Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 16/02/18. The contractual start date was in March 2017. The final report began editorial review in May 2018 and was accepted for publication in January 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Some of the authors of this report were co-authors on studies included in the systematic review but were not involved in the data extraction and quality assessment for these studies. Specifically, one or more authors have been involved with 17 out of 37 publications, across 4 out of 18 services based in London (Irene J Higginson, Wei Gao and Sara Booth), Hull (Sara Booth), Cambridge (Sara Booth, Morag Farquhar and Irene J Higginson) and Munich (Sara Booth). A committee search showed membership of the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) End of Life Care and Add on Studies that ended in February 2016 for Wei Gao, and membership of the Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) Commissioned Board 2009–15, HTA Efficient Study Designs 2015–16, HTA End of Life Care and Add on Studies and Service Delivery and Organisation (SDO) Studies Panel Member for Irene J Higginson.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Maddocks et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Chronic breathlessness

Breathlessness (also known as shortness of breath or dyspnoea) is a subjective experience around breathing discomfort that varies according to the sensation and intensity. 1,2 The experience is shaped by multiple interacting factors (i.e. physiological, psychological, social and environmental) and can lead to secondary physiological and behavioural responses. 1,2

Terminology and classification of breathlessness are evolving (Table 1). The terms ‘breathlessness’ and ‘dyspnoea’ are internationally recognised, but their definition does not reflect the nature of breathlessness that is persistent despite optimal disease management. Similarly, ‘episodic’ breathlessness has been used to highlight important spells of breathlessness that often drive hospital use,17 but with less emphasis on its often chronic duration. Terms such as ‘intractable’ and ‘refractory’ breathlessness better capture this feature of breathlessness and how challenging it can be to manage, but can also suggest a complete resistance to treatment, which is not always the case. More recent consensus work16 has since developed a definition of ‘chronic’ breathlessness that better reflects the impact on patient experience and disability, in addition to persistence despite optimal disease management.

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Breathlessness or dyspnoea2 | A subjective experience of breathing discomfort that consists of qualitatively distinct sensations that vary in intensity |

| Intractable breathlessness3 | Breathlessness that persists despite treatment of the disease |

| Refractory breathlessness4,5 | Breathlessness that persists despite optimal treatment of the underlying condition |

| Chronic breathlessness6 | Episodes of breathlessness lasting > 3 months |

| Chronic refractory breathlessness7–9 | Chronic breathlessness that is refractory to treatments for the underlying condition |

| Episodic breathlessness10–14 | Severe worsening of breathlessness intensity or unpleasantness beyond usual fluctuations13–15 |

| Chronic breathlessness syndrome16 | Breathlessness that persists despite optimal treatment of the underlying pathophysiology and results in disability for the patient |

Given the lack of universal consensus, we use ‘chronic or refractory breathlessness’ in this evidence synthesis. In line with the recent consensus work, this reflects the impact of breathlessness that persists despite optimal management on patients, while also highlighting its relentless nature and how challenging it can be to manage.

Chronic or refractory breathlessness is one of the most common, burdensome and neglected symptoms affecting patients with advanced malignant and non-malignant conditions. 16,18,19 It affects over 2 million people in the UK, including up to 98% of the 1 million people diagnosed with moderate to severe chronic lung disease,20–22 more than half of the ≥ 200,000 people with incurable cancer, 70% of those with lung cancer,23 and half of the 2 million people with chronic heart failure. 23–26 Breathlessness is also found in people with end-stage renal and liver disease, neurological diseases, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and many autoimmune diseases. 23–26 The number of people affected by breathlessness will rise globally with population ageing and increasing multimorbidity. 27

Breathlessness can be very frightening for patients and families25,26,28–31 and can have a devastating impact on their lives, severely limiting well-being and quality of life (QoL). 2,32–34 It is associated with considerable anxiety, depression, fear, social isolation, deconditioning and disability,21,28,29,31,35,36 and shortened life expectancy. 37–39 The experience of breathlessness is often compounded by multiple and interacting symptoms including cough, pain, fatigue, anxiety and depression. 25,26,33,36,40,41 For informal carers of people with breathlessness, it can result in disrupted sleep, high levels of stress and caregiver burden,29 fewer positive caring experiences,29 and feelings of being isolated, unsupported by health-care professionals, and ill-prepared for acute exacerbations. 31,35,42,43 The experience of chronic breathlessness tends to increase as the disease progresses;44,45 therefore, it can function as a marker of overall symptom burden and deterioration. 25,46,47

Current treatment and service provision

Chronic breathlessness is one of the most frequent causes of emergency department attendance and prolonged hospital admission, and results in high health, social and informal care costs. 28,29,36,48–52 It was estimated that the total annual cost of respiratory disease in the UK was £11B in 2014, representing approximately 9% of the total economic burden of illness. 53 Despite this, there remain few effective treatments for chronic breathlessness, making it a major challenge in improving palliative and end-of-life care. 18,54–57

There are limited pharmacological treatments for chronic breathlessness43,58 and there are currently no licensed medicines for the treatment of this symptom anywhere in the world. 2,59–62 Systematic reviews of effectiveness and clinical trials are available for opioids, oxygen and benzodiazepines. 3,62–67 Orally administered opioids have been found to be beneficial in the treatment of breathlessness in patients with advanced disease, but the effects are modest or small61,62 and there are concerns regarding adverse cardiac and respiratory effects of long-term use, especially in older people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). 68–71 Oxygen has a clear and accepted role in treating mildly hypoxic patients. 72–74 However, the benefit derived from oxygen in mildly or non-hypoxaemic breathless patients is similar to medical air, and there are limitations to its use (e.g. safety, cost). 67,75,76 Benzodiazepines have been found to have no beneficial effect, with some evidence of possible harm. 58,65 Although there are patient case reports of the effectiveness of antidepressants to treat chronic breathlessness, controlled trials are lacking. 77–79 Both the European Respiratory Society (ERS) and the American Thoracic Society have concluded that there is not a robust evidence base for other pharmacological agents beyond oxygen and opioids. 2,59 In addition, pharmacological treatments do not address the underlying psychosocial problems, which also perpetuate the symptom. 80

Breathlessness can be effectively managed via non-pharmacological treatments that incorporate exercise, education and behavioural interventions. 81–83 Pulmonary or cardiac rehabilitation, a multidisciplinary programme of care comprising exercise-training and education (particularly around self-management) is widely known to improve symptom burden, functional status, physical fitness and health-related QoL. 81,82 However, for those with advanced disease, there are issues with referral, limited uptake and ability to sustain engagement because of social isolation, difficulties with travel, health deterioration, impeding symptoms and potential stigma. 4,28,54,84,85 Therefore, it is important to explore interventions that may work alongside, as a bridge to or, for some, as an alternative to rehabilitation interventions, whereby outcomes may be supported via alternative mechanisms.

Holistic breathlessness services

In response to these challenges with chronic breathlessness management, holistic breathlessness services have emerged for people with advanced disease. 86–88 There is no consensus on the definition of holistic breathlessness services; however, as complex interventions, these services can be described in terms of their setting, structure and content. Core features of holistic breathlessness services include:

-

drawing on multiple specialties, typically with input from multiprofessional palliative care (e.g. doctors, physiotherapists) with or without respiratory medicine, cardiology or oncology

-

delivery by multidisciplinary team members (e.g. physicians, nurses and allied health professionals)

-

use of both pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapies, selected following a holistic assessment of individual patient and caregiver needs (physical, psychological, social and spiritual)

-

emphasising self-management, through use of education and behaviour change techniques

-

targeting improvements in patient and caregiver QoL by reducing the impact of breathlessness and related symptoms on everyday living.

Holistic breathlessness services can be offered in community, outpatient or day hospice settings, and there is variation in the extent to which families or informal carers receive direct support.

Individual studies have reported positive outcomes from these services for patients and carers including higher levels of patient satisfaction, improved self-reported breathlessness mastery, and reduced patient distress, health-care contacts and need for informal care, without increasing the overall cost to the UK NHS. 89–95 One study also suggested a potential survival advantage. 94 Alongside this, international guidelines have advocated early integration of palliative care for people experiencing chronic disease,96,97 for which chronic and/or distressing breathlessness could be a suitable indicator for referral (particularly in non-cancer conditions in which prognostication causes delays54). Yet the evidence base to inform policy and practice is poorly understood.

Scoping and need for evidence synthesis

A scoping search was undertaken to identify the size, nature and range of existing evidence relating to holistic breathlessness services, and this informed the design of the evidence synthesis. In the decade following a positive report from a randomised controlled trial (RCT) of a nurse-led service published in 1999,98 evidence relating to these services was minimal and generally of low quality because it was limited to uncontrolled service evaluations. More robust evidence has emerged in recent years, underscoring the interest and relevance of this topic to health and social care. A scoping search from 2005 onwards identified four RCTs,91,94,95,99,100 as well as a number of prospective cohort studies,101,102 qualitative studies,103–107 narrative reviews or opinion pieces3,7,18,108–122 and consensus statements. 2,56,123,124 No systematic reviews have assessed the clinical effectiveness or cost-effectiveness of these services. Although not exhaustive, the scoping exercise highlighted the need for an evidence synthesis of holistic breathlessness services, to inform clinical practice, policy and research in the future.

Aim and objectives

This project aimed to provide a comprehensive and objective summary of the current available evidence for the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of holistic breathlessness services for people with advanced malignant and non-malignant disease.

The research objectives were to:

-

describe the available evidence for holistic breathlessness services in terms of the intervention format, content, organisation and context, patient characteristics, study design and quality, and outcomes measured

-

determine the clinical effectiveness of holistic breathlessness services on symptom burden, health status and QoL

-

determine the cost-effectiveness of holistic breathlessness services from patient/caregiver, societal and NHS perspectives

-

examine the acceptability of holistic breathlessness services from the perspective of health-care professionals and patients, considering rates of referral, uptake and adherence, as well as patient experience and satisfaction

-

using individual patient data, examine predictors of treatment response, including characteristics of participants (level of impairment, symptom burden, multimorbidity) and interventions (setting, duration, professional input, delivery)

-

using stakeholder consultation, elicit stakeholders’ priorities for clinical practice, policy and research around holistic breathlessness services, including their role and delivery in relation to cardiac and pulmonary rehabilitation services.

Research group

This project was led by the Cicely Saunders Institute of Palliative Care, Policy and Rehabilitation at King’s College London (KCL), with the following collaborating institutions: University of East Anglia, Royal Brompton & Harefield NHS Trust, University of Cambridge and King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust.

The project advisory group (PAG) included a consortium of international leaders and clinical academics in palliative care and respiratory and rehabilitation research, as well as patient and carer representatives:

-

Dr Matthew Maddocks (Senior Lecturer in Health Services Research and Specialist Physiotherapist, KCL)

-

Professor Irene J Higginson [Professor of Palliative Care and Policy, Scientific Director of Cicely Saunders International and National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Senior Investigator, KCL]

-

Ms Lisa Jane Brighton (Research assistant, KCL)

-

Dr Wei Gao (Senior Lecturer in statistics and epidemiology, KCL)

-

Dr Deokhee Yi (Health Economist, KCL)

-

Dr Sabrina Bajwah (Consultant and honorary senior lecturer, KCL)

-

Dr Sara Booth (Honorary Consultant and Associate Lecturer, University of Cambridge)

-

Dr Morag Farquhar (Senior Lecturer, University of East Anglia)

-

Dr William D-C Man (Senior Lecturer/Consultant Chest Physician, Imperial College London)

-

Dr Charles Reilly (Consultant Physiotherapist, King’s Health Partners)

-

Ms Lucy Fettes (Specialist Physiotherapist, St Joseph’s Hospice and KCL)

-

Ms Alanah Wilkinson (Research Administrator, KCL)

-

Dr Nicholas Hart (Clinical and Academic Director Lane Fox Respiratory Service, Guy’s & St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust/Professor in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine)

-

Ms India Tunnard (Research Administrator, KCL)

-

Dr Sophie Miller (Specialty Training Registrar, St Christopher’s Hospice)

-

Mr Daniel Marion (patient/carer representative)

-

Ms Lesley Turner (patient/carer representative)

-

Mrs Colleen Ewart (patient/carer representative)

-

Mr Gerry Bennison (patient/carer representative)

-

Ms Margaret Ogden (patient/carer representative)

-

Mrs Sylvia Bailey (patient/carer representative).

Any changes to the protocol were reported to and approved by the PAG.

Chapter 2 Evidence synthesis methods

This project comprised an evidence synthesis of published and unpublished data through systematic review and a secondary analysis of pooled individual patient trial data, undertaken in conjunction with a transparent stakeholder consultation.

Systematic review methods

The systematic review considered quantitative, qualitative and economic studies to examine the clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and acceptability of holistic breathlessness services.

Design and registration

The systematic review and meta-analyses were conducted and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement,125 and adhered to guidelines from the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination and Methodological Expectations of Cochrane Intervention Reviews. The review protocol was prospectively registered with PROSPERO (reference number CRD42017057508). 126

Eligibility criteria

The following inclusion criteria were applied.

-

Participants: adults experiencing breathlessness related to advanced disease (described as suffering from breathlessness, dyspnoea, shortness of breath, difficulty breathing, laboured breathing and with advanced stages of diseases with a high prevalence of breathlessness) including, but not limited to, cancer (advanced local or metastatic), chronic respiratory disease [Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) stage III or IV/grade C or D], heart failure (New York Heart Association stage III or IV) or progressive neurological conditions. Studies in which ≥ 50% of participants met these definitions were included.

-

Interventions: as there is no standard definition, holistic breathlessness services were defined as services that draw on multiple specialties and disciplines, encompass pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions selected on the basis of a holistic needs assessment, enrol patients because of their breathlessness (not their diagnosis), emphasise self-management, aim to reduce the perception and impact of breathlessness and related symptoms, and are offered in outpatient, community or day hospice settings.

-

Comparators: all comparators were considered for controlled studies, including no treatment, usual care, an attention control (e.g. a patient support group without a specific focus on breathlessness) or an active control (e.g. alternative service).

-

Outcomes: health outcomes included breathlessness intensity; breathlessness affect and impact;2 anxiety and depression; physical functioning; health status or QoL; and survival. Economic outcomes included formal health and social care service utilisation and costs, unpaid caregiver costs including caregivers’ time off work, quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) derived from generic QoL measures [e.g. EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D)] and perspectives of economic analysis. Acceptability outcomes included patient flow data (uptake, adherence, completion), as well as patient and caregiver perspectives on acceptability, satisfaction and/or experience.

-

Study design: RCTs with a parallel, single-stage or cross-over design, including studies using minimisation, non-randomised studies including prospective and retrospective designs, quantitative and qualitative designs to elicit patient and caregiver satisfaction and experience.

Studies were excluded if they did not specifically target patients with breathlessness, or if interventions that targeted breathlessness used only a single treatment (e.g. physical exercise). Pulmonary rehabilitation and disease-specific services (e.g. integrated respiratory care) were deemed outside the scope of this review. Interventions that exclusively targeted service providers or carers were also excluded. Narrative reviews, opinion papers, case studies and case series with fewer than five participants were excluded.

Search strategy

Electronic searches

The following electronic databases were searched from their respective inceptions up to 2 June 2017:

-

British Nursing Index (1985)

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (1980)

-

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR)

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)

-

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE)

-

EMBASE (1980)

-

MEDLINE (1966)

-

PsycINFO (1985)

-

Science Citation Index Expanded (1985).

The search terms and strategy were developed and piloted with information specialists to ensure broad inclusivity. They were informed by literature scoping, MEDLINE medical subject heading terms and subject filters within specific databases. Subject headings and free-text terms were combined to search for population and intervention terms. The MEDLINE search strategy is shown in Appendix 1.

Hand-searching

To identify additional studies, reference lists of retrieved studies and relevant editorials and reviews, citations, textbooks and voluntary sector materials were searched. We contacted the corresponding authors of retrieved studies and active researchers to identify unpublished data or grey literature arising from meetings or conference proceedings. No language or publication status restrictions were imposed in the selection of evidence reports.

Screening of studies

Potentially eligible reports were imported into bibliographic software Endnote X7 [Clarivate Analytics (formerly Thomson Reuters), Philadelphia, PA, USA] and duplicates removed. Two researchers (SM and LJB/MM) independently screened all titles and abstracts for relevance, and independently assessed full texts of potentially eligible studies for compliance with the review criteria. Disagreements were resolved by discussion between the screening team and wider team, until consensus on eligibility was reached.

Quality assessment

All included studies were independently assessed by two researchers (LJB and MM) for methodological and reporting quality, using standardised checklists, as outlined below. Information to aid quality assessment was obtained from primary, secondary and protocol articles.

Methodological quality

The Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers (QualSyst)127 was used to assess the methodological quality of all studies. QualSyst contains two checklists with accompanying manuals to guide systematic quality assessment of quantitative and qualitative studies. For mixed-method studies, both checklists were used for the relevant component of the study and supplemented with three items that were specific to this design from the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool. 128 Scores were summarised as a percentage score of applicable items.

Randomised controlled trials were also assessed for risk bias using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool,129 which considers six domains: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of study participants and personnel, completeness of outcome data, selective reporting, and other potential sources of bias. A judgement was made for the level of risk of bias (i.e. low, high or unclear) for each domain.

Methodological quality assessments of economic evaluations were informed by the British Medical Journal checklist for authors and peer-reviewers of economic submissions. 130 Thirty-five items in study design, data collection and analysis and interpretation of results were marked as yes, no, or not clear.

Reporting quality

Established checklists were used to assess the quality of reporting (Table 2).

| Study design | Tool(s) to assess reporting quality |

|---|---|

| RCTs | CONSORT statement131 |

| Pilot/feasibility trials | CONSORT extension for pilot and feasibility studies132 |

| Quasi-experimental | Adaptation of CONSORT statement using applicable items |

| Observational | STROBE statement133 |

| Qualitative | COREQ checklist134 |

| Mixed methods | COREQ plus the most appropriate quantitative checklist |

Quality of the evidence

The quality of the body of evidence for each clinical outcome was rated independently by two members of the research team (MM/LJB and MF) using the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) approach,135 which considers study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness and publication bias. The final grade was reviewed by additional members of the PAG.

We decreased the grade if there was:

-

serious (–1) or very serious (–2) limitation to study quality

-

important inconsistency (–1)

-

some (–1) or major (–2) uncertainty about directness

-

imprecise or sparse data (–1)

-

a high probability of reporting bias (–1).

The following grades of evidence categories were then assigned for each outcome:

-

high – further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect

-

moderate – further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate

-

low – further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate

-

very low – any estimate of effect is very uncertain.

Data synthesis/data extraction and analysis

Data on the characteristics of the service, outcomes and study information were extracted from each paper by one researcher (SM/LJB) using a predesigned electronic data capture form. These were checked by a second researcher to ensure rigour (LJB/MM). Authors were contacted if additional information was needed for meta-analyses. To increase validity and ensure comprehensiveness, the analysis and interpretation were reviewed by members of the PAG including researchers, patient/carer representatives and clinicians.

Structure, organisation and delivery/service characteristics

We described the overall content and organisational aspects of services to appraise the degree of consistency or heterogeneity. 136 Data on service characteristics were tabulated with details of the associated studies, including the intervention setting (i.e. home, community, hospital), duration of service involvement and frequency of patient contact, team members by profession/specialty, patient diagnoses, and component interventions. Component interventions were tabulated and summarised narratively.

Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness

Only data from controlled studies were included to estimate effectiveness. Outcomes were analysed as continuous data when possible. Mean differences (MDs) or standardised mean differences between intervention and comparator groups were reported with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). When there were sufficient data and consistent or comparable outcomes, a meta-analysis was performed using random-effects models to estimate the overall direction, size and consistency of effects. Clinical heterogeneity assessed using the I2 statistic to quantify inconsistency across studies and the impact on the meta-analysis. 137 Separate sensitivity analyses were conducted excluding studies with a high risk of bias (< 70% QualSyst score), and removing outliers when substantial heterogeneity (I2 > 75%138) was present. In all cases, individual studies were represented only once within each analysis. We planned funnel plots to assess publication if ≥ 10 studies were included. 139 Additional findings were summarised narratively.

For health economic data, we planned to present types of economic analyses; describe the population, setting and intervention; present effect size and cost-effectiveness results for the high-quality economic evaluations;130 and perform a quantitative synthesis if sufficient data were available.

Patient acceptability and experience

Data were extracted on patient and caregiver perspectives on acceptability, satisfaction and/or experience, as well as process data regarding patient flow (including rates of referral, uptake, adherence to intervention and completion).

For qualitative or mixed-methods studies, all text (including quotations) under the headings of ‘results’ or ‘findings’ were imported verbatim into qualitative data analysis software [NVivo v12 (QSR International, Warrington, UK)]. A thematic synthesis of qualitative data involved three consecutive steps: (1) line-by-line coding of results of all included studies, (2) development of descriptive themes, incorporating themes or codes of primary studies, with particular attention to similarities and differences across and between studies and (3) new development of analytical themes, going beyond presentation of the original data. 140 The final coding frame was reviewed by members of the PAG with a variety of backgrounds (e.g. research, clinical, patient/carer representatives) to increase interpretive rigour. Findings from the quantitative surveys and patient flow data were tabulated and/or summarised narratively.

Responder analysis methods

Design

To identify patient characteristics that predict response to holistic breathlessness services, in terms of patient breathlessness mastery and distress due to breathlessness, we conducted a secondary analysis of pooled individual patient data from three RCTs. 91,94,95 These were a convenience sample of available data through project team members who were involved with, and act as, data custodians for these trials. As a result of collaborations during the trial designs, there was also a high number of variables in common across these data sets to aid pooling.

Data sources and ethics approvals

Trials included Higginson et al. ’s94 2014 trial of a 6-week service with people with advanced disease, Farquhar et al. ’s91 2014 trial of a 2-week service for people with advanced cancer and Farquhar et al. ’s95 2016 trial of a 4-week service for people with non-malignant disease. Participants in each trial had chronic or refractory breathlessness and advanced disease.

Anonymised individual patient data were obtained from the data custodians, and data sets were cleaned and harmonised. This secondary analysis of anonymised data did not require ethics approval. Each of the contributing studies followed appropriate ethics approval procedures (King’s College Hospital reference number 10/H0808/17; Cambridgeshire 2 NHS reference number 08/H0308/157).

Methods

Our study built on methods of a previous analysis of patient predictors of response to opioids. 141 The primary analysis considered an intervention response on Chronic Respiratory Disease Questionnaire (CRQ) mastery, defined by the minimal clinically important difference as an improvement of 0.5. 142 This outcome was selected as it was the primary outcome for the Higginson et al. 94 study, and a secondary outcome in the Farquhar et al. 91,95 studies.

The secondary analysis considered an intervention response on Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) distress due to breathlessness (henceforth, NRS distress), defined as an improvement of 1 point. 143 This was selected for secondary analysis as it was the primary outcome for both Farquhar et al. 91,95 studies, but not measured in the Higginson et al. 94 study.

Candidate variables (and their reference group/possible score ranges) for the primary and secondary analysis included diagnosis (reference group: COPD); predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) and baseline scores for CRQ dyspnoea; CRQ fatigue; CRQ mastery and CRQ emotional function (1 to 7); EQ-5D Utility Index (–1 to 1) and EQ-5D visual analogue scale (VAS) (0 to 100); Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) anxiety and HADS depression (0 to 21); and NRS average breathlessness in the last 24 hours (0 to 10; henceforth, NRS average). As it was not measured in Higginson et al. ,94 baseline NRS distress (0 to 10) could be included only in the secondary analysis. For all variables, the time point immediately pre intervention for each group was treated as ‘baseline’ (e.g. in the Higginson et al. 94 trial, fast-track participants’ baseline was week 1, wait-list participants’ baseline was week 6).

Variables deemed significantly related to response (p < 0.05) in univariate logistic regression models were included in the multivariate analyses. Multivariate analyses comprised backward stepwise logistic regression, in which variables with the largest non-significant (p > 0.05) p-value in the model were sequentially removed. Dependent variables were assessed for multicollinearity. To control for age, sex (reference group: male) and study of origin (refence group: Farquhar et al. 95), these variables were forced into the multivariate analyses.

To aid interpretation, variables that were significant predictors of response were categorised (when possible, using previously established groupings for that measure). The percentages of participants classified as responders for each baseline category were then tabulated.

Transparent expert consultation methods

Design

Nominal group techniques are commonly used for consultation with stakeholders, but have been criticised for lacking transparency, reliability and opportunities for clarification. 93 Although the Delphi technique overcomes these issues, this method can be time-consuming with multiple rounds of consultation, and the initial content can be shaped by a minority. Transparent expert consultation (TEC) methods have, therefore, been developed in response to these limitations,93,144 and have been successfully used to elicit recommendations in palliative and end-of-life care research. 145–149

Our TEC comprised a stakeholder consultation and follow-up online consensus survey. Like nominal group technique, the stakeholder workshop provided structured opportunities for expression of views by a group of experts. This activity was followed by a wider online consensus survey to rate the suggested priorities (similar to a single-round Delphi technique), enabling rapid consultation of multiple key stakeholders.

Participants

A wide range of stakeholders involved in the provision of care for people with chronic breathlessness were purposively selected and invited to participate in the stakeholder workshop. Service providers and commissioners, voluntary sector organisation representatives, patient and carer representatives, and health and social care practitioners from a range of specialties and professional groups were identified through contact lists of people and organisations that the research team had previously worked with, online literature and website searches, and via recommendations from participants.

The PAG members, workshop participants and those who expressed interested but were unable to attend the stakeholder workshop, were invited to complete the online consensus survey. Additional individuals from groups that were under-represented at the workshop (including service users) were also purposively invited to complete the consensus survey, using the methods described above. All participants were adults with capacity to give informed consent.

Ethics, recruitment and informed consent

Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the KCL research ethics committee (reference number LRS-16/17-4692).

A personal e-mail invitation to the stakeholder workshop was sent to purposively selected stakeholders, including a copy of the information sheet, the consent form and the workshop schedule (see Appendix 2). This provided an opportunity for attendees to consider the study information prior to the day of the workshop, at which time they were asked to provide written consent prior to the recorded discussions and data collection. Participants were reimbursed reasonable travel costs to attend the stakeholder workshop.

For the online survey, information regarding its purpose and how the data would be used was included in an attachment to the invitation e-mail and summarised at the start of the survey. Consent for the online survey was presumed through participation. A hard-copy postal consensus survey with a freepost return envelope was available to participants preferring that format.

Procedure

Identifying critical questions

The findings of the systematic review around the service components, clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and acceptability of holistic breathlessness services for people with chronic breathlessness in advanced disease were used to generate critical questions for consideration during the stakeholder workshop. Through discussion of the review findings with the PAG, three critical questions were identified:

-

How do we define and deliver ‘holistic breathlessness services’?

-

How and where can holistic breathlessness services be integrated into current practice?

-

How should the success of holistic breathlessness services be measured/monitored?

Transparent expert consultation workshop

The TEC workshop took place at the Cicely Saunders Institute of Palliative Care, Policy and Rehabilitation, KCL, on October 4 2017. Participants received a pack on arrival containing the information sheet, consent form and schedule for the day.

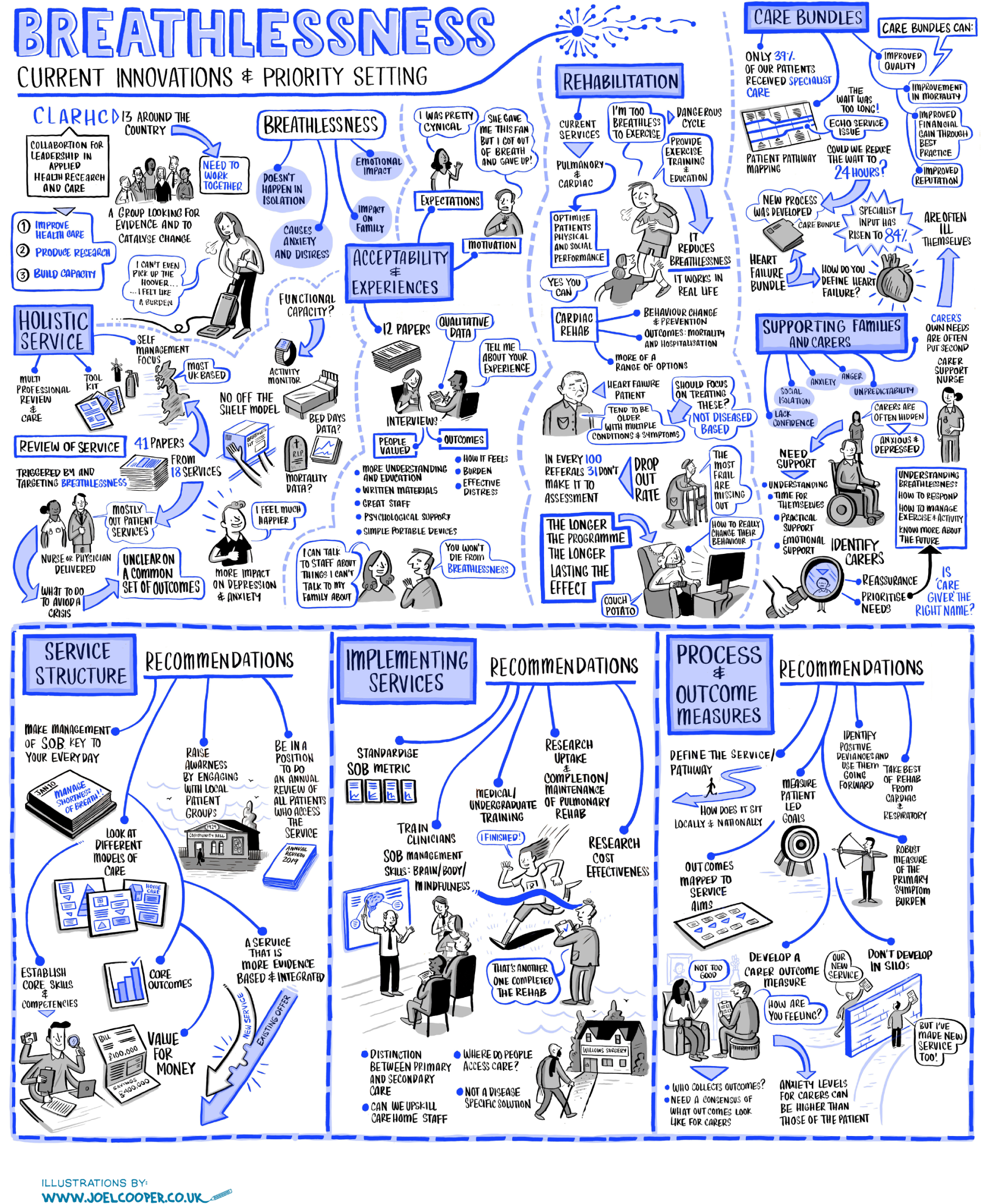

The workshop format began with whole-group presentations and discussion. The first of these presented results from the systematic review, including data on the make-up or services, common components, preliminary quantitative outcome data and qualitative data on the acceptability of breathlessness services. In addition, evidence was presented by experts on rehabilitation services, care bundles, and supporting informal carers of people with chronic breathlessness (see Appendix 2).

In parallel groups, workshop participants considered one of the three critical questions identified from the review. Participants were allocated to groups to ensure diversity of experience and roles within each. These sessions used a nominal group technique, facilitated by members of the research team using a structured process developed before the workshop (Table 3). This included completion of individual response booklets to gather individual thoughts and suggestions. Parallel-group sessions were also audio-recorded, and scribes recorded the top priorities on flip chart paper for each parallel group and to share with the wider group. 150 A live graphic recording of the whole-group and parallel-group discussions was created by an artist who was present throughout the event. The workshop closed with a summary of the day and information about the follow-on online consensus survey.

| Step | Process |

|---|---|

| Written responses | Participants wrote individual answers to ‘prompt questions’ in response booklets. These were tailored to the critical question each group was focusing on, for example ‘What are the core components of a holistic breathlessness service?’ (group 1); ‘Where should a holistic breathlessness service be based?’ (group 2); and ‘What is the ideal set of outcomes to measure for patients?’ (group 3) |

| Initial reflections | Reflections from this exercise in relation to the critical question were then discussed |

| Individual suggestions | Participants wrote individual suggestions for future practice in their response booklets, with a rationale and indication of relevance for clinical practice, policy and/or research |

| Ranking | Participants were asked to rank each of their own suggestions from highest to lowest |

| Discussion | Participants in turn read out their highest ranked suggestions and rationale, which were discussed by the group. This continued until individual lists were exhausted or time was exceeded149 |

The materials generated from the discussions throughout the day were reviewed and summarised into main themes by one researcher (LJB), including those from whole-group discussions and each parallel group. This was primarily based on the written notes, with reference to the recording when further clarification was needed. The narrative summary of salient and common points was reviewed by members of the research team to ensure an accurate and transparent reflection of the workshop discussions.

Online consensus survey

Participants’ suggestions generated from the workshop, their rational, ranking and grouping, were anonymised and entered in a Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) spreadsheet. Two members of the research team (LJB, MM) categorised the statements as relevant to clinical practice, research or policy. For instances in which participants felt that a suggestion was relevant to more than one category, it was assigned to the predominant category. Statements were ranked from most to least important, as reported by participants.

After multiple readings of the material, statements were synthesised and deduplicated. Stakeholders’ suggestions were not retained if they were deemed to be duplicates of other statements generated in this exercise, redundant (e.g. research studies known to have been conducted), unclear, outside the scope (e.g. not specific to chronic breathlessness in advanced disease) and/or ranked as low priority by the participant who wrote it. The graphic and audio-recordings, scribes’ notes and flip chart records were referred to when clarification was needed. Statements retained participants’ original language whenever possible, with amendments only to enhance clarity and avoid inflexible statements (e.g. changing ‘must’ to ‘could’). 145,147

The final list of participants’ suggestions was discussed and refined with the PAG, before being formatted into an online survey. Within the survey, three sets of participants’ suggestions relevant to research, clinical practice and policy were presented, and respondents were asked to indicate their level of agreement with each statement from 1 (strongly disagree) to 9 (strongly agree). Survey respondents were given the opportunity for free-text comments in each section and asked to select their profession/role and area(s) of expertise, with a free-text ‘other’ option if required. 144,149,151 The survey was piloted by clinical, research and patient representative members of the PAG to ensure that it was clear and user-friendly.

The survey ran for a period of 2 weeks, from 12 to 26 February 2018. Potential participants were sent a personalised e-mail invitation, followed by two reminders, to complete the online consensus survey.

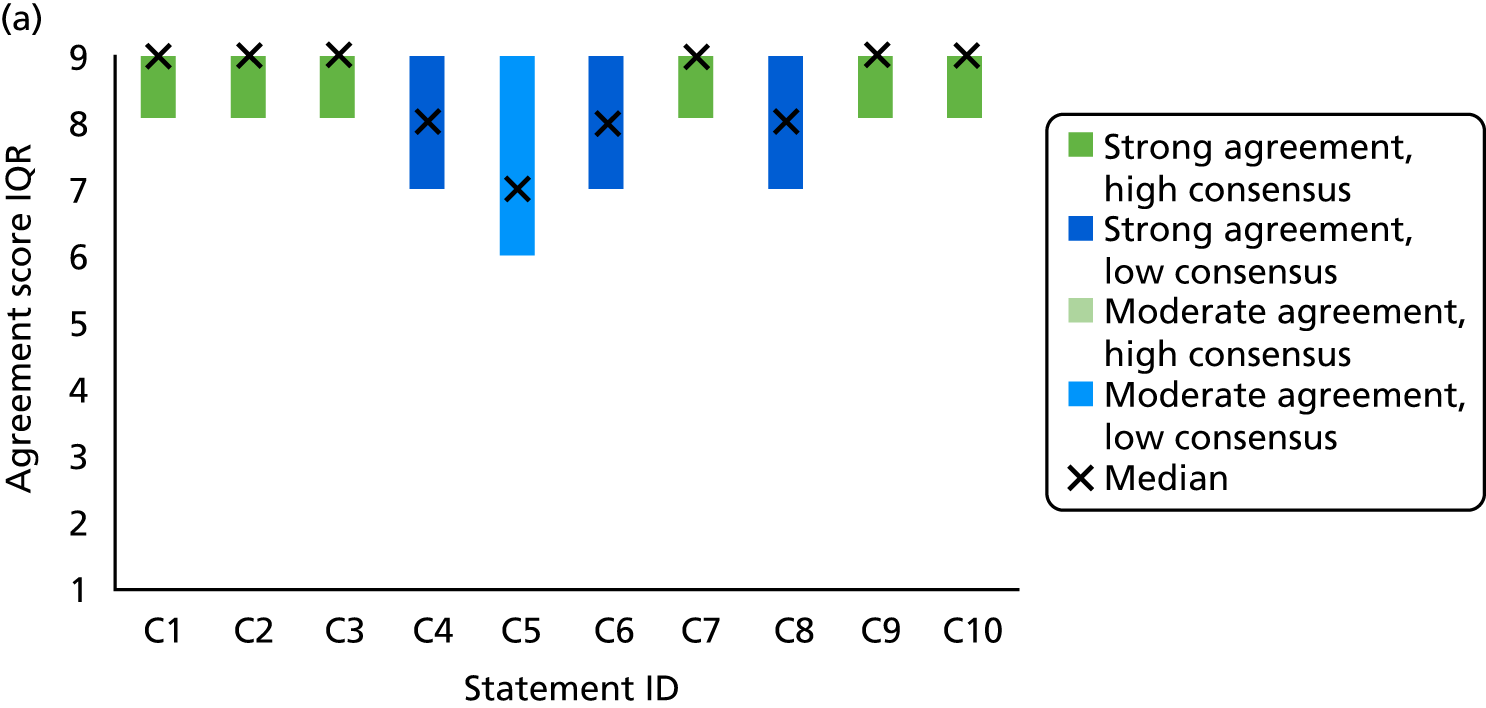

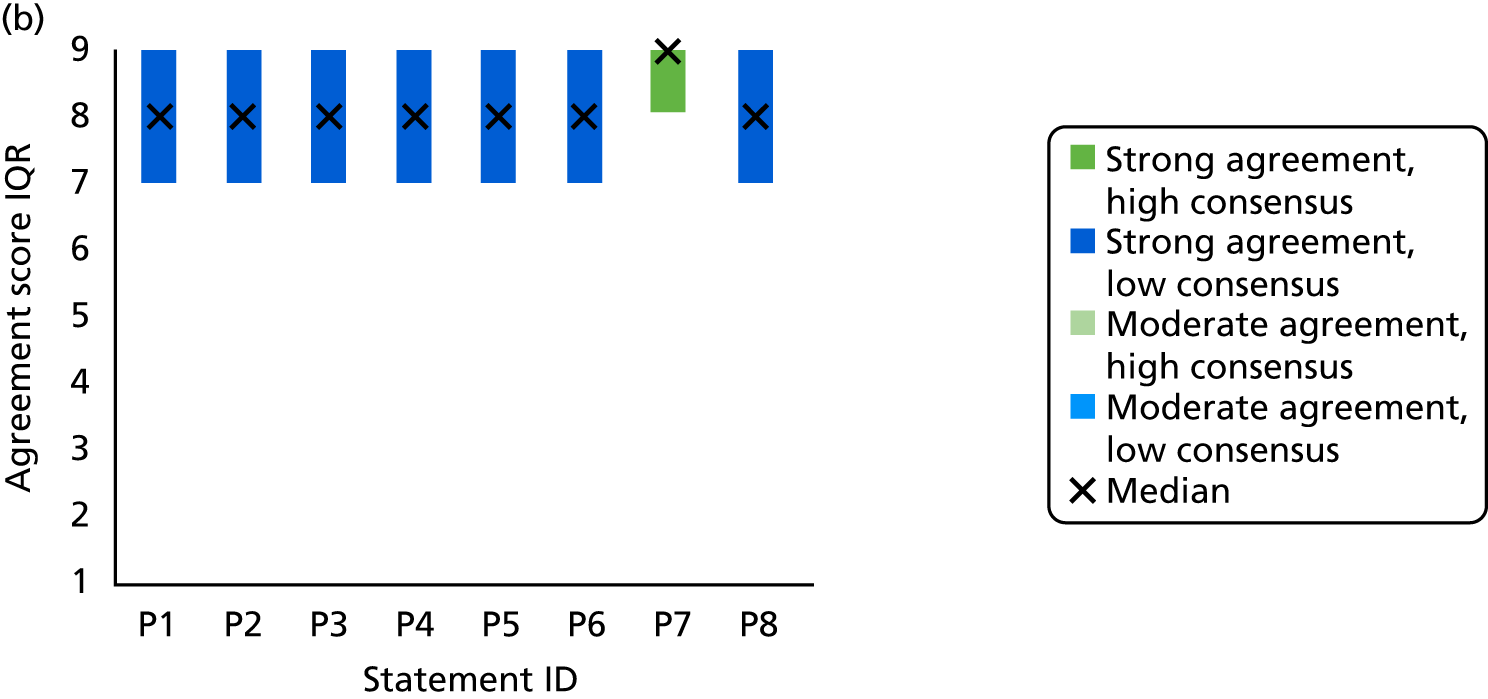

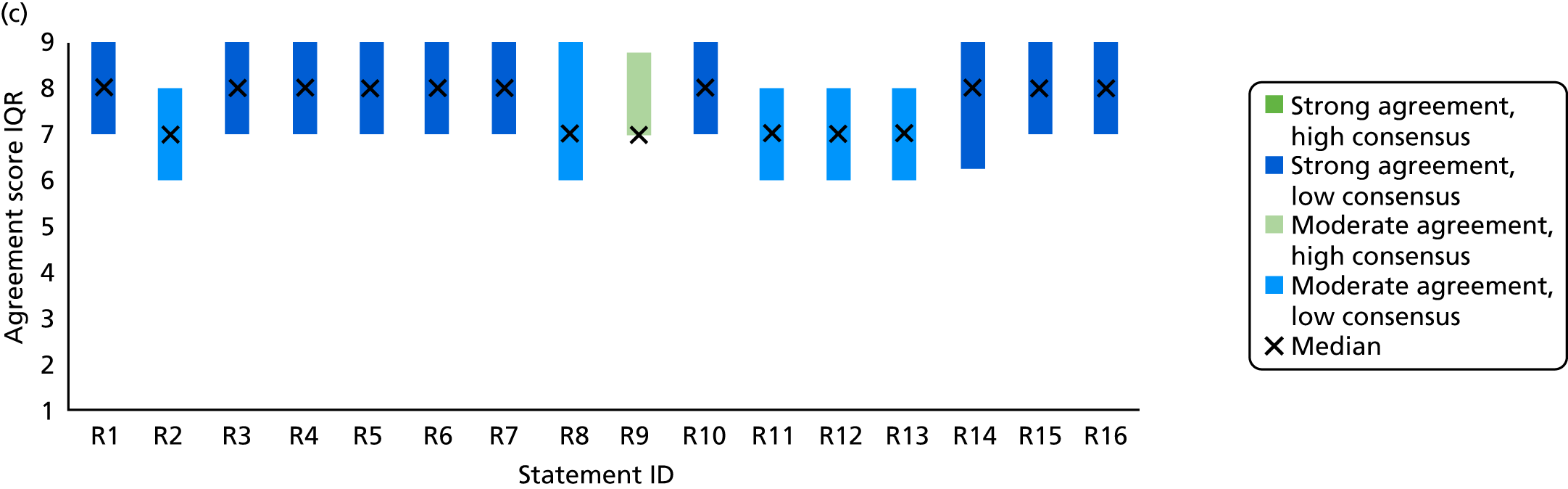

Analysis

Survey responses were analysed using descriptive statistics [frequencies, median, interquartile range (IQR), range]. Predetermined categories from previous TECs were used to determine levels of agreement and consensus146,147 (Table 4). Narrative comments were collated within each category and thematically analysed to aid understanding and provide illustrative examples of the issues raised by stakeholders’ suggestions. 152

| Median | IQR | Category |

|---|---|---|

| ≥ 8 | < 2 | Strong agreement/high consensus |

| ≥ 8 | ≥ 2 | Strong agreement/low consensus |

| < 8 to > 6 | < 2 | Moderate agreement/high consensus |

| < 8 to > 6 | ≥ 2 | Moderate agreement/low consensus |

| ≥ 4 to ≤ 6 | < 2 | No agreement/high consensus |

| ≥ 4 to ≤ 6 | ≥ 2 | No agreement/low consensus |

| < 4 to > 2 | < 2 | Moderate disagreement/high consensus |

| < 4 to > 2 | ≥ 2 | Moderate disagreement/low consensus |

| ≤ 2 | < 2 | Strong disagreement/high consensus |

| ≤ 2 | ≥ 2 | Strong disagreement/low consensus |

Patient and public involvement

In addition to the patient and public involvement (PPI) collaborators involved with the original grant application, four additional members were identified and invited to join the research team via the Cicely Saunders Institute Patient and Public Involvement Group. All were given an informal ‘role description’ to introduce them to the Institute, the project and our intentions for PPI.

The aim of PPI throughout this project was to ensure acceptable and appropriate research processes where patient/carers would be participating, include patient/carer voices throughout our consultation with stakeholders, ensure interpretation of findings were grounded in patient/carer experiences, and improve clarity and reach of dissemination.

The PPI involvement in this study used a mixture of face-to-face methods (e.g. inclusion in project advisory meetings) and remote methods (e.g. via telephone and e-mail). Involvement was flexible, with each member being more or less involved at different points in the study, in line with their availability and/or current health. The PPI members were included as members of the project team and invited to all project advisory meetings. They were invited to comment on the plain English summary and study plans, with a particular focus on recruiting PPI members for the TEC and ensuring acceptability of the workshop and online survey methods. They were involved in commenting on study findings, considering the meaning of results, and write-up and dissemination of materials and reports.

We reimbursed PPI members’ expenses and time, in accordance with NIHR INVOLVE guidance. 153 PPI members were supported by the research assistant as a key contact throughout their involvement. At the end of the study, we reflected on PPI involvement using the Guidance for Reporting Involvement of Patients and the Public 2 (GRIPP2) short form and sought feedback from the PPI members in order to share learning from our experiences.

Chapter 3 Systematic review results

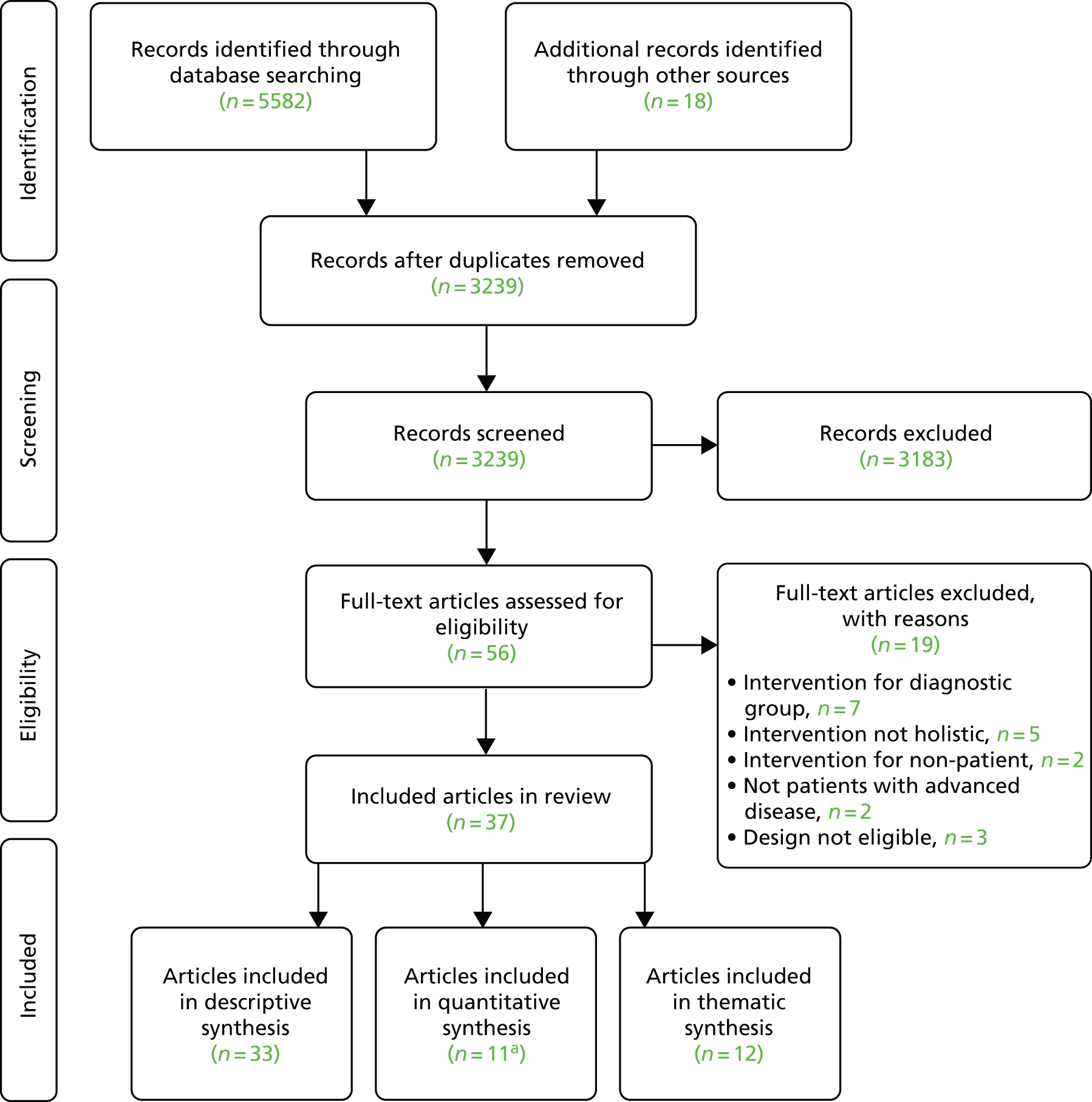

Following screening of 3239 unique titles/abstracts and 56 full papers, 37 papers were eligible for inclusion in the review (see Appendix 3 for the PRISMA flow chart). Included papers were published between 1996 and 2017 (27 since 2010) and relate to 18 separate holistic breathlessness services: 12 based in the UK, three in Canada and one each in Australia, Germany and Hong Kong. Thirty-three articles were included in the descriptive synthesis (see Appendix 4).

Data from 12 studies (11 RCTs90,91,94,95,98–100,154–157 and one quasi-experimental design156) of seven different services were included in the quantitative synthesis (see Appendix 4 for a description of all included studies). Five RCTs were designed as pilot/feasibility studies,90,99,155,157 and seven as effectiveness studies. 91,94,95,98,100,154,155 Nine studies90,91,95,98,155–158 compared the services to usual care, and two compared one versus three contacts with a service. 99,100 In one study,90 the control group were not offered training or counselling, but were encouraged to talk freely about their breathlessness and disease.

Nine studies enrolled only cancer patients,90,91,98–100,155–157 two enrolled only patients with non-malignant disease95 or COPD,154 and one study enrolled patients with any advanced disease. 94 Of the 979 total patients recruited (range 2299 to 156100), there were 757 (77.3%) with advanced cancer and 180 (18.4%) with advanced COPD; the remaining participants (4.3%) had other non-malignant diseases, including interstitial lung disease or heart failure. The controlled studies assessed a wide variety of outcome measures (see Appendix 5), the most common being breathlessness intensity,89,90,94,99,154–158 distress due to breathlessness,90,91,95,98,99,155–158 and anxiety and depression. 90,91,94,95,98,155–157

The thematic synthesis included qualitative and quantitative experience data. Qualitative data were from five services, reported across 12 papers,88,90,91,94,95,102–105,159–161 (six mixed-method studies90,91,94,95,102,103,161 and five qualitative studies88,104,105,159,160) (see Appendix 4). Almost all data were from interviews with patients and/or carers,88,90,91,94,95,102,104,105,159,160 except for one using free-text responses to a postal survey103 and one using therapist notes. 161 Altogether, this included data from 167 patients (53.9% with cancer) and up to 49 carers. Quantitative data around satisfaction with, or experiences of, the services were reported in seven studies, which represented the views of 543 patients (60.77% with cancer). 99,100,103,157,161,162,168

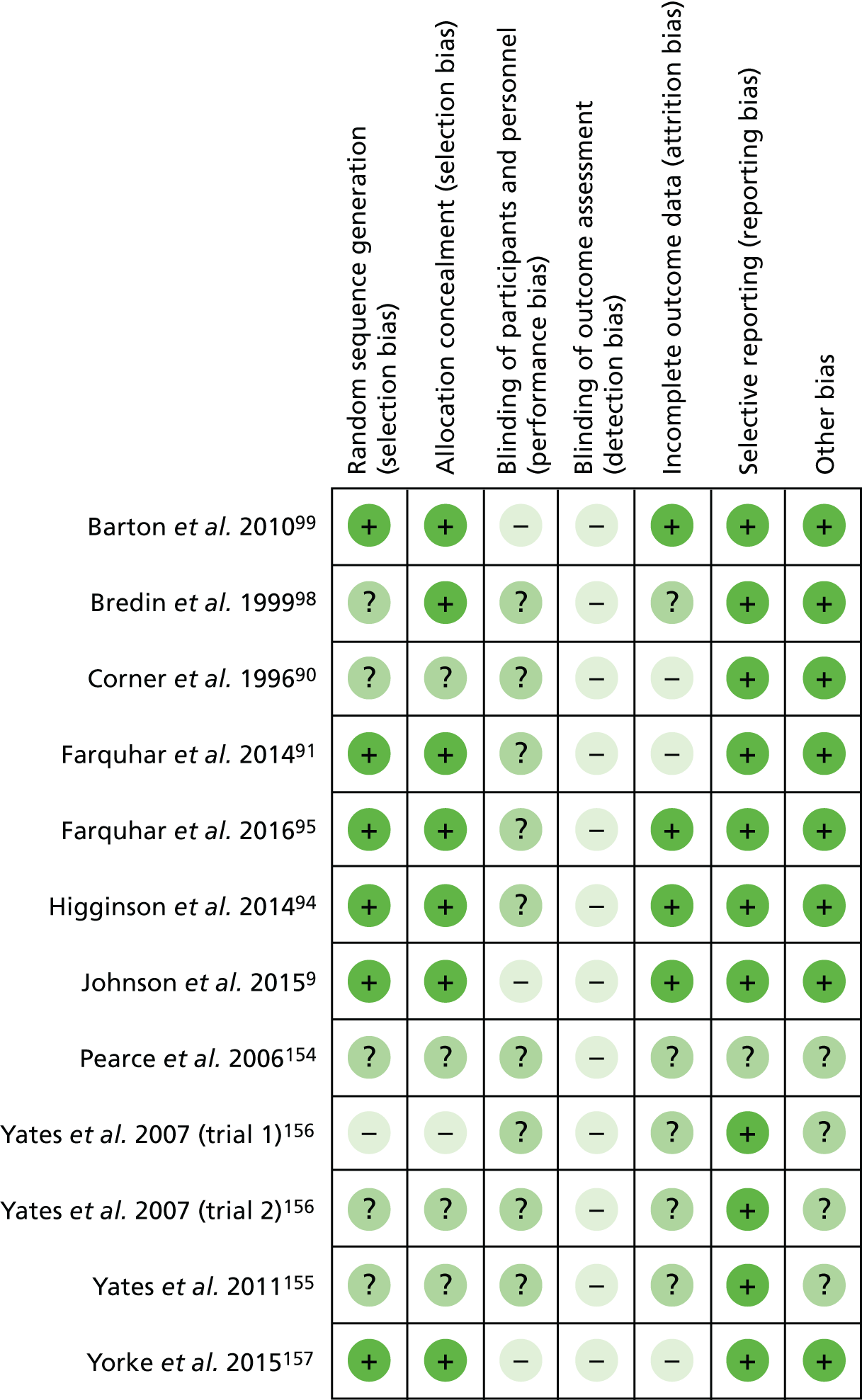

Study quality

Quality assessment scores for the studies included in the quantitative synthesis ranged from 35% to 100% (median 90.4%; see Appendix 6). Studies for which only an abstract was available received lower scores. 154–156 All studies were deemed at risk of detection bias and most at risk of performance bias, owing to the nature of the intervention that prohibited patient blinding and relied on primarily self-assessed outcomes (see Appendix 7). Just three studies reported blinding of investigators. 91,94,95

Quality assessment scores for qualitative studies ranged from 40% to 85% (median 70%; see Appendix 8). The majority of studies had clear descriptions of their objectives, with an appropriate design including methods that were clear and systematic. However, the common limitations within the qualitative studies included lack of procedures to establish credibility of the data (e.g. triangulation, member checking), and unclear reporting of the analytic methods. Moreover, none of the included studies demonstrated reflexivity in their reports by reflecting on the impact of the researchers’ own personal characteristics on the data.

For the mixed-methods studies (n = 7), quality assessment items showed that, although this design was always clearly appropriate for the aims of the study, few (n = 2) reflected on the potential limitations of integrating qualitative and quantitative data (see Appendix 9).

For studies containing economic evaluations (n = 4), quality scores ranged from 64% to 77%. Commonly low-scoring items included having a clear statement and justification for the economic viewpoint, information on the evaluation method used, and a discussion around the relevance of productivity changes (see Appendix 10).

Reporting quality

Reporting quality overall was reasonably high for RCTs and pilot/feasibility trials, and generally poorer for quasi-experimental and qualitative studies (Table 5).

| Study design | Reporting quality checklist | Papers assessed (n) | Score median (%) | Score range (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCTs | CONSORT statement131 | 5 | 81 | 53–92 |

| Pilot/feasibility trials | CONSORT extension for pilot and feasibility studies132 | 4 | 71 | 31–79 |

| Quasi-experimental | Adaptation of CONSORT statement using applicable items | 4 | 52 | 35–73 |

| Observational | STROBE statement133 | 1 | 84 | – |

| Qualitative | COREQ checklist134 | 10 | 46 | 22–68 |

Across all the experimental designs, there was limited reporting around harms and unintended consequences, or reflection on generalisability of the study findings. For RCTs and quasi-experimental studies, it was often not explicitly stated whether or not important changes had been made to methods and outcomes, or what their processes were for interim analysis and/or stopping guidelines. For quasi-experimental studies, few reported specific objectives or hypotheses, or clarified their primary and secondary outcomes. In the pilot/feasibility studies, papers often failed to define the methods and assessment measures for each study objective, or the criteria they used to judge whether or not to proceed with a definitive trial.

Papers scored with the qualitative reporting checklist were mainly mixed-methods reports, and only three were purely qualitative papers. Information frequently missing included details of the researcher and interviewer, contextual factors surrounding interviews (e.g. prior relationships between researchers and participants, and whether or not others were present during the interview), and elements with the potential to increase rigour (e.g. whether or not field notes were made, and whether or not participants commented on the transcripts and/or findings). These papers also tended not to report interview durations or full coding trees and did not reflect on data saturation or diverse cases/minor themes.

In all cases, papers published prior to the reporting checklists tended to score lower. For full reporting quality scores for each study design, see Appendix 11.

Service characteristics

Services were delivered by doctors, nurses, physiotherapists and occupational therapists, with involvement from the specialisms of palliative care, respiratory care and oncology. Most services (12/18) were short term and usually delivered to people with advanced cancer over a period of 4–6 weeks (range 1–12 weeks) via a mixture of face-to-face and telephone contacts (typically 4–6 contacts, range 1–12 contacts; see Appendix 5).

Services incorporated a wide range of intervention components, including information and education, psychosocial support, self-management strategies and other interventions (Table 6). Components most commonly included in services were breathing techniques (14/18), psychological support (12/18) and relaxation or calming techniques (11/18). A minority of services (≤ 2/18) included acupressure or transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, spiritual support, information on sleep hygiene and smoking cessation advice or support.

| Intervention | n | Servicesa |

|---|---|---|

| Information and education | ||

| Education/advice | 9 | 90,94,95,157,162–166 |

| Nutritional advice/support | 3 | 95,164,167 |

| Sleep hygiene | 2 | 95,168 |

| Smoking cessation advice/support | 1 | 95 |

| Written information | 4 | 94,95,164,166 |

| Psychosocial support | ||

| Carer/family support | 5 | 90,94,95,162,166 |

| Psychological support | 12 | 90,94,95,101,154,156,161,162,164–167 |

| Social support | 7 | 90,94,95,154,156,164,166 |

| Spiritual support | 1 | 94 |

| Self-management strategies | ||

| Breathing techniques | 14 | 90,94,95,100,101,154,156,157,161,163,164,166,168,169 |

| Emergency/crisis planning | 3 | 94,95,166 |

| Exercise plans | 5 | 94,95,164,166,170 |

| Handheld fan/water spray | 5 | 94,95,101,164,166 |

| Goal-setting | 4 | 90,95,101,166 |

| Pacing | 8 | 94,95,100,101,161,164,166,167 |

| Positioning | 4 | 94,95,164,166 |

| Relaxation/calming techniques | 11 | 90,94,95,100,101,154,161,164,166,167,169 |

| Other interventions | ||

| Acupressure/transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation | 2 | 157,170 |

| Occupational aids | 5 | 94,95,164,166,170 |

| Pharmacological review | 4 | 94,95,168,169 |

Clinical effectiveness

Breathlessness severity

Ten studies90,94,98–100,154–157 assessed the severity of breathlessness using one or more of the following measures: VAS, NRS or Borg scores (Table 7). For ‘best breathlessness’, two studies using VAS found a greater improvement in the intervention group than in the control (differences in median change 5.7, p = 0.03,98 and 1.0, p = 0.0290), and three studies with unspecified measures found a significant intervention effect [F(2,44) = 5.30; p = 0.009]156 or no difference (data not reported). 155,156 For ‘worst breathlessness’, one study using VAS found a greater improvement in the intervention group than in the control (difference in median change 3.5; p = 0.0590), whereas no significant differences were found by two studies using NRS (MD –0.35, 95% CI –1.71 to 1.01; p = 0.6194; MD 0.41, 95% CI –0.86 to 1.67; p = 0.53157), one study using VAS (difference in median change 3.8; p = 0.1498) and one with an unspecified measure155 (data not reported). For ‘average breathlessness’, one study using an unspecified measure found a greater improvement in the intervention group than in the control (difference in mean change 1.2155), whereas two studies using NRS did not (MD –0.33, 95% CI –1.28 to 0.62; p = 0.49;94 MD 0.65, 95% CI –0.49 to 1.80; p = 0.26). 157 One study using NRS found no effect on breathlessness on exertion (MD –0.73, 95% CI –1.69 to 0.22; p = 0.13)94 and one study using Borg scale ratings for breathlessness at rest and on exertion found no difference between groups (data not reported). 154 In line with their feasibility study results,99 a powered trial comparing one with three service contacts found no significant difference in NRS worst (MD 0.2, 95% CI −2.31 to 2.97; p = 0.83) or average (MD 0.3, 95% CI –2.00 to 2.62; p = 0.79) breathlessness. 158

| Descriptor | Scale | Timeframe | Studies | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barton et al.99 | Bredin et al.98 | Corner et al.90 | Higginson et al.94 | Johnson et al.158 | aPearce et al.154 | aYates et al.156 | aYates et al.155 | Yorke et al.157 | |||

| Best | VAS | Previous week | ✗ | ||||||||

| Unknown | ✗ | ||||||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||||

| Worst | VAS | Previous week | ✗ | ||||||||

| Unknown | ✗ | ||||||||||

| NRS | Previous 24 hours | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ✗ | |||||||||

| Average | NRS | – | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||

| Previous 24 hours | ✗ | ||||||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ✗ | |||||||||

| On exertion | Borg | – | ✗ | ||||||||

| NRS | Previous 24 hours | ✗ | |||||||||

| At rest | Borg | – | ✗ | ||||||||

| Now | NRS | – | ✗ | ||||||||

Breathlessness affect

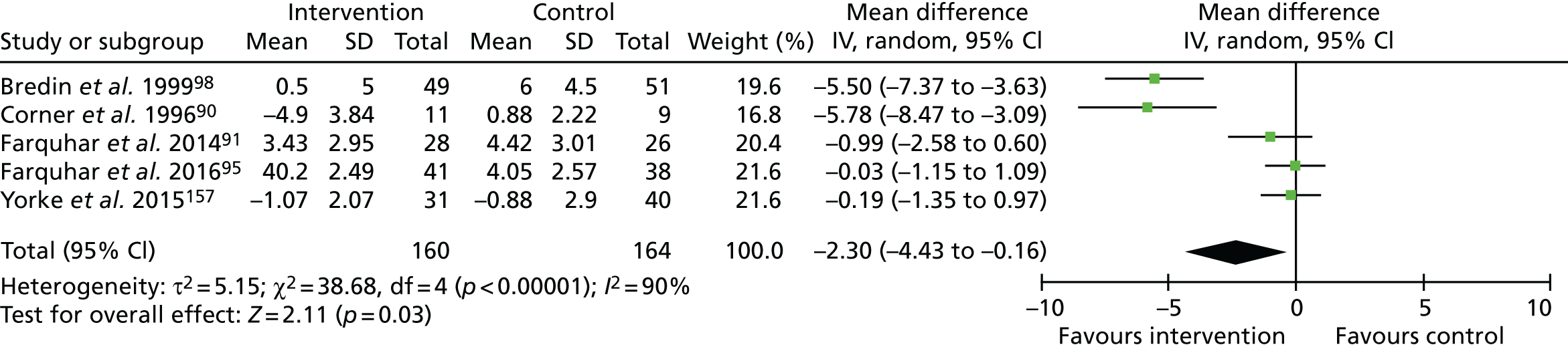

Ten studies90,91,95,98–100,155–157 assessed ‘distress due to breathlessness’ using VAS (range 0–100, higher = worse) or NRS (range 0–10, higher = worse). 91,95 Eight of these studies compared breathlessness services to usual care, three of which155,156 reported no significant difference but did not provide data. Data from five studies90,91,95,98,157 were combined in a meta-analysis (n = 324; Figure 1) that showed significantly lower NRS distress following the intervention than following the control (MD –2.30, 95% CI –4.43 to –0.16; p = 0.03). A sensitivity analysis excluding two outlier studies90,98 resulted in a reduced point estimate of effect and non-significant difference (MD –0.29, 95% CI –1.00 to 0.43; p = 0.43; I2 = 0%). Similar to the finding from the preceding feasibility study,99 a RCT testing service variations found no difference on NRS ‘coping with breathlessness’ (MD –1.7, 95% CI –4.27 to 0.90; p = 0.20),100 and significantly higher NRS distress due to breathlessness following three sessions versus one session (MD 3.9, 95% CI 0.98 to 6.91; p = 0.01). 100

FIGURE 1.

The NRS distress due to breathlessness. df, degrees of freedom; IV, inverse variable. Reproduced with permission from Brighton et al. 92 This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the licence is given, and indication of whether changes were made. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

The quality of evidence for distress due to breathlessness was rated as very low. Owing to the lack of blinding of participants or outcome assessors, plus evidence of (or unclear information regarding) attrition bias, the evidence was downgraded for risk of bias. This evidence was also downgraded for inconsistency (owing to wide variation in effect estimates across studies), and imprecision (evidenced by wide variance in point estimates and lower 95% CIs, indicating potentially very little effect).

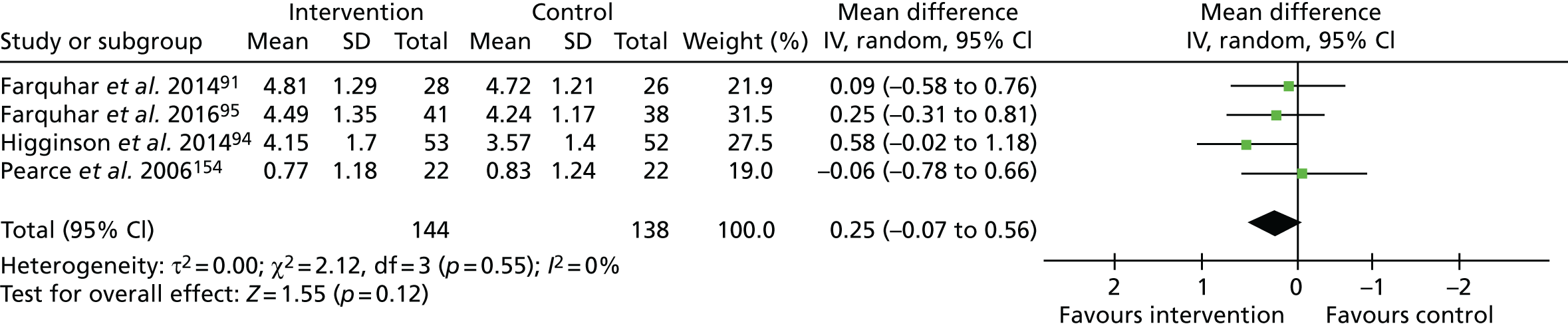

Four studies91,94,95,154 assessed ‘mastery over breathlessness’ using the CRQ mastery domain. 94,154 A meta-analysis of these data (n = 259; Figure 2) showed a statistically non-significant increase in mastery (range 1–7, higher = better) favouring the intervention (MD 0.23, 95% CI –0.10 to 0.55; p = 0.17). A sensitivity analysis excluding one study,154 deemed to be at a high risk of bias, increased the point estimate of effect (MD 0.30, 95% CI –0.06 to 0.66; p = 0.11). One study found significantly lower mastery scores after three service contacts than after one service contact (MD –0.6, 95% CI –1.06 to –0.11; p = 0.02). 100

FIGURE 2.

The CRQ breathlessness mastery. df, degrees of freedom; IV, inverse variable. Reproduced with permission from Brighton et al. 92 This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the licence is given, and indication of whether changes were made. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

One further study found improved dyspnoea-12 (range 0–36; higher = worse) scores with the intervention than with control (MD 5.19, 95% CI 0.62 to 9.75; p = 0.026). 157

We judged the quality of evidence for mastery to be low. This evidence was downgraded because we deemed the studies to have a high risk of bias due to the lack of blinding of participants or outcome assessors, plus the evidence of (or unclear information regarding) attrition bias. In addition, we downgraded this evidence for imprecision because of the wide variance in point estimates and lower 95% CIs, indicating potentially very little effect.

Psychological outcomes

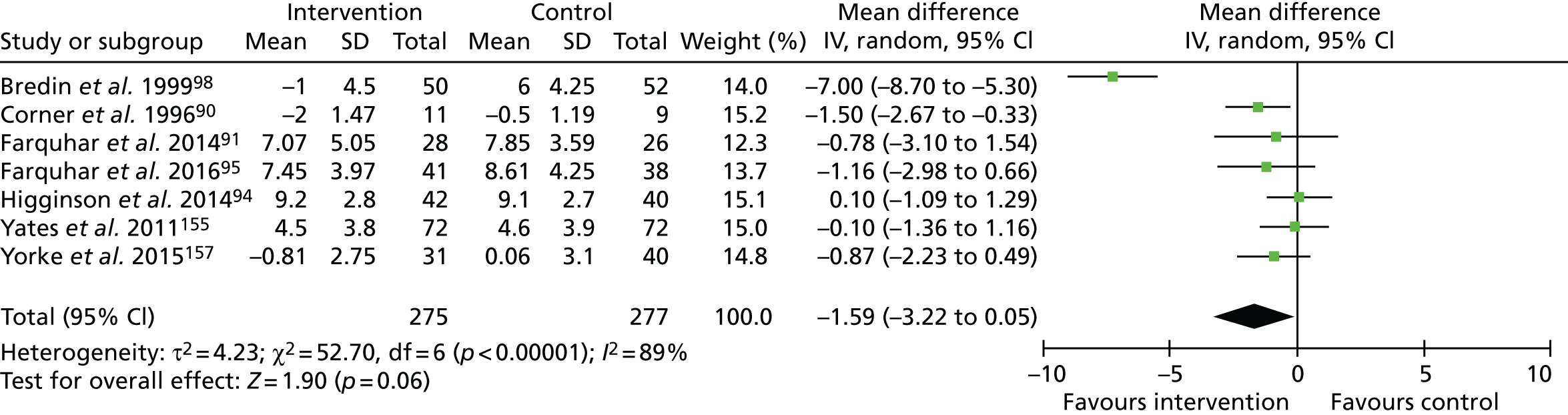

Seven studies assessed anxiety and depression using HADS. 90,91,94,95,98,155,157 Data from these seven studies (n = 552, Figure 3) showed a statistically non-significant reduction in anxiety scores (range 0–21; higher = worse), favouring the intervention (MD –1.59, 95% CI –3.22 to 0.05; p = 0.06). The sensitivity analysis, excluding one study155 deemed to be at a high risk of bias, increased the point estimate (–1.85, 95% CI –3.76 to 0.06; p = 0.06). A sensitivity analysis removing one outlier study98 resulted in a reduced point estimate but statistically significant group difference (MD –0.66, 95% CI –1.23 to –0.10; p = 0.02; I2 = 0%). No statistical differences in anxiety were reported when comparing one and three contacts. 99,100

FIGURE 3.

The HADS – anxiety. df, degrees of freedom; IV, inverse variable. Reproduced with permission from Brighton et al. 92 This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for or any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the licence is given, and indication of whether changes were made. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

We rated the quality of evidence for anxiety to be very low. This evidence was downgraded because of the risk of bias, including the lack of blinding of participants or outcome assessors, plus the evidence of (or unclear information regarding) attrition bias. We also downgraded for inconsistency (owing to wide variation in effect estimates across studies), and imprecision (evidenced by wide variance in point estimates, and lower 95% CIs indicating potentially very little effect).

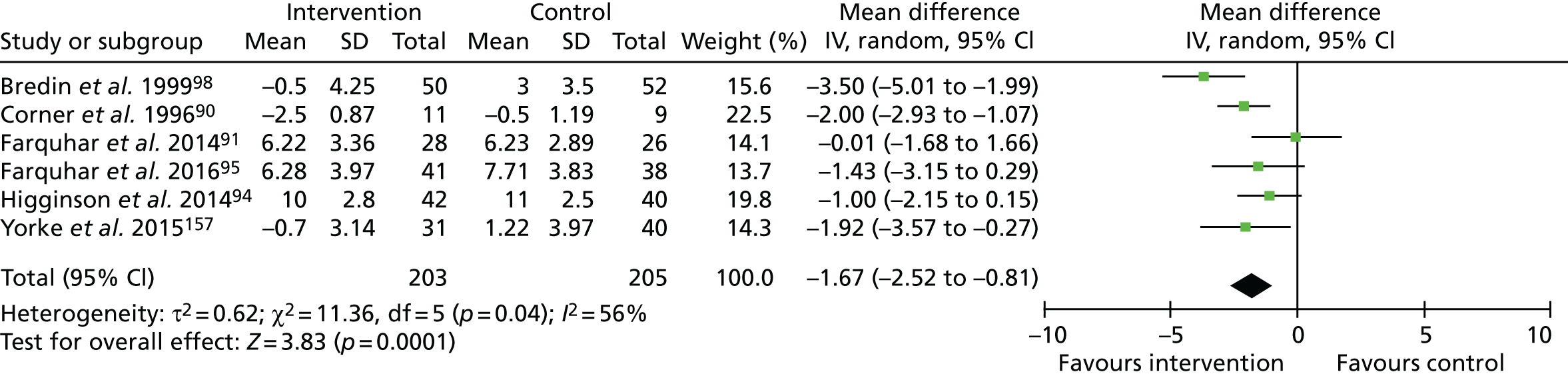

For depression, one study156 reported no difference between groups but did not provide data. Meta-analysis using the six remaining studies (n = 408, Figure 4) showed reduced depression scores (range 0–21, higher = worse) favouring the intervention (MD –1.67, 95% CI –2.52 to –0.81; p < 0.001). No statistical differences in depression were reported when comparing one and three contacts. 99,100

FIGURE 4.

The HADS – depression. df, degrees of freedom; IV, inverse variable. Reproduced with permission from Brighton et al. 92 This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the licence is given, and indication of whether changes were made. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

The quality of evidence for depression was judged to be moderate. This evidence was downgraded for risk of bias only, indicated by the lack of blinding of participants or outcome assessors, plus the evidence of (or unclear information regarding) attrition bias.

Three further studies reported no significant differences between the intervention and control groups in ‘psychological symptoms’: two using an unspecified measure (data not reported)155,156 and one using the Rotterdam Symptom Checklist (range 7–28, higher = worse; difference in median change –8; p = 0.21). 98 One study comparing one session with three sessions found no significant difference on CRQ emotion scores (MD –0.09, 95% CI –0.54 to 0.36; p = 0.69). 100

Physical function and health status/quality of life

Five studies90,91,94,95,98 assessed physical function. Two studies found greater improvements following the intervention than in the control participants using the Functional Capacity Scale (range 0–14; higher = better; MD for change 1.25; p < 0.02)90 and World Health Organization (WHO) Performance Status Scale (range 0–5, higher = worse; difference in median change 2, p = 0.02). 98 Three studies observed no difference in functional outcomes between groups assessed using the London Chest Activities of Daily Living Scale (MD –5, 95% CI –12.22 to 1.02; p = 0.10)94 or patient-reported number of times leaving their house (data not reported). 91,95

Seven studies91,94,95,98,100,154,157 included a measure of health status or QoL, none of which found significant differences between groups across the CRQ dyspnoea domain91,94,95,154 (including the comparison between one and three sessions100) or total score,94 EQ-5D index94 or VAS,94,157 and the Rotterdam Symptom Scale QoL domain. 98 Owing to heterogeneous measures, change from baseline and post-intervention scores, and cases of non-normally distributed data, we decided against meta-analysis for these outcomes.

Survival

Two studies reported survival data. 94,98 One found a significant difference in survival (generalised Wilcoxon score of 3.9; p = 0.048) in favour of the intervention. 94 Subgroup analysis found that the difference was driven by participants with non-cancer diagnoses. The remaining study, enrolling only patients with cancer, found no difference in survival across groups (data not reported). 98

Cost-effectiveness

Economic evaluation

Evidence for cost-effectiveness of the interventions was limited and non-conclusive. Four studies of three services were eligible for inclusion,91,94,95 and all used GBP 2011/12 costs. Three studies compared the service with usual care, and one study compared offering one session with offering three sessions within a service.

The perspective of the analysis for Farquhar et al. ’s91 study of their Breathlessness Intervention Service (BIS) was societal by including costs of informal care. Among patients with advanced cancer, total health/social costs including informal care for 8 weeks prior to the baseline assessment were £6137 [standard deviation (SD) £6099] in the BIS group and £5461 (SD £6099) in the usual care group. Costs between baseline and follow-up at 2 weeks were £794 (SD £866) for BIS and £1121 (SD £1635) for usual care. Intervention costs for the BIS were £119 (SD £62). Total costs were £354 lower for the BIS than for usual care (95% CI –£1020 to £246) and incremental QALY gain was 0.0002 (95% CI –0.001 to 0.002) after controlling for baseline. The chance of the BIS having lower total costs and resulting in a greater QALY gain than usual care was 80.9% according to cost-effectiveness planes. There was a 50.9% chance of the BIS being lower than usual care for total costs, and having a greater number of QALYs.

For Farquhar et al. ’s95 study of their BIS, a NHS perspective was used. Among patients with advanced non-malignant disease, total health/social costs for 8 weeks prior to the baseline assessment were £1952 (SD £3290) in the BIS group and £3630 (SD £5588) in the usual care group. Costs between baseline and follow-up at 4 weeks were £1371 (SD £2948) for BIS and £659 (SD £1253) for usual care. Intervention costs for BIS were £156 (SD £80). After adjusting for baseline values, total costs were £799 higher for BIS (95% CI –£237 to £1904) and the BIS group gained 0.003 extra QALYs (95% CI –0.001 to 0.007) than the control group. The cost per QALY for BIS was £266,333. The chance of BIS having lower total costs and resulting in a greater QALY gain than usual care was 7% according to cost-effectiveness planes.

Higginson et al. ’s94 Breathlessness Support Service (BSS) was assessed in terms of hospital inpatient days and formal care costs for 12 weeks prior to the baseline assessment. The cost of formal care was £2911 (SD £2729) for BSS and £3709 (SD £4484) for usual care. Incremental QALY gain between baseline and follow-up at 6 weeks was 0.092 (95% CI –0.23 to 0.04). No more information related to economic evaluation was reported in this paper, but a separate paper51 analysed the same data to measure the cost of care, regardless of randomisation. The total cost for all participants was £11,507 (SD £9911), which was the sum of health-care costs [£2624 (SD £3456)], social care costs [£628 (SD £1132)] and informal care costs [£8254 (SD £8777)]. Increased breathlessness on exertion was associated with higher health-care costs and informal care costs, and having a carer was associated with higher informal care costs.

Johnson et al. ’s158 trial compared one session with three sessions of a breathlessness service from a NHS perspective, including costs of the service in each arm and other health-related resource use costs. For the three-session service, there was a non-significant reduction in overall QALYs (MD –0.006, 95% CI –0.018 to 0.006) and non-significant increase in costs. There was no evidence that the additional costs were offset by lower health-related resource use costs elsewhere. The probability of the single session being cost-effective at a threshold value of £20,000 per QALY was > 80%. 100

Referral, uptake, adherence and adverse events

Of the 11 RCTs included in the analysis, fewer than half reported numbers screened for eligibility. When available, studies reported screening between 53 and 932 people for eligibility, of whom 15% to 48.6% were deemed to be eligible for inclusion. The total number of participants randomised into each trial ranged from 22 to 156. Of the participants randomised, between 50% and 90.8% of participants completed the trial to key outcome stages. Full data including reasons for attrition are described in Table 8. No adverse events were reported.

| Study authors and year | Screened (n) | Eligible, n (%) | Reasons for ineligibility/exclusion | Randomised (n) | Completed (post intervention), n (%) | Adherence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barton et al. 201099 | 53 | 22 (41.5) | Ineligible included 13 undergoing chemotherapy/radiotherapy, 5 declined, 5 too unwell, 4 prior breathlessness training, 2 unconfirmed malignancy, 1 not breathless, 1 cause of breathlessness treated | 22 | 11 (50.0) | Of 11 allocated to the three-session intervention, 5 dropped out by the fourth assessment (2 died, 2 declined, 1 too unwell). Of the 11 allocated to the single-session intervention, 6 dropped out by the fourth assessment (3 died, 2 too unwell, 1 declined) |

| Bredin et al. 199998 | NR | 119 | 16 patients excluded because of a protocol violation (one centre failed to adhere to the trial protocol and so was excluded on advice of data monitoring committee) | 103 | 60 (58.3) | Of the 52 allocated to the control, 3 refused study after randomisation, 15 withdrawn, 7 died. Of the 51 allocated to intervention, 1 refused study after randomisation, 8 withdrew, 9 died. Of the total 27 who withdrew but did not report an improvement in their breathlessness, 16 withdrew because of deteriorating condition (13 control, 3 intervention) and 4 were unhappy with the arm allocated (3 control, 1 intervention). This left 7 who withdrew for other reasons (2 control, 5 intervention) |

| Corner et al. 199690 | NR | NR | 34 patients had consented to take part in the randomised study when randomisation was stopped in response to requests from medical and nursing staff who felt that they had observed a clear benefit from the intervention strategy | 34 | 20 (58.8) | Of the 19 allocated to intervention and 15 to control, 14 patients withdrew because of deterioration (8 and 6, respectively) |

| Farquhar et al. 201491 | NR | 158 | 81 eligible patients agreed to recruitment visit, 14 of whom died or were withdrawn by service/researcher/patient | 67 | 54 (80.6) | Of the 35 allocated to intervention, 7 were lost to study (5 condition deteriorated, 2 died). Of the 32 allocated to control, 6 were lost to study as their condition deteriorated |

| Farquhar et al. 201695 | NR | 159 | 97 eligible patients agreed to recruitment visit, 10 of whom died or were withdrawn by service/researcher/patient | 87 | 79 (90.8) | Of the 44 allocated to intervention, 3 were lost to study (including 1 death) by time point 3 (conducted 4 weeks after baseline). Of the 43 allocated to control, 5 were lost to study (including 1 death) by time point 3 |

| Higginson et al. 201494 | 216 | 105 (48.6) | 11 did not meet inclusion criteria and an additional 100 were not randomised for other reasons (6 died at time of referral letter receipt, 29 declined to participate, 18 were too ill to participate, 47 unable to be contacted) | 105 | 82 (78.1) | 53 were allocated to intervention and 52 to control. By week 6, 4 died (1 intervention, 3 control), 5 withdrew (no reason) (2 intervention, 3 control), 8 withdrew because of illness (4 intervention, 4 control), and 6 were unable to be contacted (patient often hospitalised or moved away) (4 intervention, 2 control). Attrition to primary outcome was lower than estimated (22% not 40%) and so recruitment was stopped at 105 |

| Johnson et al. 2015158 | 932 | 156 (16.7) | Of the 776 excluded from enrolment, 127 had insufficient shortness of breath, 528 declined (no reason), 38 were unable to give informed consent, 32 had comorbidities/intercurrent illness, 22 required urgent medical intervention, 20 had previous pulmonary rehabilitation, and 9 had other reasons | 156 | 124 (79.5) | 52 were allocated to the three-session intervention and 104 to the single-session, but only 39 and 91 received their respective allocated intervention because 2 from each group withdrew prior; a further 11 did not receive the three-session intervention (2 too unwell, 1 only well enough to receive some, 8 no reason); and another 11 did not receive the single-session [1 did not attend (lost to follow up), 8 no reason, 1 deteriorated before, 1 not reported] |

| Yorke et al. 2015157 | 715 | 107 (15.0) | Of the 608 ineligible, 176 had absence of two or more symptoms or did not have bothersome breathlessness, 40 had poor prognosis, 55 had further treatment, 130 had recent chemotherapy, 128 had other reasons, 74 declined and 5 were reason unknown | 107 | 72 (67.3) | Of the 53 allocated to the intervention, 3 were removed from analysis (2 did not meet eligibility, 1 no baseline data), 7 dropped out during the intervention (4 too unwell, 1 died, 1 shingles, 1 declined) and 12 dropped out post intervention (1 died, 8 declined, 3 lost to follow-up). Of the 54 allocated to the control, 3 were removed from analysis (2 did not meet eligibility, 1 no baseline data) and 10 dropped out (5 died, 4 declined, 1 lost to follow-up) |

| Pearce et al. 2006154 | NR – abstract available only | 51 | NR – abstract available only | |||

| Yates et al. 2007156 | NR – abstract available only | RCT 1: n = 30; RCT 2: n = 57 | NR – abstract available only | |||

| Yates et al. 2011155 | NR – abstract available only | 144 | NR – abstract available only | |||

Experiences

Across the 11 studies with qualitative data90,91,94,95,102–106,159–161 and the five studies with quantitative data99,100,103,157,161,162,168 on participants’ satisfaction, three themes emerged with regard to experiences: valued characteristics, perceived outcomes and challenges to services.

Satisfaction

Five studies assessed overall satisfaction with their service. For one service, 18 out of 21 respondents (86%) stated that they would recommend the clinic that they attended to another breathless patient;168 for another service, 100% of patients reported high satisfaction and would recommend the service. 103 One study reported high patient satisfaction with care but data were not provided. 162 When comparing one versus three sessions with a service, satisfaction with care was higher for those receiving three sessions in the feasibility study (data not provided),99 but there was little difference between the groups in the full trial (MD 0.4). 100

Valued characteristics

Participants valued the education and information-sharing included in the services, particularly in terms of helping them understand their breathlessness, legitimising the interventions being suggested, and providing helpful written resources to refer to (Box 1). The interventions themselves (e.g. techniques for breathing, pacing, positioning, relaxation and using a handheld fan) were praised for their simplicity, portability and perceived effectiveness. The psychosocial support received through the services was also highly valued, providing opportunities for participants to have their experiences listened to and acknowledged, to receive support and reassurance, and to discuss problems beyond their breathlessness.