Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 12/64/154. The contractual start date was in November 2013. The final report began editorial review in October 2016 and was accepted for publication in March 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Tess Harris is a member of the Health Technology Assessment Primary Care and Community Preventive Interventions Panel.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Carey et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

The World Health Organization defines intellectual disability (ID) as ‘. . . a condition of arrested or incomplete development of the mind, which is especially characterized by impairment of skills manifested during the developmental period, which contribute to the overall level of intelligence, i.e. cognitive, language, motor, and social abilities’. 1 In the UK, ID is commonly referred to as learning disability. 2 This should be viewed distinct from the term ‘learning difficulty’, commonly used across UK education, which can encompass conditions such as dyslexia that do not necessarily imply intellectual impairment and, hence, learning disability. Throughout this report we will refer to learning disability as intellectual disability or ID, except when we are explicitly referring to UK documents or outputs that have used learning disability as their preferred term.

There are three core criteria that must be met for a person to be considered to have an ID:3

-

intellectual impairment (‘a significantly reduced ability to understand new or complex information’3)

-

with social or adaptive dysfunction (‘a reduced ability to cope independently’3)

-

that has started before adulthood (‘with a lasting effect on development’3).

The most common genetic cause of ID is Down syndrome,4 and every child born with Down syndrome will be considered to have some level of ID. Neurological conditions such as cerebral palsy will be strongly associated with ID,5 although they do not necessarily imply low intelligence and, hence, ID. People with other neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism may or may not satisfy all of these criteria depending on where on the autism spectrum they lie. Estimates of the prevalence of ID at all ages vary widely between 1% and 3% of the general population across the UK, the USA and other high-income countries. 6

People with ID have more significant health risks and major health problems than the general population and, as a result, are more likely to die younger. 7 In the NHS, there is evidence that people with ID receive suboptimal care, and this inequity contributes to poor health outcomes, including avoidable mortality. 5 In 2008, an independent inquiry into access to health care for people with learning disability, led by Sir Jonathan Michael, concluded that people with ID receive less effective care, leading to avoidable suffering and death. 8 In addition, the report highlighted the paucity of information on NHS health care for people with ID.

A key focus of national policy has been improving the quality of primary care for people with ID. In 2006, the Disability Rights Commission recommended the introduction of annual health checks,7 which was further supported by Sir Jonathan’s inquiry. 8 Subsequently, in 2009, a national Directed Enhanced Service (DES) was introduced in England, which funds general practices to provide annual health checks to adults with ID and requires that staff receive appropriate training. 9 The health check is intended to identify undetected health problems and improve prescribing and co-ordination with secondary care. 10 Recent systematic reviews have confirmed that health checks are effective in identifying health problems but found a paucity of evidence on their impact on health status and outcomes,11 and have stated the need for an increase in quantity and quality of research on health interventions for people with ID. 12

This study, therefore, aims to fill key knowledge gaps with a large sample evaluation of the effectiveness of annual health checks and a comprehensive study of health and health care in a national sample of adults with ID.

Health of people with intellectual disability

People with ID experience poorer health outcomes than the general population, such as increased emergency admission to hospital13 and mortality. 14 The reasons for this poorer health are complex but are not solely explained by unavoidable biological manifestations of the cause of ID. Local ID register-based studies have identified markedly higher mortality, with estimates in the age-adjusted risk of death ranging between 3 and 18 times higher than those of the general population. 5,15,16 This increased risk of death is seen across a range of conditions and is not limited to causes related to the underlying ID. Studies on disease prevalence and morbidity among people with ID, although limited, provide a similar picture, with an increased risk of epilepsy, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, infections, accidents and sensory impairment. 17–21 For example, it is estimated that about one in four people with ID suffer from epilepsy, compared with < 1% of the general population. 18 The concerns over the health of people with ID have been reinforced by findings from the Confidential Inquiry into Premature Deaths of People with Learning Disability (CIPOLD), which confirmed high premature mortality with a high proportion of unexpected deaths. 22

There is evidence to suggest that the quality of health care received by people with ID contributes to poorer health. This may be due to difficulties in communication that lead to unmet health needs, poorer access to health services and discrimination. 7 Sir Jonathan’s inquiry into access for health care for people with ID concluded that high levels of need were not being met, that people with ID receive less effective care than they are entitled to and that this leads to avoidable suffering and death. 8 The high proportion of unexpected deaths reported by CIPOLD may also indicate that serious health problems are not fully identified in people with ID, leading to poor outcomes. 22

In addition, Sir Jonathan’s inquiry highlighted the paucity of information on NHS health care for people with ID. 8 These data gaps were further summarised and described by the Learning Disabilities Observatory in 2011. 23 Current national systems do not routinely allow a description of primary care use, quality of chronic disease care, hospital utilisation and major health outcomes for people with ID. Specifically, national systems such as cancer registration, Hospital Episode Statistics (HES), mortality registration or general practice data collections (such as the General Practice Extraction Service) either do not systematically record ID or cannot provide analyses separately for people with ID. An initial analysis in 2010 of a primary care database was commissioned as part of the independent inquiry. It reported on a range of measures in people with ID and found evidence for higher rates of obesity, poor seizure control and poorer treatment of urinary tract infections (UTIs). 24 However, this limited analysis was not developed further or submitted for peer-reviewed publication, as far as we are aware. Thus, knowledge of the health of people with ID in the UK up to 2015 has still been primarily based either on selective recording, for example in hospital data, or on selected populations from local ID registers. 25 Similarly, we know very little about the cost implications of providing NHS care for people with ID.

Annual health checks

A key recommendation of Sir Jonathan’s inquiry was the creation of a scheme in primary care to provide annual health checks for people with ID, which was outlined in the 2009 national strategy for learning disability. 26 The primary purpose of annual health checks is to address access barriers experienced by people with ID and to allow the identification of unmet health needs. 9 Health checks also aim to improve prescribing and co-ordination with secondary care and are identified as a reasonable adjustment in accordance with the Disability Discrimination Act 1995. 27

Annual health checks for adults with ID were implemented as a DES for primary care in 2009. 28 This DES funds practices to provide annual health checks to adults with ID, with an emphasis on those who have higher levels of need and who are known to the local authority services. It also requires that senior practice staff attend an approved multiprofessional educational session and that all practice staff receive training to reduce attitudinal barriers and improve communication with this group of patients.

Annual health checks are currently the main NHS intervention to improve the quality of primary care for people with ID. 29 However, estimates from 2011–12 suggested that only 53% of eligible adults with ID had received an annual health check. 30 It may be that more have been invited for a health check, and for a variety of reasons had either refused or missed their arranged appointment, but this is not known. As of 2016, practices participating in the DES are required to invite registered patients on their learning disabilities register, who are aged ≥ 14 years, for an annual health check.

Evidence base for annual health checks

The presumed long-term benefit of health checks assumes that the identification of unmet health needs will lead to appropriate intervention and improvements in well-being and health outcomes. The Learning Disabilities Observatory undertook a systematic review of the evidence base for annual health checks in 2011,11 subsequently updated in 2014,12 which summarised health gains and impacts from similar interventions both in the UK and internationally. The initial review identified 38 studies (45 in the later review) that comprised a total of > 5000 individuals receiving a health check. Most studies were small and the majority were uncontrolled, with only four randomised controlled trials and two controlled studies. The higher-quality studies clearly demonstrated that health checks led to the improved detection of new health problems, with one randomised controlled trial reporting a 60% increase in the diagnosis of new problems and a matched controlled study reporting 2.54 additional health problems identified, on average, in people receiving health checks. 31,32 These studies also reported an increase in the uptake of preventative interventions such as vaccination, cancer screening and sensory testing. These conclusions are also supported by the larger number of uncontrolled studies. 11,12

Evidence on health outcomes relating to health checks is far more limited and of poorer quality. Uncontrolled studies in the UK have reported a variety of benefits of health checks, including improved seizure control and weight management. 33–36 These UK studies were small, with fewer than 100 participants. One larger before-and-after study of a domiciliary preventative intervention in the USA found a reduction in self-reported pain, falls and emergency room visits,37 whereas another larger US study suggested that health screening may help to resolve psychiatric problems by identifying physical problems. 38

The systematic reviews by Robertson et al. 11,12 concluded that there was limited evidence on the effect of health checks on health status and that further work was required to establish the effectiveness of health checks. It is highly plausible that health checks, through identifying unmet health needs and preventative interventions, will lead to an improvement in health outcomes, but evidence to confirm this is important. However, it is also possible that health needs identified in health checks may not be adequately addressed, and that implementation of health checks by non-enthusiasts, outside study settings, will not yield the same benefit in terms of newly identified health needs. For example, health checks may lead to the recording of poor seizure control in epilepsy, but appropriate management may require expertise or specialist input to review anticonvulsant medication, which may not be available.

Aims of the study

The study had two overall aims.

-

Aim 1 was to describe the health, health-care quality, equity of health care, mortality rates and NHS costs for adults with ID in a national sample.

-

Aim 2 was to evaluate the process and outcome effectiveness of annual health checks for adults with ID in primary care.

The original objectives associated with these aims are shown in Table 1.

| Aim | Objective | Location in report |

|---|---|---|

| (1) To describe the health, health care quality, equity of health care and NHS costs for adults with ID in a national sample | Quantify primary and secondary care utilisation by adults with ID, including prescribing | See Chapters 3 and 5 |

| Describe and quantify specific health risks for adults with ID | See Chapters 3 and 4 | |

| Describe the quality of primary care received by adults with ID | See Chapter 3 | |

| Determine whether or not adults with ID experience greater socioeconomic inequities than the general population | See Chapter 3 | |

| Determine annual health service costs for people with ID compared with the general population | See Chapter 3 | |

| (2) To evaluate the process and outcome effectiveness of annual health checks for adults with ID in primary care | Determine whether or not individuals receiving annual health checks experience improvement in health-care process measures and health problem identification | See Chapter 7 |

| Determine whether or not individuals receiving annual health checks experience improvement in health outcomes | See Chapter 6 | |

| Determine whether or not practice participation in the annual health check DES improves outcomes for people with ID | See Chapter 6 | |

| Identify determinants and equity of uptake of annual health checks in practices that participate in the directed enhanced service | See Chapter 7 | |

| Determine the change in health service costs in the year before and the year after an annual health check | See Chapter 7 |

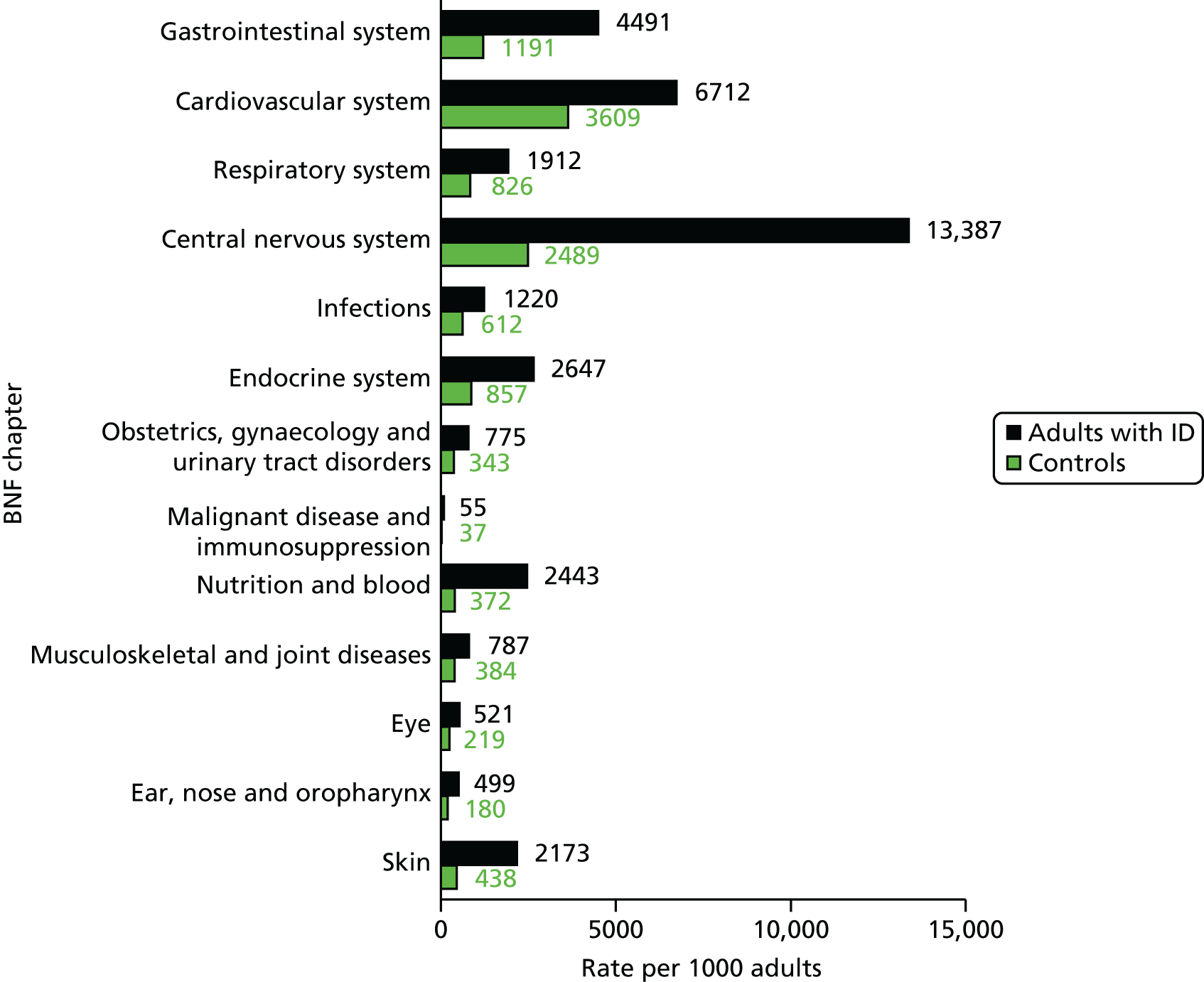

The first aim of our study, to provide a descriptive analysis of health and health-care quality for adults with ID, is explored via two distinct analyses. First, we take a snapshot of the health of the adult population with ID on 1 January 2012, registered in a large primary care database, and describe their chronic disease prevalence compared with an age- and gender-matched control group without ID (from the same general practices). Similarly, we will describe and compare the primary care utilisation of adults with ID in terms of consultations, as well as process measures and prescribing. We will provide a best estimate of annual health-care costs by applying NHS reference costs and drug tariffs for health-care events recorded, including primary care consultations, prescribing, hospital admissions and outpatient consultations.

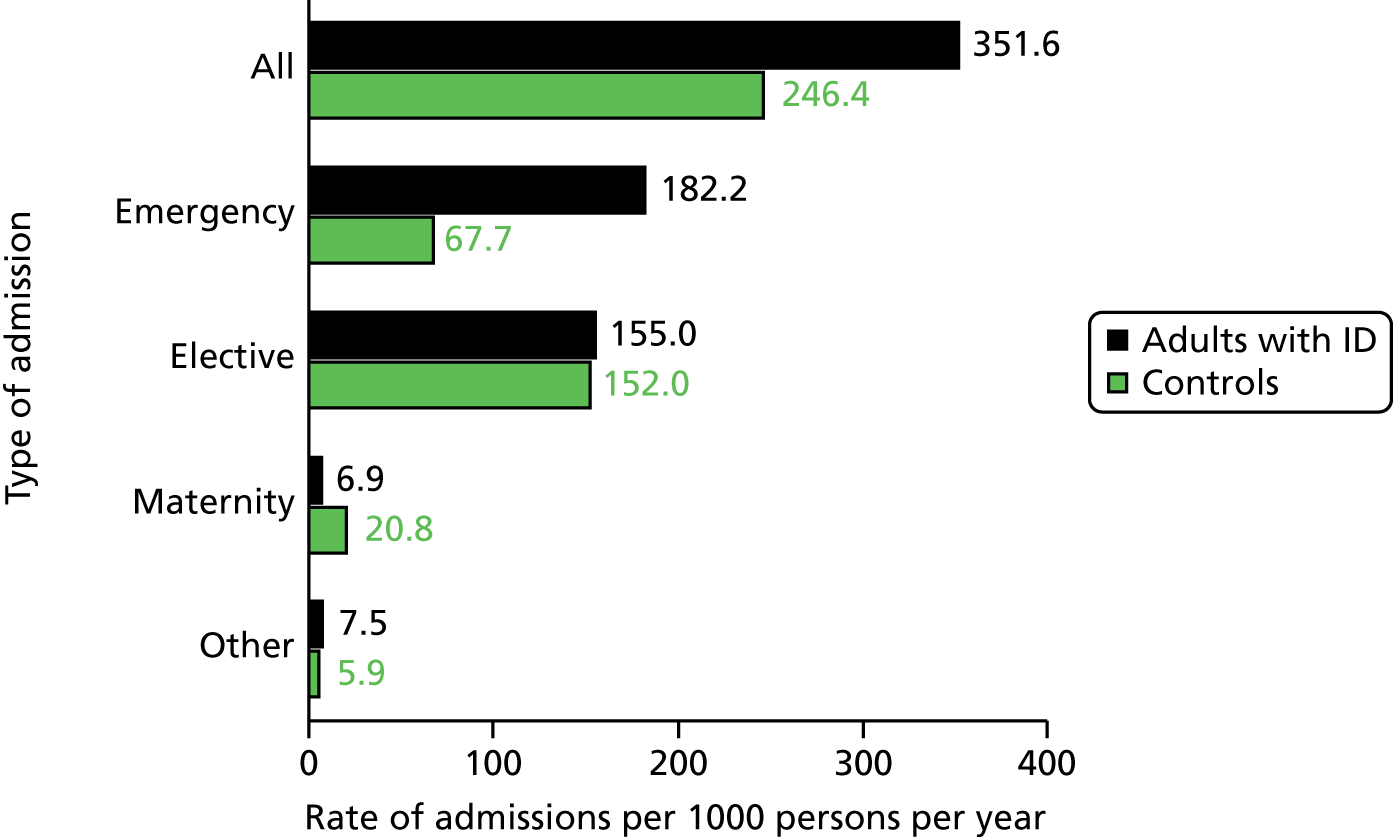

The second distinct series of analyses encompassing the first aim will follow a group of adults with ID from 2009 to 2013 to describe their secondary care utilisation. Here, we will compare and summarise emergency hospitalisations with an age-, gender- and practice-matched control group of adults without ID. For two indicator conditions [UTIs and lower respiratory tract infections (LRTIs)], which are likely to be common reasons for hospitalisation for adults with ID, we will compare their primary care utilisation in the period before the hospital admission with similarly recorded admissions within the general population. Finally, we will describe mortality patterns between 2009 and 2013 and summarise the key differences between adults with and adults without ID.

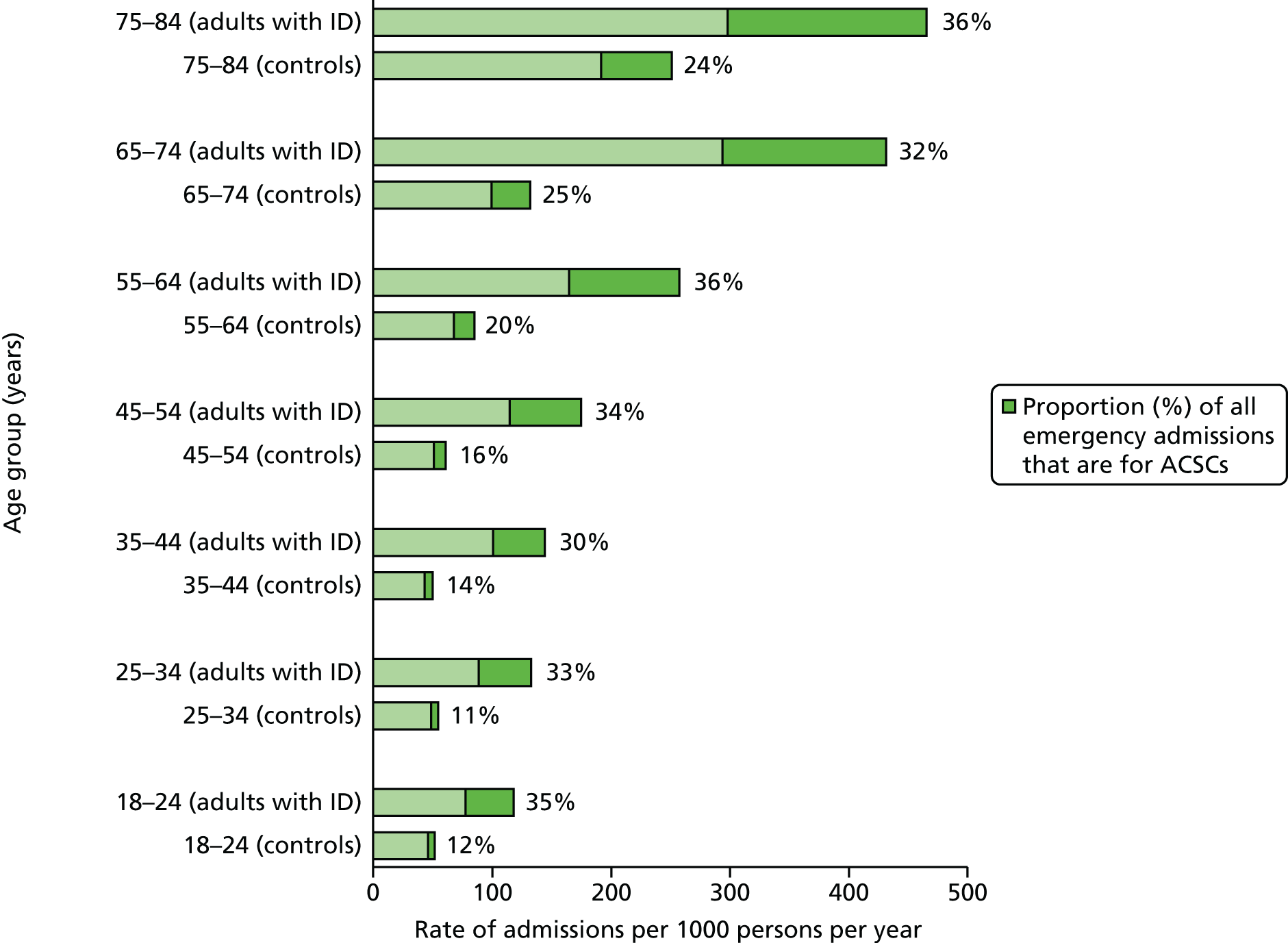

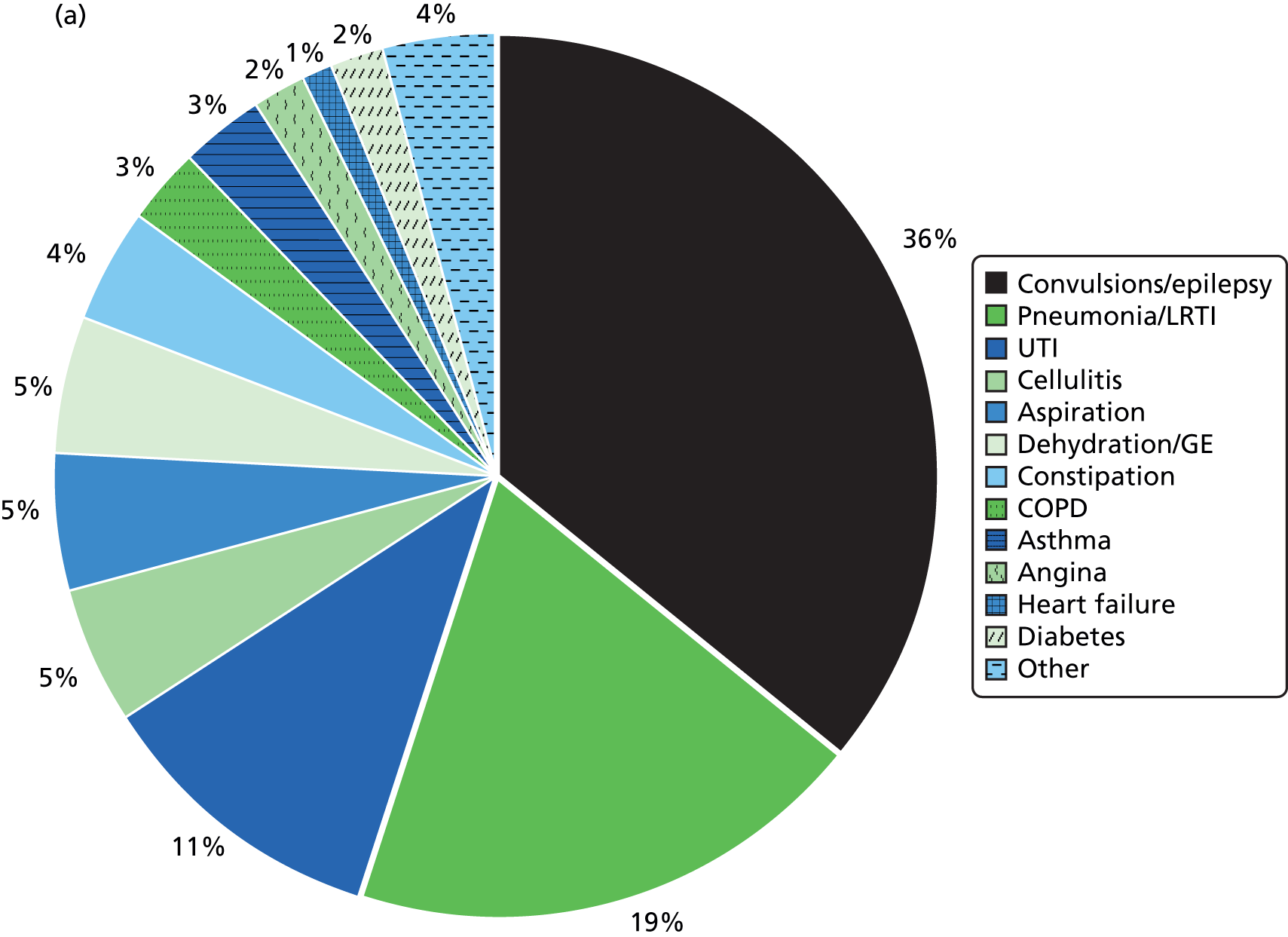

The primary outcome for the second aim (evaluation of annual health checks) was identified as emergency hospital admissions. As the evidence base suggests that health checks improve the detection of unmet health needs, the management of chronic disease and the uptake of preventative care,12 the possible longer-term health benefits of health checks may occur across a range of conditions, such as better seizure control in epilepsy, reduced cardiovascular risk and the early treatment or prevention of infection. For all of these conditions, delayed, incomplete or poor management will lead to an emergency hospital admission. Thus, emergency hospital admissions may be an important measure of quality of care for a range of conditions and a common pathway for the benefits of annual health checks. An associated reduction in emergency hospital admissions is likely to be a key measurable and valued benefit from annual health checks, as people with ID experience high levels of emergency admissions. 39 Additionally, unplanned admissions to hospital for patients with ID can be particularly stressful events, and unnecessary delays and omissions in treatment can compromise patient safety. 40

Many unplanned admissions to hospital would be expected to occur even if health checks really were having an underlying beneficial effect. Thus, we will also investigate a subgroup of emergency admissions for ambulatory care-sensitive conditions (ACSCs). 41 These admissions are thought to be potentially preventable with better clinical management in primary care. There is some variation in how ACSCs are explicitly defined,42 particularly as they were originally developed in the USA. 43 However, most definitions will include a combination of conditions for which acute management should prevent an admission (e.g. pyelonephritis) and other chronic conditions, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), for which effective preventative care may prevent admissions. However, the preventable concept of an ACSC may ultimately depend on the availability of, and referral to, alternative services such as respite care. 44 Some suggested interventions to prevent ACSCs, such as improvements in self-management education and telemedicine,44 may be less effective for patients with ID. Annual health checks may have a role to play here, and although we will have reduced power to investigate this outcome compared with all emergency admissions, emergency admissions for ACSCs may provide a more relevant estimate of effectiveness.

We will also explore a limited economic costing analyses, when our data allow. A more formal cost-effectiveness analysis is not possible using the resources in this study. In addition, a cost-effectiveness analysis would have presumed evidence of effectiveness, and it would have been premature to commit resources to such an analysis before we had determined effectiveness.

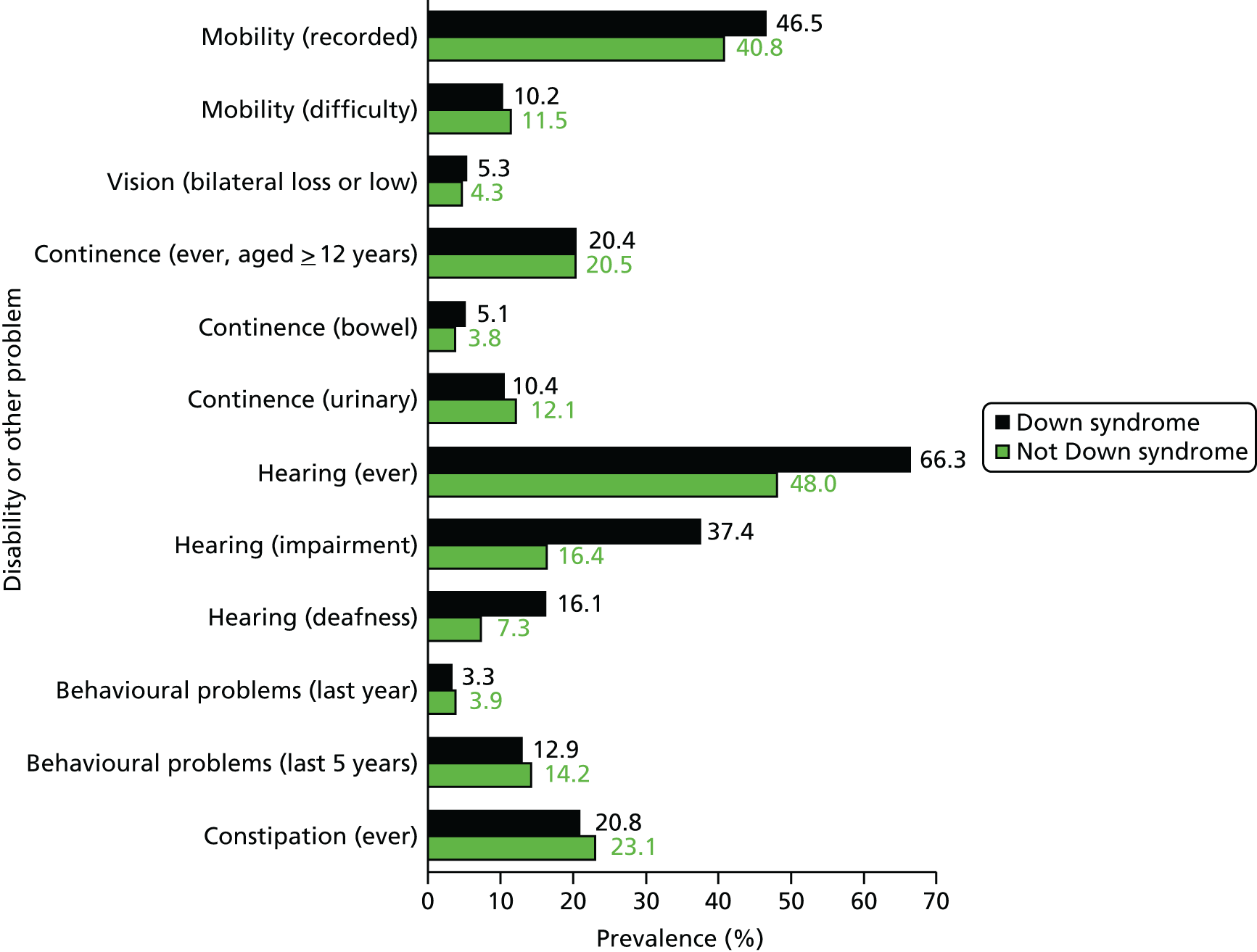

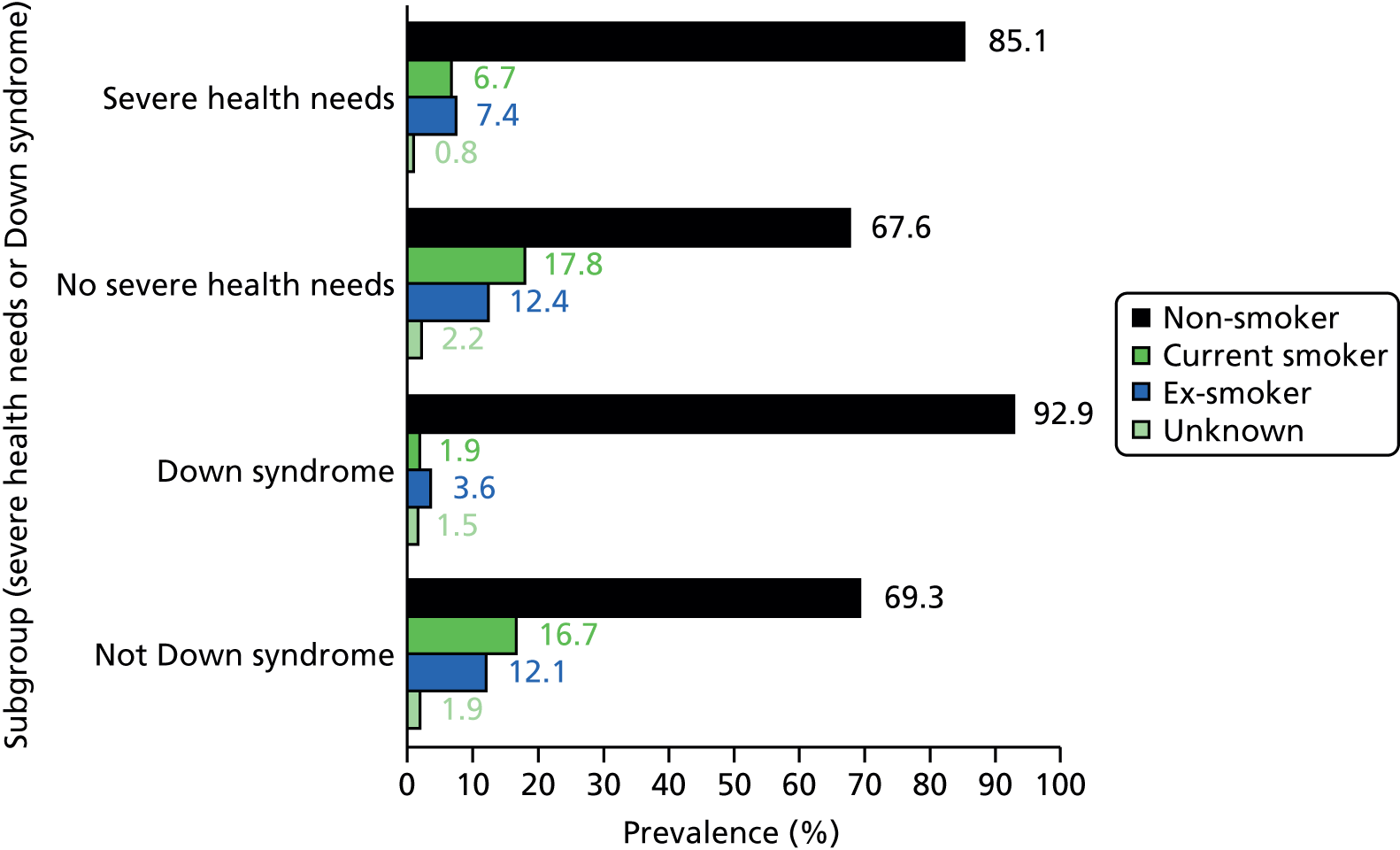

Secondary outcomes in relation to health checks included disease-specific and generic process and outcome measures. We will describe what is recorded on a patient’s electronic record at the time of a health check, and then summarise the overall impact that a health check has on a selection of process measures being carried out over time. This will include, for example, the recording of cardiovascular risk factors such as body mass index (BMI), blood pressure and smoking, as well as the recording of the uptake of cervical and breast cancer screening and influenza vaccination. We will also summarise the recording of key health areas for patients with ID, such as incontinence, constipation, mobility, vision and hearing.

Why is the research needed now?

Concerns over the quality and equity of NHS health care received by people with ID are long-standing,7 and the last few years have seen an increase in targeted NHS action to address these concerns. Specifically, in 2009, funding for annual health checks in primary care was introduced in England,30 and since 2016 the NHS has remained committed to the current DES scheme. 29 The rate of uptake of the scheme among eligible adults in 2011–12 was 53%, only a small increase since 2010–11 (48%). 30 For both clinicians and NHS policy-makers, the current economic climate may be a barrier to the wider adoption of annual health checks in primary care, or whether or not the scheme is renewed.

However, the development of Clinical Commissioning Groups may act as a catalyst for the wider implementation of annual health checks, as these groups standardise services offered by primary care in their area. Given this, an evaluation of the outcome effectiveness of annual health checks has the potential to influence policy decisions. If our study can demonstrate a clear benefit from health checks, this will strengthen the case for implementation and for ensuring access for all people with ID. Lack of evidence of any measurable benefit will not invalidate health checks, but it will raise questions over the quality of current implementation and the effectiveness of the service response to identified health needs. Our study should be able to differentiate between these two explanations and guide development of services to maximise health gain from annual health checks.

In summary, our study will evaluate the effectiveness of health checks in improving outcomes as well as processes of care and will also address the paucity of information on the quality of health care for adults with ID.

Chapter 2 Methods

The Clinical Practice Research Datalink

The Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) is a large, validated primary care database that has been collecting anonymous patient data from participating UK general practices since 1987. 45 It includes a full longitudinal medical record for each registered patient that contains coded information on medical diagnoses, prescribing and tests carried out within the practice. Additionally, referrals to specialists and secondary care settings, and lifestyle information such as smoking and alcohol status, are recorded in the CPRD. By 2015, it had been estimated to include over 4 million active patients, approximately 7% of the UK population. 45

Subject to the practice’s approval, the CPRD patient data are routinely linked to other national administrative databases by a ‘trusted third party’ via their NHS number, gender, date of birth and postcode. These databases include:

-

the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD), a small-area measure of deprivation used in England for the allocation of resources46

-

the HES database, which routinely records clinical, patient, administrative and geographical information on all NHS-funded inpatient episodes in the UK

-

Office for National Statistics (ONS) death certification data.

Quality and Outcomes Framework and learning disability

Medical diagnoses on the CPRD are recorded using Read codes. Before we extracted data from the CPRD, we carried out an extensive review of which Read codes we would use to identify patients with ID. The starting point for this was the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF). 47 The QOF was introduced in April 2004 as part of a new general medical services contract in the UK, which would remunerate practices based on performance. One key element was the creation of disease registers for many important comorbidities, such as coronary heart disease (CHD) and COPD, using sets of nationally agreed Read codes. This has had a notable impact on the recording of these diseases, such as for CHD,48 with the assumption being that it has led to diagnostic accuracy overall (e.g. for COPD). 49

Intellectual disability, classified as learning disability, has been part of the QOF since 2006. Originally there was only one indicator related to this, LD1 (‘The practice can produce a register of people with learning disability’). Although the rubric for the register suggests that all patients with ID were included, the exact specification of business rules from around this time suggested that only patients aged ≥ 18 years were included. 47 In 2014, the disease register indicator was modified to LD001 (‘The contractor establishes and maintains a register of patients aged 18 or over with learning disabilities’) to make the age criteria more explicit. However, this was changed in 2014–15 to LD003 (‘The contractor establishes and maintains a register of patients with learning disabilities’), and the associated business rules now (from version 30 onwards) allow for patients of any age to be included.

Although published national figures for the QOF learning disability register of patients are available (see Appendix 1), the change in the definition makes it difficult to consistently estimate the prevalence of ID over time. First, published denominators for the first 2 years (2006–7 and 2007–8) appear to be based on all patients, so we have had to estimate the total number of adults to obtain the prevalence of ID within adults only. The addition of non-adults to the QOF learning disability register in 2014–15 meant that no separate adult-only figures were estimated. The fall in the published prevalence from 0.48% in adults in 2013–14 to 0.44% in 2014–15 for all patients suggests that there may be still be a period of catching up for some practices to include all their patients with ID on the register.

It has been argued that the QOF learning disability register provides a poor estimate of the actual number of adults with ID in England. 39,50 This may be because the majority of these patients do not use specialised services for adults with ID and, as a result, are not well known to primary care. The prevalence estimate of 2.17% calculated by Public Health England in 201350 would mean that three out of four patients with ID are not currently on QOF learning disability registers. 51 It seems unlikely that those with a severe or profound ID would not have this recorded on their medical record, so this ‘hidden majority’ would presumably consist of patients with milder disabilities.

Identification of adults with intellectual disability in the Clinical Practice Research Datalink

Rather than rely on the QOF learning disability register to find all patients with ID in CPRD, we electronically searched the full medical record of all adults using an extended range of Read codes. Although there are over 50 Read codes used for QOF definition of learning disability (see Appendix 2), they have been chosen from the main ‘mental retardation’ hierarchical structure and, as a result, are not an exhaustive list in terms of conditions usually associated with ID. For example, a Read code for Down syndrome would not automatically put a patient on the QOF learning disability register. There are also some anomalies (e.g. the code ZS34.11 ‘learning disability’ is not on the QOF list) that we would want to account for.

To create a more extensive list of candidate Read codes for our definition of ID, we manually reviewed Read codes within relevant hierarchies, in addition to performing word searches using key terms on the full set of codes. We included a wide range of chromosomal and metabolic disorders usually associated with ID. Our intention was first to extract a group of patients with these codes, but then to refine the definition, based on all available information in the individual medical record. The key to our approach was ensuring that we were not missing a significant group of people with ID by relying on QOF codes alone.

A Read code list of 232 codes was sent to CPRD in October 2013 to identify all patients who had any of these codes recorded anywhere in their medical record. We also required patients who:

-

were fully registered with an English practice for at least 1 day between 1 April 2007 and 31 March 2013 (we subsequently defined study time from 1 January 2009)

-

were ‘acceptable’ according to CPRD data criteria that identify patients who have been fully registered with their general practitioner (GP) and who have passed CPRD data quality control checks

-

had a birth year of 1995 or earlier.

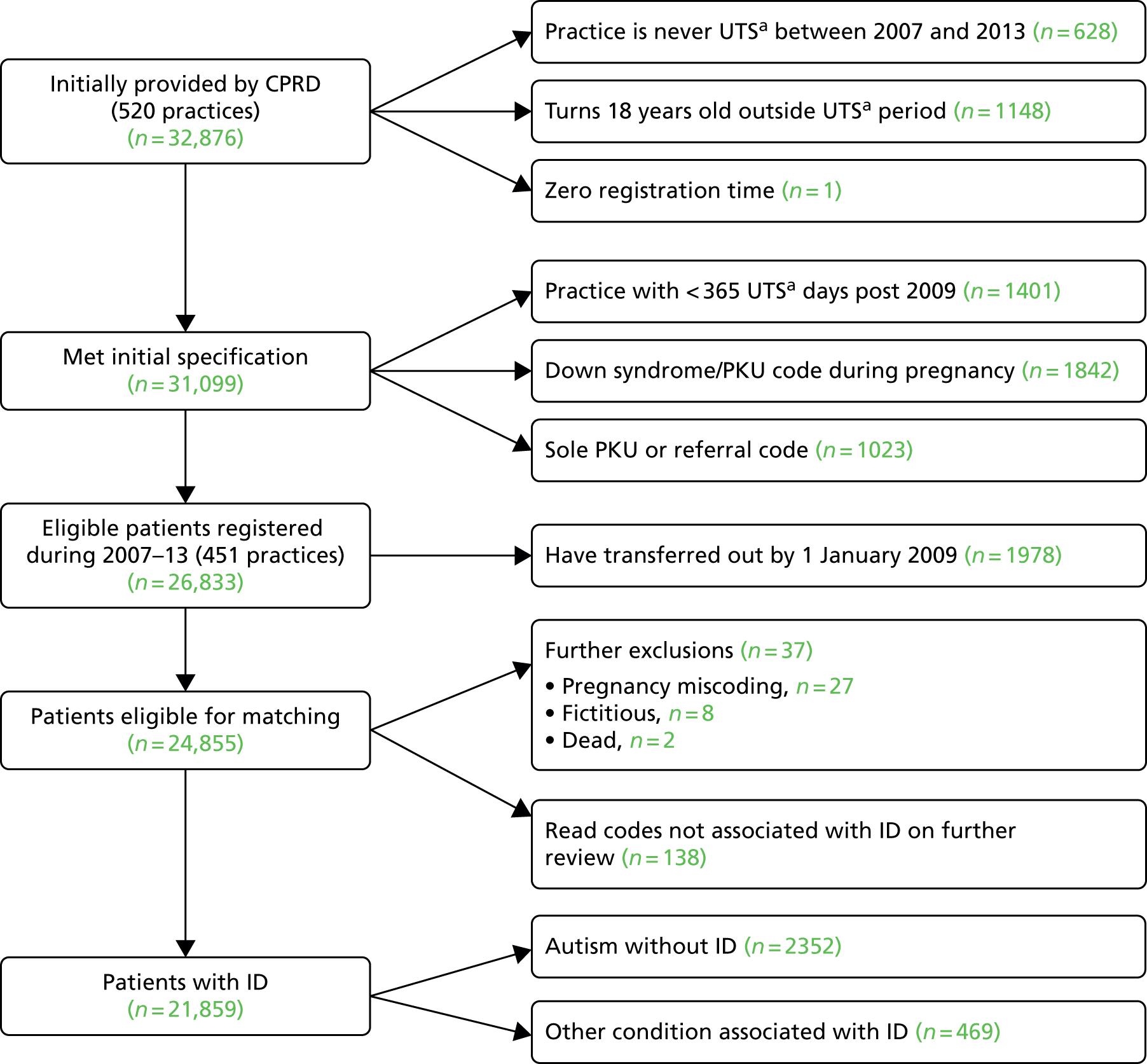

An initial group of 32,876 patients from a total of 520 English practices (Figure 1) were extracted from the complete version of CPRD. Sixty-nine practices were subsequently excluded from further consideration, as they had stopped providing data to the CPRD by 2009 or did not pass CPRD quality controls for data recording during our study period.

FIGURE 1.

Summary of identification of patients with ID. a, CPRD data criterion for when a practice starts recording data for acceptable quality. PKU, phenylketonuria; UTS, up to speed.

The initial group of 32,876 candidate patients with ID was used to help refine our Read code list. The final list included 186 Read codes (see Appendix 2), 125 of which are not part of the QOF learning disability code set. However, many of these additional codes were infrequently used because they represent very rare conditions. For these additions, we chose to include diagnoses (e.g. Down syndrome, Fragile X syndrome) and observations (e.g. ‘mental handicap problem’, ‘low IQ’), which are strongly related to ID (see Appendix 2 for more examples). We also included administration codes that directly implied that a patient had ID (e.g. ‘learning disability health exam’, ‘learning disabilities annual health assessment’). In theory, practices should be using administration codes for health checks only if a patient is on their learning disability register, but this was not absolute. Adopting the refined Read code list plus a series of exclusions (see Figure 1) allowed us to now identify 24,855 patients with ID, or with conditions associated with ID, for whom we wanted to extract age-, gender- and practice-matched controls.

Exclusions identified after first data extraction

One data issue we identified was with the erroneous historical use of some Read codes for phenylketonuria and Down syndrome in some practices. It appeared that these codes had been used in the past (mainly during 1994–6) to record screening tests for these conditions in pregnancy and infancy, and were applied inappropriately to > 2000 (≈5%) patients who would have been wrongly identified with these conditions based on a simple search for the disease codes. This was one of the main reasons for our two-stage extraction, as clustering of these patients in some practices would compromise matching in these practices.

Phenylketonuria is a cause of ID but it can also be successfully treated. In addition, all newborn babies are screened for phenylketonuria, which may explain the extra codes in the same way as the Down syndrome codes. As the prevalence of phenylketonuria is about 1 in 10,000, it was implausible for a single practice to have ≥ 100 cases (sometimes all born within 2 or 3 years). The clustering of this phenomenon by practice allowed us to quickly identify the problem and create an automated strategy for correcting it. Briefly, using electronic searches of the medical record, we identified calendar years in which a patient was pregnant (or had given birth). If during this year (or an adjacent year) this patient was recorded as having phenylketonuria or Down syndrome without any other evidence of ID in her record, she was excluded from our definition of ID. A total of 1842 patients were excluded in this way (see Figure 1). We also excluded a further 1023 patients who had a sole phenylketonuria Read code during infancy without any further confirmation. Ultimately, we decided not to include phenylketonuria in our definition of ID, so any remaining patients who were solely classified by this Read code were classed among the 469 patients designated as ‘other condition associated with ID’ (see Figure 1).

Matched population controls

A list of 24,855 potential patients with ID (‘cases’) was sent to CPRD in December 2013 (see Figure 1), and corresponding age-, gender- and practice-matched controls were extracted and sent to us in March 2014. The matching was done in house by CPRD following our specification. We required any matched control to be alive and registered on a pre-specified index date. For cases who were actively registered on 1 January 2009, and were at least 18 years old by the end of 2009, we chose 1 January 2009 as the index date. For cases who registered after this date, we chose their registration date if they were aged 18 years in that year. For cases who turned 18 years old after 2009, we chose 1 January of that year as the index date. Our choice of index date ensured that virtually all patients with ID would have a full complement of matched controls at the start of our planned longitudinal analyses. For patients with ID who remained registered from 2009 to 2013, we anticipated losing an average of about one control per patient with ID, owing to deregistration or death.

In total, 173,797 age-, gender- and practice-matched controls were extracted for the initial set of 24,855 patients who had ID or associated conditions, with 99.7% successfully matched to seven controls. Failure to match to seven controls was generally due to a few large clusters of young patients with ID in some practices.

Defining subcohorts for analyses

Further validation work after the extraction of controls identified some further exclusions (see Figure 1): 27 adults with ID who were pregnant and received their only code for ID in the year before pregnancy, eight adults with ID whose medical record appeared fictitious and two adults with ID whose record clearly indicated that they were deceased before 2009. Although we initially planned to include 2352 patients with ‘autism without ID’, as well as a further group with other related conditions (but no evidence of ID), we chose not to use these groups any further in the study. Therefore, the remainder of the report considers only the 21,859 patients with ID (see Figure 1).

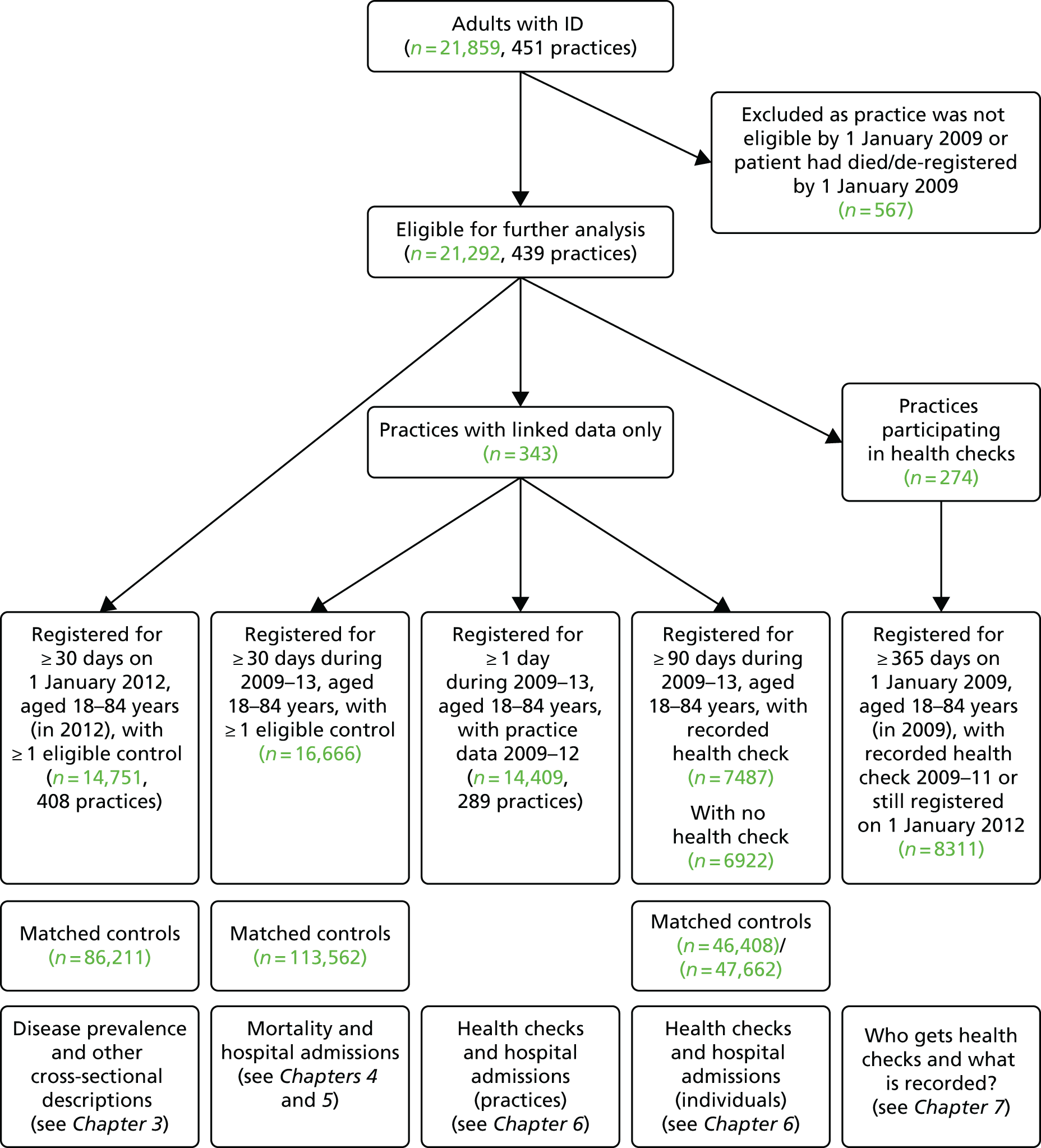

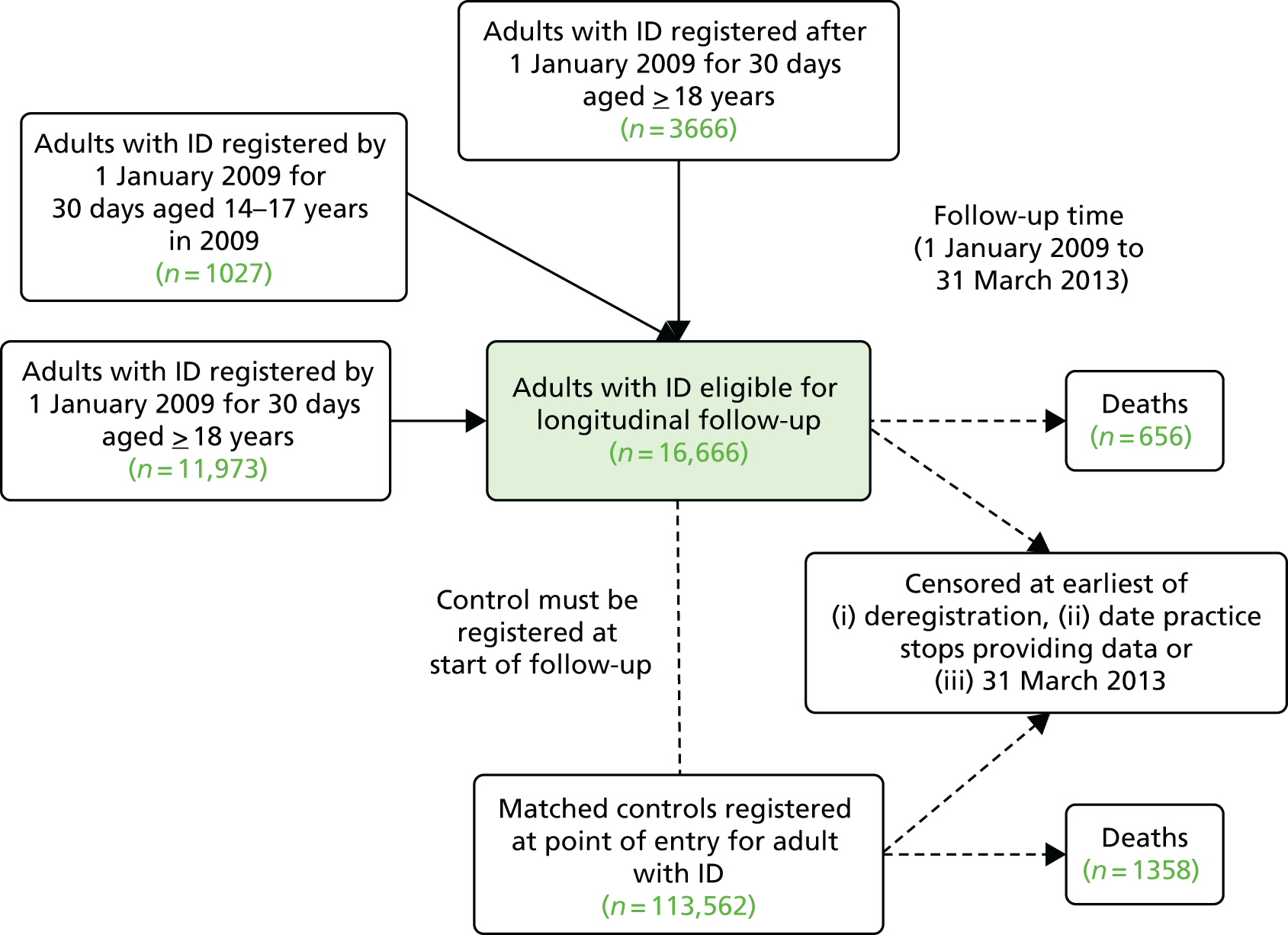

Depending on the specific analysis (e.g. cross-sectional or longitudinal), the number of adults with ID included varied (Figure 2). All analyses of individuals required a minimum registration period of 30 days with their general practice before the patient was eligible to be in our study. As anticipated, very few elderly patients aged > 85 years with ID were identified during the study, and owing to doubts over the validity of the recording of their health status, we made the pragmatic decision to include only patients aged 18–84 years at the beginning of follow-up.

FIGURE 2.

Summary of subcohorts for analyses. Note that subcohorts are overlapping and individuals may appear in multiple cohorts.

-

The cross-sectional descriptions of disease prevalence, health promotion and consultations in primary care (see Chapter 3) were based on 14,751 adults with ID who were alive and still registered on 1 January 2012 (and 86,211 matched controls). Thirty-one practices were no longer providing data to the CPRD by this date, so only 408 practices were included in this analysis.

-

The longitudinal analyses of mortality (see Chapter 4) and hospital admissions (see Chapter 5) were based on 16,666 adults with ID from the 343 practices with linkage to HES or ONS data (and 113,562 matched controls). Study follow-up time for these patients started from 1 January 2009 for those already registered and aged 18 years, or a later date for those registering later or turning 18 years old in a later year.

-

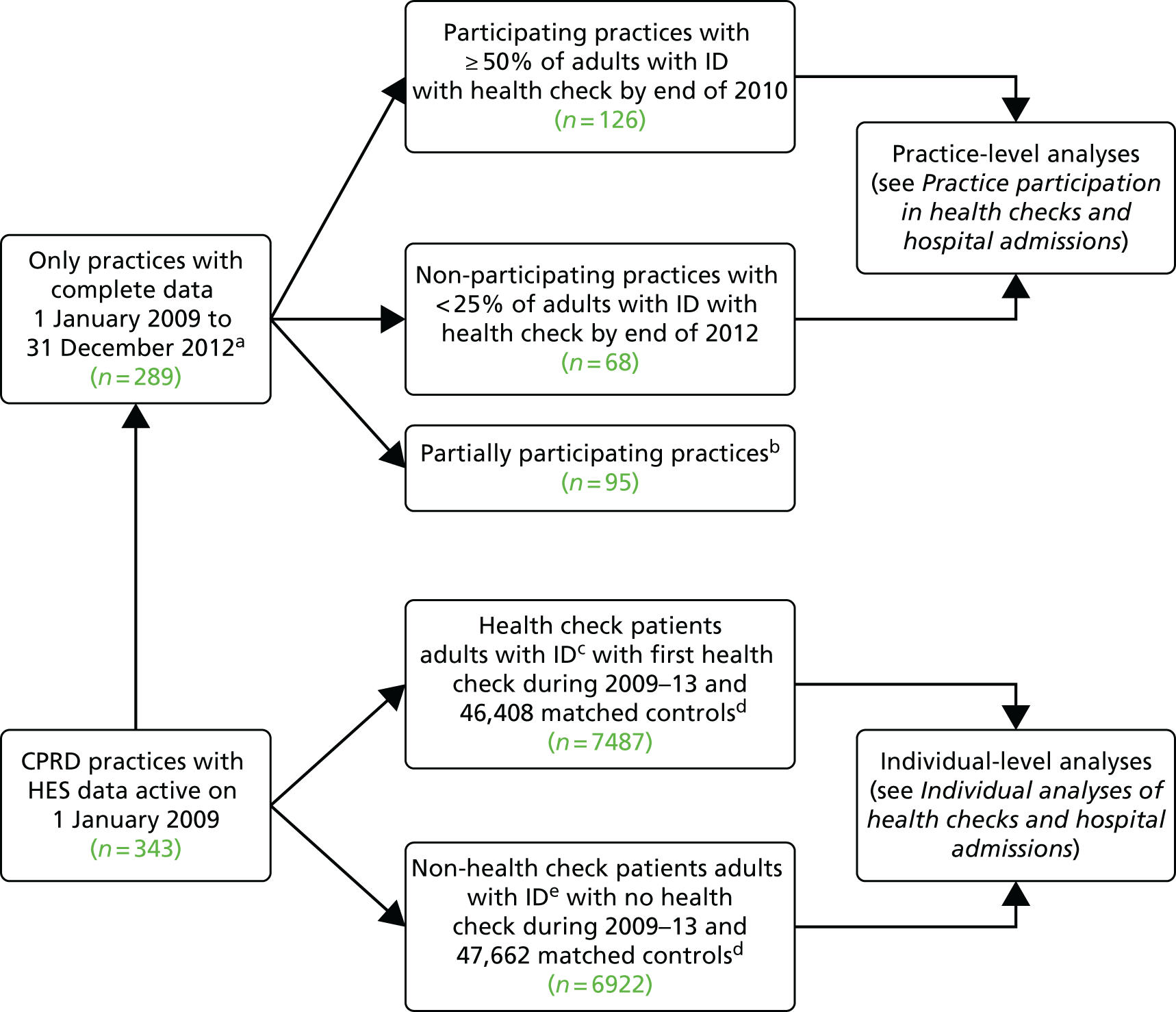

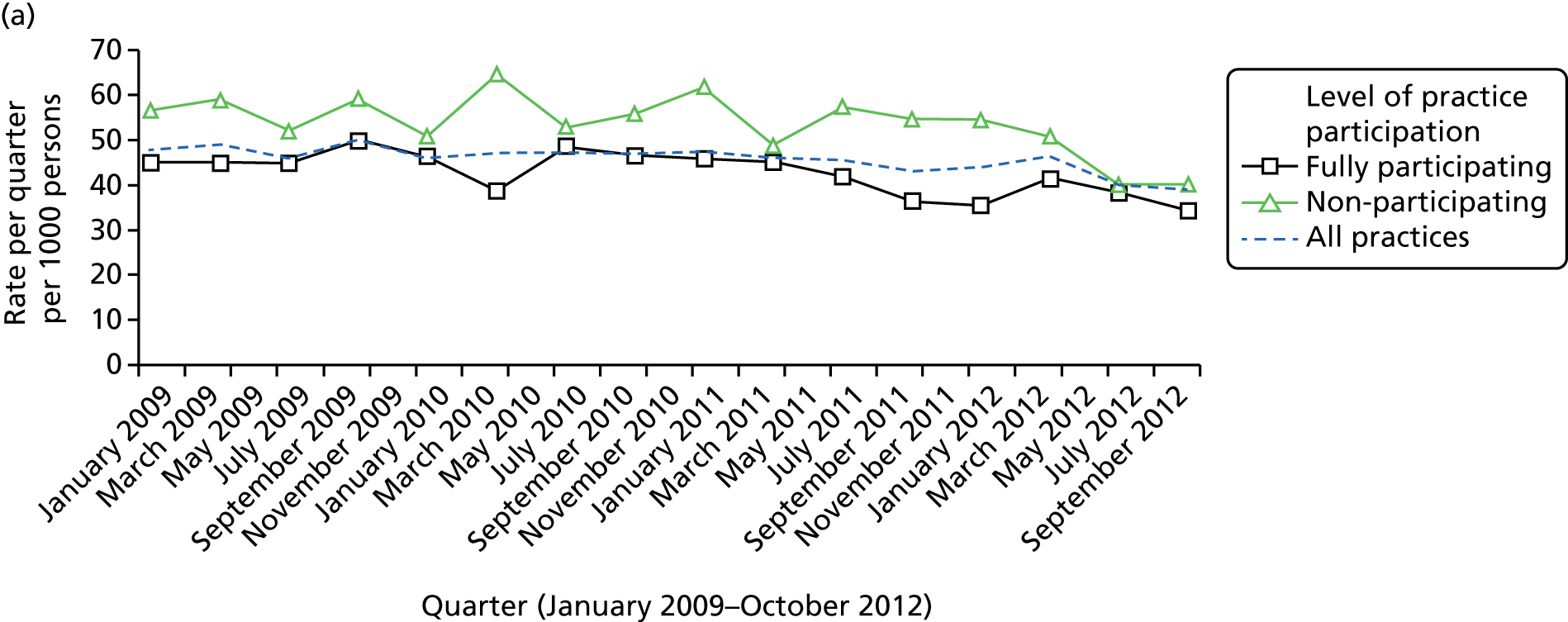

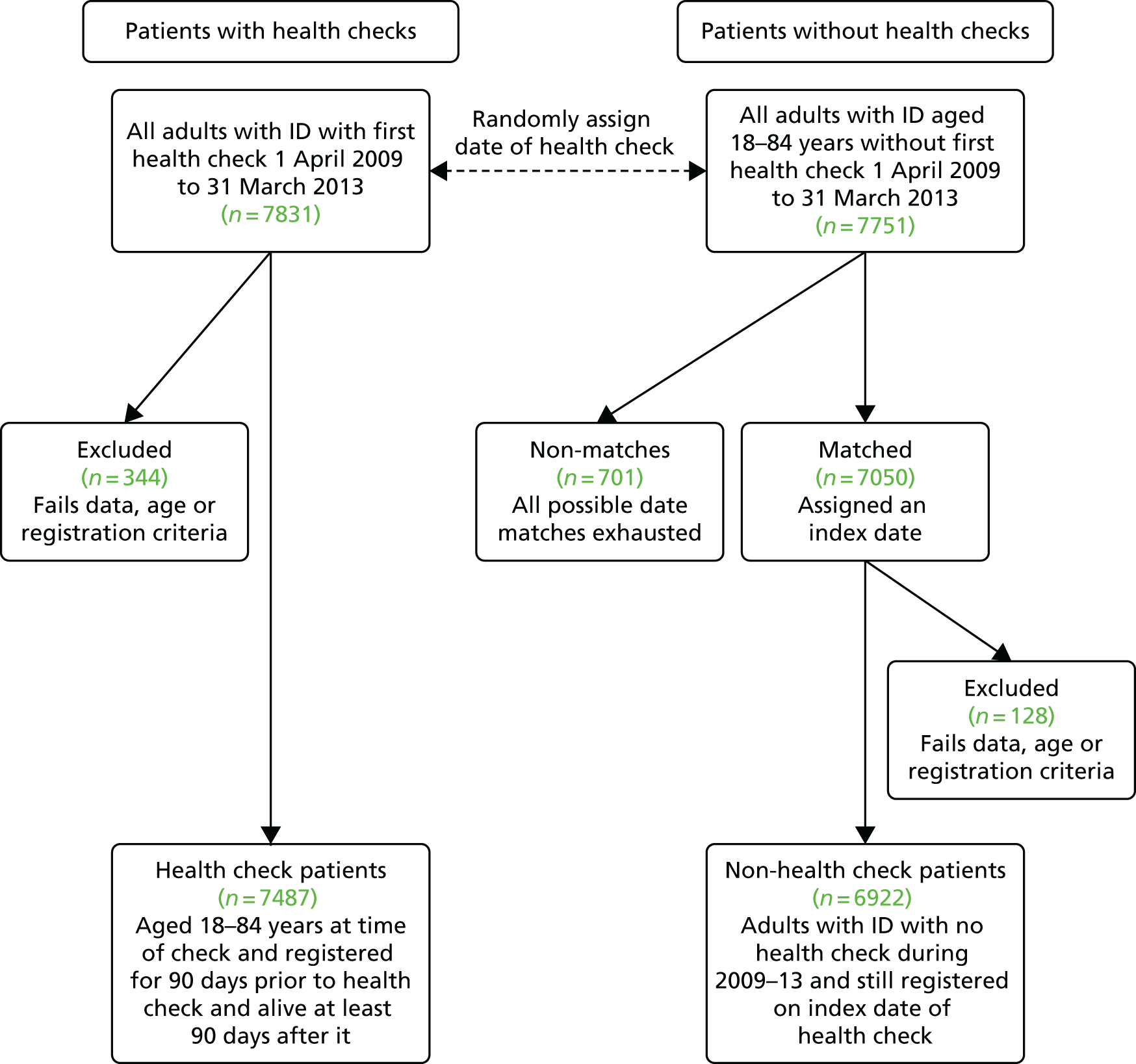

The analyses of health checks and hospital admissions had two distinct components (see Chapter 6). For the analysis carried out at practice level, we restricted to 289 practices with complete recording in CPRD during 2009–12, which identified a total of 14,409 adults with ID. For the analysis specific to individuals, we identified 7487 adults with ID with a first health check during 2009–12 (and 46,408 matched controls). A further 6922 adults with ID without health checks (and 47,662 matched controls) are also included in these analyses.

-

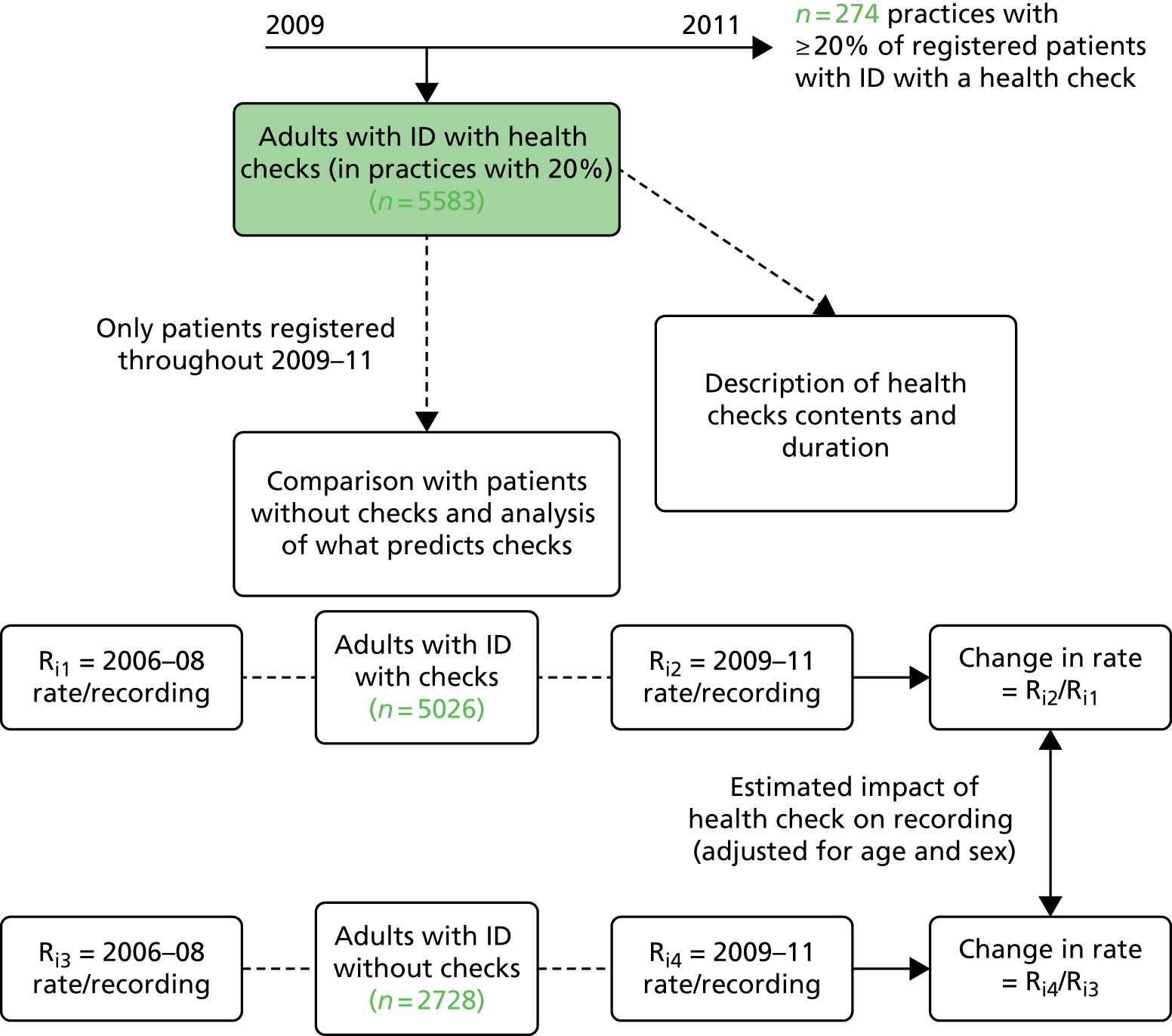

Finally, a further analysis of health checks (see Chapter 7) was based on a subset of 274 practices that had some participation in the DES (20% of eligible adults with ID must have had a health check during 2009–11). This identified a total of 8311 adults with ID who were registered on 1 January 2009 for at least 1 year.

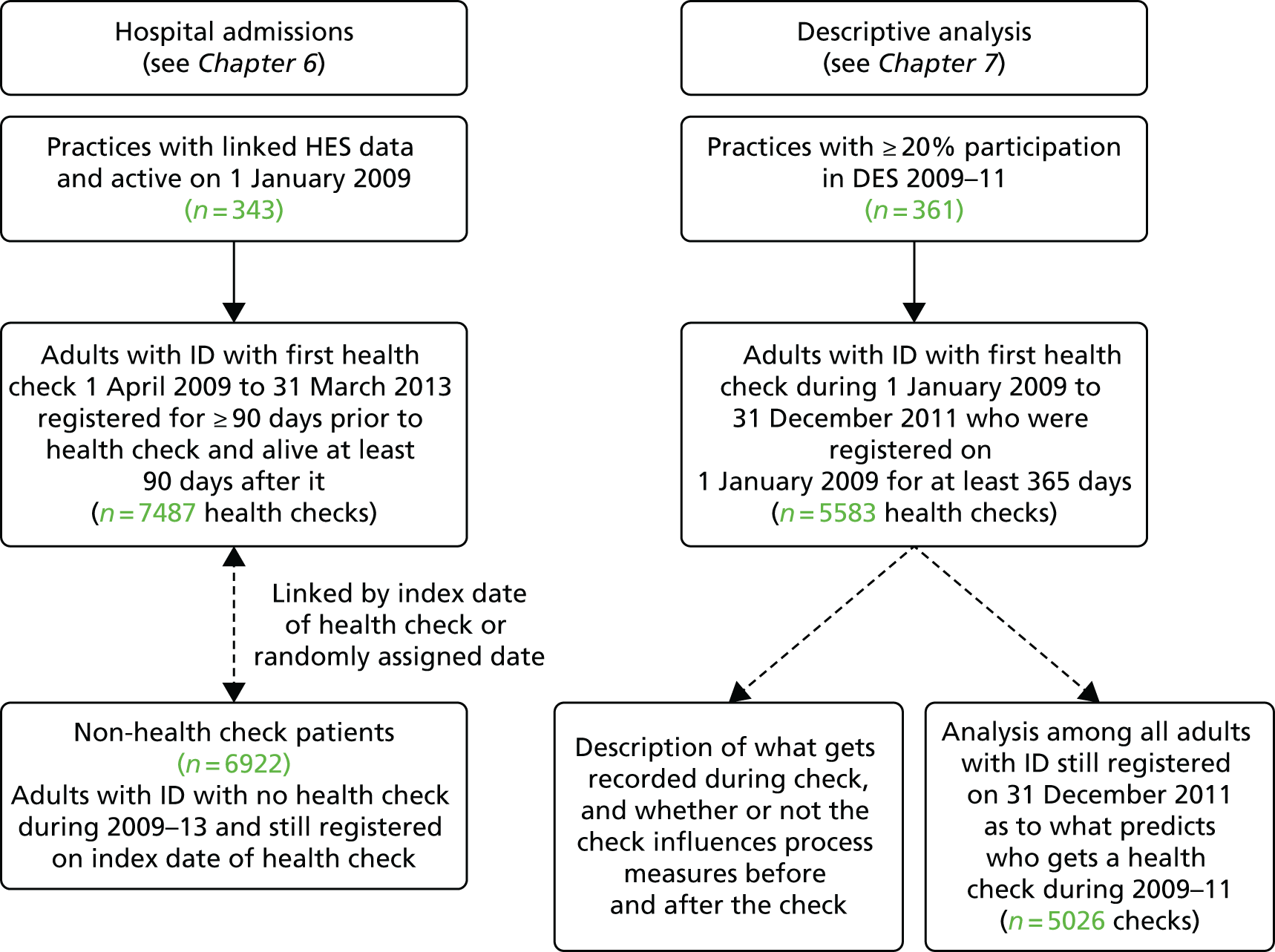

Identification of health checks

Health checks were identified by specific Read codes used by practices to facilitate future payment (69DB., 9HB3., 9HB5.; see Appendix 1). We specifically focused on first health checks carried out from 2009 onwards, as this was the point from which practices in England received remuneration for carrying them out. A small number of patients had checks recorded prior to 2009 and were not included here. Health checks up to the end of the CPRD data collection period (31 March 2013) were included. The numbers of health checks included in the relevant analyses are shown in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

Summary of health check analyses.

The analyses were divided into two distinct sections: hospital admissions in relation to health checks (see Chapter 6) and a descriptive summary of health checks (see Chapter 7). A total of 8933 first health checks were included across both analyses (with 4137 of the health checks appearing in both).

For the analysis of hospital admissions, we first only included the subset of CPRD practices (n = 343) that were actively recording data on 1 January 2009 and were linked to HES data. All patients were required to be registered with the practice for at least 90 days prior to the health check, and to be alive for 90 days after it. To be included, patients had to be aged 18–84 years at the time of their first health check. In this analysis, all patients were followed to 31 December 2013, or to their death if this was earlier. We were able to retain patients who had deregistered from their practice in the follow-up, as linkage to hospital admissions continued as long they remained resident in England. A total of 7487 adults with ID aged 18–84 years with a first health check between April 2009 and March 2013 were identified.

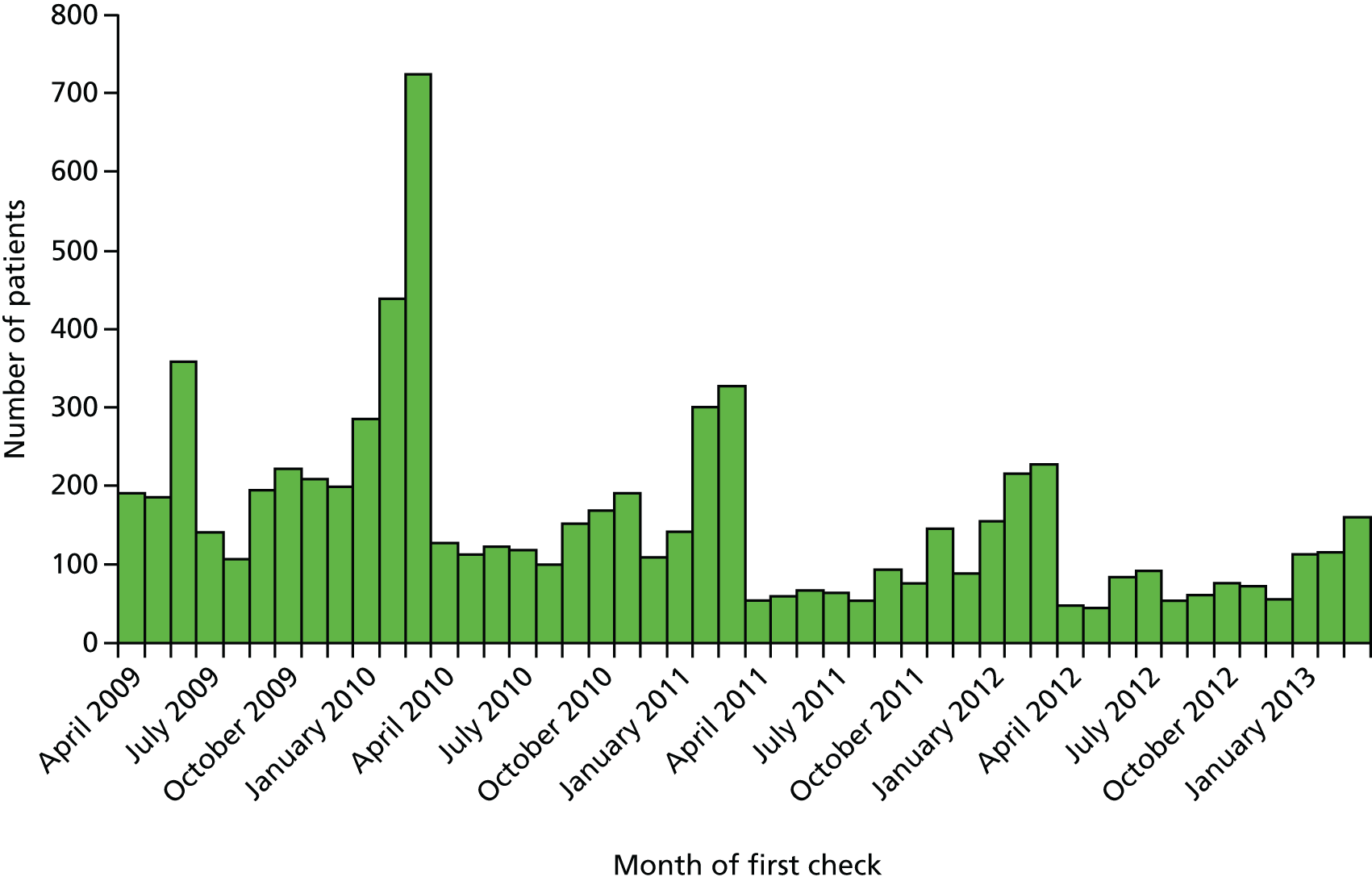

The distribution of month of first health check for the 7487 adults with ID is shown in Figure 4. As the payments for the DES are made at the end of the financial year, there are notable spikes in activity each February and March during the study. The early years (2009–10) were the most common years for a first health check, reflecting that the majority of participating practices joined the scheme during its initial years. The distribution of first health check date was used to assign a random index date to a group of 6922 adults with ID without health checks (see Figure 3). These patients formed a complementary group in our analysis of hospital admissions to check whether or not any observed changes in admissions for adults with ID were specific to those receiving health checks only.

FIGURE 4.

Distribution of month of first health check from April 2009 to March 2013.

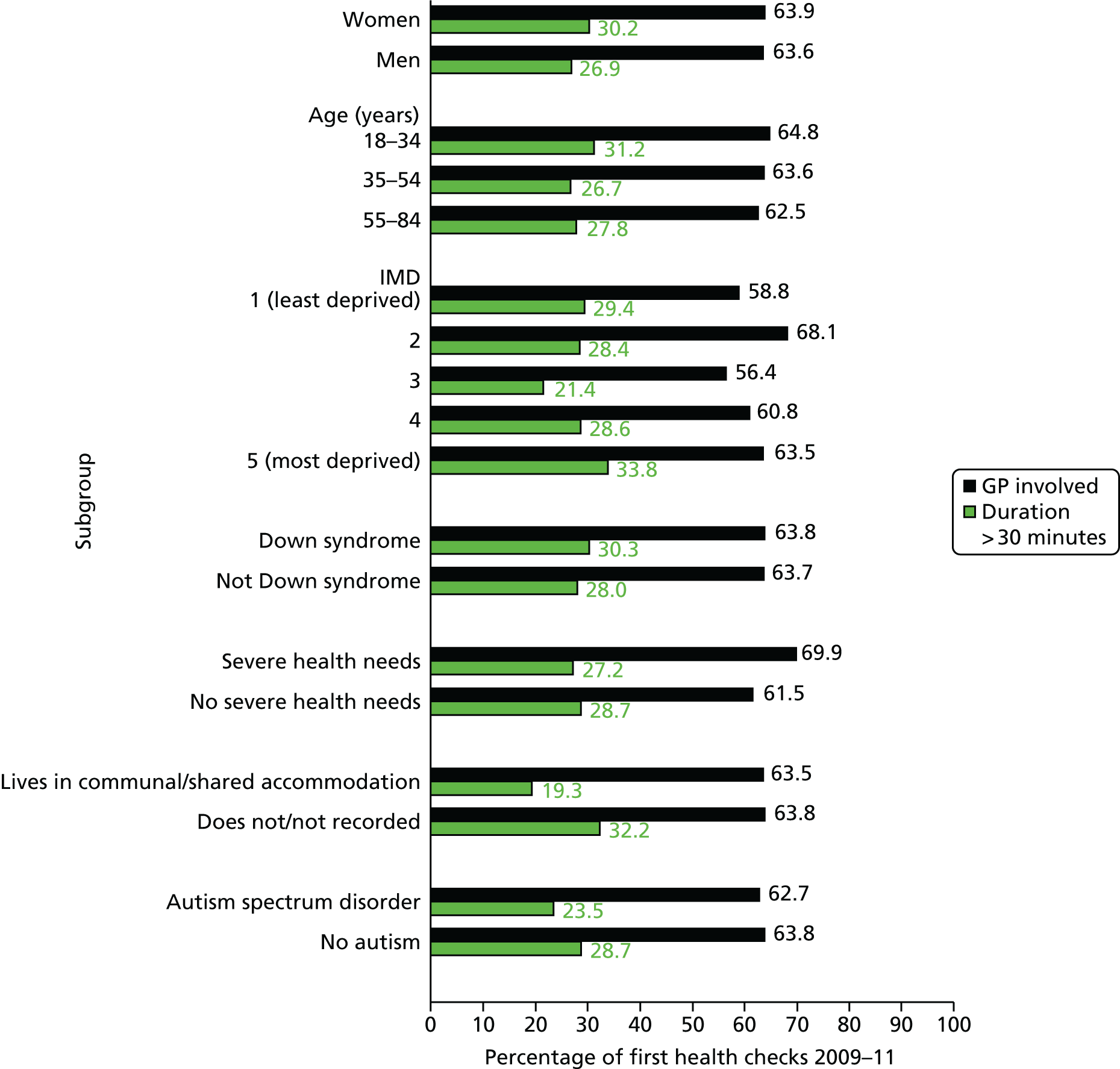

For the descriptive analysis of health checks, we included a total of 5583 first health checks made during 2009–11 (see Figure 3). We no longer restricted to practices with linked HES data, so we could include from a wider set. However, we did then restrict to 361 practices with some participation in the DES (at least 20% of adults with ID with health checks) to try to capture regular procedures around the health checks. As some of these analyses would focus on health processes in the year after the health check, we included checks only up to the end of 2011. Finally, we also carried out an analysis that investigated predictors of receiving a health check during 2009–11. We restricted to 7754 adults with ID registered throughout 2009–11, in which 5026 received a first health check during that period.

Definition of severe health needs

Although there are specific Read codes that allow for the severity of a patient’s ID to be classified (e.g. ‘Eu81500 – severe learning disability’), we found that fewer than half of our patients had such a code recorded. For example, among the 14,751 adults with ID alive and registered on 1 January 2012, only 45% had a code indicating the severity of their ID (Table 2). Among those with severity of ID recorded, and using the highest level in their record, 38% had ID classed as mild, 35% had ID classed as moderate, 24% had ID classed as severe and 3% had ID classed as profound.

| Severity of ID | n | % of all adults with ID | % of adults with ID who are men | Mean age in years (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severity recorded | 6565 | 44.5 | 57.2 | 43.5 (15) |

| Severity not recorded | 8186 | 55.5 | 58.4 | 40.9 (16) |

| Severity | ||||

| Mild | 2515 | 38.3 | 56.6 | 43.7 (15) |

| Moderate | 2298 | 35.0 | 58.7 | 43.4 (16) |

| Severe | 1567 | 23.9 | 56.6 | 43.6 (15) |

| Profound | 185 | 2.8 | 53.5 | 40.7 (14) |

With severity missing in over half of the sample, we had to consider two options. The first would be to only look at severity in the subgroup with it recorded. However, this approach is problematic, as the existence of such Read codes probably do not occur at random in our study group, and this group with severity recorded will not be representative of our total group. For example, patients in 2012 with recorded severity were a mean of 2.6 years older than those with no severity recorded (see Table 2).

Therefore, we considered an alternative approach that used Read codes that identify severity when available, and, when these codes were not present, used a selection of other codes in their record that would indicate that the patient had severe or complex health needs. We identified six health areas that encapsulated a wide range of support or severe health needs:

-

epilepsy – Read codes as per QOF definition, but excluding absence seizures

-

mobility – wheelchair use or greater problem; cerebral palsy

-

visual – blind or low vision

-

hearing – deafness, significant impairment, hearing aid use

-

continence – bowel or bladder (recorded after age of 12 years)

-

percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy feeding.

We refined this list by cross-checking the prevalence of these codes and conditions in the patients with severe or profound ID versus mild or moderate ID (the full list of codes used is provided in Appendix 2). All categories were significantly associated with severe or profound ID, with the exception of hearing impairment. However, we retained this category to enable our definition to be as complete as possible in terms of various health needs. Finally, we improved precision by imposing a restriction that for a patient to have a high level of support or severe health needs, he or she needed to fulfil two or more of these categories (Figure 5). This ensured that we were not just creating, for example, a marker for age-related frailty. The only exception to this rule was that if the patient already had Read codes indicating severe or profound ID.

FIGURE 5.

Definition of severe health needs used as a proxy for severity of ID. PEG, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy.

In the cross-sectional analyses (see Chapter 3), this approach identified a total of 3527 patients with ID with severe health needs (23.9% of all patients with ID). This group was made up of 1752 patients with severe or profound ID who are automatically included, plus the inclusion of 686 patients with mild or moderate ID and 1089 patients with no severity of ID recorded on their record. The proportion with severe health needs (13.5%) among those without severity recorded on their GP record was very similar to that estimated from those with mild or moderate ID recorded (14.3%). This suggests that those without severity recorded, as well as being younger, have primarily mild or moderate ID.

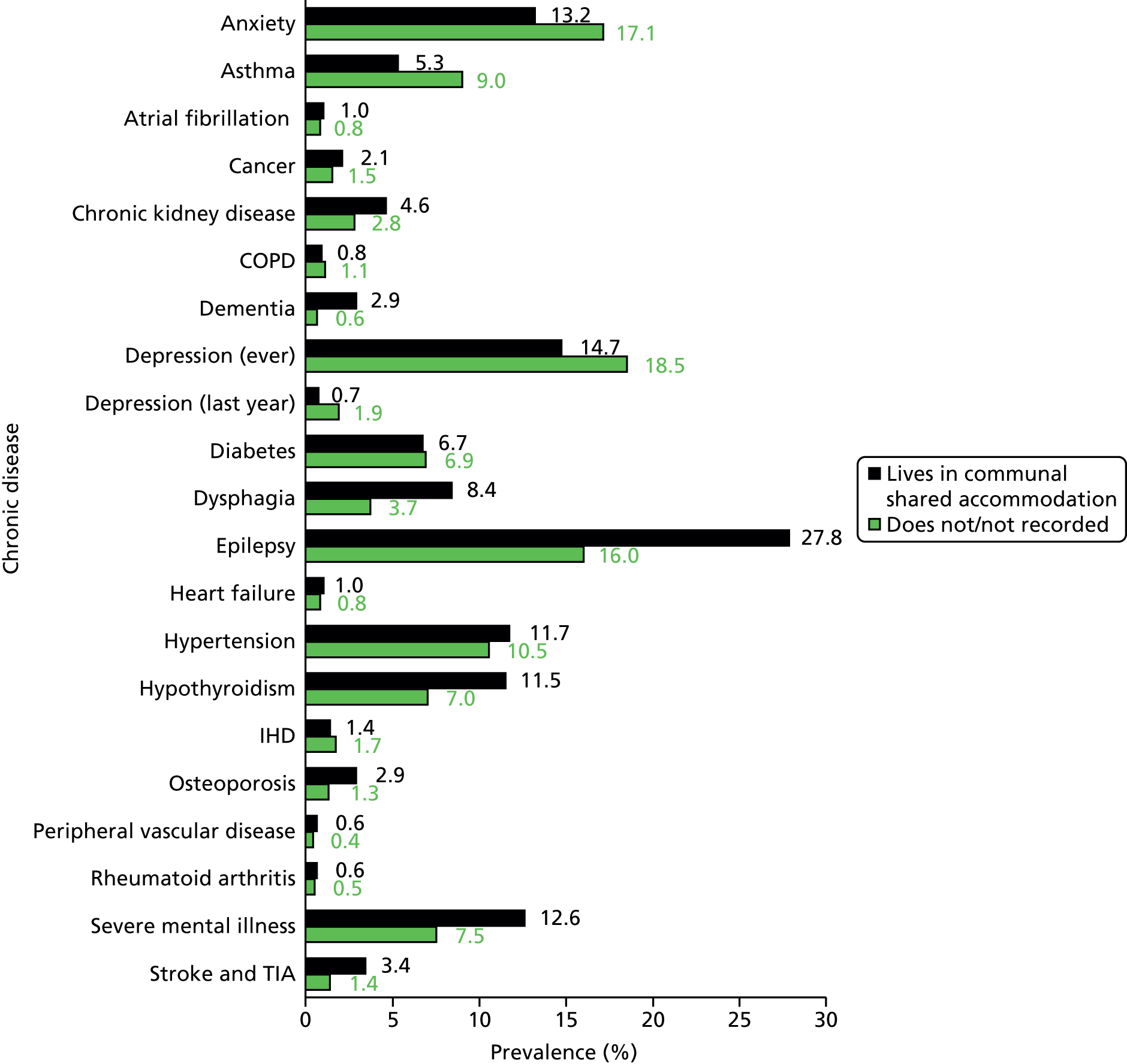

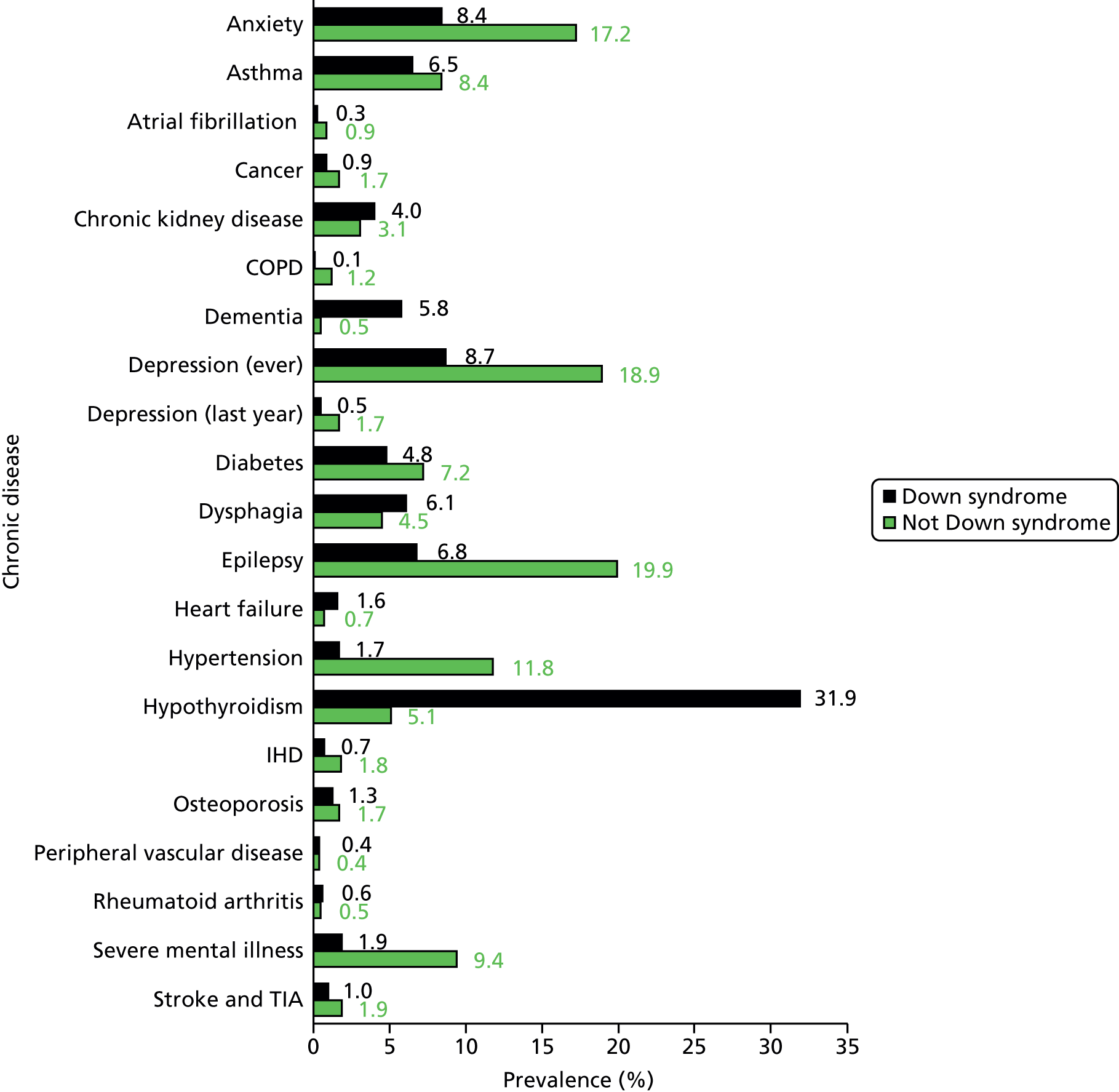

Other subgroups of interest

In addition to adults with ID with severe health needs, we identified other ID subgroups of interest: living arrangements, autism spectrum disorder and Down syndrome.

We wanted to describe the living arrangements of our patients with ID, but we were limited by the inconsistent recording of information in relation to this (e.g. carer details, or whether or not they lived with their family). The clearest distinction we could make was to identify patients who were living in dependent settings, such as residential or nursing homes, and to compare these patients with the remainder who were not classified in this way. We could primarily do this by the use of an address flag on the CPRD database, which can identify clusters of patients living at the same address. We have used this flag previously to identify elderly patients in care homes. 52 Here we assumed that the presence of three or more people with ID at the same address indicated communal or shared accommodation. The use of this address flag can vary by practice, so in addition we used some specific Read codes for living arrangements (see Appendix 3) to bolster our definition.

We also stratified analyses, when possible, by whether or not the adult with ID also had a record of autism spectrum disorder and, separately, by whether or not they had Down syndrome. The Read codes for these are provided in Appendix 3.

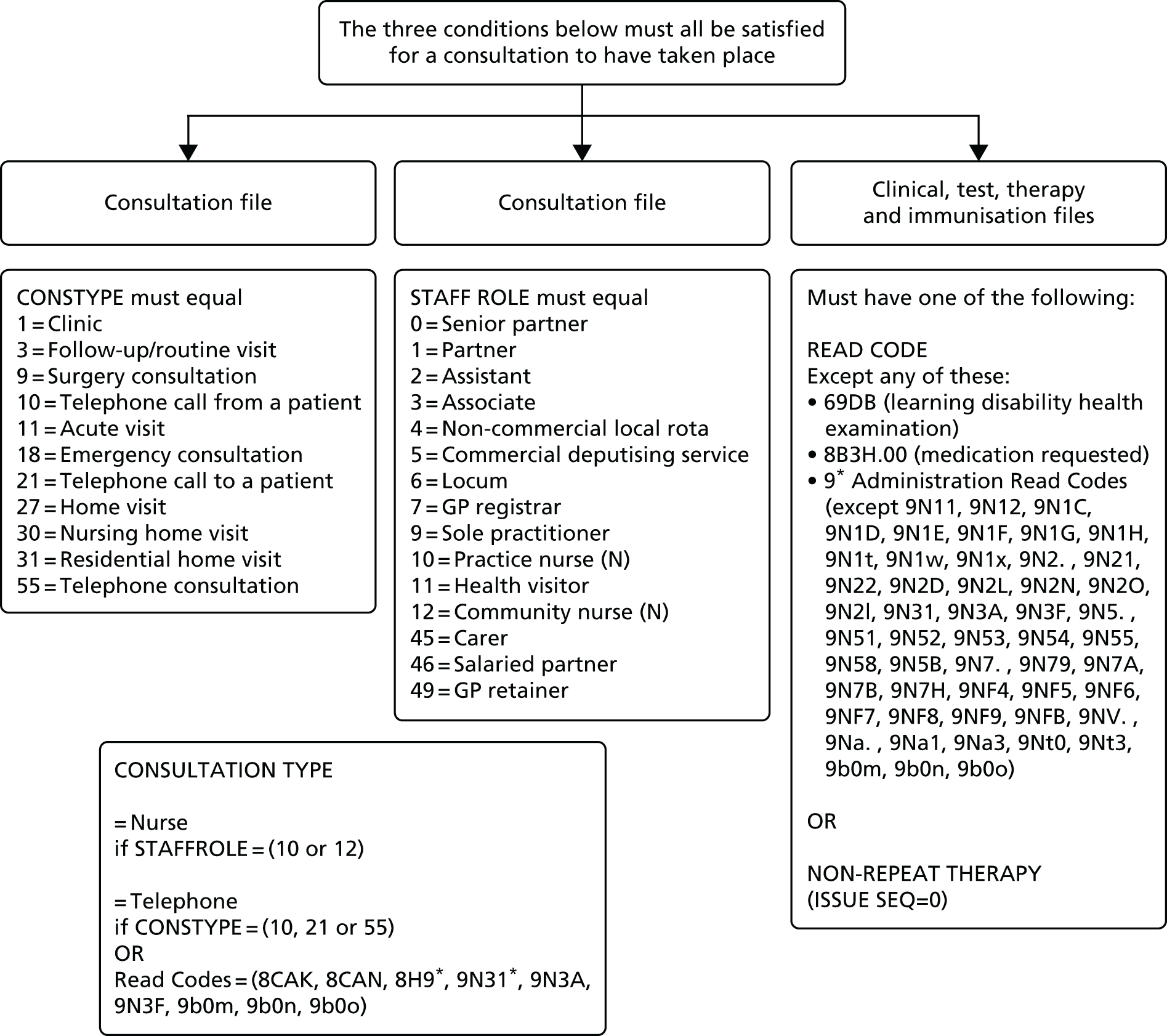

Definition of a consultation

We defined a consultation as a unique event during which the patient was seen or telephoned by a doctor or nurse. However, identifying patient consultations is not always straightforward in CPRD, as many of the administration entries on the computer system can confusingly resemble a consultation if they are not accounted for. Although there is a specific variable for ‘consultation type’, this is not consistently used across practices, and cannot solely be relied on to identify consultations.

To automate a definition of consultations in CPRD, we restricted it to events on the system for which the consultation type (e.g. surgery consultation) and staff member (e.g. senior partner) met our definition, excluding administrative events and repeat prescribing. For patients with ID, we also excluded consultations on days when a health check was recorded. Within the consultations we identified, we could further subdivide into whether the consultation had been doctor or nurse led, and whether it had been face to face (at the GP surgery or a home visit) or by telephone. Further details of the definition used for consultations are given in Appendix 4.

It is possible to ascertain the length of the patient consultation from within CPRD, using the recorded duration on the system. For face-to-face consultations with a doctor, we classified consultation length into standard (1–10 minutes) and long (> 10 minutes), excluding a small number of zero-length consultations. As each clinician has a unique identifier on the system, we could estimate continuity of care by calculating the highest proportion of doctor consultations with the same doctor. We used a cut-off point of > 50% to summarise continuity, so if a patient had a total of five consultations, they would need at least three with the same doctor to achieve this. Although other indices of continuity have been proposed,53 our summary has the advantage of being largely independent of number of consultations.

Difficulties with Hospital Episodes Statistics linkage

Of the 451 practices initially extracted by the CPRD, 353 (78%) had linkage to HES data. When the linked data set (adults with ID and controls) was provided by the CPRD in March 2014, the HES data were available only to 31 March 2012 as a result of a national postponement in the linkage of all HES data during 2014–15. As our analyses had been powered for follow-up into 2013, the uncertainty over extended linkage presented a dilemma. While waiting for this issue to resolve, we were able to proceed with analyses not involving HES data. When the HES linkage to 31 March 2013 was finally performed and delivered to us in January 2015, we then had a further issue, that patients from practices that dropped out from the CPRD during the linkage postponement could not have their follow-up extended. We made the decision to keep these patients in the analyses, but terminated their follow-up for hospital admissions outcome at 31 March 2012. This affected approximately 2.6% of all of the linked patients in the original extracted data set.

Missing entity data in the Clinical Practice Research Datalink

During the initial data acquisition, we discovered a data extraction error that existed in the complete database held by the CPRD. This had occurred between the extraction of data from the general practices and the building of the CPRD database. Briefly, the Vision system (In Practice Systems Ltd, London, UK) used by the practices allows for more complex data entries, which cannot be conveyed simply by Read codes, to be held in additional data areas called ‘entities’. For example, the diastolic and systolic measurements for blood pressure would be held this way. For three outcome measures we were interested in (medication review, diabetic retinal screening and glomerular filtration rate), we discovered significantly lower than expected recording in the CPRD, owing to an unspecified historical issue with the entity data within some practices. After raising this with the CPRD in the summer of 2014, it took another year for a potential data fix to be provided. However, the fix could be applied to current practices only, which meant that practices no longer contributing to the CPRD were unable to be corrected. Thus, our reporting of these outcomes, particularly medication review, is subject to under-recording. Sensitivity analyses, including only those practices for which a fix was possible, suggested that this under-recording may be around 5–10%. However, even when the fix could be applied, the overall low recording of recent medication reviews left us querying the data integrity for this outcome.

Economic costs

We included a descriptive analysis of NHS costs in our study. The intention was to use the CPRD and HES data to best estimate, when possible, a before-and-after cost comparison to assess the impact of annual health checks on NHS costs, and an estimate of NHS costs for care for adults with ID compared with the general population. We did not, however, commit to a formal cost-effectiveness analysis, as our data do not include some elements of NHS costs or social care costs that would be required for a robust cost-effectiveness analysis.

We identified several sources of external data to guide us in estimating NHS costs. First, the Unit Costs of Health and Social Care, produced by the Personal Social Services Research Unit,54 provided us with many key primary costs, including of consultations. We used the costings produced for 2012, which, for example, produce a guidance cost of £3.70 per minute of patient contact with a GP (including qualification costs and direct care staff costs). Duration of consultation is generally available on the CPRD, and so it is possible to estimate costs using this scaling.

Second, prescribing costs were identified by the Prescription Cost Analysis documents produced by NHS Digital. 55 This allows a net ingredient cost to be identified by drug name, form and strength, which can be linked to prescribing information on the CPRD. Again, we used 2012 costings to estimate prescribing costs.

Finally, for hospital admissions we relied on two sources of data. First, the National Schedule of Reference Costs data for NHS trusts and NHS foundation trusts costings provided costings for all elective and non-elective hospital stays. 56 We generally relied on costings for 2011–12. These costing are coded by Healthcare Resource Groups (HRGs), which are ‘standard groupings of clinically similar treatments which use common levels of healthcare resource’ (contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0)57 (we used HRG4). We then used the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD-10)58 and OPCS Classification of Interventions and Procedures version 459 codes on the HES data to translate these into HRGs using the HRG4 2011–12 reference costs Grouper software. 60

A brief summary of the data sets and assumptions used in the economic cost estimation is given in Appendix 5.

Statistical analysis

For the cross-sectional analyses (see Chapter 3), depending on the outcome being studied, we calculated prevalence, odds or relative risk ratios between patients with ID and their matched controls using conditional Poisson and logistic models (Stata Statistical Software: Release 13, 2013; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). The models were conditioned on the adult with ID–control(s) match-sets; thus, all comparisons are implicitly adjusted for matched factors: age, gender and practice (which will factor in regional and urban–rural variations). For prevalence ratios (PRs), Poisson models were fitted with robust error variances corrections to provide reliable estimates. 61 When the outcome was based on a subgroup defined not solely by age and gender (e.g. influenza vaccination among those with eligible comorbidity; see Table 12), then only match-sets that included an adult with ID and at least one control could be used. An exception to this was when we analysed attainment of QOF indicators (see Table 16), for which this approach was not feasible. As patients could not be matched in this analyses, we fitted a (non-conditional) log-binomial model adjusting for gender and age. Practice was included in the model, assuming an exchangeable correlation structure. When the outcome was number of consultations over the previous year (see Table 17), an offset for number of registered days was added to the Poisson model to allow for patients who had been registered for < 1 year. In the consultation analyses, we further adjusted for comorbidity using a weighted score of QOF conditions. 62 For analyses on consultation length and continuity, we also adjusted for total number of consultations. For cross-sectional analyses with economic cost as the outcome (see Table 20), we fitted (conditional) fixed-effects negative binomial regressions to account for overdispersion, with bias-corrected confidence intervals (CIs) produced from non-parametric bootstrap estimation (1000 simulations).

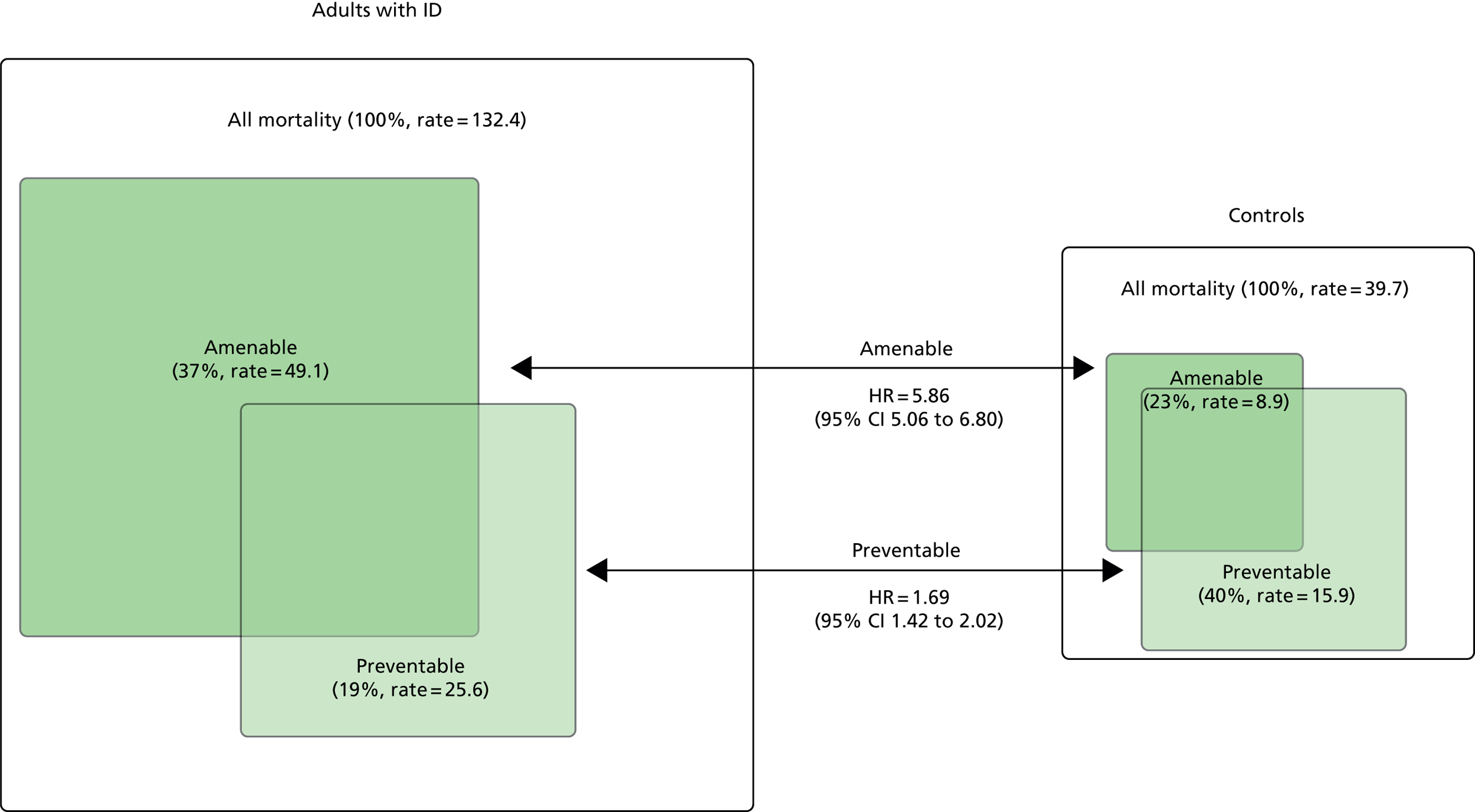

For the analyses with mortality as the outcome (see Chapter 4), we estimated crude death rates and hazard ratios (HRs) for comparisons between adults with ID and their matched controls. HRs were calculated via Cox regression (SAS version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA), with further adjustment for a weighted score of QOF conditions, which has been shown to predict mortality in the general population,62 smoking and socioeconomic status using the IMD. 46 For comparisons within subgroups (defined by the adult with ID), we compared the HRs and CIs derived from each adult with ID versus control comparison (e.g. adults with ID with Down syndrome vs. controls) and calculated p-values for these between-group differences. We additionally carried out unmatched analyses focusing only on adults with ID (see Chapter 4, All-cause mortality), fitting models that directly compared each subgroup category (e.g. those with vs. those without Down syndrome), adjusting for age and gender differences, and stratified according to practice.

For the analyses on hospital admissions (see Chapter 5), we estimated crude admission rates for adults with ID and their matched controls. Incidence rate ratios (IRRs) for emergency hospitalisation were calculated using conditional Poisson models described previously, stratifying again on match-sets and similarly adjusting for comorbidities, smoking and deprivation. For the examination of primary care utilisation preceding admission, it was not possible to preserve the matching. Instead, we used logistic regression to estimate an odds ratio (OR) for adults with ID versus controls, adjusting for differences in age and gender.

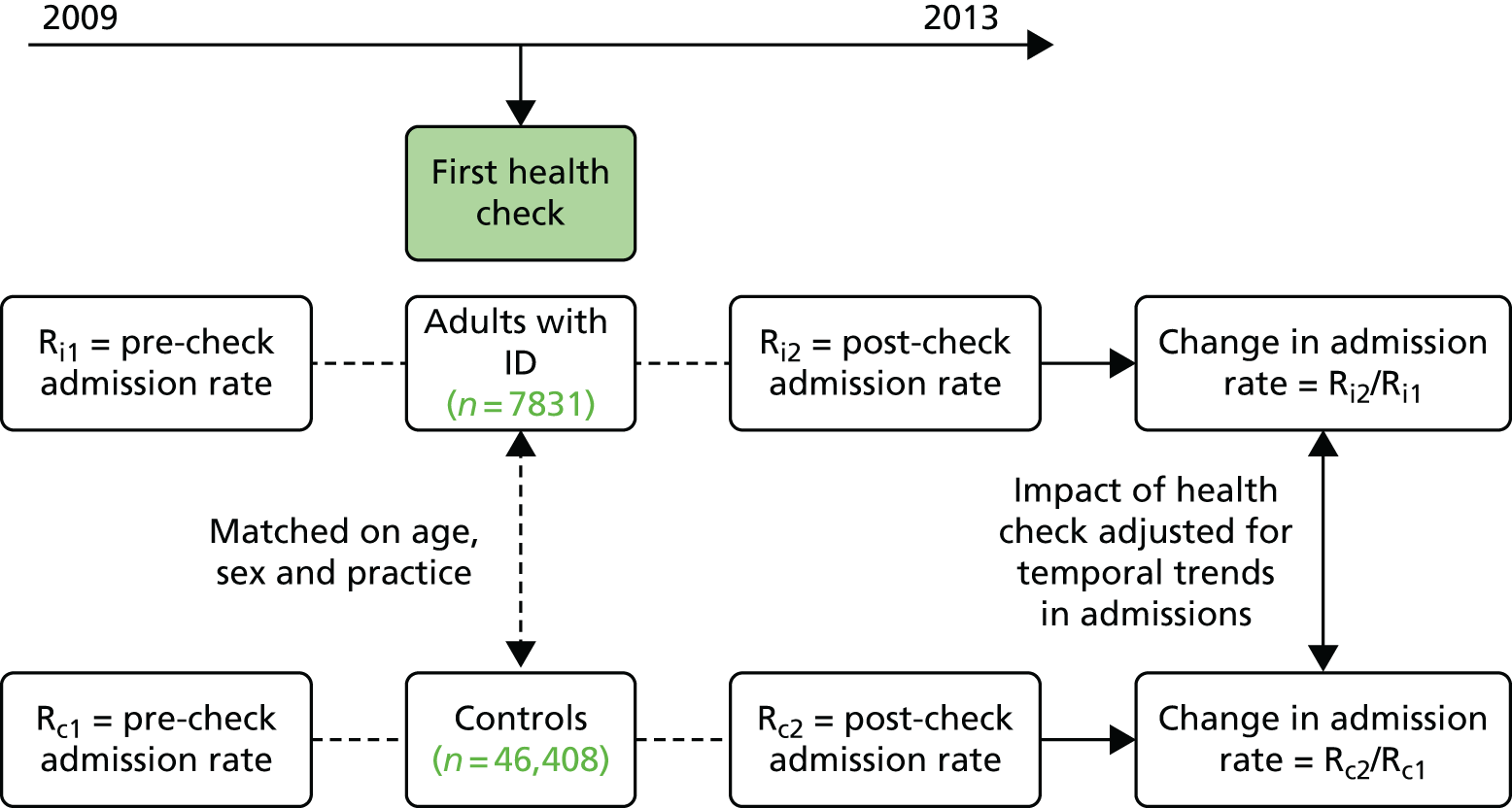

The analyses that investigated the impact of health checks on hospital admissions (see Chapter 6) primarily used the conditional Poisson model to compare the rate of change over time at a practice or individual level. At practice level, these were conditioned on practice, and all admissions from registered adults with ID in each period were counted, using an offset term to account for the total time registered. The effect of practice participation on hospital admissions was estimated by the interaction between practice participation (fully vs. none) and period (2011–12 vs. 2009–10). At individual level, we conditioned on individual as opposed to match-set, as accounting for the matching variables is not paramount in matched cohort analyses. 63 This model was fitted to adults with ID and controls separately, estimating the individual change in hospital admission rate after compared with before health check, with an offset accounting for the time registered. A combined model of adults with ID and controls with a case–period interaction provides an estimate of the effect of health checks on admission rates among adults with ID, adjusted for temporal trends in admissions. All models used a sandwich estimator to obtain robust standard errors.

The analyses of hospital admissions in individuals with health checks also considered adults with ID without health checks in two sets of sensitivity analyses to check the robustness of our findings. First, using the assigned random index date (see Identification of health checks) instead of the health check date, we simply repeated the analysis on this set of patients and their matched controls to see whether or not any observed changes in the health check patients were also observed here. Second, we also considered a direct comparison of adults with ID with and without health checks using Poisson and negative binomial models, adjusting for age, gender and selected comorbidities (severe health needs, epilepsy, dementia and Down syndrome).

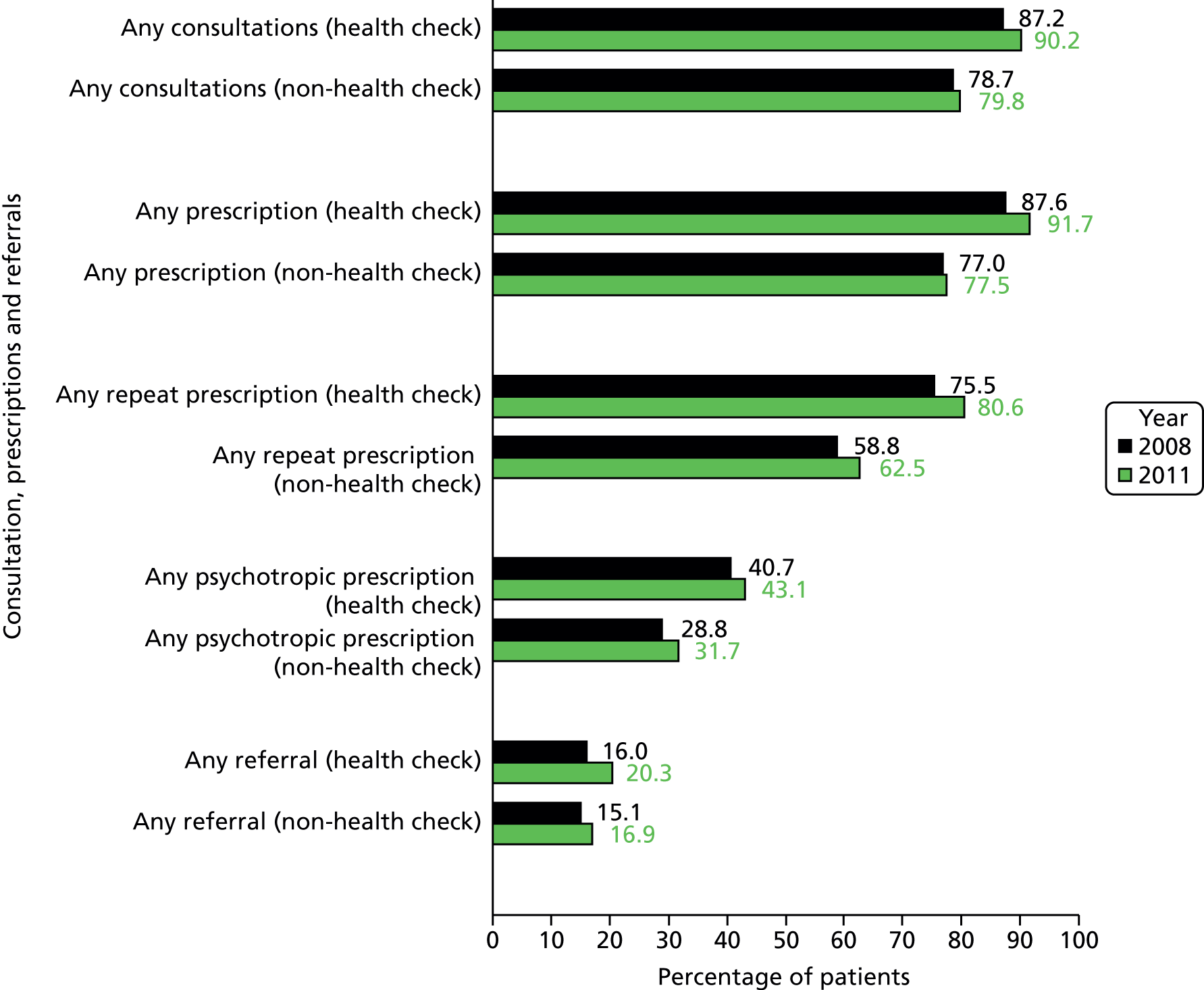

The analyses of health process measures were largely descriptive (see Chapter 7), summarising the recorded information on patient records before and after health checks. We calculated the change in consultation and prescription rates in a period before (2006–8) and during the introduction of health checks (2009–11) using conditional Poisson regression as described previously. We contrasted the change between patients with ID with and without health checks, but did not attempt a formal statistical comparison. Finally, we also carried out an analysis that investigated which factors predicted a health check among a subset of patients with ID registered during 2009–11 in practices that were carrying out health checks. Here a logistic model was fitted, with health check (yes/no) as the outcome and practice included in the model as a random effect.

Patient and public involvement

Throughout the course of the study, a collaborative approach to patient and public involvement was taken,64 and we engaged two groups through regular meetings every 8–12 weeks:

-

ResearchNet – a network of service user and staff members at St George’s, University of London, who collaboratively undertake research to develop services and improve patient experience

-

Carers Support Merton – a local group of family carers of adults with an ID.

The focus of these meetings initially was to identify important outcomes for our study and concerns for patients and carers. This involvement subsequently contributed to changes to the design of the study in terms of choice of outcomes, examination of potential modifying factors, and help in interpreting and disseminating findings.

We have summarised some of the key issues that arose from these initial meetings with ResearchNet (Table 3) and Carers Support Merton (Table 4). We tried, when possible, to explore many of these issues, such as the addition of dysphagia, aspiration pneumonia, constipation and anxiety as potential outcomes in our analysis. The focus on consultation length and continuity of care by health professionals as key measures of health-care effectiveness were important additions to the study that ultimately strengthened some of our published research findings. 66 The groups stressed the importance of living arrangements for adults with ID (e.g. living with their family) and, although the data could not adequately assess this, we were able to identify a subgroup of patients with ID who were recorded as living in shared or communal living arrangements (see Other subgroups of interest). However, not every issue raised by the groups could be adequately explored, owing to limitations with our data.

| Area | Specific details |

|---|---|

| Prominent health issues | Constipation |

| Depression (‘problems with feelings’), anxiety | |

| Diabetes | |

| Epilepsy | |

| Podiatry (‘feet’) | |

| Hearing and vision | |

| Hydrocephalus | |

| Lungs and breathing problems, aspiration pneumonia | |

| Swallowing difficulties, dysphagia | |

| Teeth | |

| Other issues affecting health | Living arrangements (such as whether they lived with their family, independently, in a residential care home or in supported living) were mentioned as an explanation for the variation in how many people had health checks and in accessing primary care generally |

| Health care for patient with ID | Seeing the same doctor, the patient’s regular doctor |

| Having long enough appointments to discuss several things | |

| Hard to make GP appointments for person with ID because they might rely on others to make the appointment or take them to the GP | |

| Health checks | The group identified some checks that they thought could keep someone healthy in future, and that should be part of health checks: BP checks, feet checks, heart checks, kidney/urine checks, blood tests, memory tests, scans and X-rays, weight measurement, smears, advice on self-examination |

| Some mentioned that the following had been particularly helpful to them from their health checks: weight loss advice, help with pain, help with depression, including tablets, regular medications for epilepsy or diabetes, calming tablets, help with addiction | |

| Dislike of health check if it led to blood tests or injections but others recognised that these could be valuable and it was possible to overcome those fears | |

| There was particular interest in the group about being able to talk about mental health issues with your doctor, particularly about being anxious or depressed. Some mentioned that more time was needed to talk about these issues |

| Area | Specific details |

|---|---|

| Diagnosis and management | Epilepsy diagnosis and management and quality of seizure control |

| Identification of depression | |

| Hearing and vision problems | |

| Vitamin D deficiency and osteoporosis diagnoses in older people | |

| Later cancer diagnoses | |

| Gout and osteoarthritis | |

| Monitoring of therapy (e.g. having thyroid function tests if on thyroxine) | |

| Medication | Concern over number of medications prescribed |

| Risks of inappropriate prescribing | |

| Overuse of antipsychotic medications for behavioural problems | |

| Monitoring of epilepsy medication | |

| Preventative care | Importance of overweight and obesity |

| Smoking in those with less severe levels of disability | |

| Screening for hypothyroidism in some conditions (e.g. Down syndrome) | |

| Organisation of care | Impact of place of residence (e.g. with family carer, in supported independent living, in group home) |

| Being able to see the same GP, length of appointments | |

| Organisation of health checks, variation in duration and place of delivery of health checks (e.g. reports of some as short as 10 minutes, some as long as 2 hours, some done over telephone, some as home visits) | |

| What is actually covered in health checks? Content should be according to the Cardiff health check, but is not always so, and there was marked variation in what was covered |

The discussion about health checks with both groups identified varied views on the effectiveness and acceptability of health checks, and differing experiences of the delivery of the health check programme. This highlighted the importance of describing process measures for the health checks, as well our main focus on changes in hospital admissions.

A qualitative research paper65 has been published further detailing the views and experiences of the members of the parent, carer and ResearchNet groups of their involvement in this research. Preliminary findings suggest almost unanimous agreement from both groups that their involvement was meaningful to them and that their participation felt genuine (see Appendix 6).

Chapter 3 Cross-sectional findings

Introduction

In presenting a summary of the health and health care of adults with ID in primary care in England, we chose to carry out a series of cross-sectional analyses on a fixed date (1 January 2012) that would be towards the end of our study period. It also had the benefit of maximising the number of CPRD practices contributing data at that time, as some practices in our study stopped contributing data later in 2012. This date allowed a total of 408 practices to be used in the cross-sectional analyses, from which a total of 14,751 patients with ID who were aged 18–84 years in 2012 were included. These patients were age, gender and practice matched to 86,211 controls without ID (see Figure 2). All patients had been registered with the practice for a minimum of 30 days.

Some of these results have already appeared in publication in Carey et al. 66 © British Journal of General Practice 2016. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/), which permits unrestricted reuse, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Prevalence of intellectual disability among adults in 2012

We were able to estimate the adult prevalence of recorded ID in primary care in 2012 by obtaining denominators by gender and 5-year age groups for all registered patients in CPRD on 1 January 2012. These totalled approximately 2.7 million patients aged 18–84 years from the eligible 408 practices. This allowed us to estimate that the 14,751 adults with ID aged 18–84 years in 2012 represented 0.54% of the total registered population for this age group. For comparative purposes, the published prevalence from QOF for 2011–12 (effectively estimated at 31 March 2012) for all adults aged ≥ 18 years was 0.45% (see Appendix 1), derived from all 8123 practices in England. Thus, our decision to include a wider set of Read codes for ID, and not just those used for the QOF learning disability register (see Appendix 2), increased our cohort of adults with ID by about 20%.

The estimated prevalence in the registered population of adults on 1 January 2012 differed by gender, with a higher rate seen in men (0.63%) than in women (0.45%). When the prevalence was estimated by age (in 2012), there were incremental reductions seen with increasing years of life. For those aged 18–34 years the prevalence was 0.72%, for those aged 35–54 years it was 0.59% and for those aged 55–84 years it fell to 0.34%.

There was considerable variation in the prevalence rate of ID when this was calculated in each of the 408 practices (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6.

Prevalence of ID by practice in adults registered on 1 January 2012.

-

Only 34 practices (8%) reported a prevalence of > 1 in 100 registered patients having ID recorded.

-

There were two notable outliers in terms of prevalence (2.22% with 61 total patients with ID and 2.68% with 114 total patients with ID). More than two in three patients with ID in these practices were estimated to be living in communal or shared accommodation, suggesting that these practices are located near such residences.

-

Although not outliers in terms of prevalence, five practices had > 120 patients with ID registered (n = 173 with prevalence of 1.07%, n = 164 with prevalence of 1.51%, n = 139 with prevalence of 0.93%, n = 124 with prevalence of 1.08% and n = 122 with prevalence of 1.56%).

-

Forty-seven practices (12%) had < 10 registered patients with ID; nine of these practices had fewer than five registered patients with ID.

Overall characteristics of adults with intellectual disability

The distribution of age (calculated in 2012) for the 14,751 adults with ID registered on 1 January 2012 is shown in Figure 7. The resulting distribution is different from the pattern seen in the general UK population,67 which is indicated by the dotted line. There are two peaks (around 18–25 years and 45–50 years) that offset the dearth in the older population with ID seen from the age of about 60 years onwards.

FIGURE 7.

Age distribution of adults with ID registered on 1 January 2012.

Further characteristics of our sample of adults with ID are shown in Table 5. The average age was 42.1 years, and 58% were male. The percentage of men among adults with ID gradually fell with age, from 61% in the youngest group (18–34 years) to 53% in the oldest group (55–84 years). Approximately three in four patients had their ethnicity recorded on their primary care record, with > 90% being recorded as white. Adults with ID with a non-white ethnicity recorded were much younger (mean 34.8 years) but were small in patient numbers, and as a result we did not pursue ethnicity further as a subgroup of interest in this report. Overall, 87% of our sample were on their practices’ QOF registers for learning disability.

| Characteristic | n | % of all adults with ID | % of adults with ID who are men | Mean age in years (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 14,751 | 100 | 57.9 | 42.1 (16) |

| Gender | ||||

| Women | 6216 | 42.1 | 0 | 43.3 (16) |

| Men | 8535 | 57.9 | 100 | 41.2 (16) |

| Age (years) in 2012 | ||||

| 18–34 | 5365 | 36.3 | 61.2 | 25.3 (5) |

| 35–54 | 6041 | 41.0 | 57.5 | 44.8 (5) |

| 55–84 | 3345 | 22.7 | 53.1 | 64.1 (7) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 10,192 | 69.1 | 56.7 | 43.1 (16) |

| Other | 921 | 6.2 | 56.0 | 34.8 (13) |

| Not recorded | 3638 | 24.7 | 61.4 | 41.0 (15) |

| ID subgroupa | ||||

| On QOF learning disability register | 12,862 | 87.2 | 58.1 | 42.1 (16) |

| Down syndrome | 1571 | 10.7 | 53.9 | 40.4 (13) |

| Autistic spectrum disorder | 1512 | 10.3 | 76.4 | 32.5 (13) |

| Has severe health needs | 3527 | 23.9 | 52.6 | 44.2 (16) |

| In communal/shared accommodation | 3138 | 21.3 | 55.8 | 49.3 (15) |

| Deprivationb | ||||

| 1 (least deprived fifth) | 1563 | 10.6 | 58.8 | 41.2 (16) |

| 2 | 2000 | 13.6 | 57.7 | 42.9 (16) |

| 3 | 2232 | 15.1 | 59.5 | 41.9 (16) |

| 4 | 2764 | 18.7 | 56.0 | 42.2 (16) |

| 5 (most deprived fifth) | 3056 | 20.7 | 57.8 | 42.4 (16) |

| Not available | 3136 | 21.3 | 57.9 | 41.7 (15) |

| Time with practice (years) | ||||

| < 1 | 1037 | 7.0 | 55.8 | 38.2 (16) |

| 1–5 | 2945 | 20.0 | 56.8 | 40.2 (16) |

| ≥ 5 | 10,769 | 73.0 | 58.3 | 43.0 (16) |

| Annual health check | ||||

| None by 1 January 2012 | 7845 | 53.2 | 58.2 | 40.3 (16) |

| At least one by 1 January 2012 | 6906 | 46.8 | 57.4 | 44.1 (15) |

About 1 in 10 of our adults with ID was recorded as having Down syndrome. Similarly, 1 in 10 had a diagnosis of autistic spectrum disorder in addition to their ID; these patients were markedly younger (mean 32.5 years) and the majority were men (76%). About one-fifth of patients with ID (21%) were identified as living in a communal setting, and this group was notably older (mean 49.3 years).

Socioeconomic status was approximated by IMD quintiles,46 linked at postcode level to the patient’s residence (linked practices only). Although there was a trend towards more adults with ID being found in increasing quintiles of IMD, representing higher deprivation, this mirrors the pattern seen in complete population extracts of CPRD,68 and reflects a small geographical bias within CPRD whereby there are comparatively fewer practices in the north of England. 45 Almost three in four adults with ID (73%) had been registered at their practice for at least 5 years. Just under half (46.8%) had received an annual health check by 1 January 2012.

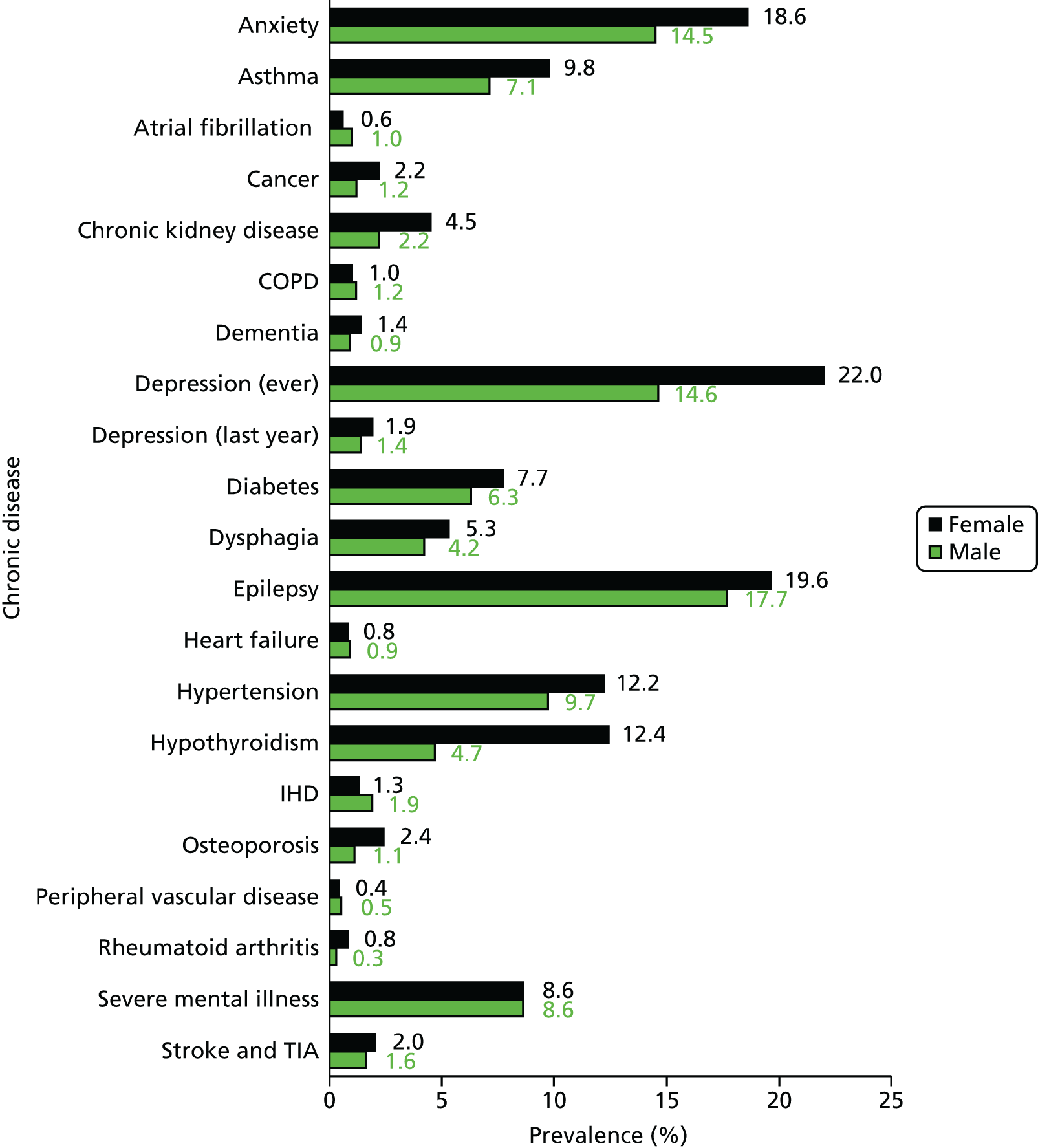

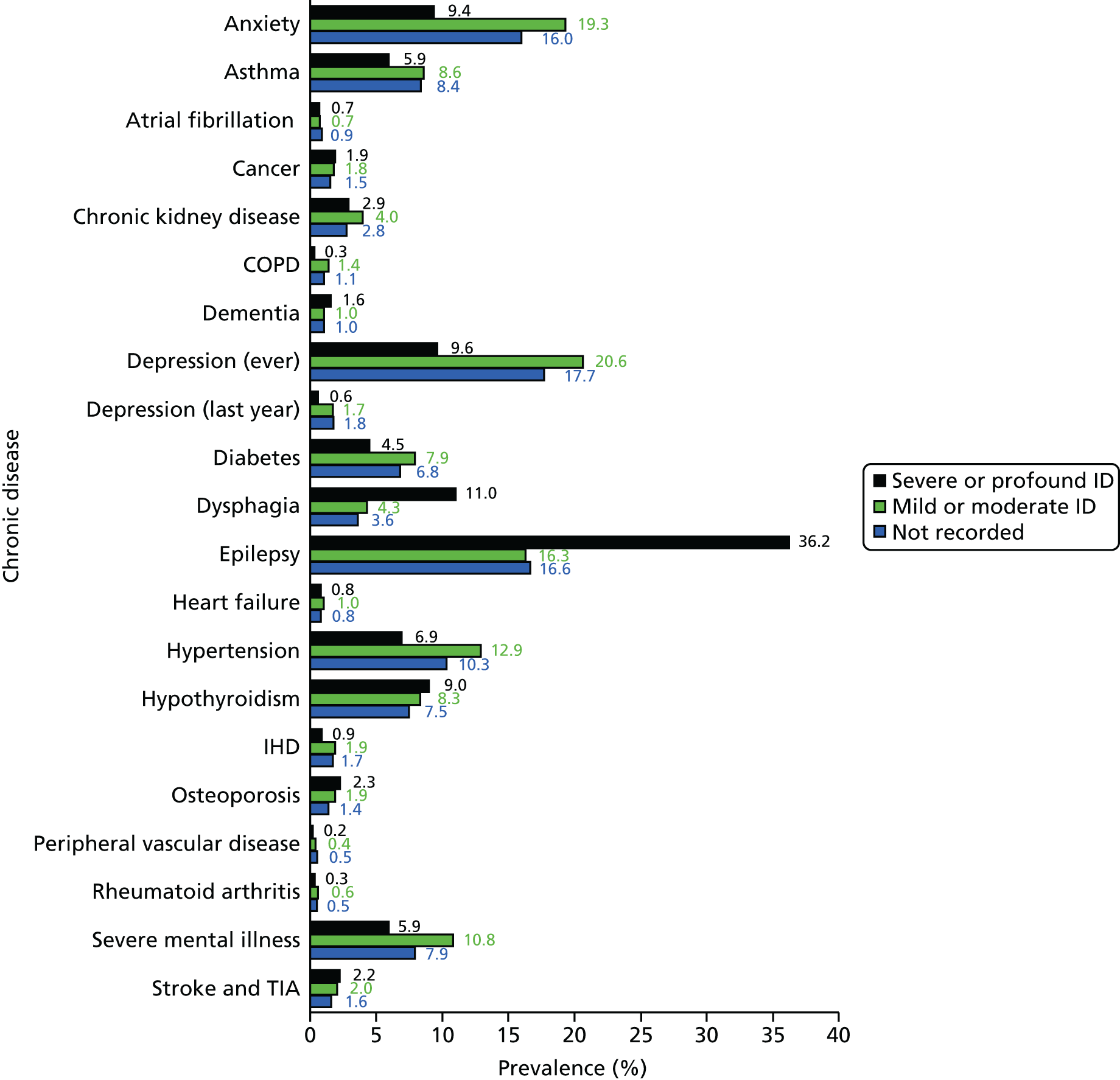

Disease prevalence among adults with intellectual disability

We chose to describe chronic disease prevalence by focusing on the range of conditions collated by the QOF. 69 For most of these conditions, we used version 26 of the business rules,70 which were in operation circa 2012–13. These identify the set of Read codes used in definitions, and for the most part stay consistent from year to year. For each condition, we searched for the presence of any Read code in the medical record up to 1 January 2012 to allow the description of prevalence. For cancer and depression, we first describe lifetime prevalence, but also include date-specific period prevalence in line with the QOF definition. For asthma, epilepsy and hypothyroidism, in line with the QOF definitions, a recent prescription was also required to give a measure of period prevalence. Severe mental illness was subdivided into schizophrenia and affective disorder. We also included additional conditions of anxiety and dysphagia.

Table 6 summarises the disease prevalences for adults with ID, compared with their controls, using PRs. These were calculated using conditional Poisson models (see Chapter 2, Statistical analysis) that take into account the matched design. Almost one in five adults with ID was recorded with epilepsy that is currently managed (18.5%), compared with < 1 in 100 adults without ID (0.7%). This represents a prevalence 25 times higher than that in controls (PR 25.33, 95% CI 23.29 to 27.57). Other large relative differences in prevalence were seen for severe mental illness (8.6% of adults with ID; PR 9.1, 95% CI 8.3 to 9.9) and dementia (1.1% of adults with ID; PR 7.5, 95% CI 6.0 to 9.5). Adults with ID had a moderately increased risk of dysphagia, hypothyroidism and heart failure (PR of between 2 and 3.5) compared with the general population. In addition, significantly higher in adults with ID (PR of between 1.5 and 2) were osteoporosis, stroke, diabetes and chronic kidney disease.

| Disease | Adults with ID (N = 14,751), n (%) | Controls (N = 86,221), n (%) | Adults with ID vs. controls, PR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anxiety | 2398 (16.3) | 12,580 (14.6) | 1.13 (1.09 to 1.18) |

| Asthmaa | 1208 (8.2) | 5717 (6.6) | 1.25 (1.18 to 1.33) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 122 (0.8) | 821 (1.0) | 0.91 (0.75 to 1.09) |

| Cancerb | 238 (1.6) | 2090 (2.4) | 0.70 (0.61 to 0.80) |

| Diagnosis since 1 April 2003 | 156 (1.1) | 1490 (1.7) | 0.65 (0.55 to 0.76) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 468 (3.2) | 1746 (2.1) | 1.64 (1.49 to 1.82) |

| COPD | 160 (1.1) | 1184 (1.4) | 0.84 (0.71 to 0.99) |

| Dementia | 160 (1.1) | 134 (0.2) | 7.52 (5.95 to 9.49) |

| Depressionb | 2609 (17.7) | 15,179 (17.6) | 1.03 (0.99 to 1.06) |

| Diagnosis since 1 April 2006 | 1626 (11.0) | 9520 (11.0) | 1.01 (0.96 to 1.06) |

| Diagnosis in last year | 237 (1.6) | 1723 (2.0) | 0.80 (0.70 to 0.92) |

| Diabetes | 1017 (6.9) | 3786 (4.4) | 1.64 (1.53 to 1.75) |

| Dysphagia | 692 (4.7) | 1263 (1.5) | 3.30 (3.01 to 3.61) |

| Epilepsya | 2731 (18.5) | 633 (0.7) | 25.33 (23.29 to 27.57) |

| Heart failure | 121 (0.8) | 324 (0.4) | 2.26 (1.84 to 2.78) |

| Hypertension | 1583 (10.7) | 10,416 (12.1) | 0.93 (0.89 to 0.98) |

| Hypothyroidisma | 1169 (7.9) | 2649 (3.1) | 2.69 (2.52 to 2.87) |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 244 (1.7) | 2316 (2.7) | 0.65 (0.57 to 0.74) |

| Osteoporosis | 246 (1.7) | 822 (1.0) | 1.84 (1.60 to 2.12) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 61 (0.4) | 423 (0.5) | 0.90 (0.69 to 1.17) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 73 (0.5) | 550 (0.6) | 0.82 (0.65 to 1.05) |

| Severe mental illness | 1266 (8.6) | 823 (1.0) | 9.10 (8.34 to 9.92) |

| Schizophrenia | 995 (6.7) | 591 (0.7) | 9.94 (8.99 to 10.99) |

| Affective disorder | 371 (2.5) | 333 (0.4) | 6.66 (5.73 to 7.73) |

| Stroke and TIA | 267 (1.8) | 944 (1.1) | 1.74 (1.52 to 1.98) |

Not all recorded disease prevalence was higher in adults with ID. Recorded lifetime prevalences of both ischaemic heart disease (IHD) (PR 0.65, 95% CI 0.57 to 0.74) and cancer (PR 0.70, 95% CI 0.61 to 0.80) were significantly lower than those seen in the general population. Although a record of depression was equally likely in adults with ID, when only diagnoses in the last year were considered, adults with ID were 20% less likely to have one recorded in their record (PR 0.80, 95% CI 0.70 to 0.92).

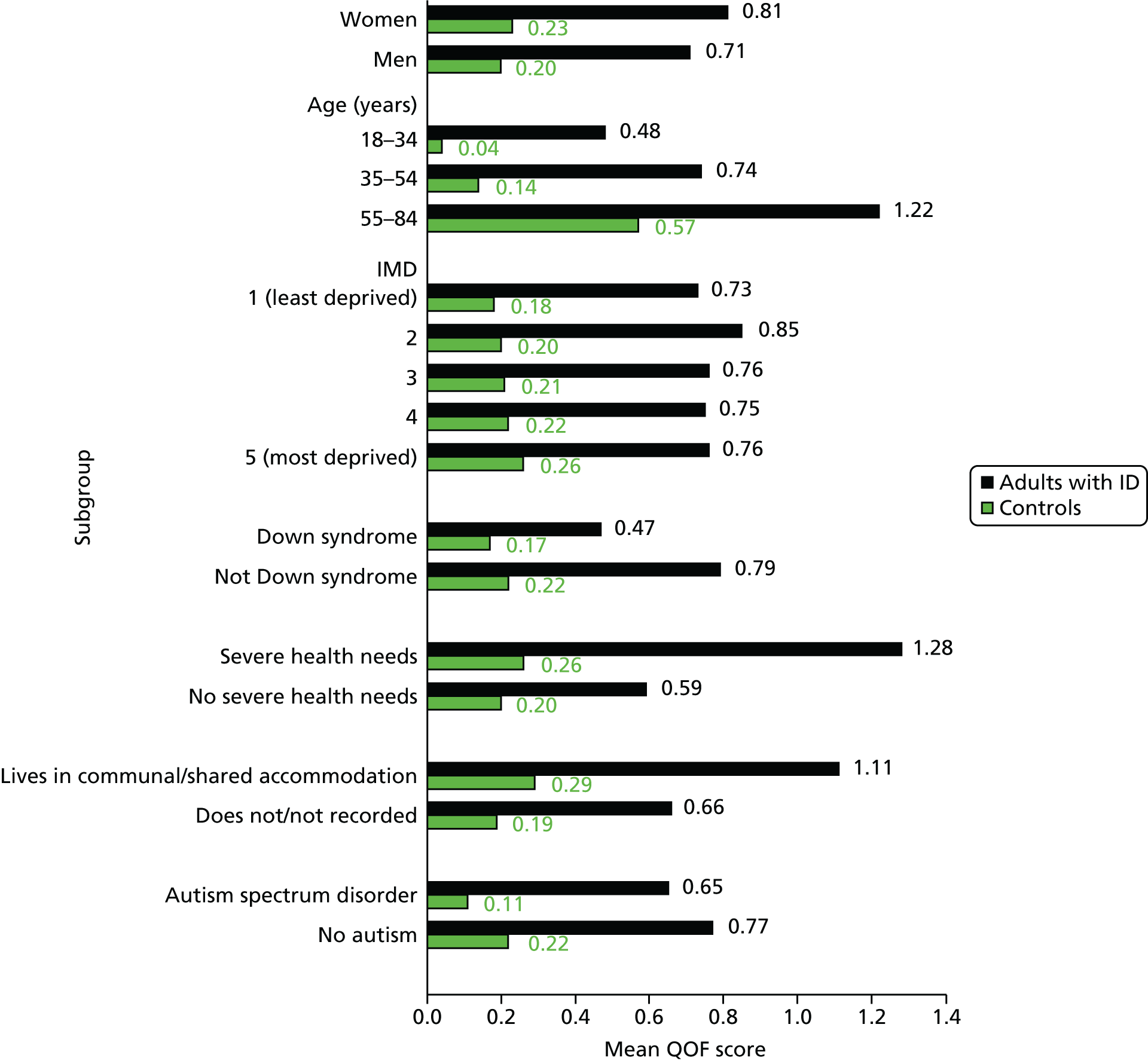

Figure 8 displays a mean count of all QOF conditions from Table 6 (excluding anxiety and dysphagia, which are not counted by QOF) in adults with ID and controls. The disparity between the groups is already evident at the age of 18 years, when the mean count is approximately three times higher among adults with ID (0.31 vs. 0.11). The higher burden of comorbidity persists through middle age, but after about 65 years of age the two lines in Figure 8 start to quickly converge. Comorbidity levels are then more similar between adults with ID and matched controls in their seventies. Among the few adults with ID in their eighties in our study (n = 116), levels of comorbidity were lower than among their matched controls.

FIGURE 8.

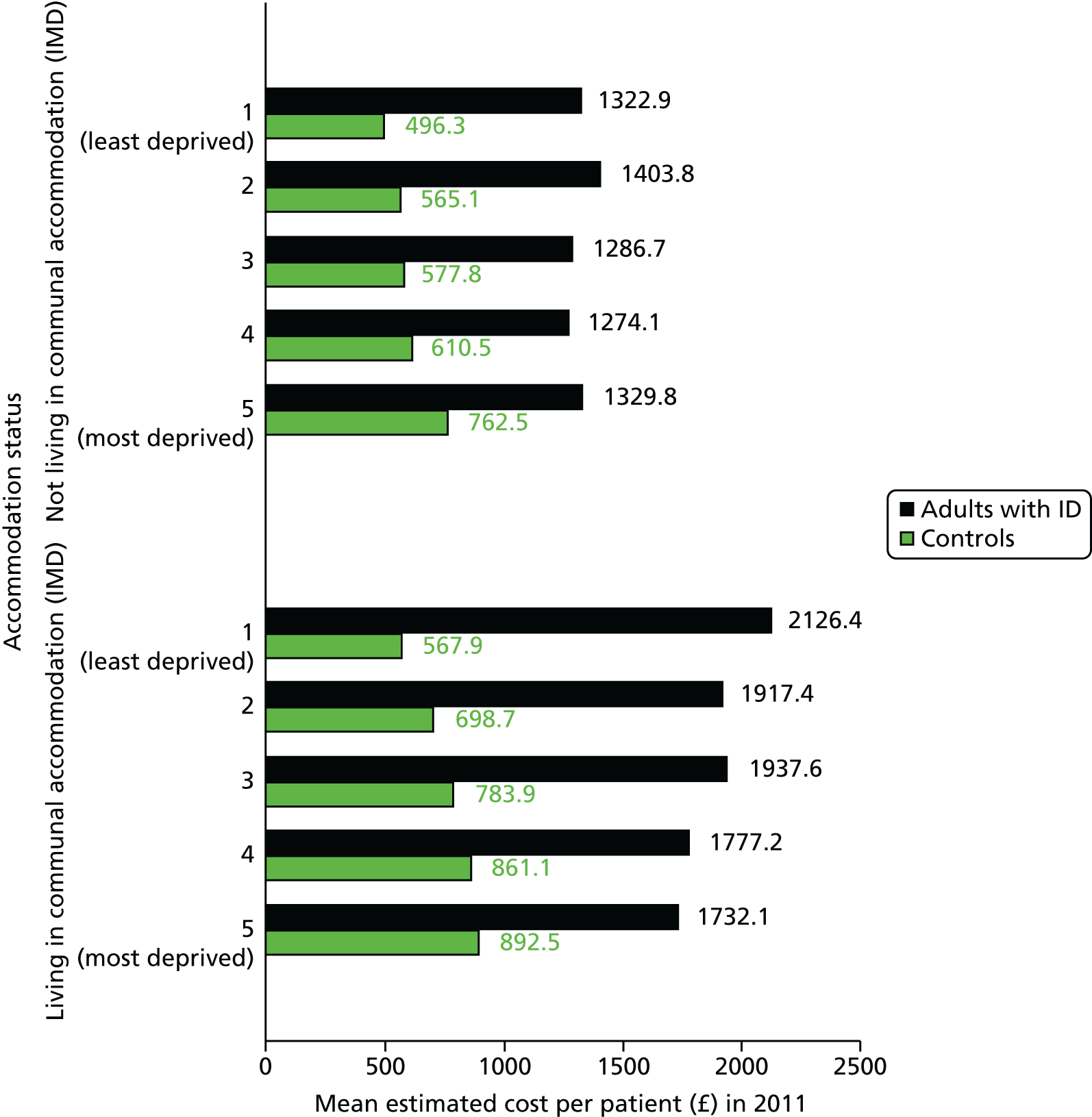

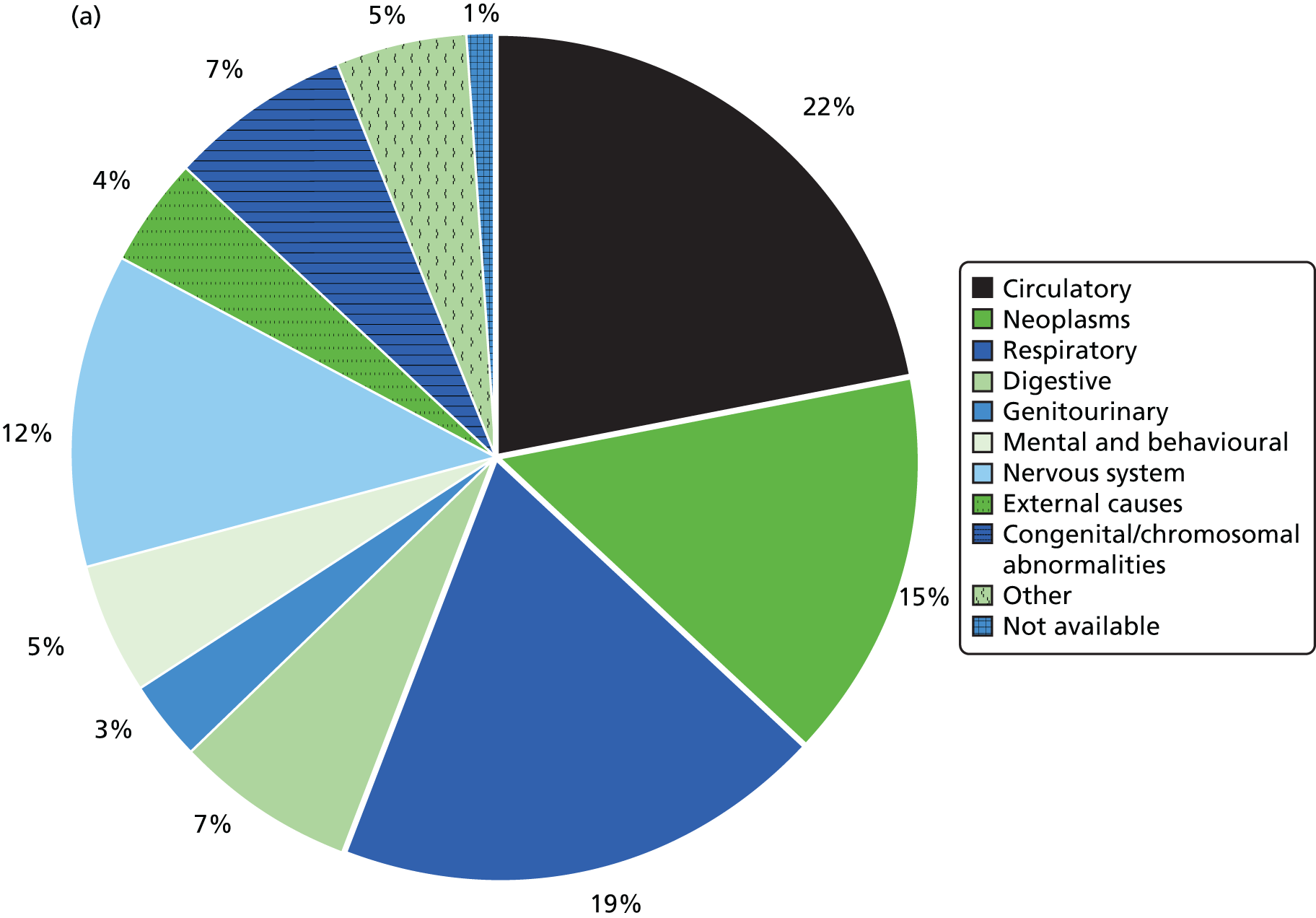

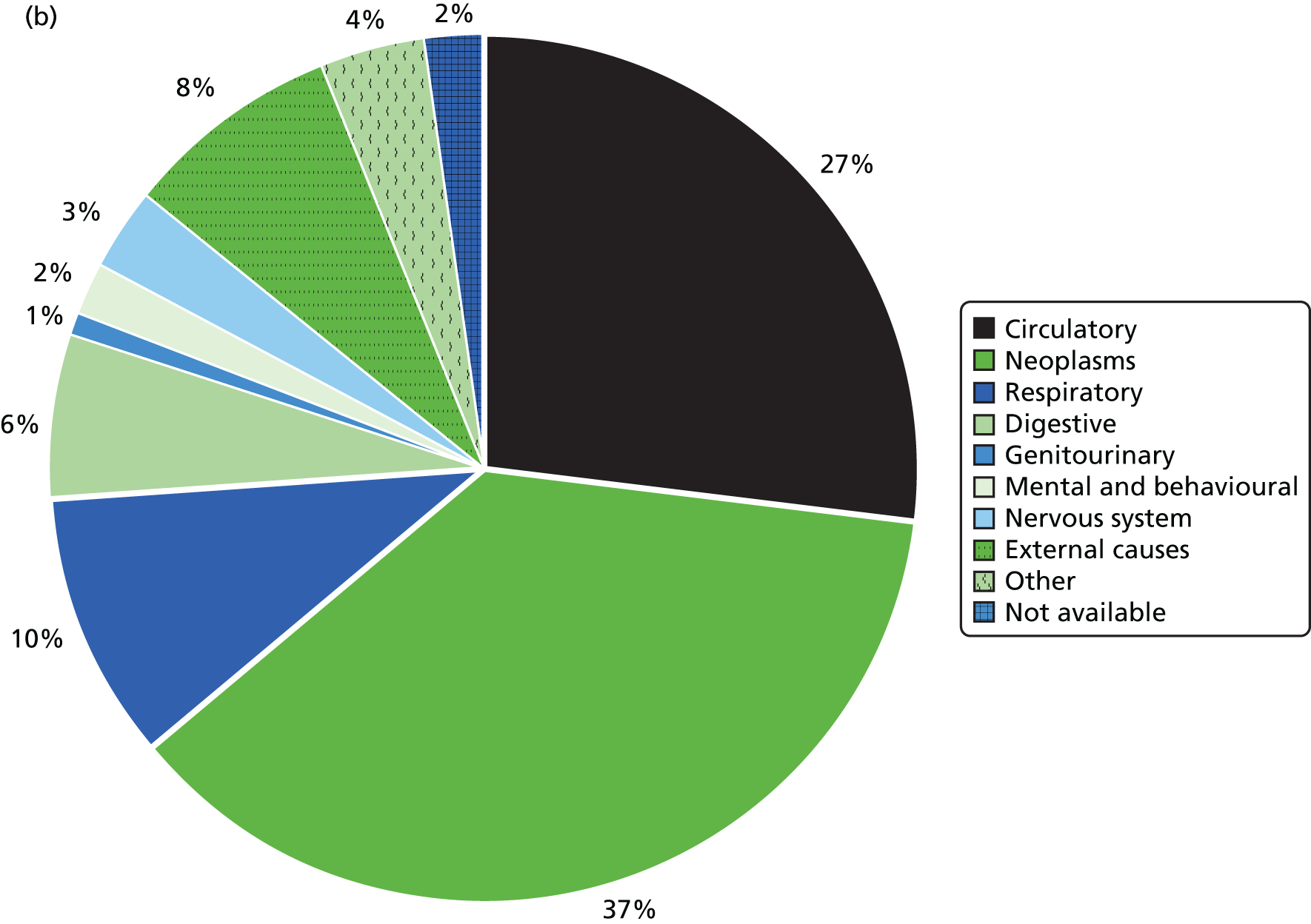

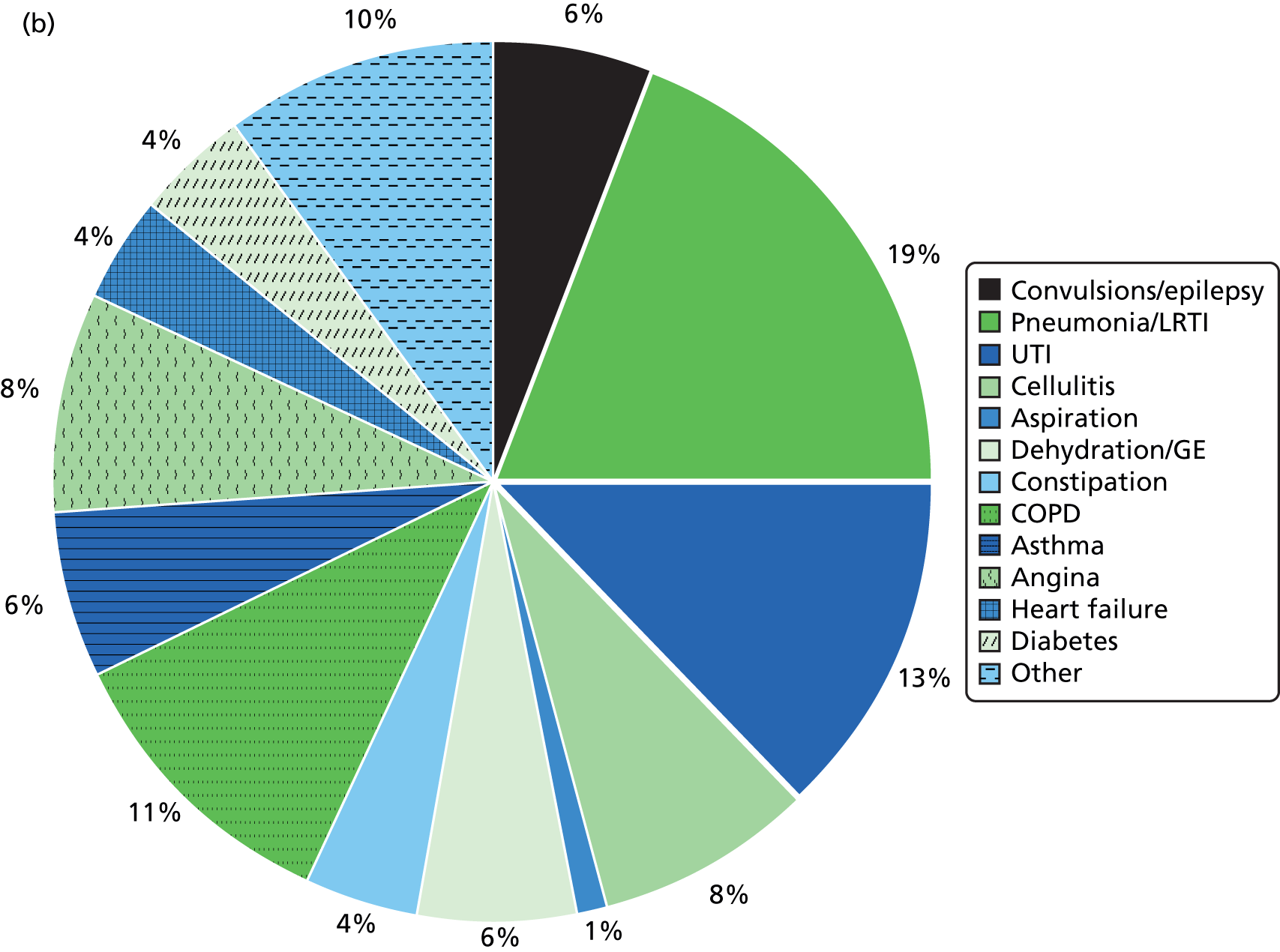

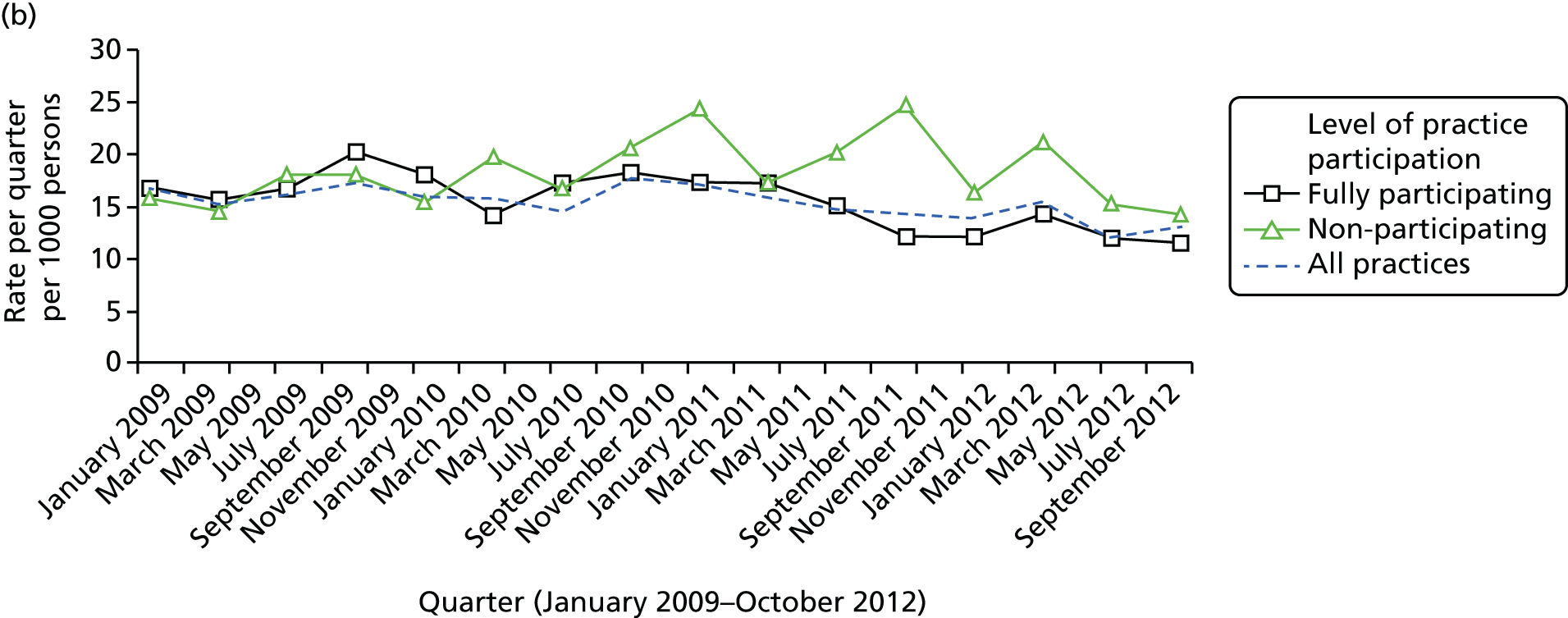

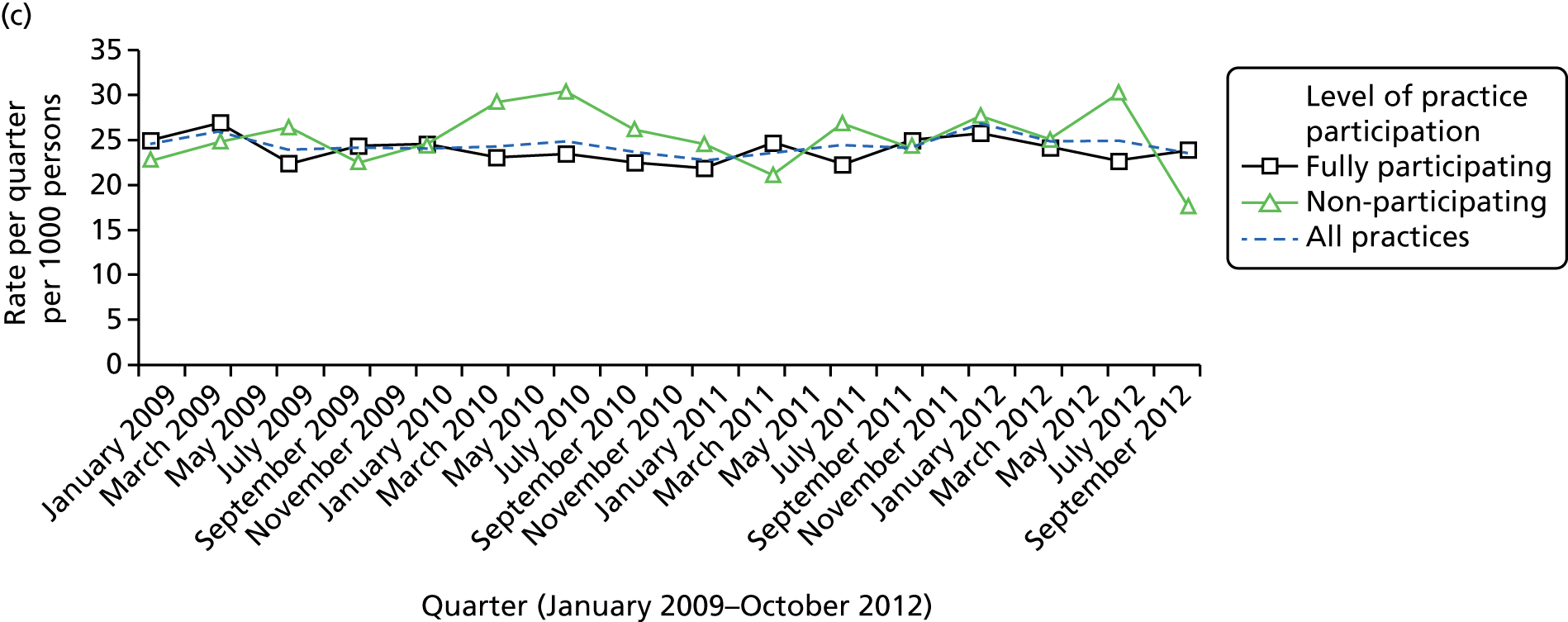

Mean number of QOF conditions by age in adults with ID and controls.