Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 14/19/16. The contractual start date was in October 2015. The final report began editorial review in February 2018 and was accepted for publication in July 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Catherine Pope reports personal fees from UK higher education institutions, personal fees from the Norwegian Centre for E-health Research, personal fees from Macmillan, McGraw-Hill Education, John Wiley & Sons and the Authors’ Licensing and Collecting Society, grants from Health Education England Wessex and Health Foundation, other from University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust and other from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Clinical Research Network, outside the submitted work. She is a member and Deputy Director of NIHR Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care Wessex, and a member of the Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) Researcher-led Panel. Joanne Turnbull is a current co-collaborator on another HSDR programme project (15/136/12).

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Turnbull et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Rationale

In England, recent policy has called for a focus on providing urgent care services that ‘minimise disruption and inconvenience’ for patients. 1 Local and national policy has centred on guiding patients to ‘get the right advice in the right place, first time,’2 reducing unnecessary emergency department (ED) attendances by providing more responsive urgent care services and providing better support for people to self-care. 1–3 However, the proliferation of different services has created an evolving, complex urgent care landscape for people to access and navigate and this has implications for the decisions and choices that are made. Effective service provision requires a deeper understanding of the factors influencing people’s help-seeking and their choices about accessing care.

The aim of our study was to identify sense-making strategies and help-seeking behaviours that can help to explain the utilisation of urgent care services. We set out to develop a conceptual framework of sense-making and help-seeking that NHS managers and commissioners could use as a foundation for health care planning. This report presents our study of how the public, health-care providers, policy-makers and decision-makers define and make sense of the urgent care landscape. It explores how service users understand and seek help, looking in detail at their choices, how they access urgent (and emergency) care services and the ‘work’ that this may involve for patients and their carers. We focus on three groups:

-

health service policy-makers – for example health-care commissioners, civil servants, and politicians in local and national government

-

health-care providers and health professionals – the organisations that provide and deliver health services and the staff employed by those services

-

health service users – patients and the general public who access and use services.

The remainder of Chapter 1 explores the urgent care context and outlines the aims and conceptual framework for the study.

Urgent care context

In most developed countries, including the UK, the USA, Canada and Australia, urgent care services are often positioned in an ill-defined space somewhere between general practice and emergency care. 1,4–7 Urgent care services are designed to assess and manage unscheduled or unforeseen conditions that arise in the out-of-hours period (typically 18:30 to 08:00 on weekdays, and all day at weekends and on public holidays). 8 The UK Keogh review, for example, describes urgent care as ‘for those people with urgent but non-life threatening needs’ with the goal of delivering:

. . . care in or as close to people’s home as possible, minimising disruption and inconvenience for patients and their families

These services have evolved slightly differently across health systems and have different names, but the services offered reflect wider shifts in care provision, notably their enrolment of new technologies to support access and care delivery,9 increasing fragmentation and differentiation of services, and a consumerist approach10,11 characterised by an emphasis on patient choice. 12,13

In the UK, a range of urgent and emergency care service developments and policy initiatives have taken place since the 1980s14 (Figure 1). These have included changes to existing services (e.g. the growth of general practice out-of-hours co-operatives and the use of telephone triage in the 1990s) and the launch of new services such as the nurse-led telephone service NHS Direct (replaced by NHS 111), NHS walk-in centres (WICs), and minor injuries units (MIUs).

FIGURE 1.

Selected key developments and policy initiatives for the delivery of emergency and urgent care. Reproduced from Turner et al. 14 Contains information licensed under the Non-Commercial Government Licence v2.0.

A key intention of urgent care services is to act as a lever for managing demand, seeking to divert people away from overburdened and overcrowded emergency services. 1–3,15 Research suggests that between 12%16 and 40% of ED attendances can be described as ‘inappropriate’,17 and some 40% of patients are discharged from the ED without treatment. 1 This finding is used to highlight a potential mismatch between the purposes for which services are provided and how they are used. Much of the existing research exploring patient help-seeking predates the expansion in the range of urgent care services offered and the introduction of the NHS 111 telephone triage service, making our investigation into sense-making and help-seeking a timely addition to the evidence base.

How this study builds on our previous work and other work

The study reported here extends our previous research, Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) 08/1819/217, completed in 2010,18 and HSDR 10/1008/10, completed in 2012. 19 The first of these examined the use of a single clinical decision support system called NHS Pathways used in three urgent and emergency care settings, focusing on how call handlers triaged and managed patients seeking 999 ambulance services and/or out-of-hours urgent care. The second expanded on this to examine the work and workforce implications of NHS 111 and was able to look at the telephone service itself, the technologies used and the wider network of urgent care provided in primary care. Both of these studies provided a deep and detailed understanding of the new NHS 111 services and delivered insights into the provision of urgent and emergency care in the English NHS. The questions to be addressed by the study move beyond our earlier organisational focus to explain how patients seek help and make choices in the increasingly complex landscape of service provision. Our analyses of call-handling services suggested that patients and the public were confused and that there was considerable variation in their experiences and knowledge of these services. Although the NHS 111 telephone service was conceived to direct patients to the most appropriate service, there is limited evidence that this has been achieved,20 and we wanted to understand this from the perspective of patients and the public, as well as of health-care professionals and policy.

By analysing patients’ experiences of urgent care, we seek to understand both the work required by patients to make sense of and navigate health care (i.e. the work or effort required) and the ways in which changes in provision (including the use of new technologies such as NHS Pathways) have become routine and embedded (i.e. normalised) as strategies for managing health-care needs.

Research aims and objectives

The overarching aim of the study was to identify sense-making strategies and help-seeking behaviours that explain the utilisation of urgent care services. We set ourselves the following objectives:

-

to describe how patients, the public, providers (professionals and managers) and shapers (commissioners and policy-makers) define and make sense of the urgent care landscape

-

to explain how sense-making influences help-seeking strategies and patients’ choices in accessing and navigating available urgent (and emergency) care services

-

to analyse the ‘work’ (the activities and tasks) for patients involved in understanding, navigating and choosing to utilise urgent care

-

to explain urgent care utilisation and identify modifiable factors in urgent care patient decision-making.

Theoretical background to the study

The underlying conceptualisation informing the study is that service users, professionals and providers are working within a system of emergency and urgent care. Urgent care services are part of a complex landscape that includes general practice out of hours, WICs and NHS 111, and have considerable overlap with EDs and 999 services (as well as wider links with other services such as general practice, pharmacies, social care and self-care). Given the well-recognised overlap between urgent and emergency care help-seeking, it is relevant to consider urgent care in a wider context that includes ambulance services, hospital EDs and a range of designated urgent care services.

For the current study we drew on sense-making perspectives21 to help understand contested meanings surrounding urgent care and to see how this might influence people’s attitudes and behaviours around service use (objectives 1 and 2). Sense-making can be understood as individuals’ attempts to structure the unknown by putting things into ‘frameworks, comprehending, redressing surprise, constructing meaning, interacting in pursuit of mutual understanding, and patterning’. 21,22 These perspectives about sense-making have encouraged us to consider patient decision-making, help-seeking behaviour and choices in ways that avoid the simple binaries of ‘appropriate’ or ‘inappropriate’ service use.

The study was informed by the notion of the ‘work’ that people do in understanding, navigating and choosing to use urgent care (objective 3). There are many theories that have conceptualised patient work, such as that of Corbin and Strauss23 and, more recently, burden of treatment theory. 24 Previous theorising around patient work has tended to focus on chronic illness, but it is a useful means of understanding patient decision-making and behaviours concerning urgent care. Existing help-seeking models are explored further in Chapter 6.

Outline of the report

The remainder of this report is structured as follows. Chapter 2 details our methodological approach. Chapter 3 presents the findings from the literature and policy review. Chapters 4 and 5 present the findings from the empirical work. Specifically, Chapter 4 examines how different groups make sense of urgent and emergency care (objective 1), and Chapter 5 examines the help-seeking behaviour, choices and work that services users in accessing, navigating and using urgent care services (objectives 2 and 3). Chapter 6 describes the development of a conceptual model of urgent care help-seeking. Chapter 7 presents the discussion, conclusions, and implications of this work (objective 4).

Chapter 2 Methods

This chapter describes the research design, data collection and analysis used in this study.

Research design

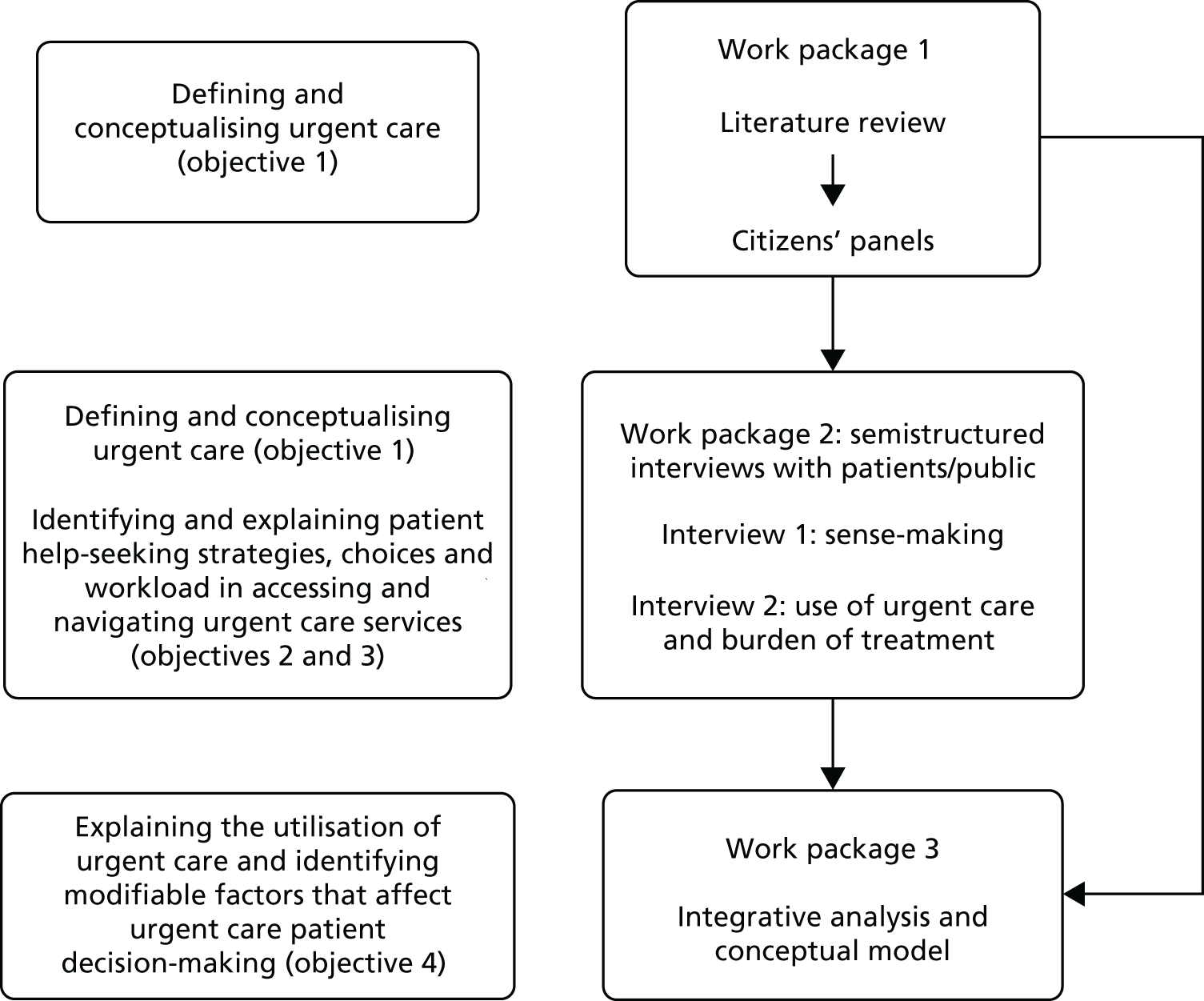

The study used a mixed-methods sequential design consisting of three integrated work packages (WPs) (Figure 2). The first WP (WP1) comprised a literature review and four citizens’ panels with service users and health-care professionals. It aimed to describe and explain how patients and the public, providers (professionals and managers), and shapers (commissioners and policy-makers) define and make sense of the urgent care landscape (objective 1). The second WP (WP2) used serial qualitative interviews to examine the role of sense-making in patient help-seeking strategies accessing and navigating available urgent (and emergency) care services (objectives 1 and 2) and to identify and describe the ‘work’ for people of navigating and using urgent care (objective 3). In WP3 we integrated our analyses of these data to construct a conceptual model of urgent care help-seeking behaviour that explains urgent care utilisation and identifies modifiable factors that affect urgent care patient decision-making (objective 4).

FIGURE 2.

Diagram of the research objectives and study design.

Methods were integrated in two ways. The first was developmentally, such that the findings from one WP informed the design and analysis of subsequent components. The literature review complemented and shaped the focus of the study, as well informing the conduct of the subsequent data collection. The meanings and definitions of urgent care identified in the review were explored in the empirical data collection with service users (interviews in WP2) and with health-care professionals (the citizens’ panels in WP1). The literature review also informed the conceptual model (WP3). Second, the results were integrated by exploring convergence and contradiction in the findings derived from different methods, using this process of ‘crystallisation’ to provide a more comprehensive account than that offered by a single method. 25

Work package 1: literature review and citizens’ panels

Literature review

A structured review of the published literature from 1990 onwards was undertaken with the primary aim of generating meanings and definitions of urgent care from the multiple perspectives of policy-makers, service providers and patients/the public. This was informed by Weick’s sense-making perspective21,26 alerting us to the possibility of contested definitions and meanings of urgent care, which in turn can have implications for people’s attitudes and behaviours associated with the use of urgent care services.

The review included policy documents (and related grey literature) as well as empirical research literature published since 1990 relating to urgent and emergency care. Although not an exhaustive systematic review, it sought to examine the evidence in relation to the following questions:

-

How do service users (patients and the public), providers (professionals and managers) and shapers (commissioners and policy-makers) define and understand urgent care differently?

-

Does the way in which patients and professionals perceive urgency influence the way in which patients seek help for urgent care problems?

Conducting the review

A review team was established to develop and manage the review (JT, GM and JP). We employed the expertise of an information specialist (Karen Welch) to undertake literature searching, and, with input from the team, Karen Welch developed the search strategy [using both free-text and database Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms where appropriate]. Joanne Turnbull, Gemma McKenna and Jane Prichard identified, screened and critically appraised the literature identified. Critical appraisal was guided by the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) tools appropriate to different types of research designs. 27

Identification and review of key policy documents and grey literature

Our review focused on policy documents and other grey literature since 1990 because many of the developments in urgent care services occurred from the 1990s onwards (see Figure 1) and we focused on the literature that could shed light on policy for urgent or unscheduled care in the UK that also included relevant references to emergency care policy. The search of the SIGLE (System for Information of Grey Literature in Europe) database focused on formal, government-level policy and local-/practice-level policies and guidelines. Specific governmental and health websites were also searched. Key sources are shown in Table 1. Reports from individual urgent care centres (UCCs) and wider policy documents dealing with health-care delivery were included when relevant (e.g. NHS Plan in England, White Papers). In total, 60 documents and information sources were reviewed (last searched November 2017). The 44 sustainability and transformation partnerships proposals were not examined in detail but were briefly examined to confirm that they did not contain important information about urgent care that was not represented in the other documents obtained.

| Type of organisation or body | Key sources |

|---|---|

| NHS organisations, Department of Health and Social Care and government sources | Department of Health and Social Care, NHS England, NHS Wales, NHS Scotland, Scottish Government Health and Social Care, House of Commons Committees reports, NHS Evidence, NHS Choices website |

| Royal colleges and professional associations | Royal College of Emergency Medicine, Royal College of General Practitioners, Royal College of Nursing, British Medical Association |

| Charities and independent bodies | The King’s Fund, The Patient Association, The Nuffield Trust, National Audit Office, Healthwatch England, Urgent Health UK |

Primary documentary research methods were used28 to identify and compare policy and service provider meanings of urgent and unscheduled care. Members of the research team read the documents to identify definitions, and a spreadsheet containing research questions about the policy context and definitions of urgent care was used to extract, examine, summarise and synthesise key information and concepts (Table 2).

| Theme | Questions asked in the data extraction |

|---|---|

| Policy context |

|

| Defining urgent care and examining meaning |

|

Identification and review of the research literature

Structured searches of the research literature were conducted in two stages. First, a detailed search on MEDLINE used a wide range of search terms and a combination of free-text and MeSH terms as well as appropriate subheadings (see Appendix 1). This initial search retrieved a large number of results and was refined to reduce the number of results. One early modification was to include the term ‘ambulatory care’ only if it was linked to urgent or unscheduled care as the term retrieved a large number of results related to hospital outpatient care rather than urgent care. The strategy combined terms relating to urgent care and non-urgent use of emergency care services (‘Set 1’) with terms that focused on patient experiences, for example patient help-seeking and decision-making (‘Set 2’), to produce a final search.

Targeted searches were then undertaken of MEDLINE In Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, EMBASE, Web of Science, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), ProQuest Sociological Search and PsycINFO around urgent and emergency care use and help-seeking (see Appendix 1). Searching was undertaken in November 2015, and updated in September 2017 to identify additional relevant literature. Studies were included if they met the criteria outlined in Table 3. International evidence was included to consider alternative models of urgent care in comparable health-care systems.

| Criteria | Included | Excluded |

|---|---|---|

| Focus of study |

Patient, health-care professional and provider perceptions of urgent and emergency care Patient decision-making, knowledge, beliefs, attitudes, expectations and experiences related to conceptualisations of urgent and emergency care |

Evidence related to specific clinical interventions for specific conditions |

| Health service |

Urgent care (e.g. general practice out of hours; NHS Direct; WICs; MIUs, NHS 111) Emergency care where focus is about the use of ED or ambulance service for ‘non-urgent’ or ‘primary care’ reasons |

General practice Hospital care not related to the ED (e.g. elective admissions; outpatients clinics) |

| Type of study/publication |

Qualitative and mixed-methods studies Quantitative studies of ED use that focused on non-urgent, ‘inappropriate’ use or on help-seeking behaviour High-quality literature reviews |

Editorials; opinion pieces; letters Conference abstracts Low-quality/unstructured reviews Quantitative or statistical reports of rates of service utilisation, satisfaction or referral |

| Study setting | UK, Europe, USA, Canada, Australia, New Zealand | All others |

| Dates of publication | 1990–2017 | Prior to 1990 |

| Language | English | Non-English |

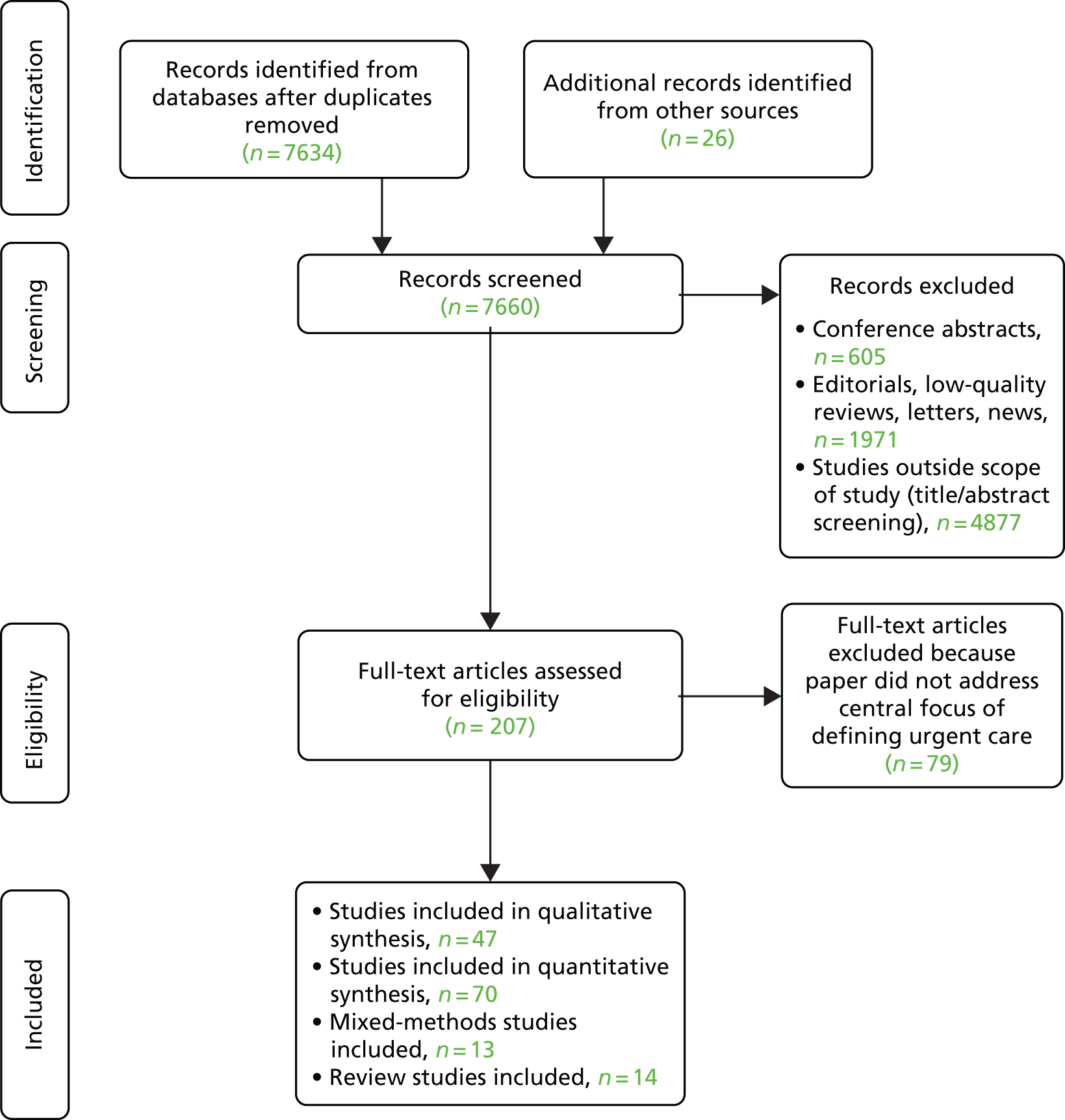

The final search retrieved 7634 results after deduplication. Twenty-six additional papers were identified through other sources (e.g. reference lists, general searching) (Figure 3). In total, 144 papers were included in the final review. Key information about the content of the papers was summarised in tables as part of the critical appraisal process against the questions in the CASP checklists, augmented with additional questions from Table 2. This aided the synthesis and identification of main themes.

FIGURE 3.

Flow diagram of search process using PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) 2009.

Citizens’ panels

A number of approaches to seeking public views is identified in the literature, including citizens’ juries and citizens’ panels. We drew on a modified citizens’ panel approach. One of the defining features of a citizens’ panel is to:

bring together a small group of people . . . and present them with a policy question. The panel listen to expert witnesses, examine the evidence, deliberate on the issues and arrive at a policy decision or set of recommendations.

p. 78829

The aim of this type of panel is to ensure deliberative and inclusive involvement directed at executing high-quality citizen contributions that can inform the policy-making process. 30 Citizens’ panels permit participants to ‘engage with evidence, deliberate and deliver recommendations on a range of complex and demanding topics’ (p. 6). 31 They provide an opportunity for citizens to challenge managerial and professional viewpoints and offer a chance for alternative perspectives to be explored. 32 We used citizens’ panels to examine urgent and emergency care policy and to deliberate on the provision of urgent and emergency care, and we asked the participants to help develop agreed definitions of urgent care.

Participants and recruitment

Guided by discussions within the research team and with our advisory board, we agreed that our main criteria for the selection of participants should maximise variation in the people and professions involved, drawn from the urgent and emergency care network of actors. Four separate panels were convened to debate and offer direction about how to define and conceptualise urgent health care. Our ‘citizens’ were drawn from (1) the Polish community, (2) a wider general population, (3) health professionals and (4) members of Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs). We purposively sampled to represent a range of perspectives and to include public, provider and policy-maker perspectives.

In our original research proposal, three panels (general public, health-care professionals and NHS commissioners) were envisaged. However, following a review of the literature, and discussion within the advisory group and research team, another panel was included comprising Polish participants. This offered an opportunity to include a group who could be characterised as more ‘marginalised’,29 and whom few previous studies had consulted on the topic of urgent care. It was also a chance to explore the views of recent migrants who have the unique experiences of two very different health-care systems. Our public panels (general population and the Polish community) reflected the populations also chosen for the more detailed qualitative interviews in WP2 (see Work package 2: the qualitative interviews).

Participants in the public panels were recruited via local community groups and networks (e.g. through community centres, local groups and organisations) and reflected the diversity of study setting (Table 4). They were recruited to act as citizens rather than as expert patients or patient representatives, and so they had varying experiences of health-care need and service use. Health-care professional and provider participants were recruited primarily from a single local NHS trust, along with some who were recruited from health-care education programmes at the university (see Table 4). The participants in the panel that was designed to elicit the views of those engaged in local policy-making and shaping were approached via CCG contacts and were representatives of local commissioning bodies (see Report Supplementary Material 1 and 2).

| Panel group | Number of participants | Characteristics of participants | Venue of panel |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mixed general public | 12 | 6 female and 6 male | Community centre |

| Polish community | 12 | 11 female and 1 male | University premises |

| Health-care professionals | 14 | 10 paramedics, student paramedics and paramedic managers; 3 student nurses; 1 student mental health nurse | NHS organisation meeting room |

| NHS shapers and commissioners | 3 | 1 commissioner and 2 representatives of local CCGs | University premises |

In total, 41 participants took part in the panels. The shapers and commissioners’ panel had three participants because of some late decisions not to attend, but the three other panels had between 12 and 14 participants. Public panel members ranged in age from 18 years to ≥ 75 years. The panel format was face-to-face deliberation over 6 hours in a single day, except for the shapers and commissioners’ panel, which took 4 hours, reflecting the smaller number of members (see Table 4). Public panel participants were offered £120 to take part [calculated in line with National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) INVOLVE rates]33 as recompense for the significant time commitment required to participate.

Conducting the citizens’ panels

Each panel took place over one day and was designed to explore a set of questions informed by the literature review, which included:

-

How would you like to see urgent care described and defined?

-

Are there circumstances in which urgent care services are particularly appropriate (or inappropriate)?

-

What benefits and risks do you think that urgent care services have for (1) patients and (2) health-care providers?

-

What principles would you wish to see underpinning developments in the provision of urgent care services?

-

What do you think are the key differences between urgent and emergency care?

-

What range of services do you think come under the heading of ‘urgent care’?

-

Do you think urgent care services – and perceptions of urgent care – have changed over time?

-

As a group how would you describe and define ‘urgent care’?

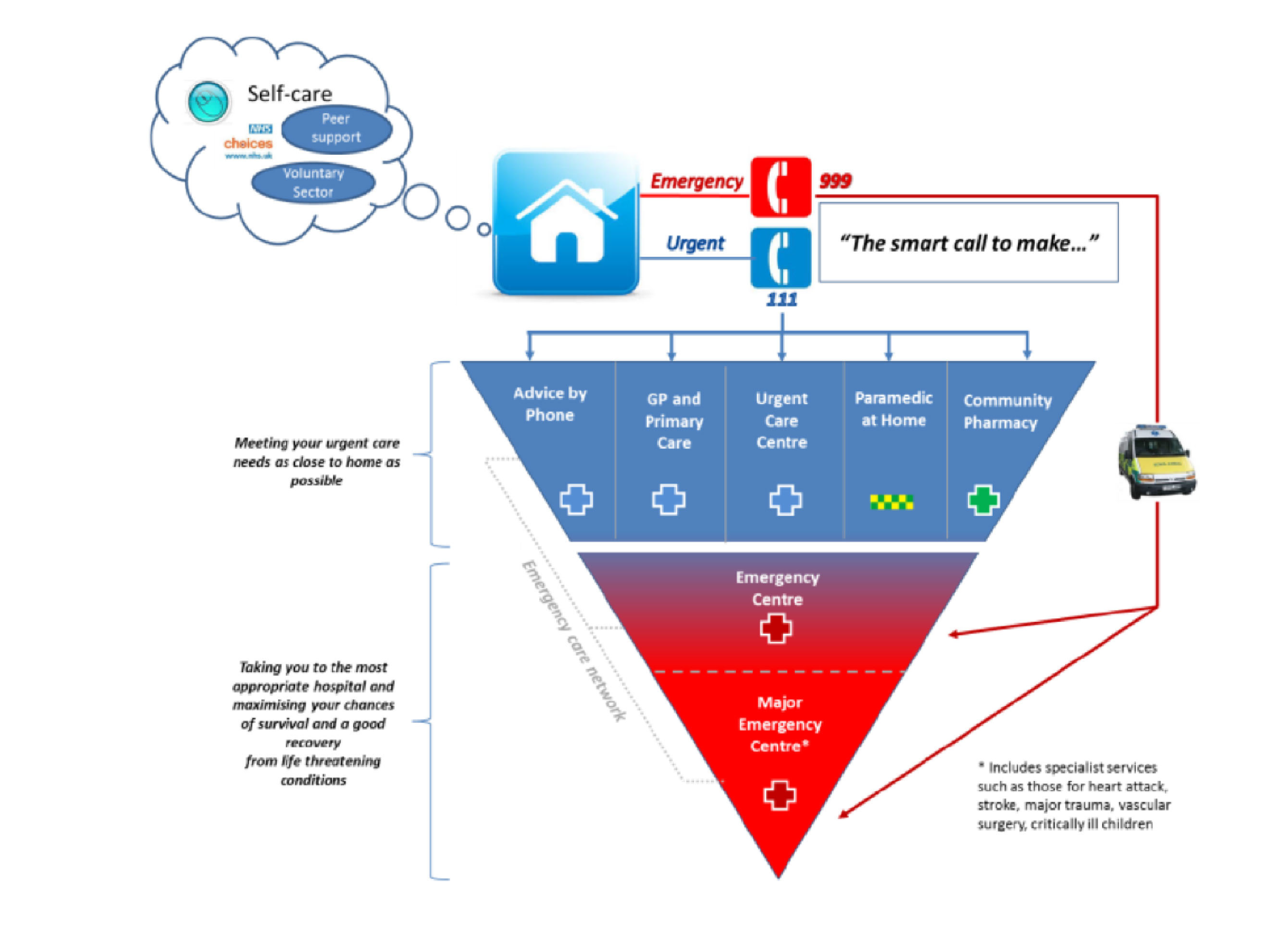

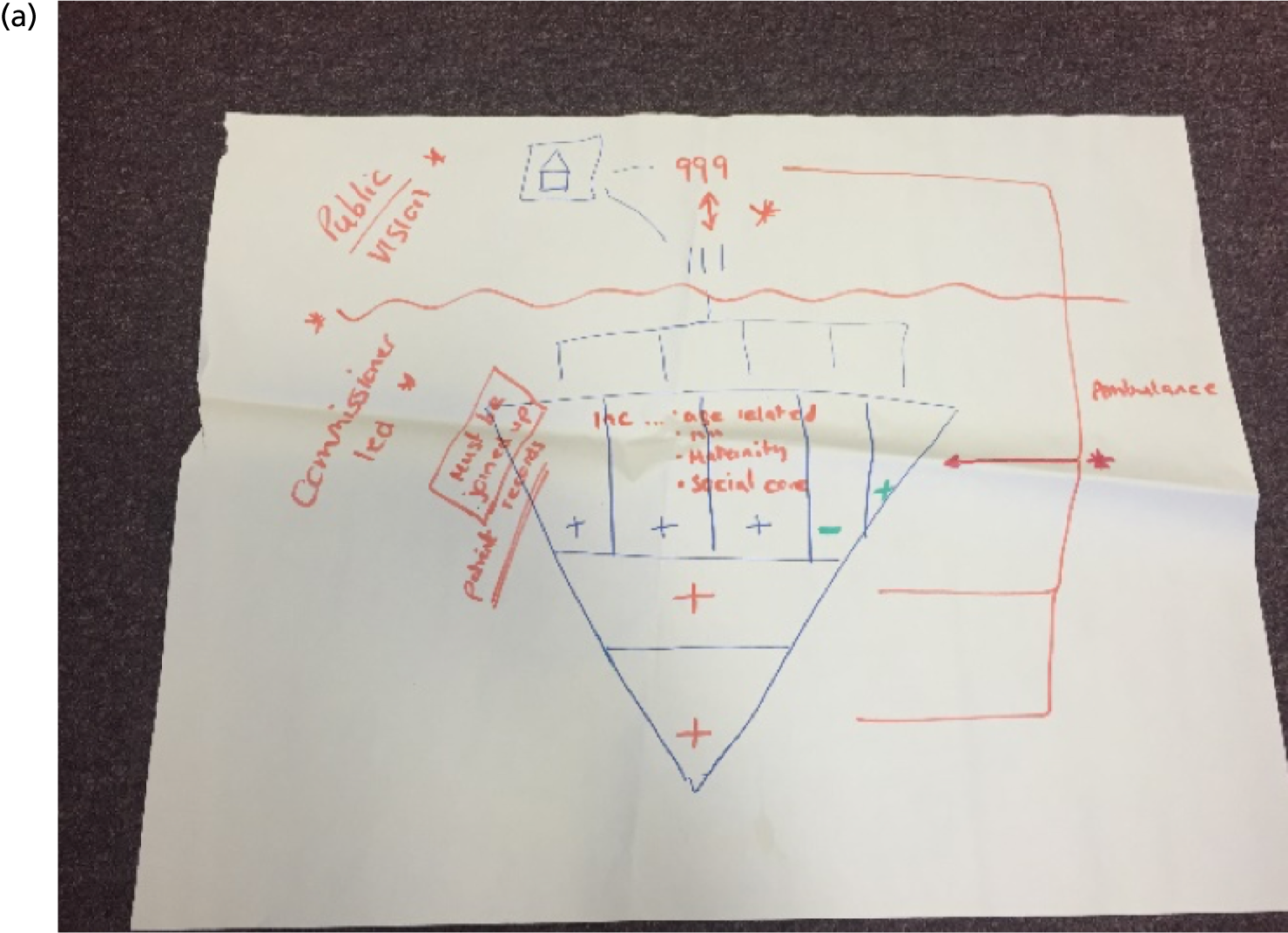

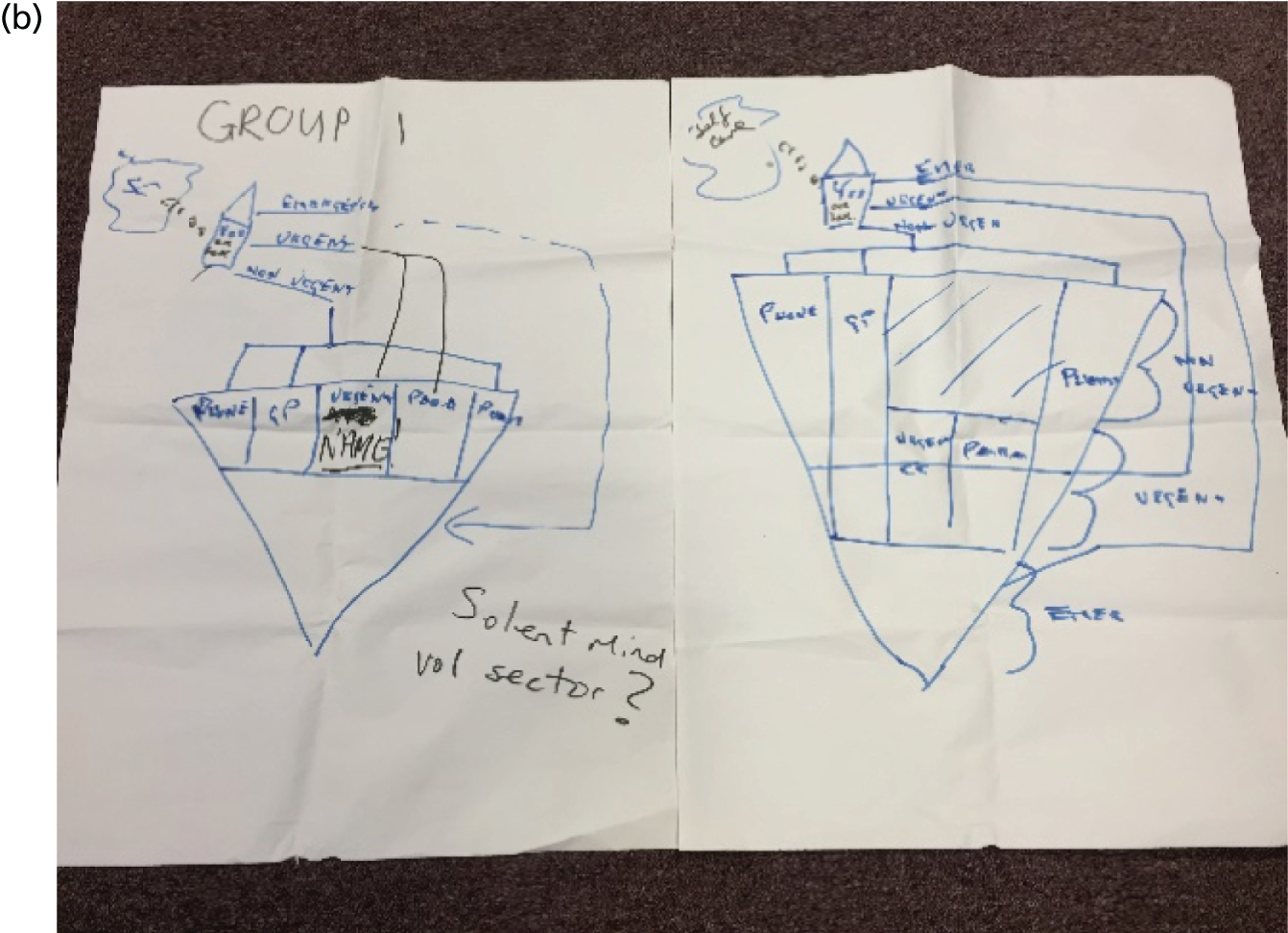

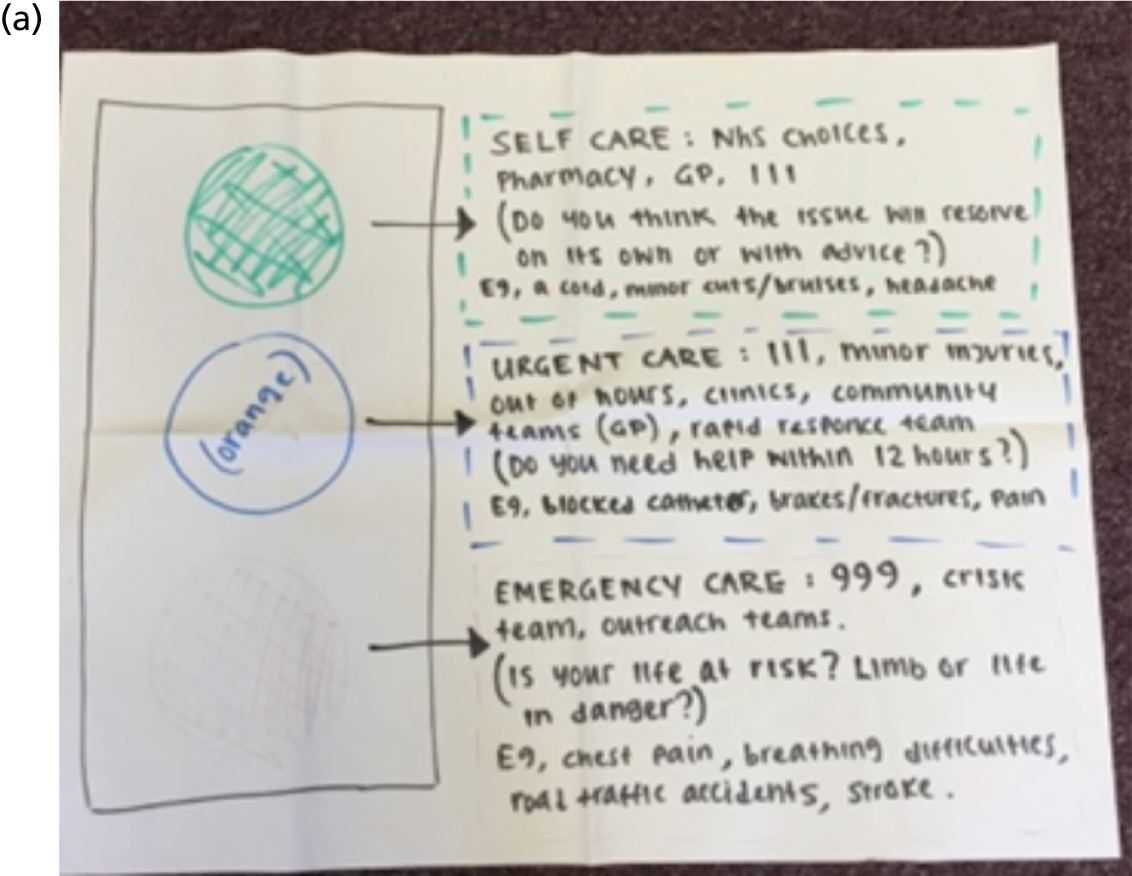

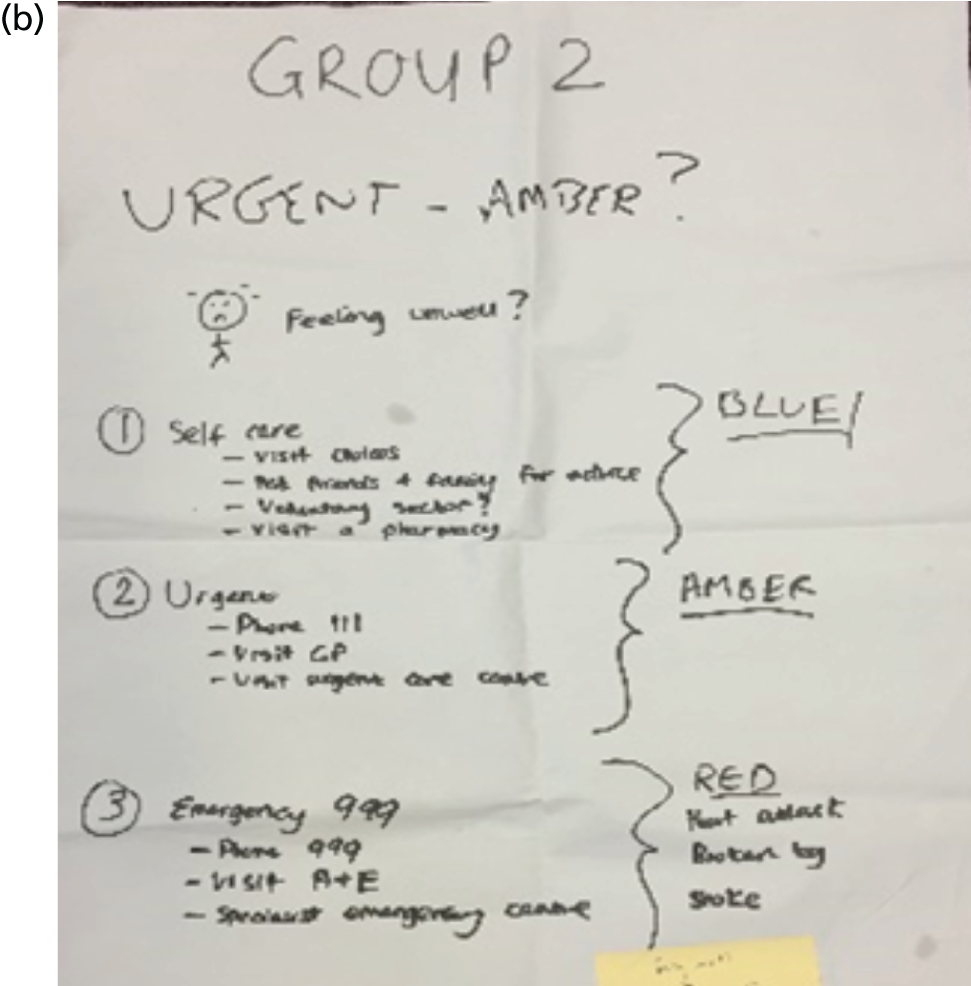

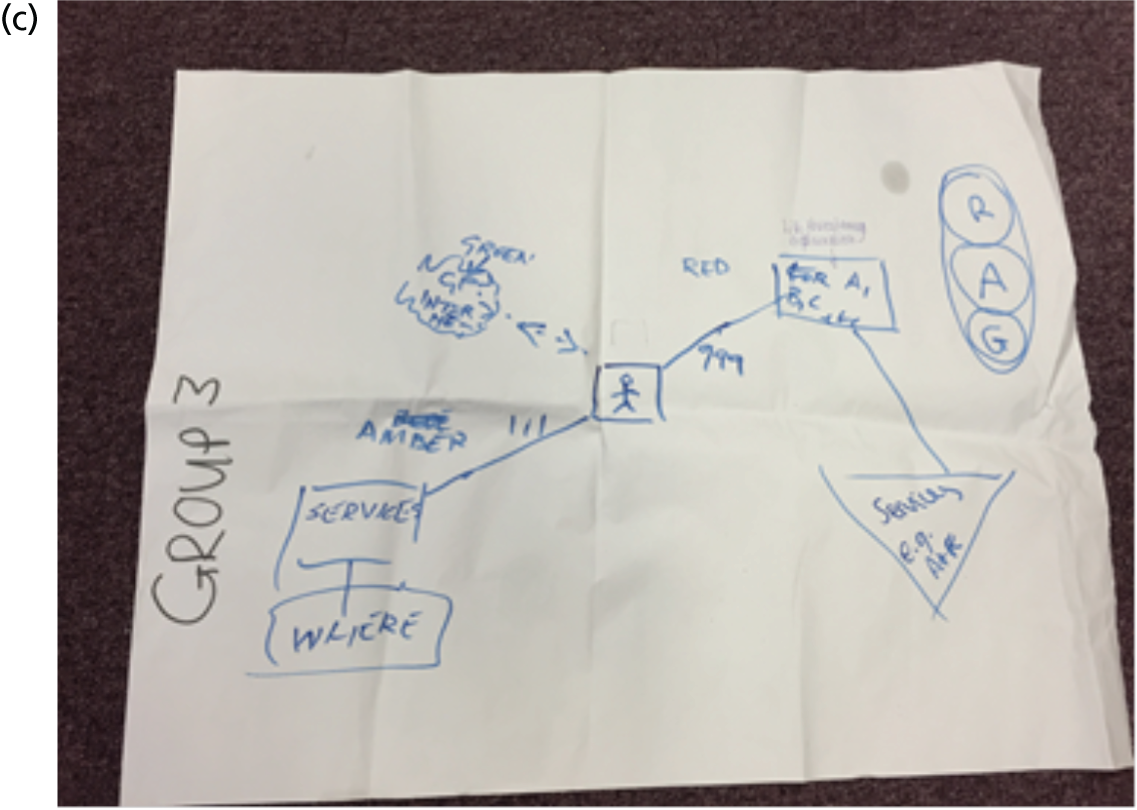

The research team prepared a set of resources (drawing on web links, videos and other visual resources) and prepared activities designed to facilitate discussion (Figure 4). Prior to the panels taking place, four individuals (drawn from the public panels) acted as a panel advisory group. These individuals were asked for their feedback about some aspects of the panel (e.g. the use of some resources in some of the activities, and the format of some activities, such as whether or not to use small discussion groups). We sought their views (through a series of telephone and e-mail discussions) on the best ways to support and facilitate citizens’ discussions during the panel to ensure that panel members would be comfortable with particular activities and tasks.

FIGURE 4.

Urgent care citizens’ panels: process model.

All participants were sent introductory material including policy statements and findings generated from the literature review. Activities on the day included:

-

brainstorming words associated with urgent care

-

discussion of hypothetical scenarios or case studies derived from the literature review

-

discussions about perceptions of different services prompted by pictures of urgent care and emergency services

-

discussion and debate centred on the diagram of urgent care presented in the Keogh review. 1

Two members of the research team attended each panel to facilitate group discussion. One of the team (GM) led the facilitation and one of the team (JT) supported the day’s events. Members of the research team adopted a neutral role, facilitating participation to ensure that the discussion stayed on topic, and to derive recommendations and reach a consensus. Each panel commenced with an introduction to the study, and then introducing panel members to each other. Some activities took place in small groups, facilitated by Joanne Turnbull and Gemma McKenna. The panel were encouraged to question the researchers about the evidence. Activities also included a large group discussion and agreement on definitions of and terms for urgent care by the end of the day, facilitated by Gemma McKenna and Joanne Turnbull. Data generated from the panel were recorded in contemporaneous notes taken by team members and by audio-recordings, as well as some written data (flip chart summaries, diagrams, and sticky notes used in the discussions). Notes and transcripts of discussions were anonymised.

Work package 2: the qualitative interviews

Qualitative interviews were used to examine, in depth, the role of sense-making in help-seeking strategies and how the respondents accessed and navigated services, and to identify and describe the ‘work’ entailed in navigating and using urgent care (objectives 1–3). To obtain a rich description, qualitative semistructured interviews were undertaken with three carefully selected groups of service users who reflected a diverse range of experiences of urgent care need (see Selection and recruitment of interview participants). A second interview was conducted with a sample of participants to explore the items raised in more detail and to overcome some of the weaknesses associated with ‘one-shot’ interview studies. This use of serial qualitative interviews proved to be effective in building rapport and relationships between interviewee and interviewer, and to generate the kinds of private accounts that may not have been revealed in a single interview. 34 This design added a prospective dimension to the study, offering the respondents and researcher time and space to reflect on and revisit topics from the initial interview, and capture changes between the two time points. The first interview probed how interviewees distinguished between routine, urgent and emergency care needs, and understandings of service availability, and examined attitudes and beliefs about urgent care services. The second interview (conducted between 6 and 12 months after the first) examined, in more detail, interviewees’ experiences of using urgent care services in the intervening months (if at all) and explored the ‘work’ entailed when navigating and accessing care.

Selection and recruitment of interview participants

Participants were sampled from the large geographical area served by a single NHS 111 provider (South Central) which covers four counties (Oxfordshire, Berkshire, Hampshire and Buckinghamshire) that are diverse in their geographic and demographic characteristics. By selecting an area covered by a single NHS 111 provider, we were attempting to recognise geographical boundaries that also ‘made sense’ within the structure of the NHS service provision. Although this setting is not the most socioeconomically deprived compared with other parts of the UK, it includes pockets of deprivation, and some lower layer super output areas are in the most deprived quintile nationally (e.g. parts of Portsmouth, Southampton, Reading and Milton Keynes). It also contains areas that are in the most affluent categories (e.g. Wokingham, New Forest and Aylesbury), as well as major cities (e.g. Portsmouth, Southampton and Oxford), and a mix of urban and accessible, and more remote rural areas.

We purposively sampled from three populations that represented particular facets of urgent care need and a range of participants in terms of socioeconomic and demographic characteristics. Two groups were chosen to reflect populations with known high use of emergency care (people aged ≥ 75 years and those aged 18–26 years), and a third group, people from the East and Central European community, was chosen to represent a population known to be increasing locally as a result of recent migration, and who may, therefore, be vulnerable because they are less familiar with NHS services. 35

Older people (aged ≥ 75 years)

This group represents a key demographic change experienced in the UK whereby the ageing population has led to a significant increase in the population aged > 80 years. 36,37 The research literature suggested that this group had higher rates of attendance at EDs and made greater use of urgent care38 than other age groups. However, this is a group for whom we lack evidence about help-seeking and decision-making around health service use. 39

Younger people (aged 18–26 years)

This group was selected because research evidence suggests that younger adults have the highest rates of ED attendance. 37 Adolescents (aged 15–19 years) are also more likely to attend UCCs than general practice40 and younger adults (aged 20–29 years) tend to access UCCs because they offer convenience and ease of access. 41

East European communities

People from the Accession 8 (A8) countries (Poland, Slovakia, Czechia, Slovenia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia) were granted rights of free movement across European Union Member States in 2004, and there have been relatively high rates of A8 migration, particularly people from Poland, into the major towns and cities in our chosen setting. Some of the rural areas in our setting have also experienced their first international migration of people from these countries. 42 This is a new and possibly growing population, but we have little research evidence about their health needs, or their knowledge of, and use of, urgent and emergency care. 43,44 There is some evidence that some ethnic and migrant groups are less likely to use urgent care and more likely to use emergency care,45 although this is contested. 46 We refer to this group as East European people, recognising that not all the participants in this group were from the A8 countries (and that the designation of Eastern Europe is contested).

As with all qualitative research, the goal of sampling is not to enable statistical representativeness but to provide a detailed and nuanced understanding. From past experience we are aware that purposive samples allow us to access a range of experiences and to capture rich data about beliefs, attitudes and experiences, and reported behaviours. To achieve an adequate final number of completed serial qualitative interviews, we aimed to conduct 105 first interviews (± 10%), recruiting approximately 35 people from each of the three population groups, and then conduct a second interview with 50% of these (± 10%). In total, we conducted 93 first interviews with 100 people (some in pairs) and 41 second interviews (Table 5).

| Interview | Population group | Number of participants |

|---|---|---|

| Interview 1 | East European people | 18 |

| Older people (aged ≥ 75 years) | 36 | |

| Younger people (aged 18–26 years) | 39 | |

| Total | 100 | |

| Interview 2 | East European people | 12 |

| Older people (aged ≥ 75 years) | 19 | |

| Younger people (aged 18–26 years) | 10 | |

| Total | 41 |

We adopted three recruitment strategies to ensure maximum variation: (1) recruitment from nine NHS urgent and emergency care services, (2) recruitment from the general population via community networks and local advertising and (3) snowball sampling via participant networks following interviews (Table 6). In our original proposal, we had expected most of our participants to be recruited via NHS services. Although we recruited nine NHS organisations to act as participant identification centres (one NHS 111 service, five EDs and three UCCs/WICs), it proved very difficult to identify and recruit participants from these sources, and only 13 participants were found via NHS sites. Poor recruitment via NHS sites may have been due to challenges in identifying individuals that matched our three population groups (there were particular sensitivities about identifying and approaching East European people). In addition, potential participants were sometimes reluctant to engage in conversations about research when attending, or calling, for an urgent care problem. We were largely reliant on staff at sites to approach people about the research on our behalf, which took place in often busy and pressured environments.

| Recruitment means | Site or source of recruitment |

|---|---|

| NHS sites |

NHS 111 service Five EDs across Hampshire and Berkshire Three MIUs/UCCs across Hampshire and Berkshire |

| Advertising across community networks and localities |

Four universities across the south 15 support and carer groups across four counties Seven local community centres and one library Five local community groups One parish council Free advertising (Gumtree website; www.gumtree.co.uk) and three local newspapers Local businesses (e.g. website/posters at a football club and in coffee shops) All-Party Parliamentary Health Group website |

Guided by discussions with our advisory group, we widened our strategy and recruited another 87 participants using a combination of community-based advertising and local media advertising to meet sample targets. To encourage greater uptake of interviews, we successfully applied to the Health Research Authority (HRA) for amended ethics approval to offer £15 in gift vouchers (per interview) to participants as an incentive to take part. (To ensure equity, we contacted those who had already taken part and also offered them this reward.)

Conduct of the interviews

The topic guide for the first interviews was informed by the literature review and the citizens’ panels, and the topic guide for the second follow-up interview drew particularly on notions of patient ‘work’ and the analyses of interview 1 (see Report Supplementary Material 3). Service users were encouraged during interview 2 to explore the networks and resources that support them in their help-seeking or illness tasks. This was aided by using a simple diagram of concentric circles on which participants captured and mapped their social networks (family, friends, groups, professionals, services and third-sector organisations) in order of importance. The location of the interview was determined by interviewee preference, and most were conducted in people’s homes, with a minority taking place at participants’ places of work or study. All interviews were digitally recorded (after consent was obtained) and transcribed, and they typically lasted between 35 minutes and 1.5 hours. The majority of interviews were conducted by the same researcher (GM) supplemented by one other (JT). Participant information sheets and consent forms can be found in Report Supplementary Material 4 and 5.

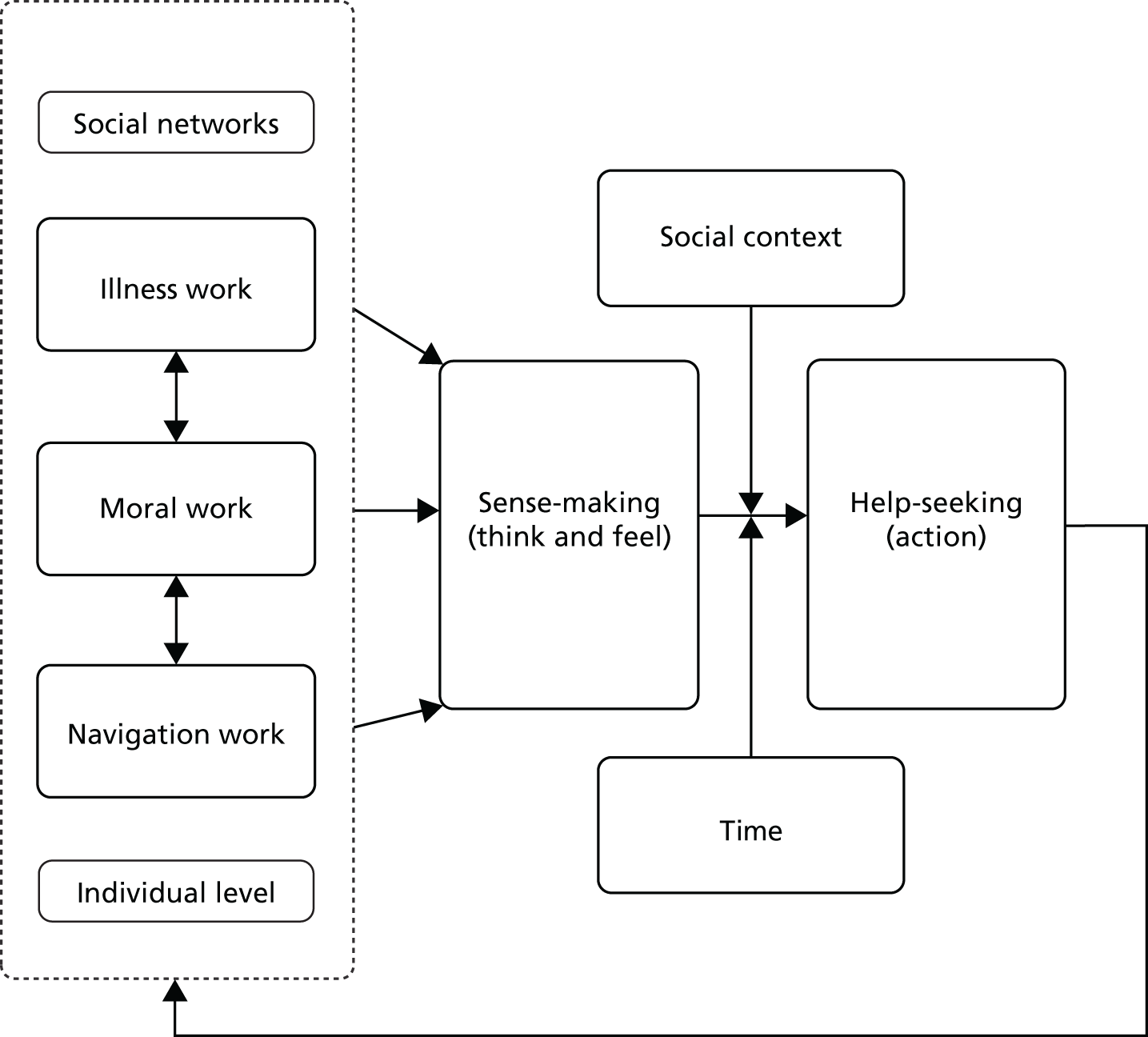

Work package 3: integrating the analysis to build a conceptual model

Data analysis began alongside data collection, initially focused on the data generated during the citizens’ panels. We undertook a thematic analysis of these data, broadly following the stages described by Braun and Clarke,47 familiarising ourselves with the data, generating initial codes and categories and then identifying themes. To facilitate analysis and discussion among the team, grids and matrices were used to chart and compare the data, and this involved the wider research team, comprising fieldworkers, researchers and clinicians.

Qualitative interview data were analysed using a data clinic approach to share and interpret data collectively, building emergent themes and developing narrative and interpretive summaries. Core team members (GM, CP, JP, AR and JT) initially read and open coded a sample of transcripts independently, and these early codes were discussed and refined to form the basis for a coding scheme that was refined and developed and applied to all transcripts. We drew on a framework analysis approach,48 looking across cases and exploring similarities and differences (paying attention to contradictory cases). These analyses were informed by conceptual ideas drawn from previous research and theorising, including work on sense-making and patient work. As the analysis developed, the themes were refined using matrix techniques to facilitate further comparisons and interpretations. Emerging themes and interpretations were shared with patient and public involvement (PPI) and advisory group members to check the credibility of these and further refine our analyses.

To build a conceptual model to explain urgent care utilisation, we drew together the findings from the literature review, citizens’ panels (WP1) and qualitative interviews (WP2) by examining codes that:

-

described and explained different conceptualisations/definitions of urgent care

-

identified, characterised and explained sense-making strategies that influenced help-seeking choices and behaviours

-

identified and characterised the ‘work’ involved in understanding, navigating and choosing to utilise urgent care.

We created lists, and taxonomies, of influences that shaped choices and reported behaviours. We recognised that interaction with urgent care services was not simply produced by individual help-seeking behaviour but was also a collective phenomenon (such that narratives and processes are shaped by the views and behaviours of multiple participants), and we used this understanding to underpin our analysis. We then explored the identified factors, exploring how they were formed related to each other and to the contexts in which they operate. We continued to use comparative analysis to identify factors that appeared common across different data sources and different care contexts. As the analysis progressed we began to use mind maps, decision trees and logic models to map our interpretations. Our data clinics allowed us to revisit the data from WPs 1 and 2 to test emerging hypotheses concerned with how sense-making and help-seeking related to each other and to identify factors that might be modifiable, which provided the basic material for a framework from which a conceptual model of relational choices about engagement with urgent care was developed.

Ethics approval

The citizens’ panels comprised members of the public (recruited from community groups and local public networks) and health-care staff. This component of the study did not require NHS ethics approval, and was approved by the University of Southampton (Ethics and Research Governance Online, number 20217). NHS/HRA ethics review was required for the qualitative interviews (WP 2) as some participants were recruited via NHS organisations (REC reference number 16/EM/0329).

Chapter 3 Results from the literature review: how do policy-makers, professionals and service users define and make sense of urgent care?

Although policy ‘frames’ urgent and emergency care, it is also shaped by those organisations that provide care and is defined by how service users access, navigate and use services. Four broad definitions of urgent care were identified from the policy and from the literature: (1) physiological symptoms, (2) relational language used to differentiate ‘urgent’ and ‘emergency’, (3) types of services and treatment they offer and (4) patients’ perceived need and legitimacy of service use (Table 7). We examine each of these in relation to policy, provider and service user perspectives and then draw together cross-cutting themes.

| Constructs in conceptualising urgent care | Description of construct |

|---|---|

| Physiological |

Nature of symptoms (e.g. seriousness; suddenness) How quickly symptoms need medical attention |

| Relational | ‘Urgent’ defined in relation to definitions of ‘emergency’ (e.g. ‘less serious’, ‘minor’) |

| Service organisation |

The type of service (e.g. MIU, WIC, UCC, NHS 111) What the service is designed to offer (e.g. convenience; care close to home; signposting; treatment; advice) Service availability (geographic location; opening times) How care is provided (e.g. telephone; UCC) |

| Perceived need and legitimacy |

Patients’ perceived need/urgency and their use of services Notions of appropriateness and legitimacy of health service use |

Policy definitions of urgent care

The current UK policy pertaining to the urgent and emergency care services landscape can be identified from the Urgent and Emergency Care Review. 1,3,49 This paints a picture of urgent and emergency care as a hierarchy of services that are distinct from one another. For those unable to self-care, the urgent care system is identified as providing services for serious health needs requiring quick attention, while the emergency care services are for those with the highest level of need who have more serious and potentially life-threatening conditions. This suggests a landscape of provision in which there is clarity around how the terms ‘urgent’ and ‘emergency’ are understood. However, closer scrutiny reveals that these concepts are ill-defined and inconsistently used. Few policy documents provide a specific working definition of what is meant by either an urgent or an emergency health-care ‘need’. 50–52 Instead, documents touch on these terms briefly when describing which services should be responsible for different needs,1,3 or, more often, there is simply an absence of a definition. 3,53–56

Physiological factors in defining urgent care

Physiological need is the definition most frequently used in policy documents to describe urgent or emergency care. This relates to the seriousness of symptoms and/or whether the need is life-threatening. 1,3,8 Examples are offered of particular conditions or symptoms as being suitable for particular services57,58 (e.g. the speed with which a person needs to be seen,56,59 the onset of illness and the time frame in which a condition or symptom requires treatment) (Table 8).

| Physiological aspects | Urgent definition | Emergency definition |

|---|---|---|

| Severity of illness or injury | Urgent but not life-threatening; not serious; ‘minor’ illness or injury; ‘short-term’ illness1,49,57,60,61 | Life-threatening; serious1,49,58,60 |

| Symptoms appropriate for different types of service | Sprains and strains; broken bones; wound infections; minor burns and scalds; minor head injuries; insect and animal bites; minor eye injuries; injuries to back, shoulder and chest57 | Loss of consciousness; an acute confused state; fits that are not stopping; persistent, severe chest pain; breathing difficulties; severe bleeding that cannot be stopped; severe allergic reactions; severe burns or scalds; heart attack; stroke; major trauma (e.g. serious road traffic accident, serious head injury)58 |

| Onset of illness | Unforeseen; acute; sudden onset or worsening of symptoms50,59 | Unforeseen; acute; sudden onset or worsening of symptoms50,59 |

| Time frame | Does not need immediate medical attention. Cannot wait until the next day. For ‘less serious yet immediate illness or injury’. Needs to be addressed quickly1 | Requires immediate attention1 |

‘Urgent’ may be described as serious but not life-threatening. 57,60 The National Audit Office describes urgent care services as being for ‘people who feel urgently ill’ (p. 37),59 while NHS Choices sets out that ‘If your injury is not serious, you can get help from a MIU or UCC rather than going to an ED’. 57

Some definitions are circular: the word ‘urgency’ is used to define the ‘urgent care’, providing little insight into what is really intended or how one might decide whether or not something is urgent. By contrast, emergency care is defined as those illnesses or injuries that are life-threatening. Broadly, descriptions that relate to emergency services include the words ‘major’ or ‘severe’, in contrast to urgent care, which can include ‘minor’ or ‘problems usually dealt with by a GP [general practitioner]’. 58 Definitions of both urgent and emergency include ‘unforeseen’ need and refer to people requiring care that is ‘unscheduled’ or ‘unplanned’. 2,50 Unscheduled care is defined as:

services that are available for the public to access without prior arrangement where there is an urgent, actual, or perceived need for intervention by a health or social care professional.

Some policies include reference to specific time frames in which particular symptoms should receive treatment; for example, a medical problem needs ‘immediate attention’. 1,57 Although physiological definitions of urgent (and emergency) need appear clear or more objective, this assumes that users are able to accurately interpret the likely seriousness of their symptoms and judge what constitutes ‘less’ or ‘more serious’ illness and/or injury in order to utilise the ‘appropriate’ service.

Relational language

A second theme in policy adds a relational dimension, contrasting emergency with urgent care. Urgent is compared with emergency as ‘not life threatening’ versus ‘life threatening’, or as ‘serious’ versus ‘more serious’. 8,49,60,62 A key example of this relational definition is the strapline for NHS 111, which is ‘when it is less serious than 999’ (the UK national emergency number). 59,62 Indeed, much of the NHS 111 advertising is presented in this way:

When you need medical help fast – but it’s not an emergency.

Policy documents sometimes group urgent and emergency care needs as a single category, labelled as unplanned or unscheduled care,8,64 and so the boundary between urgent and emergency is avoided. 52,62 It is sometimes argued that it is too difficult for patients to distinguish between services because the terms mean different things to different people. 62,65 Elsewhere it is suggested that these services need to be fully integrated and possibly co-located. 66 However, when service users self-refer to services (e.g. the ED, WICs, MIUs) they require an understanding of what different services offer,67 so it continues to be important that service users are able to disentangle these terms and these services.

The language used to conceptualise urgent care has changed over time. In policy documents from the 1990s, general practice out-of-hours services were the main source of ‘urgent care’ and urgent care was closely linked to primary care. From 2010 onwards, the term ‘out of hours’ was replaced by the term ‘urgent care’ and this began to be discussed in relation to emergency care rather than general practice. 1,3,49,61

Health service organisation and provision definitions of urgent care

Currently there are a range of emergency, urgent and routine care services. In addition to established emergency services, there has been an increase in urgent care services, for example NHS WICs, MIUs and UCCs, and other facilities. These are often overlapping and inconsistent in the services or facilities they offer and the time of day they are open (Table 9). Some policy documents define urgent and emergency care by the types of services (or the range of responses) that are available to users, but it has been recognised that efforts to increase access to urgent care by creating service choices have created a fragmented, complex service, creating further confusion. 1,65

| Urgent care services | Emergency services | |

|---|---|---|

| Type of service |

UCC (sometimes called treatment, primary care or out-of-hours centre) WIC (terms can overlap with UCC) MIU NHS 111 telephone service |

999 ambulance service ED (also still referred to as A&E) Major trauma centre |

| What the service offers | MIUs and WICs are either nurse or GP led; UCCs are usually staffed by both GPs and nurses. UCC facilities vary by location | High level of clinical service, expertise and resources to manages a full range of life-threatening illness and injury |

| Availability of services | Varies by location: some open 24/7, some have opening hours (e.g. 08:00–22:00) | 24/7 |

Urgent care has been defined by the services offered to users, including the skill level of providers and the facilities provided. Emergency care is presented as highly specialised in terms of staff and equipment:

For those people with more serious or life threatening emergency care needs we should ensure they [users] are treated in centres with the very best expertise and facilities in order to maximise the chances of survival and a good recovery.

p. 22. 1

Urgent care, on the other hand, is conceptualised as a less specialised service for everything that is not an emergency:

walk-in service developed to have a ‘see and treat’ approach to less serious yet immediate illness or injury

p. 42. 1

Elsewhere, urgent care services are defined by opening times (i.e. operating in the evenings, at night and at weekends)68 but, more recently, policy emphasis has shifted towards describing the range of ‘urgent care’ services that users might access over 24 hours (e.g. some MIUs, NHS 111).

Notions of ‘urgency’ may be defined by where a particular health problem is treated, which might be determined by what services are available in any given location at any given time of day. For example, a broken bone is classed as urgent rather than emergency (see Table 8) and therefore suitable for treatment at an UCC, but when this service is not available the patient would need to attend an ED. Thus, the definition of urgency is fluid depending on service availability:

MIUs and UCCs can treat: sprains and strains; broken bones; wound infections; minor burns and scalds; minor head injuries; insect and animal bites; minor eye injuries; injuries to the back, shoulder and chest. If no minor injuries unit in your area, these services will also be provided by an A&E department.

Patients’ perceived need

There is a recognition on the part of policy-makers and professionals that the responsibility for judging both the seriousness and the suitability of a particular service often lies with the patient. Policy documents from the UK make some reference to this:

Urgent care is the range of responses that health and care services provide to people who require – or who perceive the need for – urgent advice, care, treatment or diagnosis.

p. 12. 50

More recently, policy-makers have sought to reframe urgent care, taking into account a wider range of influences that are involved in the decision-making (e.g. perceived severity of symptoms as well as social factors such as caring commitments).

The importance of patients’ perception of their condition has led to the development of the ‘prudent layperson standard’ in the USA, which promotes a symptom-based determination of urgency. This standard was developed by listing common symptoms and conducting a large-scale survey to determine if a ‘prudent layperson’ would reasonably interpret them as an emergency. 69 What is interesting here is the recognition on the part of policy-makers and professionals that the responsibility for judging both the seriousness and the suitability of a particular service often lies with the patient, yet the decision to intervene is a professional one:

[It is the] responsibility to consider other care options prior to visiting the emergency department.

Guttman et al. 70

Language around what is ‘appropriate’ for particular services or what is a ‘genuine’ medical complaint appears in descriptions of emergency care in the research literature. However, such terms are largely absent from policy, with the exception of a sentence on NHS Choices about what is legitimate for emergency care use:

An A&E department . . . deals with genuine life-threatening emergencies, such as: loss of consciousness; acute confused state and fits that are not stopping; persistent, severe chest pain; breathing difficulties; severe bleeding that cannot be stopped [ ] Less severe injuries can be treated in urgent care centres or minor injuries units.

Provider and professional definitions of urgent care

Conceptualisations of urgent care from the provider and professional perspective place heavy emphasis on physiological definitions of urgent care and the extent to which these legitimise the use of services. Much of the research evidence is based on quantitative surveys of ED use rather than urgent care service use, and ‘urgency’ is discussed in narratives about the ‘inappropriate’ use of EDs and ambulance services. 71–77

Clinical ‘appropriateness’

Unsurprisingly, like the policy definitions discussed, the seriousness of the illness or injury appears to be evident in health-care provider conceptualisations. ‘Inappropriate’ ED use is synonymous, and interchangeable, with service use that is ‘less urgent’, ‘non-urgent’78 or ‘low acuity’79 or for ‘minor illness or injury’,16,17,80 ‘non-life-threatening health problems or injuries’81 or primary care reasons.

Physiological definitions of urgency include assessment of the severity of symptoms and how quickly symptoms need assessing or treating74,75,82–90 and/or whether the condition(s) could be assessed only in the ED or could be addressed elsewhere. 41,87,89,91–98 Many studies of inappropriate ED use do not explicitly specify how attenders were classified as ‘inappropriate’ or ‘non-urgent’. 76,99–103 However, some research has developed explicit criteria for assessing appropriate use,74,75,85,104–106 which include items that assess the severity of illness; the urgency of treatment or intervention needed; referral or transfer from other medical source; and confirmation by diagnostic testing. In such definitions, markers of appropriateness can include both presenting symptoms (prospectively defined) and diagnosis (retrospectively defined).

Koziol-McLain et al. 83 suggest that the term ‘severity’ is embedded in the ‘medical framework of physiologic dysfunction or disease’ so that emergency care is defined as ‘those health services provided to evaluate and treat medical conditions of recent onset and severity’. The term non-urgent is often used in the context of emergency care services and may describe a minor medical problem that is non-acute and non-life-threatening, and does not require immediate attention78,82,107 (i.e. it can be left for several hours or days78 and/or it is short in duration, e.g. it lasts less than 24 hours). 93 This might include symptoms such as coughs, sneezing, weakness or tiredness,72 those that are musculoskeletal,108 or cases that are deemed to require only ‘prescription, bandage, sling, dressing, and steristrips’. 109 Minor illness or injury/’non-urgent problems’ were characterised are those that could be managed by a GP (see next section). 73,78,85,104,109

Health professionals (and researchers) have defined non-urgent ED use by making reference to treating a health problem that could wait until the next day (> 12 hours) for treatment. 110 This is illustrated by a study designed to assess agreement between health-care professionals about ED attenders’ need for urgent care in an urban hospital in the USA, which used a quantitative chart review of 266 patients111 and defined urgency using terms such as ‘major’ illness or injury, whereby a possible danger exists to the patient if the condition is not medically treated within 20 minutes to 2 hours. A non-urgent or ‘minor’ injury or illness, when the patient is usually ambulatory, can be seen between 4 and 6 hours. Another US survey study measuring perceptions of urgency asked ED nurses and physicians to define urgent and non-urgent care. 112 Physicians defined ‘non-urgent’ as something that could be addressed after ≥ 1 hour without the patient’s health being affected, while nurses gave times that ranged from > 30 minutes to up to 4–6 hours.

Assessment of patient urgency differs among types of health professional irrespective of patient condition, even when the same criteria of urgency and appropriateness are applied. 99,107,111 In New Zealand, Richardson et al. 107 found that there was no clear consensus between ambulance staff, ED surgeons, registrars and consultants, ED nurses, GPs and hospital managers about a definition of ‘inappropriate’ attendance. Different groups of professionals used different factors to assess appropriateness; for example, ambulance staff were more likely to see patient admission as an indicator of appropriateness, whereas ED doctors and nurses were more likely to see patient perception of urgency or seriousness as a reliable indicator. In the USA, O’Brien et al. 71 assessed levels of agreement between internists and emergency physicians reviewing the ED nurses’ triage notes of 892 adult patients and reported only moderate agreement (κ = 0.47) between these groups. Emergency physicians were 10.3 times more likely than internists to classify those with minor discharge diagnoses as appropriate for ED care. Health professionals and patients also differ in their assessment of how quickly patients need to be seen. Poor agreement among health professionals raises questions as to how objectively ‘appropriateness’ can be measured and, in turn, how urgency can be defined.

Demarcation of definitions according to place

In defining urgency in the context of the ED, professionals and providers distinguish between condition(s) that could be assessed only in the ED and those that could be addressed elsewhere. 41,87,89,91–98 These definitions echo the ‘right place’, at the ‘right time’, treated by the ‘right professional’ phrasing found in some policy documents. However, in a study of health-care professionals’ perceptions of the effectiveness of a UK GP-led WIC, professionals were more likely to deem service use as appropriate if the user was referred from the ED. 113 A recent qualitative interview study of staff at a GP-led UCC in the UK suggested that health-care professionals believed that patients were ‘unaware of what the GP-led Urgent Care Centre is. They simply want someone to see them’. 114 They also reported that staff believed that patients used the UCC because it was convenient or because they had difficulties accessing other services (e.g. GP appointments).

There is also a strong tendency for health-care providers to define urgency in relation to the lack of emergency. The academic literature about ED use frequently uses relational terms to define degree of urgency, for example describing service use that is ‘less urgent’ (compared with something that is considered an emergency),81,99,115 although concepts of ‘less urgent’ vary. Backman et al. 99 suggest that:

Less urgent users were assessed as being more suitable for primary care and judged to be able to wait for more than 24 h for a medical examination without risk of medical harm.

Backman et al. 99 (emphasis added by authors)

Pileggi et al. 115 define urgent as ‘conditions that could possibly progress to a serious status requiring emergency intervention, perhaps those associated with significant discomfort or dysfunction at work or activities of daily living’ and less urgent as ‘conditions relating to age, distress, or potential for deterioration or complications that would benefit from interventions or reassurance within 1–2 hours’. These are different from ‘non-urgent’:

conditions that are acute and non-urgent as well as conditions which may be part of a chronic problem with or without evidence of deterioration.

Pileggi et al. 115

What these studies highlight is that urgency is often positioned in relation to emergency care, and it is less clear from these studies how urgent care problems are understood.

Value judgements about patient perceived need

Health providers and professionals sometimes recognise that patient perceived need and the subjective nature of lay assessment of symptoms are legitimate components of making sense of urgent care. However, health-care professionals also make value judgements about patient use of services and this shapes how they make sense of urgent care.

There is some evidence that health professionals recognise that service users draw on ‘rational reasons to initiate care’. This can include consideration of access to primary care and the context of how the medical problem developed. In a Canadian study, a survey of patients and physicians examined the appropriateness of WIC visits. 7. Of 142 attendances, physicians judged more than half of the visits as appropriate, compared with most patients, who scored their visits’ urgency as low or medium. The authors concluded that doctors appeared to judge patient factors such as anxiety and access to services as legitimate reasons for attending these services. Similar findings have been reported elsewhere; health-care professionals often approve of patients’ decisions and believe that they act appropriately. 116,117 A qualitative study of 87 patients and 34 health-care professionals, using interviews and direct observation, examined the decision-making patterns of families using EDs, as well as paediatric staff responses. Staff ‘incorporated the realities of daily living under trying circumstances, such as difficulty in contacting primary care for appointments, problems with transportation, financial barriers, and other practical issues’. 117

It appears that the more vulnerable the patient, the more likely the health-care provider is to take societal context into consideration when a ‘non-urgent’ visit is made or being reconsidered. Recognition of the social contexts in which people use emergency services for low-acuity problems has been acknowledged in other studies. 75,117,118 In the ED context, health professionals were more sympathetic to those perceived as ‘inappropriate’; for example, in a study of the use of unscheduled services by people with long-term conditions, health-care professionals felt that use of unscheduled care was a necessary component of care because exacerbations were inevitable in long-term conditions. 118

An American study of non-urgent ED use developed a typology of how providers conceptualised appropriateness of service use including restrictive, pragmatic and all-inclusive provider ideologies. 119 Some professionals held a pragmatic viewpoint: ED use was legitimate if other service options were limited or unavailable, including at times the need for medically non-urgent care. Conversely, other professionals believed that the ED is appropriate for only the most urgent care, that it should not, for example, be used for ‘trivial reasons’ that could be treated in primary care. What this study highlights is that, even within a single setting, health-care professionals hold a range of views about what is ‘appropriate’. This lack of consistency at the supply end raises questions about how service users can be expected to make decisions on the basis of lay knowledge alone if those with medical training have different positions on where people should go to seek care under different circumstances.

The extent to which professionals judge patients as ‘deserving’ of care is relevant to conceptualising ‘appropriateness’. Discussion about the ‘abuse’ and ‘misuse’ of services is particularly apparent in relation to emergency ambulance services. 101 In one study of ED use of ambulance services in the USA, emergency medical services (EMS) providers and patients were asked, ‘Do you think this patient’s medical problem represented a true emergency requiring EMS transport?’ (emphasis added by authors). 103 However, what constitutes a ‘true emergency’ is not defined or described. Muller et al. 102 described how [high demand] ‘inevitably make it more difficult to provide genuine emergencies with rapid treatment, leading to deterioration in the quality of emergency services’ (emphasis added by authors).

Similarly, in telephone-based UCCs, call advisors tended to construct shared understandings about the ‘inappropriate use of services’ and the extent to which patient concerns were ‘genuine’ or not. 18 This is echoed elsewhere in the out-of-hours literature that makes reference to ‘trivial and self-limiting conditions’. 120 Such findings reflect those of Jeffrey’s121 seminal paper of ED staff perceptions of appropriateness. Notions of ‘genuineness’ also featured in a survey study of GPs who were asked about the appropriateness of UK out-of-hours care use. 122 The study found that there was broad consensus about what constituted an appropriate call:

Genuineness was a key concept and the word ‘genuine’ occurred frequently, as in ‘genuine unwellness’ and ‘genuine anxiety’. Calls about potentially serious symptoms, severe symptoms or life-threatening conditions were regarded as appropriate.

Smith et al. 122

There is some evidence that health-care professionals judge some age groups as more vulnerable and that they may deem them as ‘special cases’ who either are more deserving of care or have more reason to make ‘inappropriate’ use of services, for example the elderly,78,122,123 children78,117,124 or patients who are ‘genuinely’ frightened or anxious about the threat of serious illness. 124 In an ethnographic study of ED use in the UK, professionals were more likely to perceive elderly patients and patients who articulated that they did not want to ‘bother’ services as legitimate attenders. 123 Users were also considered more favourably if they had an understanding of the other services available to them, when to approach them, and by which professional they should be seen. In the UK, a study of UCC staff identified a set of motives perceived as ‘more legitimate’ for making contact. 114 These included having acute health needs, access problems (those who ‘honestly’ cannot get an appointment with their GP) and anxiety, and also people not registered in the system (e.g. tourists, students). Conversely, less legitimate motives included convenience (‘claiming’ they cannot get an appointment) and those seen to be ‘playing’ the system.

Service user definitions of urgent care

Some research has examined service users’ help-seeking and decision-making in relation to both urgent and emergency care. From this we can extract some of the ways in which service users define and make sense of urgent care. Although perceived physical symptoms are important, other social and emotional cues, as well as service users’ beliefs and knowledge about health services, also influence the way in which service users define what is ‘urgent’.

Symptoms

Studies about symptom interpretation in relation to out-of-hours or urgent care services have highlighted that symptoms that are perceived to be prolonged, severe,41,67,79,125–128 unusual, worsening or causing pain trigger the help-seeking process. 7,120,129–135 Users’ perceptions of urgency were associated with an awareness of potentially fatal illnesses or conditions (such as meningitis and appendicitis) that were likely to compel contact with emergency or urgent care. 129,131,136 People may also call urgent care services when they are unsure about the severity of their condition67,133 and/or to rule out or prevent serious disease. 137 This suggests that urgent care services provide a preventative/risk management function. There are similar reasons for using the ED for non-urgent illness, whereby attenders typically perceive their problem as urgent or severe,138–150 recent and sudden in onset,151 and/or requiring emergency treatment or ‘immediate’ or ‘rapid’ attention. 102,110,140,152 One study found that half of all parents were unsure about the seriousness of their child’s symptoms98 and this prompted ED attendance. Pain is also a common key driver of ED attendance. 70,140,141,146,151 In a study of ED attendances for people with asthma, Becker et al. 153 sum up the dilemma that a patient faces when having to navigate definitions of urgency:

Individuals with asthma are caught in a bind by extremely narrow definitions of appropriate symptoms in the delivery of health care in the emergency department: they must not delay too long or seek help too soon.

Becker et al. 153

Studies that have compared health professionals’ perceptions of urgency of illness with those of patients attending an ED154–156 suggest that there are substantial differences. Kalidindi et al. 155 reported that most parents believed that their child’s illness required urgent care (defined as care needed within 24 hours), whereas physicians considered 30% of the ED visits as non-urgent (care that could safely wait until the next day). A New Zealand study has attempted to define a ‘health emergency’, a definition based on physiological factors. 154 This study used patient and ED ratings of urgency, and compared these with published literature and policy guidelines. The study reported congruence between the patients’ and health professionals’ perceptions of what constitutes a health emergency and suggested that a combined definition of these two perspectives would be reflected as:

A health emergency is a sudden or unexpected threat to physical health or wellbeing which requires an urgent assessment and alleviation of symptoms.

Morgans and Burgess154

However, Morgans and Burgess154 acknowledged that such physiological assessment is difficult because a health emergency is complex, changeable and not dichotomous.

One UK qualitative study that attempted to define urgent care from the user perspective67 found that participants were unable to identify a lay definition for ‘urgent care’, suggesting that ‘urgent’ could indicate the need for emergency services only or the need to be seen quickly by ‘non-emergency services’. Participants were more consistent in defining the term ‘emergency’ as an illness and/or injury requiring ‘blue flashing lights’ and an ‘ambulance’.

The literature about service users highlights the role of anxiety, feeling helpless or being unsure of what to do in relation to assessing the seriousness of symptoms when contacting urgent care41,67,120,129,132,135,157 or emergency care. 78,150,158,159 Users make contact with services for medical care, but also to seek reassurance from a health service to alleviate anxiety about symptoms. 78,135,146,151,158,160 Anxiety and reassurance appear to be viewed as a legitimate use of services from the patient perspective70,135,161 and sometimes from the professional perspective. 7,116,117,122 There is commonly a positive correlation between anxiety and level of pain151 or between anxiety and participants’ perceptions of the seriousness of the problem. 41

Ambiguous organisational arrangements

Whereas Dale et al. 162 reported that patients choosing between attendance at a MIU or an ED made an appropriate choice, other studies of urgent care have found that people often do not know where to go or who to contact, particularly at night,67,127,162 or when it is appropriate to contact a particular service. 133 A UK study of out-of-hours services found that some service users were unsure if their condition was ‘serious enough’ to warrant contact and some believed that the service was ‘only for seriously ill people’. 133

A study of an English NHS WIC reported that participants were uncertain of the centre’s purpose and its role within the health-care system. 163 A further study based on a survey suggested that most people did not make an ‘active choice’ to attend a WIC. More than half of attenders were unaware of the type of facility that they were attending, and believed that they had been treated in an ED. 164 Cook et al. 165 reported similar confusion about NHS Direct, with some participants believing that it was a WIC or that it provided an out-of-hours service.

Furthermore, service users do not always know what to expect on attending urgent care facilities. Chapple et al. 166 found that half of all interviewees expected to find a doctor at the WIC, with some suggesting that ‘nurses only deal with minor problems’. NHS staff beliefs about service users’ perceptions is that they do not distinguish between the ED, WIC or UCC, and were unaware of the UCC service and what it provides. 114 This confusion suggests that service users may not have a clear conceptualisation about what urgent care services are and what they can offer. Conceptualisations of urgent care are likely to be influenced by familiarity with, or previous experiences of, using these services. 127,128,167