Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 13/54/75. The contractual start date was in January 2015. The final report began editorial review in May 2017 and was accepted for publication in March 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Aloysius Niroshan Siriwardena reports grants from the National Institute for Health Research, the Medical Research Council, the Falck Foundation, the British Heart Foundation, the Health Foundation and the Wellcome Trust outside the submitted work.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by O’Cathain et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

The ambulance service in England

Eleven regional ambulance services provide emergency and urgent care to the population of England. In 2015/16 these services responded to almost 11 million calls at a cost of £1.78B. 1 Ten of these services respond to > 99% of calls. These services are working under increasing pressure, with demand rising at a faster rate than growth in resources. 1

Most calls are made by members of the public calling for themselves or on behalf of others, using the emergency number 999. Some calls are referred directly to the emergency ambulance service from the urgent helpline NHS 111 and some are made by health-care professionals on behalf of patients.

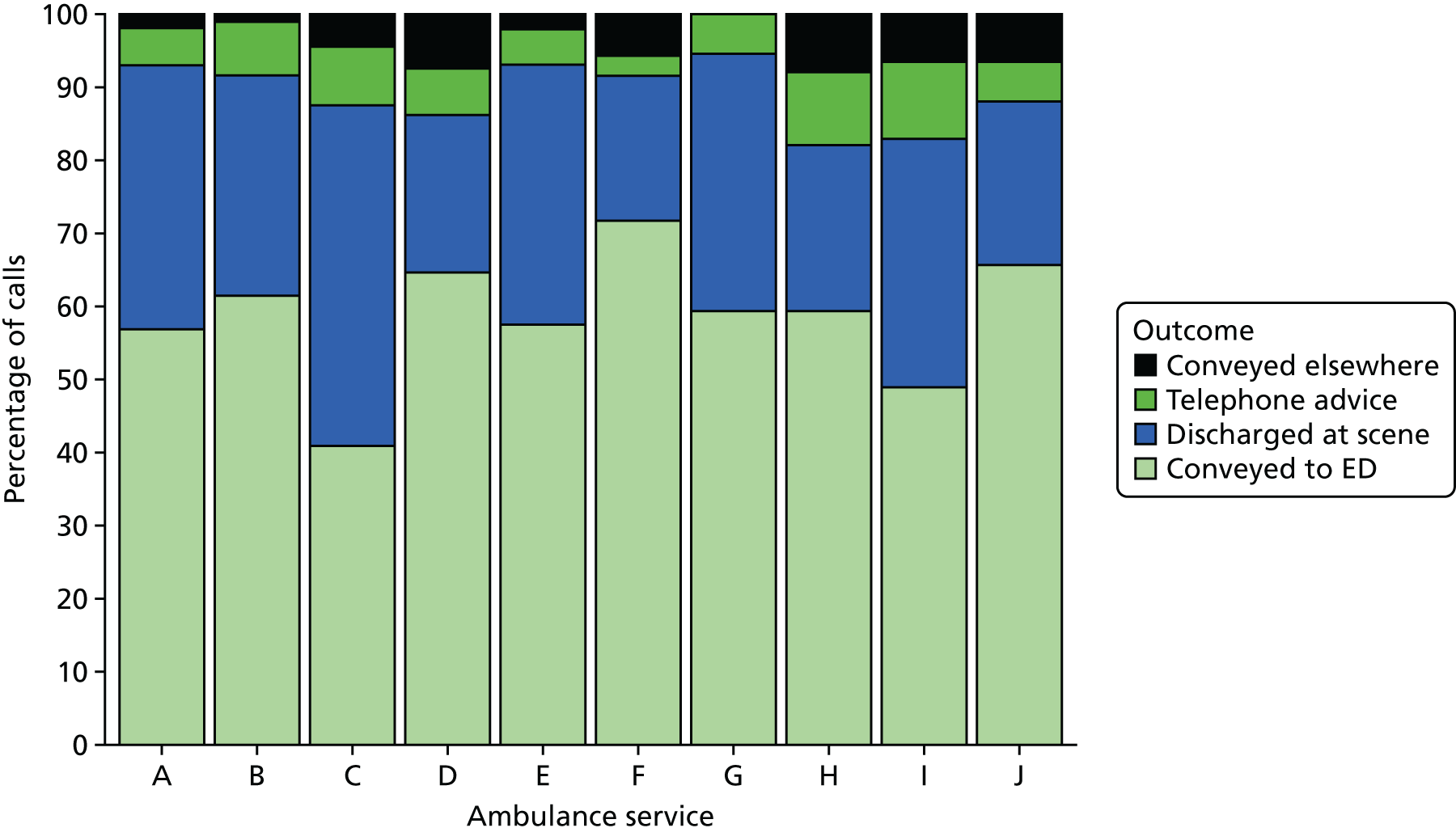

The types of responses made to calls

When patients call 999 for an ambulance, some calls end in telephone advice, some patients are sent an ambulance and are discharged at scene, some are conveyed to an emergency department, and some are conveyed to alternative services such as minor injury units and hospices. ‘Non-conveyance’ is a term used to describe a 999 call to the ambulance service that results in a decision not to transport the patient to a health-care facility. It includes calls ending in telephone advice only without the dispatch of an ambulance, and calls ending in discharge at scene, whereby an ambulance 999 call results in a face-to-face assessment of a patient by an ambulance crew at the scene without onward transport to a health-care facility. A more specific definition of non-conveyance is ‘non-conveyance to an emergency department’. By this definition, calls ending in transport to a health-care facility other than an emergency department are also viewed as non-conveyance. At the start of this study the focus was on the three types of non-conveyance to an emergency department: telephone advice only, discharge at scene and transport to an alternative to an emergency department. Ambulance services in England have developed terminology for different ambulance response types. This terminology is discussed in more detail in Chapter 2, Terminology and definitions.

Measuring performance of the ambulance service

The performance of ambulance services is measured by a set of Ambulance Quality Indicators (AQIs), which are published monthly by NHS England. 2 A key performance indicator is the proportion of life-threatening and serious calls responded to within a particular timeframe, referred to as ‘response-time targets’. Targets are set and ambulance services can be penalised financially for not meeting these targets. There are also four AQIs on different types of non-conveyance to emergency departments:

-

of the calls that receive a telephone or face-to-face response, the proportion resolved by telephone advice (‘Hear and Treat’)

-

of the calls that receive a face-to-face response from the ambulance service, the proportion managed without the need for transport to Type 1 and Type 2 accident and emergency (A&E) services

-

of the patients making emergency calls that are closed with telephone advice, the proportion with recontact via 999 within 24 hours

-

of the patients treated and discharged on scene, the proportion with recontact via 999 within 24 hours.

Benefits of non-conveyance

There are three potential benefits of non-conveyance. First, non-conveyance may offer the most appropriate response to patients’ needs. Second, emergency departments are under increasing pressure. If ambulance services can deal with patients safely and appropriately without conveyance to emergency departments then this can reduce pressure on this key service within the emergency and urgent care system. Non-conveyance to emergency departments may also affect emergency admissions; research has shown that potentially avoidable admission rates were lower in areas with higher rates of ambulance non-conveyance. 3 Third, non-conveyance can benefit the performance and sustainability of ambulance services. With ambulance services dealing with increasing demand without a similar increase in resources,1 ending low-acuity calls with telephone advice may reduce demand for ambulance journeys; discharging patients at scene may reduce the wastage of ambulance crew time if there is a need to queue outside emergency departments. Saving time and resources in this way may allow ambulance services to respond more quickly to life-threatening situations. NHS England proposed a shift within the NHS to offer care closer to patients’ homes. 4 The ambulance service in England is fulfilling this remit by dealing with a large proportion of patients by not conveying them to an emergency department unless necessary.

Variation in non-conveyance rates in England

Rates of non-conveyance have increased over time in England. Between January 2013 and December 2016 published AQIs showed that, across England, rates of calls ending in telephone advice almost doubled from 6% to 11%, and rates of patients sent an ambulance and not conveyed to an emergency department increased slightly from 35% to 38%. Non-conveyance rates have always varied between ambulance services. For the 10 large ambulance services at the end of 2016, the rate of calls ending in telephone advice varied between 5% and 17%, the rate of calls sent an ambulance but not conveyed to an emergency department varied between 23% and 51%, and overall non-conveyance rates varied between 40% and 68%. The total non-conveyance rate is not an AQI and is reported here as a crude addition to the two non-conveyance rates of each ambulance service to show that the variation between ambulance services is not explained simply by ambulance services undertaking different types of non-conveyance.

Patients’ views of non-conveyance

Patients’ views of non-conveyance in national surveys in England have generally been positive. In January 2017, 94% of patients discharged at scene recommended the service to family or friends; however, caution is needed around generalisability because the number of responses compared with numbers eligible to respond was small (311 out of a total of 213,792). 5 In 2013/14, patients who did not receive a face-to-face visit from the ambulance service were asked if they agreed with the advice given. A total of 72% said that they agreed with the advice ‘completely’, 15% agreed ‘to some extent’ and 13% said that they did not agree with the advice. 6 This was a much more reliable source of patients’ views, with a response rate of 55% from 2900 patients whose calls had ended with a call-handler or a clinician offering advice over the telephone.

Researchers have also measured patients’ views of non-conveyance using surveys, showing that 90% who received a telephone intervention were satisfied,7 and 75% of patients transferred from the ambulance service to a national telephone helpline NHS Direct were satisfied, although this was lower than for patients who were not transferred. 8 A survey of people attending emergency departments by ambulance in the USA identified that patients were willing to be transported to alternative places. 9

Patients’ views of non-conveyance have also been explored using qualitative research. Patients have been positive about not being conveyed to an emergency department. 10 A sample of ambulance service users that included patients who were offered telephone advice and patients who were discharged at scene identified positive experiences of feeling reassured by the service offered. 11 Focus groups with users of the ambulance service, exploring decision-making and safety, identified perceptions of the importance of including patients and their families in decision-making about non-conveyance as key, because they may have strong views about not wanting to go to hospital that differ from clinical views. Patients and their families also expressed concerns that the risks of telephone triage should be addressed by training staff in communication, and that a lack of awareness of the range of options used by ambulance services might lead to patients expecting conveyance to emergency departments. 12 Within this research there was a sense that patients and their families were happy to have non-conveyance as an option and even preferred it in some situations. This preference for non-conveyance was also found in a qualitative study of patients who called the ambulance service for primary care conditions because they wanted to be treated at home; this was in contrast to calling their general practitioner (GP), who they felt would be likely to send them to hospital. 13 A qualitative interview study of patients in Australia who were not transported to hospital identified high levels of satisfaction and found that some patients chose to stay at home against the clinical advice of paramedics. Reasons for this included that they had only wanted advice when they called the ambulance service, their symptoms had resolved, they did not want to wait at an emergency department, or did not want a fuss made. 14

Although there is patient support generally for non-conveyance in the research literature, it is worth noting that not all patients’ views of non-conveyance are positive. Some patients call the ambulance service for transport to an emergency department and may not want telephone advice only or to be discharged at scene.

Paramedics’ views of non-conveyance

The decision to discharge a patient at scene is complex and can be affected by a range of factors, including the high demand for ambulance services, priorities around performance management, access to care options as an alternative to the emergency department, risk tolerance when the least risky option is conveyance to an emergency department, the level of training paramedics receive, and the quality of communication and feedback for paramedics who often make non-conveyance decisions in isolation. 12 Paramedics work with the fear of litigation and can perceive a lack of support from management for their non-conveyance decisions if adverse events occur. 15 Negotiating the balance between patient safety and patient choice, together with paramedics’ own fears of litigation, can result in conveyance to an emergency department as a precaution. 16 In the past, crew members have not always completed documentation around non-conveyance because they did not perceive it to be important. 17

International perspective

Non-conveyance is undertaken in many countries around the world. 18 In the past, non-conveyance rates have been identified as varying between 23% and 33% internationally. 19 However, rates can be lower; for example, only 11.5% of incidents in 2012/13 in a region in Australia did not result in transport to hospital. 14 A recent systematic review of non-conveyance for falls in older people identified 12 studies showing that the rate varied between 11% and 56% in different studies. 20 Telephone advice by a clinician can be offered in different countries and is sometimes called ‘secondary telephone triage’. For example, 1 in 10 calls to the ambulance service in a region in Australia was dealt with by telephone. 21

Non-conveyance for specific health problems

Some research on non-conveyance has focused on the specific reasons for calling the ambulance service. Researchers have tended to study falls because this is the most common reason for calls to an ambulance service that end in non-conveyance. 20 There are interventions to facilitate discharge at scene by referring patients directly to falls services: a recent randomised controlled trial of paramedics using computerised clinical decision support when attending older people who had fallen showed an increase in referral to a falls service but no difference in non-conveyance rates. 22 In recent years researchers have started to study other health conditions or reasons for calling the ambulance service that result in non-conveyance. A study of hypoglycaemic emergencies showed that most patients stayed at home after attendance by an ambulance and a small number suffered a repeat episode within a short time period. 23 In contrast, three-quarters of calls for people with suspected seizures – a large number of which were likely to be epileptic seizures – ended in transport to hospital. 24

Respiratory problems have been identified as a common reason for calling an ambulance service in the USA, where 12% of encounters have been categorised as ‘respiratory distress’. 25 Although research studies have described the epidemiology and outcomes of ambulance service users with respiratory distress,25–28 they have focused on patients who are transported to emergency departments rather than those not conveyed. We could find only one study of non-conveyance of patients with breathing difficulties that focused on the impact of advanced paramedics on this condition. 29

Determinants of non-conveyance

No research explaining why different ambulance services have different rates of non-conveyance was found. However, there is evidence about the determinants of some types of non-conveyance internationally. 19,30 The evidence base tends to focus on patients discharged at scene19,30 and determinants can differ between countries. 19 An epidemiological study of non-conveyance in one ambulance service in the UK in 2000 at a time when 17% of patients were not conveyed found that 34% were falls, mainly in elderly people. A well-researched determinant of discharge at scene is the skill level of the attending ambulance crew. A systematic review and meta-analysis identified that paramedics with extended skills had higher non-conveyance rates than conventional paramedics, although concerns were expressed about whether all potential confounders were adjusted for within analyses of individual studies. 31

Safety and appropriateness of non-conveyance

Although some interventions to increase non-conveyance rates have been found to be effective without compromising safety,32 evidence reviews have identified some concerns about the safety of discharge at scene. 19,20 Event rates have been found to vary by staff skill-mix. For example, patients who had fallen and who were attended by advanced paramedics had lower emergency department attendance rates and hospital admission rates than those attended by paramedics. 20 A meta-analysis of the appropriateness of discharge at scene by staff skill-mix for all types of calls was equivocal. 31

A recent review of patient safety in the ambulance service is an excellent source of evidence for the safety of non-conveyance. 33 The authors concluded that the evidence base on the safety of telephone advice, discharge at scene and use of alternative pathways to emergency departments is mixed and that further research is needed. In contrast, a systematic review of telephone advice by ambulance services concluded that it was safe but that there is a need to understand its effect on demand for ambulance services. 34

The types of events measured to assess the safety and appropriateness of non-conveyance include additional calls to the ambulance service, emergency department attendance, primary care contacts, hospital admission and mortality. 20,35 There appears to be no consensus on the time period of measurement of subsequent events, which has varied considerably in different studies, for example, 48 hours, 7 days, 14 days or 28 days. 19,20,35,36

An important contextual issue when considering the safety and appropriateness of non-conveyance is that decisions around non-conveyance are negotiated between paramedics, patients and their families. 37 Patients may choose to stay at home against clinical advice and, therefore, subsequent events may not be the responsibility of the ambulance service. 14 Indeed, a national audit of recontacts with the ambulance service within 24 hours revealed that over half of patients were documented as having refused to travel. 38

Non-conveyance in the wider health system

In England, Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) are required to ensure that high-quality services are available for the health needs of the geographical populations they serve. CCGs commission a range of health services for their populations. Therefore, each CCG geographical area can have different configurations of health and social care services. Each of the 10 large regional ambulance services in England serves the populations of between 12 and 33 CCGs. Each ambulance service is commissioned by a lead commissioner on behalf of all the CCGs within the ambulance service region. 39 Non-conveyance rates may be influenced by these commissioners in two ways. First, they may take different approaches to commissioning non-conveyance. Second, they may take different approaches to configuring the range of health and social services within their health system that can offer alternatives to an emergency department when the ambulance service would like to non-convey.

Research gaps

Research is needed to understand the determinants of non-conveyance rates and of variation in non-conveyance rates between ambulance services. Non-conveyance rates vary so much between ambulance services in England that a study is necessary to identify the reasons for this. Because of the way in which services are commissioned and provided in England, and the geographical variation in provision within regions served by ambulance services, a consideration of variation within ambulance services is also important. The emphasis on discharge at scene in the evidence base suggests that there is a need to consider the provision of telephone advice only as well as discharge at scene. Because of the mixed conclusions from the evidence base on safety and appropriateness, there is a need for further research on this aspect of non-conveyance. Finally, the emphasis on falls in the evidence base means that there is also a need to consider non-conveyance for other health conditions or reasons for calling an ambulance service. Respiratory problems are a good focus because they make up a reasonable proportion of calls to the ambulance service and there is no evidence about the non-conveyance of patients who call an ambulance service for this reason.

Chapter 2 Aims and methods

Aims and objectives

The aim of the study was to explore reasons for variation in non-conveyance rates between and within ambulance services.

The objectives were to:

-

explore the perceptions of ambulance service managers, paramedics and commissioners of factors affecting variation in different types of non-conveyance

-

identify the determinants of variation between ambulance services for different types of non-conveyance

-

explore the variation in different types of non-conveyance within ambulance services

-

explore variation in the provision of telephone advice only in detail within three ambulance services

-

identify the determinants of variation between services in rates of 24-hour recontact with the ambulance service after non-conveyance

-

assess the safety and appropriateness of non-conveyance in one ambulance service

-

identify the determinants of variation when the reason for calling is ‘breathing problems’.

Setting

The research was located in 10 of the 11 regional ambulance services in England serving > 99% of the population of England. The ambulance service for the Isle of Wight was excluded because of its relatively small size.

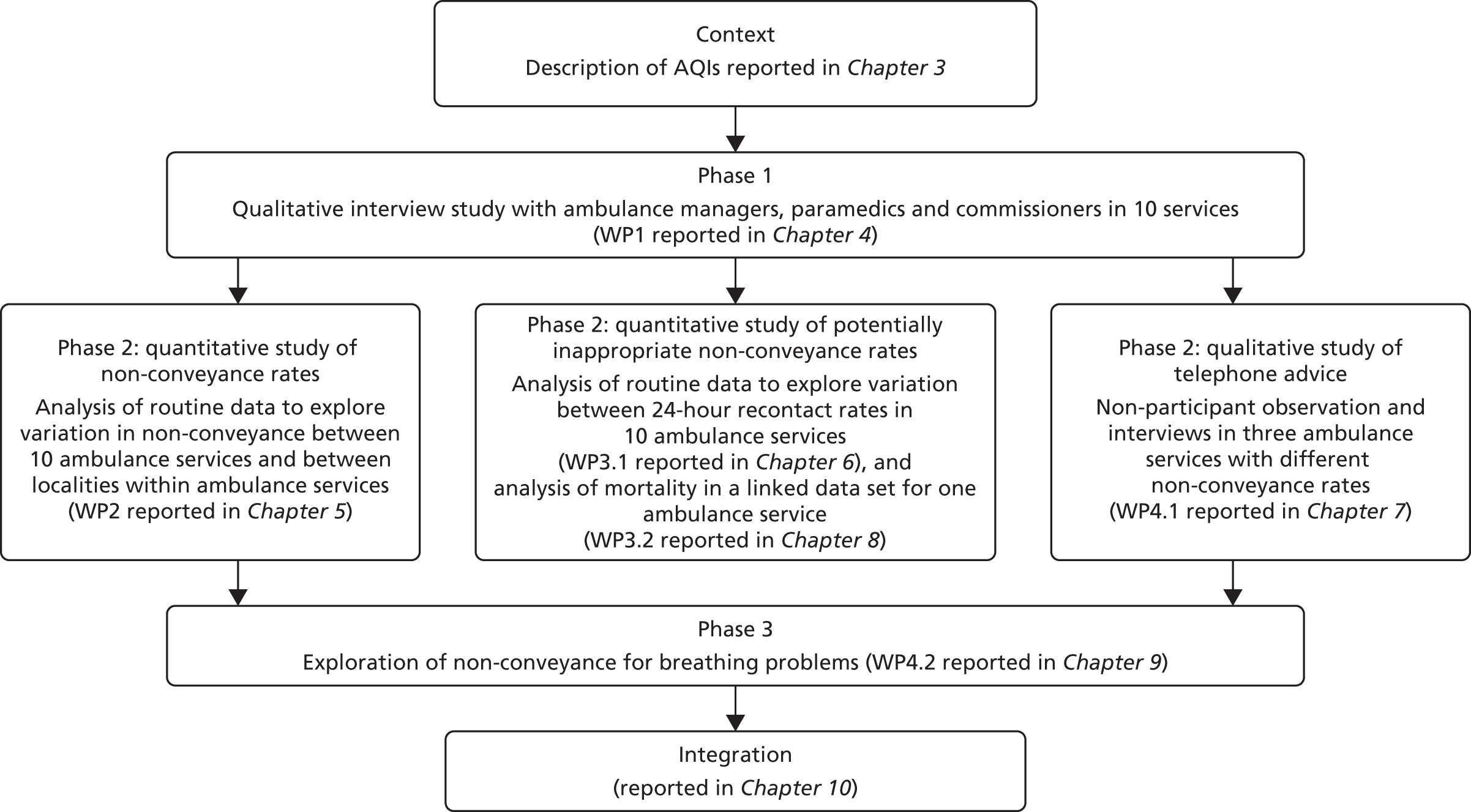

Design

The design was a phased sequential mixed methods study with five work packages (WPs) (Figure 1). In preparation for the study we described the variation in non-conveyance AQIs between ambulance services over time. In Phase 1 we undertook a qualitative interview study of managers, paramedics and commissioners from each ambulance service (WP1) in the research proposal. In Phase 2 we analysed 1 month of routine data from each ambulance service (WP2 and WP3.1), analysed a linked data set to explore safety and appropriateness (WP3.2), and undertook a qualitative study using non-participant observation and staff interviews in three ambulance services with different published rates of telephone advice only (WP4.1). In Phase 3 we conducted a substudy of non-conveyance for patients calling the ambulance service with ‘breathing problems’ (WP4.2). The detailed methods of each component are described in later chapters.

FIGURE 1.

Mixed methods study design.

Conceptual framework

It is important to publish variation in health care, to identify causes of variation and to encourage actions to deal with it. 40 Appleby’s framework of factors affecting variation in health care shaped the data collection and analysis within our study. 40 It helped us to consider the wide range of factors that might affect variation in non-conveyance rates between ambulance services so we could explore them in WP1 and test them in WP2. Factors within Appleby’s framework address the demand (e.g. population morbidity, commissioning practices) and supply (e.g. service configuration, clinical decision-making) of health care. From our literature review (see Chapter 1, Determinants of non-conveyance), we expected demand factors, such as patient age and reason for calling, and supply factors, such as the skill-mix of attending crew, to explain some variation in rates of discharge at scene. We expected ambulance services with a higher proportion of older patients calling about falls to have higher non-conveyance rates because older people and falls are more likely to be non-conveyed. We expected ambulance services with larger proportions of advanced paramedics in their workforce to have higher non-conveyance rates because these paramedics would have more training to make the clinical decisions required to discharge patients at scene. From our interviews with ambulance staff in WP1 we expected to identify a list of factors affecting non-conveyance rates at a patient, crew and organisational level, and an understanding of how these factors affected non-conveyance rates, in order to test them in WP2 and WP3.

A further conceptual framework was used for the study, namely ‘unwarranted variation in health care’,41,42 whereby some variation may be warranted owing to patient need or preference and some may be unwarranted. Unwarranted variation can be related to variation in evidence-based practice, variation in preferences held by key stakeholders, and variation in the supply of types of resource. For example, variation in non-conveyance rates between ambulance services caused by variation in the supply of advanced paramedics would be considered unwarranted. This concept shaped our analyses of variation in non-conveyance rates between ambulance services when we adjusted for differences in case mix between ambulance services (warranted variation) before testing whether or not differences in the workforce configuration (unwarranted variation) explained variation between ambulance services.

Finally, we distinguished variation that was likely to be modifiable by ambulance services from variation that was likely to be outside the control of ambulance services so that we could consider the implications of our findings for ambulance services. For example, workforce configuration is largely modifiable by ambulance services (although some aspects such as national training schemes may not be modifiable by them), whereas the availability of services in the wider emergency and urgent care system is outside the control of ambulance services.

Integration of work packages

Attention to integration is important within mixed methods studies so that the whole is more than the sum of the parts. 43 Integration occurred in a number of ways:

-

It was built in to the sequential design of the study. The main role of the qualitative interviews in WP1 was to identify potential determinants of variation in non-conveyance and how these affected non-conveyance rates. We were then able to test some of these in the quantitative analyses in WP2 and WP3 for which data were available. We also analysed the qualitative interviews in WP1 by ambulance service – treating each ambulance service as a ‘case’ – to identify organisational characteristics of ambulance services for testing as factors in WP2 and WP3.

-

We triangulated findings from the qualitative and quantitative WPs. After analysis of all WPs, integration of findings from all WPs occurred using an adapted triangulation protocol. 43,44 The qualitative interviews in WP1 helped to draw attention to potential factors affecting non-conveyance that were not tested quantitatively, and helped to identify how factors affected non-conveyance or how factors tested in the quantitative study might not capture the complexity of an issue. Thus, the qualitative interviews often facilitated interpretation of some of the quantitative findings. This integration is reported in Chapter 10. The report discussion in Chapter 11 is based on insights from Chapter 10. This integration also resulted in the reporting of some findings from the WP1 qualitative study alongside findings from the WP2 and WP3 quantitative WPs in Chapters 5–7 because they related to the content of these chapters.

-

We brought together all the potential factors affecting non-conveyance within a conceptual framework constructed from all WPs of the study. 40 This is reported in Chapter 10.

-

We undertook a multiple case study analysis in Chapter 10 by summarising findings about each ambulance service in a matrix and considering patterns across cases with different rates of non-conveyance. 45

Presentation of findings

Mixed methods research can be reported in different ways. 46 One approach is to report each WP in separate chapters and then present an integration chapter towards the end of the report. Another approach is to identify themes (usually related to research questions) and present each theme in a chapter, integrating qualitative and quantitative data or findings within each chapter. The first approach was undertaken here because each WP addressed different research questions. However, a small number of themes from the qualitative research in WP1 were highly relevant to findings in the quantitative WP2, WP3 and WP4.2. Because of this, small amounts of qualitative research are reported in largely quantitative report chapters (see Chapter 5, Results, Chapter 6, Results, Chapter 7, Findings, and Chapter 9, Findings). The presentation of findings is summarised in Figure 1.

Patient and public involvement

A patient and public involvement (PPI) representative (MM) was a co-applicant and she attended monthly project management meetings. Enid Hirst, who is a long-standing member of the Sheffield Emergency Care Forum, joined the Project Advisory Group which met four times over the project. A PPI group was established for the project. PPI members from the field of emergency and urgent care from three ambulance services met together three times a year to discuss planned data collection, emerging findings, interpretation and dissemination. The impact of PPI on the research is summarised in Chapter 11, Discussion.

Ethics and approvals

We obtained approval from the National Research Ethics Service Committee North West – Greater Manchester West (REC reference number 14/NW/1388).

We sought guidance from the Confidentiality Advisory Group of the Health Research Authority for the reuse of the linked data set created as part of the Pre-Hospital Outcomes for Evidence Based Evaluation (PhOEBE) study. As the subset of data used in the variation in ambulance non-conveyance (VAN) project was pseudonymised and there were no other identifiable data being used within the study, we were advised that an application to the Confidentiality Advisory Group was not necessary. We obtained permission to reuse the linked data set created as part of the PhOEBE study through NHS Digital’s Data Access Request Service.

Project Advisory Group

The Project Advisory Group was chaired by Professor Tom Quinn, a leading researcher in pre-hospital care. Members included Liz Harris (a paramedic), Mark Docherty (a director at an ambulance service) and Enid Hirst (a PPI representative).

Terminology and definitions

International differences in terminology

Terminology relevant to this topic differs by country. Ambulance service provision (the term used in this report) is also known as Emergency Medical Services or pre-hospital care internationally. In the UK, ambulance services are known as Ambulance NHS Trusts. Non-conveyance (the term used in this report) may be called non-transport in other countries. Telephone advice (the term used in this report) can be known as secondary telephone triage whereby patients are triaged over the telephone by a clinician after their initial triage by a call-handler. Different terms can be used to describe staff working in ambulance services. We use the term ‘call-handler’ for staff taking initial 999 calls, ‘clinicians’ for staff offering telephone advice in the clinical hub of an ambulance service, and ‘crew members’ or ‘paramedics’ for staff making decisions to discharge patients at scene or convey them to a health-care facility.

Variation in definitions used by ambulance services, national quality indicators and this study

‘Hear and Treat’ is a term used in England to describe a key type of non-conveyance, whereby a call-handler triages patients to receive advice from a clinician working within the ambulance service dispatch centre, sometimes called a clinical hub. The clinician may give information or advice to self-manage or make a formal referral to an alternative service (this last option can be called ‘Hear, Treat and Refer’.) Clinicians may also return calls for the dispatch of an ambulance if they decide that this is necessary, resulting in conveyance to an emergency department or an alternative service. The AQI definition in England for ‘Hear and Treat’ is ‘Of calls that receive a telephone or face-to-face response, proportion resolved by telephone advice (Hear and Treat)’. This includes calls ending in telephone advice by call-handlers as well as clinicians. In this study we use the terms ‘calls ending in telephone advice’ or ‘telephone advice only’, which are similar to the AQI definition. We do not use the term ‘Hear and Treat’ because it has a variety of meanings. ‘Telephone advice only’ calls in our study include whatever ambulance services included in their AQIs. They include calls for which an ambulance was not dispatched either by call-handlers or by clinicians in the clinical hub. Our attempts to identify calls ending in telephone advice by clinicians only, and to consider variation between ambulance services for rates of these calls, were not successful (see Chapter 5, Methods).

‘See and Treat’ is a term used in England to describe a key type of non-conveyance. Ambulance services dispatch an ambulance and attending crew members may discharge patients at scene with treatment, information or advice, or formally refer patients to another service. In such cases, patients are not conveyed anywhere by ambulance. The related AQI is ‘Of calls that receive a face-to-face response from the ambulance service, proportion managed without need for transport to Type 1 and Type 2 A&E’. This includes ‘See, Treat and Convey Elsewhere’ calls, which may end in transport by ambulance to a range of services other than an emergency department. In practice, ambulance services calculate this AQI based on calls for which an ambulance is dispatched but the patient is not transported to a hospital with an emergency department. People who are not conveyed because they have died are included in this indicator because they have not been conveyed to an emergency department by an ambulance. In our study we successfully distinguished patients discharged at scene from those transported to alternative services and label these ‘discharged at scene’ rather than ‘See and Treat’. These ‘discharged at scene’ patients include those who are referred to alternative health and social care services but not transported to them.

In our original research proposal we planned to explore the separate group of patients to whom an ambulance is dispatched and who conveyed to a service other than an emergency department. We were interested in these ‘See, Treat and Convey Elsewhere’ responses because of the potential benefits of not conveying patients to emergency departments, and because conveyance to lower acuity services such as minor injury units and urgent care centres posed a potential risk to patient safety. We were able to identify these calls but also learnt enough about the mix of patients within this type of ‘conveyance but not to an emergency department’ to stop at a descriptive analysis (see Chapter 5, Results).

Finally, some paramedics have advanced skills that allow them to administer a wider range of medications, undertake more advanced assessment and diagnosis, and deliver a wider range of treatments than paramedics. They have a number of labels within England and internationally. In this report we call them ‘advanced paramedics’.

Definitions of terms used are summarised in the Glossary.

Contextual factors potentially affecting non-conveyance over the study period

Over the time of the study, AQIs changed for some ambulance services. We considered this in our analyses and interpretation of findings. In January 2015, the Secretary of State for Health approved a trial of Dispatch on Disposition within the NHS England Ambulance Response Programme, allowing up to three additional minutes for making a dispatch decision with the intention that this could allow ambulance call-handlers more time to assess the clinical situation and determine the type of response needed. This started in two ambulance services in February 2015 and in October 2015 was extended to an additional four ambulance services. This had the potential to affect telephone-advice-only rates as ambulances were not sent early in the call process. This contextual change occurred after the time period covered by our routine data (November 2014).

Changes to the planned research

Most of the study was delivered as planned. However, it was not possible to deliver everything set out in the original proposal. Changes are summarised in Appendix 1.

Anonymity

We aimed to maintain anonymity of interviewees in the qualitative WPs of the study (WP1 and WP4.1). The best way of doing this was to report quantitative as well as qualitative findings for ambulance services labelled A to J. Because some ambulance services have very high or very low rates of non-conveyance, it is possible to identify them from the quantitative findings. To make the identification of services and individuals more difficult, we sometimes exclude labels for ambulance services from figures and quotations within the report, or use ‘H’ or ‘L’ to indicate high or low rates of a factor rather than give the actual rate. We also use different labels for quotations from the qualitative research at different times in the report, sometimes using the service the interviewee worked in and sometimes using the interviewee’s role. Although this looks like inconsistent labelling, it has been undertaken deliberately to preserve anonymity.

Chapter 3 Description of variation in non-conveyance rates measured by Ambulance Quality Indicators

Background

Ambulance Quality Indicators are published monthly for each of the 11 ambulance services in England. 2 Four of these AQIs relate to non-conveyance:

-

Of calls that receive a telephone or face-to-face response, the proportion resolved by telephone advice. This excludes calls that have been passed from NHS 111.

-

Of calls that receive a face-to-face response from the ambulance service, the proportion managed without the need for transport to Type 1 and Type 2 emergency departments. This includes face-to-face responses as a result of NHS 111 calls. Calls not transported to hospitals with Type 1 and 2 emergency departments are included, that is, patients discharged at scene and those conveyed to other health-care facilities (sometimes called ‘See and Convey Elsewhere’).

-

Of emergency calls closed with telephone advice, the proportion recontacting the same ambulance service via 999 within 24 hours. This excludes calls that have been passed from NHS 111.

-

Of patients treated and discharged on scene, the proportion recontacting same ambulance service via 999 within 24 hours. This excludes calls that have been passed from NHS 111.

Variation in non-conveyance Ambulance Quality Indicators over time

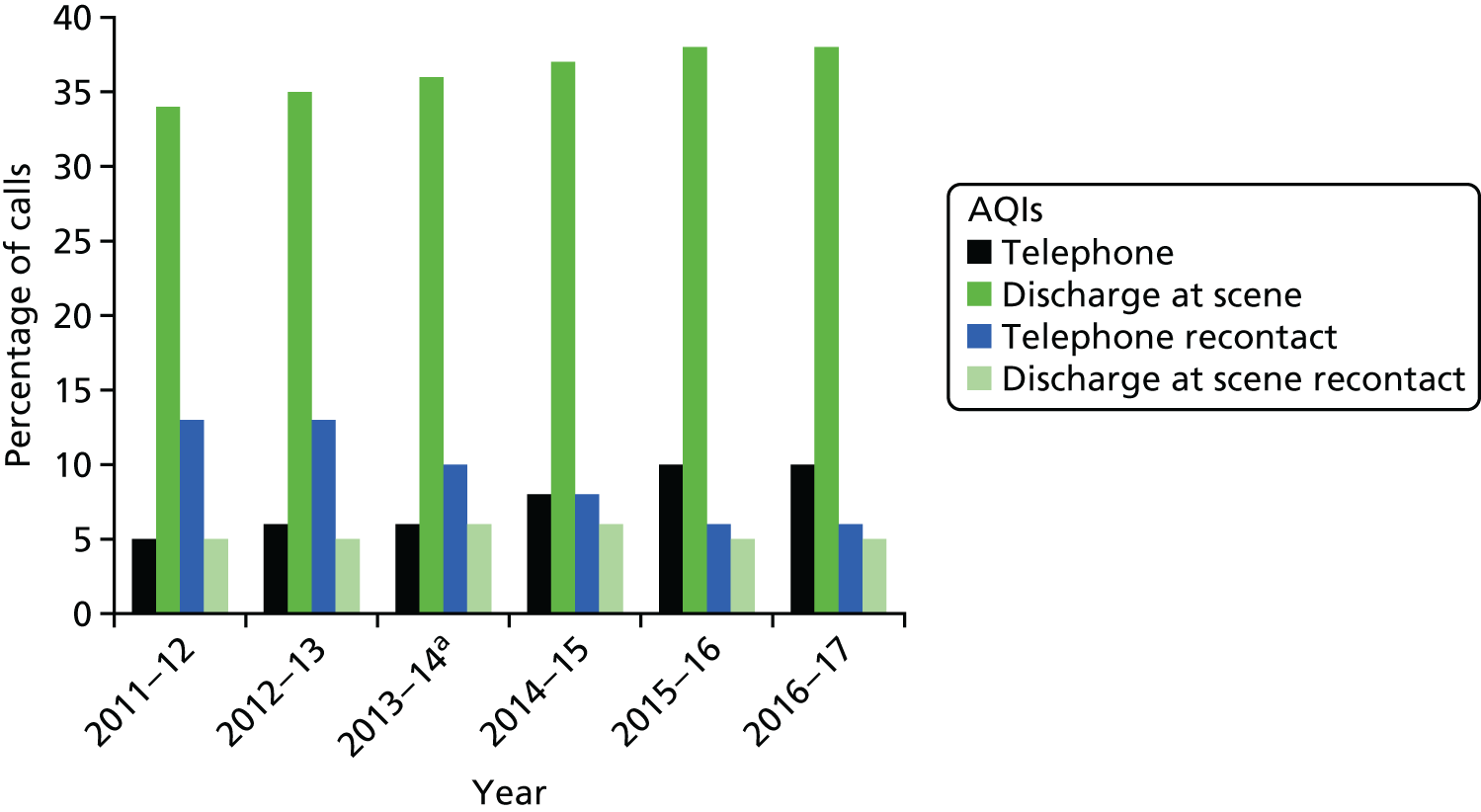

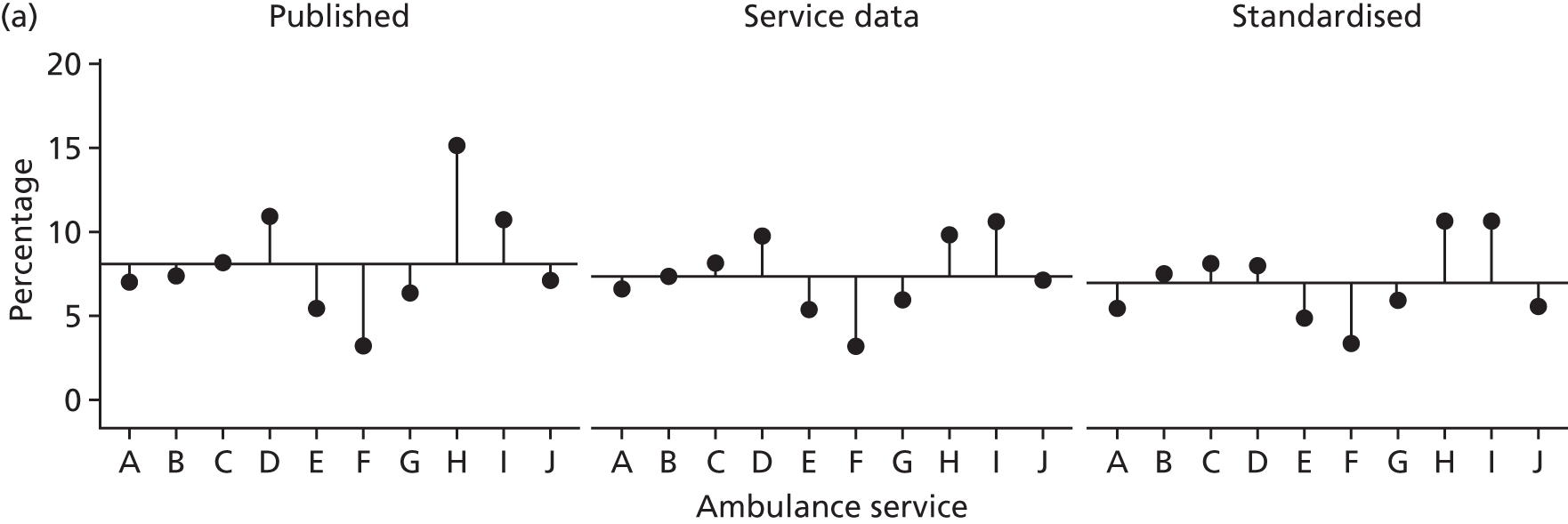

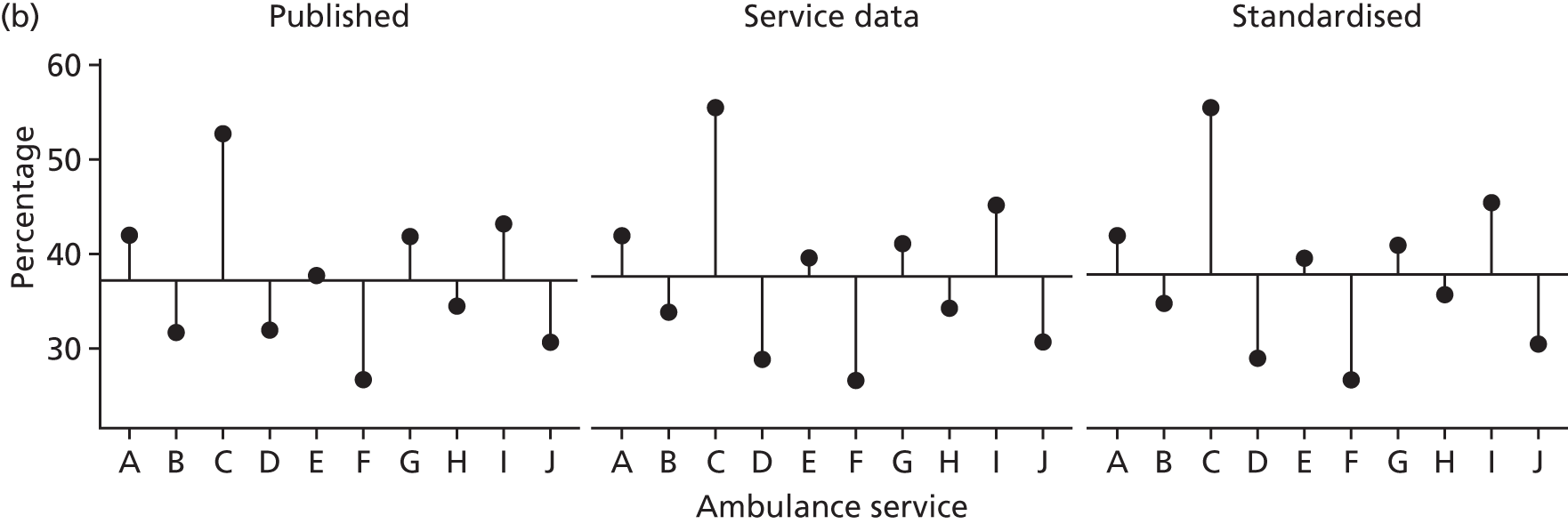

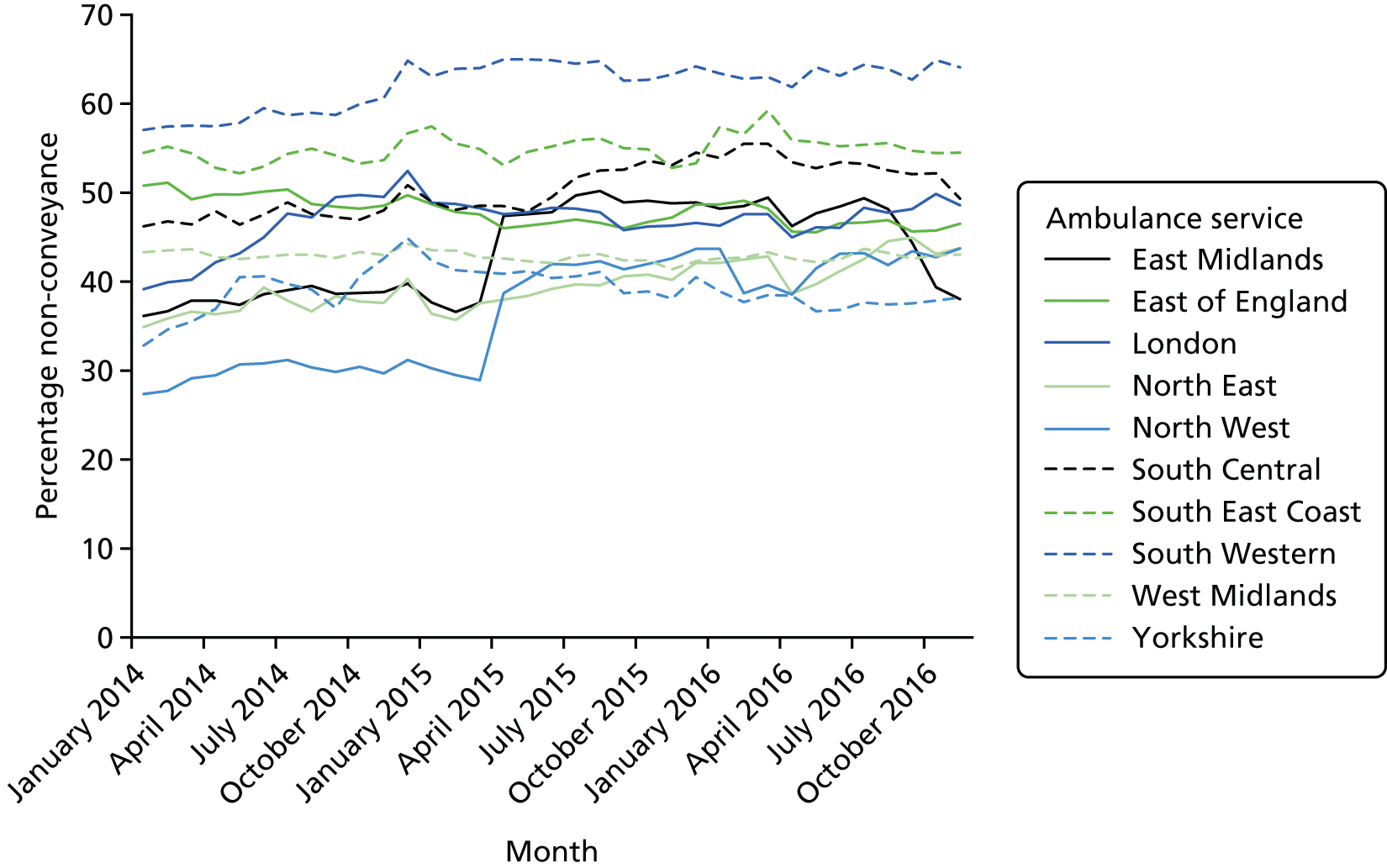

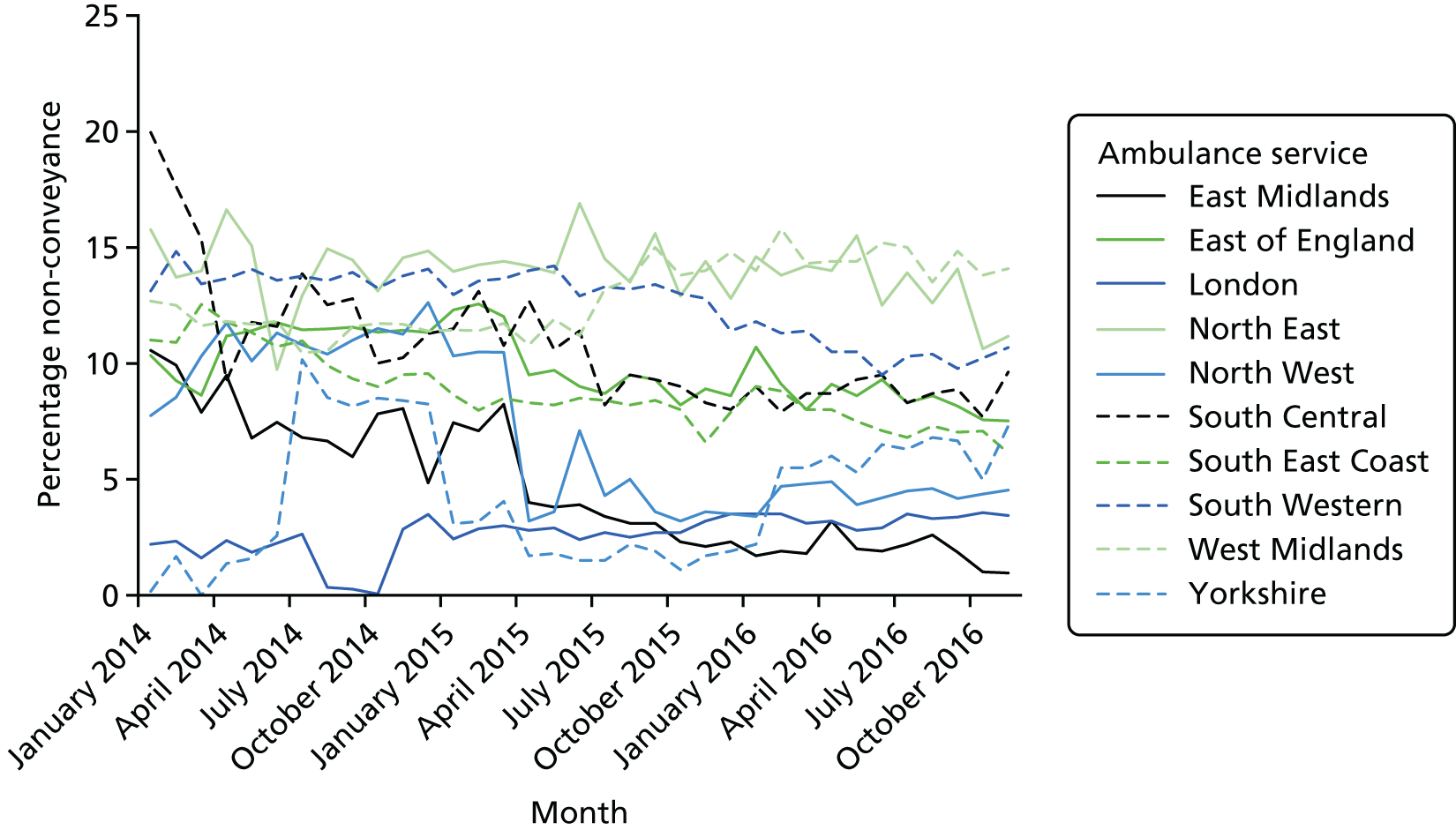

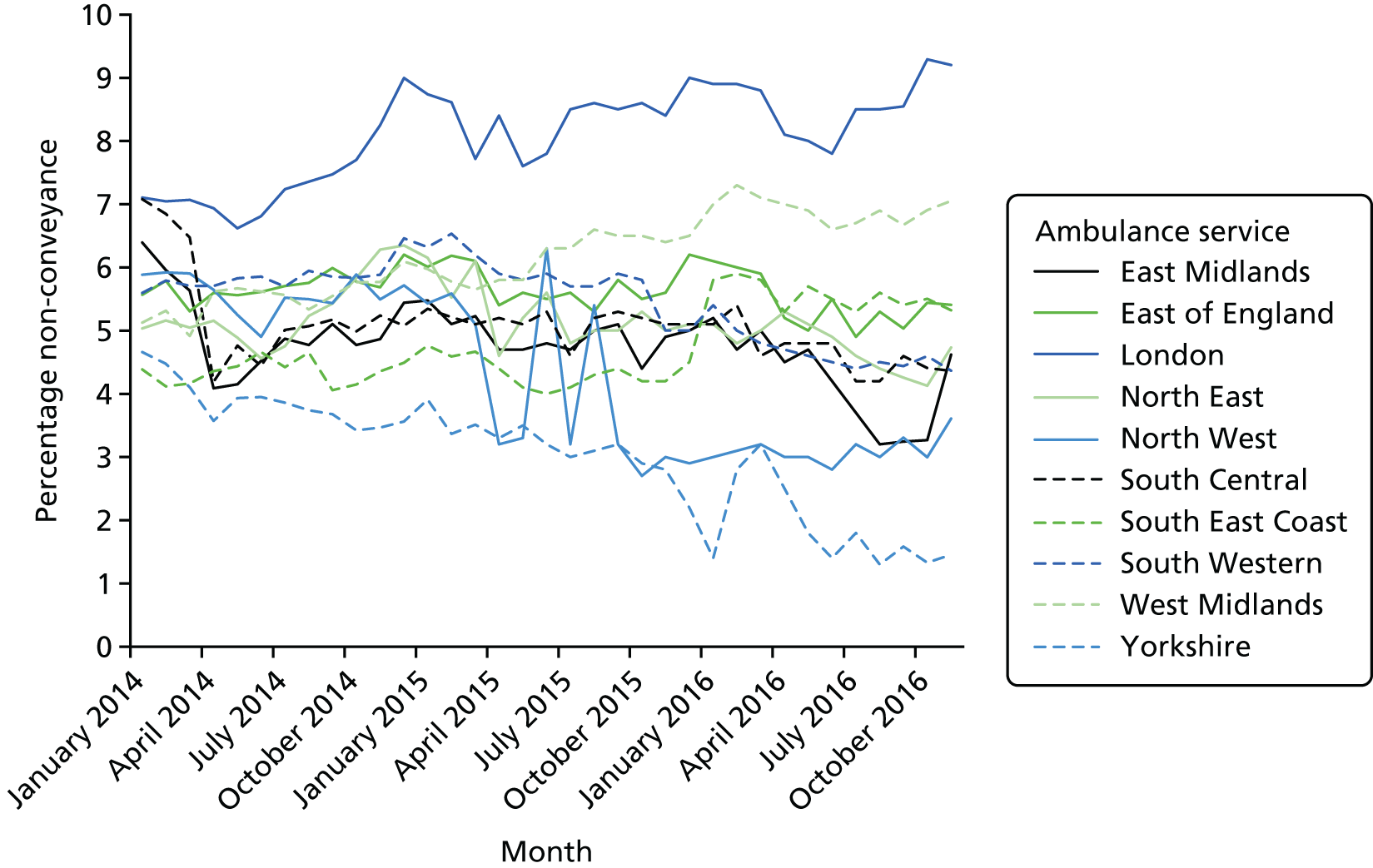

According to the published AQI data, the proportion of calls ending in telephone advice doubled to 10% and the proportion of calls sent an ambulance and not conveyed to an emergency department in England steadily increased to 38% between 2011 and 2016 (Figure 2). Twenty-four-hour recontact rates with the ambulance service decreased over time to 6% for calls ending in telephone advice and remained stable at around 5% for calls sent an ambulance but not conveyed to an emergency department.

FIGURE 2.

Variation in AQIs over time. a, Definitions of AQIs change in May 2013.

We considered seasonal variation in AQIs for England (not displayed here). The only seasonal effect noticeable in monthly data was a small peak in activity for the proportion of patients not conveyed to an emergency department during December of each year.

Variation in Ambulance Quality Indicators between ambulance services

There are 11 regional ambulance services providing care to the population of England. We decided to exclude one ambulance service offering provision to the small population of the Isle of Wight because of the relatively small number of calls it responds to compared with the other ambulance services (e.g. in September 2016, 1768 calls compared with 19,908 calls in the next largest service).

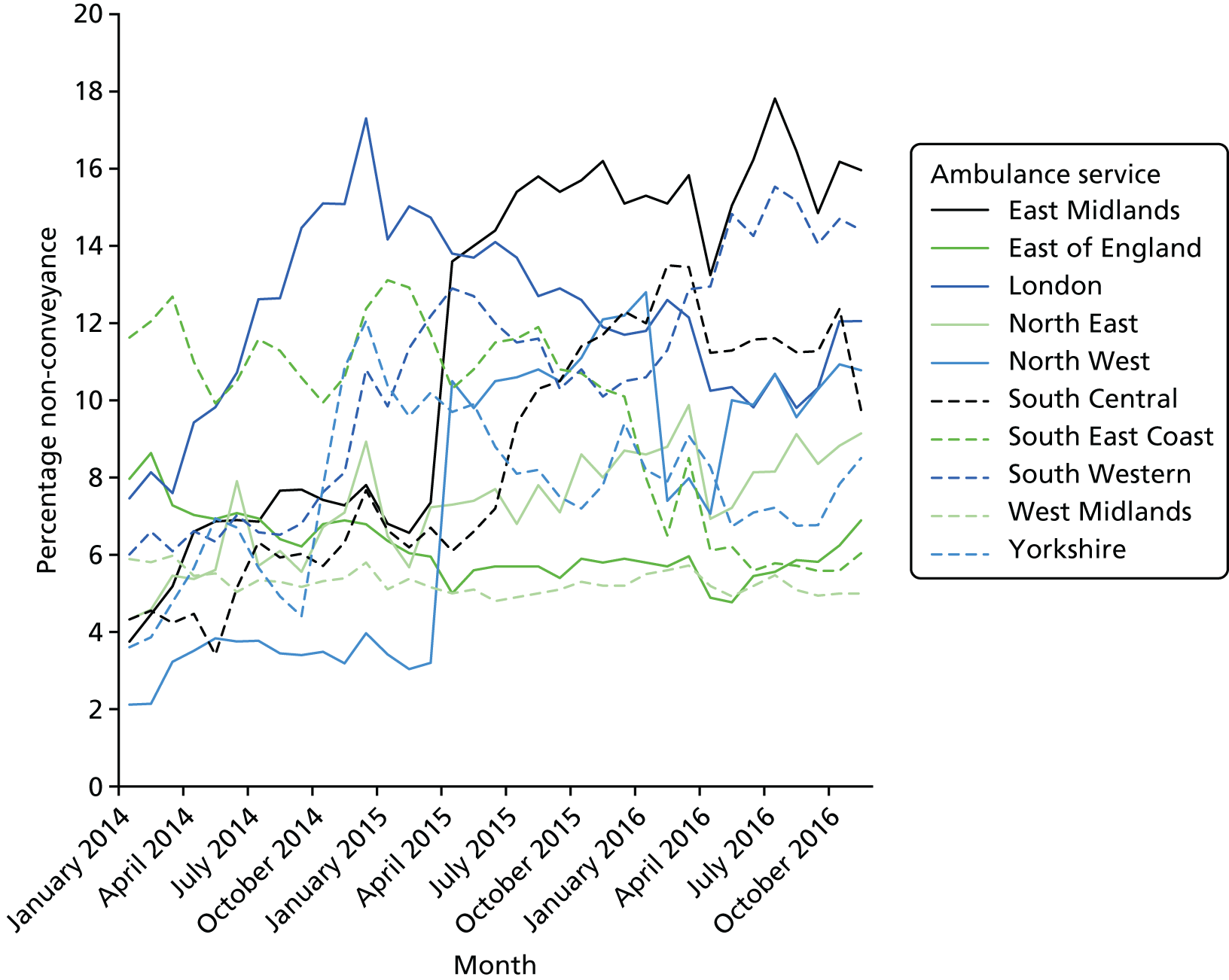

Non-conveyance rates

Variation between ambulance services for the rate of calls ending in telephone advice was threefold in November 2014 when the data for WP2 were obtained (Figure 3). The level of variation between services was similar over time, although the ranking of services was not consistent over time. There were a number of sudden shifts in rates for individual services, in particular for the Yorkshire Ambulance Service, North West Ambulance Service and East Midlands Ambulance Service. We know through another research study that in April 2015 the North West Ambulance Service stopped following national guidance and started to include hoax calls and calls closed by call-handlers (Janette Turner, University of Sheffield, 2017, personal communication). Although our analysis in WP2 was based on data prior to these sudden shifts, this indicates that individual ambulances services can change the way they calculate AQIs, which may not necessarily reflect their rate of non-conveyance.

FIGURE 3.

Variation between 10 large regional ambulance services in England: AQI percentage of calls ending in telephone advice.

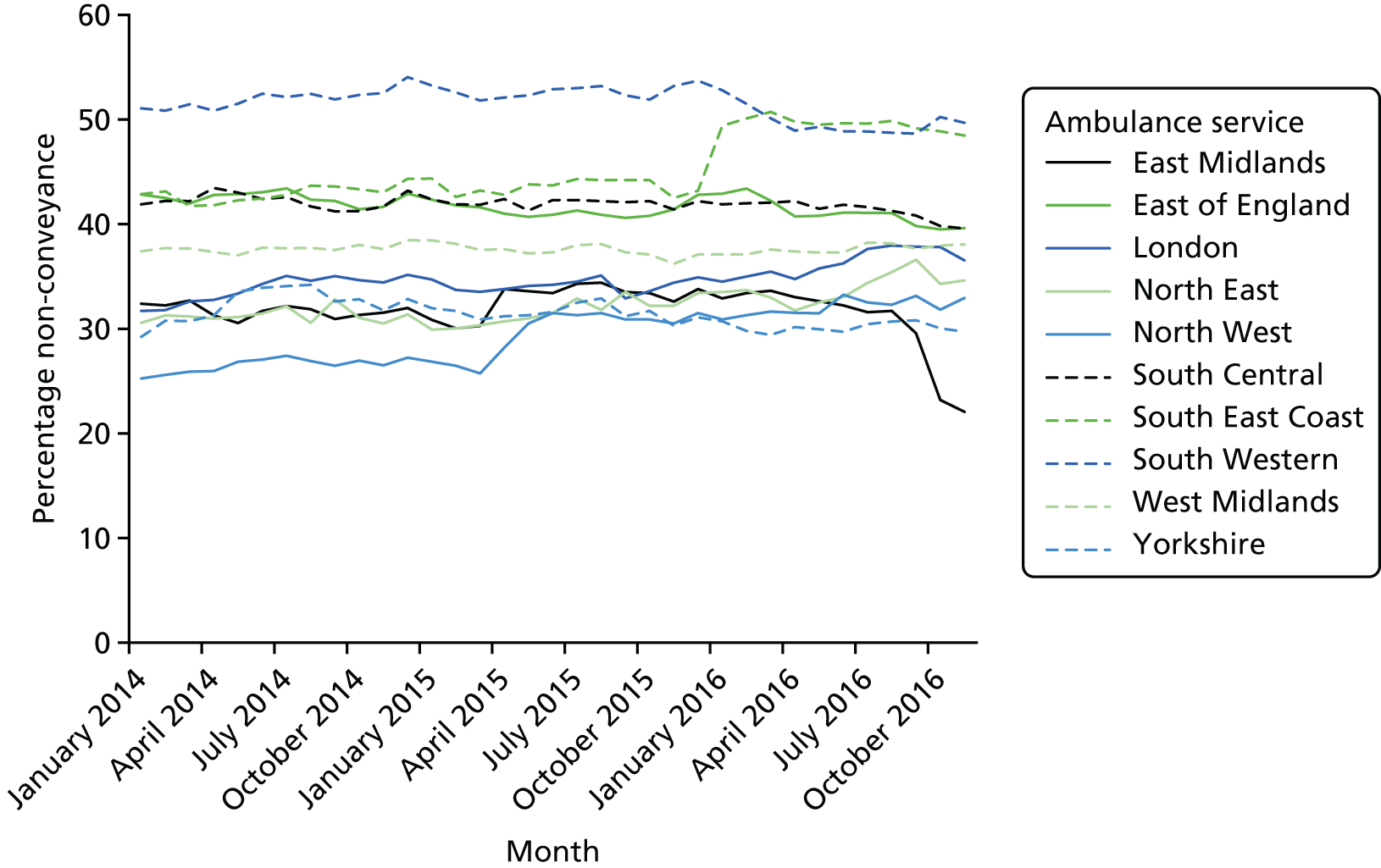

Variation between ambulance services for the rate of patients receiving an ambulance but not being conveyed to an emergency department was twofold in November 2014 when the data for WP2 were obtained (Figure 4). These calls were largely made up of patients who were discharged at scene. The variation between services was reasonably consistent over time, with services largely maintaining the same rank over time. One ambulance service had a much higher rate than the others and one had a much lower rate than the others throughout 2014. There were some sudden shifts in the AQIs for some services. This could indicate a change in the way an AQI was calculated by a particular ambulance service or a change in non-conveyance rates. Sudden shifts are likely to be related to changes in calculations, whereas slow shifts over time are more likely to be related to changes in practice. South East Coast Ambulance and North West ambulance services had sudden shifts in rates, suggesting that rates were calculated differently over this time period.

FIGURE 4.

Variation between 10 large regional ambulance services in England: AQI percentage of calls ending in non-conveyance to emergency department (most of these are discharge at scene).

Variation in total non-conveyance was calculated crudely by adding the two AQIs together, namely the percentage of telephone advice calls and the percentage of non-conveyance to an emergency department. A graph similar to those in Figures 3 and 4 was constructed and this is displayed in Appendix 2. It shows that there was a twofold difference in total non-conveyance rates between services over time, with one service having a consistently higher rate than others over time.

Recontact rates

Variation in recontact rates for the two types of non-conveyance are shown in Appendix 3. There was fivefold variation between ambulance services in recontact rates for calls ending in telephone advice. One service had a consistently high recontact rate and another had a consistently low recontact rate. There was twofold variation between ambulance services for recontact rates when an ambulance was dispatched but patients were not conveyed to an emergency department.

Relationship between non-conveyance and recontact rates

It was not the case that services with high non-conveyance rates also had high recontact rates. For example, in November 2014 when the data for WP2 were obtained, the service with the highest AQI rate for telephone advice had a 3% recontact rate compared with an 11% recontact rate for the service with the lowest AQI. The services with the highest and lowest AQI rates of non-conveyance to an emergency department once an ambulance had been sent had the same recontact rate of 6%.

Discussion

Summary of findings

Ambulance Quality Indicators showed considerable variation between ambulance services in both non-conveyance rates and recontact rates within 24 hours of non-conveyance. Sudden shifts in monthly AQIs for specific services raised concerns about the extent to which AQIs represent the actual non-conveyance rate within an ambulance service, particularly for calls ending in telephone advice.

Implications for the empirical study

-

AQI non-conveyance rates changed over time for individual services so we documented when data collection occurred for different WPs of the study and the AQIs for that time period to help interpret the findings:

-

April–December 2015 (WP1 interviews in Chapter 4)

-

November 2014 (WP2 routine data in Chapters 5 and 6)

-

January–June 2013 (WP3.1 linked data in Chapter 7)

-

November 2015–September 2016 (WP4.1 observations and interviews reported in Chapter 8)

-

-

We needed to select a month of ambulance service routine data to analyse for WP2 and WP3.1. At the start of the study in January 2015 we decided to select the latest month available. However, we avoided December 2014 because of small peaks in published AQI non-conveyance rates in December each year. We selected November 2014 instead.

-

One of the 11 services is very small so the study focused on the 10 larger services in England only. Including the small service would introduce uncertainty related to small numbers in the quantitative analyses in WP2 and WP3.1.

-

Sudden changes in monthly rates for individual ambulance services raised concerns about the AQI data, particularly for rates of calls ending in telephone advice.

Chapter 4 A qualitative interview study of stakeholders’ perceptions of non-conveyance (Work Package 1)

Background

The aim of this WP was to explore stakeholders’ perceptions of different types of non-conveyance and potentially inappropriate non-conveyance. These interviews were a source of perceptions of factors affecting non-conveyance rates generally, and perceptions of non-conveyance within each of the ambulance services.

Methods

Design

We undertook a qualitative interview study with three key stakeholder groups: (1) ambulance service managers, (2) paramedics and (3) commissioners. We selected these three groups because ambulance service managers can shape strategic decisions that affect non-conveyance at an organisational level, such as workforce configuration or investment in staff training; paramedics make daily decisions about whether or not to convey patients and can offer views on patient characteristics, workforce practices and organisational factors affecting non-conveyance; and commissioners can encourage ambulance services to undertake non-conveyance by setting targets for non-conveyance rates within contracts and offering additional investment for non-conveyance initiatives. We supplemented these interviews with documentary analysis and sent a request to each ambulance service for information about resources within each organisation.

Data collection and sampling for the interviews

We undertook semistructured interviews with staff and commissioners from all 10 ambulance services. Our intention was to undertake around five interviews per service with staff in the following roles:

-

ambulance service managers – a manager who dealt with non-conveyance and a director-level member of staff to address operational and strategic levels of the organisation

-

paramedics – an advanced paramedic and an entry-grade paramedic with no less than 1 year’s experience post qualification to include different levels of expertise

-

commissioners – the ambulance service lead commissioner

We identified a local collaborator in each service who helped to identify relevant staff for interview. In addition, managers or team leaders sent out recruitment e-mails and the study information to their teams to recruit paramedics. We contacted the relevant CCG for each ambulance service to request an interview with the ambulance service lead commissioner. Each potential interviewee was contacted by e-mail and formally invited to take part in the study. Non-responders to our initial invitation were contacted again within 1 month.

Following receipt of written informed consent, we undertook semistructured interviews mainly by telephone, although a small number of early interviews were undertaken face to face while we tested out the topic guide. One researcher undertook all the interviews. 18 The interviewer was blind to the non-conveyance and recontact rates of the interviewee’s organisation throughout data collection. The same topic guide was used for all participants and was developed based on our research objectives and discussion at our project management group. The topic guide covered perceptions of factors that affected non-conveyance at a local level, and those that were perceived to have an impact on appropriateness of ambulance non-conveyance (see Appendix 4). Interviews were digitally recorded and lasted between 40 and 90 minutes.

Data collection using documents

Prior to starting our research, we identified a number of organisational factors that might explain variation in non-conveyance rates. We were interested in organisational responsibilities and resources such as whether the ambulance service was a provider of the NHS 111 telephone service, and numbers of advanced paramedic and clinical hub staff. While analysing WP1 interviews we identified further organisational issues that we wished to measure for use in our quantitative analysis of variation in WP2 and WP3. We had intended to collect information from services using a pro forma. In practice we identified information from each ambulance service’s annual report where possible (for the period 2014–15),47–56 and where information was missing we sought to identify it from our study contact at each ambulance service. We sought information for 2014 because our quantitative data in WP2 and WP3 were for November 2014 (see Chapter 5). We identified the following characteristics as being of potential interest: population size, geographical size, software used, whether or not the ambulance service was a provider of NHS 111, the number of ‘advanced paramedics’, staff skill-mix, staff turnover, sickness absence rates, income, type of contract with commissioners, system complexity (number of CCGs/NHS acute trusts), and numbers of complaints/serious events.

We had concerns about the consistency of the information collected from documents and our contacts. When the recent National Audit Office (NAO) report was published we chose to use the information within it about individual ambulance services instead,1 with the proviso that the data were for the later period (2015–16) rather than for 2014.

Analysis

We transcribed the digital recordings of interviews verbatim. A researcher checked each transcript for accuracy by listening to the recording and correcting mistakes or filling in gaps where possible. We analysed all interviews using framework analysis. 57 First, we familiarised ourselves with the interviews by reading a sample of transcripts. Second, we developed a thematic framework based on our research questions, the topic guide and reading a sample of transcripts (EK, LBE). The thematic framework consisted of descriptive rather than conceptual themes, including types of non-conveyance, views of rates, calculation of rates, national drivers, local drivers, organisational drivers, collaborative working, workforce issues (skill-mix, culture, working patterns), triage software, patient characteristics, defining and measuring appropriate non-conveyance, commissioning, and respiratory problems. Third, we coded all transcripts to the framework, adding further emergent themes and subthemes throughout the process of coding transcripts. Three researchers undertook the coding (LBE, FF, and NA) using the qualitative software package NVivo (QSR International, Warrington, UK). Lindsey Bishop-Edwards led the process, working closely with Nisar Ahmed and Flavia Saraiva Leao Fernandes to ensure consistency of coding.

One researcher (EK) led the analysis supported by Lindsey Bishop-Edwards. Emma Knowles read extracts of transcripts within a theme within each service. She analysed the overarching theme and documented the variation in perceptions within each ambulance service, discussing findings with Lindsey Bishop-Edwards and Alicia O’Cathain. She repeated this for further themes, considering the connections between themes and refining the thematic framework by collapsing some themes together (e.g. the themes of ‘collaborative working’ and ‘the emergency and urgent care system’ were so interrelated that these were brought together).

The focus of the study was variation between ambulance services. A key difference between our analysis and the analysis for a standard qualitative interview study was the additional process of treating ambulance services as cases within the analysis, which resulted in the need to analyse and present data by ambulance service for use in the quantitative analysis in WP2 and WP3 and in the multiple case study comparison in Chapter 10. 45 A matrix was developed with ambulance services as columns and themes and subthemes as rows. Emma Knowles summarised variation in perceptions about a theme or subtheme on this matrix to allow the team to consider patterns of themes within and across ambulance services. This was undertaken blind to the non-conveyance rates. When this matrix was complete, the AQI non-conveyance rates at the time of the interviews were added to the matrix to consider patterns by non-conveyance rates. We then added data to this matrix from our documentary analysis/the NAO report1 for use in an analysis reported in Chapter 10.

Findings

Sample description

We planned to interview around 50 stakeholders. We formally invited 80 individuals to be interviewed, and undertook 50 interviews with those who consented. The main type of stakeholder who did not agree to interview was paramedics (see Appendix 5). On average we interviewed five members of staff working in, or commissioning, each of the ambulance services, ranging between four and seven participants per service. A complete range of stakeholders was obtained in eight services. Of the remaining two services, we were unable to include one of the two managers and one of two paramedics. The digital recording of one interview (a paramedic) was of such poor quality that we were unable to transcribe it and therefore did not include this in our analysis. In total, 49 of the interviews undertaken were analysed.

Interviewees identified a range of factors that they perceived to affect non-conveyance. These are summarised in Table 1. Factors that we could measure in WP2 (see Chapter 5) are simply listed here. Factors that could not be measured, and instances in which there was evidence of variation in perceptions between ambulance services, are detailed in this chapter.

| Level of factor | Factor | Details of how the factor affects non-conveyance | Tested in WP2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient | Age | Children and elderly people were discussed. Non-conveyance is lower for children because of the need to offer reassurance to parents. Mixed views on elderly people depending on complexity of health problems and social support | Yes |

| Deprivation | People from deprived areas more likely to want to go to hospital, to have to go to hospital because of higher levels of morbidity, or not to be registered with a GP so use ambulance service as primary care, leading to lower non-conveyance rates | Yes | |

| Rurality | People in rural areas do not want to go to hospital because of long distances so non-conveyance rates are higher. People living near hospitals prefer to be conveyed because it is easier than alternatives. Easier for ambulance services to convey if a hospital is nearby, leading to lower non-conveyance rates in urban areas | Yes | |

| Language barriers | Demand for ambulance services higher when patients have difficulty speaking English because they do not use alternative services. No mention of effect on non-conveyance | Yes | |

| Living alone | People who are lonely may be frequent callers to the ambulance service. Elderly fallers with no social support will be conveyed. So, if patients live alone, may have lower non-conveyance rates | Yes | |

| Poor housing | People living in chaotic situations less likely to be left at home so lower non-conveyance rates | Yes | |

| Suffering from long-term illness | People with mental health problems and diabetes mellitus can be frequent callers. Unclear effect on non-conveyance rates | Yes | |

| Expectations | See Chapter 4, Findings | No | |

| Call | Reason for calling | Falls, mental health problems and long-term conditions discussed, but these have an unclear effect on non-conveyance rates | Yes |

| Source of call | NHS 111 discussed, but has an unclear effect on non-conveyance rates | Yes | |

| Day/time of call | Family and some services not available out of hours, so non-conveyance rates lower out of hours | Yes | |

| Organisational | Triage system used | NHS Pathways described as risk averse, but has an unclear effect on non-conveyance rates | Yes |

| Motivation to undertake non-conveyance | See Chapter 4, Findings | Yes | |

| Stability | See Chapter 4, Findings | Yes | |

| Skill mix of workforce | See Chapter 4, Findings | Yes | |

| Experience of clinical decision-maker | See Chapter 4, Findings | No | |

| Support for workforce | See Chapter 4, Findings | Yes | |

| Emergency and urgent care system | Connectivity with other services in the system | See Chapter 4, Findings | Yes |

| Availability and accessibility of onward referral services | See Chapter 4, Findings | Yes | |

| Pressure at emergency departments (i.e. long handover times) | See Chapter 4, Findings | No | |

| Complexity of system | See Chapter 4, Findings | Yes | |

| National | Training of paramedics | See Chapter 4, Findings | No |

| Response-time targets | See Chapter 4, Findings | No | |

| Commissioning | See Chapter 4, Findings | Yes |

Patient-level factors: patients’ expectations

Some interviewees – mainly paramedics and managers – perceived that a range of patient characteristics influenced decision-making for non-conveyance (see Table 1), with no discernible variation in perceptions across the 10 ambulance services. A key issue, which we were unable to test in WP2 (see Chapter 5), was patients’ and their families’ expectations that an ambulance would be dispatched and patients transported to hospital. Interviewees described trying to persuade patients calling for an ambulance to seek help from other services, or make their own way to an emergency department, and noted the problem of formal complaints arising when patients did not have their wishes met:

[. . .] some people ring an ambulance and they want an ambulance and they want to go to hospital [. . .] so when you’ve assessed them and done everything and said actually, you don’t actually need to go [to an emergency department], you can go to your GP or your walk-in centre or something, some of them are a little bit off, put out a little bit, you know, well ‘I was wanting to go to hospital’. Some people that it doesn’t matter, how hard you try to explain to them that they don’t need to go to hospital [. . .] they insist that they want to go to hospital [. . .] then you’ve got, you’ve got no alternative choice, you know they have to go.

Paramedic, interviewee 41

For patients who had prior experience of non-conveyance, interviewees perceived that patients were receptive to discharge at scene and welcomed the tasks that paramedics undertook on their behalf, such as arranging a GP appointment. One interviewee expressed the concern that the popularity of discharge at scene with patients might lead to supply-induced demand from people who did not need an ambulance:

I think the patients see that they’re getting a lot within the [non-conveyance] encounter. Obviously they get more assessments than they’d get at a GP practice and they get it all in one go whereas a GP practice might bring you back for your 12-lead ECG [electrocardiogram] the next day or oxygen saturations or blood glucose test thing. Those are all sorts of things that they’d send a patient away for, then do at a later date unless they are critically ill. I think some of our ‘See and Treat’ activity going up isn’t due to us being able to deliver higher levels of care [. . .] they were never appropriate for an ambulance service.

Manager, interviewee 37

There was some suggestion that expectations differed by patient characteristics. Patients living in rural areas were described as being more receptive to discharge at scene than those in urban areas, because of the inconvenience of travelling a long distance to an emergency department and arranging their return home from that hospital facility. This was in contrast to patients living in areas of social deprivation whom interviewees perceived as more likely to expect transport to an emergency department:

[. . .] two hospitals, one is about 37 miles in one direction, and the other is about 30-something miles in the other direction, so there’s quite long distances involved. So actually people would prefer to be treated at home. There’s an expectation ‘well I only live down the road from the hospital so you’re going to take me there aren’t you’ there is the opposite here. So, you know, there is a difference in expectations.

Paramedic, interviewee 17

[patients from] socially deprived areas tend to have much more comorbidities and are generally more complex patients. But also, quite often there is an expectation that they just want to go to hospital. It’s important that you discuss with the patient [what their] ideas, concerns and expectations are, and why it would be appropriate for them not necessarily to go to hospital.

Paramedic, interviewee 26

Organisational-level factors

Motivation to undertake discharge at scene

There was considerable variation in the way that interviewees within different ambulance services described their organisation’s approach to non-conveyance, from embracing it through to viewing it as extremely risky. Interviewees in most services discussed the need to change the culture both within their service and nationally from a service that transported all patients to an emergency department to one that focused on providing care closer to home. This appeared to be particularly high on the agenda of interviewees in one service (Service C), with interviewees expressing a strong belief in non-conveyance and describing actively pursuing a goal to improve or sustain non-conveyance rates within their organisation. This service appeared to be embracing non-conveyance across the whole organisation, with interviewees in both managerial and paramedic roles highlighting a ‘whole organisation’ approach to non-conveyance. Indeed, it was the only service in which the paramedics we interviewed offered positive views of the organisational support they received for non-conveyance. Interviewees in this service also described a historical commitment to non-conveyance, viewing it as part of the established culture within that service:

[. . .] back in 2006 we were leaving, looking at leaving more asthmatic patients at home, which no one else agreed with but actually that’s been a mainstay of what we’ve done and I think we’ve just had that culture a lot longer because staff back, almost a decade ago, were leaving people at home. Whereas in some services their non-conveyance rates are awful and I think their staff have still got to get their head around that’s what their job is.

Service C, interviewee 4

[. . .] across the Trust, trying to reduce non-conveyance rates, and it’s in our strategy as well, reducing conveyance rates now by 10% over the next 5 years and we’re all part of that and staff are aware of that and obviously working towards it.

Service C, interviewee 2

Interviewees within another service (Service I) also described their organisation as embracing non-conveyance but did so in terms of a recent development over the past few years and as an aspiration for the future. Both a paramedic and manager described a drive towards optimising non-conveyance in terms of vehicles, patients, equipment, service models, education and skills in the control room of this service:

[. . .] it’s growing in aspiration. See and Treat as a service is growing in aspiration and the infrastructure around to make that happen.

Service I, interviewee 21

Interviewees from other services either talked about the influence of organisational commitment to non-conveyance generally rather than specifically within their service (Services E and G) or expressed less enthusiasm regarding their organisation’s motivation to undertake non-conveyance (Services A, B, D, H), describing the organisation as having other priorities, or staff as being resistant or fearful of the risks involved:

[. . .] there’s a resistance within the organisation to change. It’s literally bizarre. They’re under pressure but they’re looking, they’re pushing in the wrong ways to get what they want really. They push a target of getting an ambulance to a scene but they don’t look at what happens when someone gets there, what’s the decision-making around what happens next.

Service A, interviewee 17

[. . .] even some of the team leaders that I know, their idea is ‘I’ve taken the majority of my patients to hospital, I’ve still got my job’, you know [. . .]

Service H, interviewee 44

Interviewees in one service (Service F) appeared to discuss non-conveyance differently from those in the other services because the discussion was largely about the risks of non-conveyance. In particular, one manager did not want to increase non-conveyance rates because of the risks involved to ambulance crews if something went wrong. The commissioner also viewed non-conveyance as a low priority within this ambulance service and a paramedic described it as a ‘new concept’ within this service:

The CCGs and the GPs, and everybody else hate us, because, we, I won’t release the crews to just leave people at home and make a call to a GP receptionist to say I’ve left this person at home because that crew member themself doesn’t realise what he’s doing there, he’s putting himself in the coroner’s court in a non-defendable position, so unless it’s a safe structured handover recorded and shared I won’t let it happen. The fact that it does happen all over the place is another matter and I’ll, when I go round other ambulance services I do think that this point is sometimes missed.

Service F, interviewee 39

Motivation for providing telephone advice

In two services (Services C and H) there was a significant amount of discussion in relation to telephone advice. Interviewees spoke enthusiastically about the provision of telephone advice as a specialist service and perceived this initiative to be working well within their organisations. In Service C, interviewees attributed some of their success to being part of a pilot service offering longer telephone time for triage prior to dispatching an ambulance; they felt that this was increasing their rates of calls ending in telephone advice. In both services managers discussed a historical and continuing strategic vision to increase telephone advice rates through significant investment of resources in the clinical hub. One interviewee discussed a potential negative consequence of the success of their telephone advice strategy, namely supply-induced demand, with an increase in ambulance service callers seeking telephone advice:

[. . .] we have had people calling up specifically asking to speak to the clinical hub after previously being handled very well which is obviously doing the paradoxical thing of increasing the call rate, which is not something we were particularly after.

Service H, interviewee 45

In contrast, in one service (Service E) there appeared to be a lack of motivation to focus resources on telephone advice within the service. A manager described how the service had opted for a minimal number of clinicians undertaking telephone advice, and noted that non-clinical staff were undertaking telephone advice decision-making. Another interviewee in this service appeared to suggest that telephone advice was not necessarily what patients wanted and would inevitably increase the workload for the service:

[. . .] with ‘Hear and Treat’, how many complaints do you want to deal with, what’s your appetite for dealing with high level of complaints? So very simply, the more non-conveyance you do the [more] dissatisfaction you will have. People have phoned 999, they didn’t phone 999 for a chat, they phoned 999 with an expectation that an ambulance was going to appear, otherwise you would have rung 111 for a chat.

Service E, interviewee 32

A negative view of telephone advice was also apparent among interviewees in Service A on account of the risks involved in making an assessment without being able to see a patient. In Service G there appeared to be some tension between the ambulance service and the commissioner regarding the provision of telephone advice. In comparing their telephone advice rates with those of other ambulance services, Service G interviewees felt that they could increase their telephone advice activity but this was dependent on additional funding from the commissioners. The ambulance service and commissioner were currently ‘in mediation’, with the commissioner suggesting that they did not have the resources to offer additional funding.

Organisational stability and workforce challenges

Interviewees described different organisational contexts at the time of the interviews. Some services appeared to be stable, with no significant restructuring within the service. However, interviewees in four services (Services A, H, I and J) reported current or recent operational restructure. Interviewees did not expand on how this might affect non-conveyance rates, but it is possible that the ability to innovate or address a range of organisational priorities might be affected by these changes. In addition, although interviewees from all services expressed concern about the recruitment and retention of paramedics, interviewees in three services (Services A, G and H) reported significant problems with recruitment and staff shortages, which they perceived to have a negative impact on the organisation’s ability to undertake discharge at scene:

[. . .] it’s been a difficult year last year because we were in such a difficult situation. We were very much around response and all of our focus was around increasing [staff] numbers and getting the response right in the first instance, so, in fairness we were not necessarily, necessarily entertaining anything that took paramedics away from core frontline business.

Service A, interviewee 5

[. . .] front line ambulance staff are leaving their job in droves [. . .]

Service H, interviewee 44

I’ll say it again, we’re [paramedics] chasing our tails all day long just, looking for pathways that sometimes aren’t there. We’re short-staffed, we’re busy. We’re getting fatigued and tired. I don’t know the answers but in terms of non-conveyance, I think there needs to be more done

Service G, interviewee 29

Skill-mix within a service

Interviewees described how the composition of ambulance crews could differ and how this could affect non-conveyance rates. Advanced paramedics were viewed as having more confidence to discharge at scene than paramedics, and paramedics were viewed as having more confidence than crews without paramedics. Therefore, the skill-mix distribution within an ambulance service could affect its discharge-at-scene rate:

[it is] widely known, we’ve been particularly challenged by a shortage of senior clinicians, that is, paramedics. Paramedic numbers have been very low, and that will affect the decision-making of the clinicians and their confidence level. The more senior clinician you get on the ‘See and Treat’, the face-to-face element, arguably the more confidence they’ll have to make a decision not to convey, whereas if you’re running a number of non-paramedic-based ambulances, so emergency medical technicians, or student ambulance paramedics, or emergency care assistants, anything lower, generally the lower the grade the more likely the conveyance rates will be affected.

Service A, interviewee 5

Interviewees described skill-mix as being related to experience as well as to training, and some interviewees had concerns that ambulance crews with little experience or training could make non-conveyance decisions that might affect patient safety:

[We have an] incredibly young and inexperienced workforce, some of whom do a less than thorough patient assessment, leaving patients at home when it’s not safe to do so.

Service A, interviewee 16

[. . .] if they’re responding, then you need to make sure that they’ve got the appropriate trained paramedic within that skill-mix to undertake discharge at scene safely.

Service A, interviewee 23

The role of advanced paramedics

There was evidence of considerable variation in how interviewees in different ambulance services described the role of advanced paramedics in relation to their contribution to non-conveyance. In some services there was consensus among the interviewees that the advanced paramedic was an established role within the service and was perceived to be a valued resource in reducing conveyance to the emergency department (Services C, D and G). In these services, paramedics spoke positively about being able to access these practitioners and refer patients to them, and also described them as a support mechanism for seeking advice to facilitate their own decision-making regarding non-conveyance. Interviewees in these services wanted to expand this part of the workforce because of its perceived value. In contrast, interviewees in other services described limited implementation of these roles, or a recent renewed focus on them, which implied that they had possibly been neglected within the organisation in the past (Services A, E, H and J). Reasons for limited implementation of these roles included a need to focus resources elsewhere in the service or a lack of interest at an organisational level:

It’s a bit of a ‘dying on the vine’ situation. Yes we have ECPs [emergency care practitioners], a small number that were from the prerequisite arrangements. I’ll never get rid of them, but I’m not, we haven’t trained ECPs here since [a number of years].

Service E, interviewee 32

[. . .] the ECP system fell over a long time ago in [PLACE], and they never really reimplemented it in any sense.

Service H, interviewee 45

Renewed focus on advanced paramedics within an ambulance service appeared to be led by a change in key ambulance personnel management, with the employment of a new manager who valued these practitioners and their contribution to non-conveyance rates. Services viewed these practitioners differently, with some services described by interviewees as not integrating the role within the ambulance service workforce (Service D), not supporting the role (Service E), or perceiving that the role did not positively affect non-conveyance (Service H). There was also evidence that some services used these practitioners differently (e.g. some used them to target specific calls, which were perceived to have the potential for discharge at scene):

There’s no point in sending an advanced paramedic practitioner [to] the patient [that] needs transporting, but on those urgent care presentations there’s a lot more opportunity to ‘See and Treat’.

Service J, interviewee 40

Length of service of crew members

Although some interviewees expressed concerns that a lack of experience in the job could lead crew members to make unsafe decisions around non-conveyance, on the whole, interviewees perceived that paramedics who had undertaken their training more recently were more likely to consider non-conveyance as an option for a patient. Although there was no discernible variation between the views expressed by interviewees from different ambulance services, it is possible that the distribution of experience of a service’s workforce could have an impact on non-conveyance rates, whereby a ‘younger’ workforce might deliver higher rates:

[. . .] but it’s again a cultural thing, so the older staff, they join the service and everyone went to hospital, the younger staff, we have a different perspective on it which becomes apparent when you’re at jobs sometimes and the [older] crew that turns up just say ‘right, in the back of the ambulance’ irrespective of whether or not you’re halfway through an assessment.

Service H, interviewee 45

Organisational support for the workforce

Although there was a perception that ambulance crews followed protocols and policies, including formal pathways of care, when making non-conveyance decisions, many interviewees described the importance of the confidence of paramedics when deciding to discharge at scene. Indeed, one interviewee identified paramedic confidence as the most important factor affecting the decision to discharge patients at scene. Interviewees described how confidence could be improved through experience in the role, training to extend skills, mentoring in non-conveyance, the ability to discuss potential cases for non-conveyance with clinicians in the clinical hub, and being part of an organisation that was supportive of their workforce. Interviewees discussed how supportive they felt that their organisation would be if something went wrong after a decision to discharge at scene. Senior managers described the importance of supporting their workforce and understanding that a decision not to convey can be the right decision at the time, even if it appears not to be at a later stage:

I say, eradicate the fear of, the blame culture [. . .] being supportive then obviously that will then increase individuals’ confidence and ability to increase non-conveyance.

Service C, interviewee 2

[. . .] probably the most important one is the support for staff. So if we’re encouraging the staff to non-convey it’s making sure we’re supporting them in that decision and if it does go wrong, making sure again that we understand the reason why it’s gone wrong, but again continue to support the staff because they’ve probably made the right decision in the first place.

Service G, interviewee 30

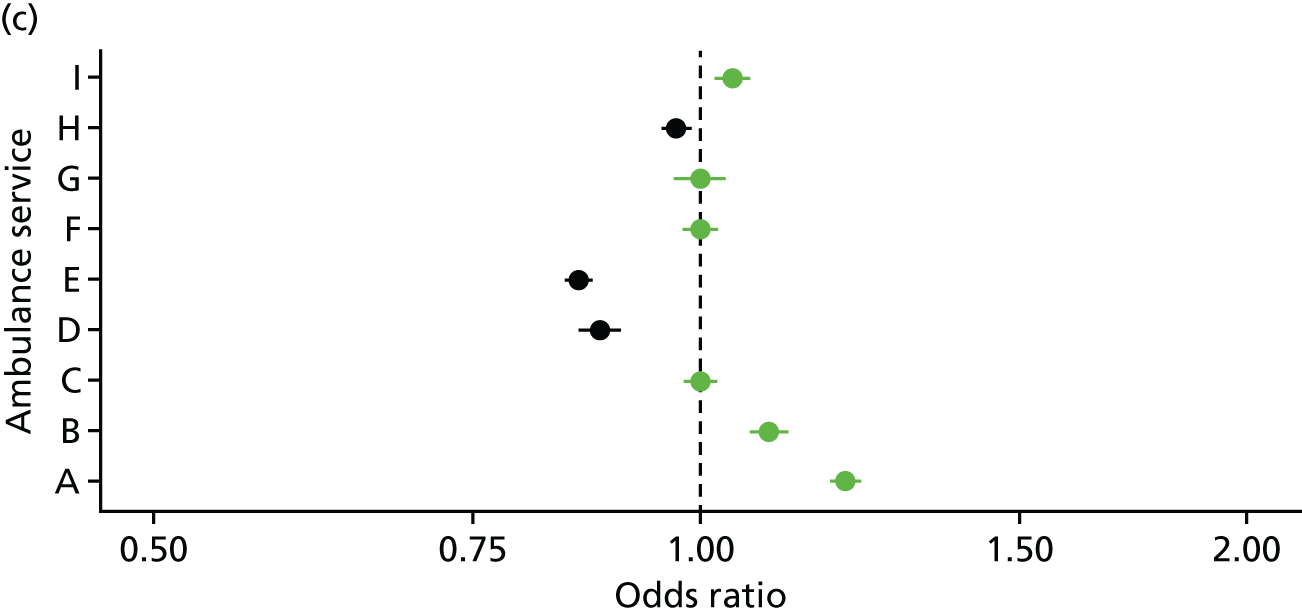

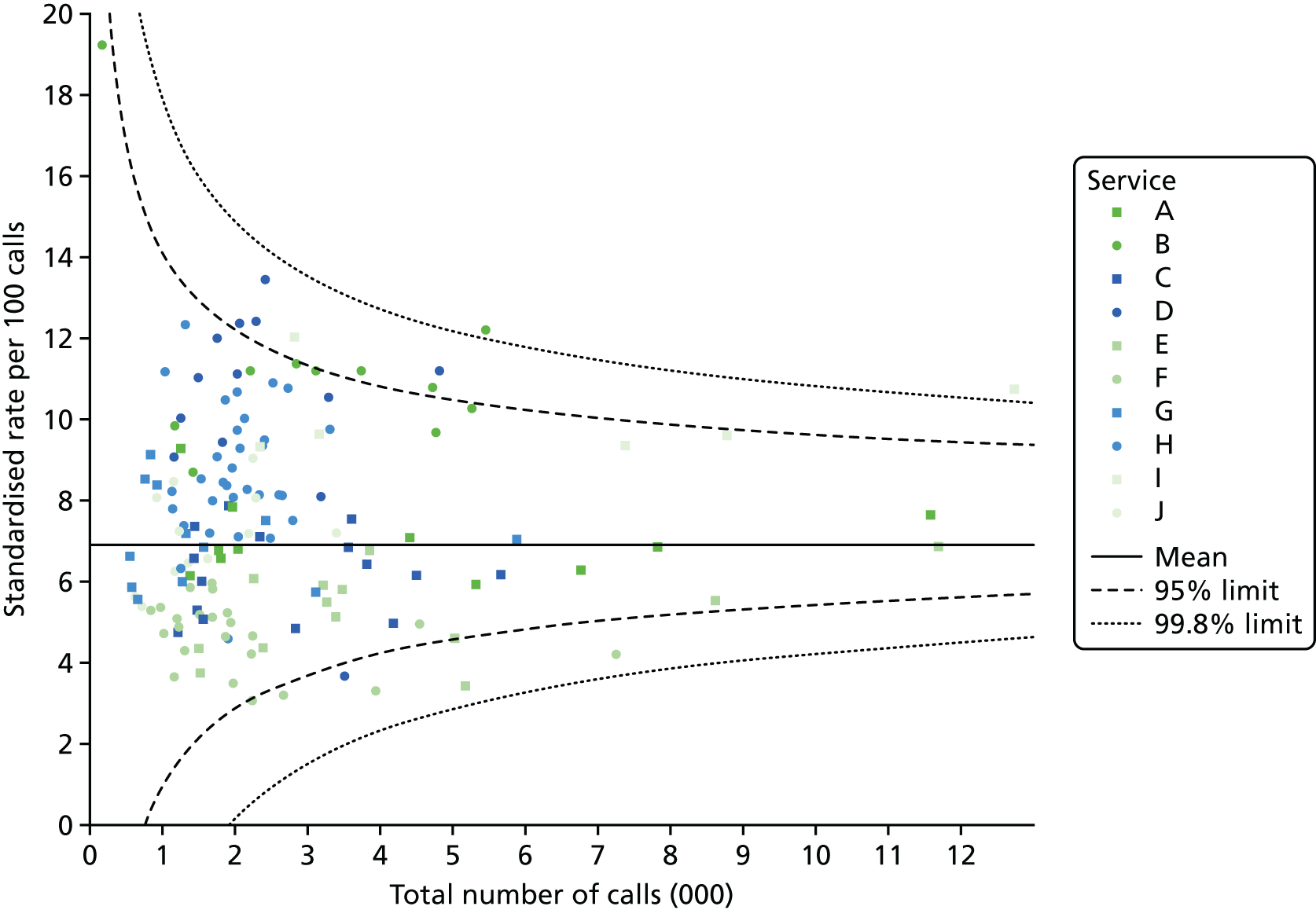

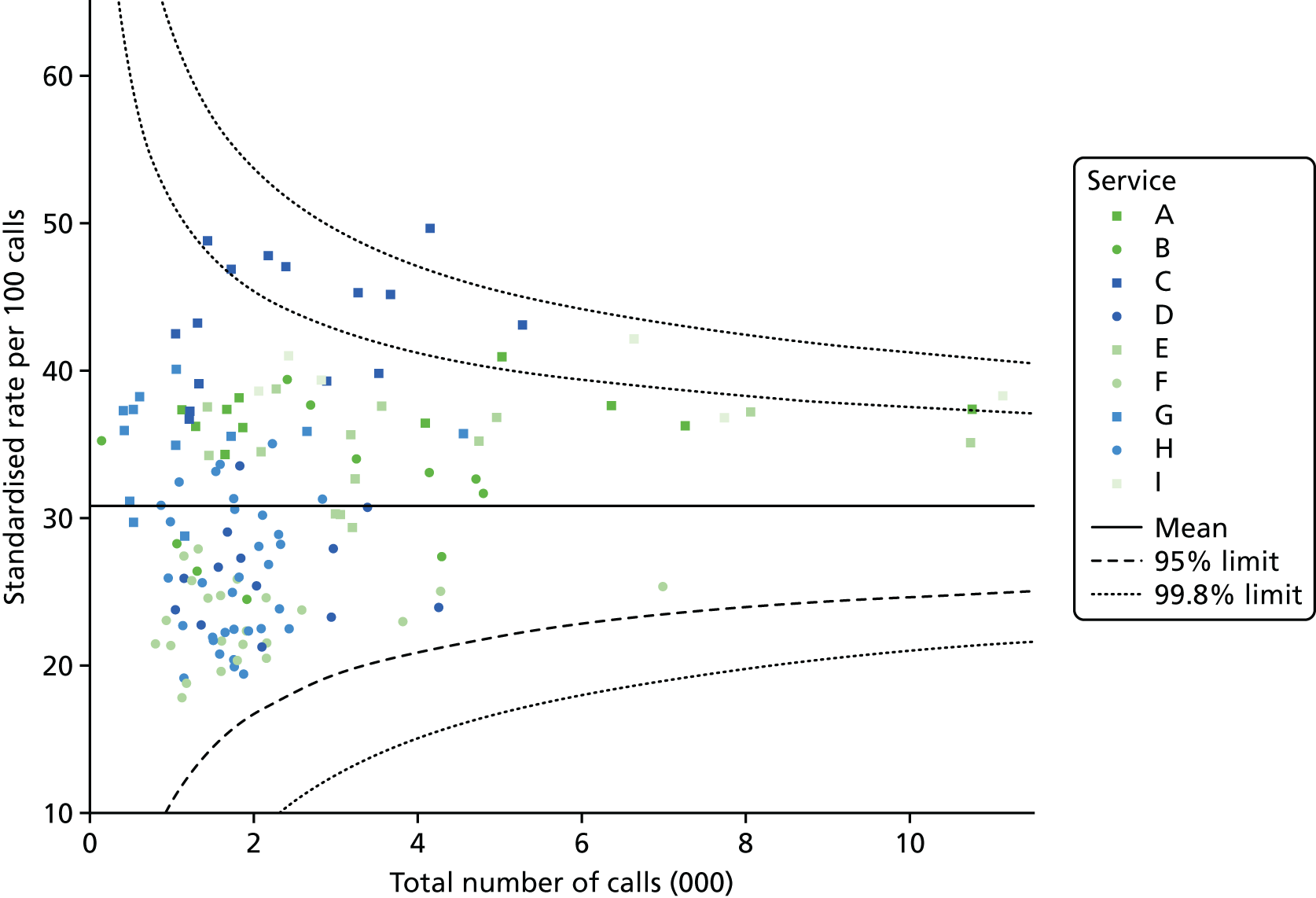

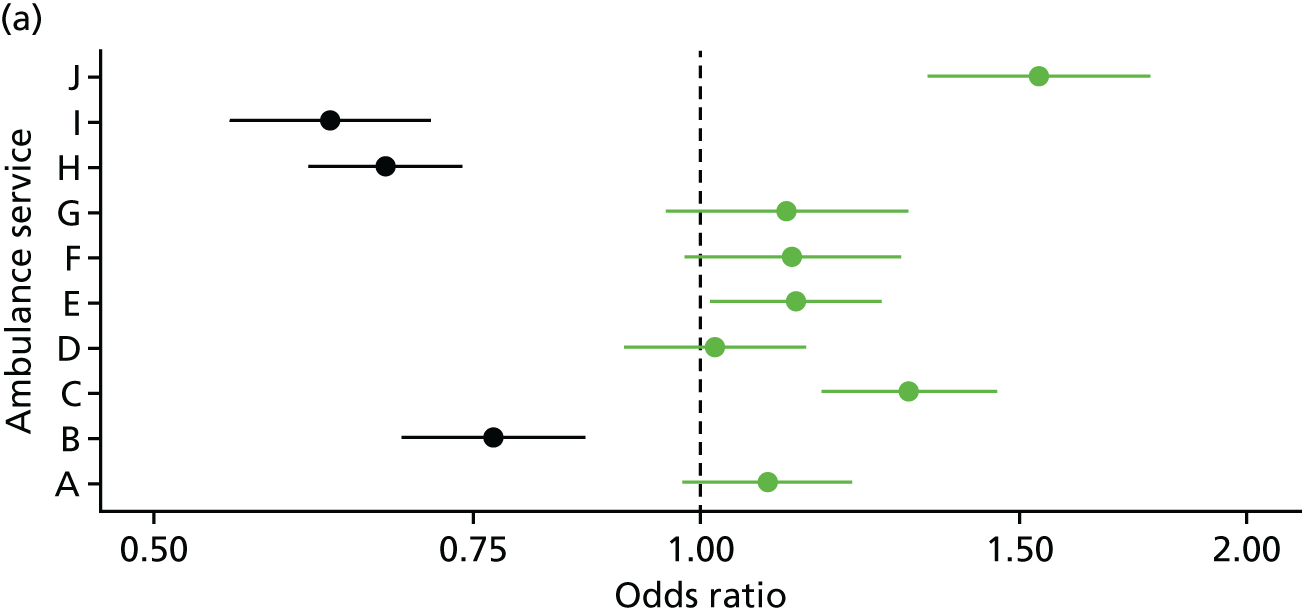

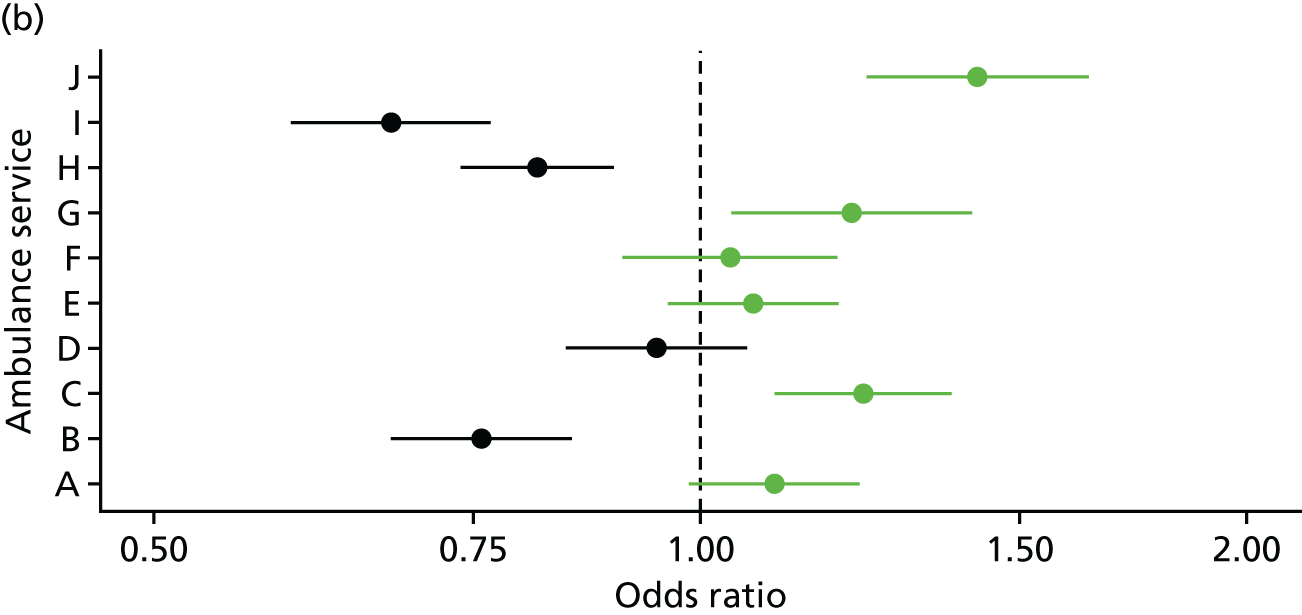

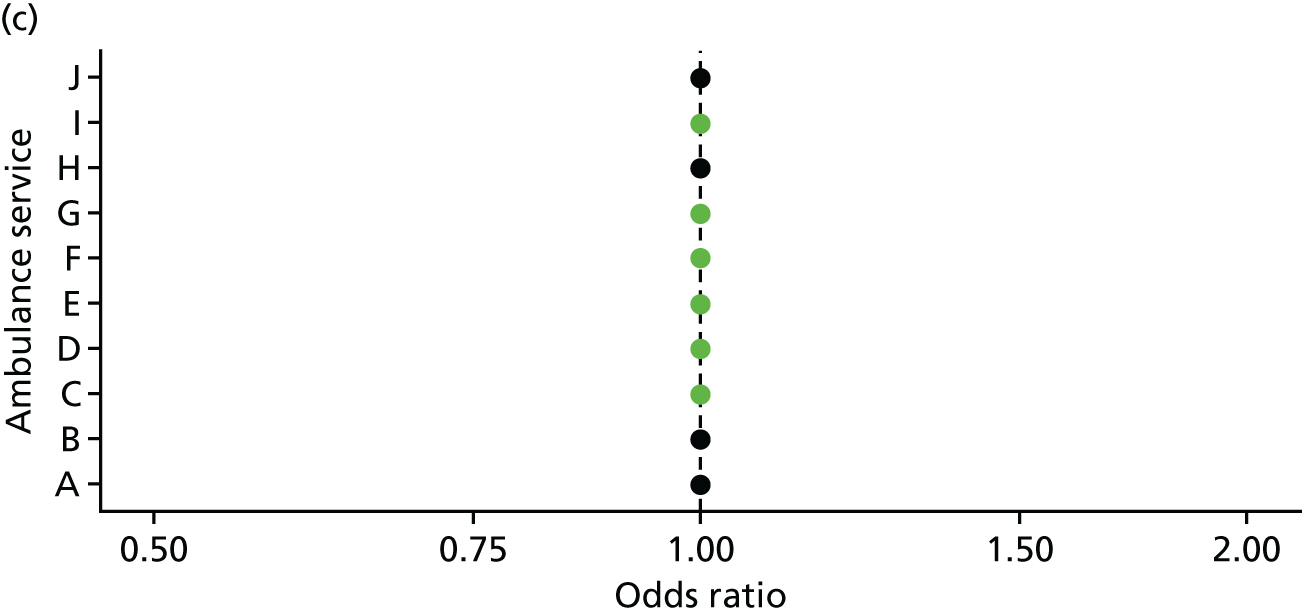

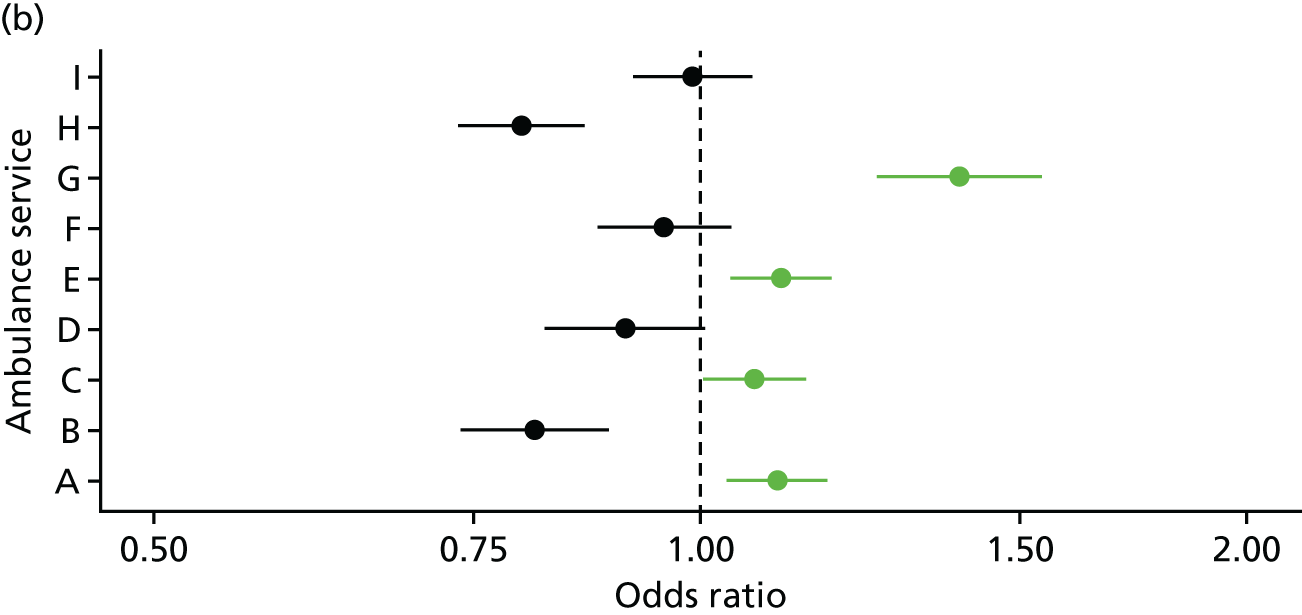

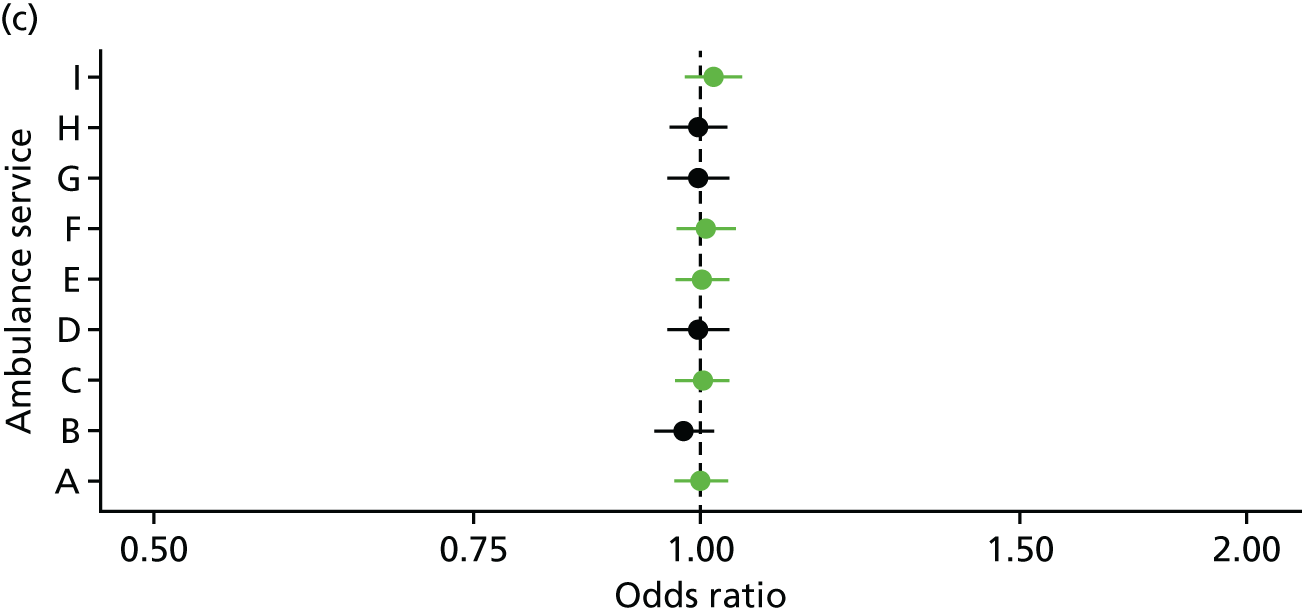

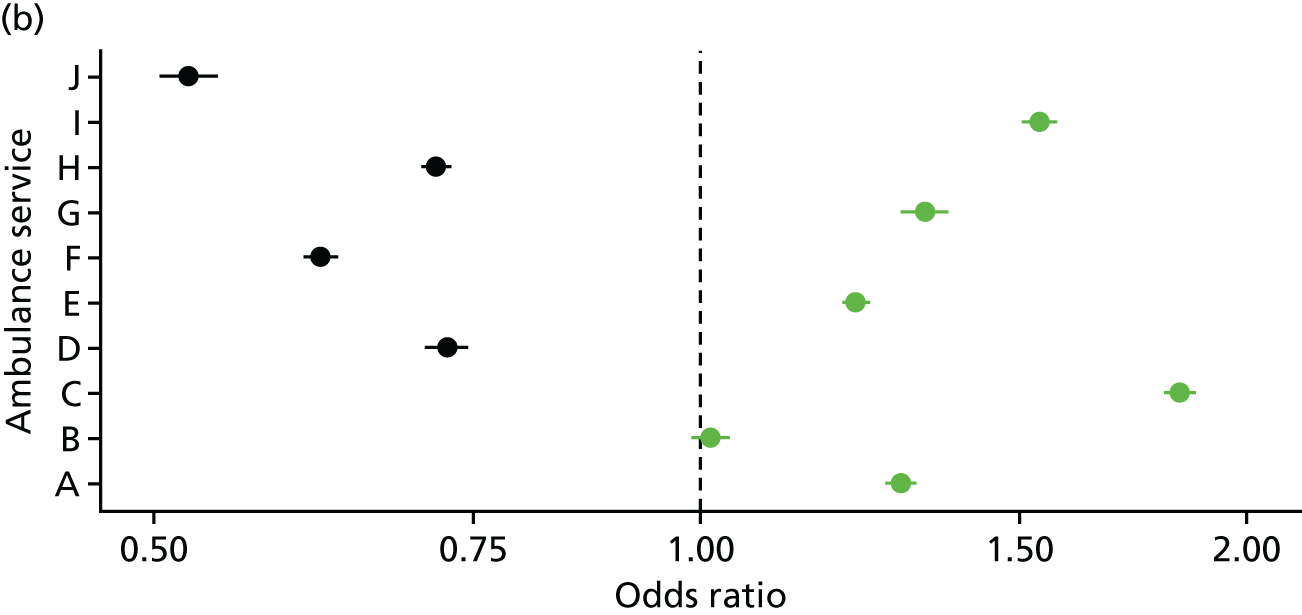

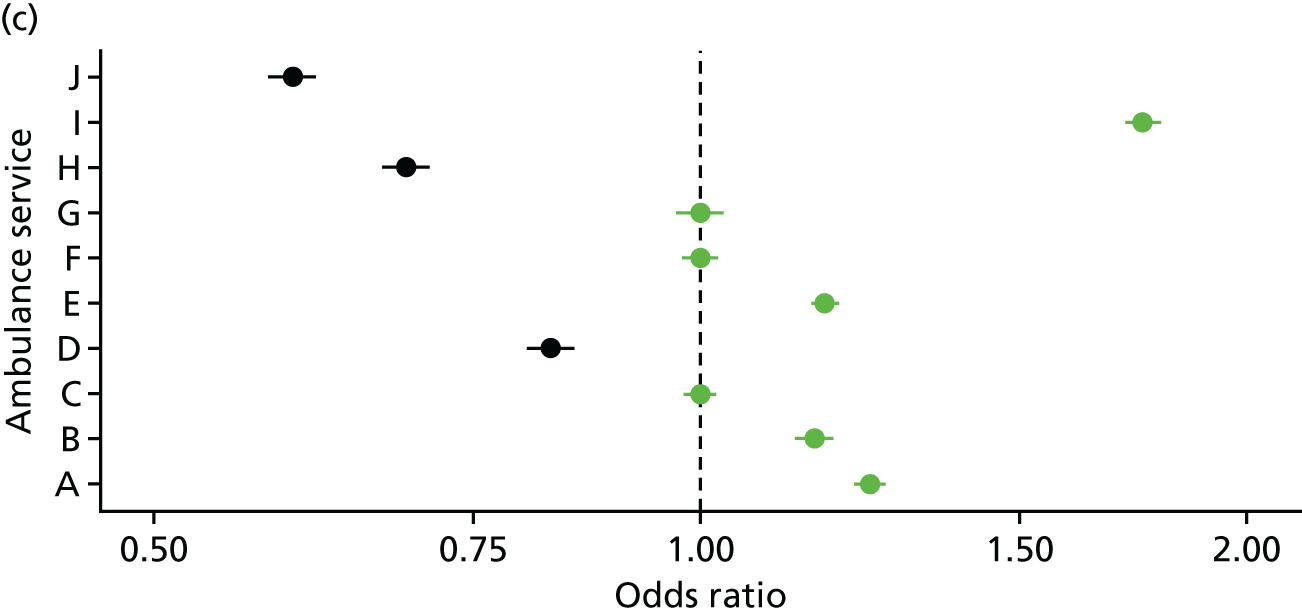

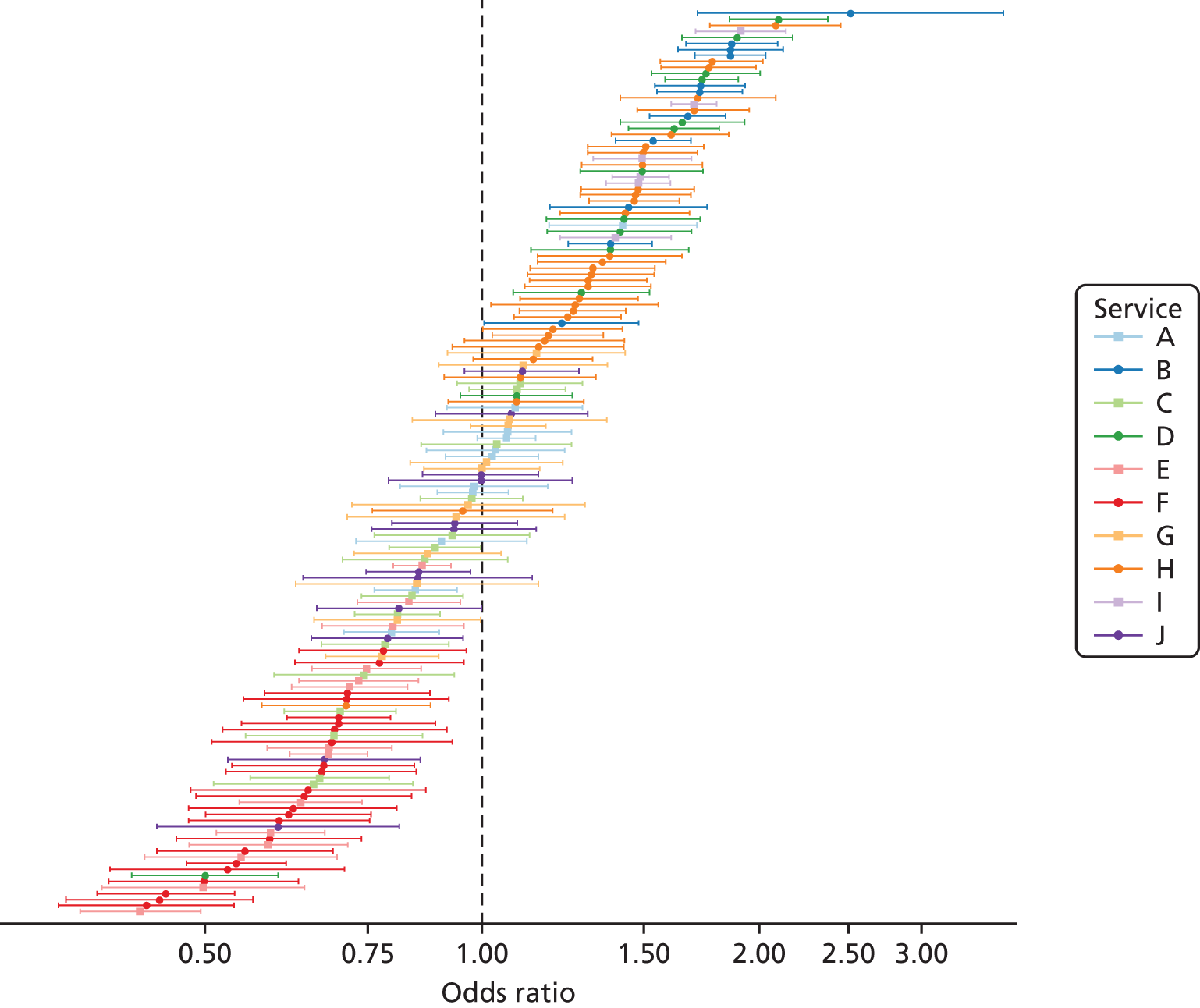

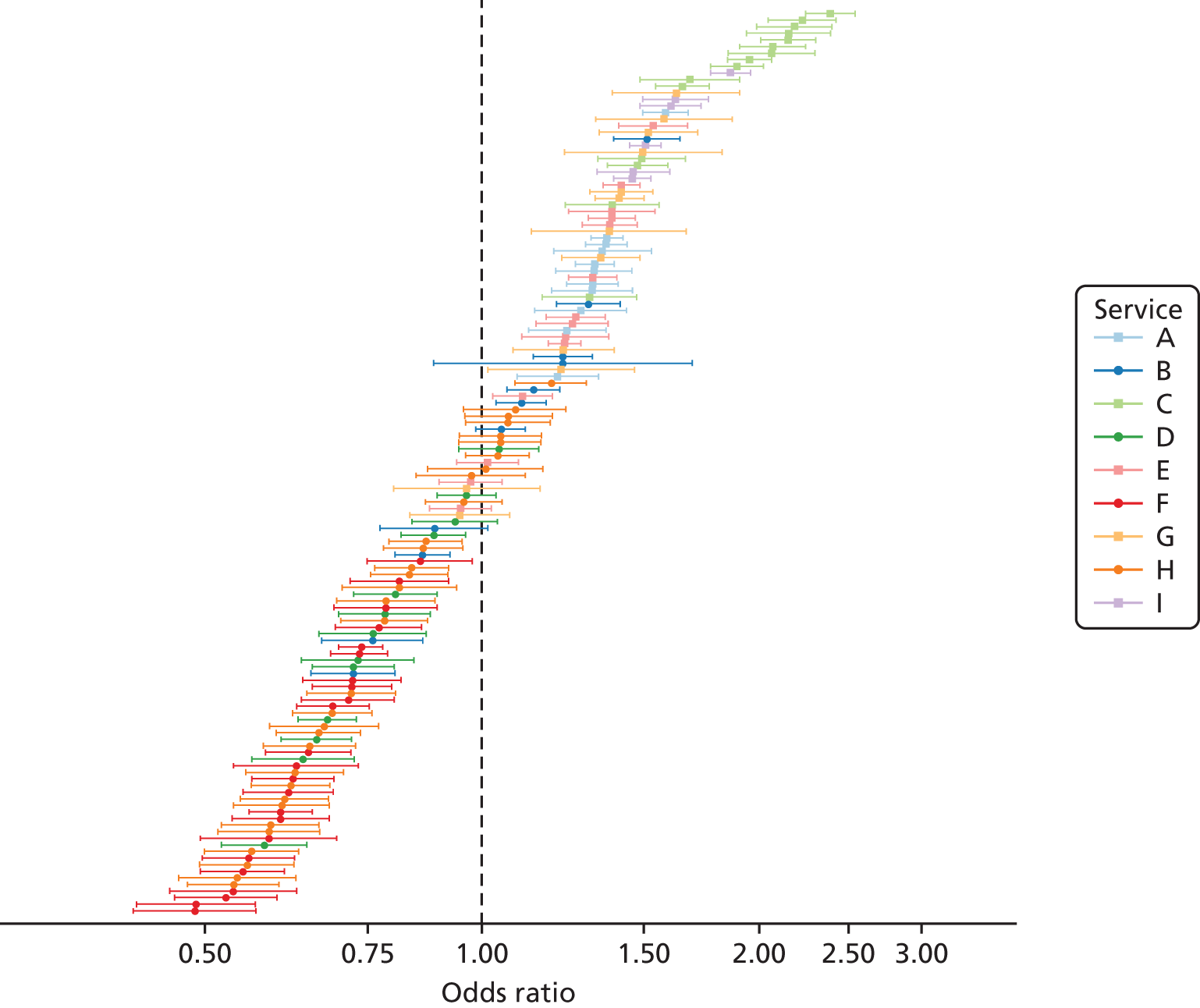

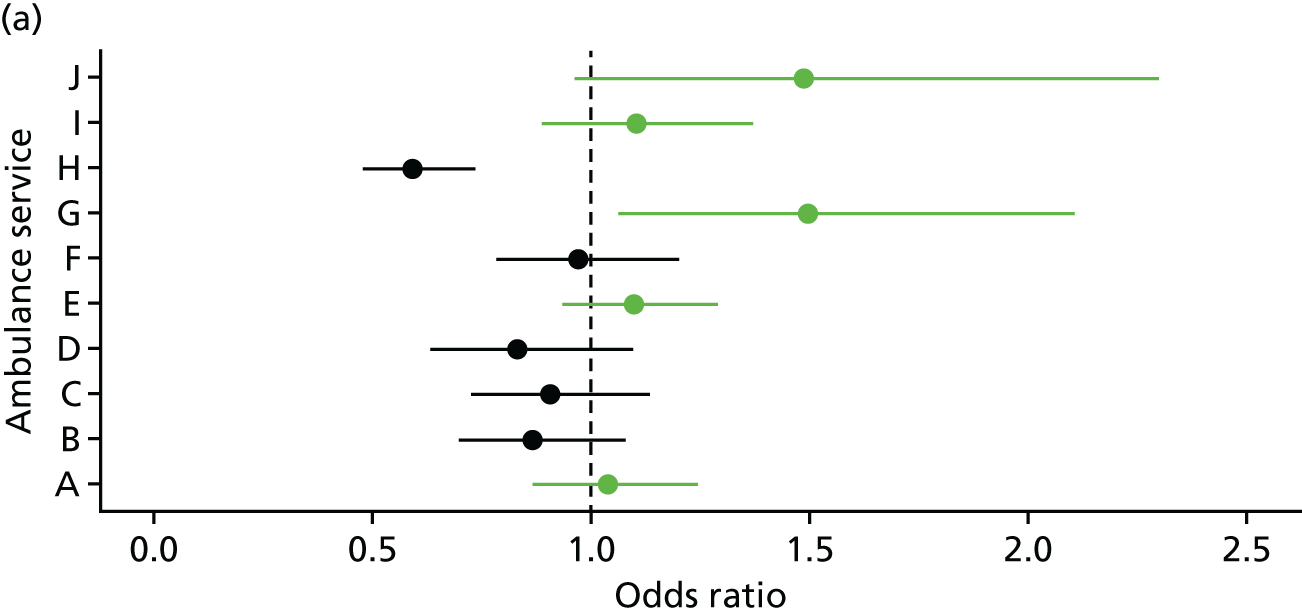

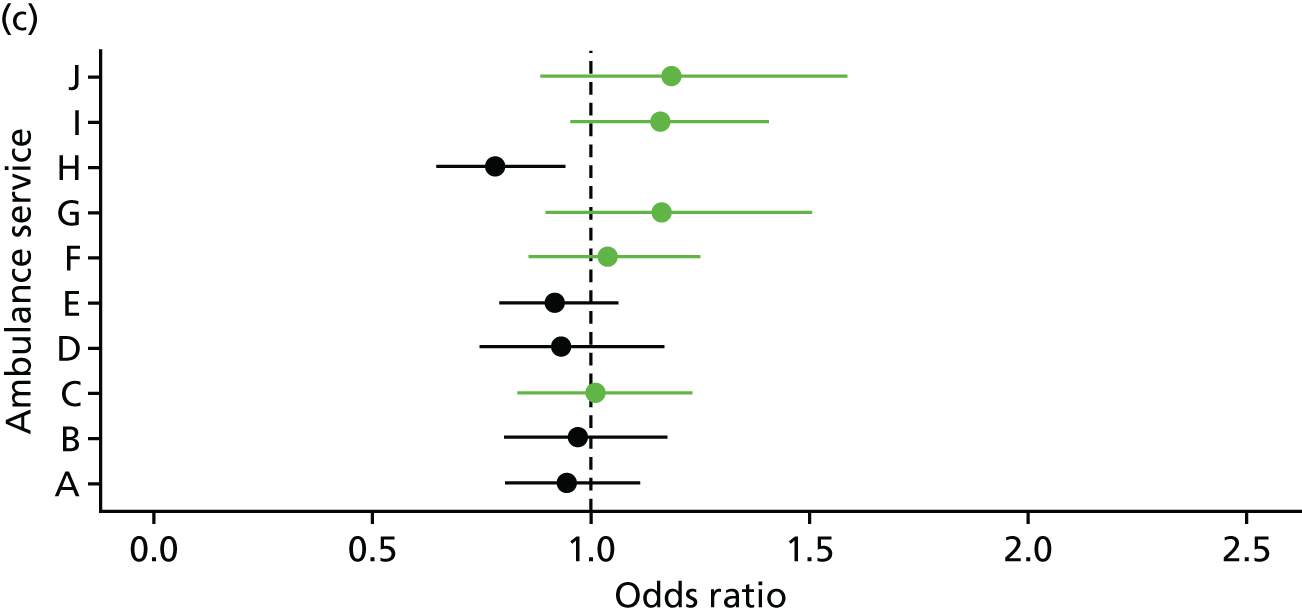

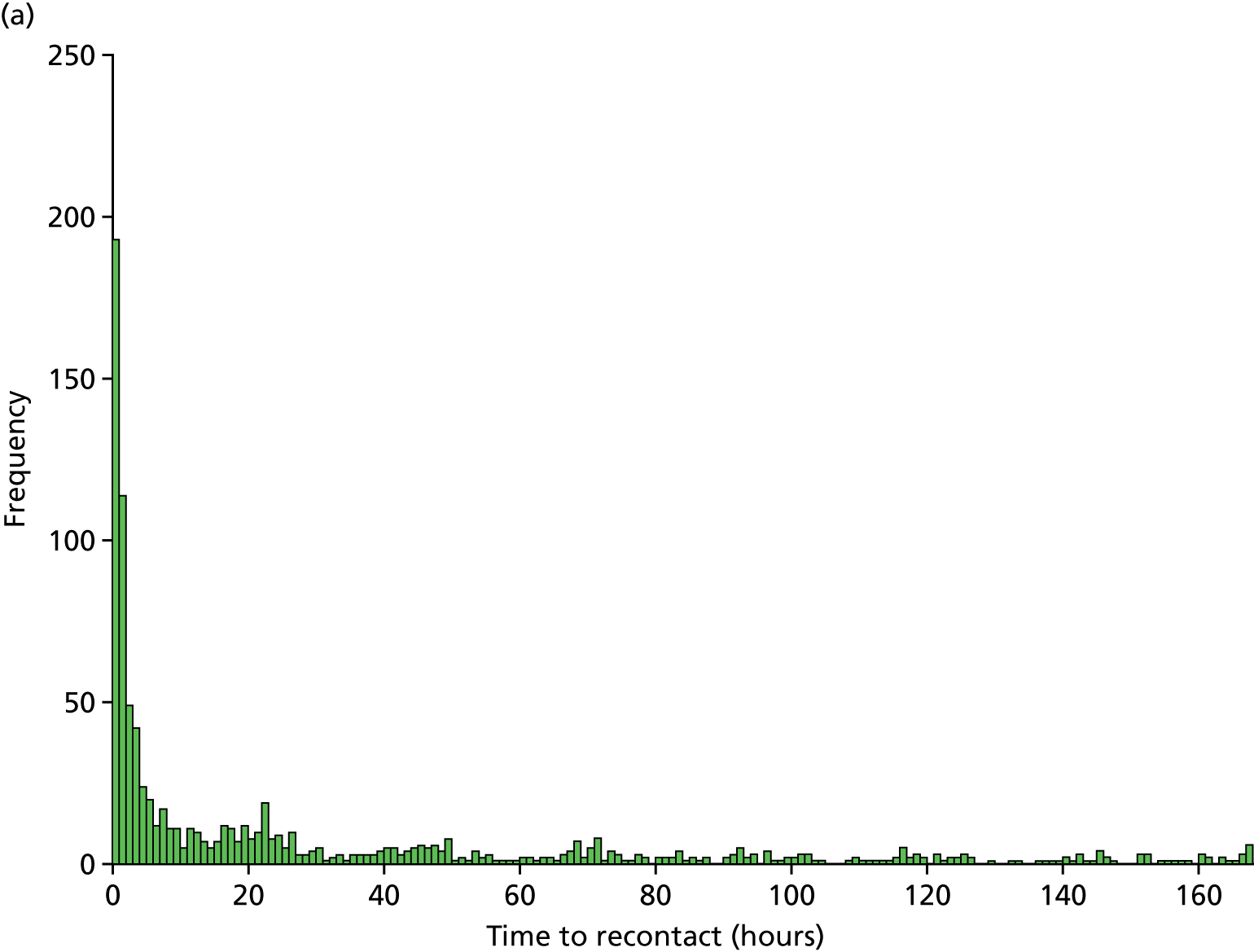

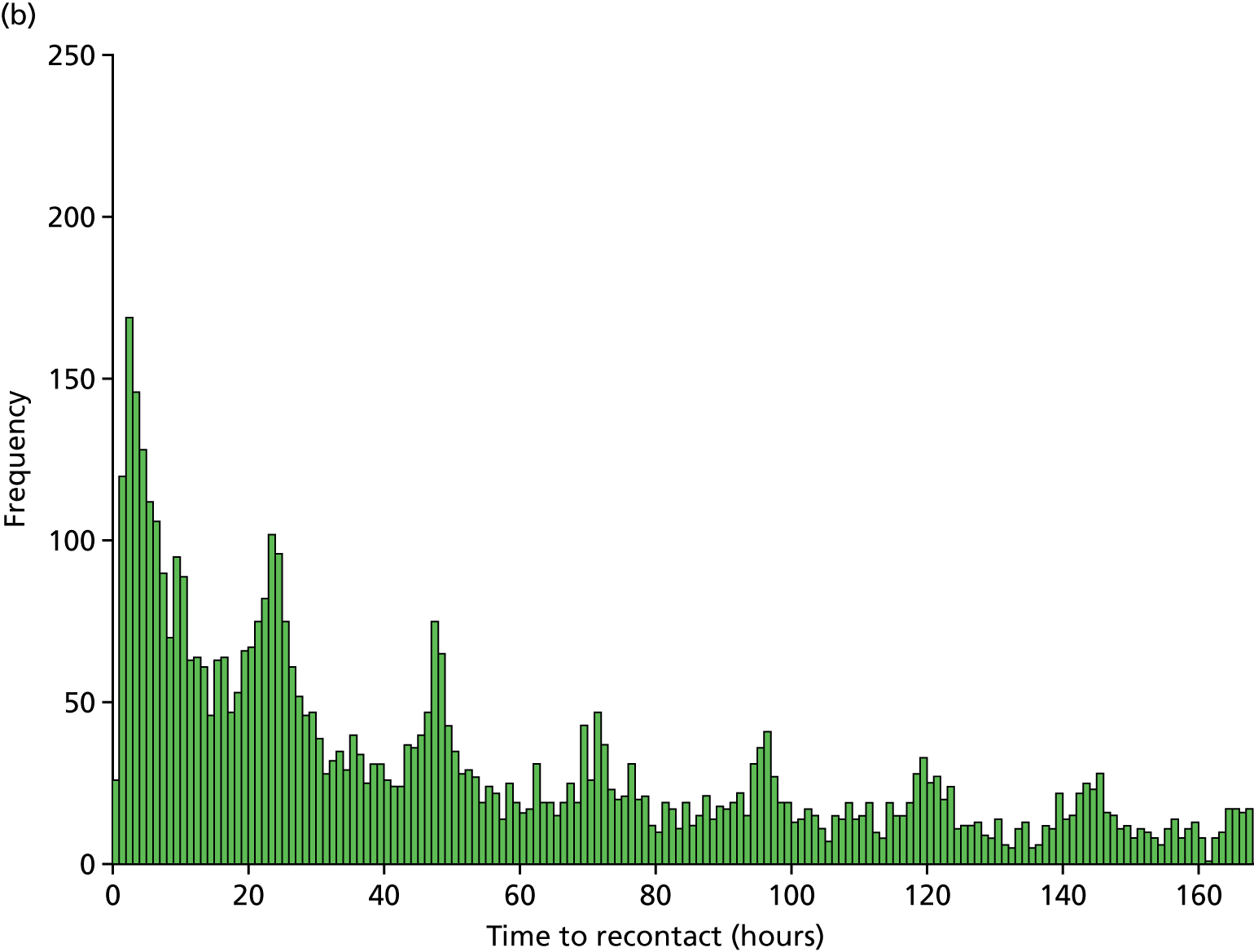

In contrast with the views of these managers, paramedics in some services openly described a fear of retribution if things went wrong (Services B, D, E, G, H and J):