Notes

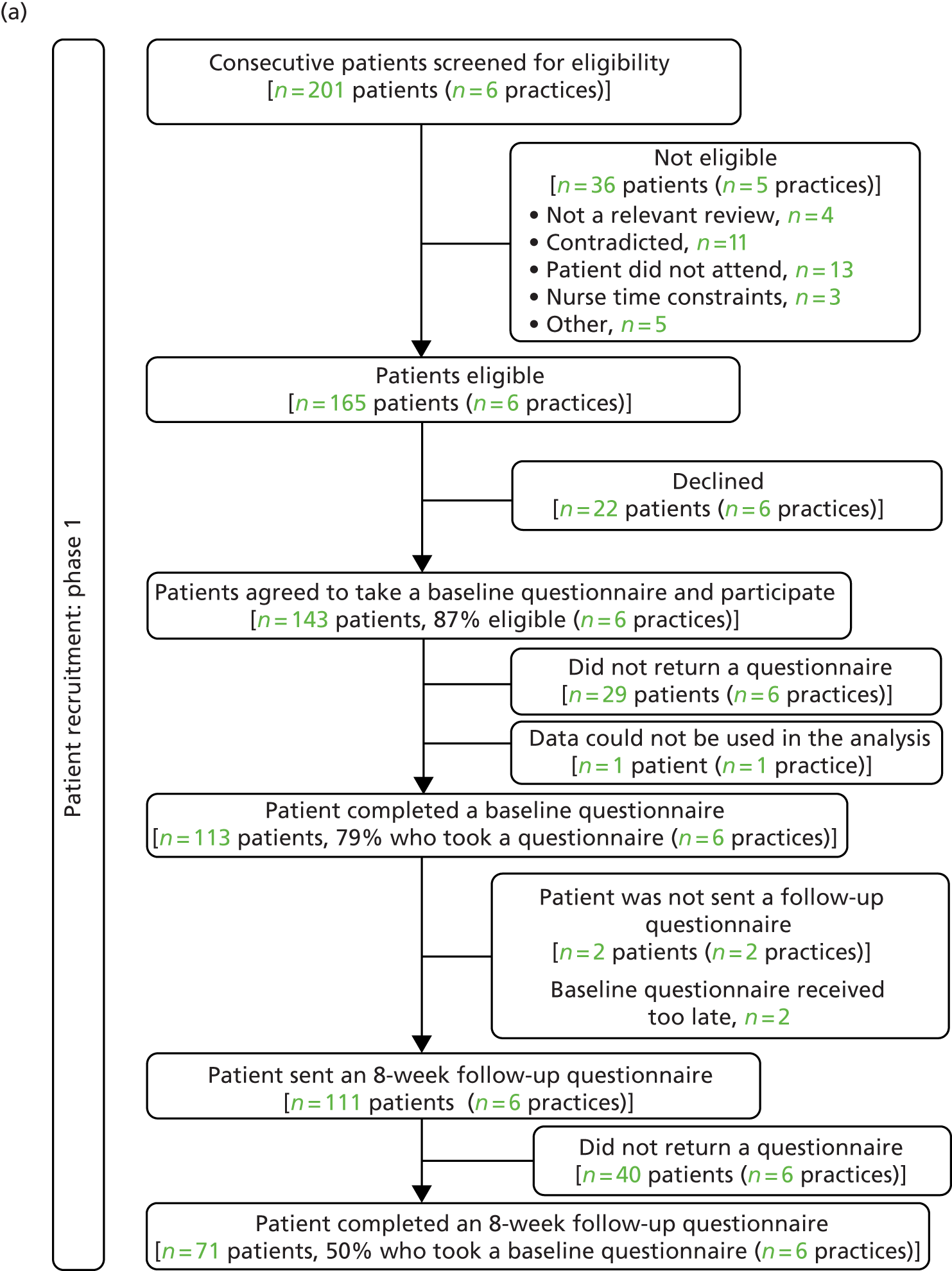

Article history

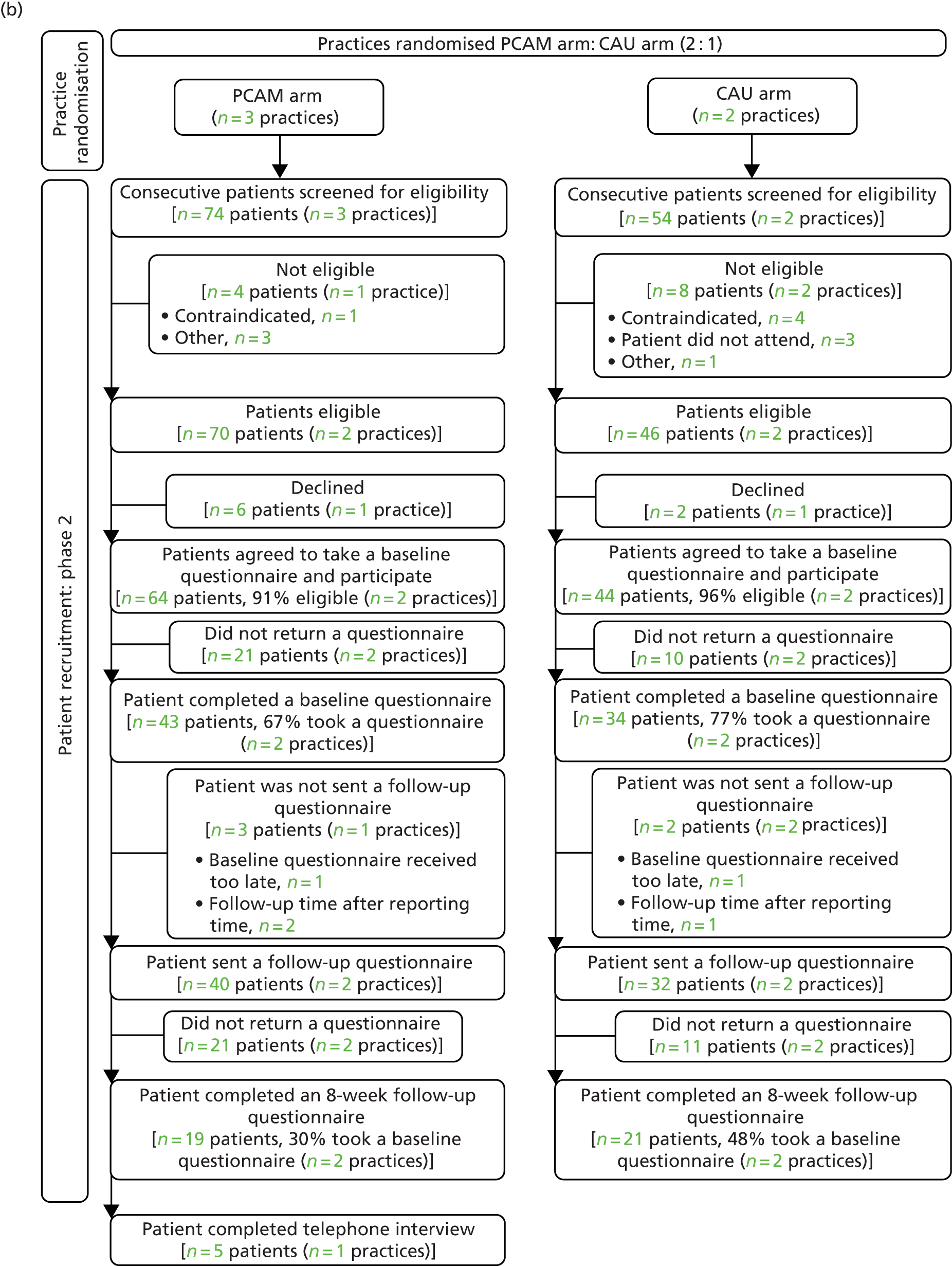

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 13/33/16. The contractual start date was in April 2015. The final report began editorial review in January 2017 and was accepted for publication in June 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Maxwell et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction, background and aims

Introduction

Over 15M people in the UK (2M in Scotland) report living with a long-term condition (LTC), with an estimated 6.5M people living with more than one condition. These numbers are projected to keep rising over the next decade. 1 A 2012 study of multimorbidity found that 42.2% of all patients in the UK had one or more morbidities. 2 People with LTCs account for 50% of general practitioner (GP) appointments (80% in Scotland), 70% of inpatient bed-days and 70% of the total health and care spending in England. 1 People with multiple morbidities use more health-care resources, including hospital beds. 3 Improving the management of LTCs has the potential to both reduce hospital-bed occupancy and improve the quality of life for this group of patients. 4

Those living in a deprived area are more than twice as likely to have a LTC as those living in more affluent areas. People with LTCs are also more likely to be disadvantaged across a range of social indicators. 5 Living with these conditions can result in additional acute and chronic stress, increasing the risk of anxiety and depression, which can, in turn, further affect their physical health and capacity for self-care.

Chronic physical illnesses are associated with increased prevalence of depression. 6 Until recently, expert guidelines recommended screening for depression in patients with diabetes mellitus (DM) and coronary heart disease (CHD); however, research found only little or no impact of screening on the recognition of depression in these patients. 7–9 Screening was mostly carried out by nurses, without training, as part of annual LTC reviews. Research has highlighted problems with nurse engagement in ‘screening’ and how the ‘tick-box’ approach of the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) might have led to the underdetection of depression in patients with LTCs. 10 Previous studies have also found that practice nurses (PNs) recognised only 16% of psychologically distressed patients attending their clinics. 11

It is well accepted that deprivation and physical and mental health are closely linked, with an understanding that a broad range of stressors, more common in deprived communities, can have a negative impact on the physical and mental health of individuals. A recent study showed that the onset of multimorbidity occurred 10–15 years earlier in people living in the most deprived areas than in those living in the most affluent areas, with socioeconomic deprivation particularly associated with multimorbidity that included mental health disorders (coexistence of physical and mental health disorders). The presence of a mental health disorder increased as the number of physical morbidities increased, and was much greater in more deprived people than in less deprived people. 2 Broader social and economic conditions influence both the incidence of, and success in treating, many conditions,12 including patient engagement in self-care practices that are essential for managing LTCs.

Engaging in health-promoting behaviour and self-care practices can be limited or even impossible when adverse social circumstances intervene. Attention to these circumstances (often patient-identified priorities) could lead to improvements in patients’ abilities to subsequently engage in self-care and achieve benefits. The Department of Health has long anticipated that, with increased self-care practices, there would be a corresponding reduction in the use of health-care resources, better quality of life and reduced mortality. The current mechanisms within the NHS for encouraging self-care practices might better acknowledge or be responsive to the barriers that are created through many patients’ disadvantaged lives. This often includes reduced health literacy, which will require a different type of input if self-care behaviours are to be understood and accommodated within difficult lives. Again, attention to recognising and addressing these broader needs and organising responses (which other sectors are better positioned to meet) will ensure the more efficient use of NHS resources. Such an approach is endorsed by the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) in its report The 2022 GP: A Vision for General Practice in the Future NHS,13 in which one of the first recommendations is about strengthening links between general practice and communities.

Supporting People with Long Term Conditions4 based its improvement programme on models from the USA (Kaiser Permanente, Pfizer and Evercare). These models are based on nurses acting as case managers who have a key role in co-ordinating services from other health and social care providers. 14 However, in primary care in the UK, this ideal has moved little beyond nurses conducting annual health checks that meet the requirements of the QOF. The RCGP promotes care planning,15 but acknowledges that coexisting mental and social circumstances may prevent such approaches. The RCGP response to QOF indicators for depression noted that ‘a holistic assessment should be part of the routine management of any patient with a LTC’. There are few validated tools for such assessment, especially for use by nurses. The development of interventions for primary care that encourage holistic assessment and action to address complex health and social needs is urgently required.

Depression screening in LTCs has now been removed from the QOF, but patient and carer groups have argued that this will serve only to remove the imperative to include assessing mental health needs in LTCs. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) now recommends that a biopsychosocial assessment is carried out, but only for patients newly diagnosed with depression, and it provides little guidance on how this should be addressed and no imperative to act on this assessment. 16

The Patient Centred Assessment Method (PCAM) tool has been developed to enable a broad assessment of needs alongside an assessment of how urgent these health or care needs are. The PCAM tool aims to help to identify and address patient biopsychosocial needs and to promote action based on the severity of these needs, including broader social problems that often lead to or exacerbate poor mental health, which can, in turn, have an impact on physical health and the patient’s ability to perform self-care. The tool encourages linking with other sectors to more appropriately address these problems for patients and to access alternative types of resources. The PCAM tool also encourages new ways of working that enhance opportunities for health promotion, even in those with few current health or social problems, to maintain healthy behaviour. It is anticipated that this will lead to improved quality of life for patients and better patient–professional interactions and relationships.

The PCAM tool is an adapted version of the Minnesota Complexity Assessment Method (MCAM), which was derived from the INTERMED (a method to assess health service needs). 17–19 The PCAM has previously been evaluated in anticipatory (Keep Well) health check clinics, which were initiated by the Scottish Government for early identification of LTCs, or risk of LTCs, in those aged 40–64 years and living in deprived communities in Scotland. 20 In an additional small-scale evaluation of the potential of the PCAM tool for use in highly vulnerable populations it was shown that the tool was perceived as having strong advantages in better managing the needs of homeless and travelling populations. 20 If the PCAM tool is shown to improve the care of people living in highly deprived communities, it could have real advantages for addressing health inequalities. The PCAM tool may also provide a more systematic approach for primary care in responding to the NICE and RCGP recommendations for biopsychosocial assessment of patients with LTCs and/or depression.

There is strong potential for the PCAM tool to make a real difference to the quality of care delivered in primary care to patients living with LTCs. The PCAM tool aims to encourage nurses to address more than just the physical care needs of their patients, or at least to determine these needs for others to address. By addressing these needs, patients could be better positioned to engage with health promotion and self-care advice and should also see improvements in their physical and mental well-being. There is also a strong potential for the PCAM tool to result in a greater range of services and support being enlisted in the care and support of those with LTCs, and especially for those patients from disadvantaged communities. This has the potential to reduce the burden on the NHS as the main or sole provider of care and support for many of these patients, who often end up with repeat hospitalisations and high levels of primary care use.

However, to date, the PCAM tool has not been evaluated for use by primary care PNs, and its potential value for addressing mental well-being in patients with LTCs has not been assessed, nor has it been subject to clinical trial to determine its impact on nurse behaviour and patient outcomes.

This research aimed to determine whether or not the PCAM tool can be used by primary care PNs to engage in holistic assessment of patients’ needs in those with LTCs, and particularly for those with multiple and complex needs. This tool encourages action to be taken based on the severity and urgency of the patient’s situation. Its use encourages a dialogue between the health-care practitioner and the patient, which serves to draw on practitioner skills, or even re-skill the practitioner in providing patient-centred holistic care, as opposed to the ‘de-skilling’ that has been reported by nurses through the tick-box mechanisms to improve quality of care. 10 It is hoped that future demonstration of the efficacy of the PCAM tool will transform how primary care engages with patients and their needs. It is also hoped that it will result in greater integration of health and social care needs and the co-ordination of meeting these needs, and that use of the PCAM tool can result in greater use of community and voluntary sector resources, as was demonstrated in the Keep Well evaluation in Scotland. The proposed PCAM tool can support making and strengthening such links, as it encourages nurses’ signposting to local (non-medical) resources. Such actions have the potential to reduce the current burden on ‘NHS-only’ use of services in the management of LTCs.

This research also aimed to determine whether or not a future full-scale randomised controlled trial (RCT) is feasible and whether or not the methods proposed for such a trial are acceptable, with the aim of developing a research protocol and application for funding for such a trial.

Aims

-

To assess the acceptability and implementation requirements of the PCAM tool for use in UK primary care, particularly in the context of PN-led annual reviews for people with LTCs.

-

To examine fidelity of the use of the PCAM tool by PNs in routine annual reviews of LTCs.

-

To assess the feasibility of conducting a full-scale trial of the effectiveness of the PCAM tool based on two potential units of analysis, namely intermediate-level nurse behaviour and longer-term patient well-being.

Research questions

Overall, this study sought to answer the following two main questions:

-

Is it feasible and acceptable to use the PCAM tool in primary care nurse-led annual reviews for those with LTCs?

-

Is it feasible and acceptable to run a cluster randomised trial of the PCAM intervention in primary care?

The pilot trial aimed to answer the following questions:

-

Can we recruit practices and nurses to take part in the study and retain them?

-

Can the practices and nurses implement study procedures correctly?

-

Are patients willing to complete questionnaires/outcome measures?

-

How many missing data are there, and does this relate to nurse- or patient-level follow-up?

-

What estimates of effect size, variance and likely intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) should be used to inform the sample size of the full study? Should the unit of analysis be at the nurse or patient level, or is it feasible or necessary to include both?

Objectives

-

To conduct focus groups with primary care staff and patients with LTCs to assess acceptability and implementation requirements.

-

To conduct a cluster RCT in eight practices and with 16 nurses to test the acceptability and feasibility of running a full-scale trial of the PCAM tool in primary care.

-

To examine the fidelity of nurse use of the PCAM tool via a sample of audio-recorded consultations before and during implementation.

-

To explore nurse and patient perceptions of using the PCAM tool in annual reviews for LTCs.

-

To conduct a process evaluation to identify possible contextual influences on study implementation.

Structure of the report

The research is reported as five related research studies (studies A to E). Chapter 2 provides an overview of the overarching study design and conceptual framework for the research, and the general methodological approach to each of the individual studies. Chapter 2 also reports on the general management and conduct of the research, including ethics approval and patient and public involvement (PPI). Chapters 3–7 report on each of the separate studies (A–E), including their methods, findings/results and a discussion of the findings and conclusions. Chapter 8 presents on overall discussion, including the strengths and limitations of our work, a reflection on our PPI and summary conclusions and recommendations.

Chapter 2 Overview of study design, methodology and general management

Design

This study included a:

-

qualitative study of GP, PN and patient views of the acceptability and implementation requirements of the PCAM tool

-

feasibility study for a cluster RCT to test the acceptability and feasibility of conducting a future effectiveness trial

-

qualitative comparison of audio-recorded nurse consultations before and during the use of the PCAM tool to assess the fidelity of its use by nurses

-

qualitative study of nurse and patient perceptions of using the PCAM tool in assessments of patients with LTCs

-

qualitative process evaluation of the implementation of the PCAM tool and the trial implementation processes.

The feasibility cluster RCT contains the potential for two units of analysis, namely nurses (changes in nurse behaviour and consultation feedback on nurses’ behaviour) and patients (patient well-being and quality-of-life outcomes).

Methodology

Study A: acceptability and implementation requirements of the Patient Centred Assessment Method

The PCAM [formerly known as the Minnesota and Edinburgh Complexity Assessment Method (MECAM)] tool was derived from ‘INTERMED’, which was developed for use in acute settings. The INTERMED assessed biopsychosocial aspects of the patient and how they related to the health-care system, which, taken together, reflect ‘case complexity’. 17–19 The purpose of the PCAM tool was to provide a practical but systematic vocabulary and action-based evaluation system that could be applied to a primary care setting to improve the care, and self-care, of patients with multiple (complex) needs. An early version, the MCAM, was developed in the USA for use by clinical teams (doctors and nurses) for the case management of patients with medically unexplained symptoms. 19 Although the conceptual basis for assessing complexity has been established via the INTERMED and MCAM, further adaptation and validation was required for use in a UK health context. This has been undertaken by the current team in the context of adapting it for use in Keep Well health screening consultations. This resulted in the development of the PCAM, as an adapted version of the MECAM, for use in the UK. It was successfully implemented and evaluated with seven Keep Well nurses, and was shown to increase non-medical referrals, especially to psychological, social and lifestyle referrals. 20 Use of the PCAM tool was embedded into the Keep Well assessment by NHS Lanarkshire and was reported by the service lead to be making ‘a real difference’ to nurse engagement with the mental and social well-being of patients. The PCAM tool is also in use in the USA, where it is undergoing further testing.

It was therefore a reasonable theoretical assumption that the PCAM tool could be of value for primary care nurse engagement with the mental and social well-being of their patients with LTCs who are at higher risk of poor mental health and social problems. However, the ‘Keep Well’ context is not entirely comparable to routine primary care. ‘Keep Well’ services involved anticipatory health checks among ‘at-risk’ populations, with more time available at each consultation. The PCAM intervention had not been reviewed by GPs or PNs, and neither had its usability and acceptability been evaluated in primary care. Furthermore, there had been no patient input to the use of the PCAM tool. This initial study aimed to assess its ‘face validity’, acceptability and implementation requirements for use with PNs and their patients with LTCs. We would also gain qualitative knowledge surrounding primary care professionals’ views and readiness to conduct biopsychosocial assessments, and whether or not this tool could prove useful to GPs in their management of depression.

This study of ‘face validity’, acceptability and feasibility of primary care nurse use of the PCAM tool was conducted via focus groups with primary care practice teams. The inclusion of different members of the practice team was important, given the role of primary care nurses as ‘employees’ of the practice, whose work is determined by the practice (GP partners). The use of the PCAM tool also requires that other appropriate professionals may need to be called on if the nurse has identified areas of need, especially urgent needs. As the PCAM tool should facilitate nurse assessment and signposting to other professionals, including GP colleagues, ‘how’ the PCAM tool would work at a practice level was also important. In addition, as the role of practice managers (PMs) in implementing new initiatives in primary care was also taken into account, these members of staff were also included in the focus group study in assessing the feasibility, acceptability and implementation requirements for the use of the PCAM tool.

The discussion of the implementation of the PCAM tool at a practice level, as well as nurse use of the tool, and the discussion of adaptations that might be needed at a practice level (e.g. more time for nurse consultations in the early stages of use) made the focus group methodology and the inclusion of the primary care team appropriate.

Study B: feasibility study of a cluster randomised controlled trial of using the Patient Centred Assessment Method intervention in primary care nurse assessments of patients with long-term conditions

A feasibility study aims to assess the acceptability and practicality of a proposed project, and whether or not an intervention should be recommended for efficacy testing. 21 This feasibility study sought to assess the feasibility of the intervention for use in primary care, test the methods and protocol for a future trial of the PCAM intervention and consider whether or not it should be recommended for efficacy testing. This also included assessing which outcomes were feasible to collect and which outcomes may perform better or be more likely to detect change or improvement as a result of the intervention.

The recruitment of practices, and nurses within these practices, raised the possibility for two levels of clustering (practice and nurse level), and the question of whether or not a matched pairs design would be possible or more appropriate. There was the possibility that there would be more variation between nurses than between practices, and the decision to randomise at the level of practices was somewhat pragmatic; it was intended to reduce the number of practices needed to recruit sufficient nurses and to minimise nurse contamination caused by exposure to the PCAM tool of the nurses randomised to care as usual (CAU), if other nurses in the practice were using the PCAM tool. However, this feasibility study also had an added complexity in that there were two levels of outcome that were being observed: change at the level of the PN and change at the level of the patient. Therefore, nurses would also be included as a unit of analysis, and we determined patient recruitment to enable this. Although the overall design of the feasibility trial is complex (with baseline and follow-up being conducted both before and after randomisation of practices), this was necessary to observe changes at both the nurse level (where patients are also evaluating nurses’ caring behaviour) and the patient level.

A matched pairs design is used to explicitly control for confounding variables to eliminate the bias of these variables. We could have aimed to match nurses based on criteria likely to influence their delivery of the PCAM. However, besides assumptions of nurse experience being important, we do not currently empirically know which nurse characteristics should be included in any block allocation of pairs. We thought about which factors could be confounding and, therefore, included nurse demographic and clinical experience data alongside (patient-reported) caring behaviour as the most likely explanatory variables we could control for in a future matched pairs design. However, if we had paired nurses in this current study, we would have needed to recruit all nurses from different practices, as we could not have nurses from the same practice being paired to receive training or no training; the potential for nurse contamination was too great. This would have increased the overall number of practices required. Our chosen design of a cluster randomised trial with the practice as the unit of cluster would enable us to decide whether or not nurse variables are a significant bias that would necessitate a matched pairs design for a full trial.

Randomisation of matched pairs at the patient level (even if we also knew the likely confounding variables at this stage) would require PCAM-trained and untrained nurses to exist within the same practice and risk contamination, or for patients from one practice to be sent to another practice for their LTC consultation. Apart from the inconvenience to patients, it is likely that caring for another practice’s patients would result in changes in nurse behaviour. It would also add significantly to the complexity, costs (researcher input for patient consent to randomisation and a lengthy recruitment process) and ethical concerns of this study. A design based solely on patient outcomes would not allow for studying any changes or impact on nurse behaviour.

We aimed to conduct a feasibility study (not a pilot of ‘fixed’ trial methods) and hoped to use our findings to determine the best outcomes and units of analysis, and to determine whether our ‘efficient’ design (based on ease of recruitment of practice, nurses and patients) was robust or if confounding variables would need to be controlled for in future randomisation processes.

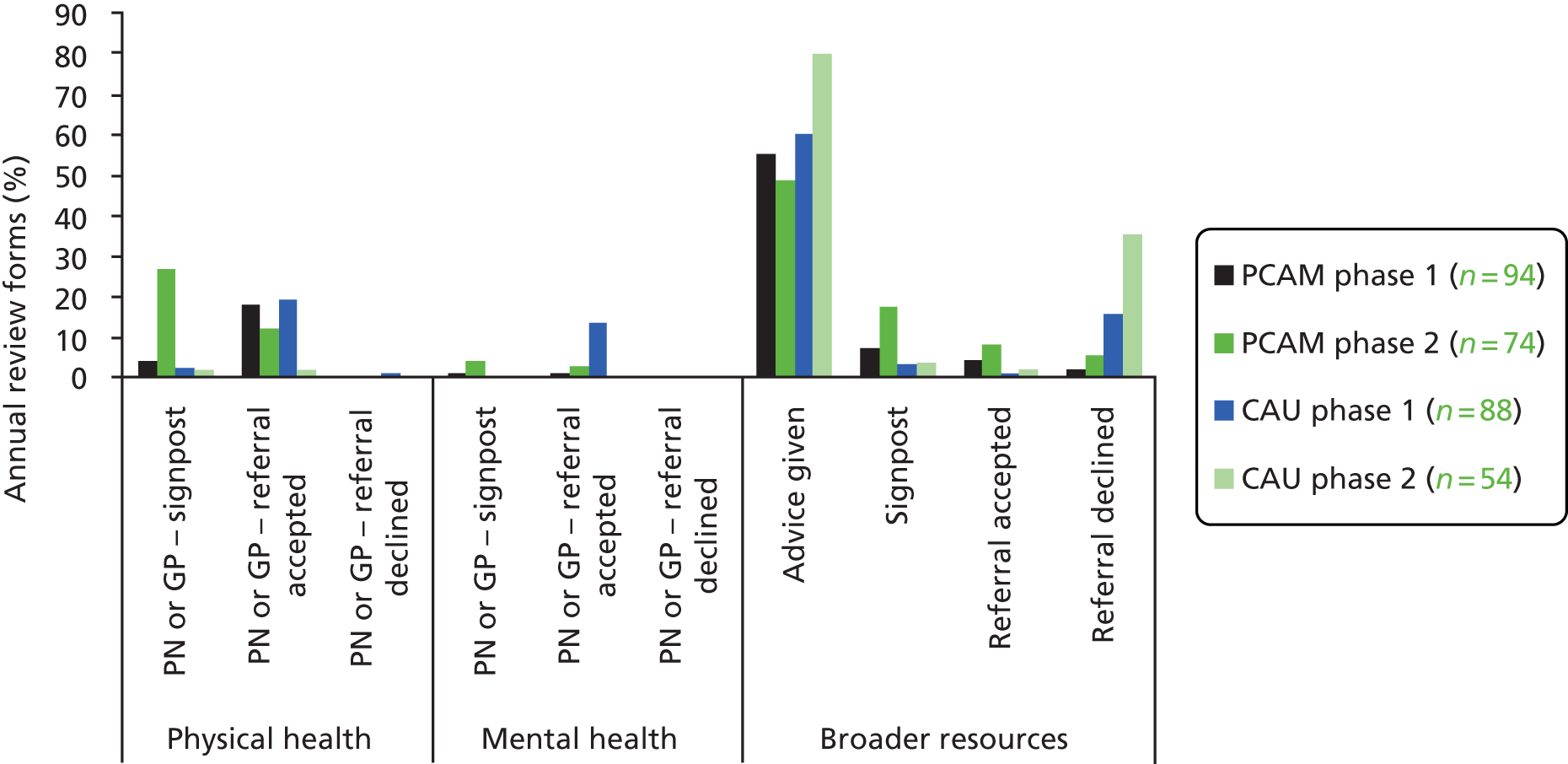

Studies or trials of complex interventions also allow for the inclusion of more than one primary outcome. A feasibility study can help to determine which outcomes are more likely to be able to detect sufficient levels of change, and the degree of change observed can help to determine the likely numbers needed in a full trial to detect a sufficient level of change. This study was set up to include the collection of potential measures of change in nurse behaviour, as well as the collection of a set of measures relating to outcomes for patients. Nurse behaviour change was measured in several ways: patient assessment of the nurses’ consultation skills, as measured by the Patient Enabled Instrument (PEI)22 and Consultation and Relational Empathy (CARE)23 measure; changes in nurse confidence with mental health, as measured by the Depression Attitude Questionnaire (DAQ);24 changes in nurse consulting behaviour, as observed before and during the PCAM intervention via the recorded and coded consultations with patients; and changes in nurse referral patterns collected before and during the PCAM intervention.

Patient assessment of nurse consultation skills (measured by the PEI and the CARE measure) can be measured only post consultation; therefore, this necessitated obtaining baseline scores for all nurses before they were randomised to the PCAM intervention or CAU and after randomisation. This then resulted in two cohorts of patients being recruited at baseline and after randomisation. The longer-term outcomes for patients following their consultation were also followed up for all nurses at baseline and post randomisation. The inclusion of nurse baseline assessment added to the complexity of the design of this study, but this serves to demonstrate the need for alternative trial methods when multilevel interventions are delivered in complex care settings such as primary care.

Patient outcomes were assessed by the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ),25 the Short Form questionnaire-12 items (SF-12)26 and the Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (WEMWBS)27 immediately post consultation and at the 8-week follow-up.

Study C: fidelity of use of the Patient Centred Assessment Method by nurses

Taking an approach based on the early work of Engel,28 the aim of the PCAM is to encourage more holistic consultations by primary care professionals (in this study, PNs) and to ensure that nurses pay attention to a broader range of the biopsychosocial needs of patients. This is done within a patient-centred framework and a chronic disease management model.

There have been many theories and models derived from the analysis of structures, processes and outcomes occurring during traditional medical consultations. 29–32 More recently, these have included the role of the patient in health-care provision, with the aim of improving quality outcomes for patients. 33,34 However, the majority of ‘consultation’ work in primary care has been focused on the interaction between the patient and the GP, with little attention to nurse consultations. More recently, with attention to changing roles in primary care, such as the ‘nurse practitioner’, there has been some discussion around which of the existing (medical) consultation models might apply to primary care nursing. 35–37

In a similar vein, there are validated coding tools for assessing communication skills and empathy in medical consultations, such as the Verona Coding definitions of Emotional Sequences,38,39 a consensus-based system for coding patient expressions of emotional distress in medical consultations, defined as cues or concerns, and the Roter Interaction Analysis System40,41 as a method for coding medical dialogue. However, these would not meet the needs of this study in assessing whether or not nurses were implementing the PCAM tool as intended, which should be assessed by determining whether or not nurses did indeed explore the biopsychosocial needs of patients and whether or not they did this in a patient-centred conversation, as opposed to a ‘tick-box’ exercise. The study therefore required the development of a bespoke coding frame, and one that could be applied systematically by more than one researcher to recorded transcripts of nurse–patient interactions.

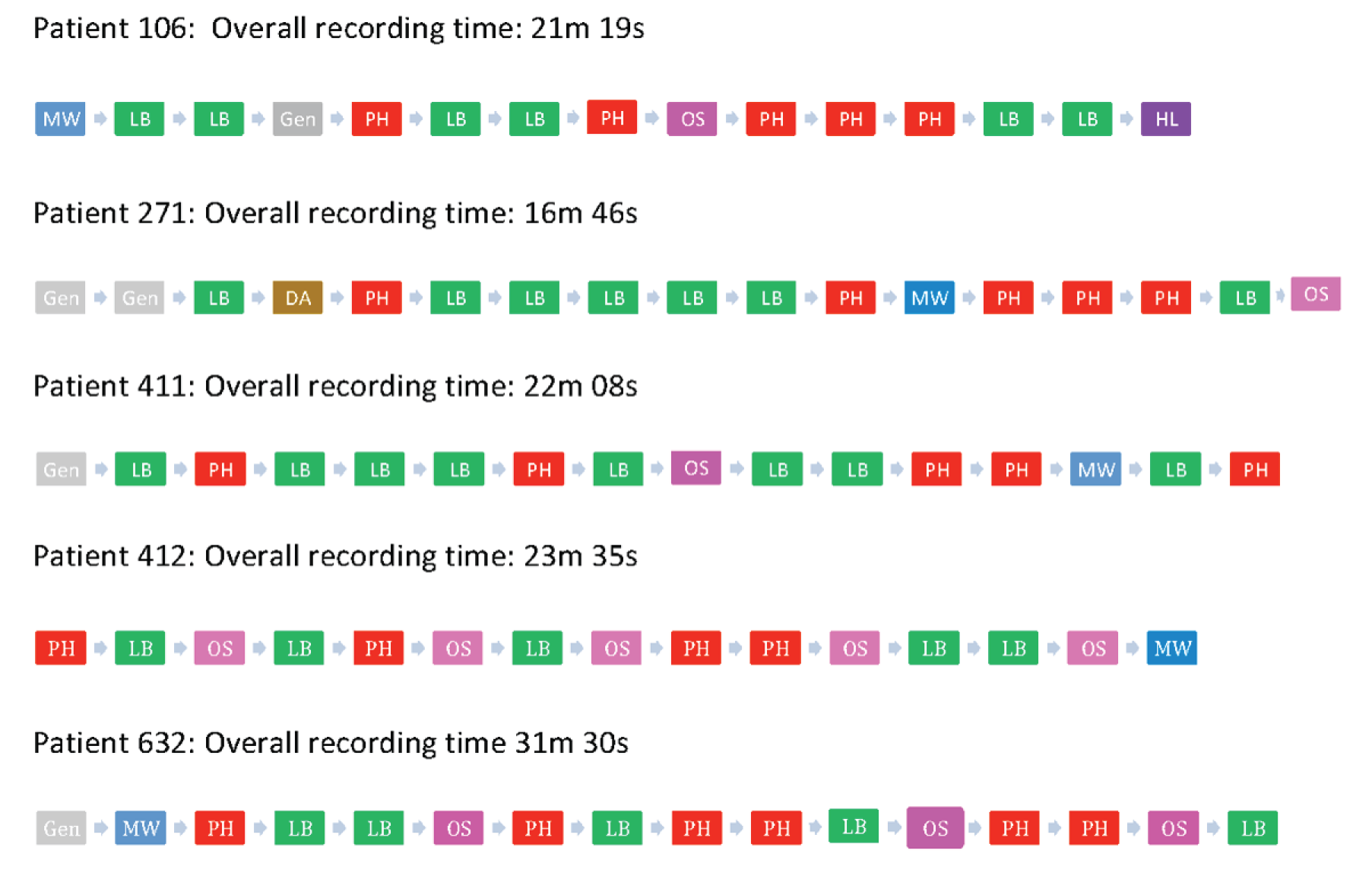

We developed a coding system for classifying conversation segments according to whether or not they address any of the domains/items within the PCAM tool (and which ones are discussed), whether or not they identify or acknowledge needs against each of the domains and whether or not they discuss potential actions against each of the domains. This coding frame was then applied to recorded consultations with a sample of nurse–patient interactions that occurred both before and after the nurses were trained in the use of the PCAM tool in order to understand whether or not they were already consulting in a way that helped to address biopsychosocial needs or if there had indeed been a change in their behaviour following training and use of the PCAM tool. The specific coding system and the analysis of recorded consultations is reported in Chapter 5.

Study D: nurse and patient perceptions of using the Patient Centred Assessment Method in long-term condition annual reviews

In assessing the acceptability and feasibility of using the PCAM tool in primary care, it was important to gain some perspectives from nurses and their patients following nurse use of the PCAM tool in patient consultations. All nurses who were allocated to receive the PCAM intervention were invited to participate in a qualitative interview of their experiences of its use. For those patients recruited by nurses to complete outcome-based questionnaires, the follow-up questionnaire contained an invitation for patients to also participate in a follow-up interview if they wished. Individual interviews were chosen because the numbers involved were small (maximum of eight nurses and two patients per nurse), and individual rather than ‘group’ experiences were important to capture at this stage. Patients were asked about their own personal experience of the consultation and any advice or actions that the nurse had initiated at this consultation.

Study E: process evaluation

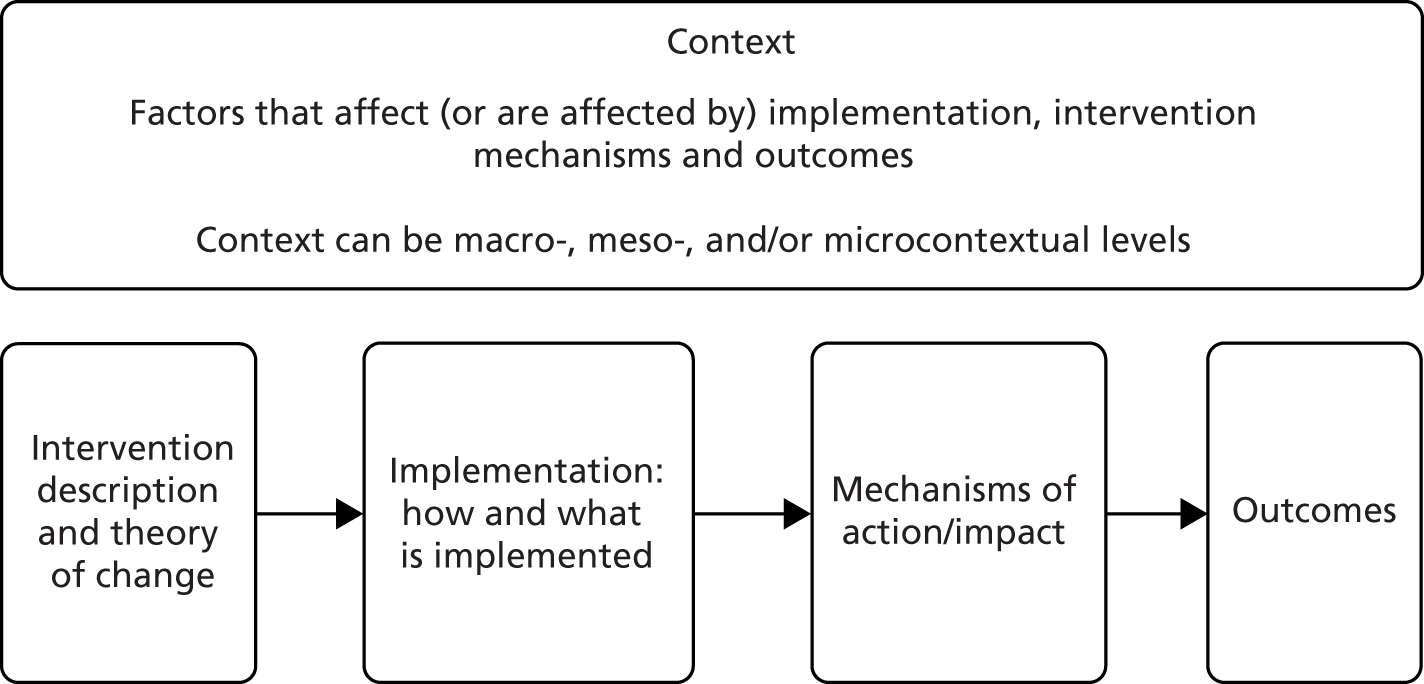

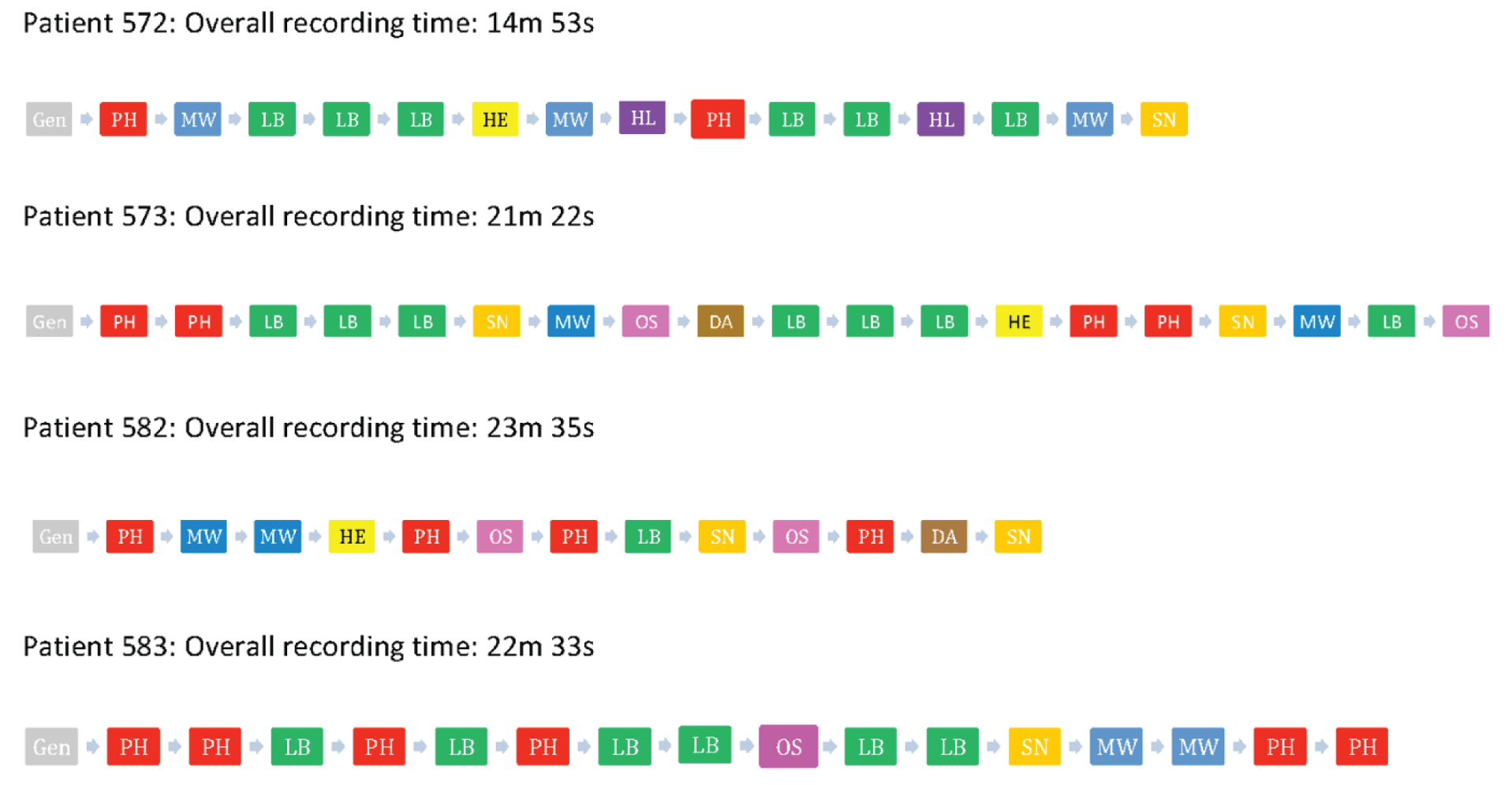

A qualitative process evaluation was conducted in order to identify possible contextual influences on both the implementation of the PCAM and the feasibility trial, and to identify any barriers to PCAM use or implementation of trial processes. This consisted of data from the early focus groups with practices and patients on the acceptability and feasibility of use of the PCAM, researcher field notes of meetings and discussions with staff and any comments made to the research team or reported by practice staff from patients during implementation, data from the final interviews with practice staff and patients, and open-ended questions on staff and patient questionnaires. The process evaluation was based on the Medical Research Council (MRC) guidance for best practice and its key components as identified by Moore et al. 42 (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Key functions of a process evaluation. Based on Moore et al. 42 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

The process evaluation aimed to gather knowledge around the implementation or use of the PCAM tool in primary care as well as around the implementation of the proposed trial methods in each of the different practice settings. The intervention description and its causal assumptions are described in The Patient Centred Assessment Method: intervention description. This will be reflected on in Chapter 7, in which the data on context, implementation and mechanisms of impact are described, including how these differed across sites.

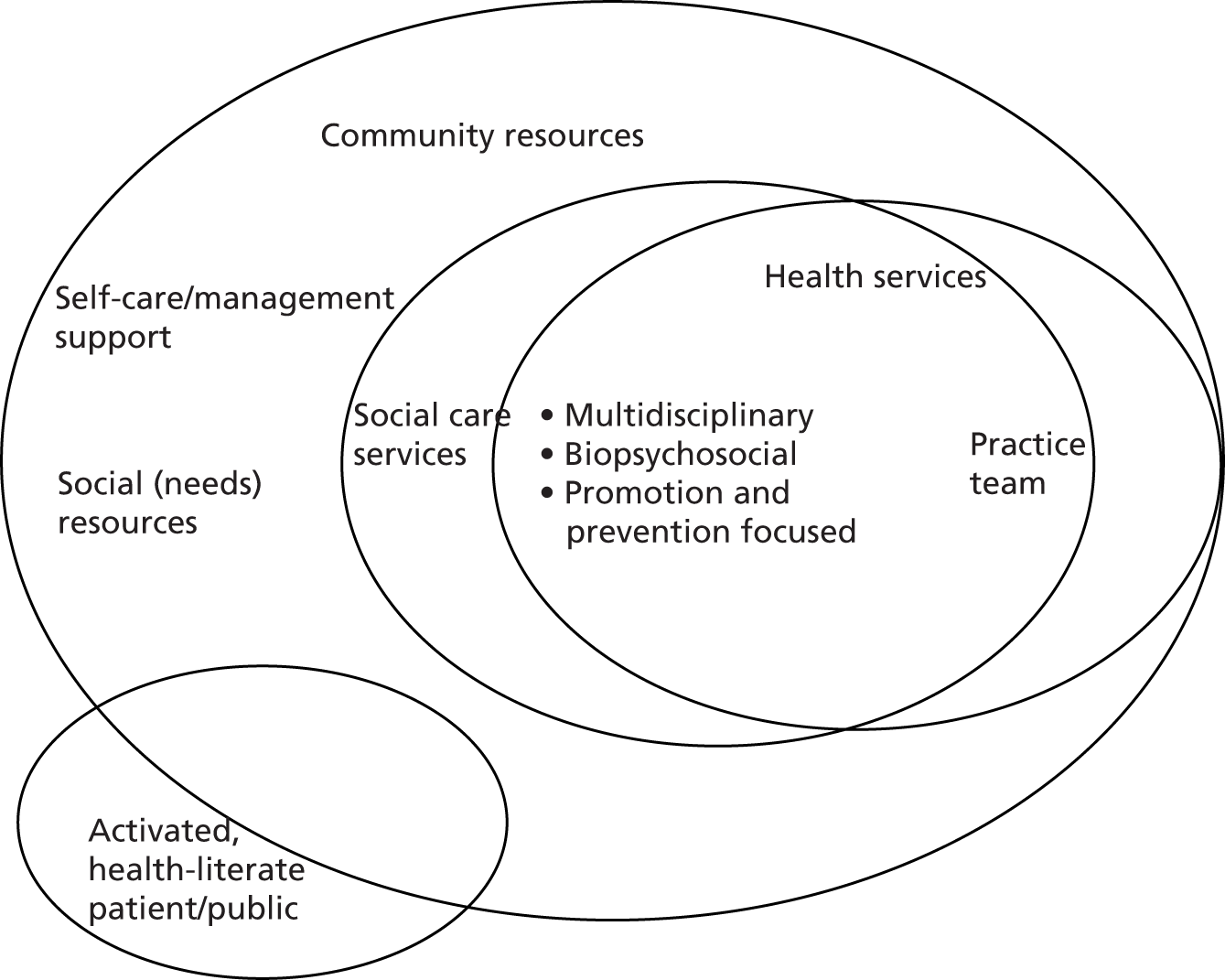

Theoretical/conceptual framework

The conceptual models used to consider how to address LTCs were influenced by the chronic care model (CCM)43 (Figure 2); however, the CCM has been criticised for failing to articulate, in greater detail, what the community resources aspect of the model could consist of. 44,45 Although the CCM provides a comprehensive and well-tested model, it suggests that the ‘informed, activated patient’ somehow sits outside the broader social influences of the community and health system. However, research on LTCs shows a compelling link with broader social determinants of health,2 and it could be useful to find a way to make these social determinants and patient experiences more central to the conceptual model. This would re-emphasise the role of broader social determinants not as outside influences on the interactions between patients and providers, but as a key part of patients’ overall experience of becoming unwell and living with a LTC. Finding ways to facilitate productive interactions throughout all levels of the patient/ provider experience then becomes the methodological challenge of adapting the CCM to a model that integrates the social determinants of health that are so central to the experience of patients living with LTCs. This research would test the role of the PCAM tool in furthering the conceptual frameworks used to understand the care and experience of patients living with LTCs.

FIGURE 2.

A model for chronic care management.

The Patient Centred Assessment Method: intervention description

The PCAM aims to provide a systematic language for the integrated assessment of a broad range of physical, mental well-being and social needs. It is also ‘action oriented’, so that if needs are identified – even if these extend the professional boundaries of providing physical health care – they will be acted on at some level. It is an intervention that fits with the CCM for the improvement of chronic illness care in that it is intended to link the health system with community supports, encourage and support self-management approaches, specifically encourage more productive (nurse) interactions with patients that should lead to more motivated patients, facilitate decision support (by nurses) to improve the care of patients and encourage a proactive practice team.

The ‘PCAM intervention’ being implemented in this feasibility study is fully described using the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist46 (see Appendix 1). It consists of three elements:

-

the PCAM assessment tool

-

a half-day (or equivalent length) training course to support the use of the PCAM tool

-

a resource pack with locally relevant and operational services to support needs identified during the nurse–patient interaction using the PCAM tool.

Following a half-day of training in use of the PCAM tool, nurses were encouraged to use the PCAM tool with 10 patients to gain confidence in its use before starting the formal implementation phase. Intervention sites were supported by the project team to assist with embedding the PCAM tool into routine practice and to support clinic participation in the research study.

The Patient Centred Assessment Method tool

The PCAM tool involves nurses making an assessment of their patient in each of the following domains:

-

health and well-being (covering physical health needs, the impact of physical health on mental health, lifestyle behaviours, mental well-being)

-

social environment (covering home safety and stability, daily activities, social networks and financial resources)

-

health literacy and communication (covering understanding of symptoms, self-care and healthy behaviour and how engaged the patient is in discussions)

-

service co-ordination (how comprehensively, and efficiently, health and social care services currently meet patient needs).

These then lead to action-oriented tasks to deal with the identified problem, which may include referral or signposting to other professionals or agencies. The PCAM tool is provided in Appendix 2.

Patient Centred Assessment Method training

The training was designed to give nurses an understanding of the social determinants of health and how social factors can influence morbidity and mortality. They also learned about the comorbidity of physical and mental ill health, building a picture of why it is important to conduct biopsychosocial assessment and address broader health needs. They were then introduced to the PCAM tool and discussed ways in which knowledge of patients’ circumstances can be elicited as part of a conversation (not a tick-box exercise), and in a naturalistic way that builds on their communication skills. For more detailed information about the PCAM training, see Appendix 3.

Patient Centred Assessment Method resource pack

The PCAM resource pack is a list of local, regional or national groups, organisations and information sources for use by PNs as potential signposting/referral opportunities for patients with LTCs.

Referral and signposting opportunities presented within the resource packs were those covering psychosocial problems within the PCAM domains. For more detailed information about the PCAM resource pack, see Appendix 4.

Control or ‘care as usual’

Nurses in control or CAU practices delivered CAU to their patients. Until April 2016 in Scotland, this was guided by the requirements of the QOF for LTCs, such as DM and CHD. During the development of this study and its funding, the QOF requirement for screening for mental health problems in LTCs was removed, but nurses could still, and indeed were encouraged by NICE guidelines to, include some attention to mental health and well-being in their annual assessments. Normal referral systems or pathways of care would be maintained for patients in the CAU practices.

Research ethics

A favourable ethics opinion for the overall study was granted by the West of Scotland Research Ethics Committee [reference number 14/WS/1161; Integrated Research Application System (IRAS) 168310]. Individual site approvals were then obtained from NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde (NHS GGC), NHS Forth Valley (NHS FV) and NHS Grampian. All changes to the protocol were reported to the Research Ethics Service and approved as minor amendments.

We ensured that all accompanying documentation sent to the NHS Ethics Committee was produced in partnership with the Health and Social Care Alliance Scotland (the ALLIANCE), which represents nearly 400 bodies and individuals working to make the lives of people with LTCs and disabilities, and the lives of unpaid carers, better. More than three-quarters of its member organisations are voluntary groups that support or represent disabled people, people living with LTCs and unpaid carers. We also recruited two PPI representatives early in this process to enable them to contribute to all study documentation prepared for the NHS Ethics Committee (letters of invitation, information and consent forms, etc.). These PPI representatives also served on our project management group (PMG) throughout the study.

Patient and public involvement

Our aims for PPI were to conduct research with members of the public, taking on board their expert advice in the design and conduct of our study, especially in relation to the presentation of our study and its materials to our patient/public/carer audience (through commenting on, and developing, research materials); ensuring continued input to the conduct of the research as members of a project steering group; and ensuring that our dissemination strategy and our key messages were clear and targeted appropriately for patient/public/carer audiences. This would ensure that the language and content of information provided were appropriate and accessible (e.g. in questionnaires and patient/participant information leaflets); the methods proposed for the study were more acceptable and sensitive to the situations of potential research participants; and our research would capture outcomes that are important to the public, and we would ensure that the findings of our research were accessible to the public. This amounted to three levels of public involvement (out of a possible six) endorsed by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), namely as joint grant holders or co-applicants on a research project, as members of a project advisory or steering group and commenting on and developing patient information leaflets or other research materials. However, we also included a further level around enhancing dissemination activity and outputs, especially for public audiences.

Patient and public involvement in preparing this application was provided via the ALLIANCE. The ALLIANCE is the national third-sector intermediary for a range of health and social care organisations. It has over 1700 members, including large, national support providers, as well as small, local volunteer-led groups and people who are disabled, living with LTCs or providing unpaid care. The ALLIANCE’s vision is for a Scotland where people of all ages who are disabled or living with LTCs, and unpaid carers, have a strong voice and enjoy their right to live well, as equal and active citizens, free from discrimination, with support and services that put them at the centre. Our key contact within the ALLIANCE was a full partner on this project and also shared the protocol with ALLIANCE members. They commented on the proposal during its development and specifically on issues of recruitment of patients, and the feasibility of patient data collection processes. They also provided current experiences of members of their health assessments in primary care to inform the feasibility and applicability of the research.

Three patient representatives were recruited to the study on a formal basis; two attended all PMG meetings and another commented on all documentation provided to the Study Steering Committee (SSC). One member of the PMG was already known to the project team from PPI in a previous study led by the RCGP. The second member of the PMG was recruited via an e-mail from NHS FV to its PPI advisors, and the PPI member recruited to the SSC was recruited in the same way. All PPI members were offered support to participate by the ALLIANCE, but no PPI member requested such support, and most were experienced as PPI representatives or felt that they had sufficient life experience to confidently participate and contribute.

The ALLIANCE representative (CH) attended all PMG meetings and was available for emotional support in relation to the PPI’s project advisory role if required. In the event that there was any concern for the health and well-being of our PPI members, we also had a GP team member (SM) who could provide some initial advice, with the proviso that they then contact their own GP. Neither Christine Hoy nor Stewart Mercer was called on to act in these capacities.

We used the NIHR cost calculator for public involvement, in conjunction with advice from the ALLIANCE about appropriate levels and methods of remuneration for patient/public involvement, to ensure that we had the funds to support this.

Project management

Margaret Maxwell was responsible for overall project delivery and worked on a day-to-day basis as required with the project manager (CH) and the two part-time research assistants (RAs).

Carina Hibberd was project manager and supervised the two part-time RAs on a day-to-day basis and conducted fieldwork alongside the RAs as required, as well as being responsible for adapting and delivering the training to nurses.

There were weekly meetings between Margaret Maxwell, Carina Hibberd and the RAs to report on study progress and timelines, and to deal with any immediate problems. Nadine Dougall and Rebekah Pratt also attended these meetings, as required, to ensure that preparation for data collection and subsequent data management and analysis were robust. Video and telephone conferencing was available to minimise time and travel when attendance was required.

Formal PMG meetings were held with all co-applicants and other members of our PMG, including our patient/carer representatives. These included a feedback report on study progress and discussion of any problems/issues arising.

An independent SSC was established with four members: Professor Brian McKinstry (University of Edinburgh, Professor of Primary Care and practising GP) to chair the committee; Dr Ruth Jepson (University of Edinburgh, Senior Scientific Advisor, Scottish Collaboration for Public Health Research and Policy); Dr Dorothy Horsburgh (Edinburgh Napier University, Senior Lecturer, nurse and specialist in LTCs); and one PPI member. Dr Horsburgh retired during the study and was replaced by Dr Debbie Baldie of Queen Margaret University. Observers such as a sponsor representative, a representative of the Scottish Primary Care Research Network (SPCRN) and any members of the research team could be invited at the request of the chairperson.

Formal SSC meetings (n = 4) were held in Edinburgh and consisted of a feedback presentation and supporting documentation, including any ethics amendments and their outcomes, interim reports to the funder (NIHR) and minutes of the PMG.

Analytical framework

Quantitative analysis

The primary outcome of the pilot trial was to determine recruitment and retention rates of PNs, and the recruitment of patients and data completion for a future cluster RCT. We also wanted to establish which nurse- and patient-level measures should constitute primary and secondary outcomes for a future cluster RCT and, hopefully, use this knowledge to determine sample size for a future trial. The study combined data collection for nurses and patients as two separate units of analysis. One of the criteria for continuation to a full-scale trial would be to determine if the number of nurses required for a cluster RCT was feasible and within reasonable cost boundaries. Such a design would also need to be sufficiently powered at the patient level, thereby testing the impact of the PCAM tool on both nurse behaviour and patient outcomes.

The characteristics of the nurses and patient groups and their related outcome measures were summarised using descriptive analysis. The related outcome measures were summarised using descriptive analysis together with estimates of precision, and any relevant change scores. Some modifications were made to the statistical analysis plan that was created at the time of requesting funding for the study. Since then, there has been a shift in expert guidance advising against all formal significance testing for pilot and feasibility study outcome measures, as these are not powered to detect statistical significance. Therefore, formal significance testing was omitted, as was the use of the multiple regression modelling approach. The focus of the analysis centred on the recruitment, data completion and attrition rates, and making use of descriptive analysis to summarise the data. The PEI and CARE measures were analysed at the nurse level and the 12-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12), SF-12 and WEMWBS were analysed at the patient level. Both units of analysis were summarised between randomisation groups, using means and standard deviations, or medians and interquartile ranges, together with change scores estimated with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The number of practices recruited and the number of nurses recruited were less than planned, and this also ruled against the use of formal regression models to explore the influence of covariates on outcome measures. In addition, as the number of clusters was so low, and as some of the follow-up data were missing, the estimation of the ICC for the outcome measures was not appropriate.

Data management and quality assurance

All paper questionnaire forms were pseudonymised and double locked. Digital data were stored on a shared, password-secured folder on the University of Stirling intranet. Questionnaire data were managed using Microsoft Access® 2007 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). The front end of the database was designed to simplify data entry and quality checking. Data were entered and quality checked (paper to digital) by a different member of the research team. This was completed for each form before follow-ups were posted. Digital data were regularly quality checked and an audit trail maintained.

Following acceptance of the study final report to the funder, identifiable patient contact details (used for focus groups and interviews) were destroyed. At this point, practices were also asked to destroy any identifiable lists of patients approached for the study. All digital and paper data have been archived and managed in accordance with the NHS Ethics Committee, research and development and University of Stirling policies.

Qualitative analysis

Qualitative data analysis of focus groups and interviews followed the social constructivist version of grounded theory, through which themes and subthemes were identified in the data. 47,48 The social constructivist approach is an iterative process of review that allows for the incorporation of existing knowledge and literature that can be drawn upon in the analysis process. 47,48 NVivo 11 (QSR International, Melbourne, VIC, Australia) software was used to help facilitate the interviews. In an iterative process, all focus group transcripts and interview transcripts were reviewed by multiple team members to identify key themes in relation to our research questions. These themes were discussed and amended until a core set was agreed for use as a final coding frame, which was systematically applied to all data. The research team met throughout the analysis process to review the emerging themes and discuss areas of agreement or divergence until consensus was reached. Additional details on the qualitative data analysis are included in Chapters 3 and 6.

The analysis was specifically intended to identify barriers to, and facilitators of, adoption/use, and was informed by the normalisation process theory (NPT). 49 The NPT offers an explanation of the work of implementation, embedding and integration, and specifically focuses on the contribution of individuals and groups as agents of change. The NPT helps to explain how practices can become embedded in organisational and professional contexts. There are four generative mechanisms to help explain how change can be adopted and embedded: coherence (sense-making), cognitive participation, collective action and reflexive monitoring. The production and reproduction of a practice requires continuous investment by agents (in this case, PNs) over time. NPT mechanisms are constrained (or aided) by the operation of norms (notions of how beliefs, behaviours and actions should be accomplished) and conventions (how beliefs, behaviours and actions are practically accomplished).

The NPT generative mechanisms and their constructs have provided a framework for analysis of the qualitative data, to help understand and think through implementation problems and to help identify techniques to solve them. This was drawn on at the start of the project, using the focus group data, to help shape improvements to the implementation process and the training materials. Researcher field notes and post-implementation interviews were then also subsequently used to identify further barriers to, and facilitators of, adoption.

Analysis of audio-recorded consultations

The analysis of audio-recordings consisted of classifying conversation segments according to whether they attended to physical health, mental well-being or social elements of care. The range of social circumstances attended to were also identified. The PCAM tool should encourage a conversation flow that attends to well-being and social circumstances throughout the consultations (not leaving it until the end, when time may be limited). The analysis, therefore, also included attention to when conversation segments appeared in the consultation. Attending to a mix of physical health, mental well-being and discussion of social circumstances through the consultation, and discussing a range of social circumstances, was considered to be maintaining fidelity to the PCAM tool. It could be the case that nurses were already familiar with a patient’s social circumstances, but they would still be expected to enquire about these – to ask how patients were getting on or about any change in circumstances. A list of codes by which to classify segments, based on the domains within the PCAM tool, was developed by the research team and consistently applied to all consultation recordings before and after nurse training in the use of the PCAM tool.

Integration and synthesis of data sets

Overall, the qualitative and quantitative analysis aimed to determine whether or not and how a future cluster trial should proceed. This included assessing whether or not recruitment, retention and data collection were achieved to a sufficient level, and whether or not the outcomes used were sensitive enough to detect change (at what level and for whom), as well as identifying any key methodological issues in converting from a feasibility or pilot trial to a full-scale trial, as established by Shanyinde et al. 50 We used a tool known as ‘A process for Decision-making after Pilot and feasibility Trials’ (ADePT). 51 The ways in which researchers decide to respond to the results of feasibility work may have significant repercussions for both the nature and degree of tension between internal and external validity in a definitive trial. The ADePT decision aid is described and reported alongside the process evaluation in Chapter 7.

Chapter 3 Study A: acceptability and implementation requirements of the Patient Centred Assessment Method

Methods

Introduction

Embedded in the overall PCAM study, this first project was designed as a qualitative study of GP practice staff, including PNs, and patient views of the acceptability and implementation requirements of the PCAM. The project aimed to elicit views on the PCAM approach as a model for conducting reviews of patients with LTCs and to identify barriers to, and facilitators of, the implementation of the PCAM tool in practice.

Recruitment and sample

Sample 1: professional staff groups

The target for this study was to conduct four focus groups, each comprising between five and eight GPs/PNs. The inclusion criteria specified that we would aim to recruit medium-sized or large GP practices (with over four partners or list sizes above 3500 patients) based in NHS GGC or NHS FV. This was to reflect the majority of practices across Scotland.

The SPCRN facilitated recruitment of GP practices for participation in the focus groups. The SPCRN selected practices from its database reflecting the same demographic mix as for the pilot trial participants, but, to avoid contamination, these were a separate set of practices from those in the feasibility trial. The SPCRN sent out 89 e-mails inviting PMs in eligible practices to participate. A minimum of 1 week after invitation letters were sent, research staff followed up by contacting 43 practices by telephone to invite their practices to participate.

Participants signed consent forms prior to the start of the focus group discussion. Participants were given a paper copy of the presentation slides for reference at the start of the focus groups. Each focus group was recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Sample 2: patients

The target was to conduct two focus groups comprising 8–10 patients per group of mixed age/sex, and which reflected the social demographics of participating practices. Patients were eligible for inclusion if they were aged over 18 years, registered with the GP practice, living with a LTC [mainly DM, CHD or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)] and required a long-term review.

Patient recruitment was facilitated by the SPCRN. With the approval of participating GP practices, the SPCRN extracted and numbered patient lists using inclusion criteria. GPs reviewed lists to exclude anyone who would have difficulty travelling to the practice or participating in a focus group (e.g. owing to cognitive or communication impairment). Eligible patients were sampled based on multiples of 5 (number 5, 10, 15, etc.). Letters of invitation were sent by the GP practice in batches of 10 until sufficient opt-in responses were received. In NHS FV, 50 letters of invitation were sent from one practice and, similarly, in NHS GGC, 100 letters of invitation were sent from one practice. Patients opted in to the focus groups via a prepaid reply slip, text, telephone or e-mail, and were then contacted by researchers to confirm attendance and to inform them about focus group arrangements.

All focus group participants signed consent forms before the start of the focus group discussion. Participants were given a paper copy of the presentation slides for reference at the start of the focus group discussions. All patient participants were given a £10 gift voucher after the focus group and travel costs were reimbursed. Each focus group discussion was recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Ethics considerations

Participants were asked at the start of each focus group discussion to not mention the names of staff or non-participants, and to respect the confidentiality of other participants. Researchers also informed patients that if they raised any questions in relation to their personal health issues during the focus group discussion, researchers could not respond to these and they were, therefore, advised to contact their GP.

Data collection

All focus groups were conducted using topic guides as a framework for discussions. Professional groups aimed to address the implementation of the PCAM tool within annual reviews of patients with the LTCs specified, along with determining any potential barriers to the use of the model and how these could be overcome. As the NPT was used as an analytic framework, the topic guides aimed to identify whether or not, and in what ways, nurses and other practice staff considered the PCAM to differ from existing ways of working; whether or not nurses and GPs could come to a collective agreement on the purpose of the PCAM; how practice staff understood what the PCAM required each of them to do; whether or not nurses and other practice staff constructed a potential value for the PCAM in the context of annual reviews; and whether or not nurses and other practice staff believed that the PCAM was an appropriate part of their work. Practical issues relating to the implementation of the embedded feasibility RCT and the PCAM in general were discussed to allow consideration to be given to how the individual requirements of different practices might be taken into account. This included discussion of what training may be needed to enable the use of the PCAM and how this could be delivered.

Patient focus groups aimed to discuss how wider psychosocial factors impacted on patients’ health and also how their LTC(s) affected their lives. Topics for discussion included what support patients needed to manage their conditions and whether or not primary care practitioners should play a role in helping them to manage life difficulties that might, potentially, have an impact on their health. The PCAM was then explained to patients and they were invited to discuss whether or not it was acceptable to them and whether or not they considered it useful in relation to their care. Patients were asked how PNs might best raise sensitive or difficult issues with them, and they were also asked about any potential barriers that nurses may experience in using the PCAM.

Data analysis

Data analysis involved constant comparison of key ideas/themes emerging from multiple staff reviews of focus group transcripts. Carina Hibberd, Eileen Calveley and Patricia Aitchison reviewed and compared patient and staff focus group transcripts as they became available. Use of the constant comparative technique within the ‘framework’ method enabled the identification of emergent themes for exploration in subsequent focus groups. 52

Data sources (focus group transcripts) were imported into an NVivo 11 database, which was then used for data management and the facilitation of analysis. Data from staff and patient focus groups were organised separately within the database. Only designated members of the research team had access to the database.

Carina Hibberd, Patricia Aitchison and Rebekah Pratt conducted initial, independent thematic analyses of focus group transcripts to devise a coding frame that was then discussed in detail by the wider analysis group (CH, PA, RP, EC and MM). Where required, analytical codes were amended at this stage by Rebekah Pratt, and descriptors were created to avoid duplication or lack of clarity in meaning. Rebekah Pratt recoded the entire data set based on the amended codes.

From this thematic analysis, a higher-level theory-driven analysis was conducted to organise coded data into more helpful explanatory themes, with attention given to reflecting on these explanations for participation, engagement, adoption and adaptation in line with NPT constructs. For the purposes of this report, the key elements of analysis that are relevant to the acceptability and feasibility of using the PCAM tool in primary care-led annual reviews for LTCs, and for answering questions on the feasibility of a cluster RCT, are presented. The theory-driven NPT analysis will be presented in a future publication.

Findings

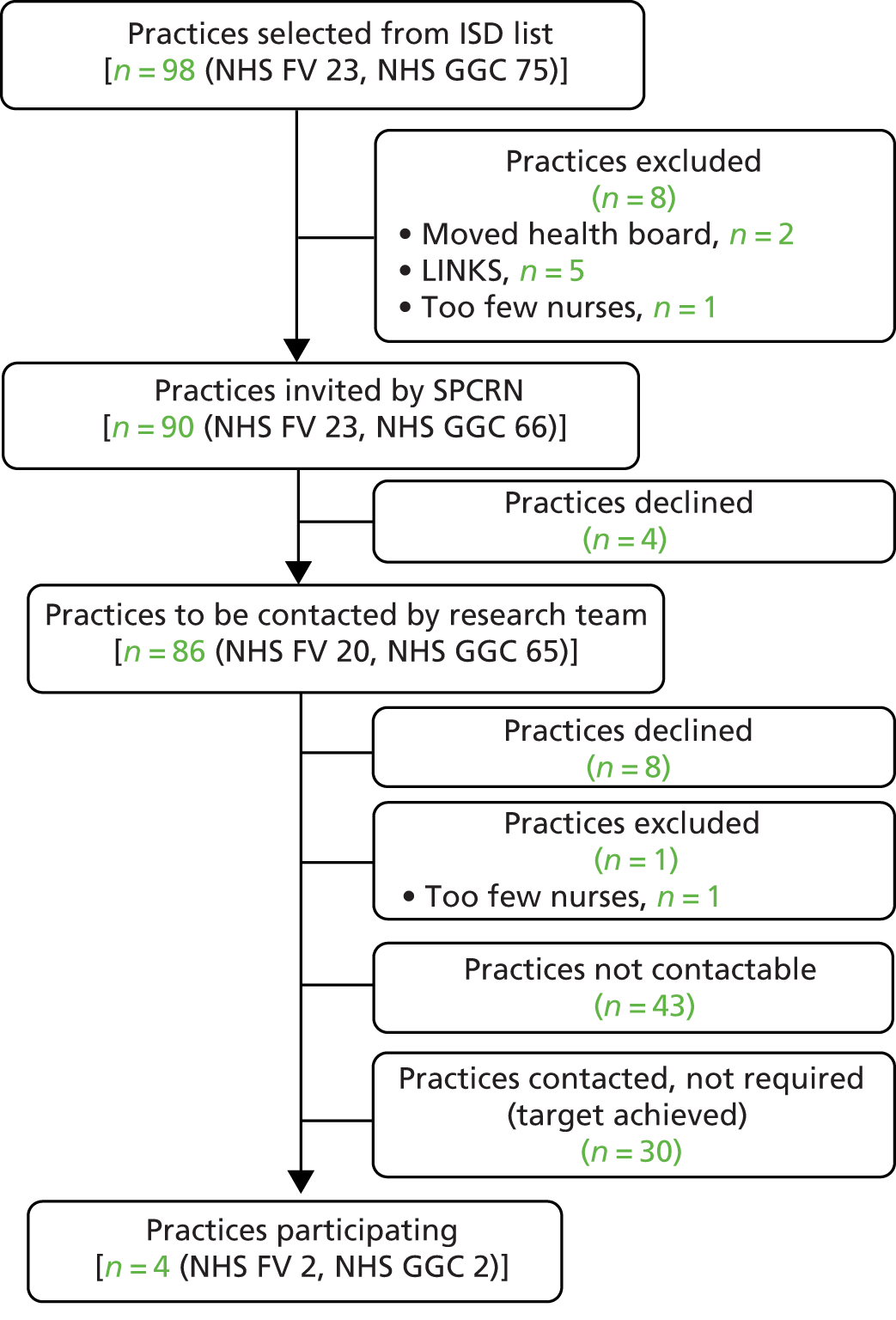

Recruitment of practices

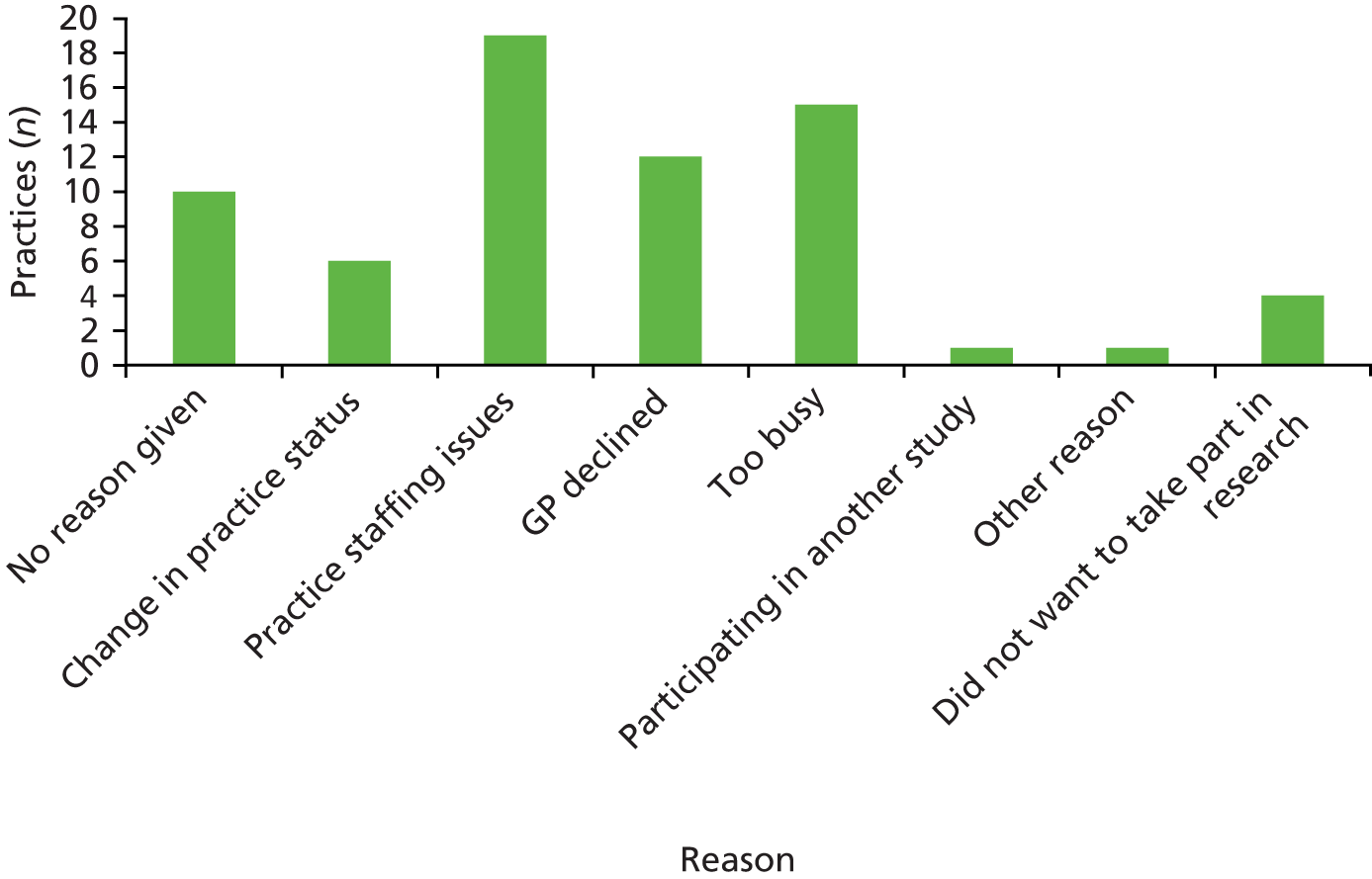

Figure 3 shows the number of GP practices contacted and subsequently recruited for focus group participation. Four practices agreed to take part in focus groups following telephone contact by researchers, two practices within NHS FV and two practices within NHS GGC. Our recruitment target for the number of focus groups was met.

FIGURE 3.

The recruitment of practices to the focus group study. ISD, Information Services Division of National Services Scotland; LINKS, National Links Worker Programme (funded by the Scottish Government to make links between people and their communities through their GP practice).

Recruitment to staff focus groups

Sixteen health-care staff participated in the four focus groups. Participating health-care staff included PNs (n = 7), GPs (n = 3), PMs (n = 3), assistant PMs (n = 1) and administrative/reception staff (n = 2). The duration of staff focus group sessions ranged between 47 and 72 minutes. The four staff focus group sessions were held in the GP practice.

Recruitment to patient focus groups

Two of the four participating GP practices agreed to host a patient focus group. A total of 27 patients returned a note of interest, of whom one could not be directly contacted, seven declined or could not attend, two agreed but did not attend and 17 attended and consented. As intended, patient focus groups included a mix of age groups and sex, and reflected the social demographics of participating practices (Table 1).

| Participants and demographics | Sex (n) | |

|---|---|---|

| Male (N = 7) | Female (N = 10) | |

| Age (years) range | 66–83 | 47–83 |

| Employment status | ||

| Retired | 5 | 6 |

| Paid/self-employed | 1 | 1 |

| Housewife/husband | 1 | 1 |

| Voluntary work | – | 1 |

| No data (long-term sickness) | – | 1 |

| LTCa | ||

| DM (type 1) | 1 | 1 |

| DM (type 2) | 3 | 6 |

| CHD | 5 | 5 |

| COPD | 2 | 2 |

One patient focus group was held in the GP practice, and one patient focus group was held in a local community centre because of limited meeting space in the GP practice. The duration of each patient focus group was 105 minutes.

Patient perceptions of living with a chronic illness

Participants described the struggle of coming to terms with living with a chronic illness. Some described a tension between rejecting their diagnosis and accepting the limitations of their condition, and how that had an impact on their ability to manage their condition. Some had been told that they had DM, but felt that being asymptomatic made it hard to believe that they really did have the condition. Some described spending time, even years, in denial about their condition. This rejection of their condition led to avoidance of doctors, being scared of coming to the clinic, not taking medications and not looking after their health. One participant reflected on rejecting her condition after a negative experience with her GP, and is now facing serious kidney damage.

Participants also reflected on the process of coming to terms with their condition, often describing a period of surprise followed by learning how to adjust and adapt to managing their condition. Some noted that there could be experiences that had a negative impact on their confidence, which may take some time to rebuild. Some described a longer process of having to come to terms with more than one condition, which may lead to more complications and care in managing their health.

During the focus group session, participants shared with each other the many limiting aspects of living with their particular condition. Some were feeling generally well, but others were navigating more complex medical needs, such as surgery and therapies. Many reflected on various losses, such as limiting their food or activities. Participants also described feeling the need to just carry on and make the best of their situation. Some felt that they should be grateful and took comfort in feeling that things could be worse:

But other than that I’m just quite happy, jog along, but every day’s a different day of course you just . . . what I can do today, I’m fine if I can, well tomorrow, but tomorrow doesn’t come, but I just suit myself how I jog along kinda thing, but as I say I can’t complain when I listen to what other people have got, you know, but I’ve enough to be going on with quite honestly [laugh]!

Patient 14

In relation to managing physical aspects of a chronic condition, participants described a period of learning about their condition, mostly through medical appointments and the development of systems to keep track of timing medications. However, participants described their challenges as not just being related to the management of their condition, but also dealing with limitations in daily life more broadly. A small number of participants in the focus groups described very positive, and even life-changing, experiences of taking part in exercise courses (as suggested by their nurse). These participants felt that exercise had led to positive changes in weight, wellness and mood:

So I went on that course and it was 12 visits to the course over a few weeks/few months, and I found that’s been a great help. What it’s actually done to me is it’s not only helped my COPD, it’s helped me mentally because I’m quite a shy person and I want to help myself but I can’t, I want people to help me but because my wife looks after my every need, but it’s to force me to get my a*** off my chair and go and do something.

Patient 34

Participants talked about how difficult it could be to make changes in their lifestyles, even when they knew that it would help with their health. They felt that changing habits around eating required constant attention and monitoring. Some felt that it was hard to ask for help with changes, partly because it took away feelings of independence. Some participants described how they also needed to manage their mental health, as there were difficult days of feeling down or not coping, and a tendency towards self-isolation:

You want to stay in and put a blanket round you but you’ve just got to kinda’ motivate yourself.

Patient 32

Although learning about their condition and how to manage it was a process participants went through, they also described the impact of their condition more widely, in terms of challenges with daily activities and lifestyle adjustments. In this sense, PCAM-related topics are consistent with the broad range of concerns that patients have about their condition.

Professional and patient views on acceptability of Patient Centred Assessment Method topic areas

Professional and patient participants were asked to reflect on how they would feel about a broader range of biopsychosocial questions, as is reflected on the PCAM assessment, being discussed in consultations relating to LTCs. To a certain extent, patient participants felt that their nurses already asked a broad range of questions about how they were and, in particular, participants felt that district nurses might observe more social and environmental aspects of a patient’s life on home visits. There was a wide range of opinions on how participants felt about the potential of being asked about biopsychosocial aspects of their health. Professional participants also reflected on this wide variety of opinions, with some participants much more familiar or comfortable than others with asking patients about the broader context of their lives. In Mental health, Health literacy and Social environment and finances, we discuss responses to these potential discussions for patient and professional respondents by general topic area.

Mental health

There was a general agreement among patient participants that nurses should, and already do, ask questions about mental health in the context of talking about the patient’s LTC. Participants talked about not necessarily always choosing to be open about their mental health, but most seemed to welcome the opportunity to talk about how they were feeling and how they were coping with their condition. There was a good level of awareness that living with a LTC could lead to depression or anxiety, and it was seen as appropriate for the nurse to ask questions about this:

Well she just kinda’ pops it into the conversation, you know, ‘how are you feeling, you’re not depressed or you’re not this . . . you know, different things, ‘are you coping with everything?’ and it’s normally yes but, you know, different people react different to it.

Patient 16

Professional participants were in agreement that discussions about mental health were an expected part of the consultation with patients with LTCs. The professional participants were able to describe the tools they used to assess mental health, and the value of the inclusion of mental health screening on the templates they follow for conducting reviews with patients. Some described conducting these questions routinely as part of their standard care:

I’ve usually asked them before they even reach their bottom on the seat really, it’s just a kind of introductory type of question isn’t it?

Professional staff participant 7

Some professional participants described some reluctance to talk about mental health with patients for fear that it would mean running out of time to do the other standardised review tasks. There were also concerns that the standard screening tools were not as easy to use with non-English-speaking patients. Professionals also shared how few of them had been able to participate in mental health training opportunities. In general, however, the conversations on mental health were described as valuable for supporting the patient in managing their condition, and may open up a broader discussion about the kind of support a patient could have in dealing with the challenges they face:

And you know they’re down and depressed and getting isolated and that’s only going to make their physical condition worse, but there’s just lots of things are kinda outwith so you’ve just maybe got to look at another way of ‘well who’s with you?’ or getting somebody else in and getting the family members are handy. For highlighting really if they’re to go and get support.

Professional staff participant 2

In summary, both patient and professional participants expressed that being comfortable with discussions about mental health was an important part of receiving care for a LTC. Patient participants were comfortable with having these conversations with the nurses, and the professional participants saw it as an important part of the care they provided.

Health literacy

Patient participants were asked how they would feel if they were asked questions about their health literacy. It was seen as appropriate that the nurse would check in about how patients wanted information and help to support them in finding better ways to get information. In general, participants described issues with retaining information, as a result of feeling ‘foggy’, difficulties concentrating or failing to remember things as well as they might have in the past. Standard written information, such as leaflets, was not seen as desirable, but being able to have information or a summary about what happened in the consultation with the doctor or nurse written down was viewed as potentially very useful:

I used to think I had a really good . . . I don’t mean a long-term memory, but I used to think I had a better memory and I was able to absorb things and retain them, but I just put it down to getting old and too many things in my head and whatever, but I’ve never even heard that before that it can affect your concentration.

Patient 31

The professional participants also highlighted the challenge of health literacy and, just like the patient participant group, they highlighted a lack of comprehension of information by patients. One professional focus group noted that their practice area had patients for whom English was a second language, which made some work challenging. One group also noted the difficulties in working with people with learning difficulties, although it was felt that there might then be a carer involved to help support communication. Generally, though, professional participants did not commonly or actively identify literacy problems in their patient populations, and when they did, it was a challenge to get assistance:

I’ve only ever referred for literacy once in I think the whole time and I phoned to where it was supposed to be referred to and it was impossible to get in touch with them but that was a wee while ago and she felt ‘no wait, leave it just now’ but maybe it’s changed, maybe it’s easier to get that referral done now, but the referral contact number that we were given at that time it didn’t actually work.

Professional staff participant 4

What was more commonly mentioned by professional participants was the need to repeat information to patients, and patients’ limited ability to recall or comprehend the information. Professional participants described their frustration at the time spent sharing information repeatedly. Some felt that it was likely that patients were just overwhelmed or overloaded with information, and some felt that patients were failing to pay attention or were not listening:

We’ll maybe explain it to them and they’ll be ‘OK, OK’ and then they go off and you think they’ve not really listened, you can tell they’re not sure, they phone back and we’ll say just make an appointment with the doctor.

Professional staff participant 10

In summary, health literacy is an area of concern for patient and professional participants. The patient participants described their frustration at a lapse in memory or comprehension. Professional participants noted a lack of information retention. Both felt that it was an important area, yet there was no discussion of patients and professionals communicating together about this topic together. As a result, some professionals may assume that patients are not listening, while some patients may be reluctant to share, unprompted, that they are having cognitive challenges. This suggested that this area of the PCAM tool could be particularly useful and seems like an acceptable area of discussion for consultations.

Social environment and finances

There was a lively exchange between patient focus group participants about the appropriateness of nurses asking questions about their patients’ social environments. It was certainly seen, by this group of participants, as something that PNs mostly do not discuss, although some felt that district nurses might be more likely to do so. Some felt that such questions should be asked of patients only if the nurses had a reason to be concerned about the patient. Some participants felt quite strongly that it was not the role of the nurse to ask questions about their patient’s social environment, while others felt that anything that might have an impact on their health should be discussed with the nurse, including information about their social environment:

I think what you’ve got to be very careful about as well as far as nurses are concerned, they’re not social workers, they’re nurses, you know, there’s only a certain amount, just what we were talking about earlier on there, there’s only a certain amount of things that we talk to nurses about and social environment, what your background is about your next door neighbour and that sort of thing, it’s not things that you would come and talk to your nurse about.

No, no that’s right. These are things that you talk to a social worker or the police or whatever, so we’ve got to be very careful that we don’t sort of categorise them in the social, because they’ve got enough on their plate without being social workers as well.

But some of these things can affect your health.