Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 12/64/187. The contractual start date was in November 2013. The final report began editorial review in June 2016 and was accepted for publication in December 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Jo Rycroft-Malone is a member of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Journals Library Board and was a commissioned work stream board member of the Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) programme when this work was funded and, subsequently, was appointed as NIHR HSDR Programme Director, a role that she currently holds. Rebecca Crane receives royalties for mindfulness-based cognitive therapy Distinctive Features, Routledge 2009. She is a non-salaried co-director of Mindfulness Network Community Interest Company (CIC), a not-for-profit social enterprise offering continuing professional development services to mindfulness-based teachers. She directs the Centre for Mindfulness Research and Practice at Bangor University, which delivers professional training for mindfulness-based teachers. Willem Kuyken is the Director of the Oxford Mindfulness Centre, a research, training and education centre that is a collaboration between the University of Oxford and the not-for-profit charity the Oxford Mindfulness Foundation. Willem Kuyken donates all speaking or consultancy fees in full, and directly, to the Oxford Mindfulness Foundation. Until 2015, Willem Kuyken was the Director of the Mindfulness Network CIC, a small not-for-profit charity offering supervision to mindfulness teachers. He relinquished this role in 2015.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Rycroft-Malone et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Mental health problems affect some one in four people throughout their lifetimes, with as many as 10% of the population affected at any one time – this is > 6 million people in the UK. 1 Depression is a major public health problem that, like other chronic conditions, typically runs a relapsing and recurring course, producing substantial decrements in health and considerable human suffering. 2,3 After many years of decline, rates of suicide are rising and suicide is the leading cause of death in men aged 15–49 years. In terms of disability-adjusted life-years, the World Health Organization consistently lists depression in the top five disabling conditions4 and in terms of years lost to disability among the top two, and forecasts that this will worsen over time. 5 Although 23% of the total burden of disease is attributable to mental health problems, only 13% of NHS health expenditure is spent on mental health. 6 Health economic analyses of the cost of anxiety and depression in the UK suggest a cost of £17B or 1.5% of the UK gross domestic product. 6,7 A major factor contributing to the economic effects of depression is the reduced capacity that sufferers have to engage in work.

The last 50 years have seen a transformation in mental health with the development of a range of psychological treatments for depression that are effective and cost-effective,8,9 and significant advances in understanding and changes in public attitudes. 10 There has been a steady reduction in stigma around mental health and, mirroring this, government policies have called for ‘parity of esteem’; that is to say that physical and mental health should receive proportionate attention and funding. 11 The substantial health burden attributable to depression could be offset through making accessible evidence-based interventions that prevent depressive relapse among people at high risk of recurrent episodes. 12 Currently, the majority of depression is treated in primary care, and maintenance antidepressants are the mainstay approach to preventing relapse. To stay well, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends that people with a history of recurrent depression continue antidepressants for at least 2 years. 13 However, there are many drivers for the use of psychosocial interventions that provide long-term protection against relapse. 14 The majority of patients express a preference for psychosocial approaches that can help them stay well in the long term and find that antidepressant medication can have unwanted side effects. The rates of adherence with medication regimes tend to be poor and in the perinatal period many women prefer an alternative to psychotropic medication. 14

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy

To address this need, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) was developed as an intervention intended to teach people with a history of depression the skills to stay well in the long term. 15 MBCT is a group-based relapse prevention programme for people with a history of depression who wish to learn long-term skills for staying well. There are session-by-session guides for MBCT teachers16 and patients. 17 It combines systematic mindfulness training with elements from cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT). It is taught in classes of 8–15 people over 8 weeks. Through the mindfulness course people learn new ways of responding that are more self-compassionate, nourishing and constructive. This is especially helpful at times of potential depressive relapse, when patients learn to recognise habitual ways of thinking and behaving that tend to increase the likelihood of relapse and can choose instead to respond adaptively.

A recent individual patient data meta-analysis of all randomised controlled trials of MBCT for recurrent depression (n = 1329) suggests that MBCT significantly reduces the rates of depressive relapse compared with those who did not receive MBCT over a 60-week follow-up (hazard ratio 0.69, 95% confidence interval 0.58 to 0.82). Furthermore, comparisons with active treatments suggest a reduced risk of depressive relapse within a 60-week follow-up period (hazard ratio 0.79, 95% confidence interval 0.64 to 0.97). 18 Usual care in these studies refers to normal health service provision in the nations in which the studies were conducted; the active comparisons were typically maintenance antidepressants. 19–21

Health economists have made the case that the modest cost of effective psychological treatments would be repaid in enhanced productivity, tax receipts and reduced disability benefits,7 to say nothing of the improvements in quality of life. Moreover, many chronic illnesses co-occur with depression, and there is a complex reciprocal relationship between the course of depression and physical conditions that affect both morbidity and mortality. 3,22–24 In terms of cost-effectiveness, MBCT is no more cost-effective than the current treatment of choice, maintenance antidepressants. 20,21 Beyond evidence from randomised trials, no implementation research to date has examined value for money;25 however, there is evidence of its acceptability to patients and referrers. 26,27 However, patients need to invest significant time in MBCT, both to attend the classes and undertake the mindfulness exercises and the group aspect of MBCT is a benefit for some, but a barrier for others. 28 The UK Network for Mindfulness-Based Teacher Training Organisations has set out good practice guidelines for training and supervision, and there is now a register of teachers who meet these guidelines. 29

NICE13 state that group-based MBCT has the strongest evidence base of all treatments designed specifically for this group and is expected to be effective for those who have had three or more episodes of depression.

This recommendation is mirrored by the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) guideline for the non-pharmaceutical management of depression in adults. 30

Yet in spite of this clear and compelling case for psychological treatments in the UK, they remain hard to access and there are marked geographical inequities in access; this reflects chronic underinvestment in mental health. There has also been a growing recognition that prevention, ideally earlier in life would be most likely to improve UK mental health. 10 A series of calls from patient groups, government policies and implementation drives have sought to ensure psychological treatments are available to those who would benefit and at stages in their lives that would have most impact. A recent task force concluded that:

The NHS needs a far more proactive and preventative approach to reduce the long term impact for people experiencing mental health problems and for their families, and to reduce costs for the NHS and emergency services.

Mental Health Taskforce. 10 Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0

National context for psychological therapies generally and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy specifically

Health care is devolved to each of the four UK nations, and within nations regions to organise care with a further degree of devolved autonomy. The key background for each of the four countries is summarised in Table 1.

| Country | Description | Key policy documents and guidelines |

|---|---|---|

| England | England has a population of 54 million. NHS England sets the priorities/direction for health and care. The budget to commission services is largely devolved to GPs and local CCGs. CCGs commission any service that meets NHS standards and costs, be they NHS hospitals, mental health trusts, social enterprises, charities or private sector health-care providers. Health and Wellbeing Boards ensure services work together | No Health without Mental Health11 is a cross-government mental health outcomes strategy for people of all ages (February 2011). It sets out a plan to improve people’s mental health and well-being and improve services for those with mental health problems. The strategy set six key objectives:

Five Year Forward View for Mental Health10 is a report from the independent Mental Health Taskforce to the NHS in England, which was published in February 2016. The taskforce was launched by NHS England and was independently chaired by Paul Farmer, Chief Executive of Mind A key feature of mental health delivery in the UK has been the large-scale roll-out of the IAPT programme.31 This has been a national investment in service delivery and therapist training to make evidence-based psychological therapies available for people with common mental health problems widely accessible in primary care. It includes extensive monitoring. Its primary focus has, until recently, been on CBT NICE published its last Depression: The Treatment and Management of Depression in Adults (Update) in 200913 |

| Northern Ireland | Northern Ireland has a population of 1.8 million. Health and social care is overseen by the Health and Social Care Board, but services are provided by six regional trusts that operate autonomously with their own budgets. Health and social care are provided in an integrated way | Service Framework for Mental Health and Wellbeing32 sets out 58 standards in relation to prevention, assessment, diagnosis, treatment and care of individuals and communities who have or at risk of developing mental health problems The Regional Mental Health Care Pathway33 launched in October 2014, commits health and social care services to deliver care that is more personalised and improves the experience of people with mental health problems, by adopting a more evidence-based/recovery-oriented approach to care across the system A Strategy for the Development of Psychological Therapy Services34 published in 2010. A strategy focused specifically on psychological therapies |

| Scotland | Scotland has a population of 5.4 million. NHS Scotland consists of 14 regional NHS boards delivering frontline health-care services. It also consists of seven special NHS boards and one public health body (Healthcare Improvement Scotland), supporting the regional boards. NHS boards in Scotland are all-purpose organisations: they plan, commission and deliver all NHS services | The Mental Health Strategy for Scotland 2012–201535 had seven key themes and 36 specific commitments that delivered over the period 2012–15 and that cover the full spectrum of mental health improvement, prevention, care, services and recovery The Mental Health (Scotland) Bill 201536 aims to enable people with mental health problems to access effective treatment quickly and easily The Mental Health in Scotland: A Guide to Delivering Evidence-Based Psychological Therapies in Scotland (The Matrix) (2011)37 is a guide to planning and delivering evidence-based psychological therapies within NHS boards in Scotland The SIGN30 is part of the public health body, Healthcare Improvement Scotland (and develops evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for the NHS in Scotland) The Doing Well By People with Depression programme (2006)38 was a 3-year initiative intended to build capacity to treat depression and to enhance access to sources of support. The programme presented an opportunity to try out ‘new’ approaches and to change existing ways of delivering interventions. Various sites included training in mindfulness-based approaches NHS Education for Scotland39 is a special health board responsible for education and training for those who work in NHS Scotland. It has been funding 8-week staff MBCT courses, CPD events and facilitated regular meetings between mindfulness leads Finally, Mindfulness Scotland40 is a charity that aims to contribute to the development of a more mindful and compassionate Scotland by working alongside the NHS and other public institutions. They offer a range of activities including teacher training and annual conferences |

| Wales | Wales has a population of approximately 3.1 million. NHS Wales (Welsh: GIG Cymru) is organised into seven local health boards. Each board is responsible for delivering all health-care services within its region | Together for Mental Health – A Strategy for Mental Health and Wellbeing in Wales41 is a 10-year strategy for improving the lives of people using mental health services, their carers and their families (October 2012). The main themes of Together for Mental Health are around promoting well-being and prevention, public partnership model, integration of care and joint working across sectors, and implementation. The Strategy is focused around six high-level outcomes and supported by a delivery plan. At the heart of the strategy is the Mental Health (Wales) Measure 2010,42 which places legal duties on health boards and local authorities to improve support for people with mental ill health |

With respect to MBCT specifically, two significant reports have drawn attention to the case for MBCT to be more widely available, arguing that for many it is an acceptable way for people with a substantial history of depression to learn skills to stay well in the long term. The Mental Health Foundation report included surveys of general practitioners (GPs) and the general public and recommended that MBCT be made more available through investment in training therapists, greater education of GPs so they know who and when to refer to mental health services and building capacity within the NHS to offer MBCT. 27 Five years later, the Mindfulness All Party Parliamentary Group (MAPPG) produced the Mindful Nation UK report43 that made four recommendations in the area of health:

-

MBCT should be commissioned in the NHS in line with NICE guidelines so that it is available to the 580,000 adults each year who will be at risk of recurrent depression. As a first step, MBCT should be available to 15% of this group by 2020, a total of 87,000 adults each year. This should be conditional on standard outcome monitoring of the progress of those receiving help.

-

Funding should be made available through the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) training programme to train 100 MBCT teachers per year for the next 5 years to supply a total of 1200 MBCT teachers in the NHS by 2020 in order to fulfil recommendation one.

-

Those living with both a long-term physical health condition and a history of recurrent depression should be given access to MBCT, especially those people who do not want to take antidepressant medication. This will require assessment of mental health needs within physical health-care services, and appropriate referral pathways being in place.

-

NICE should review the evidence for mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome, cancer and chronic pain when revising their treatment guidelines.

The National Institute for Health Research Dissemination Centre in a 2016 highlight44 noted the following.

-

MBCT may provide an alternative for people with recurrent depression, especially those who have difficulty in adhering to maintenance antidepressant medication.

-

Patients who participated in MBCT, instead of antidepressants, had similar relapse rates to those who continued with antidepressants alone.

-

MBCT was no more cost-effective than antidepressants. However, costs were similar for patients receiving MBCT and those receiving antidepressants, as were outcomes, so from a cost perspective MBCT may be a reasonable alternative.

-

Both MBCT and CBT are intensive processes requiring significant commitment of time and effort. This will not suit everyone, and in particular interviews with study participants suggest that those with other health conditions found it difficult. MBCT is typically delivered in a group setting that, again, may not suit everyone.

-

However, there is currently no clear evidence about which patients might be more or less likely to benefit from cognitive therapies, so all patients should be considered for these therapies. It is important that patients know about all the different treatment options and what they involve before making a decision.

In line with the Medical Research Council Complex Interventions Framework and leading commentators,45 the next phase of work is to determine how MBCT can be implemented in ‘uncontrolled real world’ health-care settings. 46 Indeed, the 2009 NICE guideline13 recommended that provision of MBCT in the NHS be an implementation priority.

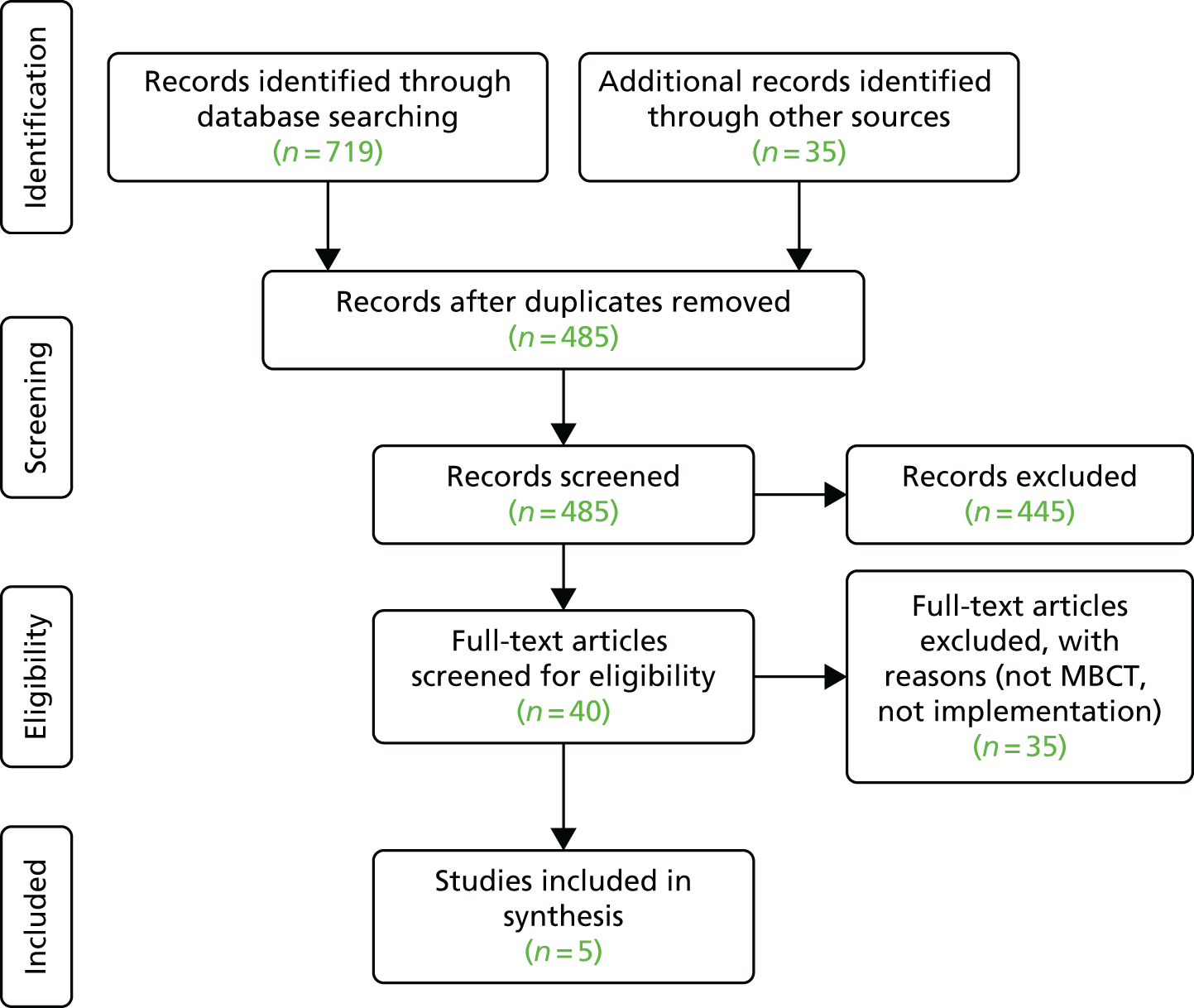

As an early step we conducted a high-level narrative review of the MBCT implementation literature (Figure 1). This included a search of MEDLINE, EMBASE and PsycINFO databases using the terms ‘Mindfulness,’ ‘Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy’ and ‘MBCT’, with either ‘Implementation’, ‘Adoption’, ‘Diffusion’, ‘Dissemination’, ‘Evidence-based Practice’, ‘Knowledge transfer’, ‘Knowledge translation’, ‘Quality improvement’, ‘Translational research’ or ‘Research utilisation’. We also included literature identified by MBCT experts. We screened 485 papers and included 40 papers for full-text assessment. We excluded studies if they were not explicitly related to both MBCT and implementation issues.

The majority of the papers were reviews and opinion pieces. A consistent theme is that although the interest in MBCT is growing,48 implementation is patchy at best. 49–51 An analysis at the level of health-care systems suggests that MBCT might best be accommodated within contemporary systems of health-care delivery, such as stepped care that seeks to match the intensity of the intervention to the needs of individuals in a series of steps. 52 A conducive organisational context is noted as important,52–54 a theme consistent with implementation of other psychological treatments. 55 A number of commentators point to the value of starting implementation by offering MBCT to health-care professionals. 52,56 Identified barriers include a lack of agreed standards for MBCT training and teaching, limited access to training and supervision, and resources (time, staff, money.)50,52,54,56,57 Finally, a number of commentators note the need to fit MBCT to the implementation setting, meaning who is the population MBCT is intended for (client/patient population) and what is the context (health-care system and cultural). 52,54,56–63

There was a small set of primary research studies. The study that informed this work is described below as the feasibility work for this study. 64 A small-scale observational study identified implementers in primary care, provided pump priming funds and monitored impact over 8 months. 65 Although small (n = 5) and observational, this suggests that resourcing enthusiastic implementers can have some impact. A population-based analysis used Canadian health survey data to simulate the number of MBCT teachers needed to provide a sustainable service to people with recurrent depression. 66 They estimated that 4.2% of the population are candidates for MBCT. Estimating that it would be acceptable to some 20% of eligible people, they recommend one MBCT teacher per 100,000 population. Such analyses are prone to numerous methodological caveats,67 but are a starting point for considering staffing resources for mental health services wishing to offer MBCT.

Very limited work has asked people from diverse backgrounds about facilitators of and barriers to mental health care. 63,68–70 Minority groups typically face additional barriers in accessing mental health care, and the way this manifests with respect to access to MBCT has, as far as we are aware, not been researched. These commentaries are North American and the applicability to a UK context is as yet underexplored.

The largely opinion-based literature alongside a very small set of preliminary primary research studies suggests that the potential to create new knowledge in this study is significant.

Feasibility work

One of the few extant implementation studies was completed as a feasibility study for this project by two of the applicants. 64 This study asked to what extent MBCT has been implemented in the health service to date and what had facilitated implementation. It was based on (1) a stakeholder workshop (n = 57), (2) a postal survey (n = 103 responses) and (3) an overview of four services that had either partially or fully integrated MBCT services. The results suggested that accessibility across the UK is very limited. Eighty-one per cent of the postal survey respondents reported that the implementation of MBCT had not yet begun in their organisation. Where implementation had started, very few respondents reported a strategic and systematic approach to implementation. Instead, successful implementation was most frequently described as being due to ‘enthusiasts’ who had driven through change, but that these initiatives largely lacked organisational commitment or integration with other services. The authors note that the limited implementation of MBCT contributes to health inequalities and misses an opportunity to translate evidence into practice. This feasibility study was based on convenience samples and was largely descriptive. It also does not offer an explanation of why MBCT implementation to date is so patchy and inequitably distributed, nor does it offer recommendations for how MBCT might best be implemented – hence the need for this study.

Summary and research aims

Even if a psychosocial intervention has compelling aims, has been shown to work, is cost-effective and is recommended by a national advisory body, its value is determined by how widely available it is in the health service. Feasibility work completed in preparation for this study indicates that NHS provision of MBCT falls well short of that envisaged in national guidance. 64 A recent British Medical Journal editorial suggests that research is needed to answer the questions, ‘What are the facilitators and barriers to implementation of NICE’s recommendations for MBCT in the UK’s health services? Can this knowledge be used to develop an Implementation Plan for introducing MBCT consistently into NHS service delivery?’. 46 Moreover, NHS England has made ‘improving access to psychological therapies’ a priority in order to focus effort and resources on improving clinical services and health outcomes. The Parity of Esteem programme71 has ‘a national ambition by end March 2015 to increase access so that at least 15% of those with anxiety or depression have access to a clinically proven talking therapy services, and that those services will achieve 50% recovery rates’ (contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0). Similar policy pledges in other UK countries aim at IAPT with a specific focus on prevention; for example, among the six high-level outcomes in the Welsh Strategy ‘Together for Mental Health’ one is ‘Access to, and the quality of preventative measures, early intervention and treatment services are improved and more people recover as a result’ (© Crown copyright 2012; contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0). 41 There is a growing commitment among policy-makers, commissioners and those delivering services to ensuring that people with mental health problems receive the evidence-based treatments they need, for example as captured in the commitments of the Mental Health Strategy for Scotland 2012–201535 or the standards of the Service Framework for Mental Health and Wellbeing in Northern Ireland from 2011. 32 The MAPPG report pointed to the need for the 2009 NICE guideline13 to be implemented in the NHS and for more MBCT teachers to be trained. 43

This research will describe the current state of MBCT implementation across the UK and develop an explanatory framework of what is hindering and facilitating its progress. As such, this study does not seek to provide confirmatory evidence of clinical efficacy, but aims to fill a gap in the evidence about the implementation of a clinically effective psychological intervention. From this framework we will develop an implementation plan and related resources to promote wider access to and use of MBCT. The implementation plan will be a coherent framework and set of resources to support implementation of MBCT within the NHS, and will be freely accessible.

Specifically we will:

-

scope existing provision of MBCT in the health service across England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales

-

develop an understanding of the perceived benefits and costs of embedding MBCT in mental health services

-

explore facilitators that have enabled services to deliver MBCT

-

explore barriers that have prevented MBCT being delivered in services

-

articulate the critical success factors for enhanced accessibility and the routine and successful use of MBCT as recommended by NICE

-

synthesise the evidence from these data sources and, in co-operation with stakeholders, develop an implementation plan and related resources that services can use to implement MBCT.

Chapter 2 Design and methods

Design

As outlined in Chapter 1, in this study our main aim was to investigate the implementation and accessibility of MBCT (a psychological therapy that has been shown to be clinically effective and cost-effective, and is recommended in NICE guidance) across the UK.

We conducted a two-phase qualitative, exploratory and explanatory study, which was conceptually underpinned by the Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (PARIHS) framework. In phase 1 we conducted interviews with participants from different regions across the UK about current provision of MBCT. In phase 2 we undertook a more in-depth study of MBCT implementation within 10 case studies. The study protocol has been previously published72 and can be found online.

Theoretical framework

The framework underpinning this study was PARIHS. 73 Co-developed by one of the investigators, PARIHS is a frequently used framework within a health service context as a guide for both implementation practice and research. It has been through a systematic process of development and refinement over a number of years. 74 PARIHS was developed as a means of understanding the complexities involved in the successful implementation of evidence into practice. Within PARIHS, successful implementation (SI) is represented as a function (f) of the nature and type of evidence (E) being implemented, the qualities of the context (C) in which it is being implemented and the process of facilitation (F) [SI = f(E,C,F)].

Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services facilitates the mapping of factors that might need attention before, during and after implementation efforts, and, as such, it provided a conceptual map for the study. The framework was used as a heuristic to inform the development of data collection tools, and was also used in the analysis process.

Phase 1: interview study

In order to obtain an overview of whether or not and how MBCT is being delivered in the four countries of the UK, and to provide an overview of the factors that have facilitated and hindered the implementation of this intervention, we conducted interviews. Interviews have been described as a ‘conversation with a purpose’, providing a ‘flexible and adaptable way of finding things out’. 75 As we had a number of objectives to explore with interview participants, we used a semistructured interview approach that allowed us to explore specific topics, but also enabled the interviewer to probe further and gave participants the flexibility to include additional relevant information. Data collection methods are described in Methods.

Phase 2: case studies

As phase 1 provided an overview of MBCT implementation across the UK, in phase 2 we wanted to gain a more in-depth and contextually embedded understanding of MBCT implementation. As such, we used a case study approach. As an empirical enquiry, case studies provide an opportunity to explore and understand how and why (in this case) MBCT implementation was more or less successful within ‘its real life context’. 76 Furthermore, a case study is appropriate for when ‘a how or why question is being asked about a contemporary set of events over which the investigator has little or no control’. 77 In this study, MBCT accessibility and implementation was the phenomenon that we wanted to study in the real-life context of NHS health services and those delivering these services. We chose to study multiple cases because we speculated that the implementation of MBCT would be different depending on the context in which it was being implemented. Studying more than one case would enable the development of a more comprehensive account of MBCT implementation. As a research design, case studies are particularly appropriate for the inclusion of multiple data collection methods enabling description and explanation (see Data collection).

Patient and public involvement

We embedded patient and public involvement (PPI) throughout the conduct of this study, informed by INVOLVE, a national advisory group that supports active public involvement in NHS, public health and social care research, and the Mental Health Research Network’s approach to best practice. 78 Patients were involved in the development of the proposal, the creation of data collection tools, the analysis of phase 1 and phase 2 data, the creation of the implementation plan and the dissemination of findings.

The PPI group comprised four people with a history of recurrent depression, all of whom have accessed MBCT and who had varying views about MBCT, from the more positive to the more sceptical. Facilitated by AG, this group met four times during the study and had access to project materials throughout as they wished. At least one member of the PPI group also attended our monthly project management meetings and both of the advisory panel meetings.

Methods

Data collection

Data were collected between 4 December 2013 and 17 July 2015.

Phase 1

Semistructured audio-recorded interviews were undertaken with individual participants from all four UK countries, by telephone or face to face (as convenient), and were guided by an interview guide (see Appendices 1 and 2). The interview guide was broadly structured around the elements of evidence, context and facilitation (the main elements of the study’s conceptual framework), and was specifically designed to capture views and information about the accessibility of MBCT, the implementation of MBCT (including facilitators and barriers), and perceived costs and benefits. The schedule was used flexibly to enable participants to contribute additional information relevant to the research objectives. Phase 1 was descriptive in nature.

Sampling

Stakeholders of relevance to this study included commissioners, managers, MBCT practitioners and teachers, and people living with depression with experience of MBCT. To ensure geographical representation we sampled within the following NHS regions: England (North, Midlands, South and London), Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland (see Chapter 3). Preparatory work involved securing the engagement of a key stakeholder within each of these regions, namely someone who had good knowledge of MBCT service delivery across the region. At the funding stage, the board asked that we randomly sample some of our participants to reduce the risk of positive accounts. Therefore, following interviews with key stakeholders within the regions we developed a list of potential participants that represented each of the groups described above in each area. We then randomly sampled from that list within each of the stakeholder groups (see Chapter 3, Sample).

Phase 2

The case studies were designed to enable a richer understanding of the implementation and accessibility of MBCT, building up an explanation from the findings of phase 1. A ‘case’ was defined as a NHS organisation in which NICE recommendations would indicate that MBCT provision should be accessible free at the point of delivery. Within each case, multiple qualitative methods (see below) were used concurrently and tailored accordingly, depending on the degree of uptake of MBCT with a case study site (see Chapter 4, Sample). As such, phase 2 was aimed at explanation, building on the description provided by phase 1. The methods used with the cases are described as follows.

Semistructured interviews

We conducted semistructured audio-recorded interviews in each site, these were our primary source of data. The interview schedules were initially informed by the findings of phase 1 so that we could test out the ideas that came from phase 1; however, in order to build up an explanation in phase 2, as data collection and familiarisation progressed, we revised the schedules to enable us to build up an explanation over cases. As such, the interview schedule evolved as we progressed with the case studies, to enable us to begin explanation building (see Appendices 1–3 for some examples). Interviews were mainly conducted face to face, but in a small number of instances where face to face was not possible, they were conducted by telephone. We stated in our protocol that we would interview up to 20 participants in each site, but as a result of reaching a point of data saturation, fewer than 20 were interviewed in some sites. A decision to stop data collection was reached by discussion between FG, HOG, JRM and WK.

We were interested in exploring some of the features of the framework that we developed from phase 1 data analysis (see Appendix 4), and, as such, questions about this were built into the schedule. Therefore, the schedule included questions relating to the MBCT implementation story, the mixture of factors that mediated the implementation of MBCT, including issues concerning the evidence base and the context of implementation.

Non-participant observation

We sought opportunities to observe naturally occurring meetings and events within each site. It was anticipated that this would provide an additional opportunity to gain insights into the context of service delivery in which MBCT may be being delivered. Observations, which were written up as field notes, were guided by drawing on a framework that included paying attention to space, actors, activities, objects, acts, time, events, goals and feelings. 79

Documentary analysis

A range of documents was collected to help contextualise and complement other data sources (see Appendix 5). We requested documents that may help us understand the implementation of MBCT in specific sites; as such, they differed across sites. Specifically, we asked for any strategy and/or policy documents about MBCT services, which would facilitate an understanding about where they were positioned within the structure of the organisation and pathways of care delivery. Additionally, we requested any meeting notes from MBCT planning meetings, business cases/proposals, service evaluations and any reports of relevance to MBCT. We were also open to the offer of relevant documents from site participants.

Context analysis

In order to gain an understanding of the broader context we gathered publicly available information about socioeconomics, ethnicity and mental health metrics (see Appendix 6). We also drew on site-specific, publicly available data, which is not referenced in order to maintain site anonymity. In combination with qualitative information gathered within sites, this enabled us to build up a description of each case (see Chapter 4, Case summaries).

The non-participant observations were conducted, and documents were gathered in order to confirm or refute claims made in the interviews.

Sampling

Sites

We purposively sampled 10 cases across England, Wales, Northern Ireland and Scotland, based on the extent of MBCT being embedded in service delivery. The number of sites was chosen during the funding process, as a reasonable number to ensure a spread of different levels of implementation and to ensure geographic coverage. Embeddedness was determined by strategy for MBCT delivery, trained staff delivering MBCT to minimum practice levels, referrers’ awareness of service, and an ongoing throughput of clients:

-

integrally embedded (four sites) – in which all the above criteria were reportedly in place at the time of discussions about accessing the case

-

partially embedded (four sites) – where strategy was less obvious and/or in the early stages of implementing it, delivery patchy and MBCT teachers were working in isolation

-

no or scarce MBCT implementation (two sites) – where there was an absence of delivery.

We also sampled to obtain some representation in relation to sociodemographic profile, prevalence of mental health problems, urban versus rural and the ethnic profile of the population served in each site.

Within sites

Within sites we used the following criteria to sample participants:

-

different stakeholders, including managers, MBCT teachers, referrers, practitioners, people living with depression and commissioners

-

ensuring we drew from participants across the organisation at macro, meso and micro levels

-

ensuring we were gathering a range of responses from those who were more and less disposed to the implementation of MBCT.

We worked with local collaborators to identify appropriate data collection opportunities and potential participants, but using the criteria above and taking care to ensure a balanced set of respondents. We did our best to ensure a balanced set of respondents by actively seeking out those people who were less positively disposed to MBCT.

Data analysis

Data were managed in Microsoft Word (2013, Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA), Microsoft Excel (2013, Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and ATLAS.ti (version 7.5.6, Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany). Audio-recorded data were fully transcribed. Hand-written field notes were converted into electronic text. All members of the research team were involved in the analysis process, which also included input from lay members (Table 2 shows who was involved in the analysis and at what points). This approach was useful for sense checking, building and refining explanations, and providing a further check on credibility.

| Stage | Activity | Who was involved |

|---|---|---|

| Familiarisation |

|

FG and HOG FG, HOG, JRM, WK, RC, AG and SM |

| Identifying the framework |

|

FG, HOG, JRM and WK PPI members FG, HOG, JRM, WK, RC, AG and SM JRM, WK, FG and HOG |

| Indexing |

|

FG and HOG |

| Charting |

|

FG, HOG, JRM and WK |

| Mapping and interpretation |

|

JRM, HOG, WK and FG FG, HOG, JRM, WK, RC, AG and SM, including PPI input Team (ongoing and not fully reported in this output) |

Data from both phases were analysed using a thematic approach informed by Ritchie and Spencer. 80 Phase 1 data analysis was nearly complete before we moved into data collection in phase 2. As such, the findings from phase 1 provided the basis of initial interview schedules for the case studies and a platform for initiating explanation building.

We used an iterative and combined inductive and deductive approach to analysis, which aimed to build, over time and data collection episodes, an increasingly explanatory account of what facilitates MBCT implementation in the UK NHS.

Use of the framework approach

We used the phases of the framework approach in the following way within each phase.

Case study analysis

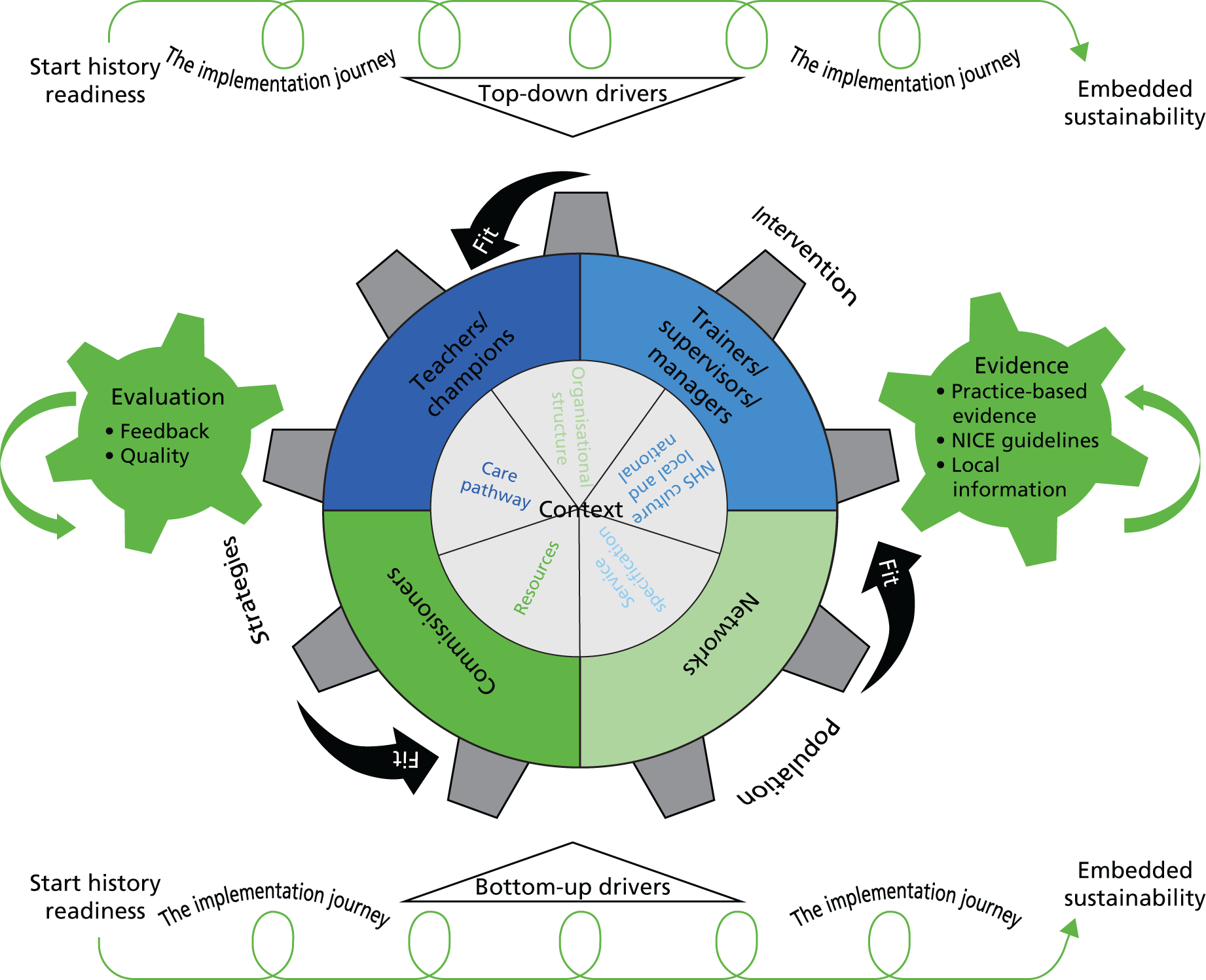

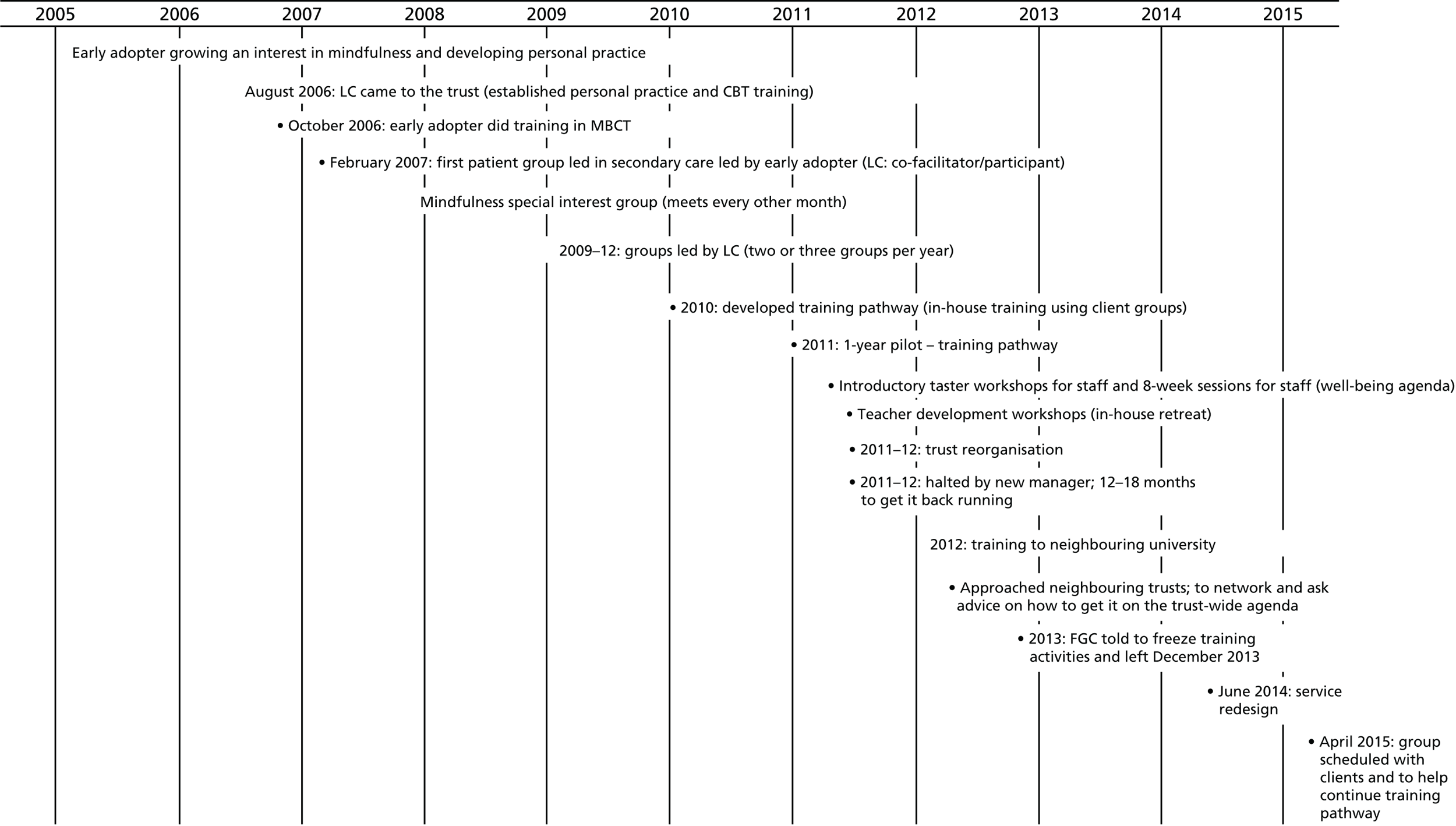

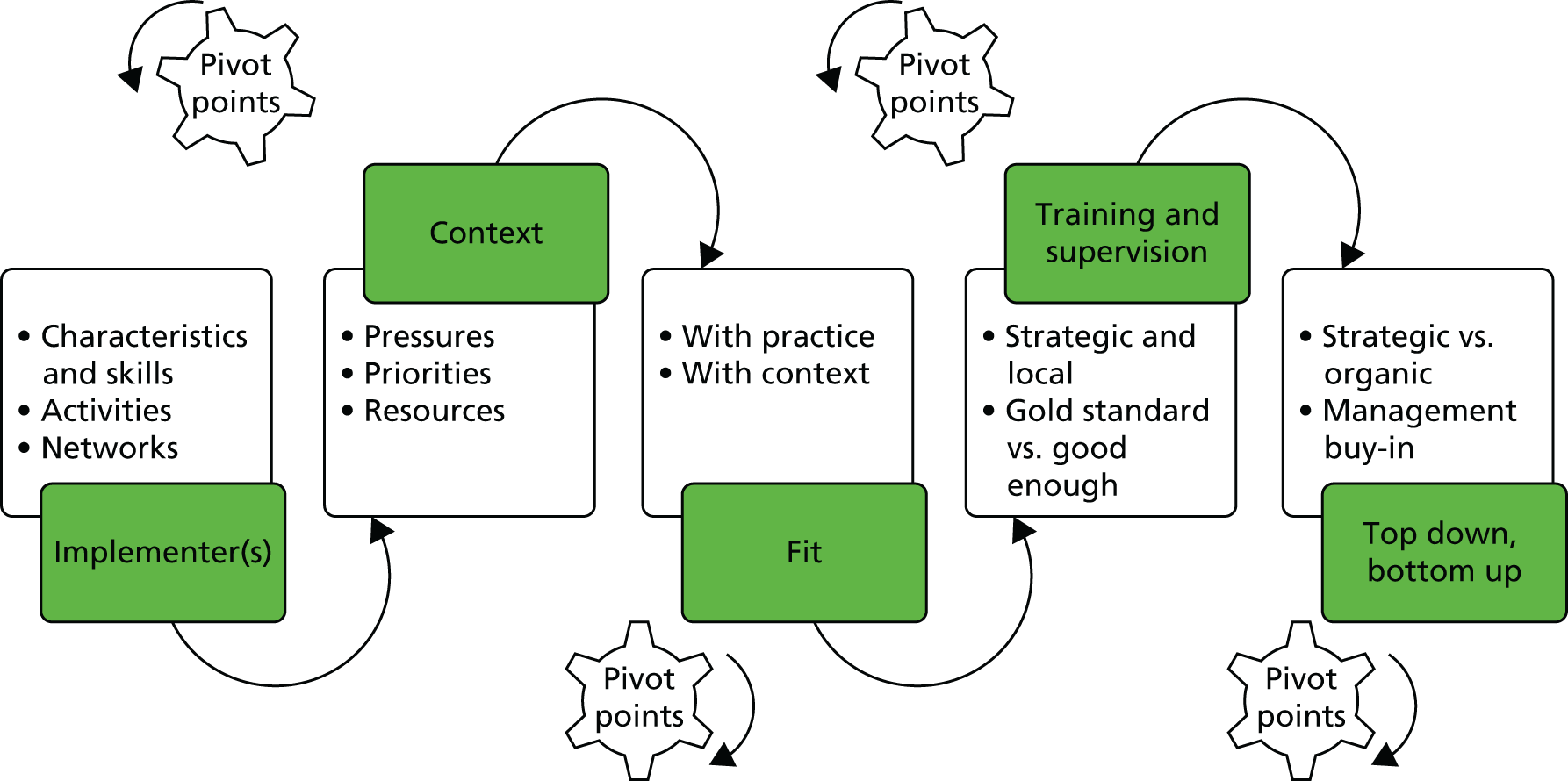

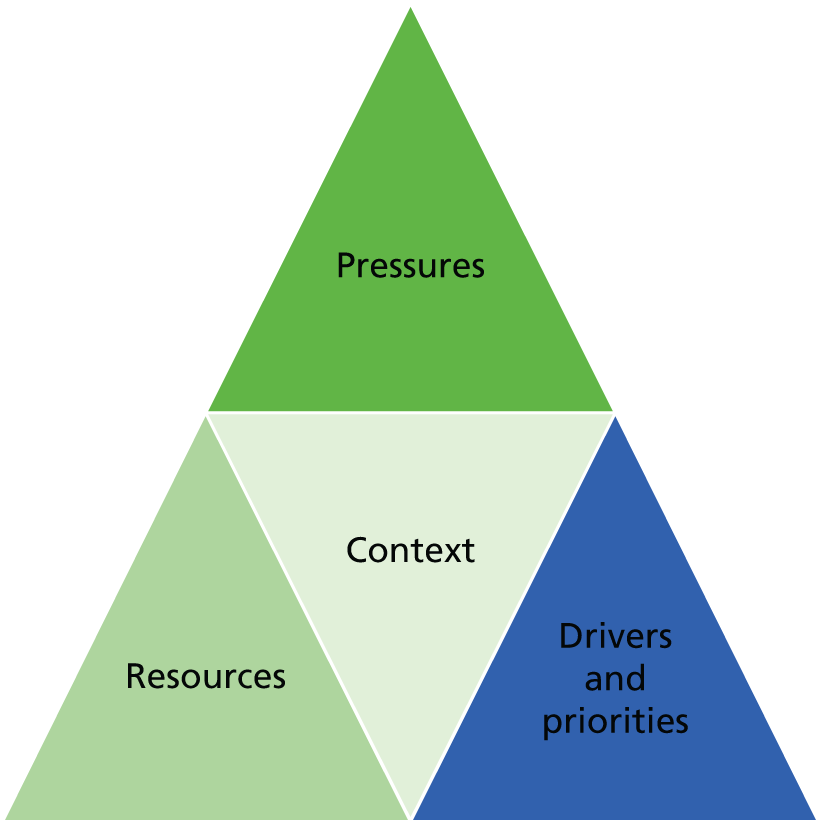

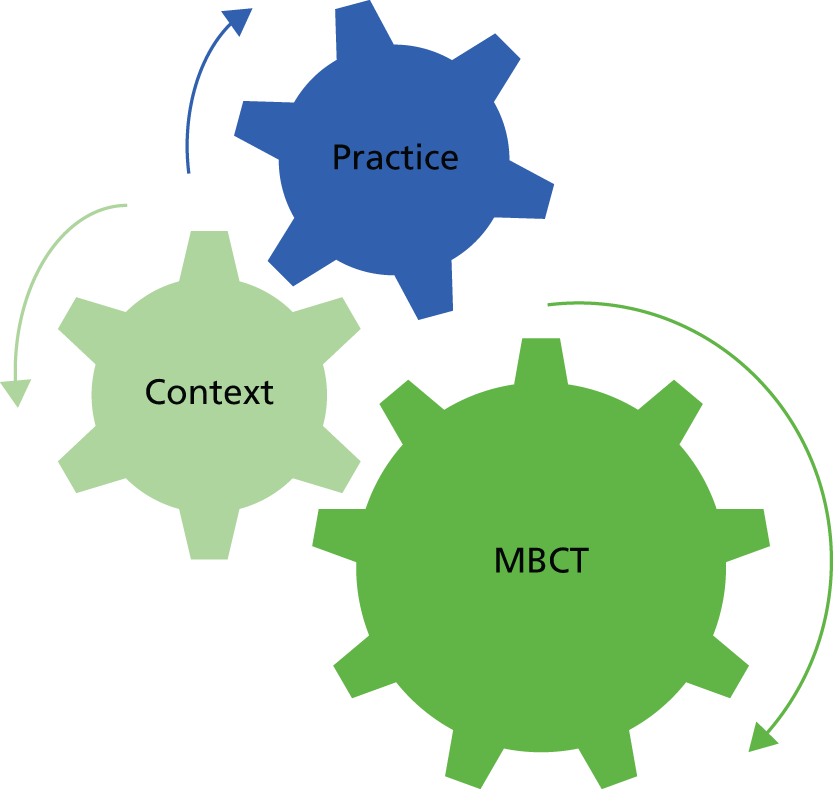

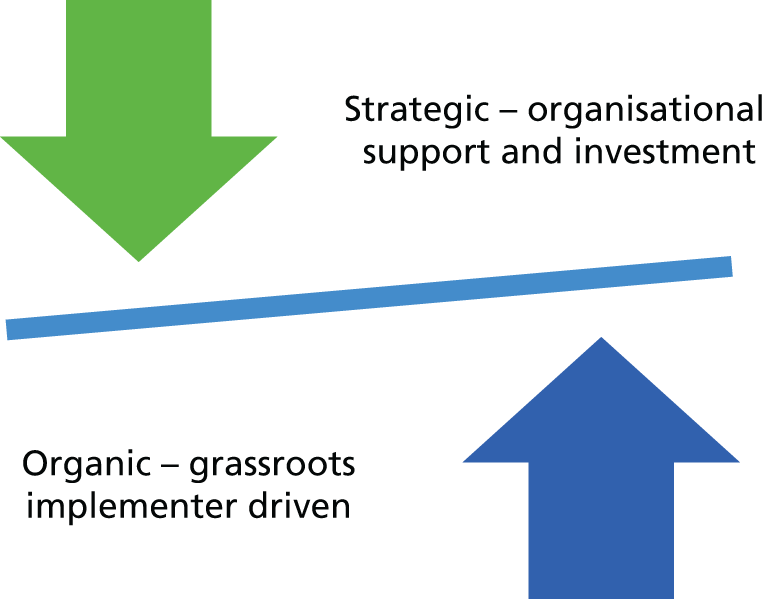

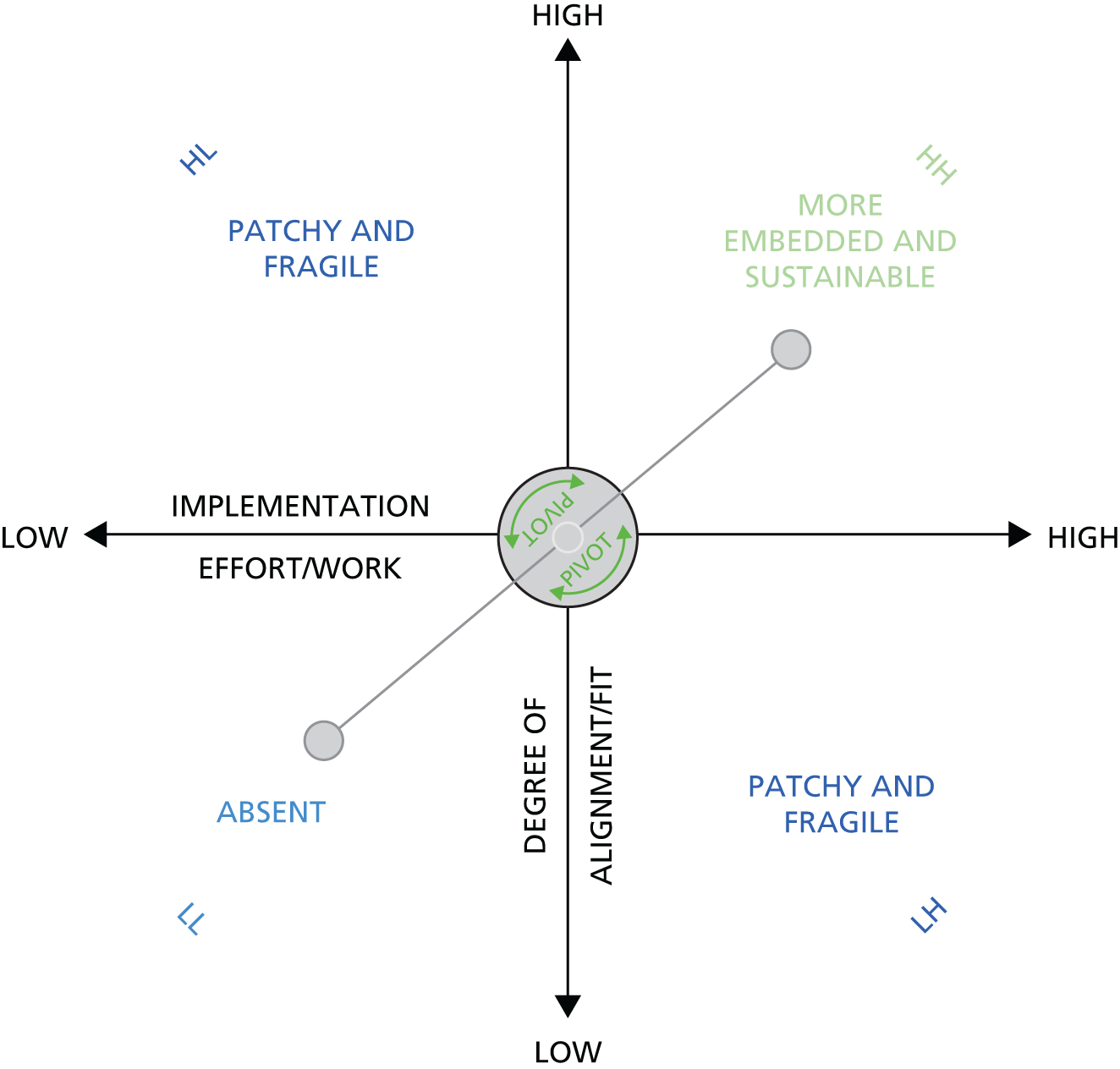

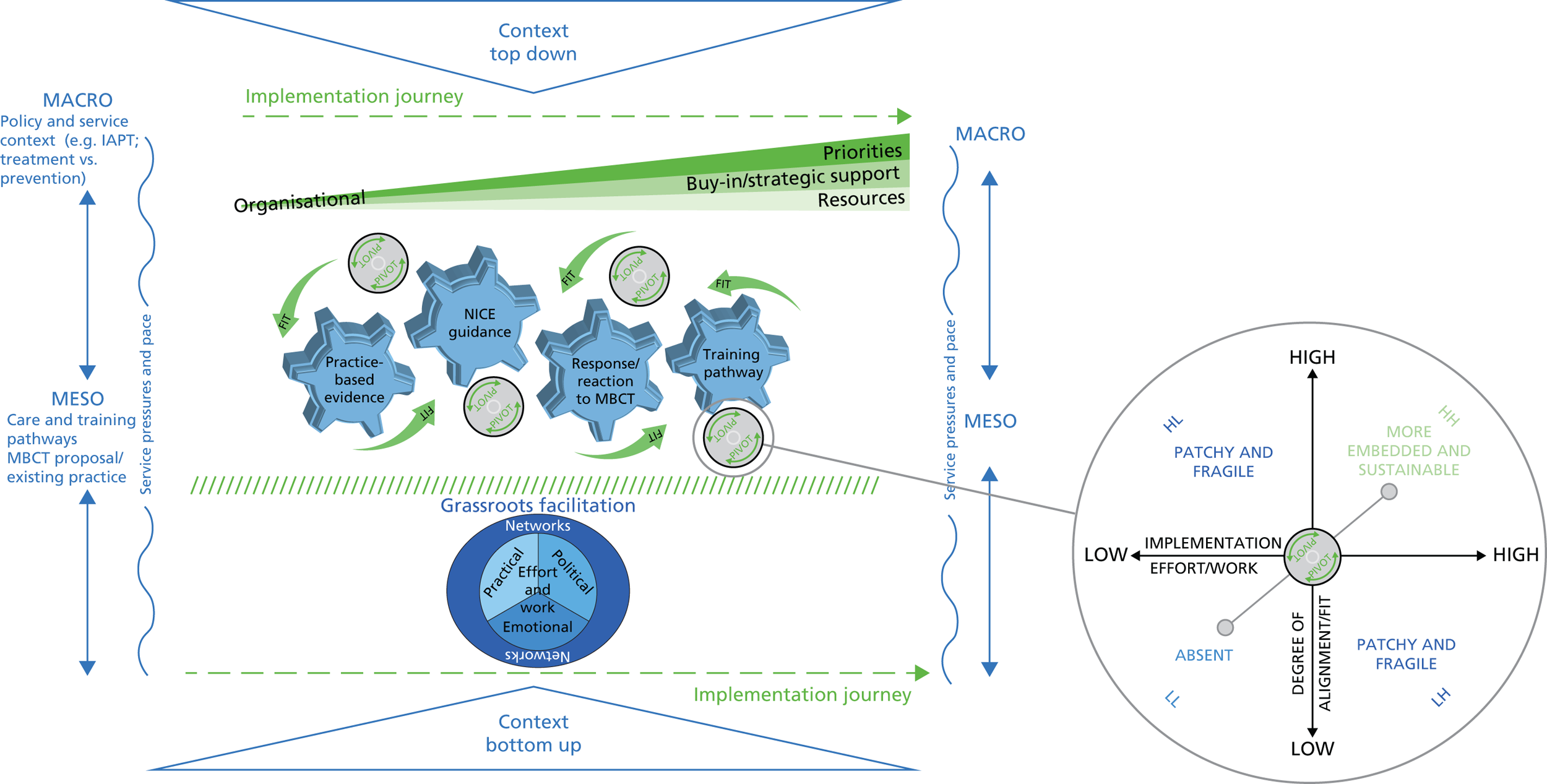

The framework approach that was applied to data analysis in phase 1 facilitated the development of a conceptual map (see Figure 2) that enabled us to move to phase 2 data collection and analysis in a purposeful way (i.e. it provided an opportunity to seek further explanation, in contrast to more description).

To create a ‘case summary’, information was gathered from interview data and then observations and documents were checked to confirm or refute (refutation rarely occurred) statements made in the interviews. This was done by reading and reviewing documents and field notes against the coding frameworks developed from interview data.

Consistent with the comparative case study, each case was viewed as ‘whole’, in that data were analysed within it before being considered across sites. A pattern-matching logic based on explanation building was used. This strategy allowed for an iterative process of analysis reflecting the variety of data sources, and the potential insight each could offer in meeting the study objectives.

Ethical issues

Permission was granted from a NHS Research Ethics Committee (reference number 13/SW/0226) in August 2013. Once ethical approval was granted, we sought approval through local research and development governance processes [National Institute for Health Research Co-ordinated System for gaining NHS Permission (CSP) reference 134133 – accessibility and implementation in UK services of an effective depression relapse programme: mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (ASPIRE)]. Principles of good practice were adhered to throughout the study.

Confidentiality and anonymity

Each participant was assigned a unique numerical identifier following the data collection episodes. To ensure anonymity and confidentiality, role descriptions (e.g. teacher, manager, commissioner or service user) have been used to describe participants in this report. To ensure anonymity we have also assigned each participant in phase 1 a number, and each case in phase 2 a name (see Table 5).

Chapter 3 Phase 1 findings

Introduction

Over the next three chapters we report the findings of this study. In this chapter we report on the findings from semistructured interviews with a sample of participants from a cross section of regions in the UK. This account is a description of stakeholders’ perceptions about the extent of accessibility to MBCT, and the factors that have both facilitated and hindered its implementation. In Chapter 4 we provide a high-level description of each case site, before moving on to a cross-case explanatory account of the different factors and features of the implementation stories participants recounted to us. Our intention in reporting our findings in this way is that we build up an increasingly rich and explanatory account of the data.

Sample

Participants in phase 1 were drawn from 40 NHS sites. The balance of participation across the UK regions is seen in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Map of phase 1 sample. Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2010.

As described in our funded protocol,72 we sampled to ensure a variation of perspectives about MBCT. With the overall aim to interview up to 70 people, we wanted to make sure that data were collected from at least one key informant per region. In the first wave of data collection we therefore collected data from champions who were either clinicians (n = 27 MBCT teachers) or clinicians with a management role (n = 20). Next, and to ensure representativeness across other stakeholder groups, we created a sampling pool of a further 91 candidates, which included 39 managers, 23 commissioners, 16 service users and 13 referrers. We then randomly sampled (as requested by the funder) across this participant pool and interviewed seven managers, four commissioners, five referrers and five service users. Our total sample for phase 1 was 68 participants. In the interests of not revealing the identity of participants, we reference the region [England (South, London, Midlands, North), Scotland, Northern Ireland, Wales] rather than the trust or health board name.

Findings

The findings are reported below using the overarching structure offered by the PARIHS framework: evidence, context and facilitation. Overall, reports from participants showed that access to MBCT was patchy, even within the same region. There were no discernible patterns in the accounts of people between the different regions or between different types of participants, but where there were differences these are noted. However, MBCT teachers shared more information about activities, facilitators of and barriers to getting MBCT used in practice as they had been at the forefront of implementation efforts and, as such, we refer to these participants as implementers in the narrative that follows.

Types of evidence

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence: brand/badge – making a case

Participants often made positive reference to the fact that MBCT is recommended within NICE guidance. Those in the position of championing MBCT stated that the fact that it appeared in NICE guidance was helpful for making the case for commissioning MBCT and/or for convincing chief executives that they should be providing it within their service and allocating resources to it. The majority of MBCT teachers identified that the NICE badge helped by giving credibility to their efforts to raise awareness of and to support implementing the intervention. The NICE badge had also been used to secure funding for training. As NICE guidance is ‘based on evidence’ (teacher, North) and associated with ‘excellence’ (manager, London), implementers said that quoting it gave them ‘ground to stand on’ (teacher, South) if questioned about implementation activities. Furthermore, it was perceived that the NICE badge had ‘opened the door’ (teacher, South) and helped to progress implementation:

I would say another facilitator is the NICE guidelines. I mean that really sort of just opened the door I would say. I think without . . . just having MBCT in the NICE guidelines, just creates a legitimacy in people’s minds that . . . I don’t think we or others could have got nearly as far with this, you know without that, and without the other research that’s you know mushrooming now in mindfulness, and that we can refer to.

Teacher, South

Evidence fit with patient and practice

Although the NICE badge was viewed positively to help make the case, the fact that MBCT was part of NICE guidance was also referred to as a ‘double edge sword’ (teacher, South). Participants expressed challenges with applying MBCT in strict accordance with the NICE recommendation(s). As such, practitioners were adapting and adopting MBCT in flexible ways:

I guess in terms of MBCT, we don’t focus specifically on relapsing depression, so we’ve kind of opened it up a little bit more, where we accepts referrals for anxiety disorders . . . we’ve had to move away from this sort of strict MBCT recurring depression, because . . . I don’t know if we get enough referrals for that.

Teacher, Scotland

Some teachers welcomed the specificity of the recommendation and were trying to remain ‘faithful to the NICE guidelines and to the evidence base, so that if we are questioned, we are stood on very solid ground’ (teacher, London). Additionally, clinicians were sometimes asked to apply MBCT to other populations not included in NICE recommendations, in these cases the guidance was used to defend decisions not to widen the criteria:

. . . and I have a sort of mindfulness operational policy document [. . .], and I guess I’m keeping it quite strict to the NICE guidance in that there’s lots of requests for clients to come who have other challenges or difficulties, but the service is quite clear, that we’re only offering it to people with recurrent depression.

Teacher, South

However, there were examples from implementers of widening the NICE-recommended criteria to make it accessible to the sort of patients they were routinely seeing. In reality practitioners reported seeing patients who were more complex than those who were ‘currently well and have had three or more episodes of depression’ so that, if they ‘stuck tightly to the NICE guidelines’ (teacher, South), there would be limited opportunity for using MBCT. The inclusion criteria were widened because participants saw ‘applicability beyond’ (teacher, South) what NICE guidance recommended:

. . . we didn’t really have many people in the services who would meet that criteria. But there was a starting BDI [Beck Depression Inventory], Beck depression score of around 19 as opposed to about 10 as I think it is in the kind of original trials that are in NICE. But still sort of mildly, sort of mildly getting towards moderately depressed. But as time went on in secondary care, the group we are running, and you start to think well I can see how this might be helpful . . . that’s just how then it started to expand if you like . . . because you begin to the see the applicability beyond that group, even though you’re moving away from NICE guidelines.

Teacher, Midlands

After seeing some benefits to a wider population than those referred to within NICE recommendations, some questioned the relevance of NICE guidance. There was also a question about whether or not the evidence underpinning the guidelines may be out of date, particularly in the context of research emerging about the relevance of MBCT to other populations (e.g. from teachers from North, South and London).

Clinical judgement

As well as the NICE guidance, participants who were actively implementing MBCT talked about needing to bring in other types of evidence from their practice to delivery, implementation and evaluation activities. Some questioned the process of how trials and guidance are developed, emphasising that their own clinical judgement was equally important to delivering and evaluating a service:

. . . a reality with randomised control trials and who gets picked . . . how they’re done and who pays for it, and then guidelines being written, and yet there’s many treatments or many developments that are not there in the guidelines that are useful; there’s a way of having clinical judgement and being able to say why it’s useful, justify your decision, justify inviting somebody to the group.

Teacher, Scotland

Client feedback

Participants also reported supplementing trial evidence with client feedback to help with tailoring of the service locally, and as evaluative information to improve provision:

. . . our course has evolved partly from feedback from the participants, and from the facilitators, on what has worked and what hasn’t, and it actually is tailored to the needs of the local population rather than to you know university studies that may not entirely be the same in terms of population as ours.

Teacher, Scotland

Although participants expressed some challenges with collating feedback, partly because of being constrained by resources, there was evidence that some had used such information systematically by collating feedback and presenting it in a way that could help with evaluation:

We have an evaluation at the end with each of the clients and what I’ve been able to do is collect their own personal feedback from their perspective and collate in a kind of graph and actually it’s quite interesting because I’d noticed particular themes that were rising from that feedback.

Teacher, Midlands

In contrast to relying on anecdotal feedback, participants from 40 sites (19 including English IAPT services) reported including the collection of standardised information from clients/patients. Standard measures included the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) for depression and the Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) pre and post intervention. The Center for Outcomes Research (CORE) measures seemed to be prevalent in secondary care settings, and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) used mostly in Scottish sites (see Appendix 8 for examples of measures used).

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy: the intervention

The following sections describe findings related to the acceptability, accessibility and adaption of MBCT.

Acceptability

Participants often referred to an awareness of ‘mindfulness’ within their organisation and more generally within the community, owing to the increasing media attention. However, there was a perception that there was less awareness of what MBCT is as an intervention. Teachers reported that they had experienced challenges in educating managers about MBCT and what it entailed, and some managers interviewed also stated that they were not aware of the full extent of formal training, supervision, personal commitment and practical needs of MBCT:

. . . there’s MBCT and then there’s mindfulness, and I guess mindfulness feels easier to talk about. I’m aware in terms of formal MBCT training, that’s not something I think we as a service has engaged in.

Manager, Wales

There were some examples of scepticism in the data whereby teachers reported that in trying to inform managers and colleagues about the intervention it had been perceived as a ‘bit of luxury’ (teacher, Scotland) because of its preventative nature, with doubts expressed about what it entails:

There are staff and managers who think that you know you do an 8-week group as a participant and then you’re off. You know, you read the Green Book and then you can teach it. So you know that attitude is a barrier, and then convincing those people that they need to do quite a bit more, can be a challenge, and that this is a therapeutic intervention, it’s not just a bit of sitting on a cushion.

Teacher, South

Data also showed that there was some scepticism among commissioners; for example, that MBCT was viewed as a little ‘alternative’ (teacher, South) and only going to be accepted by people with a ‘particular world view’ (teacher, Scotland).

The media reporting had also been seen as providing advantages as well as disadvantages in that more and more people were hearing about ‘mindfulness’ and were wanting ‘to ride along with the wave’ (teacher, Scotland). In contrast, some managers said they were hearing about ‘mindfulness’ being used across different settings, and growing perceptions about it being some sort of panacea:

. . . we need to be slightly careful about what it is and what it isn’t . . . at the moment you would almost think it was a panacea sometimes . . . any age group . . . from school children to older adults . . . almost any setting . . . from primary schools to prisons, to hospitals . . . almost any condition from psychosis to depression . . . Now I’m happy to believe that’s true, but there’s a sceptical side of me.

Manager, Scotland

Accessibility

The majority of individuals accessed MBCT service by being a patient who was already known to the service, and who had previous interventions such as CBT, so they were being referred on from within the service (e.g. teachers and managers, South, London and Scotland). Others got referred by their GP (teachers, Midlands and Scotland), and data show that increasingly trusts and health boards were accepting self-referrals. There were some examples in our data of reports of GPs being less likely to refer straight to a MBCT service; for example:

I have to say our greatest referrals have been through primary care. We did do road shows to GPs, who were very receptive, but as far as referrals go, really quite poor in directly referring.

Teacher, South

Following on from referral, many sites took steps to ensure that suitable people got access and that those being referred to the service were appropriate. Those steps included an assessment usually over the telephone and an orientation or introductory session (teachers from South, London, Midlands, North and Wales). Although it was reported that demand had increased in some sites, the amount of people who fulfilled the criteria was relatively small (teacher, North); therefore, the screening and assessing process was essential to ensure that the correct people got access. Where a thorough screening and assessment had been made, it was reported that it was less likely that people dropped out (teachers, South).

To ensure that the service was accessible, implementers reported being flexible in their delivery, such as putting on evening sessions for clients who worked during the day. Such flexibility had been important to service users:

. . . we did have to wait a bit because we did want it to be an evening group and they had to wait until there were enough people who would be doing that . . . making it accessible to people who are employed is really important . . . whereas medical appointments, employers can be flexible . . . but to have 8 weeks . . . and because it takes at least half a day because of the length of the session . . . very few employers are happy for someone to use their worktime.

Service user, London

Waiting times varied across sites, and sometimes varied within the same site; as such, some participants expressed that access was a bit of a ‘post code lottery’ (manager, Midlands; teachers, Scotland). As a result of some sites only having one or two members of staff running MBCT groups, patients could be waiting at least 2 months or sometimes longer if the service only ran one or two groups a year. Service users reported waiting a couple of weeks (North) to over 1 year (South).

. . . it was probably 3 or 4 months to starting the 8-week course, from self-referral basically, but then there was another sort of 3 months before that to find the information to know I could self-refer . . . and then it was another 3 or 4 months of the XXXX [county] experience . . . so from the decision to do something about it, to actually starting the course, it was definitely 12 months, possibly longer I would say.

Service user, South

To facilitate access to the intervention, some sites chose to use the intervention as a ‘well-being’ intervention rather than a ‘therapy’ so that it could be viewed as a self-help intervention rather than one related to mental health. This strategy had also been used in several sites where courses were being made available to staff, for example:

I think it’s kind of just by chance we have taken it as being . . . sort of being pushed as a staff well-being thing. I think that’s been quite helpful because it gets, we’re getting people who are coming along and its part of them, you know it’s their own practice, rather than necessarily selling it as something you do to patients. So I think we’re getting people who are on board with their personal practice, rather than coming along just to be facilitators. That’s been quite helpful.

Teacher, Scotland

Adaptation

As outlined earlier, MBCT had often been adapted from what is stated within NICE guidance to reflect the local service needs. Some sites had an open to everyone approach in cases where it was felt that the client would benefit. Practitioners were delivering the intervention to different populations such as those with chronic pain, anxiety or stress and also adapting to include clients who were presenting as not currently well (teachers, South and London). Some teachers reported that if patients were in partial recovery and were well enough to engage in the course, then MBCT was offered and that if they adhered to the NICE recommendation many patients would not be able to access the service and groups would not be filled.

We’re much more open with who comes onto the course, so we’re not strictly seeing people who have had three or more episodes of depression and in recovery now. We have quite a mix, so we will have people who are still feeling somewhat depressed, but they might have had a CBT intervention. We’ve had people who have had anxiety problems and they’ve had interventions in the service. We have people who are in recovery following intervention, and we have people who are non-clinical as well.

Teacher, London

There were also examples of implementers branching out to diagnoses other than depression and anxiety, and tailoring the intervention to individuals, rather than at a group of people with the same diagnosis (teachers and managers, South and Midlands). This was done partially because they see the potential benefit of the intervention to these groups (teacher, Northern Ireland) and also because of pressures from the service to include more people (teachers, Northern Ireland and Midlands) and to ‘relieve some of the waiting times for the other services as well’ (teacher, Scotland).

Our data show that there were a number of models of delivery, from pure MBCT, as stated in NICE guidance, to hybrid MBCT/mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) or MBCT/Compassionate Minds models. 81 Some practitioners reported that having the flexibility to switch from one model to the other, depending on their client group, was important and enabled responsiveness to client and local needs.

Context

Data show that context is a potentially powerful moderator of whether or not MBCT was available and accessible. The following sections identify the key contextual issues that emerged from discussions with stakeholders from across the UK regions.

Culture

Fit of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in the current NHS

Pace

As described by participants, MBCT is not an intervention that provides ‘a quick fix’ (teachers, Wales). As such, it contrasts with the pace of health services in the UK, which resulted in a number of challenges reported by participants. Practitioners stated that within a pressurised, fast-moving NHS environment it was:

. . . quite a struggle . . . to deliver the programme in a mindful way, so like all the administration around it and so on, because the culture of IAPT and primary care therapy . . . tends to be therapy on roller skates, that’s the whole culture, its bums on seats, quickly in, quickly out, have we got to recovery, off we go, quick team meeting, you know, rush, rush, rush.

Teacher, South

Furthermore, it was reported that the pace of the environment presented challenges to upholding the integrity of the approach, with some feeling pressure to deliver the intervention in fewer than eight sessions, running larger and more diverse groups with less training and supervision, described by this participant as:

. . . a real tension between integrity and fast implementation. It was quite difficult to hold the line there, and really not be drawn into providing a level of service that just didn’t seem appropriate.

Teacher, Midlands

Medical model

In contrast to many interventions delivered within health services, MBCT is concerned with well-being ‘rather than about medicine, whereas the NHS mostly is about medical treatment . . .’ (teacher, South). Some accounts from commissioners also described the predominance of biomedical approaches:

GPs are interesting . . . they’re like many doctors, more inclined to prescribe medication than they are to recommend therapy. The NICE guidance points out that a combination of both talking therapy and prescription is likely to get the most sustained and reliable outcome, but they seem unwilling to do both.

Commissioner, South

A focus on physical health, the need for recovery, and a lack of understanding or awareness of the underpinnings of MBCT, resulted in frustration for some practitioners:

. . . the medics still don’t get it. [. . .] it’s not just another treatment that helps people cope with pain . . . Because you’re working in a context that’s based on a different personal physical paradigm, and they’re not even aware that they’re based on a paradigm . . . ‘oh can you give me some CDs [compact discs] so I can give them out to patients and use them like relaxation tapes’.

Teacher, South

Competing priorities

Commissioners described tensions between finances, in general ‘most things that we do is around potential saving that can be made . . .’ (teacher, London), and for mental health services in particular:

I’m trying to get more mental health funding from the CCG [Clinical Commissioning Group] because we feel that it’s underfunded . . . but of course that is a big challenge because of the big acute trusts swallowing up all the resources.

Referrer, London

Furthermore, a tension was described between the need to deliver outcomes at pace:

We’re required to move at a pace that’s more challenging and deliver savings that are more immediate, and I think that creates a conflict between us as commissioners and the provider.

Commissioner, South

Some accounts from managers also highlighted the difficulty of managing competing pressures of throughput and quality:

. . . the commissioners are only interested in whether we meet our targets or not . . . they are interested in numbers entering treatment and moving to recovery figures . . . they’re not really interested in the quality, as long as we get our 50% moving to recovery.

Manager, Midlands

It is possible that the tensions described by commissioners and managers led to a feeling by some practitioners that MBCT was not at the forefront of priorities:

I think that sometimes sort of the MBCT stuff gets pushed to the background sometimes. That’s certainly I think been the issue, not just with the therapists but the sort of more senior staff within the service.

Teacher, Midlands

Change in the NHS

Frequent changes, organisational complexity, ‘tradition’ and ‘hierarchies’ were mentioned by participants as a challenge for changing services of any kind, and for implementing MBCT in particular. Over half of our sample described the NHS to be in a constant state of flux; for example:

. . . a massive service structure as well, so change in their service structure, and we’re going through a period of flux of it, I think for them at the moment it’s not their priority to think about it.

Teacher, South

The type of changes that were noted by participants varied, but challenges included a ‘muddle’ of services working in isolation from each other within trusts (teacher, South), changes to regional service boundaries (manager, London), attempts to integrate service pathways via ‘internal reorganisation’ (teacher, South) whole teams being moved across trusts in an ‘amalgamation of services’ (teacher, South), primary care services being merged into IAPT since 2009 (teacher, South; manager, London) with some integrating MBCT from the start and some not.

Although described as a challenging implementation context, some also recognised the potential in this by, for example, seeing an opportunity to ‘use the chaos to embed MBCT’ (teacher, South) and enabling implementation to go forward ‘under the radar’ (teacher, South).

Resources

Our data show that MBCT work was frequently informally resourced. That is to say, it depended on the enthusiasm and commitment of individual people and the goodwill of senior managers. Frequently, it appeared to be not well embedded in budgets or in staff or organisational objectives. This meant that it was consistently at risk and that improvements in delivery achieved within a trust could easily be lost due to changes in personnel or changes in budgeting. The following sections describe findings that relate to different sorts of resources.

Human resources

Participants described a lack of dedicated human resource to deliver MBCT. In areas where MBCT was being implemented, implementers tended to be lone champions. Generally, a lack of qualified teachers was described, and where there were fully trained and accredited teachers it was rare that they were dedicated to delivering MBCT; these individuals were developing MBCT services in addition to their existing role and responsibilities.

Staffing and having enough qualified teachers was described as a ‘continual headache’ (teacher, South) in the majority of regions. It was reported that in sites where there was only one qualified teacher, champions relied on support to co-facilitate from individuals who had not been trained. Furthermore, the amount of human resources could vary within one organisation; for example, one region had three or four groups per year, but in other parts of the same trust groups were not running because of a lack of qualified teachers. This resulted in potentially fragile services where there was a perception that ‘if I was to leave tomorrow, essentially that mindfulness service would die with me’ (teacher, South).

In addition to teaching and delivery resource, practitioners delivering MBCT also reported that administration support was challenging, with many relying on goodwill: ‘. . . we have to buy her an awful lot of chocolate’, with none, or ‘little admin provision’ (teacher, Scotland).

Financial

The costs associated with setting up a MBCT service were acknowledged by many participants we spoke to: ‘if you want a good solid service that is delivered because it’s based in evidence . . . yeah it costs’ (teacher, South). This included the cost of training and continued supervision. This cost was set within the context of what was described by some commissioners, as a greater challenge of funding for mental health services and of under-resourcing more generally for health services:

. . . (what’s most pressing is) trying to find ways of increasing investment in mental health services because we know that generally they are under-resourced . . . and working within a very cash-limited environment.

Commissioner, South

This included balancing resources across different psychological interventions; for example, ‘carving out this job for this MBCT practitioner, meant there was less resource for our conventional services’ (teacher, London). As such, cost was described as a barrier to the implementation of MBCT.

The consequences of these funding challenges were that often practitioners had invested their own money in developing services by, for example, delivering it in their own time, paying for their own training and ongoing supervision, and paying for venues. Practitioners reported that they had made this investment by choice because of their interest and personal commitment to MBCT.

Time

Time manifested as an important resource factor for implementation. Frequently practitioners described the relationship between funding, staffing and time as a major implementation challenge because there was a lack of capacity and capability to be able to set up and maintain a new service. As such, they spoke about feeling the pressure to deliver something as quickly as possible with no funding and, as a consequence, had invested their ‘personal time to get it up and running’ (teacher, South). Additionally, there had been challenges, with some implementers being able to ring-fence the time for attending training sessions, some being able to take time ‘in lieu’ and others working in their own time because they were unable to secure managers’ agreement.

As described earlier, the need to deliver quickly was in conflict with a therapy that requires more than attendance at a short training course. Additionally, those delivering services described that it took time to embed a new MBCT service because of the need to develop appropriate links and raise awareness with referrers. Practitioners also described the nature of the intervention and time required to deliver MBCT groups, in contrast to other group interventions:

. . . the difference between running a mindfulness group and say running one of our stress management or move management groups, which are much, much quicker to prepare and deliver.

Teacher, South

Time was also described as a barrier to getting started or making a case for MBCT: ‘we haven’t put much effort into that, because it takes too much time [. . .] it’s just unbearably time consuming to get money’ (teacher, London). Additionally, participants described time as a barrier to conducting evaluative activity:

. . . a full time clinician has to see 25 patients a week . . . It doesn’t leave you much time to do anything else . . . that’s another reason why we’ve not been able to do any evaluation and audit of our course.

Teacher, London

Practical

Many implementers talked about practical resources being the major barrier to delivering MBCT groups. Adequate physical space, in the context of many NHS organisations reducing costs by selling buildings, a lack of money to hire rooms and challenges with finding appropriate rooms (for delivering the intervention), was a challenge. There were a number of consequences of a lack of appropriate space related to intervention accessibility and delivery (Table 3 shows a summary). In contrast, those services that had more developed services did have dedicated and free access to conduct group treatments.

| Challenge | Effect |

|---|---|

| Big enough | . . . it’s not big enough to have mats on the floor. So we do very little movement practice . . .Teacher, London |

| Conducive | Finding a room that can hold 15 people, most of them lying down undisturbed, a big challenge, a big challenge . . .Teacher, South |

| . . . we hadn’t been told that the only access to get to the toilet meant you had to walk through our group, you know, oh dear, so we were in the middle of the body scan the first week and suddenly the door opens and two people walk through . . .Teacher, South | |

| Accessibility: timing | I can’t do a group in the daytime because I can’t find the appropriate room for it . . .Teacher, Scotland |

Additionally, other resource challenges for implementers related to materials:

. . . just simple things like photocopying, you know getting CDs [compact discs] and stuff like that, you know. It’s those sorts of added costs in terms of resource that aren’t really factored in unfortunately.

Teacher, Midlands

Other practical resources such as mats, cushions, compact discs (CDs), etc., were often provided by the implementers as there was no funding for such equipment from trusts or health boards.

Money, money, money, money, oh my god, one year, in order to get CDs for the course, I had to dig up all the strawberry plants out of my garden, and sell them, and colleagues helped, and we had a cake and plant sale, and raised £400 and then bought our CDs for the courses. Getting mats, I’ve had to beg and borrow every March from senior management.

Teacher, North

Facilitation

Champions and championing

Implementation of MBCT appeared to be driven by ‘passionate’ champions who were ‘willing to go the extra mile’ (teacher, South), who invested a lot of personal time and effort into making it happen and who (it was reported) would ‘probably do it for free’ if they had to (teacher, North). As described above, implementers made personal and financial commitments to initiating and sustaining services. MBCT was reported to be a big part of their personal and professional life (teacher, South) and champions often talked about ‘embodying’ mindfulness (teachers, South and Midlands), and the importance of starting off with a personal practice (teachers, Midlands and North):

I believe in mindfulness, and I do the same thing whether it’s my NHS work or my private work. The message is basically the same . . . I’m kind of encouraging people to set up the practice and then practise themselves . . . the message is please don’t use it, unless you do it yourselves.

Teacher, North

Most implementers often worked alone in championing the intervention and, therefore, services grew from the ground up through the work of MBCT practitioner/teachers. This left services fragile with concerns that losing individuals would lead to services being stopped:

. . . the champion’s stepped aside now she’s still in the background but I have a worry and a concern when the champion’s moved ’cos we’re kind of I’ve only got 2 years to go before retirement my colleague is in that place as well so I have a worry about the loss of the service yeah.

Teacher, Midlands