Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 09/1004/15. The contractual start date was in January 2012. The final report began editorial review in February 2016 and was accepted for publication in July 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Nat Wright is a member of the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment programme mental, psychological and occupational health panel.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Shaw et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Prevalence of mental illness

In a large-scale study conducted for the Office for National Statistics (ONS) in 1997,1 > 90% of prisoners had one or more of the five psychiatric disorders studied [psychosis, neurosis, personality disorder (PD), hazardous drinking and drug dependence], with remand prisoners having higher rates of disorder than sentenced prisoners. More than half (59%) of men remanded, and 40% of men sentenced, had a neurotic disorder, with the corresponding figures for women being 76% and 63%, respectively. Rates of psychosis varied from 7% in the male sentenced population to 14% in female sentenced population. In addition, 78% of male remand prisoners and 50% of female remand prisoners had a PD. Levels of substance misuse were also high, with 51% of male remand, 43% of male sentenced, 41% of female sentenced and 54% of female remand prisoners being drug dependent in the year before prison. Over 50% of the men in the sample screened positive for hazardous drinking in the year before coming into prison; the analogous figure for female prisoners was 38%. 1

The ONS survey and other studies in England and Wales have shown that psychiatric comorbidity is the norm. 2–5 Between 12% and 15% of sentenced prisoners in the ONS study1 had four or five psychiatric disorders, and many prisoners present with complex psychiatric treatment needs,5 often confounded by issues of dual diagnosis, especially of personality or substance misuse disorders.

The high prevalence of mental disorder in prisons is not confined to England and Wales. In a large-scale systematic review of serious mental disorder in 23,000 prisoners in Western countries,6 approximately one in seven prisoners had either a psychotic illness or major depression, with approximately half of male prisoners and one-fifth of female prisoners having antisocial PD.

Compounding high levels of psychiatric morbidity, prison populations have high levels of suicidal and deliberate self-harming behaviours, with prisoners at a far greater risk of suicide than the general population. In the ONS study,1 around 24% of male and 40% of female prisoners had attempted suicide at some time in their lives. Twelve per cent of male remand and 23% of female remand prisoners reported having experienced suicidal thoughts in the week before interview (rates for sentenced prisoners were considerably lower); these figures rose to 35% and 50%, respectively, when measured over the past year. After a decade of the prison suicide rate in England and Wales reducing year on year, there has been a more recent trend of increasing numbers of suicide from around 2011, attributed by commentators on penal matters to increased population pressures and overcrowding, smaller budgets and significant deliberate reductions in staff numbers. 7

Diagnosis, treatment and care: the role of the prison in-reach team

Historically, Her Majesty’s Prison Service (HMPS), through the existence of the Prison Medical Service, latterly renamed the Prison Health Service, was responsible for the provision of the majority of health-care services for prisoners. Almost all services were provided in house, ranging from primary care for everyday physical complaints through to inpatient care for those with severe mental health problems. Staff, including doctors, prison health-care officers and qualified nurses were directly employed by HMPS. For decades, the development of multidisciplinary care in prisons lagged behind such initiatives in the NHS; for example, at a time when much mental health care in the wider community was being delivered by multidisciplinary community mental health teams (CMHTs), most care in prisons was dependent on input from visiting forensic psychiatrists, with little contribution from wider clinical disciplines. 8,9

In 1999, the NHS and HMPS formed a partnership to modernise the delivery of health care in prisons, acknowledging that the then current arrangements varied considerably in terms of organisation, delivery, quality, clinical effectiveness and links with the NHS. 10 One of the early areas targeted for reform was mental health provision and, in 2001, a specific strategy for mental health, Changing the Outlook, was published. 11

The strategy document reaffirmed that the existing delivery model did not meet prisoners’ needs and was ineffective and inflexible. It was acknowledged that most prisoners with mental health problems were not so ill as to require detention under mental health legislation and, if they were not in prison, would be receiving treatment in the community rather than as an inpatient. The strategy suggested a move away from the historically held assumption that prisoners with mental health problems should be located in prison health-care centres, towards supporting prisoners with mental health problems on ‘normal’ prison wings through the establishment of multidisciplinary mental health in-reach teams. Such teams were to be funded by local primary care trusts and provide specialist mental health services analogous to those provided by CMHTs. Although it was expected that all prisoners would eventually benefit from the introduction of in-reach teams, the early focus of the teams’ work was on those with severe mental illness (SMI), utilising the principles of the care programme approach (CPA),12 in particular to help ensure continuity of care between prison and community on release.

A national evaluation of prison in-reach services reported that, in spite of the new model of care, major challenges remained. 13 In particular, in-reach services struggled to effectively target their priority client group, those with SMI. Research demonstrated that in the month following reception into custody only one-quarter (25%) of those with current SMI were assessed by in-reach services and only 13% accepted into caseload. 14 An examination of the composition of in-reach caseloads identified that only 40% had SMI. Of the 60% with no diagnosis of SMI, 42% had PD, 32% had a common mental illness and 42% had neither. Those with no current diagnosis of SMI, PD or common mental illness exhibited high rates of previous contact with mental health services (lifetime 93%) and substance misuse (69%) before custody. 13

In a parallel study of the management of prisoners with SMI on in-reach caseloads, widespread disengagement from mental health services at the point of release from custody was identified. On examination of the prison in-reach case notes for 53 service users, the authors found evidence of discharge planning for only 27 (51%) individuals; fewer still, 20 (38%), had direct contact with their CMHT before release and, of those, only four (20%) had made contact with the CMHT at follow-up 1 month later. 15 Dyer and Biddle16 highlighted that functioning within the operational constraints of a prison often makes the task of planning and preparation for discharge challenging for in-reach services because of limited resources, functioning overcapacity in the delivery of treatment programmes and/or the sudden transfer of prisoners at short notice.

Transition: reoffending and post-release mortality, health and socioeconomic factors

The transition from institutional to community living is a vulnerable period, associated with a range of negative outcomes. Reoffending by released prisoners in England and Wales continues to be a challenge for the criminal justice system (CJS). In 2013, the reoffending rate of adults released from custody was 45.8%, a rate that has remained relatively static (45–49%) since 2004. Notably, adults who served sentences of < 12 months reoffended at a rate of 59.3%, compared with 34.7% for those who served determinate sentences of ≥ 12 months. 17

Several studies have shown that released prisoners with a history of mental illness and/or comorbid substance misuse, many of whom return to unstable environments characterised by socioeconomic disadvantage, are particularly vulnerable to relapse and reoffending. A large retrospective study in the USA found that prisoners with a diagnosis of SMI were more likely than those without to have experienced multiple prison terms in the 6 years before their index offence. For example, prisoners with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder were 3.3 times more likely to have had four or more previous prison terms than prisoners with no major psychiatric disorder. 18 In a further study of the same cohort, prisoners with comorbid SMI and substance misuse were more likely to have experienced multiple prison terms than those with a single such diagnosis. 19 Similar findings were reported in a study of parole violation in which a diagnosis of SMI was found to increase the likelihood of an individual breaking the terms of their parole; a comorbid diagnosis of substance use disorder increased that risk further. 20

Prison provides an opportunity for individuals with SMI to receive mental health treatment, including participation in programmes designed to reduce and control substance misuse. However, improvement is likely to be quickly jeopardised if, on release, the person does not engage with community services to enable treatment started during imprisonment to be continued. A failure to connect with community providers of mental health and substance misuse services has been linked to the high incidence of mortality in recently released prisoners. Farrell and Marsden21 found that newly released prisoners in England and Wales were at an acute risk of drug-related death in the first 2 weeks of leaving prison, with male and female prisoners, respectively, 29 and 69 times more likely to die of drug-related causes, relative to the general population, during their first week of release. This finding was confirmed in a later meta-analysis of drug-related deaths after release, which reported that drug-using prisoners had a three- to eightfold increased risk of drug-related death in the first 2 weeks post release compared with the subsequent 10 weeks, with risks remaining elevated through weeks 3 and 4. 22 Factors such as reduced tolerance to specific drugs, the high and variable potency of street drugs, and the temptation to engage in ‘celebratory’ drug-taking behaviour on release, were suggested explanations for these findings. Similar findings were reported in a systematic review and meta-analysis of all-cause and external mortality in released prisoners, identifying that released prisoners were at a substantially increased risk of death from all causes but from drugs, suicide and homicide in particular. 23

Studies of suicide by prisoners following release bring most sharply into focus how overwhelming transition can be for some. 24,25 A study of completed suicide by released prisoners found that age-adjusted standardised mortality rates were, compared with the general population, 8.3 times higher for men in the 12 months post release; the risk was even greater for women, at 35.8 times higher. Furthermore, 21% of those who completed suicide did so within 28 days post release, with just over half (51%) of deaths occurring within 4 months of release. 24 The authors conducted a subsequent study, identifying key risk factors for suicide by released prisoners. These included increasing age > 25 years, having a psychiatric diagnosis, previous contact with psychiatric services before custody, a history of alcohol misuse and a history of self-harm. Contact with prison mental health in-reach services while in custody and being recognised as ‘at risk’ of suicide while in prison were also relevant factors. The study authors reiterated the importance of improved release planning for those prisoners most at risk, to ensure immediate engagement with community mental health services, assertive follow-up and intensive post-release support. 25

Planning to prevent discontinuity of mental health and substance misuse treatment on release is critical, but addressing socioeconomic and psychological factors that might adversely impact on service engagement is also vital. Williamson26 listed multiple health and social care needs and factors that reflected the lifelong social disadvantage experienced by many prisoners, all or any of which may negatively influence the establishment of a stable routine lifestyle outside prison. For example, prisoners were more likely to have spent time as a child in local authority care, have a poor education and have a family history of CJS contact than those who had never been imprisoned. On release from prison, 42% had no fixed abode, 50% were not registered with a local general practitioner (GP) and 60% were unemployed. Despite this, it has also been reported that prisoners’ expectations of what life will be like following release may be unrealistically high or, equally damaging, the individual may be overwhelmed by concerns about how they are going to cope. In a longitudinal qualitative study of 40 prisoners, over one-quarter of whom self-reported a mental ill health problem, many prisoners’ aspirations before release were high with regard to finding work or going back into education, overcoming their drug and alcohol misuse and/or generally regaining some stability in the community. However, in the absence of co-ordinated service planning and advice, goals were often unrealistic and, therefore, difficult for the individual to achieve. Having family or peer support helped, but individuals without this support found their plans quickly fell through, negatively impacting on their ability to manage their housing arrangements and control drug and alcohol use, with reoffending once again becoming a coping mechanism. 27

A number of other studies have reported similar findings, noting that having a safe place to live, finding employment and maintaining mental and physical well-being are high priorities on release for prisoners, particularly as good mental and physical health is viewed as very important for securing employment. The prospect of relying on hostel accommodation and entering an environment in which the misuse of drugs and alcohol by others may be commonplace was a source of anxiety for soon to be released prisoners. In addition, the stigma attached to being identified as an ‘ex-offender’, with the associated disadvantages in terms of access to employment and other opportunities, provoked high levels of anxiety. 28,29

Integrating health and social care services to meet prisoners’ needs in a holistic way on release is therefore vital to successful community reintegration. Thus, effective release planning and resettlement requires not only continuity of health care but also measures designed to meet the economic and social needs of the prisoner.

The development of integrated health and social care services

More than 40 years ago, mental health-care policy moved away from the widespread provision of care in large psychiatric institutions towards delivering care in the community. Long-term care in hospital was viewed as untherapeutic, stigmatising and costly. 30–32 It was expected that providing care in the community would enable individuals with SMI to live with greater autonomy, have a better quality of life, and maximise community links and tenure. However, it became increasingly evident that the transition to community living was not always easy or straightforward, with many people needing proactive support with their illness not only from clinical services, but also from a range of social and community agencies.

Forerunners to critical time intervention: the case management and assertive community treatment models

Case management

To address this challenge of delivering effective and multifaceted community care, case management (CM), which was initially developed in the 1980s in the USA but took hold in the UK through the 1990s, required health and social care agencies to join together to form multidisciplinary multiagency teams. 33–37 The key aims of CM are to maintain client contact with mental health services, reduce the risk of rehospitalisation and, generally, improve the client’s functioning and ability to live independently, with all actions to be co-ordinated by a case manager. A review of CM summarised the case manager’s role as assessing a client’s needs, developing a care plan, arranging for that care to be provided, monitoring the quality of care and maintaining contact with the person. 38 Although initially likened to a ‘brokerage’ role for ensuring that the range of services the client needs are in place, the authors commented that the CM model had developed over time to include elements of clinical/therapeutic input by the case manager and the use of techniques to identify and work with the client’s strengths.

However, although CM was adopted widely by service providers, its efficacy in achieving its aims has been questioned. In a randomised controlled trial (RCT), patients under the care of a case manager generally fared better during the resettlement period than patients receiving standard care based on measures of social behaviour and social integration, deviant behaviour and improved mental state; however, the difference was only significant with regard to deviant behaviour. 39 A later systematic review and meta-analysis went on to show that CM clients were more likely to maintain contact with services, but with a greatly increased rate and length of hospitalisation compared with standard care. In addition, little improvement in other measures of clinical and social outcomes and mental state were achieved. 38

More recently, and with particular relevance to the current study, the efficacy of a low-intensity CM model on increasing contact between ex-prisoners and community primary care services was the subject of a RCT undertaken in Australia. 40 On release, prisoners were given their own personalised ‘passport’ detailing their health-care needs and listing the important contacts necessary to ensure physical and psychosocial needs were met and tasks such as securing accommodation and income were taken forward. The intervention involved following up participants by telephone on a weekly basis for the first 4 weeks post release. Research follow-up involved interviews at 1, 3 and 6 months post release. The authors concluded that, compared with treatment-as-usual (TAU) participants, those receiving the intervention were more likely to be in touch with primary care and mental health services at 6 months. 40

Assertive community treatment

Assertive community treatment (ACT), again developed in the USA, adopted a multidisciplinary team approach to jointly care for small caseloads of commonly high-need and high-risk clients. 41–43 In contrast to the CM model, ACT team members are not assigned specific clients but rather bring their discrete expertise, as required, to all clients under the care of the team.

Systematic reviews of ACT compared with standard care, hospital rehabilitation and CM have indicated that ACT is more successful in maintaining client contact with services, reducing the number of admissions and average days spent in hospital, maintaining stable accommodation, increasing days in employment and increasing rates of general client satisfaction compared with standard care. Data were not sufficient for reviews to make robust comparisons between ACT and hospital rehabilitation or CM. 44,45

Critical time intervention

Critical time intervention (CTI), a variant of ACT, was developed in the USA in the 1990s. CTI was designed as a structured but, unlike ACT, specifically time-limited (to a maximum of 9 months in original trials) intervention to prevent recurrent homelessness in transient individuals with SMI moving from hospital care to the community. 46–48 The intervention had two key components: first, to strengthen ties with service providers, family and friends; and, second, to provide practical and emotional support during transition from institution to the community.

To realise the first component, case managers made appointments with key service providers and accompanied clients to those appointments following discharge from hospital. The case manager ensured that clients had a named contact at each service and facilitated the formation of a relationship between the client and provider to better ensure continued engagement. The case manager also supported the client and his family in re-establishing their relationship; if the client’s family wished to be involved in providing care, the case manager helped them to better understand their relative’s illness, the difficulties they might encounter in their role as carer and ways to resolve those situations. To achieve the second component of the intervention, the case manager maintained close contact with the client, observing how they were adapting to living in the community, stepping in, if necessary, to provide practical help with the development of skills necessary to function independently. The case manager reviewed the extent to which their input was needed throughout the intervention period to the point when they judged they could withdraw without any disruption to engagement.

In an early trial, those in receipt of CTI had significantly fewer nights’ homelessness than the TAU group: 30 compared with 91 homeless nights, respectively. In addition, the strong ties with service providers that CTI put into place persisted after the intervention was withdrawn, with survival curves showing that, after 9 months of the intervention, the differences between the groups did not diminish. The authors noted that CTI could be used in any transition scenario, for example from prison to community, to better co-ordinate and augment existing processes in place to link individuals to other important services. 46

To examine this assertion, as well as the research described in this report, the CTI model is currently being trialled in the transition of two discrete populations leaving shelters for supported or independent housing: (1) individuals previously homeless and (2) women who have experienced domestic violence. 49 In addition, a trial using CTI at the point people first make contact with mental health services in order to put in place a comprehensive and enduring network from the start is under way. 50 These studies will, in due course, add to the body of evidence with respect to the transferability of the model to other scenarios.

Critical time intervention: prison to community feasibility trial by current authors

As previously outlined, many prisoners with mental illness reach the end of their time in custody without a clear plan of how to contact services in the community, or indeed what services they require and/or are available where they live. Staff working in prison are frequently hampered in planning care by having to do so at very short notice, for example when home detention monitoring is granted or if a remand prisoner is released unexpectedly following a routine court appearance. In addition, many prisoners are still held far away from their home area and this can bring problems for staff trying to contact and co-ordinate with a range of unfamiliar community services at great geographical distance from the prison, hampering their abilities to achieve a clear handover of responsibility to external providers. Owing to increased competitive tendering within the NHS, including offender health services, even when a prisoner is in custody within their home area, the prison mental care provider is increasingly likely to be a different NHS or private organisation from the community service; thus, referral processes can be as problematic as those undertaken remotely. 51

Although engaging with mental health services in order to ‘stay well’ might be understood as important by prisoners, research shows that other matters, such as housing, financial security and re-establishing relationships with family are often more highly prioritised on release, often to the expense of attending any appointments made with the CMHT or substance misuse services. 52 As a result, it was suggested that the CTI model could be usefully adapted to better plan for transition for this population. 53

In our earlier study, the CTI model was adapted and piloted for use with a male prisoner population. 54 Case managers were identified to proactively engage with prisoners with SMI before their release from prison in order to agree a discharge plan and provide practical help to ensure, as far as possible, that the prisoner’s most pressing needs on release could be met. In addition, their role was to proactively support the person and liaise in person with service providers following release to ensure that engagement and transfer of care to community services went smoothly. The original CTI model was adapted to better reflect the stages of transition for prisoners in England; the major change was that the post-release duration of the intervention was shortened to 6 weeks, recognising that 9 months would be cost prohibitive to deliver and reflecting the views of staff and service users involved that community services in the UK were generally superior to those in the USA. The adaptation of the original model also included a vastly increased input in the pre-release period, with early preparation of a detailed discharge plan that could be activated if unexpected discharge occurred, particularly likely in the case of remand prisoners.

The feasibility of implementing this intervention was tested. Sixty prisoners were recruited to the study, with 32 randomly allocated to the CTI arm and 28 to TAU. Of these, 23 were followed up 4–6 weeks post release. Participants assigned to the CTI group were more likely to be in touch with either mental health or substance abuse services, receiving their medication, registered with a GP and in receipt of benefits than TAU participants, although only the outcomes relating to being in receipt of medication and registered with a GP were statistically significant. There were no differences in terms of social support or housing.

The key aim of the pilot was to ascertain whether or not it was feasible to deliver CTI to prisoners with SMI during their transition to the community. We concluded that, because of the intensive pre-release input required by the case manager to identify prisoners’ needs and prepare community agencies to provide services, the case manager role was best carried out by someone based in prison and working with the in-reach team. Feedback from prisoners who received the intervention was positive and case managers reported that the intervention ‘felt like the right thing to do’. Although most differences in engagement and other outcome measures proved not to be statistically significant, the support provided by the case manager, particularly in the event of a delay in the start of community service provision, was thought to be valuable by staff and service users alike.

Although the feasibility trial involved a relatively small number of participants, the potential for the CTI model to improve transition for SMI prisoners merited a larger-scale study.

Rationale for current study

Managing transition for prisoners with SMI to the community has many similarities with the meeting of the health and social care needs of previously homeless individuals with SMI leaving hospital care. These similarities were the impetus for the development of the feasibility study in the prison population using CTI.

Our pilot to test the feasibility of delivering CTI within a prison setting with adult men with SMI was successful. A larger RCT was therefore undertaken to more rigorously test the utility of CTI for improving through-the-gate engagement of male prisoners with SMI with community mental health services and to examine the cost/benefits of this approach.

The primary objective was to establish whether or not CTI is clinically effective and cost-effective for released adult male prisoners with SMI in:

-

improving engagement with health and social care services

-

reducing mental health hospital admissions

-

reducing reoffending

-

increasing community tenure through reducing time in prison.

The secondary objectives were:

-

to establish the cost-effectiveness of CTI for this population

-

to develop service model manuals and training materials to support the implementation of CTI with criminal justice agencies, the NHS and relevant third-sector organisations

-

to facilitate and promote active service user, criminal justice, third-sector and health staff participation in the research work programme, thus encouraging greater engagement between the academic community of researchers, the practice community of health and justice staff, and users of criminal justice, community-based health-care and third-sector services.

Chapter 2 Quantitative methodology

Study design

The study was designed to evaluate CTI specifically adapted for male prisoners with SMI. It was designed as a parallel two-group RCT with 1 : 1 individual participant allocation to either CTI plus TAU (intervention group) or TAU alone (control group). The main trial was supplemented with (1) an economic evaluation examining the cost-effectiveness of providing CTI (see Chapter 6) and (2) a qualitative study to explore the views and experiences of participants and professionals involved in the study (see Chapter 4).

Ethics approval

Ethics approval for the study was granted by the research ethics committee (REC) for Wales in January 2012 (reference number 11/WA/0328). The National Offender Management Service research approval was given in February 2012 (reference number 184-11). The trial was registered with the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (reference number ISRCTN98067793). In addition, all required site-specific permissions and research governance approvals, that is the research and development (R&D) approvals, were obtained from the relevant NHS trusts.

Changes to protocol

The progress of this trial was severely impacted by recruitment shortfalls at the original sites and significant delays in obtaining a number of R&D approvals at new sites. We increased the number of sites involved from three to eight. A summary of the changes to the original protocol notified to the REC is given in Table 1. Approvals were also sought for another three prison establishments but, because of significant delays in obtaining these approvals, recruitment never commenced.

| Changes to protocol | Date |

|---|---|

| Increase of study sites from three to eight | 10 February 2014 |

| Use of the Operational Criteria Checklist for Psychotic and Affective Illness rather than the Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition Axis 1 disorders to record axis I mental health diagnosis | 10 February 2014 |

Increase of study sites from three to eight

The number of study sites was increased because of slow recruitment rates in the original three sites. This was mainly caused by potential participants failing to meet one or more of the eligibility criteria. The main reasons people were ineligible were (1) not likely to be released within the lifetime of the study and (2) not likely to be discharged to the local geographical area, thus unable to be followed up. One site, which had been the site with the largest recruitment in our feasibility study, was rerolled during this study, changing it from a category B remand local prison to a category C/D resettlement establishment. This meant that the prison started to take prisoners with longer sentences, so many were not likely to be released within the lifetime of the study. In one site, the original CTI manager left and the NHS trust was unable to recruit a replacement.

Research and development approval

For three of the trusts involved, it took approximately 6 months to obtain R&D approval and, in two cases, a complaint was lodged with the concerned trusts’ medical director in order to expedite matters. Complex commissioning and provider arrangements resulted in a lack of transparency as to where responsibilities lay; this required seeking multiple permissions from several provider organisations at single sites. In addition, retendering processes resulting in the award of contracts to new provider organisations impacted negatively on recruitment. In addition, two sites that had originally agreed to take part in the research pulled out before recruitment could begin, citing staffing shortages.

Use of Operational Criteria Checklist for Psychotic and Affective Illness rather than Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition Axis 1 disorders

Before data collection commenced, the use of the Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition Axis 1 disorders (SCID-I)55 by non-clinically trained researchers was reassessed because of concerns about the specialist knowledge required for its accurate completion. The use of the Operational Criteria Checklist for Psychotic and Affective Illness (OPCRIT)56 was agreed to solve this issue, as its completion is not as dependent on expert clinical assessment skills.

Other changes to protocol not requiring research ethics committee approval

Hospital admission

The number of days in hospital, including any detention under the Mental Health Act 1983,57 was collected via case notes at each follow-up. This varied from the original protocol in which we envisaged accessing Hospital Episode Statistics (HES), a nationally collated data source. Owing to slow recruitment rates and not being able to extend the study any further we are unable to use HES data in this report because recording lags in HES would have led to greater inaccuracies than collecting the data from individual notes.

Criminal justice contact and reconviction

In the original protocol, we planned to access Police National Computer (PNC) records to compare criminal justice contact and reconviction at 12 months post release from prison. As recruitment was slow and we could not extend the study, we were unable to use PNC data because recording lags would have made the available data incomplete. We will collect PNC data after this report is submitted, as this has been formally agreed with the Greater Manchester Police Service; this will form part of our subsequent publications, which will be available for the funders.

Community tenure

In the original protocol, we stated that we would calculate community tenure by subtracting days in hospital or custody from total time in the community. However, because of the inability to collect PNC data, we were unable to do this. However, this will form part of our subsequent publications, which will be available for the funders.

Definition of engagement with community mental health team

In the original protocol, we stated that engagement would be defined as (1) having an allocated care co-ordinator and care plan, (2) receiving appropriate medical treatment for mental health problems and (3) in regular, planned contact with their care co-ordinator. This was changed to (1) evidence of having an allocated care co-ordinator, (2) evidence of having a current care plan and (3) receiving medical treatment for mental health problems. Appropriate medical treatment was changed to medical treatment, as it was not possible for the researchers collecting the data via file records alone to make decisions about appropriateness. In addition, evidence of being in regular and planned contact was difficult to collect from file information alone, as it was very often not recorded. These changes were made before analysis and with the agreement of the Trial Steering Committee.

Sites

The study sought to recruit adult male prisoners with SMI. Originally, this was to be from three prison establishments (two in the north-west and one in the south of England) but, because of recruitment difficulties, this was subsequently expanded to include a further five prison establishments (two in the north-west and three in the south of England). Table 2 provides a brief description of the function of each site. Throughout the report, to maintain anonymity, prisons will be identified only by the letters A–H.

| Establishment | Type |

|---|---|

| A | Category B local prison accepting convicted and remand prisoners from local courts |

| B | Category A high-secure site, with a category B local function for convicted and remand prisoners |

| C | At the start of the project, this prison was a category B remand local prison, but during the course of the study became a category C/D resettlement establishment |

| D | Category B local prison accepting convicted and remand prisoners from local courts |

| E | Category C training prison holding convicted prisoners |

| F | Category B local prison accepting convicted and remand prisoners from local courts |

| G | Category B local prison accepting convicted and remand prisoners from local courts |

| H | Category B local prison accepting convicted and remand prisoners from local courts |

Participants

Inclusion criteria

Participants were considered for inclusion if they met all the following criteria:

-

were male

-

had SMI

-

were a service user of the prison mental health in-reach team

-

were able to give informed consent

-

were to be released from prison within the lifetime of the study

-

release would be to an agreed geographical area local to the prison.

Severe mental illness was defined as major depressive disorder, hypomania, bipolar disorder and/or any form of psychosis including schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder and any other non-affective non-organic psychosis.

Exclusion criteria

Participants were excluded if they:

-

did not have SMI

-

were to be released outside the agreed geographical discharge area

-

posed security/safety issues that would compromise researcher/practitioner safety in prison or the community

-

were unable to give informed consent

-

had previously participated in the trial during an earlier period in custody.

Recruitment procedure

In all sites, the mental health in-reach team identified existing (at the start of the study in each site) and new (as the study continued) service users who fulfilled the inclusion criteria.

The in-reach team informed the service users of the proposed study and asked if they wished to learn more about it. If the service user expressed an interest, the in-reach team member, with the person’s permission, passed their name on to a member of the research team. A researcher then arranged a time to meet with the service user to describe the study. The potential participant was provided with all relevant clearly written information about the study and its implications. They had the opportunity to ask questions about the research and were given a minimum of 24 hours to decide if they would like to take part. Given the unique problems of gaining consent in custodial environments, careful emphasis was given to their rights to consent/not consent, including the right to withdraw at any time, without the need to give a reason for doing so, and free of any coercion or negative consequences to their mental health care or their progress in custody in general. If any concerns regarding capacity to give informed consent because of mental illness were raised, the researcher sought the opinion of the mental health in-reach team. The original signed and dated consent forms were held securely as part of the trial site file, with a copy held in the participant’s clinical records.

The likely release dates for unconvicted prisoners were predicted using the Sentencing Council Guidelines,58 based on the person’s index offence. Geographical discharge area for each prison was based on NHS R&D approval areas.

Randomisation

Eligible and consenting participants were randomised after baseline assessments were completed at the level of the individual participant to CTI or TAU by block randomisation, with randomly varying block sizes of two and four, stratified by prison. Randomisation was undertaken by the King’s College London Clinical Trials Unit, using an online system. Once the randomisation procedure had been completed, the outcome and further details about the allocated treatment were immediately communicated to the researcher and to the participant. Owing to the nature of the intervention, it was not possible to blind participants, researchers or CTI managers to the treatment allocation.

Intervention

Treatment as usual

Individuals in the control group received TAU. While still in prison, they were able to access primary care, secondary mental health and substance misuse services as would usually be the case. They also received support from criminal justice and any other third-sector organisations in the standard way.

South of England prisons (prisons C, F, G and H)

Treatment as usual at the south of England prisons was delivered by the prison mental health in-reach team and, when appropriate, other agencies. The in-reach teams aimed to complete a CPA meeting for each service user before release, inviting professionals from prison and community services. For sentenced prisoners, in-reach teams aimed to notify community teams in the relevant area of the date of release and provided them with contact details for further information as required. For remand prisoners, the teams checked HMPS and NHS information systems [Prison National Offender Management Information System (p-NOMIS; NOMS, London, UK) and SystmOne (tpp, Leeds, UK), respectively] to establish whether or not a person had been further remanded into custody and had returned to the prison following a court date. If they had not returned to custody, community teams would be notified. The extent to which this happened at each prison varied according to their resources.

At all four prisons, the in-reach teams were supported by probation officers and offender managers. In addition, a third-sector organisation provided resettlement support at prisons C, G and H; similar support was provided in conjunction with a different third-sector provider at prison C and H. A further third-sector provider provided resettlement support at prison F. One of these providers withdrew from prison H towards the end of the recruitment period.

At prison G, one NHS trust employed a criminal justice liaison nurse who followed patients from court to prison. Their main role was in planning for psychiatric hospitalisation if this was needed, but they also notified and provided information to CMHTs and GPs about released prisoners. Prison F was also eligible for this service, but the private health-care provider declined this input for the duration of this project.

North of England prisons (prisons A, B, D and E)

In prison A, the in-reach team took over care co-ordination responsibility while people were in custody. The CPA process was standardised and aimed to address all needs. Everyone on the in-reach caseload was assessed and reviewed under CPA every 6 months. If people were serving < 6 months, care co-ordination was not formally transferred and they kept contact with their CMHT. If they were not in receipt of any service in the community, in-reach tried to link them in before they left, usually 1 or 2 months before release. Staff from certain CMHTs came to the prison to complete assessments before release, but not all.

The in-reach team liaised with a range of CMHTs, community forensic mental health teams, assertive outreach services, the Personality Disorder Network, probation service, community drug and alcohol teams, homeless teams and third-sector organisations providing housing and social support. Some services, for example the Personality Disorder Network, could be accessed only from the community and, thus, no assessment process was possible pre release and service users had to attend appointments once in the community.

All mental health referrals from primary to secondary care went through a single point of access (SPA) referral system. SPA included brokering access to CMHTs, the crisis team, home intensive treatment team, adult psychology services and links to acute psychiatric wards but not to some more specialist services.

Once a service user was released, there was an expectation that the receiving community service, whether that be a new or previously involved service, would re-establish care co-ordination and follow-up the client within 7 days. Linking in with services is acknowledged to be more difficult with remand prisoners; however, the in-reach team sometimes attended court with clients.

In prison B, the in-reach team did not take over care co-ordination responsibility. Therefore, release preparation involved liaison with existing CMHTs or referring to a CMHT if the person had no contact with services before custody or has been discharged from caseload while in prison. Addressing needs, such as accommodation, was usually done by probation service staff and/or external CMHTs.

In prison D, the in-reach team assumed care co-ordination responsibility. Clients were referred to appropriate services in the community including CMHTs, drug and alcohol teams, and a range of third-sector providers. A third-sector organisation specialising in accommodation was based within the prison and the in-reach team liaised with them if needed. Service users were seen regularly leading up to, and including, the day of release. Some service users were accompanied to first community appointments on the day of release.

In prison E, the in-reach team held care co-ordination responsibilities. Release planning included needs-led liaison with services such as CMHTs, other mental health services, for example early intervention, complex care and/or criminal justice liaison teams, social services, drug and alcohol teams, rehabilitation units and accommodation services. The in-reach care remit ended at the gate, with no community activities or responsibilities.

Critical time intervention: adaptation for current randomised controlled trial

Critical time intervention is intensive CM at times of transition between the prison and community. CTI managers provide direct care where and when needed, for a limited time period. They commence their involvement with the service user in prison. For sentenced prisoners, this starts 4 weeks before discharge. For remand prisoners, or those with unpredictable dates of release, this work commences as soon as the person is on the caseload of the mental health team. The length of their involvement pre release is, therefore, ideally 4 weeks but may be shorter or longer in those with unpredictable release dates. In this adaptation of CTI, the period of contact post discharge was set at 6 weeks. The 6-week period of intervention was adopted because (1) the pilot study indicated that, by this stage, the service user would be engaged with the CMHT if that was going to occur at all; (2) it allowed a reasonable period post discharge in which adjustments to vital support systems, including accommodation and/or benefit entitlement/employment are most likely to be required; (3) to keep community caseloads low and workable for the CTI managers, some of whom were part-time; and (4) the adapted version of the intervention was heavily frontloaded with most of the vital liaison work being completed while the service user was still in prison.

The holistic intervention involved work with clients and clients’ families (when possible), as well as active liaison and joint working with relevant prison and community services. Five key areas were prioritised: (1) psychiatric treatment and medication management, (2) money management, (3) substance abuse treatment, (4) housing crisis management and (5) life-skills training. CTI is not prescriptive; it responds to the needs of each individual client. The intervention comprised four phases.

Phase 1 is conducted while the person is in prison. The CTI manager engages with the individual and develops a tailor-made discharge package based on a comprehensive assessment of the individual’s needs. This typically includes plans for engagement with community mental health treatment and addressing accommodation, financial and social support needs. The CTI manager and prisoner meet as often as required to make the discharge arrangements; pre-release contact is routinely twice weekly. In addition, the CTI manager liaises closely with community services to ensure their availability and suitability.

Phase 2 occurs immediately after release and focuses on providing very intensive personal support. In the first few weeks post discharge, the CTI manager maintains a high level of contact, including accompanying people to appointments to promote engagement and to help them establish relationships with community providers in order to facilitate the development of durable ties. The number of meetings/visits involved is directly influenced by the complexity of each person’s needs, but routinely involves up to 15 meetings per week for the first 2 weeks following discharge.

In phase 3, community services assume primary responsibility for the provision of support and services, and the CTI manager focuses on assessing whether or not the support system is adequate and functioning as planned. During this phase, the CTI manager encourages the individual to start to handle problems on their own. They meet less frequently but maintain regular contact in order to judge how the plan is working. The CTI manager remains ready to intervene if a crisis or potentially destabilising event arises. Again, the frequency of meetings is individually determined, but is typically at least weekly for 3 weeks.

In phase 4, care is fully transferred to community services in order to provide long-term support, thus work focuses on completing the transfer of care. This phase may typically consist of a meeting with the community care co-ordinator, service user and CTI manager, reviewing progress and agreeing future care. Throughout, the CTI manager will gradually reduce their role in delivering direct services to the individual. Their main function in this phase is to ensure that the most significant members of the ‘receiving’ support system meet together and, along with the individual, reach a consensus about the components of the ongoing system of support.

A manual for use by the CTI case manager was also developed to support their delivery of the intervention (see Chapter 5 and reproduced in full in Appendix 1).

Each CTI case manager received 2 days’ training on the manual, undertaken by the study’s principal investigator, a consultant forensic psychiatrist. The CTI case managers then received weekly CTI-specific supervision locally in addition to their normal clinical and/or line management supervision. In addition, group supervision was held by telephone, every 3 months, with the study principal investigator. The aim of the CTI supervision was to correct CM that was inconsistent with CTI principles and practices, provide guidance to assure that the approach was consistent with CTI principles and practices, and schedule case presentations for all new clients within a few weeks of enrolment into CTI.

All professionals who took part in this study in the role of CTI manager were qualified and experienced mental health clinicians; most were mental health nurses and one was a clinical psychologist. All had previous experience working in both prisons and either forensic community mental health services or intensive home treatment/assertive outreach teams. As such, they brought with them an extensive skill set, including existing motivational interviewing training; thus, the majority of training focused on describing the content of CTI as distinct from other ways of working in previous roles rather than clinical skills training per se.

Public and patient involvement

People with previous contact with criminal justice and mental health services were involved in study design and methods development, were Trial Steering Committee members and formed, alongside professionals, the working group which developed the intervention manual and training resources.

Data collection and management

Data were entered onto the online MACRO® (Elsevier, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) data entry system, which was hosted at the King’s College London Clinical Trials Unit. The system is compliant with good clinical practice guidelines,59 with a full audit trail, data entry and monitoring roles and formal database lock functionality.

To standardise recruitment/retention processes across the trial sites and maximise data quality, researchers were trained to use standard operating procedures for each stage of data collection. The database was designed to flag up data errors and a number of cross-checks were routinely performed as a means of ensuring that any data inconsistencies arising from either baseline assessment or follow-up were identified and resolved at the earliest opportunity.

Baseline assessment

At baseline all participants were seen by a member of the research team and the following data were collected:

-

OPCRIT+56 – the OPCRIT+ was used to obtain an Axis 1 diagnosis (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition55). OPCRIT+ is an electronic checklist of psychopathology items with algorithms for objective diagnosis of psychotic and affective disorders. Participants were asked about a range of mental health symptoms and responses entered into the OPCRIT database to produce a diagnosis. In its original format, OPCRIT data are designed to be gathered from case notes alone. 55 However, in a small pilot, it became apparent that there were frequently insufficient data in the notes alone to make a reliable diagnosis and, therefore, the case note data collection was supplemented by direct inquiry with the participant.

-

Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition Personality Disorders (SCID-II) – the SCID-II is a semistructured interview for the assessment of PD. The first part consists of eight open questions on the patient’s general behaviour, interpersonal relationships and self-reflective abilities. The second part has 140 items to be scored as 1 (absent), 2 (subthreshold) or 3 (threshold). 60 The full SCID-II interview was administered to all participants and any resulting diagnoses recorded.

-

The Michigan Alcohol Screening Test (MAST) – the MAST consists of 24 yes/no questions pertaining to lifetime use of alcohol. Each item is scored 0 or 1, with scores of ≥ 10 indicating evidence of having had a lifetime alcohol problem. 61

-

The Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST) – the DAST is similar in design to the MAST. It consists of 20 yes/no questions, each scored 0 or 1. Scores of ≥ 11 indicate substantial problems with drug abuse. 62

-

Adapted Client Services Receipt Inventory – developed from the Client Services Receipt Inventory. 63 A pro forma was developed that enabled data on a specific range of services to be collected from health-care records by the research team.

All baseline assessments were conducted between October 2012 and July 2015.

Follow-up

Follow-up data collection was scheduled to take place at three time points: 6 weeks and 6 and 12 months post release from prison. The 6-week follow-up coincided approximately with the end of the intervention delivery phase and the 12-month follow-up was designed to inform the investigation of any longer-term effects of the intervention on study outcomes. All follow-up data were collected via file information from each participant’s care team in the community. All follow-up data were collected between November 2012 and October 2015.

Outcomes

Primary outcome

The primary outcome measure was engagement with mental health services at 6 weeks post release from prison. Engagement was defined as currently being in receipt of an appropriate level of mental health care, by virtue of (1) having an allocated care co-ordinator, (2) having a current care plan and (3) receiving medical treatment for mental health problems. To create the binary engagement variable, a score of 1 was assigned if all three of these were true, and a score of 0 assigned if any or all of these were not true (i.e. they did not have an allocated care co-ordinator, they did not have a current care plan or they were not receiving medical treatment for mental health problems).

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcome measures were engagement, as defined above, with mental health services at 6 and 12 months.

Fidelity

Fidelity was assessed using an adapted version of the fidelity scale used in the Critical Time Intervention – Task Shifting study. 64 The adapted version took into account all changes to procedures from earlier CTI studies. The fidelity scale, included in this report as Appendix 2, was completed at eight time points during the intervention delivery phase.

Sample size

Original sample size justification

The original calculation for the research proposal, taking into account the attrition rate in the feasibility trial of 15%, required 100 participants randomised to each arm (CTI and TAU) to give 90% power to detect a difference at 6-week follow-up of 50% in the treatment group compared with 25% in the control group (or greater), at the conventional 5% significance level. Thus, 85 participants were required in each group at 6-week follow-up.

Revised sample size justification

Owing to slow recruitment rates, we checked our earlier assumptions after 120 participants had been randomised and found that the attrition rate was 9%. In addition, we also proposed reducing the statistical power available to detect a significant difference from 90% to 80%. The revised calculations are shown in Table 3. The number required for the primary outcome was 132.

| Power (%) | Attrition (%) | Number randomised | Number required for the primary outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| 90 | 15 | 200 | 170 |

| 90 | 9 | 188 | 170 |

| 85 | 15 | 178 | 150 |

| 85 | 9 | 166 | 150 |

| 80 | 15 | 156 | 132 |

| 80 | 9 | 146 | 132 |

Statistical analysis

The analysis and reporting of this trial was undertaken in accordance with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) 2010 statement,65 showing attrition rates and loss to follow-up. All analyses were carried out using the intention-to-treat principle, with available data from all participants included in the analysis according to the group they were randomised to, including those who did not complete therapy. In addition, the report abides to Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) guidelines.

Analysis was conducted in Stata version 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). The statistician was blinded to allocation groups until all analyses were performed.

Descriptive statistics within each randomised group are presented for baseline values. These include counts and percentages for binary and categorical variables and means and standard deviations, or medians with lower and upper quartiles, for continuous variables, along with minimum and maximum values and counts of missing values. There were no tests of statistical significance or confidence intervals (CIs) for differences between randomised groups on any baseline variables. Descriptive statistics were used to summarise assessments of feasibility and acceptability in terms of recruitment, dropouts and completeness of therapy.

The primary hypothesis for between-group differences in the primary outcome measure, engagement at 6 weeks, was analysed using a logistic regression model allowing for the site (prison in the north or south) and treatment assignment as fixed effects. Secondary outcome measures were analysed using the same modelling approach. The same models were used for the analysis of all the outcomes at 6 and 12 months. We report odds ratios and 95% CIs for all treatment effects.

Harms reporting

Definitions

Adverse event

An adverse event was defined as any untoward medical occurrence, unintended disease or injury or any untoward clinical signs (including an abnormal laboratory finding) in participants whether or not related to any research procedures or to the intervention.

Seriousness

Any adverse event will be regarded as serious if it:

-

results in death

-

is life-threatening

-

requires hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation

-

results in persistent or significant disability or incapacity

-

consists of a congenital anomaly or birth defect.

An adverse event meeting any one of these criteria was considered as a serious adverse event (SAE).

Relationship

The expression ‘reasonable causal relationship’ means to convey, in general, that there is evidence or argument to suggest a causal relationship. The research team assessed the causal relationship between reported events and trial participation according to CONSORT65 guidance (see Appendix 3).

Reporting serious adverse events

In this study, SAEs were reported to the chief investigator (JS) regardless of relatedness within 24 hours of the principal investigator (or authorised delegate) becoming aware of the event. All SAEs deemed to have a causal relationship were reported to the Trial Steering Committee. Any non-SAEs (regardless of relatedness) were not reported in this study.

Data sharing and accessibility

Study data are handled in strict accordance with the University of Manchester’s data protection policy, which can be found at: www.dataprotection.manchester.ac.uk/ (accessed 10 October 2016).

As the data contain medical details, they will be kept securely for 10 years. Participant consent forms did not specifically allow for the sharing of anonymised data to third parties. Any request for access under the Data Protection Act 199866 or Freedom of Information Act 200067 would be referred to the University of Manchester’s records office for advice before disclosure. Please contact the corresponding author for more information.

Chapter 3 Quantitative results

Trial results

Recruitment

The NHS ethics and National Offender Management Service approvals were received by February 2012 but first recruitment did not commence until October 2012. Table 4 shows the recruitment issues at each site that contributed to delays and the number of participants randomised at each site.

| Prison | Delays in commencing | Recruitment | Reason for ending | Other problems | Number recruited | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Started | Ended | |||||

| A | Obtaining R&D approval took > 5 months. Once the CTI manager had been identified, there were delays in commencement because of training needs and commitments to a previous role. The CTI manager started delivery of the intervention in November 2012 | November 2012 | April 2013 | CTI manager became pregnant and could no longer work in the prison. Host service could not find suitable replacement | 3 | |

| B | Reaching an agreement on excess treatment costs. Permission from the prison took 3 months and was not received until 20 March 2012. As the prison is part of the high-secure estate, the lengthy vetting and induction process for researchers was started early but took until 29 October 2012 | November 2012 | May 2014 | Excess treatment cost money ended | Slow recruitment | 14 |

| C | Reaching an agreement on excess treatment costs. Identifying a suitable CTI manager, first person left post unexpectedly | October 2012 | July 2014 | Excess treatment cost money ended | Rerolled to a category C/D resettlement prison so recruitment slowed | 29 |

| D | R&D approval form was received quickly; however, there were subsequent delays negotiating information technology access for the CTI manager. We had to wait several months for an Information governance meeting for this to be approved. The induction meeting at the prison was cancelled on three occasions for the researchers and four times for the CTI manager | August 2013 | May 2014 | Excess treatment cost money ended | 7 | |

| E | First contact with R&D was made on 16 October 2012. After getting no response we involved the local research network for help, but eventually complained to the medical director. The R&D manager requested that we review in-reach caseload to assess for numbers eligible and report back before R&D would approve the study. This took us 5 months to gain access to the prison and the information required. Once data had been collected, we reapproached the R&D manager who had left and the new R&D manager requested that we start the application process again | February 2014 | May 2014 | Excess treatment cost money ended | 7 | |

| F | We had first meeting at the prison on 17 October 2012. Recruitment took 9 months to begin because of a new in-reach team setting up and lack of immediate support for the project because of staffing and resource concerns. There were also long delays in obtaining permission to follow up participants in one release catchment area. One R&D took > 6 months to receive. They required a local collaborator who held a contract with the trust; however, we were not informed of this until the application had been submitted. This meant it was rejected and we had to resubmit. The trust did not identify a suitable local collaborator within a reasonable time frame. Despite chasing up on a regular basis, approval was not received until July 2013 | July 2013 | May 2014 | Excess treatment cost money ended | 35 | |

| G | Initially informed approval needed from one NHS trust, which we obtained, but then they informed us we would need two additional approvals from other NHS trusts. This appeared to be a particular issue because of the complex commissioning arrangements for health care within the south of England. None of the trusts knew which should take the lead and, therefore, one of the applications was initially rejected because of resource concerns and the imminent retendering of the service. Permission was eventually granted after 6 months | February 2014 | April 2014 | Excess treatment cost money ended | 18 | |

| H | Site approached 5 months before the service provider was because of change (January 2014). It took until March to get access, assess caseload suitability and obtain backing from the health-care provider. So when the R&D application was submitted the existing trust had 2 months left before change over. This resulted in a lengthy disagreement between outgoing and incoming providers about who should issue approval. This meant that all required trust approvals were not in place until 20 May 2014 | June 2014 | July 2015 | No longer possible because of report deadline | 37 | |

| I | The prison originally agreed to participate but then informed us that they would have to withdraw owing to staffing issues. Agreement regarding their involvement was finally reached, but this caused significant delays and took approximately 6 months. There were then no eligible recruits so the study did not start | No participants identified as eligible | 0 | |||

| J | No participants identified as eligible | 0 | ||||

| K | No participants identified as eligible | 0 | ||||

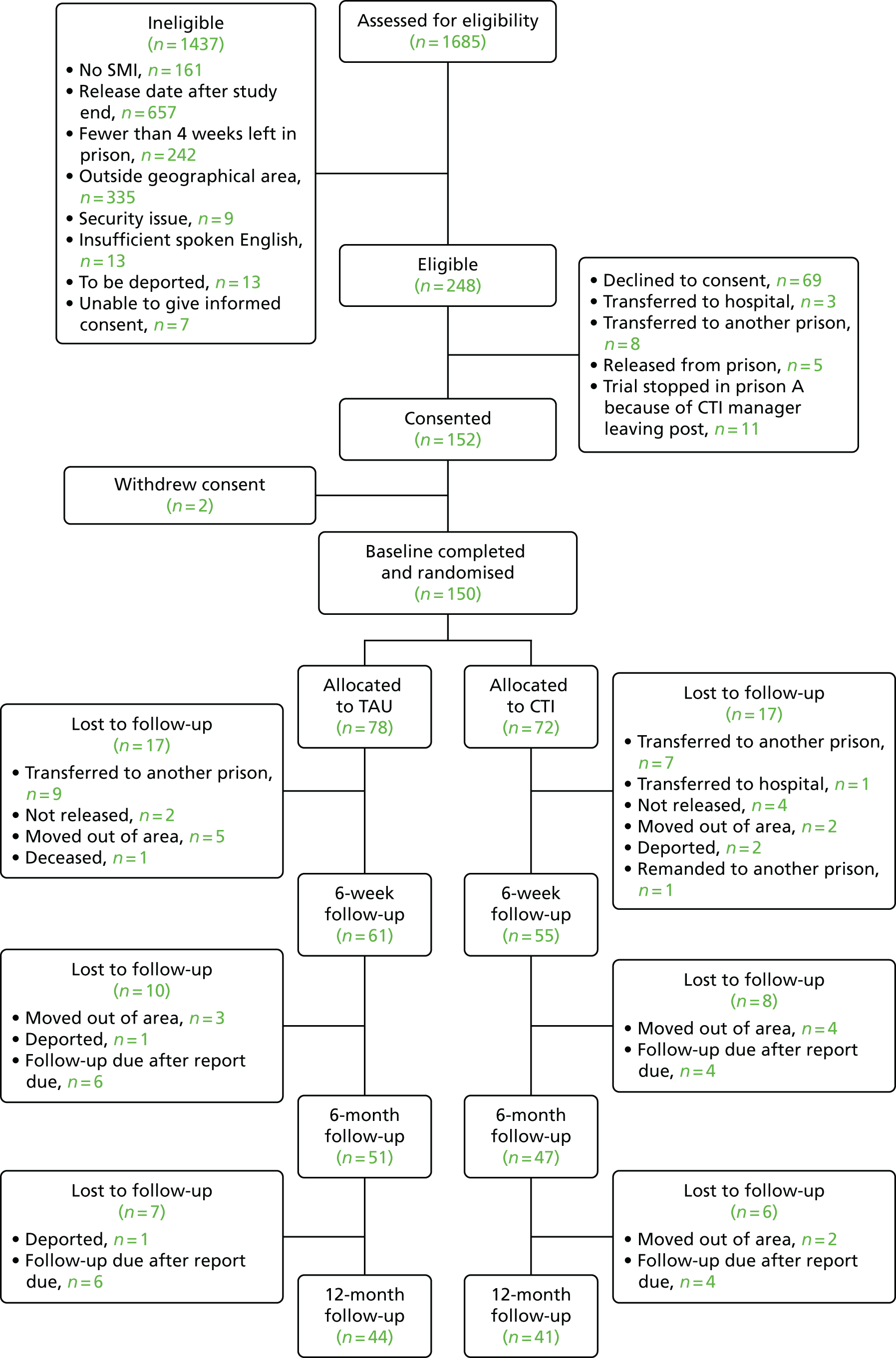

Flow of participants in the trial

In total, 150 individuals were recruited to the trial, with 72 allocated to the intervention group and 78 to the TAU group. Figure 1 presents the CONSORT65 flow diagram for the trial and summarises participant throughput from eligibility screening and randomisation to completion of the 6-week, and 6- and 12-month follow-ups, as appropriate. The diagram also reports numbers of participants who declined, did not meet inclusion criteria, were excluded from the study, withdrew following randomisation or were lost to follow-up at the 6-week, or 6- and 12-month follow-up points.

FIGURE 1.

The CONSORT flow diagram.

Baseline comparability

Table 5 presents a summary of the baseline demographics to describe the sample and demonstrate the baseline comparability of the randomised groups.

| Characteristic | Trial arm | All (N = 150) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CTI (N = 72) | TAU (N = 78) | ||

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 36.2 (9.5) | 36.5 (10.1) | 36.3 (9.8) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White | 35 (49) | 37 (47) | 72 (48) |

| Black and minority ethnic | 37 (51) | 41 (53) | 78 (52) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |||

| Single (including divorced/separated/widow) | 65 (90) | 69 (88) | 134 (89) |

| Married/partner | 7 (10) | 9 (12) | 16 (11) |

| Employment, n (%) | |||

| Unemployed/retired/benefits | 63 (88) | 71 (91) | 134 (89) |

| Employed/self-employed | 9 (12) | 7 (9) | 16 (11) |

| Living arrangements, n (%) | |||

| Alone | 56 (78) | 45 (58) | 101 (67) |

| With partner/children/family | 16 (22) | 33 (42) | 49 (33) |

| Accommodation, n (%) | |||

| House/flat | 34 (47) | 39 (50) | 73 (49) |

| Hostel/temporary accommodation | 21 (29) | 29 (37) | 50 (33) |

| Homeless/no fixed address | 17 (24) | 10 (13) | 27 (18) |

| Index offence, n (%) | |||

| Violent (including sexual offences and robbery) | 32 (44) | 38 (49) | 80 (53) |

| Non-violent (all others) | 40 (56) | 40 (51) | 70 (47) |

| Prisoner status, n (%) | |||

| Remand | 18 (25) | 28 (36) | 46 (31) |

| Convicted (unsentenced/sentenced) | 54 (75) | 50 (64) | 104 (69) |

| Time in prison current (months), mean (SD) | 12.4 (18.6) | 11.6 (19.7) | 12.0 (19.1) |

| Previous imprisonment, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 12 (17) | 14 (18) | 124 (83) |

| No | 60 (83) | 64 (82) | 26 (17) |

| Number of times in prison, mean (SD)a | 6.3 (5.7) | 7.9 (8.1) | 7.1 (7.1) |

| Axis I diagnosis (OPCRIT), n (%) | |||

| Schizophrenia | 51 (71) | 57 (73) | 108 (72) |

| Schizoaffective/schizophreniform disorder | 7 (10) | 5 (6) | 12 (8) |

| Psychosis | 3 (4) | 4 (5) | 7 (5) |

| Major depressive disorder | 9 (13) | 11 (14) | 20 (13) |

| Hypomanic episode | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| None | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 2 (1) |

| Axis II diagnosis (SCID-II), n (%) | |||

| Yes | 38 (53) | 42 (54) | 80 (53) |

| No | 34 (47) | 36 (46) | 70 (47) |

| Avoidant | 5 (7) | 7 (9) | 12 (8) |

| Dependent | 1 (1) | 2 (3) | 3 (2) |

| Obsessive–compulsive | 3 (4) | 3 (4) | 6 (4) |

| Passive-aggressive | 0 (0) | 8 (10) | 8 (5) |

| Depressive | 2 (3) | 11 (14) | 13 (9) |

| Paranoid | 6 (8) | 9 (12) | 15 (10) |

| Schizotypal | 0 (0) | 2 (3) | 2 (1) |

| Schizoid | 1 (1) | 4 (5) | 5 (3) |

| Histrionic | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Narcissistic | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Borderline | 10 (14) | 10 (13) | 20 (13) |

| Antisocial | 35 (49) | 38 (49) | 73 (49) |

| MAST | |||

| Total, mean (SD)b | 7.9 (5.7) | 6.3 (5.6) | 7.1 (5.7) |

| Cut-off points, n (%)b | |||

| ≤ 9 | 48 (68) | 61 (78) | 109 (73) |

| ≥ 10 | 23 (33) | 17 (22) | 40 (27) |

| DAST | |||

| Total, mean (SD)c | 13.8 (6.4) | 13.5 (6.9) | 13.6 (6.7) |

| Cut-off point, n (%)c | |||

| ≤ 10 | 23 (33) | 30 (39) | 53 (36) |

| ≥ 11 | 47 (67) | 46 (61) | 93 (64) |

The sample were all male, with broadly half (48%) from a white ethnic background and half (52%) from a black or minority ethnic background. The majority of the participants were single (89%), unemployed (89%) and living alone (67%). Nearly 20% of the sample said that they were homeless or had no fixed abode on arrival at prison. Proportionally more participants randomised to the CTI arm had been homeless. In relation to offending, half of the sample had committed a violent index offence. On average, participants had spent 1 year in prison at the point of baseline assessment and the majority (83%) had been in prison previously, with an average of seven previous prison terms.

In relation to mental health, all participants had an Axis I diagnosis, as determined by OPCRIT. 56 The most common primary diagnosis was schizophrenia, affecting 71% and 73% of the CTI and TAU groups, respectively. Overall, 13% of the sample was experiencing a major depressive disorder and 8% a schizoaffective/schizophreniform disorder. There were no significant differences across the intervention and TAU groups in terms of Axis I diagnoses.

In relation to Axis II diagnoses, 53% of the sample overall had at least one PD, as determined by the SCID-II assessment tool. The most common diagnosis was antisocial PD, identified in 49% of the sample overall. Thirteen per cent of the sample was identified as having borderline and 10% a paranoid PD.

In relation to drug and alcohol misuse, nearly 30% of the sample scored ≥ 10 on the MAST, indicating that they had had a severe drinking problem at some point in their life; more participants scoring over > 10 were randomised to the CTI group. In total, 64% of participants scored ≥ 11 on the DAST, indicating substantial problems with drug abuse. Table 6 presents a summary of the key service contact of the randomised groups.

| Characteristic | Trial arm, n (%) | All (N = 150), n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CTI (N = 72) | TAU (N = 78) | ||

| Previous mental health intervention, lifetime | |||

| Yes | 69 (96) | 77 (99) | 146 (97) |

| No | 3 (4) | 1 (1) | 4 (3) |

| Previous CMHT intervention | |||

| Yes | 59 (82) | 62 (79) | 121 (81) |

| No | 13 (18) | 16 (21) | 29 (19) |

| Mental health intervention in prison previously | |||

| Yes | 47 (68) | 48 (63) | 95 (66) |

| No | 22 (32) | 28 (37) | 50 (34) |

| Inpatient drug detox previously | |||

| Yes | 8 (11) | 10 (13) | 18 (12) |

| No | 64 (89) | 68 (87) | 132 (88) |

| Residential drug rehabilitation previously | |||

| Yes | 6 (8) | 9 (12) | 15 (10) |

| No | 66 (92) | 69 (88) | 135 (90) |

| Inpatient alcohol detox previously | |||

| Yes | 6 (8) | 5 (6) | 11 (7) |

| No | 66 (92) | 73 (94) | 139 (93) |

| Inpatient alcohol rehabilitation previously | |||

| Yes | 4 (6) | 6 (8) | 10 (7) |

| No | 68 (94) | 72 (92) | 140 (93) |

| First contact with mental health services (months) | |||

| < 12 | 8 (11) | 14 (18) | 22 (15) |

| > 12 | 64 (89) | 64 (82) | 128 (85) |

| Most recent contact with mental health services prior to imprisonment (months) | |||

| < 1 | 62 (86) | 59 (77) | 121 (81) |

| > 1 and < 6 | 3 (4) | 7 (9) | 10 (7) |

| ≥ 6 | 7 (10) | 11 (14) | 18 (12) |

| Most recent contact with mental health services prior to imprisonment (months) | |||

| < 1 | 62 (86) | 59 (77) | 121 (81) |

| > 1 and < 6 | 3 (4) | 7 (9) | 10 (7) |

| ≥ 6 | 7 (10) | 11 (14) | 18 (12) |

| Contact with mental health services on admission to prison | |||

| Yes | 33 (46) | 49 (63) | 82 (55) |

| No | 39 (54) | 29 (37) | 68 (45) |

| Mental health services treatment from GP on admission | |||

| Yes | 21 (29) | 27 (35) | 48 (32) |

| No | 51 (71) | 51 (65) | 102 (68) |

| Prescribed psychiatric medication on admission | |||

| Yes | 13 (18) | 10 (13) | 23 (15) |

| No | 59 (82) | 68 (87) | 127 (85) |

| Alcohol treatment on admission | |||

| Yes | 1 (1) | 3 (4) | 4 (3) |

| No | 67 (99) | 70 (96) | 137 (97) |

| Current psychological interventions (in prison) | |||

| Yes | 5 (7) | 7 (9) | 12 (8) |

| No or N/A | 67 (93) | 71 (91) | 138 (92) |

| Perceived current need for help with alcohol problem | |||

| Yes | 13 (18) | 12 (15) | 25 (17) |

| No | 59 (82) | 66 (85) | 125 (83) |

| Perceived current need for help with drug problem | |||

| Yes | 29 (40) | 19 (24) | 48 (32) |

| No | 43 (60) | 59 (76) | 102 (68) |

| Perceived current need for help with mental health problem | |||

| Yes | 55 (76) | 57 (73) | 112 (75) |

| No | 17 (24) | 21 (27) | 38 (25) |

With regard to dual diagnosis, less than half (42%; n = 63) of the sample had a diagnosis of a single Axis I condition alone. Eight (5%) had dual SMI and substance misuse issues, 56 (37%) had dual SMI and PD diagnoses and 23 (15%) had SMI, substance misuse and PD diagnoses.