Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 11/1024/02. The contractual start date was in March 2013. The final report began editorial review in January 2016 and was accepted for publication in December 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Alex D Tulloch and Faisil Sethi work as consultant psychiatrists for South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust. Faisil Sethi is vice chairperson of the National Association of Psychiatric Intensive Care Units.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Bowers et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Acute inpatient care

In psychiatric services, acute inpatient care may be defined as the short-term care and treatment of people with greater psychiatric symptom severity within accommodation that is secure and supervised 24 hours per day. Its primary purpose is to maintain the safety of patients and others, as well as to allow more substantial assessment and provide treatment that is not easily or safely deployed in community settings. Reflecting these objectives, acute inpatient care is often provided on a compulsory basis, via mental health legislation and its associated procedures. In the UK, acute inpatient care is provided primarily via the NHS, with small psychiatric hospitals or units consisting of several wards serving their local areas. These wards are staffed by a mix of qualified and unqualified nurses, supported by occupational therapists, psychologists and a range of medical staff, including consultant psychiatrists. Lengths of stay are generally between 2 and 3 weeks, and more than half of patients either are admitted compulsorily or become subject to compulsory care during the course of their stay.

Given that the justification for compulsory care is the risk that patients pose to themselves or others, and as all patients are admitted (compulsorily or not) because they are severely and acutely mentally ill, an acute psychiatric ward is typically populated by a mix of patients who may behave in a very disturbed, disorganised and risky way. Specifically, acute psychiatric inpatients may be verbally abusive, damage property, assault others, seek to escape, harm themselves, attempt suicide, refuse or resist treatment that will help them, refuse to eat, drink or wash, or behave in other ways that those around them find difficult to tolerate. In order to manage such behaviours safely and respectfully, in crisis situations the staff may use a number of different containment methods, ranging from oral sedating medication to special supervision and observation, manual restraint of the patient, rapid tranquillisation via injection, seclusion or transfer to a psychiatric intensive care unit (PICU). Although generally unheard of in current British psychiatric practice, related methods such as the use of net beds (a bed enclosed in a net cage) and mechanical restraints remain in use in other parts of the world.

Seclusion

Seclusion is the isolation of a disturbed psychiatric patient in a robust locked room. A recent literature review1 found that 12–48% of patients were secluded at least once during their admission to acute wards. Secluded patients were younger, more likely to be formally detained and less likely to suffer from depression than non-secluded patients. Sex, ethnicity and socioeconomic status had no influence on seclusion rates. Seclusion made patients feel angry, lonely, sad, hopeless, punished and vulnerable. The efficacy of seclusion in reducing aggression and injuries to staff and patients has not been evaluated. The City-128 study2 found that seclusion use on wards was associated with increased rather than reduced aggression, and that seclusion usage and provision were associated in complex ways with the proximity of a PICU and the use of locked doors on acute wards. However, these analyses were based on data aggregated at ward level at each time point and so it was not possible to estimate the effect of seclusion at the individual level. A study published in 20123 found that the outcome of seclusion (judged as the repetition of physical violence to others) was no better than that of time out (a request for the patient to stay in their own room for a period, without the door being locked); however, the sample size was modest and the analysis did not control for differences in patient characteristics.

Some hospitals in the UK have begun to end the use of seclusion. At the time of writing, around 25–50% of hospitals do not seclude patients at all and do not have seclusion rooms for acute psychiatric patients. However, in some hospitals, up to one-quarter of admitted patients are secluded once or more during the first 2 weeks of their admission. 2,3 Although many countries (e.g. the USA, Australia, the Netherlands) are running large-scale programmes to reduce seclusion use, with varying success, it is not known how some of our UK hospitals are achieving seclusion-free care or if the outcomes in terms of aggression rates and injuries are better or worse. We do know that access to seclusion rooms in UK hospitals is linked to when the unit concerned was built, with more modern units less likely to have such a room. 2 Presumably as new units have been built to replace older ones, seclusion has been eradicated with this move. However, it is not known whether or not this been accomplished by substitution (greater use of alternative forms of containment), early intervention (faster progression to manual restraint during crises leading to easier resolution), therapeutic intensity (behavioural or psychotherapeutic interventions to avert crises before they occur) or non-standard transfers (to other hospitals or services). The use of manual restraint is clearly critical, as this is a gateway measure to other coercive interventions (seclusion, a PICU, rapid tranquillisation) or a replacement for them if utilised continuously for longer durations.

The use of coercive containment methods is an area of primary concern to service users. Previous research has shown that patients rate seclusion as less acceptable than nearly every other form of containment. 4 In line with this finding, a recent report by MIND on acute inpatient care5 calls for the elimination of seclusion and manual restraint as soon as possible, and their replacement with a system based on co-operation, negotiation and mutual respect.

Most psychiatric services in the UK do use seclusion, yet there is a widespread aspiration to minimise the use of such interventions, which are unpalatable to nurses6 and patients. 5 A key practical question for managers is ‘what are the services that are not using seclusion actually doing to manage disturbed behaviour in a safe and successful manner?’. This is not a straightforward question and simply asking professionals does not generate an adequate answer. If you ask nurses at a hospital that does not use seclusion to explain how they manage without it, they will struggle to find an answer. They simply do not use it and do not feel the need for it. Yet nurses at hospitals that do use seclusion struggle to understand how others do without it and speculate that sedating drugs are given more often, and in higher doses, or that patients are held in manual restraint for long periods. These questions are critical for psychiatric service managers faced with demands to reduce reliance on coercive methods and make inpatient care more efficient. The absence of answers to these questions holds back many who might otherwise abolish seclusion use by simply decommissioning seclusion rooms or reducing the numbers of PICU beds.

Psychiatric intensive care units

When risks are higher than the norm for an acute psychiatric ward, patients can be transferred to a PICU. PICUs are small wards with higher levels of nursing and other staff, built on an open-plan design to ease observation, often (but not always) locked and sometimes (but not always) with facilities for seclusion. A recent literature review7 identified that typical PICU patients are male, younger, single, unemployed, suffering from schizophrenia or mania, from a black Caribbean or African background and legally detained, and have a forensic history. The most common reason for admission is aggression management and most patients stay for < 1 week. Only two studies provide any data on cost and, of these, only one is from the UK; this study gives a cost per patient per annum of £103,501, based mainly on staffing costs in the mid-1990s. 8 The other study, from Canada, gives a cost of CA$365 per patient per day, compared with CA$235 for an acute unit9 (i.e. a difference of 55%). Information on costs is lacking, and the cost-effectiveness of PICU care relative to acute care has never been identified or described. The same literature review7 concludes that PICUs have been very poorly evaluated for their efficacy, with only two small-scale studies carried out on single units reporting decreases in aggression. Given the expenditure on PICU care, it is anomalous that no systematic evaluation has ever taken place.

An analysis of data from the Service Delivery and Organisation-funded City-128 cross-sectional multivariate study of acute psychiatric wards of differences in access to PICU care has raised questions about outcomes. 10 Controlling for other factors, wards with greater ease of PICU access did not have lower rates of adverse incidents. PICU transfers were associated with seclusion, manual restraint and other severe containment measures, and were triggered by aggression, drug use and absconding. The findings suggest that transferring patients to a PICU may not be an effective means of reducing the frequency of adverse incidents on acute wards. Longitudinal research using individual patient-level data is required to assess whether or not this conclusion is valid.

The past few years have seen several innovations and changes to PICU provision. In some cases, a significant number of PICU beds have been allocated to the treatment of transfers of acutely mentally ill people from the prison system, leading to the reduced availability of a PICU for transfers of difficult and high-risk patients from acute psychiatric wards. At the same time, the increasing practice of keeping acute psychiatric wards locked is likely to have led to reduced transfers of patients to PICUs in order to prevent risk resulting from the patient absconding. 11,12 Finally, some new psychiatric units have opened that have no PICU provision at all, or, in other instances, PICU provision has been limited to a single site within a much larger multihospital NHS trust. The consequences and efficacy of these differing systems for managing high-risk patients has been neither compared nor evaluated on a wide scale.

Psychiatric intensive care unit care is a potentially very expensive intervention. The provision of a special ward with high staffing levels could not be anything other. However, this cost may be acceptable if outcomes are improved or savings occur as a result of reduced length of stay or reduced use of other services. Even the provision of a PICU may itself be cost neutral to some degree if it enables lower nurse staffing levels on the acute wards to which it provides a service. The question of cost and outcome, therefore, has a clear bearing on the choices service managers must make in this area. However, currently there is no research evidence on which they can draw, underscoring the need for the projects proposed here.

The Seclusion and Psychiatric Intensive Care Evaluation Study

Our research was devised to obtain answers to some of these questions and consisted of two linked studies. The first of these studies used the electronic patient record system of one NHS trust to compare patients transferred to a PICU with those who were not and, in addition, compare patients subject to seclusion with those who were not. We hoped to understand both the factors associated with the use of each intervention and if each intervention altered the associated outcomes and costs. The results of this study are presented in Chapters 2 and 3.

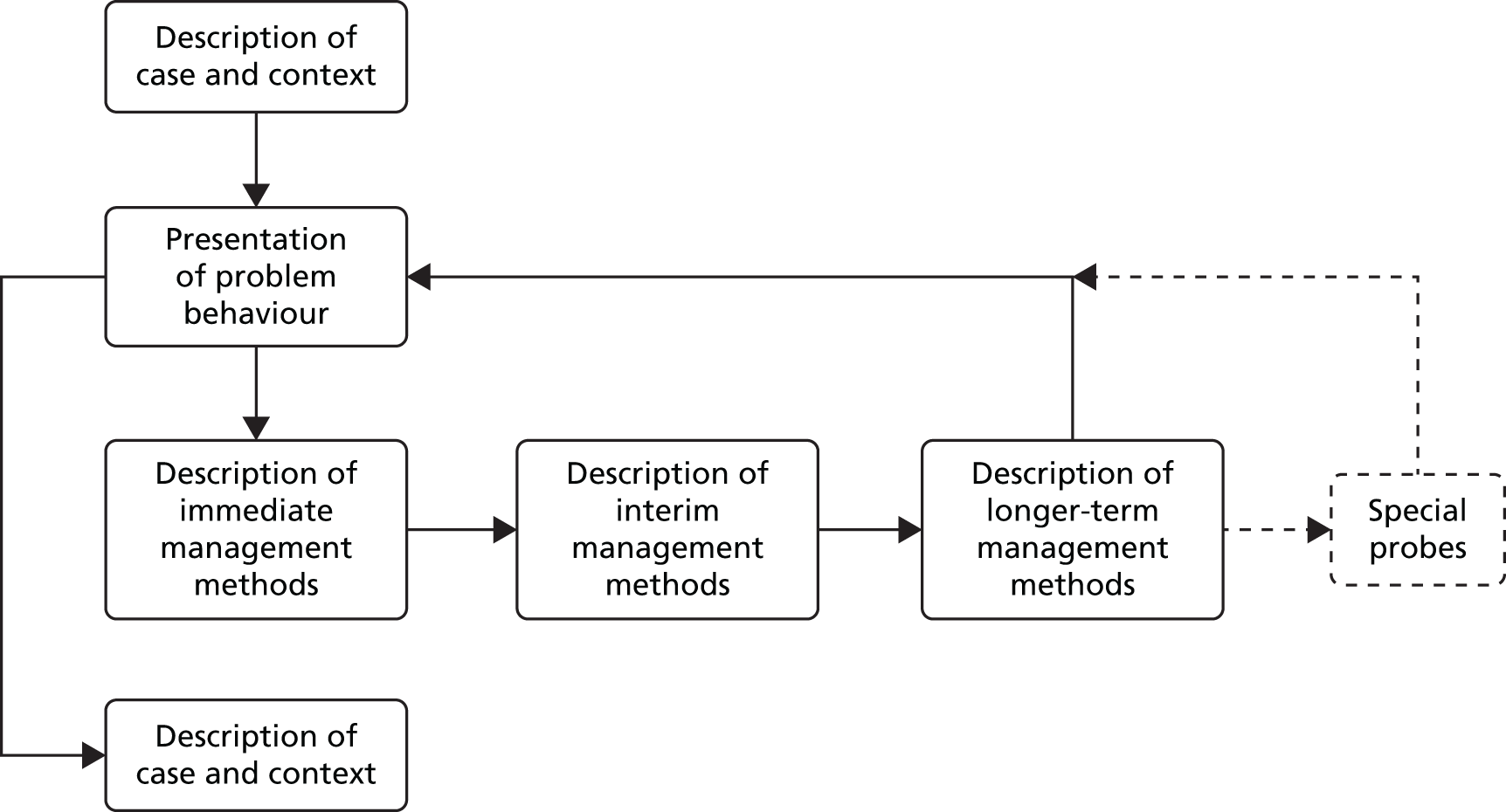

In the second study, the sets of all interventions used by nurses to manage disturbed behaviours were collected via structured interview and questionnaires. These data were collected across hospitals that did and did not have direct access of seclusion rooms or PICUs, thus making it possible to compare the differences in the management strategies used by nurses in the absence of seclusion or PICU facilities. The results of this study are presented in Chapters 4 and 5.

A final discussion (see Chapter 6) brings together the range of results obtained across the entire Seclusion and Psychiatric Intensive Care Evaluation Study (SPICES) and considers what these results might mean for future clinical care and research.

Chapter 2 Predictors of use of a psychiatric intensive care unit and seclusion

This chapter is based on data from Cullen et al. 13 under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted reuse, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Introduction

Comprehensive reviews of PICU14 and seclusion1 practices indicate that PICU patients are typically male, young (aged ≈30 years), diagnosed with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder, and legally detained, with some evidence that PICU patients are more likely than non-PICU patients to be of black African or Caribbean heritage. Although secluded patients are also likely to be young and legally detained, seclusion has not been consistently associated with either patient sex or patient ethnicity. 1 Similar to PICU patients, however, secluded patients are commonly diagnosed with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, with personality disorder also reported as more prevalent in this population. With regard to behavioural precursors, aggressive, disruptive and chaotic behaviour, acute psychosis, absconsion and self-harm are all strongly associated with the use of both a PICU and seclusion. 1,14 Although there is some evidence that these behavioural precursors differ between men and women, the extent to which patient sex is associated with PICU and seclusion duration (which one might expect to be influenced by preceding behaviours) has yet to be examined.

There are several notable limitations of the studies described in these reviews. First, many of the previous studies are descriptive in nature, for example reporting the average age or the proportion of men without reference to a control population. Furthermore, of those that have statistically compared patients receiving these treatments with general psychiatric patients, few have included an appropriate control group. Rather, studies often compare PICU and secluded patients with the entire hospital/ward population as opposed to identifying a subgroup of patients who are at risk but who do not receive these treatments. Finally, studies reporting differences in patient characteristics across treated and untreated groups have typically failed to adjust for patient behaviours that might account for these differences. In the light of these limitations, the aims of the current study were to:

-

use multiple logistic regression analyses, applied to two samples of treated (cases) and untreated subjects (controls), to determine the demographic, clinical and behavioural characteristics associated with both PICU care and seclusion

-

explore interactions between patient sex and other predictors of PICU and seclusion receipt.

Methods

The Biomedical Research Centre Clinical Records Interactive Search database

Source data

South London and Maudsley (SLaM) provides secondary mental health care to a population of approximately 1.1 million residents from four south-east London boroughs (Lambeth, Southwark, Lewisham and Croydon). The Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) Clinical Records Interactive Search (CRIS), described in detail in other studies,15–17 comprises the anonymised electronic medical records of over 200,000 patients who have been in contact with SLaM services since 2006, when electronic records were implemented across the trust. The available data are either structured data or free-text data. Structured data contain a variety of data types (numbers, dates or short standardised text) including personal details, demographic information and details of clinical activity such as appointments, dates of periods of service by clinical teams and details associated with free-text records (e.g. the date on which a particular item of correspondence was created and added to the case notes). Free-text data comprise mainly correspondence (e.g. documentation and communication concerning the patient) and progress notes that are recorded regularly by staff. CRIS is capable of extracting data in both formats, that is, information held in both structured fields and free-text entries.

Anonymisation process

The anonymisation procedure within CRIS consists of two stages. 18 In the first, patient-identifiable information is stripped from the structured data in CRIS; dates of birth are truncated to month and year of birth, ethnicity is grouped into broad categories, addresses are converted to the corresponding Office for National Statistics output area, and the names of the service user and contacts are removed. A pseudonymous identifier is created, replacing local and national identifying numbers. In a second stage, free-text data are cleaned of names: wherever names or recorded aliases for the user or their relatives are encountered in the free text, they are replaced with ‘ZZZZZ’ or similar. Once cleaned, data are organised into around 100 tables ranging from the small (tables containing infrequently used test scores) to the extremely large (e.g. the table containing free-text progress notes, which has over 10 million rows).

Ethics approval

The BRC CRIS security procedures have been reviewed by the Oxfordshire Research Ethics Committee (08/H0606/71) and the tool is treated for ethics purposes as an anonymised database: that is, access is granted after review of applications by an oversight committee. Approval for the current study was obtained from the oversight committee in March 2014.

Clinical Records Interactive Search data extraction techniques

Structured Query Language (SQL) can be used to extract data held in CRIS (both in structured fields and free text) to create data tables that can then be manipulated, merged (joined) and exported to other software such as Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) or Stata® (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). SQL allows the retrieval of records meeting specified criteria, such as those containing particular words or those that meet criteria in other linked fields (e.g. records made during a time interval defined separately for each sample of individuals). The use of SQL to interrogate the CRIS database has huge advantages, in terms of both time and accuracy, over manually searching data to identify records of relevance.

Psychiatric intensive care unit cohort

Identification of psychiatric intensive care unit cohort cases

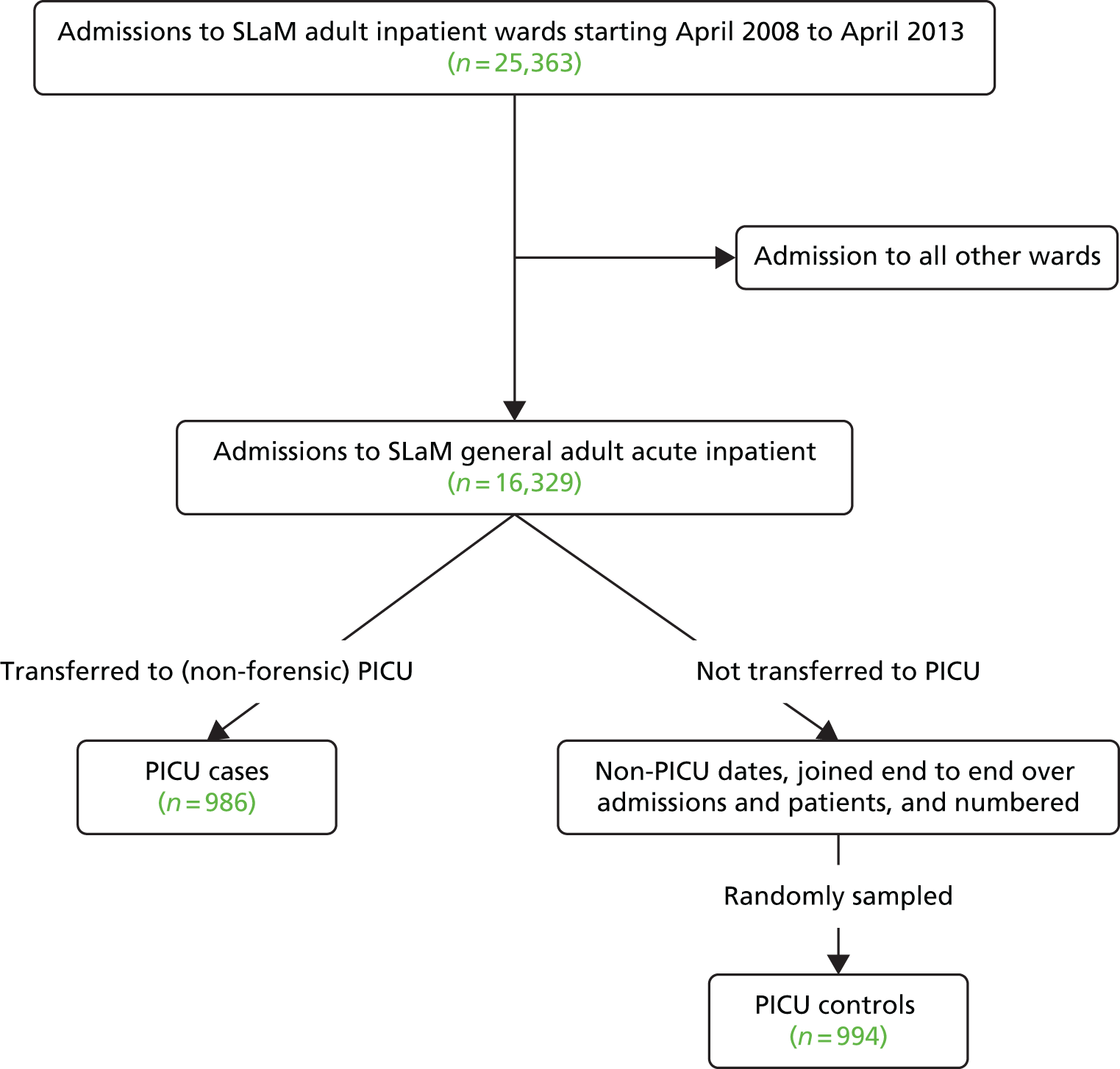

Psychiatric intensive care unit cohort services in SLaM are provided by five wards: four in general adult services (three male only and one female only) and one within the forensic inpatient service. PICU cases (n = 986) were defined as all transfers of patients from general adult acute wards to a (non-forensic) PICU ward occurring during the study period of April 2008 to April 2013. Figure 1 summarises how these PICU cases relate to all admissions during the same period. Direct admissions to a PICU from the community were excluded primarily because our method depended on being able to code behaviours in the 3 days prior to entry into the PICU and the available notes for patients just admitted to hospital were considered unlikely to suffice. In addition, as we hypothesised that factors predicting PICU transfer would differ substantially among general adult and forensic wards (and our primary interest was in the former) we also excluded transfers from forensic wards to any PICU and all transfers into the forensic PICU.

FIGURE 1.

Identification of PICU cases (treated) and controls (untreated).

Identification of psychiatric intensive care unit controls

We used SQL to obtain a control group of patients treated in general adult wards to serve as a comparison for the PICU case group (see Figure 1). These controls were randomly selected from a population of patient-day combinations – the sum of all days on which a particular patient could have been transferred to a PICU but was not. The procedure followed was this: we first created a data set that comprised all admissions to general adult wards between April 2008 and April 2013; from these admissions, we then excluded dates corresponding to periods of treatment in PICU wards, including the date of transfer to and out of the PICU ward. These non-PICU periods of time were then combined to create a data set representing all general adult (non-PICU) inpatient-days for all patients admitted during the study period. These inpatient-days were then assigned a sequential number such that each number corresponded uniquely to a particular date, within a particular admission, for an individual patient. Random numbers, corresponding to a specific inpatient date, were then generated with a sampling probability rate of 0.0017 and used to identify a PICU control group of approximately equal size to the PICU case group (n = 994). This method is truly population based, avoiding the greatest threat to the validity of case–control studies. The way that it combines the selection of a subject and a non-transfer date also increases validity. Because the method for defining behavioural predictors depends on their measurement in the period directly before transfer or non-transfer to a PICU (see Preparation of intermediate data sets), definition of a non-transfer date subsequent to selection of controls would have introduced bias: whether or not because of differential length of the at-risk period between subjects (long vs. short admission) or systematic selection of a particular point in admission.

Seclusion cohort

Seclusion cases

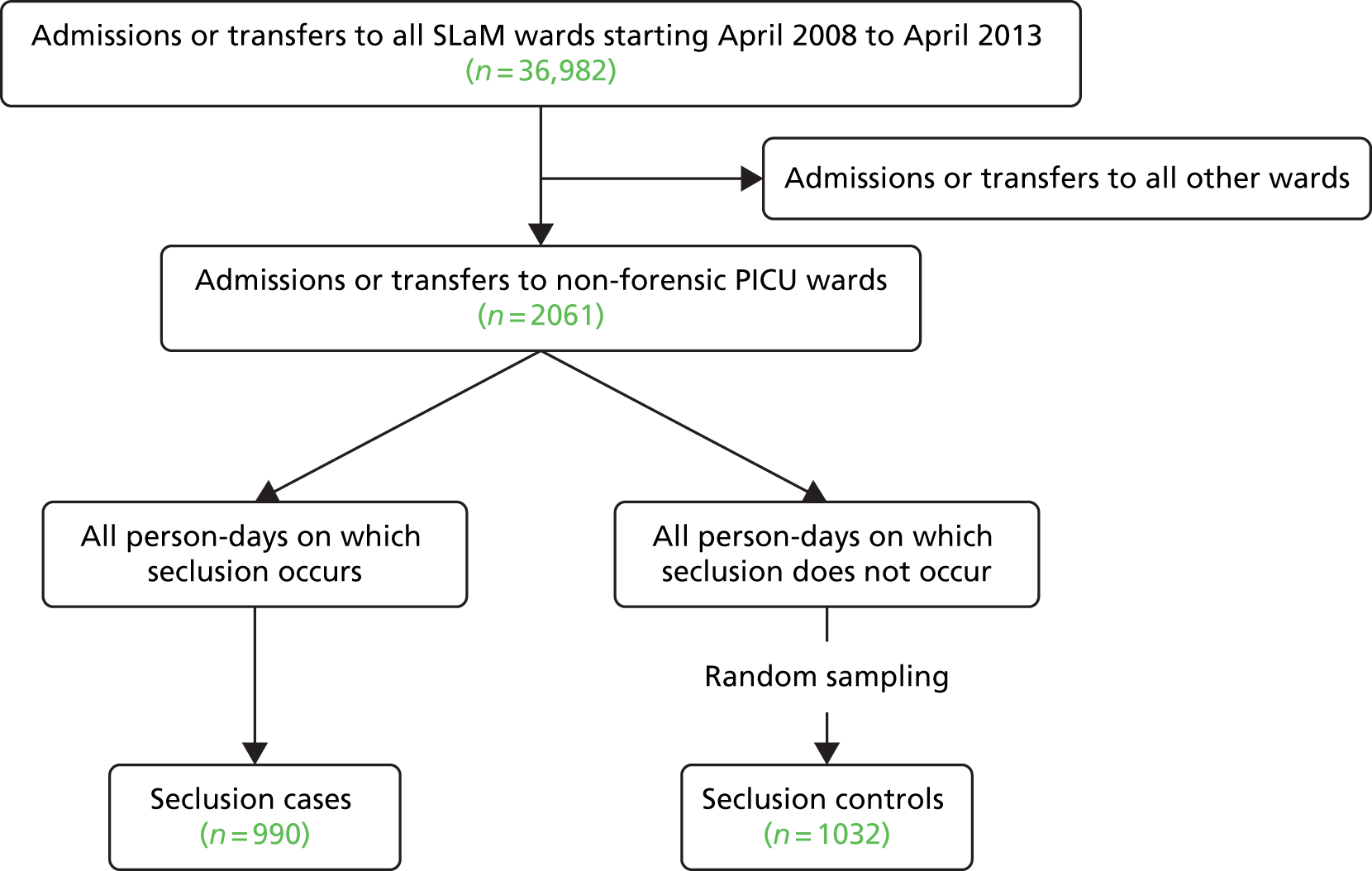

The use of seclusion is recorded in free-text progress notes within the electronic patient record rather than in any structured field. Relevant free-text data were therefore extracted and used to identify seclusion spells. Using SQL, we initially extracted progress notes containing the words ‘seclusion’, ‘supervised confinement’ or ‘solitary confinement’. We manually cleaned these to create a database comprising details of all seclusion spells occurring during the study period (n = 1478). Based on the assumption that seclusion practices across general and forensic wards might also differ substantially, seclusions occurring on forensic wards (n = 240) were subsequently excluded from the data set. We also excluded seclusions on other non-PICU wards, which formed only a small proportion of the non-forensic seclusions (n = 248), in order to reduce heterogeneity. Seclusion episodes examined in the current study were therefore those that occurred on the four non-forensic PICU wards (n = 990). Figure 2 summarises the procedure used to construct the seclusion databases.

FIGURE 2.

Identification of seclusion cases (treated) and controls (untreated).

Seclusion controls

Seclusion controls were identified using a similar procedure to that used to identify PICU controls (summarised in Figure 2). As our seclusion cases were restricted to seclusion episodes occurring on PICU wards, seclusion controls were selected by randomly sampling dates from the set of patient-days on non-forensic PICU wards where the patient was neither in seclusion, sent to seclusion or returned from seclusion. To obtain these control dates, we first extracted a data set that included dates of all non-forensic PICU ward stays occurring between April 2008 and April 2013 (note that, as we did not exclude PICU patients admitted directly from the community, the base population from which potential controls were sampled exceeds the number of cases examined in the PICU analysis). Using the manually created seclusion database described above, dates corresponding to days when a patient was in seclusion at any time were excluded. These non-seclusion PICU periods were combined and numbered sequentially. Random numbers were then generated to identify dates that corresponded to time periods when a patient was not in seclusion using a sampling probability rate of 0.016. This yielded a seclusion control group of approximately equal size to the seclusion case group (n = 1032).

Consequences of how cases and controls were defined

It is important to note that at the analysis level, ‘cases’ refer to transfers into PICU treatment and into seclusion, and not to unique patients. Similarly, as set out above, controls are non-transfers of patients into a PICU or seclusion, rather than patients who are not transferred to a PICU or into seclusion. The same patient could, in principle, feature within a data set multiple times as a case (each time they are secluded or sent to a PICU) and also as a control (on any day during which they are not transferred). This respects the fundamental principle of case–control design, which is that any patient who is at risk of the outcome of interest should be eligible for selection as a control. The fact that an individual person may contribute more than one observation to the data set may create clustering within the data, a feature that must be taken account of by the selected method of analysis.

Treatment length

The number of days in PICU treatment was calculated as the difference between the date of transfer to the PICU ward and the data of transfer away from the PICU ward (or discharge, if the same). Length of time in seclusion was calculated as the number of days between the start and end data of seclusion; durations of 0 days indicated seclusion spells that were < 24 hours’ duration.

Extraction of predictor variables

Behavioural exposures

For each intervention (PICU and seclusion), we used a two-stage process to generate a set of potential behavioural predictors for later consideration alongside other potential predictors.

First, we generated a list of potentially relevant behavioural search terms directly from a sample of free-text progress notes. Specifically, a random sample of 500 such notes recorded on the day of PICU transfer or 2 days prior to these dates was extracted along with an analogous sample of notes made on the day of a seclusion commencement or the 2 days prior. The notes were manually reviewed to identify relevant incidents preceding PICU transfer and seclusion (e.g. aggressive/chaotic behaviour and absconsion), and words commonly used by clinical staff to describe these behaviours were recorded. Any behaviour that actually occurred after PICU transfer or after seclusion had started was excluded.

The second stage of this process involved limiting this list of words to those most strongly related to incidents that occurred prior to PICU transfer/seclusion. To achieve this, we extracted another random data set of 350 progress notes recorded within any psychiatric admission but that did not occur on the day of PICU transfer/seclusion or in the 2 days prior to these dates. These records were then manually coded to identify those containing the words generated in the previous step. Before analysis, related words were grouped together; for example, absconded was grouped with abscond, absconded and absconding. Because the resulting groups would be used in a later stage of the research as a means of tagging extracted records, they were represented as regular expressions, in which literal character strings were sometimes combined with the use of a wildcard operator (*) and could be combined with Boolean operators. Table 1 lists these ‘keywords’ along with potential matches and examples of relevant, related behaviours.

| Search term | Behaviours of interest | Examples of behaviours as recorded in notes | Use in seclusion analysis | Use in PICU analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abscon* | Actual absconsion or serious attempts at absconsion |

|

Not screened | Retained |

| Abus* | Verbally abusive behaviour |

|

Retained | Retained |

| Aggress* | Verbal or physical aggression directed at others or objects |

|

Retained | Retained |

| Agitat* | Observed agitated behaviour |

|

Retained | Retained |

| Angry OR anger | Reported as behaving in an angry way |

|

Discarded | Not screened |

| Arous* | Observed aroused behaviour |

|

Discarded | Not screened |

| Assault* | Actual or attempted physical assault |

|

Retained | Discarded |

| Attack* | Actual or attempted attacks |

|

Not screened | Retained |

| AWOL | Patient recorded as AWOL |

|

Not screened | Retained |

| Demand* | Demanding of resources or change in treatment |

|

Retained | Retained |

| Hit* | Actual or attempted physical assault |

|

Retained | Not screened |

| Hostile | Reported as behaving in a hostile way |

|

Discarded | Not screened |

| Incident | Some kind of disorderly or violent incident occurred |

|

Not screened | Discarded |

| Irritable* | Observed irritable behaviour |

|

Not screened | Retained |

| Manic | Observed manic behaviour |

|

Not screened | Retained |

| Push | Pushing someone else |

|

Discarded | Not screened |

| Refus* | Refusal of staff requests/treatment |

|

Not screened | Retained |

| Restrain* | Restraint of patient by staff |

|

Retained | Not screened |

| Shout* | Shouting directed at others |

|

Retained | Retained |

| Threat* | Verbal threats of harm to others |

|

Retained | Retained |

| Threw OR throw* | Objects thrown at others or destruction of property |

|

Retained | Retained |

| Violen* | Actual physical violence |

|

Retained | Retained |

Having created two ‘transfer’ data sets and one ‘non-transfer’ data set, two multivariable logistic regression analyses were run. All keywords for PICU transfer and for seclusion transfer were entered into separate multivariable logistic regression analyses in order to identify the keywords that best discriminated between events that occurred prior to PICU transfer or, in the other analysis, seclusion and those that did not. Keywords that were significant at the 0.1 level in each of the multivariable analyses were used as search terms in the final data extraction. As will be described below, the numbers of data used in these initial steps were two orders of magnitude smaller than the row sets used for the final analyses.

Preparation of intermediate data sets

Having performed these preparatory steps, we proceeded to extract an intermediate, ‘working’ data set for each of the analyses using SQL. To the anonymous person identifier (ID) and sample date, we joined (1) sex, (2) ethnicity, (3) date of birth, (4) admission date for the current SLaM inpatient episode, (5) primary International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition19 diagnosis nearest to date of discharge and (6) legal status under the Mental Health Act (MHA)20 at midnight on the sampling date. Time between admission and the sample date was recoded as a four-level categorical variable (< 7 days, 8–21 days, 22–60 days, > 60 days) based on the distribution of the data. For a small number of observations (< 1%) we were able to code missing primary diagnosis manually based on correspondence. Primary diagnoses were extracted from structured fields or retrieved manually from admission, discharge or tribunal reports if unavailable (< 1%). When multiple records were available, which may arise, for example, when a patient receives different diagnoses at different admissions, we extracted the record closest to the sampling date (i.e. the date of PICU transfer or date of seclusion for cases and random sampling date for controls). MHA section was determined at midnight on the sampling date.

The ‘left-hand’ part of each data set described above was structured as a single row of data for each combination of person and sample date. We then joined this to any free-text progress note that (1) occurred on the sampling date – that is, the date of PICU transfer or seclusion for cases and the random sampling date for controls – or either of the 2 days prior to these dates, and (2) that contained at least one of the relevant search terms identified in the two-stage process described above. This join was performed such that each progress note required its own row in the data set; thus, for example, if three separate progress notes were joined to a single person–sample date combination, the pre-existing single row would be expanded to form three rows. Accordingly, the PICU intermediate data set comprised 22,504 data rows and the seclusion intermediate data set comprised 22,239 data rows.

The SQL script also generated additional columns containing an indicator variable for the presence or absence of each search term in the corresponding progress note. Once exported to a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet, each progress note was manually reviewed to determine whether or not the search term referred to a behaviour that actually occurred on the day of the event. The indicator variable was edited accordingly, such that in the final coded data set it represented the presence or absence of the behaviour in question. For example, a given record may have been identified using the SQL script that included the terms ‘Irritable’, ‘Aggress*’ and ‘Violen*’, with the columns associated with each of these three terms coded as 1. However, after reviewing the record, the text might actually state that the patient in question had been ‘irritable but had not shown any aggression or violence during the shift’; thus, the columns for ‘Aggress*’ and ‘Violen*’ would be changed from 1 (as coded by the SQL script) to 0.

After the data cleaning procedure was completed, both data sets were imported into Stata version 12 and the ‘max’ and ‘drop duplicates’ commands were used to collapse data across rows so that each combination of person and sample date was represented again by a single row within which each behavioural variable recorded the presence or absence of that behaviour over the entire 3-day period of sample date and two preceding days.

Statistical analyses

All analyses were conducted using Stata. The same procedure was used for the analysis of PICU and seclusion use; in all analyses, the BRC ID was included as a random effect in order to account for clustering at the patient level (i.e. within each data set a single patient could represent multiple cases or controls, by including the BRC ID as a random effect, correlations between data observations obtained by the same patient were accounted for). Univariable logistic regression analyses were first performed to examine associations between all predictor variables (demographic/clinical factors and behavioural precursors) and PICU/seclusion status. We then performed a multivariable analyses for each outcome (PICU and seclusion) that included all predictor variables, irrespective of whether or not they were significantly associated with the outcome in univariable analyses. We subsequently conducted exploratory multivariable analyses that included interaction effects between sex and all other predictor variables; that is, all predictor variables and all interaction effects (sex with all other predictors) were entered simultaneously, with subsequent removal of all effects with p ≥ 0.05. In the analyses presented in this chapter, we did not apply probability weight – as is typical in case–control studies – and therefore the intercept values are uninterpretable (weights were used in the derivation of propensity scores in Chapter 3).

Results

Predictors of psychiatric intensive care unit transfer

Sample

The PICU sample comprised 986 cases (PICU transfers) and 944 controls (PICU non-transfers). All of these observations originated from 1360 patients, of whom 693 contributed only non-PICU observations, 515 contributed only PICU observations and 152 contributed a mixture. The contribution that each group of people made to the total number of observations was as follows: those who were never transferred contributed a mean of 1.2 observations [standard deviation (SD) 0.4 observations], those who were only ever transferred to a PICU in our data set contributed a mean of 1.4 observations (SD 0.9 observations) and those who were both transferred and not transferred contributed a mean of 3.0 observations (SD 1.5 observations).

Univariable analyses

Table 2 presents the demographic and clinical characteristics for cases and controls, and the results of the univariable logistic regression analyses. PICU cases were significantly younger than controls (mean age 32.9 vs. 40.7 years, respectively; p < 0.001) and were less likely to be female [odds ratio (OR) 0.29; p < 0.001]. There was also a significant association between ethnicity and case status, whereby the likelihood of PICU transfer was approximately threefold higher among individuals of black African/Caribbean ethnicity than among those of white ethnicity (OR 2.97; p < 0.001); being of ‘other’ ethnicity was also associated with slightly elevated likelihood of PICU transfer, but this was not statistically significant. With regard to diagnosis, relative to patients with schizophrenia, those diagnosed with other psychotic disorders (including schizoaffective disorder) and bipolar disorder were significantly more likely to be transferred to a PICU ward (OR 2.04 and 3.69, respectively; p < 0.001), whereas the odds of transfer were significantly lower among those with ‘other’ diagnoses (OR 0.46; p < 0.001). Strong and highly significant associations were also observed between MHA section and PICU status, whereby patients on a civil section (section 2) and those on section 3 or a forensic section were significantly more likely to be transferred to a PICU than patients who were informal (OR 136.10 and 39.24, respectively; p < 0.001). Finally, the likelihood of PICU transfer decreased as the admission progressed in a dose–response fashion, whereby the odds of transfer were significantly lower at each subsequent time band relative to the first 7 days of the admission (p < 0.001 for all). Both ward and financial year were also significantly associated with the odds of transfer.

| Risk factor | Cases (N = 986), n (%) | Controls (N = 994), n (%) | Analyses | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||||||

| OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | |||

| Age (years) | ||||||||

| ≥ 45 | 151 (15) | 365 (37) | 1 | – | – | 1 | – | – |

| 35–44 | 220 (22) | 273 (27) | 2.62 | 1.72 to 4.01 | < 0.001 | 2.53 | 1.43 to 4.47 | 0.001 |

| 25–34 | 342 (35) | 216 (22) | 7.24 | 4.59 to 11.41 | < 0.001 | 4.35 | 2.36 to 8.01 | < 0.001 |

| < 25 | 273 (28) | 140 (14) | 9.08 | 5.52 to 14.95 | < 0.001 | 5.66 | 2.86 to 11.19 | < 0.001 |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 260 (26) | 429 (43) | 0.29 | 0.20 to 0.42 | < 0.001 | 0.11 | 0.04 to 0.28 | < 0.001 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||

| White | 273 (28) | 423 (43) | 1 | – | – | 1 | – | – |

| Black African/Caribbean | 625 (63) | 465 (47) | 2.97 | 2.08 to 4.23 | < 0.001 | 1.44 | 0.93 to 2.25 | 0.104 |

| Other | 88 (9) | 106 (11) | 1.50 | 0.87 to 2.59 | 0.148 | 1.06 | 0.54 to 2.09 | 0.865 |

| Diagnosis | ||||||||

| Schizophrenia | 353 (36) | 434 (44) | 1 | – | – | 1 | – | – |

| Other psychotic | 258 (26) | 191 (19) | 2.04 | 1.38 to 3.01 | < 0.001 | 1.53 | 0.93 to 2.49 | 0.091 |

| Bipolar disorder | 264 (27) | 131 (13) | 3.69 | 2.37 to 5.76 | < 0.001 | 1.88 | 1.08 to 3.27 | 0.026 |

| Personality disorder | 27 (3) | 49 (5) | 0.60 | 0.27 to 1.34 | 0.215 | 0.89 | 0.24 to 3.30 | 0.862 |

| Other diagnosis | 84 (9) | 189 (19) | 0.46 | 0.29 to 0.73 | 0.001 | 0.81 | 0.41 to 1.57 | 0.526 |

| MHA section | ||||||||

| Informal | 37 (4) | 445 (45) | Reference | – | – | Reference | – | – |

| Section 2 | 379 (38) | 130 (13) | 136.10 | 67.18 to 275.74 | < 0.001 | 10.58 | 5.17 to 21.66 | < 0.001 |

| Section 3/forensic | 570 (58) | 419 (42) | 39.24 | 22.16 to 69.52 | < 0.001 | 10.14 | 5.29 to 19.44 | < 0.001 |

| Time since admission (days) | ||||||||

| Male and female | ||||||||

| ≤ 7 (all) | 409 (41) | 191 (19) | Reference | – | – | |||

| 8–21 | 199 (20) | 186 (18) | 0.33 | 0.21 to 0.52 | < 0.001 | |||

| 22–60 | 188 (19) | 291 (29) | 0.13 | 0.08 to 0.20 | < 0.001 | |||

| > 60 | 190 (19) | 326 (33) | 0.09 | 0.05 to 0.15 | < 0.001 | |||

| Male | ||||||||

| ≤ 7 (all) | 1 | – | – | |||||

| 8–21 | 0.34 | 0.17 to 0.70 | 0.004 | |||||

| 22–60 | 0.40 | 0.19 to 0.83 | 0.015 | |||||

| > 60 | 0.48 | 0.23 to 1.00 | 0.050 | |||||

| Female | ||||||||

| ≤ 7 (all) | 1 | – | – | |||||

| 8–21 | 2.45 | 0.92 to 6.53 | 0.074 | |||||

| 22–60 | 1.16 | 0.42 to 3.23 | 0.775 | |||||

| > 60 | 0.92 | 0.31 to 2.72 | 0.884 | |||||

| Financial year | ||||||||

| 2008–9 | 176 (18) | 270 (27) | Reference | – | – | Reference | – | – |

| 2009–10 | 181 (18) | 208 (21) | 1.24 | 0.81 to 1.90 | 0.322 | 0.79 | 0.45 to 1.40 | 0.423 |

| 2010–11 | 225 (23) | 194 (20) | 1.86 | 1.22 to 2.84 | 0.004 | 0.87 | 0.48 to 1.58 | 0.643 |

| 2011–12 | 225 (23) | 174 (18) | 2.29 | 1.48 to 3.53 | < 0.001 | 0.63 | 0.33 to 1.21 | 0.166 |

| 2012–13 | 179 (18) | 148 (15) | 2.00 | 1.27 to 3.16 | 0.003 | 0.60 | 0.31 to 1.16 | 0.129 |

| Warda | ||||||||

| Behavioural precursors | ||||||||

| Abscon* | 143 (15) | 14 (1) | 27.28 | 12.40 to 60.04 | < 0.001 | 4.24 | 1.63 to 11.01 | 0.003 |

| Abus* | 482 (49) | 70 (7) | 31.71 | 19.29 to 52.14 | < 0.001 | 1.93 | 1.14 to 3.28 | 0.015 |

| Aggress* | 602 (61) | 58 (6) | 61.68 | 36.04 to 105.57 | < 0.001 | 3.47 | 2.02 to 5.99 | < 0.001 |

| Agitat* | 670 (68) | 140 (14) | 35.24 | 21.77 to 57.03 | < 0.001 | 3.46 | 2.12 to 5.65 | < 0.001 |

| Attack* | 275 (28) | 6 (1) | 278.01 | 12.33 to 860.36 | < 0.001 | 29.07 | 9.23 to 91.57 | < 0.001 |

| AWOL* | 96 (10) | 24 (2) | 6.90 | 89.84 to 13.68 | < 0.001 | 4.37 | 1.97 to 9.68 | < 0.001 |

| Demand* | 456 (46) | 114 (12) | 11.10 | 3.48 to 16.03 | < 0.001 | 1.19 | 0.74 to 1.90 | 0.472 |

| Irritable* | 529 (54) | 144 (14) | 13.65 | 7.68 to 20.18 | < 0.001 | 1.40 | 0.89 to 2.22 | 0.145 |

| Manic | 144 (15) | 13 (1) | 29.40 | 9.23 to 66.05 | < 0.001 | 2.97 | 1.07 to 8.23 | 0.036 |

| Refus* | 773 (78) | 418 (42) | 11.33 | 7.75 to 16.58 | < 0.001 | 0.90 | 0.60 to 1.36 | 0.619 |

| Shout* | 536 (54) | 111 (11) | 20.60 | 13.48 to 31.47 | < 0.001 | 1.28 | 0.78 to 2.09 | 0.334 |

| Threat* | 633 (64) | 66 (7) | 59.81 | 35.44 to 100.93 | < 0.001 | 3.39 | 1.94 to 5.91 | < 0.001 |

| Threw* or throw* | ||||||||

| Male or female | 316 (32) | 21 (2) | 94.29 | 42.67 to 208.38 | < 0.001 | |||

| Male | 2.63 | 1.12 to 6.20 | 0.027 | |||||

| Female | 11.18 | 3.34 to 37.40 | < 0.001 | |||||

| Violen* | 199 (20) | 5 (1) | 163.15 | 53.28 to 505.77 | < 0.001 | 4.57 | 1.35 to 15.45 | 0.015 |

All potential behavioural precursors were strongly and significantly associated with PICU status in univariable analyses (p < 0.001). Estimates of effect were notably high for ‘Threat*’ (OR 59.81), ‘Aggress’ (OR 61.68), ‘Threw/Throw*’ (OR 94.29), ‘Violen*’ (OR 163.15) and ‘Attack*’ (OR 278.01), indicating that these behaviours showed excellent ability to discriminate between events that preceded PICU transfer and randomly selected control dates.

Multivariable analyses

Multivariable logistic regression results are presented in Table 2. Although the pattern of results was similar to the unadjusted analyses, estimates of effect for all demographic/clinical factors were slightly attenuated in the adjusted model with some effects no longer reaching statistical significance. When interactions with sex were tested, those with time since admission and with throwing (threw*/throw*) were modestly significant, so the model was refitted to include these.

In the fully adjusted model, PICU status was significantly associated with age, sex, legal status and having a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. Time since admission was associated with PICU transfer only among men. Ward remained significant. Estimates of effect for all behavioural precursors were also greatly attenuated in the fully adjusted model. PICU status remained significantly associated with ‘Abscon*’, ‘Abus*’, ‘Aggress*’, ‘Agitat*’, ‘AWOL’, ‘Threat*’, ‘Threw/Throw*’ and ‘Violen*’ (p < 0.05), with the strongest association observed for ‘Attack*’ (OR 29.07). Ethnicity and financial year were entirely non-significant.

Predictors of seclusion use

Sample

The seclusion sample comprised 990 cases (seclusion transfers) and 1032 controls (seclusion non-transfers). All of these observations originated from 771 patients, of whom 285 contributed only non-seclusion observations, 203 contributed only seclusion observations and 233 contributed a mixture. The contribution that each group of people made to the total number of observations was as follows: those who were never secluded contributed a mean of 1.8 observations (SD 1.5 observations), those who were only secluded contributed a mean of 1.8 observations (SD 1.4 observations) and those who were both secluded and not secluded contributed a mean of 5.0 observations (SD 3.7 observations).

Univariable analyses

The demographic and clinical characteristics for the seclusion cases and controls are presented in Table 3. In unadjusted analyses, the likelihood of seclusion was significantly higher among younger patients and female patients (OR 2.59; p < 0.001); there was a borderline significant increase for those with black African or Caribbean ethnicity (OR 1.42; p = 0.073). Relative to a diagnosis of schizophrenia, the odds of seclusion were significantly elevated for all other diagnoses (p < 0.05) and highest for those with personality disorder (OR 3.05; p < 0.001). Patients on a civil section (section 2), but not those on section 3 or a forensic section, were significantly more likely than informal patients to be secluded (OR 7.64; p < 0.001). In comparison with the first 7 days of the admission, the odds of seclusion for each subsequent time point were decreased (p < 0.001). The effects of financial year were non-significant, but there were significant differences between wards.

| Risk factor | Cases (N = 990), n (%) | Controls (N = 1032), n (%) | Analyses | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||||||||

| OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | |||||

| Age (years) | ||||||||||

| ≥ 45 | 135 (14) | 231 (22) | 1 | – | – | 1 | – | – | ||

| 35–44 | 185 (19) | 216 (21) | 1.49 | 0.91 to 2.45 | 0.115 | 1.92 | 1.07 to 3.48 | 0.030 | ||

| 25–34 | 347 (35) | 366 (35) | 2.00 | 1.26 to 3.15 | 0.003 | 1.76 | 1.02 to 3.03 | 0.041 | ||

| < 25 | 323 (33) | 219 (21) | 2.98 | 1.83 to 4.86 | < 0.001 | 2.77 | 1.54 to 4.96 | 0.001 | ||

| Sex | ||||||||||

| Female | 354 (36) | 203 (20) | 2.59 | 1.80 to 3.73 | < 0.001 | 0.75 | 0.41 to 1.41 | 0.376 | ||

| Ethnicity | ||||||||||

| White | 199 (20) | 253 (24) | 1 | – | – | 1 | – | – | ||

| Black African/Caribbean | 690 (70) | 657 (64) | 1.42 | 0.97 to 2.08 | 0.073 | 1.17 | 0.73 to 1.87 | 0.518 | ||

| Other | 101 (10) | 122 (12) | 0.94 | 0.51 to 1.75 | 0.848 | 0.71 | 0.34 to 1.48 | 0.361 | ||

| Diagnosis | ||||||||||

| Schizophrenia | 323 (33) | 435 (42) | 1 | – | – | 1 | – | – | ||

| Other psychotic | 273 (28) | 262 (25) | 1.70 | 1.16 to 2.48 | 0.007 | 0.75 | 0.48 to 1.19 | 0.224 | ||

| Bipolar disorder | 283 (28) | 217 (21) | 2.60 | 1.72 to 3.93 | < 0.001 | 1.12 | 0.69 to 1.84 | 0.640 | ||

| Personality disorder | 24 (2) | 18 (2) | 3.05 | 1.15 to 8.13 | 0.025 | 1.56 | 0.44 to 5.50 | 0.486 | ||

| Other diagnosis | 87 (9) | 100 (10) | 1.76 | 1.03 to 3.02 | 0.039 | 1.13 | 0.58 to 2.22 | 0.715 | ||

| MHA section | ||||||||||

| Informal | 44 (4) | 119 (12) | 1 | – | – | 1 | – | – | ||

| Section 2 | 417 (42) | 170 (16) | 7.64 | 4.37 to 13.35 | < 0.001 | 1.89 | 0.90 to 3.99 | 0.094 | ||

| Section 3/forensic | 529 (53) | 743 (72) | 1.47 | 0.87 to 2.48 | 0.149 | 1.26 | 0.62 to 2.53 | 0.522 | ||

| Time since admission (days) | ||||||||||

| ≤ 7 | 395 (40) | 98 (10) | 1 | – | – | 1 | – | – | ||

| 8–21 | 235 (24) | 215 (21) | 0.16 | 0.11 to 0.24 | < 0.001 | 0.24 | 0.15 to 0.39 | < 0.001 | ||

| 22–60 | 204 (21) | 380 (37) | 0.06 | 0.04 to 0.09 | < 0.001 | 0.19 | 0.11 to 0.31 | < 0.001 | ||

| > 60 | 156 (16) | 339 (33) | 0.05 | 0.03 to 0.08 | < 0.001 | 0.24 | 0.15 to 0.43 | < 0.001 | ||

| Financial year | ||||||||||

| 2008–9 | 122 (12) | 177 (17) | 1 | – | – | 1 | – | – | ||

| 2009–10 | 171 (17) | 193 (19) | 1.15 | 0.74 to 1.81 | 0.548 | 1.23 | 0.68 to 2.21 | 0.488 | ||

| 2010–11 | 240 (24) | 215 (21) | 1.31 | 0.84 to 2.04 | 0.231 | 1.63 | 0.91 to 2.92 | 0.103 | ||

| 2011–12 | 256 (26) | 255 (25) | 1.34 | 0.87 to 2.07 | 0.188 | 1.69 | 0.96 to 2.97 | 0.070 | ||

| 2012–13 | 201 (20) | 192 (19) | 1.04 | 0.65 to 1.66 | 0.873 | 0.89 | 0.49 to 1.61 | 0.701 | ||

| Ward | ||||||||||

| A | 388 (39) | 258 (25) | 1 | – | – | 1 | – | – | ||

| B | 119 (12) | 323 (31) | 0.20 | 0.14 to 0.30 | < 0.001 | 0.19 | 0.10 to 0.35 | < 0.001 | ||

| C | 149 (15) | 237 (23) | 0.33 | 0.22 to 0.49 | < 0.001 | 0.42 | 0.23 to 0.77 | 0.005 | ||

| D | 334 (34) | 214 (21) | 1.02 | 1.10 to 1.83 | 0.922 | 1.17 | 0.72 to 1.90 | 0.533 | ||

| Behavioural precursors | ||||||||||

| Abus* | 570 (58) | 231 (22) | 7.62 | 5.70 to 10.17 | < 0.001 | 1.57 | 1.07 to 2.30 | 0.022 | ||

| Aggress* | 654 (66) | 192 (19) | 11.59 | 8.86 to 15.17 | < 0.001 | 1.96 | 1.36 to 2.83 | < 0.001 | ||

| Agitat* | 714 (72) | 286 (28) | 10.21 | 7.77 to 13.42 | < 0.001 | 1.77 | 1.25 to 2.49 | 0.001 | ||

| Arous* | 472 (48) | 124 (12) | 9.47 | 7.02 to 12.77 | < 0.001 | 1.75 | 1.19 to 2.57 | 0.004 | ||

| Assault* | 229 (23) | 25 (2) | 21.29 | 12.33 to 36.76 | < 0.001 | 3.37 | 1.81 to 6.28 | < 0.001 | ||

| Demand* | 531 (54) | 276 (27) | 3.82 | 2.97 to 4.93 | < 0.001 | 1.29 | 0.92 to 1.81 | 0.145 | ||

| Hit* | 266 (27) | 41 (4) | 11.58 | 7.55 to 17.78 | < 0.001 | 2.10 | 1.22 to 3.61 | 0.007 | ||

| Restrain* | ||||||||||

| Male and female | 554 (56) | 67 (6) | 34.47 | 23.26 to 51.09 | < 0.001 | |||||

| Male | 12.17 | 7.21 to 20.55 | < 0.001 | |||||||

| Female | 2.90 | 1.50 to 5.61 | < 0.001 | |||||||

| Shout* | ||||||||||

| Male and female | 573 (58) | 217 (21) | 6.40 | 4.93 to 8.31 | < 0.001 | |||||

| Male | 0.68 | 0.44 to 1.05 | 0.084 | |||||||

| Female | 2.97 | 1.63 to 5.42 | < 0.001 | |||||||

| Threat* | 689 (70) | 190 (18) | 18.94 | 13.75 to 26.09 | < 0.001 | 3.70 | 2.52 to 5.43 | < 0.001 | ||

| Threw/throw* | 328 (33) | 77 (7) | 8.31 | 5.86 to 11.80 | < 0.001 | 1.64 | 1.04 to 2.57 | 0.032 | ||

| Violen* | 247 (25) | 28 (3) | 16.36 | 10.06 to 26.62 | < 0.001 | 1.96 | 1.09 to 3.53 | 0.025 | ||

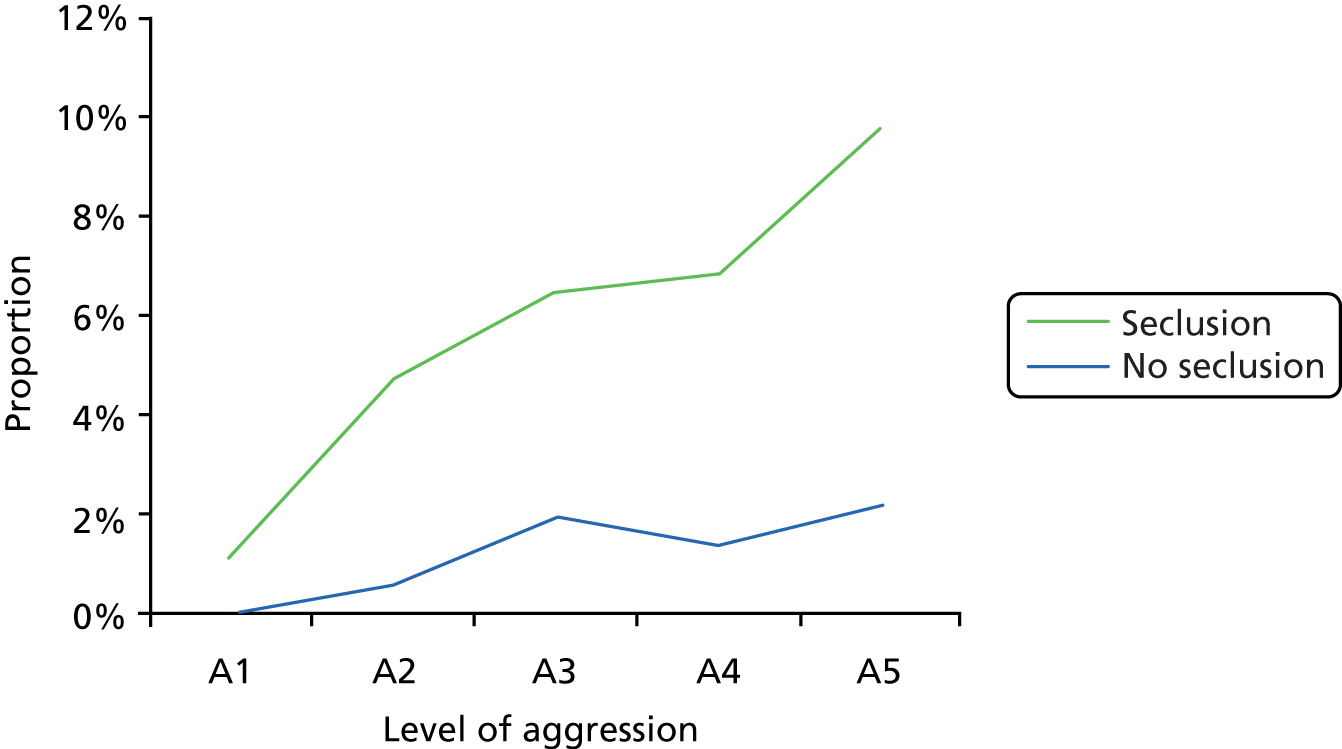

All behavioural precursors were significantly associated with seclusion status in univariable analyses (p < 0.001); estimates of effect were highest for ‘Violen*’ (OR 16.36), ‘Threat*’ (OR 18.94), ‘Assault*’ (OR 21.29) and ‘Restrain*’ (OR 34.47).

Multivariable analyses

The patterns of association between all demographic/clinical factors and seclusion were largely unchanged in the fully adjusted model. Seclusion status remained significantly associated with age, time since admission (p < 0.05) and ward. However, sex, ethnicity and diagnosis were not significantly associated with seclusion after adjustment for all demographic/clinical factors and behavioural precursors. Although ORs were substantially attenuated in the fully adjusted model, all precursors other than demanding behaviour remained significantly associated with seclusion (p < 0.05). There were significant interactions in the case of restraint and shouting, such that the effect of restraint was greater in men and there was no effect of shouting in men. An examination of variance inflation factors and standard errors (SEs) indicated minimal risk of multicollinearity (all variance inflation factors were < 4).

Discussion

In this large, methodologically robust study, we identified several demographic and clinical factors that distinguished between PICU/seclusion cases and randomly selected controls, including age, sex, ethnicity, diagnosis, MHA section and time since admission. With the exception of ethnicity and diagnosis, these factors remained significant predictors of both PICU and seclusion status after adjusting for behavioural precursors strongly associated with treatment receipt. In exploratory analyses, several statistically significant interactions were observed between patient sex and other predictors of transfer to a PICU and seclusion, indicating that the behaviours and circumstances contributing to these treatments differ between male and female patients.

Strengths and limitations

Our analyses examining the predictors of transfer to a PICU and seclusion have a number of strengths. First, the sample sizes that we achieved were distinctly in excess of those in other previous studies, increasing the precision of the estimates that we obtained. Second, we combined novel and robust measurement and sampling techniques so that we could estimate the effect of the time-varying behavioural factors that we assumed to be critically involved in selection for treatment, as well as the usually available demographic and basic clinical factors. There were, however, a number of notable limitations.

The current study was conducted within a single NHS trust, which potentially limits the extent to which the current findings can be generalised to other psychiatric hospitals (particularly those outside the UK). However, within this single NHS trust, we were able to examine practices across four PICU wards, including a female-only ward; thus, our findings may have greater generalisability than those of previous studies.

Although we examined a wide range of behavioural precursors that were identified directly from clinical events preceding treatment, we may have failed to account for some low-frequency behaviours that were not present in the initial screening subset but that may, nonetheless, be important precursors of treatment. Of note, we did not examine suicide or self-harm behaviours, both of which have been reported as antecedents of transfer to a PICU and of seclusion in previous studies. A further limitation relates to the fact that we focused only on patient characteristics. It is likely that a range of environmental factors influence the decision to initiate PICU transfer and seclusion (e.g. number of staff, staff sex, bed numbers); however, it was beyond the scope of the current study to examine these variables. Thus, we were unable to determine the impact of patient factors after accounting for external factors beyond the patient’s control. Environmental factors are particularly important as they are often dynamic (i.e. amenable to change) and, therefore, offer the opportunity to identify ways by which PICU and seclusion practices might be modified. A more difficult issue may be the potential for treatment selection to determine the recording of apparently relevant behaviours; these records may be as much accounts of a decision already taken as disinterested reports of behaviour. Naturally, there are normal concerns about the accuracy of data taken from electronic patient records, although in most cases these would be expected not to result in bias.

Finally, based on previous studies, we explored whether or not there might be important interactions between patient sex and other predictors of PICU/seclusion status. However, we did not examine other interaction effects identified in the extant literature (e.g. interactions with ethnicity and diagnosis).

Demographic and clinical predictors of treatment

Characteristics of psychiatric intensive care unit patients

In line with previous studies examining the characteristics of PICU patients, we observed that PICU patients were significantly younger and much more likely to be male than randomly selected controls. These findings are not surprising, given that both younger age and male sex are well-established risk factors for violence in acute psychiatric impatient settings. 21–23 That both factors remained highly significant predictors of PICU status after adjustment for all other demographic/clinical variables and a range of behavioural precursors (that were themselves strongly associated with PICU transfer) is, therefore, interesting, as this suggests that younger patients and men may be at greater risk of transfer to a PICU because of factors other than their aggressive behaviour. It is conceivable that this does represent a direct effect of patient sex, perhaps because of stereotyping of men as more violent and women as less violent. Thus, clinical staff may be more likely to perceive men as more risky and therefore requiring PICU admission. There may also be an important indirect effect of sex: SLaM, during the period of this study, operated three male PICU wards and one female ward, and, therefore, the supply of female PICU beds was distinctly limited. Alternatively, it may be that male and female psychiatric patients differ on other factors (e.g. frequency or severity of violence) that are relevant to PICU transfer but were not captured in the current study.

In unadjusted analyses, we additionally observed that patients of black African or Caribbean ethnicity were significantly more likely than white patients to be transferred to a PICU, a finding that is consistent with recent studies conducted in London and the South East. 24–26 This association between ethnicity and PICU status was greatly attenuated and rendered non-significant in the fully adjusted model. This finding is reassuring, as it suggests a lack of referral bias within the psychiatric inpatient system. That is, although black African or Caribbean patients were more likely than white patients to be transferred to a PICU, this was fully explained by other risk factors and behavioural precursors, indicating that PICU transfer was not associated with ethnicity per se. Similar conclusions were drawn in a previous study, conducted within the same NHS trust as that in the current investigation, which found that, although black African or Caribbean patients were more prevalent than expected (based on the ethnic composition of the entire hospital and the general population of the catchment area), black African or Caribbean PICU patients were characterised by higher levels of functional impairment than white PICU patients. 25 The current study extends these findings by statistically adjusting for a wide range of potential confounders, thereby demonstrating that these factors do indeed account for the higher likelihood of PICU transfer among black African or Caribbean patients.

In contrast to studies reporting that the majority of PICU patients have a diagnosis of schizophrenia,14 we observed that only 36% of patients transferred to a PICU had this disorder. Only patients with bipolar disorder were more likely to be transferred to a PICU after adjusting for a wide range of potential confounders. The fact that the elevated risk of PICU transfer among bipolar disorder patients remained even after adjusting for behaviours and traits commonly associated with this disorder (i.e. manic, agitated, demanding and irritable behaviour) suggests that patients with bipolar disorder may present with other behaviours that cause them to be viewed by clinical staff as needing PICU treatment.

In univariable analyses and multivariable analyses, legal status was very strongly associated with PICU status. Only 4% of PICU patients were informal (compared with 45% of non-PICU patients) and, indeed, we discovered from discussions with clinical staff that formal detention under the MHA was generally required on SLaM PICUs, suggesting that this very small number of apparently informal patients may in part even be attributable to data-coding errors (non-clinical staff were responsible for transforming MHA paperwork into the electronic patient record).

Among male patients we found a strong association between PICU transfer and time since admission, with a distinctly higher risk in the first 7 days. We are not aware of any previous studies to have investigated time since admission as a risk factor for PICU transfer, but the association is not surprising. Patients are often admitted to hospital during a period of acute illness that then improves following successful treatment; thus, we would expect chaotic/aggressive behaviour to be more prevalent early in the admission. Indeed, a large study of psychiatric inpatients reported that the majority of aggressive incidents occurred within the first 2 days of admission. 27 The fact that time since admission remained a very strong predictor of PICU transfer after adjusting for behavioural factors indicates, however, that high levels of aggression during the start of the admission may not fully account for this finding. Perhaps staff are more inclined to transfer newly admitted patients, whose behaviours and risks are not yet known, to PICU wards, whereas patients who remain in general inpatient care for longer periods may be viewed as less risky, even if both groups exhibit the same levels of aggression. Why the same pattern was not observed among women is unclear. We can formulate three potential explanations.

-

Given that the presence-specific behaviours were controlled for, there may be an underlying difference between men and women in how the intensity of disordered behaviour changes over time, with men exhibiting a greater intensity early on. This could be endogenous (determined by male illness alone) or exogenous (e.g. caused by differential patterns of substance use prior to admission).

-

Particular triggers, rather than just mental illness, are responsible in whole or in part for the kinds of incidents that lead to PICU transfer. If such triggers – for example conflicts over leave, possessions or access to mobile phones – occur in different ways for women or on female wards, then this might lead to a differential distribution of transfers over time.

-

There may a genuine issue of sex bias. Male patients may provoke greater fear early on in admission, with staff being more likely to think that they are capable of greater unpredictable violence and, therefore, being predisposed to initiate a PICU transfer.

Characteristics of secluded patients

Consistent with previous research,1 we observed that patients who were secluded during a period in a PICU were younger in age than randomly selected PICU patients who were not secluded. This association remained significant after adjusting for behavioural precursors; this again suggests that other (unmeasured) factors may contribute to the greater risk of seclusion among younger patients. We found no effect of sex on seclusion, consistent with previous case–control studies,1 but this is difficult to disentangle from the effect of ward and time period.

Previous case–control studies investigating the association between ethnicity and seclusion have yielded inconsistent findings. Studies conducted in the USA and New Zealand have reported that black/Asian patients and Maori/non-European patients, respectively, are more likely to be secluded than their white and European counterparts, yet more comprehensive studies conducted in these countries have observed no differences in seclusion rates across these ethnic groups. 1 Ethnic differences have, however, been observed in England and Wales; robust investigations conducted by the Healthcare Commission indicate that seclusion rates are higher among ethnic minority groups (black African, black Caribbean and white other) than among the white British group. 28 Our finding that seclusion status was not significantly associated with ethnicity in either unadjusted or adjusted analyses is, therefore, inconsistent with previous studies conducted in the UK. Again, it is likely that this difference in findings relates to our use of non-secluded PICU-based controls. In the underlying PICU population, individuals of black African or Caribbean ethnicity form the majority, constituting two-thirds of the total cohort (i.e. seclusion cases and seclusion controls). Thus, in the PICU population, being of black African or Caribbean ethnicity appears to confer no additional risk of seclusion.

Previous case–control studies have observed that patients with schizophrenia, other psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder and personality disorder are more likely to be secluded than other diagnostic groups, whereas patients diagnosed with depression are at lower risk. 14 We found no such effect in adjusted analyses. Thus, patient behaviours and other potential confounders appear to account for the observed differences in seclusion use across diagnostic groups.

Very few secluded patients were recorded as informally admitted to hospital (4%) on the date when transfer into seclusion occurred. Indeed, even this small number may be incorrectly coded as most PICUs require detention under the MHA as a condition of entry (see Characteristics of Psychiatric intensive care unit patients). As such, our finding that patients formally detained were not more likely to be secluded, although inconsistent with the extant literature,14 may be because we studied an entirely PICU-based sample.

Similar to the findings obtained in the PICU analyses, strong associations were observed between time since admission and seclusion status, whereby the likelihood of seclusion was greatly decreased at all subsequent time periods (although not in a dose–response fashion) relative to the first 7 days of the admission. This finding is consistent with several descriptive studies that report that the majority of seclusion incidents occur within the first 24 hours or within the first week of admission. 1 Effect sizes were attenuated in the fully adjusted model, suggesting that this finding is partially explained by higher levels of aggressive behaviour during the early stages of the admission; however, highly significant effects remained for all time periods, suggesting that we have not fully captured the range of factors that may contribute to the elevated risk of seclusion at the start of the admission. Anecdotally, it appeared from the clinical notes that many patients were transferred to a PICU in a state of distress/agitation and that seclusion was often initiated as soon as the patient arrived at the PICU ward as a precaution. Additionally, as the seclusion cohort (cases and controls) comprised all patients admitted to the PICU, including those admitted directly from the community, it is possible that we may not have been able to adequately capture (and subsequently adjust for) behavioural precursors occurring in the 3 days prior to seclusion. However, given that we observed a similar association between time since admission and PICU transfer, despite the fact that we excluded patients admitted directly from the community (for whom behavioural data would be unavailable) this suggests that this cannot be the only explanation for this finding and we again propose that this may be a strategy employed by clinical teams to safely manage patients who are newly admitted and whose level of risk is, therefore, unclear.

Behaviours associated with use of a psychiatric intensive care unit and seclusion

Behavioural precursors of psychiatric intensive care unit transfer

We identified a range of patient behaviours that preceded PICU transfer. In terms of prevalence, keywords related to difficult-to-manage and verbally aggressive behaviour (e.g. ‘Abus*’, ‘Aggress*’, ‘Agitat*, ‘Shout’ and ‘Threat*’) were common in the 3 days prior to PICU transfer and were observed in 49–68% of PICU cases. Those relating to physically aggressive behaviour (‘Threw/Throw*, ‘Attack*’ and ‘Violen*) were less frequently observed during this time period (20–32% of PICU cases) and absconsion (‘Abscon*’ and ‘AWOL’) was relatively rare (10–15% of PICU cases). These findings are broadly consistent with previous studies that have reported that aggression is the most common reason for PICU transfer (occurring in 30–50% of admissions), followed by disruptive/acutely psychotic behaviour and absconsion (each prevalent in 10–20% of cases). 7 Our findings demonstrate that, in addition to aggression and violence, a range of behaviours displayed by the patient, including rule-breaking behaviour, boundary pushing, reluctance, non-compliance and argumentativeness, underlie PICU transfer. Although these behaviours are not in themselves necessarily dangerous, by challenging the authority of staff members these behaviours often invoke an emotional reaction in staff (e.g. feelings of irritation and frustration), which may lead to staff needing to exert power and control, and, hence, initiate PICU transfer. The size of the associated effects varied, but ORs were typically in the range of 1.5 to 5; in the case of attacking behaviour, the adjusted OR was 29. The effect of throwing differed between men and women.

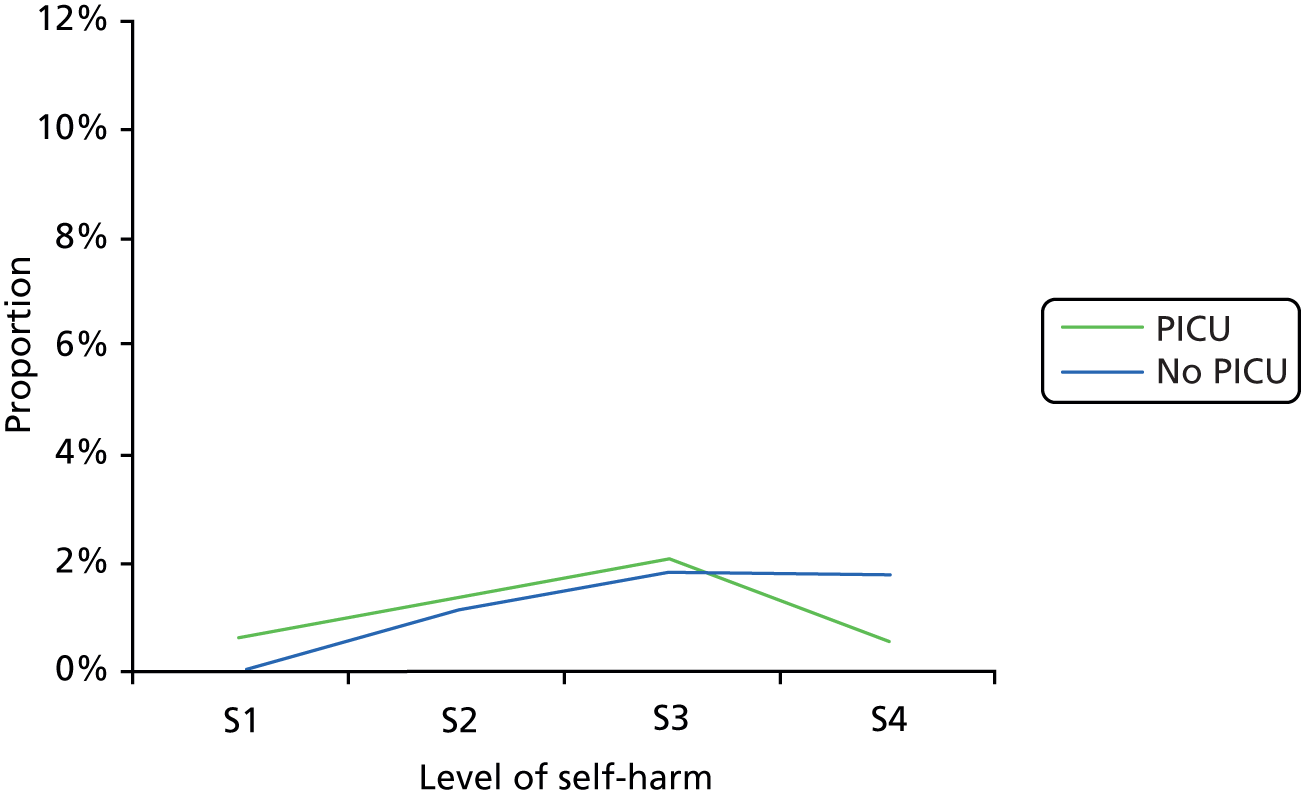

Contrasting with previous studies, self-harm appeared to be a very infrequent precursor to PICU transfer in the population that we studied. We did not identify any behavioural keywords relating to self-harm or suicidal behaviour when we reviewed a randomly selected subset of events occurring prior to PICU transfer (n = 500) from which the list of behavioural precursors was derived.

Behavioural precursors of seclusion

A comprehensive review of studies providing reasons for initiating seclusion (n = 47) indicated that the most common reason was aggression (typically aggression to objects but also verbal aggression, self-directed aggression and physical aggression), followed by psychiatric symptoms (e.g. delusion, disorientated, confused or disturbed behaviour), disruptive behaviour, absconsion and medication refusal. These findings are to a large extent consistent with those obtained in the current study. As was the case with PICU transfer, we identified several keywords related to verbally aggressive and agitated behaviour (‘Abus*’, ‘Aggress*’, ‘Agitat*’, ‘Arous*’, ‘Shout*’ and ‘Threat*’) that were highly prevalent in the period directly preceding seclusion (occurring in 48–72% of seclusion cases), whereas keywords indicating physical aggression (‘Assault*’, ‘Threw/Throw*’ and ‘Violen’) were less common (present in 23–33% of cases). Although we observed a considerable degree of overlap between PICU and seclusion keywords, there were some differences. First, absconsion keywords were notably absent in the pre-seclusion events. As noted above, this is somewhat surprising given that absconsion has been noted as an antecedent of seclusion. However, this may relate to the fact that we examined seclusions occurring on a PICU ward (as opposed to a general adult ward), where there may be fewer opportunities to abscond. Second, the clinical notes for over half of the seclusion cases were found to contain the word ‘Restrain*’. Although this keyword clearly relates to staff and not patient behaviour, and is therefore not a behavioural precursor per se, it was so strongly related to seclusion in the initial selection process that we felt that it was important to include this term in the final model.

Nearly all of the included behavioural precursors were significantly associated with seclusion status in the adjusted analysis; however, ORs were generally smaller than those observed for PICU transfer. This probably reflects the fact that although these behaviours are highly prevalent among patients who are secluded, they are also far more common in the underlying PICU population (from which seclusion controls were drawn) than among patients treated in general adult wards (from which PICU controls were drawn). The highest OR (12) was observed for ‘Restrain*’ among men, with all other remaining keywords being associated with ORs between 1.5 and 4. The effects of restraining and of shouting differed between men and women; the second finding has no obvious explanation, but it is notable that the occurrence of a restraint was much less commonly followed by seclusion among women, even though the association was still significant and of substantial size.

Implications

Previous studies have indicated that specific patient subgroups are at increased risk of PICU transfer and seclusion. However, these studies have typically lacked appropriate control groups and have also failed to account for patient behaviours that might explain this elevation in risk. In the current study, we found little evidence of referral bias in relation to ethnicity or diagnosis; after adjusting for a range of behavioural precursors and demographic/clinical factors, these factors were not associated with transfer to a PICU or seclusion. One exception to this is that patients with bipolar disorder were twice as likely to be transferred to a PICU than patients with schizophrenia, even after adjusting for behaviours typically associated with this diagnosis (i.e. mania, agitation and irritability). Presumably this simply reflects a degree of disturbance that our measures were not able to detect. However, further work to determine the reasons why clinical teams consider patients with bipolar disorder to be particularly difficult to manage in general adult wards might potentially bear fruit if it leads to strategies that can help to avoid PICU transfer.

One interesting finding was that even after accounting for a range of confounders, sex differences in the risk of transfer to a PICU and seclusion were still apparent, with men being more likely to be transferred to a PICU, whereas women demonstrated no difference in the use of seclusion that could be not be accounted for by the inclusion of other variables such as ward and time period. Overall, the influence of ward was substantial in the case of both transfer to a PICU and seclusion, supporting a key assumption of this project, which is that major differences in the use of coercive practices can coexist in apparently similar services and units.

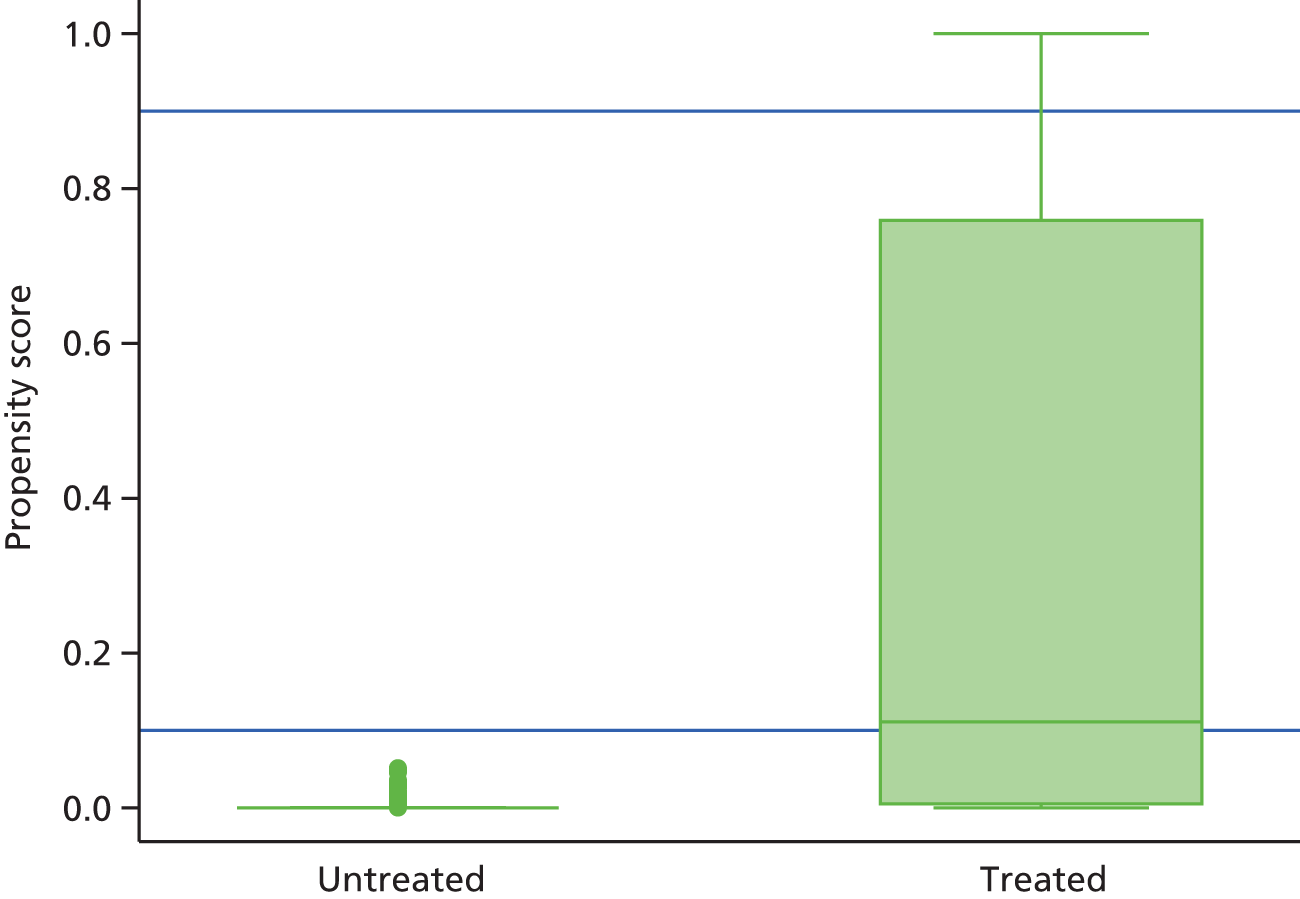

Our findings emphasise the importance of adjusting for a wide range of demographic/clinical factors and behavioural precursors when conducting any non-randomised analyses examining the effects of transfer to a PICU and seclusion on outcomes. The work presented in this chapter, therefore, has important implications for the analyses performed in Chapter 3. Thus, having identified a range of factors that clearly distinguish treated patients (i.e. those receiving PICU care or seclusion) from untreated patients, it is essential to adjust for these variables when examining the effect of PICU care and seclusion on adverse incidents, length of stay and costs.

Conclusions

The findings presented in this chapter indicate that there are a number of demographic and clinical factors that distinguish between patients who are subject to PICU transfer/seclusion and those who are not. Moreover, some of these factors (notably, patient sex, age and time since admission) remain consistently associated with treatment receipt after adjusting for a range of behavioural precursors. Patient sex was found to modify the effect of other demographic/clinical factors and behavioural precursors on treatment receipt, and was also significantly associated with both PICU and seclusion duration. These findings highlight the importance of patient sex when examining predictors and outcomes of these treatments.

Chapter 3 Effects of treatment on adverse incidents, length of stay and costs

Introduction

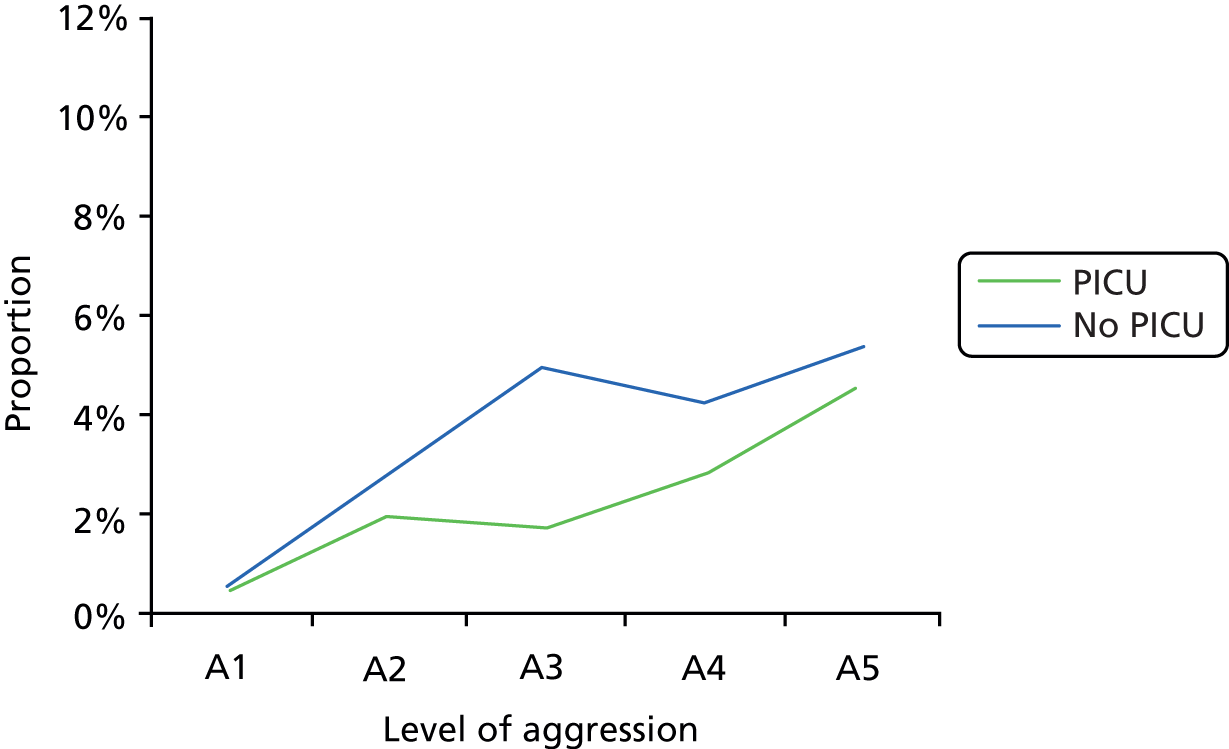

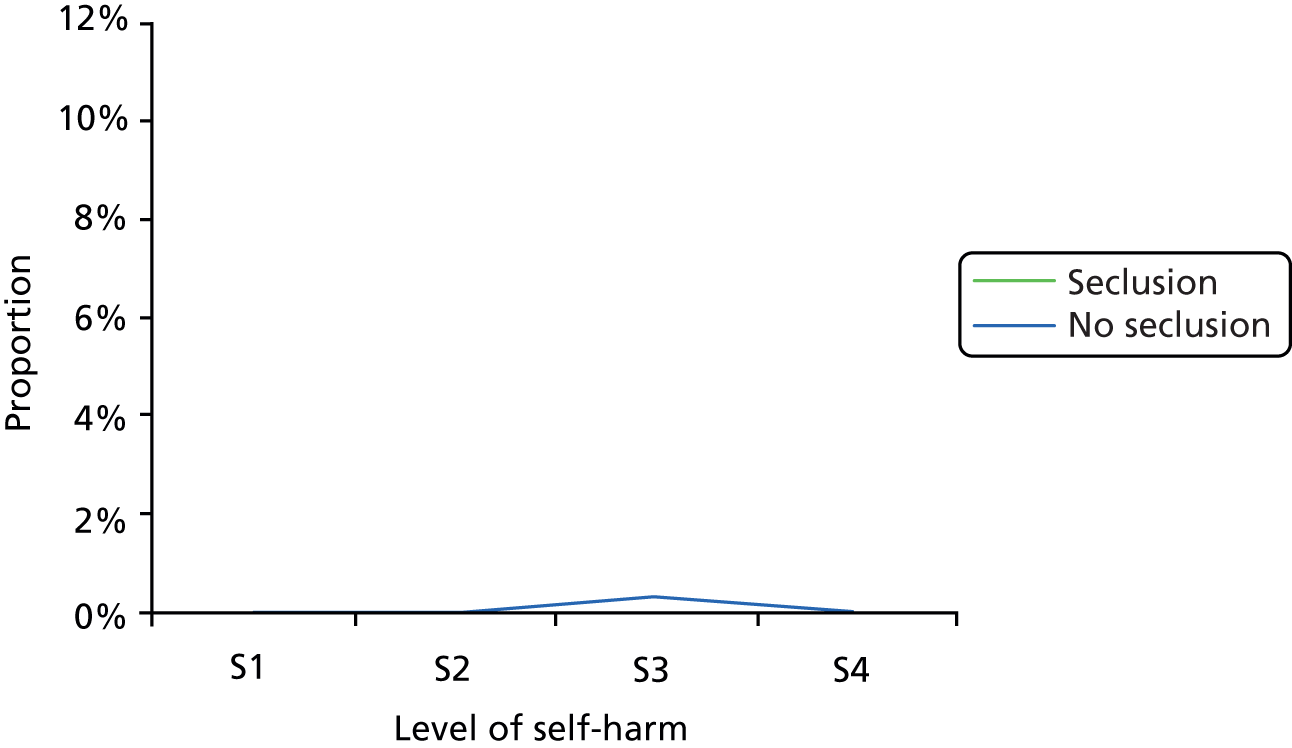

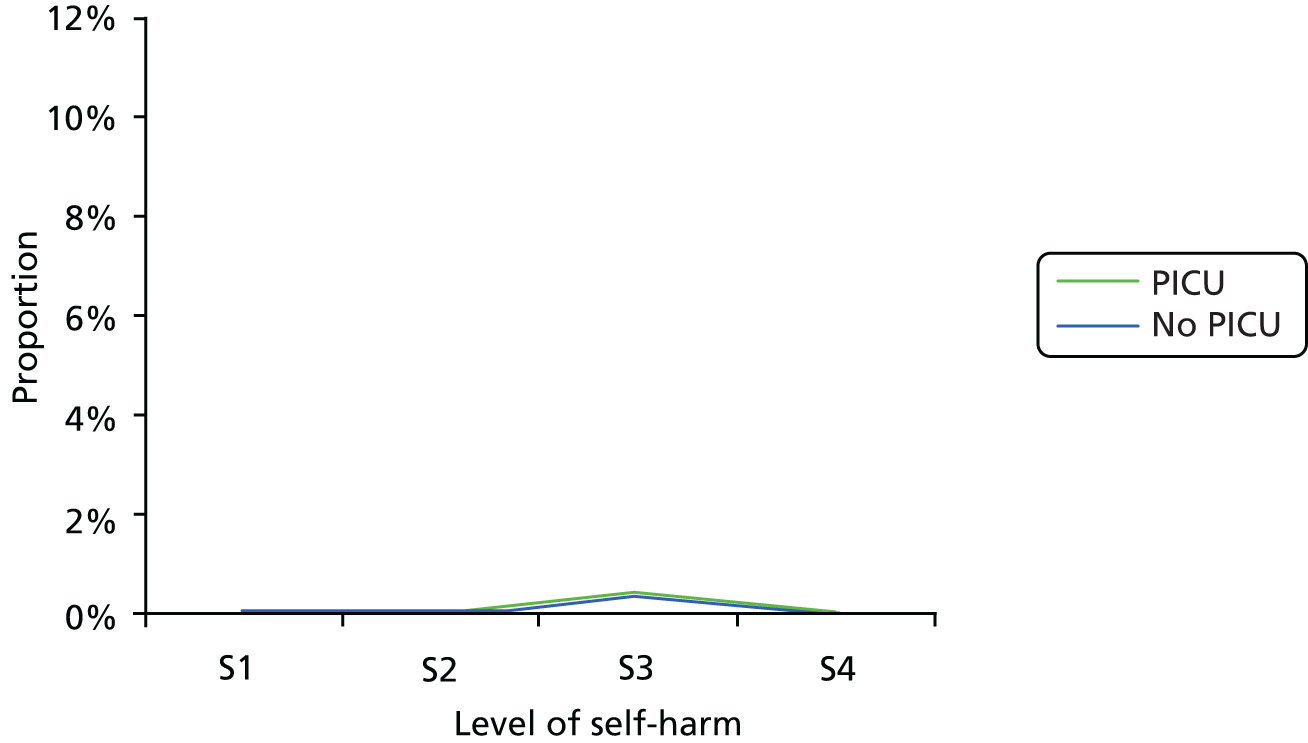

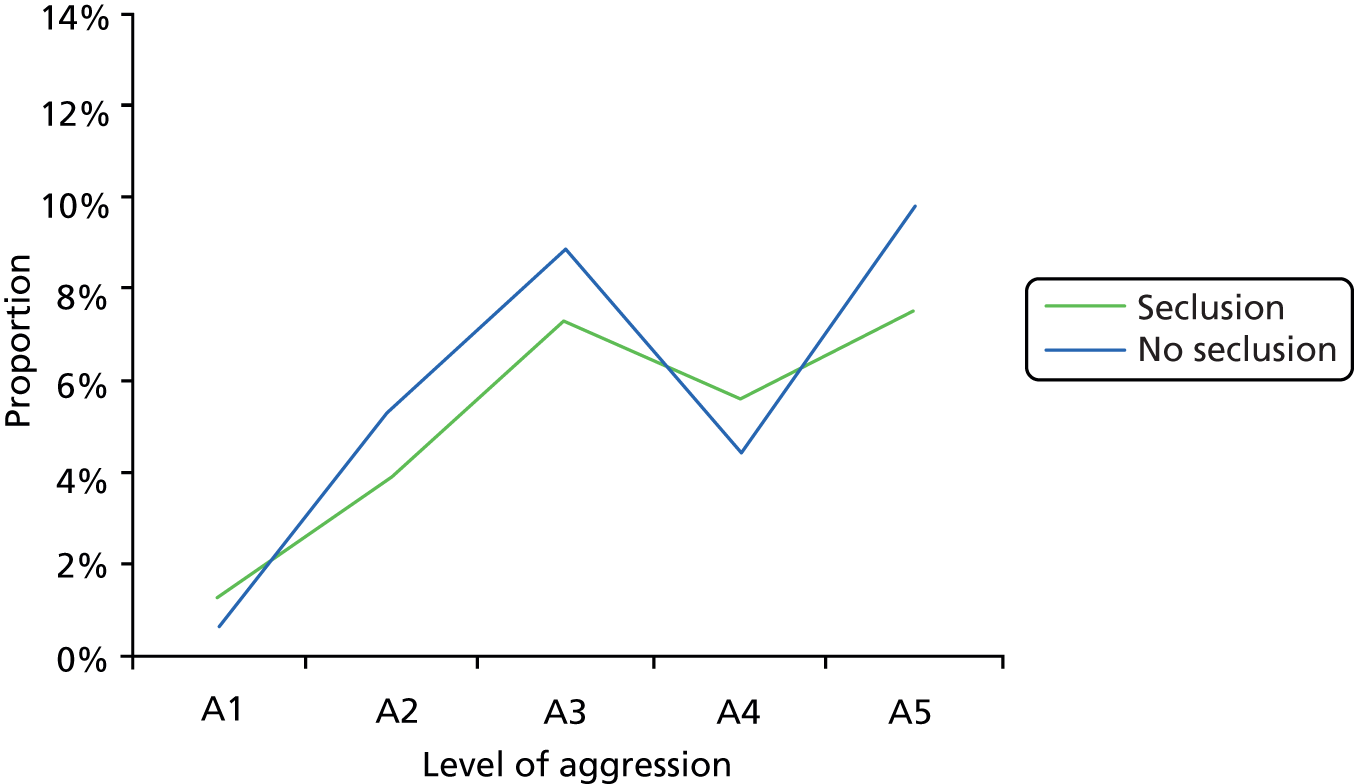

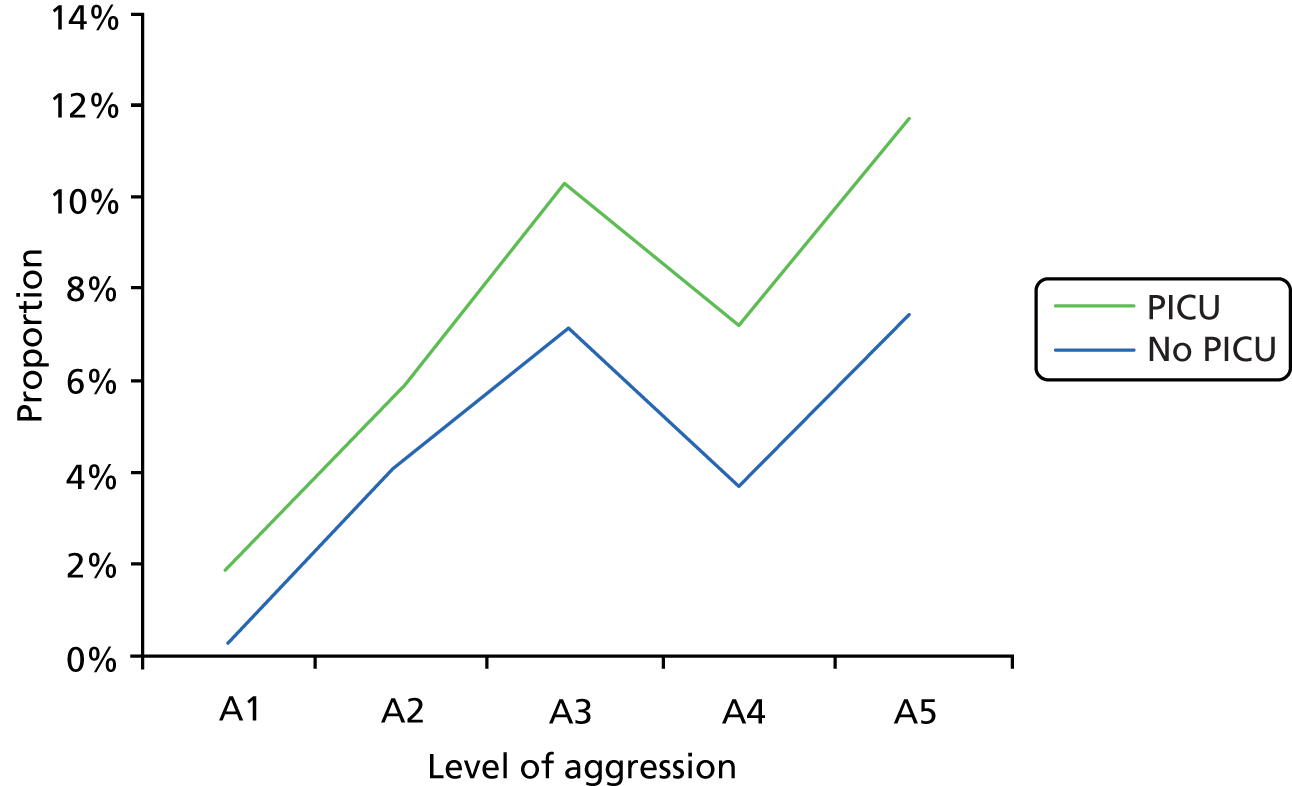

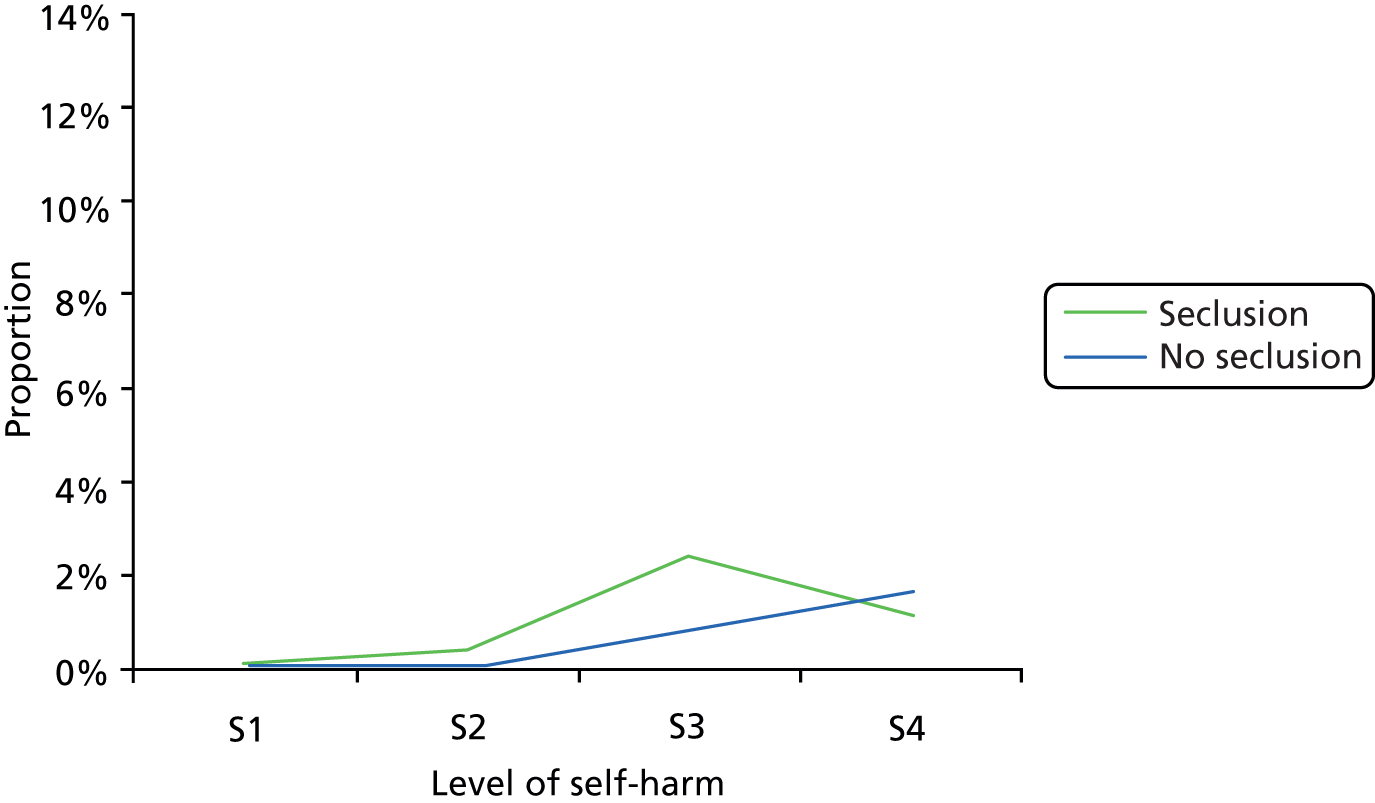

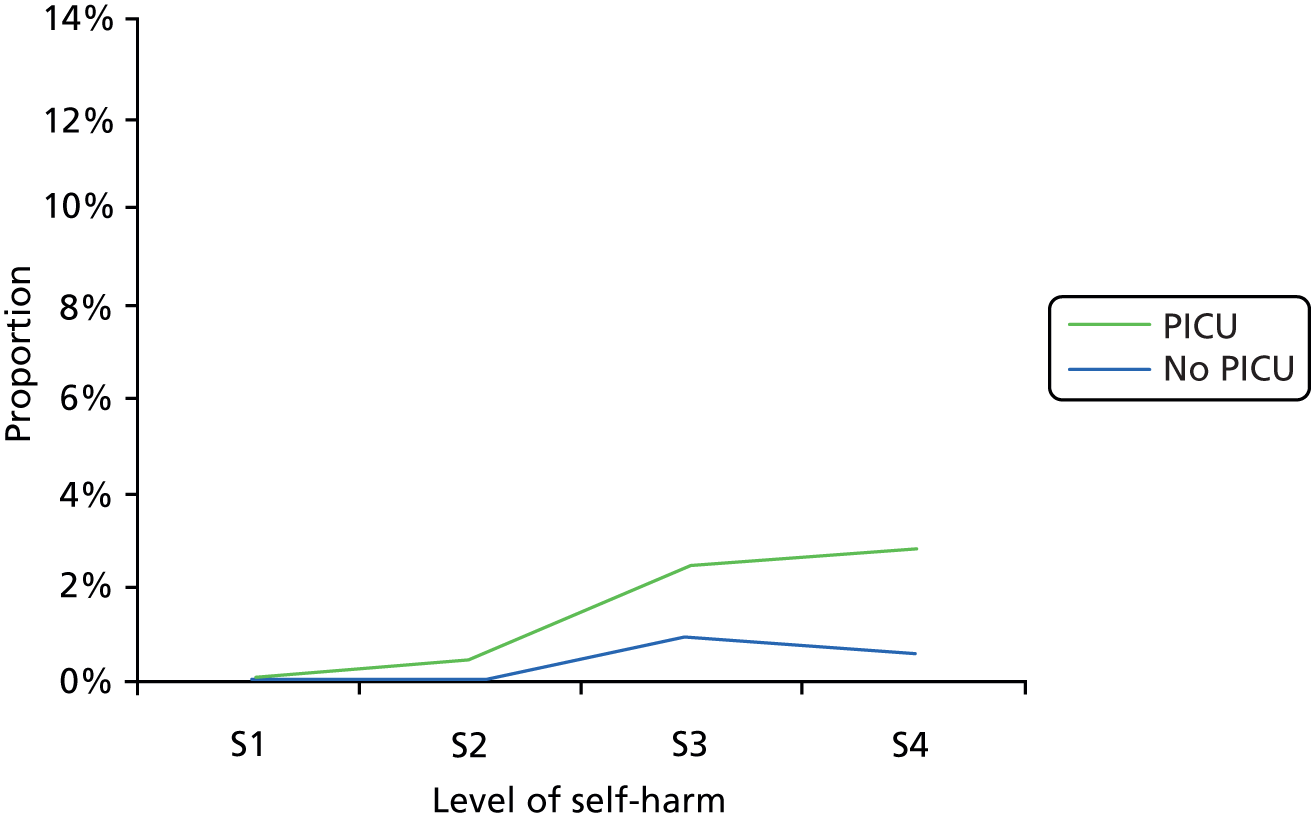

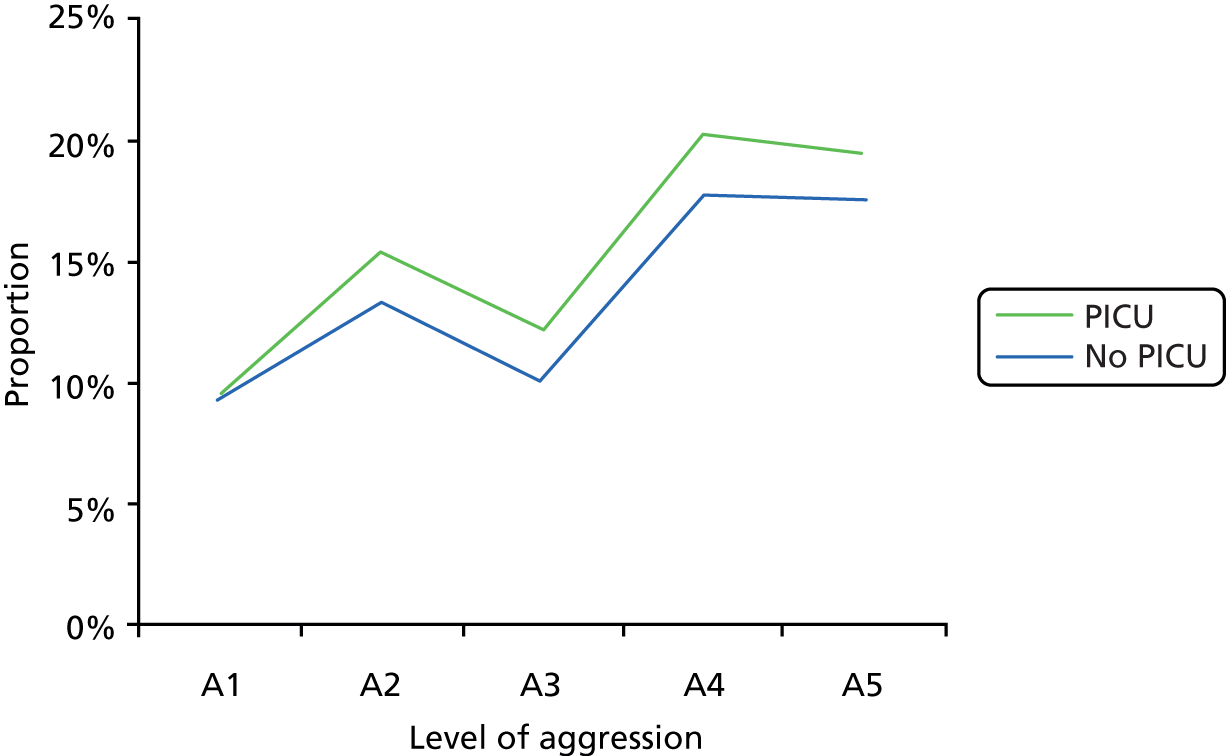

Although numerous studies have investigated predictors of PICU transfer and seclusion, the effects of these interventions on the outcomes that they aim to reduce (e.g. aggressive and agitated behaviour, length of stay and costs) have scarcely been examined.