Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 13/07/39. The contractual start date was in September 2014. The final report began editorial review in March 2017 and was accepted for publication in August 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Graham et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Context

The importance of measuring patient experience for understanding the quality of care in an organisation is indisputable. Although a wide range of approaches are used by organisations to gather feedback from patients, there is a lack of evidence on the effectiveness of the various initiatives employed and how data are used to improve the quality of care. 1 Despite a growing emphasis on using real-time methods for gathering feedback while patients are still in hospital or shortly following discharge, the effectiveness of these approaches for driving service improvement remains largely under-researched. 2,3

This study set out to provide evidence to assess how effective near real-time data collection is for driving service improvement. The focus was on measuring the relational aspects of patient care, such as compassion, dignity and emotional support. Previous measures, such as the national Adult Inpatient Survey and the national Emergency Department Survey, have focused mainly on the functional or transactional aspects of care. This means that the majority of questions on these surveys aim to assess care aspects, such as access to services, waiting times and cleanliness of hospital areas.

Specifically, the Francis Report4 revealed deficiencies in these ‘softer’ aspects of care, and evidence suggests that these aspects are important for determining overall patient experience. 1,5 The NHS National Quality Board, in 2011, agreed on the NHS Patient Experience Framework as the guide to measurement of patient experience across the NHS. Respect for patient-centred values and emotional support, and key aspects of relational care, feature in this framework.

Moreover, a real-time approach to collecting data is considered to increase the chance of feedback being put to effective use as staff have a greater sense of ownership of the results; the data are more recent and have the potential to be more granular. 1,3 However, there is some evidence that surveys administered at the point of care produce more positive results than traditional-based surveys. 6 For instance, a survey of hospital trusts on hospital-acquired infections showed that the responses from the real-time data collection were significantly more positive than those from the paper-based survey collected months after discharge. 7

Another commonly cited limitation of the quality of real-time data is potential sampling bias: respondents choose to take part rather than being selected through a formal sampling strategy. 2,3 Similarly, there is a potential for introducing sampling bias from staff, who select which patients are most suitable to provide feedback. 8 However, it has been argued by Davies and colleagues2 that the aims of real-time data collection are different and, rather than trying to accurately measure the views of all patients, the purpose is to feed back data quickly to staff so that the necessary changes can be identified and acted on. There is evidence to suggest that using real-time patient feedback approaches can drive improvement in the quality of care provided to patients. Research carried out at the Royal Devon and Exeter NHS Foundation Trust, during which feedback was collected from patients on a daily basis, revealed a number of advantages of implementing the real-time data collection, including better teamwork, fewer complaints, better communication between staff and patients and improved service delivery. 9 Other studies that have employed a real-time survey using hand-held electronic devices have shown improvement in patient experience following changes implemented as a result of the real-time data collection. 10,11

It is widely accepted that the success of any survey approach for generating improvements in patient experience requires staff engagement and their involvement in interpreting and using the results for quality improvement. 1,2,9,10,12 Davies and colleagues2 argued that organisations must have an understanding of how to use the findings from near real-time feedback data collections in order to make organisational improvements. The potential barriers to using patient feedback data for bringing about service improvement may be caused by a lack of knowledge and understanding among staff of the changes planned, defensiveness, professional autonomy and limited time and resources. 2,9 Explaining the benefits of the study to staff and dealing openly with issues of scepticism and resistance to change will increase a project’s likelihood of success. 9,12

This research used a participatory action research approach to engage staff in the process of implementing the near real-time feedback (NRTF) survey and to identify the factors that promote and limit effective use of data, such as the information and support needs of frontline staff and service leads. The research conducted by the Royal Devon and Exeter NHS Foundation Trust, mentioned above, illustrates the advantages of properly engaging staff in the implementation of a real-time patient feedback approach. The study used a cyclical change management approach (the ‘plan, do, study, act’ model), which led to raised staff morale and improved care. 9

There is growing evidence that the experiences of NHS staff and patients are closely linked; improving staff experience will improve the patients’ experiences of care. 13–16 For example, one study found that patients were more satisfied when they received treatment and support from teams that had good team processes, such as teams that communicated effectively and whose members gave support for ideas that would lead to improved patient care. 15

Our approach, which was focused on working with staff and patients to identify what needs to change, reflects the fundamental principles of organisational change theory. The ‘emergent approach’ to organisational change fits well with the context and aims of this study. This approach sees change as a process of learning as the organisation responds to internal and external factors. 17 In their literature review of organisational change management, Barnard and Stoll17 state that proponents of the emergent school, such as Kotter,18 Kanter and colleagues19 and Luecke,20 have suggested a sequence of actions that organisations should take to increase the chances of change being successful, including that a set of suggested actions are shared, establishing a sense of urgency, creating strong leadership and empowering employees.

Although it was not the aim of this research to use a tool to measure and assess ‘organisational cultures’, the study utilised findings from previous research to better understand the nature of organisational culture, how it can be assessed and measured and how such assessments can be integrated into beneficial programmes of change. 21,22 The work carried out by Mannion and colleagues21,22 informed the planning and delivery of the participatory workshops and evaluation interviews with NHS staff. Of particular relevance were the findings of the research undertaken by Mannion and colleagues22 on the needs and interests of key NHS stakeholders with regard to understanding, assessing and shaping organisational cultures.

The work by Mannion and colleagues22 has also shown what users and patients consider to be the most important cultural attributes for high-quality care. These were ‘patient-centredness’, senior management commitment, a quality focus, clear governance/accountability and safety awareness. Patient-centredness was considered to be a key component for the following reasons: it was believed to lead to better process and clinical outcomes; it challenges cultures that are not aligned with the interest of patients; and, by putting the patient at the centre of decision-making, leads to a health service that is more accountable to them. 22

Our study built on these research findings and had a special focus on ensuring that patient representatives, such as the patient collaborators at the case study sites, were involved in the participatory workshops, in reviewing the findings from the NRTF data collection and in developing the resources to be used by organisations for driving quality improvement measures that improve the relational aspects of care.

As the project specifically sought to address the recommendations of the Francis Inquiry, it was referred to as the ‘After Francis’ project.

Literature review

Person-centred care is considered to be an essential factor of high-quality health care, and looking at patient experiences is one way for trusts to measure and improve the quality of patient-centred care. 4,23,24 Patient experiences can also influence other aspects of care quality, such as better safety and effectiveness,24–26 better treatment outcomes, fewer complications and overall lower service use,27 as well as better staff experiences. 28

The Francis Report4 recently identified substantial deficiencies in emotional or relational aspects of care, which are key determinants of overall patient experience. 29,30 These aspects of care focus on the relationships staff form with patients during their time in hospital and can include communication, providing the space for patients to discuss concerns or fears and treating patients with respect and dignity. 5,26 Owing to these deficiencies, the Francis Report recommended that hospitals should place particular focus on improving relational aspects of hospital care, especially for older patients and those visiting accident and emergency (A&E) departments. 27,28 An increase in the collection, and use, of NRTF was also recommended. Current patient experience data collection tends to focus data capture on transactional aspects of care, such as cleanliness, waiting times and pain management, with only a fraction of data collection dedicated to measuring relational aspects of care.

Two instruments that predominantly measure relational aspects of care were identified;31,32 however, these instruments have not been designed or tested for use with a near real-time approach or hard-to-reach patients. Although the instruments could be used with a NRTF approach or hard-to-reach populations, they would require further testing and refinement in order to do so. For example, the Patient Evaluation of Emotional Care during Hospitalisation (PEECH) measure32 was developed and tested in Western Australia. Further validation of the measure was carried out in four English acute hospitals. 30 Another instrument that primarily measures relational aspects of care is the Consultation and Relational Empathy (CARE) measure. 31 This measure was developed and tested for clinical use in primary care settings, with special focus placed on the instrument’s applicability to patients with various social economic backgrounds. An additional four instruments that measure some relational aspects of care were found; however, the main purpose of these instruments is to measure transactional aspects of care, such as pain management, waiting times and cleanliness. 33–36

As only two existing instruments focus primarily on relational aspects of care and, of these, only one has been designed for use in hospitals, we developed and tested an instrument specifically for use with a NRTF approach in A&E departments and inpatient wards that provide care primarily to elderly patients.

Need for the research

All NHS organisations were expected to respond to the Francis Report4 and to take action to strengthen patient voice, improve frontline care and change organisational culture. The health and social care quality regulator in England (the Care Quality Commission) has subsequently published strategic and business plans that place strong emphasis on the importance of patient voice. For example, the 2013–16 Care Quality Commission strategy, titled Raising Standards, Putting People First, highlights continuous engagement and relationship-building with patients and public representatives. 37 For NHS organisations, assuring and demonstrating the quality of care that they provide is a priority as never before; there is a window of opportunity for developing and disseminating an evidence base that will support NHS quality assurance and improvement initiatives pertaining to the Francis Report. 4

There is no one ‘best’ method for capturing data about patients’ experiences of care – each method has its strengths and limitations. Real-time feedback (RTF) is mandated, as of April 2013, for adult inpatients, A&E patients and maternity service users via a national policy directive, the Friends and Family Test (FFT). As of 2014, RTF is also mandated for other areas of care provision, such as mental health services, community health care and general practice. The Francis Report4 recommends that:

Results and analysis of patient feedback including qualitative information needs to be made available to all stakeholders in as near real-time as possible, even if later adjustments have to be made.

Similarly, in the review into the quality of care and treatment provided by 14 hospital trusts in England, published in July 2013, Sir Bruce Keogh also called for real-time patient feedback, stating that:

Real-time patient feedback and comment must become a normal part of provider organisations’ customer service and reach well beyond the Friends and Family Test.

There is therefore an urgent need for research that evaluates the introduction and impact of RTF approaches in the NHS in order to establish best practice and to ensure that data collection, presentation and communication supports frontline staff, service leads and managers in effectively improving services. 2

The Francis Report4 and the published literature alike38,39 highlight ongoing concerns about the quality and consistency of care that older people receive in hospital, especially around relational aspects of care, including communication and information provision. Similarly, the Francis Report4 raises concerns about neglect and poor care in A&E, and the government has launched a review of urgent and emergency services. The first phase of the review has been completed and provides the evidence base for changes to these services. 38 By focusing on older people’s wards and emergency departments, this evaluation of the introduction of NRTF is directly relevant to current and near-future priorities for NHS staff, service leads and managers.

Although the existing national surveys capture relational aspects to a small extent, a new methodology for understanding relational aspects of care more comprehensively and using a NRTF approach is warranted. Specifically, a new way of improving hospital quality that does not require clinical staff time for its implementation is needed. If NRTF could successfully be used for improving the relational aspects of care, the approach may potentially replace other internal data collection mechanisms in hospitals.

Research objectives

The overall aim was to develop and disseminate evidence-based recommendations to support the implementation of NRTF data collection about patient experiences in the NHS. The main objective was to evaluate the impact of a NRTF survey for driving improvements in patients’ experiences of the relational aspects of care.

The research used a mix of quantitative, qualitative and participatory research approaches in evaluating the collection, communication and use of real-time data about patients’ experiences of the ‘softer’ aspects of care. The aim was to explore and understand the inputs, processes and impacts of NRTF data collection, as reflected in patient experience data and as understood by NHS frontline staff, service leads and managers. Our key research questions (RQs) were:

-

Can NRTF be used to measure relational aspects of care?

-

Can NRTF be used to improve relational aspects of care?

-

What factors influence whether or not NHS staff can use NRTF to improve relational aspects of care? Specifically, what are the barriers and enablers?

-

What should be considered best practice in the use of NRTF in the NHS?

Structure of the report

Following this introduction, Chapter 2 describes the methodology for the set-up, data collection, implementation, and evaluation and reporting phases of the project. Chapter 3 presents findings to address the question, ‘Can NRTF be used to measure relational aspects of care?’ In Chapter 4, we showcase evidence of using RTF to improve relational aspects of care and the factors that influence whether or not NHS staff can use NRTF to improve relational aspects of care, such as the barriers and enablers. Chapter 5 highlights what should be considered best practice for using NRTF for making improvements in the NHS. Chapter 6 presents a synthesis and discussion of the findings, including the robustness of the collected data. Finally, Chapter 7 showcases conclusions and implications for policy and practice, as well as recommendations for future research.

Chapter 2 Methodology and data sources

This chapter presents the quantitative and qualitative methods used to evaluate the development and implementation of a near real-time survey for improving relational aspects of care. The chapter provides an overview of the data sources and methods used to answer the four RQs guiding this work. Additional details are presented for each data collection activity, including sampling and recruitment approaches and participant characteristics.

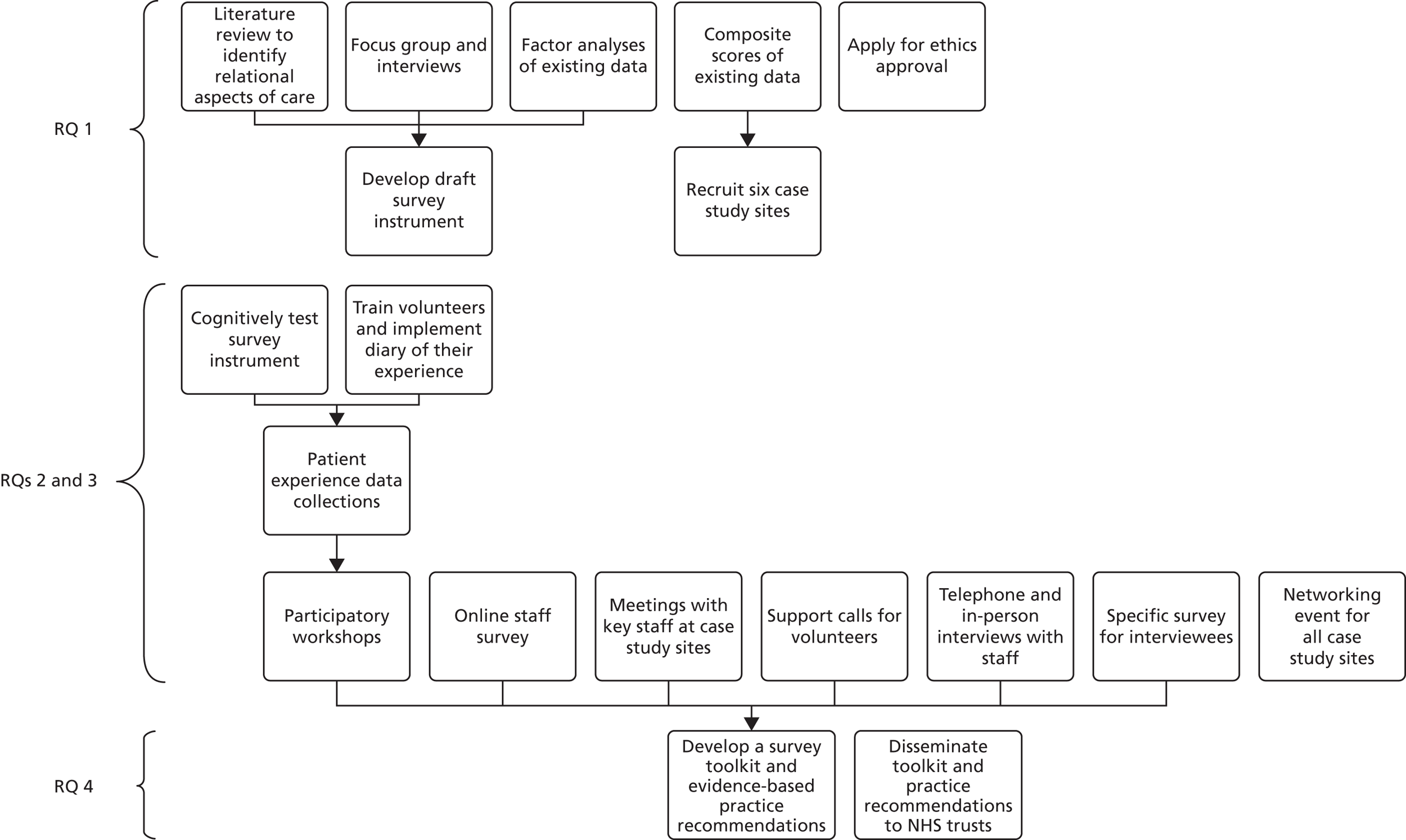

Figure 1 displays a flow chart that outlines the research activities, with arrows indicating how previously collected data feed into the subsequent research activities.

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart of research activities.

Research question 1

Table 1 presents the data collection methods and research activities that were employed to answer the first RQ, which explores whether or not NRTF can be used to measure relational aspects of care.

| RQ 1: can NRTF be used to measure relational aspects of care? | |

|---|---|

| Data collection methods | Data sources |

| Literature review to identify relational aspects of care | Published literature |

| Focus group and interviews | Recent A&E patients and hospital inpatients aged ≥ 75 years |

| Factor analyses of existing data | Existing data from the national 2012 NHS Emergency Department Survey35 and 2013 NHS Adult Inpatient Survey36 |

| Composite scores of existing data | Existing data from the national 2012 NHS Emergency Department Survey35 and 2013 NHS Adult Inpatient Survey36 |

| Other research activities | Methods basis |

| Recruit six case study sites | All trusts included in the national patient experience surveys for whom we had details |

| Develop draft survey instrument | Existing survey questions, findings from literature, focus group and interviews, and advisory group members’ suggestions |

| Apply for ethics approval | Draft survey instrument |

Literature review

An extensive search and review of the literature on existing scales used to measure relational aspects of care was conducted. Literature was accessed using the Web of Science online database, as well as the online search platforms PubMed and Google Scholar (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA). The following search terms were used to identify relevant literature:

-

relational aspects of care

-

emotional care

-

patient–doctor relationship

-

patient–doctor communication

-

patient emotional care

-

relational communication.

In addition to databases and search engines, the research team used a snowball strategy to identify seminal literature based on the citations provided in the previously accessed literature.

Focus group and interviews

To understand what patients thought constituted relational aspects of care, one focus group with individuals who had visited an A&E department in the last 3 months was conducted on 24 September 2014. Participants were recruited through adverts in local newspapers. Although seven participants confirmed their participation on the telephone, only four attended the meeting. Of the four participants, three (75%) were females and all (100%) described themselves as white British. Focus group participants ranged in age from 28 to 65 years. The focus group was conducted over the course of 2 hours and included a discussion on what constitutes relational aspects of care and a ranking of their importance using a sort card exercise. Questions asked in the focus group were designed to explore what different aspects of care mean to patients in terms of their recent experiences. As little detail on what matters most to patients is provided in existing literature it was also important to explore this. Questions asked were:

-

What comes to your mind when you think about emotional care or relational care?

-

Sometimes it seems that one or two hospital or A&E department staff members are especially good with patients all around. Did you get this sense during your recent A&E department visit? If so, what made the care these staff provided stand out?

-

During your recent A&E department visit, were these relational or emotional aspects of care present or addressed by staff?

-

Why are these relational or emotional aspects important when you receive treatment?

-

Which components are most important to patients’ overall experiences of care?

-

What relational or emotional aspects cannot be missing from a good care experience?

Eight face-to-face interviews with older adults who had recently stayed overnight in hospital were conducted in lieu of a second focus group during the week commencing 13 October 2015. Three interview participants were male (37.5%) and aged 75 or 76 years. Five interviewees were female (62.5%) and between the ages of 75 and 85 years. All participants identified themselves as white British. Interviewers utilised the same discussion questions and prompts as in the focus group. Each interviewee also completed the sort card exercise. Interviews lasted between 40 and 50 minutes each.

For the sort card exercise, 19 cards were prepared prior to the focus group and six statements were prepared during the focus group, based on aspects of relational care that arose during discussions. The previously prepared statements were based on relational aspects of care identified in the following existing survey instruments:

-

the PEECH measure32

-

the 2013 NHS Adult Inpatient Survey36

-

the 2012 NHS Emergency Department Survey35

-

the CARE measure31

-

the 27-item Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) questionnaire

-

the General Practice Patient Survey (GPPS). 33

The exercise was completed by the eight interviewees and by two groups of four focus group participants. Therefore, data were available from a total of 10 card sort activities. During the exercise participants grouped the 25 statements into three categories, namely ‘most important’, ‘quite important’ and ‘least important’. The 25 statements and their importance rankings were entered into a Microsoft Excel® 2013 file (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). The following values were assigned to each category: 2 = most important; 1 = quite important; and 0 = least important.

The focus group discussions and interviews were transcribed verbatim. Three researchers reviewed the transcriptions independently and created an initial coding framework. Comparison of frameworks highlighted extensive similarities among themes and categories. The framework with the least specific categories and which utilised participants’ own words for themes to the greatest extent was chosen for analysis purposes. It was anticipated that the framework would evolve during the coding process; however, only three additional categories were added for two themes during the coding process.

Data from the nine transcripts were then coded by assigning or coding each section or newly shared thought to the best-fitting categories or themes. Where sections of the transcripts appeared to fit under multiple themes or categories, they were coded for each. The coding process was conducted independently by two researchers, each using the software package Nvivo, version 10 (QSR International, Warrington, UK). Inter-rater reliability was computed and found to be 97%.

Factor analyses

To build on the understanding of relational aspects of care gained through the literature review, focus group and interviews with recent patients, factor analyses were conducted on patient experience data collected for the 2012 NHS Emergency Department Survey35 and the 2013 NHS Adult Inpatient Survey. 36 The purpose of these secondary data analyses was to identify a cohesive set of existing questions that measure relational aspects of care in the national surveys. At present, national inpatient and A&E department surveys do not specifically set out to measure relational aspects of care; however, they do include items which may be considered to tap into many of the aspects of relational care identified in our preliminary literature review and qualitative analyses. Survey items included in the analyses were selected based on themes of relational aspects of care identified in the literature review. Themes included patient-perceived level of security, knowledge and personal value during their hospital stay or visit. 32

Prior to conducting factor analyses, multiple imputation40 was conducted to replace missing and unscored responses to all items. For all survey questions, missing data ranged from 2% to 54%. However, the majority of survey questions had missing responses of ≤ 5%. Five imputations were completed for each survey data set. Next, factor analyses were conducted utilising data from 15 questions on the NHS Emergency Department Survey and from 18 questions on the NHS Adult Inpatient Survey. Data for both surveys were collected from separate patients and could not be linked across the two surveys. A polychoric correlation matrix for each survey was generated from the imputed data sets.

Exploratory factor analysis was then conducted on each data set using Factor v9.3 (Rovira i Virgili University, Tarragona, Spain). Each matrix was subject to two tests to determine the likely number of factors appropriate in each case. 41 The first test was parallel analysis, in which data eigenvalues are compared with those that would be obtained from random data. The second was Velicer’s minimum average partial (MAP) test, which seeks to minimise the amount of residual variance after different numbers of factors are extracted. The indicated numbers of factors were extracted using unweighted least-squares factoring and rotated (where appropriate) using Promin oblique rotation. The resulting loadings, communalities, residuals and fit statistics were examined to determine the suitability of the solution. Items were then allocated to scales on the basis of their loading patterns.

Scale analysis was conducted on the item sets for both surveys by fitting a single-factor model to each proposed scale. The resulting loadings were then used to analyse the overall reliability of the scales and the contribution of individual items. Reliability was evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega (a more general coefficient of which alpha is a special case). 42 Item contribution was evaluated using McDonald’s item information index (the ratio of communality to uniqueness). 42

Composite scores

To select six case study sites, we first sought to identify high- and low-performing trusts on the 2012 NHS Emergency Department Survey35 and the 2013 NHS Adult Inpatient Survey. 36 Both were the most recent relevant national survey administrations for which complete data sets were available. Composite scores were computed based on data collected using existing survey questions that capture relational aspects of care.

Those survey questions that were identified to most closely measure relational aspect of care in previous factor analyses were utilised to compute composite scores. Composites were computed for all respondents who had answered at least 60% of the selected questions. For the 2012 NHS Emergency Department Survey,35 only one composite score was computed for each trust as the previous factor analysis indicated one underlying factor. For the 2013 NHS Adult Inpatient Survey,36 factor analyses indicated two underlying factors of relational aspects of care. Therefore, two composite scores were computed for each trust on the inpatient survey data, based on question loadings for each factor. To allow for comparison across trusts, an average score was calculated for each trust based on the three composite scores. Trusts were then sorted by the average score to identify the top and bottom one-third of the distribution.

Recruit six case study sites

All trusts falling within the top or bottom one-third of the composite score distribution described in Composite scores were initially contacted and informed about the opportunity for participation as case study sites; however, sufficient and timely interest was not generated using this approach. Therefore, trusts falling within the middle of the ranked distribution were also contacted. At the same time, reminder messages were sent to the trusts that were initially approached.

All trusts were sent an information sheet describing the project and the case study participation opportunity. Individual telephone conference calls were held with 26 trusts to further inform them about the purpose and benefits of the study and time and resource requirements for their participation.

Following the telephone discussions, interested trusts were asked to confirm in writing their interest in participating in the study as a case study site. The first three trusts falling below and above the median of the composite score distribution from which written confirmation was obtained were selected to participate in this study.

The six case study sites participating in the research were Hinchingbrooke Healthcare NHS Trust, Milton Keynes University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, North Cumbria University Hospitals NHS Trust, Northern Lincolnshire and Goole NHS Foundation Trust, Poole Hospital NHS Foundation Trust and Salisbury NHS Foundation Trust. More details are presented about the case study sites in Chapter 3.

Develop draft survey instrument

The survey items identified as most closely related in the factor analyses were mapped to the themes of relational aspects of care identified in the literature, focus group and interviews. Additional survey questions were subsequently developed to ensure adequate coverage of each theme and that a pool of at least five survey items was available for each theme. This resulted in a pool of 62 potential survey items.

An expert advisory group, comprising nine members, was consulted at various stages of the project. Of these nine members, seven were female and two were male. The group included two patient and public representatives, two academic experts and two voluntary organisation representatives with a special focus on ageing, as well as three members of NHS organisations (specifically, one deputy chief nurse and two heads of patient experience).

During the meeting, members reviewed the themes and associated draft survey items. Under each theme, the two most representative and easy to understand questions were selected for face validity based on the following criteria:

-

Do the survey questions make sense?

-

How well do the survey questions represent their theme?

-

Which survey questions were easiest to understand?

-

Do any survey questions appear to be duplicates for this theme?

This selection process ensured that each theme was addressed with at least two survey items, while also reducing the burden placed on survey respondents by a lengthy survey instrument. Suggestions were offered for making the survey easier to understand and operate on a tablet. The researchers incorporated all suggestions, focusing on the tablet-based survey process and question wording, into the draft survey instrument.

Apply for ethics approval

The East of Scotland Research Ethics Service (EoSRES) was assigned through the NHS Integrated Research Application System to review this research, including the instrument development process. After the draft survey instrument was developed and prior to cognitive testing, the survey instrument was submitted to the same Research Ethics Service for review as a substantial amendment.

Research questions 2 and 3

Table 2 presents the data collection methods and research activities that were employed to answer the second and third RQs guiding this study. The second RQ investigates whether or not NRTF can be used to improve relational aspects of care. The third RQ aims to gather additional details on the context of the research activities to understand what factors influence whether or not NHS staff can use NRTF to improve relational aspects of care. Specifically, the third RQ aims to shed light on the different barriers to, and enablers of, using a NRTF approach for improving relational aspects of care.

|

RQ 2: can NRTF be used to improve relational aspects of care? RQ 3: what factors influence whether or not NHS staff can use NRTF to improve relational aspects of care? Specifically, what are the barriers and enablers? |

|

|---|---|

| Data collection methods | Data sources |

| Cognitively test survey instrumenta | Patients aged ≥ 75 years and A&E department visitors |

| Train volunteers and implement diary of their experiences | Hospital volunteers collecting patient feedback |

| Patient experience data collectiona | Patients aged ≥ 75 years and A&E department visitors |

| Participatory workshops | Hospital staff and patient collaborators |

| Online staff survey | Frontline staff |

| Networking event for all case study sites | Staff administering research at case study sites and frontline staff |

| Meetings with key staff at case study sites | Staff administering research at case study sites and frontline staff |

| Support calls for volunteers | Volunteers actively engaged in data collection |

| Telephone and in-person interviews with staff | Hospital and staff patient collaborators |

| Specific survey for interviewees | Staff who participated in first round of telephone interviews |

Cognitively test survey instrument

The draft patient survey was cognitively tested in three rounds with a total of 30 patients. This cognitive testing provided the basis for finalising the survey instrument. The testing took place at the following three case study sites at the beginning of May 2015:

-

Poole Hospital NHS Foundation Trust on 6 May 2015

-

Salisbury NHS Foundation Trust on 7 May 2015

-

Milton Keynes University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust on 11 May 2015.

A specific probing approach, including preprepared and spontaneous probes, was used to test each survey item with patients. 43,44 The cognitive process of responding in terms of the model described by Tourangeau45 was considered, seeking to establish consistency in:

-

comprehension – people understand what the question is asking in a consistent way that matches the intended RQ

-

retrieval – people are able to retrieve from memory the information necessary to evaluate their response to the question

-

evaluation – people are able to use retrieved information to evaluate the question meaningfully, and do this in an unbiased manner (e.g. not simply acquiescing or providing socially desirable responses)

-

response – people are able to match their evaluation to one of the available responses in a meaningful and appropriate way; the response selected adequately reflects the person’s experience.

Patients were approached on two wards and within the A&E department at each of the three trusts. Senior staff members directed the researchers to all patients who had the capacity to consent and were well enough to participate in a survey. Consenting patients then completed all survey questions, if necessary with help from a researcher. Assistance provided to respondents included reading questions and response options, entering responses or physically holding the tablet up for the patient to read. After each survey question was answered, a researcher asked two or three prepared follow-up prompts for each question. This question-by-question approach was selected as participants, who were primarily elderly patients, did not want to complete the survey and then return to discuss individual survey questions once they had already provided a response.

Specific probes were used to gauge respondents’ understanding of more complex words, such as condition, treatment and conversation. 43,44 In addition to these specific probes, if needed, spontaneous probes were also used to further assess patients’ understanding of survey questions and answer options.

Two examples of survey questions and corresponding specific probes are listed below:

-

If you have needed attention, have you been able to get a member of medical or nursing staff to help you?

-

Yes, always.

-

Yes, sometimes.

-

No, never.

-

I have not needed attention.

What do you think is meant by ‘attention’?

Who do you consider to be medical staff? Do you think they are different from nursing staff?

-

-

Has a member of staff told you about what danger signals regarding your condition or treatment to watch for?

-

Yes, completely.

-

Yes, to some extent.

-

No.

-

I have not needed this type of information.

What does ‘watch for’ mean to you?

What do you think is meant by ‘danger signals’?

-

A total of 38 patients were approached, of whom 30 completed the cognitive testing of the survey. Four elderly patients began the process but decided that they did not want to continue after a few questions and another four patients did not have the capacity to consent. Of the 30 participants, 13 were male and 17 were female. Twenty-eight patients identified themselves as white British. English was not a native language for two patients. One participant had dementia and a family member provided answers from the patient’s perspective for most survey questions. Twenty-one patients were currently inpatients in wards that provide care primarily to the elderly. The remaining nine patients were currently visiting A&E departments.

Volunteer training

Volunteer training sessions were conducted at each of the six case study sites to prepare volunteers thoroughly to collect patient feedback using the near real-time survey. The sessions lasted for 2.5–3.5 hours. As it was not possible for all volunteers involved in the data collection to attend the training, NHS trust staff, such as the project co-ordinators, patient experience leads and volunteer co-ordinators, also participated in the volunteer training. This way, additional volunteers could be trained by trust staff throughout the project.

Two members of the research team co-led the volunteer training at each site. The volunteer training was designed to address the following learning objectives:

-

understand the overarching goals of the After Francis research project

-

understand how the current RTF approach differs from existing approaches, such as the FFT

-

assist patients in reading the patient information sheet and understanding the purpose of the survey, including risks and benefits

-

obtain informed consent from patients

-

understand what constitutes capacity to consent and how to judge it based on patient’s communications

-

follow up on patient concerns, if necessary

-

provide assistance to patients by reading the survey questions and response options

-

follow standard infection control procedures for hands, tablet and patient information sheet

-

use computer tablets to administer the survey

-

understand the purpose of a weekly volunteer diary and discuss frequency and mode of administration

-

understand the patient collaborator role, descriptively termed peer researcher, and have an opportunity to ask questions or register interest.

In total, 61 volunteers were involved in the training sessions led by the research team, with further volunteers subjected to cascade training by the trained volunteers. We are unable to determine the number of volunteers who were subject to cascade training; however, we know that at least 35 individuals were trained by staff members or other volunteers at the trusts.

During the training, volunteers also practised administering the tablet-based survey to a colleague, followed by administering the survey to patients on study wards. The research team members were available to provide directions and answer any questions.

Following the initial training, the patient data collection process for volunteers was as follows:

-

check in with volunteer co-ordinator to receive ward/department assignment and collect tablet

-

report to ward manager or senior sister on the ward/department and get list of patients who should not be approached

-

approach remaining patients and enjoy interacting with them.

Volunteer diary and interviews

Volunteer diary

An online diary was made available to all volunteers who collected patient experience data on the wards and the A&E departments. The diary was in the form of an online survey, accessed via the tablets used for collecting patient experience feedback. The diary’s purpose was to provide a format for volunteers to share their experiences and challenges. All volunteers were asked to complete the diary on a weekly basis, provided they had approached patients for this project during the week.

The diary consisted of a demographic question, six closed-ended questions and one open-ended question. The six closed-ended questions prompted volunteers to rate the level of ease/difficulty in approaching and surveying patients, checking in with staff to receive information on which patients could be surveyed and the patients’ level of interest to participate in the survey. Volunteers could also indicate the reasons patients gave for not wanting to participate in the survey during the previous week. The open-ended question asked volunteers to further describe their experiences using their own language. The demographic question asked the volunteer to indicate which trust they were volunteering in.

The diary took ≤ 5 minutes to complete each week. The research team reviewed the diary entries on a weekly basis and informed the case study sites of any reported challenges so that they could be addressed immediately.

Volunteer interviews

The patient collaborators and one other volunteer were interviewed at each case study site. They shared their experiences with the tablet-based data collection, including challenges, barriers, what worked well and the perceived benefits to themselves resulting from participation in this research. Lessons learnt by the volunteers and patient collaborators were also explored.

During the month of September 2016, semistructured interviews were conducted with the volunteers involved in the project. If possible, volunteers were interviewed in pairs to encourage discussion; however, some volunteers wanted to be interviewed alone. Interviews were conducted either face to face or via telephone.

The purpose of the interviews was to understand the experience volunteers had collecting data for the After Francis project. For instance, we wanted to learn what worked well and what did not work well. Examples of some of the questions asked included:

-

What was it like being a volunteer and collecting data from patients?

-

In your opinion, what were the benefits of being a volunteer on this project?

-

What challenges did you encounter during your shifts for the After Francis project?

-

Please describe the types of support you received from staff, a volunteer co-ordinator or other volunteers?

Patient experience data collection

To understand patients’ experiences of the relational aspects of care, a 10-month-long survey data collection phase was implemented using trained volunteers to administer the survey. Data collection began during June 2015; one case study site started to collect near real-time data on 1 June 2015 and two other trusts began their data collection at a later date during the month. Two of the remaining case study sites began their data collection during the month of July and one case study site began its patient data collection in early August. Discrepancies in the dates on which case study sites began their data collection were a result of the varying times of volunteer availabilities. Moreover, most volunteer training was conducted at the beginning of June, prior to which trusts could not begin their NRTF survey data collection.

Patient experience data were collected on one to five wards/departments selected by staff at each trust. These included wards providing care primarily to patients aged ≥ 75 years and A&E departments. The recruitment targets were a minimum of 20 completed surveys per month for each ward and 50 completed surveys per month for each A&E department.

Initially, the research team planned to provide a stationary kiosk to each trust to facilitate data collection in the A&E department and two protected tablets for data collection on study wards. Four of the six sites requested a third tablet for their data collection in lieu of a stationary kiosk placed in the A&E department. These requests were made for a number of reasons, including lack of space, previous unsuccessful experiences with a kiosk in A&E and a strong desire to avoid placing a burden on staff who would be directing patients towards the kiosks. During the data collection, the remaining two trusts switched to using a tablet in the A&E department as a result of the low response rate obtained with the kiosk methodology.

Over 43 weeks of data collection, the recruitment targets were met 50 times out of the 643 potential times across the 15 participating wards. In A&E departments, recruitment targets were met 40 times out of a potential 258 times across the six sites.

An interactive reporting system using Microsoft Excel was designed by the research team to showcase weekly results from the patient experience survey. Feedback from case study sites, shared through staff interviews, the online staff survey and e-mail communications and at the participatory workshops, was used to guide the continued refinement of the reporting system to best meet the informational needs of the trusts. The reporting system continued to evolve throughout the data collection phase of the research. Specifically, weekly and monthly summaries were added to the reporting system, along with printable dashboard reports. Case study sites also requested the option to remove non-specific responses from results displayed for each survey question.

Following the 10-month data collection period, the quantitative patient experience data from all six sites were analysed using factor analyses. These are described in detail in Chapter 4. Free-text comments from all sites were combined and underwent a thematic analysis. Themes and example comments are presented in the results section of this report.

Participatory workshop

Two participatory workshops were conducted at each case study site for staff involved with the project implementation. Frontline staff, such as nurses, matrons and ward managers, were especially encouraged to attend the events. Workshops were held 3 months into patient data collection and again on completion of the data collection phase.

Prior to the workshops, project advisory group members were asked to share their thoughts and suggestions for increasing the usefulness of participatory workshops to staff involved with the project at the case study sites.

First, advisory group members discussed the usefulness of giving staff time off from their regular duties to consider and plan for improvements, as they considered it a task unable to be undertaken by administrators.

Another advisory group member stressed the importance of having a team of nurses or staff from each ward or department attending the workshops. This way, a ‘shared group perspective’ forms the basis of discussions and one person does not ‘feel overwhelmed’ by the perception of bearing the sole responsibility for improvements to patient care.

One advisory group member explained that some language used by the research team, such as ‘improvements’ or ‘changes to patient care’, may be perceived negatively by staff. The wording ‘working together for the future’ was suggested for use instead of or in addition to the current wording. Additionally, it was suggested to make the workshop content and patient data meaningful to staff by continuously relating discussions back to the patient. One way to make the data meaningful is to relate them to activities associated with the professional revalidation process for nurses. As part of this process, staff must engage in, and demonstrate, reflection and self-learning. Feedback from patients collected using the tablet-based survey can be used for this purpose, especially as responses provided in free-text comments may provide ‘personal feedback’ needed for the professional revalidation.

Advisory group members also proposed asking staff to focus on small and manageable changes for the action-planning activity. All changes must be easy to implement. In addition, a short- and long-term focus of the improvements should be apparent to staff. It was also suggested that ‘staff not shy away from understanding underlying reasons for improvements, as it may be necessary so staff can truly understand and improve patient care’.

Based on staff suggestions, participatory workshop activities were designed to provide a collaborative space for staff to interpret patient experience feedback collected as part of the project, and to maximise engagement. Staff identified and prioritised areas of patient experience that needed improvement and developed concrete action plans for each ward/department. In addition to engaging staff in a guided action-planning process, the research team sought to understand the levels of staff engagement with the near real-time data and discuss factors that encourage patients to provide feedback and staff to use the NRTF for improvements and decision-making. Finally, as part of the workshops, any barriers identified as hindering the use of NRTF could be explored as a group and mitigating strategies shared with the site leadership.

Staff survey

An online staff survey was designed to understand the types and methods of patient experience data collected and methods of data collection on the wards/departments involved in the research. In addition, the survey instrument explored the following contextual factors associated with patient experience data collection at each case study site:

-

how results from patient experience data collection are communicated to staff, including by whom and how frequently

-

preferences for communication modes and their desired frequency

-

preferred reporting formats

-

usefulness of patient experience feedback

-

perceived barriers to, and enablers of, using patient feedback

-

experiences with RTF data collection and using volunteers to collect patient feedback.

To capture changes in perceptions of and experiences with near real-time data collection, the staff survey was administered before (pre) and after (post) the patient data collection. This survey was made available to all staff working on wards and in A&E departments involved in the patient experience survey. At each case study site, an additional two wards that were not involved with the project were selected as control groups. All staff from these wards were eligible to take the online survey.

In the first administration, the survey was made available to staff in an online format. To notify staff of the upcoming survey opportunity, project leads at each trust prenotified all staff or senior staff members via e-mail, as well as in person if possible. If senior staff were notified, they were asked to pass the information on to their team members.

The survey was administered using the Snap survey platform (version 11; Snap Surveys, Tidestone Technologies, Overland Park, KS, USA) and hosted on Snap WebHost. Invitations were sent to trust contacts on 21 May 2015. Five project leads at the trusts forwarded the invitations on to their teams shortly thereafter. One trust was still awaiting the site-wide NHS permission letter, which delayed the survey invitation mailings by 2 weeks. Reminder messages were sent to project leads at the case study sites 1 week following the initial survey invitation mailings.

Owing to the low number of survey responses (see Table 3), project leads at the case study sites were asked to share any suggestions or ideas they had for increasing the number of responses for the second survey administration. The main suggestions received focused on the substitution of the online survey for of a paper-based version, which could be distributed to all staff working on the wards.

Advisory group members were also asked for suggestions to improve the response rates. Similar to staff, they suggested the use of an alternative survey format, as staff on wards are generally not provided with access to e-mail during their work hours. A paper- or a tablet-based survey version that volunteers could take to staff was suggested for use instead.

Advisory group members recommended shortening the survey, as frontline staff have limited time. It was also considered beneficial to make it clear to staff why it was important to complete the survey.

For the second administration, the research team reduced the number of questions on the survey and made it available in a paper-based format or on the tablets previously used for patient data collection. In addition, the survey prenotification, invitation and reminder messages were replaced by in-person communication from the project team with the ward/department leaders and senior staff.

The paper-based survey was printed as an A5 booklet and handed out to all staff members working on wards/departments by the senior staff members. Where possible, time was made available in ward or department meetings for staff to complete the survey. Staff placed their completed surveys into envelopes, which were collected by a trust research and development (R&D) team member and returned to the research team. The survey was available for completion over a 2-week period.

Three trusts chose to administer the survey as a tablet-based version, which was also available over a 2-week period. Using this method, R&D team members took the tablets to the wards during handover times and encouraged staff to complete the survey at that time. Table 3 presents the number of responses and selected survey administration modes for each of the two survey time points at each case study site, along with the change in number of completed staff surveys between the first and second time point.

| Case study site | Responses, % (n) | Difference in recruitment, % (n) | Mode of administration post data collection | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-patient experience data collection | Post-patient experience data collection | |||

| Hinchingbrooke | 28.2 (20) | 28.3 (41) | 105.0 (21) | Paper |

| Milton Keynes | 4.2 (3) | Not available | –100.0 (3) | Paper |

| North Cumbria | 14.1 (10) | 1.7 (3) | –70.0 (7) | Paper |

| Northern Lincolnshire and Goole | 2.8 (2) | 30.2 (52) | 2500.0 (50) | Paper and tablet |

| Poole | 16.9 (12) | 29.1 (50) | 316.7 (38) | Tablet |

| Salisbury | 33.8 (24) | 15.1 (26) | 8.3 (2) | Tablet |

Networking event for case study staff

A networking event was held on Tuesday 24 November 2016, at Harris Manchester College, Oxford, to enable key staff from each of the six case study sites to meet each other and share their experiences regarding the project. Specifically, staff provided feedback on experiences of data collection; barriers and enablers that staff had come across; impacts the data have had within the trust; and lessons learnt.

Meetings with key staff at case study sites

Five meetings with key staff from each study site were held on 24 and 25 November 2016 to coincide with the networking event. As one of the sites was unable to send a representative to the networking event, a conference telephone call was held on 2 December 2016 with four staff members involved in the project.

Support calls

To support volunteers with their data collection, the research team invited all volunteers to join them in monthly conference telephone calls. Support telephone calls were scheduled separately for each trust. During these telephone calls, volunteers could discuss any questions, comments or concerns with the research team. Conference call opportunities were available on the following dates:

-

23 October 2015

-

13 November 2015

-

4 December 2015.

Invitations to participate in calls were sent to the key contacts at the case study sites, who confirmed that they forwarded the messages and reminders on to all their volunteers currently involved in data collection for the project.

Telephone interviews with staff

Prior to implementing patient data collection, the project leads at each case study site were asked to assist the research team in scheduling 10 telephone interviews with staff who would be involved with the research project. A total of 52 interviews were conducted via telephone during the months of May and June 2015. This constituted the first round of staff interviews. Interview duration ranged between 14 and 35 minutes.

Through the interviews, we aimed to understand, in detail, the types of patient experience data currently collected at the trusts, how results are communicated, and the factors or structures that facilitate or hinder the use of patient experience data for improvement purposes. In addition, staff shared examples of improvements or changes to services that have been made based on patient experience feedback. Finally, staff shared their expectations for the upcoming patient data collection, the benefits and challenges associated with real-time data collection and the use of volunteers to collect patient experience feedback.

Some example questions and follow-up probes are as follows:

-

What types of patient experience data are your trust currently collecting? How frequently? Are any volunteers involved?

-

What procedures or structures are in place to make improvements or changes based on patient feedback?

-

What are your experiences with NRTF of patient experiences? What benefits do you anticipate? What drawbacks do you anticipate?

-

How could your trust benefit from volunteer involvement to collect NRTF? What should be considered when working with volunteers?

The following number of interviews were conducted at each case study site:

-

Hinchingbrooke Health Care Trust (n = 10)

-

Milton Keynes University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust (n = 10)

-

North Cumbria University Hospitals NHS Trust (n = 7)

-

Northern Lincolnshire and Goole NHS Foundation Trust (n = 5)

-

Poole Hospital NHS Foundation Trust (n = 10)

-

Salisbury NHS Foundation Trust (n = 10).

The roles of the interviewed staff working on wards and departments included the director of nursing, head of nursing, senior sister, senior staff nurse, deputy sister, matron, ward sister, staff nurse, lead consultant, unit lead, Foundation (year 2) doctor, health-care assistant, ward clerk and receptionist.

In addition, a lead governor and staff working in R&D departments, voluntary services and customer care were interviewed. Staff whose roles do not typically involve contact with patients were selected to participate in interviews as they were involved in collecting patient experience feedback from patients. For example, staff administered the FFT or other short surveys designed specifically for the trust to collect data from patients while they are still in hospital. Interviewees’ length of employment at the sites ranged from 6 months to 41 years.

Specific survey for interviewees

On completion of the 10-month patient data collection period, the 52 staff members across the six case study sites who participated in the initial telephone interviews were asked to complete an online survey consisting of closed and open questions. The purpose of the survey was to understand their involvement and experiences with the project and to determine how their previously shared expectations of near real-time data collection and experiences working with volunteers to collect patient experience feedback have changed. Staff were also asked about improvements to care made as a result of the NRTF collection. Similar questions were asked to those during the initial telephone interview, with answer options derived from the responses to the telephone interviews. Additional space for other answers was available.

This survey was available for completion online. It was set up in Snap and hosted on Snap WebHost. Staff received a prenotification message from their colleagues who were responsible for the implementation of the research at each case study site. Following this initial communication, the research team invited staff by e-mail to participate in the survey. The survey was available for a 2-week period in April 2016. Non-respondents received two reminder e-mails. Of the 52 staff members who participated in the initial telephone interviews, seven had left the trusts or were currently on maternity leave. Therefore, a total of 45 staff members were invited to take the online survey and 31 completed the survey, yielding a response rate of 68.9%.

In-person interviews with staff

A second round of staff interviews was conducted following the end of the patient experience data collection. Five staff members from each trust were interviewed in person or via telephone by the research team. Questions asked were similar to those asked during the first round of interviews. Instead of expectations for the data collection, we asked about their experiences with the data collection as part of this research. Interviews allowed us to explore any changes in opinions about NRTF and working with volunteers to collect patient experience feedback that resulted from their involvement in the current research. Interviews lasted between 14 and 35 minutes and staff members with the following roles participated:

-

matrons

-

ward sisters

-

deputy sister

-

director of nursing.

Research question 4

Table 4 presents the research activities that were employed to answer the fourth RQ, which explores what should be considered best practice in the use of NRTF in the NHS.

| RQ 4: what should be considered best practice in the use of NRTF in the NHS? | |

|---|---|

| Research activities | Methods basis |

| Develop a survey toolkit and evidence-based practice recommendations | Synthesis of evidence from all data sources presented under RQs 1–3 |

| Disseminate toolkit and practice recommendations to NHS trusts | Policy commentary, publication, conference presentations and toolkit launch events |

Develop a survey toolkit and evidence-based recommendations

Based on the patient experience data collection and the evaluation data collected from staff and volunteers through surveys and interviews, a toolkit was developed to share the survey instrument, including guidelines and recommendations, with other NHS hospitals. These data sources evidenced the success of the NRTF approach for improving relational aspects of care. With the help of the advisory group, the toolkit contents were developed and refined to make them more relevant and meaningful to the target audience at NHS hospitals. In addition, the advisory group selected the branding, including colours, font, title and pictures for the toolkit. Four guides and three case studies were also included alongside the survey instrument. These documents showcase the challenges, lessons learnt and impacts of the work at the case study sites. Volunteer training materials were made available to assist trusts in implementing the approach.

Disseminate toolkit and practice recommendations to NHS trusts

To share the toolkit, three regional toolkit launch and networking events were held at the following locations in February and early March 2017:

-

Novotel Paddington, London, 20 February 2017

-

Novotel Leeds Centre, Leeds, 27 February 2017

-

Harris Manchester College, Oxford, 2 March 2017.

The launch events commenced with a presentation providing an overview of the research, followed by a detailed description of the purpose and components of the toolkit. This was followed by time for questions about the content and functionality of the toolkit. Time for networking and further small group discussions were provided.

In February 2017, the toolkit was made freely available on the Picker website (URL: www.picker.org/compassionatecare, accessed 22 November 2017) and publicised through a published policy commentary. 46 In addition, the toolkit was disseminated through Twitter (Twitter, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA) and e-mails sent to our contacts at NHS trusts nationally.

Chapter 3 Using near real-time feedback to measure relational aspects of care

Results for research question 1: ‘can near real-time feedback be used to measure relational aspects of care?’

Literature review

Relational aspects of care

Person-centred care is considered to be a key component of high-quality health care and patient experiences provide one important avenue for measuring and improving the quality of patient-centred care. 4,23,24 Although patient experiences are important in and of themselves, they have also been shown to be correlated with other aspects of care quality: they are related to safety and clinical effectiveness24–26 and are associated with better treatment outcomes, fewer complications and overall lower service use,27 as well as better staff experiences. 28 Relational aspects of care have been established as more challenging to measure and improve than transactional aspects of care. 5,32

The need to strengthen relational aspects of care is consistently identified by policy-makers. 5,47 Recently, the Francis Report4 identified important deficiencies in emotional or relational aspects of care, which, the evidence suggests, are the key determinants of overall patient experience. 29,30 Relational aspects of care, also referred to as compassionate care, focus on the relationships staff form with patients during their time in hospital and can include communication, providing the space for patients to discuss concerns or fears and treating patients with respect and dignity. 5,26 Owing to the documented deficiencies, which were especially salient in experiences of older patients and those visiting A&E departments, the report of the Francis Report recommended that a special focus should be placed by hospitals on improving relational aspects of hospital care, especially for older patients and those visiting the A&E departments, as they are an important component of the patient experience, which may in turn affect treatment outcomes. 27,28 In addition, an increase in the collection and use of NRTF was recommended.

Current patient experience data collection primarily captures transactional aspects of care, such as cleanliness, waiting times and pain management. Although some relational aspects of care, such as being treated with dignity and respect and being fully informed about treatment, can be included, these have not been the focus of existing patient experience data collection.

Two instruments were found that aim to measure mainly relational aspects of care. 31,32 These instruments have not been designed or tested specifically for use with a near real-time approach or with patients who are generally considered to be harder to reach. Although the instruments might be used with this approach or hard-to-reach populations, further testing and refinement may be necessary.

The PEECH measure was developed and tested in Western Australia. 31 Emotional care was defined as the ‘interpersonal interactions that facilitate or enhance the state of emotional comfort’. 31 As part of the study, a new intervention was designed to improve emotional care on an oncology ward and the PEECH survey was created to measure the success of the intervention. The PEECH measure was developed based on a framework identified in previous research, which suggested that three components are key contributors to emotional care. These components are titled level of security, level of knowing and level of personal value. Face and content validity were assessed, as well as internal consistency of the measure. Adequate sensitivity of the PEECH measure was established for use in a ward setting. The PEECH survey contained 25 questions, constructed as Likert scales, which were grouped into three subscales matching the components described above.

Further research on the PEECH measure examined the psychometric properties of the instrument. 32 Internal consistency was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha, which ranged from 0.60 to 0.79 for the three subscales. Exploratory factor analyses were conducted to verify the internal structure of the measure and whether or not the three components or subscales could be sustained. The results showed that an additional subscale of emotional care, named level of connection, was assessed by the PEECH measure. These results further highlighted the complexity of emotional care.

The PEECH measure, which was originally developed and validated in Australia, was also validated in four English acute hospital settings. 30 Factor analyses revealed a different underlying structure of the instrument and two new factors, named personal interactions and feeling valued, emerged. These differences may in part be attributable to the different timings of the data collection. In the Australian samples, data were collected while patients were in hospital, whereas in the English samples, data were collected following discharge. The researchers concluded that further testing of the measure is warranted to inform the measurement and reporting of emotional or relational aspects of care.

Another instrument measuring primarily relational aspects of care is the CARE measure. 31 This measure was developed by researchers with the help of patients and experts in emotional care. It was developed and tested specifically for clinical use in primary care settings. A special focus was placed on the measure’s applicability to patients with various social economic backgrounds. The final instrument comprises 10 questions, which can be answered using a five-point Likert-type rating scale. A ‘does not apply’ answer option is available. The measure has not been designed or tested for use in hospitals or with a NRTF approach.

An additional four instruments were found to measure some relational aspects of care; however, their main purpose is to measure transactional aspects of care such as pain management, waiting times and cleanliness. 33–36 The instruments include the NHS Adult Inpatient Survey, the NHS Emergency Department Survey, the GPPS and the HCAHPS questionnaire. The last two instruments are described in more detail as examples below.

The GPPS, administered in primary care since 2007, focuses on waiting times, scheduling, access to a preferred doctor or practice nurse, care planning and overall satisfaction. 33 However, this survey also includes some questions which capture relational aspects of care, including having sufficient time to ask questions, staff listening to patients, obtaining clear and sufficient explanations, being treated with care and concern, and having confidence and trust in their doctor. This survey instrument has been developed and tested for use in a variety of geographic areas, as well as socioeconomically deprived practices. Question wording has been revised to ensure consistent understanding for patients with a range of disabilities. Owing to the primary focus on transactional aspects of care and the instrument’s intended use in primary care, the measure is not suitable in its current form for the measurement of relational aspects of care in hospital settings.

The 27-item HCAHPS questionnaire was developed to provide a standardised tool to capture experiences of patients on seizure monitoring units following discharge. 34 The survey was developed specifically to provide a means for comparing the experiences of patients on seizure monitoring units with the experiences of patients on other similar units. Twenty-seven questions are included in the instrument. These are answered using 4- and 10-point rating scales, as well as through dichotomous answer options.

Although the instrument focuses primarily on capturing patient experiences of the transactional aspects of care, including the provision of discharge information and the hospital environment, some relational aspects of care are also assessed. These focus on both physician and nursing care with regard to treating patients with dignity and respect, listening carefully, providing clear explanations and providing assistance to patients when requested. The survey can be used in hospital settings as a tool to capture transactional aspects of care.

In conclusion, as only two existing instruments focus primarily on relational aspects of care and, of these, only one has been designed for use in hospitals, we developed and tested an instrument specifically for use with a NRTF approach in A&E departments and inpatient wards that provide care primarily to elderly patients.

Focus group and interviews

Focus group and interview responses were analysed thematically, first separately then again in combination, using a coding framework developed specifically for these activities. This framework applied to both the individual and combined analyses. The same themes appeared across all transcripts and were mentioned at a similar rate of frequency in interviews and the focus group, suggesting that there was a general agreement on themes’ importance between the focus group and interviews.

Table 5 presents the most frequent themes and the number of occurrences found in the focus group and interview analysis. It presents a simple count of the number of times statements related to each theme were mentioned; therefore, the counts for each theme can exceed the total number of participants.

| Theme | References in (n) | Total (n) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A&E focus group | Eight inpatient interviews | ||

| Feeling informed | 12 | 26 | 38 |

| Being listened to and feeling involved in care | 3 | 19 | 22 |

| Confidence – trust in staff knowledge | 5 | 16 | 21 |

| Kindness | 2 | 16 | 18 |

| Surpassing expectations or making special effort | 3 | 14 | 17 |

| Showing empathy | 0 | 16 | 16 |

| Competent staff | 2 | 14 | 16 |

| Feeling alone, vulnerable or unnoticed | 5 | 8 | 13 |

| Efficiency | 2 | 10 | 12 |

| Staff ability to cope when understaffed | 0 | 11 | 11 |

| Feeling like a priority or adequately monitored | 0 | 11 | 11 |

| Opportunity to ask questions and knowing what to expect | 2 | 9 | 11 |

| Stress, anxiety and/or fear | 4 | 7 | 11 |

| Feeling staff were thorough | 0 | 9 | 9 |

| Feeling secure in knowledge others are in control – safe hands | 3 | 5 | 8 |

| Feeling comfortable – at ease with staff | 2 | 5 | 7 |

| Use of humour – friendly | 3 | 4 | 7 |

| Good rapport | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| Feeling respected | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| Facilitating communications with friends and family | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Emotional state | 0 | 1 | 1 |

Frequent themes

Additional details on the seven most frequent themes are presented below.

Feeling informed

The theme of feeling informed focused on how well the care staff explained the condition or treatment. This included whether or not patients were told of any danger signals to watch out for once they left hospital and whom to contact if they were concerned:

If you can’t communicate with someone adequately for the situation, the person’s not sufficiently stress free to be able to cope with what they’ve got to cope with.

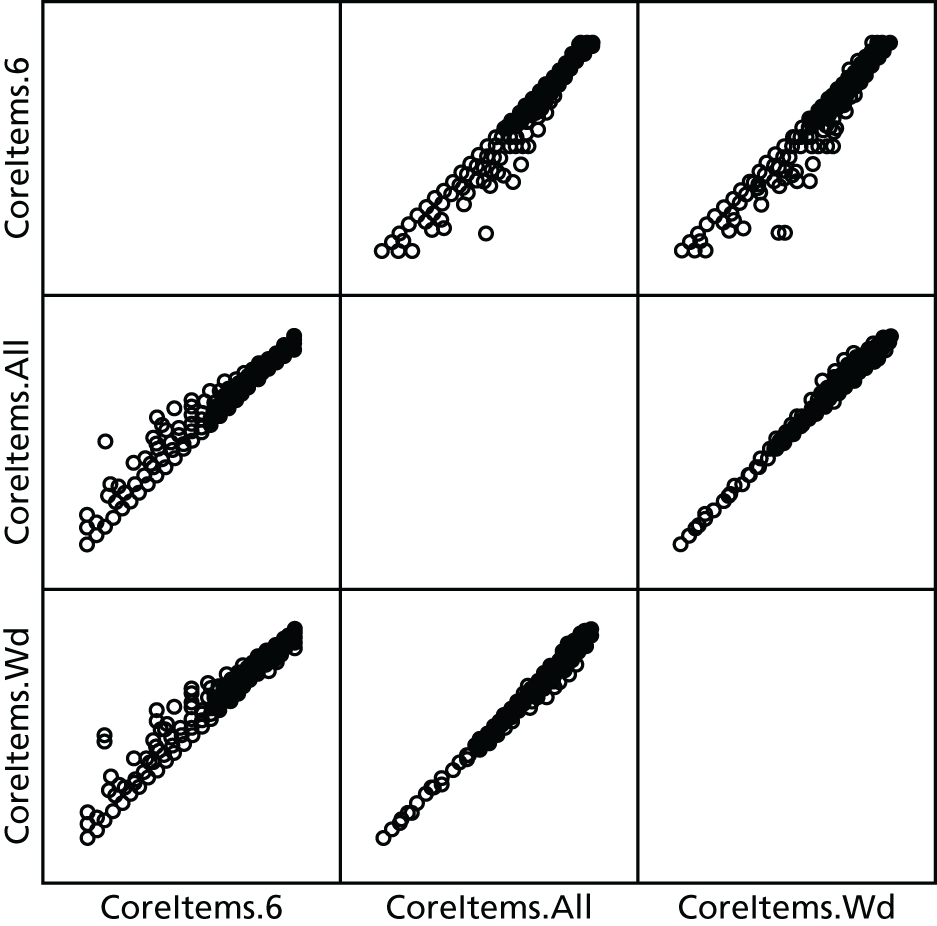

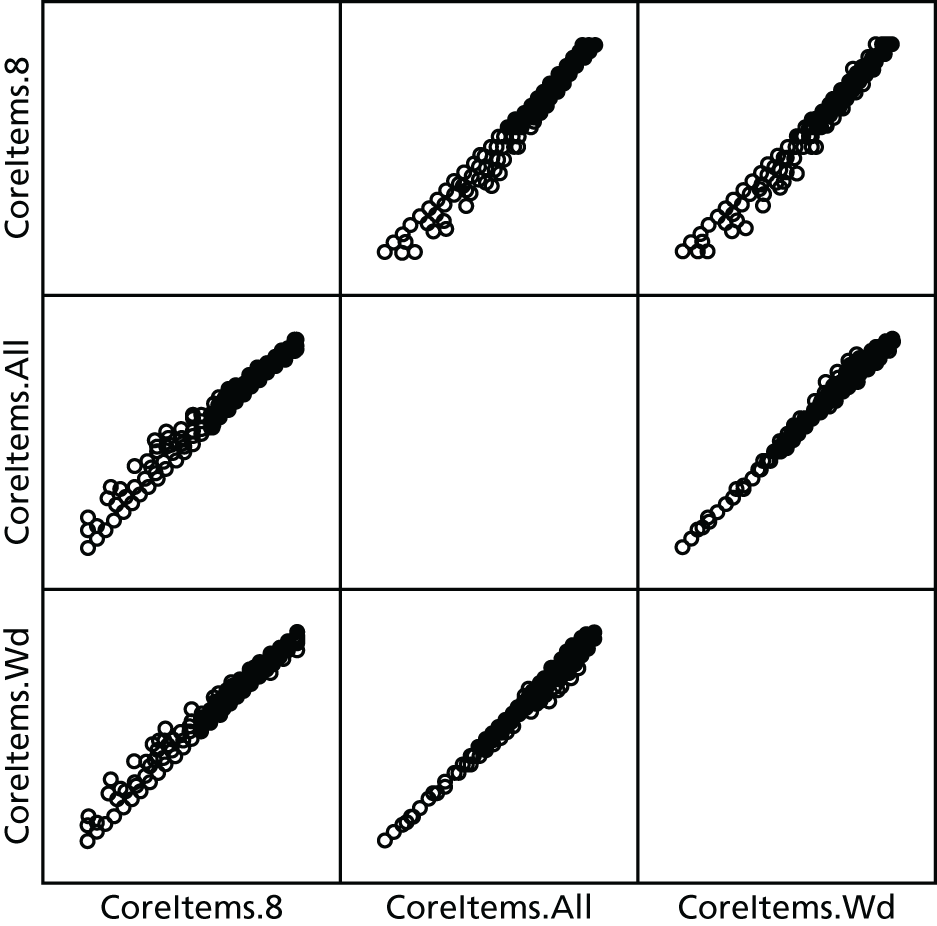

Patient