Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 13/114/60. The contractual start date was in June 2015. The final report began editorial review in July 2017 and was accepted for publication in October 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Jane Noyes reports partial reimbursement of travel and subsistence expenses to attend meetings to develop Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative Research (CERQual) from the World Health Organization, Alliance for Health Systems and Policy, Norad and Cochrane during the conduct of the study; reports partial reimbursement for travel expenses for co-chairing the Cochrane Methods Executive and membership of the Scientific Committee from Cochrane outside the submitted work; has two patents licensed for CERQual and the iCAT_SR tool, both of which were released under the Creative Commons License; and is a member of the National Institute for Health Research Dissemination Centre Advisory Group.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Cunningham et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

The design and delivery of health and social care services requires robust research evidence to aid decision-making. Drawing together a body of research through synthesis is an effective and efficient approach to evidence provision. At the time this project commenced in 2015, the Department of Health’s1 policy recognised that evidence-based decision-making required both qualitative and quantitative research. Synthesis through systematic reviews of quantitative research is well established as a means by which to contribute to evidence-based health care;2 such syntheses can indicate clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of interventions and treatments and provide information on disease epidemiology. In contrast, syntheses of qualitative research studies (we refer to these as ‘qualitative evidence syntheses’) can show patients’ experiences of, for instance, health-care services and treatments, interventions and illnesses3–5 and, thus, also have potential to inform health-care decisions. 3,6

Syntheses of qualitative research are an accepted, but relatively new, addition to the health-care evidence base. The Cochrane organisation, which aims to gather and summarise the best evidence from health-care research, established the Cochrane Qualitative Research Methods Group in 2004 to advise and produce guidance on the incorporation of qualitative evidence in Cochrane systematic reviews. 7,8 In addition, qualitative evidence syntheses have been used recently to inform, for example, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)9–11 and the World Health Organization clinical guidelines. 12

Numerous approaches for synthesising qualitative research studies exist, which are suited to different purposes and kinds of study data. 13–16 Meta-ethnography is the most widely used qualitative evidence synthesis approach in health and social care research17 and has been highly influential in the development of other synthesis approaches. 6,18,19 Meta-ethnography is suited to developing theory and can lead to new conceptual understandings of complex health-care issues, even in heavily researched fields. 6,14,15,20 As such, meta-ethnography has the potential to influence health care; indeed, evidence from meta-ethnographies has been included in, for instance, the 2009 NICE clinical guideline on medicines adherence9–11 and the 2016 Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) guideline on asthma management. 21–23

What is meta-ethnography?

Meta-ethnography is an approach to synthesising a collection of individual qualitative research studies on a particular issue or topic, for example the experience of having type 2 diabetes mellitus. 24 The theoretically based approach was developed by sociologists Noblit and Hare25 in the field of education to synthesise interpretive qualitative studies. Meta-ethnography is inductive and interpretive, focusing on ‘social explanation based in comparative understanding rather than in aggregation of data’ (p. 23);25 it does not involve simply summarising study findings, but seeks to go beyond the findings of any one study to reach new interpretations. Although originally designed to synthesise ethnographies,25 meta-ethnography can be, and has been, used to synthesise many different types of interpretive qualitative study. 2 The meta-ethnography approach is carried out through seven overlapping phases, as summarised in Figure 1 and inspired by Noblit and Hare. 25

Meta-ethnography is unique among qualitative evidence synthesis approaches in using the study author’s interpretations, that is, the concepts, themes or metaphors from study accounts, as data. The analytic synthesis process has been described as involving ‘interpretations of interpretations of interpretations’ (p. 35),25 meaning that the reviewer interprets the study author’s interpretations of the research participants’ views and experiences. The originators25 called their analytic synthesis approach ‘translation’ and ‘synthesis of translations,’ whereby translation is idiomatic, not literal. The process involves reviewers systematically comparing (translating) the meaning of concepts across primary studies to identify new overarching concepts and theories, while taking account of the impact of each study’s context on its findings. 6,25

Meta-ethnography is a complex and challenging approach with a lack of explicit guidance from the originators25 on how to conduct the analytic synthesis process and how to appraise and sample studies for inclusion. More recent methodological work has documented more detailed methods for conducting the analytic synthesis,6,26 and recognised methods for study appraisal27 and sampling now exist. 28 The uncertainties and complexity of meta-ethnography have resulted in variation in their conduct and their subsequent reporting. This is described in more detail below.

The need for reporting guidance

Reporting quality of published meta-ethnographies varies and is often poor; the analytic synthesis process is particularly poorly described. 17,29 Consequently, meta-ethnography is not currently achieving its potential to inform evidence-based health care. Users of research evidence need clear reporting of the methods, analysis and findings to be able to have confidence in, assess and use the output of meta-ethnographies.

Reporting guidelines can improve reporting quality of health-care research. 30 Numerous such guidelines now exist, including CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) for randomised controlled trials,31 PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses)32 and SQUIRE (Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence)33 for quality improvement studies. However, there is no tailored guideline for meta-ethnography reporting. A generic reporting guideline for qualitative evidence synthesis exists in the 2012 enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research (ENTREQ) statement,34 but ENTREQ’s development did not include a consensus study with academic experts and it encompasses a wide range of synthesis approaches. It was not designed specifically for meta-ethnography with its unique, complex analytic synthesis processes and so is unlikely to greatly improve meta-ethnography reporting. The need for bespoke reporting guidelines has been recognised and these have been developed recently for other unique forms of qualitative evidence synthesis, namely realist syntheses35 and meta-narrative reviews. 36 This report describes the development of bespoke meta-ethnography reporting guidance.

Developing reporting guidance

Good practice in developing reporting guidance involves a systematic, mixed-methods approach including several key steps: literature reviews, workshops involving methodological experts, consensus studies, and developing a guidance statement and an accompanying explanatory document. 37 This kind of approach has been used successfully to develop a range of reporting guidelines. 32,35,36 Rigour in developing a reporting guideline requires expert input and the use of expert consensus in agreeing its contents. 37 Seeking consensus from the wider community of experts can avoid producing a guideline biased towards the preferences of a small research team. In the case of meta-ethnography, such consensus is particularly important given that meta-ethnography and qualitative evidence synthesis methodology more broadly are still evolving and there remain areas of contention, for example whether or not, and how, to appraise studies for inclusion in a meta-ethnography.

The principal aim of a reporting guideline is to improve the completeness and clarity of research reporting, not to improve the quality of research conduct (although improved conduct may be a welcome by-effect of guideline use) and not as a means to assess the rigour of research conduct. Specific tools now exist for assessing confidence in the findings of qualitative evidence syntheses such as Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative research (CERQual);14,38 clearer, more complete reporting of meta-ethnography methods, analysis and findings can facilitate assessments of confidence using such tools.

The meta-ethnography reporting guidance (eMERGe) project has developed meta-ethnography reporting guidance39–42 in line with good practice,37 comprising a list of recommended criteria and accompanying detailed explanatory notes. The guidance does not dictate a rigid set of reporting rules; rather, the explanatory notes justify and explain the criteria to emphasise the importance of adhering to them.

Chapter 2 Aims of the project

The eMERGe project aimed to create evidence-based meta-ethnography reporting guidance by answering the following research questions:

-

What are the existing recommendations and guidance for conducting and reporting each process in a meta-ethnography, and why?

-

What good practice principles can we identify in meta-ethnography conduct and reporting to inform recommendations and guidance?

-

From these good practice principles, what standards can we develop in meta-ethnography conduct and reporting to inform recommendations and guidance?

-

What is the consensus of experts and other stakeholders on key standards and domains for reporting meta-ethnography in an abstract and main report/publication?

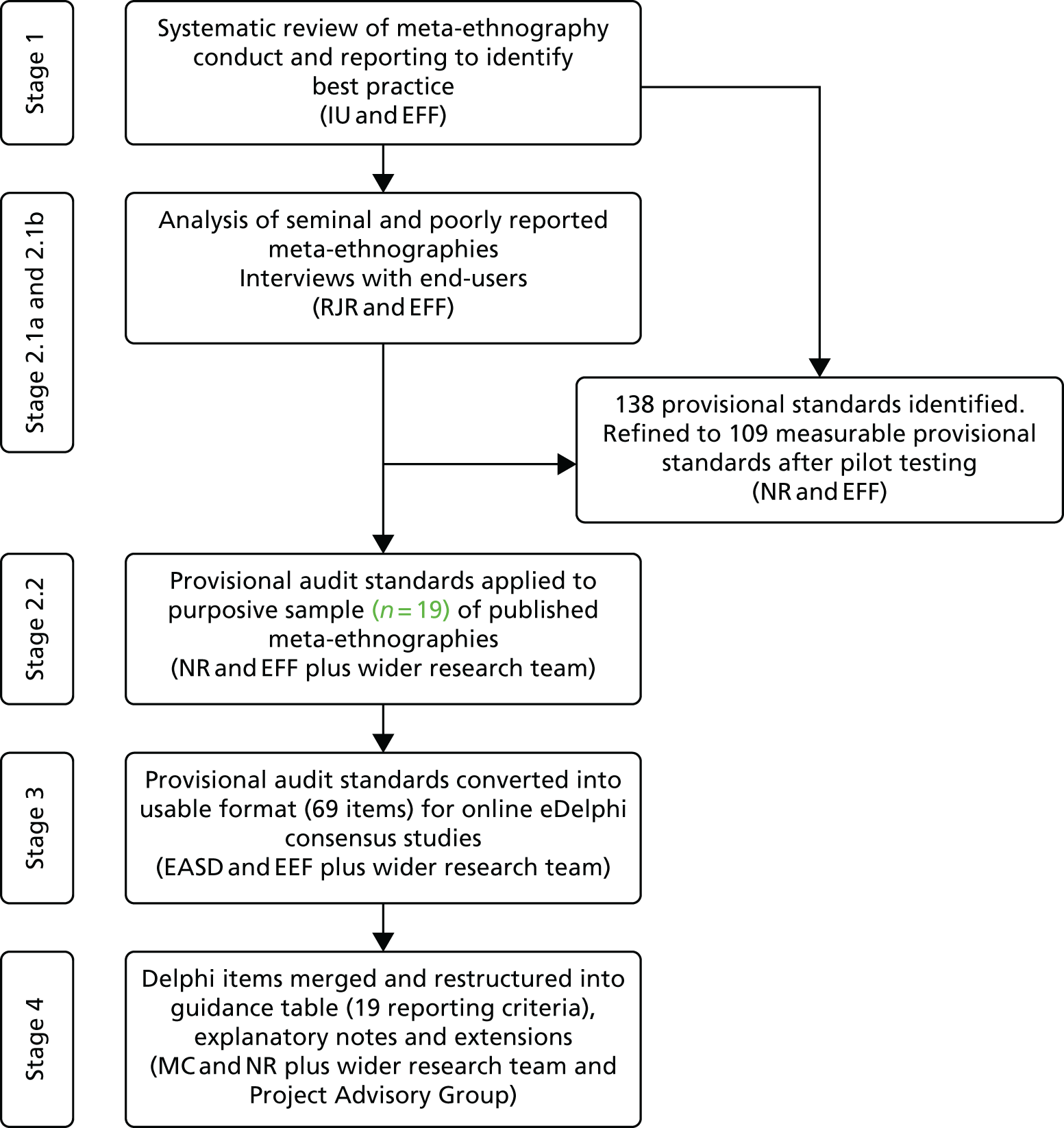

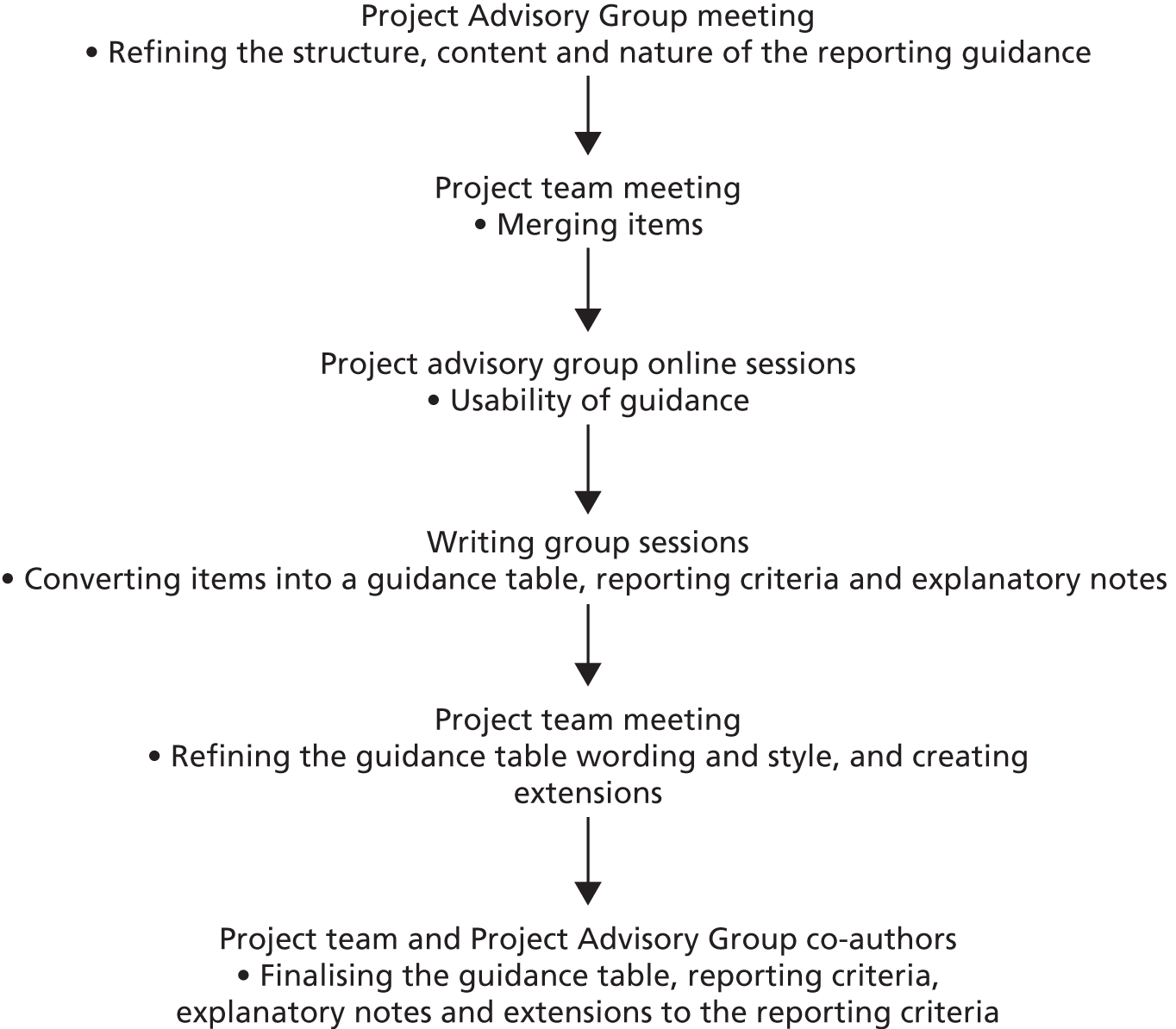

The project comprised four key stages, conducted by the project team, in consultation with one of the originators of meta-ethnography, Professor George Noblit, and supported by a Project Advisory Group of national and international academics, policy experts and lay advisors who had an active role in the development of the guidance and whose contribution was central throughout the project. The process of guidance development across the four stages of the project is outlined in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Guidance development flow chart.

Stage 1 of the project involved a systematic review of methodological guidance using comprehensive literature searches. The methods and results of the review are provided in Chapter 3. From this review, good practice principles and recommendations were identified.

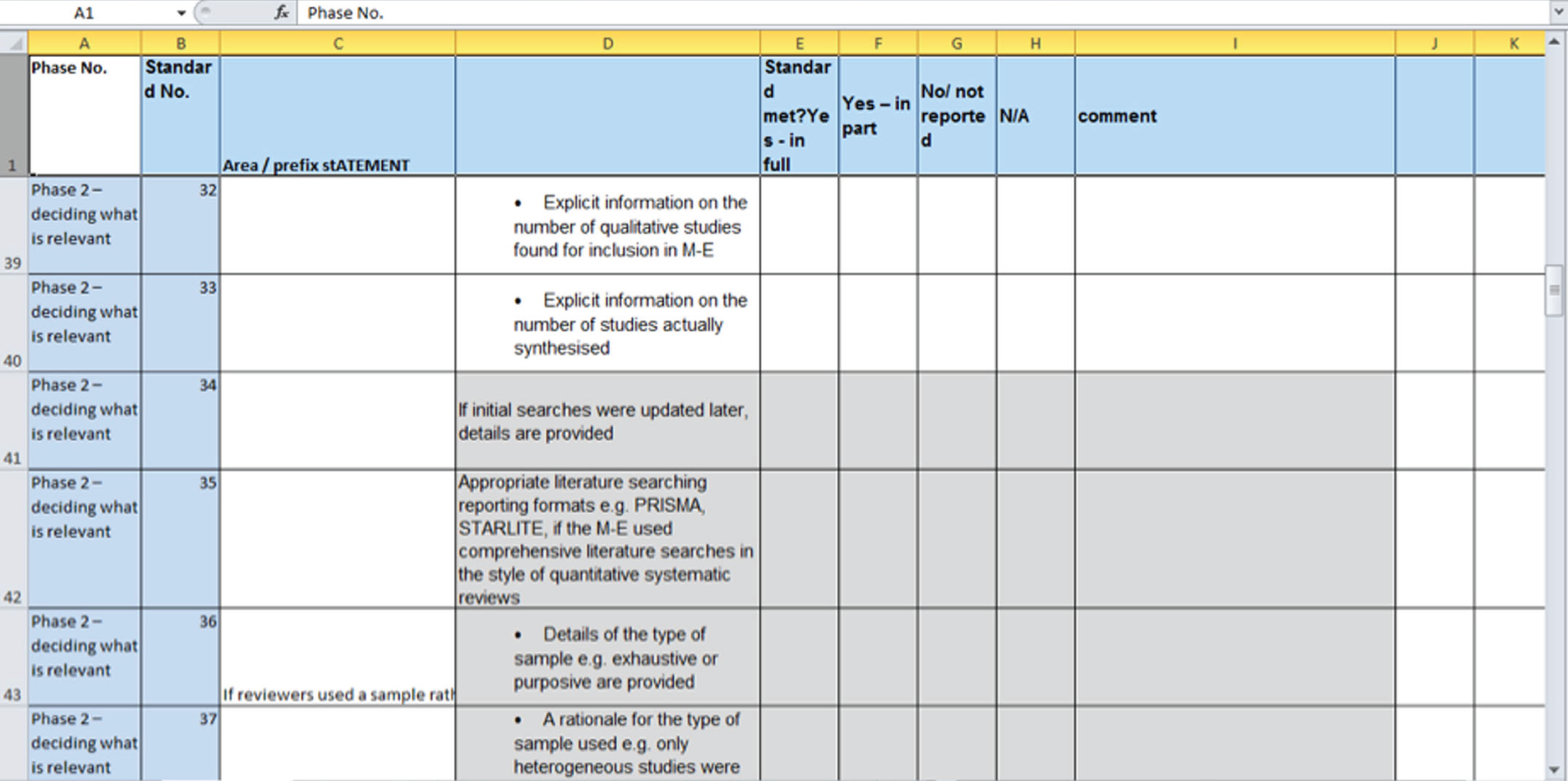

Stage 2 of the project involved a review and audit of published meta-ethnographies. There were three parts to this stage of the project: (2.1a) a documentary analysis of a sample of published seminal and poorly reported meta-ethnographies; (2.1b) an exploration of professional end-user views on the utility of seminal and poorly reported meta-ethnographies for policy and practice; and (2.2) an audit of published health- or social care-related meta-ethnographies to identify the extent to which they met the good practice principles and recommendations identified in stages 1, 2.1a and 2.1b. This stage of the project is reported in Chapter 4. As a result of stage 2, we reviewed and refined 109 provisional standards to create 69 reporting items for the eDelphi studies.

Stage 3 of the project involved finding consensus on the reporting items through an online workshop and eDelphi (Version 1, Duncan E, Swinger K, University of Stirling, Stirling, UK) consensus studies. Stage 3 of the project is reported in Chapter 5. As a result of the eDelphi consensus studies, four items failed to reach consensus and were removed from the provisional standards.

Stage 4 of the project covered developing the guidance table, reporting criteria, explanatory notes and extensions to the guidance,39–42 along with training materials to support the use of the guidance. This process was iterative and involved input from the project team and the wider Project Advisory Group. This process is described in Chapter 6.

Chapter 3 Stage 1: methodological review

Introduction

The purpose of stage 1 was to identify recommendations and guidance for conducting and reporting a meta-ethnography. Both conduct and reporting were included because it is necessary to understand what meta-ethnography is and how to conduct it, in order to know what should be reported and what constitutes good reporting.

The research question for this stage was: what are the existing recommendations and guidance for conducting and reporting each process in a meta-ethnography, and why?

Methods

A methodological systematic review of the literature, including ‘grey’ literature such as reports, doctoral theses and book chapters, was conducted to identify existing guidance and recommended practice in conducting and reporting meta-ethnography from any academic discipline. This review has been registered on PROSPERO (the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews) as registration number CRD42015024709. A key focus of the review was on the meta-ethnography analytic synthesis phases, which are complex and currently very poorly reported.

Search strategy

We first conducted comprehensive database searches that were followed by expansive searches to identify published and unpublished research in any language. These searches were iterative and evolved as the review progressed because their purpose was to build our knowledge of recommendations and guidance in conducting and reporting meta-ethnography rather than to answer a tightly defined research question. 43

To identify relevant literature, we started with seminal methodological and technical publications known to our expert academic advisors and the project team including Noblit and Hare’s book,25 detailed worked examples of meta-ethnographies and publications relating to qualitative evidence synthesis more generally (e.g. reporting guidelines for qualitative evidence synthesis approaches and reviews of qualitative syntheses including meta-ethnographies). Relevant texts were included from other disciplines that use meta-ethnography, such as education and social work. We performed citation searching, reference list checking (also known as backward and forward ‘chaining’) of the seminal texts and searched key websites (e.g. The Cochrane Library). Comprehensive database searches were also conducted to identify other methodological publications. 43 Details of databases and other sources that were searched, as well as the search terms that were used, can be found in Appendix 1 (Tables 5 and 6, respectively).

Comprehensive database searches to identify methodological publications

Searches were performed in 16 databases, in July and August 2015. The search strategy was designed in MEDLINE (Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online, or MEDLARS Online) and refined by testing against a set of key papers already known to the team. The search terms were developed and piloted in collaboration with a researcher highly experienced in the conduct of systematic reviews (RT). The terms related to meta-ethnography and qualitative synthesis, and to methodological guidance, were tailored to each bibliographic database. Reviewers also hand-searched reference lists in included texts (those meeting inclusion criteria for the review) for other relevant studies not already identified. A systematic approach was used to record and manage references, which were stored in the bibliographic software EndNote version X7.4 (Thomson Reuters, CA, USA). The list of included publications from database searches and expansive searches was shared with our academic expert advisors who suggested potential additional publications.

Screening and selection of texts to include

We originally intended to independently double-screen all references by title and abstract; however, we reviewed this decision because the highly sensitive search strategy resulted in a very large number of retrieved references from the comprehensive database searches. We reviewed our screening strategy after independent screening had started; we decided not to double-screen references from the database searches published prior to 2006 to enable us to meet our aims and project timelines. The references published pre 2006 that referred to qualitative evidence synthesis had generally been superseded and the majority of relevant references about meta-ethnography were already known to the project team and expert advisors. We were confident that any relevant publications published prior to 2006 would be identified through expansive searches and expert recommendations. However, as a precaution, titles and abstracts of references from 2005 and older (n = 1204) were electronically searched for key terms (‘ethnograph’, ‘Noblit’) to identify any that referred to meta-ethnography; references containing these terms were then screened by title and abstract by one reviewer (EFF).

Overall, titles and abstracts of 6271 references retrieved through database searches were independently double-screened and a further 1204 were screened by one reviewer. All additional references identified from other sources were double-screened. A total of seven reviewers (IU, EFF, Derek Jones, NR, JN, EASD and MM) were involved in screening retrieved publications, using the inclusion and exclusion criteria presented in Table 1.

| Criteria | |

|---|---|

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

| 1. Book, book chapter, journal article/editorial, report or PhD thesis | 1. Theses below PhD level |

| 2. Published after 1988 | 2. Published before 1988 (date of the publication of the original meta-ethnography text by Noblit and Hare25) |

|

3. Reports on methodological issuesa in conducting meta-ethnography or 4. Is a reporting guideline for, or provides guidance on, reporting qualitative syntheses including meta-ethnography |

3. Does not report on methodological issuesa in conducting meta-ethnography AND is not a reporting guideline/providing guidance on reporting meta-ethnography |

| 5. Any language | |

| 6. Any discipline or topic (not just health related) | |

Disagreements over inclusion/exclusion were resolved through discussion. A third reviewer also screened publications if the first two reviewers could not reach agreement. A final check of the full text of the articles was conducted for inclusion/exclusion before the data extraction was conducted.

Data extraction

Data were extracted in the qualitative analysis software NVivo 10.0 (QSR International, Warrington, UK), using a coders’ guidance document, which was shared by all coders. The guidance was developed by Emma F France and piloted against five key methodological publications and then discussed with the team for refinement. Four reviewers performed the data extraction (IU, EFF, Karen Semple and Joanne Coyle), working from the same guidance. Data were extracted from each included publication by only one reviewer because this was a qualitative review in which the key principles are transparency and consensus, rather than independence and inter-rater reliability. However, the completeness of the data extraction was double-checked by a second reviewer for 13 of the publications to ensure accuracy. In order to maximise the resources and time available, data were extracted from the richest and seminal publications first, as assessed by Emma F France and Isabelle Uny, and then from the other publications until all were coded and analysed. NVivo 10.0 was used to facilitate management of, and data extraction from, the publications. Guidance and recommendations from the 57 methodological texts were coded into the ‘nodes’ or data extraction categories described below, which are primarily based on Noblit and Hare’s25 seven phases of meta-ethnography conduct, with some additional categories for the data (e.g. ‘Definition or nature of meta-ethnography’) that were not specifically about the seven received meta-ethnography phases. The reason for creating these nodes was their fitness to providing an answer for the research question. The nodes at which data were extracted were:

-

definition or nature of meta-ethnography and how it differs from other qualitative evidence synthesis approaches

-

selection of a qualitative evidence synthesis approach: how to select a suitable qualitative evidence synthesis approach for one’s aim or research question (this new phase was labelled ‘phase 0’ and added by the eMERGe team).

-

Phase 1: getting started – deciding the focus of the review (e.g. guidance or recommendation on choosing a topic).

-

Phase 2: deciding what is relevant – which encompassed three subcategories –

-

quality appraisal of studies – recommendations on ways to appraise the qualities of primary studies to be included.

-

search strategies for meta-ethnography – recommendations on searching for primary texts or studies.

-

selection of studies – guidance or recommendations on the manner in which studies to be synthesised were selected.

-

-

Phase 3: reading studies – where advice or recommendation is given on how to read the studies and identify and record the concepts and metaphors contained in each study.

-

Phase 4: determining how the studies are related – determining how the concepts and metaphors used in each study relate to others and how they can be synthesised. This phase was also divided into three subcategories –

-

definition of reciprocal translation – when concepts in one study can incorporate those of another; the coding entailed defining this type of translation and identifying advice and recommendations on how this could be undertaken.

-

definition of refutational translation – where concepts in different studies contradict one another; the coding entailed defining this type of translation and identifying advice and recommendations on how this could be undertaken.

-

definition of line of argument (LOA) – when the studies identify different aspects of the topic under study that can be drawn together in a new interpretation; the coding entailed defining this type of translation and identifying advice and recommendations on how this could be undertaken.

-

-

Phase 5: translating studies into one another – the way in which metaphors and/or concepts from each study and their inter-relatedness are compared and translated into each other.

-

Phase 6: synthesising translations – how to synthesise the translations to make them into a whole that is greater than its parts.

-

Phase 7: expressing the synthesis – how the synthesis is presented, the message conveyed and for which audience.

Some other categories were also included in data extraction, which are reported on in this document:

-

issues of context in meta-ethnography

-

number of reviewers required to undertake a meta-ethnography

-

validity, credibility and transferability issues in meta-ethnography.

Data analysis

Publications were read repeatedly and compared using processes of constant comparison. Extracted data were analysed qualitatively mainly by two members of the team (IU and EFF). To support the analysis, memos were written for each category in which each reviewer could record their analysis of the data extracted at the particular node. As the analysis progressed, areas of agreement and uncertainties were noted in the memos and Isabelle Uny and Emma F France drew on each other’s understanding of the data from each node. For complex nodes (e.g. regarding conduct of phases 4, 5 or 6), each reviewer individually identified the key themes and issues in a NVivo memo and then the two coders compared what they had written to check their different interpretations. Following this, one of the coders wrote a detailed analytic memo, to which the other subsequently added more details, or which they could question in light of what they had read. For less complex or less contentious nodes (e.g. regarding conduct of phases 1, 2 or 3), one reviewer conducted the analysis, also using memos that were then checked by the other reviewer for accuracy and transparency. Throughout, each reviewer maintained an analysis journal in NVivo and any analysis decisions made at project meetings or internal meetings were logged in a folder on our shared electronic drive (all meetings were also audio-recorded for easy reference). Once completed, the initial analysis was collated and shared with the wider team and then discussed and revised to add rigour to the process and gain further perspectives on wider interpretation and analysis of the data contained in each node.

The guidance and advice provided in the included publications around each node/category varied in richness and detail. Nonetheless, the full range of practice was documented, regardless of the richness of the text. However, each reviewer also noted whether or not they felt that the texts they extracted data from were ‘rich in details’ (i.e. whether or not they were a detailed account related to meta-ethnography with in-depth explanation and rationales that went beyond description). As the analysis drew to its final stage, we detailed definitions for each of the phases as understood and described in the included publication. We summarised and analysed advice and recommendations given on the conduct of each and every phase, and noted the pitfalls and criticisms in the conduct and reporting of meta-ethnography raised by each author. The findings that emerged from the analysis are, thus, presented below.

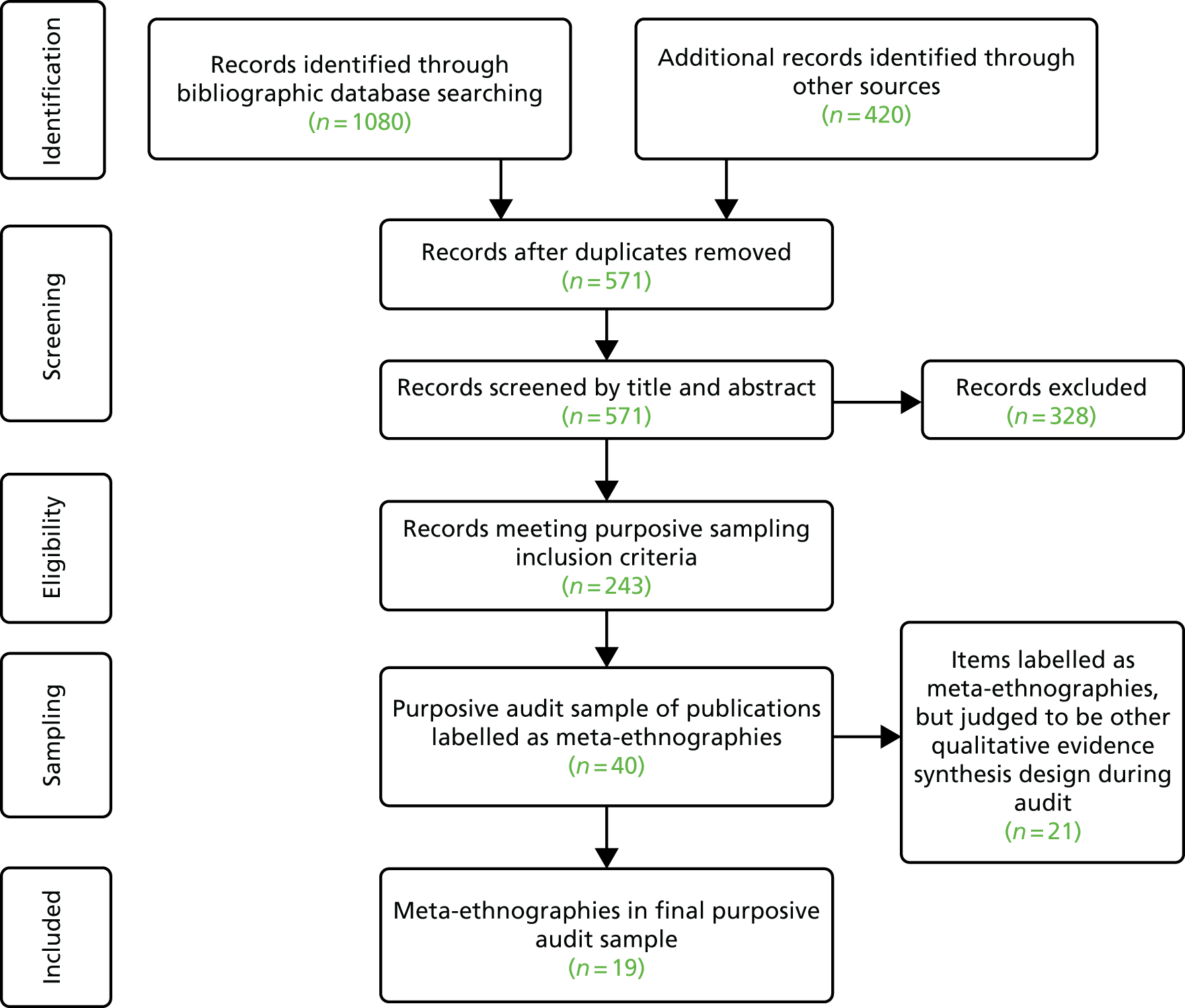

Findings

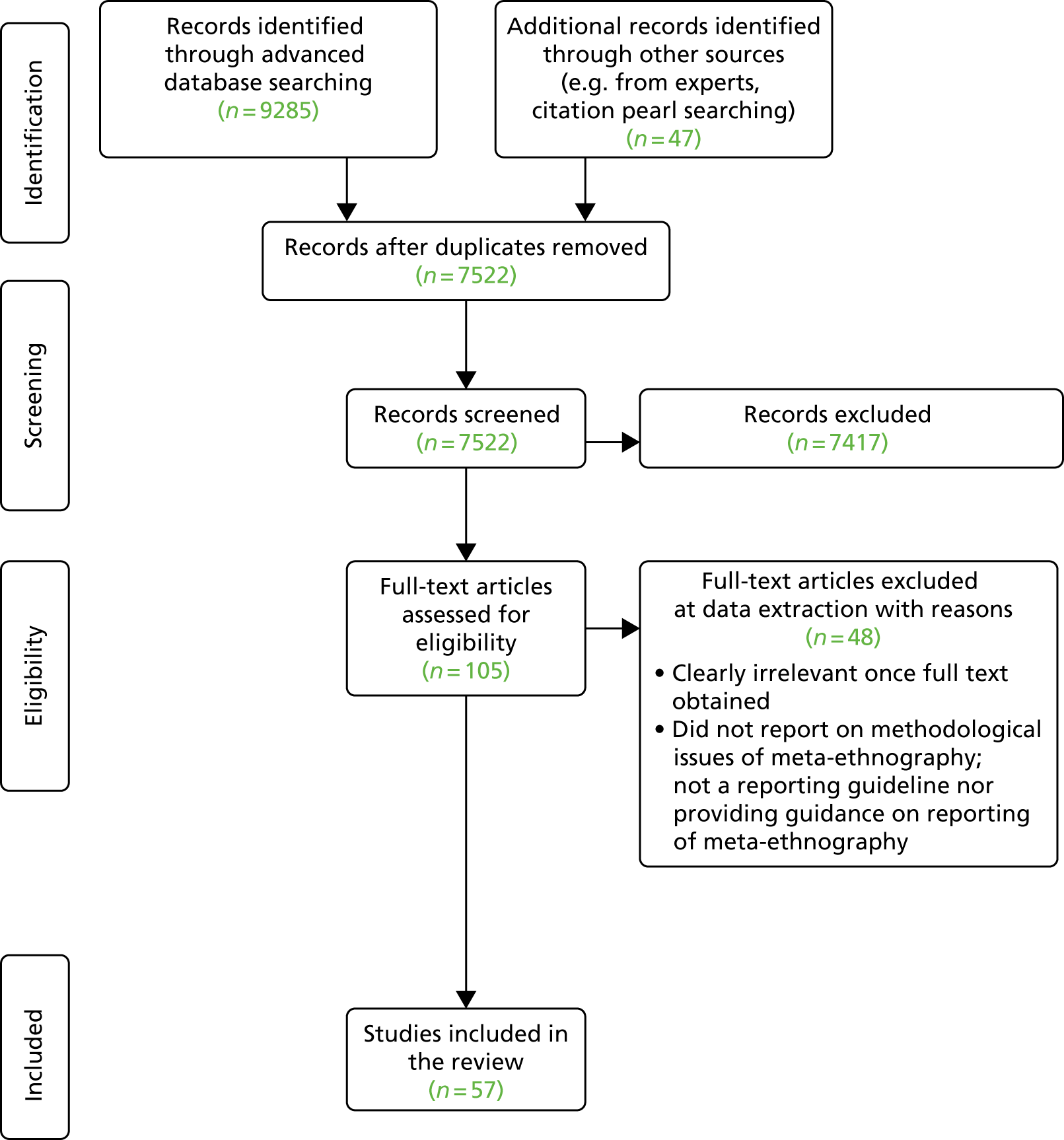

As per the PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 3), 9285 references were retrieved from the databases searches and 47 from expansive search techniques, resulting in a total of 7522 records after deduplication. A total of 7417 clearly irrelevant texts were excluded by screening title and abstract. A total of 105 papers were screened in full text. There were 48 papers excluded at full-text screening because either they were found to be clearly irrelevant once the full text was retrieved or they did not report on methodological issues of meta-ethnography, were not a reporting guideline or did not provide guidance on the reporting of meta-ethnography. This resulted in a final total of 57 included publications.

FIGURE 3.

The PRISMA flow diagram for stage 1. Adapted from Moher et al. 32 This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Those 57 publications were included for data extraction. Five were from the field of education, 46 from health and six from other disciplines. There were 19 worked examples and 30 were considered to be rich in detail. The authors of 28 publications were solely from the UK, nine solely from the USA/Canada, four solely from Scandinavia and 16 had international (multicountry) teams. The full list of the included publications and their characteristics is provided in Appendix 2.

The following subsections will cover the findings from this review for every phase of a meta-ethnography, as described in Chapter 1. The analysis of the 57 publications showed that the aspects of meta-ethnography on which most methodological uncertainties remain are those regarding the nature and definition of meta-ethnography, the methods for selecting a qualitative evidence synthesis approach (a new initial phase labelled ‘phase 0’ by the eMERGe team) and those regarding phases 4–6 of the meta-ethnography conduct (because they are complex and usually the most poorly reported in meta-ethnographies). Therefore, more space has been devoted in this report to the findings related to those particular phases. During the analysis, it became clear that some of the methodological texts were more rich in details than others and, therefore, contributed more heavily to the analysis. A table is provided in Appendix 3 that shows clearly the contribution of the major methodological publications to the categories and findings presented below. This is so that the reader is able to trace the contribution of each publication to the analysis of findings. Some of the publications are also directly referenced in the text of this report, where they made a particularly pertinent point or offered a particularly useful example. There were few publications relating to meta-ethnography reporting; most were about its conduct. On the whole, the review identified very little in the way of advice or recommendations about meta-ethnography conduct and reporting based on empirical evidence, such as from methodological research, and, rather, more evidence based on the opinion or reasoned argument of the publication authors. In the findings presented below, we have, therefore, stated whether or not the uncertainties and issues raised with regard to meta-ethnography conduct and reporting were those of the authors of the methodological text analysed, or issued from the reflections and analysis of the eMERGe team.

Definition or nature of meta-ethnography and how it differs from other qualitative evidence synthesis approaches

The analysis of the methodological texts determined that meta-ethnography is an interpretive method of synthesis rather than simply an aggregative one. It was described by Noblit and Hare25 as: ‘the comparative textual analysis of published field [qualitative] studies’, the aim of which is to create new interpretations.

A meta-ethnography analyses qualitative data in an inductive way to develop concepts, theories and models. Meta-ethnography attempts to preserve the contexts of the studies synthesised and uses a process of translation, which will be described at length in Phase 5: translating studies into one another.

Although it was conceived solely as a method of synthesis by Noblit and Hare,25 other authors have, over time, also used meta-ethnography as a systematic literature review methodology. 6 Moreover, although meta-ethnography was designed to synthesise interpretive qualitative studies, one text44 in this review argued that meta-ethnography could be used to synthesise qualitative and quantitative studies together; however, in order to do so, those authors drew on meta-ethnography to develop a new approach called ‘critical interpretive synthesis’.

There was some discussion within the methodological texts regarding what constitutes the ‘unique’ characteristics of meta-ethnography as a qualitative evidence synthesis method. According to Noblit and Hare,25 the processes that they presented in seven phases were not necessarily unique to meta-ethnography. However, they argued that the underpinning use of Turner’s theory of social explanation45 embedded in the process of translation differentiated meta-ethnography from other qualitative evidence synthesis methods. After a meeting with the eMERGe team in June 2016, Professor George Noblit provided further reflections on the process of translation as follows:

In Noblit and Hare’s text, synthesis is seen as a form of translation of accounts into one another. The nature of such translation is based on S. Turner’s Sociological Explanation as Translation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980) in which he examines comparative explanations—the essential form of meta-ethnography. Turner notes that practices, and the concepts used to describe such practices, may vary from those in another society. In doing comparisons, then one may use the concept from one society, or create a new concept, in making the comparisons of the societies. In this, explanation is a form of translation and that ‘an adequate translation would yield us claims that had the same implications in both languages’ (p. 53). Accounts can be substituted for language in this quote, for the purposes of meta-ethnography. Synthesis as translation starts with a puzzle that is of the form where one study says x, what is another study saying? Addressing this puzzle requires formulating an analogy between the studies. As we add studies, we may find that the translation/analogy offered with the initial studies does not hold up.

Professor George W. Noblit, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2016, personal communication

The analysis of the methodological texts in this review indeed showed that what is seen to distinguish meta-ethnography from other qualitative evidence synthesis methodologies is the translation process.

One of the other key characteristics of meta-ethnography, as seen by some authors, is that it aims to arrive at new interpretations greater than those of individual studies. 6,25

The main uncertainties surrounding the nature of meta-ethnography are around whether or not it could be used to synthesise both qualitative and quantitative studies, and whether or not purely descriptive studies (of which there tend to be many in health research) or deductive studies should be excluded from the synthesis.

‘Phase 0’: selecting a qualitative evidence synthesis approach

This review identified a new stage before ‘phase 1: getting started’, which was labelled ‘phase 0: selecting a qualitative evidence synthesis approach’. It relates to the rationale for choosing meta-ethnography as the qualitative evidence synthesis approach for the topic in question. This review demonstrated that better guidance is needed here to avoid reviewers choosing the wrong method of qualitative evidence synthesis or having to amend a method to suit their needs when a more suitable one might already exist.

Through stages 1 and 2 of this project, it became clear to the eMERGe team that authors of meta-ethnographies often cite Noblit and Hare25 and state that their method is meta-ethnography when, in fact, they are not conducting a meta-ethnography. A number of strategies to avoid this were identified in the review of methodological texts, including:

-

investigating other qualitative evidence synthesis approaches before choosing meta-ethnography (e.g. ensuring that an interpretive qualitative evidence synthesis is required and that the type and quantity of studies to be synthesised fit with the method selected)

-

ensuring that the synthesis research question and aim drive the choice of qualitative evidence synthesis approach (e.g. whether it aims to generate a model or theories of behaviour or experiences, or aims at conceptual and theoretical development)

-

making sure that the qualitative evidence synthesis chosen fits with the epistemological stance of the team of reviewers/the reviewer, their skills and experience of the methods used (meta-ethnography may not be best suited to novices in qualitative research)

-

ensuring that the time and resources available fit with the conduct of a meta-ethnography.

Ultimately, the review revealed that meta-ethnography needs a high level of qualitative expertise. It is a time-consuming enterprise and this must also be taken into account in phase 0. Clear guidance is required on the conduct of meta-ethnography (particularly phases 5 and 6) to help researchers choose the most suitable qualitative evidence synthesis approach.

Phase 1: getting started

Noblit and Hare25 describe this phase as:

identifying an intellectual interest that qualitative research might inform . . . In this phase, the investigator is asking, How can I inform my intellectual interest by examining some set of studies?

pp. 26–725

Ideally, a meta-ethnography aims to address a gap in knowledge, for instance by asking whether or not a qualitative evidence synthesis has previously been conducted on a particular topic or by asking whether or not it can offer new explanations of the topic. The methodological review found that authors recommended that an aim and research objectives be defined, at least in broad terms, at the start of undertaking the meta-ethnography, even if they are refined later in the process. An example of how this may be reported can be found in a worked example by Britten et al. 46 about lay experiences of diabetes mellitus and diabetes mellitus care.

Although the issues identified regarding phase 1 were not contentious, there were some uncertainties around the best way to define, or refine, the research question in a meta-ethnography as there is a link between the research question and the selection of studies to be included in the thesis (e.g. the final research question will determine which studies are included). 28,47

Phase 2: deciding what is relevant

With regard to the meta-ethnographic conduct, it bears remembering that Noblit and Hare’s25 book was published at a time when online bibliographic databases were unavailable. They created meta-ethnography as a method of synthesis but did not provide detailed guidance on selecting studies for inclusion in the synthesis. Subsequently, other researchers have applied systematic search and selection procedures to the identification and selection of studies for inclusion in a meta-ethnography.

The analysis of the methodological texts confirmed the view that published meta-ethnographies mostly use comprehensive systematic review style searches traditionally used for quantitative reviews of intervention effectiveness. However, some authors in this review stressed that this was not the only method available for meta-ethnography. For instance, some suggested that exhaustive searching may be suitable for making generalisable claims or to provide a comprehensive picture of research on a topic, whereas non-linear or purposeful searching might be more appropriate in other cases, such as meta-ethnography, where the intention is to generate a theory. Whatever the case may be, authors stressed that the search strategy ought to match the intended purpose of the meta-ethnography. One of the difficulties raised by authors, however, is that qualitative research reports are sometimes challenging to identify through electronic database searches. They therefore urged reviewers to supplement database searches with alternative methods, such as searching grey literature.

Quality appraisal and sampling for meta-ethnography

Noblit and Hare25 did not advocate a formal appraisal of studies prior to synthesis, rather, they argued that each study’s quality would become apparent by how much it eventually contributed to the synthesis. However, recent reviews of meta-ethnographies, including that carried out in the stage 2 audit of this project, indicate that most meta-ethnography reviewers conduct some form of quality appraisal of studies. 17,29

There is a wide variety of quality appraisal approaches that can be used, some judging conceptual richness (which is more rarely done) and some judging the methodological quality of primary studies (which is most commonly done). This review found that a number of meta-ethnographies use the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme,48 or adapted forms of it, to assess the quality of the primary studies. Malpass et al. 49 offer an exemplar of how the quality appraisal of the studies can be used in their synthesis of patients’ experiences of antidepressants.

This review of methodological texts showed that there is debate over whether or not formal quality appraisal is necessary or even useful in meta-ethnography. There were uncertainties around whether or not papers appraised as being of lower methodological quality should be included in the synthesis (as the findings may still be credible) and how difficult it may be to assess the quality of papers from radically different contexts. A number of authors suggested that a possible benefit of quality appraisal is the close reading of papers that it encourages, which is useful for meta-ethnography.

In terms of sampling, the review of methodological texts shows that what is seen as the optimum number of studies to synthesise in a meta-ethnography is also controversial. For instance, some argue that too many studies (n > 40) could make the translation process difficult and result in a more superficial synthesis, whereas others argue that too few studies might result in an underdeveloped conceptualisation. However, the real issue may be the number of data to be synthesised relative to the capacity of the review team rather than the number of studies per se. Some authors in this review found that there is a relationship between the research question and sampling (e.g. a narrow question can lead to a smaller sample, and starting with a wider sample and applying quality appraisal may help refine the question). The review showed that there are perceived benefits and problems with applying purposive and theoretical sampling to meta-ethnography, and that theoretical sampling in meta-ethnography has rarely been tested empirically.

Phase 3: reading the studies

The review identified various reading strategies for phase 3, such as reading while recording themes and identifying concepts (including refutational ones) and their context within the framework of the research question. Some read the papers or accounts chronologically and some started with the most conceptually rich, although there was no evidence to indicate how reading papers in different orders may affect the synthesis output. Authors of methodological texts often used tables (or mind maps) to display concepts, sometimes distinguishing concepts of the research participants from those of the primary study authors (referred to by some authors as first- and second-order concepts, respectively). Some also used phase 3 to appraise the quality of the studies. Some authors further specified the importance of reading being carried out by two or more reviewers. This review concludes, however, that one of the key uncertainties in this phase was around how to preserve the meaning of, and relationships between, concepts within and across studies when reading.

Phase 4: determining how the studies relate

Noblit and Hare25 expressed that the studies may relate in three main ways:

-

reciprocally (because they are about similar things)

-

refutationally (because they are about different things)

-

as a LOA (because they offer part of a higher meaning).

Some methodological texts in this review ventured that a well-conducted phase 3 will help to determine how studies relate to one another; however, most authors show how they related the studies in a grid or table (some detailed descriptions of how this has been reported can be found49–51). Some texts analysed in this review suggested that ‘relating studies’ is best done collaboratively by a team who interpret the concepts separately first and then come to a decision together.

We concluded that the main uncertainties about the conduct of phase 4 are:

-

whether or not it is possible to relate studies that are profoundly epistemologically different, and what is the best way to preserve the semantics and context of the metaphors or concepts contained in each study through the ‘relating’ process

-

how the order in which studies are appraised and synthesised may affect the outcome of the synthesis (e.g. use of index paper)

-

whether or not reciprocal findings in studies may tend to be given more weight than refutational ones.

Phase 5: translating studies into one another

As expressed earlier, the process of translation is key to meta-ethnography conduct. It was defined by Noblit and Hare25 as idiomatic rather than literal. From this methodological review, we can conclude that the process of translation is not a linear process but an iterative one, which aims to translate concepts from one study into another study and, thus, arrive at concepts or metaphors that embody more than one study. 52

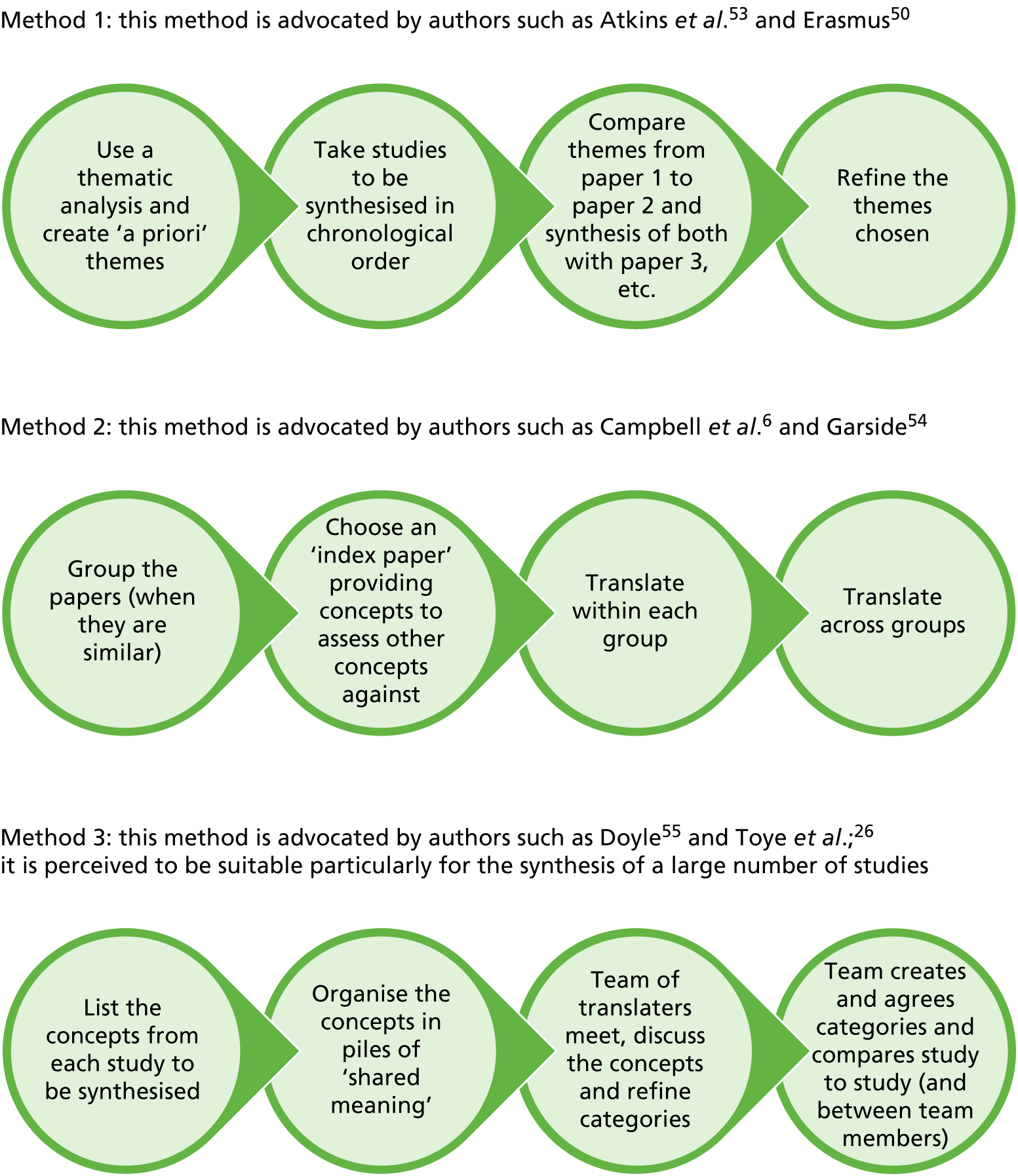

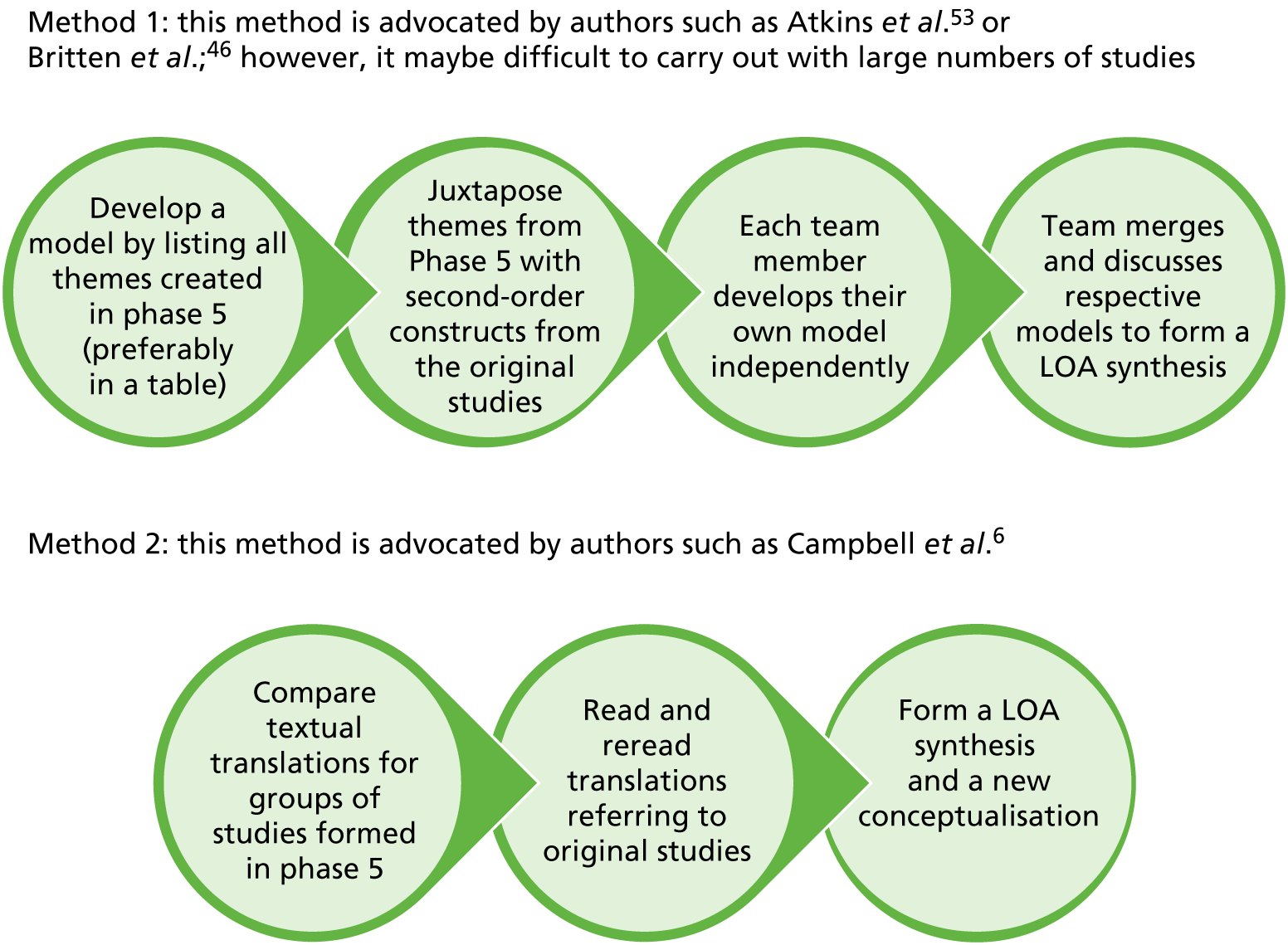

This review found that there is no single way of conducting the translation in a meta-ethnography and the various methods have not been formally compared in methodological research. However, it is the eMERGe team’s contention that whichever method of translation is used should be made explicit and transparent by the authors. The diagrams in Figure 4 were designed by the eMERGe team to represent three well-defined methods of translation described by some of the authors of the methodological texts included in this review.

FIGURE 4.

Three possible methods for the conduct of phase 5 as interpreted by the eMERGe project.

Reciprocal translation

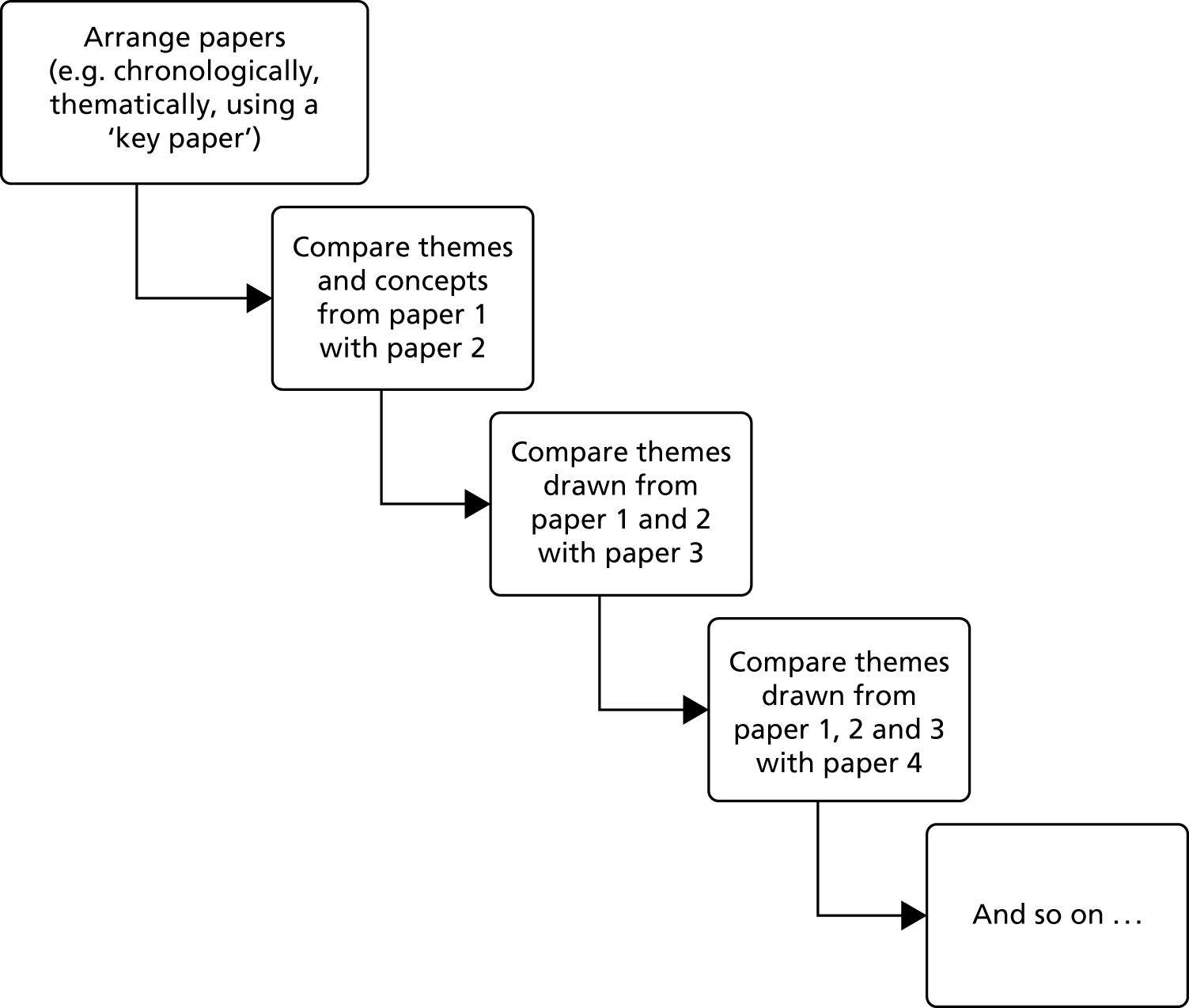

Reciprocal translation, according to Noblit and Hare25 and to a number of other authors reviewed in this study, takes place when studies are roughly about the same thing and their meaning can be interpreted into one another. The conduct of reciprocal translation was described in detail by Campbell et al. ,24,52 and their approach has been used by other authors in this review. We have summarised the approach of Campbell et al. 24,52 in Figure 5.

FIGURE 5.

Reciprocal translation process as interpreted by the eMERGe project.

A number of authors in the review recommended using tables or grids to represent the reciprocal translation analysis (a particularly detailed example of this can be seen in Malpass et al. 49).

This review found that one of the issues regarding the conduct of reciprocal translation is that it can be done in such a way as to result in a simple recoding or recategorising of themes from the primary studies rather than being interpretive. A meta-ethnography should strive to lead to new interpretations and theories of the topic under study.

Refutational translation

Noblit and Hare describe refutation as ‘an interpretation designed to defeat another interpretation’ (p. 48). 25 According to authors whose accounts are contained in this review, the purpose of a refutational translation is to explain differences and exceptions in the studies. Meta-ethnography is one of the few qualitative evidence synthesis methods that requires the researcher ‘to give explicit attention to identification of incongruities and inconsistencies’ (p. 128). 56 Some authors state that refutational translation can take place at the level of the overall studies, accounts or reports, whereas others state that it occurs at the level of themes, concepts or even findings across study accounts. It is our understanding from the review literature that it is likely that both types of refutation exist and are possible.

However, in the review, it was clear that there are uncertainties as regards how to conduct refutational translation and the review questions whether or not undertaking refutational translation makes it more difficult to develop an overarching LOA synthesis (LOA synthesis is described in Phase 6: synthesising translations, Line of argument synthesis).

Phase 6: synthesising translations

Noblit and Hare25 define this phase as follows:

Synthesis refers to making a whole into something more than the parts alone imply. The translations as a set are one level of meta-ethnographic synthesis. However, when the number of studies is large and the resultant translations numerous, the various translations can be compared with one another to determine if there are types of translations or if some metaphors and/or concepts are able to encompass those of other accounts. In these cases, a second level of synthesis is possible, analyzing types of competing interpretations and translating them into each other.

p. 2925

The manner in which the translation is synthesised depends mainly on the way phase 5 was conducted. Some authors express that, to a certain extent, translation and synthesis happen together, in an iterative manner. There is also no single way in which to carry out the synthesis. Some of the methods used by authors of worked examples of meta-ethnographies are described in two diagrams in Figure 6.

FIGURE 6.

Two possible methods for the conduct of phase 6 as interpreted by the eMERGe project.

The review indicates that there is potential to develop a theory from the synthesis in phase 6, but that very few authors describe whether or not, or how, they did this. One notable exception is Britten and Pope,51 whose worked example produced middle-range theories in the form of hypotheses that could be tested by other researchers. Part of the issue is that theory is understood differently by different authors.

Line of argument synthesis

Another type of synthesis is LOA synthesis. Noblit and Hare25 define LOA as being about inference:

What can we say of the whole (organization, culture, etc.), based on selective studies of the parts?

p. 6325

Other authors also conceive of it as a process that produces new interpretations based on the analysis and translation of the primary studies. Several authors state that you can further develop translations into a LOA synthesis, which was how Noblit and Hare25 described it. LOA is described as a synthesis that links translations and the reviewer’s interpretation. Some clear and detailed examples of how LOA synthesis has been conducted can be found in Britten and Pope. 51

It is this project team’s understanding that a LOA synthesis is distinct from the translation process and follows on from it. However, depending on the nature of the data, it may or may not be possible to achieve a LOA synthesis in a meta-ethnography. One of the main uncertainties around LOA synthesis is whether or not it may constitute a model in itself or whether or not developing a model is a further analytic step.

The uncertainties with regard to phase 6, as revealed in this review, are:

-

How strong or valid is the evidence produced by a meta-ethnography (e.g. when the interpretation in the synthesis is three times removed interpretation from the lived experience of the participants in the original studies)?

-

How does the process of translation and synthesis work in a team?

-

How transparent is the creative and interpretive synthesis process?

Phase 7: expressing synthesis

Noblit and Hare25 expressed in their book that the meta-ethnography synthesis output must be intelligible to the audience at whom it is aimed. Because of this, it could take the form of a written statement, but also could be conveyed by video or other art forms, although this has been rare. However, Noblit and Hare state:

The intention here is not to pander to the audience. Having our syntheses readily intelligible does not mean reducing the lessons of ethnographic research to an everyday or naive understanding of a culture. The focus on translations is for the purpose of enabling an audience to stretch and see the phenomena in terms of others’ interpretations and perspectives.

p. 2925

Authors in this review noted that the expression of the synthesis has to suit the audience and be clear so that policy makers and intervention planners can make use of it. However, some warned about the difficulties in remaining independent in the expression of the synthesis; Booth57 for instance expressed concerns that pressures from funders to publish new findings may influence the final product.

Issues of context in meta-ethnography

The context in a meta-ethnography concerns not only the characteristics of primary studies (e.g. the socioeconomic status of participants, their location, study setting, research designs, methodological details, and political and historical contexts), but also the context of the reviewers themselves (funding, political climate, respective expertise and world views).

The review found that authors deemed context to be important to meta-ethnography. Indeed, from their initial work on meta-ethnography, which was designed specifically to preserve the contextual aspects of studies to be synthesised, Noblit and Hare25 contended that other aggregative qualitative evidence syntheses, by contrast, were:

context-stripping [and] impeded explanation and thus negated a true interpretive synthesis.

p. 2325

For the authors in this review, taking into account the context of the studies to be synthesised was seen to bring credibility to a meta-ethnography. Authors in this review recommended laying out the context from each primary study in a grid or table for readers to see. Unfortunately, context is often a problem for meta-ethnography as it tends to be poorly reported in primary studies in health-care research. The uncertainty with regard to the issue of context is how to synthesise large numbers of studies with different contexts.

Number of reviewers required to undertake a meta-ethnography

The review showed that authors believed that there are benefits in a meta-ethnography, as with qualitative research in general, being undertaken by more than one reviewer. The reasons given were that it:

-

aids the translation process

-

leads to richer and more nuanced interpretations, as reviewers have alternative viewpoints and perspectives

-

encourages explorations of dissonance

-

brings more rigour to the process and increases the credibility of the research process.

Although an optimum number of reviewers for a meta-ethnography cannot be stated here as it has not been the subject of empirical research comparisons, the review certainly expressed that there were weaknesses in undertaking a meta-ethnography with only one reviewer, for example a lack of exploration of alternative interpretations. A review of meta-ethnographies published between 2012 and 201329 showed that the actual number of reviewers in recently published meta-ethnographies varied from one to seven, with the most common number being two or three. The composition and experience of the team of reviewers were seen as important. Findings suggest that the team must fit the aim of the synthesis and represent a range of perspectives, genders and skills (e.g. translators, data retrievers, user representatives and reviewers from different disciplines). Some authors suggested that qualitative evidence synthesis expertise is needed in the team to undertake a meta-ethnography. Other authors addressed the issue of power dynamics within the team of reviewers (e.g. different levels of seniority).

Validity, credibility and transferability issues in meta-ethnography

Within this review, the debate around validity or credibility and around generalisability or transferability in meta-ethnographies revolved around how useful or credible the findings from this type of synthesis are, as well as on whether or not they can be generalised or transferred to other settings.

Validity and credibility

Depending on the publication, the authors talked about either the validity or credibility, or sometimes the trustworthiness, of the findings; credibility and trustworthiness, rather than validity, are the terms usually used for qualitative research. Bondas and Hall58 offered some clear and concrete advice for ensuring validity in meta-ethnography:

questions such as Does the report clarify and resolve rather than observe inconsistencies or tensions between material synthesized? Does a progressive problem shift result? Is the synthesis consistent, parsimonious, elegant, fruitful, and useful (Noblit & Hare, 1988)? Is the purpose of the meta-analysis explicit?

Bondas and Hall58

For other authors, the search for disconfirming cases or studies (and the use of refutation) can enhance validity, as could the use of a multidisciplinary team, as it can improve rigour and quality. For some authors, the trustworthiness of the output of a meta-ethnography is related to how rigorously phase 2 has been conducted, that is, how data were collected (e.g. having a large number of heterogeneous studies or too few studies that were rich in details could compromise trustworthiness).

Although a few authors suggested returning to the authors of primary studies to check the validity of the metaphors used and the interpretations formed, this was seen by most as impractical and tricky. Furthermore, as Noblit and Hare25 stated, the interpretation formed by the meta-ethnography synthesis could be construed as simply one possible interpretation, not as ‘truth’. Campbell et al. 24 offered another view on validity by suggesting that ‘One possibility would be to test the relevance of the synthesis findings by presenting them to pertinent patient groups, health professions, academics and policy makers’.

Garside54 suggested that trustworthiness may be easier to establish in a qualitative evidence synthesis because the study reports are in the public domain, unlike the raw data of most qualitative primary studies, and so can be accessed by readers. To increase credibility, most authors suggested that the choice of meta-ethnography must be justified, the conduct of the synthesis clearly laid out and the place of the reviewer reflexively assessed.

Generalisability and transferability

Here, generalisability is understood to mean the degree to which findings from a particular meta-ethnography can be generalised to another sample of studies or another context. This term is most often used in more positivist-type research, and some authors in this review were doubtful of its usefulness to qualitative evidence synthesis. However, some of the authors believed that ‘generalisation across studies adds to the findings of individual studies’. 24 This was with the caveat that the heterogeneity of studies and their potential competing interpretations should still be taken into account within the synthesis. An alternative term more often used for qualitative research is ‘transferability’, meaning the ability to transfer findings to other settings and contexts.

Criticisms of meta-ethnography

Some of the main criticisms of meta-ethnography identified in the review of methodological papers included (1) the fact that, although there was some good practice in the conduct of meta-ethnography, a lot of those reviews that are labelled as such are actually critical literature reviews rather than interpretive meta-ethnographies; (2) the large number of studies selected for inclusion in some meta-ethnographies; and (3) the fact that some reviewers of meta-ethnography have used aggregative approaches in the attempt to conduct meta-ethnographies, and, in others, it is unclear what process was used to arrive at the final synthesis. Another criticism included that meta-ethnography reviewers sometimes failed to make clear how they selected their studies, whereas others offer incomplete analyses, in which first-, second- and third-order constructs are not always distinguished. Another main critique was that few meta-ethnographies actually conduct any refutational translations and few offer proper LOA syntheses, instead conducting only reciprocal translations.

Conclusions

Overall, this review of methodological texts on the conduct and reporting of meta-ethnography revealed that more clarity is required on how to conduct its various phases, particularly phases 4–6. A phase, called ‘phase 0’, was added by the eMERGe team to offer some guidance with regard to ascertaining the suitability of selecting meta-ethnography over other qualitative evidence syntheses.

This methodological review made clear that there were a number of challenges in conducting and reporting meta-ethnography as well as a number of uncertainties about how to operationalise the various phases. Overall, this has led to a blurring of the approach, whereby authors have modified the phases with little explanation, or simply bypassed some phases altogether. Thus, the review of the methodological texts on meta-ethnography sheds light on the current challenges related to the approach but also highlights the importance of developing clear guidance for the reporting of meta-ethnography.

Chapter 4 Stage 2: defining good practice principles and standards

Introduction

Stage 1 findings showed that the aspects of meta-ethnography that had most methodological uncertainties were the complex, analytic synthesis and expressing the synthesis phases (phases 4–7). Therefore, we focused our data collection and analysis in this second stage on these four phases rather than all seven. This enabled us to achieve a depth of understanding within the project’s time constraints.

Aim

To identify and develop good practice principles and standards in the reporting of meta-ethnographies on which to inform the draft reporting standards for consideration by the expert and stakeholder Delphi groups in stage 3.

Research questions

-

What good practice principles in meta-ethnography reporting can we identify to inform the draft reporting standards for consideration by the expert and stakeholder Delphi groups in stage 3?

-

From these good practice principles, what standards in meta-ethnography conduct and reporting can we develop to inform recommendations and guidance?

To address these questions, stage 2 consisted of two sequential stages:

-

stage 2.1 – documentary and interview analysis of seminal and poorly reported meta-ethnographies

-

stage 2.2 – audit of recent peer-reviewed, health- or social care-related meta-ethnographies to identify if, and how, they meet the standards and to further inform and develop the guidance and reporting criteria.

Stage 2.1: documentary and interview analysis of seminal and poorly reported meta-ethnographies

Stage 2.1 was undertaken in two stages:

-

stage 2.1a – documentary analysis of seminal and poorly reported meta-ethnographies

-

stage 2.1b – exploration of professional end-user views on the utility of seminal and poorly reported meta-ethnographies for policy and practice.

Stage 2.1a: analysis of seminal and poorly reported meta-ethnographies

Methods

We aimed to analyse and review 10–15 poorly reported and 10–15 seminal meta-ethnographies. We asked expert academics from the Project Advisory Group to recommend meta-ethnography journal articles that they judged to be seminal and those that they considered to be relatively poorly reported and to explain why. 43 In addition, published reviews of meta-ethnography quality were searched by the project team (RJR and EFF) to identify low-quality examples.

Journal articles were considered for inclusion if they were:

-

a peer-reviewed meta-ethnography journal article

-

published following Noblit and Hare’s 1988 book25

-

considered by our expert advisors and/or published reviews of meta-ethnographies to be either

-

seminal (i.e. to have influenced or significantly advanced thinking and/or to be of central importance in the field of meta-ethnography), or

-

relatively poorly reported.

-

Thirteen seminal and three poorly reported meta-ethnographies were suggested by experts. Because few poorly reported meta-ethnographies were identified, we searched three published reviews of qualitative syntheses. 17,18,29 This identified a further 13 papers as relatively poorly reported meta-ethnographies. In total, 29 meta-ethnographies were analysed: 13 considered to be seminal and 16 regarded as relatively poorly reported (see Appendix 4).

Data extraction and coding

The following data were recorded in NVivo 10.0: author(s), title, journal details (including article word limit and publication year), topic focus and aim of review, and the number of primary studies synthesised.

Data were coded deductively by Emma F France, Isabelle Uny and Rachel J Roberts using the coding frame of analytic categories based on the recommendations identified in stage 1. The qualitative analysis software NVivo 10.0 was used to facilitate management and coding.

Data analysis

Data extracts were read repeatedly by Rachel J Roberts. Data were compared with the recommendations identified in stage 1 and with one another in order to identify similarities and differences within, and between, the seminal and poorly reported meta-ethnographies. Emergent findings were presented and discussed regularly within the project team to ensure rigour and richness of interpretation and analysis.

Findings

The following similarities and differences between poorly reported and seminal meta-ethnographies were identified.

Phase 4: determining how the studies are related

Both seminal and poorly reported meta-ethnographies reported extracting themes and/or concepts from primary studies and comparing them with one another to understand the relationships between them. The most striking contrast between the poorly reported and seminal meta-ethnographies was the extent of methodological detail provided. We coded ≥ 35 lines of text under this heading in all but one of the seminal papers, with one using well over 100 lines of text. Seminal meta-ethnographies more fully described the processes used by the review team in determining how the primary studies were related and provided illustrative examples from the synthesis being reported. This more detailed reporting enabled discussion of some of the difficulties, challenges and findings encountered during these processes, as well as wider methodological or theoretical issues. In contrast, we coded between five and seven lines of text at phase 4 in all but one of the poorly reported papers.

Analysis of the seminal meta-ethnographies illustrated that these authors adopted a variety of approaches and techniques to identify the ways in which the primary studies were related. The commonality that the seminal meta-ethnographies have is their comprehension and clarity in the description and illustration of the processes used, rather than the homogeneity of the processes.

Phase 5: translating studies into one another

Reviewing the phase 5 data extracted from the seminal and poorly reported meta-ethnographies revealed similar findings to phase 4. Again, there was considerably more text coded for the seminal meta-ethnographies than for the poorly reported ones.

The poorly reported meta-ethnographies provided a very brief summary describing translation that rarely extended beyond one paragraph. This was sometimes accompanied by a table illustrating the grouping of themes or concepts identified in the primary studies. In contrast, the seminal articles provided far more detailed descriptions of the processes the review team followed when translating primary studies. Analysis of these texts supports the stage 1 finding that there are a variety of techniques and processes that can be adopted when translating studies into each other (e.g. Campbell et al. ,6 Toye et al. ,27 Britten and Pope51 and Garside et al. 59). What differentiates the seminal from the poorly reported meta-ethnographies is the far greater clarity and depth provided in reporting these techniques and processes.

Phase 6: synthesising translations

The aim of synthesising translations in meta-ethnography is to produce new concepts, a theory or insights that extend beyond that found within the primary studies. Some authors of poorly reported meta-ethnographies provided detail on how new interpretations/concepts were developed from the translated themes. This was provided in a narrative form, often accompanied by a table and/or figure, which summarised the relationship between the themes and the higher-level concept(s) that encapsulate them. Other authors either provided a summary outline of the steps suggested by Noblit and Hare25 or gave slightly more detail of how synthesising translations was carried out within the particular meta-ethnography they were reporting.

In contrast, the seminal meta-ethnographies tended to provide more detail on the processes used by the review team in synthesising translations. In describing these processes, clear linkages were made between primary study concepts, translated concepts and synthesised translations, to illustrate how the new interpretations/new concepts were developed. However, although most of the seminal papers reported extensive detailed information about the process of synthesis, some provided only brief outlines similar to those found within the poorly reported meta-ethnographies.

Phase 7: expressing the synthesis

Data coded on phase 7 tended to be in the findings and conclusions sections of papers. In contrast with findings from phases 4–6, we coded more text (typically three to five pages) from the lower-quality meta-ethnographies at this phase than was coded from the seminal meta-ethnographies (typically one or two paragraphs). This is because the lower-quality meta-ethnographies included a lot of detail (either in tables or narrative) of the different themes they had identified (i.e. lower quality meta-ethnographies tended to provide lists of the themes coded at this node). In contrast, seminal meta-ethnographies tended to have included that information in the reporting of earlier phases.

Reporting of phase 7 within the seminal meta-ethnographies focused on the detailed description of the new model that had been developed. Therefore, the seminal meta-ethnographies had a clearer delineation between reporting the different phases of the meta-ethnography, clearly describing the process of translating and synthesising data from the primary studies, and then expressing their final synthesis or interpretation in a new model or figure.

Stage 2.1b: professional end-user views on the utility of the seminal and poorly reported meta-ethnographies for policy and practice

Introduction

Ultimately, meta-ethnographies are a form of qualitative evidence synthesis that can be used to inform policy and practice. We therefore wanted to include the views of meta-ethnography end-users on the utility of published meta-ethnographies, to identify issues of reporting important to them. This was based on the assumption that the reporting needs and priorities of end-users may differ to those using meta-ethnographies within an academic capacity.

Research question

What good practice principles in meta-ethnography reporting can we identify to further inform and develop the good practice principles and standards?

Methods

Sample

Individual representatives of organisations were invited to participate if they met at least one of the following criteria:

-

works for a government or non-government organisation that uses synthesised evidence on health/social care, or develops or disseminates evidence-based health/social care guidance and advice

-

commissions qualitative evidence syntheses

-

works in a role related to the use of research evidence for health/social care policy or practice

-

is a clinical guideline developer

-

distils evidence for policy-makers

-

is a health or social care policy-maker

-

uses synthesised evidence or synthesises evidence in a professional, non-academic capacity.

A total of 23 UK-based organisations with staff meeting one or more of the above criteria were approached. One organisation, the Association of Medical Research Charities, is a member organisation that circulated an invitation to participate in the project to its 138 medical research charity members. The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) agreed to circulate the invitation to its board and panel members. In total, 18 organisations agreed to participate. However, seven organisations were not interviewed because of thematic data saturation or unforeseen practical constrains, such as staff sickness within an organisation. The final sample consisted of 11 organisations. A total of 14 people were interviewed, four more than our target. All individuals and organisations that had agreed to be interviewed were invited to participate in stage 3 of the project (stage 3.2 eDelphi consensus studies).

The 14 participants worked in a range of organisations, including non-departmental public bodies, medical research charities and royal colleges. Their areas of focus covered health services, public health and social care, with roles that included clinical guideline and audit development, advising policy-makers, development of professional education and practice, and driving and supporting health and/or social care improvements. With just one exception, none of the participants had read a meta-ethnography prior to their involvement in the project.

Ethics

The interviews were exempt from requiring research ethics approval. University ethics approval was applied for this stage of the study, but the members of the research team were advised that this was unnecessary as the participants we wished to interview were policy makers/decision-makers and interviews would be recorded via detailed note-taking only and direct verbatim quotations would not be used. Despite being exempt from the requirement of ethics committee approval, the project was conducted in accordance with ethical research guidelines.

Data collection

Each participant was sent one seminal and one poorly reported meta-ethnography identified in stage 2.1a. These were selected by the team or interviewee as they were likely to be relevant to the individual participant. Where there was doubt about the potential relevance of a seminal or poorly reported meta-ethnography, participants chose which of several potentially relevant ones they would prefer to comment on (see Appendix 5, Table 7).

Participants were asked to discuss the utility of two meta-ethnographies for their professional role. They were not told which meta-ethnography was considered seminal and which was considered relatively poorly reported. They were sent an interview guide (see Appendix 5) in advance to allow them to consider their responses when reading the articles. The questions included:

-

Were the article’s implications for policy and practice clearly reported?

-

How much confidence would you have in using the findings in your professional capacity?

-

What, if anything, is missing from the article that you would need to know to be able to implement the evidence/findings?

Participants’ responses were collected by RJR via telephone (n = 13) or e-mail (n = 1). Detailed notes were taken of participant responses during telephone data collection.

Data analysis

The detailed notes and the e-mail responses were read and reread by Rachel J Roberts and potential themes identifying the key elements that constitute good (and poor) reporting for professional end-users of meta-ethnography were developed. Initial findings were discussed by Rachel J Roberts, Isabelle Uny, Emma F France and Nicola Ring during regular team meetings, and with the wider project group during scheduled meetings.

Findings

A summary of participants’ perceptions are presented below and the differences between how professional end-users and academics approach, judge and use meta-ethnography articles are highlighted.

Judging the reporting ‘quality’ of meta-ethnographies

In contrast to the views of the eMERGe Project Advisory Group members who had originally graded the quality of the meta-ethnographies, six of the end-user participants preferred the meta-ethnography that had been categorised as being poorly reported to the one that had been judged to be seminal, for example because the seminal one was perceived to provide too much detail about methods or its findings and implications were not considered as clear as the ‘poorer’ meta-ethnography. Five participants preferred the seminal meta-ethnography and three participants were neutral with no preference shown. Participants did not consistently share the same views about the publications, that is, they did not like or dislike the same papers as one another.

The utility of meta-ethnography to inform policy and practice

Participants were asked whether or not they saw a role or relevance for meta-ethnographies within their organisation. Some of their responses highlighted benefits and uses that could apply to qualitative evidence synthesis in general and others emphasised benefits associated specifically with the processes and outcomes of meta-ethnography. Some participants particularly valued the ability of meta-ethnographies to provide a conceptual development beyond the primary studies. Although participants highlighted some potential benefits of using meta-ethnographies within policy and practice development, they said that they would be unlikely to see articles such as those they had been asked to comment on within their normal professional roles. Although peer-reviewed journal articles were commonly used by the participants in their work, only one participant had come across a meta-ethnography before. Some stated that it was unlikely that they would have seen the articles they were asked to comment on owing to the focus of or the inaccessibility of journals in which they were published.