Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 12/136/104. The contractual start date was in December 2013. The final report began editorial review in December 2016 and was accepted for publication in May 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Storey et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

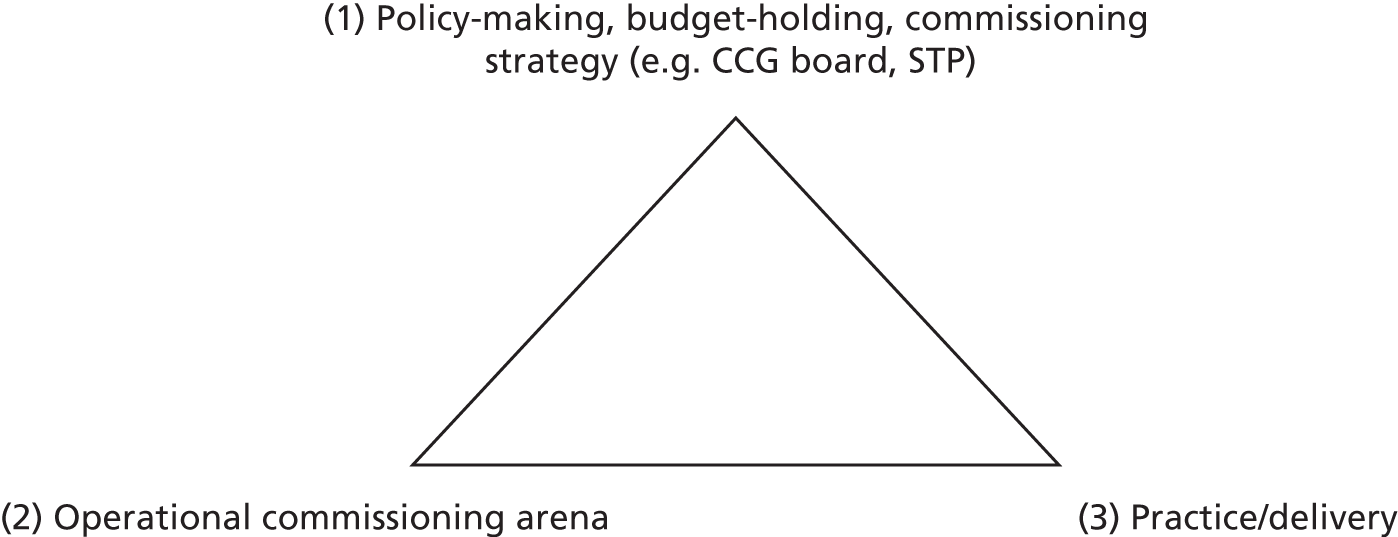

This report presents data and interpretations deriving from a National Institute for Health Research-funded study conducted from 1 November 2013 to 30 November 2016. The research was designed to shed light on the extent and nature of the mobilisation of clinical engagement and clinical leadership. The setting for this was mainly general practitioner (GP)-led Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs), but the issues and processes extend well beyond these. There were two interrelated foci: service redesign attempts as a function of clinical leadership; and CCGs as the institutional base for these efforts. CCGs were the promising, potentially enabling, platform from which would-be clinical leaders might launch their interventions. The main purpose of the research project was to understand how clinicians and others were able to use the opportunity presented by these new institutions to engage with, and indeed lead, the changes to service redesign which so many observers have insisted are fundamentally necessary for the survival of the NHS. Thus, three elements were in play at all times: the triangle of clinical leaders (the agents); the CCGs (the inner context operating within the wider context of other NHS institutions); and service redesign (the process and the potential outcome).

The project generated a unique collection of complementary data sets. These were generated through surveys, case studies, interviews, observations and analysis of documentation. The survey data results were also cross-correlated with NHS England (NHSE) ratings of CCGs. Although some of our findings confirm patterns already revealed by other research (such as the problems with widespread engagement of GPs), other findings which spell out the details of modes of clinical leadership in new service designs are unique and original. They add to the body of knowledge about service redesign in health by elaborating for the first time how this has been achieved within the commissioning domain.

The idea of ‘clinical leadership’ as something important and perhaps even vital in the modern health economy includes, but goes beyond, GPs and CCGs. There is now a much broader expectation that clinicians ‘step up’ to leadership beyond their immediate clinician-to-patient responsibility. As Lord Darzi expressed it:

Clinicians are expected to offer leadership . . . within the clinical team, to service lines, to departments, to organisations and ultimately the whole NHS. It requires a new obligation to step up, work with other leaders, both clinical and managerial, and change the system where this would benefit patients. 1

Thus, there is an ‘expectation’ and an ‘obligation’ that clinicians engage in leadership of the health service. CCGs are but one, albeit very important, example of just such an attempt to enact the expectation, obligation and opportunity. This study provides insight into the degree and the manner in which clinicians did, or did not, rise to the challenge and step up to meet the expectation described by Lord Darzi. The subsequent Lansley reforms in the 2012 legislation built on this same expectation. However, although this was the policy intent, the extent to which this expectation is actually shared and accepted by relevant agents is an empirical question.

The launch of CCGs gave clear institutional expression to the declared policy intent to enable clinical leadership. This was underpinned by a belief that clinicians, most especially GPs, would be able to understand patient priorities and would carry trust and credibility to a degree perhaps not achievable by managers acting alone. Expressed more succinctly, the idea was to put ‘GPs in charge’. All of these ideas were found in the Health and Social Care Act of 20122 and before that in the Public Health White Paper. Equity and Excellence: Liberating the NHS. 3 The Act came into operation on 1 April 2013. The original policy was for GP commissioning but, following the controversy which led to the pause in the progress of the legislation, other clinicians (such as nurses and secondary care doctors) were included in the groups and the name of the new local commission groups was changed accordingly. Our own focus on clinicians as potential leaders follows these developments, meaning that we also tracked the work of the wider group of clinicians. Although we found some nurses active in the leadership of service redesign, the main assumption among most actors in the system was that it was GPs who were the focus of attention and expectation.

From the outset, we anticipated that the policy landscape and the surrounding economic, social and political landscapes would continue to unfold and, in consequence, any response to the clinical leadership opportunities presented by CCGs would have to take those wider dynamic changes into account. There was the possibility that CCGs per se would not survive. This added an important strand to the unfolding drama. In this introduction we summarise the more important policy and contextual changes. These changes provide an important backcloth to the behaviours reported in the findings section (see Chapters 3–5) of this report.

The wider context and the policy intent

The basic policy shift, which abolished primary care trusts (PCTs) and strategic health authorities and introduced local commissioning groups led by GPs, can be seen to build on three ideas: (1) clinical leadership, (2) the use of CCGs as a platform which gave them commissioning powers and (3) the idea that these actors would use these powers to improve the quality and cost-effectiveness of the NHS and to redesign services (indeed ‘transform’ them) to make them better suited to local needs, in more effective and sustainable ways.

The policy, its ensuing reform and its legislative package was hugely controversial. The whole edifice could be seen as a massive experiment. Handing the purse strings to new groupings of GPs and disbanding existing structures came as a surprise; it had not featured in the Conservative Party Manifesto of 2010. It became mandatory for GP practices to be part of, and indeed members of, a CCG. Our research project was designed to target a set of questions which went to the heart of the package of reforms. In essence, the underlying aim was to assess how clinical leadership in and around CCGs would operate in practice. By ‘operate’ we mean what it would deliver and how it would produce any achieved outcome. In order to answer these questions, the research design was built, centrally, around a study of initiatives in specific service areas in order to map these in a manner which dug beneath the rhetoric of reform. These service areas were identified by the wide range of stakeholder informants at the scoping stage as the ones most critical to the future viability of the NHS. The service areas identified were redesigning urgent care, managing long-term conditions, care of the frail elderly and mental health.

Our central concern was how clinicians used, and were affected by, the institutional mechanisms. Lessons learned in manoeuvring through and around these carry a significance beyond the specifics of the CCG formation. The story is bigger than CCGs alone. A considerable amount of activity was initiated by clinical leaders who were not in a formal post within a CCG.

In 2012/13, the idea of facilitating clinical leadership through localised commissioning bodies was not entirely new. Former experiments included GP fundholding and related forms. As we and others anticipated, it was not long after the official launch of CCGs in April 2013 that other initiatives and other developments emerged – most notably, the NHSE-led ‘New Models of Care’ (URL: www.england.nhs.uk/ourwork/futurenhs/new-care-models/; accessed 25 October 2017). All CCGs have had to take note of, and respond in some way to, these policy thrusts. Inevitably, our research work in and around CCGs tracked these responses as they occurred in real time.

During the period since their inception, there appears to have been increasing oversight and monitoring of CCGs, most especially by NHSE and the Care Quality Commission (CQC). Some CCGs have been put into special measures, senior staff have been displaced and Ofsted-style ratings have been used to identify CCGs needing improvement or deemed to be in the ‘greatest need of improvement’ (URL: www.nhs.uk/service-search/scorecard/results/1173; accessed 25 October 2017). An interesting feature here is the way local commissioners are being held to account by central agencies in addition to the accountability to the local membership. In 2017, a number of CCG mergers were approved and further mergers leading to fewer and larger CCGs are likely to follow.

The requirement on local health economies to construct sustainability and transformation plans (STPs) also represents a game-changing initiative concerning the redesign of health and social care. Although the STPs require engagement by CCGs, local authorities (LAs) and provider trusts, there are concerns that these bodies, creations of the centre, may come to diminish the influence of CCGs. 4 A PricewaterhouseCooper report notes that the consequence of multiple initiatives has been a ‘complex middle ground’ of localism and central direction. 5

The plans focus on some common themes: reductions in secondary care provision, closure or redesignation of community hospitals and revamped primary care with larger practices. 6 The promotion of new models, which emphasises integration and collaboration, seems to point to a lower priority for competition and commissioning and a higher priority for planning and collaboration. Indeed, the NHS chief executive refers to the possibility of the ‘pooling of sovereignty to drive the changes’ planned by STPs between commissioners and provider organisations. 7 Such developments might suggest that there is increasing uncertainty whether or not CCGs will, in the future, be regarded as the natural leaders of change and service redesign or become subsidiary to the STP level.

These profound ongoing shifts in the wider context were very much borne in mind by the members of the research team as they progressed with the task of finding answers to the original set of research questions. Those questions were as follows.

Research questions

The overall aim was to assess and clarify the extent, nature and effectiveness of clinical engagement and leadership in the work of the CCGs. This was broken down into five main research questions.

-

What is the range of clinical engagement and clinical leadership modes being used in CCGs?

-

What is the extent and nature of the scope for clinical leadership and engagement in service redesign that is possible and facilitated by commissioning bodies, particularly the CCGs and the health and well-being boards (HWBs)?

-

What is the range of benefits being targeted through different kinds of clinical engagement and leadership?

-

What are the forces and factors that serve either to enable or block the achievement of benefits in different contexts, and how appropriate are different kinds of clinical engagement and leadership for achieving effective service design?

-

What can be learned from international practices of clinical leadership in service redesign in complex systems that will be of theoretical and practical value to CCGs and HWBs?

The case studies and the national surveys were used as means to generate relevant data to help answer these questions. Before we present the findings and our interpretations of those findings, it is necessary to:

-

summarise the state of knowledge about these questions as found in the existing literature

-

introduce the theoretical lens we used in undertaking the analysis found in later chapters

-

describe the research methods which we deployed in this study.

In seeking to answer the research questions we were of course aware that there were existing literatures relevant to aspects of the research agenda, most notably literatures concerning the policy context, previous initiatives prompting GP commissioning, clinical leadership more broadly and service redesign in health. Hence, before describing our research methods we now turn to an outline review of those literatures.

The policy context

Policies can be seen as ‘answers’ to actual or perceived challenges facing health and social care, hence we begin this section with a brief review of the literature on those challenges. The predominant perceived challenges during the course of this study (2013–16) was the fragmented health and social care system and the severe financial constraints.

The nature and scale of the challenges facing the NHS have been spelled out many times,8 and there have been many warnings about the non-sustainability of business as usual. Currently, capital budgets are being constrained. In this environment, the ambitious transformation plans which usually require funding may be hampered by lack of money. Failures in the joining up of fragmented services are widely seen as having an impact on care of the frail elderly in particular. 9 On the demand side, the growing ageing population with multiple morbidities and wider population ill-health associated with obesity, diabetes mellitus and other long-term conditions are well-recognised problems for which new approaches to health and social care and, indeed, wider and far-reaching ‘health of the public’ innovations will be required. 10

The fortunes of the health service and the adult social care service are intertwined. A CQC report on the state of play in 2015–16 revealed that, because of funding cuts in local government and rising demand, adult social care services were at a ‘tipping point’. 11

The responses to these challenges have been many. A common theme has been a call for a new focus on prevention, more self-care, integrated health and social care and more home-based care. 12

The main policy intervention, as far as the CCGs as institutions are concerned, was the Health and Social Care Act 20122 which established CCGs and abolished PCTs and strategic health authorities. This expressed the policy intent of an apparent devolution of power and accountability. The CCGs could be seen as the institutional expression of the policy thrust which put challenge, competition, choice and commissioning to the fore.

However, following the departure of Secretary of State for Health, Andrew Lansley, in 2012, the emphasis shifted. Following the publication of the Mid Staffordshire Report,13 patient safety, patient experience and quality of care came more to the fore and so too a fundamental shift in policy towards integrated care, community-based care and ‘new models’ which gave primacy to collaborative working and meeting the needs of patients. 14

Variability in policy and practice during the research period were all too evident. Local commissioning runs alongside more regional planning. Local initiatives are fuelled by short-term special funding such as the Prime Minister’s Challenge Fund, the Pioneers, the Vanguards, the new Care Models and the STPs. Among other things, this means that interpretation of the role of clinical leadership in CCGs, and indeed interpretations of the role of CCGs themselves, need to take account of multiple shifts in the wider landscape of health and social care.

During 2016, NHSE modified the basis of NHS planning, requiring STPs to be produced within 44 ‘footprints’. These STPs are intended to provide the local planning basis for moving towards the models for integrated service delivery outlined in the Five Year Forward View. 12 This has enforced some clustering of CCGs. Many CCGs now work closely with their neighbouring CCGs and some share an accountable officer and other members of a managerial team.

The Health and Social Care Act 20122 and the surrounding policies and initiatives set the scene for much of the debate. A critical juncture in the highly contested passage of the Bill was the ‘Pause’ and the work of the NHS Future Forum. This raised, and explored, many of the issues which are now being worked through in practice by the CCGs and their surrounding bodies. 15

The NHS Commissioning Board which became NHSE, was responsible for the authorisation of CCGs and continues to oversee, guide and influence them. 16 In Planning and Delivering Service Changes for Patients17 it stated that major service changes and reconfigurations must put patients and public first and must be clinically led. It is clear that at that time of inception, CCGs were seen as the critical instrument and agency for driving change. NHSE gave further guidance relating to clinical leadership:

Chairs, Accountable Officers, Chief Executives and Medical Directors from across the organisations involved in a service reconfiguration should exercise collective and personal leadership and accountability when considering the development of proposals for major service change. Front-line clinicians and other staff should also be involved in developing proposals and in their implementation.

NHSE17 (emphasis added in bold).

Expectations were thus set high. It sets out a process for the planning, development and implementation of major service redesigns.

In April 2014, NHSE published its plans for transforming primary care. 18 It urged a move ‘away from providing 20th century solutions that are based on a fix and treat model’. This reflects an emergent theme, which was then developed in the Five Year Forward View. 12 This set out the direction of travel to guide local decision-makers with a strong emphasis on joined-up, integrated care. Notably, there is not a lot of emphasis on CCGs as institutional leads in the Five Year Forward View, although there is this statement of intent:

Give GP-led Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) more influence over the wider NHS budget, enabling a shift in investment from acute to primary and community services.

NHSE. 12

A growing policy emphasis is on general practice and the idea of an extended multidisciplinary team surrounding GPs. A key example is the General Practice Forward View. 19 This promised accelerated funding, an expanded workforce of GPs and a more diversified workforce mix surrounding GPs, practice infrastructure improvements and major programmes of care redesign. In 2016, NHSE and NHS Improvement published the NHS Operational Guidance for 2017/18 to 2018/19 under the title Delivering the Forward View. 20 This increases primary care allocations for general practice with recurrent funding to the General Practice Access Fund.

Ironically, despite the clear and emphatic policy intent, the continued influence of the acute sector continues to be felt. This was seen in relation to the STPs, with considerable influence allotted to acute sector leaders, and is seen also in the continued funding bias. There is also a continued high-demand pressure on hospitals.

Literature on Clinical Commissioning Groups

The literature on CCGs comprises reports on the predecessor bodies to the CCGs, which included early forms of GP fundholding and commissioning; literature on CCGs while they were in shadow form leading up to April 2013; and reports on the actual operation of CCGs since they became statutory bodies in April 2013.

Since the original purchaser–provider split in the NHS, introduced by the National Health Service and Community Care Act of 1990,21 there have been many variants of clinical commissioning. The GP fundholding scheme was voluntary and it allowed GP practices to take control of a budget for certain defined services along with funds for a practice management allowance. 22 The Act allowed for ‘fund-holding practices’, and there followed a series of pilots and experiments. Most notably, the pilots and experiments included GP commissioning using fundholding (from 1991), total purchasing (from 1995 to 1998), primary care groups (PCGs) (1999) and the authorisation of PCTs. Storey et al. 23 and Sheaff et al. 24 studied commissioning under PCTs; the latter research group also, to an extent, studied the transition into shadow CCGs and, in so doing, revealed a number of important features of the way it operated in England and to a degree in other countries.

The 23-year period from 1990 to 2013 included numerous pilots and new forms. There are many relevant lessons to be drawn from the experiments and from the related literature. This fact has been noted by some helpful meta-reviews by The King’s Fund,25–27 the Institute of Education, London,28 and by PRUComm (Policy Research Unit in Commissioning and the Healthcare System). 29

Most interpretations suggested that these early forms had modest impact, but that this stemmed more from the constraints placed on the experiments rather than from the concept itself.

Studies of CCGs in shadow form again reported much uncertainty around the link between the governance/assurance level and the operational level; about links with the wider GP membership; about how to resolve conflicts of interest; and about who could make decisions about what. 30 Other work drew lessons about the motivations of GPs, their levels of involvement, engagement and influence, and of leadership by clinicians under each of the previous schemes. A conclusion was that, on balance, the evidence of impact of clinical-led commissioning was ‘limited’. 29

NHS England/Ipsos MORI, The King’s Fund and the Nuffield Trust all produced reports on CCGs in their early statutory days. 31 The King’s Fund, in conjunction with the Nuffield Trust, reported on CCGs after 1 year of operation. The King’s Fund found that less than half of GPs judged that CCGs really reflected their views; nonetheless, GPs felt that they had more influence with CCGs than they had under the PCT regime. 32 Another Nuffield Trust report noted the flaw in attempting to commission secondary care effectively without also considering primary care. 33

The Nuffield Trust team noted the progress made by CCGs in involving GP members, yet, on the other hand, noted the threats to CCGs as much of the agenda, such as STPs and Vanguards, appeared to be being driven without regard to the supposed fundamental role for CCGs. 34

In summary, studies of CCGs and their predecessor bodies tended to find that, although there was much ‘in principle’ support for the general idea of clinical leadership through commissioning, the implementation of the idea across the land (apart from a few notable pioneering exceptions) had been limited in its realisation. These reports, although providing clear descriptions of aspects of governance and engagement, paid less focused attention to actual examples of service redesign activity by CCGs and the precise work of clinical leaders – themes that we address below.

Leadership, clinical leadership and engagement

The body of literature on leadership in the English NHS, and in health services more widely, reflects the themes and concerns across many industry sectors. 35 These include the distribution of leadership within organisations; adaptive leadership; concerns about heroic charismatic leadership styles and a search for more ‘authentic’ and ethical forms of leadership; collaborative and interorganisational leadership; and whole-system leadership.

The literature on leadership in health services and on clinical leadership is extensive and we have reviewed it fully elsewhere – most notably for the NHS Leadership Academy. 36 One of the dominant themes in that body of literature is the perceived need to shift towards a compassionate mode of leadership in keeping with the caring nature of the services provided in health. 37 Another strand of literature, highly relevant to our study, is that which investigates how health-care professionals respond to policies directed towards the design of a new workforce mix in order to facilitate access and make services more affordable. 38–41 Other literature has highlighted the merits of having medics, and clinicians more generally, involved in taking up leadership positions in health services and, relatedly, in investigating the required competences. 42,43

A National Institute for Health Research-funded project on medical leadership provided data on degrees of engagement by doctors in various trusts using the Medical Engagement Scale. This project showed, as with other studies, some considerable distance between many medics and the leadership teams. 44 This work also focused on acute, specialist and mental health trusts, all of which were characterised by professional bureaucracies. As explained, our prime focus was rather different, namely to trace the extent and nature of clinical leadership using the platform afforded by the CCGs. Thus, our prime focus was on active leadership of service redesign. Often this was undertaken by informal leaders, as well as those occupying formal roles within CCGs. Attempting to lead changes in service redesign across the complex boundaries in primary and secondary care is a very different challenge.

Another central theme in the literature has been the perceived tension between, on the one hand, professional autonomy and established notions of professional practice and, on the other, the cluster of notions attached to organisational practice. Hence, the various ways in which doctors have resisted managerial attempts at organisational change and re-engineering have been extensively researched and reported in the literature. Much of this research, however, has been located in acute hospital settings where issues of competing hierarchies are at stake. As our scoping research had indicated, the more salient issues in the context of CCGs were aspects of interorganisational leadership and interprofessional leadership.

Given that the policy thrust, as seen in The wider context and the policy intent, is ostensibly towards devolved leadership, then questions are inevitably raised as to where this leadership will be located and how it will be exercised in practice. Much of the leadership work seems to get done by combinations of managers and clinicians. Indeed, sometimes managers are clinicians who hold hybrid roles. Some researchers have emphasised and illustrated the pluralistic nature of organisational leadership. 45 This refers to tendencies in many organisations for leadership to be exercised by clusters of two or three players at the top (e.g. chief executive, a chief finance officer and a chief operating officer). Extending out from this are studies which point to much wider forms of distributed leadership throughout organisations. 46–48 Informal leadership seems to be an attractive idea for some clinicians and is associated with the identity formation of leaders who practise leadership and then reflect on that practice. 49

Alternatives to top-down, planned, transformational leadership approaches have been advocated, especially in health services. These leadership approaches include the idea of mobilising action in organisations through adaptive changes and ‘adaptive leadership’;50 other related approaches include ‘appreciative inquiry’ and similar modes of action research. 51 The adaptive leadership approach makes a distinction between ‘authority’ and ‘leadership’. Instead of seeking leaders who, supposedly, know all the answers and issue these from on high, advocates such as Heifetz50 contend that leaders should be encouraged and developed who can stimulate changes in attitudes, behaviours and values. This kind of leader mobilises people to solve problems. So, leadership in these terms is ‘adaptive work’ involving many people and, through exposing and confronting internal contradictions, allowing people to find new ways of thinking and behaving. 50 Thus, in place of the heroic leader model emerges an approach which views the organisation as a system. The associated skills can be learned and tools applied to nudge the system to adapt through mobilising the efforts of multiple people. 52 This requires processual and improvisational expertise. It involves experimentation, iteration and trialling rather than linear implementation of a top-down strategy.

Storey and Holti53 found that NHS structures and culture often present numerous barriers to the effectiveness of clinical leadership for improving service co-ordination and integration from within the acute sector. Despite the barriers, they also found cases where determined doctors and other clinicians persisted in their attempts to exert positive influence on reshaping service design and delivery. 54 Other studies of the roles of clinicians and others in bringing about complex service innovations support the view that there is a need for an effective alliance between clinicians and administrative managers. Complex service innovations, such as the establishment of a region-wide network of cancer services, seem to require a multilevel and multidisciplinary array of clinical and administrative leadership roles, sometimes referred to as a ‘leadership constellation’. 55,56 This idea is reflected in the role of ‘clinical communities’. 57,58

As the above analysis indicates, there is considerable overlap between the issues researched as part of understanding leadership in health and the related domain of understanding service redesign and change in health. It is towards this last domain that we now turn our attention.

Service redesign of health and social care

Most reports of actual attempts to bring about transformative change in health care have tended to focus on the acute sector. As largely hierarchical organisations these settings have lent themselves to exploration of redesign methods derived from the business literature including, for example, business process re-engineering. 59–63 The analysis of attempts to introduce radical redesign of processes in acute hospitals reveals the complexity of such attempts and the micro-political struggles involved. 59 Consent had to be won from clinicians, and this proved to be highly conditional. 40,64–66

Professional occupational groups lay claim to ‘jurisdictions’. 66 In particular, the jurisdictional claim embraces the classification and diagnosis of a problem, the power to reason about it and to take action in relation to the identified problem. Currie et al.,40 likewise, reveal the methods used by medics to maintain existing structures, building on previous work on professional defence routines. 66,67 They found that ‘In essence, the elite actors are engaging not simply in outright “change resistance” but more subtly in institutional work designed to shape the change trajectory to ensure continued professional dominance’. It is not only clinicians who engage in institutional work when creating new forms or shoring up old ones, managers in health service redesign attempts are also heavily involved. 68

Whether or not the same kind of analysis of professional jurisdictions made in these mainly acute contexts can be transferred to the primary care setting is an open question. This is especially so in the case of CCGs, where the core institution is ostensibly a ‘membership’ organisation.

The findings from research in the acute health-care setting reflect findings and theory from the wider organisational theory literature. 69 ‘New institutional theory’ places emphasis on the shaping power of existing institutional forms on human agency and the institutional ‘work’ undertaken by actors. Institutional work is found in everyday activities, which can be seen to serve underlying purposes. To use Lawrence and Suddaby’s70 categorisation, these purposes may be to ‘create, maintain and/or disrupt institutions’. We build on the institutional work perspective in our case studies.

It is important to note that attempts at exercising clinical leadership are located within existing institutional arrangements. Clinical leadership does not operate in a vacuum. Within the context of the NHS, a great deal of institution shaping and reshaping emanates from higher-level actors, most notably NHSE and political agents; these set the direction of travel and allocate resources (financial- and legitimacy-based resources). The very origins of CCGs themselves stemmed from this source, followed by the Five Year Forward View12 and the STPs. Each of these institutional shifts was built on the assumption of the need to relocate care from hospitals to community settings. During this journey there was a move from a reliance on commissioning in a competitive market environment to large-scale planning and collaboration. Recent literature has begun to question the validity of assumptions about savings and efficiency in the shift to community care. 71 Additional challenges relate to the leadership required to implement and deliver the broad policy ideas. Our research was directed at these forms of leadership.

Studies of successful leadership of service redesign72,73 point to lessons which include distributed change leadership from both formal clinical leaders and senior managers, credible opinion leaders at the level of senior clinicians in the services concerned and ‘willing workers’ – front-line clinicians prepared to embrace the new way of working. 73

Conclusions to the literature review and implications for a research agenda

From the research reports cited above, some common threads are evident. In CCGs, as with many other membership bodies, it evidently often proves difficult to fully engage the wider membership in any meaningful way. Furthermore, these studies find that the defence of professional autonomy often competes with attempts to ‘manage’ performance across primary care. (However, our case analysis in Chapter 4 reveals some successful examples.) The body of literature also indicates that the legacy effect of past experience with practice-based commissioning and similar initiatives tended to shape perceptions and responses to new arrangements; these often leaned towards the sceptical. There remains a significant gap between the ambitious agendas for change set out in key policy papers and the reality on the ground of actions taken, to date, by most CCGs.

Key themes emerging as requiring deeper understanding include:

-

the forms of influence that clinicians are actually achieving both as commissioners and providers under CCGs and associated arrangements

-

how leaders (managers and clinicians) are able to use the CCG as a platform and resource to bring about service redesign and, as a key part of this, the balance between formal and informal opportunities for leadership

-

the impact of these emerging forms of power and influence on the achievement of more integrated and effective forms of patient care.

Chapter 2 Project design and methodology

The findings presented and discussed in this report are derived from a number of data collection ‘windows’ into the work of CCGs, of clinical leaders and of other leaders in and around CCGs. The project proceeded through a series of sequential steps in five phases as mapped in the project Gantt chart (see Appendix 1). The five main phases were as follows:

-

An extended scoping study encompassing 15 CCGs spread across England.

-

Drawing on the results of this scoping work and on a review of the relevant literature, a national survey was designed and administered with the target population being all members of the governing boards of all 210 CCGs.

-

In-depth case studies in six CCGs. This work was designed to reveal details of the processes involved in seeking meaningful service redesign through the deployment of clinical leadership and the in-depth study of a number of specific examples of attempted service redesign within these cases; the method here was to study clinical leadership in action.

-

Drawing on the lessons learned from the case study work in phase 3, a second national survey was designed. Again, the target population was all the members of all CCG governing bodies (approximately 3100 people including accountable officers, chairpersons, GPs, secondary care doctors, nurses and lay members).

-

A set of international comparisons enabled by sharing our results with leading international experts in other relevant health economies. The health systems chosen were those where there seemed to be some likely comparative resonance and thus the opportunity to generate further insights through the use of the perspective allowed by these comparisons. The main comparative economies selected were Canada, Germany, the Netherlands, Sweden and the USA.

Phase 1

As part of the initial scoping work, studies were made of a relatively large sample of 15 CCGs and their associated hinterlands of HWBs, LAs and health-care providers. In this phase of the project, the research team were looking both outwards from focal CCGs and inwards from the perspectives of relevant others. This included gathering views from relevant stakeholder bodies such as NHSE, CQC, the Faculty of Medical Leadership and Management, the National Association of Primary Care, commissioning support units (CSUs), the London Office of CCGs, NHS clinical commissioners, clinical senates and local medical committees, LAs, HealthWatch, community services and acute hospitals (managers and consultants). We attended many relevant conferences such as Commissioning Live and workshops at The King’s Fund. Simultaneous with the work in the first phase we undertook a major literature review. This review, uniquely, not only embraced the literature on clinical leadership and leadership studies more generally, but reached out into related relevant literatures on CCGs and other earlier forms of local commissioning, and the literatures on service redesign and change in health services.

The scoping phase was used to allow insight into the varied types of CCGs and to gain a sense of the range of practice across the country. Interviews were conducted with accountable officers, chairpersons and a representative sample of CCG office holders, including various clinical leads, locality leads, GP governing board members, lay members, nurses, secondary care doctors and patient and public representatives. Interviews were also conducted with LAs and with members of HWBs. The aim at this stage was to gain a ‘rounded view’ of CCG activity. This phase of the study also included observational studies of CCG board meetings and of HWBs. These were used to gain a sense of the scope of ambition and insight into which agents were engaged in what kinds of service redesign.

The aim at this scoping stage was to capture and catalogue the range of issues. It was also designed to gain exposure to varied contexts across the country – allowing access to issues as experienced in inner and outer London, in Northern and Midland towns and cities, and in rural areas. Research team members used a common semistructured interview guide. Interviews were recorded and transcribed in most instances, depending on the wishes of the interviewees.

Phase 2

The findings from this pilot phase were used to help construct the questionnaire for the first national survey of all 210 CCGs (following a merger the total later became 209) across England. In turn, the responses from that survey helped inform the selection of six core cases that were targeted for in-depth research over the ensuing 2 years. The findings from these cases helped inform the design of the final national survey that was conducted in the third year of the project.

Phase 3

Central to the research design were the core cases studies. Theory building from multiple cases has many recognised benefits – as well as challenges. 74,75 Case studies enable exposure to rich data in their real-world contexts. The main case study work phase was informed by the initial scoping work and also by the results of the national survey. In the main in-depth case studies, the focus was sharpened more directly onto explorations of specific examples of service redesign and an identification of who did what in conceiving, planning, resourcing and driving the changes.

Hence, at this stage, the framing of a ‘case’ tended to settle more directly on these service redesign initiatives rather than the CCGs per se. So, although our point of entry was into six CCGs, the case analyses focused on eight specific service redesign attempts. Once again we used a common semistructured interview guide (see Appendix 4). We worked in fieldwork teams of two, sometimes three, researchers and, again, interviews were recorded when feasible and helpful. Interviews were supplemented with relevant documentary analysis and with observations of board meetings, programme board meetings and other events relevant to the particular service redesign.

Phase 4

Phase 4 was the second national survey. This included many questions which had been part of the first survey and, hence, comparisons over the intervening time period (nearly 2 years) were enabled. Additionally, by the time this second survey was being designed the project team had gained extensive knowledge from the main case studies and this allowed a number of new and more refined questions to be posed. The key questions in the 2016 survey included assessments of the perceived power and influence of CCGs relative to other bodies. This was important because these assessments of the CCG as a potential lever could be expected to shape expectations of these actors about how far they could use these institutions as a basis to bring about meaningful redesign. If the institutions were judged to be relatively powerless, then that would be reasonably expected to blunt and limit would-be leaders in seeking to harness the CCG as an agent for change. If, conversely, the CCGs were judged to be influential, then that could raise expectations about what could be done by making use of these institutions.

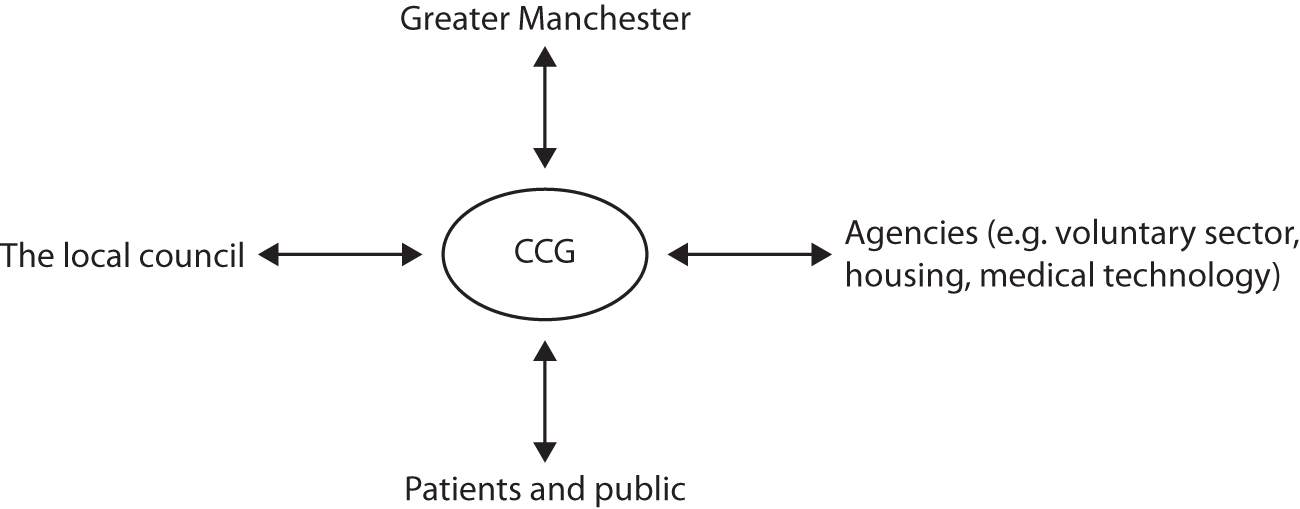

In a related set of questions we asked about the perceived influence of other relevant bodies such as NHSE (nationally and regionally), LAs, hospitals, other major provider organisations and clinical networks, and other bodies. If these other bodies were perceived as highly influential, then this might either inhibit or curb the scope for action by the CCG or it might at least indicate the need for collaborative relationships.

Other questions were asked about the degree of engagement by the wider GP membership in the affairs of the CCG. This area of questioning was designed to assess the breadth and depth of clinical engagement and leadership. Related questions were asked about the nature and degree of influence of clinical leadership in improving and redesigning services.

Phase 5

Phase 5 included a set of international comparisons. When we had collected and analysed the data from multiple sources we wanted to gain a richer perspective by examining the findings from an international comparative perspective. Part of the reasoning was to rise above parochial issues and to reassess the meaning of the findings by comparing how health-care managers and leaders in other countries were handling similar issues, even if their circumstances were not precisely the same. We also wanted to gain deeper insights into our own data and findings by exposing them to international expert teams and entering into question and answer mode with them.

We already had relevant international connections in our wider network and so we built on that basis while also inquiring about additional experts. Our initial idea had been to hold webinars for this purpose, but initial attempts made it apparent that it was difficult to gain full attendance at synchronous events across different time zones. Hence, we adapted the method by producing synoptic accounts of our findings and e-mailing them to our network of international experts. These accounts were accompanied by a structured set of questions, including questions about how similar issues, tensions and dilemmas were handled in their own settings. This proved to be an effective and efficient approach, and it triggered a constructive dialogue which was progressed iteratively. This process of international exchange allowed us deeper and more detached perspectives on the issues and findings.

Our theoretical perspective

Next we turn to an explanation of the underlying theoretic perspective that was used in this study as a means of understanding and interpreting the processes encountered in the field and in making sense of the data.

Our underlying interpretive lens is drawn from institutional theory. As the study unfolded, it became clear that the abundant initiatives and accounts we recorded about why the organisation of health and care had to be different (or why it needed in some aspects to be stable) were replays of some basic, fundamental narratives. Actors in the field (at multiple levels) were engaging in ‘institutional work’. 70,76 This work was and is designed to maintain and justify extant arrangements, to disrupt in part or whole those arrangements and/or to create new arrangements. 70,77

The unusually active state of this institutional work in the English NHS stemmed from ongoing prevalence of multiple and diverse ‘competing logics’. 78,79 The core prevailing logics were spelled out time and time again – in CCG strategy documents; in STPs and the workshops organised to prepare these plans; in NHSE statements and documents; and in our many interviews with actors at all levels and parts of the health service. A prevalent logic was the need to ‘integrate’ services across health and social care. This was the ‘dominant creative logic’ among persons seeking to disrupt extant systems and ways of working and to install new creative modes. The dominant logic, in the sense of extant practice, was fragmented organisations offering siloed services and based on an underlying notion of the value of ‘challenge and competition’. These competing logics coexisted as layers of statute and reform were laid on top of each other, pulling system actors in different directions. It was within this context that clinical leadership was being exercised or neglected. The question arises as to what form of institutional work clinicians are engaging in: are they, as some literature suggests, mainly seeking to ‘maintain’ and defend their privileged status?40 Or might we find cases where clinicians, as intended by the policy drive which established CCGs, undertake institutional work of a creative kind, which improves services for patients at scale and which deserves to be called active and constructive clinical leadership?

Despite the phenomenon of competing logics and the institutional work involved in creating, maintaining and disrupting institutions, the existence of ‘dominant logics’ has been widely noted. 80 The attachment to, and defence of, a dominant logic does not necessarily stem from a defence of self-interest. It has been noted that embedded actors often cleave to an institutional form because it has a taken-for-granted status that engenders a deep-seated belief in the necessity of the extant system. 81

The two national surveys

Using the findings from the pilot work, we constructed the first survey instrument for distribution to all members of the governing bodies of all 209 CCGs in England. A database of 3100 individual members of governing boards was constructed by tracking board papers and CCG websites. The questionnaires (see Appendix 3) were posted to this total population using their individual names and addresses. One postal reminder was then sent to those who had not responded and in that reminder letter an online version of the questionnaire was offered.

We calculated that a response of 340 would be required for 95% confidence intervals of reasonable width. For the first survey in 2014, there were 385 responses in total (12.42% of the total population of all CCG governing board members and 79% of all CCGs). For the second survey in 2016, there were 380 responses (12.26% of the total population of individuals and 77.5% of CCGs). The 18-month interval between the two surveys was designed to allow tracking of unfolding events and the maturation of the CCGs; thus, a longitudinal element was enabled.

We analysed key features of the non-responding CCGs, but there was no discernible pattern. They were distributed geographically and we could find no particular characteristic common features among the non-respondents that would distinguish them from those who did respond. In case of bias towards high-achieving CCGs, we compared our respondent CCGs with the profile of the 2016 NHSE ratings of CCGs. The resulting comparison is shown in Table 1.

| CCGs sampled | NHSE ratings profile 2015–16 (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inadequate | Requires improvement | Good | Outstanding | |

| All NHSE CCGs | 12 | 44 | 39 | 5 |

| Our CCG sample | 12 | 41 | 41 | 6 |

The very close match suggests that respondents from struggling CCGs were just as willing to respond to the survey as those from high-performing CCGs.

The main in-depth case studies

Following the pilot case study phase and the first national survey, the focus of research work shifted to the six main case studies. The selection of these core cases was informed, as planned, by the results from the first national survey and was also shaped by our knowledge of activity across potential case sites. We wanted geographical coverage so we ensured that the cases included CCGs in London, the Midlands and the North, and we also ensured coverage of urban and rural settings. Of special importance was our knowledge of the degree of service redesign activity occurring in these settings. A random selection of cases might easily have resulted in six CCGs characterised by relatively little activity. In order for us to be able to tease out the elemental processes of clinical engagement and leadership in service redesign, it was important to ensure that some of the cases had strong prima facie indications that they would be able to offer opportunities for detailed study of substantial activity, but we avoided over-reliance on the feted cases that may have enjoyed unusual and exceptional support.

Within each CCG we selected for detailed study one, or in some cases two, specific service innovations in particular areas. These focused on care of the frail elderly (usually involving cross-boundary working designed to ‘integrate’ health and social care); innovations in urgent care (usually involving cross-boundary working with GPs, acute hospitals, the ambulance service and paramedics); and/or mental health.

Within these cases there were also many research choices to be made. We used both purposeful sampling and theoretical sampling to access the most appropriate informants.

Guidelines from Lincoln and Guba82 were followed regarding ‘purposeful sampling when selecting informants within the case studies’. First, we selected informants whom we expected would have the most relevant knowledge of the background issues affecting the CCG as a whole. This cluster was broadly common across the cases (accountable officer, CCG chairperson, clinical leads, and so on). However, in addition we were sensitive to the particularities of each service redesign attempt studied. Here we used onward referral – a snowball research technique – in order to include informed and diverse perspectives appropriate to the situation. For each service redesign attempt researched, a set of interviewees was agreed with a senior sponsor of the research collaboration within the CCG. The selection of each sample was guided by the need to include the actors who had played a key role in initiating, shaping and evaluating the course of the service redesign event. This typically meant that clinical leads, programme managers and project managers, as well as some of the clinicians, were involved. In several cases we were also able to include patient representatives who had been involved in the service innovation (e.g. through sitting on the relevant programme board). In recognition of the multilayered nature of health-care reform, it was necessary to look upwards and outwards to the wider context, including area, regional and national policies and institutions which had an impact on the service areas under focal scrutiny. Thus the institutional settings usually had fuzzy boundaries which extended across primary, secondary, administrative, regulatory, professional and educational institutions.

Theoretical sampling allows the clarification of the relationships among multiple constructs. 75 It allows the revelation of unusual phenomena of diverse kinds. We used this approach in order to identify further interviewees in each case, to ensure exposure to data from informants who could add to an accumulative and iterative body of knowledge about relevant issues. The range of informants evolved with the emergent theory. Themes were pursued until little additional insight (what has been termed ‘theoretical saturation’) was gained. 83

We used three main methods within the cases. First, we conducted pre-entry documentary analysis drawing on a wide range of sources. Second, we conducted face-to-face semistructured interviews. Third, we used non-participant observation. Although interviews can be a highly efficient and effective research tool, it is recognised that they also present the challenge that bias may arise because of the efforts of image-conscious informants. This challenge was mitigated through the use of multiple interviews among diverse informants who were likely to view the issues and events from different standpoints. 84

The mode of operation was for each case study to be conducted by two members of the research team, with one of them acting as the lead investigator and contact person for that site. Some of the interviews were conducted with both researchers present, other interviews with just one researcher. In the main, interviews were recorded and transcribed. The researchers drew on a semistandard interview schedule comprising semistructured interview questions. These had to be adapted to the varying situations including, for example, the subject of the service redesign under scrutiny and the role and vantage point of the interviewee. The semistructured interview schedule was adapted accordingly. Appendix 4 shows a typical example of one such interview guideline.

Case study data analysis

As mentioned, members of the research team worked in pairs for each main case study. These subteams undertook the first stage of each data analysis process. Following Miles et al. ,84 these first-level analyses were constructed by careful reading of each individual transcript and the development of codes for exploring, describing and ordering the data for an entire case. In this way a coherent narrative of the flow of events within each case could be constructed. This was combined with a descriptive account of the issues and challenges encountered by the actors involved. These first-level reports used a common framework: (1) context, (2) focus and narrative of the case, (3) clinical leadership themes emerging and (4) emerging ideas for cross-case comparisons. The first three sections of these initial draft reports were fed back to informants in the case studies concerned, as a way of validating the accuracy of the data collected and the descriptive interpretations made.

Next, the first-level case reports were discussed, in turn, at a monthly series of research team meetings. From these discussions emerged ideas for explanatory concepts that could be applied to understand differences and similarities in the nature of clinical leadership across the cases. This process of discussion, conceptualisation and comparison between the cases led to the development of the conceptual framework for analysing the cases set out at the beginning of Chapter 4. Once again, following guidelines from Miles et al. ,84 this conceptual framework was then used to develop explanatory codes for a second level of analysis of interview, observational and documentary data in each of the cases (Table 2). This second-level analysis was carried out by two members of the research team, who were also the main authors of this report. That analysis brings together the descriptive summary of events with an explanatory analysis of the forms of clinical leadership and their relationship to the achievements and difficulties encountered in bringing about service innovation. The analyses are compared and discussed further in Chapter 5.

| Interviewee role | Number of interviews |

|---|---|

| GP chairpersons, clinical leads, other GPs | 65 |

| CCG accountable officers and other managers | 36 |

| Nurses | 8 |

| Lay members | 7 |

| Acute sector doctors and managers, mental health | 25 |

| Community health managers and nurses | 10 |

| NHSE, CQC, NHS Improvement, CSU and other agencies | 10 |

| LA representatives, councillors, chief executives and directors, public health | 9 |

| Voluntary sector | 9 |

| GP practice managers | 7 |

| Patient representatives | 8 |

| Ambulance service, paramedics | 8 |

| Total | 202 |

Survey analysis

Results from the two national surveys were analysed in three main ways. First, the responses to each of the questions were gathered together and the results presented as tables and charts. Second, a number of cross-tabulations were made in order to investigate whether or not occupants of different roles answered questions in particular ways. Third, comparisons were made between our data and the ratings of CCGs made separately by NHSE. These correlations produced some very interesting findings.

A notable feature of the completed questionnaires were the free-form questions. These elicited fulsome, useful responses. As a result of the careful preparation of the questionnaires in conjunction with a range of informants from the scoping phase, respondents readily recognised the relevance of the issues being raised and were very keen to share their thoughts. In the next chapter, the statistical results stemming from the structured questions are presented and analysed along with the free-text responses.

Public and patient involvement

We sought to involve the public and patients as far as was feasible, relevant and practicable at all stages. In the first instance, a nationally renowned patient and public involvement (PPI) representative with very extensive experience of PPI was appointed as co-chairperson of the Project Steering Committee. This representative was involved in all aspects of the research from the initial design, the oversight of research instrument construction and the review of findings at all stages, to the discussions about the dissemination of findings. During the course of the project, PPI was used mainly in relation to the specific service redesign initiatives that were the focal component of this study. These initiatives often had PPI arrangements in place and we tapped into these rather than seek to set-up new arrangements. One extension of this approach was that a member of the project team sought permission to become an active participant member of a PPI group that was associated with one of the service redesign initiatives in the core case studies. Full ethics approval from the Research Ethics Committee overseeing the project was sought and full disclosure was made to members of the PPI group. Another dimension was that in the surveys and the case studies we took steps to find out how patients and the public had been involved in the redesign of services.

Chapter 3 Findings from the national surveys

Introduction

In order to gain a broad view of the state of play across all CCGs, a national survey was designed and administered in 2014 and again in 2016. The populations targeted were the members of the governing boards of all CCGs. This included chairpersons, accountable officers, finance directors, GP members (often these were clinical leads of particular service areas), other clinicians such as nurses and the secondary care doctor representatives, directors of public health and lay members.

The first survey gleaned 385 usable responses and these represented 12.42% of the total population of all CCG governing board members and 79% of all CCGs. For the second survey there were 380 responses, which represented 12.26% of the total population and 77.5% of all CCGs. The 18- to 19-month interval between the two surveys was designed to allow tracking of unfolding events in a time series and the possible maturation (or decline) of the CCGs.

The questionnaires in both phases contained many shared themes, but the 2016 questionnaire included additional questions which were derived from the case study work that had taken place during the intervening period. Patterns of responses were also correlated with a separate data set: the ratings allocated to CCGs by NHSE for 2015/16. In comparing our survey results with the NHSE data, we used the headline rating. We considered using the component ratings that were most relevant to our study (i.e. ‘Well-led’; ‘Finance and Planning’). However, we found such high correlations between these components and the headline rating that, in practice, the headline rating proved to be sufficient.

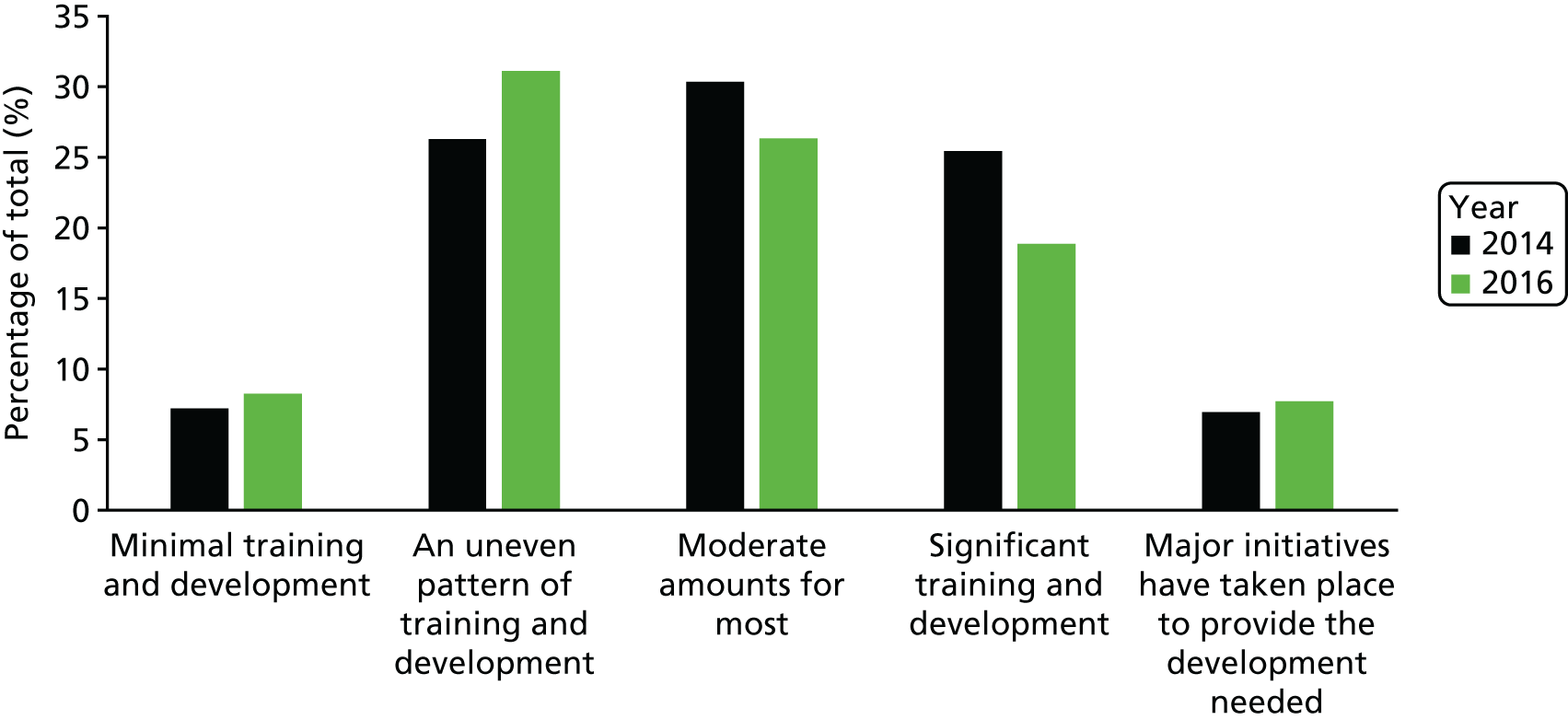

A number of core issues were investigated in both phases. The first of these was the respondents’ perceptions of the autonomy and influence of CCGs as institutions. This was assessed relative to other bodies such as NHSE, NHS Improvement and the CQC. In other words, the initial objective was to understand how important and influential the CCGs were in the wider scheme of the NHS. A second continuing theme was the relative influence of clinicians – most especially GPs – within the CCGs. This aspect was central to the project aim: do the CCGs in practice provide a platform for the meaningful exercise of clinical leadership? A third core question area was an examination of the nature of the contribution made by clinical leaders. Other more subsidiary questions covered in both surveys were: the degree of wider GP engagement; training and development offered to GP members of CCG boards; conflicts of interest; and assessments about the future role of CCGs.

The questionnaire was a combination of structured questions and a set of more open-ended questions with space for free-form answers. There was a very high response to the free-form questions – with 96% of respondents taking time to write in these sections. This was a strong indication of the extent to which respondents were engaged with the questionnaire and found it relevant and interesting. The respondents were keen to express their views and many did so with passion.

Copies of the questionnaire can be found in Appendix 3.

The profile of respondents

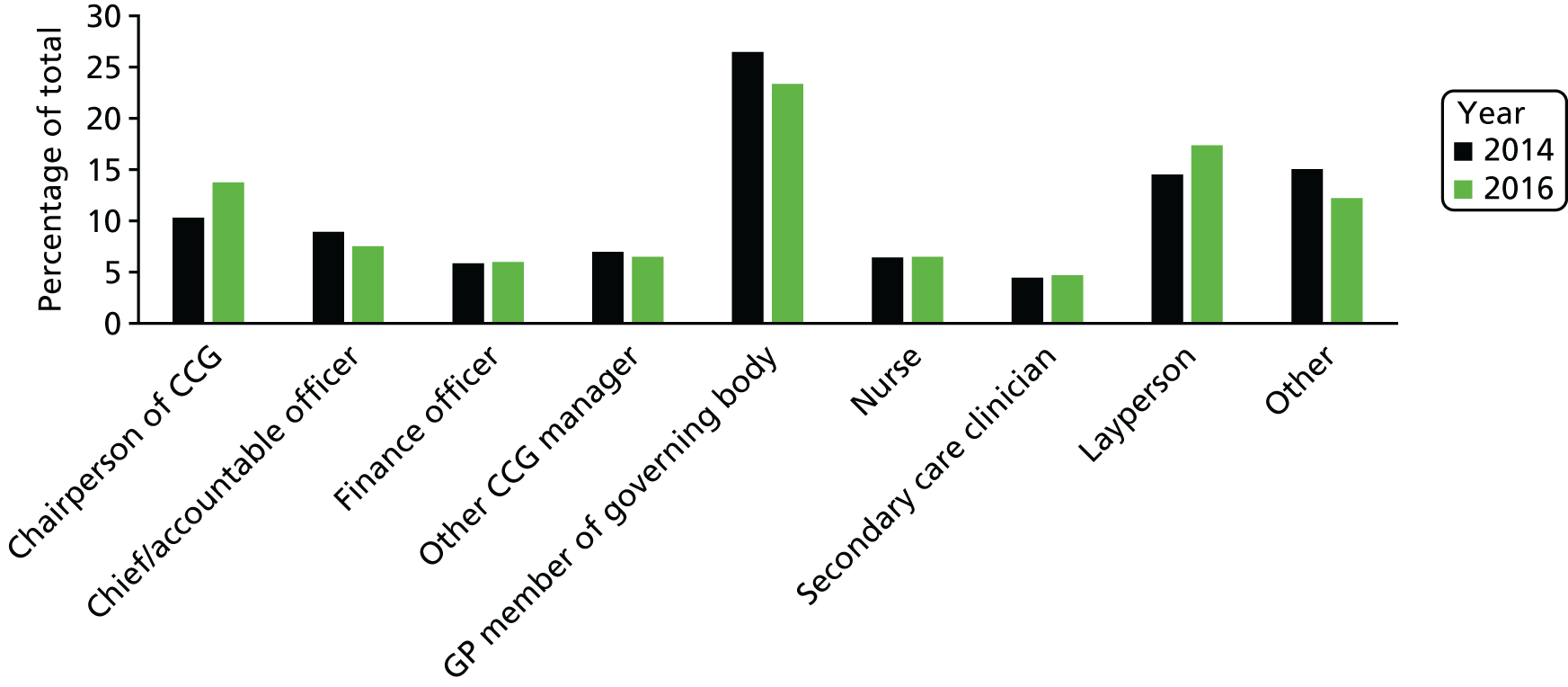

As can be seen from Figure 1, responses were received from all role categories with the numbers broadly reflecting the relative numbers sitting in these boards. Hence, GPs were the largest group of respondents.

FIGURE 1.

Roles of respondents.

The first thematic question examined was the perceived influence of CCGs. We wanted to understand what respondents thought was the scope to make a difference through these institutions.

Perceived influence of Clinical Commissioning Groups

The first main substantive question asked about the perceived influence of CCGs relative to other NHS organisations. The reason for asking about this was that the overall research question was essentially about the scope for leadership influence using CCGs as an institutional platform.

We asked board members to make a comparison of the perceived influence of their CCG relative to other bodies such as NHSE and NHS trusts. The form of the question asked for a rank ordering of the bodies most influential in shaping local health services. Figure 2 shows the results. Half of the respondents judged that their CCG was the most influential in this regard, and NHSE was ranked second. However, nearly half of the respondents did not rate their own CCG as the most influential. In the 2016 survey, some respondents under ‘other’ noted that Vanguards and STPs were emerging as influential in shaping local services.

FIGURE 2.

The relative influence of different institutions (2016).

It is clear from Figure 2 that ‘my CCG’ was seen as carrying the most influence. NHSE was seen as the next most influential institution in shaping service redesign and the growing importance of collaboration between CCGs is also indicated. However, the fact that nearly half of CCG board members themselves judged that their CCG did not exercise the most influence might be expected to be a potential curb on expectations about the exercise of leadership by CCG clinicians or other CCG players.

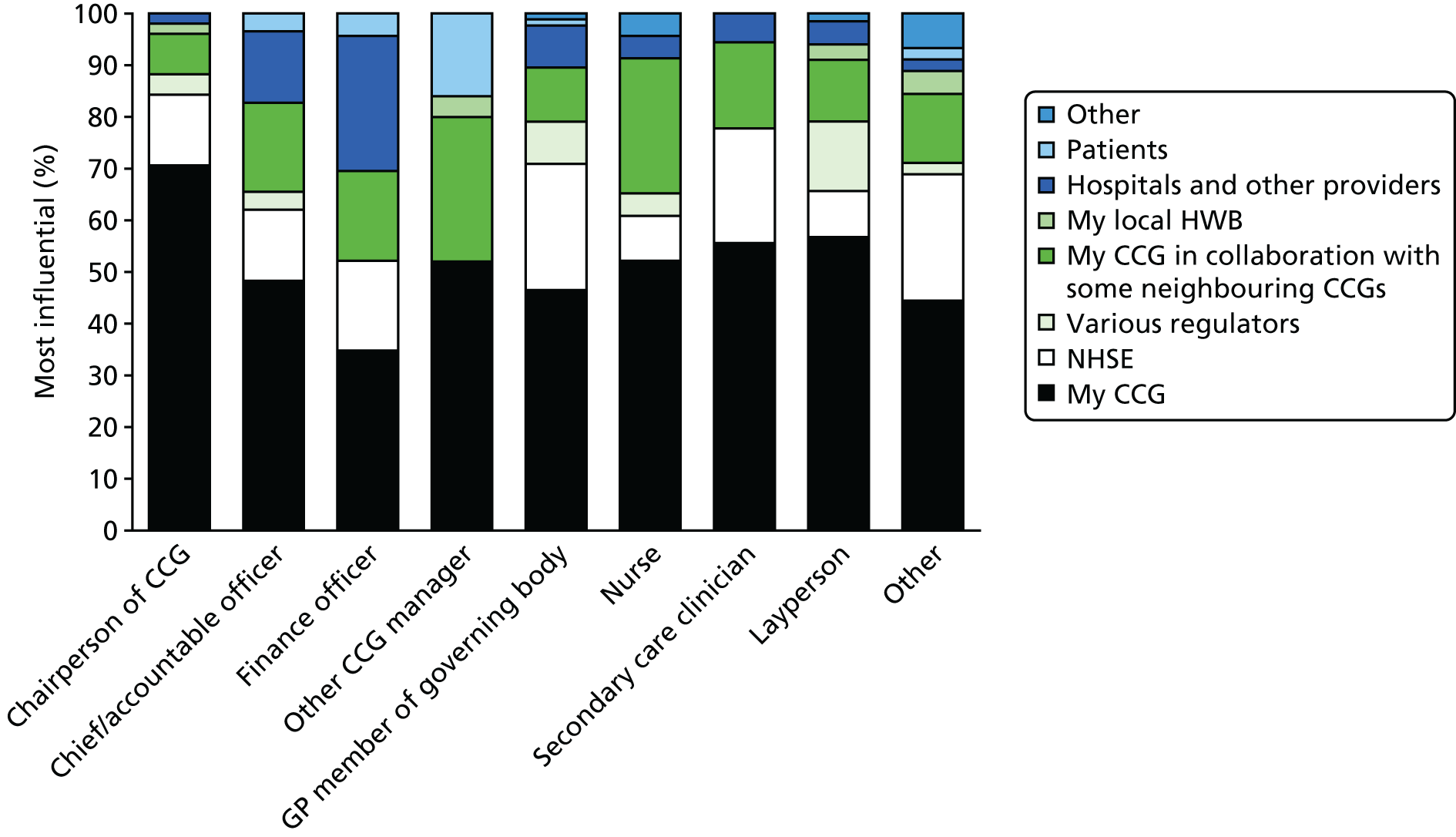

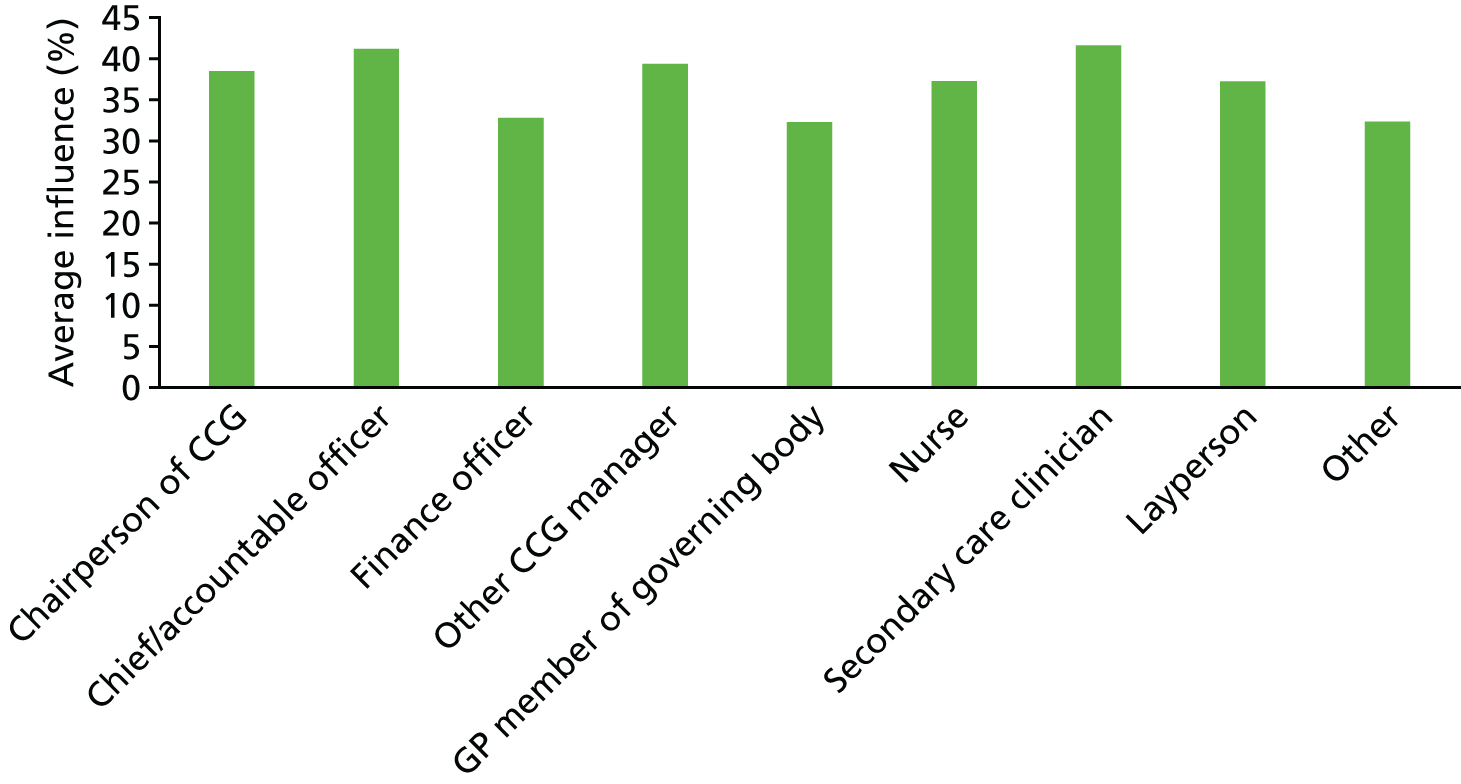

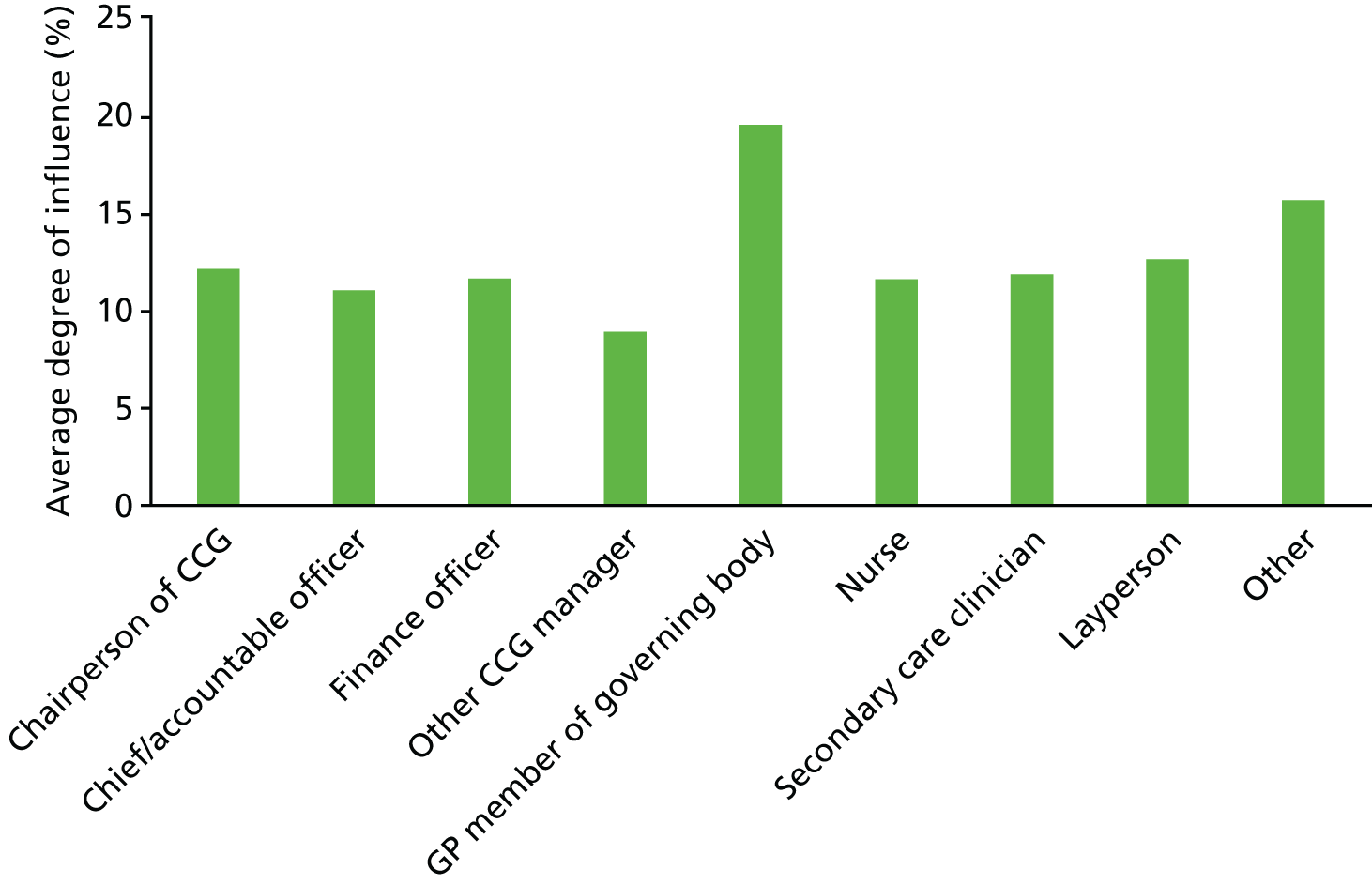

Would different role occupants have similar views? The data for the assessment of influence split by role holder are shown in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

Relative influence of different bodies as reported by different role holders.

Notably, it was the chairpersons of CCGs who were most likely to perceive their CCGs as influential. However, other role holders, most notably finance directors, did not. Less than half of accountable officers perceived their CCG to be the most influential body in shaping services. This is an especially important finding because arguably, among all of the different role holders, one would expect the accountable officers to have the clearest line of sight on the various forces at play. It would suggest that the reality of CCG influence is rather less than was implied by the policy intent as it was described at the outset of this report.

Many GPs on CCG boards reported that they were disillusioned with their CCG experience. For example:

The CCG is becoming increasingly bureaucratic and much more like a PCT. We are increasingly subject to government directives and with short deadlines. There is no space for creative solutions from the CCG. I am angry and sad at the current state of CCGs.

GP member of governing body

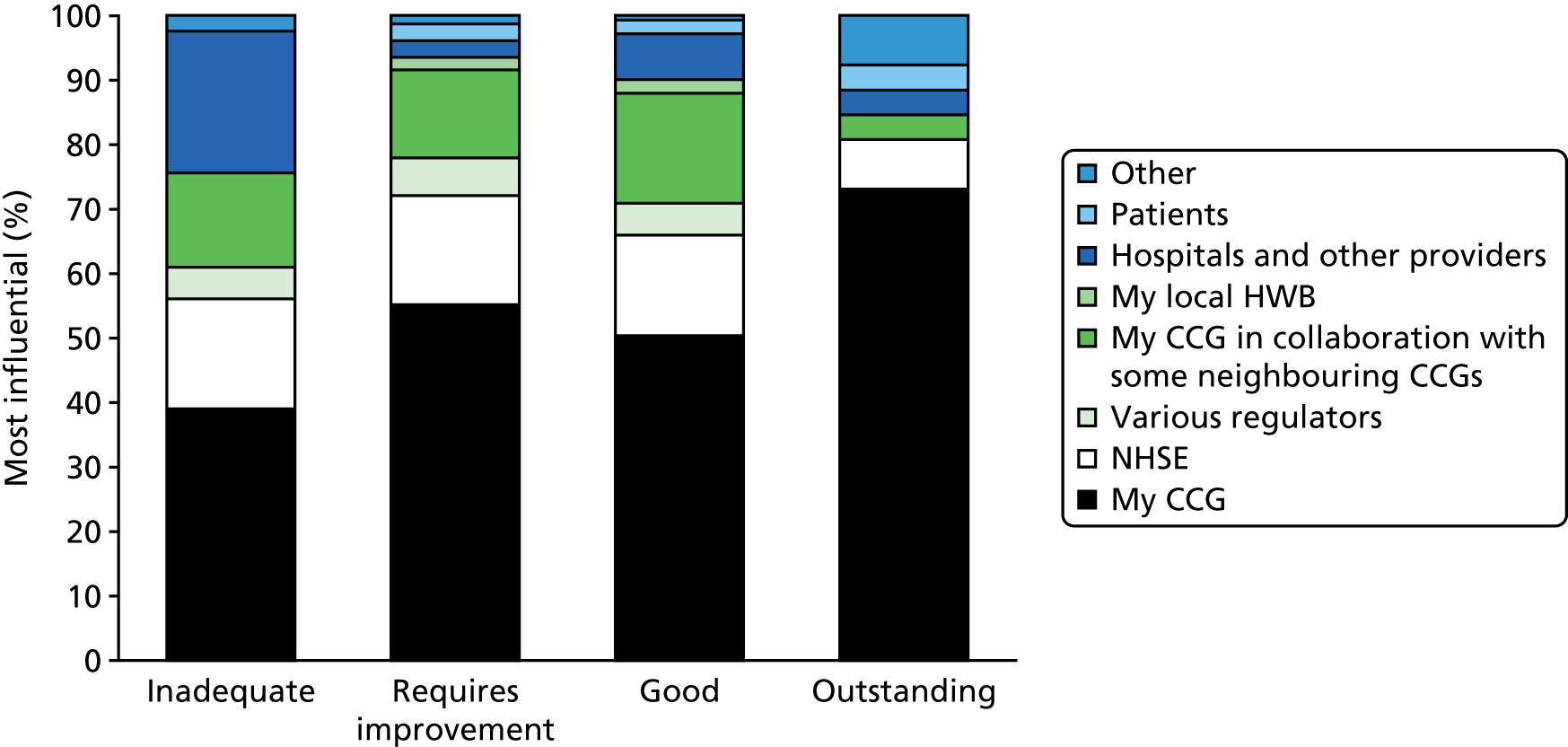

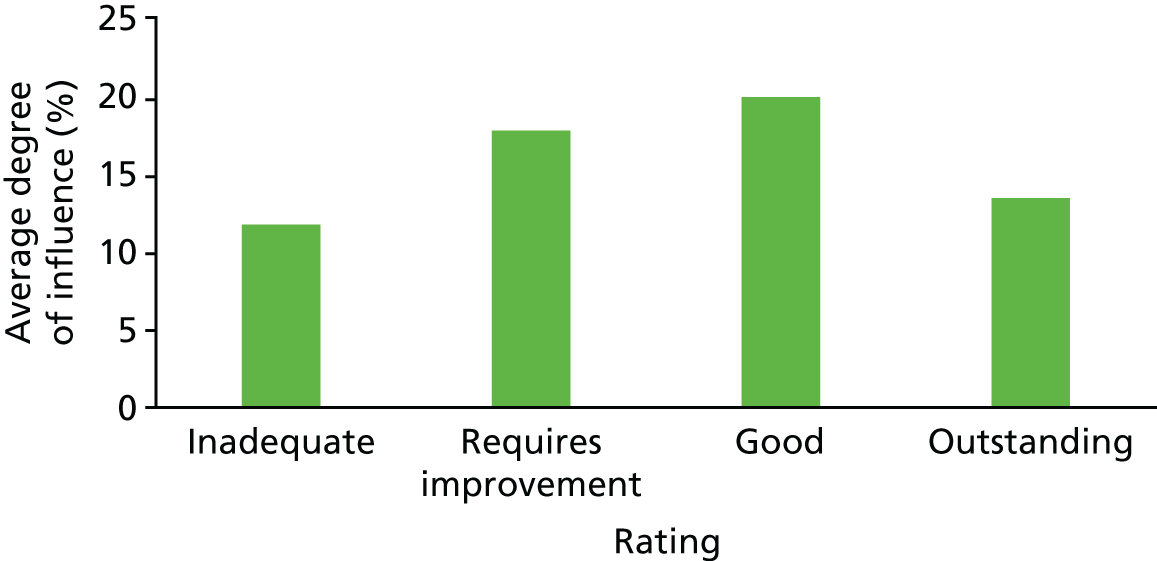

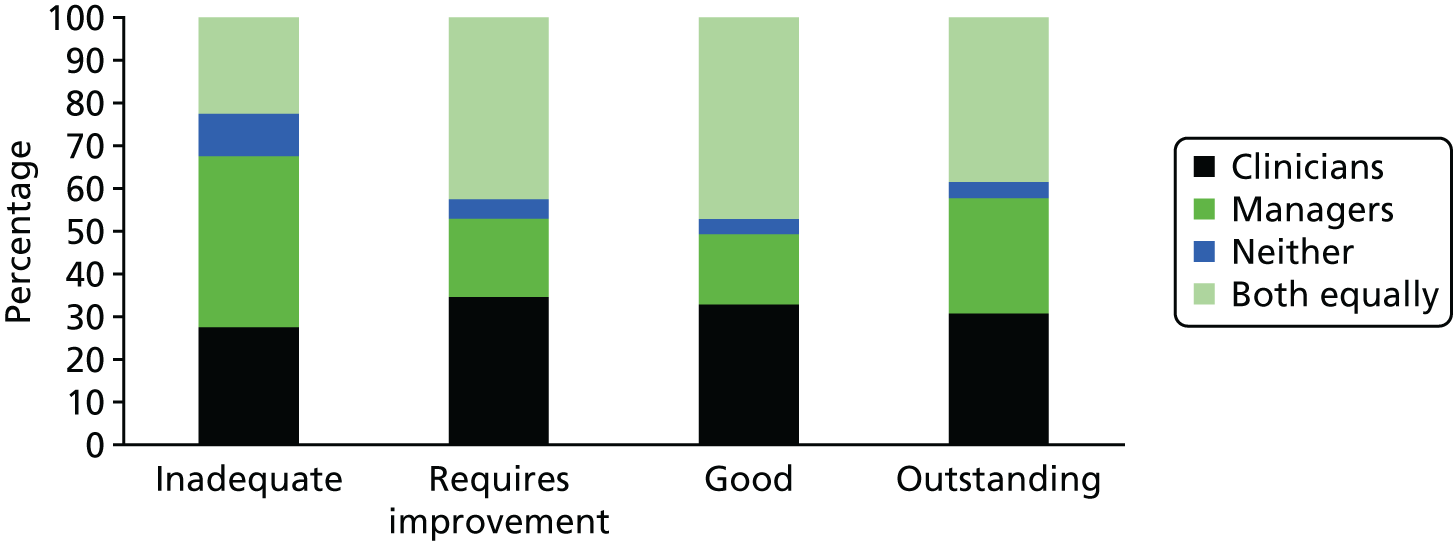

We then undertook a different analysis: the perceived relative influence of different bodies was correlated with the ratings of CCGs allocated by NHSE. The results are shown in Figure 4.

FIGURE 4.

The relative influence of different bodies (2016) by NHSE headline rating of the CCG.

The notable finding is that respondents from CCGs rated as ‘inadequate’ were far less likely to rate their CCG as having influence. In contrast, respondents from CCGs rated as ‘outstanding’ were much more likely to perceive their CCG as influential. It may be that the pattern of institutional influence is reflected in performance. Alternatively, it may be that this pattern suggests the possibility of a self-fulfilling prophesy: those expecting low impact achieved just such; conversely, those assuming that they had influence were able to exercise it. There is an alternative explanation: the low and high performers sensed the state of play and disowned or owned responsibility accordingly.

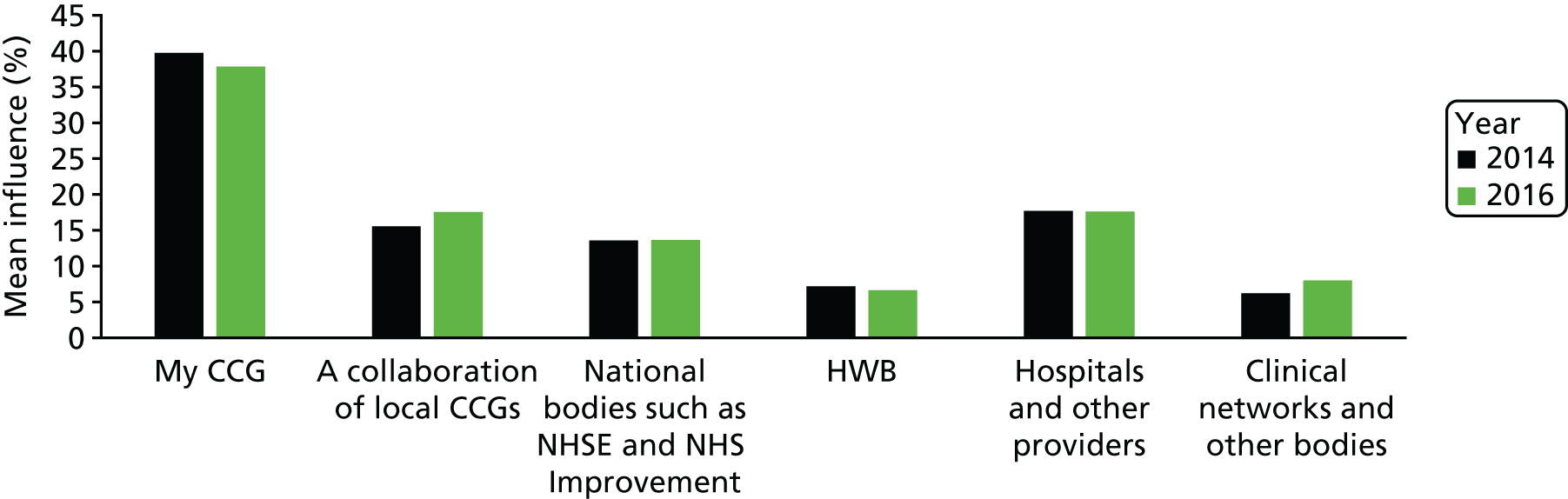

Figure 5 shows comparative data for 2014/16 with regard to perceived influence on the design of services in the local health economy. (Respondents were asked to assign a percentage rating across the institutions listed, adding up to 100%.) The pattern remained fairly stable over the 2 years. ‘My CCG’ was seen as the most influential body, but there was a slight fall-off in this assessment in 2016. There certainly seemed to be no sense of a growing influence.

FIGURE 5.

Institutions influencing service redesign.

The largest group of respondents said that their own CCG was the major player (38% of influence in 2016). However, other bodies were also seen as important, and these included NHSE (14%) and local collaborations of CCGs (18%). There were significant differences in this assessment depending on the role of the respondent with regard to their views about NHSE and NHS Improvement. GP members of the governing bodies were most likely to perceive NHSE and NHS Improvement as influential.

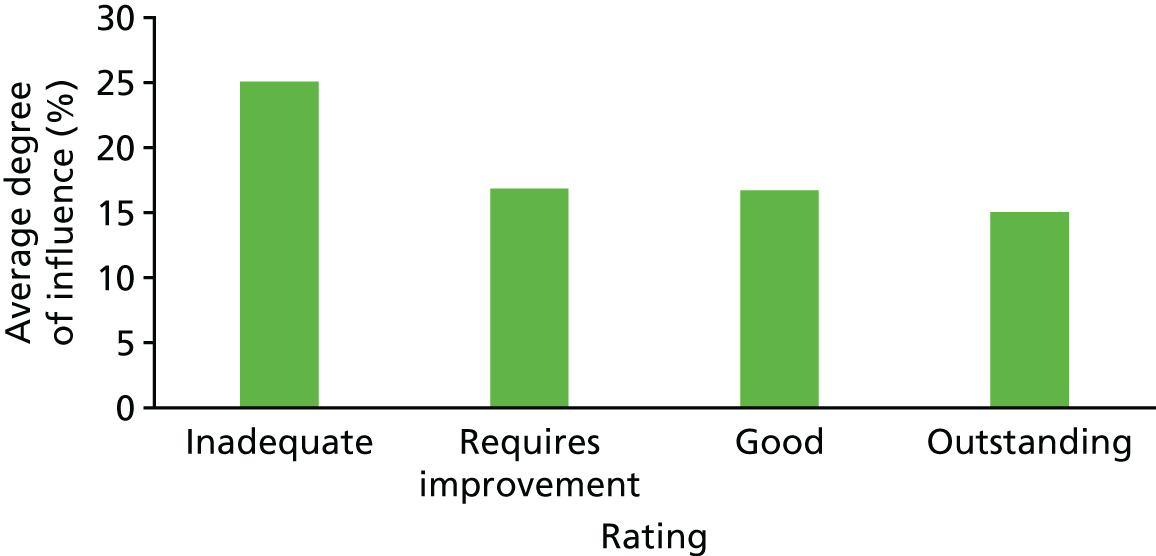

Next we looked at ratings of CCGs by perceived importance of collaboration among neighbouring CCGs. The results are shown in Figure 6.

FIGURE 6.

Rating of influence of a ‘collaboration of local CCGs’ by NHSE headline rating of CCG.

These results suggest that those respondents whose CCG was rated ‘good’ were those seeing collaboration with other CCGs as important, whereas those rated ‘inadequate’ tended to see it as less important. On the other hand, the ‘outstanding’ ones were seemingly able to be self-reliant. And perhaps they did not want to collaborate with others in case this affected their performance ratings. When asked to rate the influence exerted by hospitals and other providers, it tended to be respondents from CCGs rated as inadequate who were more likely to accord the highest influence to these bodies (Figure 7). This may reflect the reality of powerful local hospital trusts or it might reflect a lack of will or capability in tackling these providers.

FIGURE 7.

Rating of influence of ‘hospitals and other providers’ by headline rating of CCG.

The next section shifts focus from the influence of CGGs to an analysis of relative influence within them. Most especially, there was the contentious issue of whether managers or clinicians were exercising power and, relatedly, what influence, if any, other role holders such as the lay members, the secondary care doctors and the nurses had.

Influence within Clinical Commissioning Groups

Given that the policy intent, as shown in Chapter 1, was to create commissioning organisations led by clinicians – and most especially by GPs – we wanted to know whether or not these institutions had lived up to that aspiration. We began with a question which asked about the relative influence of different groups on the redesign of services. The four groups were managers, GPs, other clinicians excluding GPs and lay members. The results are shown in Figure 8.

FIGURE 8.

Influence of managers, GPs, other clinicians and lay members in the redesign of services.

In broad terms, managers and GPs were seen to be the most influential by far. In 2014, of the two, GPs were marginally ahead; however, by 2016 the rankings had reversed and managers were marginally ahead in terms of ranked influence. This is especially notable given that the majority of respondents were GPs. Other members of the governing bodies (including the lay members, secondary care doctors and nurses) were rated as far less influential.

Some answers from 2016 were then broken down to show how different kinds of respondents answered this question. The results are shown in Figures 9 and 10.

FIGURE 9.

Influence of managers, as reported by different role holders (2016).

FIGURE 10.

Influence of GPs as reported by different role holders (2016).

It was evident that finance officers tended to see managers as the most influential figures. GP members of governing boards and others (directors of public health and other managers) tended likewise to see managers as influential.

Next, we delved deeper into the perceived influence of GPs, as broken down by role of respondent. As the results in Figure 10 show, GP members of the boards were, ironically, the least convinced that they had much influence. It may be that other board members wished to maintain the official image of ‘GPs in charge’. Accountable officers, for example, may have wished to reflect the idea that they were the servants of a membership organisation.

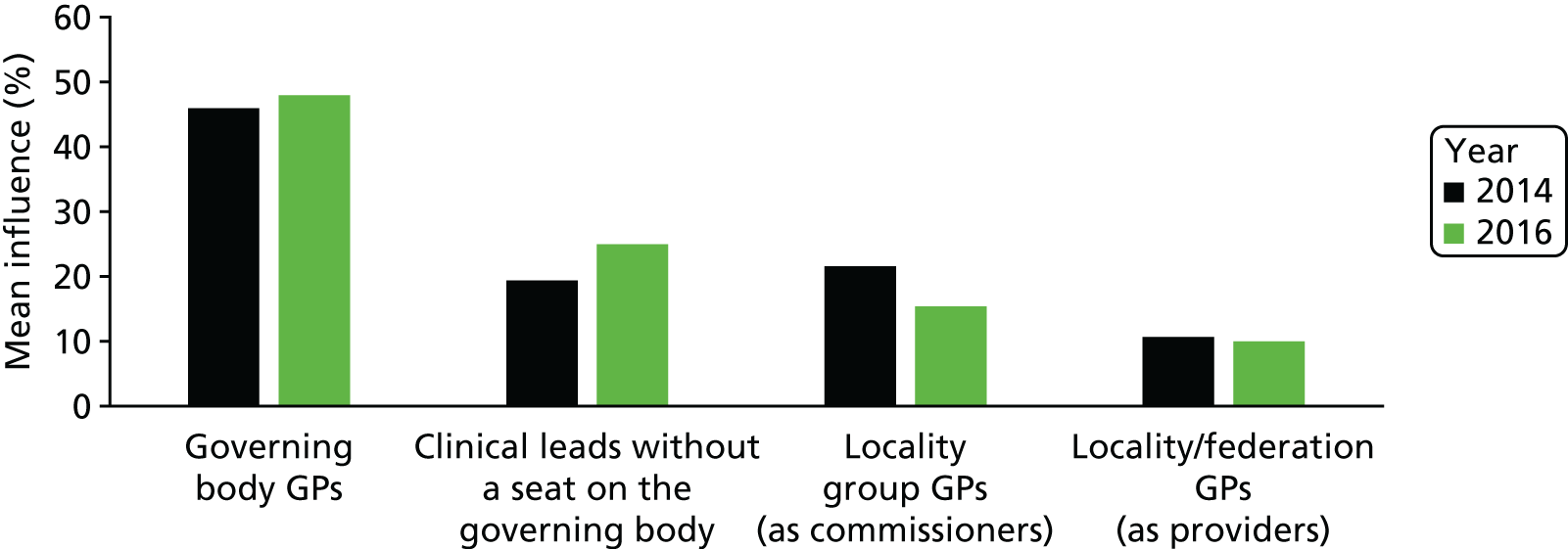

We also wanted to know in what capacity GPs were acting when they influenced service redesign. Was it as official governing members, as clinical leads who did not have a seat on the governing body, as locality leads, or as leaders of GP federations? Figure 11 shows the results for both 2014 and 2016.

FIGURE 11.

Roles of GPs shaping service redesign (2014 and 2016 compared).

Perhaps not a surprise, given the role of many respondents, GPs sitting on the governing bodies were seen as the most influential of the GP categories. Of note also was that the perceived influence of locality-level commissioning GPs declined between 2014 and 2016.

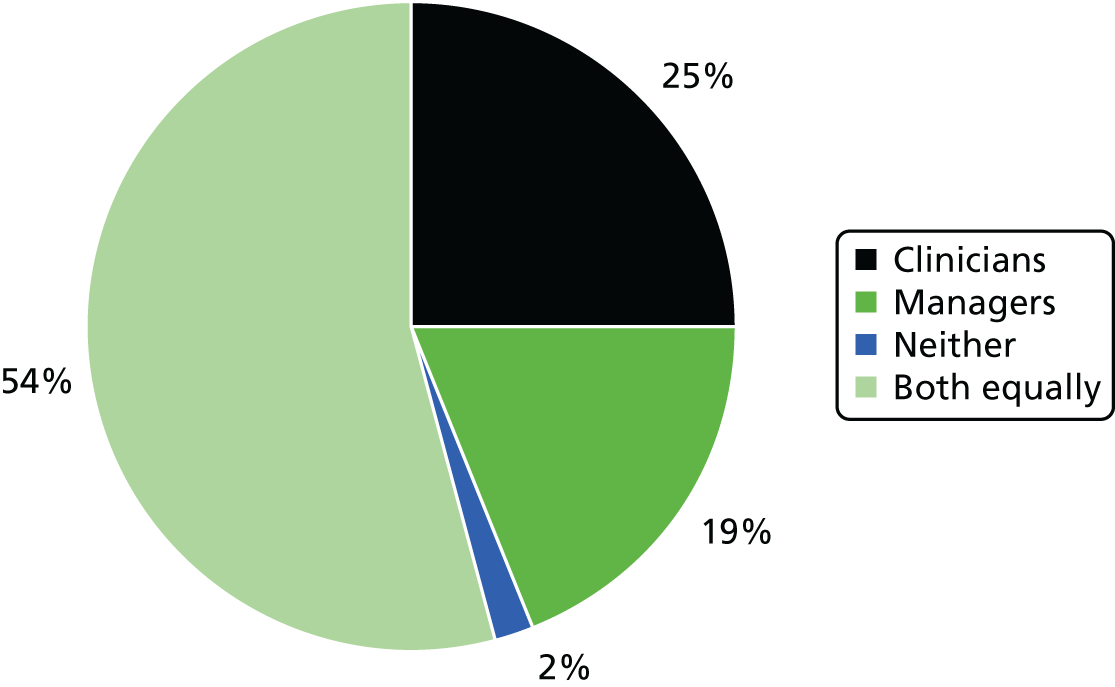

A related question concerned who sets the compelling vision. Were GPs and other clinicians making a leadership contribution through envisaging alternative service provision or was this vital leadership role filled by others? Figure 12 shows the results.

FIGURE 12.

Who sets the compelling vision for service redesign?

In 2014, the results for clinicians were the same (between 25% and 26% of respondents said that GPs set the compelling vision). The main difference between the two time periods was in the proportion of respondents who answered ‘neither’ to this question: 23% in 2014 but a mere 2% in 2016. At this later date the most common answer to the question ‘who sets the compelling vision?’ became ‘both equally’.

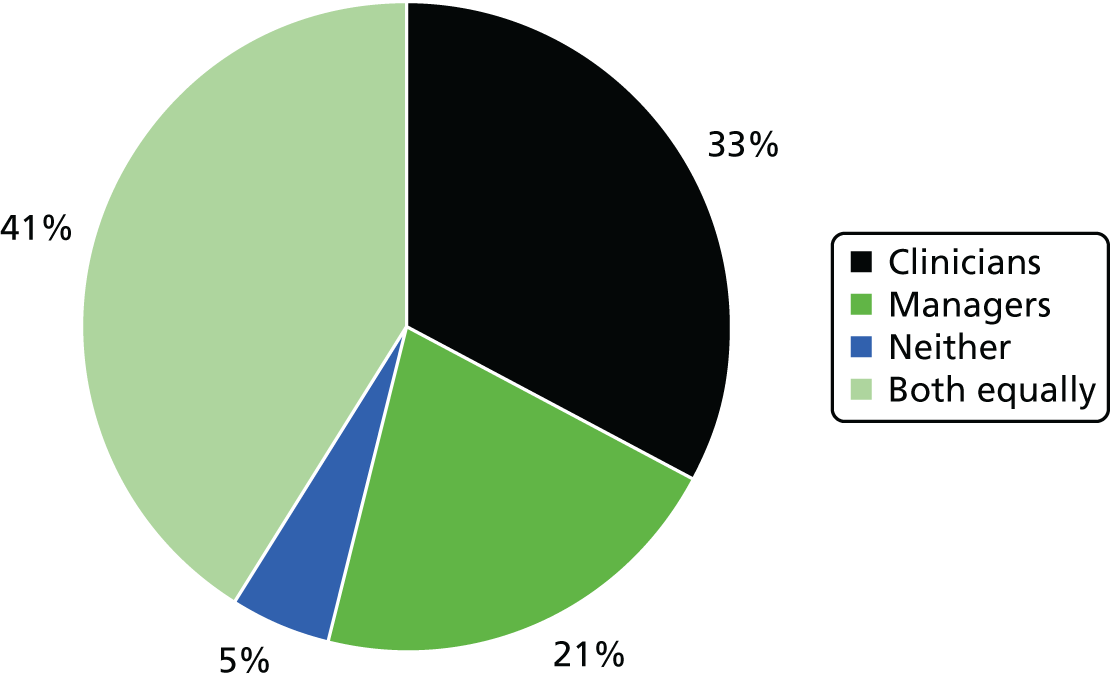

Figure 13 shows the breakdown by role of respondent to this same question. This shows that the nurses and accountable officers were most likely to say it was both equally, whereas more ‘independent’ observers (finance officers, secondary care doctors and laypersons) were more likely to name managers as key players in this regard. (Accountable officers once again played down their role.) No role group said that GPs were the ones mainly setting the compelling vision.

FIGURE 13.

Vision answers as reported by different role holders.

As shown in Figures 12 and 13, most respondents suggested that it was managers and clinicians equally who set out the compelling vision. These results suggest that the notion that GPs would be the visionaries and architects and that managers would play the role of delivery agents is not an accurate depiction of the reality in most cases. There is also more evidence here of dual leadership occurring – a particular type of distributed leadership.

We asked about communication with patients and the public, and the results are shown in Figure 14. For these stakeholders, managers acting alone or acting equally with clinicians account for 87.5% of this kind of communication. In their free-form answers, some respondents suggested that the role was mainly undertaken by managers, although clinicians might be ‘rolled out’ if some serious change was being proposed. Once again there was apparent progress between 2014 and 2016. In 2014, nearly one-quarter of respondents said that neither managers nor clinicians from the CCG were in communication with patients and the public, but in 2016 this fell to only 2%.

FIGURE 14.

Communication with patients and the public.

In a related question, we asked who provided the insights into public and patient needs. The results (shown in Figure 15) suggest that the largest part of this is done jointly with managers and clinicians, although 21% of respondents said that managers were mainly responsible for this activity.

FIGURE 15.

Who provides insight into patient needs?

The main difference revealed in Figure 16 is that respondents from CCGs rated as ‘inadequate’ were most likely to say that managers provided most expert insight into patient and public need, and they tended to regard clinicians as less active in this regard.

FIGURE 16.

Who provides insights into patient needs? by headline rating of CCG

An increasingly important theme since the formation of CCGs as independent statutory bodies has been the growth of the idea that more collaboration is required – with other CCGs and with other stakeholders, such as social services and voluntary bodies. We asked about this next.

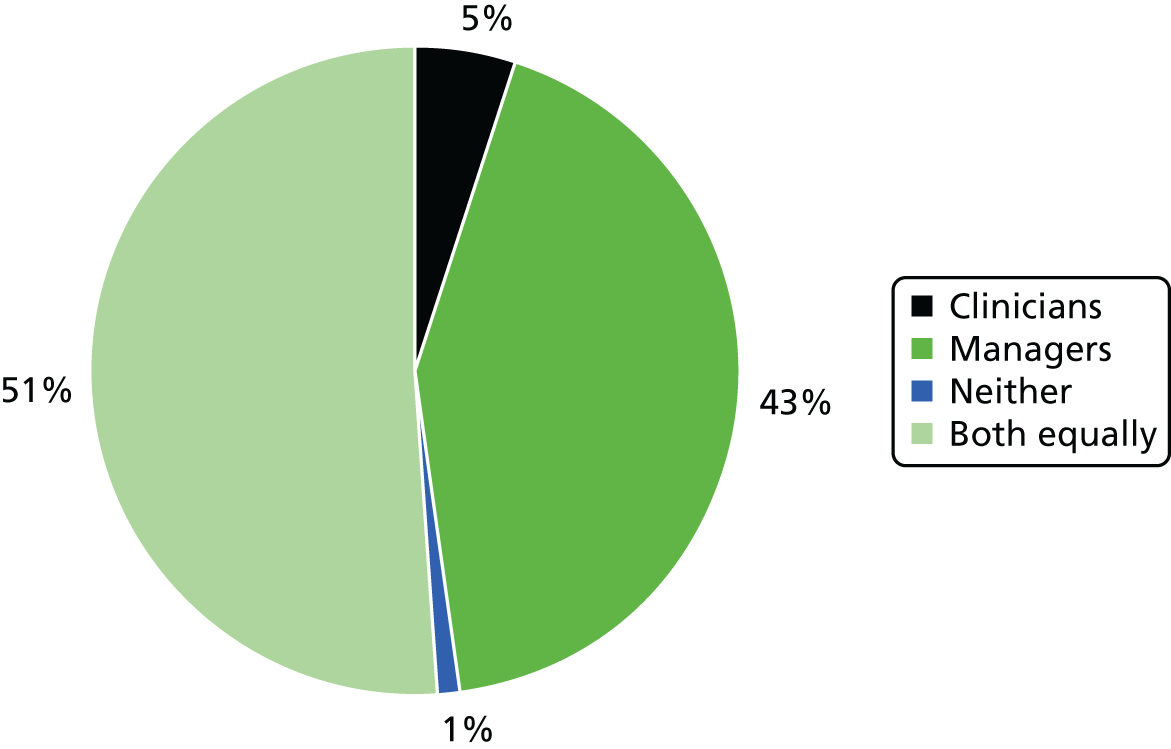

Building collaborations

The building of collaborations with providers and with other commissioners has increasingly become a vital activity for CCGs. Who would undertake this vital work? Figure 17 shows the results.

FIGURE 17.

Collaboration building.

The results suggest that half the respondents saw managers and clinicians equally involved in this. However, a very significant proportion (43%) identified managers as leading on this, and only a very small proportion (5%) argued that clinicians led on this work.

Qualitative, free-form answers added some depth and flavour to the question of the kind of contribution being made by clinical leaders.

A central reason for much of the emphasis on clinical leadership, as we noted in the literature review, relates to the idea that clinicians have the potential to make a difference through a distinctive set of contributions. We asked for free-form response answers to the question ‘What distinctive contributions do clinicians make when clinical leadership works well?‘.

The answers clustered into eight main categories of types of response, as shown in the first column of Table 3. Text in the second column is verbatim responses. Fuller tables are shown in Appendix 6.

| Type of response | Example of verbatim response |

|---|---|

| Knowledge and understanding | Clinical knowledge; local knowledge; knowledge from front-line experience; professional knowledge |

| A more clinically informed view than managers could hope to offer | |

| They understand services much better than managers | |

| We understand the bigger picture | |