Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 15/77/34. The contractual start date was in July 2016. The final report began editorial review in July 2017 and was accepted for publication in November 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Sheaff et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Origins and nature of multispecialty community providers

Multispecialty community providers (MCPs) have been proposed as a means by which the English NHS can reduce demand pressures on hospitals and general practices while improving the quality, and especially the continuity, of care for people with complex, chronic or multiple health problems, all the while contributing substantial savings to the NHS budget. As with all policies, this policy rests on a complex set of assumptions about what mechanisms will achieve these ambitious and complex policy outcomes, and in what contexts. The explicitly proposed mechanisms include new NHS organisational structures, working practices and interorganisational networks. The purpose of this realist synthesis project is to elicit an initial programme theory (IPT) about MCPs from policy-makers’ assumptions and to use international research evidence to evaluate which of these assumptions are supported by evidence, under which conditions and for which populations. We also identify any assumptions not supported by evidence. From that, we propose possible revisions to the IPT that will yield a more fully evidence-based revised logic model for achieving the policy outcomes that MCPs are intended to achieve.

To what problems are multispecialty community providers a proposed solution?

Multispecialty community providers are a proposed solution for a confluence of epidemiological, managerial and financial problems. The epidemiological aspect is the well-known absolute and relative expansion of the older age strata, people who are living longer (often because of past NHS activity) but also often with chronic and, indeed, multiple chronic conditions. The financial aspect is the restrictive fiscal policies with which UK governments responded to the financial sector market failures of 2008; they have included a policy of reducing the structural budget deficit to 2% of gross domestic product by 2020–21. 1 Given that the NHS accounts for 18.6% of public sector spending2 and hospital spending is some 44% of NHS costs,1 fiscal ‘austerity’ policies were bound to regard the costs of NHS hospitals as a ‘problem’. 2 At the time of the study, the main means of implementing this policy were sustainability and transformation plans. In practice, the term has come to refer both to the plans themselves and to the subregional network of organisations charged with implementing the plan for their area.

During the decade before the idea of MCPs emerged, English health policy had increasingly explicitly assumed that:

-

the apparent demand overload facing NHS hospitals arose largely from increasing numbers of accident and emergency (A&E) attendances

-

these attendances produced increasing numbers of unplanned admissions

-

a substantial proportion of these unplanned admissions were by older people with multiple morbidities

-

a substantial proportion of these unplanned admissions were clinically unnecessary, even iatrogenic (i.e. medical treatment harmful to the patient) and, hence, preventable3

-

once admitted, these patients often remained in hospital for an unnecessarily long time, ‘blocking’ further admissions

-

main obstacles to discharging such patients promptly from hospital were lack of:

-

general practice and/or community health services (CHSs) support necessary for the patient to return home

-

‘integration’ between these services and other frequently necessary services (e.g. therapies, mental health services)

-

residential and/or social care.

-

Therefore, certain themes recur in recent NHS policy and management. One has been that of preventing chronic illness from developing to the point at which hospital admission becomes inevitable. Proposed, and sometimes tested, methods for tertiary secondary prevention have included risk stratification leading to regular general practitioner (GP) or CHS review and, optionally, case management, usually with a nurse practitioner or ‘community matron’ as the case manager. Another method has been to divert unnecessary referrals back into primary care by means of referral-screening mechanisms and to divert unnecessary referrals and self-referrals to emergency services by ‘front door’ triage at A&E departments, diverting patients from A&E departments to on-site GP care and by ambulance paramedics liaising with CHS staff and, in certain cases, treating the patient immediately rather than transporting him/her to the A&E department for treatment there. Ways of partly substituting primary for hospital care have included establishing ‘virtual wards’ (the latest manifestation of ‘hospital at home’), strengthening community hospitals’ capacity and role, out-posting diagnostic services and outpatients clinics, intensifying primary care (in the broadest sense) and concomitantly raising the threshold for hospital admission and discharge, and establishing non-inpatient care pathways, for instance for some musculoskeletal conditions.

As new kinds of services and provider organisations have developed in NHS primary care, and the financial and demand pressures on hospitals and GPs have continued to intensify, the requirement for closer co-ordination of care between these services has become more pressing. At a national level, corresponding initiatives and experiments have included the Evercare Project, leading to the introduction of community matrons, the integrated care pilots4 and the ‘Vanguard’ projects, including, most recently, MCP pilots.

In the meantime, general practices have also independently been under increasing pressure for the same epidemiological reasons as have increased demand on A&E departments. These factors have increased the demand for GP consultations and other general practice-based clinical services (e.g. health checks, disease monitoring). There has also been a gradual but long-term increase in requirements for compliance with national clinical standards [implemented, above all, through the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF)]. This has been one source of increased managerial and data collection demands on general practice, but another has been the creation of Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs), in which GPs are intended to be the controlling actors. 5 These conditions have made it hard to recruit to the GP workforce, whose age and sex profile and size is changing correspondingly.

Therefore, the past 20 years have seen the following trends in general practice organisation. Mean general practice size has slowly, but continually, increased, with a secular reduction in the proportion of single-handed general practices. There has been a diversification of general practice organisational models, including GP partnerships employing salaried GPs, in effect the nationalisation of those practices that became primary care trust (PCT) administered, the provision of general practice by corporations, proprietary (owner-managed and, often, GP-owned) firms and nurse-led practices, the persistence of some out-of-hours (OOH) co-operatives and the conversion of others into ‘social enterprises’ (often a rather nominal change as the ownership, control and working practices often did not alter much), functional corporatisation (outside firms hired to manage GP-owned practices) and partnership mergers to make ‘super-partnerships’. Networks of general practices have developed. Primary care groups, PCTs, CCGs and GP federations were successively more highly organised examples of such networks attempting to develop joint decision-making, agreed care pathways, the introduction of more clinically specialised forms of general practice with economies of scale and scope in the provision of those services, and economies of administrative scale.

In response to these developments in general practice, and the fiscal and epidemiological pressures noted, NHS England’s Five Year Forward View (5YFV)6 and its successive elaborations adopted six general aims:

-

‘upgrade in prevention and public health’ (p. 3)

-

‘patients will gain greater control of their own care’ (p. 3)

-

‘support people with multiple health conditions, not just single diseases’ (p. 3)

-

‘comprehensive and high quality care’ (p. 5)

-

‘close the £30 billion gap’ in projected NHS funding ‘one third, one half, or all the way’ (p. 5)

-

‘enable new ways of delivering care [to] become the focal point for a far wider range of care’ (p. 20).

NHS England. 4

Five of the seven ‘new ways of delivering care’ were (1) urgent and emergency care networks, (2) ‘viable smaller hospitals’, (3) ‘specialised care’, (4) modern maternity devices and (5) enhanced health in care homes. Sixth was primary and acute care systems (PACSs), in which the essential function is the vertical ‘integration’ of hospital and primary care services for a patient list. Seventh was MCPs, in which the essential function is the horizontal ‘integration’ of primary with CHSs and social care.

What is a multispecialty community provider?

Given the above setting:

The underlying logic of an MCP is that by focusing on prevention and redesigning care, it is possible to improve health and wellbeing, achieve better quality, reduce avoidable hospital admissions and elective activity, and unlock more efficient ways of delivering care.

NHS England. 4

What are the components of this logic, in realist terms?

Multispecialty community provider outcomes

Despite the different approaches to care ‘integration’, the policy outcomes that policy-makers intended MCPs to produce most resemble those of the PACSs and were:

-

the House of Commons Health Committee mentions the Improved Access to Psychological Therapies programme waiting time standards5 in ways that hint that they should apply to mental health services generally

-

‘measurable reduction in age standardised emergency admission rates and emergency inpatient bed-day rates; more significant reductions through the New Care Model programme covering at least 50% of population’8

-

significant measurable progress in health and social care integration, urgent and emergency care (including ensuring a single point of contact), and electronic health record (EHR) sharing, in areas covered by the New Care Model programme7

-

better access to care nearer to home5 (e.g. more convenient care). 8

Multispecialty community provider mechanisms

The 5YFV6 itself describes certain mechanisms that MCPs ‘will’ or ‘would’ use. ‘Expert generalists’ (i.e. GPs) will work more intensively with patients with complex needs (e.g. frail older people; chronic conditions). Nurses, therapists and other CHS professionals will be included in MCP ‘leadership’ (management). There will be a wider range of primary care services. MCPs will draw on the ‘renewable energy’ of carers, volunteers and patients.

Multispecialty community providers ‘may include a number of variants’. 9 A longer list describes mechanisms that MCPs ‘could’ use, hinting that different variants may involve different combinations of the following:

-

fuller use of digital technology

-

fuller use of ‘new skills and roles’ (i.e. new divisions of labour)

-

extended group general practices, ‘either as federations, networks, or single organisations’6

-

general practices employing consultants or making them partners

-

such consultants (and by implication GPs) ‘work[ing] alongside’ CHS staff, pharmacists, psychologists, social workers and others

-

running local community hospitals and perhaps expanding their diagnostic services

-

GP-admitting rights to acute hospitals

-

‘in time’, GPs managing the NHS budget for their patients

-

care hubs, which perhaps may also provide OOH services.

Within MCPs, small independent general practices will continue while GPs wish it, which implies some form of networked rather than line-management relationship between these practices and the rest of the MCP.

A wide range of MCP sizes (the first wave served populations ranging from 63,000 to 330,000) and of possible governance structures is envisaged. Perhaps the most obvious are networks of independent general practices, possibly perhaps with a strong central co-ordinating body (a ‘federation’). MCPs are described as ‘extended group [GP] practices’, which might be ‘federations, networks or single organisations’ (p. 20). 4 The House of Commons Health Committee5 argued that federations allow specialised development of services and care teams while retaining the existing scale of general practices. However, MCPs might also commission specialist providers, implying a potential role for governance and co-ordination through quasi-markets. New hierarchical organisations (e.g. on the lines of NHS foundation trusts) are also foreseen. Potentially, they might also organisationally integrate general practice and CHSs, which the so-called ‘integrated’ care pilots never did. Another expected kind of single organisation is the enlarged professional partnership. The 5YFV comes close to implying that a MCP might also have the structure of a social enterprise or co-operative.

Multispecialty community provider context

Multispecialty community providers’ external relationships with the rest of the NHS will, above all, be through monitoring and a contract. The 5YFV6 expected that standardised data will enable real-time monitoring and evaluation of MCPs’ quality, outcomes, costs and benefits. NHS England is establishing a new operational research and evaluation capability to support this activity.

A ‘new voluntary contract for GPs (Multispecialty Community Provider contract)’ will be MCPs’ main financial link to NHS commissioners. Its three varieties10 are:

-

a ‘partially integrated’ contract [i.e. an additional contract supplementing the General Medical Services (GMS) contract]

-

an integrated single contract based on the GMS contract but excluding the QOF element – a whole population budget for all primary care home (PCH) and CHS services for perhaps 10–15 years

-

‘a virtual, alliance contract’.

The contractor and, by implication, overall co-ordinating body of a MCP might be a community interest company or limited liability company (both wide categories), partnership (including GP federation) or a statutory NHS provider. 4 MCPs will receive capitated payments, but not fees for service (which general practices now do, although it is not usually the main element of their income). 9 The new, longer-term contracts could follow the outcomes-based commissioning approach already being tried elsewhere in the NHS. 11

As usual for NHS organisational innovations, MCPs will be introduced in waves. For the first wave, ‘The purpose of becoming an initial site is not simply to address local needs, but to become a successful prototype that can be adapted elsewhere, designed from the outset to be replicated’. 9

Definition by example

Policy documents and recent plans for the first wave most often characterise MCPs in structural terms (which organisations will participate and collaborate) and, to a lesser extent, in terms of certain cross-organisational care processes. However, these documents expressly leave many possible varieties and options open. 6 Therefore, another way of defining a MCP is ostensibly by considering what common characteristics the first wave of MCPs have12 (see Appendix 1).

Across the 14 first-wave MCPs, the participating organisations (mostly health-care providers) will, in 11 cases, be networks (e.g. federations) of, and individual, general practices (including a super-practice and a proprietary one). Eleven MCPs will also include a NHS hospital trust, nine will include a mental health trust and eight will include a CHS trust. Eight also include one or more CCG. Local authorities, or departments thereof, are included in nine MCPs, in particular, social services (in four). Five MCPs include umbrella organisations for local voluntary organisations and another two MCPs include ‘groups’ of the same. Three MCPs involve urgent-care services (OOH, ambulance). Other, more disparate participants include Healthwatch, one local medical committee, one hospice, commercial pharmacy, NHS England and the Local Government Association (LGA).

As mechanisms, the first-wave MCPs most frequently mention establishing, or strengthening, existing multidisciplinary teams (MDTs) (eight projects). The specific composition varies, but across the projects the team participants include GPs, advanced nurse practitioners, social workers, mental health services, voluntary sector link workers and pharmacists. Next most frequently, five MCPs mention various forms of shared care planning (one of them a GP-led complex-care management service). Another partly overlapping set of five projects plans to create a physical location (‘hub’) in which to combine services and provide a single point of access to them. Three projects mention preventative care, three information technology (IT)-based mechanisms (shared health records, digital access to health care) and three preventative care (including for children and self-care). Two mention care co-ordinators or navigators and two propose to enhance local referral networks and pathways. Various other mechanisms are mentioned by only one prospective MCP (new forms of contract, extended access to GP services, mobile clinics, recruitment of hospital consultants and, contingent on projects outside the NHS, a ‘health and care garden city’).

Working definition of ‘multispecialty community provider’

The foregoing suggests that the essence and function of a MCP is horizontal ‘integration’ among the various primary care providers (general practices, CHSs, mental health, OOH, ambulance, urgent care, etc.) and related non-health services (primarily, social services and residential care). Functional (as opposed to organisational) ‘integration’ will typically mean closer care co-ordination across still-separate provider organisations rather than organisational integration, although even the latter may occur in the future. 6 However, in the meantime, MCPs will be interorganisational networks.

We put the term ‘integration’ within quotation marks because research and policy documents often conflate three distinct concepts:

-

co-ordination – the deliberate combination, connecting and sequencing of separate but interdependent resources,13 above all, individuals’ care activities, into a single care process14

-

continuity – a term covering the cross-sectional, longitudinal, flexible, informational and relational continuities of care;15–17 the common element is the non-interruption of care co-ordination

-

integration – use of a single organisational structure to co-ordinate care. 18

Research and policy documents are especially prone to saying ‘integration’ when referring to (closer) co-ordination.

Namesakes and equivalents in other health systems

Because MCPs are so new, at the start of this project there were no published studies directly concerning them. The initial scoping search of Ovid MEDLINE(R) (1946 to August week 1 2015) for variants of the term ‘multi-specialty community providers’ retrieved zero hits and the same was found when searching EMBASE, PsycINFO, Social Policy and Practice, and PubMed. Therefore, any search for evidence relevant to MCPs must be a search for studies of organisations and/or networks with at least partially similar functions to MCPs, that is, organisations or networks in other health systems or the pre-2016 NHS, which at least partly satisfy the stated definition of the function of a MCP. These MCP-equivalent entities include, but are not limited to, the following:

Gesundes Kinzigtal (Germany)

Gesundes Kinzigtal GmbH, two-thirds owned by a network of local doctors and one-third by a health-care management company, has a shared savings contract between with one large social health insurer [Allgemeine Ortskrankenkasse (AOK)] and one small one [Landwirtschaftliche Krankenkasse (LKK); for farmers]. This contract gives both sides incentives to make and share savings. Some 33,000 people (about half of the area’s population) subscribe to the scheme. Its models of care are based on the collaboration (still unusual in Germany) of doctors, hospitals, social care, nursing staff, therapists and pharmacies. The project offers ‘a set of community initiatives’,19 preventative, patient self-management and health promotion activities. 20 It has been described19 as an accountable care organisation (ACO). It provides individual treatment plans, post-discharge follow-up care and case management. It focuses on removing care pathway bottlenecks (e.g. waits for physiotherapy) and uses a single system-wide EHR.

Buurtzorg (the Netherlands)

Buurtzorg originated as a proprietary CHS nursing and allied health professional (AHP) service provider, but a very mission-led one. It now has 630 work teams whose work includes house cleaning for disabled people (Buurtdiensten), services for young people (Buurtzorg Jong), home-based rehabilitation (Buurtzorgpension) and hospice care (Buurtzorghuis). Buurtzorg charges a flat hourly fee for its work, with self-managed local teams deciding the skill mix ad hoc. The managerial infrastructure is very small. Work co-ordination relies heavily on an IT system based on spreadsheets devised by the teams themselves and a shared EHR. 21 Reflecting practice in the Netherlands generally, the teams do not include doctors (separately organised in small general practices, much as in the NHS).

Swedish vårdcentral (Sweden)

Swedish primary health care clinics (PHCCs) (vårdcentral: ‘polyclinic’) traditionally provided both primary medical care and home nursing care services (i.e. a similar function to NHS community nurses). Some offer OOH emergency services, but not OOH home visits by doctors. For-profit providers have about a 15% market share, as does Praktikertjänst, a medical co-operative. As in the UK, local authorities provide social services, with client copayment. 22 In mental health services, nurses are often the care co-ordinators but, in acute primary care, it is often the GP. Some PHCCs host outreach specialist services (e.g. neurology, geriatrics), therapy services and diagnostics. Multiprofessional teams often operate within each PHCC but generally rely on informal co-ordination. There is no universal EHR, and usually only partial data sharing among health-care providers (among which nursing homes or social services are not included). 23

In Norrtälje, Sweden, the vårdcentral model has been extended. An integrated financial administration (TioHundra Forvaltningen) administers combined (pooled) budgets for all health and social care. They commission a single publicly owned not-for-profit company, TioHundra AB, to provide integrated primary care, hospital and social care services for the whole population. Its PHCC provides medical, nursing and speech therapy services, including post-hospital nursing services for up to 2 weeks after discharge. A separate division within TioHundra AB provides all other community nursing and social care. 24,25

Accountable care organisations (the USA)

The US government’s Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMMS) defines ACOs as voluntary associations of hospitals, doctors, other health-care providers and professionals who together co-ordinate the care they provide for Medicare patients, in particular chronically ill patients. These ACOs aim to prevent medical errors and service duplication and to make cost savings that the ACO will share with the participating providers. 26

Varieties of ACO programmes have included a Medicare Shared Savings Program (as an alternative to fee-for-service payment), an Advance Payment ACO Model (supplementary incentive programme for selected participants in the Shared Savings Program) and a now discontinued Pioneer ACO Model for early adopters of co-ordinated care.

The NHS now uses the phrase ‘ACO’ to mean the commissioning of a single contract and lead contractor for most of the primary and secondary care health services in a CCG or other wide area. However, in the USA most providers that join an ACO also have non-Medicare (and, in that respect, non-ACO) patients. Provider membership of an ACO is voluntary and, therefore, providers require an incentive to join, usually the financial incentive of sharing the savings.

Awareness of these differences is necessary when interpreting findings about American ACOs for NHS use.

Patient Medical Home (the USA)

In US settings, the term ‘patient-centred medical home’ or ‘primary care medical home’ (PCMH) means something very close to group general medical practices with a stable list of registered patients (as opposed to episodically caring for patients) and providing holistic, co-ordinated, accessible, comprehensive care and also some non-medical services, that is, something similar to the UK model of general practice, with its system of patient lists, since the 1940s. 27 However, recent NHS guidance sees the PCH (a namesake of the US models) as serving a patient list of 30,000–50,000 people, having an integrated workforce, focusing on both population and personalised care, and with ‘alignment of clinical and financial drivers’. 4

Rationale for this study

It is already known that strong continuity of care (often called ‘integrated’ services) assists the delivery of effective, safe and efficient person-centred care for people with multiple morbidities in the community. 28–31 Although there are numerous published studies of care ‘integration’, they tend to focus on what prevents care ‘integration’ or to describe practical models and experiments in working practices and network structures designed to improve ‘integration’ at the disease group level. They less often examine care ‘integration’ at the level of larger populations or of networks of whole organisations, as MCPs are envisaged to be (see Multispecialty community provider mechanisms). Consequently, that body of evidence is disparate and fragmented. Reanalysis of it is needed to draw out the implications for MCPs.

The rationale for establishing MCPs implicitly presupposes that repeated unplanned admissions of older people with multiple morbidities make proportionately heavy use of NHS hospital bed-days. 32,33 Reducing these admissions would substantially reduce cost and access pressures on NHS hospital service. 34 ‘Integrated’ (or, at least, better co-ordinated) care is expected to reduce these admissions by partly replacing hospital care with non-hospital care and, hence, raise the quality and reduce the cost of NHS care. Finally, MCPs will promote such ‘integration’ of care for these patients. To varying extents, the first three of these assumptions have been verified through research (see Namesakes and equivalents in other health systems). The evidential basis of the fourth is more mixed. 35–37 The fifth, about which the present study would synthesise existing evidence, still requires evaluation.

Study aims

Overall, this study therefore aims to appraise and synthesise the diverse sources of knowledge (from the UK and internationally) to understand and test the ‘programme theories’ underpinning the idea of a MCP, elaborating and refining the programme theories to produce more strongly evidence-based logic models. Specifically we aim to:

-

map the current variants of MCPs and their component proposed ‘ways of working’

-

describe the equivalents of MCPs and of the main component mechanisms of MCPs in use internationally

-

identify the ways in which these equivalents are reported to achieve beneficial effects in terms of care integration and the other policy outcomes mentioned in policy related to MCPs, including the 5YFV, local MCP Vanguard ‘logic models’ and other ‘grey’ policy statements

-

describe the causal chains from structural and governance arrangements, through interteam and interprofessional relations and interactions, to practitioner and patient behaviour

-

hypothesise how differences in types of MCP (e.g. networks, confederations) and other external contexts affect how this chain of causation operates

-

reformulate revised logic models for MCP design and implementation.

The rationale for MCPs suggests that, in doing so, we should focus on care for patients with complex needs (i.e. patients who recurrently need services from at least two different provider organisations), for instance, patients with a single long-term condition with complex needs, combined physical and mental health problems or conditions that need both health and social care.

Chapter 2 Research questions and hypotheses

Research questions

Given this background, we addressed the following research questions:

-

How do policy-makers and top NHS managers predict that MCPs will generate the policy outcomes stated in the 5YFV? What variants of MCPs are they creating?

-

Internationally (including in the UK), what equivalents to, or components of, MCPs exist?

-

How do these equivalents and their mechanisms compare with those proposed for MCPs in the NHS?

-

What policy outcomes (comparable with those required of MCPs, rather than clinical outcomes) are these equivalents reported to produce?

-

What is the evidence about the ways in which these mechanisms of action depend on specific contexts (e.g. the presence of non-hospital beds for frail older people), that is, how do the different components of the MCP models of care produce different outcomes in different contexts?

-

What do the answers to the above questions imply for the organisational design (logic models of governance structures, internal management and working practices) of MCPs in the NHS?

As Chapter 3 explains, our method for answering these research questions was a realist synthesis of secondary data.

Chapter 3 Methods

Research design

The overall research design was a realist synthesis. Our rationale for using this method was that we wished to test from secondary evidence, the body of which was likely to be very varied in quality, types and sources, a set of assumptions about how a policy (the creation of MCPs) would produce various outcomes (better care co-ordination, etc.) in NHS contexts. Therefore, we use the terms ‘context’, ‘mechanism’ and ‘outcome’ in their realist senses. By ‘mechanism’, we mean ‘individuals’ reasoning, action and use of resources’. By ‘outcomes’, we mean the empirical, and, indeed, causal, effects of these mechanisms, intended or otherwise (e.g. emergent outcomes). By ‘context’, we mean ‘a moderator, not causally dependent on the mechanism, which is either necessary for the mechanism to produce the outcome or that intensifies the outcome that the mechanism produces’. Thus, contexts do not include intermediate outcomes (mediators). Patient and public involvement (PPI) representatives were consulted in the initial design of the research.

The realist synthesis combined three elements:

Step 1 – eliciting an IPT. Elaboration of NHS policy-makers’ assumptions regarding how MCPs can bring about their intended outcomes, which elicited the ‘initial programme theory’ for MCPs. We elicited policy-makers’ assumptions from the sources (policy documents and stakeholders) reported below (see Step 1: eliciting an initial programme theory for multispecialty community providers).

Step 2 – reviewing the evidence. A systematic search for published evidence relevant to the IPT, formal data extraction of secondary data from included studies, quality assessment of the studies and collation of the extracted data in relation to the IPT.

Step 3 – building a revised logic model. Comparing the IPT with the evidence review findings and reducing, revising and elaborating our programme theory. When programme theory and evidence differed, we removed causal links between components in the IPT for which we did not find evidential support. We then used the evidence review findings to qualify, elaborate and supplement the remaining MCP programme theory for which there was supporting evidence. That ‘logic analysis’38 produced a revised, more strongly evidence-based programme theory of MCPs, that is, an empirically informed revised logic model. 39,40

Accordingly, the project involved two searches of published literature:

-

for policy documents and other materials from which to elicit the IPT in step 1

-

for empirical research (‘evidence’) to provide secondary data for the evidence review in step 2.

The whole study was conducted to Realist And Meta-narrative Evidence Syntheses: Evolving Standards (RAMESES)41 and is reported following those standards, and in conformity with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement. 42

Step 1: eliciting an initial programme theory for multispecialty community providers

We elicited policy-makers’ assumptions about how MCPs can achieve their outcomes partly from policy documents, supplemented, as explained below (see Stakeholder think tanks), from a ‘think tank’ of MCP ‘stakeholders’.

Identifying core multispecialty community provider policy sources

The original call for proposals for this research, and the research protocol itself, focused on the 5YFV6 as the main policy source about what policy outcomes MCP are intended to produce, and the means by which policy-makers assume MCPs will do so. For this reason, we used the 5YFV as one of our focal documents in step 1.

We conducted a literature search to identify additional English policy statements on care models for people with chronic conditions. The aim of this search was to find a core set of policy documents in order to identify policy-makers’ assumptions about MCPs. This search used the Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC) database (via Ovid), which indexes policy content from the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) database (DHSC Data) and The King’s Fund database. HMIC was the only database we searched, as it was found to index all the authoritative policy papers and web pages. Search terms were selected by inspecting the titles and abstracts of the known relevant policy documents mentioned. The search used generic terms describing generic and specific interventions that appeared functionally equivalent to MCPs (e.g. ‘integrated primary and community care’) and particular international examples, such as Buurtzorg and the Wiesbaden Network for Geriatric Rehabilitation. These terms were combined using the Boolean operator ‘AND’ with terms for older people and people with chronic and complex conditions. Both sets of search terms were represented by free-text terms and indexing terms. The search was conducted on 25 August 2016 and date limited to after January 1991 (the foundation of the NHS quasi-market).

The 5YFV used partly different terminology from the other key policy documents identified by web searching. The 5YFV focused on developing ‘sustainable’ ways of organising care to tackle health inequalities, rather than on models of care to tackle chronic conditions. Therefore, we made a supplementary search of HMIC using search terms for ‘inequalities’, ‘health care’ and ‘sustainability’ – a more focused search than the first. Search terms were limited to the notes field of HMIC records, which is used to summarise the contents of a report as a supplement to the abstract that is often not included with policy literature. The search was conducted on 25 August 2016 and no date limit was used.

The results from both searches were exported to an EndNote X7 (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA) database. The search strategy and the number of hits for each search are presented in Appendix 2.

Only a handful of policy documents were identified that explained MCPs in much detail (see Chapter 1). The most informative were the ‘logic model descriptions’, which each of the first-wave MCP Vanguard sites prepared and which, as first-hand accounts endorsed by NHS England of what the MCP Vanguards were attempting to do, were especially relevant and important. The focal policy documents used from which to extract policy-makers’ assumptions about MCPs are cited in Chapter 4 and listed in Appendix 3.

Connecting and mapping mechanisms and outcomes

We first elicited as many of the policy-makers’ assumptions about MCPs as we could from the identified sources. In order to elicit the IPT, we framed or reformulated policy-makers’ assumptions in realist terms as context–mechanism–outcome configurations (CMOCs), or parts thereof, with the terms ‘context’, ‘mechanism’ and ‘outcome’ (defined as in Research design).

We articulated these CMOCs in ‘if–then’ statements, that is, statements of the assumed context and mechanism (‘if’) and outcome (‘then’); for example, if MDTs are established in the context that patients want to maintain their own health, then preventative health care will develop. This was a practical necessity as it was rare for the policy statements to specify a context (in the realist sense, i.e. under what conditions the proposed mechanism would or would not work) in addition to mechanism and outcome. Some if–then statements were describing essentially the same CMOC in different words (e.g. about electronically sharing patient information between organisations). We treated these statements as multiple formulations of the same assumption and, in effect, merged them. Many other statements referred (again, sometimes using different words) to essentially the same mechanism (e.g. ‘multi-disciplinary team’, ‘inter-professional team’, ‘cross-professional group’). In some cases, the mechanism of one statement was a subset, component or special case of the mechanism of another (e.g. ‘primary care’ and ‘primary care close to home’). Therefore, we grouped these under the same overarching mechanism. Similarly, many statements referred (again sometimes with different words) to essentially the same outcomes (e.g. ‘patient self-care and activation’ and ‘patient engagement in care and self-care’). We also grouped these accordingly.

This grouping of the if–then statements by mechanism and outcome identified from the policy-makers’ assumptions what the core MCP ‘components’ [mechanism, outcome or context (as the case might be)] were, and the ‘causal links’ between them. We identified 13 components of MCPs and 28 causal links between them, and numbered each linked mechanism and outcome so that the links between components could be traced back to the initial if–then statements.

The MCP components are inter-related in complex ways. Many MCP components were mechanisms for producing several outcomes. Many components were also assumed to be the product of several other components. Often, mechanisms were linked together in chains (‘concatenated’): the outcome of one mechanism was to set up another mechanism producing a further outcome. Producing the second mechanism was, thus, an intermediate outcome.

Next, we mapped what the policy documents assumed the causal links between the MCP components to be, which revealed the assumed chains of MCP components and their complex inter-relationships; in particular, the ways in which some mechanisms were assumed to produce or trigger others. Throughout, and, in the following chapters, we have maintained the same system of numbering for these causal links. For example, ‘(3:10)’ means that component 3 is assumed to be a mechanism that produces component 10. One way of showing the relationships between the mechanisms is by using graphics. In these graphics, we have represented each MCP component by a box containing its constituents and numbered to indicate its source(s). Arrows between components showed the causal links that the policy-makers assumed. Figure A (see Report Supplementary Material 1) shows the first such graphic, based on only the policy documents mentioned previously.

Patient and public involvement

In this study, PPI was through participation in stakeholder ‘think tanks’ (see Stakeholder think tanks). This method of participation was co-designed with PPI during the submission of our research proposal to the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR).

The stakeholder group included four members from the wider Peninsula Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC) Patient Involvement Group who expressed interest during their involvement in the preparation of the research proposal (see Appendix 4).

Stakeholder think tanks

To check our understanding of the programme theory of MCPs for any missing or misinterpreted elements, we consulted a think tank of patient and NHS ‘stakeholders’. The latter included people who would be implementing MCPs. We used these meetings to:

-

check our interpretation of the initial MCP programme theory

-

resolve ambiguities

-

add any missing components

-

advise as to which MCP components were most important and should, therefore, be prioritised in the evidence review (step 2).

Senior researchers identified stakeholders at the research group meetings. Mark Pearson provided names of service users, Helen Lloyd gave a list of policy-makers and academics and Richard Byng supplied a pool of GPs and managers working in GP surgeries. The final list encompassed stakeholders across England, including senior staff from NHS England.

We held three think tank meetings in October 2016. Participants were general practice members (GP, practice manager), service users, policy-makers (including NHS England) and a minority of academics. The researchers made field notes and (with the participants’ consent) audio-recorded the meetings in order to return to key points, if necessary. After each meeting the if–then statements and map were successively modified.

We held a further meeting with our stakeholders in March 2017 in order to check our understanding of the linkages between MCP components and we will meet the stakeholders again to discuss further how to disseminate our findings.

From the included policy sources and the think tank interpretations we arrived at 242 if–then statements (see Appendix 5).

Deduplicating and consolidating the conceptual map

Given the number of if–then statements, data reduction was necessary. When we had one link A–B–C and one A–C; the first was more informative (about mediating steps) and so we removed the second as a duplicate. We also removed non-redundant, but trivial, links (e.g. ‘if there is scope for local innovation in creating MCPs, then MCPs will be created’).

Even after consulting the stakeholder think tank, many of the if–then statements still explicitly stated only one or two of the context–mechanism–outcome (CMO) trinity, which previous studies43–47 have already shown is often the case with policy sources. In developing the conceptual map, the researchers imputed the missing assumptions from our background knowledge of the English health system and clinical practice within it. In doing so, we:

-

clearly differentiated the imputed assumptions from those explicitly stated in the policy sources

-

selected, when alternative assumptions might be imputed, those that have the strongest evidence base and were most consistent with those explicitly stated in the policy sources, avoiding the construction of a ‘straw man’ or unfairly weak interpretation.

Adding these connections produced a second graphic, Figure B (see Report Supplementary Material 1). The graphic includes the numbered ‘ifs’ and ‘thens’ behind each component in order to illustrate some (but certainly not all) of the complexity of their inter-relationships, the direction of ‘flow’ from input to output (showing which were intermediate and which were final outcomes), but also removing redundant links as explained above. This method ensured that the fully articulated initial MCP programme theory remained as comprehensible as possible while remaining as close as possible to the original policy statements. Chapter 4, The initial programme theory: multispecialty community provider components and the causal links between them formulates the IPT taken forward into step 2. Chapter 4 describes (both verbally and with a graphic), in detail, the mechanisms, intermediate outcomes, final policy outcomes and contexts that, together, comprise the fully articulated IPT for MCPs early in 2017.

Step 2: reviewing the evidence

Exploration and search strategy development

The aim of the realist evidence review was to discover an evidence base against which to ‘test’ IPT (see Step 3: building a revised logic model) and reveal whether or not the IPT omitted any important MCP components or causal links between them. Owing to the size and complexity of the corpus of relevant studies, we were also aware of the necessity for a well-defined and focused search strategy. We focused the search by:

-

Searching for concepts and terminology from the main components of programme theory, starting with the formation of MCPs and its subcomponents (see Chapter 4). This search covered all 13 components of the IPT. The search concentrated on the connections between the 13 components rather than on each component in isolation from its effects and contexts.

-

‘ANDing’ these with names of MCP-equivalent organisations, networks and projects. Chapter 1 defined ‘MCP equivalent’ as performing a similar function of horizontal co-ordination between primary medical care, domiciliary health care, other primary care health services, and social care. Sarah L Brand and Simon Briscoe assembled a list of MCP equivalents [including Chronic Care Models (CCMs)], drawing on the whole research team’s knowledge.

We developed a search in MEDLINE (via Ovid) using the above sets of terms. Search terms were represented by free-text terms and indexing terms. The final search was translated for use in a selection of topically appropriate databases, including MEDLINE, MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, PsycINFO (all via Ovid), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL; via EBSCOhost) and Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA; via ProQuest). The search was conducted on 5 December 2016 and no date limit was used. We exported the search results to EndNote X7 and deduplicated them using automatic and manual checking. The search strategies and number of hits are presented in Appendix 6.

Studies were also identified through opportunistic finds from e-mail updates from relevant journals.

Selection

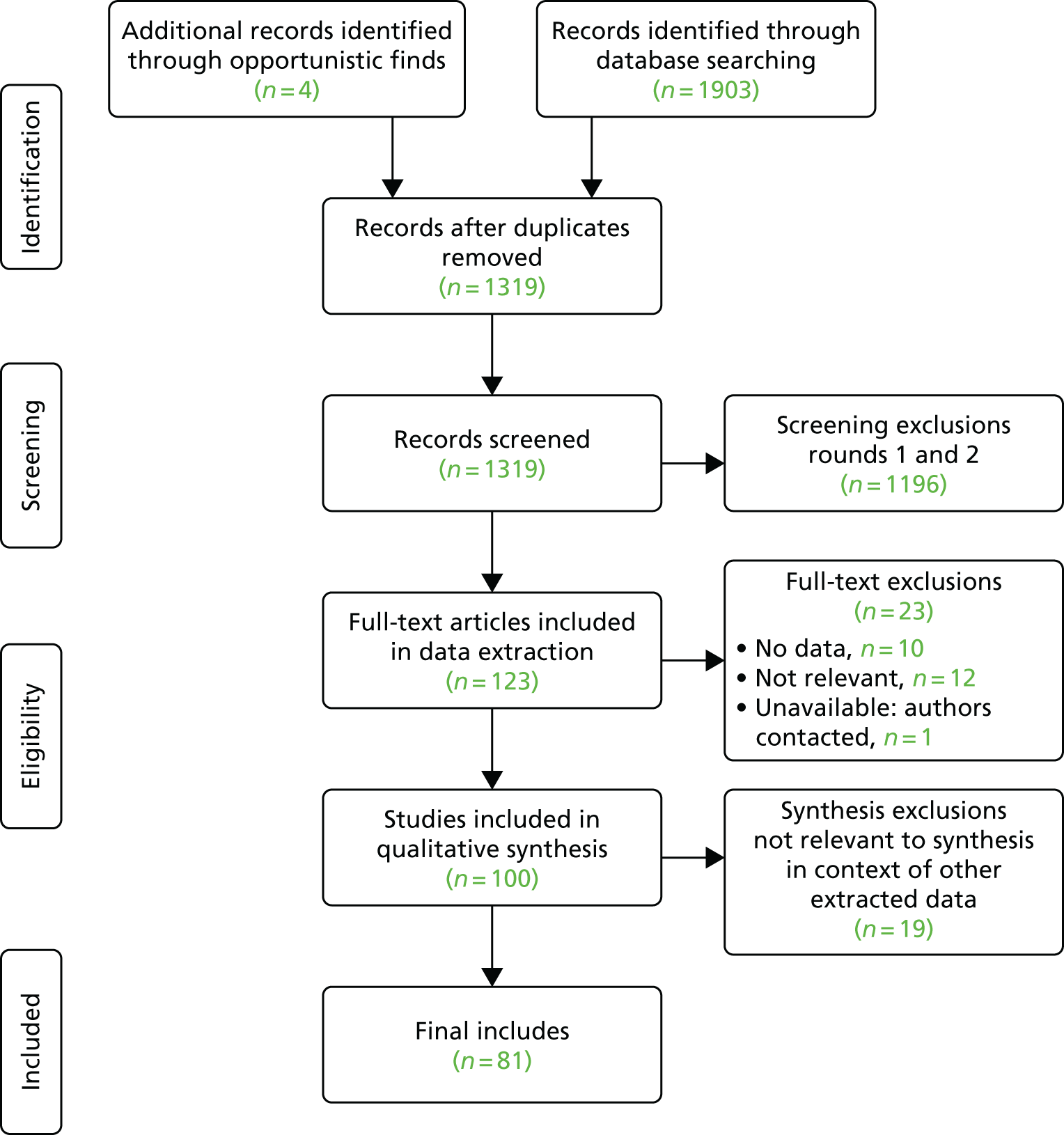

Five reviewers (RS, MP, SLB, MF and AW) between them screened 1319 titles and abstracts in the EndNote database. There were two rounds of screening. For each round, we developed a screening tool (Appendices 7 and 8), each of which went through two rounds of piloting on 10 studies (20 in total) by all reviewers. Discrepancies in tool use and include/exclude decisions were discussed and resolved after each pilot to achieve consistency in its use.

Screening stage 1

Using screening tool 1 (see Appendix 7), we selected studies about any of the 13 MCP components in the IPT (listed previously). We included only studies with empirical contents, that is, comparative effectiveness studies [randomised controlled trials (RCTs), etc.], process evaluations, reviews of primary research (if the method was stated), qualitative research, surveys, histories, descriptions of models of care, uncontrolled before-and-after comparisons, cohort studies and reanalyses of routine data. We excluded editorial letters, conference abstracts, opinion pieces, audit articles and the numerous a priori, but data-free, ‘models’ of integrated care. Next, we assessed whether or not the selected empirical studies were about horizontal interorganisational linkages in primary care, that is, between any two or more of primary medical care, CHS, ambulance, community health and mental health care, residential care, therapies, primary health care (PHC) dentistry and PHC pharmacy. If not, we excluded them. Hence, we excluded studies purely about hospitals and single-organisation studies. The first stage of screening selected 463 studies.

A second reviewer (SLB or RS) screened 10% of these (n = 99), resulting in eight discrepancies to be resolved by a third reviewer (MP).

Screening stage 2

There were too many studies to review with the time and staff available remained after first screening (n = 463). Therefore, we also excluded pre-2014 studies in order to focus on the most recent data with the assumption that later studies, especially reviews and systematic reviews (SRs), will already refer to the findings from the most important earlier studies. We then carried out a second round of screening on the remaining included studies. Using screening tool 2 (see Appendix 8), we excluded the following studies:

-

Studies that did not concern an Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) country. Realist methodology assumes that similarity of context is a pre-condition for the transferability of mechanisms from one setting to another, and OECD countries’ health systems and wider social contexts were more likely to resemble those of the UK than those of non-OECD countries.

-

Studies that were not specific to horizontal interorganisational co-ordination of primary care, that is, generalities (e.g. training) that may apply, but are not specific, to MCP-equivalent structures; ‘vertical’ (primary–secondary) not ‘horizontal’ service co-ordination; micro-management techniques, health information technologies (HITs) (e.g. medical record design, applications); and studies of purely clinical interventions (e.g. therapy methods or rules for managing polypharmacy).

Ten per cent of round 2 screening was second screened by one reviewer (SLB). Before data extraction, both rounds of screening were checked by Sarah L Brand for any coding mistakes. There were 25 coding errors and missing codes that were identified and rectified. This identified two new studies, giving us 116 included studies.

To automate later data sorting and extraction, the included studies were coded in the EndNote database according to which programme theory component(s) they were relevant to.

Data extraction and quality appraisal

The aim of data extraction was to extract evidence about the 28 causal links in the IPT (see Chapter 4). Four reviewers (RS, MP, SLB and AW) extracted data from the included studies. Each reviewer was allocated 1–4 of the 13 components. The data extraction tool (see Appendix 9) was piloted on two studies by two reviewers (SLB and RS), followed by discussion to resolve any discrepancies or other problems. For each of the 28 causal links, we sought to:

-

extract data tending to corroborate the causal link

-

extract data that were evidence against the causal link

-

extract evidence of new causal links or components not in the IPT

-

specify context(s), that is, evidence specifying the circumstances under which one component would produce another, or fail to

-

note the quantity and strength of evidence about the causal link

-

note any qualifications or limitations to the findings reported in the study from which data were being extracted

-

note which kind(s) of MCP equivalent(s) the study described, in which country and serving which care group(s).

For studies allocated to more than one reviewer (i.e. relevant to more than one component, which was most of the studies), the first reviewer extracted data and saved the data extraction form, the next reviewer extracted data from that study and then checked the first reviewer’s data extraction and added their own data extraction (if any) to the first reviewer’s form, and so on. In this way, 26 out of the 116 included studies were data extracted by two reviewers (22.4%).

Each included study was assessed for methodological quality using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT). 48 We used the MMAT because, reflecting their complex objects of study, we expected most of the studies to use mixed or qualitative methods, with some quantitative studies. Two reviewers (SLB and RS) piloted MMAT scoring on two studies, then discussed the discrepancies with the wider team to ensure consistency. Any issues arising in quality appraisal assessment were raised and discussed in team meetings during the quality appraisal stage. The data extractor(s) for each study also assessed its MMAT quality score. The MMAT provides a standardised appraisal checklist of four items (hence, scores of 0, 1, 2, 3 or 4) for qualitative studies, and the same for RCTs, non-randomised trials and descriptive quantitative research. For mixed methods, it provides a three-item checklist. Criteria for all the checklists are detailed and well specified. To assess the quality of the included SRs, we used the Assessment of Multiple Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) quality appraisal tool for SRs. 49 AMSTAR also provides well specified, consistently structured checklists for 11 characteristics indicative of, in this case, the quality of a SR, giving a total score of between 0 and 11 for each SR. MMAT and AMSTAR ratings were conducted by one reviewer. Ten per cent of these were then rated by a second reviewer (SLB, n = 9; RS, n = 3) and one discrepancy was resolved by a third reviewer (HL). The MMAT or AMSTAR rating and a narrative summary of any methodological quality issues with a study were also recorded on its data extraction form.

Collating and coding data

The data extraction tool (see Appendix 9) was structured according to the 28 causal links between MCP components in the IPT, in 11 groups according to which component was the mechanism, as opposed to the outcome, in that causal link. This structure was also the overall coding framework for the data. To automate data sorting and retrieval, we created an NVivo 11 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) database, with a node for each causal link and, therefore, the corresponding section of the data extraction tool. Within each node, subnodes corresponded to the lower-level links between the subcomponents of each MCP component. Data from all the data extraction forms were imported into the corresponding NVivo node(s). When no suitable node existed, we created new nodes, as necessary, during data extraction. These were where additions to and elaborations of the IPT began to emerge.

Step 3: building a revised logic model

Comparing the initial programme theory with the evidence review findings

The 28 causal links between the 13 MCP components were the analytic framework for this comparison. We collated the relevant contents of the completed data thematically into that framework. For the 28 causal links in the IPT, we:

-

assessed the overall evidence for the causal link

-

inducted patterns and subthemes

-

noted strengths of evidence and gaps in the evidence, including any absence of contextual information about each causal link

-

noted new causal links not in the IPT

-

noted any contradictions or ambiguities in the evidence about particular causal links.

Synthesis

For each causal link, we summarised the number and quality of studies supporting, refuting or qualifying it (see Chapter 7). We categorised the strength of each causal link’s evidential support as one of (in descending order):

-

‘substantial’ [i.e. a combination of primary studies and SR(s)]

-

‘supporting’ (i.e. multiple primary studies)

-

‘minimal’ (i.e. a single primary study)

-

‘partial support’ (i.e. some supporting evidence for parts of the underlying programme theory about that causal link – that it only operates in certain conditions, or with certain populations)

-

‘equivocal’ [i.e. evidence both for and against (but we also noted whether or not, in such cases, the evidence was predominantly on one side)]

-

‘none’ (whether evidence to the contrary or just the simple absence of any supporting evidence in the studies available to us).

A single working instance of a causal link between two components (‘minimal’ evidential support) does at least give evidence of the feasibility (‘proof-of-concept’) for that component operating as a mechanism to produce that outcome in another setting provided that the destination context has similar moderating characteristics to the original ‘proof-of-concept’ context. Equivocal evidence is, to the realist mind, a clue to the possible presence of contextual factors, which determine whether or not that mechanism will produce that outcome in different contexts for different populations and what kind or size its impact will be (e.g. the mechanism ‘works’ for one care group or in one kind of health system but not another).

Revising the initial programme theory

To convert the IPT into a revised, more strongly evidence-based logic model, we removed the causal links with no supporting evidence or where evidence existed but was against them. For causal links that had only partial support, we removed the unevidenced elements. These subtractions produced a truncated, but more strongly evidence-based, programme theory.

To that truncated version, we next added:

-

relevant causal links found in the body of evidence but omitted from the IPT

-

contextual statements of the circumstances that qualify the causal link between two MCP components, because certain specific conditions strengthen or weaken the outcome produced.

In places, the IPT was formulated ambiguously (see Chapter 4). To test it as it stood, we left these formulations untouched when comparing it with the secondary evidence. To produce a more coherent, less ambiguous, more evidence-based MCP programme theory, we separated out those concepts (e.g. ‘co-ordination’ and ‘integration’; see Chapters 4 and 6) that the policy sources had conflated.

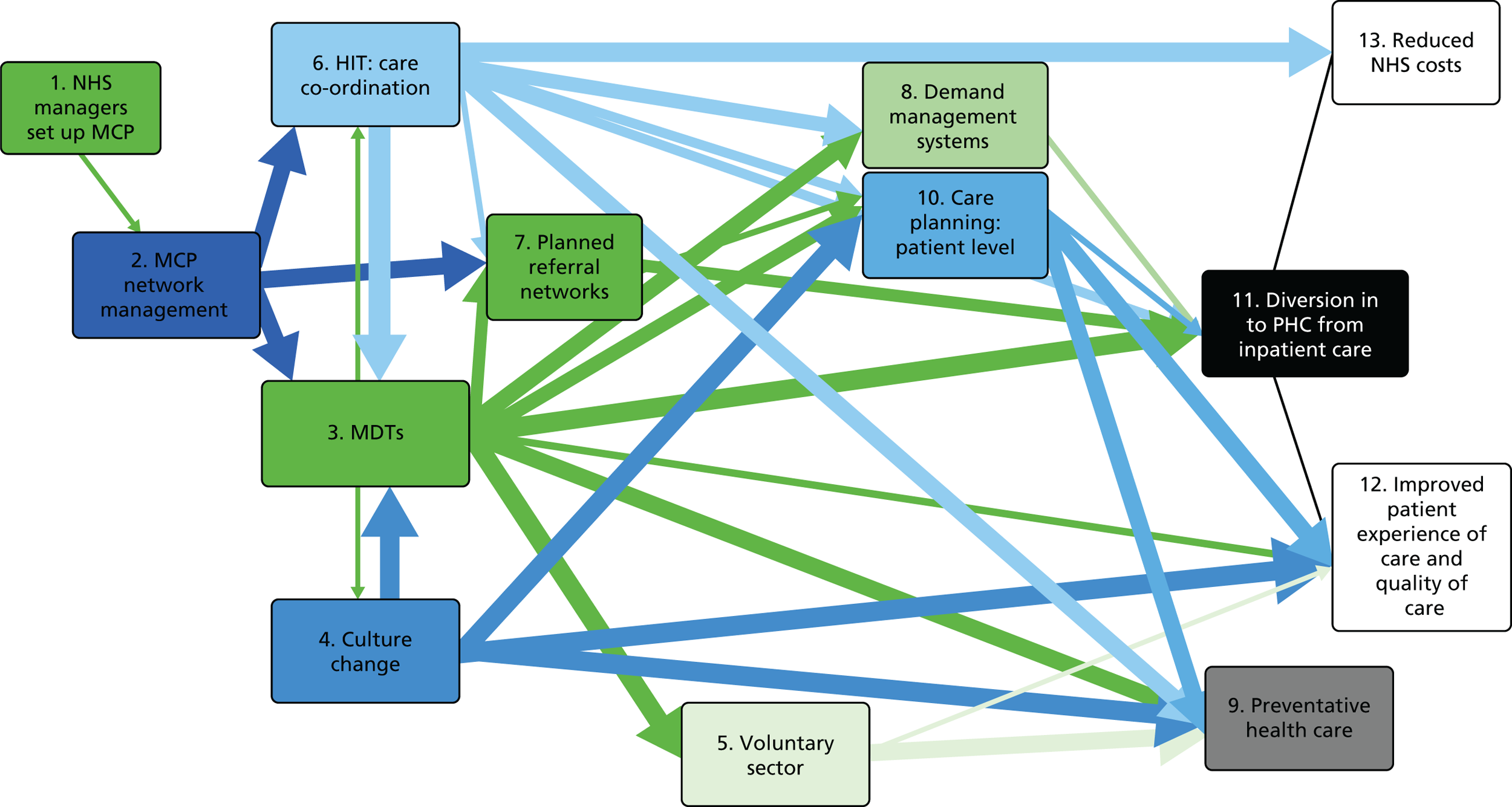

Adding further contexts and mechanisms made an already complex programme theory more complex. It would be an exaggeration, but one with a grain of truth, to say that the initial MCP programme theory had come close to assuming that, in MCPs, every component helped to produce every other component (see Chapter 4). To differentiate the critical from the non-critical causal links, we used two methods. First, using the categories described above, we also categorised the strength of evidence for each subsequently added causal link, from ‘minimal’ to ‘substantial’ (see Chapter 7). As a graphical representation, we redrew the map of the revised logic model so that the width of each link reflected the ‘strength’ of evidence for it (see Figure 5). Second, to simplify the graphical representations, we eliminated redundant links in the revised logic model, applying the same principle as previously. However, in reviewing the evidence, we included all the links, both direct and indirect.

The product of these subtractions, additions, qualifications and definitions was a revised, more strongly evidence-based programme theory for MCPs, articulated in correspondingly revised verbal, tabular and graphical presentations (see Chapter 6).

Table A (see Report Supplementary Material 2) itemises, in detail, how our methods complied with the RAMESES quality standards. 41

Chapter 4 Step 1 findings: eliciting the initial programme theory from policy sources

Outline of assumptions in policy sources

From the sources and stakeholders mentioned in Chapter 3 (and see Appendices 3 and 4), we obtained and collated 242 statements about what intermediate outcomes and final (policy) outcomes MCPs were designed to attain, by what means and in what contexts (see Appendix 5). Appendix 10 lists, in descending order of frequency, the 20 that were most frequently mentioned in the policy documents that we analysed.

Interpreting the policy sources in realist terms

The policy sources seldom explicitly formulated their assumptions about MCPs as the CMOCs, or parts thereof, which realist synthesis requires.

Underspecified policy-makers’ assumptions

The 5YFV6 and related policy documents stated in general terms that MCPs will promote the ‘integration’ of care for older people with multiple morbidities by partly replacing hospital care with non-hospital care. However, for the most part, MCP policy was unclear about which components might act as mechanisms to produce which specific outcomes. At times, policy statements asserted what should be done without expressly stating how and/or what effects doing this would have. For example, at one Vanguard site there would be ‘more ways for people to digitally access health care (including online directories of local services, and a library of helpful health apps on its website)’,8 but this idea was not explicitly connected to any policy outcomes it would produce or to contextual requirements for it to work. Other statements were so broad as to be difficult to interpret concretely (e.g. that ‘artificial boundaries between hospitals and primary care, health and social care, between generalists and specialists are broken out of’ and ‘long term conditions are better cared for’). 6

Policy-makers may have left these points underspecified so as not to foreclose MCP design options or for other reasons (as with other policies10). Policy documents said that different types of MCP might emerge but not what these variants were or what might differentiate them. They suggested possible MCP contractors,5 but proposed a wide range, including Community Interest Companies, Limited Liability Companies, partnerships (including GP federations) and statutory NHS providers. MCPs were also described as ‘extended group [GP] practices’ that might be ‘federations, networks or single organisations’ (p. 20). 6 Concomitantly, ‘general practice at scale’ might, according to the 5YFV,6 be networks of independent general practices, perhaps with a strong central co-ordinating body (a ‘federation’). The House of Commons Health Committee argued that federations allow specialisation of service and care team development but retain the existing scale of general practices. 5 Although policy documents stated that MCPs will also have an element of vertical integration, or rather co-ordination, of care, short of structurally integrating primary and secondary care, they also usually discussed MCPs separately from PACSs.

Relationships between mechanism and outcome in the policy documents were often underspecified, and there was often ambiguity over whether the terms referred to a mechanism and its context or (without differentiating) both a mechanism and its outcome:

-

‘MCP setup’ – ambiguity between a mechanism (i.e. actions by NHS managers) and a context (favourable or unfavourable background conditions).

-

‘Demand management’ – ambiguity between a mechanism for managing demand (e.g. referral screening, risk stratification) and the outcome of doing so managing demand (fewer referrals and admissions to hospitals).

-

‘Patient diversion’ – ambiguity between mechanisms for diverting patients away from hospital (e.g. providing alternative care outside hospital) and the outcome of doing so (e.g. fewer hospital admissions).

Multiplexity

If–then relationships between MCP components in the policy documents were successively linked (‘concatenated’) and multiplex. They rarely assumed that one mechanism produced just one final outcome, but more often that different mechanisms were concatenated so that the output of one was to create, or to trigger, the next. For example, policy statements expected the creation of MCPs to strengthen the management of provider networks, which would then strengthen referral networks, and then the referral network would lead to patients being diverted from hospital, and so on. The if–then relationships were multiplex in that a single mechanism was sometimes assumed to trigger several others. IT-based care co-ordination would, the policy statements jointly assumed, divert patients away from hospital, strengthen care planning at patient level and make urgent care more responsive. In reverse, the policy statements also assumed that one policy outcome would result from many mechanisms. For example, improved care planning at patient level would be the joint effect of IT-based care co-ordination plus referral networks plus demand management systems (themselves also resulting from care planning at organisational level) plus preventative care.

Translations and nomenclature

The policy documents made little explicit reference to evidence bases beyond some local evaluations. However, they often referred to two main international prototypes for MCPs, the US ACOs and PCMHs.

In NHS policy documents, the term ‘accountable care organisation’ means an ‘overarching organisation that sits above a joined up health and social care system made up of a number of different providers, from health services to the local council’. 50 Such an ACO would be certainly the predominant, perhaps sole, contractor for NHS-funded services with its local commissioner. The US Government’s CMMS defines ACOs as ‘groups of doctors, hospitals, and other health care providers, who come together voluntarily to give co-ordinated high quality care to their Medicare patients’26 (i.e. not for all patients) and provider membership is optional – differences to bear in mind when interpreting the ACO model and research for NHS use. NHS policy statements also borrow the term ‘Patient Centred Medical Home’ which, in the USA, formulates an ambition to construct something similar to what current NHS general practice (usually) is, that is, primary medical care based on the:

underlying principle of a single physician who coordinates the patient’s care and engages a team of health care providers and their patient in an individualized treatment and management plan.

Kash et al. 51

As the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) points out, general practice is (already) ‘the natural medical home for patients’. 52 In the USA, a ‘medical neighbourhood’ is understood as a group of ‘medical homes’. Finally, ‘integration’ in NHS policy documents almost never means ‘organisationally integrated’ (as it would in some countries) but, rather, the closer co-ordination of services provided by separate organisations. Many health systems pursue that aim by creating referral networks53 of providers, with each network having a ‘network administrative organisation’54 doing much of the actual co-ordinating work. Policy documents also implicitly used the term ‘prevention’ in a hitherto non-standard way to mean long-term self-care, ‘activation’ and ‘empowerment’, and patient education, rather than clinical prevention or intersectoral activity, for health promotion.

Apparent omissions

Many policy statements were implicitly in mechanism–outcome configuration, rather than a CMO configuration. From a realist perspective, it was noticeable that policy sources seldom made assumptions (even implicitly) about what contextual factors would moderate the many assumed causal links between MCP components and outcomes. Nevertheless, a few contextual assumptions were stated and are outlined below.

Compared with the policy issues covered in Chapter 1, the policy statements said little about:

-

organisational integration, in the sense of GPs, CHSs and other staff being members of the same organisation

-

lack of residential and social care

-

risk stratification and case management

-

MCPs’ relationships to the other six new models of care.

Imputing the missing causal links and contexts in the policy-makers’ assumptions

To make the policy-makers’ assumptions empirically testable, one has, at times, to impute the necessary missing definitions and terms and operationalise them. As Chapter 3 explained, we did so by:

-

asking our NHS think tank to interpret what, in practical terms, the policy statements appeared to mean to them as NHS clinicians and managers

-

cross-referring between policy statements (at the cost of assuming that the same word means the same thing in different statements)

-

exploiting the textual setting. For example, a statement about information-sharing in the context of hospital referrals and discharges was taken to refer to information sharing between hospitals and GPs, and between hospitals and CHSs

-

referring to the international prototypes that policy documents cite (see Namesakes and equivalents in other health systems), although with due attention given to differences between the original and the NHS settings

-

referring to particular named examples of plans for, or evaluations of, existing proto-MCPs. From these descriptions, the researchers abstracted the more general assumptions about how this MCP would work from its local particularities

-

calling on the researchers’ (who included clinicians) background knowledge of primary care in the NHS and of relevant research to infer what such statements were most likely to allude to, and interpret, such euphemisms as ‘leadership’ for ‘managers’ or ‘expert generalist’ for ‘GP’.

By these means, we, so far as possible, formulated and elaborated the policy statements as ‘if–then’ statements (‘if’ = M–; ‘then’ = –O, provided that C–), which realist synthesis (indeed any empirical test) requires as raw material.

The initial programme theory: multispecialty community provider components and the causal links between them

We grouped by mechanism and by outcome the 242 if–then statements obtained from the policy sources (described in Chapter 3). These 13 groups were named as MCP ‘components’ and were linked by 28 ‘causal links’. Together, these make up the top level of the initial MCP programme theory. Underlying or, rather, composing each causal link are single or multiple if–then statements, making the more detailed content of the IPT. Appendix 11 summarises the 13 MCP components in our interpretation of the policy-makers’ assumptions about MCPs.

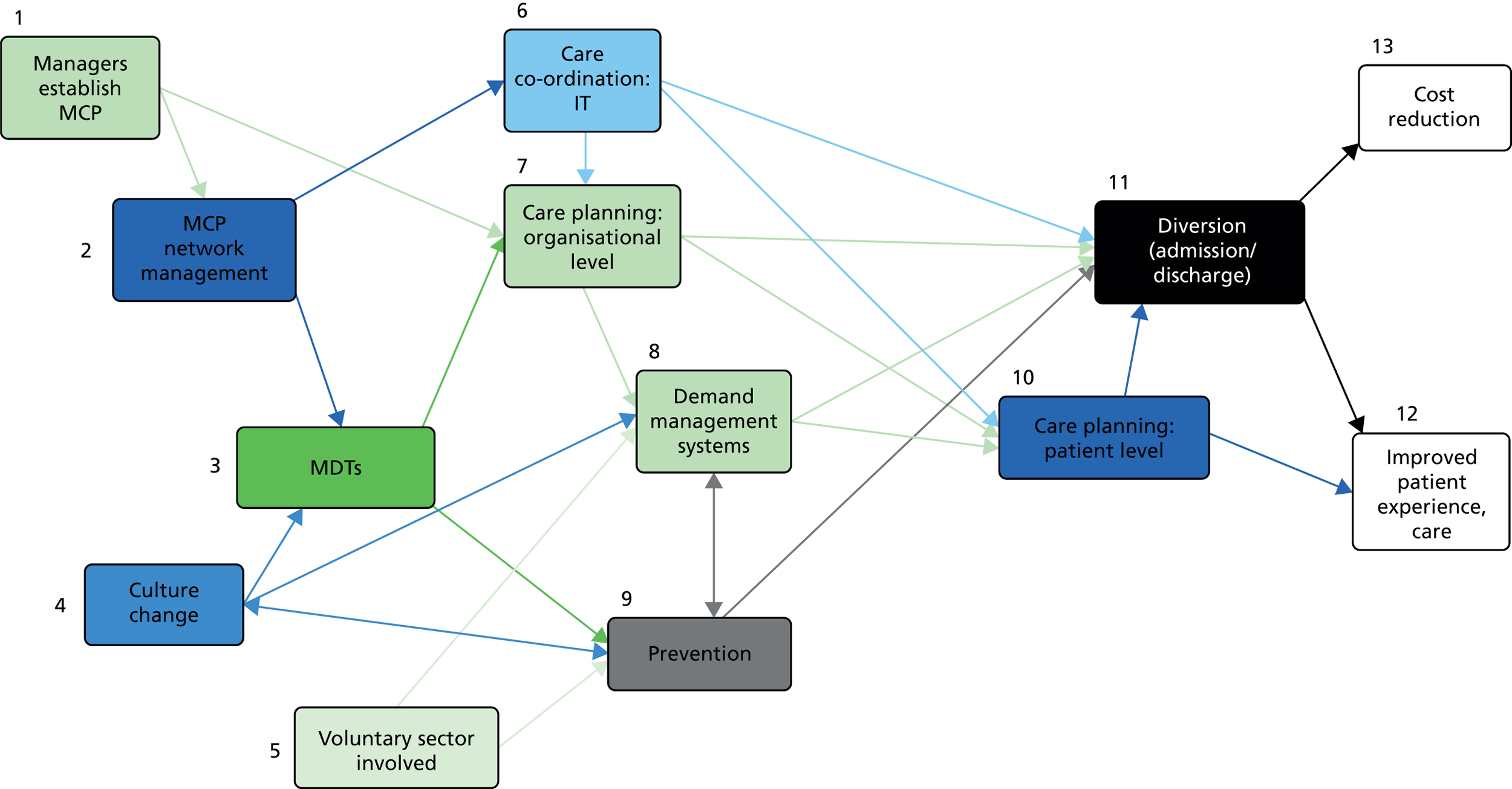

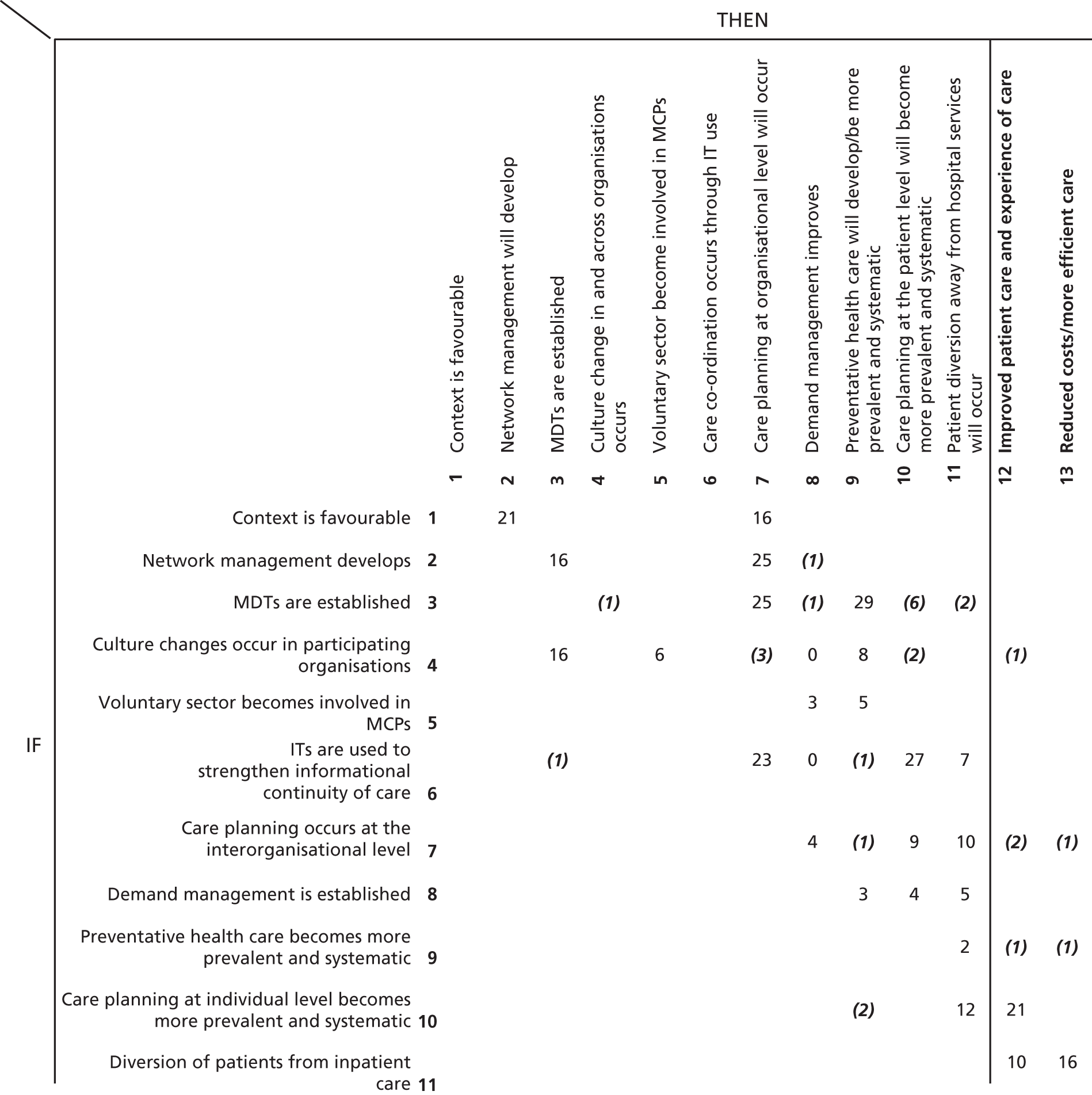

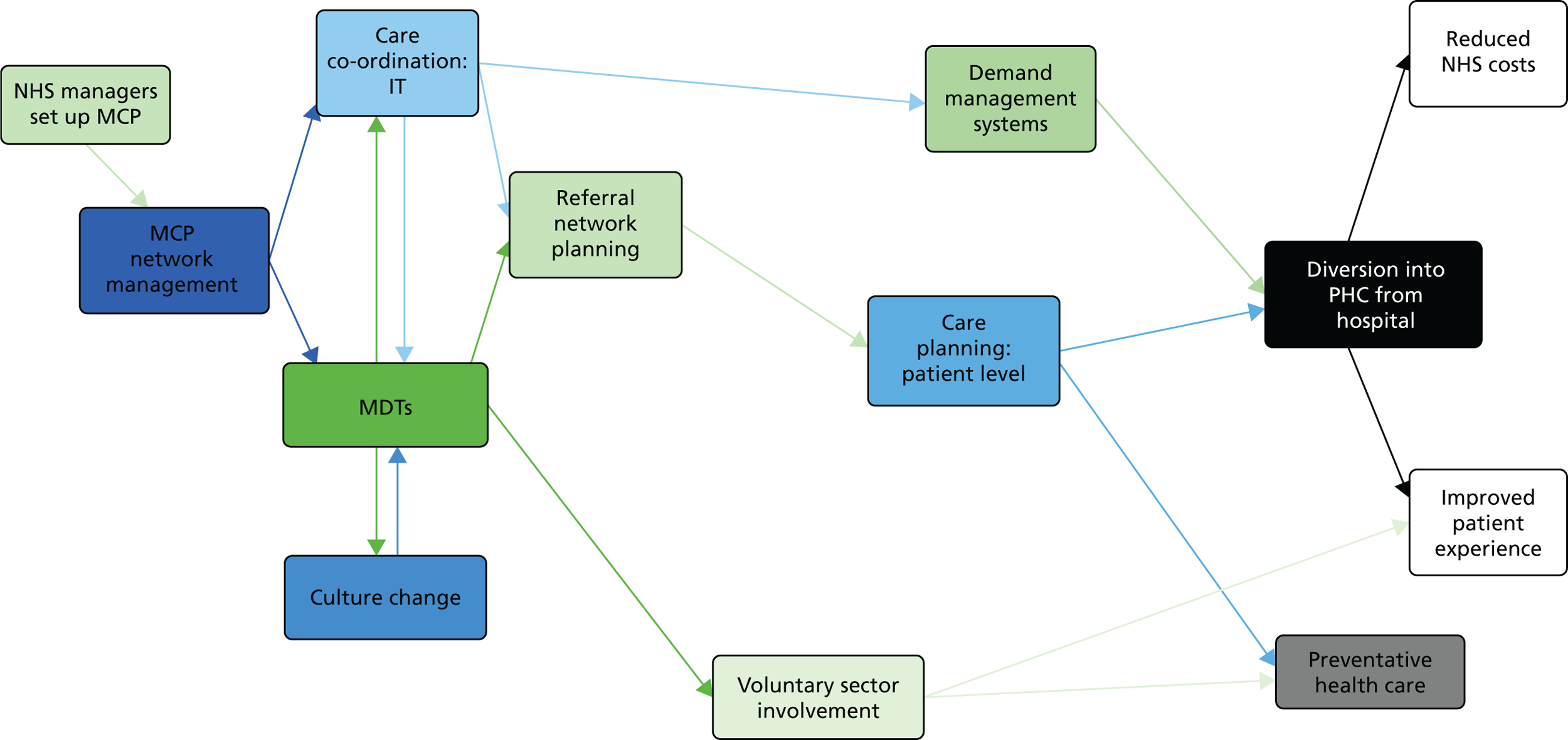

Table 1 and Figure 1 illustrate the IPT that we took forward to the evidence review. The IPT is our interpretation of the policy-makers’ assumptions (developed as described in Chapter 3, and glossed at points to explain our reasoning). This IPT is made up of 13 components and 28 causal links between them. As this review is focused on exploring the evidence for how MCPs work and not what MCPs are, it is the causal links between the 13 components and not the 13 components themselves that guide our evidence review (step 2; see Chapter 5 for results of the evidence review). Figure 1 illustrates the 28 causal links. Note that the 13 components (see Appendix 11) include the two main outcomes of MCPs [(1) component 12: patient experience and care will improve; and (2) component 13: NHS costs will reduce). Because these two ‘components’ are the intended end result of MCPs in NHS policy, in the IPT they are not the mechanism for producing any of the other 11 components, and, hence, appear only in the right-hand (‘then’) column in Table 1.

| MCP component (1–13) | IPT causal link | |

|---|---|---|

| IF | THEN | |

| 1. NHS managers establish MCPs | 2. Network management will develop | 1:2 |

| 7. Planned referral networks will develop | 1:7 | |

| 2. Network management develops | 3. MDTs will develop | 2:3 |

| 6. Care co-ordination through IT use will develop | 2:6 | |

| 3. MDTs are established | 7. Planned referral networks will develop | 3:7 |

| 9. Preventative health care will develop | 3:9 | |

| 4. Culture changes occur in the participating organisations | 3. MDTs will develop | 4:3 |

| 8. Demand management systems will develop | 4:8 | |

| 9. Preventative health care will develop | 4:9 | |

| 5. Voluntary sector becomes involved in MCPs | 8. Demand management systems will develop | 5:8 |

| 9. Preventative health care will develop | 5:9 | |

| 6. HITs are used to strengthen informational continuity of care | 7. Planned referral networks will develop | 6:7 |

| 10. Care planning for individual patients will become more prevalent and systematic | 6:10 | |

| 11. More patients will be diverted from inpatient to primary care services | 6:11 | |

| 7. Planned referral networks develop | 8. Demand management systems will develop | 7:8 |

| 10. Care planning for individual patients will become more prevalent and systematic | 7:10 | |

| 11. More patients will be diverted from inpatient to primary care services | 7:11 | |

| 8. Demand management systems develop | 9: Preventative health care will develop | 8:9 |

| 10. Care planning for individual patients will become more prevalent and systematic | 8:10 | |

| 11. More patients will be diverted from inpatient to primary care services | 8:11 | |

| 9. Preventative health care develops | 11. More patients will be diverted from inpatient to primary care services | 9:11 |

| 10. Care planning for individual patients becomes more prevalent and systematic | 9. Preventative health care will develop | 10:9 |

| 11. More patients will be diverted from inpatient to primary care services | 10:11 | |

| 12. Patient experience and care will improve | 10:12 | |

| 11. More patients are diverted from inpatient to primary care services | 12. Patient experience and care will improve | 11:12 |

| 13. NHS costs will reduce | 11:13 | |

| Other. General practice will benefit | 11:other | |

| Other. Care co-ordination and demand management systems develop | Other. Urgent care become more responsive | Other |

FIGURE 1.

Causal relationships between the 13 MCP components in the policy-makers’ IPT.

Figure 1 shows the relationships between these overall groups of causal links. Each arrow represents a generalisation from the if–then relationships stated or assumed in the policy documents. In realist terms, each arrow with its left-hand box represents a mechanism and the box at the right-hand (destination) end of the arrow represents its outcome. Table B (see Report Supplementary Material 2) shows the same relationships in tabular form.

Figure 1 shows the ‘flow’ or sequenced linkage (‘concatenation’) of the assumed causal links between components 1 and 11, through to outcomes 12 and 13 (improved care and reduced cost). Each component is assumed to be the mechanism to bring about change in later components, and those components are then assumed to be the mechanism to bring about change in yet later components; these eventually jointly lead to the MCP outcomes (far right).

Contexts

As noted, policy sources contained fuller accounts of assumed mechanisms and outcomes, and some mediating linkages, than of the contexts that might moderate the achievement of those outcomes. However, they did include some detailed assumptions, outlined below, about what initial conditions favour the establishment of MCPs, in particular the first wave (i.e. that concerned only links 1:2 and 1:7). In addition to some managerial mechanisms (a vision of a model of care;9 effective managerial and clinical leadership;9 standardised data to enable real-time monitoring and evaluation of quality outcomes, costs and benefits;9 and planning how to provide care for people with long-term conditions in primary care settings and in their own homes, with a focus on prevention9), the contextual conditions likely to be critical to enable the first wave of MCPs to bring about their intended outcomes were assumed to be:

-

existing progress towards new ways of working9

-

a financial situation that allows start-up money to be found for MCPs – local commissioners support already-agreed funding for the MCP9 existing ‘partners’, such as voluntary and community sector organisations, and ‘communities’9 are supportively engaged with the MCP. Organisations relate to each other in a collaborative, mutually helpful way. Local relationships are good

-

local NHS leadership focus on MCPs and care integration generally

-

the populations served are of a size and type likely to benefit, which we interpret as being large enough to allow economies of scale and scope in collaborative working, and with a health profile and socioeconomic mix that the MCP services can accommodate

-

a population who desire autonomy and control over their health and health care, and are likely to participate (‘engage’) in activities to maintain their own health and to help care informally for those experiencing chronic ill health

-

health professionals and organisations view those whom they care for as people, not patients

-

sufficient staff inputs (time, skill mix)

-