Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 12/5001/25. The contractual start date was in May 2013. The final report began editorial review in September 2016 and was accepted for publication in March 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Iestyn Williams is a member of the Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) Prioritisation Commissioning Panel. Glenn Robert is a member of the HSDR Prioritisation Researcher-led Panel.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Williams et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Context

All publicly funded health-care systems grapple with the challenge of meeting expanding health need with constrained resources, and this is exacerbated by long-term demographic and cultural trends. Allied to this, the NHS in England is currently facing one of the most challenging financial periods in its history, and the 2016 referendum on membership of the European Union has once again seen funding of health care return to the centre of political and media debate. 1 Part of the strategy for meeting this challenge involves the replacement or discontinuation of outmoded, obsolete, unaffordable or cost-ineffective services. This has led to the development of low-value treatment lists such as those recently advocated in the UK Academy of Medical Royal Colleges’ version of the international ‘Choosing Wisely’ initiative,2 the establishment of the Royal College of General Practitioners standing group on overdiagnosis3 and the British Medical Journal’s ‘Too Much Medicine’ campaign (see www.bmj.com/too-much-medicine). The importance of this is not just in reducing inappropriate spending but also in creating space for more innovative and effective ways of providing and delivering services.

The concern with the oversupply of medicine is one of the reasons why decommissioning – defined as the replacement, removal or reduction of health-care services and interventions – has been advocated. 4 However, in the absence of clear, evidence-informed guidance on effective decommissioning practice, the danger is that blunt and unsophisticated instruments are employed, leading to unnecessary turmoil, with no guarantee of positive outcomes,5 or to the simple avoidance of decommissioning. There is currently a lack of theoretically informed, evidence-based guidance to inform the design and implementation of decommissioning programmes. Therefore, developing a better understanding of how decommissioning programmes unfold in the NHS and elsewhere is a crucial first step towards improving policy and practice. The study reported here explores the experience of the NHS as it seeks to grapple with the challenge of decommissioning, and puts forward evidence-based suggestions for future practice.

As well as the need to address ‘too much’ medicine, the case for more substantial reconfiguration of NHS services has become a familiar theme in health policy and practice in recent years. An ageing population, increasing numbers of people living with long-term and complex conditions, and advances in medical technology and innovation mean that traditional models of care have come under political and clinical scrutiny. In addition, concerns about the quality of services following high-profile scandals such as Winterbourne View and Mid Staffordshire6 are reflected in the establishment of new regulatory structures and regimes. Reconfiguration of NHS services to meet these various challenges was a feature of the NHS Five Year Forward View published in 2014,7 which proposed new models of care such as multispeciality community providers, primary and acute care systems and a shift in investment towards primary care, prevention and self-management. This approach is intended to help reduce the £30B funding gap identified in the review7 with Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs), as the local health-care budget holders, taking responsibility for delivering such programmes of service reconfiguration. CCGs were formed in 2012 as part of a significant restructure of the NHS in England following the Health and Social Care Act (2012),8 which saw the abolishment of primary care trusts (PCTs) and strategic health authorities at regional level. In the current system, CCGs fund, plan and procure health-care services for their local communities, while NHS England, with the support of regionally based area teams, has responsibility for commissioning specialised services and selected other primary care services. Thus, decommissioning, particularly as part of wider processes of service reconfiguration, is one in a continuum of skills and activities that CCGs are expected to learn.

Most recently, the NHS has been asked to develop place-based sustainability and transformation plans (STPs) to cover all areas of NHS spending in England. 9 Local NHS leaders are required to work with local government partners to identify local priorities and reorganise services in order to improve efficiency and financial balance. Given the challenging financial climate, these plans are likely to involve some decommissioning of services and therefore to generate controversy, and the early signs are that the relative lack of public engagement in STPs will lead to opposition. 10

Changes at these levels of decision-making also fall within our definition of decommissioning, which includes interventions ranging from medicines and equipment to clinical services and patient pathways. The mechanisms and drivers for decommissioning also vary. For example, services might be reduced or removed through the application of eligibility criteria, practice guidelines and other forms of service restriction and scale-back. They may be withdrawn as a result of in-house service closure, external contract termination, service reconfiguration and formulary delisting. Quality, affordability and cost-effectiveness are typically cited as drivers of decommissioning, but other concerns such as safety, changes in demand and political imperatives may also be influential. Decommissioning implies an explicit approach in which the rationale and aims of decisions are made clear to all those involved. This definition excludes passive decommissioning, whereby interventions and services ‘wither on the vine’ through lack of use, or through processes such as organisational mergers and takeovers, which may result in de facto decommissioning of services but which are not presented as such. Our definition of active decommissioning implies a deliberate, intentional decision followed by explicit actions, irrespective of the success or otherwise of these actions in bringing about their intended aims.

In these ways we distinguish decommissioning from associated activities such as priority-setting, pathway redesign and technology coverage decision-making. Although each of these may be employed as mechanisms within a decommissioning programme, they do not necessarily involve the withdrawal and reduction of health-care interventions. Therefore, it is the explicit aim of removing, replacing or reducing existing interventions that distinguishes decommissioning from other forms of resource allocation and service-improvement initiatives that may or may not be adopted as part of a decommissioning programme.

Our definition of decommissioning is therefore broad and designed to encompass related activities such as divestment, deinsurance, discontinuance and service termination,11,12 as well as concepts such as exnovation and reverse innovation, which have also been used to describe health-care decommissioning. 13,14 The most commonly used concept in the recent health services literature is disinvestment. Typically this refers to decision-making in relation to the removal and reduction of clinical and therapeutic interventions (as opposed to broader services and organisations) and stems from health technology assessment (HTA) and the application of economic principles of cost-effectiveness analysis. While subsuming these activities, our definition of decommissioning also includes programme and service closure and/or relocation and is not confined to narrow notions of value maximisation. For example, decommissioning programmes driven by policy, patient acceptability and affordability fall within our sphere of interest.

Decommissioning as used here shares some characteristics of commissioning and the commissioning ‘cycle’. 15 Whereas the latter refers to a series of specific functions, including needs assessment, procurement and contract management, decommissioning refers to programmes of activity concerned with withdrawal or reduction in the scale and volume of services delivered. As such, decommissioning may be seen as part of a continuum of activities – alongside commissioning and recommissioning – that are often interconnected in the NHS. 16 For example, when an existing service or care pathway is being decommissioned, an alternative may need to be commissioned in order for this retreat to take place. However, decommissioning is not reducible to the commissioning function and may, for example, be instigated by provider organisations. Similarly, decommissioning takes place in health-care systems that do not have a commissioning function, whether led by government or other planners and resource allocators. 4,17

Examples of decommissioning activities include:

-

reducing investment in or access to a specific treatment (e.g. through altering formulary listing or changing treatment protocols)

-

replacing existing services with ones deemed to provide greater cost-effectiveness or a lower overall cost (including the transfer of the delivery of services into more cost-effective settings)

-

closure or discontinuation of health-care programmes and organisations, for example through non-renewal of contracts and agency downgrading.

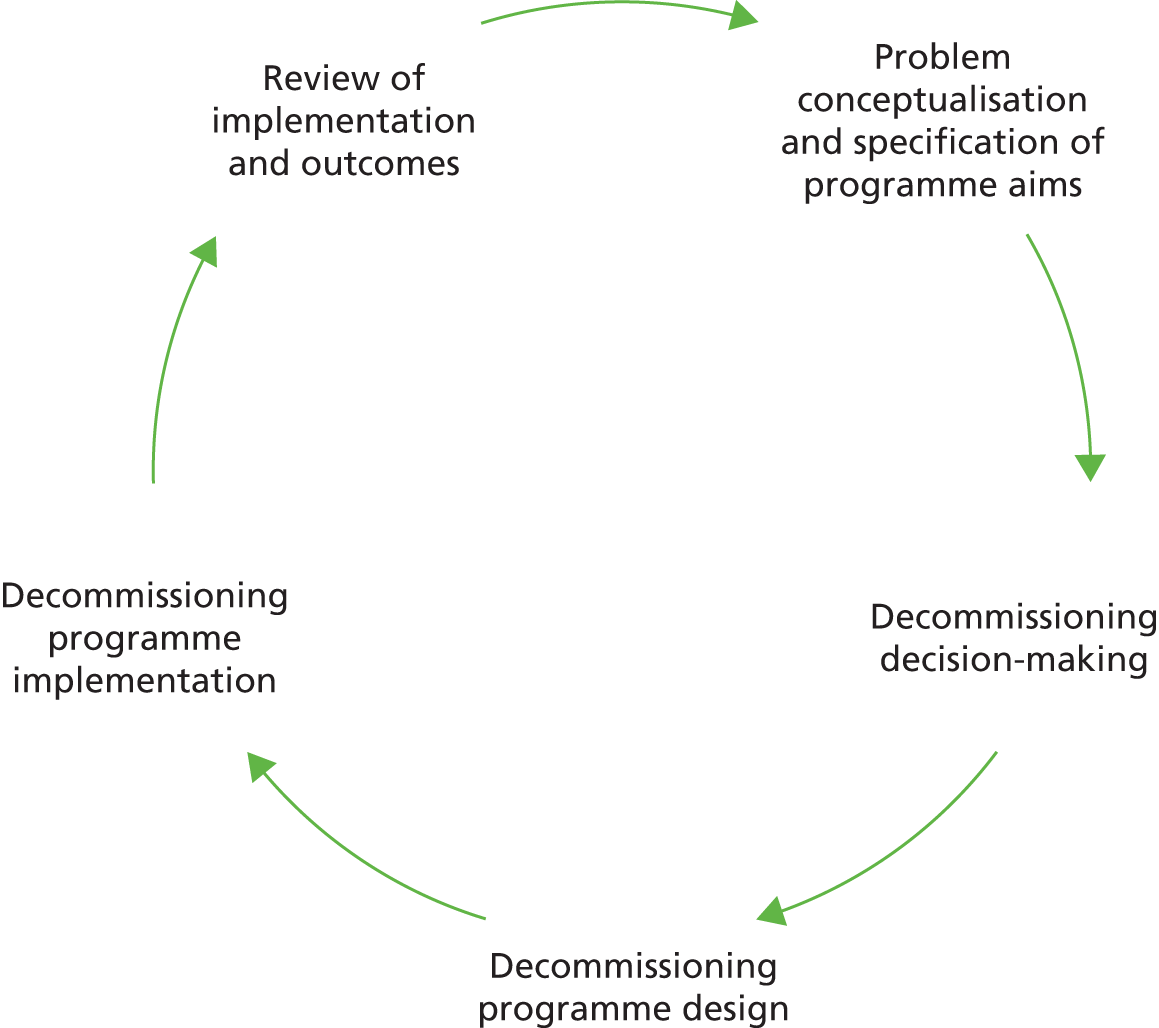

Key to each of these is the need to identify the candidates for decommissioning, as well as a requirement to design effective policies for the practical implementation of decommissioning programmes. Accordingly, at the outset of the research we developed a heuristic model of the ‘stages’ required for a typical decommissioning cycle, including the identification of need, processes for arriving at decommissioning decisions, and processes of implementation and review (Figure 1). In practice, however, progress through these stages is unlikely to be entirely predictable in terms of the exact distinction between, and the duration and sequencing of, stages.

FIGURE 1.

Stages of the decommissioning process.

Chapter 2 Research aims and objectives

The primary aim of this research is to formulate theoretically informed best-practice guidance for health-care managers by identifying and studying the factors and processes that influence the implementation and outcomes of decommissioning in the English NHS and other health systems. The study addresses the following research questions:

-

What is the international evidence and expert opinion regarding best practice for decommissioning in health care?

-

How and to what extent are NHS organisations currently implementing decommissioning?

-

What factors and processes influence the implementation and outcomes of decommissioning?

-

What are the perspectives and experiences of citizens, patient/service user representatives, carers, third-sector organisations and local community groups in relation to decommissioning?

The objectives of the research are to:

-

synthesise the existing international evidence and expert opinion on implementing decommissioning in health care

-

establish the extent and nature of decommissioning across the NHS by means of a national survey of NHS commissioners

-

carry out in-depth case studies of decommissioning in the English NHS

-

gauge the views and experiences of citizens, patient/service users, carers, third-sector organisations and local community groups in relation to decommissioning

-

develop evidence-based guidance on decommissioning for policy-makers and senior managers.

Chapter 3 Methodology

This chapter describes all aspects of study design, data collection and data analysis.

Conceptual framework for analysis

Much of the current literature on decommissioning in health care derives from evidence-based medicine and population health disciplines, and this study sought to complement this by drawing on insights from politics, systems and organisational/institutional analysis. Decommissioning programmes combine multiple interlocking processes and decision points, which mean that outcomes may be hard to predict. As well as this, theory and evidence suggests that perceived and real ‘losses’ can inhibit rates of decommissioning, thereby contributing to financial and administrative pressures on publicly funded health systems. 5 For example, Kahneman and Tversky’s prospect theory18 holds that, when faced with a risky decision, people’s attitudes concerning potential loss will be significantly different from their attitudes concerning possible gains. In other words, we value goods (or services) in our possession more highly than an equivalent service not yet experienced. The overarching theoretical framework for this project was made up of the following considerations:

-

the influence of ideas, interests and institutions on decommissioning decision-making and implementation

-

the stages of decommissioning programme design and implementation and how these influence outcomes

-

the complex processes of organisational change required to carry out decommissioning

-

process of translation associated with actor–network theory (ANT)

-

the concept of loss aversion.

Beyond this general orientation, we sought to be led in our analysis by findings from early work packages so that our most substantive work package, namely the case studies in work package 3, would be informed by a thorough appreciation of relevant aspects of context. This chapter explains how the project was sequenced so as to build our analytical tools and insights for the final synthesis and discussion of main messages and details all aspects of data collection.

Study design

The study comprises a multilevel investigation of decommissioning policies and programmes structured into four distinct but interconnecting work packages. Work package 1 was designed to address the first research question and also to inform the foci of the national survey and four case studies (work packages 2 and 3). Work packages 1 and 2 also provided a context for the analysis of findings from work package 3, enabling reflections on the transferability of findings. The case studies enabled us to explore gaps and unanswered questions identified in work packages 1 and 2. Finally, work package 4 (citizen, patient/service user representative, carer, third-sector and local community group perspectives) was added to the study following application for additional funds from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) programme. We devised and implemented this final work package in order to build upon the engagement with patients and service user representatives in work packages 1–3.

Work package 1: synthesis of evidence and expert opinion

Work package 1 addressed the research question ‘What is the international evidence and expert opinion regarding best practice for decommissioning in health care?’. This involved four activities: a summary of the extant literature, a Delphi panel of decommissioning experts, a mapping exercise and collection of qualitative decommissioning narrative vignettes.

Summary of the extant literature

At the time of commencement of the research, a number of structured evidence reviews had been completed or commissioned in which the authors identify practical constraints caused by poor indexing of decommissioning and its synonyms. 17 In order to build on work under way and to avoid these well-documented indexing problems, we opted to collate and synthesise learning from existing literature reviews.

Our approach to synthesising the existing literature therefore took the form of a ‘review of reviews’. The aim was to distil relevant messages from the evidence base on decommissioning and how this relates and applies to the specific context of the English NHS, as well as to identify knowledge gaps and unanswered questions to be pursued in subsequent phases of our research. To these ends we analysed existing reviews from the period 1990–2016 to address the following questions:

-

How are terms such as ‘decommissioning’ and ‘disinvestment’ employed in the literature?

-

What are considered to be the main determinants of successful decommissioning programmes?

-

What models and frameworks are available to guide decommissioning and how have these been evaluated?

-

What are the remaining knowledge gaps in terms of evidence and practice?

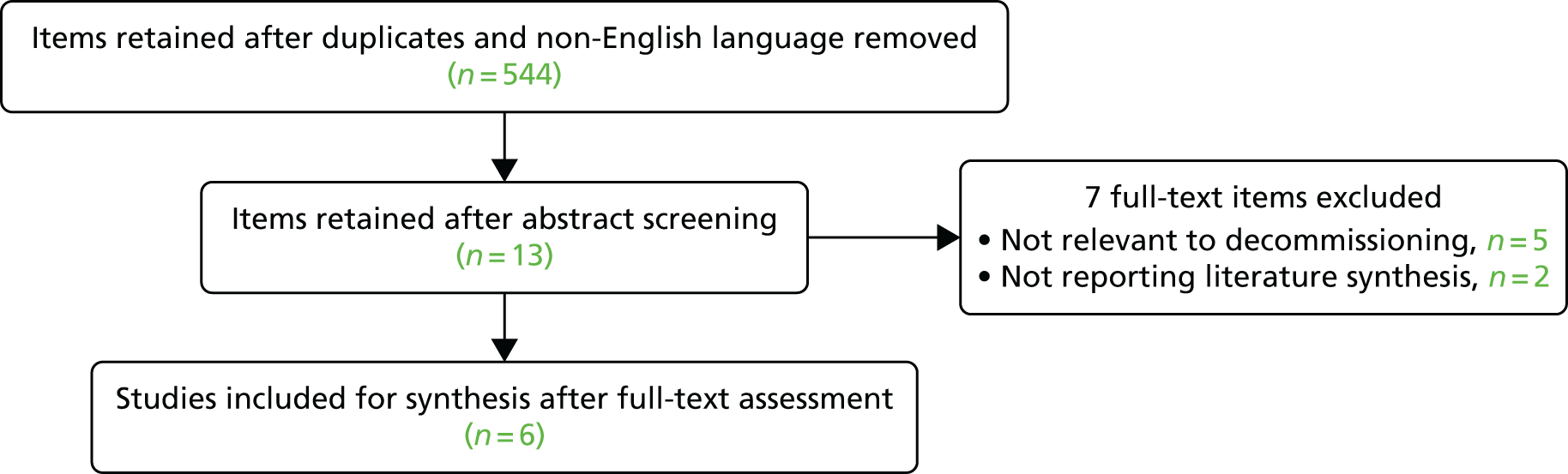

Search terms were identified from a scoping search of the literature drawing on the expertise of the authors and project advisors (Table 1 and Figure 2). Searches were carried out at the beginning and end of the project to ensure that results were up to date at the time of writing and that early results were available to inform subsequent phases of research design and analysis. Existing reviews were identified in the first instance through searches of health databases. From the initial list of search terms, ‘termination’, ‘replacement’ and ‘closure’ were removed from the searches of MEDLINE as they generated unmanageable volumes of results. The term ‘health’ was added to searches of the non-health-specific database (Social Sciences Citation Index). Snowballing searches were also conducted, including citation analysis and bibliography scanning.

| Review components | Details |

|---|---|

| Dates | No restrictions |

| Reporting | English language |

| Search terms | ‘Decommissioning’ ‘Disinvestment’ ‘Divestment’ ‘Deinsurance’ ‘Exnovation’ ‘Discontinuation’ ‘Exit’ ‘Cutback’ ‘Replacement’ ‘Delisting’ ‘Deimplementation’ ‘Undiffusion’ ‘De-adoption’ and ’review’ or ‘synthesis’ or ‘evidence’ |

| Other inclusion criteria | Included documents were reviews of empirical literature related to the replacement, removal or reduction of services (broadly defined) in health-care settings internationally |

| Database hits | HMIC (128 hits), MEDLINE (409) CINAHL (126) SSCI (44) |

FIGURE 2.

Filtering flow chart.

Synthesis of the six included literature reviews took the form of structured data extraction and tabulation against the five research questions (see Appendix 1). As the included reviews contained studies with a range of methodologies, our approach to synthesis was primarily descriptive, involving presentation rather than translation of main findings. 19 Results are presented in narrative form in Chapter 4.

Included reviews were confined to health settings and this is reflected in our synthesis. Although the scope for inclusion was wide in other respects, included reviews were somewhat skewed towards a narrow range of decommissioning types and were drawn largely from cognate disciplinary fields. In recognition of this, additional literature items uncovered during the search and retrieval process were summarised and incorporated in an unsystematic fashion. These were selected for inclusion if they were judged by the research team to complement the included reviews, for example by focusing on a wider range of decommissioning types or on relatively neglected stages of the decommissioning process (e.g. implementation). However, this process was opportunistic and non-replicable and a more in-depth evidence review was beyond the scope of our research. We put forward recommendations for future evidence synthesis in the conclusions chapter of this report (see Chapter 8).

Mapping the decommissioning landscape

In order to develop our understanding of the current decommissioning ‘landscape’ we conducted a mapping exercise of the roles and remit of agencies that might be expected to play a part in decommissioning in the NHS. No further sampling logic was employed. A list of potential organisations was drawn up by the research team and the project advisory group. Telephone interviews and/or searches of websites and official documents were carried out by two of the authors (JH and IW) in relation to each organisation, with the aim of establishing:

-

current roles and responsibilities with regard to decommissioning

-

current and planned decommissioning-related activities

-

perceptions regarding the challenges facing those leading decommissioning

-

any available good-practice guidance and other resources.

One interview was conducted at short notice and therefore was not audio-recorded, with note-taking carried out instead by the interviewer.

A key intended outcome of the mapping exercise was to inform the design of subsequent work packages and to provide a context to results emanating from the survey and case studies. Table 2 presents a list of organisations included and the method of data collection employed in each.

| Organisation | Data collection |

|---|---|

| Specialised commissioning area teams | Audio-recorded telephone interview |

| NHS Improving Quality | Audio-recorded telephone interview |

| IRP | Audio-recorded telephone interview |

| Care Quality Commission | Audio-recorded telephone interview |

| HealthWatch England | Audio-recorded telephone interview |

| Local government association | Audio-recorded telephone interview |

| NHS Clinical Commissioners | Written response and desktop research |

| NHS Confederation | Telephone interview, not recorded |

| NHS England Commissioning Development Directorate | Audio-recorded telephone interview |

| NHS Quality Board | Audio-recorded telephone interview |

| NICE | Audio-recorded telephone interview |

| NHS Alliance | Audio-recorded telephone interview |

| Monitor | Audio-recorded telephone interview |

| NCAT | Desktop research |

| OSCs | Desktop research |

Collecting qualitative decommissioning vignettes

To augment these assessments of the published research and the decommissioning landscape, we compiled a sample of retrospective accounts from individuals who had led decommissioning programmes within health and social care contexts in England. These narrative vignettes were collected through seven semistructured interviews carried out by two of the authors (JH and IW) with an opportunistic sample of local leaders of decommissioning processes identified through early mapping work and other suggestions of the advisory group. 20 The aims were to:

-

explore the stages and activities involved in a sample of recent decommissioning journeys

-

identify the actors and agencies involved in local processes of decommissioning to inform sampling for case studies conducted in work package 3

-

gain additional insight into the challenges, contexts and determinants of contemporary decommissioning processes in the NHS and related service areas.

Interviews were semistructured so as to enable core issues to be covered while allowing new themes to emerge. Three interviews were not audio-recorded at the request of interviewees, although note-taking was carried out. Table 3 provides further details of data collection.

| Interviewee | Decommissioning example | Method | Length of interview |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health-care review project lead (PCT) | Closure and relocation of walk-in centres to emergency department | Audio-recorded face-to-face interview | 1 hour |

| Public health specialist | Attempt to remove and replace a drug from a formulary | Audio-recorded telephone interview | 45 minutes |

| Commissioning manager (CCG) | Attempt to relocate anticoagulation services from acute to community settings | Audio-recorded telephone interview | 45 minutes |

| Programme manager | Planned care home closures by a County Council Adult Social Services department | Audio-recorded face-to-face interview | 1 hour |

| Clinical lead for one strand of the reconfiguration | Nationally instigated reconfiguration of children’s health-care services (paediatrics, neonatal services and obstetrics) | Audio-recorded telephone interview | 1 hour |

| CCG accountable officer | Recommissioning of a non-emergency patient transport service to an alternative provider | Telephone interview, not recorded | 45 minutes |

| CCG accountable officer | Transfer of chronic pain management service from acute to community setting | Telephone interview, not recorded | 45 minutes |

| Programme lead (CCG) | Reconfiguration of local maternity services by a CCG | Telephone interview, not recorded | 30 minutes |

Data from the mapping interviews and from the narrative vignettes were gathered, stored and analysed in accordance with best practice. Coding was carried out by two members of the research team (IW and JH) and differences resolved in discussion with a third member (GR). The primary aim of the mapping exercise was to help understand the wider context within which decommissioning activities were enacted. The primary function of the vignettes was to sensitise the research team to themes and issues to be explored in subsequent work packages. Findings from these two activities are presented in short descriptive form in the following chapter of the report (see Chapter 4).

Delphi study of research, policy and practice opinion

To help fill some of the gaps in the published evidence as regards ‘what works’ in decommissioning, we carried out an international Delphi study of expert opinion. Delphi surveys build a consensus through iterative questionnaires sent to a panel of experts and are effective in establishing a consensus in complex topic areas. 21 Developed by the RAND Corporation in the 1950s, the Delphi method was used to forecast the emergence of new technologies22 and has subsequently been used to establish research priorities in health care,23–28 as well as to generate a consensus on policy issues. 29–31 Delphi studies on policy themes share key features of the original approach including multiple rounds in which data are analysed and fed back as the basis for subsequent rounds with at least one opportunity for participants to revisit and revise their judgements on the basis of wider group responses, and anonymity for the participants who never meet or interact directly.

The first round of the Delphi study usually involves participants suggesting factors or cues that form the basis of subsequent closed questions. Participants are then sent a second questionnaire asking for their individual views on the items that they and their co-participants suggested previously. Responses are collated and returned to the participants in summary form, indicating both the group judgement and the individual’s initial judgement. Participants are then given the opportunity to revise their responses in the light of group feedback. This process may be repeated a number of times before the judgements of the participants are aggregated. 27

In this study, individuals were purposively selected from three groups (total n = 30) with expertise on the topic of decommissioning. These were researchers, policy-makers and regulators, and commissioners and providers of health-care services (Table 4). In this context ‘experts’ were understood to be individuals with experience in decommissioning in one or more of these capacities.

| Participant characteristics | Participants (n) |

|---|---|

| Country | |

| Australia | 6 |

| Canada | 3 |

| UK | 20 |

| Republic of Ireland | 1 |

| Perspective | |

| Researcher | 8 |

| Policy-maker | 10 |

| Practitioner | 12 |

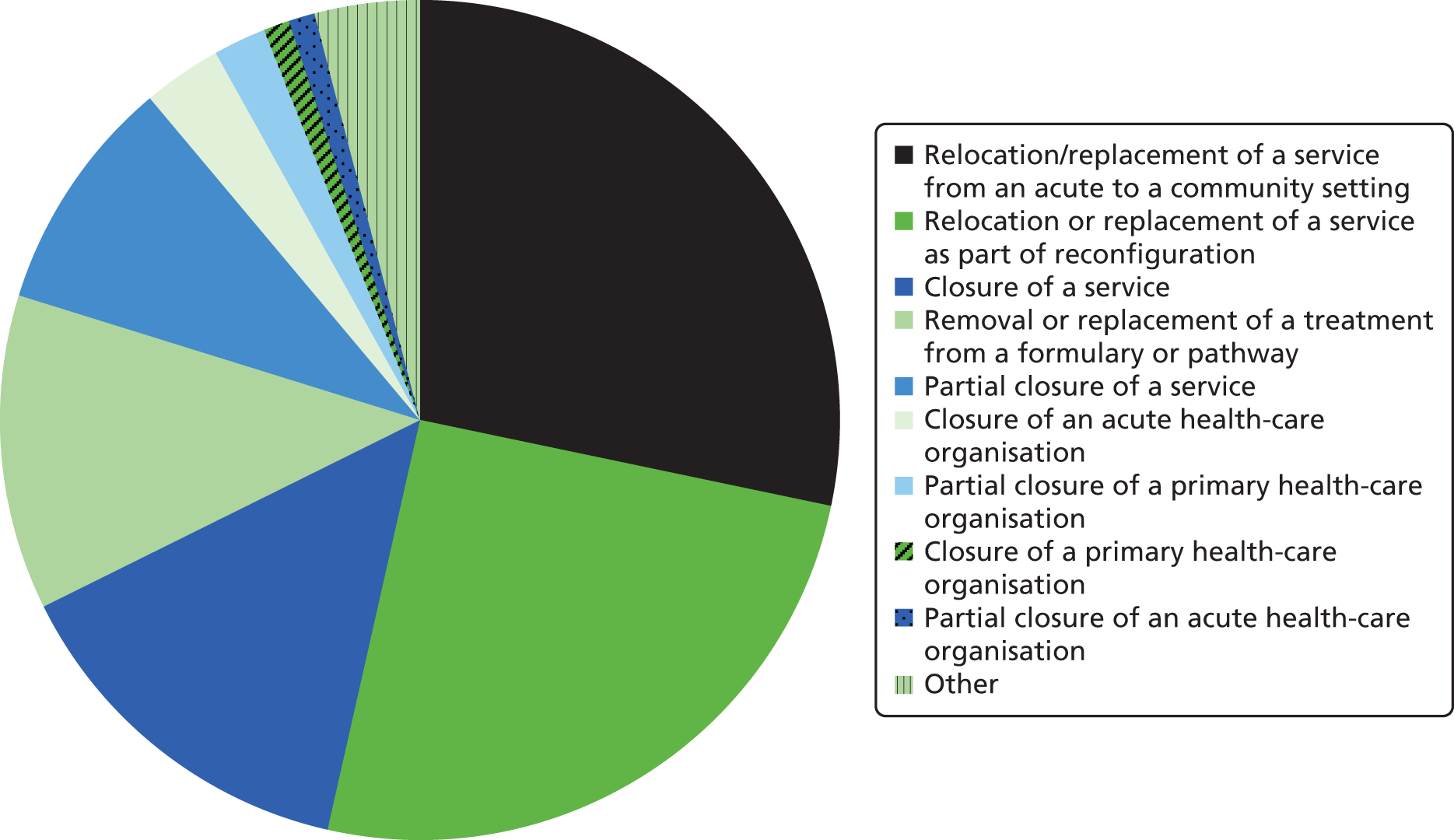

| Expertise in forms of decommissioning | |

| Removal or replacement of a treatment from a formulary or patient pathway | 2 |

| Relocation/replacement of a service as part of reconfiguration | 5 |

| Relocation/replacement of a service from an acute to a community setting | 1 |

| Closure or partial closure of a service | 2 |

| Closure or partial closure of an acute health-care organisation | 1 |

| More than one of the above (and including ‘research/policy development’) | 19 |

Candidates for the ‘research’ group were identified through the previously described searches of the published literature. Candidates for the ‘policy’ and ‘practice’ groups were identified through desktop searches and nominations from an international advisory group for the research project. An initial list of approximately 100 target respondents from the UK, Europe, North America, Australia and New Zealand were invited via e-mail to participate (see Appendix 2). Of these, 30 agreed to participate. As Table 4 shows, participants were drawn from the UK, Australia, Canada and the Republic of Ireland, although the final sample contained an over-representation of UK respondents, especially in the ‘practice’ category.

Participants were requested to consider, define and rate criteria and factors that shape the process and outcomes of decommissioning programmes. They were invited to complete three online rounds (with 1 week for completion of each one) and to suggest examples of ‘best practice’ in decommissioning. Open comment responses were analysed by the research team using open coding and constant comparison. Similar codes were grouped to identify concepts emerging from the data. A consensus was statistically operationalised by measuring whether or not group ratings were strongly polarised (e.g. 50% of respondents strongly agreeing and 50% strongly disagreeing with any statement is a strongly polarised distribution).

In round 1, participants were asked for up to five nominations for each of the following:

-

considerations that should inform decisions to implement decommissioning

-

considerations that do inform decisions to implement decommissioning

-

factors that positively shape the process of decommissioning

-

factors that negatively shape the process of decommissioning

-

factors that positively shape the outcome of decommissioning

-

factors that negatively shape the outcome of decommissioning.

They were also invited to suggest best-practice recommendations for the implementation of decommissioning decisions. Open comment fields enabled respondents to explain and/or justify their suggestions, and to raise any other issues. The anonymised, cumulative responses were then fed back to the whole panel to inform the design of round 2.

For the second round, participants were requested to rank their level of agreement with statements derived from round 1, using a four-point Likert rating scale (strongly disagree, disagree, agree and strongly agree). They were also asked to rank relative importance of the factors proposed in round 1 in shaping the process and outcomes of decommissioning, again using a Likert rating scale (very low importance, little importance, high importance and very high importance). Open comment fields enabled respondents to explain responses. The research team calculated the level of consensus in relation to the total of 88 rating scale questions in round 2 using the following thresholds:32

-

high = 70% of ratings in one category or 80% in two contiguous categories (e.g. agree and strongly agree)

-

medium = 60% of ratings in one category or 70% in two contiguous categories

-

low = 50% of ratings in one category or 60% in two contiguous categories

-

none ≤ 60% in two contiguous categories.

Anonymised, aggregated responses relating to factors with no consensus or a low level of consensus were then fed back to the Delphi panel to inform the design of round 3.

For the third round, participants were invited to reflect and comment on the round 2 results for the 17 statements that achieved no consensus or a low level of consensus, and to rank their level of agreement with the 17 statements, having had an opportunity to review the results from the panel as a whole. The final outcomes from rounds 1 to 3 were fed back to all participants and an opportunity to make further open comments provided.

Work package 2: national survey of Clinical Commissioning Groups

Work package 2 addressed the research question ‘How and to what extent are NHS organisations currently implementing decommissioning?’. This was addressed via an online national survey of NHS CCGs. The aim of the survey was to identify the volume and types of decommissioning activities planned and under way across England by CCGs and to derive self-reported data, where possible, on the implementation and outcomes of decommissioning programmes. The survey tool was developed with guidance from the project advisory group and survey questions were designed to follow up findings from work package 1 concerning the drivers of decommissioning and factors that shape and influence the process and outcome of decommissioning activities. The survey addressed the following themes:

-

extent of current engagement with decommissioning

-

current/recent decommissioning programmes

-

aims and intended outcomes of decommissioning

-

challenges and key determinants of decommissioning

-

attitudes, experiences and competencies in relation to decommissioning.

The survey was designed in SurveyMonkey® (Palo Alto, CA, USA). Before being implemented nationally, the survey was piloted with local CCG representatives identified through project team networks. The finalised data collection instrument (see Appendix 3) combined tick boxes and attitudinal questions rated according to Likert scales with additional opportunities to provide free-text responses. An additional question at the end of the survey asked respondents if they would be willing to be contacted for further information and to discuss the potential to feature as a case study in the research.

In order to administer the survey, contact details for all 211 CCGs in England (at the time of the research) were compiled from NHS England and Department of Health websites and an e-mail invitation and accompanying information sheet was sent to each CCG (see Appendix 3). Within each CCG we sought a single survey response from a member of the senior team (e.g. chair, clinical lead, accountable officer, chief finance officer or other member of senior management and/or board), and our e-mail invitation offered the option for CCGs to nominate a suitable respondent. The seniority of the respondent was an important prerequisite in order for respondents to be able to offer an authoritative account, as well as to provide strategic oversight of decommissioning activities planned or already completed by the CCG. A link to the survey was included in the e-mail invitation and respondents were provided with a time frame of 1 month in which to complete the survey. The e-mail invitation also offered CCGs the option of accessing a hard copy of the survey from the research team.

E-mail reminders and telephone follow-up were employed during the 1-month response period. The survey was also promoted via professional bodies and networks such as the NHS Confederation and NHS Clinical Commissioners. A final response rate of 27% (56 CCGs) was achieved, with the majority of CCGs opting to complete the survey via the online method and eight opting to complete it via hard copy. This response rate is comparable to other CCG surveys undertaken at the time (such as the NHS Confederation survey33). Feedback from CCGs that declined to take part suggested that time pressures and lack of capacity were key reasons.

The final sample of respondent organisations is broadly representative of the wider CCG population in terms of size, rural-to-urban ratio and performance against financial targets (see www.england.nhs.uk/2013/12/ccg-allocations and www.nhs.uk/service-search/performance/search). The sample includes an over-representation of CCGs in the Midlands, perhaps reflecting the location and profile of the lead research institution (University of Birmingham). This notwithstanding, the broadly representative sample would suggest that extrapolation of findings is warranted. However, the research team were conscious of possible selection bias with CCGs more engaged in the decommissioning agenda perhaps more likely to respond. This has led us to be cautious with regard to the claims made.

Quantitative data derived from the CCG survey were uploaded into Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) version 22 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and subjected to descriptive statistical analysis (primarily involving counting and calculation of percentages) in order to generate results about the frequency and types of decommissioning, aims and intended outcomes, methods used in decommissioning and key factors affecting decommissioning programmes. Qualitative free-text responses were coded into themes and reported alongside the quantitative data to provide further insight. As well as providing a sample of contemporary CCG decommissioning activity, the survey sensitised us to the range of types of decommissioning activities planned or under way within CCGs and their experiences of implementation thus far. These insights were important for refining our case study selection. A list of potential candidates was also compiled from CCGs that indicated that they would be willing to feature as a case study in the research.

Work package 3: decommissioning case studies

In combination with work packages 1 and 2, work package 3 addressed the research question ‘What factors and processes influence the implementation and outcomes of decommissioning?’. We used a comparative case study design across multiple study sites to generalise theoretically from within and between cases,34,35 to map the multiple interacting actors and influences and to uncover the intended/unintended consequences of decommissioning initiatives. Although each case had its own integrity in terms of theory building and potential to generate practice recommendations, we also developed common themes across case study sites using comparative case study methods and pattern matching. 35–37

Case selection

We selected four case studies in which a planned and explicit approach to decommissioning had been adopted. These were at varying stages of progression (as mapped against the stages model) in order to enable us to follow decommissioning journeys from initiation and development to implementation and, where possible, direct and indirect outcomes.

To identify potential case studies, we adopted a snowballing approach using existing contacts from the project principal investigator, advisory group, decommissioning narratives, survey responses and mapping exercise. Using these approaches, we developed a matrix of potential case study options structured around four sampling criteria (Table 5), intended to capture a diversity of decommissioning activities:

-

geography – including programmes implemented in both rural and urban settings in England

-

scale and complexity – including decommissioning programmes that vary from the relatively simple (e.g. implementation of National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) disinvestment guidance) to the highly complex (e.g. reorganisation of services across organisational and sector boundaries)

-

conflict – including programmes with a high degree of stakeholder buy-in and support and others for which there are currently (or it is anticipated that there will be) high levels of resistance and stakeholder challenge

-

programme instigation – including decommissioning programmes where national bodies play an important role and others that have been instigated and led entirely by local organisations such as CCGs.

| Criterion | Case study | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Geography | Urban | Urban | Rural | Rural/urban |

| Scale and complexity | High | Low | Low | High |

| Conflict | High | Low | Low | High |

| Programme instigation | National/regional | Local (CCG) | National (NICE) | Local (CCG) |

| Stage of decommissioning at data collection | Programme design | Programme implementation | Decision-making/programme implementation | Decision-making |

Based on these provisional sampling criteria we selected the following case studies.

-

Reorganisation of specialist services for paediatric burn care in England.

This case study was selected to fulfil the criteria of being a nationally led, complex reorganisation process involving planned service removal or reduction. The case was identified through the national mapping exercise, and access was negotiated between the project principal investigator and NHS England. In these conversations it was established that the burn care reorganisation would incorporate the decommissioning (by downgrading) of some services and that it would be closest to the ‘programme design’ phase at the commencement of fieldwork. As a national reorganisation it was anticipated that it would generate relatively high levels of conflict and that the specialised services sites would be in predominantly urban areas.

-

CCG-led decommissioning of an end-of-life (EOL) home support service.

This case study was selected to fulfil the criteria of having relatively low complexity and low conflict (although we could not be sure of this at the outset) and of being in an urban area and closest to the implementation phase of the decommissioning process. The CCG was initially identified as a potential case study through networks of the research team and access was negotiated with the CCG programme manager for the decommissioning programme.

-

Decommissioning activity by an Area Prescribing Committee (APC).

This case study was selected to fulfil the criteria of being rural, and having low complexity and relatively low conflict (although again this could not be fully established prior to commencing the case study). The intention was to observe implementation of NICE guidance by the committee and any additional decommissioning undertaken. The APC was identified following the mapping exercise through an e-mail invitation to a number of APC representatives in suitable areas, asking if they wished to showcase work in the area of decommissioning. Access was negotiated through the APC chair and research lead for the host CCG.

-

CCG-led review and planned reorganisation of local primary and acute care services.

This case study was selected to fulfil the criteria of covering an area with rural parts, which had high levels of scale, complexity and likely conflict. This case study was closest to the decision-making phase of our stages model. Access was negotiated with the programme manager for the service transformation programme following an initial approach to the research team.

Data collection

For each case study, the primary unit of analysis was the decommissioning process itself and we compiled narrative accounts of the programme of work intended and/or under way. We employed non-participant observation techniques as used successfully by the applicants in previous research. 38 Detailed field notes were taken to record the processes through which decommissioning plans were identified and drawn up, and the role of decision-making tools and frameworks in this.

For each case study, semistructured interviews were conducted with a sample of those involved (see Table 6 and Appendix 4). In all case studies, the interview sample comprised individuals involved in the design and implementation of the decommissioning programme. For case studies in the early stages of progression, a second round of interviews was conducted approximately 12 months after the initial round. These were intended to update the research team on programme progress. For case studies in the implementation phase (e.g. case study 2) the primary focus of a first round of interviews was on design and enactment of the implementation plan with a follow-up round planned to explore outcomes.

Interviews focused on:

-

the origins, aims and intended outcomes of the decommissioning programmes

-

decision-making tools and other information used to inform decommissioning programmes

-

the web of relationships between internal and external actors and influences in decommissioning design and implementation processes

-

the role of key interest groups in decommissioning, including politicians, clinicians and the public

-

outcomes, experiences and attitudes towards future decommissioning.

In summary, a total of 59 interviews were carried out in work package 3. This is somewhat less than the 90 interviews anticipated in our project plan. The main reasons for this discrepancy are as follows:

-

We placed a greater emphasis than was initially intended on observation over interviews in the case studies, as these provided a rich source of data (Table 6).

-

Data saturation was reached early in interviews for case study 3.

-

We were unable to gain access to respondents for follow-up interviews in case study 2 as some individuals had moved on from their posts.

| Case study | Number of | |

|---|---|---|

| Interviews | Observations | |

| 1. Paediatric burn care reorganisation | 17 | 3 |

| 2. Decommissioning EOL service | 13 | 0 |

| 3. Decommissioning in an APC | 10 | 4 |

| 4. CCG reorganisation of primary and secondary care | 19 | 11 |

| Total | 59 | 18 |

Data analysis

Informed by our theoretical framework, we inductively analysed interview data to explore participants’ perspectives and experiences. Analysis involved comparative case study methods and pattern matching. 36,37,39 In order to facilitate internal validity,40 all interviews were fully transcribed and we used qualitative coding software [NVivo version 11 (QSR International, Warrington, UK)] to support data storage and retrieval during the analysis phases. Two members of the research team (IW and JH) were involved in building coding frames for themes from qualitative data and compared independent coding of a subset of data to identify and address coding differences and ensure consistency. All identified themes were discussed at ‘analysis days’ attended by the core project team. External validity and transferability of analysis was addressed through detailed description and data triangulation between work packages. 40 Respondent validation was facilitated through sharing of draft case study reports with respondents (with four individuals taking up the offer to review and comment), and additional clinical expertise was drawn on in case study 1 to ensure the accurate presentation of clinical information.

In our approach to case study analysis we drew on our theoretical framework, including concepts derived from the ANT research tradition. ANT was developed by Bruno Latour, Michel Callon and John Law41 as part of the academic field of ‘Science and Technology Studies’ during the 1980s. Although it has ‘theory’ in its name, ANT is better understood as a range of methods for conducting research that aims to describe the connections that link together humans and non-humans (e.g. objects, technologies, policies and ideas). 42,43 In particular, ANT seeks to describe how these connections come to be formed, what holds them together and what they produce.

In the context of health-care service and delivery, ANT has typically been forwarded as a framework for investigating technology implementations in health-care settings (e.g. 44–46). Aside from technology implementation, ANT has also informed studies of implementing ‘Lean thinking’ in health-care organisations,47 exploring the effectiveness of quality-improvement interventions48 and the evolution of indoor smoke-free regulations (a policy innovation). 49

A key concept in ANT – particularly pertinent to the study of decommissioning processes – is what Latour called ‘the sociology of translation’. 50 By this, he meant that players interact to build heterogeneous networks of human and non-human actors, forming alliances and mobilising resources as they strive to convert an idea into reality. The central focus of ANT in the context of our study is, therefore, the process by which a decommissioning project is ‘brought into being’ through the process of translation and how it changes over time. The picture is always a dynamic one, as actors interrelate, define one another and realise their goals (or not) by mobilising intermediaries, such as technical artefacts, texts, human skills and other resources. 51,52 Translation is achieved by displacements that require discourse and the exercise of power, and it may or may not achieve the desired outcome. This continuous, organic realignment of people and non-human actors is what Latour50 calls the ‘chain of transformation’. What emerges may not be a unified, shared goal; indeed, the concept of the ‘network’ is that different actors often have conflicting goals, and outcomes are the result of struggles between different interest groups and the flow of power through the network. Callon51,52 summarised the process of translation as four ‘moments’ or phases:

-

problematisation – the definition of the nature of the problem in a specific situation by an actor (a group or an individual) and the consequential establishment of dependency

-

interessement – ‘locking’ other actors into the roles that were proposed for them in the actor’s programme for resolving that problem

-

enrolment – the definition and interrelation of the roles that were allocated to other actors in the previous step

-

mobilisation – ensuring that supposed spokespersons for relevant collective entities are properly representative of those entities.

Prior to beginning our study we felt that ANT and the concepts briefly outlined above would enable us to explore decommissioning processes in novel ways by helping to describe the multiple interacting actors and influences in our four case studies; to consider why such actors and processes appear to ‘behave’ differently in different settings or at different times; and to draw attention to the unintended consequences of decommissioning processes (as well as the anticipated ones). We also proposed that applying an ANT perspective would help us to explore several common themes that, from the literature, appear to impede successful outcomes of decommissioning processes, namely:

-

one or more interest groups may feel threatened by substantive change

-

external actors may feel insufficiently consulted and involved in decision-making processes

-

stalemates between coalitions of interests

-

the role of power and politics.

In drawing on ANT, we needed to ‘follow the actors’ in our case studies and to analyse how these actors themselves define what is going on. However, it should be noted that the empirical scope of the case studies was not as expansive as is usually found in the ANT tradition and precluded us from, for example, extending our analysis into all levels of health-care decision-making and activity. It would therefore be inappropriate to cast our case studies as full actor–network analyses or to make inferences about the full actor networks at play. Instead, we have drawn on Callon’s51 summary of the translation process to make sense of smaller-scale case studies that were primarily interview led and supported with observational and documentary analysis. We have recast the Callon framework in the following language to be more accessible to practitioner audiences. These form a structure for presenting and analysing findings:

-

the role of evidence and other resources in identifying and framing a need for decommissioning

-

alliance building (e.g. analysing context, attending to interests and power relations) as part of a decommissioning process

-

social acceptance (analysing engagement strategies, attempts to gain wider acceptance) for the solution of decommissioning

-

implementation and institutionalisation of a decommissioning decision.

It is important to note that several criticisms have been made of ANT that are relevant to our study of decommissioning processes. Building on Robert et al. ,53 these include the following:

-

ANT fails to attend to the various ways in which macro-level structures (e.g. external regulatory bodies or the Department of Health in the context of our study) shape and modify the process of social interaction and practices; by ignoring such institutional sources of power, ANT is criticised for having little to say about the systematic exclusion that prevents some social groups from having a voice in, for example, decommissioning processes.

-

How to delineate an actor network (with a view to studying it) presents a methodological problem. The network is open, and hence must be artificially defined by the researcher. There is an argument for not defining the actor networks in advance but rather seeing what emerges as key in any particular study.

-

May54 suggests that ANT may also be limited in terms of accounting for everyday micro-level practice and assisting with practical problem-solving.

Summary of patient and public involvement activities in work packages 1–3

A key aim in each of these work packages was that public, service user and patient (PSUP) expertise and input voices would be included. PSUP expertise was recruited to the research team and advisory group and a subgroup was convened to discuss PSUP activities at strategic intervals during the research. We also sought to build PSUP activities into the research design in a number of ways. In work package 1, patients and service user representatives were invited to form part of the Delphi panel. However, all of those invited declined to participate, citing concerns that they did not consider themselves sufficiently ‘expert’ to take part. In work package 3 we anticipated that patient input would feature in each of the decommissioning case studies and that public engagement or consultation would feature in a subset of these. We therefore utilised site-specific mechanisms for involvement, for example by observing and participating in public engagement events held as part of the case study 4. However, in case studies 1, 2 and 3, opportunities for engagement beyond interviews with individual patient/public representatives were limited by the modest PSUP activities of the decommissioning processes themselves. As a result, and acting within the constraints of our research ethics approval, we were limited in the extent of additional engagement that we were able to undertake. This raised concerns with regard to (1) the breadth of perspectives on the research topic that we were able to collect and (2) opportunities to feed back research findings to these audiences.

As a result of these concerns, the research team applied for and secured NIHR HSDR funds to build an additional work package into the project, designed to strengthen our understanding of decommissioning from citizen, patient/service user representative, carer, third-sector organisation and local community group perspectives.

Work package 4: citizen, patient/service user representative, carer, third-sector organisation and local community group perspectives

To mitigate for gaps in the data, a further work package was put in place that was targeted towards a series of further stakeholder groups for whom decommissioning might be important. It was intended to recruit participants representing citizens, patient/service user groups, carers and community/third-sector organisations. The aim of the work package was to investigate the perspectives and experiences of citizens, patient/service user representatives, carers, third-sector organisations and local community groups in relation to decommissioning, and to address the following research questions:

-

What are the views and experiences of citizens, patient/service user representatives, carers, third-sector organisations and local community groups in relation to health and social care decommissioning?

-

How do these compare with those of policy-makers, practitioners, health-care leaders and researchers?

-

How might these perspectives be brought together in order to improve equity and acceptability in decommissioning?

To address these questions we undertook the data collection activities described below.

Focus group discussions

We carried out three deliberative focus groups, each with approximately 10 participants sampled with the intention of achieving a diversity of age, gender and ethnicity. 55 Focus groups involved combinations of citizens/members of the public, representatives of national citizen organisations (e.g. HealthWatch) and patient organisations (general and specific), community organisations and independent third-sector organisations. In the focus groups, some participants also self-identified as NHS patients/service users. The logic of this sampling was simply to recruit individuals more likely to be affected by (as opposed to being responsible for) decommissioning.

Potential participants for the focus groups were contacted through HealthWatch England, National Voices, the Department of Health Voluntary Sector Strategic Partner Programme, Carers UK, patient representative and advocacy organisations such as the National Association for Patient Participation and Shaping Our Lives, researchers with particular expertise and interest in patient and public experience and engagement and individuals involved in patient and public engagement identified in work package 3. No NHS organisations were contacted, in accordance with the terms of our research ethics approval. Participants were not required to have direct previous experience of decommissioning, although it transpired that a substantial proportion of those who consented to take part did have, having been directly affected by decommissioning.

The focus groups were intended to sensitise us to the issues and perspectives and so questions were open ended, encouraging wide-ranging discussion. At least two facilitators were involved in each of the focus groups (IW, SB and JH) and examples of decommissioning scenarios were used to prompt discussion (see Appendix 5). Each discussion lasted for approximately 1.5 hours and the final 30 minutes was taken up with the co-design of questions for a follow-up Delphi study of expert opinion, drawing specifically on the experiences and perspectives of citizens, patient/service users, carers, third-sector organisations and local community groups.

Delphi study of citizen, patient/service user representatives, carer and community groups, and third-sector organisations

Drawing on these insights we implemented a second three-round, online Delphi survey in order to compare views on drivers of decommissioning with those expressed by the first Delphi panel (work package 1) on drivers of decommissioning and to elucidate a consensus on best practice for the engagement of patients and the public in decommissioning processes, from the perspective of citizens, patients/service user representatives, carers and community groups and third-sector organisations. 28,30 The letter of introduction (see Appendix 6) incorporated the suggestions of participants in the focus groups about accessibility, as did the decision to replace the term ‘decommissioning’ with the phrase ‘move or take away services’.

The approach to analysis and consensus-building was as described in Chapter 3, Delphi study of research, policy and practice opinion. The final sample for the second Delphi study comprised third-sector organisations that provide support to, and advocacy/representation of, service users and carers (including, among others, Shaping our Lives, National Voices, Carers UK, National Development Team for Inclusion, the Mental Health Providers Forum, the Voluntary Organisations Disability Group, the National Care Forum and National Association for Voluntary and Community Action); other patient and public representative organisations (including HealthWatch England, National Association for Patient Participation, the Race Equality Foundation and patient expert groups); and selected academics specialising in public involvement and/or patient experience. Following advice from our advisory group, we restricted the scope to the English NHS rather than seeking respondents from other countries. More detail on respondents is provided in Table 7.

| Role (self-identified) | Participants, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Patient | 14 (56) |

| Service user | 8 (32) |

| Carer | 8 (32) |

| Community/third sector | 14 (56) |

| Member of the public | 11 (44) |

| Academic specialist in PPI | 2 (8) |

| NHS patient representative | 2 (8) |

| No response | 1 (4) |

| Total responsesa | 25 |

Of the 50 individuals and organisations invited, 26 agreed to participate. Female participants made up the majority of respondents (15, 60%). Eighteen described themselves as ‘white British’ or ‘white English’, with five describing themselves as ‘non-white’, ‘European’ or ‘other’. Ten respondents indicated that they had a disability and a further two provided no response to this question. Older age groups were over-represented within the sample, with two respondents aged between 25 and 34 years, four between 35 and 44 years, four between 45 and 54 years, seven between 54 and 65 years and seven > 65 years.

In round 1, participants were asked about their experiences of decommissioning, including good and bad aspects of these experiences. They were then asked ‘What if any do you think are good reasons to move or take away services?’ The same question was then asked in relation to ‘bad’ reasons and the reasons behind such a decision in reality. They were also asked how they would wish to be involved ‘if the NHS was thinking about moving or taking away services in your local area or nationally’. Open-text comment boxes were provided in relation to each of the questions. The anonymised, cumulative responses were then fed back to the whole panel to inform round 2.

In round 2, participants were asked to rank their level of agreement with statements derived from round 1, using the four-point Likert rating scale and consensus thresholds employed in Delphi study 1. The statements related to:

-

good reasons to move or take away services

-

bad reasons to remove or take away services

-

the reasons why these decisions were made in practice.

Respondents were also asked to choose the three reasons that they considered were most justifiable/least justifiable/most influential in practice.

Two more questions asked respondents to review lists of statements deriving from their first-round comments about how they would like to be involved and which methods they thought most important to employ. They were then invited to select the three that they considered most important.

The anonymised, cumulative responses relating to those factors that achieved a low level of consensus or no consensus were fed back to the whole Delphi panel to inform round 3. In round 3, participants were asked to reflect and comment on the round 2 results for the 19 statements that achieved a low level of/no consensus and to rank their agreement with these statements, having had an opportunity to review the results from the panel as a whole. They were also given an opportunity to comment on the combined three highest and lowest ranking statements from each of the questions.

The final outcomes from rounds 1 to 3 were fed back to all participants and further open comments were invited.

Integrating across the empirical strands of the study

Work package 1 informed the foci of the national survey and four case studies (work packages 2 and 3). The case studies enabled us to explore gaps and unanswered questions identified in work packages 1 and 2. Work packages 1 and 2 gave a context to the analysis of findings from work package 3, enabling reflections on transferability of findings. Finally, work package 4 enabled us to compare and contrast these perspectives with those of patients, community groups and carers and to mitigate shortcomings in the involvement of these groups in earlier work packages. In these ways, the various stages of the project were integrated.

As well as using data from work packages to inform the development of subsequent work packages, each was designed to answer specific research questions. Work package 1 addressed the question ‘What is the international evidence and expert opinion regarding best practice in decommissioning health care?’. Work package 2 addressed the question ‘How and to what extent are NHS organisations currently implementing decommissioning?’. Work package 3 addressed the question ‘What factors and processes facilitate the successful implementation and outcomes of decommissioning?’. Finally, work package 4 addressed the question ‘What are the perspectives and experiences of citizens, patient/service user representatives, carers, third-sector organisations and local community groups in relation to decommissioning?’. In our final synthesis and discussion, we brought together insights from each of these data sources to address the main aim of the research, which was to formulate theoretically grounded, best-practice guidance for health-care managers by identifying the factors and processes that influence the successful implementation and outcomes of decommissioning health services.

Research ethics approval

Research ethics approval was secured from the University of Birmingham. As well as having all research plans and materials approved, the research team discussed ethical dimensions throughout the research project, including, for example, issues of informed consent, anonymity and researcher–respondent relations.

Chapter 4 Findings from the review of reviews, mapping and narrative vignettes and Delphi study of experts

This chapter presents results from the various strands of work package 1, including the evidence summary, the mapping exercise, the narrative vignettes and the Delphi panel.

Evidence summary

In this section we present findings from a narrative synthesis of the existing literature against our research questions. 19 Table 8 provides details of the included reviews.

| Author/year | Relevant research aims/question | Review type | Scope | Data sources | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gallego et al. 201056 | To identify current approaches to reducing ineffective or cost-ineffective interventions and programmes | Systematic |

|

Seven papers identified | Approaches to disinvestment found to employ CER and/or PBMA. Authors note barriers relating to evidence, politics and ethics |

| Leggett et al. 201257 | To review the literature on health technology reassessment in practice | Systematic |

|

40 literature items identified | Authors conclude that the field of health technology reassessment is in its infancy and there is a lack of practical knowledge to guide implementation. There is a need to build expertise and knowledge in this regard |

| Polisena et al. 201358 | To identify case studies of disinvestment in health care | Systematic search for case studies |

|

14 case studies identified | Approaches to decommissioning include tools such as PBMA, CER and procedural justice models such as A4R |

| Mayer and Nachtnebel 201559 | To elucidate factors that facilitate implementation | Systematic database search and unsystematic hand search |

|

Seven programmes identified | Authors identify the following as important to implementation: political will, transparent processes and physician engagement |

| Niven et al. 201560 | To describe the literature on de-adoption, document current terminology and frameworks | Systematic |

|

109 literature items identified (65% original research) | Identifies a ‘large body of literature’ describing current approaches, although additional research is required to determine an ‘ideal strategy’ |

| Parkinson et al. 201517 | To review how reimbursement policy decision makers have sought to . . . disinvest from drugs | Expert |

|

Unclear | Full decommissioning (referred to as ‘delisting’) is rare. Other methods include restricting treatment, price/reimbursement reductions and encouraging generic prescribing |

How are terms such as ‘decommissioning’ and ‘disinvestment’ employed in the literature?

In their review, Niven et al. 60 document the terminology employed in the literature, identifying 43 separate terms currently in usage, which they go on to map on to a conceptual framework made up of de-adoption ‘phases’ (identification of low-value practices, facilitation of the de-adoption process, evaluation of de-adoption outcomes, and sustaining de-adoption). This mirrors to some extent the stages model that we outlined in Chapter 1, albeit without the ‘programme design’ stage, reflecting the authors’ focus on clinical rather than organisational interventions. ‘Disinvestment’ is reported to be the most prevalent term in the literature, although the authors advocate ‘de-adoption’ as more suited to a process rather than a decision point.

Four of five other reviews employ the more established term ‘disinvestment’,17,56,58,59 whereas Leggett et al. 57 employ the term ‘reassessment’ in keeping with their specific interest in this area. The earliest of the six reviews56 locates the term ‘disinvestment’ within the HTA movement and notes the tendency for prescriptions for practice following a HTA model. As noted, each of the reviews confines its scope to clinical/therapeutic interventions and, notwithstanding Niven et al. ’s60 preference for ‘de-adoption’, this area of decommissioning has become synonymous with the term ‘disinvestment’. In most definitions of the term, ‘disinvestment’ contains a normative component in its emphasis on improved health outcomes:

The complete or partial withdrawal of resources from health care services and technologies that are regarded as unsafe, ineffective or inefficient, with those resources shifted to health services and technologies with greater clinical- or cost-effectiveness.

Polisena et al. 58

Parkinson et al. 17 employ the term ‘disinvestment’ in a more expansive way to include restrictions on prescribing, price negotiations and the encouragement of generic prescribing, with ‘delisting’ used to refer to complete disinvestment. This very broad definition appears to signal a break with the narrower scope of previous usages of the term.

What are the current and previous levels and types of health-care decommissioning as reported in previous studies?

The scope of each of the six reviews is primarily confined to (1) activity that is commonly known as disinvestment (incorporating the principle of cost-effectiveness maximisation) and (2) health technologies (i.e. treatments and interventions). The reviews’ reporting of decommissioning activity rates is similarly circumscribed. Furthermore, the approach taken to reporting prevalence of decommissioning varies across the reviews. Leggett et al. 57 and Parkinson et al. 17 focus on formal programmes instigated at the national level. Polisena et al. 58 and Mayer and Nachtnebel59 identify and analyse case study decommissioning programmes (n = 14 and n = 7, respectively). Niven et al. 60 offer the most extensive synthesis of decommissioning (or disinvestment) levels, from candidate identification through to ‘sustaining de-adoption’. In summary, the following messages can be identified in relation to levels of decommissioning (with particular focus on the NHS in England):

-

Some decommissioning has been instigated at national and local levels across Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries.

-

Overall rates are reported as being somewhat low, although recent reviews appear to show an increase.

-

At the national level, the focus has been on comparative effectiveness research and HTA, whereas for lower tiers of decision-making, economic frameworks such as programme budgeting and marginal analysis (PBMA) have been advocated.

-

NICE is often the main focus of reported decommissioning activities in England.

-

Safety (or harm reduction) is the most common driver of decommissioning programmes that are successfully implemented, with cost-effectiveness, for example, being far less likely to be cited as the primary driver.

-

‘Passive’ or ‘implicit’ forms of decommissioning are more common than ‘active’ or ‘explicit’ forms.

-

Restriction (e.g. to patient subgroups) is more common than full withdrawal (or ‘delisting’).

-

Considerable attention has been paid to the identification of decommissioning candidate interventions and the assembling of lists of those deemed suitable for either removal or reduction in provision.

What are considered to be the main determinants of successful decommissioning programmes?

The reviews report some common impediments (or ‘barriers’) to the implementation of planned decommissioning. These include a lack of resource for research into candidate technologies for replacement or removal. 56 Later reviews, for example by Mayer and Nachtnebel,59 note that attempts have since been made to address this evidence deficit.

The reviews also identify consistent and widespread ‘resistance to change’ from stakeholders, including patients and clinicians. 58 This can be because of ‘sunk costs’57 or ‘losses’ experienced by clinicians, patients and manufacturers of interventions considered for decommissioning. Parkinson et al. 17 elaborate on the logic of these impediments, referring to restrictions to ‘patient and prescriber choice’ and ‘perverse incentives’ created by payment regimes for clinicians. They observe that ‘there may be resistance to changing prescribing behaviours in the face of established clinical training and practice paradigms’. 17 The resulting lack of ‘will’ among political, clinical and administrative actors is the most consistently cited barrier. 56,59 Perhaps not surprisingly, early and effective stakeholder management is foregrounded in good-practice recommendations in the reviews.

What models and frameworks are available to guide decommissioning and how have these been evaluated?

Gallego et al. 56 report HTA and other methods for establishing lists of candidates for disinvestment as being one of the main sources of support for health systems and techniques, such as PBMA, as a means of putting these into practice. Beyond this, the authors identify a lack of ‘formal structures, processes or mechanisms’ to support practice. 56 Polisena et al. 58 also identify PBMA and HTA as two of the most prominent tools for supporting decommissioning, even though these are not deployed simultaneously in their case study examples. They also identify the application of the accountability for reasonableness (A4R) model – based on four process conditions for decision-making – in three case study disinvestment processes. Leggett et al. 57 focus on health technology reassessment (HTR) programmes and find one ‘model’ for reassessment.

In relation to implementation, Mayer and Nachtnebel59 compare top-down approaches based on mandated decisions and forced compliance, with bottom-up approaches where disinvestment is encouraged and facilitated and led by those working at the ‘coal-face’. They conclude that while top-down approaches can engender resistance, bottom-up approaches require voluntary engagement that may not be forthcoming in all cases. They therefore advocate a combination of both approaches.

As well as low-value lists, Niven et al. 60 identify the following ‘common mechanisms’ for supporting de-adoption processes:

Restructuring of funding associated with the given practice, changes to local and/or regional policies, and more consistent integration of health technology reassessment within existing health technology assessment programs.

Niven et al. 60

Parkinson et al. 17 identify a variety of means by which candidates for disinvestment might be identified, including assessment processes for new and existing drugs and consultation with stakeholders. In relation to implementation, they considered restricting the use of drugs and reducing the process to be more ‘acceptable politically’ than full withdrawal.

Mayer and Nachtnebel59 devote some attention to the need to sustain change and the need for financial/human resource capacity and organisational levers:

For government-initiated programs, tying a program to existing controlling tools (e.g., maintenance of a catalogue of benefits, conditional coverage, coverage under evidence development) and establishing new tools (e.g., coverage of new technologies provided only that ineffective technologies are removed concurrently) could facilitate the implementation of reassessment processes.

Niven et al. 60