations55 reported that conventional contact tracing is insufficient for the detection of chains of transmission in some harder-to-reach communities. The study found that 12 of 20 cases with confirmed recent transmission could be determined by DNA fingerprinting only. The authors highlighted that DNA fingerprinting not only provides important information regarding recent infection of one patient by another; it also allows structural weaknesses in an investigation to be identified.

Tuberculosis detection and diagnosis tools

Thirteen papers37,38,44,54,56,57,60,63,72,79,90,104,110 highlighted how the specific test used for screening for latent or active TB infection proved to be important during contact-tracing investigations. Four papers considered how the process of contact tracing could be influenced by the particular test. 37,38,57,104 In the first of these,37 the authors reported that the uptake and completion of chemoprophylaxis may be higher when latent TB infection is diagnosed with interferon gamma release assays (IGRAs) rather than TSTs. This finding was echoed in a second paper,104 which similarly found that contacts tested using IGRAs were more likely to complete screening.

One study of particular relevance to specific populations outlined the need for difference in the testing process for individuals in congregate settings versus other contacts. This investigation57 reported that testing should be carried out for high-risk groups as soon as possible, and again 10–12 weeks later. For other individuals, the authors recommended that testing was performed only once, at 10–12 weeks after exposure.

A further study38 described the effects of a change in policy regarding the follow-up of contacts. Previously, close contacts had been invited for follow-up annual radiological surveillance. Under the changed policy, close contacts were either discharged or referred to the chest clinic following their initial screening, with no annual follow-up. The study found that, compared with the results of the previous protocol, fewer contacts were unnecessarily screened. However, as a result of the new policy, referrals to the chest clinic increased, and the number of contacts given chemoprophylaxis also increased.

Nine further papers44,54,56,60,63,72,79,90,110 provided evaluations regarding the usefulness, effectiveness or cost-effectiveness of IGRAs [either QuantiFERON®-TB-Gold In-Tube (QFT-G) assay (Quest Diagnostics, NJ, USA) or the T-SPOT®. TB test (Oxford Diagnostic Laboratories, Oxford, UK)] instead of, or in addition to, TSTs. Borgen et al. 44 concluded that use of IGRAs could improve the positive predictive value of testing, and also enables TST for those with bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) vaccination. Another study similarly concluded60 that IGRAs are more sensitive than TSTs in detecting latent TB infection. The authors of this literature review recommended that a positive TST should be followed by IGRAs, as IGRAs may be superior to TSTs in predicting latent infection becoming disease (although they recognised that this finding was not consistent across all of the literature). They also recommended that, when only a TST is used, a cut-off point for positivity must be decided regarding sensitivity versus specificity. The likelihood of infection and BCG status should be considered.

Other papers echo the superiority of IGRAs over TSTs for detecting latent TB infection. 54,56,72 Diel et al. 54 estimated that the use of IGRAs (either QFT-G or T-SPOT. TB) as a replacement for the TST would decrease the number of contacts to be investigated by approximately 70%. IGRAs were described as particularly useful for people who show tuberculin reactivity due to past BCG vaccination. 63 An economic modelling study from Canada cautions against the widespread use of QFT-G. 90 This study found that the most cost-effective strategy was to administer QFT-G in BCG-vaccinated contacts, and to reserve the TST for all others (at an incremental net monetary benefit cost of CA$3.70 per contact). The least cost-effective strategy was to administer QFT-G in all contacts (an incremental net monetary benefit cost of CA$11.50 per contact). Trieu et al. 110 similarly concluded that QFT-G was particularly useful for contacts from countries with BCG coverage; however, they also raised the issue of cost. The authors estimated that QFT-G was 16 times more expensive than TSTs. They also highlighted the need for field workers to be trained in taking blood samples, and that specimens needed to be transported to a laboratory for analysis within 16 hours of collection. In addition to people who are BCG vaccinated, the authors recommended the use of the test with people who are hard to follow up, such as homeless people, as the test requires only a single encounter.

The authors of another study79 constructed an economic model to compare high-resolution computed tomography with chest radiography (in combination with QFT or a TST) for the detection of active TB during contact investigations. The study found that a strategy that comprised QFT followed by high-resolution computed tomography yielded the greatest benefits at the lowest cost. High-resolution computed tomography, rather than chest radiography, was therefore recommended to evaluate and manage contacts with active TB infection.

Moderating factors

We grouped factors that could reportedly influence (or moderate) an investigation into those relating to available resources, those relating to systems and those relating to the population.

Resources

Studies described how contact investigations are complex, challenging and labour-intensive, and require the immediate availability of a large workforce. 41,64 Screening was described as costly, and diverted staff from other duties. 100 National standards in Canada6 outline the need for good organisation, and adequate staffing and resources.