Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 12/5002/01. The contractual start date was in September 2013. The final report began editorial review in December 2016 and was accepted for publication in August 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Sophie Staniszewska is a member of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre Patient and Public Involvement Reference Group and is Associate to Professor Kate Seers (NIHR Health Services and Delivery Research Commissioning Board).

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Currie et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Conceptual problem

The research study was commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) programme, under its knowledge mobilisation theme, following a number of other studies commissioned under the same theme in recent years. Such studies tend to empirically focus on the organisational level of knowledge mobilisation. Analysis and research-informed suggestions tend to lean towards the panacea of knowledge brokering (see, for example, a previous NIHR HSDR study by the same principal investigator, GC, 09/1002/051). Although knowledge brokering was proposed as a solution, Graeme Currie and colleagues criticised the concept and practice because it fails to account for the capacity of the organisation to mobilise knowledge. In this study, we extend the knowledge-brokering solution by accounting for the contextual intricacies that affect knowledge mobilisation. We enhance the evidence base for effectively mobilising knowledge through a system level of analysis regarding capacity to mobilise knowledge (e.g. of a complete commissioning network, which encompasses health-care providers and other organisations supplying commissioning intelligence). ‘Absorptive capacity’ (ACAP) represents such a concept, which can be applied at the health-care system level of analysis. 2 ACAP maps on to the term ‘critical review capacity’, and can be applied to consider the empirical case of health-care commissioning networks. In so doing, our study addresses a need for the development of a model of ACAP that is more tailored to health care, a need that was encompassed within the original NIHR HSDR call for commissioned studies. 3

We highlight studies of ACAP in health care that are already published. 4–6 We seek to develop a model of knowledge mobilisation focused on ACAP of health-care commissioning networks, but one that is more widely transferable across the health-care system. Within our study, we draw on a more generic literature to set out some of the expected characteristics of health care that affect dimensions of ACAP and its antecedent combinative capabilities. 7–13 We then consider distinctive features of the health-care context that may affect ACAP.

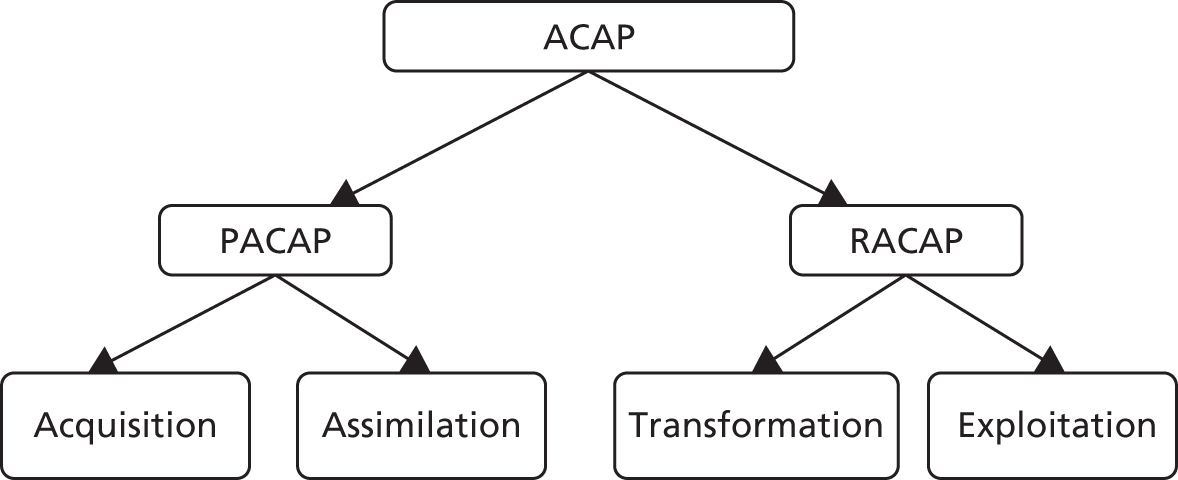

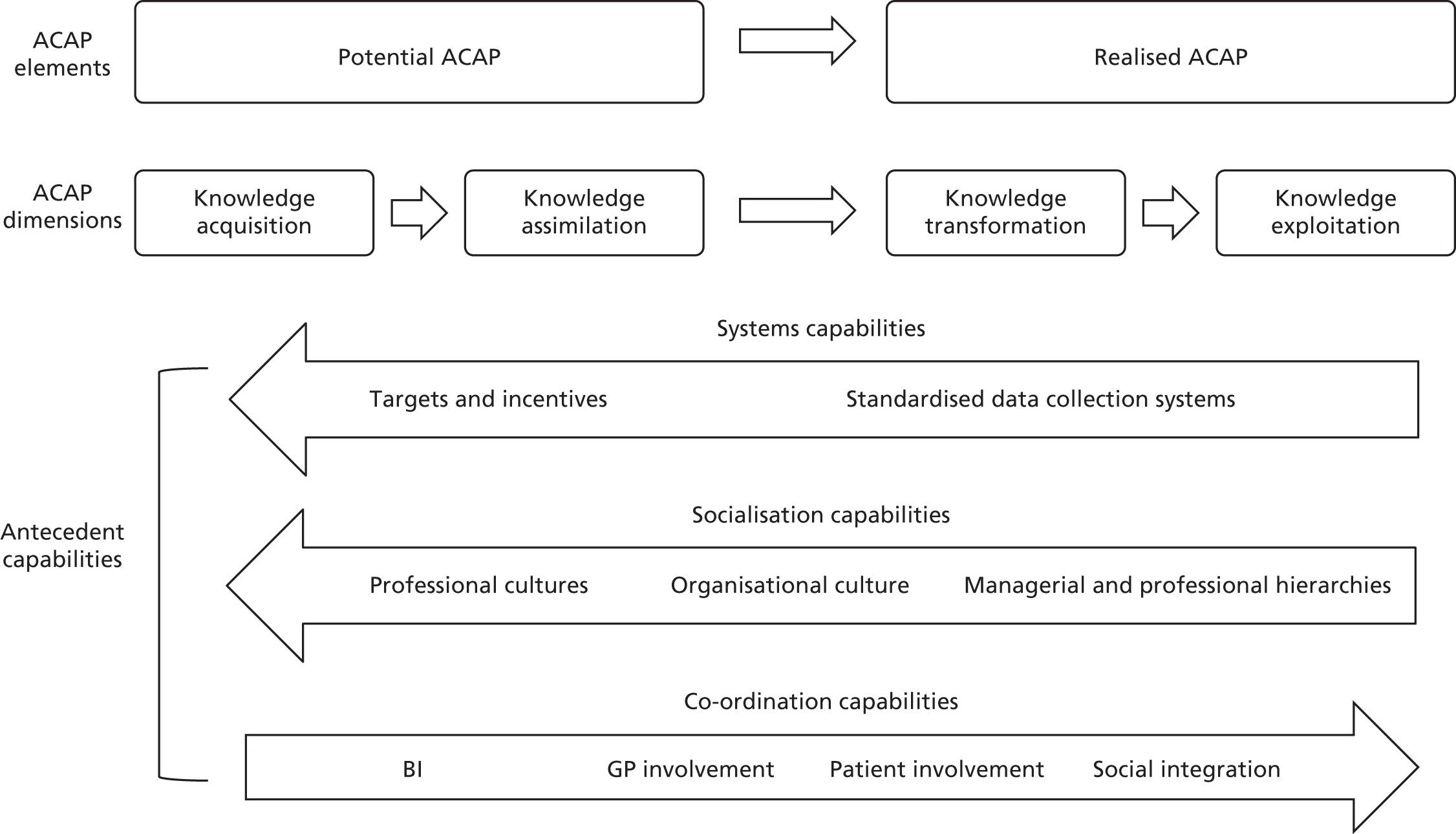

Applying the concept of ACAP, we argue that knowledge mobilisation occurs within overlapping processes, which can be conceptualised as acquisition, assimilation, transformation and exploitation of knowledge. These processes are influenced by combinative capabilities: systems capabilities, socialisation capabilities and co-ordination capabilities. Systems capabilities, such as targets and incentives and standardised data sets, can limit the type of knowledge acquired and used to guide service interventions. Socialisation capabilities, represented by professional and organisational cultures and associated professional–managerial relations, can limit knowledge mobilisation across occupational groups. Co-ordination capabilities can overcome the barriers of systems and socialisation capabilities, encouraging more flexible approaches to the four stages of knowledge mobilisation. In particular, this study highlights the importance of general practitioner (GP) involvement, patient and public involvement (PPI), business intelligence (BI) and social integration mechanisms, which further enhance knowledge mobilisation in health-care settings.

Practical problem

Our study provides help with the challenge the NHS faces in the wake of recent structural reform, but also supports the long-standing concern of policy-makers and research institutions, including NIHR, about the ability of the NHS to translate different types of evidence into transformative action for service development.

With respect to the long-standing translation challenge for the NHS, the development and validation of an ACAP model contextualised for the health-care system offers considerable promise to address knowledge mobilisation at the levels of individual, group and organisational behaviour, as well as systems-level behaviour. Particularly in financially parsimonious times, Quality, Innovation, Productivity and Prevention (QIPP) gains are likely to be realised through better mobilisation of existing knowledge from both formal and local informal sources, rather than necessarily generating new knowledge. A model of ACAP contextualised for the case of the health-care system will guide action regarding how this might be realised. The case of intervention to reduce potentially avoidable elderly admissions into hospitals represents an exemplary tracer study revealing lessons for other complex areas.

Recent government policy in England emphasises that services in the NHS can be improved through the increased involvement of clinicians and service users at local levels. These policy developments have resulted in the creation of Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs), devolving financial decision-making and commissioning of services to clinicians based in general practice, and thereby giving them greater freedom to respond to the needs of local client groups. 14,15 Our study is particularly timely in the face of NHS commissioning reforms, but we note that knowledge mobilisation in commissioning is a long-standing concern evident in previous primary care trust (PCT) arrangements, and is likely to extend to any other commissioning structures and processes in the future. In short, our study is intended to produce and disseminate analytical lessons regarding the enhancement of critical review capacity beyond current arrangements, and with a focus on the wider commissioning network, not merely on CCGs as organisational entities. Our analytical lessons also extend beyond the tracer study of elderly care. We suggest that the challenge of commissioning high-quality elderly care in a productive but preventative way is exemplary of a more general challenge of commissioning complex care, which often encompasses more than a single disease pathway and crosses boundaries within and outside the NHS.

With respect to current structural reform, should CCG-led commissioning networks fail to develop critical review capacity (which our study conceives as ACAP) for commissioning, structural reform is unlikely to succeed. Commissioning networks developing critical review capacity depends on enhancing antecedents for ACAP, that is, understanding how combinative capabilities of the commissioning network affects ACAP. We emphasise that our study is concerned not just with CCGs, which represent the centrepiece organisations in current reforms, but with the commissioning network as a whole, inclusive of a wide range of organisations. So, if CCGs were to be supplanted in a future round of structural reform, our focus on the commissioning network as a whole means that our study still holds practical relevance. Our stance regarding the wider commissioning network, rather than focusing on CCGs alone, is supported by Swan et al. ,16 who, in their study of previous commissioning arrangements, highlight the multilevel interdependencies around commissioning that mean that any commissioning organisations, such as CCGs, need to build effective relationships with, for example, the NHS Commissioning Board, including their local area teams; GPs and their practices; public health; local authorities; commissioning support units (CSUs); acute hospitals and other providers, such as community health, mental health and care homes providers; and other bodies that may provide commissioning intelligence, such as out-of-hours services, emergency services, the Care Quality Commission and Healthwatch England.

Research examining critical review capacity related to the new commissioning arrangements is scarce as a result of how new the organisational networks are. Limited research that does examine new commissioning networks highlights a need to increase critical review capacity for evidence-based decision-making through not just acquiring knowledge, but also using that knowledge. 17

Specifically, CCGs struggle to commission effective, targeted interventions for reducing potentially avoidable elderly care hospital admissions. Our study will indirectly reduce some of the uncertainty that hospitals face and that manifests itself in crises such as a lack of hospital beds in winter, as commissioning networks improve their ability to mobilise knowledge to commission interventions to prevent potentially avoidable elderly care admissions to hospital.

Regarding patient benefit, there is strong evidence that patient/carer experience of care and clinical outcome improves through being kept out of hospital. For the NHS, potentially avoidable admissions prove to be difficult and costly to manage. Frail elderly admissions, many of which can safely be avoided, are both clinically and economically deleterious. 18,19 Noting considerable variation in admissions, it is estimated that bringing provision up to best practice in England could result in savings of £132M,20 and a reduction of 7000 beds. 17 Proactive integrated care can reduce the proportion of frail elderly patients who go to hospitals. 21,22 Good care is diligent care that recognises and responds to signs of deterioration in early stages. Social support in the community is also important for people with both physical and mental impairment, with approximately half of all elderly patient admissions fulfilling the criteria for dementia. 23 Evidence might be used to commission community care that is sensitive to clinical pathways, recognises that most people have comorbidity and reduces potentially avoidable admissions of older patients. 19,24

Taking account of the above, we empirically focus on the service domain of elderly care, specifically a tracer study of capacity to mobilise knowledge to reduce otherwise avoidable admissions into hospital. This, as highlighted above, is particularly relevant to the case of ‘frail’ older people, a population group that our research sought to focus on in interviews with key stakeholders in CCG-led commissioning networks. However, as evident in empirical material, there is some slippage in our characterisation of the group we seek to reduce avoidable admissions of. This reflects the varied capacity of our 13 comparative cases of commissioning networks to acquire and use knowledge for intervention targeted at frail elderly patients rather than the larger, more general, group of older patients (over-65s who are not ‘frail’). We apologise in advance for what might appear to be imprecision, but argue that it derives from empirical data that we wanted to use effectively.

In considering a commissioning network’s acquisition and use of evidence, it is not our intention to set priorities for CCGs or to say how different sources of evidence (e.g. academic research, voluntary sector, PPI, GPs’ experiential knowledge and BI) might be combined. We suggest that different forms of evidence should be deemed to be of different levels of importance depending on the decision to be made, but nevertheless do not go about assessing this. What we would say is that ‘effective’ commissioning demands that CCGs acquire and use pluralist types of evidence in making decisions about service interventions. We stress that, although it is one thing to acquire evidence, such as that about the patient experience, it is another thing to use such evidence. Effective commissioning demands both acquisition and use.

Research question

Our conceptual contribution is the development of a model of ACAP encompassing its four dimensions (acquisition, assimilation, transformation and exploitation) and its three antecedent combinative capabilities (co-ordination, systems and socialisation), which are applicable to a wide range of health-care organisations. Our overarching empirical research question (RQ) is: how can we enhance ACAP of CCG-led commissioning networks in health care to inform decisions to reduce potentially avoidable elderly care acute hospital admissions?

Aims

The aims of this study are to:

-

develop a conceptual model of ACAP and an associated ACAP tool that are contextualised to the health-care case and are of practical use across the health-care system

-

enhance the critical review capacity (conceived as ACAP) of CCG-led commissioning networks in commissioning interventions to reduce potentially avoidable admissions of elderly people into acute hospitals, and other complex commissioning domains.

Objectives

The objectives of this study are to:

-

assess the development of critical review capacity, conceived as ACAP, of the new CCG-led commissioning networks

-

enhance the development of critical review capacity, conceived as ACAP, of the new CCG-led commissioning networks

-

support the acquisition and utilisation of patient experience knowledge to enhance the critical review capacity, conceived as ACAP, of commissioning networks

-

develop and provide face validation for a self-reflection ACAP tool for use by CCG-led commissioning networks and other health-care organisations, to enhance their critical review capacity

-

bridge the gap between potential and realised critical review capacity or ACAP of CCG-led commissioning networks.

Our study is formative, not merely summative. Following staged analysis, we intervene to enhance the critical review capacity of commissioning networks in a staged process throughout the study. In particular, we feed back to participating CCG-led commissioning networks in real time, and we develop the ACAP tool across the necessary wide range of health-care organisations to ensure its applicability beyond commissioning networks.

Research methods

We adopt mixed methods (mainly semistructured interviews, but also PPI focus groups, observation, secondary data and, in the future following validation, the ACAP psychometric tool) to examine comparative cases of commissioning networks regarding external and internal contingencies around their critical review capacity and to conceptualise critical review capacity as ACAP. See Chapter 3 for more detail.

Study governance

A strategic advisory group governed the study (meeting four times throughout the course of the study). Alongside this strategic advisory group, a distinctive PPI group was formed, which met regularly (also meeting four times throughout the course of the study). Our thanks go to Tony Sargeant (Chairperson of the strategic advisory group and PPI group) and his colleagues, who, beyond providing the necessary governance for our study, provided invaluable advice that shaped our empirical endeavour and, in particular, helped develop and provide face validation for the ACAP tool. The PPI group’s reflections on our study and its findings are presented in Chapter 10.

Structure of the report

We commence with a literature review, which outlines and critiques the ACAP concept before discussing its recent application to health care (see Chapter 2). Following this, we outline our research design (see Chapter 3). We then set out our empirical findings across five chapters: constraints of socialisation and systems capabilities (see Chapter 4), GP involvement (see Chapter 5), PPI (see Chapter 6), BI (see Chapter 7) and social integration (see Chapter 8). This is followed by a chapter that discusses the development of the ACAP tool, exhibits its dimensions and suggests how it might best be used (see Chapter 9). We then present our PPI group’s reflections on our study and its findings (see Chapter 10). Finally, we have a concluding discussion, within which we highlight our contribution to cumulative knowledge, practical implications, transferability of findings and further research (see Chapter 11).

Chapter 2 Absorptive capacity and clinical commissioning

Our literature review is not ‘systematic’ in the way that other epistemic communities, such as clinical science, might expect. Rather, it is one that is more selective, focusing on the focal empirical organisation of commissioning organisations and the mobilisation of knowledge within their decision-making, specifically the theoretical concept framing the analysis (ACAP). As set out below, commissioning organisations, particularly CCGs, enjoy very limited coverage in academic literature as they are relatively new organisations. Meanwhile, regarding ACAP, we focused on higher-quality journals in business and management regarding its generic model, and when considering its application to health-care settings, again, we note a very limited coverage.

Introduction

Recent reforms in NHS England have seen the introduction of CCGs, which lead commissioning networks, replacing the previous commissioning structures of PCTs (see Timmins25 for an in-depth overview of the policy progression from PCTs to CCGs). It is proposed that CCGs will increase positive clinical outcomes, financial management and service effectiveness through the creation, assimilation and exploitation of existing clinical guidelines and new innovations. 15,26,27 For these processes to take place, CCGs will need to critically review the external information they receive before assimilating, transforming and exploiting this knowledge through their commissioning decisions.

Given that CCGs are new organisations, literature on their critical review capacity for intelligent commissioning is sparse. Nevertheless, early scoping studies highlight the weak critical review capacity among CCGs,17 which was also apparent in their predecessors, PCTs. 16,28 One study produced a live simulation with a number of new CCGs to explore how they would adapt to some of the challenges they may face in the next few years. 17 The results indicated some areas of concern as GPs leading the groups struggled to work in a proactive, innovative way, acknowledging that they were overwhelmed by transactional demands that reduced their critical review capacity. These concerns have been echoed more recently, as researchers question whether or not commissioning reforms have actually led to increased performance and quality in health-care delivery. 29

Studies highlight that the quality of services delivered by health-care organisations is improved when the organisational capacity for learning and integration of diverse sources of knowledge is developed. 30–32 Recently, academic studies have highlighted how the concept of ACAP,2 derived from private sector settings, can be applied to health-care organisations to address how they might enhance service interventions by improving their critical review capacity. 3–5,33,34 In this chapter, we outline the concept of ACAP, which describes an organisation’s ability to acquire, assimilate, transform and exploit knowledge from the environment, improving competitive advantage2,13 in the context of CCGs. We highlight that the realisation of an organisation’s critical review capacity comes from reducing the variance between its potential absorptive capacity (PACAP) and its realised absorptive capacity (RACAP). Following this, we explore the antecedents to ACAP, known as combinative capabilities, highlighting how they can enhance or stymie the critical review capacity of organisations. 9–12 Finally, we highlight the importance of four co-ordination capabilities for enhancing the critical review capacity of CCGs.

Absorptive capacity

The concept of ACAP was first coined by Cohen and Levinthal2 to describe an organisation’s ‘ability to identify, assimilate, and exploit knowledge from the environment’. Lane et al. 9 hail ACAP as ‘one of the most important constructs to emerge in organisational research in recent decades’. Since its inception, ACAP has been seen as a core element of increasing critical review capacity, but the dynamics of enhancing ACAP are theoretically underdeveloped. 6,9

In this study, we adopt Zahra and George’s13 conceptual framework of ACAP, which characterises four activities of pulling in external knowledge that are crucial for the development of ACAP: (1) identifying and accessing relevant knowledge through acquisition processes; (2) analysing and interpreting this knowledge through assimilation; (3) integrating existing knowledge with the newly assimilated knowledge through transformation; and (4) refining and developing existing organisational routines and behaviours through exploitation of the transformed knowledge.

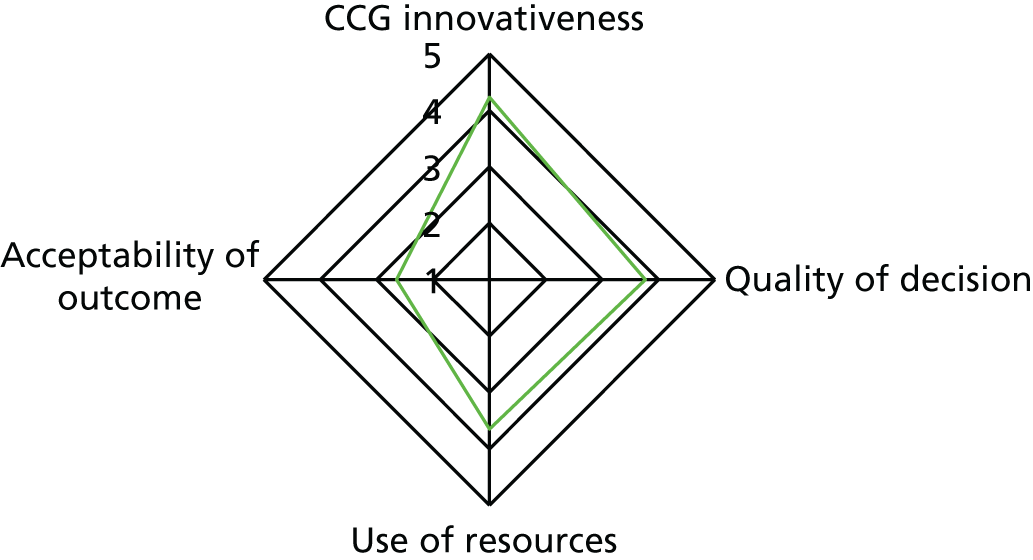

We recognise that health care represents a distinctive environment compared with private sector research and development (R&D) contexts in which much of the empirical work around ACAP has taken place. This renders some of the dimensions of the ACAP literature less relevant to health care, but, at the same time, brings others to the forefront. 5 In particular, in application of ACAP theory to literature, it is important to recognise two interacting and complementary elements: PACAP, the ability to acquire and assimilate knowledge; and RACAP, the ability to put newly acquired knowledge into action within the organisation through transformation and exploitation (as outlined in Figure 1). It is the variance between PACAP and RACAP that accounts for performance differences among organisations, with a decrease in variance crucial to enhancing ACAP. 13 In the following section, we discuss PACAP and RACAP in the context of CCGs.

Potential absorptive capacity

Zahra and George13 conceptualise an organisation’s PACAP as its ability to acquire and assimilate diverse sources of knowledge. The role of CCGs is to use external knowledge and guidance to identify areas for improvement in services and to base commissioning decisions on this knowledge. 35 Acquiring information is the first step in the critical review process and is suggested to result in better commissioning outcomes. 36,37

Knowledge is expected to be acquired from central institutions, such as the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), which provides standardised advice and clinical guidelines about service provision and prescribing practices. 27 Exposure to these guidelines aims to reduce clinical variation and ensure that quality improvement decisions are embedded in the processes of CCGs. 27,35 However, it is important to acknowledge that these guidelines are not necessarily objects to be immediately internalised by professionals, but rather information processes that can be interpreted and translated to suit the organisational context. 38

The need for substantial infrastructure to assist in the acquisition of this information has been demonstrated in the USA, where clinical commissioners rely heavily on information technology (IT) and management systems to guide their critical decision-making. 39 The first challenge in increasing the effectiveness of CCGs, therefore, needs to focus on a more systematic mechanism for the diffusion of NICE clinical guidelines. 27 This has been recognised in government policy, and national efforts are under way to increase the scope of central knowledge acquisition by CCGs. 15,27

The second element of PACAP, assimilation, will rely on the skills and combined knowledge of the CCG. To become authorised, CCGs needed to fulfil certain criteria pertaining to a mix of professionals and stakeholder engagement, strong conformity to central governance and financial performance measures, collaborative working with other CCGs, and demonstrable strong leadership. 15 A mix of professional skills and knowledge should therefore be embedded in the organisation from conception, increasing the capacity for assimilation of external knowledge. This is the fundamental premise of CCGs, and providing a central role for clinicians in decision-making is crucial as they can assimilate their expert knowledge in response to the needs of their service users. 14,15 Decisions relating to managerial or financial information may be harder for clinicians to assimilate, highlighting the importance of managerial expertise as a component of the board and of increased training for clinicians. 26,39

Initial consideration of the PACAP of CCGs suggests that it should be realised provided that the infrastructure and support systems are in place to increase the acquisition of central guidance and the assimilation of managerial or financial information. The interventions required to increase PACAP are relatively structural, taking the form of BI functions, which we discuss later.

Realised absorptive capacity

Realised absorptive capacity refers to the transformation and exploitation processes of an organisation. 13 In order to effectively transform assimilated knowledge into commissioning decisions, CCGs need to engage in processes demonstrated by effective corporate boards, in particular constructive conflict, which encourages open discussion and sharing of ideas. 40–42 Previous studies on innovation adoption in health care have demonstrated these processes occurring with positive outcomes, but have acknowledged that these groups are usually uniprofessional. 38,43 As previously acknowledged, CCGs are required to represent multiple professional skills and knowledge bases. 15 Although this will increase the potential for constructive conflict and subsequently enhance the critical review capacity of these groups, there is also the increased potential for destructive, emotional conflict as a result of professional stereotypes and social hierarchies, leading to a reduction in performance and a lack of candid discussion. 41,44

The highly professionalised context of CCGs will compound the potential for destructive conflict as a result of existing professional hierarchies and existing board behaviours, undermining ACAP. Professional bureaucracies are characterised by the formal knowledge and power of highly trained experts and represent an institution in which knowledge is individualistic, hierarchical and separated into functional specialties. 45 In these contexts, the sharing of information across functional boundaries among professionals is limited, and the powerful status of expert professionals can inhibit knowledge sharing and transfer with non-experts, even when the group itself exhibits goal congruence. 45,46 This has been shown in similar medical groups in the USA, where a key element of effective groups was the ability to reconcile business goals and needs with the commissioning of high-quality health care. 39 How clinical and non-clinical members of CCGs will reach these decisions is, as yet, unclear.

The final element of ACAP, exploitation, will be influenced by the professionalised context of the wider institution, which will have an impact on the extent to which decisions made by commissioning groups can be diffused into the organisational network. Growth and development of tacit knowledge results from building on existing social relationships. In this way, what an organisation has done before will predict what it will do in the future. 47 Context is a major determinant of capacity for knowledge exchange and assimilation, and deeply ingrained existing organisational structure and social networks will have developed institutionalised channels of communication. 48 Encouraging innovation, rather than institutionalised routines and behaviours, is particularly difficult because the collective mindset of organisational members presents significant barriers to change and adaptation, resulting in the ‘non-spread’ of innovations, a problem associated with highly professionalised contexts, and one that has been acknowledged as an issue within the NHS. 43,49

Within health-care organisations, academic commentators highlight that acquisition of external knowledge is less of a problem than actual use (i.e. assimilation, transformation and exploitation) of that evidence to drive quality improvement. 3–5,33 It is the RACAP of CCGs that needs to be addressed to enhance critical review capacity. The existing institutional and professional hierarchies, behaviours and cultures will influence the potential for constructive conflict, information sharing and subsequent comprehensive decision-making. Candid discussion and equal power distribution may not be possible, undermining the potential for critical reviewing capacity as more powerful CCG members take the lead. These existing cultural and social mechanisms are also reflected in the problems encountered when exploiting the clinical decisions within the larger organisation. Knowledge and innovations will be shared and diffused throughout existing institutionalised channels of communication and will have to be internalised into the existing organisational behaviour to have an impact. This can be difficult in a heavily institutionalised context.

Reducing the variance between potential absorptive capacity and realised absorptive capacity: the influence of combinative capabilities

It would appear from the literature review that any interventions aimed at increasing the effectiveness of CCGs need to be focused on increasing RACAP. The ability to transform and exploit knowledge throughout the organisational network, and to implement innovations and recommendations, is a fundamental need for CCGs. Consequently, when considering critical review capacity in health care, there is a need for research into how organisational antecedents affect ACAP, which takes into account organisational context, the role of individuals and groups, and associated power and politics. 8,9,12,13 This requires more focus on social mechanisms, as the CCG will need to develop the ability to share and transform information and knowledge to make critical decisions. The difficulties associated with knowledge sharing and transfer cannot be resolved through redesign of governance structure because of the socially embedded nature of tacit knowledge, which is a key element of critical decision-making in social contexts. 50

Although existing research into ACAP has engendered deeper understanding of the organisational conditions that have an impact on organisational knowledge processes, literature in this theoretical domain remains focused on knowledge acquisition, rather than its use,6 and there is a lack of detailed understanding of the antecedent capabilities for enhancing ACAP, and in particular of reducing the variance between PACAP and RACAP. 8,11 What is clear is that there are antecedents to ACAP, specifically known as combinative capabilities. 10,12 As noted previously, health-care organisations represent a distinctive context compared with private sector R&D contexts, in which much of the empirical work around ACAP has taken place, and, as such, combinative capabilities will influence the four ACAP mechanisms in health-care organisations in a particular way. 5 Van den Bosch et al. 11 distinguish three types of combinative capabilities that influence ACAP: socialisation capabilities, system capabilities and co-ordination capabilities. In the following section we discuss these capabilities in the context of CCGs.

Socialisation capabilities

Socialisation capabilities refer to an organisation’s ability to produce a shared ideology and develop a distinct group identity. The social processes associated with this capability are often seen as most influential in the development of ACAP within professional organisations. 6,13 Health-care organisations exemplify the professional bureaucracy archetype,51 within which professional organisation is likely to represent a key influence on socialisation capability, limiting ACAP as described in the following paragraphs.

External knowledge interacts with strong organisational cultures and structures, so that socialisation capability within health-care organisations restricts the development of ACAP. 11 Thus, power and status linked to professional roles are likely to have an impact on health-care organisations’ ability to exploit new knowledge. 3,33 For example, Berta et al. 4 note the role of doctors in subverting an organisation’s learning capacity in relation to the adoption of new clinical guidelines into practice, based on formal evidence. Similarly, Ferlie et al. 49 note that deeply ingrained organisational structures and social networks within health-care organisations engender institutionalised epistemic communities of professional practice, which exist in silos, relatively decoupled from one another. This may have an impact on socialisation capabilities, as professional training and early career experience may engender a custodial role orientation whereby professionals orientate narrowly towards their peers, rather than across the health-care delivery system. 52

This stymies the search for external knowledge that lies outside current ways of thinking among powerful professional groups. The shared culture or ideologies represented by socialisation capabilities enables the transformation and exploitation of new knowledge, but those same cultures may represent a ‘mental prison’ that limits the potential of absorption of external knowledge, particularly when that knowledge may contradict shared beliefs. 10 The implication is that employees need to be exposed to diverse knowledge sources, but transformation and exploitation of this knowledge will be enhanced only when it complements existing knowledge sources. 13

Further to this, knowledge is more likely to be transferred and shared within organisations, rather than with external stakeholders, as they have shared experiences in terms of expertise and training in addition to a shared collective identity. 12 Finally, there is considerable but variable agency for actors to influence knowledge acquisition, assimilation, transformation and exploitation. 4 In particular, powerful groups of actors may influence knowledge absorption processes to achieve their goals. 5,10

Systems capabilities

System capabilities refer to formal knowledge exchange mechanisms such as written policies, procedures and manuals that are explicitly designed to facilitate the transfer of codified knowledge. 11 The primary virtue of systems capabilities is that they provide a memory for staff handling routine situations in an organisation, with the result that staff can react quickly, increasing the efficiency of knowledge exploitation. For example, within health-care contexts, admissions data or other patient information may be collected and collated in certain ways to comply with the demands of external agencies and legal requirements regarding sharing of data. Such data may (or may not) prove useful for CCGs to monitor trends, such as the local patterns of GP referrals of older people into hospitals, potentially allowing CCGs to distinguish between necessary and avoidable admissions. Alternatively, systems capabilities may take the form of clinical guidelines, such as those set by NICE, or mandatory priority setting by top-down government initiatives, such as the continuing influence of the National Commissioning Board over CCGs. System capabilities such as pre-existing policy in the realm of organisational incentives, legislation and system-level dissemination mechanisms or initiatives, which afford access to external resources and influencers, formalise but narrow knowledge acquisition and assimilation and, at the same time, restrict exploratory learning, innovation and transformation. 4

Health-care organisations are subject to New Public Management reform that frames performance through financial incentives and regulation. Encompassed within systems capabilities, such government policy affords access to external resources, and directs and formalises acquisition and assimilation of knowledge. However, it narrows the search for new external knowledge and the scope for processing of that knowledge, as managers in health-care organisations ‘gameplay’ to ensure compliance with policy requirements around their governance. 31,53 Pulling in external knowledge within health-care organisations towards quality improvement appears to be particularly directed towards compliance with government regulation and performance management54 in a way that is likely to limit the search and utilisation of external evidence, limiting the level of ACAP.

Co-ordination capabilities

Co-ordination capabilities refer to lateral forms of communication or structures, such as education and training, job rotation, cross-functional interfaces and distinct liaison roles. In contrast to socialisation and systems capabilities, co-ordination capabilities increase the scope of external knowledge acquired and assimilated, and may also engender greater organisational flexibility regarding subsequent transformation and exploitation of knowledge (subsequently reducing the variance between PACAP and RACAP). Hence, to enhance ACAP, managers might attend to organisational mechanisms associated with co-ordination capability. 8,11 The aim for organisational managers, in developing co-ordination capabilities, is to establish ties with external sources of new knowledge (enhancing acquisition and assimilation) and to support this through establishing dense networks of ties within the organisation (enhancing transformation and exploitation). 8 Thus, organisation managers might seek to enhance ‘social integration mechanisms’, such as boundary-spanning or liaison mechanisms and roles and communities of practice, and seek to decentralise authority and decision-making. 2,9,12 For example (as discussed in General practitioner involvement), within CCGs, the increased involvement of GPs within the commissioning structures might act as a co-ordination capability, as doctors have been noted as holding a mediating role in communication (or lack of) across jurisdictional boundaries. 4

Co-ordination capabilities could be a mechanism that facilitates mediation between the effects of socialisation and systems capabilities. This is particularly evident in professionalised organisations, as co-ordination capabilities facilitate development and dissemination of internal knowledge, which is commonly tacit, as well as external, codified knowledge. 33 This enhances ACAP by ensuring that external knowledge is effectively combined with prior knowledge held by front-line clinicians, informing the commissioning and delivery of health care.

Co-ordination capabilities in commissioning

Identifying and enhancing co-ordination capabilities is particularly important in complex organisational settings, such as health care, ‘where . . . the ability to engage in flexible, knowledge exchange and generation across hierarchy and function – are essential to organisational performance’. 33 However, as noted previously, the influence of intraorganisational dynamics on co-ordination capabilities has received little attention in the existing literature, within both health care and the wider body of organisational research. 12 Although dimensions of co-ordination capability have been identified within health-care settings,3,4,32 there is a lack of understanding of how such co-ordination capabilities work to enhance ACAP, and how development of co-ordination capabilities might be supported. Drawing on the ACAP literature outlined above, it appears that there are key elements of co-ordination capabilities that could be drawn on to improve the critical review capacity of CCGs: information support systems, social integration mechanisms, clinical participation in decision-making, appropriate leadership and, more generally, social relations with diverse group inside and outside the organisation. 33 In the specific context of CCGs, we conceptualise these co-ordination capabilities as four mechanisms: GP involvement, PPI, BI functions and social integration mechanisms.

General practitioner involvement

The policy emphasis on the need for medical involvement in organisational decision-making and commissioning relies on influence through formal managerial roles. 14,55,56 Structurally positioned across managerial and professional boundaries, doctors occupying these spaces take on leadership roles over their ‘rank and file’ colleagues who are not involved in organisational decision-making. 57 Those doctors discharging medical responsibilities alongside a managerial role are seen as crucial drivers of policy-led change in health-care organisations, and they are expected to proactively steer their professional colleagues towards organisational aims. 58

Doctors involved in organisational management can, arguably, exert influence outwards to control external forces intruding on the profession, while, at the same time, enjoying influence and control over their colleagues. 59,60 As a result, policy aspirations assume that doctors in formal management roles should be able to influence organisational decision-making, as they occupy an established, powerful role and voice within a dominant coalition with general managers, controlling health services. 61–63 Consequently, medical involvement in decision-making should act as a co-ordination capability, as doctors are able to acquire, assimilate and transform information from different sources and in different ways from general managers, overcoming issues of systems and socialisation capabilities.

However, doctors involved in management represent both the professional agenda and its disciplining by a managerial one, resulting in a lack of credibility with their rank and file professional peers, or a lack of influence over managerial decision-making. As such, managerial and professional aims may not be aligned as doctors enact medical management roles, with consequent deleterious effects on rank and file doctors’ involvement in organisational decision-making. 64 Furthermore, medical managers are seen as encouraging the ‘colonisation’ of managerial priorities in professional practice, standards and discourse. 59,65–68 Rank and file doctors may prove resistant to such soft governance mechanisms, again with deleterious effects on their involvement in organisational decision-making. 62 Even where studies show that formal involvement of doctors in decision-making results in better organisational performance, such as those set within the US health-care system,55,56 exactly how they influence decision-making is unclear. 63

The studies cited in the preceding paragraphs characterise doctors involved in organisational decision-making as a homogeneous group: a substratum of the profession ascending into formalised medical management roles, exerting influence over rank and file peers. This represents an oversimplification of doctors’ involvement in organisational decision-making and neglects a consideration of differences between forms of medical influence. 59,64 The potential emergence of doctors who influence organisational decision-making from outside formalised managerial roles (i.e. those who do not occupy a formal position spanning medical and managerial perspectives, but nevertheless engage with managerial decision-making) is neglected in both policy and research. 69,70 This is problematic, and results in policy approaches to organisational improvement that do not consider the potential benefits offered by involving doctors through alternative, non-formal, arrangements.

In the context of CCGs, the involvement of GPs in formal commissioning roles is crucial. 14 Commissioning organisations in England are multidisciplinary, yet GPs arguably exert the most power and influence, reinforced by their increasing fiscal responsibilities and involvement in commissioning. 71,72 However, not all GPs are engaged in formal roles, resulting in intraprofessional variation, as some focus on clinical, rather than managerial, interests, whereas others take on a unique level of responsibility for strategic decision-making through commissioning leadership roles. 67,73 Further to this, a recent report by Robertson et al. 29 highlighted that increased GP involvement in commissioning has not necessarily been translated into improvements in health-care delivery. They highlight dwindling levels of GP engagement in formal commissioning roles, and advocate the need to develop new roles for GPs that allow them to maximise their potential contribution to CCG decision-making processes without needing to withdraw from clinical work.

In summary, although GP involvement should, theoretically, act as a co-ordination capability to enhance critical review capacity of CCGs, recent work suggests that this potential is not being realised. 17 More research is needed into exactly how doctors influence organisational decision-making,63 with a specific focus on the challenges faced when co-opting GPs into formal commissioning roles in CCGs. 29

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement is a global priority in health-care settings and is assumed to empower communities, improve service decisions, provide democratic accountability and contribute to higher-quality services. 74,75 Despite the benefits of PPI for health and social care services,76 much existing research suggests that, although there is strong policy support, its potential contribution is stymied by contested terminology, limitations in the underpinning evidence base, different attitudes to PPI and variable attempts at implementation. 77,78 Commentators note the impact of professional hierarchies on the translation of PPI policy into practice in public sector organisations,79–81 but neglect the impact of managerial influences on PPI. 82 This is surprising, considering that recent research highlights how PPI representatives attempt to increase their influence by working more closely with managers,83 suggesting that changes in managerial context may represent a means by which to enhance involvement.

In NHS England, PPI is reflected in policy advocating patient choice and shared decision-making, from the individual level of care to the development and improvement of health services. 84,85 The importance of PPI in CCGs is also reflected in the central focus on the involvement of service users in commissioning decisions, driving patient-focused decision-making that is theoretically autonomous from top-down control.

The new commissioning arrangements, in particular the renewed focus on public and clinical involvement, distinguish CCGs from their commissioning predecessors, which were criticised for being managerially focused with limited, tokenistic engagement with the public. 86,87 This is reflected in the new legal requirements for commissioning organisations to engage with the public at multiple stages of the commissioning process. 88 However, reflecting other policies relating to PPI, the interpretation of what PPI ‘is’, or how the public should be integrated into commissioning decisions, is vague. Commentators suggest that this ambiguity is key to CCGs, as they theoretically have more flexibility and autonomy from top-down control, creating contexts that have the potential to develop PPI according to their local needs and organisational cultures. 89 CCGs, therefore, offer insight into the varying ways that policy will be interpreted and implemented within the commissioning context.

Patient and public involvement should act as a co-ordination capability in a similar way to GP involvement, overcoming limitations of systems capabilities by broadening the scope of information being acquired, assimilated and transformed into service design. However, although patient involvement is a key policy imperative, making the vision of fully integrated PPI in commissioning has historically been challenging. 90 Although CCGs go some way towards improving previous commissioning systems, commissioners are still criticised for a lack of progress in fully involving the public in decisions about their own health and service provision. 91 In particular, researchers note how, when commissioners are preoccupied with meeting immediate performance management demands, or responding to centrally determined policy mandates, the patient voice is the first to be sidelined and ignored during commissioning processes. 17

Business intelligence

The third co-ordination capability alluded to in the literature relates to the BI functions available to CCGs. In policy, BI comes from CSUs, which were set up to provide IT, human resources and strategic BI support to CCGs. 92 CSUs arguably provide transactional information (such as admissions details from secondary care, and insight into spending in the regional area) as well as more transformational insights, such as intelligence around service redesign. As such, BI functions act as a potential co-ordination capability by mediating limitations of systems capabilities, as discussed in Chapter 7.

Initially, CCGs were able to decide whether or not to retain BI services in-house, encouraging relational interactions with commissioners and operating under the umbrella of the NHS Commissioning Board. 93 However, from 2016, policy mandates that CSUs become independent businesses to introduce competition into the market and encourage more strategic BI offerings to CCGs. Policy-makers suggest that the potential added value of outsourcing BI functions results from the fact that their services are bought in by CCGs in a competitive market, encouraging CSUs to move beyond the limitations of transactional information provision and towards more strategic approaches to health-care improvement. 94

However, the success of CSUs working in transformative partnership with CCGs is ambiguous and requires further research. First, policy notes that CSUs vary in size, capacity, capability and commercial skills. 93 This is also the case for CCGs, meaning that there will be variation between cases in both the way they engage with CSUs (i.e. in-house or outsourced) and the way they are able to transform the information from CSUs into service design at a local level. Associated with this variation is a concern that CCGs initially lacked the understanding required to be ‘intelligent customers’, and were unsure of how to use CSUs to enhance their critical review capacity. 93

Second, in the context of this study, NHS England has considerable influence over CSUs and the subsequent monitoring and guiding of activities of CCGs. Rather than encouraging truly transformational BI through relational interactions with CCGs, this close link with NHS England may reduce BI to transactional interactions with CCGs, which we noted previously as a limitation of CCG systems capabilities. 54 As a consequence, Petsoulas et al. 95 note that CCGs may be distrustful of CSUs, as they resent being required to outsource business functions that previously existed in-house. Therefore, whether or not a competitive market for CSUs will encourage more strategic, transformative relationships between commissioners and CSUs, rather than perpetuating fragmented, transactional interactions driven by central performance management systems, remains to be seen.

Social integration

There is a distinct imperative, both in policy and in research literature, for health and social care provision to be better co-ordinated. 96,97 When CCGs first began operating, social integration was promoted through health and well-being boards. 88 However, these boards were quickly criticised for excluding local organisations and leaders central to care integration, and focusing more on politically driven issues of public health rather than acting as an integration mechanism. 98

In response to the criticism of the perceived failure of health and well-being boards, pooled budgets, in the form of the Better Care Fund, were set up to encourage the development of integrated care teams, with a focus on reducing emergency admissions to hospital. 99 Integrated care teams work by taking a joined-up approach to complex, holistic care for patients who often have comorbidity. 19,24 It is crucial to strengthen integrated community care, through intelligent commissioning, so that care is holistic and sensitive to patient need, and there is strong evidence that integrated care teams can reduce the proportion of elderly patients being admitted into acute hospitals. 21,22 It is estimated that integrating health and social care could result in savings of £132M,20 and a reduction of 7000 beds. 17

In addition to the importance of integrating health and social care, close working with the voluntary sector is increasingly noted in policy as a crucial element of social integration mechanisms. 100 A report for NHS England highlights the potential benefits of engaging voluntary organisations in both the commissioning and provision of complex service arrangements. 101 Voluntary organisations are able to work with health and social care providers, often crossing institutional barriers, which can enhance patient outcomes, particularly for frail or vulnerable patients. 102,103 However, despite the potential benefits of engaging with voluntary sector organisations, research into how commissioning organisations engage with the third sector during commissioning processes is unclear and requires further exploration.

Despite a policy focus on the need for integrated health and social care,88,100 and increased involvement of the voluntary sector,101 the outcomes of integrated teams in practice are ambiguous. 104 Addicott105 notes two key approaches to facilitating social integration attempts: relational (nurturing trust and building relationships between providers) and transactional (holding providers to account for outcomes, streamlining patient care and facilitating the flow of money between providers). However, socialisation and systems capabilities, in the form of funding, governance, accountability and information systems, act as a limiting influence on the ability of service integration. 96 Social integration mechanisms, although noted as potential mechanisms through which to overcome these limitations, are seen as complex and often risky for commissioners, reducing the appetite for true social integration in a number of CCGs. 17,105

Conclusions

Absorptive capacity is a theoretical concept that can be used to explore critical review capacity in organisations. 2 Of particular importance is the consideration of variance between PACAP (acquisition and assimilation) and RACAP (transformation and exploitation), an area that has been highlighted for future research. 8 Although the majority of research concerning ACAP is limited to the private sector, in this chapter we reported the potential benefits when applied to the health-care context of CCGs, outlining previous research that suggests that health-care organisations might apply ACAP concepts to enhance service interventions by improving their critical review capacity. 3–5,33

In particular, we highlighted the important, yet underdeveloped, effect of combinative capabilities on the reduction in variance between PACAP and RACAP. Indeed, Van den Bosch et al. 11 call for future research to assess not just ACAP stages but how combinative capabilities affect the acquisition, absorption and use of new knowledge for improved organisational performance. The literature suggests that systems and socialisation capabilities act to reduce ACAP in a more pronounced way in health-care organisations. 8 This highlights the need for health-care organisations to develop co-ordination capabilities to offset the effects of systems and socialisation capabilities so that their ACAP is enhanced.

The four co-ordination capabilities that are identified as important in the context of CCGs are GP involvement, PPI, BI functions and social integration mechanisms. Each of these co-ordination capabilities has the potential to mediate some of the barriers of systems and socialisation capabilities, which characterise complex organisational contexts. However, although policy identifies the development of these four elements as a priority for CCGs, the extent to which each is able to reduce the variation between CCG PACAP and RACAP, enhancing critical review capacity, is unclear.

Chapter 3 Research design

Introduction

To explore how CCGs can enhance their critical review capacity for intelligent commissioning, we followed a tracer study:106 that of commissioning interventions to reduce avoidable admissions of older persons into hospitals. For the NHS, potentially avoidable admissions prove difficult and costly to manage. Frail elderly admissions, many of which can safely be avoided, are both clinically and economically deleterious. 17–20 Avoiding admissions is a matter of improving care in the community, which is particularly important for people with both physical and mental impairment, with approximately half of all elderly patient admissions fulfilling the criteria for dementia. 23

Elderly care admission avoidance was therefore chosen as a tracer study owing to its central importance, particularly in the face of the austere financial climate facing health care. As such, the study contributes to system transformation that takes costs out of hospitals, and links to local transformational efforts around QIPP, a significant part of which focuses on system improvement and cost reduction in elderly care. Our study aims to reduce some of the uncertainty that hospitals face and that manifests itself in crises, such as a lack of hospital beds in winter, as CCGs improve their ability to anticipate fluctuations in demand and commission interventions to prevent potentially avoidable elderly care admissions to hospital. Improvement in organisational and clinical outcomes is enhanced by our consideration of joint commissioning across health and social care, noted as particularly challenging,96,105 with Swan et al. ’s16 2012 study of PCTs further highlighting complex, multilevel interdependencies in commissioning decisions across organisations. Practically, we suggest that the relationship between CCGs and acute hospitals may be prone to tension in this area as productivity gains ensue through transfer of care outside hospitals, so, in this regard, the tracer is interesting.

Further to the theoretical reasoning for selecting elderly care admission avoidance as the tracer study, the issue was viewed as a particularly pressing issue by the CCG leads whom we interviewed in an exploratory study. However, the results from this study are not limited to care of older people, as application of the ACAP concept allows theoretical generalisation to other commissioning domains. 107 In other words, although we focus specifically on commissioning processes related to elderly care, the underpinning processes and findings are generalisable to a broad range of commissioning issues.

Our overarching RQ is as follows: how can we enhance ACAP of CCG-led commissioning networks in health care to inform decisions to reduce potentially avoidable elderly care acute hospital admissions? This breaks down into three linked RQs:

-

How do CCG external relationships and system antecedents to new commissioning arrangements affect CCG critical review capacity?

-

What features of CCG organisational context (i.e. internal capacity) affect CCG critical review capacity?

-

How do we reduce the variation between PACAP and RACAP?

Case studies

We follow a comparative case study approach,108 focusing on 13 CCGs in NHS England, allowing generation of more robust analysis, alert to contextual contingencies, when considering the antecedents of critical review capacity. Case study research involves a multilevel approach to the understanding of in-depth, dynamic settings, and can expand knowledge of individual, group, organisational and social phenomenon by allowing researchers to examine real-life events in a rich, holistic context. 107 Case study research does not attempt to select statistically representative samples, instead focusing on events or programmes that provide a unique conceptual insight into a theoretical framework at different levels of analysis. 107,109,110 Interviewing participants from different hierarchical levels and organisational positions will provide different perspectives on phenomenon, an essential element of multiple case research. 111,112

Case study research explains processes such as how we enhance CCG critical review capacity. Comparative case analysis allows generation of more robust analysis, particularly when concerned with drawing out contingencies, such as those external and internal contingencies framing CCG critical review capacity. 111 Comparative case analysis also accommodates heterogeneity of CCGs, and our study sites are representative of heterogeneity nationally.

The eventual sample of 13 CCG-led commissioning networks is representative of their characteristics (Table 1); however, we faced a considerable challenge in accessing empirical sites, that is, we approached many more potential empirical cases. Commonly, we experienced some interest and an invitation to discuss our study with a key stakeholder, often the chief operating officer, but were then passed down the CCG organisation to a GP commissioning lead or commissioning manager. Beyond the chief operating officer, other stakeholders sought to translate our research intent towards something else of more operational priority (at which point we politely disengaged). Our overall impression was that CCGs remained rather passive about developing their critical review capacity, even though, in our eyes, this was necessary to achieve their strategic remit set out by policy-makers.

| CCG characteristics | CCG A | CCG B | CCG C | CCG D | CCG E | CCG F | CCG G | CCG H | CCG I | CCG J | CCG K | CCG L | CCG M |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subject of specific focus | Integrated teams | Integrated teams | Patient involvement | Patient involvement | BI | Integrated teams | Patient involvement | Integrated teams | GP involvement | Voluntary sector/integrated teams | Integrated teams | GP involvement | BI |

| Population served | 93,000 | 128,000 | 128,000 | 270,000 | 897,300 | 239,550 | 327,754 | 167,800 | 270,000 | 167,000 | 108,300 | 428,100 | 8.3M |

| Area | Urban | Mixed | Mixed | Rural | Rural | Mixed | Mixed | Rural | Rural | Rural | Mixed | Rural | Urban |

| Budget (£) | 145,500 | 200,843 | 200,000 | 410,889 | 1,461,432 | 125,950 | 549,310 | 289,615 | 410,000 | 289,615 | 4.3B | 738,514 | 10B |

However, once we negotiated access to our 13 empirical cases, we asked each CCG to suggest a commissioning issue related to elderly care admission avoidance that was currently important in their organisation. The focus of each case fell broadly into the four categories of co-ordination capabilities highlighted in the literature review (see Chapter 2): GP involvement, PPI, BI functions and social integration. The demographic spread of each CCG, and their specific commissioning focus discussed during interviews, is outlined in Table 1.

Interviews

Comparative case studies were underpinned by qualitative fieldwork, with data gathering mainly via 159 semistructured interviews,113 most of which were conducted by the fieldworker (research fellow employed on the study), with the principal investigator for the study conducting a smaller number to ‘keep in touch’ with the primary data. Interview schedules were informed by themes generated from the literature review, which was thematic and followed narrative models. 114 In-depth interviews allow researchers to understand how the respondent views the world without researcher preconceptions being imposed on them, and to generate rich data with minimal researcher reactivity. 115,116 Individual interviews allow an insight into how large-scale transformations are experienced and are affected by the interactions of individuals, and they focus on how these interactions are embedded in the social and cultural context. 117 Semistructured interviews offer a much richer account of how the interviewees’ experiences, knowledge, ideas and impressions are considered and documented. Interviewees are less constrained by the researchers’ pre-understanding and there is space for the negotiation of meanings, so some level of mutual understanding is reached. 118

Our sample of interviewees from the 13 CCG-led commissioning networks represented stakeholders who were seen to be central to the commissioning process, and in many cases carried some ‘managerial’ responsibility for commissioning. We also engaged with ‘lay members’ of the CCG, individuals without clinical backgrounds who participated in PPI groups, or who acted in a lay member capacity on the CCG governing body. With assistance from the relevant CCG chief operating officer in exploratory interviews designed to engage CCGs in our study, we identified some respondents a priori, and then followed a snowball sampling pattern119 until the themes emerging from interviews were theoretically saturated. To ensure that the extended commissioning network was considered, interviews were not limited to those working within CCGs but also encompassed those working in hospitals, in addition to public health and local government professionals concerned with provision and commissioning of older people’s care. Further to this, to reflect the ongoing politicised nature and top-down control that remains within health-care contexts, we interviewed six NHS England staff, including three of the NHS Commissioning Board local area team leads linked to our focal CCG empirical cases. After we obtained ethics approval from local NHS research ethics committees and R&D departments, a total of 159 participants were interviewed (Table 2).

| Occupation/organisation | CCG A | CCG B | CCG C | CCG D | CCG E | CCG F | CCG G | CCG H | CCG I | CCG J | CCG K | CCG L | CCG M | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinician (GP or nurse) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 8 | 0 | 36 |

| CCG managerial staff (finance, strategy, governance, etc.) | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 10 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 7 | 7 | 12 | 60 |

| Secondary care provider | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 12 |

| Tertiary care provider | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15 |

| Local authority | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 13 |

| PPI representative | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 17 |

| NHS England representative | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Total | 10 | 12 | 11 | 6 | 17 | 10 | 17 | 12 | 6 | 14 | 16 | 16 | 12 | 159 |

Within each CCG network, we undertook semistructured interviews and asked respondents to describe the commissioning process, focusing on the four processes encompassed within knowledge mobilisation, embedded in an organisation’s ACAP (acquisition, assimilation, transformation and exploitation), and their antecedents or combinative capabilities. We did not directly invoke technical terms such as ACAP and capabilities, but asked more general questions, such as the following: ‘How do you acquire data and information about elderly care hospital admissions?’; ‘How do you use such data and information?’; ‘What are the barriers to using data and information?’; and ‘How are these barriers mediated?’. Participants were also encouraged to speak freely about their experiences of commissioning processes, and interview themes were guided by issues arising during the conversation.

As we gathered data, we sought to collect rival explanations for the phenomena reported, in a spirit of scepticism about reporting of events and actions. We sought to collect discrepant evidence to develop a plausible rival description of events and activities. In short, we sought to challenge our explanation of knowledge mobilisation by CCG-led commissioning networks as one focused on ACAP. There were specific explanations of poor use of knowledge mobilisation by CCG networks. More generally, top-down policy pressures, power differentials with large acute providers and bureaucratic tendencies of CCG employees converged, meaning that knowledge mobilisation was poor. Theoretically, the concept of ACAP provides an explanation for poor knowledge mobilisation.

Patient and public involvement during the study

Although the overarching study was concerned with enhancing decision-making processes for commissioning organisations, specifically related to interventions to reduce avoidable admissions of older people into hospital, we were also interested in PPI in CCG networks. Although only three of our networks explicitly asked us to explore PPI, it was a central component of our interview schedule at each site. Over the course of the study, distinct variations in managerial interventions shaping PPI involvement were noted, leading to different outcomes for PPI influence on service development at each site. Although all commissioning networks had formalised structures for public engagement, the managerial influences on PPI varied immensely (this is discussed in detail in Chapter 6).

In addition to questions relating to ACAP, as outlined above, we also asked interviewees to describe how information or opinions were acquired from the public and through what structures this took place; how feedback was used with other forms of data to determine the needs of the local community; how information from PPI was used to design services; and what the influences on PPI were. In addition, when possible, the research team intended to attended public engagement forums or meetings at each site. This was limited, in most cases, by managerial reluctance for us to observe meetings and, for this reason, was restricted to six observations of PPI meetings occurring over three sites (those specifically interested in their public engagement). Extensive hand-written field notes were taken during observations and used to supplement analysis of themes related to PPI.

In addition to the focus on PPI during research, the research group itself had a strong PPI focus. The study advisory board, which meets yearly, is chaired by Tony Sargeant, patient involvement champion. In addition to the research staff on the board, Andrew Entwistle, lay specialist in patient involvement, and Graham Martin, academic specialist in patient involvement, were key members of the study advisory board. This group was heavily involved in the design of the study, the ongoing planning and response to themes emerging, the analysis of the findings and the dissemination plans for the findings. Further to this, Tony and Andrew also sat on the study PPI group. This group met at least twice a year to receive regular study updates from the research team and to triangulate study analysis. They offered insight into the direction of research and highlighted issues that the research team may not have isolated as influences on critical review capacity in CCGs. Finally, the PPI group were also involved in the dissemination of research. Crucially, the ACAP psychometric tool was coproduced between the researchers and PPI group in an iterative manner (see Chapter 10 for further details). Their meetings were audio-recorded by Sophie Staniszweska (co-investigator), who continues to work with the group to produce some user-led publications or study outputs.

Analysis

Semistructured interviews lasted between 45 minutes and 1 hour and were audio-recorded and transcribed. Initial coding was carried out by one member of the research team (research fellow) following template analysis. Coding was then discussed with the principal investigator, with the research fellow and principal investigator jointly engaging in further rounds of coding as we moved towards more abstracted theoretical themes. Coded material was organised in a hierarchical manner to provide general, parallel and subcategory codes to allow analysis at different levels of specificity. This allowed a flexible and adaptive approach to research analysis, with some a priori codes drawn from literature review, but with the detail of these and how they inter-related induced from analysis of the data. 120,121 Observational field notes and documentary evidence from the CCG networks helped generate early contextual understanding of empirical sites,122 but the data presented draws solely on interview transcripts. Coding was facilitated through the use of the software program NVivo 11 (QSR International, Warrington, UK), which produced a more rigorous and transparent approach to data analysis. 123

We checked our emerging analysis with the study PPI group, research team and study advisory board, and through iterative feedback with each CCG site, to inductively identify how the four co-ordination capabilities (GP involvement, PPI, social integration and BI functions) were evident in interview transcripts. This was then refined by coding for examples of the three combinative capabilities: barriers of systems capabilities, barriers of socialisation capabilities and co-ordination capabilities as a mediator. An example of the coding structure is presented in Table 3. Following this, we present the findings of each of these co-ordination capabilities in detail.

| CCG characteristic | Systems | Socialisation | Co-ordination |

|---|---|---|---|

| GP involvement | Trying to find out what the CCG wanted of us and whether I thought that was what I could deliver for them . . . To be honest, there was quite a lot of uncertainty about what they wanted me to do here . . . they didn’t seem to know what to do with me at firstCCG L, interview 4 | There is still a problem for them in that there are still people in the system who are old PCT SHA staff so still see themselves as the old PCT SHA sort of ‘You’ll do what I say’ type, but I actually think that’s probably improvingCCG H, interview 4 | If you get buy-in from the GPs it’s a lot easier to get the service running. And they can tell you whether it will work or not, where the problems might be. So that’s always importantCCG I, interview 3 |

| BI | We no longer have that data coming directly to us, therefore we have to access it from the CSU, the Clinical Support Unit, and quite often we have sort of . . . Prior to my coming here there was a list of data which it was agreed we would have access to regularly. My understanding is that we are not always being given access to the data that we require from the CSU and I’m not entirely sure why that is. I’m actually waiting for a phone call. Someone was supposed to phone me yesterday so we’d have the conversation about what’s happening. Our access to data is currently quite limitedCCG M, interview 5 | I think it’s very easy to become just an analyst where you’re just this is the process, there’s the number, churn the numbers out, give them an overarching this is how we’ve got to the numbers, but then to understand the question that they’ve asked in the first place you probably need to be there to react to what they react to when they see that number in front of themCCG M, interview 9 | They started from the fact that they’ve got a single acute provider working across two sites with basically unsustainable services, in their view, into the long term because of insufficient capacity. So they wanted to run a reconfiguration programme to design a new clinical model for that patch and then out of that clinical model to run all the processes necessary to try to identify a preferred option for reshaping their hospital system . . . now we’re helping them design their primary care strategy, their community services strategy and helping them properly work out what the implications are for primary care, community care, social care, mental health services of their intended shift of activity out of the acute sector, which is the bit that everyone struggles to doCCG M, interview 12 |

| Integrated teams | I think we’re quite advanced in recording of information, but generally community services are quite poor at really understanding what their services are and what they cost and how they’re deliveredCCG G, interview 10 | It was complicated before the reforms; now it is just . . . it’s unworkable and we’re seeing this with cancer, we’re seeing it with specialised commissioning, we’re seeing it with general practice. It’s just bonkers the current system. Fragmentation along relatively arbitrary lines denies the complex interrelationships between the components of delivery of good care. The fragmentation between health and social care was bad enough and now we’ve broken health care up you’ve probably got seven different players pulling bits of the service in different directions to meet their own requirements and of course the person who gets left in the gap is the patientCCG J, interview 7 | So the idea of the [integrated team] is to be multiprofessional. So you’ve got clinicians, commissioners, service providers, researchers . . . Not the voluntary sector if I’m honest, although we’ve got good contacts building with the voluntary sector, but we’ve got representation from all those groups, so when the team discuss a problem you’ve got all those voices around the table which I think is what makes it quite uniqueCCG K, interview 5 |