Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 12/5002/20. The contractual start date was in September 2013. The final report began editorial review in June 2016 and was accepted for publication in January 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

John Powell works part-time (0.5 whole-time equivalent) for the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence as a Consultant Clinical Adviser in the Centre for Health Technology Evaluation. John Powell is a member of the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment and Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation Editorial Board and was previously a member of the NIHR Journals Library Editorial Group. David Sharp was a NHS employee at the beginning of the project, and the NHS is an organisation that funds and uses research. David Sharp currently works at Optum Healthcare, an organisation that sells commercial services to the NHS.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Swan et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Relevant literature and research context

In this chapter, we provide an overview of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) brief, as well as the literature that can be drawn on to address this brief. We will consider the research needs of the NHS in the light of the knowledge mobilisation literature, which offers a strong theoretical foundation for this type of research. We should note that the aim of this project was not to provide a systematic literature review: several reviews have been conducted previously in this domain. Rather, to identify relevant literature, we began by consulting previous NIHR final reports and scholarly works focused on evidence use in commissioning practice. 1,2 As these were rather few, we then turned to reviews of evidence use in health-care management and, in particular, to recent studies of evidence use in practice. 3–11 We also accessed the literature reviewed, more broadly, by leading scholars in the field in our work in editing our own book on knowledge mobilisation in health care. 12 We combined these sources with other specific works, as relevant to particular topics of interest (e.g. research in clinical commissioning, innovation capabilities and so forth). Given the current gap in knowledge on evidence use in commissioning, we address questions about what counts as evidence, when it counts, how it is used and how it is created in order to develop a conceptual framework for the study.

Introduction to the research

Sustained and successful innovation in health-care services, driven by the best available evidence, is critical to the survival of England’s NHS. 5,13 A major provider of authoritative evidence is the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). NICE synthesises and publishes authoritative evidence that is widely considered to be ‘gold standard’. New legislation places NICE at the heart of reforms in health and social care to ensure that patients receive high-quality and cost-effective care. 14 At the same time, more stringent measures to accelerate the uptake and implementation of NICE recommendations are being proposed. Expectations are higher than ever that this evidence will drive innovation as well as lower the costs of service delivery in the NHS.

Much of the responsibility for innovation in the NHS now lies with Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs), which are tasked with the design and procurement of health-care services. Multiple evidence-based products are available to commissioners in making informed decisions, including NICE guidance (e.g. guidelines) and quality standards and metrics [e.g. Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF), CCG Outcomes Indicator Set].

However, fragmentation and variation in the uptake of evidence in health-care decision-making is widely noted. 2,3,15 It is clear that the (abundant) supply of evidence-based products does not always connect to the needs of health-care decision-makers. 1,16 This is especially so when dealing with the kinds of complex, time-dependent and political decision situations faced by health-care managers. 16,17 Walshe and Rundall17 aptly note that the:

constrained, contested, and political nature of many managerial decisions, [make] it difficult for managers to apply research evidence even when it is available.

p. 44517

Thus, a major challenge for NHS commissioning groups is to proactively and strategically consider how they can be better equipped to take hold of, and use, evidence in decisions. A key challenge then, lies in ‘building high learning capacity and appropriate core competencies in NHS organisations, rather than relying on a technological fix’. 5

The imperative for NHS organisations to innovate sits alongside the need to make savings, often by adept commissioning. These objectives can be met only by improving existing services. The need for commissioning managers to use sound evidence is, therefore, greater than ever. 1 In the light of this, organisational capabilities to use evidence in their pursuit of service redesign are especially important and need to be carefully nurtured. Our study, thus, focuses on capabilities to use evidence in service redesign initiatives led by commissioning groups. It seeks to provide an important practical resource for the frontline managers and the clinical leaders of commissioning organisations who will be responsible for making some tough decisions over the coming years. The focus of our work, then, is on improving NHS commissioning organisations’ capabilities to use evidence in decision-making.

Aims and objectives

As stated in our original protocol, the aims of the research were to identify the capabilities (organisational and managerial) that NHS CCGs need to become better users of authoritative evidence. Given our focus on evidence use among social groups in organised settings, we take a knowledge-based view of organisations. 18 As Grant19 comments:

. . . organizational capability, defined as a firm’s ability to perform repeatedly a productive task which relates either directly or indirectly to a firm’s capacity for creating value through effecting the transformation of inputs into outputs.

With this in mind, the objectives of our research were to:

-

Study how authoritative evidence travels into, and is used by, different CCGs (by documenting ‘evidence journeys’).

-

Compare and contrast the travel of evidence across CCGs to understand how and why variations in evidence use occur in practice.

-

Create a toolkit to guide CCGs to better use evidence. Specifically, the tool will help CCGs to assess and improve their capabilities to use evidence. It will be built on process models of how evidence travels in the real world, rather than on abstract accounts.

Our aims and objectives have not changed, but it was apparent from our initial literature search and fieldwork that to understand authoritative evidence use we also needed to consider how commissioners use other forms of evidence too. We had also intended to examine ‘disinvestment’ and ‘investment’ decisions, but it became apparent that, in reality, these are two sides of the same coin. That is, commissioners’ decisions about what not to do occur only when deciding what to do in service design. Hence, the two cannot be practically disentangled when looking at the ways evidence travels in practice, at least in this context.

In the following sections, we outline how our research contributes to the NIHR brief and describe the commissioning landscape as our research context. We then outline our theoretical approach, drawing from ‘knowledge mobilisation’ and evidence-based management (EBMgmt) health-care literatures. 20 Although much can be learned about the ways in which evidence is used in the NHS from these literatures, we conclude that further work is needed to articulate how organisations can improve their capabilities to use evidence more effectively. 1

Response to the National Institute for Health Research Health Services and Delivery Research commissioning brief

This study was funded in response to the NIHR Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) programme’s call for ‘research to improve knowledge transfer and innovation in healthcare delivery and organisation’ (HSDR call number 12/5002). The call builds on the Cooksey report21 particularly the observed ‘T2 gap’ between the research output and transfer into practice. The call emphasised research that generates actionable findings to help the NHS make better use of evidence. The three main themes were:

-

research on ‘pull’ by managers (increasing the receptivity and research/innovation capacity of organisations and individual managers)

-

research on ‘push’ by researchers (making the research product/innovation more usable)

-

research on knowledge linkage and exchange (bringing service decision-makers and researchers/industry together in different ways).

The NIHR call focused specifically on the evidence used by organisations and managers to inform decisions about services, rather than on evidence informing clinical interactions, into which there had already been substantial research. 22 Notably, the call sought to build on previous work on ‘knowledge translation’, for example by the Canadian Institute of Health Research, to improve the translational work of NHS management and organisations. The call was premised on the idea that knowledge translation includes a diverse array of activities and should be understood as highly complex, not only in technical, but also in social, organisational and political terms. 6

Research on ‘pull’ by managers

Our study responds directly to the first theme in the NIHR brief for research on evidence ‘pull’. Specifically, we sought to ‘assess the capacity in healthcare organisations to accelerate innovation’ (p. 4 of the brief) by identifying capabilities for evidence use in commissioning decisions. This aim followed directly from earlier NIHR-funded research, including our own, showing how knowledge and evidence was used by commissioning managers in primary care trusts (PCTs) (Service Delivery and Organisation reference 08/1808/244)3 and by NHS chief executives (Service Delivery and Organisation reference 09/1002/36). 5 Findings of those studies indicated the importance of mobilising different kinds of evidence and local knowledge in a timely manner, managing interfaces across project stages, proactively building and managing relationships to create coalitions and building personal knowledge. 2

Informed by previous work, we use the metaphor of the ‘evidence journey’ in our study to capture our emphasis on the flow of evidence into and through practices of commissioning and the capabilities that influence this flow. We intend to:

-

identify key capabilities to use evidence

-

produce a process-based model (roadmap) aimed at improving capabilities by showing the route by which evidence becomes effective in decision-making

-

develop a ‘toolkit’ as a resource for CCGs to assess their evidence-use capabilities.

Research on ‘push’ by knowledge producers

A secondary contribution of our study relates to the theme on evidence ‘push’ by knowledge producers. We also consider the ways in which guidance is produced and communicated, and how this shapes its mobilisation and usage in context. This part of our research begins to explain, albeit in a preliminary way, how the properties of evidence and expectations about the user inscribed in the evidence matter to the way it travels in commissioning organisations.

Research context: the shifting commissioning landscape (2013–16)

Our study began in October 2013, just 6 months after CCGs took over from PCTs. CCGs are part of the government’s attempt to improve health services by bringing the commissioning closer to the community. CCGs differ from PCTs in size and composition. CCGs are much larger and are led by general practitioners (GPs), whereas health-care managers ran PCTs. Commissioning GPs must work alongside managers, consultants, nurses, patients and other experts to manage resources. These groups work together to plan, contract, monitor and transform health care. 23 NHS reforms have sought to create commissioning supported (but not led by) external commercial and not-for-profit providers, changing the relationship between managers and clinicians. Evidence use in commissioning has no doubt been influenced by new modes of working between CCGs and external providers. 1 This shift means there is a need to identify opportunities for learning with regard to developing and sustaining capabilities to use evidence in commissioning.

At last count, 211 CCGs had responsibility for about two-thirds of the NHS budget between them. CCGs can commission any services as long as they meet NHS standards and local needs. Importantly, the Health and Social Care Act 201224 compels CCGs to use evidence to assure the quality of commissioned services. Such evidence is, for the most part, produced by NICE in the form of ‘authoritative guidance, standards, and information’. 25 NICE guidance is considered important so that patient experiences are improved and costs are reduced. 2 However, as above, the uptake of NICE guidance and products has been patchy in commissioning, and recent NIHR research suggests that this shows no sign of changing soon. 1

A key difference around evidence use from these reforms is that some support functions that were formerly ‘internal’ are now ‘external’. 1 Data production, management and analysis is now the remit of commissioning support units (CSUs), whereas PCTs often had dedicated information support managers. These ‘external’ organisations want to support commissioners to make better informed choices. However, a recent qualitative study suggests that this is proving extremely problematic. 1 Wye et al. 1 conclude that:

One consequence of . . . competing organisations . . . was to curtail freely exchanged knowledge transfer . . . organisational boundaries not only frustrated knowledge exchange but also established substantial barriers to the NHS clients’ scope for strengthening commissioning skills . . .

p. xxvii1

This suggests that, although commissioning decisions are now taken by GPs at ‘the coal face’ of service delivery, the ways in which evidence reaches decision-making in commissioning is just as (if not more) varied now as it was in the past.

Theoretical approach: knowledge mobilisation

The so-called ‘gap’ between creating knowledge and using it in practice remains a persistent problem. 23 Policy initiatives aimed at closing the gap include Academic Health Sciences Centres, Biomedical Research Centres and Units, Genetics Knowledge Parks and Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRCs), and new programmes of research (such as this one). NICE was renamed in 2013, following the Health and Social Care Act, in part to emphasis its role in closing the gap. Such initiatives are reinforced by the social and economic costs of not using evidence. 25

However, outcomes have been mixed,5 and it seems that the underpinning assumptions about knowledge may be, in part at least, to blame. 20 Problems still tend to be framed in terms of transferring knowledge in a linear sequence from producer to user. 21 This view treats knowledge as objective facts (e.g. ‘best evidence’) established by scientists and scientific methods, synthesised and captured (e.g. in NICE guidelines) and transferred to users who will pick it up and use it. The limitations of this transfer view as a means of understanding evidence in health care have been well rehearsed (e.g. see Swan et al. 12 for details). While we do not wish to rehash these here, most converge on the observation that health systems often fail to optimally use the substantive body of research evidence available to them. 26

First, linear models depict decision-making as rational process, whereby knowledge travels as objective ‘facts’ from producers to users who rationally decide based on the best information. This objectifies knowledge and divorces it from context and so greatly underestimates its fundamentally social nature and its basis in practice. As critics note, ‘knowing’ is inextricably tied to ‘doing’, and it is divisions of practice (e.g. professional, occupational and organisational) that create divisions of knowledge, and power, in organisations. 15,27,28

Second, health-care settings comprise multiple professional groups, partaking in different practices, with naturally different interests. Experts (e.g. GPs, consultants, nurses and patients) usually seek to use evidence that fits their own ‘epistemic stances’, frames and values. This means that what counts as ‘best’ knowledge and evidence is often contested. 6

Third, the transfer view sees knowledge as an object (e.g. a piece of evidence), divorces it from its context of production and its use (e.g. how things become evidential), and ultimately sees evidence users as merely ‘information sponges’. 29 The knowledge transfer view fails to adequately address the point that mobilising knowledge across boundaries created by different kinds of practice is always a political process. 5 As Crilly et al. 4 note:

The importance of power contests among occupational groups in health systems makes it appropriate to temper positivistic and purely technical approaches to knowledge management with scepticism.

p. 74

Despite these criticisms, the idea of ‘knowledge transfer’ remains pervasive among policy, practitioner and academic groups, with many still attempting to resolve the ‘gap’ between evidence and practice. Indeed, the very notion of a ‘gap’ separates the production and supply of knowledge (or push) from its use (or pull), and places the root of the problem in the hands of ‘users’ who fail to ‘take up’ evidence. The premise is that, if we communicate ‘good’ evidence well, the ‘user problem’ will be resolved. Even the well-informed NIHR programme brief that funded our study called for ‘push’ and ‘pull’ research. This view also predominates the evidence-based medicine (EBM) movement (with its emphasis on ‘the hierarchy of evidence’) and has also been incorporated into streams of research on EBMgmt and implementation science. 1,30 Recently, Greenhalgh et al. 30 argued for a return to ‘real’ evidence-based decision-making, whereby ‘those who produce and summarise research evidence must attend more closely to the needs of those who might use it’. 30

Along with others, we seek to go beyond linear views, which we see as particularly ill-suited to understanding managerial work in health care. 31 When problems are multifaceted, complex and ambiguous, relevant knowledge is not produced in a linear way but, instead, is co-produced through interactions among participating actors. 2 For example, CCGs must account for a multitude of considerations when deciding how to design a service, including quality of care, cost of service delivery and capacity to deliver. Such decisions invoke multiple forms of knowledge and expertise: science alone is not the way to effective decision-making. 31 As Wright et al. 16 put it:

Situated expertise – which is underpinned, in part, by personal experience and judgment – is needed in the handling, adaptation and communication of this evidence . . . evidence does not speak for itself, and neither does it allow decision processes to be enacted without context-sensitive judgement.

p. 17516

We adopt, then, a ‘knowledge mobilisation’ approach, embracing situated and social processes. 20 We pay attention to how evidence is circulated, transformed and arrived at by decision-makers. We define knowledge mobilisation as ‘a proactive process that involves efforts to transform practice through the circulation of knowledge within and across domains’. 12 We share with others the view that evidence is not only passed around as objective facts, but that things become evidential as a result of practice. 9 This approach is underpinned by the following theoretical premises adapted from Swan et al. :12

-

Knowledge is social and context specific; evidence exists in midlines, communities of practice and other collectives that sustain, legitimise and transform it.

-

Knowledge claims depend on people’s epistemic and interpretive frames; what counts as evidence may be contested across professional and occupational groups.

-

At any point certain actors or collectives purposefully pursue knowledge mobilisation; understanding this is, therefore, fundamental to understanding evidence use.

-

Agents produce knowledge across multiple contexts, or ‘domains of action’; how evidence is used in one context (e.g. in the practices of CCGs) is nested within, and shaped by, what happens in another (e.g. in the practices of NICE).

-

Knowledge mobilisation results from complex interactions under specific conditions (often referred to as institutional context); context matters to evidence use.

-

Social relationships and networks (formal and informal) matter to the mobilisation of knowledge; who brokers evidence is important to its use. 32

-

Politics, legitimacy and interests inform knowledge mobilisation; evidence does not speaks for itself, and what counts as evidence may change over time. 3,5

-

Knowledge does not travel untouched through social interactions; evidence is modified at the point of decision-making.

-

Knowledge mobilisation is a transformation process; the same evidence (e.g. NICE guidelines) can be used differently in different organisational contexts. 33

The consequence of adopting this approach goes beyond mere theoretical premises, however; it has concrete implications for the way the ‘gap’ between research and practice is dealt with. In brief, knowledge transfer deals with the robustness and diffusion of evidence, while knowledge mobilisation considers social practice differences that cause different ways of knowing and doing. 12 In knowledge transfer, the gap is closed by creating more research and knowledge in a more timely fashion, upskilling stakeholders to use this evidence and encouraging research cultures in organisations. Conversely, knowledge mobilisation addresses the gap by facilitating and leveraging social processes to circulate knowledge, connecting across boundaries, understanding the role of artefacts and recognising the realities of context.

Knowledge mobilisation and evidence-based management

Evidence-based management literature gained importance in the mid-2000s, having stemmed from the EBM movement. 3 Given its origins, it is unsurprising that the EBMgmt has become particularly salient in health care. Debates about EBMgmt relate to definition and, indeed, whether or not there is good evidence for EBMgmt. 7,34 Some take a rationalistic approach, seeing EBMgmt, similar to its forerunner EBM, as a practice of ‘using scientific knowledge to inform the judgment of managers and the process of decision-making in organisations’. 35 The underlying premises are more akin to a knowledge transfer model, and the key challenge is to ensure the uptake of best scientific knowledge by managers to optimise the rationality of the choices they make. This traditional approach to EBMgmt is criticised for:

-

privileging scientific facts as the objective ‘truth’, which fails to account for the contested nature of knowledge16,31,36

-

underestimating the complexity of management (vis-à-vis professional disciplines such as medicine) and the incompleteness of scientific evidence alone in arriving at management decisions in politically-charged situations17,37

-

lacking support from empirical research on evidence use, which notes the importance of social context in determining what forms of knowledge and information become ‘evidential’, and when, in decision-making2,38

-

losing the importance of situated expertise and judgement of the decision-maker. 10,16,39

Others take a view akin to knowledge mobilisation, recognising that ‘organisational realities seldom map unproblematically onto their idealised “evidence-based” representations’. 33 Furthermore, case study research on evidence use in health-care management suggests that, although practitioners often value scientific evidence [such as NICE guidelines and randomised controlled trial (RCT) data], the way in which they actually use evidence in practice is very different. 32 The complexity of management decisions and organisational context means, also, that the outcomes of evidence use are hard to predict. 40 Walshe and Rundall17 highlight that EBMgmt is challenged by the ‘constrained, contested, and political nature of many managerial decisions, it may be difficult for managers to apply research evidence even when it is available’. 17 These studies reveal that decision-makers, via co-production, mobilise evidence with others. 2 Arndt and Bigelow thus see evidence as ‘an artefact of the social processes that lead to its creation’. 40 That is, things become evidential during, not prior to, decision-making. As Crilly et al. 4 put it:

The original model of strict hierarchies of evidence within clinical practice, transmitted in a linear and rational manner, has been supplanted by a more human and interactive model.

p. 384

This stream of research tells us quite a lot about what types of evidence are likely to be used, and also a bit about when they are likely to be used, in commissioning decisions.

What counts as evidence?

Traditionally, EBM was seen as a means to ensure effective clinical interactions between health-care professionals, patients, families and carers. 41 Decisions were to be based on authoritative, universally applicable evidence from scientific research, including RCTs and evaluation studies. 42 The internal validity associated with scientific research was seen to justify causal links between evidence and clinical behaviour. 43,44 Indeed, evidence champions argued that ‘rational and systematic application of science [brings] about effective, efficient, and accountable practice’. 45 NICE has major responsibility for collating and disseminating this type of evidence in the UK. 13 It is now expected that this type of evidence will be used to ‘organise, structure, deliver, and finance’41 health-care service provision, too.

Although authoritative evidence is still emphasised (e.g. in the ‘hierarchy of evidence’), the role of other evidences is also recognised. In one study, Gabbay and Le May22 showed that primary care clinicians rarely accessed or used explicit research-based evidence but relied on ‘mindlines’, which were informed by colleagues’ experiences and their interactions with each other and with the knowledge, mostly tacit, of opinion leaders, patients and other experts. Indeed, it has been said that there is ‘little compelling support that scientific evidence is treated differently to other types of information’. 43 As Crilly et al. note, ‘even in the medical arena, which draws on experimental, replicable and ostensibly generalisable knowledge, the notion of a hierarchical evidence is contentious’. 4 These findings are also echoed in more recent studies of evidence use commissioning. Wye et al. 1 conducted a study (parallel to ours) of knowledge exchange between commissioners and external providers. They found that commissioners sought information from many sources to build a case for action, defend their position and navigate their proposals through the system. Information was clustered into four primary types:

-

‘people-based’ sources (relationships, ‘whole-picture’ views, experience, contracting and procurement expertise and information on finance, budgets and performance)

-

‘organisation-based’ sources (NICE guidelines, Department of Health information such as National Outcome Frameworks and information from NHS Improving Quality, Public Health, CSUs, ‘think tanks’, such as The King’s Fund, Royal Colleges and other providers)

-

‘tool-based’ sources (electronic software tools, national benchmarking, national and local dashboards, and project management tools)

-

‘research-based’ sources (journals, search engines, universities, Cochrane reviews, regional networks, such as CLAHRCs, Academic Health Science Networks and electronic newsletters).

Wye et al. 1 note, however, that access to data in their study was obtained mainly through external providers; given the timing (in the transition period from PCTs to CCGs), commissioning organisations proved more difficult to enlist. This might have provided a somewhat broader picture of sources of evidence (especially authoritative sources) than those actually used by commissioners. 1 Even so, the study suggested that, for clinical commissioning, local clinical knowledge from GPs about service provision was prioritised: ‘Local information often trumped generalised research-based knowledge or information from other localities’. 1 Most often, this evidence was acquired interpersonally through ‘conversations and stories, as oral methods were fast and flexible, which suited the changing world of commissioning’. 1

Our previous study used a more direct, detailed ethnography of commissioners’ evidence use in redesigning services. 2 Case studies of four PCTs showed the need to source information creatively so that it was fit for purpose. Evidence use entailed a ‘heterarchy’ rather than a hierarchy of evidence, with local and interpersonal practical knowledge and information being coupled with other scientific sources. Evidence did not ‘speak itself’ but needed to be advocated by experts or authorities. Interestingly, a wider sample of commissioning managers suggested that ‘the single most important source of evidence was examples of best practice from other organisations’. 2 Harvey et al. 46 also describe different kinds of evidence, particularly ‘theoretical’ (how and why something works) ‘empirical’ (efficacy) and ‘experiential’ (personal experiences) evidence. They note that the ‘. . . complexity and context-dependent nature of implementation [makes it] impractical to prioritise one type . . . over others’. 46 This work raises questions about what counts as evidence in CCG decision-making, and so this will be an initial focus of our study. 46

This literature suggests that, in addition to NICE, commissioning stakeholders may mobilise a range of other evidences in their decision-making. Thus, we respond to calls to ‘broaden and deepen our understanding of what counts as “evidence” and which types of evidence are best used to inform differing aspects of clinical decision making’. 47

When is evidence used?

To better understand when evidence is used, we draw from studies of innovation processes that recognise complex problems and developing new practical means of dealing with them. 48 Rogers’ very widely cited work refers to three broad stages of innovation: ‘initiation’, ‘adoption/decision’ and ‘implementation’. 49 Responding to criticism that ‘stages’ are an overly linear and rationalised depiction of innovation processes, Clark et al. 50 developed, instead, their ‘Decision Episode Framework’. This suggests that innovation processes unfold in a series of recursive and overlapping ‘decision episodes’. 50,51 These entail the awareness of new ideas to formulate a problem (‘agenda formation’), designing, sorting and selecting potential solutions (‘selection’), introducing these (‘implementation’), and, finally, embedding them into organisation routines (‘routinisation’). It is important to recognise that these are seen as episodes of work, with feedback loops between them. For example, at any point during the selection or even the implementation of a solution, new problems may arise that require the reformulation of the initial problem (agenda formation).

There are different concerns across episodes, from a focus on matters at stake, to practical design of usable solutions, to outcomes and issues of sustainability. Bledow et al. 52 see innovation as resulting from a dissatisfaction with old ideas (‘thesis’), which, in turn, motivates new ideas (‘antithesis’). Synthesis between ideas creates innovation.

Kyratsis et al. 9 usefully applied a process approach, albeit in a different context: a study of the use of evidence in decisions about technology adoption in nine acute care organisations. They found that the practitioners involved (clinicians, nurses and non-clinical managers) held diverse ‘evidence templates’ when seeking and using evidence. These cognitive templates stemmed from the different practical experiences, professional identities and training of these groups, resulting in different ways of defining and making sense of what constituted acceptable and credible evidence in decisions. All groups drew on a ‘practice-based’ template, using experiential practical knowledge as evidential in their decisions. However, whereas clinicians drew mainly from a ‘biomedical-scientific’ template, prioritising science-based, peer-reviewed and published evidence, non-clinical managers drew more from a ‘rational-policy’ template, preferring evidence based on cost, productivity and fit with policy imperatives. Nurses, in contrast, drew from all three templates. Importantly, different evidence was valued at different points of the process, depending on who the key actors were at the time and how they made sense of the problems within their professional domain.

. . . local trials, and the need for ‘pragmatic evidence’, were deemed important by decision-makers in the early stages of innovation adoption. For innovations (and especially those that require changes in practices or processes), creating an evidence base will require agreement about what is regarded as a legitimate epistemological basis for verifying and validating evidence and relevant knowledge.

p. 1369

Evidence use is not, then, a one-off event. It reflects the priorities present at a particular point in time. It is entirely plausible that different evidences will have differing utility and weight across episodes of innovation work. 52 For example, RCTs may be used as evidence when identifying solutions to a problem, whereas financial data may be used to understand feasibility.

Certain types of evidence relevant in one episode may also be questioned or disregarded in another. Recognising this, we use a processual approach in our own methods and analysis,53 tracing evidence use in service redesign over decision episodes. As Wright et al. observe, ‘deeper insights are uncovered when decisions are investigated in ways that “open up” the role of the decision-maker and of the context in the processes leading to the commitment to action’. 10 Keeping with a knowledge mobilisation approach allows us to understand forms of agency that may make decisions evidence based. It can be expected that multiple evidences will be used and that different capabilities may apply across different episodes of commissioning work in service redesign.

How is evidence used: capabilities for evidence use

Although the literature says much about what evidence is used and when it is used, how it is used is less clear. It is important to understand, also, how evidence comes to be used in practice. In other words, what capabilities are required to actually use evidence? Existing research, noted above, points to the fundamental importance of understanding the social and political processes underpinning evidence-based decision-making. Much of the literature from both the UK and Canada points to the social discursive aspects of evidence use. 54

However, questions remain unanswered about ‘the detailed process by which ideas are captured from outside, circulated internally, adapted, reframed, implemented and routinised in a service organisation’. 30 Crilly et al. conclude that ‘NHS Boards should take a clear view on organisational design elements needed to support knowledge mobilisation’. 4 These elements include ensuring that capabilities (including appropriate work practices and enabling organisational conditions) are in place. A few insights can be found in the literature about these capabilities.

First, evidence-based decision-making involves mobilising knowledge across diverse experts, including patients. Recent health-care research shows that stakeholders bring their own values and sense-making to any decision, which informs how evidence is sought out, shared and applied in transforming services. 1 Professional differences influence the use of evidence, too, with McGivern et al. 11 showing clinical consultants as having the ‘power, knowledge, and self-confidence’ to critique NICE guidelines. Other clinicians (e.g. GPs) in this study were shown to ‘not have the time’ and were too ‘overwhelmed’ by the range of guidelines. Instead, these stakeholders worked to balance research findings with local needs. In that study, management saw NICE guidelines as a means for stakeholders to reach consensus and avoid negative consequences from regulatory bodies. 11

Second, just having appropriate experts and evidence present does not guarantee evidence-based decisions. Actors also pursue particular purposes, with varying degrees of influence (they have agency, in other words). The issue of who searches for, synthesises and presents evidence is, therefore, important. 7 When this happens may also be important, as different priorities beckon at different points (ensuring sufficient evidence to solve a problem, identify solutions in our context, etc.). ‘Knowledge brokers’, or individuals who make knowledge embedded in one community available to another, may enable such evidence sharing. 6

Third, research points to the subjective aspects of evidence use and the importance of human judgement. 5 Harvey et al. 46 describe evidence ‘as forms of knowledge seen as “credible”’, while Freeman and Sweeney55 suggest that use relies on perceived ‘relevance’. In a study of hospital organisations, Jones and Exworthy56 describe how different ‘frames of reference’ shape perceived relevance. They show that framing an issue in terms of clinical necessity engages practitioners with change. Frames may be strengthened through co-construction and discussion. Champions or opinion leaders may also communicate certain evidences and push them into dominance. 57

Broader insights can be gained from organisation studies. Organisational structures (e.g. networks) underpinned by trust-based relationships are said to promote the ‘open sharing’ required to innovate. 58 Crilly et al. argue that ‘Relationships trump organisational design . . . Connective ability of individuals is more important than organisational structure when it comes to making organisations effective’. 4 Another influential stream of research is ‘resource-based theory’ (and, its successor, the knowledge-based view), which points to the importance of resources, especially knowledge, in improvement. 59 It is argued that ability to integrate, build and reconfigure internal and external competences to address rapidly changing environments informs competitiveness.

The work outlined to this point sensitises us to the kinds of capabilities NHS organisations and managers may need to use evidence. Indeed, in one of the few studies of capabilities for evidence use in commissioning, Swan et al. 2 show that evidence use in PCTs entails timely evidence use, managing interfaces across the project and proactively building and managing relationships. By better understanding what counts as evidence, when it counts and how it comes to count as evidence, we can begin to develop capabilities to enable evidence use in decision-making. As Ferlie et al. 5 note, the imperative for mobilising knowledge and evidence in NHS organisations lies not in producing ever more information, but in ‘building high learning capacity and appropriate core competencies in NHS organisations’. 5 We seek to understand capabilities for using different types of evidence in the decision-making that occurs across episodes of work involved in CCG innovation.

How is evidence produced?

A knowledge mobilisation approach reminds us that the use of evidence in one domain (e.g. commissioning) is intertwined (or ‘nested’) with the machineries of its production in another. 12 We thus consider, also, the ways in which evidence is produced by considering ‘inscribed meanings’. 60 This research suggests that a ‘programme of action’ or ‘script’ is inscribed in all artefacts. 60–62 Inscribed meanings constitute a sort of instruction manual for the artefact. Designers of artefacts take a view of how it should be used in order to perform its expected function. Akrich et al. describe how the large part of the work of producers involves ‘defining the characteristics of their objects [and] making hypotheses about . . . the world into which the object is inserted’. 60

Inscribed actions exist in everyday objects such as door handles, which carry the programme of action ‘pull the door’. Actions are also inscribed on the internet, where readers of underlined blue text are invited to click and follow related links. In similar ways, evidence is an inscribed artefact. The inscribed use of evidences must be translated into practice through a relational and negotiated process that requires work, time and motivation. 12 Encounters between scripts and users can broadly result in three possible scenarios:

-

Scripts may persuade actors to play the proposed roles through training, coercion or discipline. 63 If scripts differ from established actions and actors subscribe to them, the artefact produces change. For example, a NICE guideline highlighting risks of current methods may change behaviour.

-

More often, users try to descript artefacts and modify actions to fit what they already do. 60 Users try to adapt the artefact to their ‘tastes, competences, motives, aspirations, [and] political prejudices’ through reinvention. 60 It has been suggested that ‘if potential adopters can adapt, refine, or otherwise modify the innovation to suit their own needs, it will be adopted more easily’. 64 For example, NICE guidelines may be disassembled and used selectively when they fit existing priorities and work patterns.

-

Reinvention has limits, however, which may cause users to ignore, disregard or resist the artefact. The third scenario is, therefore, one of non-use. Coercion can be applied, but users may find ways to circumvent the impositions of the artefact. They may, for example, revert to workarounds or utilise artefacts in a ceremonial way only. For example, NICE guidelines may be ignored or their appropriateness for a particular population may be questioned.

Previous studies suggest that scenarios 2 and 3 often apply in health. 63,64 We set out to explore what sort of evidence users are inscribed in evidence production in order to develop further insights into the use of authoritative evidence in commissioning.

Conceptual framework

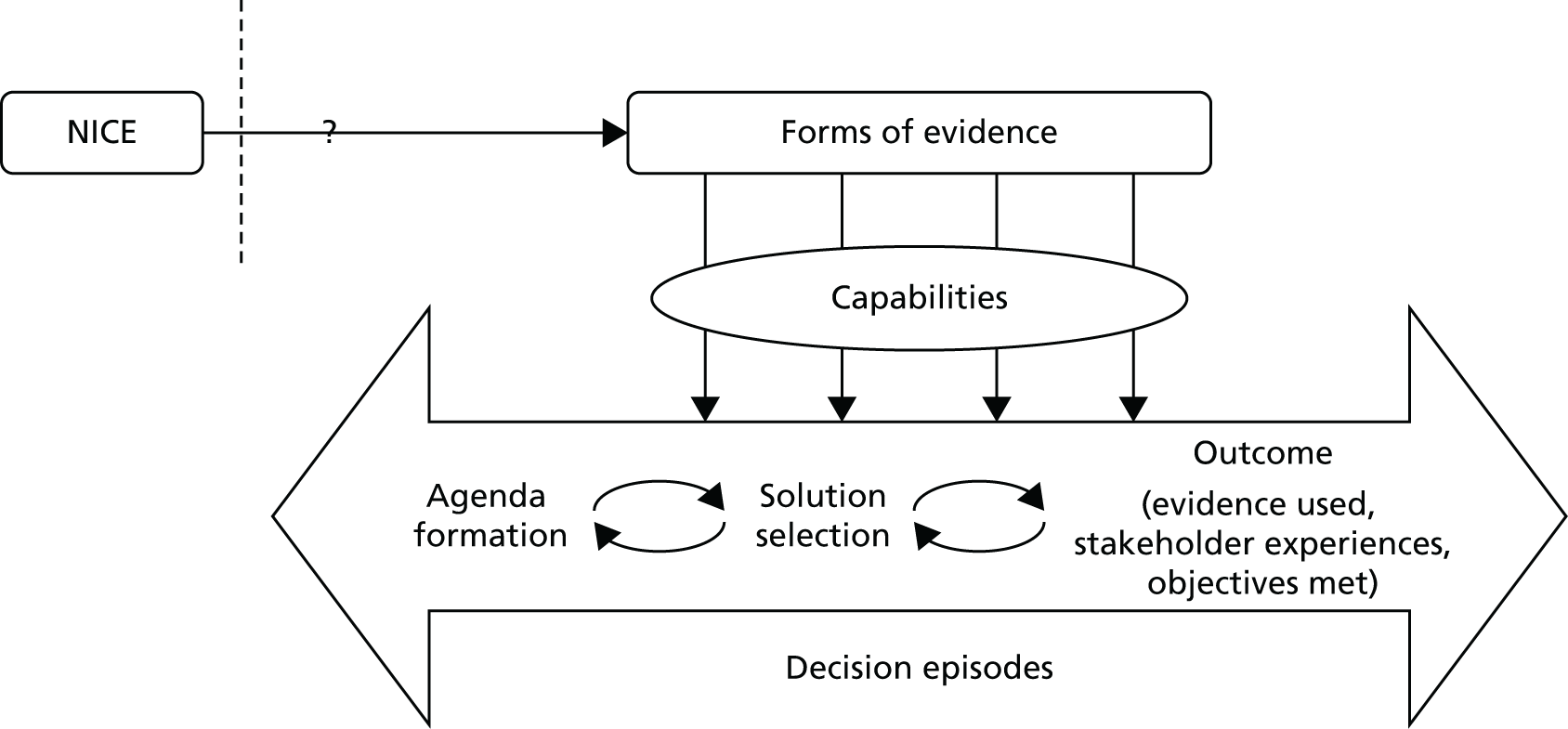

Figure 1 summarises the conceptual framework for our study. It links capabilities to use evidence to evidence production (e.g. NICE), decision episodes and outcomes. The framework provides a holistic approach to explaining evidence use and how this links to variation in process outcomes. It builds on three principles (from the review above).

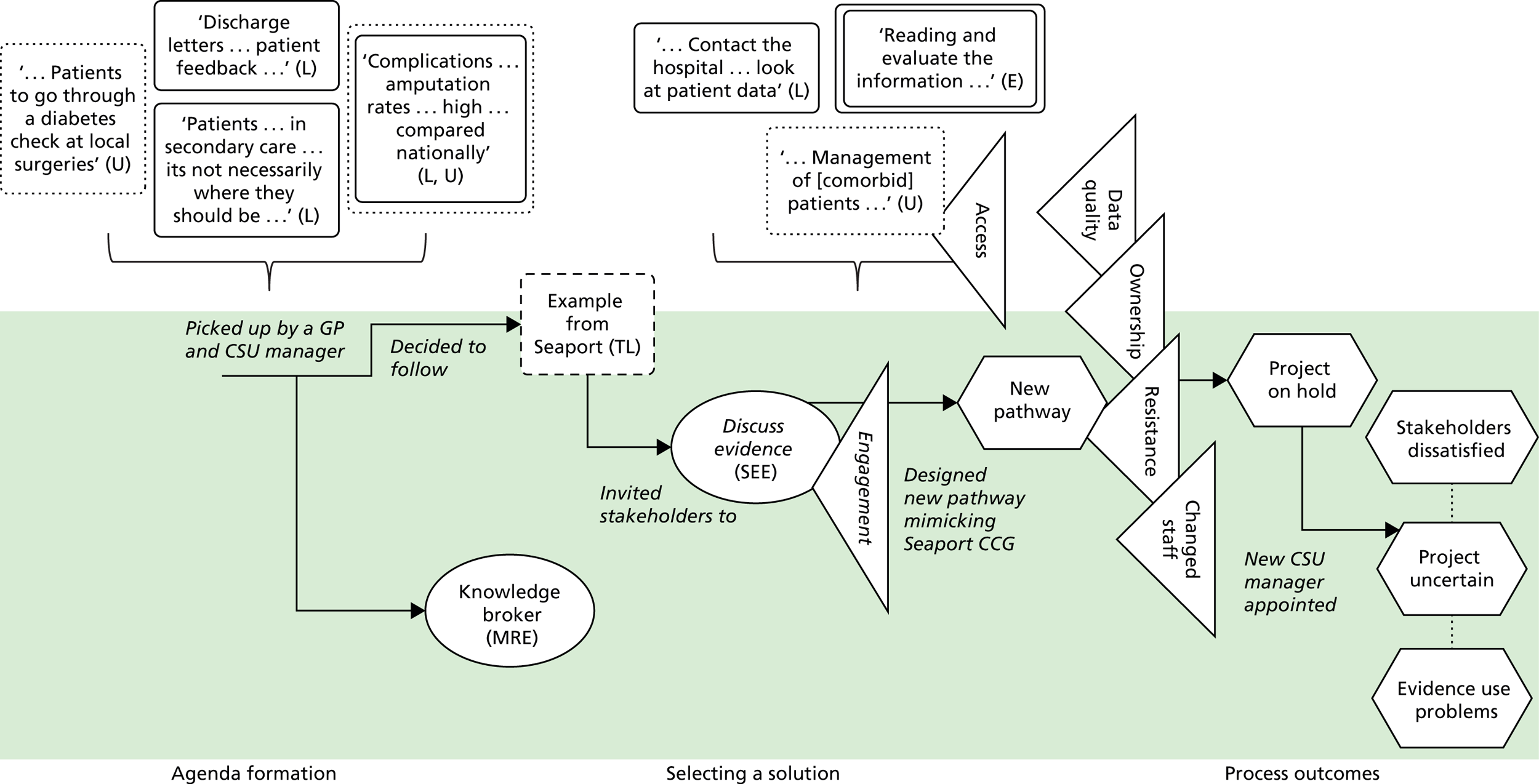

FIGURE 1.

Conceptual framework for the research.

-

It is processual. 53 It takes on board the point that mobilising evidence entails dynamic practices (e.g. sourcing, interpreting and creating evidence) that unfold over time in an iterative, episodic way (hence the double-headed arrows and decision episodes in Figure 1). As per previous work on organisational change, the journey is conceived as an often uncertain process to reflect the ongoing realities of commissioning management decisions, which are far from linear or ‘rational’. 65 It is also more practical because it reflects the situations that managers face, rather than a more idealised version of events. Hence, it helps to provide a direct link from research findings to actionable recommendations for improvement.

-

Our model is underpinned by a knowledge mobilisation approach that sees evidence use as a social and practical accomplishment requiring capabilities: that is, knowing how and when, not just what. Knowledge mobilisation theorising makes us understand evidence use as a skilful performance, situated in context, in which agency, practices and processes matter. 12 We see capabilities as the practices and enabling conditions needed to pursue and accomplish a particular purpose (evidence use in this case), rather than as static variables, or fixed characteristics of individuals and organisations. Capabilities can be applied at the organisational (e.g. resource management) and group level (e.g. role structures).

-

The model will help us to explain variations in evidence use by comparing similar cases, as other authors have done. 66 We will compare and contrast evidence journeys across different CCGs dealing with similar kinds of redesign. We examine, in particular, if (hence the question mark in Figure 1) and how authoritative evidence (e.g. NICE) makes its way into CCGs, along with other forms of evidence. As per our protocol, ‘outcomes’ are to be assessed qualitatively, including evidence use (the extent to which a range of evidences were sourced, interpreted and engaged with), stakeholder experience (the extent to which stakeholders were satisfied or dissatisfied with the process) and objectives met (the extent to which original objectives were met and, if not, whether or not change to them was justified).

Chapter summary

In sum, this research provides an in-depth examination of the use of evidence across NHS organisations (CCGs) in order to identify capabilities for relatively more successful outcomes. As our review of the literature indicates, authoritative evidence never stands alone but must be judiciously combined with other forms of evidence. Viewing evidence use as a process of knowledge mobilisation provides a more realistic (and, therefore, more useful) account. The study develops a process model that articulates the dynamics of evidence use, without losing sight of local work practices, power dynamics and context. This allows us to begin to generate relevant ideas and tools for improvement in practice.

Chapter 2 Methods

Research on evidence ‘pull’

As described in the introduction, our research responds to the NIHR commissioning brief by aiming, primarily, to understand so-called research ‘pull’ by managers by studying evidence journeys in practice (as evidence travels through CCGs). We contribute (as a secondary aim) to the understanding of ‘push’, by considering, also, the start of the journey (i.e. how certain evidence products are made by producers). The following objectives have been operationalised to achieve these aims:

-

to study how authoritative evidence travels in, and is used by, different CCGs, that is, to document ‘evidence journeys’

-

to compare and contrast the travel of evidence across CCGs and analyse comparatively ‘evidence journeys’

-

to create a process model, a roadmap and a toolkit that will guide CCGs in becoming better users of evidence.

Research design

A key parameter case study design was used to compare processes across organisations. Key parameters are similar to inclusion/exclusion criteria. They ensure that a similar process is observed in different but comparable contexts. In our case, redesigns had to be informed by recently released non-mandatory guidance [e.g. on diabetes and on musculoskeletal (MSK) conditions] and had to be considered a CCG priority. As Barley and Kunda note, ‘the design’s forte is that it enables researchers to articulate more clearly how key contingencies differently shape work practices and, hence, engender different patterns’. 67 As per our protocol, data collection combined real-time observations in two CCGs with retrospective inquiry in six further CCGs, based on interviews and available texts. Process analytical methods, as per Langley,53 were used to order to each case from start to finish using temporal bracketing strategies. Innovative service redesign involves iterative, overlapping episodes of work. 51 Process perspectives account for these episodes, changing relationships, and interpretations over time. 68

Patient and public involvement and a Scientific and Stakeholder Advisory Panel (SSAP) also shaped the research. Through UNTRAP (University/User Teaching and Research Action Partnership), which is a partnership between users of health and social care services and carers, and the universities of Warwick and Coventry and the NHS, we engaged service users/carers interested in research and teaching. Two UNTRAP members participated in our SSAP, which also included NHS managers, key opinion leaders and academics. The UNTRAP members provided invaluable feedback throughout the life of the project from the research design stages through to the final report write-up. They were especially helpful with regard to the analysis and reporting, ensuring that the language used was accessible and relevant to service users. They also shared their experiences of health care with us in the light of our findings, which was useful for us in understanding and ensuring the relevance of our research. The SSAP directed us in our research design and interpretation of emerging findings.

Data collection

The first aim of our research was to understand evidence use in the CCG context. In our original project protocol, it was promised that ‘we will select, in close consultation with our Scientific and Stakeholder Advisory Panel, two particular forms of evidence from NICE aimed at innovation in service delivery (not just minor adjustment). We select one piece of evidence recommending pathway changes on the basis of emerging scientific evidence (“Do recommendations”, e.g. NICE Clinical Guidelines on Diabetes in children), and another recommending decommissioning of certain healthcare services or treatments (“Do not do recommendations”, e.g. regarding mucolytic drugs as per NICE guidance CG101 [Clinical Guidelines]).’ We also took into account the date of NICE guideline release, the care setting, the likely cost consequences and the clarity of guidelines for a commissioning audience.

We met our protocol objectives by taking the following actions. We accessed a list of all NICE guidelines released (post 2011). The project team created a shortlist of all those guidelines that were released since January 2012, and that were likely to be picked up by commissioners. We then created a survey targeting senior NHS commissioning managers to identify which NICE guidelines were likely to be important for service redesigns. Thirteen CCG leaders (mostly chief executive officers and associate directors) responded to a list of health needs and were asked: ‘tick if you are confident that your organisations will actually use the following guidelines in commissioning over the next 12 months’. The responses are shown in Table 1. The findings were presented to 15 CCG leaders in November 2013. Feedback was the following: ‘NICE guidelines are not used directly by CCGs’, ‘We are not confident the choices [list of guidelines] offered reflect the priorities of the organisation’, ‘There is no formal process [in our organisation] for using NICE guidelines’, ‘NICE does not drive commissioning . . . it’s clinical outcomes, performance of service (e.g. referral rates, spending)’. Commissioners also told us that decisions on what not to do nearly always result from decisions on how to do things better. In other words, they are two sides of the same coin.

| Clinical area | CCGs, % (n) |

|---|---|

| Hip fracture | 58.30 (7) |

| Diabetic foot problems | 50.00 (7) |

| Common mental health disorders | 50.00 (6) |

| Ovarian cancer | 41.70 (5) |

| Lung cancer | 41.70 (5) |

| Infection control | 41.70 (5) |

| Service users’ experience in mental health | 33.30 (4) |

| Prostate cancer | 33.30 (4) |

| Pressure ulcers | 33.30 (4) |

This was an invaluable exercise for the project team, because it meant that we had to rethink our narrative, which had thus far been focused on ‘how NICE guidelines are used in commissioning’. We quickly realised that we had to be pragmatic for the purposes of this research and select a commissioning process that was of importance to CCGs and in which the use of evidence (the recently produced NICE guidelines identified above) was likely to be relevant and important. In further conversations with CCG leaders, we narrowed down our focus to two core areas of care: MSK services and diabetes services. These were two areas of ‘high importance’ for a large majority of CCGs for service redesign (i.e. CCGs had approved business cases and sponsored related service redesign projects). They were also areas in which key NICE guidelines had been released since January 2012. The implications were that it would be feasible for us to collect meaningful data in accordance with our research protocol, if we focused on relevant redesign projects. We discussed our choices and thinking with our multiexpert SSAP. We explained our rationale for choosing MSK and diabetes services as the focus of our study, and the panel readily endorsed our decision. Retrospectively, it proved a good decision to focus on these two areas, as we were able to recruit a large number of CCGs in our research as a result.

Eight CCGs were used to maximise opportunities to capture variation, while paying attention to the contextual dimensions. We contacted CCGs with varied spend, deprivation and geography through recommendations from Dr David Sharp (then a director at NHS England), internet searches and existing NHS contacts. 69 The CCG names have been changed for anonymity. Four CCGs were working on diabetes services (Seaport, Greenland, Rutterford and Chelsea) and four were working on MSK services (Horsetown, Stopton, Coalfield and Shire). The Yorkshire and Humber Health Intelligence is used to classify CCGs in Table 2. The NHS measures mortality resulting from cardiovascular, respiratory, liver and cancer diseases among those aged < 75 years, as well as emergency room admission for alcohol and death from treatable disease, as CCG performance indicators. Greenland CCG scored in the best 25% for all indicators, while Rutterford CCG scored in the top 25% for some and in the middle for others. Horsetown CCG scored in the middle range on all indicators. Seaport, Chelsea, Coalfield and Shire CCGs scored in the middle range for some indictors and in the bottom 25% for others. Stopton CCG scored in the bottom 25% for all indicators.

| CCG | Young population, above-average black and Asian ethnic groups, moderate deprivation | Older population, rural, low deprivation levels | Average age, deprivation, low population |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seaport | ✓ | ||

| Greenland | ✓ | ||

| Rutterford | ✓ | ||

| Chelsea | ✓ | ||

| Coalfield | ✓ | ||

| Shire | ✓ | ||

| Horsetown | ✓ | ||

| Stopton | ✓ |

We were referred to a ‘key stakeholder’ in the redesign (e.g. a consultant). We explained the purpose of the research and asked them to participate. We also asked them to help us recruit other stakeholders. Open-ended interviews were used,70 with items related to organisational background (e.g. roles and structures), redesign rationale, evidence use, redesign process, supports, outcomes and challenges. This allowed narratives to develop that provide rich, complex accounts. 53,71 When we felt that richer explanations would follow, we interrogated responses with additional probes and follow-up questions.

The participants were informed of the purpose of the study, that participation was voluntary and that data would be anonymised. We use an ‘ethnographic approach’ to understand, in a systematic way, the conduct of people studied from their own perspective. We see the ethnographic approach as a scientific description of peoples and cultures with their customs, habits and mutual difference rather than complete submersion as per ethnography. 68 The interviews were completed in a location of participants’ choice, and they were recorded and transcribed verbatim. The qualitative interviews lasted between 45 and 90 minutes.

We averaged about five stakeholder interviews per CCG (n = 35 stakeholders were interviewed in total), which was fewer than we had expected in our protocol because CCGs were newly established when our project was designed and at that time we did not know the size of redesign groups. During data collection, we soon realised that the number of stakeholders actively involved in each redesign project was lower than we had expected. We countered this shortcoming by conducting follow-up interviews to learn about the outcomes of the redesign work as necessary (n = 77 interviews were completed in total).

In addition to interviews, we observed meetings in two CCGs to gain close familiarity of the groups’ decision processes as they unfolded ‘in vivo’ over time (over approximately 12 months in each case). 72 There were also fewer meetings to observe than we had estimated in our original protocol. Redesign meetings tended to occur once every 2 months and were often disrupted or postponed (other pressures were intense at the time, given that CCGs were still being embedded). This meant that, even if we had been able to start observations from February 2014 (as per protocol), we would only ever have been able to complete an average of 14 observations per CCG. Although we gained access to one CCG (Horsetown) early on in the project, we could not access the second until September 2015. This reduced the number of observations further. These changes reflect the realities of commissioning. Indeed, in many cases, groundwork for decision-making is through conversations over dinner or at coffee, and so we could not always capture this. This groundwork then informs the decisions that go through more formal channels. Meetings lasted, on average, between 2 and 4 hours and were concerned with planning, problem solutions and the evaluation of potential changes. All changes to the protocol are summarised in Table 3.

| Protocol | Final report | Rationale | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | Select two forms of evidence from NICE related to ‘do’ and ‘do not’ recommendations | Focused on how NICE guidelines are used in commissioning | Commissioners told us decisions not to do nearly always result from decisions on how to do things better. In other words, they are two sides of the same coin |

| Data collection | 40 observations plus 40 interviews at two CCGs, plus 120 ethnographic interviews across six additional CCGs | We averaged about five stakeholders per CCG (77 interviews), plus nine observations | There were fewer stakeholders involved and fewer meetings to observe |

Field notes and memoing (researcher reflections on field notes) were used to capture observations, ensure that research objectives were being met and add trustworthiness to the data. 11 Notes were handwritten and typed up as soon as possible. We also collated documents related to the redesign, including those shared by interview participants and those identified through internet searches. Fieldwork is summarised in Table 4.

| Location | Participants | Documents used | Observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seaport | Diabetes consultant (3), diabetes nurse specialist, GP, diabetes specialist nurse with responsibility for education and training | Published papers on the project (4) | |

| Greenland | GP lead on project, GP, CSU project manager, non-executive hospital director, transformation and innovation CSU lead (2) | Presentations (2), HSCIC evaluation | |

| Rutterford | Diabetes nurse consultant (2), transformation manager, chief accountable officer | Board presentation, final report, board papers (2), evaluation paper | |

| Chelsea | Contracting manager, diabetes consultant (1), commissioning manager, patient representative from Diabetes UK | Evaluations (Right Care and HSCIC), service specification, newspaper report | |

| Coalfield | Senior commissioning manager (5), clinical lead for MSK, clinical director, CCG chairperson, support manager for patient engagement | Board papers (2), CCG reports (2) | |

| Shire | Commissioning manager (2), GPwSI (2), GPwSI and consultant, clinical service manager, clinical therapies lead, deputy director of planning and development | Board papers (3), Right Care evaluation | |

| Horsetown | Two GPs, four physiotherapists, CCG director, senior commissioning manager, radiologist, orthopaedic surgeon, commissioning manager | Terms of reference, agenda, reports, e-mails, model of care, provider’s proposal, minutes | Four meetings |

| Stopton | Senior commissioning manager (5), head of therapies, clinical assessment team lead, GP, orthopaedics consultant, rheumatology consultant, physiotherapist, hospital representative | Meeting agendas, minutes, board papers, evaluation presentation | Five meetings |

Ethics approval

Individuals invited to take part in this study were made aware that their participation was voluntary and that their information would be confidential and anonymised. The participants were given the opportunity to ask questions and given time to decide whether or not to take part in the study. Data are stored in locked filing cabinets in locked offices on university premises. Computer files are password protected and stored on the network drives (not local hard disks) of password-protected computers. Detailed plans for handling ethics issues were approved by a NHS Research Ethics Committee.

Data analysis

We developed detailed case descriptions of redesign projects at each CCG. 53 These were assembled from reading and rereading all interview data, observation notes and collated documents for a specific case and written by the team member who had been most closely connected with the data collection. The case descriptions were initially structured chronologically, resulting in lengthy narrative accounts of what happened, when and why, with particular reference to any information that became evidential during the process, and supported by original quotations or excerpts from field notes. However, as the emphasis in our research is on improvement, not just understanding and rich description, we decided to avoid overly lengthy discussions of raw data in order to make our case studies more accessible to practitioners. To achieve this, we rewrote each case according to analytical themes, in which we sought to identify the following.

Evidence use

From the literature, and in consultation with our SSAP, we considered NICE and other evidences. 22,42 Evidence was defined as information with an evidentiary value in decisions. 2 Information is legitimised as evidence not through production but through use. Some information (even NICE guidelines) may be questioned or dismissed as evidence by decision-makers. Therefore, our first step was to identify evidences used. Here, we used deductive and inductive approaches. Deductive template analysis was used here, as we expected evidences already in the literature to appear in our data. 73 We looked at studies of commissioning work, noted the evidences used and searched for these in transcripts. 1,2 We were also open to emergent themes when searching for evidence used in our reading of cases. 74

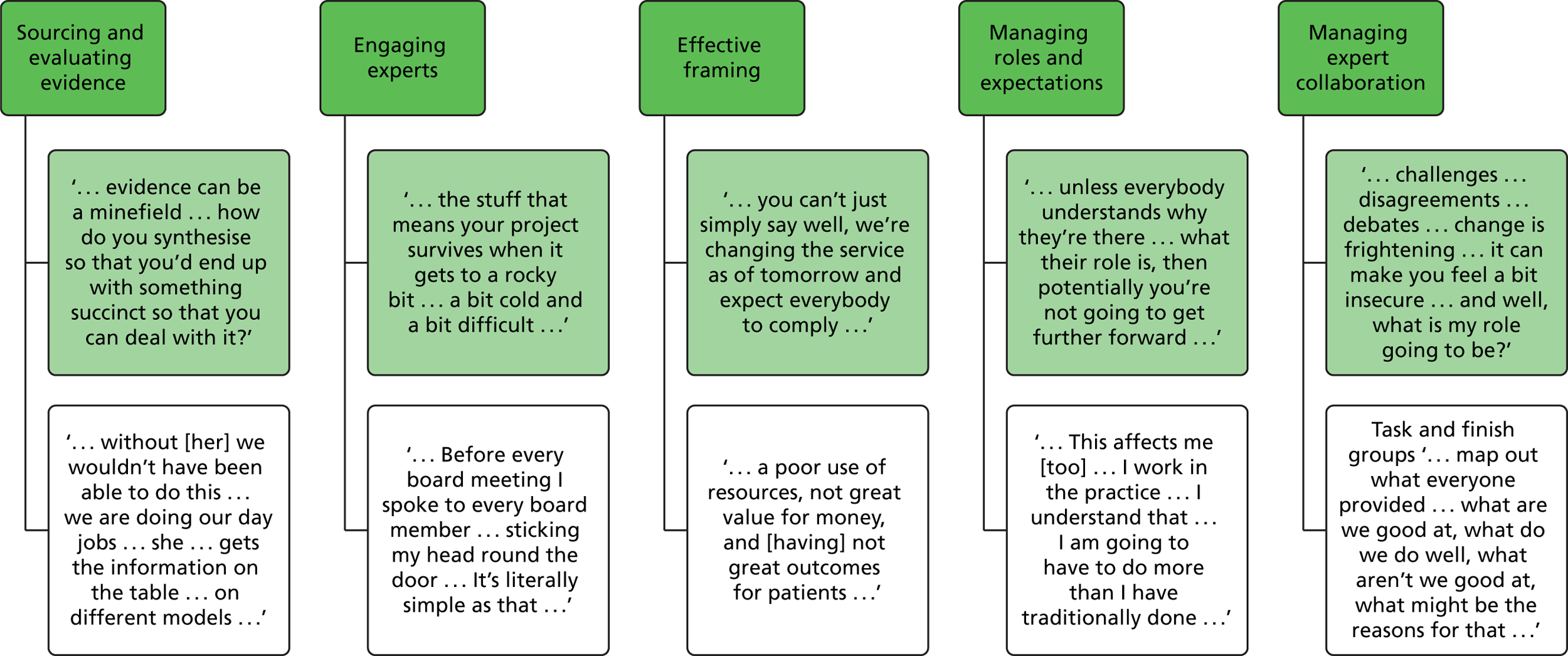

Capabilities for evidence use

Inductive coding was used to identify evidence-use capabilities. 74 We collated data on evidence use via open coding. 75 Common excerpts were placed in provisional categories (first-order). Categories were then integrated into higher-order researcher-induced themes via axial coding so the team could identify themes from the data. 74 Themes were compared and discussed to decide final classifications. Team members then searched each transcript for any talk on capabilities that appeared to enable evidence use in situ. Themes were also compared against those found in previous research and adjusted when appropriate, thus iterating between data and theory, as suggested by others. 74

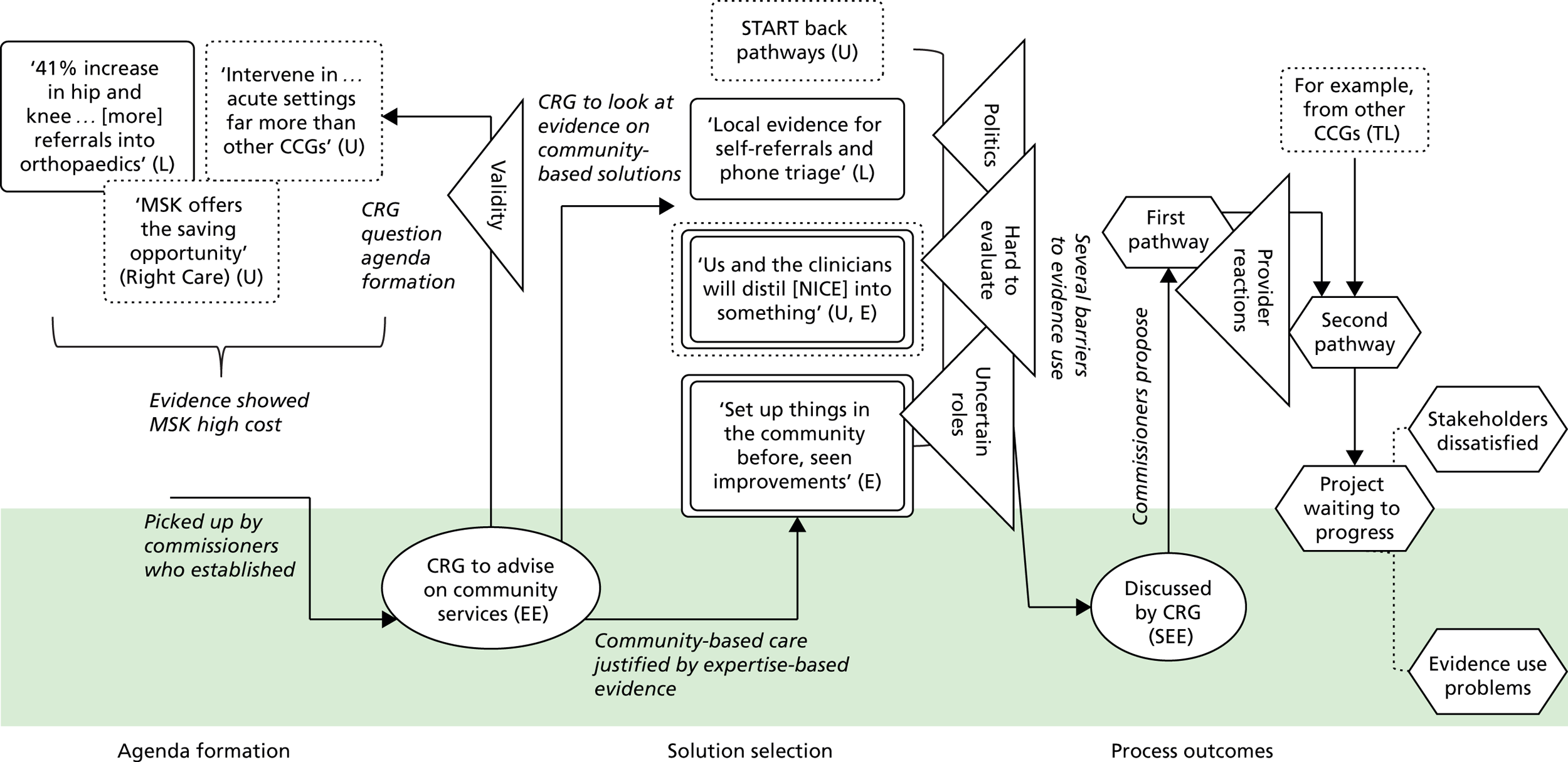

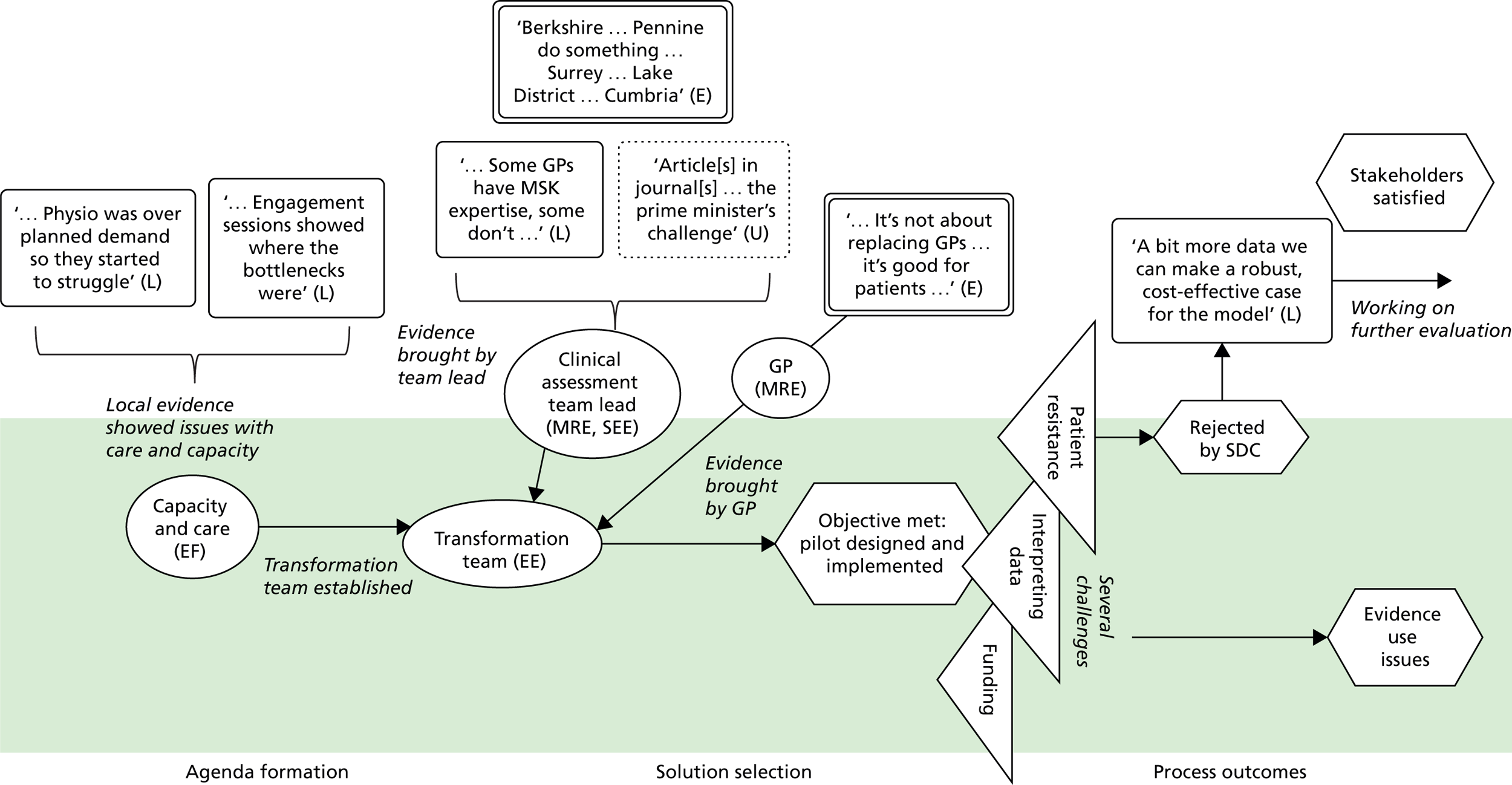

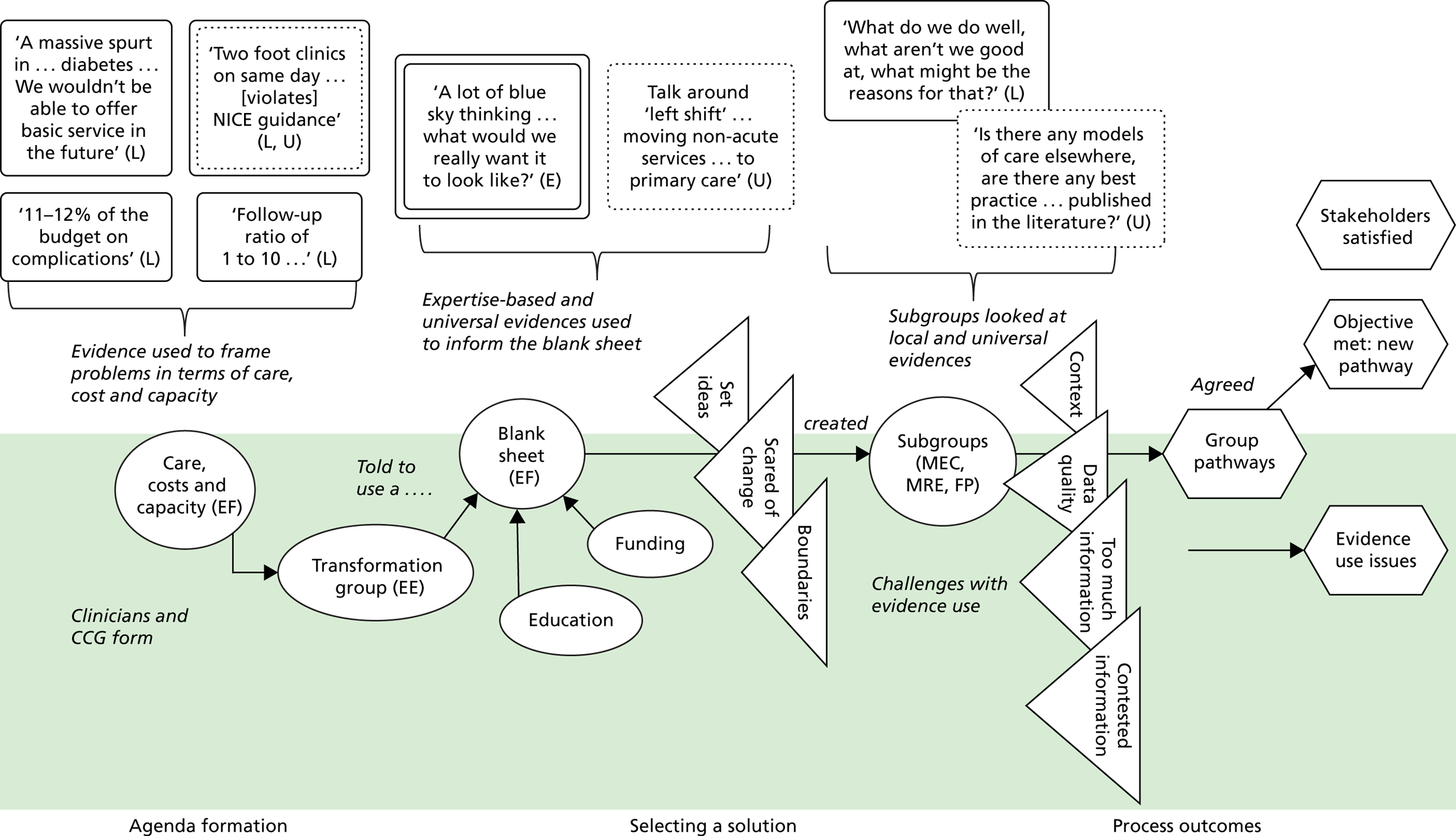

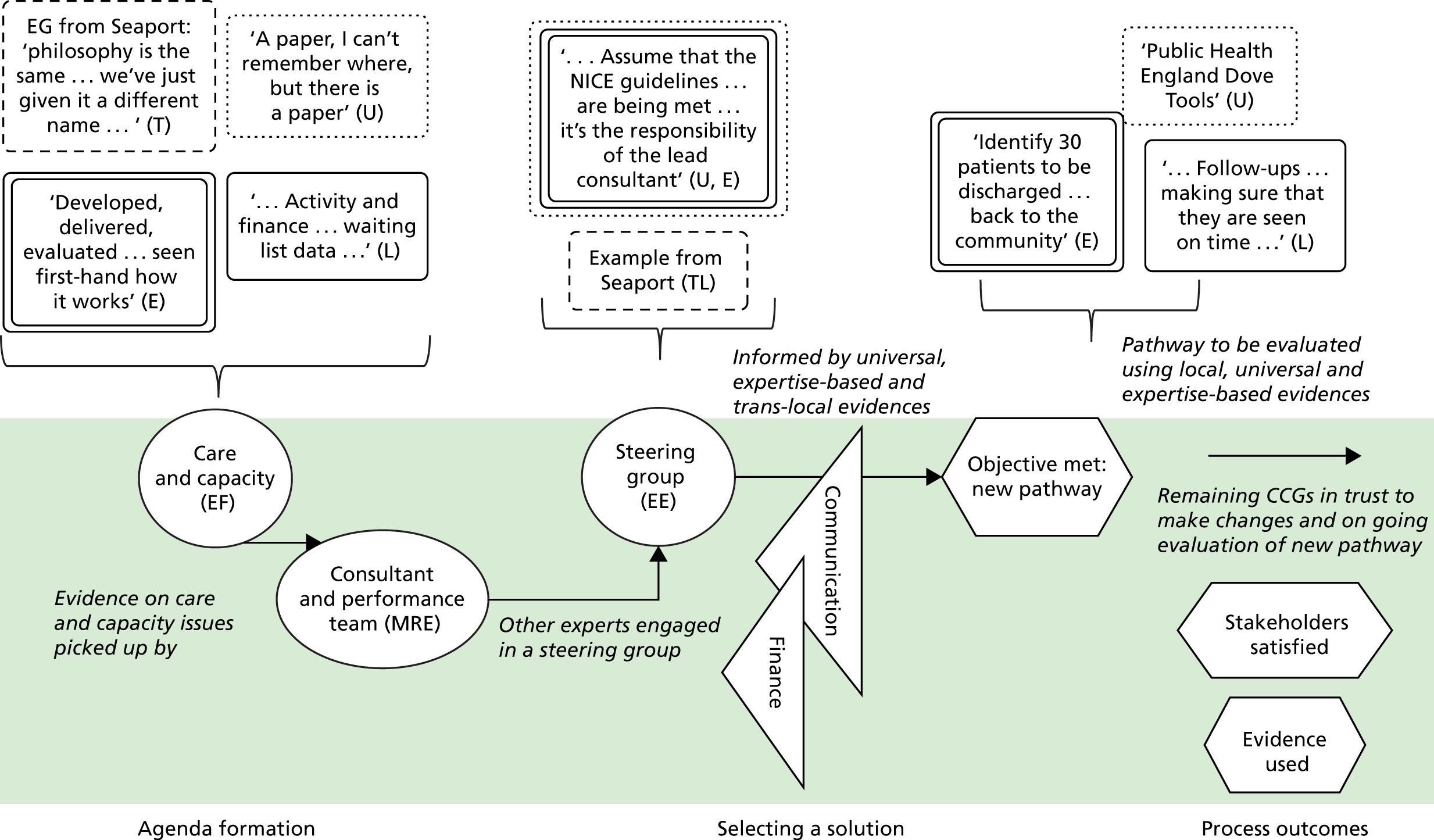

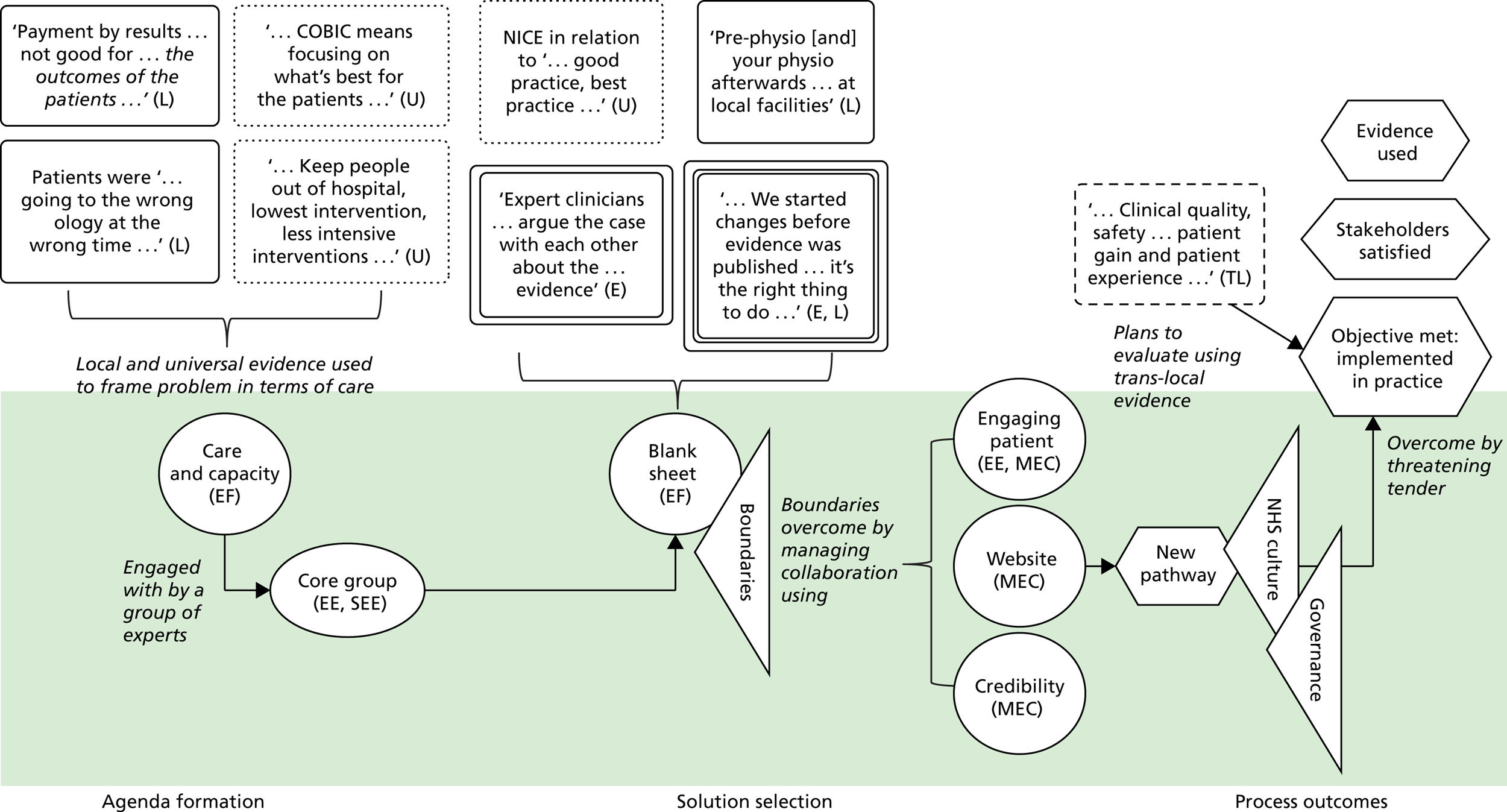

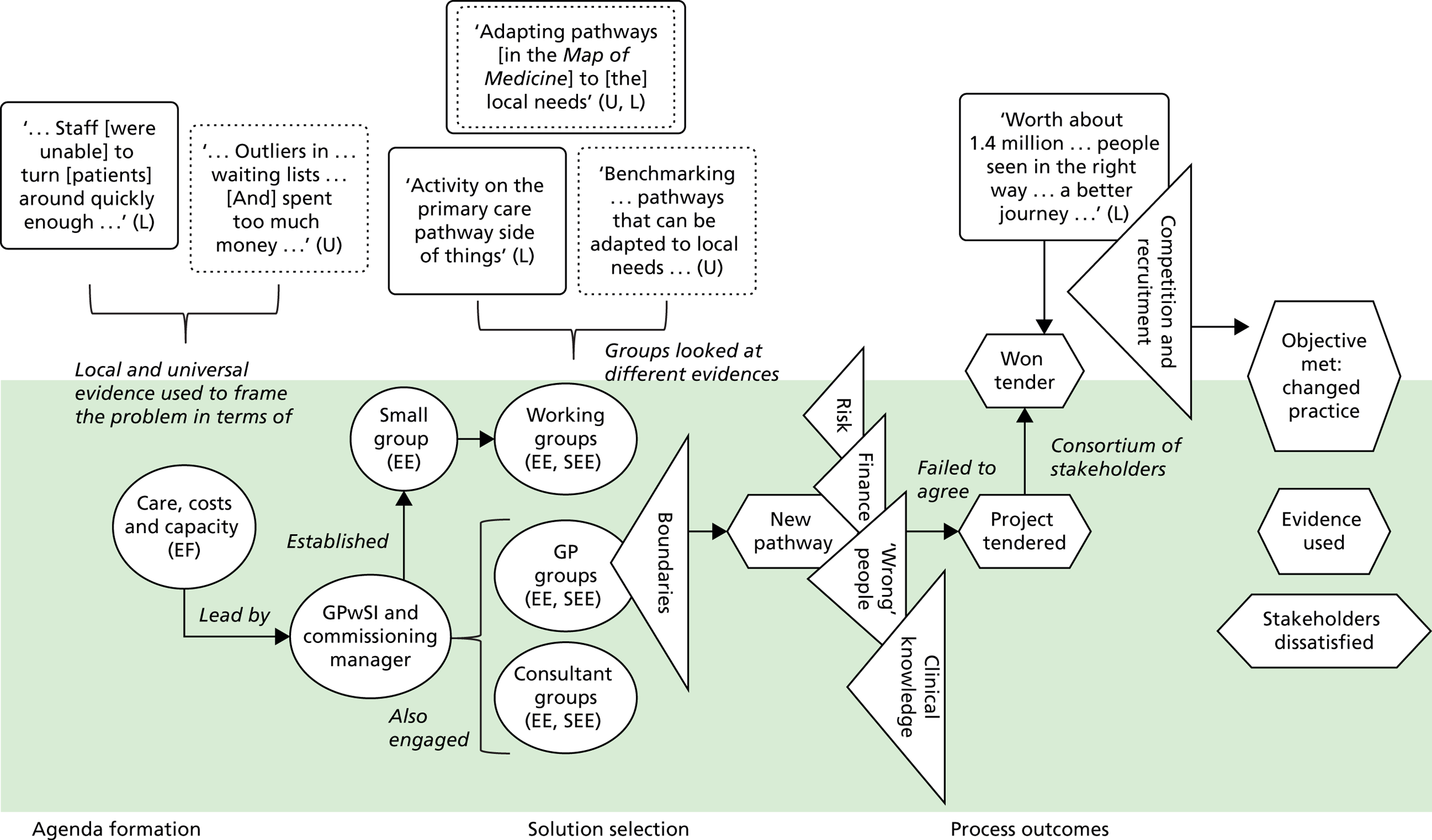

Process mapping

Process maps were created to identify patterns of evidence use, capabilities and outcomes within and across cases. 53,76 In these we draw out the chronology of critical events in redesign work. 74 To give structure to our cases, we inductively labelled the episodes of work as they appeared in the raw data. As seen in the literature review, episodes (sometimes labelled ‘phases’) of work are often used in innovation literatures to give structure to process studies. 32,51 We prefer the labelling ‘episode’ to highlight the often non-sequential nature of the work activities entailed.

Cross-case comparisons

Building on within-case analyses, and following Stake,77 we then conducted cross-case comparisons. To do this, team members examined cases to identify ‘prominent themes’ in each and ‘common patterns’, as well as major differences in evidence use. The team then assembled to compare and contrast similarities and differences across cases and to come to tentative assertions about the capabilities that appeared to influence the CCGs’ evidence use, as well as any significant aspects of context. As we were interested in capabilities to use evidence, we also mapped these against process outcomes, identified broadly and indicated qualitatively in terms of evidence use (the extent to which a range of evidences were sourced, interpreted and engaged with), stakeholder experience (the extent to which stakeholders were satisfied with the process) and objectives met (the extent to which the original objectives had been met and, if they had not, whether or not any change to them was justified).

These tentative findings were presented to the SSAP and non-Warwick team members for further discussion and verification. Following this, the findings were presented at our one-day national multistakeholder engagement workshop (n = 46) at which further feedback and verification was elicited. These steps were important in helping to achieve trustworthiness in our analysis. 71 Having identified evidences and capabilities, and compared across cases, we summarised our findings into a toolkit for use by commissioning stakeholders. The questions for this toolkit were also piloted at our national engagement workshop and were modified accordingly.

Research on evidence ‘push’

Our original protocol aimed to trace the evidence journey in CCG commissioning, including the place at which evidence ‘enters’ the journey, as guidelines and other forms of evidence-based products. Here, we conducted a further small-scale exploratory study in one large guidance-producing organisation, in which we considered the ways in which projected users are inscribed in published evidence. Our objectives were to understand:

-

the user image inscribed in published evidence products

-

how an evidence producer believes products will be used in general, and by CCGs.

Over the course of 6 months, during 2015–16, we carried out eight interviews, spoke less formally with other evidence producers and consulted a number of documents, some publicly available and some internal. Informants included project managers and clinical staff involved in the production of the evidence (n = 4); and staff involved in communication, marketing and other customer-facing activities (n = 4). We also observed one visit of an evidence producer to a CCG. We asked questions about the following in semistructured interviews:

-

how the design and production of evidence (e.g. guidance, advice, quality standards) is organised and the nature of the products

-

how products are made available to users and how this has changed over the years

-

a scenario question (according to critical incident interview),78 in which interviewees were asked to focus on a specific product (guidance, quality standard or other) and describe how it is actually used, with examples.

All interviewees gave informed consent. Interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. The same inductive coding method was used as described above for identifying capabilities.

Summary of research methods

We conducted two phases of research to understand evidence ‘push and pull’. The findings were shared with case study participants via feedback and with our SSAP by e-mails and meetings. In the next chapters, we present findings from phase 1. We describe what evidences are used (see Chapter 3), and then capabilities for use (see Chapter 4). Building on this in Chapter 5, we show evidences and capabilities in practice through four analytically-structured cases (two on diabetes services and two on MSK services). The remaining cases are shown in Appendices 1–4.

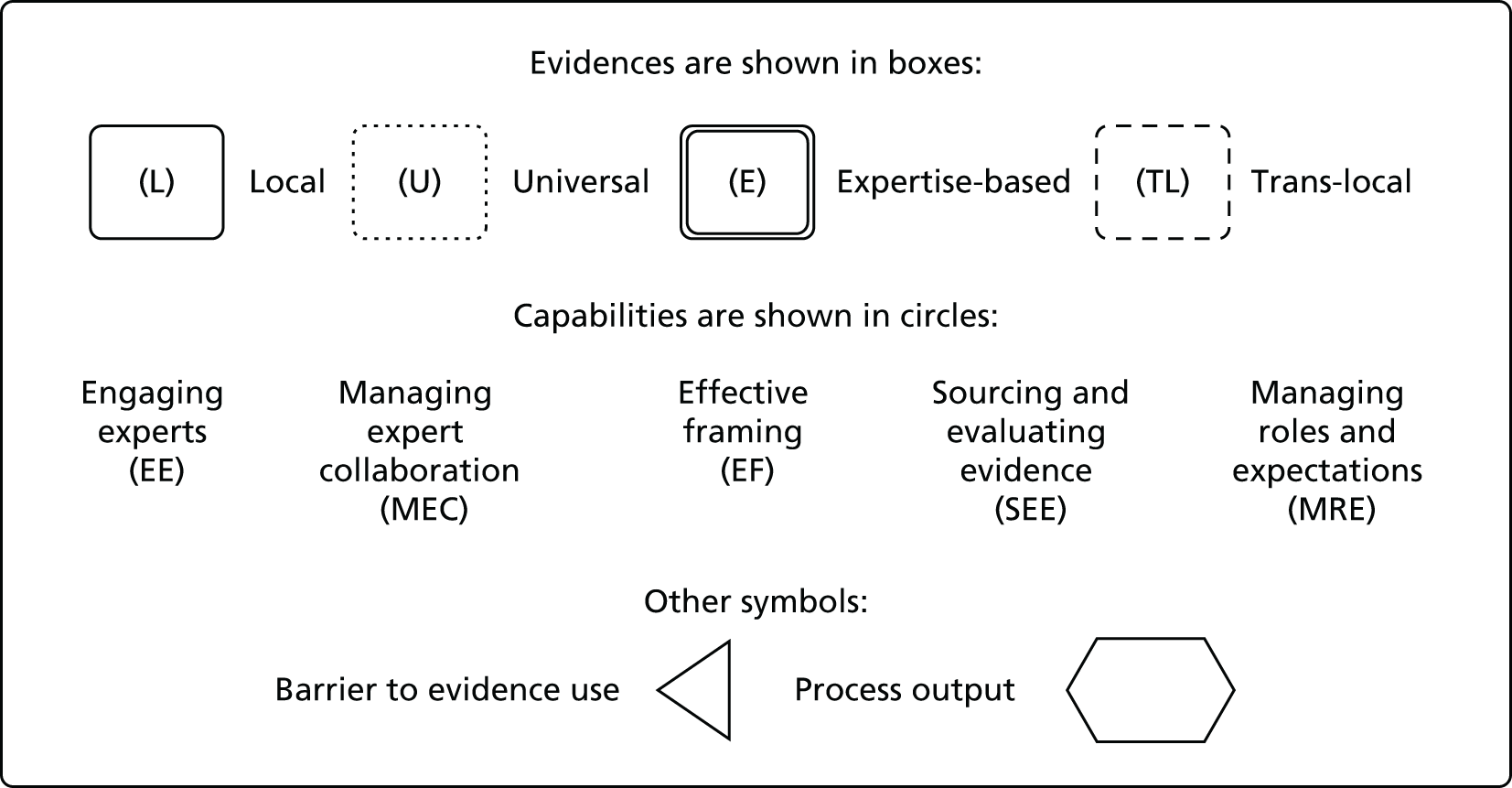

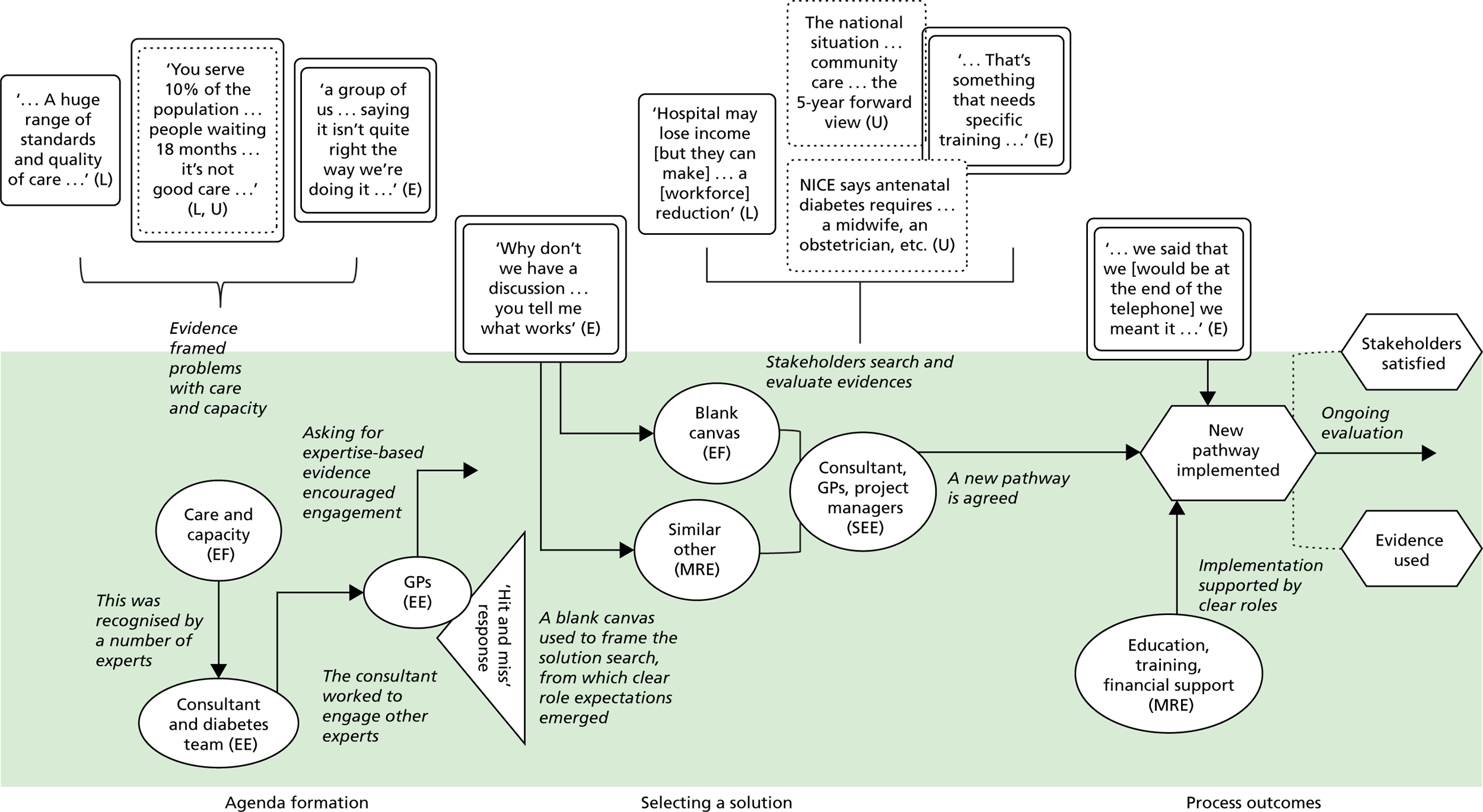

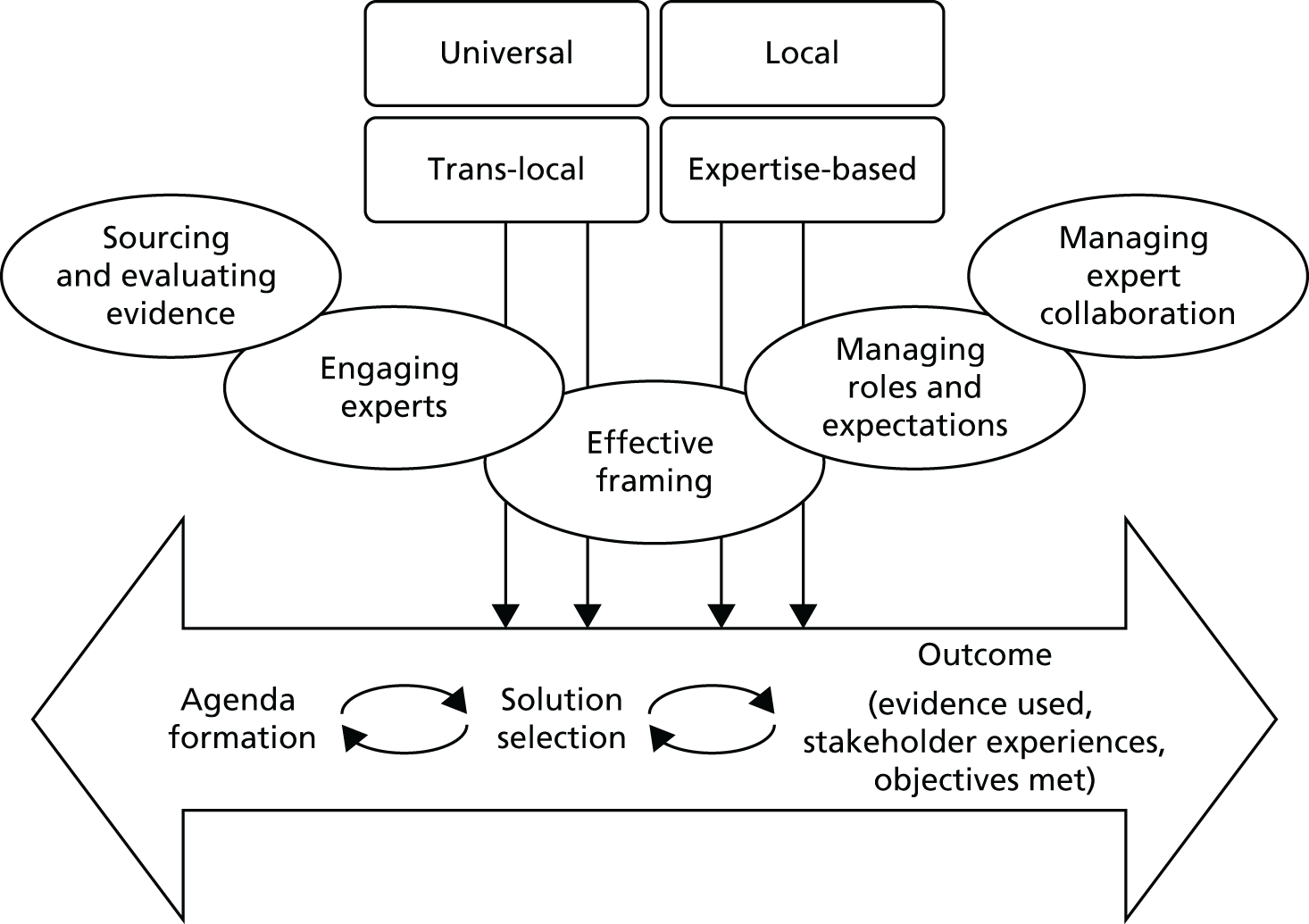

Chapter 3 Clinical Commissioning Group evidence use

We see evidence as information that enables understanding and legitimises judgements. 2 In the first phase of our study, four categories of evidence were identified in our analysis. These were labelled as ‘universal’, ‘local’, ‘expertise-based’ and ‘trans-local’. These labels reflect what kinds of evidence were used in terms of their source. As seen in Chapter 1, universal (i.e. evidence produced through scientific methods that is held to be widely applicable), local and expertise-based have been discussed in the literature to some extent already, while trans-local evidence is more uniquely identified in our study. 1,2

Universal evidence

Information produced by formalised or scientific investigation in institutions or organisations that are deemed to have legitimate authority (e.g. universities, NICE and national bodies) is commonly treated as evidence. 1 This type of evidence is produced systematically through scientific method (e.g. RCTs and NICE guidelines) and/or standardised nationally (e.g. QOF data), so it is considered robust, rigorous, widely applicable and authoritative. Because this type of evidence is expected to be used widely, it has been termed ‘universal’. 2 We think of universal evidence as produced from the ‘top down’. Universal evidence includes NICE guidance, but also NHS reports, public health data, Right Care guidance and academic papers, among others. Previous studies showed the importance of this type of evidence in decision-making in commissioning work. 1,2

Stakeholders also described mobilising universal evidence to understand ‘good practice, best practice’ (Chelsea CCG). They were aware, for example, of ‘what’s being proposed in the Five Year Forward [View]’ (Seaport CCG), the NHS-produced document setting out a vision of ‘GPs, nurses, community health services, and hospital specialists [providing] integrated out-of-hospital care’. 79 A consultant at Seaport CCG described using NICE to inform service design, in this case because it mandates that antenatal diabetes has ‘a midwife, an obstetrician, a consultant, and a scanning machine’. Evidence from academia was also used, including ‘studies about how do you improve service provision, about impact . . . tools’ (Coalfield CCG). Interestingly, some kinds of universal evidence appeared to be more prominent than others. Cochrane reviews were not, for example, referred to in any case (at least directly), whereas NICE guidance was referred to rather more often.

As in other studies, the rigour of universal evidence was understood, but its usability and relevance was questioned. NICE guidelines in particular were problematic, with stakeholders seeing them as ‘very long . . . it’s like reading a book!’ (Horsetown CCG). 1 Furthermore, in order to be widely applicable, this kind of evidence had, by definition, to be abstracted from any particular context, which often left commissioners puzzling over how to apply it in their own setting. At Rutterford CCG, for example, stakeholders described how ‘on top of all of that [NICE] guidance, you have to put in what is going on locally . . . and what is available’.

Local evidence

Information produced and collected locally within CCGs or in their immediate locale was also, and very often, treated as evidence. 1,2 This information is wide ranging, including patient profiles, local activity and performance data, finance data, contracting models and monitoring outcomes. It may also include externalised observations and experiences of stakeholders. Unlike universal evidence, this type of evidence is seen as more readily ‘to hand’ for those involved in commissioning decisions and, therefore, ‘useful’.

Across all cases, local evidence featured heavily in the conversations among commissioning groups. It was used to show problems, for example ‘a 41% increase in hip and knee replacements’ (Horsetown CCG) or ‘you serve only 10% of the population [in the hospital]’ (Seaport CCG). Local evidence was also used to identify solutions to problems, for example ‘The CCG have done a piece [of research] that sort of says . . . 70% of activity can be stripped out [from the hospital]’ (Greenland CCG). Alongside these ‘hard’ numerical data, stakeholders also relied on softer tacit knowledge about the local area: ‘a lot of patients . . . being followed up in secondary care, which is not necessarily where they should be’ (Greenland CCG).

Evidence collected in the local area gives meaning in context, and so it is not surprising that is has been shown as important in the broader literature, too. 1,2 Although readily available at a relatively low cost (in terms of search time and effort, at least), this type of evidence is not subject to the same scrutiny as universal evidence, and so issues around its validity could often arise. 80

Expertise-based evidence

Information based on the experiences and expertise of individuals could also be treated as evidence. Expertise-based evidence can be sourced from health-care providers, colleagues, patients, families, carers and many other groups. 1,2 Stakeholders in our cases used expertise-based evidence to form agendas. At Seaport CCG, for example, the consultant describes how ‘the idea [for the redesign] came from . . . a group of us registrars’ because ‘we always used to talk about it, saying it isn’t quite right the way we’re doing it’. Expertise-based evidence was also used to identify solutions. At Horsetown CCG, for example, commissioners chose community-based solutions because they had ‘set up things in the community before [and seen] the cost reduction . . . the better patient experience’.

Expertise-based evidence is personal, embodied and value-laden. It is often transferred through narratives. It possesses few characteristics of scientific rigour; this evidence is very relevant to context. We noted that individuals with clinical backgrounds who were considered charismatic and were respected tended to be considered holders of ‘expertise’. Although anecdotal, our observation reflects the study by Wright et al. 10 how one individual (‘Dr Clancy’) influenced service redesign in an Australian emergency department.

Trans-local evidence