Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 13/182/07. The contractual start date was in December 2015. The final report began editorial review in July 2016 and was accepted for publication in November 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Gillian Parker has in the past received, and is currently in receipt of, a number of other research grants from the National Institute for Health Research, all won in open competition.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Thomas et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Policy and research interest in carers – those who provide support, on an unpaid basis, to ill, disabled or older people to enable them to live in their own homes – has grown in importance over the past 30 years. Since the first UK review of evidence on carers,1 the national and international body of research literature has grown substantially. It now covers data on, inter alia, the prevalence of caregiving, the impact and outcomes of caring on people with caregiving responsibilities, issues related to combining paid work and care, and the effectiveness of support and services for carers. Although some studies cover carers in general, others examine issues from the perspective of specific subgroups of carers, for example older carers, children and young people who provide care, and carers of people with specific conditions. Likewise, studies adopt different designs, ranging from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) to small-scale qualitative pieces of work.

Since 1995, the UK government has introduced legislation and policy measures aimed specifically at carers, as well as setting up the cross-departmental Standing Commission on Carers. The revised 2008 national strategy for carers2 contained the then-government’s 10-year vision for carers. The ‘next steps’ document,3 published 2 years later, outlined a cross-departmental approach to carers policy from identification to support; this also highlighted the need to develop the evidence base on supporting carers. The document pointed out that, although much is now known about the challenges that carers face and the impact that caring can have, much less is known about how to improve outcomes for carers. In May 2016, NHS England launched a toolkit4,5 to assist with identifying and assessing carer health and well-being as part of its ongoing commitment to carers. 6,7 The toolkit includes a template ‘Memorandum of Understanding’ to help local partners work collaboratively to support carers.

In 2009, the Department of Health commissioned a meta-review for the Standing Commission on Carers from the Social Policy Research Unit at the University of York to inform their thinking about how best to improve outcome for carers, as well as identifying future research areas. 8

The overall aim of that review was to provide the Department of Health with an overview of the evidence base relating to the outcomes and cost-effectiveness of support for unpaid carers of ill, disabled or older people. The specific objectives of the proposed study were:

-

to undertake a scoping review of existing literature reviews, including systematic reviews, on support and interventions for carers

-

to map out the extent, range and nature of the identified reviews on support and interventions for carers

-

to summarise the main findings of the identified reviews

-

to identify gaps and weaknesses in the evidence base.

The review encompassed carers of all ages (including children and young adults) supporting adults, including those making the transition from children’s to adults’ services, but did not cover people supporting adults with mental health problems except in the scoping work.

The review followed a protocol with inclusion and exclusion criteria, search terms, search strategy, quality control tools and approach to data extraction and synthesis.

The following parameters for the review were used:

-

include literature reviews published since 2000 to date and written in English only

-

no geographical restriction, that is, include reviews covering both national and international research

-

include published reviews only, that is, exclude research in progress and grey literature.

The overall conclusion of the meta-review was that the strongest evidence of effectiveness of any sort was in relation to education, training and information for carers. These types of interventions – particularly when active and targeted rather than passive and generic – appeared to increase carers’ knowledge and abilities as carers. There was some suggestion that this might also improve carers’ mental health or their coping; however, the review concluded that this possibility remained to be tested rigorously in research specifically designed to do so and that explored both effectiveness and costs.

Beyond this, there was little convincing evidence about any of the interventions included in the reviews. This was not the same as saying that these interventions had no positive impact. Rather, what the review revealed was poor-quality primary research, often based on small numbers, testing interventions that had no theoretical underpinning, with outcome measures that might have little relevance to the recipients of the interventions.

The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) is keen to update the evidence in this area. Given the increase in published evidence since the original meta-review,8 and the introduction of the latest Care Act in 2014,9 an updated meta-review was considered helpful to inform both the NHS and possible future research commissioning in relation to the needs of different types of carers and information on types of support interventions.

For the update, we set out to assess what is known about effective interventions to support carers of all ages supporting adults who are ill, disabled or older. We adopted a pragmatic approach given the limited time and resources available.

Chapter 2 Methods

Introduction

We adapted, as necessary, the methods adopted in the original meta-review. 8

Search strategy

The database search strategies from the original meta-review were checked and updated. Updates were necessary for some of the strategies to account for changes to the search interface or provider, or where new indexing terms had been introduced or changed since the searches were last run in August 2009.

The searches were rerun in January 2016 on all of the databases searched in the original meta-review: Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), EMBASE, Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC), Health Technology Assessment database, MEDLINE, MEDLINE In Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, NHS Economic Evaluations Database, PsycINFO, Social Care Online, Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) and Social Services Abstracts. In addition, PROSPERO was searched to identify any recently completed systematic reviews.

As with the original meta-review, a study design search filter was used to limit the search to reviews only, if an appropriate filter was available. When possible, searches were restricted to records added to the database during the period 2009–16. All searches were restricted to English-language papers only.

Owing to the higher than anticipated volume of hits from the database searches and the time constraints of the project, we did not undertake any supplementary searches.

The records retrieved from each database were downloaded and imported into EndNote X7.4 (Thomson Reuters, CA, USA) for deduplication. The records were then further deduplicated against the EndNote library containing the original results from the 2009 searches. The total number of results after the deduplication process was 10,094. A further 72 results of potentially relevant systematic reviews were found from PROSPERO.

The search strategies and results for each database can be found in Appendix 1.

Study selection and quality assessment

The search results were downloaded in EndNote X7.4 and split equally between two reviewers, who screened the titles and abstracts to eliminate obviously irrelevant items. A 20% sample was split equally between two additional reviewers to double screen. In addition, one reviewer used text-mining software in EPPI-Reviewer 4 (Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London, UK) to assess all of the records excluded at titles and abstracts stage to ensure that no relevant records had been missed during the single reviewer initial screening stage. Full-text copies were subsequently ordered or downloaded for potentially relevant records. We applied a cut-off date of 31 March 2016 for the receipt of full papers that had been ordered. We used a Microsoft Excel® 2013 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) spreadsheet to record full-paper screening decisions simultaneously for study selection and quality assessment, using the inclusion/exclusion criteria in Table 1 and the quality assessment criteria in Box 1 (taken largely from the original meta-review). 8 The screening of full papers was carried out by two reviewers independently, with disagreements resolved by discussion or the involvement of a third reviewer if necessary.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Population of interest | |

|

|

| Types of interventions | |

|

|

| Geographical coverage | |

|

|

| Language | |

|

|

| Period of interest | |

|

|

| Type of literature review | |

|

|

The set of criteria applied to relevant reviews embodies seven questions:

-

Is there a well-defined question?

-

Is there a defined search strategy?

-

Are inclusion/exclusion criteria stated?

-

Are study designs and number of studies clearly stated?

-

Have the primary studies been quality assessed?

-

Have the studies been appropriately synthesised?

-

Has more than one person been involved at each stage of the review process?

The criteria are scored as follows: yes = 1; in part = 0.5; and no or not stated = 0. High-scoring reviews (i.e. those reviews that scored ≥ 4) will go forward for full data extraction for the meta-review. Only brief summary information will be extracted from reviews of lower quality (i.e. those scoring < 4).

Reproduced from Parker et al. ,8 with permission from the Social Policy Research Unit, University of York.

As well as selecting reviews based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, we assessed the quality of the reviews to inform which were subject to full review.

The quality assessment criteria that we used (see Box 1) are adapted from those developed by Egan et al. 10 in their systematic meta-review of psychosocial risk factors in home and community settings. These criteria had themselves been adapted for epidemiological reviews from two critical appraisal guides: the University of York’s Centre for Reviews and Dissemination’s (CRD) DARE criteria for quality assessment of reviews11 and a systematic review tool created by Oxman and Guyatt. 12

The first review, as commissioned by the Department of Health, did not include the carers of adults with mental health problems, except in the scoping work. 8 The main reason for this was the very different nature of the literature in this area. The concept of ‘carers’ for adults with mental health problems, even when these problems are severe and enduring, is more difficult to define than in other areas, and in some parts of the literature it remains contested. This difficulty is reflected in the nature of interventions evaluated; although these may be targeted at family members, their intended outcome is usually improved mental health for the adult being supported. The literature can also encompass interventions for people with drug and alcohol dependencies, which raises the same issue: that although interventions may have an impact on family members (or ‘carers’), this is not usually their primary purpose. We have discussed these challenges and complexities in reviewing this area elsewhere. 13,14 However, the search strategies for the first review did not exclude interventions for carers of adults with mental health problems, so that the likely size of the evidence base could be estimated. No reviews focused on carers in this area were actually identified in the first review. 8

We took the same approach to searching in the updated review, to allow us to see whether or not the evidence base had grown. This time we did find reviews in this area, which we included in the updated work reported here. However, the issues relating to the definitions of ‘carers’ in this field, and the nature of intervention, remain.

Post-protocol decisions prior to data extraction

From the initial searches and selection, it was clear that there had been substantial development in the volume, content and complexity of the literature since the original meta-review was carried out in 2010. Consequently, > 100 reviews were selected for potential inclusion in the update. It appeared that the average quality of reviews identified had improved since the first review, which potentially offered the opportunity for a ‘best evidence’ approach. Given the time and resource available, we needed to find a way to focus attention on those reviews that would provide the most robust information. Therefore, we revisited a number of decisions from the original protocol to focus our work.

The following post-protocol issues were discussed and agreed.

-

Review protocols were excluded on the basis that:

-

in their current form they were not a published systematic review and, therefore, they failed to meet our inclusion criteria

-

CRD’s PROSPERO database had been searched to locate publications from relevant protocols (we contacted the authors of such protocols but there were no available publications)

-

for older protocols we would expect our search strategy to have picked up relevant publications (given that not everything is registered on PROSPERO).

-

-

Conference abstracts were excluded on the basis that:

-

in their current form they were not a full systematic review publication and, therefore, they failed to meet our inclusion criteria

-

they did not provide sufficient detail to allow them to be assessed for inclusion

-

we were confident that our robust search strategy would have identified any relevant reviews underpinning these conference abstracts.

-

-

We found one review15 of interventions for carers of people with delirium. After discussion, we excluded this on the basis that delirium is an acute condition that would be expected to resolve. ‘Carers’ of people with delirium might thus be so for a very short period of time, whereas the focus of our work, and of NIHR’s interest, was on people who carry caring responsibility over an extended period.

-

We also found three reviews16–18 of case or care management. Although these examined outcomes for carers, they were excluded for two reasons:

-

Case or care management, as currently understood in the UK context, is less an intervention and more a framework within which needs are identified and assessed, care is planned, interventions and services are delivered and ongoing needs are monitored. Any type or number of specific interventions or services (or none), both for the ill or disabled person and (less frequently) the carer, might thus be delivered as a result of receiving case/care management.

-

The focus of case/care management is the ill or disabled person, albeit that the carer’s needs might also be considered during assessment and care planning.

-

The growth in the literature since the first review posed other challenges; for example, there were reviews that dealt with dyad interventions, interventions directed at the ill or disabled person and/or carers, and multiple-component interventions. There was also the issue of geographic coverage, whereby it was not clear if interventions or delivery contexts were fully transferable to UK health and social care systems. We also encountered the issue, evident in the original meta-review, of reviews in which the main focus was not on outcomes for the carer, but such outcomes were reported. We discussed these issues prior to data extraction and agreed a consistent way forward on whether to include or exclude. We included reviews of interventions aimed at patient–carer dyads only when carer outcomes were reported separately. When carer outcomes were reported but were not the main focus, a judgement was made as to the usefulness of this contribution to our meta-review. In relation to geographic applicability, we focused on reviews of interventions from developed countries with similar health-care systems, regardless of any differences in payment arrangements. We included multicomponent interventions on the basis that identifying the differential effectiveness of component parts may be limited to what was reported by the review authors.

Applying the adapted quality assessment criteria and scoring system by Egan et al. 10 used in the original meta-review revealed 61 high-quality systematic reviews. This was a larger proportion than expected. However, we noted that a review could achieve high-quality status using this system on the basis of adequate reporting of research question, search strategy, inclusion criteria and study designs/numbers but with insufficient attention to quality assessment, synthesis and transparency in the review process. Reviews with such shortcomings would be scrutinised closely for overall reliability, or may fail altogether the criteria for inclusion in DARE. DARE is a database of quality-assessed systematic reviews meeting specific criteria that was produced by the CRD, University of York; included are reviews that evaluate the effects of health and social care interventions, including delivery and organisation of services. Full details of the DARE process are available. 11 Therefore, we decided to refine the scoring system in the original meta-review and introduce a second tier of criteria (using the quality threshold for DARE) to further differentiate the ‘high’-quality reviews by splitting them into ‘high’ and ‘medium’ quality.

To be classed as ‘high’ quality, reviews had to reach a minimum score of 4 points, comprising (as mandatory) 1 point each for inclusion criteria, search strategy and synthesis and, additionally, 1 point for either quality assessment or number/design of included studies.

Most of the reviews identified at this stage were about ill or disabled people with specific conditions or impairment, for example dementia, stroke or cancer. Therefore, prior to data extraction of the included high-quality reviews, we grouped them according to impairment or condition to establish any discernible patterns and weightings in the evidence base. After this, we examined the distribution of reviews, by quality and by condition/impairment. This allowed us to adopt a ‘best evidence available’ approach to each of the condition/impairment areas identified.

Twenty-seven reviews were reclassified as high quality and progressed to detailed data extraction. The remaining 25 reviews (i.e. those that were high quality using the adapted Egan et al. 10 criteria but failed to meet the threshold for inclusion on DARE) were classed as medium quality, and we proceeded to basic data extraction. Bibliographic details were provided for nine reviews of low quality (using the adapted Egan et al. 10 criteria).

Data extraction

We followed the approach to data extraction used in the original meta-review. 8 For data extraction of high- and medium-quality reviews, we developed and piloted data collection forms for the first 11 reviews. For high-quality reviews, we summarised the review characteristics by target carer group, sociodemographic information, intervention (and comparator, when reported), outcomes, cost-effectiveness, number/study design and location of included studies, and findings. We then recorded key information according to the seven outcomes measured in the original meta-review, as follows: physical health, mental health, burden and stress, coping, satisfaction, well-being or quality of life, ability and knowledge. When it was unclear where best to place the review authors’ description of the outcome in our list of seven categories, this was discussed and agreed between two reviewers. For basic data extraction of medium-quality reviews, we summarised target carer groups, sociodemographic information, interventions (and comparators, when reported), a brief summary of outcomes measured, cost-effectiveness, number/study design and location of included studies. All data extraction forms were constructed as Microsoft Word® 2013 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) tables. For low-quality reviews, we recorded bibliographic detail only. Data extraction was carried out by one reviewer and checked by a second. Appendix 2 provides a summary of review characteristics for the high-quality reviews. All other data extraction tables are available on request.

Synthesis

Given the substantial growth in volume and complexity of the literature since the original meta-review,8 we adopted a pragmatic approach to the synthesis. We focused our synthesis primarily on the included high-quality reviews, aiming to identify any intervention effect (positive or negative, derived from narrative or quantitative synthesis), size of effect or heterogeneity, together with details of the population, intervention/comparator and outcome. We followed with a discussion of review quality, (when possible) highlighting the better-quality primary studies relating to any findings of interest. We then summarised information from the medium- and low-quality reviews to establish any material differences from the high-quality reviews in terms of review coverage.

Public and patient engagement

We engaged early with a group of carers who were known to us and were willing to give their views on the overall findings of our review. We had originally intended to involve the carers at an earlier stage of the work. However, discussion with the carers suggested that it was a better use of their time to ask them to comment on the draft findings, rather than to ask them to come to meetings in which they would be involved in a process that, because we were updating a previous meta-review, had relatively little scope for change and was largely technical.

A draft version of the report was sent to four individuals who had agreed to help, all of whom were female relatives (spouses and daughters) of people with different types of dementia. All were aged < 70 years. We provided them with a short brief on the purpose of the project and how we thought they might be able to help put the results into context, and asked them to share their views within 4 weeks. We offered the carers various options for feeding back their views: meeting the research team over a cup of coffee, talking to a researcher over the telephone or providing written comments. All chose to provide written comments via e-mail. In the end, however, only two of the carers were able to return comments in the time available.

Chapter 3 Results

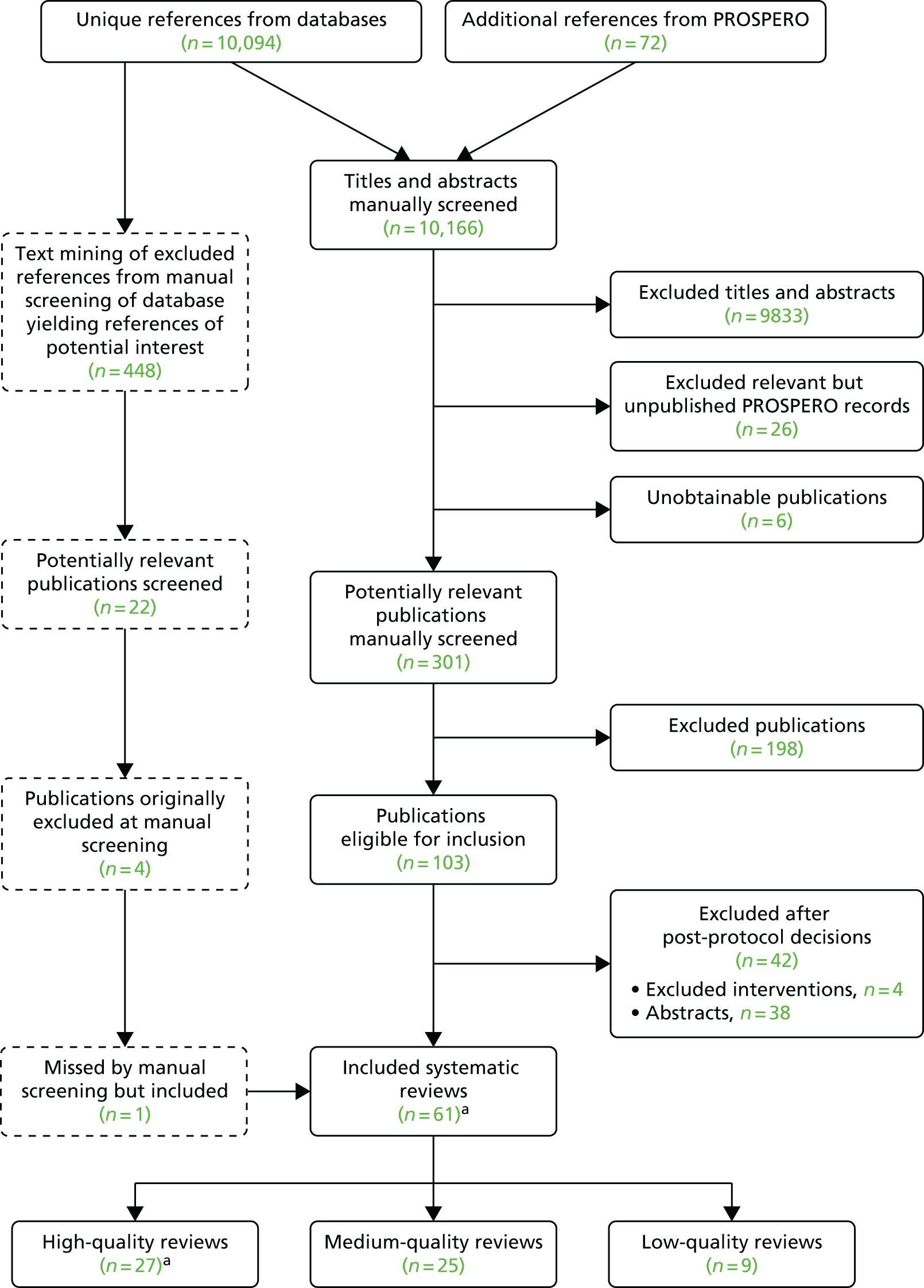

We initially identified 103 systematic reviews. Applying our post-protocol decision on a higher threshold for quality assessment (based on DARE), we finally included 61 reviews (27 of high quality, 25 of medium quality and nine of low quality). One of the 25 medium-quality reviews was identified through the text-mining exercise. We excluded 38 reviews only published in abstract form and four reviews with excluded interventions (delirium and case management). Figure 1 provides details.

FIGURE 1.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow chart. a, One review had two publications.

In this chapter, we start by presenting the results from reviews we defined as high quality. We have grouped the findings from different reviews in relation to impact on carers’ physical health, mental health, burden and stress, coping, satisfaction (with the intervention), well-being or quality of life, and ability and knowledge. We further subgroup according to the condition of the person the carer was helping. We conclude with a summary on the cost-effectiveness of interventions to support carers, followed by a summary of conclusions drawn by the reviews. The full details of all of the included high-quality reviews are given in Tables 2–9 and Appendix 2. To complete the evidence picture, we then outline the other reviews classed as medium quality (see Table 10) and low quality (see Table 11), highlighting any substantive differences from the high-quality reviews in terms of types of carers, interventions and outcomes. The full bibliographic details are included in the References.

Overview of the high-quality reviews

Twenty-seven high-quality reviews (28 papers) (including eight Cochrane reviews) were included in this meta-review. 19–46 The details of the quality scoring of these reviews are given in Table 2.

| First author, year of publication | 1. Is there a well-defined question? | 2. Is there a defined search strategy? | 3. Are inclusion/exclusion criteria stated? | 4. Are study design and number of studies clearly stated? | 5. Have the primary studies been quality assessed? | 6. Have the studies been appropriately synthesised? | 7. Has more than one person been involved at each stage of the review process? | Total score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carers of people with dementia | ||||||||

| Boots, 201419 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 6.5 |

| Chien, 201120 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 6 |

| Eggenberger, 201321 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 6.5 |

| Godwin, 201322 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.5 | 5.5 |

| Hurley, 201423 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 6.5 |

| Jensen, 201524 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Lins, 201425 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Marim, 201326 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 6.5 |

| Maayan, 201427 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| McKechnie, 201428 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 6.5 |

| Orgeta, 201429 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Schoenmakers, 201030 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 5.5 |

| Smith, 201432 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 6.5 |

| Vernooij-Dassen, 201131 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Carers of people with cancer | ||||||||

| Lang, 201433 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 6.5 |

| Northouse, 201034 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0.5 | 5 |

| Regan, 201235 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Waldron, 201336 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Carers of people with stroke | ||||||||

| aCheng, 201237 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 6.5 |

| aCheng, 201438 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Ellis, 201039 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 6.5 |

| Forster, 201240 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Legg, 201141 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Carers of people with various conditions at the end of life | ||||||||

| Candy, 201142 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Gomes, 201343 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| Nevis, 201444 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0 | 5.5 |

| Carers of people with mental health problems | ||||||||

| Macleod, 201145 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0 | 5.5 |

| Yesufu-Udechuku, 201546 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

Of the reviews, 1419–32 focused on interventions for carers of people with dementia, four33–36 focused on carers of people with cancer, four37–41 focused on carers of people with stroke, three42–44 focused on carers of people with various conditions at the end of life and two45,46 focused on carers of people with mental health problems. Not all reviews reported the geographic location of the included primary studies. When this was reported, coverage was worldwide. Many studies originated in the USA and Europe (including several in the UK). When sociodemographic data were reported, carers in general were white, female and spouses or adult children, with the age at which they started their caregiving roles ranging from their early forties up to at least 70 years.

In general, the review characteristics were highly variable. When data were extracted on statistical heterogeneity, this is reported (focusing on where intervention effects are indicated) in the results that follow.

A wide range of interventions was included (see Appendix 2 and Tables 3–9). Multicomponent interventions were the focus in many reviews; those with psychosocial or psychoeducational content featured prominently,28,34–38,46 as did those containing education and/or communication skills training. 21,24,26,40,44,45 Other (more specific) interventions included stroke liaison workers,39 volunteer mentoring,32 meditation-based activity,23 art-making classes33 and home-based exercise. 29 Control or comparator groups (when reported) were usual care, no control, other active intervention, wait list or placebo. The details of what was delivered to control groups were sparse or were not reported. Many different outcome measures were reported (see Appendix 2 and Tables 3–9).

Quality of the primary studies

A quality assessment of primary studies was carried out in 2519–21,23–33,35–46 of the 27 included reviews. In most cases, it was possible to determine at least the overall quality of the included studies. However, Shoenmakers et al. 30 applied quality assessment only as an inclusion criterion and did not report further on the quality of the primary studies. In Ellis et al. ,39 only selective coding was carried out, making it impossible to gauge the overall quality. In Eggenberger et al. ,21 quality assessment criteria were presented in the paper, but detailed results were not. Similarly, in Macleod et al. ,45 risk of bias was reported to have been assessed, but the results of this were not presented. Two reviews22,34 did not perform any quality assessment of primary studies.

When it was possible to determine from results reported in the reviews, the methodological quality of primary studies was variable. In reviews targeting carers of people with dementia, only one26 specifically reported that all of the included studies had a low risk of bias. 26 A majority of studies in another review20 was reported as being of high or moderate quality, and a further review presented an average quality score of 75 out of 100. 32 In other reviews, the quality of primary studies appeared to be moderate,23,25,29 variable19,21,28 or very low. 27 One review described overall quality as satisfactory;31 another reported separately on the quality of primary studies for different outcomes (overall low to moderate). 24 In reviews targeting carers of people with cancer, one33 suggested that studies were of moderate quality,33 one35 reported moderate to strong evidence35 and one36 reported fair to good-quality evidence. 36 Limitations and variable study quality were also reported in reviews of interventions for carers of people with stroke. 37,38,40,41 Reviews addressing carers of people with various conditions at the end of life indicated studies of unclear quality,42 mixed-quality studies43 or studies at serious risk of bias, particularly in those focusing on carer outcomes. 44 Low- to moderate-quality primary studies were reported in one review46 focusing on carers of people with mental health problems. 46

Approach to synthesis

In most reviews, the analysis was grouped by intervention or outcome. The multicomponent nature of many interventions meant that it was difficult to identify causal relationships. Eleven reviews undertook narrative synthesis19,21–23,28,32,35,36,43–45 and six undertook quantitative synthesis. 20,26,27,29,30,34 Ten reviews24,25,31,33,37–42,46 contributed both narrative and quantitative syntheses. Two references37,38 relate to the same review.

Overlap of primary studies

From the outset, it was clear that there was some overlap of primary studies in the reviews we included. The effect of this overlap is difficult to judge without substantial additional analysis, but it could run the risk of exaggerating effects from the undue influence of individual studies, and present difficulties arising from contradictory assessments of the same study.

Carer outcomes

Physical health

Evidence about carers’ physical health was reported in seven reviews (in eight papers). 28,34,35,37–39,42,43 Physical health (when defined) included physical distress, physical functioning, somatic complaints, perceived or subjective health status and sleep improvement. Some formal outcome measures were reported. All results are presented in Table 3.

| First author, year of publication | Type of interventions | Outcome | n/N | Measures used | Synthesis approach (summary statistic) | Meta-analysis results | 95% CI | p-value | Outcome calculated at |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Or summary of narrative synthesis | |||||||||

| Carers of people with dementia | |||||||||

| McKechnie, 201428 | Computer-mediated psychosocial (complex multifaceted) interventions with/without professional support | Physical health | 2/14 | HSQ-12; Caregiver Health and Health Behaviours scale | Narrative | No intervention effects | Unclear | ||

| Carers of people with cancer | |||||||||

| Northouse, 201034 | Psychoeducation, skills training, therapeutic counselling | Physical functioning | 7/29 | NR | Meta-analysis (Hedges’ g) | 0.11 | –0.05 to 0.27 | NS | Post intervention: 0–3 months |

| Psychoeducation, skills training, therapeutic counselling | Physical functioning | 6/29 | NR | Meta-analysis (Hedges’ g) | 0.22 | 0.04 to 0.41 | < 0.05 | Post intervention: 3–6 months | |

| Psychoeducation, skills training, therapeutic counselling | Physical functioning | 2/29 | NR | Meta-analysis (Hedges’ g) | 0.26 | 0.02 to 0.49 | < 0.05 | Post intervention: ≥ 6 months | |

| Regan, 201235 | Couples-based psychosocial interventions | Physical distress | 2/23 | SRHS; PAL-C; BCTRI; FACT-G; EPIC; SF-36 | Narrative | Significant reductions following disease management, psychoeducation/telephone counselling intervention (one study) and a multicomponent ‘FOCUS’ intervention (one study). Results were not reported for one study | Unclear | ||

| Carers of people with stroke | |||||||||

| Cheng, 2012,37 201438 | Psychosocial, group and individual interventions; many were multifaceted Counselling and psychoeducation |

Physical functioning | 2/18 | SF-36 | Narrative | No significant differences for counselling, social problem solving or physical exercise training | Unclear | ||

| Counselling and psychoeducation | Somatic complaints | 1/18 | SF-36 | Narrative | No significant differences for social problem-solving interventions | Unclear | |||

| Counselling and psychoeducation | Perceived health status | 4/18 | SF-36 | Narrative | No significant differences for social problem-solving, counselling, psychoeducation or social support interventions | Unclear | |||

| Counselling and psychoeducation | Physical functioning (for all interventions) | 4/18 | Various, including SF-36 or global family assessments | Meta-analysis (SMD) | –0.14 | –0.37 to 0.09 | 0.23 | Immediately post intervention | |

| Counselling and psychoeducation | Physical functioning (for all interventions) | 4/18 | NS differences for subgroup analysis by intervention | Unclear | |||||

| Counselling and psychoeducation | Somatic complaints | 2/18 | Various, including SF-36 or global family assessments | Meta-analysis (SMD) | –0.10 | –0.37 to 0.16 | 0.45 | Immediately post intervention | |

| Counselling and psychoeducation | Somatic complaints | 2/18 | NS differences for subgroup analysis by intervention | ||||||

| Ellis, 201039 | Stroke liaison workers for patients and carers: proactive and structured approach; reactive and flexible approach; proactive and focused approach | Caregiver subjective health status (includes carer strain but unable to separate) | 15/16 | Majority used a measure of Carer Strain Index | Meta-analysis (SMD) | 0.04 | –0.05 to 0.14 | 0.37 | Unclear |

| Carers of people with various conditions at the end of life | |||||||||

| Candy, 201142 | Usual care plus direct interventions for carers | Sleep improvement | 1/11 | Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index; Actigraph Sleep Watch | Narrative | No difference in sleep improvement for brief behavioural intervention | End of intervention | ||

| Gomes, 201343 | Home palliative care vs. usual care | Pre-bereavement physical function, general health, pain | 2/23 | SF-36 subscales | Narrative | Moderate evidence of no statistically significant differences apart from physical functioning (p < 0.05) | Unclear | ||

| Post-bereavement physical function, general health, pain | 3/23 | SF-36 subscales | Narrative | Conflicting results | Unclear | ||||

| Reinforced vs. standard home palliative care | General health | 2/23 | GHQ-12 and GHQ-28 | Narrative | Moderate evidence of no statistically significant differences | Unclear | |||

| Carers of people with mental health problems | |||||||||

| No reviews | |||||||||

Carers of people with dementia

A narrative synthesis in McKechnie et al. ,28 focusing on computer-mediated psychosocial interventions (with or without professional support), reported no intervention effects on the physical health outcome for carers (two studies, both of medium quality). Physical health was not defined in this review, but outcome measures were reported, such as the Health Status Questionnaire-12 and the Caregiver Health and Health Behaviours Scale.

Carers of people with cancer

Two reviews34,35 reported improved physical health outcomes for carers of people with cancer. 34,35 In Regan et al. ,35 a narrative synthesis showed reductions in physical distress following couples-based psychosocial support involving disease management, psychoeducation, telephone counselling and the development of family coping skills (two studies, one of strong and one of moderate quality). In Northouse et al. ,34 a meta-analysis revealed a small statistically significant intervention effect for physical functioning (a range of self-care behaviours and sleep quality) beyond 3 months from the delivery of multicomponent psychoeducation activities (six studies, quality not reported).

Carers of people with stroke

Two reviews37–39 provided narrative and quantitative syntheses, neither of which revealed any significant group differences or intervention effects on the physical health of carers of people with stroke. Across the reviews, physical health was defined as physical functioning, somatic complaints and carer subjective health status. Interventions in these reviews were dissimilar (the first review focused on multicomponent psychosocial activities; the second review focused on stroke liaison workers). In Ellis et al. ,39 a large proportion (15 out of 16) of included studies was used in the meta-analysis (quality scores were not reported).

Carers of people with various conditions at the end of life

Two reviews42,43 provided narrative syntheses for physical health outcomes. When defined beyond general health, physical health included sleep quality; outcome measures included Short-Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36) subscales, General Health Questionnaire (GHQ)-12 and GHQ-28, and specific sleep quality measures. The results generally showed no improvements or showed conflicting results. However, in Gomes et al. 43 there was a statistically significant effect for physical functioning following home palliative care (not defined further) in two studies (at unclear or high risk of bias).

Carers of people with mental health problems

No reviews were identified that addressed physical health for carers of people with mental health problems.

Mental health

Carers’ mental health was a frequently reported outcome in the 24 included reviews. 19–25,27–35,37–43,45,46

Mental health was variably defined (when reported). The terms depression, anxiety, psychological distress and self-efficacy were commonly used. Some reviews defined the outcome more broadly as psychological well-being or carer mental health. The outcome measures were generally well reported and diverse. Frequently used measures were the Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), Brief Symptom Inventory, Beck Depression Inventory, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) and the GHQ-12 and GHQ-28. The following results focus primarily on the detail for positive intervention effects. Providing further detail on reviews showing no significant effects for mental health outcomes was not considered to be informative, but a brief summary of results from these reviews is provided below. All results are reported in Table 4.

| First author, year of publication | Type of interventions | Outcome | n/N | Measures used | Synthesis approach (summary statistic) | Meta-analysis results | 95% CI | p-value | Outcome calculated at |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Or summary of narrative synthesis | |||||||||

| Carers of people with dementia | |||||||||

| Boots, 201419 | Internet-based interventions including information, caregiving strategies and support | Depression | 2/12 | Unclear | Narrative | Small significant improvement | Unclear | ||

| Self-efficacy | 4/12 | Unclear | Narrative | Small significant improvement | Unclear | ||||

| Chien, 201120 | Support groups led by professionals or other trained group members | Overall mental health | 19/30 | NR | Meta-analysis (Hedges’ g) | –0.44 | –0.73 to 0.15 | End of intervention | |

| Overall mental health | 6/30 | NR | Meta-analysis (Hedges’ g) | –0.53 | –1.07 to 0.01 | NR | Follow-up of 1–3 months | ||

| Depression | 17/30 | NR | Meta-analysis (Hedges’ g) | –0.40 | –0.72 to –0.08 | NR | End of intervention | ||

| Depression | 6/30 | NR | Meta-analysis (Hedges’ g) | –0.57 | –1.09 to –0.05 | NR | Follow-up of 1–3 months | ||

| Eggenberger, 201321 | Face-to-face communications skills training (small groups or individually) | Depression | 1/4 | HDRS | Narrative | One study reported a mean decline of depression levels from 6.9 (SD 4.1) to 6.3 (SD 4.5); p < 0.041 | Unclear | ||

| Godwin, 201322 | Technology-driven multicomponent support including information and social support: Caregiver’s Friend | Depression | 1/8 | CES-D | Narrative | Significant decrease in depression compared with control | Unclear | ||

| REACH | Depression | 1/8 | CES-D | Narrative | Significant reductions in depression | 6 and 18 months’ follow-up | |||

| Caregiver’s Friend or REACH | Anxiety | 2?/8 | STAI | Narrative | Both reported significantly decreased anxiety compared with control | Unclear | |||

| Hurley, 201423 | Meditation-based intervention | Depression | 7/8 | CES-D; HDRS; SCL-90; POMS | Narrative | Five studies (including two RCTs) found statistically significant reductions in depression score pre–post intervention; two studies (including one RCT) found non-statistically significant trends for reduced scores. There were mixed results at follow-up | End of intervention or follow-up (4 weeks to 4 months) | ||

| Jensen, 201524 | Educational interventions aimed at teaching skills relevant to dementia caring | Depression | 2/7 RCTs | CES-D; Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale | Meta-analysis (SMD) | –0.37 | –0.65 to –0.09 | 0.010 | 5 to 6 months’ follow-up |

| Depression | 1/7 | CES-D; Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale | Meta-analysis (SMD) | 0.12 | –0.15 to 0.38 | NR | 15 months’ follow-up | ||

| Lins, 201425 | Telephone counselling with or without additional intervention | Self-efficacy | 4//9 RCTs | Caregiving Self-efficacy by Steffen; Self-Efficacy Scale by Fortinsky | Narrative | Mixed results from two RCTs of telephone counselling without additional intervention. Positive effects were reported in the control groups. Mixed results reported following telephone counselling with video sessions and workbook; positive effects were noted in both intervention and control groups (two studies) | Unclear | ||

| Depressive symptoms | 4/9 RCTs | CES-D; BSI | Narrative | Mixed results over time after telephone counselling with (one RCT) or without (two RCTs) video sessions. A statistically significant group difference was reported favouring telephone counselling combined with video sessions and a workbook (one RCT) | Unclear | ||||

| Telephone counselling without other intervention | Depressive symptoms | 3/9 RCTs | CES-D; GDS; BSI; BDI; | Meta-analysis (SMD) | 0.32 | 0.01 to 0.63 | 0.0444 | Unclear | |

| Telephone counselling combined with video sessions | Anxiety | 1/9 RCTs | BSI | Narrative | Anxiety significantly reduced over time in both interventions and control groups | Unclear | |||

| Maayan, 201427 | Interventions providing respite care vs. no respite | Depression | 1/4 RCTs | HDRS | Meta-analysis (MD) | 0.18 | –3.82 to 3.46 | NR | Unclear |

| Respite vs. polarity therapy | Depression | 1/4 RCTs | CES-D | Meta-analysis (MD) | 6.0 | 0.31 to 11.69 | NRa | Unclear | |

| Respite vs. no respite | Anxiety | 1/4 RCTs | Hamilton Anxiety Scale | Meta-analysis (MD) | 0.05 | –3.76 to 3.86 | NR | Unclear | |

| Psychological distress | 1/4 RCTs | BSI | Meta-analysis (MD) | 0.04 | –0.29 to 0.37 | NR | Unclear | ||

| McKechnie, 201428 | Computer-mediated psychosocial interventions (complex and multifaceted) with and without professional support | Depression | 7/14 | CES-D; Composite measure (detail NR) | Narrative | Four studies found improvements in CES-D; three medium-quality studies found no effect (when reported) | Unclear | ||

| Anxiety | 2/14 | STAI | Narrative | Reduction in STAI | Unclear | ||||

| General Mental Health | 3/14 | GHQ; HSQ-12; HSQ-20; subscales from Revised Ways of Coping | Narrative | Three studies generally did not find any intervention effect | Unclear | ||||

| Self-efficacy | 3/14 | Caregiving self-efficacy scale | Narrative | There were inconsistent findings across one high-quality study and two medium-quality studies | Unclear | ||||

| Orgeta, 201429 | Home-based supervised endurance or aerobic exercise; telephone-based exercise; 12-week exercise programme | Depression | 3/4 RCTs | BDI; 11-item Iowa short form for CES-D | Meta-analysis (SMD) | –0.35 | –0.73 to 0.03 | 0.07 | Unclear |

| Depression | 2/4 RCTs | BDI only | Meta-analysis (SMD) | –0.35 | –0.73 to 0.03 | NR | Unclear | ||

| Anxiety | 2/4 | Taylor Manifest Anxiety Scale (short form) | Meta-analysis (SMD) | –0.22 | –0.60 to 0.16 | 0.26 | Unclear | ||

| Schoenmakers, 201030 | Active intervention in a dementia care home Using psychological interventions |

Depression | 15/26 | GHQ-12 or -28; CES-D, Zung Depression Scale, BDI, PST-BSI | Meta-analysis (MD) | 0.03 | –0.42 to 0.35 | 0.86 | Unclear |

| Depression | 15/26 | GHQ-12 or GHQ-28; CES-D, Zung Depression Scale, BDI, PST-BSI | Meta-analysis (MD) | Authors report no significant change to results following sensitivity analysis | Unclear | ||||

| Using communication technologies | Depression | 2/26 | Unclear | Meta-analysis (MD) | 0.07 | –2.62 to 2.75 | 0.96 | Unclear | |

| Using case management | Depression | 3/26 | Unclear | Meta-analysis (MD) | –0.32 | –0.73 to 0.091 | 0.13 | Unclear | |

| Smith, 201432 | Volunteer mentoring – peer support | Anxiety and depression | 2/4 | HADS | Narrative | Peer support: one study found no positive improvements in depression, but ‘after secondary analysis, peer support was found to have a modest buffering effect on depressive symptoms for carers experiencing the most stressful situations’ | Unclear | ||

| Volunteer mentoring – telephone befriending | Anxiety and depression | 1/4 | HADS | Narrative | Telephone befriending: no improvement was found for carers in the intention-to-treat population but carers receiving the befriending intervention for at least 6 months reported a statistically significant improvement in depression scores (p = 0.04) | Final follow-up at 15 months | |||

| Vernooij-Dassen, 201131 | Cognitive reframing (one element of CBT) | Anxiety | 4/11 RCTs | STAI; HAM-A; BSI anxiety subscale | Meta-analysis (SMD) | –0.21 | –0.39 to –0.04 | NR | Unclear |

| Depression | 6/11 RCTs | CES-D, BDI, BSI depression subscale; MAACL depression subscale | Meta-analysis (SMD) | –0.66 | –1.27 to –0.05 | NR | Unclear | ||

| 5/11 RCTs (removal of one RCT owing to heterogeneity) | CES-D, BDI, BSI depression subscale; MAACL depression subscale | Meta-analysis (SMD) | –0.24 | –0.42 to –0.07 | NR | Unclear | |||

| Carers of people with cancer | |||||||||

| Lang, 201433 | Art-making class/creative arts interventions: art therapy | Anxiety | 2/2 | BAI | Meta-analysis (WMD) | 4.83 | 3.12 to 6.55 | < 0.001 | Unclear |

| Northouse, 201034 | Psychoeducation, skills training, therapeutic counselling | Self-efficacy | 8/29 | NR | Meta-analysis (Hedges’ g) | 0.25 | 0.03 to 0.47 | < 0.05 | During first 3 months of intervention |

| 4/29 | NR | Meta-analysis (Hedges’ g) | 0.20 | 0.03 to 0.37 | < 0.05 | 3–6 months post intervention | |||

| 1/29 | NR | Meta-analysis (Hedges’ g) | 0.29 | 0.03 to 0.56 | < 0.05 | 6 months post intervention | |||

| Distress and anxiety | 16/29 | NR | Meta-analysis (Hedges’ g) | 0.20 | 0.08 to 0.32 | < 0.05 | During first 3 months of intervention | ||

| 11/29 | NR | Meta-analysis (Hedges’ g) | 0.16 | 0.03 to 0.29 | < 0.05 | 3–6 months post intervention | |||

| 6/29 | NR | Meta-analysis (Hedge’s g) | 0.29 | 0.06 to 0.51 | < 0.05 | 6 months post intervention | |||

| Depression | 16/29 | NR | Meta-analysis (Hedges’ g) | 0.06 | NR | NR | During first 3 months of intervention | ||

| 11/29 | NR | Meta-analysis (Hedges’ g) | 0.06 | NR | NR | 3–6 months post intervention | |||

| 3/29 | NR | Meta-analysis (Hedges’ g) | –0.03 | NR | NR | 6 months post intervention | |||

| Regan, 201235 | Couples-based psychosocial interventions | Psychological distress | 7/23 | Various | Narrative | Significant improvements for intervention partners vs. control (two studies); within-group improvements from baseline (three studies); improvements for intervention partners compared with control group partners (four studies); within-group improvements at the final follow-up compared with baseline (one study) | Unclear | ||

| Carers of people with stroke | |||||||||

| Cheng, 2012,37 201438 | Psychosocial, group and individual interventions Psychoeducation, behaviour and cognitive–behavioural interventions |

Anxiety | 3/18 | NR | Narrative | Inconsistent findings between studies of psychoeducation, behaviour and cognitive–behavioural interventions | Unclear | ||

| Psychoeducation or social problem-solving | Depression | 3/18 | NR | Narrative | Inconsistent findings for psychoeducation and social problem-solving | Unclear | |||

| Individual or group counselling, social support or social problem-solving | Psychological health | 3/18 | NR | Narrative | Inconsistent findings for individual or group counselling, social support or social problem-solving | Unclear | |||

| Psychoeducation or social support | Depression | 5/18 | NR | Meta-analysis (SMD) | 0.14 | –0.19 to 0.46 | 0.41 | Post intervention | |

| Psychological or counselling | Psychological health | 5/18 | NR | Meta-analysis (SMD) | 0.12 | –0.07 to 0.31 | 0.22 | Post intervention | |

| Ellis, 201039 | Stroke liaison workers for patients and carers | Caregiver mental health | 13/16 RCTs | NR | Meta-analysis (SMD) | –0.02 | –0.12 to 0.08 | 0.67 | Unclear |

| Caregiver subjective health status (includes measure of carer strain but cannot separate) | 15/16 RCTs | NR | Meta-analysis (SMD) | 0.04 | –0.05 to 0.14 | 0.37 | Unclear | ||

| Forster, 201240 | Passive education interventions | Depression | 2/21 RCTs | HADS | Narrative | No significant differences were reported for passive information studies | Unclear | ||

| Active education interventions | Depression | 1/21 RCTs | HADS | Narrative | Carers in the active intervention group were significantly less depressed than those in control groups (p < 0.0001, no figures reported) | Unclear | |||

| Passive or active education interventions | Psychological distress | 4/21 RCTs | NR | Meta-analysis (OR) | 1.13 | 0.65 to 1.97 | 0.65 | Unclear | |

| Legg, 201141 | Non-pharmacological interventions | Anxiety | 1/8 RCTs | NR | Narrative | No significant differences reported | Unclear | ||

| Teaching ‘procedural knowledge’ | Depression | 5/8 RCTs | HADS; GHQ-28; CES-D | Narrative | One RCT reported significant effects on depression for ‘teaching procedural knowledge’ (MD –0.61, 95% CI –0.85 to –0.37; p < 0.001) | Unclear | |||

| Information and support | Depression | 2/8 | HADS; GHQ-28; CES-D | Meta-analysis (SMD) | –0.06 | –0.31 to 0.18 | 0.62 | Unclear | |

| Psychoeducational interventions | Depression | 2/8 | HADS; GHQ-28; CES-D | Meta-analysis (SMD) | 0.20 | –0.17 to 0.57 | 0.28 | Unclear | |

| Carers of people with various conditions at the end of life | |||||||||

| Candy, 201142 | Usual care plus direct interventions for carers | Psychological distress | 8/11 RCTs | HADS; CES-D | Meta-analysis (SMD) | –0.15 | –0.28 to –0.02 | 0.020 | End of interventions |

| Gomes, 201343 | Home palliative care vs. usual care | Pre-bereavement outcomes: psychosocial well-being | 6/23 | SF-36 subscales | Narrative | Conflicting results for home palliative care vs. usual care | Unclear | ||

| Post-bereavement outcomes: grief | 4/23 | Various measures | Narrative | Strong evidence of no statistically significant differences between groups | Unclear | ||||

| Post-bereavement outcomes: psychological well-being | 5/23 | SF-36 subscales | Narrative | Conflicting results | Unclear | ||||

| Reinforced vs. standard home palliative care | Psychological well-being | 2/23 | HADS; STAI | Narrative | Moderate evidence of no statistically significant difference | Unclear | |||

| Intensity of grief | 1/23 | NR | Narrative | Limited evidence of no statistically significant difference | 4 months after patient death | ||||

| Caregiver distress | 1/23 | CBrI | Narrative | Limited evidence of positive effect in favour of added component | Unclear | ||||

| Carers of people with mental health problems | |||||||||

| Macleod, 201145 | Support from community mental health nurses – education | Somatic symptoms, anxiety, insomnia, social dysfunction, severe depression | 1/68 | NR | Narrative | No effects on somatic symptoms, anxiety, insomnia, social dysfunction or severe depression | Unclear | ||

| Support from community mental health nurses – family education | Anxiety and distress | 2/68 | NR | Narrative | A decrease in depression | Unclear | |||

| Support from community mental health nurses – family interventions | Depression | 6/68 | NR | Narrative | One study out of six reported a decrease | Unclear | |||

| Support from community mental health nurses – mutual support | Mood | 1/68 | NR | Narrative | Improved mood | Unclear | |||

| Yesufu-Udechuku, 201546 | Interventions delivered by health and social care services Psychoeducation compared with control |

Psychological distress | 2/21 RCTs | GHQ-12 and GHQ-28; BDI; K10; CIS-Rb | Meta-analysis (SMD) | –0.30 | –0.84 to 0.24 | NR | End of intervention |

| 2/21 RCTs | GHQ-12 and GHQ-28; BDI; K10; CIS-Rb | Meta-analysis (SMD) | –0.34 | –0.76 to 0.08 | NR | 6-months’ follow-up | |||

| 1/21 RCTs | GHQ-12 and GHQ-28; BDI; K10; CIS-Rb | Meta-analysis (SMD) | –1.79 | –3.01 to –0.56 | NR | Over 6-months’ follow-up | |||

| Support group | Psychological distress | 1/21 RCTs | GHQ-12 and GHQ-28; BDI; K10; CIS-Rb | Meta-analysis (SMD) | –0.99 | –1.48 to –0.49 | NR | End of intervention | |

| 1/21 RCTs | GHQ-12 and GHQ-28; BDI; K10; CIS-Rb | Meta-analysis (SMD) | –0.99 | –1.48 to –0.49 | NR | Up to 6-months’ follow-up | |||

| Psychoeducation plus support | Psychological distress | 1/21 RCTs | GHQ-12 and GHQ-28; BDI; K10; CIS-Rb | Meta-analysis (SMD) | –0.28 | –0.84 to 0.29 | NR | Over 6 months post intervention | |

| Problem-solving bibliotherapy | Psychological distress | 1/21 RCTs | GHQ-12 and GHQ-28; BDI; K10; CIS-Rb | Meta-analysis (SMD) | –1.57 | –1.79 to –1.35 | NR | End of intervention | |

| 1/21 RCTs | GHQ-12 and GHQ-28; BDI; K10; CIS-Rb | Meta-analysis (SMD) | –1.54 | –1.95 to –1.13 | NR | Up to 6-months’ follow-up | |||

| Self-management | Psychological distress | 1/21 RCTs | GHQ-12 and GHQ-28; BDI; K10; CIS-Rb | Meta-analysis (SMD) | –0.32 | –0.73 to 0.09 | NR | End of intervention | |

| Practitioner-delivered vs. postal psychoeducation | Psychological distress | 1/21 RCTs | GHQ-12 and GHQ-28; BDI; K10; CIS-Rb | Meta-analysis (SMD) | –0.38 | –1.0 to 0.25 | NR | End of intervention | |

| 1/21 RCTs | GHQ-12 and GHQ-28; BDI; K10; CIS-Rb | Meta-analysis (SMD) | 0 | –0.62 to 0.61 | NR | Up to 6-months’ follow-up | |||

Carers of people with dementia

The reviews of interventions for carers of people with dementia focused mainly on depression, anxiety and self-efficacy. These outcomes are highlighted in the following sections. Other outcomes analysed were psychological distress, psychological well-being, carer mental health and general mental health.

Depression

Narrative syntheses revealed positive intervention effects on depression in Eggenberger et al. 21 following a home-care education intervention with professional support (one good-quality study); Boots et al. ,19 relating to web-based carer support interventions (two studies, one of higher quality and one of lower quality); Godwin et al. ,22 focusing on the Caregiver’s Friend: Dealing with Dementia (involving the delivery of positive caregiving strategies via text and video) or Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health (REACH) interventions (two studies, quality not reported); Hurley et al. ,23 relating to meditation-based interventions (five studies, although the results were mixed at follow-up; all of moderate quality); Lins et al. ,25 for combined telephone counselling, video sessions and workbook (one moderate-quality study); McKechnie et al. ,28 for computer-mediated interventions (four studies, all of high quality); and Smith and Greenwood,32 for anxiety and depression after a befriending intervention (one study after 15 months, of high quality). Quantitative syntheses showed statistically significant positive intervention effects on depression in Jensen et al. ,24 following educational interventions (two studies, one of high quality and one of low quality; no evidence of statistical heterogeneity at I2 = 0%); Vernooij-Dassen et al. ,31 in relation to cognitive reframing (six studies, all of which had some methodological limitations); Chien et al. ,20 for carer support groups (17 studies with high statistical heterogeneity at I2 = 86.03%; six studies maintained the effect at 1–3 months’ follow–up; the studies were of moderate to high quality); and Lins et al. ,25 for depressive symptoms after telephone counselling (three studies of moderate quality; no evidence of statistical heterogeneity at I2 = 0%).

Anxiety

Narrative syntheses showed positive intervention effects for anxiety in Godwin et al. 22 focusing on the Caregiver’s Friend and REACH interventions (number of studies unclear, no quality reported); and McKechnie et al. 28 after computer-mediated interventions (two studies of high quality). Quantitative syntheses showed statistically significant positive intervention effects for anxiety in Vernooij-Dassen et al. 31 following cognitive reframing interventions (four studies, all of which had some methodological limitations).

Self-efficacy

Narrative syntheses showed a small positive intervention effect for self-efficacy in Boots et al. 19 after internet-based support interventions (four studies, one of high quality and three of low quality). In Lins et al. ,25 there were generally mixed effects, but positive effects were noted in the control group (four studies of telephone counselling with or without additional intervention, all of mixed quality).

Other reviews27,29,30 reported mixed, inconclusive or non-significant results for mental health outcomes. No negative intervention effects were reported.

Carers of people with cancer

Improvement in psychological distress was reported in Regan et al. 35 after couples-based psychosocial help (seven studies; intervention vs. control or within groups from baseline; moderate to strong quality). Statistically significant pooled effects were reported for reductions in anxiety following art therapy in Lang and Lim33 (two studies of moderate quality) and in Northouse et al. 34 for distress and anxiety in the first 6 months after psychoeducation interventions, which then increased from small to moderate at beyond 6 months (16 studies, quality not reported). In the same review, a similar positive and statistically significant intervention effect was reported for improved self-efficacy (eight studies, quality not reported) and small, non-statistically significant intervention effects were recorded for depression (18 studies, quality not reported).

Carers of people with stroke

Interventions aiming to improve mental health for carers of people with stroke mainly included psychoeducation and/or counselling, social support and problem-solving, and information provision. There were generally no significant findings and/or the findings were inconsistent. 37–41 When reported, the overall quality of primary studies in these reviews was variable or fair. Legg et al. 41 reported a statistically significant reduction in depression following an intervention focusing on ‘teaching procedural knowledge’ (formal multidisciplinary training of caregiver in the prevention and management of common problems related to stroke) (one study of higher quality). In Forster et al. 40 there was a statistically significant reduction in depression in the active information provision intervention group (one study at some risk of bias).

Carers of people with various conditions at the end of life

Home palliative care and other multicomponent interventions were used to target mental health in carers of people with various conditions at the end of life. Gomes et al. 43 suggested that a reinforced version of home palliative care (comprising added brief psychoeducation delivered by care advisors) had a positive effect on carer distress (one study of lower quality). A meta-analysis in Candy et al. 42 showed reductions in psychological distress at the end of interventions comprising multiple components (eight studies; no evidence of statistical heterogeneity at I2 = 0%; low-quality evidence).

Carers of people with mental health problems

In Macleod et al. ,45 improvements were reported for depression following family interventions (one study, quality not reported), for mood following a mutual support intervention (one study, quality not reported), and for anxiety and distress following supportive family education (two studies, quality not reported); all interventions actively involved carers (e.g. through family education and mutual support assisted by mental health nurses). In addition, statistically significant effects were reported in Yesufu-Udechuku et al. 46 for psychological distress after 6 months’ follow-up of psychoeducation (one study of high quality) and up to 6 months’ follow-up after a support group intervention (one study of low quality). In the same review, problem-solving bibliotherapy [not defined by the review, but a definition can be found in Wikipedia47 (see Glossary)] was found to be effective in reducing psychological distress up to 6 months’ follow-up (one study of moderate quality).

There were no effects on somatic symptoms, anxiety, insomnia, social dysfunction or severe depression following an education intervention in Macleod et al. 45 (one study, quality not reported). Similarly, absence of intervention effect was reported in Yesufu-Udechuku et al. 46 for psychoeducation up to 6 months with or without support (three studies of low quality), and following a self-management intervention (one study of moderate quality) for psychological distress.

Burden and stress

Carer burden and stress was reported in 21 reviews (22 papers). 19–31,33,34,37,38,40,41,43,45,46

Burden and stress were not well-defined outcomes in most reviews, but various outcome measures were reported: the Zarit Burden Scale, the Caregiver Appraisal Inventory, the Caregiver Strain Index (CSI) and others. The measurement tools used in respect of burden were fairly consistent across the reviews. All results are reported in Table 5.

| First author, year of publication | Type of interventions | Outcome | n/N | Measures used | Synthesis approach (summary statistic) | Meta-analysis results | 95% CI | p-value | Outcome calculated at | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Or summary of narrative synthesis | ||||||||||

| Carers of people with dementia | ||||||||||

| Boots, 201419 | Internet-based interventions | Burden | 4/12 | Unclear | Narrative | Mixed results | Unclear | |||

| Stress and strain | 1/12 | Unclear | Narrative | Small significant reduction | Unclear | |||||

| Chien, 201120 | Support groups led by professionals or other trained group members | Burden | 24/30 | Unclear | Meta-analysis (Hedges’ g) | –0.23 | –0.33 to –0.13 | NR | Unclear | |

| 24/30 | Unclear | Meta-analysis (Hedges’ g) | In sensitivity analysis authors reported that effects persisted over time | Unclear | ||||||

| Eggenberger, 201321 | Communication skills | Burden | Unclear | Unclear | Narrative | No significant improvement of family caregiver burden, albeit one study reported a positive effect on burden | Unclear | |||

| Godwin, 201322 | Technology-driven multicomponent support: Caregiver’s Friend | Stress and strain | 1/8 | CSI | Narrative | Significantly reduced stress and strain | Unclear | |||

| ComputerLink | Stress and strain | 1/8 | CSI | Narrative | No overall reduction in strain but reductions were reported for relationship and emotional strain | Unclear | ||||

| Hurley, 201423 | Meditation-based interventions | Burden | 5/8 | Zarit Burden Interview (various versions); RMBC | Narrative | Three studies (including one RCT) found statistically significant reductions in levels of burden pre–post intervention; one study found a non-significant trend and one study found no difference in pre–post intervention levels. There were mixed results at follow-up | Unclear | |||

| Jensen, 201524 | Educational interventions aimed at teaching skills | Burden | 5/7 RCTs | Zarit Burden Scale | Meta-analysis (SMD) | –0.52 | –0.79 to –0.26 | < 0.0001 | Unclear | |

| Shorter intervention length | Burden | ?/7 | Zarit Burden Scale | Meta-analysis (SMD) | –0.86 | –1.24 to –0.47 | NR | Unclear | ||

| Longer intervention length | Burden | ?/7 | Zarit Burden Scale | Meta-analysis (SMD) | –0.36 | –0.60 to –0.13 | Unclear | Unclear | ||

| Lins, 201425 | Telephone counselling with or without additional intervention | Distress | 2/9 RCTs | Scale B of SCB; TCIAT | Narrative | Mixed results for telephone counselling without additional intervention (one RCT). No significant difference between groups following telephone counselling with video sessions and workbook (one RCT) | Unclear | |||

| Burden | 2/9 RCTs | CAI; subunits Upset and Annoyance from RMBC | Narrative | Results of telephone counselling combined with video sessions were not reported (one RCT). No difference between groups following telephone counselling combined with video sessions and workbook (one RCT); and telephone counselling without additional interventions (one RCT) showed reductions in both intervention and control groups (statistical significance not reported) | Unclear | |||||

| Telephone counselling without additional intervention | Burden | 4/9 RCTs (moderate quality) | Zarit Burden Interview; CAI; SCB; RMBC including subunits | Meta-analysis (SMD) | 0.45 | –0.01 to 0.90 | 0.005 | Unclear | ||

| Marim, 201326 | Interdisciplinary education and support programmes | Burden | 7/7 RCTs | Zarit Burden Interview | Meta-analysis (MD) | –1.79 | –4.27 to 0.69 | 0.16 | Unclear | |

| Sensitivity analysis – removal of heterogeneous RCTs | Burden | 4/7 | Zarit Burden Interview | Meta-analysis (MD) | –1.62 | –2.16 to –1.08 | < 0.00001 | Unclear | ||

| Maayan, 201427 | Respite care | Burden | 1/4 RCTs | Zarit Burden Scale | Meta-analysis (MD) | –5.51 | –12.38 to 1.36 | 0.12 | Unclear | |

| Respite care vs. polarity therapy | Stress | 1/4 RCTs | PSS | Meta-analysis (MD) | 5.80 | 1.43 to 10.17 | 0.0093 | Unclear | ||

| McKechnie, 201428 | Computer-mediated psychosocial interventions (complex multifaceted) | Stress and burden | 9/14 | RMBC | Narrative | Five medium-/high-quality studies found positive intervention effects. There were inconsistent findings across the remaining studies | Unclear | |||

| Orgeta, 201429 | Home-based supervised endurance or aerobic exercise; telephone-based exercise promotion; 12-week exercise programme | Perceived stress | 3/4 RCTs Involving two analyses of two RCTs |

PSS | Meta-analysis (SMD) | –0.18 –0.19 |

–0.45 to 0.08 –0.57 to 0.19 |

0.17 0.33 |

Unclear Unclear |

|

| Burden | 2/4 RCTs | SCB | Meta-analysis (SMD) | –0.43 | –0.81 to –0.04 | 0.03 | Unclear | |||

| Burden | 2/4 RCTs | SCB | Narrative | Two other meta-analyses using the same two RCTs for same outcome but using different tools (unclearly reported) found NS differences | Unclear | |||||

| Schoenmakers, 201030 | Active intervention in home care – psychosocial intervention | Burden | 6/26 | Zarit Burden Interview; Lawton Subjective Burden Instrument | Meta-analysis (MD) | –2.94 | –6.28 to 0.40 | 0.08 | Unclear | |

| Respite | Burden | 2/26 | Zarit Burden Interview; Lawton Subjective Burden Instrument | Meta-analysis (MD) | 0.30 | 0.12 to 0.48 | 0.001 | Unclear | ||

| Vernooij-Dassen, 201131 | Cognitive reframing (one element of CBT) | Burden | 3/11 RCTs | Zarit Burden Interview; Caregiver Strain instrument | Meta-analysis (SMD) | –0.14 | –0.32 to 0.03 | 0.12 | Unclear | |

| Stress or distress | 4/11 RCTs | Revised Burden Interview; PSS; investigator developed scales | Meta-analysis (SMD) | –0.24 | –0.40 to –0.07 | 0.0059 | Unclear | |||

| Stress | 3/11 RCTs | Revised memory and behaviour checklist | Meta-analysis (SMD) | –0.21 | –0.45 to 0.03 | 0.09 | Unclear | |||

| Carers of people with cancer | ||||||||||

| Lang, 201433 | Art-making class | Stress | 1/2 | Salivary cortisol | Narrative | Clinically effective in reducing stress among family caregivers. There was no statistically significant reduction in mean cortisol level; 0.089 (SD 0.05) to 0.087 (SD 0.06) | Unclear | |||

| Creative arts intervention | Stress | 1/2 | DABS | Narrative | A statistically significant reduction in stress in family caregivers from baseline 13.27 (SD 6.00) to post intervention 9.85 (SD 5.84; p = 0.001) | Unclear | ||||

| Northouse, 201034 | Psychoeducation; skills training; therapeutic counselling | Burden | 11/29 RCTs | NR | Meta-analysis (Hedges’ g) | 0.22 | 0.08 to 0.35 | < 0.001 | During 3 months post intervention | |

| Psychoeducation; skills training; therapeutic counselling | Burden | 5/29 | NR | Meta-analysis (Hedges’ g) | 0.10 | NR | NR | 3–6 months post intervention | ||

| Carers of people with stroke | ||||||||||

| Cheng, 2012,37 201438 | Psychosocial, group and individual interventions Psychoeducation and counselling |

Burden | 6/18 | CBS; CSI | Narrative | Inconsistent findings were reported | Unclear | |||

| 6/18 | CBS; CSI | Narrative | Authors report similar results for subgroup analysis by intervention | Unclear | ||||||

| Psychosocial interventions (counselling and psychoeducation) | Burden | 5/18 | Various | Meta-analysis (SMD) | –0.04 | –0.25 to 0.17 | 0.70 | Immediately post intervention | ||

| 5/18 | Various | Meta-analysis (SMD) | Authors report similar results were found for subgroup analysis by intervention | Unclear | ||||||

| Forster, 201240 | Passive or active education | Burden | 3/21 RCTs | Various | Narrative | No evidence of effect for passive information compared with control (one UK RCT). Conflicting results were reported for active information interventions (two RCTs, one UK) | Unclear | |||

| Legg, 201141 | Non-pharmacological interventions including support and information; teaching procedural knowledge/vocational education, psychoeducation | Stress or strain | 1/8 RCTs | CSI | Narrative (SMD) | –8.67 | –11.39 to –6.04 | 0.001 | Unclear | |

| Global measures of stress or distress | 2/8 RCTs | GHQ-28 | Narrative | No significant differences | Unclear | |||||

| Support and information interventions | Global measures of stress or distress | 2/8 RCTs | CSI, author defined | Meta-analysis (SMD) | –0.29 | –0.86 to 0.27 | 0.11 | Unclear | ||

| Psychoeducational interventions | Stress or strain | 2/8 RCTs | Zarit Burden Inventory; Relatives’ Stress Index | Meta-analysis (SMD) | 0.01 | –0.34 to 0.36 | 0.94 | Unclear | ||

| Carers of people with various conditions at the end of life | ||||||||||

| Gomes, 201343 | Home palliative care vs. usual care | Pre-bereavement: burden | 3/23 | Montgomery–Borgatta Caregiver Burden Scale; Zarit Burden Inventory | Narrative | Conflicting results | Unclear | |||

| Reinforced vs. standard home palliative care | Caregiver burden | 3/23 | Caregiver Demand Scale; CSI; Zarit Burden Inventory | Narrative | Conflicting results | Unclear | ||||

| Carers of people with mental health problems | ||||||||||

| Macleod, 201145 | Support from community mental health nurses Education |

Burden | 5/68 | NR | Narrative | Mixed findings from studies evaluating education intervention | Unclear | |||

| Supportive family education | Burden | 6/68 | NR | Narrative | Mixed findings for supportive family education with five (four RCTs) studies reporting a decrease in burden and one RCT reporting no significant changes between groups | Unclear | ||||

| Behavioural family therapy | Burden | 6/68 | NR | Narrative | Reductions in carer burden was reported in six studies (three RCTs) for behavioural family therapy | Unclear | ||||

| Cognitive–behavioural family therapy | Burden | 6/68 | NR | Narrative | Mixed results were reported for cognitive–behavioural family therapy with five studies reporting no change in carer burden; one study reported a reduction in carer burden but low number of participants | Unclear | ||||

| Other family interventions | Burden | 8/68 | NR | Narrative | For other intervention approaches only one study out of eight reported improvements for carer burden | Unclear | ||||

| Community support services | Burden | 7/68 | NR | Narrative | Five of seven studies reported reduced burden as a result of assertive community treatment (two studies), clinical case management (one study), home counselling (one study) and multidisciplinary support (one study) | Unclear | ||||

| Mutual support groups | Burden | 2/68 | NR | Narrative | Improvements in burden were reported | Unclear | ||||

| Day-care services | Burden | 3/68 | NR | Narrative | Inconsistent findings | Unclear | ||||

| Supportive family educations | Stress | 1/68 | NR | Narrative | One RCT reported reduced stress for supportive family education | Unclear | ||||

| Yesufu-Udechuku, 201546 | Delivered by health and social care services: psychoeducation vs. postal psychoeducation | Family burden | 1/21 RCT (low quality) | NR | Meta-analysis (SMD) | –0.41 | –1.04 to 0.21 | NR | End of intervention | |

| 1/21 RCT (low quality) | NR | Meta-analysis (SMD) | –0.41 | –1.03 to 0.22 | NR | Up to 6-months’ follow-up | ||||

Carers of people with dementia

For carer burden, narrative syntheses showed statistically significant pre–post intervention reductions (although mixed results at follow-up) for meditation-based interventions in Hurley et al. 23 (three studies of seemingly low to moderate quality). Reductions in burden were found for both intervention and control groups in Lins et al. 25 following telephone counselling without additional intervention (one study at low to unclear risk of bias). Stress and burden were reduced following computer-mediated interventions in McKechnie et al. 28 (five medium- to high-quality studies out of nine in total; the remaining studies had inconsistent findings).