Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 12/5002/19. The contractual start date was in September 2013. The final report began editorial review in April 2016 and was accepted for publication in January 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Ferlie et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Study context and research objectives

This study analyses the early development of recently created English health-care organisations, namely Academic Health Science Networks (AHSNs), charged with accelerating the diffusion of health-improving and wealth-creating innovations across English health care. We will study how AHSNs approach their innovation diffusion and knowledge mobilisation tasks. We also take an agency perspective and explore the possible role of ‘knowledge leaders’ (KLs) in these regional sites.

The study responds to the Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) research brief 12/15002, ‘Research to Improve Knowledge Transfer and Innovation in Healthcare Delivery and Organisation’, which included relevant themes relating to increasing ‘research pull’ by health-care managers and promoting interactive and boundary spanning knowledge translation (KT).

The policy and organisational context

First, we outline the policy and organisational contexts before considering academic literatures that surfaced in our early protocol (although we develop our literature review in Chapter 3). The diagnosis at the policy level is that the UK NHS has been good at the invention of new treatments and products, but poor at their diffusion: ‘while the NHS is recognised as a world leader in invention, the spread of those inventions within the NHS has often been slow, and sometimes even the best of them fail to achieve widespread use’. 1

Accelerating the diffusion of promising innovations and more effective knowledge mobilisation across the health-care field has been a recurrent concern in recent English health policy (we review these policy texts more fully later). This policy-level concern has helped to create a new supporting institutional architecture for knowledge mobilisation, of which the AHSNs are an important part.

An emergent academic literature reflects on evolving UK health research policy. Walshe and Davies’ historical analysis of policy documents notes a shift from initial goals of knowledge production to later ones of ‘knowledge mobilisation’, which could embed the results of the research now produced more quickly into practice. 2

From the mid-2000s onwards, significant health and economic policy documents encouraged better translational research capacity at a macro level. The Cooksey Review outlined novel wealth generation goals for the health-care sector in addition to traditional health improvement goals. 3 It urged better system capacity in KT so that new scientific knowledge could flow ‘from bench to bedside’ speedily. The Cooksey Review’s characterisation of the so-called translation 2 gap – the long time taken for a promising innovation to roll out from pilot sites across the health-care field – is of particular interest here. 3

The Darzi Review4 further sought to support more rapid roll-out of evidence-based innovations in health care. It helped to invent a new organisational form (or, rather, imported it to England from well-known American sites, such as Johns Hopkins Medicine). It was stated that a ‘small’ number of leading edge and internationally competitive Academic Health Sciences Centres (AHSCs) would be created (only five in the first 2009 tranche) to bring together basic science, clinical practice and education and training and to stimulate more and speedier interactions between these three traditionally loosely coupled domains. 4

Further institutional change came with the first tranche of regionally based Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRCs) (2008) to encourage applied health research to improve patient outcomes across their areas. They should develop collaborations between NHS organisations and local universities and work to narrow the second translation gap. We review this important policy stream fully later.

And now Academic Health Science Networks . . .

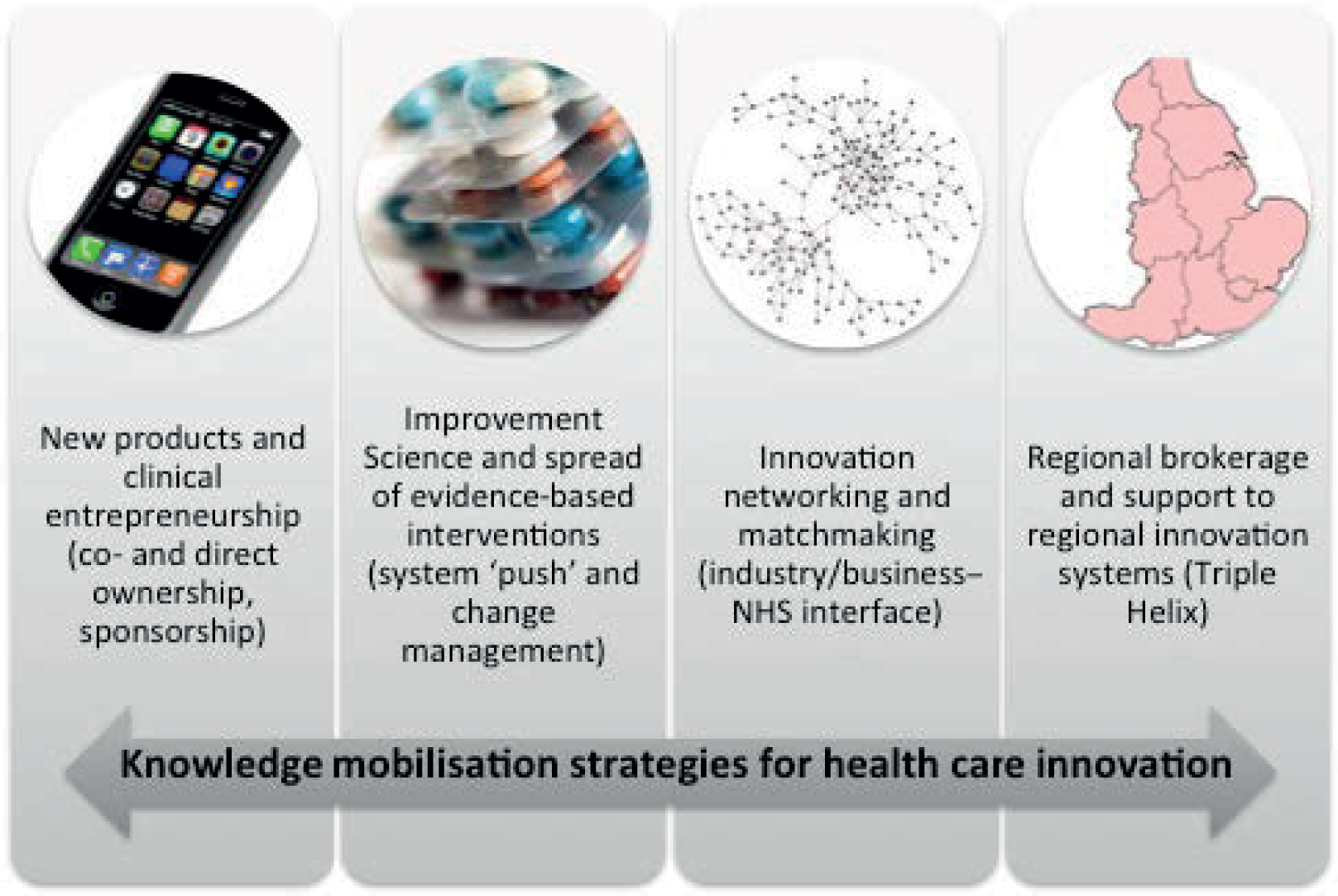

A recent institutional change has been the Department of Health’s (DH’s)1 proposal to introduce – and then the decision to license (during 2013/14) – 15 AHSNs. AHSNs now cover all of England, unlike the AHSCs, which are concentrated in a few research-intensive universities. They broadly have a regional footprint with a population of 3 or 4 million. The foundational policy document was intriguingly called Innovation, Health, and Wealth, recognising the potential economic importance of the health-care sector and its contribution to science-led growth, as well as traditional health improvement goals. 1

This document saw AHSNs as part of a ‘delivery system’ for enhanced innovation. They would promote health-related goals: ‘their goal will be to improve patient and population health outcomes by translating research into practice and implementing integrated health care services. Working with AHSCs, they will identify high impact innovations and spread their use at pace and scale throughout the networks’ (p. 19). 1 They would also provide industry with a readily accessible NHS ‘lead customer’ and would ‘strengthen the collaboration between clinicians and other practitioners and the medical technology industry on which innovative product development so often depends’.

Briefly, AHSNs can be defined as small and multisectoral organisations that operate on a network basis, rather than as a hierarchy. They are organised as ‘managed networks’, which work to national policy objectives, and are monitored on their progress rather than more traditional tacit and professionally dominated clinical networks. 5

Academic Health Science Networks are membership-based organisations that receive some (relatively modest and time limited) NHS funding, but are also expected to generate subscriptions from their members. There is variation in their configurations and approaches, dependent on local circumstances, but all should promote both health and wealth objectives. They have a small management team, which would often include a non-executive part-time chairperson, a chief executive officer (CEO), a commercial director and support staff.

They have a catalytic and change management-orientated role in promoting the diffusion of innovations in complex multisectoral systems, including local universities, the NHS and private firms. They seek to contribute to broader culture change in making the NHS more open to industrial partners.

The academic and theoretical context

Any empirically grounded study of AHSNs should be informed by academic and theoretical literature so that it has a conceptual basis. We now draw on the literature review in our protocol to outline the initial academic emplacement of the study (www.nets.nihr.ac.uk/projects/hsdr/12500219), although our arguments are developed further in the full literature review later undertaken (see Chapter 3).

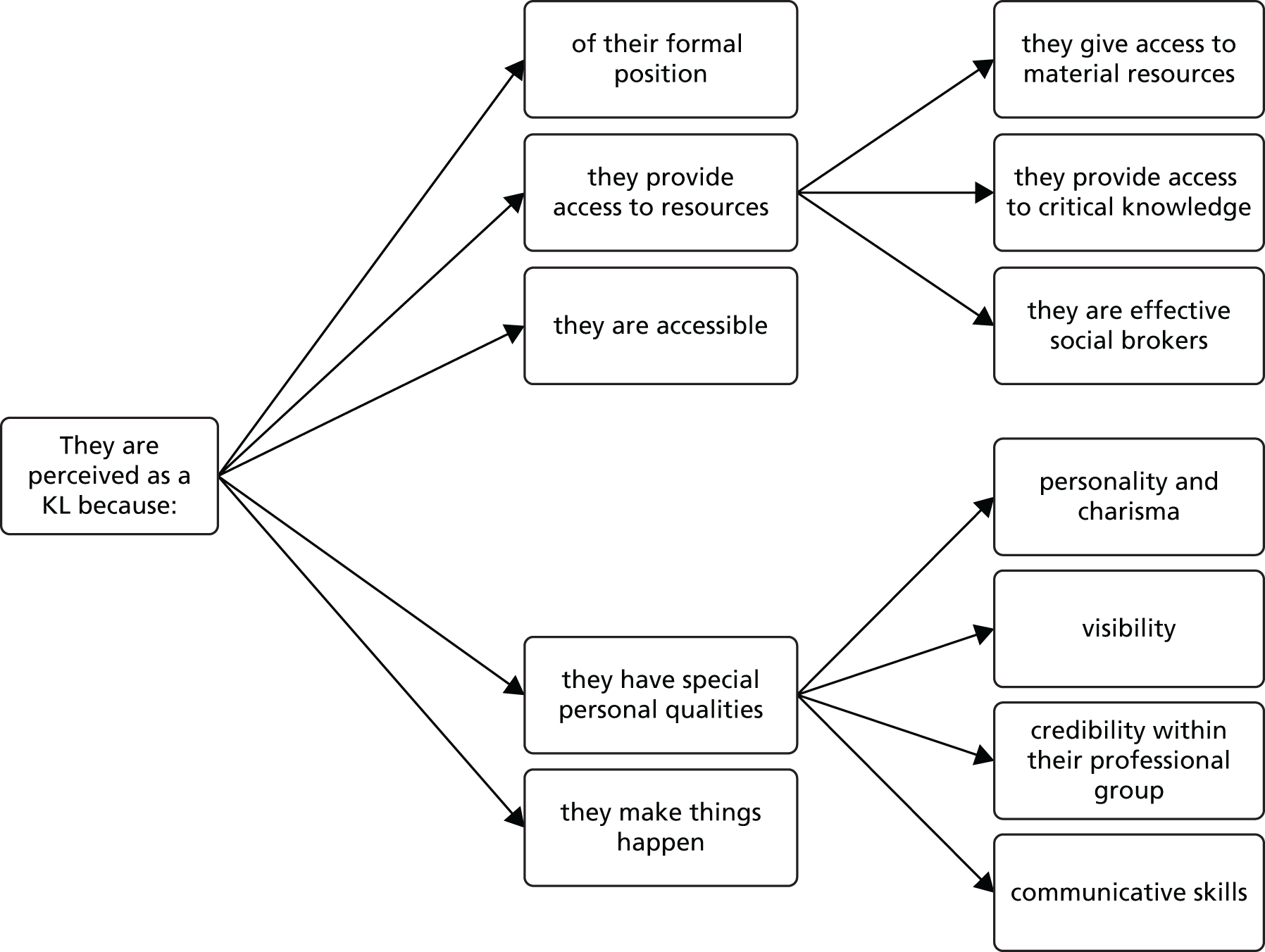

First, our protocol argued that the well-established diffusion of innovations literature6,7 needs consideration. Coleman et al. ’s6 classic early study of the diffusion of medical innovations (the timing of a clinician’s decision to prescribe a new antibiotic) highlighted the role of informal clinical networks in spreading knowledge about innovation. This study also found an important group of clinical ‘opinion leaders’ as influential in adoption decisions and explored their characteristics.

Rogers7 distinguishes the role of ‘early adopters’ as individuals well integrated into a local social system who act as the first port of call for advice and information about innovation. They play an important role in the ‘take-off’ stage of the diffusion of an innovation by spreading positive evaluations to colleagues. They draw on strong interpersonal networks and credibility to persuade others, and are also moderately more ‘cosmopolitan’ (e.g. attending more scientific conferences or having a national professional leadership role) than followers, while combining these attributes with strong local credibility. This perspective suggests that agency from credible opinion leaders may be important in innovation take-off.

A further issue concerns the long-term sustainability of health-care innovations. 8 Innovations may be adopted but later unadopted rather than undergo routinisation into everyday practice. A study of NHS service improvement, for example, noted pervasive ‘improvement evaporation’,9 with rapid reported improvements associated with short-term bursts of change management activity but followed by regression to the status quo. An implication is that longitudinal analyses of the career of innovations over time is required to assess any evaporation effects.

Second, the initial protocol suggested that literature on knowledge leadership in health-care organisations was important. Specifically, we built on two recently completed studies on the leadership of knowledge in health-care organisations previously undertaken by researchers on the proposal. Nicolini et al. 10 explored knowledge mobilisation practices undertaken by CEOs in the NHS trusts, using shadowing methods. Although the study sheds useful light on how information and knowledge enter these senior managers’ thinking, by its nature it offers limited evidence as regards how such knowledge is shared more widely. This current project extends this earlier study by retaining a focus on senior managerial agency, but examines the wider knowledge networks of what we originally termed AHSN very senior managers (VSMs), who could be either general managers or clinical–managerial hybrids.

More recently, Swan et al. ’s edition11 explores knowledge mobilisation processes in health care from a practice perspective. ‘Knowledge mobilisation’ is construed as a proactive process that involves efforts to transform practice through the circulation of knowledge within and across different practice domains. Knowledge is not a thing that people ‘have’, but it is what they ‘do’ and involves questions of who they are (or identity).

Dopson et al. 12 explored health-care managers’ accessing and use of management knowledge, rather than the more conventional focus on the implementation of guidelines by clinicians. Despite some calls for an evidence-based management movement that replicated evidence-based medicine (EBM), Dopson et al. 12,13 found few texts based on evidence-based management. Instead, radically different forms of management knowledge (such as business school faculty or management consultant-authored texts, often from American authors) were present. So, knowledge leadership may be exercised internationally, as influential texts may be written by international authors (often American) and imported. A second implication is that codified texts (such as bestselling books) could be important,14 in addition to local knowledge practices.

Dopson et al. 12 identified opportunities for local knowledge leadership within the health-care organisations studied. One important competence was brokering the movement of knowledge across distinct knowledge domains, epistemic boundaries and different institutions, encouraging its absorption by more than one organisation or profession. This finding is relevant to the AHSNs, as they too operate in a multisectoral and multiprofessional context.

Fischer et al. 14 ask how leaders influenced by research-based management knowledge mobilise such knowledge. The KLs found12 often had a strong desire for formal knowledge or a ‘will to know’, apparent throughout their personal biographies and over time. They might complete PhDs (Doctors of Philosophy degrees) in a related area or write and publish articles and books. These ‘KLs’ were not merely facilitators and translators of management knowledge, but rather personally deeply immersed in – and committed to – producing and diffusing such knowledge.

A third theoretical perspective explored in our protocol was that of ‘absorptive capacity’ (ABCA) drawn from the resource-based view of the firm in strategic management. The resource-based view sees the firm as a bundle of tangible and also intangible assets where a key intangible asset is the (variable) corporate ability to develop and exploit its fundamental knowledge base. 15 High ABCA may partly depend on well-positioned individuals who ‘stand at the interface of either the firm and the external environment or at the interface between subunits within the firm’16 as boundary spanners. In reading ABCA articles, we will explore how they conceive of agency.

Knowledge networks in health care and related settings were a fourth and final area of academic literature in our protocol. Within network-based organising, less formal, more interactive and interpersonal forms of communication and knowledge exchange across traditional boundaries assume greater prominence.

A generic management literature suggests that social and informal networks17 help staff to acquire and process knowledge in and across organisations. A recent study examined knowledge flows empirically in eight NHS managed networks5 (e.g. Managed Cancer Networks). The ASHNs are another example of the managed network form.

Strong interpersonal networks can potentially spread information and knowledge and build high ‘social capital’. Yet very dense networks also create closed cliques that stifle innovation, so one argument is that a network with more ‘weak ties’ may be more functional than one with fewer strong ones. 18 So, we shall be interested to map different networks in the AHSNs, to explore variation (how open/closed they are and how they evolve over time) and to explore any influence on innovation processes. We also noted that academic literature on knowledge flows in biotechnology clusters19 will be important.

Research aims and research questions

Following our early review of policy and academic literatures, our overall aims were defined in the initial protocol as follows:

-

to shed light on the dynamics of knowledge circulation, sharing and exchange that take place within and around newly formed AHSNs

-

to deepen understanding of the role of VSMs in triggering and instigating the knowledge mobilisation activities that are the core of the remit of the AHSNs

-

to explore how and why certain VSMs develop a strong engagement with knowledge exchange events and mobilisation strategies and how they have become ‘KLs’ within the research utilisation network instituted by the AHSN.

The specific research questions (RQs) are:

-

What role does ‘knowledge networking’ play both formally (in national and regional AHSN knowledge exchange fora) and informally (i.e. in VSMs’ professional and local networks) within knowledge mobilisation strategies and practices in AHSNs?

-

How is the ‘knowledge’ (in particular about knowledge mobilisation strategies and practices) discussed at these fora diffused by a group of engaged VSMs in their AHSNs?

-

Is there a subgroup of VSMs emerging who are highly engaged with such knowledge mobilisation events and who appear to act as KLs in their AHSNs?

-

If so, what explains such knowledge leadership behaviours?

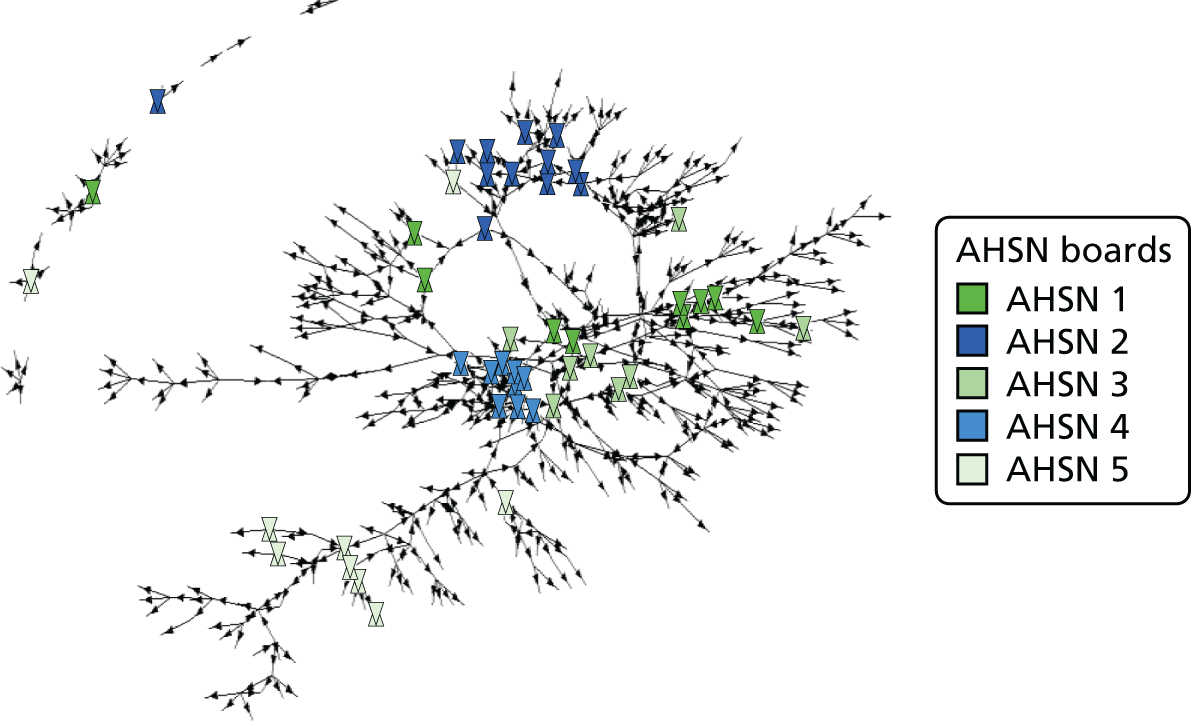

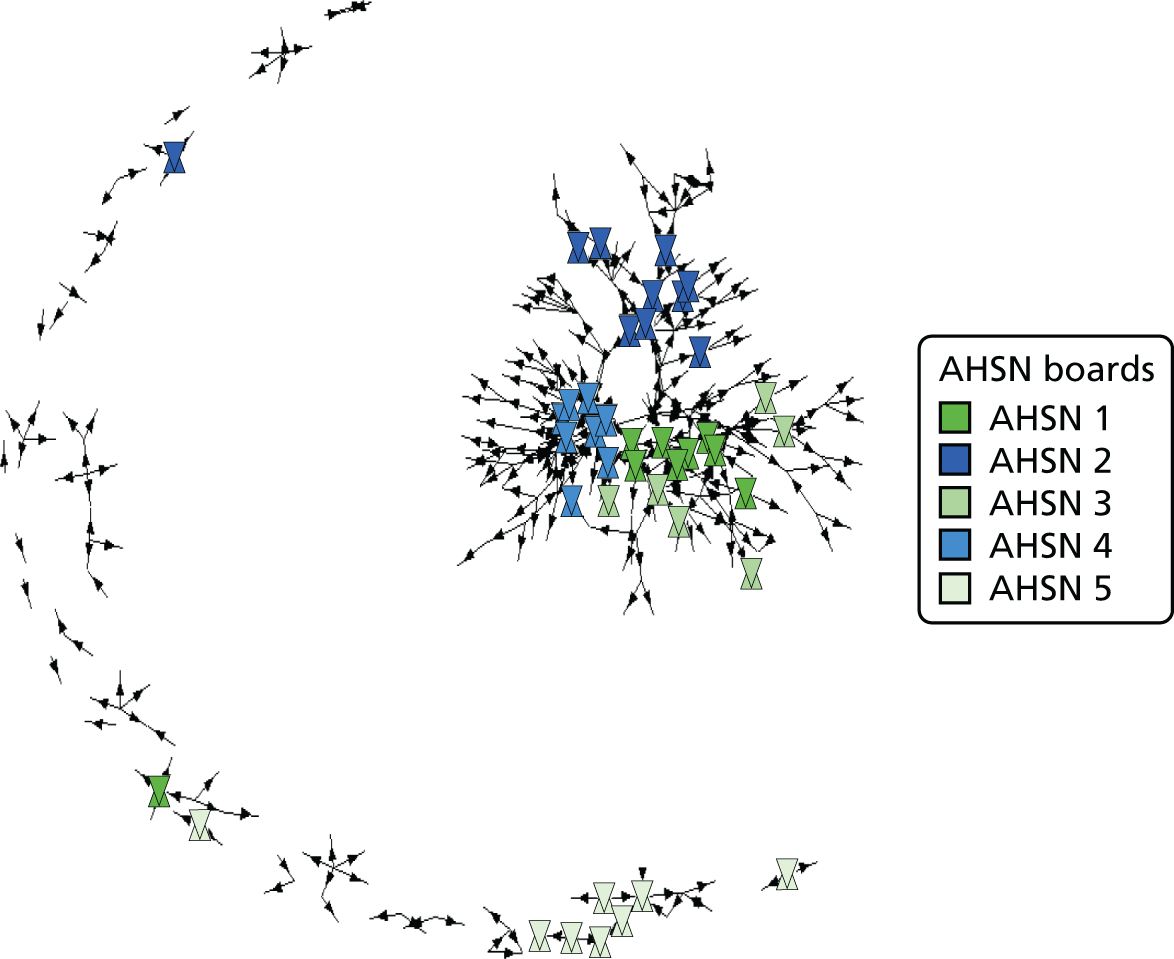

We will report the results of the study by the various work packages (WPs) outlined in our protocol [note that there were some unavoidable amendments, as noted in our methods (see Chapter 2)]. Chapter 3 is the literature review, and this is followed by the findings from our policy-level interviews and texts presented in Chapter 4. In Chapters 5 and 6, we introduce the regional case studies and use social network analysis (SNA) to investigate the national and regional ‘knowledge networking’ supporting AHSNs at their early stage of development. Here, we highlight the role played by AHSN boards but also by other key actors as knowledge ‘brokers’. To build on this work, Chapter 7 explores the diffusion of this knowledge by AHSN senior managers, teams and stakeholders, and illustrates the models of knowledge mobilisation and innovation spread in action through an analysis of our ‘innovation tracers’. Finally, Chapter 8 sheds light on the role and activities of KLs.

Having outlined the policy, organisational and academic contexts of the study, we move on to specify further our research design in Chapter 2.

Chapter 2 Study design and research methodology

Introduction and overview

Overall, the study uses a mixed-methods design to study the early development of AHSNs, including an analysis of the wider health-care policy landscape, a SNA of knowledge networks, comparative case studies of the evolution of five AHSNs, including 10 ‘micro tracers’, and an examination of leadership dynamics. We used four types of research methods:

-

qualitative semi-structured interviews and case studies

-

SNA and accompanying surveys

-

observations of national and regional meetings and events

-

analysis of secondary documents (i.e. policy papers, AHSN official publications and website materials, board minutes and grey literature).

The project aim was to assess the early development of AHSNs and their specific knowledge exchange efforts; in addition, we aimed, to explore senior managers’ knowledge leadership strategies, specifically in relation to knowledge mobilisation. We tracked developments within five AHSNs, tracing their espoused knowledge mobilisation strategies and practices in use to meet health improvement and wealth creation policy objectives. Below, we provide an overview of our WPs, followed by a more detailed discussion of the methods used. A few approved adaptations from the original protocol are also described and the rationale for these is explained.

Research ethics and NHS governance

In advance of the study start date, we contacted the NHS Research Ethics Service (now located in the Health Research Authority) to establish whether or not NHS Research Ethics approval was required. An e-mail from the National Research Ethics Service (August 2013) confirmed that our study was not defined as ‘research’ for NHS purposes and that NHS Research Ethics Committee (REC) review would not be necessary because our study involved staff only and would not access patients or patient-sensitive data.

Our host university still required ethics review. We therefore submitted our research plans and early data collection materials to the King’s College London (KCL) REC, which granted full approval in November 2013 [reference REP(EM)/13/14-12]. Ethics permission from KCL was later extended to reflect a short (6-week) extension granted by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). Furthermore, as we progressed with the study and developed new materials (e.g. the SNA survey and interview protocols), we submitted these texts as ‘modifications’ to the KCL REC as supplementary documents, which were also granted approval.

Although the study was deemed to be low risk for NHS purposes, owing to the nature of the study (exploring networks with a wide geographic reach), we needed NHS governance permission across many NHS sites that we might visit to undertake face-to-face interviews. However, AHSNs invariably cut across large areas, with typically 10–30 NHS trusts and 5–25 Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) per region, depending on local arrangements. To manage this complexity, we sought guidance from KCL’s local Research and Development (R&D) Governance Team located at Guy’s and St Thomas’s Foundation Trust (FT)/KCL Biomedical Research Centre (BRC). With support from this team, we applied for our study to be added to the NIHR Clinical Research Network (CRN) portfolio and completed relevant forms via the Integrated Research Application System. Site-specific access was granted, along with appropriate research passports for the researchers visiting NHS trusts when these were required locally. Only a very small number of NHS trusts did not provide governance permission and we were careful to avoid visiting these sites.

We had to deal with multiple NHS trust R&D offices and submit study accruals centrally, yet these were also sometimes requested by individual sites. In this way governance was highly complex in a network-based study of this kind and we often encountered duplication of processes (e.g. recruitment reporting). The Health Research Authority may now have simplified the NHS governance process for more recent similar studies; certainly we would welcome streamlined NHS permission systems, especially for low-risk studies involving staff and service evaluations.

We are especially grateful to the research and governance team based at Guy’s and St Thomas’s FT, who advised us throughout the course of this study.

Scoping work, site selection and policy analysis (work package 1, leading to work package 5)

First of all, we accessed the original prospecti from all 15 AHSNs, securing an initial overview of network objectives and their remit. Following our protocol, our sampling strategy was to ensure variation in our sample of five AHSNS, both geographically (rural/urban and north, midlands and south) and according to whether or not they had an AHSC at the time of licensing. We also wanted to include some regions with a well-developed health/biosciences capacity, given the strong policy and academic interest in regional innovation systems. In addition, there was a pragmatic consideration of which AHSNs would provide access for our 30-month study.

With our partner at Universities UK (UUK) and our Study Steering Committee (SSC) members, we discussed as a team which sites to approach. We were aware that AHSNs were being established in different ways post licensing: some were hosted by NHS trusts, others as companies limited by guarantee. We successfully achieved a balanced sample of five AHSNs following our selection rules, including a spread of AHSNs with different regional economies and hosting arrangements.

Policy interviews and documentary analysis (time points 1 and 2)

We first undertook desk research and reviewed relevant UK health, life sciences and economic policy documents (2003–15), including, but going well beyond, the core Innovation, Health and Wealth (IHW)1 text to trace the longer-term and broader policy trajectory.

Having undertaken this desk research and a literature review (see Chapter 3), we had identified several interesting papers on knowledge mobilisation, leadership and the triple helix model of knowledge production. However, we were also aware of the newness of AHSNs and some important knowledge gaps in the literature on issues such as knowledge leadership in the health sector. We therefore devised our time point 1 (T1) semi-structured policy interview schedule (see Appendix 1) to help us understand, in greater detail, the wider context of our study and policy background, including perspectives on barriers to public sector innovation. For example, we asked respondents to share their views on the perceived opportunities for AHSNs nationally and the leadership skills required for this kind of networked endeavour.

Through discussions with our policy partner (UUK) and reading of policy documents, we identified eight key individuals who had fed into central policy and AHSN development and/or with expertise in the NHS innovation landscape. We successfully recruited eight policy informants early in the study, who helped us to understand in detail the origins of IHW1 and the policy context. We later located additional life sciences, health policy and other government texts to help understand the longer-term evolution of this policy stream, and one of the team members constructed a chronological review highlighting the major developments over time, used as a reference point throughout the study (see Appendix 2). We found publications and strategic reviews going beyond the NHS and DH to include texts from the Her Majesty’s Treasury and Department for Business, Innovation and Skills (BIS), such as those analysing life sciences strategy or university–industry collaboration.

We returned to this WP towards the end of the study following our protocol and given our ambition to capture the development of AHSNs over time. We undertook further semi-structured policy interviews at time point 2 (T2), speaking with eight more respondents (four of whom contributed to a group discussion in the same policy-focused organisation). These later interviews (in 2016) focused on themes from our empirical analysis of prior material and were designed to ensure that the information captured was up to date (see Appendix 3). For example, questions picked up on newer policy developments in the health/life sciences field, such as the accelerated access review (AAR), and the longer-term impact of financial conditions on the health sector and process of NHS innovation adoption (a theme picked up during other qualitative interviews during the study). We also asked about AHSNs’ perceived effectiveness since their inception, thoughts about IHW1 5 years on and comments on recent regional developments in the health and life sciences sectors (e.g. devolution to Manchester; the emergence of MedCity in London).

Interviews lasted 45 minutes to 1 hour and were digitally recorded and professionally transcribed with informed consent (as with all of the interviews conducted during the study). Policy participants responded in an independent (rather than organisational) capacity and comments are not attributed. The transcripts were analysed by two researchers against a number of specified thematic areas, as outlined further below and in Chapter 5.

So, in all, we conducted discussions with 16 individuals. In these interviews we explored perceptions of regional variations that could affect the careers of AHSNs and extent to which knowledge mobilisation strategies were seen as emerging at AHSN level. We were especially interested in exploring the broadening of the NHS innovation landscape to include the stimulating of economic growth and how the rising growth agenda brought together the health and life sciences sectors and other important actors, such as universities, small and medium enterprises (SMEs) and large firms. Policy interviewees across both time points offered an overview from different perspectives – government, business/industry, academic and NHS policy.

For data analysis, we organised and then analysed T1 policy interview transcripts around the following thematic headings: (1) respondents’ perceptions of this health and economic policy stream; (2) reflections on challenges in innovation within the NHS; (3) recommendations on topics/authors to cover further (a section not reviewed here for reasons of space); (4) early thoughts about the nature of and regional contexts facing AHSNs, their opportunities and major challenge; and (5) preferred AHSN leadership styles, and reflections on their innovation and knowledge mobilisation models and approaches. For the T2 analysis, we cross-referenced the more recent empirical data against our earlier policy data analysis (T1) and data derived from the five AHSN case studies, creating newer themes such as on national and regional trends (e.g. central policy aimed at devolution in England).

In addition, access was granted to the ‘AHSN Network’, a national forum for all 15 managing directors (MDs)/CEOs hosted by ZPB Associates. Three meetings were attended by one researcher, plus one national Commercial Directors’ Forum. Informal discussions also took place around these meetings with persons from other AHSNs, which helped us to understand AHSN metric development and wealth creation strategies more broadly. Another researcher attended NHS Expo in 2015. These various sources informed our analysis throughout this report.

Literature review (work package 2)

The team originally proposed a literature review methodology based on the Chartered Association of Business Schools list of business management top ranked journals. We were encouraged by NIHR expert reviewers to amend this approach to a wider and ‘evidence-informed’ form of review. We then devised an alternative, more thematically focused, review methodology to identify high-quality and/or relevant papers from various disciplinary sources and to capture ‘grey literature’, such as commentary pieces about UK health policy.

A four-phase structured review method was devised. This approach was driven by our RQs and was intended to allow adequate coverage across a range of disciplines including inter alia, management, health care, business and political science. A consequence of broadening the search parameters – and steering away from the Chartered Association of Business Schools ranked journals – was that this WP expanded vastly, given the complexity of searching a dispersed literature base that also included journals of varying quality (see our later discussion of study limitations). We found – as have other health researchers20 – that it is most challenging to synthesise such social science, policy and health-care literatures without investing very significant resources, expertise and time. In the ABCA field, for example, there are a few very well-cited and enduring articles by key authors (e.g. Cohen and Levinthal;16 Zahra and George15) that are foundational texts. Where these articles take the form of theory development or a critical synthesis, the conventional health services research (HSR) notion of making a judgement about ‘high-quality evidence’ becomes problematic.

Phase 1: keyword terms and expert input

Working with an expert librarian, we first identified key terms from the conceptual framework outlined in the study protocol. To ensure validity, we e-mailed a provisional list of our search terms to nine academic experts, who contributed some further suggestions. The team next developed succinct Boolean word strings from this list (see Appendices 4 and 5).

Phase 2: data extraction and targeted search

An experimental search to test our keywords was then conducted, yielding > 4000 papers. This finding demonstrated that, because our themes were very broad in scope (e.g. leadership), the final search strategy should be broken down into manageable component parts. Our final data extraction strategy therefore developed iteratively, building on trial searches on major databases and discussions between two researchers and the librarian. We eventually decided to hone in on three theoretical angles to make the review more manageable:

-

networks and networking practices of top managers in knowledge-intensive settings/networked organisations and, more specifically, the potential agency of leaders (i.e. as brokers, KLs, or persons having ABCA or, conversely, displaying the ‘dark side’ of networks)

-

empirical studies not focusing on the role of individual leaders (agency), but providing macro- or middle-level insights about networks and collaborations, especially in the public sector, heath care or related knowledge-intensive settings (e.g. biotechnology, pharmaceutical)

-

academic and grey literature on knowledge mobilisation policy, including CLAHRCs, AHSCs and other NHS institutional architecture, plus academic health science systems abroad.

This final, three-pronged search strategy (what we refer to as ‘6a’, ‘6b’ and ‘6c’) was executed across four databases in the period January–February 2014:

-

ABI/INFORM®

-

ProQuest [including Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts, EconLit (American Economic Association’s electronic bibliography), International Bibliography of the Social Sciences, Worldwide Political Science Abstracts]

-

OvidSP [including MEDLINE, EMBASE, Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC) and Social Policy and Practice]

-

Web of Science.

Additional searches were also run on Google Scholar (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA), Social Policy & Practice, HMIC and The King’s Fund database (reviewed for grey/policy literature). A separate yet interconnected hand-search of policy documents on life science and NHS innovation policy was undertaken to inform our policy analysis (repeated at different time intervals to keep knowledge up to date).

The results of the final search were limited to papers published in scholarly journals, conference proceedings, books and texts published in English from 1995 to 2014. All results (abstracts) were saved to EndNote X7 for Windows (Thomson Reuters, CA, USA) and duplicate entries were removed. Our review again captured > 4000 initial papers and required substantial reduction. We then developed inclusion and exclusion criteria to screen abstracts and remove irrelevant papers, of which there were many (see Appendices 6–9 for further details).

Phase 3: abstract selection and critical appraisal

An appraisal of a reduced number of abstracts was then conducted by paired researchers to build consensus about important conceptual and thematic areas and to provide some inter-rater reliability.

The detailed frameworks for selecting abstracts are provided in Appendices 7 and 8, but in Box 1 we outline the general guiding principles:

Applied SNA.

Formal and informal leadership within mandated networks.

Formal leaders’ personal networks (e.g. CEOs).

Leadership within informal networks (e.g. communities of practice, clusters).

Relevant high technology industries and regional clustering (e.g. science parks).

Knowledge spill-overs and university–industry knowledge transfer.

Triple helix of industry/university/government relations.

Collaborative knowledge production and strategies in health care.

NHS innovation (and barriers).

ABCA.

Open innovation.

Thematic exclusionsClinical/medical education/pedagogy.

Clinical decision-making.

Highly specialist clinical research (e.g. pharmacogenetics).

Local government programmes without a health/life sciences focus.

Health-care evaluations lacking a network/knowledge exchange focus.

Supply chain management and highly specialist management studies.

R&D networks lacking a health focus.

Industrial districts/clusters/regional innovation systems in less relevant industries and sector (e.g. food science, petrochemicals, banking and financial, automobiles).

Triple helix applied to developing economies without a high-level theoretical contribution.

Having gone through the relevance criteria above, we exported a manageable number of electronic abstracts to a Microsoft Excel® database (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) to sift for quality. At this point we accessed full papers and organised references across nine key thematic areas (see Appendix 9). We then applied a scoring system to rate full papers (working in pairs), taking into account journal impact factor (1 year), methods, theory, interest/novelty and relevance (a 0–3 scale was applied across these dimensions, with 3 being high). Appling these indicative quality metrics helped to identify superior papers (around 4 to 15 papers, depending on the theme), which were generally those strong on theoretical explanation and empirical data presentation and relevant to our RQs. We were aware that certain journals (e.g. The Lancet) have high impact scores that can skew metricised results, and, therefore, also noted Google citation scores and ensured that relevance was retained as a key criterion for selecting papers.

We finally discussed relevant papers as a wider team, as well as how to organise the literature review write-up. A group of highly rated papers (n = 105) was selected for the report and these papers were clustered into the thematic areas already identified. We finally recorded some methodological reflections from this WP.

Phase 4: literature review and final write up

An original, descriptive draft of the literature review stood at nearly 30,000 words. For greater brevity, we moved to select > 60 full papers, with the researchers most involved in case writing choosing ‘higher priority’ articles they saw as having most relevance to the empirical analysis of the cases. This interactive selection process helped link underpinning theory and the empirical case material. These selected articles are discussed in this report, and the remaining 40 or so ‘lower priority’ articles were summarised in radically shortened form. As such, all the articles fully discussed have survived two tests of review: first, academic quality and, second, relevance to our cases. The length of the literature review has been radically reduced and in the latest revision has moved away from discussing individual papers to exploring overall key themes.

Reflections, limitations and conclusions

Some methodological observations on this work package

We made several observations during the data extraction phase. First, our evolving searches revealed that few papers connected major theoretical concepts – such as the ‘triple helix’, or ‘ABCA’ – with a specifically leadership/agency or ego-network focus, a point we discuss in more depth in our findings. Second, given the newness of AHSNs in 2013 (when our study commenced), there was a lack of literature available on this dimension of UK knowledge mobilisation policy (i.e. mandated networks for health innovation as opposed to research translation). This necessitated a review of emerging work on academic science-based organisational forms and policy, for example, searches on The King’s Fund database and a review of material on CLAHRCs and AHSCs as comparable topics. Third, our expert librarian indicated that it was extremely difficult to retrieve ‘a near perfect set of relevant references’ even with complex keyword/Boolean combinations; therefore, multiple databases needed to be searched with some flexibility – including a separate search run on Google Scholar – because databases have strengths and weaknesses and use different algorithms. We observe that a single ‘jackpot’ search strategy is unlikely to prove successful when dealing with a broad social science knowledge base and a spectrum of search variables, or when attempting to integrate social science and health-care databases. Our searches identified a large number of irrelevant results (ranging from 3000 to 4000+ abstracts), indicating the diversity of published material that is returned on extensive social science topics such as networks, innovation and leadership, even if Boolean search strings are applied systematically. Our solution to this issue was to break down our search strategy into thematic areas based on the questions in our study protocol and to conduct parallel searches using carefully constructed search strings. This made the review more manageable.

Indeed, a problem of systemic reviews is that important theoretical papers can be missed as a result of the search delimiters applied (e.g. date ranges). This was especially the case for the ‘6a’ search on leadership, networks and agency. We found Google Scholar useful for applying narrower search terms and less complex Boolean strings, here picking up on grey literature as well as highly cited journal articles.

We reflect that this literature review module was much more time-consuming than originally anticipated and the results were not easy to interpret. We adopted a protocol-driven review methodology at the outset to achieve inclusivity, breadth and depth. This is an approach stemming from a medical tradition but which fits less well within diffuse social science based fields, which we needed to draw on. With the benefit of hindsight, we would adopt a looser and more narrative approach moving from early exploratory readings and snowballing out from highly relevant, well-cited studies, with the flexibility to include newer articles and classic theoretical papers in a more inductive manner.

We conclude that pragmatic, narrative or ‘realist’ approaches may be suitable for such interdisciplinary literature reviews, rather than conventional systematic or highly structured methods. The various literatures that we identified varied markedly in terms of their empirical focus, methods and theoretical framing so they were difficult to ‘synthesise’. Our findings echo Greenhalgh and Peacock’s20 observations in their literature review of the diffusion of innovations in health-care organisations. We note that our review did not surface many relevant economic or service evaluations of specific health innovations and their impact as this angle was not part of our original brief.

During the course of our research we did identify a number of published internal AHSN reports providing evidence of the effectiveness of a number of innovations we studied (see Chapter 7). For reasons of anonymity we do not cite these papers in this report, but we observe that further research in this area may wish to incorporate a review of such available outputs where the innovations to be explored are known in advance or can be disclosed.

Social network analysis (work packages 3 and 4)

What is social network analysis and how can it be applied to our research questions?

Social network analysis is a theoretical perspective and methodology for mapping and understanding the relationships and structures of networks. 21 When studying such networks, we may be interested in ‘social capital’, or the personal network of contacts or resources individuals have access to,22 or, at a higher level, the relationships, partnerships and collaborations that create networked organisational systems. The method is well suited to analysing newly formed, complex or dynamic systems, such as AHSNs and associated regional innovation systems.

Technically, for analytical purposes, a ‘social network’ is seen as a set of ‘nodes’ connected by a set of ‘ties’. These nodes and ties can be represented visually in the form of network graphs or so-called sociograms. Nodes can be actors such as individuals, groups or organisations and are represented visually as points in a network graph. Ties are the connecting links or relations, describing the means through which nodes are interconnected, and are represented as lines in a network graph.

We applied SNA techniques to investigate AHSN knowledge mobilisation activity to support our research aim of tracking knowledge exchange circulations around newly formed AHSNs and to answer our first RQ: what role does ‘knowledge networking’ play in supporting the knowledge mobilisation strategies and practices of AHSNs? Specifically, in this report, SNA as a method is used to:

-

track the national and regional knowledge circulations emerging around AHSNs and generate comparative regional cases with accompanying metrics

-

study knowledge networking that supports wealth and health knowledge circulations, including the role of AHSN leadership in triggering these activities

-

identify a cohort of ‘knowledge brokers’ (individuals who are important for information sharing and the cross-fertilisation of knowledge because they connect otherwise disconnected parties) and ‘KLs’ – individuals who are perceived as highly knowledgeable about health-care innovation and who are effective at mobilising knowledge across geographic and sectoral boundaries.

Mapping knowledge mobilisation networks

We ran a large-scale SNA survey at two time periods to map knowledge circulations supporting population health improvement and wealth creation in the participating AHSNs. Two social network mapping surveys were run: the first (T1, April–November 2014) was launched towards the end of the AHSNs’ first year of licensing and ran for several months; the second was initiated a year later and was live for 1 month (T2, October–November 2015). The survey questions were developed in consultation with our SSC. The questionnaire was then piloted online and assessed through cognitive interviews with AHSN leadership teams and AHSN stakeholders in April 2014. Both surveys were web-hosted and AHSN communications teams provided help with their promotion through their newsletters and social media channels.

These data captured knowledge networks mobilised to support innovation since the AHSNs had been established and during their early life cycle. The T1 data focused on new innovative knowledge circulations ‘in the last 6 months’ (i.e. during the AHSNs’ early set up stage) that supported health improvement and wealth creation. The T2 data focused on connections made through AHSNs ‘in the last 12 months’ that had provided actionable knowledge to support wealth creation. For both surveys, we drew on the IHW definition of ‘innovation’, as per Table 1.

| Survey questions based on IHW definition of ‘innovation’ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Innovation: health | ||||

| New ideas or research | New ideas or research for improving health | New products or services for improving health | Products or services | New application of existing idea, service or product |

| New ideas or research for creating wealth | New products or services for creating wealth | |||

| Innovation: wealth | ||||

The social network surveys featured a range of questions that allowed us to elicit a ‘network’ of individuals linked as knowledge sharing contacts. We asked further questions about the nature of the knowledge being mobilised through these networks and were subsequently able to investigate:

-

knowledge networks to support health improvement (Health-Net)

-

knowledge networks to support wealth creation (Wealth-Net)

-

‘strong tie’ networks of contacts who regularly exchanged knowledge and had known one another for 10 years or more (Old ties-Net)

-

knowledge networks leading to implementation (Implem-NET)

-

knowledge networks providing access to contacts (Broker-Net)

-

knowledge networks based on new ideas (Ideas-Net)

-

knowledge networks providing political influence or leverage (Power-Net)

-

knowledge networks providing trustworthy advice, guidance or information (Trust-Net).

Sampling strategy: identifying individuals as key knowledge contacts supporting health-care innovation

Traditionally, social network studies begin with a roster of names and researchers seek to plot connections between listed actors (‘nodes’) depending on the relation (or ‘ties’) of interest – in this case, the knowledge exchange. We immediately faced a challenge because knowledge circulations around AHSNs did not have a clear boundary, that is, they were cross-sector, cross-industry or cross-geography (regional, national and international) and encompassed a wide variety of individuals with different sets of expertise. Moreover, the key individuals active in these knowledge networks were largely unknown at the start of our research so it was not possible to assemble a roster of names.

Given the unknown parameters of AHSN knowledge-sharing networks and to avoid recruiting a list of ‘usual suspects’, we chose to design a survey tool that would evolve through a peer-driven sampling mechanism. We borrowed from network sampling methods used to uncover ‘linked’ individuals in hidden populations or where there are no clear sampling boundaries (i.e. respondent-driven or snowball sampling techniques commonly used, for example, in epidemiology and studies of drug users). 23–25 These sampling methods identify and recruit to the study a set of ‘seed’ individuals fitting the research parameters, who are asked to nominate other relevant individuals who are then recruited in turn. (See additional note on SNA design in Appendix 10.)

In this spirit, and to ensure that our sample was relevant to AHSNs, we began by inviting four VSMs in each of our five AHSN sites to complete the T1 social network survey (this same cohort also took part in the first wave of qualitative interviews). The survey included questions about the respondent and asked them to name up to five key contacts who had ‘over the past 6 months’ been ‘most active in circulating innovative knowledge’ defined as ‘to support new ideas or perspectives, new research, products or services for health improvement or wealth creation’.

We then invited to the survey the people nominated as key knowledge contacts by AHSN leaders. The survey was rolled out over a series of waves and halted at either a maximum of four waves or when sufficient saturation was reached (that is, when people were starting to be renamed and the structure of networking began to close in). Each wave of survey participants therefore consisted of the contacts named in the prior round. Importantly, this meant that the sample of individuals we derived for the knowledge sharing networks would be created via peer nominations and not constructed by our research team.

Social network data are usually collected in a systematised way; this is most often achieved using surveys, but it also takes place through structured interviews, whereby respondents are asked questions about their personal attributes, their contacts and the attributes of their contacts. Using a variety of survey questions, we elicited the names, job titles and employing organisation, industry, sector and professional expertise of a sample of individuals perceived by their peers as being important for knowledge circulation to support AHSNs. We also asked about the type of knowledge exchanged (and, for the T2 survey, included an additional question about if/how knowledge was implemented). We developed these survey questions and accompanying response categories with our SSC and through piloting with AHSNs and stakeholders. (See the SNA survey in Appendices 11 and 12.)

The final sample included AHSN leadership and core teams as well as wider stakeholders [general practitioners (GPs) and CCGs, academics, SMEs, bloggers, NHS trusts, local authorities, large corporations and government departments].

Response rates

The SNA survey yielded data on a total of 1016 individuals perceived as being key to knowledge mobilisation supporting health-care innovation linked to AHSNs (T1, n = 818; T2, n = 198).

At T1, we used a non-probability sampling technique based on peer referrals over several waves. The population was ‘hidden’ in the sense that we did not know (before the study) who were the key knowledge mobilisers supporting AHSN activity. The SNA helped us to identify these individuals and to map the structure of knowledge networking at national and regional levels. Response rates become difficult because we did not know the total size of the population and respondents were not selected from a sampling frame. Furthermore, we did not seek to recruit all nominated contacts (i.e. at the final wave we had to cease recruitment and, therefore, draw an artificial boundary). Our intention was thus to capture a subset of the knowledge circulations around AHSNs.

Given that we had a ready sample of names, we invited to the T2 survey everyone who participated and/or was nominated at T1 (resulting in a 24.2% response rate). The numbers for T2 were perhaps lower mainly because of attrition (bounced e-mails/turnover of roles) or respondent fatigue, but also because the survey was live for a much shorter time and we did not roll over subsequent waves (because the sample size was large to begin with). See Table 2 for more details.

| Time point | Respondents (n) |

|---|---|

| T1 | 818 |

| T2 | 198 |

| Total | 1016 |

Triangulation of data

From the SNA we derived a list of individuals perceived by their peers to be important to AHSN knowledge mobilisation. We conducted qualitative interviews with a subset of these individuals, in addition to the initial cohort of AHSN leaders who took part in the SNA and qualitative interviews. To help us to identify interviewees, we visualised the knowledge mobilisation networks for each AHSN region (see Chapters 5 and 6). This enabled us to see where individuals were located vis-à-vis each other in terms of their social networks (i.e. some individuals were positioned close to or distant from the AHSN and thus operated in distinct knowledge clusters, some were part of overlapping cliques, some were more peripheral). These relative social network positions were assessed to aid our selection, alongside a spreadsheet listing each person’s employing organisation, organisational role and sector.

For each AHSN region, we selected for interview individuals occupying different social positions and a range of organisational roles (see below for further detail).

Consulting the SNA visual and considering attribute data in tandem thus allowed us to select a diverse sample of interesting interviewees, including regional actors in senior and operational roles in the NHS, but also in academia, large firms and SMEs [see Time point 1 interviews with Academic Health Science Network senior managers and teams (work package 3) and Regional interviews with ‘knowledge contacts’ and stakeholders (work package 3)] and also most prominent national ‘KLs’ who were mobilising knowledge across regions (see Time point 2 interviews and ‘knowledge leaders’). We cross-checked the validity of the SNA survey nominations during our qualitative interviews by providing further opportunity to name other important knowledge mobilisers (see Appendices 13 and 14). Interim SNA results were also presented to AHSN boards and other stakeholders to ascertain whether or not findings resonated and we received a positive response to this feedback.

Social network analysis

The network data were analysed in UCINET (Analytic Technologies, Harvard, MA, USA)26 and Microsoft Excel. In this report, our analysis investigates the structure and composition of knowledge networks for each AHSN region, compares knowledge networking for health improvement with knowledge networking for wealth creation and identifies key players (such as central actors, and within- and cross-region brokers).

The main data set produced was a network of who exchanges knowledge with whom, the type of knowledge exchanged and attributes of knowledge contacts forming the network. We extracted several subnetworks from these data, for example to compare the structure and composition of AHSN region knowledge mobilisation networks and to investigate the relationship between different facets of these networks (trust, implementation, old contacts, etc.). (See the list of subnetworks in Appendix 10 and Chapter 6 for an exploration of results.)

The survey data required a large amount of cleaning before analysis. Notwithstanding the input errors and duplicate records, it was also necessary in many cases to match up and merge attribute data for consistency. For example, if a person is a survey respondent and also nominated as a knowledge contact, we would have two records for this person: one from the survey response and the second from his or her referrer. In these instances, we would keep the attribute data selected by the person themselves (i.e. their self-categorisation as a very senior leader, middle/clinical manager or non-manager) and their self-identification of professional expertise category. This was important only for the attribute data file and not for the relations data file (which need not be consistently matched between alters, i.e. person A can name person B as a knowledge contact but person B need not reciprocate).

Limitations

There are various limitations associated with SNA studies of this type. 27,28 We outline these below.

The very essence of SNA is based on exploring interdependency in linked samples; a network can be a network only if the nodes are connected, and social networks do not form randomly. There are inherent selection biases in the way people nominate contacts (i.e. choosing similar people/best friends, what can be referred to more technically as homophily, or overstating the status of contacts). 29 These are natural characteristics of the data itself and provide the network with shape and structure – the very things we are interested in capturing for our comparative analysis. Attempts were made to limit some kinds of selection biases, for example by not placing delimiters on nominations by sector, geography or hierarchy and allowing the sample to evolve through peer responses.

The data we collected represent only a subset of AHSN knowledge. There will, of course, have been many more knowledge exchanges, and it was impossible to capture all such activity, and so we do not intend the case networks to be generalisable. 28 Two subpoints become pertinent here: (1) our network sampling method yielded a convenience sample specific to the UK context and (2) the SNA data also provide temporal snapshots rather than dynamic images or understanding of process (we instead capture this through our qualitative elements).

We highlight that the AHSNs had different set-up stages, which affected the timing of our fieldwork, and these staggered starting points meant that the time taken to collect data varied between regions. Moreover, because we could not specify from the onset who would be invited to the survey, significant time was spent obtaining NHS governance permission to cover every NHS site in our five AHSN regions, plus additional NHS trusts and CCGs where the networks spanned across geographies. However, we believe that the data set SNA provides a good baseline that maps early knowledge mobilisation networks around the AHSNs and that will be useful for longitudinal and comparative research in the future.

It is also important to note that many standard inferential statistics do not apply because social network data violate case independency criteria as respondents are not sampled independently from their population (because they are linked samples). Instead, the metrics used in this report are based on permutation approaches, applied to calculate sampling distributions directly from observed networks using random assignment/matrix manipulation across thousands of trials under the assumption that null hypotheses are true (in other words, to calculate the likelihood that the observed network would have occurred by chance). We therefore avoid using these data to make predictions and focus instead on the different type of networking structures that emerged between AHSN regions and the differences between networks used to support health and wealth and to identify a cohort of key actors/KLs.

Qualitative data collection and analysis (work packages 3–5)

Time point 1 interviews with Academic Health Science Network senior managers and teams (work package 3)

The quantitative SNA WP was complemented by qualitative and case study-based work. This additional module was deemed necessary owing to the complexity of knowledge mobilisation (which occurs at multiple levels) in practice and so there was a need to capture the ‘doing’ of AHSN knowledge work as it happens, from understanding the early stages of setting up the networks, through to investigating the role of social networking and leadership in relation to innovation spread. Over the course of the study, we conducted a total of 135 qualitative interviews over various WPs. Below we provide more details.

First, we sampled four members from each of the AHSN senior leadership teams (in our protocol, termed VSMs following the term used in some earlier literature, although on the advice of our SSC we later dropped this term). Our sampling strategy at this stage was as follows: MD/CEO level, chairperson, commercial director and other senior figures (e.g. deputies or chief operating officer). These interviews were guided by broad themes coming from the literature review and our original study protocol. They lasted approximately 60 minutes, and were recorded and transcribed. In these interviews (n = 20), we specifically wanted to understand the processes and persons involved in the early establishment of the particular AHSN, any priorities for action and formal strategies devised since the AHSN had been established, and the nature of local interactions to support innovation spread within the NHS and wider regional health economy. Questions included asking senior leaders if there were any objectives that they personally wanted to see the AHSN achieve, and how they would describe the local health innovation system currently. (Please see Appendix 13 for the full protocol questions.)

With successful access to five AHSNs achieved, supplementary informal meetings with AHSN senior teams took place. These meetings confirmed access to the sites and two members of the research team were then designated as leads for each AHSN. The team undertook the collection of key AHSN-level documents (business plans, protocols, reports) and secured invitations to attend some local events and meetings to help understand the work of the AHSNs more broadly (e.g. innovation launches, joint meetings with other health or education groups). Observations and early meetings such as these were especially helpful for identifying ‘innovation tracers’ to follow during the study (see Chapter 7).

Regional interviews with ‘knowledge contacts’ and stakeholders (work package 3)

Further interviews were then undertaken with ‘knowledge contacts’ named in the SNA (see above) and triangulated with early VSM interview data. We first consulted SNA visuals to identify regional actors beyond AHSN core team members to include a wider set of AHSN stakeholders (e.g. industry and academia). Our sampling then moved beyond the SNA to pick up contacts mentioned during early qualitative interviews (e.g. important ‘go to’ persons for innovation, or those performing key roles within AHSN teams). We located persons, for example, involved in delivering AHSN projects and/or contributing to regional AHSN strategy (e.g. board members and AHSN programme managers/leads). Finally, we undertook some purposive sampling to ensure adequate representation from agencies that emerged as significant, such as heads of local enterprise partnerships (LEPs) and hospital and higher education institution (HEI) commercialisation leads. We did, however, impose a limiting sampling criterion: that ‘knowledge contacts’ had to be located within the AHSN region being studied because our emphasis in this stream of work was on local knowledge mobilisation and networks. These interviews explored topics such as the respondent’s involvement with the local AHSN, knowledge mobilisation, AHSN-led initiatives, perceptions of knowledge leadership and networking strategies. (See Appendix 14 for the interview schedule.)

Time point 2 interviews and ‘knowledge leaders’

Towards the end of the study (late 2015 onwards; T2), we undertook a small number of follow-up interviews with AHSN MDs/CEOs where possible (see Appendix 15 for the interview protocol). Owing to high turnover in AHSN leadership, however, such ‘catch-up’ interviews were not always possible. We explored with those MDs we could access persistent network leadership challenges, learning points, recent developments and perceptions of the evolution of their AHSN. There was also a final tranche of interviews undertaken in early 2016. These later interviews were extremely useful in gathering more recent data on the spread of some specific innovations, which had been initially explored in earlier interviews. Given the very early development of AHSNs at that stage (2014), spread/knowledge mobilisation data were necessarily not well developed and they were better picked up at the end of the study, suggesting the strength of a longitudinal approach.

An initial protocol aim was to identify 25 individuals who stood as prominent ‘KLs’ in the AHSN landscape for interview. We moved to a more operational definition of the concept of ‘knowledge leadership’, which we understood to be persons nominated by peers (in the quantitative SNA data) in three or more different AHSN regions. These people could be seen as having national, as opposed to regional, profiles. Our earlier WPs had explored within-region knowledge contacts and knowledge mobilisation and exchange efforts, but here we wanted to understand who was perceived as influential in a wider innovation landscape and how they operated to achieve their pan-regional impact or presence.

To progress this strand of work, we returned to our literature review, which suggested some characteristics of KLs. We used the literature review to inform the design of our interview questions for KLs (see Appendix 16). During the previous qualitative interviews with regional knowledge contacts, we had also asked respondents to identify persons considered as ‘KLs’ (see Appendix 14), along with why. This gave us an early qualitative data set about knowledge leadership characteristics to supplement our literature review.

We then analysed the aggregate data set of SNA survey results to identify pan-regional KLs using two criteria. The first was in-degree centrality index, which is based on the number of times a person was nominated as a key contact by their peers; the second criterion was the number of geographic regions that an individual was named in alongside the betweenness centrality index.

Using these methods, we could identify a small number of individuals (n = 14) whose reputation and influence spanned three or more AHSNs. From this point, we refer to them as ‘national knowledge mobilisation beacons’ (or ‘national beacons’ for short) to differentiate them from people identified as important regional actors who were often admired for their skills but who did not cut across regional boundaries to the same extent. A lead researcher undertook in-depth face-to-face or telephone interviews with these ‘beacons’, which explored their biographies, motivations, influence mechanisms and personal strategies of knowledge mobilisation. We also collected more ‘micro’ information about their daily activities, skills and professional outlook to understand the roots of their successful knowledge leadership behaviours. These interviews with ‘beacons’ therefore fulfilled our research objective to probe into the biography and attitudes of proactive KLs, exploring how they might be engendering a more knowledge-oriented culture in and around AHSNs and within the health-care field more widely.

Nevertheless, we should add that this cohort was a difficult group to recruit, given their seniority and the huge demands on their time. We successfully recruited 9 out of a possible 14 (another respondent indicated their willingness to take part, but could not do so within the period of the study). We also identified fewer pan-regional KLs than predicted in our original protocol. 25

All these qualitative interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. The transcripts were coded thematically and analysed using an inductive procedure, with the support of NVivo 10 software (QSR International, Warrington, UK).

In total, we conducted 135 interviews across these various WPs (also including the AHSN case study tracers). More detail is provided in Table 3.

| Interviews | AHSN 1 | AHSN 2 | AHSN 3 | AHSN 4 | AHSN 5 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AHSN senior managers (T1, T2) | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 23 |

| Knowledge contacts | 13 | 15 | 14 | 14 | 9 | 65 |

| Knowledge mobilisation tracers | 7 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 22 |

| Policy interviews (T1, T2) | 16 | 16 | ||||

| KLs | 9 | 9 | ||||

| Total completed | 135 | |||||

Case studies of five Academic Health Science Networks (work package 5)

The qualitative modules also included five comparative cases of AHSNs. The design of the case study module reflected basic principles of organisational process analysis,30–32 which is a well-known school within management research. Process scholars are interested in how organisations as a whole evolve over time and how they achieve (generally intermediate) organisation-wide outcomes such as varying performance levels. There is often an interest in exploring the organisational correlates of high performance. Organisations are also seen as embedded in their wider contexts, which creates conditions of path dependence.

Although process research is not sectorally specific, it has been widely applied in UK and also in international studies to investigate processes of change in health-care organisations. 33 One of the research team has used these process methods in previous large-scale NHS-based organisational studies. 5 This process approach encourages us to generate a holistic understanding of the AHSN as a whole, over time and seen as embedded in a regional context. ‘Stronger’ case study designs are here seen as those that are comparative and longitudinal in nature rather than a single case, and as relating well to theory and conceptualisation as well as local empirics. These basic principles underpinned our approach to case study work.

We generated a basic template to organise the material in the same manner across the five cases to facilitate comparisons; thematic recognition and pattern recognition (see Appendix 17). The researchers engaged in the case study write-ups met face to face to present and discuss drafts of cases to encourage debate, critique and then movement to a more shared understanding. Long initial descriptive case reports were prepared, which were then radically shortened and made more consistent to fit with tight length constraints here.

As well as writing these macro-level cases, we also undertook two ‘micro’ studies of specific tracers in each case to reveal concrete knowledge mobilisation activity in action (see Chapter 7 and Appendix 17 for a list of interview questions). The tracers enabled us to explore each AHSN’s strategic approach to promoting innovation spread at pace and scale as enacted at the local level and over time (and thus help us assess the extent of knowledge mobilisation achieved in practice). We note that the tracers were selected in consultation with the AHSNs so there may be some positive bias, in that they may have been perceived as areas where the AHSN would be likely to make good progress.

Dissemination and engagement (work package 6)

Reflecting our study protocol, the team also engaged in numerous engagement activities during the study, as follows.

Interim face-to-face feedback was provided to all five participating AHSNs during the summer of 2015 at board/executive level. The findings were well received and validated demerging empirical findings (post-T1 SNA). The feedback from AHSN leaders subsequently informed the T2 SNA design. Presentations and short summaries were provided to the five sites.

A well-attended end of study event took place (2 June 2016 at UUK and organised in conjunction with UUK; see below for more details). Delegates were invited from industry, academic and NHS communities, and also included our SSC members. Members of AHSN teams were also invited (across the 15 nationally), and some AHSN sites had direct input, with AHSN leaders speaking on panels.

The team were made aware of various reports and studies about AHSNs/IHW that emerged in the period 2014–16, such as an Institute for Public Policy Research report, ‘Unleashing innovation across the NHS’,34 and a later project by RAND Europe – University of Manchester35 that evaluated IHW implementation. Contact was made with the latter research team and arrangements were discussed for co-operation between the studies, which the Manchester team may hopefully be able to take forward as their study will end at a later date than ours. Conversations with a relevant HSDR project team were also conducted early in the study (Professor Alison Bullock at Cardiff University, HSDR 12/5002/04).

Two members of the research team gave a well-attended seminar at Imperial College Health Partners in late 2015 to communicate academic thinking to this important grouping. Two researchers (Jean Ledger and Daniela D’Andreta) presented at the Health Services Research Network conference in 2015. From this event, links were made with NHS Improving Quality (NHS IQ) and The Health Foundation (the latter held a SNA event). Daniela D’Andreta also attended NHS Expo 2015.

The team presented a short summary of their research to the 15 AHSN leads in their national meeting in May 2016. The team presented a draft version of the policy chapter at the Organisational Behaviour in Health Care Conference at the University of Cardiff in April 2016.

Study Steering Committee and patient and public involvement

We are grateful for a very active SSC that met three times during the course of the project and provided very helpful advice. It was chaired by Professor James Barlow of Imperial College London, an expert in health-care innovation. Our members included an AHSN MD, a NHS director of research and innovation, a management school professor and two patient/public representatives.

Our patient and public involvement (PPI) representatives were recruited through the University of Warwick’s University/User Teaching and Research Action Partnership (UNTRAP) group, which organises service user involvement on research projects. We found the involvement of patient representatives useful for providing insights about how new health interventions and developments might be geared more towards patient benefit. One of our representatives was aware of other relevant knowledge exchange initiatives (e.g. digitech) linked to their local university and brought with them a breadth of knowledge owing to their engagement with the local health research community and patient experience.

Public engagement and partnership

For the purposes of this study, the greater emphasis was on public engagement and targeted dissemination involving communities interested in health innovation and the NHS; specifically, we sought to engage policy-makers, AHSN leaders, AHSN stakeholders, NHS employees, regional agencies and representatives of professional bodies (including industry).

Connectivity in this regard was made possible through a close and productive working relationship with UUK, with a senior dedicated person attached to the research team as an advisor. Our contact there was able to keep us in touch with contemporary policy developments in both the university and health-care sectors, as well as senior persons in the policy and health-care landscape. In addition, UUK hosts ‘HSR UK’, a professional network and series of events for the health delivery research community, which includes an annual symposium that we attended in 2015 to present our work.

We held a successful end of project conference at UUK in June 2016 to feed back results, which attracted interest and good attendance from senior AHSN staff and a number of other stakeholders from different communities (e.g. think tanks, academia, SMEs, consulting and Public Health England). The design of the day involved thematic sessions with presentations from the research team and responses from senior figures in the field to promote dialogue. We circulated our presentation slides to attendees after the event.

Variation against study protocol

In the initial protocol, we proposed attending an ‘AHSN forum’ to provide access to national-level events. Owing to developments beyond our control, and reflecting the fact that AHSNs were only just emerging and coming to fruition in 2013, which was the time of our study launch, this forum was no longer meeting. Instead, the team negotiated access to attend some meetings of a later national grouping of AHSN MD/CEOs, hosted by ZPB Associates, facilitated by a member of the SSC. We remain grateful for the permission from AHSN leaders to do so and also to the AHSN commercial directors who granted similar access to their national meetings.

Our SSC advised the research team that AHSN boards and executives would be especially interested in (1) how AHSNs compare; (2) what health/wealth networks look like visually; and (3) the regional and national picture. When the team engaged in face-to-face meetings with AHSNs, they reflected these helpful observations. Indeed, the end of study event has been expanded to include diverse stakeholders.

The May 2015 SSC supported the research team’s suggestion to undertake some qualitative interviews by telephone given the wide spread of actors across geographically dispersed AHSN regions to expedite the logistics of data collection.

Owing to various delays encountered, the NIHR kindly granted the team a no-cost, 6-week extension.

Summary of agreed changes to protocol

-

Agreement to observe national AHSN Network meetings in place of the ‘AHSN forum’, which was by then defunct (agreed at SSC, 5 May 2015 at University of Warwick).

-

Move to some telephone interviews to reduce long-distance fieldwork (agreed at same SSC).

Concluding remarks

Our study design is complex and covers a number of (interlinked) WPs. We now have doubts about our earlier decision to adopt a systematic review methodology, given the diffuse nature of the field we encountered. However, the triangulation of SNA and our qualitative data can be seen as a strength. The comparative and longitudinal nature of the case studies/tracers module can also be seen as a strength, enabling us to plot the spread of selected innovations over time. The set of 10 tracers is an interesting and distinctive database.