Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 12/177/13. The contractual start date was in September 2014. The final report began editorial review in December 2017 and was accepted for publication in July 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Tessa Crilly is a member of the National Institute for Health Research Journals Library Editorial Group. Iestyn Williams is a member of the Health Services and Delivery Research Prioritisation Commissioning Panel.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Davidson et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction and context

The evolution and diversification of community hospitals in England has not been matched by research on such institutions. There is no consistent definition and little is known of the numbers of community hospitals, their distribution and the services and facilities they offer. Although two parallel National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)-funded projects have explored the nature and scope of service provision models of community hospitals and international comparisons1 and the efficiency and effectiveness of community hospitals,2 the primary aim of this study was to provide a comprehensive analysis of their profile, characteristics, patient experience and community value.

In this introductory chapter, we briefly describe the origins and development of community hospitals in England, before setting out the policy context and providing a brief summary of previous research about the role and function of community hospitals, patient experience and their community engagement and value. A formal review of the evidence was funded as part of the NIHR 12/177 call on research into community hospitals (see Pitchforth et al. 1) and so was beyond the remit of this study.

Community hospital development

Community hospitals [previously known as ‘cottage hospitals’ or ‘general practitioner (GP) hospitals’] have been part of the landscape for health care in England since 1859, evolving to offer local health-care services and accessible facilities to support patients and their families and enable patients to return home (and to work) as soon as possible. 3 The cottage hospital model was widely emulated: within a period of 30 years, more than 240 were established. 4 By 1895, only three counties in England had not developed one.

Loudon’s research5 illustrated that all cottage hospitals opened with inpatient beds for the sick and injured and a room for operating. However, over the decades, their services and facilities evolved in parallel with medical and nursing developments. The visionary report by Lord Dawson in 19216 saw such hospitals as part of a wider move to population health, playing a role in integrated service hierarchies by providing facilities in which GPs and interdisciplinary teams could work together to offer preventative and curative medicine.

In 1948, cottage hospitals were transferred to the NHS. Traditions of voluntary support and local involvement were maintained with the formation of local hospital Leagues of Friends, with a national association being established in 1949 [URL: www.attend.org.uk/about-us/national-association-of-leagues-of-friends (accessed 8 October 2018)]. There was little change in the number of cottage hospitals between 1948 and 1960, and they remained largely outside government attention.

Government policy

In 1962, the Hospital Plan7 heralded the centralisation of services, threatening many cottage/GP hospitals with closure. In practice, the plan’s proposed closures were pursued only partially and more positive alternative futures were envisaged for cottage hospitals. Through the work of Rue and Bennett,8,9 the concept of the ‘community hospital’ emerged, signifying co-location of GP practices and hospital facilities and facilitating integration of GPs and consultants. 10 National policy identified the need to strengthen the role of the family doctor and community hospital services, recognising their role, particularly in post-acute care, but also in integrated health provision. 11

Over the following 20 years, community hospitals barely featured in central policy or local plans12 until the government’s strategy document Opportunities in Intermediate Care,13 in which the role of community hospitals was conceptualised as providing either ‘substitutional’ care as an alternative to a general hospital or ‘complex care in the community’. Six years later, Keeping the NHS Local: A New Direction of Travel14 emphasised that community hospitals could:

provide a more integrated range of modern services at the heart of the local community.

Keeping the NHS local: A New Direction of Travel,14 p. 4.

In 2006, Our Health, Our Care, Our Say15 gave further impetus to the idea, calling for a shift of resources from secondary care to the community in order to prevent unnecessary acute admissions. The potential for outpatient clinics to take place in community settings and better use of community hospital services and intermediate care facilitating admission prevention were key themes in this shift of services and financial resources. In 2008, there was further policy encouragement16 for primary and community services to play a vital role in meeting the policy aim of care closer to home.

However, there was no explicit national strategy for community hospitals in England. This contrasted with the prioritisation of such facilities in Scotland. 17 In England, devolved responsibility as part of the NHS Five Year Forward View18 and sustainability and transformation plans (STPs) within 44 health and social care ‘footprints’ have led to proposals for a fundamental reconfiguration of services. The configurations being proposed, and, in some areas, being implemented, are a combination of:

-

community hospitals with beds – these are either existing community hospitals or community wards created in general hospitals, which are expected to serve an area wider than their immediate local population

-

community hubs – community hospitals without beds, being redeveloped with a role wider than health and social care to incorporate health promotion, well-being and welfare and involving the voluntary as well as the statutory sectors.

In some locations, reconfiguration has led to the threatened closure of community hospitals and significant planned reductions in the number of community hospital beds. Elsewhere, there has been an investment in community hospitals. Neither investment in nor closure of community hospitals has been informed by authoritative guidance. 19

Given their history, strong local support from GPs and communities as well as a continued policy focus on care closer to home, important questions are being asked about the role, function and value of community hospitals. In order to inform such discussions, it is important to define, map and profile the characteristics of community hospitals in England, examine patient experience and explore their support from, and value to, local communities.

Research on community hospitals

The effect of this history of evolution and diversification, exacerbated by the twists and turns of English health-care policy, has been to make classification, and, therefore, assessment, of the role and value of community hospitals far from straightforward. We lack a universally accepted definition of a community hospital. Although Ritchie and Robinson20 point to numerous descriptive studies indicating a distinct and important role within health-care delivery, they nevertheless conclude that definitive evidence is lacking.

The most positive assessments, such as those by Seamark et al. ,21 highlight characteristics such as links with local communities, GP involvement, multidisciplinary rehabilitation services and diagnostic facilities, which suggest that community hospitals should have a significant role in the evolution of intermediate care. This notion is echoed by Heaney et al. 22

Internationally, a similar picture has been observed, for example by Pitchforth et al. 1 They echo British work in concluding that community hospitals defy ‘the formulation of a single, overarching definition’ (p. 47) (contains information licensed under the Non-Commercial Government Licence v2.0).

Overall, although these studies have identified several features that seem common to many community hospitals, an agreed definition remains elusive. Nevertheless, they provide a starting point for a ‘working definition’:

-

A hospital with < 100 beds serving a local population of up to 100,000, providing direct access to GPs and local community staff.

-

Typically GP-led or nurse-led with medical support from local GPs.

-

Services provided are likely to include inpatient care for older people, rehabilitation and maternity services, outpatient clinics and day care as well as minor injury and illness units, diagnostics and day surgery. The hospital may also be a base for the provision of outreach services by multidisciplinary teams (MDT).

-

Will not have a 24-hour accident and emergency (A&E) department nor provide complex surgery. In addition, a specialist hospital (e.g. a children’s hospital, a hospice or a specialist mental health or learning disability hospital) would not be classified as a community hospital.

Recognising these gaps, the aim of our first work package was to undertake a national mapping study to identify, locate and yield a set of characteristics to develop a definition and typology and, thereby, address the question: what is a community hospital?

Research on patient experience of community hospitals

There is a notable lack of systematic and in-depth research into patient experience in community hospitals. There are few high-quality and/or multicentre studies, with most being adjunct to research that is primarily focused on aspects of care delivery and largely based on experiences of inpatient services, with a tendency to rely on survey methods focusing on satisfaction rather than on more qualitative approaches to explore patient experience.

The literature contains three broad themes relating to patients’ experiences of community hospitals: (1) environment and facilities, (2) delivery of care and (3) staff.

Environment and facilities

Many previous studies of community hospitals focused on the functional aspects of care, asking patients to give feedback on, for example, access to services, the quality and range of facilities and equipment, the environment and atmosphere, and levels of cleanliness.

Patients in these studies valued a close proximity to family and friends when using community hospitals, as well as the opportunity to interact with patients from the same geographical location,23–26 the homely and friendly atmosphere,24–26 the orientation to older people,27 the level of cleanliness,24,25,28 the availability of single-room accommodation,23,24,29 and the quality, choice and presentation of food. 23,24,29,30 However, some patients felt that community hospitals could be noisy environments23,26 and others reported long periods of boredom. 23,25,31 Few studies appeared to go on to explore how these environmental factors affected patients’ experiences of care.

Delivery of care

Several studies also focus on the technical aspects of care. Community hospital inpatients were often satisfied with their care, comparing this favourably with experiences in acute care,24,32 and valuing greater continuity of care,24,25 information sharing23,26,33,34 and the potential for longer lengths of stay. 26,29,31,35 However, rehabilitation and ongoing needs were reported as not always being met on discharge. 31

Staff

A subset of these studies also focus on the more relational aspects of care. Community hospital staff were often perceived more positively than those at district general hospitals (DGHs); they were experienced as being kind, caring, friendly, knowledgeable and committed to seeing people as individuals. 23–26,29,32 However, at times, patients lacked confidence in the technical skills of some staff,25 preferring to go to an acute hospital when requiring more complex medical expertise. 26

Notwithstanding these insights, the evidence base remains underdeveloped and focuses primarily on the functional and technical aspects of care. Bridges et al. 35 argue that patients’ and relatives’ narratives rarely focus on the functional or technical aspects of care. Instead, they often relate to the more relational and interpersonal aspects of their experience. Similarly, our previous research into older peoples’ experience of moving across service boundaries36 found that, although health and social care services often focus on the physical aspects of transition (e.g. relocating from one setting to another), older people tended to talk about transition in terms of the psychological (e.g. changes in their identity or sense of self) and social (e.g. changes in their relationships with partners, family and friends) impacts.

These insights from, and gaps within, the existing research, combined with a concern for what matters to patients and how that is understood and represented, shaped the aim and methodological approach of work package 2, which addresses the question: what are patients’ experiences of community hospitals?

Research on community engagement and value

Community hospitals are often known to, and are valued by, their communities37 and can play an important part in responding to the health and social care needs of local (often rural) populations. It has been suggested that support for, and satisfaction with, community hospitals by the public has been considerable,38 and this has been echoed by the GP population in such areas. 39,40 However, Heaney et al. 22 identify a striking lack of research into the wider role that community hospitals may play in the communities in which they are located. We suggest that there is a similar dearth of research on the role that communities play in supporting community hospitals.

Forms and levels of voluntary and community support

A key gap in the literature is empirical analysis of voluntary and community support for community hospitals in England. Hospital Leagues of Friends (the main conduit of such support) have been the subject of only one published UK academic study. 41 Existing national survey evidence does not allow for the identification of health-related voluntary activity in anything but the most general terms. 42

Broader research on engagement with other health settings gives an indication of the significance of voluntary support in the field. Naylor et al. 42 estimate that approximately 2.9 million people regularly volunteer for the health sector as a whole in England. The study by Galea et al. 43 of NHS acute trusts in England found that, on average, they involve 471 volunteers, making a total of 78,000 people who together contribute a total of 13 million hours per year. Volunteers undertake a considerable range of roles – as many as 100 – within NHS hospitals. 44 Naylor et al. 42 note that volunteers are increasingly involved in both strategic roles and roles that involve direct patient contact.

Previous studies of voluntary income for the NHS or other specific subsectors of health care45 have focused on relatively large organisations or have used data at the level of District Health Authorities, meaning that levels of support for individual institutions cannot be identified. 46

Engagement patterns and variations

Evidence on specific patterns of engagement within community hospitals is very limited. Historical evidence of voluntary income for the pre-NHS period hospitals, however, suggests that considerable variations may well persist. 47,48 More generally, national surveys of volunteering show that rates and levels of volunteering differ by socioeconomic status, employment status, age, strength of religious affiliation, ethnicity, disability and region. 49 Mohan and Bulloch50 report strong social and geographical gradients in voluntary activity and identify a ‘civic core’ delivering the bulk of voluntary effort. Prosperous, well-educated, middle-aged population groups dominate the civic core. 51 These studies suggest that voluntary support for community hospitals might be expected to vary between and within communities. Such national samples, however, cannot provide detail on voluntarism in individual types of organisation (such as community hospitals) and on the nature of voluntary activities within them.

The outcomes and impact of voluntary support

Describing different forms of voluntary support or counting the numbers of volunteers or the levels of voluntary income raised will give a measure of activity, but not of difference made. It is also important to consider the outcomes of such activities, such as contribution to patient experience and/or the quality of services in the hospital. This moves us to a level of considering and assessing impact and value. Direct or intended outcomes, for example, may include enhanced patient experience. Indirect, or unintended, outcomes include whether or not community engagement has wider spillover for the community in the form of raised levels of social capital, for example (elsewhere we refer to this as latent value). Unfortunately, capturing outcomes, impact or value is by no means simple. Although some elements lend themselves to quantification (e.g. funds raised, numbers of volunteers recruited), others are harder to identify and rely on self-reports by stakeholders, who may not be without their own interests and biases.

A small number of studies have considered the outcomes of certain forms of community engagement for hospitals and for the wider health-care system. There have, for example, been some attempts to measure the financial value of volunteering to individual hospitals, although with considerable limitations. 52,53 The qualitative research of Naylor et al. 42 with volunteers, patients, commissioners and service providers, and the Mundle et al. 54 review of literature on volunteering in health and social care both found that volunteers have a positive impact on health and social care systems in a number of ways. Identified impacts included improving the experience of care and support, strengthening the relationships between services and community, improving public health and supporting integrated care. The findings of another study, however, somewhat contradicted this: Milton et al. 55 found no existing evidence of positive impact on population health or quality of health services and failed to identify any studies that had attempted to determine the impact of community engagement on wider health outcomes.

There is even less evidence of the impact of such activities in community hospitals (or health-care services more generally) on the wider community. Indeed, there is very little evidence of the outcomes of volunteering on communities more generally, beyond general suggestions that volunteering contributes to community-level social capital development, which, in turn, contributes to community vitality, sustainability and resilience. 56 None of these focus specifically on the outcomes and impact of voluntary support in/through community hospitals.

Finally, distributional effects require attention. As noted above, underlying theories of voluntary action predict that its distribution (whether expressed in terms of funding or volunteering) will reflect variations between communities in resources, the availability of leadership and the idiosyncratic preferences of donors, rather than a needs-based allocation of resources. 57,58 How these processes work out is a contingent matter. Voluntary effort and charitable giving are known to be capricious and unpredictable. Salamon59 articulates four weaknesses: (1) philanthropic insufficiency (and variability), (2) paternalism, (3) amateurism and (4) parochialism. As levels of forms of voluntary action in community hospitals are likely to vary, so too are its outcomes.

The social value of community hospitals

Although it is often assumed that community hospitals are important to their local communities, the specifics of this relationship are under-researched. There have been many assertions recently about the concept of ‘social value’, particularly in relation to public service reforms and following the Public Services (Social Value) Act 2012,60 which enjoined commissioners of public services to take account of ‘economic, social and environmental wellbeing’ when placing public service contracts. With an increasing emphasis on outcomes-based commissioning, a consideration for the social value of a service offered the potential to move beyond purely financial considerations. As Dayson61 notes, however, ‘what constitutes social value and how to measure it is contested’. Citing Phills et al. ,62 Dayson goes on to suggest that ‘social value can be described as the benefits created for society through efforts to address social needs and problems’; these benefits, or values, may be economic, social or environmental and may be experienced by certain individuals, groups of individuals or society as a whole. 63 Social value is not exclusively associated with a particular organisational form, but there has been a strong association with voluntary organisations through the suggestion that the voluntarism and pro-social motivations for behaviour within such organisations add value to their activities.

There is little existing evidence on the social value of community hospitals to the communities in which they are based. More generally, however, wider literature points to the significance of hospitals and other institutions to communities, and rural communities in particular, as a source of collective identity and in contributing to a sense of place. 57–59,64 Research from New Zealand65 found small hospitals to be a source of civic pride and security and a symbol of legitimacy. Jones66 proposes Giddens’s67 concept of ‘ontological security’ as a way of understanding the ‘deep sense of reassurance’ that hospitals contribute to the communities in which they exist.

Developing these ideas further, Prior et al. 68 presented a typology (subsequently further developed by Farmer et al. 64) of the ‘added-value’ contributions of health services to remote rural communities at institutional and individual level, incorporating economic, social and human capital.

History provides a guide as to why such community attachment is important. In the pre-NHS era, although competition between doctors in a crowded medical marketplace also drove innovation, many hospital foundations were originally motivated by community needs, and the memorialisation of those fallen in war was also significant. Thus, symbolic value was inbuilt from the outset. Nationalisation did not quell the fires of attachment, with many Leagues of Friends established within a few years of the establishment of the NHS in 1948. The flames of community resistance were fanned by proposals for centralisation, as described by Mohan’s69 analysis of the 1962 Hospital Plan for England and Wales and the associated resistance to closures; it is hardly surprising that when hospitals had been established largely by local voluntary effort, proposals to remove them by the state would be fiercely resisted.

Broader social changes may plausibly be said to be associated with attachment to local hospitals: as the fabric of communities thins out (e.g. through closures of major employers) and as community ties are weakened (e.g. by longer commuting patterns) then mobilisation for remaining institutions becomes more important; international studies confirm this, particularly within the context of hospital closures. 70

In response to gaps in the knowledge of the role that voluntary and community action plays in supporting community hospitals, and that community hospitals play in their local communities, the aim of work package 3 was to undertake robust and systematic quantitative and qualitative research to address the research question: what does the community do for its community hospital, and what does the community hospital do for its community?

Summary

Community hospitals have been a part of the health-care landscape in England since the mid-nineteenth century. Over time, they have evolved into a diverse set of institutions, which some have suggested defy a single overarching definition. Although community hospitals are generally recognised as playing an important role in our health-care system, particularly through the provision of intermediate care, the evidence base to support their development is relatively weak. The lack of a universally accepted definition makes any measurement and assessment difficult; to date, we know little about their profile and characteristics, for example. Although existing evidence generally suggests positive patient experience, there is a tendency for this to rely on small-scale or functionally focused studies. Despite historic indications of strong levels of community support, there is very little evidence of how communities support community hospitals today and what value community hospitals represent to these communities. This study sets out to address these gaps in evidence by exploring the profile, characteristics, patient (and carer) experience, community engagement and value of community hospitals.

Having introduced the study and framed it within the existing literature, we move now to Chapter 2, which sets out the aims, objectives and research questions in more detail, followed by a full discussion of the approaches adopted in addressing them. In Chapter 3, the findings from the national mapping exercise locating, profiling and defining community hospitals are presented. In Chapter 4, we revisit our emerging definition in the light of qualitative findings from our nine case studies. Chapter 5 sets out the findings relating to patient and carer experiences, and Chapters 6 and 7 explore community engagement and value, respectively. Finally, Chapter 8 distils the findings from across the different research elements and relates them back to the existing literature to provide a new understanding of the profile, patient experience, community engagement and value of community hospitals.

Chapter 2 Research objectives, questions and methodology

In the light of the unfolding policy context and gaps within the existing literature outlined in Chapter 1, and informed by conversations with key stakeholders (see Patient and public involvement), this study aimed to provide a comprehensive analysis of the profile, characteristics, patient and carer experience and community engagement and value of community hospitals in contrasting local contexts. The specific objectives were to:

-

construct a national database and develop a typology of community hospitals

-

explore and understand the nature and extent of patients’ and carers’ experiences of community hospital care and services

-

investigate the value of the interdependent relationship between community hospitals and their communities through in-depth case studies of community value (qualitative study) and analysis of Charity Commission data (quantitative study).

In meeting these aims and objectives, the study addressed three overarching research questions (each with an associated set of more specific subquestions as summarised in Table 1):

-

What is a community hospital?

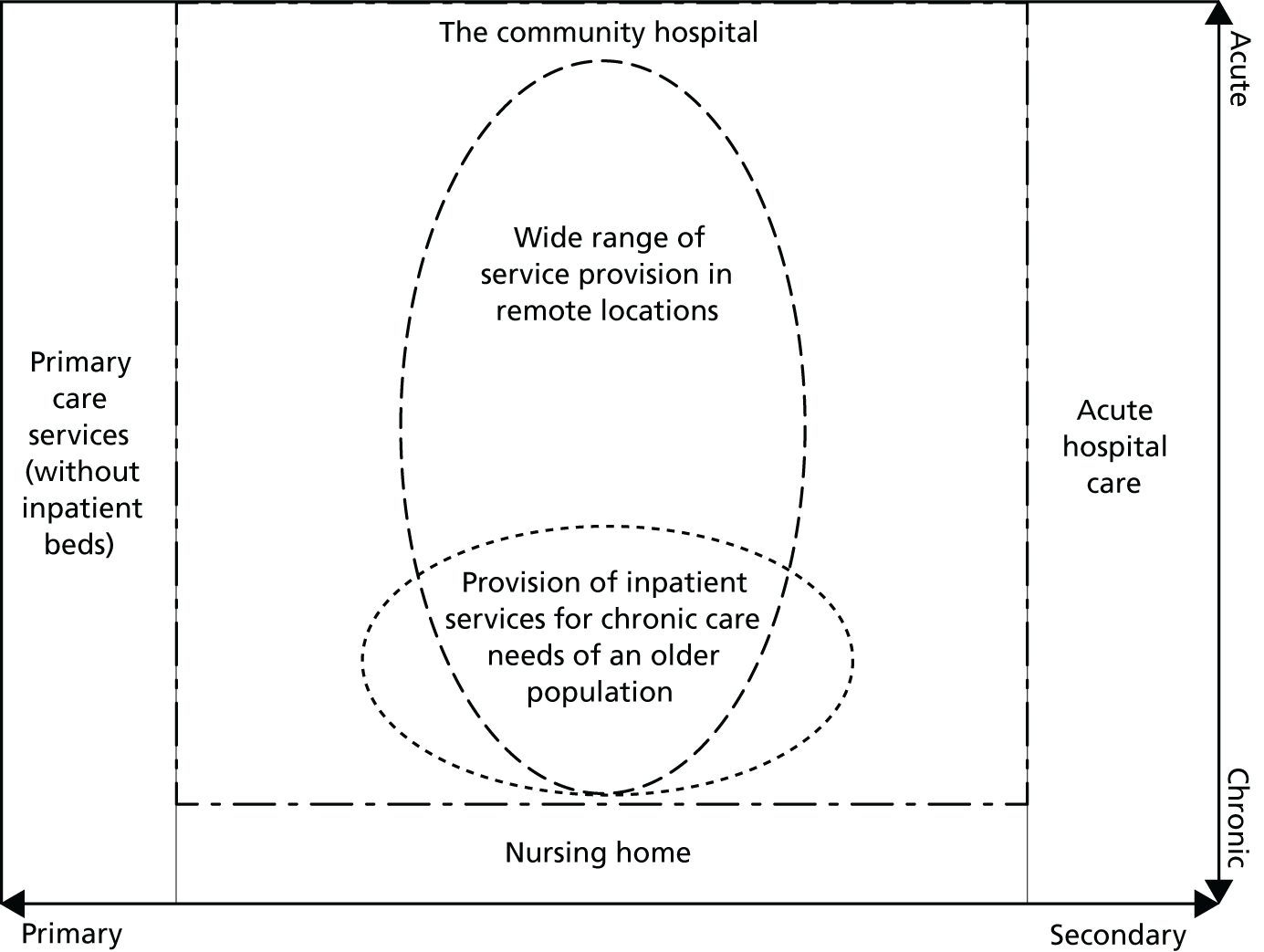

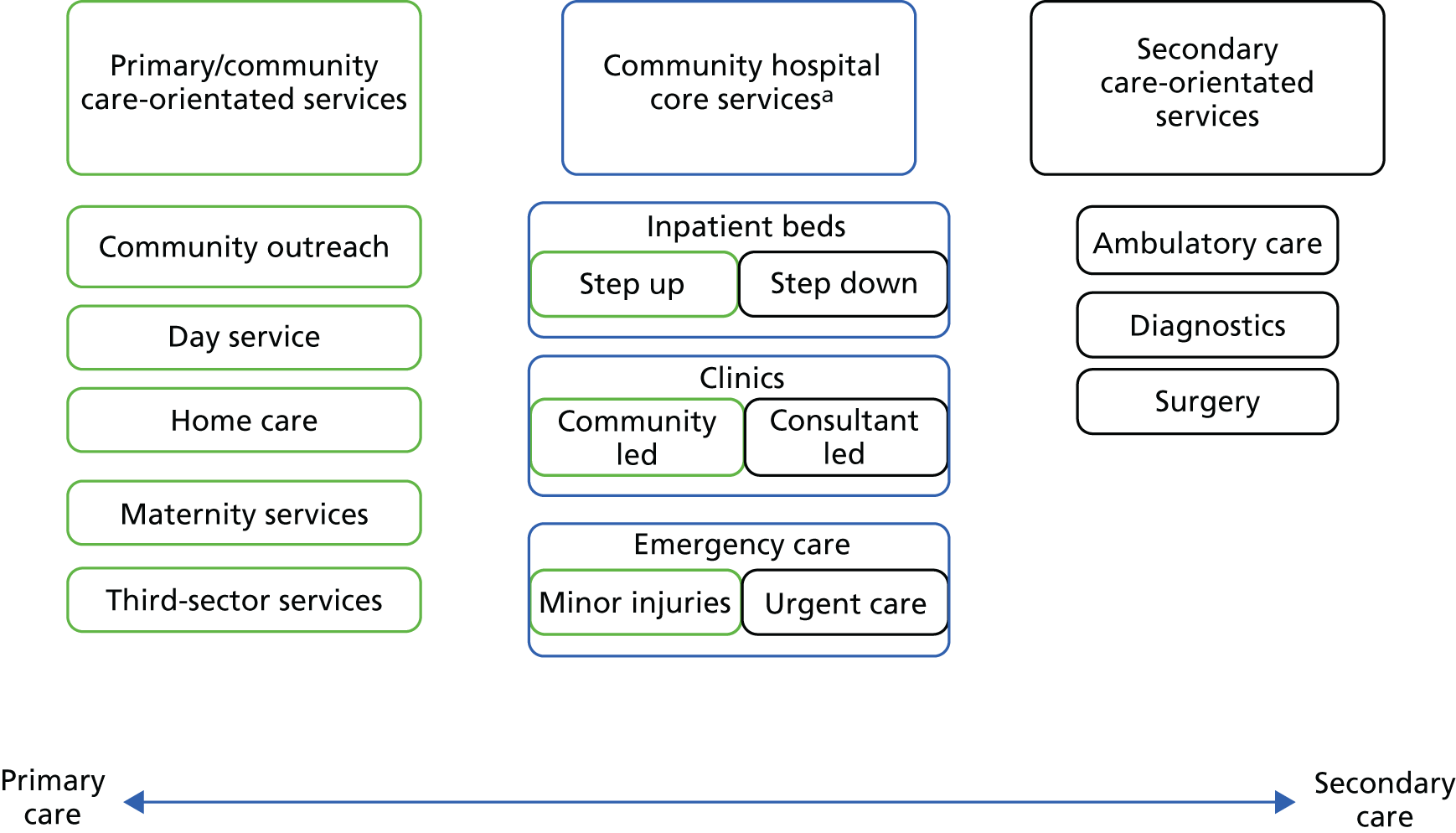

In addressing this question, we drew on existing definitions and conceptualisations of ‘community hospitals’ as outlined in Chapter 1, Research on community hospitals. Although our emphasis here was primarily empirical and descriptive, we were nevertheless guided by, and sought to contribute to, theoretical debates on definitions of community hospitals and their place within wider health and care systems, drawing on concepts of rural health care, chronic disease and complex care burden, integrated care and clinical leadership.

-

What are patients’ (and carers’) experiences of community hospitals?

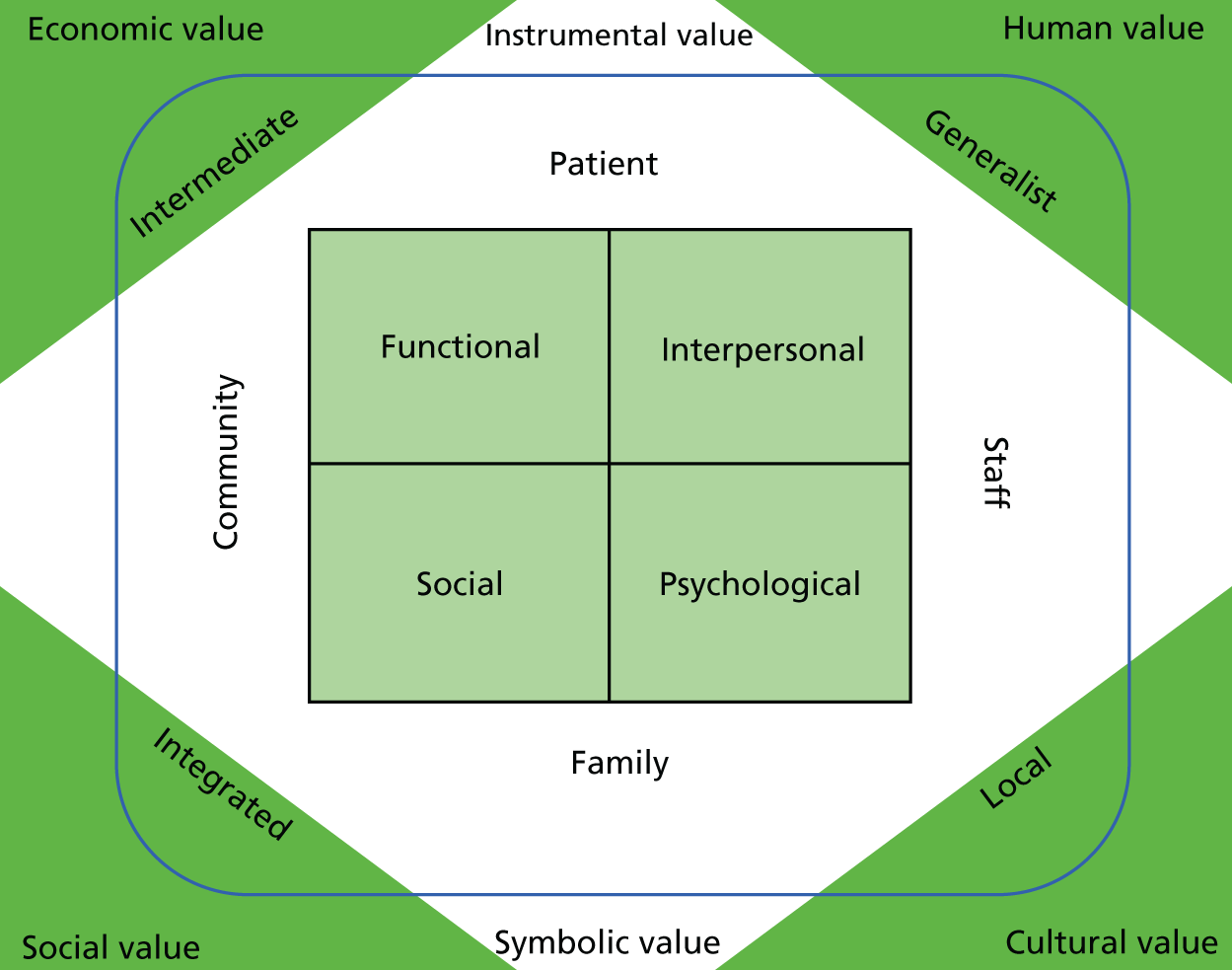

This element of the study was designed to contribute to the conceptualisation of the distinctive elements of community hospitals as understood through the ‘lived experiences’ of patients, rather than just satisfaction ratings. Here, we were influenced by prior analysis of the functional, technical and relational components of patient experience (e.g. environment and facilities, delivery of care, staff) alongside a more theoretical interest in the interpersonal, psychological and social dimensions of patient experience.

Very early on in our study, through conversations with patient and public involvement (PPI) stakeholders, we recognised the importance of exploring and understanding the experience not only of patients but also of family carers, and hence we extended our initial question to include both patients’ and carers’ experiences.

-

What does the community do for its community hospital, and what does the community hospital do for its community?

In addressing this question, we drew on notions of voluntarism and participation and brought together thinking from the separate bodies of literature on volunteering, philanthropy and co-production. This led us to question not just the level of voluntary support for community hospitals but also the different forms it took, how this varies between and within communities, how it is encouraged, organised and managed, and what difference it makes (outcomes). We also drew on notions of social value, including existing typologies, that encouraged us to question different forms of value (e.g. economic, social, human, symbolic) and different stakeholder groups (e.g. staff, patients, communities).

| Objective (work package) | Research question | Subquestions | Research phase | Data collection |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. To construct a national database and develop a typology of community hospitals | What is a community hospital? |

|

National mapping |

|

| 2. To explore and understand the nature and extent of patients’ experiences of community hospital care and services | What are patients’ and carers’ experiences of community hospitals? |

|

Case studies |

|

| 3. To investigate the value of the interdependent relationship between hospitals and their communities | What does the community do for its hospital and what does the community hospital do for its community? |

|

Charity Commission data analysis |

|

|

Case studies |

|

Given the diversity of the questions, we do not set out to provide an over-riding hypothesis or unified theoretical framework for the study as a whole. Instead, these concepts, frameworks and debates served as ‘sensitising categories’, shaping our approach to study design as well as data collection and analysis. 71 We return to these in Chapter 8 and augment them with new concepts that emerged from our analysis.

In addressing these diverse questions, we adopted a multimethod approach with a convergent design. Quantitative methods were employed to provide breadth of understanding relating to the questions concerning ‘what’, ‘where’ and ‘how much’, whereas qualitative methods provided depth of understanding, particularly in relation to questions of ‘how’, ‘why’ and ‘to what effect’.

The research was conducted in three distinct (although temporally overlapping) phases, each with a number of different associated elements and research methods: (1) mapping (database construction and analysis through data set reconciliation and verification), (2) qualitative case studies (semistructured interviews, discovery interviews, focus groups) and (3) quantitative analysis of charity commission data. Table 1 summarises the study objectives, questions and research methods. Each of the three phases of research are discussed in turn through the following sections of this chapter, before the final sections discuss data integration, PPI and ethics.

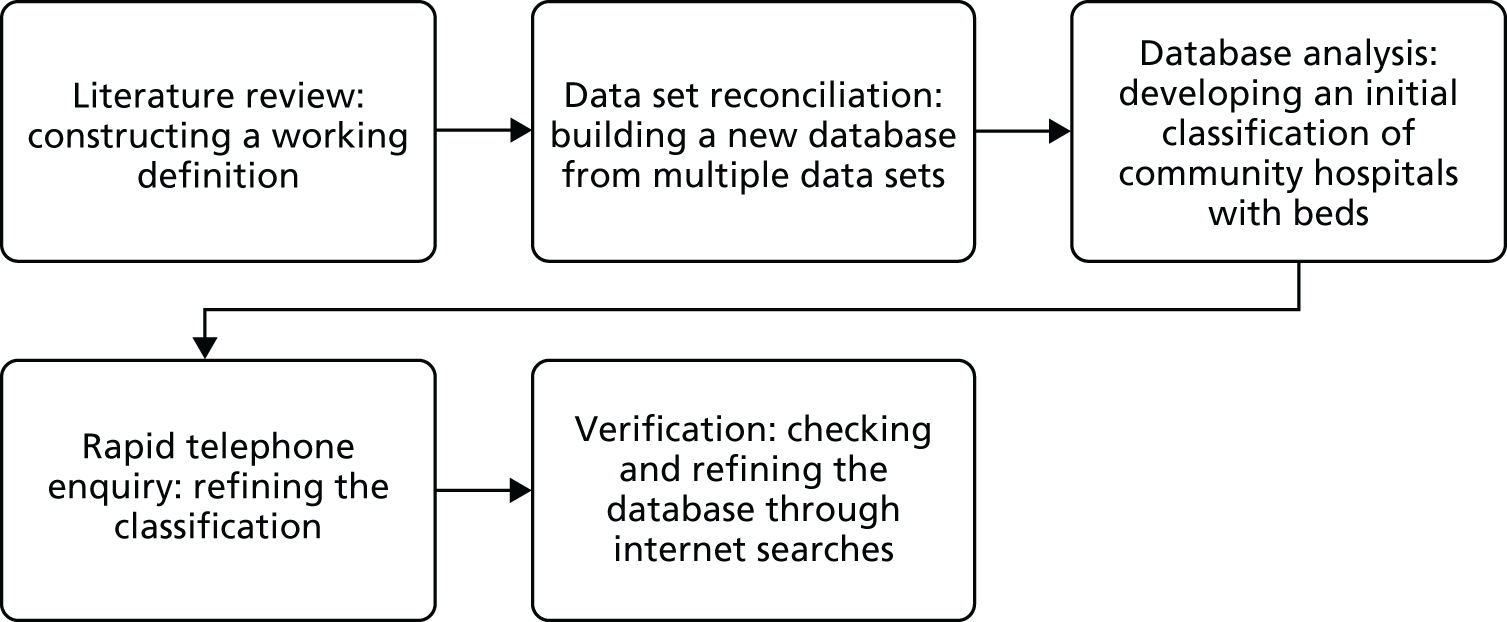

Phase 1: mapping and profiling community hospitals

Phase 1 of the research involved a national mapping exercise to address the first study question ‘what is a community hospital?’. It aimed to map the number and location of all hospitals in England to then provide a profile and definition of community hospitals. A database of characteristics would enable the profiling of community hospitals, inform a typology and support a sampling strategy for subsequent case studies. Data were collected from all four UK countries but, in accordance with the brief of the study, this report focuses on England. Reference is made to Scotland’s data as they were important in developing the methodology. The structure of the mapping comprised five elements:

-

literature review – constructing a working definition: (see Chapter 1)

-

data set reconciliation – building a new database from multiple data sets

-

database analysis – developing an initial classification of community hospitals with beds

-

rapid telephone enquiry – refining the classification

-

verification – checking and refining the database through internet searches.

The flow of activities is depicted in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Structure of the national mapping exercise.

Literature review: constructing a working definition

We developed a working definition of a community hospital as drawn from the literature (and as outlined in Chapter 1):

-

A hospital with < 100 beds serving a local population of up to 100,000 and providing direct access to GPs and local community staff.

-

Typically GP led, or nurse led with medical support from local GPs.

-

Services provided are likely to include inpatient care for older people, rehabilitation and maternity services, outpatient clinics and day care as well as minor injury and illness units, diagnostics and day surgery. The hospital may also be a base for the provision of outreach services by MDTs.

-

Will not have a 24-hour A&E nor provide complex surgery. In addition, a specialist hospital (e.g. a children’s hospital, a hospice or a specialist mental health or learning disability hospital) would not be classified as a community hospital.

The initial enquiry was framed around a ‘classic’ community hospital. The term was drawn directly from the Community Hospital Association 2008 classification,72 describing classic community hospitals as ‘local community hospitals with inpatient facilities’ (i.e. with beds) and as distinct from community care resource centres (without beds), community care homes (integrated health and social care campus) or rehabilitation units. Although the term ‘classic’ was initially helpful in setting the boundaries of the study, it presented ongoing problems, such as whether it described all community hospitals with beds or a subset within that. Throughout the study, therefore, we have adopted the term ‘community hospital’ and omitted the adjective ‘classic’. Our focus, however, has remained on community hospitals with beds.

Data reconciliation: building a new database from multiple data sets

There was no up-to-date comprehensive database of community hospitals in England. The NHS Benchmarking Network [URL: www.nhsbenchmarking.nhs.uk (accessed 8 October 2018)] membership database was not comprehensive and could not be used to populate our hospital-level database because the data were anonymised. For this reason, one of our first tasks was to compile a new database, by bringing together existing health-care data sets, each of which provided different fields of information needed to test our working definition and to map and profile community hospitals.

Two types of data sets were collected. Centrally available data sets formed the starting point for the mapping study, providing codified data (see Appendix 1). As none of these centrally available data sets provided a comprehensive picture, it was necessary to supplement them through extensive internet searching and by talking to people in the field, as well as drawing on the expertise of research team members.

The base year for major data sets was 2012/13. Data were difficult to access, not comprehensive and spread across a greater number of sources. Four data sets were used:

-

Community Hospital Association databases of community hospitals (one from 2008 and another from 2013)

-

Patient-Led Assessments of the Care Environment (PLACE) 2013 [replacing the former Patient Environment Action Team programme]

-

Estates database – Estates Returns Information Collection (ERIC) 2012

-

NHS Digital activity by site of treatment 2012/13.

Barriers to obtaining site and activity data included (1) specific difficulties in the period 2012/13 when primary care trusts (PCTs) were being disbanded and clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) were being established (with effect from 31 March 2013) and (2) processes and caution in NHS Digital associated with releasing patient-sensitive data (even though we had not requested patient-based data). Quality problems were associated with the ‘location of treatment’ code, which was central to our enquiry identifying community hospitals but did not appear to be well used in England, leading to examples of missing data and inconsistent labels (described under reconciliation and duplication). The code also lacked stability as it changed with each new NHS reconfiguration in England.

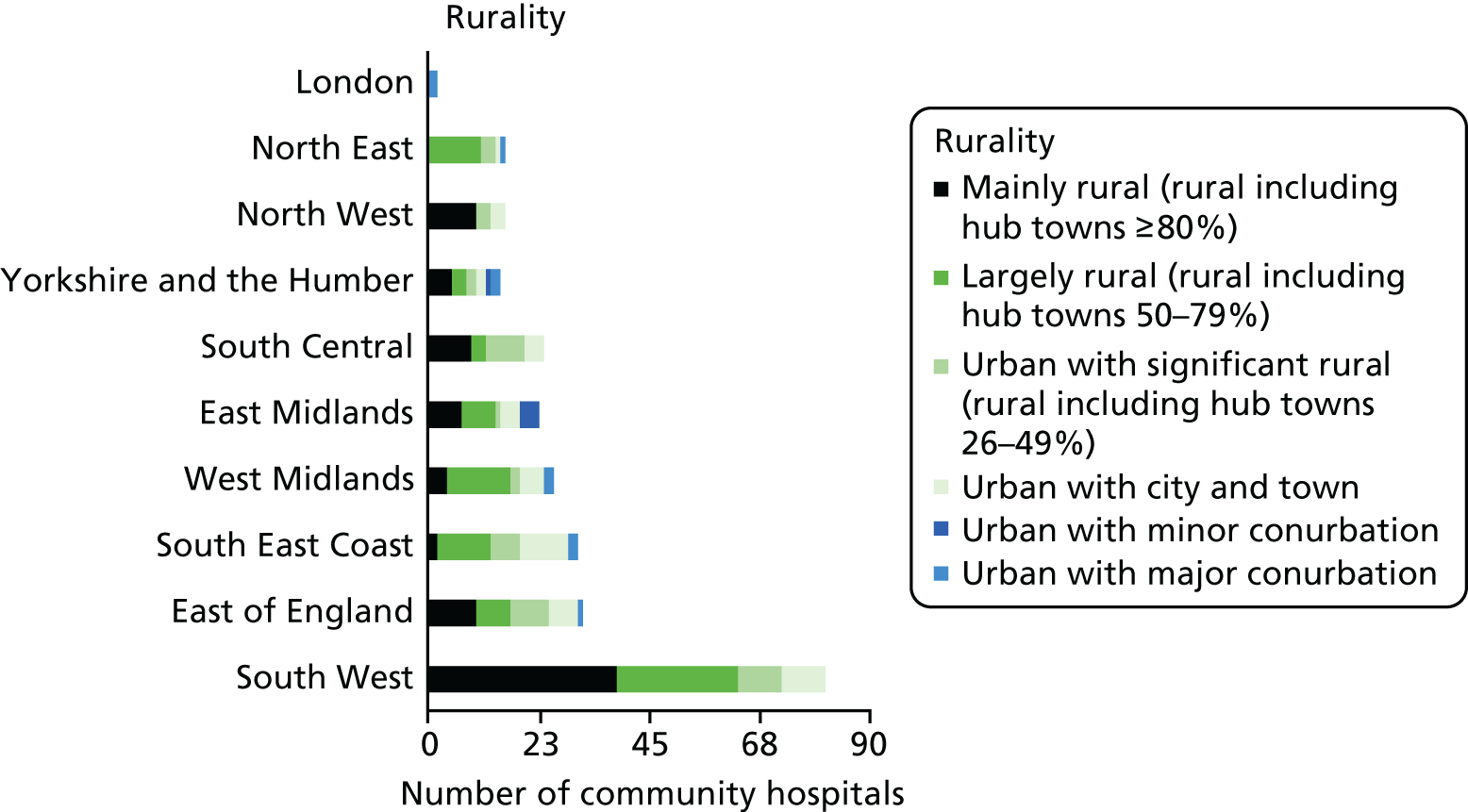

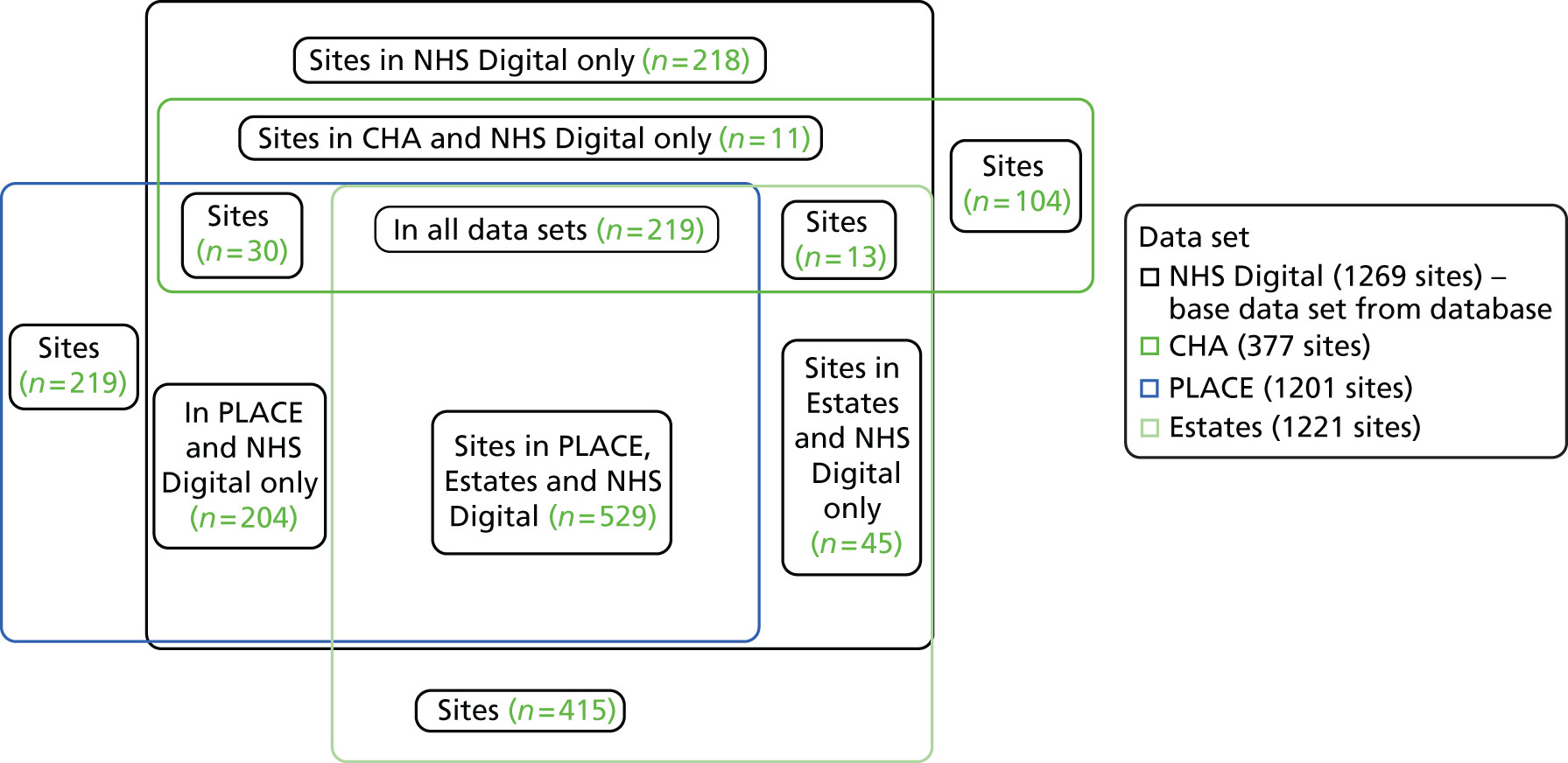

The core data set for England, supplied by NHS Digital, was a list of all hospitals in England, based on ‘site of treatment code.’ Figure 2 shows the relationship between national data sets.

FIGURE 2.

The relationship between four England data sets. CHA, Community Hospitals Associations.

The new database, populated through our reconciliation of these various data sets, provided a census of community hospitals at 2012/13, which was updated to August 2015 (e.g. when a hospital closed and then redeveloped, formed a new hospital replacing two old community hospitals, closed beds on a temporary basis and changed its name).

Database analysis: developing an initial classification of community hospitals with beds

Although the focus of this report is on England, it is important to mention our work on mapping community hospitals in Scotland, as this was instrumental in developing our approach to classifying data for England. Data sets on community hospitals in Scotland [Information Services Division (ISD) and government community hospital data sets: community hospital, general hospital, long-stay/psychiatric hospital, small long-stay hospital] were both more accessible and more comprehensive, lending themselves to early analysis (see Appendix 2).

An initial classification of hospitals in England was developed, informed by categories set out by Estates (community hospital, general acute hospital, long-stay hospital, multiservice hospital, short-term non-acute hospital, specialist hospital, support facility, treatment centre) and PLACE (acute/specialist, community, mental health only, mixed acute and mental health/mental health, treatment centre). It was combined with specialty classifications based mainly on NHS Digital inpatient activity data and developed further through analysis of Community Hospitals Association (CHA) data and discussions within the study team (Table 2).

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| Based mainly on inpatient specialtya | Based on the percentage of the hospital’s total occupied bed-days |

| Acute hospital | < 8% general practice with spread of consultant specialties |

| Small general hospital | 0% general practice with spread of consultant specialties, but < 100 beds |

| General medicine | > 75% general medicine with limited other specialties |

| GP | 80% + general practice specialty |

| GP with other specialties | > 1.9% and < 80% general practice specialty with psychiatry, rehabilitation, general medicine |

| Geriatric medicine | 0% general practice specialty with ≥ 85% geriatric medicine |

| Geriatric mixed specialties | 0% general practice specialty with geriatric medicine, general medicine and psychiatry representing the bulk of occupied beds |

| Geriatric psychiatric | 0% general practice specialty (> 80% geriatric psychiatry) |

| Rehabilitation hospital | Rehabilitation and nursing episode represent ≥ 90% of inpatient specialty (rehabilitation is a specialty label that is applied to two different types of hospital. At a general level it describes hospitals that provide rehabilitation for patients discharged from hospital to enable them to become fit to go home. At a specialist level, it describes facilities treating neurological or musculoskeletal impairment) |

| Learning disabilities | ≥ 90% learning disabilities and mental health (ex-Older Adults Mental Health) specialty |

| Mental health | 0% general practice with geriatric, adolescent, general mental health, learning difficulties, rehabilitation and community medicine representing the bulk of occupied bed-days |

| Hospice | Palliative medicine |

| Specialist | Maternity, children and cancer |

| Surgical | Independent hospital specialising in surgery (mainly trauma and orthopaedic) |

| No beds | No occupied bed-days recorded by NHS Digital, even though fieldwork suggested that beds did exist |

Rapid telephone enquiry: refining the classification

Analysis of the Scotland data suggested that the code ‘GP specialty’ was a defining feature of community hospitals, but early analysis of the England data showed that this was less transferable. If we relied on GP specialty coding alone, many known community hospitals would be excluded from our database: not all community hospital inpatient beds in England were coded to GPs.

A short piece of empirical data collection was undertaken to understand the link between the specialty codes and practice and to test the working definition (based on the literature and on the Scottish data) that community hospitals were predominantly GP led. A telephone questionnaire was designed by the study team (see Appendix 3) and piloted through the CHA.

Seven hospitals from five specialty category codes (≥ 80% GP, < 80% GP and mixed specialties, general medicine, geriatric medicine, geriatric mixed specialties) were randomly selected. The test sample of 35 was reduced by four as a result of closure or conversion to nursing homes. The research team called the hospitals to gain contact details of the matron or ward manager (n = 20; the small sample size highlighting the difficulty of identifying leadership, especially when the community hospital is represented by a single ward), e-mailed the questionnaire, conducted telephone interviews with staff to complete the questionnaire (taking 10–20 minutes each), transcribed notes and returned the completed questionnaire to respondents (n = 12). Analysis of these telephone interviews gave us confidence in the specialty coding, while also confirming the need to be more expansive in our working definitions and categorisations.

Verification: checking and refining the database through internet searches

The mapping enquiry was finalised through five iterations of searching and checking. The CHA consulted its database and membership list (from both 2008 and 2013). A full internet search took place at two points, in February 2015 and August 2015, taking account of hospital closures and changes of function up to 2014/15, with further validation and amendments up to August 2015. By the end of the study, the 2012/13 data set, based on the NHS Digital Spine using ‘site of treatment code’, had been validated through a check of every potential community hospital. A total of 366 sites were examined through web-based and telephone enquiries, including 60 that were not present on the NHS Digital database (see Appendix 4 for the list of community hospitals with beds).

Phase 2: case studies

In order to explore patient and carer experience of community hospitals and aspects of community engagement and value, we undertook qualitative case studies. Although the initial aim of the case studies was to address the second and third research questions, the findings also enabled new insights into the first study question of ‘what is a community hospital’.

The decision to adopt a comparative case study design73 across multiple community hospital sites was influenced by three factors. First, given the gaps in the literature highlighted in Chapter 1, it would be useful to uncover different aspects of the patient experience, community engagement and value of community hospitals and enable the identification and analysis of common themes (looking for similarities, differences and patterns) both within and across cases. 74–76 Second, it provides a suitable way of ‘exemplifying’ sites,77 given the variety of ownership models and locations. Third, it is useful in enabling an examination of ‘complex social phenomena’,78 and, in particular, the social, functional, interpersonal and psychological factors that shape patient experiences, as well as those that influence community engagement and value. Below, we summarise the approach to case study selection for work packages 2 and 3, before moving on to discuss the research elements used.

Selection of case study sites

In selecting case study sites, we adopted a ‘realist’ approach to sampling,79 moving back and forth between categories identified from the literature as being important for patient experience and community value and our learning about the characteristics of community hospitals identified from the mapping exercise. In order to reflect the diversity of community hospitals (highlighted in the literature and mapping), we selected cases in contrasting locations with different numbers of beds, ranges of services, ownership/provision and levels of voluntary income and deprivation.

To allow for a particular focus on variations in voluntary support for community hospitals, hinted at through the national mapping exercise and identified as a particular gap in the existing literature, we selected pairs of hospitals across four Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) areas with contrasting levels of voluntary income but similar levels of deprivation. This would allow for a good comparison within and between cases (e.g. why two community hospitals within one CCG area, with similar levels of deprivation, have contrasting levels of voluntary support, given that previous research has tended to suggest a strong negative correlation between deprivation and voluntary activity).

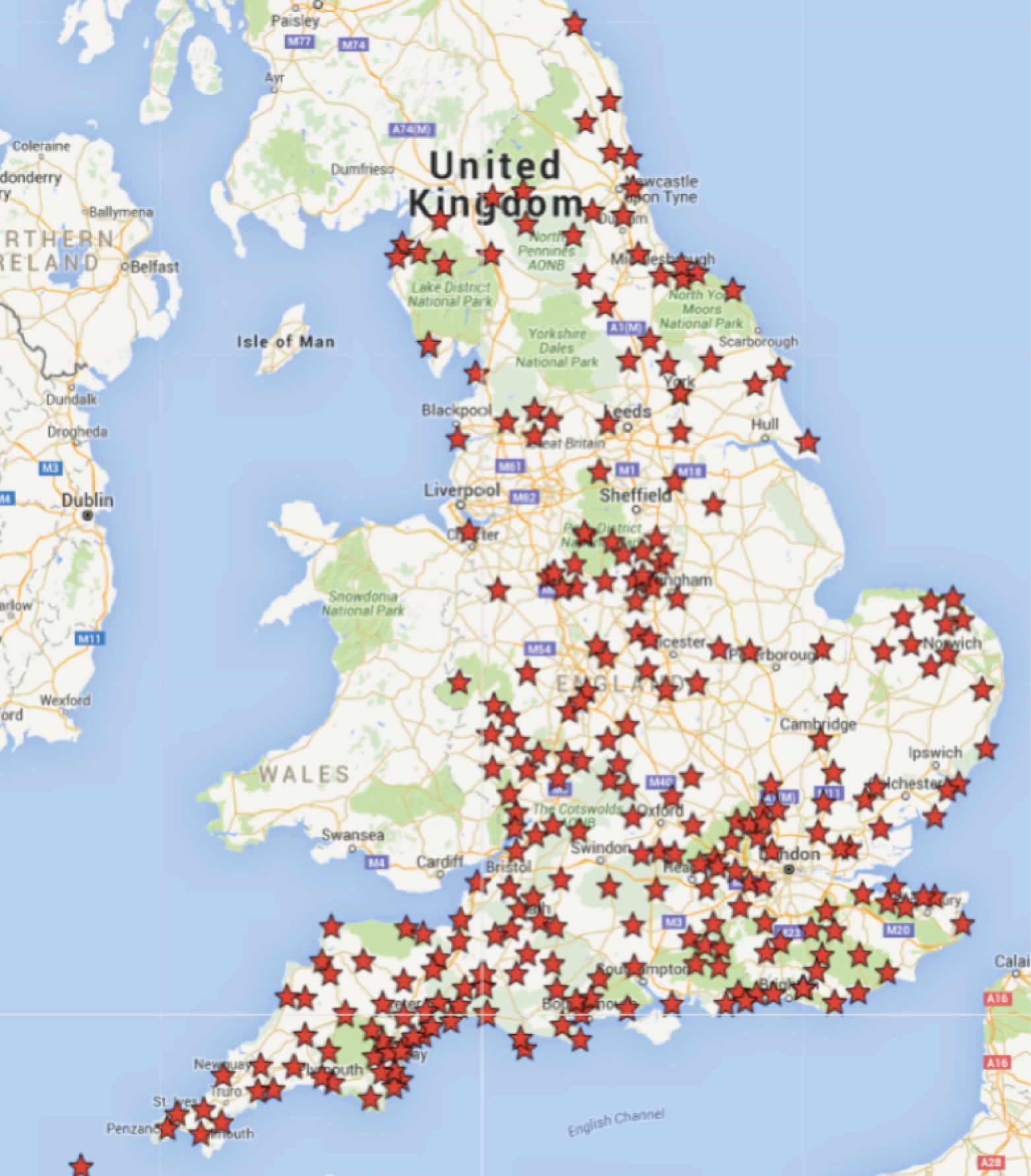

Using these criteria, we selected eight case studies of hospitals of different sizes, ages and service profiles located across England (although mostly concentrated in the south, reflecting the national pattern of community hospital development; see Figure 7) in areas of contrasting levels of deprivation. Six of the buildings were owned by, and their main inpatient service was provided by, the NHS. Two were owned by the NHS but their main inpatient services were provided by a community interest company (CIC). We added a ninth case study, owned by a charity, to increase diversity in terms of ownership/provision (as there were very few examples of independently owned community hospitals, it was not possible to identify a matched pair). Table 3 provides a summary of the nine case studies selected, according to the data that were available from the mapping exercise. Fuller qualitative descriptions are provided in Chapter 4 and Appendix 5.

| Geography | Reference | Owner (main provider) | Urban rural codea | Available beds, n | Time period (% m2) | MSOA IMDb | Average voluntary income in past 5 years (£) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre 1948 | 1948–64 | 1965–84 | 1985–2004 | 2005–13 | |||||||

| South | CH1 | NHS (NHS) | 2 | 19 | – | 9 | 4 | 76 | 11 | 27.48 | 19,680.53 |

| CH2 | NHS (NHS) | 1 | 37 | – | – | – | – | 100 | 28.7 | 86,699.93 | |

| CH3 | NHS (CIC) | 3 | 33 | – | – | – | – | – | 4.68 | 97,641.65 | |

| CH4 | NHS (CIC) | 3 | 31 | – | – | – | – | – | 3.01 | 21,571.90 | |

| CH5 | NHS (NHS) | 2 | 19 | 100 | – | – | – | – | 14.78 | 55,398.18 | |

| CH6 | NHS (NHS) | 3 | 22 | 32 | – | 32 | 36 | – | 12.84 | 102,957.30 | |

| CH7 | Charity (NHS) | 2 | 13 | – | – | – | 100 | – | 33.04 | 423,521.20 | |

| North | CH8 | NHS (NHS) | 1 | 9 | – | – | 59 | 42 | – | 21.21 | 1370.79 |

| CH9 | NHS (NHS) | 1 | 28 | – | – | 90 | 10 | – | 19.04 | 23,817.45 | |

Case study data collection

The case studies involved seven research elements, as summarised in Table 4. All elements were conducted over five visits to each case study. Across all case study sites and research methods, 241 people participated in the study through interviews and 130 people participated through 22 focus groups; a small number of people who participated in individual interviews also participated in focus groups (see Appendix 6 for full details).

| Method | Focus (respondent) | Focus (theme) | Numbers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scoping |

|

|

|

| LRG |

|

|

|

| Semistructured interviews |

|

|

|

| Discovery interviews |

|

|

|

| Semistructured interviews |

|

|

|

| Focus groups |

|

|

|

| Telephone interviews |

|

|

|

Scoping

Scoping visits were made to each of the case studies in order to build relationships with key stakeholders (primarily matrons and chairpersons of Leagues of Friends), gather background information on the hospitals and local communities, identify potential study participants and collect key documents and data. Documents selected included hospital histories, annual reports, local service information (when available) and media coverage. Reviewing these helped to provide a basic understanding of the cases prior to the main fieldwork visits and added to our profiling of each of the case study hospitals.

We also aimed to gather hospital-level data from patient-reported experience measures (PREMs)80 and the revised Friends and Family Test (FFT). 81 However, none of the case study community hospitals collected PREMs data, as this had only recently been required of community providers. Although all sites collected FFT scores, we were able to access data for only seven of the nine case studies because, in the remaining two cases, the trust compiled data at trust rather than hospital level and it was not possible to disaggregate the data. Furthermore, the FFT data were not strictly comparable as some scores covered inpatient care only, whereas others covered both inpatient and outpatient care.

Local reference group

We established a local reference group (LRG) in each of our case studies to bring local people together to steer, support and inform the research at the local level. These LRGs comprised key members of hospital staff, the League of Friends, volunteers and local voluntary and community groups, some of whom had also been patients and/or carers. Their role was to help build a picture of the local context to inform subsequent data collection elements, build support for the study within the local community and reflect on emerging findings and their implications for local practice. There were two LRG meetings per case study during the local fieldwork stage: one at the start of the fieldwork period (which focused on mapping the community hospital services and community links) and one at the end (which focused on discussing the emerging findings and their potential implications). The first LRG meeting for CH3 and CH4 was joint (for convenience) but the second meeting was separate. Following completion of the fieldwork and analysis, each LRG received a report of the findings relating to their specific case study (i.e. alongside this national report, we produced nine local reports).

Semistructured interviews with staff, volunteers and community representatives

We conducted semistructured interviews with staff (n = 89 staff across the nine cases), community stakeholders (n = 20) and volunteers (n = 35). Although most of the interviews were with single respondents, some were with two or, very occasionally, three people (depending on respondent preferences). Respondents were selected through purposive sampling79 guided by the scoping visits, the initial LRG and snowballing. Each of the interviews explored the profile of the hospital and the local context, perceptions of patient and carer experience, and community engagement and value. The emphasis placed on the different sets of questions, however, varied between the groups of respondents (e.g. more time was spent on community engagement and value within the community stakeholder interviews, although we still asked questions relating to hospital profile and perceptions of patient/carer experience). Interviews were nearly all conducted face to face, although a small number were conducted via telephone, at respondent preference. Interviews with staff, volunteers and stakeholders lasted, on average, 60 minutes. All were digitally recorded and later transcribed verbatim.

Discovery interviews with patients

Rather than focusing on satisfaction levels, or other quantifiable measures of experience, the study was concerned with exploring the lived experience of being a patient using community hospital services. Lessons from previous studies show that gathering experiences in the form of stories enhances their power and richness,36 so we selected an experience-centred interview method82 that drew on the principles of narrative approaches83 and, particularly, discovery interviewing. 84 Narrative approaches invite respondents to tell their stories uninterrupted, rather than respond to predetermined questions, giving control to the ‘storyteller’. This approach can elicit richer and more complete accounts than other methods85,86 because reflection enables respondents to contextualise, and connect to, different aspects of their experiences. Discovery interviewing helps to capture patients’ experiences of health care when there may be pathways or clinical interventions central to patient experience. 87 As such, after a general opening question, our interviews focused around a very open question inviting respondents to tell their story of being a patient at the community hospital. We followed this by asking respondents to consider a visual representation we had developed of factors found in previous research to have shaped patient experience, to prompt people’s memories and thoughts (see Appendix 7 for an example of the discovery interview).

Our aim was to interview six patients from each case study. Our final sample across all sites was 60 patients. The small sample size reflected the in-depth nature of the interviews. We sought, as far as possible, to select patients with a mix of demographics (particularly in terms of gender), care pathways (particularly in terms of step up/step down) and services used (inpatient/outpatient). Potential participants were identified by the hospital matron and/or lead clinician and/or service leads. Each was written to by the hospital with a request to participate in the study and was sent an information sheet and an opt-in consent form. Patients who were willing to participate sent their replies directly to the study team. Written consent was provided prior to the commencement of the interview. In line with the Mental Capacity Act 2005 Code of Practice,88 we made provision for the appointment of consultees when potential respondents lacked the capacity to consent to participation in the study, although this was not utilised.

Although many of our respondents were current inpatients, we also spoke to some inpatients who had been recently discharged and to outpatients from a range of different clinics. Outpatients who agreed to participate tended to be those using services several times a week (e.g. renal patients) or over a longer period of time (e.g. those with chronic conditions), rather than one-off users. Interviews with patients lasted between 30 and 90 minutes, were digitally recorded (in all cases except for two because of respondent preference/requirements) and transcribed verbatim. At the end of the interviews, we asked respondents to complete a short pro forma to gather basic demographic and service information for analysis purposes.

Semistructured interviews with carers

Semistructured interviews were conducted with carers in order to explore their experience of using the community hospital as a carer of an inpatient. Our aim was to interview three carers per case study; in total we spoke to 28 carers across the nine sites. Carers were either related to, or close friends of, patients (either current or recent) at the hospital. In most cases, we interviewed carers of patients who had also been interviewed, but in some cases carers were not directly linked to patients involved in the study (indeed, some carers were reflecting on the experience of caring for a patient who had recently died).

The main focus of the interviews was on the experience of being a carer of someone at the hospital, with our initial question reflecting the narrative approach adopted for patients by asking respondents to tell us their story of using the hospital. In addition, as the respondents were typically local residents, we also asked questions about their perceptions of patient experience, about local support for, and engagement with, the hospital and of value. Interviews with carers lasted, on average, 60 minutes. All were digitally recorded and later transcribed verbatim.

Focus groups

We conducted focus groups with members of MDTs, volunteers and community stakeholders. Although we had anticipated conducting each of the three focus groups in each of the case study sites, this was not always possible owing to practical reasons; for example, in some of the case study sites there were very few volunteers, making it difficult to organise a focus group. We ran focus groups with MDTs in eight of the nine case studies, involving a total of 43 respondents; with volunteers in six of the case studies, involving a total of 33 respondents; and with community stakeholders in eight of the cases, involving 54 respondents. Individual focus group respondents were selected through purposive sampling. We worked with LRGs and other key contacts to identify potential participants, each of whom was written to and asked to participate.

The focus groups complemented the interviews, enabling the inclusion of a wider range of perspectives in the study and, in particular, allowing us to observe the emergence of discussion, consensus and dissonance among groups of participants. They lasted, on average, 90 minutes and were digitally recorded and transcribed in full.

Telephone interviews with managers and commissioners

We conducted telephone interviews to explore the views of senior managers of provider organisations and commissioners of community hospitals. The nine case studies were based in five CCG areas where the main inpatient services were provided by four NHS trusts and one integrated health and social care CIC. Our aim was to interview one respondent from each of the providers and CCGs. In total, we spoke to five provider and four CCG representatives. The interviews explored the strategic context for the community hospitals involved in the study, alongside the perceptions of these senior stakeholders of patient experience and the value of community hospitals. The interviews lasted, on average, 60 minutes and were digitally recorded and later transcribed in full.

Qualitative case study data analysis

We adopted a thematic approach to qualitative data analysis, aided by the use of NVivo 11 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) for data management and exploration. Our approach was both inductive, with themes emerging from the data, and deductive, framed by our research questions and ongoing reading of the literature. Initial themes and codes were developed after three members of the team (AEP, DD and NLM), who collectively had been responsible for the case study data collection, reviewed the transcripts. The emerging themes, codes and associated findings were discussed at wider study team meetings, at the LRG meetings for individual case studies and at annual learning events that brought together participants from across the case studies. A refined coding frame was then tested by the same three members of the research team each coding a sample of transcripts; this led to a further refinement of the codes, while also helping to ensure that each of the researchers was adopting a similar approach.

In this report, we focus in particular on across-case comparisons, highlighting themes that emerged across the case studies, emphasising key points of similarity and difference between the cases, as relevant. In addition, we have produced individual reports for each of the local case study sites that have shared findings from our within-case analysis, as relevant for each individual hospital. Comparative analysis, including of the paired cases, will be developed further in future research articles, in which a focus on more specific aspects of the study will allow more space for presentation of such work.

Throughout the analysis, unique identifiers were used for the transcripts/respondents to help ensure confidentiality and anonymity. Sites were assigned a number (e.g. CH1) and respondents given a letter: patient (P), family carer (CA), staff (S), volunteer (V), community stakeholder (CY) and senior manager or commissioner (T), with sequential numbering, date of interview and initials of researcher added to provide an audit trail. This basic coding method is used throughout the report (e.g. CH1, S01 represents the first staff member to be interviewed at the first community hospital case study site). It is worth noting, however, that, although respondents were identified by a key characteristic (e.g. patient or staff) and their transcripts labelled as such, the boundaries between these categories were not discrete: many community stakeholders, for example, had also been patients or carers, and many staff were also members of the local community.

Phase 3: quantitative analysis of Charity Commission data

Collating data on charitable finance and volunteering support

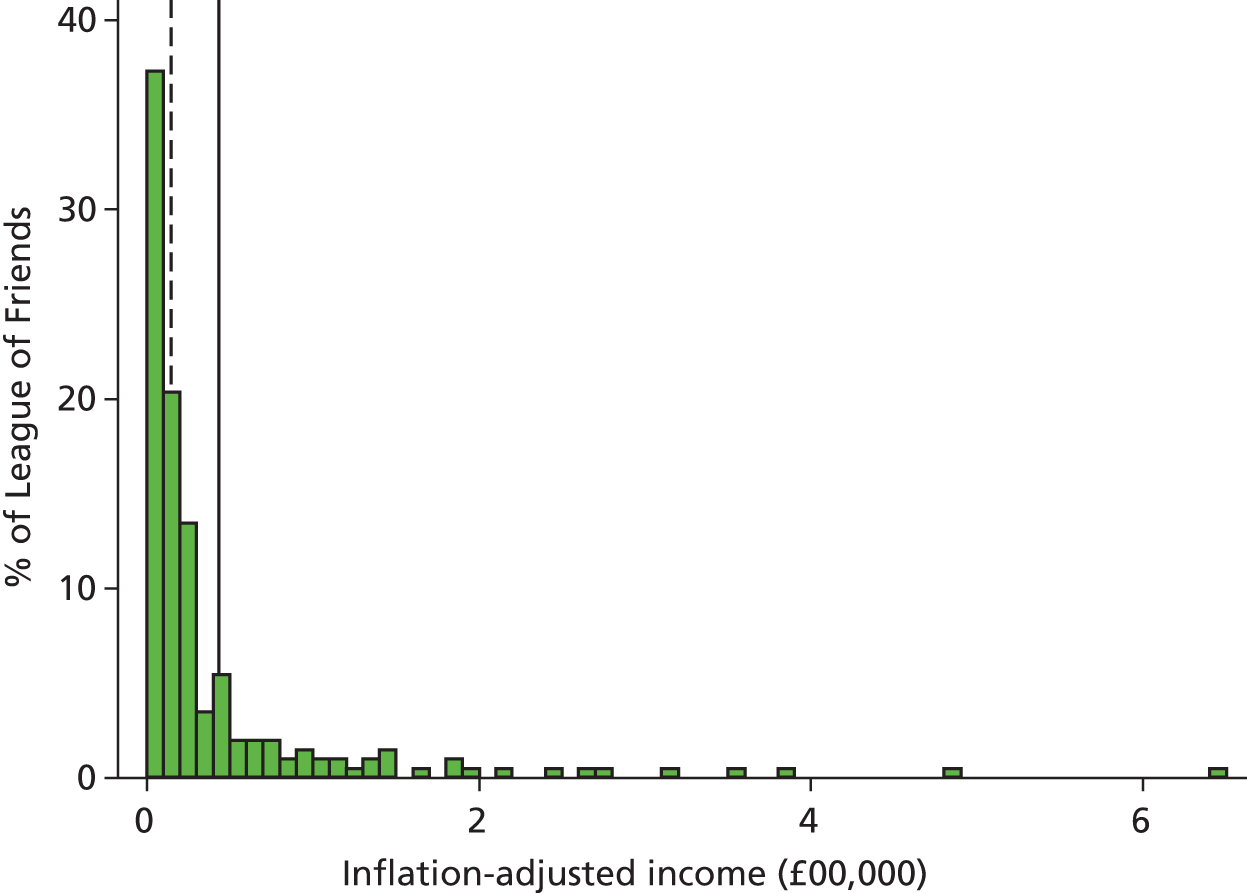

The third phase of our research involved the quantitative analysis of data from the Charity Commission on voluntary income and volunteering for community hospitals across England. The aim of this activity was to examine charitable financial and volunteering support for community hospitals by investigating:

-

variations in the likelihood that hospitals receive support through a formal organisational structure such as a League of Friends, and if so, variations in its scale (in financial terms) between communities

-

uses of the funds raised (e.g. capital development, equipment, patient amenities).

We captured financial and volunteering data for registered charities from the Charity Commission (the Commission). The Commission holds details of organisations that have been recognised as charitable in law and that hold most of their assets in England, or have all or the majority of their trustees normally resident in England, or are companies incorporated in England. The data are described more fully in Appendix 9.

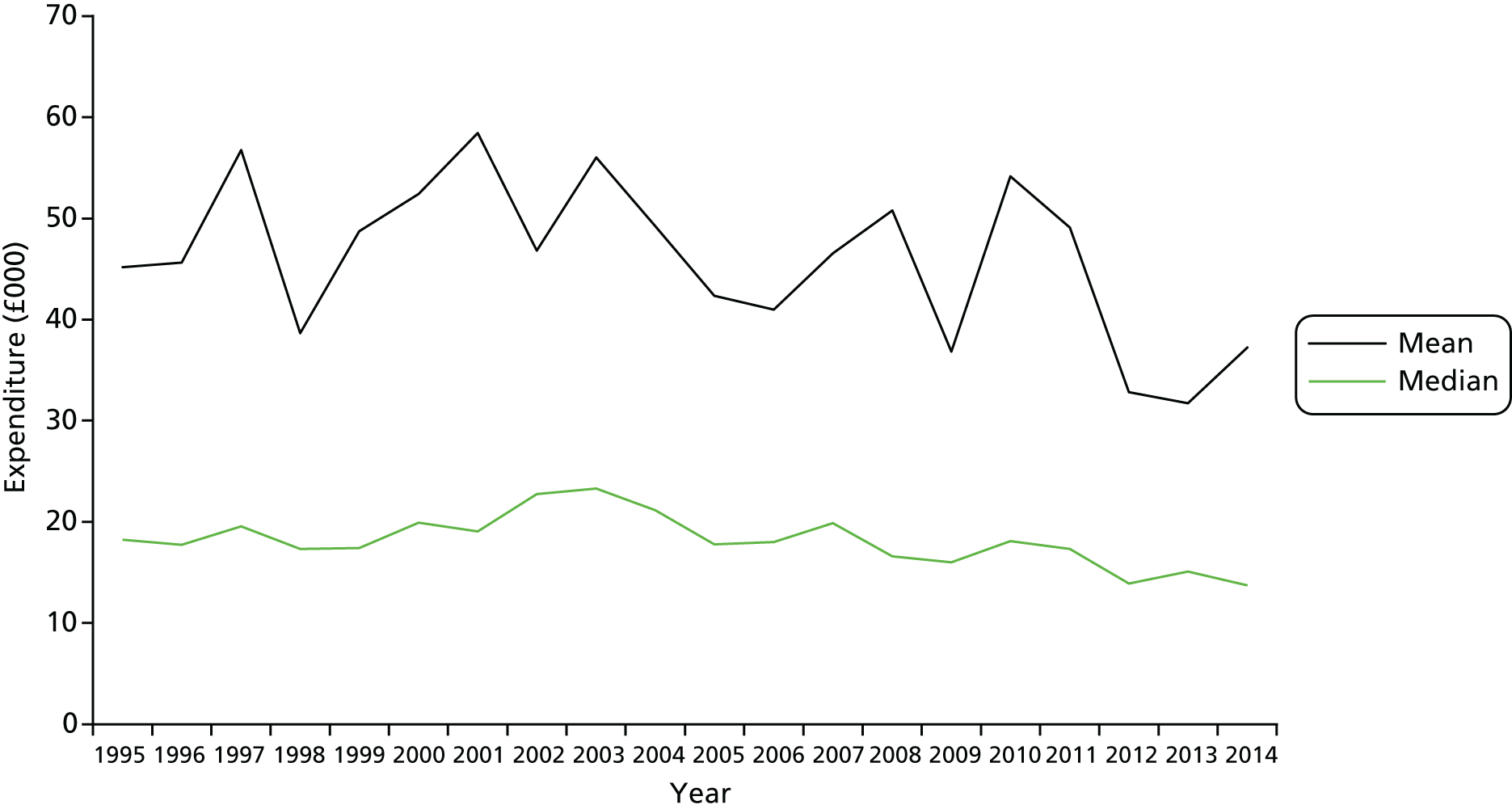

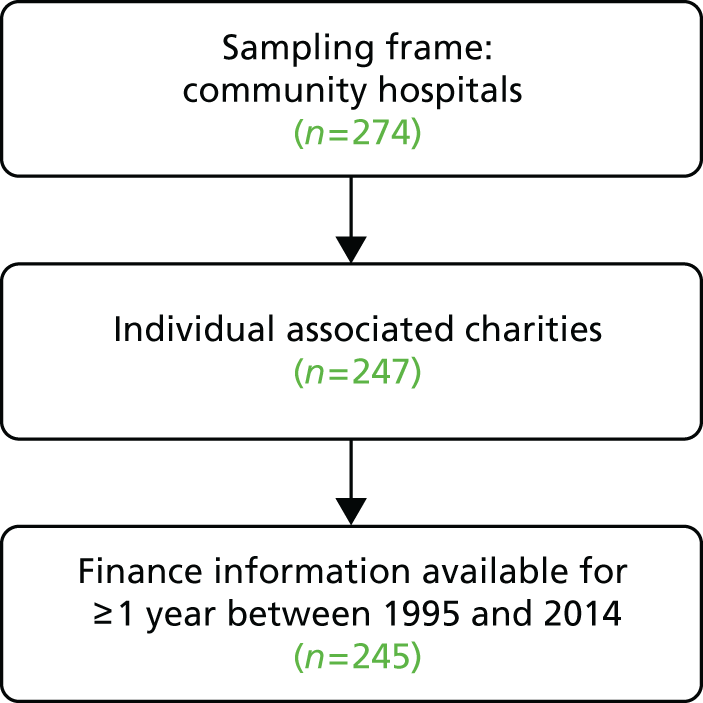

Subject to a small number of exceptions, all charities in England with incomes of > £5000 must register with the Commission and submit financial statements consisting of trustees’ annual reports (returns) and annual accounts. The accounts of those charities whose income or expenditure exceeds a threshold of £25,000 are made available on the Commission’s website. 89 Charities that have income and expenditure of < £5000 a year have (since 2009) been exempted from the need to register. We identified 274 hospitals in England that satisfied the inclusion criteria for this research project (Figure 3). We used the Charity Commission’s data to identify charities that support each of these hospitals, matching by name or through examining lists of charities registered in the locality where the hospital is based.

FIGURE 3.

Community hospital and charities sampling frame.

We also directly approached eight non-registered charities (usually those with an income of < £5000 a year) that were known to have been established to support specific community hospitals, but received no usable data relating to them. Four hospitals in our data set were registered as charities themselves but were excluded from the analysis because they are exceptional cases of charitable action.

We found that 247 of these charities were registered in their own right (labelled ‘individual associated charities’ in Figure 3). The remainder were what is known as ‘linked’ charities, that is, entities associated with larger charitable organisations serving a NHS trust comprising several institutions. These ‘linked’ charities were excluded because it was not possible to disaggregate the support they provide to individual components of the trust. Financial information was available for the period from 1995 to 2014 (only small numbers of observations were available for years prior to that because digitisation of the register began only in the early 1990s).

Measurements

Financial information for at least 1 year between 1995 and 2014 was available for 245 charities in England, and this information formed the final sample for this part of the study. The number of non-zero financial reports to the Commission in each year ranged from 181 (1996) to 226 (2007). The data, covering the period to 2014, were the latest available at the time of analysis (2016). See Appendix 9 for full details of available charity reports by year. All financial information in this paper is presented at constant 2014 prices.

Using the Charity Commission website, we obtained copies of these accounts for those selected charities whose expenditure or income exceeded £25,000 in any one year. This gave data covering 358 separate financial years; the number of accounts available is shown in Table 5.

| Year | Number of accounts |

|---|---|

| 2008 | 91 |

| 2009 | 55 |

| 2010 | 49 |

| 2011 | 52 |

| 2012 | 41 |

| 2013 | 70 |

We focused on the period from 2008 to 2013, when between 41 and 91 charities of interest generated at least one such financial return. Numbers vary because an individual charity may or may not exceed the £25,000 threshold at which its accounts are presented via the Charity Commission’s website, depending on fluctuations in its finances.

Charity accounts aggregate income and expenditure figures into a small number of general categories. These provide relatively little detail on income and expenditure and may even aggregate quite different sources of expenditure within the same funding stream. As such, to probe income sources and the application of expenditure in more detail, data were captured from the notes to the accounts of these charities. The extensive income data that were generated (21,733 items) were categorised to provide useful insights into sources of income. Classifying the expenditure of charities was not undertaken because of the complexity of the data and the limits to the usefulness of such an exercise. Appendix 9 provides further details of the extraction, classification and analysis of income and expenditure data.

Contribution: number of volunteers and estimates of input

The Charity Commission guidelines90 require charities to record their best estimates of the number of individual UK volunteers involved in the charity during the financial year, excluding trustees (see Appendix 9).

Before 2013, data on volunteer numbers were often sparse, but, since that date, efforts have been made to gather more detailed information. Approximately 73,000 charities had supplied between one and three non-zero returns of their volunteer counts in the three years between 2013 and 2015, including > 90% of our charities. We calculated the average number of volunteers for the period in question. To provide an upper-bound estimate, we also take the maximum value returned for each charity.

Volunteer hours were estimated using regular survey data (Home Office Citizenship Survey, 2001–10; Community Life survey, 2012 onwards). We take the average number of hours per week reported by those who say they have given unpaid help to organisations during the previous year. This is approximately 2.2 hours. This is a minimum estimate and it may be that the actual numbers are larger than these survey data would imply. If we make the assumption that these are probably fairly regular volunteers, a higher figure of 3.05 hours per week is given if we take the average number of hours reported by those who say they volunteer either at least once a week or more frequently, or at least monthly but less frequently than once a week.

There are no studies that would tell us with any certainty whether or not volunteers in these kinds of organisations put in more or fewer hours than the volunteering population generally. We then multiply these two estimates of time inputs by the average and maximum volunteer numbers, respectively, to give the number of hours contributed by volunteers over the course of the year (assuming 46 weeks of volunteering a year). These can be converted to full-time equivalent numbers by dividing by 37.5 (hours per working week) and 46 (weeks per working year).

Opinions differ on the best method for calculating a cash equivalent for the value of volunteer labour. The lowest is to use the national minimum wage; others might include an estimate of the replacement cost (i.e. what it would cost the organisation to employ people to do the same tasks if they had to pay them), but this assumes knowledge of the tasks being undertaken. The national minimum wage for the period for which we have the most comprehensive volunteering data (2013–15) was £6.50 per hour. 91

Data convergence and integration

Although the quantitative (phases 1 and 3) and qualitative (phase 2) data were collected separately, they could nevertheless be considered ‘integrated’ because the different research elements were explicitly related to each other within a single study and in such a way ‘as to be mutually illuminating, thereby producing findings that are greater than the sum of the parts’. 92 Data triangulation, convergence and integration occurred in a number of different ways, at different stages of the research.

In phase 1 of the research, a revised definition and set of characteristics captured within the database was used to support development of a typology and informed the case study sampling for phase 2. For phase 3, the database informed the sample of charities selected for analysing voluntary income and volunteering data and providing additional data fields to be linked to the Charity Commission data.

Although the national quantitative data provided breadth to the study, these were limited and left questions unanswered. The local qualitative data brought depth to the question ‘what is a community hospital’, by helping to build a picture of the history, context and change over time. Qualitative interviews in work packages 2 and 3 were conducted concurrently, and triangulation of data between stakeholder, volunteer, staff, carer and patient interviews helped validate findings and strengthen our understanding of patient and carer experiences and community engagement and value.

In addition, the combination of researchers working on more than one work package, reflexive team meetings and the involvement of different representations in the team [CHA, University of Birmingham and Crystal Blue Consulting (London, UK)] allowed for healthy dialogue, debate and analysis. Emerging findings from each phase of the research were, for example, shared through internal working papers and discussed regularly at whole project team meetings.

Patient and public involvement

Our commitment to PPI ensured that patients, carers and the public were involved in this study before and during its conduct. PPI involvement in the study design was facilitated by one of the researchers (HT), who first consulted with 10 PPI members of the Swanage Health Forum, representing the League of Friends; a GP practice Patient Participation Group; Swanage Carers; Partnership for Older People’s Programme; Wayfinders; the Senior Forum; the Health and Wellbeing Board; Cancare; a public Governor for Dorset Healthcare NHS Trust; and a retired GP. This group provided an endorsement of the study’s proposed focus and methodology.

At the national level, 13 board members of CHA (four GPs, six nurses, two managers and one League of Friends member) co-produced the initial research proposal. Two members then became part of the study steering group, which met regularly throughout the study, supported the development of research materials and supporting documentation, helped facilitate access to potential case studies, contributed to the local and national reports and reviewed several drafts. We also engaged with approximately 100 delegates at three CHA annual conferences (presentations and workshops focused on working with findings) that included not only practitioners but members of community hospital Leagues of Friends.

In addition, a cross-study steering group, chaired by Professor Sir Lewis Ritchie, University of Aberdeen, provided guidance across all three Health Services and Delivery Research community hospital studies, with representation from the CHA, Attend (National League of Friends) and the Patients Association, alongside the three study teams. The steering group met seven times over the period of this study, offering opportunities to share findings and explore experiences between the studies.

As described in Local reference group, at the local level we established LRGs within each of our case study sites to bring local people together (hospital staff, volunteers and community members, a number of whom were patients and/or carers) to steer, support and inform the case study research. To facilitate cross-case learning, we brought together representatives from each of the LRGs three times to share experiences, identify best practice and network. Event themes reflected each of the three research questions, and the days offered time for case study representatives to work together, share across sites, hear from national experts, contribute to the ongoing development of the study and reflect on emerging findings and their implications.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was provided by the University of Birmingham, in line with the Department of Health and Social Care’s Research Governance Framework, for work package 1 (national mapping) and elements of work package 3 (quantitative charitable finance and volunteering support data). The university also provided sponsorship for the whole study. The qualitative case studies required full ethics review through the National Research Ethics Service as they involved interviews with patients and carers and interviews and focus groups with NHS staff, volunteers and community stakeholders. The Wales Research Ethics Committee 6 reviewed this research and provided a favourable ethics opinion (study reference number: 16/WA/0021).

Summary

Informed by key stakeholder engagement and a review of the policy context and existing literature, this study explored the profile, characteristics, patient and carer experience, community engagement and value of community hospitals in England through a multimethod approach. The research was conducted in three overlapping phases – mapping, case studies and Charity Commission data analysis – that, together, involved a range of qualitative and quantitative methods. Data for each phase were collected and analysed separately but iteratively, with emerging findings discussed regularly through a range of mechanisms, including whole project team meetings and internal working papers. We involved key national and local stakeholders throughout the study, from design, through to data collection and analysis, and reporting and dissemination.

Having framed the study (see Chapter 1) and described our research methodology (see Chapter 2), we now move on to share the findings. Chapters 3–7 describe the findings emerging from different elements of the study, and Chapter 8 brings those findings together and discusses them in relation to the wider literature and their significance for knowledge and practice.

Chapter 3 Defining and mapping community hospitals: the national picture

This chapter addresses our first research question, ‘what is a community hospital?’, by reporting the findings of the national mapping work that identified, located and profiled the characteristics of community hospitals (see Chapter 2, Phase 1: mapping and profiling community hospitals). This chapter also shows how the working definition of community hospitals has been modified in response to findings and draws a typology from distinguishing characteristics.

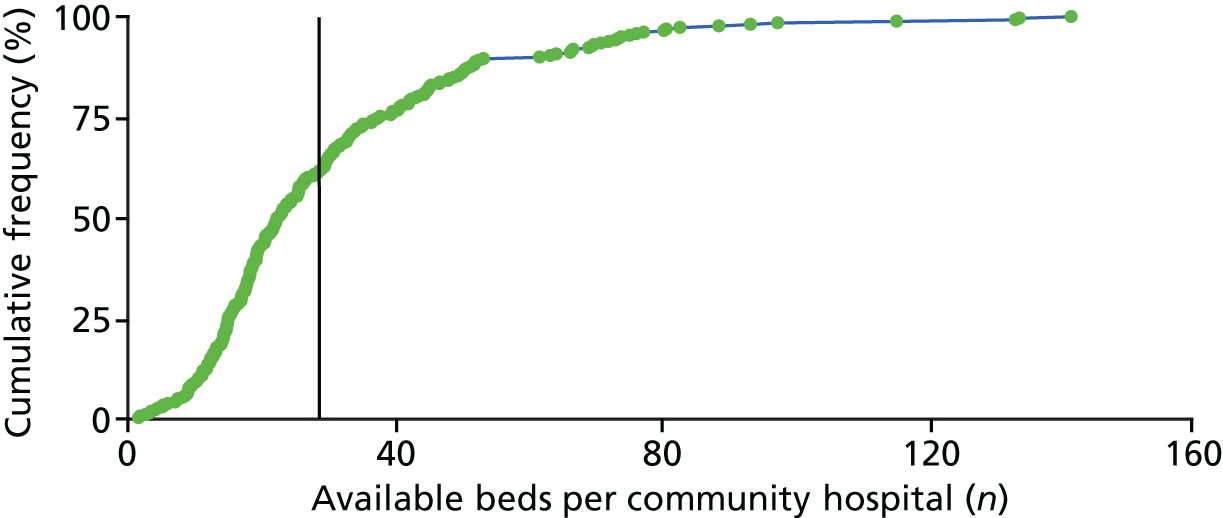

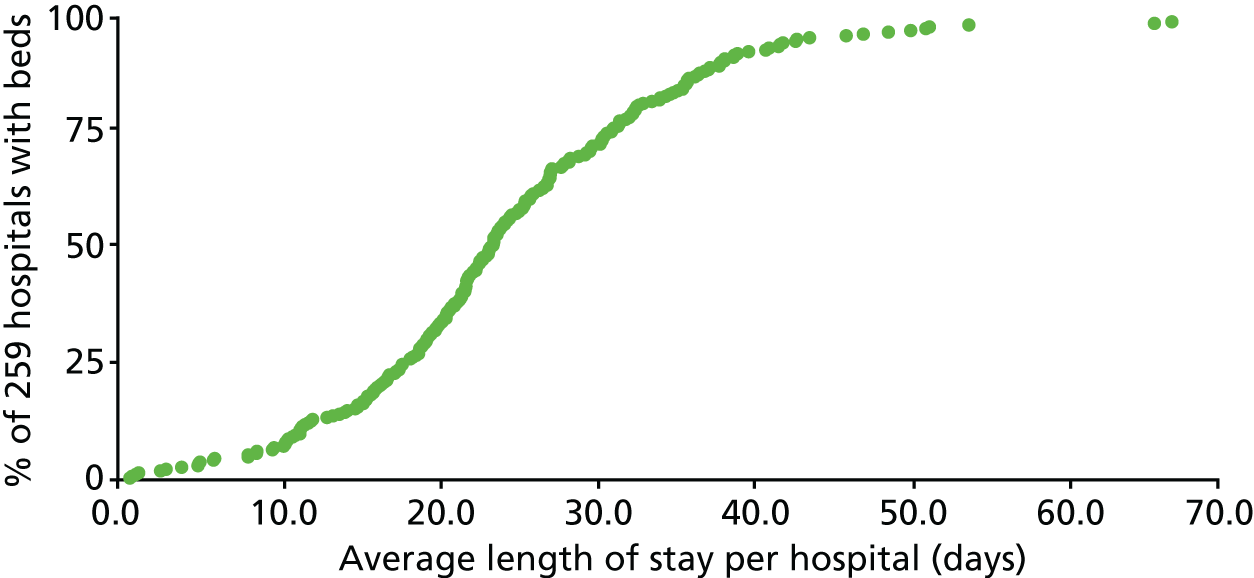

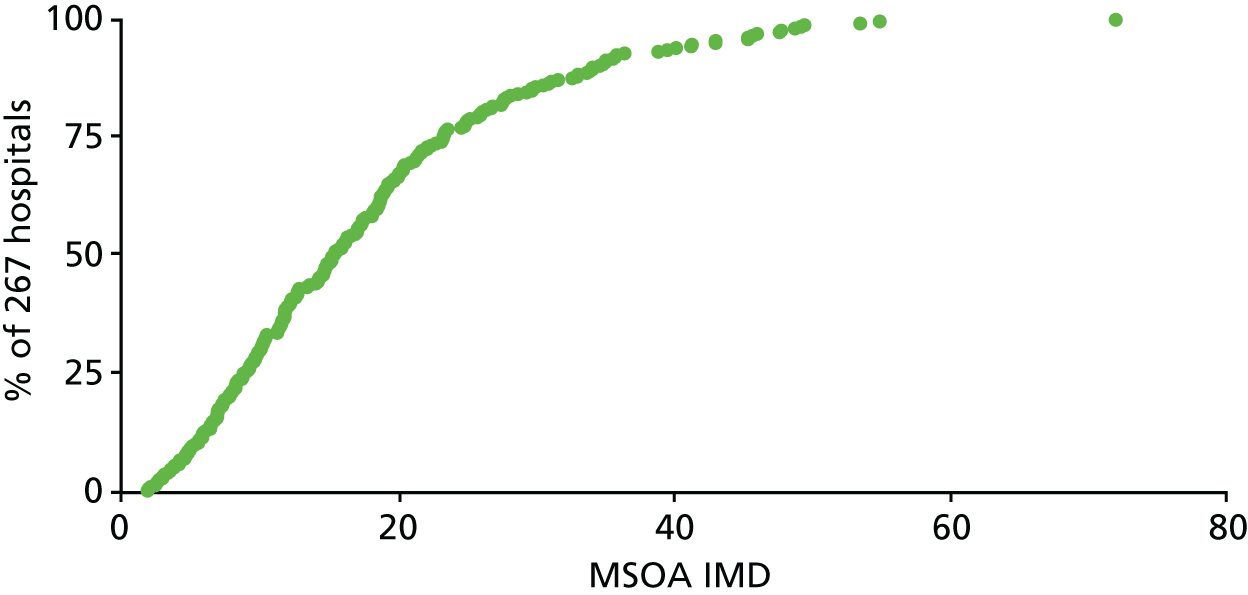

Set of community hospitals