Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 13/54/34. The contractual start date was in September 2015. The final report began editorial review in January 2018 and was accepted for publication in November 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Peter Bullock is Chief Executive of Age UK North Staffordshire and reports that a contract between Keele University and Age UK was set up to enable Age UK support workers to deliver the intervention during the study. Carolyn A Chew-Graham, Simon Gilbody and Peter Bower are and have been in receipt of funding from the National Institute for Health Research outside the submitted work. Simon Gilbody is a member of the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Commissioning Board, HTA Efficient Study Designs, HTA End of Life Care and Add-on Studies and HTA Funding Boards Policy Group.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Burroughs et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Context and background

Definitions and epidemiology

Depression is a major global public health burden, and by 2030 depressive disorders are predicted to be the second leading cause of disease burden and disability worldwide. 1 Anxiety and depression often coexist and are prevalent among older people, with up to 20% of older people reporting symptoms of depression. 2,3

Should the prevalence rates for these mental health problems remain stable in the future, we are still likely to witness an increase in the total number of older people with mental health problems owing to demographic changes (i.e. an ageing population). This will lead to an increased demand for treatment and an increased burden on health and social care. 4 Untreated anxiety and depression present a particular challenge and lead to increased health and social care utilisation and mortality. 5

Living with comorbidities (the presence of one or more additional conditions) is a common occurrence in later life: 36% of people aged 65–74 years and 47% of people aged ≥ 75 years experience a limiting chronic condition, and comorbidities present a significant risk to mental health. 6 The presence of long-term physical conditions increases the prevalence of depression and anxiety; for example, up to 30% of people with diabetes experience depression and up to 25% of people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) experience anxiety. 7 The presence of two or more long-term physical conditions increases the likelihood of depression by as much as seven times. 8

For older people with undetected depression, longer-term prognosis is poorer than for those whose depression is known by their general practitioner (GP). 9

Older adults face adversity in the areas of health, bereavement and loss, which is associated with depression. Isolation, loneliness and loss may be important contributors to anxiety and depression. This has clinical relevance for psychological interventions for older adults to consider social context and social support. 10

Depression and anxiety in older people are poorly detected and can be poorly managed in primary care,11 particularly in people with chronic physical ill health. 12 One impediment to detection is that older people may not present to their GP with depression because of the stigma they perceive about mental health problems. 13 Older people with chronic physical illness may normalise their depression, or view it as a ‘justifiable’ cause of low mood. 12–14 As a result, older people may hold negative views about help seeking. 15 Diagnosis and treatment led by a narrow biomedical model may overlook important social and contextual factors of mental health that can inform management. 16 One way around this is to treat people with mild to moderate depression and anxiety in a way that underserved individuals, such as older people, find non-stigmatising.

Management of anxiety and depression in older adults

The National Service Framework for Older People17 made specific references for the improvement of health-care services in England. The framework suggested that older adults who have mental health problems should have access to specialist older people’s mental health services with integrated social service elements, provided by the NHS and local councils, to ensure effective diagnosis, treatment and support. This framework was followed by a new older people’s mental health service development guide from the Department of Health and Social Care, Everybody’s Business,18 which made it clear that older people’s mental health spans health and social care, physical and mental health and mainstream and specialist services. The strategy document No Health Without Mental Health19 emphasises the importance of improving outcomes for people with mental health problems through high-quality services, for people of all ages, that are accessible to all.

A total of 90% of people with mental health problems are managed in primary care, and the population of older adults is no exception, with most older people with GP-recognised anxiety and/or depression being managed solely in primary care. In addition, older adults are under-represented in referrals to Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT). 20–22

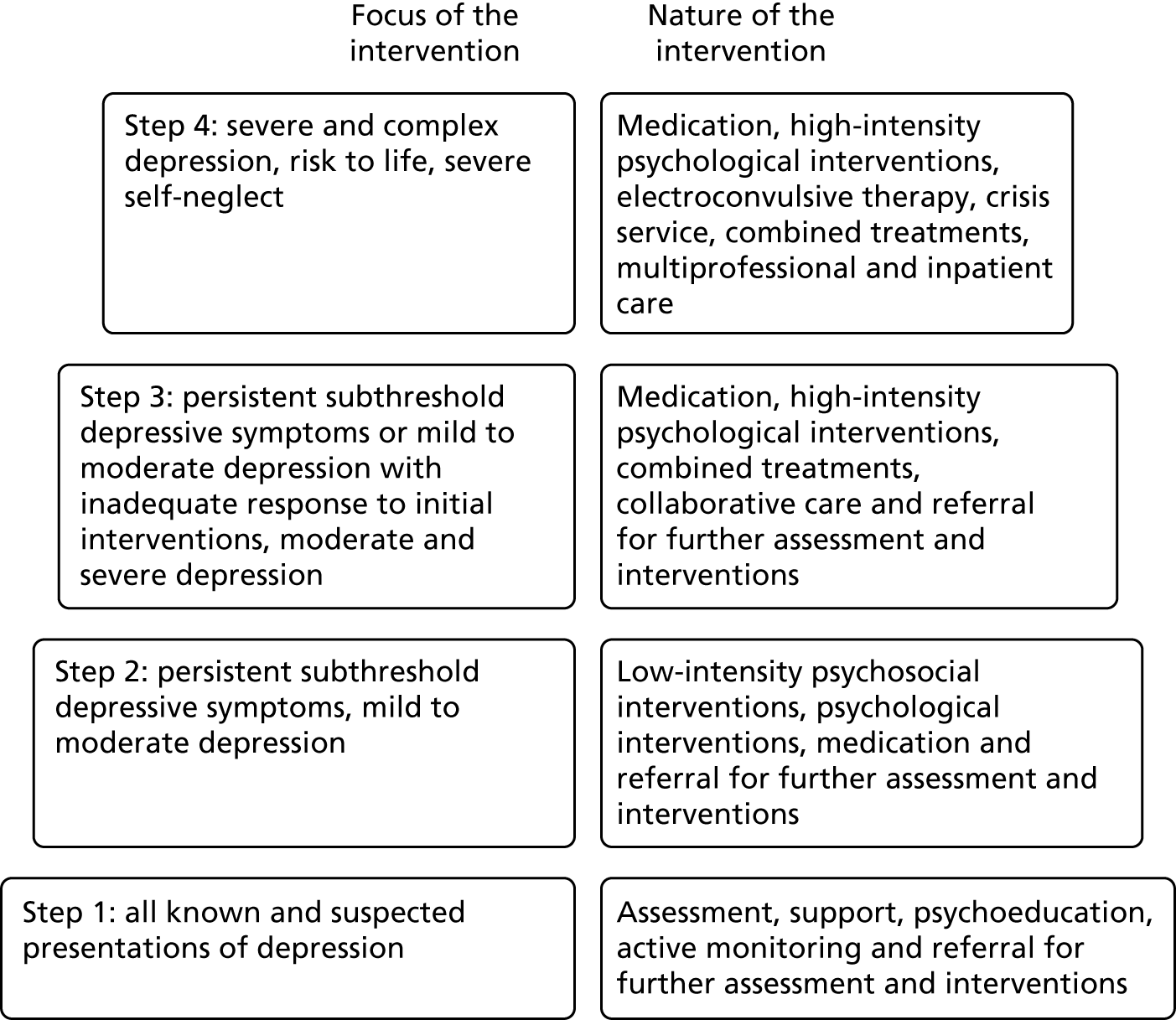

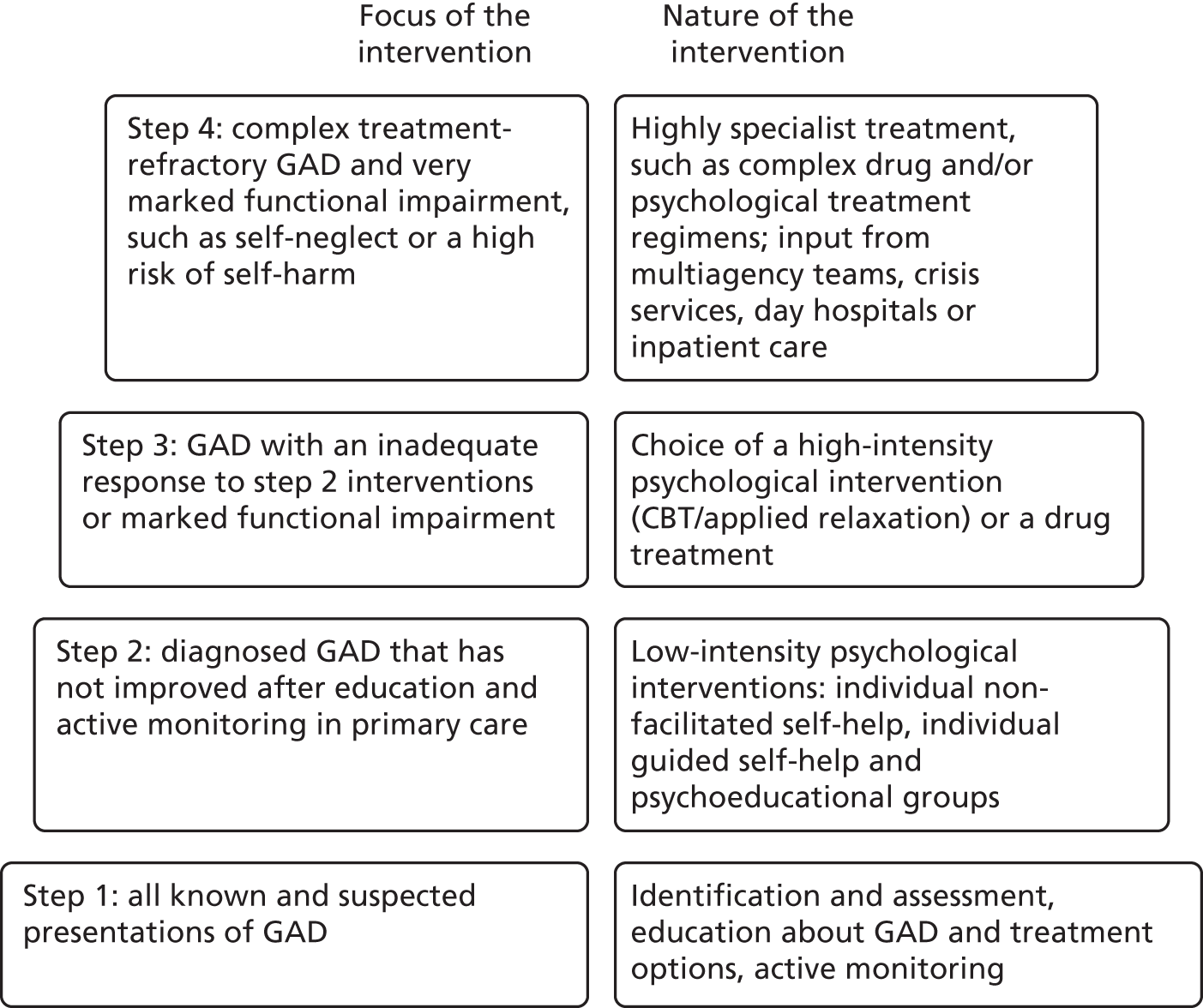

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)’s guidelines for depression23 and anxiety24 advocate a stepped care approach in the management of depression and anxiety, as outlined in Figures 1 and 2.

FIGURE 1.

The NICE stepped care model for depression. 23 © NICE 2009 Depression: Treatment and Management of Depression in Adults. Clinical Guideline 90. Available from www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg90 All rights reserved. Subject to Notice of rights. NICE guidance is prepared for the National Health Service in England. All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn. NICE accepts no responsibility for the use of its content in this publication.

FIGURE 2.

The NICE stepped care model for anxiety. 24 CBT, cognitive–behavioural therapy; GAD, generalised anxiety disorder. © NICE 2011 Generalised Anxiety Disorder and Panic Disorder in Adults: Management. Clinical Guideline 113. Available from www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg113 All rights reserved. Subject to Notice of rights. NICE guidance is prepared for the National Health Service in England. All NICE guidance is subject to regular review and may be updated or withdrawn. NICE accepts no responsibility for the use of its content in this publication.

The NICE guidelines advocate that mild to moderate ‘cases’ of anxiety and depression are offered, at steps 1 and 2, advice about lifestyle by GPs and low-intensity interventions, respectively, which may include provision by non-statutory or third-sector bodies. There is limited evidence of the effectiveness of such providers in improving patient outcomes.

The NICE guidelines for common mental disorders25 emphasises the need to promote access to services for people with common mental health disorders from a range of socially excluded groups including older people, with suggestions, such as using different explanatory models of common mental health disorders, interventions in the person’s home or other residential settings or assistance with travel, and signposting to self-help and support groups.

Evidence base for the management of depression in older adults

A range of individual treatments has been shown to be effective in older people, including antidepressants and psychosocial interventions. 26 Antidepressants may not be an acceptable option for older people and, therefore, concordance is likely to be poor. 15 In addition, evidence repeatedly suggests that older people are not referred for ‘talking treatments’. 22 There is evidence that befriending (a one-to-one intervention) is effective in reducing depression in older people. 27 Befriending has been defined as ‘a relationship between two or more individuals which is initiated and supported and monitored by an agency that has defined one or more parties as likely to benefit. Ideally the relationship is non-judgemental, mutual, and purposeful, and there is a commitment over time’. 28

Lester et al. 29 suggest that befriending provides older people with desired opportunities to develop social ties that they perceive as reciprocal, to share intimacies and establish trust. Moriarty and Manthorpe30 emphasise the need for further research to evaluate the effectiveness of befriending-type interventions.

Other literature, however, suggests that a one-to-one intervention for older people with depression is insufficient: according to a systematic review of interventions for isolated and depressed older people,31 9 out of the 10 effective interventions included were group activities with an educational or support input, whereas six of the eight ineffective interventions provided one-to-one social support, advice and information or health-needs assessment. Therefore, befriending alone is unlikely to achieve a lasting effect, and the practitioner delivering the intervention needs to encourage change in behaviour and activity in the older person.

We attempted to conduct a systematic review32 into the effectiveness of psychosocial interventions for treating depression and anxiety in older people to evaluate which interventions are effective. The aim was to identify which components of psychosocial interventions are most effective in reducing the symptoms of depression and anxiety in older people, which was to inform the NOTEPAD (NOn-Traditional providers to support the management of Elderly People with Anxiety and Depression) intervention. However, the studies identified in the search were too heterogeneous for a metasynthesis, with divergent statistical tests and reporting, follow-up periods, depression scales and control conditions (see Appendix 1). Nine of the interventions were group-based activities and a major difficulty is disentangling the effectiveness of the activity from the effectiveness of being part of a group regardless of the activity that is taking place. Collaborative care as a framework for delivery or complex multicomponent interventions seem to be the most effective. Individual components such as cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) and group reminiscence are also promising. However, the study reporting the effectiveness of group reminiscence did not differentiate the reminiscence therapy from socialising as part of a group.

Loneliness and isolation are risk factors for developing depression and anxiety10 and, because increasing age is associated with loneliness and isolation, new methods of treatment of depression and anxiety among older people should focus on addressing loneliness. Kharicha et al. 33 suggested that older people experiencing, or at risk of, loneliness may not consider that primary care has a role in alleviating this. In addition, they reported that older people with characteristics of loneliness generally know about local resources but do not consider services advertised as being for ‘lonely older people’ to be desirable or helpful. Participants in their qualitative study reported that group-based activities with a shared interest are preferred to one-to-one support or social groups.

Behavioural activation (BA) is a short-term CBT-based intervention known to be effective in the management of depression, which can be delivered by practitioners who do not have specialist mental health training. 34 BA focuses on activity scheduling to encourage participants to approach activities that they may have previously enjoyed but are currently avoiding owing to increasing life changes (e.g. loss of spouse), or to develop new activities, and on analysing the function of cognitive processes (e.g. rumination) that serve as a form of avoidance. Participants are thus refocused on their goals and valued directions in life. The main advantage of BA-oriented interventions over traditional CBT for depression is that it may be easier to train non-clinical staff to deliver the intervention. 34 BA within a collaborative care model forms the cornerstone of trials35–39 in which the intervention is delivered by psychological well-being practitioners. 30,35–37 In addition, behavioural therapies have been shown to be effective in older people. 40,41 BA is therefore likely to be effective in older adults with anxiety and depression.

In the CASPER plus (CollAborative care for Screen-Positive EldeRs with major depression) trial,42–44 the BA intervention was acceptable for many of the older adults with depression and could readily be delivered over the telephone, following a face-to-face meeting. This approach may be able to reduce the stigma of the label of mental illness and resolve misconceptions around antidepressant medication prescribed by GPs. 29,30 However, some participants reported that the intervention was intrusive, and felt that talking and thinking about their symptoms made them feel uncomfortable.

An observation among all trials of people with depression has been the failure to integrate these effective elements of care into routine primary care services. 31,44

Collaboration with the third sector

The argument for working with the third sector, specifically Age UK, is based on previous collaborations with Age UK, and that older adults may find third-sector services less stigmatising.

Age UK has funded previous evaluations such as ‘Fit as a fiddle’45 and ‘Call me’. 46 Fit as a fiddle was a £15.1M portfolio of activities funded by the Big Lottery Fund and delivered across the nine English regions between 2007 and 2009. The aim was to increase the opportunities for older people to undertake physical activities and improve their eating habits, contributing to an overall improvement in mental health. The evaluation demonstrated a significant improvement in physical and mental well-being and an increase in volunteering capacity. The model has been accepted by Age Action Alliance as the preferred model for delivering healthy ageing services. Findings from the Call me project demonstrated that tailoring activities to a participant’s interests increases engagement in social activities and participant satisfaction and encourages sustainability.

Rationale for the NOTEPAD study

There is a need to improve the quality of care for older people with anxiety and depression. Improving quality of care means addressing not only the effectiveness of interventions but also the issue of limited access to acceptable care.

Older adults are a vulnerable and underserved group, often experiencing difficulty in accessing mental health care. 47 This is compounded by social isolation, loneliness and economic deprivation. 36,48 Given the ageing population and the public health implications of depression in older people, it is clear that acceptable community interventions focused on older people with anxiety and depression are needed. 49

Previous studies, such as Dowrick et al. ,50 explored ways to improve access for particular patient groups with limited access to care (e.g. older people). In the AMP (Access to Mental Health in Primary Care) study,50 psychological well-being practitioners (seconded from local IAPT services) delivered a brief psychosocial intervention to older people, which participants found to be acceptable. 51 In the same programme,50 third-sector workers were trained to deliver a similar intervention to South Asian women. Delivery by therapists or mental health practitioners is costly, which makes an intervention less likely to be commissioned in the NHS. Whether or not third-sector workers can deliver such an intervention to older people, and whether or not it is acceptable to patients and effective in improving outcomes, is unknown.

A further argument for increasing social participation is that loneliness and depression are strongly associated in older people52 and loneliness is an independent risk factor for depression. 48 Evidence from the USA53 suggests that for lonely older people there is a potential benefit from a social group or educational activities. Thus, it is reasonable to postulate that group activity might be a useful adjunct to treatment for mild to moderate depression.

Further evidence from a systematic review of social interventions targeting loneliness in older people54 suggests that the most successful interventions for loneliness, measured by improvement in the domains of physical, mental and social health, tend to be group based and participatory and offer some activity. 55–58 Such community-based interventions have been shown to have additional benefits in terms of social inclusion and social cohesion. 59–61

It has been argued that creativity plays an important role in later life and has positive implications for health and well-being and the maintenance of social networks by older people. 62–65 Creative activity has also been shown to provide therapeutic benefits,66 further evidenced by the rise in community-based ‘art for health’ across the UK. 67

A report from the Baring Foundation68 argues that the arts are an effective way to tackle loneliness, offering opportunities to connect and contribute, and to develop friendships and a sense of being valued, so that resilience is enhanced. It also notes that they are often overlooked by older people’s services. Despite the growing call for a diverse range of support for older people, there remains a paucity of evidence on what works best and Dickens et al. 54 suggest that there is a need for more studies to add to the evidence base.

From the literature, it is likely that the ideal intervention would be a tailor-made, flexible combination of elements, with some individual psychological therapy if necessary, followed by a group-based social activity that the participant might find enjoyable and/or meaningful.

In this older population, however, there are likely to be barriers to recipients of BA resuming previously enjoyed activities, such as difficulties with transport or lack of confidence. One solution would be for support workers (SWs) to initially accompany participants to activities to support their attendance.

The proposed intervention was supported by a wide theoretical basis, including social identity theory69 and self-concept theory,70 which examine how a person’s self-concept is affected by membership of social groups, and self-efficacy theory,65 which is highly relevant to health behaviours and posits that self-efficacy can be directly influenced by modelling or social persuasion within groups. These theories indicate how group interventions might help to foster good mental health framed within a critical gerontology approach. Critical gerontology challenges traditional notions of ageing as problematic and burdensome, and argues for older people to be seen as assets and contributors to the societies in which they live. This approach emphasises diversity and the need to take account of the wide range of issues that profoundly structure the experience of ageing, including life-course, sex, health and disability, socioeconomic status, ethnicity, sexual orientation and the physical environment. 71

Whether or not third-sector workers can deliver such an intervention to older people, and whether or not it is acceptable to patients and effective in improving outcomes, is unknown.

Summary

The overall aim of the NOTEPAD study was to explore whether SWs from the third-sector organisation Age UK North Staffordshire can deliver a non-stigmatising psychosocial intervention to support and manage older people with anxiety and depression recruited from primary care.

Research aims and objectives

This was a study composed of three phases, each informed by a patient and public involvement and engagement (PPIE) group:

-

phase 1 – qualitative work with older people and third-sector providers, plus a consensus group to refine the intervention, training, SW manuals and patient participant materials

-

phase 2 – recruitment and training of SWs

-

phase 3 – feasibility study to test recruitment procedures and assess fidelity of delivery of the intervention; interviews with study participants, SWs and GPs to assess acceptability of the intervention and impact on routine care.

Aims

Phase 1: to refine a community-based psychosocial intervention for older people with anxiety and/or depression, to be delivered by non-traditional providers (NTPs)/SWs in the third sector.

Phase 2: to determine whether or not NTPs/SWs can be trained to deliver this intervention to older people with anxiety and/or depression.

Phase 3: to determine if it is feasible to recruit and randomise patients, to pilot procedures and to conduct a process evaluation to provide essential information and data to inform an application for a full randomised trial.

Objectives

Phase 1: to refine a psychosocial intervention to be delivered by third-sector NTPs/SWs to older people with anxiety and/or depression.

Phase 2: to assess feasibility of recruiting and training NTPs/SWs to participate in the study and to assess fidelity of delivery of the psychosocial intervention to older people with anxiety and/or depression.

Phase 3: to answer the questions below.

-

Feasibility:

-

Can we recruit general practices to participate in a study to evaluate the feasibility of this approach?

-

Can we recruit and retain older adult participants in a randomised study, including the completion of follow-up questionnaires?

-

Can the NTPs/SWs deliver a psychosocial intervention to older people with anxiety and/or depression?

-

Can this intervention be implemented in routine NHS service delivery?

-

-

Process evaluation:

-

Do older people find working with an Age UK SW, and joining groups, acceptable?

-

What are the perspectives of the SWs about training, support to deliver the intervention, and how did they find working with older people in a more structured way?

-

Were the manuals developed to support training and delivery of the psychosocial intervention acceptable and useful to SWs?

-

What did participating primary care clinicians understand by the study and how did it impact on their work?

-

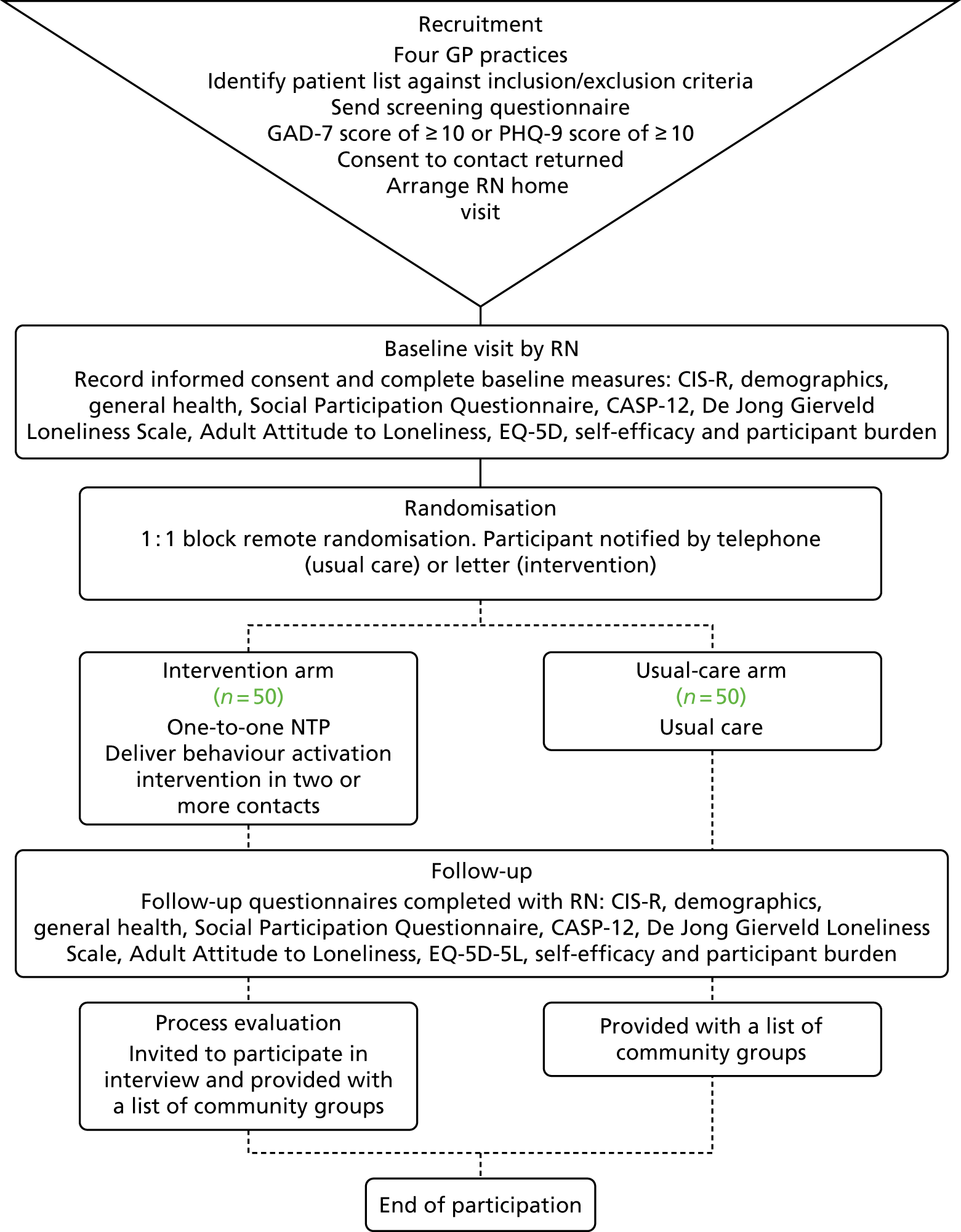

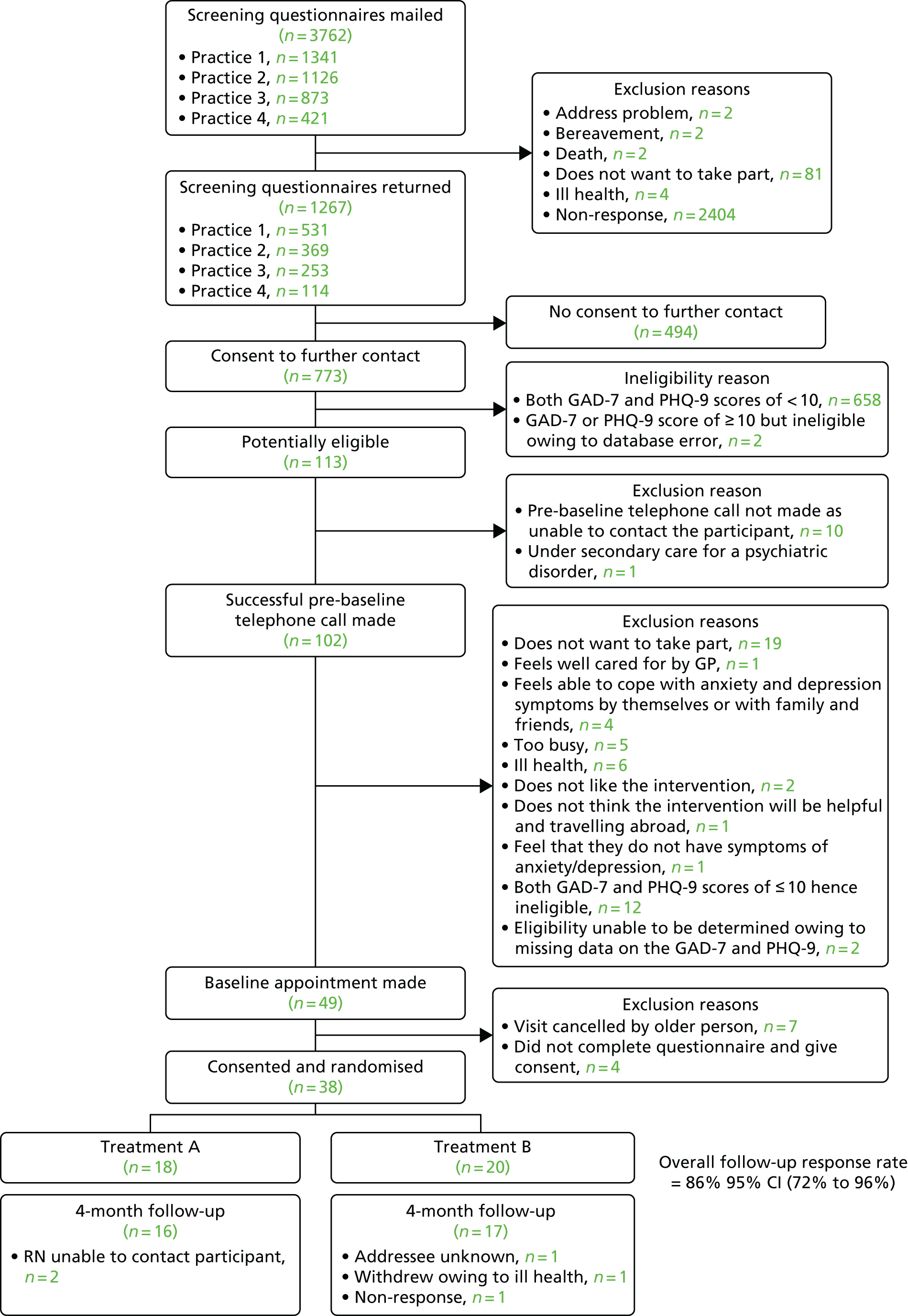

Figure 3 illustrates how the three phases link together.

FIGURE 3.

Model of the NOTEPAD study phases. TAU, treatment as usual.

Chapter 2 Qualitative study to inform the NOTEPAD intervention

The following description of the qualitative study is informed by our research output, Kingstone et al. 49 Content from this publication has been reproduced and/or adapted for the purposes of this report under the creative commons licence. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Aims and objectives

The objective of phase 1 of the NOTEPAD study was to inform the refinement of the psychosocial intervention to be delivered by SWs recruited from the third sector to older people with anxiety and/or depression. Based on the previous work of the research team, and on the existing literature, it was anticipated that the intervention would comprise a two-stage process of one-to-one contact, utilising BA, based on the principles of CBT, and including the option of signposting to a group activity.

In addition, an objective of phase 1 was to contribute to the development of training for the SWs, including the development of manuals for the SWs and for patient participants.

Design and setting

Ethics approval was obtained from the Keele University Ethical Review Panel on 23 September 2015.

Patient and public involvement and engagement

A PPIE group was established to support the development of the whole NOTEPAD study. The group helped to create the NOTEPAD logo and strapline ‘Supporting Mental Strength’.

The PPIE group suggested that the term ‘non-traditional providers’ used in the application for funding was unlikely to be acceptable to older people, and suggested that the term ‘support workers’ would be more appropriate.

The PPIE group suggested that the terms ‘depression’ and ‘anxiety’ may not be acceptable to older adults owing to stigma and could limit engagement with the study. Alternative terms ‘low mood’ and ‘stress’ were suggested by the PPIE group members and used thereafter. The term ‘stress’ is not clinically equivalent to anxiety; however, the research team accepted that there is sufficient overlap between these terms to support exploration in the qualitative interviews.

The PPIE group provided advice on the design of participant-facing documents (e.g. participant information sheet, consent forms), on the language and terminology used and on the layout of documents.

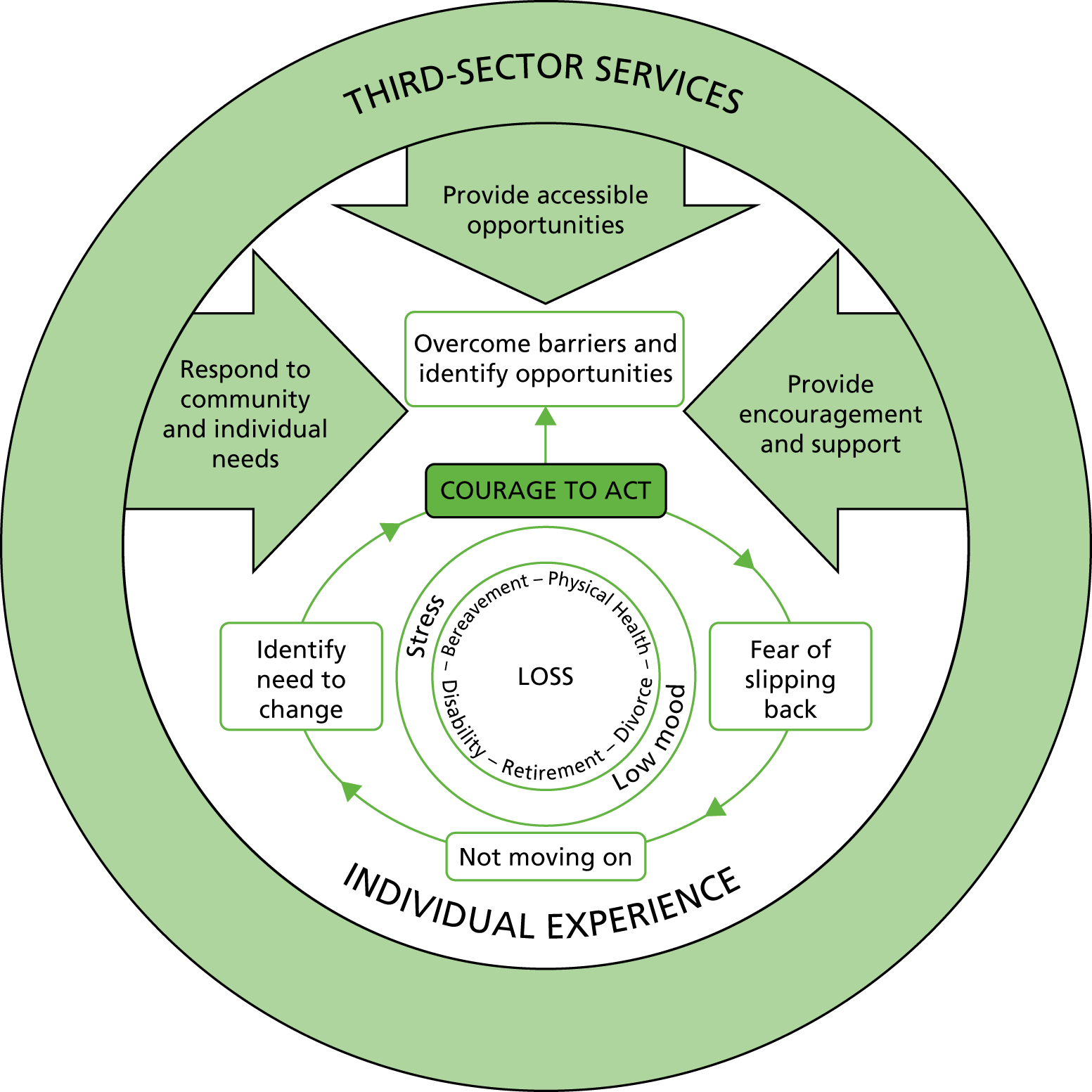

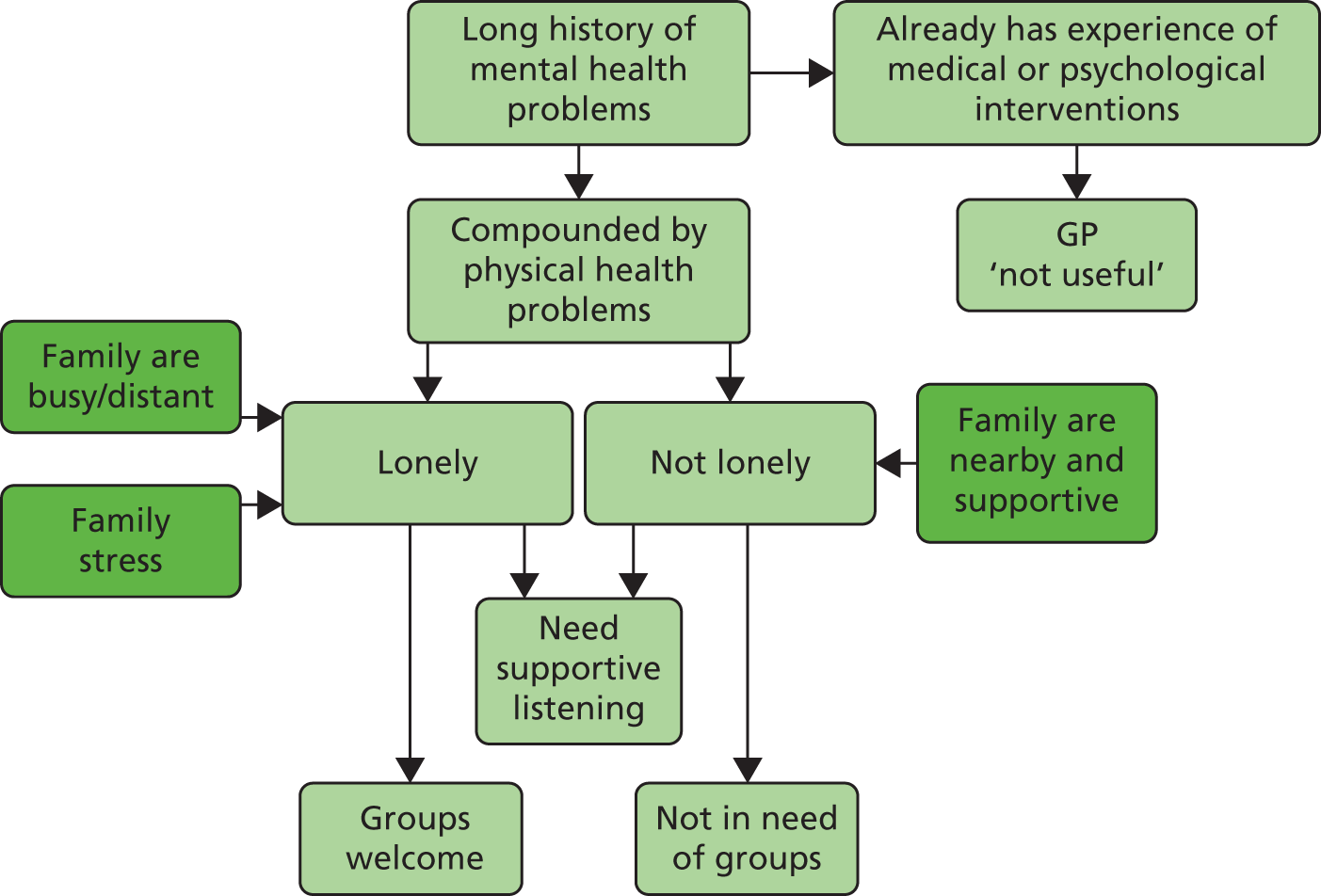

Towards the end of the qualitative study, the results of the emerging analysis were presented to the PPIE group, and they contributed to the development of a model that mapped the perspectives of older adults and third-sector workers on older adult responses to loss, which informed the intervention (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Older people’s and third-sector service responses to distress and loss in later life. Reproduced from Kingstone et al. 49 This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Methods

Qualitative methods were used to explore older people’s experiences of, and perspectives on, low mood and stress, and third-sector workers’ perspectives on working with people suffering from mental health problems. In addition, the views of participants on how to manage low mood and stress were sought, along with what an intervention delivered by third-sector workers to older people might look like.

Semistructured interviews were used to generate data.

The approach to sampling was purposive. We sought to recruit older adults (aged ≥ 65 years) living in the community and interested in sharing their views about experiencing low mood and/or stress in old age. We also sought to recruit individuals who were either in paid employment or volunteering with third-sector organisations and involved in the provision of community-based support for older people who may or may not experience low mood and stress.

Recruitment

Researchers (TK and HB) attended group activities (e.g. keep fit classes, line dancing classes, knitting groups and luncheon clubs) hosted in North Staffordshire by third-sector organisations with which the research team had established links [for example, Age UK North Staffordshire, Royal Voluntary Service (www.royalvoluntaryservice.org.uk), Beth Johnson Foundation (www.bjf.org.uk)]. With the assistance of activity group leaders, the researchers explained the study and distributed participant information packs comprising an invitation letter, a participant information sheet, a consent to further contact slip and a prepaid envelope. Snowball sampling72 was used to reach older people who did not attend groups and participant information packs were provided to group attendees to share with friends. Packs were also provided to non-statutory workers to distribute to service users outside these groups (e.g. befriending, signposting services). On return of consent to further contact slips, prospective participants were contacted to confirm willingness to participate and to arrange a convenient time and place for the interview, typically a private room at the community-based venue where group activities were held. Written consent was recorded immediately before the interview. Interviews lasted between 30 and 60 minutes.

Third-sector workers were identified through third-sector organisations (e.g. Age UK North Staffordshire, Royal Voluntary Service and Beth Johnson Foundation). Worker information packs were distributed via team managers within these organisations and contained equivalent information to the participant information packs for older people (as described). On return of consent to further contact slips, prospective participants were contacted to confirm willingness to participate and to arrange a convenient time and place for the interview.

Informed consent

The study was verbally explained to prospective participants and information packs were distributed. On return of consent to further contact slips, prospective participants were contacted to confirm willingness to participate and to arrange a convenient time and place for the interview, usually a private room at the community-based venue where group activities were held. Written consent was recorded immediately before the interview: two consent forms were signed, with the participant given a copy to keep.

Topic guides

Two topic guides were used: one for older people and one for third-sector workers. The topic guide for older people contained a series of open questions (see Appendix 2) to act as a basis for the discussion and explore their views on mood problems/depression and anxiety, seeking help and from where, and acceptable management approaches. Older people’s views on (and any experiences of) third-sector workers delivering one-to-one interventions were explored.

The topic guide for third-sector workers (see Appendix 3) also contained a series of open questions. They were used as a basis for the discussion and to explore perspectives on, and experiences of, working with older people, recognising depression or anxiety, concerns over working with people with anxiety and/or depression, and how receptive workers would be to receiving training to deliver a psychosocial intervention to older people.

Data coding and analysis

All interviews were digitally recorded with consent and transcribed by an external company. The transcripts were checked against the digital recording by HB or TK. The study was exploratory in nature; thus, thematic analysis was used to analyse the data. 73 Coding of the transcripts was undertaken by five members of the research team from different professional backgrounds to increase the trustworthiness of the analysis. 74 All transcripts were coded inductively by the first and second authors; the third, fourth and last authors independently coded five transcripts each. Each data set (older people, third-sector workers) was coded separately, and then comparisons across the two data sets were made. Data were stored and managed in NVivo 10 (QSR International, Warrington, UK).

Themes and subthemes emerging from the coding were discussed in team meetings and modified to account for alternative interpretations. The key themes and a model of the analysis were agreed.

Results

Participants

Interviews were completed with 19 older people and 9 third-sector workers (demographic information is provided in Tables 1 and 2).

| ID | Sex | Age (years) |

|---|---|---|

| Older adult 1 | Female | 72 |

| Older adult 2 | Female | 76 |

| Older adult 3 | Male | 65 |

| Older adult 4 | Female | 70 |

| Older adult 5 | Female | 76 |

| Older adult 6 | Female | 66 |

| Older adult 7 | Female | 78 |

| Older adult 8 | Female | 67 |

| Older adult 9 | Female | 86 |

| Older adult 10 | Female | 76 |

| Older adult 11 | Female | 77 |

| Older adult 12 | Female | 85 |

| Older adult 13 | Female | 83 |

| Older adult 14 | Female | 76 |

| Older adult 15 | Female | 70 |

| Older adult 16 | Female | 80 |

| Older adult 17 | Female | 67 |

| Older adult 18 | Female | 69 |

| Older adult 19 | Female | 74 |

| ID | Sex | Role |

|---|---|---|

| Worker 1 | Female | Volunteer (unpaid) |

| Worker 2 | Female | Worker (paid) |

| Worker 3 | Female | Worker |

| Worker 4 | Male | Volunteer |

| Worker 5 | Female | Worker |

| Worker 6 | Female | Worker |

| Worker 7 | Female | Worker |

| Worker 8 | Female | Volunteer |

| Worker 9 | Female | Volunteer |

Findings

Analysis of the interview data revealed the following themes: experiencing multiple forms of loss; distress as a personal burden to bear; having courage and providing/receiving encouragement; opportunities to increase self-worth; and barriers, tensions and gaps in service provision. Each theme is described below; data are given to support the analysis and each data extract labelled with a participant identifier (ID).

A conceptual model was developed to map older adult and third-sector worker perspectives on older adult responses to loss (a key contributing factor to low mood and stress). The contribution of this analysis to refinement of the intervention and the NOTEPAD feasibility study is described.

Experiencing multiple forms of loss

The older people we interviewed described multiple forms of loss in later life, which contributed to feelings of low mood and stress. The forms of loss described included loss of significant relationships (i.e. with spouses, friends, confidantes), changes to physical health and mobility (e.g. osteoarthritis, joint replacement operations), changes in capabilities and established activities (e.g. driving, employment roles) and loss of control of daily life (e.g. burden of providing caregiving).

Typically, older people experienced combinations of these losses. For example, one older person described a sequence of losses, which affected how she dealt with her own low mood:

My husband died and I had a hip replacement and then, 3 months after, I fell and broke the other [hip] . . . I’m trying to get over that now but, of course, I’ve had to give my work up, which doesn’t help because you’re more or less stuck in the house 24 hours.

Older adult 14

The experience of successive losses contributed to a sense of decline – of being on a ‘downward slope’ (older adult 6) or in a ‘downward trend’ (older adult 17).

This experience of loss was typically experienced as a crossroads when older adults found themselves thrown back onto their own resources. They described coming to the realisation that they would have to choose whether to make a conscious effort to get out of the house and forge new social links or to avoid participation and stay indoors. Several interviewees reflected that they feared that the latter choice could result in ‘giving up’ and becoming isolated.

Workers recognised the habitual nature of staying indoors:

A lot of people I see are in their late 80s, early 90s; they have become used to staying at home. I wouldn’t say they’re housebound; they’ve got out of the habit of going out.

Worker 4

The worker implies an important distinction between older people who are housebound (i.e. owing to physical health impairment) and those who are ‘out of the habit’ of getting out from their home environment. Thus, not going out has become a habitual behaviour for some older people and is not a result of physical impairment, centralising the importance of behaviour to overcome social isolation and losses attributable to this.

Distress as a personal burden to bear

One older adult described the way in which her friend coped with low mood as follows: ‘it was her cross and she would carry it’ (older adult 12). This metaphor captures common experiences of older people with low mood or stress: it is a personal burden for older people to bear. One older adult described:

I had six major operations within about 3 years. So that really knocked me off my pedestal and nobody really knows . . . That’s the thing. Depression. Nobody knows what you’re going through . . . you put on a smile and everybody thinks you’re fine, you’re doing alright, aren’t you? But they don’t realise inside that you’ve been through a hell and back and you’re suffering.

Older adult 10

The invisibility of such distress, as described, implies an opportunity to control the perceptions of others. A reluctance to share mental health experiences with others was apparent:

You don’t really want to pick up the phone and talk to friends because if you’re miserable I’m not going to make her miserable, you know. You’ve got to do something for yourself.

Older adult 5

The reluctance stems from not wanting to burden other people; to share their misery. Some older people did describe sharing these apparent burdens with their GP, seeking to obtain support, but people reported disappointment that they were prescribed antidepressants. Some older people reported taking antidepressants whereas others reported that this was not an acceptable course of action and that their problems remained unresolved.

Workers acknowledged that some older people may not want to talk about mental health problems, such as anxiety, with them:

Somehow anxiety has got a capital A; they might talk about feeling a bit low or something, so I think people don’t always find it easy to identify.

Worker 5

Older men were particularly identified as a group reluctant to discuss mental health. However, workers described being able to overcome reluctance to talk and perceived stigma around mental health by providing time and developing trust:

[P]eople do, once they trust you, feel that they can confide, and so people have talked about issues around mental health and you listen . . . Quite often it has been enough just to listen but sometimes we would encourage people to have a chat with the GP or maybe direct them towards some counselling.

Worker 5

The opportunity to establish meaningful, quality relationships and develop listening skills was felt to be important to facilitate disclosure of mood problems to others.

Having courage and receiving/providing encouragement

Older people described themselves as having to build up courage and determination to participate in group activities, despite suggesting that this may help to alleviate their feelings of low mood and/or stress. One participant described actualising their sense of courage, referring to the time that they discovered an advert for a group activity:

I thought, ‘that sounds good’, but, of course, I hadn’t got the courage because, as I said, [my husband had] only been gone 3 or 4 months. ‘Well’, I thought, ‘I’ll cut the thing off the [newspaper]’, which I did, and I popped it into this thing in the kitchen. I had to take it out from time to time and look at it. It took me 6 months to find the courage to, to phone up.

Older adult 1

Courage was an important part of accepting the need to reach out and make social contact. One participant described requiring ‘grim determination’ (older adult 5), perhaps indicating how difficult it was to find the necessary courage to engage in a new social activity.

Older people indicated a fear of slipping backwards with regard to sustaining a change in behaviour and continuing to attend and participate in group activities. Sustaining courage and motivation can be challenging, as one participant describes:

[O]nce you drop something it’s so difficult to pick up again afterwards. You think ‘oh, I haven’t been for a long while; what will they think of me if I turn up now?’ you know. But it takes a lot of willpower and not everybody’s got that willpower.

Older adult 10

In counterpoint to the courage that older people described, workers identified the importance of providing encouragement. Workers expressed empathy towards older people, seeking to initiate new social activities and practical help, as the following worker describes:

They need that encouragement to go to the befriending group. I do make contact with everybody a week before to remind them, to say ‘do you need a taxi?’, ‘do you need a lift?’

Worker 4

Attention and encouragement may act to support an older person’s own sense of courage to overcome challenges of low confidence. Encouragement was reported to be essential to support joining in any new activity.

Opportunities to increase self-worth

Older adults described how both one-to-one support and participation in group activities were valuable in improving mood and reducing the distress associated with loss. One older adult participant described attending an exercise class as an opportunity for respite from being a caregiver for her husband:

I don’t work, but this is my ‘day off’ where I come and enjoy the exercising. I enjoy being with the people . . . I love my husband, don’t get me wrong, but it’s just nice. He’s in, I can have the car, I can come down here, and it’s just a release sometimes, just to switch off and everything.

Older adult 16

Participation in group activities was valued for several reasons: the provision of opportunities to develop social relationships and participate in activities and roles, to redevelop or maintain a routine and to experience a change of environment.

Participation in group activities also supported a sense of self-worth within the group, as one participant described: ‘I really enjoy it and I’m the tea lady’ (older adult 15). It was clear that participation could also include assuming specific roles within these groups; others described providing supportive roles for newcomers to the groups.

Workers acknowledged the importance and range of benefits and opportunities that participating in group activities had for older people. One worker described an exercise group in the following way:

It isn’t just about sticking the music on and moving your arms and legs, it’s about the interaction with you and the folks in the group and the interaction between each [participant] . . . just going once a week, say to an exercise group, when they have maybe suffered from depression for 2 years and have never been out of the house maybe following a bereavement, it’s more than a lifeline.

Worker 5

Acknowledging the significance of the social element of group activities (i.e. that these are not solo activities but performed in groups) is important because it has implications for older people in terms of maintaining participation, self-confidence and social relationships.

However, workers recognised that group settings were not appropriate for everyone:

Even though some of them are still fairly mobile, that lack of confidence, I think, of being in a group situation has put them off trying.

Worker 4

When addressing inertia, it is important to provide support and encouragement to overcome apprehension and lack of confidence regarding group activities.

Barriers to, tensions and gaps in service provision

Internal (intrapersonal) and external (interpersonal and systemic) barriers were identified from the experiences of older people. Lack of acceptance and difficulties in acknowledging need (i.e. poor mental health arising from social isolation or loss of meaningful activities) among older people presented a barrier to engagement with the third-sector services; this was evidenced in the continuation of avoidance-style behaviours and social withdrawal. One older adult described how she coped with her low mood: ‘if I feel a bit low, I put the television on’ (older adult 12). Another shared her views about her friend whom she describes as experiencing low mood:

She has no hobbies, no interests at all . . . But she still gets very low and, to my mind, almost enjoys it. That sounds odd, I suppose, but it’s become a way of life and she doesn’t mind saying so.

Older adult 17

A lack of opportunities to engage in activities may perpetuate this cycle of social withdrawal. For some of the older adult participants, suitable opportunities were considered to be lacking, providing a further disincentive to increase social contact.

Transport was identified as a barrier to participation in group activities. Some older people in the study were still able to drive and used their own transport to access these groups, whereas others could no longer drive and described public transport as either unsuitable or non-existent: ‘There is no community transport here at all’ (older adult 9). Workers acknowledged transport as an issue in the provision of services:

This is a problem that we have. We know that there are people that are stuck at home . . . but it’s just getting them out and transport is always an issue.

Worker 3

Although some workers reported that they provided transport to older people, using their own vehicle, the capacity to maintain this raised concerns about sustainability:

In the past I might have taken people – picked people up a bit more – but we just haven’t got the capacity to do that.

Worker 6

Financial cuts to services were described by older people and third-sector workers, which were typically attributed to current policies of fiscal austerity and remained an ongoing concern. Workers would often talk to service users during group activities about financial cuts and service losses, as one older adult describes:

[She’s] always saying they’re cutting back on the company where she works for, Age UK, you know. It’s such a shame because a lot of people need these groups.

Older adult 16

When services had been cut, gaps in provision had not been filled and so the needs of those older people who had utilised these services went unmet.

Workers described tensions around the boundaries of their roles as facilitators of group activities (in a paid or voluntary capacity) and responsibility for older people experiencing mental health problems. Workers identified a lack of mental health training:

We kind of work, maybe, try and instinctively to chat to people and reassure them. We don’t really know if that’s making much of a difference.

Worker 6

Workers had concerns about managing boundaries with older people who presented severe mental health needs:

You would need to have . . . good boundaries, I think, when you’re working with people . . . so you don’t get drawn in to all sorts of things that are going on with that person’s life.

Worker 6

This concern was shared by others and reflected a lack of sufficient, tailored training. Workers also identified a tension in the lack of collaboration between third-sector and primary care services, important in the context of clients with apparent mental health needs (e.g. older people with dementia or clients who self-harm).

Conceptual model

The conceptual model illustrated in Figure 4 is derived from the thematic analysis of the interview data. The experience of loss, as a contributing factor to the mental health needs of older people, is central to the model. How older people respond to this loss varies and is individualised, with courage required to accept that a problem exists and to do something about it. Not moving on, and not acknowledging a need arising from social isolation or the loss of meaningful activities, may then lead to inactivity and increasing social withdrawal. The identification of opportunities to support self-worth is important, as is the capacity to overcome barriers (e.g. access, transport, low confidence). Third-sector organisations provide a crucial support role (e.g. through provision of group activities). It is this population of increasingly socially withdrawn older people who are at risk of being overlooked by the services offering support.

Views about the proposed NOTEPAD intervention

Overall, older people and third-sector workers in this study were positive about the potential for an intervention to be delivered by third-sector workers as part of the NOTEPAD study. However, participants felt that it might take some skilled intervention to persuade older people with low mood or stress to take part in the study, specifically group activities:

If you’ve got a person who wants to sit in the house and not do anything and is not willing to do anything, nothing on this earth will get you out of it.

Older adult 3

Older people in the study did not typically associate Age UK North Staffordshire with providing mental health services. Workers confirmed during interview that mental health services were not typically provided by the Age UK North Staffordshire. Workers identified training needs, the need for supervision and the opportunity to debrief as important in the development of the intervention for the NOTEPAD study:

You need access to a supervisor and I think depending on when you were having contact with the individuals concerned you would need to be able to debrief. If you had an urgent concern, you would need to be able to debrief straight after . . . you probably also need to be writing something down.

Worker 5

Documenting interventions and actions seemed important. Regarding the design of the intervention, the inclusion of one-to-one and group activities was identified as important:

You’ve got to try and get them out. You can’t just listen to what they say and don’t do anything. Get them to join things like – to join things like this and keep going, you know? Keep going for them and it’ll do them good because then they – like they’ll be talking to ordinary people [older people] but ordinary people know just as much as some psychiatrists.

Older adult 2

Group activities were not seen as suitable for everybody, and one-to-one interventions were considered essential to provide the opportunity to develop trusting relationships:

Depression. Nobody knows what you’re going through. And my relatives and friends, you know, you put on a smile and everybody thinks you’re fine, you’re doing alright, aren’t you? But they don’t realise inside that you’ve been through a hell and back and you’re suffering, and nobody knows . . . I, I got no sympathy from anybody from what I’d been through . . . You know, it is very very difficult and, and if, it’s partly that no sympathy that makes you depressed. If you’ve got somebody there helping you, you don’t get depressed, if you’ve got somebody there with you, you know. [. . .] You need, you need somebody there.

Older adult 1

Furthermore, having a worker accompany an older adult to new group settings was considered crucial to providing support and much needed encouragement:

I wouldn’t mind at all if somebody came, picked me up, took me out and brought me back again, that would be lovely! Yeah! [Laughter] Yes, [when I was depressed] it took a lot of will to go and do them [group activities], but I knew myself that I had to do them because if I didn’t it wouldn’t do me any good at all.

Older adult 1

Table 3 summarises the contribution of the qualitative study to the design of the intervention.

| Aspect of study | How intervention has been adapted |

|---|---|

| Facilitating relationships and trust |

|

| Facilitating self-management (and ongoing data gathering) |

|

| Maintaining participant engagement |

|

| Supporting third-sector workers |

|

Patient and public involvement and engagement

During the analysis of the interview data, a meeting was held with our PPIE group during which the findings were discussed. Members of the group suggested that the analysis resonated with their experiences (and experiences of older people they are in contact with) and that the model made sense to them. The group discussed how the analysis could inform the design of the intervention and contributed to Table 3.

Discussion

Summary of results

The themes presented map out how experiences of loss contributed to the mental health of older people in a community sample, their engagement with third-sector services, and the provision of these services by those involved in delivery. The process is depicted in the conceptual model (see Figure 4).

The experience of loss was described in multiple forms and was a central theme from the interviews. Loss and its ramifications for older people is a complex and individualised experience; responses to loss, although supported by third-sector services, are influenced by biographical factors (e.g. existing support networks, a sense of one’s own courage, and personal agency). Older people described a reluctance to talk about mental health problems with friends, for fear of burdening them, and described difficulty in acknowledging the need to do so. Those participants who self-identified as experiencing low mood or stress said that they would talk to third-sector workers once a trusting relationship had been developed. Older people in this study were already actively participating in group activities in an effort to maintain social networks and roles, reporting that this did support good mental health; older people valued being members of these groups because of the opportunity for social interaction and to support self-confidence. The role of courage and to receive (or provide) encouragement was highlighted as important in supporting this participation, highlighting a key function of third-sector workers. Older people revealed an ongoing concern of slipping back to avoidance behaviours; this suggests that maintaining positive behaviours requires ongoing support and encouragement. The findings highlighted and informed important areas for development of the intervention for the NOTEPAD feasibility study: facilitating relationships and trust, the importance of self-management as an integral part of the intervention, maintaining participant engagement and supporting third-sector workers.

Comparison with previous literature

The analysis supports other research that identifies the need to take a broader perspective on mental health and its management than a biomedical model permits. For instance, Burroughs et al. 13 described how GPs normalised and justified depression among older people as a social problem, reinforced by GPs’ sense of powerlessness to respond; they perceived that there were very limited options available to them. In the present study, older people identified feelings of distress as a personal burden. Many disclosed antidepressant usage but that their problems remained unresolved, and older people in this study took it on themselves to identify opportunities to attend group activities, which supported their social mental health. Maintaining participation in activities and social interaction seemed important for older people in this study to support their quality of life and mental health, as identified in other research,75,76 but also to support coping with, and moving on from, the experience of loss. The process of ‘moving on’ has been identified previously in relation to depression;14 the role of others (the case managers in the trial) was seen as important in providing encouragement to increase activity and social participation. Chew-Graham et al. 15 described perceived stigma as preventing older people from sharing mental health problems with their GP, which may relate to the fear of burdening others that has been described. In the present qualitative study, a link between loss (in multiple forms) and anxiety and depression was identified; thus, third-sector workers may be well placed, with greater contact time, to develop relationships, support disclosure and respond to mental health risk factors. Targeting loss, supporting responses of older people to loss, and overcoming avoidance-type behaviours that may lead to rumination may be a useful point of entry for third-sector services.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths

This study explored multiple perspectives on anxiety and depression among older people in the community and identified the central role of loss as a potential contributing factor in such mental health problems. Recruiting older people from community groups means that we accessed the views of people not necessarily accessing primary care. This is the first study to our knowledge to report the views of third-sector workers on supporting older people with anxiety/depression (stress and low mood) and the potential role they might play. The analysis contributed to the refinement of the NOTEPAD intervention.

Interviews were conducted with older people who were already accessing group activities and services in their local community; thus, the perspectives of older people who do not attend community groups are not reported. We did not specifically recruit participants who were experiencing or had experienced low mood or stress.

The views of housebound individuals were limited to those shared by other participants; that is, some participants shared the views of others whom they knew to be potentially housebound. These views may have been shared as a means of supporting social comparisons. This limitation occurred despite efforts from the researchers to recruit more broadly. A male perspective was lacking. This may have been a result of the recruitment strategy, which focused on local groups (which were mostly attended by women). A ‘Men in Sheds’ group was attended by the researchers, but no-one agreed to participate in an interview. More broadly, this also reflects a lack of male-oriented activity groups available in the community.

Summary

This phase of the study identified the central role of loss in later life as a potential contributing factor in mental health problems; the findings have important implications for the proposed feasibility study, training of third-sector workers delivering the intervention and clinical practice. Third-sector workers reported regular contact with older people presenting apparent mental health problems and needs related to the community; typically, such contact occurred at group activities and services not designed to respond to mental health needs nor with staff or volunteers appropriately trained. Phase 1 affirmed that, with appropriate training, third-sector workers could be well placed to deliver a low-intensity psychosocial intervention to older people, as recommended in the stepped care approach in NICE guidelines for anxiety and depression, and would provide both older people and primary care professionals with choice for management. The analysis contributed to the refinement of the NOTEPAD intervention and the development of the SW training, SW manual, and the resources intended for study participants. This will be discussed in Chapter 3.

Chapter 3 Phase 2: refining and delivering the NOTEPAD intervention

Aims

The aims of phase 2 of the NOTEPAD study were to:

-

identify the effective components of an intervention that aims to improve the management of depression and anxiety, reduce social isolation, increase participation and promote good mental health in older people

-

develop, refine and integrate interventions that respond to patients’ self-reported difficulties and may include lifestyle and activity advice, psychoeducation, BA techniques (a simple CBT-based intervention) and referral to existing third-sector resources (which might include referral to a befriending service, patient or carers group, Age UK or other local groups) to reduce social isolation

-

develop training for SWs from the third sector (Age UK) to enable them to conduct the assessment and deliver the psychosocial intervention

-

develop a manual for the SWs to structure the intervention and support and supervise their work with study participants

-

develop resources for study participants to use with a SWs’ support.

Refining the intervention

The intervention was built on the literature, the research team’s previous experience39,42,76 and consensus achieved in an expert group.

The evidence base underpinning the NOTEPAD study is outlined in Chapter 1. The systematic review (see Appendix 1) confirmed the premise of the application; that the ideal intervention would be a tailor made combination of individual psychological support and subsequent group-based social activity that the participant might find enjoyable and/or meaningful. Our review suggested that reminiscence therapy might be useful but that the effects were not well differentiated from the effects of merely socialising as part of a group.

The research team drew on previous interventions that incorporated BA that they had been responsible for developing and delivering within trials. 39,42,76 BA is a structured programme of reducing the frequency of negatively reinforced avoidant behaviours in parallel with increasing the frequency of positively reinforcing behaviours to improve functioning and mood. The intervention for this study was to include signposting to local agencies and activities, when acceptable to the study participants, and the SWs were encouraged to accompany the study participants to a first visit to a group. The intervention was designed to be delivered by SWs recruited from Age UK North Staffordshire.

The research team considered that adaptations would need to be made to the information gathered at the initial session by the SW. Older adults are more likely to experience long-term health problems and a reduced level of functioning, with their psychological status often closely linked to their physical functioning. 77 Additional questions regarding health conditions and their impact were therefore thought to be needed as part of the initial assessment by the SW. The team considered that the SWs should adopt a person-centred approach. Depression in older adults is associated with impaired social support;78 therefore, additional questions regarding social contacts and family were felt to be important, especially as we anticipated that signposting to local groups to reduce social isolation should be an integral part of the intervention. The team felt that the risk assessment in the intervention and the suicide ideation protocol in the feasibility study – available on the project webpage [see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr/135434/#/ (accessed 20 March 2019)] – should be adapted to enquire about past passive and past active suicide ideation as well as current plans and preparations, as past suicidality is a risk factor for current suicidal behaviour. 79

The qualitative study conducted in phase 1 (see Chapter 2) highlighted important areas for inclusion in the intervention for the NOTEPAD feasibility study: the need for an empathic relationship and the development of trust, acknowledgement of loss, the importance of self-management as an integral part of the intervention, maintenance of participant engagement, and the need for adequate support for the SWs delivering the intervention.

At the PPIE meetings in January and September 2016, participants were presented with results of the qualitative study and an outline of the proposed intervention. Comments from the group were also sought on examples of patient manuals used in previous trials39,42,76 and views taken to present and discuss further at the consensus group. Members of the PPIE group particularly commented on the size (A4) of the example materials, which they felt were not convenient for carrying or storing. In addition, the group felt that the manuals used in the previous trials39,42,76 contained too much jargon and that the text needed breaking up with more illustrations and pictures. The PPIE group also strongly felt that the term ‘non-traditional provider’ would not be appealing or understandable to older adults and suggested that the term ‘support workers’ should be used.

The consensus expert group was held in January 2016 to draw together the evidence base, views from the PPIE group and findings from the qualitative study. The group comprised clinicians (GPs, psychiatrists, IAPT practitioners), academics and researchers with knowledge and expertise about the management of older people’s mental health. During development of the funding application, it had been agreed that the intervention would use the principles of BA plus signposting to existing third-sector resources. The group members were tasked with responding to outstanding questions posed by the research team and achieving consensus by the end of the day in the following areas:

-

What intervention for anxiety?

-

How many sessions in the intervention?

-

Should we use a measure/assessment of mood within the NTP/SW–study participant consultations?

-

How should the participant manual look?

-

What are the implications of phase 1 for the SW training?

The group discussion resulted in a consensus as presented in Table 4 and Box 1.

| Intervention component | Consensus |

|---|---|

| Intervention for anxiety |

‘Keep it simple’; focus on BA rather than a separate intervention labelled ‘for anxiety’ to avoid ‘complicating things’ for SWs. Activity scheduling should also help anxiety symptoms The key is to the ensure that SWs can recognise where anxiety is a problem:May include active relaxation (e.g. scheduling deep-breathing exercises) |

| Psychosocial intervention |

Four to six sessions: mixed face-to-face and telephone sessions; face-to-face session initially to establish a relationship (unless an older person expressed preference for all telephone contacts) Venue (if face-to-face session) following patient preference: home, GP practice (if negotiated with GP) or Age UK venue The SW accompanying the person to a group will be considered equivalent to one session Delivered over 8 weeks (maximum 12 weeks). Perhaps weekly for three or four weeks, then spread out; final ‘booster’ session where ‘ending’ is dealt with, and ‘staying well’ strategies put in place Duration: face-to-face session up to 1 hour; telephone session up to 30 minutes ‘Reminder’ phone call the day before a session, if possible (in addition to six sessions) The role of family/carers to be recognised; may try to engage in facilitating increased activity, but the SW should try to achieve privacy in interactions/consultations Only one session will be considered to be a ‘drop-out’ |

| Use of measure to assess change |

Whichever scale is used, Clinical Global Impression or Patient Global Impression, it has to be person-centred, simple and meaningful The mood thermometer might be a more acceptable (to SWs and study participants) instrument to use |

| Patient manual |

The intervention is not guided self-help; thus, the patient ‘manual’ should be simple, clear and short. An existing Age UK leaflet is a good example Content could be built up over time and thus more tailored to the individual Key information to be included:Title should be something like: ‘Follow your plan, not your mood’ Format: colourful and bright; clear language; include photographs of local area Include a pen Mixed views on format: organiser, folder or leaflet(s) |

| Directory of resources |

Use the term ‘list’ rather than ‘directory’ so that details of specific activities/services can be given to the older person once their interests have been explored – will feel tailored to the individual Details can be kept by older person in the patient manual (particularly if in organiser format) |

Deliver training over 2 to 3 days.

Include information on anxiety and depression.

Ensure that risk assessment and managing risk is covered.

Explain and provide the rationale for BA.

Instruct SW to:

-

establish and maintain a relationship with the older person

-

pick up cues

-

identify/clarify the problem

-

deliver the BA intervention face to face and/or by telephone

-

safeguard

-

plan to end contact

-

work with families/carers (and ensure time/privacy with the older person)

-

make telephone contact

-

explain how to use patient resources/manual

-

document contact (noting duration and activity within the session)

-

provide digital recordings of some SW–patient sessions.

Explain what to take to supervisions.

Explain when to contact the GP.

Explain working within a research study (while remaining person-centred).

Ensure inclusion of role play (with simulated patient) to emphasise concept of ‘person-centredness’.

The SW manual needs to fit with the patient manual; the SWs should feel comfortable working with the study participants and in supporting them to use the participant manual.

The NOTEPAD materials can be found on the project web page [see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr/135434/#/ (accessed 20 March 2019)].

The final NOTEPAD intervention

At a PPIE meeting in February 2016 the NOTEPAD intervention, as agreed at the consensus meeting, was presented to the group and supported by members.

The final intervention is outlined against the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist80 in Table 5.

| Item number | Item | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Brief name | NOTEPAD intervention |

| 2 | Why |

Anxiety and depression are underdiagnosed and undermanaged in older adults. Current interventions may not be not acceptable to older people. Loneliness and depression are strongly associated. There is limited evidence for the effectiveness of one-to-one interventions, such as befriending, for depressive symptoms. There is evidence that the most successful interventions for anxiety and depression in older people, measured by improvement in the domains of physical, mental and social health, tend to be group based and participatory and offer some activity (social or educational). BA has a good evidence base for older adults with depression Third-sector services are increasingly commissioned to provide these services but the effectiveness of non-traditional or third-sector providers delivering a psychosocial intervention has not been tested |

| 3 | What: materials |

Resources for study participants Set of training slides SW manual [All available on the project webpage – see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr/135434/#/ (accessed 20 March 2019)] |

| 4 | What: procedures | The SW intervention is described in Table 4 (see ‘Psychosocial intervention’ row) and here [and on the project webpage – see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr/135434/#/ (accessed 20 March 2019)] |

| 5 | Who provided |

SWs recruited from Age UK employees Recruited using advertisement and interview Training given as described in Box 1 and Delivering the support worker training [and on the project webpage – see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr/135434/#/ (accessed 20 March 2019)] |

| 6 | How | One-to-one face-to-face and/or telephone session with or without the SW accompanying the study participant to a local group |

| 7 | Where |

One-to-one face-to-face session in the patient’s home, or a local third-sector provider (depending on study participant’s preference) and/or telephone sessions. The SW may also accompany the study participant to a local group The SW can claim for intervention contact time and travel costs. See Appendix 4 for breakdown of costs |

| 8 | When and how much | Up to six sessions (up to 1 hour face-to-face contact and up to 30 minutes telephone contact) with reminder phone calls prior to sessions |

| 9 | Tailoring | Intervention was refined as described in Table 4 (see ‘Psychosocial intervention’ row) and here, and training will emphasise that the intervention needs to be flexible to accommodate the needs of the study participant |

| 10 | Modifications | No modifications planned during the feasibility study |

| 11 | How well: planned | Fidelity to be assessed via digital recordings of the SWs’ first two contact sessions |

| 12 | How well: actual | See Chapter 5 |

The NOTEPAD participant resources

Format and content

As described in Tables 4 and 5, the format of the patient manual was discussed at PPIE meetings and with consensus groups, building on existing manuals developed by the research team for previous studies. It was agreed (see Table 4) that we would need to make adaptations to the language and content and that information in the manual would need to tailored to meet the needs of older adults. 81 In addition, we noted the suggestion from the PPIE group that the manual should take the form of an organiser to which additional, relevant information could be added. In addition, as suggested by the PPIE group, we acknowledged the need to use a larger font and simple language. We also included photographs of the local area to break up the text.

We intended to include, in the manual, examples of older people or case studies with which study participants could identify, and these needed to be age and context appropriate, including bereavement and loss of role, to facilitate engagement and make the information easier to relate to.

Functional equivalence and keeping well

The importance of staying well was thought to be an integral part of the intervention and the participant manual. To this end, the manual had sections added on the importance of helping patients to identify functionally equivalent activities, and a ‘Keeping Well Plan’ to prompt participants to continue to identify functionally equivalent activities which might replace previously enjoyed activities that they were no longer able to undertake.

At a PPIE meeting in February 2015, a draft A5 patient material file was presented to the group. This was well received, with particularly positive feedback on the personalisation of the file via the addition of a photograph of the patient’s allocated SW and on the ability of the SW to offer relevant information for the participant to add to their file.

Materials developed for NOTEPAD participants can be found on the project web page [see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr/135434/#/ (accessed 20 March 2019)].

Support worker manual

The SW manual was developed by members of the training team (CC-G, HB, KL, DB and LG), with input from co-investigator Peter Bullock from Age UK North Staffordshire. The manual supported the SW training and complemented the participant resources. The manual included suggestions to the SWs about how to introduce aspects of the NOTEPAD intervention, for example establishing the problem, and included a section on risk assessment, which was covered in the SW training.

The SW manual can be found on the project web page [see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr/135434/#/ (accessed 20 March 2019)].

Recruitment of support workers

Support workers were recruited from Age UK North Staffordshire via a job advertisement giving extensive information about the NOTEPAD study. This was devised by Peter Bullock (Chief Executive, Age UK North Staffordshire) and Heather Burroughs. Peter Bullock personally drew the attention of suitable workers to the advertisement, answered any questions that they had and encouraged them to apply by submitting a written application. The applicants were then shortlisted and selected for interview. Peter Bullock and Heather Burroughs interviewed the applicants, and six of the eight applicants were appointed. At the suggestion of the NOTEPAD study steering committee (SSC), a seventh, substitute worker was also recruited to ensure that we had enough SWs should any of them drop out.

Characteristics of recruited support workers

The previous experience, expertise and training of the SWs, as described by the SWs, in the area of mental health are outlined in Table 6.

| SW | Characteristic | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Highest educational qualification | Training in field of mental health | Work in the field of mental health | |

| 1 | Masters | Training (2 days) about anxiety and depression in a community group setting | Better able to identify people with anxiety and depression in own groups following training |

| 2 | University degree | Counselling certificate | No |

| 3 | University degree |

Psychology as part of degree Counselling diploma |

Yes, as Samaritans (www.samaritans.org) volunteer and for victim support |

| 4 | GCSE | Dementia awareness training | Some clients have dementia |

| 5 | University degree |

Counselling training Drugs and alcohol |

Alcohol and drug addiction service |

| 6 | A level | Certificate in counselling | No |

Delivering the support worker training

The NOTEPAD training was developed from training used in previous trials,37,39,42,76 modified in line with suggestions made at the consensus group meeting (see Table 4 and Box 1).

The training was delivered over 3 days at Keele University in May 2016 by the training team (CC-G, HB, KL, DB and LG). The training was supported by a set of slides and the SW manual. Skills practice was facilitated by the use of simulated patients (SPs) recruited from the pool used for educational events at Keele University School of Medicine.