Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 12/177/14. The contractual start date was in March 2014. The final report began editorial review in April 2016 and was accepted for publication in October 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Edwin van Teijlingen declares membership of the HTA Clinical Trials Board.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Pitchforth et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Community hospitals form an established component of health-care provision. 1 Historically, in the UK, community hospitals have been defined as local hospitals that are typically staffed mainly by general practitioners (GPs) and nurses to provide care in a hospital setting, often for predominantly rural populations. 2 However, the notion of a community hospital has evolved over time, with a wider range of service delivery arrangements and models developing across England and the UK more widely. These include services that support the rehabilitation and recovery of patients, allowing them to resume independent living more quickly,3 and community care homes or service models that do not include inpatient beds but that provide specialist care alongside primary care and outreach services. 4 Thus, community hospitals exist in a variety of forms, differing in the nature and scope of services provided, the models of ownership and management, and the level of integration with other services. This diversity of service delivery models reflects the needs of the local populations served, as well as broader changes in the nature of the delivery of health-care services. 5 For example, advances in medical technology have made it possible to provide many services closer to the patient, with interventions that would previously have required a hospital environment now carried out in ambulatory settings. 6 With concerns about the perceived high costs of hospital care, there is increasing interest in moving care into the community in order to increase accessibility, in particular in dispersed populations, and so enhance the responsiveness of the system, and, potentially, to reduce costs.

Available evidence suggests that community hospitals may offer advantages over larger hospitals for some patients. For example, studies examining the impact of rehabilitation care for older people found that the community hospital setting was associated with greater independence at 6 months than the district general hospital setting. 7–11 Other work has pointed to the potential role of community hospitals in providing palliative care. 12 It is reported that community hospitals are perceived as friendly and service-user centred; for example, evidence from the 2011 Scottish Inpatient Patient Experience Survey found that community hospitals scored above the national average on many questions concerning patient experience,13 and it has been suggested that community hospitals offer a better experience of care than acute hospitals by allowing more integration with patients’ families and home life.

Others have pointed to a strong tradition of community hospitals providing more integrated care. 14 This core feature of the ‘traditional’ community hospital assumes a renewed importance given the rising burden of chronic disease, creating a complex set of health and social care needs, in particular among those with multiple chronic conditions, alongside frailty at old age. Meeting those needs requires the development of delivery systems that bring together a range of professionals and skills from both the cure (health-care) and care (long-term and social care) sectors. 15 Failure to better integrate or co-ordinate services along the care continuum may result in suboptimal outcomes, such as potentially preventable hospitalisation, medication errors or adverse drug events. 16 A recent commitment by national partners to support service integration emphasised the use of existing structures to align the NHS, public health and adult social care outcomes,17 and it has been suggested that community hospitals may act as a hub for care integration and the provision of care closer to home. 14 More recently, the NHS England Five Year Forward View18 has called for the removal of barriers in how care is provided, including between primary and secondary care and between health and social care, and a small number of vanguard sites have included community hospitals as part of integrated primary and acute care systems and multispecialty community providers. 19

Against this background, there is thus potential for community hospitals and related service delivery models to assume a more strategic role in the local health economy to integrate service provision and thereby address some of the challenges arising from service fragmentation in particular. Furthermore, there is an opportunity to learn from the experiences of other countries in order to inform and help advance the future development of community hospitals in England. However, given the evolving nature of the notion of the community hospital in England and across the UK, there is a need to understand better the role of different models of community hospital provision within the wider health economy and their capacity and capability to integrate services locally. It will be particularly important to understand the nature and scope of services provided by what may be considered a ‘community hospital’, as well as its specific functions and delivery models.

The proposed research seeks to contribute to filling this gap by, first, reviewing the evidence base on community hospitals and equivalent service delivery models nationally and internationally, examining a range of organisational characteristics as well as outcomes. Second, we draw on experiences in other countries on the contribution of community hospitals to the health-care system by assessing equivalent service delivery models. Scotland has a long and rich tradition of community hospitals,13 and relevant approaches have also been described with reference to, for example, Finland,20 Norway,21,22 and, more recently, Italy, in the context of the 2012 reorganisation of hospital care. 23 Evidence from other countries offers opportunities for mutual learning and consideration of alternative policies, or policy transfer, where appropriate. 24

Aims and objectives

The proposed research seeks to answer five principal research questions:

-

What is the nature and scope of service provision models that can be considered under the umbrella term ‘community hospital’ in England and other high-income countries?

-

What is the evidence of effectiveness and efficiency of community hospitals and comparable service models in England and other high-income countries, including in terms of patient outcomes?

-

What is the wider role and impact of community engagement in community hospital service development and provision?

-

How do models that are comparable to community hospitals in England operate, and what is their role within the wider system of service provision in other countries?

-

What is the potential for models that are comparable to community hospitals in England to perform an integrative role in the delivery of health and social care in other countries?

To address these questions, we used a range of methods: a scoping review, a systematic review, a review of five countries (Australia, Finland, Italy, Norway and Scotland) and in-depth case studies (four cases in three countries – Finland, Italy, Scotland).

Structure of the report

The report is organised as two main parts: (1) reviews of current literature and an evidence synthesis; and (2) international country review and comparison. Chapters are broadly organised, within this structure, in line with the principal research questions. In Part 1, Chapters 2 and 3 relate to research questions 1 and 2, respectively, both of which report literature reviews that draw on the same search strategy but employ different methodological approaches. Specifically, Chapter 2 uses a scoping review to describe the nature and scope of service models that can be considered as ‘community hospital’, whereas Chapter 3 presents the findings of a systematic review of the evidence of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of such models. In Part 2, Chapters 4, 5 and 6 address research question 4, that is, how models that are comparable to community hospitals in England operate and their role within the wider system of service provision in other countries. Chapter 6 presents a comparative analysis of the nature, scope and distribution of relevant service delivery models in Australia, Finland, Italy, Norway and Scotland, using a review of the published and grey literature following a structured data collection template and key informant interviews. Chapter 5 reports on a detailed multiple case-study analysis of two innovative models of community hospitals in Scotland, and Chapter 6 describes a cross-case analysis of four case studies, including those in Scotland and one each in Finland and Italy. Research question 3 on the wider role and impact of community engagement in community hospital service development and provision and question 5 on the potential for relevant models to perform an integrative role in the delivery of health and social care were understood as aspects to be addressed across the different components of this study. However, as demonstrated, we were unable, as part of the evidence reviews, to identify robust published evidence that assessed the aspect of community engagement (question 3) in a systematic way. Important issues relating to community engagement were brought out in the case studies but this did not emerge as a key area of focus in the country review.

The report concludes with Chapter 7, which provides overarching observations emerging from the different study components, discusses options for community hospital provision that are relevant to NHS England and makes a set of recommendations for future research. The appendices provide supplementary materials relating to data collection and provide individual country and case-study reports. The country reviews reported here reflect the situation in the relevant setting as of March 2016.

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement (PPI) was important throughout our study, particularly as patients were not among our study participants. We outline how we worked with PPI representatives throughout the project from the proposal stage to completion.

Proposal stage

In preparation for the research proposal, we shared our research plan with a PPI panel, INsPIRE. Panel members were asked to comment on the following:

-

Is the lay/plain English summary understandable (if not, please could you offer suggestions from a lay perspective)?

-

Is the extent and quality of service user and carer involvement in the research satisfactory and could people be involved in any other way?

-

Are the proposed research questions important and relevant to service users?

-

Is the proposed research likely to be beneficial to service users?

-

Do you have any other comments on the research plan, research questions or methods suggested?

-

Is our plan for PPI involvement throughout the study appropriate?

Patient and public involvement respondents commented that the proposed research was of value and made suggestions for improvement, noticing that some of the wording remained too technical. PPI members also suggested that it may be useful to present the models of community hospital that we identify in diagrammatic or schematic form. We have used schematic representation as appropriate in Chapter 2.

During the project

For the duration of the project, we sought to recruit two PPI representatives. Following conversation with the co-ordinator of the INsPIRE group, we drafted a job description to explain the project and what would be expected of the representatives (see Appendix 1).

We were able to recruit two patient representatives, Kate Massey and Hamish McBride. Kate Massey commented on the research plan at the proposal stage as a member of INsPIRE and was recruited to the study from there. Hamish McBride was recruited though professional networks. Kate Massey has been an active PPI member on several health service research projects. Hamish McBride is a retired GP with experience of working in a community hospital in rural Scotland. In addition to providing PPI support to this project, Kate Massey was a member of the cross-project steering group. She attended one meeting in person and when unable to attend in person, she provided input remotely.

A number of the points made by the patient representatives during the meetings related more generally to the relevance and accessibility of the work to patients and members of the public. The representatives also commented on each individual component of the study, highlighting issues that seemed particularly important and seeking clarification from the research team in some cases. We noted all of these points for development of the next draft.

Towards the end of the study, we shared drafts of the outputs and followed up individuals for comment and suggestions, which were useful in finalising our report. At this stage, comments from the representatives were particularly useful with regard to the abstract and plain English summary. Once the final report is submitted, we shall seek our PPI representatives’ advice in order to maximise the impact of our study and effectively implement our dissemination plan.

Steering group and co-ordination with related studies

This study was one of three studies that were funded by the Health Services and Delivery Research programme of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) to undertake research into community hospitals. The concurrent studies were ‘A comprehensive profile and comparative analysis of the characteristics, patient experience and community value of the classic community hospital’ (HSDR project number 12/177/13) led by Professor Jon Glasby at the University of Birmingham and ‘A study to understand and optimise community hospital ward care in the NHS’ (HSDR project number 12/177/04) led by Professor John Young at Bradford Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust. The three projects were supported by a cross-project steering group to provide guidance for the research in order to maximise synergies between the three studies. Chaired by Professor Sir Lewis Ritchie, University of Aberdeen, the steering group included representation from the Community Hospitals Association, research, and patient and public associations. The steering group met with members of the three research teams three times over the course of the research presented in this report. The steering group created an open environment in which to share findings and experiences between the projects, as well as to avoid duplication of efforts. For example, our international study was commissioned specifically not to include England or to focus on patients and the role of community in detail, as these issues are central to the study being led by Professor Jon Glasby (HSDR project number 12/177/13). The projects have different durations but the findings from the international experience, presented in this report, have been actively incorporated into the other two studies where appropriate. Joint publications, which synthesise the results of the different studies, will also be pursued, strengthening the relevance of the international evidence to England.

Ethics approval and research governance

Ethics approval was granted by the University of Bournemouth Research Ethics Committee (reference 4857) on 2 October 2014. Details of the ethics application and process are available upon request from the corresponding author. All appropriate local research governance checks were made and approvals given. For the case studies, each research site was responsible for obtaining the appropriate local research governance approvals as per local guidance.

Part 1 Literature reviews and evidence synthesis

Chapter 2 Community hospitals in selected high-income countries: a scoping review of approaches and models

Introduction

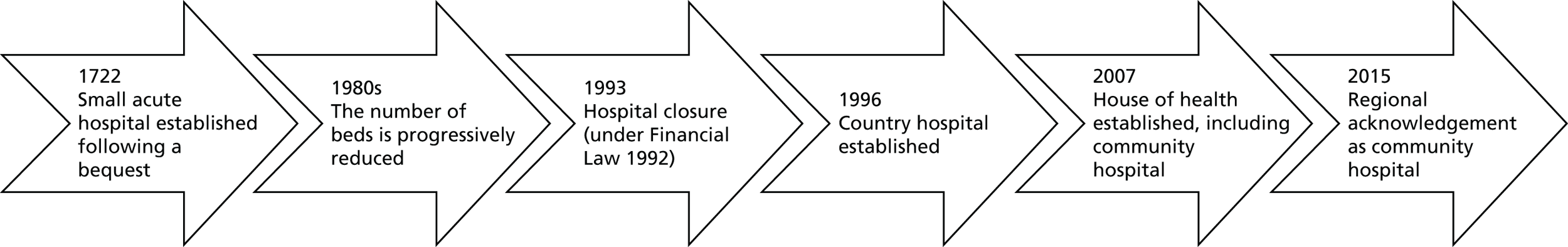

Community hospitals have been an established component of health-care provision in the UK for many decades, frequently evolving from local cottage hospitals, which predated the formation of the NHS in 1948. 1 Community hospitals have typically been staffed mainly by GPs and nurses to provide care in a hospital setting, often for predominantly rural populations. 2 They usually sit at the interface between primary and secondary care25 and may provide a diverse range of services including inpatient, outpatient, diagnostic, day care, primary care and outreach services. 1

In England there has been increasing policy focus and government investment into shifting the delivery of medical care to community settings,26,27 with calls for the development of a new generation of community hospitals and services that would be responsive to local needs and at the forefront of health-care innovation. 28–30 The 2014 NHS Five Year Forward View proposed new models of care to be developed in England, which would allow for integration across organisational boundaries, and highlighted the potential role for community hospitals in delivering more integrated care locally by bringing together community, primary and secondary care services. 18 Similar visions have been expressed in other system contexts. 13,23 Although there is potential for community hospitals to assume a more strategic role in service delivery, the precise role that these service structures should take is not clear. A 2006 review by Heaney et al. 1 found that the role of community hospitals has been viewed in different ways, as step-down facilities, as an extension of primary care or as an alternative to secondary care. A wider range of service delivery arrangements have also been described, such as community care resource centres, community care homes and intermediate care or rehabilitation units. 28,29,31,32 Heaney et al. 1 also found that community hospitals serve primarily an older population and are staffed by a range of professionals, including GPs, nurses, allied health professionals and visiting specialists. However, the authors highlighted a lack of robust evidence for the role of community hospitals, indicating a need to understand better the different roles that community hospitals can fulfil, and their capacity and capability to integrate or collaborate with other health and care services.

Commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research (England and Wales), this scoping review updates a review by Heaney et al. 1 published in 2006. It aims to describe different models of community hospitals in selected high-income countries. From this understanding of the nature and scope of services provided and their specific functions, we seek to inform the future development of community hospitals.

Methods

We carried out a scoping review33 following the approach proposed by Levac et al. 34 Given our interest in comprehensively mapping literature that provides insight into community hospital models, we chose a scoping review methodology, which does not exclude evidence based on study design or quality. The review extends the 1984–2005 time frame of the Heaney et al. 1 integrative thematic review and builds on it using comparable search terms and conceptual understanding of the ‘community hospital’. However, it differs fundamentally in its specific interest in models of care and thus in the scope and nature of its reported findings. In addition, unlike Heaney et al. ,1 our review includes non-English language papers.

Given the range of definitions of a community hospital available in the literature (Table 1), we developed a working definition to guide our review. After reviewing these definitions, and having sought expert opinion from members of our cross-project steering group, we stipulated that a community hospital (1) provides a range of services to a local community; (2) is led by community-based health professionals; and (3) provides inpatient beds.

| Definition | Reference |

|---|---|

| A GP community hospital can be defined as a hospital where the admission, care and discharge of patients is under the direct control of a GP who is paid for this service through a bed fund, or its equivalent | Royal College of General Practitioners2 |

| A community hospital is a local hospital, unit or centre providing an appropriate range and format of accessible health-care facilities and resources. Medical care is normally led by GPs, in liaison with consultant, nursing and allied health professional colleagues as necessary, and may also incorporate consultant long-stay beds, primary care nurse-led and midwife services | Ritchie and Robinson25 |

| Many countries have a lower tier of hospital, sometimes called a community hospital. These typically have ≤ 50 beds and provide basic diagnostic services, minor surgery and care for patients who need nursing care but not the facilities of a district general hospital | McKee and Healy35 |

| A service that offers integrated health and social care and is supported by community-based professionals | UK Department of Health26 |

| A local hospital, unit or centre that is community based, providing an appropriate range and format of accessible health-care facilities and resources. These will include inpatient beds and may include outpatients, diagnostics, surgery, day care, nurse-led care, maternity, primary care and outreach services for patients provided by multidisciplinary teams | Community Hospitals Association4 |

We searched PubMed, EMBASE, Scopus, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), PsycINFO, British Nursing Index, Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC), Social Care Online, and Health Business Elite in June 2014 for literature published since 2005, using the principal search terms ‘community hospital’, ‘cottage hospital’, ‘GP beds’ or ‘intermediate care’. The full PubMed search strategy, which was adapted for the other databases we used, is shown in Box 1.

“Hospitals, Community”[Mesh] OR “Hospitals, Group Practice”[Mesh] OR “Hospitals, Rural”[Mesh] OR (“Hospitals”[Mesh] AND “Family Practice”[Mesh]) OR (“Hospitals”[Mesh] AND “Rural Health Services”[Mesh]) OR (“Family Practice”[Mesh] AND “Hospital-Physician Relations”[Mesh]) OR “Hospital Bed Capacity, under 100”[Mesh] OR (“Family Practice”[Mesh] AND “Bed Occupancy”[Mesh]) OR “Intermediate care facilities”[Mesh]

OR

“cottage hospital”[All Fields] OR “cottage hospitals”[All Fields] OR “community hospital”[All Fields] OR “community hospitals”[All Fields] OR (“gp”[All Fields] AND (“beds”[MeSH Terms] OR “beds”[All Fields] OR “bed”[All Fields])) OR “gp beds”[All Fields] OR “general practitioner hospital”[All Fields] OR “general practitioner hospitals”[All Fields] OR ((“community”[All Fields] OR “rural”[All Fields]) AND “hospitals, maternity”[MeSH Terms]) OR “intermediate care” [All Fields]

NOT

(“Africa”[Mesh] OR “Africa, Western”[Mesh] OR “Africa, Central”[Mesh] OR “South Africa”[Mesh] OR “Africa, Southern”[Mesh] OR “Africa, Northern”[Mesh] OR “India”[Mesh] OR “China”[Mesh] OR “South America”[Mesh] OR “Developing Countries”[Mesh])

Limit results to years 2005–present.

Reproduced from Winpenny EM, Corbett J, Miani C, King S, Pitchforth E, Ling T, et al. Community hospitals in selected high income countries: a scoping review of approaches and models. Int J Integr Care 2016;16:13. 36 This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0.

Three researchers (CM, SK and JC) screened titles and abstracts of identified records against a set of inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 2), which were informed by our working definition. The researchers independently screened the same 300 records and compared their results in order to ensure consistency in deciding on study eligibility. The remaining titles and abstracts were then screened by one of the three researchers. Full texts of potentially eligible studies were retrieved and reassessed against the inclusion and exclusion criteria by one reviewer, and checked by a second reviewer. Disagreements or uncertainties between reviewers were resolved by discussion within the wider research team.

| Study characteristics | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Setting | High-income country with comparable health-care systems that provide universal access (i.e. Canada, Australia, New Zealand and high-income countries in Europe) | Low- and middle-income country; non-European country (except Canada, Australia, New Zealand) |

| Facility type | Meets all of the following criteria:

|

Facility that offers specialist services only GP- or nurse-led beds within secondary or tertiary hospitals |

| Outcomes | A description of the nature and scope of delivery models or services provided | Provides synthesis and discussion of the delivery model only Does not describe the delivery model or services provided by individual community hospitals |

| Study type | Experimental study (RCT, cluster-RCT, quasi-RCT), qualitative study and observational study | Editorial, commentary, review |

| Publication type | Journal article, report, dissertation, book and professional journal | Conference abstract, study protocol |

| Publication year | Published in 2005 and after | Published before 2005 |

| Language | All languages | N/A |

Data were extracted from each study on the features of the hospital model (e.g. management, staffing, ownership) and the specific services offered. Data extraction was undertaken by the three researchers with some duplicate extraction to check for consistency of the approach. Data were analysed drawing on the principles of narrative synthesis, which has been recommended as the most appropriate approach for analysing diverse evidence. 37

Given this diversity, and the fact that this was designed as a scoping review aimed to provide an overview of the existing literature, a formal quality assessment of the included studies was not conducted. However, during data extraction researchers commented on the nature of the evidence presented and any particular concerns as to the quality of the study.

Findings

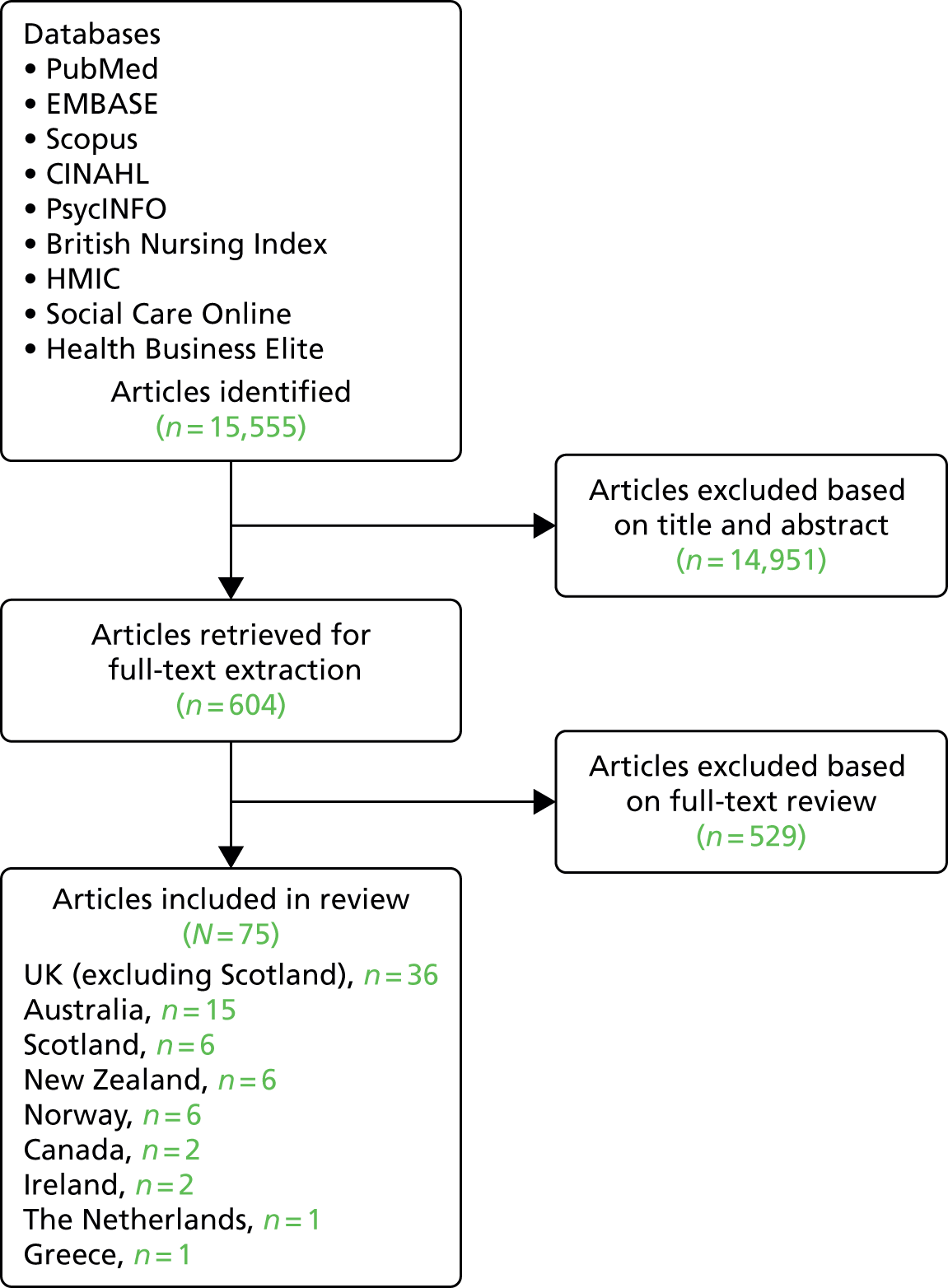

Our searches identified a total of 15,555 records following the removal of duplicates. After initial screening of titles and abstracts, we considered 604 references for full-text review, and, of these, 75 studies were identified as eligible for inclusion (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Studies eligible for inclusion. Reproduced from Winpenny EM, Corbett J, Miani C, King S, Pitchforth E, Ling T, et al. Community hospitals in selected high income countries: a scoping review of approaches and models. Int J Integr Care 2016;16:13. 36 This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0.

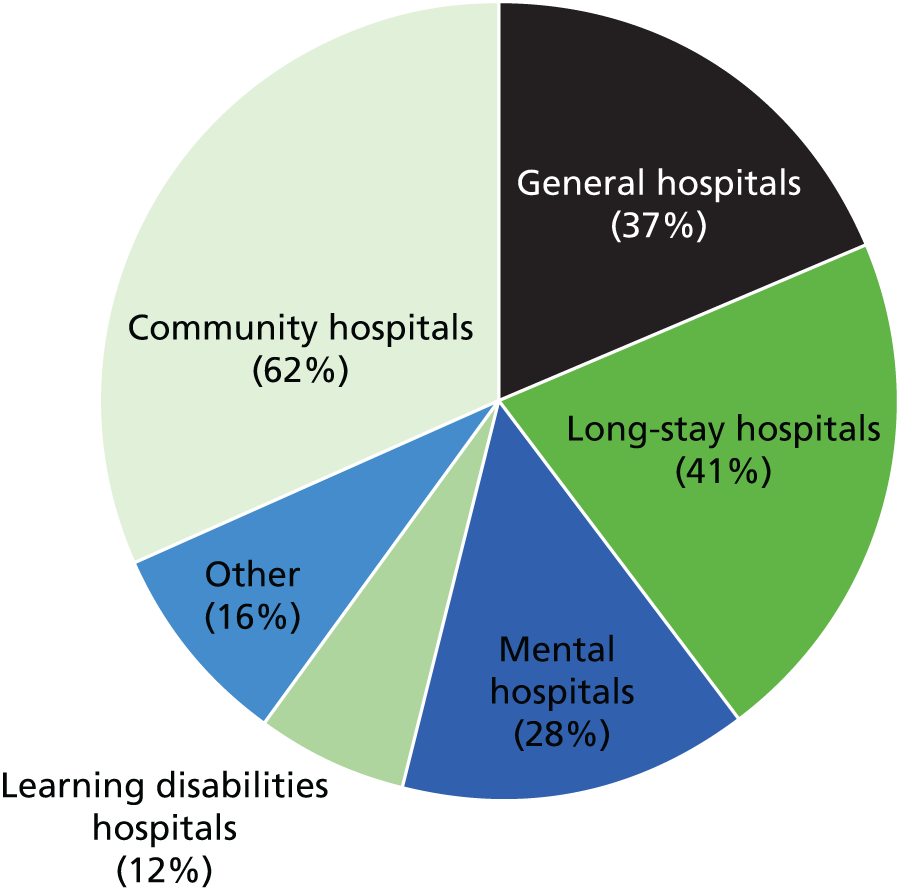

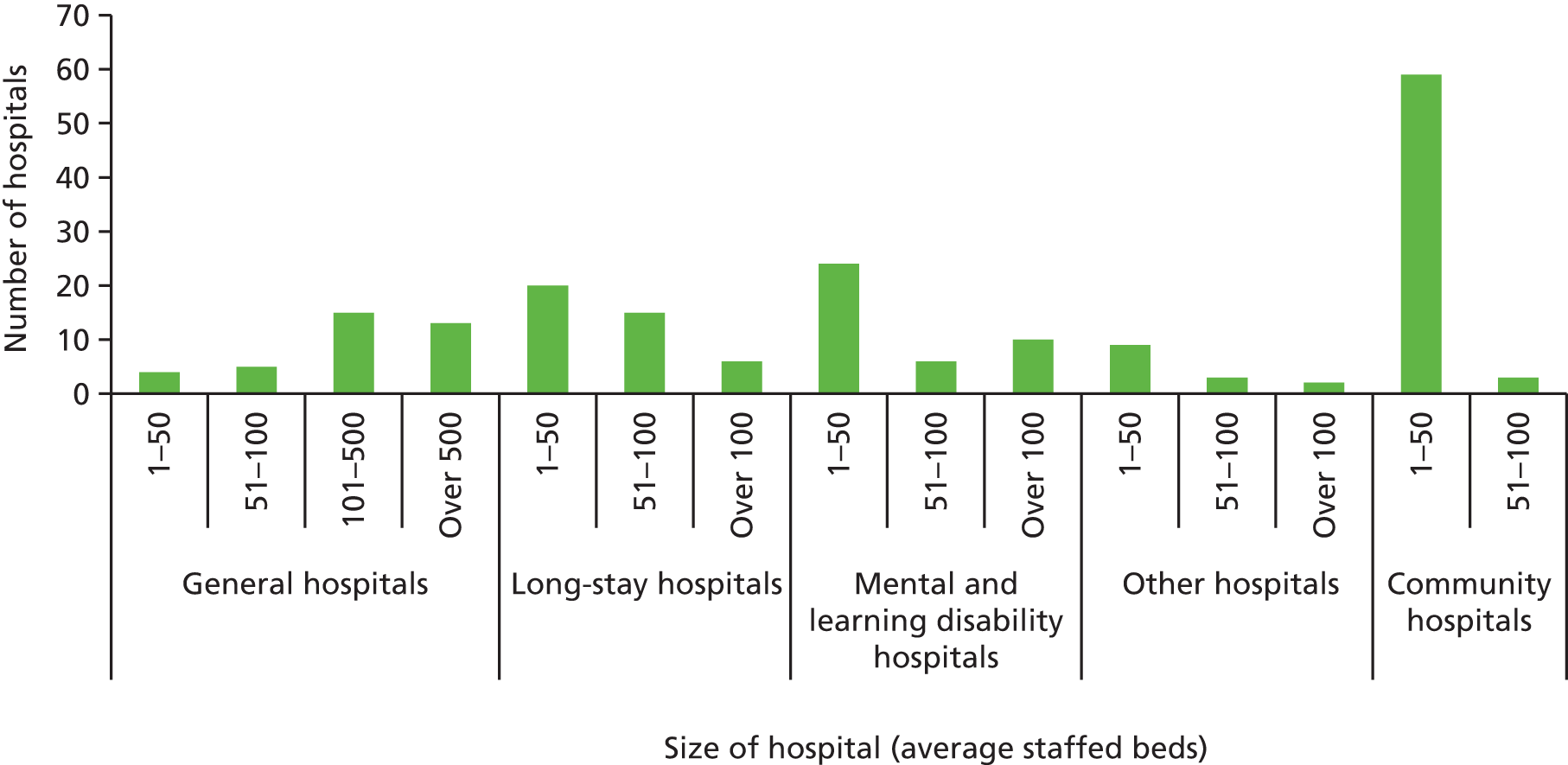

The majority of studies were descriptive or used a qualitative design, while 11 studies used a randomised controlled trial (RCT) design. Included studies fell broadly into the following categories: descriptions of one or more community hospitals (n = 14); descriptions of development of new facilities or procedures within a community hospital (n = 9); reports of particular services within community hospitals (n = 12); studies of patients’ or family members’ experiences of care within community hospitals (n = 4); studies presenting surveys of community hospitals or units within community hospitals (n = 5); or studies reporting on specific outcomes of care delivered by community hospitals (n = 9). The largest number of studies were set in England and Wales (n = 36), followed by Australia (15), New Zealand (6), Norway (6), Scotland (6), Canada (2), Ireland (2), the Netherlands (1) and Greece (1).

Table 3 provides an overview of selected data from eligible studies, including the range of services provided by the community hospitals, as well as the types of staff involved in delivering the services. It should be noted that for many of the studies found, reporting of details of the hospital model was not the primary aim, and information presented here was taken from background or introductory information provided.

| Country | Number of papers retrieved | Facility designation | Services discussed in the literature | Staffing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| England and Wales | 36 | Community hospital | A large proportion of articles focused on non-acute inpatient services (e.g. post-acute care, rehabilitation or palliative care). Fewer articles looked at outpatient services, urgent care such as in minor injury units, and acute inpatient care. Other services that were discussed more rarely include health promotion, surgery, mental health care, primary care, social care and maternity care | Care led by GPs, nurses and/or community geriatricians, supported by specialist consultants and other practitioners |

| Scotland | 6 | Community hospital | Studies reported on non-acute inpatient services, outpatient services, urgent care services, acute inpatient care, surgery, mental health care and maternity care | Not reported |

| Norway | 6 | Intermediate care hospital Community hospital |

All articles discussed provision of non-acute inpatient services, particularly intermediate care. Other services included outpatient services, urgent care services, acute inpatient care, mental health care and maternity care | GPs, nurses and allied health professionals |

| New Zealand | 6 | Rural hospital | Articles reported on the provision of non-acute inpatient services, outpatient services, urgent care services, acute inpatient care, surgery and primary care | GPs, MOSSes, nurses and allied health professionals, visiting specialists |

| Australia | 15 | Rural hospital | Articles reported on the provision of non-acute inpatient services, outpatient services, urgent care services, acute inpatient care, surgery and primary care | GPs, nurses, midwives and allied health professionals |

| Regional hospital | ||||

| Base hospital | ||||

| Canada | 2 | Rural hospital | Articles report on provision of acute and non-acute inpatient care, urgent care services, surgery, mental health care and maternity care | Family physicians |

| Greece | 1 | Hospital-health centre | Reports on provision of inpatient, outpatient, primary care and preventative health services | Doctors and nurses |

| Ireland | 2 | Community hospital | The articles report on provision of non-acute inpatient services and outpatient services | Nurses and allied health professionals, with input from GPs and geriatricians |

| Netherlands | 1 | GP hospital | The article reports on provision of acute and non-acute inpatient care, outpatient services | GPs and nurses with support from paramedics and specialists |

Range of services provided by community hospitals

Community hospitals provide a wide range of services, across a broad spectrum of care provision, from preventative38,39 and primary care40,41 through to outpatient services,42–44 inpatient medical care,21,45 surgery,46,47 minor injury care48 and accident and emergency (A&E) care. 40,49 Within these broad areas, there was considerable diversity of the types of services provided, and a number of studies further reported on the implementation of new types and methods of service provision not previously available within the community hospital setting, such as point-of-care testing,41 fracture clinics50 or chemotherapy. 51 Community hospitals that provided a wide range of services were common in Australia, New Zealand and Canada, reflecting the geographical needs of these countries in ensuring provision of locally accessible primary, secondary and emergency care services in remote rural areas.

However, providing comprehensive services in these settings was reported to be challenging, because of limited capacity or access to specialist expertise to deliver services required to meet the needs of the local population. For example, one study set in New Zealand reported that of 35 selected medical conditions and procedures that may be needed for acutely ill patients, only about 70% could be performed in any one of a group of rural hospitals. 52 A cross-sectional survey of emergency departments in rural hospitals in Canada found that, with the exception of basic laboratory and radiography services, the majority had limited access to professional and support services. For example, only 5% of hospitals had access to a paediatrician, 26% had access to a surgeon and less than one-third had access to ultrasound equipment (28%), a computerised tomography scanner (20%) or an intensive care unit (17%). 53

Studies of community hospitals in England and Scotland typically reported on the provision of non-acute inpatient services, particularly post-acute geriatric care, rehabilitation services and palliative care. 7,54–58 Indeed, several UK community hospitals provide exclusively, or largely, non-acute inpatient care to chronically ill or older populations. 7,38,56 Similarly, community hospitals in Ireland tend to focus on services for older people such as respite care, rehabilitation, palliative care long-stay facilities and community-based assessment. 59,60

Studies of community hospitals in Norway also described a focus on intermediate care, targeted at people who would otherwise face unnecessarily prolonged hospital stays or inappropriate admission to acute inpatient care, including chronically ill and older patients. 9,61,62 A specific case of a community hospital is Hallingdal Sjukestugu in central Norway. 21,22 Described as a ‘decentralised specialist healthcare service’, it is led by GPs under telephone supervision by hospital specialists who are located in an acute hospital (Ringerike sykehus), which is 170 km away and administers and funds the community hospital. It includes an inpatient department, which functions as an intermediate care unit, along with outpatient psychiatric and somatic services, somatic day care, a somatic inpatient department, as well as a pre-hospital ambulance and air ambulance services.

There were only a small number of studies of community hospitals in countries other than England, Scotland, Australia, New Zealand and Norway, as noted earlier. One study set in the Netherlands described a community hospital that was established as an experiment after closure of a former district general hospital west of Amsterdam. 63 Its 20 beds were designated as ‘GP beds’ for GPs treating their own patients, ‘recovery beds’ for the rehabilitation of post-surgery patients or ‘nursing home beds’ for patients awaiting a place in a nursing home. Services reported were low-level care and observation and included diagnostic facilities (e.g. laboratory and radiography), allied health services (e.g. physiotherapy, occupational therapy and speech therapy) and outpatient clinics.

A number of studies described and evaluated the development of new outpatient services in community hospitals. Examples include a treatment and diagnostic centre for gynaecology,64 and a nurse-consultant-led clinic for patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain,42 both set in the UK. Several studies reported on outpatient services that were developed in collaboration with larger hospitals, such as services for people with eating disorders, which used videoconferencing to connect participants in community hospital sites and a specialist service within a large urban hospital for weekly therapy sessions. 65 Another example was the development of a teleopthalmology service by a regional hospital in Western Australia together with eye specialists in Perth, which allowed digital images to be transmitted to the specialists for diagnosis. 44 Two studies described outreach chemotherapy services, delivering chemotherapy cycles in community hospitals by staff based at a larger hospital or care centre. 51,66 Finally, two studies described the role of community hospitals in the provision of maternity services. This included one study set in Australia, which reported on a rural community hospital providing pregnant women with access to monthly ultrasound, specialist maternity advice by telephone, and an obstetrician outpatient clinic several times a year. 67 Another study, also set in Australia, described a midwifery-led model of care within a rural hospital, providing low-risk women the option to give birth at their local hospital. 68

Staffing of community hospitals

The community hospital workforce includes GPs, generalist and specialist nurses, allied health professionals (e.g. physiotherapists, occupational therapists, dietitians) and health-care assistants. This staff mix is described in studies of community hospitals in the UK,56 Norway,61 the Netherlands63 and Australia. 69 In many hospitals GPs are in charge of hospital management70 or have ultimate responsibility for patients and beds. 63,71 In New Zealand the community hospital workforce also includes the non-specialist Medical Officers of Special Scale (MOSSes),52,72 a non-training position for a doctor who has not yet specialised. 73

Staffing models were described in which MOSSes constitute the core of the medical workforce, supported by nursing staff and allied health professionals, together with back-up GPs or visiting specialists. 72,74 In many community hospitals, medical doctors were reported to represent a small proportion of community hospital staff, and were not available on site at all times. For example, a survey of New Zealand rural hospitals reported that 14% of hospitals had a GP on site at all times and 41% had a facility for the GP to spend the night in the hospital,52 whereas a study of the 10 community hospitals of the Powys region in Wales noted that none of these had resident medical doctors, including GPs. 71 Elsewhere, studies reported on-site availability of GPs only during weekdays, such as in a 12-bed intermediate care hospital in Norway;61 however, GPs are generally available to provide care at night and at weekends, with on-call GPs committed to provide out-of-hours cover. 41,71,74,75

In some countries, a shortage of medical staff is reportedly an issue. This was the case in New Zealand, where 9% of medical staff positions were unfilled and 24% were filled by locums,76 and in Greece. 39 One study in Australia68 described difficulties experienced by a rural hospital in recruiting sufficiently skilled hospital medical officers, eventually leading to the closure of the maternity service. However, in this particular case it was possible to substitute medical officers with midwives, permitting reopening of the service 6 weeks after its initial closure.

The role of specialists

Given that many community hospitals described in studies included in this review do not tend to have GPs on site full time, it is perhaps not surprising that on-site presence of specialists is even less common. In most cases, the specialist tends to perform an intermittent or remote supervisory role. 59,68 Models of such supervision include weekly oversight by a consultant from the nearest acute hospital,54 or regular educational visits. 59 One study from New Zealand reported on consultant surgeons who undertake visits to community hospitals over a distance of 150 km at least twice per week. 72 In more remote areas, specialist visits may be less frequent, as in the case of the delivery of obstetrician outpatient clinics several times per year,67 or of specialist eye care offered by visiting specialists for 1 week two times a year in Australia. 44

This limited or remote specialist involvement means that GPs and nurses are required to be flexible in their roles and to demonstrate a broad spectrum of skills. 21,41 For example, GPs may perform minor surgery or caesarean sections68 and have ‘multiple roles’, which include ward duty, GP clinics and emergency unit on-call, such as in a 20-bed rural hospital in Victoria, Australia. 77 Small regional hospitals in the Northern Territory in Australia are staffed with GPs trained to perform emergency and elective surgery. 47 As for nurses, they may have to demonstrate skills in areas such as clinical procedures, diagnosis, leadership, patient-centred care, interprofessional communication, spiritual guidance and bereavement support,78 or to master some relatively complex diagnostic tools (e.g. for stroke54 or chest pain48).

The role of nurses

The importance of the nurse’s role was particularly emphasised in community hospitals where, in addition to requirements for a broader skill set, they hold greater managerial 59 and patient-related responsibility than in larger hospitals. 79 Senior nurses or midwifes are often in charge of managing a unit or the whole hospital, as in the case of the 18 community hospitals reported on in Ireland. 59 They may be responsible for the patient from admission to discharge,80 without the patient seeing a doctor. 77 In other cases, nurses were in charge of the development and implementation of a specific specialist service, such as a chronic musculoskeletal pain service42 or a mental health liaison service. 81 Steers et al. ,82 based on a review of the evidence of providing palliative care in community hospitals in the UK, concluded that GPs generally acknowledged their dependence on nursing staff to support them to make timely management decisions following the admission of patients.

Collaboration and integration with other services

Community hospitals tend to be highly collaborative and integrated with primary care and secondary care as well as with third-sector or community organisations. 83 This is facilitated through the community hospitals’ role along the patient pathway, its function as a physical site for the co-location of services, and through a shared workforce with primary care and close collaborative working with acute specialists, described above.

For example, one of the functions community hospitals may take on is the provision of post-acute care. A study of the effect of an intermediate care hospital in central Norway on the discharge process from acute to community care found that the community hospital had a role in facilitating integration between care levels. 61 Staff at the acute hospital saw the community hospital providing ‘an extension of a hospital department’, while those in primary care viewed it ‘as a buffer that provided preparations for discharge of the patients’. Staff of the community hospital were reported to liaise effectively with both acute and primary care, sharing information through medical records as well as further direct communication where necessary.

Physical co-location of different services also offers opportunity for collaboration and integration. Included studies report co-location of primary care, community care and social care services within the community hospital. 38,84,85 A perhaps unusual case is that of a community hospital in Oxford, England, which was transferred to form a unit within a large tertiary teaching hospital. Special financial arrangements (a monthly fee) allows for staff from the acute hospital, such as the specialist gerontologist, senior registrar and senior house officer, to support community hospital staff. 56

Given the core involvement of GPs in the delivery of community hospital services as described above, typically working in their practice in addition to delivering shifts in the hospital, they provide opportunity to build strong links between the community hospital and primary care. 52,63 Indeed, in the UK, continuity of care delivered by local GPs known to the patient and their family was cited as one of the benefits of care in a community hospital. 45

Strong collaboration was also reported between community hospitals and specialists located in acute hospitals, and a number of studies described different models of collaboration. For example, specialists from a nearby acute hospital are frequently reported to be available to provide remote advice and support when needed, for example by telephone or videoconferencing. 80 We described earlier the example of the community hospital Hallingdal Sjukestugu in central Norway, which is funded and administered by an acute hospital with patients legally under the acute hospital’s professional responsibility. 21 As such, the specialist at the acute hospital must approve admissions to the community hospital and the community hospital GPs are under remote supervision from acute hospital specialists.

In many cases, collaboration between community hospitals and larger hospitals or specialists has been described as a means to maximise local provision of services. 47 One example is the reopening of the maternity unit in Mareeba District Hospital in Queensland, Australia, as a midwifery-led model of care, described above. 68 The unit is supported by an obstetrician at the base hospital who oversees all emergency care and pregnancy complications.

In many cases, collaboration between the community hospital and other health services is supported by the introduction of new technologies. Examples include a shared electronic health record to help facilitate links between the community hospital and primary care in Norway61 or a telemedicine link between the community hospital and a larger hospital. Use of telemedicine often involved direct interaction between the specialist and the patient, such as a teleophthalmology service in Australia. 44 Other examples include the provision of a medical oncology outreach clinic, whereby oncologists from a larger hospital review patients in the community hospital using video conferencing equipment,69 therapy sessions delivered by videoconference,65 videoconference fracture clinics,50 telepharmacy86 and remote commenting by radiographers. 87 In the Grampian region of Scotland, a minor injuries telemedicine network connects 15 minor injury units in community hospitals to the emergency department at the regional teaching hospital. 80 Patients are seen by trained community hospital nurses, who can seek advice as required from medical staff and consultants based at the teaching hospital emergency department.

Ownership of community hospitals

Most community hospitals described in studies included in this review are public hospitals, which are the responsibility of local or regional health authorities (RHAs) with regard to funding, management and commissioning of services. However, reflecting the specific system context in different countries, ownership and management may take different forms. For example, an intermediate care department in Trondheim in the north of Norway was established at a teaching nursing home to provide care for older patients initially admitted to the city acute hospital, but who no longer require acute medical supervision. 9 The goal was to create a new link between specialist care at a general acute hospital and community home care to aid recovery before final discharge of the patient to their own home. Under the Norwegian decentralised model of health-care provision, the nursing home falls under the responsibility of the municipality.

One other example is that of a community hospital in Norfolk in the east of England, which is operated as a social enterprise following the closure of inpatient beds previously operated by the NHS in 2005. 88 In addition, a 28-bed community hospital in Oxford, England, was described earlier. Considered ‘unfit for purpose’, it was integrated as a unit within a nearby acute tertiary hospital. 56

Discussion

This scoping review explored the range of community hospitals in high-income countries as described in the published literature. We note that there is not one definition of a community hospital, and we identified a number of service delivery ‘models’ than can be broadly subsumed under the heading of a community hospital, which we defined as (1) providing a range of services to a local community; (2) being led by community-based health professionals; and (3) providing inpatient beds. We found that community hospitals may provide a wide spectrum of health services, including preventative and primary care, inpatient and outpatient services, medical and surgical care, and acute and chronic care. Within these broad categories there is wide variation in the specific services and level of service provided, typically reflecting the needs of the local population and the availability of other health services, as well as the interests of local practitioners in service development.

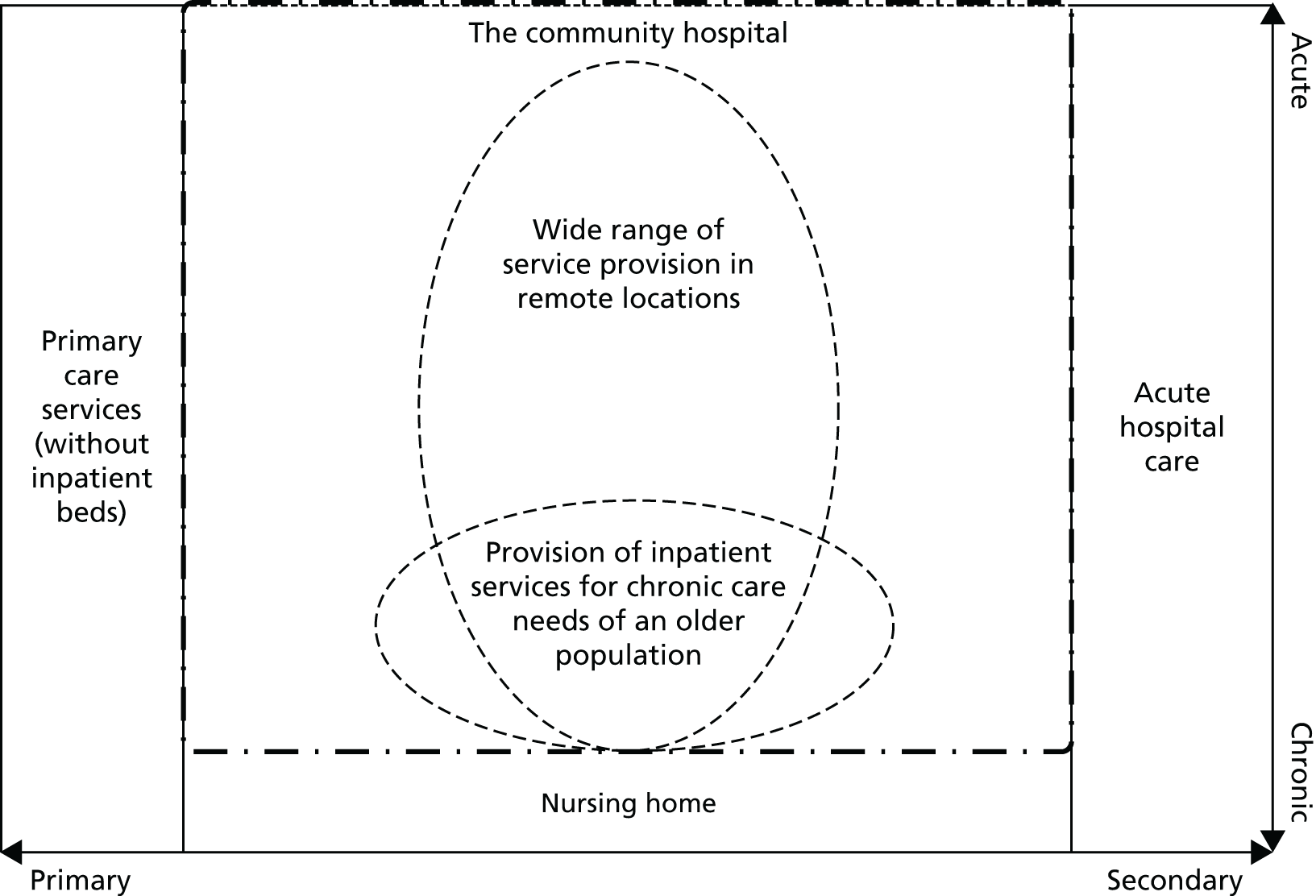

Figure 2 presents a graphical depiction of our understanding of the nature and scope of services provided by community hospitals, based on our review of the evidence presented in this study. This diagram may provide a helpful way to conceptualise the remit of community hospitals, obviating the need to provide a precise definition for this inherently diverse concept.

FIGURE 2.

Nature and scope of services provided by community hospitals. Reproduced from Winpenny EM, Corbett J, Miani C, King S, Pitchforth E, Ling T, et al. Community hospitals in selected high income countries: a scoping review of approaches and models. Int J Integr Care 2016;16:13. 36 This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0.

As shown, community hospitals occupy the space between, and to some extent encompass, primary care services and acute hospital care. The dashed box outline in Figure 2 indicates this flexibility in the boundaries between community hospital services and other levels of care. In addition, community hospitals may deliver care across a range of services from acute to chronic care. There are examples of community hospitals that focus on the delivery of non-acute inpatient care, such as post-acute care or rehabilitation care for an older population, and others that deliver a wide range of health care to a whole population, often in geographically remote locations where alternative services are not readily available. These potential areas of focus are indicated by the dashed circles in Figure 2; however, as we have seen, community hospitals are characterised by their wide diversity.

Our literature search considered studies that have been published since 2005, building on a previous review by Heaney et al. 1 We note that our findings show many similarities with the previous review regarding the role of community hospitals within health-care provision and the types of services offered. We did not identify studies on certain specific services described by Heaney et al. ,1 such as cardiac care; however, the literature reviewed in the present study reported on a more diverse range of service provision with such services often supported by acute specialists working remotely. We also found evidence of a wider use of telemedicine than described previously.

Limitations of the review

Our review has a number of limitations. We focused on community hospitals defined as those that provide inpatient beds, are led by community-based health professionals, and provide a range of services to a local community, and our findings are thus constrained within these a priori definitions. We also have captured literature pertaining to services that may form part of a community hospital, but for which the relevant study does not mention the community hospital itself, for example those studies examining midwifery units that may be located in community hospitals. 89

As a scoping review, which aimed to map the evidence on community hospitals, this review did not assess the quality of the evidence, nor did it assess the effectiveness of the different types of community hospitals. Although not within the remit of our scoping review methodology, the heterogeneity of the studies identified would have precluded any meta-analysis. We therefore cannot derive any conclusion about which service formations may be most appropriate. Furthermore, our review focused on published studies and we therefore do not capture information on factors that have not been studied or, indeed, on community hospitals that have not been reported on in the range of sources we considered for the review. Similarly, we have found little evidence on topics that are difficult to measure or analyse. These limitations suggest the need for more systematic interrogation of practice in community hospitals through primary research.

Despite these limitations, our review enhances understanding of the current role of community hospitals in a number of high-income countries, allowing it to help inform future policy and practice. One key feature that is apparent is the flexibility and adaptability of the community hospital model. This may be an important advantage allowing response to future changes in population health needs and other changes in health service delivery. In England, the 2014 NHS Five Year Forward View set out how the health service should better adapt to the changing system environment. 18 The rising number of people with multiple chronic conditions, an ageing population and increasing patient expectations, alongside technological advances and new approaches to practice and funding, are all altering the way health care is delivered by providers and accessed by service users. 18 Among the measures set out in this long-term view, a set of new care delivery options have been proposed as a means to better meet the changing needs and challenges the system is facing. Within these the community hospital may be seen to take a core role through provision of a community hub which already hosts a wide range of services, provides a setting for integration between different health and social care organisations, and has strong links with the local community.

Evidence reviewed provided many examples for the provision of particular specialist services in community hospital settings, including inpatient and outpatient services, which can be delivered in community hospital settings on a routine or intermittent basis, often with the aid of technology. These findings provide important insights to inform the wider policy debate on shifting care into the community. 20 Joint working arrangements such as visits by travelling surgeons, shared posts across community and acute hospitals, or the use of telemedicine have allowed an increase in the range of services available in community hospitals, as well as the level of specialisation of care delivered within community hospitals. Future technological developments allowing medical care to be delivered at a distance may be able to expand the role of community hospitals further.

One important issue to consider, which was outside the scope of this study, will be the cost-effectiveness of provision of services in a community hospital compared with in other settings. Despite ongoing government interest in provision of services closer to home, it may be that some services are most cost-effective when provided at scale in a specialist centre. This will vary by service and it will be important to examine in detail the different services provided and the costs and benefits of provision in different settings.

Conclusion

This scoping review, drawing on literature from 10 high-income countries over the past 10 years, found that community hospitals reported in the literature operate in a manner that situates them at the boundary of primary care, acute hospital care and nursing home care and may provide services which span each of these domains. Different community hospitals offer services that range from preventative and primary care to inpatient surgical or medical care, and service provision tends to be delivered by generalist doctors and nurses, with specialist physicians visiting occasionally to deliver particular services in some cases. Our analysis suggests that community hospitals can provide a diverse range of services, responding to different geographical and health system contexts. The literature highlighted the collaborative working at community hospitals between those from primary, community and secondary care, and this integrative role may be particularly important in the design of future models of care delivery, where emphasis is placed on continuity of care and collaboration between those traditionally situated in different care sectors.

Chapter 3 Community hospitals in high-income countries: a systematic review of the evidence on effectiveness and cost-effectiveness

Introduction

As countries are striving to find ways to create systems that are more responsive to the changing needs of an ageing population, different service delivery models are being considered that seek to better integrate services along the care continuum to meet the often complex care needs of people with multiple chronic and long-term conditions. 90 In England, a growing policy focus on care integration and on shifting services closer to people’s homes has led to renewed interest in community hospitals and the potential role they can have in delivering more integrated care at local levels. 18

Community hospitals have formed an established component of health-care provision in the UK for decades. 1 Defined as local hospitals that are typically staffed mainly by GPs and nurses and provide a diverse range of care to mostly rural populations, community hospitals have been associated with a wide range of benefits for patients, in particular around accessibility and a sense of a friendly atmosphere but also improved outcomes in terms of independence and rehabilitation. 29,58,91 Comparable models have also developed outside the UK, offering services that sit on the continuum between primary and secondary care, often with a particular focus on older patients. 22,92 However, as demonstrated elsewhere, the overall evidence for their effectiveness and cost-effectiveness has remained limited. 1

Given the renewed policy interest, highlighting the potential for a more strategic role of community hospitals in shaping service delivery locally, it seems timely to revisit the evidence base on their clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness. Linked to the scoping review exploring international approaches and models of community hospital care (see Chapter 2), this chapter examines the available evidence on the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of community hospitals nationally and internationally. With an identical search strategy, time frame and definition of ‘community hospital’ to the scoping review, this review further updates and expands on the thematic review by Heaney et al. 1 However, by addressing the specific question of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of community hospitals, it differs fundamentally in its thematic interest and thus in the focus of its reporting.

Methods

This review is reported in line with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA). 93 Chapter 2 presents the full search strategy (see Box 1) and the definition of ‘community hospital’ (see Table 1) used. The protocol for this review was not registered.

Unlike our scoping review methodology (see Chapter 2), to be included in this review studies had to assess patient health outcomes, patient and carer experience or satisfaction measures, organisational outcomes or cost-effectiveness compared with other hospital settings, including acute hospitals. Measures assessed could be qualitative or quantitative and studies had to be set in high-income countries with health-care systems comparable with that of England (Table 4).

| Study characteristics | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Countries | High-income countries with comparable health-care systems that provide universal access (i.e. Canada, Australia, New Zealand and high-income countries in Europe) | Low- and middle-income countries; non-European countries (except Canada, Australia, New Zealand) |

| Hospital type | Community hospitals that meet all of the following criteria:

|

|

| Comparators | Care provided in other settings, including general hospitals | Audits of care provided in a community hospital, with no comparison |

| Comparison made in the discussion (e.g. against best practice, guidelines or data from the literature) | ||

| Outcomes | Quantitative measures of efficiency | No outcomes measured |

| Quantitative measures of effectiveness | ||

| Qualitative measures of effectiveness | ||

| Patient outcomes to include health measures, patient satisfaction, patient experience | ||

| Study types | Experimental (RCTs, cluster RCTs, quasi-RCTs), qualitative and observational studies | Conference abstracts |

| Editorials, letters or commentaries | ||

| Vignette studies or hypothetical cases | ||

| RCT protocols | ||

| Publication year | Published in 2005 and after | Published before 2005 |

| Language | All languages | – |

Screening and data extraction proceeded as described in Chapter 2, Methods, and papers were assessed against the inclusion and exclusion criteria for this review (see Table 4) at the stage of full-text screening. Titles and abstracts were screened by three researchers (CM, SK and JC) against the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and the process was repeated for full texts. Data were extracted on features of the hospital model, population covered and outcomes evaluated. Extraction was undertaken by the same three researchers and data were checked for consistency between the three; disagreements or uncertainties were resolved by discussion within the wider research team.

Papers were assessed for quality of reporting of underlying studies by three researchers (EW, JC and SK), following checklists provided by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence in their Guidelines Manual. 94–96 For cost-effectiveness studies, we drew on a checklist for assessing economic evaluations. 97 Assessments were verified by a second researcher for accuracy, and disagreements were resolved through discussion. Quality assessments were used to inform an understanding of the weight of the evidence base and not as a basis to exclude papers. Given the diverse nature of evidence, a narrative synthesis approach was used for analysis. 37 Meta-analysis of data was not conducted owing to the small number of studies included and the diversity of outcome measures applied therein.

Findings

We identified 15,555 independent records, of which 604 studies were retrieved for full-text extraction (Figure 3). A total of eight studies (represented by 17 papers) met our inclusion criteria.

FIGURE 3.

Literature included in the study.

An overview of the included studies is given in Table 5. There were seven papers reporting on four RCTs,7,9,10,62,66,98,100 and two papers reporting on qualitative research embedded in two of the RCTs. 8,55 There were a further four papers reporting on three qualitative studies, and one paper on an observational cohort study. 45,54,58,61,102 An additional three papers reported on cost (effectiveness) analyses embedded in three of the aforementioned RCTs. 11,62,99 Of the aforementioned papers, the cohort study and a RCT also reported on some cost-analyses. 66,102 Two of the studies (across four papers) reported on research conducted in Norway, and the remainder were set in England.

| Study description | Paper | Design | Primary outcomes measured | Study setting | Overall quality assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-centre post-acute care RCT, underpinning the PATCH study | Green et al. (2005)7 | RCT |

|

A community hospital and an acute hospital in England | Low risk of bias |

| Young et al. (2007)98 | Secondary analysis of RCT |

|

Unclear | ||

| O’Reilly et al. (2006)99 | Cost-effectiveness analysis embedded within RCT |

|

High quality | ||

| Green et al. (2008)55 | Qualitative interview study embedded within RCT |

|

Medium quality | ||

| PATCH study | Young et al. (2007)10 | RCT |

|

Five acute hospitals and seven community hospitals in England | High quality |

| Young and Green (2010)100 | Secondary analysis of RCT |

|

Unclear | ||

| O’Reilly et al. (2008)11 | Cost-effectiveness analysis embedded within RCT |

|

High quality | ||

| Small et al. (2009)8 | Qualitative interview study embedded within RCT |

|

Medium quality | ||

| Intermediate care at a community hospital as an alternative to long-term acute hospital care | Garåsen et al. (2007)9 | RCT |

|

A community hospital and an acute hospital in Norway | Low risk of bias |

| Garåsen et al. (2008)62 | 12 month follow up of RCT |

|

Low risk of bias | ||

| Garåsen et al. (2008)101 | Cost analysis embedded within RCT |

|

Medium quality | ||

| Chemotherapy provision in community hospitals | Pace et al. (2009)66 | Crossover RCT with some cost analysis |

|

Specialised cancer centre and chemotherapy outreach clinics in four community hospitals in England | Low risk of bias |

| Emergency admissions of older patients | Stapley et al. (2007)102 | Observational (cohort) study and cost analysis |

|

An acute hospital and five community hospitals in England | Unclear |

| End-of-life care in community hospitals | Hawker et al. (2006)45 | Qualitative interview study |

|

Six community hospitals in England (comparisons drawn with acute hospital care) | Medium quality |

| Payne et al. (2007)58 | Qualitative interview study |

|

Medium quality | ||

| Stroke rehabilitation | Dobrzanska et al. (2006)54 | Qualitative focus group study |

|

A community hospital in England (comparisons drawn with acute hospital care) | Low quality |

| Role of intermediate care community hospital in patient discharge to primary care | Dahl et al. (2014)61 | Qualitative interview and focus group study | Health professionals’ experiences of patient discharge to primary care | Acute hospital, community hospital and primary care service in Norway | Medium quality |

Five studies in 13 papers reported on the provision of post-acute care at community hospitals,7–11,54,55,61,62,98–101 one examined chemotherapy at community hospitals,66 one considered emergency admissions102 and one study presented data on end-of-life care across two papers. 45,58 The majority of papers focused on patient outcomes (health,7,9,10,61,62,66,98,100 experience and satisfaction7,8,10,54,55,58,66), whereas two measured staff experience. 8,61 Other outcomes measured included organisational and resource efficiencies61 and family and carer experience. 7,45,58 With the exception of one study on chemotherapy, all studies concerned an older population (aged ≥ 55 years). 66

All studies reported in the papers compared community hospital care with care delivered in an acute hospital setting. The quality of papers included varied from high (n = 7) (i.e. all aspects of study methodology were well reported and the authors used an acceptable methodology), medium/moderate (n = 6) (i.e. details were not fully reported for some criteria, but otherwise the authors used an acceptable methodology) and low (n = 1) (i.e. an unacceptable methodology was used) to unclear or unknown quality (n = 3) (i.e. there was insufficient evidence to make a firm judgement) (see Appendix 2).

Patient health outcomes

Post-acute care

Four studies in seven papers evaluated health outcomes in a post-acute setting. 7,9,10,61,62,98,100 In their high-quality RCT, Young et al. 10 used the Nottingham Extended Activities of Daily Living Scale to assess independence 6 months after treatment in patients randomised to receive either intermediate care at a community hospital or usual care at an acute hospital. The study showed a significant increase in independence at 6 months in the community hospital compared with usual care [mean difference = 3.27, 95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.26 to 6.28; p = 0.03], supporting findings from the previous single-centre study by the same group (mean difference = 5.30, CI = 0.64 to 9.96). 7 In the multicentre trial, similar proportions of both groups died before follow-up (p = 0.33), and, among those living at home before admission, similar proportions of both groups were discharged to a care home, died before discharge (p = 0.08) or continued to live at home (p = 0.426) at 6 months. 10 Conversely, anxiety levels 1 week post discharge showed a greater increase in the community hospital group (p = 0.03) as assessed using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS).

Additional analyses of both RCTs found a trend towards worse independence outcomes for patients who were transferred to the community hospital late or not at all (p = 0.072 for the multicentre trial). 98,100 Pairwise comparisons in both studies showed significant differences in favour of patients who were transferred to the community hospitals early compared with those who remained at the acute hospital for longer.

A high-quality RCT set in Norway compared provision of intermediate care at a community hospital with continued care at an acute hospital. 9 Care at the community hospital was associated with a decrease in readmissions for the same complaint within 60 days [odds ratio (OR) 2.77, 95% CI = 1.18 to 6.49; p = 0.03] and an increase in independence from home care (OR 1.21, 95% CI = 0.59 to 2.52; p = 0.02) compared with the acute hospital. There was no significant difference in the proportion of deaths at 6 months (p = 0.23), but at 12 months a significantly smaller proportion of patients had died in the community hospital group (p = 0.03). 62 The number of patients living in nursing homes and total number of bed-days at 6 months did not differ significantly between settings, but the acute hospital group had fewer days of initial inpatient care (p = 0.00) and the community hospital group had fewer inpatient days for readmissions (p = 0.04). 9 No significant differences were found at 12 months in the number of admissions, acute hospital bed-days or for long-term primary-level care needs, which the authors link to a loss of power to reveal differences owing to the high proportion of deaths during follow-up. 62

Chemotherapy provision

A high-quality crossover RCT compared chemotherapy in outreach locations at four community hospitals with chemotherapy delivered in a dedicated cancer centre. 66 The community hospitals had not previously delivered chemotherapy and in all settings treatment was delivered by a hospital chemotherapy team. No safety issues or adverse reactions were reported in community hospitals and there were no significant differences between the treatment groups either in toxicity levels (using Chemotherapy Symptom Assessment Scale) or in anxiety and depression (using HADS).

Patient and carer experience and satisfaction

Palliative care

One qualitative study on end-of-life care (in two medium-quality papers) asked patients and their family carers about care in community hospitals compared with acute hospital care, and suggested that the community hospital was perceived as preferable. 45,58 Hawker et al. 45 reported that bereaved carers expressed more satisfaction with community hospitals than with their nearest acute hospital, valuing ease of access for visits, pleasant environment and facilities, familiarity between staff and families and sensitive and kind nursing staff. Participants also commented that staff seemed to care more for the patients and had more time to spend with them than at the acute hospital. These findings were supported in Payne et al. ,58 as patients reported the community hospital to be cleaner, more comfortable, better located and more flexible in responding to individual needs. Study participants also particularly valued the continuity of care offered by GP-led community hospitals. Both papers, however, reported concerns related to a lack of contact with qualified nursing staff and noise levels in community hospitals. Older patients also highlighted the lack of facilities and qualified staff for complex medical procedures, when compared with the acute setting. 58

Chemotherapy provision

In Pace et al. ’s66 crossover RCT, some 97% of patients chose to receive their remaining chemotherapy treatment at a community hospital rather than a cancer centre. Data from the Chemotherapy Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire showed that patients were significantly more satisfied with the community hospital than with the cancer centre for accessibility (mean difference = 1.05, p < 0.001), environment (mean difference = 2.79, p < 0.001), technical aspects of nursing care (mean difference = 0.58, p < 0.01) and interpersonal aspects of nursing care (mean difference = 0.4, p < 0.05) . There was no significant difference in global satisfaction between the settings.

Post-acute care

Three studies set in England reported high patient satisfaction and preference for community hospitals for post-acute care and rehabilitation across five papers. 7,8,10,54,55 One low-quality qualitative study reported that patients discharged to the community hospital for rehabilitation after stroke appreciated the convenient location, which made it easier for relatives to visit. 54 The community hospital was also perceived to be less confusing and safer than the acute hospital because of its small size, and patients appreciated having a choice of location.

Young et al. ’s10 multicentre and Green et al. ’s7 single-centre RCTs found only minor differences in patient and carer satisfaction between community and acute hospital groups. In the Young et al. 10 trial, patient satisfaction with their own recovery was similar for both groups but greater at 1 week after discharge for community hospital groups (OR 2.12, 95% CI = 1.3 to 3.46; p = 0.004). Green et al. 7 reported that patient and carer satisfaction with community services was also similar for both groups, but greater for the community hospital group at 3 months after recruitment (OR 3.43, 95% CI = 1.05 to 11.24). They found no difference between groups for emotional distress in carers, or in effect on the carer burden.

Two medium-quality qualitative papers nested within the two RCTs found patients’ and carers’ experiences of care in community hospitals generally compared favourably to equivalent care in acute hospitals. 8,55 Patients were reported to value the location, food, staff attitudes, the physical environment and the ambience of the community hospital, including single-bed accommodation, which was perceived to be more home-like. 55 These findings were supported by Small et al. ,8 who reported that patients and carers described the community hospital as more ‘homely’ and valued its accessibility. There was a perception, as expressed by one carer, that the community hospital’s home-like environment would promote recovery through encouraging the self-care activities needed after discharge. This was contrasted with views on the acute hospital, where the philosophy of care was seen to be focused on ‘medical efficiency’.

Staff experience and organisational effectiveness

Post-acute care

Staff experiences of delivering post-acute care to older patients in community hospitals were generally described to be positive in two studies reported in two qualitative papers set in England and Norway. 8,61 In England, Small et al. 8 carried out interviews with community hospital staff, who reported that the community hospital provided a distinctly homely, calm and pleasant setting, where social interaction was encouraged and patients’ relatives were involved in patient care. Community hospitals’ orientation towards older people was also considered important. Conversely, in describing their workplace, acute hospital staff emphasised care attributes such as ‘medical efficiency’ and high standards and described a lack of stimulation for patients. At the same time, staff in both settings highlighted shared understandings of the importance of providing holistic and patient-centred post-acute care.

The study in Norway reported that the introduction of a community hospital as a ‘bridge’ between acute and primary care had improved staff experience of discharge processes, including timeliness, patient preparation for transition and communication between the different levels of care. 61 Primary care staff were satisfied that patients with complex needs were ‘shielded’ from fast discharge from the acute hospital. Staff interviewed for the study felt that, overall, the community hospital liaised effectively with both acute and primary care, with staff at the acute hospital describing the community hospital ‘as an extension of a hospital department’, whereas those in primary care commented that the community hospital served ‘as a buffer that provided preparations for discharge of the patients’.

Cost and cost-effectiveness

Treatment costs in post-acute care