Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 12/5005/04. The contractual start date was in September 2013. The final report began editorial review in September 2016 and was accepted for publication in February 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

David Jayne is a member of the Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation Strategy Group. There are no competing interests to declare in relation to Intuitive Surgical.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Randell et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Overview

This chapter introduces our study and is organised into three main sections. We begin by explaining what is meant by robot-assisted surgery (RAS). We then provide some background to the study design. This study was a realist process evaluation alongside a randomised controlled trial (RCT) comparing laparoscopic surgery and RAS [the RObotic versus LAparoscopic Resection for Rectal cancer (ROLARR) trial]. We describe the trial and explain what both realist evaluation and process evaluations are. We then define the research aim and objectives. We conclude the chapter by describing the structure of the remainder of the report.

From open to laparoscopic to robot-assisted surgery

In the 1990s, laparoscopic techniques were introduced to surgical practice; these were initially for benign conditions but later extended to the treatment of cancer. Instead of creating large abdominal wounds, the surgeon is able to perform operations using small ‘key-hole’ incisions, through which cameras and instruments are passed. This removes much of the abdominal access trauma. The clinical benefits of laparoscopic surgery were soon realised, including less postoperative pain, shorter hospitalisation, quicker return to normal function and improved cosmetic effect. 1–3 These benefits were outlined in 2007 by Lord Darzi in Saws and Scalpels to Lasers and Robots – Advances in Surgery; he also pointed to how such less invasive techniques allow for the increased use of day surgery, helping to cut waiting times for operations. 4 The use of laparoscopic surgery was also promoted in Delivering Enhanced Recovery – Helping Patients to Get Better Sooner After Surgery, published in 2010. 5 The following year, in Improving Outcomes: A Strategy for Cancer, the Department of Health highlighted encouragement of the uptake of less invasive techniques as an important part of ensuring improved access to high-quality surgery. 6 In addition to patient benefits, laparoscopic surgery is cost-effective for health-care providers,7 the increased operating costs offset by shorter inpatient stays and decreased wound care costs. 3

The restricted abdominal access of laparoscopic surgery comes at a price. Laparoscopic operations are technically more challenging than open surgery, due to the two-dimensional (2D) operative image, instrumentation with limited freedom of movement and reduced tactile feedback. The uptake of laparoscopic surgery has, therefore, been slow; in 2003, the uptake of colorectal laparoscopic surgery was 5%, and this increased to only 40% over the 9 years to 2011,8 despite it being recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence since 2006. 9

Robot-assisted surgery was developed in an attempt to solve some of the limitations of laparoscopic surgery. The da Vinci® robot (Intuitive Surgical, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) is currently the only commercially available robotic platform for soft tissue surgery (although alternatives to the da Vinci robot, developed by other manufacturers, are expected to come onto the market in 2017). It is a master–slave (or console-manipulator) system, whereby the surgeon sits at a console to control the arms of the robot. Depending on the model, the robot has three or four robotic arms; one arm holds the camera, while the other arms hold a variety of surgical instruments, all of which are inserted into the patient. The robot provides a stable camera image with a three-dimensional (3D) field of view, intuitive instrument handling, tremor elimination, motion scaling and EndoWrist® (Intuitive Surgical, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) instruments, which provide increased freedom of movement. This enables the surgeon to achieve greater precision and control, and reduces some of the technical challenges associated with traditional laparoscopy.

In 2010, the da Vinci robot was reported to cost around £1.3M, with annual maintenance fees of £70,000. 10 As the technology has developed, the price has increased; the latest model of the da Vinci robot costs about £1.7M and there are annual maintenance fees of about £140,000 per robot. 11 Despite the cost, there has been rapid growth in the purchase of da Vinci robots, first in the USA but with Europe quickly following suit. Between 2007 and 2011, the number of da Vinci robots installed in the USA increased from 800 to 1400,12 while in 2011 the number of da Vinci robots installed worldwide reached 2300. 13

In the UK, there has been enthusiasm for RAS among both clinicians and policy-makers, with the Department of Health in 2009 putting RAS forward as an example of new technology supporting the delivery of more effective patient care, helping to meet the goals set out in High Quality Care for All. 14 The first purchase of a da Vinci robot by a NHS hospital occurred in 2001. 15 By 2009, there were nine robots in use in the UK, with three NHS trusts planning to acquire a robot in the following 12 months. 16 By 2012, the number of robots had increased to 27,15 while indications from Intuitive Surgical suggest that by the summer of 2016 there were 61 da Vinci robots in use in the UK. RAS is primarily used in urology; in 2011 over 50% of radical prostatectomies in the UK were carried out using RAS. RAS has been expanding across the surgical disciplines, also being used in gynaecology, ear, nose and throat, colorectal, cardiology and paediatrics.

However, a lack of high-quality evidence concerning the impact of RAS on patient outcomes has led to a more cautious approach among policy-makers in recent years. In February 2014, NHS England announced that it would be reviewing the evidence for RAS to inform future policy and advised that NHS trusts should not purchase further da Vinci robots until that was completed. The first review considered evidence for RAS in the curative treatment of prostate cancer. Two RCTs comparing laparoscopic surgery and RAS found that, although there was no difference in oncological outcomes, RAS offered health-related quality-of-life benefits for patients, in terms of higher rates of continence and sexual function. 17,18 As a consequence of this, in July 2015, NHS England recommended that RAS should be offered as a choice, alongside open and laparoscopic surgery, and when considered clinically appropriate, to all patients with localised prostate cancer. 19

Given the high costs of RAS, with the cost-effectiveness of RAS depending on the number of operations for which the da Vinci robot is used,20 it could be anticipated that NHS trusts that have purchased a da Vinci robot would be seeking to maximise its use. However, the implementation of RAS can be challenging, and there have been reports of da Vinci robots being introduced but then underused. 10 Although accounts of the introduction of RAS suggest a number of factors that are important for successful integration, these accounts come from small case series (descriptive non-randomised studies) undertaken in single institutions, typically by dedicated RAS enthusiasts,3 so little is known about the contextual factors that are necessary for the successful integration of RAS more broadly. Therefore, this study seeks to systematically explore the processes involved in successfully introducing this new technology into the operating theatre (OT).

Robot-assisted surgery is a complex intervention, by which we mean that it is an intervention aimed at producing change in the delivery and organisation of health-care services and that comprises a number of separate components that may act both independently and interdependently. 21,22 These components are not only technological but also organisational and social, and they can all impact on the extent to which RAS is successfully introduced and on subsequent process and patient outcomes. A significant feature of RAS is the way in which it changes the spatial configuration within the OT, with the surgeon at a distance from the patient and the OT team, as shown in Figure 1. While the OT team works with a 2D image of the surgical site, the surgeon’s visual attention is focused on the 3D image provided by the robot, prohibiting face-to-face communication during the operative part of the procedure. More generally, the size of the robot introduces physical space constraints, resulting in a new choreography of movement around the patient. 23 The impact of this change in spatial configuration on communication and teamwork in the OT is not a topic that has been explored in previous evaluations of RAS, which have typically focused on the role of the surgeon. 24 Two small studies have looked specifically at differences in communication between laparoscopic surgery and RAS. One study compared communication in eight operations using laparoscopic surgery (four cholecystectomies and four prostatectomies) and 12 using the da Vinci robot (five cholecystectomies and seven prostatectomies). 25 The other study compared communication in two cholecystectomies, one using laparoscopic surgery and one using endoVia Medical’s (endoVia Medical, Inc., Norwood, MA, USA) Laprotek surgical robot, where it was the first experience for both the surgeon and scrub practitioner of using the robot on a patient. 26,27 Both studies found a significant increase in oral communication between the surgeon and the OT team in RAS, particularly in relation to the orientation and localisation of organs and the manipulation of instruments,25–27 with the effect found to be more pronounced in teams that have less experience of RAS. 25 What these studies do not provide is a consideration of the non-verbal co-ordination that has been shown to be an important aspect of teamwork in the OT or of the strategies the OT team employs to manage the differences in communication and teamwork. 28,29 Neither do they explore the additional contextual factors beyond the technology that affect communication and teamwork.

FIGURE 1.

Spatial configuration in laparoscopic surgery and RAS.

Another significant feature of RAS is the way it changes the information available to the surgeon to inform decision-making. In open surgery, surgeons work primarily with visual and tactile information. In laparoscopic surgery, although tactile information is reduced, experimental studies have revealed that, by touching with the instruments, surgeons are still able to determine features of objects, such as shape, texture and consistency. 30,31 In contrast, in RAS the surgeon receives no tactile information, raising questions about how the surgeon’s decision-making is affected. The nature of the decision-making tasks of the OT team may also be affected by RAS. As the surgeon is no longer in the sterile field, more of the burden falls on the rest of the team to respond in the event of a complication, increasing the importance of the team having a shared awareness of what is happening in the surgical site and how far they are through the procedure. 32 In response to this, interest has emerged in large surgical displays that integrate diverse sources of information,33,34 which could have benefits in the context of RAS. However, this requires an understanding of what information each member of the team needs to work effectively and safely, and how that information can best be communicated. 35

Introducing the study

To explore the issues identified above, regarding how RAS becomes integrated into practice and how it impacts communication, teamwork and decision-making in the OT, we undertook a realist process evaluation alongside a RCT comparing laparoscopic surgery and RAS. Therefore, before presenting the aim and objectives of this study, we introduce the trial and provide a description of process evaluation and realist evaluation.

ROLARR

The current study was conducted alongside an international, multicentre RCT entitled ROLARR, which was funded by the Medical Research Council Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation programme. 36 The trial sought to establish whether or not RAS improves surgical outcomes in comparison with traditional laparoscopic surgery for the curative treatment of rectal cancer. The assumption underpinning the ROLARR trial was that RAS would facilitate fine tasks, such as dissection and suturing, enabling the surgeon to overcome the challenges experienced in traditional laparoscopic surgery. All of the patients entered into the trial underwent either an anterior resection or an abdominoperineal resection. For patients randomised to the intervention arm of the trial, the surgeon could choose to either undertake the operation totally robot-assisted or undertake a hybrid operation in which the first phase of the operation (mobilisation of the splenic flexure) is undertaken laparoscopically but the rectal mesorectal dissection is undertaken with robot assistance. The primary outcome of interest was conversion to open surgery, which was considered to reflect the ease of surgery; if RAS makes surgery technically easier, there should be fewer conversions to open surgery. The secondary outcomes included the accuracy of the surgery and intraoperative and postoperative complications.

Process evaluations

A process evaluation is ‘a study which aims to understand the functioning of an intervention, by examining implementation, mechanisms of impact, and contextual factors’. 37 Although the RCT design continues to be considered the most reliable method of determining effectiveness,21 process evaluations are now considered to be an essential part of designing and evaluating complex interventions if evaluations are to inform policy and practice. 38 Process evaluations are typically undertaken alongside a trial,39 although there is increasing interest in using process evaluations during the feasibility and piloting phase38 so as to inform the definitive trial, and process evaluations may also be undertaken after a trial. 40 Guidance recommends that process evaluations combine qualitative and quantitative data. 37–39

In examining implementation, process evaluations look at what was delivered, in terms of fidelity (whether or not the intervention was delivered as intended) and dose (how much of the intervention was delivered). 38 This is particularly important in multicentre trials in which the intervention may be implemented in different ways in different sites,39 and so understanding differences in what was delivered can assist in interpreting differences in results. It is also important to look at how the intervention was delivered, in terms of, for example, education and training, support, and communication and management processes. 38 Without this, effective aspects of the intervention may go unmeasured, raising concerns about the validity and reliability of the results of an evaluation41 and preventing replication. 42 For example, an important component of RAS may be the training delivered to the OT team, but if this element of the intervention is not reported and described, health-care organisations may introduce RAS without an equivalent level of training and are unlikely to achieve the same impact.

As well as capturing what and how the intervention is delivered, process evaluations explore the mechanisms through which interventions bring about change,43 which provides important understanding concerning how the impacts of the intervention might be replicated by similar interventions in the future. 38 Alongside this, it is important to capture information about the context in which the intervention is delivered, as an intervention may have different effects in different contexts. 39 Context here is taken to mean anything external to the intervention that may reduce or increase its impact, such as pre-existing circumstances, skills, organisational norms, resources and attitudes. 37

While the objectives of process evaluations have been defined as ‘to assess fidelity and quality of implementation, clarify causal mechanisms and identify contextual factors associated with variation in outcomes’,44 process evaluations do vary in terms of aims. 38 In this study, we wanted to capture what was delivered and how it was delivered within the UK ROLARR sites. All of the centres participating in ROLARR had introduced RAS prior to joining the trial, so there were likely to be variations in how RAS was implemented across the sites. Because ROLARR is an international trial and this study was looking at the UK sites only, it would not be feasible to use the data to understand variations in outcomes across the trial as a whole; in addition, given the relatively small number of operations undertaken by some sites, it is questionable how meaningful it would be to use the data to interpret differences between the UK sites. Nonetheless, given the reported challenges of integrating RAS into routine surgical practice and the fact that this topic has not been explicitly considered by existing studies of RAS, it was considered that an account of the different ways in which RAS was implemented in the UK ROLARR sites, in terms of what was delivered (e.g. totally robot-assisted operations or hybrid operations), how it was delivered (e.g. staff training, organisation of teams) and staff perceptions of the value of those different approaches would provide important information for health-care organisations considering introducing RAS.

In terms of clarifying causal mechanisms, our objective was not primarily to understand how RAS impacts the trial outcome of conversion to open surgery. Complex interventions have the potential to produce unintended consequences, which may be beneficial or harmful, and process evaluations have been identified as providing an opportunity to systematically identify and quantify unexpected unintended outcomes. 45 We wanted to capture impacts outside the scope of the trial, about how RAS, in comparison with laparoscopic surgery, impacts communication, teamwork and decision-making in the OT, and understand how and in what contexts those impacts occurred; thus, to explore this, we carried out a realist evaluation.

Realist evaluation

The evaluation of complex interventions requires a strong theoretical foundation,46 and realist evaluation provides this through a process of eliciting, testing and refining stakeholders’ theories of how an intervention works. Consequently, realist evaluation has been used for studying the implementation of a number of complex interventions in health care. 47 In realist evaluation, interventions in and of themselves are not seen as determining outcomes. Rather, interventions are considered to offer resources to recipients, and outcomes depend on how recipients make use (or not) of those resources, which will vary according to the context. Consequently, patterns in the outcomes of interventions are demi-regularities, the influence of contextual factors making them only semipredictable. 48,49 Realist evaluation seeks to answer not only the question of ‘what works?’ but ‘what works for whom, in what circumstances, and why?’. 50 It seeks to understand not only in what contexts the intended outcomes are achieved, but also unintended outcomes. Further details of how the principles of realist evaluation were applied in this study are provided in Chapter 2.

Aim and objectives

The aim of this study was to understand how and in what circumstances RAS produces both intended and unintended outcomes. The study had the following research objectives:

-

To contribute to the interpretation and reporting of the results of ROLARR by investigating how variations in implementation of RAS, and the context in which RAS is implemented, impact on outcomes such as operation duration, conversion to open surgery and complications.

-

To produce actionable guidance for health-care organisations on factors likely to facilitate the successful implementation and integration of RAS.

-

To produce actionable guidance for OT teams on how to ensure effective communication and teamwork when undertaking RAS.

-

To provide data to inform the development of tools and technologies for RAS to better support teamwork and decision-making.

Structure of the remainder of the report

Chapter 2 provides the details of the study design and research methods used. (Details of the study management, including patient and public involvement in the study, are provided in Appendix 1.) Chapter 3 presents the candidate theories that were developed in preparing the proposal and the literature, regarding both the integration of new technologies in health care and communication, teamwork and decision-making within the OT, that informs them. Chapters 4 and 5 report on phase 1 of the realist evaluation, during which the candidate theories were added to and refined, through the elicitation of stakeholders’ theories about how and in what contexts RAS becomes introduced into routine surgical practice and how and in what contexts RAS impacts communication, teamwork and decision-making in the OT. At the end of phase 1, the theories were prioritised for empirical testing in phase 2, and this process and the resulting decisions are described in Chapter 6. The results of phase 2, during which we sought empirically to test the refined theories, are presented in Chapters 7 and 8. In phase 3, we sought to assess to what extent our findings from colorectal surgery were applicable to other surgical specialties through interviews with surgeons and OT teams in these specialties, and the results of this are described in Chapter 9. Chapter 10 concludes the report by summarising the findings of the study in relation to our original objectives, discusses the strengths and limitations of this research and outlines priorities for future research.

Chapter 2 Design and methods

Realist evaluation

As described in Chapter 1, realist evaluation involves a process of eliciting, testing and refining theories of how an intervention works. 51 Realist evaluation does not employ particular methods of data collection, but a mixture of qualitative and quantitative methods is encouraged. 52 Whereas qualitative methods may be best for gathering data on the processes and contexts of an intervention, quantitative data is desirable for understanding an intervention’s impacts. The stages of a realist evaluation, and how they relate to the phases of the current project, are presented in Figure 2. This report reflects the current guidance for the reporting of realist evaluations. 53

FIGURE 2.

A three-phase realist process evaluation.

A note on theory

Given the focus within realist evaluation on the elicitation, testing and refinement of theories, an explanation of how this term is understood within realist evaluation is necessary. Although theories may sometimes be considered to be abstract and irrelevant, separate from the everyday experience of practitioners, the term can also be used simply to refer to practitioners’ ideas and thoughts about how an intervention works. 54 This is how the term is used in realist evaluation. From a realist standpoint, effective theories typically combine both substantive theory and stakeholders’ theories that are derived from experience. 51,54

Realist theories define the mechanism through which a particular outcome is achieved, whereby the mechanism consists of a resource that the intervention provides and the recipients’ reasoning about and response to that resource, and the context in which that mechanism will be activated. Thus, realist theories are often presented in the format Context + Mechanism = Outcome, or C + M = O, referred to as a context–mechanism–outcome (CMO) configuration. The activation of a mechanism should not be thought of as an on/off switch; rather, there is a continuum of activation, which will affect the outcome. 55 For example, there are varying degrees to which an OT team may feel enthusiastic towards RAS, depending on the context.

Phase 1: theory elicitation and refinement

Phase 1 of the study was concerned with theory elicitation and refinement, the first stage in a realist evaluation. The purpose was to refine and add to the candidate theories developed in the process of preparing the proposal for this study. Theory elicitation can be carried out in a number of ways, such as interviewing stakeholders, reviewing the existing literature on the topic, identifying relevant theories from the literature, or some combination of these approaches. To begin our realist evaluation, we carried out a review of literature related to the use of RAS, focusing on the identification of stakeholders’ theories. This is useful to track the history and adaptation of complex interventions, which can reveal important learning about technology implementation and evaluation. 56 The refined set of theories was then presented to members of the OT teams in interviews during which they were asked to refine, develop and add to the theories based on their direct experience of RAS. Ethics approval for this phase of the study was granted by the School of Healthcare Research Ethics Committee of the University of Leeds (reference number SHREC/RP/339).

Literature review

This review constituted the first ‘theory elicitation’ stage of a realist review. Whereas in a full realist review published evidence is used to test and refine stakeholders’ theories,52 our purpose was to catalogue the theories to be refined and tested in subsequent stages of the study. The details of the methods of this review can be found in Appendix 2.

Teacher–learner cycle interviews

Realist evaluation provides a unique approach to undertaking interviews, referred to as ‘teacher–learner cycle’ interviews. 51 In teacher–learner cycle interviews, the researcher’s theory is the subject matter. An iterative approach is taken, whereby the researcher first teaches the interviewee about the theories they want to explore within the interview. The researcher then invites the interviewee to use their experience of the intervention to reflect on these theories, refining and adding to them, so the interviewee is using their experience to teach the researcher. In interviews with members of OT teams with experience of colorectal RAS, we used this approach to refine and test our literature-based theories.

Settings and participants

The ROLARR team identified that 10 English NHS trusts were using RAS for colorectal surgery at the time of the interviews. Of these 10 trusts, six had met the inclusion criterion for participation in ROLARR, in that surgeons had to have undertaken a minimum of 10 rectal cancer resections using RAS. The other four trusts did not meet this inclusion criterion and thus had not participated in the trial. We invited surgeons and OT teams in all 10 trusts to participate in our phase 1 interviews. By involving both trusts involved in ROLARR and trusts not involved in ROLARR, we ensured that the OT teams involved in the study varied in their level of experience with RAS.

Agreement to participate was obtained and research governance approval was granted at all 10 trusts. However, at one trust, despite numerous attempts at contact by the research team, it was not possible to arrange an interview with the surgeon. Therefore, interviews were conducted across nine sites, including all six of the English ROLARR sites. The staff information sheet for this phase of the study is provided in Appendix 3.

Given the study’s concern with teamwork, it was considered essential that we capture the perspectives of all of the professional groups that make up the OT team. 57 Therefore, a snowball sampling strategy was used. 58 At each trust, one of the colorectal surgeons was interviewed first, and he or she then helped us to identify other members of the OT team to interview. As well as surgeons, interviewees included surgical trainees, theatre nurses, operating department practitioners (ODPs) and anaesthetists. Details of the number of interviews undertaken in each site are provided in Table 1. Although we had initially intended to undertake 10 interviews per trust, recruiting interview participants at some trusts proved challenging (described further below), and therefore there was significant variation in the number of interviews undertaken per trust. In total, 44 interviews were conducted across the nine trusts between November 2013 and August 2014.

| Site | Role | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgeon | Trainee surgeon | Anaesthetist | Nurse | ODP | Other | ||

| 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 13 |

| 2 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | ||||

| 4 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | ||

| 5 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 | |||

| 6 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 6 | ||

| 7 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 7 | |

| 8 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |||

| 9 | 1 | 1 | |||||

| Total | 12 | 5 | 6 | 12 | 7 | 2 | 44 |

Data collection

The interviews were semistructured. Using an interview topic guide designed by the research team, participants were first asked about when and how RAS was introduced into their hospital. This allowed us to trace the processes of implementation across the nine trusts, helping to identify contextual differences. The participants were then presented with theories taken from the literature and asked to reflect on whether or not, and in what ways, those theories fitted with their own experiences. Open-ended questions were also included to surface new areas for investigation. Thus, the interviews were designed to support both ‘theory gleaning’ and ‘theory refinement’. 59 The questions asked varied according to the participants’ roles, designed to reflect the experience of RAS each participant would have as a result of their role. After each interview, the interview topic guide was reviewed and, when necessary, revisions were made to incorporate new theories and refinements to theories, so that these could be explored in subsequent interviews (see Appendix 4 for the initial interview topic guide).

Interviews in most trusts were undertaken by telephone, although there were exceptions. Interviews were conducted in person at the NHS trust local to the research team. In addition, in three NHS trusts telephone interviews were difficult to organise, as the individual OT team members were in theatre and unavailable when at work. In these three trusts, agreement was obtained for members of the research team to attend on an audit day, when no operations were scheduled, and interview those staff who were available and consented to the interview. All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. The interviews ranged from 29 minutes to 1 hour 40 minutes. The average (mean) length of interview was 53 minutes.

Data analysis

An iterative approach to data collection and analysis was taken. As there was often little or no time between interviews, an approach was developed that assisted the team in maintaining an overview of the ways in which the theories were being refined and added to through the interviews, which also supported refinement of the interview topic guide. A working document was maintained that contained the list of theories being explored in the interviews. Following each interview, the researcher would review the list of theories, noting the interviewee’s support for or disagreement with the theories and any refinements to the theories suggested by the interviewee, as well as adding any new theories that emerged in the interview.

In preparation for the Study Steering Committee (SSC) meeting at which theories were to be prioritised for testing (discussed further below), more formal analysis was undertaken using framework analysis, an approach developed for analysing qualitative data for applied policy research. 60 At this point, 23 interviews had been completed. Framework analysis was chosen because it supports systematic and comprehensive data analysis, is well suited to working with large data sets, allows for both inductive and deductive analysis, enables both between- and within-case analysis, is an approach that has previously been used within realist evaluation studies61 and was an approach members of the research team were familiar with. Three members of the research team identified and agreed codes for indexing the data, informed by the interview topic guide and reading of a subset of three of the interview transcripts, as well as familiarity with the interviews through conducting those interviews. These codes focused on capturing how our original theories were expanded, supported and refined, and how different contextual features shaped the mechanisms through which RAS was perceived to become integrated into practice and to impact on communication, teamwork and decision-making. The interview transcripts were entered into NVivo 10 (QSR International, Melbourne, Australia) software for qualitative data analysis. The three members of the research team then indexed four interview transcripts to test the applicability of the codes and assess agreement. When there was variation in the indexing, the codes were refined and definitions were clarified. The refined codes were applied to all transcripts. The indexed data were summarised in a series of matrix displays, created in NVivo 10, to build up a picture of the data as a whole. 62 This involves the abstraction and synthesis of the data while also referencing the original text. There was one matrix display per theme (implementation, teamwork and communication, and decision-making) and, in each matrix display, a row for each interviewee. As data collection continued, new interview transcripts were entered into NVivo 10, indexed and added to the matrix displays.

In the final stage, mapping and interpretation, the matrix displays were used to make both within-case comparisons, exploring intraorganisational and micro aspects of context, such as role, and between-case comparisons, to explore interorganisational aspects of context, returning to the original data when necessary. Narrative summaries of these patterns in the data were written up in a series of working documents, organised by theme. The three members of the research team then went through the narrative summaries, discussing them and comparing the findings with the theories presented in the interviews, in order to develop a refined set of theories.

Phase 2: empirical testing of theories

The purpose of phase 2 of the study was to collect and analyse data to test key theories from phase 1. To do this, we worked with our SSC, patient panel and the clinical members of the research team in order to prioritise the theories. The protocol for this phase of the study was then reviewed and revised, to ensure that we would be gathering the data necessary for testing the selected theories. Data were collected across four case sites, using a combination of methods, including structured observation and video recording of robot-assisted and laparoscopic rectal cancer resections, questionnaires to assess perceived mental and physical workload associated with robot-assisted and laparoscopic operations, and semistructured interviews. Ethics approval for this phase of the study and for phase 3 was granted by the National Research Ethics Service Committee Yorkshire & The Humber – Leeds West (reference 13/YH/0153).

Prioritisation of theories

From a realist perspective, there is an infinite number of potential influences on the interactions between a complex intervention and its intended recipients, and an infinite number of potential impacts resulting from those interactions. 50 It would be impossible to test all of the theories that account for those interactions and, therefore, it is necessary to take some theories on trust, possibly to be tested at some later point, while focusing attention on the testing of other theories. To assist in the process of determining which theories to test, at the SSC meeting and the patient panel meeting, preliminary findings from the interviews were presented and discussion was focused on what outcomes were most important to consider. Once the analysis of the phase 1 interviews was complete, a subset of possible theories to test was identified, based on a consideration of the strength of support offered in the interviews for those theories, the extent to which they concerned outcomes identified by the patient panel and SSC as being important, and the feasibility of testing those theories. This subset was presented to the clinical members of the research team, to capture their perspectives on which theories were most important to test.

Settings and participants

A multisite case study was used63 to generate findings with relevance beyond a single setting. 64 There is no consensus regarding how many case sites to include in a multisite case study. 63 The number of sites depends on the number of aspects of the context anticipated to impact on the phenomenon of interest,63 while also involving a trade-off between breadth and depth of investigation. 65 Four sites were used to enable the identification of organisational-level factors that impacted the deployment of the robot, while providing confidence in the generalisability of findings across sites. This approach has been successfully deployed by members of the research team in a previous multisite case study of the introduction of new technologies. 66 Therefore, it was decided that four case sites would be selected from the nine trusts included in phase 1. Case sites were purposively sampled to ensure variation in the experience of the surgeon and the team with RAS, as this was identified as an important contextual factor in the prioritised theories. In addition, we made sure that the case sites included both large teaching hospitals and district general hospitals, and that three of the case sites were participating in the ROLARR trial and one was not.

Once agreement to participate in phase 2 of the study was obtained from the appropriate colorectal surgeon at each site, visits were made to the sites to explain the study to other surgeons and members of the OT team and to answer any questions or address any concerns (see Appendix 5 for the staff information sheet and Appendix 6 for the staff consent form). Research governance approval was then obtained from each trust for phases 2 and 3.

Once data collection began, it was typically the colorectal surgeon or the research nurses at each site who obtained written consent from patients for us to observe and video record their operations (see Appendix 7 for the patient information sheet and Appendix 8 for the patient consent form). In each of the ROLARR case sites, while recruitment to ROLARR continued, we observed operations involving patients in the trial. Once recruitment to ROLARR ended, and in the case site not participating in ROLARR, we initially used the same inclusion and exclusion criteria as the ROLARR trial, to ensure that the operations observed were comparable (see Appendix 9). Following challenges in recruitment, the inclusion criteria were extended slightly, although these changes were discussed with the clinical members of the research team to ensure that they would not change the nature of the operation observed. Although we observed both laparoscopic and robot-assisted operations in each site, the number of laparoscopic and robot-assisted operations observed in each site depended on the extent to which these two techniques are used within the site and, for case sites in the ROLARR trial, the randomisation of patients to the different arms of the trial.

There is no consensus regarding how many periods of observation are necessary to provide an adequate overview of current practice in a particular setting. 65 We initially proposed to observe 10 rectal cancer resections in each site (n = 40), on the basis that this would be a feasible number to observe within the time frame of the project and would provide over 200 hours of data, which would constitute a substantial corpus. However, the number of suitable operations varied substantially between sites, and data collection at one site ended early due to RAS no longer being used at that trust. In total, between June 2014 and November 2015, we observed 22 rectal cancer resections, 16 robot assisted and six laparoscopic, and we were able to secure 202 hours of data collection, as many of the operations were longer than we had initially anticipated. In addition, the observation of a further 10 colorectal operations was undertaken across three of the sites at different points during data collection, five of which were robot assisted. These provided the opportunity to learn more about colorectal surgery and become familiar with the setting, to trial the structured observation tool OTAS (Observational Teamwork Assessment for Surgery) we would be using and to get to know theatre staff. Details of the number of operations observed in each site are provided in Table 2. In consultation with our SSC, we agreed that we had collected a substantial corpus of data that achieved the anticipated number of hours of observation. Therefore, rather than continue data collection beyond the proposed period, we focused on data analysis.

| Site | Robot assisted | Laparoscopic | Other colorectal robot assisted | Other colorectal open/laparoscopic | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observation only | Observation and video | Observation only | Observation and video | Informal observation only | Informal observation only | ||

| 1 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 15 | |

| 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||

| 6 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 7 | ||

| 7 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 8 | |

| Total | 8 | 8 | 5 | 1 | 5 | 5 | 32 |

Data collection

Structured observation

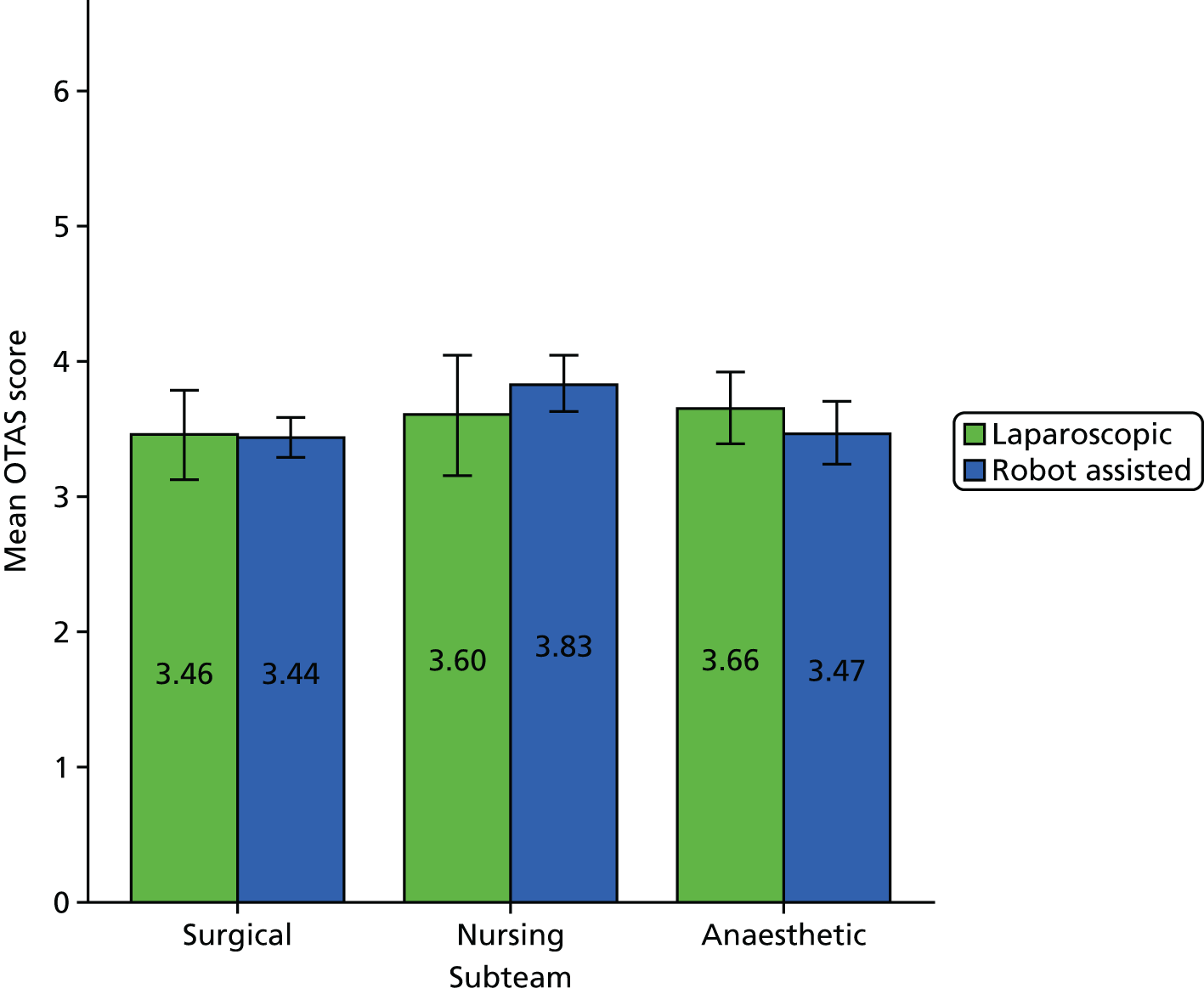

Observation is crucially important for understanding teamwork in the OT. 67 Existing studies point to the significance of non-verbal communication in the OT, and the tacit nature of the knowledge that underlies such practices means that it is rarely revealed through interview studies. 29 We selected OTAS, a structured observation tool, for assessing teamwork in the operations we observed. 68 We chose to use OTAS rather than other non-technical evaluation tools related to surgery, such as NOTSS (Non Technical Skills for Surgeons), because, first, it considers the teamwork skills of all professional groups within the OT69 and, second, it considers, and provides separate ratings for, team behaviours that seemed particularly relevant to testing our candidate theories, such as team monitoring and situational awareness. OTAS has been shown to be applicable to various branches of surgery68 and has demonstrated construct validity,70 content validity71 and reliability, minimising error and bias in data collection and therefore increasing confidence in the validity of the findings. 72 OTAS has also demonstrated good inter-rater reliability with short-term training. 32 Further details of OTAS and the training undertaken by members of the research team in preparation for data collection are provided in Appendix 10.

Video recording

To complement the OTAS measures, we also conducted video recordings of teamwork in the OT, adopting the workplace studies approach. 73–75 The value of video recordings is that they capture not only oral communication but also non-verbal communication, such as gesture, gaze and tool manipulation, that has been shown to be important for teamwork in the OT. 29,76 Another benefit of video recordings is that they are permanent, allowing for repeated analysis. They also facilitate collaborative analysis. Additionally, video recording had been used successfully in a number of studies concerned with the impact of teamwork on surgical performance,28,77–87 providing a useful set of background materials with which we could compare and contrast our findings.

For each operation we video recorded, we used two Panasonic high-definition video cameras (model HC-X920; Panasonic UK, Bracknell, UK). These were positioned, on tripods, to capture the surgeon’s perspective on the surgical scene as well as the conduct of the surgical assistant and the scrub practitioner. We used two Sennheiser EK100 wireless lapel microphones (Sennheiser electronic GmBH & Co. KG, Wedemark, Germany), one attached to the surgeon and one attached to the first assistant (which captured the talk of both the first assistant and the scrub practitioner). Video recording began once the patient was draped and stopped before the patient was woken up.

We had initially intended to video record all of the operations that we observed. However, when data collection began, it became apparent that two researchers needed to be present for video recording to be used, so that they could monitor the position of the cameras (although the position of the cameras was fairly static, the movement of the OT team and/or equipment meant that a camera might need to be quickly moved out of the way) and manage the other forms of data collection. Therefore, operations were video recorded only when two researchers could be present. Because there is already a body of video-based studies of laparoscopic surgery, and because most of the robot-assisted operations we observed were hybrid operations, including a laparoscopic phase, we prioritised the video recording of the robot-assisted operations. We collected video data across three sites, video recording eight robot-assisted operations and one laparoscopic operation. This provided us with a total of 52 hours of recordings but, as we used two cameras, this totals 104 hours of video data, which constitutes a substantial corpus. Fifty-two hours of video recording is in line with the number of data collected in other video-based studies of surgical work. 81,85,87

Ethnographic observation

Ethnography, the study of people in their environments where the researcher participates in the setting in order to collect data,65 has been argued as an essential approach for studying the introduction of technology into health-care settings. 88 Ethnographic methods, such as non-participant observation, have also been used in previous realist evaluations as part of the process of theory testing and refinement. 89,90 In addition to recording field notes about the teamwork behaviours relevant for OTAS, the researchers recorded details of behaviours and interactions that fell outside the scope of OTAS. This provided an account of what happened during the operation, and before and after it, which was particularly important for those operations we were not able to video record. The researchers also recorded incidents of observer effects (e.g. participants asking ‘what are you writing?’) to allow an analysis of whether or not participants’ awareness of the researchers’ presence changed over time. 91 Following data collection, field notes were written up. When two researchers observed an operation, their notes were combined to provide a single account of the operation.

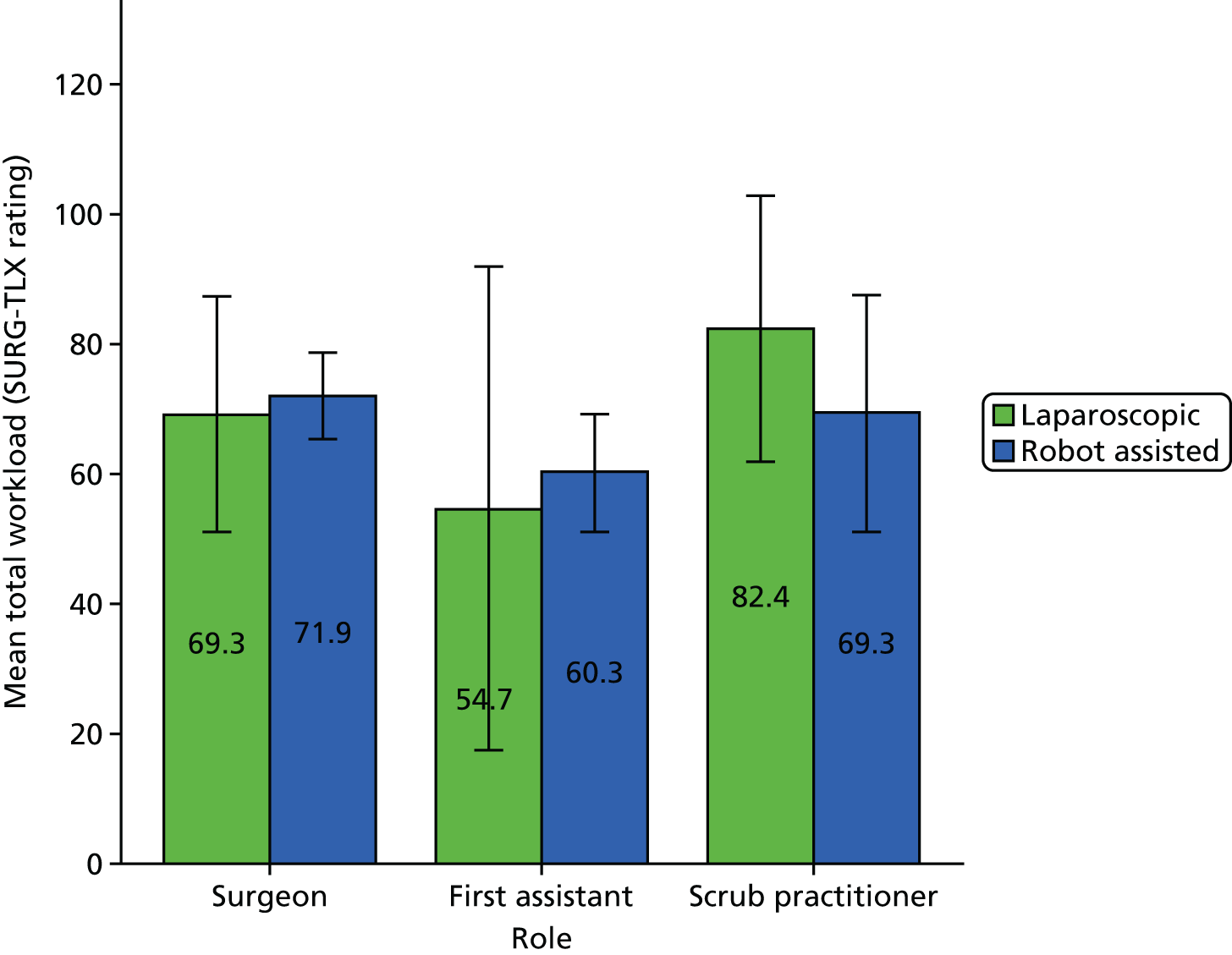

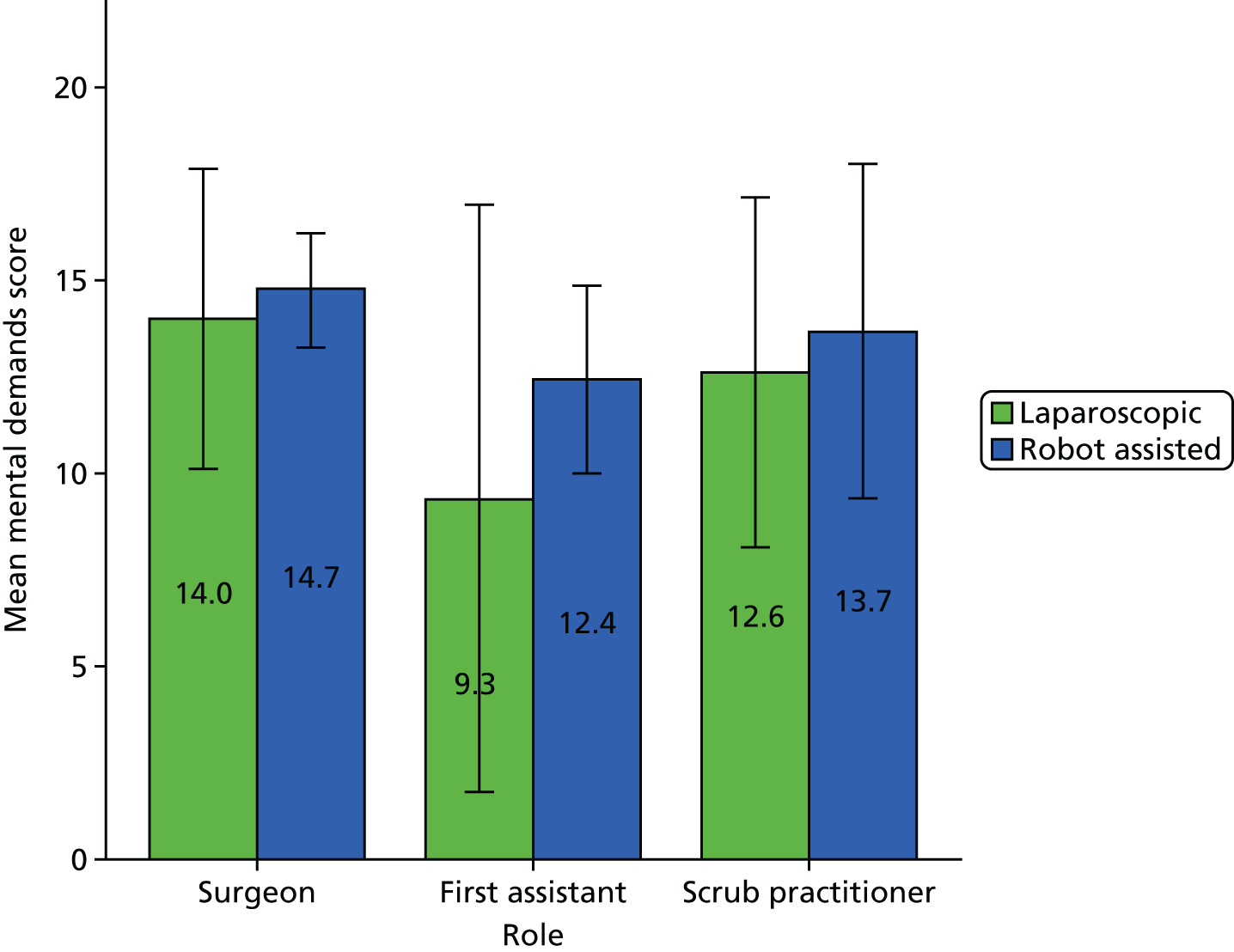

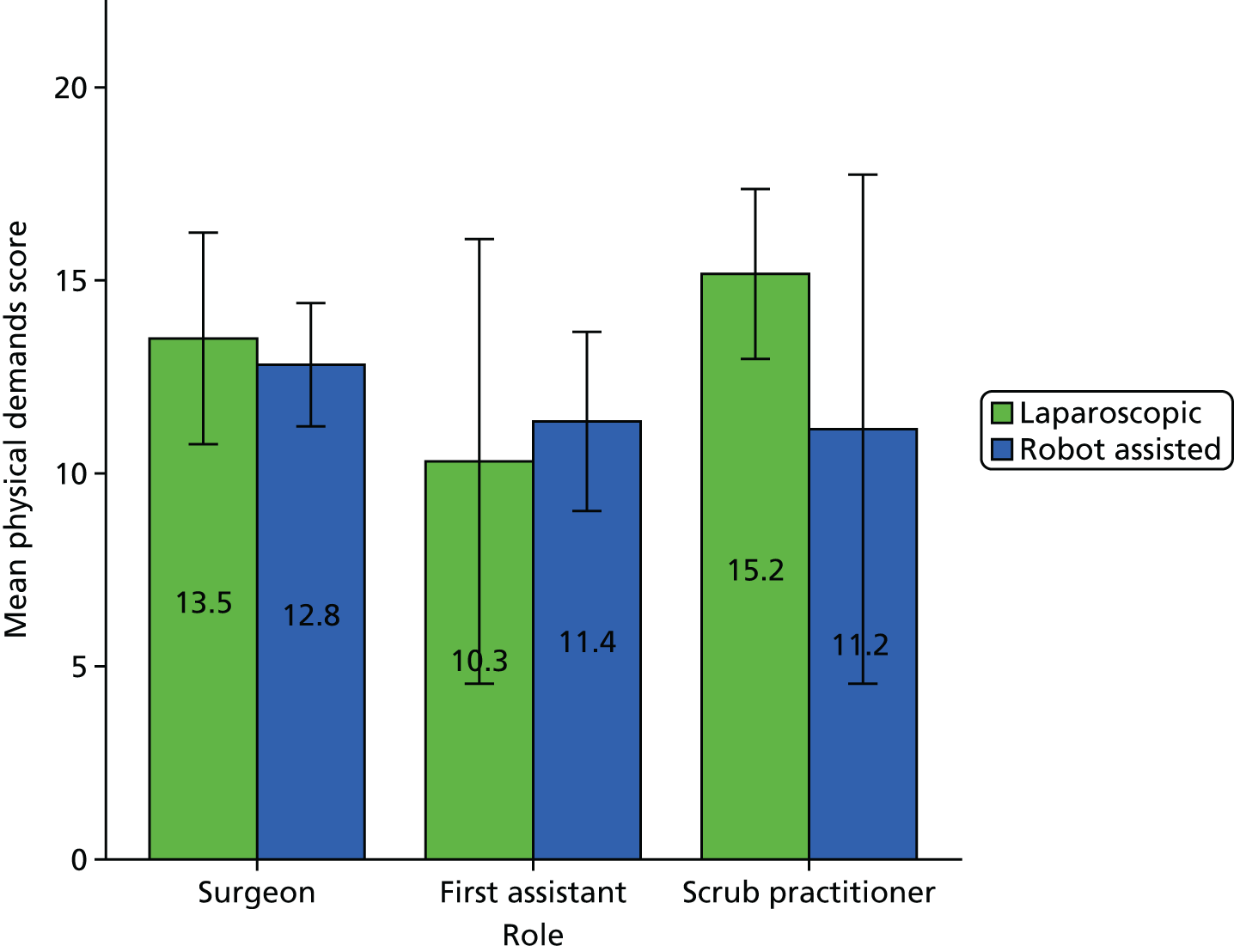

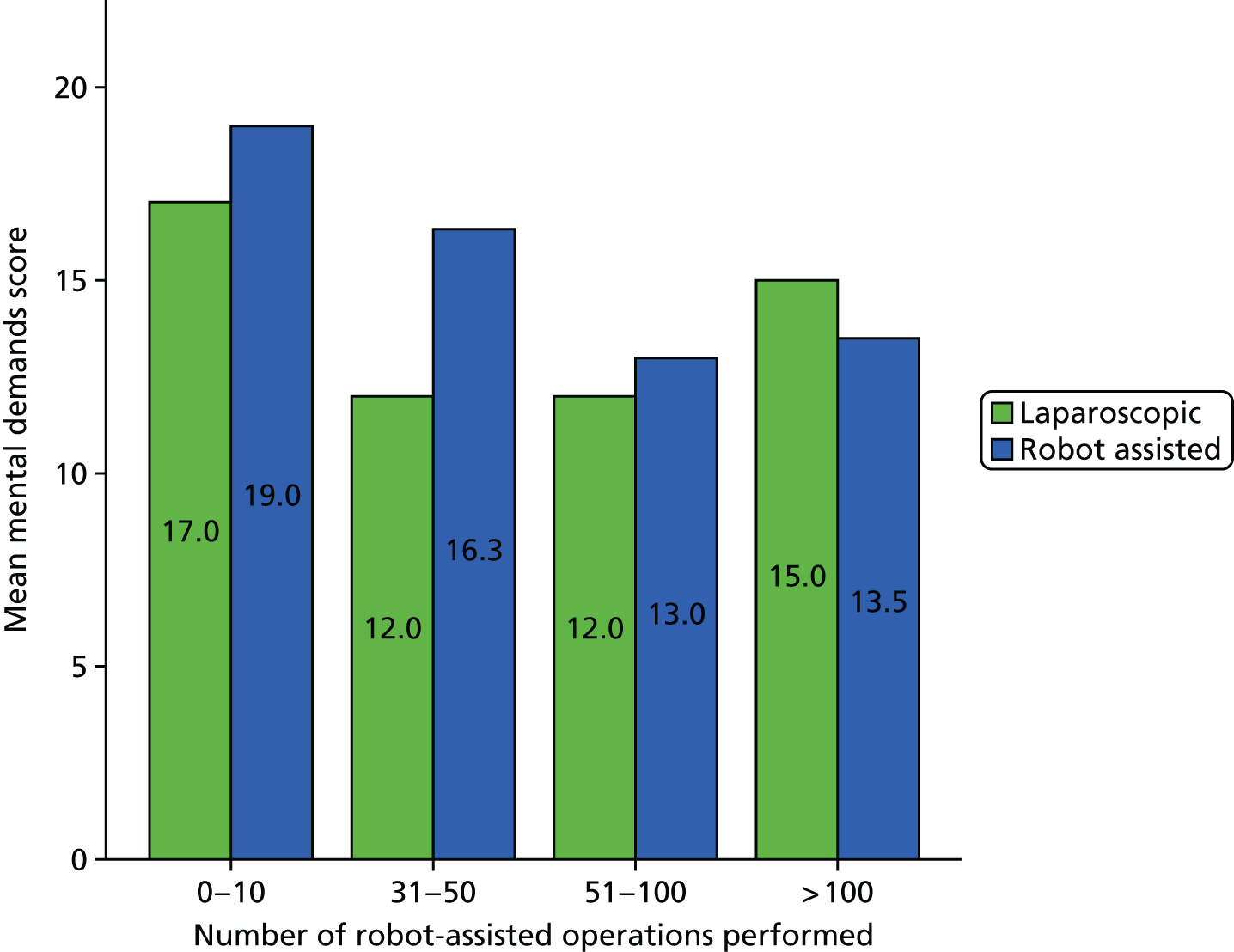

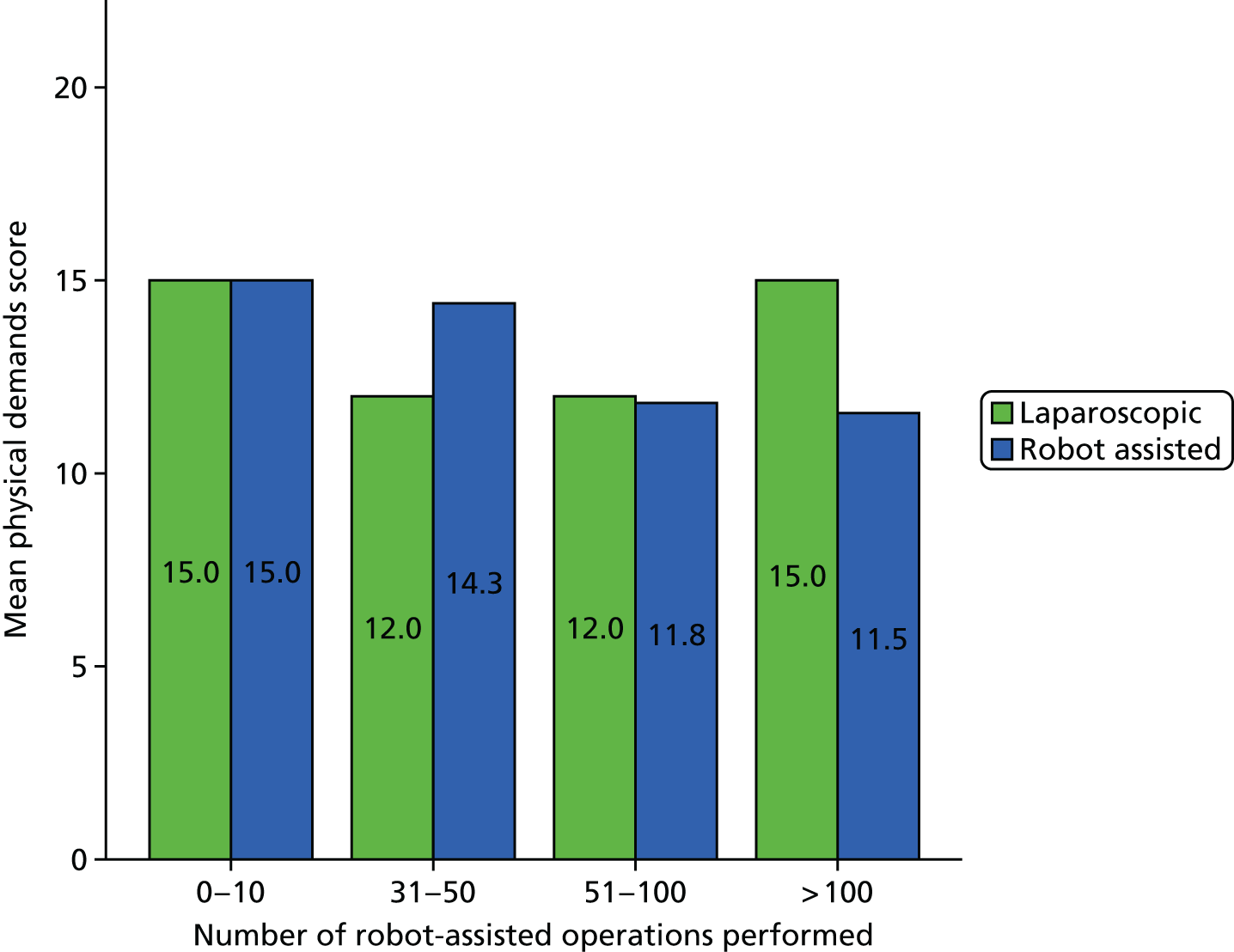

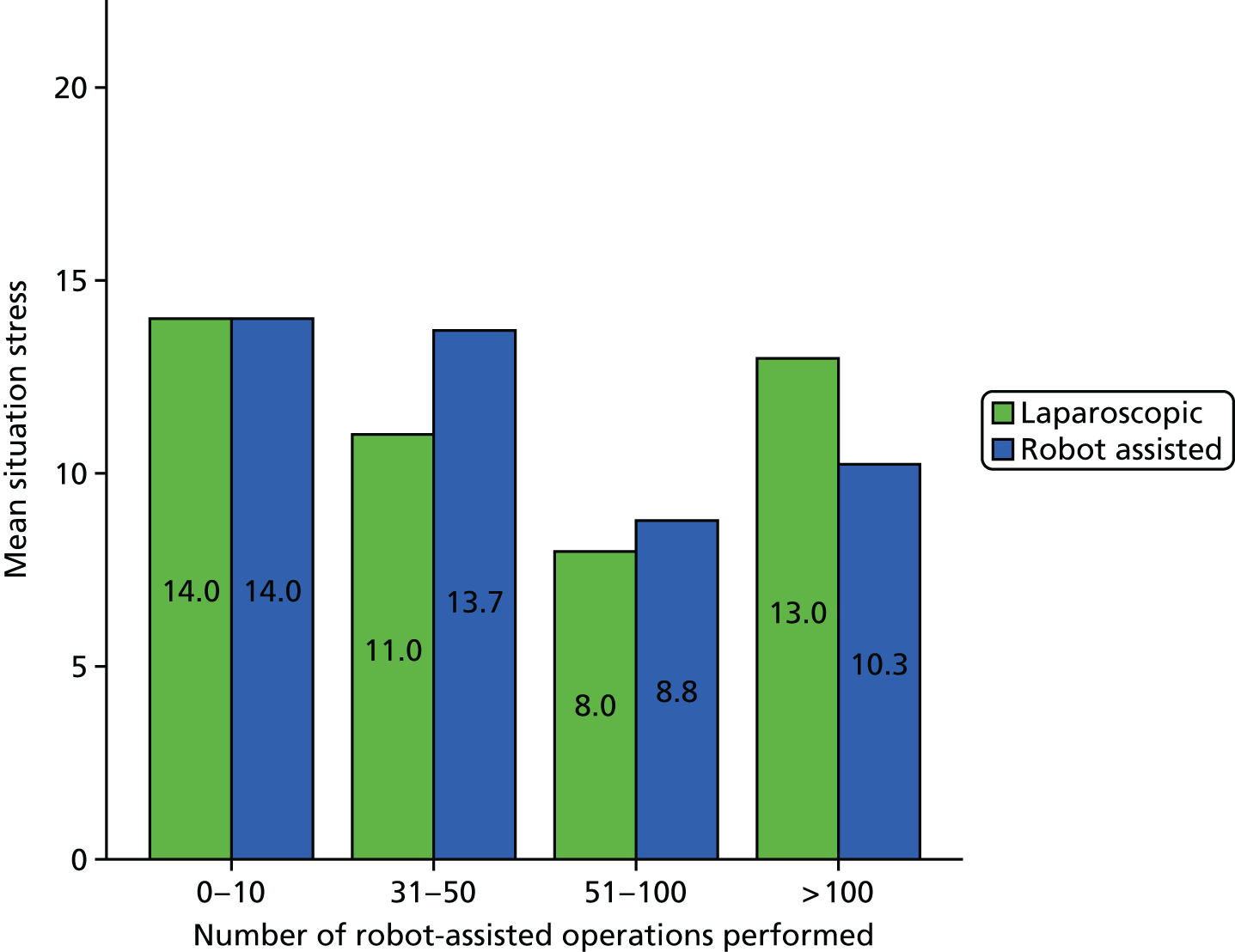

SURG-TLX questionnaire

Use of the SURG-TLX questionnaire was not included in our original protocol but was added on completion of phase 1, as a result of theories elicited in phase 1 and taken forward for testing regarding the impact of RAS on mental and physical stress. The SURG-TLX is a multidimensional rating procedure for measuring the subjective workload associated with an operation,92 and is adapted from the NASA Task Load Index (NASA-TLX), the most widely used measure of workload in human factors research. 93 Development of the SURG-TLX was informed by qualitative research that has identified key intraoperative stressors. 92 The subscales included in the SURG-TLX are mental, physical and temporal demands, and task complexity, situational stress and distractions. The use of the six subscales provides valuable information about sources of workload and, relative to unidimensional workload ratings, has been found to reduce variability among participants in the overall workload score. 94 Each subscale is subjectively rated on a 21-point visual analogue scale, from very low to very high.

We developed a questionnaire based on the SURG-TLX, with additional questions about the participant’s role and their levels of experience of RAS and laparoscopic surgery. Although the SURG-TLX was initially designed to be completed by the surgeon, in more recent research it has been provided to all members of the OT team. 95 We gave the questionnaire to staff following each operation we observed, prioritising getting responses from the surgeon, the first assistant and the scrub practitioner. A total of 55 questionnaires were completed. Details of the number of questionnaires collected in each site are provided in Table 3.

| Site | Role | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgeon | First assistant | Scrub practitioner | Circulating practitioner | ||

| 1 | 7 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 21 |

| 5 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | |

| 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 12 | |

| 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 18 |

| Total | 20 | 16 | 12 | 7 | 55 |

Semistructured interviews

At the end of each operation we undertook brief semistructured interviews with some of those who participated in the operation. The researchers endeavoured to undertake interviews with the surgeons whenever possible. In most cases this was unproblematic, but sometimes the surgeons needed to leave the OT immediately. Additional interviews were undertaken with other members of the team when their availability allowed. In the interviews we sought to gather data on those outcomes that cannot be easily gathered by other means, particularly those relating to the perceptions of members of the OT team (e.g. perceptions of the quality of teamwork and others’ engagement during the operation), and perceptions of RAS as an opportunity for training. The interviews also provided an opportunity for the researcher to ask questions about aspects of the operation not immediately intelligible to an observer. As data collection progressed, we also used these interviews as an opportunity to discuss the revisions to our theories, using the teacher–learner cycle described above. A total of 30 postoperation interviews were undertaken. Details of the number of interviews undertaken in each site are provided in Table 4.

| Site | Role | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgeon | Trainee | Nurse/ODP | Anaesthetist | ||

| 1 | 5 | 4 | 9 | ||

| 5 | 2 | 2 | |||

| 6 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 7 | |

| 7 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 12 |

| Total | 17 | 4 | 8 | 1 | 30 |

Within realist evaluation, it is recommended not only to undertake interviews in the early phases of the study but also to schedule interviews after observations, when the interviews ‘are guided and informed by incidents arising from the observations’ in order to allow further theory testing and theory consolidation. 59 We undertook a series of longer interviews with surgeons once the observations had been completed and a preliminary analysis of the data was complete, in order to fill in gaps in our understanding regarding why particular events observed during the operations happened. Again, these interviews were semistructured and used the teacher–learner cycle, with the researcher asking questions informed by our revised theories so that participants could support or refine our theories. Although we had hoped to be able to review clips of videos with the surgeons in these interviews, this proved not to be feasible, so instead we produced descriptions of the events we wanted to explore and presented these to our interviewees. All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. A total of four such interviews were undertaken.

Data analysis

An iterative approach to data collection and analysis was taken, to enable the ongoing testing and refinement of the theories and the gathering of further data in the light of such revisions. Field notes were entered into NVivo 10 following transcription. As a first step in analysing the data, we produced a series of matrix displays based on the case dynamics matrices described by Miles and Huberman. 62 Although these are normally produced once the data have been indexed, we found it helpful to go straight to producing the matrices, as a way of getting an overview of the data and keeping our analysis focused on the testing of our theories. A matrix display was created for each theory and, with one row for each robot-assisted operation, we summarised the anticipated contextual factors from the theories (whether or not they were present), other contextual factors that appeared to exert influence, anticipated mechanisms from the theories (whether or not they appeared to be at play), other mechanisms that appeared to be at play, and anticipated and unanticipated outcomes. We used data from the field notes, interviews undertaken after the operations, responses to the SURG-TLX questionnaire and the OTAS ratings.

As we began to write up the analysis based on the matrix displays, further questions became apparent, so we returned to the field notes for additional information. This involved indexing the data, using codes relevant to the questions and inductive codes to capture other aspects of the contexts, mechanisms and outcomes relevant to our theories.

Analysis of Observational Teamwork Assessment for Surgery

There was substantial variation within robot-assisted operations in terms of how much of the operation was robot-assisted (mean 45%, range 15–64%). Consequently, we combined the data from the robot-assisted and laparoscopic operations and ran a Pearson product-moment correlation to determine the relationship between the percentage of operation that was robot assisted (with laparoscopic operations being 0% robot assisted) and the overall OTAS score. Following this, correlations between the percentage of operation that was robot assisted and OTAS scores for specific subteams and constructs were calculated using the Pearson product-moment correlation (see Chapters 7 and 8). A one-way independent analysis of variance (ANOVA), with the first assistant’s experience of RAS as an independent variable, was performed to determine whether or not there was a relationship between the first assistant’s experience and the surgical subteam co-ordination score.

Analysis of SURG-TLX

A Pearson product-moment correlation was run to determine the relationship between the SURG-TLX overall score and the percentage of operation that was robot assisted. Following this, the analyses focused on specific subscales as they related to the theories being tested (see Chapter 8).

Analysis of video data

For the analysis of the video data, we took several complementary approaches. First, we followed standard methods outlined in the field of workplace studies,96 which draw heavily on ethnomethodology97 and conversation analysis. 98,99 This involves four key stages: (1) a preliminary review of the data to identify short episodes of co-ordination between OT team members, which allows the analyst to begin to identify activities, phenomena or notable extracts that may provide fruitful avenues for further enquiry; (2) detailed transcription of selected extracts using standard orthographies in conversation analysis to detail the temporal organisation of actions and activities – talk, bodily conduct and tool use;100 (3) close consideration of the extracts to unpack the situations and contexts in which these episodes occur and to reveal potential interactional patterns and practices; and (4) a further review of the data to identify and interrogate similar and contrasting examples. The first stage of this analysis was undertaken by multiple members of the research team through a series of ‘video review sessions’. Given the complex and highly specialised character of the setting, a number of video extracts and preliminary analytic observations were discussed with clinical members of the research team and the SSC.

Second, we undertook a quantitative analysis of video data using the video analysis software Transana (University of Wisconsin-Madison Center for Education Research, WI, USA). Although this had not been in our initial protocol, the initial analysis of the OTAS data suggested little variation across operations, while initial analysis of the SURG-TLX data suggested variation that cannot be explained purely by whether or not the operation is robot assisted. Therefore, we felt it necessary to gather additional quantitative data to support our testing of the theories, and the video data provided a good resource for this purpose. The use of these data was also based on an acknowledgement that the impacts we were interested in (e.g. engagement) vary over the course of an operation, while OTAS and SURG-TLX provide data on only the operation as a whole. Through the initial analysis based primarily on the field notes described above, we were able to establish a focus for this quantitative analysis of the video data. Plans for the quantitative analysis of the video data were discussed with the clinical members of our team to ensure that the measures being used were considered to have clinical relevance. Quantitative analysis focused on the time taken for a first assistant to respond to a surgeon’s request. Details of how this analysis was undertaken are provided in Appendix 11.

Phase 3: assessing generalisability of theories

The objectives of phase 3 were (1) to assess the extent to which the theories resulting from phase 2 were generalisable to other surgical specialties and to refine them so that they had wider applicability; and (2) to use the findings of the study to explore ideas for tools and technologies to better support teamwork and decision-making in RAS. The first of these objectives was achieved through undertaking interviews with surgeons and OT teams in other surgical specialties in our phase 2 case sites. The second objective was achieved through a 1-day workshop held at the University of Leeds.

Interviews with other surgical specialties

Settings and participants

Interviews were undertaken at the three phase 2 case sites that were continuing to undertake RAS. Surgeons, theatre nurses, ODPs and trainee surgeons from surgical specialties in which RAS is being used were included. A total of 13 participants were interviewed between May and July 2016. Details of the number of interviews undertaken in each site are provided in Table 5. At site 1, we interviewed two urology surgeons and one urology surgical trainee. The ODPs at site 1 all worked in urology but some had previous experience of working in colorectal surgery. At site 6, because the theatre nurses and ODPs worked across all three specialties in that trust that used the robot (urology, gynaecology and colorectal), all had participated in earlier phases of the study. At site 7, we interviewed one urology surgeon and one upper gastrointestinal (GI) surgeon.

| Site | Role | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgeon | Trainee surgeon | Nurse | ODP | ||

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 8 | |

| 6 | 1 | 2 | 3 | ||

| 7 | 2 | 2 | |||

| Total | 4 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 13 |

Data collection

Interviews were conducted face to face at sites 1 and 6 and undertaken by telephone at site 7. At site 1, the interviews with the ODPs were undertaken as a group interview owing to restrictions in the participants’ availability. All other interviews were individual interviews. The interviews were semistructured and conducted using the teacher–learner cycle, as in phase 1. In each interview, participants were first asked about their experience of RAS and how RAS was introduced into their specialty, in order to identify contextual differences across the specialties related to experience and the processes of implementation. The theories that resulted from phase 2 of the research were then described and the participant was invited to comment, expand and discuss the theories based on their experience of RAS. When a theory did not fit with the interviewee’s experience, the researcher probed to identify the contextual factors that limited the applicability of the theory to the interviewee’s specialty. As in phase 1, the interview topic guide was revised as the interviews progressed. All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. The interviews ranged in length from 14 minutes to 47 minutes, with the average (mean) length being 30 minutes.

Data analysis

An iterative approach to data collection and analysis was taken as in phase 1, with an initial review of interview transcripts enabling refinements to theories to be explored in subsequent interviews. Once all interviews were completed, a more formal analysis was undertaken using framework analysis. Having read through the interview transcripts, codes for indexing the data were identified, including both codes based on the interview topic guide (largely relating to the theories, as well as codes relating to the process of implementing RAS) and subcodes based on variations to the theories that emerged in the interviews. The interview transcripts were entered into NVivo 10 and indexed. A matrix display was created in NVivo 10 to summarise the indexed data, with a row for each interviewee. For the stage of mapping and interpretation, the matrix displays were used to compare the findings with the theories presented in the interviews, in order to come up with a final set of theories.

A 1-day workshop on designing for robot-assisted surgery

In July 2016 we held a workshop at the University of Leeds entitled ‘Designing for robotic surgery: challenges and opportunities’. The workshop had 25 attendees, made up of a mixture of engineers, computer scientists, psychologists, social scientists, surgeons, theatre nurses, ODPs and members of our patient panel. The findings from the study were presented and then participants were asked to consider the implications of the findings for the design of RAS. When we first envisioned the workshop, before beginning the study, we had anticipated that it would be purely about designing technology, whether designing surgical robots or designing other technologies for the OT that support RAS. However, given the issues that came up in the study around training and the influence of the physical configuration of technology and people in the OT on teamwork, participants were invited to think beyond the design of technology if they so wished.

Chapter 3 An initial theory of robot-assisted surgery

Overview

In preparing the proposal for this study, based on existing knowledge regarding how technology becomes embedded into health-care practice and the nature of communication, teamwork and decision-making in the OT, and consideration of the broader surgical safety literature,101,102 we developed a series of candidate theories for further exploration. In this chapter, we present that literature and the resulting candidate theories with which we started this study.

Integrating robot-assisted surgery into surgical practice

The successful introduction of technology involves interactions between individual clinicians and their work environment until the technology becomes embedded (routinely incorporated into everyday work) and integrated (sustained over time) into routine practice, a process known as ‘normalisation’. 103 Factors impacting the integration of health-care technologies include the skill mix and motivation of users; the acceptability of the technology to clinicians and patients; training; division of labour and workload; organisational culture; and whether or not the introduction of the technology was clinician led. 104,105

When there is a mismatch between the technology and the work practice of the users, users may, both individually and as a group, adapt the technology (system tailoring) and the way they work (task tailoring), both behaviours that have previously been reported in the OT. 106 Such ‘workarounds’ can often lead to a variety of ‘unintended consequences’ that may result in processes and outcomes that are undesirable and/or were unanticipated when the technology was introduced. 107–110

Normalisation process theory suggests that, for successful integration to occur, four key constructs need to be considered: (1) coherence: sense-making – where individuals make sense of the new technology and how it differs from existing practice; (2) cognitive participation – the process of engaging individuals with the introduction of the technology; (3) collective action – how the work processes are adapted and altered to make the intervention happen; and (4) reflexive monitoring – the formal and informal appraisal of the benefits and costs of the intervention. 46,103,111 This suggests that if members of the OT team have been able to ‘make sense’ of RAS, have been engaged in the process of implementation, have been able to adapt their work processes and are able to identify potential benefits of its introduction, it is more likely to become embedded into surgical practice, being used routinely and successfully for surgical operations when it offers benefits to the patient.

Meanwhile, reports of the use of RAS highlight that there is a learning curve for the whole team112 and point to the need for a highly motivated113 and/or dedicated robotic team. 114–116 This suggests that when the OT team is experienced in RAS and members are motivated, RAS is more likely to become embedded into surgical practice.

Communication and teamwork in the operating theatre

The successful performance of a surgical operation is dependent on collaboration among staff from different professional groups. In the UK, the team brought together to perform an operation typically consists of:

-

a consultant surgeon

-

a first assistant – a role performed by a surgical trainee, a theatre nurse or an ODP who has undertaken first assistant training, or occasionally by another consultant surgeon, in which they are working within the sterile field and are responsible for assisting the surgeon in carrying out the operation, particularly assisting with retraction

-

a scrub practitioner – a role performed either by a theatre nurse or by an ODP, working within the sterile field, in which they are responsible for supporting the surgeon in carrying out the operation, particularly ensuring the availability and the sterility of surgical instruments and passing them to the surgeon as they are needed

-

a circulating practitioner – a role performed either by a theatre nurse or by an ODP, working outside the sterile field and responsible for supporting those within the sterile field, particularly the scrub practitioner, by obtaining the necessary equipment and liaising and co-ordinating with others within the OT and in the wider operating department

-

an anaesthetist – working outside the sterile field, responsible for providing anaesthesia and for monitoring and treating, as necessary, the effects of the anaesthetic and the surgery

-

an anaesthetic assistant – a role performed either by a theatre nurse or by an ODP, working outside the sterile field, who assists the anaesthetist in the administration and monitoring of anaesthesia.

This complex division of labour requires team members to use their different skills to collaboratively accomplish a single, principal activity. 28

Communication and teamwork in the OT is a topic that has received much attention over recent years, due to failures in communication and teamwork being identified as key factors in adverse events in the OT. 72 Communication in the OT is defined as ‘the quality and quantity of information exchanged among members of the team’. 117 It has been found to be variable in both quality and quantity, with a lack of formal exchanges between staff about essential information and the completion of basic procedural tasks. 118 There is considerable distraction and interruption in the OT,119 which may negatively impact on communication and teamwork. 120 Communication in the OT may suffer from poor timing, missing or inaccurate information, failure to resolve issues and the exclusion of key individuals. 121 Communication and teamwork failures are a common source of surgical flow disruptions, defined as deviations from the natural progression of an operation, and surgical errors have been found to increase significantly with increases in flow disruptions. 122 Even when communication and teamwork failures do not result in an adverse event, they can limit the surgical team’s ability to compensate for a major event,123 whereas effective teamwork in the OT can reduce the number of small problems and prevent them from escalating to more serious situations. 124 Thus, teamwork and communication are both considered to be markers of surgical excellence. 125

While such work on the relationship between communication and teamwork in the OT and patient safety has been important in highlighting the significance of this area, a limitation of existing work is that too often the emphasis has been on applying the label of failure, rather than seeking to understand and explain, with the terms communication and teamwork often being used interchangeably. 126 The ‘workplace studies’ literature provides an alternative view of communication and teamwork in the OT. Drawing on ethnographic data and naturalistic video recordings, workplace studies are concerned with the interplay of talk, visual conduct and the use of tools and technologies in the achievement of work in complex settings. 73,75 Such studies emphasise the careful collaboration and co-ordination that is an essential part of surgical practice, and illustrate how oral communication is just one strategy used for ensuring smooth co-ordination among team members. 28 This literature draws on the concept of awareness, used to refer to the ways in which members of a team display their activities to, and monitor the activities of, their team members in order to support their collaborative work. 127,128 As such, awareness is seen as essential for effective collaborative work. Such awareness is typically characterised as being ‘effortless’,128 and workplace studies point to the way in which, when co-located, co-operating actors are able to align and integrate their activities through such mutual display and monitoring. 127 For example, there are a number of strategies that scrub practitioners draw on to ensure the smooth passing of instruments in a safe and timely manner. Before the operation, the scrub practitioner will organise potentially relevant instruments, positioning and orientating them so they can be grasped or handed safely. During the operation the scrub practitioner will pay attention to the actions of the surgeon and may reorganise the instruments according to when, based on the sequence of actions observed, the scrub practitioner anticipates they will be required, which also enables the surgeon to take the instrument from the table directly. 28 Through this careful attention to the ongoing work, the scrub practitioner is also able to anticipate when an instrument is required, obviating the need for an oral request from the surgeon. This would be an example of what is referred to as by-product awareness, being generated in the course of activities, in contrast to add-on awareness, whereby team members do additional work either to display to colleagues the status of the work and their activities or to monitor their colleagues’ work. 129 Such studies would imply that the separation of the surgeon from the rest of the OT team in RAS would impact co-ordination because team members are less able to monitor the surgeon’s actions.

Such studies also point to the operation as a moment of training and the embodied conduct used for this purpose; surgeons combine talk and gesture to enable trainees to follow and make sense of a surgical procedure, supported by timely and relevant contributions from other members of the surgical team, and draw on the surgical trainee’s talk and gesture to determine their level of understanding. 87 In laparoscopic surgery, all team members have access to the same view of the surgical site, but talk and gesture are used to ensure that others see what the surgeon sees. 130 This would suggest that the separation of the surgeon and the trainee in RAS and their different views of the surgical site is likely to impact on training.

Decision-making in the operating theatre

Decision-making is an important component of surgical expertise. 131 Despite flexible decision-making strategies being a behavioural marker of surgical excellence,125 there is a paucity of research on decision-making in the OT, and what research there is tends to focus solely on the decision-making of the surgeon. 132,133 Factors that affect the surgeon’s decision-making in the OT include instrument complexity,133 although the decision-making strategy used (rapid, intuitive mode vs. deliberate comparison of alternative courses of action) is not affected by whether the surgery is open or laparoscopic. 134

Situational awareness is defined as the perception of elements in the environment, the comprehension of their meaning and the projection of their status in the near future. 135 The surgeon’s position in the console suggests a reduction in the surgeon’s situational awareness, which would have implications for the surgeon’s decision-making. For example, Klein,136 in his recognition primed decision (RPD) model, highlights the importance of context or situation in ‘triggering’ mental models that guide decision-making in numerous complex decision situations. One model of intraoperative decision-making suggests a continuous cycle where, with the preoperative plan in mind, the surgeon assesses the situation, reconciles new information with existing information and, subsequently, implements a revised course of action. 137 In this cycle, through the use of existing mental models, information may be actively sought or, by remaining observant of what is happening in the OT, perceived without active seeking. Such theories would suggest that a reduction in situational awareness has the potential to negatively impact surgeon decision-making. This is supported by studies that have found that better situational awareness of the surgeon is associated with fewer surgical errors. 138,139

While the decision-making theories described above all focus on individual cognition, the theory of distributed cognition encourages us to think about not only what information the surgeon has access to but also what information other members of the team have access to and how that information is propagated through the system. 140 The spatial configuration of OT teams is not arbitrary but affords particular views of the patient, the rest of the team and different tools and technologies, with the result that different team members have access to different information to inform their decision-making. 141 Consequently, any change to the spatial configuration is likely to have an impact on decision-making. What is key is how that information is shared. For example, Hazlehurst et al. 142 describe how, in cardiac surgery, the surgeon and perfusionist each have only partial access to the information necessary for a successful outcome, with situational awareness for both being achieved through oral exchange.

In RAS, the surgeon is not able to see the patient directly, so to maintain situational awareness he or she is more dependent on the rest of the team communicating the status of the patient. 23,57

Summary

Through consideration of the literature presented above, we developed the following candidate theories for further exploration.

-

Inexperienced team: when the OT team is less experienced in RAS (C), they have more difficulties in setting up and positioning the robot, which can reduce the ease with which OT team members have access to the patient on the operating table (M), resulting in increased operation duration, conversion to open surgery and complications (O).

-

Experienced team: when OT teams are motivated to use RAS and as they become more familiar with the equipment through repeated use (C), they are better able to develop strategies to overcome difficulties created in this reconfigured environment (M), resulting in effective co-ordination, teamwork and communication and reduced operation duration (O).

-

Team involvement: if the whole OT team can feel the advantages of RAS outweigh its disadvantages and are involved in the decision to introduce it (C), they will be more motivated to work together to develop solutions to problems that may arise when they are using it to carry out operations (M), supporting the integration of RAS into routine practice (O).

-

Co-ordination: when the surgeon is separated from the rest of the OT team (C), the team is less aware of the surgeon’s actions, making it more difficult to co-ordinate their actions during the operation (M) and so the operation takes longer (O).

-

Training: when surgeons and trainees have different views of the surgical site (C), it is harder for the surgeon to explain what is happening and monitor the trainee’s understanding (M), resulting in the trainee not learning as much as they would in other forms of surgery (O).

-