Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 11/2004/50. The contractual start date was in March 2013. The final report began editorial review in May 2016 and was accepted for publication in December 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Fiona Burns reports personal fees and other from Gilead Sciences Ltd and personal fees from Janssen HIV, outside the submitted work. Caroline Sabin reports personal fees from Gilead Sciences Ltd, ViiV Healthcare, Janssen-Cilag and Bristol-Myers Squibb, outside the submitted work. Steve Morris is a member of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Services and Delivery Research Programme Funding Board, which funded this research. He is also a member of the NIHR Public Health Research Funding Board and the NIHR Programme Grants for Applied Research expert subpanel.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Howarth et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

The introduction of combination antiretroviral therapy (ART) has led to a dramatic reduction in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-associated morbidity and mortality. 1 The life expectancy for successfully treated people living with human immunodeficiency virus (PLWH) in the UK is now similar to that of the general population2 and ART is also recognised as an effective means of reducing HIV transmission. 3 However, the individual and public health benefits of HIV treatment can be achieved only if PLWH are aware that they are HIV positive, have linked into care and have sustained engagement with care thereafter. Although interest in this area has increased over the past decade and retention in HIV care is now a key measure of quality performance for HIV service providers in the UK,4 it remains a major challenge, with little evidence available on how to optimise engagement in care (EIC). 5 The Retention and Engagement Across Care services for HIV positive patients in the UK (REACH) study set out to explore, describe and understand attendance of PLWH at HIV outpatient services in order to support the development of cost-effective interventions to improve EIC.

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV and AIDS (UNAIDS)6 set a target that, by 2020, 90% of PLWH should know their HIV status; 90% of those with diagnosed HIV should be on ART; and 90% of people receiving ART should be virally suppressed. The number of PLWH in the UK is estimated to be 107,800 (2.8 per 1000 population aged 15–59 years),7 and only 75% are estimated to be aware of their infection. Once diagnosed, however, year-on-year retention in HIV care is generally good, with only 5% of HIV patients in the UK reported as ‘lost to follow-up’ (LTFU) in any 1 year. On the other hand, cumulative drop over a 10-year period could be as high as one in five patients8 and an analysis of UK cohort data has shown that 17.4% of HIV patients are potentially LTFU. 9 Although the majority of those in HIV care (90%) are on ART and 90% are virally suppressed, we should consider the serious consequences for those who drop out of care. Published studies show that poorer health outcomes, including failure to suppress the viral load, increased drug resistance, reduced cluster of differentiation 4 (CD4) response and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)-defining illness, are consistently reported among HIV patients who engage poorly with care. 5,10,11 Furthermore, poor engagement in HIV care is associated with increased mortality. 12–14

The REACH study is particularly timely in the current context of expanded HIV testing and the development of ‘test and treat’ as a form of secondary HIV prevention. 15 Innovative models of care to improve early diagnosis of HIV must be complemented by strategies to promote long-term integration into care in order to realise the benefits of wider testing and treatment on the future spread of HIV in the UK.

The REACH study set out to examine those who are attending clinics but not at the optimal level, as well as those LTFU. Missed outpatient appointments also have significant resource implications for service providers, with the financial cost of missed appointments to the NHS estimated to be between £585M and £1B. 16–18 National outpatient non-attendance rates, which vary from 5% to 16%, are higher among younger patients and those in deprived areas18 and unpublished data from London HIV clinics indicate that outpatient non-attendance for PLWH can be as high as 25%. Retaining HIV patients in care may also reduce emergency department visits and hospitalisation,19,20 and the resultant financial costs.

In order to explore patterns of retention and engagement in HIV care, it is essential to adopt a valid and reliable measure, and yet there is no gold standard measure of engagement in HIV outpatient care. Researchers have assessed retention in care in a number of different ways. 21–25 These measures have their own strengths and weaknesses,26 but none of them takes into account the fact that frequency of attendance is related to changes in treatment and health status and may also be affected by external forces or changes in clinic policy. In the UK, for example, guidelines at the time the REACH study was conducted indicated that patients should be seen within 2–4 weeks of starting ART and every 3–6 months for routine monitoring on ART if they were considered ‘stable’, with good adherence and an undetectable viral load. 27 Given that frequency of monitoring is dependent on treatment and health status and that gaps between clinic visits may vary quite considerably within the current guidelines, the REACH study aimed to develop a measure of EIC that would be sensitive to changes at an individual or clinic level over time. This measure was then to be applied to an investigation of the health and economic impacts of disengaging from HIV care.

A better understanding of the factors associated with retention in HIV care and a means to predict disengagement is essential for both individual and public health benefit. Previous studies have examined the association between engagement in HIV care, as defined by one of the measures described above, and background characteristics. Although health service provision and populations of PLWH vary from country to country, these studies suggest that PLWH are less likely to disengage from care if they are male,8 older,8,21,28,29 white8,22 and men who have sex with men (MSM)22,23 and have started ART. 8,21 Socioeconomic factors and education have been highlighted in relation to disparities in EIC30,31 and complex patient groups, such as intravenous drug users, migrants and the newly diagnosed, are more likely to disengage from care. 23 Although recent diagnosis is associated with poor retention in care,8 there is also an indication that EIC can diminish over time. 22

Some studies have used qualitative methods and psychometric measures to try and understand why patients do not engage with care. HIV stigma is found to be a significant barrier32–35 and health beliefs may also deter people from attending for care. 36 A qualitative study on non-attendance of HIV clinics in Scotland highlighted issues of mental health, isolation, stigma, poverty and complex social circumstances as contributing to disengagement from care. 37 The REACH study set out to collect extensive quantitative and qualitative data and bring this evidence together to better understand who disengages from HIV care and why.

There have been, to our knowledge, no trials to evaluate interventions to improve engagement in HIV care in the UK. Although a number of interventions have been tested in the USA, a recent systematic review found only 13 published studies on which to base its analysis. 38 The population of PLWH and health-care system are very different in the USA and REACH provides the data to develop interventions for the UK context. Simple changes in the way services are delivered may be effective16 and the REACH study also helps us understand whether or not and how previous interventions to improve EIC in other health-care settings are likely to meet the diverse needs of PLWH in the UK. In this way, REACH provides a crucial bridge from research that purely describes the associations with engagement in HIV care to the development of innovative strategies to maintain patient retention. The data were used, first, to develop a diagnostic retention risk tool to help clinicians identify newly diagnosed patients at risk of disengaging from care and, second, to design and cost behaviour change interventions aimed at improving engagement in HIV care.

Retention in HIV care is vital for treatment success at both individual and population levels. Good engagement is associated with improved adherence, virological and immunological outcomes and survival. 15 It is important to develop NHS services that are flexible and responsive to the needs of the service users and that align to the wider NHS priorities of driving and achieving quality and efficiency within service delivery. The ultimate aim of the REACH study is to ensure the effective use of resources to improve engagement in HIV care and optimise health outcomes.

Aims and objectives

The REACH study aimed to explore, describe and understand HIV outpatient attendance in PLWH, in order to develop cost-effective interventions to optimise their EIC.

Its objectives were to:

-

examine HIV outpatient attendance patterns among PLWH

-

identify predictive factors of disengagement

-

investigate the potential health and financial costs of disengaging from care

-

develop a retention risk assessment tool

-

understand the situational, environmental, behavioural and social factors influencing outpatient attendance

-

develop intervention models to improve EIC, to be tested in future studies.

The full protocol has been published on the National Institute and Health Research Health Service and Delivery Research Programme website. The REACH Management Team met quarterly and benefited from an Advisory Group made up of a clinician from each of the recruitment sites and a patient representative, and a Study Steering Committee made up of four independent experts (see Appendix 1). The Advisory Group met every 6 months and the Study Steering Committee met once a year. In between meetings, communication was electronic, including a quarterly progress update.

Chapter 2 Methods

This chapter describes the methods used to address the aims and objectives of the study. Different methodologies were adopted to address the broad range of objectives that the study sought to address and the following description of them is divided up according to the three key phases of the study:

Phase 1: analysis of the UK Collaborative HIV Cohort database and predictive modelling

During this phase, we explored HIV outpatient attendance (objective 1), identified predictive factors of disengagement (objective 2) and investigated the potential health and financial costs of disengagement (objective 3).

Phase 2: examining patient experience

The second phase of this study comprised quantitative and qualitative methods to understand the factors that influence outpatient attendance (objective 5). Findings contributed to the development of a retention risk assessment tool (objective 4) and informed development of intervention models to improve EIC (objective 6).

Phase 3: key informant study

The final phase of the study aimed to understand the factors that influence outpatient attendance (objective 5) from the service providers’ perspective. It informed development of intervention models to improve EIC (objective 6).

After this, we describe how we calculated the costs for our proposed intervention models and the patient and public involvement in the study.

Phase 1: analysis of the UK Collaborative HIV Cohort data

In this section, we describe phase 1 of the study, which consisted of a detailed analysis of the UK Collaborative HIV Cohort (UK CHIC) database, including an exploration of attendance patterns and factors associated with disengagement from care.

Outpatient attendance patterns among people living with HIV

The UK CHIC collates routine data relating to the clinical care and treatment of PLWH aged ≥ 16 years across many of the UK’s largest HIV services (the data set utilised for the present analyses included data from 15 HIV clinics) since 1 January 1996. The UK CHIC records incorporate additional mortality data provided by Public Health England.

We explored the use of group-based trajectory modelling for identifying clusters of individuals following similar, distinctive progressions of attendance over age or time. 39–41 These methods were applied to the UK CHIC data set in order to distinguish distinct broad groupings of individuals according to their pattern of engagement with the aim of identifying a unique, statistical snapshot of the key characteristics of this complex population. We collaborated with Dr Tracy Glass at the Basel Institute for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, who has utilised a similar technique to explore and describe patient adherence to ART in the Swiss HIV Cohort Study. 42 Once the trajectories are identified, logistic regression analysis can then be used to predict the probability of an individual being in a particular group according to a particular set of risk factors.

Group-based trajectory analysis is usually applied to a fixed period of time during which individuals are exposed to a condition or data are collected at fixed points in time and a measure of their response can be plotted over time. We therefore developed an EIC algorithm in order to define whether patients were in care or out of care for each month of follow-up.

Development of engagement in care algorithm

As we know that frequency of HIV clinic attendance is related to changes in treatment and health status, our aim was to incorporate clinical factors into our new measure of retention in HIV care.

In the absence of complete data on clinic attendances in the UK CHIC data set, we used CD4 counts, viral loads, haemoglobin measures and ART treatment start or switch dates as markers of clinic attendance. Patients often return for repeat laboratory tests over a short period of time to confirm unexpected findings, resulting in clusters of attendances around a single ‘index’ date. As we did not want to consider each attendance within a cluster as an independent visit and wanted to be able to plot whether patients were in care or out of care for each month of follow-up, we grouped attendances into ‘care episodes’, defined as months (period of 30.4 days since entry into the study) where at least one visit occurred. For each care episode, we established the lowest CD4 count measured in that month (and the change from the previous value), the highest HIV viral load (and the status of this measurement relative to other consecutive values) and the patient’s treatment status.

In order to decide which key clinical factors should be incorporated the EIC algorithm, semistructured, face-to-face interviews were conducted with eight HIV physicians (from August 2013 to February 2014) who had a range of clinical experience and were selected from five of the HIV outpatient clinics where we planned to conduct our primary data collection. We asked physicians to tell us when they planned to see each of their last 10 patients again (number of weeks/months) and why.

A total of 73 patients were discussed in these interviews. One patient was excluded from the analysis because the time of their next appointment was dependent on awaited test results. The time of the next scheduled appointment was missing for another patient and not available for a further five patients who had not attended their last scheduled appointment at the time of the physician interviews. We conducted a content analysis of these qualitative data. For each patient, we noted the time to the next scheduled appointment and the key reason given by their physician. We then identified factors under which to code the key reasons.

The time of the next scheduled appointment in the 66 patients included in the analysis ranged from 1 week to 6 months, with a median of 3 months. Five factors were identified from the content analysis of the interview data as instrumental to the timing of the next scheduled appointment. The first factor can be summarised as ‘routine’ where patients were stable and required routine follow-up. These appointments were mostly arranged for 4–6 months after the previous visit. A routine follow-up appointment was arranged for 3 months’ time for one pregnant woman. Physicians talked about how they extended routine visits to every 6 months when patients were well and stable, both on treatment and in their psychosocial circumstances. The second factor is summarised as ‘virological’ where the next appointment was based on change in viral load (uncontrolled or virological breakthrough). Changes in viral load brought the next scheduled appointment forward to 1–2 months after the last. The third factor, ‘treatment’, described where the next appointment was related to starting ART or changing an existing ART regimen. Patients were given a next appointment date between 2 and 12 weeks later, depending on the treatment start date and virological response or when treatment was planned to start. The fourth and fifth factors were ‘psychosocial’ where mental health or psychosocial issues were identified as instrumental and ‘physical comorbidities’ where a range of physical comorbidities were given as the key reason for the timing of the next appointment. Follow-up appointments of between 1 week and 4 months were arranged depending on psychosocial issues (from specific concerns about mental health to more general needs for social support) and comorbidities: both of which required earlier follow-up even when patients were otherwise stable on treatment.

The data from the physician interviews were used as the basis for developing the EIC algorithm. Although psychosocial well-being and comorbidities were key factors in determining the expected time between patients’ visits, data on these variables are not captured in the UK CHIC data set. We therefore used the clinical data that were available (HIV diagnosis, AIDS diagnosis, treatment start dates, CD4 count and viral load) to determine the patient’s treatment and health status. These data were then used to estimate the expected time to the next scheduled care episode, in accordance with the data collected in the physician interviews. Table 1 shows when the next care episode was expected, according to the specified conditions. Using the EIC algorithm, we cannot consider follow-up after the patient’s last reported care date and it therefore focuses on intermittent periods of disengagement rather than LTFU. It should furthermore be noted that treatment guidelines introduced in the UK in October 2015 (after our physician interviews had been conducted) recommend starting ART irrespective of CD4 count. 43 This should be incorporated into the EIC algorithm when applied to EIC after October 2015.

| Conditions at time of initial care episodea | Next care episode expected within |

|---|---|

| Within 1 month of HIV diagnosis | 2 months |

| AIDS diagnosis | 2 months |

| Started ART | 2 months |

| Started new combination ART regimen | 2 months |

| Not on ART | |

| CD4 ≤ 350 cells/mm3, any drop in CD4 | 2 months |

| CD4 ≤ 350 cells/mm3, no drop in CD4 | 4 months |

| CD4 = 351–499 cells/mm3 | 4 months |

| CD4 ≥ 500 cells/mm3, CD4 drop ≥ 100 cells/mm3 | 4 months |

| CD4 ≥ 500 cells/mm3, CD4 drop < 100 cells/mm3, viral load ≥ 100,000 copies/ml | 4 months |

| CD4 ≥ 500 cells/mm3, CD4 drop < 100 cells/mm3, viral load < 100,000 copies/ml | 6 months |

| Already started ART | |

| Viral load > 200 copies/ml | 2 months |

| Viral load = 51–200 copies/ml, does not appear to be a blipb | 2 months |

| Viral load = 51–200 copies/ml, appears to be a blip | 4 months |

| Viral load ≤ 50 copies/ml, CD4 ≤ 200 cells/mm3 | 4 months |

| Viral load ≤ 50 copies/ml, CD4 > 200 cells/mm3 | 6 months |

The EIC algorithm gives the shortest expected gap between care episodes at 2 months. This is to allow for the fact that clinic visits might occur at any point during the month or care episode into which they are grouped. If the patient was within 1 month of diagnosis, had an AIDS diagnosis, started ART or changed ART at the initial care episode, the next care episode was expected within 2 months. If the patient was not on ART at the initial care episode, the next care episode was expected within 2–6 months, depending mainly on CD4 count. If the patient had started ART, it was expected within 2–6 months, depending on viral load. We used 6 months as the maximum time between visits, as described in the physician interviews. If more than one condition applied at the time of the initial care episode, the next care episode was expected within the least number of months associated with those conditions.

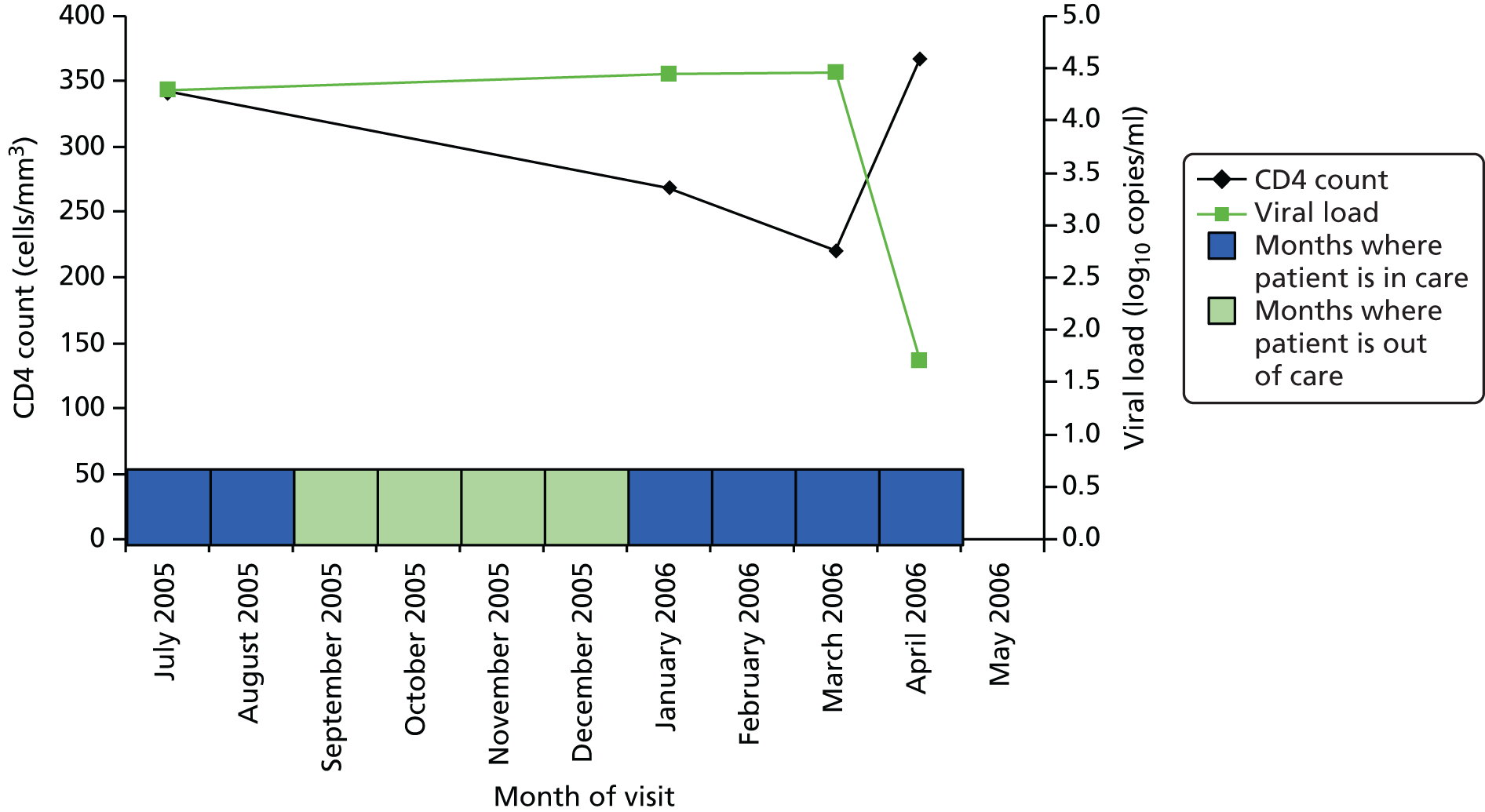

Figure 1 shows an example of how the EIC algorithm is applied to an individual case. The date of the next observed care episode determines whether or not the patient has attended before or after the expected date, and each patient-month is then classified as being in care (where it occurs on or before the time of the next expected care episode) or out of care (where it occurs after the time of the next expected care episode) accordingly. This example begins in July 2005 when the patient was not pregnant, not recently diagnosed, did not have an AIDS diagnosis and was not on ART. Because she was not on ART, we are interested in her CD4 count – which was < 350 cells/mm3 and which had dropped (although that is not shown here), so we expect to see her again within 2 months. However, she did not reattend until 6 months later. Thus, July and August are defined as being in care (blue shading), but September to December are out of care (green shading). At the visit in January 2006, her CD4 count had continued to drop, so we expect to see her again within 2 months. She reattended in March 2006 so January and February are defined as being in care. In March 2006 she started ART, so we expect to see her within 2 months and she comes back within a month, remaining in care.

FIGURE 1.

Measurement of engagement in HIV care applied to an individual care.

Group-based trajectory analysis

We then applied the EIC algorithm to the group-based trajectory analysis. Patients with complete laboratory data who attended a participating UK CHIC clinic on at least two occasions between 1 January 2000 and 31 December 2011 were included in the analysis. Follow-up for each person was considered until the last recorded laboratory marker or clinic visit prior to (or on) 31 December 2011. As we were interested in patterns of attendance from diagnosis onwards, we excluded patients who had been diagnosed before 1 January 2000.

Whereas group-based trajectory analysis is usually applied to a fixed period of time, the exposure period (or time since diagnosis) was highly variable in our analysis and related to the outcome measure of being in care or out of care. It was difficult to apply patterns of engagement to the 12-year period of follow-up for the whole cohort because individuals contributed longer and shorter periods of follow-up, which also varied according to the time that the patient entered or left the cohort. In an attempt to overcome this, we examined patterns of attendance for people diagnosed over three 3-year periods (2000–2, 2003–5 and 2006–8). Although this controls the start point for the analysis to some extent, it does not account for the fact that patient end points will vary over the course of the trajectories. We excluded attendance over the last year of follow-up from the analysis, as this may skew the trajectories.

With group-based trajectory analysis, the researcher determines the number of trajectories each time the analysis is run in order to test which number of trajectories gives the best fit. Models were tested with one to five trajectories for each of the three diagnosis periods and the optimal model (which indicates the optimal number of trajectories) was selected for each of the three diagnosis groups. This was based on statistical fit, by comparing the Bayesian information criterion (BIC), and interpretability. Twice the difference between the BIC for the two models under comparison is used for this purpose. 39 The plots and patterns of attendance from our group-based trajectory analysis are presented and described in Chapter 3. However, this analysis resulted in three different models (one for each of the 3-year diagnosis periods), which we consider to be the minimum number of models to reflect the range of diagnosis dates over a 12-year period. This makes their use in further analysis of associated factors and outcome problematic.

Association with clinical outcomes

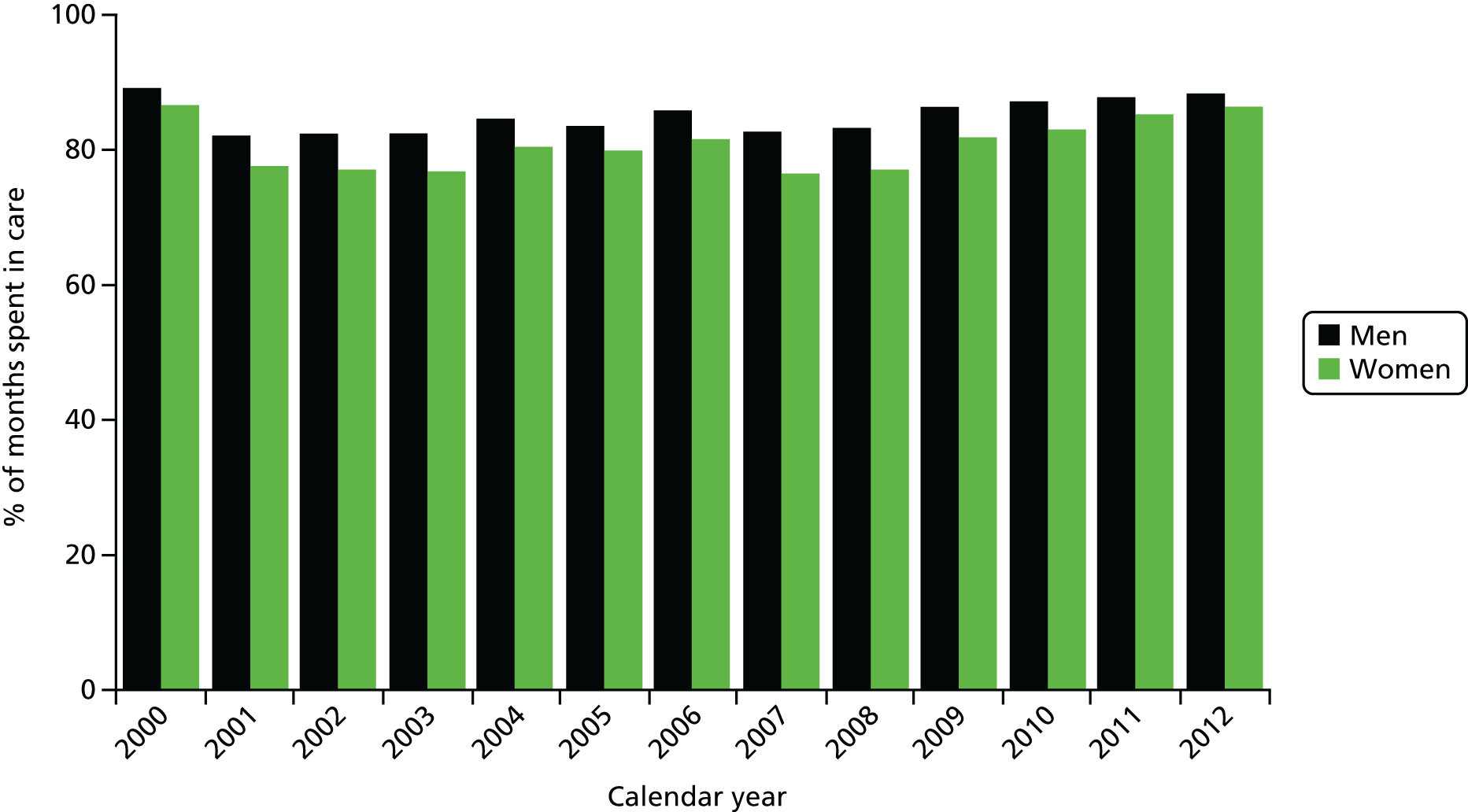

In view of the limitations of using the findings from our group-based trajectory analysis in further analysis to examine the associated clinical outcomes, we decided to use the proportion of time in care as a more straightforward and fitting measure of engagement in HIV care for further analysis. The individual case shown in Figure 1, for example, was out of care for 4 of her 10 months’ follow-up and in care for 6 of her 10 months’ follow-up = 60% of months. The EIC measure, furthermore, provides an alternative to the idea that disengagement from care requires an individual to be LTFU for a specified period of time which does not lend itself to quantifying the typical length of disengagement or proportion of patients that re-engage with care, as described in our protocol.

In the following analysis, all patients who attended a participating UK CHIC clinic on two or more occasions between 1 January 2000 and 31 December 2012 were included. The proportion of months in which patients were engaged in HIV care was calculated overall and for patient subgroups defined by gender, age group (< 25, 25–45 and > 45 years), ethnic group (white, black African, other and unknown), mode of HIV acquisition (sex between men, sex between men and women, injection drug use and other/unknown), currently on ART (yes, no), nadir and current CD4 count (both classified as < 200, 200–349 and ≥ 350 cells/mm3), participating clinic, calendar year (2000–3, 2004–7, 2008–12) and time since entry in the study (< 1, 1–5, 5–10 and > 10 years). Each patient-month was then treated as a separate entry in a multivariable logistic regression model with the aim of identifying demographic and clinical factors associated with that month being in care. The analyses were performed using PROC GENMOD in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) with generalised estimating equations used to take account of the repeated entries within each individual patient.

Cox models were used to assess the association between mortality and (i) the cumulative proportion of months a person had been in care; and (ii) the cumulative proportion of months a person was in care prior to ART. For analysis (i), patient follow-up started on the date of entry to the UK CHIC study and ended at the date of death or 6 months after the patient’s last clinic attendance, whichever occurred first. Each person’s total period of follow-up was split into consecutive monthly intervals (as described above) and the cumulative proportion of previous months a patient had been in care at the start of the month was calculated for each month of follow-up. In this way, we were able to include the EIC covariate as a continuous time-updated covariate with each person’s EIC evolving over time in the model. One of the main limitations of analyses that investigate associations between EIC and mortality, particularly where a time-updated covariate is used, is the potential for reverse causality whereby those who are sickest may attend for care more frequently in the months leading up to death. This may make it appear that higher levels of EIC are associated with an increased risk of mortality. In order to reduce the potential for this to bias our analyses, all measures of EIC were lagged by 12 months to separate the assessment of EIC and the mortality outcome by a period of 1 year. At any given time over follow-up (i.e. at the start of each patient-month that is included in the model), therefore, the lagged value of EIC that was entered into the model was the value that was available 12 months earlier. Thus, our estimate of the relative hazard (RH) associated with EIC will provide a description of the ability of our EIC measure to predict mortality events that occur at least 1 year into the future. Note that, by definition, this approach will necessarily restrict analyses to those who had attended clinic for > 1 year, as individuals who die within the first 12 months of follow-up will not contribute any EIC values to the model and will therefore be excluded. In our primary analyses, we adjusted for the demographic factors of age, year, gender, mode of acquisition and ethnic group (all fixed covariates). This was followed by additional adjustment for receipt of ART as a binary time-updated covariate. We next adjusted for the latest CD4 count, as a continuous time-updated covariate and lagged by 12 months, to investigate whether or not any association seen was explained by the fact that those with the lowest EIC values already had lower CD4 counts at the time of measurement of EIC. Finally, we adjusted for the unlagged values of CD4 – this analysis explored whether or not any residual association between EIC and mortality was mediated by lower CD4 counts over the following 12 months.

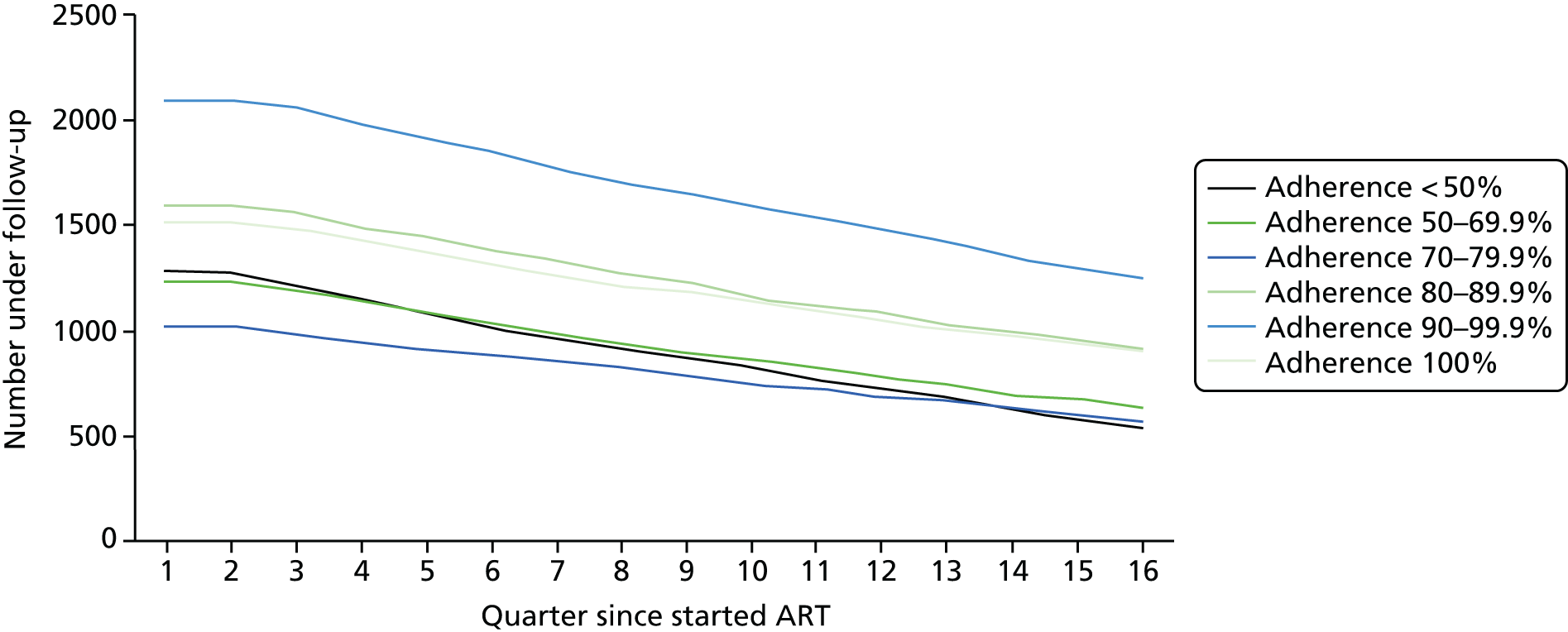

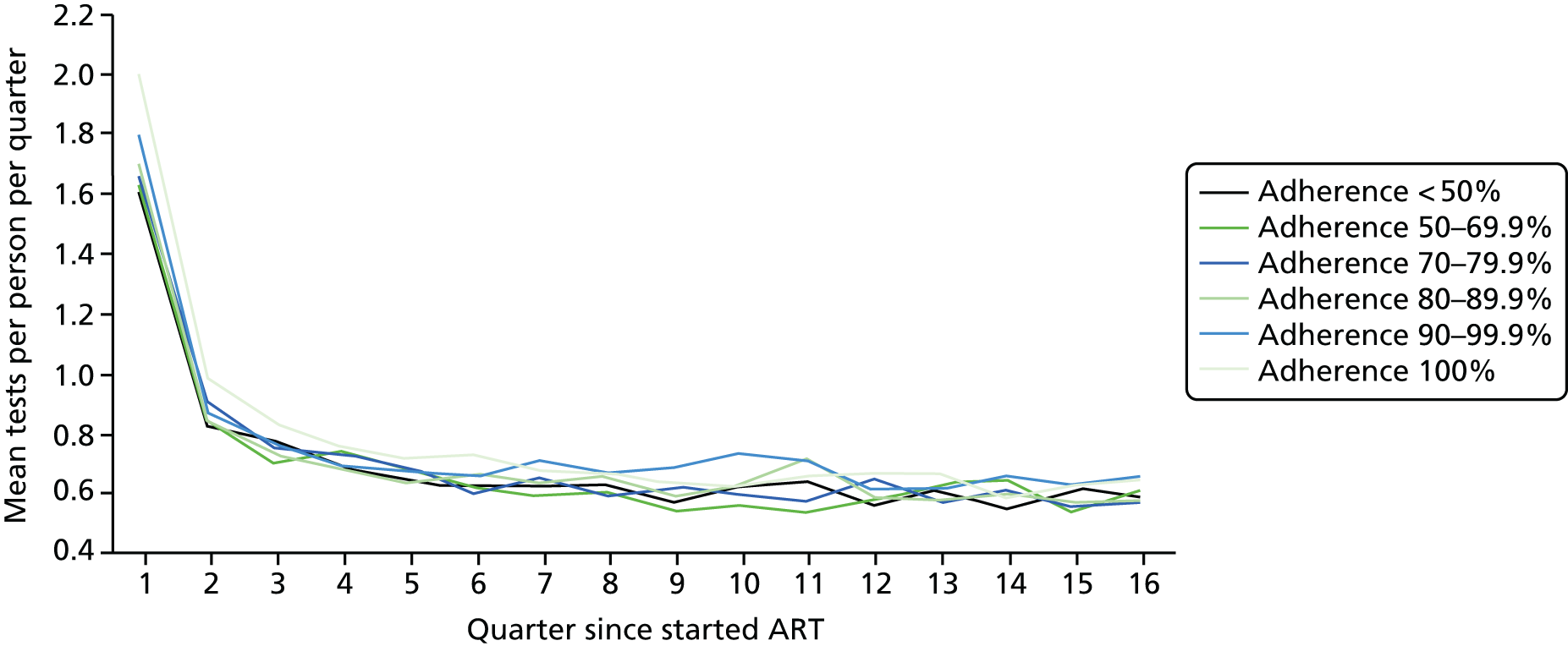

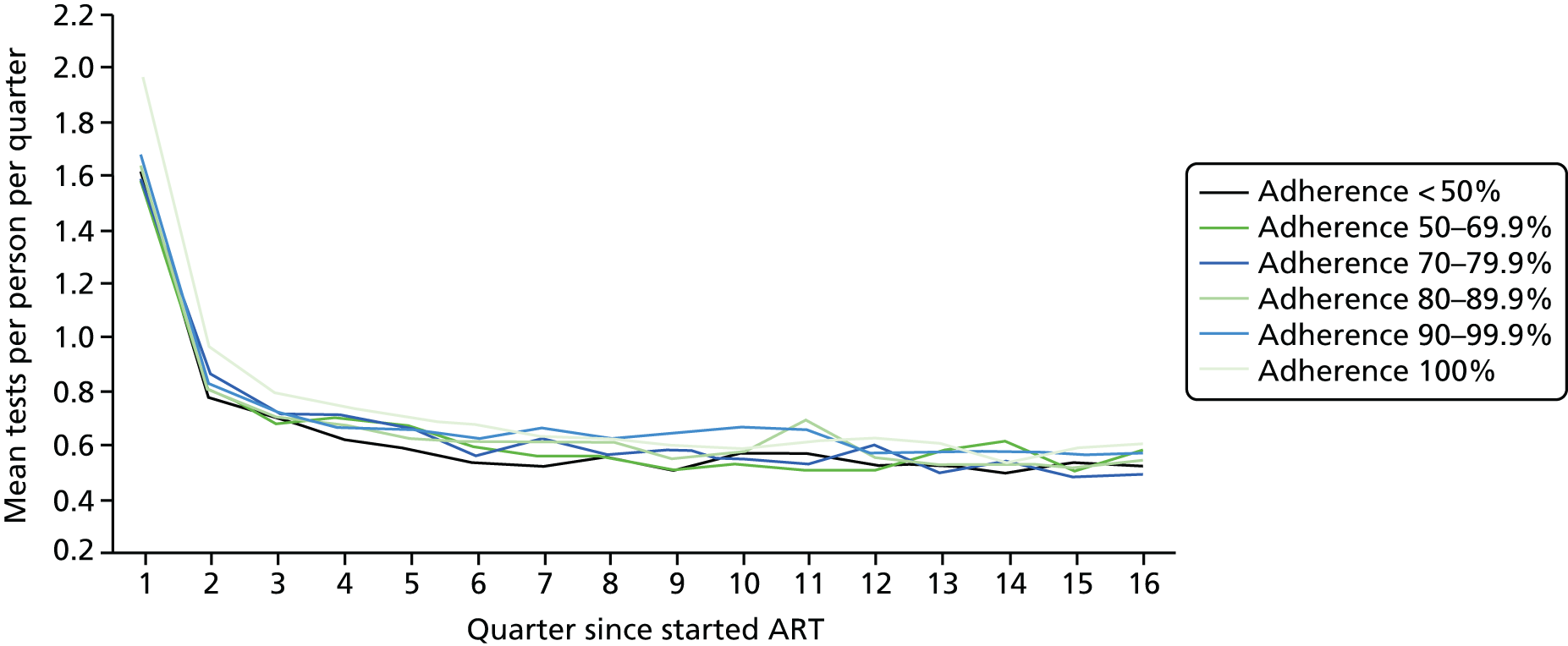

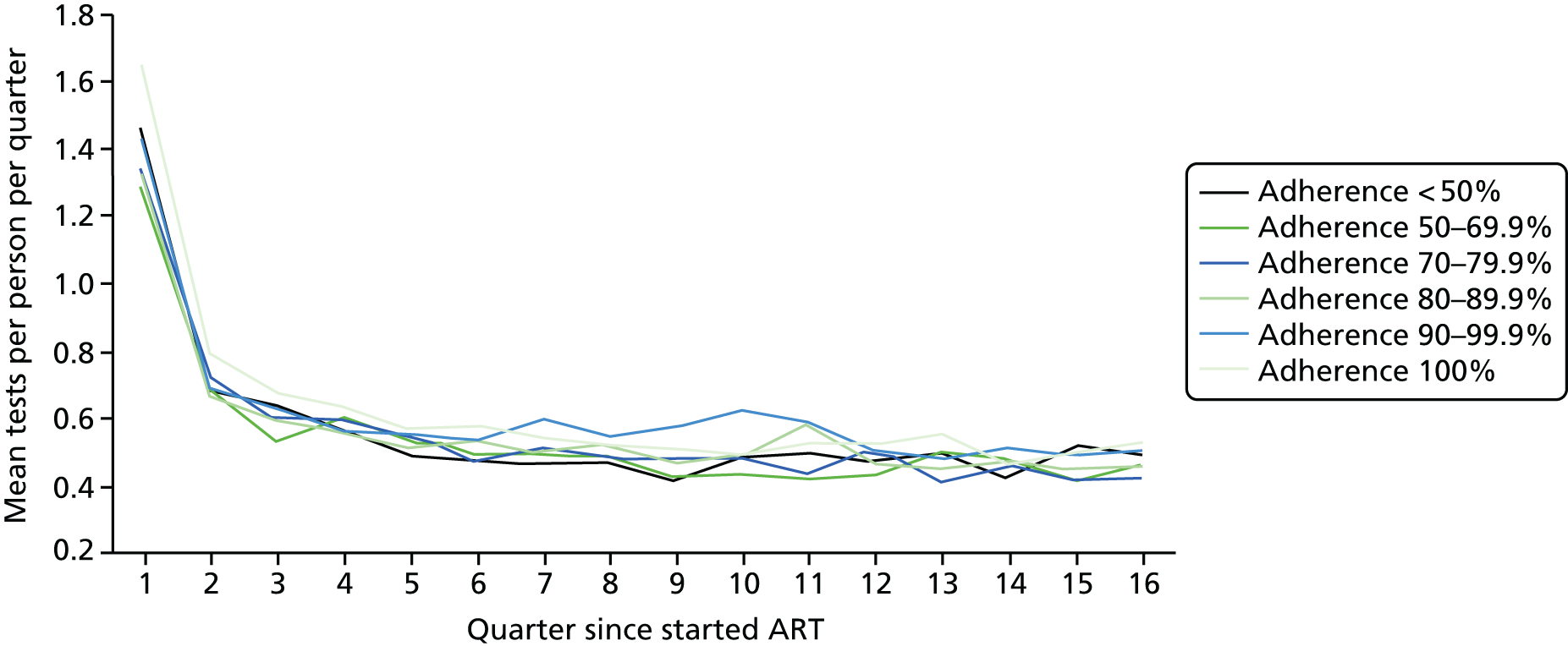

For analysis (ii), we calculated the EIC prior to ART in the subset of patients who initiated ART and who had been under follow-up at the clinic for at least 1 year prior to ART start (to ensure that the estimate of EIC was based on sufficient patient-months to provide a robust estimate). To explore the potential for confounding, patients were first stratified into six groups based on their pre-ART EIC. The groups (< 50%, 50–69.9%, 70–79.9%, 80–89.9%, 90–99.9% and 100%) were chosen primarily for ease of clinical interpretation and to ensure that each group was of sufficient size to permit robust analyses. Associations between the pre-ART EIC value and the various demographic and clinical factors at ART start were then identified. Next, Cox models considered the association between EIC (as a fixed baseline covariate) and mortality after ART initiation; follow-up started at ART initiation and ended at 6 months after the patient’s last visit or death – whichever of the two occurred first. We first adjusted for age, year, gender, mode of acquisition and ethnic group, then type of ART received [protease inhibitor (PI)-based regimen, non-nucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI)-based regimen, other regimen (including those on both a PI and NNRTI)], then the CD4 count and viral load at ART start (fixed covariates) and then, finally, the latest CD4 count and viral load (as time-updated covariates) measured after ART start. As before, these last analyses investigate whether or not any associations between pre-ART EIC and post-ART mortality can be explained by poorer CD4/viral load responses on ART.

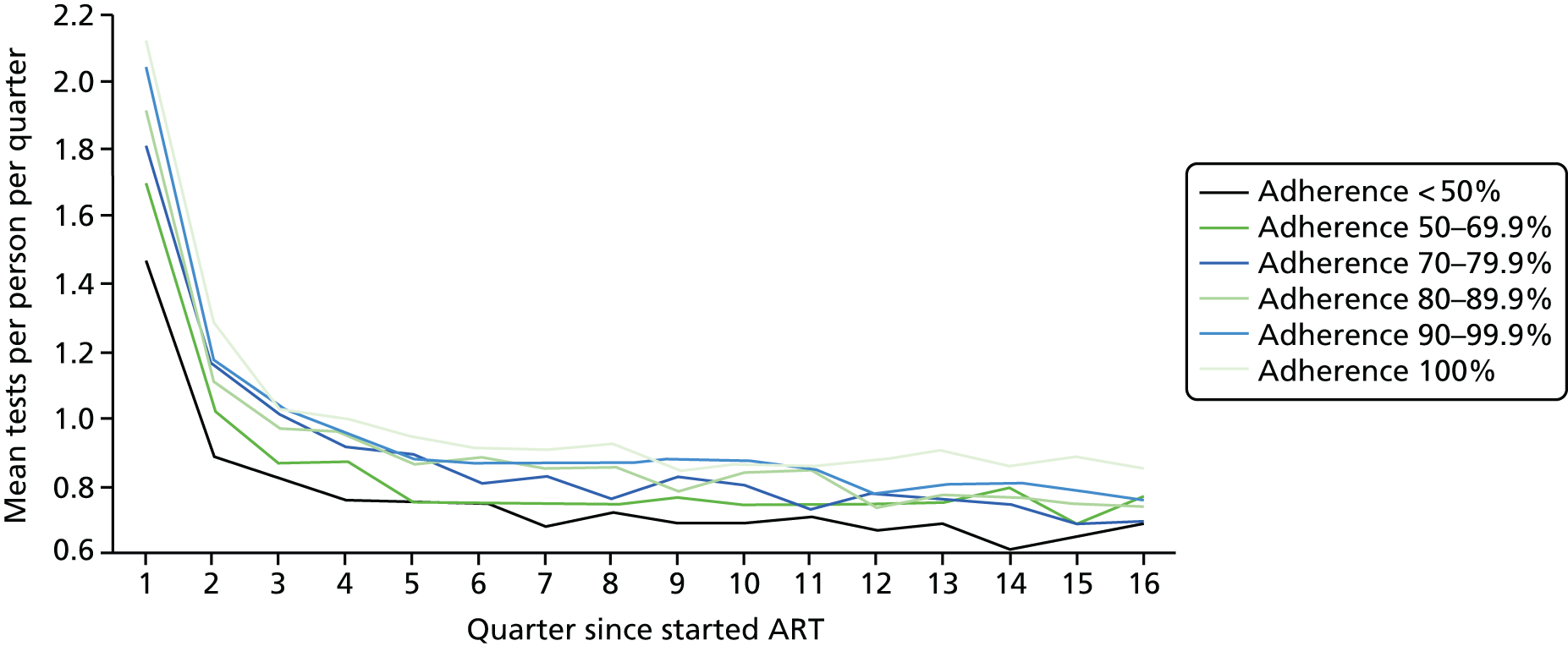

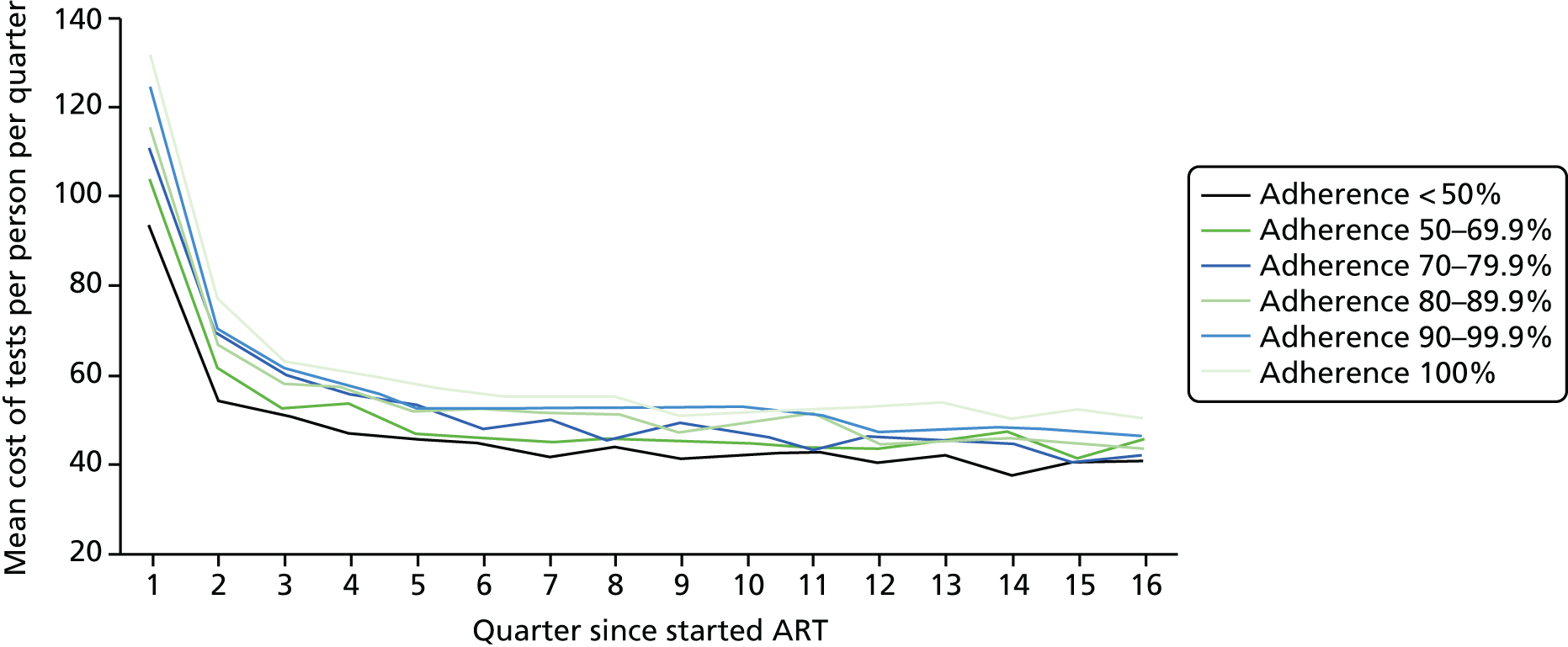

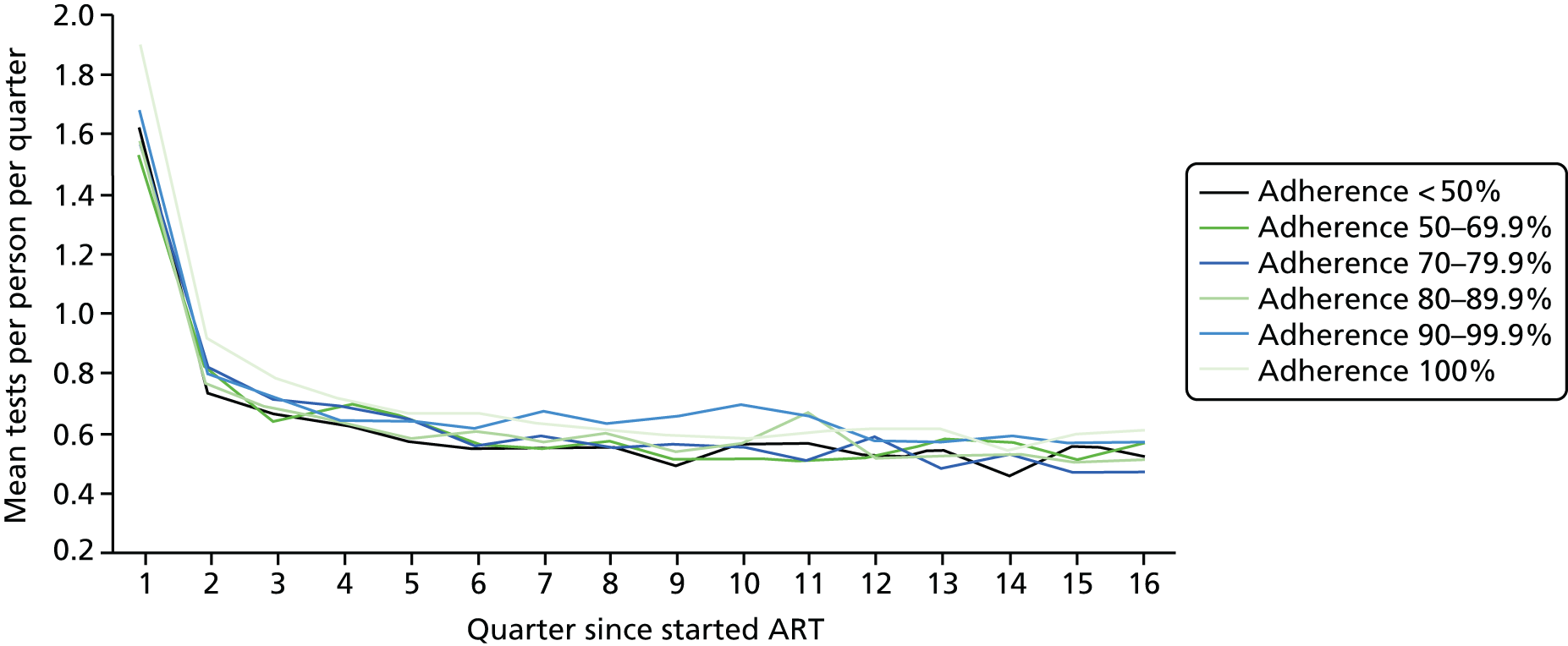

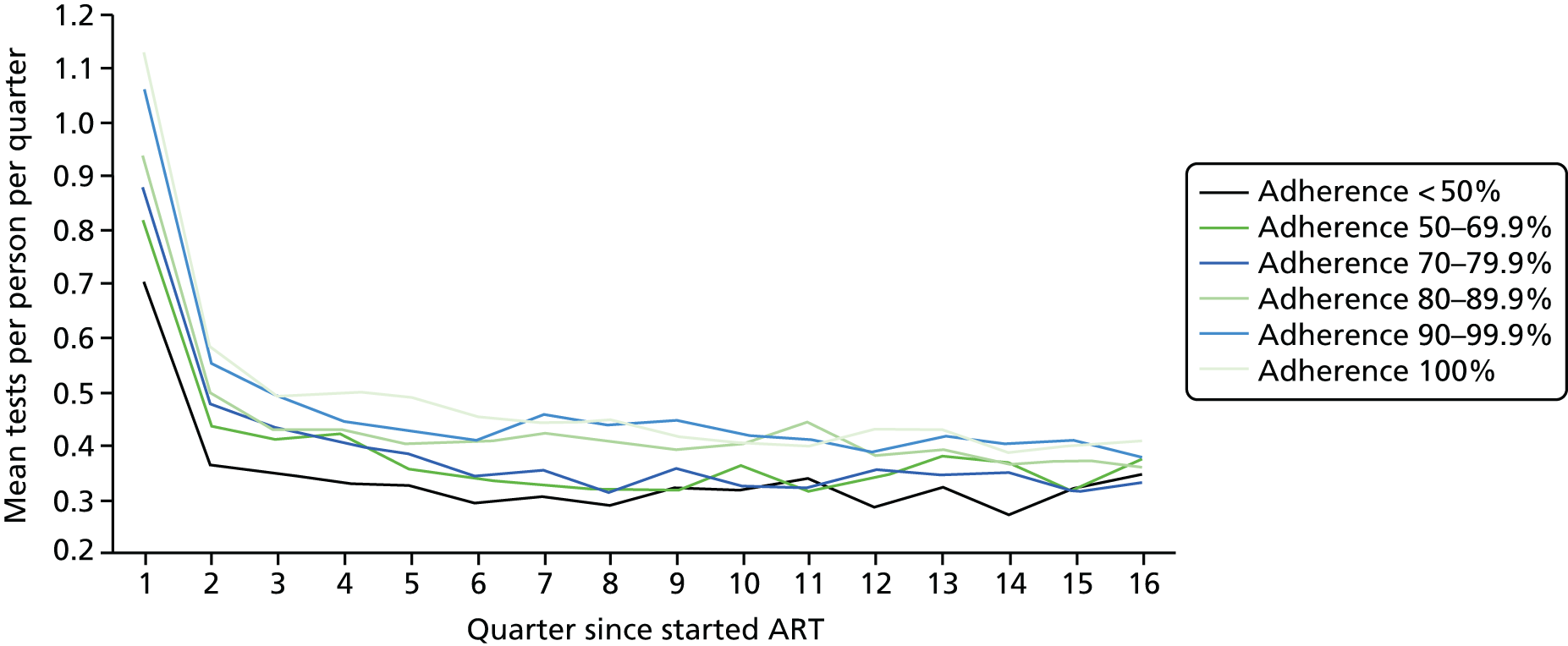

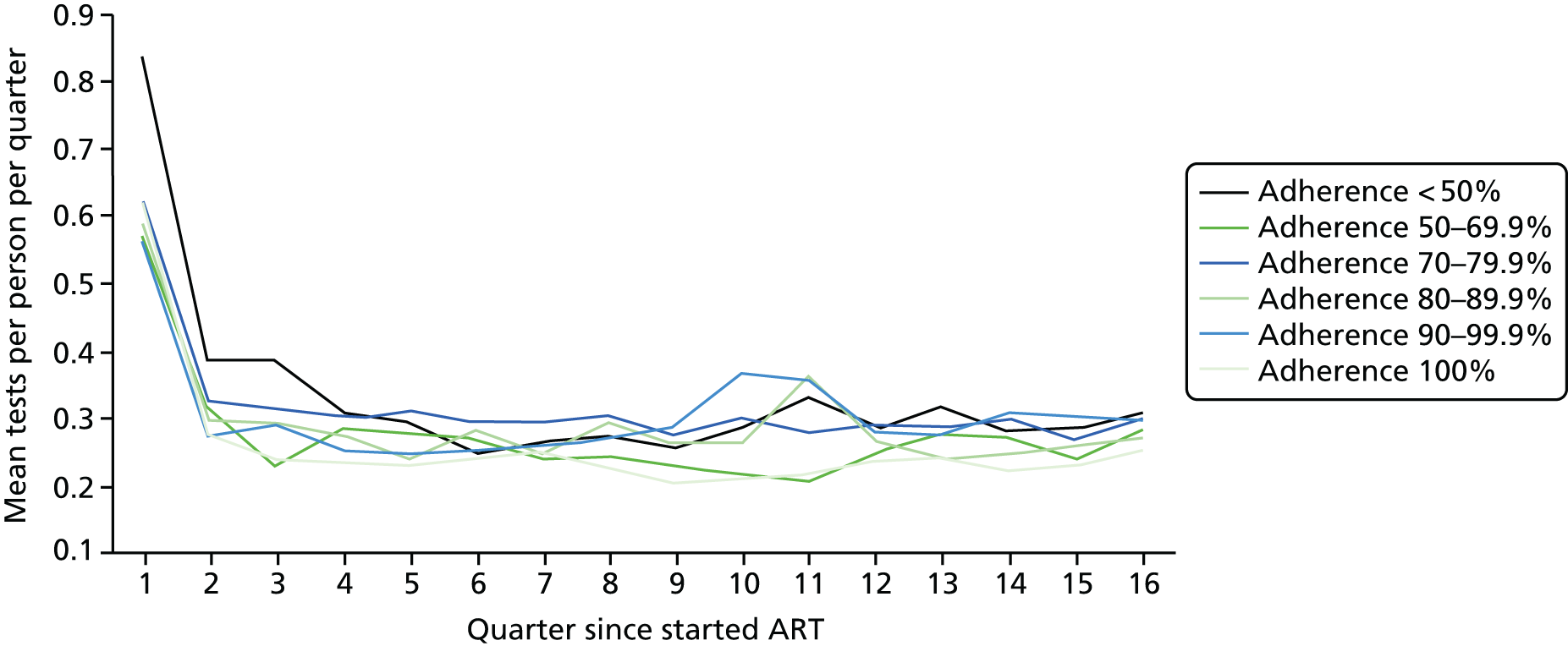

Association with laboratory tests and costs

For our health economic analysis, we planned to measure the impact of disengagement on HIV management costs. As noted in our study protocol, such an analysis was likely to be difficult as it would be limited by the lack of NHS resource utilisation data captured in UK CHIC. Given the limited data for some but not all clinics on outpatient clinic attendances and inpatient stays we therefore limited our study to a descriptive analysis to selected laboratory test costs, which are reliably collected in UK CHIC across participating clinics.

Using the ART data set from analysis (ii), we calculated the total number of laboratory tests performed within each pre-ART EIC group within each 3-month period of follow-up after ART start until the end of the fourth year after starting ART. We included the following tests:

-

CD4

-

HIV viral load

-

liver function tests

-

cholesterol

-

high-density lipoprotein

-

low-density lipoprotein

-

triglycerides

-

full blood count

-

urea

-

creatinine

-

glucose

-

bone health.

Liver function tests included one or more of the following blood tests: alkaline phosphatase, alanine transaminase, aspartate aminotransferase or bilirubin. Full blood counts included haemoglobin and/or platelets. A patient was recorded as having a liver function test or full blood count if they had one or more of the constituent tests on the same day. Bone health profiles were identified when a patient had a phosphate test.

We divided the number of tests by the group size in each 3-month period (which declined over time) to calculate the mean number of tests per patient per quarter, with the group size in each period determined on the basis of the patient’s first and last visit dates, regardless of whether or not she/he had actually attended for care in that period. Unit costs were applied to each laboratory test and summed across all tests, and the mean cost per patient was calculated within each EIC and time stratum. The unit costs were mean costs from two HIV clinics in London, measured in 2016 GBP. The unit costs are summarised in Table 2.

| Test | Test cost (£) |

|---|---|

| CD4 | 22.27 |

| Viral load | 32.91 |

| Liver function tests | 4.68 |

| Cholesterol | 0.75 |

| High-density lipoprotein | 0.94 |

| Low-density lipoprotein | 0.47 |

| Triglycerides | 0.78 |

| Full blood count | 3.65 |

| Urea | 0.59 |

| Creatinine | 0.55 |

| Glucose | 0.76 |

| Bone health | 1.33 |

Mean costs for the six pre-ART EIC groups were then plotted by quarter in the 4 years following ART start. Given the limitations of the data we do not undertake formal tests of differences between groups over time, but focus on descriptive trends. We were particularly interested in investigating whether or not pre-ART EIC affected testing and test costs after starting ART, and in particular whether or not costs became higher in the less engaged groups over time if their health declined, at a more rapid rate than in those who had a higher pre-ART EIC value.

Although we had planned to incorporate the development of a retention risk tool into the first phase of the study, the Management Team agreed that the REACH survey would provide a richer source of data than the UK CHIC data set to identify clinical and non-clinical factors that may predict disengagement. This analysis was therefore moved into phase 2 of the study and is described as follows.

Phase 2: survey, patient interviews, focus groups

Phase 2 of the study consisted of a quantitative survey followed by a nested qualitative substudy. Ethical approval for this phase of study was obtained from the National Research Ethics Service Committee London – City Road & Hampstead (reference 14/LO/0039). NHS permission for research (research and development approval) was granted by the local NHS trusts.

Phase 2a: quantitative component – questionnaire and clinical data collection

Population and setting

A cross-sectional self-completion survey was conducted with adult men and women (aged ≥ 18 years) attending seven London clinics for HIV care between May 2014 and August 2015. Patients were excluded from the study if they had been diagnosed with HIV within the previous 4 months or were unable to provide informed consent. The cohort sizes, composition and models of service delivery varied across the recruitment centres, contributing to the generalisability of the findings:

-

Ambrose King Centre, The Royal London Hospital

-

Bloomsbury Clinic, Mortimer Market Centre

-

Clifden Centre, Homerton University Hospital

-

Greenway Centre, Newham University Hospital

-

Harrison Wing, St Thomas’ Hospital

-

Ian Charleson Day Centre, Royal Free Hospital

-

Kobler Day Care Unit, Chelsea and Westminster Hospital.

Survey sample size

The target sample size was 1000 patients from HIV clinics across London. We aimed to recruit a total of 250 irregularly attending patients and 250 non-attending patients with a comparison group of 500 regularly attending patients (definitions are given in Survey recruitment), providing over 80% power when either disengaged group is compared with the control group to detect a difference in the prevalence of a suspected predictor of disengagement when the population difference is 56% versus 44% or 14% versus 7%, at a 5% significance level.

Survey recruitment

Five of the seven clinics began recruitment in May 2014 and two additional sites began in November and December 2014. Each site recruited patients until they reached their target of 200 patients or 14 August 2015, whichever was the sooner.

Originally it was planned to apply the patterns of attendance identified in phase 1 to our survey sampling. We had envisaged using patient records and electronic/clinical databases to derive an attendance pattern to each patient. However, we decided against this strategy for three reasons. First, we did not find group-based trajectory analysis to be a useful method of identifying patterns of patient attendance that could be used for sampling. Second, applying the EIC algorithm to recruiting patients in each of the clinics would be too complex to undertake. Third, although the UK CHIC analysis explores patterns of attendance over time, we needed to be able to capture current behaviour for the purposes of the survey. We therefore developed a simple algorithm that could be used by research staff in the clinics to recruit patients based on their recent attendance behaviour.

Each clinic aimed to recruit a total of 200 patients who had attended in the following way in the past year:

-

100 regularly attending patients

-

who had attended all intended HIV clinical appointments in the past year

-

-

50 irregularly attending patients

-

who had missed one or more intended HIV clinical appointments (which had not been rescheduled within 1 month) in the past year

-

-

50 non-attending patients

-

who had experienced a period of non-attendance for a year or more at any HIV service that ended within the past year or continued to the present day.

-

Patients were approached by a member of the local research team and asked if they would like to take part in the study. They were given an information sheet summarising the study and its key objectives, and including contact details for the Project Management Team. The local research staff explained the purpose of the study and answered any questions, and patients provided informed consent to participate. Patients were encouraged to complete the questionnaire at the clinic but if they did not have time to do this, they could take the questionnaire with them and return it using a pre-paid envelope. There was also the option to complete the questionnaire online, but very few patients were offered this alternative and only two responses were returned in this way.

Patients who completed a questionnaire at the clinic, handed it back to local research staff in a sealed envelope in order to keep their responses confidential. The completed questionnaires were collected from clinics on a regular basis.

Towards the end of the data collection period, when targeting non-attending patients, clinics were able to send out a letter approved by the Ethics Committee inviting them to participate along with a copy of the questionnaire and return envelope.

Study questionnaire

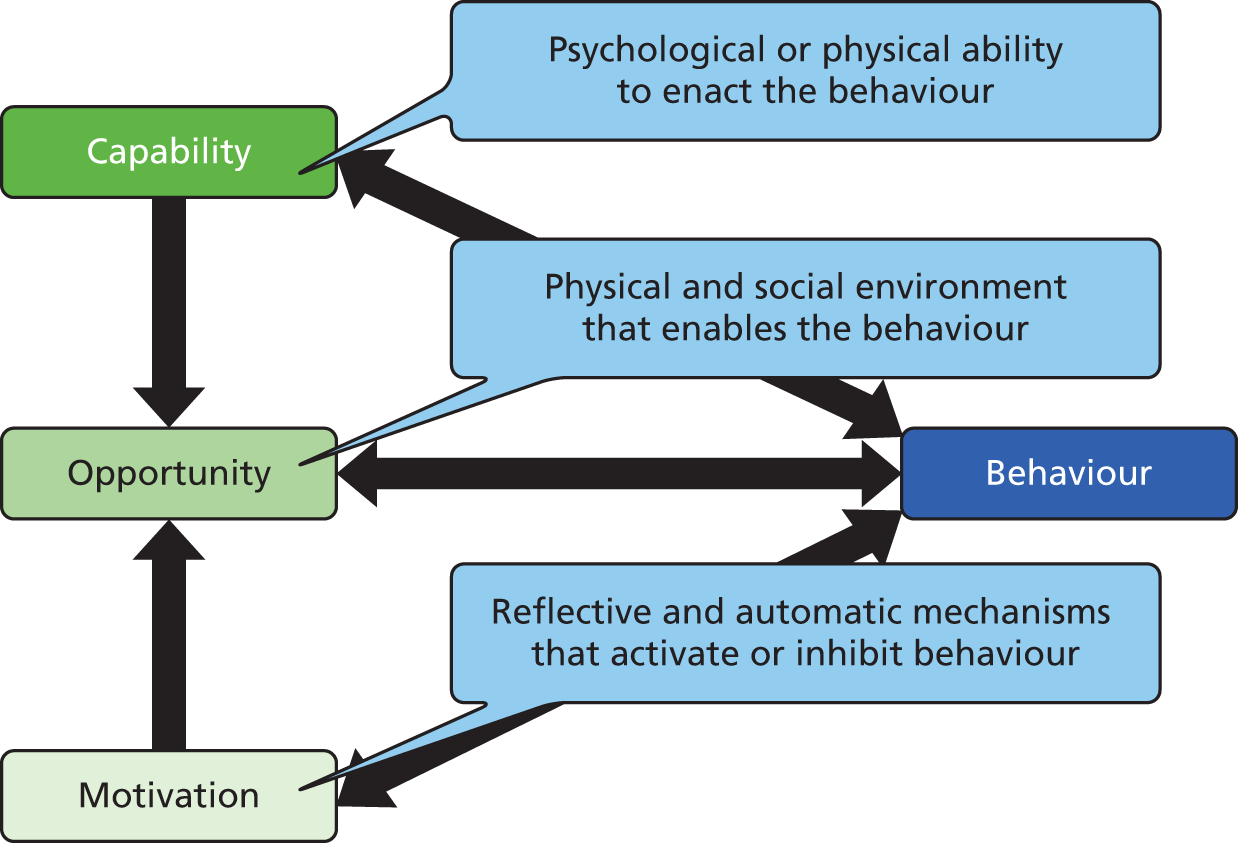

The anonymised pen-and-paper questionnaire was completed in clinics where it was linked to clinical data. It contained 80 questions and took about 20–30 minutes to complete (see Appendix 2). Questions were based on variables from the COM-B (‘capability’, ‘opportunity’, ‘motivation’ and ‘behaviour’) model (Figure 2), which proposes that behaviour occurs as an interaction between three necessary conditions of capability, opportunity and motivation. 45 The COM-B model is at the centre of an integrative framework of behaviour change interventions, the behaviour change wheel comprising nine intervention functions and seven policy categories. It provides a framework for developing, evaluating and synthesising interventions, including selecting behaviour change techniques in the development process.

FIGURE 2.

The COM-B model of behaviour. Adapted from the original figure (see Michie et al. 45) through inclusion of description of the three domains. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

A framework for REACH primary research (see Appendix 3) was created to aid our variable selection. The framework brought together the COM-B model, the associated domains of behavioural influence from the theoretical domains framework46 and related constructs, as well as factors associated with engagement requiring change that were identified in an in-depth report on non-attendance of HIV services in Scotland. 37 Thus, when selecting which items should be included in the questionnaire, we could ensure that we had adequate measures from the different sections of the framework, including the three key domains of capability, opportunity and motivation.

Whenever possible, the questionnaire incorporated validated items used in other large-scale behavioural surveys but new questions were developed where we were unable to find published measures. Items from the following scales were included: three items from Household Food Insecurity Access Scale;47 all seven items from the Strive Internalised Stigma scale;48 three items from the environmental mastery subscale of the Psychological Well-Being Scales (PWB);49,50 five items from the Duke-UNC Functional Social Support Questionnaire (DUFSS);51 all four items from the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ4);52 all three items from the European AIDS Clinical Society screening questions for neurocognitive impairment;53 and two items from the Health Information Competence Scale. 54,55 We used the following five items from the 11-item Belief about Medicines Questionnaire (BMQ):56,57

-

my health, at present, depends on these medicines

-

having to take these medicines worries me

-

my health in the future will depend on these medicines

-

I sometimes worry about becoming too dependent on these medicines

-

these medicines give me unpleasant side effects.

We used all five items from the Medication Adherence Report Scale (MARS). 58 We did not use any of the framing statements from the BMQ or MARS due to the limited amount of space in the questionnaire.

The questionnaire content was piloted to test feasibility and acceptability among five PLWH, including a patient representative with extensive experience of working with people who have difficulties engaging in HIV care. The questionnaire was piloted to test keywords and constructs with five PLWH. The content was modified in the light of this feedback.

The final questionnaire was a 24-page printed A5 booklet. In addition, a computer-assisted self-interview (CASI) version was developed, programmed in survey software and tested for the study. However, most of the clinics preferred to use the paper version and the CASI version was only offered to a minority of patients at two of the clinics and electronic responses were returned by two patients. The questionnaire was divided into the following sections:

General information: gender, age, ethnic group, country of birth, immigration status, language, relationship status, children, pregnancy, work status, education, religion, sexual orientation, poverty, accommodation and hunger.

Life with HIV: date of diagnosis, place of diagnosis, activity, HIV disclosure, stigma, environmental mastery, caring responsibilities, domestic abuse, social support, support groups and recreational drug use.

Health and health care: health status, mental health, professional support, neurocognitive impairment, general practitioner (GP) registration, inpatient stays, health information competence.

Human immunodeficiency virus care: reasons for missed appointments, number of clinics attended, frequency of attendance, time at present clinic, travel to clinic, clinic hours, mode of consultations, clinic recommendation, appointment booking, reasons for attending, communication with reception staff, nurse and doctor, and treatment explanation.

Medicines: beliefs about medicines, ART status, home delivery service, medication adherence and reasons for not taking ART.

Linked clinical data

Consent to participate included linking questionnaire responses to routine clinical data. The clinical data consisted of:

Background data: age, gender, transmission group, country of birth, date of diagnosis, ART status. These variables were checked against the questionnaire data and final variables were derived for analysis.

Clinical data: patient complexity according to category 3 criteria of the HIV and AIDS Reporting System (HARS),59 pregnancy at diagnosis, HIV-related inpatient stays, CD4 count at diagnosis or first recorded, CD4 count at ART initiation, most recent CD4 count, viral load at diagnosis or first recorded, most recent viral load, AIDS-defining illness, hepatitis C coinfection, hepatitis B coinfection, mental health and drug/alcohol dependency.

Survey data processing

Clinics were asked to keep a log of all patients who were approached to take part in the study. Each patient was given a unique study number that was written on the front of their questionnaire and entered into a study log. The study log was maintained securely at the clinic. In addition to the unique study number, it contained the date of attendance, clinic number and some basic demographics (age, gender, ethnic group), as well as the outcome of the approach. Local research staff checked the patients’ attendance pattern over the past year to assign them to one of the three attendance groups and this information was added to the study log. Local staff transferred an anonymised version of the clinic log (without clinic number) to the Project Management Team on a monthly basis.

The completed paper questionnaires were entered into IBM SPSS Statistics version 22 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) by a data entry clerk and a randomly selected sample of one-third of the questionnaires were checked for accuracy of data inputting.

Survey analysis

Survey data were analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 22 and Stata 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). The following description of the survey analysis begins with the analytical approach used in developing the retention risk tool, followed by the analytical approach used to explore factors associated with poor retention to care.

Analysis for retention risk tool

The retention risk tool is an equation that can be used to calculate the predicted probability that a patient will disengage from care. If the tool or algorithm that we have developed here is externally validated in an independent population, it could be used to help clinicians identify newly diagnosed patients at risk of disengaging from care. It would ultimately be a practical diagnostic tool that could be incorporated into clinical practice for multidisciplinary caregivers of HIV patients. Although we had originally planned to use UK CHIC data to develop the tool, the REACH survey provides a richer data set for this purpose.

Univariable associations were explored (using the chi-squared test and the Student’s t-test) between variables derived from responses to the questionnaire and clinical data from patients’ notes and whether or not individuals had recently disengaged from care. For this analysis, we compared regular attenders (RAs) with a combined group of irregular attenders (IAs) and non-attenders (NAs). The decision to combine IAs and NAs was made because the key purpose of the tool in the clinical setting will be to identify someone at risk for any type of disengagement at the point of diagnosis. This should then be followed up with a needs assessment for those identified as being at risk in order to intervene appropriately.

Variables were considered for inclusion in the retention risk tool (and thus included in the univariable analysis) if they were potentially predictive of future disengagement at the time of diagnosis (i.e. variables that pre-exist or may pre-exist diagnosis). As the tool will be tested and used in clinics not included in this study, we excluded the clinic currently attended from the model. We excluded variables that would have occurred after HIV diagnosis, such as HIV service use or HIV disclosure but we included time taken to get to clinic and mode of transport, as these are more likely to remain fixed after HIV diagnosis. We also excluded variables if they were not applicable to all patients or had very high levels of missing data (> 40%). We excluded scales because the incorporation of several items may result in missing data that would be problematic for their use in a practical tool. Responses to psychometric measures, in addition, may change over time. We excluded measures of recent physical or mental health that were current or had reference periods of < 6 months, as these may have been caused by HIV. We excluded variables with very low prevalence (< 5%), as this may not provide sufficient variability to be appropriate for modelling. All items needed to be suitable for collection at the patient’s baseline assessment with a HIV clinician.

Investigation of the 27 candidate variables for inclusion in the model indicated that the mean number of missing data was 2.9% and the maximum number was 7.9%. The majority of variables (n = 21) had < 5% missing data and six had 5–10% missing data. In view of the complicated nature of data imputation and the small number of missing data, we conducted the analysis excluding missing data listwise, whereby all data are removed for cases that have one or more missing values.

Variables that met the above criteria and were significantly associated (p < 0.05) with disengagement from HIV care were included in logistic regression modelling. We used backwards-stepwise binary logistic regression to select the best set of predictive variables associated with disengagement from care. It is important to bear in mind that, when testing models, the general rule of thumb for not over fitting the model is that there should at least 10 cases per covariate in the model. 60 To this end, we fitted the models by adding variables in blocks, which followed a chronological order. First, we fitted the block 1 variables to determine which combination had the best predictive power, then we added the block 2 variables and so on, until all blocks and all 27 variables had been added. The following blocks were applied:

-

block 1: fixed sociodemographic variables

-

block 2: sociodemographic variables that are subject to change over time

-

block 3: variables about circumstances of HIV diagnosis

-

block 4: health, mental health and drug use, ever reported

-

block 5: mental health and drug use, within the past 5 years

-

block 6: variables about potentially transient circumstances

-

block 7: variables about getting to the clinic.

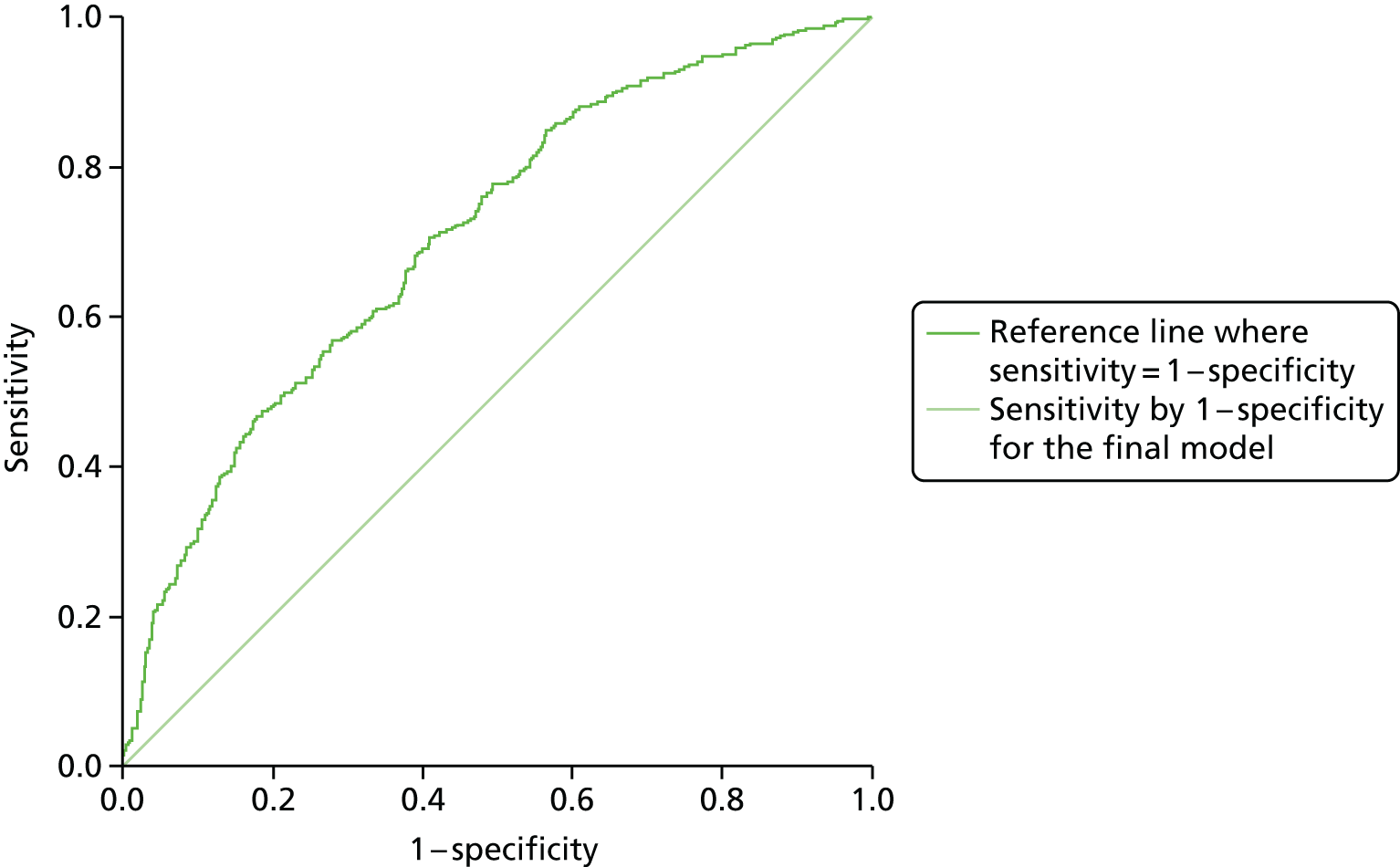

Standard methods for assessing model effectiveness were used. 61–64 The Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test was used to measure model calibration. A p-value that is above the threshold for statistical significance, in this case p > 0.05, indicates that the data predicted by the model are not significantly different from the observed data. Model discrimination was tested using the c-statistic or area under the receiver operating characteristic (AUROC) curve. A value of 0.9–1.0 is considered excellent, 0.8–0.9 is good, 0.7–0.8 is fair, 0.6–0.7 is poor and ≤ 0.6 is worthless. The c-statistic, pseudo-R2 and minus twice the log-likelihood (–2LL) were used to examine effectiveness and compare models. When comparing models, the Cox–Snell pseudo-R2 gives an estimation of the proportion of the outcome variable explained by the predictive variables and a smaller value of –2LL indicates that the model is a better fit. The regression coefficients were used to calculate each person’s probability of disengagement and this was compared with their observed risk in order to examine the sensitivity and specificity of the model.

The face validity of the model was tested by asking clinicians whether or not the predictive variables corresponded to their clinical experience. As the model was developed using the complete REACH survey data set in order to ensure sufficient statistical power, its external validity will need to be tested in a future study by applying the tool to a sample of patients to be followed over a 24-month period to determine if it predicts future disengagement from care.

Analysis of factors associated with engagement in HIV care

We used univariable analysis (chi-squared and the Student’s t-test) to examine associations between variables derived from responses to the questionnaire and clinical data from patients’ notes and membership of attendance groups: RAs, IAs and NAs. Multivariable analysis was used to derive parsimonious sets of variables that are independently associated with engagement in HIV care. As different proportions of RAs, IAs and NAs were recruited from each of the clinics, multivariable analysis also allowed for adjustment by clinic where the respondents were recruited. In addition to clinic, we adjusted for background factors in all models. We used backwards-stepwise multinomial logistic regression to select the best sets of predictive variables associated with irregular and non-attendance, compared with regular attendance. The stepwise method takes standard confounding between variables into account by including and excluding explanatory variables from the model, according to the degree of correlation with the dependent variable. It controls for the effects of the other independent variables as they are entered and can therefore be used to establish the most parsimonious model. Interaction terms were not included in this analysis. We included predictive variables that were significantly associated (p < 0.05) with the attendance groups in the univariable analysis in the models. We collapsed categories where this did not change the statistical association with the dependent variable. We excluded significantly associated variables that did not have any predictive value such as how often respondents expected to have a routine consultation. In order to avoid overfitting the data, we used separate models to explore the association between attendance and background factors, HIV diagnosis and health service use, factors relating to capability, motivation, opportunity (relating to social influences), opportunity (relating to barriers), use of ART and clinical data.

In order to derive two final models for variables associated with irregular and non-attendance, we included variables that the above multinomial logistic regressions indicated were associated with irregular and non-attendance in binary logistic regression. Variables were added to the models in the following order, as described above:

-

block 1: clinic attended and demographic variables

-

block 2: other background variables

-

block 3: mental and physical health in the past year or more

-

block 4: other variables.

The final two models were selected on the basis of having the highest Cox–Snell pseudo-R2 and thereby explaining the highest proportion of the outcome variables.

Phase 2b: qualitative component – individual patient interviews

Exploratory, face-to-face, semistructured interviews were undertaken with a purposively selected sample of men and women who had attended the HIV clinics where survey recruitment was taking place from June 2014 to February 2015. Eligible participants were men and women living with HIV aged ≥ 18 years. Patients were excluded from the individual interviews if they were unable to provide informed consent or if they had acquired HIV through vertical transmission as another study [Adolescents and Adults Living with Perinatal HIV (AALPHI) cohort study of HIV-infected young people]65 was recruiting these patients for individual interviews concurrently.

Patient interview sample size

We planned to recruit a sample of up to 40 men and women. Table 3 shows the quota matrix describing the sampling plan to ensure maximum diversity in terms of attendance pattern and key characteristics. Our primary quotas were attendance pattern and combined gender and sexual orientation. We wanted to oversample IAs and NAs to ensure that a range of their experiences were captured in our interview data. We also wanted to recruit sufficient numbers of gay and bisexual men, heterosexual men and women in order to provide sufficient data to explore their potentially diverse experiences.

| Irregularly attending (n = 20) | Gay male (n = 6–7) | Heterosexual male (n = 6–7) | Female (n = 6–7) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PWID (n = 1–2) | UK born (n = 3–4) | Black African (n = 3–4) | Black African (n = 4–5) |

| Not on treatment (n = 1–2) | Non-UK born (n = 3–4) | Other ethnicity (n = 3–4) | Other ethnicity (n = 2–3) |

| Diagnosed in past 2 years (n = 1–2) | Younger (n = 3–4) | Younger (n = 3–4) | Younger (n = 3–4) |

| Older (n = 2–3) | Older (n = 2–3) | Older (n = 2–3) | |

| Non-attending (n = 10) | Gay male (n = 3–4) | Heterosexual male (n = 3–4) | Female (n = 3–4) |

| PWID (n = 1–2) | UK born (n = 2–3) | Black African (n = 1–2) | Black African (n = 2–3) |

| Not on treatment (n = 1–2) | Non-UK born (n = 1–2) | Other ethnicity (n = 1–2) | Other ethnicity (n = 1–2) |

| Diagnosed in past 2 years (n = 1–2) | Younger (n = 2–3) | Younger (n = 2–3) | Younger (n = 2–3) |

| Older (n = 1–2) | Older (n = 1–2) | Older (n = 1–2) | |

| Regularly attending (n = 10) | Gay male (n = 3–4) | Heterosexual male (n = 3–4) | Female (n = 3–4) |

| PWID (n = 1–2) | UK born (n = 2–3) | Black African (n = 1–2) | Black African (n = 2–3) |

| Not on treatment (n = 1–2) | Non-UK born (n = 1–2) | Other ethnicity (n = 1–2) | Other ethnicity (n = 1–2) |

| Diagnosed in past 2 years (n = 1–2) | Younger (n = 2–3) | Younger (n = 2–3) | Younger (n = 2–3) |

| Older (n = 1–2) | Older (n = 1–2) | Older (n = 1–2) |

Our secondary quotas were age, ethnicity, injecting drug use, treatment status and recent diagnosis. Examination of the literature suggests that age might impact on attendance and we therefore wanted to recruit participants who were both younger and older than 35 years of age. We wanted to ensure adequate representation of black Africans, who are particularly affected by HIV but, as black Africans form a very small minority of gay and bisexual men, we sought diversity in this group by recruiting men born in the UK and those born outside the UK. We also aimed to recruit small numbers of injecting drug users, people who had not started ART and those diagnosed within the past 2 years, to understand their experiences, as the literature indicates that they are at risk of disengaging from care.

Patient interview recruitment

Posters were displayed and fliers were available in the study clinics. Local research staff gave patients an information sheet and explained what the interview entailed to ascertain whether or not they were interested in taking part. If patients agreed, their contact details were passed on to the Project Management Team and AH contacted them to discuss the interview. Some patients contacted AH directly, having seen a flier or poster at their clinic. Two interviewees took part in a follow-up interview after participating in one of the focus groups (FGs) (see Phase 2c: community focus groups). AH checked eligibility according to a set of screening questions (see Appendix 4) and patients were selected to ensure a range of characteristics and experiences. Clinics were kept informed of the patients who had been interviewed; as the cells in the quota matrix were completed, they targeted patients with particular characteristics.

Interviews were arranged at a mutually convenient time. They were conducted face to face and took place on university or NHS trust premises. One patient was interviewed at their work place. At the beginning of each interview, the information sheet was explained, any questions were answered and patients provided informed consent to participate. Interviews took about 60–90 minutes. All participants were given a £20 high street shop voucher at the end of the interview to cover any transport costs and as a small token of thanks. They were offered a copy of the interview transcript and a copy of the findings from the study.

Patient interview content

Interviews were based on a topic guide (see Appendix 5) that was developed with reference to the COM-B model, as described in the questionnaire development. The sections covered:

Human immunodeficiency virus diagnosis and link to services – HIV diagnosis, starting HIV care, use of other HIV services, change over time and frequency of attendance.

Current HIV clinic attendance – expectations, appointment booking, travel to clinic, facilities, communication with reception staff, nurse and doctor, peer support and suggested improvements.

Reasons for attending regularly and irregularly – last appointment missed and suggestions.

Living with HIV – physical and emotional impacts, HIV disclosure, social support, stigma and other barriers.

Taking ART – adherence and home delivery service.

Other NHS services – GP.

Other barriers and facilitators to HIV care – off-putting experiences, agencies and individuals.

Interview data processing

Interviews were digitally recorded (with permission) and transcribed verbatim by a professional transcription service.

Interview analysis

We used framework analysis, a method for analysing qualitative data, developed on the basis of the extensive experience of researchers at the National Centre for Social Research, London. 66 It aims to condense what respondents say in their interviews into a format that facilitates inspection of data across themes and within individuals. At the same time the analyst aims to maintain closeness to the original data, by adopting respondent terminology as far as possible.

Four researchers read through three interview transcripts that were selected to represent different participant characteristics (one RA, one IA and one NA). They marked thoughts and possible themes, and met to discuss these. An index was drawn up covering the themes derived from this discussion and it was circulated for comment and revised in the light of these comments. Themes were categorised according to the COM-B model under the headings identified in the framework for REACH primary research (see Appendix 3).

Two of the above researchers coded the data using computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software, NVivo version 10 (QSR International, Warrington, UK). The use of this software facilitates flexible and effective data management and enables easy retrieval of pieces of text from material that can be voluminous and unstructured. 67

Two researchers coded each transcript individually. During this process, they checked each other’s coding and discussed refinements to the index. 66 Where it became clear that data were not sufficient to support a theme, categories were collapsed or where there were associations between themes, they were combined.

NVivo generates a complete list of quotations for each respondent under each theme heading, providing an overview of each theme while encapsulating the respondent’s contribution to it. Relevant data were retrieved using NVivo and reference was made to the original transcripts where necessary, to ensure that data from each respondent are not taken out of context or misunderstood. The data were then summarised under the theme headings, which included placing data for more complex themes into the framework using a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet (2010; Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA), with the themes across the top and respondents listed down the left hand side. The aim of this process was to fill each cell with a summary of the relevant data, keeping as closely as possible to the original data by condensing its meaning and using respondent terminology as far as possible.

The next stage of the analysis was to pull together the key themes in the data to address the objective of this part of the study that is to understand the factors that influence outpatient attendance.

Phase 2c: community focus groups

The individual interviews were supplemented by community FGs. These groups were used to uncover alternative perceptions that may be articulated in a different, non-medicalised setting. Their stated purpose was to explore patients’ experiences, service preferences and perceived barriers to accessing HIV services.

For this part of the study, we considered recruiting up to four FGs of six to eight adults who did not attend the HIV clinic regularly or had stopped going to the clinic (now or in the past). We decided to recruit a total of three groups to represent the two main groups that are affected by HIV (gay men and black African men and women) and a third group to represent other people affected by HIV. These groups were to consist of:

-

gay and bisexual men

-

African men and women

-

non-African men and women.

Focus group recruitment

The FGs were facilitated by a UK Community Advisory Board (UK-CAB) representative and coinvestigator who recruited participants via community contacts (including the UK-CAB forum, YMCA, Positive East, Positively UK, African HIV Policy Network, African Eye Trust, Africa Advocacy Foundation, Terrence Higgins Trust, Body & Soul, NAZ, Organisation of HIV Positive African Men, GMFA and Metro). Posters were sent to community venues and those who were interested in taking part contacted MS directly. MS checked their eligibility according to a set of screening questions. They were eligible to take part if (i) they had not seen a doctor or nurse specialist at a HIV clinic for at least a year; or (ii) if they had ever not seen a doctor about their HIV for a year or more; or (iii) they had missed and not rescheduled at least one appointment at their HIV clinic in the past year. They were asked about their country of birth, ethnic group and sexual orientation but chose to participate in the FG with which they identified. As there were no volunteers for the non-African men and women’s group, this group was cancelled.

The two remaining groups took place in the evening in the Mortimer Market Centre, central London, in January 2015. They were jointly facilitated and refreshments were provided. As with the patient interviews, the information sheet was explained at the beginning of the group and participants had the opportunity to ask questions before signing the consent form. All participants were given £30 at the end of the group to cover expenses and as a token of thanks, and were offered a copy of the findings from the study.

Focus group content, processing and analysis

The FGs were based on a topic guide covering the same key topics as the patient interviews: link to services, experience of using current HIV clinic, reasons for attending regularly and irregularly, reasons for stopping attending, taking ART, stigma, social support, other NHS services. The gay and bisexual men’s group took just over an hour and the African men and women’s group took just over 2 hours. They were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim.

It was intended that the FGs may serve to access people who fail to engage with medical services but continue to engage with an extended community network. However, all participants were currently engaged in HIV care and, as the data from the FGs were very similar to that from the individual interviews, they were combined for the purposes of analysis. The same index that had been developed for the interviews was applied to their coding and the same analysis procedures were adopted, as described above.

Phase 3: key informant study

We aimed to conduct semistructured interviews with up to 25 service providers and funders to explore ways to optimise patient engagement and potential costs. The sampling frame was defined according to key constituencies in the field of HIV service provision: clinical services, public health, academia, voluntary sector, health promotion and policy.

Key informant recruitment

Organisations and individuals within them were identified for each of the key constituencies. All prospective informants were approached by e-mail and, if they agreed, a 30-minute interview was arranged and conducted by telephone, Skype™ (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) or face to face. All face-to-face interviews were conducted at mutually convenient locations. Participants were offered a copy of the interview transcript and a copy of the findings from the study. At the time of conducting the interviews, all participants were informed that their contribution would be anonymous. However, it became clear that some participants might prefer for their contribution to be acknowledged. They were therefore asked if they would prefer to be named in any publication of the findings and nine of the participants said that they would like to be identified.

Key informant content, processing and analysis

A topic guide was used to explore why patients miss appointments, what interventions or service improvements would help and what resources were needed (see Appendix 6). The interviews took about 30 minutes. Again, they were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim.

As the key informant data were much shorter and less in-depth than the patient data – with participants talking about their professional experiences rather than in-depth and more lengthy discussion of their personal experiences – we used a more expedient method of analysis. Rather than coding all the transcripts in NVivo, we moved straight to summarising the data under theme headings that emerged from the data. AH conducted this analysis, reading and rereading the transcripts and organising the emerging data within the context of the COM-B model. In order to validate this analysis, FB and AE each read three transcripts (a total of six between them) and then examined the summary to see whether or not it fitted their understanding of the data.

Intervention costs

Using the methods described above, we put together four interventions that might be tested to improve engagement with care. We then undertook a preliminary evaluation of the costs of the four proposed interventions, after developing detailed descriptors of each. All costs were calculated according to 2015/16 GBP figures. Costs were calculated from a NHS and personal social services perspective. 68 The interventions would each incur a mixture of staff and non-staff costs. The former would include a range of staff types from consultants to unpaid peer support workers. The descriptors for each intervention included estimates of the amount of time each member of staff would spend on that intervention. To these we then applied unit costs per staff type obtained from published sources. 69 We valued the estimated non-staff costs (e.g. transport allowance, food allowance, telephone allowance, room hire, production of posters, leaflets and pocket guides) using market prices. We calculated the total cost of each intervention and then divided this by an estimate of the number of patients likely to receive the intervention to calculate the mean cost per patient. For three of the interventions, we calculated the costs over a 6-month period making assumptions about the number of contacts made by each patient during this time; for the fourth intervention, we calculated mean one-off costs per patient making assumptions about clinic size. The output is a series of indicative costs for each intervention, which can then be evaluated more formally in subsequent prospective studies.

Patient and public involvement

We have engaged with the public and patients at all stages of our project. Our patient and community engagement has been facilitated through the UK-CAB, a network for community HIV treatment advocates across the UK. Since the inception of the project, a representative from the UK-CAB has been involved as a co-applicant and member of our Management Team. She was responsible for recruiting PLWH to participate in our FGs and contributed to the design of the publicity material and the content of the FG topic guide. Our community representative and researcher/project manager jointly facilitated the FGs.

In addition, our Study Steering Committee and Advisory Group have both included community representatives who have contributed to the design and management of the research through these channels. They have provided valuable individual feedback our patient materials, including the content of the questionnaire and topic guides.

The questionnaire was also piloted on five PLWH and considerably revised on the basis of their input. We have interviewed three patient representatives who have contributed their expertise to the study as key informants.

At the time of writing, our findings have only recently been finalised but we will feed back to service user groups from the participating clinics over the coming months and lay summaries of our research findings will be available to patients attending for HIV care at participating sites. We will also host a dissemination and networking event for all key stakeholders in the coming months.

Chapter 3 Findings: patterns and associations with engagement in HIV care

In this chapter, we present findings from our analysis of UK CHIC data to explore patterns of engagement in HIV care, factors associated with poor engagement and the associated health and financial costs. We begin with the findings from the group-based trajectory analysis that we explored as a method for describing attendance patterns of attendance over time. The findings address the following objectives of the study, to:

-

examine HIV outpatient attendance patterns among PLWH

-

identify predictive factors of disengagement

-

investigate the potential health and financial costs of disengaging from care.

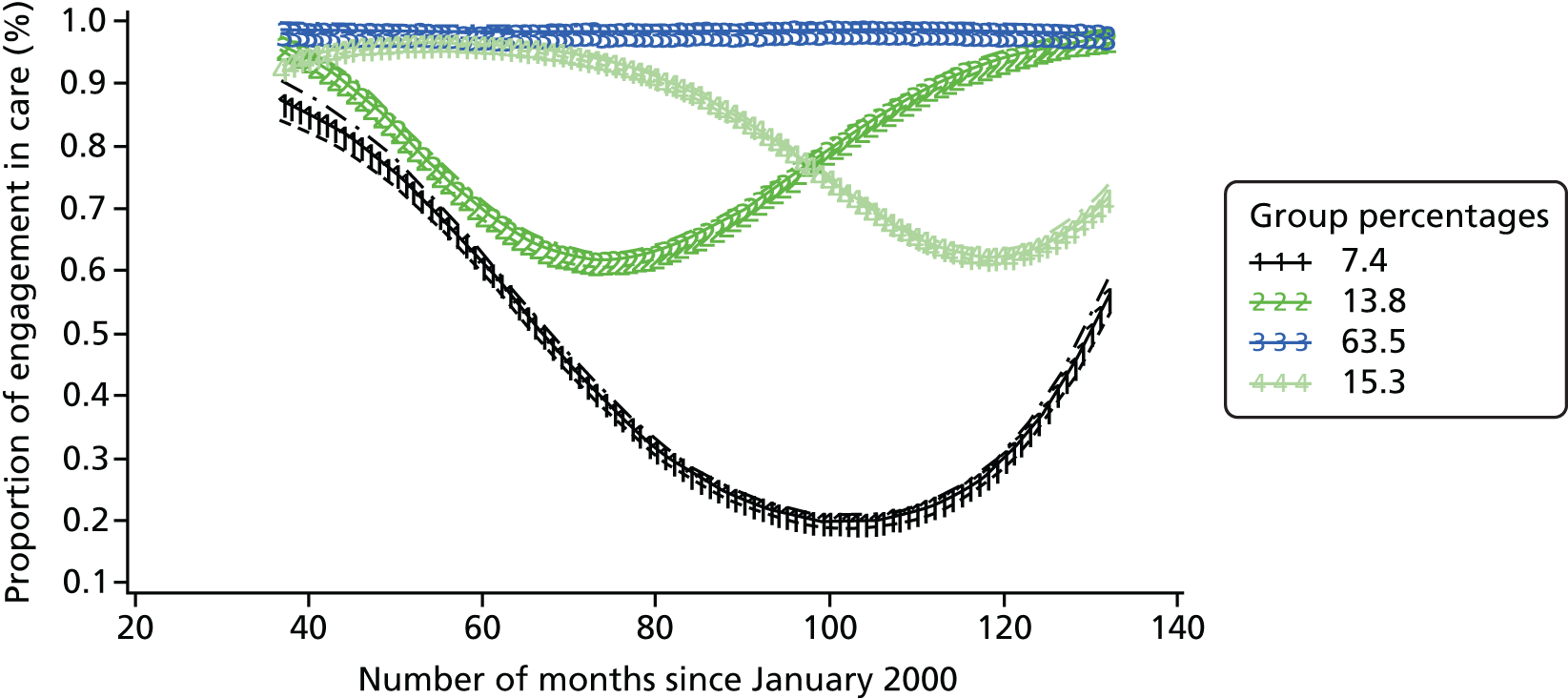

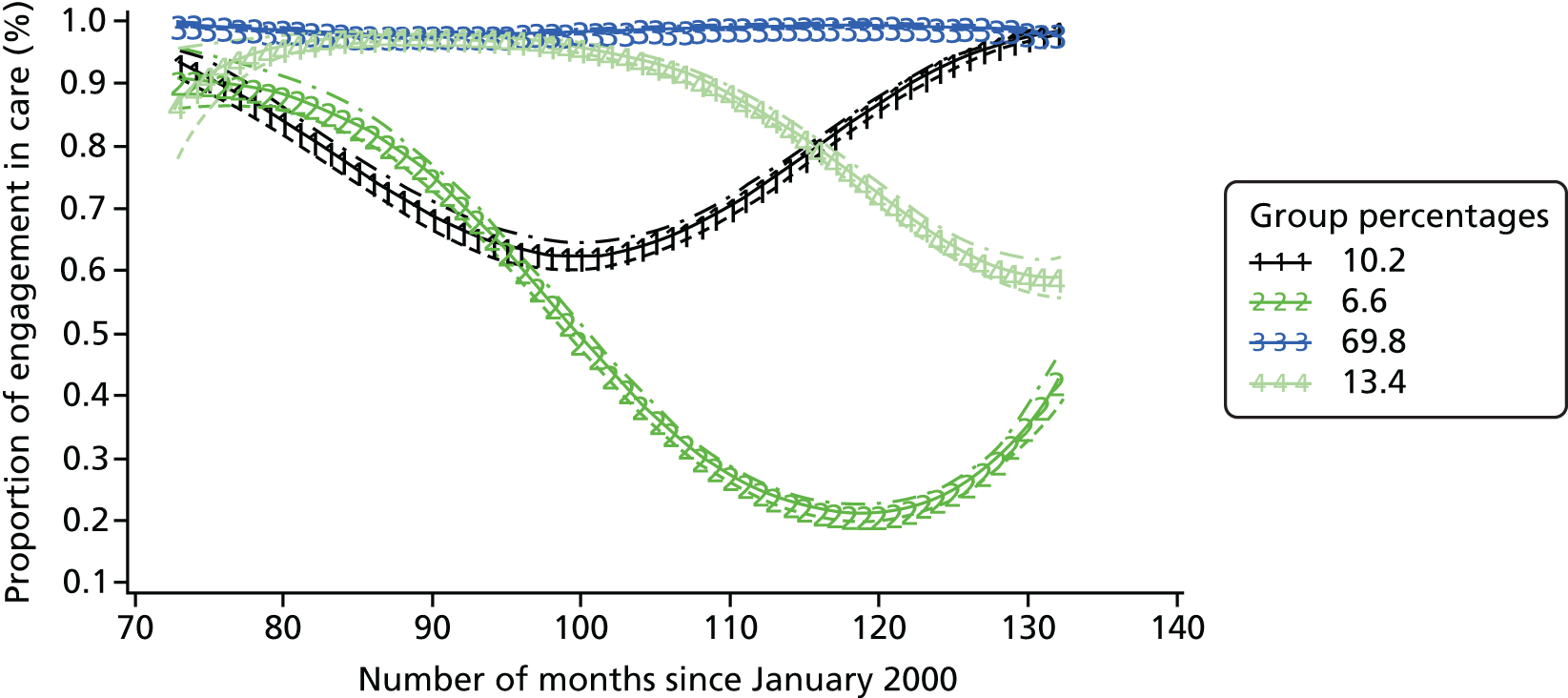

Group-based trajectory analysis of patterns of engagement

We examined patterns of attendance for patients who were divided up into three groups: 6110 patients diagnosed between 2000 and 2002; 6747 patients diagnosed between 2003 and 2005; and 5615 patients diagnosed between 2006 and 2008. We compared the fit of the models for plots with one to five trajectories for each of these three diagnosis periods using the BIC and examined the interpretability of the trajectory plots. A total of 15 models of attendance trajectories were examined (five models for each of the three diagnosis groups).

The patterns of trajectories for the five models (with one to five trajectories) were similar across diagnosis groups. The proportions of patients following these trajectories were also similar across the three diagnosis groups. Figures 3–5 illustrate the similarity of the shape of the trajectories and proportion of patients following each of the trajectories when models with four trajectories were specified. This similarity provides a measure of confidence in the robustness of the models. Although the lowest BIC indicates the best model, as the number of trajectories increased, the BIC gradually decreased for all three diagnosis groups, as did twice the difference between the BIC for the alternative (more complex) model and the null (simpler) model (Table 4). This method did not help to determine the best model for this analysis and we therefore selected the final models on the basis on interpretability.

FIGURE 3.

Attendance trajectories for four groups, diagnosed 2000–2.

FIGURE 4.

Attendance trajectories for four groups, diagnosed 2003–5.

FIGURE 5.

Attendance trajectories for four groups, diagnosed 2006–8.

| Number of trajectories in model | Patients grouped according to time of diagnosis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosed 2000–2 (n = 6110) | Diagnosed 2003–5 (n = 6747) | Diagnosed 2006–8 (n = 5615) | ||||

| BIC | 2 × diffa | BIC | 2 × diff | BIC | 2 × diff | |

| 1 | –161,085.9 | –128,142.0 | –55,608.4 | |||

| 2 | –122,569.4 | 77,033.0 | –97,366.4 | 61,551.3 | –41,745.1 | 27,726.6 |

| 3 | –114,602.5 | 15,933.8 | –91,340.6 | 12,051.4 | –39,447.8 | 4594.5 |

| 4 | –110,540.6 | 8123.8 | –88,026.2 | 6628.8 | –38,235.3 | 2425.1 |

| 5 | –108,123.9 | 4833.4 | –86,285.8 | 3480.9 | –37,924.3 | 621.9 |