Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 11/1024/06. The contractual start date was in March 2013. The final report began editorial review in March 2016 and was accepted for publication in September 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Völlm et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Forensic psychiatry is a subspecialty of psychiatry that operates at the interface between law and psychiatry. It is concerned with patients who have committed an often serious offence and may be detained in highly restrictive secure settings. The purpose of this detention is twofold: care for and treatment of the patient (i.e. to improve mental health and facilitate recovery) and protection of the public from harm from the offender (i.e. reduce the risk the patient poses). This dual function can cause tensions and dilemmas for the practitioner, who has potentially incompatible duties to the patient, to third parties and to the wider community. 1–4 These tensions remind us that the social and political context is crucial in medical decision-making generally, and even more so in the field of forensic psychiatry. For example, several authors have noted the current risk-aversive narrative in European and US societies, driving psychiatric practice to become more and more restrictive and potentially leading to increased lengths of stay (LoS) in forensic psychiatric settings. 5

Detention of mentally disordered offenders

The detention of mentally disordered offenders (MDOs) in the UK is regulated by a complex set of laws and regulations, of which mental health legislation, namely the Mental Health Act (MHA) of 1983,6 amended in 2007, is the most relevant. Unlike in other European legislations, which require reduced responsibility as a prerequisite for a person’s entry into the forensic psychiatric system, detention of MDOs in forensic settings in England and Wales is independent of criminal responsibility and determined solely on the basis of the person’s mental condition at the time of sentencing or transfer. The criteria for the detention of MDOs according to section 37 (hospital order: an order made by the court at the time of sentencing) of the MHA are, therefore, similar to those for non-offending patients under section 3 (admission for treatment) of the Act. MDOs may be detained if ‘the offender is suffering from a mental disorder . . . of a nature or degree which makes it appropriate for him to be detained in a hospital for medical treatment and appropriate medical treatment is available’. 6 Prisoners who are sentenced to a prison sentence can later be transferred to a forensic psychiatric facility, even years into their sentence,6 according to similar criteria. No further stipulation is made with regard to the nature or level of risk posed. The requirement of ‘appropriate treatment’ being ‘available’ has been interpreted as being met by very limited therapeutic input (e.g. nursing care only) or when a patient refuses to engage as long as the therapy is ‘available’. 7–9 There is no proviso that treatment offered has to be effective for the individual patient.

Detention in forensic care is generally not time-limited, and discharge depends on whether or not the individual is deemed to have made sufficient progress that they no longer present a risk. Discharge and transfer (e.g. to a less secure facility) is governed by a number of bodies (responsible clinician, hospital managers, mental health tribunals, Ministry of Justice) without further involvement of the sentencing court. The advantage of this framework is that it allows access to psychiatric care for those in need at any time. On the other hand, the fact that individuals with full criminal responsibility may be – and often are – held well beyond the time they would have been incarcerated had they received a prison sentence as a non-mentally-disordered individual, and the involvement of a political body in decision-making about discharge, are ethically problematic. 10

Services for mentally disordered offenders in the UK

Forensic psychiatric services may be provided in different levels of security – high, medium and low secure – as well as community forensic psychiatric services. High secure services cater for patients who ‘require treatment under conditions of high security on account of their dangerous, violent or criminal propensities’11 and ‘pose a grave and immediate danger’,12 medium secure services are for those presenting ‘a serious danger to the public’12 and low secure services are for those ‘who pose a significant danger to themselves and others’. In addition, ‘enhanced’ medium secure services are provided for women ‘who require enhanced levels of intervention and treatment . . . and for whom current medium secure services are not appropriate’. This tiered system has developed historically as described below; it allows – in theory – movement along a ‘treatment pathway’, where individuals move from more to less restrictive settings. Such provision in the least restrictive setting is essential not only for legal and ethical reasons but also for financial reasons. Forensic psychiatric services are high-cost, low-volume services: in England and Wales bed costs for high secure provision are approximately £275,000 per annum per patient; in medium secure care this figure is about £175,000. Forensic care consumes £1.2B per annum, 1% of the entire NHS and 10% of the mental health budget. 12–14

In the UK, the first forensic service was Broadmoor Hospital in Berkshire, which opened in 1863. Two other high secure hospitals opened in the 20th century: Rampton Hospital in Nottinghamshire in 1912, and Ashworth Hospital in Merseyside in 1990 (although this was formed through the merger of two existing services with a much longer history). Until the 1970s, these three high secure hospitals were the only provision for secure care in the UK. This brought with it challenges for rehabilitation, both because of the geographical distance of these services from patients’ home areas and due to the large gap in security between high secure care and general adult provision with nothing in between. Forensic service provision was, therefore, made subject to a review, and the Butler Committee15 subsequently recommended that smaller and more local ‘regional secure units’ (later to be known as medium secure units) be developed. The first such unit was opened at the end of the 1970s, and by the mid-1980s full national medium secure provision had been established. Medium secure beds are provided by the NHS but also (just under 50%) in the independent sector,16 which may provide for individuals with diagnoses/presentations for which there is insufficient capacity within NHS services.

Given these refigurations, it is not surprising that bed numbers in high and medium secure care have fluctuated, although, notably, the overall number of secure beds has risen. Security has also been tightened, partly due to specific concerns and high-profile inquiries (e.g. the Fallon Inquiry)17 and partly due to a less tolerant and more security-conscious attitude in society as a whole. Bed numbers in high secure care reached their peak in 1973 – before the introduction of medium secure services – with 2300 beds. By the beginning of the 1990s, there were 1700 high and 600 medium secure beds. 16 The latest figures are just under 800 beds in high secure care and just under 3200 for medium secure care. 12 A significant factor in the shift from high to medium secure care was the implementation of the ‘accelerated discharge programme’, as described below. 18

Management and commissioning of secure care

Arrangements for commissioning services for secure care have changed considerably over the years. 17 For high secure services, responsibility moved gradually from the Home Secretary to the Ministry of Health, which centrally managed the three high secure hospitals until the 1980s. From 1989 to 1996, this function was performed by the Special Hospitals Service Authority before full integration of the three ‘special’ hospitals into NHS trusts. The Department of Health11 maintains close oversight of these institutions, however, and issues the Directions on Safety and Security and visits by children to high-security psychiatric services. These Directions outline policies and procedures to be followed in running such hospitals (e.g. screening of visitors, possessions allowed in rooms, search procedures, mail monitoring). No equivalent document exists for medium secure care, although best practice is described in the Department of Health Best Practice Guidance. 19 The Quality Network for Forensic Mental Health Services, led by the Royal College of Psychiatrists College Centre for Quality Improvement, also issues Medium Secure Standards20 supported by NHS England, which are reviewed through self- and peer-review. These arrangements are voluntary, but most medium secure providers participate.

Each of the three high secure hospitals serves a defined catchment population for men diagnosed with a mental illness or personality disorder (PD). Only Rampton Hospital caters for women, patients with intellectual disabilities and deaf patients in high secure care. In addition, at the time of the study, services for individuals with so-called dangerous and severe PDs were operational at Rampton Hospital. These specialist services are national services. All NHS medium secure units cater for their catchment area’s mentally ill patients, although not all accept women, individuals with PDs or those with intellectual disabilities; for such patients, commissioners will identify other services, including those outside the catchment area or in the independent sector.

Secure care, like other ‘specialised services’, is commissioned by NHS England nationally (unlike other products that are commissioned through the 209 Clinical Commissioning Groups) through a complex set of arrangements. Secure care comes under the Mental Health National Programme of Care,21 which develops clinical strategies and expected outcomes for the services under its umbrella. Clinical advice on service specifications, commissioning policies, innovation and quality is provided to the National Programme of Care through topic-specific Clinical Reference Groups (relevant here is mainly the high and medium secure Clinical Reference Group, which feeds into the forensic pathway group, which was ‘formed to provide oversight for all secure services and to ensure consistency of approach and effective pathway planning’). 22 Clinical Reference Groups are constituted by clinicians, service users, commissioners and trust representatives. In addition to these structures, there are four regional teams that contract services informed by the specifications developed by the Clinical Reference Groups.

Treatment in secure care and outcomes

Forensic psychiatric services deal with individuals with complex histories, psychopathology and needs. More often than not, these patients have histories of emotional, physical and/or sexual abuse, neglect, deprivation and changes in caregivers. They frequently show early behavioural problems, substance abuse and offending. Their psychopathology is not easily assigned to just one of the International Classification of Diseases23 or Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders24 categories; comorbidity between so-called serious mental illness (such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorder) and PDs is common. Given this complexity, it is not surprising that rigorous evidence of ‘what works’ in secure care is limited. 25 Interventions typically tackle a range of treatment needs, and may include pharmacological, individual and group psychological interventions to improve symptoms as well as to reduce risk (e.g. of violent and sexual offending). More than in other areas of psychiatry, the therapeutic milieu, with clear structures and boundaries, 24-hour nursing care, prosocial modelling, occupational activities, etc., plays a crucial role, and these more general aspects are almost impossible to disentangle from specific, time-limited psychological interventions. Despite these challenges, some evidence has emerged for the effectiveness of pharmacological interventions, psychoeducation and cognitive–behavioural approaches in high secure care, and reoffending rates following discharge from secure care are more favourable than those following release from prison (for a recent review see Fazel et al. 25).

Long stay in forensic settings

Concerns that a number of patients stay for too long in levels of security that are too high were first raised following studies in the 1990s, based on assessments by the patients’ own teams as well as independent multidisciplinary reviews, highlighting that between one-third and two-thirds of patients resident in high secure settings do not require that level of security (e.g. Maden et al. ,26 Reed,27 Pierzchniak et al. 28 and Thomas et al. 29). The inadequate provision of beds in less secure settings and inefficiencies in the system of transfer/discharge were thought to be significant factors in the delayed transfer of patients to more appropriate levels of security. The Tilt Report, commissioned to review the security at all three English high secure hospitals, also concluded that about one-third of the patients could be safely managed in lower levels of security. 30 These findings led to the establishment of a national ‘accelerated discharge programme’, which ran from 2002 to 2004 and led to the move of 400 patients and the reduction in high secure beds. At the same time, there were discussions regarding a need to open ‘long-stay’ services for some of these patients identified as requiring longer-term, but not necessarily high secure, care, and a small number of such wards were commissioned. Similar issues have been raised again in the recent high secure capacity review (E Kane, J Cattell, A Raza, C Duggan, R McDonald, University of Nottingham, 2015, unpublished report, available from the author on request only), with calls to independently review patients who fulfil certain criteria in relation to age and LoS.

There are three main methods to measure LoS. 31

-

Admission sample: all patients admitted during a particular period are included and their LoS calculated from admission to discharge.

-

Census sample: all patients resident in the setting of interest on a particular date. LoS is calculated from their date of admission to this point.

-

Discharge sample: including patients discharged during a particular period. LoS is calculated from their date of admission to this discharge date.

Most of the studies on LoS have used discharge samples (i.e. comparing cohorts with longer and shorter LoS to determine their different characteristics). This method has many advantages, including the relative ease with which such samples can be obtained, the calculation of ‘true’ LoS (completed care episodes) and the consistency of the legal and policy context at time of discharge. However, this method is less suited to predict factors that affect LoS, as there will be a number of confounders as a result of different admission criteria at the different times of admission in the cohort. Obviously, if one is interested in the characteristics and needs of patients who remain in the system and may have little prospect of discharge, then a census sample is the most suitable method, which is why this method was chosen for our study. The most significant drawback of this method is that it does not include completed care episodes and is, therefore, less suited to identifying factors predictive of LoS.

There is no accepted standard for LoS in either high or medium secure care. For medium secure care, the original guidance from government, based on the recommendations in the Glancy32 and Butler15 reports, suggested an upper limit of LoS of 2 years. However, a number of studies have demonstrated that this LoS is far exceeded in a large proportion of cases (see literature review in Chapter 4). For high secure care, earlier studies have identified an average LoS of about 8 years33 but, again, no shared standard exists as to from what LoS onwards individuals should be considered ‘long-stay patients’.

Length of stay in forensic psychiatric settings far exceeds that in general psychiatric services, although only a few studies have compared these two settings directly. A recent study,34 based on a 1-night census of a catchment area of a 1.2 million population in North London in 1999, found a median LoS of 79 days in non-forensic beds, whereas for forensic settings this figure was 1367 days. Of general psychiatric patients, 23.4% stayed for > 1 year and 17.9% stayed for > 5 years, whereas the corresponding figures for forensic patients were 81.2% and 39.1%, respectively. For high secure care, research in England has found an average LoS of about 8 years, and about 15% stay for ≥ 10 years. 35 International studies36 have found figures – at first glance – of comparable magnitude, with an average LoS of around 10 years, although these figures are based on the end point of discharge into the community, whereas in England the LoS in settings of different security levels have to be added up to calculate overall LoS in secure care.

Research identifying the factors associated with long stay and the characteristics and needs of those who stay in secure care for extended periods of time is limited, although some important insights have been gathered. One early study at Broadmoor Hospital33 identified severity of index offence as the most important factor for personality disordered patients, while for those with mental illness, psychopathology was a more relevant predictor of LoS. Studies in medium secure settings have identified severity of psychopathology, psychiatric history, seriousness of offending, patients being on ‘restriction orders’ (requiring Ministry of Justice permission for transfer), non-engagement in interventions, dependency needs and lack of step-down facilities as factors associated with long stay. 37–42 (See Chapter 4 for a full review of factors.)

Patients’ experiences

It is now widely accepted that obtaining the views of the recipients of health care is an essential element in the evaluation of mental health services. However, the evaluation of forensic mental health services is one area in which this principle has not been widely applied. A number of studies have explored the needs of service users in forensic settings from staff perspectives (e.g. Reed and Lyne43 and Jacques et al. 38). There has, however, been a shift away from using the views of professionals towards accessing and representing the views of recipients of care. 44

A considerable number of quantitative and qualitative studies, both UK based and international, have explored forensic patients’ experiences and perspectives relating to a range of topics surrounding their stay in forensic secure care. A substantial number of quantitative studies have used standardised measures to measure forensic patients’ perspectives on, for example, quality of life (e.g. Walker and Gudjonsson45 and Swinton et al. 46), service satisfaction (e.g. Ford et al. 47 and Bressington et al. 48) and recovery (e.g. Green et al. 49). The use of standardised measures to measure forensic patients’ satisfaction/quality of life/needs within services provides an opportunity to identify and prioritise patient-centred issues for future service development (e.g. Walker and Gudjonsson45). Data collected from these standardised measures can also generate estimates of resources required while representing an evidence-based approach to planning effective forensic psychiatric health care. 50

There has, however, been some scrutiny of studies using standardised measure questionnaires when exploring participants’ perspectives. For example, Rankin51 raised concerns with regard to studies using patient satisfaction surveys, which tend to favour the agenda of those asking the questions and often fail to account for what aspects of services those using the services are most satisfied and dissatisfied with. Swinton et al. 46 argued that it is important to explore patients’ subjective perspectives on what quality of life means to them without the use of standardised measures.

A number of qualitative studies have explored patient perspectives of secure care in relation to their social environment, including general experiences of and attitudes towards being in secure care (e.g. Ford et al. 47 and Yorston and Taylor52) and their time-use through participation in therapeutic and occupational activities. 53–56 In one interesting study, the perceptions of male offenders with psychosis of determinants of LoS in high secure care appear to have much in common with what one would expect in the wider community; patients in the sample tended to favour at least 5 years of detention in a secure hospital for a person with psychosis who had killed another, regardless of their mental state, but for minor property damage they felt that improvement in mental state should be the key determinant of discharge. 57 There is, however, little research explicitly exploring the views of long-stay patients on their experiences of care and desired service provision.

Nurses’ experiences

Mental health nursing is a complex and demanding task comprising different components such as supervision, forming therapeutic relationships, administering medication and maintaining a rehabilitative and social atmosphere on the wards. 58 According to Harrison et al. ,59 the profession is chosen by people who want to make a difference, seek opportunities for a patient-centred approach and are passionate about mental health. Owing to the long contact time and being the closest to patients – compared with other professions – nurses are the professional group engaging most in caring interactions and ensuring that patients’ treatment goals are met. 60,61

Forensic psychiatric nursing differs significantly from general psychiatric nursing for a number of reasons. 62 First, forensic psychiatric nurses face a dual obligation of ‘custody’ and ‘caring’. 63 Second, the patient group forensic psychiatric nurses work with is highly complex, as outlined earlier in this chapter. An additional challenge in working with patients in secure forensic settings is their often very long institutional stay. Life experience, empathy and clinical experience are the three identified key strengths in forensic psychiatric nursing. As secure services are highly restrictive for the individual, potentially impacting on their quality of life, providing a comfortable environment with sufficient recreational and educational opportunities, with an understanding of the different needs of each of the individual patients, is a priority64 and nurses can play an important role in this task. Their perceptions of long-stay patients and views on their care may, therefore, be of particular relevance, in addition to those of clinicians who hold overall responsibility for the patient’s care.

Carers’ experiences

The role of ‘forensic carer’ is difficult to define, but ‘at its core involves practical and emotional support provided to relatives across different secure settings. Forensic carers [carry] a significant emotional burden’. 65

A study by Amy et al. 66 found that a focus on carers had increased in general psychiatry, but had not done so to the same extent in forensic psychiatry. Consistent with this observation, very little information had been recorded about the experience of forensic carers until a recent report from the University of Central Lancashire. 65 This study was commissioned by the Scottish Forensic Quality Network and Support in Mind Scotland, and focused on forensic carers in Scotland. However, it can be reasonably assumed that their experience is similar to that of forensic carers in England.

The report relied on qualitative interviews with carers and identified some key themes. First, the emotional burden of carers is multilayered but is rarely addressed, so carers may effectively become incarcerated with their relative.

I can’t move on with my life, I feel like I’m stuck, I mean my job, I go to work but I don’t enjoy it and I can’t wait till the day is over, I don’t know if that’s because with my son or what but yeah I think it’s changed me as a person. I haven’t got any desires to go on holidays and do things, I feel I’ve changed quite a bit really . . .

Mother65

Many carers reported guilt and feeling responsible for their relatives’ behaviour while at the same time feeling powerless and helpless.

Issues regarding contact with their loved ones add to the stress experienced. Visiting their relative can be stressful and there appear to be inconsistencies across services where support for carers is concerned. Some staff were seen as being ‘empathetic and compassionate’ while others were perceived to ‘behave like prison wardens . . . you don’t experience courtesy’. Nevertheless, carers continue to visit, often travelling many miles, yet are never able to see their relative engaged in normal day-to-day activities or to meet the people they live with. Their loved ones’ experiences can feel like another world.

Carers also reported a lack of involvement in their relatives’ care and feeling that no one listened to their views or provided them with information, both generally and in relation to their relative’s care. Confidentiality seems to be one of the limiting factors in this context.

Although the study cited here noted that some improvements had been made, it was concluded that much still needs to be done. It is clear, therefore, that it is important to involve carers – as well as patients – in any service user input into research, including its interpretation and dissemination.

International perspective

Few papers have been published describing forensic psychiatric care in individual countries,18,67–69 and the literature on international comparisons is scarce. However, these comparisons are important, particularly as discussions regarding service reorganisation and cost improvements become more imperative worldwide. 70 International comparisons may stimulate national debate and improve the development of best practice.

A number of European Union (EU)-funded studies36,71,72 have begun comparing legal frameworks and service provisions in psychiatry, forensic psychiatry and prisons in a number of EU member states. Complex differences in patient populations, diagnoses, legal frameworks and service provision as well as cultural, political and public expectations lead to heterogeneity as to who is admitted to forensic care and how such care is provided. 36 Important differences between countries exist in the exclusion of individuals with certain conditions (e.g. PDs, substance abuse), the importance (or otherwise) of criminal responsibility in psychiatric (as opposed to criminal justice) disposal, whether or not transfer from prison to a psychiatric setting is possible after sentencing, etc.

Data from previous studies (e.g. Salize and Dressing36) indicate a wide variation in the number of forensic psychiatric patients per 100,000 inhabitants, but little is known about the LoS in relevant services, although the Netherlands and Germany have also reported an increase in LoS (e.g. Giesler73 and Nagtegaal et al. 74). Some countries have developed policies and services specifically for long-stay forensic populations, and these provisions are of particular interest to our study.

The research questions that arise from this literature are:

-

What is known about the LoS, characteristics and needs of long-stay patients, factors predictive of LoS and best practice in the care of these patients? (Literature review.)

-

What is the LoS profile of the current high and medium secure forensic psychiatric population in England? [Work package (WP) 1.]

-

How many long-stay patients are currently resident in high or medium secure care? (WP1.)

-

What are the characteristics, care pathways and mental health, psychosocial and service needs of these long-stay patients? (WP2.)

-

Which patient and non-patient factors are associated with long stay? (WP2.)

-

Are there different categories of long-stay patients with distinct needs and, if so, what are they? (WP2.)

-

What are the experiences of long-stay patients in forensic care? (WP3.)

-

What are the ethical and legal issues associated with long-stay secure forensic services? (WP4.)

-

Which service models could meet the needs of the different long-stay groups, improve resource use and quality of life of this patient group, and what are factors potentially impeding their implementation? (WP4.)

Chapter 2 Study aims and objectives

Overall aim

The overall aim of this project was to provide a comprehensive description of long-stay patients in high and medium secure settings in order to inform future service developments to improve the quality and cost-efficiency of care and management of such patients.

Objectives

Length of stay in secure care

We will identify:

-

the LoS profiles of the current high and medium secure population in England

-

the estimated number of long-stay patients in these settings according to our pre-defined criteria.

Characteristics and needs of long-stay patients

We will:

-

describe characteristics of long-stay patients, including sociodemographics, psychopathology, criminal history and risk

-

describe their care pathways and reasons for prolonged stay

-

describe their current and future mental health, psychosocial and service needs through file review and information from responsible clinicians

-

develop a categorisation of long-stay patients according to current presentation and future needs.

Patient experience of long stays

Using qualitative patient interviews we will identify:

-

patients’ perceptions of their treatment pathways, long-term needs and acceptable service provision to maximise their quality of life

-

effects of prolonged stay in secure settings on quality of life.

Service innovation

Using expert interviews, stakeholder consultation, workshops and a Delphi exercise we will:

-

describe existing service models for long-stay secure forensic psychiatric care in different European countries

-

describe essential and desirable characteristics of long-stay forensic units

-

explore the ethical and legal challenges of such care, drawing on the experience from other countries

-

explore the views of clinicians, managers, commissioners, policy-makers and other relevant professionals on long-stay forensic care

-

develop potential service models, identify potential hindrances regarding their implementation and make recommendations regarding implementation and evaluation, including economic evaluation.

In addition to these aims and objectives, it was felt that it would be helpful to thoroughly review the literature on long stay to inform our research and interpretation of findings.

Although not initially identified in the protocol, our service user reference group (SURG; see Chapter 11) identified the lack of perspective of carers of patients resident in secure settings. We therefore added carers as a group of stakeholders whose views would be explored.

Chapter 3 Research design and methods

Overview of study design

This study consisted of four WPs to address the research questions using a mixed-methods approach. In brief, we pursued the aims and objectives described above by:

-

undertaking a survey of units to identify the percentage of long-stay patients (WP1)

-

analysing their characteristics, treatment pathways and future needs using detailed case analyses and clinician questionnaires (WP2)

-

completing a series of qualitative interviews with patients (WP3)

-

conducting extensive consultation with stakeholders (senior clinicians and managers, including those with commissioning roles, clinical academics, legal professionals, commissioners and policy-makers) (WP4).

Table 1 gives an overview of the WPs, methods and their correspondence to the research questions. This chapter gives an overview of the methods employed; these methods are expanded on in Chapters 4–9.

| WP | Research questions | Methods |

|---|---|---|

| WP1: LoS in secure care | What is the LoS profile of the current high and medium secure forensic psychiatric population in England? How many long-stay patients are currently resident in high or medium secure care? |

Cross-sectional survey of patient population resident at selected units on 1 April 2013 Collection of basic patient characteristics through medical records Quantitative analysis |

| WP2: characteristics and needs of long-stay patients | What are the characteristics, care pathways and mental health, psychosocial and service needs of long-stay patients? Which patient and non-patient factors are associated with long stay? Are there different categories of long-stay patients with distinct needs and, if so, what are they? |

Detailed file-reviews of long-stay sample Consultant questionnaires Quantitative analysis, including logistic regression and cluster analysis |

| WP3: patient experience of long stay | What are the experiences of long-stay patients in forensic care? | Long-stay patient interviews Qualitative analysis |

| WP4: service innovation | What are the ethical and legal issues associated with long-stay in secure forensic services? Which service models could meet the needs of the different long-stay groups, improve resource use and quality of life of this patient group and what are factors potentially impeding their implementation? |

Description of international service models Stakeholder interviews Focus groups Workshops Delphi exercise |

Defining ‘long stay’

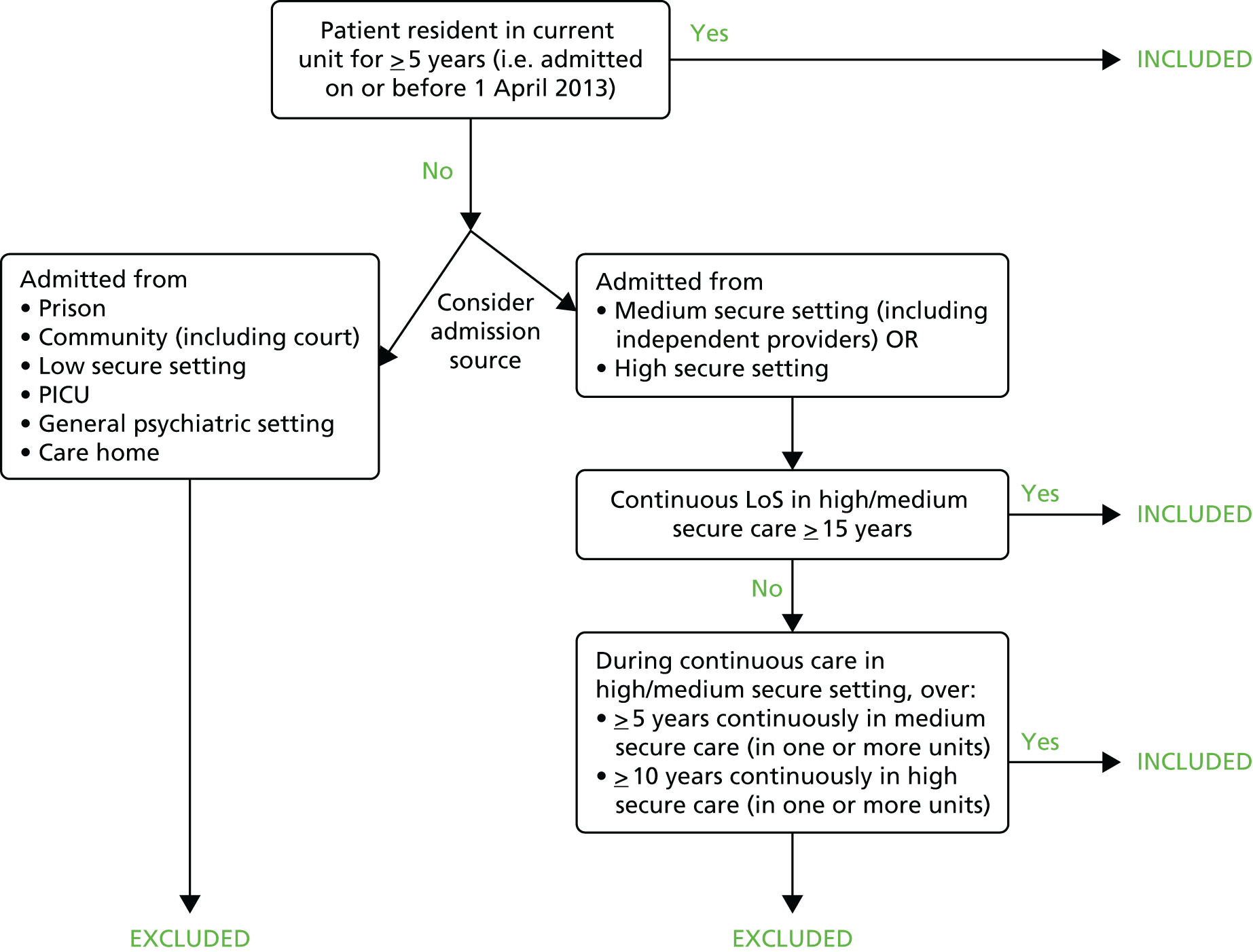

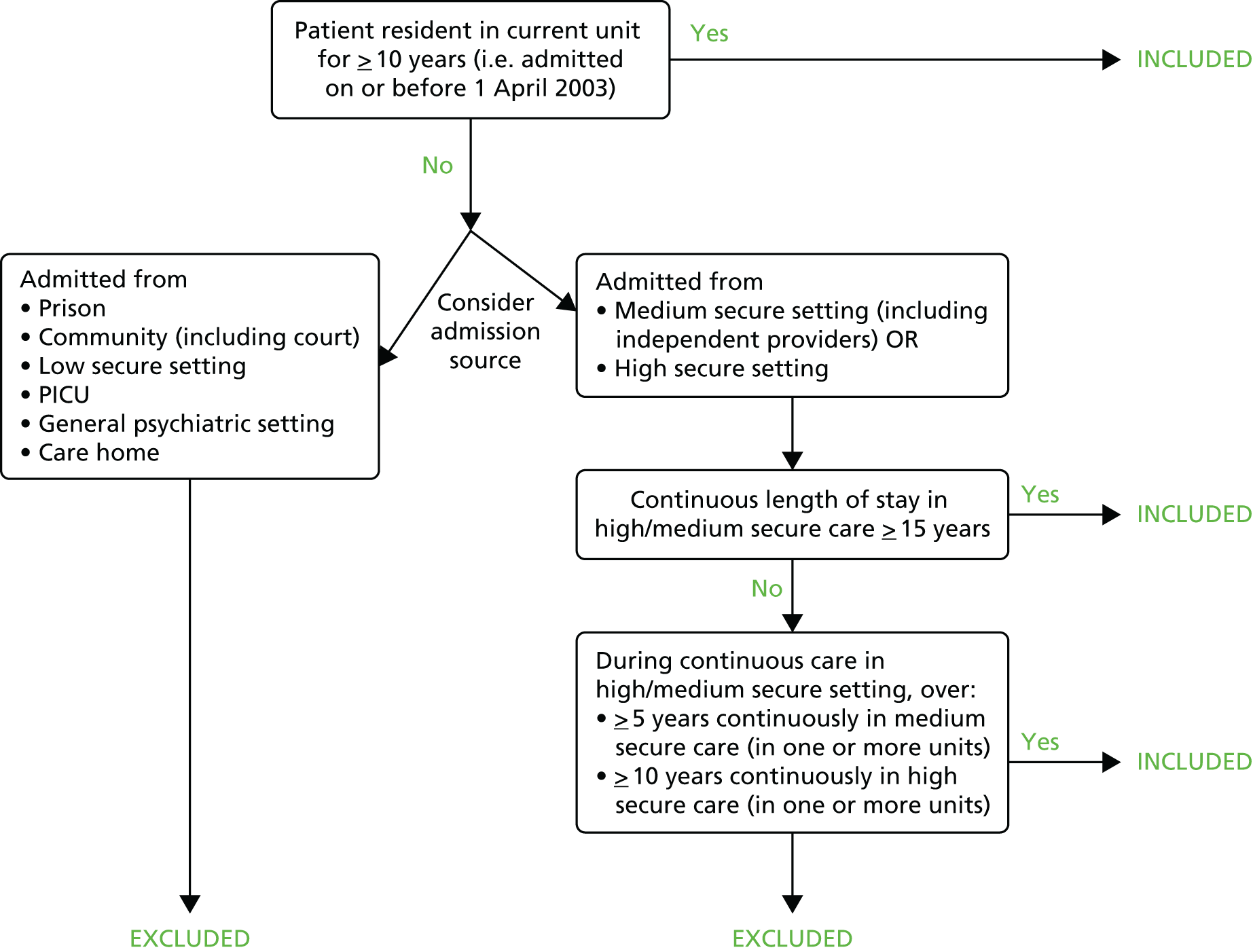

As outlined above, there is currently no accepted standard for LoS in either high or medium secure care. Our piloting data from one high secure care setting suggested that just over 15% of patients stayed for over 10 years. For medium secure care, the literature suggests that between 10% and 20% stay for ≥ 5 years. In the Netherlands, a country that has a designated long-stay service, at the time of the inception of the study, about 15% of the entire Dutch forensic population were staying in such services (although the cut-off point in years is lower there: 6 years). We therefore aimed to use a LoS cut-off point that would capture a similar proportion of patients. This decision was guided by the consideration that the population included should be large enough in size to provide meaningful conclusions for service developments (i.e. not so small that only a very limited number of patients would be included and not so large that a substantial proportion of patients would be captured). On balance, a cut-off point capturing around 15–20% of the population seemed appropriate. For allocation to ‘long-stay’ status, total time of continuous admission in high and/or medium secure care was taken into account, even if that time was spent in different units, according to the following criteria (Figures 1 and 2):

-

≥ 5 continuous years in medium secure care or

-

≥ 10 continuous years in high secure care or

-

a combination of the high and medium secure settings totalling ≥ 15 years of continuous secure care.

FIGURE 1.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria for long stay in medium secure care. PICU, psychiatric intensive care unit.

FIGURE 2.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria for long stay in high secure care. PICU, psychiatric intensive care unit.

Work packages

Work package 1 used a cross-sectional design to identify the LoS profile of the current high and medium secure population in England and to estimate the total number of long-stay patients. This consisted of collecting data on LoS (from admission to current setting to census date 1 April 2013) and basic patient characteristics (date of birth, gender, ethnicity, admission source, MHA section and type of current ward) of all patients resident on the census date at the three high secure hospitals and 23 medium secure units. When patients were admitted from other medium or high secure units, data were obtained on their total LoS in (medium/high) secure care to establish whether or not they fulfilled our inclusion criteria.

Work package 2 involved the collection of detailed data about the long-stay patients. To describe the characteristics of this population and identify their care pathways, we collected in-depth clinical, offending and risk data (in an anonymised form) using detailed file reviews and information from patients’ responsible clinicians. We also established factors associated with prolonged stay and developed subcategories of long-stay patients.

Work package 3 used semistructured interviews with a purposively sampled subset of long-stay patients, identified in WP2, to explore their perspectives and experiences of long stay, including their experiences of treatment pathways, strengths and weaknesses of current service provision, impact on quality of life, perceived reasons for long stay and long-term needs. An exploration of the concept of services specifically designed for long-stay patients was also included.

Work package 4 utilised a range of qualitative methods (e.g. semistructured interviews, focus groups) to describe existing service models for long-stay secure forensic psychiatric care internationally, to explore the views of key stakeholders on the issues of long stay, and to identify potential ethical, legal and practical challenges in the care of long-stay patients and in the implementation of potential changes to service provision, including specific services for long-stay patients. Potential service improvements for long-stay patients in the UK were drawn from the data from this WP as well as the patient interviews in WP3.

Sampling units

To use time efficiently, we devised a sampling strategy by unit rather than by patient. All three high secure units in England were included owing to the particular ethical challenges and resource implications of providing care in these facilities. There were approximately 57 medium secure units in England in the (then) 10 Strategic Health Authorities (regions), 34 in the NHS and 23 in the independent sector. A stratified cluster sampling frame was adopted with 23 medium secure units, comprising 14 NHS and 9 independent units, drawn according to sector, geographical region, size and specialisation (e.g. patient groups and designated purpose such as treatment, rehabilitation), with oversampling of units specialising in particular patient groups, including women and patients with intellectual disabilities. This sample represents approximately 40% of all medium secure units in England. One medium secure unit was included in regions with one to three units, two were included in regions with four or five units, three were included in regions with six or seven units, four were included in regions with eight or nine units and five were included in one region with 10 medium secure units. If there was a possible choice of units, taking into account geographical and provider mix, a unit was picked at random from those potentially eligible.

From the units initially approached, one independent provider unit could not be included as it had closed at the time of approach. We tried to replace this independent unit with another: the first one approached declined to participate without giving reasons; the next approached declined owing to potential resource implications. Of the NHS medium secure units initially approached, one declined because of potential conflict with their business interests, another declined because of concerns regarding the data collection procedure, and a third agreed to participate but there then followed excessive delays in communications. Two other medium secure units were recruited to replace these units. Replacement units were drawn from the same Strategic Health Authority region. To maintain the overall sampling approach, independent units were replaced by independent units and NHS units were replaced by NHS units. Table 2 lists the units finally included alongside the resulting patient numbers included in WP1 and WP2. One high secure unit participated in WP1 only.

| Region | Total number of units | Units included | NHS/independent | Patients, total (WP1) | Number of long-stay patients (WP2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High secure hospitals | 3 | Ashworth | NHS | 190 | 41 |

| Broadmoor | NHS | 196 | N/A | ||

| Rampton | NHS | 329 | 75 | ||

| Total | 715 | 116 | |||

| Medium secure hospitals | |||||

| North East | 3 | Ridgeway | NHS | 77 | 19 |

| North West | 10 | Edenfield | NHS | 128 | 21 |

| Scott Clinic | NHS | 48 | 0 | ||

| Calderstones | NHS | 43 | 10 | ||

| The Spinney | Independent | 58 | 29 | ||

| Yorkshire | 4 | Humber Centre | NHS | 67 | 23 |

| Stockton Hall | Independent | 89 | 25 | ||

| East Midlands | 5 | Arnold Lodge | NHS | 84 | 11 |

| St Andrew’s Northampton | Independent | 151 | 16 | ||

| West Midlands | 5 | Reaside Clinic/Ardenleigh | NHS | 115 | 4 |

| St Andrew’s Birmingham | Independent | 25 | 2 | ||

| East of England | 9 | Norvic Clinic | NHS | 45 | 9 |

| Brockfield | NHS | 76 | 18 | ||

| Kneesworth House | Independent | 49 | 17 | ||

| St John’s House | Independent | 24 | 6 | ||

| London | 8 | North London Forensic Service | NHS | 143 | 25 |

| John Howard Centre | NHS | 130 | 19 | ||

| North London Clinic | Independent | 27 | 2 | ||

| South East | 6 | Hellingly | NHS | 40 | 3 |

| The Dene | Independent | 21 | 4 | ||

| South Central | 5 | Chadwick Lodge | Independent | 35 | 6 |

| South West | 2 | Fromeside | NHS | 67 | 14 |

| Langdon Hospital | NHS | 30 | 2 | ||

| Total | 57 | 23 | 14 NHS, 9 independent | 1572 | 285 |

Data collection

Work package 1

We collected data that were easily available through medical records departments for all patients resident in participating units on 1 April 2013. We identified a contact at each site and asked them to enter the relevant data into a Microsoft Excel® spreadsheet (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and return it to the research team in fully anonymised form. A unique identifier code was assigned to each patient at this point to allow their data to be tracked throughout the project. Units were paid administrative time for this task. From these data, we were able to identify long-stay patients for WP2.

Work package 2

To maintain anonymity, data for WP2 were collected by unit staff (e.g. trainee doctors, audit department staff, research nurses or Mental Health Research Network study officers where local arrangements had been made to that effect). The research team worked with a data collector at each site who was responsible for identifying long-stay patients and conducting subsequent file reviews. Any cases of uncertainty were fed back to the research team for discussion and final decision.

Once data collectors had been identified at each site and appropriately trained, they were given the list of identified long-stay patients at their unit (using the unique identifier code assigned during WP1) and asked to access all current and historical electronic and paper records for those patients. They then completed a data collection pro forma and returned this to the research team either electronically or by post. We achieved a 100% response rate for WP2. During the course of the study, several data collectors left their post and new ones had to be identified and retrained, causing delays to data collection. We paid units for staff time for this data collection.

Consultant questionnaires

For those long-stay patients still resident in the unit at the time of WP2 data collection, a questionnaire was given to the responsible clinician to ascertain their view of the patient’s security, dependency, treatment and political needs, both currently and for the future, and any potential reasons for their long stay. 64 Questionnaires were distributed by our local data collectors.

Work package 3

In WP3, a series of qualitative, semistructured interviews was conducted with a sample of 40 long-stay patients. The participants were purposively sampled from eight of the participating units (two high secure, three NHS medium and three independent medium). A topic guide was used and employed flexibly to explore participants’ views on the reasons for their long stay, their current situation and moving on. The interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim prior to analysis.

Work package 4

Work package 4 employed a number of methods of data collection, including semistructured interviews of international experts and experts from the UK (senior clinicians and managers, including those with commissioning roles, clinical academics, legal professionals, commissioners and policy-makers). In addition to these individual interviews, which were conducted mainly by telephone owing to the wide geographical spread of experts, focus groups were held at three different national/international forensic psychiatric conferences. Three focus groups were conducted with nursing staff in a high secure facility and three with carers of patients in high and medium secure settings. We also facilitated two workshops, one entitled ‘International service models for long-stay patients in forensic psychiatry’ held in October 2014 and the other called ‘Setting up databases in forensic psychiatric services – challenges and solutions’ held in October 2015 (see Appendices 16 and 17). Afternoon workshops at these events allowed for in-depth exploration of pertinent issues. Minutes were taken and their content was fed into Chapter 9 and the overall discussion. We also conducted a small Delphi survey on experts’ views on forensic psychiatric services for long-stay patients. Finally, we conducted an explorative comparative study of patient characteristics of long-stay patients in England and the Netherlands.

Data processing of quantitative data

The data we received for both WP1 and WP2 went through several stages of cleaning. Any missing data queries or inconsistencies were sent back to our contact person to be rectified. For WP2, this task was time-consuming because of the complexity of the data. The research team checked pro formas for inconsistencies, obvious errors and missing data, and any queries were clarified with the data collectors. In some cases this took several months, which caused delays to data collection and subsequent analysis. During this process, some issues arose concerning the interpretation of data, which needed clarification to keep the data consistent for all patients. These issues were discussed in the first instance with the data collector and were then taken back to the research team for further discussion. When decisions were reached they were recorded in one document entitled ‘Issues and decisions made about data entry’, which was circulated to all members of the research team and used during data entry to ensure consistency.

During this process, some discrepancies appeared between data received during WP1 and the data subsequently received as part of WP2 for the same patient (e.g. regarding admission source or MHA status). These were investigated by the WP2 data collector where possible. When WP1 information appeared correct following this process, WP2 data were corrected accordingly. However, most often the information collected during the file reviews in WP2 appeared correct. After careful consideration in the team as well at the Study Steering Committee (SSC), we decided nevertheless not to correct WP1 data in these cases. This was because we had more detailed information from patients’ files for long-stay patients only and correcting this information in WP1 for long-stay patients only would have introduced systematic bias. The only variable that was altered was long-stay status. If a patient was identified as a long-stay patient in WP1 but after further investigation during WP2 this turned out not to be the case, their long-stay status was changed in WP1.

Data analysis

Quantitative data analysis

Separate data files were created for WP1 and WP2. WP1 data analysis was performed using Stata 13. Significant within-cluster dependency was identified within the medium secure sample; therefore, a multilevel approach was taken. For the high secure sample this was not the case, and a fixed-effects model was therefore chosen.

For WP2, data were entered into a SPSS (Statistical Product and Service Solutions; version 21, IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) file. Descriptives were calculated for medium and high secure samples separately and differences between long-stay patients and non-long-stay patients were reported. Predictors for LoS were computed using multilevel binary logistic regression with MLWin software (version 2.35; Centre for Multilevel Modelling, Bristol, UK). Class analysis was performed using latent component analysis.

Qualitative data analysis

A thematic analysis was conducted using a framework approach75 to organise data into the topic guide’s main areas of enquiry. Within these areas, data were subject to open coding76 to identify categories that represented key issues discussed by participants. During this process, themes emerged within each of the areas.

Research approvals

Work packages 1 and 2 used routinely collected data only that were compiled by unit staff and transferred to the research team in a fully anonymised form. These WPs were deemed to constitute service evaluations as per confirmation by the research and development department of Nottinghamshire Healthcare NHS Trust, the host institution. Although, for consistency of data collection, it would have been preferable for our own researchers to collect the data at the different sites, the ethical and governance hurdles involved would have been prohibitive. Following a meeting with research and development staff at all collaborating sites at the beginning of the project, the process of data collection finally adopted was felt to be the most appropriate for this study. During these discussions some units raised concerns regarding the level of detail in WP2, in particular as some patients in secure settings have unique characteristics. We therefore removed a number of data fields or changed them to minimise the risk of patients being identifiable; this included, for example, the number of victims of homicide and dates of convictions. Units were offered the option to exclude certain high-profile patients if they felt that data could not be provided in a way that would exclude incidental identification. One high secure unit excluded one patient under this procedure.

Work package 3 involved patient interviews; this part of the study therefore required and received NHS Research Ethics Committee approval (REC reference 13/EM/0242). WP4 involved a mixture of research activities; the focus group with carers required and obtained separate NHS Research Ethics Committee approval (REC reference 15/em/0218), and research and development approval was obtained as required.

Project management

The study was hosted by Nottinghamshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust and supported by a Project Management Group (PMG), a SURG and a SSC. The individuals in these groups provided a wide range of knowledge, skills, experience and expertise including researchers and advisors with academic skills, but also those with lived experience in secure care, caring for someone in secure care, working in NHS hospitals, independent hospitals, third-sector organisations and prison settings, including senior managers and clinicians. To ensure that the research was relevant to all stakeholder groups, as well as academically sound, this collaboration between service users, clinicians and academics was crucial throughout the research process. Details of memberships of these groups can be found in Appendix 2.

The PMG and the SURG met quarterly, with the latter meeting more frequently at the early and later phases of the project. The SSC met biannually and was chaired by an independent senior academic, Barbara Barratt (Senior Lecturer in Health Economics at King’s College London). The role was originally held by Janet Parrott (Consultant Forensic Psychiatrist at Oxleas NHS Foundation Trust) but she stepped down from the position part way through the study to avoid potential conflict with her role at one of the recruiting trusts. The role of the SSC was to ensure that the protocol was followed, that deadlines were met and that the research was conducted ethically, as well as to provide advice and support to the research team with regard to any emerging challenges and the wider context for the interpretation of findings.

Chapter 4 Literature review on long stays in forensic settings

Searches

We carried out electronic searches of four databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature) from 2000 to 9 November 2015 using the search strategy listed in Appendix 3. This search was overinclusive, yielding a total of 13,493 citations after duplicates were removed. These were screened, retaining those providing relevant information on any of the following in forensic inpatient settings:

-

definition or identification of long-stay patients

-

LoS profiles

-

factors predictive of LoS

-

characteristics or needs of long-stay patients

-

patients’ experiences of long-stay, including quality of life

-

service models for long-stay secure psychiatric care.

The reference list of each included document was checked for any additional relevant citations.

Study characteristics

A total of 38 documents (32 peer-reviewed journal papers, four reports and two theses) were included (Table 3). 12,26,28,29,33,34,37,39–42,57,74,76–99 Eleven countries were represented: the UK (n = 2212,26,28,29,33,34,37,39–42,77–80,82,84,86,87,89,92,97), the USA (n = 490,94,96,99), Ireland (n = 281,98), Germany [n = 293 (one of which was personal communication: Dönisch-Seidel, Ministerium für Gesundheit, Emanzipation, Pflege und Alter des Landes Nordrhein-Westfalen, 2013)], Croatia (n = 257,88), Australia (n = 185), Malaysia (n = 183), New Zealand (n = 195), Norway (n = 191), the Netherlands (n = 174) and Sweden (n = 176). The studies from the UK had samples drawn from high secure (n = 529,33,78,84,89), medium secure (n = 1426,37,39–42,77,79,80,82,86,87,92,97) and mixed secure (n = 312,28,34) settings. The Norwegian study was based in a ‘maximum’ secure setting. 91 The remaining 15 studies were of forensic samples in countries that do not differentiate security into levels in the same way. Thirty-two of the 38 studies had samples that were predominantly male (75% to 99% of sample) and four were all-male. 37,84,88,97 Two UK studies had samples drawn from a women’s medium secure unit. 40,87

| Study/report | Country | Security level | Sampling period | Study design | Sample size | Men in sample (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andreasson et al.76 | Sweden | FS | 1999–2005 | Retrospective, admission sample | 125 | 81 |

| Brown and Fahy37 | UK | Medium | 2002–6 | Retrospective, discharge sample | 157 | 100 |

| Brown et al.77 | UK | Medium | 1983–97 | Census sample, inpatients on census day each year | 404 | 75 |

| Butwell et al.78 | UK | High | 1986–95 | Retrospective, resident sample (all patients resident in study period) | 3263 | 82 |

| Castro et al.79 | UK | Medium | 1995–8 | Retrospective, admission sample | 166 | 82 |

| Coid et al.80 | UK | Medium | 1988–94 | Retrospective, admission sample | 2608 | Mostly male |

| Davoren et al.81 | Ireland | FS | 2010–14 | Prospective, admission sample | 279 | 83 |

| Dell et al.33 | UK | High | 1972–4 | Retrospective, admission sample | 187 | Mostly male |

| Edwards et al.82 | UK | Medium | 1983–96 | Retrospective, admission sample | 225 | 85 |

| Fong et al.83 | Malaysia | FS | January–February 2007 | Cross-sectional, resident sample | 112 | 90 |

| German Ministry of Justicea | Germany | FS | December 2011 | Government statistics, census sample | 2097 | Mostly male |

| Glorney et al.84 | UK | High | 2000–1 | Retrospective admission sample | 63 | 100 |

| Green and Baglioni85 | Australia | FS | Census point | Census sample, survival analysis to census point | 670 | 82 |

| Kennedy et al.39 | UK | Medium | 1987–93 | Retrospective, admission sample | 31 | 87 |

| Knapp et al.86 | UK | Medium | 1994–8 | Retrospective, admission/discharge sample, all patients admitted and discharged between 1994 and 1998 | Mostly male | |

| Long and Dolley40 | UK | Medium | 2002–10 | Retrospective, admission sample | 70 | 0 |

| Long et al.87 | UK | Medium | Opening–2012 | Retrospective, discharge sample | 60 | 0 |

| Maden et al.26 | UK | Medium | 1980–94 | Longitudinal cohort; discharge sample; patients discharged from 1980 to 1994 and followed for 6.6 years | 234 | Mostly male |

| Margetić et al.57 | Croatia | FS | September–November 2011 | Subsample of patients resident | 52 | Mostly male |

| Margetić et al.88 | Croatia | FS | September–November 2011 | Retrospective, resident sample | 56 | 100 |

| McKenna41 | UK | Medium | Autumn 1994 | Retrospective, discharge sample | 100 | 84 |

| McKenna et al.89 | UK | High | 1995 | Retrospective, subsample of patients resident | 15 | 93 |

| Nagtegaal et al.74 | Netherlands | FS | 1990–2009 | Overview of LoS in forensic psychiatric hospitals in the Netherlands | Mostly male | |

| Noblin90 | USA | FS | 1999–2008 | Retrospective, resident sample | 767 | Mostly male |

| Pierzchniak et al.28 | UK | High and medium | 1995 | Retrospective, resident sample | 176 | 85 |

| Renkel and Rasmussen91 | Norway | ‘Maximum’ | 1987–2000 | Retrospective, admission sample | 82 | 99 |

| Ricketts et al.92 | UK | Medium | 1983–99 | Retrospective, admission sample | 504 | 82 |

| Ross et al.93 | Germany | FS | 2009–10 | Retrospective, resident sample | 137 | Mostly male |

| Rutherford and Duggan12 | UK | High and medium | 2006 | Government statistics, whole population of patients December 2004 | Mostly male | |

| Shah et al.42 | UK | Medium | 1999–2008 | Retrospective, discharge sample | 259 | 90 |

| Sharma et al.34 | UK | High and medium | November 1999 | Census study, patients resident one night | 185 | Mostly male |

| Silver94 | USA | FS | 1976–85 | Retrospective longitudinal study of insanity defendants admitted in study period | 6572 | Mostly male |

| Skipworth et al.95 | New Zealand | FS | 1976–2004 | Retrospective, admission/discharge sample, patients admitted in 1976, discharged in 2004 | 135 | 83 |

| Steadman et al.96 | USA | FS | 1971–6 | Retrospective, resident sample, insanity aquittees | 225 | 87 |

| Thomas et al.29 | UK | High | 2003 | Retrospective study, patients resident in 2003 | 1008 | 84 |

| Vitacco et al.99 | USA | FS | 2007–10 | Retrospective, discharge sample | 127 | 78 |

| Wilkes97 | UK | Medium | 2001–11 | Retrospective, discharge sample | 198 | 100 |

| Wright et al.98 | Ireland | FS | 1997–2003 | Retrospective, admission sample | 986 | 86 |

Definitions of ‘long stay’

We first identified the 10 studies in which a long-stay subgroup had been differentiated from a shorter-stay subgroup using a prospectively defined threshold. These studies date from 1987 to 2014, with samples covering the period from 1972 to 2011. Four countries were represented: the UK (n = 733,39,40,42,82,92,97), the USA (n = 199), Ireland (n = 198) and Germany (n = 193).

A threshold of 2 years was used in four studies of medium security in the UK10,39,42,97 and in one study of a forensic hospital in Ireland. 98 A similar threshold was used by Long and Dolley,40 also in the UK, who selected a threshold of 21.6 months based on a median split of their female medium secure sample. Thresholds of 2 years and additionally 5 years were used by Edwards et al. ,82 who observed that admission duration exceeded 5 years in > 10% of their UK medium secure sample. It would appear that in these cases the researchers were following the original guidance from government, based on the recommendations in the early Glancy32 and Butler15 reports that suggested an upper limit of a LoS of 2 years.

An earlier UK study of Broadmoor high secure patients by Dell et al. 33 used an 8-year threshold, the authors observing that 53% of those with a ‘psychopathic disorder’ and 42% of those with a ‘mental illness’ classification of the (then) MHA were ‘long-termers’ who were detained for > 8 years. A threshold of 10 years was used in Germany by Ross et al. ,93 who found that 15% of their sample had a LoS that exceeded 120 months.

In contrast, a much shorter threshold of 45 days was used by Vitacco et al. 99 to differentiate short-term from longer-term care in North America, although the authors note that this figure was chosen to align with the standard 45-day period used in forensic services in North America for initial inpatient assessment and that most individuals (approximately 75%) are committed for lengthier inpatient treatment.

It is difficult to draw any firm conclusions from these findings, other than to observe that although no shared standard exists as to the LoS beyond which individuals should be considered as ‘long-stay patients’, UK researchers tend to choose a threshold that aligns with the official LoS recommendations, even though a significant proportion of patients stay longer than the 2-year period recommended.

Length of stay in forensic settings

Figures on LoS of ‘long(er)-stay’ patients were given in 16 of the included studies (Table 4; only studies that give LoS figures separately for the whole sample and for a subsample of long-stay patients are shown). These were published between 1987 and 2015 with samples covering the period from 1972 to 2011. Five countries were represented: the UK (n = 1212,26,28,33,34,39–42,82,92,97), Germany (n = 193), the USA (n = 199), Malaysia (n = 183) and Ireland (n = 198). Thirteen studies supplied LoS as a mean value; only five provided medians, which are arguably a better measure of central dispersion for a variable that commonly has a non-normal (‘skewed’) distribution.

| Study | Country | Security level | Study period | Sample | LoS for whole sample | LoS for long-stay subgroup |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dell et al.33 | UK | High secure | 1972–4 | 187 patients admitted in study period | 44.4% had a LoS of > 8 years | |

| Edwards et al.82 | UK | Medium secure | 1983–96 | 225 patients admitted in study period | Mean 26 months (9 days to > 9 years) | 50% had a LoS of > 2 years 10% had a LoS of > 5 years |

| Fong et al.83 | Malaysia | Forensic | January–February 2007 | 112 patients resident in study period | Median 7 years (3 months to 47 years) | 34% had a LoS of > 10 years |

| Kennedy et al.39 | UK | Medium secure | 1987–93 | 31 patients admitted in study period | Mean 34.3 months for a LoS of > 2 years | |

| Long and Dolley40 | UK | Medium secure | 2002–10 | 70 female patients admitted in study period | Mean 29.9 months for a LoS of > 21.6 months | |

| Maden et al.26 | UK | Medium secure | 1980–94 | 234 patients discharged 1980 and 1994, 6.6 years’ follow-up | Mean 10 months | 9% had a LoS of > 2 years |

| McKenna41 | UK | Medium secure | 1994 | 100 discharged patients | Mean 30.1 weeks Median 15 weeks |

10% had a LoS of > 1.5 years 4% had a LoS of > 2 years |

| Pierzchniak et al.28 | UK | High and medium secure | 1995 | 176 patients resident in North London area | Mean 61.8 months | Mean 117.4 months (high secure subgroup) |

| Ricketts et al.92 | UK | Medium secure | 1983–99 | 504 patients admitted in study period | 13.1% had a LoS of > 2 years | |

| Ross et al.93 | Germany | FS | 2009–10 | 137 patients resident in study period | Mean 139.6 months for a LoS of > 10 years | |

| Rutherford and Duggan12 | UK | High and medium secure | 2004 | Whole population of patients December 2004 | 66% had a LoS of > 2 years 27% had a LoS of > 10 years 9% had a LoS of > 20 years 3% had a LoS of > 30 years |

|

| Shah et al.42 | UK | Medium secure | 1999–2008 | 259 discharged patients | Mean 749 days Median 428 days |

33.6% had a LoS of > 2 years 9.3% had a LoS of > 5 years |

| Sharma et al.34 | UK | High and medium secure | November 1999 | Census study of 185 patients resident one night in November 1999 | Mean 74.9 months Median 45 months |

39.1% had a LoS of > 5 years |

| Vitacco et al.99 | USA | FS | 2007–10 | 127 discharged patients | Mean 61.6 months | Mean 77.7 months for a LoS of > 45 days |

| Wilkes97 | UK | Medium secure | 2001–11 | 198 discharged male patients | Mean 25.2 months Median 21.2 months (6 to 136.5 months) |

45% had a LoS of > 2 years |

| Wright et al.98 | Ireland | FS | 1997–2003 | 986 patients admitted in study period | Mean 60 days | 3.4% had a LoS of 1–2 years 2.6% had a LoS of > 2 years |

It is clear that there is considerable variation in these figures, reflecting the heterogeneity of the samples (e.g. countries); for example, for medium secure samples the proportion with a LoS of > 2 years ranged from 2.6% to 66% (average of 27.9%).

Geographical variation

There was evidence of considerable geographical variation within the UK. For example, Coid et al. 80 studied 2608 patients admitted to medium secure settings in seven different regions between 1988 and 1994 and found that the mean LoS ranged from 25.0 months in one region (Mersey) to 59.1 months in another (North West Thames).

Gender variation

Three studies considered male and female patients separately. Each found that women tended to experience shorter LoS than men. In a prospective cohort study of 279 patients admitted between 2010 and 2014 to a forensic hospital in Ireland and followed up for a total of 66 months, Davoren et al. 81 found mean LoS figures of 304.3 days (median 60 days) for men and 202.6 days (median 24 days) for women. Edwards et al. 82 calculated LoS in a retrospective study of 225 patients consecutively admitted between 1983 and 1996 to a UK medium secure setting; for the 30 who were still inpatients at the end of October 1998, admission duration was calculated to that date. Eighteen patients had stayed > 5 years; only one (5.5%) of these was female, whereas 14.7% of the overall sample were women. In a census study of 607 forensic inpatients in Australia, Green and Baglioni85 obtained a mean LoS of 115 days (median 40 days) for men and 124 days (median 61 days) for women.

Change in length of stay over time

Findings are inconsistent regarding change in LoS over time. Butwell et al. 78 calculated LoS per episode, defined as from date of admission to discharge or census date (31 December 1995), whichever came first, and found no change from 1986 to 1995 in UK high secure hospitals. In contrast, Brown et al. 77 examined LoS over a 15-year period at a medium secure setting in the UK. The average LoS was calculated by taking the mean LoS of all inpatients on the same census day, rather than calculating the average on discharge, so that those patients who did not achieve discharge were included in the yearly average. They found an increase from 1992 to 1997. Ricketts et al. ,92 in a UK study of 504 medium secure patients admitted between 1983 and 1999, calculated the mean duration of admission for those who had been discharged. They found that the proportion staying longer than 2 years rose from 7% in 1983–7 to 16.2% in 1991–5, before falling to 12.3% in 1995–9.

Characteristics of long-stay patients in forensic settings

Twenty-four studies reported on differences between long(er)-stay and shorter-stay subgroups that were statistically significant using univariate analyses. These studies date from 1983 to 2015, with samples covering the period from 1971 to 2014, as shown in Tables 5 and 6. Nine countries were represented: the UK (n = 12), the USA (n = 4), Ireland (n = 2), Australia (n = 1), New Zealand (n = 1), Croatia (n = 1), Germany (n = 1), Malaysia (n = 1) and Sweden (n = 1). Ten studies took place in medium secure settings, two took place in high secure settings and 12 were in settings where such levels of security were not differentiated in this way.

| Factor | Number of studies | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample at least 75% male | Female-only sample | All studies | |

| Demographics | |||

| Male | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Older age on admission | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| White | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Unemployed before admission | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Female | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Unmarried | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| No formal education | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Not being a parent | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Socially disadvantaged | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Buddhism as a religion | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Criminal history | |||

| History of violence | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| History of serious offences | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Younger at first violent incident (according to HCR-20 H2) | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Younger at first conviction | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Younger when first sentenced | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Longer total prison sentence duration | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| History of sexual offences | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Index offence | |||

| Greater severity of index offence | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| Violent index offence | 4 | 1 | 5 |

| Murder or homicide as index offence | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Arson as index offence | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Index offence sexually motivated | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Index offence apparently motiveless | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Long prison sentence in conjunction with ‘diminished responsibility’ for index offence | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| MHA classification | |||

| Restriction order (MHA section 37/41) | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Criminal MHA section | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Hospital order (MHA section 37) | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Transitional MHA section (e.g. transferred prisoner status as remand or sentenced) | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Psychiatric history | |||

| Admitted from a high-security setting | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Multiple previous inpatient admissions | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Previous contact with child and adolescence psychiatric services | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Younger when first admitted to forensic psychiatry | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| History of psychiatric treatment/longer psychiatric history | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Time in another unit as an extracontractual referral | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Not admitted from a high-security setting | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Admitted from a general psychiatric inpatient unit or prison | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Risk and current treatment | |||

| Breaches of security regulations/serious non-compliance with ward rules | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| History/risk of absconding | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Greater number of adverse events during treatment | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| DUNDRUM-1 triage security scale (higher scores on most items) at pre-admission assessment | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Seclusion needed following admission | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Inappropriate behaviour during treatment | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Violent behaviour during treatment | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Threats during treatment | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Lower therapy attendance | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Conditional release failure | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Diagnosis, symptoms and traits | |||

| Schizophrenia/other psychotic disorder/psychotic symptoms | 5 | 1 | 6 |

| Cognitive/organic deficit | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Substance abuse | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Higher overall symptomatology score (BPRS) | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Comorbid medical illness | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Severe mental impairment | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Greater severity of primary diagnosisa | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| PD | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Paranoid personality traits (MCMI-III) | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Schizotypal personality traits (MCMI-III in last 6 months of stay) | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Borderline personality traits (MCMI-III in last 6 months of stay) | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Higher hostility, tension, excitement and motor hyperactivity scores (BPRS) | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Higher psychological distress score (CANFOR) | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Other | |||

| DUNDRUM-2 triage urgency scale (higher scores on most items) at pre-admission assessment | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Factor | Number of studies | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample at least 75% male | Female-only sample | All studies | |

| Demographics | |||

| Good ongoing contact with family | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Black | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Younger age on admission | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Being a parent | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Better professional qualifications | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Better school qualifications | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Migrated to current country of residence | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Employed prior to first psychiatric diagnosis | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Longer period of employment before admission | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Criminal history | |||

| Admitted from the community | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Legal status ‘sentenced’ on admission | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Index offence | |||

| Criminal conviction | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Not found criminally responsible for index offence | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Severely violent index offence | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Civil section (e.g. MHA section 3) | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Psychiatric history | |||

| Past engagement in individual and group therapy | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Risk and current treatment | |||

| Engagement in psychological therapies and/or group activities | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Higher therapy attendance | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Working in the hospital | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Diagnosis, symptoms and traits | |||

| Affective disorder | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Adjustment disorder | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Psychotic disorder | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Mood disorders | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| PD | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| PD (HCR-20) | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Psychopathic disorder | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Schizophrenia ‘in remission’ | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Higher ‘co-operativeness’ trait score (TCI) | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Higher ‘negative attitudes’ score (HCR-20) | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Higher current GAF score | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Other | |||

| Discharged to penal system | 1 | 0 | 1 |

A total of 60 characteristics were identified as being associated with a longer LoS. Some inconsistency might be anticipated, given the heterogeneity of studies and the different ways in which LoS was defined and samples were chosen. Nonetheless, a pattern emerges such that a longer LoS appears to be associated with a history of violent and/or serious offending, greater severity of index offence, greater psychopathology, being detained under a criminal section of the MHA (in the UK), being subject to ‘restriction orders’, being admitted from high security, being non-compliant with treatment and being older on admission. We found no evidence that LoS was related to medication dosage; for example, Renkel and Rasmussen91 found no differences in LoS between those on normal dosages and those on higher dosages of antipsychotic medication for a sample of 82 patients admitted between 1987 and 2000 to a Norwegian maximum security forensic setting.

A total of 31 characteristics were identified as being associated with a shorter LoS. These included having good ongoing contact with family members, being black, having a criminal conviction as an index offence and being engaged in treatment. It is interesting to note that one study reported a severely violent index offence as being associated with a shorter LoS. 42 The authors observed that although this finding might appear to have little face validity, their cohort contained a significant number of patients with no previous violence or convictions prior to the index offence and few or no previous psychiatric admissions. This, they suggest, may explain why a severely violent index offence is significantly associated with a shorter length of admission; they note that characteristics associated with long stay in medium security identified in their study are seldom associated with a severely violent index offence, and this can result in shorter admissions for severe violence.

Needs of long-stay patients

Three UK studies provided additional information on the ‘needs’ of patients currently receiving high secure care. Thomas et al. 29 focused on all patients resident in 2003 and Glorney et al. 84 reviewed the 63 male patients admitted between 2000 and 2001; both studies were of high secure samples and used the forensic version of the Camberwell Assessment of Need. Pierzchniak et al. 28 studied 176 high and medium secure patients resident in 1995 using a variety of measures. The key needs identified in these studies were:

-

risk reduction

-

daytime activities

-

physical health

-

treatment for alcohol misuse

-

treatment for drug problems

-

safety to others

-

safety to self (female patients)

-

psychotic symptoms/mental health recovery

-

therapeutic engagement

-

education

-