Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 12/129/10. The contractual start date was in January 2014. The final report began editorial review in February 2016 and was accepted for publication in September 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

At the time of the study, Antony Arthur was a member of the National Institute for Health Research Health Services and Delivery Research commissioning board and Jill Maben was a member of the National Institute for Health Research Health Services and Delivery Research researcher-led panel.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Arthur et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction and background

Introduction

Our study set out to develop a training intervention for health-care assistants (HCAs) that could improve the relational care provided to older people in hospital. We examined whether or not such an intervention could be tested in a cluster randomised controlled trial. This chapter describes the context and background to the Can Health-care Assistant Training improve the relational care of older people? (CHAT) study. In this chapter we also consider the structure and role of the HCA workforce and the needs of the older people they care for. We describe how we use the term ‘relational care’ with reference to our study and briefly review previous attempts to evaluate interventions to improve the quality of relational care. Elsewhere in this report (see Chapter 2) we describe how the wider context of our study has changed over the period that the study was designed and conducted, particularly in relation to the Francis report1 and the Cavendish review. 2 The ways in which we drew on specific literature to influence the training intervention we developed and tested is presented in Chapter 5.

The care of older people in hospital

Those aged > 75 years now account for 24% of all hospital admissions, an increase of 57% over the previous decade, with the average hospital stay for this age group simultaneously decreasing from 15.2 to 9.4 days. 3 The quality of health care delivered to older people has come under increased scrutiny. A report by The King’s Fund cited 32 initiatives from statutory bodies, charities and campaign groups drawing attention to deficiencies in how older people are cared for. 4 The King’s Fund’s Point of Care programme was a response to a more general concern about ‘not getting the basics right’ in the care for older people. 5,6

In a NHS inpatient survey nearly one-fifth of respondents did not feel that they were always treated with respect and dignity. 7 Attitudes of staff is the second highest area of concern within complaints made to the NHS. 8 When the Care Quality Commission reviewed ‘the state of health and adult social care services’ in 2012, they found that many providers were ‘struggling in areas such as dignity and respect, nutrition, care and welfare’. 9 The devastating impact that deficiencies in care delivery can have on individuals can be seen in the Patients Association’s report10 of 13 cases of care failures.

Relational care

The focus of the CHAT study was the relational care provided to older people in hospital. Relational aspects of care include dignity, empathy and emotional support as distinct from functional or transactional aspects of care, such as access to services, waiting times, food and noise levels. 11 As most health-care interactions involve both transactional and relational elements, it follows that attempts to improve the quality of care have to go beyond methods that address only the transactional aspects of care and examine ‘how staff relate to patients, their mind sets, attitudes and feelings’. 12

In a synthesis of qualitative evidence of older patients’ and relatives’ experiences of hospital care,13 it was the relational aspects of care that affected whether care experiences were perceived as good or bad. Three themes that underscored older people’s understanding of relational care were identified: older people’s need for reciprocity (‘connect with me’), maintaining their identity (‘see who I am’) and sharing decision-making (‘include me’). Evidence from survey data is consistent with this. NHS patients responding to surveys report that emotional support, empathy and respect are the aspects of care that they consider most important. 14

For Nolan et al.,15 it is relationships ‘between patients, their families, staff from all disciplines, and the wider community’ that lie at the heart of health care. In shifting attention towards ‘relationship-centred’ care rather than person-centred care, emphasis is placed on care interactions (two-way) rather than on an oversimplified view of individual needs (one way). Although few would argue against patient-centred or relationship-centred care being of fundamental importance in how patients are cared for, there is a lack of clarity among staff at all levels as to what this actually means in practice. 16 Abstract concepts need to be operationalised in a way that is meaningful to staff at all levels.

In deconstructing ‘dignified care’, respectful communication was found to be a key element. 5 In a review of studies of physician–patient communication, physician qualities such as empathy, friendliness, courtesy and listening were associated with positive patient outcomes. 17 Hospital patients report that preservation of dignity requires respectful communication and forms of address18 and, for older patients in particular, the need for staff to show an interest in them, kindness, timeliness and attention to ‘the little things’. 19 In attempts to help health-care organisations focus on the experience of users, there have been occasional examples of organisations outside the public sector working with NHS organisations to develop ‘customer focus’, such as the work undertaken between Musgrove Park Hospital and John Lewis (Michelle Jennings, Musgrove Park Hospital Customer Care Programme Partnership with John Lewis, 2012, personal communication). Health-care staff are often uncomfortable with the notion of patients as consumers or customers,20 and acute health-care staff often hold the view that hospitals are not the best place of care for older patients, suggesting that care delivery is often provider led rather than user led.

Maintaining identity is a key element in how older people judge their interactions with paid carers,21 and both patients and their relatives comment on the importance of staff ‘seeing the person behind the patient’. 6 Life-story work is the process of gaining knowledge and information about an individual’s life that staff can use to enhance the care they provide and evidence for its clinical effectiveness is predominantly qualitative. 22 Although life-story work was originally developed for people with dementia, it is increasingly being used beyond dementia care settings and long-stay care settings. 23 In acute care settings, the challenge is for staff to get to know older patients over increasingly shorter patient stays in hospital.

The clinical support workforce

Nurses have often been targeted as both the source of the problem and the solution to concerns about loss of dignity for patients in hospital. 6 However, within the NHS, HCAs have become an increasingly important section of the workforce, particularly in relation to older people. The proportion of HCA time delivering direct and indirect patient care is approximately 60%, nearly twice that of registered nurses. 24

In England, there are approximately 130,000 HCAs employed in NHS hospital and community services. 25 Demographically, HCAs tend to differ from registered nurses, more closely resembling the ethnic diversity of the patient population they serve,24 and are likely to be a more ‘static’ part of the workforce. Over half (54.1%) are aged between 40 and 59 years, 15.8% are from ethnic minority backgrounds, 84.3% are female and most are on NHS pay band 2 (56.5%) or band 3 (36.0%). 25

The work of health-care assistants

The problems of invisibility, marginalisation and subordination of the ‘caring’ work of nurses,26 are likely to be replicated in HCAs whose work often gets little recognition, even from other staff (OS) groups. 27 Case studies28 and observational data29 suggest that HCA work in hospital is predominantly ‘bedside’ or involving routine technical tasks directly or indirectly related to patient care. Daykin and Clarke’s observational study30 of relationships between NHS hospital ward nurses and HCAs, identified a ‘strongly hierarchical’ organisation of care, with nurses having greater variety in their work, but often prevented from attending to patients by their responsibilities for administering medication and doing paperwork. HCA work by contrast tended to be concerned largely with physical aspects of care, often at the expense of negotiation or conversation with patients. In a survey of 1893 HCAs,31 when asked about the duties they performed, respondents reported talking to/reassuring patients and relatives (97%); making beds (86%); bathing patients (83%); telephone liaison with patients, relatives or other departments (83%); patient observations (82%); and feeding patients (79%).

Ethnographic observational data of HCAs working in dementia wards suggest that support in carrying out such a challenging role is drawn from the formation of close-knit groups of HCAs who are sometimes disconnected from the wider ward team,32 resulting in HCAs feeling alienated from the organisation in which they work. 33 Although the proximity to patients means that HCAs gather a lot of information about patients in their care, there are not always clear mechanisms to transfer knowledge from HCAs to nurses. 28,29 Schneider et al. 27 also found evidence of variable communication between HCAs and the wider ward team about patient care, with HCAs feeling ‘at risk’ if they stepped outside the boundaries of their role.

Health-care assistant skill development

Training for HCAs has hitherto been ad hoc, variable and marked by a tendency to focus on tasks and competencies, with little attention paid to relational care. Although investments in staffing and work environments are prerequisites for high-quality care,19,34 historically HCAs have been viewed as the ‘untrained workforce’, leading to an assumption that they are without training needs. 35 HCAs and nurses are largely in favour of more formal training for HCAs, although a blurring of role boundaries is of concern to both staff groups. 36 Among employing organisations there is a lack of consistency in HCA training and how HCAs interface with registered nurses. 37 Moreover, it appears that HCAs often lack confidence in pursuing the few training opportunities available to them. 24,27

Belatedly, and perhaps driven by economic imperatives, skill development of the support workforce has started to receive much greater attention. From an employer’s point of view, by developing the skills of HCAs and creating a better career pathway, there are economic benefits, as any increase in the proportion of the support workforce is ‘likely to be rewarded with significant financial returns’. 38 The Shape of Caring: A Review of the Future Education and Training of Registered Nurses and Care Assistants made a number of recommendations about the support workforce, specifically the need to value the care assistant role, widening access to enable HCAs who may wish to pursue a career in nursing and increasing the quality of education for HCAs. 39 The Council of Deans for Health40 have noted that, although there are an increasing number of initiatives in training and role development for HCAs, there are problems of variability in access and quality, poor communication between employers and education providers, and a workplace culture that often affords low priority to the personal development of HCAs.

Interventions to improve relational care

The following is not a systematic review of interventions to improve the quality of relational care. Interventions within the studies that we have identified all share a broad aim of seeking to improve relational care, person-centred or relationship-centred care and better communication or increased empathy on the part of health-care personnel looking after older people in hospital or care home settings. However, they are highly variable in the nature of the interventions studied and the target populations of those giving and receiving care. Many interventions that have been studied were designed to improve care for older people with dementia who make up a significant proportion of the older population in hospital and care homes.

Evaluations identified were typically small in scale and without a control group. Measurement of patient or resident outcomes was rare but one exception was a small study undertaken in a Dutch nursing home setting. 41 Nursing aids were individually trained to communicate effectively with residents by using positive speech and biographical statements. Although there were no direct effects of the intervention on the problem behaviours or psychopathology of residents, caregiver distress was reduced.

Bryan et al. 42 asked 157 participants in a course on communication to rate various aspects of their competence. The workshop package focused on the care worker’s own communication skills, ways to enhance these skills, different communication impairments, effects on interaction and practical ways to help. It included exercises, discussion and video material. Participants rated themselves before and after the workshop and reported an increase in confidence, reduced frustration and greater recognition of the need to allow more time to communicate with some individuals. Participants also felt that their attitudes towards and their ability to care for older people with communication difficulties had improved as a result of the training.

A review of 12 trials of interventions to enhance communication in dementia care in various care settings43 concluded that communication skills training in dementia care can improve quality of life and well-being of people with dementia and increase the quality of interactions between staff and people with dementia. The reviewers suggested that organisational features, such as incentives and ‘booster’ sessions for participants, might improve the sustainability of positive effects from communication interventions. In a Cochrane systematic review,44 some evidence was found that reminiscence therapy for people with dementia improves mood, cognition and staff knowledge of patient backgrounds and relieves caregiver strain, but trials are few and often small. When compared with communication skills training, a story-sharing intervention for nursing home residents and nurse aides improved mutuality and empathy. 45 A qualitative study of the introduction of a biographical approach to care in a general hospital setting found that relationships were strengthened between staff and patients and staff and relatives. 46

In a pilot study set in two nursing homes, nursing assistants received a multicomponent intervention to increase awareness of person-centred care using video-taped biographies of residents and video-tapes of resident–carer interactions. Following training, residents’ perceptions of relationship closeness were increased. Nursing assistants’ perceptions of satisfaction and closeness, and resident satisfaction also increased. 47 To determine the impact of a HCA education programme on the quality of care for older people living in a residential home in New Zealand a pre- and postintervention evaluation study was undertaken. The proportion of observations of resident care conducted after the training that were considered ‘appropriate and adequate’ increased. 48

Summary

Older people make up a large and increasing proportion of NHS hospital patients. There have been growing concerns about suboptimal standards of care that disproportionately affect older patients. Relational care can be understood as the way in which staff relate to patients as distinct from the transactional elements of care interactions. There is evidence that older people and their relatives judge their experience of hospital care in terms of how staff ‘connect with them’, help maintain their identity and involve them in decisions about their care. Although health-care staff are often uncomfortable with the notion of patients as ‘customers’, many of the things that older people believe are important (courtesy, respectful communication and attending to ‘the little things’) have a clear overlap with good customer care provided in non-health-care settings.

Health-care assistants deliver an increasing amount of the direct care of older patients in hospital. There is inconsistency in training and expectations, variability in roles and responsibilities within the ward setting and uncertainty about the interface between HCAs, the wider clinical team and visitors or relatives. Greater attention has recently been paid to the role of the HCA and their training needs. The evidence base for training interventions for HCA training in relational care is characterised by small-scale studies with a focus on dementia, and outcomes of acceptability rather than efficacy that are measured at caregiver level rather than the level of patients or care home residents.

Chapter 2 Methodological overview

Introduction

This chapter provides an overview of the CHAT study, its aims and the structure of the report. We describe the two phases of the CHAT study and how these relate to and inform each other. The methodological frameworks used in relation to each of the study elements are described and justified. We also report study oversight arrangements and how public and patient involvement informed the study from outset to completion.

Aims of the study

The original aims of the study were to:

-

understand the values-based training needs of HCAs in maintaining the dignity of, and affording respectful care to, older patients in acute NHS settings

-

develop a values-based training intervention for HCAs designed to address the needs of older patients for high-quality relational care

-

assess the feasibility of a cluster randomised controlled trial to compare the performance of the developed training intervention for HCAs with current training in improving the care of older patients in acute NHS settings.

Overview of study

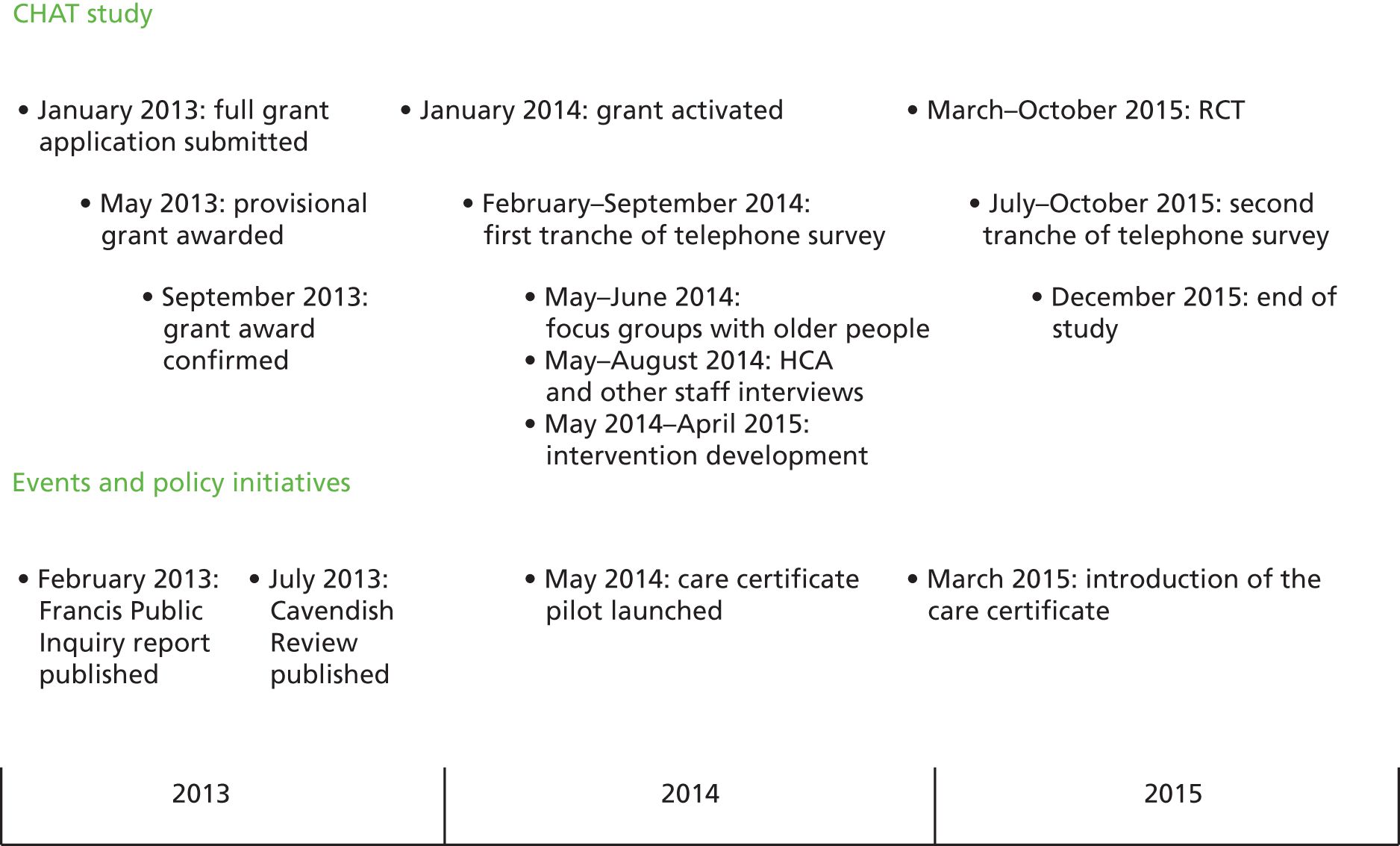

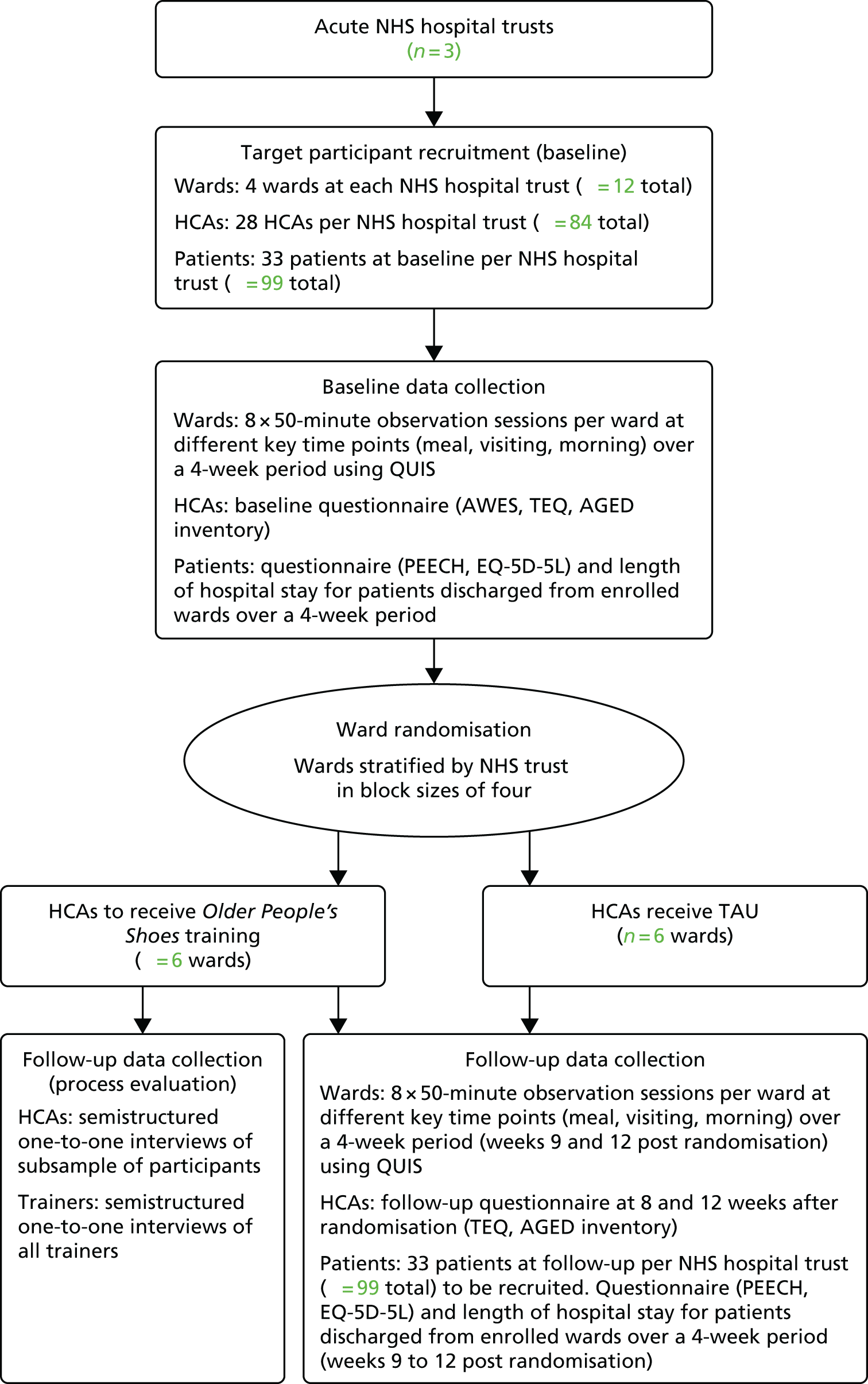

The study was conducted in two sequential phases across three study centres. Phase 1 (scoping and intervention development) was designed to address aims 1 and 2, and phase 2 (feasibility cluster randomised controlled trial and process evaluation) addressed aim 3. The overall study design is illustrated in Figure 1 and described in the following sections.

FIGURE 1.

Overview of CHAT study components and processes.

Phase 1

We conducted a telephone survey of all NHS trusts in England to understand what training as usual (TAU) looked like for HCAs caring for older people in hospitals in England. We wished to establish the structure, content and variability of HCA training and, in particular, training in providing relational care of older patients in hospital. Respondents to the survey were those responsible for HCA training within their trust. The methods and findings from the telephone survey are reported in detail in Chapter 3.

The qualitative component of phase 1 comprised focus groups of older people (or their carers) with recent experience of hospital care, together with interviews of HCAs and other hospital staff undertaken in each of the three study centres. These methods and findings are described and reported in Chapter 4. The purpose of these focus groups was to understand the care experiences of older people and their expectations of the training HCAs should receive. The purpose of the interviews with HCAs and members of staff who worked alongside them was to gain insights into staff perceptions of the challenges that HCAs face in caring for older people in hospital and to explore interviewees’ perceptions of training needs in this area of care.

A new training intervention for HCAs to improve the relational care of older people was developed as part of the study. The process of creating this training intervention, Older People’s Shoes™, is described in Chapter 5. The training intervention drew on several sources: the interviews conducted in phase 1, existing evidence from the literature, an expert panel and learning about customer care practices of four retail organisations.

Phase 2

The second phase of the CHAT study was a feasibility cluster randomised controlled trial and process evaluation. This compared TAU for HCAs with the new HCA training in relational care of older people, that is, the Older People’s Shoes intervention. The unit of randomisation was the hospital ward. Outcomes were assessed at the level of ward, HCA and patient. The purpose of the feasibility trial and the process evaluation was to determine the feasibility and viability of a definitive trial. Methods are described and findings reported in Chapter 6.

The process evaluation was conducted in parallel with the feasibility trial. This consisted of observations of the delivery of the intervention, follow-up interviews with trainers and HCA learners, and learners’ evaluation following training. The process evaluation is reported in Chapter 7.

Methodological frameworks

Owing to the nature of the study design and the range of methods used to address the aims, we drew on a number of methodological frameworks to inform our study. The HCA training intervention developed as part of this study and the feasibility testing of it as part of a trial was informed by the most recent guidance on the development and evaluation of complex interventions. 49 Of the four stages (or elements) of the process from development through to implementation of a complex intervention, the focus within our study was on development (phase 1 of the CHAT study) and feasibility/piloting (phase 2). Our aim was to follow this guidance when possible, up to but not including a definitive evaluation:

Best practice is to develop interventions systematically, using the best available evidence and appropriate theory, then to test them using a carefully phased approach, starting with a series of pilot studies targeted at each of the key uncertainties in the design, and moving on to an exploratory and then a definitive evaluation.

Medical Research Council,49 p. 8

In designing the feasibility study for a randomised controlled trial we used Kirkpatrick’s four-level evaluation model,50 and measured outcomes at each level: reaction (measured by course evaluation), learning (change in empathy and in stereotypical attitudes towards older people), transfer (observations of relational care delivery) and results (patient experience of the relational care they receive). The measurement of distal outcomes of health-care training is challenging. In the Older People’s Services and Workforce Interventions: a Synthesis of Evidence (OPSWISE) study for clinical support workforce developments,51 of the 76 papers identified, only two were reports of randomised controlled trials (Kuske et al. 52 and Clare et al. 53) and only one observed level 4 (care home resident) outcomes. 53

The Kirkpatrick training evaluation model has been criticised for a lack of attention to the environment in which trainee skills are practised. 54 This was in part addressed by the phase 2 process evaluation for which we drew on recently published guidance. 55 A range of methods was used to inform our understanding of the different contexts in which the training intervention was delivered, the process of intervention delivery and the mechanisms of impact.

The changing context of health-care assistant training

Between submission of the grant application for this study in January 2013 and the end of the study period in December 2015, the landscape of health-care delivery generally, and the care of older people and the work of HCAs specifically, underwent a number of changes. Our study needs to be understood in the light of certain events and reactions to those events, which occurred during this period (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Policy-related events and CHAT study timeline.

In February 2013, the Francis report1 into the failings in care at Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust was published. A number of the findings of the public inquiry were particularly relevant to the present study. These included the observation that failings occurred predominantly on wards for older people’s care. The work and training of HCAs was also subject to scrutiny, with Francis highlighting the inconsistency between employers in how HCAs are trained and the lack of a common standard against which to assess competence. There was a clear acknowledgement that HCA work requires skill and training.

Francis recommended that ‘the aptitude and commitment of candidates for entry into nursing to provide compassionate basic hands-on care to patients should be tested by a minimum period of work experience, by aptitude testing and by nationally consistent practical training’. 1 This referred specifically to aspiring nurses and not to HCAs, but resulted in pre-nursing students being recruited as HCAs within a number of trusts during the survey period as part of the pre-nursing experience pilot. 56

Perhaps the most important outcome of the Francis report, with respect to this study, was that a review of training and recruitment of health and social care support workers was immediately recommended by the Secretary of State. The review, led by Camilla Cavendish, was published in July 2013. 2 The terms of reference for the review included recruitment, training, supervision, support and public confidence with respect to health and social care support workers. The recommendations of the review were guided by two principles: to try to reduce complexity and bureaucracy and to replicate what the best employers are already doing. Although the Cavendish review2 is a seminal work on health and social care support workers, it conveys only a broad picture with respect to the content of the training currently given to health and social care support workers. With respect to the NHS as an employer, Cavendish identified great diversity in training and support for HCAs, little correlation between pay and performance and insufficient supervision.

Cavendish proposed a Certificate of Fundamental Care known more widely as the ‘Care Certificate’. She asked that the Care Quality Commission require all new workers to have achieved this certificate before working unsupervised. Her review recommended that the Nursing and Midwifery Council should determine how best to draw elements of the practical nursing degree curriculum into the certificate. Health Education England, local education and training boards and employers were asked to have nursing students and HCAs complete the certificate together. Cavendish also recommended a rigorous system of quality assurance for training, which links funding to outcomes, so that money would not be wasted on ineffective courses.

The Care Certificate was piloted by 13 NHS trusts during the period May to September 2014 and was launched widely in March 2015. To be awarded the Care Certificate, an individual HCA needs to have been assessed in meeting 15 standards of care. 57 Of particular relevance to our study are the standards of ‘working in a person-centred way’, ‘communication’ and ‘privacy and dignity’.

Study management

The project was led by the University of East Anglia. At each of the other two centres there was a lead investigator. To co-ordinate work across the centres, weekly teleconferences were held involving the three members of research staff employed on the grant and the lead investigators. During the study period five project management group meetings and five steering group meetings were held. The project management group included all of the investigators, leads in each of the three trusts and the three research staff (one from each of the three academic institutions). Its remit was to manage and co-ordinate study activities across the three centres and ensure milestones were achieved. The remit of the steering group was to guide the study so that it maintained relevance to the wider community of stakeholders, to provide governance in terms of the conduct of the study, to monitor progress and to challenge the research team so that assumptions were questioned and methodological quality upheld.

The composition of the steering group altered slightly between phase 1 and phase 2 to comply with the National Institute for Health Research requirement of a 75 : 25 split between independent and non-independent members. 58 In both phases, independent members included representatives from the wider academic community, patients and the public, The King’s Fund, other NHS organisations and the Royal College of Nursing. In phase 2, steering group membership was extended to include an independent statistician, health economist and a HCA, and non-independent members were restricted to the lead investigator from each centre.

Public and patient involvement in the CHAT study

This was a complex study and our approach to public and patient involvement (PPI) was based on the principles that such involvement should be meaningful, respectful, relevant and collaborative. The complexity of the study was not simply because of the nature of the intervention but because of the complexity of the effect mechanism of which we wished to test the feasibility. For many interventions the person receiving the intervention is the target for the potential benefit. This is only partly true in our study where a training intervention was designed for HCAs to improve the relational care of older people in hospital. We took the view at the grant application stage that those whom this study would benefit were both HCAs (the proximal target group for our intervention) and older people who receive care in hospital and their visitors (the distal target group). This is consistent with the Kirkpatrick model for evaluating training interventions. 50 The voices of both these groups therefore needed not just to be heard but also to be at the heart of the content and delivery of the training intervention and, moreover, to inform the way in which staff and patient participants were recruited to the study. The overall purpose of PPI was, therefore, to ensure that both the intervention and the research process would be relevant and acceptable to staff, patients and their visitors.

Presubmission of the grant

Prior to the activation of the grant we worked with the Public and Patient Involvement in Research (PPIRes) group, an organisation hosted by the South Norfolk Clinical Commissioning Group. 59 The PPIRes group brings together volunteer members of the public to collaborate with researchers in local trusts and universities in Norfolk and Suffolk and to develop proposals from the initial idea through to dissemination. At the time of writing it has a panel of approximately 70 lay members. Prior to submission of the grant application we worked with the PPIRes co-ordinator to plan the PPI in the study and to invite panel members to be involved in the development of the application. Twenty-six volunteers responded and a summary of the study document was circulated via the PPIRes co-ordinator for review. The purpose of this was twofold: first, to get informal feedback from panel member views on the questions the study sought to address and on its proposed methods; and, second, to identify potential panel members who might wish to play a more active role should the study be funded. Views on the study were positive. A question was raised on whether or not the staff group should be extended beyond HCAs to OS. This highlighted the potential breadth of application for the intervention, but the focus of the commissioning brief prevented us from incorporating this suggestion. Some panel members expressed uncertainty as to the role of a HCA, and this was an early reminder of the need to check our assumptions about the ability of patients and relatives to distinguish members of the HCA workforce from other care staff. A discussion group was also organised in which all available documents were circulated in advance and six volunteers attended a 3-hour meeting to discuss the application in detail.

Recruitment and study documents

Prior to our application for ethics clearance to conduct phase 1 staff interviews and focus groups with older people, the PPIRes co-ordinator arranged a meeting (7 November 2013) of four panel members and the principal investigator. The purpose of the meeting was to review participant-facing study documents. Consent and participant information sheets based on NHS template documents were adapted in the light of detailed discussion at the meeting. Changes were made to simplify expression of interest forms and participant information sheets. The focus group prompt guide was also adapted, with suggestions made as to how to explain what we meant by relational care to focus group participants. At this point, two of the group became the PPI representatives for the CHAT study and remained so for the duration of the study period. Margaret McWilliams has been a PPIRes member for over 10 years. Her interest in this project stemmed from a carer perspective and a short hospital stay, which emphasised the importance of HCAs and how essential it was to be kept informed of what was going to happen as part of your daily routine. Margaret runs a hearing aid clinic for Norfolk Hearing Support Services where she speaks to many older people about their experiences. Janet Gray has been a PPIRes member for 2 years and is the carer of her parents and relatives who have experienced many hospital stays.

Focus groups

A later section of the report details our work with older people’s organisations to assist with raising awareness of, and recruitment to, the focus groups (see Chapter 4, Recruitment). In addition, we were keen for PPI representatives to play a key role in the conduct of the focus groups themselves. As our PPI representatives were based at one of the three study centres, local PPI representatives were recruited for this purpose at the other two centres. The contribution of the PPI representative was determined by their own preference and, therefore, varied at each centre. At one focus group, for example, a PPI representative chaired the discussion. At all three focus groups the PPI representative worked with the facilitator to welcome participants as they arrived, clarified facilitator topics and participant discussion as needed and alerted the facilitator to participants who indicated that they had a view to express but were reticent about joining in the discussion.

Intervention development

The process of intervention development is described fully in Chapter 5. The core intervention development team included our two PPIRes representatives together with a HCA from one of our partner trusts working on a ward caring for older people. Collectively, the PPI members worked to keep the focus on the needs of older users of hospital services and to ensure that the training intervention was designed with HCA learners firmly in mind. The group met on four occasions and formed a close knit team to produce what became the Older People’s Shoes training intervention. Roles inevitably became less demarcated and all team members became involved in all aspects of intervention development including structure, content, delivery, and proofreading training materials. We consider that the final product was substantially strengthened by this invaluable contribution. In addition, our HCA representative worked with researchers shortly prior to intervention delivery to ensure that activities were credible to reflect the work experience of HCAs in busy hospitals.

Study oversight

Details of the trial steering group are provided in Study Management. Membership of that group included our two PPIRes representatives as well as a HCA representative recruited via the Royal College of Nursing Health Practitioner Committee. The steering committee provided oversight to all aspects of the study. Our PPI and HCA representatives were vocal and enthusiastic members of this committee, providing sound and thoughtful advice at each stage of the research. They were also very supportive of the research team at points in the process when we hit challenges.

Feedback and reflection on the process of public and patient involvement in the CHAT study

For a relatively short project (2 years) we felt that both the process and outcome of PPI within the CHAT project was successful. We forged strong relationships over a short space of time. Soon after the study end point, the PPIRes co-ordinator conducted an informal meeting with our two PPI representatives to hear their views on the PPI process. Both PPI representatives commented on how much they had enjoyed being part of the team and that the experience had been rewarding. They felt their contribution was valued and they appreciated being included in communications beyond formal meetings. They felt that their views had been sought and respected by the steering group, with the chairperson of that group ensuring that they were actively involved in discussions. They were appreciative of travel arrangements for meetings being organised well in advance. Working alongside our HCA representatives had assisted them in understanding the nature of a HCA’s work, and, by extension, the focus of the study from both a user’s and a caregiver’s perspective.

Summary

The CHAT study was undertaken in centres in England and was conducted in two phases: (1) scoping and intervention development and (2) feasibility testing and process evaluation. In phase 1, data were collected in the form of a telephone survey of NHS hospital trusts, focus groups of older people and interviews with HCAs and staff working with HCAs. Following a process of intervention development, the second phase consisted of a feasibility cluster randomised controlled trial and process evaluation. The training intervention and feasibility testing was informed by guidance on the development and evaluation of complex interventions and the design of the feasibility study was informed by Kirkpatrick’s four-level evaluation model. 50 The study was managed by the principal investigator at the University of East Anglia and through regular team meetings with the other two centres. Governance arrangements included project management group meetings and five steering group meetings. The backdrop to the study was a rapidly changing landscape in terms of policy developments and initiatives relating to HCA work, most notably the publication of the Francis report,1 and the implementation of the Care Certificate following the Cavendish review. 2 PPI was central to each element of the study and was essential in ensuring that both the intervention and the research process were relevant and acceptable to staff, patients and their visitors.

Chapter 3 A national telephone survey of current provision of health-care assistant training in relational care for older people

Introduction

This chapter describes the methods and reports the findings of a telephone survey of acute NHS trusts in England to establish the structure, format and extent of training for HCAs in delivering relational care.

Telephone survey: methods

Purpose

The purpose of the telephone survey was to understand the current provision of HCA training, particularly with regard to relational care for older people. This would provide insight into how a new training intervention in relational care for HCAs could be effectively delivered within the context of current training provision in acute NHS hospitals. The objectives of the telephone survey were to understand (1) current training and support processes, (2) the extent of training content with respect to relational care and care specific to older people and (3) perceived challenges in delivering HCA training.

Sampling frame and eligibility

All NHS acute hospital trusts in England were eligible to take part. Trusts were identified from the Health and Social Care Information Centre,60 which places each trust into one of six categories (large, medium, small, multiservice, specialist and teaching). The one key contact at each trust eligible to take part in the telephone survey was a person with responsibility for designing, managing, delivering or overseeing the training of HCAs.

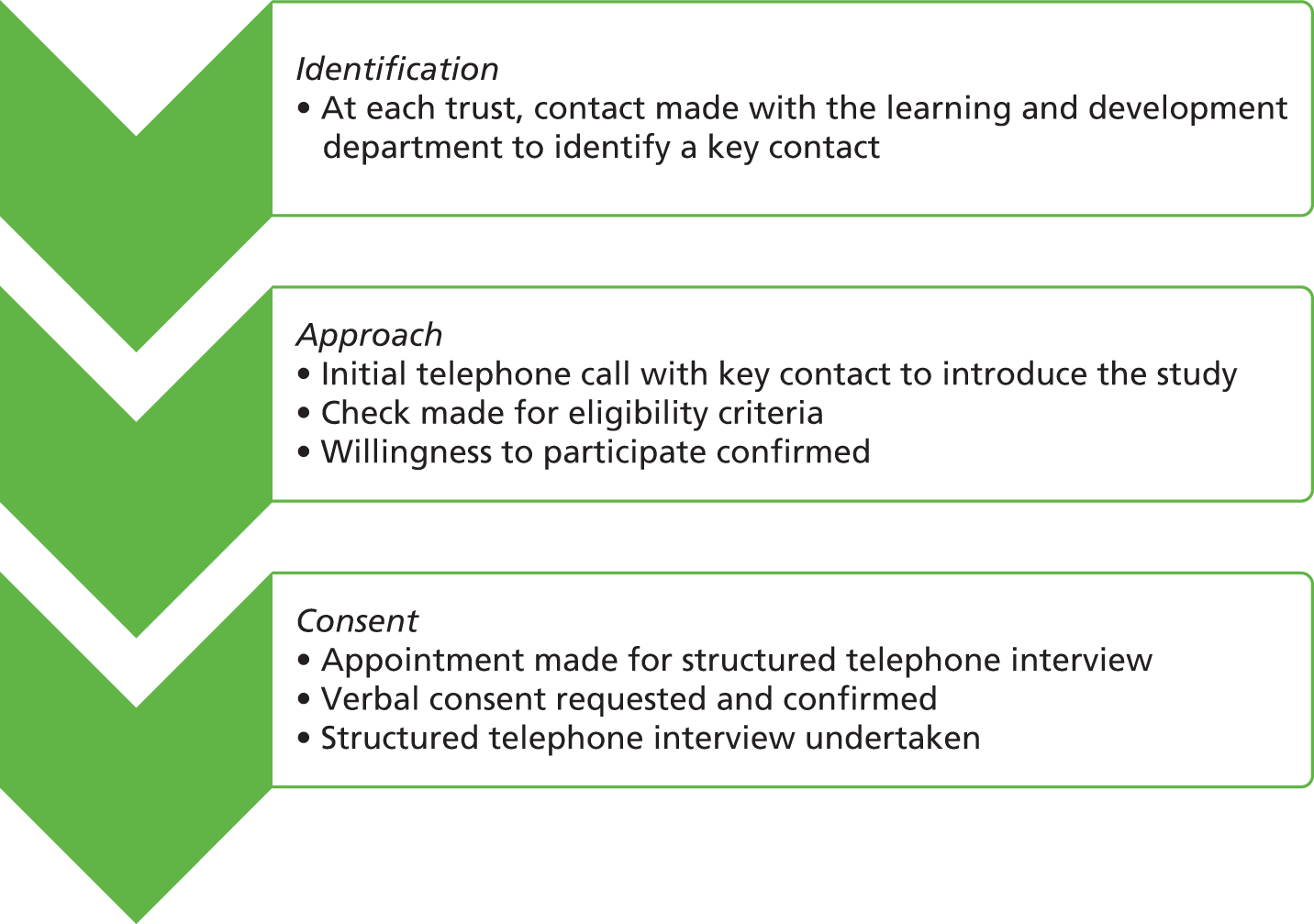

Recruitment

Recruitment to the telephone survey was carried out by four researchers employed on the study grant. The recruitment process is illustrated in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

Telephone survey recruitment process.

Identification

To identify the key contact, telephone contact was made with the learning and development department of the trust. When the researcher was unable to successfully identify the key contact for HCA training following five direct approaches to a trust over a minimum of a 3-week period, then no further approaches were made to the trust.

Approach

Once the key contact at a trust was identified, attempts were then made to establish contact with them and request their participation in a telephone interview. When the key contact responsible for HCA training was successfully identified but the researcher was unsuccessful in engaging in a two-way communication with this person (by either e-mail or telephone) following three direct approaches over a minimum 3-week period, no further attempts were made. When the key contact responsible for HCA training was successfully identified but within a minimum 3-week period the researcher was (1) unable to establish a mutually convenient time to conduct the telephone interview or (2) unsuccessful in completing the telephone interview at a minimum of two pre-agreed and mutually convenient times with the key contact, then no further contact was made.

Consent

Key contacts who were willing to take part were asked to identify a convenient date and time to take part in a structured telephone interview. Consent to participate and audio-record the structured telephone interview was requested and provided verbally.

Data collection

The survey was carried out over two periods: between February 2014 and September 2014, and then between July 2015 and October 2015. This was because of the early departure of a researcher at one centre and the period of time that elapsed before a replacement could be made.

Process

The structured telephone interviews followed a schedule designed to take approximately 30 minutes (see Appendix 1). It was scripted to ensure completeness but delivered in an unscripted, friendly and informal manner.

Content

Interview questions fell into three broad categories: (1) training and support processes, (2) content of HCA training and (3) challenges associated with training the HCA workforce.

We asked the key contact questions about what training a HCA starting work at that particular trust would receive with respect to duration, where it takes place and what is taught. We asked about ward-based training and support for new HCAs with respect to whether or not HCAs were supernumerary for any specific period or had support through formal mentoring or a less formal buddy system. We asked about training of long-standing members of the HCA workforce and whether or not there were differences in training for HCAs working in different clinical areas. We asked how long the training programme they had been describing had been in place with or without modification and whether or not there were any plans in place to develop HCA training at their trust. To explore whether or not any specific training was provided about the care of older people we asked one question verbatim: ‘in terms of the particular needs of older patients, which of those needs do you address in HCA training?’ No prompts were given. Telephone survey respondents were asked about what they saw as the challenges involved in training the HCA workforce. At the end of each structured telephone interview the researcher asked whether or not there was anything else in relation to HCA training that had not already been covered and that the participant wished to mention.

Data management, coding and analysis

Data were collected in a paper-based case report form and in audio files. Audio files were recorded using a portable digital voice recorder connected to a standard telephone. A unique identifier code was assigned to each trust. Audio data were uploaded and stored locally on secure servers. Structured telephone interview data were extracted from audio files and case report forms to a spreadsheet. Extracted data were anonymised and either coded for analysis or described accordingly. To categorise HCA training content, two researchers (CA and FN) coded data retrospectively using a shared template.

Counts and percentages of non-missing data were used to describe categorical data, and means with their standard deviations (SDs) were used to describe continuous data. A key development in the interim between the two periods of time during which the survey was conducted was the introduction in March 2015 of the Care Certificate. To check for any bias that this may have caused, we compared trusts interviewed before and after the national launch of the Care Certificate, using unpaired t-tests for continuous variables and chi-squared tests for categorical variables. A similar process was used to examine non-response bias comparing trusts that took part with those who did not. For categorical variables, where one or more cells had expected cell counts of five or less, Fisher’s exact test was used. All data analysis was conducted in Stata version 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Ethical considerations and ethics approvals

We were mindful that the care of older people in hospitals has been subject to recent criticism. 1 The telephone survey was undertaken at a time at which HCA training has been the focus of national attention. 2 This required our approach to both recruitment and the conduct of the telephone interview to be sensitive. Potential and actual participants were assured that the focus of the survey was to get a national picture of HCA training in acute NHS hospital trusts rather than identify particular failings. The researchers made it clear to the key contacts interviewed that individual trusts would not be identifiable in any reporting of survey findings.

Permission to undertake the telephone survey was provided by the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee at the University of East Anglia on 19 December 2013 (reference number 2013/2014-19).

Telephone survey: findings

Sample

Of the 161 acute NHS trusts approached to take part in the survey, a total of 113 (70.2%) structured telephone interviews were completed (Table 1). Of those trusts that took part, the mean number of whole-time equivalent staff was 4646, and there was no evidence that size of staffing establishment differed between participating and non-participating trusts (p = 0.43). Across Health and Social Care Information Centre trust type (small, medium, large, multiservice, specialist or teaching) the proportion of trusts that responded did not vary (p = 0.94). Trusts were surveyed in one of two time periods over the study duration and the proportion participating was lower during the second period (56.9% vs. 80.9%; p < 0.001). Trusts approached in the second period included those that had not refused in the first period but were more difficult to establish contact with. The second period took place after many trusts had been involved in preparing for the introduction of the new Care Certificate that was officially launched in March 2015. Two-thirds (66.1%) of the key contacts at participating trusts were involved in the direct delivery of HCA training, whereas in the remainder the key contact had a more strategic role in HCA training.

| Trust, survey and respondent factors | Telephone survey completed | p-value | All trusts (N = 161) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (N = 113) | No (N = 48) | |||

| Staff WTE mean (SD) | 4645.6 (2710) | 4294.4 (2292) | 0.43a | 4540.9 (2590.4) |

| Trust type, n (%) | ||||

| Small | 27 (71.1) | 11 (29.0) | 0.94b | 38 |

| Medium | 26 (72.2) | 10 (27.8) | 36 | |

| Large | 25 (67.6) | 12 (32.4) | 37 | |

| Multiservice | 4 (80.0) | 1 (20.0) | 5 | |

| Specialist | 11 (61.1) | 7 (38.9) | 18 | |

| Teaching | 20 (74.1) | 7 (25.9) | 27 | |

| Survey period, n (%) | ||||

| Prior to Care Certificate | 72 (80.9) | 17 (19.1) | 0.001c | 89 |

| Following Care Certificate | 41 (56.9) | 31 (43.1) | 72 | |

| Role of contact in HCA training, n (%) | ||||

| Direct delivery | 74 (66.1) | |||

| Strategic planning | 38 (33.9) | |||

| Unknown | 1 | |||

Structure of health-care assistant induction training

Key contacts at just under half of participating trusts (50/110, 45.4%) reported induction programmes of 1 week or less, with the remainder having longer induction programmes and 1 in 10 having HCA programmes of between 2 and 3 weeks (Table 2). It was the norm for new HCAs to have a mentor or buddy (98/113, 86.8%), with only eight trust key contacts (7.1%) saying this was not the case. When respondents reported the type of mentor for those trusts with a system of mentoring or buddying, these were senior HCAs (n = 50, 46.3%), registered nurses (n = 16, 14.8%) or either (n = 17, 15.7%). New HCAs were accorded supernumerary status at most of the participating trusts (n = 81, 71.7%), the remainder reporting that new HCAs were not supernumerary or that supernumerary status was dependent on other factors. Many trusts indicated that the duration and type of support on wards was at the discretion of the ward manager. There was no evidence of differences between trusts surveyed at each time period with respect to how HCA induction was structured (analysis not shown).

| HCA induction variables | All trusts (N = 113), n (%) |

|---|---|

| Length of training (classroom based) | |

| < 1 week | 19 (17.3) |

| 1 week | 31 (28.1) |

| > 1 week to 2 weeks | 49 (44.6) |

| > 2 weeks to 3 weeks | 11 (10.0) |

| Missing | 3 |

| Mentor or buddy allocation | |

| Yes | 98 (86.8) |

| Informal | 6 (5.3) |

| No | 8 (7.1) |

| Do not know | 1 (0.9) |

| Mentor or buddy type | |

| Registered nurse | 16 (14.8) |

| Senior HCA or registered nurse | 17 (15.7) |

| Senior HCA | 50 (46.3) |

| Varies | 17 (15.7) |

| No mentor | 8 (7.4) |

| Missing | 5 |

| Supernumerary status | |

| Yes | 81 (71.7) |

| Varies/depends | 16 (14.2) |

| No | 16 (14.2) |

Content of health-care assistant induction training

One-third (n = 37, 32.7%) of trust key contacts reported content within their HCA training induction programme that we considered to be relational care (Table 3). When asked specifically about induction training that was related to the care of older people, 43 (38.1%) trust respondents referred to subject areas such as privacy, dignity and respect (n = 30, 27.3%) and communication skills (n = 24, 21.8%), all considered by the researchers to involve relational care. Only two respondents (1.8%) said that their trust covered the subject of ‘customer care’. Dementia care was reported as being included in HCA induction programmes by the majority of respondents (n = 94, 85.5%). Other training induction content relevant to older people and reported by survey respondents was nutrition and hydration (n = 31, 28.2%), falls (n = 25, 22.7%) and sensory/physical impairment (n = 23, 20.9%). Nearly one-third of respondents (n = 35, 31.5%) said that they made no distinction during induction training between the needs of older people and those of any age group. Nearly all trust respondents interviewed prior to the national launch of the Care Certificate reported plans to develop HCA training (56/57, 98.3%) compared with 73.7% (28/38) of trusts surveyed after the national launch (p < 0.001), suggesting changes were just starting to be introduced in the intervening period.

| Training content | All trusts (N = 113),a n (%) |

|---|---|

| Relational care (not age specific) | 37 (32.7) |

| Relating to older people | |

| Dementia | 94/110 (85.5) |

| Stroke | 3/110 (2.7) |

| Sensory/physical impairment | 23/110 (20.9) |

| End-of-life care | 15/110 (13.6) |

| Continence | 7/110 (6.4) |

| Falls | 25/110 (22.7) |

| Nutrition/hydration | 31/110 (28.2) |

| Skin care | 13/110 (11.8) |

| The ageing process | 7/112 (6.3) |

| Privacy, dignity and respect | 30/110 (27.3) |

| Communication | 24/110 (21.8) |

| Person-centred care, compassion | 19 (16.8) |

| Safeguarding, values and behaviours | 16 (14.2) |

| Customer care | 2 (1.8) |

| Relational care | 43 (38.1) |

| No age distinction made | 35/111 (31.5) |

Challenges of training health-care assistants

Reported challenges related to training HCAs were categorised under four headings: the wider context, resource limitations, ward engagement and HCA-related challenges (Table 4). The most frequently cited challenge for delivering training to the HCA workforce was getting staff released from wards to attend (n = 53, 46.9%). Whether this was because of a lack of ward manager engagement with HCA training delivered at trust level or simply because of a lack of staffing resource is not possible to determine from our data. However, many respondents unsurprisingly cited resource limitations as a challenge. Trust key contacts reported challenges of being limited not just in terms of funding but also in relation to the availability of assessors, mentors and training venues. The wider context of opportunities (or lack of opportunities) for HCAs to develop their role was highlighted by some, together with the difficulties associated with HCA training rarely recognised beyond an individual trust. The highly diverse nature of the HCAs in terms of their care experience and academic ability was the most cited challenge relating to members of the HCA workforce.

| Challenges | All trusts (N = 113), n (%) |

|---|---|

| Wider context | |

| Retention (HCAs leaving for nursing training or development opportunities) | 15 (13.3) |

| Lack of career progression for HCAs (no opportunities for HCAs to develop apart from through nursing training) | 16 (14.2) |

| Transferability of training (training not being accepted across trust/trusts) | 4 (3.5) |

| Lack of accreditation (HCA qualifications not nationally accredited) | 5 (4.4) |

| Ward engagement | |

| Release from ward (getting HCAs released from ward to attend training) | 53 (46.9) |

| Manager engagement (encouraging managers to engage with HCA training) | 17 (15.0) |

| Staff motivation (lack of motivation in existing staff to support and nurture new HCAs) | 10 (8.8) |

| HCA related | |

| Diversity in HCA recruits (differences in experience, academic qualifications, values) | 19 (16.8) |

| Computer skills (HCAs not always computer literate, making e-learning a problem) | 6 (5.3) |

| Numeracy and literacy problems | 8 (7.1) |

| Lack of confidence (HCA recruits lacking confidence/not feeling valued) | 3 (2.7) |

| Language problems (problems caused by English being a second language for some recruits) | 3 (2.7) |

Training beyond induction

The variability of the extent and nature of training after induction meant that insights into this area of HCA training were gleaned through open-ended questioning. Once the initial training/induction period was over, many trusts reported that HCAs had access to ongoing training, although the emphasis was on training newly employed personnel. Only one trust reported that they had received funding allowing them to put both new and existing HCA staff through the Care Certificate. One trainer suggested that restricted access to training affected the ability to retain good HCAs, thereby increasing HCA turnover and creating a ‘vicious circle’. Although many trusts reported having postinduction training available, this varied greatly in terms of structure, focus and content. The target group for this training also varied greatly between trusts. Some reported holding regular HCA study days covering an array of specialist skills; however, these sessions were rarely mandatory and tended to be at the discretion of ward managers. Owing to time and resource constraints some trusts had opted for an e-learning approach and offered packages in areas including dementia and end-of-life care.

One trust offered monthly open-access support worker sessions, which could be tailored to the needs of the individual, and another trust ran a weekly skills refresher day open to both registered nurses and HCAs. However, an ad hoc approach to training was the norm for most trusts. Many telephone survey respondents were unaware of the content of specialist training available to staff, as this was carried out on the ward by clinical trainers. Again, this training was governed by managerial requirements and limited by time constraints.

Summary

In a national survey of 113 of the 161 acute hospital trusts in England, which was designed to capture data on the current provision of HCA training, particularly relational care for older people, we found HCA induction to be highly variable, lasting between a few days and up to 3 weeks. One-third of interviewees reported content within their HCA training induction programme that we considered to be relational care. Only two respondents said that their trust covered the subject of ‘customer care’, whereas the majority reported the inclusion of dementia care in HCA induction programmes. The majority of new HCAs are provided with a mentor or buddy and 72% of trusts treat new HCAs as supernumerary. Reported challenges in training HCAs were related to resource limitations, engaging ward managers and the diverse nature of the HCA workforce. The most frequently cited challenge for delivering training to the HCA workforce was getting staff released from wards to attend. Emphasis was placed on induction but much less on ongoing training, which is typically devolved to ward managers. Older people’s needs are addressed in HCA training, but there was little evidence that relational care is seen as a priority within that.

Chapter 4 A qualitative investigation into the training needs of health-care assistants with respect to relational care of older people

Introduction

This chapter describes the methods and reports the findings of two components of the study: first, a series of focus groups with older people and carers with experience of hospital care to explore their expectations of the care provided by HCAs; and, second, qualitative interviews with HCAs and other NHS staff to identify the training needs and preferences for a training intervention to improve HCA relational care of older people.

Focus groups: methods

Purpose

To inform the content of the HCA training intervention we ran three focus groups (one in each centre) of older people and carers with experience of acute care. We wished to identify these groups’ experience of relational care as provided by HCAs. We wanted to understand the values-based training needs of HCAs in maintaining the dignity of, and affording respectful care to, older patients in acute NHS settings from the perspective of those they care for. Each focus group aimed to gather a broad range of perspectives from older people who had been an inpatient, or a carer of an inpatient, at an acute NHS trust. The purpose of focus groups is to explore people’s experiences, attitudes and feelings on a topic in a way that capitalises on group interaction. 61,62 Interaction enables participants to build on other people’s input and to ask questions of each other, as well as to re-evaluate and reconsider their own understanding of their specific experiences. 63

Setting and eligibility

Focus groups were carried out in non-clinical settings in venues that had disabled access and transport links. At each centre transport was arranged for participants who required it, and costs were reimbursed for others. Eligible participants were former hospital inpatients at any acute NHS trust aged ≥ 65 years or the carer of a former inpatient aged ≥ 65 years. Although not an eligibility criterion, we prioritised those whose experience of an inpatient stay was at least 3 months and no longer than 6 months prior to the focus group meeting on the basis that this would avoid any very raw emotions in a group setting, while maximising the chances of recall.

Recruitment

Identification

At each centre the recruitment strategy was adapted, when necessary, to reflect the local context and use existing networks. In centre 1, the team engaged a county-wide Older People’s Forum, which approved the study and passed on details of local branches. In centre 2, the research team worked with the national and local branches of Age UK. In centre 3, a number of outreach avenues were identified through local knowledge, networking and internet searches.

Approach

Potential focus group participants made expressions of interest by completing a form (see Appendix 2) that had been distributed in a variety of ways. In centre 1 the chairpersons of four local branches of a county-wide Older People’s Forum were sent details of the study and asked to circulate details at a meeting or by e-mail. The researchers also offered to present the study at a branch meeting, and two branches accepted this offer. In centre 2, advertisements were placed in two editions of the national Age UK newsletter and an item sent out with two local Age UK newsletters. The researcher attended a local event in an Age UK campaign and presented to a local Age UK Older People’s Advisory Group. In centre 3, the researcher presented the study to seven community organisations of older people and/or carers during previously convened meetings. In addition, an item appeared in the newsletter of one of these groups, and in that of two local Healthwatch groups.

In all centres the local researcher followed up written expressions of interest by telephone or e-mail depending on the potential participant’s preference. During these exchanges further explanation was given on the study and what participation would entail and a participant information sheet was provided (see Appendix 3). Exchanges were also used to check eligibility and to collect broad contextualising information about the potential participant, including whether they were an ex-patient or carer of one (or both) and, when relevant, time since last discharge from an inpatient stay, length of last stay and hospital attended. This information was gathered to allow purposive sampling of participants to include women and men, patients and carers, a range of ethnic groups and experiences in different hospitals. Additional information (including transportation requirements, mobility, capability and any other carer assistance required) was also collected at this stage and used to facilitate focus group attendance. At the point of recruitment it was explained to volunteers that sampling would take place at the end of the recruitment process, with the aim of getting a balance of men and women and patients and carers. When capacity to give informed consent was in doubt, volunteers were not selected to take part in the group.

Consent

During follow-up exchanges a judgement was made on the potential participant’s ability to provide informed consent. Verbal consent to participate was taken during these exchanges with potential participants once any questions had been answered. Four weeks before the focus group, letters were sent to all those who had expressed an interest in taking part. Those not purposely sampled for invitation to one of the focus groups were given a brief explanation as to why this was the case, informed that the number of expressions of interest had exceeded the number of places within the group and thanked for the interest they had shown in the study. Letters of invitation, which were provided to all selected participants, included details of the focus group. Consent forms were posted out 1 week ahead of the focus group to allow ample time for further consideration. Written consent was obtained at the focus group meeting, prior to the start of discussion and audio-recording.

Data collection

Process

Focus groups were designed to run for up to 2 hours and refreshments were provided. Ground rules were established before the discussion started (see Appendix 4). The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim, and individual participants were identified by participant number. At each centre the focus group discussion was attended by two members of the research team and a PPI representative. Although the part they played varied between centres, PPI representatives played a bridging role between the research team and focus group participants. The roles and responsibilities of each facilitator were agreed beforehand. The participants were given gift vouchers to thank them for their time and effort.

Content

The discussion followed a topic guide (see Appendix 5). The focus group topics explored participants’ experiences and expectations of inpatient care, views on what ‘good care’ looked like, what training participants thought HCAs needed in order to improve their delivery of relational care and their recommendations on how good customer care from retail organisations might be applied to a ward setting. A summary is shown in Table 5.

| Areas explored | Questions askeda |

|---|---|

| What is important when an older person is first brought on to a new ward |

|

| What relational care looks like according to older patients and carers |

|

| Views on getting to know patients |

|

| Recommendation for training intervention |

|

| Experiences of relational care outside hospitals |

|

Data management, coding and analysis

An analysis of focus group transcript data was carried out in NVivo version 10 (QSR International, Warrington, UK). Data were initially coded in NVivo, using a framework of codes aligned to the broad themes suggested by topic guide, for example what people want when they arrive on a ward, examples of good relational care (in hospitals and in other settings) and what staff should know about individual older patients. This was followed by more detailed analysis using an inductive approach in which data within themes were examined and interpreted to draw out more refined themes and conceptual nuances.

Given that the purpose of the focus group was to inform the development of a training intervention for HCAs to improve their delivery of relational care, analysis focused on thematic content, and not behaviour or non-verbal data. 64 As focus groups are valuable for the interactions between participants, instances of consensus, contradiction and controversy were sought and used in presenting the findings. 61 Data were not analysed for differences between groups or along lines of sex or ethnicity. However, the relationship between patient and carer needs was examined.

Ethical considerations and ethics approvals

At the start of the focus group meeting, participants were reminded that data would be anonymised and kept confidential and were asked to maintain the anonymity and confidentiality of other participants. Thinking about and discussing experiences of and around hospital stay can be upsetting. At each focus group one member of the research team was given responsibility for looking after any participants should they be upset and wish to withdraw from the discussion. At the end of the discussion participants were provided with details of the local trust’s patient advice and liaison service should they wish to discuss their experiences further. Six months after the focus group, an update on the study was sent to all focus group participants, letting them know how their views were being used.

Permission to undertake the focus groups was provided by the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee at the University of East Anglia on 19 December 2013 (reference number 2013/2014-19).

Interviews with health-care assistants and other staff: methods

Purpose

Semistructured one-to-one interviews with HCAs and OS (principally nursing staff) in the three centres were conducted to elicit their perspectives on what good relational care of older people looks like, what a training intervention for HCAs should contain and what style of training delivery was likely to be most effective. These interviews allowed us to understand the context of providing relational care to older patients, any barriers to training access or implementation of training and to investigate the perceived training needs of HCAs with respect to relational care.

Setting and eligibility

At each centre we worked with a partner acute NHS hospital trust. The three trusts were all teaching hospitals: one in London, one in a rural county and one in the Midlands. Wards caring for older people in the trusts were purposively sampled to reflect a wide range of HCA experience on different types of ward (health care of older people, general medical and orthopaedic). Our intention was to ensure that the training intervention developed would be relevant to HCAs with different levels and types of workplace experience. Eligible ‘OS’ were those who directly manage HCAs on recruited wards (ward managers and staff nurses), who work alongside HCAs on recruited wards (e.g. allied health professionals) or managers with responsibility at the division or trust level.

Recruitment

Identification

At each trust we worked with a senior member of nursing staff who identified which of their wards had a majority of older patients, and recommended the four most appropriate wards for a researcher to approach HCA interviewees (subject to the ward manager’s agreement). Participating ward managers were asked to suggest other relevant staff groups or individuals we might invite to interview.

Approach

The study was presented to ward managers on the four identified wards at one-to-one meetings with the local researcher. Once they had agreed to facilitate the study, it was presented more widely, initially at a handover meeting and, subsequently, during several visits to the ward. Researchers explained the study and what taking part would involve and answered any questions. Potential interviewees were left with a participant information sheet (see Appendix 6) and an expression of interest form to be completed if they were happy for the local researcher to contact them about participating in the study (see Appendix 7).

Consent

Verbal consent to take part in interviews was obtained after potential interviewees had had the opportunity to read the participant information sheet, and a time and date was then arranged for the interview. Written consent was taken immediately prior to the interview.

Data collection

Process

The interviews were audio-recorded with the interviewee’s permission. Audio files were transcribed verbatim. The transcripts were then anonymised and later pseudonymised. The interviews were carried out in a quiet room (e.g. empty day room or office) on trust premises.

Content

Rather than ask interviewees about views and experiences of a narrow definition of ‘relational care’, we asked a number of differently framed questions around ‘good care’ that would allow us to draw inferences about relational care and the role of HCAs in providing it. Interviews were designed to explore these perceptions of ‘good care’ and the training needs of HCAs with respect to relational care for older people.

We were keen to ensure that the training intervention (to be designed and feasibility tested in subsequent elements of the study) could be implemented in the ‘real world’. We therefore wanted to understand (1) what working on older people’s wards was like and (2) the difficulties in providing good relational care. We also wanted to know what support we could provide to HCAs through the intervention that would help them to provide relational care in challenging circumstances. We therefore asked about barriers to implementing training and what might be done at the point of delivery to facilitate implementation of training.

Topic guides for HCAs and OS were broadly similar (see Appendix 8), but recognised differences in their knowledge and experience. The areas explored and the key topics covered are presented in Table 6. Seven interviews across two of the three trusts were carried out after an imposed hiatus and the topic guides were modified slightly to get feedback on an early draft outline of the HCA training intervention.

| Areas explored | Key HCA interview topics | Key interview topics for other staff |

|---|---|---|

| What are HCAs and other staff members’ views on what ‘good care’ looks like? | What HCAs can do to make patients feel cared about | Examples of good care by a HCA |

| What HCAs can do to make being in, or having a relative in, hospital less distressing | What HCAs can do to make being in, or having a relative in, hospital less distressing | |

| Barriers to, and facilitators of, getting to know patients | Barriers to, and facilitators of, getting to know patients | |

| Personal experiences of good customer care (what providers did and what it felt like) | Personal experiences of good customer care (what providers did and what it felt like) | |

| Views on applying customer care lessons to an acute setting | Views on applying customer care lessons to an acute setting | |

| If you had an elderly relative in hospital, what would be most important to you about the way they were cared for? | ||

| HCAs training needs in relational care for older people | Work history | Challenges in caring for older people |

| Challenges in working as a HCA caring for older people | Thoughts on available training for HCAs/training gaps at the trust (including lack of training to address identified work challenges) | |

| Aspects of their role they feel most/least confident about | ||

| Training received at the trust and elsewhere (including most useful training; exploring any training on relating to patients or in dealing with identified work challenges) | ||

| Perceived training gaps | ||

| Recommendations for the delivery method, style and timing of a training intervention for HCAs | Difficulties in accessing training | Content and methods of any training previously recommended by HCAs |

| Content and methods of any memorable training | Recommended delivery style for HCA training on relational care | |

| Preferred training delivery style | ||

| Implementing any training on relational aspects of care | Barriers to, and facilitators of, implementing any training on relational aspects of care | Barriers to, and facilitators of, implementing any training on relational aspects of care |

| Problems in implementing trust’s HCA training policy | ||

| Later interviews only | ||

| Thoughts on draft outline of training intervention | Views on the purpose, topics, timing, structure, delivery, underpinning values and title of a draft outline | |

Data management, coding and analysis

The interview data from each trust were coded in NVivo by the local researcher using a coding framework developed from initial readings of the transcripts and agreed by the study team. This collaborative work to identify themes ensured validity and reliability of the analysis. The coding framework included broad themes specifically directed towards the aim of the study (to develop a training intervention for HCAs to improve relational care of older people). The analysis used both deductive and inductive approaches.

Examples of deductive themes were organisation- and patient-related challenges in HCAs’ work, the role of HCAs in relational care (categorised using the study team’s understanding of what relational care consisted of), experiences of good customer care and perceived gaps in training. Other themes were imposed to inform how we framed the intervention and managed practical arrangements, as well as giving important contextual data to help us interpret our findings on the feasibility of the intervention.

Following this process of deductive data extraction, a more detailed thematic analysis of the whole data set was then carried out in NVivo by one researcher, using an inductive approach and the constant comparative method in order to enhance analytical rigour65 and the credibility and ‘trustworthiness’ of the findings. 66 At this stage, subthemes such as ‘tensions inherent in HCAs’ work’ emerged from interviewees’ accounts.

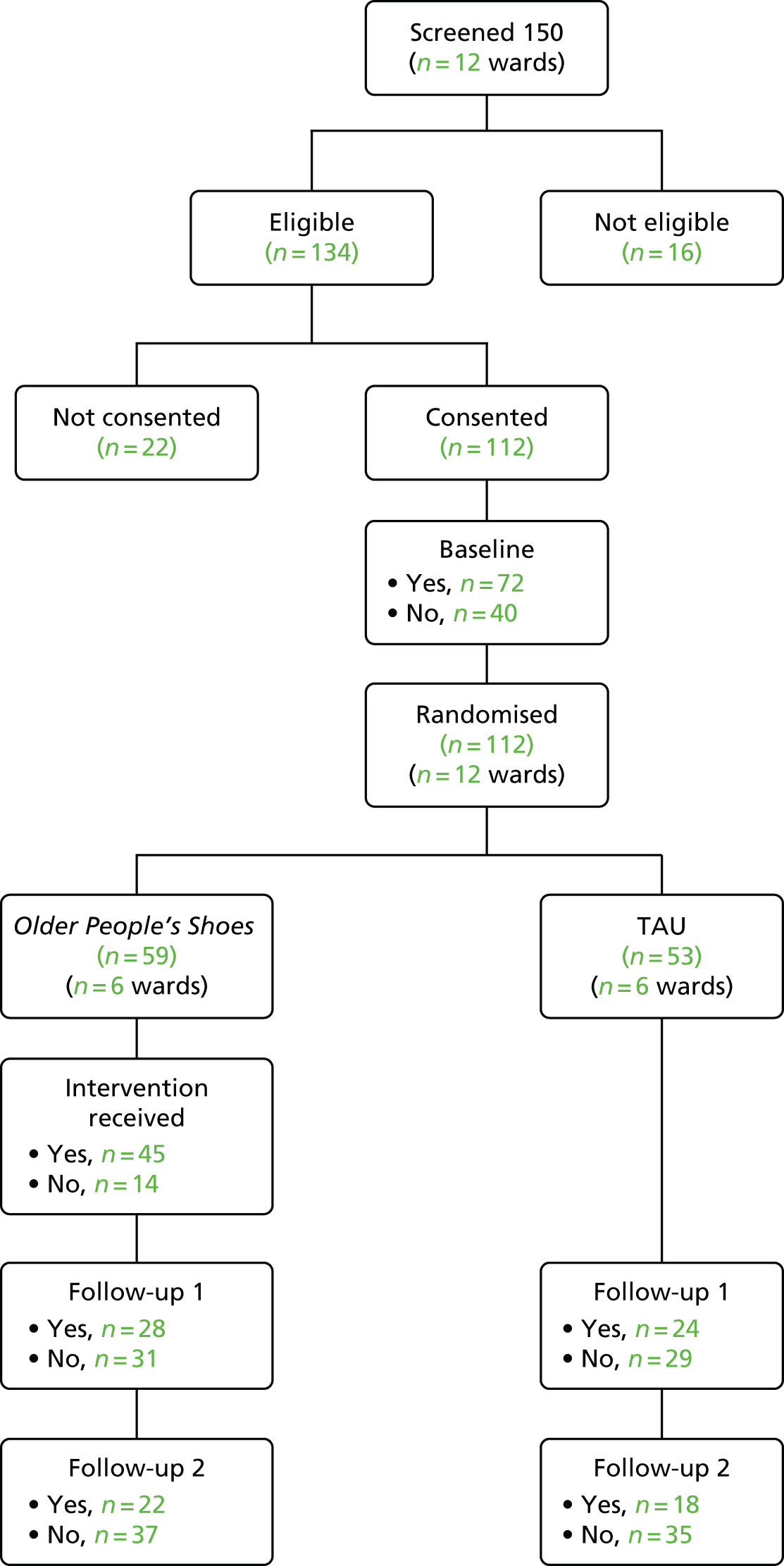

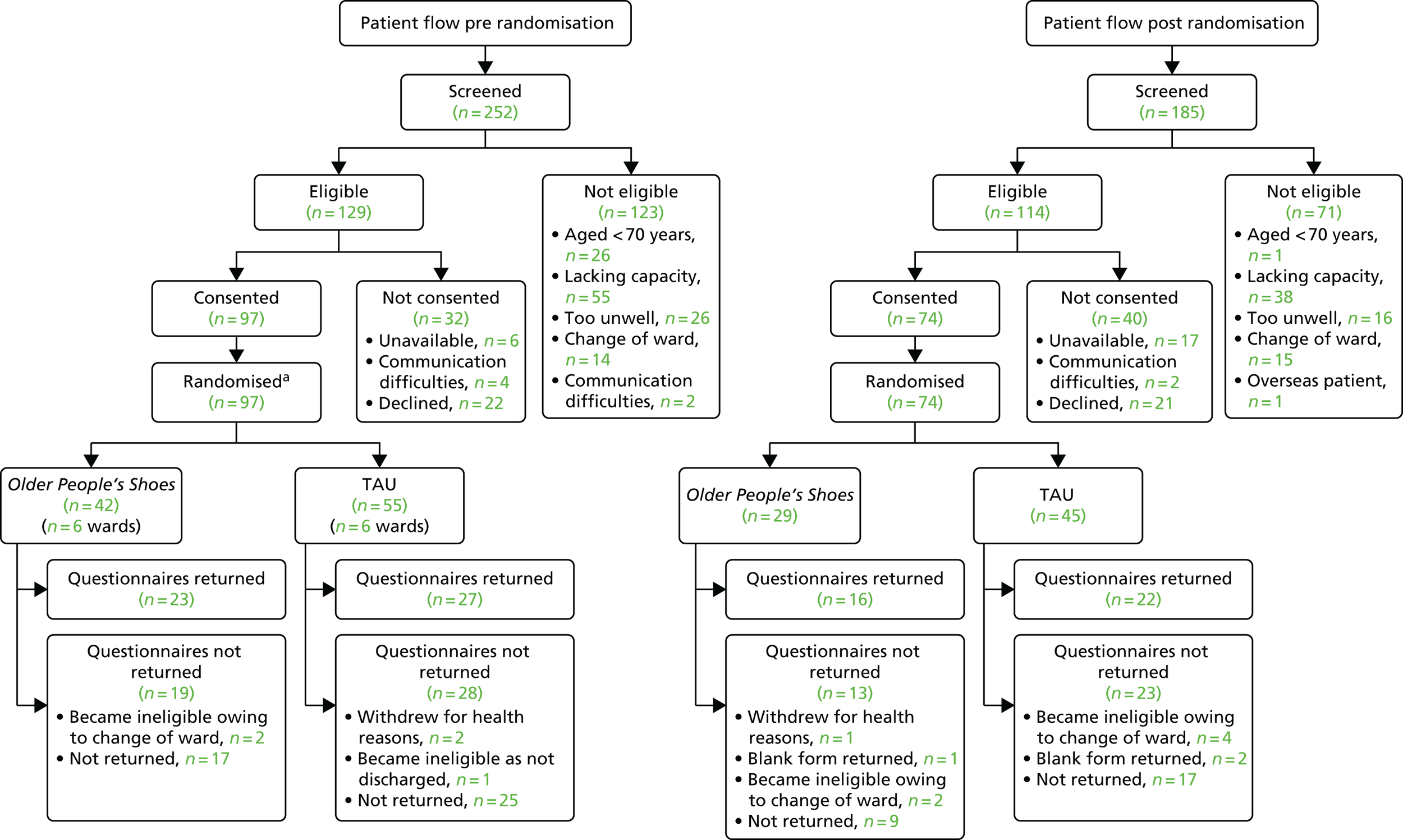

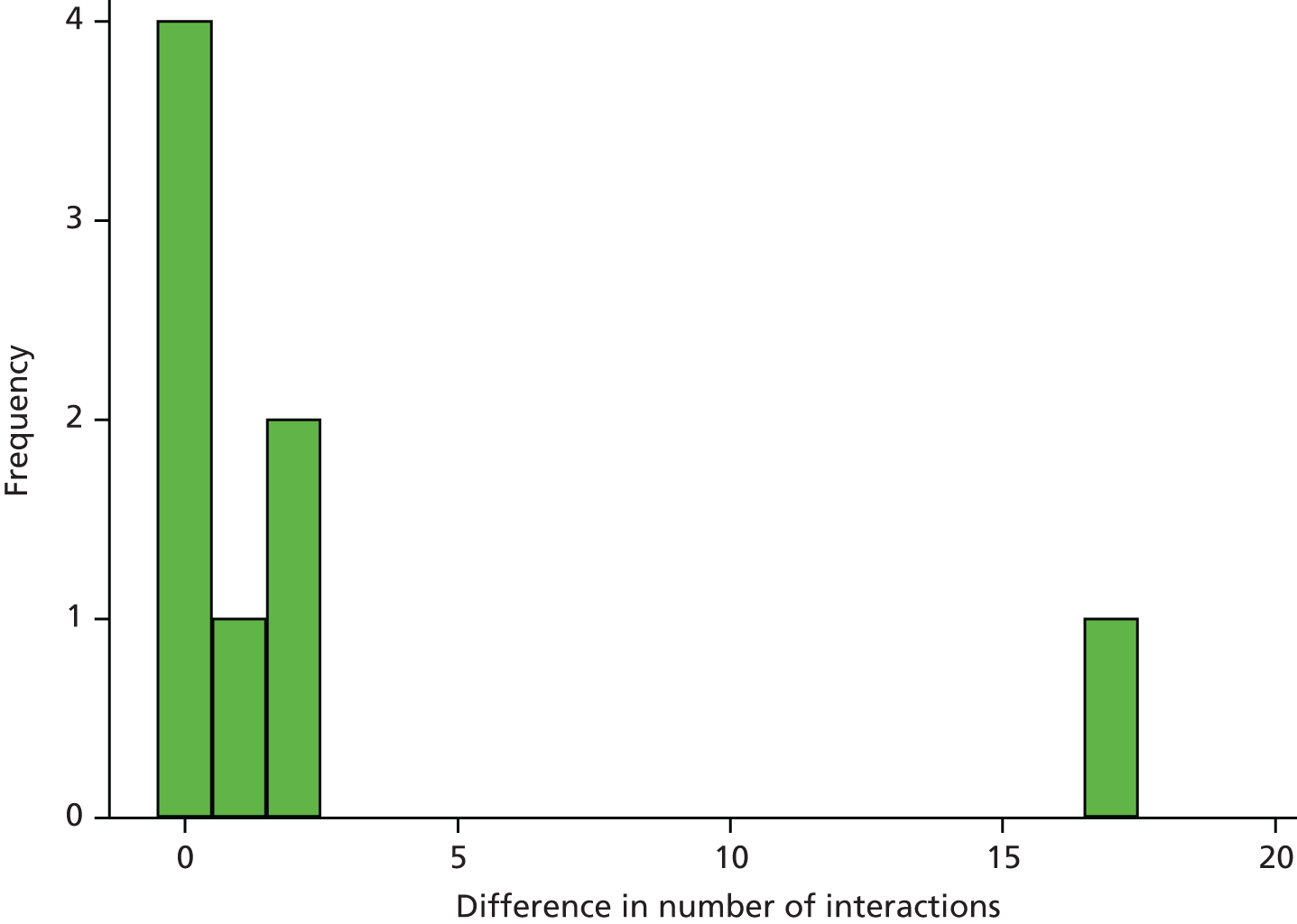

The interview and analysis process was iterative. This meant that we were able to use findings from earlier interviews to inform subsequent interviews. For instance, we used early findings on ‘challenges in HCAs’ work’ to frame a question used in later interviews about whether or not interviewees thought such challenges could usefully be addressed in training.