Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 12/5002/18. The contractual start date was in October 2013. The final report began editorial review in February 2016 and was accepted for publication in July 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Disclaimers

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Wilson et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Context

The NHS is facing severe funding constraints both now and in the medium term. A funding gap of up to £30B has been forecast by 2020–1. 1 In challenging times, innovation is increasingly advocated as crucial to the long-term sustainability of health services, and the greatest potential for savings may be found by increasing efficiency and reducing variations in clinical practices. 1,2 However, it is important that the NHS takes steps to ensure that only the most effective, best-value health-care interventions and service improvements are adopted and that procedures and practices that have been shown to be ineffective are no longer used.

To do this well, commissioners need to be fully aware of the strength of the underlying evidence for interventions and new ways of working that promise to deliver more value from the finite resources available. The Health and Social Care Act 20123 has now embedded research use as a core function of the commissioning arrangements of the health service. The Secretary of State for NHS England (previously the NHS Commissioning Board) and each Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) must now, in the exercise of its functions, promote (1) research on matters relevant to the health service and (2) the use in the health service of evidence obtained from research.

NHS commissioners therefore have a key role in improving uptake and use of knowledge to inform commissioning and decommissioning of services, and there is a substantive evidence base on which they can draw. In the UK there has been significant and continued investment in the production of research evidence on the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of interventions to inform health-care decisions and choices. However, uptake of this knowledge to increase efficiency, reduce practice variations and to ensure best use of finite resources within the NHS is not always realised. This is in part through system failings to fully implement interventions and procedures of known effectiveness. 4,5 There has also been rapid, sometimes policy-driven, deployment of unproven interventions despite known uncertainties relating to costs, impacts on service utilisation and clinical outcomes, patient experience and sustainability;6 the NHS has also been slow to identify and disinvest in those interventions known to be of low or no clinical value. 7

Despite advances in the conduct and reporting of systematic reviews and recognition of their importance in health-care decision-making,8,9 their potential impact on processes is not yet realised. Although it is widely acknowledged that different sources of knowledge combine in evidence-informed decision-making10 and that the process itself is highly contingent and context dependent,11 a number of challenges have undermined the usefulness of systematic reviews in decision-making contexts. 8,12–17 These barriers include difficulties in locating and appraising relevant reviews; the review reports’ lack of timeliness or user-friendliness; and the real or perceived failure of reviews to address relevant questions, contextualise the findings, or make actionable policy recommendations.

One way in which these barriers can be overcome is through the provision of resources that adapt and present the findings of systematic reviews in a more directly useful form. Three types of review-derived products (summaries of systematic reviews, overviews of systematic reviews and policy briefs) aimed at policy-makers and other stakeholders have been postulated. 18 Summaries encapsulate take-home messages and add value by, for example, assessing the findings’ local applicability. Overviews of systematic reviews identify, select, appraise, and synthesise all known systematic reviews in a given topic area. Policy briefs identify, select, appraise and synthesise systematic reviews, other research studies, and context-specific data to address all aspects of a policy question. Alongside presentational issues, it has also been proposed that efforts should focus on the environment within which decision-makers work. 14 It is recognised that structural supports and facilitated strategies are required to ensure the capacity to acquire, assess, adapt and apply evidence obtained from research in decision-making. However, the best way to deliver this may be context specific, and evidence of effectiveness of interventions and strategies is lacking.

Public health specialists have traditionally supported and facilitated the use of research evidence in a commissioning context. 19,20 Those trained in public health and working in commissioning were more likely to report using empirical evidence than other senior commissioners, who were more likely to use colloquial evidence generated locally. 20 With the relocation of the specialty to local authorities, public health input now has a more limited role in commissioning processes. CCGs will need access to a variety of different evidence sources and expert involvement to ensure that evidence obtained from research continues to be incorporated into decisions made for their populations. 20 However, who is responsible for ensuring the absorptive capacity for research use,21,22 and that CCGs recognise and understand valuable research-based knowledge, is less clear. Although the Health and Social Care Act 20123 outlines research use as a statutory duty, operational guidance to commissioners also appears to significantly underplay the potential of research, and there are no explicit requirements relating to the use of evidence obtained from research. 23

An initiative aiming to enhance the uptake of evidence obtained from research in decision-making was developed as an adjunct to the implementation theme of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC) for Leeds, York and Bradford. 24 The Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) developed a demand-led knowledge translation service aimed at NHS commissioners and senior managers in provider trusts. The service attempted to address known barriers to systematic review uptake and use and aimed to make best use of existing sources of synthesised research evidence to inform local decision-making. Rapid evidence briefings were produced in response to requests from local NHS decision-makers who required an independent assessment of evidence to inform a specific ‘real world’ decision or problem. The rationale for this demand-led service was that addressing real decisions or problems in collaboration with those directly affected should mean that research evidence is more likely to be used and have an impact on decision-making.

Development of the service was informed by a scoping review of existing resources,25 previous CRD experience in producing and disseminating the internationally renowned Effective Health Care and Effectiveness Matters series of bulletins and initial iterative interactions with decision-makers on a range of mental health topics. We sought to address a number of known content, format and communication barriers to research use. 8,12,13,15–17 We targeted answering policy-relevant questions, ensuring timeliness of response, and delivering non-technical summaries with key messages, tailored to the relevant audience. As interactions between researchers and decision-makers might be expected to facilitate the ongoing use of research knowledge in decision-making we also instigated a process of ‘linkage and exchange’. 26 Although evidence was lacking on how best to do this13 and the time and resource costs required for both sides was unclear, the benefit of interactions between managers and researchers was theoretically grounded. Specifically, ongoing positive intergroup contact27 can be effective at generating positive relations between members of two parties when there is institutional support, equal status between those involved, and co-operation in order to achieve a common goal. 28 Contact has most benefit if those involved identify both with their own group and the overarching organisation to which they both belong. 29

The evidence briefing service adopted an approach that was both consultative and responsive and involved building relations and having regular contact (face to face and e-mail) with a range of NHS commissioners and managers. This enabled the team to discuss issues and, for those that required a more considered response, formulate questions from which contextualised briefings could be produced and their implications discussed. In doing so, we utilised a framework designed to clarify the problem and frame the question to be addressed. 30 Each evidence briefing produced would summarise the quality and the strength of identified systematic reviews and economic evaluations, but go beyond effectiveness and cost-effectiveness to consider local applicability, implications relating to service delivery, resource use, implementation and equity.

The evidence briefing service had some early impacts, notably including work to inform service reconfiguration for adolescent eating disorders and enabling commissioners to invest in more services on a more cost-effective outpatient basis. 31 Later work that assessed the effects of telehealth technologies (use of communication and information technologies that aim to provide health care at a distance) for patients with long-term conditions informed a decision to disinvest from a costly and much criticised technology deployment. Full details of the early briefings produced under the auspices of the NIHR CLAHRC for Leeds, York and Bradford can be found at www.york.ac.uk/crd/publications/evidence-briefings/.

Although feedback from users was consistently positive, the evidence briefing service had been developmental and no formal evaluation had been conducted. The service as constituted was also a resource-intensive endeavour and made use of the considerable review capacity and infrastructure available at the CRD. As such, we needed to establish how much value was added over alternative or more basic approaches. This was especially important as passive dissemination of systematic review evidence can have impact particularly when there is a single clear message and there is awareness by recipients that a change in practice is required. 15

As part of our developmental work we conducted a systematic review of products and services aimed at making the results of systematic reviews more accessible to health-care decision-makers. 25 This highlighted a lack of formal evaluation in the field. Indeed, most identified evaluations focused on perceived usefulness of products and services and not on actual impact. This study therefore aimed to address a clear knowledge gap and to help clarify which elements of the service were of value in promoting the use of research evidence and may be worth pursuing further.

This research was also timely because of the current and future need to use research evidence effectively to ensure optimum use of resources by the NHS, both in accelerating innovation and in stopping the use of less effective practices and models of service delivery. It therefore addressed a problem that faces a wide variety of health-care organisations, namely how to best build the infrastructure it needs to acquire, assess, adapt and apply research evidence to support its decision-making. For CCGs, this includes fulfilling its statutory duties under the Health and Social Care Act 2012. 3

Chapter 2 Methods

Primary research question

Does access to a demand-led evidence briefing service improve uptake and use of research evidence by NHS commissioners compared with less intensive and less targeted alternatives?

Secondary research questions

Do evidence briefings tailored to specific local contexts inform decision-making in other CCGs?

Does contact between researchers and NHS commissioners increase use of research evidence?

This was a controlled before-and-after study involving CCGs in the North of England. The original protocol is available online (see www.nets.nihr.ac.uk/projects/hsdr/12500218) and has also been published in the journal Implementation Science. 32 There were three phases:

-

phase 1 – pre intervention: recruitment and collection of baseline outcome data (survey)

-

phase 2 – intervention: delivery of study interventions

-

phase 3 – post intervention: collection of outcome measures (survey) and qualitative process evaluation data (interviews, observations and documentary analyses).

Setting, participants and recruitment

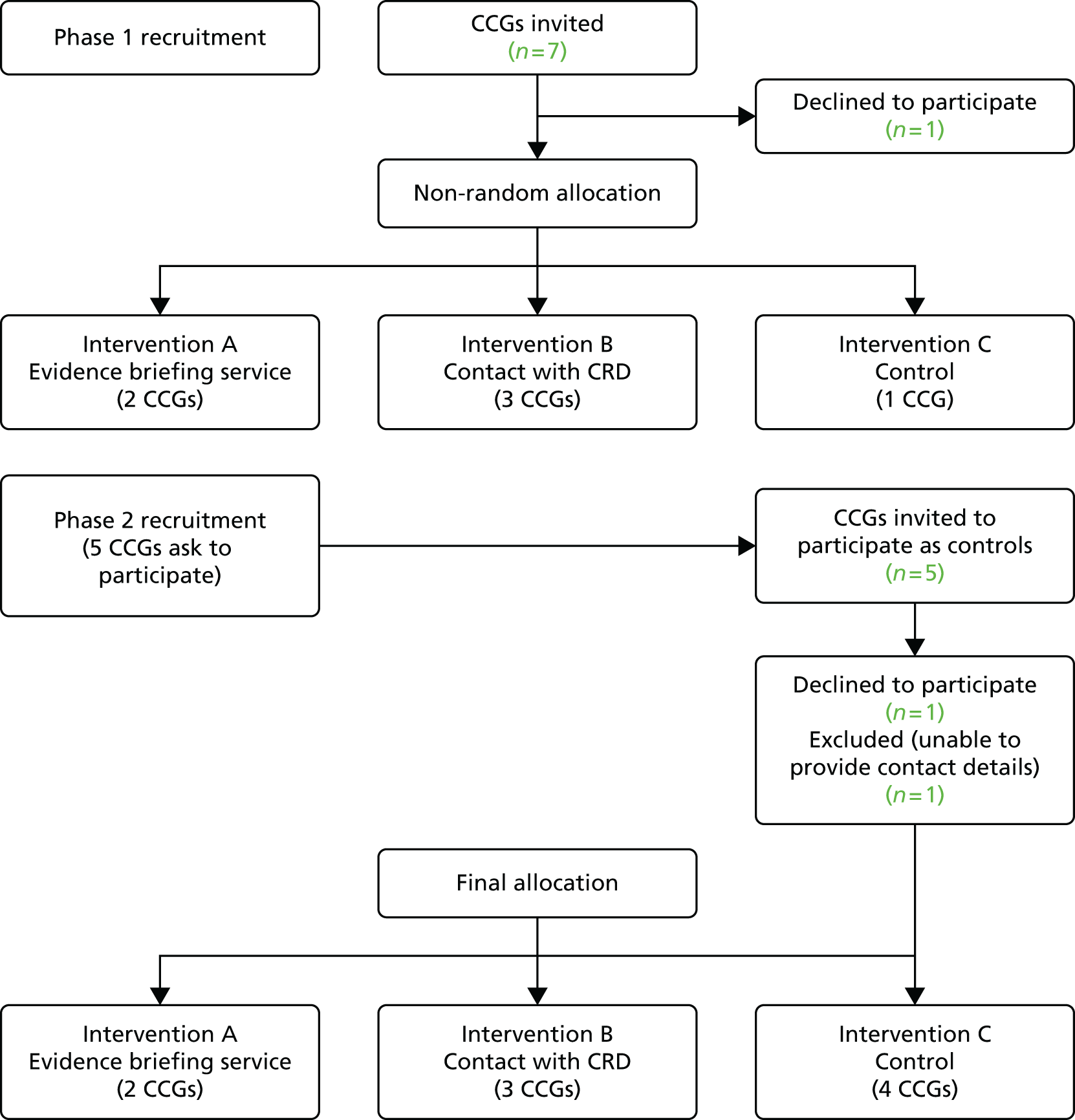

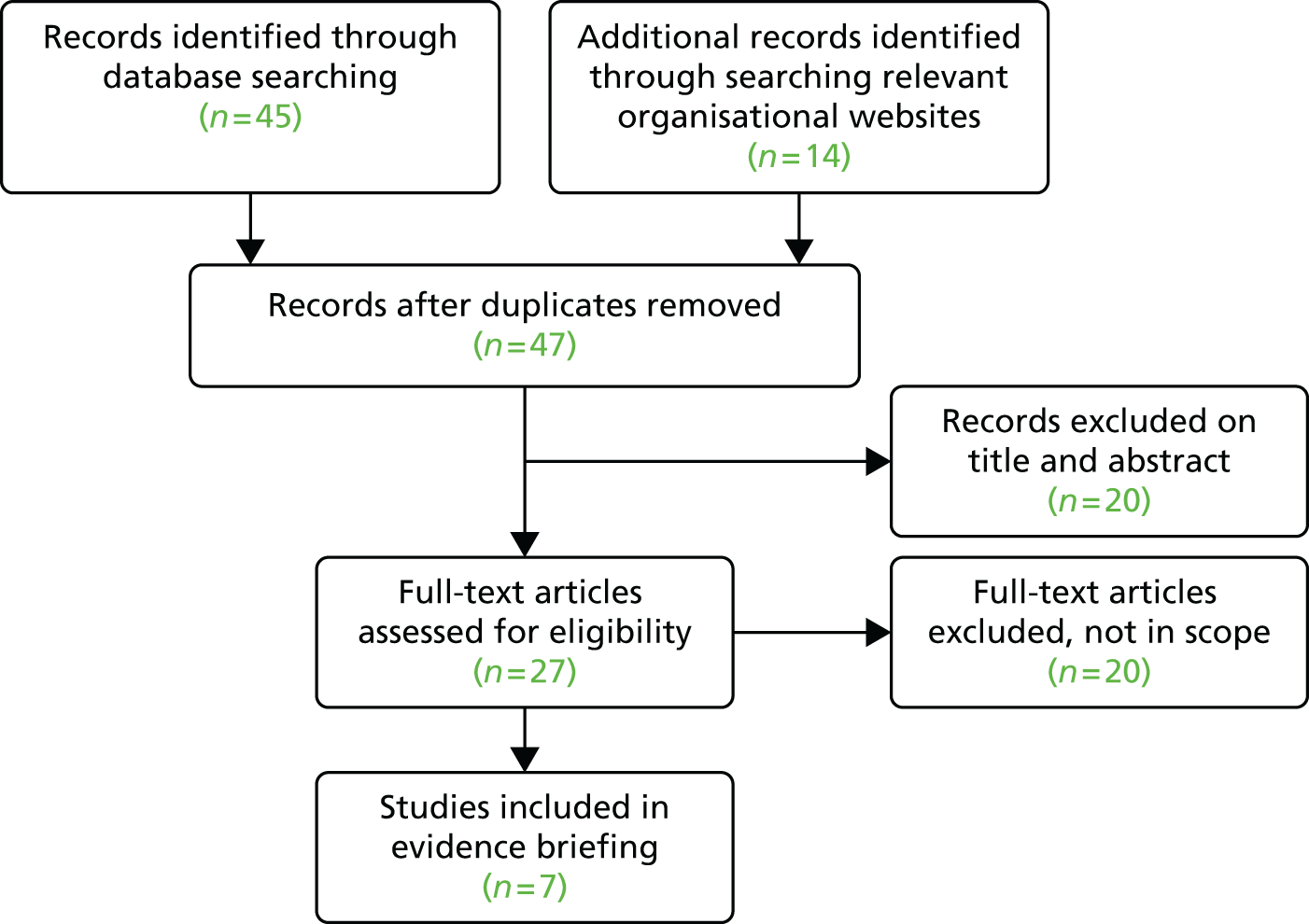

Nine CCGs from one geographical area in the north of England were the original focus of this study. The recruitment process is presented as a flow diagram in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of CCG recruitment.

When designing the study, we had anticipated that we would invite nine or ten CCGs from the geographical area based on the 2012/13 primary care trust (PCT) cluster arrangements. By the start of the study, some consolidation in the proposed commissioning arrangements had occurred in the transition from PCTs to CCGs and so the Accountable Officers of the resulting seven CCGs were contacted, told the nature of the study and invited to participate. Of these, six agreed to participate. One CCG declined, intimating that it could not participate in any intervention. No CCG asked for financial reimbursement for taking part in the study.

Clinical Commissioning Groups that agreed to participate were asked to provide details of all governing body and executive members, clinical leads and any other individuals deemed as being involved in commissioning decision-making processes. These individuals were then contacted by the evaluation team and informed of the study aims.

We had originally intended to randomly allocate CCGs to interventions. However, a combination of expressed preferences (one CCG indicated that it would like to be a ‘control’) and the prospect of further consolidation in commissioning arrangements meant that this was not feasible. Taking these factors into account, two CCGs were allocated to receive on-demand access to the evidence briefing service, three coterminous CCGs (who were likely to merge) received on-demand access to advice and support from the CRD team and one to a ‘standard service’ control arm.

After the initial allocation, we were approached by a research lead from a CCG in a neighbouring geographical area who had heard about the study and indicated that he and colleagues in other CCGs were also keen to participate.

The research team then had discussions with representatives of five CCGs at two research collaborative meetings. At these meetings, we explained that any CCGs willing to participate would be recruited as ‘standard service’ controls, but would be offered the opportunity to receive on-demand access to the CRD evidence briefing service after the follow-up phase was complete. Three CCGs agreed to participate. A fourth CCG initially agreed to participate but failed to provide contact details for any personnel involved in commissioning processes, despite repeated requests from the research team to do so. As we would therefore be unable to collect baseline data, rather than delay the start of the intervention phase, the team informed the CCG that it would have to be excluded from the study.

Characteristics of participating Clinical Commissioning Groups

In total, nine CCGs agreed to participate and were able to provide contact details for personnel involved in commissioning processes.

A1

The CCG covers a population of around 150,000 with 27 member practices. The CCG is strongly aligned to the local authority, with which it is coterminous, and also works closely with a range of other organisations such as NHS England, local NHS providers and neighbouring CCGs.

It is in one of the 20% most deprived local authorities in the country with considerable inequality between the most and least affluent areas within the borough; deprivation is, therefore, higher than the England average. Average life expectancy is also lower than the England average. Around 23% of children and 26% of adults are classified as obese. Rates of recorded diabetes, alcohol-related hospital stays, smoking-related deaths, early cardiovascular deaths and early cancer deaths are higher than the England average.

The CCG is the lead commissioner for the local NHS trust, which provides general hospital services and hosts many community services for a wide geographic area. Many specialist hospital services are provided by general and teaching hospitals outside the district. The CCG is small, as it has delegated most of its commissioning functions to the local Commissioning Support Unit (CSU). The CCG nonetheless demonstrates an interest in extending its commissioning reach, as it has taken on joint commissioning responsibility for primary medical care with NHS England from 2015/16. This is intended to give greater commissioning power to the CCG and will help to drive the development of new integrated models of care, such as multispecialty community providers and primary and acute care systems. The CCG is also a pioneer site for developing integrated care.

The CCG has worked in partnership with the local authority and third-sector providers to complete the Better Care Fund plan, which identifies four key transformation schemes. It has received over £12M in Better Care funding for 2015/16 to assist in delivering greater integration of services.

A2

The CCG covers a population of around 300,000, and has 45 member practices. Deprivation is lower than the England average and average life expectancy is lower than the England average. Around 17% of children and 26% of adults are classified as obese. Rates of recorded diabetes, alcohol-related hospital stays, smoking-related deaths and early cancer deaths are higher than the England average. Early cardiovascular deaths are slightly lower than the England average.

The CCG is coterminous and works closely with the local authority, as demonstrated by a partnership agreement for the management of continuing health-care patients. This reflects a stated aim about the need to join up patient care not just in health, but also in social care. CCG plans are also closely aligned with the priority areas of the Health and Wellbeing Board, and a Joint Health and Wellbeing Strategy has been developed with partners. The CCG has been involved in overseeing commissioning of a Specialist Emergency Care Hospital, the first purpose-built emergency care hospital in England, which opened in June 2015.

In 2015, the CCG began to cocommission primary medical care through a joint commissioning arrangement with NHS England. In addition, the CCG is part of a NHS vanguard site that is testing the new integrated primary and acute care systems. The CCG also received £22M in Better Care funding in 2015/16 to support the integration of health and social care.

B1–B3

During the course of the study, three participating CCGs merged to form a single statutory body with > 60 member practices. The new CCG covers a population of around 500,000. Deprivation is higher than the England average and average life expectancy is lower than the England average across these populations. In part of the locality, 23% of children and 22% of adults are classified as obese; rates of alcohol-related hospital stays, smoking-related deaths, early cardiovascular deaths and early cancer deaths are higher than the England average. Rates of recorded diabetes are lower than the England average. In a second locality, 22% of children and 23% of adults are classified as obese; rates of recorded diabetes, alcohol-related hospital stays, smoking-related deaths, early cardiovascular deaths and early cancer deaths are higher than the England average.

The strategic aim of the CCG is to improve the health and well-being of the population through a range of measures underpinned by the key principles of prevention. These include early intervention, integrated and co-ordinated primary, community, secondary and social care services, and timely access to secondary care services for those requiring hospital admissions. The CCG is the host commissioner for a large teaching hospital trust, which provides general hospital services, prescribed specialised hospital services and community-based services. The CCG is also host commissioner for a second hospital trust, which principally provides hospital services.

The original constituent CCGs received a combined £35M in Better Care funding in 2015/16: one CCG (B1) also received £2M in the second wave of funding from the Prime Minister’s Challenge Fund for improving access to general practice. The CCG now shares joint commissioning responsibility for primary medical care with NHS England.

C1

The CCG covers a population of > 250,000 and is made up of 51 member practices which cover five localities. The CCG faces challenges including a growing ageing population with escalating health needs, poor health compared to the rest of the England and excess deaths, particularly from heart disease, cancer and respiratory problems. The local community is affected by lifestyle factors such as obesity, smoking and alcohol abuse which pose a major risk to health and well-being.

Deprivation is higher than the England average and average life expectancy is lower than the England average. Twenty-one per cent of children and 27% of adults are classified as obese. Rates of recorded diabetes, alcohol-related hospital stays, smoking-related deaths, early cardiovascular deaths and early cancer deaths are higher than the England average.

The CCG works closely with the coterminous local authority and aims to tackle jointly identified local needs by working closely with the local community and engaging with a wide range of local partners to ensure the very best health and social care. To this end, the CCG also sits on the local Health and Wellbeing Board.

The CCG is one of the largest for its population size, having chosen to discharge the bulk of its commissioning responsibilities in-house, with a minority being undertaken by the CSU. The CCG is host commissioner for a large district general hospital, and a specialist eye hospital, which between them also provide many prescribed specialised services that are commissioned by NHS England. The vast majority of the CCG’s expenditure on hospital services is within the local health-care system.

The CCG received £22M in Better Care funding to support the integration of health and social care. Under cocommissioning arrangements, the CCG has assumed full responsibility for commissioning general practice services.

C2

The CCG covers a population of > 250,000 made up of 40 member practices. The CCG covers a large and diverse geographical area, which includes some of the most deprived communities in England and some of the most rural areas of the country.

In one locality within the CCG, the average life expectancy for both men and women is lower than the England average. A large proportion of the population is aged ≥ 50 years and this is set to rise. Meanwhile, rates of coronary heart disease, hypertension and depression are higher than the England average. There is a similar picture in another locality with regard to ageing and life expectancy, although there are higher rates of coronary heart disease, hypertension and obesity. This is also mirrored in a third locality, which also has greater deprivation, as 74% of lower super output areas are in the 30% most deprived nationally and 30% are in the 10% most deprived.

Under cocommissioning arrangements, the CCG has assumed full responsibility for commissioning general practice services and therefore has delegated responsibility for commissioning. A key element of the CCG’s 2-year operational and 5-year strategic plan is the Better Care Fund, which sees a single pooled budget across the CCG and other key stakeholders, including the local authority. The CCG received £21M in Better Care funding in 2015/16.

C3

The CCG covers a population of around 300,000 with 40 member practices. The CCG is coterminous with two local authorities. Deprivation is higher than the England average and average life expectancy is lower than the England average. Twenty-one per cent of children and 31% of adults are classified as obese; rates of alcohol-related hospital stays, smoking-related deaths, early cardiovascular deaths and early cancer deaths are higher than the England average; rates of recorded diabetes are equivalent to the England average. In one locality, 21% of children and 26% of adults are classified as obese; rates of alcohol-related hospital stays, smoking-related deaths, early cardiovascular deaths and early cancer deaths are higher than the England average; rates of recorded diabetes are lower than the England average.

Under cocommissioning arrangements, the CCG jointly commissions general practice services with NHS England. The CCG also draws on the CSU to provide a wide range of functions to enable delivery on priorities. The CCG works as part of the Health and Wellbeing Board for each local authority. The CCG recognises the importance of collaboration as highlighted by local action plans for single pooled budgets for health and social care services as part of the Better Care Fund, funding for which amounted to £19M in 2015/16.

C4

The CCG covers a population of around 300,000 with 46 member practices. The CCG is coterminous with two local authorities. Deprivation is higher than the England average and average life expectancy is lower than the England average. In one locality 23% of children and 24% of adults are classified as obese and in a second locality, 23% of children and 28% of adults are classified as obese. Rates of recorded diabetes, alcohol-related hospital stays, smoking-related deaths, early cardiovascular deaths and early cancer deaths are higher than the England average.

The CCG aims to tackle health inequalities and ensure that everyone has the right access to care at the right time, regardless of where they live in the area. There is recognition that this requires collaborative working and relationships are being developed with local partners including member practices, local authorities, Healthwatch and local third-sector providers. A key priority has been the development of a joint vision to improve services for the vulnerable and elderly.

The CCG received £20M in Better Care funding in 2015/16. The CCG jointly commissions general practice services with NHS England.

Baseline and follow-up assessment

We collected data for our two primary outcome measures (perceived organisational capacity to use research evidence and reported research use) at baseline (phase 1) and again 12 months after the intervention period was completed (phase 3).

Main study Clinical Commissioning Groups

The survey instrument (see Appendix 1) was the means by which we collected these data. It was designed to collect four sets of information that assess the organisations’ ability to acquire, assess, adapt and apply research evidence to support decision-making. Section 1 was based on a tool originally devised by the Canadian Health Services Research Foundation33,34 and then modified by the SUPPORT (SUPporting Policy relevant Reviews and Trials) Collaboration. 35 The SUPPORT Collaboration included additional domains designed to assess the extent to which the general organisational environment supported the linking of research to action;36 specifically the production of research, efforts to communicate research findings (‘push’), and efforts to facilitate the use of research findings (‘user pull’).

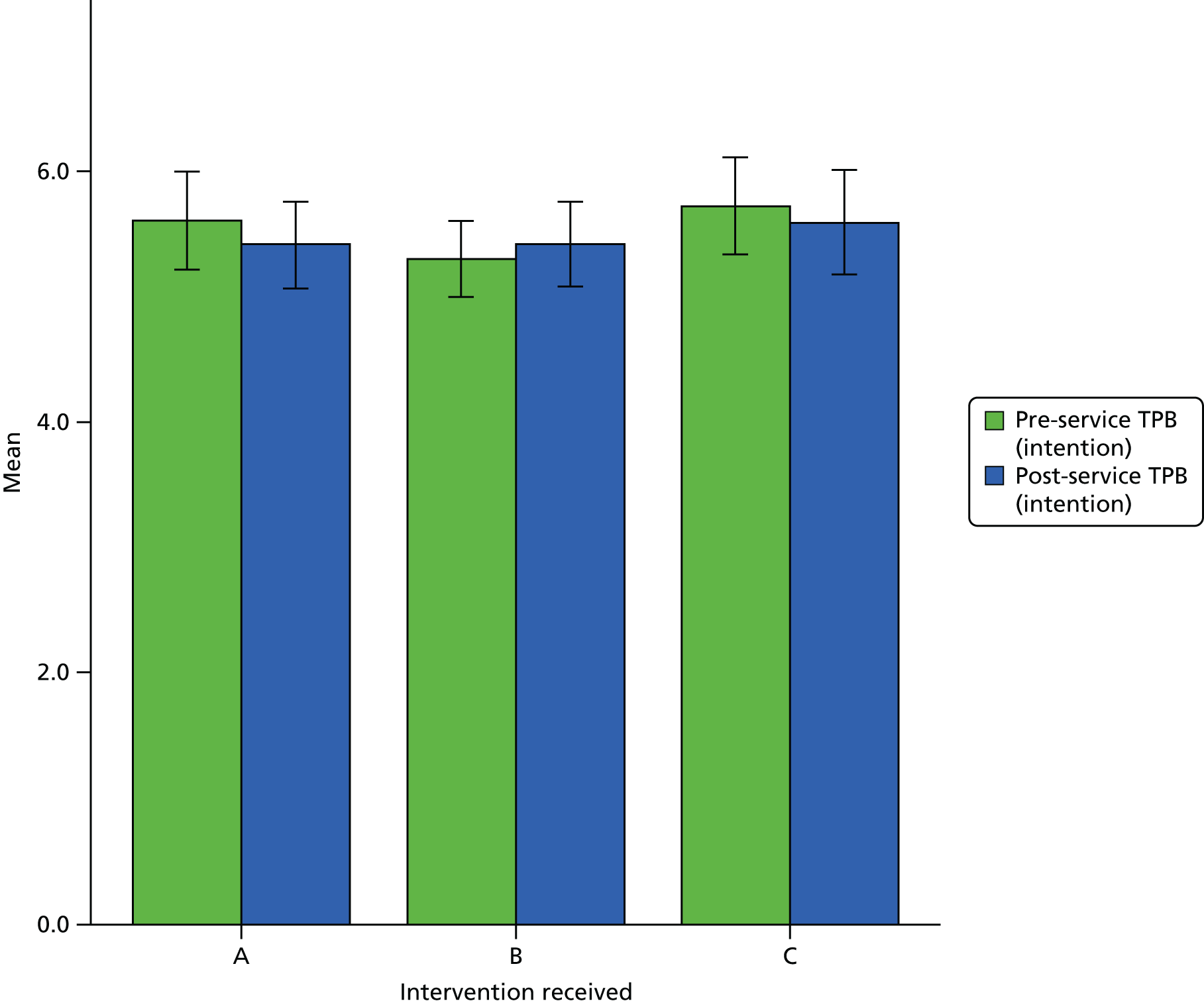

Section 2 was based on a modified version of a tool designed to be administered as part of a planned trial evaluating the effects of an evidence service specifically designed to support health system policy-makers in finding and using research evidence. 37,38 This Canadian tool was itself based on the theory of planned behaviour, a widely used theoretical framework for understanding and predicting behaviours. 39 We used this to assess the intentions of individual CCG staff to use research evidence in their decision-making. The theory of planned behaviour is useful for examining intentions and behaviours of CCG decision-makers as it provides a (validated) model of how the social action involved in using research is shaped by three key variables: attitudes (i.e. beliefs and judgments), subjective norms (i.e. normative beliefs and judgments about those beliefs) and perceived behavioural control (i.e. the perceived ability to enact the behaviour). These three variables drive intentions to behave, which in turn shape future behaviour. 40–42 Lavis et al. 37 and Wilson et al. 38 highlight a compelling rationale for the utility of the theory of planned behaviour as an explanatory framework for at least some of the variability (in the influence on intentions and behaviour) in health care professionals and – in theory – policy-makers:

-

About 39% of the variance in intention and about 27% of the variance in behaviour can be explained by theory of planned behaviour constructs.

-

Producing valid and reliable measures of key theory of planned behaviour constructs for use with health-care professionals is feasible.

-

The proportion of the variance in health-care professionals’ behaviour explained by their intentions was similar in magnitude to that found in the broader literature.

-

The agency relationship – between health-care professionals and patients – is not dissimilar to the agency relationship between policy-makers and others.

It was clear from preliminary discussions and our previous contact with CCG decision-makers that they were aware of the desirability of using research and often expressed an intention to use research (indeed, this was one of the principal drivers for our research), but that other mediating factors impacted on their ability to enact these intentions. Using the theory of planned behaviour allowed us to model an important proportion of at least some of the drivers for any eventual behaviour reported or observed.

Section 3 was designed to evaluate the changes to the nature of the (proposed) interactions, both within the participating sites and between commissioners and researchers. Participants are asked how much contact they have had with researchers in their job (quantity), and how successful the interaction (quality) had been, using an existing modified measure. 43 This section included questions regarding the extent to which the interactions were perceived as friendly and co-operative, and as helping to achieve the goals of both managers and researchers. The extent to which those involved in the interaction are perceived as being on an equal footing, without either group dominating, and the extent to which the contact is perceived as being supported by the CCGs, and the NHS more generally, was examined. Participants were also asked to indicate the extent to which their status as a NHS manager/lead is important to them (in-group identification) and to what extent they see themselves and researchers as part of one overarching group committed to achieving the same things (superordinate identification). In addition, we included measures of perceptions of researchers in general using a generalised intergroup attitude scale. 44

Section 4 captured information on individual respondent characteristics, which was collected to help understand any variation in responses.

The language used in all sections was adapted to match the NHS commissioning context and readability was first piloted with the study advisory group. The sections were ordered by importance beginning with the primary outcome measure, the organisational use of evidence. The instrument was then piloted to assess ease of completion, time to complete, appropriateness of language and face validity with a small group of commissioning staff from outside the study setting. Feedback suggested that the questionnaire was comprehensive but feasible, especially as its administration would be solicited rather than unsolicited. As a result of the feedback and in anticipation of some fall in responses as a result of fatigue, we deliberately chose to prioritise the primary outcome measure as the first section on the questionnaire.

National survey of Clinical Commissioning Groups

A second survey instrument that included only the questions from Section 1 in the main case site survey was used to collect data from other CCGs across England. This was delivered at baseline and then again post intervention.

Survey administration: main sites

Each participating CCG supplied a list of names and e-mail addresses for potential respondents. These were checked by a member of the evaluation team and where inaccurate or missing details were identified, these were sourced and corrected. Survey instruments were sent by personalised e-mail to identified participants via an embedded URL. The online questionnaire was hosted by the Survey Monkey website (www.surveymonkey.com). Reminder e-mails were sent out to non-respondents at 2, 3 and 4 weeks. A paper version of the questionnaire was also posted out and telephone call reminders were made by the research team. In addition, the named contact in each CCG sent an e-mail to all their colleagues, encouraging completion.

Survey administration: national Clinical Commissioning Groups

As CCGs were new and evolving entities at the time of the study, we needed to be able to determine if any changes viewed from baseline were linked to the intervention(s) and were not just a consequence of the development of the CCG(s) over the course of the study. To guard against this maturation effect/bias, and to test the generalisability of findings, we administered the instrument to all English CCGs to assess their organisational ability to acquire, assess, adapt and apply research evidence to support decision-making. The most senior manager (chief operating officer or chief clinical officer) of each CCG was contacted and asked to complete the instrument on behalf of their organisation. For the national survey we used publicly available information (NHS England and CCG websites) supplemented by telephone calls to CCG headquarters to construct our sampling frame consisting of every CCG in England.

Interventions

Participating CCGs received one of three interventions aimed at supporting the use of research evidence in their decision-making.

-

Intervention A: contact plus responsive push of tailored evidence.

-

Intervention B: contact plus an unsolicited push of non-tailored evidence.

-

Intervention C: unsolicited push of non-tailored evidence (‘standard service’).

Intervention A: contact plus responsive push of tailored evidence

Clinical Commissioning Groups in this arm received on-demand access to an evidence briefing service provided by research team members at the CRD. In response to questions and issues raised by a CCG, the CRD team synthesised existing evidence together with relevant contextual data to produce tailored evidence briefings to a specified time scale agreed with the CCG. Full details of the evidence briefing production process are presented in Chapter 3. Based on developmental work undertaken as part of the NIHR CLAHRC for Leeds, York and Bradford, the project was resourced so that the team could respond to six to eight substantive issues during the intervention phase.

The CRD intervention team was formulated to provide regular advice and support on how to seek solutions from existing evidence resources, commissioning question framing and prioritisation. Advice and support was to be delivered via telephone or e-mail or face to face. As this was planned as a demand-led service CCGs in this arm could contact the intervention team at any time to request their services. Contact initiated by the CRD intervention team was made on a monthly basis and was expected to include discussion of progress on ongoing topics, identification of further evidence needs and discussion of any issues around use of evidence. The team also flagged any new systematic reviews and other synthesised evidence relevant to CCG priorities.

The evidence briefing team also offered to provide training on how to acquire, assess, adapt and apply synthesised existing evidence. Training (which was dependent on demand/uptake) would depend on the needs of the CCG but it was anticipated that this could cover question framing, priority setting, identifying and appraising systematic review evidence, assessing uncertainty and generalisability.

Intervention B: contact plus an unsolicited push of non-tailored evidence

Clinical Commissioning Groups allocated to this arm received on-demand access to advice and support from the CRD as those allocated to receive on-demand access to the evidence briefing service. However, the CRD intervention team did not produce evidence briefings in response to questions and issues raised but instead disseminated the evidence briefings generated in the responsive push intervention.

Intervention C: ‘standard service’ unsolicited push of non-tailored evidence

The third intervention constituted a ‘standard service’ control arm; thus, an unsolicited push of non-tailored evidence. In this, the CRD intervention team used their normal push-and-pull processes to disseminate the evidence briefings generated in intervention A and any other non-tailored briefings produced by the CRD over the intervention period.

The intervention phase ran from the end of April 2014 to the beginning of May 2015. As this study was evaluating uptake of a demand-led service, the extent to which the CCGs engaged with the interventions was determined by the CCGs themselves.

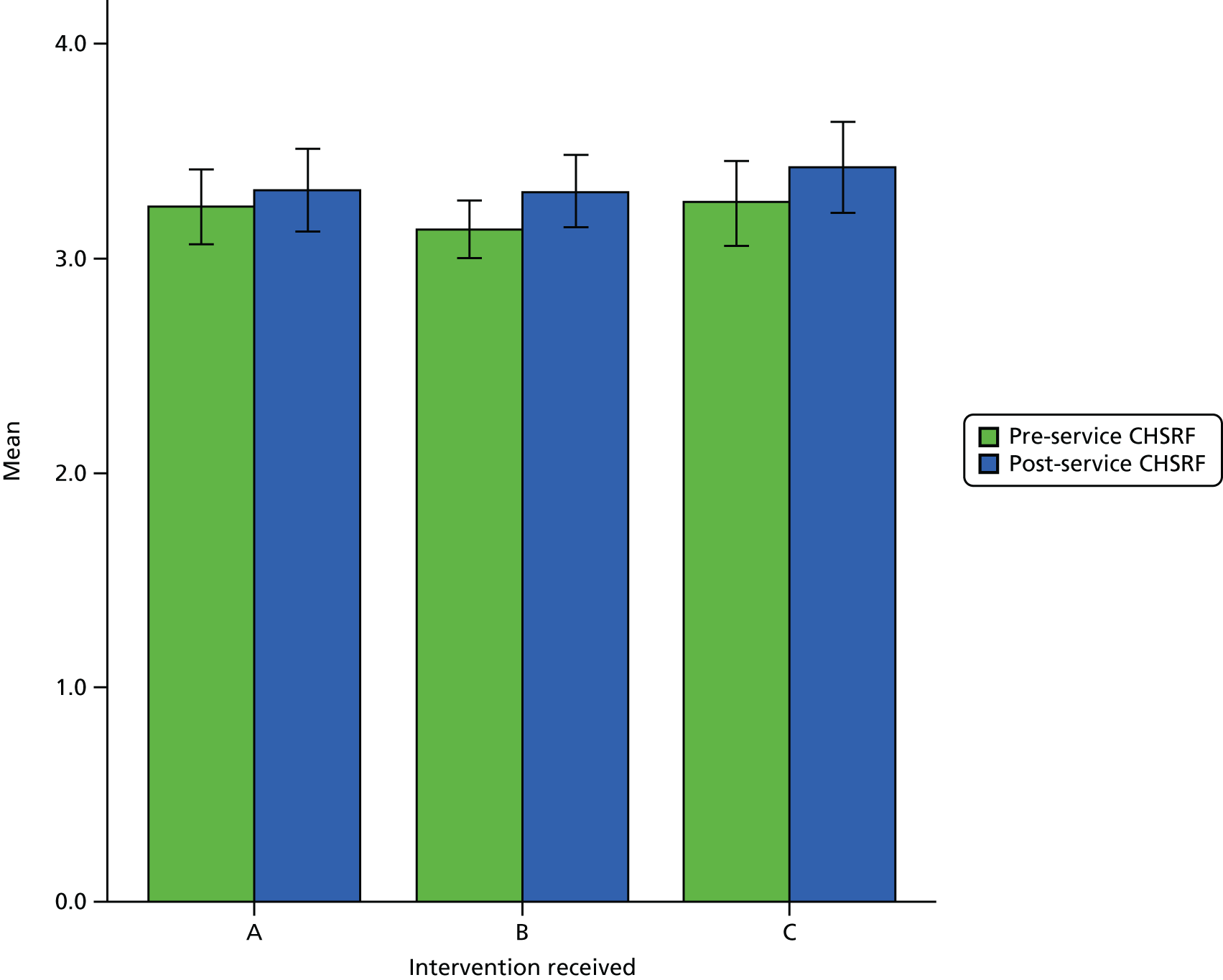

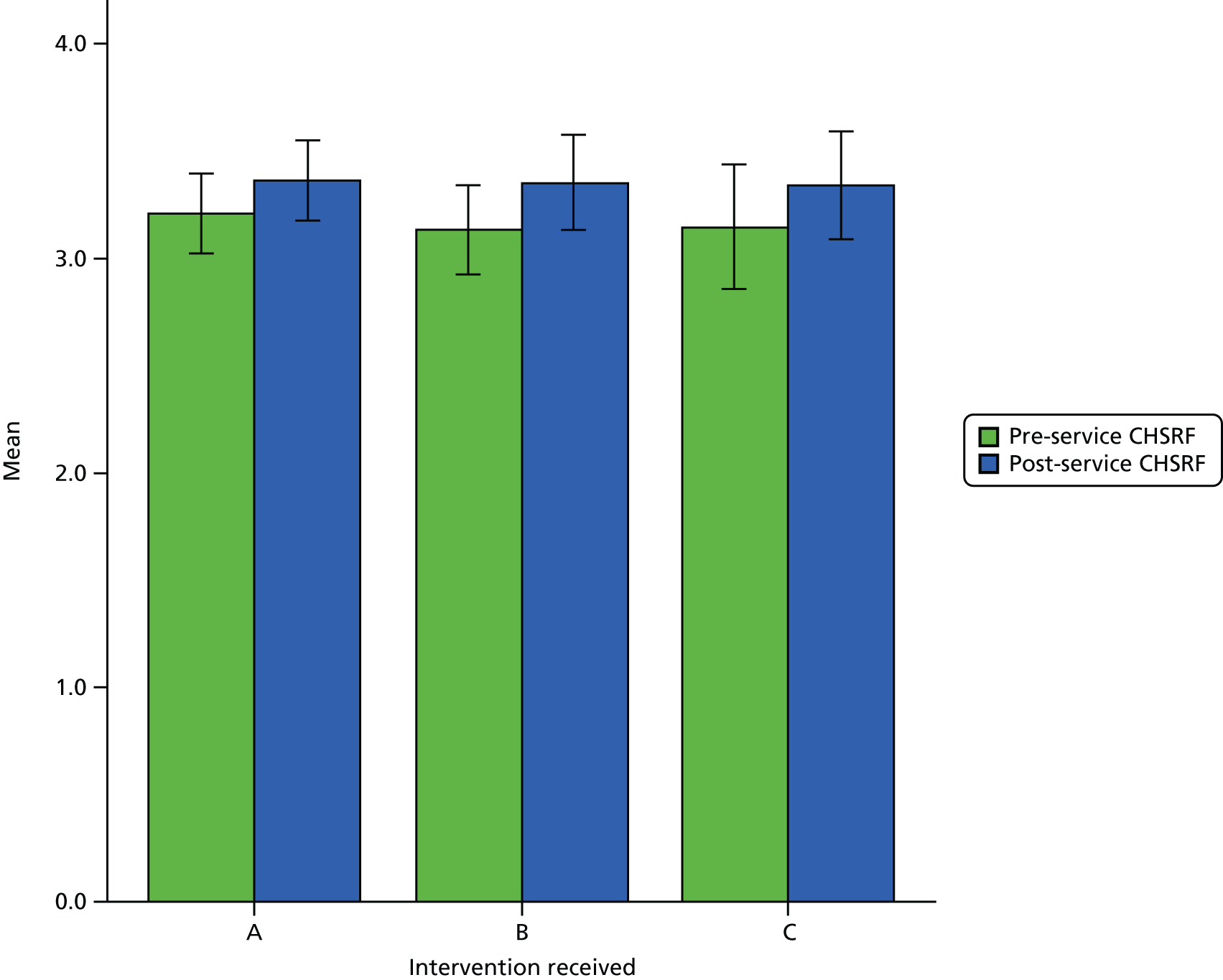

Quantitative analysis

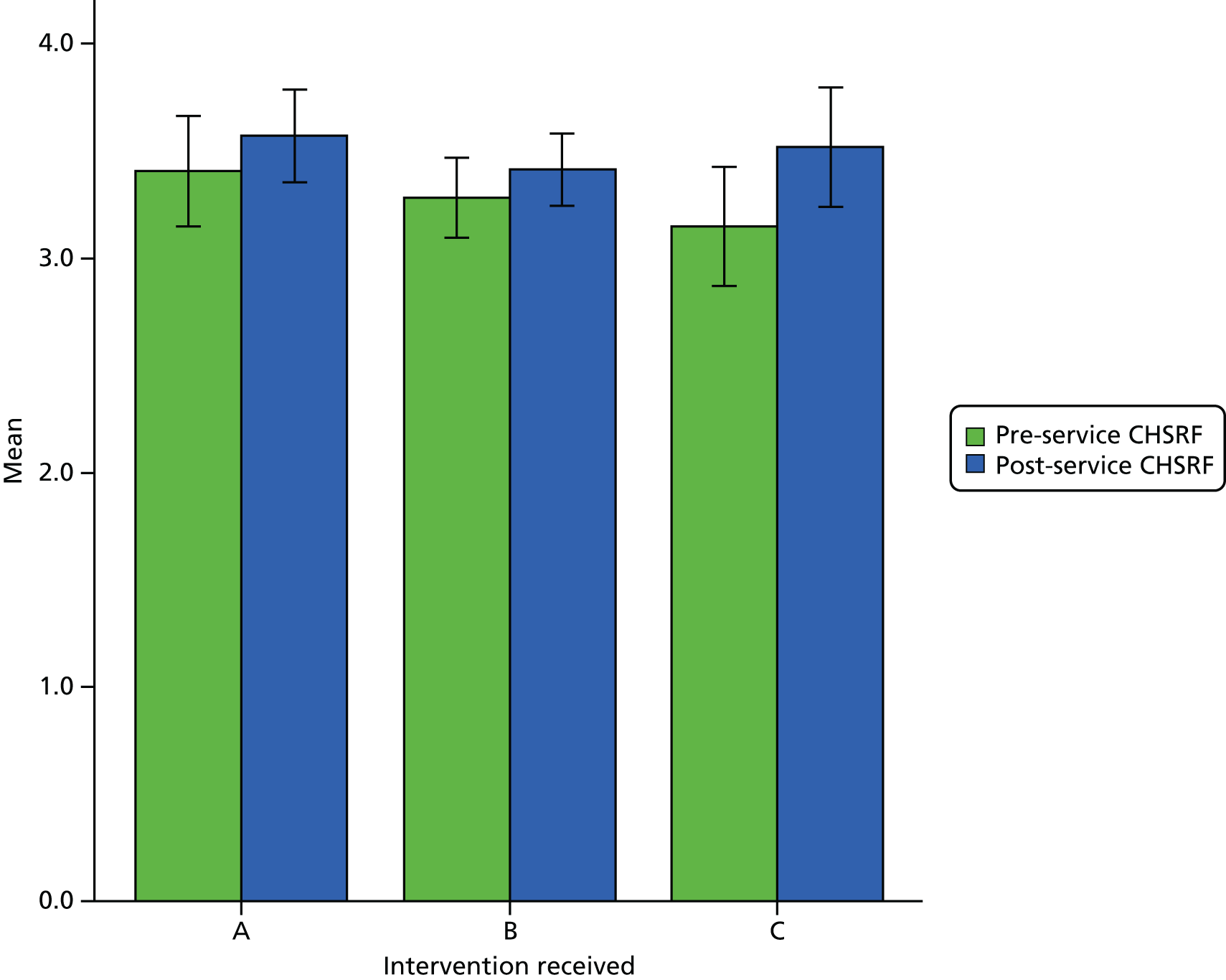

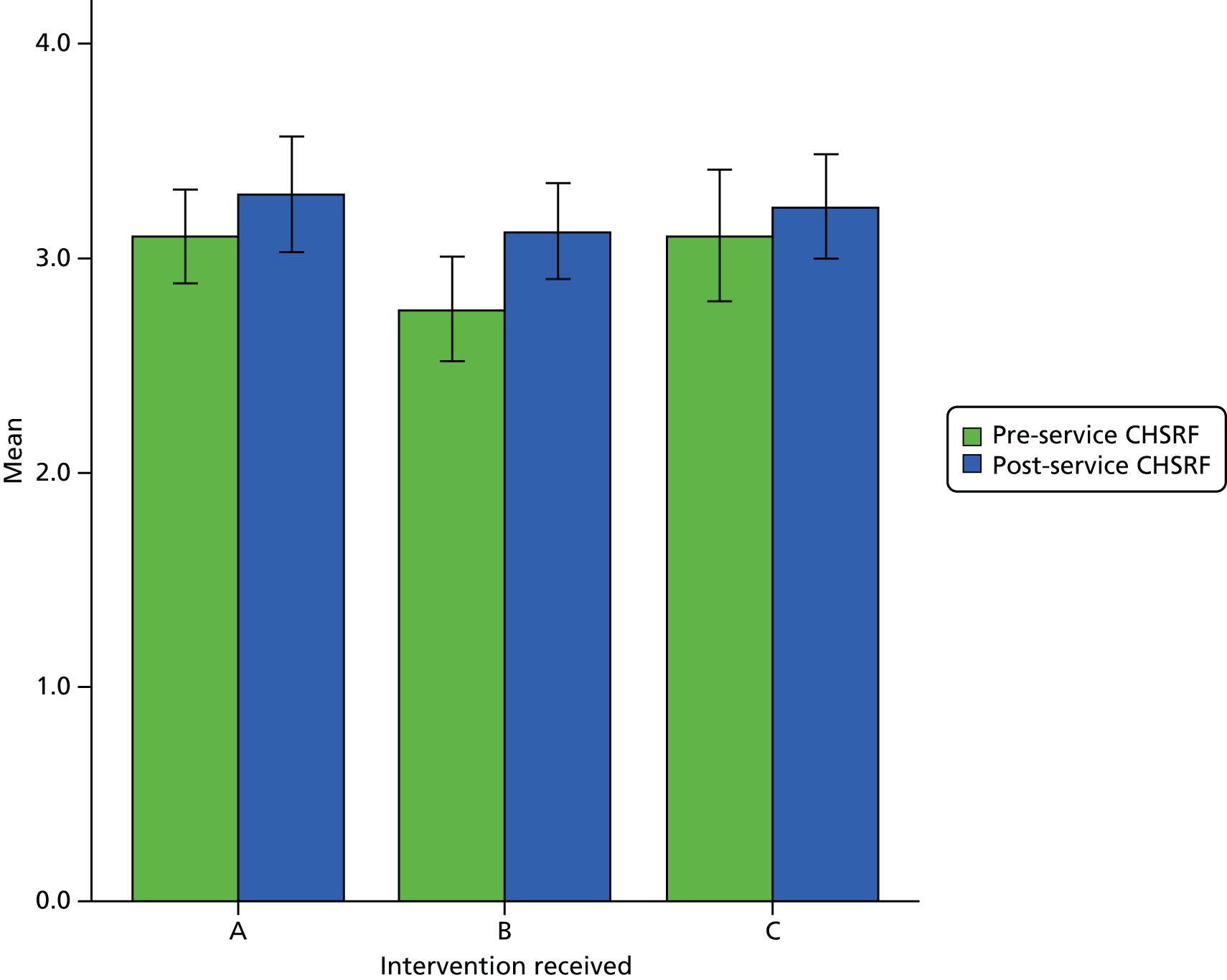

The primary analysis measured the impact of study interventions on two main outcomes (perceived organisational capacity to use research evidence and reported research use) at two time points: baseline (pre intervention) and 1 year later (post intervention). The key dependent variable was CCG-perceived organisational capacity to use research evidence in their decision-making as measured by Section 1 of the survey instrument (see Appendix 1). We also measured the impact of interventions on our second main outcome of perceived research use (see Appendix 1, Section 3) and CCG members’ intentions to use research (see Appendix 1, Section 2). These were treated as continuous variables and for each we calculated the overall mean score, any subscale means, related standard deviations and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) at two time points pre and post intervention.

Secondary analysis assessed any relationships between the model of evidence briefing service (intervention) received and three further continuous independent variables measuring individual demographic characteristics (e.g. job role, clinical or other qualifications) and the quality and frequency of contact with researchers on the two outcome measures.

In our original protocol we (rather optimistically) held out the possibility that the data might allow for a more complex multivariate analysis, which would take into account clustering effects associated with CCGs or NHS Regions. There were insufficient data of sufficient quality to allow for such an analysis. When measures were non-normal, we transformed the data (logarithmically) where necessary and possible. Analysis was undertaken using IBM Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) Statistics, version 22.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) and Stata statistical software version 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

We undertook a number of statistical comparisons:

Chi-squared tests of independence were performed to examine the relation between the model of evidence briefing service received and the biographical characteristics of respondents.

To examine the hypothesis that CCGs would differ in their capacity to acquire, assess, adapt and apply research evidence to support decision-making as a result of receiving one of the interventions, we undertook a factorial analysis of variance [(ANOVA) SPSS, version 22.0, general linear model procedure], comparing the main effect of a single independent variable (CCG status) on a dependent variable (capacity to acquire, assess, adapt and apply research evidence to support decision-making) ignoring all other independent variables (i.e. the effect ignoring the potential for confounding from other independent factors). Thus, we assessed the main effects of time and intervention received and the interaction effect (effects of all independent variables on a dependent variable) of both time elapsed and of the intervention on domain scores. Thus, we had one independent variable (the type of intervention) and one repeated measures variable [the total score and domain subscore(s) at baseline and 1 year later].

To examine the hypothesis that the intervention would impact on CCG’s collective intention to use research evidence for decision-making, a factorial ANOVA using the SPSS (version 22.0) general linear model repeated measures procedure was conducted to compare the main effects of time and evidence briefing service received and the interaction effect of time and evidence briefing on intention to use research evidence (using a measure derived from the theory of planned behaviour – see the ‘intention’ component of the study questionnaire, Qs 41–43). As the theory of planned behaviour (in the context of this study) predicts that intention to use research evidence for decision-making will be positively correlated with attitude, group norms and perceived behavioural control in the CCGs according to the intervention it received, we also examined the main effects of time and evidence briefing service received and the interaction effect of time and evidence briefing on these variables.

To examine the effects of (1) perceived contact and (2) the amount of perceived contact with the evidence briefing service, (3) institutional support for research, (4) a sense of being equal partners during contact, (5) common in-group identity, (6) achievement of goals and (7) perceptions of researchers generally, we undertook a mixed 3 (intervention: A vs. B vs. C) × 2 (time: baseline vs. outcome) ANOVA using SPSS (version 22.0), with the intervention as a between-subjects independent variable, and repeated measures on the second factor, time.

Missing data

Missing data and attrition between baseline and 1-year follow-up were issues. Although only ≈16–20% of questionnaires had missing data at baseline, at follow-up more than half the responses were missing or incomplete. As analysing only the data for which we had complete responses would have led to potentially biased results,45 and as anticipated at bid and protocol stages, the use of multiple imputation techniques was required. 46 SPSS multiple imputation processes were used. We assumed that data were missing at random (visual comparison of original versus imputed data and significance testing of response and non-response data impact on outcome variables – see Chapter 4). Five imputed data sets were created and the data imputed were the dependent variables of the capacity score derived from Section 1 of the survey instrument, theory of planned behaviour variables and the measures of perceived quality and quantity of contact with researchers.

We used guidance on interpreting effect sizes in before-and-after studies to examine the clinical/policy significance of any changes. 47

Blinding

Baseline and follow-up assessments and the qualitative aspects of the research were undertaken by a separate evaluation team. The CRD evidence briefing team members were blinded from both baseline and follow-up assessments until after all the data collection was complete. The CRD evidence briefing team were made aware of baseline and follow-up response rates. Participating CCGs were also blinded from baseline and follow-up assessments and analysis.

Qualitative evaluation

To internally (within the context of the local health economy) validate the self-reported data collected in phases 1 and 3 and to explore the decision-making processes within each case site, we collected qualitative data. This was also an opportunity to explore CCGs’ experiences of working with the CRD intervention team and to feed back directly on the service it received. The qualitative data collected via observations and interviews were used to address the following questions:

-

What do commissioners consider to be ‘evidence’?

-

How is research evidence used in the commissioning decision-making processes in CCGs?

-

What is the perceived impact of a demand-led evidence briefing service on organisational use of research evidence?

-

What were commissioners’ experiences of the evidence briefing service?

-

How could the evidence briefing service be improved?

Change to protocol

Part of our original plan (outlined in the study protocol) was to collect and analyse documentary evidence of the use of evidence in decision-making using executive and governing body meeting agendas, minutes and associated documents. This component aimed to capture reported actual use of research evidence in decision-making, whereas our primary outcome measures focused on intention to do so. This was to be supplemented with interviews to explore perceived use of evidence and any unanticipated consequences.

Early in the intervention phase, it became apparent that this approach may not be feasible. With a few exceptions, we found a lack of recorded evidence of research use (a finding in itself), as executive and governing body meetings were mainly used to ratify recommendations and so would not tell us anything about sources or processes. With research use and decisions occurring elsewhere and often involving informal processes, we decided to undertake four case studies to explore use of research evidence in decision-making in the intervention sites. The case studies were three case site CCGs and one commissioning topic involving all CCGs across the region (low-value interventions). The Project Advisory Group approved this change in October 2014. Within the case studies, three types of data were collected: documents, observations and interviews.

Documents

Documentation was obtained from participating CCGs on request and through searches of publicly accessible documents on CCG websites. For the case studies, 55 policy documents, governing body papers and evidence documents supporting decision-making were sourced from CCGs. To understand how participants engaged with and used evidence in their decision-making, we utilised themes emerging from previous NIHR Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR)-funded research examining ‘evidence’ use in commissioning processes. 48

Observations

In the absence of documentary evidence of decision-making, the aim of the observations was to capture the role and use of evidence in decision-making discussions and to identify topics to inform the subsequent interviews. One evaluation team researcher (KF) attended meetings at different stages of the decision-making process for one commissioning topic (low-value interventions) that cut across all CCGs. Relevant meetings were identified by key contacts within each organisation and included only formal decision-making contexts. Observation notes were taken during each meeting and non-participant observations were conducted with full knowledge and permission of attendees.

Interviews

To add richness and depth, in-depth qualitative interviews were undertaken with named contacts and key informants in participating CCGs. Interviews aimed to explore perceptions of the use of research evidence locally and experiences of interacting with the evidence briefing service, as well as any unanticipated consequences of the work. A topic guide was devised to explore engagement with the CRD intervention team and to capture aspects of influencing theories. This guide was piloted with general practitioner (GP) commissioners in a different CCG for feedback on language and operability of the guide. Feedback was positive and indicated that the guide was suitable for the purposes of the study. Interviews took place at the end of the intervention phase. The purposive sampling criteria included commissioners (board or executive team members and commissioning managers) who had had contact with the evidence briefing service.

Interview participants were invited to interview initially via e-mail and they received a participant information sheet electronically. In the case of non-response, e-mails were followed by telephone calls to the participant or via their personal assistant (where appropriate). A second e-mail was sent to those who could not be contacted by telephone. Participants were given the opportunity to ask questions about the research before agreeing to participate. Two evaluation team researchers (KF and CT) conducted the interviews face to face. All interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed by an external transcription company. Interviews were scheduled to last 1 hour.

Informed consent was obtained at the start of interviews. Participants were offered the opportunity to ask any questions about the process (but the researcher did not answer any questions relating to the evidence briefing service itself in order to avoid bias) prior to giving consent. Interviewees were given the opportunity to view direct quotations (and their immediate context) prior to publication.

In total, 39 participants were contacted and invited to participate. Of these, 21 agreed to participate, one delegated participation to a colleague and four agreed to discuss participation but despite repeated attempts were unable to schedule a time to do so. Seven participants declined (one no longer worked at the CCG, two declined because of time commitments and lack of knowledge of the evidence briefing service, one because of a job change and four gave no reason). The remaining six participants did not respond to repeated invitations.

Analysis and data integration

This was a mixed-methods study using a sequential explanatory strategy. Initial integration was of the three forms of qualitative data. Data from interview, observation and documentary analysis were uploaded into analysis software and combined to generate a descriptive account of the use of evidence in decision-making within each case. The primary point of data integration was the analysis stage in which themes generated by qualitative analysis were used to help us to understand variation in quantitative outcomes.

Qualitative analysis

Analysis was by constant comparison and used the qualitative data analysis software package NVivo, version 10 (QSR International Pty Ltd, Melbourne, VIC, Australia) to organise and manage the data. Our analytical approach was both deductive (developing themes from the research questions and survey instruments employed) and inductive (new themes emerging from the accounts of key informants). This process was iterative, the researcher returned to the original data several times, reviewing codes and revising each case-study narrative. During this process, data were integrated in three ways. First, interviews were categorised according to the intervention received and differences in the themes generated by each interview were compared and contrasted across each case. Once all data had been collected, one researcher (KF) developed a coding framework based on initial readings of the interview data without grouping by case. Cases were coded systematically with categories emerging from the data itself as well as from the research questions and theories and research literature relating to evidence-informed decision-making. These categories were reviewed by members of the research team (CT, ML, PW and KF) in order to focus the next iteration of coding. KF then reviewed and recoded all transcripts grouped as case studies. At the same time KF conducted text searches of all documentation and observation notes (text searches and manual review of observation notes) to understand the role of evidence obtained from research in decision-making. Identified terms were examined individually to understand the textual context of its use. Finally, themes generated by interviews were compared with those arising from documentary evidence to identify any conflict or consistency between local perceptions of the use of evidence and recorded use of evidence. Analysis of each type of data was integrated into case summaries for each of the three CCG case studies. For example, evidence of the use of research in documentation was used to explore support or refute descriptions given in interviews. Transcripts were randomly selected for review by CT to identify additional themes and to challenge conclusions made by KF.

Summaries describing the characteristics of each case and the local health economy were developed by two researchers (ML and LB). These were used to set the context of the case study and to inform discussion. Some themes were identified in advance from the research questions and theories and research literature relating to evidence-informed decision-making, others emerged from the data during analysis. The researcher was also alerted to concepts and themes while observing meetings during the intervention period. These were explored or reignited during the interview analysis period. The researcher sought confirmation or deviation from these concepts in transcripts and by revisiting notes from observations. Case summaries were developed that drew on data from all sources. Once these had been created, KF returned to the original data to identify any deviation from the narratives created. The second point of data integration was the analysis stage in which themes generated by qualitative analysis were used to help us to understand variation in quantitative outcomes.

Ethics and governance

This study was granted research ethics permission by the Department of Health Sciences, University of York Research Ethics Board. Appropriate research governance approval was also obtained.

Organisation-level consent granting permission to contact staff was obtained from each participating CCG. Individual participants had the opportunity to discuss any aspect of the study and their involvement in it with the research team at any stage of the study. Completion of questionnaires was anonymised and CCGs were informed of response rates but not of individuals’ participation. Interview participants and those present at observed meetings gave informed consent to their participation. None of the interventions involved any direct risks or burdens to the CCGs involved.

Patient and public involvement

The primary focus of this study was interventions targeted at NHS staff undertaking core roles within CCGs, so the active involvement of the public or service users in the design of this project was not sought. Patient and public involvement was provided through lay representation on the Project Advisory Group and through the development of the Plain English summary. We also committed to produce a summary of our findings in plain English and to ensure that these are shared with lay members of governing bodies in all of the participating CCGs.

Chapter 3 The evidence briefing service

The evidence briefing service was provided by team members at the CRD, University of York. In response to CCG requests, the team followed a well-established methodology to produce summaries of the available evidence together with the implications for practice within an agreed time frame. This chapter describes the introduction of the service to the intervention arm of the study, production of the briefings and the topics covered, including detailed examples.

Introducing the service

For the five participating CCGs allocated to receive contact via interventions A and B, we offered to come and explain the nature of the evidence briefing service and the aims of the study at the next available executive team meeting. Three of the five CCGs accepted the offer. Face-to-face meetings were arranged with representatives of the remaining two CCGs (who were also two of the three CCGs likely to merge). At each meeting, we outlined the aims of the study and highlighted the free advice and support for evidence-informed commissioning being made available from the CRD. Specifically, we offered help on clarifying issues, formulating questions and advice on how to make best use of the research evidence relevant to the commissioning challenges it faced. Recent work on telehealth undertaken for a CCG outside the study setting was used to illustrate how the evidence briefing process worked and what the CCG could expect in terms of a response to any questions it raised. At the meetings, we emphasised that participation in the study would help the CCG to fulfil its statutory duties under the Health and Social Care Act 2012,3 but also stressed that as this was a demand-led service; the extent to which the CCG engaged with the service was entirely at its own discretion.

After each meeting, a personalised e-mail was sent to all Executive Team members, clinical leads and commissioning managers within the CCG restating the aims of the study and the nature of the offer from the CRD.

For co-ordination purposes we suggested that each CCG nominate a senior person who we could liaise with and could act as the conduit for all CCG requests. Once named contacts were identified, they were invited to discuss areas of interest with their colleagues and get in touch and discuss their needs with the evidence briefing team. Each named contact was then met individually face to face to discuss the evidence briefing process, the nature of support being offered and to identify any initial CCG priorities.

Producing the evidence briefings

The process for producing evidence briefings followed that developed as part of the TRiP-LaB (Translating Research into Practice in Leeds and Bradford) theme of the NIHR CLAHRC for Leeds, York and Bradford and by the CRD as part of its core contract under the NIHR Systematic Reviews Programme. 30

On receipt of each request, an attempt was made to define the research question to be addressed in terms of population, intervention, comparator and outcome. 49 This was done via discussion with the named contact and/or the individual(s) making the request. Discussions rarely involved more than three named individuals as decision-making processes were found to be largely informal and rarely involved minuted meetings or gatherings of CCG staff. Most interactions around priority topics and questions were either telephone or e-mail based (> 500 e-mails relating to the formulation of questions and the production and dissemination of briefings were received or sent over the course of the study). Relevant contextual information, and, in particular, the background to the request being made, were also sought from the individuals making the request.

In some instances, interest in a topic was identified but a specific research question could not be framed initially. In such cases, we produced evidence notes, which aimed to provide a quick scope of the available evidence in the area. This then helped to frame the question(s) to be explored by subsequent, more focused, evidence briefings.

Identifying the content

As with our earlier developmental work,30 the evidence briefings were based on existing sources of synthesised, quality-assessed evidence and applied to the local context. Searches for relevant systematic reviews and economic evaluations were performed by the researchers responsible for each briefing. The core sources searched for evidence were:

-

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE)

-

NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED)

-

Health Technology Assessment (HTA) database

-

International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO)

-

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR).

During the course of the study, NIHR funding for the production of two databases, DARE and NHS EED, ceased. The CRD continued to conduct weekly searches, systematic reviews and economic evaluations until the end of December 2015. From January 2015 onwards, when searching for systematic reviews, the briefing researchers undertook additional searches of PubMed using the ‘Review’ filter and NHS Evidence using the ‘Systematic review’ filter.

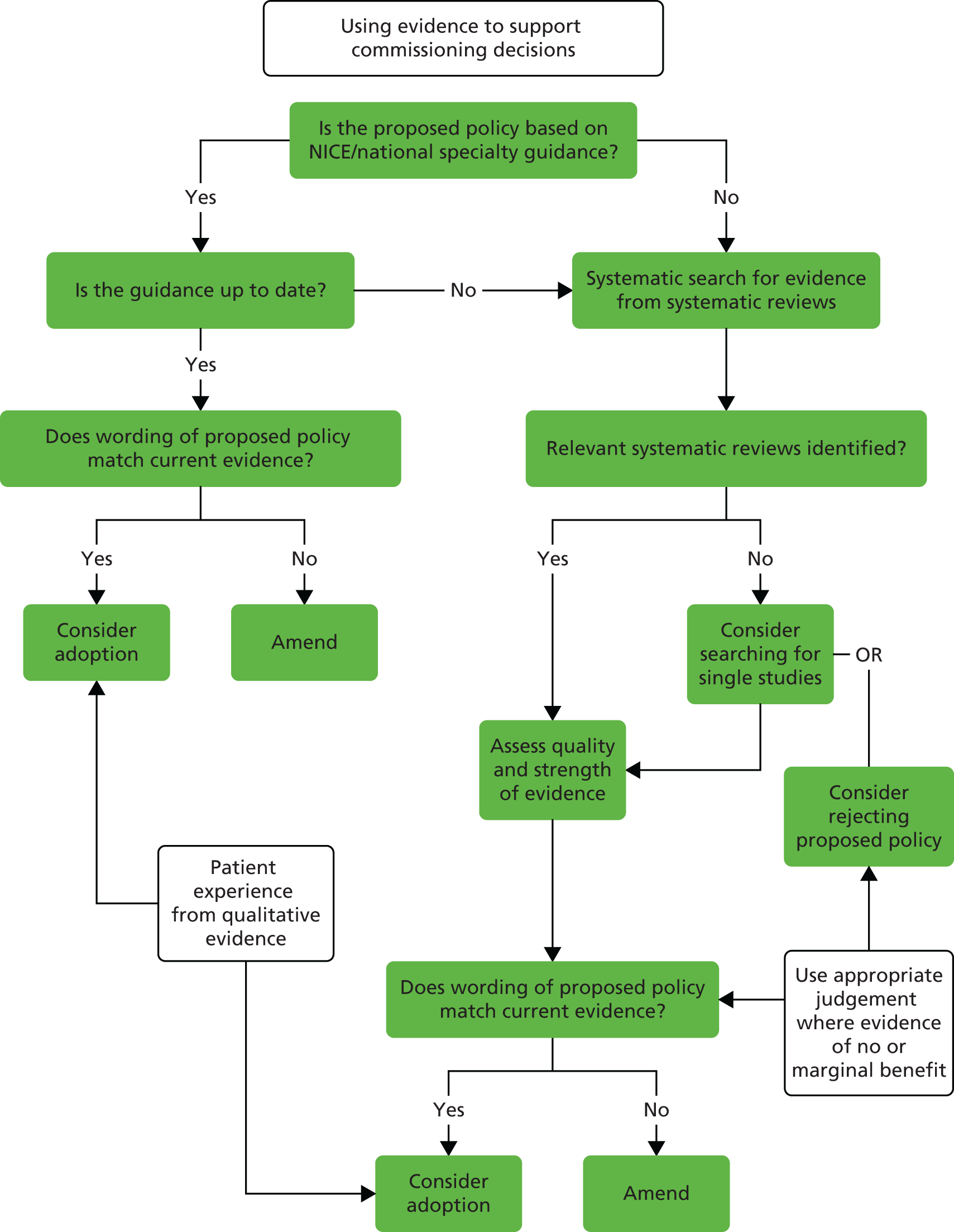

For topics that were likely to be impacted by national guidance, we searched the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) website. Additional sources were also searched for relevant policy reports and for other grey literature. These included the websites of The King’s Fund, Nuffield Trust, Health Foundation, Nesta, NHS England and the NIHR Journals Library. If systematic review evidence was limited, recent primary studies (published from 2010 onwards) were identified by searches of PubMed.

Data extraction and quality assessment

We stored the literature search results in a reference management database [EndNote (Thomson Reuters, CA, USA)]. One researcher screened all titles and abstracts obtained through the searches for potentially relevant content. Two researchers then independently made decisions on content most relevant to the questions to be addressed. Once selected, data were extracted into summary tables by one researcher and checked by another. Throughout this process discrepancies were resolved by consensus or where necessary by recourse to a third researcher.

Systematic reviews and economic evaluations included in DARE and NHS EED meet basic criteria for quality and a significant number have been critically appraised in a structured abstract. Where a critical abstract was not available, or was identified through other sources, we applied the well-established CRD critical appraisal processes for DARE and NHS EED (see www.crd.york.ac.uk/crdweb/HomePage.asp). For systematic reviews, the specific aspects assessed were the adequacy of the search; assessment of risk of bias of included studies; whether or not study quality was taken into account in the analysis and differences between studies accounted for; any investigation of statistical heterogeneity; whether or not the review conclusions were justified. When systematic review evidence was limited and primary research was identified, quality was assessed using the appropriate Critical Appraisal Skills Programme tool for the study design. 50 We included only evidence from primary studies that were judged to be well conducted. Quality assessments were performed by one researcher and checked by a second; discrepancies were resolved by consensus or recourse to a third researcher where necessary.

Presentation and dissemination

The presentational format for evidence briefings was based on our previous experience producing the renowned Effective Health Care and Effectiveness Matters series of bulletins (www.york.ac.uk/crd/publications/archive/)51,52 and from CRD guidance on disseminating the findings of systematic reviews. 49 With the exception of the independent appraisal of the evidence underpinning the proposed policies for musculoskeletal (MSK) procedures, evidence briefings took the following format:

-

front page bullet point summary of key actionable messages

-

background section describing the topic and the local context

-

evidence of effectiveness: a summary of systematic review findings (or primary studies if necessary); critical appraisal of the strength of the evidence; assessment of generalisability

-

evidence of cost-effectiveness: summary of economic evaluations and their findings; critical appraisal

-

implementation considerations based on the evidence, for example, implications for service delivery, patient and process outcomes, and health equity

-

references.

Evidence briefings were formatted using InDesign (Adobe, San Jose, CA, USA) desktop publishing software and were reviewed and edited by a second researcher and the principal investigator before being approved for circulation. Once approved, evidence briefings (and evidence notes) were e-mailed as an attachment to the named contact and to the individual(s) who made the initial request. The e-mail included the headline messages from the briefing, a request to circulate and an offer both to discuss the findings further (either by telephone or face to face) and to respond to any questions or clarifications that readers may have. Each evidence briefing was also e-mailed to the named contacts at other CCGs using the same format.

Each evidence briefing was published (with metadata) on the CRD website, and a record added to the HTA database. HTA database records contain full bibliographic details, hyperlinks and contact information for the organisation publishing the report. Indexing on the HTA database increased the likelihood that anyone searching for related terms on linked platforms such as The Cochrane Library, NHS Evidence, TRiP (Turning Research into Practice) Database and The Knowledge Network of NHS Scotland would identify any relevant evidence briefing as part of their search.

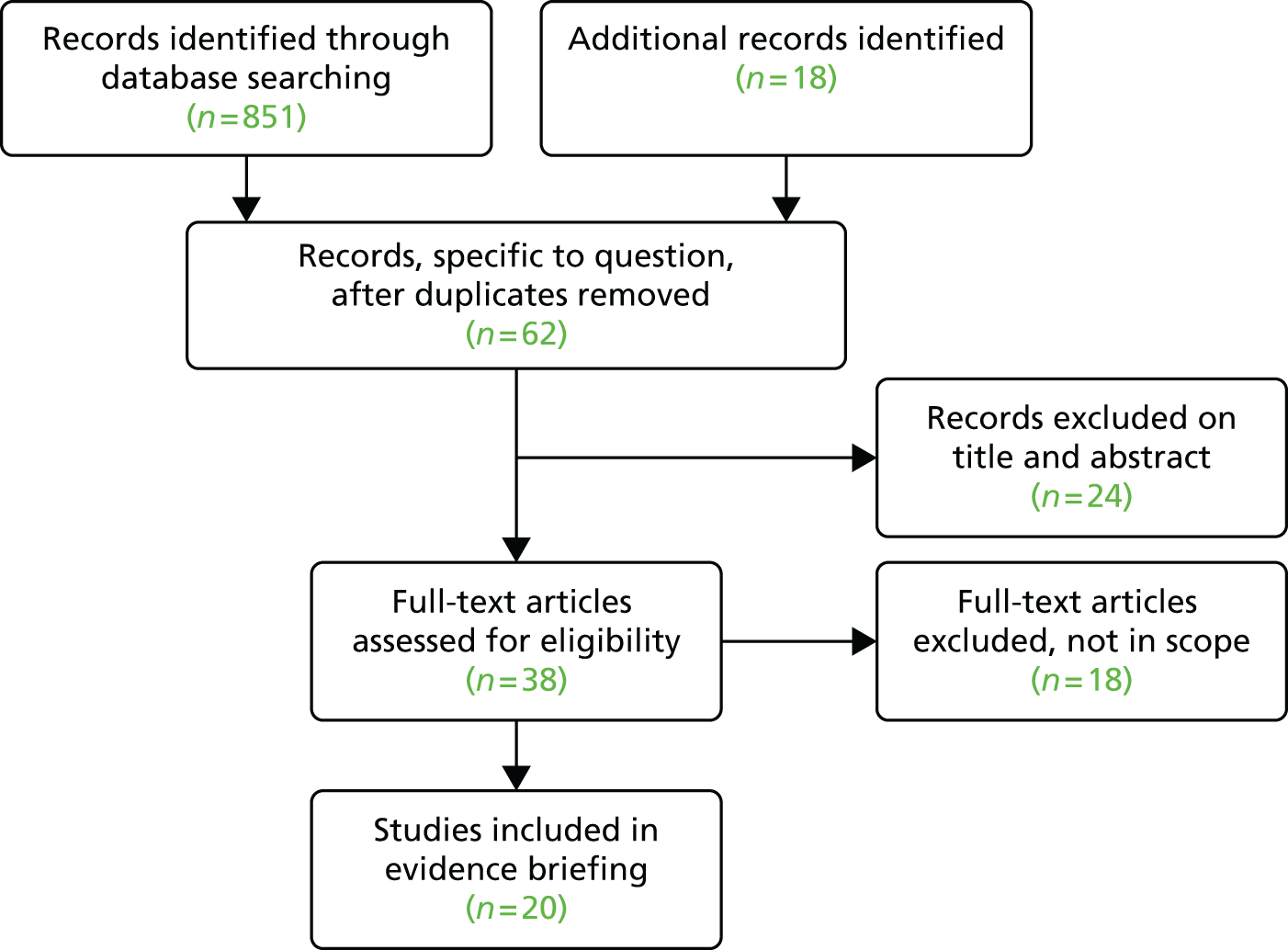

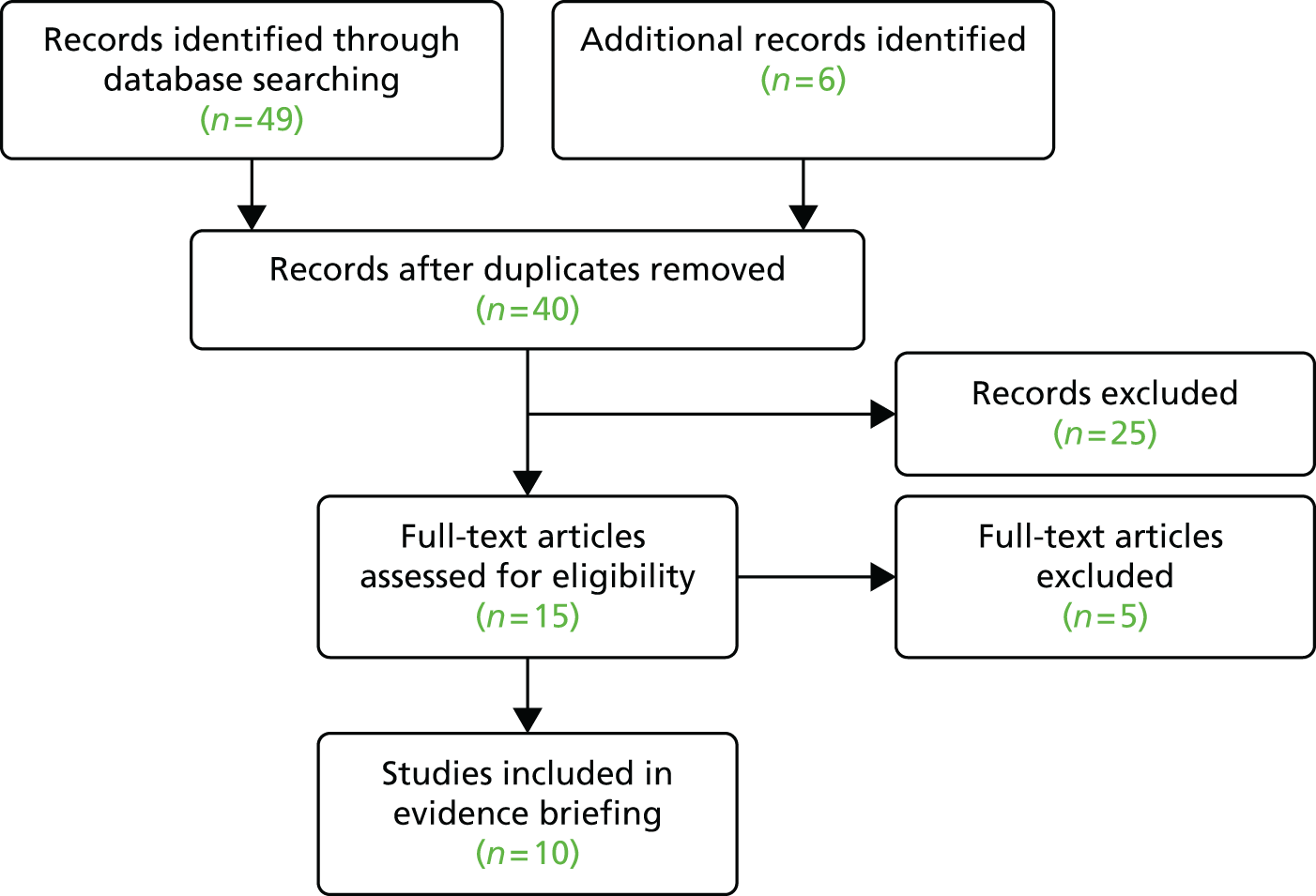

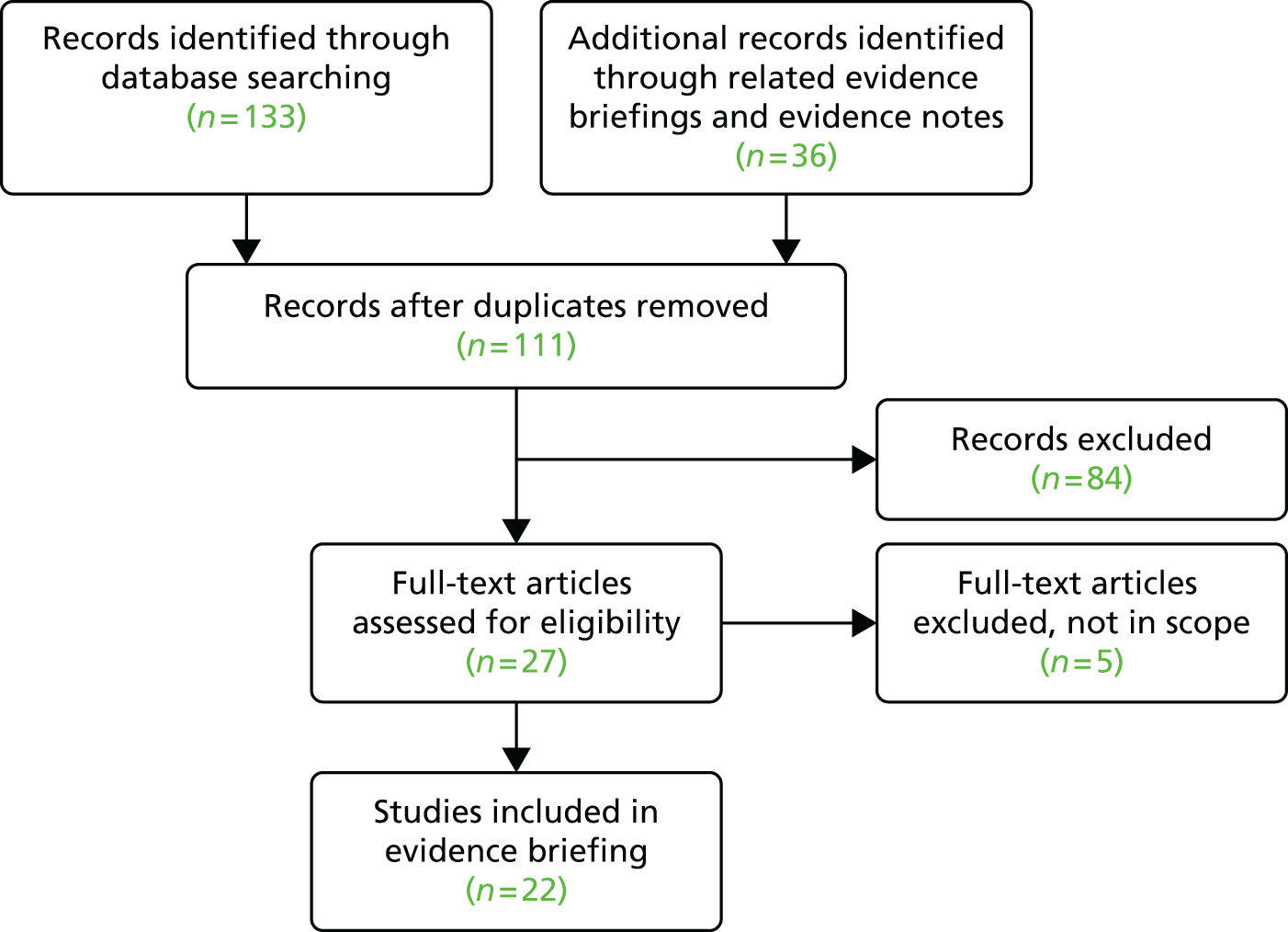

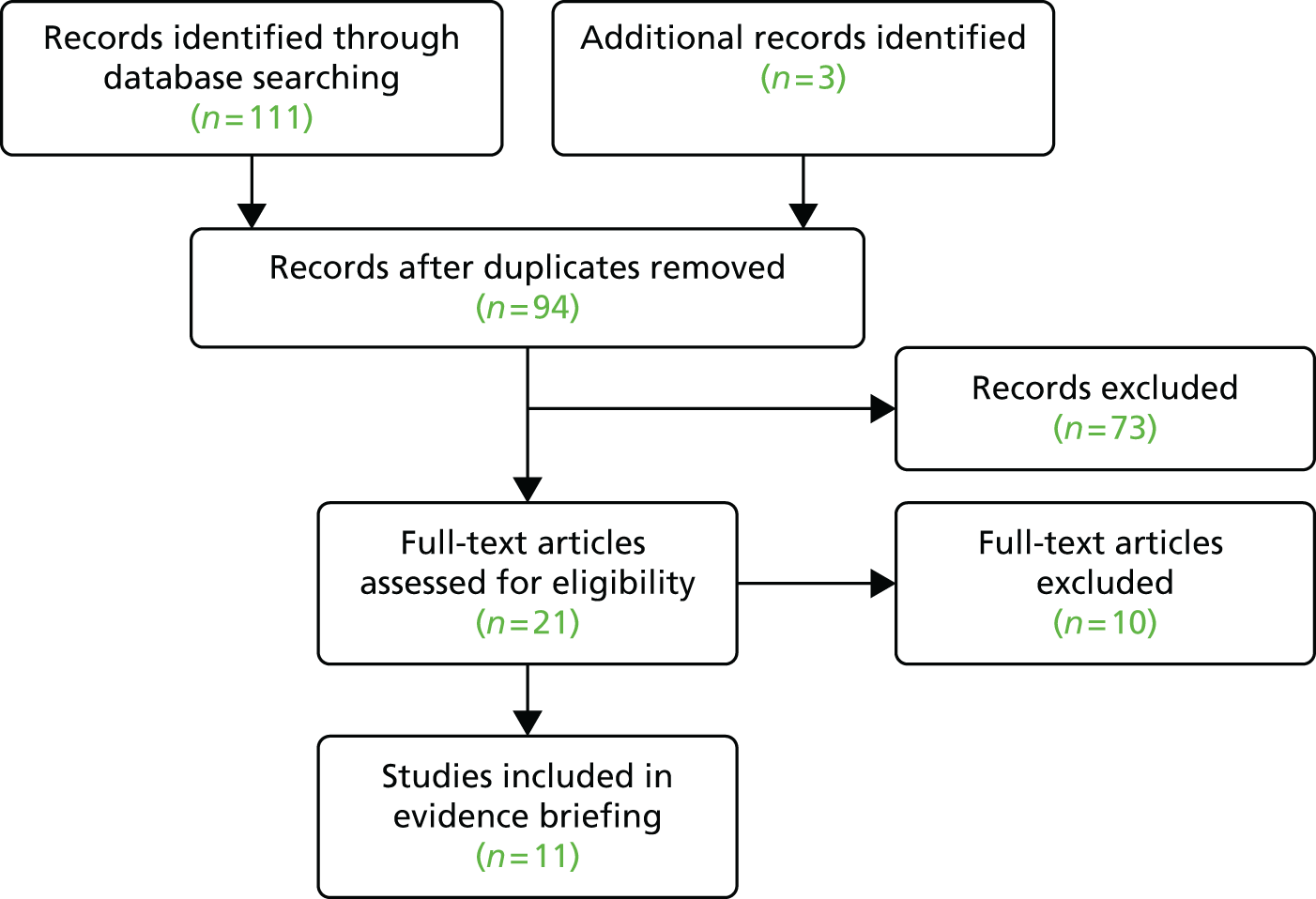

Questions addressed by the evidence briefing service

Over the course of the study we addressed 24 questions raised by the participating CCGs, 17 of which were addressed during the intervention phase (see Table 1). The majority of requests were focused on options for the delivery and organisation of a range of services and way of working rather than on the effects of individual interventions. Vignettes for each topic addressed are presented in Appendix 3. The evidence briefings are available at www.york.ac.uk/crd/publications/evidence-briefings/ (accessed 9 June 2016).

Types of evidence use

Requests for evidence briefings from the CCGs served different purposes. Four broad categories of research use have been proposed. 8,53,54 Conceptual use is when new ideas or understanding are provided and, although not acted on in direct and immediate ways, these influence thinking towards options for change. Instrumental use is when evidence directly informs a discrete yes/no, should we invest/disinvest decision-making process. Symbolic (or tactical) use refers to those instances in which research evidence is used to justify or lend weight to pre-existing intentions and actions. The final category is imposed when there are organisational, legislative or funding requirements that research be used.

For each evidence briefing and note produced, we employed these categories to classify the underlying purpose driving the type of research use. Although our interpretation is subjective, the classification presented in Table 1 is derived from a consensus-based approach. Most of the requests we received were categorised as conceptual. These were not directly linked to discrete decisions or actions but were requested to provide new understanding about possible options for future actions. Symbolic drivers for evidence requests included a pre-existing decision to close a walk-in centre, a successful challenge fund bid to implement self-care and decisions to implement GP telephone consultations. Questions categorised as instrumental related to explicit disinvestment or investment decisions. There were no instances that we considered to represent an imposed use of research.

| Source | Topic | Question | Date asked | Output produced | Way in which the research was used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | Urgent care services | Evidence for implementing an ‘urgent care hub’, consolidating out-of-hours provision on a single site adjacent to an A&E department, with front-door triage assessing patients for both facilities | November 2013 | Evidence briefing | Symbolic |

| A1 | Supporting self-management: helping people manage long-term conditions | Rapid summary of the evidence relating to self-care | January 2014 | Evidence note | Symbolic |

| All | Urgent care services | Evidence to inform urgent and emergency care systems | March 2014 | Evidence briefing | Conceptual |

| A1 | Loneliness and social isolation | Interventions to reduce loneliness and social isolation, particularly in elderly people | April 2014 | Evidence briefing | Conceptual |

| A1 | Supporting self-management: helping people manage long-term conditions | Self-care support for people with COPD | April 2014 | Evidence briefing | Conceptual |

| All | Low-value interventions | Identify relevant recommendations from the NICE Do Not Do database | May 2014 | Evidence note | Conceptual |

| A2, All | Low-value interventions |

|

July 2014 | Evidence briefing | Instrumental |

| A1 | Community pharmacy minor ailments service | Identify evidence to inform a review of the community pharmacy minor ailments service | July 2014 | Evidence note | Conceptual |

| A1 | Integrated community teams | Evidence for effects of integrated community teams including any examples of best practice | August 2014 | Evidence note | Conceptual |

| A2 | Psychiatric liaison | Models of psychiatric liaison implemented in general hospital settings | July 2014 | Evidence note | Instrumental |

| A1 | ‘One-stop shop’ screening model for diabetes | Does implementing a comprehensive one-stop shop annual review and screening model for diabetes have an adverse impact on either the quality or uptake? | September 2014 | Evidence note | Symbolic |

| A2 | Frailty | What evidence/validated tools are there for frailty risk profiling in an A&E context? | October 2014 | Short e-mail note sufficient to address question. Later followed up with a related issue of Effectiveness Matters on recognising and managing frailty in primary care | Conceptual |

| A2 | Unplanned admissions from care homes | What is the evidence for effects of interventions to reduce inappropriate admissions and deaths in hospital of patients from care homes | October 2014 | Evidence briefing | Conceptual |

| A2 | Social prescribing | What is the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness evidence of social prescribing programmes in primary care? | October 2015 | Evidence note and then later updated into evidence briefing | Conceptual |

| A1 | Supporting self-management: helping people manage long-term conditions | What is the evidence for the effects of mobile telephone apps to help people to manage their own care? | November 2015 | Evidence note | Instrumental |

| A1 | Supporting self-management: helping people manage long-term conditions | What is the evidence for the effects of interventions to promote shared decision-making? | November 2015 | Evidence note | Conceptual |

| A1 | Supporting self-management: helping people manage long-term conditions | What is the evidence for interventions to support promoting patient-centred care-planning consultations? | November 2015 | Evidence briefing | Conceptual |

| A1 | Supporting self-management: helping people manage long-term conditions | Evidence for lay-led self-care education programmes generally as part of creating an environment and culture that supports self-care | November 2015 | Evidence briefing | Conceptual |

| A1 | Supporting self-management: helping people manage long-term conditions | An evidence-based steer in how to give patients the confidence and skills to effectively self-manage their long-term conditions | November 2015 | Evidence briefing | Conceptual |

| A2 | Accountable care organisations | What is the evidence for accountable care organisations? | April 2015 | Evidence note | Conceptual |

| A2 | Enhancing access in primary care | What is the evidence for extended hours, telephone consultation/triage, and role substitution in enhancing access to primary care? | June 2015 | Evidence briefing | Conceptual |

| A2 | Telehealth for COPD | What lessons can be learned from previous evaluations of the implementation of telehealth for COPD? | July 2015 | Evidence note | Instrumental |

| A1 | Participatory democracy | What is the evidence for different methods of patient/public engagement in decision-making | August 2015 | Evidence note | Conceptual |

| All | Low-value interventions: existing hernia and hysterectomy policies | Independent review of evidence for existing hernia and hysterectomy policies | August 2015 | Instrumental |

In addition to the evidence briefings and notes, we also circulated other CRD-generated content known to be of relevance and interest to participating CCGs. Effectiveness Matters is a short, four-page summary of research evidence about the effects of important interventions for practitioners and decision-makers in the NHS.

During the study period, a number of these bulletins were produced by the CRD in collaboration with the Improvement Academy of the Yorkshire and Humber Academic Health Science Network [www.york.ac.uk/crd/publications/effectiveness-matters (accessed 9 June 2016)]. When topics aligned with the stated areas of interest of the intervention CCGs, relevant issues of Effectiveness Matters were circulated to the named contacts for onward dissemination within the CCG. The issues of Effectiveness Matters that were circulated were as follows:

-

Dementia carers: evidence about ways of providing information, support and services to meet the needs of carers for people with dementia (May 2014)

-

Preventing pressure ulcers in hospital and community care settings (October 2014)

-

Preventing falls in hospital and community care settings (October 2014)

-

Recognising and managing frailty in primary care (January 2015)

-

Acute kidney injury: introducing the 5 ‘R’s approach (December 2015).

Other questions raised but not addressed

Other topics of interest were raised by CCGs around the beginning of the intervention period but were not addressed as individual evidence briefings or notes. Some were not pursued, as CCGs deemed other topics to be of higher priority, whereas others were constituent parts of other published or planned briefings. Details of questions raised are presented in Table 2.

| Source | Topic | Covered by other outputs? |

|---|---|---|

| Urgent and emergency care | ||

| A2 | Triaging minor ailments out of A&E | Covered by urgent care services briefing |

| Elderly care | ||

| A2 | Risk stratification for frail elderly | Covered by short e-mail note on validated tools for frailty risk profiling in an A&E context and Effectiveness Matters: Recognising and Managing Frailty in Primary Care (Spring 2015) |

| B1–3 | Seamless falls service | Covered by Effectiveness Matters: Preventing Falls in Hospital and Community Care Settings (Autumn 2014) |

| A1 | Falls pathway review | Covered by Effectiveness Matters: Preventing Falls in Hospital and Community Care Settings (Autumn 2014) |

| A1 | Do regular reviews including an agreed care plan of management reduce unnecessary admissions and attendances and improve patient preferences for end-of-life care? | Circulated earlier CRD evidence briefing on advanced care planning |

| Community-based care | ||

| B1–3 | Multidisciplinary preventative community care including supported discharge, virtual wards and GP-led case management | Some aspects covered by unplanned admissions from care homes briefing |

| Mental health | ||

| A2 | Evidence to inform the delivery of new community-based care pathways for adult mental health services | Circulated earlier CRD evidence briefing on integrated pathways in mental health |

| A2 | Child and adolescent mental health service early intervention and prevention | Not addressed |

| A1 | Substance misuse liaison in urgent/emergency care | Not addressed |

| Neurology | ||

| A1 | For patients with a neurological diagnosis, does access to a local multidisciplinary hub help improve well-being and reduce unnecessary health-care attendances and long-stay admissions? | Not addressed |

| Prescribing | ||

| A2 | Reducing prescribing spend and waste | Not addressed |

| A1 | Medicines management in care homes | Not addressed |

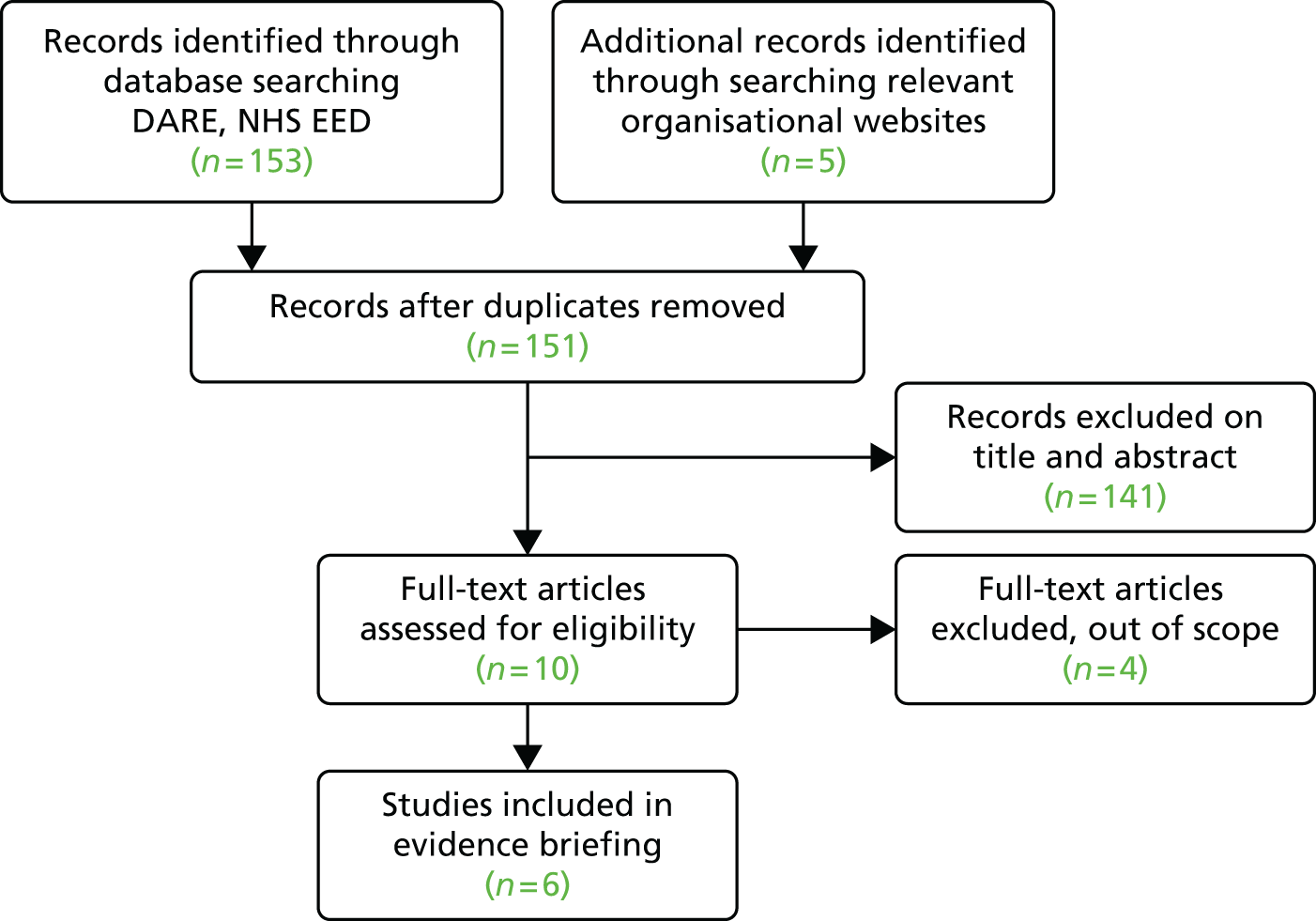

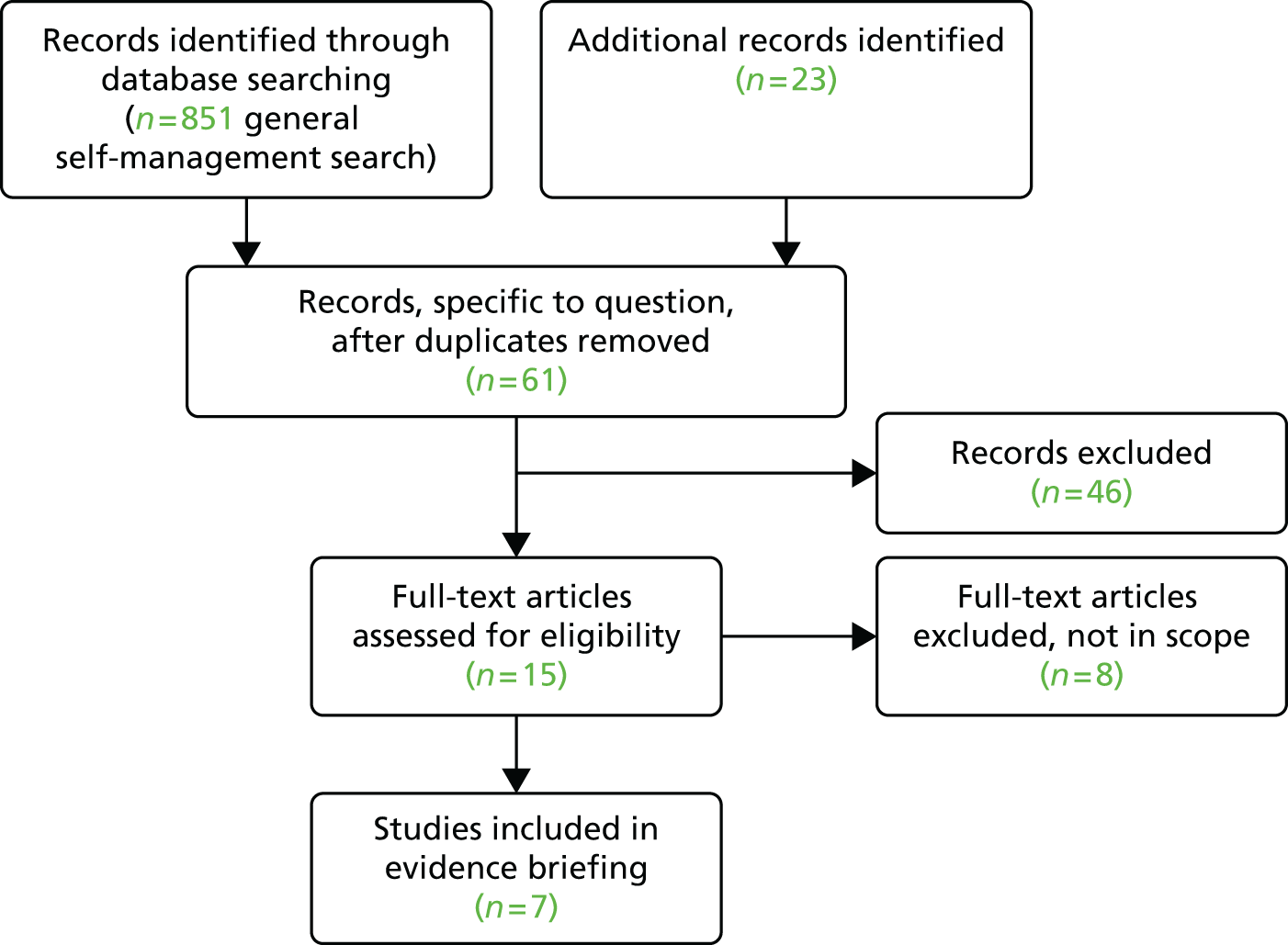

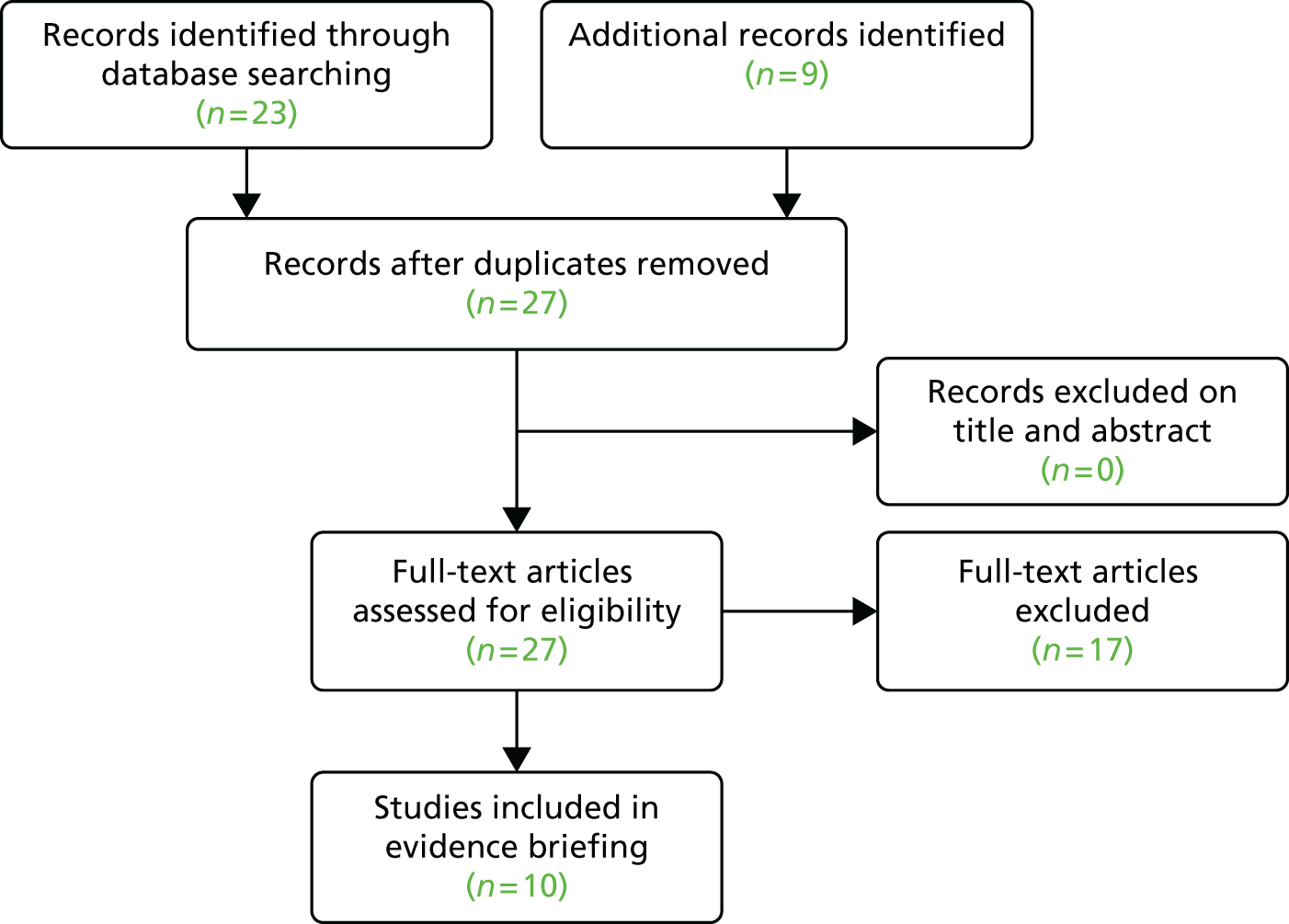

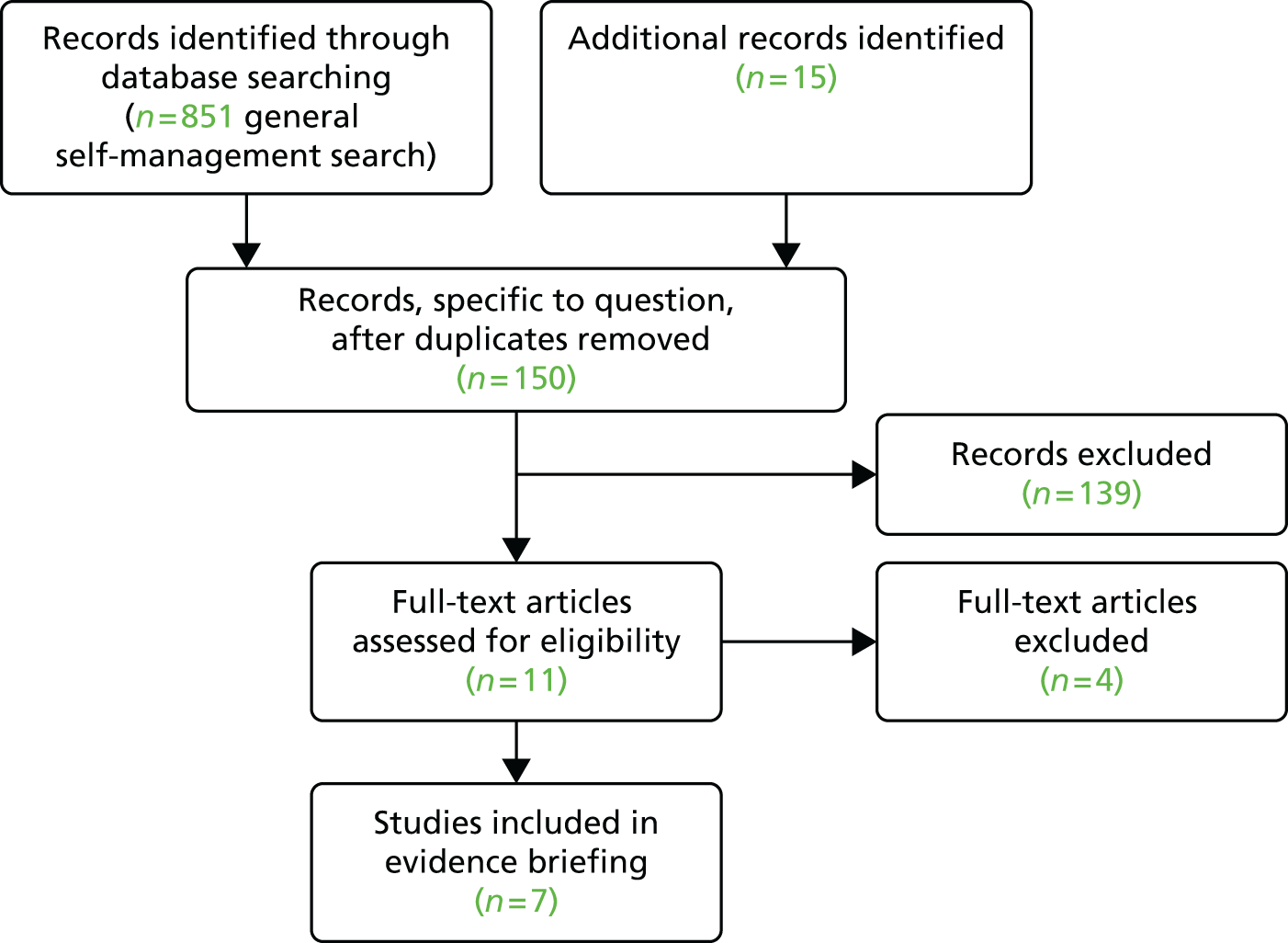

Training