Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 12/5001/21. The contractual start date was in May 2013. The final report began editorial review in November 2016 and was accepted for publication in May 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Forsyth et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2017 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Definition of older prisoners

The definition of an older person in prison is socially constructed. Wahidin et al. 1 noted that minimum cut-off ages as low as 45 years have been used in previous studies of older prisoners to obtain reasonable participant numbers. Both in the USA and the UK, the most frequently used minimum cut-off ages for defining ‘older’ prisoners are 50 or 55 years. 2,3 It is argued that 50 years old is an appropriate age at which to commence preventative health-care measures to reduce the financial burden and improve the health of older prisoners. 4 Furthermore, it has been suggested that prisoners aged ≥ 50 years have the physical appearance and health problems equivalent to those of a person aged 60 years living in the community. 4,5 The usefulness of providing minimum cut-off ages for defining older prisoners has been questioned. Yorston and Taylor6 emphasised the importance of considering levels of service need rather than simply referring to chronological age cut-off points when identifying older prisoners.

Studies exploring older prisoners’ health and social care needs have provided some supporting evidence to suggest that 50 years should be used as a minimum cut-off age to define older prisoners. A cross-sectional survey of older prisoners in the north-west of England found that prisoners aged 50–59 years have similar health and social care needs to those aged ≥ 60 years living in the community, thus suggesting it to be an appropriate cut-off point. 7 Fifty years is, therefore, the minimum cut-off age throughout the current study, unless otherwise indicated.

The increasing number of older prisoners

There has been a recent, considerable increase in the number of older prisoners across many developed countries, including the USA,8 Japan,9 Canada,10 Australia,11 France,12 England and Wales. 13 It is estimated that, by 2030, one-third of all prisoners in the USA will be ≥ 55 years old, equating to > 400,000 prisoners, a 4400% increase from 1980. 8

In England and Wales, people aged ≥ 50 years currently account for 15% of the prison population, with 12,577 in this age group in prison. 14 Those aged ≥ 60 years are the fastest growing age group in the prison estate and, strikingly, the number of prisoners aged ≥ 70 years old is projected to increase by 35% by 2020. 15

The rise in the number of older prisoners is a consequence of a number of factors. The increase is, in part, the result of an ageing population and increases in the number of older people committing crimes. 16 Importantly, it is also a consequence of changes to sentencing practices, with courts sentencing higher numbers of older people to increased periods of imprisonment. 17 The introduction of indeterminate sentences has also contributed to the increase. 18 Furthermore, enhanced forensic evidence and enhanced reporting resulted in greater numbers being convicted for crimes committed in previous decades. 19 In England and Wales, 42% of men in prison aged > 50 years have been convicted of sex offences, the most common offence for this group. 13

The policy context

There is no national strategy for the care of older prisoners, despite repeated recommendations. 19–22 However, prisoners should have access to the same quality and range of health services as they would receive in the community. 22,23 The formal process of passing on the responsibility of employing health-care staff and delivering health care from the prison service to the NHS was completed in 2006 and, since then, all NHS standards and policies apply in prison.

The most relevant NHS policy to older prisoners is the National Service Framework (NSF) for Older People. 24 This aimed to ensure ‘fair, high quality, integrated health- and social-care services for older people’ and outlined eight key standards for the NHS and partners in local authority and community sectors to meet. 24 The NSF incorporated a short paragraph concerning older adults’ care in prison, emphasising the need for collaborative working to support older offenders. Strikingly, Her Majesty’s Chief Inspector of Prisons (HMCIP)18 review of older prisoner care found that that many of the NSF standards were not being met in prison.

A wide range of definitions of social care are employed in the community. 25 Research conducted with staff working in prisons has suggested that there is a lack of agreement concerning this definition. 26 Some staff adopted broad definitions of social care that included assistance with finances, housing and employment, whereas others used narrower definitions, referring only to personal care concerns such as washing and dressing. Without clear agreement of what social care is, it is difficult to determine who is responsible for its provision to older prisoners. This lack of clarity has previously been acknowledged. 27,28 Where social care is provided, it has largely, and inappropriately, been seen as the sole responsibility of prison health-care services, as opposed to a wider multidisciplinary obligation. 18

In July 2012, the government published the white paper, ‘Caring for our future: reforming care and support’, which detailed the reform of adult social care in England and Wales. The white paper described a lack of clarity concerning responsibility for assessing and providing social care support to prisoners. 29 The resultant Care Act,30 introduced in 2014, clearly stipulated that the local authority where the prisoner resides was responsible for providing social care. The extent to which local authorities have become involved in the care of older prisoners and the form this has taken since the introduction of the 2014 Care Act is unknown. Cornish et al. 31 have recommended that a review of the implementation of the 2014 Care Act across the English and Welsh prison estate should be undertaken.

Health and social care needs

Physical health needs

Older prisoners have multifaceted health problems. 7,20,27,32,33 However, to date, only a small number of studies in the UK have identified older prisoners’ physical health status. Hayes et al. 7 found that 93% of their sample of older prisoners aged ≥ 50 years had some form of physical illness. In addition, Fazel et al. 34 identified that 85% of prisoners aged ≥ 60 years had one or more major illness reported in their medical notes.

Four studies have examined the physical health status of older prisoners in England and Wales since the 1980s. 7,27,32,35 These studies are summarised in Table 1. The prevalence rate for each illness varies between studies, reflecting the adoption of different assessment measures, and data collection and sampling methods. Kingston et al. 32 report considerably lower prevalence rates than the other studies, which is possibly a result of the low response rates (51%), indicating that those experiencing poorer health may have been less likely to participate. Excluding the Kingston et al. 32 study, the findings presented in Table 1 indicate that older prisoners have higher rates of genitourinary, haematological, audio/sensory, cardiovascular, respiratory and endocrine illnesses than reported figures from both their younger counterparts in prison38 and those aged ≥ 65 years living in the community. 39

| First author and year of publication | Measures | Age (years) | Sample size | Illnesses reported (%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Central nervous system | Genitourinary | Haematological | Auditory/sensory | Cardiovascular | Musculoskeletal | Respiratory | Endocrine | Cancer | ||||

| Senior et al., 201327 | Note review | ≥ 60 | 100 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | 38 | n/a | 33 | 19 | 3 |

| Hayes et al., 20127 | Burvill grid36 | ≥ 50 | 262 | 17 | 47 | 3 | 49 | 49 | 57 | 78 | 21 | n/a |

| aKingston et al., 201132 | Note review, SF-1237 | ≥ 50 | 237 | n/a | 6 (4) | 2 (1) | 9 (4) | 22 (18) | 23 (24) | 9 (8) | 5 (5) | 1 (2) |

| Fazel et al., 200134 | Burvill grid36 | ≥ 60 | 203 | n/a | 13 | 3 | 6 | 35 | 24 | 15 | 10 | n/a |

| Bridgewood et al., 199538 | Self-report | 18–49 | 992 | n/a | 1 | 0 | 4 | 3 | 16 | 15 | 2 | n/a |

| Prior, 199639 | Self-report | 65–74 | 16,443 | n/a | n/a | 1 | n/a | 29 | 25 | 12 | 9 | n/a |

There has been very little research regarding the extent to which older prisoners’ physical health needs are met. Fazel et al. 40 explored whether or not older prisoners received medication for their diagnosed health conditions. They found that 85% of prisoners with cardiovascular disease, 78% with endocrine disorders and 65% with musculoskeletal conditions recorded in their medical notes were prescribed medication for these issues. Hayes et al. 20 aimed to identify the met and unmet needs of older adults in prison through a cross-sectional survey. Physical health needs were the second most common type of perceived unmet need (n = 52, 33%). Senior et al. 27 also used the CANFOR to explore older prisoners’ needs on entry into prison and found that 22% (n = 22) reported unmet needs concerning their physical health. This percentage is lower than in the Hayes et al. 20 study and may reflect older prisoners prioritising other issues, rather than their physical health, immediately on entry into prison.

Mental health needs

There is a limited number of studies concerning the mental health of older prisoners. Reported overall rates of mental disorder among older prisoners vary from 50% to 61%. 8,32,35 The most commonly reported diagnosis within the three studies was depressive disorder (12–34%). Murdoch et al. 41 explored depression in elderly life-sentenced prisoners using the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) and reported that 48% scored within the mild depression range and 3% scored within the severe depression range. Senior et al. 27 also used the GDS to identify depression among older prisoners newly received into custody, reporting lower rates of mild depression (31%) but higher rates of severe depression (23%), suggesting that those newly received into prison are more likely to be suffering from severe depression than those at other points in their sentence. This supports previous research indicating that the initial entry period is particularly risky in terms of prisoners’ mental health. 42 Two studies27,40 have explored older prisoners’ treatment for depression. Fazel et al. 40 found that only 14% of the sample from their cross-sectional survey who had achieved caseness for depression were being treated with antidepressants. Similarly, the Senior et al. 27 study explored treatment for depression during the 4 weeks after prison entry, reporting that 17% of older prisoners who showed symptoms of depression were prescribed antidepressants. However, it is not known whether these symptoms of depression were a temporary result of prison entry or a longer-term illness. Furthermore, the extent to which other forms of treatment for depression were provided to participants was not explored. No research has explored other treatment options for older prisoners suffering from depression.

Research suggests that rates of personality disorder among older prisoners range from 20% to 30%. 7,35 Fazel et al. 40 also reported that 8% of their sample had an antisocial personality disorder, which is lower than reported among younger prisoners. 43 No research has been conducted regarding the specific treatment needs of older prisoners with personality disorders.

Dementia has been identified as a growing issue for prisons;43 however, very limited research has been conducted. It is argued that the highly structured routine of prison can mask symptoms of dementia. 43 However, it is estimated that between 1% and 2% of older prisoners experience dementia,32,35 similar to rates of dementia found in older people living in the community but much lower than rates among older people at different stages of the criminal justice system. 35 This suggests that either older people with dementia are successfully diverted from prison and/or individuals with dementia are less likely or able to commit crimes of a severe nature for which they become imprisoned. 35

One study has identified the extent to which older prisoners with psychiatric illness received appropriate medication. Fazel et al. 40 reported that 18% (n = 11) of older prisoners in their sample with any recorded psychiatric illness were receiving targeted medication. This was considerably lower than the number of older prisoners with any physical health problem receiving targeted medication, as previously discussed. Yorston44 has argued that there is a need for communication between old-age psychiatrists and forensic psychiatrists at local and national levels to prevent the needs of older mentally ill prisoners from being overlooked. Current mental health services for older prisoners are limited and inequitable to services provided in the community, with very few specialist old-age forensic psychiatry services. 44

Few studies have explored substance misuse among older prisoners in England and Wales. Fazel et al. 35 reported that 5% of their sample misused or were dependent on substances at the time of interview. However, the authors acknowledged that the study failed to examine lifetime substance misuse. Hayes et al. 7 found that 33% of their sample had lifetime substance misuse disorder. A greater number of older prisoners reported lifetime alcohol misuse (30%) than drug misuse (9%). This differs greatly from the younger prison population. Singleton et al. 45 found that 43% of the general prison population aged 16–64 years were drug dependent. In the USA, Arndt et al. 46 examined the prevalence of substance abuse among 10,652 offenders using data from interviews conducted on prison entry, and found that 71% of prisoners aged ≥ 55 years reported a substance misuse problem. They were more likely to abuse only alcohol than their younger counterparts, who were more likely to misuse alcohol and drugs. Many of the older prisoners had abused substances for > 40 years, but had never received treatment. There is a paucity of research evaluating older prisoners’ substance misuse treatment in England and Wales.

Social care needs

Older prisoners often have complex social care needs as a result of their multifaceted health needs and the ageing process. 18,19 Few studies have examined the social care needs of older prisoners, but evidence suggests that older prisoners experience a lack of appropriate support in this area. 19,28,47 Hayes et al. 20 conducted the most recent study regarding older prisoners’ social care needs, reporting that accommodation was the most commonly unmet need. Further evidence for a lack of appropriate and timely support with housing was provided by Senior et al. ,27 whose findings revealed that older prisoners were frequently unaware of where they were going to be living in the community in the months, weeks and even days prior to release. Without confirmation of accommodation on release, older prisoners felt unable to plan for other aspects of their resettlement into the community, such as health care or financial issues.

Older prisoners are required to negotiate narrow doorways and to walk long distances, often without handrails, while in prison. 47 Hayes et al. 7 found that over one-third of older prisoners in their sample had some level of functional need in activities of daily living (ADL), with 11% having personal care needs, in over half of whom they were unmet. A US study48 explored prison activities of daily living (PADL) in 120 female prisoners aged > 55 years. These included dropping to the floor for alarms, getting to the canteen for meals, hearing orders from staff and climbing on and off the top bunk. Over two-thirds (69%) reported impairment in PADL, whereas only 16% reported difficulties in standard ADL tasks. Consequently, the authors emphasised the importance of considering PADL when assessing older prisoners’ needs, rather than just the standard ADL. 48 Further research is required to establish the extent to which older prisoners demonstrate difficulties with PADL within the context of English and Welsh prisons.

Strikingly, there have been examples of other prisoners inappropriately providing personal care (such as washing, dressing and assistance with incontinence issues) to older prisoners as part of ‘buddy’ schemes. 19 This may be inappropriate because ‘buddies’ may not be adequately trained and may exploit others. However, some prisoners may have no choice but to receive this type of support, even though it is not in line with the principle of equivalence. However, there is no evidence to determine how widespread this practice is, nor what type or extent of training and support ‘buddies’ receive to undertake the role or to what extent they are vetted or supervised. There are occasions when buddy schemes may be appropriate, for example when the buddies of prisoners with mobility difficulties push wheelchairs, carry food trays and clean cells. However, such schemes are relatively rare and no published research has evaluated their effectiveness or appropriateness. 18,49

Limited research has considered older prisoners’ social support networks. In the Hayes et al. 27 study, nearly half of prisoners were imprisoned far from their home, making contact with social support networks difficult. A total of 40% received no visits at all. Furthermore, 20% rarely left their cell during opportunities for socialisation with other prisoners. Many older prisoners have elderly parents, siblings and friends who have difficulties travelling to visit them, and they may have been be disowned by their families, particularly if they have committed sexual offences. 18 The impact of this lack of social support networks for older prisoners has not been fully explored.

The care pathway

Assessment of need and care planning

Professionals conducting health and social care assessments with older people in the community face a number of challenges, namely the under-reporting of need, poor-quality tools, variations in assessments across professions and geographical areas and a lack of agreement among professionals working in different sectors. 50–53 The NSF for older people introduced processes to improve assessment procedures, most notably the introduction of the Single Assessment Process (SAP). 24 The aims of the SAP were to standardise assessments across different organisations and geographical areas, raise the standard of assessment, assist with information sharing, prevent duplication and ensure a comprehensive assessment of need. 24 Studies have suggested some improved identification of older adults’ health and social care needs; however, the extent to which these improvements are a result of the SAP is unknown. 50

Prisons are required to conduct health assessments for all new prisoners on reception into custody. 54 The current standardised reception health assessment tool, introduced in 2004, is designed to identify immediate health concerns, with a recommended second health screen conducted at a later date to allow prisoners to discuss their health needs in more depth. However, research suggests that there are low completion rates for the second, non-mandatory health screen. 55 A further criticism is that it is too often viewed as a one-off process, as opposed to a continuous pathway to care. 56 The tool does not investigate social care need.

The Department of Health57 guidance entitled A Pathway to Care for Older Prisoners: A Toolkit for Good Practice recommends the use of health and social care assessments specifically designed for older prisoners, with reassessments and revised care planning taking place at least every 6 months. There is no standardised older prisoner health and social care assessment in England and Wales; however, some establishments have developed their own. Cooney and Braggins58 reported that 40% of establishments in their survey had no specific assessments in place for older prisoners. Senior et al. 27 found that 81% had not established specialised assessments for older people on prison entry. The specialised assessments introduced in some establishments have not been evaluated, and anecdotal evidence suggests that they are not always delivered systematically to all prisoners. Consequently, in the majority of prisons, the identification of health-care need for older prisoners is largely dependent on information obtained by the generic screening instrument. 59 It is known that, if health issues are not identified at reception, they are unlikely to be detected throughout a person’s time in prison. 60

Health and social care services

There are limited examples of older prisoners being provided with additional specialised services; however, in general, they receive the same treatment as younger prisoners. The implications of being treated the same as younger prisoners have been discussed. 61 Crawley61 conducted interviews with those aged ≥ 65 years in two prisons where there were separate wings for older prisoners, and in two with no such separation. Sustained observations of prisoners’ daily life were also conducted. Crawley61 found that prison officers had to find a balance between consistency and flexibility when supporting older prisoners. She highlighted that ‘treating everyone the same does not always equate to equality’. Crawley61 used the term ‘institutionalised thoughtlessness’ to describe the ways in which ‘prison regimes simply roll on, with little reference to the needs and sensibilities of the old’. Examples included not being provided with sufficient time to move from one location to another or to complete specific activities, being provided with hard chairs and top bunks to sleep on, insufficient warm clothing in cold weather, queuing for long periods of time for medication, unavailability of grab rails in the showers and being unable to go outside for exercise because exercise areas lack seating or a readily accessible toilet. These examples suggest that older prisoners are being ‘doubly punished’ because, in addition to their loss of freedom, they experience inadequate care that is not equivalent to that in the community. 58

Release and resettlement

The post-release period poses particular risks for prisoners in terms of their physical and mental health. 62 Research has identified complex relationships between reoffending and nine key factors, namely education, employment, drug and alcohol misuse, attitudes and self-control, institutionalisation and life skills, housing, financial support and debt, family networks, and mental and physical health. 62 However, 42% of released prisoners are of no fixed abode, 50% have no general practitioner (GP), 50% reoffend within 2 years, debt problems for one-third worsened whilst in custody and 60% are unemployed. 63

Recent research conducted by Wilson64 has explored how prisoners with serious mental health illness seek help after leaving prison. In this study, 63% identified housing and 35% identified financial assistance as one of their two most important service needs; only 12% selected treatment services, thus emphasising the importance of meeting basic needs as well as providing treatment services on release from prison. Released prisoners are also at a greater risk of suicide than the general population, particularly in the first few weeks after their release. 65 Furthermore, discharged prisoners have an increased risk of drug overdose. 66 Consequently, it is essential that contact with care services is maintained on release from prison. 67,68 The National Association for the Care and Resettlement of Offenders recommends that the resettlement needs of every offender should be considered from the start of their prison sentence,69 although little is known regarding the extent to which this is realised because there is a paucity of research concerning discharge planning for prisoners. The UK government has argued that effective release planning is a key priority to reduce barriers to resettlement. 70 However, it has been argued that the current discharge planning process and a lack of effective multiagency working are current barriers to effective resettlement in the UK71 and the USA. 68

The HMCIP review of older prisoner care identified grave concerns that needs were not planned or provided for after release,18 based on identifying only four prisons in England and Wales that provided specific resettlement support for older prisoners. It repeated its previous recommendation72 that the specific resettlement needs of older prisoners should be accurately assessed and provided for on release. The Department of Health’s toolkit for good practice provided recommendations around preparing older prisoners for release and supporting their transition into the community. 73 The Department of Health stipulated that release planning should involve the conduction of a pre-release health and welfare assessment, a face-to-face assessment by a social worker, collaboration with external organisations and the organisation of a care package. This guidance also emphasised the importance of monitoring the progress of released prisoners to ensure that they have access to the appropriate services.

A limited number of studies have explored older prisoners’ concerns and issues about release prior to discharge. 74,75 Findings suggest that older prisoners struggle disproportionately with resettlement as a result of reduced support networks and their increased likelihood of health and mobility problems. In addition, older prisoners experience intense anxieties about their release, and inadequately understand the resettlement process. Key concerns include where they are going to live and how they will get there; their physical safety (for convicted sex offenders in particular); loss of personal possessions and support networks; and access to health-care support for chronic illness. Concerns prior to discharge are so intense that many feel that it would be better to stay in prison. In spite of these increased needs, older prisoners’ resettlement needs are often ignored; it has been suggested that this is because they are generally considered less of a risk75 and are less assertive than younger peers. 76

One study explored whether or not older prisoners’ fears about release became reality. Forsyth et al. 77 conducted interviews with older prisoners prior to and after release, and reported that older prisoners perceived release planning to be effectively non-existent. Those due to reside in Probation Approved Premises were very anxious about the prospect and were concerned about sharing accommodation with younger people who may abuse substances and be physically violent towards them. However, interviews with older prisoners after release revealed that the immediate health and social care needs of those housed in Probation Approved Premises were generally fairly well met. Many with complex social care needs were inappropriately housed; for example, some wheelchair users were housed in accommodation accessed by steps, meaning that they could not enter or exit the premises independently. Similarly, a lack of suitably adapted bathroom facilities compromised safety and independence in this aspect of self-care. It is possible that the Offender Rehabilitation Bill (2013–14)78 will improve this situation. The Bill proposed the introduction of 70 resettlement prisons, with offenders being sent to a prison close to their release destination at least 3 months prior to discharge. The extent to which this will improve release planning for all prisoners, including those in older age, is as yet unknown.

Rationale for the current study

In summary, there has been an increase in the number of older prisoners across developed countries, including England and Wales. Older prisoners have more health needs than younger prisoners and those of the same age living in the community. They also have a multitude of social care needs that are difficult to meet within the constraints of prison. There is no national strategy for older prisoners’ care, in spite of repeated calls for one to be developed. Consequently, the care of older prisoners is currently generally ad hoc and largely unco-ordinated. The Older prisoner Health and Social Care Assessment and Plan (OHSCAP) was developed through action research by prison staff, health-care staff and older prisoners themselves at one prison in England. It is a structured approach for identifying and managing the health and social care needs of older prisoners and consists of an assessment, care plan and review of these needs. During a pilot study (Service Delivery Organisation programme reference number 08/1809/23027) in the same prison, it was found to be both feasible and acceptable to patients, as well as being effective at reducing older prisoners’ unmet health and social care needs.

This study aimed to build on previous work by evaluating the effectiveness and acceptability of the OHSCAP in a larger-scale, randomised controlled trial (RCT).

The objectives of the study were to:

-

train prison staff to deliver the OHSCAP

-

implement the OHSCAP in a number of prisons in England

-

evaluate the efficacy of the OHSCAP in improving:

-

the meeting of older male prisoners’ health and social care needs (primary outcome)

-

health-related quality of life (HRQoL)

-

depressive symptoms

-

functional health and well-being and ADL.

-

-

assess the quality of care plans produced through the OHSCAP

-

explore the experiences of older prisoners receiving the OHSCAP, and staff involved in conducting the OHSCAP

-

evaluate the cost-effectiveness of the OHSCAP compared with treatment as usual (TAU).

Research questions

-

Does the use of the OHSCAP compared with TAU improve:

-

proportion of met health and social care needs

-

HRQoL

-

depressive symptoms

-

functional health and well-being and ADL

-

quality of health and social care planning

-

cost-effectiveness?

-

-

What are the facilitators of, and barriers to, the implementation and operation of the OHSCAP?

Hypotheses

Primary hypothesis

The OHSCAP will significantly increase the proportion of met health and social care needs 3 months after prison entry, compared with TAU controls.

Secondary hypothesis

Compared with TAU controls, the OHSCAP will significantly improve the following at 3 months after prison entry:

-

HRQoL

-

depression

-

functional health and well-being

-

quality of health and social care planning.

Chapter 2 Randomised controlled trial methodology

Study design

The study was designed to evaluate the OHSCAP. It consisted of a parallel two-group RCT with 1 : 1 individual participant allocation to either the OHSCAP intervention plus TAU (intervention group) or TAU alone (control group). The main trial was conducted alongside (1) an audit of the fidelity, and quality, of implementation of the OHSCAP (see Chapters 4 and 5), (2) economic evaluation examining the cost-effectiveness of providing the OHSCAP (see Chapters 8 and 9) and (3) a nested qualitative study to explore the views and experiences of participants and professionals involved in the study (see Chapters 6 and 7). The protocol containing trial design and methods protocol is included as Appendix 1.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval for the study was granted by the Research Ethics Committee for Wales in May 2013 (reference number 13/WA/0108). National Offender Management Service (NOMS) research approval was provided in July 2013 (reference number 2013-115). The trial was registered with the International Standard RCT Number ISRCTN11841493. Additionally, all required site-specific permissions and research governance approvals (research and development) were obtained from the relevant NHS trusts.

Changes to protocol

-

Increase in number of sites.

We closely monitored data collection to ensure that we would meet our targets. It became apparent that we needed to add further sites in order to meet the follow-up target of 392 participants. Additional sites were selected for pragmatic reasons while still ensuring that we had included a range of prison types. Consequently, the number of sites increased from 4 to 10. We are confident that the increase in number of sites had no impact on the overall study design.

-

Increase in baseline target.

As we progressed into the trial, it became apparent that our attrition rate was much higher than the expected 10%, at almost 20%. This was mainly because of retention issues in the local (remand) prison sites, where it proved to be harder than expected to identify individuals who would remain in custody for the 3-month follow-up period. As a result of this, we extended our recruitment period and increased our baseline recruitment target to a maximum of 502 participants at baseline, from the original target of 462.

-

Changes to assessment tools.

A number of changes were made to the assessment tools before data collection commenced. The SF-3679 was replaced by the Bristol Activities of Daily Living Scale (BADLS)80 because it was considered more appropriate for use in prison. The Client Service Receipt Inventory81 was replaced by the Secure Facilities Service Us Schedule (SF-SUS)82 for the same reason. We also added the following tools in order to describe the sample: the Operational Criteria Checklist for Psychotic and Affective Illness (OPCRIT),83 PriSnQuest84 and the Burvill grid. 36

Sites

The study aimed to recruit male prisoners aged ≥ 50 years. Originally, this recruitment was to be from four prison establishments in the north of England, but, as a result of recruitment difficulties, this was subsequently expanded to include a further six prison establishments. A range of prisons including open, training and high-security prisons were involved.

Participants

Inclusion criteria

To be eligible for inclusion, participants had to:

-

be aged ≥ 50 years

-

have a known release date (convicted) or likely release date (unconvicted) of at least 3 months after their prison entry date.

Exclusion criteria

The following individuals were excluded:

-

those who did not have the capacity to consent

-

those considered by prison or health-care staff not safe to interview alone as a result of their current risk assessment

-

those previously included in the study.

Procedure

Recruitment procedure

An administrator within each of the prisons identified potential participants who fulfilled the inclusion criteria. They did this by running a search on all prisoners newly received from court into their establishment on the prison computer system [Computer – National Offender Management Information System (C-NOMIS)]. An administrator was selected for this role because they did not need to access health information, but they did need to access sentence information. It would not have been appropriate for the members of staff delivering the OHSCAP to conduct the initial approach because this would have affected anonymity, and may have then had an impact on the support the TAU group received. The administrators were also required to inform potential participants of the proposed study. If the service user expressed an interest in learning more, the administrator requested their permission to pass their name on to a member of the research team. A researcher then arranged a time to talk to the potential participant to discuss the study further and ask them to consider participating in it.

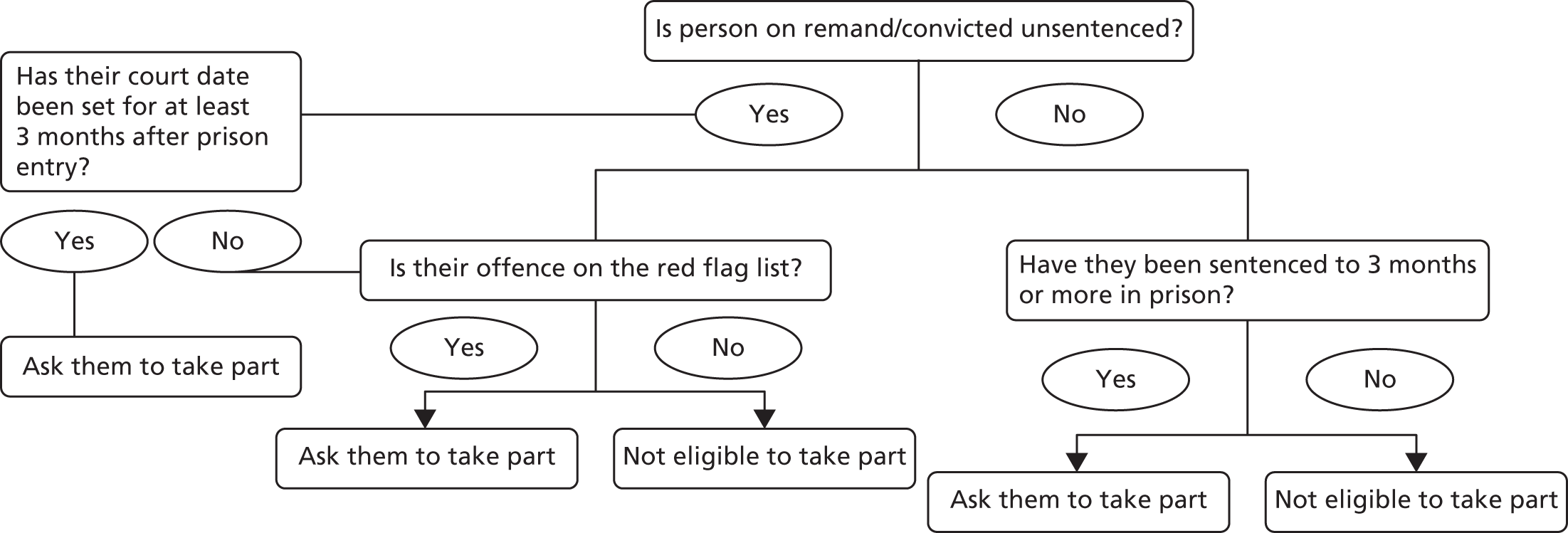

Release dates for unconvicted prisoners were predicted using an adapted version of an algorithm developed for a previous study. 85 The algorithm and accompanying offence list is appended (see Appendix 2).

Consent

Informed consent was sought from all potential participants prior to taking part. Researchers explained the project, provided an information sheet and described the relevant ethical rights as part of the consent process. Sensitivity was shown to the high levels of learning difficulties and vulnerability in this population, with researchers reading and explaining the information sheet, when required, and remaining aware of the potential for any coercion.

All participants were informed that participation was voluntary and that they were free to withdraw at any point, with their decision to participate or otherwise having no bearing on the future care they received or their other legal rights.

Confidentiality

Participants were all informed of the arrangements to ensure confidentiality, including the limits of this, and data protection.

During the consent process, the limits of confidentiality were clearly outlined with participants. Participants were informed that all information disclosed during the research process was confidential unless (1) the information imparted revealed real risks of harm (e.g. self-harm, suicide, violence towards others) that needed to be acted on to safeguard the participant or others; and/or (2) the participant revealed criminal activity previously unknown to a relevant authority. This covered the potential for reporting previously undisclosed offending outside custody, or criminal offences committed while in prison including, but not limited to, illicit drug importation/use, importation or possession of other prohibited items (e.g. mobile phones), assaults on other prisoners and/or other criminal activity (e.g. continuing involvement with crime outside prison). How a required breach of confidentially would be dealt with depended on the circumstances. Risks of self-harm or suicide would involve the researcher either starting self-harm management processes [Assessment, Care in Custody and Teamwork (ACCT)] if the risk had not been previously identified, or liaising with staff directly to contribute to a person’s ongoing care under ACCT if the risk was already known. Reporting of previous/current criminal activity would be reported to the prison’s security department using routine procedures.

No circumstances arose that required a breach of confidentiality.

Each participant was allocated a unique participant identification number. This identifier was used to link participants’ study data with identifiable data, which were stored securely and separately.

Individuals lacking capacity

Researchers received training in assessing capacity using the two-stage process outlined in the Mental Capacity Act (2005). 86 If there was any indication that an individual lacked the capacity to consent, that individual was excluded from participation.

Randomisation

An individual-level randomised design was selected for two key reasons. First, it was anticipated that there would be minimal contamination because older prisoners are not usually systematically identified on entry into prison and, therefore, the older prisoner lead does not usually come into contact with the older prisoners unless specific issues arise. Second, a clustered or stepped-wedge design was considered; however, such designs would not have been feasible to implement because many more institutions would be required to participate, thus having an impact on cost and time.

Randomisation was undertaken by the Manchester Academic Health Science Centre Clinical Trials Unit (MAHSC-CTU). Participants were randomised to receive the OHSCAP or TAU. The MAHSC-CTU provided a telephone-based central randomisation service for the trial. The allocation method was minimisation with a random element using imbalance scores over the margins of two factors: institution and baseline number of unmet needs (0, 1, 2, 3, ≥ 4). With minimisation, the group allocated to the next participant is dependent on the characteristics of existing participants. 87 The aim is that the allocation of each participant should minimise the imbalance across groups. In order to achieve this, provisional imbalance scores were calculated (one for each trial arm assuming allocation of the case to that arm). The imbalance score was Sum (|n1 – n2|), where the sum is taken over the observed levels of each factor of the ‘case at hand’ and n1 and n2 are the accrued cases to date in the two trial arms for the given levels, including the provisional allocation. If the imbalance scores were tied, we considered imbalance in the totals in each arm without reference to the factors. Allocation was made to the arm that would yield lower imbalance with probability 0.75 or with probability 0.5 if scores were tied. This random allocation sequence was generated by David Ryder [statistician, Clinical Trials Unit (CTU)].

The procedures for randomisation were as follows. Once a participant had consented to participate and had been confirmed as eligible for the trial, and the baseline assessments were completed, contact was made with the MAHSC-CTU to be allocated a participant identification number and allocated to either the intervention or the TAU group. The following information was provided: a trial password (allocated by the project manager), the centre name, the participant’s initials and date of birth, and the caller’s name. A participant identification number was allocated immediately, followed by, via e-mail, the result of allocation to intervention or TAU.

Blinding

When possible, RCTs should be double blinded, that is, the participants and researchers should not be aware of which group they have been allocated to. 88 Participants unavoidably became aware of which group they had been allocated to when they received the intervention. Furthermore, the researchers did know which group some of the participants belonged to because 14 of the participants in the intervention group were invited to take part in qualitative semistructured interviews. Within the current study, however, quantitative data analysis was conducted blind. Identifying variables were removed by a statistician at the CTU before the data were provided to the researcher conducting the analysis.

Intervention

The OHSCAP was developed and implemented as part of a previous study funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Service Delivery and Organisation programme. An action learning group (including prisoners, NHS staff and prison staff) at one prison in England developed the OHSCAP. 27

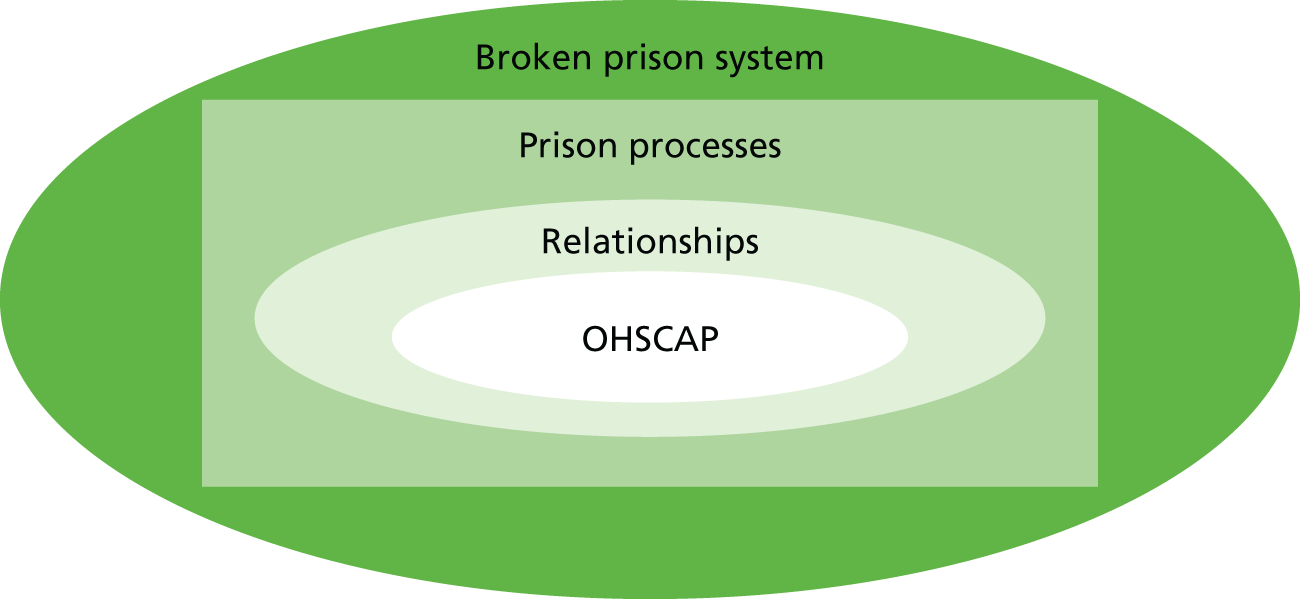

The OHSCAP is a structured approach for better identifying and managing the health and social care needs of older prisoners. The previous study showed that the OHSCAP was acceptable to prisoners and staff, could be integrated into current prison/health-care processes, assisted effective multiagency working, provided an opportunity for prisoners to raise concerns that would have otherwise gone unreported and could be successfully conducted by a prison officer.

The OHSCAP is paper based and information collected is uploaded onto existing prison, health and offender management computer programs. A copy of the OHSCAP is appended (within the OHSCAP manual; see Appendix 3). The first page of the OHSCAP includes instructions for completion and background information. A table for collecting basic demographic information including name, age, date of birth and NOMS number is also included. The OHSCAP consists of an assessment, a care plan and reviews of these.

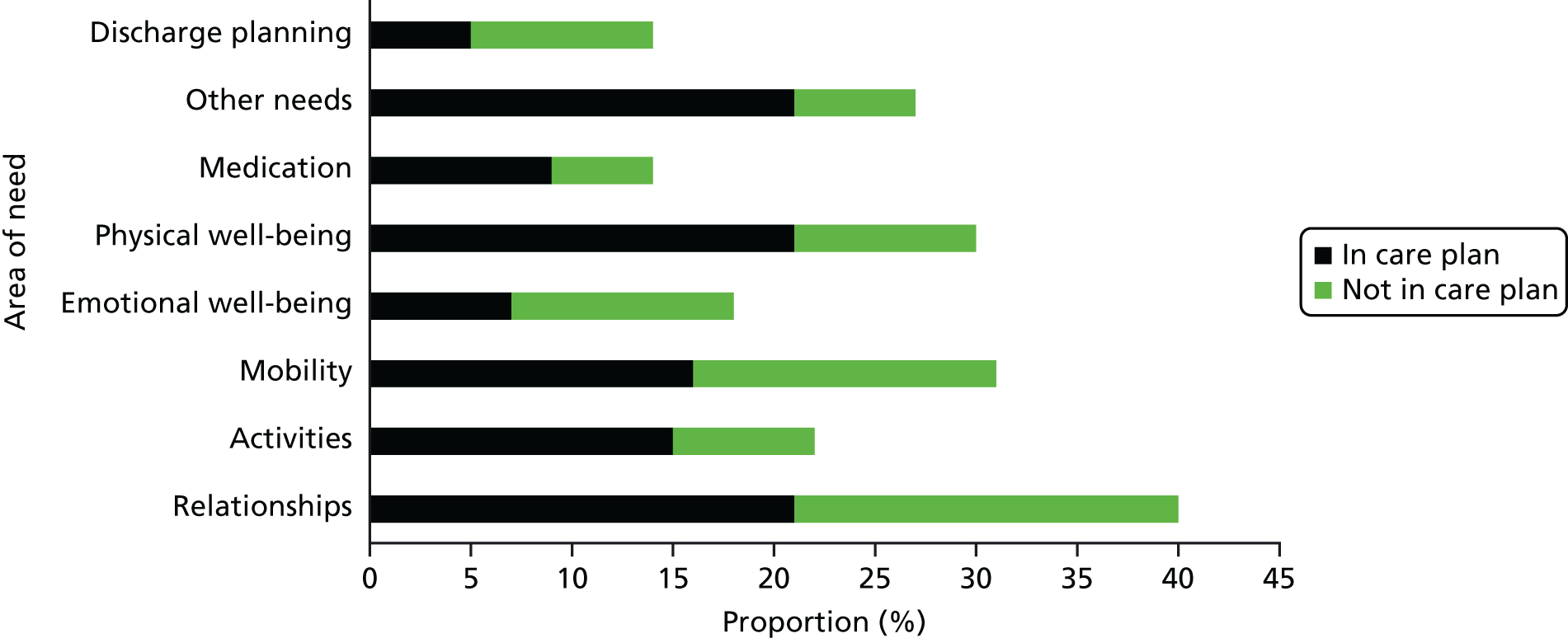

The assessment includes a series of open questions to facilitate discussion, and is divided into three key parts, namely social, well-being and discharge planning. The social assessment includes open questions around relationships, activities and mobility. The well-being assessment includes exploratory questions around emotional well-being, physical well-being, and medications and treatment. A section for other concerns is also incorporated. The final section of the assessment includes open questions around discharge planning. A series of ‘trigger’ open questions are included for each of these sections. A place for the signatures of those conducting the assessment and the prisoner is also incorporated.

The care plan consists of a matrix with five columns. These are (1) issue raised from assessment, (2) aim of the proposed action, (3) action (including by whom and when), (4) date to be reviewed and rationale and (5) status of action.

The review section includes space for a date and details of the reviewer. It also takes the form of a matrix and includes the following columns: (1) progress since last review, (2) action planned and (3) next review with rationale.

The assessment is conducted approximately 1–2 weeks after an older prisoner enters prison. This was based on discussion in the action learning group around the wealth of information that is both asked of and provided to other prisoners, immediately after they arrive in prison, and around how prisoners are suffering from ‘entry shock’ and would find it difficult to cope with a further assessment during the initial entry period. In addition, it was felt that older prisoners require a period to settle into the prison in order to be able to identify their needs effectively. The older prisoner lead accesses the prison’s computer system, C-NOMIS, on a daily basis to identify any prisoners aged ≥ 50 years newly received from court into the prison, whose known release date (convicted prisoners) or likely release date (unconvicted), is at least 3 months after prison entry. The older prisoner lead conducts the assessment on a one-to-one basis with the older prisoner. The care plan is completed in conjunction with the older prisoner, who is provided with a copy of the OHSCAP. In addition, a summary of the OHSCAP is entered onto the prison computerised information system (C-NOMIS) and a copy of the OHSCAP is scanned onto the prison computerised clinical records (SystmOne; The Phoenix Partnership, Leeds, UK) and probation computer records (Offender Assessment System). The older prisoner lead conducts reviews as considered necessary and develops further action plans. Reviews of care plans involve ensuring that actions have been completed and pursuing these as necessary.

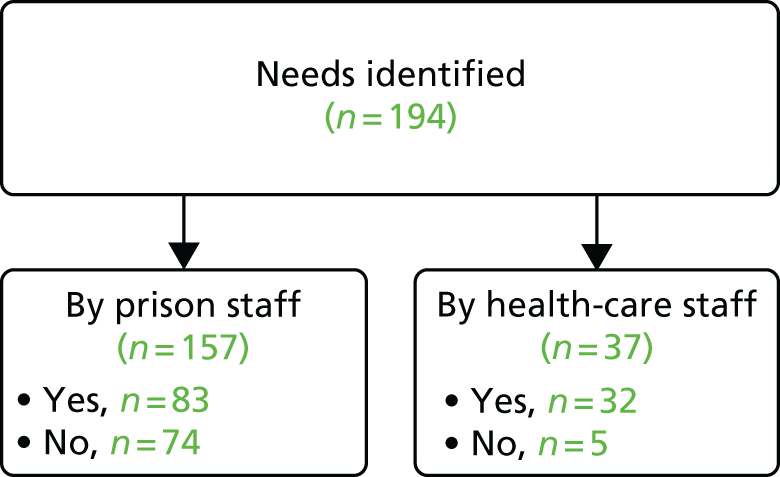

It was initially intended that the older prisoner leads, who are usually prison officers, would deliver the intervention. This followed the recommendation of an earlier action learning group comprising prisoners, NHS staff and prison staff at one particular prison who decided that they would be the most appropriate individuals to conduct the OHSCAP in their establishment. The previous study found that prisoners were happy to discuss their health and social care issues with prison officers. However, in 6 of the 10 sites in this study, health-care workers delivered the OHSCAP, as this was deemed by senior managers at the sites to be more appropriate or more achievable within their prison at the time the project was being set up. This was largely because of the benchmarking process that was taking place at the time, which was resulting in a reduction in prison officers and the loss of some roles, including the disability liaison officer (DLO) in some establishments. The DLO is responsible for supporting prisoners with disabilities. They assess the needs of disabled prisoners and try to ensure that adaptations are made when necessary. The DLO is often given the responsibility of supporting older prisoners as well. How they do this varies from prison to prison, but may include facilitating older prisoner groups. The OHSCAP facilitator received training before commencing this work.

Training

All of the OHSCAP facilitators were trained to deliver the OHSCAP, in line with the OHSCAP manual (see Appendix 3). Throughout the study, two training sessions were held at the University of Manchester, which were attended by facilitators from all study sites. Some of the facilitators attended both sessions and were able to share experiences and good practice, having already completed the OHSCAP process with some prisoner participants. Ongoing support was also offered by Dr Elizabeth Walsh, who has vast experience as a clinician within prison settings. She acted as a mentor to facilitators and was contactable by telephone and e-mail, should they have any questions or need any reassurance. Additional site-specific training sessions were provided at prisons that joined part-way through the study in an attempt to bolster recruitment.

Treatment as usual

Treatment as usual included the standard, non-age-specific health assessment carried out at prison entry. 59 Support provided as TAU varied from prison to prison, but included interventions such as older prisoner social groups, peer carers and healthy man checks. Ongoing assessments and interventions followed local procedures at each establishment. Previous research has indicated that the identification of health and social needs and subsequent care planning is generally ad hoc and inadequate. 55

Data collection and management

The following outcome measures were used at baseline and 3 months after prison entry.

Primary outcome measure

The primary outcome measure was the mean number of unmet health and social care needs at 3 months, as measured by the Camberwell Assessment of Need – Short Forensic Version (CANFOR). 89 CANFOR includes 25 domains, namely accommodation, food, looking after the living environment, self-care, daytime activities, physical health, psychotic symptoms, information about condition and treatment, psychological distress, safety to self, safety to others, alcohol, drugs, company, intimate relationships, sexual expression, childcare, basic education, telephone, transport, money, benefits, treatment and access to anti-recidivist interventions for sexual offending and arson. Participants are asked to identify if they have no need, a met need or an unmet need in each of these domains. The extended version of this tool incorporates the perspectives of carers or members of staff working with participants. The short version of the tool was selected because of previous difficulties experienced during the pilot study27 in identifying a member of staff who knew the older prisoner well enough to answer these questions. This was a particular challenge immediately after entry into the prison. A limitation of the tool is that it provides respondents only with an opportunity to state whether their needs in each domain are met or unmet, rather than any indication of the extent to which this is the case. Furthermore, it does not provide specific details about which areas of the domains are met/unmet. However, the CANFOR is the only validated tool available for assessing need among forensic populations. In addition, it has been successfully used in previous studies with older prisoners. 7,20,27

Secondary outcome measures

-

Functional health and well-being and ADL as measured by BADLS. 80 The BADLS measure incorporates the 20 domains of preparing food, eating, preparing drink, drinking, dressing, hygiene, teeth, bath/shower, toilet/commode, transfers, mobility, orientation (time), orientation (space), communications, telephone, housework/gardening, shopping, finances, games/hobbies and transport. The scale was originally designed for patients with dementia, but has recently been used with an older prisoner population. 7,20 Hayes et al. 7,20 omitted items 18 (money) and 20 (transport) because they are not relevant to prisoners, and more relevant versions of these items are covered in the CANFOR. 89 This approach was also adopted for the current study. Total scores were not used because this would affect the internal consistency of the measure. Items were, therefore, to be examined separately.

-

Depression as measured by the Geriatric Depression Scale – short form (GDS-15). 90 The GDS-15 contains 15 questions, which may be answered with ‘yes’ or ‘no’. Each item to which a response of ‘yes’ indicates depression generates a score of 1. A total scale score of ≥ 5 suggests mild depression, and guidelines suggest that further investigation is required, and a total score of ≥ 10 almost always indicates severe depression. The scale has been validated for use with older people and has been used with older prisoners in a previous study. 41 Murdoch et al. 41 adapted question 12 of the assessment from ‘Do you prefer to stay at home rather than go out and do new things?’ to ‘Do you go on association?’. Association refers to prisoners leaving their cells to mix with other prisoners and participate in games and/or other social events. The current study also made this alteration to the question to make it appropriate for prison use.

-

Health-related quality of life as measured by the EuroQoL-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L). 91 The EQ-5D-5L is a standardised assessment that has been widely adopted and validated in a variety of different populations. 92 The EQ-5D-5L encompasses the following five domains of health: mobility; ability to self-care; ability to undertake usual activities; pain/discomfort; and anxiety/depression. For each of these, five options are provided (e.g. no problem, slight problem, moderate problem, severe problem, unable). The EQ-5D-5L will be used because the current study is part of a broader study measuring the cost-effectiveness of the OHSCAP. The EQ-5D-5L is recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) to enhance the comparability of different studies. 92 The visual analogue scale aspect of this tool was excluded to reduce participant burden, as this aspect of the tool is not widely used. This was administered face to face. The face-to-face version of this tool was not available when this research commenced.

-

Bespoke OHSCAP research tool. The extent to which specific health and social care needs had been addressed was measured by the bespoke OHSCAP tool specifically designed for the study. It has been necessary to design a specific tool because no standardised assessments will measure improvements in specific issues for older prisoners, such as hearing instructions, receiving information about their release or delays in receiving medication. The bespoke OHSCAP research tool is based around the three sections of the OHSCAP assessment, that is, physical health, well-being and discharge from prison. A number of specific topics are addressed in each of these sections. For each topic, participants are asked if they are experiencing difficulties, if they are receiving help and whether or not they have an unmet need in this area.

The following tools were also used at baseline to describe the sample.

-

PriSnQuest. 84 PriSnQuest consists of seven questions, each with yes or no responses. A score of three or more indicates that a further assessment for mental health is required. PriSnQuest has been selected because it has been developed from other standardised assessments, is widely used in prison and is short, reducing participant burden.

-

Burvill grid to measure physical health. 85 The Burvill grid was used to obtain data on the physical health of participants. The Burvill grid categorises physical disorders into different body systems. Each system is rated according to severity of the disorder (coded 0 = absent, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe) and disability as a consequence of the disorder (coded 0 = none, 1 = little, 2 = some, 3 = great deal). Physical problems are also defined as acute or chronic. A disorder is considered chronic if it has been present for at least the previous 3 months. The Burvill grid has been used in previous studies of older prisoners. 20,35

All data were collected between 28 January 2014 and 6 April 2016.

Fidelity

The fidelity, and quality, of implementation of the OHSCAP were assessed using an audit tool specifically designed for this study (see Appendix 4 and Chapters 4 and 5).

Sample size

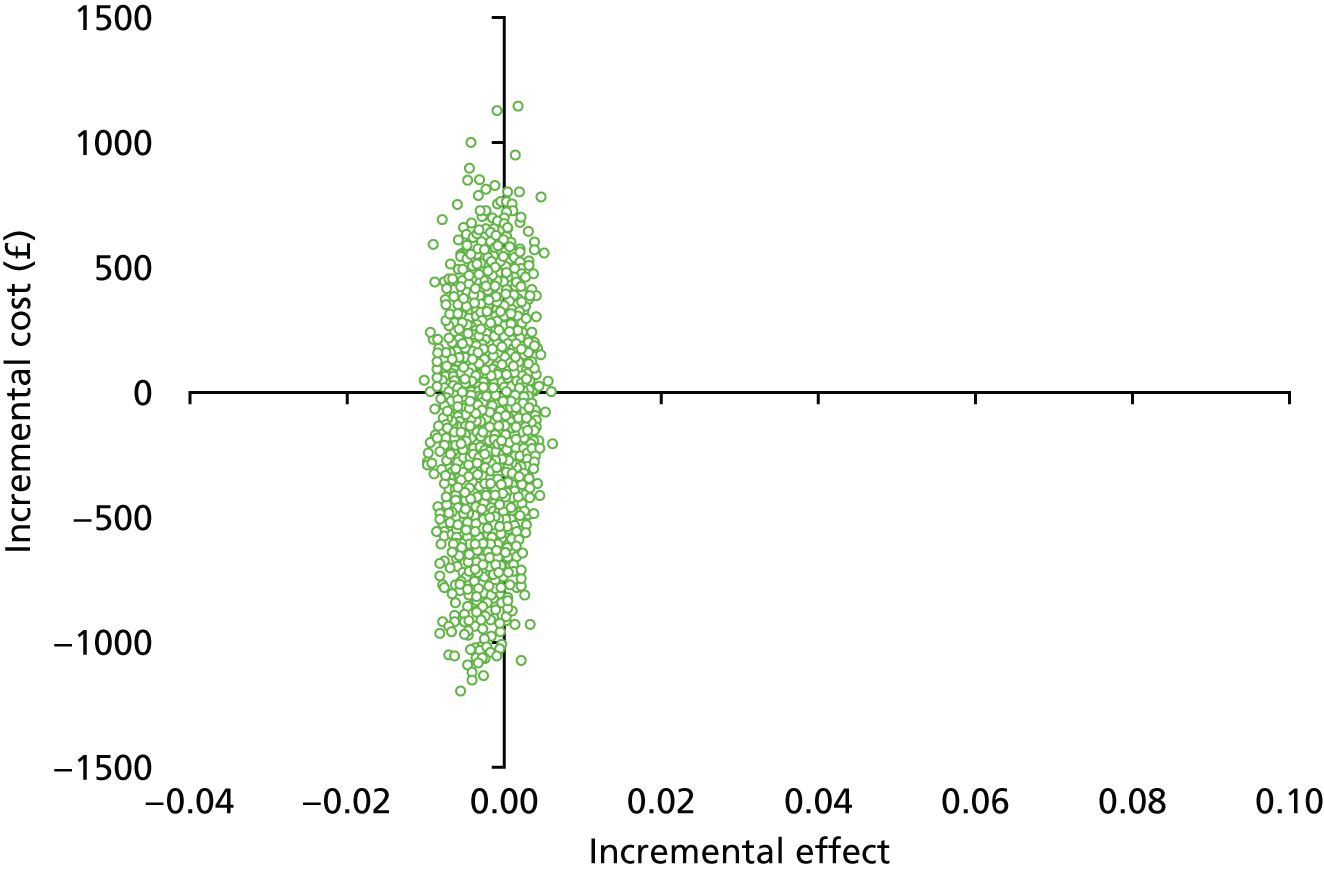

From our previous work (a cross-sectional study assessing the unmet needs of 100 older prisoners at baseline) the mean number of unmet needs was assumed to be 2.71 [standard deviation (SD) 2.65 unmet needs]. The distribution of unmet needs, ranging from 0 to 25, was unsurprisingly positively skewed, with a median number of unmet needs of 2. Although we did not have supporting data, we assumed that this distribution would be broadly similar at 3 months’ follow-up in the TAU group. The purpose of the current study was to see if the average number of unmet needs can be reduced with the OHSCAP intervention. For the study to be practice-changing, we believed that at least a 30% reduction, to a mean of 1.90 unmet needs, was required, and thus powered the study proposal accordingly [mean 1 = 2.71, mean 2 = 1.90 (= 0.7 × mean 1), common SD 2.65 unmet needs, implies n = 169 participants per group for 80% power in a two-tailed t-test at a 5% level of significance]. A 1 : 1 randomised trial employing a two-tailed t-test at the 5% level of significance would require 169 per group for 80% power if the true means are 2.71 and 1.90 unmet needs and the common SD is 2.65 unmet needs. As the distributions would be quite skewed, it was considered preferable at the planning stages to use a non-parametric Mann–Whitney U-test. The asymptotic relative efficiency of this test is at worst 0.864 compared with the t-test, and so a conservative approach is to inflate the proposed sample size accordingly, that is, 169/0.864 = 196 per group. Linear regression was used to analyse the primary outcome measure with bootstrapping to account for skewness, and adjust for minimisation factors (institution and baseline measures of unmet need). This allowed for a more sophisticated approach than would have been adopted if we had used the Mann–Whitney U-test as originally planned and, consequently, we will have > 80% power. The trial stopped when we achieved sufficient numbers at baseline to estimate that we would reach our follow-up target.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were carried out using the intention-to-treat principle with data from all participants included in the analysis, including those who did not complete the OHSCAP assessments.

Analysis was conducted in Statistical Product and Service Solutions, version 20 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistics within each randomised group are presented for baseline values. These include counts and percentages for binary and categorical variables, and means and SDs, or medians with lower and upper quartiles, for continuous variables, along with minimum and maximum values and counts of missing values. There were no tests of statistical significance or confidence intervals (CIs) for differences between randomised groups on any baseline variable.

It was important to verify that the characteristics of participants that may influence the outcome were distributed evenly between groups at baseline, so that any difference in outcome could be attributed to the intervention. 93 The minimisation process used as part of the randomisation procedures ensured balance between the TAU and intervention groups. Prognostic variables are described for each of the groups to demonstrate that the randomisation procedure has been properly conducted. 93

Primary outcomes

The primary hypothesis for the change in the mean number of unmet needs, as measured by the CANFOR, was analysed using appropriate regression models. We adjusted for baseline characteristics used in the minimisation process, for example site and number of unmet needs at baseline. We used bootstrapping to account for the skewness in the outcome of the data. The 95% CIs were calculated around all key effect size measures and two-sided p-values were reported.

In addition to analysing the mean number of unmet needs, we used a Poisson model to analyse the data as counts.

The CANFOR was used because it was the most appropriate available tool for assessing unmet health and social care needs within the prison population. The research team were, however, aware that there were certain domains of the CANFOR that the OHSCAP specifically aimed to address and some domains of the CANFOR that the OHSCAP did not aim to address. The research team therefore felt that it would be useful to analyse the data separately for the specific domains of the CANFOR that were considered most relevant to the OHSCAP. The aim of this analysis was to gain a more detailed understanding of the specific domains of the CANFOR that the OHSCAP appeared to assist more with and of which domains the OHSCAP was less able to address.

Logistic regression was used to conduct this analysis, with adjustment for site and number of unmet needs at baseline. Table 2 shows the ratings the research team applied to each of the domains for relevance to the OHSCAP. The highest value is 3 and the lowest is 1.

| Domain number | Domain | Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Accommodation | 3 |

| 2 | Food (meeting dietary needs) | 3 |

| 3 | Looking after living environment | 3 |

| 4 | Self-care | 3 |

| 5 | Daytime activities | 3 |

| 6 | Physical health | 3 |

| 7 | Psychotic symptoms | 3 |

| 8 | Information about conditions and treatment | 3 |

| 9 | Psychological stress | 3 |

| 10 | Safety to self | 3 |

| 11 | Safety to others | 2 |

| 12 | Alcohol | 2 |

| 13 | Drugs | 2 |

| 14 | Company | 3 |

| 15 | Intimate relationships | 1 |

| 16 | Sexual expression | 1 |

| 17 | Childcare | 1 |

| 18 | Basic education | 3 |

| 19 | Telephone | 3 |

| 20 | Transport | 1 |

| 21 | Money | 3 |

| 22 | Benefits | 2 |

| 23 | Treatment | 3 |

| 24 | Sexual offending | 2 |

| 25 | Arson | 1 |

Secondary outcomes

Similar approaches were adopted for the secondary outcomes, with the form of regression depending on the distribution of the particular outcome. Linear models were used for continuous outcomes, and logistic regression for binary outcomes. Bootstrapping was used only with linear regression. For each of the secondary outcome measures we adjusted for establishment at baseline and for that specific secondary outcome measure at baseline.

Missing data

Data completeness and accuracy were confirmed by the MAHSC-CTU during the data entry process. If, during the data collection and inputting processes, a field was found to have been left blank, the Data Manager at the CTU raised a query and the research team clarified whether the missing information could be obtained or confirmed that it was not available. This assisted in preventing unexplained missing data. The research team conducted further checks to ensure that the data were complete and accurate. Missing data were minimal and, therefore, it was not necessary to compute any missing data.

Database and data entry checks

All data entry checks were conducted by the CTU throughout the duration of the trial. Any missing or inconsistent data were clarified with sites through the data query/correction process. In line with the CTU’s policies, 100% of critical fields and 2% of non-critical fields were quality checked.

Harms reporting

Definitions

Adverse event

An adverse event (AE) was defined as any untoward medical occurrence, unintended disease or injury, or any untoward clinical signs (including an abnormal laboratory finding), in participants, whether or not related to any research procedures or to the intervention.

Seriousness

Any AE will be regarded as serious if it:

-

results in death

-

is life-threatening

-

requires hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation

-

results in persistent or significant disability or incapacity

-

consists of a congenital anomaly or birth defect.

An AE meeting any one of these criteria was considered a serious adverse event (SAE).

Relationship

The expression ‘reasonable causal relationship’ means, in general, that there is evidence or argument to suggest a causal relationship. The research team assessed the causal relationship between reported events and trial participation according to the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT)65 guidance.

No harms were reported that were considered to be related to this trial.

Reporting serious adverse events

In this study, SAEs were reported to the Chief Investigator (JS), regardless of relatedness, within 24 hours of the principal investigator (or authorised delegate) becoming aware of the event. All SAEs deemed to have a causal relationship were reported to the Trial Steering Committee. Any non-serious AEs, regardless of relatedness, were not reported in this study.

Patient and public involvement

The current study is informed by a previous NIHR-funded study (Service Delivery and Organisation 08/1809/230). As part of the previous study, older prisoners at one prison in England designed the OHSCAP as active members of an action learning group. The OHSCAP was piloted as part of the current research. Prisoners successfully participated in the action learning group and have since reported that they valued the opportunity to be involved in shaping future services. The information the prisoners provided was extremely valuable, and informed the content, and format, of the OHSCAP, for example the specific inclusion of open questions to facilitate discussion. These discussions have also informed the development of the current study. Furthermore, Dr Stuart Ware is a co-applicant and Project Management Group member. Dr Ware is an ex-older prisoner and founder member of the Restore Support Network (RSN), a support network for older prisoners. His involvement has been highly valuable and an important mechanism for ensuring we have considered the needs of older prisoners throughout the current study. Additionally, we had two service user representatives sit on the independent Trial Steering Committee for this study.

Chapter 3 Randomised controlled trial results

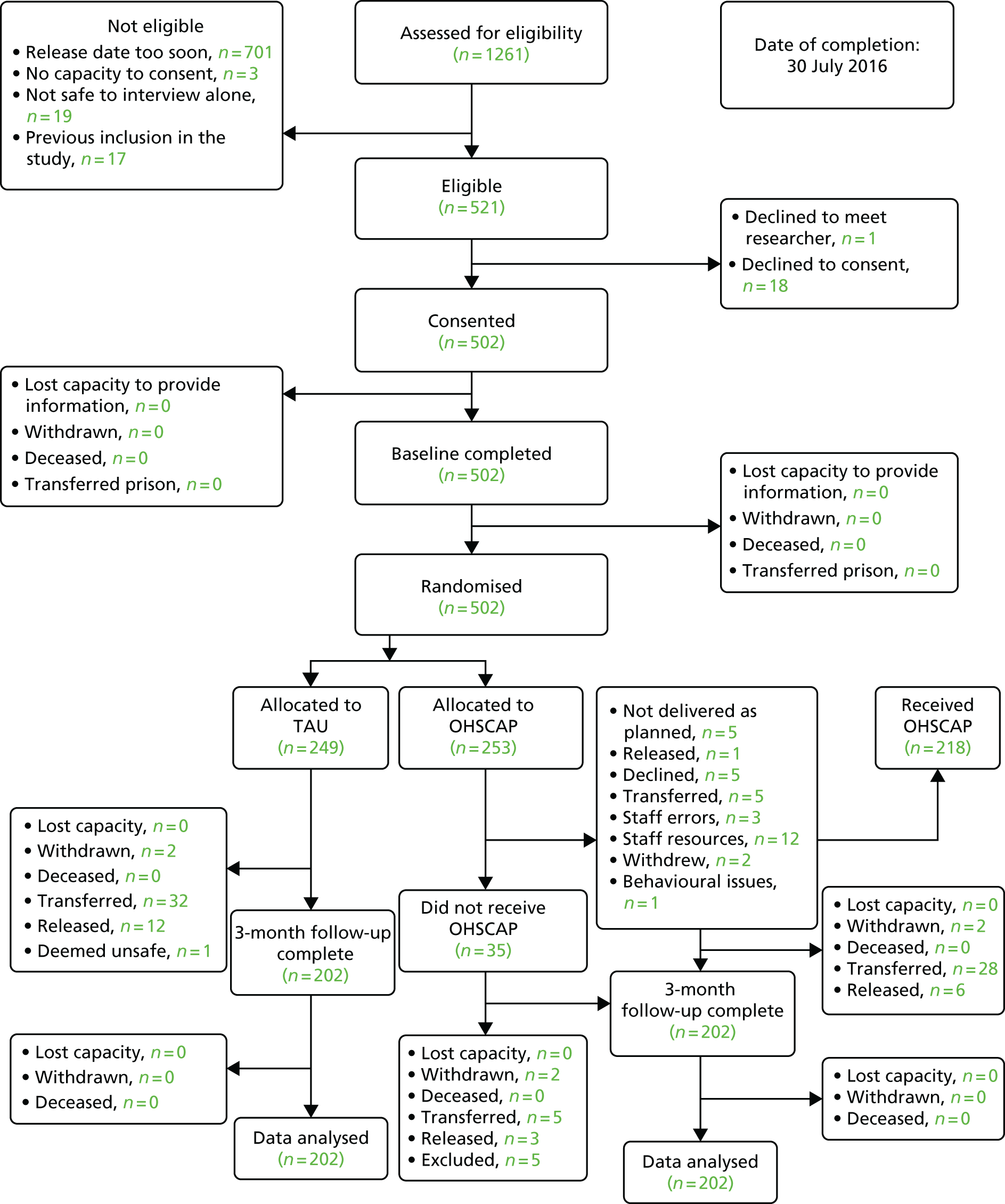

In total, 1261 older prisoners were screened for inclusion in the study. Of these, 521 were eligible for inclusion; informed consent was obtained and baseline assessments were conducted with 502 participants. The study CONSORT flow diagram detailing refusals, loss to follow up, etc., is given in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

The CONSORT flow diagram.

Baseline comparability

Table 3 displays a summary of the baseline demographics in order to describe the sample and illustrate the baseline comparability of the randomised groups.

| Demographic | Trial arm | All (N = 497) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TAU (N = 249) | OHSCAP (N = 248) | ||

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 59 (7.8) | 57 (7.0) | 58 (7.4) |

| Age group (years), n (%) | |||

| 50–54 | 101 (41) | 118 (48) | 219 (44) |

| 55–59 | 56 (22) | 56 (23) | 112 (23) |

| 60–64 | 42 (17) | 35 (14) | 77 (16) |

| 65–69 | 18 (7) | 22 (9) | 40 (8) |

| 70–74 | 21 (8) | 8 (3) | 29 (6) |

| 75–79 | 8 (3) | 8 (3) | 16 (3) |

| 80–84 | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 2 (0) |

| 85–89 | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 1 (0) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) |

| Establishment, n (%) | |||

| Establishment 1 (Local) | 52 (21) | 52 (21) | 104 (21) |

| Establishment 2 (Local) | 1 (0) | 3 (1) | 4 (1) |

| Establishment 3 (Local) | 57 (23) | 59 (24) | 116 (22) |

| Establishment 4 (High security) | 22 (9) | 26 (10) | 48 (10) |

| Establishment 5 (Open) | 46 (19) | 46 (18) | 92 (19) |

| Establishment 6 (Training) | 26 (10) | 22 (9) | 48 (10) |

| Establishment 7 (Open) | 12 (5) | 7 (3) | 19 (4) |

| Establishment 8 (Training) | 5 (2) | 6 (3) | 11 (2) |

| Establishment 9 (Training) | 11 (4) | 10 (4) | 21 (4) |

| Establishment 10 (Training) | 17 (7) | 17 (7) | 34 (7) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White British | 206 (85) | 226 (91) | 432 (87) |

| Other white | 9 (3) | 5 (2) | 14 (3) |

| White and black Caribbean | 2 (1) | 0 (0) | 2 (0) |

| Black Caribbean | 7 (3) | 0 (0) | 7 (1) |

| Other black | 7 (3) | 2 (1) | 9 (2) |

| Indian | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 4 (1) |

| Pakistani | 6 (2) | 3 (1) | 9 (2) |

| Other Asian | 2 (1) | 1 (0) | 3 (1) |

| Other | 8 (3) | 7 (3) | 15 (3) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | 2 (0) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |||

| Single | 82 (33) | 69 (28) | 151 (30) |

| Married (partner) | 97 (39) | 114 (46) | 211 (43) |

| Divorced | 40 (16) | 37 (15) | 77 (16) |

| Separated | 17 (7) | 15 (6) | 32 (6) |

| Widowed | 13 (5) | 12 (5) | 25 (5) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) |

| Employment status, n (%) | |||

| Employed full-time | 80 (32) | 96 (39) | 176 (35) |

| Employed part-time | 9 (4) | 12 (5) | 21 (4) |

| Unemployed but casual work | 2 (1) | 3 (1) | 5 (1) |

| Unemployed | 40 (16) | 36 (14) | 76 (15) |

| Long-term sickness (on benefits) | 47 (19) | 40 (16) | 87 (18) |

| Long-term sickness (employed) | 11 (4) | 10 (4) | 21 (4) |

| Retired | 54 (21) | 38 (16) | 92 (19) |

| Carer | 4 (2) | 7 (3) | 11 (2) |

| Other | 2 (1) | 6 (2) | 8 (2) |

| Living circumstances, n (%) | |||

| Alone | 106 (43) | 93 (38) | 199 (40) |

| With spouse/partner/children | 49 (19) | 63 (25) | 112 (22) |

| With spouse/partner (no children) | 51 (21) | 52 (21) | 103 (21) |

| With children only | 15 (6) | 9 (4) | 24 (5) |

| With parents | 9 (4) | 11 (5) | 20 (4) |

| With other friends/family | 17 (7) | 16 (7) | 33 (7) |

| Probation approved premises | 2 (0) | 1 (0) | 3 (1) |

| Nursing home | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) |

| Other | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) |

| Accommodation, n (%) | |||

| Homeless/no fixed abode | 7 (3) | 1 (0) | 8 (2) |

| Hostel | 4 (1) | 4 (2) | 8 (1) |

| House or flat | 225 (91) | 235 (95) | 460 (93) |

| Nursing home | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) |

| Sheltered accommodation | 4 (2) | 1 (0) | 5 (1) |

| Bungalow | 6 (2) | 1 (0) | 7 (1) |

| Other | 3 (1) | 5 (3) | 8 (2) |

| Main offence, n (%) | |||

| Violence against a person | 33 (13) | 29 (12) | 62 (12) |

| Sexual offence | 98 (39) | 109 (44) | 207 (42) |

| Robbery | 5 (2) | 7 (3) | 12 (2) |

| Burglary | 10 (4) | 9 (3) | 19 (4) |

| Theft and handling | 2 (1) | 8 (3) | 10 (2) |

| Fraud and forgery | 22 (9) | 21 (10) | 43 (9) |

| Drug offences | 52 (21) | 36 (14) | 88 (18) |

| Other | 24 (8) | 28 (11) | 52 (10) |

| Missing | 3 (1) | 1 (0) | 4 (1) |

| Prisoner status, n (%) | |||

| Remand | 41 (17) | 37 (15) | 78 (16) |

| Convicted, unsentenced | 13 (5) | 8 (3) | 21 (4) |

| Convicted, sentenced | 195 (78) | 203 (82) | 398 (80) |

| Participant has been in prison before, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 132 (53) | 123 (49) | 242 (48) |

| No | 117 (47) | 125 (51) | 255 (52) |

| Times been in prison before, mean (SD) | 5.23 (7.2) | 4.43 (6.7) | 4.82 (6.9) |

The sample were all male (100%) and the majority were white British (87%). The mean age of the sample was 58 years; 92 (33%) were aged ≥ 60 years, 43% were married or had a partner and 35% were employed full-time at the time of imprisonment. One hundred and ninety-nine (40%) were living alone and 460 (93%) were living in a house or flat before being sent to prison.

Sexual offences were the most common type of index offence (42%), followed by drug (18%) and violent offences (12%). Eighty per cent had been convicted and sentenced. Just over 50% had not been in prison before, and on average participants had been in prison five times previously. Forty per cent were residing on a general wing for convicted prisoners, 25% on an induction wing and 25% on a vulnerable prisoners unit. Prisoners are able to move from basic to standard, and then to enhanced, status if they obey prison rules and demonstrate good behaviour. These statuses have an impact on a number of prisoner entitlements including the number and length of weekly visits and the amount of money they are allowed to spend within the prison. The majority of participants were on a standard regime (66%), as opposed to having basic or enhanced status (Table 4).

| Criminogenic details | Trial arm | All (N = 497) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TAU (N = 249) | OHSCAP (N = 248) | ||

| Type of wing, n (%) | |||

| Remand/induction | 58 (23) | 68 (27) | 126 (25) |

| Convicted | 100 (41) | 96 (39) | 196 (40) |

| Vulnerable prisoners unit | 60 (24) | 67 (27) | 127 (25) |

| Health care | 6 (2) | 3 (1) | 9 (2) |

| Category A/closed secure unit | 2 (1) | 1 (0) | 3 (1) |

| Segregation | 0 (0) | 1 (0) | 1 (0) |

| Detox and drug free | 7 (2) | 4 (2) | 11 (2) |

| Older person | 9 (4) | 6 (3) | 15 (3) |

| Other | 7 (3) | 2 (1) | 9 (2) |

| Current regime, n (%) | |||

| Basic | 6 (2) | 2 (1) | 8 (2) |

| Standard | 158 (64) | 172 (69) | 330 (66) |

| Enhanced | 85 (34) | 74 (30) | 159 (32) |

The majority scored < 3 on PriSnQuest (80%), indicating that they did not require any further mental health assessment at the time the interview was conducted. The most common mental illness was general anxiety disorder (6%, identified via OPCRIT). The mean number of body systems acutely affected, according to the BADLS, was 0.2, and the mean number chronically affected was 2.1 (Table 5).

| Mental and physical health measure | Trial arm | All (N = 497) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TAU (N = 249) | OHSCAP (N = 248) | ||

| PriSnQuest score, n (%) | |||

| 3+ | 52 (21) | 46 (19) | 98 (20) |

| < 3 | 197 (79) | 202 (81) | 399 (80) |

| OPCRIT diagnosis, n (%) | |||

| Psychosis | 8 | 5 | 12 |

| Schizophrenia | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Depression | 5 | 8 | 12 |

| Anxiety disorder | 17 | 16 | 33 |

| Personality disorder | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Harmful use of drugs | 25 | 9 | 34 |

| Harmful use of alcohol | 11 | 15 | 26 |

| Other | 5 | 3 | 5 |

| Total acute severity score, mean (SD) | 0.3 (0.7) | 0.4 (0.9) | 0.3 (0.8) |

| Total chronic severity score, mean (SD) | 4.3 (3.3) | 3.5 (3.2) | 3.9 (3.3) |

| Total acute disability score, mean (SD) | 0.2 (0.7) | 0.2 (0.7) | 0.2 (0.7) |

| Total chronic disability score, mean (SD) | 3.7 (3.4) | 2.9 (2.97) | 3.2 (3.2) |

| Number of systems acutely affected, mean (SD) | 0.2 (0.4) | 0.2 (0.5) | 0.2 (0.4) |

| Number of systems chronically affected, mean (SD) | 2.3 (1.5) | 1.8 (1.4) | 2.1 (1.5) |

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was the total number of unmet needs as measured by the CANFOR (Table 6). The individual domains of the CANFOR that were considered most relevant and important were also examined individually (Tables 7 and 8). Logistic regression was conducted for the domains of the CANFOR that > 30 participants stated that they had an unmet need for. There were no significant differences between the two groups at 3 months’ follow-up (Table 7). When the log linear negative binominal regression model was run, the results were unchanged from the Poisson model.

| Unmet needs | Time point | Analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Follow-up | ||||||

| TAU (n = 249) | OHSCAP (n = 248) | TAU (n = 202) | OHSCAP (n = 202) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p-value | N | |

| Total number of unmet needs,a mean (SD) | 2.84 (2.311) | 2.57 (1.978) | 2.06 (2.114) | 2.03 (2.066) | 0.088 (–0.276 to 0.449) | 0.621 | 404 |

| Total number of unmet needs (count using Poisson model) | – | – | – | – | –0.078 (–2.16 to 0.061) | 0.272 | 404 |

| Domain | Trial arm, n (%) | Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TAU (N = 202) | OHSCAP (N = 202) | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p-value | N | |

| Psychological stress | |||||

| Met need | 26 (41) | 21 (40) | 1.104 (0.514 to 2.373) | 0.800 | 115 |

| Unmet need | 37 (59) | 31 (60) | |||

| Food | |||||

| Met need | 98 (52) | 110 (58) | 0.716 (0.456 to1.125) | 0.148 | 376 |

| Unmet need | 89 (48) | 79 (42) | |||

| Self-care | |||||

| Met need | 5 (23) | 3 (19) | 1.617 (0.289 to 9.048) | 0.584 | 38 |

| Unmet need | 17 (77) | 13 (81) | |||

| Daytime activities | |||||

| Met need | 100 (65) | 106 (67) | 0.924 (0.572 to 1.493) | 0.747 | 312 |

| Unmet need | 54 (35) | 52 (33) | |||

| Physical health | |||||

| Met need | 120 (72) | 103 (71) | 1.093 (0.659 to 1.812) | 0.731 | 312 |

| Unmet need | 46 (28) | 43 (29) | |||

| Information about conditions and treatment | |||||

| Met need | 5 (9) | 4 (6) | 1.344 (0.327 to 5.528) | 0.682 | 120 |

| Unmet need | 50 (91) | 61 (94) | |||

| Money | |||||

| Met need | 1 (5) | 2 (8) | 0.602 (0.047 to 7.715) | 0.696 | 47 |

| Unmet need | 21 (95) | 23 (92) | |||

| Domain | Trial arm, n (%) | N | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TAU (N = 202) | OHSCAP (N = 202) | ||

| Accommodation | |||

| Met need | 9 (56) | 6 (55) | 27 |

| Unmet need | 7 (44) | 5 (45) | |

| Looking after living environment | |||

| Met need | 13 (39) | 11 (31) | 69 |

| Unmet need | 20 (61) | 25 (69) | |

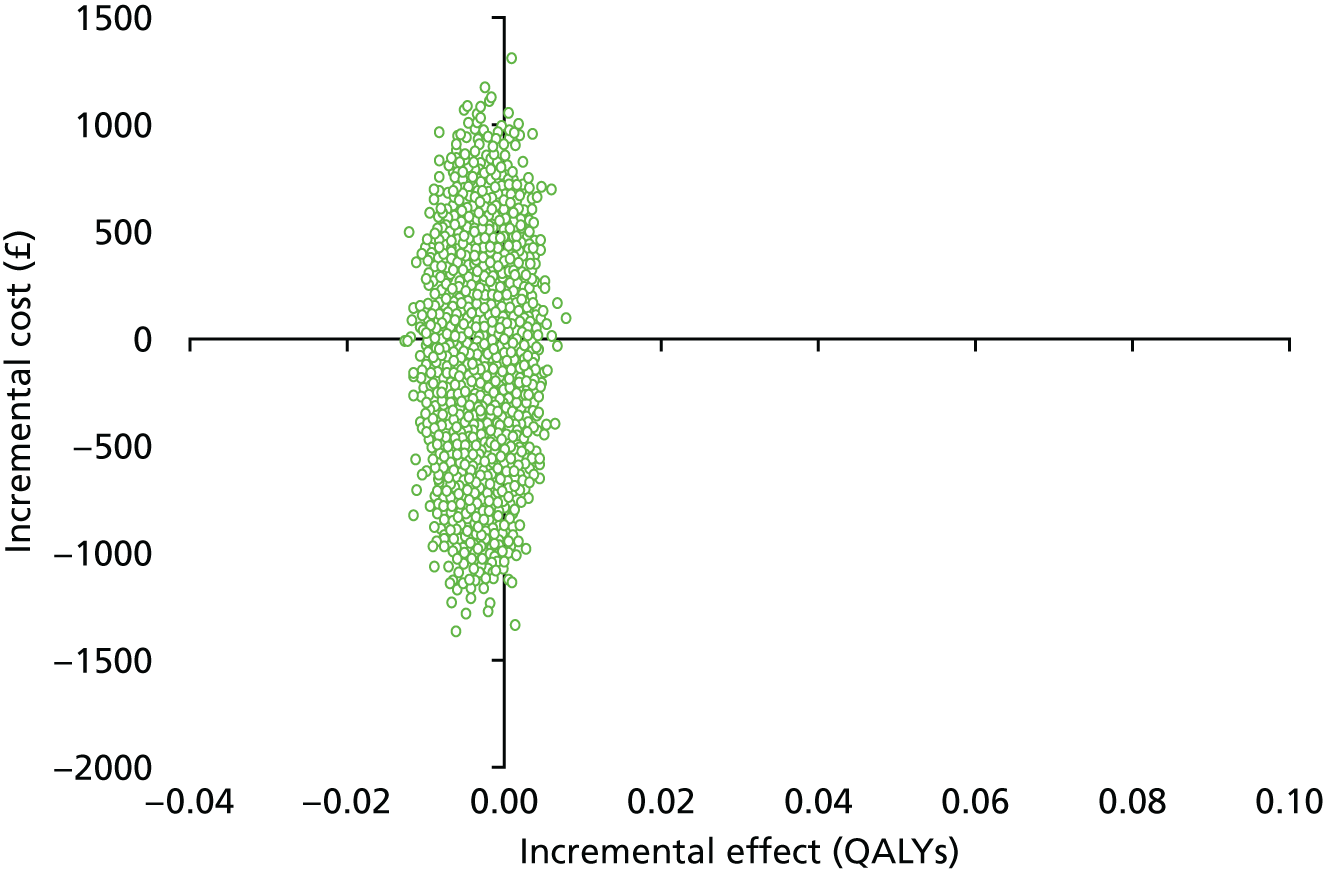

| Psychotic symptoms | |||