Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 11/1021/02. The contractual start date was in January 2013. The final report began editorial review in July 2016 and was accepted for publication in March 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Claire Goodman is a Senior Investigator at the National Institute for Health Research.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Goodman et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2017 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Introduction

Older people living in care homes are some of the oldest and frailest in society. They have entered a care home because they can no longer live in their own homes. 1 Care homes provide 24-hour personal care, and some care homes provide nursing care; however, residents still rely on primary health-care services for access to medical care and referral to specialist services.

The relationship between the NHS and care homes is a symbiotic one. 2–5 Care homes, as independent providers, are the main providers of long-term care for older people and, increasingly, respite and end-of-life care. The majority of care home residents have cognitive impairment, multiple morbidities and complex care needs defined by high functional dependency and unpredictable clinical trajectories. 6–8 In this context, good health outcomes depend on effective day-to-day social care and vice versa.

Despite this, how the NHS works with care homes is variable and often inequitable. 9,10 A number of different models of care provision have developed to address the identified inequity. This study considers what elements or characteristics of these different services support residents’ health and maintain efficient and effective working between NHS services and care homes.

Care homes

Approximately 433,000 older or physically disabled people live in care homes in the UK, with 90% of residential and nursing care services now delivered by independent providers. A care home can offer personal care and 24-hour support (previously called ‘residential homes’), on-site nursing in addition to this (previously called ‘nursing homes’) or both types of care (sometimes referred to as ‘dual registered homes’). Care home residents account for 4% of the population aged 65 years or older. 11,12 There are over three times as many care home beds as there are acute hospital beds in the UK, and approximately 10% of care home residents receive funding from the NHS. For the majority of residents their care is either self-funded, paid for from the state social care budget or via a mix of state social care funding with top-up from residents or their families. 12,13 Care homes are heterogeneous in terms of how these different funding sources make up their income and in how they structure themselves as businesses. A report described the sector as a ‘highly polarised marketplace’. 12 Providers that focus on private payers are relatively financially secure, while those reliant on public funding are vulnerable to the government’s austerity measures, financial losses and threat of closure. 12

The Burstow Commission on Residential Care14 found that only one in four people would consider moving into a care home if they became frailer in later life, while 43% said that they would definitely not move. Care homes were represented by many as an accommodation of last resort. The Commission argued that negative media coverage of care homes, despite many examples of innovative high-quality care for people with complex needs and dementia, has an impact on how staff and managers feel about their jobs and how their work is valued by wider society.

Most care home residents are female, over 85 years old and in the last years of life. The majority of care home residents have dementia, are in receipt of seven or more medications and a significant proportion live with depression, mobility problems, incontinence and pain. 6,9,15–18 They are a population that needs access to health care and ongoing review. The common perception that care homes are a ‘problem’ to the NHS is open to challenge. In addition to being the main providers of long-term care for older people, care homes provide multiple services to the NHS, including respite care, intermediate care and re-enablement services. Admission to emergency departments and acute hospitals from care homes may, contrary to the public narrative, be as much a consequence of how primary and emergency health-care services respond to calls for help from the care home sector as they are a reflection of care decisions by care home staff. 19 Residents’ close proximity to the end of life, however, provides an opportunity to establish advanced care plans enabling care homes to play an active role in responding to health concerns in situ, avoiding emergency hospital admissions as a consequence. 20

Health-care provision to care homes

There is a lack of shared understanding about what represents an ideal package of care that should be provided by the NHS to care homes. 21–24 Aspects of care related to the management of health problems are often undertaken by care home staff, whether or not they are qualified nurses. 25 These include non-pharmacological management of behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia, monitoring the impact of pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapies, doing routine dressings and administering complex drug regimens. These arrangements are usually informally negotiated and vary between different homes and parts of the country. As a consequence, the extent to which the opportunity and financial costs of such health-care interventions are borne by the care home sector vary between regions.

Effective working between the health and residential care sectors is fundamental to residents’ quality of life and may influence how often residents are admitted to hospital and how long they stay there once admitted. But models of service delivery to care homes are many and ill defined. 26,27 Services at the interface between care homes and the NHS often have differing goals and funding sources, and operate in diverse ways. Although most regard integrated working as a vital objective, definitions of integrated care differ and few interventions to improve health-care delivery have been developed in collaboration with care home staff, residents and their families. Primary care services are frequently delivered from a distance and are reliant on how care home staff interpret residents’ health status. Inherent tensions can develop when NHS services favour models of care that focus on diagnosis, treatment and episodic involvement, while care home providers prioritise ongoing support and relationships that foster continuous review of care. 19 How to establish effective integrated working, and the models of service delivery that could facilitate this, remain unclear.

Rationale for the research

We have described a heterogeneous care home market and a range of context-sensitive variables that shape how services are provided. Cumulatively, these make it unlikely that a single model of health service delivery can promote effective working for all care homes and at all times. If there are generalisable patterns that underpin effective models of care, it is more likely that these will be at the level of recurrent features or explanatory mechanisms already manifested within multiple service models and potentially applicable across multiple models in the future. As Pawson et al. 28 have noted, much that is effective in health-care delivery is submerged, routine and taken for granted. Identifying these features and making them explicit is key to delivering effective care.

Aims and objectives

This study set out to identify, map and test the features or explanatory mechanisms of existing approaches to health-care provision to care homes in relation to five key outcomes: (1) medication use and review; (2) use of out-of-hours services; (3) hospital admissions, including emergency department attendances and length of hospital stay; (4) resource use; and (5) user satisfaction.

The overall aim of this study was to use a theory-driven realist evaluation approach29 to identify ways in which the delivery of existing NHS services to care homes may be optimised for the ongoing benefit of residents, relatives and staff, and the best use of NHS resources. It addressed the following research questions.

-

What is the range of health service delivery models designed to maintain care home residents outside hospital?

-

What features (in realist evaluation terms: mechanisms) of these delivery models are the ‘active ingredients’ associated with positive outcomes for care home residents?

-

How are these features/mechanisms associated with key outcomes, including medication use; use of out-of-hours services; resident, carer and staff satisfaction; unplanned hospital admissions (including A&E); and length of hospital stay?

-

How are these features/mechanisms associated with costs to the NHS and from a societal perspective?

-

What configuration of these features/mechanisms would be recommended to promote continuity of care at a reasonable cost for older people resident in care homes?

Structure of the report

Chapter 1 describes the background and the rationale for the study. Chapter 2 describes the research approach and methods, providing detail about the study design, data collection and analysis. Chapter 3 presents the findings of the review of surveys of health-care provision to care homes and the review of reviews. This is followed by the realist synthesis of health-care provision to care homes in Chapter 4. Chapter 5 introduces phase 2, with detail about the case study sites’ recruitment, participant characteristics and the organisation of health care in each site. Chapter 6 summarises the case study findings on care home residents’ service use and related costs, medication use and staff satisfaction. Chapter 7 revisits the findings of phase 1 and, based on phase 2 findings, presents context–mechanism–outcomes (CMOs), which capture how health-care services work (or not) with care homes. Chapter 8 discusses the findings and their implications for commissioning and the organisation and provision of NHS services to care homes.

Chapter 2 Research approach and methods

This study built on earlier descriptive work that had mapped how the NHS works with care homes without on-site nursing provision. 2 This chapter provides a brief overview of how the study was organised and managed. It also gives the rationale for using realist-driven approaches to evidence synthesis and evaluation in order to answer the research questions and to move beyond descriptive accounts of the NHS working with care homes. It describes the two phases of the study, data collection and analysis and, finally, notes the changes that were made to the originally funded protocol. This chapter is complemented by two published protocols on phases 1 and 2. 1,30

Study organisation and management

The study was overseen by a management group made up of the researchers and the study research team, which met four times a year, and a Study Steering Committee (SSC) that met twice a year. The overall role of the SSC was to ensure that the study was conducted in line with the protocol, and that the design, execution and findings were valid and appropriate for care home residents, relatives and the organisations involved in their care. A list of members and their relevant expertise is provided in the appendices (see Appendix 1).

Specifically, the study steering group were asked to do the following:

-

provide expert advice and guidance on all aspects of the study; individual members provided expertise for the different study phases

-

ensure that the project was running according to the time schedule

-

address any identified risks within the study and ensure that the appropriate procedures were in place to militate against these

-

contribute to a discussion of any issues arising from either the conduct or analysis of the study

-

debate the emergent theoretical propositions from phase 1 of what supported health-care working with care homes and the emergent findings from phase 2

-

read and comment on any reports and other relevant study outcomes

-

act as a link between the project and other related research studies, NHS and charitable organisations interested in the way that care homes work together with the NHS.

Public involvement in research

Public involvement in research (PIR) was integrated into the study from project design and management to dissemination. This was achieved through PIR review of the study design and research process, PIR support with resident recruitment and feedback on emergent findings presented at the SSC meetings and the analysis workshop.

Public involvement in research members with direct experience of visiting close relatives and friends over long periods of time (years) in care homes were recruited through two established university patient and public involvement groups. One member had supported recruitment of care home residents in a previous study. Her role had been to spend time talking with those residents who wanted more time to talk about their involvement in the study.

User involvement in the study design and research process

Members of the PIR group at the University of Hertfordshire (John Wilmott and Marion Cowe) and the University of Nottingham (Kate Sartain and Michael Osborn) were involved in the development of the study proposal and were also asked to review resident information booklets, summary and consent forms. PIR members also attended the SSC meetings.

Users as participants in recruitment with care home residents

Public involvement in research members who had an honorary contract with the university were involved in the support of resident recruitment in the care homes. PIR members were also involved in the development of a study information video for care home residents.

Analysis workshop

A member of the PIR group (Kate Sartain) actively participated in a 2-day analysis workshop together with the study management group where the emergent findings from the study sites were discussed.

Realist methods

Realist methods are based on a theory-driven approach to evidence review and evaluation that argues that reality is ‘objective’ and knowable but interpreted through cognition and senses. To explain why interventions work, these methods seek to identify the underlying mechanisms that can elucidate how different outcomes are obtained and how contexts influenced this process. 28,29,31

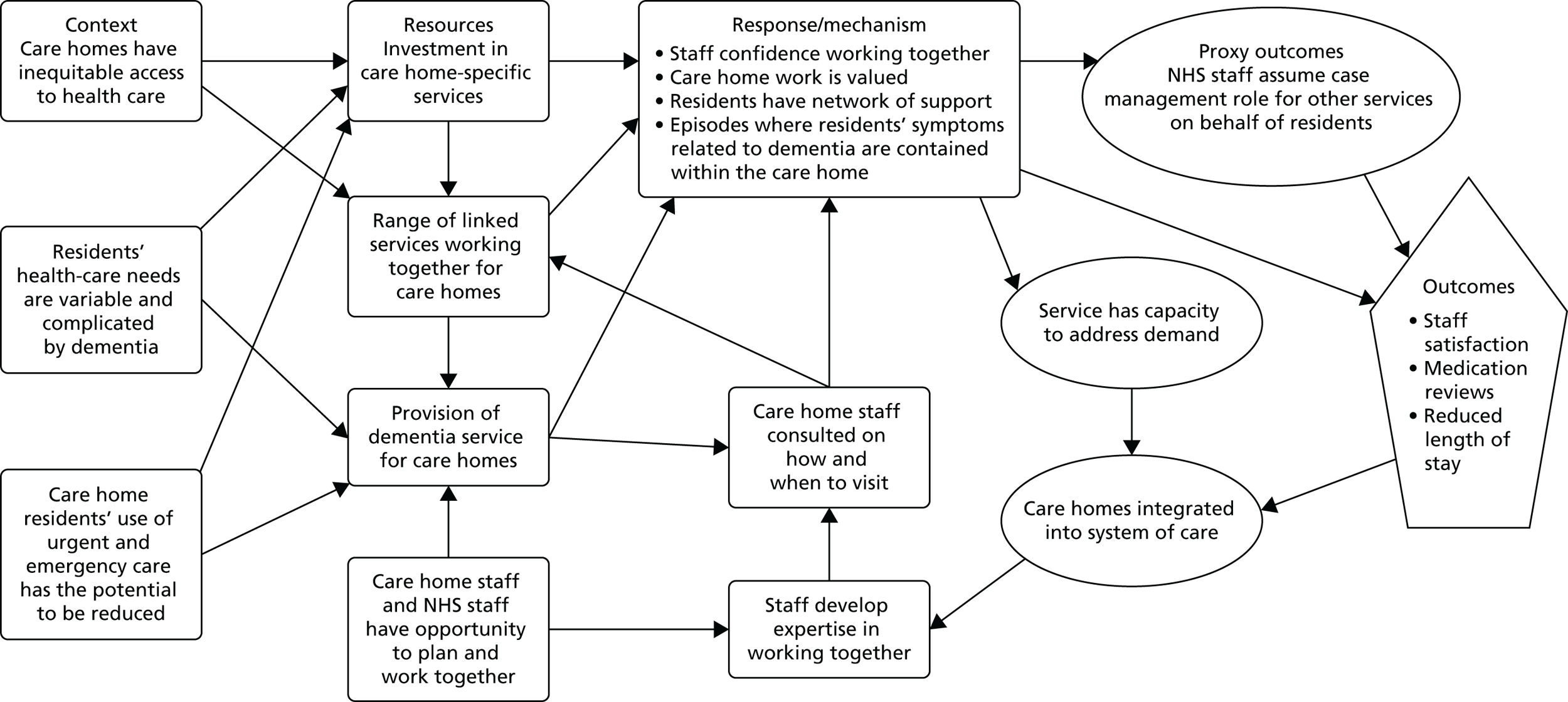

We defined health-care provision to care homes as a series of complex social processes involving multiple contributors over extended periods of time, where uptake and use of resources can vary widely depending on residents’ needs, organisational structures and local resources. Thinking of service delivery to care homes in this way enabled us to consider the heterogeneity of approaches used and consider the multiplicity of conditions in which they are enacted to provide an explanatory account of how one approach may work, when, for whom and why. It allowed us to go beyond descriptive accounts of the organisation of care, and the perceived barriers to and enablers of this, to provide plausible, evidenced explanations of observed outcomes and the mechanisms associated with these, while acknowledging and explaining the influence of context. We conceptualised different approaches to health-care provision to care homes as programmes that can be deconstructed to understand how key elements or factors in their working (mechanisms) may trigger a change or effect (outcome), and which contextual conditions or resources (context) are necessary to sustain changes. Box 1 describes how context (C), mechanism (M), outcomes (O) and programme theory as the analytical tools of realist approaches were operationalised for the purposes of this study.

Context can be broadly understood as any condition that triggers and/or modifies the behaviour of a mechanism, that is, the ‘backdrop’ conditions (which may change over time). For example, education and qualifications of care home staff, history of working relationships between visiting HCPs and care home staff and residents’ functional abilities.

Mechanism (M)A mechanism is the generative force that leads to outcomes. Often denotes the reasoning (cognitive or emotional) of the various ‘actors’, that is, care home staff, residents, relatives and visiting HCPs. Identifying the mechanisms goes beyond describing ‘what happened’ to theorising ‘why it happened, for whom, and under what circumstances.’

Outcomes (O)Intervention outcomes, for example a reduction in episodes of unplanned hospital admissions, medication management, staff confidence and costs.

Programme theorySpecifies what mechanisms are associated with which outcomes and what features of the context will affect whether or not those mechanisms operate. The programme theory encapsulates ideas about what needs to be changed or improved in how NHS services work with care home staff, and what needs to be in place to achieve an improvement in residents’ health and organisations’ use of resources.

HCP, health-care professional.

Pawson R, Greenhalgh T, Harvey G, Walshe K. Realist review — a new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. J Health Serv Res Policy 2005;10:21–34. 32

Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Westhorp G, Pawson R. Realist methods in medical education research: what are they and what can they contribute? Med Educ 2012;46:89–96. 33

This realist evaluation included a realist synthesis as part of the process of developing and refining programme theory. Integrating different forms of knowledge (using both primary and secondary sources) to explain complex phenomena in this way is consistent with a realist understanding of research. It enables us to identify those contextual factors that are necessary across a range of interventions to trigger the desired mechanisms.

Method

Phase 1

This was designed to address questions 1 and 2 as outlined in Chapter 1, which were:

-

What is the range of health service delivery models designed to maintain care home residents outside hospital?

-

What features (in realist evaluation terms: mechanisms) of these delivery models are the ‘active ingredients’ associated with positive outcomes for care home residents?

Phase 1 completed a realist review of existing evidence to develop a theoretical understanding and working propositions of how different contexts and mechanisms influence how the NHS works with care homes, paying specific attention to five outcomes of interest that could then be refined and tested in the case studies that comprised phase 2.

The five outcomes of interest were identified by the research team as consistent with service priorities across the NHS, care home and local authority organisations. These were agreed through consultation with the SSC and the stakeholder organisations that they represented. These were as follows.

Admission to hospital, including emergency department attendances and length of hospital stay

The extent to which residents are enabled to receive care in situ in the care home can reflect both care home staff confidence and how they are able to access services, support and guidance from health-care services. Repeated admissions, particularly in the context of ambulatory care-sensitive conditions or towards the end of life where they might be regarded as inappropriate, can be avoided where proactive collaborative advanced clinical planning is embedded within systems of care. 19,20,34–36

Often the decision to admit an older person to hospital is appropriate and cannot be avoided. However, the length of hospital stay is influenced by how easy it is to discharge the older person to the care home, which in turn is influenced by the relationship between care homes and primary care services, and the relationship of both with secondary care. 37

Use of out-of-hours services

Use of out-of-hours services can be an indication of the level of anticipatory care, joint planning, day-to-day NHS support received and care home staff capacity, confidence and ability to deal with residents’ unexpected health-care needs. For care homes, the quality of advice and support they receive out of hours, often over the telephone, can influence decisions to support a person in the care home or call an ambulance. 38

Medication use and review

The majority of care home residents take seven or more medications. 1,17 Evidence suggests that residents are vulnerable to prescribing and administration errors and that review of medication, using agreed criteria,17 can improve the quality of prescribing and medication use. Regular review can also highlight other issues and act as a focus for making proactive decisions about care.

User satisfaction

Older people, including those with cognitive problems, can express what is important to them in their health care, their preferences for who else is involved in discussing health-care decisions and who should take responsibility for the day-to-day management of their health care. 39 Satisfaction with care in this setting needs to include the multiple perspectives of residents, family members and care home staff as recipients of health-care services. 40

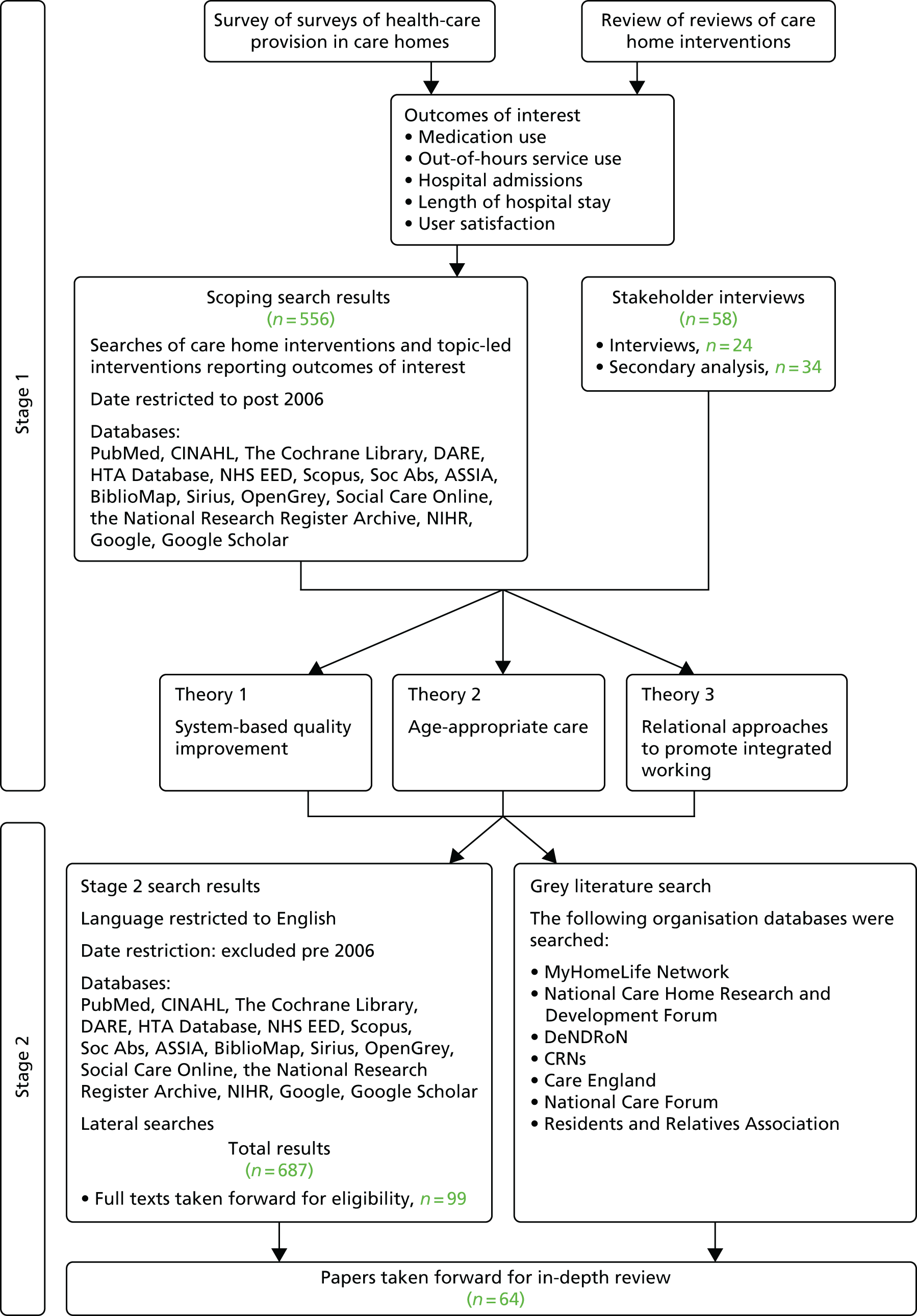

The realist review took an iterative three-stage approach and was structured in line with Realist And MEta-narrative Evidence Syntheses: Evolving Standards (RAMESES) guidance on the organisation and reporting of realist syntheses. 31 First, scoping searches and stakeholder interviews were used to identify sources of policy, legislative and professional thinking that could help to explain how health-care services and care homes work with each other. Second, the findings were used to develop theoretical propositions that could be tested using the literature on health-care provision to care homes, in order to explain why an intervention may be effective in some situations and not others. Third, the findings were reviewed with our study steering group. We have published the phase 1 protocol. 30

Concept mining, scoping of the evidence and development of programme theories

To gain a preliminary understanding of what supported good health-care provision to care homes, we conducted a series of stakeholder interviews with key informants involved in the commissioning, provision and regulation of health care to care homes, as well as recipients of care (residents and relatives). This was followed by a review of surveys of health-care services provided to care homes, a review of reviews on care home interventions and a supplementary scoping literature review to begin to identify further the underlying assumptions and theories of what supported effective working in care homes.

Stakeholder interviews

The purpose of the interviews was to help inform and refine the focus of the evidence review, clarify terms, identify key headings or ‘theory areas’ and linked questions that should be asked in the development of data extraction forms in the evidence review. 41,42 A more detailed account of the method and findings is published elsewhere. 43

The interviews explored a number of areas of uncertainty. The priority that the NHS places on cost management, appropriate use of resources and service efficiency is well known. There is, however, less clarity about the level of evidence commissioners require in order to make judgements about services to care homes and how to measure effectiveness when working in and with care homes. It is also unclear how contexts of care (e.g. history of provision, size of care homes, leadership, care homes with on-site nursing and those without) influence demand on NHS services. Finally, it is unclear what care homes and their representatives, residents and relatives recognise as constituting effective health care.

For the purposes of this study, a stakeholder was defined as someone who had the relevant experience or knowledge to be able to express the view of the group or organisation that they represented. 44 Consequently, we selected individuals who either had responsibility for the commissioning, organisation or monitoring of NHS provision to care homes, or direct experience as care home residents. The interviews addressed current patterns of commissioning and provision, examples of success and failure, how continuity of care was achieved, processes that supported integrated working and the anticipated impact of policy change in rapidly changing health and social care economies.

Recruitment

To capture regional, historical and organisational differences, we identified a purposive sample of NHS and local authority commissioners, senior managers from care home organisations and the Care Quality Commission (CQC). Relevant organisations were approached and invited to nominate people we could approach to interview. We also interviewed a small sample of care home managers and residents who were invited to take part through My Home Life, an organisation that works with care homes to promote best practice. The extended time required to secure resident stakeholder interviews limited the number who participated and, following discussion with the SSC, we supplemented these interviews with a secondary data analysis on 34 resident interviews from an earlier study, looking specifically at how they described what constituted ‘good health care’. 2

Interviews

Interviews were conducted face to face unless a participant requested a telephone interview. Participants were asked to provide a stakeholder view, in other words to use their experience and expertise, for example, as a care home manager, to inform what a good service should look like, rather than to provide a solely personal account. To facilitate this, the interview prompts addressed current patterns of commissioning and provision. Prompts for residents focused on what they believed good health care to care homes should comprise to inform and test our understanding of the processes that characterise how health care is provided to care homes and how these work. Interviews asked about examples of success and failure, how continuity of care was achieved, what ‘good’ working between NHS services and care homes looked like, and the mechanisms of particular service models necessary to achieve the desired outcomes. All interviews were recorded and fully transcribed. To organise and structure the analysis, data were entered into NVivo version 11 (QSR International, Warrington, UK).

The secondary analysis of the resident interviews enabled us to consider what their descriptions revealed about being health-care recipients and what they identified as important.

The interview element of the study was reviewed and supported by the University of Hertfordshire Ethics Committee (reference number NMSCC/12/12/2/A).

Analysis

Data were initially mapped against the interview prompts. There were three stages to the analysis. First, there was a process of familiarisation, decontextualisation and segmenting of data into separate and defined categories that were close to how participants had described the issues. Second, there was a comparison within and between categories and identification of preoccupations, differences and themes. Third, there was identification of relationships and emergent hypotheses about how the favoured approaches worked, and what was necessary to support their implementation.

Scoping of the published evidence

To provide an overview of current provision of health care to care homes we reviewed published sources using a review of surveys of the range and type of services provided to care homes, a review of existing systematic reviews and a supplementary scoping review to ensure that the literature had been adequately summarised.

We had initially proposed to survey the care home field in the UK to understand the current range of provision to the sector. The review of surveys was suggested as an alternative approach by the SSC based on the assertion that the care home field had been subject to a number of large national surveys in the period immediately prior to our period of research but that there had been a systematic failure to collate these surveys or to consider how they informed each other to establish an overview of care provision in care homes. To be eligible for inclusion in the review of surveys, publications had to focus on health-care delivery to care homes in the UK and had to have been completed since 2008.

The review of existing systematic reviews was added to further enable us to capture a range of approaches to service provision for care homes that may not have been identified in the review of surveys. A review of reviews was chosen as a way of approaching the published literature based on the assumption that detailed summaries of the included studies would be an efficient way of identifying the bulk of potentially relevant studies. It allowed us to examine relevant studies in a consistent way. Literature published since 2006 was included. This was a pragmatic decision to capture literature that was likely to be relevant to current systems of health-care provision to care homes.

As a final step, a further scoping review was undertaken to ensure that no key literature considering models of health-care delivery to care homes had been overlooked in the review of surveys or review of reviews. Box 2 summarises the search terms, databases and e-networks used in phase 1 (i.e. the review of surveys, review of reviews and scoping of the literature). Realist review approaches are iterative, so these searches were refined, expanded and repeated as we tested emergent ideas about what supported health-care services to achieve the outcomes of interest. Database searches were supplemented by online searches conducted on the websites of prominent care home research groups, voluntary sector providers of care homes, other care home organisations and their representative and professional organisations. The websites of NHS strategic health authorities were searched to identify care home initiatives referred to in their annual reports (up to March 2013).

‘Care homes health care survey’, ‘residential care health care survey’, ‘nursing homes health care survey’, ‘older people health care homes survey’, ‘older people health residential care survey’, ‘older people health nursing homes survey’, ‘health service provision care homes survey’, ‘health service provision nursing homes survey’, ‘health service provision residential care homes survey’, ‘long term care health care survey’ and ‘long term care health service provision survey’.

Electronic databasesMEDLINE (PubMed), CINAHL, BNI, EMBASE, PsycINFO, DH Data and The King’s Fund were searched. In addition, we contacted care home-related interest groups and used lateral search techniques, such as checking reference lists of relevant papers and using the ‘cited by’ option on WoS, Google Scholar (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) and Scopus, and the ‘related articles’ option on PubMed and WoS.

E-networksE-networks requests for information were made to ECCA (now known as Care England), Care Home Providers Alliance, My Home Life Network, National Care Home Research and Development Forum, the PCRN, clinical study groups of the NIHR DeNDRoN and NIHR Age and Ageing network.

Inclusion criteriaPublications post 2006 of any research design, unpublished and grey literature, policy documents and information reported in specialist conferences. Studies relevant to UK systems of health care that addressed one or more of the outcomes of interest. Studies that were not UK-based but where there was transferable learning relevant to the UK models of service provision were included.

Exclusion criteriaStudies where the health-care provision to care homes was very different from UK models of care were treated with caution or excluded, for example where medical support is in house (as in the Netherlands) or the level of care would be closer to hospital-level provision (as can be the case in the USA). Studies were excluded if the focus of the intervention or project only involved care home staff and/or a research team, that is, there was no input from visiting HCPs.

BNI, British Nursing Index; CINAHL, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; DeNDRoN, Dementias and Neurodegenerative Diseases Research Network; DH, Department of Health; ECCA, England Community Care Association; HCP, health-care professional; NIHR, National Institute for Health Research; PCRN, Primary Care Research Network; WoS, Web of Science.

Citations yielded from the above searches were downloaded into and organised using EndNote [Clarivate Analytics (formerly Thomson Reuters), Philadelphia, PA, USA] bibliographic software. All papers were independently screened by two members of the research team.

For the review of surveys, data extraction was structured to capture forms of NHS service provision for care homes in England in terms of frequency, location, focus and purpose and, where possible, funding.

The review of reviews and scoping review also extracted data about the structure and function of the different types of service provision to care homes as well as considering in greater detail how services were developed, who was involved and how they had affected, or considered, the outcomes of interest for our study (admissions to hospital, length of stay, out-of-hours service use, medication use and user satisfaction). Because of substantial heterogeneity in the studies reviewed we did not pool studies in a meta-analysis. Instead a narrative summary of findings was completed.

The combined findings of the above were used to develop propositions about possible CMO configurations and linked ‘if then’ statements that were debated and refined within the team about what might support health-care provision to care home residents.

Theory refinement and testing

This step involved taking the theoretical propositions and possible CMO configurations derived from the interviews, review of surveys and review of reviews that captured the emergent programme theories of how health-care services worked with care homes.

Detailed reading of the literature from the earlier stages of the review was accompanied by lateral searches of references retrieved from article bibliographies, driven by emerging theoretical constructs where it was clear that additional data were required from underpinning research studies. This more in-depth consultation of the literature was used to look for data that supported, refuted or augmented the possible CMO configurations identified in the earlier reviews. Analysis focused on interventions that drew on theories about the assessment of frail older people in the last years of life, system-driven quality improvement schemes in primary care and theories of integrated working that emphasised relational, participatory and context-sensitive approaches in care home settings (see Appendices 2 and 3).

In keeping with realist enquiry methods, equal consideration was given to negative and positive outcomes and inconsistencies in accounts of what works, when and with what outcomes. We retained the inclusion and exclusion criteria used for the initial scoping. Quality assessment was based on the opportunities for learning and testing emergent theory. Thus practitioner accounts of innovation were considered as evidence alongside empirical research.

Four reviewers (CG, SLD, MZ and MH) independently screened titles and abstracts to identify relevant documents, which were retrieved and assessed according to the inclusion criteria. All included papers were read by Claire Goodman and one of the three reviewers.

Data extraction focused on how health care was organised, funded, provided and delivered, how the underlying assumptions and theoretical framework (if identified within a particular study or group of studies) were articulated, and whether or not this fitted with the focus of our review in terms of the underlying theory and the impact of the intervention on the outcomes of interest. Our approach drew on Rycroft-Malone et al. ’s42 approach to data extraction in realist synthesis that questions the integrity of each theory, considers the competing theories as explanations to why certain outcomes are achieved in similar and different settings and compares the stated theory with observed practice.

Analysis and synthesis

A realist analysis of data adheres to a generative explanation for causation and looks for recurrent patterns of outcomes and their associated mechanisms and contexts (CMO configurations). 31 As the review progressed, the discussion focused on particular papers and sources that offered competing accounts of why or how an intervention was chosen and why it had, or had not, worked. We concentrated on what appeared to be recurrent patterns of contexts and outcomes in the data (demi-regularities) and then sought to explain these through the means (mechanisms) by which they occurred.

The review’s preliminary findings were presented to the study advisory group for further discussion and challenge. This iterative discussion process compared the stated theory with the evidence reviewed. We discussed how and why different mechanisms were triggered by the different approaches to providing health care to care homes. The findings were then used to structure the recruitment and sampling approach for testing in phase 2.

Phase 2

The case study phase of the project addressed research questions 3 to 5:

-

How are these features/mechanisms associated with key outcomes, including medication use; use of out-of-hours services; resident, carer and staff satisfaction; unplanned hospital admissions (including to an A&E department); and length of hospital stay?

-

How are these features/mechanisms associated with costs to the NHS and from a societal perspective?

-

What configuration of these features/mechanisms would be recommended to promote continuity of care at reasonable cost for older people resident in care homes?

Phase 1 findings indicated that we should target service delivery models that acknowledge and support the interactional nature of decision-making between care home staff and visiting health-care professionals (HCPs), for example by supporting increased contact from NHS practitioners, structured meetings and joint review of residents’ needs. The explanatory theory of interest and supporting CMO configurations, with the potential to explain why some or all of the outcomes were achieved (or not), was one that specified what needed to be in place to trigger, support and sustain mechanisms that generated trust, mutual obligation, recognition of how care homes worked and a common purpose. The review suggested that particular activities within different service models were important contextual factors (or possibly mechanisms). These included education, training and ongoing support of care home staff; employment of HCPs to work with care homes; opportunities for regular review and discussions between care home staff and professionals; and the allocation of resources to increase the frequency of visits by and involvement of primary care service staff.

A case study approach was chosen to facilitate a detailed description of processes of care and a comparison of the delivery of health care over a sustained period of time to care homes and their residents, across three geographically discrete sites. Specifically, we aimed to identify three sites where health-care provision had been designed to reflect some or all of the contexts identified in the review and particularly those that might support relational working.

Ethics approval

The phase 2 case study was reviewed and given a favourable opinion by the Social Care Research Ethics Committee on 29 January 2014 (Ethics Committee reference number 13/IEC08/0048).

Sampling and recruitment

Initially we proposed to select one Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) area as an example of usual care, that is, one with an approach to commissioning and care delivery for care homes in its area where there was little or no differentiation between commissioning of services provided to people living at home and those in care homes. It became clear, however, that national preoccupations with unplanned hospital admissions meant that it was unlikely that a site would not have any intervention or initiative operating that involved care homes. We therefore approached and recruited a site where the main route for access to medical and specialist care was through the general practitioner (GP) and the General Medical Services (GMS) contract, but the county had also invested in care home manager leadership training (site E below).

We identified six CCGs/geographical areas within England that were each operating a distinctive approach to delivering health care in care homes and within 2 hours’ travelling distance of our two research centres.

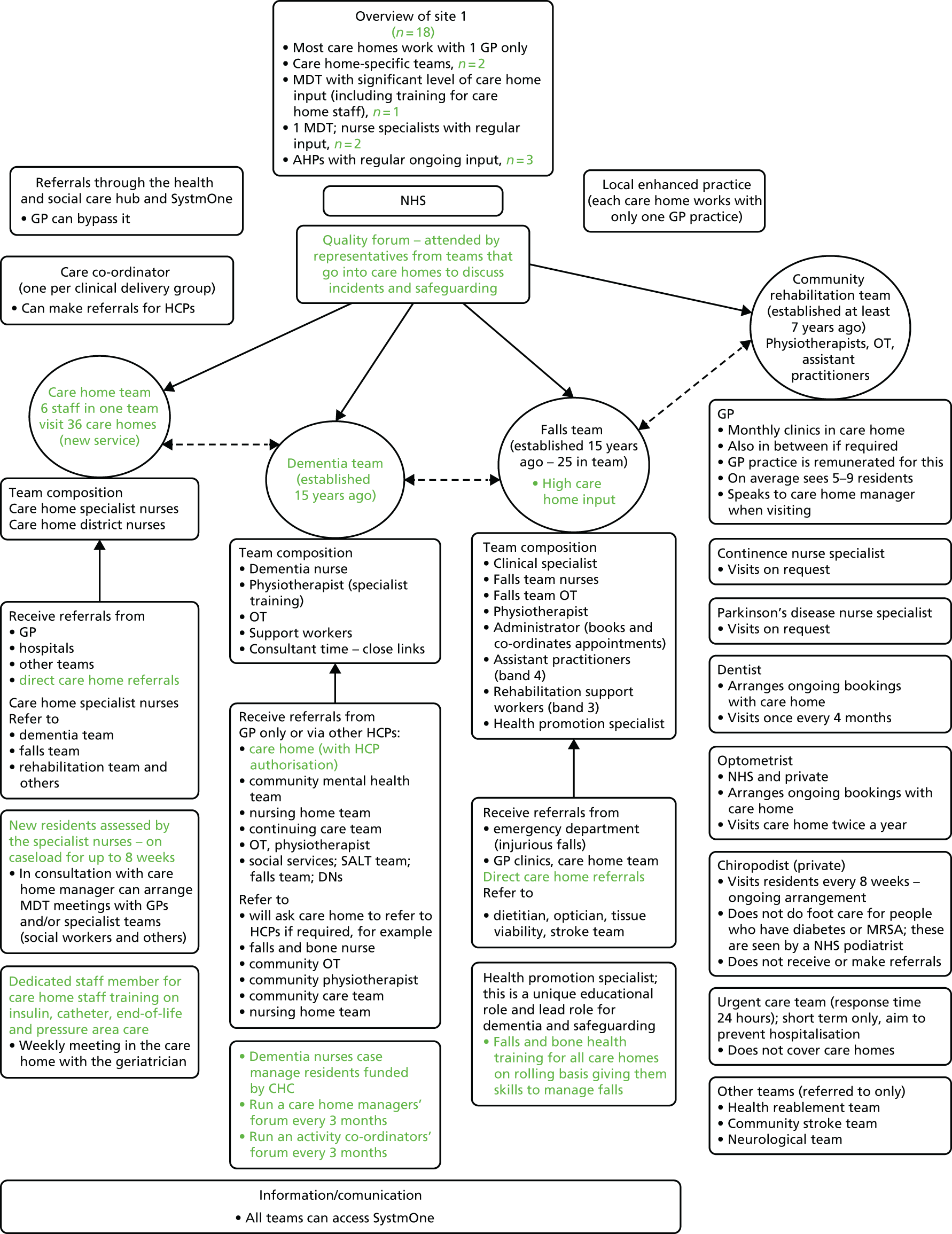

-

Site A: CCG investment in care home specialist provision, which included care home specialist teams, linked specialist dementia care, falls prevention teams and involvement of community geriatricians.

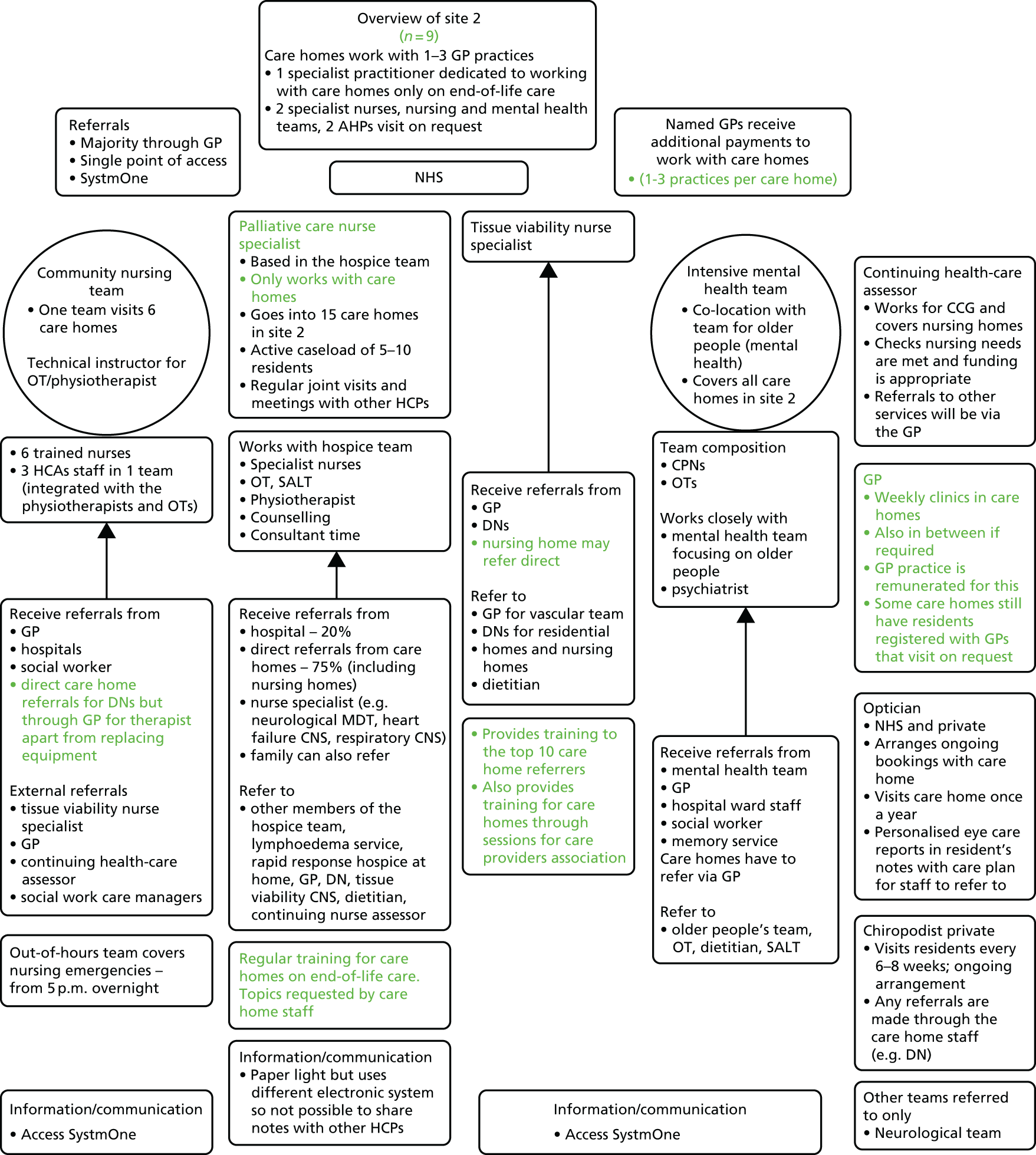

-

Site B: CCG provision of financial payments to specific GP practices to work with care homes and deliver on specific areas of care complemented by the commissioning of training and education in care homes for residents with complex care needs. The initiative required care homes to register with one practice, CCG investment in a multidisciplinary out-of-hospital team, a 24/7 resource covering health and social care to avoid admission to hospital, supported early discharge and home-based rehabilitation. The team included care homes in its remit and had access to beds with care within a care home environment where a patient needed added intensity of care.

-

Site C: CCG investment in community matron support for care homes and a series of topic-specific initiatives to improve medication management and access to end-of-life care, and to prevent and reduce pressure ulcers in care homes.

-

Site D: CCG investment in support to care homes that focused on the creation of a single team for care homes led by a community matron, set up to work closely with GP practices.

-

Site E: geographical area that had a long history of innovation in care home working, for example pioneered intermediate care beds in care homes and where multiple care homes were actively involved in the Enabling Research in Care Homes (ENRICH45) network.

-

Site F: geographical area where there had been training and investment across the county in care home manager leadership training and development. CCG investment in care homes was based on GMS contracts with linked services designed to reduce unplanned admissions from across the community.

In four sites (A, B, C and D) the service proposition to care homes was delimited by the geographical boundaries of the local CCG, as the models of care had been specifically commissioned by CCGs in response to the challenge of providing health care to care homes. To fully understand the service proposition in these areas, it was necessary to ensure both the permission and the engagement of the local CCG to ensure that the necessary access to sites and staff stakeholders would be supported. These sites were therefore approached for recruitment by the research team contacting the CCG and the commissioners with responsibility for care homes and one via the organisation that had organised the training and development programme for care home staff in the county.

Two CCGs (C and D) expressed an initial interest in participating and received information about the study, and the researchers had preliminary telephone conversations with commissioner/site representatives. In one area the chairperson of the CCG decided against participation and in the other site the research team decided not to pursue the collaboration, as the CCG was still in the early stages of introducing changes as to how it worked with care homes.

In site E interest was expressed from specific care home managers; despite this interest, geographical proximity and participation in the ENRICH45 network, the team decided that site F offered more opportunities for learning.

At the last site (F), the relevant contextual factor – investment in a leadership and management framework – was not geographically bounded within a single CCG’s footprint because the service was delivered as a county-wide initiative by a national charity. The approach to the local care home leadership and management network was therefore made through the national charity, rather than the multiple CCGs that commissioned services with which the care homes might be required to interface. The managers comprising the network agreed, unanimously, to participate in the study.

When the sites were confirmed, 72 care homes that met our inclusion criteria were invited to participate in the study.

Selecting and recruiting homes for involvement in the study

Area A (investment in specialist care home provision) was recruited to the study and identified as study site 1, area B (provision of financial incentives to GPs) was identified as study site 2 and area F (care home leadership and management framework) as study site 3; four care homes were recruited in each site. All sites were in England and were located in the Midlands and the east of England (including the east coast).

Although the identification of service delivery models was theory driven, based on the findings of phase 1 we focused, as far as possible, on ‘typical’ homes, that is, those with 25 beds or more (the median size of care homes with and without nursing provision is 25 beds and 48 beds, respectively) and those identified as having contact with a range of NHS services comparable to the common patterns of service delivery identified in phase 1. We aimed to recruit care homes from a range of ownership categories, including large corporate providers, more localised single-home providers or small chains and third-sector charitably funded homes. We did not specifically seek to recruit either NHS- or local authority-funded homes as these now represent exceptional models of funding care. 12

Our exclusion criteria were care homes with specialist registration for alcohol and drug abuse or learning difficulties; those with bed numbers outside the interquartile range; those whose manager had been in post for < 6 months; and those providing specialist care services commissioned by the NHS. From the remaining homes, in sites 1 and 2, all homes that had contact with the services of interest were sent a letter inviting them to participate in the study. This was followed up by a telephone call from the study researcher to give them further information and to set up a meeting with managers who were interested in participating. In site 3, initial contact with care homes was made by the charitable organisation that provided leadership training. Here the details of interested managers, following their consent to be contacted, were passed on to the researcher to communicate directly. In all sites, meetings were arranged with managers to give them further information and to answer any queries about the study and what it involved.

From those willing to participate in the study in principle, care homes were selected to include those with and without on-site nursing and registration for dementia care. To enhance opportunities for comparison we aimed, as far as possible, to match the first four care homes recruited in site 1 with the remaining eight care homes in the other two sites, based on resident population, staffing ratios and geographical proximity to a NHS acute hospital providing secondary care.

Support for recruitment and participation was achieved in one of the sites through collaboration with the local Clinical Research Network, which recruited participating homes to be part of the ENRICH45 network alongside the research undertaken as part of this study.

Recruiting residents from participant homes

The challenges of recruiting older people to research in care homes are well documented. 46,47 Based on previous studies, and with the support of the ENRICH45 network and experienced PIR members, we aimed to achieve the maximum possible recruitment of residents. Where residents lacked mental capacity to give consent and had no contactable personal consultee, we employed a robust protocol using nominated consultees to boost recruitment. Those residents attending for respite care only, or those who were identified by care home staff as terminally ill (i.e. in the last weeks of life) or too ill to participate were excluded.

Sample size

Based on three areas and the purposive sampling framework outlined, we expected to recruit a resident sample of 263–438 based on 60–100% recruitment. Our target number of care home staff was 60 (five per home) to reflect a range of seniority and skill and – depending on GP attachment and models of service delivery – between two and three GPs, two and three NHS nurses (district nurses/specialist nurses) and two and three therapists per home, representing a maximum of 168 participants. Where possible we aimed to interview the chairperson or members of the participating CCG (between three and five) and the Health and Wellbeing Boards (n = 3) about current and projected patterns of service delivery to care homes.

Conducting the case studies

The longitudinal mixed-methods design enabled us to do two things: (1) to track the resource use of residents, particularly their use of emergency and out-of-hours services and (2) to understand how over time the different expressions of relational working between NHS and care staff were achieved and with what outcomes. It also enabled us to study if particular residents (e.g. those who frequently used resources) benefited more or less from the different mechanisms of care provision and whether or not there were differences in responsiveness and flexibility as residents’ needs changed over time.

Data collection with each of the study care homes was conducted over a period of 12 months following the baseline data collection.

Baseline data collection

Baseline descriptors for residents were collected from their care home records to provide the basis for a comparison of the population studied within the four care homes across the three study sites.

Following piloting with care home staff, we used a modified version of the international Resident Assessment Instrument (interRAI) items for use in assisted living facilities, to record information on residents’ clinical and functional status48 for modified interRAI-assisted living. 49 This tool was amended to allow for differences in terminology between Australia – where the tool was developed – and the UK and to remove sections that were not relevant to care home residents in UK care homes. It combined assessment items relating to clinical characteristics with activities of daily living (ADL) and cognitive function that relate to staff care time. 50 interRAI is a standardised assessment instrument for older adults with frailty,49 widely used outside the UK and internationally validated, that provided the study with data of cross-national comparability. The tool comes with a number of validated protocols that automatically generate subscores for a number of clinical syndromes, common diagnoses and patterns of dependency. Based on the experience of the SHELTER study,51 which collected data from 4156 care home residents across eight countries using a version of the interRAI for long-term care facilities (LTCFs) and included 507 residents across nine facilities in the UK, it was believed to be feasible for the interRAI to be completed by care home staff (including care assistants) following training from the research team.

Data on medication use at baseline were collected from Medication Administration Record (MAR) sheets. Thereafter, monthly changes to medications (additions, subtractions, substitutions) were collected from the MAR sheets and annotated longhand into the study database.

Descriptive case studies of continuing care as delivered to care home residents

The case studies provided descriptive data on resident characteristics and resource use, and qualitative data about how health-care provision to care homes was seen as supporting (or not supporting) relational working between the NHS and care homes. Case descriptions were built iteratively, taking account of audio-recorded interviews with residents and family members, care home staff, health and social care commissioners, GPs, NHS nurses and allied health professionals. Observation of NHS care delivery occurred when researchers were in the care homes; this included, for example, observation of meetings between NHS and care home staff and their contact with residents. These were documented as fieldwork notes and included in the qualitative analysis as memos. Care home policies and procedures that focused on residents’ health care were also reviewed. Participants were interviewed at least once over the 12 months. Interviews were semistructured. Interview schedules were initially focused to further inform and enable iteration of the CMO relationships and mid-range theory emerging from phase 1 of the study and were modified over time as these conceptual frameworks evolved. Schedules drew on work on continuity of care and work52–54 on integrative processes, which previously highlighted that service provision can only be meaningfully understood from the level of the patient or, in this case, the resident. All interviews were recorded and fully transcribed.

Care home staff were recruited as volunteers from among the broader workforce of the care homes. Posters were placed in staff areas of the care homes. In addition, staff were made aware of the study and the opportunity to participate in focus groups/interviews when researchers were visiting homes to support routine collection of resident-level outcome measures. Managers played a supporting role in helping to recruit staff but were advised not to coerce them to participate.

Health-care professionals were identified for interview on the basis that they were frequent visitors to the care homes, as established through the monthly service use reviews of participating residents and liaison with the care home link staff. Where required, permission was sought from service managers for the researchers to contact individual HCPs inviting them to participate in the study. To maximise recruitment from this group, telephone interviews were conducted with those staff unable to meet face to face, rather than risk losing their relevant perspectives from the study altogether.

General practitioners who had a role in providing residents with the care homes were identified through discussions with care home staff and were then contacted individually to request participation in a one-to-one interview. Where this failed to recruit participants, GPs were approached collectively via the CCG to take part in a focus group discussion on working with care homes.

Informed by the findings of the realist synthesis, interviews focused on the experience of providing and receiving health care in care homes. For residents and carers, we focused on what was important in relation to satisfaction with the services and how they saw relationships with care home staff and health-care practitioners contributing to this. For care home staff we focused on their satisfaction with the health-care services provided to the care homes and what they viewed as the priorities for NHS services when supporting residents’ health care. Researchers provided feedback about how residents had been found to use services and used these to elicit care home staff views and experiences of working together with health-care practitioners. Face-to-face interviews with care home managers at this stage aimed to capture any changes in the way that health services were provided over the data collection period and to compare and contrast their satisfaction with, and perceptions of, health service provision with those of their staff. Health-care staff were asked to consider the research team’s understanding of how they worked with care home staff, and other HCPs, NHS priorities for residents’ care and how satisfied they were in working with the care home. For GPs, we focused on how they worked together with care homes to provide care for residents, their level and type of contact with other NHS HCPs and their priorities for care, with a greater focus on their role in medication management. A final set of interviews and focus groups shared details from the process analysis and the emergent conceptual frameworks regarding the outcomes of interest and asked care home managers to consider the extent to which these resonated with their experiences.

Care home staff satisfaction surveys (staff outcomes)

To supplement qualitative data on staff satisfaction, we conducted a survey to take account of staff members’ overall satisfaction with continuing health-care services. We used the Quality-Work-Competence (QWC) questionnaire as the basis of this, developed and validated by Hasson and Arnetz55 as a mechanism for collecting data on care home staff competence, work stress, strain and satisfaction. The key area of interest, in keeping with the outcomes of interests stated at the start of the study and reflecting the focus of our programme of work specifically around health care and the contextual and mechanistic factors required to support good health outcomes, was the extent to which staff were satisfied with the health services provided within and between regions. We therefore only used the subset of QWC questions focused around quality of care.

Resource use outcome measures

A bespoke pro forma for collecting service use data was developed with the participating care homes to collect data on the community services that visited participating residents. These discussions were informed by the review of surveys undertaken in phase 1 that reported the range and variability in services accessed by care home residents. Following initial discussions, the specific services to be recorded for residents on a monthly basis were collated in a pro forma, which included the main service use outcomes of interest – namely out-of-hours services, unplanned hospital admissions (including A&E) and length of hospital stay. Each care home was visited by a researcher on a monthly basis at least, but usually more frequently. This helped to maintain working relationships with the care homes to verify and support up-to-date contemporaneous completion of forms.

Two designated members of the care home staff (study link staff) were identified who had responsibility for supporting resident and relative recruitment, day-to-day data collection on resource use, informing us of key events in the care home (e.g. CQC inspections, staff changes, etc.) and liaising with NHS services (see Appendix 5). These data were checked and the details were clarified by researchers from care home records and in discussion with the care home staff.

We had planned to cross-check the service use data obtained from the reviews of residents’ care home notes with data extracted from their medical notes, including information on hospital admission and length of stay, out-of-hours and emergency ambulance service use and referrals to other health-care services in the preceding 12 months. If this was not acceptable we aimed to do a 10% reliability check with residents’ GP records. At the end of data collection and despite multiple attempts, including support from the Clinical Research Network, we were unable to access resident data from GP notes. This reflected real difficulties in recruiting GP colleagues to all parts of the research study.

Analysis and synthesis

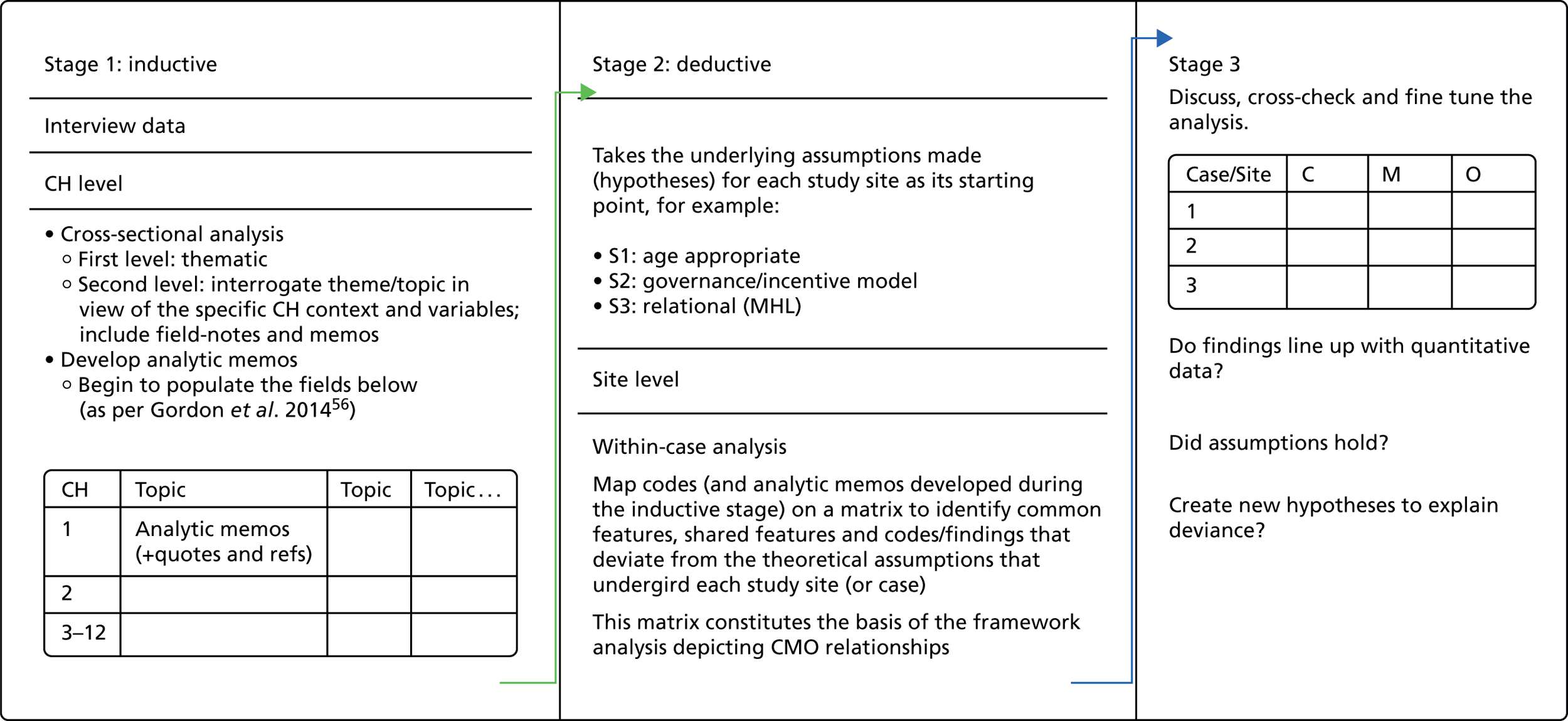

Qualitative data were analysed in stages (see also Figure 1).

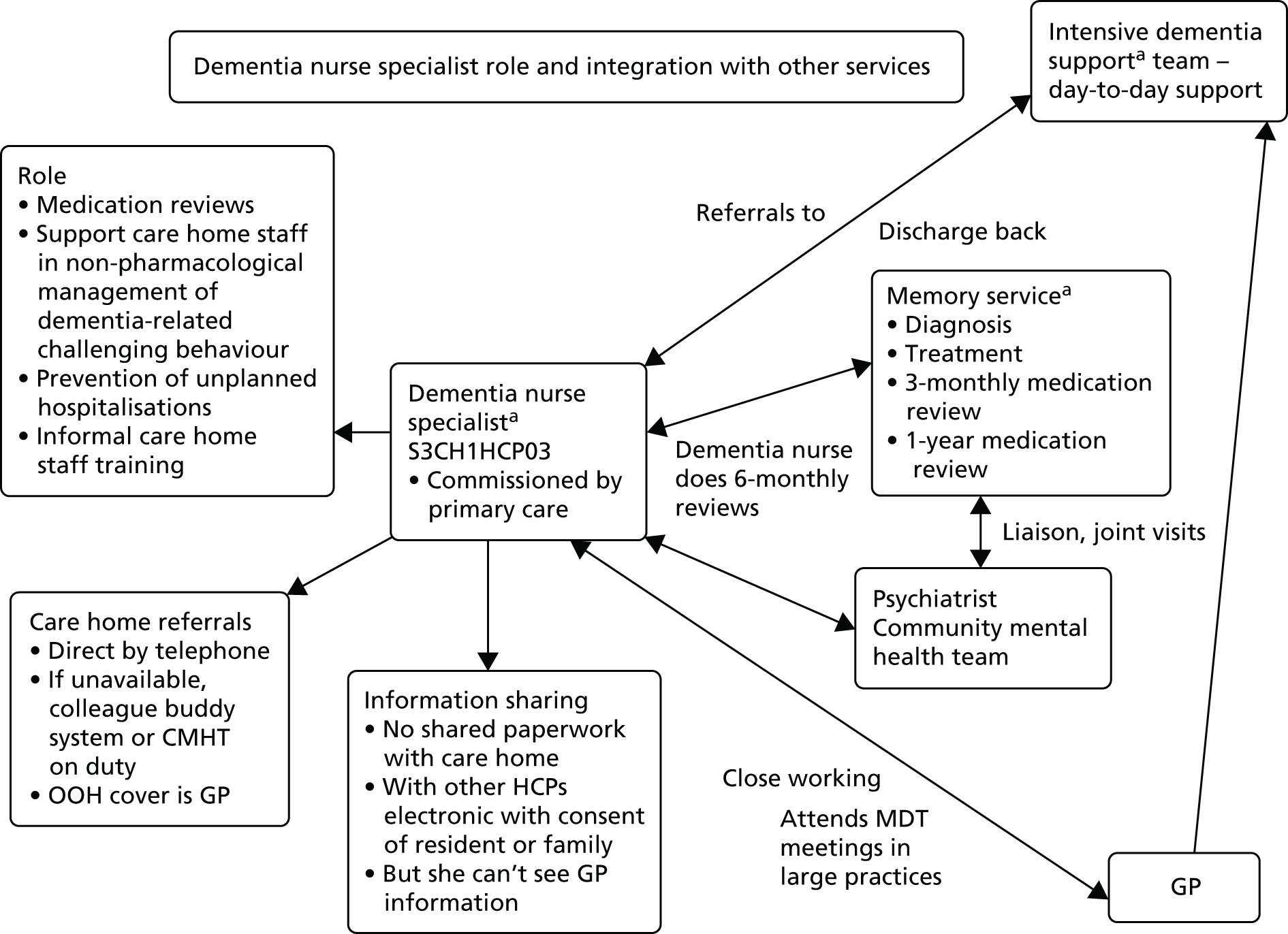

FIGURE 1.

Data synthesis. CH, care home; MHL, My Home Life.

Stage 1

The initial data analysis commenced with the participant interviews, on the basis that an understanding of the provision and structure of health-care services to care homes would facilitate interpretation of the data from the other participant groups. The first level of analysis focused on the participants’ transcripts. The data were analysed both inductively and deductively, initially at the care home level, followed by a within-case analysis of the three study sites. All interview and focus group transcripts were entered into NVivo. Each transcript was coded thematically according to the responses given to the interview questions together with other variables including role, remit and the use of shared documentation. At the second level of analysis, each theme or topic was interrogated to identify the features and structure of health-care delivery to the care homes and the way that the services were organised. This included field notes and memos that were compiled during the data collection process. Analysis at the care home level was followed by a within-case analysis in which each study site, and the four care homes within it, constituted a case.

Stage 2

In stage 2, deductive data analysis was driven by the theoretical assumptions on which each study site had been selected for the study from the phase 1 findings and possible within- and cross-case CMO configurations, that is, sites were loosely characterised as study site 1, an ‘age-appropriate model of care’, study site 2, a ‘governance model’ and study site 3, a ‘relational model’ of working. 57 Drawing on the analysis from stage 1, the characteristics of each model were identified as well as the common features and differences across the sites, together with any data that did not rest on the assumptions underpinning the models. Coding of the transcripts was also conducted for the study outcomes, medication use and management, satisfaction, unplanned hospitalisation including length of stay, out-of-hours service use and A&E use. In line with the findings from the realist review, examples of relational working between HCPs and care home staff were identified and analysed to highlight their associated features.

The resulting data were used to provide a detailed description of the intervention, the outcomes at different levels, context conditions and mechanisms in order to facilitate the identification of the emerging CMOs. 58

Quantitative data analysis

In order to assess the economic outcomes for each of the sites, it was necessary to apply costs to the service use frequency data, collected by month from the patient records. Unit costs were identified from national and published sources. These unit costs were multiplied by the frequency of events for each of the resource use items and a new variable was generated containing the costs, at an individual resident level for that resource item. The frequency variables and costs were then aggregated over time and resource type. The resulting data set contained a set of eight frequency variables of resource use and the corresponding eight variables containing the summative total costs for that resource type, at an individual resident level. Two total cost variables were also generated: the summative total costs at an individual resident level, including all eight health resource types, and all costs, except hospital admissions, which were separated out because inpatient episodes were infrequent events, but costly when they occurred.

Missing data were assessed across all resource use items by way of frequency tables. When a positive response had been recorded for one or more health resource variables for a particular time point, nested by individual resident, any missing values for other resource items were assumed to be zero values. When this rule led to missing data for one or more time points for an individual, the observations for the resident were counted as missing and the resident was dropped from the complete-case analysis. Using this approach, the percentage of complete cases at each month was calculated. Beyond 6 months, when 85% of resident records were complete, the frequency of missing data increased to > 20% (and was 45% at 12 months). Hence 6 months was selected as the primary end point for the analysis.

To verify that inadvertent bias was not introduced by conducting the economic analyses based on those residents with complete data at 6 months, we compared the distribution of baseline variables for all residents recruited to the cohort as a whole and those included in the economic analysis, and no statistically significant difference in baseline variables was detected.

Considering associations between baseline variables, costs and outcome variables

The mean and standard deviation (SD) for each of the summary categories of service use and costs and total costs, broken down by site, were computed. Pairwise comparison between sites for health resource use was conducted using Pearson chi-squared tests; sample t-tests were used for site comparisons of costs.

We used Poisson regression to explore whether or not the site was a significant predictor of service use and total costs after the interRAI scores and the derived variables that we had developed for this study (cognitive impairment, number of comorbidities and medication count), as well as the interaction between the site and these variables, were entered in the regression equation. Poisson regression is a technique that can be used with infrequent count data, such as the service use data. We first entered each of the interRAI clinical syndrome variables [ADL hierarchy scale (sADLH), short ADL hierarchy scale (sADLSF), cognitive performance scale (sCPS), communication scale (sCOMM), clinical syndrome for pain (sPAIN_1) and pressure ulcer risk scale (sPURS)], as well as each of the derived variables (cognitive impairment, number of comorbidities and medication count) in a Poisson regression equation with each of the service use variables separately.

As an example, a regression equation would use sADLH to predict primary care contacts, GP contacts, out-of-hours contacts, community contacts, A&E visits, ambulance use, secondary care number of admissions, secondary care duration and secondary care non-admissions separately. Then, another regression equation would use sADLSF to predict each of the service use variables separately. As this was an exploratory analysis, we selected predictors based on whether or not they were significant in the univariate analysis at a p-value of < 0.10.

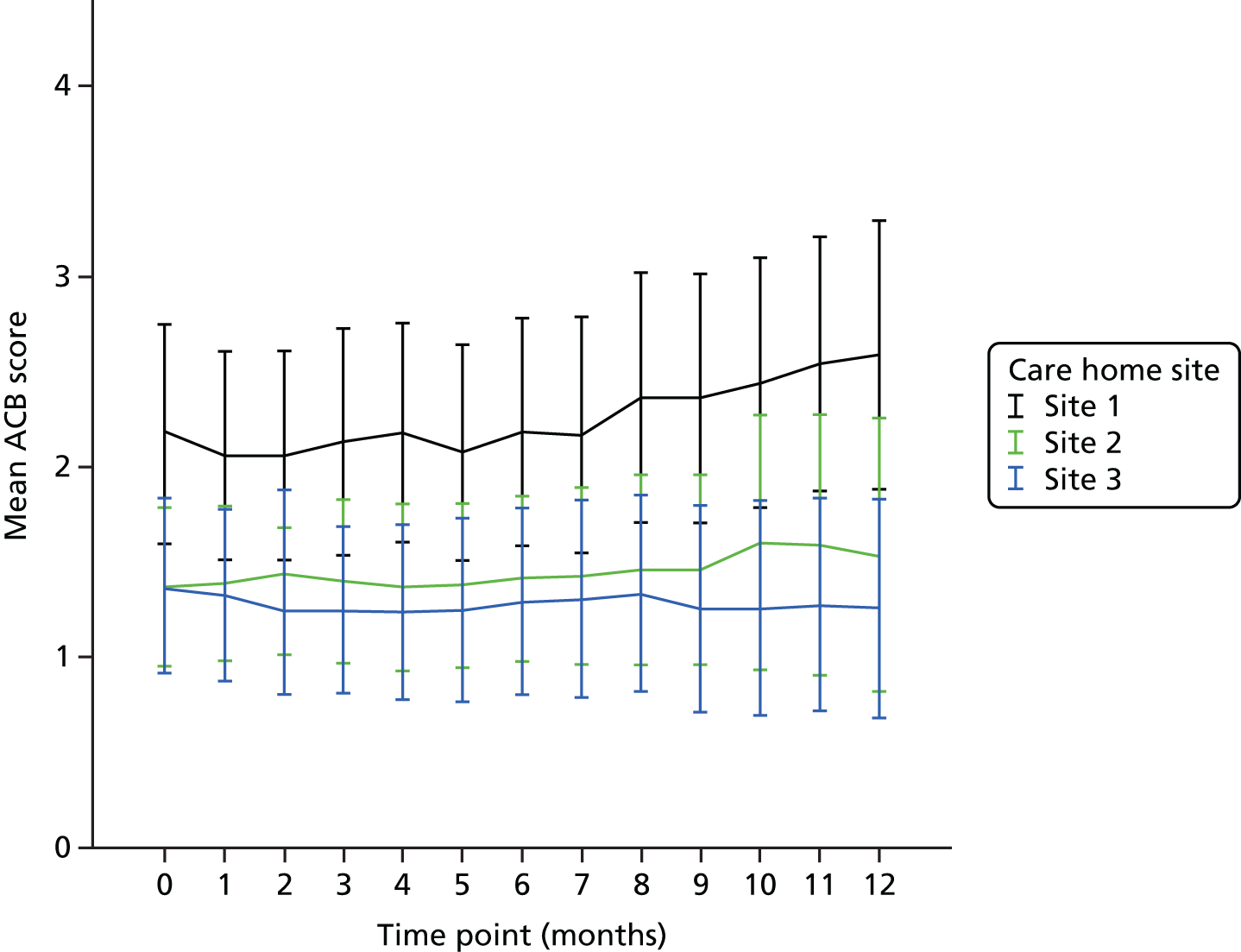

Medication analysis

Medication analysis focused on total medication, antibiotic and opioid counts and anticholinergic burden (ACB) scoring using the ACB scale produced by Aging Brain Care [www.agingbraincare.org/uploads/products/ACB_scale_-_legal_size.pdf (accessed October 2017)]. This was based on the guidance of the study steering group that identified an expansive list of prescribing decisions that could indicate optimal or suboptimal prescribing in the care home setting – ranging from number of antibiotics, painkillers and antihypertensives to more comprehensive indices including the STOPP/START criteria59 and Medication Appropriateness Indices. 60 The eventual recommendation of this group was to use the ACB scale as a proxy measure that incorporated antipsychotic and antihypertensive prescribing rates, and to count opioids and antibiotics separately. ACB scoring and the allocation of medications to antibiotic and opioid categories were conducted by a consultant geriatrician (ALG).

For baseline medication data, counts and distributions were summarised using means (SDs) and medians (range) for parametric and non-parametric data, respectively. Differences between sites were considered using the analysis of variance (ANOVA) statistical method and Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA for parametric and non-parametric data, respectively. Opioid and antibiotic prescription were treated as dichotomous variables (present/absent) – because the majority of residents were taking only one of each of these medications – and were thus compared between sites using Pearson’s chi-squared test.

Follow-up data comprised total drug, antibiotic and opioid counts, and ACB scores for each month of follow-up. These were used to calculate total drugs/resident, antibiotics/resident, opioid/resident and ACB/resident, which were plotted as line graphs with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to enable comparison in prescribing trends over time.

Staff satisfaction

Staff satisfaction questionnaires were analysed similarly to medication data, with counts and distributions summarised using means (SDs) and medians (range) for parametric and non-parametric data, respectively. Differences between sites were considered using ANOVA and Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA for parametric and non-parametric data, respectively. Categorical variables were compared between sites using Pearson’s chi-squared test.

Analysis workshop

A 2-day analysis workshop was used to feed back emergent findings from the three sites to the research management team together with a member of the PIR group (Kate Sartain), in order to discuss the results from the quantitative data and the qualitative data and evidence supporting different CMO configurations both within and across the case study sites.

To enable comparison, home-, resident- and staff-level data were analysed and reported on a site-by-site basis. A matrix61 was generated, with the rows representing sites and columns organised to reflect both the key propositions developed from phase 1 and the data generated from resource use. This was used to facilitate qualitative cross-case analysis, taking account of similarities and differences between and across the three sites. Attention was paid to what the data revealed about the inter-relationships between the mechanism and context of care and how these linked to the outcomes of interest. 52,54

Analysis was iterative and reflected the analytic stages followed in phase 1; it focused on what was revealed about the actual intervention or mechanism, the observed outcomes, the context conditions and underlying mechanisms. This was compared with the theoretical propositions from phase 1 to establish the conditions under which the mechanisms work (or not) and their transferability across different settings.

Chapter 3 Results from the review of surveys and the review of reviews

Introduction

This chapter presents the findings that address the first question of the OPTIMAL study:

-

What is the range of health service delivery models designed to maintain care home residents outside hospital?

The first half of the chapter concerns the analysis from the review of published surveys of health-care provision to care homes. The second half provides a summary of the review of published reviews’ findings about the focus and priorities of health-care research in and with care homes. The chapter provides an overview of the organisation of health care for care homes with a particular, but not exclusive, focus on UK services. A paper on the review of surveys has been published elsewhere. 4

Review of surveys

To complement the searches of the databases (summarised in Chapter 2), forward citations and online searches of NHS websites and e-mail requests, we reviewed the websites of eight academic centres known for their work in care home research, four charities, seven care home provider representative bodies and 12 NHS, social care and professional organisation sites with responsibilities for care homes. Data extraction and analysis were completed in 2013.

Sixteen surveys completed since 2008 were identified and fifteen were included. Five focused on GP service provision to care homes, while also collecting data on specialist services. Ten focused on specialist services to care homes or were topic specific, for example, focusing on dementia services or end-of-life care. One survey62 considered the care home nurses’ work environment, staffing levels, quality of care, meeting residents’ needs and financial pressures on the home, but this was not included as there were no data on externally provided health-care provision/nursing support to care homes. Only two surveys included residents, one of which also included relatives of residents who were unable to participate because of cognitive impairment. The main methods of data collection were postal or online surveys, although some used face-to-face interviews with care home residents and telephone interviews with GPs.

The surveys are summarised in Tables 1 and 2. Table 1 shows, in order of publication date, those surveys that focused on GP services, and Table 2 lists those focusing on specialist services or topics.

| Author, title; year (home type) | Aims | Survey details | Sample size/response | GP services | Other services |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Morris J, Patients Association/University College London/BGS Clinical Quality Steering Group, 2008, personal communication, internal report (nursing homes in England) | Do care home staff and GPs get enough information about new residents? | Face-to-face or telephone interviews on one occasion with 11 care home managers and six GPs who worked with them using standardised questionnaires for care home managers and GPs, including some overlapping questions. Service-related questions included the following services: GPs, tissue viability, mental health, end-of-life and palliative care, geriatrician, old age psychiatry, audiology, ophthalmology, podiatry, physiotherapy, occupational therapy and community pharmacist | Eleven care homes selected to reflect a range of care homes in terms of size, location and residents | From nursing home interviews (n = 9), seven out of nine care homes had a single designated GP – five did weekly clinics, one visited daily and the other 2-weekly | All care homes had access to an ophthalmologist or optician, tissue viability support and support with mental health/behavioural problems |

| Do GPs and care home staff feel supported by primary and secondary care? | The care homes ranged in size from 39–118 beds | From GP interviews (n = 6), three out of six did either yearly or 6-monthly medication reviews | According to GPs, five care homes had access to palliative care support | ||

| Four homes had access to audiology and podiatry, two of which were provided by the care home organisation | |||||

| Three care homes had access to the geriatrician and old age psychiatrist; the others had no or ad hoc access | |||||

| Three had access to a physiotherapist whom they employed directly | |||||

| No care homes had access to occupational therapy services or a community pharmacist | |||||

| 2. Gladman and Chikura, Medical Crises in Older People;63 2011 (care homes with and without on-site nursing) | To conduct a review of current service provision to elderly residents in 252 care homes across the county | Postal survey. Data were collected on 20 services, including falls, GP, pharmacist, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, end of life, mental health, DN, podiatry, community geriatrician, nurse practitioner, dietitian, community matron, long-term conditions, tissue viability, continence, dementia, optometrist, SALT, stroke rehabilitation | One hundred and eighteen responses (47% response rate) | All homes allowed their residents to register with the practice of their choice – (one care home was served by up to 16 practices) | Ninety-seven per cent of care homes had access to pharmacy, 92% to a DN and 89% to a dietitian |

| Most visits were on request, GPs offered regular surgeries, others found it hard to get visits | Most services available on request rather than routinely with the exception of pharmacists | ||||

| Forty-two per cent of care homes did not have regular GP visits | The services available to the least number of care homes included nurse practitioner (34%), community geriatrician (42%; 9% of care homes had regular visits from the community geriatrician) and long-term conditions team (43%) | ||||

| Twenty-three per cent of care homes could not access SALT, physiotherapy or occupational therapy services | |||||

| An example of specific care home services: a nurse-led team that worked closely with care homes to liaise with NHS services and offer training and support to care homes, medication reviews | |||||

| 3. Gage et al., Integrated working between residential care homes and primary care: a survey of care homes in England;64 2012 (care homes without on-site nursing) | The APPROACH study survey 1: to establish the extent of integrated working between care homes and primary and community health and social services | A self-completion, online questionnaire of open and closed questions designed by the research team to establish the primary health-care service provision to care homes and their experience of integrated working with those services | Sent to a random sample of residential care homes in England in 2009 (n = 621) with more than 25 beds | All care homes received GP services – 81% worked with more than one practice |