Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 14/154/07. The contractual start date was in November 2015. The final report began editorial review in November 2017 and was accepted for publication in March 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Gridley et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Carers are the mainstay of the support system for disabled and frail children and adults. The UK 2011 Census1 identified almost 6 million people who defined themselves as carers, over half of whom cared for > 50 hours per week. In total, UK carers provide the equivalent of 17 million working hours of care per week. Furthermore, both the population of carers overall and the proportion who provide the longest hours of care have increased since the 2001 Census.

Carers are most likely to be over the age of 50 years, and are more likely than others of the same age to report poor or indifferent health, and, although people who become carers are more likely than others to be in poor health before they become carers,2 caring (further) affects both physical and mental health. 3

Evidence of the effectiveness of specific ‘carer interventions’ is poor (see below), but we do know that mainstream services for the people who carers support also help carers themselves. 4,5 However, the most recent nationally representative survey of carers showed that only 11% of the people being supported by carers had a visit from a paid home help or care worker at least once per month. Although in most cases carers said that visits from home carers were ‘not needed’, 25% of those not in contact did express some type of need. The proportions of people receiving visits from all other types of health or social care staff at least once per month were even smaller, and with similar levels of expressed need for most. 6 Further analysis of these data has compared them with those from a similar 1985 survey. This has shown that, despite an intensification in caring activity and impact over the past 30 years, and policy preoccupations with supporting carers, smaller proportions of the people who carers help now receive health and social care support and smaller proportions of carers experience respite. 7

Carers of people with dementia are potentially an even more disadvantaged group than the generality of carers. They experience repeated transitions in their personal, social, economic and psychological lives as the dementia journey progresses, and a substantial body of literature has documented the impact of becoming and being a carer for a person with dementia. 8 They are more likely to report negative physical and psychological outcomes than otherwise similar carers who support people without dementia. 9–11 Spouses who care for partners with dementia are themselves often elderly and frail, although some of those who care for parents may also still have responsibility for their own children.

Without carers, the health and social care system would be hard pressed to provide alternative care for people with dementia. 12,13 However, despite considerable policy interest in dementia over recent years,13–15 and a (largely separate) policy stream designed to ensure that carers are supported,16–19 evidence about how best to support carers through the dementia ‘journey’ remains elusive. This is largely because of the relative paucity and poor quality of existing evaluative research. 20–22 A particular weakness in the evidence base is the lack of studies that can throw any light on the cost-effectiveness of interventions to support carers. When there is evidence of effectiveness, there is rarely evidence of costs, whether to health and social care services or to carers and families themselves.

There is one dementia-specific, specialist nursing service in the UK that targets support at the carers of people with dementia – Admiral Nursing (AN) – and it is this that we have evaluated here.

What is Admiral Nursing and what do we know about its impact?

Admiral Nursing, based within the charity Dementia UK, is the only UK-based, dementia-specific, specialist nursing service that targets carers of people with dementia. The service was first piloted in Westminster in 1990 and as of June 2018 provides support via 85 teams (staffed by 221 nurses) around the country.

Admiral Nursing services vary in their composition, remit, funding models, case mix and other key characteristics, although they all work to a core set of values to support carers and family members of people with dementia. Some are commissioned and/or hosted by the NHS, whereas others are commissioned and/or hosted by local authorities or third-sector organisations. AN services are currently found in memory assessment services, community AN teams, care homes, hospitals, palliative and end-of-life care settings and third-sector settings. The service also runs a national helpline (Admiral Nursing DIRECT), which was established in 2008 and was staffed by an additional 31 nurses at the time the research was carried out.

Dementia UK describes the AN service thus:

Admiral Nurses are specialist dementia nurses who work closely with families living with the effects of dementia. They provide psychological support, expert advice and information to help families understand and deal with their thoughts, feelings and behaviour and to adapt to the changing situation. Admiral Nurses seek to improve the quality of life for people living with dementia and their families by using a range of interventions to help people live positively with the condition and to develop skills to improve communication and maintain relationships. Admiral Nurses also uniquely join up different parts of the health and social care system and enable the needs of family carers and people with dementia to be addressed in a coordinated way. They provide consultancy and education to professionals to model best practice and improve dementia care in a variety of care settings.

All Admiral Nurses are mental health nurses who have specialised in the care of people with dementia. However, although they do increasingly work with people with dementia, their main objective is to support carers and family members of the person with dementia.

A recent systematic evidence synthesis by Bunn et al. 24 scoped the existing literature about AN to determine, among other things, the scope, nature and key attributes of the AN role. This work identified two main themes that underpinned Admiral Nurses’ work with carers:

-

relational support (including taking a carer-centred approach, providing individually tailored support and being a ‘friend’)

-

co-ordination and personalisation of support (including facilitating access to other services and support, collaborating with other service providers and advocating on the carer’s behalf).

A third theme related to organisational and delivery issues, including the management of caseload, providing care across the dementia journey, the definition of the role and the dynamics of relationships with other parts of the health and social care system for people with dementia.

As these descriptions suggest, AN has all of the key characteristics of a complex intervention, as defined in the Medical Research Council guidance on the evaluation of such interventions. 25 It can involve large numbers of (and interactions between its) components, significant numbers and difficulty of behaviours for those who deliver and receive the intervention, targets for change at more than one organisational level, numerous and variable outcomes, and flexible and tailored delivery of the intervention.

The Bunn et al. 24 synthesis suggested that carers value the emotional support and education that Admiral Nurses provide and that their expectations of what Admiral Nurses might provide and what they actually do provide largely match. However, it also pointed out that, although there has been some qualitative research and one quantitative evaluation of AN outcomes in the past,26 the evidence base on their effectiveness, costs, cost-effectiveness and relationships to other health and social care services was still very limited.

The need for the research

The evidence synthesis from Bunn et al. ,24 commissioned by Dementia UK itself, showed that few studies provided evidence about outcomes for carers or evaluated the specific inputs of AN services. However, the synthesis also found little clear evidence about the cost-effectiveness of any other model of community-based support for people with dementia and their carers.

More recently, an updated metareview of evidence on support for carers suggested that contact between the carers of people with dementia and other people who know about dementia may improve some aspects of carers’ mental health and their perceptions of burden and stress. 21 However, very different types of intervention seemed to produce this effect, and it was often not clear what control groups were experiencing as ‘usual care’, making it difficult to come to robust conclusions about how best to provide support.

In 2009, the Department of Health and Social Care announced a new role, the dementia adviser, which was intended to enable ‘easy access to care, support and advice following diagnosis’ (© Crown copyright 2009. Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0). 13 This model appears to have been widely adopted,27 but navigating the complex health and social care system after diagnosis remains an obstacle to effective care and support,5,12 and people with dementia have recently been shown to receive less primary preventative health care than people without dementia. 28 In fact, dementia advisers were never intended to provide intensive support at the level offered by specialist services, such as Admiral Nurses,13 and qualitative evidence suggests that there continues to be a demand for a more intensive approach. 24

Indeed, a systematic review of case-management programmes for people with dementia29 concluded that the intensity of case management interventions was one of two factors determining the magnitude of their effects, the other being the integration level of the system in which the case managers worked.

Most recently, and since our research was completed, the review to update the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline on dementia30 identified only one cost–utility analysis on the subject of care planning, review and co-ordination for people with dementia or their carers. This analysis did suggest that intensive case management could result in cost savings, but the impact on quality of life was equivocal. 31

The review also identified moderate-quality evidence for a reduction in ‘carer burden’, along with improvements in quality of life for people with dementia and reduced rates of entry into residential care for those offered case management versus usual care. Across the studies, larger gains were seen in interventions with more frequent follow-up in which the case manager was a nurse and contact was made face to face in the person’s home.

Previous research has suggested that specialist nurses could be particularly effective in enhancing the continuity of care for people with complex conditions32 and that the disease-specific knowledge of specialist nurses in particular is highly valued by recipients. 33 Specht et al. 34 compared the outcomes of an existing dementia case management service with those of a new nurse care management model and found benefits to carer stress, well-being and endurance potential in the nurse care management group. From anecdotal evidence accompanying their study, the authors suggested that it could have been that having a nurse, in particular, leading the care management of the person with dementia and their carer led to these differences, as the nurse was able to pick up and help to manage associated health concerns, but they did not demonstrate this robustly. 34 A more recent systematic review of the evidence for ‘key worker type support roles’ for people with dementia and their carers concluded that one of the key ingredients of success was the support worker having a skilled background (i.e. they were a nurse, an occupational therapist or a social worker trained in dementia). 35

The detailed implications for research outlined in the Bunn et al. 24 synthesis included the need to:

-

evaluate the specific input of AN practitioners, set alongside outcomes for carers

-

explore the in-reach and training role of AN in acute hospitals, care homes and other practice settings and practitioners

-

investigate the contribution of AN services from the perspectives of other health and social care stakeholders

-

understand the profile of carers whom AN services support.

In the work we report here, we hoped to throw light on these types of issues by building on the earlier evidence and our existing partnership with Dementia UK to develop a rigorous quantitative and qualitative approach to address our main research question:

What are the costs and benefits for carers, families and people with dementia of providing specialist nursing support?

However, in addressing this question, we also wanted to explore the wider effects on health and social care of specialist support services for carers of people with dementia and the impact that receiving services has on carers’ navigation of other parts of the health and social care system.

As Bunn et al. 24 point out, as others have experienced,36 and as we know from our recent research on an intervention in dementia care,37 there are substantial challenges in setting up and carrying out an evaluation of complex interventions, and particularly in the area of dementia care.

Reflecting both the lack of current evidence and the difficulty of generating new evidence, our proposed project therefore had a dual purpose. The first aim was to make the best use of the existing data to examine outcomes for carers alongside inputs from AN, while also exploring the perceived systemic impact of specialist nursing support for carers. The second purpose was to test the feasibility of collecting outcomes and costs data and then to undertake exploratory research comparing the outcomes and costs of specialist nursing to support the carers of people with dementia against ‘usual care’, which might include other forms of carer support services.

Exploring how specialist community nursing services can support carers has the potential to reduce financial costs for health and social care services and, more importantly, social, health and financial costs for carers themselves. It also fits closely with current policy preoccupations, not only in relation to dementia and carers per se, but also in relation to the role of specialist community-based nurses in supporting the health and well-being of adult carers. 38 Among other issues, Compassion in Practice39 outlines clearly the need for carers and those they support to receive help from community-based practitioners who are experienced and knowledgeable, for the improved use of specialist roles and for greater harnessing of expertise to provide good-quality support. All of these and many other issues outlined in this policy document have clear relevance to the provision of specialist dementia nursing.

Without carers, the UK health and social care system would be unable to cope with the additional demands placed on it; finding effective and efficient ways of supporting carers to continue caring, if this is what they and the person they care for want, is thus of key importance in a country dealing with an ageing population. However, despite carers’ potential vulnerability and the repeated policy focus on the need to support them, we seem to be little nearer to delivering adequate support than we were when the first national survey of carers was carried out in 1985. 40

We currently know very little about the services available to carers of people with dementia across England, how carers engage with them and whether or not they answer carers’ needs. This study is a first step in understanding the national picture and preparing for a future full-scale evaluation.

Chapter 2 Study design and methods

In this chapter, we describe the detailed aims and objectives of the study, its design and the methods used to carry out the six work packages (WPs) that made up the project.

Design

In the absence of a secure evidence base for cost-effective interventions to provide support for carers of people with dementia, any high-quality evaluation will provide value. However, as the Medical Research Council guidance on the evaluation of complex interventions advises, it is important not to rush to a full-scale summative evaluation, such as a randomised controlled trial, before developing an understanding of the context within which interventions are delivered, their potential effects and the feasibility of a full-scale formal evaluation. 25 Developing such an understanding is what we aimed to do by adopting a mixed-methods approach, using secondary analysis of an existing administrative data set, along with primary quantitative and qualitative data collection.

We hoped that this approach would allow us to make the best use of existing and newly collected data to explore the potential effects and costs of specialist support for carers of people with dementia, while at the same time exploring the feasibility of formal evaluation in subsequent research. The work was thus intended to address two major uncertainties identified in the Bunn et al. 24 review:

-

limited quantitative evidence on the effectiveness, costs and cost-effectiveness of AN services, addressed by:

-

secondary analysis of the AN administrative database to identify preliminary evidence on the effectiveness (outcomes) of AN services

-

a survey of carers using AN services and carers in similar areas without AN services to generate preliminary evidence on the effectiveness and costs of AN services

-

-

an understanding of the relationship of AN with other health and social care services, addressed by:

-

an analysis of the AN administrative database to describe any (other) service support begun or discontinued after input from AN services

-

an analysis of all service receipt by carers using AN services and by carers in similar areas without AN services, using statistical methods to control for possible confounding variables

-

an in-depth exploration, in four case study areas, with health and social care commissioners and service providers of the impact of specialist dementia services, including AN, on the perceived impact on other health and social care services.

-

Patient and public involvement

This project was made possible by a partnership between the research team and Dementia UK, a third-sector organisation that campaigns for and supports people with dementia and their carers. AN is a Dementia UK service, and the charity had, for some time, sought support to explore its outcomes. Discussions between the research team and Dementia UK thus formed the basis of the original proposal.

In designing the study, we also consulted extensively with carers and people with dementia through the White Rose (University of York, University of Sheffield and University of Leeds) collaboration on dementia, cognition and care. Specialist nursing support for carers (or, more accurately, its lack) was one of the main priorities for future research identified through consultation. When the current project commenced, we continued to work with two of the carers on the White Rose consultation group, both of whom joined the project steering group and contributed throughout.

We also worked with Together in Dementia Everyday (TiDE), a national network of carers hosted by the Life Story Network community interest company, to establish a virtual advisory group of seven carers of people with dementia who were consulted throughout the project to advise on study design, project documentation and question wording for the survey. The group facilitator, a former carer herself, linked this group with the project steering group, attending meetings of the latter to present the views of the carers’ group. A further three carers regularly attended the steering group. This arrangement allowed carers to express their views in a facilitated and supportive environment. We found this approach to be of great value: carers were empowered to be both critical and supportive of the research, and their accounts of the lived experience of caring undoubtedly improved the project.

Towards the end of the project, we held a stakeholder workshop to discuss the study findings and their implications. Members of the virtual advisory group and other carers linked to the project were invited and supported to attend, and one-third of those who booked to attend the day said that they were current or former family carers. This workshop was extremely helpful to the research team in testing out the findings (see Appendix 1), and the presence of so many carers ensured that the implications and the next steps were grounded in the real-world experiences of those caring for people with dementia.

Aims and objectives

The aims of the project were to:

-

explore the processes, the individual and system-wide impacts and the effect on outcomes and costs of specialist support for carers of people with dementia (using the largest such service – AN – as an exemplar)

-

produce guidance to inform service delivery, organisation, practice and commissioning of specialist support for such carers.

Using a mixed-methods approach, the objectives were:

-

to carry out secondary analysis of an existing administrative database maintained by AN to explore the relationships between the characteristics of carers and people with dementia, AN service type and input and outcomes

-

using qualitative methods (interviews, focus groups and cognitive interviewing) with carers, to develop and test data collection methods to inform a subsequent cost-effectiveness evaluation

-

to conduct a survey of carers of people with dementia with and without access to AN services, in order to explore the effect on outcomes and costs of AN services, compared with usual care, and to determine the feasibility of a large-scale evaluation

-

using qualitative methods (face-to-face interviews with health and social care stakeholders in four case sites – two with and two without AN services), to explore the perceived system-wide impact of providing specialist support services for carers of people with dementia, compared with usual care

-

to implement new data collection methods to facilitate future evaluative research in AN, which could be used by other dementia service providers

-

to build on the findings of all elements of the project and work with key stakeholders to devise best-evidence guidelines for service organisation and commissioning.

Methods

The project had six interlinked WPs. In this section, we outline the main methods of each, as originally planned. Because of the mixed-methods design we adopted, further details of the methods that we actually used are provided in the individual chapters below.

Work package 1: secondary analysis of the Admiral Nursing administrative data set

Work package 1 prepared the administrative data maintained by AN for research purposes and then analysed the data to explore the links between carer characteristics, the characteristics of the person with dementia, AN input and outcomes over time (objective 1).

The data set

Admiral Nursing has maintained a database of its activities with individual carers since 2005. Data on carers’ personal characteristics, support needs, burden and physical and mental health, and some details of the person being cared for and on services provided, are collected by AN when it carries out its first assessment of carers’ needs, and these are entered into the data record. Data on variables, such as needs, burden and health, as well as AN input, are also collected at follow-up, allowing the exploration of outcomes over time. Needs assessment is carried out using AN’s own tool, with standard coding.

On the day when the anonymised data were securely transferred to the research team (11 March 2016), these included 24,825 records in a Microsoft Excel® 2013 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) data set and were made up of both ‘primary’ carers and other family members defined as secondary carers, as well as cases that were now closed. It also included records that log follow-up data for primary carers. Owing to the size of the database, the data were split into several data sets (see Table 8) to ease transfer and data manipulation. Dementia UK transformed the data into a format that was compatible with the data analysis software package that was being used for analysis [IBM Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) Statistics version 24 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA)], while ensuring that the baseline and follow-up data on individuals remained linked across the data sets.

Based on a preliminary discussion with AN, we expected to find data for 1360 carers whose needs were assessed at both baseline and at least one follow-up point. For a small number of carers, the data set also included standardised outcome measures, of which the Zarit Burden Inventory41 is the one most often completed. In September 2014, around 3% of open cases of carers had a completed Zarit Burden Inventory in their record.

Preparation of data for analysis

Admiral Nursing provided a cleaned and anonymised data set containing the records of carers who had used the service since 2005. However, as would be the case with any administrative data set, the following issues had to be addressed before we could export the data and start the analysis for research purposes:

-

Creating flat structures for all of the data, to allow linking across individual records.

-

As maintained by AN, each question in the needs assessment tool and the standardised outcome measures is entered on a separate row in the Excel spreadsheet. For example, the answers to questions 1–22 for the first carer who completed the Zarit Burden Inventory appear in the first 22 rows of the relevant sheet in the Excel spreadsheet. These data had to be converted into a flat structure (with all 22 answers in a single row) to allow us to easily and securely link the answers to the rest of the record for that carer. AN carried out this work, but it created substantial challenges, which are described in Chapter 3.

-

-

Linking baseline and follow-up (outcome) records for individual carers.

-

Each carer in the database had a unique identifier, but follow-up data were recorded in a separate file. We therefore needed to use the identifier to create single records for those carers for whom follow-up data were available. Although it had originally been planned that AN would carry out this work, it was eventually done at the University of York.

-

-

Devising a coding framework for data currently entered as text.

-

The research team reviewed all of the data and liaised with Dementia UK to ensure that they understood the concepts and questions behind the data, the mode of data entry – that is, entered by staff or system-generated – and the data codes that existed in the data sets received. For example, data related to needs assessments were already coded from 0 to 3. We accessed the relevant assessment documents and, when appropriate, spoke with members of the Dementia UK data team to clarify coding systems, so that we were able to determine the meaning of each code (for the example given above, this was 0 = no need, 1 = need currently met, 2 = unmet need, 3 = not known).

-

Some data, such as the carer relationship to the person with dementia, country of birth and risk screening, were in text form. These forms of data had to be transformed into numerical codes to enable analysis. Two members of the research team (GP and FA) reviewed the text and identified summary categories for these data using filtering commands in Excel, and the data were recoded accordingly.

-

In two of the data sets – daily activity log and risk screening – the data were qualitative and extensive. To carry out the planned analysis, we needed to create numerical (categorical) data from the text. We started to develop a coding framework by taking a systematic sample of records and examining the text for commonalities and differences in the text for each ‘question’, and then devised and piloted the coding framework. Once the coding framework was finalised, we aimed to apply it to all textual material, thereby creating categorical variables. However, after reading the data and identifying the initial codes, we felt that these data required more in-depth qualitative analysis to maintain data integrity and to illustrate the complexity of cases that Admiral Nurses were dealing with and that clients were experiencing. A summary of these qualitative data is provided in Chapter 3.

-

-

Creating variables to summarise the type of AN service received.

-

We had planned to create descriptive variables for the current AN services, using another AN data set that logged service details, including team composition and size, geographical area covered, referral processes, funding source and staff complement. This would have allowed us to explore relationships between service characteristics and outcomes. We encountered considerable challenges in this part of the planned work, mainly because of difficulties in accessing information about teams that were in existence when we did the work and the impossibility of obtaining data for teams that no longer existed. We therefore did not, in the end, conduct these analyses.

-

Analysis

We first used analysis of this unique data set to provide a detailed picture of the carers who have used AN services. We then attempted to use records when needs assessment had been carried out at more than one point to explore how AN input affected outcomes. We had hoped to carry out a range of univariate, bivariate and multivariate (regression) analyses and to establish the links between type and intensity of AN input, service user characteristics and needs and outcomes. The initial univariate and bivariate analyses were intended to explore patterns of change in the outcomes, create change variables and identify service types. The generalised regression and multilevel approaches would then explore the unique and inter-related contributions of carer characteristics, service input and team types to outcomes. For reasons explained in Chapter 3, we were unable to progress beyond the univariate and bivariate analyses. However, the large amount of work that has gone into turning an administrative data set into something that can be used for research lays the base for multivariate exploration in the future.

Individual AN services have changed over time in their characteristics and functions, and, since 2005, some have ceased to operate, whereas others have started up. We could not, therefore, use the data simply to ‘describe’ AN services. However, we did use the data to analyse what type of work was done, and used this to develop a picture of the AN service ‘offer’.

All analyses were carried out by the University of York team.

Work package 2: develop and test data collection methods for the survey and the new data set

Work package 2 was designed to establish a data collection framework and processes for the survey in WP 3 (objective 2).

There were two elements to the package. First, we wanted to establish what outcomes are important to carers in terms of their actual or anticipated use of specialist nursing support. Second, we needed to identify robust ways of measuring those outcomes, that were acceptable to and feasible for carers, both for our survey in WP 3 and for use in service settings (WP 5). The in-depth exploration of the acceptability and the feasibility of the framework and processes was an essential element, given the acknowledged challenges of evaluative research in dementia care.

Sample

We identified two areas with an AN service and two areas without and recruited carers in each, aiming for a total sample of around 30 carers, with a wide range of characteristics and circumstances. The details of the recruitment processes and outcomes are provided in Chapter 4.

Although we had initially planned to hold focus groups on the University of York campus, we soon realised that it would be more convenient for carers to hold these groups in meeting places (churches, community centres, etc.) that were local to the carers’ own homes. We also offered carers the option of an individual interview by telephone or in their home, or somewhere else to suit them. We offered to pay for the costs of substitute support for the person with dementia when this would help the carer to participate.

Methods

Developing the survey

We talked to carers twice, using focus groups or, when requested, individual interviews.

At the first contact, we used in-depth qualitative methods to explore with carers the outcomes that they would like to experience if receiving support from specialist dementia services that were focused on carers. For those who lived in areas without AN services, we first described the support that they might get from such a service, so that they could focus their responses on this type of service.

At the end of each group session or interview, we fed back the learning from the discussion and worked with the carers to finalise the outcomes they wanted us to take forward to the next stage of work. We recorded the groups and interviews (with carers’ permission), but did not fully transcribe all of them. After the interviews, we reviewed the recordings, first to ensure that we did not miss any outcomes in the summing up and, second, to carry out a brief analysis of the material, under each of the outcomes identified. We used the framework principles of case- and theme-based analysis and data reduction through summarisation and synthesis42 to do this.

We then identified robust, standardised measures that are available to assess the main outcomes that carers had identified. In doing this, we were guided by the work that Early detection and timely INTERvention in DEMentia (INTERDEM) has done to identify good-quality outcome measures in dementia care. 43 This work and the measures that we selected – the EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D),44 Adult Social Care Outcomes Toolkit (ASCOT) for Carers (ASCOT-Carer) (the ASCOT-Carer measure was used in the study with permission from the University of Kent on an all rights reserved basis. The measure should not be used for any purposes without the appropriate permissions from the University of Kent. Please visit www.pssru.ac.uk/ascot or email ascot@kent.ac.uk to enquire about permissions)45 and the Family Caregivers’ Self-Efficacy for Managing Dementia (SEMD) scale46 – are described in detail in Chapter 4.

The questionnaire had a dual purpose within our proposed work. First, it was to collect data on the carers of people with dementia in areas with and areas without AN for WP 3 (see Work package 3: survey and analysis of outcomes and analysis of outcomes and costs) and, second, it was to provide the basis for a draft data collection framework for AN to use routinely (see Work Package 5: implement a new data collection system for Admiral Nursing and promote it to other dementia service providers). The questionnaire included:

-

Questions on the demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of the carer and of the person with dementia (e.g. age, sex, ethnicity, education and household resource level).

-

Instruments that measured the outcomes that were important to carers (see above and Chapter 4).

-

Questions on the time and resource use associated with caring. These included unpaid (informal) care time, out-of-pocket costs for care services, health [e.g. hospital appointments, general practitioner (GP) appointments], social care (e.g. home care) and non-statutory sector resources. These also included questions on specialist dementia services accessed by the carer (both AN and other services).

We then carried out cognitive interviews with carers. These explored the carers’ understanding of the questionnaire and its acceptability to them. We also talked to them about the feasibility of carers completing a questionnaire of this type online and in hard copy, and the pros and cons of self-completion versus face-to-face or telephone interviews.

We tested the administration of the survey, both electronically and in hard copy, with a small number of carers (n = 9) who had been involved with the earlier work and with members of our carers’ virtual advisory group and our steering group.

The survey was developed within, and administered using, Qualtrics [February 2017; www.qualtrics.com (Provo, UT, USA and Seattle, WA, USA)]. This is sophisticated, internet-based survey software that allowed us to produce and distribute high-quality online questionnaires. We also produced a paper version of the questionnaire, which is reproduced in Appendix 2.

Work package 3: survey and analysis of outcomes and costs

The key aims of WP 3 were to address objective 3 by:

-

understanding the characteristics of carers, the people with dementia whom they support and their outcomes and costs with and without AN services

-

exploring the effect on outcomes and costs of AN by comparing relevant carer outcomes and costs in areas with and areas without AN services

-

evaluating the feasibility of recruiting carers and collecting their outcomes via online and postal questionnaires in future research.

Rationale for our chosen survey design

Our aim in this section of the proposed work was to compare the carers of people with dementia who used AN services with those who did not (who received ‘usual care’), both to judge the likely effect of AN services on carers’ outcomes and to assess the costs of AN services against any benefits that might be identified.

Admiral Nursing is the only specialist nursing service for the carers of people with dementia, so we felt relatively sure that carers in non-AN areas would not be receiving any carer-focused, dementia-specific services. Other services that both AN and non-AN carers might use include visits from community-based mental health nurses, home care services and social work input. However, we expected to see substantial heterogeneity, given the diversity of support services for people with dementia and their carers and the diversity of provision across the country. It is possible that AN services substitute for other forms of services that carers might otherwise have received. However, at the outset, we thought that it was more likely, given the objectives of AN services, that they would enhance carers’ access to other services, via signposting and direct liaison.

We had hoped to strengthen our analysis by also surveying a small number of carers who lived in AN areas but did not use AN services. The substantial challenges of identifying those not using AN services, described in more detail in Chapter 5, meant that we did not achieve this secondary aim.

Choice of design

Our chosen design was a cross-sectional survey. We chose this approach because the carers of people with dementia are a precious research resource, and longitudinal data collection would impose additional burdens on them and, in all likelihood, reduce response rates over time. However, we intended that the design of the sampling and analysis strategies would allow us to carry out a robust cross-sectional comparison between those who did and those who did not use AN services.

First, the sample selection processes aimed to reduce heterogeneity, both within the AN services being evaluated and between carers in areas with and without AN services.

Choice of sampling frame

We generated simple, two-stage cluster samples of local authority (LA) areas that had ‘standard’ AN services (see below for a definition) and broadly similar (matched) LA areas without AN services. We then intended to carry out proportionate random sampling of current users of AN services in the former areas and of carers in contact with TiDE in the latter areas to generate the respondents for the survey. For the reasons described in detail in Chapter 5, identifying carers in non-AN areas was extremely challenging and we were not able to carry out this element of the design. We did, however, carry out proportionate sampling of carers in our selected AN services.

‘Standard’ model of Admiral Nursing services

As outlined in Chapter 1, AN services vary in their composition, remit, funding models, case mix and other key characteristics. For the purposes of this WP, however, we needed to compare the outcomes from services that were typical of the majority. We therefore selected areas with AN services that delivered a ‘standard’ model, which, after discussion with AN, we defined as services that:

-

were based in the community (rather than in a long-term care setting)

-

provided support mainly to carers when supporting a person still living in a private household

-

were funded to provide support to any carer (thus excluding third-sector-funded services that provided support only to a subgroup of carers).

Matched areas

We defined ‘broadly similar’ areas in terms of statistical neighbourhood, as defined by the Chartered Institute of Public Finance and Accountancy (CIPFA)’s statistical model (www.cipfastats.net/default_view.asp?content_ref=18003; accessed 16 October 2018). Statistical neighbourhood is used by local authorities themselves, and across government, to allow comparisons between authorities that are similar in terms of population size and characteristics, such as age distribution, deprivation and ethnicity. For example, the Department of Health and Social Care has developed an interactive adult social care efficiency tool (www.gov.uk/government/publications/adult-social-care-efficiency-tool; accessed 16 October 2018), which compares local authorities’ performance on service provision to, and expenditure on, older people and people with a learning disability. It was this latter tool that we eventually used to match areas.

Sample size

Sample size calculation for cross-sectional surveys of populations is simple when the sole aim of the survey is to describe the population within given statistical tolerances. Similarly, sample size calculation is relatively simple when the sole aim is to compare outcomes between equivalent groups that vary only in their receipt or not of an intervention. However, this calculation does also require prior knowledge about, or an indication of, what size of effect one might be expecting, or what average level of a chosen outcome one might expect to see in the selected population prior to intervention.

In our survey, we wished both to describe and to draw inferences about what effect using AN services might have on carers of people with dementia. Although our sampling strategy (see above) was intended to reduce some of the likely variation between users and non-users of AN services, we also needed to control for any other differences between them that would become evident after collecting data. This was so that we could feel confident that we were seeing the effect (if any) of AN services on measured outcomes, and not the effect of some other differences between carers.

It was challenging to find any up-to-date population-based evidence about the average levels of (for example) the quality of life of carers of people with dementia, or any UK-based comparative studies that might hint at possible effect sizes from similar types of intervention.

Given these challenges, we took a pragmatic approach to sample size calculation using three different approaches. The first was a simple population survey sample calculation. The second was a sample calculation for comparative research, using the effect sizes found in a randomised controlled trial of community occupational therapy in the Netherlands47 that aimed to help carers to use ‘effective supervision, problem solving, and coping strategies’ with a view to sustaining both their own and the person with dementia’s ‘autonomy and social participation’. This intervention also included similar input for the person with dementia and found very substantial differences on a range of outcomes at the 3-month follow-up point. We then assessed how many independent variables could be included in a multivariate analysis, based on the sample sizes generated by these two approaches. The results of these calculations are in Table 9 in Appendix 3.

A pragmatic decision about an achievable sample size, within reasonable resource use, took us to a decision about original sample size somewhere between the two figures of 26 and 640 generated by this process. Assuming that we would need to control for up to 20 independent variables in a regression analysis, we calculated that an achieved sample of 320 participants would be needed to detect differences of the size observed in the Graff et al. 47 study.

We assumed that the response rate in non-AN areas might be lower than that for AN users [e.g. 50%, rather than the 60% we had achieved in a recent survey of carers in another National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)-funded project]. 37 Subsequent discussion with AN prompted us to reduce the anticipated response rate further to 30%. Taken together, to achieve 160 participants in each group, we needed to sample around 480 carers from AN services and 480 carers in non-AN areas: a total of 960 carers.

While preparing the original proposal, the team had discussions with staff at Dementia UK about the likely caseloads that might be found in individual AN services. Although services varied in size, the general view was that an average of 35 active cases per site was likely. We therefore needed to sample at least 16 teams to achieve our required sample size (again assuming a 30% response rate for this group). This also gave us the recommended minimum number of 30 clusters (15 AN areas and 15 matched non-AN areas) for this type of survey design.

Admiral Nursing teams identified carers who were currently using the service in the selected AN areas. A range of approaches was used to identify carers in the non-AN areas (see Chapter 5).

When the number of cases per AN team was greater than needed for sampling, we used proportionate random sampling to generate the required numbers.

Methods

Survey

In our 16 AN areas, we asked the AN services to identify carers of people on their current caseload and to facilitate distribution of the questionnaire developed in WP 2. We also worked with a range of statutory and non-statutory organisations to identify carers of people with dementia in the 16 matched, non-AN areas. In both cases, we offered the option of electronic and paper-based delivery, depending on individual preferences. Our earlier discussions with AN had suggested that electronic distribution would be the preferred option for AN carers but, in reality, this was not the case, as many selected services did not have e-mail addresses for the carers. We therefore ended up with a majority of AN returns on paper and, because of the way in which we sampled them, a majority of electronic returns from carers in non-AN areas. Further details of this are in Chapter 5 and a copy of the paper questionnaire is in Appendix 2.

For paper-based questionnaires, we included a leaflet explaining our study and its objectives, the questionnaire and a prepaid envelope for returning directly to the research team. For questionnaires delivered electronically, we attached the same leaflet to an e-mail, which also provided a unique electronic link to the survey.

We offered carers a £10 voucher on receipt of their completed questionnaire to thank them for taking the time and the effort to answer the questions and contribute to our research.

Further details of the sample identification and selection and the questionnaire administration are in Chapter 5.

Data entry

Data gathered via Qualtrics were initially exported as an Excel spreadsheet, which, after some editing, was exported to statistical software (SPSS and Stata®, StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) for analysis. Data returned via paper-based questionnaires were checked for quality and then entered into Qualtrics manually.

Analysis

We carried out a number of descriptive and econometric analyses that enabled us to understand the characteristics of carers and the person they support and how these related to their outcomes and costs, with and without AN services. We also used data on responses to the survey to assess the feasibility of future research to collect data on carers and the people with dementia they care for via online and postal questionnaires.

The analysis plan was designed to include the exploration and analysis of outcomes and costs, and also methodological learning.

Describing outcomes

The first stage described the characteristics of carers and explored their relationship with outcomes. The univariate and bivariate analyses explored carers’ demographic and socioeconomic characteristics; the characteristics of the person with dementia; carer-specific variables, such as type and hours of care provided; scores on our selected outcome measures; and resource use and costs.

This preliminary work also allowed us to compare the overall characteristics of the AN carers and people with dementia with the characteristics of carers and people with dementia in the non-AN areas. This enabled us to specify potential confounding variables for the subsequent analysis of outcomes and costs, as well as to establish the representativeness of carers who had completed the survey.

In the second stage of the analysis, we costed the health and social care services used by carers using national unit costs when available, or using the local unit costs of services otherwise. A descriptive analysis of the resources used by carers, and the costs of those resources, was carried out, and the relationship between the carers’ characteristics, the characteristics of the person with dementia, outcomes and costs was evaluated. The relationship between costs to the health and social care sector by type of area (with and without AN), controlling for the characteristics of the carer and the person with dementia, was of particular interest, as it might indicate whether or not AN services can generate savings in the health and social care sector by providing support to carers.

Analysis of outcomes and costs

Building on stages 1 and 2, we then carried out an analysis of outcomes and costs using regression analysis, propensity score matching (PSM) and an instrumental variables (IVs) approach to establish the associations between the carers’ characteristics, costs and outcomes.

The analysis aimed to evaluate the costs and effects associated with AN compared with usual care for carers. Our focus was on carers, given that AN was primarily designed to support the carer rather than the person with dementia. A broad perspective was taken to account for the costs falling on the NHS, social services and voluntary-sector services.

The aim was that the primary analysis would involve an analysis of outcomes and costs using the NICE reference case for health-care interventions taking the NHS and Personal Social Services (PSS) perspective. 48 This includes the costs falling on the NHS and PSS budgets and the outcomes that were relevant to carers. The costs falling on the NHS and PSS budgets included hospital appointments, primary care appointments (GP, nurse and so on), home care funded by the LA and the AN service itself. Resource use was costed using published, national average unit costs49,50 and NHS reference costs51,52 when available, so that the cost analysis was as generalisable across England as possible.

In addition, we ran a descriptive analysis to compare out-of-pocket costs and other informal (unpaid) care costs across AN and non-AN carers.

Dealing with comparability and unknown confounders

Given the non-randomised, cross-sectional nature of the data collection process, quantifying an association between outcomes and the availability of AN services requires us to be sure that carers responding to the survey in areas with and in areas without AN services are comparable in observed and unobserved factors that might affect outcomes.

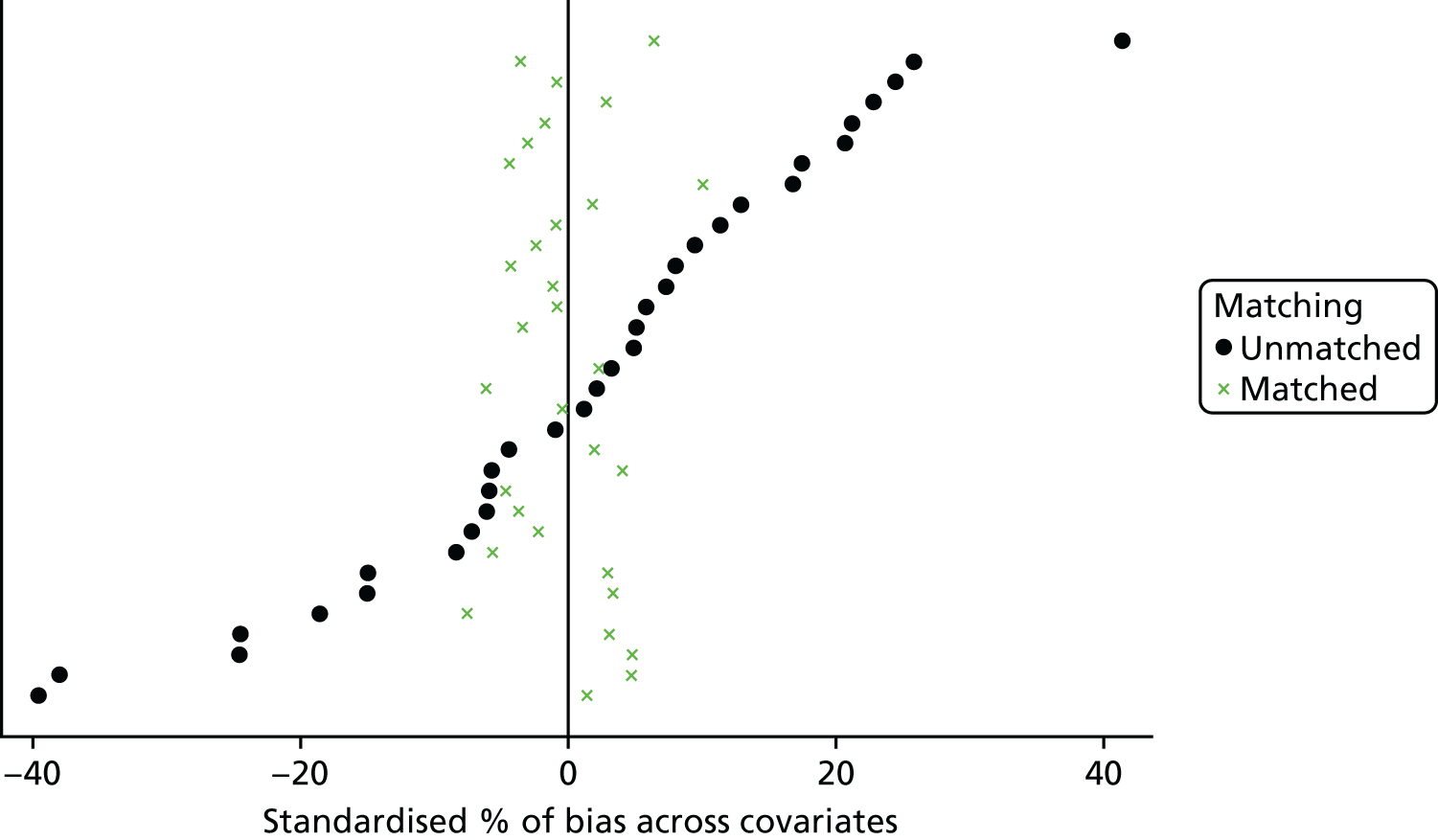

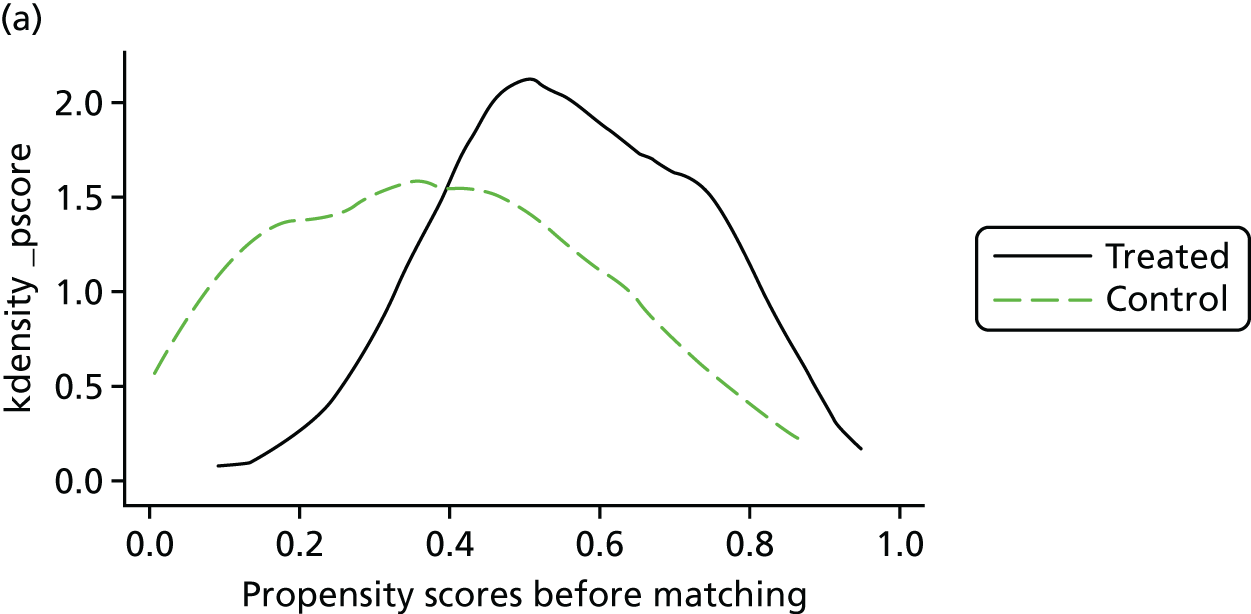

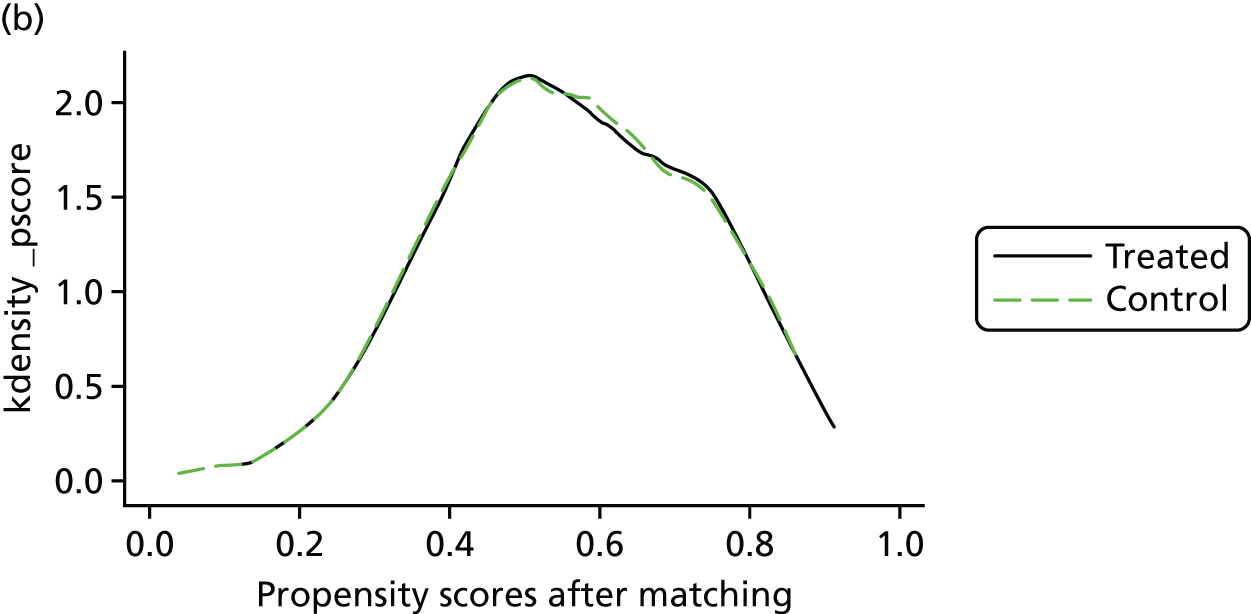

For this reason, the analysis was in five stages, described in detail in Chapter 6: descriptive analysis, linear regression analysis, PSM, IV analysis and sensitivity analysis. We conducted the descriptive analysis to understand the characteristics of the sample and to select the variables to use in the subsequent analyses. With the linear regression analysis, we analysed the associations between having AN services and outcomes and costs, controlling for the observed differences between carers with and without AN services. We used PSM to generate comparable groups of carers with and without AN services. 53

Linear regression and PSM can deal only with observed differences in the two groups of carers. We had some concerns that there might be unobserved differences (i.e. differences in characteristics on which we could not collect data). The implication was that carers in non-AN areas would not represent carers in AN areas in the absence of AN services, even after controlling for observed characteristics. This is known as selection bias (also known as confounding or endogeneity).

The IV approach may reduce the risk of selection bias in the presence of good instruments. The instrument was the travel time between the carer and the AN provider. Carers living far from the AN provider may not be eligible, because the service is limited to a specific geographical area. Moreover, carers living at long travel distances from the AN provider may be less likely to be informed about AN than carers living in proximity to AN teams; thus, carers living near AN providers may be more likely to be eligible for or to access the service. Similar to Forder et al. ,54 we used the type of LA as an instrument. The type of LA may indeed determine the LA’s culture and, in turn, the LA’s propensity to invest in services for carers; the culture, however, will not have a direct effect on the carer’s outcomes.

Work package 4: understand the wider impact of specialist support for carers of people with dementia

The effects of specialist dementia services may extend beyond individual outcomes and resource use, having effects also at a system level. For example, if services enable carers to care for longer or help them to remain healthy, they may reduce costs to both health and social care systems. WP 4 explored with health and social care stakeholders what they perceived to be the system-wide effects of supporting carers of people with dementia, with a specific emphasis on specialist nursing support of the type AN provides.

Sample

We selected two areas with AN services that delivered a ‘standard’ model, defined in the same way as for WP 3 (see ‘Standard’ model of Admiral Nursing services in Work package 3: survey and analysis of outcomes and analysis of outcomes and costs).

We then selected two areas that did not have AN services but that were broadly similar areas to those with AN services. We selected areas that were also selected for WP 3 in the hope that we could triangulate our qualitative and quantitative findings in these areas (thus treating them as case studies). For reasons explained in Chapter 7, it was not possible to triangulate the findings as originally envisaged.

Within each area, we identified the key health and social care stakeholders in dementia care and support for carers. This included both statutory and third-sector (e.g. senior managers of local Age UK or Carers UK) stakeholders. We started with the main health service or social care commissioner for dementia services in each area and then used snowballing techniques to identify other stakeholders.

We intended to grow the sample until we were learning nothing new (i.e. we achieved saturation of the data) and expected to identify between 12 and 15 key stakeholders in each area to achieve saturation. Chapter 7 describes the outcomes of this approach.

Methods

We carried out in-depth, semistructured interviews with stakeholders that explored the perceived system-wide impact of carer services, such as AN, compared with ‘usual care’ (objective 4).

The interview aide-memoire covered the following topics:

-

the current provision and cost of support for carers of people with dementia

-

the perceived impact of support for carers of people with dementia (or its lack) on other health and social care services

-

the balance between the costs and benefits of supporting carers

-

future plans for (further) developing support for carers of people with dementia.

In the AN areas, we also covered topics specific to AN, such as commissioning arrangements and intentions.

We also used this stage to explore the feasibility of implementing routine collection of outcome and resource use data.

Work package 5: implement a new data collection system for Admiral Nursing and promote it to other dementia service providers

Using the learning from WP 2, we worked with AN services to develop a new data collection framework to provide the data required for future evaluative research, while also meeting their administrative needs. This built on the work in prior stages to understand the feasibility for dementia service providers, and acceptability to carers, of using a range of validated outcome measures as part of routine data collection.

Following the general shape of the survey questionnaire, we expected the framework broadly to include socioeconomic data, quality-of-life measures (both generic and carer-specific), informal carer time and health and social care resource use, as well as administrative data that describe AN activity and input for individual carers. We aimed to pilot the new framework with one AN team to test its feasibility in the field and to work with Dementia UK to inform its approach to routine data collection across all services going forward.

Further details about the ways in which this WP was carried out are in Appendix 1.

Work package 6: develop best-evidence guidance for service commissioning and the delivery of support for carers of people with dementia

The final stage of our project was a stakeholder workshop that presented the findings of all elements of our research. We worked with stakeholders during a full-day event to begin drafting a statement about the current evidence for specialist support for carers of people with dementia, how different models of support might influence outcomes and how to collect data at a local level so that they inform both service development and evaluation.

We invited a range of stakeholders, including carers, decision-makers from health and social care commissioning and provider organisations (including those in the third sector) and local and regional policy-makers. Key points from this workshop are presented in Appendix 1. These fed into a summary of the project findings, which was circulated to participants and other stakeholders and is now available as a project output. 55

Chapter 3 Analysis of the Admiral Nursing administrative data set

Work package 1 of the project focused on preparing Dementia UK’s AN administrative data set for analysis of its routinely collected data for research purposes. The aim of this analysis was to help to understand the characteristics of carers who use AN services and the characteristics of the person they care for, the type and level of input carers receive from AN services and the outcomes carers experience when using AN services. As outlined in Chapter 2, because of the size of the database, the data were split into several data sets to ease transfer and data manipulation. Table 8 (see Appendix 3) provides an overview of the data sets received.

Analysis

Each data set was initially analysed separately and, when appropriate and practical, then joined and analysed alongside other data sets.

Some data held within the database were collected at a single point in time and some were longitudinal. Data collected at a single time point – usually at entry to the service – included information about the sociodemographic characteristics of carers, agencies involved in the case at admission to AN and other family members involved. We analysed these data descriptively.

The Likert scale-derived data about the needs of the dyad of the carer and the person with dementia were longitudinal. There were two main data sets with such repeated measures, both related to needs assessment. One data set held data from an older version of the AN service’s own needs assessment form and the other held data from a new version of the form. The current needs assessment contained 18 questions and the legacy assessment contained 19 questions. Most of these were about comparable topics, but the response options were different. On the legacy needs assessment, the five-point Likert scale responses were about whether or not there was a need that required intervention and the severity/urgency of that need/intervention (i.e. none, minimal, some, considerable, urgent). The current needs assessment tool used a four-point Likert scale to ascertain whether or not there was a need that might require intervention, but did not refer to the severity or urgency of that need/intervention (i.e. no need, needs currently met, unmet need, not known). The legacy assessment asked a specific question about information in relation to understanding dementia symptoms, but this was not included in the current tool. The current tool included a question about risk that was not on the legacy tool (see Appendix 3, Table 10). Because of these differences, the two data sets were analysed separately.

The data sets held legacy needs assessments for 2074 carers and current needs assessments for 2541 carers. Some carers were assessed up to eight times using the legacy needs assessment and up to nine times using the current needs assessment; however, the majority of carers had only one assessment recorded (see Appendix 3, Table 11). To ensure that we would be able to detect any changes in needs assessment over time while retaining an adequate sample size, we limited the analysis of assessments to carers’ first three assessments. To be able to do this, we undertook additional restructuring of the data sets.

First, we conducted a match-text analysis on unique identification numbers to identify carers who had been assessed using both assessment formats. This showed that 51 carers were assessed using both the legacy and the current assessments forms. The analysis of these 51 cases across the two data sets confirmed that the legacy needs assessments were completed before the current needs assessments. Thus, we were able to remove the 51 duplicate cases from the current needs assessment data set.

Second, when we received the data, they were not in any particular date order. On speaking with the administrator of the database, it became clear that, when the data were converted from their original structure to the required ‘flat’ structure (as outlined in Chapter 2), they had been ordered by the date on which they were entered onto the system rather than the date on which assessments were undertaken. To correct this problem, we had to convert the data set back to its original structure and then restructure it again into a flat format in order of the dates of the assessments. Assessments without dates were removed from the data set being analysed.

Finally, we removed all cases in which there were fewer than three assessments on each of the forms. This left us with active data sets of 157 cases for the legacy needs assessment and 201 cases for the current assessment (see Appendix 3, Table 12).

These longitudinal data were then subject to descriptive analyses and Friedman’s tests to analyse the variance in responses to the needs assessment questions over three consecutive time points. The Friedman test is appropriate for examining differences in ordinal values over time when the samples are related (as they are here) and produces a chi-squared statistic. When the results of the Friedman test were significant, we then carried out Wilcoxon signed-rank post hoc tests with Bonferroni adjustment, resulting in a significance level set at a p-value of < 0.017, to establish which pairs of needs assessment data accounted for the differences.

The cases data set

Of all of the data sets, the ‘cases’ data provided the most complete and up-to-date overview of clients of AN services, with information about all 24,825 current and previous clients. Of these client cases, 85% were closed (see Appendix 3, Table 13). When relevant, the findings are presented to enable a comparison of closed (previous), open (current; 14%) and waiting-list (future; 1%) client cases.

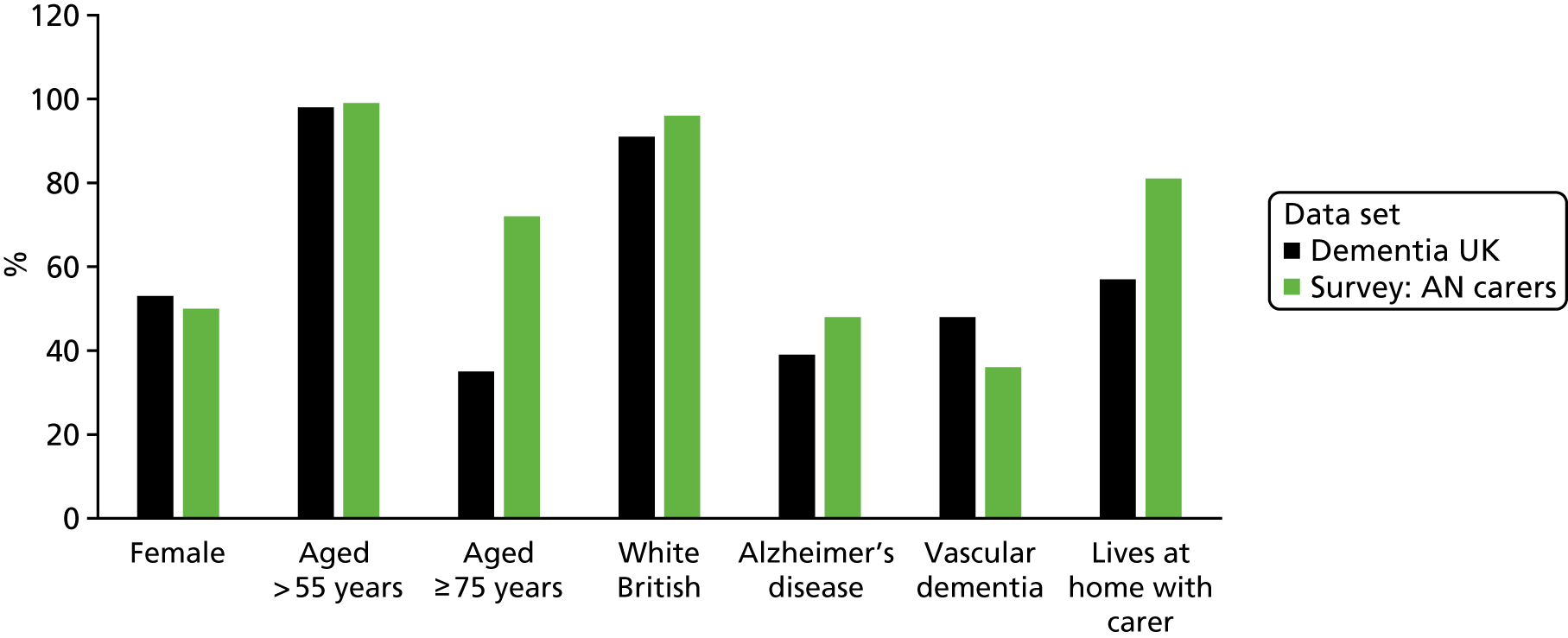

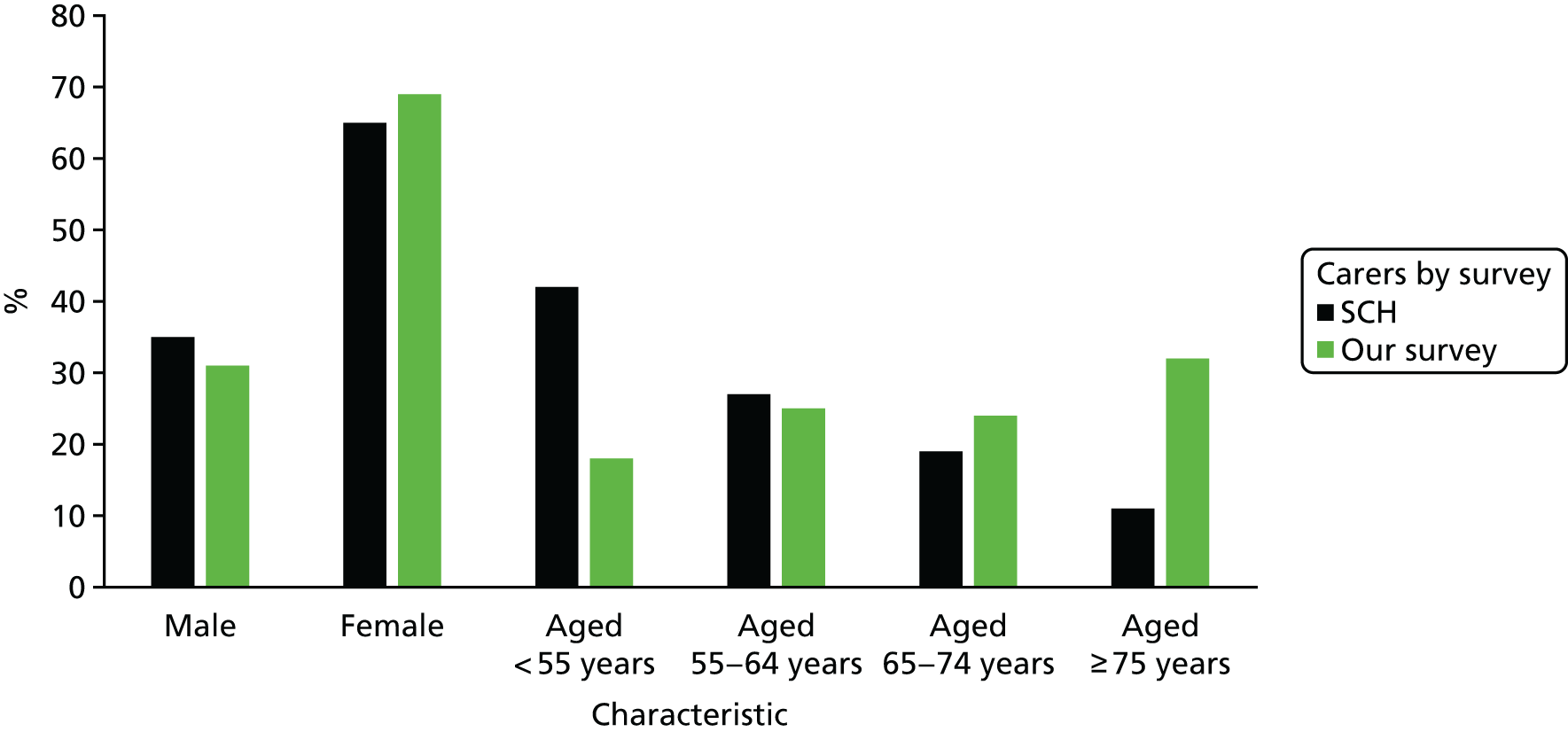

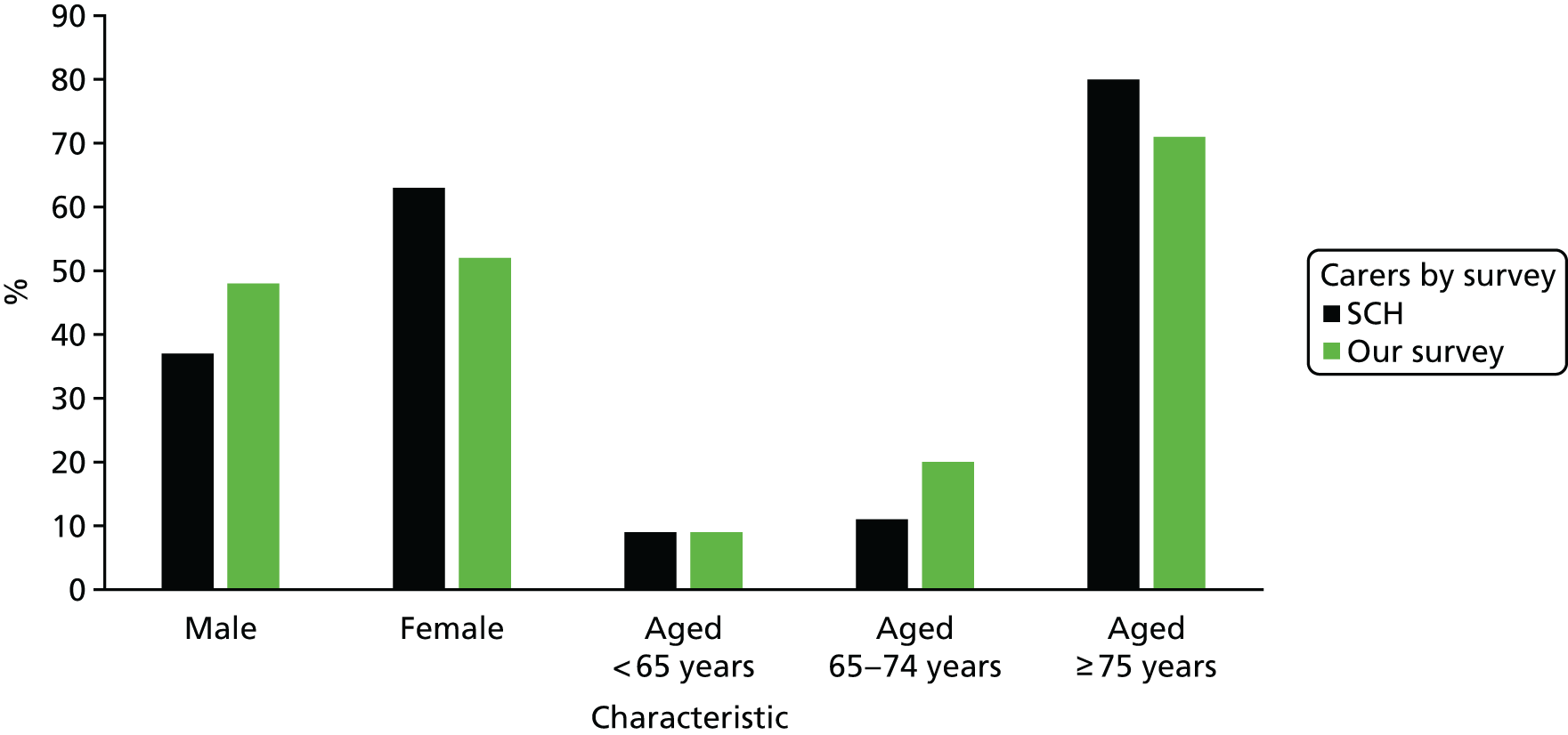

Demographics of carers and people with dementia

Almost three-quarters of carers (71%), whether previous or current clients, were the main carer for the person with dementia. Information about living situation was recorded for only one-quarter of the people with dementia. Most lived with their main carer (57%) or alone (14%). Most carers were female (70%), whereas the people with dementia were split almost equally in terms of sex (53% female, 47% male). Over three-quarters of carers (77%) were > 55 years of age, as, unsurprisingly, were most people with dementia (98%). Almost two-thirds of the primary carers were retired, but an important minority (15%) were in full-time employment. Ninety-one per cent of both the carers and the people with dementia were described as being of white ethnicity (see Appendix 3, Tables 14–19).

Table 20 in Appendix 3 shows the relationship between the age of carers and the age of people with dementia. Almost one in three carers (32%) were in the oldest age group (aged ≥ 75 years) and were caring for someone in the oldest age group. The similarity in age is not surprising, given that the majority of carers (88%) receiving support from the AN service were married and were most likely supporting their spouse or partner (see Appendix 3, Tables 21 and 22).

Diagnoses

Seventy per cent of the cases in the cases data set reported whether or not the person with dementia had been diagnosed when they were referred to the AN service; almost half of these people had been formally diagnosed. When a diagnosis was recorded, the most common were Alzheimer’s disease (39%) and vascular dementia (30%). Table 23 in Appendix 3 shows that there was little variation in diagnoses among closed, open or waiting-list client cases, although open cases were somewhat less likely yet to have received a diagnosis, as might be expected.

Service provision

The intensity of input that carers received from Admiral Nurses was recorded for current clients. In almost half of the cases, when the data were entered into the data set, Admiral Nurses were still working with carers to determine their longer-term input requirements (45%). Almost one-third of carers (31%) were recorded as receiving a medium level of intervention, which could include, for example, monthly one-to-one meetings and planned telephone, e-mail or group contacts between meetings (see Appendix 3, Table 24). Carers classified as being in the ‘holding pool’ (13%) had the lowest level of intervention: 3- to 6-monthly telephone or face-to-face contacts, and contact at other times if initiated by the carer. Eleven per cent of carers were in the intensive category: the highest level of intervention that Admiral Nurses provide. Intensive support could be monthly or more frequent visits in combination with support group attendance and could include both planned and unplanned contacts and multiagency working.

This analysis suggests that Admiral Nurses are accessible through different routes and at times when carers need them and thus are able to provide a responsive and flexible service, responding to carers’ requirements at different times. By enabling those carers who need the least amount of support to request additional contacts if necessary, Admiral Nurses empower carers to take the helm as they travel through their caring journey.

Daily activity log data set

Support given by Admiral Nurses

As outlined in Chapter 2, we undertook a thematic analysis of a sample of the textual data that Admiral Nurses recorded about their daily work and that was entered in the daily activity log data set. This illustrated the wide variety of tasks that Admiral Nurses undertook to support carers. We categorised these as:

-

assessment and monitoring

-

discussion, information provision and advice

-

care co-ordination

-

emotional support/counselling

-

practical support.

Admiral Nurses also provided education to other service providers and professionals involved in their clients’ and the wider community’s care, and organised and ran carers’ groups. These last two roles are not discussed here because no detail was provided in the data set about what these roles entailed.

Assessment and monitoring

As the range of data listed in Appendix 3, Table 8 shows, Admiral Nurses formally assessed carers, their needs for support and the risks that they might be experiencing. The textual data from the daily activity log showed that, as appropriate, they also undertook assessments of the person with dementia, such as the Mini Mental State Examination, to help in planning and providing support to the carer. In addition to these more formal assessments, Admiral Nurses monitored carers’ mood and mental health during contacts, so that input could be adapted to respond to carers’ changing needs. One of the key assessments that Admiral Nurses undertook was risk assessment, which we analyse later in the chapter.

Discussion, information provision and advice

One of the central roles that Admiral Nurses played was spending time with carers, giving them the opportunity to discuss their practical concerns and fears and gain confidence. The data indicated that, drawing on their expertise about dementia to provide relevant and timely information and advice, Admiral Nurses talked with carers about managing the person with dementia’s behaviour, including safety and changing needs, addressed fears about the future, provided advice about coping strategies and identified services that might help in caring for the person with dementia and/or supporting the carer.

Care co-ordination

Admiral Nurses made and ‘chased up’ referrals to other services on carers’ behalf and also facilitated carers’ ability to lead referrals themselves by providing relevant forms. This helped to provide carers and people with dementia with timely access to services. The data indicated that they provided a conduit for communication between the carer/person with dementia and services, providing both sides with updates on progress with referrals and care management decisions, including transitions between different care settings. Admiral Nurses also took a lead role in co-ordinating care, liaising with, for example, health, social care and benefit services, the LA and community police services. An interesting part of their role was liaising with community policing to implement strategies to minimise risks that people with dementia might face, for example opening the door to untrustworthy people. The work of the police service in relation to dementia is not well explored in the existing literature on dementia care,56 but could serve to reduce both the risk to the person with dementia and the carer’s levels of anxiety.

Emotional support and counselling

The main way that Admiral Nurses supported carers emotionally was spending time listening to them. Their emotional support focused on helping carers to see that it was beneficial to care for themselves as well as the person with dementia, encouraging them to have confidence in their ability as a carer and being there when carers needed reassurance or guidance about how to deal with a new situation. Their expertise about dementia and the symptoms that might occur meant that Admiral Nurses were able to reassure carers about behaviour that the person with dementia was displaying and about the future and the services that would be able to support them. They could also help carers to appreciate that respite care for the person with dementia could be beneficial for both of them.

Practical support

Admiral Nurses also provided practical support to make caring more manageable. Alongside helping carers to understand and complete benefit forms, apply for voucher schemes, and register with their GP as a carer, Admiral Nurses also helped by visiting the person with dementia while he or she was in respite care, so that carers could have a proper break and be reassured that the person would be visited. Some Admiral Nurses also helped by collecting and delivering medications and continence aids and taking medical equipment to respite facilities.

These data showed the variety of roles that Admiral Nurses adopted, including providing support for people with dementia themselves, to help support their client in their caring role.

Risk screening data set

The sample of data reviewed in the risk assessment data set showed that up to 40% of dyads were judged to be at some form of risk. Risks could be related to:

-

Health conditions – such as mobility, sensory impairments and medical conditions – that could increase the risk of falling, infection, constipation and pressure ulcers.

-

Abuse of the person with dementia, including physical, psychological, financial, sexual, social and verbal abuse.

-

Intentional or accidental self-harm in terms of dietary intake, alcohol use, wandering, suicidal ideation and refusing care.

-

The person with dementia harming others physically, verbally or psychologically. Some carers also expressed concern to Admiral Nurses about the person with dementia’s sexualised behaviour to strangers and about their reluctance to give up driving, thus putting other people at risk.

Admiral Nursing records indicated that Admiral Nurses advised carers about minimising both the risk of these problems occurring and the impact of the risks on themselves and the person with dementia. Admiral Nurses also worked with other agencies when appropriate, such as social service safeguarding teams, the police and other health care-providers, to minimise risks.

Referral data set

Referral data described which services referred the carer to AN services and to what services carers and/or people with dementia were referred. A wide variety of professionals and services, as well as family members, referred carers to AN services. Over one-third of referrals came from mental health services, including psychiatrists, community psychiatric nurses (CPNs) and memory clinics (see Appendix 3, Table 25). However, almost one-fifth of clients self-referred to the service.

Admiral Nurses referred clients onto other services for particular support, including to social services, occupational therapy and day care services. In their efforts to support the carer, Admiral Nurses also sometimes referred the person with dementia to other services, including to other health-care professionals, such as physiotherapists, district nurses and social services, and specialist psychiatric support, including consultant psychiatrists and CPNs. It is not possible to be sure from the administrative data whether or not this referral represented the first contact that carers and the person with dementia had with these services or if they were ongoing/previous clients of the service and the Admiral Nurse was making a referral for review or a rereferral. As the next section shows, very few dyads were not using any services.

‘Agencies involved in the case’ data set