Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 11/2003/58. The contractual start date was in January 2013. The final report began editorial review in October 2017 and was accepted for publication in July 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Chiara Bucciarelli-Ducci has received personal fees from Circle Cardiovascular Imaging (Calgary, AB, Canada). Chris A Rogers is a member of the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Commissioning Board. Barnaby C Reeves reports former membership of the HTA Commissioning Board (from January 2012 to 31 March 2016) and the HTA Efficient Study Designs Board (October–December 2014). He also reports current membership of the HTA Interventional Procedures Methods Group and Systematic Reviews Programme Advisory Group (Systematic Reviews National Institute for Health Research Cochrane Incentive Awards and Systematic Review Advisory Group).

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Harris et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background and rationale

Cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) is a non-invasive imaging technique that assesses heart structure and function with high spatial and temporal resolution. The use of CMR has increased in recent years in all subgroups of acute coronary syndrome (ACS) patients, including those who activate the primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI) pathway. 1 It is not clear whether or not having CMR influences patient management or reduces the length of hospital stay or the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs) in these patients. Systematic reviews from 2014 highlighted the lack of high-quality, adequately powered studies to establish the prognostic value of CMR findings in patients who activate the PPCI pathway. 2,3 Similarly, few studies have assessed how CMR changes patient management, despite the fact that cardiologists believe that CMR brings about important changes in management. 4

Primary percutaneous coronary intervention

Primary percutaneous coronary intervention is the primary therapeutic approach for restoring blood flow to the heart in ACS patients who have had a ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). Currently, across the UK ≈97% of patients with a STEMI who received any reperfusion treatment were treated with PPCI. 5 Management of the in-hospital stay and follow-up after PPCI is determined by the final infarct size, the presence or absence of comorbidities and patient characteristics. About 10% of patients with ACS who activate the PPCI pathway (i.e. those that present with chest pain and ST-elevation or chest pain and new-onset left bundle branch block on electrocardiogram) are found to have unobstructed coronary arteries on angiography and, therefore, do not receive PPCI. There are no long-term outcome data from well-designed, multicentre trials on CMR use in different subgroups of patients who activate the PPCI pathway. There are also no studies reporting on the cost-effectiveness of CMR in these patients (or indeed patients from other clinical areas), which makes decision-making regarding the provision of CMR services within the NHS difficult.

Subgroups of patients who activate the primary percutaneous coronary intervention pathway and may benefit from cardiovascular magnetic resonance

Two subgroups of patients were identified in the protocol as having the potential to benefit from CMR: (1) patients with multivessel disease and (2) patients with unobstructed coronary arteries on angiography.

It is estimated that 40–65% of the patients presenting with a STEMI have multivessel disease (depending on the baseline characteristics, e.g. age, of the population studied). 6–11 There is ongoing debate about the optimal treatment strategy for these patients. Three main treatment management strategies have been proposed/are currently used: (1) conservative, PPCI of the infarcted artery followed by medical therapy (unless ischaemia occurs), (2) staged, in which only the infarct-related artery is treated acutely and other lesions are treated at a later date and (3) aggressive, percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) of all significant lesions at the time of PPCI.

The role of CMR in patients with multivessel disease is undefined. CMR allows the volume of ischaemic or poorly perfused myocardium to be quantified but it is not known whether or not access to CMR to plan further revascularisation influences management. Since the Primary percutaneous coronary Intervention Pathway Activation (PIPA) study was commissioned, there has also been a rapid increase in the use of fractional flow reserve (FFR) testing (a guide wire-based procedure done through a standard diagnostic catheter at the time of a coronary angiography) to assess ischaemia; this technology is available to interventional cardiologists in the catheter laboratory. CMR is comparable to FFR for detecting ischaemia; studies have shown excellent diagnostic accuracy of perfusion CMR to detect areas of ischaemia identified by FFR. 12,13 However, while FFR may be appropriate in symptomatic, high-risk patients for whom the benefit of an invasive approach to ischaemia testing may outweigh the risks (i.e. the likelihood of revascularisation is high; therefore, lesions can be revascularised at the same time as the FFR), the benefit is less clear in asymptomatic multivessel disease patients. CMR may, therefore, have a role in selecting patients who will receive the greatest benefit from these invasive procedures. The non-inferiority of CMR in managing patients with multivessel disease is the subject of the magnetic resonance perfusion imaging to guide management of patients with stable coronary artery disease (MR-INFORM) trial. 14

The reported variation in the incidence of normal coronary angiograms in patients activating the PPCI pathway is between 3% and 16%. 15,16 It is in this group that cardiologists believe that CMR has the greatest potential to change patient management. In these patients, the lack of an accurate diagnosis may result in inappropriate treatment and/or follow-up,17,18 associated with a poorer prognosis. 19 A definitive diagnosis of myocardial infarction (MI) or not is also important so that these patients can be managed and followed up appropriately. Studies have shown that CMR can facilitate differential diagnosis in the context of a normal coronary angiogram,20–22 providing a definitive diagnosis (e.g. MI, myocarditis, Takotsubo cardiomyopathy) in 65–90% of these patients. 20,23,24 Although the prognostic implications of non-MI CMR abnormalities are not known, two studies showed that the pattern of CMR abnormalities in myocarditis was predictive of long-term outcome. 25,26

The benefit of CMR to other subgroups of patients who activate the PPCI pathway is less clear. However, given that not all of these patients will have access to centres with dedicated CMR facilities, there is potential for health inequality across the UK, which needs to be identified. Therefore, the population of interest for this study (target population) includes all ACS patients who activate the PPCI pathway, regardless of whether or not they receive PPCI.

Rationale for the study

We wanted to set up a multicentre, prospective cohort study (registry) in ACS patients who activate the PPCI pathway by linking routinely collected data from hospital information systems (HISs) with follow-up data from Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) and the Office for National Statistics (ONS). The aims of the registry were to document CMR activity in patients who activate the PPCI pathway and to provide information on CMR use, uptake over time, patients’ characteristics associated with being referred for CMR, the impact of CMR on patient management (e.g. early discharge of a patient with a normal coronary angiogram or the placement of an additional stent for a patient with multivessel disease) and the prognostic value of CMR after PPCI.

We were uncertain whether or not it would be feasible to set up a registry in this patient population using routinely collected data. In particular, we were uncertain if we could (1) easily identify the eligible population, (2) implement a ‘light-touch’ consent system across multiple hospitals and (3) extract and link data sets from multiple HISs in different hospitals. We also wanted (4) to provide a reliable estimate of the CMR rate in patients who activate the PPCI pathway and (5) to define a ‘proxy’ primary composite outcome, acceptable to cardiologists and other stakeholders (e.g. clinical commissioners) as representing a clinically important change in management as a result of an eligible patient having undergone CMR (e.g. expected to prevent future MACEs). Item number 5 was included so that the registry would be able to assess effectiveness in the medium term. A long-term objective of the registry would be to compare the incidence of MACEs in patients who do or do not have CMR after the index event, but the low frequency of MACEs means that the study would have to accrue over 37,000 subjects to detect a clinically important reduction in the incidence of MACEs with adequate power.

Chapter 2 Aims and objectives

The aim of the study was to evaluate the feasibility of setting up a UK multicentre registry study to document CMR use in patients who activate the PPCI pathway. There were three elements to the study, listed below with the associated objectives.

-

A. To determine whether or not it is feasible to set up a CMR registry in this patient population by linking sources of routinely collected data.

-

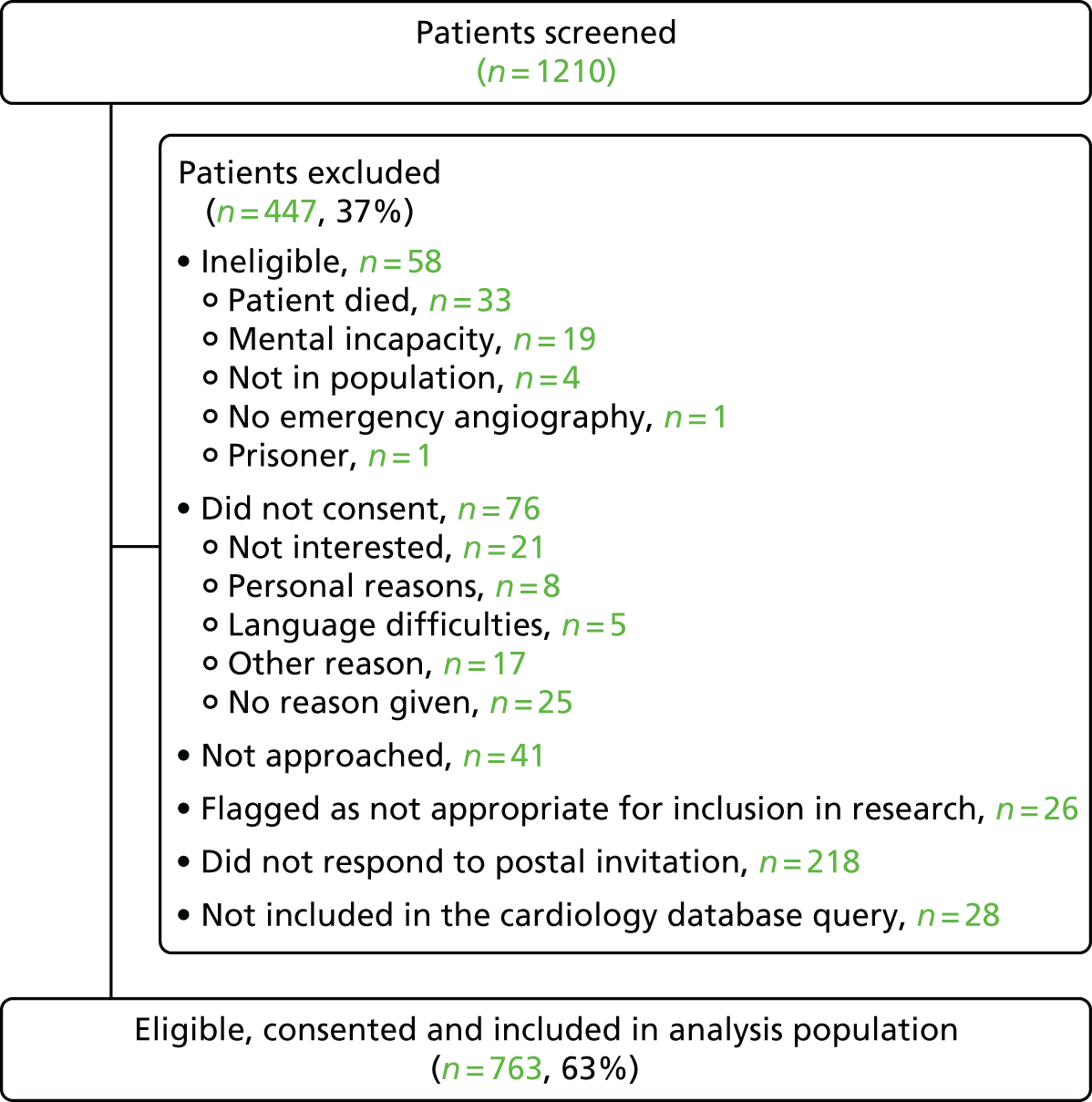

Objective A1: to implement consent and establish patient consent rate.

-

Objective A2: to provide evidence of whether or not data linkage and extraction can be carried out across PPCI centres.

-

Objective A3: to determine whether the registry can be compiled from hospital episode data [HES and Patient Episode Database Wales (PEDW)] rather than multiple HISs.

-

-

B. To estimate the proportion of the target population who have CMR at two centres with dedicated CMR facilities and to describe resource use and associated costs of having CMR after PPCI.

-

Objective B1: to estimate the proportion of the target population who get a CMR scan following PPCI pathway activation.

-

Objective B2: to develop simple cost-effectiveness models in relevant subgroups of patients who activate the PPCI pathway in order to identify key drivers of cost-effectiveness for CMR imaging in patients who activate the PPCI pathway.

-

-

C. To identify an outcome measure representing a definitive change in clinical management, conditional on having undergone CMR, that would be credible to cardiologists and other stakeholders as an interim measure of the value added by doing CMR.

-

Objective C1: to define, using formal consensus methods, a treatment/process outcome that will constitute a definitive change in clinical management arising from having undergone CMR.

-

Objective C2: to identify patient subgroups in whom CMR use is indicated using formal consensus methods and illustrative data from the registry.

-

Objective C3: to determine whether or not hospital episode data adequately capture the main changes in clinical management that are identified using formal consensus.

-

Objective C4: to pilot the implementation of a primary outcome that is based on the changes in management, for which consensus was achieved using hospital episode data.

-

Conditional on the success of achieving objectives A, B and C, there was a final objective, D, for which we envisaged that we would define the research objectives and calculate the sample size needed for a cohort study to achieve the aim of evaluating the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of CMR after PPCI pathway activation, with respect to the outcome identified by objective C.

Changes to objectives during the study

The objectives described above comprise all objectives that were studied rather than the objectives at the outset. The following objectives were added or modified during the course of the study.

With respect to objective A3, we faced several challenges when identifying the eligible population and implementing patient consent in the PPCI centres. These are described in detail in Chapter 3. We therefore wanted to determine whether or not we could identify ACS patients who activate the PPCI pathway in hospital episode data in order to determine whether or not a future registry in this patient population could be set up solely from hospital episode data (Chapter 4, Identifying the eligible study cohort and cardiovascular magnetic resonance exposure in hospital episode data).

With respect to objective B2, we originally planned to identify key cost drivers empirically, by describing resource use and associated costs of having CMR after PPCI pathway activation from HES and PEDW data for participants during follow-up of the cohort. We experienced considerable delays in obtaining HES data, which prevented us from doing this. Therefore, the economists used an alternative approach, seeking secondary sources of data as inputs into economic decision models to identify the key drivers of cost-effectiveness, that is the model parameters that most influence estimates.

With respect to objective C4, we had initially intended to collect follow-up data from each participating hospital to identify the changes in clinical management that could result from CMR (defined through the formal consensus). However, we realised early on that this would not be possible for a proportion of our cohort because many patients whom we recruited had their treatment at the PPCI centres but were quickly repatriated to their local hospital. We therefore decided that following the cohort through hospital episode data would provide more complete data because follow-up data would be available for all patients regardless of which hospital (within England or Wales) they attended after their index admission/procedure.

With respect to objective C3, some of the cardiologists in the research team were sceptical about our ability to pick up potential changes in clinical management resulting from CMR using HES and PEDW data. They highlighted that changes in clinical management may be too subtle to be captured in a data set that records only information about inpatient, outpatient and accident and emergency (A&E) attendances. In contrast, electronic data sources in many hospitals capture a range of additional information, for example prescribing data and patient-level nursing observation data. We therefore designed a questionnaire requesting specific information from the referring cardiologists about how CMR changed management in all patients in our study who were referred for a CMR. We determined whether or not changes in management described in the questionnaire were adequately reflected in hospital episode data [see Chapter 6, Implementation of a primary outcome based on the changes in management for which consensus was achieved (objectives C3 and C4)].

Major delays with the study

The major delay to the study was receiving the HES/ONS linked data set from NHS Digital. Below is a timeline of our data request and the processing of our application:

-

24 June 2013 – application was submitted to NHS Digital. We were told that our application would be processed closer to the time at which we required the data (September 2014), because our request was straightforward and the data set would not take long to assemble.

-

March 2014 – NHS Digital commissioned an independent review into data release and stopped processing all applications.

-

March 2015 – NHS Digital began processing our application.

-

August 2016 – linked HES/ONS data received.

This process added a 23-month delay to the study.

Chapter 3 Methods

Feasibility prospective cohort study (objectives A1, A2, A3 and B1)

Parts of this text have been reproduced from Brierley et al. 27 © Article author(s) (or their employer(s) unless otherwise stated in the text of the article) 2018. All rights reserved. No commercial use is permitted unless otherwise expressly granted. This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Study population

We aimed to approach all ACS patients who activated the PPCI pathway. This population included all patients who underwent an emergency angiogram, whether or not they received PPCI. We included patients if they were aged ≥ 18 years and underwent an emergency angiogram, defined as taking place within 2 hours of arrival at the hospital, unless specified otherwise by local protocols. We excluded patients if they were prisoners or lacked mental capacity to consent. There were no changes to the eligibility criteria during the study recruitment period. The study was reviewed and approved by the National Research Ethics Committee South West-Central Bristol (reference number 12/SW/0326).

Setting

Four NHS hospitals in England and Wales hosting 24/7 PPCI centres took part:27 the Bristol Heart Institute (University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust), Leeds General Infirmary (Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust), Morriston Hospital (Abertawe Bro Morgannwg University Health Board, Swansea) and University Hospital of Wales (Cardiff & Vale University Health Board). Two of these hospitals (Bristol and Leeds) were defined as ‘coronary magnetic resonance (CMR) centres’, that is hospitals that had a dedicated CMR service. The other two hospitals (Swansea and Cardiff) were defined as ‘non-CMR centres’, that is hospitals that did not have access to a dedicated CMR service.

Patient identification and consent

Each hospital implemented its own methods for identifying and consenting patients. Most eligible patients were identified manually (e.g. by checking catheter laboratory records, by checking the local cardiology database or both). One of the participating hospitals set up a database query (including the search terms ‘PPCI’, ‘QueryNot’ and ‘QuerProc’) in the local cardiology database to flag up eligible patients. However, the query was broad and relied on data input by staff in the catheter laboratory, which changed in ‘real-time’. This made identification of some eligible patients difficult. For example, if a patient was originally marked as ‘PPCI’ but was subsequently found to have an unobstructed coronary artery on the angiogram, the ‘PPCI’ label was removed, but no further information was added, necessitating manual searches by local research staff to identify whether or not the patient was eligible.

We gave eligible patients information about the study once they had recovered sufficiently from their angiography and consented them before they were discharged from hospital (see Appendix 1 for a copy of the consent form). In some hospitals, this was often not possible because of quick repatriation to the originating hospital or research staff not being available over the weekend. Patients who could not be approached in person were sent study information and consent forms by post. Postal consents were managed locally at each hospital. We requested consent to use all the information collected by the hospital in relation to the patients’ suspected MI (index admission) and all the information related to subsequent NHS care and vital status in the first 12 months following the index admission. 27

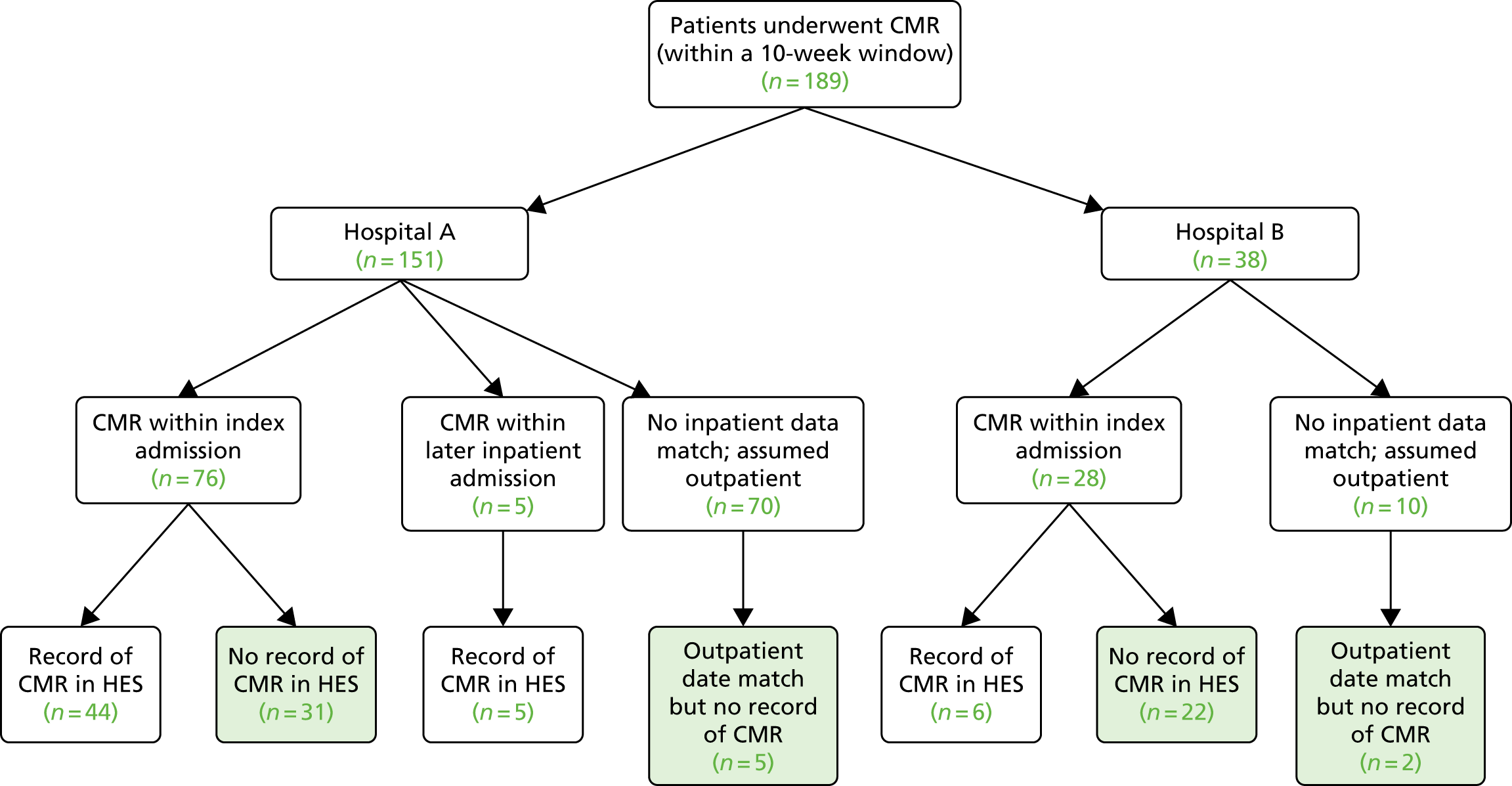

Exposure

Patients were classified as exposed if they received CMR within 10 weeks of the index admission (whether during the index admission or subsequently as an outpatient). CMR had to be documented (i.e. CMR report, including the date of the CMR) in the clinical radiology information system (CRIS) or similar imaging database when the date/time of the CMR was < 10 weeks (70 days) after the date of the index admission.

Data collection: index procedure

We asked each hospital to provide the following data from local HISs for all recruited patients:

-

basic demography [local Patient Administration System (PAS)/British Cardiovascular Intervention Society (BCIS) Central Cardiac Audit Database (CCAD)]

-

clinical characteristics on presentation at the index admission, peri- and post-procedural (PPCI) characteristics {local catheter laboratory database [e.g. Siemens (Munich, Germany) CARDDAS in Bristol]/BCIS-CCAD}

-

echocardiography (ECHO) and CMR reports (local imaging databases, e.g. Picture Archiving and Communication System, CRIS, CRIS in Bristol)

-

biochemistry [local biochemistry databases, e.g. Virtual Pathology Laboratory System/Integrated Clinical Environment (ICE) in Bristol]

-

medications on discharge (local biochemistry database, e.g. ICE in Bristol).

Each hospital had the option to submit a linked data set (i.e. the participating hospital linked data from different HISs within the hospital) or unlinked data extracts from each of the above categories with a unique patient identifier in each extract. We established a data linkage model at Bristol (by liaising with the appropriate HIS managers at University Hospitals Bristol NHS Foundation Trust) and informed the other hospitals that we would undertake linkage at Bristol based on this model, although the decision about how to submit the data was left to each participating hospital. 27

We collected a limited anonymised data set to characterise the eligible patients who were not recruited, that is those who declined to consent or did not respond to an invitation to consent before study recruitment ended. Hospitals were provided with a look-up table containing the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD)28 or Welsh Index of Multiple Deprivation (WIMD)29 for English or Welsh postcodes, so that the anonymised data sets could contain information on deprivation, both as scores and ranks, without including postcodes, which might have compromised anonymity. IMD and WIMD are calculated from combined information from several domains (e.g. income, employment, education, health) to produce an overall relative measure of deprivation.

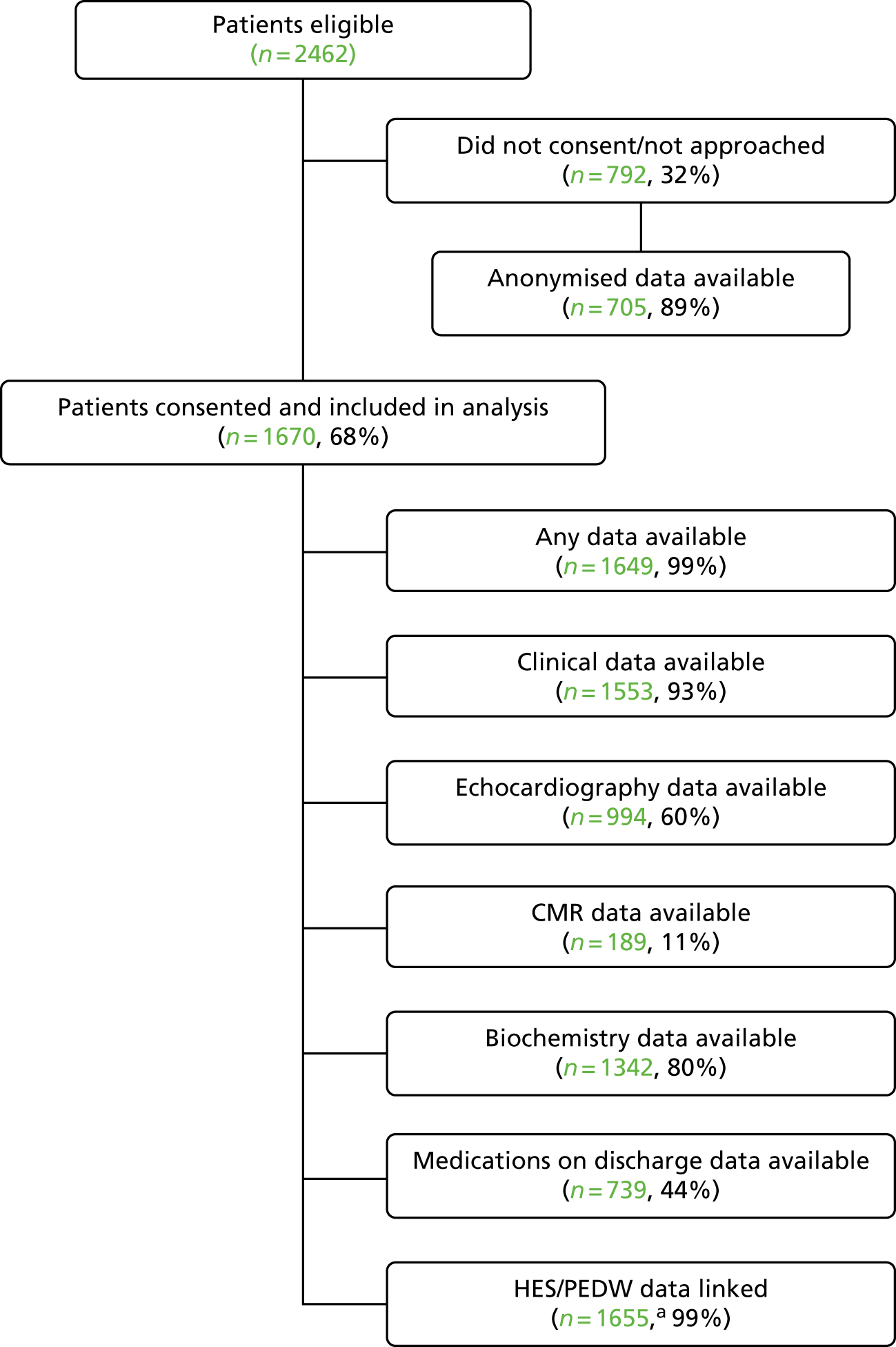

Data collection: follow-up

For subsequent inpatient and outpatient activity in the 12 months following the index admission, we applied to NHS Digital to link our data set with HES (i.e. inpatient, outpatient, A&E and critical care data) for the hospitals in England and to NHS Wales Information Service (NWIS) for PEDW (which collects equivalent information for NHS Wales hospitals) for the hospitals in Wales. Inpatient episode data (HES and PEDW) contain details of hospital admissions (including dates of admission and discharge) and main diagnoses/procedures. Outpatient data contain appointment dates and consultant specialty. A&E data contain dates, methods and sources of arrival at hospital.

NHS Digital routinely links HES with ONS mortality data. Mortality data were unavailable through NWIS, so the two Welsh hospitals provided these data for their patients. Identifiers and evidence of signed consent were submitted via a secure portal to NHS Digital and NWIS; HES, ONS and PEDW data were received with our unique patient identifier embedded within each file for linkage.

Admissions data were provided as data relating to an episode (i.e. admission under one consultant), but we restructured the data to relate to a ‘continuous inpatient spell’ regardless of any transfers to another consultant that may have taken place within the same admission. 30 We created a data set containing the admissions data that included the index admission and the admissions, outpatient, critical care and A&E data in the 12 months after the index admission. This was used to characterise the frequency and duration of outpatient follow-up, unscheduled cardiac-related hospital readmissions and cardiac-related investigations/procedures, such as diagnostic angiography, repeat PCI or cardiac surgery up to 1 year after the index admission.

We assumed that, if patients had any HES/PEDW data (e.g. admissions, outpatient and A&E), data not recorded in any of the data sets were absent (i.e. patient did not have an episode) rather than missing (i.e. data not entered). In addition, for those patients with a CMR within 10 weeks of their index admission, outpatient visits that occurred within this window were excluded from any counts.

Main outcome measures

The main prespecified outcome measures were feasibility parameters (criteria that would have to be met before making the decision to progress to setting up a full registry):

-

patient consent implemented at all four hospitals

-

data linkage and extraction from multiple local HISs achieved for > 90% of consented patients at all four hospitals

-

local data successfully linked with HES and PEDW for > 90% of consented patients at all four hospitals

-

CMR scan requested and carried out for ≥ 10% of patients activating the PPCI pathway in CMR hospitals. 27

Feasibility of compiling the registry from hospital episode data

We tested the feasibility of compiling the registry entirely through hospital episode data. We determined whether or not we could identify the following from hospital episode data:

-

the index event (PPCI or emergency angiography, cohort entry)

-

CMR within 10 weeks of the index event (exposure)

-

relevant subgroups of the population in which CMR may influence clinical management [identified through formal consensus, see Formal consensus study (objectives C1 and C2)]

-

clinical outcomes [MACEs, comprising death, MI, stroke, repeat PCI and a coronary artery bypass graft (CABG)].

We identified events corresponding to the index admission, exposure or outcome in HES and PEDW data sets (inpatient and outpatient) using the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD-10)31 and the Office of Population Censuses and Surveys (OPCS) classification procedure codes. 32 The index admission was identified from the inpatient data set using the OPCS codes for PCI (K49, K50, K75) and ICD-10 codes for ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) (I21.0, I21.1, I21.2, I21.3) to identify PPCI patients, and OPCS codes for angiography (K63.3, K63.5 or K63.6) with a method of admission coded as emergency to identify patients who underwent an emergency angiogram. We identified exposure (OPCS code U10.3) in the inpatient and outpatient data sets. We regarded all procedure codes within 1 day of the index admission (PCI and emergency angiography) or subsequent CMR to relate to the same event recorded in our HIS data set. Clinical outcomes were identified using the following codes: ICD-10 I21 for MI and I64 for stroke, and OPCS K49, K50 or K75 for PCI and OPCS K40, K41, K42, K43, K44, K45 or K46 for CABG. A full list of codes is shown in Appendix 2.

Sample size considerations

This was a feasibility study. We aimed to recruit sufficient patients to address the study objectives, not to provide a definitive answer to questions about the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of CMR in patients who activate the PPCI pathway. None of the objectives was analytic and, therefore, a power-based sample size justification was not appropriate.

Objective A2 and objective B1 required quantitative estimates to be reported. The target sample size of 1600 patients was assessed as sufficient to allow these proportions to be estimated with satisfactory precision. For example, we expected that ≥ 90% of patients who were invited to take part in the study would give consent; the 95% confidence interval (CI) for this proportion would be 88.4% to 91.4%. Similarly, we estimated that 12.5% of the target population would have CMR, although this proportion was less certain. The 95% CIs for proportions 5%, 10% and 15% would be, respectively, 4.0% to 6.2%, 8.6% to 11.6% and 13.3% to 16.8%.

Data analysis

Data were analysed using Stata/IC® version 13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). The analysis of feasibility outcomes was descriptive, with quantitative results expressed as counts, percentages and 95% CIs. Feasibility was assessed by comparing descriptive statistics with the corresponding criteria. We compared patients who did not consent (and for whom we received anonymised data) with those who did consent using standardised mean differences (SMDs). 27,33 We used means and standard deviations (SDs), or medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs), for continuous variables and number (per cent) for categorical variables to report the demographic variables and baseline characteristics of patients recruited from the four hospitals.

Clinical events were expressed as rates per 1000 person-years at risk, along with 95% CIs calculated using the Poisson distribution. Time at risk of death was calculated as the time from index admission to death for those known to have died within 12 months, or the time from index admission to the calendar date on which death data were provided for that site. Any time at risk of death of > 12 months was capped at 12 months.

Time at risk for MI, stroke, repeat PCI and CABG was calculated as the time from index admission to the event, or the time from index admission to the calendar date that follow-up data were provided for that site. If the patient died before experiencing the event, the time at risk of death was time from index admission until death. Any time at risk of death of > 12 months was capped at 12 months.

Formal consensus study (objectives C1 and C2)

Parts of this text have been reproduced from Brierley et al. 27 © Article author(s) (or their employer(s) unless otherwise stated in the text of the article) 2018. All rights reserved. No commercial use is permitted unless otherwise expressly granted. This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

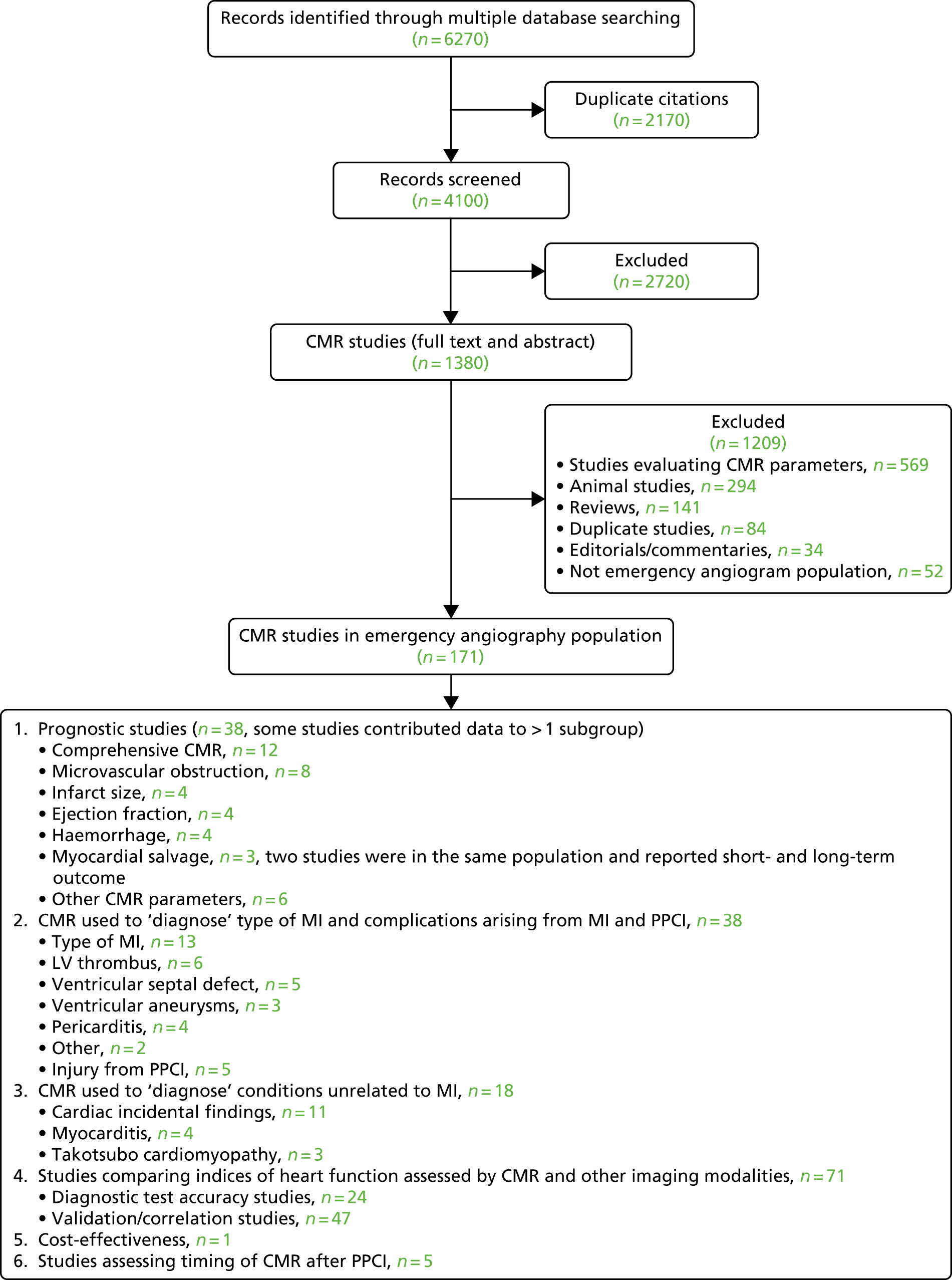

Literature review

We searched for studies reporting the impact of CMR on prognosis, patient management and risk stratification in the population of patients who activate the PPCI pathway. We intended to identify studies providing background knowledge to inform the formulation of statements about how CMR could change patient management in specific subgroups and as supporting evidence for the final consensus statements. We did not intend to carry out a formal quantitative systematic review of the effectiveness of CMR in the target population.

We searched without restriction by study design or search terms related to outcomes, so that we could determine the full extent of the literature in this area and identify all studies that used CMR in our population. Thus, the search identified studies that had diverse objectives and measured a range of outcomes (e.g. clinical outcomes, changes in patient management, classifications of patients into prognostic groups, new diagnoses). The search was conducted on MEDLINE, EMBASE, The Cochrane Library, Web of Science (Citations Index and Proceedings) and Bioscience Information Service (BIOSIS) (date range for all searches: 1950 to 16 January 2014). The following search terms were used, both as free text and medical subject headings (MeSH) when possible: ‘acute coronary syndrome’, ‘myocardial infarction’, ‘angioplasty’, ‘percutaneous coronary intervention’ and ‘cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging’. We applied no restriction on publication date or language. The literature search is shown in Appendix 3.

We included all studies reporting the use of CMR in patients undergoing PPCI or patients who activated the PPCI pathway but did not proceed to PPCI (e.g. had an emergency angiogram). We excluded studies investigating the use of CMR in populations with stable coronary artery disease or patients with non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), because these patients do not routinely undergo emergency angiography. One researcher triaged the titles and abstracts identified by the search to remove duplicate reports of the same study and studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria. Reference lists of full-text papers were scanned to ensure that no additional studies had been missed during the search.

The broad search identified many different types of study (e.g. diagnostic, prognostic, controlled or uncontrolled, prospective or retrospective, cohort studies) and case reports. They were grouped as follows: (1) studies assessing the prognostic value of a comprehensive CMR scan or specific CMR markers, (2) studies in which CMR was used to ‘diagnose’ a specific feature (e.g. type of MI) or complication arising from the index MI [e.g. left ventricular (LV) thrombus, ventricular septal defect (VSD)], or procedure-related complications, (3) studies in which CMR was used to ‘diagnose’ incidental findings or conditions unrelated to MI, (4) studies in which indices of heart function (e.g. myocardial viability, necrosis, perfusion, myocardium at risk, ischaemia) assessed by CMR and other imaging modalities [e.g. ECHO and single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT)] were compared and (5) other studies not fitting into any of the categories above.

Formulation of consensus statements

An expert group was convened, consisting of two cardiologists with CMR expertise (CBD and JPG), two interventional cardiologists from sites participating in the feasibility study (SHD and RAA), one cardiac network director (SB), two methodologists (BCR and MP), two statisticians (CAR and JMH), one health economist (SW or EAS) and the study manager (RCB). Draft statements were generated independently by three cardiologists (CBD, JPG and SHD) based on their cardiological expertise and by one methodologist (MP) based on evidence from the literature review. The cardiologists and methodologist had no prior communication with each other. The cardiologists were advised to be as inclusive as possible at this stage and to not be concerned about the strength or quality of the evidence available to support their draft statements.

Three members of the expert group (study manager, RCB; systematic reviewer, MP; and cardiologist with CMR expertise, CBD) collated the statements, organised them according to patient subgroup and standardised the wording of each statement. A 1-day meeting was organised for all members of the group. The structure of the meeting was as follows: an introduction to the aims of the study and the formal consensus process; a review of each statement in turn, considering the relevance, format and wording of each statement; and a discussion about the structure of the survey. Key papers from the literature review were circulated to all members of the group prior to the meeting and these were also considered in the discussions. At the meeting, it was decided that each statement would benefit from a ‘supporting paragraph’, citing key references from the literature review, to provide background information and put the statement in context.

The structure of the process used to generate the statements is summarised in Table 1. We documented all of the discussions that led to the final statements.

| Step | Description |

|---|---|

| Literature review | Published literature was identified on the use of CMR in patients who activate the PPCI pathway and the patient subgroups that may benefit from CMR |

| Generate draft statements | Statements were generated independently in writing by clinical and non-clinical members of the internal group using systematic review and clinical expertise |

| Collate statements | Statements were categorised into patient subgroups and reworded into a standard style |

| Expert group meeting | All members of the expert group convened for a 1-day meeting during which the consensus process was introduced and each statement was discussed in turn. Discussions focused on the relevance, format and wording of each statement, and on how to structure the online survey |

| Generate final list of statements | A final list of statements was produced based on internal group meeting discussions. Each statement was accompanied by a supporting paragraph presenting ‘key’ supporting references from the literature |

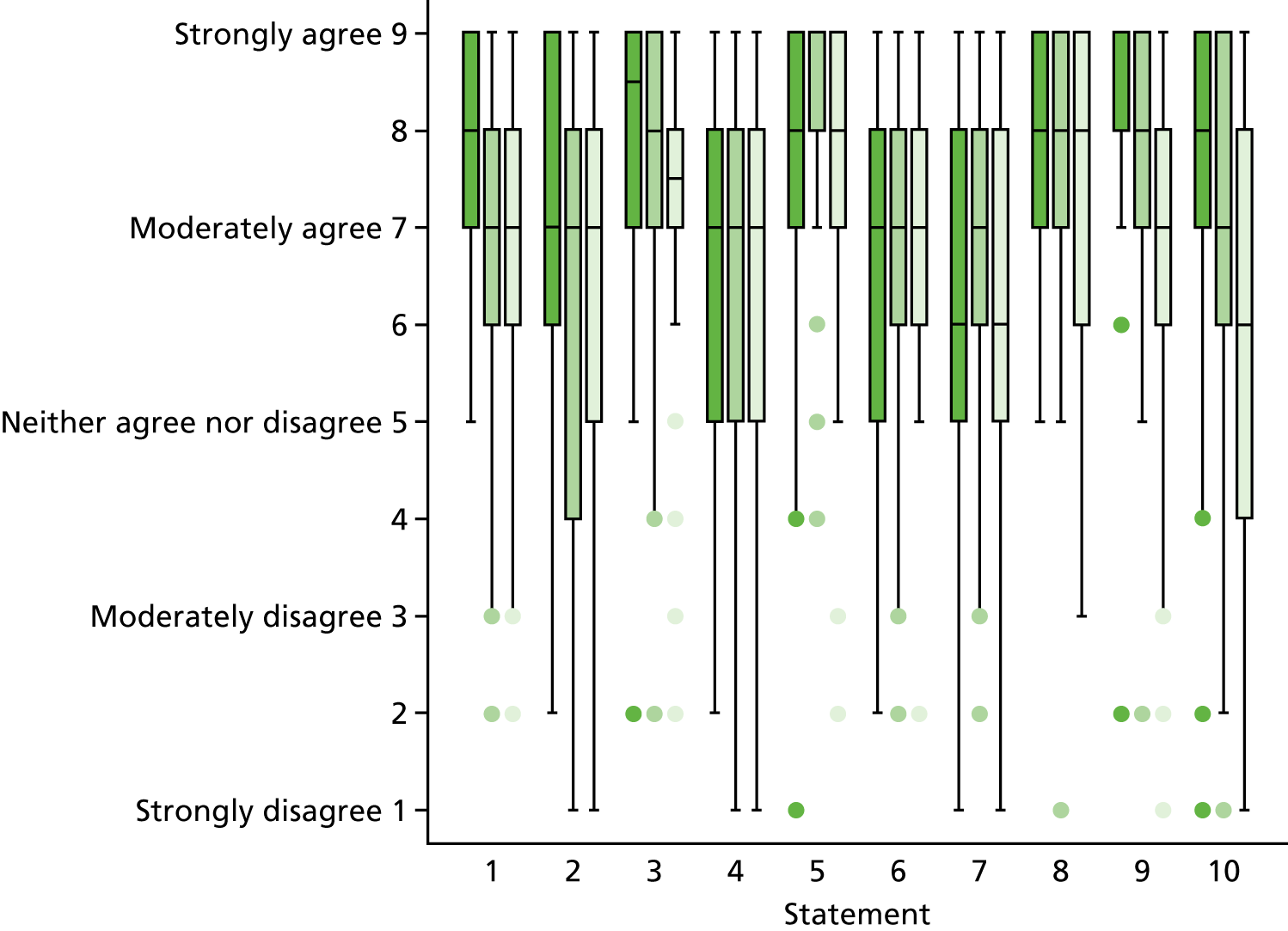

Survey design

Statements and supporting paragraphs were worded in a consistent manner and collated in the form of a web-based survey (SurveyMonkey®, Palo Alto, CA, USA) (see Appendix 4). The survey included an introductory page explaining the purpose and layout of the survey and instructions about how to complete it. Each statement was followed by its supporting paragraph that contained links to Portable Document Format (PDF) references. Each statement was accompanied by a nine-point Likert scale asking the respondent to indicate whether or not he/she agreed with the statement (with 1 indicating ‘completely disagree’ and 9 ‘completely agree’). There was also a free-text box for each statement for respondents to comment in and justify their score.

Expert panel

Establishing the expert panel

Clinicians in the working group identified consultant cardiologists with CMR, interventional, ECHO, electrophysiology and heart failure expertise from across the UK (see Acknowledgements). The cardiologists were invited by e-mail to form an expert consensus panel.

Completion of first survey

The expert panel completed the survey independently. Responses were collated and analysed by members of the working group.

Face-to-face meeting

The expert panel attended a face-to-face meeting, chaired by a non-cardiology clinician experienced in facilitating formal consensus panels. The meeting was also attended by non-clinical members of the working group, whose role was to introduce the study, describe the structure of the formal consensus process, provide study-related information and take minutes of the meeting. The expert panel discussed each statement and anonymised responses to the first survey in turn and agreed on modifications to the survey.

Completion of the modified survey

The survey was modified by members of the working group as agreed in the face-to-face meeting (see Appendix 4). 4 The expert panel completed the modified survey independently and rated the statements a second time.

Extension of survey to other UK cardiologists

The survey was extended to other UK cardiologists through the British Cardiovascular Society, which advertised the survey in their monthly newsletter to members (over 2 consecutive months). We offered an incentive to encourage participation: the option of entering a prize draw for an iPad (Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA, USA).

Main outcome measure

A definition of a primary outcome measure (acceptable to cardiologists and other stakeholders) that represents a definitive change in clinical management arising from a patient having CMR.

Criteria for consensus

Data for each statement are shown as medians and IQRs. A median score ≥ 7 and an IQRs 6–9 was considered to be in agreement, or consensus, that the change in management described by the statement was clinically important. These statements were used to identify the patient subgroups perceived to benefit from CMR and define the treatment/process outcome that constitutes a definitive management change as a result of having CMR. A median score ≤ 3 and an IQR 1–3 was considered to be in consensus that the statement did not constitute a clinically important change in management. Data were analysed using Stata/IC version 14.

Implementation of a primary outcome based on the changes in management for which consensus was achieved (objectives C3 and C4)

Patient subgroups

Patient subgroups were identified from HIS data extracts provided by hospitals. When this was not possible, hospital episode data (the admissions data sets) were used to identify the ICD-10 diagnostic codes associated with the index admission.

Manual review of patient notes

We undertook a review of patient notes because of the uncertainty regarding the identification of the subgroup of patients with unobstructed coronary arteries. Forty-seven patients were selected, all identified as having unobstructed arteries in hospital A at the time of the index event. We undertook a thorough review of their patient notes to identify the reason why they activated the PPCI pathway.

Identifying changes in management

We used HES/PEDW inpatient and outpatient data to identify changes in management defined through the formal consensus in the 12 months after the index admission (cohort entry). For those patients who underwent CMR, any outpatient appointments that occurred between the index admission and the date of CMR were excluded. We decided not to use the A&E data set because most of the changes in management identified in the formal consensus were unlikely to occur in the A&E setting.

Cardiologist members of the clinical team identified key clinical ‘events’ that they expected to reflect the important changes in management characterised through the consensus process. For example, new non-ischaemic diagnoses (an important change in management resulting from CMR) were identified as Takotsubo cardiomyopathy, myocarditis, pericarditis, endocarditis and coronary spasm.

We then compiled a list of ICD-10 and OPCS codes representing the key clinical events with the help of a clinical coder. Most changes in management encompassed a number of ICD-10/OPCS codes, for example the use of additional diagnostic tests during follow-up required OPCS codes for positron emission tomography (PET), ECHO, intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) or pressure wire. We identified the changes in management in HES/PEDW for each statement (patient subgroup) separately. The full code list used to identify changes in management is shown in Appendix 2.

Implementation of the consensus statements

We calculated the frequency of all events representing changes in management (e.g. number of new diagnoses, additional diagnostic tests, number of outpatient appointments) in patients who did/did not receive CMR for each patient subgroup in the 12 months following the index admission. We also calculated the time to first event for each change in management (e.g. time to first new diagnosis, time to the first diagnostic test, time to next revascularisation in patients with multivessel disease) and summarised these with medians and IQRs. We did not compare differences between patients who did/did not receive CMR in any of the subgroups because we were interested primarily in the feasibility of identifying relevant events; the number of patients in most subgroups was also small.

Cardiovascular magnetic resonance questionnaire

We determined whether or not the changes in management identified in HES/PEDW accurately reflected the changes in management implemented by the cardiologists who referred patients in the study for CMR. We designed a questionnaire based on the patient subgroups identified in the formal consensus (see Appendix 5) and asked all referring cardiologists to complete it for each patient whom they referred for CMR. The questionnaire asked about whether or not and how CMR changed management (using tick boxes and free text). We used the questionnaire to identify whether or not the changes in management reported by cardiologists were accurately reflected in HES/PEDW, and whether or not there were additional changes in management that could not be picked up from HES/PEDW.

Health economic study (objective B2)

We built two separate cost-effectiveness models to explore the impact of CMR for two patient subgroups: (1) multivessel disease and (2) unobstructed (normal) coronary arteries.

-

Model 1: simulated the costs and effects of introducing CMR for patients with multivessel disease, compared with current practice.

-

Model 2: simulated the costs and effects of introducing CMR for patients with normal coronary arteries, compared with current practice.

From these two models, inferences can be made about the likely drivers of the cost-effectiveness of introducing CMR for all patients who activate the PPCI pathway, because, in practice, this is how CMR might be introduced, and is, therefore, the key issue for policy-makers.

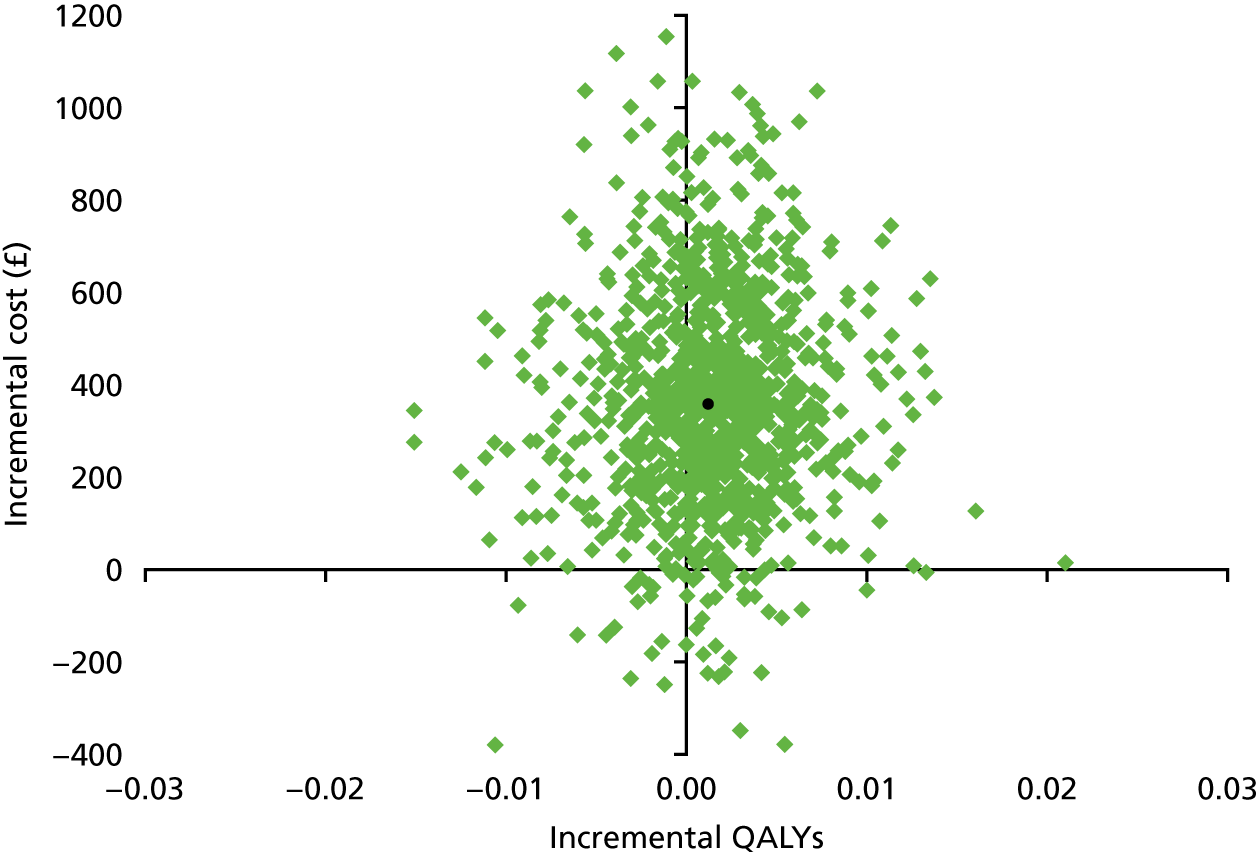

The decision trees model the patient pathway after PPCI pathway activation to 1 year. Each possible patient pathway within the model is associated with a probability, and each pathway incurs costs and outcomes. The analysis was conducted from a NHS and personal social services perspective. 34 Outcomes were measured in quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs), a composite measure of quality and quantity of life.

The structure of the model for patients with multivessel disease is described next, along with the sources of parameter estimates, before the model for patients with normal coronary arteries is considered.

Model 1: patients with multivessel disease

This model was designed to address the question ‘Which is the most cost-effective type of ischaemia testing for patients with multivessel disease who activate the PPCI pathway?’

When the study started, stress ECHO was the ischaemia-testing option commonly used and the study was comparing this with CMR. During the study, the use of FFR increased35 and, therefore, this test was included as an additional arm in the model. Thus, the model compares the cost-effectiveness of three ischaemia testing options: (1) CMR, (2) pressure wire and (3) stress ECHO.

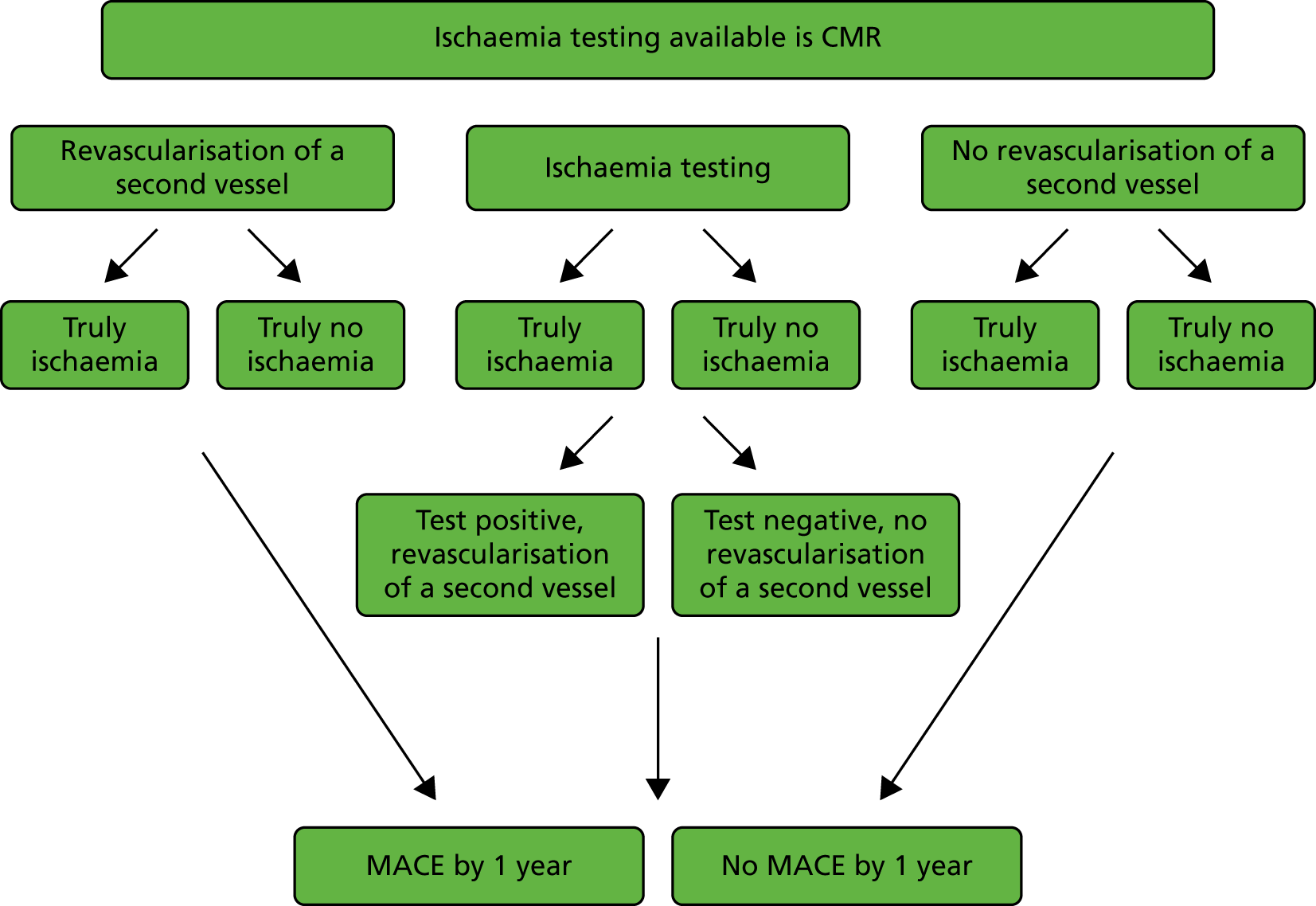

The cohort of patients of interest are those who activate the PPCI pathway, have their index angiography and PPCI, and are identified as having multivessel disease (commonly defined as stenosis of > 50% from the angiogram). This model considers the patient pathway thereafter: whether or not to treat non-culprit lesions with a second revascularisation, the need (or not) for ischaemia testing to help determine the need for the revascularisation of a second vessel and any MACEs that occur. Figure 1 summarises the scenarios in the patient pathways included in the model structure for one arm of the model (CMR).

FIGURE 1.

Scenarios in the patient pathway included in the model structure for patients with multivessel disease.

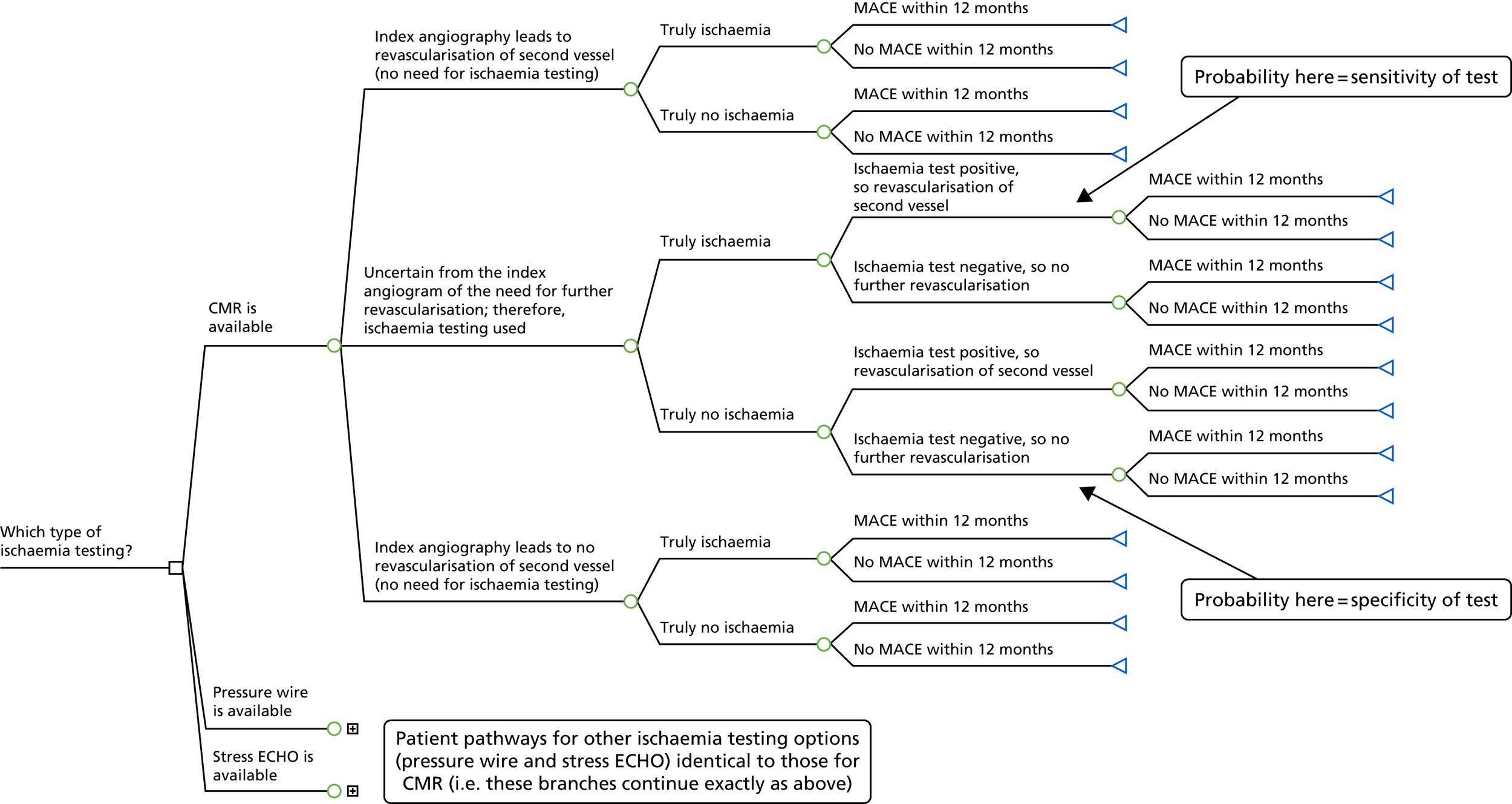

The model structure (shown in detail in Figure 2 splitting into three arms, representing the three different types of ischaemia testing) considered the following: the top branch models the scenario in which the ischaemia-testing option available is CMR, the middle branch models the scenario for pressure wire and the bottom branch models the scenario for stress ECHO. The structure of each of these three main arms is the same for each scenario, but the associated probabilities, costs and outcomes for each arm vary.

FIGURE 2.

Model 1 structure: patients with multivessel disease.

Reproduced with permission from Stokes et al. 36 © Author(s) (or their employer(s)) 2019. Re-use permitted under CC BY. Published by BMJ. This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the licence is given, and indication of whether changes were made. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Considering the CMR arm, the decision tree first divides the starting cohort of patients after PPCI in accordance with the results of their index angiography. A clinician may determine that a patient requires or does not require the revascularisation of a second vessel directly from their angiogram, without the need for ischaemia testing; alternatively, there may be uncertainty from the index angiogram of the need for further revascularisation, and, therefore, ischaemia testing is used, in this case CMR. For each of these three categories, patients are then divided by whether or not they truly have ischaemia.

Patients whose index angiography leads to a firm decision on revascularisation are then divided by whether or not they had any MACEs in the 12 months after PPCI. MACE is a composite end point of all-cause mortality, MI, stroke and revascularisation.

Patients for whom ischaemia testing is needed are divided in accordance with whether that test result was positive, and therefore assumed to result in the revascularisation of a second vessel, or negative. Thereafter, patients are divided by whether or not they had a MACE in the 12 months after PPCI.

Although the model structure is the same for each of the ischaemia testing options, there are differences in the timing of events between these arms for patients who have ischaemia testing that leads to a second revascularisation. For CMR and stress ECHO, this is a two-step process, that is a patient has the ischaemia test and then separately has revascularisation of a second vessel. For pressure wire, this all happens in the catheterisation laboratory at the same time, that is a patient has their diagnostic angiography and pressure wire, and, if required, has their PCI at the same time (note that this is entirely separate and subsequent to their index angiography and PPCI). This affects costs, but not the model structure.

Data for the multivessel disease model

Most model parameters were populated with estimates derived from the literature. The following sections describe how transition probabilities, costs and outcomes were estimated to 1 year.

Probabilities for the multivessel disease model

Table 2 shows the probabilities used in the model and their sources. These are the probabilities associated with each branch in the model; probabilities along pathways are multiplied together in the analyses. MEDLINE searching was used to identify relevant papers, and was conducted using MeSH and keywords for each imaging type (e.g. exp/pressure-wire or pressure-wire.mp or fractional flow reserve.mp and exp/myocardial infarction). Any relevant reviews were read in order to identify relevant references, and references and citations of any relevant references were checked for prior or more recent published work.

| Branch of model | Base-case value (positive/total) | Distribution for PSA | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| For each ischaemia testing option | |||

| Probability that index angiography leads to revascularisation of second vessel | 0.30 (30/100)a | Dirichlet | Expert opinion within the PIPA study team |

| Probability of uncertainty following index angiography and need for ischaemia testing | 0.60 (60/100)a | ||

| Probability that index angiography leads to no revascularisation of second vessel | 0.10 (10/100)a | ||

| Index angiography leads to revascularisation of second vessel | |||

| Probability of true ischaemia | 0.84 (598/709) | Beta | FAME37 |

| Probability of MACE by 12 months, true ischaemia | 0.09 (18/202)b | Beta | Smits et al.38 |

| Probability of MACE by 12 months, truly no ischaemia | 0.13 (54/432)b | Beta | Smits et al.38 |

| Uncertainty following index angiography and need for ischaemia testing | |||

| Probability of true ischaemia | 0.35 (218/620) | Beta | FAME37 |

| Index angiography leads to no revascularisation of second vessel | |||

| Probability of true ischaemia | 0.35 (218/620) | Beta | FAME37 |

| Probability of MACE by 12 months, true ischaemia | 0.31 (71/231)b | Beta | Smits et al.38 |

| Probability of MACE by 12 months, truly no ischaemia | 0.13 (54/432)b | Beta | Smits et al.38 |

| CMR or pressure wire | |||

| Uncertainty following index angiogram and need for ischaemia testing, true ischaemia | |||

| Probability of ischaemia test positive and revascularisation | 1c | Beta | |

| Probability of MACE by 12 months, revascularisation | 0.09 (18/202)b | Beta | Smits et al.38 |

| Probability of MACE by 12 months, no revascularisation | 0.31 (71/231)b,d | Beta | Smits et al.38 |

| Uncertainty following index angiogram and need for ischaemia testing, truly no ischaemia | |||

| Probability of ischaemia test positive and revascularisation | 0c | Beta | |

| Probability of MACE by 12 months, revascularisation | 0.13 (54/432)b,d | Beta | Smits et al.38 |

| Probability of MACE by 12 months, no revascularisation | 0.13 (54/432)b | Beta | Smits et al.38 |

| Stress ECHO | |||

| Uncertainty following index angiogram and need for ischaemia testing, true ischaemia | |||

| Probability of ischaemia test positive and revascularisation | 0.70 (32/46) | Beta | Gurunathan et al.39 |

| Probability of MACE by 12 months, revascularisation | 0.09 (18/202)b | Beta | Smits et al.38 |

| Probability of MACE by 12 months, no revascularisation | 0.31 (71/231)b | Beta | Smits et al.38 |

| Uncertainty following index angiogram and need for ischaemia testing, truly no ischaemia | |||

| Probability of ischaemia test positive and revascularisation | 0.23 (39/171) | Beta | Gurunathan et al.39 |

| Probability of MACE by 12 months, revascularisation | 0.13 (54/432)b | Beta | Smits et al.38 |

| Probability of MACE by 12 months, no revascularisation | 0.13 (54/432)b | Beta | Smits et al.38 |

In the base-case analyses, CMR and pressure wire were treated as reference standards and both were assumed to have 100% sensitivity and specificity. Therefore, the probabilities and outcomes are the same in these arms and they differ only in terms of costs.

The probabilities of MACEs were estimated from Smits et al. ,38 in which MACE was defined as a composite end point of all-cause mortality, non-fatal MI, revascularisation and cerebrovascular events at 12 months. Outcomes for subgroups of patients in the trial were used to estimate MACE for three groups of patients: (1) truly ischaemic patients who had a second revascularisation (p = 0.09), (2) truly ischaemic patients who did not have a second revascularisation (p = 0.31) and (3) truly not ischaemic patients, whether or not they had a second revascularisation (p = 0.13). Based on subgroups of the trial patients, the probability of a MACE at 12 months for truly ischaemic patients who had a second revascularisation was actually lower than for patients without ischaemia. This might seem anomalous, but is a genuine finding. Although the probability estimates for these three subgroups were all based on ≥ 200 patients, only 18 truly ischaemic patients who had a second revascularisation had a MACE; these findings might be an artefact of modest numbers, and larger studies might show different results.

Costs for the multivessel disease model

For each ischaemia testing strategy considered, the costs included were the cost of ischaemia testing (CMR, pressure wire or stress ECHO) if required, the cost of revascularisation of a second vessel, costs associated with adverse events included in MACEs (both the initial inpatient costs and subsequent costs post discharge), costs of cardiac medications and cardiac rehabilitation offered to all patients and additional health-care costs beyond hospital discharge to 1 year, including follow-up outpatient appointments for all patients.

Unit costs were largely obtained from NHS Reference Costs 2015 to 201640 and are shown in Table 3; details of assumptions made in estimating unit costs are also provided in Table 3. NHS Reference Costs provide upper and lower quartiles around mean estimates; the difference between the mean and the upper quartile was captured and used as a crude estimate of standard error (SE) in the probabilistic sensitivity analyses (PSAs) (described in Model analyses). When this was not possible, the SE was assumed to be 20% of the mean cost. All costs were parameterised using a gamma distribution in the PSAs.

| Resource | Unit cost, £ (SE) | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Revascularisation of second vessel (assumed to be PCI) | 2682 (533) | NHS Reference Costs 2015 to 2016.40 Elective Inpatient. Weighted average of codes EY40 and EY41, Standard/Complex Percutaneous Transluminal Coronary Angioplasty |

| CMR | 264 (154) | NHS Reference Costs 2015 to 2016.40 Diagnostic Imaging. Weighted average of all Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Imaging Scan codes |

| Angiography and pressure wire | 1340 (374) | NHS Reference Costs 2015 to 2016.40 Day case. Weighted average of code EY42, Complex Cardiac Catheterisation |

| Angiography, pressure wire and revascularisation (as a single catheter laboratory admission) | 2971 (594) | Cost of revascularisation above, and angiography and pressure wire above, minus the cost of an angiography, £1051 (NHS Reference Costs 2015 to 2016.40 Day case. Weighted average of code EY43, Standard Cardiac Catheterisation) |

| Stress ECHO | 182 (3) | NHS Reference Costs 2015 to 2016.40 Outpatient procedures. Cardiology. EY50Z, Complex Echocardiogram |

| MACE | 3251 (650) | The proportion of each component of MACE was taken from Smits et al.38 and a weighted average of the costs of each component was calculated, based on the unit costs below |

| Revascularisation (PCI) | 2682 | As above |

| Revascularisation (CABG) | 10,944 | NHS Reference Costs 2015 to 2016.40 Elective Inpatient. Weighted average of codes ED26, ED27, ED28 Complex/Major/Standard Coronary Artery Bypass Graft |

| MI | 2177 | NHS Reference Costs 2015 to 2016.40 Non-elective long stay. Weighted average of code EB10 A, Actual or Suspected Myocardial Infarction |

| Stroke | 3723 | NHS Reference Costs 2015 to 2016.40 Non-elective long stay. Weighted average of code AA22, Cerebrovascular Accident, Nervous System Infections or Encephalopathy |

| Death | 0 (0) | |

| Cardiac rehabilitation | 364 (73) | Assume offered eight sessions, but only 50% uptake, so cost four sessions (one first and three follow-up appointments, individual costs below) |

| First appointment | 97 | NHS Reference Costs 2015 to 2016.40 Consultant Led. 327, Cardiac Rehabilitation. Non-Admitted Face-to-Face Attendance, First |

| Follow-up appointment | 89 | NHS Reference Costs 2015 to 2016.40 Consultant Led. 327, Cardiac Rehabilitation. Non-Admitted Face-to-Face Attendance, Follow-Up |

| Cardiac medications for treatment of MI (all once daily by mouth). Assumed given for 12 months (or 6 months for patients who died) | ||

| Aspirin (75 mg) | 0.04 | BNF41 |

| Prasugrel (Efient®; Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, IN, USA) (5 mg) | 1.70 | BNF41 |

| Atorvastatin (80 mg) | 0.07 | BNF41 |

| Bisoprolol (2.5 mg) | 0.02 | BNF41 |

| Ramipril (2.5 mg) | 0.04 | BNF41 |

| Total daily cost | 1.87 | |

| Total annual cost | 683 (137) | |

| Outpatient follow-up appointment (assumed to occur at 4–6 weeks and 6 months post discharge) | 122 (22) | NHS Reference Costs 2015 to 2016.40 Consultant-led appointments. Non-Admitted Face-to-Face Attendance, Follow-Up. Cardiology |

| Additional health-care costs to 1 year | 2221 (444) | The Office of Health Economics’ estimate of the annual cost per person of NHS care, inflated to 2015/16 prices using the hospital and community health services inflation index.42,43 For patients who die, costs are assumed to be half of this (£1111) |

| Additional health-care costs to 1 year for those with a MACE | 263 (53) | MI and stroke were assumed to be associated with continuing care costs post discharge. Costs from Greenhalgh et al.44 were inflated to 2015/16 prices.42 Separate costs were provided for disabling and non-disabling stroke. According to Davies et al.,45 58% of strokes are disabling; this percentage was used to weigh the two continuing care costs for stroke. Additional costs to 1 year associated with a MACE were calculated by weighting estimates of the annual costs of MI and stroke by the number of patients with these complications across the number of patients with a MACE, from Smits et al.38 |

Outcomes for the multivessel disease model

Outcomes were measured in QALYs. Estimates of survival and quality of life utility weights were obtained from the literature and combined to estimate the QALYs gained to 1 year. As death is one of the components of MACEs, patients without a MACE are all alive at 1 year in the model. The probability of dying in the first year was taken from the same source as the MACE estimates above, and was 8% for patients with a MACE. 38

The Tufts Cost-effectiveness Analysis Registry46 was searched for appropriate utility weights. This registry is a database of 5655 cost–utility analyses on a wide variety of diseases and treatments and has 21,900 utility weights. Search terms such as ‘primary percutaneous coronary intervention’ and ‘major adverse cardiac events’ were used. Estimates from the Swedish Early Decision reperfusion Study (SWEDES) by Aasa et al. 47 were deemed to be the most appropriate; this study measured health status using the EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) in a group of PPCI patients, and quality weights were obtained using the UK EQ-5D tariff. 47 Patients completed the EQ-5D at three time points: baseline (within 3 days of randomisation, at the end time of index hospitalisation), and at 1 and 12 months. Mean utilities for patients were 0.72, 0.77 and 0.77 at each time point, respectively. Although the patient group included some patients with a MACE, here the estimates are applied to patients without a MACE.

Quality-adjusted life-years were calculated assuming a patient’s utility changed linearly between each time point, so between baseline and 1 month, and between 1 and 12 months. Patients who died were assumed to die midway through the time period (i.e. at 6 months); their utility was assumed to change linearly between time points up to death, and a value of zero was given from death onwards. A QALY estimate for patients without a MACE – who, therefore, were all alive at 1 year – was calculated based on the utilities provided by Aasa et al. 47 For the QALY estimate for patients with a MACE 8% of patients were assumed to die,38 this was used to produce a weighted average for patients alive and dead at 1 year, based on the utility weights and assumptions above. A utility decrement of 0.05 was then applied to this weighted average to reflect the reduced quality of life of patients with a MACE compared with those without a MACE. 48 QALY estimates for patients who had revascularisation of a second vessel were modified to assume their utility for month 1 was repeated for month 2. QALY estimates used in the model are summarised in Table 4. QALYs were parameterised using a beta distribution in the PSAs and a SD of 0.09 was assumed, as used elsewhere. 49

| Patient group | Mean QALYs to 1 year |

|---|---|

| No revascularisation of a second vessel and MACE | 0.686 |

| No revascularisation of a second vessel and no MACE | 0.768 |

| Revascularisation of a second vessel and MACE | 0.684 |

| Revascularisation of a second vessel and no MACE | 0.766 |

Model 2: patients with normal coronary arteries

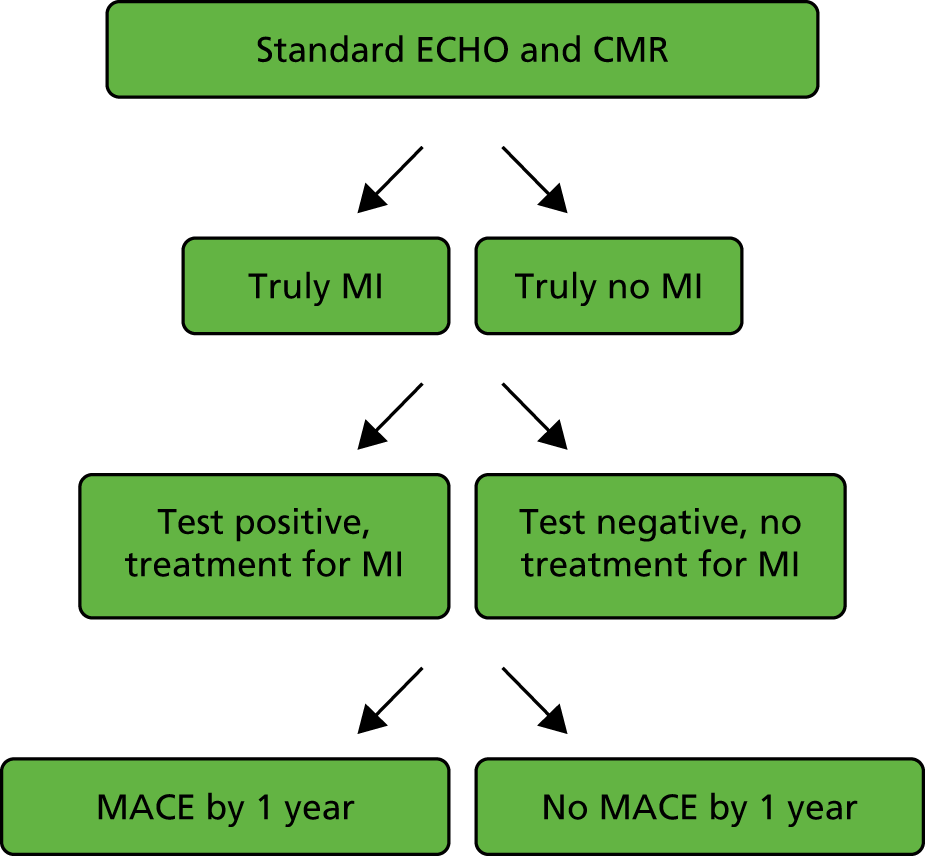

For a starting cohort of patients with normal coronary arteries, this model compares standard ECHO and CMR with standard ECHO only, and is designed to address the question: ‘Is it cost-effective to introduce CMR in patients with normal coronaries who activate the PPCI pathway?’. For the standard ECHO and CMR arm of the model, Figure 3 summarises the scenarios in the patient pathways included in the model structure.

FIGURE 3.

Scenarios in the patient pathway included in the model structure for patients with normal coronaries.

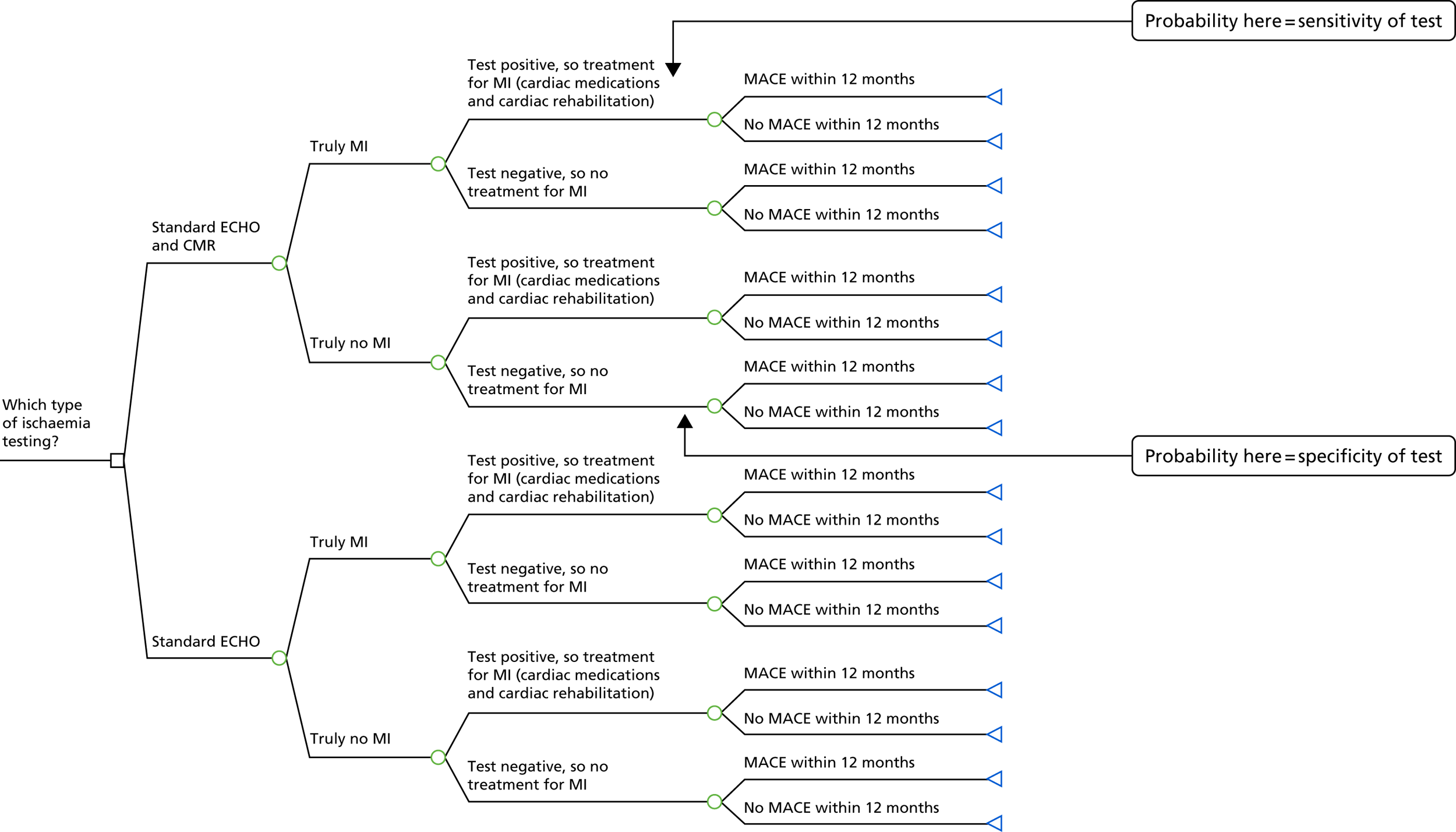

The model structure, shown in detail in Figure 4, is split into two main arms (branches): the top branch represents standard ECHO and CMR and the bottom branch represents standard ECHO only. The structure is the same in each arm, and starts by dividing patients into those who truly did have a MI and those who truly did not. Patients are then divided according to their ischaemia test result. For those with a positive test result, and therefore assumed to have had a MI, treatment for MI in the form of cardiac medications and cardiac rehabilitation will be given. Those with a negative test result will be treated for other causes of their chest pain, and given fewer cardiac medications or none at all. Thereafter, patients are divided into whether or not they had a MACE within 12 months. A MACE is defined in the same way as above: a composite end point of all-cause mortality, MI, stroke and revascularisation.

FIGURE 4.

Model structure for patients with normal coronaries (no blocked arteries).

Reproduced with permission from Stokes et al. 36 © Author(s) (or their employer(s)) 2019. Re-use permitted under CC BY. Published by BMJ. This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the licence is given, and indication of whether changes were made. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Data for the normal coronaries model

The decision tree for patients with normal coronaries was set up in a similar way to the model for patients with multivessel disease. The following sections describe how transition probabilities, costs and outcomes were estimated to 1 year, the majority of which were derived from the literature.

Probabilities for the normal coronaries model

Table 5 shows the probabilities used in the model and their respective sources. From initial MEDLINE searching, a 2016 review paper by Dastidar et al. 55 identified the first paper to use CMR for diagnosis in patients with normal coronaries,20 and this was confirmed by later reviews. All citations of the Assomull et al. 20 paper were reviewed, and relevant (English) results read. Two meta-analyses were identified,50,56 and the citations of these papers were also reviewed, as were the references of more recent papers. In a final check to ensure that key papers had been identified, MEDLINE searching of keywords, such as ‘myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary arteries’, and synonyms was conducted (there are no relevant MeSH terms).

| Branch of model | Base-case value (positive/total) | Distribution for PSA | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| For both arms | |||

| Probability of truly having had a MI | 0.24 (429/1801) | Beta | Pasupathy et al.50 |

| Standard ECHO and CMR | |||

| Probability of ischaemia test positive and treatment for MI | MI | 1a | Beta | |

| Probability of MACE within 12 months | treatment for MI | 0.21 | Beta | Kang et al.,51 Pathik et al.52 |

| Probability of MACE within 12 months | no treatment for MI | 0.26b | Beta | Kang et al.,51 Pathik et al.52 and Lindahl et al.53 |

| Probability of ischaemia test positive and treatment for MI | no MI | 0a | Beta | |

| Probability of MACE within 12 months | treatment for MI | 0.03b | Beta | Kang et al.,51 Pathik et al.52 |

| Probability of MACE within 12 months | no treatment for MI | 0.03 | Beta | Kang et al.,51 Pathik et al.52 |

| Standard ECHO | |||

| Probability of ischaemia test positive and treatment for MI | MI | 0.47 (25/53)c | Beta | Dastidar et al.54 |

| Probability of MACE within 12 months | treatment for MI | 0.21 | Beta | Kang et al.,51 Pathik et al.52 |

| Probability of MACE within 12 months | no treatment for MI | 0.26 | Beta | Kang et al.,51 Pathik et al.52 and Lindahl et al.53 |

| Probability of ischaemia test positive and treatment for MI | no MI | 0.62 (93/151)c | Beta | Dastidar et al.54 |

| Probability of MACE within 12 months | treatment for MI | 0.03 | Beta | Kang et al.,51 Pathik et al.52 |

| Probability of MACE within 12 months | no treatment for MI | 0.03 | Beta | Kang et al.,51 Pathik et al.52 |

In the base-case analyses, standard ECHO and CMR was treated as a reference standard and assumed to have 100% sensitivity and specificity. Alternative scenarios were considered in sensitivity analyses.

Although there is evidence in the literature of the probability of a MACE, the definition frequently varies and studies follow patients for varying lengths of time. Although mortality at 1 year in patients with normal coronaries is lower than in patients with obstructed vessels,50,57 it is still significant; a recent systematic review estimated this to be 4.7%. 50

For the group as a whole, Kang et al. 51 reported MACEs at 12 months in 7.8% of patients with no or < 50% coronary artery stenosis. Their definition of a MACE included death, MI and ischaemic target vessel revascularisation, but did not include stroke. It should also be noted that, although the study began with 372 patients with no or < 50% coronary artery stenosis, only 126 had follow-up data at 12 months.

Three studies52,58,59 were identified that reported MACE for patients with normal coronaries, broken down by different CMR diagnoses. Pathik et al. 52 reported MACE for 0.27 (7/26) patients diagnosed with MI, and for 0.05 (5/99) patients not diagnosed with MI (diagnosed with myocarditis, cardiomyopathy or normal CMR) over a median of 24 months (n = 125). In the other two studies58,59 of 124 and 87 patients, no MACE outcomes were observed in the non-MI patients. The MACE estimates reported in Pathik et al. 52 were converted to continuous rates (events were assumed to occur evenly over the median 24 months of follow-up). The ratio of events in the MI patients compared with the non-MI patients was six, and was used with the overall estimate of a MACE at 1 year from Kang et al. 51 (0.078), and the estimate of the underlying probability of patients truly having a MI from Pasupathy et al. 50 (0.24), to calculate estimates of the probability of a MACE in patients who truly had a MI and in those who did not have a MI. This generated probability estimates of a MACE of 0.21 for patients with MI, and 0.03 for patients without a MI. However, we needed estimates of MACE based not only on whether or not patients had a MI, but also on whether or not they had treatment for a MI. The estimate generated for patients with MI (0.21) was assumed to apply to patients who had treatment. The hazard ratio reported by Lindahl et al. 53 for a MACE for patients who were taking statins compared with those who were not (0.77) was used to adjust this estimate of a MACE for patients who had a MI and treatment, to give a probability of a MACE for those with MI but without treatment of 0.26. For patients without MI, the probability of a MACE of 0.03 was assumed to apply regardless of whether or not treatment was given. A SE of 0.10 was assumed for the PSA for these probabilities. Although Pathik et al. 52 was the only source found to estimate the ratio of events in MI patients compared with non-MI patients (in patients with normal coronaries), it is important to highlight that the estimated ratio of six raised concerns among the study team as being very high, and that lower values are explored in sensitivity analyses.

The sensitivity and specificity of standard ECHO were estimated from Dastidar et al. 54 The pre-CMR diagnosis reported was treated as the standard ECHO diagnosis, and the post-CMR diagnosis was assumed to be the true underlying diagnosis. It was assumed that those with a pre-CMR diagnosis of MI or uncertain would have been given treatment for MI, and, therefore, patients in these categories were combined for the purposes of the sensitivity and specificity calculations.

Costs for the normal coronaries model

For each ischaemia testing strategy considered, the costs included were the cost of ischaemia testing (standard ECHO, CMR), the cost of treatment for MI in the form of cardiac rehabilitation and medications, the cost of medications for non-MI causes, costs associated with adverse events included in MACEs (both the initial inpatient costs and subsequent costs post discharge), and additional health-care costs beyond hospital discharge to 1 year, including a follow-up appointment for all patients. Unit costs were obtained from national sources40,41 and are shown in Table 6; details of assumptions made in estimating unit costs are also provided in Table 6. As for the unit costs used in the previous model, when mean and upper quartile unit costs were available, the difference was used as a crude estimate of SE in the PSAs, otherwise the SE was assumed to be 20% of the mean cost. Costs were parameterised using a gamma distribution in the PSAs.

| Resource | Unit cost, £ (SE) | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Standard ECHO | 72 (22) | NHS Reference Costs 2015 to 2016.40 Diagnostic Imaging. Outpatient. RD51 A, Simple Echocardiogram, ≥ 19 years |

| CMR | 264 (154) | NHS Reference Costs 2015 to 2016.40 Diagnostic Imaging. Weighted average of all Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Imaging Scan codes |

| Cardiac rehabilitation | 364 (73) | Assume offered eight sessions, but only 50% uptake, so cost four sessions (one first and three follow-up appointments, individual costs below) |

| First appointment | 97 | NHS Reference Costs 2015 to 2016.40 Consultant Led. Cardiac Rehabilitation. Non-Admitted Face to Face Attendance, First |

| Follow-up appointment | 89 | NHS Reference Costs 2015 to 2016.40 Consultant Led. Cardiac Rehabilitation. Non-Admitted Face to Face Attendance, Follow-Up |

| Cardiac medications for treatment of MI (all once daily by mouth) | ||

| Aspirin (75 mg) | 0.04 | BNF41 |

| Clopidogrel (75 mg) | 0.05 | BNF41 |

| Atorvastatin (80 mg) | 0.07 | BNF41 |

| Bisoprolol (2.5 mg) | 0.02 | BNF41 |

| Ramipril (2.5 mg) | 0.04 | BNF41 |

| Total daily cost | 0.22 | |

| Total annual cost | 80 (16) | |

| Treatment for non-MI cause (cardiac medications): total daily cost | 0.11 | Assume that half of these patients are taken off cardiac medications above (these medications are given for cardiomyopathy but not for myocarditis) |

| Outpatient follow-up appointment (assumed to occur at 4–6 weeks post discharge) | 122 (22) | NHS Reference Costs 2015 to 2016.40 Consultant-led appointments. Non-Admitted Face to Face Attendance, Follow-Up. Cardiology |

| MACE | 2808 (562) | The proportion of each component of MACE was taken from Pathik et al.,52 and a weighted average of the costs of each component was calculated, based on the unit costs provided in Table 2. Given the small number of MACE events, calculations were based on MI and non-MI patients combined |

| Additional health-care costs to 1 year | 2221 (444) | The Office of Health Economics’ estimate of the annual cost per person of NHS care inflated to 2015/16 prices using the hospital and community health services inflation index.42,43 For patients who die, costs are assumed to be half of this (£1111) |

| Additional health-care costs to 1 year for those with a MACE | 1602 (320) | MI and stroke were assumed to be associated with continuing care costs post discharge. Costs from Greenhalgh et al.44 were inflated to 2015/16 prices.42 Separate costs were provided for disabling and non-disabling stroke. According to Davies et al.45 58% of strokes are disabling; this percentage was used to weigh the two continuing care costs for stroke. Additional costs to 1 year associated with MACE were calculated by weighting estimates of the annual costs of MI and stroke by the number of patients with these complications across the number of patients with MACE, from Pathik et al.52 |

Outcomes for the normal coronaries model

The QALY estimates used in the model are shown in Table 7. Searches of the Tufts Cost-effectiveness Analysis Registry46 did not yield any utility weights that were specific to patients with normal coronaries; therefore, the estimates in Aasa et al. 47 were also used here. The QALY estimate for patients without a MACE who were all alive at 1 year was calculated directly from the utilities in Aasa et al. 47 For the QALY estimate for patients with a MACE, 8% of patients were assumed to die based on the same source as the MACE estimates above;52 this was used to produce a weighted average for patients alive and dead at 1 year, based on the utility weights and assumptions described previously, and a utility decrement of 0.05 was again applied to reflect the reduced quality of life of patients with a MACE. 48 The study team felt that the estimate of the proportion of patients with a MACE who die was low; therefore, a higher proportion (50%) is explored in the sensitivity analyses.

| Patient group | QALYs to 1 year |

|---|---|

| MACE within 12 months | 0.686 |

| No MACE within 12 months | 0.768 |

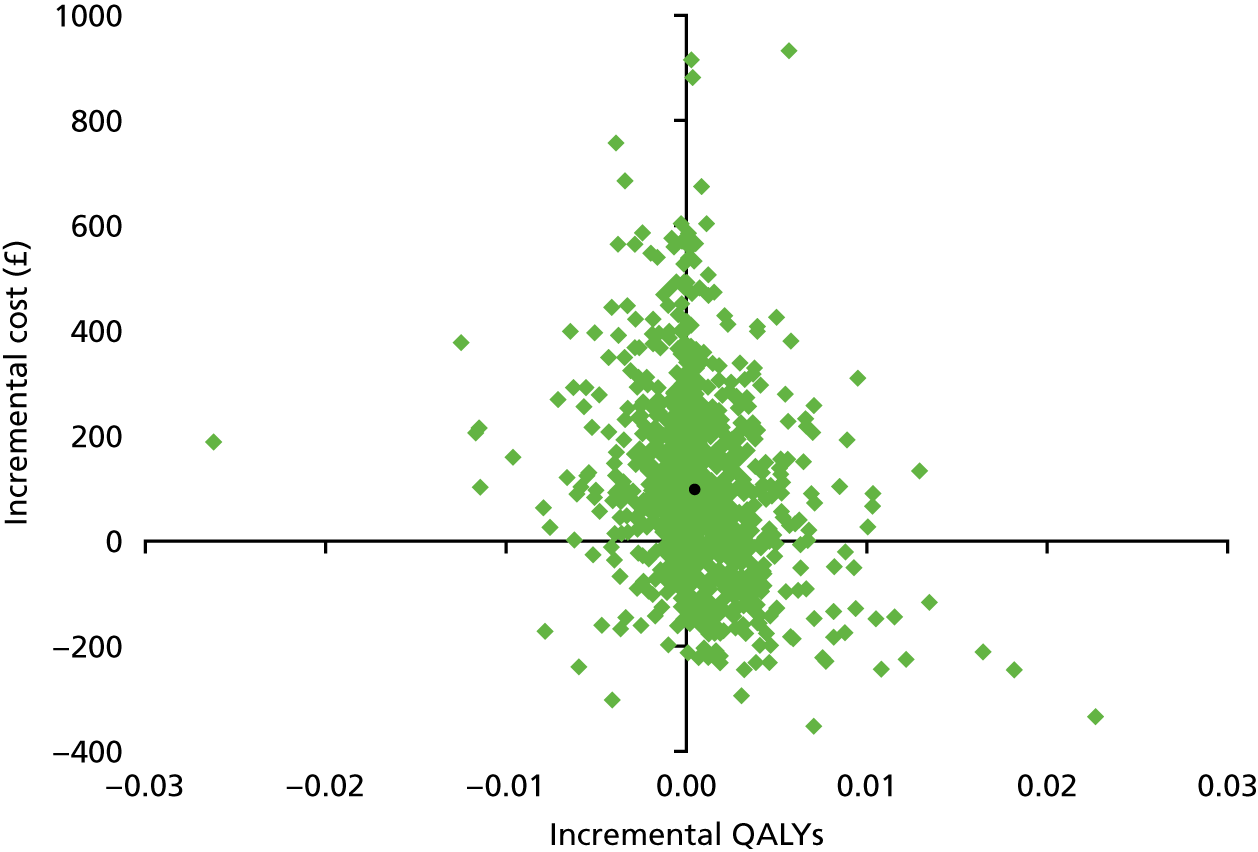

Model analyses