Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 13/114/93. The contractual start date was in June 2015. The final report began editorial review in December 2017 and was accepted for publication in May 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Rowan Harwood reports that he sat on the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment Primary Care, Community and Preventative Interventions Topic identification panel from 2014 to 2017. This panel had no relationship to the VOICE study.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Harwood et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

People living with dementia in hospital

Around 850,000 people live with dementia in the UK, and this is projected to rise to 1 million people by 2025. 1 Dementia is common in acute hospitals, with approximately 25% of beds occupied by a person living with dementia. 2,3 Best practice and policy aim to ensure that older people are treated close to home whenever possible, but hospital admission remains necessary for many acute ailments and crises that commonly affect older people, and is likely to remain so. Patients present to hospital with a range of medical emergencies, such as fractures, urinary tract infection, pneumonia or stroke. Such presentations are frequently complicated by falls, immobility, pain, delirium, dehydration or incontinence. 4 During a hospital admission, patients need health care to cure their acute illness, manage exacerbations of chronic conditions, relieve symptoms, restore function and prevent complications. To do this, health-care professionals carry out a range of health-care tasks or activities, such as information gathering, physical assessments, medical investigations, administering medications and physiotherapy. People living with dementia also need support with other aspects of care, such as eating and drinking, washing and dressing, sleeping and safety, known as the ‘fundamentals of care’. 5 Much of the work of hospital health-care professionals involves these tasks;6 effective communication is a prerequisite of effective care.

People living with dementia are vulnerable and need attention to the psychological and emotional aspects of their care as well as the physical, not least to avoid distress and the challenging behaviours that may result. An acute hospital admission can be a frightening experience for those who do not understand it. There is ample evidence that hospital staff feel ill-equipped to care for, and effectively communicate with, people living with dementia. 7,8 The person living with dementia is usually acutely unwell. The complications of delirium or pain may contribute to distress and disorientation, making assessment and interaction more complex than usual. The environment is busy, unfamiliar and often noisy. The thrust of assessment and treatment is towards rapid evaluation, intervention and discharge, leaving little time for rapport building, giving comfort and nuanced communication with those with communication challenges.

Counting the Cost: Caring for Older People with Dementia on Hospital Wards2 reported that nursing staff and nurse managers found caring for people living with dementia to be challenging. Key areas of concern related to managing difficult or challenging behaviours and maintaining safety and communication.

Communication is not solely the responsibility or role of nursing staff. When admitted to hospital, people living with dementia will encounter, and be cared for by, a wide range of health-care professionals, including doctors, nurses, health-care assistants, pharmacists, social workers and allied health professionals (AHPs), such as physiotherapists, speech and language therapists, occupational therapists and dietitians. They also encounter domestic staff, cleaners, porters and hospital volunteers. Some of the key aspirations set out in the Prime Minister’s Challenge on Dementia 20209 are for all hospitals to become dementia-friendly care settings, and for all NHS staff to have training on dementia appropriate to their role.

Outcomes of hospital care for people living with dementia are worse than for people without cognitive impairment. 10,11 People living with dementia have longer lengths of stay, higher readmission rates and a greater likelihood of dying than people without dementia admitted for the same condition. 12 One-quarter of cognitively impaired patients will have died within 3 months of a hospital admission. 6

One possible contributor to this differential is communication difficulties. These are associated with preventable adverse events in the general hospital population,13 length of stay, poorer functional outcome and institutionalisation among stroke patients. 14–16 Studies in residential care have found evidence that poor staff communication, such as use of ‘elderspeak’ (infantilising communication), may exacerbate problem behaviours, such as resistance to care17 and physical and verbal aggression. 18 Both of these increase costs of care. 19 Relatives of people living with dementia report that ineffective communication can result in the exclusion of patients, and care lacking in dignity and respect. 2 Good communication facilitates person-centred care.

Communication problems in dementia

Dementia presents a particular challenge to communication. People living with dementia may experience deterioration in their communication abilities, as well as problems in memory, disorientation, recognition, reasoning and decision-making. 20 People living with dementia often have impaired comprehension and expression, including word-finding difficulties, lack of coherence and repetition of thoughts. As dementia progresses, communication can deteriorate to a state when no intelligible speech is used. 21

The level of communication disability experienced by a person living with dementia will be influenced by contextual factors external to themselves, such as the environment22 and the communication skills of their ‘communication partners’. 23 Hospitals are difficult environments for people living with dementia and rely on an assessment model based on intensive and repeated questioning. People living with dementia may be unable to communicate their needs (such as pain or need for the toilet), and carers may struggle to understand what the person is trying to convey. Such communication breakdown can lead to unmet need, poor care and distress. 24

Data from Counting the Cost: Caring for People with Dementia On Hospital Wards2 indicated that 72% of nursing staff felt that they lacked particular skills to communicate effectively with people living with dementia and wanted additional training. In one acute hospital, staff reported lacking confidence in providing care to people living with dementia, and having received little or no dementia-specific communication skills training. 25 Staff experience stress and reduced job satisfaction arising from challenging interactions with people living with dementia. 7,26

The Equality Act 201027 obliges public services to make ‘reasonable adjustments’ to ensure that services are accessible to all regardless of ‘protected characteristics’ including disability. Such adjustments can be argued to include the communication skills of staff. Reports into poor care for patients within the NHS have highlighted the need for improved communication between hospital staff and patients to reduce errors and improve care. 28 The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline29 on care of people with dementia highlights poor communication between the person living with dementia and staff as a factor associated with emotional and behavioural problems. The Building a Safer NHS for Patients report30 recommended communication skills training for health-care professionals.

The importance of nursing staff regularly engaging with their patients in ‘constructive and friendly interactions’ was emphasised by Francis. 28

The government’s position paper Patients First and Foremost: The Initial Government Response to the Report of Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry31 advocated improved education and training on dementia, with a commitment to ‘listen most carefully to those whose voices are weakest and find it hardest to speak for themselves’.

Cowdell et al. 32 observed interactions between health-care professionals and people living with dementia in the acute hospital. Almost all communication was related purely to physical care. Many interactions demonstrated elements of ‘malignant social psychology’,33 such as ignoring, infantilisation, disempowerment, stigmatisation, accusation, imposition and disparagement, despite the health-care professional’s belief that they were being kind. 32 The structured non-participant observation method of dementia care mapping has been used to study care delivery for cognitively impaired older adults. Communication by health-care professionals during routine physical care tasks was frequently brief or absent, with a lack of introductions and courtesies, and even ignoring the patient. Patient-initiated interactions were often deflected by health-care professionals, with promises of attention later. Person-centred care, when it was observed, was time-consuming, particularly if the person living with dementia had a communication problem. 6,34

Communication competencies

The ability to communicate sensitively and achieve meaningful interaction is a core competency for supporting people living with dementia. The National Minimum Training Standards for health-care support workers and adult social care workers in England include ‘effective communication’. 35 There is a wealth of advice on communicating with people living with dementia. This includes eliminating distractions, ensuring that hearing aids are working, taking time, positioning oneself in full view and at the same level, speaking clearly and calmly, and using short, simple sentences. 24 There is also a body of practical expertise among mental health professionals. More abstract components, such as the use of body language, making the person living with dementia feel valued or appropriate turn-taking, can be difficult to describe.

Small et al. 36 identified 10 recurrently recommended strategies, of which they found only three had a positive impact on observed communication breakdowns between family caregivers and people living with dementia (eliminating distractions, simple sentences, yes/no questions). One strategy (slow speaking rate) resulted in more breakdowns, a finding confirmed in other studies. 37,38 A slow speaking rate is disliked by older people,39 but is still recommended in a number of current guidelines (e.g. from the Alzheimer’s Society24). The use of closed (‘yes/no’) questions for successful communication is supported,21 but open questions have been found to be useful for facilitating personal conversations about feelings and concerns. 40 Sentence comprehension can be improved by limiting utterances to one proposition,41 paraphrasing and verbatim repetitions. 37 When presented with vignettes, nurses perceived carers who use simplified language as less patronising, and people living with dementia as more competent. 42 Critical communications from caregivers predict negative behaviours43 and, therefore, positive and affirming communications are recommended. 44

Perceptions about communication may differ from objective evidence from recorded interactions. Recommended communication strategies were thought to be helpful by family caregivers and health-care professionals, but both overestimated effectiveness when audio-recordings of interactions were analysed. Despite this, fewer communication breakdowns were observed when recommended communication strategies were used than when they were not. 36

A systematic review45 of the experiences of communication by people living with dementia during interactions with both family caregivers and health-care professionals identified 15 studies. A single study46 explored the views of the person living with dementia, and 14 studies reported the experiences of family caregivers and health-care professionals. Communication difficulty was a common finding. Wang et al. 47 used content analysis of 15 interviews with nurses to explore these difficulties further, and identified two themes. ‘Different language’ referred to the sense that the health-care professional and the patient spoke different languages and so could not understand each other. ‘Blocked messages’ indicated that health-care professionals struggled to interpret patients’ needs and emotions owing to impaired verbal communication and flat affect. In one study,48 nursing staff deconstructed communication with people living with dementia into ‘being in’ communication, whereby they tried to attune themselves to patients’ feelings and attempted to understand the perspective of the person living with dementia, and ‘doing’ communication, which involved using techniques such as active listening, allowing time to talk and asking questions.

The literature does not identify clear communication strategies that can be used for training to overcome communication barriers for health-care professionals and people living with dementia in the acute hospital setting.

Communication skills training

Research suggests that communication skills cannot be improved through experience alone. 49 Skills can be acquired and retained with appropriate teaching, and this leads to greater confidence in communication. 50–52 For training to be effective it needs to be practical, with opportunities to practice and receive feedback. 53,54 Transferring learnt communication skills to clinical practice happens best when courses contain role play with simulated patients (SPs), structured constructive feedback and discussion led by a trained facilitator. 50–52

Reviews of communication skills training interventions for health-care professionals suggest that communication skills can be improved when communicating with a non-communication impaired patient population,55–57 but evidence for their impact on patient health outcomes is uncertain. 53

A systematic review58 of communication skills training in dementia care identified 12 studies, but none was based in acute hospitals or involved the training of doctors. Four interventions were delivered in the patient’s own home, mostly one to one, with a focus on individualised training of the carer, and were not generalisable to hospital staff. The other eight interventions were delivered in care homes, with marked variability in duration (from 3 hours’ training59 to 15 hours’ training plus 2 weeks’ supervised working). 60 Care home studies that used questionnaires and observational measures showed positive effects on the knowledge, skills and attitudes of trained staff, but recommended communication techniques were not always clearly defined and outcome measures were inconsistent.

A systematic review61 of interventions to improve communication between people living with dementia and nursing staff during daily care reported insufficient published evidence to draw firm conclusions. The review included six studies and focused solely on long-term care facilities. Interventions varied in duration, intensity and type, from a single lecture62 to 4 weeks of work-based training. 63 Five out of the six studies showed significant effects on at least one communication outcome, but interpretation of the clinical relevance of these was limited by methodological quality and inconsistency of outcome definition.

Although the literature gives some guidance on communication skills training competencies, minimal evidence comes directly from the general hospital. Most empirical work is based on family and nurses or carers as communication partners, with no studies of doctors or AHPs. To develop an effective communication skills training intervention for interacting with people living with dementia in acute hospitals, we need a better understanding of what works in this setting through basic research to explore the communication problems and how they can be overcome. 54 Recommended attitudes, techniques and approaches cannot simply be assumed to be effective.

Conversation analysis

Conversation analysis (CA) is a well-established sociolinguistic qualitative method for the analysis of social interaction and communication64–66 that has been used to develop successful communication skills training interventions in fields such as stroke,66 psychosis67 and primary care. 68 For example, in stroke care, the recommended ‘supported conversation’ approach to training health-care staff and volunteers to communicate better with people with aphasia69 was based on empirical work using CA to explore the communication of video-recorded volunteers. 70 The skills needed for successfully communicating with people with aphasia were characterised around the concepts of ‘revealing competence’ and ‘acknowledging competence’. The training emerging from this was found to be effective in several trials. 71,72 CA of outpatient consultations between psychiatrists and clients expressing delusional views has demonstrated how the alternative approaches taken by psychiatrists can lead to a change in client responses and thus to more or less constructive consultations73 and this has also been developed into a tested training intervention. 67 CA has also shown that different communication approaches might be more effective at different times. For example, in conversations about advanced decisions and end of life, CA has shown that a direct approach from health-care professionals is harder for the client to deflect and is necessary when an immediate decision is needed, whereas more easily deflected indirect approaches are more appropriate to encourage patient-led decisions when there is more time and a greater priority on avoiding communication breakdown. 74

The existing literature supports the use of fundamental research using CA to collect evidence about communication between health-care professionals and people living with dementia in hospital, and to use this to develop training.

Conclusion

This introduction has outlined that communication problems faced by people living with dementia are common in the acute hospital setting and contribute to problems for staff and poorer experiences and outcomes for patients. Staff feel underqualified to communicate effectively with people living with dementia to deliver satisfactory and fulfilling care. We have identified a lack of evidence to support specific communication training interventions for health-care professionals working with people living with dementia in the acute hospital setting. To improve care, and rise to the challenges set by the public and policy-makers around dementia-friendly hospitals, a deeper understanding is required of how health-care professionals in acute hospitals communicate with people living with dementia, which aspects and techniques are good and which cause communication breakdown.

The specific research questions to be answered in this project were:

-

What should we teach? What constitutes good communication skills, including content, linguistics, context and facilitators that overcome communication challenges experienced between health-care professionals and people living with dementia?

-

How should we teach it? What are the components of an effective communication skills training intervention for health-care professionals caring for people living with dementia and how should this training be delivered?

-

Can we teach it? Is this communication skills training intervention feasible, acceptable and effective?

To answer these questions the following empirical research was undertaken:

-

An update of a systematic review on the content and effectiveness of dementia communication skills training courses. 58

-

Conversation analysis of video-recorded encounters, supplemented by observations, to analyse the structure of communication patterns used by health-care professionals to communicate with people living with dementia.

-

Development of a novel communication skills training intervention based on the findings of the CA, systematic review, expert consensus and service user experience. This included a pilot study to test the training course in real time with selected health-care professionals.

-

An evaluation of the effectiveness of the communication skills training intervention on intermediate outcomes using a before-and-after (B–A) design to assess acceptability of the course and changes in self-assessed competence and confidence, dementia communication knowledge and communication behaviours in health-care professionals who completed the training.

-

An interview study of a sample of the health-care professionals who participated in the training and clinical managers, to examine the acceptability and experience of the training and the importance of this training to the skills of the ward-based clinicians.

Chapter 2 Systematic review

Introduction

The only systematic review58 of communication skills training in dementia care that we found included papers published up to 2010. None of the 12 studies identified was undertaken in a hospital, the training interventions were varied and the methodological quality of the evaluations was generally poor. This review concluded, however, that communication skills training in dementia care led to an increase in positive interactions and improved quality of life for people living with dementia. It also reported a significant impact on the communication skills, knowledge and competencies of both professional and family caregivers.

The aim of the current systematic review was to update the previous review, in order to inform the development of a new communication skills training course and to identify suitable outcome measures for the evaluation. In doing so, we aimed to identify current knowledge on the content, didactic approach and effectiveness of dementia communication skills training courses in various care settings. Specific questions for the review were:

-

What types of communication skills training were evident, taking theory and content into account?

-

What didactic methods were used to deliver the training?

-

What contextual factors (e.g. location, organisation) have been studied, with what results?

-

What is the evidence of the effectiveness of communication skills training, and on what outcomes?

Methods

We developed the search strategy following that described by Eggenberger et al. ,58 in conjunction with a research librarian, and extended it to include online dementia communication skills training. We initially searched for primary research published between January 2010 and August 2015. We updated the review in August 2017 with searches for articles published between August 2015 and August 2017. Electronic bibliographic databases were searched, including MEDLINE, Allied and Complementary Medicine Database (AMED), EMBASE, PsychINFO, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), Web of Science and OpenGrey. Search terms were adapted for use across different databases, including key word and medical subject heading (MeSH) term searches, when appropriate. Box 1 shows the inclusion and exclusion criteria and Figure 1 describes the results of the search and screening process.

-

Title and abstract in English. Translation was sought if a study meeting final criteria had a full text not in English.

-

Evaluation by randomised controlled trials, clinical controlled trials and B–A studies.

-

Trainee population including any health-care professionals, care staff, family caregivers, students or volunteers.

-

Patient population comprised people living with dementia, defined by any criteria and living in any setting.

-

Intervention aimed to improve trainees’ communication with people living with dementia. If the training also incorporated other topics, communication had to form an essential part. Communication skills training could be in a group or one to one, face to face or not. Online learning was included.

-

Use and method of control was recorded.

-

Outcomes included any quantitative outcomes, including at the level of the patient or caregiver.

-

Qualitative or review articles.

-

Intervention studies aimed at training people living with dementia directly, or mixed-patient populations when the training was not specific to the needs of people living with dementia.

-

Communication was not the stated aim, or an essential part of training.

-

Psychosocial interventions aiming to reduce caregiver stress or burden.

-

Cognitive, language or other therapies aimed at changing the person living with dementia’s impairments or functioning.

-

Specifically named approaches with primary non-communication goals including validation, reminiscence, reality orientation, cognitive stimulation and dementia care-mapping.

-

Studies with solely qualitative outcomes.

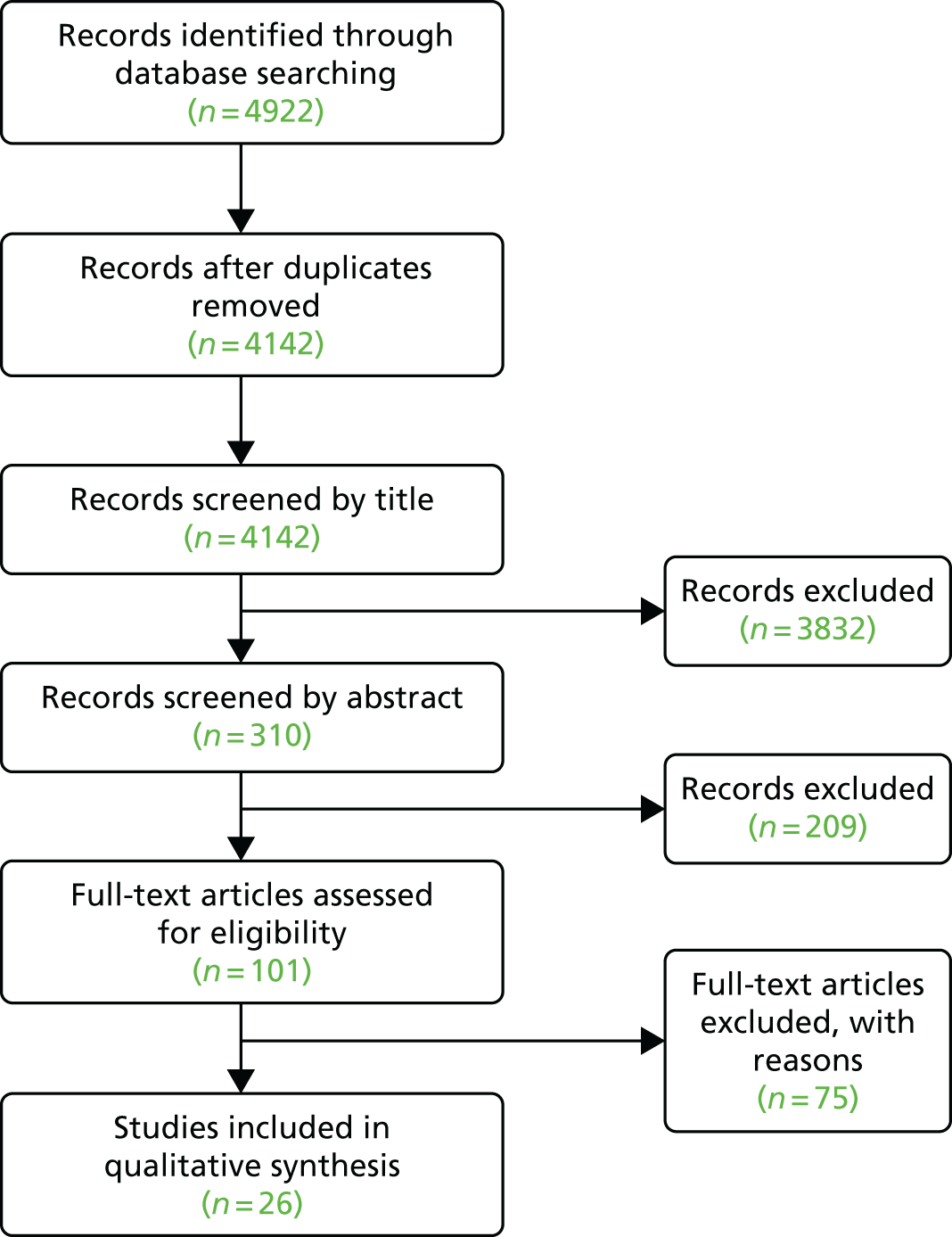

FIGURE 1.

Communication skills training systematic review 2010–17, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) diagram.

As an example, the search strategy for MEDLINE was a keyword search of:

word group 1 communicat* OR interaction* OR behaviour* OR behaviour* AND

word group 2 train* AND

word group 3 dementia OR Alzheimer* OR “cognitive impairment*” OR “behavioral disturbance*” OR “behavioural disturbance”.

Papers were screened by two researchers (RO’B and RA). Disagreement on whether or not texts met inclusion criteria was resolved by a third reviewer (SG or RH). Methodological quality and risk of bias were assessed using standard criteria, based on the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Review Group Data Collection checklist75 and the Quality Assessment Tool for Before–After Studies with No Control Group. 76 Data were extracted from all studies by two reviewers using standardised forms.

Descriptive data were collected on the:

-

theory or model underpinning the intervention and method of development

-

context for training

-

type of participants

-

duration and model of delivery

-

teaching methods.

The primary outcome data collected were the effectiveness of the training intervention, measured quantitatively, as behavioural changes, or as changes in knowledge, skills, attitudes and well-being, and reported reliability and validity of measures. The systematic review protocol was registered on the PROSPERO database CRD42015023437 (www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=23437) (accessed 21 August 2018).

Results

We identified 101 studies for full-text review. No full text was identified or accessible for 25 of these. Twenty-one studies were conference abstracts in which no journal paper or report had been published, despite contacting the authors. Two were protocol papers for which the research had not been completed. Two were Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) theses from the USA that could not be obtained and that had not been published. Of the 76 papers with full text available, three required translation into English.

Papers were assessed by two reviewers. Following the full-text review, 49 papers did not meet the inclusion and exclusion criteria. In addition, one study was excluded as it was a duplicate publication under different authorship. This left 26 studies that met the inclusion criteria (see Table 1). Reasons for exclusion included communication training not being the primary aim or a substantial part of the programme, not being specifically aimed at people living with dementia, qualitative studies, protocol papers with no further publications and studies not being training interventions. There was insufficient homogeneity in outcomes for a meta-analysis of the results.

Characteristics of included studies

Table 1 summarises the characteristics of the 26 studies included. Four were randomised controlled trials (RCTs), seven were controlled clinical trials (CCTs), and 15 were B–A study designs. One study was a secondary analysis of one of the RCTs. 101 Duration of direct training varied from one 45-minute workshop to 120-minute workshops fortnightly for 6 months. The modal length of training was 4 hours.

| Study authors and year of publication | Design | Number of participants | Country | Setting | Type of participants | Duration | Mode of delivery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ampe et al., 201777 | CCT | 90 across 18 clusters | Belgium | Care home | Care home staff | Two 4-hour workshops | Group |

| Beer et al., 201278 | RCT | 47 | USA | College | Nursing Aide Students | 45-minute workshop | Group |

| Broughton et al., 201179 | CCT (cluster) | 52 | Australia | Care home | Care home staff | 1.5-hour session (50-minute DVD) | DVD |

| Chao et al., 201680 | B–A | 105 | Taiwan | Long-term care facilities | Nurses | 4-hour lecture and 4-hour workshop plus interenet-based learning activities | Group and online |

| Cockbain et al., 201581 | B–A | 104 | UK | Medical school | Medical students (first year clinical) | 2-hour workshop | Group |

| Conway and Chenery, 201682 | RCT | 34 | Australia | Community care | Care staff | 1-hour training and other activities | Group and 1 : 1 |

| da Silva Serelli et al., 201783 | B–A | 25 | Brazil | Assisted living residences | Nurses and caregivers | 4-hour workshop and other activities | Group and individual |

| DiZazzo-Miller et al., 201484 | B–A | 45 | USA | Not stated | Family caregivers | Three 2-hour workshops | Group |

| Elvish et al., 201485 | B–A | 71 | UK | Hospital | Hospital staff, including doctors | Four 1.5-hour sessions | Group |

| Engel et al., 201686 | CCT | 214 | Germany | Unclear | Family caregivers | 10 2-hour sessions | Group |

| Franzmann et al., 201687 | CCT | 116 | Germany | Nursing home | Nurses/caregivers | 12 2-hour workshops | Group |

| Galvin et al., 201088 | B–A | 540 | USA | Hospital | Hospital staff | One 7-hour session | Group |

| Gitlin et al., 201089 | RCT | 237 | USA | Home | Family caregivers | More than nine 1-hour OT sessions and one 1-hour nurse session and four telephone reviews | 1 : 1 advice to dyad |

| Goyder et al., 201290 | B–A | 25 | UK | Care home | ‘Non-qualified’ care home staff | Two unspecified workshops plus up to 2 hours of additional training delivered in three or four sessions | Mixed: group training and 1 : 1 |

| Haberstroh et al., 201191 | CCT (and time series) | 22 | Germany | Home | Family caregivers | Five 2.5-hour workshops | Group |

| Hobday et al., 201092 | B–A | 40 | USA | Care home | Care home staff – ‘certified nursing assistants’ | Approximately one 1-hour online session | E-learning |

| Irvine et al., 201293 | B–A | 68 | USA | Care home | Care home staff – direct care workers and nurses | Approximately one 2-hour online session | E-learning |

| Karel et al., 201694 | B–A | 38 | USA | Long-term care | Mental health providers and nurses | Approximately 17.5 hours in total | Group |

| Karlin et al., 201495 | B–A | 21 | USA | Care home | Care home staff – ‘mental health providers’ |

Two and a half-day workshops and 25 1.5-hour weekly telephone consultation 17.5-hours direct and 39 hours calls |

Mixed: group workshops and 1 : 1 support |

| Levy-Storms et al., 201696 | B–A | 15 | USA | Nursing home | Certified nursing assistants | 4 hours in total | Group |

| Liddle et al., 201297 | CCT | 29 | Australia | Home | Family caregivers | Two 45-minute DVD sessions | DVD |

| Mason-Baughman and Lander, 201298 | B–A | 14 | USA | Not stated | Family caregivers, friends, others | One workshop, unspecified duration | Group |

| Passalacqua and Harwood, 201299 | B–A | 18 | USA | Care home | Care home staff – care assistants | Four 1-hour weekly workshops | Group |

| Sprangers et al., 201562 | CCT (cluster) | 24 | The Netherlands | Care home | Care home staff – ‘nursing aides’ | One or two 1 : 1 sessions, duration unspecified | 1 : 1 coaching |

| Weitzel et al., 2011100 | B–A | 80 | USA | Hospital | Hospital staff – varied | 12-minute DVD | DVD |

| Williams et al., 2017101 | RCT | 29 staff trained: 42 dyads with29 staff and 27 PLWD analysed | USA | Nursing home | Nursing staff | 3 hours in total | Group and 1 : 1 |

Methodological quality and risk of bias

Two RCTs were assessed as being of high methodological quality with robust allocation methods and measures to prevent cross-contamination of intervention and control groups. 82,102 Blinding of participants to a training intervention was impossible. Many of the outcomes were self-reported by participants, such as ratings of their confidence, attitudes or well-being. This presents a risk of social desirability bias as trainees are likely to rate themselves as better following communication skills training. When studies used more objective measures, such as tests of knowledge or observational measures of behaviour, their psychometric properties were seldom reported.

Review questions

We present findings in relation to each question posed for the review.

What theoretical frameworks or models underpin communication skills training in dementia care?

Thirteen studies referred to a theoretical framework, but there was little consistency between them (Table 2). Five studies supported their training approach using educational theory and three developed their intervention around a communication theory. One intervention used person-centred dementia care as a basis, and one used a clinically derived theory of behavioural techniques. Other theories included caregiver stress and shared decision-making.

| Study authors and year of publication | Framework |

|---|---|

| Educational theory | |

| Beer et al., 201278 | ‘Learning centred classroom’ motivational framework |

| Broughton et al., 201179 | ‘Knowledge translation process’ |

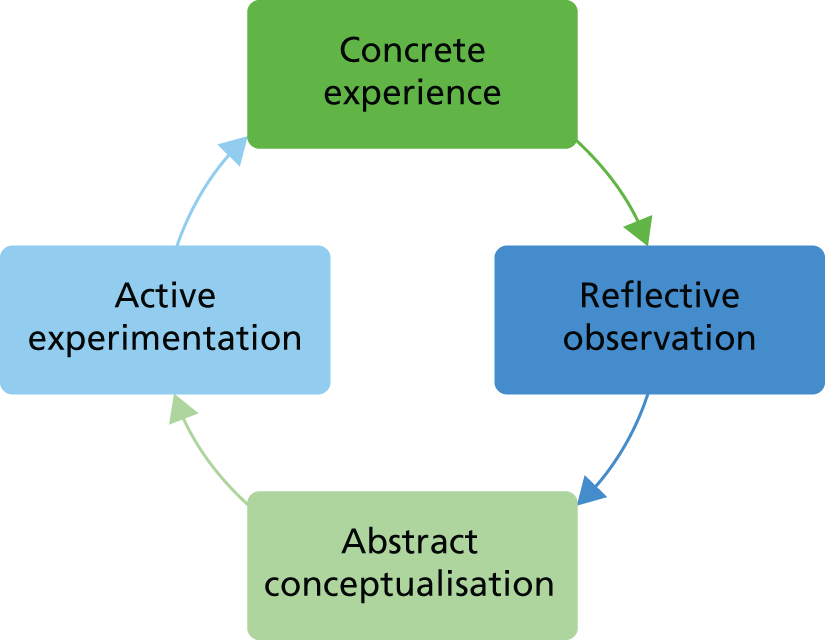

| Chao et al., 201680 | Adult learning theory (see Knowles, 1984,103 1996104) |

| Cockbain et al., 201581 | Seven principles of andragogy and Kirkpatrick’s evaluation levels |

| Liddle et al., 201297 | ‘Knowledge translation process’ |

| Communication theory | |

| Franzman et al., 201687 | TANDEM communication model developed by Haberstroh; stress-strain concept |

| Haberstroh et al., 201191 | Developed TANDEM communication model |

| Sprangers et al., 201562 | Communication enhancement model |

| Other theory | |

| Ampe et al., 201777 | Three-step model of shared decision-making |

| Elvish et al., 201485 | Social cognitive theories |

| Gitlin et al., 201089 | Stress health process model, relating problem behaviours to carer stress |

| Levy-Storms et al., 201696 | Kohler’s105 theory of behavioural techniques to enhance emotional connectedness |

| Passalacqua and Harwood, 201299 | VIPS model106 based on person-centred care for people living with dementia33 |

Twelve studies referenced a theory to underpin the development of their training. One drew on two theoretical frameworks. 87 Several theories were used by more than one study but none was clearly dominant.

Teaching methods used

We examined the pedagogical approaches that the studies used. Table 3 summarises the methods used in the studies. Most of the studies of group communication skills training used a combination of didactic teaching, group discussions, self-reflection, videos and role play, supported by written materials. Seven used ‘homework’, either before training or between sessions. Ten studies used training digital versatile discs (DVDs) or e-learning to give maximum access to a large workforce across care homes and hospitals. Three DVD studies used actors to re-enact narratives illustrating good and bad communication practice. Two studies used real-life clips of interactions. 78,96 Three studies reported online training. A total of 12 studies used videos as part of their training.

| Study authors and year of publication | Method or tool | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Didactic presentation | Written materials | Online or DVD materials | Role play/SPs | Homework | Group discussion, activity or exercises | Video-recordings | Theory | Self-reflection, shared experience | Problem-based learning | Individual advice to dyad | |

| Ampe et al., 201777 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓✓ RP | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓✓ | ||||

| Beer et al., 201278 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓✓ | ✓✓ | |||||||

| Broughton et al., 201179 | ✓ | ✓✓ DVD | ✓ | ||||||||

| Chao et al., 201680 | ✓✓ | ✓ | ✓✓ internet | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Cockbain et al., 201581 | ✓ | ✓✓ SP | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Conway and Chenery, 201682 | ✓✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| da Silva Serelli et al., 201783 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| DiZazzo-Miller et al., 201484 | ✓ | ✓ RP | ✓ | ||||||||

| Elvish et al., 201485 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Engel et al., 201686 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Franzmann et al., 201687 | ✓✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓✓ | ||||||

| Galvin et al., 201088 | ✓✓ | ✓ | ✓ case studies | ||||||||

| Gitlin et al., 201089 | ✓ | ✓✓ | |||||||||

| Goyder et al., 201290 | ✓ DVD | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Haberstroh et al., 201191 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ RP | ✓ case studies | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ group | ||||

| Hobday et al., 201092 | ✓ | ✓✓ internet | ✓ | ||||||||

| Irvine et al., 201293 | ✓ | ✓✓ internet | ✓ | ||||||||

| Karel et al., 201694 | ✓✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Karlin et al., 201495 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ RP | Weekly telephone calls | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Levy-Storms et al., 201696 | ✓✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Liddle et al., 201297 | ✓ | ✓✓ DVD | ✓ | ||||||||

| Mason-Baughman et al., 201298 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Passalaqua and Harwood, 201299 | ✓ | ✓ RP | ✓ | ✓ and guided visualisation | ✓ | ||||||

| Sprangers et al., 201562 | ✓✓ observation with feedback | ✓ | |||||||||

| Weitzel et al., 2014100 | ✓✓ DVD | ||||||||||

| Williams et al., 2017101 | ✓✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Totals | 17 | 19 | 10 | 7 | 7 | 15 | 12 | 8 | 8 | 2 | 5 |

The need for practising communication skills and gaining feedback53,55 was supported by the use of role play, simulation or ‘live’ skills practice in seven studies. In one study,81 simulation was the principal training method, with positive effects on confidence, although their measure was not validated.

Context of study as it relates to outcomes

There was huge diversity in the setting and focus of the studies identified (see Table 1). They were conducted in eight different countries, with most from the USA, and comprised a total of 2103 trainees. Settings for the training included 14 care homes, eight private settings (including assisted living residences), three acute hospitals and two higher education institutions. Trainee participants included care and nursing assistants, family caregivers, health-care professionals (including doctors) and students of these professional groups. Control conditions included no intervention, self-help literature and (in a train-the-trainer intervention) training by a different facilitator. Therefore, no general inferences could be drawn concerning the interaction between context and effectiveness of the interventions.

Evidence of effectiveness of communication skills training

We investigated the outcome measures used in each study and whether or not there was any change in these measures that could be attributed to the interventions studied.

Observational checklists

Five studies measured the observed behaviour of trainees. Ampe et al. 77 used the validated OPTION (observing patient involvement in decision-making) scale of shared decision-making107 to measure the degree of involvement of residents and families in discussions and advanced care planning. This comprised a five-point scale to measure the degree to which advanced care planning was discussed, and there was no statistically significant change. Levy-Storms et al. 96 coded specific communication behaviours and residents’ responses in video-recordings using time-sampling methods. The checklist for communication behaviours was based on four therapeutic communication techniques taught in the intervention. Coders were blinded to pre- or post-intervention status and achieved acceptable inter-rater reliability (mean kappa = 0.64). The prevalence of therapeutic communication behaviours increased significantly after training, but the frequency of residents’ refusals of food was unchanged.

Williams et al. 102 used video-recordings to complete staff communication behaviour checklists and residents’ behaviours based on the Resistiveness to Care Scale. 108 Coders were blinded and adequate inter-rater reliability was achieved (90% agreement). Results showed that staff use of ‘elderspeak’ (a communication style characterised by simplistic language, slowed speech, elevated pitch and volume, and inappropriately intimate terms of endearment) reduced significantly after intervention, as did resident resistance to care, and neither persisted at the 3-month follow-up.

Two other studies62,100 used a checklist of positive and negative communication behaviours to rate ‘live’ observations, without rater blinding. Both studies reported statistically significant improvements in specific skills. Sprangers et al. 62 reported acceptable inter-rater reliability on their two checklist measures (75% and 79%), but Weitzel et al. 100 reported no psychometrics.

The results suggest that observing trainee behaviours as an outcome measure is possible, but did not always demonstrate change.

Self-ratings by trainees

Self-ratings of confidence in dementia communication by trainees were used in seven studies (Table 4). All reported significant gains following the communication skills training, although in one case this was on a single subscale. 90 One study that reported psychometric properties found a significant and meaningful difference on their measure. 85 Six studies reported measures related to attitude (Table 5). Of these, only one found a significant effect. 93 Nine studies measured change in knowledge following the training intervention (Table 6). All studies reported gains. Most knowledge tests were developed by individual studies, with a focus on the learning outcomes of their training, and some based on other knowledge tests or translated tests (e.g. Conway et al. ,82 Chao et al. 80). Overall, there was evidence of knowledge gain from training, although the validity of the measures used in the studies was often uncertain.

| Study authors and year of publication | Number of participants | Self-rating measure used | Result reported | Validity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cockbain et al., 201581 | 144 | Single question: rate confidence in communicating | Post > pre | None reported |

| Conway and Chenery, 201682 | 34 | Self-efficacy questionnaire based on inventory of geriatric nursing self-efficacy | TG > CG | Adequate psychometrics reported |

| Elvish et al., 201485 | 71 | CODE | Post > pre | Adequate psychometrics reported |

| Galvin et al., 201088 | 540 | Five confidence items: one communication | Post > pre on each item | None reported |

| Gitlin et al., 201089 | 237 | Five-item caregiver confidence scale using new activities in past month (not communication) | TG > CG | None reported |

| Goyder et al., 201290 | 25 | Sense of competence in dementia scale | Post = pre for whole scale; post > pre for ‘building relationships’ subscale | Adequate psychometrics reported |

| Irvine et al., 201293 | 68 | VST, two items of four scenarios: confidence in knowing what to do next and how to alter the behaviour 20-item self-efficacy measure |

Post > pre Stable on repeated baseline, post > pre |

VST self-efficacy acceptable retest reliability (r = 0.63) Self-efficacy measure acceptable retest reliability (r = 0.76) |

| Study authors and year of publication | Number of participants | Self-rating of attitude | Results | Validity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chao et al., 201680 | 105 | Communication skills attitudes scale translated into Chinese | Post = pre | Adequate psychometrics |

| Conway and Chenery, 201682 | 34 | Approaches to dementia questionnaire | Post = pre | Adequate psychometrics |

| Engel et al., 201686 (in German) | 214 | Family questionnaire | TG > CG | Not reported |

| Goyder et al., 201290 | 25 | Approaches to dementia questionnaire | Post = pre | Not reported |

| Irvine et al., 201293 | 68 | 18-item attitude measure | Stable on repeated baseline post = pre | Previous study reports acceptable retest reliability (r = 0.7) |

| Passalacqua and Harwood 201299 | 26 |

Empathy: interpersonal reactivity index Attitudes to ageing, dementia and person-centred care |

Post = pre Hope item post > pre For the rest, post = pre |

Items taken from longer validated measures |

| Study authors and year of publication | n | Knowledge test | Results | Validity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Broughton et al., 201179 | 52 | 17-item open questionnaire on ‘Strategies to support communication & memory’ |

TG showed post > pre; CG did not Overall TG = CG |

Not clear Open questions, blind-rated tests |

| Chao et al., 201680 | 105 | Communication skills knowledge scale (translated into Chinese) | Post > pre at 4 and 16 weeks | Content validity index 0.92; Cronbach’s alpha = 0.94 |

| Conway and Chenery, 201682 | 18 | Communication support strategies in dementia knowledge test | Post > pre | None reported |

| DiZazzo-Miller et al., 201484 | 45 | 18-item ‘Knowing how to assist in five areas of ADLs’ questionnaire (six questions on ‘communication and nutrition’) | TG > CG on each of five modules; biggest effect for ‘communication’ module |

Content validity No other psychometrics reported |

| Elvish et al., 201485 | 71 | 16-item knowledge in dementia scale (two items specifically on communication) | Post > pre |

Psychometrics reported Test published |

| Galvin et al., 201088 | 540 | 9-item ‘Knowledge about dementia’ scale | Post > pre | None reported |

| Hobday et al., 201092 | 40 |

15-item MCQs ‘Dementia Knowledge Test’ Test published |

Post > pre |

Cronbach’s alpha = 0.94 No other psychometrics |

| Irvine et al., 201293 | 68 | Video situation knowledge test, four scenarios: MCQs for each about ‘what to do next’ |

No change on repeated baselines post > pre |

Used previously by same group but no psychometrics reported |

| Liddle et al., 201297 | 29 | Communication and memory support in dementia test |

TG showed post > pre (NS) CG, post = pre |

No psychometrics reported Blinded markers used |

Discussion

This review aimed to identify and evaluate training interventions designed to improve communication in dementia care. Papers published between 2010 and 2017 were evaluated to update the systematic review by Eggenberger et al. ,58 which included papers published to 2010. Communication skills training research for people living with dementia has increased substantially since 2010. Twenty-six studies were identified, mostly B–A designs of variable methodological quality. They used a range of theoretical approaches, and spanned different settings. Few studies were directly applicable to our situation, not being based in acute hospitals or not aiming to improve health-care professionals’ communication with people living with dementia.

Studies demonstrated different teaching approaches, although it was not possible to assess the effectiveness of specific methods. Traditional methods, such as didactic presentations, reading materials and group discussions were popular, as were video-recordings, DVDs and online materials. Role play and simulations were also used. The duration of direct training ranged from a single 45-minute workshop to 120-minute fortnightly workshops for 6 months.

Studies evaluated the effectiveness of the training interventions using a range of outcome measures, including ratings of observed trainee behaviours and subjective ratings of confidence, attitude and knowledge. Several studies developed their own measures or adapted them from previously published measures. Trainees’ communication behaviours showed a variable response to training. Two of the five studies measuring this aspect reported statistically significant improvements in confidence and knowledge after training.

Previous studies indicate that role play and simulations are both viable and acceptable teaching approaches. The review also shows that most interventions used a combination of several approaches to teaching skills. There is evidence that trainee knowledge and confidence improves after training. However, given the heterogeneity of the studies included in this review, it is difficult to draw conclusions about what constitutes optimal communication skills training. The low numbers and poor quality of relevant studies suggest that there is no existing intervention that could be adapted or used in acute care.

Chapter 3 Conversation analytic study

Introduction

Conversation analysis is a sociolinguistic method for studying patterns in real-life communication encounters. It analyses what communication partners actually do, rather than what they think or say they do.

To understand how health-care professionals communicate with people living with dementia, and to what effect, we conducted a study using CA to analyse video-recordings of real ward encounters. Patients, family members and health-care professionals often cannot articulate the tacit knowledge they use when communicating, no matter how expert they are, but video-based research can specify such knowledge and skills. CA is a research method that originated in sociology but draws on insights from other disciplines, such as psychology and linguistics. 109 Its aim is to study the structure and order of naturally occurring talk during interactions. The method has been widely used to study health-care interactions. 64,110–112 We focused on identifying the everyday challenges of communicating with people living with dementia in the acute inpatient setting and, importantly, the communication skills that may overcome these issues.

We harnessed the potential of video-based research by using CA to:

-

classify verbal and non-verbal practices and patterns within health-care interactions involving experienced clinical communicators

-

analyse how the broad recommendations for good practice actually get implemented and operationalised

-

analyse episodes in which there are challenges to the operationalisation of interactions and the ways these challenges are managed.

Methods

The study took place on eight acute geriatric medical (health care of older people) wards in a single large teaching hospital. It was approved by the Yorkshire and The Humber – Bradford Leeds NHS Research Ethics Committee (reference number 15/YH/0184). We adapted protocols for recruitment, consent and data collection used by team members during previous studies of dementia6 and CA studies. 54,66 These protocols were developed with patient and public involvement (PPI) input.

Participation eligibility

We included male and female patient participants who were aged ≥ 65 years and had been admitted to an acute geriatric medical ward. All had a diagnosis of dementia recorded in medical notes, and ward staff reported that they had difficulties communicating. Health-care professional participants were eligible if they were a registered health-care professional (doctor, nurse or AHP). Any relatives or friends of patient participants or other health-care professionals or students present during data collection also participated in the study, subject to consent.

Patient participants were excluded if they did not speak English, were unable to give informed consent and we were unable to obtain consultee agreement, they had a diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease or they were assessed by the clinical team as likely to die within 7 days.

Recruiting and consenting participants

Participant recruitment was carried out by two clinical researchers (RO’B and RA), both Health and Care Professions Council-registered speech and language therapists.

Recruitment of health-care professionals began in August 2015, in advance of the recruitment of people living with dementia. Health-care professionals were recruited by personal approach or via ward managers. We aimed to recruit health-care professionals who were considered by peers to be ‘good communicators’ or ‘good with patients living with dementia’. We aimed to achieve a spread across categories of health-care professionals (doctors, nurses and therapists). We obtained written informed consent from the health-care professional. Table 7 gives details of the health-care professionals recruited and video-recorded. Video-recordings with AHPs comprised five with physiotherapists, three with speech and language therapists and two with occupational therapists. Those with nurses comprised 11 staff nurses, one advanced nurse practitioner and seven mental health nurses. Those with doctors comprised three consultants and eight junior or middle-grade doctors.

| Health-care professional | Number of | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Health-care professionals recruited | Health-care professionals recruited and then video-recorded | Videos collected | |

| Nurses | 19 | 11 | 19 |

| AHPs | 11 | 6 | 10 |

| Doctors | 11 | 9 | 12 |

| Total | 41 | 26 | 41 |

Patient participants were approached by a clinician working on the ward who introduced the patient to the researchers, if willing. The researcher discussed the study with the patient, and assessed their mental capacity to give or withhold consent to participate. In accordance with the Mental Capacity Act 2005,113 patients were supported in their understanding by the speech and language therapist researcher, for example using a simplified, one-page information sheet, and by showing them the video camera. The two speech and language therapist researchers independently assessed the clinical severity of communication impairment.

No patients in this study had mental capacity to give informed consent, and the requirements of the Mental Capacity Act 2005113 were followed. A family member or informal carer was approached and, following explanation of the study, asked to give consultee agreement. Given the sensitive nature of making video-recordings of patients while in hospital, we did not include participants if they had no family or other personal consultee.

In response to a suggestion arising from pre-study PPI, written informed consent was sought from any relatives or friends who wanted to be included in the video-recording of the interaction between a patient and a health-care professional. This process allowed us to potentially include sensitive conversations between health-care professionals and people living with dementia, in which best practice would be to involve a relative or friend.

After an encounter had been filmed, participants and personal consultees were shown the video on a tablet computer and asked for further consent or agreement for dissemination (e.g. in teaching, at conferences or on material posted to the internet).

Data collection

Data collection was carried out by clinical researchers Rebecca O’Brien and Rebecca Allwood. Interactions on acute geriatric medical wards between health-care professionals and people living with dementia were video-recorded. To identify suitable interactions for recording, researchers talked to ward staff at the beginning of each day about what encounters were expected to occur with consented patients (e.g. an occupational therapist assessment, a consultant doing a ward round). We sought to record routine interactions for staff. We did not film intimate interactions, such as washing, dressing or toileting. All of the video-recorded interactions were initiated by the health-care professional.

The research speech and language therapists set up the equipment to video-record the encounter. A camera with a wide-angle lens was used to maximise capture, connected to a remote microphone worn by the health-care professional, when appropriate. Separate audio-recordings were made using a digital audio-recorder. Cameras, audio-recorders, microphones and the researcher were positioned to be minimally disruptive to the interaction. To maintain confidentiality, any patient name visible to the camera was covered up in advance of recording or edited out afterwards. We recorded the conversations for as long as they lasted.

In total, 41 conversations were video-recorded between September and December 2015. This resulted in a total of 378 minutes of data from 26 patient participants (10 men and 16 women) and 26 health-care professional participants. Eleven (27%) video-recordings included a person with dementia who had mild communication impairment, 22 (54%) who had moderate communication impairment and eight (19%) who had severe communication impairment. Patients could be filmed more than once with a different health-care professional, so some staff and patients appeared up to three times in our data set. The average length of a recording was 9 minutes and 24 seconds, with a range of 2–30 minutes. The video-recordings included thousands of conversational turns, each encapsulating many interactional behaviours. Recordings were digitised and stored in accordance with the University of Nottingham data protection policy. Each encounter was allocated a code to indicate the patient and health-care professional while maintaining anonymity.

Brief observational field notes on the context of each interaction were recorded by the researcher to identify any contextual events that may have influenced the interaction.

Analysis

Data preparation and analysis were carried out by the research speech and language therapists, supported by Suzanne Beeke and Alison Pilnick, the VideOing to Improve dementia Communication Education (VOICE) study’s expert conversation analysts. Recordings were transcribed verbatim using CA notation, by professional transcribers, then anonymised and analysed using CA. The conventions of CA notation are described in Appendix 1.

Conversation analysis was used to reveal the structure of encounters, in terms of interactional phases, and recurrent and systematic interactional features and patterns. This method is well established in the field of doctor–patient interaction. 64,111,112

A core objective of the analysis was to generate recommendations for practice. As a result, we were particularly interested in identifying communication strategies that would be ‘teachable’.

A selection of recordings was viewed by the team, alongside their CA transcriptions, to identify key phases and patterns of interaction. Data were then organised into collections of cases illustrating similar phenomena, which were examined to identify (1) the talk used by health-care professionals when faced with challenges in communicating across different clinical encounters and (2) patients’ interactional responses to health-care professional talk. Within the relevant sequences, close attention was paid to patterns of similarity and difference in the details of talk and body movement, in order to identify those health-care professional practices that appeared most effective.

We drew on relevant evidence generated by other CA studies of health-care talk, as required by the CA approach, as a means of ensuring the robustness, validity and generalisability of findings. 64,68 Procedures to verify and validate findings included group data analysis sessions with experienced CA researchers on the VOICE study team, and sessions at external centres of excellence for CA and health-care research, along with consultation with dementia clinicians and PPI representatives, using raw or disguised data according to the level of consent gained.

All names in our data have been changed to protect anonymity.

Results

Phases of the encounter

In this data set, health-care professionals completed a wide variety of health-care interventions, including medical ward rounds, medication administration, recording of vital signs, leg ulcer dressing, swallow assessments, assistance with eating and drinking, assessment and support with walking, and assessment of activities of daily living.

Our analysis commenced by ascertaining the phases of ward-based hospital encounters. The CA literature highlights the ‘institutional nature’ of health-care interactions. 114 These follow a more predictable structure than ordinary conversation. The phase structure of institutional interactions affects how the health-care encounter is progressed by those involved, because speakers normatively orient to the transitions between phases. Although phases do not follow an exact sequence in all interactions, being described as ‘vague orderly’ by Jefferson,115 trying to identify an overarching structure is important.

There is extensive literature114,116–121 examining the phase structure of a variety of health-care encounters, but we found only a single CA study122 assessing the structure of ward-based, acute hospital encounters that analysed admissions interviews. Consequently, we drew on other contexts for comparison. Research in nursing and medical encounters describes an opening phase, followed by the presenting problem or complaint. 119–121 An information-gathering phase, which may be an examination or assessment, is followed in medical encounters by diagnosis and treatment recommendations,119 whereas in nursing encounters this may be described using terms such as ‘counsel’121 or ‘intervention’. 120 All describe ending with a closing phase.

Despite the diversity of tasks in the current data set, a broad five-phase structure was evident: opening, reason for the visit, information gathering, the ‘business’ phase and closing.

All encounters commenced with an opening phase, which incorporated social greetings and personal identifiers, frequently with the health-care professional using the patient’s name, their own name and their role. Unlike other health-care professionals, nursing staff appeared not to introduce themselves by name or identify their role to patients, perhaps because their consistent presence in a ward bay for a 12-hour shift did not warrant repeated introductions, unlike for staff with a more transient presence.

In the next phase, health-care professionals introduced their reason for the visit, because they were the initiators of these interactions. This represents a fundamental difference between our data set and previous CA findings for medical encounters, in which the patient initiated the interaction or presented a problem to the health-care professional. In most cases in our data set, health-care professionals were explicit about the purpose of their visit. The exception to this was in routine ward rounds, when doctors tended to lead with a typical physicians’ opening question of ‘How are you feeling today?’, presumably as an invitation to encourage patient troubles-telling. 64

In some cases, the next phase was one of information gathering. This phase was highly varied, including history-taking questions about current concerns and symptoms (‘Do you feel sick?’ ‘Any pain anywhere?’), and recent events (‘Did you sleep well?’), as well as attempts to establish patient wishes or concerns (‘What would you like to happen?’). On occasion, tasks were completed without a significant information gathering phase.

Given the heterogeneity of reasons for the health-care encounters, the phase in which these interventions were undertaken was designated the ‘business’ phase. Tasks included recording vital signs; physical examinations; assessment of, and assistance with, physical, cognitive, swallowing and everyday functioning abilities; and completion of care tasks, such as taking medications, feeding and personal care. All included a component of physical action on the part of the health-care professional and patient, working more or less collaboratively.

The closing phase of the encounter was typically initiated by the health-care professional and included planning for future conversations, or the arrangement of care activities or assessments.

Features prioritised for in-depth analysis

The ‘business’ and closing phases were notable because they were frequently associated with interactional trouble around (1) requests and refusals and (2) closings. We focused on these for in-depth analysis.

The ‘business’ phase regularly involved the health-care professional conducting health-care tasks with the person living with dementia, which were achieved through request sequences by the health-care professional. CA research123 suggests that refusals in response to requests are dispreferred (i.e. avoided or less favoured than alternatives), and usually accompanied by extensive explanation or mitigation. However, analysis indicated that in 28 of the 41 recordings (68%), patients responded to a request with some level of reluctance or refusal, often repeated refusal, and with little or no mitigation.

We also identified recurring interactional difficulties in bringing these encounters to a close, along with examples of more successful closing phases.

Requests and refusals

Definitions of requests vary, but typically they are expressions intended by a speaker to ask something of the recipient, such as an action. ‘Directives’ can be distinguished from requests as ‘telling’ people to do something, instead of ‘asking’. 124,125 CA studies of requests,124,126,127 across a range of data sets, have established that they can be analysed in terms of ‘entitlement’ and ‘contingency’. A speaker displays, by the format of their request, how entitled they are to ask the recipient to do something (entitlement), and acknowledges the perceived difficulty of the task and potential barriers to completion for the recipient (contingency).

In this study we designate the term ‘request’ to identify talk in which the health-care professional attempts to get a patient to do an action (such as ‘lift your leg’), and also for utterances that ask permission for the health-care professional to conduct an action involving the patient (e.g. ‘Can I lift your leg?’). Compliance with a request can take the form of an immediately embodied response (e.g. patient lifts leg) completed without comment, a purely verbal response, or both. Rejection may occur, but this contravenes general interactional preferences, and, when refusal occurs, speakers typically carry out interactional work to mitigate rejection, such as hesitations or giving explanations for refusal that clarify their failure to comply. 106

In our data, during each task the health-care professional issued a set of requests for action from the patient, or requested permission to act. For example, when examining a patient’s chest, the health-care professional might request permission to listen to the chest, then ask the patient to adjust their clothing, lean forward and take repeated deep breaths. Each of these individual requests requires a certain degree of physical action or passive co-operation from the patient to be ‘successfully’ completed (from the viewpoint of the health-care professional). The health-care professional interpreted the patient’s response to their requests through the patient’s verbal responses and through their embodied (non-verbal) response, that is, whether or not they completed the action.

Responses from patients could be classified in terms of whether they agreed to the request, refused the request or their response was ambiguous, and also whether responses were exhibited in a verbal or embodied (non-verbal) way (Box 2).

Four of the 28 encounters displaying refusal included separate examples of purely embodied (non-verbal) refusals as well as verbal refusals. Only two comprised non-verbal refusals alone. The refusals were classified as overt refusals (verbal and non-verbal), mitigated refusals and passive non-responses. It was not possible to characterise a small minority of refusals and these cases were excluded from analysis.

Overt refusals

Patients responded with overt verbal refusals in 13 episodes over nine encounters without any mitigation (in the following extracts, HCP stands for health-care professional, and PAT stands for patient):

In the above example, the patient gives no non-verbal indication that she intends to comply following her ‘no’ response. Purely non-verbal overt refusals without any verbal mitigation occurred in six encounters; examples included the patient deliberately turning their head away from an approaching spoon, closing their mouth against a cup and moving their arm from a position needed to take a blood test.

Mitigated refusals

Mitigated refusals were noted in 14 encounters, with 11 of these containing multiple instances. Patients presented three clear accounts to support their reasons for refusal: lack of ability, lack of willingness and lack of perceived need. Some refusals were followed by words that were difficult to interpret, and it was not possible to assess whether or not this constituted a mitigation.

Lack of ability

People living with dementia in hospital are likely to have impairments as a consequence of acute or chronic ill health, making it unsurprising that lack of ability, or lack of confidence in their ability, to do the requested task might explain, in part, refusal or reluctance to comply:

Lack of willingness

On occasion, however, patients explicitly stated that they did not want to carry out the requested action, as the following assertions from different encounters demonstrate:

At times, patients explained their reluctance in terms of contingencies that could be legitimately expected to reduce their engagement, such as pain.

Lack of perceived need

Sometimes patients justified their refusal by clearly stating a lack of perceived need:

Patients questioning the necessity of the requested action indicates a mismatch between their perception of medical or social needs and how these were perceived by the health-care professional. In the following extract, the patient dismissed any problem with her arm, even though it was in plaster (but not easily visible as it was under her cardigan at the time of this encounter):

The patient repeatedly counters the health-care professional’s initial request, and ensuing explanations and requests. The health-care professional is presented with a dilemma of having to address a health-care need in a patient who lacks insight into that need.

Unclear talk

In a number of instances, patients clearly indicated reluctance or refusal, but additional verbal content was ambiguous and may have been an attempt at mitigation. In the context of dementia, in which linguistic and cognitive impairments have an effect on reasoning and language, a patient may struggle to justify their refusal. In such ambiguous circumstances, these patient comments were often treated as mitigated refusals by the health-care professionals, for example:

Passive non-responses

Ten encounters involved health-care professional requests that failed to elicit any obvious verbal or embodied response from the patient. It is possible that non-responses were a deliberate choice to refuse the requested action, a failure to understand the request or to appreciate that a response was required, or an inability to undertake or complete the action requested combined with the inability to convey this. CA does not allow exploration of potential reasons for non-response unless evident in the talk. If a patient’s interactional behaviour lacks any additional relevant information, then the hearer (health-care professional or analyst) may only speculate about reasons for refusal. However, the manner in which the health-care professional reacts to such non-responses indicates their interpretation of the non-response, as they attempt to engage the patient in willing co-operation with their planned intervention.

Health-care professional requests preceding a refusal

In an effort to understand the high rate of refusals in this data set, we analysed the nature of health-care professionals’ requests that preceded overt and mitigated refusals. Alternative request patterns that elicited successful responses were sought in order to pinpoint potentially trainable practices.

Health-care professionals’ requests preceding overt refusals indicated sensitivity to the concepts of entitlement and contingency, both of which can be considered to be ‘high’ or ‘low’. In most cases, health-care professionals displayed low to moderate entitlement to make their request, with high contingency, suggesting a potential lack of ability or willingness to engage on the part of the patient.

Low entitlement, high contingency requesting

In some of the overt refusal sequences, health-care professionals displayed extremely low entitlement to make requests of the people living with dementia. In the most striking case, shown in Extract 6, a nurse uses the ‘I was wondering’ format (lines 5–7), described in calls to out-of-hours general practitioner (GP) services by Curl and Drew. 122 The health-care professional is asking permission to help the patient with the task of ‘relieving some pressure on your bottom’, meaning that the patient needs to stand up. This initial request for permission resulted in a considerably delayed but unmitigated ‘no’ from the person living with dementia in line 9:

By saying ‘just wondering’, the health-care professional clearly exhibits her doubt about whether or not the person living with dementia will comply with the request. The health-care professional does not ‘know’, she can only ‘wonder’ if the proposed course of action will be considered reasonable or acceptable by the patient. The health-care professional’s ‘wondering’ suggests that she anticipates contingencies limiting the patient’s ability or willingness to grant the request. Framing her proposal as an offer to help with an intervention indicates that the health-care professional felt that the patient may be unable to complete the task unaided. We postulate that use of low entitlement and high contingency requesting presents the patient with a clear option to refuse the request.

The nurse demonstrates a positive orientation towards patient choice, empowerment and autonomy, consistent with current ‘best practice’ thinking about person-centred dementia care. 33,128 However, the tendency of health-care professionals to project low entitlement to request actions from patients in these data, although appearing warm and respectful of the patient’s autonomy, presents a clear opportunity for refusal in interactional terms. If a person living with dementia is uncertain about where they are or why they are in hospital, and unclear who the health-care professional is (all of which was evident in our data set), then this low-entitlement request may fail to convey the urgency or importance of an intervention and fail to identify the requester as an expert professional. Therefore, the patient may not appreciate the consequences of a refusal. Our analysis suggests that the unintentional consequence of asking in this low-entitled, apparently ‘person-centred’, way is that a health-care professional may be inadvertently communicating that the interaction or intervention is of low priority, making a refusal seem inconsequential and, therefore, more likely.

Overt refusals in our data were also preceded by very low-entitled ways of requesting, structured with the permission-seeking prefaces ‘Is it alright if I . . .?’ or ‘Is it OK if I . . .?’, as in Extract 7, in which a junior doctor wishes to examine a patient’s chest during a routine encounter:

Here, the health-care professional leads with a permission-seeking question, ‘Is it OK if I have a listen to your chest?’, which demonstrates the conditional ‘if’ and implies the possibility that the request will not be acceptable to the patient.

‘Middle’ levels of entitlement and contingency

Health-care professionals also requested actions, which were subsequently overtly refused, using questioning, modal verb formats, such as ‘would you . . .?’ and ‘can you . . .?’. In the literature,124 these are recognised as having higher entitlement than ‘wondering’ requests. The modal verbs will/would and can/could invoke the patient’s willingness or ability to engage with the request.

Prior to the following exchange, the health-care professional had spent many minutes trying to verbally encourage and physically support a person living with dementia to eat his lunch, as he paced the ward, refusing to sit down. An example of a ‘would you’ request format then follows:

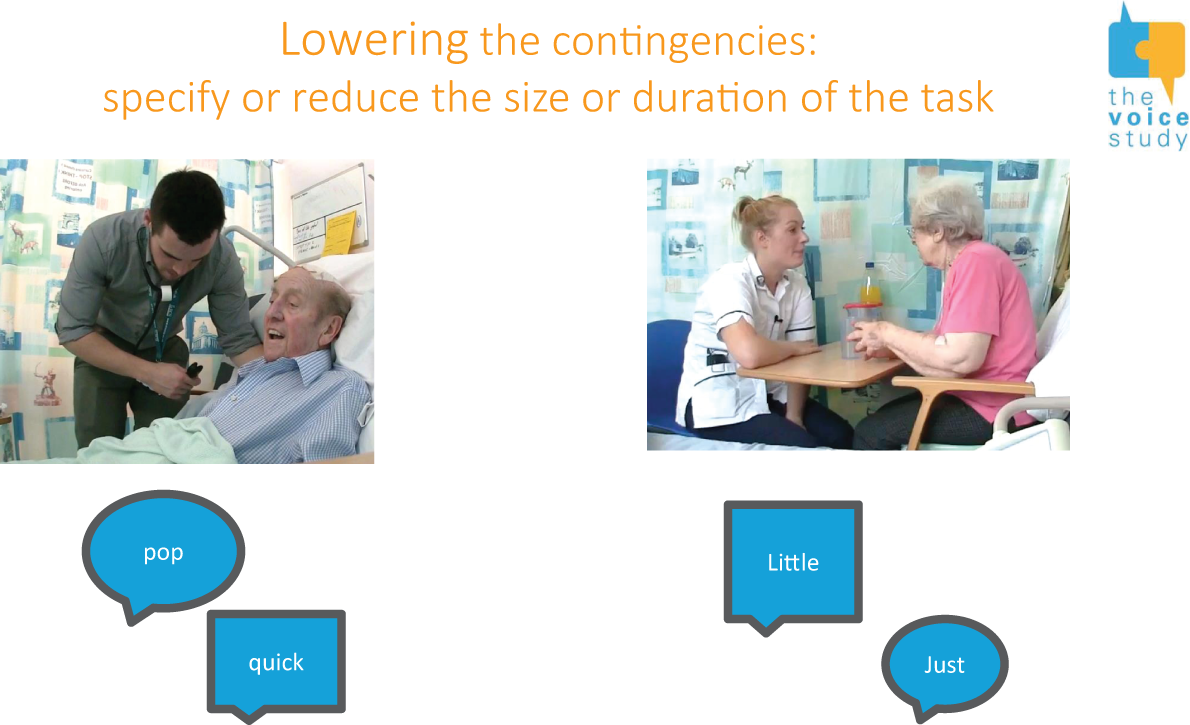

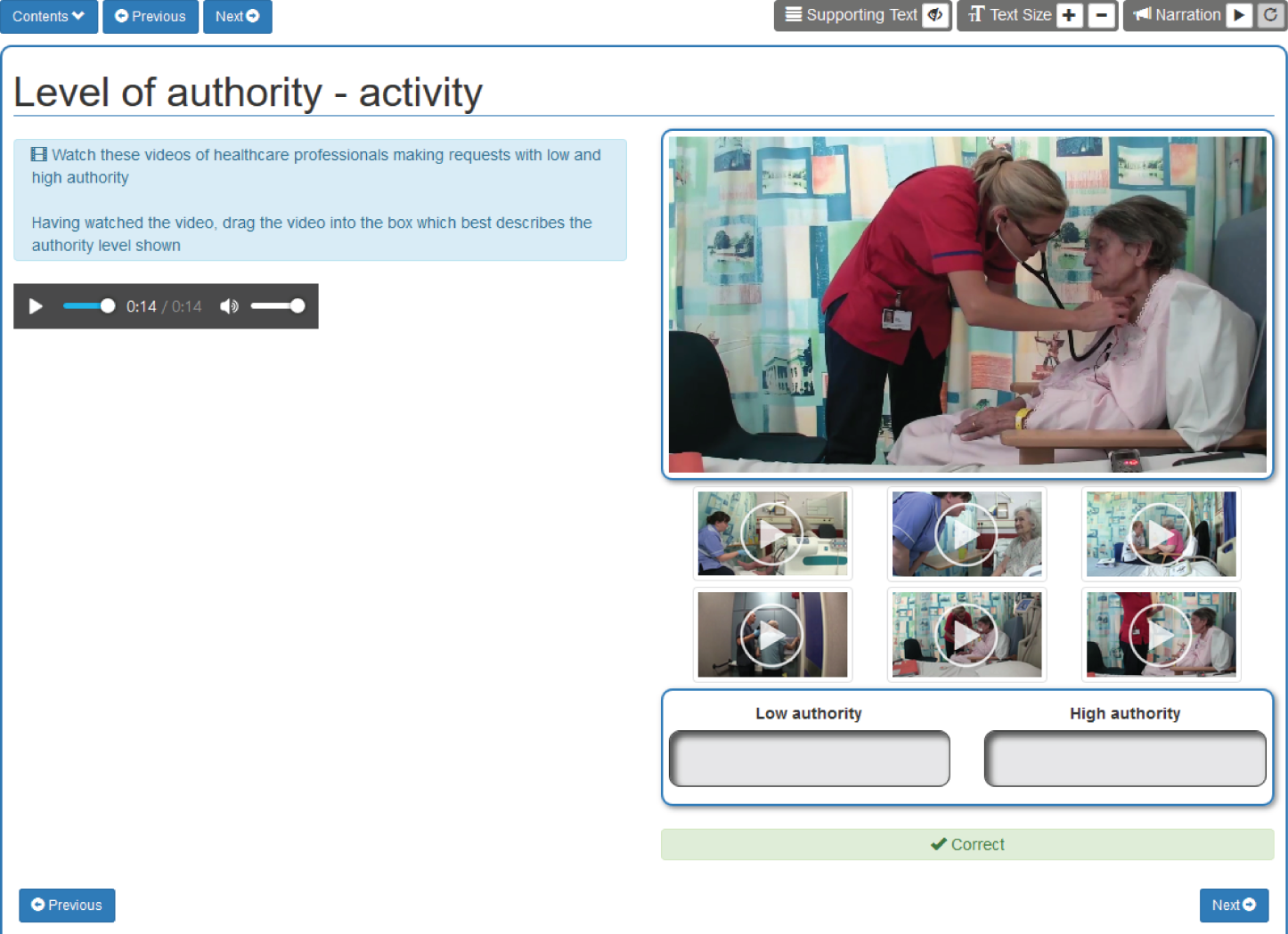

The patient chooses to emphatically decline more food. By posing the question in a ‘would you like?’ format, the option to decline is presented and signals ‘not liking’ as a possible contingency on which basis the patient has the choice to accept or decline.