Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 12/209/53. The contractual start date was in May 2014. The final report began editorial review in October 2016 and was accepted for publication in August 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Kinderman et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Scientific background

Dementia in society

There are currently > 850,000 people living with a diagnosis of dementia in the UK. 1 As well as the biological changes associated with a dementia process, which can lead to a range of cognitive difficulties, dementia is associated with numerous psychological and social consequences. Sixty-one per cent of people living with dementia have reported feeling anxious or depressed, 40% have reported feeling lonely and just over one-third do not feel part of their community. 1 This poses a major threat to the quality of life of a large number of people in our society and is in direct conflict with the National Dementia Strategy, the aim of which is to help people with dementia to ‘live well with dementia’. 2 The cost of dementia to the UK each year is estimated to be £26B. 3 We live in an ageing population and the issues associated with dementia will continue to increase. The status quo is unsustainable. Providing good-quality care to people with dementia will continue to be a concern over the coming years.

In 2007, the Alzheimer’s Society published Dementia UK. 4 This report stated that:

Dementia must be made a publicly stated national health and social care priority. This must be reflected in plans for service development and public spending.

In 2009, Living Well With Dementia: A National Dementia Strategy2 was published, outlining the government’s plan for providing quality services in dementia care. Dementia has been highlighted as a government priority. In 2015, the prime minister launched a programme of work5 that aims to deliver major improvements in dementia care and research by 2020. The focus of this is improving the services provided for people with dementia, with the view that England could become the best country in the world for dementia care and support, for people with dementia, their carers and families to live, and for undertaking research into dementia.

Dementia is widely feared in society6 and, traditionally, people with dementia have been among the most devalued, experiencing the double stigma of old age and cognitive impairment. Kitwood7 suggested that personhood (i.e. the state of being a person) is bestowed on us by the treatment of others. The stigma and misperceptions surrounding dementia and the resulting reactions of people towards those living with dementia have led to care practices that can undermine the humanity and personhood of an individual with dementia. 7 The literature highlights issues such as removing all choice and personal autonomy from people with dementia,8 restraint, and restrictions on ‘wandering’. It is clear that there are occasions when human rights for people with dementia are unnecessarily limited and their application is not routinely considered in clinical decision-making. 9 It is essential that approaches are adopted that maintain the humanity of an individual and challenge the stigma associated with dementia that people often report feeling.

Human rights

Human rights are brought into UK law through the Human Rights Act. 10 They represent the fundamental ways in which a person can expect to be treated simply by virtue of being human. Although human rights are based on values held for centuries, they became formalised following the atrocities of the second world war, in particular the Holocaust. It was acknowledged that human beings can inflict dreadful suffering on each other and that explicit statements on our rights as human citizens were required. The articles of the Human Rights Act are broad-ranging, covering physical, psychological and social issues, and they represent the minimum standard of treatment that we should expect. Table 1 outlines the articles of the Human Rights Act.

| Part I | The convention rights and freedoms |

| Article 2 | The right to life |

| Article 3 | The right not to be tortured or treated in an inhuman or degrading way |

| Article 4 | The right to be free from slavery or forced labour |

| Article 5 | The right to liberty and security |

| Article 6 | The right to a fair trial |

| Article 7 | The right to no punishment without law |

| Article 8 | The right to respect for private and family life, home and correspondence |

| Article 9 | The right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion |

| Article 10 | The right to freedom of expression |

| Article 11 | The right to freedom of assembly and association |

| Article 12 | The right to marry and found a family |

| Article 14 | The right not to be discriminated against in relation to any of the rights contained in the European Convention |

| Protocol 1: Article 1 | The right to peaceful enjoyment of possessions |

| Protocol 1: Article 2 | The right to education |

| Protocol 1: Article 3 | The right to free elections |

| Protocol 13: Article 1 | Abolition of the death penalty |

The United Nations adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948. 11 The European Convention on Human Rights,12 created in 1950 by the Council of Europe, was the first post-war attempt to unify Europe and institutionalise the shared values of democracy, human rights and the rule of law. The UK was among the first states to ratify the Convention and British jurists were highly influential in its design. The Human Rights Act10 incorporates most of the Convention rights into UK law. It came into force across the UK in October 2000.

Human rights law, including the rights composing the Human Rights Act, can be understood through the FREDA (Fairness, Respect, Equality, Dignity and Autonomy) principles. 13 The FREDA principles are not law in and of themselves. They are the values that run through the rights protected by the Human Rights Act and are at the heart of high-quality health and social care.

Human rights in health care

Where, after all, do human rights begin? In small places, close to home – so close and so small that they cannot be seen on any map of the world. Yet they are the world of the individual person . . .

Eleanor Roosevelt, 195814

Human rights are diagnosis neutral and compel us to treat everyone as human beings regardless of the difficulties they may be experiencing. They also recognise, however, that, in certain complex cases, a balance may need to be struck in order to meet competing rights of different individuals or to protect an individual from unwarranted risk, and rights may need to be limited. A human rights based approach describes the process of using the articles of the Human Rights Act in a very practical way to influence daily life. 15 A human rights based approach to care both allows for that balance to be considered and provides a lens through which such difficult decisions can be made. Failure to take the human rights of the service user into account can also lead to legal suits that impose an additional financial burden and undermine public confidence in services. 16,17 The NHS Constitution for England states that the NHS:

. . . has a duty to each and every individual that it serves and must respect their human rights.

Not only is it unlawful for NHS organisations to work in a way that is incompatible with human rights, but the application of a human rights based approach establishes minimum standards of care that help to safeguard individuals, particularly those who are vulnerable. They also remind us that individuals require a great deal more than safeguarding in order to maintain their self-respect and sense of dignity. The culture of organisations has led, on occasion, to staff delivering task-orientated, risk-averse care that fails to consider the human rights of an individual. 16 Human rights, in this context, can therefore be viewed as codifications of how relationships can be understood and the social obligations we hold as human beings. 19

The Human Rights Act10 is law; however, in health-care settings, it needs to be translated into a clear set of principles that guide everyday practice, bridging the gap between the legal system and good-quality health care. 20 Human Rights in Healthcare21 achieves this translation by outlining the key ingredients of a human rights based approach. An alternative but similar construction is found within the PANEL principles. 8 The PANEL principles are participation, accountability, non-discriminatory, empowerment and legality, and these are defined more fully in Table 2. They represent the guiding principles for organisations to follow to maximise the chances of the services they deliver aligning with a human rights based approach.

| PANEL principle | Description |

|---|---|

| Participation | To ensure that all stakeholders are meaningfully engaged in the service |

| Accountability | To ensure that there is clear accountability and transparency to services being provided |

| Non-discriminatory | To ensure that particular attention is paid to vulnerable groups |

| Empowerment | To ensure the empowerment of all stakeholder groups |

| Legality | Looking at things through a human rights lens and ensuring that all actions taken are legal |

Making the link between law and ethical practice is not the only step required. There is also a need to translate the concepts of a human rights based approach into practical strategies that can facilitate the everyday decision-making of staff; in other words, there is a need to make ‘choices guided by values’22 and by the more practical elements of a human rights based approach, such as proportionality (i.e. responding to situations in a way that is appropriate in magnitude and degree), the fit with other legal frameworks such as the Mental Health Act23 and Mental Capacity Act,24 proactive strategies (predicting responses to events through knowledge of the person and responding before a negative event occurs) and balancing rights and risks to make sensible decisions.

The disability model of dementia

Discussions around dementia and the difficulties it causes to individuals have historically been dominated by a medicalised notion of dementia, in which there is no cure and nothing can be done other than watch the person decline. 25 More recent social movements to recognise dementia as a disability26 have opened up opportunities to frame dementia within a rights based approach. The United Nations’ Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities27 aims to ensure that, ultimately, people living with a disability do not experience discrimination and that their rights are maintained and promoted. The UK has ratified the Convention, which means that all UK laws and policies should be compliant with it. 28 As a result, people living with dementia should be able to utilise the Convention to protect and promote their rights.

Human rights and dementia

Although there is still limited empirical work being carried out specifically in the area of dementia and human rights, the last few years have seen an expansion of this topic as an area of focus. Several charters of human rights have been produced29,30 that aim to influence policy related to dementia. Literature also exists considering some of the major issues that may threaten an individual’s human rights. Laird31 has provided examples of how fundamental human rights can be violated in health-care settings:

[S]ituations cited by British Institute of Human Rights include failure to change soiled bed sheets, neglect leading to pressure ulcer development, not helping people to eat when they are too frail to eat themselves, excessive force used to restrain people and washing or dressing people without regard to dignity.

Laird,31 p. 6

It is notable, however, that the majority of publications are focused at a policy level32 or are discussion papers reviewing a concept33 as opposed to attempts to apply a human rights based approach in practice and evaluate its effectiveness. In 2016, Dementia Alliance International launched The Human Rights of People Living with Dementia: From Rhetoric to Reality. 34 Although this was a move to ensure that people living with dementia are aware of their rights, it stopped short of outlining the specific applications of a human rights based approach. In addition, the Dementia Engagement and Empowerment Project (DEEP) has worked alongside people with dementia to produce Our Dementia, Our Rights. 35 Although this was a real attempt to raise the issue of rights in the collective minds of society, and to produce a document in an accessible format, it did not evaluate the impact that the practical application of human rights law could have on the day-to-day lives of people living with dementia.

Since the work of Tom Kitwood,7 it has been widely accepted that person-centred principles are important in the provision of high-quality dementia care. These principles have, however, been criticised for being vague and difficult to research and enforce. 36 There are high levels of congruence between the fundamental principles of person-centred care and a human rights based approach, such as empowerment and inclusion. 37 A human rights based approach gives backbone and a legal framework to person-centred principles,37 potentially making them clearer to operationalise and more accessible to rigorous research.

Human rights training

Although there are various models of training to promote human rights awareness,38 there is limited evidence of their efficacy in terms of behavioural change. 39 These models include:

-

values and awareness model – this focuses on transmitting basic knowledge of human rights

-

accountability model – this assumes that participants will already be involved in the protection of individual and group rights and focuses on professional responsibility in relation to this

-

transformational model – this is geared towards empowering individuals who have previously experienced human rights abuses to both recognise human rights abuses and commit to their prevention.

The suggested common themes in these models are fostering and enhancing leadership, coalition and alliance development and personal empowerment. 38

Attitudinal change for staff through human rights awareness training may be more effective when there is emphasis on staff’s emotional responses and defences and the impact of organisational culture. 39 Reflections on rights awareness training in both dementia and intellectual disabilities services suggests that change might be achieved through placing ethical decision-making centrally. This has been termed ‘dilemma-based learning’. 37

Human rights evaluation

The need to evaluate human rights initiatives is often overlooked and there is no real consensus about how to evaluate them. 40 It has been argued that the evaluation of human rights based approaches is problematic for a number of reasons, including a belief that legal concepts should be monitored rather than evaluated, a fear that evaluation will lead to legal ramifications and a distaste for quantifying the extent of human misery and abuse when rights are not being upheld. 37

Donald40 provides a clear framework for evaluating human rights based approaches in health-care services. This framework encourages the exploration of human rights knowledge and understanding; skills in applying human rights based approaches; attitudes, perspectives and values; and, ultimately, the outcome and impact of applying the approach for the realisation of human rights. There is an argument that this is more palatable, as it allows researchers to directly assess the process and impact of the human rights based approaches rather than attempting to quantify abuses.

Rationale for research

Cultures of care

It may be comforting to assume that the human rights of the most vulnerable people in our society are routinely upheld and promoted by those tasked with caring for them. Unfortunately, the sad truth is that this is not always the case. The Francis report,41 arising from the lack of care provided at Mid-Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust, highlighted the importance of creating the:

. . . right culture of care . . .

to ensure that people are treated in ways that promote dignity and respect.

The Care Quality Commission (CQC) routinely uncovers practices that threaten the human rights of people living with dementia. For example, in one care home, inspectors noted that many residents stayed in bed all day for no apparent reason. When the inspectors questioned staff about this practice, they were told, ‘One side [of the house] we get up Monday, Wednesday and Friday. The other side we get up Tuesday, Thursday, Saturday’. 42 This is obviously unacceptable and in direct conflict with the principles of the Human Rights Act. 10

When considering the moral imperative we all hold to protect the vulnerable, it has been highlighted that ‘compassion is the basis for all morality’. 43 If we want to develop cultures of care in which person-centred care is a reality, then it has been suggested that ‘the NHS must be a fertile soil for meaningful caring relationships’. 44 The work of Buber and Smith45 encouraged viewing relationships as ‘I-Thou’, thereby engaging on a human-to-human level with the people we provide care and support for, as opposed to ‘I-It’, which adopts a detached task-orientated approach whereby people are viewed as jobs to be done and tasks to be completed. It has been suggested that, in many care settings, ‘the gap between the rhetoric and the reality remains uncomfortably wide’46 when we are considering models of person-centred care. There is no obligation to carry out person-centred care other than knowing that it is the right thing to do. With their statutory weight, human rights approaches can strengthen person-centred approaches47 and maximise the chances that they will be adopted.

Training and care

The training currently given to care providers does not automatically feel congruent with the aim of producing compassionate, person-centred cultures of care. It is recognised that there are major failings in the training of staff who provide care, particularly those who work in the care home sector. The CQC found that, of those care homes told to improve after a visit, 71% had significant training gaps, with dementia care, safeguarding and the Mental Capacity Act faring worst. 48 This is particularly worrying given that > 70% of people who are residents of care homes are living with dementia,1 and that the very fact that a person resides in a care home increases the chances that there will be queries about their capacity.

In providing training we are assuming that we are equipping people to make complex clinical decisions on a day-to-day basis. In reality we are often training people to become task orientated and driven. Models of training that include real-life situations tend to produce better outcomes with more emotional attachment to them. 37

Care planning

The availability of a good-quality person-centred care plan does not automatically ensure that good-quality person-centred care is provided, but it does provide a template by which the standard of care can be judged. In 2017, NHS England stated that:

. . . care planning is a crucial element in delivering improved care for people living with dementia.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)’s50 quality standard statement 4 for dementia requires that each person has a personalised care plan. There are models of good-quality care planning, such as enhanced care planning, but these are often not adopted. Traditional care planning approaches adopted in NHS services, such as the care programme approach (CPA), do not always lend themselves to the full involvement of people living with dementia because of the somewhat restrictive nature of their content and a focus on risk assessment. 51 It has been suggested that the CPA maintains:

. . . a system which too often defines people by their diagnosis and medication . . .

and

. . . finds it difficult to recognise the whole person and the unique individual . . .

Any model of quality dementia care recognises the centrality and importance of an in-depth knowledge of the person, their wishes and their preferences in providing support that is person centred and, therefore, is more likely to uphold their human rights. 53 It follows, therefore, that a good-quality care plan should be a vehicle for collating this detailed knowledge about a person and their care.

Decision-making in care settings

It is recognised that ‘making decisions that concern people’s health and quality of life creates complex ethical dilemmas, and one has to choose among alternatives’. 54 This can lead to decisions that have an impact on an individual’s human rights. For example, Robinson et al. 9 explored the area of balancing risks and rights in relation to wandering. They highlighted that staff often act in particular ways, such as having a locked-door policy, because they are worried about being viewed as negligent. The implementation of a human rights based approach may provide staff with a more comprehensive and robust framework in which decisions can be made, drawing on human rights principles, particularly proportionality, least restrictive practice and proactive strategies, rather than relying on the most risk-adverse approach. 37

Rationale

We are existing in systems where the care provided to some of the most vulnerable people in society is failing to meet their complex needs. Additionally, we are not equipping our workforces to meet these needs because of woeful lack of investment in their development.

This project will build on the existing literature exploring how the human rights of people living with dementia can be undermined and unnecessarily restricted within traditional models of care but expand the focus to look at an operationalised model of providing care that embeds a human rights based approach. The proposed intervention aimed to put human rights at the heart of care planning and service delivery. A human rights based approach was chosen as the appropriate focus for this project because not only does the NHS have a legal requirement to uphold the human rights of service users, but it is recognised that quality care is both person centred and respectful of an individual’s human rights. 55

Embedding a human rights based approach through the application of the ‘Getting It Right’ assessment tool56 and training package aimed to maximise quality of life and well-being for people with dementia and provide a framework for staff to make decisions about care within a human rights based approach, using the principles of proportionality, proactive strategies, positive risk-taking and use of least restrictive practices.

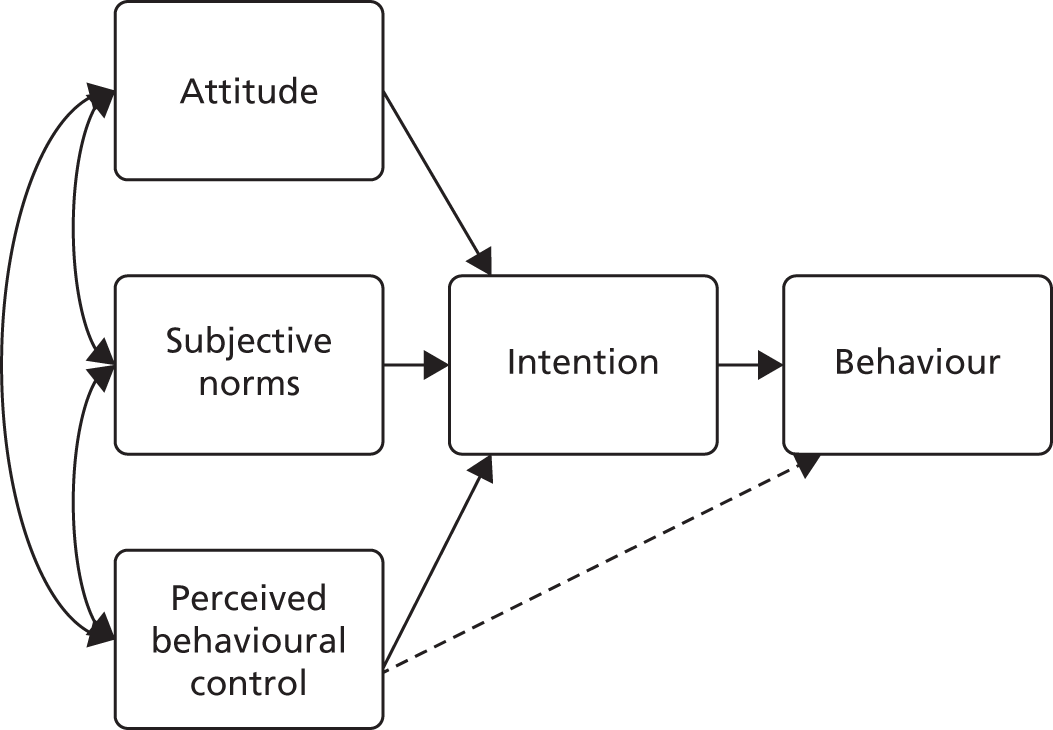

Conceptual framework

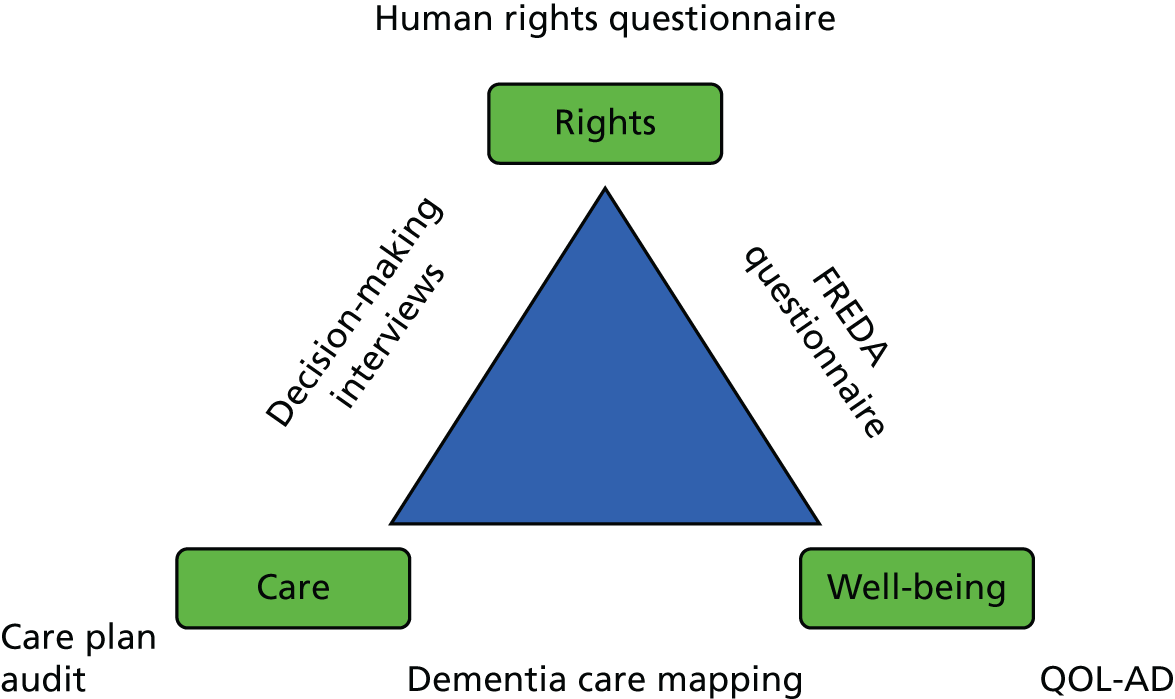

The underlying conceptual framework for the study was that the introduction of a human rights based approach to health care would lead to improvements in the well-being of people with dementia and the care they receive. This is summarised in Figure 1, which highlights how the outcome measures used allowed the exploration of these areas and the links between them. Specifically, the Quality of Life in Alzheimer’s Disease (QOL-AD)57 allowed a measurement of changes in subjective well-being but did not explain why these changes had taken place. The care plan audit measured the documented standard of care that a person should be receiving and also tapped into increases in human rights based language, etc., which would suggest that the human rights based nature of the intervention had an effect over and above simply providing generic training. However, care plans do not capture the actual care that is delivered and how it affects well-being. Dementia care mapping (DCM) was used to explore whether or not care provided on a unit changed and the effect that this had on the well-being of service users on the unit.

FIGURE 1.

Conceptual framework for the study. QOL-AD, Quality of Life in Alzheimer’s Disease.

The completion of human rights knowledge and attitude questionnaires measured changes in these areas pre and post training but did not look at the impact that these had on staff in their everyday working lives and how they affected service user well-being. Staff interviews were conducted to explore whether or not the introduction of a human rights based approach led to differences in decision-making processes when considering care issues. Similarly, the FREDA-based questionnaire was included to allow the team to explore whether or not service users felt that their human rights were respected more after the intervention.

Aims and objectives

Aim

To establish whether or not the application of a human rights based approach to health care leads to significant improvements in the care and well-being of people with dementia in hospital inpatient and care home settings.

Specific objectives

-

To investigate whether or not the application of a human rights based approach to health care, as opposed to treatment as usual, leads to significant improvements in the quality of life of people with dementia in hospital inpatient and care home settings, as measured by scores on the QOL-AD scale. 57

-

To explore whether or not training on the application of a human rights based approach to health care leads to identifiable improvements in the quality of staff decision-making, as measured by vignette-based interviews with staff.

-

To explore whether training in the application of a human rights based approach to health care, and the use of the ‘Getting It Right’ assessment tool,56 as opposed to the standard care planning procedure, leads to identifiable improvements in the person-centred quality of service users’ care plans, as measured by care plan audits.

-

To explore whether the application of a human rights based approach to health care leads to changes in the well-being of family carers of people with dementia who are in hospital inpatient and care home settings, as measured by the Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (WEMWBS)58 and the Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI). 59

-

To validate a novel human rights and well-being questionnaire for dementia inpatient care.

-

To explore the costs and consequences of human rights training for staff looking after people with dementia in hospital and care home settings in terms of patient-reported well-being, care plan development, staff stress, family member well-being and overall quality of care, compared with usual patient management.

Chapter 2 Trial design and methods

Study design

The study was designed to evaluate whether or not the application of a novel human rights based intervention could improve the standard of care delivered in dementia inpatient wards and care home settings as opposed to treatment as usual.

The research employed a cluster randomised design to compare the impact of implementing the intervention (i.e. the training package, the ‘Getting It Right’ assessment tool56 and booster sessions) at 10 intervention sites with 10 control sites. The control sites continued with treatment as usual. No active placebo was indicated. It was acknowledged that there may have been significant variation in what constituted treatment as usual across the sites involved in the study.

Data collection points were at baseline (see randomisation) and at 4 months post intervention. Training was delivered at the intervention sites and booster sessions were given over a 3-month period post training.

Intervention package

The intervention package being applied was a novel human rights based intervention package that had previously been piloted within the host trust (Mersey Care NHS Foundation Trust). It consisted of three linked elements.

-

A one-day training package delivered to staff from the intervention unit at a time and place that was convenient to the site. The training was delivered by co-applicant Sarah Butchard, who jointly developed the intervention package and is an experienced clinical psychologist and senior clinical teacher. It was based on dilemma-based learning, utilising clinical scenarios that commonly occur in dementia services. It incorporated both direct learning about a human rights based approach and its utility in dementia and the practical application of the human rights based assessment tool (‘Getting It Right’56).

-

The completion of ‘Getting It Right’56 (see Appendix 1), which was based on person-centred principles and on the learning from enhanced care planning. 53 The aim of using the tool was to build up a person-centred care plan that was explicitly linked to the FREDA principles. Each unit was given multiple copies of the assessment tool following the training and requested to complete the assessment with both new and existing residents on the unit. There was no stipulation made as to how many assessments needed to be competed at each unit. It was emphasised that any member of staff, not just those who were qualified, could complete the assessment with residents, and that it was more important that it was completed by someone who had a good relationship with that resident.

-

Monthly booster sessions were delivered by Sarah Butchard to address issues arising from the application of the assessment tool. Three booster sessions were offered, one per month, following the training. These adopted a consultation model and allowed staff to reflect on any difficulties they had in applying the assessment tool.

Ethics approval and research governance

A protocol was submitted for ethics consideration to the National Research Ethics Service committee North West – Haydock (reference number 14/NW/1117) in June 2014 and it was approved in August 2014. No requests for alterations were made before approval was granted. For participating NHS sites, approval was also sought from the relevant NHS trust research and development department.

The trial was registered with the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Register Number (ISRCTN) Registry under the reference number ISRCTN94553028 (www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN94553028).

Patient and public involvement

Ensuring that people living with dementia were meaningfully involved in all aspects of the study was seen as essential because of the congruence of this with the key aims of the project: to ensure dignity and respect while remembering that the individuality of human needs does not diminish with the passage of time or diagnosis.

People living with dementia and their carers were included in all stages of the study; they were fully involved in the development of both the assessment tool and the FREDA-based questionnaire [IDEA (Identity, Dignity, Equality and Autonomy)] through a series of focus groups and consultation exercises.

Two people living with dementia and a carer were key members of the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and contributed fully to these meetings throughout the study, advising on its smooth and ethical running.

Alongside this, a patient and public involvement (PPI) reference group was set up that included service users, carers and other interested stakeholders. This group worked on the wider issues having an impact on, and evolving from, the research, such as the perception of human rights among people living with dementia.

People living with dementia and carers also co-facilitated the post-study interviews with staff who had completed training to examine views on acceptability.

The group was consulted about the results of the study and their comments have been incorporated into the discussion.

Participants

The populations to be investigated during this study were people living with dementia, their carers and the staff of NHS inpatient dementia wards and care homes. All of the people living with dementia were either an existing resident of or a new admission to the ward or care home. ‘Carers’ in this context referred to family members, or significant others, of the people living with dementia. People living with dementia did not need to have a carer in order to be involved in the study.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were broad and are outlined below in relation to both sites (clusters) and individual participants at these sites.

Clusters

All inpatient ward sites were NHS dementia specific. Care homes were included if caring for people with dementia was a part of the facility’s core business and if they currently had enough residents with dementia to fulfil the requirements of the study.

Individuals within clusters

The main inclusion criterion for individuals within the cluster was having a diagnosis of dementia. Although issues such as age, severity of dementia and length of time at the setting were recorded, they were not inclusion/exclusion criteria. The main exclusion criterion for an individual was not having the capacity to consent and having no proxy available to support them in this.

Setting

The research was conducted in dementia inpatient wards within NHS trusts and in care homes. Table 3 shows the sites that participated in the study and their basic characteristics.

| Site | NHS trust or care home | Intervention or control | Number of beds | Total number of staff | Number of day staff | Average number of staff on shift |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dale Park | Care home | Intervention | 44 | 38 | 38 | 7 |

| Redholme Memory Care | Care home | Control | 55 | 47 | 35 | 9 |

| Abbotsbury | Care home | Intervention | 20 | 23 | 19 | 5 |

| Finch Manor | Care home | Intervention | 89 | 85 | 51 | 18 |

| Avalon | Care home | Control | 20 | 31 | 19 | 5 |

| Acacia Court | Care home | Control | 26 | 16 | 16 | 5 |

| Irwell Ward | NHS trust | Control | 17 | 43 | 33 | 6 |

| Meadowbank Ward | NHS trust | Intervention | 13 | 45 | 23 | 9 |

| Tudorbank | Care home | Control | 46 | 34 | 24 | 7 |

| Greenacres | Care home | Intervention | 41 | 38 | 20 | 5 |

| Cherry Ward | NHS trust | Intervention | 11 | 37 | 23 | 8 |

| Whiston & Halton Wards | NHS trust | Control | 20 | 50 | 35 | 6 |

| Leigh Ward | NHS trust | Control | 23 | 36 | 24 | 6 |

| Hollins Park | NHS trust | Intervention | 18 | 32 | 21 | 6 |

| Larkhill Hall | Care home | Intervention | 66 | 63 | 37 | 11 |

| Cressington Court | Care home | Control | 56 | 59 | 32 | 9 |

| Macclesfield | NHS trust | Intervention | 15 | 47 | 43 | 7 |

| The Harbour | NHS trust | Control | 36 | 91 | 73 | 10 |

| Thomas Leigh | Care home | Control | 19 | 40 | 13 | 4 |

| St Luke’s | Care home | Intervention | 56 | 78 | 51 | 22 |

Although the initial aim was to recruit 10 NHS wards and 10 care homes, practicalities resulted in eight NHS wards and 12 care homes being recruited. In reality, however, far more people living with dementia are care home residents than are admitted to specialist dementia wards. It is estimated that one-third of people with dementia live in care homes. 60 It is harder to obtain specific figures on those accessing specialist dementia wards, but figures for the local regions where the study was carried out suggest that only 1.5% of people living with dementia will need support on a specialist dementia inpatient ward. 61 It is, therefore, reasonable that more care homes than wards were included if the figures are to represent the population of people living with dementia.

Sample size

The sample size was based on the primary outcome measure, the QOL-AD scale,57 and on conservative figures on several parameters.

Effect size

The literature indicated that previous similar research yielded effect sizes of 0.6. 62 It is necessary to be more conservative given practical experience, and hence an effect size of 0.5 was used when calculating the sample size.

Intraclass correlation coefficient

Other trials utilising the QOL-AD scale have applied an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.02 based on pilot work. 63 As this was a different intervention and the difference between groups/clusters was the important aspect, we chose to apply a more conservative ICC of 0.05.

Sample size

The sample size was calculated based on detecting an effect size of 0.5 in the QOL-AD scale57 using a two-sided t-test. To achieve 80% power with a significance level of 0.05, and an ICC of 0.05, a sample size of 10 clusters with 11 individuals per group was required. Based on prior research, a retention rate of 77%64 was accounted for, which required a sample size of 10 clusters with 14 individuals per group. This resulted in a total sample of 280 participants.

Family carer well-being was explored via the WEMWBS. 58 The study had aimed to recruit a family caregiver for each participant but it was acknowledged that, in reality, this would not be possible. The sample size for this group was therefore dictated by the number of participants who had a family carer willing to take part in the trial. Vignette-based staff interviews were developed to explore the decision-making strategies employed. The aim was to recruit 50% of staff at each site. Similarly, as the care plan audit was designed specifically for this trial, a more pragmatic approach to sample size was taken. A sample was taken of 50% of all care plans at a particular site.

Recruitment procedure

Initial expressions of interest to be involved in the study were invited from local NHS trusts and care homes via existing networks and contacts. A decision was made to recruit initially within the north-west of England owing to logistical and financial constraints.

The research team also worked closely with the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) ENRICH (Enabling Research in Care Homes) programme to identify care homes that identified themselves as willing to participate in research and to support care homes in being involved in the study. Initially all care homes in the north-west area that had been identified as research ready were approached and invited to take part in the study.

Characteristics of sites

The sites recruited varied in terms of their size, current levels of occupation and proportion of residents living with dementia. Table 4 outlines these characteristics at both baseline and follow-up. It is evident from these figures that even if a care home was not branded as exclusively for people living with dementia, a high proportion of residents were living with this condition.

| Site | Time point | Number of | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beds | Service users | Service users with dementia | ||

| Redholme Memory Care | Baseline | 55 | 48 | 48 |

| Follow-up | 55 | 50 | 50 | |

| Irwell Ward | Baseline | 17 | 13 | 12 |

| Follow-up | 17 | 12 | 11 | |

| Dale Park | Baseline | 44 | 42 | 41 |

| Follow-up | 44 | 42 | 41 | |

| Acacia Court | Baseline | 26 | 23 | 23 |

| Follow-up | 26 | 24 | 24 | |

| Abbotsbury | Baseline | 20 | 18 | 13 |

| Follow-up | 20 | 18 | 15 | |

| Avalon | Baseline | 20 | 18 | 18 |

| Follow-up | 20 | 19 | 18 | |

| Tudor Bank | Baseline | 46 | 37 | 16 |

| Follow-up | 46 | 40 | 20 | |

| Greenacres | Baseline | 41 | 39 | 13 |

| Follow-up | 41 | 32 | 8 | |

| Meadowbank Ward | Baseline | 13 | 12 | 12 |

| Follow-up | 13 | 13 | 13 | |

| Cherry Ward | Baseline | 11 | 11 | 11 |

| Follow-up | 11 | 11 | 11 | |

| Hollins Park | Baseline | 18 | 11 | 11 |

| Follow-up | 18 | 14 | 13 | |

| Leigh Ward | Baseline | 23 | 19 | 16 |

| Follow-up | 23 | 19 | 11 | |

| Larkhill Hall | Baseline | 66 | 60 | 44 |

| Follow-up | 66 | 66 | 46 | |

| Cressington Court | Baseline | 56 | 44 | 32 |

| Follow-up | 56 | 40 | 31 | |

| Whiston & Halton Wards | Baseline | 20 | 18 | 18 |

| Follow-up | 20 | 18 | 13 | |

| Macclesfield | Baseline | 15 | 11 | 11 |

| Follow-up | 15 | 11 | 11 | |

| Finch Manor | Baseline | 89 | 72 | 55 |

| Follow-up | 89 | 71 | 55 | |

| Thomas Leigh | Baseline | 20 | 18 | 18 |

| Follow-up | 19 | 18 | 18 | |

| St Luke’s | Baseline | 56 | 54 | 54 |

| Follow-up | 56 | 50 | 50 | |

| The Harbour | Baseline | 36 | 28 | 28 |

| Follow-up | 36 | 29 | 28 | |

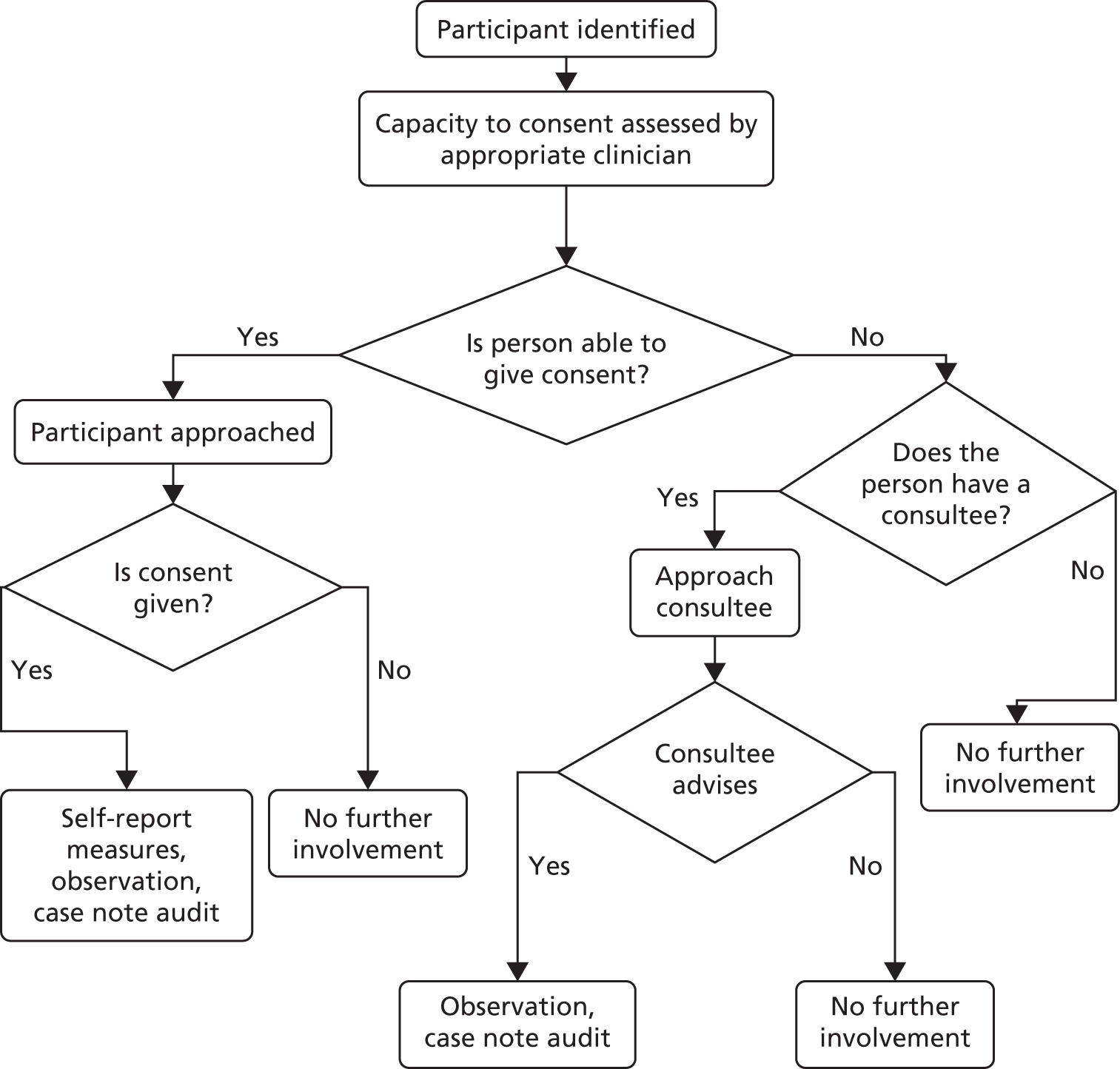

Informed consent

Obtaining informed consent is always an ethical dilemma when working in dementia care, and particularly when working with people in the later stages of dementia. The very fact that people are living in care homes or on a dementia ward means that they are likely to be in the later stages. The team acknowledged that people in the later stages, and particularly those without carers, are vulnerable to potential abuses of rights, and, therefore, it was important that they were included in the study. Every attempt was made to obtain informed consent from every potential participant, in line with the Mental Capacity Act. 24 Experienced clinical staff assessed the capacity of each potential participant, in line with best practice in research governance and the recommendations of the Mental Capacity Act,24 and individuals gave (or withheld) consent if they were able to do this themselves. If a person was not able to give informed consent, they were not asked to complete the self-report measures. Although the QOL-AD scale57 was chosen specifically because it is claimed to be suitable for people in the later stages of dementia, it was felt reasonable to assume that if a person was unable to give informed consent, then completion of the measure would be too cognitively complex for them. There was no reason for people without a family caregiver to be excluded from the study if they were able to give informed consent to participate.

When possible, when a person was unable to give consent, and therefore unable to complete the self-report measures, someone (either a family carer or a staff member) was invited to complete a proxy QOL-AD scale.

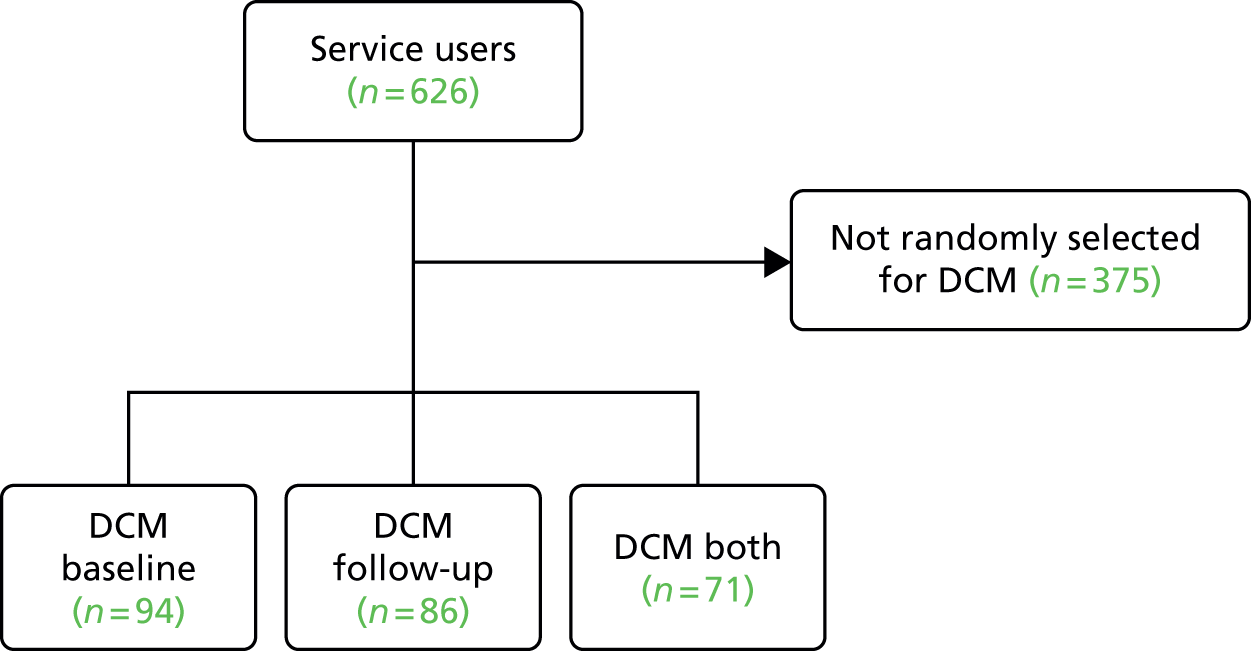

If a person was unable to give informed consent, and so they were not included in the self-report element of the study, they could still be included in DCM in cases when a nominated consultee could be identified. When it was not possible to identify a nominated consultee, or if the consultee advised against including the individual in the study, the person was not included in any aspect of the research. Informed consent was sought at both baseline and follow-up. Figure 2 presents a flow chart outlining these issues.

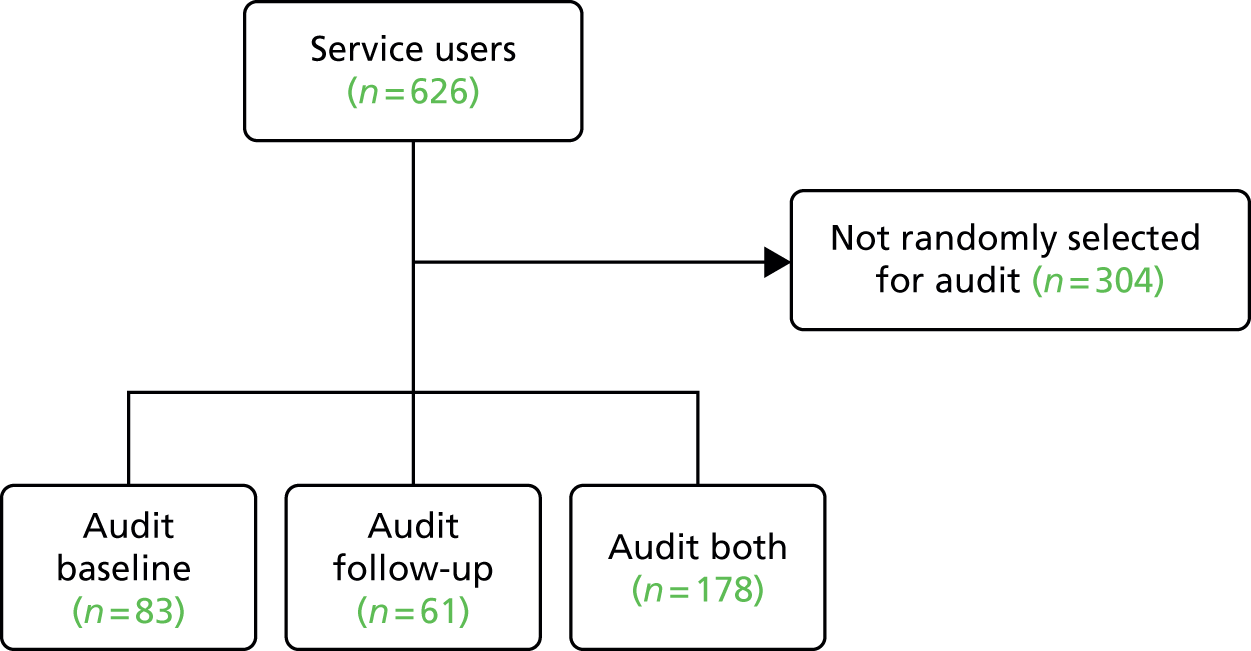

FIGURE 2.

Flow chart to illustrate the process of consent and participation.

Ethics arrangements

Both research assistants had regular contact with other members of the research team and were encouraged to share any concerns that they encountered during data collection. In addition, a TSC and a Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) were established, and these met regularly. Any serious concerns and issues that may have reached the threshold of a serious adverse event were taken to the TSC and/or the DMEC, as appropriate, and discussed thoroughly. Minutes of these meeting were kept and shared with NIHR. No reportable serious adverse events were identified during the study. Issues that were discussed with the committees as potential difficulties included changes to the protocol (which are outlined later in this report) and concerns about quality of care.

Randomisation

The randomisation of clusters was achieved by secure web access to the remote randomisation system at North Wales Organisation for Randomised Trials in Health (NWORTH) (https://nworth.bangor.ac.uk/randomisation/), Bangor University, using a dynamic adaptive randomisation algorithm. 65 The randomisation was performed by dynamic allocation to protect against subversion while ensuring that the trial maintained good balance to the allocation ratio of 1 : 1 across the trial. The complete list randomisation system was used and, therefore, there was an exact allocation of the sites to groups. No stratification variables were used for randomisation.

It is recognised that randomisation would usually take place after baseline measures were completed to avoid any bias generated by participants knowing which group they were in. In this study, however, it was not possible to do this. Site staff needed to know in advance when their training would take place so that practical arrangements could be made for staff to attend the training (e.g. ensuring that the site had adequate staff cover). Similarly, if baseline measures were completed too far in advance of the training, then there was a risk that factors other than the intervention would influence any changes identified. For this reason, sites were randomised before the baseline measures were collected. To minimise the effects of allocation to group before baseline measures were taken, the information given about the exact nature of the training provided, particularly its focus on human rights, was revealed only to those staff who needed to know it for planning (e.g. ward managers).

Allocation concealment

A web-based system was used to cluster randomise each recruited site. A complete-list randomisation was used, meaning that an even number of sites were entered into the system and allocated, at random, half to the usual-care group and half to the training group. The result was not seen until the allocation process was complete, and it was seen only by those who had access to the system. It was also possible to provide a blinded allocation report for the people who needed to be blinded to group allocations; groups were named group 1 and group 2 rather than control and intervention.

Implementation

Following recruitment, the web-based system generated the random allocation sequence. Sites were enrolled by the trial team, specifically the trial manager, Sarah Butchard, after which the web-based system completed the assignment of sites to the control or intervention group. If a service user was willing and able to consent to participate in the study, then they were included. Consent was obtained directly from the service user if possible; if this was not possible, then a proxy, usually a member of staff, was asked to provide consent on the service user’s behalf.

Blinding

Service users, research assistants who were collecting the data and the trial statistician were blinded. Service users received daily care and did not know whether or not staff had received the training. Staff members were obviously unblinded at follow-up as they knew whether or not the unit had received the training. Research assistants attended the sites to complete assessments and did not know to which group a site had been assigned. The trial statistician was able to see the data labelled as group 1 and group 2. The unblinding of the trial results occurred at a results meeting attended by members of the independent monitoring committees.

Data collection and management

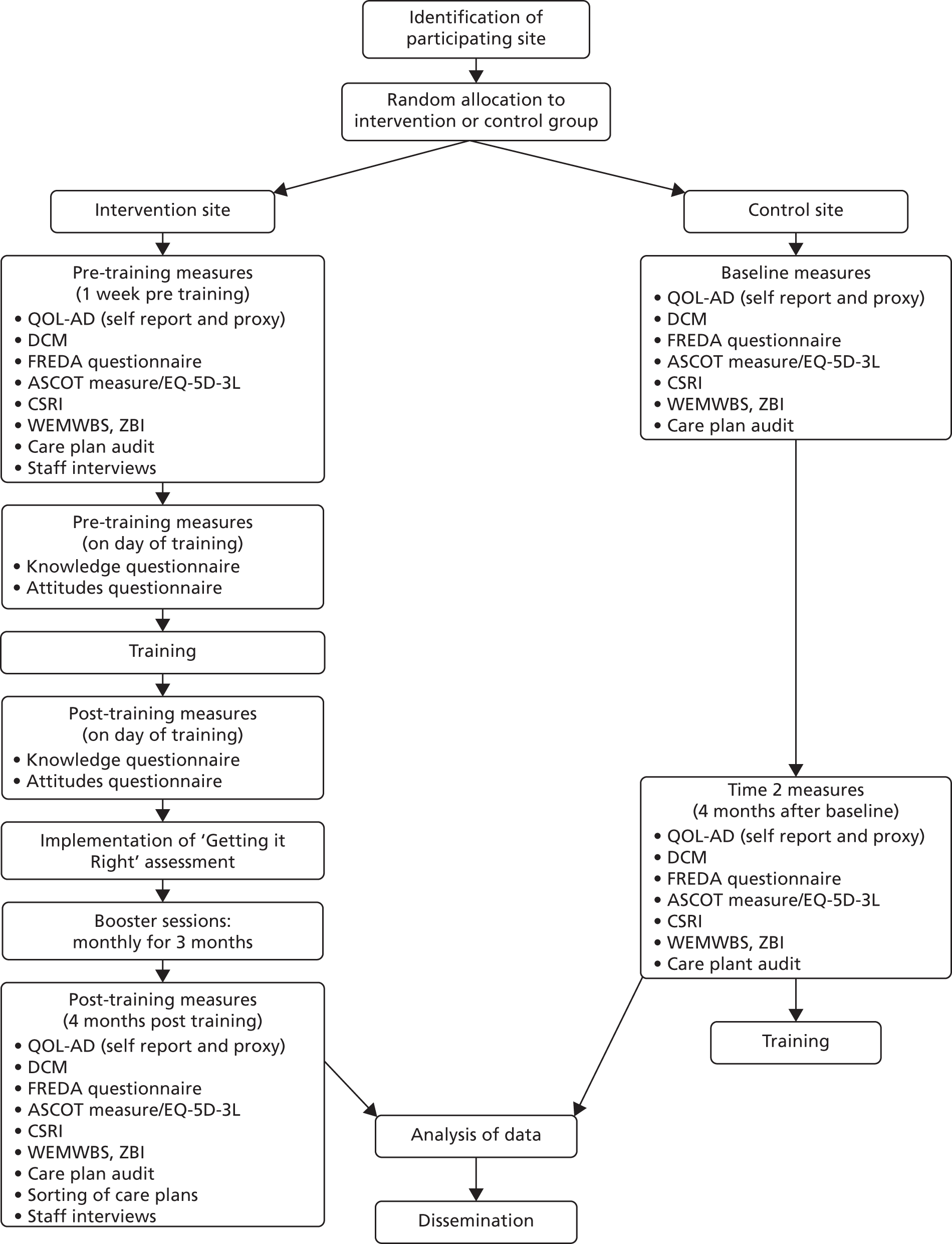

The primary and secondary outcome measures were completed at baseline and then at 4 months after baseline. Figure 3 outlines the data collected at each time point. All measures were completed by two research assistants, who spent a week at each unit completing measures at each time point.

FIGURE 3.

Flow chart to illustrate the process of data collection. ASCOT, Adult Social Care Outcomes Toolkit; EQ-5D, EuroQol-5 Dimensions.

Dementia care mapping was completed first at each site to reduce the chances of the research assistants becoming unblinded at follow-up, as it was less likely that they would come across the assessment tools during this process. Table 5 shows the breakdown of tasks at each site.

| Day | Planned activities |

|---|---|

| 1 | DCM |

| 2 | Care plan audits |

| 3 |

Self-report/proxy measures Staff interviews |

| 4 |

Self-report/proxy measures Staff interviews |

| 5 |

Self-report/proxy measures Staff interviews |

All of the research data were collected on paper at the sites, and these were considered to be the source data. The data were then stored at the University of Liverpool for entry into the electronic system. These source data relevant to the participants’ outcome measures were managed through MACRO, an electronic data-capture system provided by NWORTH. MACRO 4.2 (Elsevier, London, UK; www.elsevier.com/solutions/macro) was used from 18 April 2015 to 15 December 2015, and MACRO 4.4 was used from 15 December 2015 onwards. MACRO meets regulatory compliance for the designing of electronic case report forms, data entry, data monitoring and data exporting, as well as good practice guidelines. MACRO has built-in systems for an audit trail and quality assurance.

A step-by-step cleaning process was implemented for the trial data, which was outlined in the data management plan written for the study. A random sample of 5% of the case report forms at each time point was selected for source data verification. This essentially involved cross-checking the data held in MACRO with the paper source data. If the percentage error rate for each site was > 2%, further checking was initiated based on this finding. A further 10% of randomly chosen case report forms could be checked, or if a systematic error was found with a particular item, then detailed checking of that item would be completed.

Further screening of the data was completed at all time points to identify outliers of potential errors.

Development of the intervention

The intervention for this trial was the introduction of a novel human rights based assessment tool, ‘Getting It Right’,56 into dementia wards and care homes. This tool was rooted in the principles of person-centred care and was specifically developed by Mersey Care NHS Foundation Trust to improve the person-centred nature of care plans and to ensure that the human rights of the service user were considered. Following human rights training by the British Institute of Human Rights, the assessment tool56 was developed by a project team at Mersey Care NHS Foundation Trust, which consisted of service user representatives, carers, researchers and staff from disciplines including nursing, clinical psychology, occupational therapy and psychiatry.

The tool was designed to be completed by a staff member and the service user collaboratively and, thus, encouraged both parties to consider the human rights that should be recognised during the service user’s stay in care. More specifically, the tool maps these human rights onto a wide range of areas of care, including preferences of food and drink, preferred name and access of visitors. The function of the tool was to generate a person-centred care plan that would maximise the person’s quality of life while they were on the unit and help to ensure that their human rights were acknowledged and upheld. The staff member was supported by a complementary manual and the end product was a care plan that could be kept by the service user as well as serving as the basis for the subsequent care that the person would receive. The tool was designed to be user friendly, with bold print, pictorial representations and clear, colour-coded sections.

To aid the implementation of the assessment tool, a staff training package was also developed. This took the form of one-day training, split between providing a general introduction to human rights and their relation to health care, and providing advice and instructions on how to correctly administer the tool. The training package utilised ‘dilemma-based learning’37 and included a specially designed and commissioned DVD (digital versatile disc) containing dramatised care-based scenarios that encourage interactive learning of human rights based approaches when making clinical decisions. During the training, participants were prompted to engage in discussions about how they would respond to clinical situations using a human rights-focused approach. As such, the training was framed as adopting the values and awareness model of human rights training. 38

The training was designed to be delivered to all grades and professions of care unit staff. This was the model used in the pilot phase when staff attending training encompassed a range of both (e.g. ward manager, registered nurses, support workers, domestic staff, occupational therapists and physiotherapists). The key issue was that training was provided to the team as a whole, in line with evidence that this increases discussion of the issues and allows staff to support each other in embedding the training into practice.

Following the initial training, each site was also offered three monthly booster sessions to help build their confidence in embedding the approach.

The ‘Getting It Right’ tool56 and associated training package were piloted within Mersey Care NHS Foundation Trust, and underwent an evaluation using a number of outcome measures: a specifically designed audit tool, vignette-based semistructured interviews, and human rights knowledge and attitude questionnaires.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome measure

Service user well-being

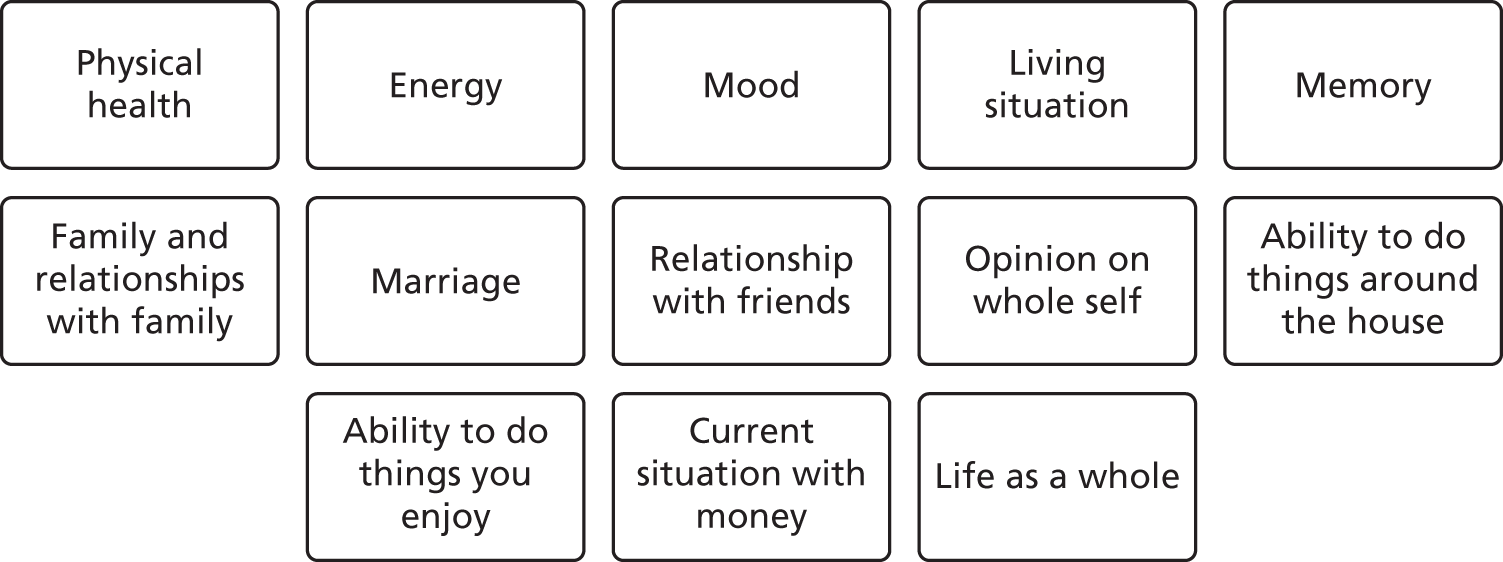

The primary outcome measure used in the research was the QOL-AD57 scale to assess the subjective well-being of the person with dementia. The European consensus on outcome measures for psychosocial intervention research in dementia care66 states that the QOL-AD scale is the measure of choice when looking at quality of life, as it is brief, has demonstrated sensitivity to psychosocial intervention, correlates with health-utility measures and can be used by people with Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores of as low as 3.

The QOL-AD proxy version was also used with both staff and family caregivers to elicit the views of those supporting the person living with dementia.

Secondary outcome measures

Family carer well-being

It is recognised that caring for someone with dementia can be stressful. 67 Family carer well-being was therefore also assessed to explore whether or not it was improved by the application of a human rights based approach on a unit. This was assessed using the WEMWBS,58 and the ZBI59 explored carers’ perceptions of caring responsibilities.

Standard of care

A care plan audit was conducted at each site to provide a measure of the documented plan of care for each service user. An audit tool was specifically designed for the study, which was based on the gold standards of person-centred care in dementia care settings as outlined in the enriched care planning for people with dementia model53 and with a human rights based focus. The aim was to establish whether or not human rights based training is an explanatory variable for any changes in care and well-being observed over and above a standard training package, as the tool allowed the presence of human rights based language and concepts in care plans to be directly assessed.

The standard of care provided at the site and its link to well-being was assessed via DCM,68 an observational assessment yielding quantitative measures of well-being and ill-being for an individual with dementia.

Staff decision-making

Decision-making was explored through vignette-based interviews at the participating sites with staff of various grades. It was felt that this qualitative element of the study served several purposes. It provided an outcome in its own right, in that it explored how staff make decisions in difficult complex situations. The interviews also aimed to provide more information on the mediators of any effect observed, as questions were asked directly about decision-making and what assists with this. If the intervention was successful, then more human rights based language and a clearer framework for decision-making would be seen in the post-intervention interviews.

Knowledge of human rights

To assess knowledge acquisition during the training, pre- and post-training measures of human rights knowledge were collected via a human rights knowledge questionnaire, as recommended by A Guide to Evaluating Human Rights Based Interventions in Health and Social Care. 40 These data were collected on the day of the training. A human rights attitudes questionnaire was also used to look at changes in attitudes both pre and post training. Again, data from this were collected on the day of training.

Health economics

The trial also conducted a cost–consequences analysis, in which the consequences included patient-reported health-related quality of life [EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L)], patient-reported well-being (QOL-AD57), family member well-being (WEMWBS58 and ZBI59) and overall quality of care [Adult Social Care Outcomes Toolkit (ASCOT69) and CSRI].

Development of outcome measures specific to the study

Care plan audit tool

A care plan audit tool was developed specifically for the study as there was no existing measure available that would capture the information required, namely the person-centred nature of the care plan and specific references to human rights language. The audit tool was based on the gold standards of person-centred dementia care as laid out in Enriched Care Planning for People with Dementia: A Good Practice Guide to Delivering Person-centred Care,53 a document derived from Kitwood’s principles of person-centred care. 7

The audit tool employed a ‘tick-box’ format, which meant that data could be expressed as a percentage as well as a raw number for both baseline and follow-up, and then compared formally. There is, however, also the capability to capture more qualitative data, which would allow for reflection on the person-centred nature of care plans and the inclusion of human rights based language in these. If the intervention was successful, it would be expected that care plans post training would be more person centred and include more human rights based language.

Vignette-based interviews

Interview schedules were developed by combining the areas of enhanced care planning from Kitwood’s model of dementia care7 and the human rights considered most relevant to health care. Ten vignettes were constructed that, between them, covered all relevant areas using examples from clinical practice. Using hypothetical examples such as these avoided asking directly about care provision, which may not lead to responses that reflect true practice owing to demand characteristics and staff concerns about the perceived potential repercussions of their responses.

Knowledge and attitudes questionnaires

The human rights knowledge and attitudes questionnaires were adapted from the original learning disabilities questionnaires outlined in A Guide to Evaluating Human Rights Based Interventions in Health and Social Care. 40

Issues of specificity

It is important that the outcome measures utilised allowed exploration of the specificity of the intervention in improving care and well-being over and above the application of general training. This has been addressed in a number of ways.

-

The care plan audit measured the documented standard of care that a person should be receiving but also tapped into increases in human rights based language and concepts that would suggest that the human rights based nature of the intervention had an effect over and above simply providing generic training.

-

The completion of human rights knowledge and attitude questionnaires measured changes in these areas pre and post training but did not look at the impact that this had on staff in their everyday working lives and how it affected service user well-being.

-

Staff interviews were conducted to explore whether or not the introduction of a human rights based approach leads to differences in their decision-making processes when considering care issues. Again, this would be evaluated through the identification of key phrases and concepts in the transcripts that would specifically indicate that a human rights based approach had a direct influence on daily decision-making.

-

The FREDA-based questionnaire enabled the team to explore whether or not service users felt that their human rights were respected and upheld more after the intervention.

Taken together, these elements allowed an evaluation of the proposal that the human rights based approach outlined had benefits that would not be seen by generic training.

Development of the FREDA assessment tool

Although there is recognition that violations of human rights can occur in health-care settings, little has been done to attempt to quantify the extent to which this occurs. To this end, work was undertaken to develop and begin validating a questionnaire measure based on the FREDA principles in order to assess how well individuals subjectively experience their human rights as being upheld.

The FREDA principles have been used elsewhere in health care to aid individuals’ understanding of their human rights. 70 However, the validity of these constructs has not been empirically tested. Therefore, the initial stage of this tool development was to consult with service users and their carers.

Items for the FREDA questionnaire were first generated from focus groups with people living with dementia and their carers. Participants came to one of two focus groups to discuss the care that they had received in relation to their human rights. The main aim of the focus groups was to investigate whether or not the FREDA principles adequately covered areas relevant to dementia care, along with eliciting examples of when such principles were valued or disregarded. All participants consented to the data generated by the focus groups being used in relation to the development of the human rights agenda.

People in the later stages of dementia are often excluded from consultation because of the increased communication and comprehension difficulties that can arise as the condition progresses. Given that this measure would be exploring the potential violations of an individual’s rights, it felt important that this group of people who may be vulnerable to having their human rights undermined were included in the consultation. A method developed by Kate Allen71 was utilised, which involves showing the person living with dementia a picture of an unknown person and asking them to reflect on how that person would feel in a particular situation and what advice they would give them. It is suggested that this elicits more information than asking direct questions about the treatment that they have received. This method was used on a dementia inpatient ward within Mersey Care NHS Foundation Trust and the information elicited was incorporated into the data collected from the focus groups.

Following the focus groups and ward interviews, the information was themed and statements were developed that reflected these themes. Grouping these statements together revealed four overarching themes: identity, dignity, empowerment and autonomy. The developing questionnaire was, therefore, named the IDEA questionnaire.

This resulting questionnaire was piloted with a group of people living with dementia in the community. As a result of this piloting phase, some changes were made to the structure and phrasing of items on the measure (e.g. removing any double negatives from the questions).

Changes to protocol

Despite the suggestion that the QOL-AD scale is suitable for people whose MMSE scores would imply that they have severe symptoms of dementia, in practice it became evident very quickly that there were limited numbers of people living with dementia on the inpatient wards and care homes who were able to complete the self-report version of the measure. Although every effort was made to identify and recruit all service users at each site who could complete this, it was also necessary to utilise proxy reports for those people who could not complete the questionnaire themselves. In these cases, a family caregiver was first sought, and, if none was identified, then a member of staff was asked to complete the proxy version. In total, 357 proxy measures were completed and, of these, 345 were completed by staff members.

Although the initial aim was to recruit 50% of staff from each site for an interview, it soon became apparent that this would not be practical. At each site a percentage of staff worked only night shifts and there were also many staff who were not available during the data collection week owing to annual leave, rota patterns, and so on. Therefore, a more pragmatic approach was taken and eight staff members per site were recruited to take part in the decision-making interviews.

Although it had been envisaged initially that booster sessions would last 2 hours, this was not practical when visiting the sites. In general, managers were not happy to release staff for this length of additional time and chose to speak directly to the team members themselves rather than involving other members of staff. Many of the booster sessions were refused.

It was proposed that the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale – Cognitive subscale (ADAS-Cog) be used to compare the cognitive abilities of people living in care homes with those of people on NHS wards. In practice, the majority of people living with dementia were unable to complete the assessment and, in addition, a large number of people refused to complete it. Given the small numbers collected, it was not possible to make a comparison between the groups. For this reason, no attempts were made to complete the scale at follow-up.

Fewer carers than expected were recruited to the study. The research assistants were surprised that many of the care home residents did not have visitors, and often when visitors were present they did not want to complete questionnaires as they felt that this would interrupt their time with the resident. As a result, the numbers of questionnaires completed were not large enough to allow meaningful comparisons to be made.

Statistical analysis

Missing data

There are two types of missing data possible in this data set: missing items within questionnaires at a time point and missing measures at a time point.

In the case of items missing within a questionnaire, the following approach was taken. If a missing value rule existed for a questionnaire, then this was utilised. Over and above this, if ≤ 25% of the items in a questionnaire were missing, then these were replaced with a pro-rated individual item score.

It was expected that there would be participants missing at follow-up who were present at baseline and vice versa and so the analysis model was influenced by this. The data were assessed for differences between those present at both baseline and follow-up and those present only at baseline for possible predictors to be included in the sensitivity models.

Baseline characteristics

Participant demographics, including age and gender, were reported, and split by allocated group, for baseline and follow-up. The type of dementia patients were living with was also included, when appropriate. There was no statistical comparison of the data for the two groups.

Interim analyses

No interim analyses were planned or scheduled to be completed. During the trial, no additional analyses were identified or requested by the DMEC.

Primary effectiveness analyses

The original model of analysis was planned to be a multilevel analysis of covariance model. Owing to the very nature of the wards and care homes, it was understandable that, for a number of reasons, participants present at baseline might not be present at follow-up. Therefore, a linear mixed model was used to assess the effect of time (baseline or follow-up) and group (control or intervention) and interaction of time and allocated group. The model also included site as a random effect. The main effect of interest was the group effect.

As it became evident that the ability to collect self-report data on the primary outcome measure was limited, proxy data were collected in the absence of self-report data. An additional term (self-report vs. proxy) was added to the model to assess the importance of this difference. If it was found that this term was significant, then separate analyses of self-report and proxy data were completed. This understandably affects the number of data available for the analysis and would have implications for the power of the study. The alternative was to include a self-report versus proxy and condition (group) interaction. This assesses whether or not there is a consistent difference between self-report and proxy data in both groups. The former model of analysis was chosen to allow simpler, more intuitive understanding of the data. Either way, the power of the models that could be applied would have been affected by the implications of using a mixture of proxy and self-report data.

Secondary effectiveness analyses

A linear mixed model was applied for all secondary outcome measures when appropriate. For the knowledge and attitudes questionnaire, data were collected pre and post training for the intervention group and only at baseline for the control group. This precluded the use of the linear mixed model to establish a group effect, and therefore a paired sample t-test was used to establish whether or not there was a difference in score before and after training.

Additional analyses

As indicated the significance of covariates, age, gender, DCM score, dementia type and whether or not the person had a carer were investigated by adding these to the linear mixed model.

It was also noted that one site had a different follow-up time from the other sites, with only 11 weeks in follow-up rather than the established 16 weeks. This nuance was investigated by allowing the time variable to vary for this site.

Economic analyses

Based on the Medical Research Council’s guidelines for the evaluation of complex interventions,72 our standard operating procedure for economic evaluation alongside pragmatic randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and experience in the conduct of economic evaluation alongside trials of psychosocial interventions in dementia care,63,73 we, from a public sector, multiagency perspective:74–79

-

fully costed the human rights staff training programme, distinguishing between set-up/training costs and running costs, with the former amortised over 3 years

-

collected service use data using an adapted Client Service Receipt Inventory, which recorded participants’ frequency of contacts with hospital services and selected community-based services at baseline and follow-up; participants’ medication usage was also recorded and service use was costed using national unit costs for the price year 2014–1580,81

-

conducted a cost–consequences analysis in which the consequences included patient-reported well-being (QOL-AD57), family member well-being (WEMWBS58 and ZBI59) and overall quality of care (ASCOT).

The EQ-5D-3L was included for participants with mild to moderate dementia to allow comparison with other published studies, and with previous trials, but a cost–consequences approach rather than cost–utility analysis was undertaken because of the range of relevant outcomes spanning the person with dementia, their family members, hospital and care home staff and objective measures of care quality.

Dementia care mapping

Dementia care mapping is an observational tool. A trained observer (mapper) records the behaviours of several participants for a specified amount of time (in this case 6 hours) to gain an insight into participants’ day-to-day experience. Owing to ethical reasons, observations can take place only in communal areas. After a 5-minute period, the mapper records a Behaviour Category Code that indicates what the individual was doing. Alongside this, a mood and engagement (ME) value is recorded, indicating how engaged the individual was and if their mood was positive or negative. Table 6 summarises the definitions of each score for ME.

| Mood | ME value | Engagement |

|---|---|---|

| Very happy, cheerful. Very high positive mood | +5 | Very absorbed, deeply engrossed/engaged |

| Content, happy, relaxed. Considerable positive mood | +3 | Concentrating but distractible. Considerable engagement |

| Neutral. Absence of overt signs of positive or negative mood | +1 | Alert and focused on surroundings. Brief or intermittent engagement |

| Small signs of negative mood | –1 | Withdrawn and out of contact |

| Considerable signs of negative mood | –3 | |

| Very distressed. Very great signs of negative mood | –5 |

Dementia care mapping is an established approach that looks at person-centred care in practice. This measure was completed for all sites at both baseline and follow-up. The study focused on one aspect of DCM that records the ME levels of up to eight participants living with dementia within a 6-hour time frame. The ME score for each unit at both baseline and follow-up were recorded and compared to look for changes in the quality of care provided.

Qualitative analysis

There were two sets of data in the study that were analysed qualitatively. These were the staff decision-making interviews and the post-study interviews with intervention sites. Both sets of data were analysed using thematic analysis as outlined by Braun and Clarke. 83 Thematic analysis is a method for identifying, analysing and reporting patterns (themes) within data. At its most basic, it organises and describes the data set in rich detail. In reality, however, it frequently goes further and interprets various aspects of the research topic. 84 Table 7 outlines the stages of thematic analysis proposed by Braun and Clarke. 83

| Phase | Description of the process |

|---|---|

| 1. Familiarising yourself with your data | Transcribing data (if necessary), reading and re-reading the data, noting down initial ideas |

| 2. Generating initial codes | Coding interesting features of the data in a systematic fashion across the entire data set, collating data relevant to each code |

| 3. Searching for themes | Collating codes into potential themes, gathering all data relevant to each potential theme |

| 4. Reviewing themes | Checking if the themes work in relation to the coded extracts (level 1) and the entire data set (level 2), generating a thematic ‘map’ of the analysis |

| 5. Defining and naming themes | Ongoing analysis to refine the specifics of each theme, and the overall story the analysis tells, generating clear definitions and names for each theme |

| 6. Producing the report | The final opportunity for analysis. Selection of vivid, compelling extract examples, final analysis of selected extracts, relating back of the analysis to the research question and literature, producing a scholarly report of the analysis |

Staff interviews

Data from the staff decision-making interviews were initially analysed as one data set using thematic analysis, as outlined by Braun and Clarke. 83 An inductive, or ‘bottom-up’, approach85 to data analysis was taken. An inductive approach assumes that the themes are derived directly from the data86 as opposed to imposing the data onto a pre-existing model.

From this analysis, themes were identified related to staff decision-making strategies. Themes were not combined as fully as they would usually be in thematic analysis, as it was felt important to identify specific, rather than general, decision-making strategies in this context. The interviews were then reanalysed to identify the frequency with which these strategies were discussed in each group (i.e. intervention baseline, intervention follow-up, control baseline and control follow-up).

Post-training interviews

Semistructured interviews were conducted with staff at intervention sites on an opportunistic basis. This included managerial staff, members of staff who attended training and those who did not attend training. The interviews were completed by a research assistant and a member of the PPI reference group. Interviews were recorded, transcribed and inductively, then subsequently deductively, analysed using thematic analysis. Each site was individually analysed to identify the main themes from each site. The main theme of management style was then deductively analysed using Bass and Avolio87 characteristics of active/transformational and passive/transactional management styles to identify descriptions of these characteristics within each site and how these affect descriptions of the relationships that service users and family members have with staff. Some sites were unable to accommodate the interviews owing to changes in management and lack of staffing.

Chapter 3 Trial results

Flow of participants in the trial

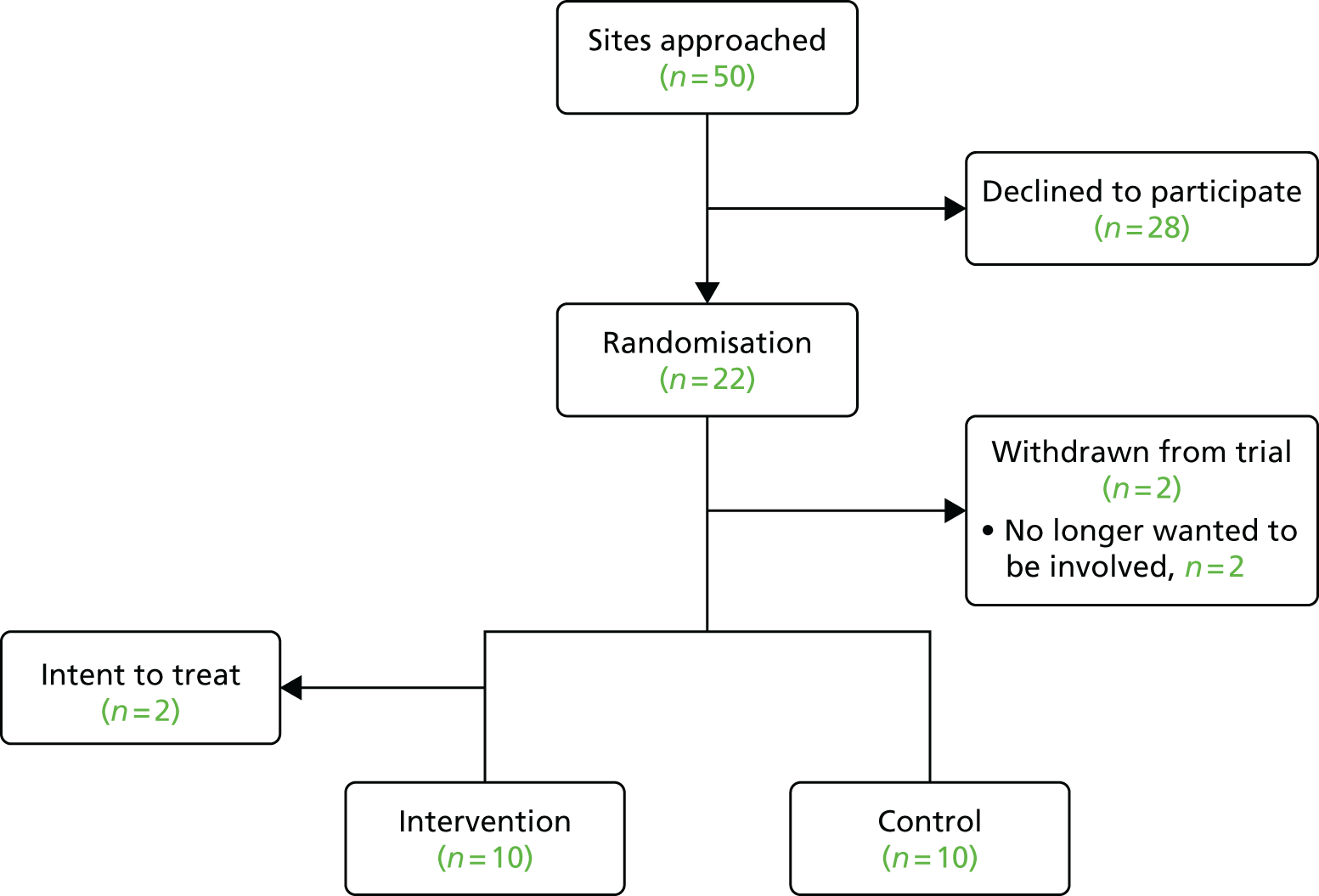

Sites