Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 11/1025/05. The contractual start date was in April 2013. The final report began editorial review in May 2016 and was accepted for publication in November 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Jacobs et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Context and literature review

The organisation of community pharmacy in the UK

As private businesses contracted to provide NHS dispensing and medicines-related services, community pharmacies play a key role in UK health-care systems. Community pharmacies constitute a range of organisational forms under different types of ownership, such as national multiple (chain) pharmacies and supermarkets, small and medium-sized chains, and local independent pharmacies operating between one and five premises.

The community pharmacy contractual framework for England was introduced in 2005 (with revisions in 2011 and 2015) to meet the objectives set out in the 2003 White Paper, A Vision for Pharmacy in the New NHS. 1 These included helping to tackle health inequalities, supporting self-care and responding to the diverse needs of patients and communities. The contract specifies three levels of service provision. Essential services, which all community pharmacies are required to provide, include dispensing, repeat dispensing and clinical governance requirements. Advanced services, including medicines use reviews (MURs), the new medicines service (NMS) introduced in 2011, and the influenza vaccination service introduced in 2015, are not mandatory and require training and a declaration of competence by the pharmacist. Enhanced and locally commissioned services, which until 2013 were commissioned by primary care trusts (PCTs), are now commissioned by NHS England, clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) and local authorities. These services are commissioned to meet locally assessed needs and include minor ailment schemes, smoking cessation clinics and medicines management services for long-term conditions. Similar contractual frameworks exist for Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, although there are some regional differences.

The extension of the community pharmacist’s role from traditional dispensing duties into a range of clinical areas that were once the remit of only family doctors is part of a general move to embrace the philosophy of ‘pharmaceutical care’ within the profession. 2 It is widely supported by pharmacists3 – who see it as an opportunity to utilise their extensive clinical knowledge of medicines to greater effect – and service commissioners – who recognise the opportunities to improve service access and quality for patients, reduce some of the burden on general practitioners (GPs)’ workload and potentially to save money through role substitution, the reduction of waste medicines (through improved medicines understanding and adherence) and the prevention of medicines-related unplanned hospital admissions.

One important aspect of recent health-care policy in the UK has been to increase patient choice and access to services. Together with a raft of pro-market policies, this has sought to increase the range and diversity of professionals and provider organisations able to offer advice and services. The election of the Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition government in 2010 saw the introduction of further health-care reforms, with the drive towards independent sector provision of health care being stepped up (‘any qualified provider’). 4 However, concerns have been raised over the quality and safety of patient care delivered by private sector organisations,5 which need to balance the pressures of delivering quality services within the context of a for-profit business. Community pharmacies are private businesses and established providers of NHS-funded services. As such, they provide an ideal exemplar in which to begin to unpack concerns over conflicting commercial pressures versus improving quality and safety.

Definitions of clinical productivity

Productivity can be simply defined as the ratio of outputs to inputs in the production process. In industry, ‘outputs’ can be measured as the number of units of production per day, for example. However, in health care, where a positive patient experience and high-quality services are necessary to ensure maximum patient benefit, the amount of time spent per patient may be more important than the volume of services delivered. In this way, ‘clinical’ productivity, it could be argued, differs from more traditional definitions of productivity in that it encompasses not only the quantity of services provided, but also the quality of those services. Indeed, in 2005, the University of York’s Centre for Health Economics and the National Institute for Economic and Social Research suggested improved methods for measuring productivity that captured measures of quality as well as service activity. 6 ‘Inputs’ often refer to expenditure on labour, capital and materials.

The majority of studies examining clinical productivity in health care have been conducted in hospital settings in the USA and have measured clinical productivity in purely quantitative terms, for example numbers of procedures performed or patients seen, hours per case or, often, ‘relative value units’, which are a measure of value used in the USA to reimburse health-care services that take into account the time, training, skills and intensity needed to deliver a particular service. Studies of clinical productivity generally do not take into account the quality or outcomes of the services delivered.

For the purposes of this study, we sought to examine clinical productivity in terms of both the quantity and quality of services delivered by community pharmacies. The quality of pharmacy services is associated with individual patient benefit and is important to consider alongside the quantity (range and volume) of services delivered because the more patients that receive a high-quality service, the greater the effect the service will have on patient benefit and the health of the public. Conversely, high volumes of low-quality services have a potential cost both to the NHS and to patients/customers. The study did not seek to derive a single metric of ‘clinical productivity’ (obtaining ‘input’ data for individual pharmacies would not have been possible due to commercial sensitivities); rather, it explored the different components of clinical productivity simultaneously to gain a better understanding of how they might vary, their inter-relationships and the influence of organisational characteristics.

No commonly accepted definition of quality in community pharmacy has yet been developed7 and robust measures of quality in community pharmacy of proven validity and reliability are rare. 8 Moreover, it can be difficult to attribute patient outcomes to the quality of the service delivered by the community pharmacy when that is only one element of the care pathway experienced by the patient. For the purposes of this study, the quality of community pharmacy services has been operationalised in terms of overall patient satisfaction, satisfaction with the information received by the patient about their medication, their adherence to their medication and the safety climate within which the pharmacy operates. These measures of quality were selected on the basis of the availability of validated instruments and because they are likely to be influenced directly by the pharmacy itself. However, the construct of quality in community pharmacy and the influence of organisational characteristics were also explored more widely in the qualitative study (see Chapter 6, Definitions of quality).

The relationship between organisational characteristics and clinical productivity in health care

Research into variation in clinical productivity within health care and the organisational factors that influence this is inconclusive. In their extensive review of the relationship between organisational factors and performance, Sheaff et al. 9 concluded that, ‘There is no consistent or strong relationship between organisational size, ownership, leadership style, contractual arrangements for staff or economic environment (competition, performance management) and performance’. In primary care the evidence is even more limited. However, more recent studies have been able to utilise data now available from the UK Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) to investigate variation in the performance of general practices. Studies have found that some practice characteristics, notably practice size, ratio of practitioners to patients, levels of nurse staffing and team climate, may be associated with variation in performance, in addition to local levels of population deprivation and need. 10–14 A study of the role of incentives in a range of primary care settings concluded that incentives led to higher levels of attainment of quality targets and a reduction in variation in quality relating to deprivation in general practice; a shift towards treatments that pay more in general dental practice; and the provision of increased volumes of incentivised services in community pharmacy. However, it also found that incentives had some unintended consequences in relation to whether or not the additional investment actually represented value for money with a number of opportunity costs arising out of an increasing focus on incentivised activities. 15,16

The relationship between organisational characteristics and clinical productivity in community pharmacy

Evidence is emerging to suggest that organisational factors may influence the levels of clinical productivity in community pharmacies. MURs aim to help patients manage their medicines more effectively, by increasing their understanding, identifying problems and providing feedback to prescribers. Research published not long after the introduction of the 2005 contractual framework suggested that the volume of MUR provision by pharmacy chains was almost twice that of independent pharmacies17,18 and that this difference may be primarily profit driven, prioritising service quantity over quality. 18 There is also some evidence that locally commissioned enhanced services were more likely to be provided by chain pharmacies than independent pharmacies and that provision was greater in deprived and urban areas. 19 Other research into the implementation of pharmaceutical care services by community pharmacies worldwide has identified a number of organisational barriers to and facilitators of their provision, including the physical environment (particularly adequate space and privacy), organisational culture and leadership, having the necessary staffing and skill mix, relationships with GPs, equipment and technology, and work overload/conflicting workloads. 20 Studies of the implementation of MURs in English pharmacies suggest that although delegation of dispensing duties to pharmacy technicians or other support staff (to free up pharmacists’ time) is supported by pharmacists, constant workload demands and interruptions still prevent pharmacists from conducting MURs. 15 Yet pharmacists, particularly those working for large chain pharmacy organisations (‘multiples’), are under intense pressure to meet financial targets, including conducting specified numbers of MURs. 18 This may detract from not only the effectiveness of the MURs conducted,21 but also the extent to which they may represent true role substitution and cost efficiency.

Previous research also suggests that the quality of community pharmacy services may be influenced by organisational factors. A realist review of studies describing aspects of organisational culture in community pharmacy, its antecedents and outcomes, highlighted longstanding evidence of the dichotomy in organisational values in this sector (professional vs. business) as a result of community pharmacy services being provided by private sector organisations. 22 A subsequent survey of community pharmacists provided evidence of a significant relationship between organisational culture, particularly the balance between business and professional values, and pharmacists’ work stress and the potentially detrimental effect on patient safety of working within an intensely targets-driven culture. 23,24 Moreover, there is evidence that the organisational culture extant within pharmacies under different types of ownership may differ (Dr Sally Jacobs, University of Manchester, 2012, personal communication) and that ownership type may be associated with variation in work stress. 23 Evidence from a number of studies has described a relationship between workload and working patterns on pharmacists’ work-related stress,23,25,26 and the role of the pharmacist’s manager (particularly whether or not they are a pharmacist themselves) in determining job satisfaction. 27 Other research has suggested that organisational factors may be associated with the occurrence of dispensing errors24,28 and qualitative research on locum pharmacists has raised concerns that patients are put at risk because of the increasing reliance on temporary staff. 29 This is of particular importance in a sector of health care in which around one-quarter of all pharmacists work as self-employed locums. 30

Clinical productivity in community pharmacy and the wider health-care economy

Research suggests that up to 50% of patients with a chronic condition do not take medicines as prescribed. 31 Non-adherence to medicines is known to cause poorer health outcomes and unscheduled hospital admissions. In the UK, as many as 6.5% of adult hospital admissions are estimated to be medicines related and 30% of these cases are caused by non-adherence to medicines for chronic illness. 32 In 2014/15, £15.6B was spent on non-elective inpatient costs and £2.5B on accident and emergency admissions. 33 Therefore, it could be estimated that approximately £352M was spent on such unplanned hospital admissions in relation to medicines non-adherence.

Another key concern in health care is medicines waste in the primary and community sectors, which has been estimated to cost the NHS approximately £300M per year, equivalent to approximately £1 in every £25 spent on primary care and community pharmaceutical and allied products use, and 0.3% of total NHS expenditure. 34 This figure includes an estimated £110M worth of unused prescription medicines that are returned to community pharmacies over the course of the year and an additional £90M retained in individuals’ homes at any one time.

Community pharmacies are well placed to deliver services to improve patients’ understanding of medicines and their use. Interventions such as pharmacist-led medication reviews have been shown to improve adherence,35 and there is some evidence that increased adherence has a direct impact on treatment success and patient outcomes,36 thus improving health-care efficiency. It is for this reason that MURs were originally introduced to ensure that patients have a better understanding of their medicines, thus achieving better adherence and avoiding unnecessary waste and unplanned hospital readmissions.

NHS investment in community pharmacy services is substantial and, until 2015, was growing year on year. The total budget agreed for the provision of pharmaceutical services in England was £2.8B in 2014/15,37 making up a considerable part of overall NHS expenditure. Over 978 million prescriptions were dispensed by community pharmacists in England in 2014/15, an increase of almost 48.5% over the previous 10 years. 38 The number of enhanced services delivered had risen to 30,962 in 2010/11 and almost 3.2 million MURs and 0.8 million NMS interventions were conducted in England in 2014/15. 38

Service payments for advanced and enhanced pharmaceutical services are based on a fee-for-service structure, although there is a cap of 400 on the number of MURs for which a pharmacy will be paid annually. This raises questions over whether or not the NHS is getting value for money, particularly in light of the concerns raised above that commercial pressures may drive some community pharmacy organisations to prioritise quantity over quality in delivering MURs. To try to address these concerns, targeted MURs and the NMS were introduced in 2011. However, there is still a pressing need for the NHS as service commissioners to gain an understanding of the relationship between the quantity and quality of service provision as key elements of clinical productivity in the context of private businesses such as community pharmacy organisations. This need has been heightened by the reorganisation of the NHS and the dissolution of PCTs in 2013. With the commissioning of community pharmacy services passing to the newly formed NHS England area teams, CCGs and, for the first time, local authorities, the commissioning landscape has become fractured; there has been a loss of organisational memory and a depletion of pharmacy commissioning manpower, knowledge and skills.

This study was designed to address this need for service commissioners. An understanding of the organisational requirements for maximising clinical productivity in terms of both quantity and quality of service provision could help in the development of a set of organisational standards against which to assess applying pharmacies as part of the pharmacy contract approval process or for commissioning advanced and enhanced services. A better understanding of the inter-relationships between the quality and quantity of service provision in private sector organisations could also help to inform improvements in service payment structures and contract monitoring processes to help ensure that the NHS is getting value for money from the services it commissions. With studies of the impact of community pharmacy services on patient outcomes – in particular medicines understanding and adherence – still scarce, this study sought to provide such insights. Finally, for community pharmacy organisations themselves, knowledge of the organisational characteristics associated with higher levels of productivity (both quality and quantity) are likely to be of benefit to them as businesses and employers without compromising benefits to patients and customers.

Chapter 2 Aim and objectives

The overarching aim of this study was to inform the commissioning of NHS general pharmaceutical services in England by exploring variation in clinical productivity (levels of service delivery and service quality) in community pharmacy organisations and identifying the organisational factors associated with this variation.

The objectives were to:

-

explore variation in levels of service delivery across a representative sample of community pharmacies in England

-

investigate the relationships between organisational characteristics and levels of service delivery

-

investigate the inter-relationships between organisational characteristics, levels of service delivery and service quality

-

examine the mechanisms by which organisational factors influence both levels of service delivery and service quality

-

develop a toolkit to inform commissioning processes to improve clinical productivity in community pharmacy.

Chapter 3 Design and methodology

Theoretical framework

The design of this study was informed by organisational theory, in particular the framework proposed by Michie and West39 describing the relationships between organisational context (environment, structure and culture) and performance in health care. Moreover, it utilised the theoretical framework developed by Halsall et al. 7,40 for assessing the quality of community pharmacy services in terms of ‘accessibility’ (influenced by available structures and processes), ‘effectiveness’ (measured through patient, pharmacy, societal and health outcomes) and ‘positive perception of the experience’ (both from the patients’ and the pharmacists’/staff’s perspective). In addition, the study design was influenced by the comprehensive review of the body of work previously conducted by Jacobs et al. 22 describing the culture of community pharmacy organisations, its antecedents and outcomes. Each of these theoretical perspectives underpinned the design of both quantitative and qualitative data collection tools and informed the analysis, integration and interpretation of the data collected in this mixed-methods study.

As described previously (see Chapter 1, Definitions of clinical productivity), ‘clinical productivity’ has been defined and operationalised in a number of different ways in the research literature, but it is not commonly used in the context of community pharmacy. For the purposes of this study, clinical productivity was defined in terms of both quantity of service delivery (e.g. volume and range of essential and advanced services delivered) and service quality (e.g. satisfaction with information about and adherence to medicines).

Stakeholder engagement

From the outset, the study engaged a multidisciplinary project advisory group. Membership of this group consisted of lead pharmacists from NHS commissioning organisations in each of the five original study sites, senior representatives from two community pharmacy provider organisations, an independent pharmacist and representative of the Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee (PSNC), two patient representatives (see Chapter 3, Patient and public involvement) and members of the research team. Each of these individuals was given the opportunity to contribute to the study design of the original proposal, for example, on methods of data collection, the disclosure of commercially sensitive information and other ethical issues, and patient and public involvement (PPI). The advisory group met together four times over the duration of the project, keeping the study grounded in the needs of the different stakeholder groups, providing guidance throughout the study and facilitating access to research sites.

In addition, concerted efforts were made to engage with the community pharmacy sector. Early on, a number of concerns had been voiced by community pharmacy organisations about the study including the workload demands on participating pharmacists, study access to commercially sensitive data and how the findings would be interpreted and used. The study was also due to commence at the time of the 2013 reorganisation of the NHS, which had led to fears of decommissioning of community pharmacy services within the sector and further sensitivities around the research. Advice was sought from the PSNC in relation to obtaining consent from participating organisations. The PSNC also disseminated the study plans to local pharmaceutical committees (LPCs) covering the areas in which the study was to be conducted. Subsequently, the study team contacted each of these LPCs and attended a number of LPC meetings (although others declined the offer). Explicit support for the study was obtained from four LPCs.

Also approached were the Company Chemists’ Association (CCA), which represents the nine biggest pharmacy multiples [Boots (Boots UK Ltd, Nottingham, UK), LloydsPharmacy (LloydsPharmacy Ltd, Coventry, UK), The Co-operative Pharmacy (Co-operative Pharmacy, Manchester, UK), Rowlands Pharmacy (Rowlands Pharmacy, Runcorn, UK), Tesco Pharmacy (Tesco plc, Welwyn Garden City, UK), Morrisons (Morrisons Supermarkets plc, Bradford, UK), Sainsbury’s (J Sainsbury plc, London, UK), Superdrug (Superdrug Stores plc, Croydon, UK) and Asda (Asda Stores Ltd, Leeds, UK)], which together make up approximately 50% of the community pharmacy market). The CCA would not offer its endorsement of the study, but instead requested that its member companies were approached individually to ascertain their level of support. This process led to four of the nine multiples declining to participate, which had important consequences for the stage 1 sample size and representativeness and, thus, led to a significant study amendment (see Chapter 3, Study Design, Stage 1, Sample).

Patient and public involvement

This study sought to integrate PPI into all stages in the research process from the design of the study through to interpretation of the data, toolkit development and dissemination of the findings.

Advice was received on early drafts of the original project proposal from an involvement and partnership manager of a local NHS trust, which not only helped with the design of the PPI element but also informed the research design. Their involvement at this stage also helped with the recruitment of PPI representatives to the project advisory group.

Two PPI representatives were recruited to the project advisory group, both of whom had previous experience advising on health services research studies. One was an older patient with a number of long-term conditions and who was involved in running a hospital-based cardiac patient group. The other was the main carer for a sibling with mental health (MH) problems and who was involved in running a carers’ support group. Both were regular users of community pharmacy services to support medicines usage. Both were given the opportunity to feed into the research proposal, which helped inform the methodology and strategies for dissemination from a patient/public viewpoint. Involvement in the project advisory group aimed to provide grounding for the study throughout in the experiences and needs of pharmacy patients.

In addition, presentations were made to local patient groups at key stages of the study to explain what we were doing and why, describe aspects of the methodology (e.g. patient survey) and to present early findings. Feedback was invited after each presentation to inform the development of data collection tools and survey methodology, and to help with interpretation of the findings.

Last, the two PPI advisory group representatives and two other members of the public recruited through an external PPI group were invited to contribute to the workshop for service commissioners and other pharmacy stakeholders held towards the end of the study to inform the development of the commissioning toolkit (see Chapter 3, Commissioners’ workshop and toolkit development).

Setting

The study was originally designed to be conducted in five geographical locations across England described by now obsolete PCT administrative boundaries. This design was appropriate given the original plan of obtaining pharmacy service activity data from the PCTs as service commissioners (although this was later changed – see Chapter 3, Study Design, Stage 1, Data sources). The original five sites were purposively selected to cover a geographically diverse range of affluent/deprived areas of dense/sparse populations and included one healthy living pharmacy (HLP) pathfinder site.

However, non-participation in the study by a number of national community pharmacy chains (see Chapter 3, Stakeholder engagement) necessitated an expansion of the number of sites from five to nine to maintain sample size. A pragmatic decision was made to expand the original five areas to adjoining sites to build on the now-existing relationships made with local National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) clinical research networks (CRNs) that were helping with aspects of data collection while maintaining the geographical and sociodemographic diversity of the sites. A brief description of each area and its community pharmacy provision is provided in Table 1.

| Commissioning locality (based on original PCT boundaries) | Description | Number of community pharmacies | Number of independents (five or fewer branches) (%) | Average number of prescription items dispensed per month per pharmacy 2010–11 | Average number of MURs per pharmacy 2010–11 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Merseyside (pop. 1,160,000) | An extensive area of NW England with a mixture of urban and rural areas, with areas of affluence and high deprivation | 314 | 123 (39.2) | 6899 | 207 |

| Trafford (pop. 212,800) | Predominantly affluent urban area of NW England with some areas of deprivation | 59 | 22 (37.3) | 6413 | 244 |

| Central and Eastern Cheshire (pop. 453,000) | Predominantly affluent suburban/rural area of NW England with pockets of deprivation | 98 | 20 (20.4) | 6672 | 241 |

| Cambridgeshire (pop. 607,000) | Predominantly rural county in SE England with few urban settlements. Predominantly affluent with pockets of deprivation | 101 | 35 (34.7) | 6311 | 200 |

| Peterborough (pop. 178,000) | Urban area in SE England, ethnically diverse with areas of high deprivation | 41 | 19 (46.3) | 6013 | 168 |

| Hertfordshire (pop. 1,095,000) | A large rural and suburban area of SE England. Predominantly affluent with pockets of deprivation | 238 | 137 (57.6) | 5712 | 218 |

| Sheffield (pop. 547,000) | Large urban area, ethnically diverse with areas of high deprivation. HLP pathfinder site | 118 | 29 (24.6) | 7663 | 217 |

| Doncaster (pop. 291,600) | Predominantly urban area of NE England with some rural areas. Areas of high deprivation | 73 | 13 (17.8) | 7235 | 218 |

| Rotherham (pop. 255,000) | Predominantly urban area of NE England with some rural areas. Areas of high deprivation | 58 | 13 (22.0) | 7535 | 219 |

Study design

This was a mixed-methods study with a number of strands of both quantitative and qualitative data collection over two stages, followed by a workshop for service commissioners and other community pharmacy stakeholders designed to inform the development of a commissioning toolkit through discussion of the study findings.

Stage 1

The first stage of the study was purely quantitative, combining analysis of existing data sets with primary data collection to examine variation in levels of service delivery across community pharmacies (objective i) and to investigate associations between organisational characteristics and levels of service delivery (objective ii).

Sample

The original plan was to approach all community pharmacies in the original five study areas to participate (n ≈ 632). Based on a 5% level of statistical significance and assuming a non-response rate of 33% (i.e. 420 pharmacies would respond), this would have provided the study with > 90% power to detect a correlation as small as 0.16 between organisational factors and clinical productivity. Even if the non-response rate reached 50%, the study would still have > 80% power to detect such a correlation.

However, non-participation in the study by four national community pharmacy chains (see Chapter 3, Stakeholder engagement) required the exclusion of all associated pharmacies from the original sample. Extending the study into nine geographical areas (as described above), with the exclusion of the non-participating chains, provided an overall sample size of n = 817. Based on a 5% level of statistical significance and assuming a non-response rate of 50% (i.e. 410 pharmacies would respond), this gave the study 90% power to detect a correlation as small as 0.16 between organisational factors and clinical productivity. Even if the non-response rate reached 66%, the study would still have 77% power to detect such a correlation. A lower response rate was anticipated following the negative response to the study received from some parties during the stakeholder engagement process (see Chapter 3, Stakeholder engagement).

Lists of names and full addresses for all pharmacies commissioned to provide NHS services in their area were obtained from each PCT (subsequently NHS England area teams) represented in the study, together with their organisational ‘F’ code (a unique NHS organisational identifier), obtained with the permission of LPCs. Pharmacies belonging to non-participating chains were removed manually.

Data sources

Community pharmacy activity data

The original plan had been to obtain monthly service activity data for pharmacies in the sample from service commissioners (PCTs at the time the study was designed). PCTs were then responsible for the routine collection of data from pharmacies in respect of delivery of the general pharmaceutical services contract including monthly dispensing volume and numbers of advanced (MURs and NMS interventions) and enhanced services. Provisional agreement from PCT lead pharmacists that these data would be provided for each pharmacy, identified by postcode and organisational ‘F’ code, had been obtained from the original five study sites.

However, the 2013 reorganisation of the NHS and subsequent fragmentation of the commissioning of general pharmaceutical services between NHS England (essential and advanced services), CCGs (locally commissioned services – previously enhanced services) and local authorities (locally commissioned services – public health) coincided with the start of this study. In order to ensure consistency in the data obtained and to lessen the burden placed on the new, pared down, commissioning bodies, it was decided to request these data instead from the NHS Business Services Authority (BSA), which are responsible for collating the data on the community pharmacy contract for payment purposes.

With approval from the NHS England Senior Information Risk Owner, monthly data for all pharmacies in England for the period April 2011 to October 2013, inclusive, were requested from the NHS BSA. Variables included numbers of dispensed items, numbers of MURs declared, numbers of NMS interventions declared and numbers of a range of (unspecified) enhanced services. The data set requested also included the organisational ‘F’ code (premises), ‘Y’ code (head office) and postcode identifiers for each pharmacy for data linkage purposes only. Once all data sets (including stage 2 survey data) were linked, however, all data were anonymised through removal of these identifiers.

Survey of community pharmacies

An 8-sided self-completion questionnaire (see Appendix 1) was distributed to all pharmacies (bar those belonging to non-participating chains) in the nine study areas in February 2014 to collect data on their organisational characteristics. Distribution of the questionnaire, together with a participant information sheet, covering letter and reply-paid envelope, was by post, addressed to the lead pharmacist, with an option to complete a web-based version developed using the Qualtrics (Qualtrics, Provo, UT, USA) online survey platform. Two postal reminders (including additional copies of the questionnaire) were sent at 3-week intervals.

Information was collected on key organisational characteristics, which have been shown in previous research to influence care provision. 18,19,22–24,26,27,29 These included items on:

-

ownership type [supermarket, multiple (> 200 branches), medium-sized chain (26–200 branches), small chain (6–25 branches), independent (< 6 branches)]

-

location (geographical and physical)

-

contract and opening hours

-

staffing and skill mix (numbers and types of pharmacists and other pharmacy staff)

-

use of locums (number, frequency and regularity of locum use)

-

working hours/patterns of main pharmacist (hours worked per week, shift patterns)

-

management structure (pharmacy manager is pharmacist or not, pharmacist managed by pharmacist or non-pharmacist)

-

pharmacy/general practice integration

-

organisational culture

-

safety climate.

Most of these items were developed from items validated through previous community pharmacy surveys conducted by the research team.

Organisational culture was measured using the Pharmacy Service Orientation (PSO) tool validated for use in community pharmacies,42 which has been used successfully in a recent postal survey of English community pharmacies to discriminate between different types of pharmacy organisation (Dr Sally Jacobs, personal communication). This short tool is scored on the basis of three 1–10 semantic differential scales whereby respondents are asked to rate their pharmacy’s ‘orientation’ (patient vs. product), ‘focus’ (quality vs. quantity) and ‘pharmacists’ work’ (professional vs. technical). A tick placed on a vertical line is scored as a whole number between 1 and 10; a tick placed between two vertical lines is scored as the halfway point (e.g. 1.5, 2.5, etc.). The PSO variable for each pharmacy is calculated as the mean of the three semantic differential scales. Higher scores indicate a pharmacy more closely aligned to the patient, quality and professional work (the pharmaceutical care paradigm)2 than to the product, quantity and technical work (the traditional pharmacy role).

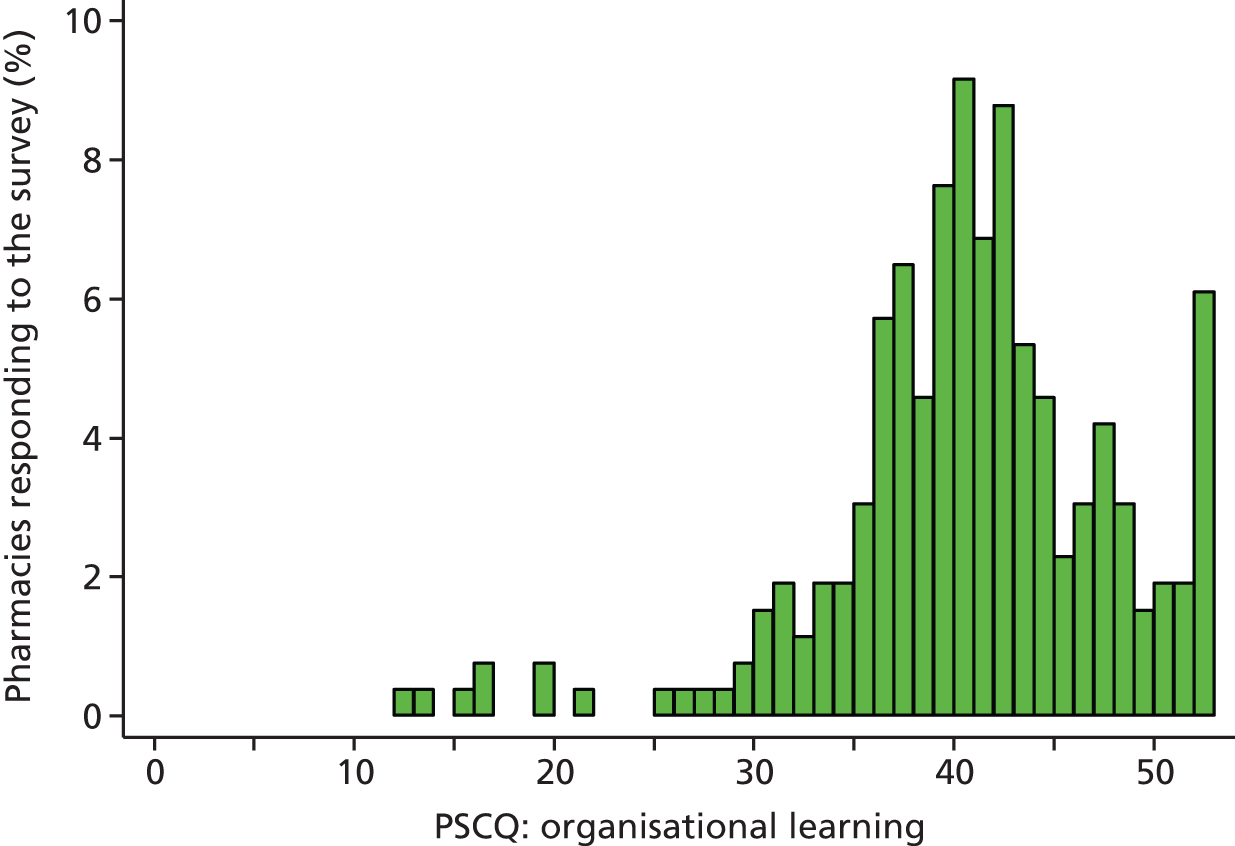

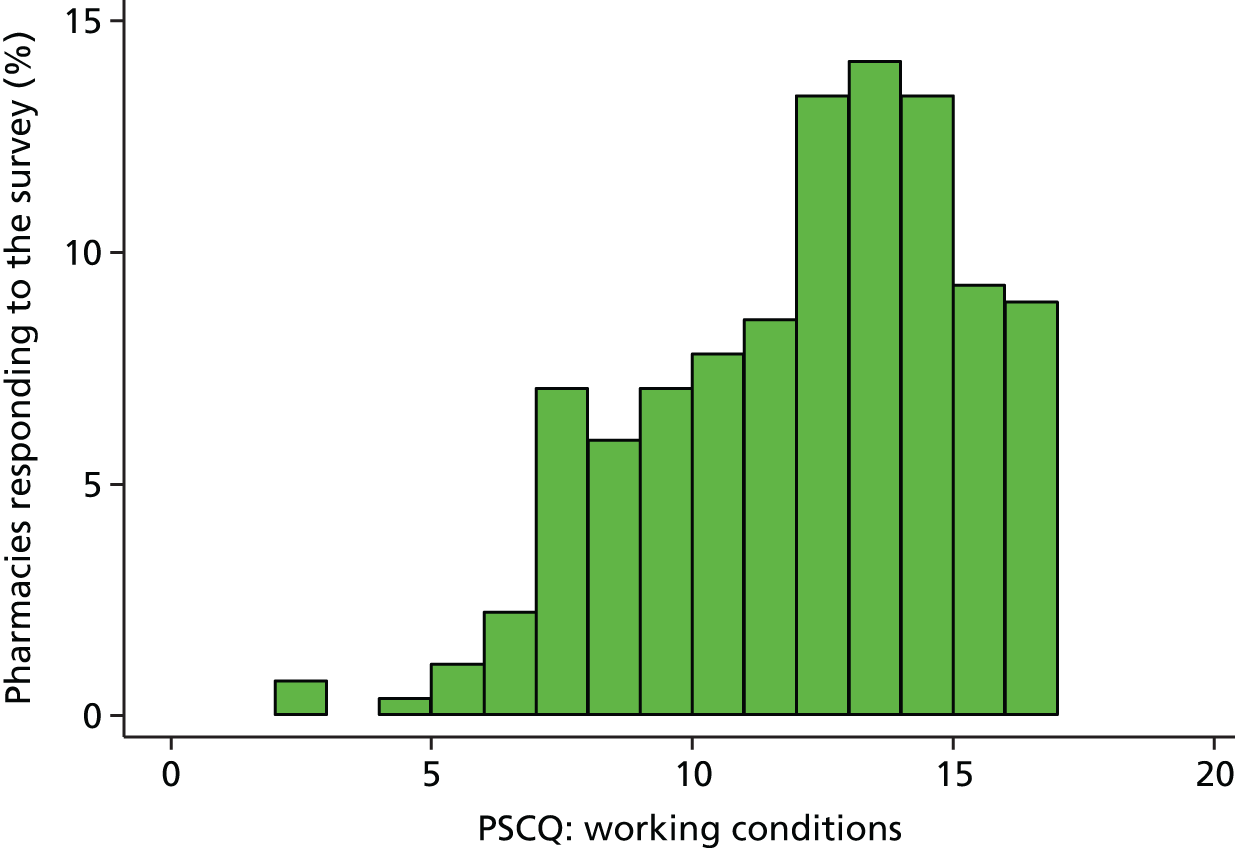

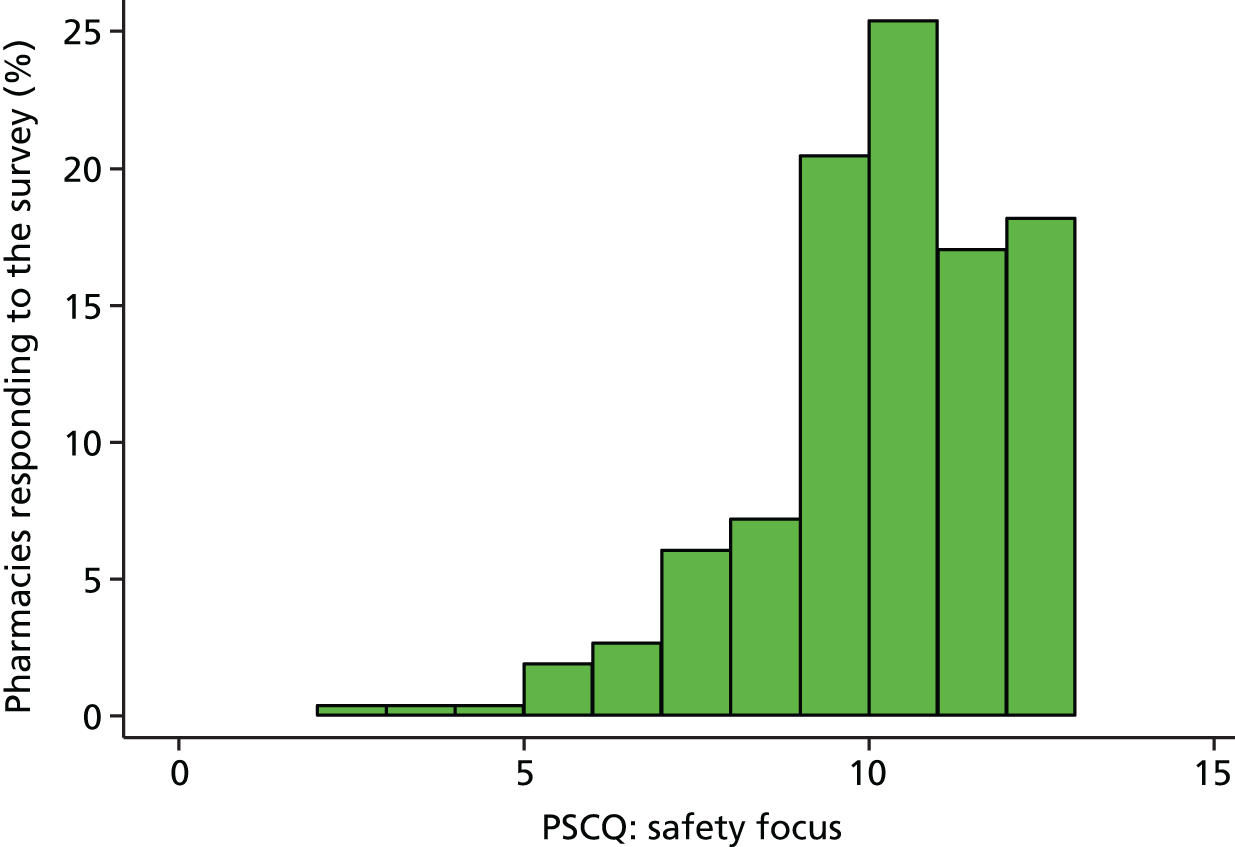

The questionnaire also collected data on safety climate using the validated Pharmacy Safety Climate Questionnaire (PSCQ), which captures the pharmacy’s collective attitudes and behaviours regarding patient safety. 43,44 This 24-item questionnaire, scored on a five-point Likert scale (from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) elicits four domains of safety climate: organisational learning (willingness to develop and maintain safety), blame culture (propensity to blame individuals when an incident occurs), working conditions (the extent to which the working environment supports safe working) and safety focus (the priority given to safety in day-to-day work). Higher scores correlate with safer working conditions apart from for ‘blame culture’, which is reverse scored.

The questionnaire was piloted with a sample of community pharmacy managers, recruited through existing contacts, using cognitive interviewing techniques. 45 Nine interviews were carried out with pharmacists and non-pharmacist pharmacy managers based at separate pharmacies, covering six different companies (two independents, three large multiples and one medium-sized multiple). The questions were redrafted, through an iterative process, during the cognitive interviewing period, to allow suggested changes to be piloted in later interviews. Further piloting was undertaken on the final version and pharmacist and non-pharmacist colleagues within Manchester Pharmacy School piloted the online questionnaire.

Secondary demographic and socioeconomic data sets

Determinants of the demographic, socioeconomic and health-needs status of the population within the immediate individual pharmacy locality were obtained from national secondary data sets. These included (1) the income deprivation domain of the 2010 English Indices of Multiple Deprivation (IMDs),46 allowing the comparison of relative levels of material deprivation local to community pharmacies; (2) Office for National Statistics 2011 Census data47 reporting the proportion of the local population who, for example, have a self-reported limiting long-term illness or are aged ≥ 65 years. Local determinants were attributed to pharmacies by linking pharmacy postcodes to super output areas, which are geographical units of approximately 1500 people. Super output areas are commonly used to measure and compare the local concentration, extent or weighted averages of population characteristics; and (3) local area health need and pharmaceutical services information were sourced from the 2011/12 QOF disease prevalence data48 for conditions for which community pharmacies (can) provide clinical services [e.g. coronary heart disease (CHD), asthma].

There are some limitations to attaching super output area data to individual community pharmacies, particularly in the case of supermarket pharmacies and city centre/shopping centre pharmacies, which are more likely to serve a wider and less easily defined population. However, almost 90% of people either visit the same pharmacy all of the time or one pharmacy most often and for a similar proportion, the main pharmacy they visit is located near where they live or their GP. These proportions are even greater for those with long-term conditions (i.e. those more likely to take in prescriptions to dispense or to be offered a MUR). In the absence of pharmacy lists or data collected directly in relation to pharmacy customers, these are therefore the best available data.

Data preparation and analysis

Data from paper questionnaires returned (n = 260) were entered onto a SPSS database (version 20; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) and merged with data extracted from online questionnaire returns (n = 25). Frequencies and cross-tabulation were used to check for outliers, missing data, double-digit entry and variable inconsistencies, and all errors corrected with reference to original questionnaire returns. A double data entry check was performed on a 15% sample of responses (41/285) to assess the accuracy of data entry (0.4% errors detected).

Data from the community pharmacy questionnaire were ‘merged’ with both the national activity data and the demographic and socioeconomic data using the organisational ‘F’ code and postcode. Data for only one pharmacy could not be matched to the national data sources due to the removal of the study identification (ID) by the respondent.

Two series of regressions were conducted: one on the stage 1 survey data set (n = 277, following removal of returns from distance selling pharmacies; linked to activity and demographic/socioeconomic data); the other on the national data set [n = 10,973 following exclusion of pharmacies with extremely high or low annual dispensing volumes relative to other pharmacies (outliers, n = 60) and those for which a full set of data for 2012/13 was unavailable] of community pharmacy activity (linked to demographic and socioeconomic data sets but not to organisational variables).

The unit of analysis was the individual pharmacy. When analysing the subset of pharmacies that participated in the survey, the geographical study site was treated as a fixed effect given that we were not planning to generalise to pharmacies outside the nine study sites. For the national data, we had the entire population of pharmacies at the time and, in such circumstances, hypothesis testing is not recommended as there is no wider population to which the results are generalisable. However, we treat this exploratory analysis as though it were on a sample of pharmacies that could ever have existed (in the past, currently or in the future).

The outcomes of primary interest were yearly dispensing volume and yearly volume of advanced services (separately, MURs conducted and NMS interventions claimed for). These were calculated by summing individual monthly data for the latest financial year available in the national data set (April 2012 to March 2013 inclusive). The secondary outcomes of interest were numbers and volume of enhanced services and safety climate (domains of the PSCQ). However, the data on enhanced services obtained from the NHS BSA proved to be incomplete because of local payment mechanisms for these services often bypassing the BSA management information system; therefore, the planned analysis of enhanced service activity was not possible.

Initially, the variation in our primary and secondary outcome measures was investigated using appropriate summary statistics [mean/standard deviation (SD) or median/interquartile range (IQR)]: these are also reported by key organisational factors (e.g. ownership type). Using Stata statistical software (version 13; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA), a series of univariable linear (for dispensing volume), ordered logistic (for advanced services, following categorisation of the original scale variables) or multivariate linear (for safety climate) regression models were fitted to determine which pharmacy-level organisational variables (for the survey sample only) and/or areal-specific demographic, socioeconomic and health-needs variables were associated with each outcome. To ensure the multivariable examination of all variables likely to have an association with the outcome, a conservative p-value of 0.2 was employed to indicate a significant association. Independent variables meeting this criterion were then included in an appropriate multivariable regression model to determine if their association persisted on controlling for other factors. Study site and pharmacy ownership type were added to the model at this point. Variables were retained in the ‘final’ model, along with ownership type and study site and after removal of collinear ones, if significance at p = 0.05 was achieved.

When analysing data from the survey of pharmacies from each of the nine study sites, probability weights were applied, in order to make the sample of respondent pharmacies more representative of the population of pharmacies in their area. The weight equates to the number of pharmacies of each ownership type, within their commissioning locality (as described by the original PCT or PCT cluster), that each respondent pharmacy ‘represents’ and is calculated as the ratio of the number of each pharmacy type within the locality to the number of each pharmacy type within the locality that responded to the survey (i.e. the inverse of the probability of response). Weights varied from 4/3 to 6.5, which is a narrow range.

Stage 2

The second stage of data collection incorporated both quantitative and qualitative elements. Quantitative methods examined the inter-relationships between organisational characteristics, levels of service delivery and service quality (objective iii). Qualitative methods explored issues around levels of service delivery and service quality in community pharmacies, their relationship and the mechanisms by which they are influenced by organisational characteristics (objective iv).

Sample

Study sites

Forty-one community pharmacies were randomly selected from the stage 1 community pharmacy survey respondents to be invited to participate in stage 2 using the stratified sampling strategy outlined in Table 2. The plan in the original proposal had been to select 40 pharmacies from across the original five study sites – two of each ownership type (supermarket, multiple, small/medium-sized chain, independent) from each NHS area – but this was modified slightly following the expansion in the number of study sites and once the distribution of respondents to the stage 1 survey was known. To recruit pharmacies, letters of invitation, study information sheets and letters of endorsement from the corresponding LPC (when available) were sent out by post, addressed to a named pharmacist. This was followed up 1 week later with a telephone call to discuss the study with the lead pharmacist and further e-mail and telephone communication as required to recruit pharmacies. Agreement from the head office was also sought for pharmacies belonging to chains. When a selected pharmacy declined to participate in stage 2, or when the selected pharmacy did not offer MURs or was unlikely to conduct enough MURs to provide the required sample of patients for the patient survey, they were substituted by another pharmacy of the same type, from the same NHS area, chosen at random. This process of substitution continued until all potential pharmacies in each cell were used up. Thereafter a ‘next best’ approach was taken to maintain the overall distribution of the sample as far as possible.

| Site | Independents | Small and medium-sized multiples | Large multiples and supermarkets | N/K | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cambridgeshire and Peterborough | 2 (17) | 2 (5) | 2 (15) | (0) | 6 (37) |

| C&E Cheshire | 2 (5) | 2 (5) | 2 (13) | (0) | 6 (23) |

| Doncaster and Rotherham | 2 (6) | 2 (6) | 2 (15) | (0) | 6 (27) |

| Hertfordshire | 2 (37) | 2 (9) | 2 (19) | (1) | 6 (66) |

| Merseyside | 3 (29) | 3 (28) | 3 (32) | (3) | 9 (92) |

| Sheffield | 2 (8) | 2 (5) | 2 (10) | (0) | 6 (23) |

| Trafford | 1 (5)a | 0 (0)b | 1 (5) | (0) | 2 (10) |

| Total | 14 (107) | 13 (58) | 14 (109) | (4) | 41 (278) |

Once pharmacies had agreed to participate, a training session lasting up to 1 hour was organised for the lead pharmacist and any other staff who may be involved. Pharmacies were provided with the study materials (patient questionnaire packs, distribution instructions booklets, study poster, prompt stickers, eligibility flow charts, log sheets) and taken through the process of questionnaire distribution and eligibility/ineligibility criteria.

Pharmacies were offered a flat fee of £200 for participating in the study, which recognised their involvement in the training session, logging and monitoring of questionnaire distribution, and optional participation in the stage 2 stakeholder interviews. In addition, service support costs were offered by the NIHR CRNs at a rate of £11 for each patient questionnaire returned to the research team.

Subjects (patient survey)

Each pharmacy recruited for stage 2 of the study was asked to distribute a self-completion questionnaire to two samples of 30 consecutive walk-in patients following receipt of (a) dispensing and (b) MUR services. Calculation of the size of the sample required was based on detecting a 2-point difference in patient-average Satisfaction with Information about Medicines Scale (SIMS) scores (see Data sources) between any pair of ownership types. Assuming that the population SD of SIMS scores is 5 points,49–51 in a sample of 40 pharmacies, 30 patients per pharmacy would be required to detect such a difference with 80% power, at the 5% level of statistical significance. Furthermore, assuming a non-response rate of 50% and an intrapharmacy correlation coefficient of 0.05, 1200 patients in receipt of dispensing services and 1200 patients undergoing a MUR would need to be surveyed (n = 2400 in total).

Patients who had received the NMS were not surveyed as this was a newly introduced service still requiring time to ‘bed in’. Furthermore, the NMS was, at the time, undergoing a national evaluation having only been commissioned until March 2013 and it was not known if the service would continue to be commissioned. Patients in receipt of enhanced or locally commissioned services were not surveyed as the provision of these services in different pharmacies and geographical locations is highly variable.

A number of inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to the sample.

The inclusion criteria were as follows:

-

walk-in patients only

-

received either a MUR or a NHS dispensing service from the pharmacy

-

aged ≥ 18 years

-

sufficiently fluent in English to be able to understand and complete the questionnaire.

The exclusion criteria were as follows:

-

those presenting private prescriptions (including veterinary prescriptions)

-

those presenting NHS prescriptions for appliances (elasticated garments, wound management products) or borderline substances

-

emergency supplies requested by a member of the public or a prescriber

-

patients receiving supervised consumption (including, but not limited to, methadone and buprenorphine).

Selecting only walk-in patients excluded those unable to visit the pharmacy themselves (often those more disabled or ill and older people) who account for, on average, around 1 in 4 prescriptions dispensed. 52 However, this was done for a number of methodological reasons. First, MURs are conducted opportunistically and in store in the vast majority of patients, already excluding those not visiting the pharmacy in person. Second, for those using dispensing services by proxy, variation in satisfaction with information received about medicines is far less likely to relate to the quality of the service provided by the pharmacist or pharmacy staff (e.g. it may relate to the way in which their proxy relayed the information given; the patient may be more likely to rely on a different health professional for information about their medicine). Furthermore, including both walk-in patients and those collecting medicines by proxy using consecutive sampling would risk wide variation in the proportions of each type of patient in the samples achieved for different pharmacies (contingent on population demographics), thus making direct comparisons of outcomes less robust.

To avoid the potential problem of cherry-picking, the importance of distributing questionnaires to consecutive patients to avoid research bias was stressed during the training session described above and pharmacies were informed that spot checks would be made on progress. To facilitate this, pharmacists/pharmacy staff were required to keep a log of all questionnaires distributed and researchers remained in regular telephone contact with each of the pharmacies throughout the period of recruitment.

Subjects (qualitative interviews)

Semistructured interviews were conducted during stage 2 of the study with front-line and superintendent pharmacists and service commissioners. Up to 50 interviews were sought with stakeholders, selected purposively to include at least one service commissioner (representatives from NHS England area teams and CCGs) from each of the nine geographical areas and a cross-section of front-line/superintendent pharmacists and pharmacy ownership categories across the study sites. As rules of thumb, between six and eight in-depth interviewees are required to reach data saturation in homogenous samples (i.e. no new themes will emerge by recruiting further participants), or between 30 and 50 per study, taking into account the nature and diversity of the population. 53

Data sources

Patient survey

A self-completion questionnaire (see Appendix 2) was distributed by the pharmacist/pharmacy staff in each of the participating pharmacies to two consecutive samples of eligible patients as described above. After their MUR or on receipt of their prescribed medication, patients were handed an envelope containing the questionnaire, participant information sheet and cover letter, and a reply-paid envelope for return of the completed questionnaire directly to the research team.

The eight-sided questionnaire contained the following sections:

-

reasons for visiting the pharmacy (service received, usual pharmacy or not, choice of pharmacy)

-

a 15-item community pharmacy patient satisfaction scale54 and a single item measuring overall satisfaction with visit

-

medication and information/advice received (number of medicines taken, new or repeat medication received, nature of information/advice received, category and continuity of advice-giver)

-

the 17-item SIMS55

-

the 5-item Medication Adherence Report Scale (MARS)56

-

the 8-item Beliefs about Medicines Questionnaire (BMQ)57

-

background data (sociodemographic, existing conditions).

There is a lack of validated instruments for measuring overall satisfaction with community pharmacy services based on sound theoretical underpinning. 58 Tinelli et al. ’s54 patient satisfaction scale was selected as it was developed in the UK, was relatively brief, was non-disease or medication specific, and it had been validated in a study of cognitive services in community pharmacy. The SIMS, MARS and BMQ are of proven reliability and validity, and have been widely used in research studies in a number of settings (including pharmacy) across a range of conditions and in several countries. 49–51,55,59–62

The patient satisfaction scale lists 15 statements that respondents are asked to rate on a five-point Likert scale, from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) according to how they felt about their visit to a pharmacy. In addition, following cognitive interview piloting, a ‘not applicable’ option was provided, which was scored 3 (equivalent to ‘neither agree nor disagree’). Following recoding of items 14 and 15, which are reverse scored, the mean item response was calculated (to take account of any missing items, up to a maximum of two) to give an overall satisfaction score ranging from 1 to 5, whereby higher scores indicate higher levels of self-reported satisfaction with the pharmacy visit.

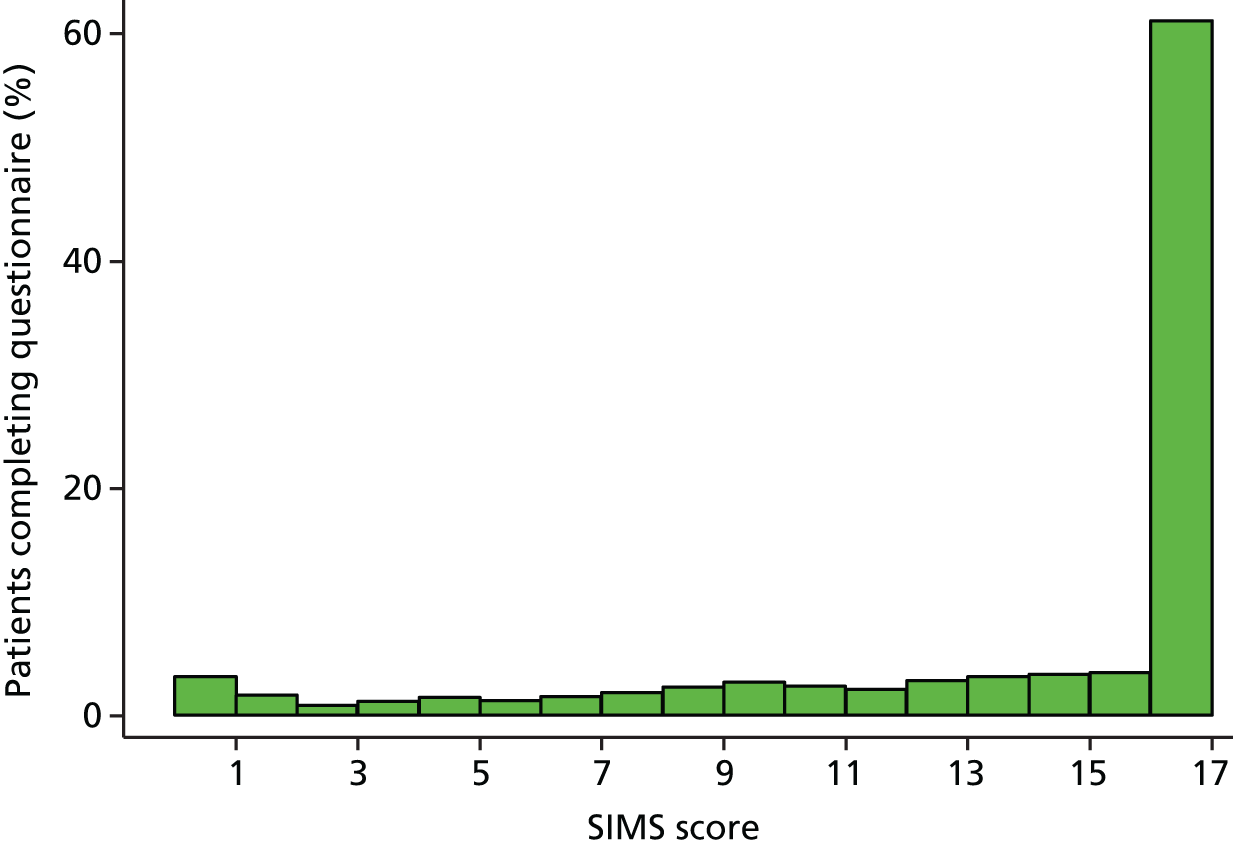

The SIMS lists 17 statements that respondents are asked to rate according to the amount of information that they have received as follows: ‘too much’, ‘about right’, ‘too little’, ‘none received’ or ‘none needed’. Responses indicating that the patient is satisfied with the amount of information received (‘about right’ or ‘none needed’) are scored 1. Responses indicating that the patient is dissatisfied with the amount of information received (‘too much’, ‘too little’ or ‘none received’) are scored 0. In this study, missing data imputation was undertaken on a per-item, per-person basis, up to a maximum of two items. For each missing item, a unit response was imputed if a uniformly distributed random number (between 0 and 1) exceeded the observed probability of a unit response on that item in participants who had completed all SIMS items and had the same SIMS score prior to the imputation of that item. A zero response was imputed otherwise. Responses for all items were summed to give a total satisfaction score ranging from 0 to 17, where higher scores indicate higher levels of self-reported satisfaction with information received. For the purposes of this study, because of a highly skewed distribution (see Chapter 5, Service quality: stage 2 patient survey data set analysis), this score was recategorised as follows: 0–5, 6–10, 11–16 and 17.

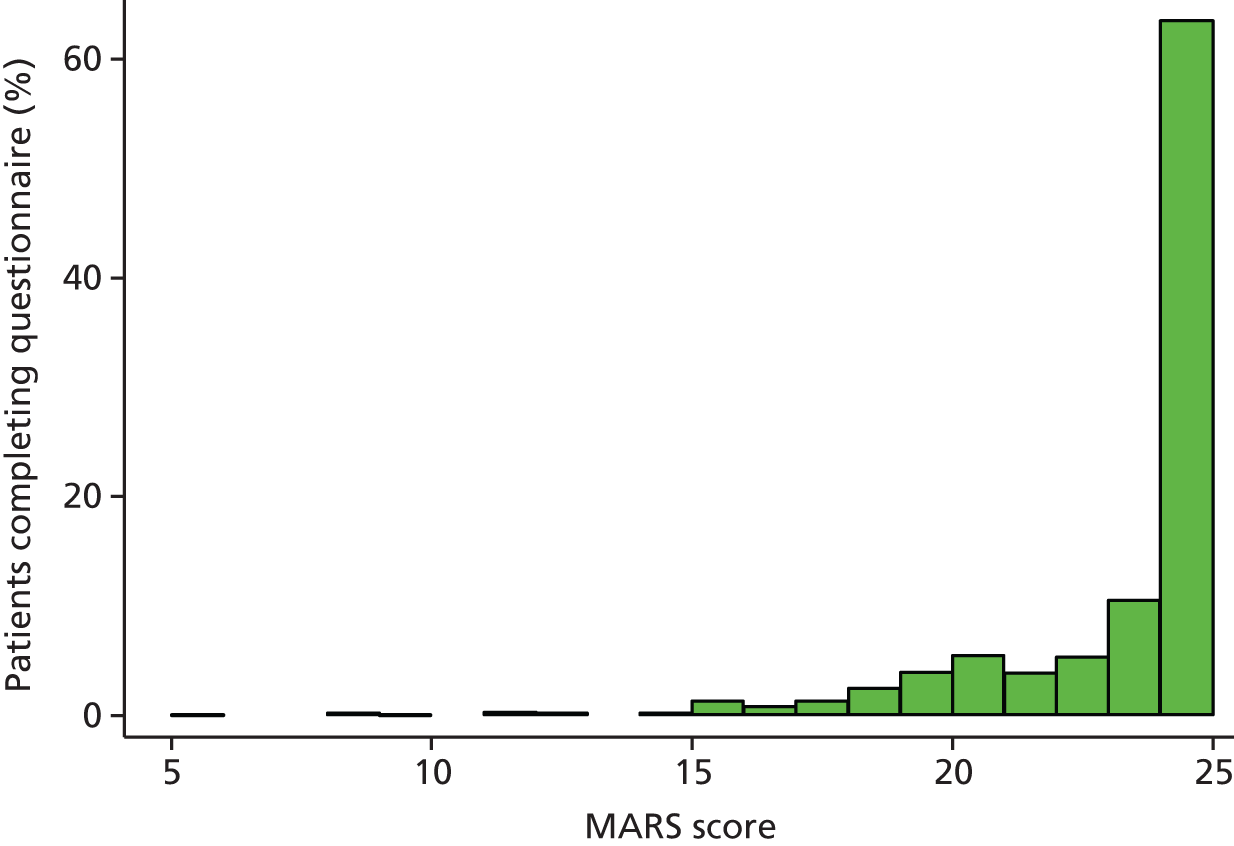

The MARS lists five statements that respondents are asked to rate according to the frequency with which they engage in non-adherent behaviour as follows: ‘always’, ‘often’, ‘sometimes’, ‘rarely’ or ‘never’. Responses are scored from 1 (always) to 5 (never) and summed giving a scale ranging from 5 to 25, whereby higher scores indicate higher levels of self-reported adherence. No imputation of missing data was carried out for MARS items as it was fully completed by > 90% of respondents. For the purposes of this study, due to a highly skewed distribution (see Chapter 5, Service quality: stage 2 patient survey data set analysis), this score was dichotomised as follows: ≤ 20 = ‘low adherers’; > 20 = ‘high adherers’.

The BMQ lists eight statements that respondents are asked to rate according to the strength of their views about medicines in general as follows: ‘strongly agree’, ‘agree’, ‘uncertain’, ‘disagree’ or ‘strongly disagree’. Responses are scored from 5 (strongly agree) to 1 (strongly disagree). Two scales (‘general harm’ and ‘general overuse’), ranging from 4 to 20, are derived through summation of four of these items each, in which higher scores indicate stronger beliefs that medicines are harmful or that medicines are overused by doctors, respectively.

The questionnaire was piloted with a sample of community pharmacy users, recruited through existing contacts, using cognitive interviewing techniques. 45 Nine interviews were carried out. The questions were redrafted, through an iterative process, during the cognitive interviewing period, to allow suggested changes to be piloted in later interviews. Further piloting was undertaken on the final version through presentation and feedback at project advisory group and PPI group meetings.

Qualitative interviews

The qualitative study took a broadly phenomenological approach63 to explore the views and experiences of pharmacists, pharmacy managers and commissioners directly involved in the provision of community pharmacy services. This approach uses one-to-one interviews to develop first-hand accounts of the subjective experiences of individuals. From these accounts, common themes can be derived to understand the meanings individuals attach to the lived experience. 64

Semistructured, face-to-face and telephone interviews were conducted with pharmacy and commissioning representatives from across all study sites, as described above. Topic guides specific to each stakeholder group (see Appendix 3 for the pharmacist interview topic guide) were developed from the aims of the research and the research literature and covered the following areas:

-

background information about the respondent and their organisation

-

defining clinical productivity

-

the quality and quantity of community pharmacy services (definitions, levels achieved, organisational and other influences)

-

recent changes in clinical productivity (organisational and other influences)

-

maximising clinical productivity and how this could be achieved

-

measuring and monitoring clinical productivity.

Lines of questioning explored the relationship between the quantity and quality of service provision in community pharmacies, opportunities and barriers to maximising clinical productivity in this setting and the mechanisms by which different organisational characteristics may help or hinder this objective. A prompt sheet listing the organisational factors of interest to the study (see Appendix 3) was sent to interviewees in advance for reference during the interview.

Data preparation and analysis

Quantitative data

Data from patient questionnaires returned were entered onto a SPSS database. Frequencies and cross-tabulation were used to check for outliers, missing data, double digit entry and variable inconsistencies, and all errors corrected with reference to original questionnaire returns. A double-data entry check was performed on a 10 per cent sample of responses (100/1008) to assess the accuracy of data entry (0.06% errors detected).

Data from the patient questionnaire were merged with data from the pharmacy questionnaire using the pharmacy organisational F code. Of course, data from the latter source did not vary between patients attending the same pharmacy and, with this in mind, the responses of such patients to the patient questionnaire could be correlated; this was accounted for in all analyses in order to ensure that incorrect inferences were not made.

The unit of analysis was the patient. As alluded to above, patients are ‘clustered’ within pharmacy and this ‘multilevel’ structure was taken into account in all analyses at this stage. In addition, all regression models ‘control’ for the type of questionnaire distributed (dispensing or MUR).

The outcomes of primary interest were overall patient satisfaction, satisfaction with information about medication (measured on the SIMS) and self-reported medication adherence (measured on the MARS). Initially, each of these outcomes was tabulated and/or summarised using appropriate summary statistics; they are also reported by pharmacy ownership type.

Using Stata statistical software, a series of univariable linear (for overall satisfaction), ordered logistic (for SIMS) or binary logistic (for MARS) regression models were fitted to determine which patient- and pharmacy-level organisational variables and/or areal-specific demographic, socioeconomic and health-needs variables were associated with each outcome. To ensure the multivariable examination of all variables likely to have an association with the outcome, a conservative p-value of 0.2 was employed to indicate a significant association. Independent variables meeting this criterion were then included in an appropriate multivariable regression model to determine if their association persisted on controlling for other factors. Variables were retained in the ‘final’ model, after removal of collinear ones, if significance at p = 0.05 was achieved.

In order to simplify the calculation of the weights at this stage, we decided not to include any of the information from the stage 1 sampling process, but to create weights that represented only the stage 2 responses of the patients from the individual participating pharmacies. Pharmacies do not have a ‘fixed patient list’ (such as is the case for general practice) and we therefore made the assumption that pharmacy ‘population size’ was proportional to its dispensing volume (as calculated in stage 1). The stage 2 weight (which was equivalent for each patient attending the same pharmacy) was then derived as the inverse of the ratio of the percentage of the overall response at each pharmacy (n/1008) to the percentage of the dispensing volume reported at each pharmacy (when the denominator here is the total number of items dispensed across the participating pharmacies).

Qualitative data

All interviews were audio-recorded with consent and transcribed verbatim for analysis by a University of Manchester-approved supplier following strict data protection policies and procedures for data storage and transfer.

Interview data were thematically analysed using the framework approach65 using NVivo 10 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) qualitative analysis software to manage the process. Framework analysis involves five steps: (1) familiarisation, (2) developing a thematic framework, (3) indexing, (4) charting and (5) mapping and interpretation. In the current study, two researchers (TF and FB) undertook the first four steps collaboratively, developing the thematic framework through independent familiarisation with different sets of interview transcripts initially, followed by close discussion and agreement of the themes identified. Themes were derived from the interview topic guide in the first instance and latterly from the data themselves. When consensus could not be reached, a third researcher (SJ) was brought in. The agreed thematic framework was applied to the data and charted by TF and FB, but the final stage of mapping and interpretation was undertaken by the chief investigator (SJ).

Integration of stage 1 and stage 2 findings

Integration of the findings from the different stages and methodologies employed by the study was an important final step to building a rounded picture of the factors associated with variation in clinical productivity in community pharmacies. Methods of synthesis incorporated elements of triangulation of the data and also illustration and explanation of one set of findings by another. 66 For example, when findings from the survey indicated a significant association between particular organisational characteristics and productivity in terms of quantity of service provided, the qualitative data from interviews with stakeholders were interrogated to obtain information on the mechanisms of that association. We also looked for alternative explanations when findings from different stages of data collection diverged. This process of integration formed the basis of the discussion (see Chapter 8) and will provide the basis for any recommendations we make to service commissioners regarding commissioning processes, to community pharmacy organisations regarding their provision of NHS pharmaceutical services and to patient/public audiences regarding medicines usage.

Commissioners’ workshop and toolkit development

The final objective (v) of the study was to develop a toolkit informed by the study findings to help service commissioners improve their contracting processes with community pharmacies to promote clinical productivity (both quality and quantity) and, hence, value for money. To do this, a half-day workshop was organised in July 2015, in partnership with NHS Primary Care Commissioning (PCC), to which commissioners from the new NHS commissioning structures (NHS England and CCGs) from across the North West of England and further afield were invited. In addition, a number of community pharmacy representatives were invited, including from the PSNC, Pharmacy Voice (umbrella organisation incorporating the CCA, Association of Independent Multiple Pharmacies and National Pharmacy Association) and community pharmacy multiples, together with four members of the public.

The workshop was used to present the findings from the study and invite discussion and feedback in small mixed-group sessions, facilitated by the PCC (see Appendix 4 for the programme). The groups each recorded key discussion points on flipcharts and these were brought back to the larger group for final discussion. The PCC collated the findings of the discussions and these directly informed the first draft of the toolkit to which the research team added supporting summaries of the research evidence from the study. The toolkit (see Appendix 5), which will be made available electronically to service commissioners nationally through PCC channels, links to the six stages in the NHS commissioning cycle67 and provides guidance and supporting evidence for commissioners at each stage.

Research ethics

Research ethics approval was obtained for this study from the National Research Ethics Service Committee West Midlands – Edgbaston (13/WM/0137), which was subsequently endorsed by the University of Manchester Research Ethics Committee (reference number 13025). Site-specific NHS research governance approval was obtained from all of the relevant local NHS research and development offices.

Chapter 4 Findings: associations between organisational characteristics and levels of service delivery

Community pharmacy survey response rate and sample characteristics

Of the 817 questionnaires distributed, 285 were returned completed to the research team, 260 by post and 25 online. A further nine were returned undelivered. Eight questionnaires that had been completed by distance-selling pharmacies (those dispensing by post and not face to face) were removed from the sample. The total valid response rate was therefore 34.6% (277/800).

Descriptive statistics for each of the key independent variables used in the analysis of community pharmacy activity in the survey data set (and, later, in the analysis of quality outcomes in Chapter 5) are presented in Table 3.

| Variable | Sample data, n (%) | N |

|---|---|---|

| Job title (respondent) | ||

| Owner | 55 (20.1) | 273 |

| Manager | 168 (61.5) | |

| Other pharmacist | 50 (18.3) | |

| Type of pharmacy | ||

| Independent (< 6 stores) | 111 (40.1) | 277 |

| Small multiple (6–25 stores) | 41 (14.8) | |

| Medium-sized multiple (26–200 stores) | 9 (3.2) | |

| Large multiple (> 200 stores) | 91 (32.9) | |

| Supermarket | 25 (9.0) | |

| Geographical location | ||

| City centre | 18 (6.6) | 274 |

| Large town | 43 (15.7) | |

| Small town | 81 (29.6) | |

| Suburb | 96 (35.0) | |

| Village/rural | 36 (13.1) | |

| Pharmacy open for ≥ 3 years | ||

| No | 22 (8.0) | 274 |

| Yes | 252 (92.0) | |

| HLP | ||

| No | 192 (72.2) | 266 |

| Yes | 74 (27.8) | |

| Pharmacy contract held | ||

| Standard 40 hours | 230 (84.2) | 273 |

| 100 hours | 30 (11.0) | |

| Other | 13 (4.8) | |

| Opening hours per week | ||

| Mean (SD) | 55.8 (17.4) | 274 |

| Median (IQR) | 50 (45–56) | |

| Range | 36–104 | |

| Number of staff working on a typical day | ||

| Mean (SD) | 5.4 (2.2) | 268 |

| Median (IQR) | 5 (4–6.5) | |

| Range | 1–18 | |

| Pharmacists working on a typical day | ||

| 1 | 219 (80.5) | 272 |

| ≥ 2 | 53 (19.5) | |

| Registered pharmacy technician (typical day) | ||

| No | 159 (58.2) | 273 |

| Yes | 114 (41.8) | |

| ACT (typical day) | ||

| No | 209 (75.7) | 276 |

| Yes | 67 (24.3) | |

| Use of locums | ||

| Not regularly | 118 (42.6) | 277 |

| Regularly | 159 (57.4) | |

| Is the pharmacy manager a pharmacist? | ||

| No | 30 (10.9) | 274 |

| Yes | 244 (89.1) | |

| Work pattern of main pharmacist | ||

| Standard hours (8 a.m.–6 p.m.) | 165 (59.6) | 277 |

| Non-standard | 112 (40.4) | |

| Average daily working hours of main pharmacist | ||

| Mean (SD) | 9.2 (1.1) | 270 |

| Median (IQR) | 9.0 (8.5–9.75) | |

| Range | 5–15 | |

| Organisational culture (PSO) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 7.3 (1.4) | 269 |

| Median (IQR) | 7.5 (6.5–8.2) | |

| Range | 3.5–10 | |

| Relationship with nearest GP surgery | ||

| Very good | 136 (49.1) | 277 |

| Good | 83 (30.0) | |

| Satisfactory/poor/none | 43 (15.5) | |

| No GP surgery identified | 15 (5.4) | |

The proportion of independently owned pharmacies in this sample of respondents was comparable to the national figure of 38.9% in March 2014. 38 Nearly two-thirds were located in small towns or suburbs with only a small proportion in city centres or rural settings. Most were established pharmacies operating on a standard contract; over one-quarter were either accredited as having, or working towards, HLP status.

There was a wide range of staffing levels with three-fifths of the pharmacies in this sample operating on a one-pharmacist model. Approximately two-fifths of pharmacies employed a pharmacy technician on a typical day, one-quarter employed an accuracy checker or accuracy-checking technician (ACT), and around 10% had a non-pharmacist pharmacy manager. Over half regularly used locum pharmacists on a daily or weekly basis. Weekly opening hours varied between 36 and 104 hours, and the average daily working hours of the main pharmacist, two-fifths of whom worked non-standard hours (shifts or extended working days), ranged from 5 to 15 hours.

As a measure of organisational culture, the mean (SD) PSO score in this sample was 7.3 (1.4), which was higher (i.e. more closely aligned to the patient, quality and professional work than to the medicine, quantity and technical work) than the mean value of 6.3 (1.8) found in a previous survey of 903 English community pharmacists (Dr Sally Jacobs, personal communication). The majority of pharmacies reported good or very good working relationships with their main GP surgery, where one could be identified: only 14% of pharmacies had not had any face-to-face contact with their main GP surgery over the previous 12 months and that contact had most commonly been made with the practice receptionist (82% of pharmacies) and least often with a practice pharmacist (17%). Sixty-four per cent of pharmacies in contact with their main GP surgery reported having had face-to-face contact with a GP in the previous 12 months.

Community pharmacy activity: stage 1 community pharmacy survey data set analysis

The first series of regression analyses conducted in stage 1 of the study were on quantity: annual dispensing volume, MURs and NMS interventions for 2012/13 for those pharmacies responding to the stage 1 survey (n = 277). This was to explore the associations between the organisational characteristics of the pharmacy, the socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of the local population and pharmacy activity.

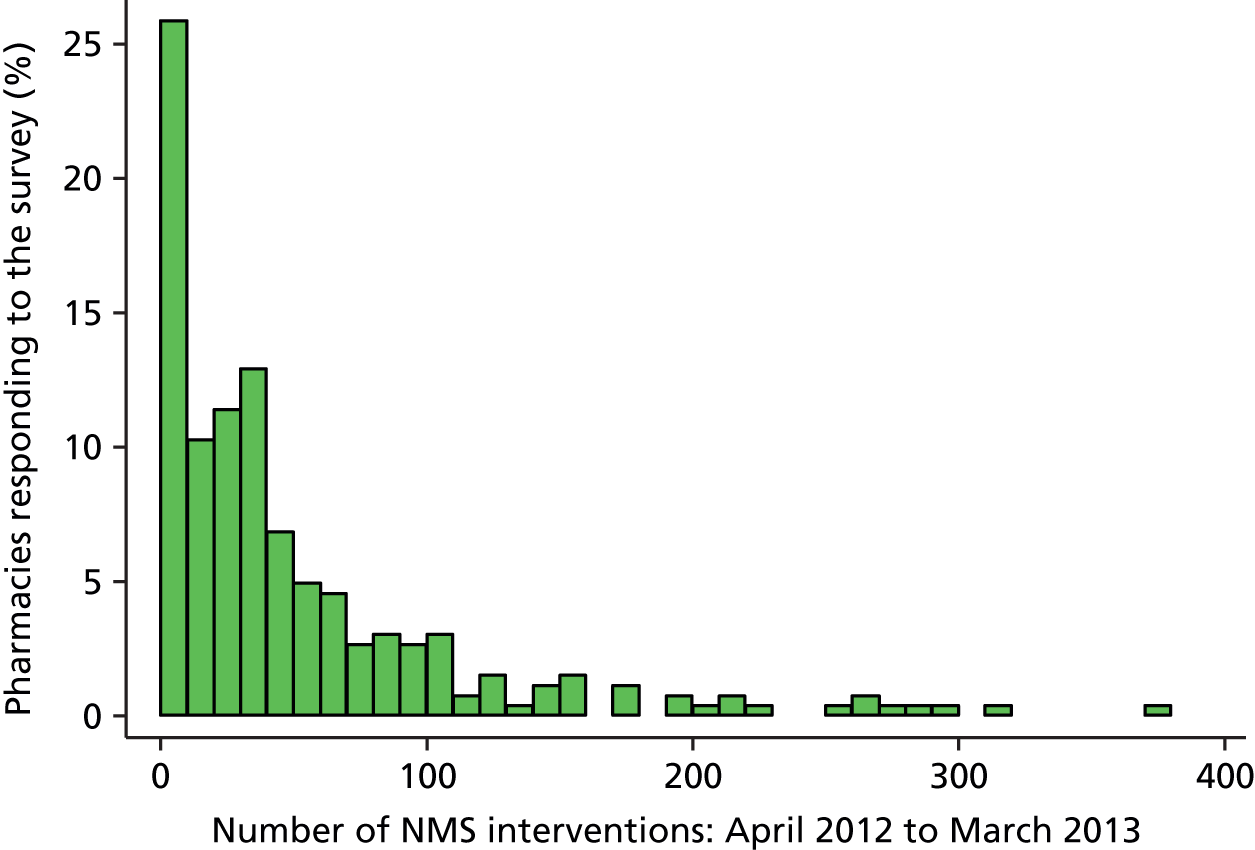

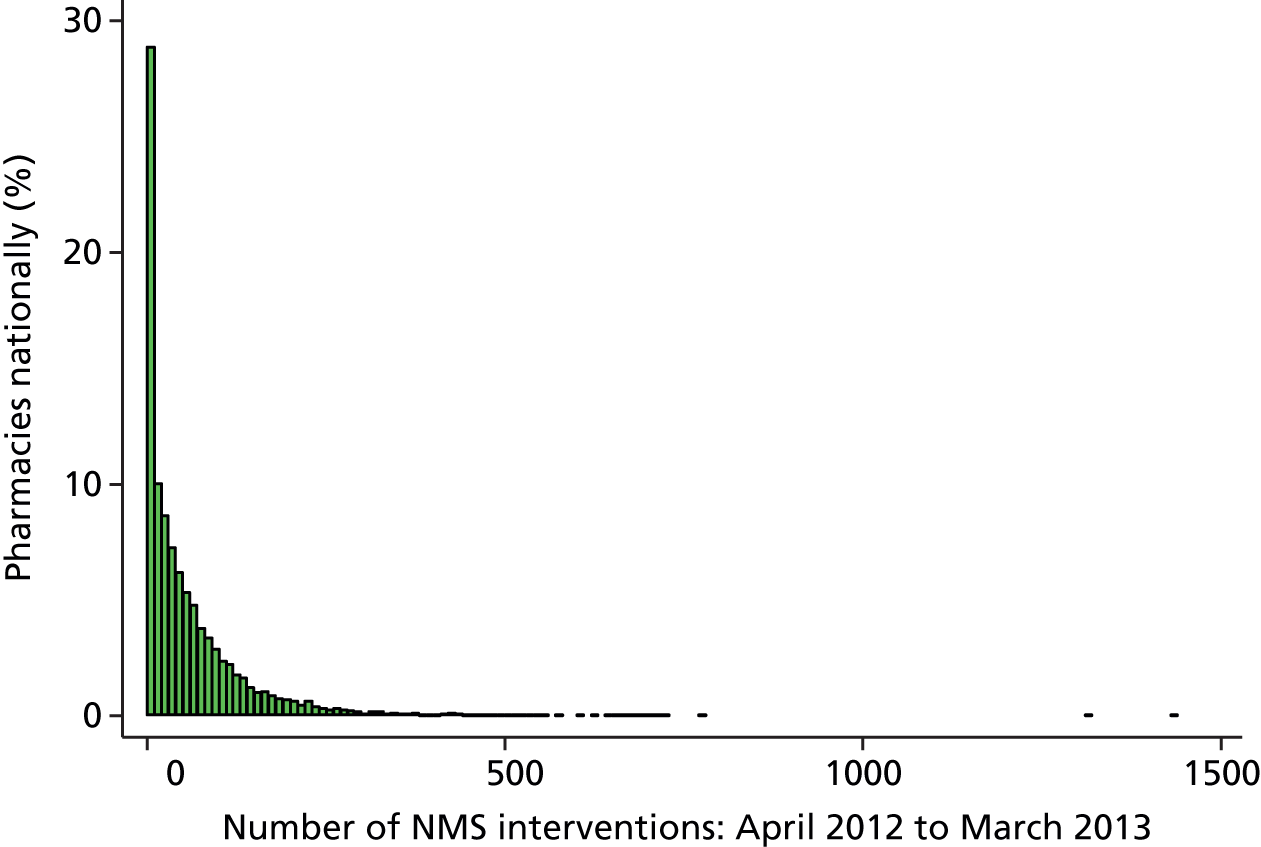

Summary statistics for annual dispensing volume, MURs conducted and NMS interventions, broken down by pharmacy ownership type, are presented in Table 4. Although this table presents summary statistics for each pharmacy ownership category, for the purposes of the subsequent regression analyses, ‘ownership type’ was collapsed into three categories – (1) independent, (2) small/medium-sized multiple and (3) large multiple/supermarket – to account for the small numbers of medium-sized multiples and supermarkets. The distributions of each of these primary outcome variables are given in Figures 1–3.

| Pharmacy ownership type | Number of items dispensed | Number of MURs | Number of NMS interventions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Independent (< 6 stores), n = 103 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 87,523 (55,181) | 165.2 (150.8) | 48.5 (76.2) |

| Median | 70,846 | 127 | 19 |

| IQR | 51,410–106,247 | 14–298 | 0–49 |

| Range | 5529–326,961 | 0–509 | 0–376 |

| Small multiple (6–25 stores), n = 35 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 76,271 (27,963) | 273.9 (139.6) | 53.3 (57.1) |

| Median | 72,338 | 312 | 38 |

| IQR | 59,796–93,441 | 154–402 | 14–68 |

| Range | 19,313–143,981 | 0–415 | 0–258 |

| Medium-sized multiple (26–200 stores), n = 9 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 72,688 (36,223) | 226.3 (128.6) | 48.1 (51.2) |

| Median | 59,135 | 219 | 29 |

| IQR | 51,025–101,212 | 131–320 | 2–68 |

| Range | 33,499–141,046 | 52–412 | 0–148 |

| Large multiple (> 200 stores), n = 91 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 90,131 (37,567) | 283.7 (114.8) | 49.6 (53.4) |

| Median | 82,814 | 303 | 32 |

| IQR | 62,607–120,209 | 196–397 | 15–67 |

| Range | 22,536–225,460 | 0–473 | 0–297 |

| Supermarket, n = 25 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 53,868 (30,142) | 333.5 (95.8) | 67.2 (50.4) |

| Median | 56,547 | 386 | 46 |

| IQR | 25,595–75,730 | 281–400 | 33–101 |

| Range | 13,654–126,993 | 113–408 | 17–201 |

| Total, n = 277 | |||

| Mean (SD) | 83,221 (44,848) | 238.7 (145.3) | 51.3 (63.3) |

| Median | 74,187 | 261 | 31 |

| IQR | 53,869–104,810 | 114–386 | 8–67 |

| Range | 5529–326,961 | 0–509 | 0–376 |

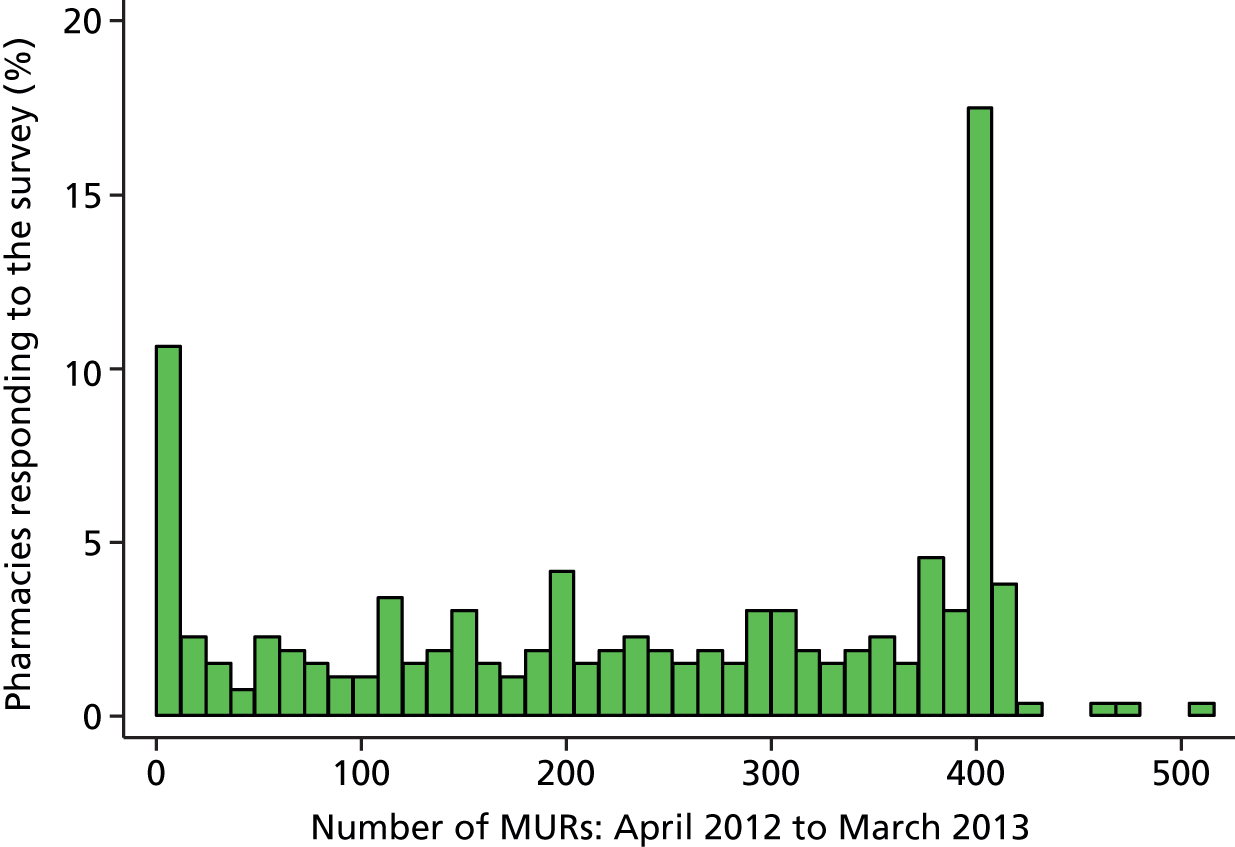

FIGURE 1.

Distribution of the annual dispensing volume for pharmacies responding to the stage 1 survey (n = 277).

FIGURE 2.

Distribution of the annual number of MURs conducted by pharmacies responding to the stage 1 survey (n = 277).

FIGURE 3.

Distribution of the annual number of NMS interventions conducted by pharmacies responding to the stage 1 survey (n = 277).

The median dispensing volume for the sample was 74,187 items per year with an IQR of 53,869–104,810. Supermarkets had the lowest annual dispensing volumes and large multiples had the highest (see Table 4). The distribution of annual dispensing volumes was positively skewed (see Figure 1); linear regression of the logarithmic value of dispensing volume was therefore used in its analysis to eliminate the long right-hand tail.